-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Genome-Wide Association Study in Mutation Carriers Identifies Novel Loci Associated with Breast and Ovarian Cancer Risk

BRCA1-associated breast and ovarian cancer risks can be modified by common genetic variants. To identify further cancer risk-modifying loci, we performed a multi-stage GWAS of 11,705 BRCA1 carriers (of whom 5,920 were diagnosed with breast and 1,839 were diagnosed with ovarian cancer), with a further replication in an additional sample of 2,646 BRCA1 carriers. We identified a novel breast cancer risk modifier locus at 1q32 for BRCA1 carriers (rs2290854, P = 2.7×10−8, HR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.09–1.20). In addition, we identified two novel ovarian cancer risk modifier loci: 17q21.31 (rs17631303, P = 1.4×10−8, HR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.17–1.38) and 4q32.3 (rs4691139, P = 3.4×10−8, HR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.17–1.38). The 4q32.3 locus was not associated with ovarian cancer risk in the general population or BRCA2 carriers, suggesting a BRCA1-specific association. The 17q21.31 locus was also associated with ovarian cancer risk in 8,211 BRCA2 carriers (P = 2×10−4). These loci may lead to an improved understanding of the etiology of breast and ovarian tumors in BRCA1 carriers. Based on the joint distribution of the known BRCA1 breast cancer risk-modifying loci, we estimated that the breast cancer lifetime risks for the 5% of BRCA1 carriers at lowest risk are 28%–50% compared to 81%–100% for the 5% at highest risk. Similarly, based on the known ovarian cancer risk-modifying loci, the 5% of BRCA1 carriers at lowest risk have an estimated lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer of 28% or lower, whereas the 5% at highest risk will have a risk of 63% or higher. Such differences in risk may have important implications for risk prediction and clinical management for BRCA1 carriers.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003212

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003212Summary

BRCA1-associated breast and ovarian cancer risks can be modified by common genetic variants. To identify further cancer risk-modifying loci, we performed a multi-stage GWAS of 11,705 BRCA1 carriers (of whom 5,920 were diagnosed with breast and 1,839 were diagnosed with ovarian cancer), with a further replication in an additional sample of 2,646 BRCA1 carriers. We identified a novel breast cancer risk modifier locus at 1q32 for BRCA1 carriers (rs2290854, P = 2.7×10−8, HR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.09–1.20). In addition, we identified two novel ovarian cancer risk modifier loci: 17q21.31 (rs17631303, P = 1.4×10−8, HR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.17–1.38) and 4q32.3 (rs4691139, P = 3.4×10−8, HR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.17–1.38). The 4q32.3 locus was not associated with ovarian cancer risk in the general population or BRCA2 carriers, suggesting a BRCA1-specific association. The 17q21.31 locus was also associated with ovarian cancer risk in 8,211 BRCA2 carriers (P = 2×10−4). These loci may lead to an improved understanding of the etiology of breast and ovarian tumors in BRCA1 carriers. Based on the joint distribution of the known BRCA1 breast cancer risk-modifying loci, we estimated that the breast cancer lifetime risks for the 5% of BRCA1 carriers at lowest risk are 28%–50% compared to 81%–100% for the 5% at highest risk. Similarly, based on the known ovarian cancer risk-modifying loci, the 5% of BRCA1 carriers at lowest risk have an estimated lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer of 28% or lower, whereas the 5% at highest risk will have a risk of 63% or higher. Such differences in risk may have important implications for risk prediction and clinical management for BRCA1 carriers.

Introduction

Breast and ovarian cancer risk estimates for BRCA1 mutation carriers vary by the degree of family history of the disease, suggesting that other genetic factors modify cancer risks for this population [1]–[4]. Studies by the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2 (CIMBA) have shown that a subset of common alleles influencing breast and ovarian cancer risk in the general population are also associated with cancer risk in BRCA1 mutation carriers [5]–[11]. In particular, the breast cancer associations were limited to loci associated with estrogen receptor (ER)-negative breast cancer in the general population (6q25.1, 12p11 and TOX3) [8]–[11].

To systematically search for loci associated with breast or ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 carriers we previously conducted a two-stage genome-wide association study (GWAS) [12]. The initial stage involved analysis of 555,616 SNPs in 2383 BRCA1 mutation carriers (1,193 unaffected and 1,190 affected). After replication testing of 89 SNPs showing the strongest association, with 5,986 BRCA1 mutation carriers, a locus on 19p13 was shown to be associated with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers. The same locus was also associated with the risk of estrogen-receptor (ER) negative and triple negative (ER, Progesterone and HER2 negative) breast cancer in the general population [12], [13].

The Collaborative Oncological Gene-environment Study (COGS) consortium recently developed a 211,155 SNP custom genotyping array (iCOGS) in order to provide cost-effective genotyping of common and rare genetic variants to identify novel loci that explain the residual genetic variance of breast, ovarian and prostate cancers and fine-map known susceptibility loci. A total of 32,557 SNPs on the iCOGS array were selected on the basis of the BRCA1 GWAS for the purpose of identifying breast and ovarian cancer risk modifiers for BRCA1 mutation carriers. Genotype data from the iCOGS array were obtained for 11,705 samples from BRCA1 carriers and the 17 most promising SNPs were then genotyped in an additional 2,646 BRCA1 carriers. In this manuscript we report on the novel risk modifier loci identified by this multi-stage GWAS. No study has previously shown how the absolute risks of breast and ovarian cancer for BRCA1 mutation carriers vary by the combined effects of risk modifying loci. Here we use the results from this study, in combination with previously identified modifiers, to obtain absolute risks of developing breast and ovarian cancer for BRCA1 mutation carriers based on the joint distribution of all known genetic risk modifiers.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All carriers participated in clinical or research studies at the host institutions, approved by local ethics committees.

Study subjects

BRCA1 mutation carriers were recruited by 45 study centers in 25 countries through CIMBA. The majority were recruited through cancer genetics clinics, and enrolled into national or regional studies. The remainder were identified by population-based sampling or community recruitment. Eligibility for CIMBA association studies was restricted to female carriers of pathogenic BRCA1 mutations age 18 years or older at recruitment. Information collected included year of birth, mutation description, self-reported ethnic ancestry, age at last follow-up, ages at breast or ovarian cancer diagnoses, and age at bilateral prophylactic mastectomy and oophorectomy. Information on tumour characteristics, including ER-status of the breast cancers, was also collected. Related individuals were identified through a unique family identifier. Women were included in the analysis if they carried mutations that were pathogenic according to generally recognized criteria.

GWAS stage 1 samples

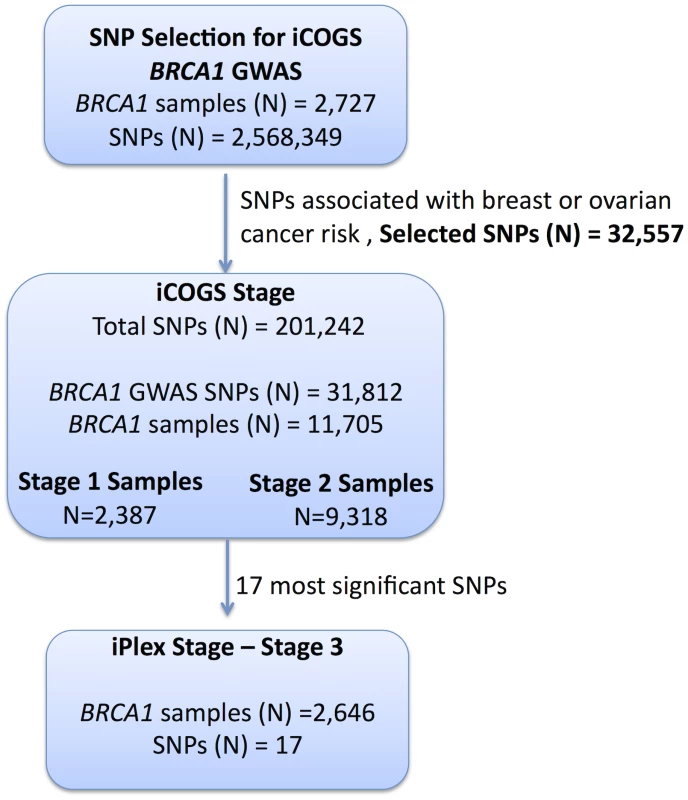

A total of 2,727 BRCA1 mutation carriers were genotyped on the Illumina Infinium 610K array (Figure 1). Of these 1,426 diagnosed with a first breast cancer under age 40 were considered “affected” in the breast cancer association analysis and 683 diagnosed with an ovarian cancer at any time were considered as “affected” in the ovarian cancer analysis. “Unaffected” in both analyses were over age 35 (Table S1) [12].

Fig. 1. Study design for selection of the SNPs and genotyping of BRCA1 samples.

GWAS data from 2,727 BRCA1 mutation carriers were analysed for associations with breast and ovarian cancer risk and 32,557 SNPs were selected for inclusion on the iCOGS array. A total of 11,705 BRCA1 samples (after quality control (QC) checks) were genotyped on the 31,812 BRCA1-GWAS SNPs from the iCOGS array that passed QC. Of these samples, 2,387 had been genotyped at the SNP selection stage and are referred to as “stage 1” samples, whereas 9,318 samples were unique to the iCOGS study (“Stage 2” samples). Next, 17 SNPs that exhibited the most significant associations with breast and ovarian cancer were selected for genotyping in a third stage involving an additional 2,646 BRCA1 samples (after QC). Replication study samples

All eligible BRCA1 carriers from CIMBA with sufficient DNA were genotyped, including those used in Stage 1. In total, 13,310 samples from 45 centers in 25 countries were genotyped using the iCOGS array (Table S2). Among the 13,310 samples, those that were genotyped in the GWAS stage 1 SNP selection stage are referred to as “stage 1” samples, and the remainder are “stage 2” samples. An additional 2,646 BRCA1 samples “stage 3” were genotyped on an iPLEX Mass Array of 17 SNPs from 12 loci selected after an interim analysis of iCOGS array data and were available for analysis after quality control (QC) (Figure 1). Carriers of pathogenic mutations in BRCA2 were drawn from a parallel GWAS of genetic modifiers for BRCA2 mutation carriers. BRCA2 mutation carriers were recruited from CIMBA through 47 studies which were largely the same as the studies that contributed to the BRCA1 GWAS with similar eligibility criteria. Samples from BRCA2 mutation carriers were also genotyped using the iCOGS array. Details of this experiment are described elsewhere [14]. A total of 8,211 samples were available for analysis after QC.

iCOGS SNP array

The iCOGS array was designed in a collaboration among the Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC), Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium (OCAC), the Prostate Cancer Association Group to Investigate Cancer Associated Alterations in the Genome (PRACTICAL) and CIMBA. The general aims for designing the iCOGS array were to replicate findings from GWAS for identifying variants associated with breast, ovarian or prostate cancer (including subtypes and SNPs potentially associated with disease outcome), to facilitate fine-mapping of regions of interest, and to genotype “candidate” SNPs of interest within the consortia, including rarer variants. Each consortium was given a share of the array: nominally 25% of the SNPs each for BCAC, PRACTICAL and OCAC; 17.5% for CIMBA; and 7.5% for SNPs of common interest between the consortia. The final design comprised 220,123 SNPs, of which 211,155 were successfully manufactured. A total of 32,557 SNPs on the iCOGS array were selected based on 8 separate analyses of stage 1 of the CIMBA BRCA1 GWAS that included 2,727 BRCA1 mutation carriers [12]. After imputation for all SNPs in HapMap Phase II (CEU) a total of 2,568,349 (imputation r2>0.30) were available for analysis. Markers were evaluated for associations with: (1) breast cancer; (2) ovarian cancer; (3) breast cancer restricted to Class 1 mutations (loss-of-function mutations expected to result in a reduced transcript or protein level due to nonsense-mediated RNA decay); (4) breast cancer restricted to Class 2 mutations (mutations likely to generate stable proteins with potential residual or dominant negative function); (5) breast cancer by tumor ER-status; (6) breast cancer restricted to BRCA1 185delAG mutation carriers; (7) breast cancer restricted to BRCA1 5382insC mutation carriers; and (8) breast cancer by contrasting the genotype distributions in BRCA1 mutation carriers, against the distribution in population-based controls. Analyses (1) and (2) were based on both imputed and observed genotypes, whereas the rest were based on only the observed genotypes. SNPs were ranked according to the 1 d.f. score-test for trend P-value (described below) and selected for inclusion based on nominal proportions of 61.5%, 20%, 2.5%, 2.5%, 2.5%, 0.5%, 0.5% and 10.0% for analyses (1) to (8). SNP duplications were not allowed and SNPs with a pairwise r2≥0.90 with a higher-ranking SNP were only allowed (up to a maximum of 2) if the P-value for association was <10−4 for analyses (1) and (2) and <10−5 for other analyses. SNPs with poor Illumina design scores were replaced by the SNP with the highest r2 (among SNPs with r2>0.80 based on HapMap data) that had a good quality design score. The analysis of associations with breast and ovarian cancer risks presented here included all 32,557 SNPs on iCOGS that were selected on the basis of the BRCA1 GWAS.

Genotyping and quality control

iCOGS genotyping

Genotyping was performed at Mayo Clinic. Genotypes for samples genotyped on the iCOGS array were called using Illumina's GenCall algorithm (Text S1). A total of 13,510 samples were genotyped for 211,155 SNPs. The sample and SNP QC process is summarised in Table S3. Of the 13,510 samples, 578 did not fulfil eligibility criteria based on phenotypic data and were excluded. A step-wise QC process was applied to the remaining samples and SNPs. Samples were excluded due to inferred gender errors, low call rates (<95%), low or high heterozygosity and sample duplications (cryptic and intended). Of the 211,155 markers genotyped, 9,913 were excluded due to Y-chromosome origin, low call rates (<95%), monomorphic SNPs, or SNPs with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) P<10−7 under a country-stratified test statistic [15] (Table S3). SNPs that gave discordant genotypes among known sample duplicates were also excluded. Multi-dimensional scaling was used to exclude individuals of non-European ancestry. We selected 37,149 weakly correlated autosomal SNPs (pair-wise r2<0.10) to compute the genomic kinship between all pairs of BRCA1 carriers, along with 197 HapMap samples (CHB, JPT, YRI and CEU). These were converted to distances and subjected to multidimensional scaling (Figure S1). Using the first two components, we calculated the proportion of European ancestry for each individual [12] and excluded samples with >22% non-European ancestry (Figure S1). A total of 11,705 samples and 201,242 SNPs were available for analysis, including 31,812 SNPs selected by the BRCA1 GWAS. The genotyping cluster plots for all SNPs that demonstrated genome-wide significance level of association or are presented below, were checked manually for quality (Figure S2).

iPLEX analysis

The most significant SNPs from 4 loci associated with ovarian cancer and 8 loci associated with breast cancer were selected (17 SNPs in total) for stage 3 genotyping. Genotyping using the iPLEX Mass Array platform was performed at Mayo Clinic. CIMBA QC procedures were applied. Samples that failed for ≥20% of the SNPs were excluded from the analysis. No SNPs failed HWE (P<0.01). The concordance among duplicates was ≥98%. Mutation carriers of self-reported non-European ancestry were excluded. A total of 2,646 BRCA1 samples were eligible for analysis after QC.

Statistical methods

The main analyses were focused on the evaluation of associations between each genotype and breast cancer or ovarian cancer risk separately. Analyses were carried out within a survival analysis framework. In the breast cancer analysis, the phenotype of each individual was defined by age at breast cancer diagnosis or age at last follow-up. Individuals were followed until the age of the first breast cancer diagnosis, ovarian cancer diagnosis, or bilateral prophylactic mastectomy, whichever occurred first; or last observation age. Mutation carriers censored at ovarian cancer diagnosis were considered unaffected. For the ovarian cancer analysis, the primary endpoint was the age at ovarian cancer diagnosis. Mutation carriers were followed until the age of ovarian cancer diagnosis, or risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) or age at last observation. In order to maximize the number of ovarian cancer cases, breast cancer was not considered as a censoring event in this analysis, and mutation carriers who developed ovarian cancer after a breast cancer diagnosis were considered as affected in the ovarian cancer analysis.

Association analysis

The majority of mutation carriers were sampled through families seen in genetic clinics. The first tested individual in a family is usually someone diagnosed with cancer at a relatively young age. Such study designs tend to lead to an over-sampling of affected individuals, and standard analytical methods like Cox regression may lead to biased estimates of the risk ratios [16], [17]. To adjust for this potential bias the data were analyzed within a survival analysis framework, by modeling the retrospective likelihood of the observed genotypes conditional on the disease phenotypes. A detailed description of the retrospective likelihood approach has been published [17], [18]. The associations between genotype and breast cancer risk at both stages were assessed using the 1 d.f. score test statistic based on this retrospective likelihood [17], [18]. To allow for the non-independence among related individuals, we accounted for the correlation between the genotypes by estimating the kinship coefficient for each pair of individuals using the available genomic data [16], [19], [20] and by robust variance estimation based on reported family membership [21]. We chose to present P-values based on the kinship adjusted score test as it utilises the degree of relationship between individuals. A genome-wide level of significance of 5×10−8 was used [22]. These analyses were performed in R using the GenABEL [23] libraries and custom-written functions in FORTRAN and Python.

To estimate the magnitude of the associations (HRs), the effect of each SNP was modeled either as a per-allele HR (multiplicative model) or as genotype-specific HRs, and were estimated on the log-scale by maximizing the retrospective likelihood. The retrospective likelihood was fitted using the pedigree-analysis software MENDEL [17], [24]. As sample sizes varied substantially between contributing centers heterogeneity was examined at the country level. All analyses were stratified by country of residence and used calendar-year and cohort-specific breast cancer incidence rates for BRCA1 [25]. Countries with small number of mutation carriers were combined with neighbouring countries to ensure sufficiently large numbers within each stratum (Table S2). USA and Canada were further stratified by reported Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ) ancestry due to large numbers of AJ carriers. In stage 3 analysis involving several countries with small numbers of mutation carriers, we assumed only 3 large strata (Europe, Australia, USA/Canada). The combined iCOGS stage and stage 3 analysis was also stratified by stage of the experiment. The analysis of associations by breast cancer ER-status was carried out by an extension of the retrospective likelihood approach to model the simultaneous effect of each SNP on more than one tumor subtype [26] (Text S1).

Competing risk analysis

The associations with breast and ovarian cancer risk simultaneously were assessed within a competing risk analysis framework [17] by estimating HRs simultaneously for breast and ovarian cancer risk. This analysis provides unbiased estimates of association with both diseases and more powerful tests of association in cases where an association exists between a variant and at least one of the diseases [17]. Each individual was assumed to be at risk of developing either breast or ovarian cancer, and the probabilities of developing each disease were assumed to be independent conditional on the underlying genotype. A different censoring process was used, whereby individuals were followed up to the age of the first breast or ovarian cancer diagnosis and were considered to have developed the corresponding disease. No follow-up was considered after the first cancer diagnosis. Individuals censored for breast cancer at the age of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy and for ovarian cancer at the age of RRSO were assumed to be unaffected for the corresponding disease. The remaining individuals were censored at the last observation age and were assumed to be unaffected for both diseases.

Imputation

For the SNP selection process, the MACH software was used to impute non-genotyped SNPs based on the phased haplotypes from HapMap Phase II (CEU, release 22). The IMPUTE2 software [27] was used to impute non-genotyped SNPs for samples genotyped on the iCOGS array (stage 1 and 2 only), based on the 1,000 Genomes haplotypes (January 2012 version). Associations between each marker and cancer risk were assessed using a similar score test to that used for the observed SNPs, but based on the posterior genotype probabilities at each imputed marker for each individual. In all analyses, we considered only SNPs with imputation information/accuracy r2>0.30.

Absolute breast and ovarian cancer risks by combined SNP profile

We estimated the absolute risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer based on the joint distribution of all SNPs that were significantly associated with risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers based on methods previously applied to BRCA2 carriers [28]. We assumed that the average, age-specific breast and ovarian cancer incidences for BRCA1 mutation carriers, over all modifying loci, agreed with published penetrance estimates for BRCA1 [25]. The model assumed independence among the modifying loci and we used only the SNP with the strongest evidence of association from each region. We used only loci identified through the BRCA1 GWAS that exhibited associations at a genome-wide significance level, and loci that were identified through population-based GWAS of breast or ovarian cancer risk, but were also associated with those risks for BRCA1 mutation carriers. For each SNP, we used the per-allele HR and minor allele frequencies estimated from the present study. Genotype frequencies were obtained under the assumption of HWE.

Results

Samples from 11,705 BRCA1 carriers from 45 centers in 25 countries yielded high-quality data for 201,242 SNPs on the iCOGS array. The array included 31,812 BRCA1 GWAS SNPs, which were analyzed here for their associations with breast and ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers (Table S2). Of the 11,705 BRCA1 mutation carriers, 2,387 samples had also been genotyped for stage 1 of the GWAS and 9,318 were unique to the stage 2 iCOGS study.

Breast cancer associations

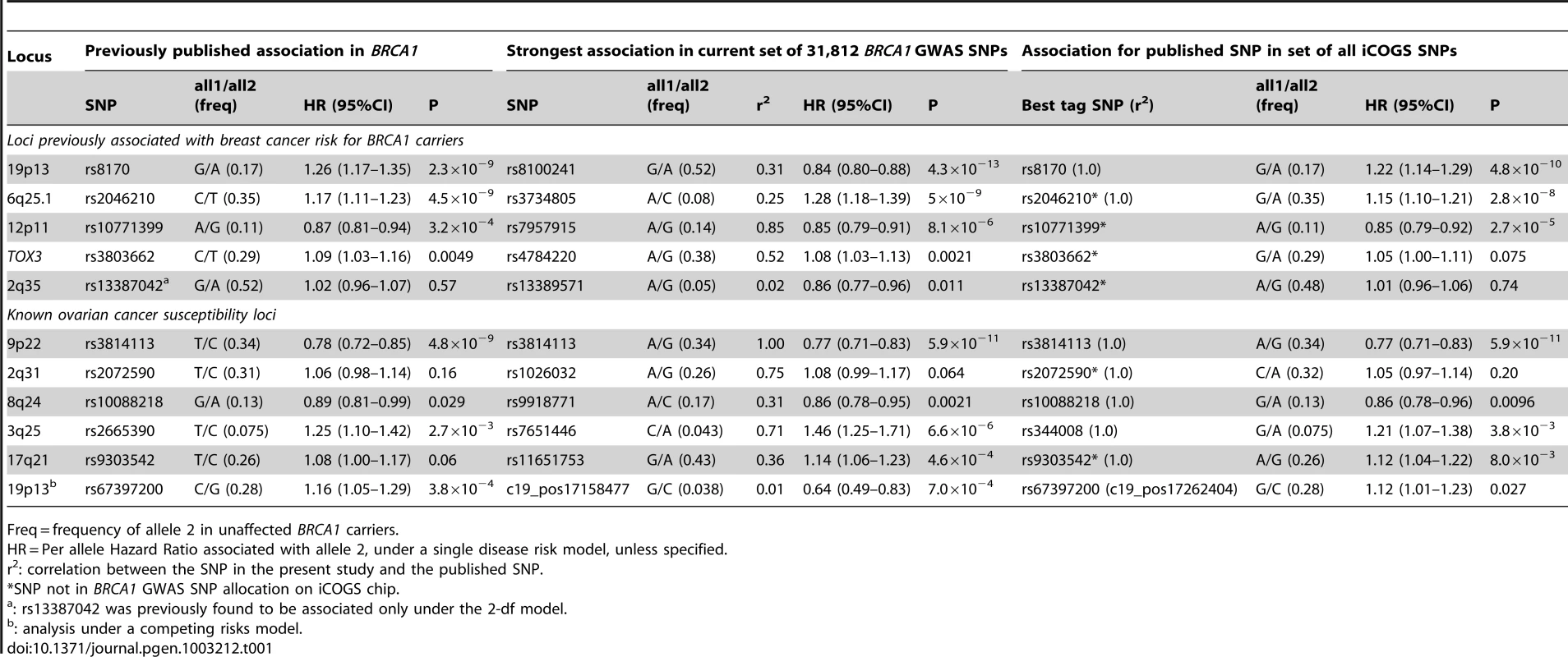

When restricting analysis to stage 2 samples (4,681 unaffected, 4,637 affected), there was little evidence of inflation in the association test-statistic (λ = 1.038; Figure S3). Combined analysis of stage 1 and 2 samples (5,784 unaffected, 5,920 affected) revealed 66 SNPs in 28 regions with P<10−4 (Figure S4). These included variants from three loci (19p13, 6q25.1, 12p11) previously associated with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers (Table 1). Further evaluation of 18 loci associated with breast cancer susceptibility in the general population found that only the TOX3, LSP1, 2q35 and RAD51L1 loci were significantly associated with breast cancer for BRCA1 carriers (Table 1, Table S4).

Tab. 1. Associations with breast or ovarian cancer risk for loci previously reported to be associated with cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers.

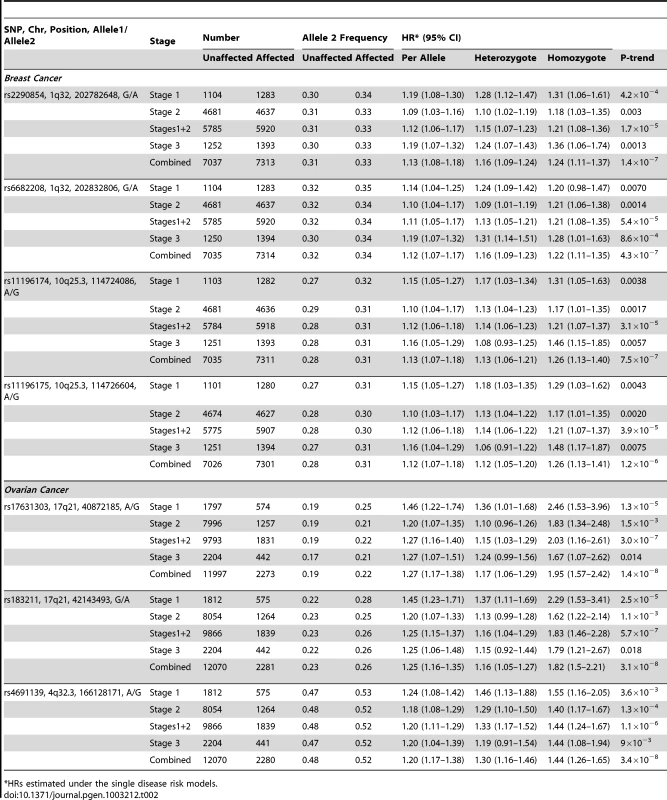

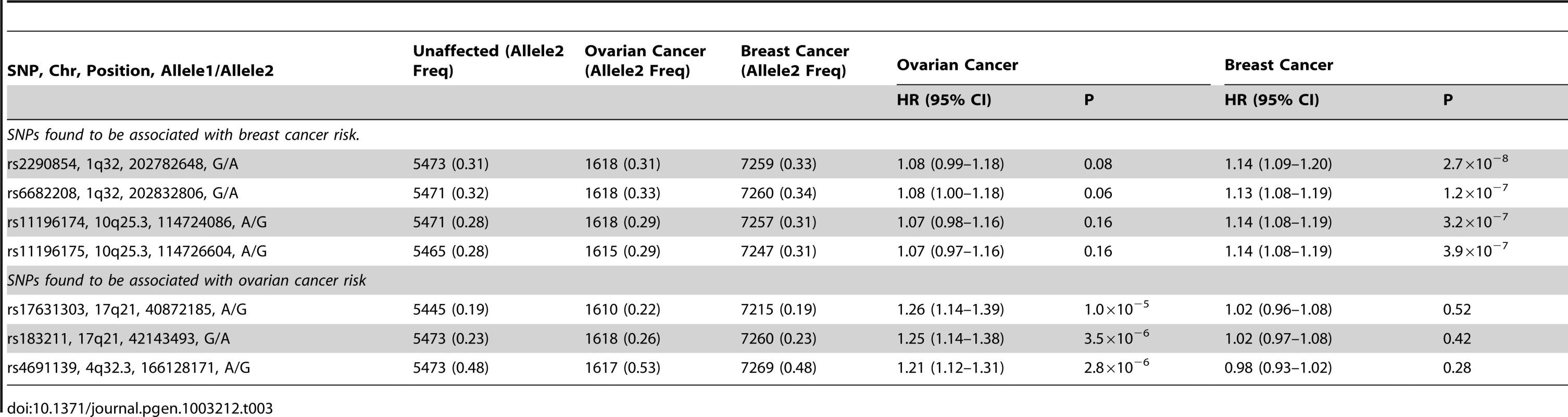

Freq = frequency of allele 2 in unaffected BRCA1 carriers. After excluding SNPs from the known loci, there were 39 SNPs in 25 regions with P = 1.2×10−6–1.0×10−4. Twelve of these SNPs were genotyped by iPLEX in an additional 2,646 BRCA1 carriers (1,252 unaffected, 1,394 affected, “stage 3” samples, Table S5). There was additional evidence of association with breast cancer risk for four SNPs at two loci (P<0.01, Table 2). When all stages were combined, SNPs rs2290854 and rs6682208 (r2 = 0.84) at 1q32, near MDM4, had combined P-values of association with breast cancer risk of 1.4×10−7 and 4×10−7,respectively. SNPs rs11196174 and rs11196175 (r2 = 0.96) at 10q25.3 (in TCF7L2) had combined P-values of 7.5×10−7 and 1.2×10−6. Analysis within a competing risks framework, where associations with breast and ovarian cancer risks are evaluated simultaneously [17], revealed stronger associations with breast cancer risk for all 4 SNPs, but no associations with ovarian cancer (Table 3). In particular, we observed a genome-wide significant association between the minor allele of rs2290854 from 1q32 and breast cancer risk (per-allele HR: 1.14; 95%CI: 1.09–1.20; p = 2.7×10−8). Country-specific HR estimates for all SNPs are shown in Figure S5. Analyses stratified by BRCA1 mutation class revealed no significant evidence of a difference in the associations of any of the SNPs by the predicted functional consequences of BRCA1 mutations (Table S6). SNPs in the MDM4 and TCF7L2 loci were associated with breast cancer risk for both class1 and class2 mutation carriers.

Tab. 2. Associations with breast and ovarian cancer risk for SNPs found to be associated with risk at all 3 stages of the experiment.

HRs estimated under the single disease risk models. Tab. 3. Analysis of associations with breast and ovarian cancer risk simultaneously (competing risks analysis) for SNPs found to be associated with breast or ovarian cancer.

Both the 1q32 and 10q25.3 loci were primarily associated with ER-negative breast cancer for BRCA1 (rs2290854: ER-negative HR = 1.16, 95%CI: 1.10–1.22, P = 1.2×10−7; rs11196174: HR = 1.14, 95%CI: 1.07–1.20, P = 9.6×10−6), although the differences between the ER-negative and ER-positive HRs were not significant (Table S7). Given that ER-negative breast cancers in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers are phenotypically similar [29], we also evaluated associations between these SNPs and ER-negative breast cancer in 8,211 BRCA2 mutation carriers. While the 10q25.3 SNPs were not associated with overall or ER-negative breast cancer risk for BRCA2 carriers, the 1q32 SNPs were associated with ER-negative (rs2290854 HR = 1.16, 95%CI:1.01–1.34, P = 0.033; rs6682208 HR = 1.19, 95%CI:1.04–1.35, P = 0.016), but not ER-positive breast cancer (rs2290854 P-diff = 0.006; rs6682208 P-diff = 0.001). Combining the BRCA1 and BRCA2 samples provided strong evidence of association with ER-negative breast cancer (rs2290854: P = 1.25×10−8; rs6682208: P = 2.5×10−7).

The iCOGS array included additional SNPs from the 1q32 region that were not chosen based on the BRCA1 GWAS. Of these non-BRCA1 GWAS SNPs, only SNP rs4951407 was more significantly associated with risk than the BRCA1-GWAS selected SNPs (P = 3.3×10−6, HR = 1.12, 95%CI:1.07–1.18, using stage 1 and stage 2 samples). The evidence of association with breast cancer risk was again stronger under the competing risks analysis (HR = 1.14, 95%CI: 1.08–1.20, P = 6.1×10−7). Backward multiple regression analysis, considering only the genotyped SNPs (P<0.01), revealed that the most parsimonious model included only rs4951407. SNPs from the 1000 Genomes Project, were imputed for the stage 1 and stage 2 samples (Figure S6). Only imputed SNP rs12404974, located between PIK3C2B and MDM4 (r2 = 0.77 with rs4951407), was more significantly associated with breast cancer (P = 2.7×10−6) than any of the genotyped SNPs. None of the genotyped or imputed SNPs from 10q25.3 provided P-values smaller than those for rs11196174 and rs11196175 (Figure S7).

Ovarian cancer associations

Analyses of associations with ovarian cancer risk using the stage 2 samples (8,054 unaffected, 1,264 affected) revealed no evidence of inflation in the association test-statistic (λ = 1.039, Figure S3). In the combined analysis of stage 1 and 2 samples (9866 unaffected, 1839 affected), 62 SNPs in 17 regions were associated with ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 carriers at P<10−4 (Figure S3). These included SNPs in the 9p22 and 3q25 loci previously associated with ovarian cancer risk in both the general population and BRCA1 carriers [6], [7] (Table 1). Associations (P<0.01) with ovarian cancer risk were also observed for SNPs in three other known ovarian cancer susceptibility loci (8q24, 17q21, 19p13), but not 2q31 (Table 1). For all loci except 9p22, SNPs were identified that displayed smaller P-values of association than previously published results [5]–[7].

After excluding SNPs from known ovarian cancer susceptibility regions, there were 48 SNPs in 15 regions with P = 5×10−7 to 10−4. Five SNPs from four of these loci were genotyped in the stage 3 samples (2,204 unaffected, 442 with ovarian cancer). Three SNPs showed additional evidence of association with ovarian cancer risk (P<0.02, Table 2; Table S5). In the combined stage 1–3 analyses, SNPs rs17631303 and rs183211 (r2 = 0.68) on chromosome 17q21.31 had P-values for association of 1×10−8 and 3×10−8 respectively, and rs4691139 at 4q32.3 had a P-value of 3.4×10−8 (Table 2).

The minor alleles of rs17631303 (HR = 1.27, 95%CI:1.17–1.38) and rs183211 (HR = 1.25, 95%CI: 1.16–1.35) at 17q21.31 were associated with increased ovarian cancer risk (Table 2). Analysis of the associations within a competing risks framework, revealed no association with breast cancer risk (Table 3). The ovarian cancer effect size was maintained in the competing risk analysis but the significance of the association was slightly weaker (P = 2×10−6–1×10−5). This is expected because 663 ovarian cancer cases occurring after a primary breast cancer diagnosis were excluded for this analysis. The evidence of association was somewhat stronger under the genotype-specific model (2-df P = 1.6×10−9 and P = 2.6×10−9 for rs17631303 and rs183211 respectively in all samples combined) with larger HR estimates for the rare homozygote genotypes than those expected under a multiplicative model (Table 2).

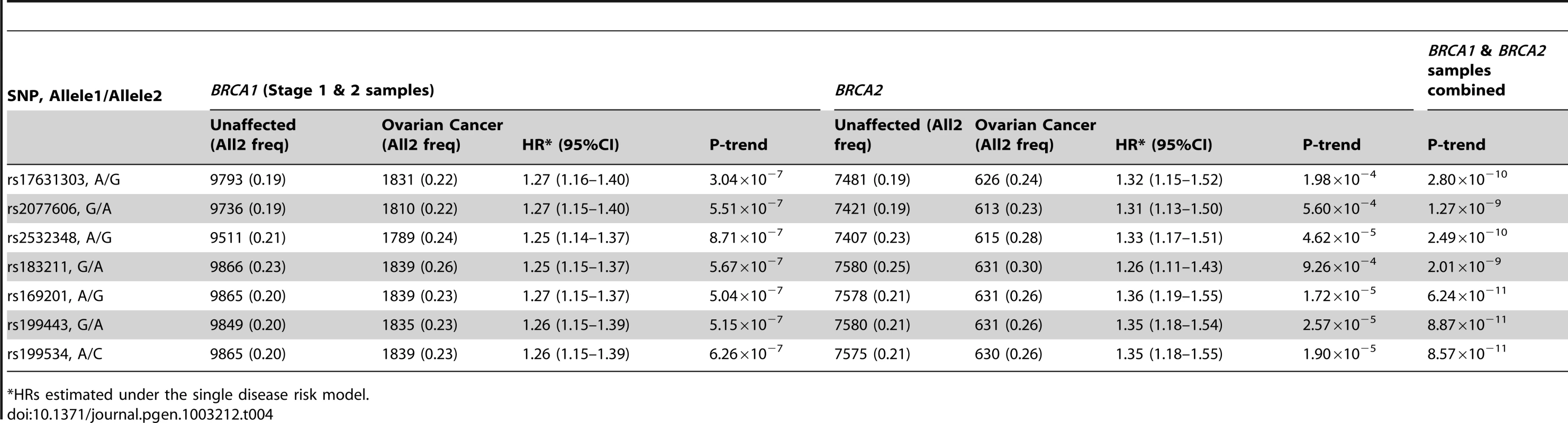

Previous studies of the known common ovarian cancer susceptibility alleles found significant associations with ovarian cancer for both BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers [6], [7]. Thus, we evaluated the associations between the 17q21.31 SNPs and ovarian cancer risk for BRCA2 carriers using iCOGS genotype data (7580 unaffected and 631 affected). Both rs17631303 and rs183211 were associated with ovarian cancer risk for BRCA2 carriers (P = 1.98×10−4 and 9.26×10−4), with similar magnitude and direction of association as for BRCA1 carriers. Combined analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers provided strong evidence of association (P = 2.80×10−10 and 2.01×10−9, Table 4).

Tab. 4. Associations with SNPs at the novel 17q21 region with ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers.

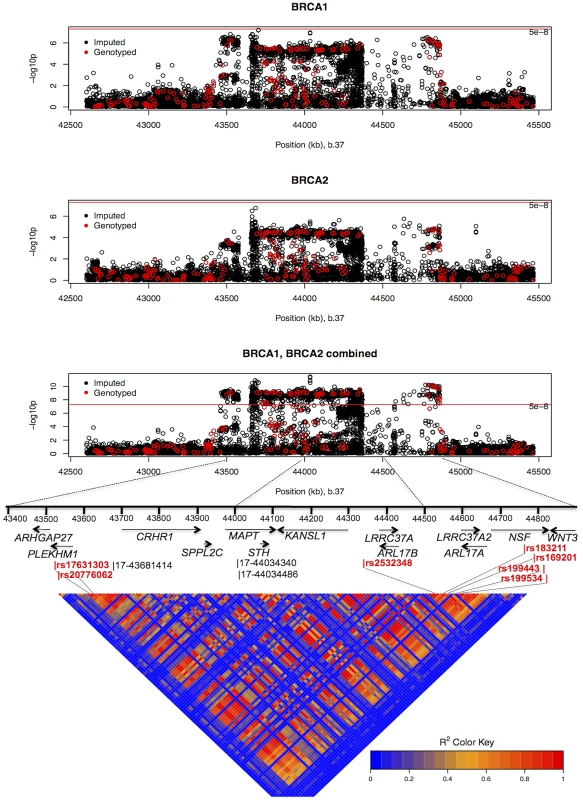

HRs estimated under the single disease risk model. The combined analysis of stage 1 and 2 samples, and BRCA2 carriers, identified seven SNPs on the iCOGS array (pairwise r2 range: 0.68–1.00) from a 1.3 Mb (40.8–42.1 Mb, build 36.3) region of 17q21.31 that were strongly associated (P<1.27×10−9) with ovarian cancer risk (Table 4, Figure 2). Stepwise-regression analysis based on observed genotype data retained only one of the seven SNPs in the model, but it was not possible to distinguish between the SNPs. Imputation through the 1000 Genomes Project, revealed several SNPs in 17q21.31 with stronger associations (Figure 2, Table S8) than the most significant genotyped SNP in the combined BRCA1/2 analysis (rs169201, P = 6.24×10−11). The most significant SNP (rs140338099 (17-44034340), P = 3×10−12), located in MAPT, was highly correlated (r2 = 0.78) with rs169201 in NSF (Figure 2). This locus appears to be distinct from a previously identified ovarian cancer susceptibility locus located >1 Mb distal on 17q21 (spanning 43.3–44.3 Mb, build 36.3) [30]. None of the SNPs in the novel region were strongly correlated with any of the SNPs in the 43.3–44.3 Mb region (maximum r2 = 0.07, Figure S8). The most significantly associated SNP from the BRCA1 GWAS from the 43.3–44.3 Mb locus was rs11651753 (p = 4.6×10−4) (Table 1) (r2<0.023 with the seven most significant SNPs in the novel 17q21.31 region). An analysis of the joint associations of rs11651753 and rs17631303 from the two 17q21 loci with ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 carriers (Stage 1 and 2 samples) revealed that both SNPs remained significant in the model (P-for inclusion = 0.001 for rs11651753, 1.2×10−6 for rs17631303), further suggesting that the two regions are independently associated with ovarian cancer for BRCA1 carriers.

Fig. 2. Mapping of the 17q21 locus.

Top 3 panels: P-values of association (−log10 scale) with ovarian cancer risk for genotyped and imputed SNPs (1000 Genomes Project CEU), by chromosome position (b.37) at the 17q21 region, for BRCA1, BRCA2 mutation carriers and combined. Results based on the kinship-adjusted score test statistic (1 d.f.). Fourth panel: Genes in the region spanning (43.4–44.9 Mb, b.37) and the location of the most significant genotyped SNPs (in red font) and imputed SNPs (in black font). Bottom panel: Pairwise r2 values for genotyped SNPs on iCOG array in the 17q21 region covering positions (43.4–44.9 Mb, b.37). The minor allele of rs4691139 at the novel 4q32.3 region was also associated with an increased ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 carriers (per-allele HR = 1.20, 95%CI:1.17–1.38, Table 2), but was not associated with breast cancer risk (Table 3). No other SNPs from the 4q32.3 region on the iCOGS array were more significantly associated with ovarian cancer for BRCA1 carriers. Analysis of associations with variants identified through 1000 Genomes Project-based imputation of the Stage 1 and 2 samples, revealed 19 SNPs with stronger evidence of association (P = 5.4×10−7 to 1.1×10−6) than rs4691139 (Figure S9). All were highly correlated (pairwise r2>0.89) and the most significant (rs4588418) had r2 = 0.97 with rs4691139. There was no evidence for association between rs4691139 and ovarian cancer risk for BRCA2 carriers (HR = 1.08, 95%CI: 0.96–1.21, P = 0.22).

Absolute risks of developing breast and ovarian cancer

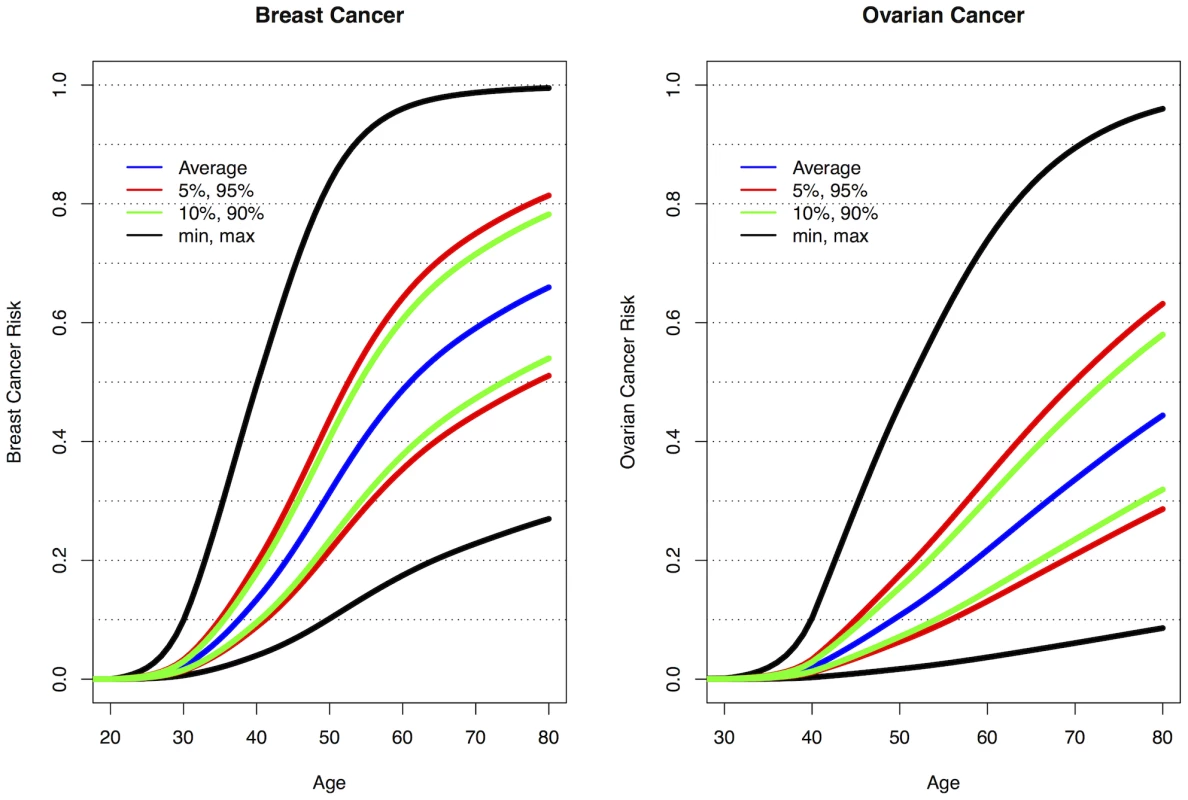

The current analyses suggest that 10 loci are now known to be associated with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers: 1q32, 10q25.3, 19p13, 6q25.1, 12p11, TOX3, 2q35, LSP1 and RAD51L1 all reported here and TERT [31]. Similarly, seven loci are associated with ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers: 9p22, 8q24, 3q25, 17q21, 19p13, 17q21.31 and 4q32.3. Figure S10 shows the range of combined HRs at different percentiles of the combined genotype distribution, based on the single SNP HR and minor allele estimates from Table 1, Table 2, and Table S4 and for TERT from Bojesen et al [31] and assuming that all SNPs interact multiplicatively. Relative to BRCA1 mutation carriers at lowest risk, the median, 5th and 95th percentile breast cancer HRs were 3.40, 2.27, and 5.35 respectively. These translate to absolute risks of developing breast cancer by age 80 of 65%, 51% and 81% for those at median, 5th and 95th percentiles of the combined genotype distribution (Figure 3, Figure S10). Similarly, the median, 5th and 95th percentile combined HRs for ovarian cancer were 6.53, 3.75 and 11.12 respectively, relative to those at lowest ovarian cancer risk (Figure S10). These HRs translate to absolute risks of developing ovarian cancer of 44%, 28% and 63% by age 80 for the median, 5th and 95th percentile of the combined genotype distribution (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Predicted breast and ovarian cancer absolute risks for BRCA1 mutation carriers at the 5th, 10th, 90th, and 95th percentiles of the combined SNP profile distributions.

The minimum, maximum and average risks are also shown. Predicted cancer risks are based on the associations of known breast or ovarian cancer susceptibility loci (identified through GWAS) with cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers and loci identified through the present study. Breast cancer risks based on the associations with: 1q32, 10q25.3, 19p13, 6q25.1, 12p11, TOX3, 2q35, LSP1, RAD51L1 (based on HR and minor allele frequency estimates from Table 1, Table 2, and Table S4) and TERT [31]. Ovarian cancer risks based on the associations with: 9p22, 8q24, 3q25, 17q21, 19p13 (Table 1) and 17q21.31, 4q32.3 (Table 2). Only the top SNP from each region was chosen. Average breast and ovarian cancer risks were obtained from published data [25]. The methods for calculating the predicted risks have been described previously [28]. Discussion

In this study we analyzed data from 11,705 BRCA1 mutation carriers from CIMBA who were genotyped using the iCOGS high-density custom array, which included 31,812 SNPs selected on the basis of a BRCA1 GWAS. This study forms the large-scale replication stage of the first GWAS of breast and ovarian cancer risk modifiers for BRCA1 mutation carriers. We have identified a novel locus at 1q32, containing the MDM4 oncogene, that is associated with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers (P<5×10−8). A separate locus at 10q23.5, containing the TCF7L2 gene, provided strong evidence of association with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 carriers but did not reach a GWAS level of significance. We have also identified two novel loci associated with ovarian cancer for BRCA1 mutation carriers at 17q21.31 and 4q32.2 (P<5×10−8). We further confirmed associations with loci previously shown to be associated with breast or ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers. In most cases stronger associations were detected with either the same SNP reported previously (due to increased sample size) or other SNPs in the regions. Future fine mapping studies of these loci will aim to identify potentially causal variants for the observed associations.

Although the 10q25.3 locus did not reach the strict GWAS level of significance for association with breast cancer risk, the association was observed at all three independent stages of the experiment. Additional evidence for the involvement of this locus in breast cancer susceptibility comes from parallel studies of the Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC). SNPs at 10q25.3 had also been independently selected for inclusion on the iCOGS array through population based GWAS of breast cancer. Analyses of those SNPs in BCAC iCOGS studies also found that SNPs at 10q25.3 were associated with breast cancer risk in the general population [32]. Thus, 10q25.3 is likely a breast cancer risk-modifying locus for BRCA1 mutation carriers. The most significant SNPs at 10q25.3 were located in TCF7L2, a transcription factor that plays a key role in the Wnt signaling pathway and in glucose homeostasis, and is expressed in normal and malignant breast tissue (The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)). Variation in the TCF7L2 locus has previously been associated with Type 2 diabetes in a number of GWAS. The most significantly associated SNPs with Type 2 diabetes (rs7903146 and rs4506565) [22], [33] were also associated with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers in stage 1 and 2 analyses (p = 3.7×10−4 and p = 2.5×10−4 respectively); these SNPs were correlated with the most significant hit (rs11196174) for BRCA1 breast cancer (r2 = 0.40 and 0.37 based on stage 1 and 2 samples). This raises the possibility that variants in this locus influence breast cancer indirectly through effects on cellular metabolism.

We found that SNPs at 1q32 were primarily associated with ER-negative breast cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers. There was also evidence of association with ER-negative breast cancer for BRCA2 mutation carriers. SNPs at the 1q32 region were independently selected for inclusion on iCOGS through GWAS of breast cancer in the general population by BCAC. In parallel analyses of iCOGS data by BCAC, 1q32 was found to be associated with ER-negative breast cancer [34] but not overall breast cancer risk [32]. Taken together, these results are in agreement with our findings and in line with the observation that the majority of BRCA1 breast cancers are ER-negative. However, they are not in agreement with a previous smaller candidate-gene study that found an association between a correlated SNP in MDM4 (r2>0.85) and overall breast cancer risk [35]. The 1q32 locus includes the MDM4 oncogene which plays a role in regulation of p53 and MDM2 and the apoptotic response to cell stress. MDM4 is expressed in breast tissue and is amplified and overexpressed along with LRRN2 and PIK3C2B in breast and other tumor types (TCGA) [36]–[38]. Although fine mapping will be necessary to identify the functionally relevant SNPs in this locus, we found evidence of cis-regulatory variation impacting MDM4 expression [39]–[41] (Text S1, Table S9, Figure S11), suggesting that common variation in the 1q32 locus may influence the risk of breast cancer through direct effects on MDM4 expression.

Several correlated SNPs at 17q21.31 from the iCOGS array provided strong evidence of association with ovarian cancer risk in both BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. A subsequent analysis of these SNPs, which were selected through the BRCA1 GWAS, in case-control samples from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium (OCAC), revealed that the 17q21.31 locus is associated with ovarian cancer risk in the general population [Wey et al, personal communication]. Thus, 17q21.31 is likely a novel susceptibility locus for ovarian cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers. The most significant associations at 17q21.31 were clustered in a large region of strong linkage disequilibrium which has previously been identified as a “17q21.31 inversion” (∼900 kb long) consisting of two haplotypes (termed H1 and H2) [42]. The minor allele of rs2532348 (MAF = 0.21), which tags H2, was associated with increased ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers (Table 4). The 1.3 Mb 17q21.31 locus contains 13 genes and several predicted pseudogenes (Figure 2), several of which are expressed in normal ovarian surface epithelium and ovarian adenocarcinoma [43]. Variation in this region has been associated with Parkinson's disease (MAPT, PLEKHM1, NSF, c17orf69) progressive supranuclear palsy (MAPT), celiac disease (WNT3), bone mineral density (CRHR1) (NHGRI GWAS catalog) and intracranial volume [44]. Of the top hits for these phenotypes, SNP rs199533 in NSF, previously associated with Parkinson's disease [45] and rs9915547 associated with intracranial volume [44] were strongly associated with ovarian cancer (P<10−9 in BRCA1/2 combined). Whether these phenotypes have shared causal variants in this locus remains to be elucidated. Further exploration of the functional relevance of the strongest hits in the 17q21.31 locus (P<10−8 in BRCA1/2 combined) provided evidence that cis-regulatory variation alters expression of several genes at 17q21, including PLEKHM1, c17orf69, ARHGAP27, MAPT, KANSL1 and WNT3 [39], [41] (Table S9, Figure S12), suggesting that ovarian cancer risk may be associated with altered expression of one or more genes in this region.

Our analyses revealed that a second novel locus at 4q32.3 was also associated with ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carries (P<5×10−8). However, we found no evidence of association for these SNPs with ovarian cancer risk for BRCA2 mutation carriers using 8,211 CIMBA samples genotyped using the iCOGS array. Likewise, no evidence of association was found between rs4691139 at 4q32.3 and ovarian cancer risk in the general population based on data by OCAC data derived from 18,174 cases and 26,134 controls (odds ratio = 1.00, 95%CI:0.97–1.04, P = 0.76) [46]. The confidence intervals rule out a comparable effect to that found in BRCA1 carriers. Therefore, our findings may represent a BRCA1-specific association with ovarian cancer risk, the first of its kind. The 4q32.2 region contains several members of the TRIM (Tripartite motif containing) gene family, c4orf39 and TMEM192. TRIM60, c4orf39 and TMEM192 are expressed in normal ovarian epithelium and/or ovarian tumors (TCGA).

In summary, we have identified a novel locus at 1q32 associated with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers, which was also associated with ER-negative breast cancer for BRCA2 carriers and in the general population. A separate locus at 10q23.5 provided strong evidence of association with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 carriers. We have also identified 2 novel loci associated with ovarian cancer for BRCA1 mutation carriers. Of these, the 4q32.2 locus was associated with ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 carriers but not for BRCA2 carriers or in the general population. Additional functional characterisation of the loci will further improve our understanding of the biology of breast and ovarian cancer development in BRCA1 carriers. Taken together with other identified genetic modifiers, 10 loci are now known to be associated with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers (1q32, 10q25.3, 19p13, 6q25.1, 12p11, TOX3, 2q35, LSP1, RAD51L1 and TERT and seven loci are known to be associated with ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers (9p22, 8q24, 3q25, 17q21, 19p13 and 17q21.31, 4q32.3).

As BRCA1 mutations confer high breast and ovarian cancer risks, the results from the present study, taken together with other identified genetic modifiers, demonstrate for the first time that they can result in large differences in the absolute risk of developing breast or ovarian cancer for BRCA1 between genotypes. For example, the breast cancer lifetime risks for the 5% of BRCA1 carriers at lowest risk are predicted to be 28–50% compared to 81–100% for the 5% at highest risk (Figure 3). Based on the distribution of ovarian cancer risk modifiers, the 5% of BRCA1 mutation carriers at lowest risk will have a lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer of 28% or lower whereas the 5% at highest risk will have a lifetime risk of 63% or higher. Similarly, the breast cancer risk by age 40 is predicted to be 4–9% for the 5% of BRCA1 carriers at lowest risk compared to 20–49% for the 5% at highest risk, whereas the ovarian cancer risk at age 50 ranges from 3–7% for the 5% at lowest risk and from 18–47% for the 5% at highest risk. The risks at all ages for the 10% at highest or lowest risk of breast and ovarian cancer are predicted to be similar to those for the highest and lowest 5%. Thus, at least 20% of BRCA1 mutation carriers are predicted to have absolute risks of disease that are different from the average BRCA1 carriers. These large differences in cancer risks may have practical implications for the clinical management of BRCA1 mutation carriers, for example in deciding the timing of interventions. Such risks, in combination with other lifestyle and hormonal risk factors could be incorporated into cancer risk prediction algorithms for use by clinical genetics centers. These algorithms could then be used to inform the development of effective and consistent clinical recommendations for the clinical management of BRCA1 mutation carriers.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. AntoniouA, PharoahPD, NarodS, RischHA, EyfjordJE, et al. (2003) Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet 72 : 1117–1130.

2. AntoniouAC, Chenevix-TrenchG (2010) Common genetic variants and cancer risk in Mendelian cancer syndromes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 20 : 299–307 S0959-437X(10)00044-4 [pii];10.1016/j.gde.2010.03.010 [doi].

3. BeggCB, HaileRW, BorgA, MaloneKE, ConcannonP, et al. (2008) Variation of breast cancer risk among BRCA1/2 carriers. JAMA 299 : 194–201.

4. SimchoniS, FriedmanE, KaufmanB, Gershoni-BaruchR, Orr-UrtregerA, et al. (2006) Familial clustering of site-specific cancer risks associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 : 3770–3774.

5. CouchFJ, GaudetMM, AntoniouAC, RamusSJ, KuchenbaeckerKB, et al. (2012) Common cariants at the 19p13.1 and ZNF365 loci are associated with ER subtypes of breast cancer and ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 21 : 645–657 1055-9965.EPI-11-0888 [pii];10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0888 [doi].

6. RamusSJ, KartsonakiC, GaytherSA, PharoahPD, SinilnikovaOM, et al. (2010) Genetic variation at 9p22.2 and ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 103 : 105–116 djq494 [pii];10.1093/jnci/djq494 [doi].

7. RamusSJ, AntoniouAC, KuchenbaeckerKB, SoucyP, BeesleyJ, et al. (2012) Ovarian cancer susceptibility alleles and risk of ovarian cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Hum Mutat 33 : 690–702 10.1002/humu.22025 [doi].

8. AntoniouAC, SpurdleAB, SinilnikovaOM, HealeyS, PooleyKA, et al. (2008) Common breast cancer-predisposition alleles are associated with breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Am J Hum Genet 82 : 937–948.

9. AntoniouAC, SinilnikovaOM, McGuffogL, HealeyS, NevanlinnaH, et al. (2009) Common variants in LSP1, 2q35 and 8q24 and breast cancer risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Hum Mol Genet 18 : 4442–4456 ddp372 [pii];10.1093/hmg/ddp372 [doi].

10. AntoniouAC, KartsonakiC, SinilnikovaOM, SoucyP, McGuffogL, et al. (2011) Common alleles at 6q25.1 and 1p11.2 are associated with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Hum Mol Genet 20 : 3304–3321 ddr226 [pii];10.1093/hmg/ddr226 [doi].

11. AntoniouAC, KuchenbaeckerKB, SoucyP, BeesleyJ, ChenX, et al. (2012) Common variants at 12p11, 12q24, 9p21, 9q31.2 and in ZNF365 are associated with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res 14: R33 bcr3121 [pii];10.1186/bcr3121 [doi].

12. AntoniouAC, WangX, FredericksenZS, McGuffogL, TarrellR, et al. (2010) A locus on 19p13 modifies risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers and is associated with hormone receptor-negative breast cancer in the general population. Nat Genet 42 : 885–892 ng.669 [pii];10.1038/ng.669 [doi].

13. StevensKN, VachonCM, LeeAM, SlagerS, LesnickT, et al. (2011) Common breast cancer susceptibility loci are associated with triple negative breast cancer. Cancer Res 0008-5472.CAN-11-1266 [pii];10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1266 [doi].

14. GaudetMM, KuchenbaeckerKB, VijaiJ, KleinRJ, KirchhoffT, et al. (2013) Identification of a BRCA2-specific Modifier Locus at 6p24 Related to Breast Cancer Risk. PLoS Genet 9: e1003173 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003173.

15. RobertsonA, HillWG (1984) Deviations from Hardy-Weinberg proportions: sampling variances and use in estimation of inbreeding coefficients. Genetics 107 : 703–718.

16. AntoniouAC, GoldgarDE, AndrieuN, Chang-ClaudeJ, BrohetR, et al. (2005) A weighted cohort approach for analysing factors modifying disease risks in carriers of high-risk susceptibility genes. Genet Epidemiol 29 : 1–11.

17. BarnesDR, LeeA, EastonDF, AntoniouAC (2012) Evaluation of association methods for analysing modifiers of disease risk in carriers of high-risk mutations. Genet Epidemiol 36 : 274–291 10.1002/gepi.21620 [doi].

18. AntoniouAC, SinilnikovaOM, SimardJ, LeoneM, DumontM, et al. (2007) RAD51 135G→C modifies breast cancer risk among BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from a combined analysis of 19 studies. Am J Hum Genet 81 : 1186–1200.

19. AminN, van DuijnCM, AulchenkoYS (2007) A genomic background based method for association analysis in related individuals. PLoS ONE 2: e1274 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001274.

20. LeuteneggerAL, PrumB, GeninE, VernyC, LemainqueA, et al. (2003) Estimation of the inbreeding coefficient through use of genomic data. Am J Hum Genet 73 : 516–523 10.1086/378207 [doi];S0002-9297(07)62015-1 [pii].

21. BoosDD (1992) On generalised score tests. American Statistician 46 : 327–333.

22. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium (2007) Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature 447 : 661–678 nature05911 [pii];10.1038/nature05911 [doi].

23. AulchenkoYS, RipkeS, IsaacsA, van DuijnCM (2007) GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics 23 : 1294–1296 btm108 [pii];10.1093/bioinformatics/btm108 [doi].

24. LangeK, WeeksD, BoehnkeM (1988) Programs for pedigree analysis: MENDEL, FISHER, and dGENE. Genet Epidemiol 5 : 471–472.

25. AntoniouAC, CunninghamAP, PetoJ, EvansDG, LallooF, et al. (2008) The BOADICEA model of genetic susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancers: updates and extensions. Br J Cancer 98 : 1457–1466.

26. MulliganAM, CouchFJ, BarrowdaleD, DomchekSM, EcclesD, et al. (2011) Common breast cancer susceptibility alleles are associated with tumor subtypes in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2. Breast Cancer Res 13: R110 bcr3052 [pii];10.1186/bcr3052 [doi].

27. HowieB, MarchiniJ, StephensM (2011) Genotype imputation with thousands of genomes. G3 (Bethesda) 1 : 457–470 10.1534/g3.111.001198 [doi];GGG_001198 [pii].

28. AntoniouAC, BeesleyJ, McGuffogL, SinilnikovaOM, HealeyS, et al. (2010) Common Breast Cancer Susceptibility Alleles and the Risk of Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers: Implications for Risk Prediction. Cancer Res 70 : 9742–9754 0008-5472.CAN-10-1907 [pii];10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1907 [doi].

29. MavaddatN, BarrowdaleD, AndrulisIL, DomchekSM, EcclesD, et al. (2012) Pathology of breast and ovarian cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2 (CIMBA). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 21 : 134–147 1055-9965.EPI-11-0775 [pii];10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0775 [doi].

30. GoodeEL, Chenevix-TrenchG, SongH, RamusSJ, NotaridouM, et al. (2010) A genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for ovarian cancer at 2q31 and 8q24. Nat Genet 42 : 874–879 ng.668 [pii];10.1038/ng.668 [doi].

31. BojesenS, PooleyKA, JohnattySE, BeesleyJ, MichailidouK, et al. (2012) Multiple independent TERT variants associated with telomere length and risks of breast and ovarian cancer. Nat Genet In Press.

32. MichailidouK, HallP, Gonzalez-NeiraA, GhoussainiM, DennisJ, et al. (2012) Large-scale genotyping identifies 41 new loci associated with breast cancer risk. Nat Genet In Press.

33. SladekR, RocheleauG, RungJ, DinaC, ShenL, et al. (2007) A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature 445 : 881–885 nature05616 [pii];10.1038/nature05616 [doi].

34. Garcia-ClosasM, CouchFJ, LindstromS, MichailidouK, SchmidtMK, et al. (2012) Genome-wide association studies identify four ER-negative specific breast cancer risk loci. Nat Genet In Press.

35. AtwalGS, KirchhoffT, BondEE, MontagnaM, MeninC, et al. (2009) Altered tumor formation and evolutionary selection of genetic variants in the human MDM4 oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 : 10236–10241 0901298106 [pii];10.1073/pnas.0901298106 [doi].

36. CurtisC, ShahSP, ChinSF, TurashviliG, RuedaOM, et al. (2012) The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature 486 : 346–352 nature10983 [pii];10.1038/nature10983 [doi].

37. LaurieNA, DonovanSL, ShihCS, ZhangJ, MillsN, et al. (2006) Inactivation of the p53 pathway in retinoblastoma. Nature 444 : 61–66 nature05194 [pii];10.1038/nature05194 [doi].

38. WadeM, WahlGM (2009) Targeting Mdm2 and Mdmx in cancer therapy: better living through medicinal chemistry? Mol Cancer Res 7 : 1–11 7/1/1 [pii];10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0423 [doi].

39. FairfaxBP, MakinoS, RadhakrishnanJ, PlantK, LeslieS, et al. (2012) Genetics of gene expression in primary immune cells identifies cell type-specific master regulators and roles of HLA alleles. Nat Genet 44 : 501–510 ng.2205 [pii];10.1038/ng.2205 [doi].

40. GeB, PokholokDK, KwanT, GrundbergE, MorcosL, et al. (2009) Global patterns of cis variation in human cells revealed by high-density allelic expression analysis. Nat Genet 41 : 1216–1222 ng.473 [pii];10.1038/ng.473 [doi].

41. GrundbergE, AdoueV, KwanT, GeB, DuanQL, et al. (2011) Global analysis of the impact of environmental perturbation on cis-regulation of gene expression. PLoS Genet 7: e1001279 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001279.

42. StefanssonH, HelgasonA, ThorleifssonG, SteinthorsdottirV, MassonG, et al. (2005) A common inversion under selection in Europeans. Nat Genet 37 : 129–137 ng1508 [pii];10.1038/ng1508 [doi].

43. BowenNJ, WalkerLD, MatyuninaLV, LoganiS, TottenKA, et al. (2009) Gene expression profiling supports the hypothesis that human ovarian surface epithelia are multipotent and capable of serving as ovarian cancer initiating cells. BMC Med Genomics 2 : 71 1755-8794-2-71 [pii];10.1186/1755-8794-2-71 [doi].

44. IkramMA, FornageM, SmithAV, SeshadriS, SchmidtR, et al. (2012) Common variants at 6q22 and 17q21 are associated with intracranial volume. Nat Genet 44 : 539–544 ng.2245 [pii];10.1038/ng.2245 [doi].

45. Simon-SanchezJ, SchulteC, BrasJM, SharmaM, GibbsJR, et al. (2009) Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson's disease. Nat Genet 41 : 1308–1312 ng.487 [pii];10.1038/ng.487 [doi].

46. PharoahP, TsaiYY, RamusS, PhelanC, GoodeEL, et al. (2012) GWAS meta-analysis and replication identifies three new susceptibility loci for ovarian cancer. Nat Genet In Press.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Ubiquitous Polygenicity of Human Complex Traits: Genome-Wide Analysis of 49 Traits in KoreansČlánek Alternative Splicing and Subfunctionalization Generates Functional Diversity in Fungal ProteomesČlánek RFX Transcription Factor DAF-19 Regulates 5-HT and Innate Immune Responses to Pathogenic Bacteria inČlánek Surveillance-Activated Defenses Block the ROS–Induced Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein ResponseČlánek Deficiency Reduces Adipose OXPHOS Capacity and Triggers Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Mice

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 3- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

- Délka menstruačního cyklu jako marker ženské plodnosti

- Intrauterinní inseminace a její úspěšnost

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Power and Predictive Accuracy of Polygenic Risk Scores

- Rare Copy Number Variants Are a Common Cause of Short Stature

- Coordination of Flower Maturation by a Regulatory Circuit of Three MicroRNAs

- Ubiquitous Polygenicity of Human Complex Traits: Genome-Wide Analysis of 49 Traits in Koreans

- Genomic Evidence for Island Population Conversion Resolves Conflicting Theories of Polar Bear Evolution

- Mechanistic Insight into the Pathology of Polyalanine Expansion Disorders Revealed by a Mouse Model for X Linked Hypopituitarism

- Genome-Wide Association Study and Gene Expression Analysis Identifies as a Predictor of Response to Etanercept Therapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Problem Solved: An Interview with Sir Edwin Southern

- Long Interspersed Element–1 (LINE-1): Passenger or Driver in Human Neoplasms?

- Mouse HFM1/Mer3 Is Required for Crossover Formation and Complete Synapsis of Homologous Chromosomes during Meiosis

- Alternative Splicing and Subfunctionalization Generates Functional Diversity in Fungal Proteomes

- A WRKY Transcription Factor Recruits the SYG1-Like Protein SHB1 to Activate Gene Expression and Seed Cavity Enlargement

- Microhomology-Mediated Mechanisms Underlie Non-Recurrent Disease-Causing Microdeletions of the Gene or Its Regulatory Domain

- Ancient Evolutionary Trade-Offs between Yeast Ploidy States

- Differential Evolutionary Fate of an Ancestral Primate Endogenous Retrovirus Envelope Gene, the EnvV , Captured for a Function in Placentation

- A Feed-Forward Loop Coupling Extracellular BMP Transport and Morphogenesis in Wing

- The Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus Resistance Genes and Are Allelic and Code for DFDGD-Class RNA–Dependent RNA Polymerases

- The U-Box E3 Ubiquitin Ligase TUD1 Functions with a Heterotrimeric G α Subunit to Regulate Brassinosteroid-Mediated Growth in Rice

- Role of the DSC1 Channel in Regulating Neuronal Excitability in : Extending Nervous System Stability under Stress

- –Independent Phenotypic Switching in and a Dual Role for Wor1 in Regulating Switching and Filamentation

- Pax6 Regulates Gene Expression in the Vertebrate Lens through miR-204

- Blood-Informative Transcripts Define Nine Common Axes of Peripheral Blood Gene Expression

- Genetic Architecture of Skin and Eye Color in an African-European Admixed Population

- Fine Characterisation of a Recombination Hotspot at the Locus and Resolution of the Paradoxical Excess of Duplications over Deletions in the General Population

- Estrogen Mediated-Activation of miR-191/425 Cluster Modulates Tumorigenicity of Breast Cancer Cells Depending on Estrogen Receptor Status

- Complex Patterns of Genomic Admixture within Southern Africa

- Yap- and Cdc42-Dependent Nephrogenesis and Morphogenesis during Mouse Kidney Development

- Molecular Networks of Human Muscle Adaptation to Exercise and Age

- Alp/Enigma Family Proteins Cooperate in Z-Disc Formation and Myofibril Assembly

- Polycomb Group Gene Regulates Rice () Seed Development and Grain Filling via a Mechanism Distinct from

- RFX Transcription Factor DAF-19 Regulates 5-HT and Innate Immune Responses to Pathogenic Bacteria in

- Distinct Molecular Strategies for Hox-Mediated Limb Suppression in : From Cooperativity to Dispensability/Antagonism in TALE Partnership

- A Natural Polymorphism in rDNA Replication Origins Links Origin Activation with Calorie Restriction and Lifespan

- TDP2–Dependent Non-Homologous End-Joining Protects against Topoisomerase II–Induced DNA Breaks and Genome Instability in Cells and

- Recurrent Rearrangement during Adaptive Evolution in an Interspecific Yeast Hybrid Suggests a Model for Rapid Introgression

- Genome-Wide Association Study in Mutation Carriers Identifies Novel Loci Associated with Breast and Ovarian Cancer Risk

- Coincident Resection at Both Ends of Random, γ–Induced Double-Strand Breaks Requires MRX (MRN), Sae2 (Ctp1), and Mre11-Nuclease

- Identification of a -Specific Modifier Locus at 6p24 Related to Breast Cancer Risk

- A Novel Function for the Hox Gene in the Male Accessory Gland Regulates the Long-Term Female Post-Mating Response in

- Tdp2: A Means to Fixing the Ends

- A Novel Role for the RNA–Binding Protein FXR1P in Myoblasts Cell-Cycle Progression by Modulating mRNA Stability

- Association Mapping and the Genomic Consequences of Selection in Sunflower

- Histone Deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) Regulates Chromosome Segregation and Kinetochore Function via H4K16 Deacetylation during Oocyte Maturation in Mouse

- A Novel Mutation in the Upstream Open Reading Frame of the Gene Causes a MEN4 Phenotype

- Ataxin1L Is a Regulator of HSC Function Highlighting the Utility of Cross-Tissue Comparisons for Gene Discovery

- Human Spermatogenic Failure Purges Deleterious Mutation Load from the Autosomes and Both Sex Chromosomes, including the Gene

- A Conserved Upstream Motif Orchestrates Autonomous, Germline-Enriched Expression of piRNAs

- Statistical Analysis Reveals Co-Expression Patterns of Many Pairs of Genes in Yeast Are Jointly Regulated by Interacting Loci

- Matefin/SUN-1 Phosphorylation Is Part of a Surveillance Mechanism to Coordinate Chromosome Synapsis and Recombination with Meiotic Progression and Chromosome Movement

- A Role for the Malignant Brain Tumour (MBT) Domain Protein LIN-61 in DNA Double-Strand Break Repair by Homologous Recombination

- The Population and Evolutionary Dynamics of Phage and Bacteria with CRISPR–Mediated Immunity

- Long Noncoding RNA MALAT1 Controls Cell Cycle Progression by Regulating the Expression of Oncogenic Transcription Factor B-MYB

- Surveillance-Activated Defenses Block the ROS–Induced Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response

- DNA Topoisomerase III Localizes to Centromeres and Affects Centromeric CENP-A Levels in Fission Yeast

- Genome-Wide Control of RNA Polymerase II Activity by Cohesin

- Divergent Selection Drives Genetic Differentiation in an R2R3-MYB Transcription Factor That Contributes to Incipient Speciation in

- NODULE INCEPTION Directly Targets Subunit Genes to Regulate Essential Processes of Root Nodule Development in

- Spreading of a Prion Domain from Cell-to-Cell by Vesicular Transport in

- Deficiency in Origin Licensing Proteins Impairs Cilia Formation: Implications for the Aetiology of Meier-Gorlin Syndrome

- Deficiency Reduces Adipose OXPHOS Capacity and Triggers Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Mice

- The Conserved SKN-1/Nrf2 Stress Response Pathway Regulates Synaptic Function in

- Functional Genomic Analysis of the Regulatory Network in

- Astakine 2—the Dark Knight Linking Melatonin to Circadian Regulation in Crustaceans

- CRL2 E3-Ligase Regulates Proliferation and Progression through Meiosis in the Germline

- Both the Caspase CSP-1 and a Caspase-Independent Pathway Promote Programmed Cell Death in Parallel to the Canonical Pathway for Apoptosis in

- PRMT4 Is a Novel Coactivator of c-Myb-Dependent Transcription in Haematopoietic Cell Lines

- A Copy Number Variant at the Locus Likely Confers Risk for Canine Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Digit

- Evidence of Gene–Environment Interactions between Common Breast Cancer Susceptibility Loci and Established Environmental Risk Factors

- HIV Infection Disrupts the Sympatric Host–Pathogen Relationship in Human Tuberculosis

- Trans-Ethnic Fine-Mapping of Lipid Loci Identifies Population-Specific Signals and Allelic Heterogeneity That Increases the Trait Variance Explained

- A Gene Transfer Agent and a Dynamic Repertoire of Secretion Systems Hold the Keys to the Explosive Radiation of the Emerging Pathogen

- The Role of ATM in the Deficiency in Nonhomologous End-Joining near Telomeres in a Human Cancer Cell Line

- Dynamic Circadian Protein–Protein Interaction Networks Predict Temporal Organization of Cellular Functions

- Nuclear Myosin 1c Facilitates the Chromatin Modifications Required to Activate rRNA Gene Transcription and Cell Cycle Progression

- Robust Prediction of Expression Differences among Human Individuals Using Only Genotype Information

- A Single Cohesin Complex Performs Mitotic and Meiotic Functions in the Protist

- The Role of the Arabidopsis Exosome in siRNA–Independent Silencing of Heterochromatic Loci

- Elevated Expression of the Integrin-Associated Protein PINCH Suppresses the Defects of Muscle Hypercontraction Mutants

- Twist1 Controls a Cell-Specification Switch Governing Cell Fate Decisions within the Cardiac Neural Crest

- Genome-Wide Testing of Putative Functional Exonic Variants in Relationship with Breast and Prostate Cancer Risk in a Multiethnic Population

- Heteroduplex DNA Position Defines the Roles of the Sgs1, Srs2, and Mph1 Helicases in Promoting Distinct Recombination Outcomes

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Fine Characterisation of a Recombination Hotspot at the Locus and Resolution of the Paradoxical Excess of Duplications over Deletions in the General Population

- Molecular Networks of Human Muscle Adaptation to Exercise and Age

- Recurrent Rearrangement during Adaptive Evolution in an Interspecific Yeast Hybrid Suggests a Model for Rapid Introgression

- Genome-Wide Association Study and Gene Expression Analysis Identifies as a Predictor of Response to Etanercept Therapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání