-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Origin-Dependent Inverted-Repeat Amplification: A Replication-Based Model for Generating Palindromic Amplicons

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002016

Category: Viewpoints

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002016Summary

article has not abstract

Introduction

Models proposed to explain the generation of palindromic (or quasipalindromic) structures during segmental amplification almost invariably begin with double-stranded DNA breaks that are repaired in different ways—for example, by end-to-end fusion at short inverted repeats, by non-allelic homologous recombination at low copy repeats, or by break-induced replication at regions of microhomology. However, the specific class of amplicons that consists of interstitial inverted triplications has no completely satisfactory explanation. By examining the molecular structure of a specific amplicon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, we derived a model that does not require an initiating double-stranded break but rather invokes an underappreciated potential error in replication to explain the generation of an initial hairpin-capped linear intermediate. The model furthermore can explain the final structure and the pathway for forming this and other types of amplicons in both yeast and humans. Because the model requires the presence of both an origin of replication and short, closely spaced, flanking inverted repeats, we call this model Origin-Dependent Inverted-Repeat Amplification (ODIRA).

Background

Exposure to environmental stress often selects for cells that have amplified genes involved in the amelioration of that stress. Sometimes the connection between the gene amplification and stress makes intuitive sense, such as the amplification of the gene for dihydrofolate reductase when yeast or mammalian cells are treated with methotrexate [1], [2]; in other cases, the link is less obvious [3]. To explain the mechanisms involved in the localized amplification of specific genomic loci, models have been proposed based on the DNA structures of the end products of amplification [4]–[6]. Many of the current models begin with a double strand DNA (dsDNA) break and implicate DNA fusions (either homologous or non-homologous), Break-Induced Replication (BIR), Microhomology/Microsatellite-Induced Replication (MMIR), and/or inverted or directly repeated sequences that adopt unusual secondary structures for their repair [4]. From the molecular analysis [7] of a yeast strain that contains amplified copies of the gene for the high affinity sulfur transporter, SUL1 [3], we derived a new general model that explains the generation of interstitial tandem inverted repeat arrays of chromosome segments in yeast and in human cancers, and of de novo congenital inverted triplications and other chromosomal rearrangements. We propose that cells commit a singular error in replication: the ligation of the nascent leading strand to the nascent lagging strand at the replication fork. This model can potentially explain the origin of many palindromic rearrangements and their structural, enzymatic, and genetic requirements.

A Unique Class of Genomic Rearrangements

In the past dozen years, examples of patients with various types of developmental and physical abnormalities have been found to harbor de novo triplications with an inverted central copy for regions of chromosomes 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13, and 15 [8]–[16]. In three of the cases, where the parent of origin could be determined, the inverted triplication was found to be composed of alleles from both homologs of one of the parents in a 2∶1 ratio, consistent with the hypothesis that the event occurred in a meiotic or a pre-meiotic division [8], [14], [15]. In all cases of de novo triplications with an inverted central copy, the distal portion of the chromosome was retained. This finding appears to eliminate models such as the Breakage-Fusion-Bridge model of McClintock [17], at least in their simplest forms, as models that invoke a dsDNA break cannot easily explain the retention of distal sequences.

The SUL1 Amplicon: A Yeast Model for Human Inverted Triplications

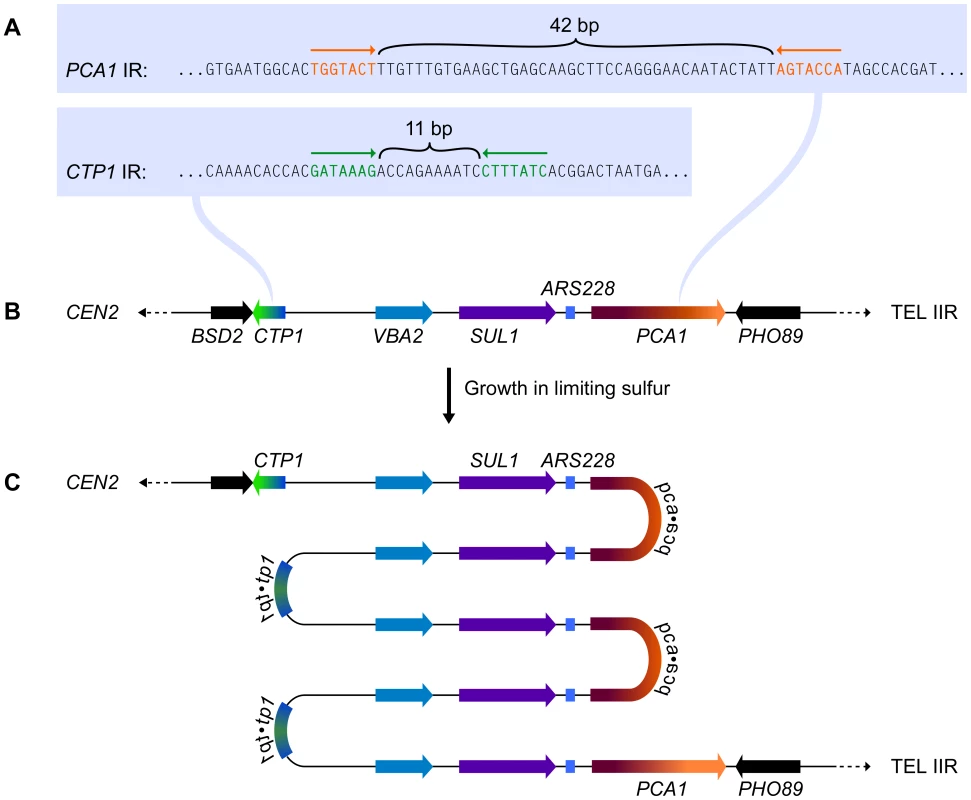

Subjecting wild-type yeast to long-term growth in medium that is limiting for sulfur selects for cells that have amplified the SUL1 (high affinity sulfur transporter) locus along with variable amounts of flanking DNA [3]. To understand the chromosomal structure of one particular amplification event, Araya et al. [7] sequenced the genome of a strain selected under sulfur limitation. The novel junction sequences they identified—occurring at 7-bp, closely spaced, inverted repeats (Figure 1A) in the nearby genes CTP1 and PCA1 (Figure 1B)—allowed them to deduce the structure of the amplicon: a 5× tandem array of alternating head-to-head/tail-to-tail copies of an approximately 11-kb region that contains SUL1 and the adjacent origin of replication, ARS228 (Figure 1C). Southern blot analysis confirmed the inverted nature of the 11-kb tandem repeats of the SUL1 locus [7], and array comparative genome hybridization (CGH) confirmed the retention of distal chromosome II sequences [3]. This SUL1 amplicon therefore contains several important features of the human inverted triplication syndromes and provides a model for understanding the formation of this type of amplification event.

Fig. 1. The chromosomal context for SUL1 amplification.

(A) The inverted repeat sequences in CTP1 and PCA1 that define the breakpoints of a specific SUL1 amplification event [7]. (B) The structure of the wild type SUL1 locus that includes the nearby origin of replication, ARS228. (C) The inferred structure of the head-to-head/tail-to-tail 5× SUL1 amplification product recovered after selective growth of a haploid yeast strain in medium limiting for sulfur. Applying Existing Models to Explain the SUL1 Amplicon

Many models have been proposed to explain genomic rearrangements. Such models include recombination, repair or replication mechanisms that invoke an initial dsDNA break or the 3′ end of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) [4]. The presence of short inverted repeats flanking the rearrangement breakpoints of the SUL1 amplicon might suggest mechanisms that involve the formation of hairpins through intrastrand annealing in the exposed ssDNA in one of the parental strands at a replication fork or the extrusion of a cruciform in duplex DNA, leading ultimately to a hairpin-capped dsDNA break. Replication of the hairpin-capped linear would generate an iso-dicentric chromosome (with the hairpin at its center) that would then be subject to Breakage-Fusion-Bridge (BFB) cycles [17]. Upon capture of a telomere at the resulting break, a stable chromosome with alternating head-to-head and tail-to-tail repeats and a terminal deletion would be recovered. However, comparing this proposed structure to the chromosome actually recovered in the haploid strain used for the sulfur-limited selection, it is clear that BFB cycles cannot readily explain this particular SUL1 amplification event as the distal sequences were retained. In addition, BFB cannot easily explain the human triplications with an inverted center copy as BFB is inherently an intrachromosomal event and the three triplications where the parent of origin was studied clearly included DNA from both homologs of one of the parents. We explored all of the existing models in a similar way, but were unable to explain simultaneously the generation of an uneven number of copies of amplified genes in an alternating head-to-head/tail-to-tail tandem configuration, the perfect reuse of both proximal and distal break sites, the retention of distal chromosomal segments, and the creation of genetically mixed amplicons through any of the existing models that used a DNA break as the initiating event.

An Origin-Dependent Inverted-Repeat Amplification Model Explains the SUL1 Amplicon

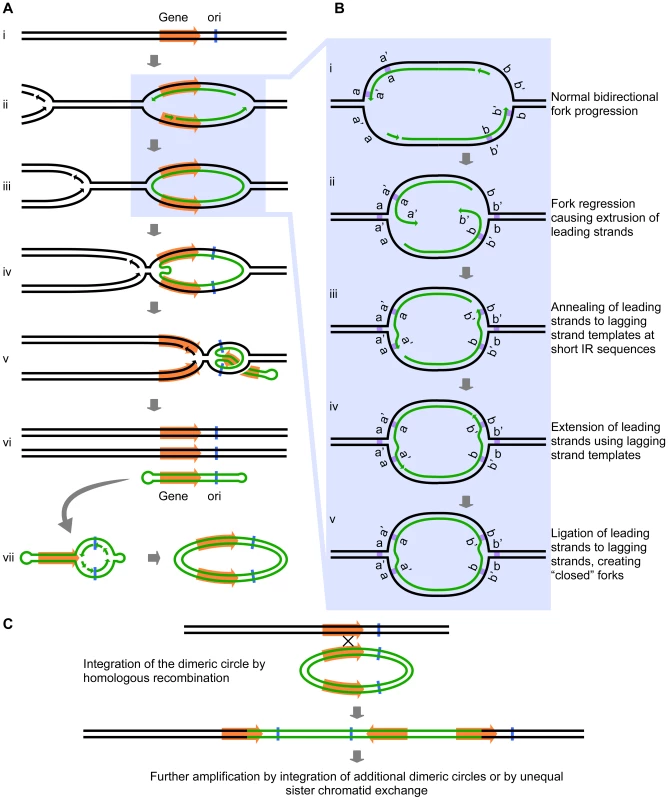

Intrigued by the inclusion of a potential origin of replication (ARS228) in the SUL1 amplicon (Figure 1), we wondered whether the presence of bidirectional forks might play a role in the amplification process beyond the proposed mechanisms of break-induced replication (BIR), microhomology-microsatellite-induced replication (MMIR), fork stalling and template switching (FoSTeS), or serial replication slippage (SRS) [4], [18]–[20]. The short inverted repeats and their close spacing (i.e., within the size of eukaryotic Okazaki fragments) could permit an aberrant replication intermediate to form if one or both of the replication forks regressed by just a few base pairs. In this scenario, the 3′ end of the leading strand of a replication fork initiated at the origin ARS228 (Figure 2Ai and Aii) becomes detached from the leading strand template after synthesis of the second copy of the short inverted repeat has occurred. The detached end then anneals to its complement in the single-stranded portion of the lagging strand template (Figure 2Bi, Bii, and Biii). In this new location, the 3′ end primes synthesis on the lagging template (Figure 2Biv) and becomes ligated to the adjacent Okazaki fragment of the lagging strand, creating a continuous DNA strand between the two nascent strands at the fork—a “closed” fork (Figure 2Bv).

We have illustrated the aberrant event occurring at the oppositely oriented forks on both sides of ARS228 (Figure 2Aiii), thereby generating a self-complementary, circular DNA intermediate that is annealed to the two parental strands but with “closed” forks that are unable to progress into the adjacent chromosomal regions. To complete replication of the chromosome and permit segregation of the two parental chromosome strands, an approaching fork from a nearby origin on either or both sides of the closed loop would facilitate the branch migration or fork reversal at the closed forks through a combination of both topological and enzymatic forces [21], [22]. As the advancing forks replicate through the region of the annealed circular molecule (Figure 2Aiv and Av), a linear duplex with hairpins at both ends (a “dog bone”; Figure 2Avi) is released. Because the displaced fragment contains the origin ARS228, the “dog bone” could be converted to a dimeric circular molecule by replication in the next S-phase (Figure 2Avii).

Fig. 2. The Origin-Dependent Inverted-Repeat (ODIRA) model for Amplification of chromosomal segments.

(A) An overview of the release of a closed circular, self-complementary intermediate that arises from aberrant replication. (B) Details of the mechanism that leads to ligation of the leading and lagging strands at short, closely spaced, inverted repeats (IRs; labeled as a a′ and b b′). (C) Replication and reinsertion of the inverted dimeric amplicon into the genome by homologous recombination. See text for detailed explanations. Up to this point there are three interesting features of the model: first, within the dimeric circle are the inverted SUL1 genes and the rearrangement breakpoints that satisfy the sequencing results of Araya et al. [7]; second, there were no dsDNA breaks, hairpin cleavages, or DNA repair processes required; and third, the presence of the dimeric circle confers a selective advantage on the cell because that cell now has three copies of SUL1. Missegregation of the dimeric circle can cause multiple copies of the circle to accumulate, providing a further selective advantage. At some later time, the amplification event can be stabilized by the integration of one of the dimeric plasmids back into the chromosomal SUL1 locus by conventional homologous recombination (Figure 2C). To achieve the five copies of SUL1 [7], two independent integrations of the inverted-repeat, dimeric circular molecule would be required. Other ways to generate the 5× copies include extrachromosomal concatemerization of the dimeric molecule—by the rolling circle model proposed by Futcher for the yeast 2-micron plasmid [23]—before integration into the chromosome or by unequal sister chromatid recombination after the initial integration of the dimeric circle. In the case of the human triplication disorders, the “dog bone” intermediate generated from one homolog in a division prior to meiosis would replicate to generate the dimeric inverted circle and then integrate by homologous recombination into the other homolog during meiosis to generate the observed 2∶1 allele ratio in the inverted triplication chromosome.

In comparison to existing models, this new model is relatively simple, requiring only a single type of error in replication to generate the extrachromosomal intermediate in amplification. The model demands (1) that the amplicon contain an origin of replication, both to generate the self-complementary single-stranded circular intermediate and to convert it to an extrachromosomal dimeric, inverted-repeat plasmid; (2) that pairs of inverted repeats flank the origin in close enough proximity to each other that each pair could lie within a single Okazaki-sized single-stranded gap; and (3) that the dimeric plasmid integrates into a chromosome by homologous recombination. The fact that the creation and integration of the circular intermediate do not need to occur in the same cell cycle greatly increases the chances of recovering the final chromosomal amplicon. The high density of potential origins in the yeast and human genomes (yeast, one every ∼20 kb, OriDB at http://www.oridb.org/index.php; human, one every ∼68 kb; [24]) and the frequency of closely spaced (≤65 bp) inverted 7 bp repeats (one every ∼250 bp; BJB, unpublished; based on random scans of 100 kb segments of the yeast genome using the “Palindrome” program at http://mobyle.pasteur.fr/cgi-bin/portal.py?form=palindrome) suggest that amplification by this mechanism need not be limited to specific loci.

Extension to Other Amplification and Genome Rearrangement Events in Yeast and Humans

The simplicity of our model makes it appealing, but is there existing evidence to support it? We have characterized a second independent SUL1 amplicon that mimics the features of the sequenced SUL1 amplicon [7], but with different potential inverted repeats at the junctions (C. Payen and M. J. Dunham, unpublished results). A search of the literature failed to uncover any model that includes all of the features we have described; however, strand switching from leading to lagging at a replication fork has been proposed to occur in bacteria [25], [26]. We found reports that transformation of both yeast and mammalian cells with hairpin capped linear molecules (“dog bones”) resulted in the expected dimeric inverted circular plasmids after replication in vivo [27], [28]. We have independently confirmed that ARS fragments capped with hairpins are converted to palindromic dimers in yeast (M. M. Walker, M. K. Raghuraman, and B. J. Brewer, unpublished results). This dimerization preserves the terminal sequences of the capped ARS fragments, distinct from the dimerization of uncapped linear fragments reported by Kunes et al. [29]. We also searched for more examples of gene amplification that could be explained by our model and found several instances in both yeast and mammalian cells where the end products or the intermediates are consistent with such a ligation of leading to lagging strands at a replication fork.

The first example involves amplification of the gene for dihydrofolate reductase (DFR1 in yeast and DHFR in Chinese hamster ovary cells). A subset of independent DHFR amplification events in Chinese hamster ovary cells contains chromosomally integrated repeats of alternating orientations that include one or more replication origins in each repeat [2], a pattern very similar to the chromosomally amplified SUL1 locus of yeast. The structures of yeast chromosomally amplified DFR1 amplicons were not determined; however, one methotrexate-resistant survivor maintained the amplified copies of DFR1 as extrachromosomal 11-kb circular molecules composed of an inverted dimer of the DFR1 gene and the adjacent origin of replication ARS1524 [1]. While the authors did not sequence the junctions, several examples of short inverted repeats occur in the genome at the margins of the amplified region. In all respects, this circular inverted dimer of DFR1 exactly conforms to the expelled and replicated, extrachromosomal molecule predicted by our model (Figure 2Avii and Figure 3-I).

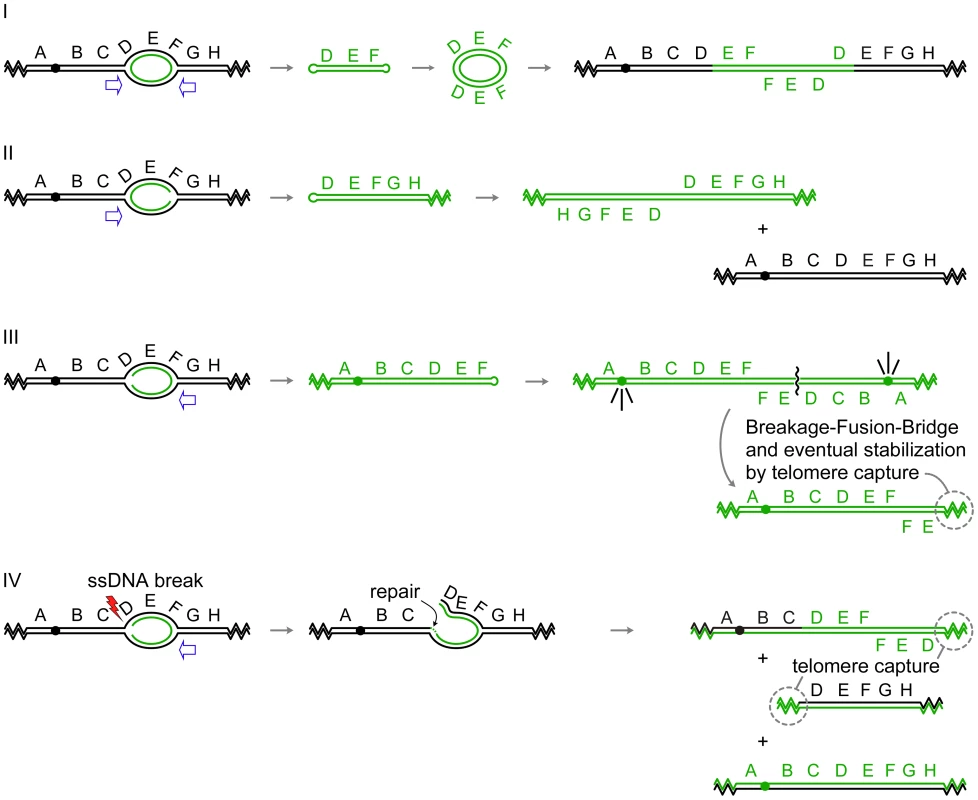

Fig. 3. Palindrome formation and resolution by ODIRA generates a range of amplification products.

In each of the examples I–IV, initiation of replication from an origin near the sequence labeled E generates bidirectional forks that have progressed through the flanking sequences D and F. In the four scenarios depicted, either one or both of the replication forks becomes “closed” by ligation of the leading strand to the lagging strand. Open arrows indicate the direction that flanking replication forks move to expel the “closed” fork intermediate by branch migration. (I) In this example, both forks “close.” Replication forks approaching from either direction (open arrows) will release the hairpin-capped linear that contains genes D, E, and F. Subsequent replication of this “dog bone” molecule generates a dimeric, palindromic circular molecule that can reintegrate through homologous recombination into the original chromosome, or into a homolog if one is present, or by random integration elsewhere in the genome. These steps are described in detail in Figure 2. (II) In this example, the fork closest to the centromere “closes” while the telomere proximal fork remains active, fusing with distal replicons to allow replication of segments G, H, and the right telomere. The fork moving outward from the centromere (open arrow) will dislodge a fragment that has a hairpin at one end and a telomere at the other. Subsequent replication results in an isochromosome containing genes D–H. These acentric chromosomes are relatively stable in yeast [30], [32], and in human cells stability can be improved by the acquisition of a neocentromere [52] or by chromosome tethering [53], [54]. (III) In this example, only the distal fork closes. Completion of replication by a fork from the telomere proximal side of the closed fork releases a similar intermediate as in (II). Replication of the fragment with a hairpin near gene F generates an isochromosome that contains the centromere and genes A–F. Cycles of BFB will occur until the break is healed by the addition of a telomere. (IV) This example begins as the one in (III); however, the fork near gene D suffers a ssDNA break. Repair of this break by ligation of the broken strand to the nascent strand generates a branched intermediate that can be resolved by a fork moving in from the region of genes G and H. Two aberrant chromosome fragments are generated by this resolution, both requiring telomere addition to become resistant to nucleases. The fragment containing the centromere is an “inv dup del” chromosome indistinguishable from a chromosome generated by BFB (III). The fate of the acentric fragment is expected to be similar to that of an acentric isochromosome. A second example from the yeast literature is the amplification of the ADH4 gene in adh1 cells that had been treated with antimycin A [30], [31]. In this case, the amplicon was most frequently found as an acentric isochromosome (Figure 3-II) of approximately 40 kb encompassing the terminal ∼20 kb of the left arm of chromosome VII. In this terminal segment of chromosome VII are two potential origins of replication (likely ARSs at 8 and 17 kb on chromosome VII; OriDB, http://www.oridb.org/) that lie on either side of the ADH4 gene. The junctions of independent isolates were mapped by restriction digestion and Southern blotting and found to lie in a roughly 2-kb region [30] that contains more than ten pairs of interrupted short inverted repeats.

A third example of an extrachromosomal inverted amplicon similar to the case of ADH4 just described was generated from an artificial construct on the left arm of chromosome V in haploid strains of yeast [32]. The CUP1 and SFA1 genes, along with inverted human Alu sequences separated by a 12-bp spacer, were inserted near the CAN1 gene, and clones resistant to copper and formaldehyde were selected. The most common amplicon recovered consisted of an ∼80-kb inverted dimeric linear (Figure 3-II) with the Alu sequences at the center and a copy of the native origin, ARS504, near each telomere. It should be noted that in all cases, the cells also retained a full-length copy of chromosome V. The implication of this finding is that during the generation of the CUP1/SFA1 isochromosome, chromosome V did not suffer a double-stranded break.

The generation of the extrachromosomal DFR1, ADH4, and CUP1/SFA1 amplicons can be easily explained by our model, as each contains one or more origins of replication and appropriately placed short inverted repeats. Amplification of DFR1 would require “closure” at both of the diverging forks (Figure 3-I), similar to what we have proposed for SUL1, while amplification of ADH4 or CUP1/SFA1 would require only a single event in the fork moving toward the centromere (Figure 3-II). In all four of these cases an acentric, extrachromosomal, nearly perfect palindromic DNA molecule, either circular or linear, is the result. Similar examples can be found in mammalian cells: hairpin-capped linear fragments are maintained as palindromic extrachromosomal tiny episomes (ETEs; [28]); double-minute chromosomes [33], isochromosomes [34], and homogeneously staining regions (HSRs; [35], [36]) with inverted repeat architecture have all been recovered from tumor cell lines; and well-characterized isochromosomes in humans occur at regions that contain large inverted repeats [37]–[39].

While many of the extrachromosomal molecules described so far lack centromeres, we wish to point out that our model could also provide the starting point for the Breakage-Fusion-Bridge cycle described by Barbara McClintock [17] if just the fork moving away from a centromere were to experience ligation of the leading strand to the lagging strand (Figure 3-III). Subsequent expulsion and replication of this hairpin would create an isodicentric chromosome that would form a bridge at anaphase, be broken at cytokinesis, and undergo repair by fusion in the next cycle. The chromosome becomes stable when the broken end acquires telomeric sequences either by de novo telomere addition or by recombination with another chromosome [40]. There are many examples of such chromosomes in the clinical literature of de novo chromosomal abnormalities [41]—chromosomes that end in an inverted duplication but are missing the terminal portion of the original chromosome (also known as an “inv dup del” chromosome).

Our model also provides a second way to generate “inv dup del” chromosomes without cycles of BFB (Figure 3-IV). After generating a closed fork at the telomere-proximal fork, the fork proceeding toward the centromere could suffer a single-stranded break in one of the parental strands at the fork. Subsequent resolution of the closed fork by replication/branch migration and addition of a telomere to the broken end would generate the same structure that is usually attributed to breakage of isodicentric chromosomes by BFB. It is interesting that “inv del dup” chromosomes were the predominant class of rearranged chromosomes found by Narayanan et al. [32] when selecting for the loss of a marker that was distal to the Alu inverted repeats on yeast chromosome V.

Replication Delays and Gene Amplification

In our model for inverted amplicons, a closed fork can form when both copies of a short inverted repeat lie within a single-stranded gap on the lagging strand of a replication fork. Therefore, as long as the space between the inverted repeats is not greater than the Okazaki gap on the lagging strand, both the length of the inverted repeat and the amount of time the repeats persist in a single-stranded form would influence the probability of forming a closed fork at that particular position. The 320-bp inverted Alu sequences that were placed centromere proximal to the SFA1 and CUP1 genes on the left arm of yeast chromosome V increased the formation of extrachromosomal amplicons between 250 - and 11,000-fold, depending on the percent identity between the repeats, and a 25,000-fold increase in the formation of “inv dup del” chromosomes when the repeats were perfect matches [32]. The degree of identity between the repeated Alus would certainly influence the probability of cross-fork annealing, but the presence of the inverted repeat has also been shown to slow progression of the replication fork as much as 6-fold [42], providing more time for the fork to “close.”

Other methods of slowing fork progression would also be expected to increase the formation of closed forks. Two recent yeast papers describe dicentric, palindromic chromosomes that were created by interfering with replication fork progression in yeast. Mizuno et al. [43] placed inverted replication termination sequences at the ura4+ locus of fission yeast and followed the fate of the chromosome over time after induction of the fork-blocking factor Rts1. Both acentric and dicentric palindromic chromosomes were generated at high frequency at inverted repeats within their artificial construct, but, to their surprise, no double-stranded breaks were detected as a precursor. Paek et al. [44] obtained an isodicentric palindromic version of the budding yeast's chromosome VII at naturally occurring inverted repeats by disrupting replication in a checkpoint mutant. By studying the formation of the isodicentric chromosome in various mutant strains, they ruled out any involvement of double-stranded break repair pathways, post-replication repair, and break-induced replication. The authors of both papers suggested that some form of aberrant template switching was involved, although the models they proposed were topologically complex and/or lacked specific details. Our model of origin-dependent, inverted-repeat amplification could be the common mechanism that explains both of these chromosomal rearrangements.

Applying replication stress to mammalian cells in culture, in the form of carcinogens and/or mutagens, has been found to cause the release of circular inverted-repeat intermediates from the genome. For example, Cohen et al. [45] found that the origin region of an integrated SV40 genome in a Chinese hamster cell line is expelled from the chromosome as a circular inverted repeat amplicon. They also observed, under the same experimental treatments, extrachromosomal circular molecules of genomic DNA [46] that we predict would also contain an origin of replication. Cohen et al. [45] proposed a mechanism called “U-turn” replication in which the leading strand folds back on itself and primes a second strand using the nascent leading strand as template. Although they did not specifically predict the importance of an origin of replication or the short, closely spaced inverted repeats, or suggest how the open end of the hairpin would be repaired, their U-turn model proposed that the hairpin essentially replicates itself out of the chromosomal context. The open end is then sealed by some unspecified mechanism and the hairpin capped linear molecule is subsequently replicated to create the dimeric, inverted, circular molecule.

More recent studies of human cancers by genome-wide analysis of palindrome formation revealed a widespread increase in the frequency of palindromic sequences (detected by their ability to “snap-back” after denaturation) that are sometimes associated with the ends of amplified regions as inferred from array CGH [47], [48]. While the authors did not distinguish between chromosomal and extrachromosomal palindromes, it is possible that they were detecting the same type of circular inverted dimeric molecules studied by Lavi and colleagues [45], [46].

Conclusions and Future Directions

There are many pathways—including repair, recombination, and replication—that contribute to genome rearrangements. Our model of Origin-Dependent Inverted-Repeat Amplification provides a simple way to generate a specific class of inverted amplicons. To determine just how frequent amplification might occur by our proposed mechanism requires a better cataloging of the structure of the amplified DNA. Array CGH and deep sequencing can pinpoint regions of the genome that are amplified with respect to a reference genome, but they do not distinguish between extrachromosomal and integrated copies—nor do they determine the chromosomal location or orientation of the additional, integrated copies unless the novel junctions are specifically looked for among the non-aligning sequencing reads. More complete analysis of both yeast and human amplicons is definitely needed. In the clinical literature, there is a recurring comment that triplications with inverted central copies are vastly underreported and therefore underappreciated (for example, [8]). While there are striking structural similarities between events in yeast and human cells, the scale of the chromosomal rearrangements is vastly different. For example, the sizes of the regions in the triplication disorders can be several megabases. Is it reasonable to expect the displacing forks to be able to travel such long distances? Clearly the answer is not known, but as a point of comparison, when BIR was first described in yeast it seemed amazing that a single fork could traverse the entire length of a yeast chromosome arm [49], [50]. A second way in which yeast and mammalian cells differ is in their propensity to undergo homologous recombination in response to double-stranded breaks: yeast is extremely proficient at mitotic homologous recombination, while in human cells non-homologous events predominate [51]. To generate the inverted triplication disorders, the dimeric circle must undergo homologous recombination with the chromosome. However, because the human inverted triplication disorders occur in meiosis, homologous recombination might in fact be favored.

Our pathway, in addition to being rather simple, is novel and noteworthy for several reasons. First, it suggests a unifying mechanism for a diverse set of gene amplification outcomes (tandem inverted repeats, inverted double minutes, terminal inverted duplication/deletions, and isochromosomes; Figure 3). Second, the causative event is not a double-stranded break but is an error in replication—transfer of the 3′ end of the leading strand to the lagging strand template at the same fork. Third, the 3′ end of the leading strand does not need to cover much territory in search of homology as the complementary lagging strand template is just angstroms away. Fourth, there is no obvious need to relocate polymerases or helicases at the fork to restart replication from the 3′ end of the displaced strand, as the lagging strand machinery would be available for this purpose. Fifth, the “closed” fork should be displaceable from the parental strands by branch migration brought about by the combination of the enzymatic activities of the helicases and topoisomerases that travel with the fork that approaches from the neighboring origin and the positive supercoils that accumulate ahead of it. Sixth, the displaced circle is an autonomously replicating entity, so the creation of the intermediate and its reintegration into the chromosome need not be temporally coupled. Seventh, the model supplies an alternate method to McClintock's BFB for generating “inv dup del.” And finally, many of the steps in the model we have presented are experimentally testable—perhaps most easily in yeast where it is possible to select directly for desired amplification events and where the starting constructs and genetic backgrounds can be manipulated, but also during clonal expansion of transformed mammalian cells in culture.

Zdroje

1. HuangTCampbellJL 1995 Amplification of a circular episome carrying an inverted repeat of the DFR1 locus and adjacent autonomously replicating sequence element of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 270 9607 9614

2. MaCLooneyJELeuTHHamlinJL 1988 Organization and genesis of dihydrofolate reductase amplicons in the genome of a methotrexate-resistant Chinese hamster ovary cell line. Mol Cell Biol 8 2316 2327

3. GreshamDDesaiMMTuckerCMJenqHTPaiDA 2008 The repertoire and dynamics of evolutionary adaptations to controlled nutrient-limited environments in yeast. PLoS Genet 4 e1000303

4. HastingsPJLupskiJRRosenbergSMIraG 2009 Mechanisms of change in gene copy number. Nat Rev Genet 10 551 564

5. VialardFMignon-RavixCParainDDepetrisDPortnoiMF 2003 Mechanism of intrachromosomal triplications 15q11-q13: a new clinical report. Am J Med Genet A 118A 229 234

6. WangJReddyKSWangEHaldermanLMorganBL 1999 Intrachromosomal triplication of 2q11.2-q21 in a severely malformed infant: case report and review of triplications and their possible mechanism. Am J Med Genet 82 312 317

7. ArayaCLPayenCDunhamMJFieldsS 2010 Whole-genome sequencing of a laboratory-evolved yeast strain. BMC Genomics 11 88

8. DevriendtKMatthijsGHolvoetMSchoenmakersEFrynsJP 1999 Triplication of distal chromosome 10q. J Med Genet 36 242 245

9. EckelHWimmerRVollethMJakubiczkaSMuschkeP 2006 Intrachromosomal triplication 12p11.22-p12.3 and gonadal mosaicism of partial tetrasomy 12p. Am J Med Genet A 140 1219 1222

10. OunapKIlusTBartschO 2005 A girl with inverted triplication of chromosome 3q25.3→q29 and multiple congenital anomalies consistent with 3q duplication syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 134 434 438

11. ReddyKSLoganJJ 2000 Intrachromosomal triplications: molecular cytogenetic and clinical studies. Clin Genet 58 134 141

12. RiveraHBobadillaLRolonAKunzJCrollaJA 1998 Intrachromosomal triplication of distal 7p. J Med Genet 35 78 80

13. VerheijJBBoumanKvan LingenRAvan Lookeren CampagneJGLeegteB 1999 Tetrasomy 9p due to an intrachromosomal triplication of 9p13-p22. Am J Med Genet 86 168 173

14. UngaroPChristianSLFantesJAMutiranguraABlackS 2001 Molecular characterisation of four cases of intrachromosomal triplication of chromosome 15q11-q14. J Med Genet 38 26 34

15. MercerCLBrowneCEBarberJCMaloneyVKHuangS 2009 A complex medical phenotype in a patient with triplication of 2q12.3 to 2q13 characterized with oligonucleotide array CGH. Cytogenet Genome Res 124 179 186

16. HarrisonKJTeshimaIESilverMMJayVUngerS 1998 Partial tetrasomy with triplication of chromosome (5) (p14-p15.33) in a patient with severe multiple congenital anomalies. Am J Med Genet 79 103 107

17. McClintockB 1941 The Stability of Broken Ends of Chromosomes in Zea mays. Genetics 26 234 282

18. PayenCKoszulRDujonBFischerG 2008 Segmental duplications arise from Pol32-dependent repair of broken forks through two alternative replication-based mechanisms. PLoS Genet 4 e1000175

19. ChauvinAChenJMQuemenerSMassonEKehrer-SawatzkiH 2009 Elucidation of the complex structure and origin of the human trypsinogen locus triplication. Hum Mol Genet 18 3605 3614

20. ChenJMChuzhanovaNStensonPDFerecCCooperDN 2005 Intrachromosomal serial replication slippage in trans gives rise to diverse genomic rearrangements involving inversions. Hum Mutat 26 362 373

21. KaplanDLDaveyMJO'DonnellM 2003 Mcm4,6,7 uses a “pump in ring” mechanism to unwind DNA by steric exclusion and actively translocate along a duplex. J Biol Chem 278 49171 49182

22. OlavarrietaLMartinez-RoblesMLSogoJMStasiakAHernandezP 2002 Supercoiling, knotting and replication fork reversal in partially replicated plasmids. Nucleic Acids Res 30 656 666

23. FutcherAB 1986 Copy number amplification of the 2 micron circle plasmid of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Theor Biol 119 197 204

24. CadoretJCMeischFHassan-ZadehVLuytenIGuilletC 2008 Genome-wide studies highlight indirect links between human replication origins and gene regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 15837 15842

25. AhmedAPodemskiL 1998 Observations on template switching during DNA replication through long inverted repeats. Gene 223 187 194

26. KugelbergEKofoidEAnderssonDILuYMellorJ 2010 The tandem inversion duplication in Salmonella enterica: selection drives unstable precursors to final mutation types. Genetics 185 65 80

27. CoteAGLewisSM 2008 Mus81-dependent double-strand DNA breaks at in vivo-generated cruciform structures in S. cerevisiae. Mol Cell 31 800 812

28. HaradaSUchidaMShimizuN 2009 Episomal high copy number maintenance of hairpin-capped DNA bearing a replication initiation region in human cells. J Biol Chem 284 24320 24327

29. KunesSBotsteinDFoxMS 1990 Synapsis-mediated fusion of free DNA ends forms inverted dimer plasmids in yeast. Genetics 124 67 80

30. DorseyMPetersonCBrayKPaquinCE 1992 Spontaneous amplification of the ADH4 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 132 943 950

31. WaltonJDPaquinCEKanekoKWilliamsonVM 1986 Resistance to antimycin A in yeast by amplification of ADH4 on a linear, 42 kb palindromic plasmid. Cell 46 857 863

32. NarayananVMieczkowskiPAKimHMPetesTDLobachevKS 2006 The pattern of gene amplification is determined by the chromosomal location of hairpin-capped breaks. Cell 125 1283 1296

33. WahlGM 1989 The importance of circular DNA in mammalian gene amplification. Cancer Res 49 1333 1340

34. ItalianoAAttiasRAuriasAPerotGBurel-VandenbosF 2006 Molecular cytogenetic characterization of a metastatic lung sarcomatoid carcinoma: 9p23 neocentromere and 9p23-p24 amplification including JAK2 and JMJD2C. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 167 122 130

35. NonetGHCarrollSMDeRoseMLWahlGM 1993 Molecular dissection of an extrachromosomal amplicon reveals a circular structure consisting of an imperfect inverted duplication. Genomics 15 543 558

36. SchreinerBGretenFRBaurDMFingerleAAZechnerU 2003 Murine pancreatic tumor cell line TD2 bears the characteristic pattern of genetic changes with two independently amplified gene loci. Oncogene 22 6802 6809

37. BarboutiAStankiewiczPNusbaumCCuomoCCookA 2004 The breakpoint region of the most common isochromosome, i(17q), in human neoplasia is characterized by a complex genomic architecture with large, palindromic, low-copy repeats. Am J Hum Genet 74 1 10

38. LangeJSkaletskyHvan DaalenSKEmbrySLKorverCM 2009 Isodicentric Y chromosomes and sex disorders as byproducts of homologous recombination that maintains palindromes. Cell 138 855 869

39. ScottSACohenNBrandtTWarburtonPEEdelmannL 2010 Large inverted repeats within Xp11.2 are present at the breakpoints of isodicentric X chromosomes in Turner syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 19 3383 3393

40. YuSGrafWD 2010 Telomere capture as a frequent mechanism for stabilization of the terminal chromosomal deletion associated with inverted duplication. Cytogenet Genome Res 129 265 274

41. ZuffardiOBonagliaMCicconeRGiordaR 2009 Inverted duplications deletions: underdiagnosed rearrangements?? Clin Genet 75 505 513

42. VoineaguINarayananVLobachevKSMirkinSM 2008 Replication stalling at unstable inverted repeats: interplay between DNA hairpins and fork stabilizing proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 9936 9941

43. MizunoKLambertSBaldacciGMurrayJMCarrAM 2009 Nearby inverted repeats fuse to generate acentric and dicentric palindromic chromosomes by a replication template exchange mechanism. Genes Dev 23 2876 2886

44. PaekALKaocharSJonesHElezabyAShanksL 2009 Fusion of nearby inverted repeats by a replication-based mechanism leads to formation of dicentric and acentric chromosomes that cause genome instability in budding yeast. Genes Dev 23 2861 2875

45. CohenSHassinDKarbySLaviS 1994 Hairpin structures are the primary amplification products: a novel mechanism for generation of inverted repeats during gene amplification. Mol Cell Biol 14 7782 7791

46. CohenSLaviS 1996 Induction of circles of heterogeneous sizes in carcinogen-treated cells: two-dimensional gel analysis of circular DNA molecules. Mol Cell Biol 16 2002 2014

47. TanakaHBergstromDAYaoMCTapscottSJ 2005 Widespread and nonrandom distribution of DNA palindromes in cancer cells provides a structural platform for subsequent gene amplification. Nat Genet 37 320 327

48. TanakaHCaoYBergstromDAKooperbergCTapscottSJ 2007 Intrastrand annealing leads to the formation of a large DNA palindrome and determines the boundaries of genomic amplification in human cancer. Mol Cell Biol 27 1993 2002

49. LlorenteBSmithCESymingtonLS 2008 Break-induced replication: what is it and what is it for? Cell Cycle 7 859 864

50. MalkovaAIvanovELHaberJE 1996 Double-strand break repair in the absence of RAD51 in yeast: a possible role for break-induced DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93 7131 7136

51. SonodaEHocheggerHSaberiATaniguchiYTakedaS 2006 Differential usage of non-homologous end-joining and homologous recombination in double strand break repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 5 1021 1029

52. MurmannAEConradDFMashekHCurtisCANicolaeRI 2009 Inverted duplications on acentric markers: mechanism of formation. Hum Mol Genet 18 2241 2256

53. KandaTOtterMWahlGM 2001 Mitotic segregation of viral and cellular acentric extrachromosomal molecules by chromosome tethering. J Cell Sci 114 49 58

54. KandaTWahlGM 2000 The dynamics of acentric chromosomes in cancer cells revealed by GFP-based chromosome labeling strategies. J Cell Biochem Suppl Suppl 35 107 114

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Genetic Regulation by NLA and MicroRNA827 for Maintaining Nitrate-Dependent Phosphate Homeostasis inČlánek c-di-GMP Turn-Over in Is Controlled by a Plethora of Diguanylate Cyclases and PhosphodiesterasesČlánek Viral Genome Segmentation Can Result from a Trade-Off between Genetic Content and Particle Stability

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 3- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Hypogonadotropní hypogonadismus u žen a vliv na výsledky reprodukce po IVF

- Molekulární vyšetření pro stanovení prognózy pacientů s chronickou lymfocytární leukémií

- Prof. Petr Urbánek: Potřebujeme najít pacienty s nediagnostikovanou akutní intermitentní porfyrií

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Whole-Exome Re-Sequencing in a Family Quartet Identifies Mutations As the Cause of a Novel Skeletal Dysplasia

- Origin-Dependent Inverted-Repeat Amplification: A Replication-Based Model for Generating Palindromic Amplicons

- Testing for an Unusual Distribution of Rare Variants

- Limited dCTP Availability Accounts for Mitochondrial DNA Depletion in Mitochondrial Neurogastrointestinal Encephalomyopathy (MNGIE)

- FUS Transgenic Rats Develop the Phenotypes of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration

- Repeat Associated Non-ATG Translation Initiation: One DNA, Two Transcripts, Seven Reading Frames, Potentially Nine Toxic Entities!

- Initial Mutations Direct Alternative Pathways of Protein Evolution

- Dopamine Signalling in Mushroom Bodies Regulates Temperature-Preference Behaviour in

- Sensing of Replication Stress and Mec1 Activation Act through Two Independent Pathways Involving the 9-1-1 Complex and DNA Polymerase ε

- Genetic Regulation by NLA and MicroRNA827 for Maintaining Nitrate-Dependent Phosphate Homeostasis in

- Identification of a Novel Type of Spacer Element Required for Imprinting in Fission Yeast

- Chiasmata Promote Monopolar Attachment of Sister Chromatids and Their Co-Segregation toward the Proper Pole during Meiosis I

- Global Analysis of the Relationship between JIL-1 Kinase and Transcription

- H3K9me2/3 Binding of the MBT Domain Protein LIN-61 Is Essential for Vulva Development

- REVEILLE8 and PSEUDO-REPONSE REGULATOR5 Form a Negative Feedback Loop within the Arabidopsis Circadian Clock

- A Novel Unstable Duplication Upstream of Predisposes to a Breed-Defining Skin Phenotype and a Periodic Fever Syndrome in Chinese Shar-Pei Dogs

- Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 Controls the Embryo-to-Seedling Phase Transition

- A Role for Set1/MLL-Related Components in Epigenetic Regulation of the Germ Line

- Genome-Wide Association Analysis Identifies Variants Associated with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease That Have Distinct Effects on Metabolic Traits

- A Genome-Wide Association Study of Upper Aerodigestive Tract Cancers Conducted within the INHANCE Consortium

- Ancestral Mutation in Telomerase Causes Defects in Repeat Addition Processivity and Manifests As Familial Pulmonary Fibrosis

- Ultra-Deep Sequencing of Mouse Mitochondrial DNA: Mutational Patterns and Their Origins

- Phenotype Restricted Genome-Wide Association Study Using a Gene-Centric Approach Identifies Three Low-Risk Neuroblastoma Susceptibility Loci

- The Toll-Like Receptor Gene Family Is Integrated into Human DNA Damage and p53 Networks

- Polycomb Targets Seek Closest Neighbours

- Widespread Hypomethylation Occurs Early and Synergizes with Gene Amplification during Esophageal Carcinogenesis

- c-di-GMP Turn-Over in Is Controlled by a Plethora of Diguanylate Cyclases and Phosphodiesterases

- Estimating Divergence Time and Ancestral Effective Population Size of Bornean and Sumatran Orangutan Subspecies Using a Coalescent Hidden Markov Model

- Rif1 Supports the Function of the CST Complex in Yeast Telomere Capping

- A Tradeoff Drives the Evolution of Reduced Metal Resistance in Natural Populations of Yeast

- Quantifying the Underestimation of Relative Risks from Genome-Wide Association Studies

- Population-Based Resequencing of Experimentally Evolved Populations Reveals the Genetic Basis of Body Size Variation in

- Triplet Repeat–Derived siRNAs Enhance RNA–Mediated Toxicity in a Drosophila Model for Myotonic Dystrophy

- The FUN30 Chromatin Remodeler, Fft3, Protects Centromeric and Subtelomeric Domains from Euchromatin Formation

- Viral Genome Segmentation Can Result from a Trade-Off between Genetic Content and Particle Stability

- Environmental Sex Determination in the Branchiopod Crustacean : Deep Conservation of a Gene in the Sex-Determining Pathway

- Systematic Detection of Polygenic Regulatory Evolution

- The SUMO Isopeptidase Ulp2p Is Required to Prevent Recombination-Induced Chromosome Segregation Lethality following DNA Replication Stress

- Uncoupling Antisense-Mediated Silencing and DNA Methylation in the Imprinted Cluster

- Role of the Drosophila Non-Visual ß-Arrestin Kurtz in Hedgehog Signalling

- Differential Genetic Associations for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Based on Anti–dsDNA Autoantibody Production

- COMPASS-Like Complexes Mediate Histone H3 Lysine-4 Trimethylation to Control Floral Transition and Plant Development

- H3 Lysine 4 Is Acetylated at Active Gene Promoters and Is Regulated by H3 Lysine 4 Methylation

- Diverse Roles and Interactions of the SWI/SNF Chromatin Remodeling Complex Revealed Using Global Approaches

- A Bow-Tie Genetic Architecture for Morphogenesis Suggested by a Genome-Wide RNAi Screen in

- Roles of () in Oocyte Nuclear Architecture, Gametogenesis, Gonad Tumors, and Genome Stability in Zebrafish

- A Molecular Phylogeny of Living Primates

- Roles of the Espin Actin-Bundling Proteins in the Morphogenesis and Stabilization of Hair Cell Stereocilia Revealed in CBA/CaJ Congenic Jerker Mice

- A Cholinergic-Regulated Circuit Coordinates the Maintenance and Bi-Stable States of a Sensory-Motor Behavior during Male Copulation

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Whole-Exome Re-Sequencing in a Family Quartet Identifies Mutations As the Cause of a Novel Skeletal Dysplasia

- Origin-Dependent Inverted-Repeat Amplification: A Replication-Based Model for Generating Palindromic Amplicons

- FUS Transgenic Rats Develop the Phenotypes of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration

- Limited dCTP Availability Accounts for Mitochondrial DNA Depletion in Mitochondrial Neurogastrointestinal Encephalomyopathy (MNGIE)

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání