-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

Reklamais a Long Non-coding RNA in JNK Signaling in Epithelial Shape Changes during Drosophila Dorsal Closure

Changes in cell shape affect many critical cellular and bodily processes, like wound healing and developmental events, and when gone awry, metastatic processes in cancer. Evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways govern regulation of these cellular changes. The Jun-N-terminal kinase pathway regulates cell stretching during wound healing and normal development. An extensively studied developmental process is embryonic dorsal closure in fruit flies, a well-established model for the regulation and manner of this cell shape changes. Here we describe and characterize a processed, long non-coding RNA locus, acal, that adds a new layer of complexity to the Jun-N-terminal kinase signaling, acting as a negative regulator of the pathway. acal modulates the expression of two key genes in the pathway: the scaffold protein Cka, and the transcription factor Aop. Together, they enable the proper level of Jun-N-terminal kinase pathway activation to occur to allow cell stretching and closure.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004927

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004927Summary

Changes in cell shape affect many critical cellular and bodily processes, like wound healing and developmental events, and when gone awry, metastatic processes in cancer. Evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways govern regulation of these cellular changes. The Jun-N-terminal kinase pathway regulates cell stretching during wound healing and normal development. An extensively studied developmental process is embryonic dorsal closure in fruit flies, a well-established model for the regulation and manner of this cell shape changes. Here we describe and characterize a processed, long non-coding RNA locus, acal, that adds a new layer of complexity to the Jun-N-terminal kinase signaling, acting as a negative regulator of the pathway. acal modulates the expression of two key genes in the pathway: the scaffold protein Cka, and the transcription factor Aop. Together, they enable the proper level of Jun-N-terminal kinase pathway activation to occur to allow cell stretching and closure.

Introduction

A large fraction of the eukaryotic genome codes for non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), which are very abundant and diverse, yet mostly uncharacterized and of unknown functions [1,2]. Nevertheless, some are critical players in gene expression regulation. Non-coding RNAs encompass different classes of molecules. The best-characterized ncRNAs are small RNAs. Broadly, small RNAs recruit silencing machinery to mRNAs to inhibit translation and/or target them for degradation [3]. Small ncRNAs characterization was facilitated because they base-pair with cognate mRNA targets, and interact with common protein complexes to regulate gene expression [4].

In contrast, long non coding RNAs (lncRNAs) encode a diverse group of ncRNAs, which may be part of different molecular complexes, and can stimulate or inhibit gene expression [5]. Recognized lncRNAs range from 200 nucleotides to several kilobases [6]. Since they do not have evident sequence motifs for annotation, their identification and relevance has remained elusive. In addition, many have low expression levels, hindering isolation and characterization. Next-generation RNA sequencing uncovered many lncRNAs (over 50% of transcribed species [2,7]), increasing dramatically their number and repertoire [8]. Despite this, in most cases contribution of lncRNAs to gene expression regulation or other still awaits genetic and functional validation.

In Drosophila melanogaster some lncRNAs have been annotated [9], and play important roles in gene expression, as in vertebrates [10]. In spite of extensive genetic screens, forward genetics identification of lncRNAs has been very limited, as they are found to fine-tune gene expression with mild phenotypical contributions.

Here we characterize a Drosophila lncRNA with strong embryonic phenotypes and lethality. Mutations in this locus, acal, result in partially penetrant dorsal closure (DC) defects due to Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling over-activation. This results in failure of DC, leading to a lethal dorsal open phenotype.

During DC, lateral epidermal sheets stretch over a dorsal extra-embryonic cell layer, the amnioserosa, and fuse at the dorsal midline [11]. The JNK signaling pathway regulates DC, and is activated at the dorsalmost row of epidermal cells, the leading edge cells (LE), which act as a signaling center for DC ([12], reviewed in [13]).

In these epidermal cells, JNK activation induces expression of cytoskeleton and adhesion regulators for cell stretching [14]. JNK activation at the LE spreads the morphogenetic rearrangement by inducing the signaling ligand decapentaplegic (dpp), a fly homolog of vertebrate BMPs. Dpp signals to lateral epidermal cells and amnioserosa to promote cell shape changes [15,16]. This response induces stretching of lateral epithelia in absence of cell proliferation, and final zippering.

It is not known how JNK activation is triggered at the LE, nor completely known how LE restriction occurs. The JNK signaling pathway is an evolutionarily conserved, MAPK-type signaling pathway. It consists, at its core, of a cascade of kinases, from JN4K (the gene misshapen in flies), to JN3K (slipper), JN2K (hemipterous), and finally JNK proper (basket). Activated JNK–bound to a scaffold protein called Connector of kinase to AP1 (Cka)–, phosphorylates the transcription factor Jra (Drosophila Jun). Jra, together with Kayak (Drosophila Fos), constitute the AP-1 transcription complex activating JNK target genes. Besides Jra, JNK also phosphorylates Anterior open (Aop), leading to Aop nuclear export, de-repressing JNK target genes. The JNK pathway is required for orchestration of embryonic dorsal closure, but also for wound healing and in response to certain stressful conditions [13].

During DC JNK activity is restrained from the lateral epidermis partly by aop, although this transcription factor also functions earlier in the tissue in a positive way by promoting epidermis differentiation, preventing ectopic mitoses [15]. The ‘raw-group genes’: raw, a pioneer protein, and ribbon, a transcription factor (rib, [17,18]) also restrict JNK activation in the lateral epithelia. Another member, puckered (puc), coding for a JNK phosphatase, acts in a feedback loop in the LE, dephosphorylating active JNK, and stopping signaling. JNK activation is also antagonized in the amnioserosa by pebbled (peb), which codes for a transcription factor [19].

We show here that acal lncRNA partly mediates Raw JNK signaling antagonism in the lateral epidermis. acal partakes in regulating expression of the scaffold protein Cka [20]. This explains partly raw function (raw as an acal regulator), and provides a framework for JNK activity down-regulation at the lateral epidermis during DC. We find that mutations in acal also alter the expression of aop, balancing JNK activation. acal also shows a genetic interaction with Polycomb, suggesting a relationship between acal and the Polycomb repressive complex. Overall, this provides a rationale for acal DC phenotypes.

Results

acal is a novel ‘dorsal open’ gene

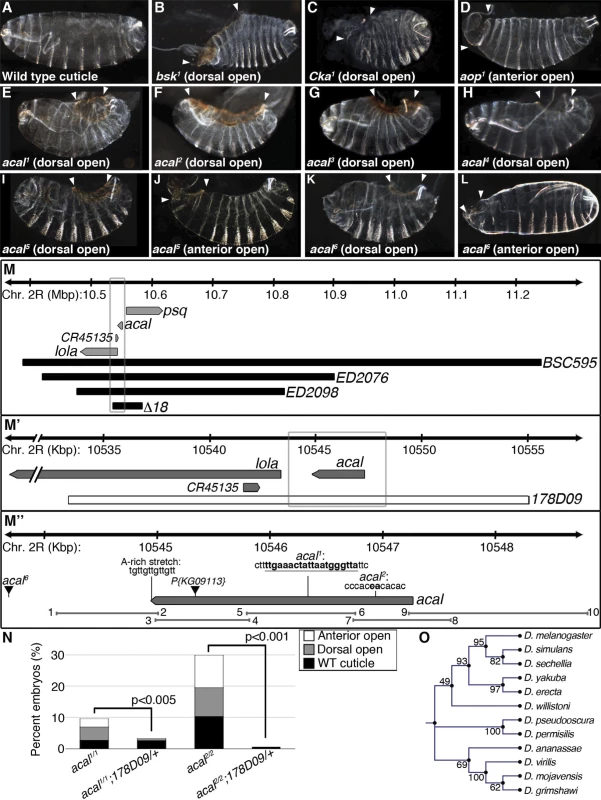

Mutations in fly JNK signaling genes—like bsk, the fly JNK gene [12], Cka [20], and aop [15]—lead to an embryonic lethal condition with a dorsal hole in the cuticle (Fig. 1B–D). This ‘dorsal open’ phenotype has been used to identify JNK and other DC genes [13].

We identified a lethal locus where a fraction of mutant embryos die with dorsal closure defects. We called it acal, or ‘boat’ in Náhuatl, due to the cuticular appearance of mutants. Two alleles, acal1 and acal2(Fig. 1E–F), are lethal excisions of P{KG09113}, a viable and fertile P-element transposon insertion at 47A13 (Fig. 1M’’). Three more EMS alleles were isolated over acal1 and acal2 by lack of complementation (acal3, acal4, and acal5, Fig. 1G–J). A sixth lethal mutant allele is a mapped P element insertion in the locus, P{GS325ND3} (Fig. 1K-L and M’’). All mutations are lethal, with embryonic, larval, and pupal phenocritical periods. No adults are ever observed. A fraction of mutant embryos have DC defects, with holes in either the dorsal or anterior ends of embryos (Figs. 1E–L and S1A). Dorsal or anterior holes are the only cuticular defects seen in these mutants.

Fig. 1. Molecular and genetic characterization of acal mutants.

(A-L) Cuticular analysis of DC defects. In all figures, embryos are shown in a lateral view, with dorsal up and anterior left. Arrowheads show extent of cuticular holes. (A) Wild type cuticle. (B-D) bsk1 (JNK), Cka1, and aop1 mutant phenotypes. (E-L) acal mutants. (M-M’’) Schematic representation of the acal locus. (M) Deficiencies used to map acal mutants to the intergenic region between lola and psq (for simplicity, other genes are not depicted). Boxed area in (M) is amplified in (M’). (M’) The genomic rescue construct,178D09, spans the full acal genomic region, CR45135, and a small part of lola 5’. Boxed area in (M’) is amplified in (M’’). (M’’) Parental insertion P{KG09113} for acal1 and acal2 and insertion site of acal6 are shown. Molecular lesions of acal1 and acal2 are highlighted in bold. A putative poly-adenylation site is also depicted. Primer pairs numbers and amplicons used to sequence mutant alleles are also depicted. (N) A genomic rescue transgene significantly suppresses acal DC mutant phenotypes. Only mutant embryos with cuticle defects are shown, mutants surviving embryogenesis are not depicted (and constitute the open space above bars to amount to a hundred percent). In this and all figures, unless noted, mutant embryos were selected by lack of GFP expression, present in control embryos (possessing balancer chromosomes that express GFP). Number of animals analyzed: acal1/1 = 217, acal1/1;178D09 = 314, acal2/2 = 192, acal2/2;178D09 = 159. Chi square tests were used to assess significance. (O) Similarity tree of acal homologs among some sequenced Drosophilids. Bootstrap values are shown. Further genetic characterization is shown in S1 Fig. acal mutants have an extended phenocritical period, since a fraction of mutant embryos die without cuticular defects, and finally another fraction of mutant embryos survive embryogenesis and die later during larval stages up to the beginning of pupariation. This means that acal is required at various times during development. Larval lethality varies from 10 to 50% depending on the allele studied, and pupal death from 3 to 40%. As stated, no adult homozygous mutant flies are ever recovered, except 1–2% adult acal6 escapers. In this work, we focus on the embryonic mutant phenotypes. Using these embryonic phenotypes, mutant alleles conform to an allelic series with acal5 as the strongest, and acal1 as the weakest (S1A Fig.).

acal maps to an intergenic unannotated region and to SD08925

We used deficiencies uncovering P{KG09113} to map acal in complementation tests, and established a 100 kb interval where acal maps. This interval includes three annotated genes: longitudinals lacking (lola), pipsqueak (psq), and CR45135 (Fig. 1M). acal mutations complement lola and psq alleles (S1 Table). Besides, lola and psq have different embryonic mutant phenotypes from acal, with no cuticular phenotypes, like dorsal or anterior holes ([21,22] and S7A Fig.). CR45135 is not characterized, but partially overlaps a lola exon, so CR45135 mutations should affect lola. Moreover, many lola lethal insertions overlap this gene [23].

A previous report showed that there is at least another locus whose mutation complements lola and psq, despite being unannotated [24]. This mutation, l(2)00297, suppresses the peb1 heat-shock sensitive rough eye phenotype. acal mutant alleles also suppress, in our experimental conditions, this subtle but clear phenotype (S1B Fig.). This suggests that acal and l(2)00297 are allelic, and is independent evidence of a lethal locus between lola and psq.

Another paper independently reports the existence of a long non-coding transcript approximately 4 kb from the start of lola [21]. The size of this transcript is stated as 4 kb, but this was an approximation, as the evidence supports a maximum size of 3.4 Kb, since this cDNA hybridized to a 2.8 and a 0.6 Kb neighboring restriction fragments in Southern blots ([21], and Edward Giniger, personal communication).

An EST in Flybase, SD08925, sequenced partially at the 5’ end, maps 3.8 kb away from lola, precisely where Giniger et al. report the location of their ‘alpha’ long non-coding transcript [21]. We believe this transcript is the same as SD08925. We sequenced fully this EST (Genbank accession number # KJ598082). SD08925 is 2.3 kb long, poly-adenylated, and a single exon. Its genomic 3’ end bears an A-rich stretch (Fig. 1M’’), characteristic of poly-adenylation sites [25]. We also obtained a 2.3 kb weak Northern blot signal (compared to control Rp49), demonstrating SD08925 expression, and confirming that SD08925 is a full-length cDNA. This band was detected throughout the life cycle and was nearly absent in the ∆18 deficiency strain uncovering the locus by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (S1C-D Fig.). Consistent with the weak Northern signal, RNA-seq and microarray data show low SD08925 expression levels [26,27].

We sequenced 4.7 kb of the SD08925 genomic region in acal mutant and control lines. In these and following experiments, we selected and separated mutant embryos from heterozygous controls by lack of embryonic GFP-expression due to a balancer chromosome (see Materials and Methods). Within this region, we found a 20 base pair insertion in acal1. The acal1 lesion is 1031 bp away from P{KG09113}, at +931 of the cDNA, a position conserved in closely related species. Similarly, we found a 2 bp deletion 1630 bp away from P{KG09113} within the 5’ end of SD08925 in acal2, in a conserved region. In acal5 SD08925 expression is significantly reduced(Fig. 1M’’, Fig. 2A and D and 3A).

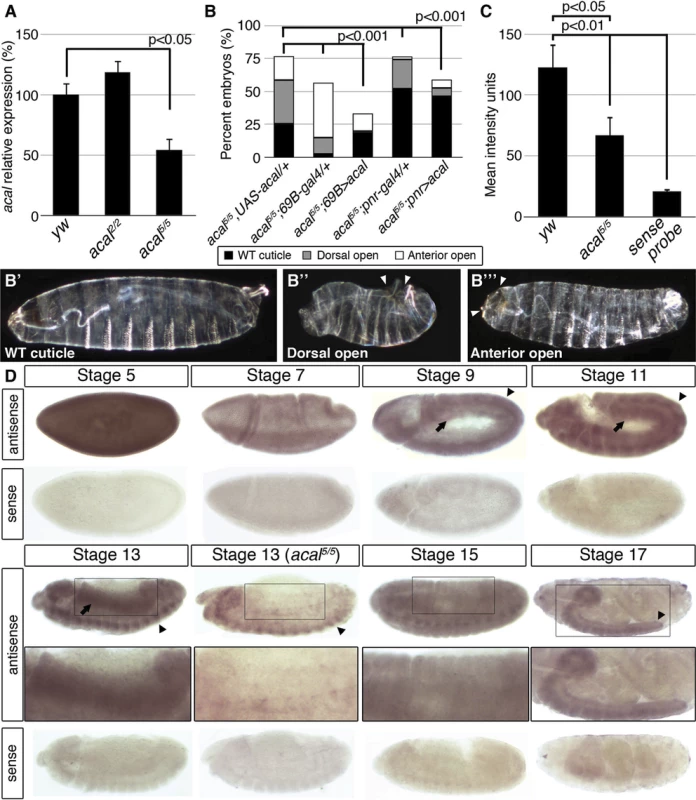

Fig. 2. acal expression is required in the lateral epidermis during DC.

(A) acal expression in wild type and mutant embryos during DC stages, as determined by qPCR. Means of three independent experiments run twice, +/− SEM. Student’s t test was used to assess significance. (B) Targeted ectodermal (69B-gal 4 driver) and lateral epidermis (pnr-gal 4 driver) expression of wild type acal in acal mutants. Only dead embryos are classified, mutants surviving embryogenesis constitute the remaining percentage to amount to a hundred percent (open space above bars). (B’-B’’’) are examples of acal5/5; 69B>acal embryos with no cuticular phenotype, wild type in appearance (B’), with a dorsal open phenotype (B’’), or with an anterior open phenotype (B’’’). Compared with acal5/5 mutants, the cuticular phenotypes are the same, but they differ significantly in the abundance (expression of acal significantly reduces the number of mutant embryos that die and that have cuticular phenotypes). In these and following experiments, cuticular phenotypes do not change, unless otherwise stated. No new cuticular phenotypes are found; thus, examples are not depicted in all figures. Numbers analyzed: acal5/5,UAS-acal/+ = 240, acal5/5;69B-gal4/+ = 441, acal5/5;69B>acal = 237, acal5/5;pnr-gal4/+ = 435, acal5/5;pnr>acal = 130. Statistical significance was calculated using chi square tests. (C) Quantification of in situ hybridization shown in (D) in stage 13 embryos (acal5/5, n = 10; yw, n = 6). acal mutants have significantly lower expression levels in lateral epithelia; chi square test. (D) acal in situ hybridization in embryos throughout embryonic development. Wild type embryos are yw, and mutant is acal5/5. Arrows indicate expression in the lateral epidermis and arrowheads point to expression in the central nervous system. Sense (negative) controls are also shown. Insets show boxed areas in stages 13, 15, and 17 embryos. See also S2 Fig. Fig. 3. acal is a processed long non-coding RNA.

(A) acal full-length transcript sequence conservation plot compared to other dipterans, and pairwise alignments between acal in D. melanogaster and its homologs (adapted from the UCSC genome browser). Location of molecular lesions in acal1 (1) and acal2(2) are marked within brackets after an ‘X’ in the transcript (gray arrow). Above the plot is the location of the probes used for small RNA Northern blots in (E) and in S3 Fig. (B) Protein coding potential of acal and other well known coding (white) and non-coding (black) RNAs. pipsqueak (psq) is a transcription factor and basket (bsk) codes for JNK. polished rice (pri) and pncr003 are polycistronic and code for small peptides. roX1 (RNA on the X1), iab-4 (infra-abdominal 4), and Heat shock RNA ω (Hsrω) are long non-coding RNAs. bereft (bft) is a microRNA precursor. Negative values correspond to non-coding scores, and positive values are for protein coding RNAs. Asterisks denote significantly coding or non-coding scores. (C) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR of total [T], cytoplasmic [C], and nuclear [N] RNA against acal, Rp49 (protein coding gene), and bantam microRNA precursor (pre-ban). [G] is the genomic control. (D) Band intensity of acal cytoplasmic and nuclear amplification, compared to total RNA amplification. Means of 5 independent experiments +/− SEM. Significance was assessed using Student’s t test. (E) Small RNA Northern blots for acal A and B probes, using wild type embryos [E] and pupae [P] RNA. Sizes were estimated from 4 independent experiments. In acal1 and acal2, no trace of the original P element was found. We reasoned that both lesions, found 1–2 Kb away from the original insertion site (which is in itself viable and fertile), are likely consequences of P-element imprecise excisions and repair, due to nicking and repair of the DNA break, leading to lethality, and responsible for the acal1 and acal2 mutant phenotypes, respectively. In both cases, the changes are not present in any of the other strains (genome reference assembly, yw wild type control, parental strain, or other acal mutants). acal6 is a P-element insertion mapping to the locus, 3 Kb 5’ from the transcription start site. We found no differences in the sequence in the 4.7 kb genomic region sequenced centered around the SD08925 transcribed region for acal3, acal4, and acal5. The sequenced genomic region includes the whole transcript, plus some neighboring 5’ and 3’ sequences (Fig. 1M’’), suggesting that mutations in acal3, acal4, and acal5 lie outside the transcript. This is consistent with a regulatory nature for these alleles, rather than molecular lesions within the transcribed region, like acal6.

We performed a genomic rescue experiment (Fig. 1M’–N), rescuing fully the embryonic lethality of acal1 and acal2 mutants with a ∼20 kb genomic construct called 178D09. 178D09 spans a small portion of the 5’ region of lola, wholly the SD08925 transcript region, plus ∼7 kb upstream of SD08925 in the intergenic region between SD08925 and psq (Fig. 1M’). Besides the 5’-most exon of lola, which is part of the untranslated 5’ leader sequence of some lola splice variants and CR45135, no other transcript is included, except SD08925. SD08925 expression levels are not changed in rescued embryos versus controls, presumably due to endogenous regulatory sequences maintaining overall low expression levels (S1E Fig.). SD08925 is conserved in eleven Drosophila species surveyed, and recognizable in A. gambiae (Fig. 1O; 3A). Together, these data are consistent with a low-expression locus involved in DC.

We quantified SD08925 expression during DC in acal2 and acal5 mutant embryos by qRT-PCR. acal2 expression is similar to wild type, but, as stated, acal5 expression is significantly reduced (Fig. 2A). This is consistent with acal5 being a regulatory mutant, although other interpretations are possible. To ensure consistency, whenever possible we performed experiments with multiple acal mutant alleles, with similar results. These data are also consistent with SD08925 coding for acal. In contrast, using primers that detect all lola isoforms, or all psq isoforms (both loci have alternative splicing) no significant differences in expression levels are seen in acal1, acal2, acal5, and acal6 (S7C Fig.).

In order to more rigorously test whether SD08925 is acal, we generated a UAS transgene containing only the complete SD08925 cDNA (2.3 kb). We expressed this construct in acal5 mutants, using the 69B ectodermal driver. This resulted in significant rescue of acal5 DC defects and reduction of embryonic lethality (Fig. 2B–B’’’). 69B over-expression of UAS-acal in acal5 mutants significantly increased SD08925 expression (40%, S2A Fig.). We also show that pnrMD237 gal4 (pnr-gal4) driven expression of SD08925 rescues DC defects in acal5 (Fig. 2B). Regardless of the nature of acal5, augmenting SD08925 expression in the mutant significantly rescues the embryonic phenotypes, arguing that reduction of acal expression is responsible for the acal5 DC and embryonic lethality phenotypes. Taken together, (1) the complete lack of complementation to each other and similar mutant phenotypes of all six acal alleles (but complementation to and dissimilar to mutant phenotypes of the neighboring lola and psq loci), (2) the molecular mapping of acal1, acal2, and acal6 to the SD08925 locus, (3) the significant genomic and UAS-acal rescues for acal1, acal2, and acal5, and (4) the significantly reduced SD08925 expression in acal5 both by qRT-PCR and in situ hybridization (see below), compared to no differences in lola and psq expression levels in acal1, acal2, acal5, and acal6 establish the SD08925 locus as the acal locus.

acal embryonic expression

In situ hybridization with SD08925 in wild type embryos revealed a dynamic expression pattern, mainly in two tissues: the lateral epidermis and the central nervous system. At early stages, the transcript is detectable throughout the embryo but falls at gastrulation (Fig. 2D). From germband retraction to DC, expression is seen in germband derivatives, mainly the lateral epidermis and nervous system (Fig. 2D). This is consistent with a role in DC and the UAS-acal rescue in the ectoderm and/or lateral epidermis (Fig. 2B). Later, expression appears in the mesoderm, but the bulk of expression is in the condensing nervous system and closing lateral epithelia. At the end of embryogenesis, expression occurs in the nervous system (Fig. 2D).

In acal5 mutant embryos, expression is significantly reduced in the lateral epithelium during DC, consistent with acal5 being a regulatory mutant and with the UAS rescue (Fig. 2B–D). Nervous system expression is not altered in acal5 during DC stages, but decreases significantly later (S2B–C Fig.).

acal is a processed, long non-coding RNA

Is SD08925, from now on referred to as the acal transcript, translated? The acal transcript is 2.3 kb long and could potentially code for protein(s). The locus is also evolutionarily conserved in other dipteran species (Fig. 3A), but not outside Diptera.

We find that in the dipteran species examined, the locus is devoid of conserved open reading frames (ORFs), sporting only variable, non-conserved ORFs ranging from 33 up to 243 nucleotides in size (S3A Fig.), even though other regions of the transcript are conserved (Fig. 3A; S3B Fig.). Unlike short ORF-bearing transcripts like polished rice (pri, [28]), the putative short ORFs in SD08925 and homologues have no common motifs. The deduced protein sequences of these ORFs in D. melanogaster show no homology with annotated proteins, and are not present in Drosophila proteomics databases (see Materials and Methods). Using an algorithm that measures coding potential [29], based on six different criteria [(1) feasibility of ORFs, (2) coverage of ORFs within transcript, (3) presence of in-frame initiation and stop codons, (4) number of hits in BLASTX, (5) high quality in any given BLASTX hit, and (6) whether any given hit is in frame with the predicted ORFs], we determined that acal has an extremely low coding potential, similar to other characterized long non-coding RNAs (Fig. 3B).

Genes harboring short ORFs have been erroneously classified as long non-coding RNAs, and later found to code for small peptides [28,30,31]. Does acal code for short, translated ORFs? Genes coding for short ORFs still have a protein coding score, unlike acal (Fig. 3B), and are exported to the cytoplasm for translation. In contrast, many non-coding RNAs reside in the nucleus. We detected acal transcripts enrichment in a nuclear fraction, different from Rp49, a protein-coding mRNA (Fig. 3C–D). As control, we also detected a small enrichment in the nuclear fraction of pre-bantam (ban), a well-known miRNA precursor. The enrichment is small, likely because it is quickly processed to mature ban. acal nuclear enrichment also suggests a non-coding nature.

High-throughput RNA sequencing projects have deeply annotated small RNAs in the Drosophila genome [32]. Within acal, we found two groups of sequence reads reported to appear under various experimental conditions that did not qualify as functional small RNAs. We designated these groups of reads as acal-A and acal-C (Fig. 3A), and performed small RNA Northern blotting, reasoning these could be the mature products of the acal transcript. With this Northern protocol, larger RNA fragments are not detected, but small RNA species are well separated. Using the acal-A probe, we found evidence of acal fragmentation throughout the life cycle of the fly, particularly during pupal stages (Fig. 3E; S3C). Instead of a roughly 22-nucleotide fragment, we found a group of small bands from about 50 to 118 nucleotides (Fig. 3E). These bands are not detectable in regular agarose gels due to their size. In contrast, acal-C did not reveal evidence of processing (S3C Fig.). We used two additional probes, acal-B and acal-D, to look for evidence of further processing. acal-D revealed no processing (S3C Fig.), but acal-B revealed at least a 59 nucleotides-long fragment (Fig. 3E). Both acal-A and acal-B fall within conserved positions of the gene at the 3’ end (Fig. 3A); acal-B lies within a 60 nucleotide-long conserved region, a size coincidental with the band we found in small RNA Northern blots (for detail, see S3B Fig.). In conclusion, we have evidence that the 3’ half of the acal transcript undergoes processing, whereas the 5’ half does not. Unfortunately, as the signal we detected was mostly from pupae, we could not test mutants, because mutants die as embryos and larvae, and never reach pupation proper. Taken together, we propose acal is an unconventional long non-coding RNA partially processed into small fragments.

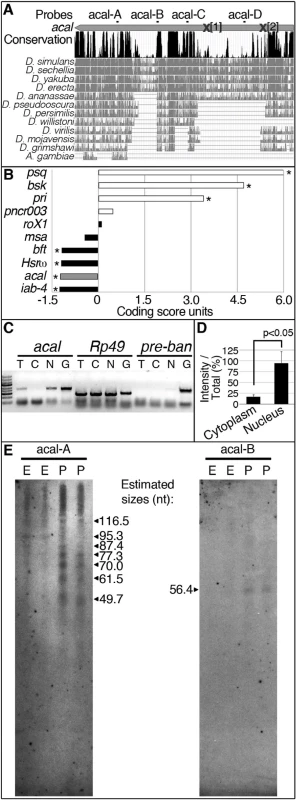

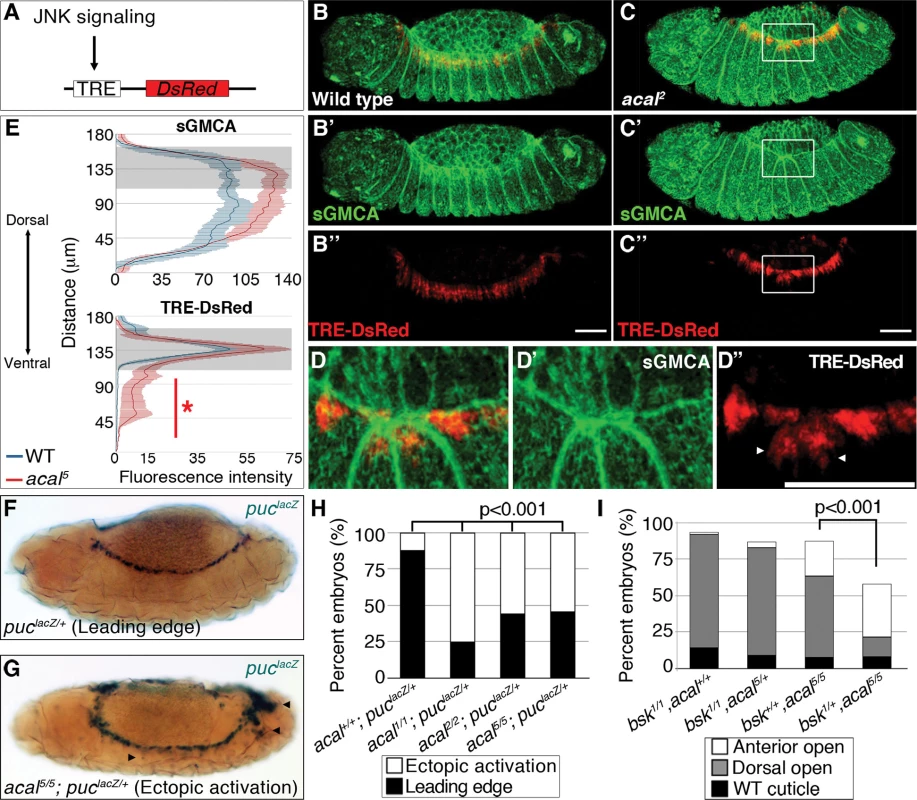

acal down-regulates JNK signaling during DC

We next studied JNK signaling, the DC trigger, to characterize DC defects in acal. We tracked and quantitated expression of a DsRed reporter under control of an AP-1 response element, TRE (Tetradecanoylphorbol acetate Response Element, see Fig. 4A and [33]). In parallel, we tagged cellular membranes using sGMCA, a fusion protein of the actin-binding domain of Moesin and GFP [34]. These constructs were expressed in an acal mutant and wild type backgrounds. In stage 13 wild type embryos, TRE-DsRed marks only the LE [a very faint amnioserosa DsRed positive staining is also present (Fig. 4B, 4B’’)]. At this stage, lateral epidermal cells are stretching towards the dorsal side (Fig. 4B, B’). In acal mutants, the TRE-DsRed is ectopically expressed in the lateral epidermis and in some amnioserosa cells (Fig. 4C–E). Quantitation of the signal uncovers significantly higher JNK activation levels in the lateral epidermis of acal mutants, and a significantly higher sGMCA signal, consistent with the observed mis-stretching and local accumulation of lateral epithelial cells at the border of the epithelium during DC (Fig. 4E). Ectopic JNK activation coincides with mis-stretching of the lateral epidermis, seen as a contraction of the epithelium where JNK ectopic activation occurs (Fig. 4C–D). Similar results are seen at later DC stages (S4A–D Fig.). JNK ectopic activation in the amnioserosa of acal mutants is likely a consequence of lateral epithelium defects, as acal rescue solely in the lateral epithelium rescues DC defects. Significant ectopic JNK reporter activity in the lateral epidermis underneath the leading edge cells and in the amnioserosa was also observed using another weaker acal allele (acal2) (S4E–G Fig.), with a GFP-based TRE JNK activity reporter [33]. Results for acal2 are normalized for nuclear density. This strongly suggests that acal DC defects are due to JNK gain-of-function signaling in more lateral epidermal cells, resulting in disorganized stretching.

Fig. 4. Ectopic JNK signaling activation in acal mutants.

(A) TRE-DsRed works as an AP-1 responsive element driving expression of DsRed. (B–B’’) Wild type embryos, (C–D’’) acal2 mutants. sGMCA is a marker for cortical cytoskeleton (green in B, C, and D). (B–D) Images are representative of five embryos per condition. (D–D’’) Boxed area in C. Ectopic TRE-DsRed activity is shown (arrowheads). Scale bars in (B, C, and D) are 50 μm. (E) Mean fluorescence intensity +/− SEM of sGMCA and TRE-DsRed in acal5 mutants and in control embryos. Leading edge region is highlighted in gray. n = 5 for each condition. For both channels, distributions are significantly different (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, asterisk and bar depicting significant ectopic JNK activation in lateral epithelia ventral to the LE, p<0.001). (F-H) puclacZ staining of control (F) and mutant (G) embryos. Arrowheads in (G) mark ectopic puclacZ activation. (H) Quantification of acal mutant phenotypes using puclacZ heterozygosity as JNK signaling reporter and genetic sensitized background. Mutant embryos were selected by lack of eve-lacZ staining, present in balancer chromosomes. Number of embryos analyzed: acal+/+;puclacZ/+ = 108, acal1/1;puclacZ/+ = 229, acal2/2;puclacZ/+ = 48, acal5/5;puclacZ/+ = 62. See also S4 Fig. (I) Genetic interaction between bsk1 and acal5 mutants. Only the dead embryos are classified, the mutants surviving embryogenesis are the remaining percentage to amount to a hundred percent (open space above bars). Number of animals analyzed: bsk1/1;acal+/+ = 154, bsk1/1;acal5/+ = 210, bsk+/+;acal5/5 = 391, bsk1/+;acal5/5 = 166. Significance in (H-I) was calculated using chi square tests. As a second and independent means to study the consequences of acal mutations in JNK activity, we over-activated JNK signaling in acal mutant and control embryos by expressing both a constitutively active form of the JNK kinase, Hep (HepACT), and a wild type version of the same gene (Hep) in the ectoderm (using 69B-gal4). We found that expressing hepACT in acal heterozygotes results in significantly stronger and more penetrant closure defects compared to wild type embryos expressing hepACT (S4I Fig.), exacerbating the hepACT over-expression phenotypes and supporting the notion that acal mutants promote increased JNK activity. We also see the appearance of a new phenotype, ‘early’ embryonic death, where embryos die without forming a cuticle. Over-expression of hep in acal heterozygotes has milder effects, but significantly leads to an increase in death of fully formed embryos in acal heterozygotes, compared to wild type embryos over-expressing Hep (S4H Fig.). Homozygosity for acal5 together with hepACT over-expression, or for acal2 together with hep over-expression, lead to significant further increases of the respective mutant phenotypes (S4H-I Fig.). These hep gain-of-function experiments together with acal loss-of-functions are all consistent with a role for acal in negative regulation of JNK activity during dorsal closure in the lateral epithelium.

We then corroborated this in two other independent ways: using a second JNK signaling reporter, and performing genetic interactions with JNK mutants. If acal acts to negatively regulate JNK activity, then in acal mutants we should see enhanced JNK reporter line expression (similar to the TRE results, above), or suppression of acal phenotypes in partial JNK loss-of-function.

puc is a transcriptional target of JNK signaling coding for a JNK phosphatase, a negative feedback loop that halts JNK. pucE69 is a lacZ enhancer trap allele (from now on referred to as puclacZ). Heterozygosity for puclacZ provides a JNK sensitive signaling reporter, and a sensitized background disrupting the feedback loop [18]. Despite decreased puc dosage in puclacZ heterozygotes, in approximately 90% of embryos, JNK signaling is restricted to LE (Fig. 4F–H). In acal homozygotes (acal1, acal2, or acal5), heterozygous for puclacZ, the proportion of embryos with ectopic puclacZ expression in amnioserosa and lateral epidermis significantly grows to around 50% or more, similar to JNK ectopic activation with TRE-constructs (Figs. 4G–H and S4A–G).

acal mutants heterozygous for puclacZ also show more extreme cuticle phenotypes. This is consistent with a potentiation of the puc effect on acal phenotypes, both genes acting to counteract JNK signaling (S5A Fig.).

Finally, we reduced JNK dosage to see whether it would ameliorate acal mutant phenotypes. Heterozygosity for bsk1, a JNK loss-of-function mutation, significantly suppresses acal5 phenotypes (Fig. 4I), meaning that JNK signaling over-activation of acal mutants depends on JNK itself. Conversely, acal5 heterozygosity does not alter the bsk1 mutant phenotype (Fig. 4I), consistent with acal mutant phenotypes dependent on JNK. We confirmed this genetic interaction in a different genetic background and found similar results (S5B Fig.). Taken all data together, the (1) two types of JNK reporters (TRE-based and puclacZ ) tested with several acal alleles, and (2) genetic interactions for several acal alleles with bsk and puc (loss-of-function), and hep (ectopic expression), all establish acal as a negative regulator of JNK signaling.

We next tested if acal mutations interact with dorsal open group mutations known to act in the amnioserosa, in order to determine if acal could have a function in this tissue. We used peb308, a hypomorphic mutation that affects peb expression in the amnioserosa, and, consequently, DC [19]. The peb308 DC defects were not modified in an acal sensitized background, consistent with acal required only in the lateral epidermis (S5C Fig.).

The pioneer protein Raw and acal act together to counteract JNK signaling

acal might interact with other negative regulators of JNK signaling. raw, a conserved gene of unknown molecular function, counters JNK signaling in the lateral epithelium, like acal. raw and acal have very similar expression patterns during DC (Fig. 2D for acal; for raw see [17]). Raw function is genetically positioned at the level of JNK [35], like acal, and Jra [17]. raw mutant cuticular phenotypes are stronger than acal, with dorsalized embryos consequence of dpp ectopic expression at the lateral epidermis (see Fig. 5A–B and Fig. 6E–F, [17]).

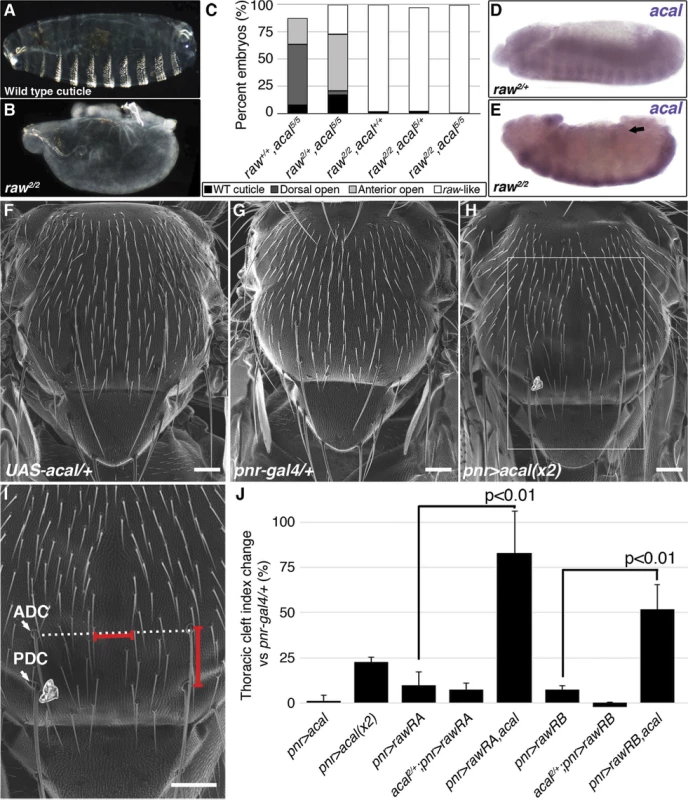

Fig. 5. raw and acal act together to counteract JNK signaling.

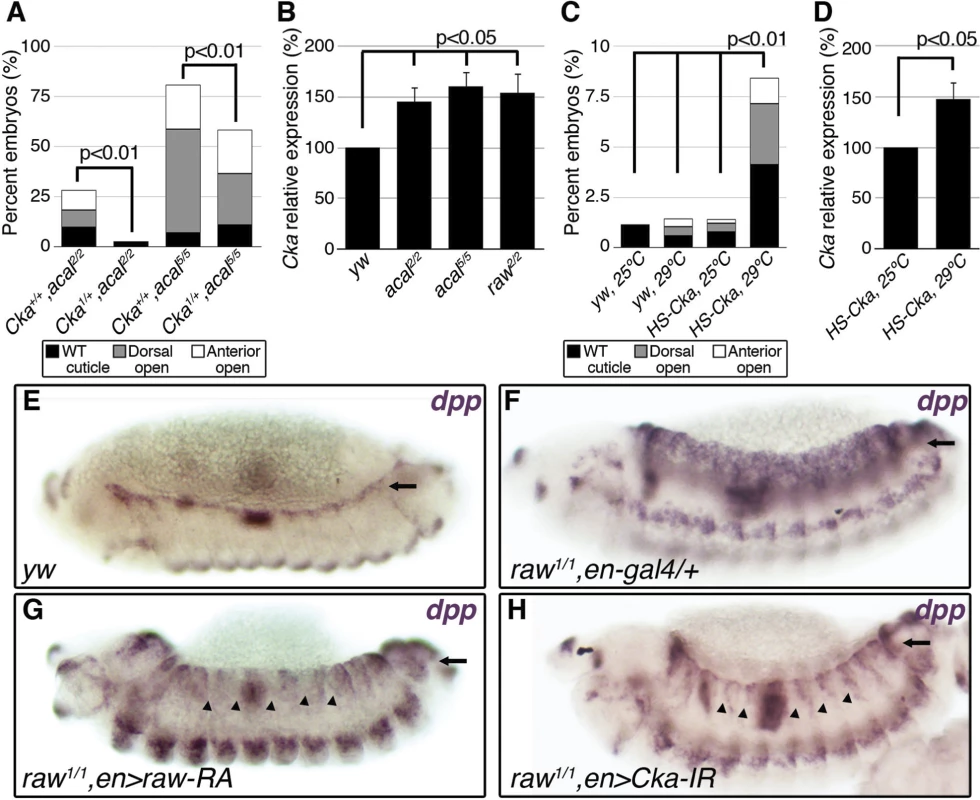

(A) Wild type cuticle. (B) Cuticle phenotype of raw mutant embryo. (C) Genetic interaction between raw2 and acal5 mutants. raw-like phenotype is depicted in (B). In raw+/+; acal5/5 mutants a small percentage survives embryogenesis, and constitute the open space above the bar to amount to a hundred percent total. Number of animals analyzed: raw+/+,acal5/5 = 391, raw2/+,acal5/5 = 139, raw2/2,acal+/+ = 366, raw2/2,acal5/+ = 152, raw2/2,acal5/5 = 208. Significance was assessed with chi square tests. (D-E) acal in situ hybridization in raw2 mutants (n = 45; D) and heterozygous siblings (n = 106; E). Arrow in (E) points to decreased acal expression in the lateral epidermis. See also S5 Fig. (F-I) Scanning electron micrographs of dorsal views of adult thoraces, anterior is up. Scale bars are 100 μm. (F) UAS-acal/+ control, (G) pnr-gal4/+ control, and (H) over-expression of two UAS-acal copies. The white box in (H) is amplified in (I), depicting distances (red lines) measured to determine the thoracic cleft index, using anterior dorso-central (ADC) and posterior dorso-central (PDC) bristles as references (see Materials and Methods). (J) Percentage change of thoracic cleft index for different experimental conditions. Mean of 15 flies +/− SEM. Significance was calculated using ANOVA and Bonferroni correction. Fig. 6. Cka is downstream of raw and acal.

(A) Genetic interaction between Cka and acal mutants. Number of animals analyzed: Cka+/+,acal2/2 = 192, Cka1/+,acal2/2 = 219, Cka+/+,acal5/5 = 391, Cka1/+,acal5/5 = 171. (B) Cka relative expression in wild type and mutant embryos, as determined by qPCR. (C) Expression of a heat-shock inducible Cka transgene results in DC defects. Number of animals analyzed: yw, 25°C = 526, yw, 29°C = 591, HS-Cka, 25°C = 2006, HS-Cka, 29°C = 3227. (D) Cka expression increase due to heat shock in hs-Cka flies was confirmed by qPCR. For (A,C) embryos surviving embryogenesis represent the open space above the bar to amount to one hundred percent total of embryos analyzed. Chi square tests were used to calculate significance. For (B,D) represents the means of three independent experiments run twice +/− SEM. Significance was assessed using Student’s t test. (E-H) dpp in situ hybridization experiments, showing JNK-induced dpp expression (arrows). (E) Wild type embryo. (F) raw1/1,en-gal4/+ control, showing dpp ectopic activation (arrow). (G) Expression of UAS-rawRA with en-gal 4, which expresses gal 4 at posterior compartments of each segment. Arrowheads show cell-autonomous suppression of dpp ectopic expression. (H) Silencing of Cka with an RNAi construct (UAS-Cka-IR) under en-gal 4 also suppresses dpp ectopic expression in posterior compartments of raw1 mutants (arrowheads). raw mutants have dpp ectopic expression during DC in rows of cells ventral to the leading edge ([17] and S6C Fig.). acal ectopic expression in the posterior part of each segment of these embryos (en-gal4 driver) reduces cell-autonomously dpp over expression (S6D Fig.). This is consistent with acal acting to inhibit JNK pathway on the lateral epithelium during DC. On their own, acal mutant embryos are not dorsalized (Fig. 1E-L), and show no clear ectopic dpp over-expression (S6A–B Fig.), yet at least under conditions of dpp over-expression, acal can repress dpp. Altogether, this argues that acal is a negative regulator of JNK activity, and that it has a subtler effect to that of raw.

We analysed genetic interactions between acal and raw. Heterozygosity for raw2 increases the embryonic lethality of acal5 embryos, with a quarter phenocopying the raw2 dorsalized phenotype (‘raw-like phenotype’, Fig. 5C). acal5 heterozygosity does not enhance the already strong raw2 homozygous condition, and double homozygotes do not show a stronger phenotype. Similar results are observed between acal2 and raw1 (S6E Fig.). These genetic interactions are consistent with acal acting downstream of raw.

We looked for acal expression in raw mutants, and found that acal lateral epidermis expression is significantly decreased in these embryos (Fig. 5D–E). This suggests that raw regulates acal lateral epidermis expression. Nervous system acal expression is unchanged in these raw mutant embryos, acting as an internal control. This also ties in with acal5 being a regulatory mutant with reduced lateral epithelium expression (Fig. 2D), and suggests a raw dependent acal control module for the lateral epidermis. Consistent with acal acting downstream of raw, as a raw effector, 69B-gal4 UAS-acal expression partially rescues the raw dorsalized cuticle phenotypes (S6F–H Fig.), as expected from the dpp in situ hybridization in raw mutants over-expressing acal (S6D Fig.). Altogether, these results indicate that acal mediates part of Raw function during DC.

raw over-expression in the lateral epidermis of wild type embryos has no effect in DC, in spite of the strong raw loss-of-function phenotype [17]. Likewise, acal over-expression in wild type embryos has no DC effects (embryonic lethality of 69B>acal embryos is around 1%, n = 791; also pnrMD237>acal shows no lethality or overt phenotypes, with equal numbers of control and over-expression siblings, n = 104). These lack of gain-of-function phenotypes for both genes indicate that raw/acal JNK negative regulation has a limit beyond which it cannot be exercised further during dorsal closure, suggesting other regulatory mechanisms might act in concert.

Thoracic closure during metamorphosis also depends on JNK signaling, much like DC does [36,37] Altering JNK signaling at the notum anlagen results in an antero-posterior cleft spanning the adult thorax (Fig. 5G–H). Some JNK signaling loss-of-function conditions have cleft thoraces [38,39]. This process has been used also in miss-expression screens for JNK signaling, where gain-of-function phenotypes are repeatedly encountered [40]. We thus used thorax closure as a model where we might be able to study acal and raw gain-of-function conditions. For this, we hypothesized that acal and/or raw over-expression at the notum anlagen could result in a cleft phenotype, using pnr-gal4 (expressed at the dorsal heminota, equivalent to the lateral epidermis, Fig. 5F–H). pnr-gal4 also provides a sensitized genetic background, as heterozygosity for this allele generates a mild thoracic phenotype, increasing the sensitivity of the assay [41].

Thoracic cleft was not enhanced by raw notum over-expression, as quantified by a ‘Thoracic cleft’ index (Fig. 5I-J; Materials and Methods). Similar results were observed for RawRA or RawRB isoforms, generated by alternative splicing (Fig. 5J). In contrast, two copies of the UAS-acal transgene had a significant effect (one copy was ineffective; Fig. 5H–J). If raw over-expression induces acal, adding more acal would then lead to a more extreme phenotype, as adding two transgene copies of acal do in the dorsal thorax. Simultaneous over-expression of acal and raw single copy transgenes had a significant synergistic effect, inducing stronger cleft formation (Fig. 5J). Both raw isoforms show synergism with acal. This is consistent with raw positively regulating acal, and both counteracting JNK signaling. Taken together, these results show that acal and Raw act together to counteract JNK signaling, acal downstream of raw. This is consistent with Raw acting at the level of JNK and/or Jra, as our experiments with acal point.

Expression of Cka, a JNK scaffold, is regulated by Raw and acal

Both raw and acal act genetically at the level of JNK (Fig. 4I; [35]). Yet raw has been shown to act also at the level of Jra [17]. Could raw do both? Could raw via acal modulate a mediator of both JNK and Jra, for example? Cka is a scaffold protein that interacts with JNK and Jra [20]. We tested whether acal and Cka interact genetically. acal DC defects are dependent on Cka, since heterozygosity for Cka1 rescues the acal mutant phenotype (Fig. 6A). This is in fact a stronger genetic interaction than that seen with bsk (JNK) mutants. Moreover, Cka expression is similarly significantly increased (to 50% above control values) in both acal and raw mutants (Fig. 6B). Conversely, acal embryonic over-expression (gain-of-function) leads to a significant reduction in Cka expression in otherwise wild type embryos, although this condition bears no observable phenotypic consequences (Fig. 7D).

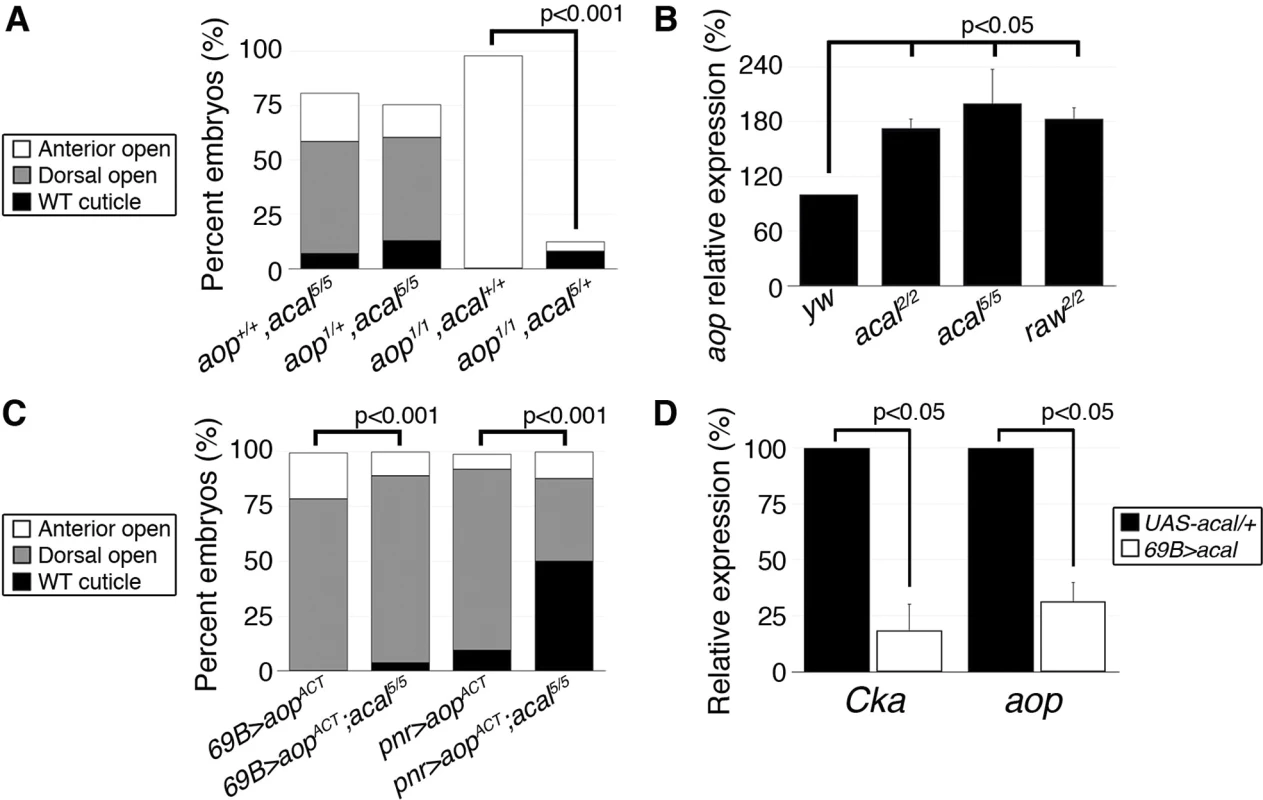

Fig. 7. acal regulates aop expression.

(A) Genetic interaction between aop and acal mutants. Embryos surviving embryogenesis represent the open space above bars to amount to a hundred percent total embryos analyzed. Number of animals analyzed: aop+/+,acal5/5 = 391, aop1/+,acal5/5 = 253, aop1/1,acal+/+ = 269, aop1/1,acal5/+ = 185. (B) Relative expression of aop in wild type and mutant embryos, as determined by qPCR. (C) Expression of a constitutive active aop transgene (UAS-aopACT) in the ectoderm (69B-gal4) or in the lateral epidermis (pnr-gal4), of wild type or acal mutant embryos. Number of animals analyzed: 69B>aopACT = 642, 69B>aopACT;acal5/5 = 210, pnr>aopACT = 310, pnr>aopACT;acal5/5 = 180. (D) acal over-expression under the 69B-gal4 driver results in significantly decreased Cka and aop expression. In (B) and (D), graphs show mean values +/− SEM of at least three independent experiments run twice. To test the raw-acal-Cka genetic pathway, we silenced Cka to see if it suffices to rescue the raw mutant phenotype, using again the strong raw mutation-dependent dpp over-expression phenotype as readout (Fig. 6E–F). If this pathway is true, expressing Cka RNAi in the en-gal4 expression pattern in raw mutants would silence dpp expression only at posterior compartments of each segment, the anterior compartments serving as internal controls. We found that Cka knockdown suppresses cell-autonomously raw ectopic dpp expression (Fig. 6F versus 6H), similar to rescuing raw function with UAS-rawRA (Fig. 6F–G). Taken together, both the loss-of-function as well as the ectopic expression results argue in favor of raw acting through acal down-regulating JNK signaling by regulating Cka expression, and accommodates the apparently conflicting results that raw acts at the JNK and/or Jun levels. Genetic interactions do not imply direct interactions, and so, acal, as a raw mediator, could act indirectly on Cka and regulate in this way JNK and Jra.

Cka sole over-expression should alter DC. Using a heat-shock inducible Cka, hs-Cka [20], we found that 29°C treatment of embryos throughout development significantly induces DC defects (Fig. 6C). Heat-shock induction indeed increases Cka expression (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these results define a novel regulatory path for JNK signaling, raw counteracting Cka expression through acal.

acal fine-tunes DC by regulating aop expression

Does acal interact with other DC regulators? Aop serves at least two functions during DC. In the lateral epidermal cells, Aop promotes tissue differentiation by preventing ectopic mitoses. As an extension, in the LE, it has a second function preventing ectopic and precocious expression of JNK activity and of AP-1 target genes, and thus, acting against dorsal closure, an activity countered by JNK via phosphorylation. Hence, over-expression of a constitutively active Aop (aopACT) that cannot be inactivated by JNK in the LE, results in DC defects due to lack of JNK targets expression. On the other hand, aop loss-of-function leads to anterior holes in the cuticle and faulty DC resulting from both ectopic mitoses in the tissue, and JNK over-activation. The wild type stretching lateral epithelium is a post-mitotic, competent tissue for DC in part due to aop dual roles (i.e., mitosis and precocious DC repression [15]). So, aop regulation can be a nodal, sensitive point for DC regulation. Genetic analyses show that acal and aop interact. acal mutations powerfully rescue aop loss-of-function, but aop loss-of-function does not alter acal mutants, showing that acal acts above or at the level of aop (Fig. 7A). Indeed, we found that aop expression is significantly increased in acal and raw mutants (Fig. 7B). Conversely, acal over-expression in wild type embryos leads to a significant reduction of aop expression (Fig. 7D), without phenotypic consequences (similar to Cka), consistent with a modulatory role for acal.

In accordance with an acal role as JNK negative regulator, aopACT that presumably locks in the post-mitotic nature of the lateral epithelia, while preventing JNK target gene expression, is countered by acal mutants, more so if aopACT expression is less widespread (Fig. 7C). A possible explanation for the puzzling interactions between acal and aop, resides in the dual nature of aop function in the LE and the lateral epidermis. In wild type embryos, aop is only phosphorylated and inactivated at the LE by JNK. Expressing aopACT conceivably affects only the JNK-regulated function of aop (i.e., its role in the LE). Thus, the JNK over-activation seen in acal mutants might compensate partially for LE aopACT. In contrast, in aop mutants, low aop levels throughout the epidermis might be partially restored to more wild type levels by acal loss-of-function conditions, as acal mutants over-express aop. Taken together, by regulating aop expression, acal can powerfully influence DC. In summary, we show that acal critically regulates both positive (Cka) and positive/negative (aop) components of JNK signaling.

acal acts in trans during DC

How does acal regulate expression of other genes? One possibility is that acal acts in cis, exerting an effect on neighboring genes, something reported for other lncRNAs [10,41]. To study this possibility, we made use of a Gene Search insertion line, a transposon that can lead to ectopic expression outwards in both directions from the insertion side. GS88A8 maps in the same interval as acal. Using gal4 lines, GS88A8 generates ectopic expression of neighboring genes, namely lola and psq [42]. We used the 69B-gal4 line to drive ectopic expression from GS88A8 in the embryonic ectoderm. If acal negatively regulates neighboring genes (lola and psq) and they are relevant for DC, then ectopic expression from GS88A8 should phenocopy acal mutant phenotypes. Instead, this condition mainly leads to larval and pupal lethality plus some adult escapers (S7B Fig.), with hardly any embryonic phenotypes, consistent with unaltered lola and psq expression profiles in acal mutants (S7C Fig.). Moreover, acal mutations complement lola and psq mutations (S1 Table), and mutations in these genes lead to different embryonic phenotypes (S7A Fig.). Altogether, we conclude that it is not very likely that acal acts in cis during DC.

Some long non-coding RNAs work in trans. One possibility is as part of chromatin remodeling complexes, for instance, although other mechanisms are possible [43,44]. In order to explore whether acal might function through remodeling complexes, we performed genetic interactions with Polycomb3 (Pc3) mutants. Pc is a critical member of the Pc chromatin repressive complex 1 (PRC1, [45]). acal and Pc3 double heterozygotes show novel strong wing defects [significantly twisted wings, with reduced posterior territory (S8A and F Fig.)]. Consistently, this interaction is seen with raw mutant alleles, albeit to a lesser degree (S8B Fig.). Cka and aop do not show this interaction (S8C–D Fig.).

acal5 also significantly enhances the Pc3 extra sex combs phenotype, as does raw1(aop1 reduces extra sex combs, presumably due to a repressive function in sex combs formation, S8G–I Fig.). These non-allelic non-complementation results are reminiscent of the ‘extended-wing’ phenotype used to detect direct interactors / components of other chromatin remodeling complexes, like the brahma or kismet complexes [46], suggesting a common regulatory pathway for acal, downstream of raw, with PRC1. The fact that raw and acal show the same genetic interactions with Pc, but not Cka and aop, underscores the fact that Cka and aop are downstream from the former two (raw and acal), as regulatory targets in the same signaling cascade.

Discussion

Several lines of evidence show that acal is a putative nuclear, processed, lncRNA, whose mutations are homozygous lethal, with requirements in DC. We show that acal mutants (three of which map molecularly to the SD08925, or acal, locus) fail to complement each other, but complement neighboring genes (lola and psq), regulate the same downstream genes (Cka and aop), have the same JNK negative regulation function [evidenced by two different reporter gene systems and genetic interactions with several JNK pathway component (bsk, hep, and Cka) and regulator genes (puc, raw, and aop)], are rescued by the SD08925 locus, with one allele having significantly reduced SD08925 expression, and all having similar mutant phenotypes and phenocritical periods. The locus produces a nuclear 2.3 Kb transcript with low coding potential that is processed into smaller pieces. Altogether, these data establish acal as a lncRNA locus in DC.

lncRNAs are ubiquitous species, probably tied to most biological processes. Yet, few have been characterized [47]. They fine-tune target abundance in multiple ways [1]. lncRNA species probably form diverse complexes with multiple mechanisms of action, and are not a rigorously defined class of molecules. Identifying lncRNA mutants with clear phenotypes in genetic models is a clear way forward. acal has an extremely low coding potential and no evolutionarily conserved ORFs. The putative acal ORFs show no homology to known peptides / proteins. Unlike short-ORF bearing transcripts [48], these putative ORFs have no sequence redundancy among them, reliable Kozak sequences, or high coding potential. This places acal as a non-translated transcript.

acal is a Dipteran-conserved locus. As many lncRNAs, it is not broadly conserved across species. acal RNA is processed into smaller fragments. These fragments have probably been missed in high-throughput sequencing projects due to RNA cut-off sizes [32]. acal functions in trans to regulate DC, as DC defects can be rescued in trans with a wild type full-length cDNA targeted to the epidermis.

acal foci for DC is the lateral epidermis. JNK loss-of-function result in lack or reduction of lateral epidermal cells stretching. In contrast, negative regulators, such as peb, puc, and raw also cause DC defects, due to disorganized and / or precocious cell stretching [13]. In acal mutants, cells also stretch in a disorganized manner. Predictably, reducing bsk gene dosage significantly reduces acal defects in DC, and JNK activity monitors show enhanced JNK function in acal mutants. This prompted study of acal and other negative regulators.

raw male gonad morphogenesis defects are ameliorated by bsk gene dosage reduction [35]. acal and raw collaborate to down-regulate JNK signaling at the lateral epidermis. In situ hybridization experiments, embryonic genetic interactions, and raw and acal over-expression studies in the thorax, put raw upstream of acal, yet they do not strictly phenocopy. This means that raw has other effectors. raw mutant embryos are dorsalized due to strong ectopic dpp expression in the lateral epidermis [17]. acal mutants do not dorsalize or show overt dpp misregulation. Furthermore, since Raw is localized in the cytoplasm, and acal is present in the nucleus, it is reasonable to assume that Raw regulates acal expression indirectly. Over-expression of either raw or acal in wild type embryos has no discernible effect on DC ([17] and this work), yet simultaneous over-expression in the thorax disrupts thorax closure, and acal over-expression reduces both Cka and aop transcript levels.

Cka expression is elevated in raw and acal mutants. Genetically decreasing Cka levels rescues DC defects in raw and acal mutants. Consistently, Cka over-expression itself causes DC defects. Work in the mammalian Cka functional homologue JIP-3 has shown this scaffold protein up-regulated under stress conditions. JIP-3 depletion and over-expression directly influence JNK activity [49]. Together with our results, these findings show that JNK scaffolds are an important point for JNK regulation, since augmenting scaffold availability augments JNK activity. In fact, this has been demonstrated biochemically for Cka [20].

Another critical JNK regulatory point by acal is aop. aop is also over-expressed in acal mutants, and down-regulated in acal over-expression. aop plays a complex role in DC making the tissue ready early, before DC, by preventing mitosis and early activation of JNK targets. For this, Aop function is required in the LE and lateral epidermal cells ventral to the LE [15]. Later, aop is inhibited by the JNK pathway only in the LE, allowing target gene expression there. In cells ventral to the LE, acal (together with raw) prevents JNK activation. In these cells there is no JNK activity to inhibit aop, yet aop expression regulation must be effected. This may be accomplished by acal (and raw). Thus, controlling aop levels, like Cka levels, may be a critical point for DC. For both genes, acal acts genetically as a repressor, with the net result of allowing JNK activity only in the LE in wild type.

In acal mutants, Cka over-expression leads to JNK ectopic activation in more lateral epithelium cells. However, the fact that aop is also over-expressed in acal mutants may mask a stronger JNK over-activation, as JNK signaling may inhibit at least in part Aop function, Aop being a JNK direct target. Future work will focus on how acal fine-tunes these signaling genes (Fig. 8).

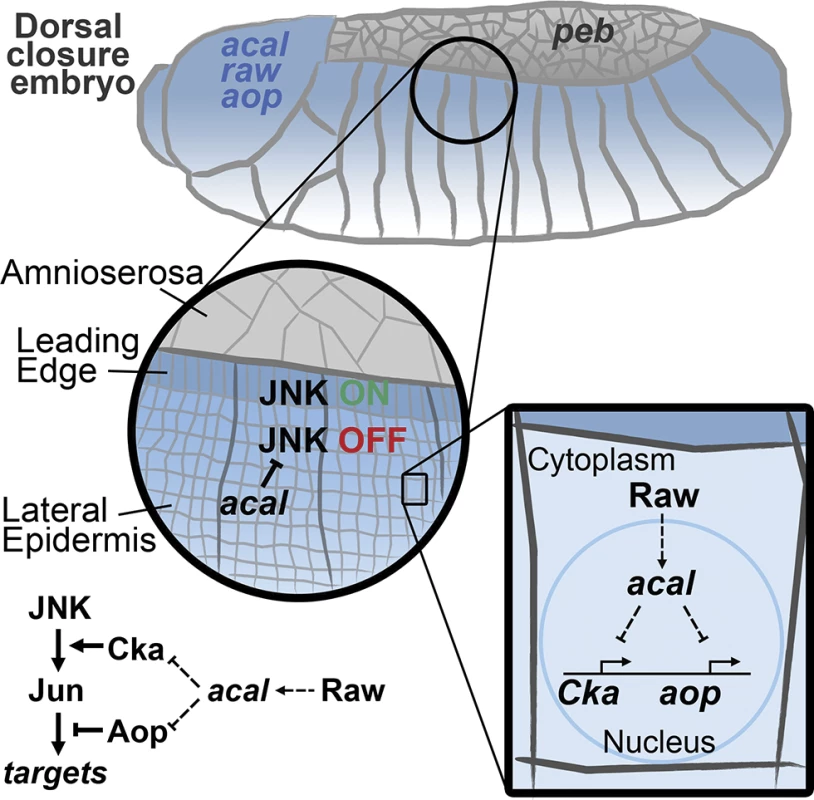

Fig. 8. Model for acal function during DC.

acal, expressed in the lateral epidermis (blue), restrains JNK activation to the leading edge cells. Raw, also expressed in the lateral epidermis, regulates acal expression. In turn, acal regulates the expression of Cka and aop to fine-tune JNK signaling. Not depicted is aop positive role during DC. We show here that acal function modifies gene expression. Whether this is direct, as has been proposed for other lncRNAs [45,50], or is done in some other fashion, is not yet clear. acal interacts genetically with Pc (raw, that regulates acal, also interacts with Pc). This opens the interesting possibility that acal acts directly with chromatin remodeling complexes, as has been demonstrated for other Pc interactors [42,51–53]. Yet other possibilities and/or indirect modes are clearly plausible.

In conclusion, we show that a lncRNA locus is required for DC regulation and JNK signaling. lncRNAs have not been implicated before in JNK signaling, and hence, this adds a new layer of control in JNK regulation.

Materials and Methods

For detailed protocols, please refer to S1 Protocol.

Fly husbandry

Detailed description of stocks is available in S1 Protocol. Crosses were done at 25°C under standard conditions. For heat-shock treatments (hs-Cka and peb1 experiments), animals were maintained at 29°C throughout development.

Cuticle preparations

Mutant embryos were processed as in [54]. Cuticles were examined under a dark field microscope.

Molecular mapping and rescue

4.7 kb of genomic DNA encompassing the acal locus of homozygous embryos was PCR amplified, cloned, and sequenced. The SD08925 clone was sequenced fully. A genomic (178D09) and a UAS-cDNA (UAS-acal) rescue constructs were synthesized and employed.

In situ hybridization and LacZ staining

For in situ hybridization, embryos were fixed, hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes, and developed with alkaline phosphatase-NBT/BCIP. Pixel intensity was quantified using ImageJ. For LacZ staining, embryos were fixed and developed with X-Gal.

Northern blots

Northern blots were done according to standard procedures [55]. Small RNA Northern blots were resolved by PAGE, and hybridized with labeled DNA oligonucleotides.

Nuclear fraction preparation

Embryos were dechorionated and processed for nuclei low-salt extraction by centrifugation. Supernatant was recovered as the cytoplasmic fraction. Both fractions were homogenized in TRIzol.

cDNA synthesis, semi-quantitative PCR, and real time PCR

RNA was purified and retro-transcribed with M-MLV reverse transcriptase. Semi-quantitative PCR and real time PCR were done by standard methods. Densitometry analysis was done using ImageJ. Primers used are listed in S2 Table.

Fluorescence microscopy

Z-stacks of embryos undergoing DC were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 780 microscope and processed using ImageJ. Fluorescence intensity was calculated using ImageJ.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

For imaging eyes and thoraces, animals were cold anesthetized, attached to SEM stubs with carbon paint and glue, and imaged under high vacuum in a JEOL JSM-6060.

Thoracic cleft index and wing angle quantification

Measurements were done with iVision software.

Adult leg preparation

Adult male thoraces were digested with potassium hydroxide and mounted for viewing and quantification of sex combs.

Bioinformatics

acal homologous sequences were extracted from the Flybase Genome Browser [56]. Multiple sequence alignments were done with the CLC sequence viewer software (http://www.clcbio.com). Putative translated ORFs were analyzed with BLAST and compared in the Drosophila PeptideAtlas server [57]. Protein coding capacity was calculated according to [29].

Statistics

All tests were done as implemented in GraphPad software or according to Kirkman, T. W. (http://www.physics.csbsju.edu/stats/).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mattick JS (2009) Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nat Rev Genet 10 : 155–159. 19188922

2. Fatica A, Bozzoni I (2014) Long non-coding RNAs: new players in cell differentiation and development. Nat Rev Genet 15 : 7–21. doi: 10.1038/nrg3606 24296535

3. Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E (2011) Gene silencing by microRNAs: contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat Rev Genet 12 : 99–110. 21245828

4. Okamura K, Ishizuka A, Siomi H, Siomi MC (2004) Distinct roles for Argonaute proteins in small RNA-directed RNA cleavage pathways. Genes Dev 18 : 1655–1666. 15231716

5. Batista PJ, Chang HY (2013) Long noncoding RNAs: cellular address codes in development and disease. Cell 152 : 1298–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.012 23498938

6. Rinn JL, Chang HY (2012) Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem 81 : 145–166. 22663078

7. Li Z, Liu M, Zhang L, Zhang W, Gao G, et al. (2009) Detection of intergenic non-coding RNAs expressed in the main developmental stages in Drosophila melanogaster. Nucleic Acids Res 37 : 4308–4314. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp334 19451167

8. Ilott NE, Ponting CP (2013) Predicting long non-coding RNAs using RNA sequencing. Methods 63 : 50–59. 23541739

9. Young RS, Marques AC, Tibbit C, Haerty W, Bassett AR, et al. (2012) Identification and properties of 1,119 candidate lincRNA loci in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome Biol Evol 4 : 427–442. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evs020 22403033

10. Gummalla M, Maeda RK, Castro Alvarez JJ, Gyurkovics H, Singari S, et al. (2012) abd-A regulation by the iab-8 noncoding RNA. PLoS Genet 8: e1002720. 22654672

11. Campos-Ortega JA, Hartenstein V (1997) The embryonic development of Drosophila melanogaster. Berlin; New York: Springer. xvii, 405 p. p.

12. Riesgo-Escovar JR, Jenni M, Fritz A, Hafen E (1996) The Drosophila Jun-N-terminal kinase is required for cell morphogenesis but not for DJun-dependent cell fate specification in the eye. Genes Dev 10 : 2759–2768. 8946916

13. Rios-Barrera LD, Riesgo-Escovar JR (2013) Regulating cell morphogenesis: the Drosophila Jun N-terminal kinase pathway. Genesis 51 : 147–162.

14. Homsy JG, Jasper H, Peralta XG, Wu H, Kiehart DP, et al. (2006) JNK signaling coordinates integrin and actin functions during Drosophila embryogenesis. Dev Dyn 235 : 427–434. 16317725

15. Riesgo-Escovar JR, Hafen E (1997) Drosophila Jun kinase regulates expression of decapentaplegic via the ETS-domain protein Aop and the AP-1 transcription factor DJun during dorsal closure. Genes Dev 11 : 1717–1727. 9224720

16. Wada A, Kato K, Uwo MF, Yonemura S, Hayashi S (2007) Specialized extraembryonic cells connect embryonic and extraembryonic epidermis in response to Dpp during dorsal closure in Drosophila. Dev Biol 301 : 340–349. 17034783

17. Bates KL, Higley M, Letsou A (2008) Raw mediates antagonism of AP-1 activity in Drosophila. Genetics 178 : 1989–2002. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.086298 18430930

18. Marts KL, Higley M, Letsou A (2008) Raw mediates antagonism of A98) puckered encodes a phosphatase that mediates a feedback loop regulating JNK activity during dorsal closure in Drosophila. Genes Dev 12 : 557–570. 9472024

19. Reed BH, Wilk R, Lipshitz HD (2001) Downregulation of Jun kinase signaling in the amnioserosa is essential for dorsal closure of the Drosophila embryo. Curr Biol 11 : 1098–1108. 11509232

20. Chen HW, Marinissen MJ, Oh SW, Chen X, Melnick M, et al. (2002) CKA, a novel multidomain protein, regulates the JUN N-terminal kinase signal transduction pathway in Drosophila. Mol Cell Biol 22 : 1792–1803. 11865058

21. Giniger E, Tietje K, Jan LY, Jan YN (1994) lola encodes a putative transcription factor required for axon growth and guidance in Drosophila. Development 120 : 1385–1398. 8050351

22. Grillo M, Furriols M, Casanova J, Luschnig S (2011) Control of germline torso expression by the BTB/POZ domain protein pipsqueak is required for embryonic terminal patterning in Drosophila. Genetics 187 : 513–521. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.121624 21098720

23. St Pierre SE, Ponting L, Stefancsik R, McQuilton P, FlyBase C (2014) FlyBase 102--advanced approaches to interrogating FlyBase. Nucleic Acids Res 42: D780–788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1092 24234449

24. Wilk R, Pickup AT, Hamilton JK, Reed BH, Lipshitz HD (2004) Dose-sensitive autosomal modifiers identify candidate genes for tissue autonomous and tissue nonautonomous regulation by the Drosophila nuclear zinc-finger protein, hindsight. Genetics 168 : 281–300. 15454543

25. Retelska D, Iseli C, Bucher P, Jongeneel CV, Naef F (2006) Similarities and differences of polyadenylation signals in human and fly. BMC Genomics 7 : 176. 16836751

26. Arbeitman MN, Furlong EE, Imam F, Johnson E, Null BH, et al. (2002) Gene expression during the life cycle of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 297 : 2270–2275. 12351791

27. Celniker SE, Dillon LA, Gerstein MB, Gunsalus KC, Henikoff S, et al. (2009) Unlocking the secrets of the genome. Nature 459 : 927–930. 19536255

28. Kondo T, Hashimoto Y, Kato K, Inagaki S, Hayashi S, et al. (2007) Small peptide regulators of actin-based cell morphogenesis encoded by a polycistronic mRNA. Nat Cell Biol 9 : 660–665. 17486114

29. Kong L, Zhang Y, Ye ZQ, Liu XQ, Zhao SQ, et al. (2007) CPC: assess the protein-coding potential of transcripts using sequence features and support vector machine. Nucleic Acids Res 35: W345–349. 17631615

30. Galindo MI, Pueyo JI, Fouix S, Bishop SA, Couso JP (2007) Peptides encoded by short ORFs control development and define a new eukaryotic gene family. PLoS Biol 5: e106. 17439302

31. Tupy JL, Bailey AM, Dailey G, Evans-Holm M, Siebel CW, et al. (2005) Identification of putative noncoding polyadenylated transcripts in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 : 5495–5500. 15809421

32. Berezikov E, Robine N, Samsonova A, Westholm JO, Naqvi A, et al. (2011) Deep annotation of Drosophila melanogaster microRNAs yields insights into their processing, modification, and emergence. Genome Res 21 : 203–215. doi: 10.1101/gr.116657.110 21177969

33. Chatterjee N, Bohmann D (2012) A versatile PhiC31 based reporter system for measuring AP-1 and Nrf2 signaling in Drosophila and in tissue culture. PLoS One 7: e34063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034063 22509270

34. Kiehart DP, Galbraith CG, Edwards KA, Rickoll WL, Montague RA (2000) Multiple forces contribute to cell sheet morphogenesis for dorsal closure in Drosophila. J Cell Biol 149 : 471–490. 10769037

35. Jemc JC, Milutinovich AB, Weyers JJ, Takeda Y, Van Doren M (2012) raw functions through JNK signaling and cadherin-based adhesion to regulate Drosophila gonad morphogenesis. Dev Biol 367 : 114–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.04.027 22575490

36. Zeitlinger J, Bohmann D (1999) Thorax closure in Drosophila: involvement of Fos and the JNK pathway. Development 126 : 3947–3956. 10433922

37. Riesgo-Escovar JR, Hafen E (1997) Common and distinct roles of DFos and DJun during Drosophila development. Science 278 : 669–672. 9381174

38. Glise B, Bourbon H, Noselli S (1995) hemipterous encodes a novel Drosophila MAP kinase kinase, required for epithelial cell sheet movement. Cell 83 : 451–461. 8521475

39. Biswas R, Stein D, Stanley ER (2006) Drosophila Dok is required for embryonic dorsal closure. Development 133 : 217–227. 16339186

40. Peswas R, Stein D, Stanley ER (2006) Drosophila Dok is required for embryonic dorsal closure. Development 133 : 217–227. cell sheet movement. Cell 83 : 451–461.1050.

41. Li M, Wen S, Guo X, Bai B, Gong Z, et al. (2012) The novel long non-coding RNA CRG regulates Drosophila locomotor behavior. Nucleic Acids Res 40 : 11714–11727. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks943 23074190

42. Ferres-Marco D, Gutierrez-Garcia I, Vallejo D, Bolivar J, Gutierrez-Aviing RNA CRG regulates Drosophilailencers and Notch collaborate to promote malignant tumours by Rb silencing. Nature 439 : 430–436. 16437107

43. Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L, Pandolfi PP (2011) A ceRNA hypothesis: the Rosetta Stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell 146 : 353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.014 21802130

44. Tay Y, Karreth FA, Pandolfi PP (2014) Aberrant ceRNA activity drives lung cancer. Cell Res 24 : 259–260. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.21 24525785

45. Schwartz YB, Pirrotta V (2013) A new world of Polycombs: unexpected partnerships and emerging functions. Nat Rev Genet 14 : 853–864. doi: 10.1038/nrg3603 24217316

46. Gutierrez L, Zurita M, Kennison JA, Vazquez M (2003) The Drosophila trithorax group gene tonalli (tna) interacts genetically with the Brahma remodeling complex and encodes an SP-RING finger protein. Development 130 : 343–354. 12466201

47. Grote P, Wittler L, Hendrix D, Koch F, Wahrisch S, et al. (2013) The tissue-specific lncRNA Fendrr is an essential regulator of heart and body wall development in the mouse. Dev Cell 24 : 206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.12.012 23369715

48. Ladoukakis E, Pereira V, Magny EG, Eyre-Walker A, Couso JP (2011) Hundreds of putatively functional small open reading frames in Drosophila. Genome Biol 12: R118. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-11-r118 22118156

49. Xu B, Zhou Y, O K, Choy PC, Pierce GN, et al. (2010) Regulation of stress-associated scaffold proteins JIP1 and JIP3 on the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase in ischemia-reperfusion. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 88 : 1084–1092. doi: 10.1139/y10-088 21076496

50. Tsai MC, Manor O, Wan Y, Mosammaparast N, Wang JK, et al. (2010) Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science 329 : 689–693. 20616235

51. Jones RS, Gelbart WM (1990) Genetic analysis of the enhancer of zeste locus and its role in gene regulation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 126 : 185–199. 1977656

52. Lagarou A, Mohd-Sarip A, Moshkin YM, Chalkley GE, Bezstarosti K, et al. (2008) dKDM2 couples histone H2A ubiquitylation to histone H3 demethylation during Polycomb group silencing. Genes Dev 22 : 2799–2810. doi: 10.1101/gad.484208 18923078

53. Herz HM, Madden LD, Chen Z, Bolduc C, Buff E, et al. (2010) The H3K27me3 demethylase dUTX is a suppressor of Notch—and Rb-dependent tumors in Drosophila. Mol Cell Biol 30 : 2485–2497. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01633-09 20212086

54. Nerz HM, Madden LD, Wieschaus E (1980) Mutations affecting segment number and polarity in Drosophila. Nature 287 : 795–801. 6776413

55. Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T (1989) Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. 545 p.

56. Marygold SJ, Leyland PC, Seal RL, Goodman JL, Thurmond J, et al. (2013) FlyBase: improvements to the bibliography. Nucleic Acids Res 41: D751–757. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1024 23125371

57. Loevenich SN, Brunner E, King NL, Deutsch EW, Stein SE, et al. (2009) The Drosophila melanogaster PeptideAtlas facilitates the use of peptide data for improved fly proteomics and genome annotation. BMC Bioinformatics 10 : 59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-59 19210778

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek 2014 Reviewer Thank YouČlánek Closing the Gap between Knowledge and Clinical Application: Challenges for Genomic TranslationČlánek Discovery of CTCF-Sensitive Cis-Spliced Fusion RNAs between Adjacent Genes in Human Prostate CellsČlánek K-homology Nuclear Ribonucleoproteins Regulate Floral Organ Identity and Determinacy in ArabidopsisČlánek A Nitric Oxide Regulated Small RNA Controls Expression of Genes Involved in Redox Homeostasis inČlánek Contribution of the Two Genes Encoding Histone Variant H3.3 to Viability and Fertility in MiceČlánek The Genetic Architecture of the Genome-Wide Transcriptional Response to ER Stress in the Mouse

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 2- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- IVF a rakovina prsu – zvyšují hormony riziko vzniku rakoviny?

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- 2014 Reviewer Thank You

- Systematic Cell-Based Phenotyping of Missense Alleles Empowers Rare Variant Association Studies: A Case for and Myocardial Infarction

- African Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Alleles Associated with Protection from Severe Malaria in Heterozygous Females in Tanzania

- Genomics of Divergence along a Continuum of Parapatric Population Differentiation

- microRNAs Regulate Cell-to-Cell Variability of Endogenous Target Gene Expression in Developing Mouse Thymocytes

- A Rolling Circle Replication Mechanism Produces Multimeric Lariats of Mitochondrial DNA in

- Closing the Gap between Knowledge and Clinical Application: Challenges for Genomic Translation

- Partially Redundant Enhancers Cooperatively Maintain Mammalian Expression Above a Critical Functional Threshold

- Discovery of Transcription Factors and Regulatory Regions Driving Tumor Development by ATAC-seq and FAIRE-seq Open Chromatin Profiling

- Mutations in Result in Ocular Coloboma, Microcornea and Cataracts

- A Genome-Wide Hybrid Incompatibility Landscape between and

- Recurrent Evolution of Melanism in South American Felids

- Discovery of CTCF-Sensitive Cis-Spliced Fusion RNAs between Adjacent Genes in Human Prostate Cells

- Tissue Expression Pattern of PMK-2 p38 MAPK Is Established by the miR-58 Family in

- Essential Role for Endogenous siRNAs during Meiosis in Mouse Oocytes

- Matrix Metalloproteinase 2 Is Required for Ovulation and Corpus Luteum Formation in

- Evolutionary Signatures amongst Disease Genes Permit Novel Methods for Gene Prioritization and Construction of Informative Gene-Based Networks

- RR-1 Cuticular Protein TcCPR4 Is Required for Formation of Pore Canals in Rigid Cuticle

- GC-Content Evolution in Bacterial Genomes: The Biased Gene Conversion Hypothesis Expands

- Proteotoxic Stress Induces Phosphorylation of p62/SQSTM1 by ULK1 to Regulate Selective Autophagic Clearance of Protein Aggregates

- K-homology Nuclear Ribonucleoproteins Regulate Floral Organ Identity and Determinacy in Arabidopsis

- A Nitric Oxide Regulated Small RNA Controls Expression of Genes Involved in Redox Homeostasis in

- HYPER RECOMBINATION1 of the THO/TREX Complex Plays a Role in Controlling Transcription of the Gene in Arabidopsis

- Mitochondrial and Cytoplasmic ROS Have Opposing Effects on Lifespan

- Structured Observations Reveal Slow HIV-1 CTL Escape

- An Integrative Multi-scale Analysis of the Dynamic DNA Methylation Landscape in Aging

- Combining Natural Sequence Variation with High Throughput Mutational Data to Reveal Protein Interaction Sites

- Transhydrogenase Promotes the Robustness and Evolvability of Deficient in NADPH Production

- Regulators of Autophagosome Formation in Muscles

- Genomic Selection and Association Mapping in Rice (): Effect of Trait Genetic Architecture, Training Population Composition, Marker Number and Statistical Model on Accuracy of Rice Genomic Selection in Elite, Tropical Rice Breeding Lines

- Eye Selector Logic for a Coordinated Cell Cycle Exit

- Inflammation-Induced Cell Proliferation Potentiates DNA Damage-Induced Mutations

- The DNA Polymerase δ Has a Role in the Deposition of Transcriptionally Active Epigenetic Marks, Development and Flowering

- Contribution of the Two Genes Encoding Histone Variant H3.3 to Viability and Fertility in Mice

- Membrane Recognition and Dynamics of the RNA Degradosome

- P-TEFb, the Super Elongation Complex and Mediator Regulate a Subset of Non-paused Genes during Early Embryo Development

- is a Long Non-coding RNA in JNK Signaling in Epithelial Shape Changes during Drosophila Dorsal Closure

- A Pleiotropy-Informed Bayesian False Discovery Rate Adapted to a Shared Control Design Finds New Disease Associations From GWAS Summary Statistics

- Genome-wide Association Study Identifies Shared Risk Loci Common to Two Malignancies in Golden Retrievers

- and Hyperdrive Mechanisms (in Mouse Meiosis)

- Elevated In Vivo Levels of a Single Transcription Factor Directly Convert Satellite Glia into Oligodendrocyte-like Cells

- Systemic Delivery of MicroRNA-101 Potently Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Repressing Multiple Targets

- Pooled Sequencing of 531 Genes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Identifies an Associated Rare Variant in and Implicates Other Immune Related Genes

- Abscission Is Regulated by the ESCRT-III Protein Shrub in Germline Stem Cells

- Temperature Stress Mediates Decanalization and Dominance of Gene Expression in

- Transcriptome Wide Annotation of Eukaryotic RNase III Reactivity and Degradation Signals

- The Exosome Component Rrp6 Is Required for RNA Polymerase II Termination at Specific Targets of the Nrd1-Nab3 Pathway

- Sex-specific -regulatory Variation on the X Chromosome

- Regulation of Toll-like Receptor Signaling by the SF3a mRNA Splicing Complex

- Modeling of the Human Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma Chromosome Translocation in Mouse Myoblasts Using CRISPR-Cas9 Nuclease

- Asymmetry of the Budding Yeast Tem1 GTPase at Spindle Poles Is Required for Spindle Positioning But Not for Mitotic Exit

- TIM Binds Importin α1, and Acts as an Adapter to Transport PER to the Nucleus

- Antagonistic Roles for KNOX1 and KNOX2 Genes in Patterning the Land Plant Body Plan Following an Ancient Gene Duplication

- The Genetic Architecture of the Genome-Wide Transcriptional Response to ER Stress in the Mouse

- Fatty Acid Synthase Cooperates with Glyoxalase 1 to Protect against Sugar Toxicity

- Region-Specific Activation of mRNA Translation by Inhibition of Bruno-Mediated Repression

- An Essential Role of the Arginine Vasotocin System in Mate-Guarding Behaviors in Triadic Relationships of Medaka Fish ()