-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Elevated Expression of the Integrin-Associated Protein PINCH Suppresses the Defects of Muscle Hypercontraction Mutants

A variety of human diseases arise from mutations that alter muscle contraction. Evolutionary conservation allows genetic studies in Drosophila melanogaster to be used to better understand these myopathies and suggest novel therapeutic strategies. Integrin-mediated adhesion is required to support muscle structure and function, and expression of Integrin adhesive complex (IAC) proteins is modulated to adapt to varying levels of mechanical stress within muscle. Mutations in flapwing (flw), a catalytic subunit of myosin phosphatase, result in non-muscle myosin hyperphosphorylation, as well as muscle hypercontraction, defects in size, motility, muscle attachment, and subsequent larval and pupal lethality. We find that moderately elevated expression of the IAC protein PINCH significantly rescues flw phenotypes. Rescue requires PINCH be bound to its partners, Integrin-linked kinase and Ras suppressor 1. Rescue is not achieved through dephosphorylation of non-muscle myosin, suggesting a mechanism in which elevated PINCH expression strengthens integrin adhesion. In support of this, elevated expression of PINCH rescues an independent muscle hypercontraction mutant in muscle myosin heavy chain, MhcSamba1. By testing a panel of IAC proteins, we show specificity for PINCH expression in the rescue of hypercontraction mutants. These data are consistent with a model in which PINCH is present in limiting quantities within IACs, with increasing PINCH expression reinforcing existing adhesions or allowing for the de novo assembly of new adhesion complexes. Moreover, in myopathies that exhibit hypercontraction, strategic PINCH expression may have therapeutic potential in preserving muscle structure and function.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003406

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003406Summary

A variety of human diseases arise from mutations that alter muscle contraction. Evolutionary conservation allows genetic studies in Drosophila melanogaster to be used to better understand these myopathies and suggest novel therapeutic strategies. Integrin-mediated adhesion is required to support muscle structure and function, and expression of Integrin adhesive complex (IAC) proteins is modulated to adapt to varying levels of mechanical stress within muscle. Mutations in flapwing (flw), a catalytic subunit of myosin phosphatase, result in non-muscle myosin hyperphosphorylation, as well as muscle hypercontraction, defects in size, motility, muscle attachment, and subsequent larval and pupal lethality. We find that moderately elevated expression of the IAC protein PINCH significantly rescues flw phenotypes. Rescue requires PINCH be bound to its partners, Integrin-linked kinase and Ras suppressor 1. Rescue is not achieved through dephosphorylation of non-muscle myosin, suggesting a mechanism in which elevated PINCH expression strengthens integrin adhesion. In support of this, elevated expression of PINCH rescues an independent muscle hypercontraction mutant in muscle myosin heavy chain, MhcSamba1. By testing a panel of IAC proteins, we show specificity for PINCH expression in the rescue of hypercontraction mutants. These data are consistent with a model in which PINCH is present in limiting quantities within IACs, with increasing PINCH expression reinforcing existing adhesions or allowing for the de novo assembly of new adhesion complexes. Moreover, in myopathies that exhibit hypercontraction, strategic PINCH expression may have therapeutic potential in preserving muscle structure and function.

Introduction

Numerous human diseases, including muscular dystrophies [1], [2] and cardiomyopathies [3], [4], result from mutations that alter muscle contraction. The evolutionary conservation and genetic tractability of Drosophila melanogaster have made it an attractive system in which to characterize these genes and mutations [5], [6]. A collection of mutants in Drosophila exhibits myopathy due to muscle hypercontraction, leading to a range of phenotypes from flightless adults to early lethality [7]–[12]. Upon hypercontraction, these mutants can compensate in a variety of ways. Through a genetic response, specific mutations in genes such as the Myosin heavy chain (Mhc) can decrease overall actomyosin force, which is sufficient to suppress hypercontraction defects [11], [13]. Hypercontraction can also induce compensatory changes in gene expression. For instance, expression profiling of MhcSamba hypercontraction mutants suggested an extensive actin cytoskeletal remodeling response, as well as upregulation of non-muscle myosin phosphatase expression to promote relaxation of the actomyosin cytoskeleton [14]. Notably, upregulation of genes for integrin adhesive complex (IAC) proteins like Paxillin and Talin was observed as well [14]. This suggests that increasing the expression levels of IAC proteins can strengthen integrin-based adhesions at muscle termini to cope with the increased mechanical stress of muscle hypercontraction. Integrin-mediated adhesion has been shown to help maintain muscle cytoarchitecture and sarcomeric integrity [15], and mechanical force regulates the rate of integrin turnover [16]. Consistent with a key role for IAC gene expression in responding to muscle contraction, genes including UNC-97/PINCH show decreased mRNA levels in C. elegans muscles developed in the microgravity of spaceflight [17]. Furthermore, review of the ground controls (deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE36358) also reveals increased UNC-97 mRNA levels under conditions of hypergravity. This supports the idea that modulating gene expression of IAC components may be an evolutionarily conserved mechanism to adapt to widely divergent levels of mechanical stress to maintain muscle integrity.

Flapwing (Flw) is a serine/threonine Protein Phosphatase 1β (PP1β) that acts broadly upon many phosphorylated protein substrates, but it is required solely for its activity in dephosphorylating non-muscle myosin regulatory light chain (MRLC), encoded by spaghetti squash (sqh) in Drosophila [11]. Phosphorylation of Sqh causes an activating conformational change that promotes contraction of the actomyosin cytoskeleton. Sqh dephosphorylation is a key step in actomyosin relaxation. Thus strong loss-of-function mutants in flw exhibit hyperphosphorylation of non-muscle myosin. Notably, though flw does not genetically interact with the muscle version of MRLC (Mlc2) [10], the main defect observed in flw mutants is hypercontraction of myofibrillar myosin, eventually resulting in detachment of striated muscles and subsequent lethality at both larval and pupal stages [10]. Though not directly responsible for the generation of contractile force, non-muscle myosin is necessary for the proper development of myofibrils [18]. Hyperphosphorylation of Sqh disrupts actin cytoskeletal dynamics in many cell types, but the consequences appear greatest in contractile muscle tissue, both in larval body wall muscle and in adult indirect flight muscle [10]. The molecular connection between hypercontracted cytoskeleton and hypercontraction and detachment of muscle myofibrils is indirect, and currently not well defined.

We hypothesized that the flw muscle hypercontraction phenotype could be rescued by strengthening the anchoring of muscles at integrin-based adhesion sites to better withstand the force of hypercontraction. We show here that moderately elevated expression of the IAC protein PINCH alleviates the phenotypes of flw mutants. PINCH is an integrin-associated LIM domain adaptor protein encoded by the steamer duck (stck) gene in Drosophila. PINCH is part of an evolutionarily conserved, high affinity protein complex comprised of Ras Suppressor 1 (RSU1), Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) and Parvin that is targeted to the cell membrane at sites of integrin adhesion [19]–[22]. This complex of proteins has a critical role in adhesion maintenance, particularly in muscle attachment. In Drosophila, null mutants in PINCH, ILK, and Parvin each die late in embryogenesis as a consequence of failure of integrin-based muscle attachment sites within the segmental musculature [23]–[25]. Null mutations in RSU1 show milder defects in integrin adhesion between the epithelial layers of the wing [19]. Notably, mammalian α-Parvin and ILK have been shown to be negative regulators of contractility in certain cellular contexts [26], [27]. The RSU1, PINCH, ILK and Parvin proteins have been shown to mutually stabilize each other [19], [22], [28]–[30], suggesting that the complex as a whole might help delay the onset or reduce the extent of the damage exhibited in hypercontraction mutants by stabilizing adhesions. Data presented here support this idea. We show that PINCH must be capable of directly binding both ILK and RSU1 in order to suppress the defects of the flw mutant.

We demonstrate that structural stabilization of integrin-based adhesions by PINCH is likely to be a mechanism for the rescue of flw mutants. PINCH does not appear to alleviate hypercontraction of the myofibrils, as muscle attachment is better maintained even in the presence of muscle hypercontraction. We also eliminate phospho-regulation as a plausible mechanism, as elevated PINCH expression does not alter the phosphorylation status of the only essential Flapwing substrate, MRLC/Sqh. We show that moderately elevated expression of PINCH partially rescues another hypercontraction mutant, the Samba1 allele of Mhc. Furthermore, we show that among a panel of IAC proteins tested, elevated expression of Talin also affords marginal rescue of Samba1 hypercontraction defects. However, transgenic Talin expression is unable to afford rescue of flw larval lethality, underscoring the specificity of PINCH expression in strengthening adhesion under multiple conditions of hypercontraction. These studies have broad implications for understanding and treating a variety of myopathies and muscle degenerative diseases.

Results

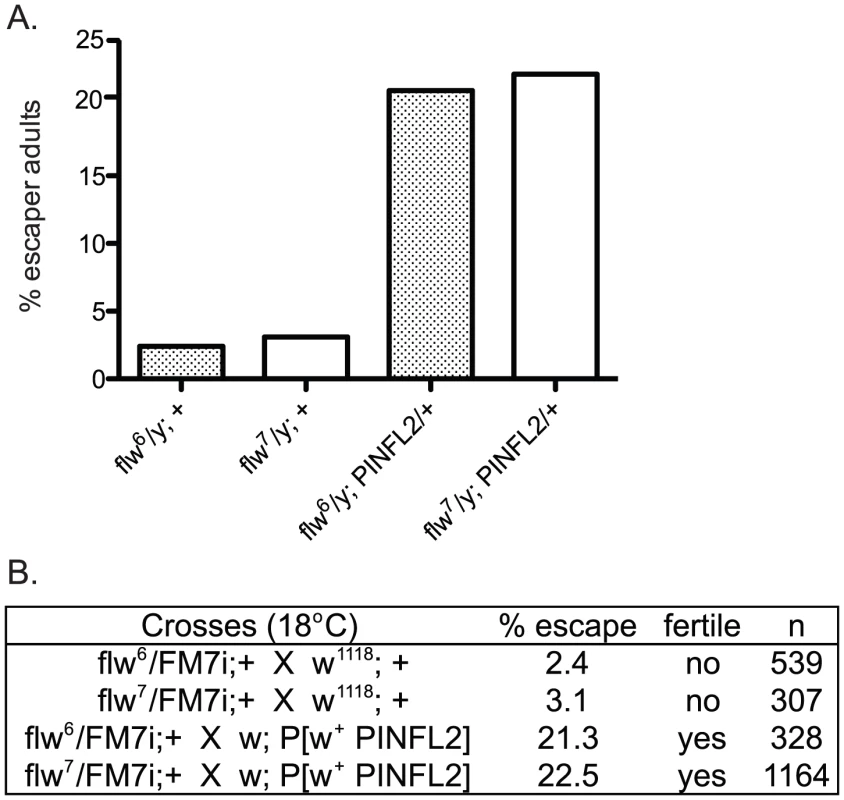

In a recent report, an interaction between mammalian Protein Phosphatase-1 (PP1) and the integrin-associated protein PINCH was described [31]. Because of the similar muscle detachment phenotypes exhibited by loss-of-function mutants for both PINCH [23] and PP1β [10] in the fly, we set out to test whether the Drosophila proteins also interact. Our analyses included two recessive alleles of the PP1β family member, flapwing. flw6 is a point mutant with decreased substrate affinity, and flw7 contains a lacZ enhancer trap inserted in the flw 5′ UTR which reduces the level of Flw expression [10]. Both of these mutants are strong loss-of-function alleles, but do not entirely eliminate Flapwing phosphatase activity or protein expression in male hemizygotes. In a wild type PINCH background, we combined a wild type PINCH-Flag transgene expressed from the native PINCH promoter with each of these flw alleles. We observed that expression of transgenic wild type PINCH-Flag significantly increased the frequency of hemizygous flw adult male escapers, and restored their fertility (Figure 1A, 1B). These crosses were done at 18°C because the frequency of adult escapers for any genotype was extremely low if reared at 25°C. A second, independent insertion line expressing wild type PINCH-Flag recapitulates the increased frequency of adult escapers (data not shown).

Fig. 1. Expression of transgenic PINCH increases the number of flw adult male escapers and restores their fertility.

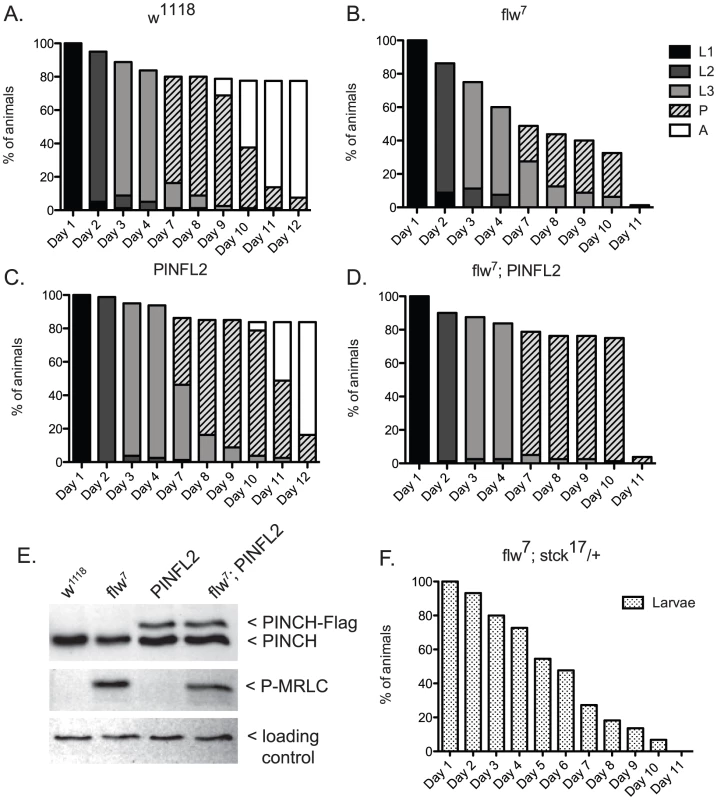

A.) Bars show the frequency of escapers of the indicated genotypes. B.) The genetic crosses employed are shown, as well as the fertility status of the escapers. n is the total number of progeny of all genotypes resulting from the cross. To more carefully characterize the spectrum of defects in flw mutants, we assessed the viability across development at 25°C of male hemizygotes selected from balanced stocks. Compared to a wild type w1118 control, we found significant larval lethality—approximately 70% of flw7 larvae failed to successfully pupariate, and of the 30% that do form pupae, essentially all arrest development prior to adult eclosion (Figure 2A, 2B). Expression of transgenic PINCH-Flag in a wild type background at approximately 40% of endogenous levels had no significant effect on progression to adulthood when compared to wild type animals (Figure 2A, 2C, 2E). However, this modest expression of PINCH-Flag fully rescued the larval lethality of the flw7 mutant (Figure 2B, 2D, 2E). At 25°C (unlike the 18°C data in Figure 1), pupal lethality is not rescued by elevated expression of PINCH-Flag (Figure 2D), which may reflect a more stringent requirement for Flapwing phosphatase activity in the pupa to adult transition at higher temperature. The larval lethality of the flw6 allele is similarly rescued by PINCH-Flag expression (Figure S1). Because of the similarity between flw6 and flw7 in 1) the number of adult escapers at 18°C, 2) the developmental profile at 25°C, and 3) the rescue of larval lethality by expression of transgenic PINCH, we focus on flw7 in the remaining experiments.

Fig. 2. Expression of PINCH-Flag fully rescues the larval lethality of the flw7 mutant independently of MRLC/Sqh dephosphorylation.

A–D) For each genotype, graphs show the percentage of animals of the given developmental stage at the indicated time points. Pupae present at the final time point shown in A and C eventually eclosed as adults, whereas pupae in B and D subsequently arrested. E) Representative western blot of four-day-old L3s confirms that PINCH expression is elevated in the PINFL2 and flw7; PINFL2 larval lysates (transgenic PINCH is 44% of endogenous levels for both samples, by densitometric analysis) and that PINFL2 expression does not affect the phosphorylation state of MRLC/Sqh. The ribosomal protein RACK1 is used as a loading control. F) Survival of flw7; stck17/+ larvae (n = 44) is plotted against time. We also tested whether a reduction in PINCH exacerbates flw lethality. Decreasing PINCH dosage using a heterozygous stck17 mutation in the flw7 background was challenging due to a high rate of balancer breakdown in the required crosses. However, the limited number of flw7; stck17/+ animals that were isolated exhibited complete larval lethality (n = 44) (Figure 2F). These data confirm that reducing PINCH gene dosage indeed enhances flw lethality.

One way that increased PINCH-Flag expression could rescue flw larval lethality is through reversing protein hyper-phosphorylation that results from flw loss-of-function. Because the sole essential activity of Flapwing is the dephosphorylation of non-muscle myosin regulatory light chain (MRLC)/Sqh [11], we examined the phosphorylation state of MRLC/Sqh in larval lysates. As expected, phospho-MRLC was elevated significantly in flw7 lysates as compared to wild type w1118 controls (Figure 2E). However, statistical analysis of four independent replicate experiments showed that expression of PINCH-Flag, either in wild type flies or in the flw mutant background, had no effect on the phosphorylation state of MRLC (Figure 2E). These data indicate that regulation of MRLC phosphorylation state by PINCH is not the mechanism for the genetic suppression we observe between flw and PINCH.

We also examined the phosphorylation states of several other phospho-proteins that have been connected to PINCH: Akt [31], JNK [19], and ERK [32]. We found that phosphorylation of these proteins is not consistently elevated in larval lysates from flw mutants (data not shown), indicating either that Akt, JNK, and ERK are not actively signaling in these samples, are not substrates of Flapwing, or that other phosphatases compensate to appropriately dephosphorylate Akt, JNK and ERK in the flw mutant. While it is formally possible that PINCH could contribute to the phospho-regulation of non-essential Flapwing targets, it seems unlikely that phospho-regulation is a major contributor to the suppression of flw lethality observed upon elevated PINCH expression.

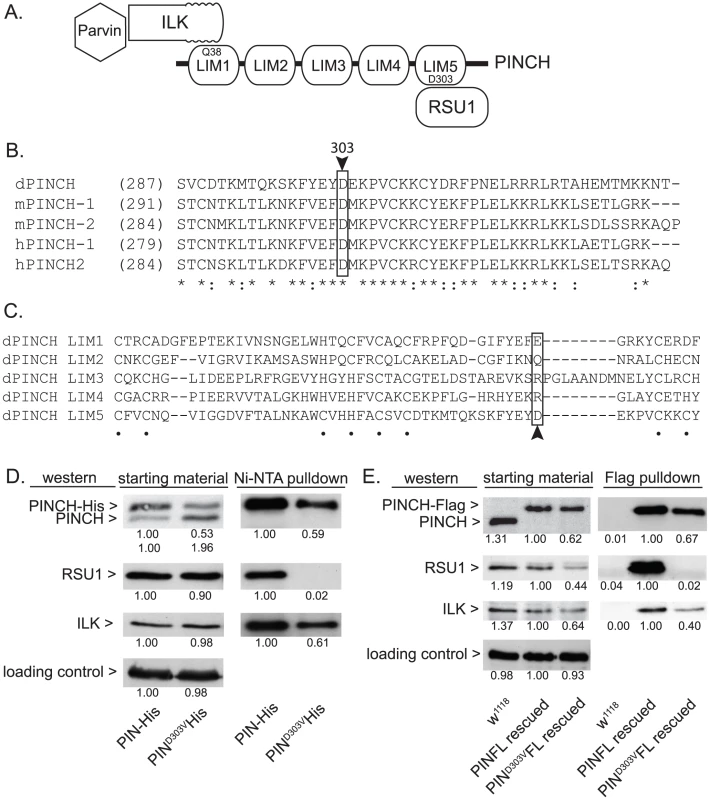

In order to molecularly dissect the mechanism by which PINCH is suppressing flw larval lethality, we employed several mutants of PINCH that disrupt binding of its known partners, Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) and Ras Suppressor 1 (RSU1) (Figure 3A). One of these mutants, PINCHQ38A, has previously been shown to disrupt binding of ILK to LIM1 of PINCH (Figure 3A) [30], [33], [34], allowing us to test whether ILK binding and PINCH-ILK complexes are participating in the suppression of flw lethality. We were also interested in testing the contribution of RSU1 binding to LIM5 of PINCH (Figure 3A), and the role PINCH-RSU1 complexes. Mutations in PINCH that disrupt RSU1 binding have not yet been described. Therefore, we designed a modified yeast two-hybrid screen to identify point mutations in LIM5 of PINCH that specifically disrupt binding to RSU1 while otherwise preserving the structure and function of PINCH. We identified PINCHD303V as a strong candidate. Among PINCH LIM5 sequences, D303 is highly evolutionarily conserved (Figure 3B), suggesting its importance for the proper functioning of PINCH. However, D303 is a variable residue within the general LIM consensus sequence (Figure 3C) and can therefore be altered without destroying overall LIM structure. The disruption of RSU1 binding was tested by inserting the D303V mutation into full length, Histidine-tagged PINCH expressed in Drosophila S2 cells. In the cell lysates used for purification, we routinely observe that PINCHD303V-His is present at reduced levels as compared to wild type PINCH-His. PINCH that is not bound to RSU1 has previously been shown to be less stable [19], [35]. Even so, Ni-NTA purification of the PINCH-His complexes confirms that PINCHD303VHis, in contrast to a wild type PINCH-His control, clearly does not co-purify with RSU1 (Figure 3D). Moreover, PINCHD303VHis retains the ability to bind to ILK (Figure 3D), indicating that folding and stability of the mutant PINCHD303V have not been completely destroyed.

Fig. 3. PINCHD303V mutation disrupts binding to RSU1.

A) Schematic of PINCH showing its 5 LIM domain structure. The N-terminal ankyrin repeat of ILK binds to LIM1 of PINCH via PINCHQ38. Parvin associates with PINCH indirectly via binding to the ILK pseudokinase domain. RSU1 binds to LIM5 of PINCH through PINCHD303. B) Sequence alignment of the C-terminus of fly, mouse and human PINCH sequences demonstrates the conservation of D303 (boxed with arrowhead). Asterisks denote invariant residues, and colons denote conserved residues. C) Sequence alignment using the 5 individual LIM domains of Drosophila PINCH shows that D303 (boxed with arrowhead) is a variable residue within LIM sequences. Dots denote the zinc binding residues. D) Ni-NTA pull-downs of wild type PINCH-His and PINCHD303VHis expressed in S2 cells show a disruption of RSU1 binding only in the D303V mutant while ILK binding is preserved. E) Flag immunoprecipitations of adult fly lysates from PINCH null mutants rescued with either wild type PINCH-Flag or PINCHD303VFlag transgenes. w1118 is used as a negative control that does not express Flag. ILK, RSU1 and a PINCH transgene are all expressed in the starting material. PINCHD303VFlag pulls down ILK but fails to co-precipitate RSU1. In both D and E, densitometric analyses were conducted to compare levels of protein between samples and quantification is provided below each blot. α-tubulin was used as a loading control and values for PINCH, RSU1 and ILK were adjusted to account for variation in loading. To further confirm that the PINCHD303V mutation disrupts RSU1 binding, we next expressed PINCHD303VFlag in flies using the native PINCH promoter. In a wild type genetic background where the transgene is expressed at low levels, we did not observe any obvious dominant effects (data not shown). When this transgene was introduced into the stck17/stck18 PINCH null background, viable rescued adults were produced at 90% of the expected frequency (n = 209). In soluble extracts made from these rescued adults, PINCHD303VFlag is routinely present at levels that are reduced compared to animals expressing either endogenous PINCH or rescued with the wild type PINCH-Flag transgene. In an effort to understand why PINCHD303V is present at lower levels, we performed semi-quantitative RT-PCR on mRNA isolated from adult flies lacking endogenous PINCH and rescued with either wild type, Q38A, or D303V versions of the PINCH transgene. These mRNAs differ only in the sequence of a single codon. We find that levels of each transgenic message are equal (Figure S2), confirming that differences in the levels of PINCH protein occur post-transcriptionally. Additionally, levels of protein for RSU1 and ILK were reduced in the PINCHD303VFlag animals (Figure 3E), likely reflecting a well-characterized destabilization of the proteins in this complex when intact PINCH complexes are disrupted [19], [22], [28]–[30]. While PINCHD303VFlag rescued animals are viable as adults, wing blisters are frequent, the wings are often observed in a “held up” posture (similar, for example, to mutations in the Troponin genes wupA and wupB [12]), and the rescued adults are flightless. These phenotypes are comparable in severity to those of the viable RSU1 null mutant [19], and demonstrate the importance of the PINCH-RSU1 interaction. Flag pull-downs from rescued adult lysates confirm that both ILK and RSU1 strongly associate with wild type PINCH-Flag. Similar to the cell culture experiments, PINCHD303VFlag clearly retains the ability to bind ILK, but no RSU1 is detected in the PINCHD303VFlag pull-downs (Figure 3E). This confirms that the PINCHD303V mutation effectively disrupts the binding of RSU1.

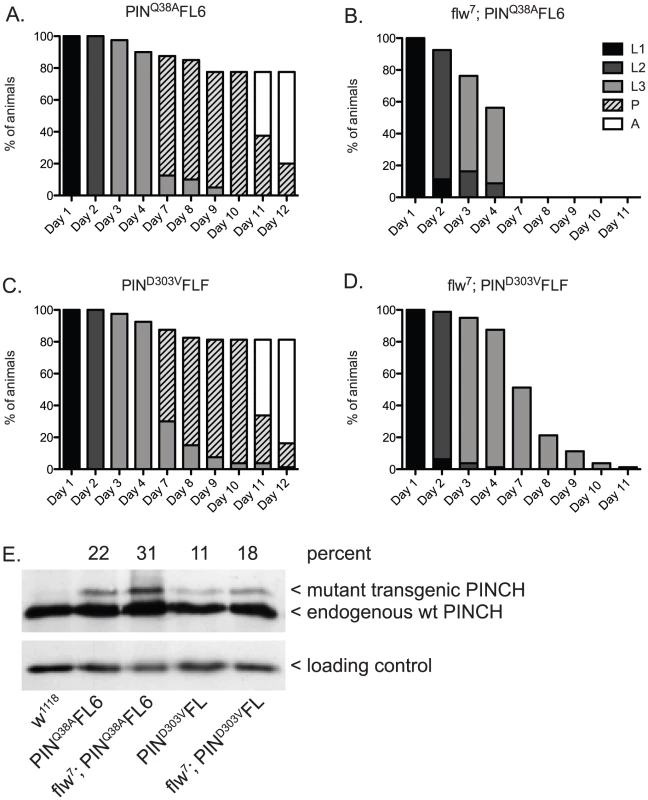

Similar to the experiment (Figure 2) in which we suppressed larval lethality by expressing wild type PINCH-Flag in the flw7 background, we expressed low levels of transgenic PINCHQ38AFlag along with endogenous wild type PINCH (Figure 4B, 4E). Unlike wild type PINCH-Flag expression, expression of the PINCHQ38AFlag mutant in the flw7 background does not allow for suppression of larval lethality (Figure 4B compare to Figure 2B). This occurs despite viability of the PINCHQ38A transgene expressed in a wild type background that is comparable to the wild type w1118 control (Figure 4A compare to Figure 2A), and the full rescue of stck null mutants by PINCHQ38A [35]. These data indicate that PINCH-ILK complexes participate in the suppression of flw larval lethality. Expression of PINCHQ38AFlag, which differs from the wild type transgenic protein in only a single amino acid and in its ability to bind ILK, has no capacity to promote pupariation in the flw mutant.

Fig. 4. PINCH associates with ILK and RSU1 in order to suppress the larval lethality of flw7 mutants.

Survival curves show normal developmental progression upon expression of transgenic PINCHQ38AFlag (A) or PINCHD303VFlag (C) alone. Pupae present at day 12 subsequently progress to adulthood. Upon introduction of the mutant PINCH transgenes into a flw7 background (B,D), arrest during the larval stages is observed. E) Western blot plus densitometric analysis for PINCH shows the relative level of expression of the mutant Q38A and D303V transgenes as a percentage of endogenous PINCH. The ribosomal protein RACK1 was used as a loading control. Next, we tested for suppression of flw larval lethality by co-expressing transgenic PINCHD303VFlag along with endogenous wild type PINCH in the flw7 background (Figure 4D, 4E). Like PINCHQ38AFlag, low levels of expression of PINCHD303VFlag do not suppress flw larval lethality. Despite the pupal and adult viability of PINCHD303VFlag expressed in a wild type background (Figure 4C, 4E), pupariation was never observed in the flw7; PINCHD303VFlag animals (Figure 4D). Taken together, this suggests that intact ILK-PINCH-RSU1 complexes are necessary for the rescue observed in the flw mutant upon expression of transgenic PINCH. It is interesting to note that not only do the mutant PINCH transgenes fail to rescue flw7 lethality, they in fact exacerbate the larval lethality, eliminating pupariation entirely. We comment on possible mechanisms for this enhancement as well as its implications below.

How does increased expression of PINCH and formation of functional PINCH complexes allow for improved survival of flw mutant larvae? One possibility is that in order to cope with the downstream effects of compromised protein dephosphorylation and a constitutively contracted actomyosin cytoskeleton, increased levels of PINCH and its associated binding partners strengthen integrin-dependent adhesions. Mutant analyses of PINCH and ILK in the fly indicate that these proteins have a role in maintaining embryonic muscle attachment [23], [24], and both Drosophila and C. elegans RNAi experiments confirm a role for these proteins in adult muscle maintenance [15], [36], [37]. If moderately elevated expression of PINCH leads to stronger adhesions, this may allow the flw mutants to better withstand the elevated mechanical stress they experience. To test this idea, we performed a series of morphological and functional assays to characterize flw mutants.

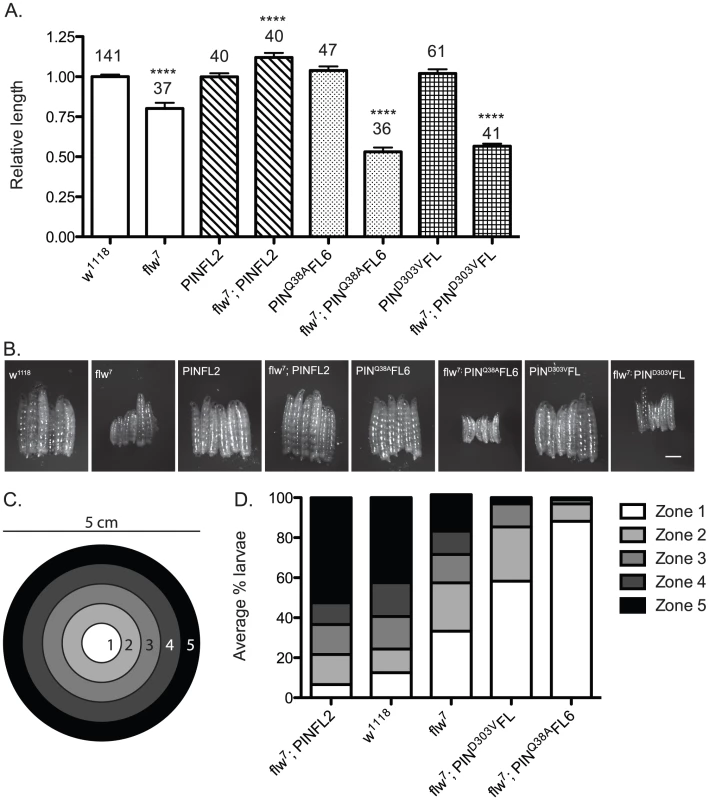

In addition to reduced viability, flw7 mutant larvae have decreased and more variable size as compared to a w1118 wild type control (Figure 5A, 5B). The small size of the flw larvae may result from either developmental delay or arrest, or be a secondary effect of feeding deficits due to poor muscle function. Expression of PINCH-Flag alone does not affect larval size (Figure 5A, 5B). However, elevated expression of PINCH-Flag in the flw mutant produces animals that are significantly larger than even the w1118 wild type control (Figure 5A, 5B). Likewise, expression of either PINCHQ38AFlag or PINCHD303VFlag alone has no effect on larval size (Figure 5A, 5B). However, expression of PINCHQ38AFlag or PINCHD303VFlag in the flw background fails to restore normal larval size and yields animals that are significantly smaller than the flw mutant alone (Figure 5A, 5B).

Fig. 5. Moderately elevated expression of wild-type PINCH rescues the size and motility defects of flw7 mutants.

A) The lengths of four-day-old larvae were measured, normalizing to the mean of a parallel w1118 control. Mean±SEM for each genotype is shown, with the number of animals measured (n) shown above the bar on the graph. **** indicates p<0.0001 compared to the w1118 control. B) Representative phase contrast images of six L3 larvae of the indicated genotypes. Scale bar = 1 mm. C) The larval motility assay uses a 5 cm grape agar plate divided into zones as shown. D) The average percentage of larvae located in each zone at the end of the motility assay is plotted for the indicated genotypes, arranged in order of decreasing motility. We next analyzed these same genotypes of animals in a motility assay that measures spontaneous larval crawling through five zones on a grape juice agar plate (Figure 5C). Wild type w1118 larvae, as well as matched samples expressing the PINCH-Flag, PINCHQ38AFlag or PINCHD303VFlag transgenes, exhibit robust and comparable levels of larval motility (Figure 5D and Figure S3). flw larvae exhibit decreased motility, which is rescued by PINCH-Flag expression (Figure 5D). In fact, the flw7; PINFL2 animals are significantly more motile than even the wild type controls, perhaps due to their larger size. Expression of either PINCHD303VFlag or PINCHQ38AFlag respectively in the flw7 mutant fails to rescue larval motility and increasingly exacerbates the motility defects of flw7 animals (Figure 5D). These data show that 1) moderately elevated expression of PINCH rescues muscle function required for larval crawling, and 2) mutant PINCH transgenes that cannot form functional ILK-PINCH-RSU1 complexes fail to rescue larval size and motility, as well as overall viability.

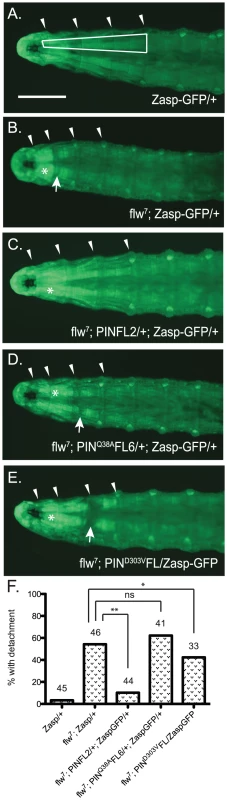

Assessing structural integrity of the muscle in the flw larvae presents several technical challenges: antibody reagents cannot penetrate the larval cuticle of intact animals, and the physical manipulations required for dissection introduce structural defects not present in the intact larvae, particularly because the muscle integrity in these animals is already compromised. To circumvent these issues, we crossed the flw7 mutant with a Zasp66ZCL0633 P-element insertion line, which contains a GFP coding sequence inserted into the genomic locus for the muscle-specific PDZ protein, Zasp66 [38]. Zasp-GFP localizes normally to muscle Z-lines and has been extensively used to visualize muscle structure without the need for dissection in a variety of genetic backgrounds [39]. Although there is failure in pupation later in development, the insertion of GFP into the Zasp66 locus does not significantly impact the viability or motility of the flw7 mutant larvae at the four-day time point we used to analyze muscle integrity (Figure S4). flw mutants are reported to exhibit larval muscle detachment [10], and indeed in the flw7; Zasp-GFP larvae we observe frequent detachment, particularly in the Ventral Intersegmental (VIS) muscles. Because of the ease with which the VIS muscles can be scored for detachment, we have used this group of muscles as a read-out for muscle integrity. Zasp-GFP controls show very little detachment of the VIS muscles (Figure 6A, 6F). Additionally, expression of a single copy of the PINCH-Flag, PINCHQ38AFlag or PINCHD303VFlag transgenes in the Zasp-GFP background does not alter the normal attachment of the VIS muscles (Figure S5). However, flw mutants show frequent VIS muscle detachment (Figure 6B, 6F) that is partially rescued by expression of a single copy of the wild-type PINCH-Flag transgene (Figure 6C, 6F). Notably, hypercontraction, evidenced by areas of saturated Zasp-GFP signal (Figure 6B–6E, asterisks), is still frequently observed in the flw7; PINFL2/+; Zasp-GFP/+ animals (Figure 6C). This is consistent with the idea that PINCH is not eliminating hypercontraction, but rather stabilizes integrin adhesions to prevent muscle detachment and subsequent larval lethality in the flw mutants. In contrast to the robust rescue of detachment observed upon transgenic expression of wild type PINCH-Flag in the flw7 mutant, expression of PINCHQ38AFlag does not rescue detachment, and the PINCHD303VFlag transgene does not rescue muscle detachment to the same extent (Figure 6D–6F). The frequency of detachment upon transgenic PINCH expression mirrors the level of lethality observed in four-day-old larvae of the corresponding genotype (Figure 2, Figure 4, Figure S5). These data suggest that an increase in the number of intact PINCH-ILK-RSU1 complexes enables retention of muscle attachments in the flw mutant background.

Fig. 6. Moderately elevated expression of PINCH rescues muscle detachment defects of the flw7 mutant.

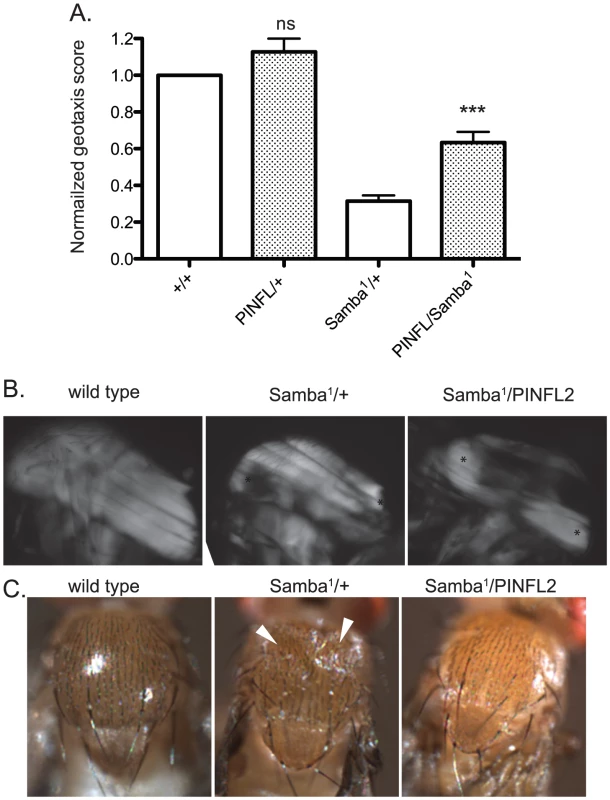

A–E) Representative images of four-day-old larvae of the indicated genotypes are shown. Ventral view allows the VIS muscles to be rapidly scored on a dissecting microscope. One of the medial pair of VIS muscles is boxed in A. White arrowheads show the relevant segment boundaries (T1,T2,T3). Areas of hypercontraction are indicated with an asterisk. Detachments are characterized by a gap in the GFP signal (arrow) Scale bar = 1 mm. F) The graph shows the percent of total animals in which the VIS muscles exhibit detachment. Number of animals examined of each genotype, pooled from triplicate experiments, is shown above the bars. ** indicates p<0.005, * indicates p<0.05, and ns indicates p>0.05. If moderately elevated expression of PINCH is rescuing flw phenotypes by stabilizing integrin-based adhesions, increased expression of PINCH might also be expected to rescue the phenotypes of other hypercontraction mutants. To test this, we employed a dominant hypercontraction mutant in muscle Myosin Heavy Chain called MhcSamba1 [14]. The molecular lesion of MhcSamba1 is in the ATP binding/hydrolysis domain, producing muscle hypercontraction by a direct molecular mechanism distinct from the flw mutants. The muscle defects of MhcSamba1 are apparent in heterozygous adults in a geotaxis assay in which animals are induced to climb [15], [40]. MhcSamba1 heterozygous mutant adults exhibit poor climbing ability that is significantly improved upon expression of transgenic PINCH-Flag (Figure 7A). These data support the idea that increased expression of PINCH generally stabilizes muscle attachments where hypercontraction is present.

Fig. 7. Increased expression of PINCH-Flag rescues geotaxis defects and thoracic indentation, but does not reverse hypercontraction of the IFM in the Samba1 mutant.

A) For each genotype, a normalized geotaxis score from >5 independent assays is plotted as the mean±SEM. *** indicates p<0.001 and ns indicates p>0.05 when compared to the corresponding control data. B) Representative polarized light images of thoraces show that the IFM in the Samba1 mutant exhibits hypercontraction that is not rescued upon expression of PINCH-Flag. Asterisks indicate areas of hypercontraction within the structure of the IFM. C) A dorsal view shows that the thoracic indentations prevalent in Samba1/+ adults are rescued upon expression of transgenic PINCH-Flag. White arrowheads indicate the areas of indentation. To further characterize the rescue of Samba1 mutants by transgenic PINCH-Flag expression, we examined indirect flight muscle (IFM). IFM hypercontraction can be seen by polarized light microscopy in the Samba1 mutant ([9] and Figure 7B), and renders these animals flightless [9]. Consistent with the idea that elevated PINCH expression is stabilizing integrin attachments rather than reversing hypercontraction, the IFM of Samba1/PINCH-Flag adults does not resemble wild type IFM, but continues to exhibit hypercontraction (Figure 7B), and these flies remain flightless (data not shown). As a consequence of IFM hypercontraction, a portion of Samba1/+ animals (39%, n = 70) exhibit visible external thoracic indentations in freshly eclosed adults ([9] and Figure 7C). Although expression of PINCH-Flag in the Samba1 heterozygotes does not rescue IFM hypercontraction, it dramatically improves the thoracic indentation phenotype (2% indented, n = 62) (Figure 7C).

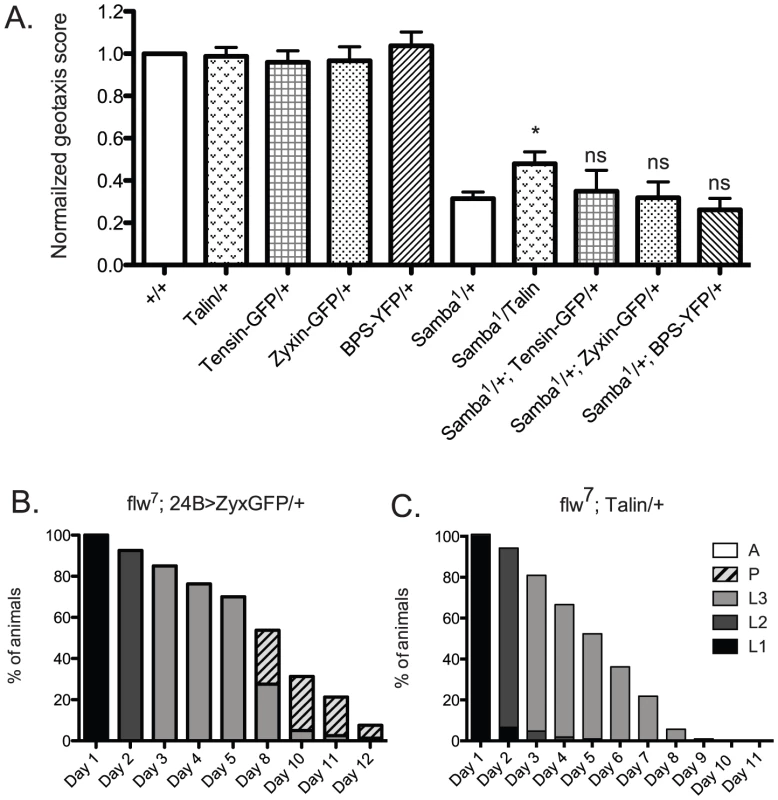

We next wanted to determine whether increased expression of other integrin adhesive complex (IAC) components might be protective under conditions of hypercontraction, or whether PINCH is unique in this regard. To test this, beginning with the geotaxis assay in the Samba1/+ mutant background, we employed a panel of IAC transgenic proteins to assess suppression of hypercontraction-induced climbing defects. This panel included ILK-GFP and Tensin-GFP controlled by their native promoters, FAK-GFP and Zyxin-GFP expressed using the Gal4-UAS system and the muscle-specific 24B driver, and Ubi-βPS-Integrin-YFP and Ubi-Talin expressed from the ubiquitin promoter. From among this panel, ILK-GFP was not overexpressed and FAK-GFP expression was lethal prior to adulthood [41], so these proteins were not tested in the geotaxis assay. Western analyses demonstrated increased expression of Zyxin-GFP, βPS-Integrin-YFP, and Talin in adult fly lysates (data not shown). We could not confirm expression of Tensin-GFP because of lack of antibody reagents, but this transgene has previously been shown to express, as it rescues null mutations in the Tensin gene blistery [42]. The presence of the Tensin-GFP, Zyxin-GFP, and βPS-Integrin-YFP transgenes had no significant effect on the climbing ability of Samba1 mutants (Figure 8A). Of the additional IAC proteins tested, only transgenic Talin expression resulted in a modest improvement of the geotaxis score for the MhcSamba1 mutant (Figure 8A). Rescue of IFM hypercontraction and thoracic indentation was not observed with expression of transgenic Talin (data not shown). This suggests that if increased expression of Talin does strengthen integrin adhesions, it is unlikely to do so in the same manner as PINCH.

Fig. 8. Increased expression of a panel of IAC proteins has little effect on hypercontraction mutants.

A) For each genotype, a normalized geotaxis score from >5 independent assays is plotted as the mean±SEM. * indicates p<0.05, and ns indicates p>0.05 when compared to the Samba1/+ data. B) Survival data for flw7; 24B>Zyxin-GFP/+ is not significantly different than flw7 alone (compare to Figure 2B). Pupae present at day 12 do not progress to adulthood. C) Survival data for flw7; Ubi-Talin/+ shows that larval lethality is increased compared to flw7 alone (see Figure 2B). In efforts to bolster the Samba1 geotaxis data, we further analyzed two of the panel of IAC proteins in the flw genetic background: Zyxin and Talin. We first analyzed the effect of Gal4-UAS expression of Zyxin-GFP from the muscle-specific 24B driver on the developmental profile of flw7. Animals expressing 24B>Zyxin-GFP alone show normal developmental progression (data not shown). As predicted from the lack of rescue of Samba1 geotaxis, we see no significant difference in either the rate of larval or pupal lethality upon expression of Zyxin-GFP in the flw7 mutants (Figure 8B, compare to Figure 2B). Next, we showed that upon expression of Ubi-Talin in the flw7 background, we did not observe any rescue of larval lethality (Figure 8C). In fact, pupariation was blocked entirely in flw7; Talin/+ animals. Because transgenic Talin expression does not uniformly rescue both of the hypercontraction mutants tested, the biological significance of the marginal rescue by Talin in the Samba1/+ geotaxis assay is unclear. Moreover, these data suggest a high degree of specificity in the rescue of multiple hypercontraction phenotypes by PINCH expression.

Discussion

In this report, we tested whether elevated expression of the IAC protein PINCH, as a means to strengthen integrin-based adhesions, can alleviate the phenotypes associated with muscle hypercontraction. We show that moderately elevated expression of PINCH dramatically rescues the lethality as well as the size, motility and muscle attachment defects associated with the myosin phosphatase hypercontraction mutant, flw. The interaction of PINCH with its binding partners ILK and RSU1 is required for rescue. Elevated PINCH expression neither alters the phosphorylation state of the essential Flapwing substrate MRLC, nor alleviates the hypercontraction observed in the larval VIS muscles, but instead may rescue through the stabilization of integrin-mediated adhesions. This idea is further supported by the partial rescue of the climbing deficits of an independent hypercontraction mutant in muscle myosin heavy chain, MhcSamba1, as well as the rescue of its thoracic indentation phenotype, without reversal of the hypercontraction evident in the IFM.

Initial work on this project included testing for interactions between PINCH and PP1 phosphatase family members in Drosophila. Data in mammalian cells shows that PP1α binds to PINCH via a KFVEF sequence motif present in LIM5 of PINCH, and that binding inhibits the phosphatase activity of PP1α [31]. We tested extensively for direct binding between Flapwing and PINCH in Drosophila using a variety of biochemical approaches, but were unable to demonstrate a physical interaction (data not shown). Moreover, if PINCH-PP1 binding and inhibition were evolutionarily conserved, we predicted that elevated expression of PINCH in Drosophila should exacerbate the defects of a flw hypomorph and lead to further hyper-phosphorylation of Flapwing targets like MRLC. We did not observe either of these things—rather, elevated expression of PINCH rescued flw phenotypes and had no effect on the phosphorylation state of the Flapwing target MRLC. There are several possible explanations for these discrepancies. First and least interesting, a PINCH-PP1 direct binding interaction may simply not be conserved in Drosophila—an idea we cannot disprove with negative biochemical data. Second, Flapwing is a PP1β family member rather than PP1α. While there is a high degree of sequence similarity between the two branches of the PP1 family, the distinguishing residues might play a key role in specifying PINCH binding. Our experiments do not address whether PINCH directly binds and inhibits PP1α isoforms in Drosophila, but rather show that PINCH is having a distinct and separate effect under conditions of PP1β loss-of-function via the stabilization of integrin-based adhesions. Third and most intriguing, the role of RSU1 in the PINCH-PP1α interaction is not yet clear. Both RSU1 and PP1α bind to LIM5 of mammalian PINCH. We have shown that PINCHD303 is a key residue for the binding of RSU1. Notably, the mammalian PINCHKFVEF motif that is responsible for PP1α binding [31] spans the immediately adjacent residues corresponding to 298–302 in the fly protein, which are moderately well conserved (KFYEY). As such, the binding interface on PINCH that participates in PP1α binding is likely to be overlapping with the RSU1 binding interface. It remains to be determined whether PINCH can bind both RSU1 and PP1α simultaneously, whether binding of PINCH to RSU1 and PP1α is mutually exclusive, or whether RSU1 rather than PINCH directly binds PP1α. Mutational analyses on the KVFEF motif of mammalian PINCH disrupted the association with PP1α [31], but it is formally possible that the KFVEF mutant disrupts RSU1 binding, preventing RSU1-PP1α complexes from docking on PINCH. Further studies on the mammalian versions of these proteins will be necessary to distinguish between these possibilities.

Expression of the binding mutants, PINCHQ38AFlag and PINCHD303VFlag, resulted in strong phenotypes in the context of Flapwing loss-of-function, eliminating pupariation entirely. Of note, expression from the Ubi-Talin transgene or the presence of the Zasp66-GFP gene trap had the equivalent effect of failed flw pupariation. This suggests that in the flw background, developmental events required for pupariation are particularly prone to disruption by alterations in the IAC. This makes the dramatic rescue of flw pupariation upon expression of PINCH-Flag all the more remarkable.

Expression of PINCHQ38AFlag and PINCHD303VFlag produces no dominant effects in a wild type background. There appears to be plasticity in IAC formation/maintenance to tolerate the presence of a small fraction of incomplete mutant PINCH complexes [35]. However, expression of the mutant PINCH transgenes creates a background that is sensitized to further perturbations. Upon flw loss-of-function, the presence of incomplete mutant PINCH complexes has severe and reproducible consequences on viability, size, and motility. There is a clear synergistic effect of combining flw loss-of-function and the corresponding alterations in protein phosphorylation, with expression from the mutant PINCH transgenes.

Our data suggest that PINCHQ38AFlag and PINCHD303VFlag participate in the formation of incomplete/unproductive PINCH complexes that may act dominantly in the flw background. This is consistent with numerous examples in cell culture in which overexpression of mutant forms of PINCH titrates away crucial binding partners to dominantly affect processes such as protein localization and cell spreading [34], [43]–[47]. The effect of mutant PINCH expression on the viability of flw animals is substantial, despite the relatively small amount of PINCHQ38AFlag and PINCHD303VFlag protein that is expressed (approximately 20–30% of endogenous PINCH). This may occur because of the mutual protein stabilization phenomenon exhibited by RSU1-PINCH-ILK-Parvin complexes [19], [22], [28]–[30]. It is plausible that incomplete complexes containing mutant PINCH may be destabilized and more rapidly turned over, resulting in insufficient numbers of intact complexes to maintain optimal adhesive function in the flw background. Indeed, in C. elegans muscle, incomplete integrin adhesive complexes have been shown to accelerate the rate of IAC protein degradation to disrupt myofibrillar and mitochondrial morphology [36], [37].

PINCH-Flag expression rescues the phenotypes of three different hypercontraction mutations: flw6 and flw7 in non-muscle myosin phosphatase, and MhcSamba1 in muscle myosin heavy chain. This strongly supports the idea that elevated PINCH expression strengthens integrin-based adhesion, and more robust adhesion can mitigate hypercontraction-induced muscle damage. Transgenic expression of additional IAC components from readily available stocks was first tested by geotaxis in the MhcSamba1 mutant because of the ease of generating Samba1 heterozygotes expressing transgenic IAC proteins. The results from this panel of transgenes were mixed. Some IAC proteins did not readily overexpress (ILK-GFP), suggesting that tight regulation induces more rapid turnover upon increased gene expression. Overexpression of another IAC protein was lethal (24B>FAK-GFP) and it therefore could not be tested in the rescue of adult Samba mutant phenotypes. Increased expression of several additional IAC proteins had no effect (24B>Zyxin-GFP, Tensin-GFP, Ubi-βPS-Integrin-YFP). Lack of rescue could result if increased expression does not serve to strengthen adhesions because that component is not limiting for IAC formation or function. Alternatively, if the IAC transgene is not adequately expressed in the appropriate tissues (e.g.: both muscle and tendon cells into which they anchor), the transgenic protein will be unable to effectively strengthen adhesion. The 3kb PINCH promoter employed appears to have a useful expression pattern in this regard. It remains to be seen whether other promoters and other IAC genes can direct expression that will strengthen adhesion to the same degree. It will be interesting in future studies to delineate which IAC proteins are limiting at muscle attachments as well as other adhesion sites, as better techniques to determine relative expression levels and stoichiometry are developed. Interestingly, Talin and Paxillin expression was upregulated in the microarray studies of the Samba mutants [14], suggesting that upregulation of select IAC proteins is a compensatory response to hypercontraction that is utilized in vivo. With elevated expression of PINCH-Flag, partial rescue of the Samba and flw defects was observed. This suggests that PINCH might be a limiting component of IACs, and increasing PINCH expression might serve to strengthen existing complexes and/or allow the assembly of additional IACs. Thus, strategic expression of PINCH, and perhaps other IAC proteins as well, may serve to preserve or protect muscle structure and function and may have therapeutic potential in myopathies that exhibit hypercontraction.

Methods

Drosophila Stocks

flw6, flw7 (also known as flwG0172), P[GawB]how24B, and Zasp66ZCL0663 were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. MhcSamba1 [9], stck17 and stck18 [23] have been previously described. Transgenic stocks include PINCH-Flag and PINCHQ38AFlag [30], UAS-Zyxin-GFP [48], ILK-GFP [24], UAS-FAK-GFP [41], Ubi-βPS-Integrin-YFP [49], Tensin-GFP [42], and Ubi-Talin [50].

Measuring Frequency of Adult Escapers

Crosses between w; PINFL2 and both flw6/FM7i and flw7/FM7i were set at 18°C and progeny counted. The percent escape was calculated as 100×[flw males/(total number of female progeny/2)]. Escaper male hemizygotes were tested for fertility by crossing to w1118 virgin females.

Survival Analyses

Stocks of the indicated genotypes were placed in cages and allowed to lay for approximately 6 hours on yeasted grape agar plates at 25°C. Except where noted, >80 animals of the appropriate genotype were selected from stocks as early L1s (24–30 hours) and placed on fresh grape agar plates. For stocks that are FM7i balanced, flw hemizygous males were selected by sorting against the GFP expressed from the FM7i balancer chromosome. A cross between flw7/FM7i and FM7i/Y; stck17/TM3, twi>GFP was used to generate flw7; stck17/+ animals, by selecting against the GFP expressed on both balancer chromosomes. On subsequent days, the number of viable animals at each stage of development was counted and live animals were moved to a fresh plate. Putative larval stages were determined by size. In Figure 2F, the small number of animals in each cohort precluded this determination, and total larvae were counted without respect to putative stage. Any pupae present continued to be counted until the final time point presented in the graphs, when they were scored for viability by the presence of visible and healthy looking adult structures with no signs of necrosis or dehydration. All viable pupae were kept an additional 7 days to determine if they eventually eclosed as adults. A wild type w1118 control was included to determine baseline lethality arising from experimental manipulation of the samples. Graphical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism.

For each analysis that involves a PINCH transgene, one of at least two independent insertion lines that were analyzed is shown, to confirm that the results were not dependent upon the locus of the transgene insertion.

Western Analyses

Four-day-old L3 larvae were homogenized in RIPA buffer with phosphatase inhibitors and normalized by protein content (BioRad DC protein assay). Antibodies employed were anti-PINCH [23], anti-RSU1 [19], anti-ILK (BD #611802), anti-P-MRLC/Sqh (Cell Signaling), and anti-RACK1 [51] or anti-α-tubulin 12G10 (DSHB) as a loading control. All western analyses were performed at least three times and representative blots are shown. Densitometric analyses of western blots were performed using Image J.

Modified Yeast Two-Hybrid Screen

In prior experiments that mapped the site of RSU1 interaction to LIM5 of PINCH, we constructed a LIM5 bait and RSU1 prey that activated an ADE2 reporter in a yeast two-hybrid system [19], [52]. Employing a low-fidelity polymerase, we amplified the LIM5 region of PINCH and sub-cloned it into the bait vector to create a randomly mutagenized LIM5 bait library. The RSU1-binding function of LIM5 is unaffected in most library clones, which display ADE2 reporter activity. In a fraction of the colonies, the LIM5-RSU1 interaction is disrupted. On non-selective plates, lack of ADE2 reporter activity allows a pink-colored precursor in the adenine biosynthetic pathway to accumulate. We analyzed pink colonies resulting from the co-transformation of the mutagenized PINCH LIM5 bait library and wild type RSU1 prey. Total DNA was isolated, and LIM5-encoding DNA was PCR amplified and sequenced. Frame shifts, truncations, or point mutations in the zinc ligands were not considered further. Sequence alignments were done using Clustal X.

Plasmid Construction, Ni-NTA Pull-Downs, and Flag Immunoprecipitations

PCR mutagenesis of a previously described pMT-PINCHwt-His construct [19] was used to introduce an Aspartate to Valine mutation at position 303 in the dPINCHa cDNA. pMT-PINCHwtHis and pMT-PINCHD303VHis were stably transfected into S2 cells using standard methods and expression induced by the addition of CuSO4. S2 cell lysates were prepared in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.9, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton-X 100) plus protease inhibitors, and were incubated with Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen), clarified by centrifugation, washed with lysis buffer, then boiled in 2× Laemmli sample buffer prior to western blotting.

Transgenic flies carrying PINCHD303VFlag were generated by PCR mutagenesis of a previously described pCasper construct containing genomic PINCHwt-Flag [30]. This DNA construct was injected into embryos for p-element transposition by Genetic Services Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Transgenic flies were then crossed into a PINCH null background (stck17/stck18). Adult fly lysates were prepared in lysis buffer plus protease inhibitors, clarified by centrifugation and 0.45 µm filtration, and were incubated with anti-Flag M2 agarose (Sigma), washed, and boiled in 2× Laemmli sample buffer for western blotting.

RT–PCR

Twelve adult flies per sample were lysed in 350 µl RLT Buffer using Qiashredder columns (Qiagen), and RNA was extracted using RNEasy Mini Kits (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. RT-PCR was conducted with 50 ng RNA per reaction using the Access RT-PCR System (Promega), with the following primers: PINCH-Flag (Forward: 5′GCACTGGCATGTGGAACATT3′, reverse: 5′ACTAGTCTACCTGTCATCGTC3′), GAPDH (Forward: 5′CAACTTCTGCGAAACGACAA3′, Reverse: 5′TGTCCTCCAGACCCTTGTTC3′).

Larval Size and Motility Assays

Larvae of the given genotypes were sorted at 24–30 hr after egg lay and analyzed when they reached 4 days of age (3rd instar). Prior to size measurements, larvae were heat fixed by rapidly submerging in boiling embryo wash (0.1% Triton X-100, 0.7% NaCl), and bright field images captured on an Olympus MVX10 dissecting microscope. Length measurements of individual larvae were normalized to the mean of a matched wild type w1118 control. To measure larval motility, we adapted an existing protocol [53]. Eight four-day-old L3s of the desired genotype were placed onto a room temperature, 5 cm grape agar plate marked with zones of 5 concentric circles (Figure 5B). After acclimating for at least 5 minutes, all 8 animals were moved into zone 1, and the assay started. At 60 sec, the zonal location of all 8 animals was recorded. These measurements were performed in triplicate for each group of 8 larvae, and data for ≥4 independent sets (≥32 animals) were collected. The relative distribution of animals at the end of the motility assay was plotted in GraphPad Prism, using the mean percent of animals present in each zone.

Ventral Intersegmental Muscle Morphology

Four-day-old L3s of the given genotypes were generated in a cross with flw7/FM7i; Zasp-GFP. Larvae were quickly heat fixed by rapidly submerging in boiling embryo wash (0.1% Triton X-100, 0.7% NaCl), then the Zasp66-GFP pattern in the Ventral Intersegmental (VIS) muscles was examined using an Olympus MVX10 GFP-dissecting microscope. Any animal in which the medial pair of VIS muscles does not correctly span body segments T1-T3 is scored as detached. Discontinuities in the Zasp-GFP signal are characteristic of breaks/detachments in the VIS muscles. Areas of hypercontraction are characterized by intense Zasp-GFP signal, as the Z-lines are more closely spaced. For each genotype, analyses were conducted in triplicate. Paired t tests were performed to determine statistically significant differences between genotypes.

Geotaxis Assays

Assays were done according to a previously described protocol [15], [40]. At least 50 flies of each genotype were tested. In each assay, 10 adult flies (<48 hours post-eclosion) were transferred to an empty vial and lightly tapped to the bottom. The number of flies that climbed to a height of 7 cm within 8 seconds was recorded. For each vial, the measurement was repeated 4 times and averaged. To control for minor variations in assay conditions, all data points were normalized to a wild type control sample that was collected and analyzed in parallel (ie: the number of wild type flies that met climbing criterion was converted to a geotaxis score = 1.0, to which other genotypes were compared). At least five sets of normalized data were used to graph a geotaxis score±SEM. Paired t tests were performed to determine statistically significant differences between genotypes.

Polarized Light Microscopy of Indirect Flight Muscle

IFM was analyzed as described previously [54], with several modifications. Briefly, adult flies of the indicated genotypes (n>20) were collected and dehydrated first in 100% ethanol, then in 100% isopropanol. Heads and abdomens were removed to speed equilibration. Thoraces were cleared >1 hour in xylenes, followed by >1 hour in BABB (1∶2 Benzyl Alcohol∶Benzyl Benzoate), then imaged in BABB using two external polarizing filters in conjunction with an Olympus MVX10 dissecting microscope. Thoracic indentations resulting from IFM hypercontraction were scored in >50 animals of each genotype upon visual inspection of freshly eclosed adults on a dissecting microscope.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. CohnRD, CampbellKP (2000) Molecular basis of muscular dystrophies. Muscle Nerve 23 : 1456–1471.

2. MendellJR, BoueDR, MartinPT (2006) The congenital muscular dystrophies: recent advances and molecular insights. Pediatr Dev Pathol 9 : 427–443.

3. SeidmanJG, SeidmanC (2001) The genetic basis for cardiomyopathy: from mutation identification to mechanistic paradigms. Cell 104 : 557–567.

4. JacobyD, McKennaWJ (2012) Genetics of inherited cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 33 : 296–304.

5. FerrusA, AcebesA, MarinMC, Hernandez-HernandezA (2000) A genetic approach to detect muscle protein interactions in vivo. Trends Cardiovasc Med 10 : 293–298.

6. VigoreauxJO (2001) Genetics of the Drosophila flight muscle myofibril: a window into the biology of complex systems. Bioessays 23 : 1047–1063.

7. BeallCJ, FyrbergE (1991) Muscle abnormalities in Drosophila melanogaster heldup mutants are caused by missing or aberrant troponin-I isoforms. J Cell Biol 114 : 941–951.

8. DeakII, BellamyPR, BienzM, DubuisY, FennerE, et al. (1982) Mutations affecting the indirect flight muscles of Drosophila melanogaster. J Embryol Exp Morphol 69 : 61–81.

9. MontanaES, LittletonJT (2004) Characterization of a hypercontraction-induced myopathy in Drosophila caused by mutations in Mhc. J Cell Biol 164 : 1045–1054.

10. RaghavanS, WilliamsI, AslamH, ThomasD, SzoorB, et al. (2000) Protein phosphatase 1beta is required for the maintenance of muscle attachments. Curr Biol 10 : 269–272.

11. VereshchaginaN, BennettD, SzoorB, KirchnerJ, GrossS, et al. (2004) The essential role of PP1beta in Drosophila is to regulate nonmuscle myosin. Mol Biol Cell 15 : 4395–4405.

12. HomykTJr, EmersonCPJr (1988) Functional interactions between unlinked muscle genes within haploinsufficient regions of the Drosophila genome. Genetics 119 : 105–121.

13. NongthombaU, CumminsM, ClarkS, VigoreauxJO, SparrowJC (2003) Suppression of muscle hypercontraction by mutations in the myosin heavy chain gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 164 : 209–222.

14. MontanaES, LittletonJT (2006) Expression profiling of a hypercontraction-induced myopathy in Drosophila suggests a compensatory cytoskeletal remodeling response. J Biol Chem 281 : 8100–8109.

15. PerkinsAD, EllisSJ, AsghariP, ShamsianA, MooreED, et al. (2010) Integrin-mediated adhesion maintains sarcomeric integrity. Dev Biol 338 : 15–27.

16. Pines M, Das R, Ellis SJ, Morin A, Czerniecki S, et al.. (2012) Mechanical force regulates integrin turnover in Drosophila in vivo. Nat Cell Biol.

17. HigashibataA, SzewczykNJ, ConleyCA, Imamizo-SatoM, HigashitaniA, et al. (2006) Decreased expression of myogenic transcription factors and myosin heavy chains in Caenorhabditis elegans muscles developed during spaceflight. J Exp Biol 209 : 3209–3218.

18. BloorJW, KiehartDP (2001) zipper Nonmuscle myosin-II functions downstream of PS2 integrin in Drosophila myogenesis and is necessary for myofibril formation. Dev Biol 239 : 215–228.

19. KadrmasJL, SmithMA, ClarkKA, PronovostSM, MusterN, et al. (2004) The integrin effector PINCH regulates JNK activity and epithelial migration in concert with Ras suppressor 1. J Cell Biol 167 : 1019–1024.

20. DoughertyGW, ChoppT, QiSM, CutlerML (2005) The Ras suppressor Rsu-1 binds to the LIM 5 domain of the adaptor protein PINCH1 and participates in adhesion-related functions. Exp Cell Res 306 : 168–179.

21. LiF, ZhangY, WuC (1999) Integrin-linked kinase is localized to cell-matrix focal adhesions but not cell-cell adhesion sites and the focal adhesion localization of integrin-linked kinase is regulated by the PINCH-binding ANK repeats. J Cell Sci 112(Pt 24): 4589–4599.

22. FukudaT, ChenK, ShiX, WuC (2003) PINCH-1 is an obligate partner of integrin-linked kinase (ILK) functioning in cell shape modulation, motility, and survival. J Biol Chem 278 : 51324–51333.

23. ClarkKA, McGrailM, BeckerleMC (2003) Analysis of PINCH function in Drosophila demonstrates its requirement in integrin-dependent cellular processes. Development 130 : 2611–2621.

24. ZervasCG, GregorySL, BrownNH (2001) Drosophila integrin-linked kinase is required at sites of integrin adhesion to link the cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol 152 : 1007–1018.

25. VakaloglouKM, ChountalaM, ZervasCG (2012) Functional analysis of parvin and different modes of IPP-complex assembly at integrin sites during Drosophila development. J Cell Sci

26. KogataN, TribeRM, FasslerR, WayM, AdamsRH (2009) Integrin-linked kinase controls vascular wall formation by negatively regulating Rho/ROCK-mediated vascular smooth muscle cell contraction. Genes Dev 23 : 2278–2283.

27. MontanezE, WickstromSA, AltstatterJ, ChuH, FasslerR (2009) Alpha-parvin controls vascular mural cell recruitment to vessel wall by regulating RhoA/ROCK signalling. EMBO J 28 : 3132–3144.

28. StanchiF, GrashoffC, Nguemeni YongaCF, GrallD, FasslerR, et al. (2009) Molecular dissection of the ILK-PINCH-parvin triad reveals a fundamental role for the ILK kinase domain in the late stages of focal-adhesion maturation. J Cell Sci 122 : 1800–1811.

29. MederB, HuttnerIG, Sedaghat-HamedaniF, JustS, DahmeT, et al. (2011) PINCH proteins regulate cardiac contractility by modulating integrin-linked kinase-protein kinase B signaling. Mol Cell Biol 31 : 3424–3435.

30. EliasMC, PronovostSM, CahillKJ, BeckerleMC, KadrmasJL (2012) A crucial role for Ras Suppressor-1 (RSU-1) revealed when PINCH and ILK binding is disrupted. J Cell Sci

31. EkeI, KochU, HehlgansS, SandfortV, StanchiF, et al. (2010) PINCH1 regulates Akt1 activation and enhances radioresistance by inhibiting PP1alpha. J Clin Invest 120 : 2516–2527.

32. ChenK, TuY, ZhangY, BlairHC, ZhangL, et al. (2008) PINCH-1 regulates the ERK-Bim pathway and contributes to apoptosis resistance in cancer cells. J Biol Chem 283 : 2508–2517.

33. XuZ, FukudaT, LiY, ZhaX, QinJ, et al. (2005) Molecular dissection of PINCH-1 reveals a mechanism of coupling and uncoupling of cell shape modulation and survival. J Biol Chem 280 : 27631–27637.

34. ZhangY, ChenK, TuY, VelyvisA, YangY, et al. (2002) Assembly of the PINCH-ILK-CH-ILKBP complex precedes and is essential for localization of each component to cell-matrix adhesion sites. J Cell Sci 115 : 4777–4786.

35. EliasMC, PronovostSM, CahillKJ, BeckerleMC, KadrmasJL (2012) A crucial role for Ras suppressor-1 (RSU-1) revealed when PINCH and ILK binding is disrupted. J Cell Sci 125 : 3185–3194.

36. ShephardF, AdenleAA, JacobsonLA, SzewczykNJ (2011) Identification and functional clustering of genes regulating muscle protein degradation from amongst the known C. elegans muscle mutants. PLoS ONE 6: e24686 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024686.

37. EtheridgeT, OczypokEA, LehmannS, FieldsBD, ShephardF, et al. (2012) Calpains mediate integrin attachment complex maintenance of adult muscle in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet 8: e1002471 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002471.

38. Quinones-CoelloAT, PetrellaLN, AyersK, MelilloA, MazzalupoS, et al. (2007) Exploring strategies for protein trapping in Drosophila. Genetics 175 : 1089–1104.

39. SchnorrerF, SchonbauerC, LangerCC, DietzlG, NovatchkovaM, et al. (2010) Systematic genetic analysis of muscle morphogenesis and function in Drosophila. Nature 464 : 287–291.

40. LealSM, NeckameyerWS (2002) Pharmacological evidence for GABAergic regulation of specific behaviors in Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurobiol 50 : 245–261.

41. GrabbeC, ZervasCG, HunterT, BrownNH, PalmerRH (2004) Focal adhesion kinase is not required for integrin function or viability in Drosophila. Development 131 : 5795–5805.

42. TorglerCN, NarasimhaM, KnoxAL, ZervasCG, VernonMC, et al. (2004) Tensin stabilizes integrin adhesive contacts in Drosophila. Dev Cell 6 : 357–369.

43. StanchiF, BordoyR, KudlacekO, BraunA, PfeiferA, et al. (2005) Consequences of loss of PINCH2 expression in mice. J Cell Sci 118 : 5899–5910.

44. ChenH, HuangXN, YanW, ChenK, GuoL, et al. (2005) Role of the integrin-linked kinase/PINCH1/alpha-parvin complex in cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. Lab Invest 85 : 1342–1356.

45. ZhangY, ChenK, GuoL, WuC (2002) Characterization of PINCH-2, a new focal adhesion protein that regulates the PINCH-1-ILK interaction, cell spreading, and migration. J Biol Chem 277 : 38328–38338.

46. ZhangY, GuoL, ChenK, WuC (2002) A critical role of the PINCH-integrin-linked kinase interaction in the regulation of cell shape change and migration. J Biol Chem 277 : 318–326.

47. GuoL, WuC (2002) Regulation of fibronectin matrix deposition and cell proliferation by the PINCH-ILK-CH-ILKBP complex. Faseb J 16 : 1298–1300.

48. RenfranzPJ, BlankmanE, BeckerleMC (2010) The cytoskeletal regulator zyxin is required for viability in Drosophila melanogaster. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 293 : 1455–1469.

49. YuanL, FairchildMJ, PerkinsAD, TanentzapfG (2010) Analysis of integrin turnover in fly myotendinous junctions. J Cell Sci 123 : 939–946.

50. BecamIE, TanentzapfG, LepesantJA, BrownNH, HuynhJR (2005) Integrin-independent repression of cadherin transcription by talin during axis formation in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol 7 : 510–516.

51. KadrmasJL, SmithMA, PronovostSM, BeckerleMC (2007) Characterization of RACK1 function in Drosophila development. Dev Dyn 236 : 2207–2215.

52. JamesP, HalladayJ, CraigEA (1996) Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144 : 1425–1436.

53. DialynasG, FlanneryKM, ZirbelLN, NagyPL, MathewsKD, et al. (2012) LMNA variants cause cytoplasmic distribution of nuclear pore proteins in Drosophila and human muscle. Hum Mol Genet 21 : 1544–1556.

54. FyrbergE, BernsteinS, VijayRaghavanS (1994) Basic Methods for Drosophila muscle biology. Methods Cell Biol 44 : 237–258.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Ubiquitous Polygenicity of Human Complex Traits: Genome-Wide Analysis of 49 Traits in KoreansČlánek Alternative Splicing and Subfunctionalization Generates Functional Diversity in Fungal ProteomesČlánek RFX Transcription Factor DAF-19 Regulates 5-HT and Innate Immune Responses to Pathogenic Bacteria inČlánek Surveillance-Activated Defenses Block the ROS–Induced Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein ResponseČlánek Deficiency Reduces Adipose OXPHOS Capacity and Triggers Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Mice

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 3- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Power and Predictive Accuracy of Polygenic Risk Scores

- Rare Copy Number Variants Are a Common Cause of Short Stature

- Coordination of Flower Maturation by a Regulatory Circuit of Three MicroRNAs

- Ubiquitous Polygenicity of Human Complex Traits: Genome-Wide Analysis of 49 Traits in Koreans

- Genomic Evidence for Island Population Conversion Resolves Conflicting Theories of Polar Bear Evolution

- Mechanistic Insight into the Pathology of Polyalanine Expansion Disorders Revealed by a Mouse Model for X Linked Hypopituitarism

- Genome-Wide Association Study and Gene Expression Analysis Identifies as a Predictor of Response to Etanercept Therapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Problem Solved: An Interview with Sir Edwin Southern

- Long Interspersed Element–1 (LINE-1): Passenger or Driver in Human Neoplasms?

- Mouse HFM1/Mer3 Is Required for Crossover Formation and Complete Synapsis of Homologous Chromosomes during Meiosis

- Alternative Splicing and Subfunctionalization Generates Functional Diversity in Fungal Proteomes

- A WRKY Transcription Factor Recruits the SYG1-Like Protein SHB1 to Activate Gene Expression and Seed Cavity Enlargement

- Microhomology-Mediated Mechanisms Underlie Non-Recurrent Disease-Causing Microdeletions of the Gene or Its Regulatory Domain

- Ancient Evolutionary Trade-Offs between Yeast Ploidy States

- Differential Evolutionary Fate of an Ancestral Primate Endogenous Retrovirus Envelope Gene, the EnvV , Captured for a Function in Placentation

- A Feed-Forward Loop Coupling Extracellular BMP Transport and Morphogenesis in Wing

- The Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus Resistance Genes and Are Allelic and Code for DFDGD-Class RNA–Dependent RNA Polymerases

- The U-Box E3 Ubiquitin Ligase TUD1 Functions with a Heterotrimeric G α Subunit to Regulate Brassinosteroid-Mediated Growth in Rice

- Role of the DSC1 Channel in Regulating Neuronal Excitability in : Extending Nervous System Stability under Stress

- –Independent Phenotypic Switching in and a Dual Role for Wor1 in Regulating Switching and Filamentation

- Pax6 Regulates Gene Expression in the Vertebrate Lens through miR-204

- Blood-Informative Transcripts Define Nine Common Axes of Peripheral Blood Gene Expression

- Genetic Architecture of Skin and Eye Color in an African-European Admixed Population

- Fine Characterisation of a Recombination Hotspot at the Locus and Resolution of the Paradoxical Excess of Duplications over Deletions in the General Population

- Estrogen Mediated-Activation of miR-191/425 Cluster Modulates Tumorigenicity of Breast Cancer Cells Depending on Estrogen Receptor Status

- Complex Patterns of Genomic Admixture within Southern Africa

- Yap- and Cdc42-Dependent Nephrogenesis and Morphogenesis during Mouse Kidney Development

- Molecular Networks of Human Muscle Adaptation to Exercise and Age

- Alp/Enigma Family Proteins Cooperate in Z-Disc Formation and Myofibril Assembly

- Polycomb Group Gene Regulates Rice () Seed Development and Grain Filling via a Mechanism Distinct from

- RFX Transcription Factor DAF-19 Regulates 5-HT and Innate Immune Responses to Pathogenic Bacteria in

- Distinct Molecular Strategies for Hox-Mediated Limb Suppression in : From Cooperativity to Dispensability/Antagonism in TALE Partnership

- A Natural Polymorphism in rDNA Replication Origins Links Origin Activation with Calorie Restriction and Lifespan

- TDP2–Dependent Non-Homologous End-Joining Protects against Topoisomerase II–Induced DNA Breaks and Genome Instability in Cells and

- Recurrent Rearrangement during Adaptive Evolution in an Interspecific Yeast Hybrid Suggests a Model for Rapid Introgression

- Genome-Wide Association Study in Mutation Carriers Identifies Novel Loci Associated with Breast and Ovarian Cancer Risk

- Coincident Resection at Both Ends of Random, γ–Induced Double-Strand Breaks Requires MRX (MRN), Sae2 (Ctp1), and Mre11-Nuclease

- Identification of a -Specific Modifier Locus at 6p24 Related to Breast Cancer Risk

- A Novel Function for the Hox Gene in the Male Accessory Gland Regulates the Long-Term Female Post-Mating Response in

- Tdp2: A Means to Fixing the Ends

- A Novel Role for the RNA–Binding Protein FXR1P in Myoblasts Cell-Cycle Progression by Modulating mRNA Stability

- Association Mapping and the Genomic Consequences of Selection in Sunflower

- Histone Deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) Regulates Chromosome Segregation and Kinetochore Function via H4K16 Deacetylation during Oocyte Maturation in Mouse

- A Novel Mutation in the Upstream Open Reading Frame of the Gene Causes a MEN4 Phenotype

- Ataxin1L Is a Regulator of HSC Function Highlighting the Utility of Cross-Tissue Comparisons for Gene Discovery

- Human Spermatogenic Failure Purges Deleterious Mutation Load from the Autosomes and Both Sex Chromosomes, including the Gene

- A Conserved Upstream Motif Orchestrates Autonomous, Germline-Enriched Expression of piRNAs

- Statistical Analysis Reveals Co-Expression Patterns of Many Pairs of Genes in Yeast Are Jointly Regulated by Interacting Loci

- Matefin/SUN-1 Phosphorylation Is Part of a Surveillance Mechanism to Coordinate Chromosome Synapsis and Recombination with Meiotic Progression and Chromosome Movement

- A Role for the Malignant Brain Tumour (MBT) Domain Protein LIN-61 in DNA Double-Strand Break Repair by Homologous Recombination

- The Population and Evolutionary Dynamics of Phage and Bacteria with CRISPR–Mediated Immunity

- Long Noncoding RNA MALAT1 Controls Cell Cycle Progression by Regulating the Expression of Oncogenic Transcription Factor B-MYB

- Surveillance-Activated Defenses Block the ROS–Induced Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response

- DNA Topoisomerase III Localizes to Centromeres and Affects Centromeric CENP-A Levels in Fission Yeast

- Genome-Wide Control of RNA Polymerase II Activity by Cohesin

- Divergent Selection Drives Genetic Differentiation in an R2R3-MYB Transcription Factor That Contributes to Incipient Speciation in

- NODULE INCEPTION Directly Targets Subunit Genes to Regulate Essential Processes of Root Nodule Development in

- Spreading of a Prion Domain from Cell-to-Cell by Vesicular Transport in

- Deficiency in Origin Licensing Proteins Impairs Cilia Formation: Implications for the Aetiology of Meier-Gorlin Syndrome

- Deficiency Reduces Adipose OXPHOS Capacity and Triggers Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Mice

- The Conserved SKN-1/Nrf2 Stress Response Pathway Regulates Synaptic Function in

- Functional Genomic Analysis of the Regulatory Network in

- Astakine 2—the Dark Knight Linking Melatonin to Circadian Regulation in Crustaceans

- CRL2 E3-Ligase Regulates Proliferation and Progression through Meiosis in the Germline

- Both the Caspase CSP-1 and a Caspase-Independent Pathway Promote Programmed Cell Death in Parallel to the Canonical Pathway for Apoptosis in

- PRMT4 Is a Novel Coactivator of c-Myb-Dependent Transcription in Haematopoietic Cell Lines

- A Copy Number Variant at the Locus Likely Confers Risk for Canine Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Digit

- Evidence of Gene–Environment Interactions between Common Breast Cancer Susceptibility Loci and Established Environmental Risk Factors

- HIV Infection Disrupts the Sympatric Host–Pathogen Relationship in Human Tuberculosis

- Trans-Ethnic Fine-Mapping of Lipid Loci Identifies Population-Specific Signals and Allelic Heterogeneity That Increases the Trait Variance Explained

- A Gene Transfer Agent and a Dynamic Repertoire of Secretion Systems Hold the Keys to the Explosive Radiation of the Emerging Pathogen

- The Role of ATM in the Deficiency in Nonhomologous End-Joining near Telomeres in a Human Cancer Cell Line

- Dynamic Circadian Protein–Protein Interaction Networks Predict Temporal Organization of Cellular Functions

- Nuclear Myosin 1c Facilitates the Chromatin Modifications Required to Activate rRNA Gene Transcription and Cell Cycle Progression

- Robust Prediction of Expression Differences among Human Individuals Using Only Genotype Information

- A Single Cohesin Complex Performs Mitotic and Meiotic Functions in the Protist

- The Role of the Arabidopsis Exosome in siRNA–Independent Silencing of Heterochromatic Loci

- Elevated Expression of the Integrin-Associated Protein PINCH Suppresses the Defects of Muscle Hypercontraction Mutants

- Twist1 Controls a Cell-Specification Switch Governing Cell Fate Decisions within the Cardiac Neural Crest

- Genome-Wide Testing of Putative Functional Exonic Variants in Relationship with Breast and Prostate Cancer Risk in a Multiethnic Population

- Heteroduplex DNA Position Defines the Roles of the Sgs1, Srs2, and Mph1 Helicases in Promoting Distinct Recombination Outcomes

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Fine Characterisation of a Recombination Hotspot at the Locus and Resolution of the Paradoxical Excess of Duplications over Deletions in the General Population

- Molecular Networks of Human Muscle Adaptation to Exercise and Age

- Recurrent Rearrangement during Adaptive Evolution in an Interspecific Yeast Hybrid Suggests a Model for Rapid Introgression

- Genome-Wide Association Study and Gene Expression Analysis Identifies as a Predictor of Response to Etanercept Therapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání