-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Rif1 Supports the Function of the CST Complex in Yeast Telomere Capping

Telomere integrity in budding yeast depends on the CST (Cdc13-Stn1-Ten1) and shelterin-like (Rap1-Rif1-Rif2) complexes, which are thought to act independently from each other. Here we show that a specific functional interaction indeed exists among components of the two complexes. In particular, unlike RIF2 deletion, the lack of Rif1 is lethal for stn1ΔC cells and causes a dramatic reduction in viability of cdc13-1 and cdc13-5 mutants. This synthetic interaction between Rif1 and the CST complex occurs independently of rif1Δ-induced alterations in telomere length. Both cdc13-1 rif1Δ and cdc13-5 rif1Δ cells display very high amounts of telomeric single-stranded DNA and DNA damage checkpoint activation, indicating that severe defects in telomere integrity cause their loss of viability. In agreement with this hypothesis, both DNA damage checkpoint activation and lethality in cdc13 rif1Δ cells are partially counteracted by the lack of the Exo1 nuclease, which is involved in telomeric single-stranded DNA generation. The functional interaction between Rif1 and the CST complex is specific, because RIF1 deletion does not enhance checkpoint activation in case of CST-independent telomere capping deficiencies, such as those caused by the absence of Yku or telomerase. Thus, these data highlight a novel role for Rif1 in assisting the essential telomere protection function of the CST complex.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002024

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002024Summary

Telomere integrity in budding yeast depends on the CST (Cdc13-Stn1-Ten1) and shelterin-like (Rap1-Rif1-Rif2) complexes, which are thought to act independently from each other. Here we show that a specific functional interaction indeed exists among components of the two complexes. In particular, unlike RIF2 deletion, the lack of Rif1 is lethal for stn1ΔC cells and causes a dramatic reduction in viability of cdc13-1 and cdc13-5 mutants. This synthetic interaction between Rif1 and the CST complex occurs independently of rif1Δ-induced alterations in telomere length. Both cdc13-1 rif1Δ and cdc13-5 rif1Δ cells display very high amounts of telomeric single-stranded DNA and DNA damage checkpoint activation, indicating that severe defects in telomere integrity cause their loss of viability. In agreement with this hypothesis, both DNA damage checkpoint activation and lethality in cdc13 rif1Δ cells are partially counteracted by the lack of the Exo1 nuclease, which is involved in telomeric single-stranded DNA generation. The functional interaction between Rif1 and the CST complex is specific, because RIF1 deletion does not enhance checkpoint activation in case of CST-independent telomere capping deficiencies, such as those caused by the absence of Yku or telomerase. Thus, these data highlight a novel role for Rif1 in assisting the essential telomere protection function of the CST complex.

Introduction

Telomeres, the specialized nucleoprotein complexes at the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes, are essential for genome integrity. They protects chromosome ends from fusions, DNA degradation and recognition as DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) that would otherwise lead to chromosome instability and cell death (reviewed in [1]). Telomeric DNA in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, as well as in nearly all other eukaryotes examined to date, comprise short TG-rich repeated sequences ending in a short single-stranded 3′ overhang (G tail) that corresponds to the strand bearing the TG-rich repeats. The addition of telomeric repeats depends on the action of telomerase, a specialized reverse transcriptase that extends the TG-rich strand of chromosome ends. Recruitment/activation of this enzyme requires the Cdc13 protein that binds to the telomeric TG-rich single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) [2]–[6]. The direct interaction between Cdc13 and the Est1 regulatory subunit of telomerase is essential for telomerase recruitment, and it is disrupted by the cdc13-2 mutation that leads to gradual telomere erosion and accompanying senescence [2], [4], [7].

The average length of S. cerevisiae telomeric 3′ overhangs is 12–14 nucleotides, although it can increase to ∼50 nucleotides during the late S/G2 phase of the cell cycle [8]–[10]. While single-stranded telomeric G-tails can arise after removal of the last RNA primer during lagging-strand replication, the blunt ends of the leading-strand telomere must be converted into 3′ overhangs by resection of the 5′ strand. This 5′ to 3′ nucleolytic degradation involves several proteins, such as the MRX complex, the nucleases Exo1 and Dna2 and the helicase Sgs1 [10], [11]. Cyclin-dependent kinase activity (Cdk1 in S. cerevisiae) is also required for generation of the extended single-stranded overhangs in late S phase [12], [13]. As Cdk1 activity is low in G1, telomere resection can occur only during S/G2 [8], coinciding with the time frame in which G-tails are lengthened and can serve to recruit telomerase.

Keeping the G tail in check is crucial to ensure telomere stability, and studies in budding yeast have shown that Cdc13 prevents inappropriate generation of ssDNA at telomeric ends [2], [14], [15]. This essential capping function depends on Cdc13 interaction with the Stn1 and Ten1 proteins to form the so-called CST (Cdc13-Stn1-Ten1) complex. This complex binds to telomeric ssDNA repeats and exhibits structural similarities with the heterotrimeric ssDNA binding complex Replication protein A (RPA) [16], suggesting that CST is a telomere-specific version of RPA. Loss of Cdc13 function through either the cdc13-1 temperature sensitive allele or the cdc13-td conditional degron allele results in telomere C-strand degradation, leading to activation of the DNA damage checkpoint [13], [14], [17], [18]. Similarly, temperature sensitive mutations in either STN1 or TEN1 genes cause telomere degradation and checkpoint-mediated cell cycle arrest [19]–[21]. Interestingly, Stn1 interacts with Pol12 [22], a subunit of the DNA polymerase α (polα)-primase complex with putative regulatory functions, while Cdc13 interacts with the polα catalytic subunit of the same complex [7], suggesting that CST function might be tightly coupled to the priming of telomeric C strand synthesis. In any case, it is so far unknown whether the excess of telomeric ssDNA in cst mutants arises because the CST complex prevents the access of nuclease/helicase activities to telomeric ends and/or because it promotes polα-primase-dependent C strand synthesis.

In addition to the capping function, a role for the CST complex in repressing telomerase activity has been unveiled by the identification of cdc13, stn1 and ten1 alleles with increased telomere length [2], [21], [23], [24]. The repressing effect of Cdc13 appears to operate through an interaction between this protein and the C-terminal domain of Stn1 [25], [26], which has been proposed to negatively regulate telomerase by competing with Est1 for binding to Cdc13 [4], [24].

A second pathway involved in maintaining the identity of S. cerevisiae telomeres relies on a complex formed by the Rap1, Rif1 and Rif2 proteins. Although only Rap1 is the only shelterin subunit conserved in budding yeast, the Rap1-Rif1-Rif2 complex functionally recapitulates the shelterin complex acting at mammalian telomeres (reviewed in [27]). Rap1 is known to recruit its interacting partners Rif1 and Rif2 to telomeric double-stranded DNA via its C-terminal domain [28]–[30]. This complex negatively regulates telomere length, as the lack of either Rif1 or Rif2 causes telomere lengthening, which is dramatically increased when both proteins are absent [30]. The finding that telomere length in rif1Δ rif2Δ double mutant is similar to that observed in RAP1 C-terminus deletion mutants [30] suggests that Rap1-dependent telomerase inhibition is predominantly mediated by the Rif proteins. However, Rif proteins have been shown to regulate telomere length even when the Rap1 C-terminus is absent [31], suggesting that they can be brought to telomeres independently of Rap1.

In addition to negatively regulate telomere length, Rap1 and Rif2 inhibit both nucleolytic processing and non homologous end joining (NHEJ) at telomeres [32]–[34]. Telomeric ssDNA generation in both rif2Δ and rap1ΔC cells requires the MRX complex [33], and the finding that MRX association at telomeres is enhanced in rif2Δ and rap1ΔC cells [33], [35] suggests that Rap1 and Rif2 likely prevent MRX action by inhibiting MRX recruitment onto telomeric ends. Interestingly, the checkpoint response is not elicited after inactivation of Rap1 or Rif2, suggesting that either the accumulated telomeric ssDNA is insufficient for triggering checkpoint activation or this ssDNA is still covered by Cdc13, which can inhibit the association of the checkpoint kinase Mec1 to telomeres [36]. Notably, Rif1 is not involved in preventing telomeric fusions by NHEJ [32] and its lack causes only a slight increase in ssDNA generation at a de novo telomere [33]. These findings, together with the observation that Rif1 prevents telomerase action independently of Rif2, indicate that Rif1 and Rif2 play different functions at telomeres.

As both CST and the shelterin-like complex contribute to telomere protection, we asked whether and how these two capping complexes are functionally connected. We found that the viability of cells with defective CST complex requires Rif1, but not Rif2. In fact, RIF1 deletion increases the temperature sensitivity of cdc13-1 cells and impairs viability of cdc13-5 cells at any temperature. Furthermore, the rif1Δ and stn1ΔC alleles are synthetically lethal. By contrast, the lack of Rif2 has no effects in the presence of the same cdc13 and stn1 alleles. We also show that cdc13-1 rif1Δ and cdc13-5 rif1Δ cells accumulate telomeric ssDNA that causes hyperactivation of the DNA damage checkpoint, indicating that loss of Rif1 exacerbates telomere integrity defects in cdc13 mutants. By contrast, deletion of RIF1 does not enhance either cell lethality or checkpoint activation in yku70Δ or est2Δ telomere capping mutants. Thus, Rif1 is required for cell viability specifically when CST activity is reduced, highlighting a functional link between Rif1 and CST.

Results

Rif1, but not Rif2, is required for cell viability when Cdc13 or Stn1 activities are reduced

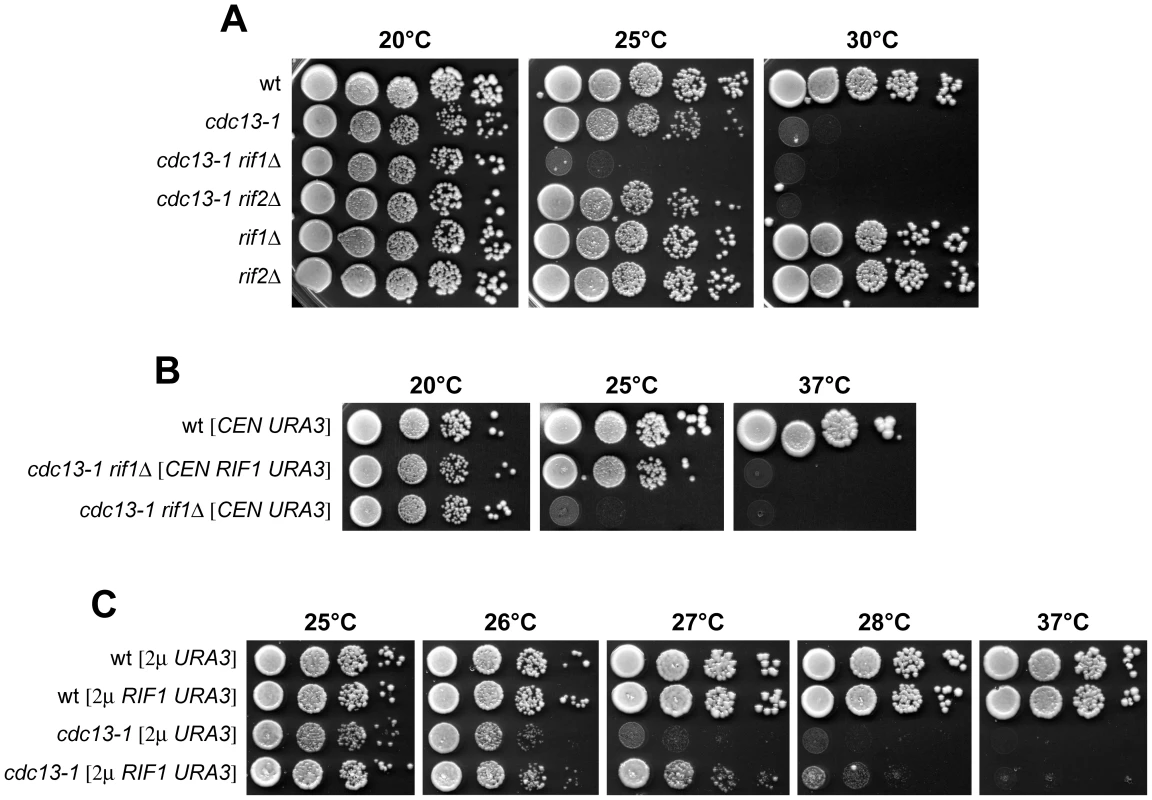

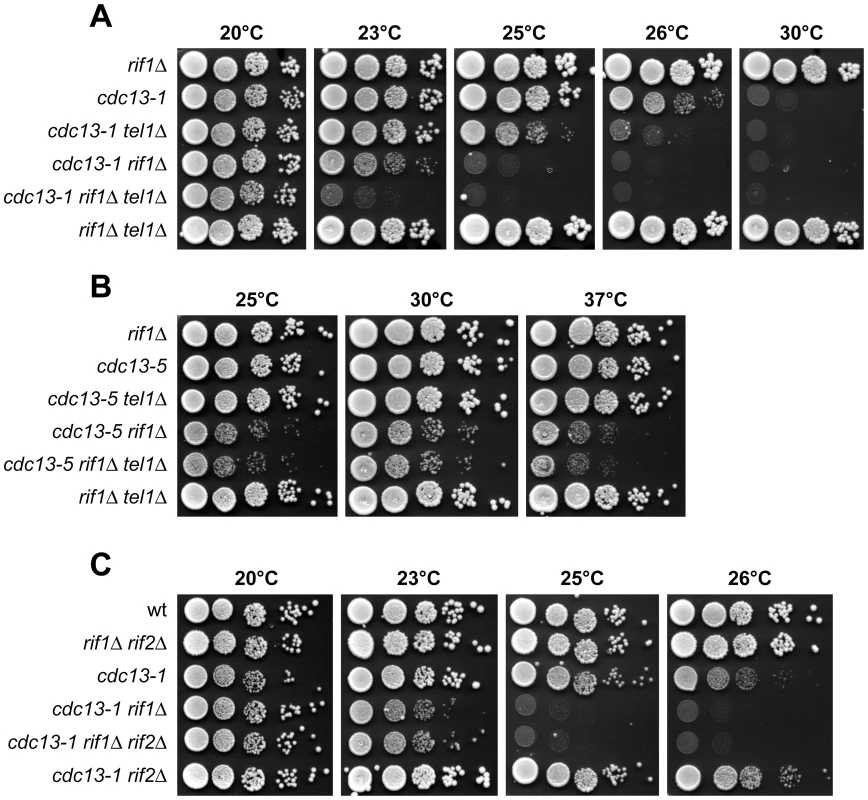

Yeast cells harbouring the cdc13-1 temperature-sensitive allele of the gene encoding the essential telomeric protein Cdc13 are viable at permissive temperature (20–25°C), but die at restrictive temperature (26–37°C), likely due to accumulation of ssDNA at telomeres caused by the loss of Cdc13 capping functions [14]. As also the shelterin-like complex contributes to the maintenance of telomere integrity, we investigated its possible functional connections with Cdc13 by disabling either Rif1 or Rif2 in cdc13-1 cells. Deletion of RIF2 did not affect cdc13-1 cell viability in YEPD medium at any tested temperature (Figure 1A). By contrast, cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells showed a maximum permissive temperature for growth of 20°C and were unable to grow at 25°C, where cdc13-1 single mutant cells could grow at almost wild type rate (Figure 1A). The enhanced temperature-sensitivity of cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells was due to the lack of RIF1, because the presence of wild type RIF1 on a centromeric plasmid allowed cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells to grow at 25°C (Figure 1B). The synthetic effect of the cdc13-1 rif1Δ combination was not uncovered during a previous genome wide search for gene deletions enhancing the temperature-sensitivity of cdc13-1 cells [37], likely because that screening was done at 20°C, a temperature at which cdc13-1 rif1Δ double mutants do not show severe growth defects (Figure 1A). Our data above indicate that Rif1, but not Rif2, is required to support cell viability when Cdc13 protective function is partially compromised.

Fig. 1. Synthetic effects between the rif1Δ and cdc13-1 mutations.

(A) Strains with the indicated genotypes were grown overnight in YEPD at 20°C. Serial 10-fold dilutions were spotted onto YEPD plates and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 2–4 days. (B–C) Strains containing the indicated plasmids were grown overnight at 20°C in synthetic liquid medium lacking uracil. Serial 10-fold dilutions were spotted onto plates lacking uracil that were incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3–5 days. If the lack of Rif1 in cdc13-1 cells increased the temperature-sensitivity by exacerbating the telomere end protection defects of these cells, Rif1 overexpression might suppress the temperature sensitivity caused by the cdc13-1 allele. Indeed, high copy number plasmids carrying wild type RIF1, which had no effect on wild type cell viability, improved the ability of cdc13-1 cells to form colonies on synthetic selective medium at the semi-permissive temperature of 26–27°C (Figure 1C).

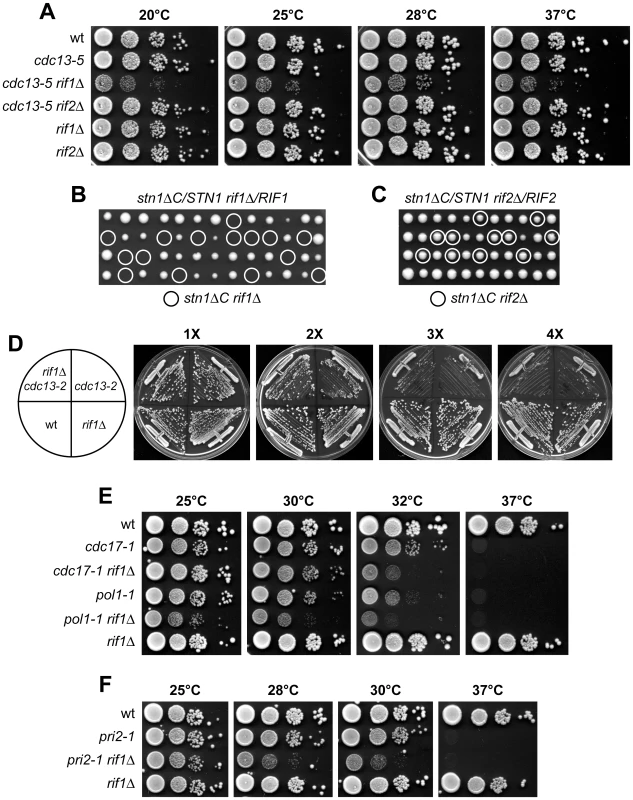

The function of Cdc13 in telomere protection is mediated by its direct interactions with Stn1 and Ten1, leading to formation of the CST complex (reviewed in [38]). In addition to the capping function, the CST complex is implicated in repression of telomerase action [2], [21], [23], [24]. This CST-dependent negative regulation of telomerase can be separated from CST capping function, as yeast cells either carrying the cdc13-5 allele or lacking the Stn1 C-terminus (residues 282–494) (stn1ΔC) display extensive telomere elongation but no or minimal growth defects [24]–[26]. We evaluated the specificity of the genetic interaction between rif1Δ and cdc13-1 by analysing the consequences of deleting RIF1 and RIF2 in cdc13-5 or stn1ΔC cells. Deletion of RIF1 turned out to reduce cell viability of cdc13-5 mutant cells at any temperatures, while deletion of RIF2 did not (Figure 2A). Furthermore, meiotic tetrad dissection of stn1ΔC/STN1 rif1Δ/RIF1 diploid cells did not allow the recovery of viable stn1ΔC rif1Δ double mutant spores (Figure 2B), indicating that rif1Δ and stn1ΔC were synthetic lethal. By contrast, viable rif2Δ stn1ΔC spores were found with the expected frequency after tetrad dissection of stn1ΔC/STN1 rif2Δ/RIF2 diploid cells (Figure 2C). The observed synthetic phenotypes suggest that both stn1ΔC and cdc13-5 cells have capping deficiencies and that the lack of Rif1 enhances their protection defects. Consistent with this hypothesis, cdc13-5 and stn1ΔC mutants were shown to accumulate telomeric ssDNA, although the amount of this ssDNA was not enough to invoke a DNA damage response [24], [25]. We conclude that Rif1, but not Rif2, is required to support cell viability when a partial inactivation of CST capping function occurs.

Fig. 2. RIF1 deletion affects viability of both cdc13-5 and stn1ΔC cells.

(A) Strains with the indicated genotypes were grown overnight in YEPD at 25°C. Serial 10-fold dilutions were spotted onto YEPD plates and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 2–4 days. (B–C) Viability of spores derived from diploids heterozygous for the indicated mutations. Spores with the indicated double mutant genotypes are circled. (D) Meiotic tetrads from a CDC13/cdc13-2 RIF1/rif1Δ diploid strain were dissected on YEPD plates. After ∼25 generations on the dissection plate, spore clones from 20 tetrads were subjected to genotyping and concomitantly to four successive streak-outs (1X to 4X), corresponding to ∼25, ∼50, ∼75 and ∼100 generations of growth, respectively. All tetratype tetrads behaved as the one shown in this panel. (E–F) Cell cultures were grown overnight in YEPD at 25°C. Serial 10-fold dilutions were spotted onto YEPD plates that were incubated at the indicated temperatures for 2–3 days. A Cdc13 specific function that is not shared by the other subunits of the CST complex is its requirement for recruitment/activation of telomerase at chromosome ends [2]–[6]. Cdc13-mediated telomerase recruitment is disrupted by the cdc13-2 mutation, which leads to progressive telomere shortening and senescence phenotype [4]. We therefore asked whether RIF1 deletion influences viability and/or senescence progression of cdc13-2 cells. Viable cdc13-2 rif1Δ spores were recovered after tetrad dissection of cdc13-2/CDC13 rif1Δ/RIF1 diploid cells (data not shown), indicating that the lack of Rif1 does not affect the overall viability of cdc13-2 cells. When spores from the dissection plate were streaked on YEPD plates for 4 successive times, the decline in growth of cdc13-2 and cdc13-2 rif1Δ spores occurred with similar kinetics (Figure 2D), indicating that RIF1 deletion did not accelerate the senescence phenotype of cdc13-2 cells specifically defective in telomerase recruitment. Taken together, these genetic interactions indicate that Rif1, but not Rif2, has a role in assisting the essential function of the CST complex in telomere protection.

The CST complex functionally and physically interacts with the polα-primase complex [7], [21], [22], [25], which is essential for telomeric C-strand synthesis during telomere elongation. Thus, we analyzed the genetic interactions between rif1Δ and temperature sensitive alleles affecting DNA primase (pri2-1) [39] or polα (cdc17-1 and pol1-1) [40], [41]. Both cdc17-1 rif1Δ and pol1-1 rif1Δ cells were viable, but their temperature-sensitivity was greatly enhanced compared to cdc17-1 and pol1-1 single mutants (Figure 2E). Similarly, the maximal permissive temperature of the pri2-1 rif1Δ double mutant was reduced relative to that of pri2-1 single mutant cells (Figure 2F). Moreover both pol1-1 rif1Δ and pri2-1 rif1Δ cells showed growth defects even at the permissive temperature of 25°C (Figure 2E and 2F). Thus, Rif1, like CST, functionally interacts with the polα-primase complex.

The lack of Rif1 enhances the DNA damage checkpoint response in cdc13 mutant cells

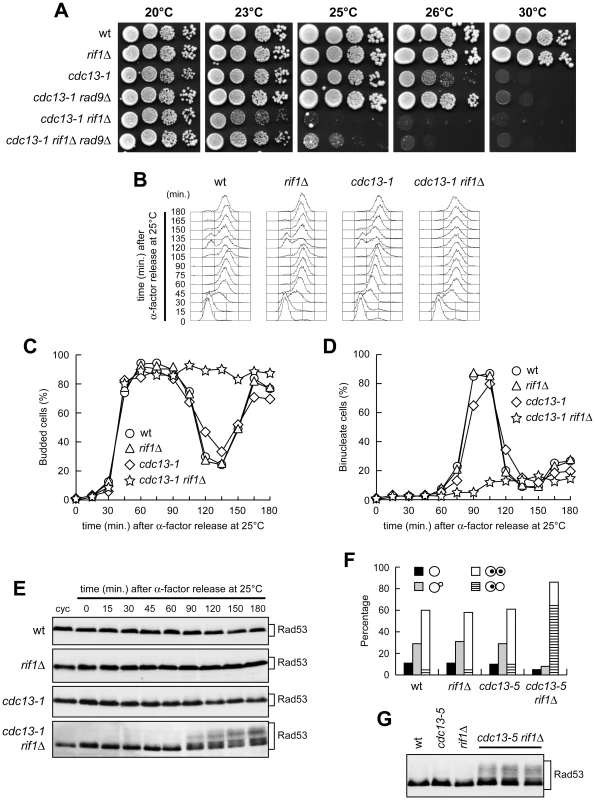

The synthetic effects of combining rif1Δ with cdc13 and stn1 mutations suggest that Rif1 might normally assist the Cdc13 and Stn1 proteins in carrying out their essential telomere protection functions. It is known that cdc13-1 cells undergo checkpoint-dependent metaphase arrest when incubated at the restrictive temperature [14]. Failure to turn on the checkpoint allows cdc13-1 cells to form colonies at 28°C [42], [43], indicating that checkpoint activation can partially account for the loss of viability of cdc13-1 cells. We then asked whether the enhanced temperature sensitivity of cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells compared to cdc13-1 cells might be due to upregulation of the DNA damage checkpoint response. Deletion of the checkpoint gene RAD9, which partially suppressed the temperature sensitivity of cdc13-1 mutant cells, slightly improved the ability of cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells to grow at 23–25°C (Figure 3A), indicating that the synthetic interaction between Rif1 and Cdc13 can be partially alleviated by checkpoint inactivation. Furthermore, when wild type, rif1Δ, cdc13-1 and cdc13-1 rif1Δ cell cultures were arrested in G1 with α-factor at 20°C (permissive temperature) and then released from G1 arrest at 25°C (non-permissive temperature for cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells), they all replicated DNA and budded with similar kinetics after release (Figure 3B and 3C). However, most cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells then arrested in metaphase as large budded cells with a single nucleus, while wild type, cdc13-1 and rif1Δ cells divided nuclei after 75–90 minutes (Figure 3D).

Fig. 3. Metaphase arrest and checkpoint activation in cdc13 rif1Δ cells.

(A) Strains with the indicated genotypes were grown overnight in YEPD at 20°C. Serial 10-fold dilutions were spotted onto YEPD plates and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 2–4 days. (B–E) Cell cultures exponentially growing at 20°C in YEPD were arrested in G1 with α-factor and then released from G1 arrest in YEPD at 25°C (time zero). Samples were taken at the indicated times after release from α-factor for FACS analysis of DNA content (B), for determining the kinetics of bud emergence (C) and nuclear division (D), and for western blot analysis of Rad53 using anti-Rad53 antibodies (E). cyc, cycling cells. (F–G) Cell cultures were grown exponentially in YEPD at 25°C. (F) The frequency of cells with no, small or large buds was determined by analyzing a total of 200 cells for each strain. The percentage of large budded cells with one or two nuclei was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy. (G) Rad53 in cell cultures exponentially growing at 25°C was visualized as in panel E. Three independent cdc13-5 rif1Δ strains were analyzed. To assess whether the cell cycle arrest of cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells was due to DNA damage checkpoint activation, we examined the Rad53 checkpoint kinase, whose phosphorylation is necessary for checkpoint activation and can be detected as changes in Rad53 electrophoretic mobility. Rad53 was phosphorylated in cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells that were released from G1 arrest at 25°C, whereas no Rad53 phosphorylation was seen in any of the other similarly treated cell cultures (Figure 3E).

RIF1 deletion caused a checkpoint-mediated G2/M cell cycle arrest also in cdc13-5 cells. In fact, exponentially growing cdc13-5 rif1Δ cell cultures at 25°C contained a higher percentage of large budded cells with a single nucleus than rif1Δ or cdc13-5 cell cultures under the same conditions (Figure 3F). Furthermore, Rad53 phosphorylation was detected in these cdc13-5 rif1Δ cells, but not in the rif1Δ and cdc13-5 cell cultures (Figure 3G). Thus, the lack of Rif1 results in DNA damage checkpoint activation in both cdc13-1 and cdc13-5 cells under conditions that do not activate the checkpoint when Rif1 is present.

The synthetic interaction between Rif1 and CST is independent of rif1Δ-induced telomere overelongation

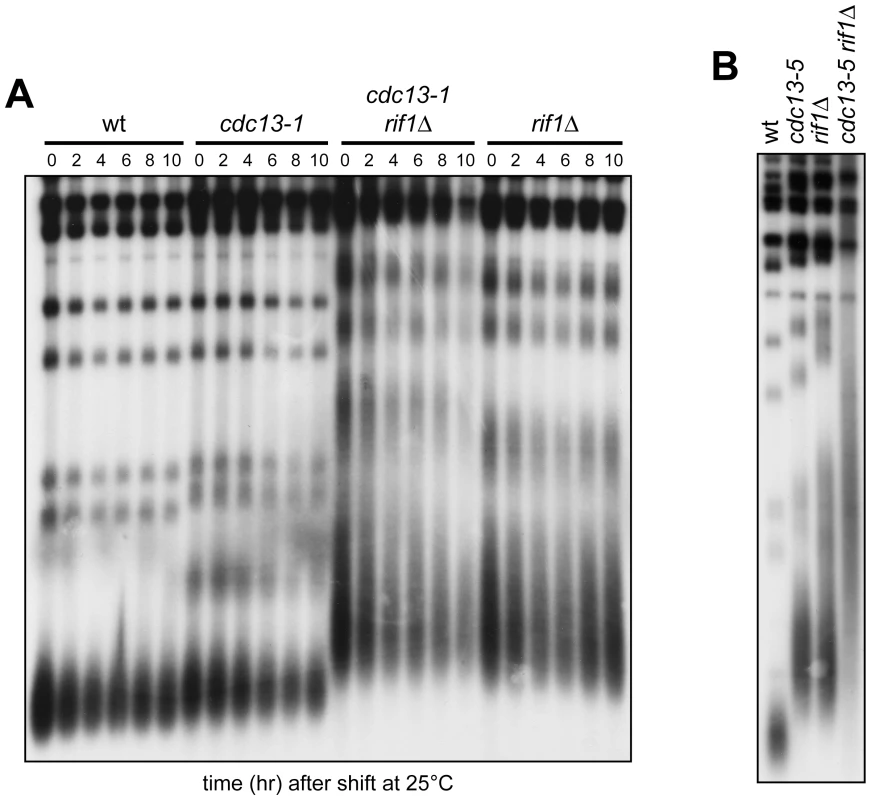

The lack of Rif1 is known to cause telomere overelongation [29]. Thus, we examined telomere length in cdc13-1 rif1Δ double mutant cells. The length of duplex telomeric DNA was examined after transferring at 25°C cell cultures exponentially growing at 20°C, followed by Southern blot analysis with a TG-rich probe of XhoI-digested genomic DNA prepared at different times after shift at 25°C (Figure 4A). As expected [29], rif1Δ mutant cells had longer telomeres than wild type and cdc13-1 cells (Figure 4A). Telomeres in cdc13-1 rif1Δ double mutant cells either at 20°C or after incubation at 25°C were longer than those of wild type and cdc13-1 cells, but undistinguishable from those of rif1Δ cells (Figure 4A). Not only RIF1 deletion, but also the cdc13-5 mutation is known to cause telomere overelongation [24] (Figure 4B). Interestingly, when telomere length was analyzed in cdc13-5 rif1Δ double mutant cells grown at 25°C, telomeres were longer in cdc13-5 rif1Δ double mutant cells than in cdc13-5 and rif1Δ single mutants (Figure 4B), indicating that the cdc13-5 mutation exacerbates the telomere overelongation defect caused by the lack of Rif1.

Fig. 4. Native telomere length in cdc13 rif1Δ cells.

(A) Cells with the indicated genotypes exponentially growing in YEPD at 20°C were shifted at 25°C at time 0. Cells were collected at the indicated time points after shift and XhoI-cut genomic DNA was subjected to Southern blot analysis using a radiolabeled poly(GT) telomere-specific probe. (B) XhoI-cut genomic DNA extracted from cells with the indicated genotypes exponentially growing at 25°C was subjected to Southern blot analysis as in panel A. The finding that telomeres in cdc13-1 rif1Δ double mutant cells at 25°C were longer than those of cdc13-1 cells, but undistinguishable from those of cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells grown at 20°C (Figure 4A) suggests that the growth defects of cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells at 25°C are not due to rif1Δ-induced telomere overelongation. Telomere lengthening in rif1Δ mutant cells is telomerase-dependent [44] and requires the action of the checkpoint kinase Tel1 that facilitates telomerase recruitment [45], [46]. To provide additional evidences that loss of viability in cdc13 rif1Δ mutants occurs independently of rif1Δ-induced alterations in telomere length, we asked whether RIF1 deletion was still deleterious in cdc13-1, cdc13-5 and stn1ΔC cells in a context where telomeres cannot be elongated due to the lack of Tel1 [45]. We found that TEL1 deletion did not alleviate the growth defects of cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells (Figure 5A). Rather, cdc13-1 tel1Δ and cdc13-1 rif1Δ tel1Δ cells showed an enhanced temperature sensitivity compared to cdc13-1 and cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells, respectively, presumably due to the combined effects of loss of a telomere elongation mechanism and inability to protect telomeres from shortening activities. Furthermore, the growth defects of cdc13-5 rif1Δ double mutant cells were similar to those of cdc13-5 rif1Δ tel1Δ triple mutant cells (Figure 5B). Finally, viable stn1ΔC rif1Δ tel1Δ mutant spores could not be recovered after meiotic tetrad dissection of stn1ΔC/STN1 rif1Δ/RIF1 tel1Δ/TEL1 diploid cells (data not shown), indicating that stn1ΔC and rif1Δ were synthetic lethal even in the absence of Tel1.

Fig. 5. Effect of deleting TEL1 or RIF2 on growth of cdc13 rif1Δ cells.

Cells with the indicated genotypes were grown overnight in YEPD at 20°C (A and C) or 25°C (B). Serial 10-fold dilutions were spotted onto YEPD plates that were then incubated at the indicated temperatures for 2–4 days. As telomere lengthening is dramatically increased when both Rif1 and Rif2 are absent [30], we also investigated whether the absence of Rif2 exacerbates cdc13-1 rif1Δ growth defects. As shown in Figure 5C, cdc13-1 rif1Δ rif2Δ cells formed colonies at the maximum temperature of 20°C and behaved similarly to cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells. We therefore conclude that the synthetic interaction between rif1Δ and cdc13 alleles is not due to rif1Δ-induced alterations in telomere length, but it is a direct consequence of Rif1 loss.

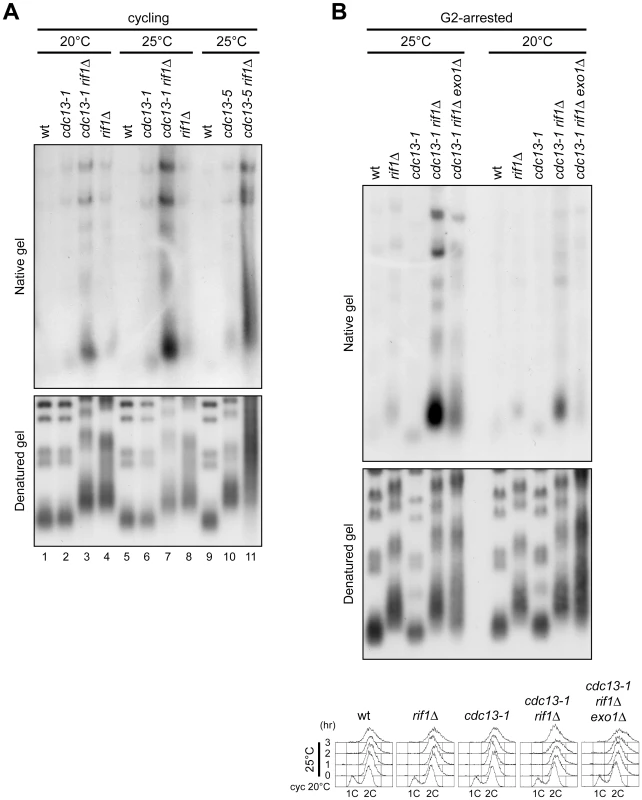

The lack of Rif1 causes generation of telomeric ssDNA in cdc13 cells

It is known that cdc13-1 cells at 37°C accumulate telomeric ssDNA that triggers checkpoint-mediated cell cycle arrest [14]. Thus, we investigated whether cdc13-1 rif1Δ and cdc13-5 rif1Δ cells contained aberrant levels of single-stranded TG sequences at their telomeres that could be responsible for loss of viability in cdc13-1 rif1Δ and cdc13-5 rif1Δ cells at 25°C. The integrity of chromosome ends was analyzed by an in-gel hybridization procedure [9], probing for the presence of single-stranded TG sequences. Both cdc13-1 and rif1Δ single mutants either grown at 20°C (Figure 6A, lanes 2 and 4) or incubated at 25°C for 3 hours (Figure 6A, lanes 6 and 8) showed only a very slight increase in single-stranded TG sequences compared to wild type (Figure 6A, lanes 1 and 5). By contrast, cdc13-1 rif1Δ double mutant cells contained higher amounts of telomeric ssDNA than cdc13-1 and rif1Δ cells already at 20°C (Figure 6A, lane 3) and the amount of this ssDNA increased dramatically when cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells were incubated at 25°C for 3 hours (Figure 6A, lane 7). A similar telomere deprotection defect was observed also for cdc13-5 rif1Δ cells grown at 25°C (Figure 6A, lane 11), which displayed an increased amount of telomeric ssDNA compared to similarly treated wild type and cdc13-5 cells (Figure 6A, lanes 9 and 10).

Fig. 6. RIF1 deletion enhances ssDNA formation at native telomeres of cdc13 cells.

(A) Wild type and otherwise isogenic cdc13-1, cdc13-1 rif1Δ and rif1Δ cell cultures exponentially growing at 20°C (lanes 1–4) were incubated at 25°C for 3 hours (lanes 5–8). Wild type and otherwise isogenic cdc13-5 and cdc13-5 rif1Δ cell cultures were grown exponentially at 25°C (lanes 9–11). Genomic DNA was digested with XhoI and single-stranded telomere overhangs were visualized by in-gel hybridization (native gel) using an end-labelled C-rich oligonucleotide. The same DNA samples were separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, denatured and hybridized with the end-labeled C-rich oligonucleotide for loading and telomere length control (denatured gel). (B) Cell cultures were arrested in G2 with nocodazole at 20°C (right) and then transferred at 25°C in the presence of nocodazole for 3 hours (left), followed by analysis of single-stranded telomere overhangs (top) as in panel A, and FACS analysis of DNA content (bottom). Because the length of single-stranded G overhangs increases during S phase [8], the strong telomeric ssDNA signals observed in cdc13-1 rif1Δ cell cultures at 25°C (Figure 6A) might be due to an enrichment of S/G2 cells. We ruled out this possibility by monitoring the levels of single-stranded TG sequences in cdc13-1 rif1Δ cell cultures that were arrested in G2 with nocodazole at 20°C and then transferred to 25°C in the presence of nocodazole for 3 hours (Figure 6B). Similarly to what we observed in exponentially growing cell cultures, G2-arrested cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells at 20°C displayed increased amounts of ssDNA compared to each single mutant under the same conditions, and incubation at 25°C led to further increase of this ssDNA (Figure 6B). Taken together, these findings indicate that the lack of Rif1 causes a severe defect in telomere protection when Cdc13 activity is partially compromised.

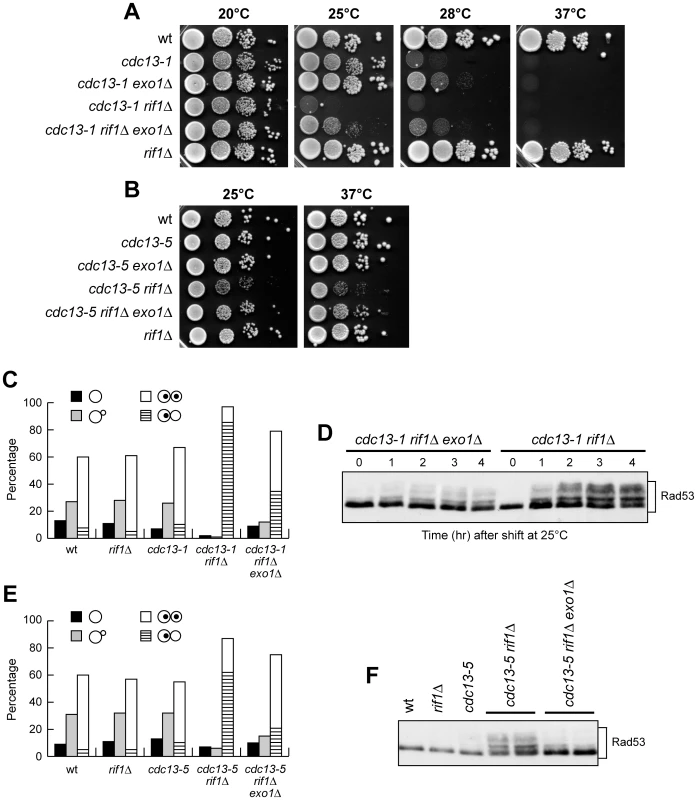

The lack of Exo1 counteracts DNA damage checkpoint activation and telomeric ssDNA accumulation in cdc13 rif1Δ cells

If telomeric ssDNA accumulation contributes to checkpoint activation in cdc13-1 rif1Δ and cdc13-5 rif1Δ cells, then mutations reducing ssDNA generation should alleviate the arrest and relieve the lethality caused by the lack of Rif1 in cdc13-1 and cdc13-5 background. Because the Exo1 nuclease contributes to generate telomeric ssDNA in cdc13-1 cells [47], we examined the effect of deleting EXO1 in cdc13 rif1Δ cells. When G2-arrested cell cultures at 20°C were transferred to 25°C for 3 hours, cdc13-1 rif1Δ exo1Δ triple mutant cells contained significantly lower amounts of telomeric ssDNA than cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells (Figure 6B). A similar behaviour of the triple mutant was detectable even when G2-arrested cultures where kept at 20°C, although the quantity of telomeric ssDNA accumulated by cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells at this temperature was lower than at 25°C (Figure 6B). Furthermore, EXO1 deletion partially suppressed both the temperature-sensitivity of cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells (Figure 7A) and the loss of viability of cdc13-5 rif1Δ cells (Figure 7B), further supporting the hypothesis that reduced viability in these strains was due to defects in telomere protection.

Fig. 7. EXO1 deletion partially suppresses cell lethality and checkpoint activation in cdc13 rif1Δ cells.

(A–B) Serial 10-fold dilutions of cell cultures grown overnight in YEPD at 20°C (A) and 25°C (B) were spotted onto YEPD plates and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 2–4 days. (C–D) Cell cultures exponentially growing in YEPD at 20°C were shifted to 25°C. (C) The frequencies of cells with no, small or large buds and of large budded cells with one or two nuclei were determined after 3 hours at 25°C as in Figure 3F, by analyzing a total of 200 cells for each strain. (D) Western blot analysis with anti-Rad53 antibodies of total protein extracts prepared at the indicated times. This experiment was repeated three times with similar results. (E–F) Cultures of cells with the indicated genotypes, exponentially growing at 25°C in YEPD, were analyzed as in panels C (E) and D (F), respectively. Two independent cdc13-5 rif1Δ and cdc13-5 rif1Δ exo1Δ strains were analyzed for Rad53 phosphorylation. Exo1-mediated suppression of the cdc13 rif1Δ growth defects correlated with alleviation of checkpoint-mediated cell cycle arrest. In fact, when cell cultures exponentially growing at 20°C were incubated at 25°C for 3 hours, the amount of both metaphase-arrested cells and Rad53 phosphorylation was reproducibly lower in cdc13-1 rif1Δ exo1Δ cells than in cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells (Figure 7C and 7D). Similar results were obtained also with cdc13-5 rif1Δ exo1Δ cells growing at 25°C, which accumulated less metaphase-arrested cells and phosphorylated Rad53 than similarly treated cdc13-5 rif1Δ cells (Figure 7E and 7F). Thus, both cell lethality and checkpoint-mediated cell cycle arrest in cdc13 rif1Δ cells appear to be caused, at least partially, by Exo1-dependent telomere DNA degradation.

The lack of Rif1 does not enhance the checkpoint response to CST-independent capping deficiencies or to an irreparable DSB

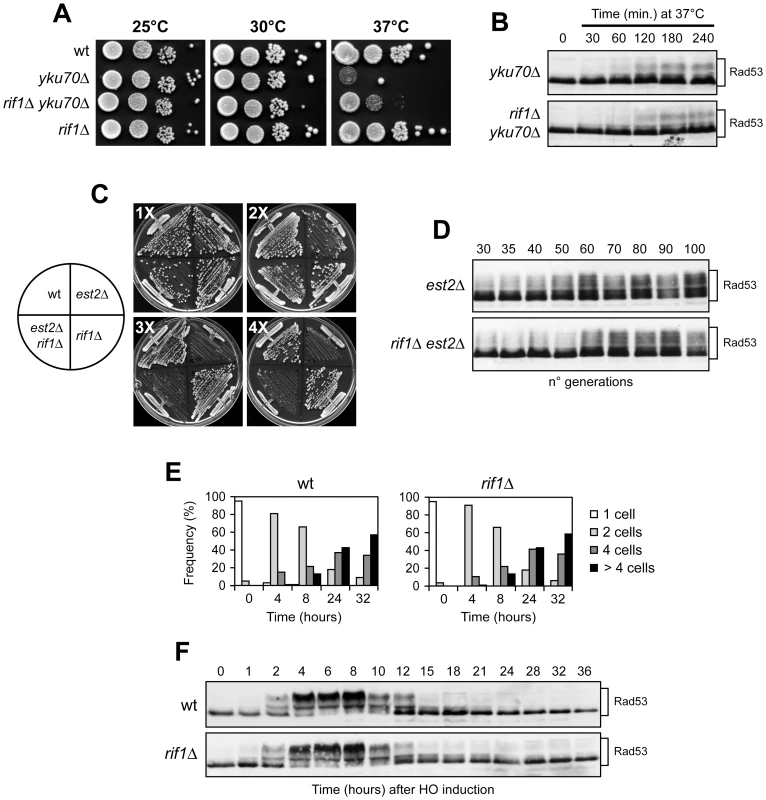

The lack of Rif1 might increase the lethality of cells with reduced CST activity just because it causes a telomere deprotection defect that exacerbates the inherent telomere capping defects of cdc13 or stn1 mutants. If this hypothesis were correct, RIF1 deletion should affect viability also of other non-CST mutants defective in end protection. Alternatively, Rif1-CST functional interaction might be specific, thus reflecting a functional connection between Rif1 and CST. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we analyzed the effects of deleting RIF1 in Yku70 lacking cells, which display Exo1-dependent accumulation of telomeric ssDNA, as well as checkpoint-mediated cell cycle arrest at elevated temperatures (37°C) [47], [51]. Loss of Yku in est2Δ cells, which lack the telomerase catalytic subunit, leads to synthetic lethality, presumably due to the combined effects of telomere shortening and capping defects [48]–[50], [52]. As expected [53], yku70Δ cells were viable at 25°C and 30°C, but they were unable to form colonies at 37°C (Figure 8A). Similarly, yku70Δ rif1Δ double mutant cells grew well at 25°C and 30°C (Figure 8A) and did not show Rad53 phosphorylation when grown at 25°C (Figure 8B, time 0). Furthermore, similar amounts of phosphorylated Rad53 were detected in both yku70Δ and yku70Δ rif1Δ cell cultures that were kept at 37°C for 4 hours (Figure 8B), indicating that loss of Rif1 does not enhance the telomere protection defects already present in yku70Δ cells. Consistent with a previous observation [54], RIF1 deletion partially suppressed the temperature sensitivity (Figure 8A) and the telomere length defect (data not shown) caused by the lack of Yku70, suggesting that the elongated state of the telomeres could be the reason why yku70Δ rif1Δ cells can proliferate at 37°C.

Fig. 8. RIF1 deletion does not influence the checkpoint response to CST-independent telomere capping deficiencies or to an irreparable DSB.

(A) Cell cultures with the indicated genotypes were grown overnight in YEPD at 25°C. Serial 10-fold dilutions were spotted onto YEPD plates and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 2–3 days. (B) Cell cultures exponentially growing in YEPD at 25°C were shifted to 37°C at time 0. Rad53 was visualized at the indicated time points as in Figure 3E. (C) Meiotic tetrads from a EST2/est2Δ RIF1/rif1Δ diploid strain were dissected on YEPD plates. After ∼25 generations, spore clones from 20 tetrads were subjected to genotyping and to four successive streak-outs (1X to 4X), corresponding to ∼25, ∼50, ∼75 and ∼100 generations of growth, respectively. All tetratype tetrads behaved as the one shown in this panel. (D) After ∼25 generations of growth on the dissection plates, est2Δ and est2Δ rif1Δ spore clones were propagated in liquid YEPD medium. At the indicated generations, protein extracts were subjected to western blot analysis with anti-Rad53 antibodies. (E–F) Checkpoint response to an irreparable DSB. (E) YEP+raf G1-arrested cell cultures of wild type JKM139 and its isogenic rif1Δ derivative strain were spotted on galactose-containing plates that were incubated at 28°C (time zero). At the indicated time points, 200 cells for each strain were analyzed to determine the frequency of single cells and of cells forming microcolonies of 2, 4 or more than 4 cells. (F) Galactose was added at time zero to cell cultures of the strains in panel E exponentially growing in YEP+raf. Protein extracts were subjected to western blot analysis with anti-Rad53 antibodies. Checkpoint activation can also be induced during telomere erosion caused by insufficient telomerase activity [55], [56]. Thus, we asked whether RIF1 deletion accelerated senescence progression and/or upregulated checkpoint activation in cells lacking the telomerase catalytic subunit Est2. Meiotic tetrads were dissected from a diploid strain heterozygous for the est2Δ and rif1Δ alleles, which are recessive and therefore do not affect telomere length in the diploid. After 2 days of incubation at 25°C (approximately 25 generations), spore clones from the dissection plate were both streaked for 4 successive times (Figure 8C) and propagated in YEPD liquid medium to prepare protein extracts for Rad53 phosphorylation analysis at different time points (Figure 8D). Similar to what was previously observed [44], RIF1 deletion did not accelerate senescence progression in est2Δ cells, as est2Δ rif1Δ clones showed a decline in growth similar to that of est2Δ clones (Figure 8C). Furthermore, est2Δ and est2Δ rif1Δ cell cultures showed similar patterns of Rad53 phosphorylation with increasing number of generations (Figure 8D). Thus, the lack of Rif1 does not enhance either DNA damage checkpoint activation or senescence progression during telomere erosion caused by the lack of telomerase.

Finally, because the telomerase machinery is known to be recruited to an unrepaired DSB [57], we ruled out the possibility of a general role for Rif1 in inhibiting checkpoint activation by examining activation/deactivation of the checkpoint induced by an unrepaired DSB. To this end, we used JKM139 derivative strains, where a single DSB can be generated at the MAT locus by expressing the site-specific HO endonuclease gene from a galactose-inducible promoter [58]. This DSB cannot be repaired by homologous recombination, because the homologous donor sequences HML or HMR are deleted. As shown in Figure 8E, when G1-arrested cell cultures were spotted on galactose containing plates, both wild type and rif1Δ JKM139 derivative cells overrode the checkpoint-mediated cell cycle arrest within 24–32 hours, producing microcolonies with 4 or more cells. Moreover, when galactose was added to exponentially growing cell cultures of the same strains, Rad53 phosphorylation became detectable as electrophoretic mobility shift in both wild type and rif1Δ cell cultures about 2 hours after HO induction, and it decreased in both cell cultures after 12–15 hours (Figure 8F), when most cells resumed cell cycle progression (data not shown). Thus, Rif1 does not affect the checkpoint response to an irreparable DSB. Altogether these data indicate that Rif1 supports specifically CST functions in telomere protection.

Discussion

Both shelterin and CST complexes are present in a wide range of unicellular and multicellular organisms, where they protect the integrity of chromosomes ends (reviewed in [38]). Thus, the understanding of their structural and functional connections is an important issue in telomere regulation. We have approached this topic by analysing the consequences of disabling the shelterin-like S. cerevisiae proteins Rif1 or Rif2 in different hypomorphic mutants defective in CST components. We provide evidence that Rif1, but not Rif2, is essential for cell viability when the CST complex is partially compromised. In fact, RIF1 deletion exacerbates the temperature sensitivity of cdc13-1 mutant cells that are primarily defective in Cdc13 telomere capping functions. Furthermore, cells carrying the cdc13-5 or the stn1ΔC mutation, neither of which causes per se DNA damage checkpoint activation and growth defects [24], [26], grow very poorly or are unable to form colonies, respectively, when combined with the rif1Δ allele. By contrast, RIF1 deletion does not affect either viability or senescence progression of cdc13-2 cells, which are specifically defective in telomerase recruitment. This Cdc13 function is not shared by the other CST subunits, suggesting that Rif1 is specifically required to support the essential capping functions of the CST complex.

Cell lethality caused by the absence of Rif1 in both cdc13-1 and cdc13-5 cells appears to be due to severe telomere integrity defects. In fact, telomeres in both cdc13-1 rif1Δ and cdc13-5 rif1Δ double mutant cells display an excess of ssDNA that leads to DNA damage checkpoint activation. Deleting the nuclease EXO1 gene partially restores viability of cdc13-1 rif1Δ and cdc13-5 rif1Δ cells and reduces the level of telomeric ssDNA in cdc13-1 rif1Δ cells, indicating that cell lethality in cdc13 rif1Δ cells is partially due to Exo1-dependent telomere DNA degradation and subsequent activation of the DNA damage checkpoint.

Although Rif1 and Rif2 interact both with the C-terminus of Rap1 and with each other [29], [30], our finding that only Rif1 is required for cell viability when Cdc13 or Stn1 capping activities are reduced indicates that Rif1 has a unique role in supporting CST capping function that is not shared by Rif2. Earlier studies are consistent with the idea that Rif1 and Rif2 regulate telomere metabolism by different mechanisms [30], [31], [35]. Furthermore, while the content of Rif2 is lower at shortened than at wild type telomeres, the level of Rif1 is similar at both, suggesting that these two proteins are distributed differently along a telomere [59]. Finally, inhibition of telomeric fusions requires Rif2, but not Rif1 [32].

Noteworthy, although RIF1 deletion is known to cause telomere overelongation [29], the synthetic interaction between Rif1 and CST occurs independently of rif1Δ-induced alterations in telomere length. In fact, the lack of Tel1, which counteracts rif1Δ-induced telomere overelongation [45], does not alleviate the growth defects of cdc13 rif1Δ cells. Furthermore, deletion of RIF2, which enhances telomere elongation induced by the lack of Rif1 [30], does not exacerbate the synthetic phenotypes of cdc13 rif1Δ double mutant cells. Thus, loss of viability in cdc13 rif1Δ cells is not due to telomere overelongation caused by RIF1 deletion, but it is a direct consequence of Rif1 loss.

By analyzing the effects of combining RIF1 deletion with mutations that cause telomere deprotection without affecting CST functions, we found that the functional interaction between Rif1 and the CST complex is highly specific. In fact, the lack of Rif1 does not enhance the DNA damage checkpoint response in telomerase lacking cells, which are known to experience gradual telomere erosion leading to activation of the DNA damage checkpoint [55], [56]. Furthermore, RIF1 deletion does not upregulate DNA damage checkpoint activation in yku70Δ cells, which display Exo1-dependent accumulation of ssDNA and checkpoint-mediated cell cycle arrest at 37°C [47]–[51]. This is consistent with previous observations that comparable signals for G strand overhangs can be detected on telomeres derived from yku70Δ and yku70Δ rif1Δ cells [54], indicating that RIF1 deletion does not exacerbate the end protection defect due to the absence of Yku. By contrast, the lack of Rif1 partially suppresses both temperature-sensitivity and telomere shortening in yku70Δ cells (Figure 8A) [54], possibly because the restored telomere length helps to compensate for yku70Δ capping defects. Notably, although RIF1 deletion leads to telomere overelongation in cdc13-1 and cdc13-5 mutants, this elongated telomere state does not help to increase viability in cdc13-1 rif1Δ and cdc13-5 rif1Δ cells.

The simplest interpretation of the specific genetic interactions we found between Rif1 and CST is that a functional connection exists between Rif1 and the CST complex, such that Rif1 plays a previously unanticipated role in assisting the CST complex in carrying out its essential telomere protection function. Indeed, this functional interaction is unexpected in light of Rif1 and CST localization along a telomere. In fact, while CST is present at the very ends of chromosomes, Rif1 is thought to be distributed centromere proximal on the duplex telomeric DNA [59]. However, as yeast telomeres have been proposed to fold back onto the subtelomeric regions to form a ∼3-kb region of core heterochromatin [60], [61], this higher-order structure could place Rif1 and CST in close proximity, thus explaining their functional interaction.

The function of Rif1 in sustaining CST activity cannot be simply attributable to the Rif1-mediated suppression of ssDNA formation at telomeres, as rif1Δ cells show only a very slight increase in ssDNA at both native (Figure 6) and HO-induced telomeres [33] compared to wild type. Furthermore, although deletion of Rif2 leads to increased amounts of telomeric ssDNA [33], cdc13-1 rif2Δ, cdc13-5 rif2Δ and stn1ΔC rif2Δ double mutants are viable and do not display growth defects. Finally, other mutants defective in telomere capping or telomere elongation (yku70Δ and est2Δ) are perfectly viable in the absence of Rif1.

One possibility is that Rif1 physically interacts, directly or indirectly, with the CST complex. Indeed, human Stn1 was found to copurify with the shelterin subunit TPP1 [62], suggesting the existence of CST-shelterin complexes in mammals. Unfortunately, we were so far unable to coimmunoprecipitate Rif1 with Cdc13 or Stn1, and further analyses will be required to determine whether Rif1 and the CST complex undergo stable or transient association during the cell cycle.

Indeed, not only 5′-3′ resection, but also incomplete synthesis of Okazaki fragments is expected to increase the size of the G tail during telomere replication. The yeast CST complex genetically and physically interacts with the polα-primase complex [7], [22], [25] and the human CST-like complex increases polα-primase processivity [63], [64]. Furthermore, the lack of CST function in G1 and throughout most of S phase does not lead to an increase of telomeric ssDNA [13], suggesting that the essential function of CST is restricted to telomere replication in late S phase. Altogether, these observations suggest that CST may control overhang length not only by blocking the access of nucleases, but also by activating polα-primase-dependent C-strand synthesis that can compensate G tail lengthening activities. Based on the finding that Rif1 regulates telomerase action and functionally interacts with the polα-primase complex (Figure 2), it is tempting to propose that Rif1 favours CST ability to replenish the exposed ssDNA at telomeres through activation/recruitment of polα-primase, thus coupling telomerase-dependent elongation to the conventional DNA replication process.

The recent discoveries that human TPP1 interacts physically with Stn1 [62] and that CST-like complexes exist also in S. pombe, plants and mammals [65]–[68] raise the question of whether functional connections between the two capping complexes exist also in other organisms. As telomere protection is critical for preserving genetic stability and counteracting cancer development, to address this question will be an important future challenge.

Materials and Methods

Strains and plasmids

Strain genotypes are listed in supplementary Table S1. Unless otherwise stated, the yeast strains used during this study were derivatives of W303 (ho MATa ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3 can1-100). All gene disruptions were carried out by PCR-based methods. The cdc13-1 mutant was kindly provided by D. Lydall (University of Newcastle, UK). The cdc13-2 mutant was kindly provided by V. Lundblad (Salk Institute, La Jolla, USA). The stn1ΔC and cdc13-5 alleles carried a stop codon following amino acids 282 and 694 respectively [24], [25], and were generated by PCR-based methods. Wild type and cdc13-1 strains carrying either the 2 µ vector or 2 µ RIF1 plasmid were constructed by transforming wild type and cdc13-1 strains with plasmids YEplac195 (2 µ URA3) and pML435 (2 µ RIF1 URA3), respectively. The strains used for monitoring checkpoint activation in response to an irreparable DSB were derivatives of strain JKM139 (MATa ho hmlΔ hmrΔ ade1 lys5 leu2-3,112 trp1::hisG ura3-52 ade3::GAL-HO), kindly provided by J. Haber (Brandeis University, Waltham, MA, USA) [58]. To induce HO expression in JKM139 and its derivative strains, cells were grown in raffinose-containing yeast extract peptone (YEP) and then transferred to raffinose - and galactose-containing YEP.

Cells were grown in YEP medium (1% yeast extract, 2% bactopeptone, 50 mg/l adenine) supplemented with 2% glucose (YEPD) or 2% raffinose (YEP+raf) or 2% raffinose and 2% galactose (YEP+raf+gal). Synthetic complete medium lacking uracil supplemented with 2% glucose was used to maintain the selective pressure for the 2 µ URA3 plasmids.

Southern blot analysis of telomeres and in-gel hybridization

Genomic DNA was digested with XhoI. The resulting DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose gel and transferred to a GeneScreen nylon membrane (New England Nuclear, Boston), followed by hybridization with a 32P-labelled poly(GT) probe and exposure to X-ray sensitive films. Standard hybridization conditions were used. Visualization of single-stranded overhangs at native telomeres was done by in-gel hybridization [9], using a single-stranded 22-mer CA oligonuleotide probe. The same DNA samples were separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, denatured and hybridized with an end-labeled C-rich oligonucleotide for loading control.

Other techniques

For western blot analysis, protein extracts were prepared by TCA precipitation. Rad53 was detected using anti-Rad53 polyclonal antibodies kindly provided by J. Diffley (Clare Hall, London, UK). Secondary antibodies were purchased from Amersham and proteins were visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescence system according to the manufacturer. Flow cytometric DNA analysis was determined on a Becton-Dickinson FACScan on cells stained with propidium iodide.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. LongheseMP 2008 DNA damage response at functional and dysfunctional telomeres. Genes Dev 22 125 140

2. NugentCIHughesTRLueNFLundbladV 1996 Cdc13p: a single-strand telomeric DNA-binding protein with a dual role in yeast telomere maintenance. Science 274 249 252

3. EvansSKLundbladV 1999 Est1 and Cdc13 as comediators of telomerase access. Science 286 117 120

4. PennockEBuckleyKLundbladV 2001 Cdc13 delivers separate complexes to the telomere for end protection and replication. Cell 104 387 396

5. BianchiANegriniSShoreD 2004 Delivery of yeast telomerase to a DNA break depends on the recruitment functions of Cdc13 and Est1. Mol Cell 16 139 146

6. ChanABouléJBZakianVA 2008 Two pathways recruit telomerase to Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomeres. PLoS Genet 4 e1000236 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000236

7. QiHZakianVA 2000 The Saccharomyces telomere-binding protein Cdc13p interacts with both the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase α and the telomerase-associated Est1 protein. Genes Dev 14 1777 1788

8. WellingerRJWolfAJZakianVA 1993 Saccharomyces telomeres acquire single-strand TG1-3 tails late in S phase. Cell 72 51 60

9. DionneIWellingerRJ 1996 Cell cycle-regulated generation of single-stranded G-rich DNA in the absence of telomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93 13902 13907

10. LarrivéeMLeBelCWellingerRJ 2004 The generation of proper constitutive G-tails on yeast telomeres is dependent on the MRX complex. Genes Dev 18 1391 1396

11. BonettiDMartinaMClericiMLucchiniGLongheseMP 2009 Multiple pathways regulate 3′ overhang generation at S. cerevisiae telomeres. Mol Cell 35 70 81

12. FrankCJHydeMGreiderCW 2006 Regulation of telomere elongation by the cyclin-dependent kinase CDK1. Mol Cell 24 423 432

13. VodenicharovMDWellingerRJ 2006 DNA degradation at unprotected telomeres in yeast is regulated by the CDK1 (Cdc28/Clb) cell-cycle kinase. Mol Cell 24 127 137

14. GarvikBCarsonMHartwellL 1995 Single-stranded DNA arising at telomeres in cdc13 mutants may constitute a specific signal for the RAD9 checkpoint. Mol Cell Biol 15 6128 6138

15. LinJJZakianVA 1996 The Saccharomyces Cdc13 protein is a single-strand TG1-3 telomeric DNA-binding protein in vitro that affects telomere behavior in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93 13760 13765

16. GaoHCervantesRBMandellEKOteroJHLundbladV 2007 RPA-like proteins mediate yeast telomere function. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14 208 214

17. WeinertTAKiserGLHartwellLH 1994 Mitotic checkpoint genes in budding yeast and the dependence of mitosis on DNA replication and repair. Genes Dev 8 652 665

18. LydallDWeinertT 1995 Yeast checkpoint genes in DNA damage processing: implications for repair and arrest. Science 270 1488 1491

19. GrandinNReedSICharbonneauM 1997 Stn1, a new Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein, is implicated in telomere size regulation in association with Cdc13. Genes Dev 11 512 527

20. GrandinNDamonCCharbonneauM 2001 Ten1 functions in telomere end protection and length regulation in association with Stn1 and Cdc13. EMBO J 20 1173 1183

21. XuLPetreacaRCGasparyanHJVuSNugentCI 2009 TEN1 is essential for CDC13-mediated telomere capping. Genetics 183 793 810

22. GrossiSPuglisiADmitrievPVLopesMShoreD 2004 Pol12, the B subunit of DNA polymerase α, functions in both telomere capping and length regulation. Genes Dev 18 992 1006

23. GrandinNDamonCCharbonneauM 2000 Cdc13 cooperates with the yeast Ku proteins and Stn1 to regulate telomerase recruitment. Mol Cell Biol 20 8397 8408

24. ChandraAHughesTRNugentCILundbladV 2001 Cdc13 both positively and negatively regulates telomere replication. Genes Dev 15 404 414

25. PetreacaRCChiuHCNugentCI 2007 The role of Stn1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomere capping can be separated from its interaction with Cdc13p. Genetics 177 1459 1474

26. PuglisiABianchiALemmensLDamayPShoreD 2008 Distinct roles for yeast Stn1 in telomere capping and telomerase inhibition. EMBO J 27 2328 2339

27. PalmWde LangeT 2008 How shelterin protects mammalian telomeres. Annu Rev Genet 42 301 334

28. ConradMNWrightJHWolfAJZakianVA 1990 RAP1 protein interacts with yeast telomeres in vivo: overproduction alters telomere structure and decreases chromosome stability. Cell 63 739 750

29. HardyCFSusselLShoreD 1992 A RAP1-interacting protein involved in transcriptional silencing and telomere length regulation. Genes Dev 6 801 814

30. WottonDShoreD 1997 A novel Rap1p-interacting factor, Rif2p, cooperates with Rif1p to regulate telomere length in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev 11 748 760

31. LevyDLBlackburnEH 2004 Counting of Rif1p and Rif2p on Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomeres regulates telomere length. Mol Cell Biol 24 10857 10867

32. MarcandSPardoBGratiasACahunSCallebautI 2008 Multiple pathways inhibit NHEJ at telomeres. Genes Dev 22 1153 1158

33. BonettiDClericiMAnbalaganSMartinaMLucchiniG 2010 Shelterin-like proteins and Yku inhibit nucleolytic processing of Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomeres. PLoS Genet 6 e1000966 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000966

34. VodenicharovMDLaterreurNWellingerRJ 2010 Telomere capping in non-dividing yeast cells requires Yku and Rap1. EMBO J 29 3007 3019

35. HiranoYFukunagaKSugimotoK 2009 Rif1 and Rif2 inhibit localization of Tel1 to DNA ends. Mol Cell 33 312 322

36. HiranoYSugimotoK 2007 Cdc13 telomere capping decreases Mec1 association but does not affect Tel1 association with DNA ends. Mol Biol Cell 18 2026 2036

37. AddinallSGDowneyMYuMZubkoMKDewarJ 2008 A genome wide suppressor and enhancer analysis of cdc13-1 reveals varied cellular processes influencing telomere capping in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 180 2251 2266

38. Giraud-PanisMJTeixeiraMTGéliVGilsonE 2010 CST meets shelterin to keep telomeres in check. Mol Cell 39 665 676

39. LongheseMPJovineLPlevaniPLucchiniG 1993 Conditional mutations in the yeast DNA primase genes affect different aspects of DNA metabolism and interactions in the DNA polymerase α-primase complex. Genetics 133 183 91

40. CarsonMJHartwellL 1985 CDC17: an essential gene that prevents telomere elongation in yeast. Cell 42 249 257

41. PizzagalliAValsasniniPPlevaniPLucchiniG 1988 DNA polymerase I gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: nucleotide sequence, mapping of a temperature-sensitive mutation, and protein homology with other DNA polymerases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85 3772 3776

42. WeinertTAHartwellLH 1993 Cell cycle arrest of cdc mutants and specificity of the RAD9 checkpoint. Genetics 134 63 80

43. ZubkoMKGuillardSLydallD 2004 Exo1 and Rad24 differentially regulate generation of ssDNA at telomeres of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cdc13-1 mutants. Genetics 168 103 115

44. TengSCChangJMcCowanBZakianVA 2000 Telomerase-independent lengthening of yeast telomeres occurs by an abrupt Rad50p-dependent, Rif-inhibited recombinational process. Mol Cell 6 947 952

45. ChanSWChangJPrescottJBlackburnEH 2001 Altering telomere structure allows telomerase to act in yeast lacking ATM kinases. Curr Biol 11 1240 1250

46. GoudsouzianLKTuzonCTZakianVA 2006 S. cerevisiae Tel1p and Mre11p are required for normal levels of Est1p and Est2p telomere association. Mol Cell 24 603 610

47. MaringeleLLydallD 2002 EXO1-dependent single-stranded DNA at telomeres activates subsets of DNA damage and spindle checkpoint pathways in budding yeast yku70Δ mutants. Genes Dev 16 1919 1933

48. GravelSLarrivéeMLabrecquePWellingerRJ 1998 Yeast Ku as a regulator of chromosomal DNA end structure. Science 280 741 744

49. PolotniankaRMLiJLustigAJ 1998 The yeast Ku heterodimer is essential for protection of the telomere against nucleolytic and recombinational activities. Curr Biol 8 831 834

50. BertuchAALundbladV 2004 EXO1 contributes to telomere maintenance in both telomerase-proficient and telomerase-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 166 1651 1659

51. BarnesGRioD 1997 DNA double-strand-break sensitivity, DNA replication, and cell cycle arrest phenotypes of Ku-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94 867 872

52. NugentCIBoscoGRossLOEvansSKSalingerAP 1998 Telomere maintenance is dependent on activities required for end repair of double-strand breaks. Curr Biol 8 657 660

53. FeldmannHWinnackerEL 1993 A putative homologue of the human autoantigen Ku from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 268 12895 12900

54. GravelSWellingerRJ 2002 Maintenance of double-stranded telomeric repeats as the critical determinant for cell viability in yeast cells lacking Ku. Mol Cell Biol 22 2182 2193

55. LundbladVSzostakJW 1989 A mutant with a defect in telomere elongation leads to senescence in yeast. Cell 57 633 643

56. IJpmaASGreiderCW 2003 Short telomeres induce a DNA damage response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 14 987 1001

57. OzaPJaspersenSLMieleADekkerJPetersonCL 2009 Mechanisms that regulate localization of a DNA double-strand break to the nuclear periphery. Genes Dev 23 912 927

58. LeeSEMooreJKHolmesAUmezuKKolodnerRD 1998 Saccharomyces Ku70, Mre11/Rad50 and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell 94 399 409

59. McGeeJSPhillipsJAChanASabourinMPaeschkeK 2010 Reduced Rif2 and lack of Mec1 target short telomeres for elongation rather than double-strand break repair. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17 1438 1445

60. de BruinDZamanZLiberatoreRAPtashneM 2001 Telomere looping permits gene activation by a downstream UAS in yeast. Nature 409 109 113

61. Strahl-BolsingerSHechtALuoKGrunsteinM 1997 SIR2 and SIR4 interactions differ in core and extended telomeric heterochromatin in yeast. Genes Dev 11 83 93

62. WanMQinJSongyangZLiuD 2009 OB fold-containing protein 1 (OBFC1), a human homolog of yeast Stn1, associates with TPP1 and is implicated in telomere length regulation. J Biol Chem 284 26725 26731

63. GoulianMHeardCJGrimmSL 1990 Purification and properties of an accessory protein for DNA polymerase α/primase. J Biol Chem 265 13221 13230

64. CasteelDEZhuangSZengYPerrinoFWBossGR 2009 A DNA polymerase α-primase cofactor with homology to replication protein A-32 regulates DNA replication in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 284 5807 5818

65. MartínVDuLLRozenzhakSRussellP 2007 Protection of telomeres by a conserved Stn1-Ten1 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104 14038 14043

66. SongXLeehyKWarringtonRTLambJCSurovtsevaYV 2008 STN1 protects chromosome ends in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105 19815 19820

67. SurovtsevaYVChurikovDBoltzKASongXLambJC 2009 Conserved telomere maintenance component 1 interacts with STN1 and maintains chromosome ends in higher eukaryotes. Mol Cell 36 207 218

68. MiyakeYNakamuraMNabetaniAShimamuraSTamuraM 2009 RPA-like mammalian Ctc1-Stn1-Ten1 complex binds to single-stranded DNA and protects telomeres independently of the Pot1 pathway. Mol Cell 36 193 206

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Genetic Regulation by NLA and MicroRNA827 for Maintaining Nitrate-Dependent Phosphate Homeostasis inČlánek c-di-GMP Turn-Over in Is Controlled by a Plethora of Diguanylate Cyclases and PhosphodiesterasesČlánek Viral Genome Segmentation Can Result from a Trade-Off between Genetic Content and Particle Stability

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 3- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- IVF a rakovina prsu – zvyšují hormony riziko vzniku rakoviny?

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Whole-Exome Re-Sequencing in a Family Quartet Identifies Mutations As the Cause of a Novel Skeletal Dysplasia

- Origin-Dependent Inverted-Repeat Amplification: A Replication-Based Model for Generating Palindromic Amplicons

- Testing for an Unusual Distribution of Rare Variants

- Limited dCTP Availability Accounts for Mitochondrial DNA Depletion in Mitochondrial Neurogastrointestinal Encephalomyopathy (MNGIE)

- FUS Transgenic Rats Develop the Phenotypes of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration

- Repeat Associated Non-ATG Translation Initiation: One DNA, Two Transcripts, Seven Reading Frames, Potentially Nine Toxic Entities!

- Initial Mutations Direct Alternative Pathways of Protein Evolution

- Dopamine Signalling in Mushroom Bodies Regulates Temperature-Preference Behaviour in

- Sensing of Replication Stress and Mec1 Activation Act through Two Independent Pathways Involving the 9-1-1 Complex and DNA Polymerase ε

- Genetic Regulation by NLA and MicroRNA827 for Maintaining Nitrate-Dependent Phosphate Homeostasis in

- Identification of a Novel Type of Spacer Element Required for Imprinting in Fission Yeast

- Chiasmata Promote Monopolar Attachment of Sister Chromatids and Their Co-Segregation toward the Proper Pole during Meiosis I

- Global Analysis of the Relationship between JIL-1 Kinase and Transcription

- H3K9me2/3 Binding of the MBT Domain Protein LIN-61 Is Essential for Vulva Development

- REVEILLE8 and PSEUDO-REPONSE REGULATOR5 Form a Negative Feedback Loop within the Arabidopsis Circadian Clock

- A Novel Unstable Duplication Upstream of Predisposes to a Breed-Defining Skin Phenotype and a Periodic Fever Syndrome in Chinese Shar-Pei Dogs

- Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 Controls the Embryo-to-Seedling Phase Transition

- A Role for Set1/MLL-Related Components in Epigenetic Regulation of the Germ Line

- Genome-Wide Association Analysis Identifies Variants Associated with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease That Have Distinct Effects on Metabolic Traits

- A Genome-Wide Association Study of Upper Aerodigestive Tract Cancers Conducted within the INHANCE Consortium

- Ancestral Mutation in Telomerase Causes Defects in Repeat Addition Processivity and Manifests As Familial Pulmonary Fibrosis

- Ultra-Deep Sequencing of Mouse Mitochondrial DNA: Mutational Patterns and Their Origins

- Phenotype Restricted Genome-Wide Association Study Using a Gene-Centric Approach Identifies Three Low-Risk Neuroblastoma Susceptibility Loci

- The Toll-Like Receptor Gene Family Is Integrated into Human DNA Damage and p53 Networks

- Polycomb Targets Seek Closest Neighbours

- Widespread Hypomethylation Occurs Early and Synergizes with Gene Amplification during Esophageal Carcinogenesis

- c-di-GMP Turn-Over in Is Controlled by a Plethora of Diguanylate Cyclases and Phosphodiesterases

- Estimating Divergence Time and Ancestral Effective Population Size of Bornean and Sumatran Orangutan Subspecies Using a Coalescent Hidden Markov Model

- Rif1 Supports the Function of the CST Complex in Yeast Telomere Capping

- A Tradeoff Drives the Evolution of Reduced Metal Resistance in Natural Populations of Yeast

- Quantifying the Underestimation of Relative Risks from Genome-Wide Association Studies

- Population-Based Resequencing of Experimentally Evolved Populations Reveals the Genetic Basis of Body Size Variation in

- Triplet Repeat–Derived siRNAs Enhance RNA–Mediated Toxicity in a Drosophila Model for Myotonic Dystrophy

- The FUN30 Chromatin Remodeler, Fft3, Protects Centromeric and Subtelomeric Domains from Euchromatin Formation

- Viral Genome Segmentation Can Result from a Trade-Off between Genetic Content and Particle Stability

- Environmental Sex Determination in the Branchiopod Crustacean : Deep Conservation of a Gene in the Sex-Determining Pathway

- Systematic Detection of Polygenic Regulatory Evolution

- The SUMO Isopeptidase Ulp2p Is Required to Prevent Recombination-Induced Chromosome Segregation Lethality following DNA Replication Stress

- Uncoupling Antisense-Mediated Silencing and DNA Methylation in the Imprinted Cluster

- Role of the Drosophila Non-Visual ß-Arrestin Kurtz in Hedgehog Signalling

- Differential Genetic Associations for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Based on Anti–dsDNA Autoantibody Production

- COMPASS-Like Complexes Mediate Histone H3 Lysine-4 Trimethylation to Control Floral Transition and Plant Development

- H3 Lysine 4 Is Acetylated at Active Gene Promoters and Is Regulated by H3 Lysine 4 Methylation

- Diverse Roles and Interactions of the SWI/SNF Chromatin Remodeling Complex Revealed Using Global Approaches

- A Bow-Tie Genetic Architecture for Morphogenesis Suggested by a Genome-Wide RNAi Screen in

- Roles of () in Oocyte Nuclear Architecture, Gametogenesis, Gonad Tumors, and Genome Stability in Zebrafish

- A Molecular Phylogeny of Living Primates

- Roles of the Espin Actin-Bundling Proteins in the Morphogenesis and Stabilization of Hair Cell Stereocilia Revealed in CBA/CaJ Congenic Jerker Mice

- A Cholinergic-Regulated Circuit Coordinates the Maintenance and Bi-Stable States of a Sensory-Motor Behavior during Male Copulation

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Whole-Exome Re-Sequencing in a Family Quartet Identifies Mutations As the Cause of a Novel Skeletal Dysplasia

- Origin-Dependent Inverted-Repeat Amplification: A Replication-Based Model for Generating Palindromic Amplicons

- FUS Transgenic Rats Develop the Phenotypes of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration

- Limited dCTP Availability Accounts for Mitochondrial DNA Depletion in Mitochondrial Neurogastrointestinal Encephalomyopathy (MNGIE)

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání