-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

H3 Lysine 4 Is Acetylated at Active Gene Promoters and Is Regulated by H3 Lysine 4 Methylation

Methylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me) is an evolutionarily conserved modification whose role in the regulation of gene expression has been extensively studied. In contrast, the function of H3K4 acetylation (H3K4ac) has received little attention because of a lack of tools to separate its function from that of H3K4me. Here we show that, in addition to being methylated, H3K4 is also acetylated in budding yeast. Genetic studies reveal that the histone acetyltransferases (HATs) Gcn5 and Rtt109 contribute to H3K4 acetylation in vivo. Whilst removal of H3K4ac from euchromatin mainly requires the histone deacetylase (HDAC) Hst1, Sir2 is needed for H3K4 deacetylation in heterochomatin. Using genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), we show that H3K4ac is enriched at promoters of actively transcribed genes and located just upstream of H3K4 tri-methylation (H3K4me3), a pattern that has been conserved in human cells. We find that the Set1-containing complex (COMPASS), which promotes H3K4me2 and -me3, also serves to limit the abundance of H3K4ac at gene promoters. In addition, we identify a group of genes that have high levels of H3K4ac in their promoters and are inadequately expressed in H3-K4R, but not in set1Δ mutant strains, suggesting that H3K4ac plays a positive role in transcription. Our results reveal a novel regulatory feature of promoter-proximal chromatin, involving mutually exclusive histone modifications of the same histone residue (H3K4ac and H3K4me).

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001354

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001354Summary

Methylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me) is an evolutionarily conserved modification whose role in the regulation of gene expression has been extensively studied. In contrast, the function of H3K4 acetylation (H3K4ac) has received little attention because of a lack of tools to separate its function from that of H3K4me. Here we show that, in addition to being methylated, H3K4 is also acetylated in budding yeast. Genetic studies reveal that the histone acetyltransferases (HATs) Gcn5 and Rtt109 contribute to H3K4 acetylation in vivo. Whilst removal of H3K4ac from euchromatin mainly requires the histone deacetylase (HDAC) Hst1, Sir2 is needed for H3K4 deacetylation in heterochomatin. Using genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), we show that H3K4ac is enriched at promoters of actively transcribed genes and located just upstream of H3K4 tri-methylation (H3K4me3), a pattern that has been conserved in human cells. We find that the Set1-containing complex (COMPASS), which promotes H3K4me2 and -me3, also serves to limit the abundance of H3K4ac at gene promoters. In addition, we identify a group of genes that have high levels of H3K4ac in their promoters and are inadequately expressed in H3-K4R, but not in set1Δ mutant strains, suggesting that H3K4ac plays a positive role in transcription. Our results reveal a novel regulatory feature of promoter-proximal chromatin, involving mutually exclusive histone modifications of the same histone residue (H3K4ac and H3K4me).

Introduction

Histones are covalently modified on many lysine residues. The outcome of these modifications is either to modify chromatin structure directly or provide docking sites for the binding of non-histone proteins [1]. The same chemical modification (e.g. methylation) on different residues can lead to distinct outcomes. Moreover, some histone modifications function in a combinatorial fashion to generate different functional outcomes [2]-[4]. This led to the notion that histone modifications may represent an epigenetic code that influences gene expression and serves as a “memory” of cell identity during development of cell lineages [5]-[6]. The recent development of high resolution mass spectrometry has enabled the identification of a great number of new histone modifications [7]-[9]. Elucidation of the functions of these new modifications is greatly facilitated in model organisms where, in contrast to vertebrate cells, histone gene mutations that abolish specific modifications can be readily introduced.

Histone H3 lysine 4 is a highly studied residue whose modification is important for many biological processes in a wide range of species [10]-[11]. The genomic localisation of H3K4 methylation (H3K4me) has been conserved through evolution. It is highly regulated and generally associated with transcriptionally active genes [12]-[18]. H3K4 tri-methylation (H3K4me3) is a hallmark of transcriptional start sites and is generally followed by H3K4me2 and H3K4me1 along gene coding regions [19]-[22]. The multiple functions of H3K4 are mediated by a number of chromatin-associated proteins that selectively bind to some of the four methylation states of H3K4: unmethylated, mono-, di - or trimethylated [23]-[37]. In yeast, H3K4 is methylated by Set1, a SET domain containing protein and a homolog of Trithorax. Set1 is part of a complex termed COMPASS (complex of proteins asociated with Set1) [38]-[42]. The regulation of the different forms of H3K4me is complex and requires not only the components of COMPASS, but also a trans-histone pathway which involves mono-ubiquitylation of H2B lysine 123 [43]-[44].

A close link exists between H3K4me2 and -me3 and acetylation of the H3 tail. H3K4me3 is often found together with acetylation of other residues (i.e. K9, K14, K18, K23 and K27) on the same H3 molecules [45]-[49]. In a subset of yeast genes, H3K4me3 directly binds to the PHD finger domain of Yng1, a subunit of the NuA3 histone acetyltransferase (HAT) complex that modifies H3K14, which couples the acetylation and methylation of H3 on different residues [33]. In contrast, through the recruitment of the SET3 complex, H3K4me2 in coding regions promotes deacetylation of H3 in the wake of RNA polymerase II (RNApol II) [50]. These results suggest that there is a highly dynamic and coordinated interplay between histone H3K4 methylation and the enzymes that control H3 acetylation during transcription.

Despite extensive studies of histone H3K4 methylation, the functional implications of other modifications that occur on the same residue have not been investigated. Here, we identified H3K4 acetylation (H3K4ac) in S. cerevisiae using mass spectrometry and a highly specific antibody that we developed. We found that GCN5 and, to a lesser extent, RTT109 are needed for both H3K4ac and H3K9ac in vivo. H3K4 deacetylation in euchromatin is mainly dependent upon HST1, and partly on SIR2. In contrast, removal of H3K4ac from heterochromatin requires SIR2 only. Genome-wide ChIP experiments revealed that H3K4ac is generally found upstream of H3K4me3 in active gene promoters, a pattern which has been conserved at many human CD4+ T-cell promoters [51]. We further demonstrate that H3K4me2 and –me3 mediated by the COMPASS complex limits global levels of H3K4ac at promoters and prevents it from spreading into the 5′-ends of coding regions. Using a genetic approach to separate the functions of H3K4ac and H3K4me, we identified a subset of S. cerevisiae genes whose expression depends upon H3K4ac, but not H3K4me. Altogether, our results strongly support a positive role for H3K4ac in gene transcription and identify a novel interplay between two modifications of the same histone residue.

Results

Histone H3 lysine 4 is acetylated in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

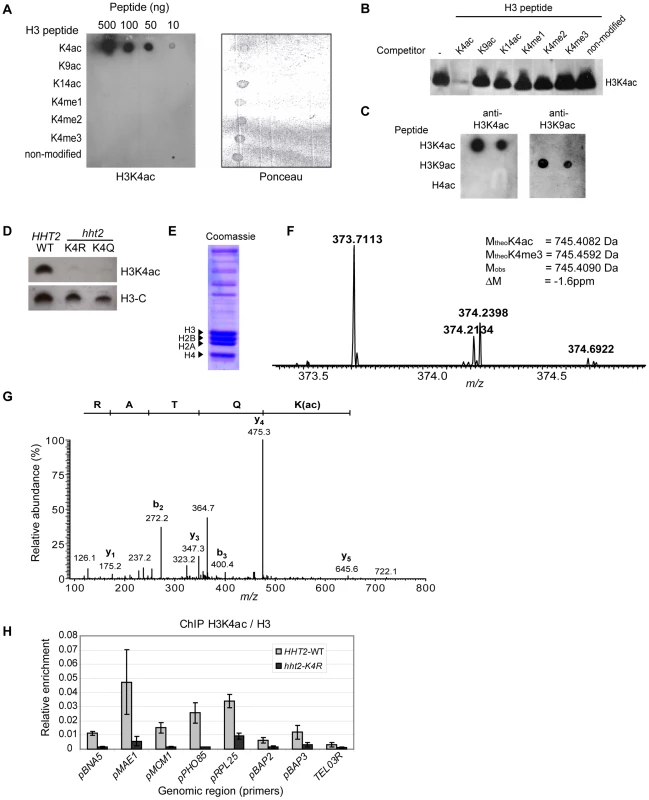

One of the most studied and conserved histone modifications is H3K4 methylation (H3K4me), which is tightly linked to transcription in many species [10]. Because of this, and the fact that methylation and acetylation of the same lysine residue are mutually exclusive, we investigated whether H3K4ac was present in S. cerevisiae, a powerful model organism for genetic analysis. For this purpose, we raised an antibody against H3K4ac and confirmed its specificity with peptide binding assays and immunoblotting competition assays (Figure 1A, 1B). Previous studies have detected the presence of H3K4ac in human cells and an antibody was made commercially available, however the specificity of this antibody was questioned as it showed cross-reactivity against the acetylated H4 N-terminal tail and H3K9ac peptides [51]-[52]. In contrast, our antibody does not show any strong cross-reactivity against H3K9ac or tetra-acetylated H4 peptides (Figure 1C).

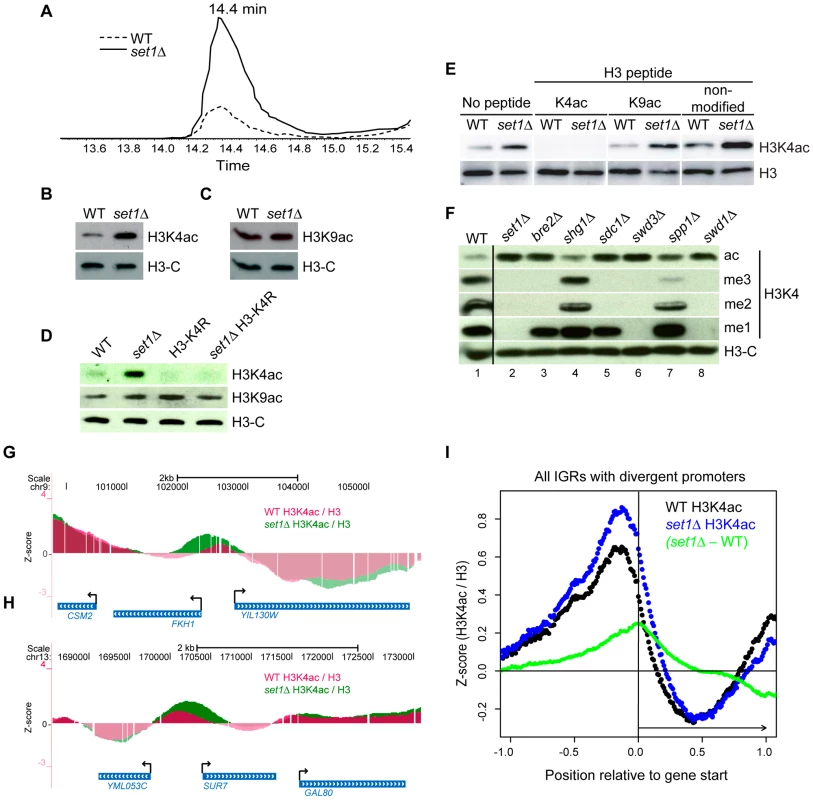

Fig. 1. H3K4 Is Acetylated in S. cerevisiae.

(A) Synthetic peptides derived from the histone H3 N-terminal tail (residues 1 to 10) with modifications at different residues were applied to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was incubated with the H3K4ac antibody, a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, and signals visualised by chemiluminescence (left). Ponceau S staining showing that all the peptides bound to nitrocellulose (right). (B) Immunoblots carried out with nuclear extracts from mouse thymocytes. The membrane was cut into strips and incubated with H3K4ac antibody that was pre-incubated with the indicated competitor peptides (1 µg/ml), resulting in a molar ratio of approximately 1000∶1 (peptide:antibody). (C) Dot blots of synthetic peptides (100ng each) containing H3K4ac, H3K9ac, and tetra-acetylated histone H4, (K5, 8, 12, 16)ac, were incubated with H3K4ac and H3K9ac antibodies. Antibody binding was detected as described above. (D) Whole-cell lysates from strains expressing either WT or mutant versions of H3 were analysed by immunoblotting for H3K4ac or a non-modified C-terminal peptide of H3. (E) Coomassie stained gel of histones purified from exponentially growing yeast cells. (F) Doubly charged precursor ion with the expected m/z ratio for tryptic peptide 3-TKacQTAR-8. The experimental and theoretical masses of the non-charged peptides are indicated in the inset along with the mass difference between the empirically determined and the predicted mass of the K4-acetylated peptide. (G) MS/MS spectrum of the doubly charged precursor ion with m/z 373.7113. The peptide sequence is shown from its C-terminus to its N-terminus above the spectrum. (H) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were analysed by quantitative PCR to determine the abundance of H3K4ac relative to non-modified H3 ChIP at different loci in WT and H3-K4R cells. We readily detected a single H3K4ac band in immunoblots of extracts prepared from wild-type (WT) S. cerevisiae cells (Figure 1D). Importantly, there was no H3K4ac signal in extracts from cells that express either H3-K4R or H3-K4Q as the only source of H3 (Figure 1D). We also confirmed the presence of H3K4ac by mass spectrometry (MS). Histones were isolated from exponentially growing yeast cells (Figure 1E). After trypsin digestion, histone peptides were analysed by nano-LC MS/MS. In histones purified from wild-type cells, we identified a doubly charged precursor ion with the expected mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) for the tryptic peptide 3-TKacQTAR-8. The m/z ratio for the monoisotopic form of this precursor ion was determined with high accuracy as 373.7113 (Figure 1F). The experimental mass of the non-protonated peptide corresponding to this precursor ion (745.4070 Da) was in excellent agreement (−1.6 ppm) with the theoretical mass expected for a K4-acetylated peptide (745.4082 Da) and clearly different from the predicted mass of a peptide containing trimethylated K4 (745.4592 Da). Fragmentation of this precursor peptide by collision-activated dissociation resulted in b - and y-type ion series (Figure 1G) with diagnostic fragment ions (e.g. the mass difference between the y3 and y5 fragments and the mass of the b2 fragment) that unambiguously proved the presence of an acetyl group on H3K4. However, technical limitations precluded us from determining the abundance of H3K4ac by MS. Using synthetic peptides, we found that the tryptic peptide containing H3K4ac was extremely poorly retained during reverse phase HPLC. Because of this we were not able to accurately assess the stoichiometry of H3K4 acetylation.

To investigate the presence of H3K4ac in chromatin, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) in strains expressing either H3-WT or H3-K4R. Our initial screen of various genomic regions by qPCR revealed a strong enrichment of H3K4ac (relative to ChIP of non-modified H3) at some gene promoters (MAE1, PHO85, RPL25) a modest enrichment at other genes (BNA5, MCM1, BAP2, BAP3) and a very low enrichment at a region ∼1 Kb from telomere III-R (TEL03R) (Figure 1H). These results are consistent with our genome-wide ChIP-chip data showing an enrichment of H3K4ac in euchromatin at the promoters of highly transcribed genes (see below). We performed control experiments to confirm the target lysine specificity of our antibody in ChIP assays. The ChIP signal obtained with the H3K4ac antibody dropped significantly at all regions tested in the H3-K4R strain (Figure 1H). As an average for all the promoters tested, the signal obtained by ChIP with our H3K4ac antibody in the WT strain is about 7-fold higher than the non-specific signal (noise) derived from the H3-K4R strain. The average signal-to-noise ratio increases to 9-fold when considering only the four promoters where the signal is most abundant in WT cells. Certain promoters show a higher background, such as the RPL25 promoter (3-fold signal-to-noise), which may reflect some degree of non-specific binding of our H3K4ac to other acetylated lysine residues present in proteins in the vicinity of the RPL25 promoter. Nevertheless, our H3K4ac-specific enrichment values are comparable with previously published ChIP data using acetyl-lysine specific antibodies, where the signal-to-noise ratio ranged from 3 to 10-fold [53]. These results validate the specificity of our antibody in ChIP assays and confirm the presence of H3K4ac in gene promoters.

H3K4 acetylation depends upon GCN5 and RTT109

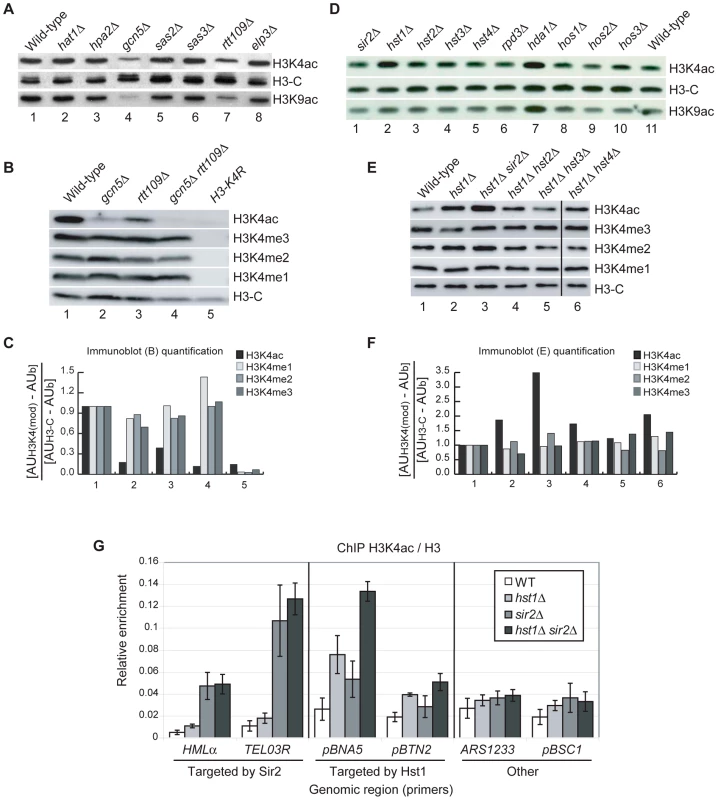

To screen for potential HATs that act on H3K4, we monitored H3K4ac by immunoblotting extracts derived from strains carrying gene disruptions of previously identified HATs. Using this approach, we found that GCN5 and RTT109 were required for H3K4ac in vivo (Figure 2A, lanes 4 and 7). Consistent with a recent report [54], gcn5Δ and rtt109Δ single mutants also exhibited lower levels of H3K9ac than WT cells (Figure 2A). A gcn5Δ rtt109Δ double mutant showed levels of H3K4ac comparable to the background observed in histones from H3-K4R cells (Figure 2B, 2C), suggesting that, as is the case for H3K9ac, GCN5 and RTT109 are responsible for essentially all H3K4ac in yeast.

Fig. 2. HATs and HDACs That Contribute to H3K4ac In Vivo.

(A–B) Whole-cell lysates prepared from strains with deletions of known HAT encoding genes were analysed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (C) Quantification of the immunoblots shown in (B). Signals for each band were expressed in Arbitrary Units (AU) and, after background subtraction (AUb), normalised to the H3-C signal measured in each strain. (D–E) Whole-cell lysates obtained from strains with deletions of known HDAC encoding genes were analysed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (F) Quantification of the immunoblots shown in (E), calculated as described above. (G) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed by quantitative PCR to determine the abundance of H3K4ac at different loci in WT, hst1Δ, sir2Δ or hst1Δ sir2Δ strains. The six target regions were divided into three groups: regions targeted by Sir2, gene promoters targeted by Hst1 and other gene regions not targeted by Sir2 or Hst1. The TEL03R primers amplify a portion of ARS319, a unique sequence region approximately 1 Kb from the telomeric repeats on the right arm of chromosome III. Results are expressed as a ratio of ChIP signals obtained from the same extracts with antibodies against H3K4ac and a non-modified H3 C-terminal peptide. H3K4 deacetylation is dependent upon HST1 and SIR2

To identify potential HDACs responsible for H3K4 deacetylation we repeated our immunoblotting screen with extracts from different HDAC deletion mutants. This revealed that H3K4 deacetylation is, at least in part, dependent upon HST1 and HDA1 (Figure 2D, lanes 2 and 7). Deletion of HDA1 also led to an increase in H3K9ac, whereas the hst1Δ mutant showed an increase in H3K4ac but not H3K9ac (Figure 2D, bottom panel). Because of this, we focussed our experiments on Hst1. S. cerevisiae Hst1 is a member of a family of five NAD+-dependent HDACs, known as sirtuins because of their homology to Sir2. These enzymes are readily inhibited by nicotinamide, one of the products of the deacetylation reaction. Consistent with this, exposure of WT cells to nicotinamide caused an increase in H3K4ac (Figure S1). Treatment of hst1Δ cells with nicotinamide led to a further increase in H3K4ac (Figure S1), which suggested that other sirtuins also contribute to H3K4 deacetylation. We analysed H3K4ac in a collection of sirtuin double mutants and found that deletion of SIR2 in cells lacking Hst1 increased H3K4ac above the levels observed in WT cells and hst1Δ single mutants (Figure 2E, 2F, lanes 1-3). This suggests that SIR2 can compensate for the loss of HST1 for global deacetylation of H3K4. In S. cerevisiae, Sir2 promotes heterochromatin formation through histone deacetylation in specific chromosomal regions, namely the silent mating type loci (HMRa and HMLα ), sub-telomeric regions and a subset of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) repeats [55]. By immunoblotting whole-cell extracts, we found no global increase in H3K4ac in a sir2Δ single mutant (Figure 2D, lanes 1 and 11). We hypothesised that, in WT cells, Sir2 might deacetylate H3K4 mainly at heterochromatic loci, which represent a relatively small fraction of the genome. To test this hypothesis, we performed ChIP in WT, hst1Δ, sir2Δ and hst1Δ sir2Δ double mutant cells at different euchromatic and heterochromatic regions known to be deacetylated by Hst1 and Sir2 respectively: the promoters of BNA5 and BTN2, targeted by Hst1 [56], a sub-telomeric region (TEL03R) and the silent mating type locus HMLα, targeted by Sir2 [55]. We also analysed an origin of replication (ARS1233) and the BSC1 gene promoter, which are not known to be targeted by either Sir2 or Hst1. The sir2Δ single mutation elevated H3K4ac at the TEL03R and HMLα heterochromatic loci to levels comparable to those observed in the hst1Δ sir2Δ double mutant (Figure 2G). The deletion of HST1 had virtually no effect at these regions. We therefore conclude that H3K4 deacetylation in heterochromatic regions is solely dependent upon SIR2. Conversely, deletion of HST1 increased H3K4ac at the promoters of BNA5 and BTN2, but not at other euchromatic regions (Figure 2G). The SIR2 deletion affected H3K4ac only slightly at those loci whereas the hst1Δ sir2Δ double mutant showed higher levels of H3K4ac than in any of the single mutants (Figure 2G). This is consistent with a previous study [57] and suggests that Sir2 can also contribute to deacetylate H3K4 at Hst1-targeted loci.

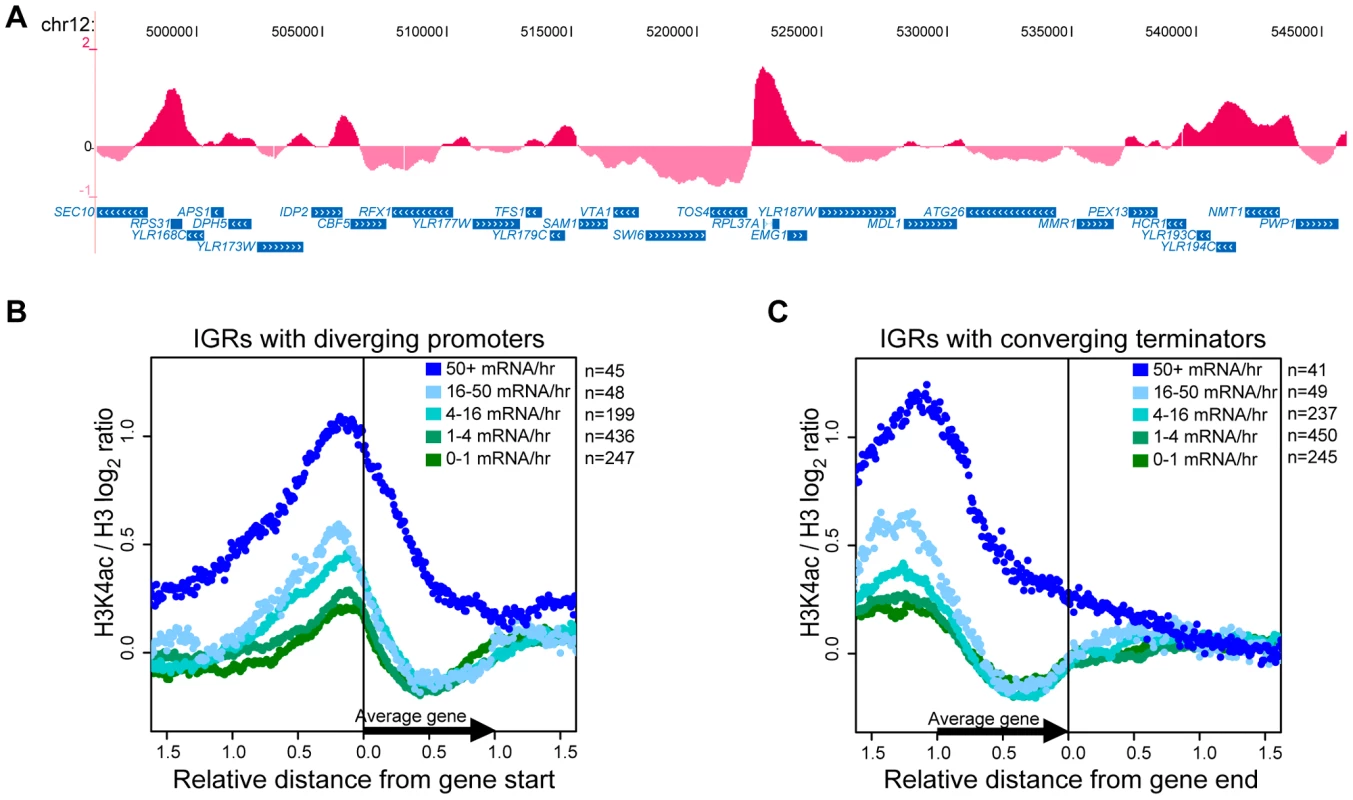

Genome-wide presence of H3K4ac in euchromatin and active promoters

To localise H3K4ac throughout the genome, DNA recovered from ChIPs was analysed with high-resolution tiling arrays (Affymetrix 1.0R). Nucleosome density was controlled by normalising H3K4ac to the results of a ChIP experiment performed from the same cell lysates using an antibody against the non-modified C-terminal tail of H3 (H3-C).

The data showed that H3K4ac peaks are distributed along all chromosomes and relatively low levels of H3K4ac are observed at most sub-telomeric regions (Figure S2). This is most apparent on chromosome III, where H3K4ac is markedly depleted in large sub-telomeric regions that encompass HMLα and HMRa (Figure S2), where Sir2 was previously shown to promote histone deacetylation. Closer manual inspection of the results using the UCSC genome browser [58] indicated that the strongest peaks of H3K4ac are located at highly transcribed genes, such as ribosomal protein genes. Two examples (RPL37A and RPS31) are highlighted in Figure 3A. We performed a systematic analysis aimed at determining whether H3K4ac was generally enriched at promoters. For this purpose, we aligned H3K4ac data derived from genes with upstream intergenic regions (IGRs) that contain divergent promoters. Based on this criterion, these IGRs are devoid of DNA sequences corresponding to 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) and transcriptional termination sequences. This analysis revealed that H3K4ac peaks slightly upstream of the 5′-ends of genes (Figure 3B). Furthermore, the degree of H3K4ac enrichment correlated with transcriptional activity (as measured in [59]). For the most highly transcribed genes (50+ mRNA/hr), H3K4ac peaks upstream and appears to spread into coding regions (Figure 3B). In less frequently transcribed genes, H3K4ac also peaks just upstream of 5′ends, but sharply drops in coding regions (Figure 3B). We performed a similar analysis for genes that have converging 3′-ends. The corresponding IGRs contain 3′-UTRs and transcriptional termination sequences, but are devoid of promoters. These chromosomal regions revealed only a modest enrichment for H3K4ac in the most highly transcribed gene group (Figure 3C, coordinates 0.0 and beyond). This effect probably results from the aforementioned spreading of H3K4ac peaks over the whole body of highly transcribed genes (compare Figure 3B and 3C). From this data, it is clear that H3K4ac peaks at gene promoters and the degree of enrichment is proportional to the rate of transcription.

Fig. 3. H3K4ac Is Enriched at Promoters of Transcribed Genes.

(A) Examples of the localisation pattern of H3K4ac along a 50 kb segment of chromosome 12, as displayed on the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) [58]. The data (purple) are represented as a log2 ratio of H3K4ac over non-modified H3 C-terminus ChIP signals and represent the average of 3 biological replicates. The names, position and orientation of ORFs (S. cerevisiae assembly Oct. 2003) are shown (blue) at the bottom of each panel. (B–C) Systematic analyses of the genome-wide location of H3K4ac / H3-C ChIP signals at: (B) 5′-ends of ORFs with divergent promoter regions. (C) 3′-ends of ORFs with convergent terminator regions. The data was aligned to the closest 5′- or 3′-end of ORFs, normalised for gene length and sub-divided into 5 groups according to transcriptional activity (mRNA/hr) [59]. For simplicity, the relative position value for each data point was rounded to the nearest hundredth. The y-axes show the abundance of H3K4ac (average of three biological replicates) as a function of relative position along the nearest gene (x-axes). H3K4ac is upstream of H3K4me3 at gene promoters

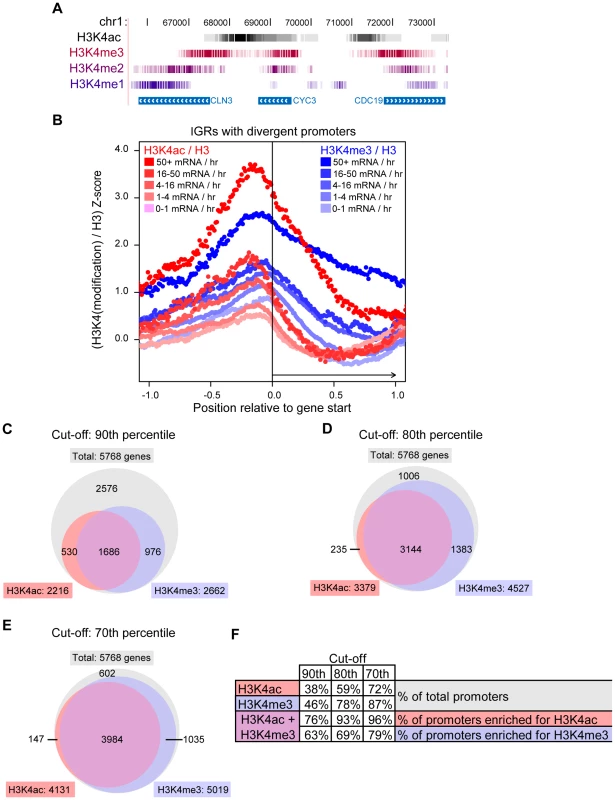

We found that H3K4ac was enriched at transcriptionally active promoters (Figure 3B) and it has been reported that H3K4me3 is also present at this location in active genes [20]. To explore the relationship between H3K4ac and H3K4me, we compared our genome-wide H3K4ac localisation data with the previously published high-resolution data for H3K4me1, -me2 and -me3 [60]. Strong peaks of H3K4ac were generally located upstream of H3K4me3 in gene promoters, followed by the typical pattern of H3K4me2 and H3K4me1 enrichment along coding regions (Figure 4A and more examples in Figure S3). There is a considerable overlap between H3K4ac with H3K4me3, although their localisation patterns are not identical. We repeated the H3K4me3 ChIP-chip under our conditions (as described for H3K4ac) and our results (data not shown) produced an enrichment pattern nearly identical to the Kirmizis et al. dataset [60]. Systematic analysis showed that H3K4me3 spreads further into coding regions than H3K4ac in moderately and highly transcribed genes (from 4 to 50+ mRNA/hr) (Figure 4B). The peak intensity for the H3K4ac signals are slightly upstream of H3K4me3 (Figure 4B), which is consistent with the UCSC track observations (Figure 4A).

Fig. 4. H3K4ac Is Located Upstream of H3K4me3.

(A) The H3K4ac / H3 (black) ChIP-chip data were aligned with the H3K4me3 (burgundy), -me2 (purple) and -me1 (blue) data from [60] and displayed in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). Each vertical line represents one probe in the dataset and the intensity of the color is proportional to the enrichment of the modification. For clarity, only the probes with a log2 ratio above 0 are shown for each dataset. (B) Systematic alignement of H3K4ac / H3 (red shades) and H3K4me3 / H3 (blue shades) ChIP-chip data at intergenic regions (IGRs) with divergent promoters (as in Figure 3B). The raw ChIP-chip data were converted into Z-scores in order to be compared on the same scale (see Material and Methods). (C–E) Venn diagrams illustrating the overlapping number of promoters that are enriched for H3K4ac or H3K4me3. The cut-off indicates the H3K4(mod) / H3-C Z-score threshold at which a given promoter was judged to be enriched in either H3K4ac or H3K4me3. For example, with a cut-off at the 90th percentile (C), the red circle contains the number of promoters that have H3K4ac / H3 signal ratios in the top 10% of the genome. (F) A table displaying the data from the Venn diagrams as percentages. To investigate whether this pattern was evolutionarily conserved, we examined the localisation of H3K4 modifications in human CD4+ lymphocytes from previously published ChIP-seq data [19], [51]. Manual inspection of the data with the UCSC genome browser revealed H3K4ac and H3K4me3 overlapping at many transcriptional start sites, but H3K4ac was slightly upstream of H3K4me3 (representative examples are shown in Figure S4). Interestingly, H3K4ac peaks also overlap with RNApol II more closely than H3K4me3 at these genes (Figure S4), suggesting a function for H3K4ac in transcriptional regulation in human cells. From these data, we conclude that H3K4ac is present at transcribed gene promoters, and is adjacent to a unidirectional gradient of H3K4me3, -me2 and -me1 that proceeds from promoters into coding regions. This pattern of H3K4 modifications has been conserved during evolution.

Genome-wide overlap of H3K4ac and H3K4me3 at promoters

To investigate and compare the proportion of promoters that are enriched in H3K4ac or H3K4me3, we transformed the log-ratio data into Z-scores (see Materials and Methods). This was performed to normalise datasets with different scales, thus allowing a direct comparison of the H3K4ac and H3K4me3 datasets. We then established a threshold value above which a promoter was judged enriched in H3K4ac or H3K4me3 relative to H3. When the cut-off was set at the 90th percentile (only promoters with enrichment values scoring in the top 10% of all values), H3K4ac was found to be enriched at 38% of all gene promoters, whereas H3K4me3 was enriched at 46% of promoters (Figure 4C and 4F). Of the promoters enriched in H3K4ac, 74% were also enriched in H3K4me3. This value increased to 93% when the cut-off was set to the top 80th percentile (Figure 4D and 4F) and 96% at the top 70th percentile (Figure 4E and 4F), indicating that most promoters enriched in H3K4ac also have a significant enrichment in H3K4me3. However, a smaller proportion of H3K4me3-enriched promoters also contain H3K4ac: 63%, 69% and 79% for the top 90th, 80th and 70th percentile cut-offs respectively (Figure 4F). From this we conclude that, genome-wide, H3K4me3 is enriched at a greater number of promoters than H3K4ac, and that most promoters which harbour H3K4ac are also enriched in H3K4me3.

Set1-mediated H3K4me2 and me3 limit the accumulation of H3K4ac

Since H3K4ac and H3K4me3 overlap considerably at the promoters of many genes, we sought to determine if there is a competition for the lysine 4 substrate. Based on mass spectrometry, we found that a SET1 deletion caused a global increase in H3K4 acetylation (Figure 5A). This result was corroborated by immunoblotting data showing that H3K4ac, but not H3K9ac was elevated in set1Δ cells (Figure 5B, 5C). The immunoblotting result truly reflected an increase in H3K4ac in set1Δ cells, rather than cross-reaction to other sites of acetylation, because no signal was observed in set1Δ H3-K4R mutant cells (Figure 5D). In addition, an H3K4ac peptide, but not H3K9ac or non-modified K4 peptides, could compete the signal observed with the K4ac antibody in WT and set1Δ cells (Figure 5E). Set1 is part of COMPASS, a complex that has multiple subunits which contribute to the different degrees of H3K4 methylation (me1, me2 or me3) [61]-[63]. To determine which subunits of COMPASS were important to limit the accumulation of H3K4ac, we performed immunoblots using strains with single gene deletions of all the COMPASS subunits. Cells lacking SET1, BRE2, SDC1, SWD3 or SWD1 have in common a complete absence of H3K4me2 and me3, but mutations of these genes differentially affect H3K4me1 (Figure 5F). For instance, bre2Δ and sdc1Δ mutants have WT levels of H3K4me1 (Figure 5F, lanes 1, 3 and 5), whereas set1Δ, swd3Δ and swd1Δ mutants lack all forms of H3K4me (lanes 2, 6 and 8). Nonetheless, relative to WT cells, all these mutants increased H3K4ac to similar degrees (Figure 5F, compare lane 1 with lanes 2, 3, 5, 6 and 8). An spp1Δ mutant with nearly normal levels of H3K4me2, but reduced H3K4me3 showed a moderate increase of H3K4ac (Figure 5F, lanes 1 and 7). In striking contrast, an shg1Δ mutant that retained normal levels of H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 did not show a significant increase in H3K4ac compared with WT cells (Figure 5F, lanes 1 and 4). These results argue that the increase in H3K4ac observed in several mutants of the COMPASS complex occurs mainly because of the absence of H3K4me2 and me3, rather than a lack of H3K4me1.

Fig. 5. The COMPASS Complex Limits Global Levels of H3K4ac and Confines H3K4ac Localisation to Promoter Regions.

(A) Extracted ion chromatogram showing the retention time of peptide 3-TKacQTAR-8 during reverse phase HPLC and its relative abundance in WT and set1Δ cells. (B–F) Whole-cell lysates from the indicated mutants were analysed by immunoblotting. In (E), a peptide competition assay was performed as described in Figure 1B. (G–H) Examples of the localisation pattern of H3K4ac in either WT (purple) or set1Δ (green) strains at two genomic regions displayed using the UCSC genome browser (genome.ucsc.edu) [58]. The data represents the normalised (Z-score) log2 ratio of H3K4ac over H3-C (see Materials and Methods). (I) Systematic analyses of H3K4ac in WT versus set1Δ cells in all intergenic regions (IGRs) that contain divergent promoters. The raw H3K4ac ChIP-chip data in WT or set1Δ cells were normalised either against their respective H3-C ChIP (black: WT, blue: set1Δ), converted into Z-scores (see Material and Methods) and aligned relative to the 5′-end of the corresponding ORF (normalised as described in Figure 3). The difference between the set1Δ and WT datasets (set1Δ - WT, green) is also shown. Since a global reduction in H3K4me2 and me3 led to an increase in H3K4ac, we wished to investigate if the opposite was also true. Immunoblots of cell lysates prepared from gcn5Δ and gcn5Δ rtt109Δ strains, with strongly reduced H3K4ac, showed no significant increase in any form of H3K4me (Figure 2B, 2C). Conversely, we observed no apparent decrease in H3K4me1, me2 or me3 in cells with elevated levels of H3K4ac (hst1Δ or hst1Δ sir2Δ, (Figure 2E, 2F). Therefore, although H3K4ac increases in mutant cells lacking H3K4me2 and me3, changes in H3K4ac do not influence global levels of H3K4 methylation. These results suggest that the relative abundance of H3K4ac does not merely reflect a simple competition for the H3K4 substrate.

Set1 regulates H3K4ac at promoters and the 5′ end of coding regions

To see if the deletion of SET1 led to a change in the genome-wide distribution of H3K4ac, we performed ChIP-chip experiments to compare the localisation of H3K4ac in set1Δ and WT cells. Manual inspection of the data in the UCSC Genome Browser revealed changes in the distribution and the relative abundance of H3K4ac in set1Δ cells, at several gene promoters. For example, at the FKH1 and SUR7 genes, H3K4ac is increased at the promoter region and spreads towards the coding region in the set1Δ strain (Figure 5G, 5H). Systematic alignment of divergent promoter regions showed that the deletion of SET1 led to a global increase in the relative abundance of H3K4ac at gene promoters (Figure 5I, blue versus black dots). We also observed a slight shift of H3K4ac towards the 5′ ends of the coding region in set1Δ cells (Figure 5I). To better assess the changes in localisation of H3K4ac in the set1Δ strain, the H3K4ac ChIP-chip data from WT cells were subtracted from those of set1Δ cells. This analysis clearly showed that the strongest difference in H3K4ac occurs at position 0 relative to gene start (Figure 5I, green dots), which corresponds to the 5′ ends of coding regions. The fact that the shoulder of the H3K4ac peak in the set1Δ strain is skewed over downstream sequences argues that this increase is not merely due to increased peak signal in set1Δ cells, since this would lead to a symmetric increase in each shoulder. Instead, this shows that, on average, H3K4ac spreads further into the 5′ ends of coding regions in set1Δ cells. We also observed a global decrease in H3K4ac at the 3′ ends of coding regions in set1Δ mutants (Figure 5I). The significance of this decrease is unknown. Nevertheless, we can conclude that the global increase in H3K4ac observed in set1Δ mutant cells by MS and immunoblotting occurs more prominently at the promoters and 5′ ends of coding regions relative to other regions.

The global average increase of H3K4ac in set1Δ cells likely occurs at a subset of genes and not all genes. Manual inspection of the datasets clearly shows that the H3K4ac pattern remains unaffected at certain genes, for example GAL80 and YML053c (Figure 5H). To provide further evidence that the increase in H3K4ac observed in the set1Δ strain did not occur equally at all genes, we performed ChIP-qPCR experiments in WT and set1Δ strains at three genes: CPA2, ARG7 and FKH1. These genes were selected because they respectively showed little, moderate and large changes in H3K4ac in set1Δ strains according to our initial observations in the UCSC Genome Browser. Our ChIP-qPCR analyses confirmed the ChIP-chip results for H3K4ac in the set1Δ strain (Figure S5A-S5C). Therefore, although the absence of H3K4me2 and me3 leads to a global increase in H3K4ac (Figure 5A, 5B), ChIP assays demonstrate that the increase in H3K4ac is more prominent at some genes than others.

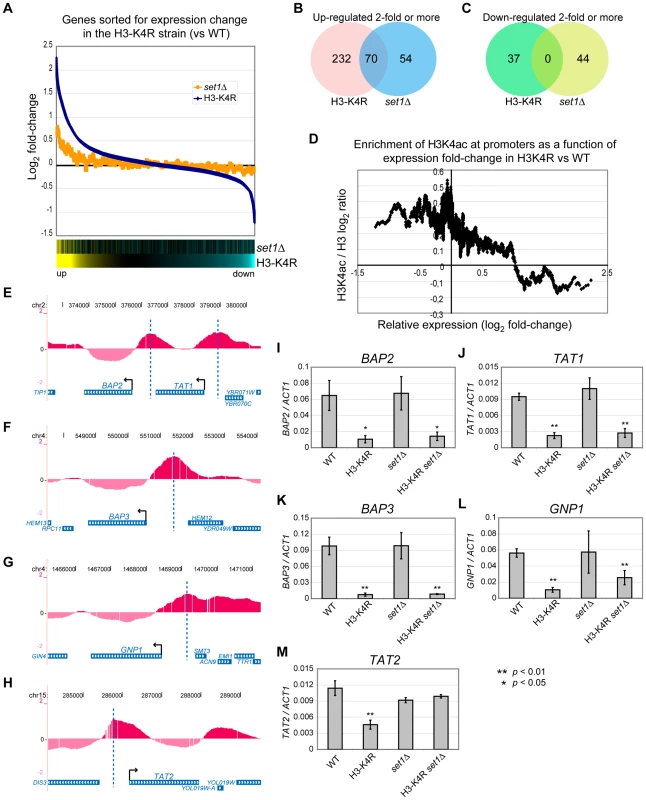

H3K4ac and gene expression

Since H3K4ac is enriched at highly transcribed gene promoters, we explored the possibility that H3K4ac might play a role in gene transcription. Genetic analysis of the function of H3K4ac is complicated by the fact that mutation of H3K4 abolishes both acetylation and methylation. To circumvent this problem, we compared the global mRNA profile of a set1Δ strain, which lacks H3K4me but retains H3K4ac, with that of an H3-K4R mutant where both H3K4 acetylation and methylation are lost. In order to get a global view of the expression profiles in both mutants, we ranked the genes by log2 fold change in mutant strains relative to WT cells (Figure 6A). At one end of the spectrum, we found many genes that are up-regulated in both the H3-K4R and the set1Δ mutant strains (Figure 6A, left part). Many of these genes are up-regulated only in H3-K4R mutant cells (Figure 6A, 6B). One possibility is that expression of some of these genes may be affected simply because of the lysine-to-arginine mutations, rather than a lack of modification. However, there is considerable overlap between the genes up-regulated in H3-K4R and set1Δ mutant strains (Figure 6B). We conclude that the repressed state of these genes in WT cells is likely to be dependent on H3K4me, rather than H3K4ac. This is consistent with previous reports showing a repressive function for SET1 [64]-[66].

Fig. 6. Global mRNA Expression Profiles of set1Δ and H3-K4R Mutant Strains.

(A) Graph of mRNA expression fold-change relative to WT cells in the H3-K4R (blue) and set1Δ (yellow) strains for all the analysed genes. The genes were ranked according to log2 fold-change in the H3-K4R strain and a sliding average (window = 50, step = 1) was applied to the data on the y-axis. The bottom panels are heat map illustrations of the log2 fold-change, where yellow indicates an increase in mRNA abundance in the mutant strains relative to WT cells and blue indicates a decrease. (B–C) Venn diagrams showing the overlap between groups of genes up-regulated (B) or down-regulated (C) at least two-fold when either the H3-K4R or the set1Δ strain is compared with WT cells. (D) Graph of the H3K4ac / H3 ratio at the promoter regions of each gene (average for from −200 to +1bp relative to the start codon) derived from the ChIP-chip data as a function of their log2 fold-change in mRNA abundance in the H3-K4R mutant strain versus WT cells (derived from the mRNA expression microarray data). A sliding window average was applied to the data on both axes (window = 50, step = 1). (E–H) Localisation of H3K4ac near genes that belong to the ontology group of “amino acid transporters” and are poorly expressed in H3-K4R mutants compared with WT cells: (BAP2/YBR068C, TAT1/YBR069C, BAP3/YDR046C, GNP1/YDR508C, TAT2/YOL020W). The start sites of these genes are indicated by arrows and vertical dashed lines indicate the peaks of H3K4ac in their upstream regions. The display is from the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). (I–M) RT-qPCR analyses of RNA extracted from the indicated strains (WT, H3-K4R, set1Δ, H3-K4R set1Δ). The values were normalised to ACT1. The data represent an average of three biological replicates. At the other end of the spectrum, we found a group of genes which were down-regulated in the H3-K4R strain, but were unaffected in the set1Δ strain (Figure 6A, right part), suggesting a positive role for H3K4ac in the expression of these genes. We identified 37 genes that were down-regulated 2-fold or more in the H3-K4R strain and 44 in the set1Δ strain. Strikingly, there was no overlap between these two groups of genes (Figure 6C), suggesting a function of H3K4 in gene expression that is independent of methylation. We next compared the H3K4ac abundance at promoter regions in WT (from our ChIP-chip dataset) with the expression change of the gene in the H3-K4R strain. The genes that are down-regulated in the H3-K4R strain have high levels of H3K4ac at their promoters in WT cells (Figure 6D), which is consistent with a direct role of H3K4ac in gene expression. Gene ontology term enrichment analysis of the genes down-regulated 2-fold or more in the H3-K4R strain, but whose expression was not affected in a set1Δ strain, identified genes encoding amino acid transporters (p = 1.42×10−5): BAP2/YBR068C, TAT1/YBR069C, BAP3/YDR046C, GNP1/YDR508C, TAT2/YOL020W. Inspection of our ChIP-chip data for these genes confirmed that they all had high levels of H3K4ac at their promoters in WT cells (Figure 6E-6H). We confirmed by RT-qPCR that these genes are down-regulated in an H3-K4R strain, but unaffected in a set1Δ strain (Figure 6I-6M). In contrast to the other RNAs that we monitored, the expression of the TAT2 RNA was unexpectedly restored in a set1Δ H3-K4R double mutant strain, suggesting an indirect effect of the SET1 deletion on this gene (Figure 6M). Taken together, our data suggest that H3K4ac has a positive and direct role in the transcription of a subset of yeast genes.

Discussion

Histone H3K4 methylation is an extensively studied modification in a wide range of organisms, and particularly in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Using MS and highly specific antibodies we demonstrated that H3K4 is also acetylated in budding yeast. An earlier study of histone modifications had shown that both H3K4ac and H3K4me exist in human, mouse and ciliates [52] and, very recently, in Schizosaccharomyces pombe [67]. The versatility of genetic tools available in S. cerevisiae, and the ability to mutate histone H3K4, has enabled us to uncover a positive function for H3K4ac in the expression of a subset of genes that carry H3K4ac in their promoters. The presence of H3K4ac at active gene promoters has been conserved in human CD4+ cells [51], which suggests a similar role for H3K4ac in gene expression in mammals. We also discovered that the COMPASS complex and H3K4me2 and me3 appear to globally limit the abundance of H3K4ac at promoters and its spreading into the 5′-coding regions of many genes.

Acetylation of the H3 N-terminal tail by specific HATs

Our targeted screen of known HAT-encoding genes has allowed us to identify GCN5 and RTT109 as responsible for H3K4ac in vivo. Gcn5 is the catalytic subunit of the ADA, SAGA, SLIK/SALSA transcriptional co-activator complexes [68] and has been highly conserved during evolution [69]. Our results are consistent with the fact that Gcn5 has been shown to acetylate multiple lysine residues within the H3 N-terminal tail [70]-[71] and is localised to active gene promoters dispersed throughout the genome [56]. Interestingly, RTT109 is also important for the acetylation of H3K4. Furthermore, the gcn5Δ rtt109Δ double mutant has markedly less H3K4ac than the single mutants. Collectively, our results indicate that GCN5 and RTT109 promote H3K4ac via different pathways and/or in different contexts. If they were fully redundant, there should be no decrease in H3K4ac in the single mutants, which is not the case. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that they may also have partially redundant functions in mediating H3K4ac. RTT109 encodes a HAT that mediates H3K56ac [72]-[75], which is involved in nucleosome assembly during DNA replication and the DNA damage response [76]-[78]. In addition, Rtt109 has recently been implicated in acetylating H3K9 and H3K27 in vivo and in vitro [54], [79]-[80]. As is the case for H3K4ac, H3K9ac and H3K27ac are virtually undetectable by immunoblotting and mass spectrometry in gcn5Δ rtt109Δ cells [79]. Therefore, the same HATs are responsible for the bulk of both H3K4 and H3K9 acetylation.

H3 N-terminal tail acetylation and gene transcription

The genome-wide localisation pattern of H3K4ac showed strong peaks at the promoters of active genes. This enrichment has also been observed in the genome-wide patterns of other acetylated lysines in the H3 N-terminal tail, such as H3K9ac, H3K14ac and H3K18ac [20]-[21], suggesting that these modifications often occur together on chromatin. Our microarray analysis identified a relatively small group of genes (37 genes down-regulated by 2-fold or more, Figure 6C) that require H3K4ac, but not H3K4me, for normal expression. However, based on our ChIP-chip data, many other promoters contain high levels of H3K4ac. It is tempting to speculate that acetylation of H3K4 functions in a partially redundant manner with other sites of acetylation at many promoters to increase accessibility to the transcriptional initiation machinery and thereby facilitate gene expression. Interestingly, our gene ontology term analyses revealed a group of amino acid transporter genes (BAP2, BAP3, TAT1, TAT2, GNP1) that are co-regulated by levels of extracellular amino acids [81]-[84]. An interesting possibility is that the transcription factors involved in their expression require H3K4ac either alone or in combination with other acetylated residues to specifically promote initiation of these genes.

Regional and functional specificity of HST1 and SIR2

We identified a role for HST1 in global deacetylation of H3K4 in euchromatin. HST1 encodes a class III HDAC found in at least two complexes. Hst1 is part of a complex with Sum1 and Rfm1 [85]-[86]. Interestingly, the deletion of SUM1 did not result in a significant global increase in H3K4ac based on immunoblotting (data not shown). Hst1 has also been found as a sub-stoichiometric subunit of the SET3 complex (SET3C) [87], which represses middle-sporulation genes during mitosis [88]. However, neither deletion of HOS2 (encoding the main HDAC in the complex) (Figure 2C), nor that of any other components of SET3C led to a global increase in H3K4ac (data not shown). Our results suggest that Hst1 might act in a non-targeted manner to promote global deacetylation of H3K4. Alternatively, Hst1 might be part of another, as yet unidentified complex involved in H3K4 deacetylation.

Interestingly, we also observed some redundancy between HST1 and SIR2 for deacetylation of H3K4 in euchromatic regions. In specific conditions, Hst1 and Sir2 have been shown to act outside of the chromosomal regions where they “normally” exert their functions. For example, overexpression of HST1, but not HST2 or HST3, can specifically compensate for the loss of silencing at HMRa that occurs in a sir2Δ mutant [89]. Our results are also consistent with studies showing a strong connection between these two genes. Both genes share 71% identity in their sequence over 84% of the length of HST1 [90]. SIR2 was previously shown to affect the expression of euchromatic genes when HTZ1 and SET1 were deleted [91] and to interfere with the firing of a number of replication origins [92]. Moreover, studies of chimaeric proteins demonstrated that the N-terminal domains of Hst1 and Sir2 control the chromosomal location and function of both proteins. In contrast, other domains of Hst1 and Sir2 could be swapped, supporting the notion that these enzymes have similar substrate specificity [93]. We propose here that H3K4 is an important target for deacetylation by both Hst1 and Sir2. HST1 and SIR2 are both part of the same phylogenetic branch (subgroup Ia) of NAD+-dependent HDACs (class III) that also includes human SIRT1 and Drosophila Sir2 [94], which are, therefore likely candidates for deacetylation of H3K4 in these organisms.

Patterns of mutually exclusive histone modifications

The relationship between H3K4ac and H3K4me differs from that of other modifications that occur on the same lysine residue. The best studied case is that of H3K9, which is either acetylated or methylated. H3K9ac and H3K9me are present at different genomic regions [51] and have opposing roles in transcriptional regulation. H3K9ac is found in promoter regions and stimulates transcription through the recruitment of TFIID [95], whereas H3K9me2 and me3 contribute to gene repression and pericentric heterochromatin structure by binding HP1 proteins through their chromo-domains [96]-[97]. In this case, deacetylation of H3K9 is essential for the establishment of H3K9 methylation [98]-[100]. Another example is H3K36ac and H3K36me3, which are respectively present in promoters and coding regions of transcriptionally active genes [101]. In contrast to these modifications, H3K4ac overlaps considerably with H3K4me3 in promoter regions. Furthermore, H3K4me2/me3 globally limit the levels of H3K4ac, which suggests the existence of mechanisms to establish the correct patterns of localisation of these mutually exclusive modifications. For example, H3K4me2/me3 could prevent H3K4ac from occurring in gene coding regions by simple competition for the H3K4 substrate. Another possibility is that H3K4 methylation might be a prerequisite step in a negative feedback loop that enables Hst1 to fine tune the levels of H3K4 acetylation in promoters and 5′-coding regions. Mechanisms that confine H3K4ac to some promoters may contribute to prevent spurious transcriptional initiation events [102] or attenuation of transcriptional initiation [66]. The potential to restrict the spreading of histone H3K4ac suggests a novel function for H3K4 methylation and reveals a previously unrecognised layer of chromatin regulation linked to the regulation of transcription in vivo.

Materials and Methods

H3K4ac antibody production and validation

Immunisation procedures and animal handling were carried out by Eurogentec. Sera from ten animals were screened prior to immunisation. Rabbits were immunised with the following peptide: ART(acetyl-K)QTARKSC. The efficiency of antibody production was monitored using ELISA. The antibody was affinity-purified using the same peptide coupled to a Sulfolink column (Thermo) and its specificity tested by dot blots with synthetic peptides and experiments where 1 µg/ml of the peptides were incubated with the antibody prior to immunoblotting.

Yeast strains and media

For most experiments, yeast strains were grown at 30°C in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose). A complete list of yeast strains is available in Table S1.

Whole-cell lysates and immunoblots

Yeast whole-cell lysates were prepared using an alkaline lysis protocol [103]. Essentially, 5×107 cells were resuspended in 500 µl of distilled water and 500 µl of 0.2 M NaOH was added. After 5 min at room temperature, cells were spun down, and resuspended in 100 µl SDS-PAGE sample buffer, boiled for 3 min and spun down again. About 7 µl (equivalent to 3.5×106 cells) of supernatant was typically loaded per lane and, after electrophoresis through an SDS-15% polyacrylamide gel, proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes using a semi-dry apparatus with in 29 mM Tris, 193 mM glycine, 0.02% SDS, 5% methanol for 2 h at 1 mA /cm2 (set maximum:15 V). We used the following dilutions for antibody incubations: anti-H3K4ac: 1/500, anti-H3-C (AbCam ab1791 or home-made): 1/10 000, anti-H3K9ac (Millipore 07-539): 1/10 000, anti-H3K56ac (Millipore 07-677): 1/5000.

Histone sample preparation and mass spectrometry

Histones were acid extracted from set1Δ hst1Δ cells essentially as described previously [104], except that we added 100 mM sodium butyrate and 100 mM nicotinamide in the nuclear isolation buffer and wash buffers. H3 was purified and digested as previously described [105]. Intact core histones (approximately 10 µg of total protein acid extract) were separated using an Agilent 1200 HPLC system equipped with a fraction collector. Separations were performed using an ACE C8 column (5 µm, 300 Å), 150×4.6 mm i.d., with a solvent system consisting of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water (v/v) (A) and 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile (v/v) (B). Gradient elution was performed from 5–70% B in 60 minutes at 0.7 ml/min. Fractions were collected in conical tubes in 60 second time slices. Individual histone peaks that eluted over multiple fractions were pooled together. Histone fractions were evaporated in a Speed-Vac. Dried fractions were resuspended in 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate (without pH adjustment) and digested overnight at 37°C using 1 µg of trypsin. Samples were acidified with 5% TFA in water (v/v) prior to LC-MS/MS analysis. Tryptic digests of histone extracts were injected onto a Thermo Electron LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer equipped with an Eksigent nanoLC separation module. Samples were loaded onto a C18 trapping column at 10 µL/min using 0.2% formic acid (v/v) in water. Peptides were eluted onto a C18 analytical column (10 cm×150 µm i.d.) at 0.6 µl/min. Gradient elution was performed using a solvent system of 0.2% formic acid in water (A), and 0.2% formic acid in acetonitrile (B). Peptides were separated by gradient elution from 0 to 70% B in 60 minutes. For mass calibration, we used an internal lock mass [protonated (Si(CH3)2O))6; m/z 445.12057]. In each data collection cycle, one full MS scan (m/z 300–2000) was acquired in the Orbitrap (60000 resolution setting, automatic gain control (AGC) target of 106), followed by 3 data-dependent MS/MS scans in the LTQ (AGC target 10000; threshold 5000) for the 3 most abundant ions and collision induced dissociation (CID) for fragmentation.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Extracts containing fragments for chromatin imunoprecipitation (ChIP) were prepared as follows. 200 ml of exponentially growing cells (O.D.600 of 0.6 to 0.8) in YPD were treated with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 minutes. Formaldehyde was quenched with 0.125 M of glycine and cells were washed three times in cold water. Pellets (approximately 1.2×109 cells) were resuspended in 1.2 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 30 mM sodium butyrate, complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail, Roche), and split into three tubes. After adding one volume of glass beads to each sample, cells were disrupted using a bead beater (Disruptor Genie, Scientific Industries) at maximal speed for 2h at 4°C. After removing the glass beads, the lysates were transferred to fresh tubes and sonicated for 15 minutes (30 seconds ON, 30 seconds OFF) at high intensity in a Bioruptor (Diagenode) connected to a water cooler at 4°C. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation and pooled into a 2 ml tube. After addition of 800 µl of fresh lysis buffer and mixing, lysates were clarified again by centrifugation. 4 µl of lysate (1% of the whole cell extract, WCE) was kept aside as an input control. For immunoprecipitation, aliquots of 400 µl were prepared for each ChIP and mixed with the appropriate antibody: either 5 µl of anti-H3K4ac, 5 µl of anti-H3-C (Abcam ab1791), 3 µl of anti-H3K4me3 (Abcam ab8580) for at least 1h at 4°C. Before use, Dynabeads M-280 coupled to sheep anti-rabbit IgG (InVitrogen) (30 µl per ChIP) were washed in lysis buffer containing 5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin. The beads were added to each lysate and incubated at 4°C for at least 1 h. Beads were washed twice with lysis buffer, twice with lysis buffer containing 500 mM NaCl, twice in wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 250 mM LiCl, 0.5% Nonidet-P40, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA) and once in TE (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA). To elute the DNA, 100 µl of a 10% Chelex 100 (Biorad) suspension in water was added to the beads (as well as to the 1% WCE) and incubated at 100°C for 10 minutes. Tubes were then cooled and treated with 0.2 µg/µl ribonuclease A at 50°C for 30 min, followed by 0.2 µg/µl proteinase K at 50°C for 30 min. Samples were incubated again at 100°C for 10 min to inactivate the proteinase K and then cooled down and spun down to get rid of debris. 80 µl of each supernatant was kept at −20°C for qPCR or ChIP-chip analysis.

ChIP-chip

All ChIP-on-chip datasets have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus [106] and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE27307 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE27307). Samples were processed according to the Affymetrix protocol for amplification, fragmentation and labelling of DNA for hybridisation to a GeneChip S. cerevisiae Tiling 1.0R Array (www.affymetrix.com). All ChIP-chips were performed in triplicate from independent colonies. Pre-processing of the data was carried out with the Affymetrix Tiling Analysis Software with default settings at 200bp bandwidth and expressed as a log2 ratio of the ChIP signal obtained for modified H3 (K4ac or K4me3) over that obtained from non-modified C-terminal H3 ChIP. The datasets used in Figure 4C and Figure 5F, 5G were normalised using the standard score (Z-score) equation: Z = (x−µ)/σ, where x is the [log2 (H3K4(mod) / H3-C)] raw value for each probe; µ is the mean raw value of all probes and σ is the standard deviation of the raw values for all probes. The resulting datasets have a normal distribution with a mean value of 0 and a standard deviation value of 1, and thus can be compared directly on the same scales. Data was displayed on the UCSC genome browser with the October 2003 S.cerevisiae genome assembly (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). Systematic alignment of ChIP-chip data to gene promoters and terminators were performed using the database management tools provided in the web application Galaxy (http://main.g2.bx.psu.edu/) and graphics were created with R (http://www.r-project.org/).

Promoter enrichment analyses and Venn diagrams

Gene promoters were defined as a genomic region −500 bp to +100 bp relative to gene start. Promoters containing Z-score values above the threshold value (90th percentile: Z>1.28 ; 80th percentile: Z>0.84 ; 70th percentile Z>0.52) were compared using the web application BioVenn (http://www.cmbi.ru.nl/cdd/biovenn/).

RNA extraction and expression analysis using microarrays

Total RNA was extracted from three independent colonies using the hot phenol method as described previously [107]. A total of 7 µg of RNA were processed for microarray analysis using the One-Cycle Target Labeling package from Affymetrix and hybridised to a GeneChip Yeast Genome 2.0 Array following the manufacturer's instructions (http://www.affymetrix.com/). Probe intensity data was pre-processed using the mas5 program of the R-Bioconductor software (http://www.bioconductor.org/index.html) [108]. The data from either H3-K4R or set1Δ mutants were normalised to their WT counterpart and the genes were sorted according to log2 fold change. The log2 fold change values for all genes are presented in Table S2 and represented graphically in Figure S6. For RT-qPCR analyses, 1 µg of total RNA was treated with DNase I, which was then inactivated following the manufacturer's instructions (DNA-free kit, Ambion). RT was performed using the First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit with M-MLV RT (Invitrogen) and oligo-dT primers, following the manufacturer's instructions.

Quantitative PCR

1 µl of the ChIP sample was mixed with 50 nM of region-specific primers and SYBR Green JumpStart Taq ReadyMix (Sigma) in a total volme of 20 µl and analysed on an Opticon real-time PCR machine (MJ Research/Bio-Rad). Relative binding values were extrapolated by subtracting the Ct of non-modified H3-C to that of modified H3 (K4ac or K4me3), and converting the ΔCt with the following formula: x = 2(−ΔCt), where x represents the relative binding value of modified H3 on non-modified H3-C.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. KouzaridesT

2007 Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128 693 705

2. SunZW

AllisCD

2002 Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates H3 methylation and gene silencing in yeast. Nature 418 104 108

3. DoverJ

SchneiderJ

Tawiah-BoatengMA

WoodA

DeanK

2002 Methylation of histone H3 by COMPASS requires ubiquitination of histone H2B by Rad6. J Biol Chem 277 28368 28371

4. FischleW

TsengBS

DormannHL

UeberheideBM

GarciaBA

2005 Regulation of HP1-chromatin binding by histone H3 methylation and phosphorylation. Nature 438 1116 1122

5. JenuweinT

AllisCD

2001 Translating the histone code. Science 293 1074 1080

6. TurnerBM

2002 Cellular memory and the histone code. Cell 111 285 291

7. TrelleMB

JensenON

2007 Functional proteomics in histone research and epigenetics. Expert Rev Proteomics 4 491 503

8. BrumbaughJ

PhanstielD

CoonJJ

2008 Unraveling the histone's potential: a proteomics perspective. Epigenetics 3 254 257

9. ZhangL

EugeniEE

ParthunMR

FreitasMA

2003 Identification of novel histone post-translational modifications by peptide mass fingerprinting. Chromosoma 112 77 86

10. ShilatifardA

2008 Molecular implementation and physiological roles for histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methylation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20 341 348

11. RuthenburgAJ

AllisCD

WysockaJ

2007 Methylation of lysine 4 on histone H3: intricacy of writing and reading a single epigenetic mark. Mol Cell 25 15 30

12. BernsteinBE

HumphreyEL

ErlichRL

SchneiderR

BoumanP

2002 Methylation of histone H3 Lys 4 in coding regions of active genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 8695 8700

13. StrahlBD

OhbaR

CookRG

AllisCD

1999 Methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 is highly conserved and correlates with transcriptionally active nuclei in Tetrahymena. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 14967 14972

14. SchneiderR

BannisterAJ

MyersFA

ThorneAW

Crane-RobinsonC

2003 Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation patterns in higher eukaryotic genes. Nat Cell Biol

15. SchubelerD

MacAlpineDM

ScalzoD

WirbelauerC

KooperbergC

2004 The histone modification pattern of active genes revealed through genome-wide chromatin analysis of a higher eukaryote. Genes Dev 18 1263 1271

16. Santos-RosaH

SchneiderR

BannisterAJ

SherriffJ

BernsteinBE

2002 Active genes are tri-methylated at K4 of histone H3. Nature 419 407 411

17. GuentherMG

LevineSS

BoyerLA

JaenischR

YoungRA

2007 A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell 130 77 88

18. NgHH

RobertF

YoungRA

StruhlK

2003 Targeted recruitment of Set1 histone methylase by elongating Pol II provides a localized mark and memory of recent transcriptional activity. Mol Cell 11 709 719

19. BarskiA

CuddapahS

CuiK

RohTY

SchonesDE

2007 High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129 823 837

20. PokholokDK

HarbisonCT

LevineS

ColeM

HannettNM

2005 Genome-wide Map of Nucleosome Acetylation and Methylation in Yeast. Cell 122 517 527

21. LiuCL

KaplanT

KimM

BuratowskiS

SchreiberSL

2005 Single-Nucleosome Mapping of Histone Modifications in S. cerevisiae. PLoS Biol 3 e328 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030328

22. ZhangX

BernatavichuteYV

CokusS

PellegriniM

JacobsenSE

2009 Genome-wide analysis of mono-, di - and trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol 10 R62

23. FlanaganJF

MiLZ

ChruszczM

CymborowskiM

ClinesKL

2005 Double chromodomains cooperate to recognize the methylated histone H3 tail. Nature 438 1181 1185

24. WysockaJ

SwigutT

XiaoH

MilneTA

KwonSY

2006 A PHD finger of NURF couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with chromatin remodelling. Nature 442 86 90

25. LiH

IlinS

WangW

DuncanEM

WysockaJ

2006 Molecular basis for site-specific read-out of histone H3K4me3 by the BPTF PHD finger of NURF. Nature 442 91 95

26. ShiX

HongT

WalterKL

EwaltM

MichishitaE

2006 ING2 PHD domain links histone H3 lysine 4 methylation to active gene repression. Nature 442 96 99

27. MartinDG

BaetzK

ShiX

WalterKL

MacDonaldVE

2006 The Yng1p plant homeodomain finger is a methyl-histone binding module that recognizes lysine 4-methylated histone H3. Mol Cell Biol 26 7871 7879

28. ShiX

KachirskaiaI

WalterKL

KuoJH

LakeA

2007 Proteome-wide analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae identifies several PHD fingers as novel direct and selective binding modules of histone H3 methylated at either lysine 4 or lysine 36. J Biol Chem 282 2450 2455

29. LanF

CollinsRE

De CegliR

AlpatovR

HortonJR

2007 Recognition of unmethylated histone H3 lysine 4 links BHC80 to LSD1-mediated gene repression. Nature 448 718 722

30. MatthewsAG

KuoAJ

Ramon-MaiquesS

HanS

ChampagneKS

2007 RAG2 PHD finger couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with V(D)J recombination. Nature 450 1106 1110

31. VermeulenM

MulderKW

DenissovS

PijnappelWW

van SchaikFM

2007 Selective anchoring of TFIID to nucleosomes by trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4. Cell 131 58 69

32. SimsRJ3rd

MillhouseS

ChenCF

LewisBA

Erdjument-BromageH

2007 Recognition of trimethylated histone H3 lysine 4 facilitates the recruitment of transcription postinitiation factors and pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell 28 665 676

33. TavernaSD

IlinS

RogersRS

TannyJC

LavenderH

2006 Yng1 PHD finger binding to H3 trimethylated at K4 promotes NuA3 HAT activity at K14 of H3 and transcription at a subset of targeted ORFs. Mol Cell 24 785 796

34. OoiSK

QiuC

BernsteinE

LiK

JiaD

2007 DNMT3L connects unmethylated lysine 4 of histone H3 to de novo methylation of DNA. Nature 448 714 717

35. HuangY

FangJ

BedfordMT

ZhangY

XuRM

2006 Recognition of histone H3 lysine-4 methylation by the double tudor domain of JMJD2A. Science 312 748 751

36. PenaPV

DavrazouF

ShiX

WalterKL

VerkhushaVV

2006 Molecular mechanism of histone H3K4me3 recognition by plant homeodomain of ING2. Nature 442 100 103

37. Santos-RosaH

SchneiderR

BernsteinBE

KarabetsouN

MorillonA

2003 Methylation of histone H3 K4 mediates association of the Isw1p ATPase with chromatin. Mol Cell 12 1325 1332

38. RoguevA

SchaftD

ShevchenkoA

PijnappelWW

WilmM

2001 The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Set1 complex includes an Ash2 homologue and methylates histone 3 lysine 4. Embo J 20 7137 7148

39. KroganNJ

DoverJ

KhorramiS

GreenblattJF

SchneiderJ

2002 COMPASS, a histone H3 (Lysine 4) methyltransferase required for telomeric silencing of gene expression. J Biol Chem 277 10753 10755

40. MillerT

KroganNJ

DoverJ

Erdjument-BromageH

TempstP

2001 COMPASS: a complex of proteins associated with a trithorax-related SET domain protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 12902 12907

41. BriggsSD

BrykM

StrahlBD

CheungWL

DavieJK

2001 Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation is mediated by Set1 and required for cell growth and rDNA silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev 15 3286 3295

42. NagyPL

GriesenbeckJ

KornbergRD

ClearyML

2002 A trithorax-group complex purified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required for methylation of histone H3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 90 94

43. Vitaliano-PrunierA

MenantA

HobeikaM

GeliV

GwizdekC

2008 Ubiquitylation of the COMPASS component Swd2 links H2B ubiquitylation to H3K4 trimethylation. Nat Cell Biol 10 1365 1371

44. DehePM

GeliV

2006 The multiple faces of Set1. Biochem Cell Biol 84 536 548

45. JiangL

SmithJN

AndersonSL

MaP

MizzenCA

2007 Global assessment of combinatorial post-translational modification of core histones in yeast using contemporary mass spectrometry. LYS4 trimethylation correlates with degree of acetylation on the same H3 tail. J Biol Chem 282 27923 27934

46. ZhangK

SiinoJS

JonesPR

YauPM

BradburyEM

2004 A mass spectrometric “Western blot” to evaluate the correlations between histone methylation and histone acetylation. Proteomics 4 3765 3775

47. NightingaleKP

GendreizigS

WhiteDA

BradburyC

HollfelderF

2007 Cross-talk between histone modifications in response to histone deacetylase inhibitors: MLL4 links histone H3 acetylation and histone H3K4 methylation. J Biol Chem 282 4408 4416

48. YoungNL

DimaggioPA

Plazas-MayorcaMD

BalibanRC

FloudasCA

2009 High-throughput characterization of combinatorial histone codes. Mol Cell Proteomics

49. HazzalinCA

MahadevanLC

2005 Dynamic acetylation of all lysine 4-methylated histone H3 in the mouse nucleus: analysis at c-fos and c-jun. PLoS Biol 3 e393 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030393

50. KimT

BuratowskiS

2009 Dimethylation of H3K4 by Set1 recruits the Set3 histone deacetylase complex to 5′ transcribed regions. Cell 137 259 272

51. WangZ

ZangC

RosenfeldJA

SchonesDE

BarskiA

2008 Combinatorial patterns of histone acetylations and methylations in the human genome. Nat Genet 40 897 903

52. GarciaBA

HakeSB

DiazRL

KauerM

MorrisSA

2007 Organismal differences in post-translational modifications in histones H3 and H4. J Biol Chem 282 7641 7655

53. SukaN

SukaY

CarmenAA

WuJ

GrunsteinM

2001 Highly specific antibodies determine histone acetylation site usage in yeast heterochromatin and euchromatin. Mol Cell 8 473 479

54. FillinghamJ

RechtJ

SilvaAC

SuterB

EmiliA

2008 Chaperone control of the activity and specificity of the histone H3 acetyltransferase Rtt109. Mol Cell Biol 28 4342 4353

55. RuscheLN

KirchmaierAL

RineJ

2003 The establishment, inheritance, and function of silenced chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Biochem 72 481 516

56. RobertF

PokholokDK

HannettNM

RinaldiNJ

ChandyM

2004 Global position and recruitment of HATs and HDACs in the yeast genome. Mol Cell 16 199 209

57. HickmanMA

RuscheLN

2007 Substitution as a mechanism for genetic robustness: the duplicated deacetylases Hst1p and Sir2p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet 3 e126 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030126

58. KarolchikD

BaertschR

DiekhansM

FureyTS

HinrichsA

2003 The UCSC Genome Browser Database. Nucleic Acids Res 31 51 54

59. HolstegeFC

JenningsEG

WyrickJJ

LeeTI

HengartnerCJ

1998 Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell 95 717 728

60. KirmizisA

Santos-RosaH

PenkettCJ

SingerMA

VermeulenM

2007 Arginine methylation at histone H3R2 controls deposition of H3K4 trimethylation. Nature 449 928 932

61. DehePM

DichtlB

SchaftD

RoguevA

PamblancoM

2006 Protein interactions within the Set1 complex and their roles in the regulation of histone 3 lysine 4 methylation. J Biol Chem 281 35404 35412

62. SchneiderJ

WoodA

LeeJS

SchusterR

DuekerJ

2005 Molecular regulation of histone H3 trimethylation by COMPASS and the regulation of gene expression. Mol Cell 19 849 856

63. MorillonA

KarabetsouN

NairA

MellorJ

2005 Dynamic lysine methylation on histone H3 defines the regulatory phase of gene transcription. Mol Cell 18 723 734

64. DietvorstJ

BrandtA

2008 Flocculation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is repressed by the COMPASS methylation complex during high-gravity fermentation. Yeast 25 891 901

65. CarvinCD

KladdeMP

2004 Effectors of lysine 4 methylation of histone H3 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are negative regulators of PHO5 and GAL1-10. J Biol Chem 279 33057 33062

66. PinskayaM

GourvennecS

MorillonA

2009 H3 lysine 4 di - and tri-methylation deposited by cryptic transcription attenuates promoter activation. Embo J 28 1697 1707

67. XhemalceB

KouzaridesT

2010 A chromodomain switch mediated by histone H3 Lys 4 acetylation regulates heterochromatin assembly. Genes Dev 24 647 652

68. BakerSP

GrantPA

2007 The SAGA continues: expanding the cellular role of a transcriptional co-activator complex. Oncogene 26 5329 5340

69. NagyZ

ToraL

2007 Distinct GCN5/PCAF-containing complexes function as co-activators and are involved in transcription factor and global histone acetylation. Oncogene 26 5341 5357

70. VogelauerM

WuJ

SukaN

GrunsteinM

2000 Global histone acetylation and deacetylation in yeast. Nature 408 495 498

71. ZhangW

BoneJR

EdmondsonDG

TurnerBM

RothSY

1998 Essential and redundant functions of histone acetylation revealed by mutation of target lysines and loss of the Gcn5p acetyltransferase. Embo J 17 3155 3167

72. CollinsSR

MillerKM

MaasNL

RoguevA

FillinghamJ

2007 Functional dissection of protein complexes involved in yeast chromosome biology using a genetic interaction map. Nature 446 806 810

73. HanJ

ZhouH

HorazdovskyB

ZhangK

XuRM

2007 Rtt109 acetylates histone H3 lysine 56 and functions in DNA replication. Science 315 653 655

74. DriscollR

HudsonA

JacksonSP

2007 Yeast Rtt109 promotes genome stability by acetylating histone H3 on lysine 56. Science 315 649 652

75. SchneiderJ

BajwaP

JohnsonFC

BhaumikSR

ShilatifardA

2006 Rtt109 is required for proper H3K56 acetylation: a chromatin mark associated with the elongating RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem 281 37270 37274

76. LiQ

ZhouH

WurteleH

DaviesB

HorazdovskyB

2008 Acetylation of histone H3 lysine 56 regulates replication-coupled nucleosome assembly. Cell 134 244 255

77. ChenCC

CarsonJJ

FeserJ

TamburiniB

ZabaronickS

2008 Acetylated lysine 56 on histone H3 drives chromatin assembly after repair and signals for the completion of repair. Cell 134 231 243

78. MasumotoH

HawkeD

KobayashiR

VerreaultA

2005 A role for cell-cycle-regulated histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation in the DNA damage response. Nature 436 294 298

79. TangY

HolbertMA

DelgoshaieN

WurteleH

GuillemetteB

2011 Structure of the Rtt109-AcCoA/Vps75 Complex and Implications for Chaperone-Mediated Histone Acetylation. Structure 19 221 231

80. BurgessRJ

ZhouH

HanJ

ZhangZ

2010 A role for Gcn5 in replication-coupled nucleosome assembly. Mol Cell 37 469 480

81. DidionT

RegenbergB

JorgensenMU

Kielland-BrandtMC

AndersenHA

1998 The permease homologue Ssy1p controls the expression of amino acid and peptide transporter genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol 27 643 650

82. NielsenPS

van den HazelB

DidionT

de BoerM

JorgensenM

2001 Transcriptional regulation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae amino acid permease gene BAP2. Mol Gen Genet 264 613 622

83. SchmidtA

HallMN

KollerA

1994 Two FK506 resistance-conferring genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, TAT1 and TAT2, encode amino acid permeases mediating tyrosine and tryptophan uptake. Mol Cell Biol 14 6597 6606

84. ZhuX

GarrettJ

SchreveJ

MichaeliT

1996 GNP1, the high-affinity glutamine permease of S. cerevisiae. Curr Genet 30 107 114

85. RuscheLN

RineJ

2001 Conversion of a gene-specific repressor to a regional silencer. Genes Dev 15 955 967

86. McCordR

PierceM

XieJ

WonkatalS

MickelC

2003 Rfm1, a novel tethering factor required to recruit the Hst1 histone deacetylase for repression of middle sporulation genes. Mol Cell Biol 23 2009 2016

87. PijnappelWW

SchaftD

RoguevA

ShevchenkoA

TekotteH

2001 The S. cerevisiae SET3 complex includes two histone deacetylases, Hos2 and Hst1, and is a meiotic-specific repressor of the sporulation gene program. Genes Dev 15 2991 3004

88. XieJ

PierceM

Gailus-DurnerV

WagnerM

WinterE

1999 Sum1 and Hst1 repress middle sporulation-specific gene expression during mitosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Embo J 18 6448 6454

89. BrachmannCB

ShermanJM

DevineSE

CameronEE

PillusL

1995 The SIR2 gene family, conserved from bacteria to humans, functions in silencing, cell cycle progression, and chromosome stability. Genes Dev 9 2888 2902

90. DerbyshireMK

WeinstockKG

StrathernJN

1996 HST1, a new member of the SIR2 family of genes. Yeast 12 631 640

91. VenkatasubrahmanyamS

HwangWW

MeneghiniMD

TongAH

MadhaniHD

2007 Genome-wide, as opposed to local, antisilencing is mediated redundantly by the euchromatic factors Set1 and H2A.Z. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 16609 16614

92. CramptonA

ChangF

PappasDLJr

FrischRL

WeinreichM

2008 An ARS element inhibits DNA replication through a SIR2-dependent mechanism. Mol Cell 30 156 166

93. MeadJ

McCordR

YoungsterL

SharmaM

GartenbergMR

2007 Swapping the gene-specific and regional silencing specificities of the Hst1 and Sir2 histone deacetylases. Mol Cell Biol 27 2466 2475

94. FryeRA

2000 Phylogenetic classification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic Sir2-like proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 273 793 798

95. AgaliotiT

ChenG

ThanosD

2002 Deciphering the transcriptional histone acetylation code for a human gene. Cell 111 381 392

96. LachnerM

O'CarrollD

ReaS

MechtlerK

JenuweinT

2001 Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 creates a binding site for HP1 proteins. Nature 410 116 120

97. BannisterAJ

ZegermanP

PartridgeJF

MiskaEA

ThomasJO

2001 Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature 410 120 124

98. ShankaranarayanaGD

MotamediMR

MoazedD

GrewalSI

2003 Sir2 regulates histone H3 lysine 9 methylation and heterochromatin assembly in fission yeast. Curr Biol 13 1240 1246

99. NakayamaJ

RiceJC

StrahlBD

AllisCD

GrewalSI

2001 Role of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in epigenetic control of heterochromatin assembly. Science 292 110 113

100. ReaS

EisenhaberF

O'CarrollD

StrahlBD

SunZW

2000 Regulation of chromatin structure by site-specific histone H3 methyltransferases. Nature 406 593 599

101. MorrisSA

RaoB

GarciaBA

HakeSB

DiazRL

2007 Identification of histone H3 lysine 36 acetylation as a highly conserved histone modification. J Biol Chem 282 7632 7640

102. PinskayaM

MorillonA

2009 Histone H3 lysine 4 di-methylation: A novel mark for transcriptional fidelity? Epigenetics 4

103. KushnirovVV

2000 Rapid and reliable protein extraction from yeast. Yeast 16 857 860

104. EdmondsonDG

SmithMM

RothSY

1996 Repression domain of the yeast global repressor Tup1 interacts directly with histones H3 and H4. Genes Dev 10 1247 1259

105. DrogarisP

WurteleH

MasumotoH

VerreaultA

ThibaultP

2008 Comprehensive profiling of histone modifications using a label-free approach and its applications in determining structure-function relationships. Anal Chem 80 6698 6707

106. EdgarR

DomrachevM

LashAE

2002 Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res 30 207 210

107. SchmittME

BrownTA

TrumpowerBL

1990 A rapid and simple method for preparation of RNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res 18 3091 3092

108. GentlemanRC

CareyVJ

BatesDM

BolstadB

DettlingM

2004 Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol 5 R80

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Genetic Regulation by NLA and MicroRNA827 for Maintaining Nitrate-Dependent Phosphate Homeostasis inČlánek c-di-GMP Turn-Over in Is Controlled by a Plethora of Diguanylate Cyclases and Phosphodiesterases

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden