-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Loss-of-Function Mutations in Cause Metachondromatosis, but Not Ollier Disease or Maffucci Syndrome

Metachondromatosis (MC) is a rare, autosomal dominant, incompletely penetrant combined exostosis and enchondromatosis tumor syndrome. MC is clinically distinct from other multiple exostosis or multiple enchondromatosis syndromes and is unlinked to EXT1 and EXT2, the genes responsible for autosomal dominant multiple osteochondromas (MO). To identify a gene for MC, we performed linkage analysis with high-density SNP arrays in a single family, used a targeted array to capture exons and promoter sequences from the linked interval in 16 participants from 11 MC families, and sequenced the captured DNA using high-throughput parallel sequencing technologies. DNA capture and parallel sequencing identified heterozygous putative loss-of-function mutations in PTPN11 in 4 of the 11 families. Sanger sequence analysis of PTPN11 coding regions in a total of 17 MC families identified mutations in 10 of them (5 frameshift, 2 nonsense, and 3 splice-site mutations). Copy number analysis of sequencing reads from a second targeted capture that included the entire PTPN11 gene identified an additional family with a 15 kb deletion spanning exon 7 of PTPN11. Microdissected MC lesions from two patients with PTPN11 mutations demonstrated loss-of-heterozygosity for the wild-type allele. We next sequenced PTPN11 in DNA samples from 54 patients with the multiple enchondromatosis disorders Ollier disease or Maffucci syndrome, but found no coding sequence PTPN11 mutations. We conclude that heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in PTPN11 are a frequent cause of MC, that lesions in patients with MC appear to arise following a “second hit,” that MC may be locus heterogeneous since 1 familial and 5 sporadically occurring cases lacked obvious disease-causing PTPN11 mutations, and that PTPN11 mutations are not a common cause of Ollier disease or Maffucci syndrome.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002050

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002050Summary

Metachondromatosis (MC) is a rare, autosomal dominant, incompletely penetrant combined exostosis and enchondromatosis tumor syndrome. MC is clinically distinct from other multiple exostosis or multiple enchondromatosis syndromes and is unlinked to EXT1 and EXT2, the genes responsible for autosomal dominant multiple osteochondromas (MO). To identify a gene for MC, we performed linkage analysis with high-density SNP arrays in a single family, used a targeted array to capture exons and promoter sequences from the linked interval in 16 participants from 11 MC families, and sequenced the captured DNA using high-throughput parallel sequencing technologies. DNA capture and parallel sequencing identified heterozygous putative loss-of-function mutations in PTPN11 in 4 of the 11 families. Sanger sequence analysis of PTPN11 coding regions in a total of 17 MC families identified mutations in 10 of them (5 frameshift, 2 nonsense, and 3 splice-site mutations). Copy number analysis of sequencing reads from a second targeted capture that included the entire PTPN11 gene identified an additional family with a 15 kb deletion spanning exon 7 of PTPN11. Microdissected MC lesions from two patients with PTPN11 mutations demonstrated loss-of-heterozygosity for the wild-type allele. We next sequenced PTPN11 in DNA samples from 54 patients with the multiple enchondromatosis disorders Ollier disease or Maffucci syndrome, but found no coding sequence PTPN11 mutations. We conclude that heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in PTPN11 are a frequent cause of MC, that lesions in patients with MC appear to arise following a “second hit,” that MC may be locus heterogeneous since 1 familial and 5 sporadically occurring cases lacked obvious disease-causing PTPN11 mutations, and that PTPN11 mutations are not a common cause of Ollier disease or Maffucci syndrome.

Introduction

Cartilage tumor syndromes are characterized by multiple cartilaginous bone tumors that develop in childhood, often causing significant morbidity and predisposing to chondrosarcoma. Tumors can form as exostoses (on the surface of bone), as in the autosomal dominant, multiple osteochondroma (hereditary multiple exostoses) syndromes (MO; MIM 133700 and 133701), or as endosteal tumors (within bone), as in the sporadically occurring multiple enchondromatosis disorders (MIM 166000) Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome. In MO, mutations in EXT1 or EXT2, which encode heparan sulfate glycosyltransferases, affect chondrocyte orientation in the growth plate [1]. A small percentage of patients with Ollier syndrome have mutations in PTH1R, which encodes the receptor for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related protein, causing altered chondrocyte differentiation in the growth plate [2]. The cause of Maffucci syndrome is unknown [3]. Patients with MO do not develop endosteal tumors, and patients with Ollier disease or Maffucci syndrome do not develop exostotic tumors [1], [3], [4].

Patients with metachondromatosis (MC; MIM 156250) form exostotic and endosteal tumors (Figure 1). Fewer than 50 cases of MC have been published since Maroteaux's initial description in 1971 [5]. Exostotic lesions in MC occur frequently in the digits, involve metaphyses and epiphyses, and tend to grow toward the joint; in contrast, exostotic lesions in MO occur frequently in the long bones, involve only the metaphyses, and tend to grow away from the joint [6]–[11]. MC exostotic lesions can also spontaneously decrease in size and completely regress [6], [7], [9], [12]. Endosteal lesions in MC are common in the metaphyses of long bones and in the pelvis [7]–[11]. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head, due to endosteal tumors, has been a frequent complication in patients with MC [7], [8], [13]–[15]. Hand deformity due to endosteal tumors is uncommon in patients with MC, whereas it is often a significant problem for patients with Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome [3]. Finally, malignant transformation has only been reported in one patient with MC, whereas it has been more frequently reported in patients with MO, Ollier disease, and Maffucci syndrome [3], [4], [16]. The distinct distribution and clinical behavior of lesions in patients with MC, suggest that MC is pathophysiologically distinct from these other cartilage tumor syndromes. We therefore sought to better characterize MC and to determine its genetic basis.

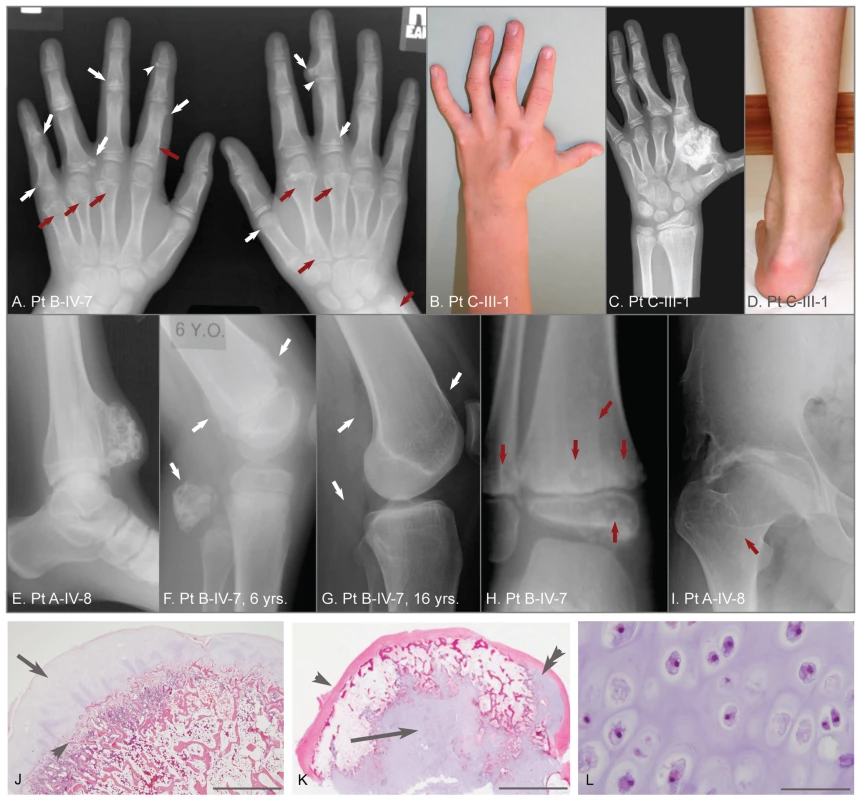

Fig. 1. Clinical, radiographic, and histologic features of metachondromatosis.

(A) Hand radiographs of participant B-IV-7, taken when 8-years-old. Exostotic lesions (white arrows) are present in the phalanges and metacarpals, and arise from the metaphysis (arrows) or epiphysis (arrowheads). Exostoses tend to point toward the adjacent joint. Endosteal lesions (red arrows) cause metaphyseal expansion. (B, C, D) Hand photograph and radiograph, and foot photograph of participant C-III-1 taken when 9-years-old, depicting mild shortening and deformity of the digits, a large exostotic lesion arising from the second metacarpal bone in the hand, and ankle enlargement superior to the malleoli due to exostoses of the tibia and fibula. (E) Ankle radiograph of participant A-IV-8 taken when 19-years-old depicting a recurrence of a previously excised exostotic lesion of the distal tibia that spans the physis. (F, G) Lateral knee radiographs of participant B-IV-7, taken at 6 years and 16 years, respectively. Note that multiple exostotic lesions of the distal femur and proximal fibula (white arrows) seen when 6-years-old (F) have regressed in the absence of surgical intervention by 16-years of age (G). (H) Ankle radiograph of participant B-IV-7, taken when 5-years-old, demonstrating radiolucency associated with endosteal lesions (red arrows) in the tibia and fibula, and mild metaphyseal flaring. Despite combined metaphyseal and epiphyseal involvement, this individual's linear growth was not affected. (I) Hip radiograph of participant A-IV-8 taken when 22-years-old depicting an endosteal lesion of the femoral neck (arrow) that has caused degeneration of the femoral head and spurring of the acetabulum. (J) Low power photomicrograph of an hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained section through an exostosis that had been excised from a patient with hereditary multiple exostoses. Note this exostosis is a typical osteochondroma, having a well-developed surface cartilaginous cap (arrow) and endochondral bone immediately below (arrowhead). The scale bar represents 0.15 cm (K) Photomicrograph of an H&E stained exostotic lesion excised from participant A-IV-5 when 5-years-old. This lesion is predominantly covered by a fibrous cap (arrow) and has only a small, eccentric cartilaginous cap (double arrowhead). The majority of cartilage in this, and in 14 other exostoses from patients with MC that have been analyzed, is found within a central core (arrow) and has bone formation occurring at the periphery of this cartilage core. The scale bar represents 0.5 cm. (L) High-power image of the central cartilage core shows chondrocytes with prominent cytoplasm no organization typical of a growth plate. The scale bar represents 100 µm. Results

Patient selection

We diagnosed participants as having MC based upon the presence of both multiple exostotic and endosteal cartilaginous lesions as previously described [5]–[10], [15]. We excluded from analysis participants with solitary lesions, contiguous endosteal lesions suggestive of Ollier disease, soft tissue lesions suggestive of Maffucci syndrome, or radiographs suggestive of MO. We included participants who had clinical and radiographic features of MC, even if they lacked a positive family history. For each patient, the clinical history and radiographs were reviewed by at least 3 authors. MC patients from 17 unrelated families from 9 countries were identified (Supplementary Table 1). All participants gave their informed consent following the guidelines of each referring institution. In 10 families disease segregation is consistent with autosomal dominant inheritance. In 7 families, the disease is suspected to have arisen de novo. Immediate family members of patients with sporadically occurring MC were interviewed and examined, although detailed imaging was not performed. For 8 familial cases, blood or DNA was available from additional family members.

Clinical and pathologic features of metachondromatosis

Figure 1 depicts features seen in affected participants with MC. No phenotypic differences could be found between sporadic or familial cases of MC. Radiographs identify exostotic and endosteal lesions of the digits (Figure 1A–1C) and long bones (Figure 1E–1H), along with degenerative hip disease secondary to endosteal lesions in the femoral neck (Figure 1I). Spontaneous regression of exostotic lesions is seen in radiographs obtained 10 years apart in the same patient (Figure 1F,1G). Also depicted in Figure 1 are histopathologic features that distinguish exostoses in patients with MO from those in patients with MC, based upon a comparison of 30 exostoses excised from children with MO and 15 exostotic lesions excised from 3 affected individuals with MC. Exostoses in children with MO have cartilage caps with endochondral bone growth immediately beneath the cap (Figure 1J). In contrast, exostoses in children with MC have a predominantly fibrous cap and a core of disorganized cartilage surrounded by trabecular bone (Figure 1K, 1L). In all MC cases, the lesions were bilateral and not obviously confined to a single body segment as in Ollier or Maffucci patients.

Linkage analysis

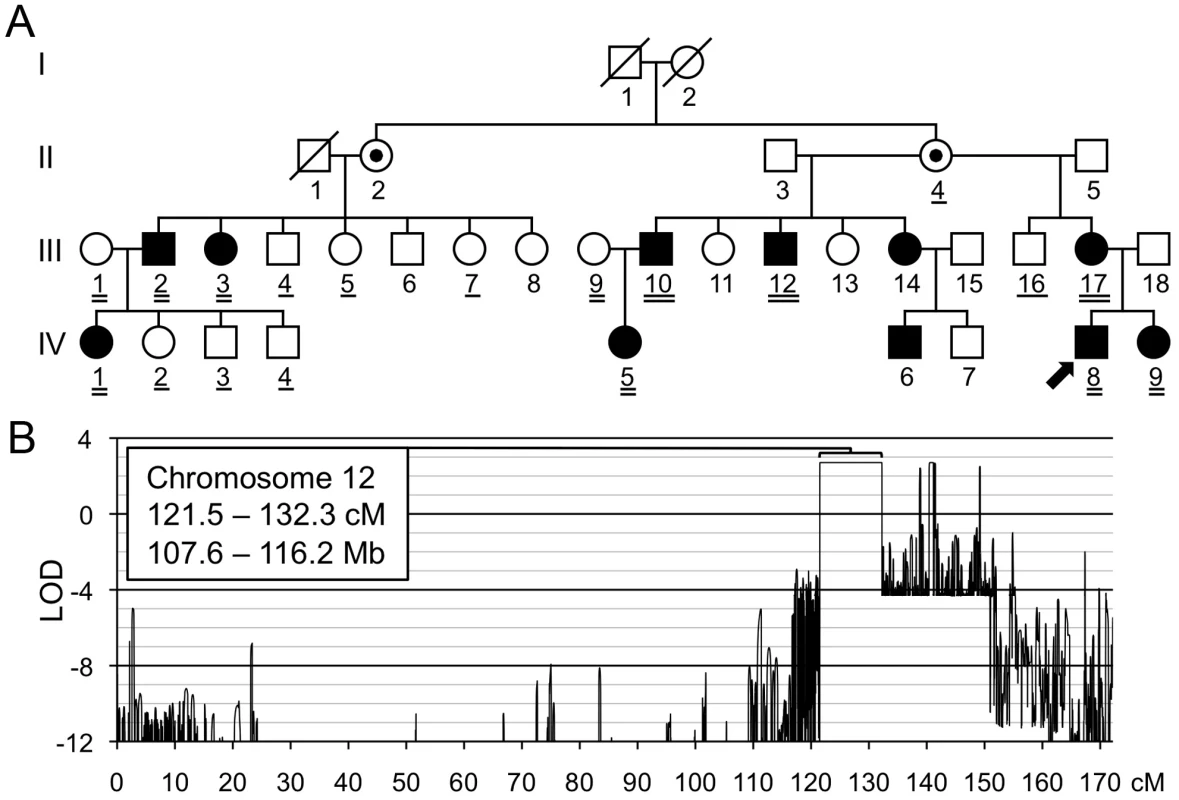

We performed linkage analysis in the largest family (Family A, Figure 2A) to identify a genetic locus for MC. Raw genotype data were generated using Affymetrix 6.0 SNP arrays and multipoint parametric linkage analysis of the autosomal genome was performed using MERLIN [17]. Because non-penetrance and non-ascertainment are potential confounding factors in the diagnosis of MC, we analyzed only founders and affected individuals (Figure 2A). Although this limited the maximum attainable LOD score to 2.7, which is lower than the genome-wide significance threshold of 3.3, the dense marker set ensured a reasonable probability that only one large interval that achieved the maximum LOD score would be observed, with the remainder of the genome being excluded.

Fig. 2. Linkage mapping of metachondromatosis to chromosome 12q.

(A) Pedigree of the family (Family A) used to define the metachondromatosis candidate interval. Affected individuals have filled symbols. Individuals who were not examined but who were assumed to be obligate carriers have interior dots. An arrow identifies the proband. Participants whose DNA was used for linkage analysis are double underlined. Those participants with a single or double underlines were tested for the PTPN11 mutation, after the mutation had been identified in participants A-III-10 and A-IV-5 by targeted array capture and Illumina sequencing. (B) LOD score plot of chromosome 12. Only one interval, larger than 1 cM, in the entire genome attained the maximum LOD score of 2.7. Several autosomal intervals, each smaller than 1 cM, also achieved maximum or positive LOD scores (Figure S1). These likely represent either genotyping errors or short ancestral haplotypes that are coincidental with linkage. The physical coordinates shown are derived from GRCh37/hg19. We identified a single interval on chromosome 12, from 121.5 to 132.3 cM, that attained the maximum LOD score of 2.7 (Figure 2B). No other autosomal interval >1 cM yielded a peak LOD score >−1.9. Several intervals <1 cM attained LOD scores >0 (Figure S1), but we considered these unlikely to be candidate intervals and instead assumed they represented either unfiltered genotyping errors or short ancestral population haplotypes, rather than familial haplotypes inherited from a common ancestor.

Multiplexed targeted genomic capture and sequencing of linkage interval

We next performed array-based capture, followed by Illumina GAII sequencing, using bar-coded DNA libraries created from 16 individuals in 11 families. We sequenced 1 affected individual in 8 families, 2 affected individuals in 1 family, and 2 affected and 1 unaffected individual in 2 families (Table S1). We prepared bar-coded genomic DNA libraries, having an average insert size of 150 bp, using sheared DNA from each of the 16 individuals (Figure S2). We performed array-based targeted capture by pooling each DNA library and hybridizing the pooled sample to an Agilent Technologies 1M SureSelect DNA capture array containing 973,952 probes targeting 844,339 bp within the 8.6 Mb candidate interval, including 88.4% and 98.6% of UCSC exons and CCDS coding sequence, respectively. After hybridization and elution, the captured DNA was PCR amplified, purified to remove primer dimers, and sequenced on two lanes of an Illumina GA II.

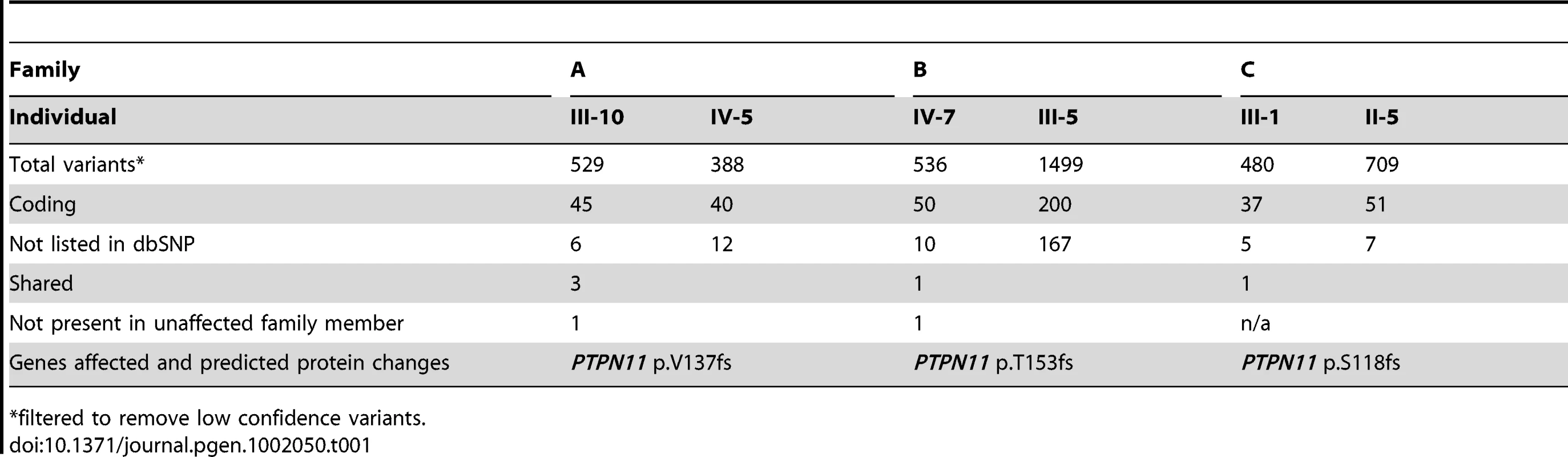

We obtained 50 million, 80 bp, single-end reads. Novobarcode software was used to sort the reads according to their 3 bp barcode, and Novoalign was used to align the reads to the reference genome (hg19). We obtained between 1 and 6 million reads for each individual. Among individuals, an average of 61% (±2%) of the aligned reads mapped to regions targeted by the capture array (Figure S3A). Of the bases targeted by the capture array, 75% (±7%) had a read depth of at least 5×, which diminished to 55% (±14%) after the removal of PCR duplicates (Figure S3B). Twenty percent of targeted bases were not captured. In the 3 families for which pairs of affected family members were sequenced, total filtered variants in the candidate interval (388–1499 per individual) were analyzed to find variants shared by both affected individuals from the same family (Table 1). In all 3 families, frameshift mutations in exon 4 of PTPN11 were the only novel coding variants present in both affected family members and, for Families A and B, absent in the unaffected individual. Family A had a 5 bp deletion, Family B had a more complex deletion/insertion, and Family C had a 2 bp deletion (Table S1). In the remaining 8 families for which only 1 affected individual per family was sequenced, there were 18 novel coding variants present in ≥3 reads, one of which was a nonsense mutation in exon 13 of PTPN11 (p.Q506X) (Figure S4). We used Sanger sequence analysis of PCR amplimers to demonstrate that affected family members from these 4 families had PTPN11 mutations, and that unaffected family members lacked PTPN11 mutations.

Tab. 1. Novel coding variants identified in three metachondromatosis families.

*filtered to remove low confidence variants. Sanger sequence analysis of the 15 coding exons of PTPN11 in the 7 families for whom we had not found mutations by array capture and Illumina-sequencing detected a 1 bp deletion in exon 11 in 1 of the 7 families (Family D). This deletion was within a 98 bp segment that had been targeted but not captured in any of the DNA samples. Another family (F) had a splice-acceptor site mutation (AG>CG) in intron 5 in 2 affected siblings, but not in either parent. The siblings' mother was clinically affected with MC, although less severely than her children. The mother was the first in the family to have MC and was the only member of the family who was included in the Illumina sequencing. The site of the splice-site mutation identified in her children was covered 25× in her DNA sequence and was always wild-type, as were her Sanger sequence results. These data suggest the mother is mosaic for a PTPN11 mutation and that the family's mutation would have been found by Illumina sequencing had we initially sequenced her children's DNA.

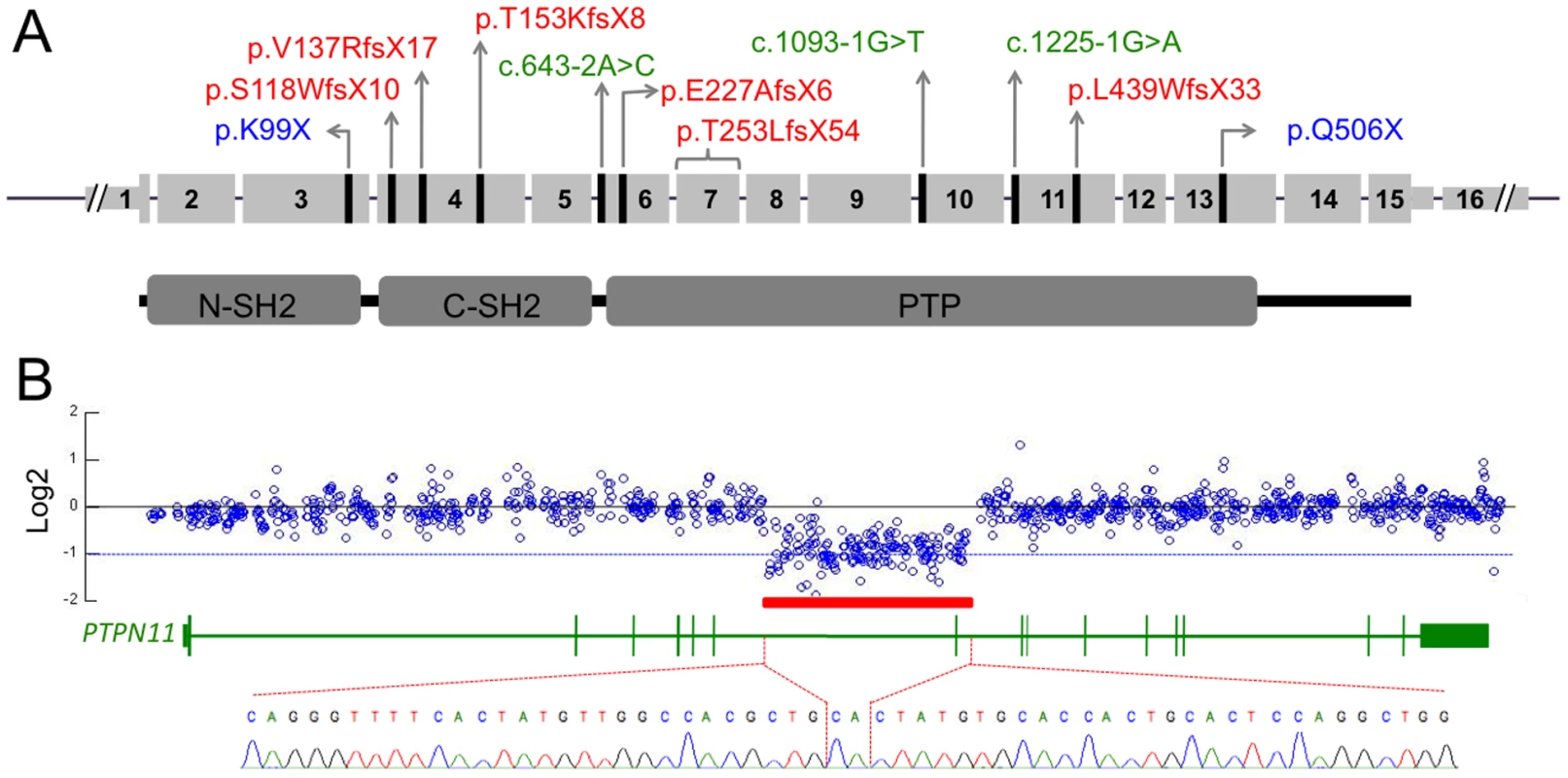

We subsequently collected DNA from an additional 6 MC families. Sanger sequence analysis revealed a nonsense mutation involving exon 3 (p.K99X) in one family (I), and a splice site mutation in intron 9 (c.1093-1G>T) in another family (G). In total, we found PTPN11 mutations in 10 of 17 families. Five mutations were frameshift, 2 were nonsense, and 3 disrupted a splice-acceptor site (Figure 3A, Table S1). Each family had a different mutation and mutations were scattered across the gene (Figure 3A). In two families without mutations we had performed aCGH and did not find evidence of PTPN11 intragenic deletions or duplications (Table S1). We did not have other family members' DNA samples from the one familial MC patient who lacked a PTPN11 mutation to be able to test for locus heterogeneity by linkage analysis.

Fig. 3. PTPN11 mutations identified in MC participants.

(A) Schematic of the exonic structure of PTPN11 (above) and the corresponding protein structure of SHP2 (below). The locations of mutations that were identified in MC are indicated with black lines. Predicted protein changes are indicated for the nonsense (blue) and frameshift (red) mutations, while the cDNA designation is indicated for the splice-site mutations (green). (B) Log2 values of the number of Illumina reads obtained per 50 bp window in participant S, divided by the average number of reads obtained in other participants whose DNA was captured simultaneously using the second capture array. Shown are all 50 bp windows spanning regions of PTPN11 targeted by the array, with the corresponding exonic structure of PTPN11 shown below. The red bar indicates a region spanning exon 7, in which the average log2 value is approximately −1, suggesting a heterozygous deletion. PCR amplification and sequencing of the breakpoint, using primers on either end of the deletion, indicate that 14,629 bp of sequence have been deleted and replaced with a single CA dinucleotide. Multiplexed targeted genomic capture and sequencing of PTPN11 and associated genes

To test whether the patients without PTPN11 coding mutations had noncoding mutations in PTPN11 or had mutations in other genes, we designed a second Agilent 1M capture array. Firstly, we included probes to target the entire PTPN11 gene, excluding Alu repeats. Secondly, we included probes targeting the exons of 74 genes that function in the same pathways as PTPN11, including the Ras/MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways (Table S2). Thirdly, we included probes targeting the exons of the MO genes EXT1 and EXT2, to determine whether any of our patients lacking mutations and classic radiographic features of MC had been misdiagnosed. Barcoded genomic libraries for an individual from each of the 7 MC families without PTPN11 coding mutations and from 2 families originally referred with MC, but whose radiographic features were more consistent with MO, were pooled and hybridized to the capture array. The captured DNA was then sequenced using two lanes of Illumina GAII 42 bp single end sequencing. For each barcoded sample, 4.3 (±1.2) million reads were obtained, of which 37% (±7%) mapped to regions targeted by the array (Figure S3A). Of the bases targeted by the array, 85% (±6%) were covered by a read depth of at least 10×, which dropped to 83% (±8%) after the removal of PCR duplicate reads (Figure S3B).

Identified variants with a quality score >20 were filtered to remove SNPs listed in the SNP database (version 132) and the 1000 genomes project (Nov. 2010 release). No PTPN11 coding mutations were found. We then analyzed the noncoding regions and identified one 3′ UTR mutation, and 7 intronic mutations, of which 6 were in LINE elements or other repetitive regions (Table S3). All intronic mutations were at least 300 bp from the nearest exon and, using an online splice prediction tool (http://genes.mit.edu/GENSCAN.html), were not predicted to alter splicing. We then analyzed variants identified in the exons of the 76 other genes included in the capture array (Table S2). No nonsense, frameshift or splice site mutations were identified. Of the missense mutations that were present in more than 4 independent sequencing reads, 4 were nonsynonomous (ERBB2 p.S1050L, MTOR p.P1408S, MVP p.R49S, SOS2 p.D952N) and 4 were synonomous (PIK3C2B p.D478D, RAF1 p.L351L, MAP2K2 p.D140D, MVP p.T199T). Further experiments will be needed to determine if any of the novel noncoding PTPN11 mutations or novel variants in the other genes are disease causing.

We next analyzed the sequencing read depth across the PTPN11 locus to detect deletions or duplications. In one individual (Patient S), we identified an ∼15 kb region spanning exon 7 that contained half as many reads as would be expected based upon the read depths of the other patients included in the capture array (Figure 3B). As expected, PCR primers that flank this 15 kb region failed to produce amplimers when wild-type genomic DNA was used as template. However, PCR amplification using genomic DNA from Patient S yielded an ∼700 bp PCR product and Sanger sequence analysis of this product indicated that 14,629 bp of genomic sequence (chr12 : 112,897,487–112,912,115) had been replaced with a single CA dinucleotide (Figure 3B). In addition, PCR amplification and sequencing of PTPN11 in peripheral blood cDNA from this patient, using a forward primer in exon 6 and a reverse primer in exon 8, detected a mutant cDNA that lacked exon 7 (data not shown). The loss of exon 7 results in a frameshift with introduction of a premature stop codon (T253LfsX54).

The read depth of the remaining 76 genes targeted by the array was also analyzed to detect deletions or duplications. Two patients initially included in the study, but on radiographic review were felt more likely to have MO than MC, were found to have deletions involving EXT1 (Figure S5). In one patient (Q), the first exon of EXT1 contained half as many reads over its 1.8 kb as expected (Figure S5A). In a second patient (N), all exons of EXT1 had half as many reads as expected (Figure S5A). In additional to skeletal lesions, this patient has developmental delay, microcephaly and mild dysmorphism, suggesting a possible contiguous gene deletion syndrome. EXT1 deletions were confirmed in both patients by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) (Figure S5B, S5C).

PTPN11 loss-of-function mutations in metachondromatosis

Our finding of nonsense, frameshift, and splice-site mutations in multiple exons, as well as a large deletion, suggests that MC-causing PTPN11 alleles are loss-of-function. We tested this hypothesis by performing Western blots on whole protein extracts from white blood cells and from an excised exostotic lesion in a patient (B-IV-7) with a PTPN11 frameshift mutation in exon 4. An anti-SHP2 antibody that recognizes an epitope amino-terminal of the polypeptide encoded by the frameshifted exon detected only full-length, wild-type SHP2 protein (Figure S6).

Loss of PTPN11 wild-type alleles in the cartilage cores of MC exostoses

We next determined whether MC exostoses arise from a “second hit,” similar to what has been observed in autosomal dominant MO [18]. We looked for a second hit in cells of the cartilage core of an MC lesion (e.g., Figure 1K) by performing microdissection, PCR amplifying the mutation containing exon, and Sanger sequencing the amplimers. In tumors from two different patients (A-IV-5, A-IV-8), with a 5 bp frameshift mutation in exon 4, we observed a clear excess of mutant sequence versus wild-type sequence in the tumors' cartilage cores, as compared to the patients' peripheral blood and bone/marrow from the lesion (Figure 4A). We quantified the amount of mutant versus wild-type sequence, by extracting DNA from the cartilage core of patient A-IV-8, PCR amplifying exon 4, and subcloning amplimers to determine the percent that contained the mutant allele. Forty-four of 52 individual subclones contained the mutant allele, which is significantly higher (p<0.001) than expected for a heterozygous mutation. In contrast, 58% of subclones (34/59) from adjacent unaffected bone/bone marrow contained the mutant allele, which is not significantly different from the expected value of 50% (p = 0.24). These data are consistent with an MC exostosis arising from a second hit (loss of the wild-type allele) within a cell that ultimately contributes to the lesion's cartilage core.

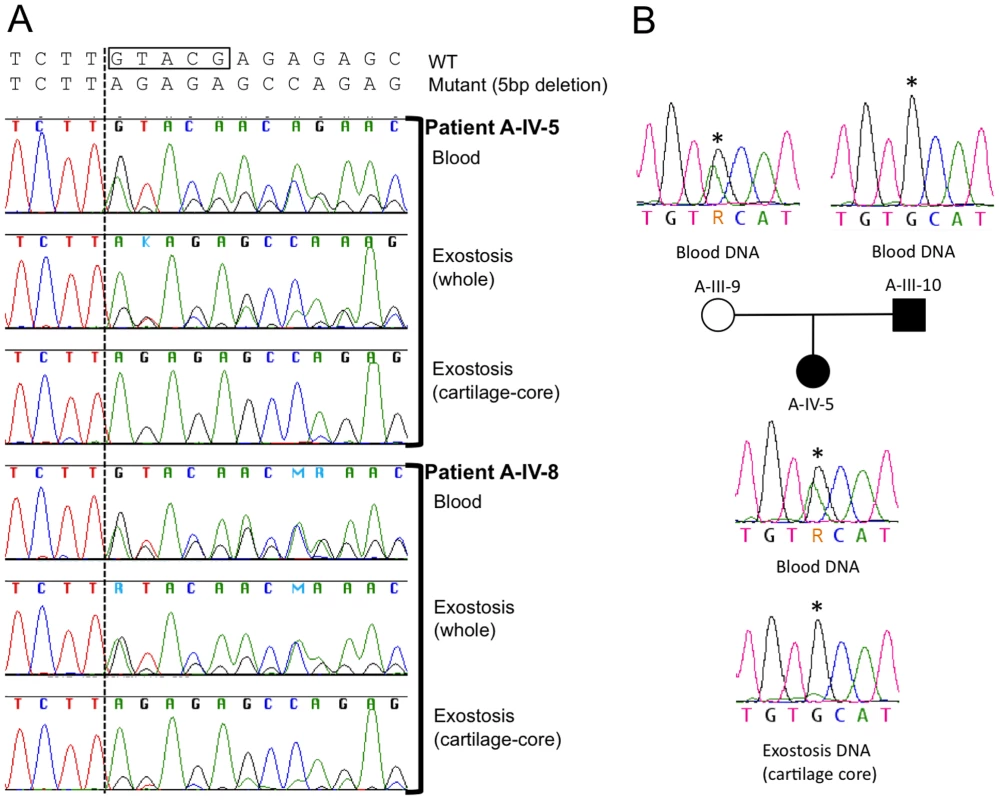

Fig. 4. Loss of the wild-type PTPN11 allele in the cartilage of two exostoses.

(A) Electropherograms of PCR amplified template DNA that had been extracted from whole blood, a section of an exostosis, or the cartilage core of the same exostosis. Exostoses were available from patients A-IV-5 and A-IV-8. The site of the 5 bp deletion in exon 4 of PTPN11 in both patients is indicated with a box. Note that that the heights of the peaks corresponding to the mutant sequence are markedly reduced in amplimers from the cartilage-core compared to amplimers from blood or from a section that contains cartilage, bone and fibrous tissue. This is consistent with loss-of-heterozygosity in the cartilage component of the exostoses. (B) Electropherograms of PCR amplified template DNA extracted from blood from participants A-III-9, A-III-10 and A-IV-5, as well as DNA extracted from the cartilage core of the exostosis from participant A-IV-5 shown in (A). Blood DNA electropherograms indicate that participants A-III-9 and A-IV-10 are heterozygous at a position (asterisk) in intron 11 of PTPN11. This is the site of a known common polymorphism (rs41279092). Exostosis cartilage DNA electropherograms have a reduced adenine peak height at this position. This suggests that the wild-type PTPN11 allele inherited from the unaffected parent (A-III-9), which carries an adenine at this position, has been lost in cells that contribute to formation of the exostosis' cartilage core. Because the mutant allele is 5 bp shorter than wild-type PTPN11 in these two patients, we tested for loss of heterozygosity at a second polymorphic site in PTPN11 to control for potential PCR bias in amplifying the exon with the deletion. In their peripheral blood DNA, patient A-IV-5 and her unaffected mother are heterozygous for a benign polymorphism in intron 11 of PTPN11 (rs41279092). The abundance of this SNP, which is in the wild-type PTPN11 allele, was markedly reduced in the lesion's cartilage core, again consistent with LOH occurring in the cell that drives formation of the cartilage core (Figure 4B).

PTPN11 mutations are not found in other cartilaginous tumor syndromes

We finally asked whether mutations in PTPN11 are associated with other cartilaginous tumor syndromes. We sequenced the coding exons of PTPN11 in 38 lesions excised from patients with Ollier disease, 2 peripheral blood samples from patients with Ollier disease, 15 lesions excised from patients with Maffucci syndrome, 4 solitary enchondromas, 9 chondrosarcomas (1 polyostotic), and 3 osteochondromas without EXT1 or EXT2 mutations. We did not find PTPN11 coding sequence mutations in any patient sample. In 24 percent of the samples we observed heterozygosity for noncoding SNPs that are known common variants, suggesting that large PTPN11 gene deletions and other causes of LOH are not frequently associated with these other cartilaginous tumors.

Discussion

We identified 17 unrelated families with MC. Clinical features were similar to previously published cases [5]–[10], [15]. The exostoses of MC had been assumed to be identical to the osteochondromas of MO; however, we demonstrate that they are histologically unique lesions with a large cartilaginous core (Figure 1J–1L). We combined linkage analysis in a single MC family with DNA capture and parallel sequencing of bar-coded DNAs from several MC families to identify mutations in PTPN11 as a cause of MC. In MC patients without PTPN11 coding sequence and splice site mutations, we generated and pooled barcoded DNAs, and performed a second targeted capture that included the entire PTPN11 gene and exons from 76 other genes. This led us to detect an ∼15 kb deletion in a patient by analyzing the depth of sequencing reads (Figure 3B). In total, we found likely disease-causing PTPN11 mutations in 11 of 17 families.

Concurrent with our studies of MC, Sobreira et al. (2010) reported PTPN11 mutations in 2 MC families [11]. They performed whole-genome sequencing (WGS) in a single affected individual who was a member of family in which MC was segregating. This approach also required these investigators to include linkage data to reduce the number of novel potentially disease-causing heterozygous changes that are identified by WGS [19], [20]. The investigators next identified an independently arising PTPN11 mutation in an unrelated patient to strengthen the evidence for causality. However, having only studied genomic DNA and finding frameshift mutations in the same exon (exon 4) in their two unrelated patients, Sobreira et al. (2010) could not definitively determine the mechanism by which PTPN11 mutations cause MC.

Missense mutations in PTPN11 have previously been identified in patients with Noonan, Noonan-like, and LEOPARD syndromes, as well as in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia [21]. In these disorders, the mutations are gain-of-function and/or dominant negative for SHP2, which is the PTPN11 protein product [22], [23]. SHP2 is a protein tyrosine phosphatase and an important intracellular signaling molecule linking several growth factor receptors to the Ras/MAPK and other signaling pathways (Reviewed in [24]). Therefore, frameshift mutations in exon 4 might also create an abnormal protein product by altering PTPN11 mRNA splicing. Alternatively, the frameshift mutations might result in loss-of-function because of nonsense mediated mRNA decay or rapid degradation of a truncated SHP2 polypeptide. Our finding of nonsense, frameshift, and splice-site mutations in multiple exons, as well as a whole-exon deletion, suggests that MC-causing PTPN11 alleles are loss-of-function. We tested this hypothesis by performing Western blots on whole protein extracts from white blood cells and from an excised lesion containing affected and unaffected tissue, and detected only full-length, wild-type SHP2 protein (Figure S6), confirming that the mutant alleles are loss-of-function.

Exostoses in MO originate from the “second hit” mutations [18]. Mice with conditional alleles at the EXT1 locus demonstrate that only a few cells having two mutant alleles are sufficient to cause other cells to become misdirected and form an exostosis [25]. By performing microdissection, we found evidence for loss of the wild-type PTPN11 alleles in the majority of cells within the cartilage cores of exostoses from two MC patients (Figure 4), consistent with a “second hit.” Recently, Bauler et al. used a ubiquitously expressed Ert2-Cre driver in 6–8 week-old Ptpn11 floxed mice to generate mice that were Ptpn11-null in multiple tissues. Among the consequences of completely deleting SHP2 was the appearance of ectopic cartilage islands in the animals' metaphyseal trabecular bone and growth plates [26]. These findings are consistent with the distribution of endosteal tumors and exostoses seen in patients with MC. The findings in mice with homozygous deletion of Ptpn11 contrast with the absence of skeletal lesions in mice that have heterozygous loss-of-function mutations [27]. We suspect that mice with heterozygous mutations have a much lower incidence of noticeable “second hits” compared to humans because they have fewer skeletal cells and shorter lifespans. Homozygous inactivation of Ptpn11 solely in mouse chondrocytes may be required to enable a detailed understanding of how SHP2 deficiency leads to tumorigenesis.

We did not detect PTPN11 mutations in 6 of 17 patients with MC phenotypes, including 1 patient with a family history of MC and 5 patients who are the first affected members in their families. DNA is not available from other affected family members of the familial case to determine whether MC exhibits locus heterogeneity. Two patients with de novo disease did have DNA variants found in the 3′ UTR and/or in introns. None of these variants are in likely regulatory regions or in regions important for mRNA splicing; however, we cannot conclude they are benign. Furthermore, we cannot exclude the possibility that patients with de novo disease are somatic cell mosaics for PTPN11 mutations that are not present in white blood cell DNA, similar to the mildly affected mother in Family F who had two affected children. Despite these caveats, MC could be locus heterogeneous, similar to Noonan syndrome, which can be caused by mutations in PTPN11 or in other components of the Ras/MAPK pathway [28]; however, our targeted capture and sequencing of 74 genes that included most of the Ras/MAPK and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways did not find an obvious mutation in another gene in any of the 6 PTPN11 mutation-negative MC patients.

We found no evidence of PTPN11 coding mutations in other cartilage tumor syndromes, including Ollier disease and Mafucci syndrome. Although sequencing was performed on lesional tissue rather than whole blood, it is possible that we may have missed causative mutations that are present in only a subset of cells within the lesion. We may also have missed mutations in the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions of PTPN11 contained within exons 1, 15, and 16, that we did not sequence in these patients. Based on our finding heterozygosity for noncoding SNPs in many of these samples, it is unlikely that large PTPN11 gene deletions or other causes of LOH are common in these syndromes. Despite the aforementioned limitations of our mutation detection method, our data are consistent with the separation of MC from the other cartilage tumor syndromes based on clinical and pathologic features.

In conclusion, we combined linkage analysis in a single family with DNA capture and parallel sequencing of bar-coded DNAs from several families to identify mutations in PTPN11 as a cause of MC. The advantages of this approach are its ability to identify a region of interest, then simultaneously sequence affected individuals from multiple unrelated families, and then focus on genes for which novel SNPs or other mutations are seen in more than one family, all at reasonable cost (∼$10,000 in consumables). In patients with MC and PTPN11 mutations, we conclude that the mutations are loss-of-function since the mutant protein is not expressed, and that the loss of the remaining wild-type allele via a “second hit” is responsible for the formation of the exostoses. Since we did not detect PTPN11 mutations in all MC families, MC may be locus heterogeneous, although we have not found evidence after sequencing more than 70 genes that function in related pathways. Finally, precisely how mutations in PTPN11 give rise to the exostoses and endosteal tumors in patients with MC is not yet known. However, this question can now be addressed since mice with alleles of Ptpn11 that can be conditionally inactivated in temporal and site-specific manner are available [26], [29].

Materials and Methods

Ethics

Informed consent was obtained through a Children's Hospital Boston IRB approved protocol. Specimens and/or DNA received from external institutions were collected under IRB approved protocols at host institutions and received coded without identifying information.

Linkage analysis

Raw genotype data were generated for multiple members of family A using Affymetrix 6.0 SNP arrays, and genotypes were called using Affymetrix Genotyping Console with the Birdseed v2 algorithm and a confidence threshold of 0.02. SNPs with <100% sample call rate or pedigree minor allele frequency of 0 were removed, then multipoint parametric linkage analysis of the remaining 421,922 autosomal and 17,169 X-linked SNPs was performed using MERLIN and its derivative MINX, respectively, with Affymetrix Caucasian allele frequencies and deCODE Genetics genetic map positions. The disease allele frequency was estimated at 1E-7, and phenocopies and non-penetrance were not permitted (affectation probability 0/1/1). Because non-penetrance and non-ascertainment are potential confounding factors in MC, we analyzed only founders and affected individuals.

Barcoded genomic libraries

To generate genomic libraries for each individual, 2 µg of genomic DNA were first sheared to ∼100 bp–200 bp using Adaptive Focused Acoustics following the manufacturer's protocol (Covaris, Inc). Blunt-ended fragments were generated using an End-it DNA End-Repair kit (Epicenter), purified using Agencourt AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter), and eluted in 10 mM Tris Acetate, pH 8.0. The fragments were A-tailed using the Klenow fragment (NEB), purified, eluted in 1× Quick Ligase Buffer (Quick Ligation kit, NEB), and incubated with Quick T4 DNA ligase and 100 µM barcoded-adapters (Table S4) to create a library of adapter-ligated fragments. A different barcoded adapter was used for each genomic DNA library. Each library was again purified using Agencourt AMPure XP magnetic beads and eluted in 40 µl of 10 mM Tris Acetate, pH 8.0. Libraries used for hybridization to the first capture array were amplified according to two strategies: 3 µl amplified for 18 cycles in four 50 µl PCR reactions (Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase, Finnzymes), or 2 µl amplified for 11 cycles in one 50 µl PCR reaction that was then purified and amplified for 17 cycles in ten 50 µl PCR reactions (FastStart Taq DNA polymerase, Roche). For the libraries used for hybridization to the second capture array, 13 µl was amplified for 15 cycles in ten 50 µl PCR reactions (Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase, Finnzymes). Primers are provided in Table S5. Sizes of amplified libraries were confirmed to be between 200–300 bp necessary for Illumina GA II sequencing prior to hybridization (Figure S2).

Capture array design

To enrich regions of interest in the linked interval for sequencing, we used an Agilent Technologies 1M SureSelect DNA capture array. Target regions were defined using the UCSC Genome Browser and included: the union of exons from multiple GRCh37/hg19 gene, mRNA, and Alt Events tracks; 30 bp of proximal and distal intronic flanking sequence; and 1000 bp of upstream promoter sequence. Targets were padded with 60 bp of additional proximal and distal flanking sequence to promote uniform capture coverage, for a total size of 1,187,477 bp. Probes were designed against NCBI36/hg18 using the Agilent eArray software (https://earray.chem.agilent.com/earray/) and translated coordinates, with 60-nt length, 3-nt spacing, and repetitive elements masked. The resulting 243,488 probes spanned 844,339 bp (GRCh37/hg19), and included 71.1%, 72.2%, 88.4%, and 98.6% of the padded target, unpadded target, UCSC exons, and CCDS coding sequence, respectively. The probes and their reverse complements were each applied in duplicate to the capture array for a total of 973,952 probes.

For the second 1M SureSelect DNA capture array, Biomart (http://uswest.ensembl.org/biomart/) was used to obtain the Ensembl NCBI37/hg19 coordinates for the exons of 76 genes (Table S2). Exons were padded with 90 bp to define a 718,566 bp target region. eArray was used to design 568,634 probes to target the repeat masked sequences of this region (91%). The target region for PTPN11 was defined as 93,180 bp spanning 1 kb upstream to 2 kb downstream of the gene. Repeat masker (http://www.repeatmasker.org/) was used to mask only Alu repeats (37% of the region) resulting in a target region of 61,365 bp, for which 55,205 probes were designed using eArray. All probes were 60-nt in length and spaced every 1-nt. The capture array was designed to include all probes (623,839 total), as well as the reverse complement of every 2nd probe and every 17th probe, for a total of 972,455 probes.

Array hybridization

For the first capture array, 1.4 µg of each of the 16 amplified libraries was pooled and hybridized to the array following Agilent's SureSelect DNA Capture Array protocol version 1.0. Different blocking oligonucleotides (Table S5) were added to the hybridization. After elution from the array, half of the captured library was amplified in five 50 µl PCR reactions for 18 cycles using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) and post-capture primer pair (Table S5), purified using an E-Gel CloneWell (Invitrogen) to remove primer dimers, and re-amplified using fifteen PCR cycles with the same primer pair. The amplified library was again purified to eliminate primer dimers using E-Gel. For the second capture array, 2 µg of each of the 12 amplified libraries was pooled and hybridized to the array. After elution, half of the captured library was amplified in five 50 µl PCR reactions for 15 cycles and purified using Agencourt AMPure XP magnetic beads. Further details of the array design and methods for sequence analysis are provided in the supporting information. Additional methods for Illumina data analysis, copy number analysis, Sanger sequence analysis of PTPN11 (Table S6), DNA extraction from lesional tissue, PCR product subcloning experiments, aCGH analysis, MLPA (Table S7), and immunodetection of SHP2 are also provided in the supporting information (Text S1).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. BovéeJVMG 2008 Multiple osteochondromas. Orphanet journal of rare diseases 3 3

2. CouvineauAWoutersVBertrandGRouyerCGérardB 2008 PTHR1 mutations associated with Ollier disease result in receptor loss of function. Hum Mol Genet 17 2766 2775

3. PansuriyaTCKroonHMBovéeJVMG 2010 Enchondromatosis: insights on the different subtypes. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 3 557 569

4. SilveCJüppnerH 2006 Ollier disease. Orphanet journal of rare diseases 1 37

5. MaroteauxP 1971 [Metachondromatosis]. Z Kinderheilkd 109 246 261

6. KennedyLA 1983 Metachondromatosis. Radiology 148 117 118

7. BassettGSCowellHR 1985 Metachondromatosis. Report of four cases. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume 67 811 814

8. IkegawaSNaganoAMatsushitaTNakamuraK 1992 Metachondromatosis: a report of two cases in a family. Nippon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi 66 460 466

9. HermanTEChinesAMcAlisterWHGottesmanGSEddyMC 1997 Metachondromatosis: report of a family with facial features mildly resembling trichorhinophalangeal syndromePediatr Radiol 1997 Nov;27(11):864. Pediatric radiology 27 436 441

10. BovéeJVMGHameetmanLKroonHMAignerTHogendoornPCW 2006 EXT-related pathways are not involved in the pathogenesis of dysplasia epiphysealis hemimelica and metachondromatosis. J Pathol 209 411 419

11. SobreiraNLMCirulliETAvramopoulosDWohlerEOswaldGL 2010 Whole-genome sequencing of a single proband together with linkage analysis identifies a Mendelian disease gene. PLoS Genet 6 e1000991 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000991

12. ShawBA 1996 Resolving neonatal osteochondroma: a case report and literature review. Am J Orthop 25 226 228

13. KeretDBassettGS 1990 Avascular necrosis of the capital femoral epiphysis in metachondromatosis. Journal of pediatric orthopedics 10 658 661

14. WengerDRBirchJRathjenKTobinRBillmanG 1991 Metachondromatosis and avascular necrosis of the femoral head: a radiographic and histologic correlation. Journal of pediatric orthopedics 11 294 300

15. HunterAGKozlowskiKHochbergerO 1995 Metachondromatosis. Can Assoc Radiol J 46 202 208

16. MavrogenisAFSkarpidiEPapakonstantinouOPapagelopoulosPJ 2010 Chondrosarcoma in metachondromatosis: a case report. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume 92 1507 1513

17. AbecasisGRChernySSCooksonWOCardonLR 2002 Merlin–rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat Genet 30 97 101

18. BovéeJVCleton-JansenAMWuytsWCaethovenGTaminiauAH 1999 EXT-mutation analysis and loss of heterozygosity in sporadic and hereditary osteochondromas and secondary chondrosarcomas. Am J Hum Genet 65 689 698

19. LupskiJRReidJGGonzaga-JaureguiCRio DeirosDChenDCY 2010 Whole-genome sequencing in a patient with Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. N Engl J Med 362 1181 1191

20. RoachJCGlusmanGSmitAFAHuffCDHubleyR 2010 Analysis of genetic inheritance in a family quartet by whole-genome sequencing. Science 328 636 639

21. JorgeAALMalaquiasACArnholdIJPMendoncaBB 2009 Noonan syndrome and related disorders: a review of clinical features and mutations in genes of the RAS/MAPK pathway. Horm Res 71 185 193

22. KontaridisMISwansonKDDavidFSBarfordDNeelBG 2006 PTPN11 (Shp2) mutations in LEOPARD syndrome have dominant negative, not activating, effects. J Biol Chem 281 6785 6792

23. TartagliaMZampinoGGelbBD 2010 Noonan syndrome: clinical aspects and molecular pathogenesis. Mol Syndromol 1 2 26

24. GrossmannKSRosárioMBirchmeierCBirchmeierW 2010 The tyrosine phosphatase Shp2 in development and cancer. Adv Cancer Res 106 53 89

25. JonesKBPiomboVSearbyCKurrigerGYangB 2010 A mouse model of osteochondromagenesis from clonal inactivation of Ext1 in chondrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA

26. BaulerTJKamiyaNLapinskiPELangewischEMishinaY 2010 Development of severe skeletal defects in induced SHP-2-deficient adult mice: a model of skeletal malformation in humans with SHP-2 mutations. Dis Model Mech

27. SaxtonTMHenkemeyerMGascaSShenRRossiDJ 1997 Abnormal mesoderm patterning in mouse embryos mutant for the SH2 tyrosine phosphatase Shp-2. EMBO J 16 2352 2364

28. DenayerEDevriendtKde RavelTVan BuggenhoutGSmeetsE 2010 Tumor spectrum in children with Noonan syndrome and SOS1 or RAF1 mutations. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 49 242 252

29. GrossmannKSWendeHPaulFECheretCGarrattAN 2009 The tyrosine phosphatase Shp2 (PTPN11) directs Neuregulin-1/ErbB signaling throughout Schwann cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106 16704 16709

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Incorporating Biological Pathways via a Markov Random Field Model in Genome-Wide Association StudiesČlánek Survival Motor Neuron Protein Regulates Stem Cell Division, Proliferation, and Differentiation in

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 4- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Is Co-Expressed with Closely Adjacent Uncharacterised Genes Spanning a Breast Cancer Susceptibility Locus at 6q25.1

- The Liberation of Embryonic Stem Cells

- Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis Identifies Regions on 7p21 () and 15q24 () As Determinants of Habitual Caffeine Consumption

- A Sustained Dietary Change Increases Epigenetic Variation in Isogenic Mice

- The Exocyst Protein Sec10 Interacts with Polycystin-2 and Knockdown Causes PKD-Phenotypes

- Incorporating Biological Pathways via a Markov Random Field Model in Genome-Wide Association Studies

- Survival Motor Neuron Protein Regulates Stem Cell Division, Proliferation, and Differentiation in

- Identification and Functional Validation of the Novel Antimalarial Resistance Locus in

- Does Positive Selection Drive Transcription Factor Binding Site Turnover? A Test with Drosophila Cis-Regulatory Modules

- Protein Phosphatase 2A Controls Ethylene Biosynthesis by Differentially Regulating the Turnover of ACC Synthase Isoforms

- Ribosomal DNA Deletions Modulate Genome-Wide Gene Expression: “–Sensitive” Genes and Natural Variation

- Reciprocal Sign Epistasis between Frequently Experimentally Evolved Adaptive Mutations Causes a Rugged Fitness Landscape

- Variable Pathogenicity Determines Individual Lifespan in

- Evolution of Vertebrate Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 3 Channels: Opposite Temperature Sensitivity between Mammals and Western Clawed Frogs

- Towards Establishment of a Rice Stress Response Interactome

- Mouse Genome-Wide Association and Systems Genetics Identify As a Regulator of Bone Mineral Density and Osteoclastogenesis

- Quantitative Fitness Analysis Shows That NMD Proteins and Many Other Protein Complexes Suppress or Enhance Distinct Telomere Cap Defects

- Highly Precise and Developmentally Programmed Genome Assembly in Requires Ligase IV–Dependent End Joining

- PDP-1 Links the TGF-β and IIS Pathways to Regulate Longevity, Development, and Metabolism

- Genome-Wide Association Study Using Extreme Truncate Selection Identifies Novel Genes Affecting Bone Mineral Density and Fracture Risk

- Eight Common Genetic Variants Associated with Serum DHEAS Levels Suggest a Key Role in Ageing Mechanisms

- 14-3-3 Proteins Regulate Exonuclease 1–Dependent Processing of Stalled Replication Forks

- HDA6 Regulates Locus-Directed Heterochromatin Silencing in Cooperation with MET1

- Epigenetic Regulation of Cell Type–Specific Expression Patterns in the Human Mammary Epithelium

- Enhanced Statistical Tests for GWAS in Admixed Populations: Assessment using African Americans from CARe and a Breast Cancer Consortium

- Beyond Missing Heritability: Prediction of Complex Traits

- An Evolutionary Genomic Approach to Identify Genes Involved in Human Birth Timing

- Long-Lost Relative Claims Orphan Gene: in a Wasp

- PTG Depletion Removes Lafora Bodies and Rescues the Fatal Epilepsy of Lafora Disease

- Chromatin Organization in Sperm May Be the Major Functional Consequence of Base Composition Variation in the Human Genome

- GWAS of Follicular Lymphoma Reveals Allelic Heterogeneity at 6p21.32 and Suggests Shared Genetic Susceptibility with Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma

- Loss-of-Function Mutations in Cause Metachondromatosis, but Not Ollier Disease or Maffucci Syndrome

- DNA Damage, Somatic Aneuploidy, and Malignant Sarcoma Susceptibility in Muscular Dystrophies

- The Phylogenetic Origin of Coincided with the Origin of Maternally Provisioned Germ Plasm and Pole Cells at the Base of the Holometabola

- Genome Analysis Reveals Interplay between 5′UTR Introns and Nuclear mRNA Export for Secretory and Mitochondrial Genes

- Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Soluble ICAM-1 Concentration Reveals Novel Associations at the , , , and Loci

- The Complete Spectrum of Yeast Chromosome Instability Genes Identifies Candidate CIN Cancer Genes and Functional Roles for ASTRA Complex Components

- Dynamic Regulation of H3K27 Trimethylation during Differentiation

- Phosphorylation-Dependent Differential Regulation of Plant Growth, Cell Death, and Innate Immunity by the Regulatory Receptor-Like Kinase BAK1

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- PTG Depletion Removes Lafora Bodies and Rescues the Fatal Epilepsy of Lafora Disease

- Evolution of Vertebrate Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 3 Channels: Opposite Temperature Sensitivity between Mammals and Western Clawed Frogs

- Survival Motor Neuron Protein Regulates Stem Cell Division, Proliferation, and Differentiation in

- An Evolutionary Genomic Approach to Identify Genes Involved in Human Birth Timing

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání