-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Enterohemorrhagic Hemolysin Employs Outer Membrane Vesicles to Target Mitochondria and Cause Endothelial and Epithelial Apoptosis

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) strains cause diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome resulting from toxin-mediated microvascular endothelial injury. EHEC hemolysin (EHEC-Hly), a member of the RTX (repeats-in-toxin) family, is an EHEC virulence factor of increasingly recognized importance. The toxin exists as free EHEC-Hly and as EHEC-Hly associated with outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) released by EHEC during growth. Whereas the free toxin is lytic towards human endothelium, the biological effects of the OMV-associated EHEC-Hly on microvascular endothelial and intestinal epithelial cells, which are the major targets during EHEC infection, are unknown. Using microscopic, biochemical, flow cytometry and functional analyses of human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMEC) and Caco-2 cells we demonstrate that OMV-associated EHEC-Hly does not lyse the target cells but triggers their apoptosis. The OMV-associated toxin is internalized by HBMEC and Caco-2 cells via dynamin-dependent endocytosis of OMVs and trafficked with OMVs into endo-lysosomal compartments. Upon endosome acidification and subsequent pH drop, EHEC-Hly is separated from OMVs, escapes from the lysosomes, most probably via its pore-forming activity, and targets mitochondria. This results in decrease of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential and translocation of cytochrome c to the cytosol, indicating EHEC-Hly-mediated permeabilization of the mitochondrial membranes. Subsequent activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 leads to apoptotic cell death as evidenced by DNA fragmentation and chromatin condensation in the intoxicated cells. The ability of OMV-associated EHEC-Hly to trigger the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in human microvascular endothelial and intestinal epithelial cells indicates a novel mechanism of EHEC-Hly involvement in the pathogenesis of EHEC diseases. The OMV-mediated intracellular delivery represents a newly recognized mechanism for a bacterial toxin to enter host cells in order to target mitochondria.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 9(12): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003797

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003797Summary

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) strains cause diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome resulting from toxin-mediated microvascular endothelial injury. EHEC hemolysin (EHEC-Hly), a member of the RTX (repeats-in-toxin) family, is an EHEC virulence factor of increasingly recognized importance. The toxin exists as free EHEC-Hly and as EHEC-Hly associated with outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) released by EHEC during growth. Whereas the free toxin is lytic towards human endothelium, the biological effects of the OMV-associated EHEC-Hly on microvascular endothelial and intestinal epithelial cells, which are the major targets during EHEC infection, are unknown. Using microscopic, biochemical, flow cytometry and functional analyses of human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMEC) and Caco-2 cells we demonstrate that OMV-associated EHEC-Hly does not lyse the target cells but triggers their apoptosis. The OMV-associated toxin is internalized by HBMEC and Caco-2 cells via dynamin-dependent endocytosis of OMVs and trafficked with OMVs into endo-lysosomal compartments. Upon endosome acidification and subsequent pH drop, EHEC-Hly is separated from OMVs, escapes from the lysosomes, most probably via its pore-forming activity, and targets mitochondria. This results in decrease of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential and translocation of cytochrome c to the cytosol, indicating EHEC-Hly-mediated permeabilization of the mitochondrial membranes. Subsequent activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 leads to apoptotic cell death as evidenced by DNA fragmentation and chromatin condensation in the intoxicated cells. The ability of OMV-associated EHEC-Hly to trigger the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in human microvascular endothelial and intestinal epithelial cells indicates a novel mechanism of EHEC-Hly involvement in the pathogenesis of EHEC diseases. The OMV-mediated intracellular delivery represents a newly recognized mechanism for a bacterial toxin to enter host cells in order to target mitochondria.

Introduction

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) are global causes of diarrhea and its severe extra-intestinal complication, hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) [1]. HUS, the most common cause of acute renal failure in children, is a thrombotic microangiopathy resulting from microvascular endothelial injury in the kidneys and the brain [1]. EHEC produce a spectrum of virulence factors, which plausibly play a role in the pathogenesis of HUS. In addition to Shiga toxins (Stx), which are the major EHEC virulence factors involved in the microvascular endothelial injury [1], [2], several other EHEC toxins can trigger or contribute to this pathology [3]-[6]. The importance of the contribution of EHEC hemolysin (EHEC-Hly) [7], also designated EHEC toxin (Ehx) [8] is increasingly recognized [6], [9].

EHEC-Hly is a 107 kDa pore-forming cytolysin, which belongs to the RTX (repeats-in-toxin) family [7], [8], [10]. The toxin and its activation and secretion machinery are encoded by the EHEC-hlyCABD operon, in which EHEC-hlyA is the structural gene for EHEC-Hly. The EHEC-hlyC product mediates posttranslational activation of EHEC-Hly, and the EHEC-hlyB - and EHEC-hlyD-encoded proteins transport EHEC-Hly out of the bacterial cell [7], [11], [12]. The contribution of EHEC-Hly to the pathogenesis of HUS is supported by the ability of the toxin to injure microvascular endothelial cells [6]. Moreover, the pro-inflammatory potential of EHEC-Hly [9], its production by the vast majority of EHEC strains associated with HUS [13], [14], and expression of the toxin during infection as demonstrated by the development of anti-EHEC-Hly antibodies in most HUS patients [7] and by increased EHEC-hlyA transcription levels in patients' stools [15] offer additional support of the role of EHEC-Hly in the pathogenesis of human diseases.

By investigating the status of EHEC-Hly in bacterial supernatants, we identified two forms of the toxin: a free, soluble EHEC-Hly, and an EHEC-Hly associated with outer membrane vesicles (OMVs), which are released by EHEC bacteria during growth [16]. Similar to the free toxin, the OMV-associated EHEC-Hly binds to human erythrocytes and causes hemolysis. The association with OMVs significantly increases the stability of the toxin and thus prolongs its hemolytic activity compared to the free, soluble form [16] indicating that the OMV-associated EHEC-Hly is a biologically efficient form of the toxin.

The free EHEC-Hly lyses human microvascular endothelial cells [6], most likely via pore formation in the cell membranes as was demonstrated for this toxin form using artificial lipid bilayers [10]. However, the biological consequences of interactions of OMV-associated EHEC-Hly with human microvascular endothelial cells, a major site of injury during HUS, and intestinal epithelial cells, the first barrier encountered by EHEC during infection, are unknown. Therefore, we investigated EHEC-Hly-harboring OMVs for their ability to bind to these cells, to deliver the toxin intracellularly and to trigger cell injury. Additionally, we determined intracellular trafficking of the toxin and of OMVs and the mechanism resulting in cell injury. We demonstrate that OMV-associated EHEC-Hly is internalized by the host cells via the OMVs, but separates from its carriers and subsequently targets mitochondria, triggering apoptosis via the intrinsic caspase-9-dependent pathway.

Results

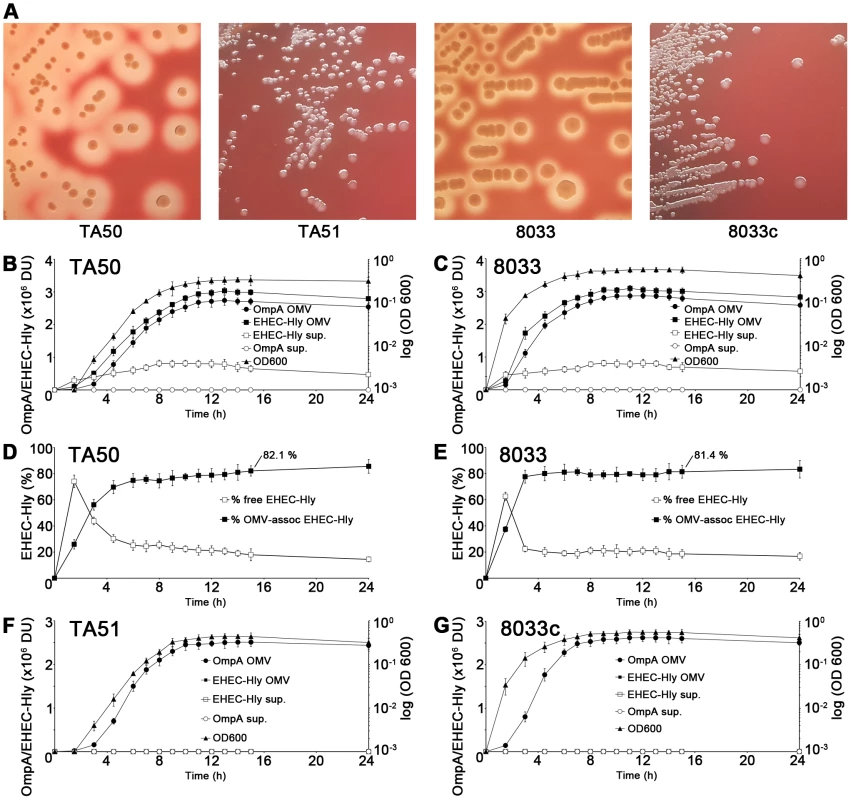

EHEC-Hly rapidly binds to OMVs in growing bacterial cultures

EHEC-Hly is secreted from bacterial cells via type 1 secretion system [8], independently of OMVs, and rapidly binds to OMVs due to its high affinity to these structures [16]. To determine the kinetics of EHEC-Hly secretion, OMV production and EHEC-Hly-OMV association in strains TA50 (E. coli K-12 MC1061 harboring EHEC-hlyCABD operon from E. coli O26:H11) and 8033 (E. coli O103:H2 patient isolate) that both produce biologically active EHEC-Hly (Figure 1A), the strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. At defined time intervals OMVs were collected by ultracentrifugation and the OMV fractions (pellets) and resulting supernatants were analyzed for the presence of OMVs and EHEC-Hly using immunoblotting with antibodies against outer membrane protein OmpA (a common component of OMVs of Gram-negative bacteria [17]-[19]) and EHEC-Hly, respectively, followed by densitomeric quantification of the signals. In both strains, the OmpA and EHEC-Hly signals in OMV fractions increased in parallel with bacterial growth, most rapidly during logarithmic phase; in contrast, EHEC-Hly signals in OMV-free supernatants (free EHEC-Hly) remained low throughout the 24 h incubation period (Figure 1B, 1C). This indicated that EHEC-Hly secreted by strains TA50 and 8033 rapidly binds to OMVs released by growing bacteria. The percentage of OMV-associated EHEC-Hly (from the total amount of the toxin present at each time) progressively increased up to 4.5 h of incubation in strain TA50 (72% of total EHEC-Hly OMV-associated) and up to 3 h of incubation in strain 8033 (78% of total EHEC-Hly OMV-associated), and then remained relatively unchanged until 24 h (Figure 1D, 1E). In 15 h cultures of strains TA50 and 8033, from which OMVs used in this study were isolated, 82.1% and 81.4%, respectively, of the total EHEC-Hly was associated with OMVs (Figure 1D, 1E). Quantitative analyses of these OMVs revealed that they contained 3.03±0.8 µg (TA50) and 3.01±0.6 µg (8033) of EHEC-Hly per ml of OMV preparation, corresponding to 5.1±1.2 µg and 4.9±1.1 µg, respectively, of EHEC-Hly per mg of total OMV protein (Figure S1A). Altogether, these experiments demonstrated that the majority of EHEC-Hly secreted by strains TA50 and 8033 rapidly binds to OMVs and that the OMV-associated EHEC-Hly is thus the major form of the toxin in these strains. OMVs, but not EHEC-Hly were present in OMV fractions prepared from control non-hemolytic (Figure 1A) strains TA51 (TA50 vector control) and 8033c (EHEC-hlyA-negative derivative of 8033), and none of these strains produced free EHEC-Hly (Figure 1F, 1G).

Fig. 1. Hemolytic phenotypes and kinetics of EHEC-Hly secretion, OMV production and EHEC-Hly-OMV association in strains used in this study.

(A) Strains were grown on enterohemolysin agar for 24 h at 37°C and the plates were examined for hemolysis. Colonies of EHEC-Hly-producing strains TA50 and 8033 are surrounded by zones of hemolysis, whereas no hemolysis is present around colonies of EHEC-Hly-negative strains TA51 and 8033c. The relative contribution of free and OMV-associated EHEC-Hly to hemolysis observed on enterohemolysin agar is unknown. (B, C, F, G) EHEC-Hly-producing strains TA50 (B) and 8033 (C) and EHEC-Hly-negative strains TA51 (F) and 8033c (G) were grown in 1 l of LB broth for 24 h. At each time point of 1.5 h, 3 h, 4.5 h, 6 h to 15 h, and 24 h a 50 ml aliquot of each culture was collected, bacteria were removed by centrifugation and supernatants were sterile filtered. OMVs were pelleted from the filtered supernatants by ultracentrifugation and proteins from supernatants after ultracentrifugation were precipitated with 10% TCA. After resuspending in 100 µl of 20 mM TRIS-HCl, aliquots (9 µl) of the OMV fractions and TCA-precipitated supernatants were separated by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted with anti-EHEC-Hly or anti-OmpA antibody, and signals were quantified densitometrically and expressed in arbitrary densitometric units (DU). Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the optical density of the cultures at 600 nm (OD600) at each time. (D, E) The percentage of EHEC-Hly associated with OMVs in strains TA50 (D) and 8033 (E) at each time interval was calculated as the percentage of the densitometric signal of OMV-associated EHEC-Hly from the total EHEC-Hly signal (i.e. the sum of OMV-associated and free EHEC-Hly signals). Data in panels B-G are expressed as means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. Characterization of EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs

To determine whether or not EHEC-Hly is tightly associated with TA50 and 8033 OMVs, we first performed density gradient fractionation of the OMV preparations and analyzed the fractions for the presence of OmpA and EHEC-Hly using immunoblotting. EHEC-Hly was detected in the same OMV density gradient fractions, which also contain OmpA (Figure S1B), suggesting its tight association with OMVs. To confirm this observation, TA50 and 8033 OMVs were subjected to a dissociation assay (see Materials and Methods). Treatment of the OMVs with salt (1 M NaCl), alkali (0.1 M Na2CO3) or chaotropic reagent (0.8 M urea) did not release EHEC-Hly from OMVs, as demonstrated by the toxin recovery in OMV pellets after ultracentrifugation (Figure S1C). In contrast, exposure of the OMVs to 1% SDS, which totally disrupts membranes, released EHEC-Hly from the pellet to the supernatant (Figure S1C). These experiments demonstrated that EHEC-Hly is tightly associated with TA50 and 8033 OMVs.

To gain insight into biochemical composition of EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs, we characterized OMVs from strains TA50 and 8033 for the presence of the outer membrane, periplasmic, inner membrane and cytoplasmic components of bacterial cells, as well as for DNA. Immunoblot analyses using antibodies against marker proteins of the respective compartments demonstrated that OMVs from each strain contain the outer membrane and periplasmic proteins, but not proteins of the inner membrane and the cytoplasm (Figure S1D). Presence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of the bacterial outer membrane as a component of TA50 and 8033 OMV membrane was shown using electron microscopy and immunogold staining with antibodies against the respective bacterial LPSs (Figure 2A, 2D). Analysis of OMVs for DNA using Pico green assay revealed DNA in intact OMVs, both untreated and DNase-treated, and in OMVs that were lysed after the DNase treatment (Table S1). This suggests that the DNA is located inside OMVs where it is protected against DNase degradation. No evidence of EHEC-Hly-encoding gene (EHEC-hlyA) was found in OMV-associated DNA using PCR (Table S1). The nature of this DNA is yet unknown.

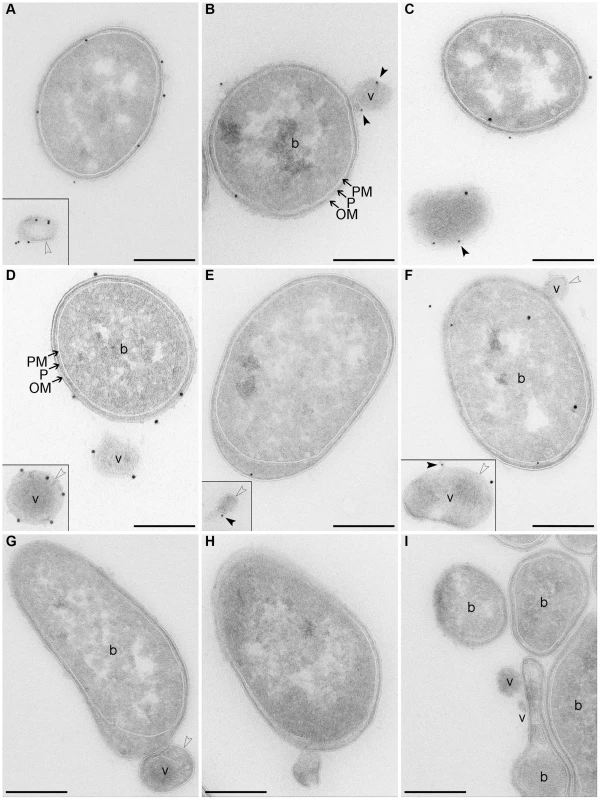

Fig. 2. Electron microscopy of OMV-producing bacterial cultures.

(A–F) Immunogold staining of ultrathin frozen sections of overnight LB agar cultures of strains TA50 (A–C) and 8033 (D–F) using anti-E. coli LPS antibody (recognizing all E. coli LPS types) (A) or anti-O103 LPS antibody (D), anti-EHEC-Hly antibody (B, E), or anti-EHEC-Hly antibody and either anti-E. coli LPS antibody (C) or anti-O103 LPS antibody (F); primary antibodies were detected using Protein A Gold with gold particles of 15 nm (anti-LPS antibodies) or 10 nm diameter (anti-EHEC-Hly antibody). (G, H) Ultrathin frozen sections of TA50 (G) and 8033 (H) overnight LB agar cultures stained with Protein A Gold alone, without anti-LPS (G) or anti-EHEC-Hly (H) antibody. (I) Ultrathin frozen section of overnight LB agar culture of EHEC-Hly-negative strain TA51 stained with anti-EHEC-Hly antibody and Protein A Gold with gold particles of 10 nm. Samples were analyzed using a FEI-Tecnai 12 electron microscope. Examples of bacterial cells (b) and OMVs (v) are indicated. Black frames delineate OMVs that were located at longer distances from the OMV-producing bacteria and, therefore, were detected in different microscopic fields. Arrows indicate bacterial outer membrane (OM), periplasmic space (P), and plasma (inner) membrane (PM). Empty arrow heads depict a membrane bilayer surrounding OMVs and black arrow heads depict EHEC-Hly located on OMV surface. Scale bars are 300 nm. Note that using electron microscopy of immunostained ultrathin cryo-sections only 10% - 15% of the total antigen present in the section can be detected [76] explaining relatively low numbers of LPS and EHEC-Hly signals observed. Electron microscopy of ultrathin cryo-sections of TA50 and 8033 LB agar cultures demonstrated blebbing of OMVs from the surface of growing bacteria (Figure 2B, 2F–2H) as well as free OMVs that had already been released from bacterial cells (Figure 2A, 2C–2F). The OMVs are surrounded with a membrane bilayer (Figure 2A, 2D–2H), which - like the bacterial outer membrane - immunoreacts with an antibody against the respective bacterial LPS (Figure 2A, 2D) indicating that the OMV membrane has been derived from the bacterial outer membrane. Staining with anti-EHEC-Hly antibody visualized the toxin on the surface of budding or already released OMVs (Figure 2B, 2E). Double staining with anti-EHEC-Hly and anti-LPS antibodies confirmed an association of the toxin with the OMV membrane (Figure 2C, 2F). No immunogold signals were present in sections of TA50 and 8033 cultures stained only with Protein A Gold in the absence of anti-LPS (Figure 2G) or anti-EHEC-Hly (Figure 2H) antibody, and no EHEC-Hly signals were found in a section of LB agar culture of non-hemolytic strain TA51 stained with anti-EHEC-Hly antibody and Protein A Gold (Figure 2I) demonstrating the specificity of the immunogold staining.

EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs cause hemolysis but fail to lyse human microvascular endothelial and intestinal epithelial cells

Biological activity of OMV-associated EHEC-Hly was verified by the ability of TA50 and 8033 OMVs to cause hemolysis. The hemolysis appeared after 20 h of incubation and steadily increased up to 32 to 36 h, when it reached a plateau (Figure S1E). However, the TA50 and 8033 OMVs used in the hemolytic dose (300 ng of OMV-associated EHEC-Hly) did not lyse human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMEC) and intestinal epithelial cells (Caco-2) even after 48 h of incubation as no release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) could be observed (Figure S1E). The lack of the lytic potential of OMV-associated EHEC-Hly towards HBMEC and Caco-2 cells prompted us to investigate other effects of the OMV-associated toxin on these cells.

EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs bind to and are internalized by HBMEC and Caco-2 cells

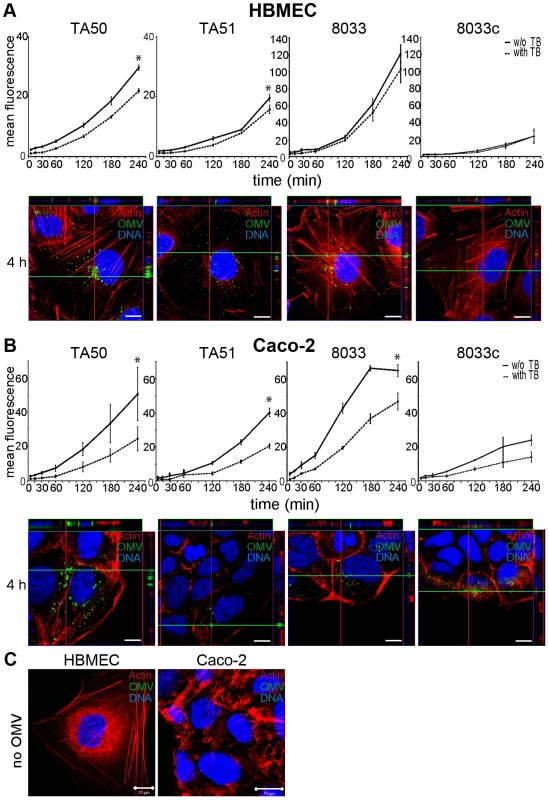

To determine if EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs associate with HBMEC and Caco-2 cells, the cells were incubated with OMVs labeled with the fluorescent membrane dye 3,3 dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine perchlorate (DiO) and the kinetics of OMV uptake was monitored using flow cytometry (Figure 3A, 3B). To distinguish internalized from cell-bound but non-internalized OMVs, extracellular DiO-OMV fluorescence was quenched with trypan blue. DiO-labeled TA50 and 8033 OMVs bound to each cell line within 5 min of incubation, and the OMV-cell associations steadily increased up to 3 to 4 h (Figures 3A, 3B). The proportions of trypan blue non-quenched TA50 and 8033 OMVs also steadily increased during time (Figure 3A, 3B) and reached 73.6% and 84.4% in HBMEC and 48.1% and 72% in Caco-2 cells, respectively, after 4 h (Table S2). This indicated that large parts of OMVs were internalized after 4 h, even though the proportions of internalized OMVs were, in particular in Caco-2 cells, significantly lower than those of cell-bound OMVs (Figure 3A, 3B). EHEC-Hly-free DiO-labeled OMVs TA51 and 8033c also bound to cellular membranes and were internalized by each cell line in a time-dependent manner, but their cell associations were less than those of the respective EHEC-Hly-harboring OMVs (Figure 3A, 3B). To confirm the OMV internalization, HBMEC and Caco-2 monolayers were incubated with DiO-labeled OMVs for 4 h and native cells were analyzed for fluorescence before and after trypan blue quenching using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy and confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). Most of DiO-labeled OMVs were found to be located within cell bodies and these OMVs were not quenched with trypan blue demonstrating that they had been internalized (Figure S2).

Fig. 3. EHEC-Hly-containing and EHEC-Hly-free OMVs bind to and are internalized by HBMEC and Caco-2 cells.

(A) HBMEC and (B) Caco-2 cells were incubated with DiO-labeled OMVs from strains TA50, TA51, 8033 or 8033c for the times indicated and fluorescence was measured using a flow cytometer before (total cell-associated OMVs) and after (internalized OMVs) trypan blue quenching. Data are expressed as geometric means of fluorescence intensities from 10,000 cells after subtraction of background fluorescence of cells without OMVs, and are presented as means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments; * significant difference between cell-bound and internalized OMVs after 4 h (p<0.05). In addition, cells incubated with OMVs were analyzed using CLSM. OMVs (green) were detected using rabbit anti-E. coli LPS antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, actin (red) was counterstained with phalloidin-TRITC and nuclei (blue) with DRAQ5. (C) HBMEC and Caco-2 cells were incubated for 4 h with OMV buffer (20 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 8.0) instead of OMVs and analyzed using CLSM as described above. Pictures were taken using a laser-scanning microscope (LSM 510 META microscope, equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.4 oil immersion objective). All three fluorescence images were merged and confocal Z-stack projections are included in all images in panels A and B. The cross hairs show the position of the xy and yz planes. Scale bars are 10 µm. Visualization of the OMV interactions with HBMEC and Caco-2 cells using CLSM of fixed and stained cells agreed with the flow cytometry. OMVs from all strains were associated with cellular membranes after 15 min and the OMV cell adherence and internalization increased with time. After 4 h nearly all OMVs were internalized and accumulated in the perinuclear regions (Figure 3A, 3B, panels 4 h). No OMV signals were observed in cells incubated for 4 h with OMV buffer (20 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 8.0) in lieu of OMVs (Figure 3C), and in OMV-treated cells stained with secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG) in the absence of primary (anti-E. coli LPS) antibody (Figure S3A). Taken together, these experiments showed that both EHEC-Hly-harboring OMVs and EHEC-Hly-free OMVs adhered to and were internalized by HBMEC and Caco-2 cells and that EHEC-Hly is not necessary for but might contribute to these processes.

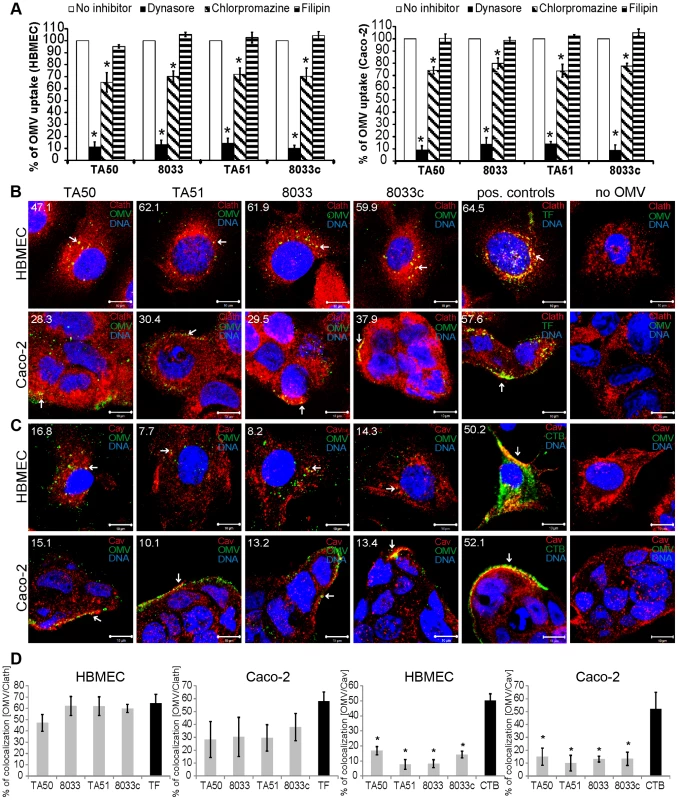

EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs are internalized via dynamin-dependent endocytosis

OMVs from bacterial pathogens can enter host cells via lipid raft/caveolae-dependent or clathrin-dependent endocytosis [20], [21]. To characterize the endocytic pathway utilized by EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs, we first determined effects of various inhibitors of endocytosis on uptake of rhodamine isothiocyanate B-R18-labeled TA50 and 8033 OMVs, as well as EHEC-Hly-free control OMVs (TA51, 8033c) by HBMEC and Caco-2 cells. Dynasore, an inhibitor of dynamin-1, which promotes scission of endocytic vesicles from plasma membrane [22], inhibited the OMV uptake to 10% – 14% and to 9% – 14% of their uptake by untreated HBMEC and Caco-2 cells, respectively (p<0.05) (Figure 4A). Significant inhibition of OMV uptake (to 65% – 72% of control in HBMEC and to 74% – 79% of control in Caco-2) (p<0.05) was also caused by chlorpromazine, an inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis [23] (Figure 4A). In contrast, filipin, a cholesterol-sequestering agent that disrupts lipid rafts and caveolae [24] had no significant inhibitory effect on OMV uptake (Figure 4A). These experiments indicated that endocytosis of EHEC-Hly-containing and EHEC-Hly-free OMVs is dynamin-dependent and might be clathrin-mediated.

Fig. 4. EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs are internalized via dynamin-dependent endocytosis.

(A) OMVs from strains TA50, 8033, TA51 or 8033c labeled with rhodamine isothiocyanate B-R18 were incubated for 4 h with HBMEC and Caco-2 cells that had been pretreated (1 h) with inhibitors of endocytosis including dynasore (80 µM), chlorpromazine (15 µg/ml), or filipin III (10 µg/ml) or remained inhibitor-untreated (control). Fluorescence was measured using a plate reader and OMV uptake (reflected by fluorescence intensity) in the presence of each inhibitor was expressed as the percentage of OMV uptake by control, inhibitor-untreated cells. * significantly decreased (p<0.05) compared to control cells (unpaired Student's t test). Data are presented as means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. (B, C). HBMEC and Caco-2 cells were incubated with TA50, TA51, 8033 or 8033c OMVs or with TF-488 or CTB-488 (positive controls) or with 20 mM TRIS-HCl buffer (no OMV) for 10 min and analyzed by CLSM. OMVs were stained with rabbit anti-E. coli LPS antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (green), and clathrin (B) or caveolin (C) were stained using the respective mouse monoclonal antibody and Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (red). Nuclei were stained with DRAQ5 (blue). Pictures were taken using a laser-scanning microscope (LSM 510 META microscope equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.4 oil immersion objective). All three fluorescence images were merged and consisted of one optical section of a z-series with a pinhole of 1 airy unit. Colocalized red and green signals appear in yellow (examples depicted by arrows). Scale bars are 10 µm. The percentages of colocalizations between OMVs and clathrin or caveolin (and TF-488/CTB-488 and clathrin/caveolin) were calculated using BioImageXD6 colocalization tool and are indicated by white numbers (averages from at least five different samples) in the images and depicted graphically in panel (D). To further explore relative contribution of clathrin versus caveolin to OMV endocytosis and to gain insight into the role of EHEC-Hly in this process, HBMEC and Caco-2 cells were incubated with EHEC-Hly-containing (TA50, 8033) and EHEC-Hly-free (TA51, 8033c) OMVs for 10 min and colocalization of OMVs with clathrin and caveolin was determined using CLSM. In HBMEC, colocalization rates of OMVs with clathrin ranged from 47.1% to 62.1% and were similar to that of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated transferrin (TF-488) (64.5%), a well-established marker for clathrin-mediated endocytosis [25] (Figure 4B, 4D). In Caco-2 cells, colocalization rates of OMVs with clathrin were between 28.3% and 37.9% (Figure 4B), being lower, but not significantly, than that of TF-488 (57.6%) (Figure 4B, 4D). In contrast to clathrin, colocalization of OMVs with caveolin (7.7% – 16.8% in HBMEC and 10.1% – 15.1% in Caco-2 cells) was in each cell line significantly lower than that of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated cholera toxin B subunit (CTB-488) (50.2% and 52.1%, respectively), a marker for caveolin-mediated endocytosis [24] (Figure 4C, 4D). No colocalization signals with clathrin or caveolin were observed in cells treated with 20 mM TRIS-HCl in lieu of OMVs (Figure 4B, 4C). No significant differences were observed in any cell line between clathrin colocalization rates of EHEC-Hly-containing (TA50, 8033) and EHEC-Hly-free (TA51, 8033c) OMVs (Figure 4D) indicating that the clathrin-mediated endocytosis of OMVs does not require EHEC-Hly. In summary, these experiments showed that EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs are internalized by HBMEC and Caco-2 cells via dynamin-dependent and largely clathrin-mediated endocytosis and that the OMV endocytosis occurs independently of the presence of EHEC-Hly.

EHEC-Hly is internalized via OMV endocytosis and subsequently translocates into mitochondria

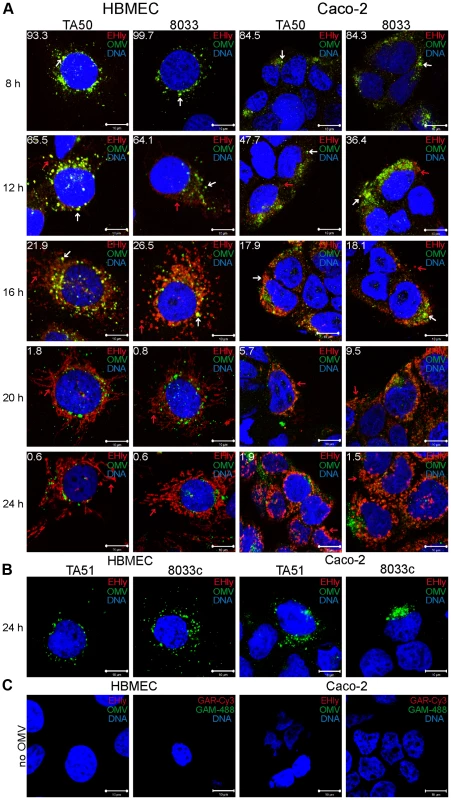

To assess if EHEC-Hly was internalized with OMVs and to monitor its association with OMVs during intracellular trafficking, cells were incubated with TA50 or 8033 OMVs for 1 h to 24 h and analyzed by CLSM. Association of the toxin with OMVs was quantified by calculating colocalization rates of OMV and EHEC-Hly signals at each time. In both HBMEC and Caco-2 cells, EHEC-Hly colocalized with OMVs up to 8 h of incubation. At this time point the colocalization rates of OMVs and EHEC-Hly reached 93.3% – 99.7% in HBMEC and 84.3% – 84.5% in Caco-2 cells and the OMV/EHEC-Hly complexes were localized predominantly in perinuclear regions (Figure 5A, panel 8 h, Figure S4A). After 12 h, EHEC-Hly remained partially associated with OMVs (64.1% – 65.5% colocalization in HBMEC and 36.4% – 47.7% colocalization in Caco-2 cells), but the toxin began to be dissociated from OMVs as demonstrated by its appearance also outside the OMVs (Figure 5A, panel 12 h, Figure S4A). The separation of EHEC-Hly from OMVs continued until 16 h (21.9% – 26.5% colocalization in HBMEC and 17.9% – 18.1% colocalization in Caco-2 cells), when most of the toxin was located outside OMVs in the form of granular and tubular patches (Figure 5A, panel 16 h, Figure S4A). After 20 h to 24 h the toxin was separated entirely from the perinuclear OMVs (0.6% colocalization in HBMEC and 1.5% – 1.9% colocalization in Caco-2 cells after 24 h) and accumulated in a cell compartment resembling mitochondria (Figure 5A, panels 20 h and 24 h, Figure S4A). The presence of EHEC-Hly in mitochondria was confirmed by strong (>80%) colocalization of the toxin with mitotracker, a fluorescent dye that specifically stains mitochondria [26] (Figure 6). No EHEC-Hly, but only OMVs were detected in cells incubated for 24 h with EHEC-Hly-free OMVs from strains TA51 and 8033c (Figure 5B). Neither OMVs nor EHEC-Hly were found in control cells treated with 20 mM TRIS-HCl instead of OMVs (Figure 5C) and in OMV-treated cells stained with secondary antibodies in the absence of primary antibodies (Figure S3B); this confirmed the specificity of the signals observed in cells treated with EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs.

Fig. 5. EHEC-Hly separates from OMVs during intracellular trafficking.

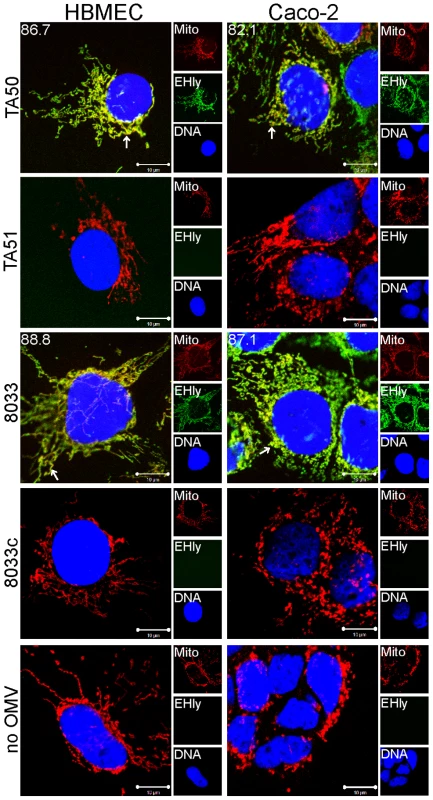

(A) HBMEC and Caco-2 cells were incubated with TA50 or 8033 OMVs for the times indicated and analyzed using CLSM. OMVs were stained using mouse anti-E. coli LPS antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (green), and EHEC-Hly (EHly) was stained using rabbit anti-EHEC-Hly antibody and Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (red). Nuclei were stained with DRAQ5 (blue). Pictures were taken and processed as described in the legend to Figure 4. Colocalized red and green signals appear in yellow (examples are indicated by white arrows). Red arrows indicate examples of red signal of EHEC-Hly dissociating from OMVs during time. The percentages of colocalization between OMVs and EHEC-Hly were calculated using BioImageXD6 colocalization tool and are indicated by white numbers (averages from at least five different samples). (B) HBMEC and Caco-2 cells were incubated for 24 h with EHEC-Hly-free OMVs from strains TA51 or 8033c and stained as described in panel A. (C) HBMEC and Caco-2 cells were incubated for 24 h with 20 mM TRIS-HCl (OMV buffer) instead of OMVs and stained for OMVs and EHEC-Hly as described in panel A or stained with secondary antibodies in the absence of primary antibodies. Scale bars in all panels are 10 µm. Fig. 6. EHEC-Hly colocalizes with mitochondria.

HBMEC and Caco-2 cells were incubated with EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs from strains TA50 and 8033 or with EHEC-Hly-free OMVs from strains TA51 and 8033c (controls) or with 20 mM TRIS-HCl buffer in lieu of OMVs for 24 h. EHEC-Hly (EHly) was stained with anti-EHEC-Hly antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (green) and mitochondria (Mito) were stained with MitoTracker Orange CMTMRos (red). DNA was stained with DRAQ5 (blue). Pictures were taken using a laser-scanning microscope (LSM 510 META microscope, equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.4 oil immersion objective). All three fluorescence images were merged (left panels; colocalized red and green signals appear in yellow and examples are depicted by arrows) and single fluorescence channels are shown in the right panels. Pictures consisted of one optical section of a z-series with a pinhole of 1 airy unit. Scale bars are 10 µm. Note that mitotracker signals in cells treated with EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs (TA50, 8033) are slightly diffuse compared to those in cells treated with EHEC-Hly-free OMVs (TA51, 8033c) and in OMV-untreated cells, likely because of reduction of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential induced by EHEC-Hly at this time (see Figure 11E, 11F). To confirm that the intracellular EHEC-Hly signals detected in cells treated with EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs (Figure 5A, panels 8 h to 24 h) represent indeed only the OMV-delivered toxin, we incubated in a control experiment HBMEC and Caco-2 cells for 24 h with a sublytic dose of free recombinant EHEC-Hly prepared from strain TA50. In contrast to OMV-delivered EHEC-Hly, which was at this time already located in mitochondria (Figure 5A, panel 24 h, Figure 6), free EHEC-Hly remained restricted to the cell surface up to 24 h without entering cells (Figure S4B). This confirmed that EHEC-Hly detected intracellularly in HBMEC and Caco-2 cells exposed to EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs originates solely from the OMV-delivered toxin. The apparent increase of EHEC-Hly intracellular signals during time (Figure 5A, panels 8 h to 24 h) plausibly results from a gradual dissociation of EHEC-Hly from OMVs entering continually cells and accumulation of the toxin in mitochondria. Importantly, this experiment clearly showed that association of EHEC-Hly with OMVs is a prerequisite for its internalization by host cells and that OMVs serve as vehicles for the intracellular toxin delivery. Taken together, these data demonstrate that in HBMEC as well as in Caco-2 cells EHEC-Hly is internalized via OMVs and remains associated with the OMVs for at least 8 h. The OMV/EHEC-Hly complexes are trafficked towards perinuclear regions where EHEC-Hly dissociates from OMVs and subsequently targets mitochondria by an OMV-independent process. Because EHEC-Hly was never observed in the endoplasmic reticulum or the trans-Golgi-network (Figure S4C, S4D), we further investigated whether the toxin might be released from OMVs in endo-lysosomal compartments, which also accumulate in perinuclear regions.

EHEC-Hly is released from OMVs in CD63-positive endo-lysosomal compartments

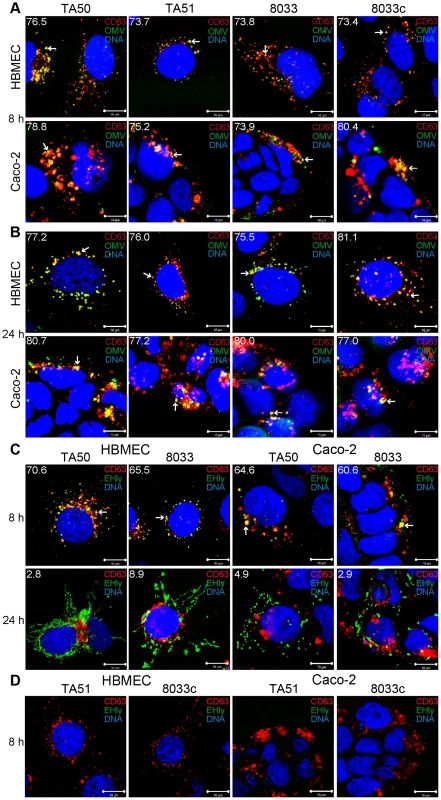

To determine localization of OMVs and EHEC-Hly in endo-lysosomal compartments, we analyzed their colocalizations with the lysosome-associated membrane protein 3 (LAMP3/CD63) after 8 h, 16 h and 24 h of incubation. In all time intervals, EHEC-Hly-positive (TA50 and 8033) and EHEC-Hly-negative (TA51 and 8033c) OMVs strongly (>70%) colocalized with CD63-positive compartments in both HBMEC and Caco-2 cells (Figure 7A, 7B, Figure S5A, S5D). In contrast to OMVs, and in accordance with its time-dependent separation from OMVs (Figure 5A), EHEC-Hly strongly colocalized with CD63-positive compartments after 8 h (65.5% – 70.6% in HBMEC and 60.6% – 64.6% in Caco-2 cells) (Figure 7C, panel 8 h, Figure S5E), but the colocalization significantly decreased after 16 h (24.6% – 26.0% in HBMEC and 25.5% – 27.8% in Caco-2 cells) (Figure S5B, S5E) and 24 h (2.8% – 8.9% in HBMEC and 2.9% – 4.9% in Caco-2 cells) (Figure 7C, panel 24 h, Figure S5E). No EHEC-Hly was detected in cells treated with EHEC-Hly-free OMVs (Figure 7D), and no OMVs and EHEC-Hly were detected in control cells treated with OMV buffer instead of OMVs (Figure S5C), as well as in OMV-treated cells stained with secondary antibodies in the absence of primary antibodies (Figure S3A). Altogether, these data indicated that after its internalization via OMVs, EHEC-Hly trafficks together with OMVs into CD63-positive endo-lysosomal compartments, from where it is subsequently released and translocates to mitochondria, while OMVs remain in the CD63-positive compartments for up to 24 h.

Fig. 7. Colocalization of OMVs and EHEC-Hly with endo-lysosomal compartments detected with anti-CD63 antibody.

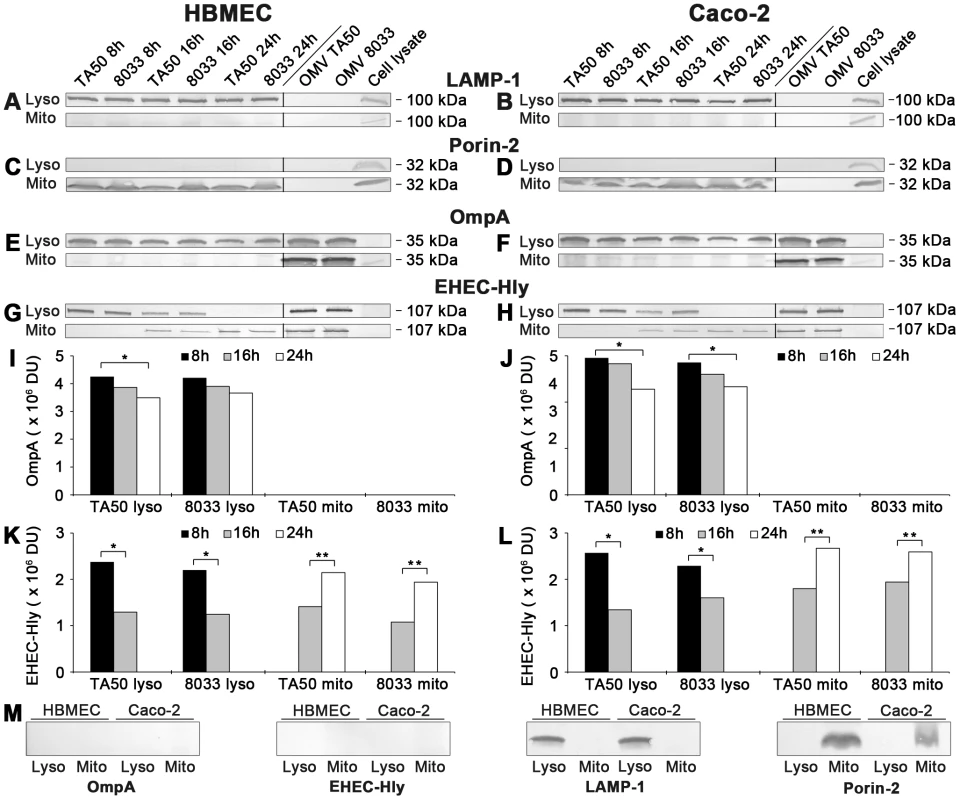

(A, B) HBMEC and Caco-2 cells were incubated with EHEC-Hly-containing (TA50 or 8033) or EHEC-Hly-free (TA51 or 8033c) OMVs for 8 h (A) and 24 h (B). OMVs were stained with rabbit anti-E. coli LPS antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (green), lysosomes with mouse anti-CD63 antibody and Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (red), and nuclei with DRAQ5 (blue). (C, D) HBMEC and Caco-2 cells were incubated with EHEC-Hly-containing (TA50 or 8033) (C) or EHEC-Hly-free (TA51 or 8033c) OMVs (D) for 8 h and 24 h and stained as described above except that in lieu of OMVs, EHEC-Hly (EHly) was detected with rabbit anti-EHEC-Hly antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (green). Pictures were taken and processed as described in the legend to Figure 4. Colocalized red and green signals appear in yellow (examples indicated by arrows). White numbers indicate the percentages of OMVs (A, B) and EHEC-Hly (C) colocalized with CD63-positive compartments (averages from at least five different samples) calculated using the BioImageXD6 colocalization tool. Scale bars are 10 µm. The images in panel D (8 h of incubation) are also representative of 24 h (no EHEC-Hly was detected in cells treated with EHEC-Hly-free OMVs at any of these time points). To confirm the CLSM-based data on the trafficking of OMV-EHEC-Hly complexes into endo-lysosomal compartments (Figure 7A, 7C, panels 8 h) and the subsequent separation of EHEC-Hly from OMVs (Figure 5A) and its translocation to mitochondria (Figure 5A, Figure 7C, panel 24 h, Figure S5B), we isolated lysosomes and mitochondria from HBMEC and Caco-2 cells incubated with TA50 or 8033 OMVs for 8 h, 16 h and 24 h, and determined the presence of OMVs and EHEC-Hly in these subcellular compartments using immunoblotting with anti-OmpA and anti-EHEC-Hly antibody, respectively. The identity of the isolated fractions was confirmed by the detection of LAMP-1, a lysosomal marker protein, and porin-2, a mitochondrial marker protein, in the respective fractions (Figure 8A–8D). As demonstrated by OmpA immunoblotting, both TA50 and 8033 OMVs were present in lysosomal fractions of HBMEC and Caco-2 cells after 8 h, 16 h and 24 h of incubation, but were not found in mitochondrial fractions at any of these time points (Figure 8E, 8F, 8I, 8J). In contrast to OMVs and in accordance with the microscopic analysis (Figure 7C, Figure S5B, S5E), strong EHEC-Hly signals were detected in lysosomal fractions after 8 h, but they significantly decreased after 16 h and were undetectable after 24 h of incubation (Figure 8G, 8H, 8K, 8L). In parallel with its time-dependent disappearance from lysosomes, EHEC-Hly appeared in mitochondria, which contained no EHEC-Hly after 8 h, but clear signals were detected after 16 h and they further significantly increased until 24 h (Figure 8G, 8H, 8K, 8L). No signals with anti-OmpA and anti-EHEC-Hly antibodies were detected in lysosomal and mitochondrial fractions of control, OMV-untreated HBMEC and Caco-2 cells (Figure 6M). The Western blot analyses of purified lysosomal and mitochondrial fractions thus confirmed the CLSM-based results by demonstrating that both OMVs and EHEC-Hly are trafficked to lysosomes, from which EHEC-Hly is subsequently released and translocates to mitochondria. OMVs remain in lysosomes where they are apparently degraded during time as indicated by decreasing OmpA signals in both HBMEC and Caco-2 cells after 16 h and 24 h of incubation (Figure 8I, 8J).

Fig. 8. Detection of OMVs and EHEC-Hly in lysosomal and mitochondrial fractions of cells treated with EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs.

(A-H) Lysosomes (Lyso) and mitochondria (Mito) were isolated from HBMEC and Caco-2 cells, which had been incubated with OMVs TA50 or 8033 for 8 h, 16 h and 24 h as described in Materials and Methods. The lysosomal and mitochondrial fractions were analyzed using Western blot for marker proteins of each respective fraction including LAMP-1 (A, B) and porin-2 (C, D), and for OMVs (anti-OmpA antibody) (E, F) and EHEC-Hly (G, H). Signals elicited from the lysosomal and mitochondrial fractions at each time are shown in the first part of each immunoblot, whereas the second part (separated by a line) includes controls run at the same gel (isolated OMVs TA50 and 8033 and cell lysates). The sizes of immunoreactive bands are indicated along the right sides of the blots. (I–L) Densitometric quantification of OmpA (I, J) and EHEC-Hly (K, L) signals shown in E, F and G, H, respectively, using Quantity One software; * significantly decreased (p<0.05) compared to 8 h; ** significantly increased (p<0.05) compared to 16 h (unpaired Student's t test). (M) Immunoblots of isolated lysosomal and mitochondrial fractions from control, OMV non-treated HBMEC and Caco-2 cells with the antibodies indicated. Bafilomycin A1 inhibits translocation of EHEC-Hly from endo-lysosomal compartments to mitochondria

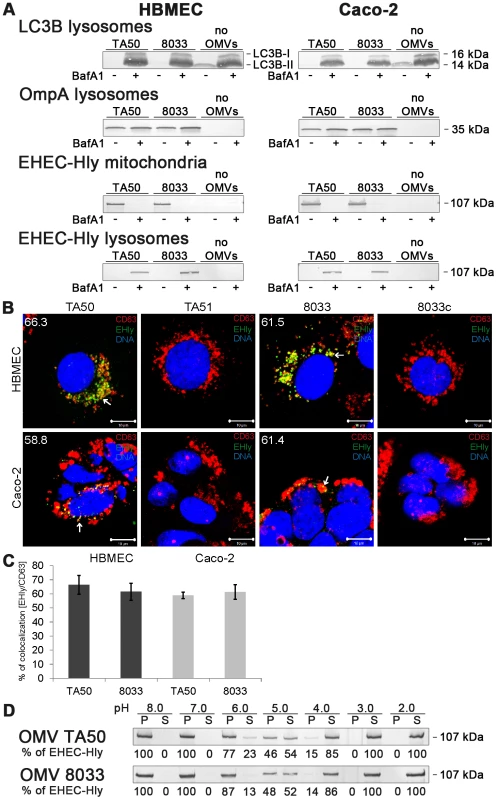

To gain insight into a mechanism involved in translocation of EHEC-Hly from endo-lysosomal compartments to mitochondria, we used bafilomycin A1 (BafA1), a specific inhibitor of vacuolar-type H+-ATPase that inhibits acidification of lysosomes by inhibiting the proton pump in their membrane [27]. BafA1-pretreated and control, untreated cells were incubated with TA50 or 8033 OMVs for 24 h and presence of OMVs and EHEC-Hly in lysosomes and mitochondria was determined using Western blot analyses of isolated lysosomal and mitochondrial fractions and CLSM. The efficiency of the BafA1 treatment was verified using immunoblotting with anti-light chain 3B (LC3B) antibody, which detects an increased amount of processed LC3B-II in the presence of BafA1 [28] (Figure 9A). As shown in Figure 9, TA50 and 8033 OMVs were found in lysosomal fractions of HBMEC and Caco-2 cells regardless of absence or presence of BafA1 (Figure 9A, panels OmpA lysosomes), indicating that BafA1 does not influence trafficking of EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs to lysosomes. In contrast, EHEC-Hly, which was after 24 h already present in mitochondria of BafA1-untreated cells (Figure 9A), was found in lysosomal fractions but not in mitochondrial fractions of BafA1-treated cells at this time point (Figure 9A) indicating that the toxin was trapped in lysosomes that failed to acidify. This was supported using CLSM of BafA1-treated HBMEC and Caco-2 cells where EHEC-Hly strongly colocalized with CD63 positive endo-lysosomal compartments after 24 h of incubation (Figure 9B, 9C), in contrast to its absence from lysosomes and presence in mitochondria of BafA1-untreated cells at this time point (Figure 7C, panel 24 h). These experiments showed that endosomal acidification is necessary for EHEC-Hly translocation from endo-lysosomal compartments to mitochondria.

Fig. 9. Bafilomycin A1 inhibits translocation of EHEC-Hly from lysosomes to mitochondria.

(A) HBMEC and Caco-2 cells either pretreated with bafilomycin A1 (BafA1+) (100 nM, 1 h) or BafA1-untreated (BafA1-) were incubated with TA50 or 8033 OMVs or without OMVs for 24 h. Lysosomal and mitochondrial fractions were isolated and analyzed for OMVs and EHEC-Hly using immunoblot with anti-OmpA and anti-EHEC-Hly antibody, respectively. Efficiency of BafA1 treatment was verified using immunoblot with anti-LC3B antibody which detects an increased amount of processed LC3B-II in the presence of BafA1. The sizes of immunoreactive bands are indicated along the right side of Caco-2 cell blots. (B) BafA1-pretreated HBMEC and Caco-2 cells were incubated with TA50 or 8033 OMVs (or with control EHEC-Hly-free TA51 or 8033c OMVs) for 24 h and analysed using CLSM. Lysosomes were stained with anti-CD63 antibody and Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (red), EHEC-Hly (EHly) with anti-EHEC-Hly antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated IgG (green), and nuclei with DRAQ5 (blue). Pictures were taken and processed as described in the legend to Figure 4. Colocalized red and green signals appear in yellow (examples indicated by arrows). The percentages of colocalizations of EHEC-Hly with CD63-positive compartments were calculated using the BioImageXD6 colocalization tool and are shown (averages from at least five different samples) by white numbers in images in panel B and graphically in panel (C). Scale bars are 10 µM. (D) TA50 and 8033 OMVs were treated (1 h, 37°C) with TRIS-HCl buffer with pH ranging from 8.0 to 2.0; samples were ultracentrifuged and the pellets (P) (containing OMV-associated EHEC-Hly) and supernatants (S) (containing EHEC-Hly that had separated from OMVs) were analyzed for EHEC-Hly using immunoblotting. EHEC-Hly signals in P and S fractions were quantified densitometrically and the percentage of EHEC-Hly present in the P and S fraction at each particular pH was calculated from the total EHEC-Hly signal. Because EHEC-Hly first needs to be separated from OMVs for translocation to mitochondria, we further tested if EHEC-Hly separation from OMVs is pH-dependent. To this end, we exposed TA50 and 8033 OMVs to a pH range from 8.0 to 2.0 for 1 h, ultracentrifuged the samples and analyzed the presence of EHEC-Hly in pellets (OMV-associated EHEC-Hly) and in supernatants (separated EHEC-Hly) using immunoblot (Figure 9D). In both OMV preparations a pH-dependent dissociation of EHEC-Hly from OMVs occurred. The dissociation started at pH 6.0, reached >50% at pH 5.0 and was almost complete at pH 4.0 (Figure 9D). Because the pH range where EHEC-Hly dissociates from OMVs resembles the acidic pH of lysosomes (∼5.0) [27], this experiment thus indicated that trapping of EHEC-Hly in lysosomes of BafA1-treated cells and the failure of the toxin's translocation to mitochondria is likely to be due to the inability of EHEC-Hly to separate from OMVs in lysosomes that fail to acidify after BafA1 treatment.

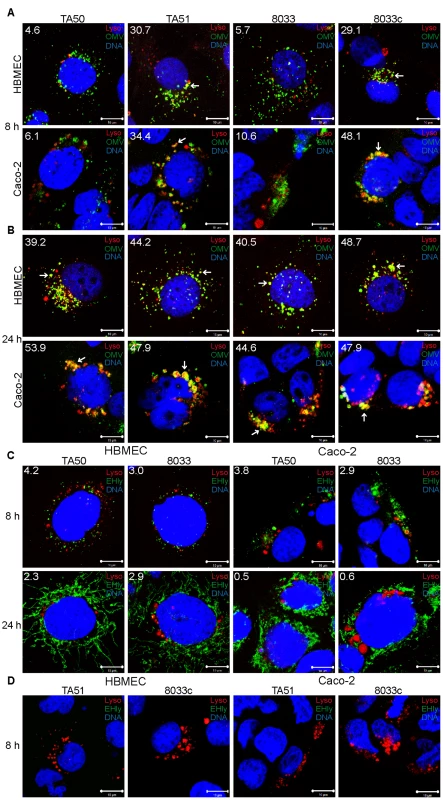

Releasing of EHEC-Hly from lysosomes leads to a transient loss of lysosomal function

Following its separation from OMVs in acidified lysosomes, EHEC-Hly has to escape from lysosomes in order to reach mitochondria. Because EHEC-Hly is a pore-forming toxin we hypothesized that it might be released from lysosomes by damaging the lysosomal membrane. To test this hypothesis, we incubated HBMEC and Caco-2 cells with EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs TA50 or 8033 or with EHEC-Hly-free OMVs TA51 or 8033c (used as controls) for 8 h, 16 h, and 24 h, and analyzed the colocalization of OMVs and EHEC-Hly with functional lysosomes using lysotracker. Since lysotracker detects only lysosomes that retain their acidic (physiological) pH, the detection of lysosomes by lysotracker would be diminished in the case of EHEC-Hly-mediated lysosomal pore formation and the resulting increase in lysosomal pH. Indeed, after 8 h of incubation, when EHEC-Hly is detected together with OMVs in CD63-positive endo-lysosomal compartments (Figure 7A, 7C, panels 8 h) and in isolated lysosomes (Figure 8E-8H, 8 h), we observed only a low degree of colocalization of TA50 and 8033 OMVs with functional/acidified lysosomes stained by lysotracker in both HBMEC (4.6% and 5.7%, respectively) and Caco-2 cells (6.1% and 10.6%, respectively) (Figure 10A). In contrast, EHEC-Hly-free TA51 and 8033c OMVs demonstrated significantly higher colocalization with lysotracker-stained lysosomes in both HBMEC (30.7% and 29.1%, respectively) and Caco-2 cells (34.4% and 48.1%, respectively) (Figure 10A, Figure S6C). These observations suggested an EHEC-Hly-mediated effect on the acidification of lysosomes. Notably, the colocalization rates of TA50 and 8033 OMVs with functional lysosomes increased after 16 h and 24 h of incubation, when they were nearly identical to those of TA51 and 8033c OMVs (Figure 10B, Figure S6A, S6C). This correlated with gradual disappearance of EHEC-Hly from CD63-positive compartments (Figure 7C, panel 24 h, Figure S5B, S5E) and from isolated lysosomes (Figure 8G, 8H, 8K, 8L, 16 h and 24 h) at these time points. This suggested that the ability of lysosomes to acidify was restored after EHEC-Hly had been released. The involvement of EHEC-Hly in the impaired acidification of lysosomes caused by TA50 and 8033 OMVs was directly supported by the observation that EHEC-Hly did not colocalize with lysotracker-stained lysosomes after 8 h of incubation (Figure 10C, panel 8 h), although it was present in lysosomes stained with anti-CD63 antibody (Figure 7C, panel 8 h, Figure S5E) and in isolated lysosomal fractions (Figure 8G, 8H, 8K, 8L, 8h) at this time. Compared to this, the lack of colocalization of EHEC-Hly with lysotracker-stained lysosomes at later time points (16 h and 24 h; Figure S6B and Figure 10C, panel 24 h, respectively) resulted from a significant decrease of the toxin amount (16 h) and its absence from lysosomes (24 h) (Figure S5B, S5E, Figure 7C, panel 24 h; Figure 8G, 8H, 8K, 8L), which was due to EHEC-Hly translocation to mitochondria (Figure S5B, Figure 7C, panel 24 h; Figure 8G, 8H, 8K, 8L). Taken together, these experiments suggest that EHEC-Hly is released from lysosomes via its pore-forming activity which might perforate the lysosomal membrane, thereby enabling the toxin to escape and subsequently translocate to mitochondria.

Fig. 10. Releasing of EHEC-Hly from lysosomes leads to a transient loss of lysosomal function.

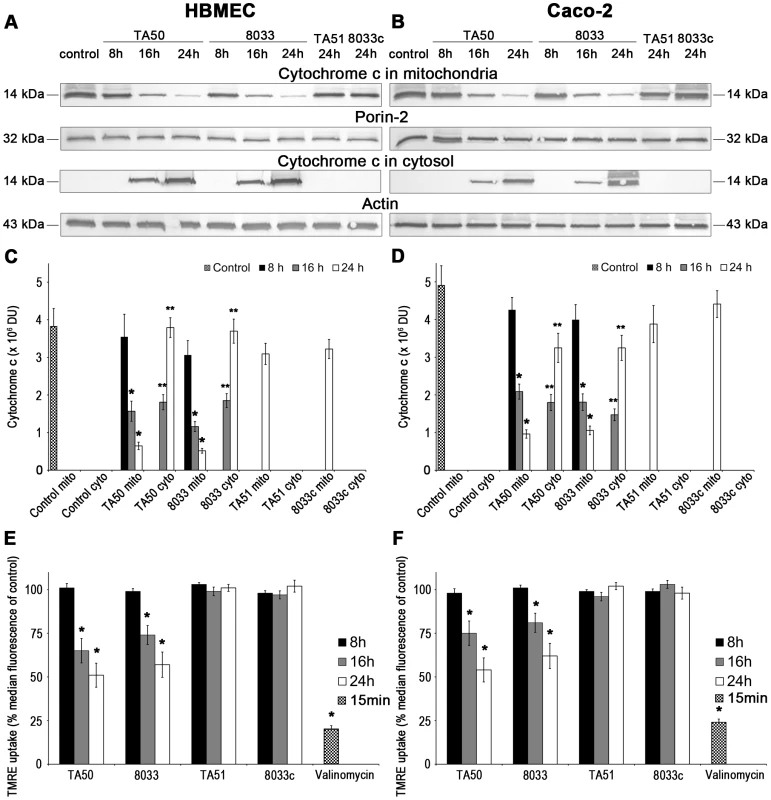

(A, B) HBMEC and Caco-2 cells were incubated with EHEC-Hly-containing (TA50 or 8033) or EHEC-Hly-free (TA51 or 8033c) OMVs for 8 h (A) and 24 h (B). OMVs were stained with rabbit anti-E. coli LPS antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (green), lysosomes with Lysotracker Red DND-99 (red) and nuclei with DRAQ5 (blue). (C, D) HBMEC and Caco-2 cells were incubated with TA50 or 8033 OMVs (C) or with TA51 or 8033c OMVs (D) for 8 h and 24 h. EHEC-Hly (EHly) was stained with rabbit anti-EHEC-Hly antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (green), lysosomes with Lysotracker Red DND-99 (red), and nuclei with DRAQ5 (blue). Pictures were taken and processed as described in the legend to Figure 4. Colocalized red and green signals appear in yellow (examples in panels A and B are depicted by arrows). White numbers indicate the percentages of OMVs or EHEC-Hly colocalized with Lysotracker Red DND-99-positive lysosomes (averages from at least five different samples) calculated using the BioImageXD6 colocalization tool. Scale bars are 10 µm. The pictures shown in panel D (8 h of incubation) are also representative of 24 h (no EHEC-Hly was detected in cells treated with EHEC-Hly-free OMVs at any of these time points). Translocation of EHEC-Hly into mitochondria permeabilizes the mitochondrial membranes in HBMEC and Caco-2 cells

Since mitochondria are central components in intrinsic apoptosis [29], we investigated if translocation of EHEC-Hly into mitochondria triggers this pathway. The key event in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway is the permeabilization of the mitochondrial membranes; the outer membrane permeabilization leads to the release of pro-apoptotic proteins (such as cytochrome c) from the mitochondrial intermembrane space to the cytosol, and permeabilization of the inner membrane dissipates the mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔΨm) [29]. Incubation of HBMEC and Caco-2 cells with TA50 or 8033 OMVs for 8 h, 16 h and 24 h resulted in a steady decrease of cytochrome c in the mitochondrial fractions and a steady increase of cytochrome c in the cytosolic fractions (Figure 11A-11D). The kinetics of the cytochrome c release from mitochondria to the cytosol correlated with the kinetics of EHEC-Hly separation from OMVs and its translocation to mitochondria (Figure 5A, panels 8 h, 16 h, 24 h). Moreover, TA50 and 8033 OMVs caused a time dependent decrease in uptake of tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE), a mitochondrial potential-sensitive dye, by HBMEC and Caco-2 cells (Figure 11E, 11F). After 24 h, the TMRE uptake dropped to 52% (TA50 OMVs) and 57% (8033 OMVs) of control in HBMEC, and to 54% (TA50 OMVs) and 62% (8033 OMVs) of control in Caco-2 cells (Figure 11E, 11F). No change in TMRE uptake and no cytochrome c release from mitochondria to the cytosol was elicited by EHEC-Hly-free TA51 and 8033c OMVs (Figure 11A-11F). Thus, translocation of EHEC-Hly to mitochondria results in release of cytochrome c and a decrease of ΔΨm supporting the toxin-mediated permeabilization of the outer and the inner mitochondrial membrane.

Fig. 11. Translocation of EHEC-Hly to mitochondria results in cytosolic cytochrome c release and ΔΨm decrease.

(A, B) HBMEC (A) and Caco-2 cells (B) were incubated for the times indicated with EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs TA50 or 8033 (20 µg of OMV protein containing 100 ng of EHEC-Hly) or with corresponding protein amounts of EHEC-Hly-negative OMVs TA51 or 8033c or left untreated (control). Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were isolated and immunoblotted with anti-cytochrome c antibody. After stripping, membranes were reprobed with antibody against porin-2 (mitochondrial marker) or actin (cytosolic marker). The sizes of immunoreactive bands are indicated. (C, D) Intensities of the cytochrome c signals in mitochondrial (mito) and cytosolic (cyto) fractions shown in panels A and B were quantified in HBMEC (C) and Caco-2 cells (D) using densitometry, expressed in arbitrary densitometric units (DU) and are presented as means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. * Significantly decreased (p<0.05) compared to mitochondrial cytochrome c in control cells; ** significantly increased (p<0.05) compared to cytosolic cytochrome c in control cells (unpaired Student's t test). Mitochondrial cytochrome c signals in control cells (control mito) were almost identical after 8 h, 16 h and 24 h and are therefore shown as means ± standard deviations from all times. No cytochrome c was detected at any time in cytosol of control cells (control cyto). (E, F) HBMEC (E) and Caco-2 cells (F) were incubated with EHEC-Hly-containing or EHEC-Hly-free OMVs as indicated in A and B and ΔΨm was determined by uptake of TMRE using flow cytometry. Median fluorescence of OMV-treated cells was expressed as the percentage of the median fluorescence of control untreated cells (defined as 100%). The values represent means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. * Significantly decreased (p<0.05) compared to control cells (unpaired Student's t test). Valinomycin (100 nM, 15 min) was a positive control. EHEC-Hly induces activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3, but not of caspase-8

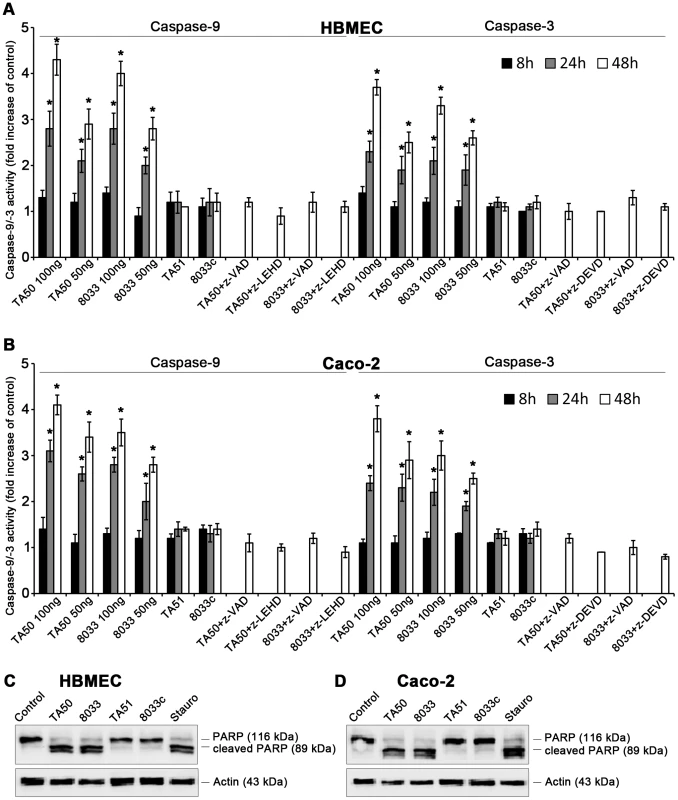

Upon its release from mitochondria to the cytosol, cytochrome c binds together with the apoptosis-activating factor-1 and ATP/dATP to pro-caspase-9, leading to its cleavage and activation [29], [30]. Active caspase-9, the initiator caspase of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, cleaves and activates effector caspases including caspase-3 [29], [30]. EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs TA50 and 8033 caused time - and dose-dependent activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 in HBMEC and Caco-2 cells, which peaked after 48 h (Figure 12A, 12B). At this point the activity of caspase-9 was up to 4.3-fold increased in HBMEC and up to 4.1-fold increased in Caco-2 cells, and the activity of caspase-3 was up to 3.7-fold increased in HBMEC and up to 3.8-fold increased in Caco-2 cells compared to those in control, OMV-untreated cells (Figure 12A, 12B). In contrast, the activity of caspase-8, the initiator caspase of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway [31], in cells treated with TA50 or 8033 OMVs remained at baseline (<1.2-fold increase) for the duration of the experiment (Figure S7). Activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 in each cell line was inhibited by pre-treatment with the specific caspase inhibitors (z-LEHD-fmk and z-DEVD-fmk, respectively) and with the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk (Figure 12A, 12B). No activation of caspase-9 or caspase-3 was observed in cells treated with EHEC-Hly-free OMVs TA51 or 8033c (Figure 12A, 12B).

Fig. 12. EHEC-Hly induces activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 and PARP cleavage.

(A, B) HBMEC (A) and Caco-2 cells (B) were incubated with different doses of TA50 or 8033 OMVs (20 µg or 10 µg of OMV protein containing 100 ng or 50 ng of EHEC-Hly, respectively) or with 20 µg of EHEC-Hly-negative OMVs (TA51 or 8033c) for the times indicated or remained untreated. Cells were lysed, the lysates were incubated with colorimetric substrates of caspase-9 (Ac-LEHD-pNA) or caspase-3 (Ac-DEVD-pNA) and the color intensity, which is proportional to the level of caspase enzymatic activity, was measured spectrophotometrically. The activity of each caspase in OMV-treated cells was expressed as a fold-increase of that in untreated cells (defined as 1). Specific inhibitors of caspase-9 (z-LEHD-fmk), caspase-3 (z-DEVD-fmk) or pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk were added to cells 30 min before treatment with OMVs containing 100 ng of EHEC-Hly. Data are shown as means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. * Significantly increased (p<0.05) compared to control cells (unpaired Student's t test). (C, D) HBMEC (C) and Caco-2 cells (D) were incubated with TA50 or 8033 OMVs (100 ng of EHEC-Hly) or with TA51 or 8033c OMVs (20 µg of OMV protein) for 48 h or remained untreated (negative control). Cells treated with 1 µM staurosporin (Stauro) for 3 h served as a positive control. Presence of uncleaved PARP (116 kDa) and the PARP cleavage product (89 kDa) in cell lysates was determined using an immunoblot with anti-PARP antibody; anti-actin antibody was used as a loading control. The results are representative of two independent experiments. In accordance with activation of caspase-3, the poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), one of the major targets of caspase-3 in mammalian cells [32], was cleaved in HBMEC and Caco-2 cells treated with TA50 or 8033 OMVs (Figure 12C, 12D). EHEC-Hly-free TA51 and 8033c OMVs, which did not activate caspase-3 (Figure 12A, 12B), did not cleave PARP in any cell line (Figure 12C, 12D). Hence, translocation of EHEC-Hly to mitochondria and the resulting cytochrome c release into the cytosol activates caspase-9, but not caspase-8, and triggers the intrinsic apoptotic pathway.

EHEC-Hly triggers DNA fragmentation in HBMEC and Caco-2 cells

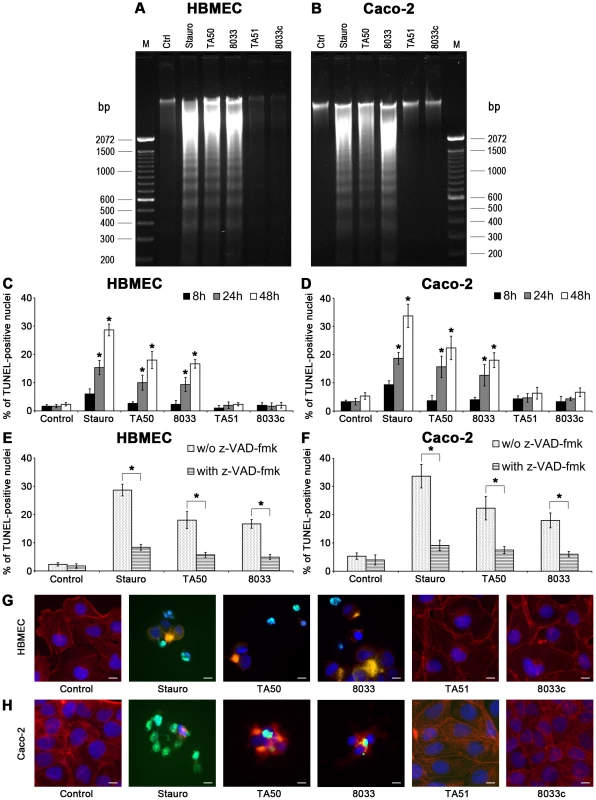

We further analyzed HBMEC and Caco-2 cells treated with TA50 or 8033 OMVs for DNA fragmentation, the signature of the apoptotic phenotype [29], [31], [33]. Each of the OMVs elicited a characteristic DNA ladder pattern resulting from internucleosomal DNA cleavage during apoptosis [33] in each cell line (Figure 13A, 13B). Similar DNA patterns were observed in cells treated with the apoptosis-inducing reagent staurosporin. In contrast, no DNA ladder appeared in cells treated with EHEC-Hly-free OMVs TA51 or 8033c (Figure 13A, 13B), indicating that EHEC-Hly triggers the mechanism(s) leading to DNA fragmentation.

Fig. 13. EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs cause DNA laddering and formation of TUNEL-positive nuclei.

(A, B) HBMEC (A) and Caco-2 cells (B) were incubated with EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs (TA50 or 8033; 100 ng of EHEC-Hly) or EHEC-Hly-free OMVs (TA51 or 8033c; 20 µg of OMV protein) for 48 h. Cellular DNA was separated on agarose gel and visualized after staining with Midori Green Advance. M, molecular size marker (100 bp DNA ladder). Untreated cells (Ctrl) were a negative control and cells treated with 1 µM staurosporin (Stauro) a positive control. (C, D) HBMEC (C) and Caco-2 cell (D) were incubated for the times indicated with TA50, 8033, TA51 or 8033c OMVs in the amounts shown above or with 1 µM staurosporin or remained untreated (control). After TUNEL reagent staining, the proportions of TUNEL-positive nuclei were determined by fluorescence microscopy and expressed as the percentage of total number of cells examined. Data are means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. * Significantly increased (p<0.05) compared to control cells (unpaired Student's t test). (E, F) HBMEC (E) and Caco-2 cells (F), either without or after pretreatment with pan-caspase inhibitior z-VAD-fmk were incubated for 48 h with TA50 or 8033 OMVs or with 1 µM staurosporin and the percentages of TUNEL-positive nuclei were determined as described above. Data are means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. * Significantly decreased (p<0.05) compared to non-pretreated cells (unpaired Student's t test). (G, H). Photomicrographs of TUNEL reagent-stained HBMEC (G) and Caco-2 cells (H) incubated for 48 h with the probes indicated or remained untreated (control). TUNEL-positive nuclei stain green, other nuclei blue (DAPI) and actin red (phalloidin-TRITC). Bars are 10 µm. DNA fragmentation in individual cells was visualized using TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase [TdT]-mediated dUTP nick end labeling) assay [34]. HBMEC and Caco-2 cells were exposed to TA50 or 8033 OMVs for 8 h to 48 h and the percentage of TUNEL-positive nuclei was determined microscopically. In each cell line, the percentage of TUNEL-positive nuclei increased over time and peaked after 48 h (Figure 13C, 13D). Pretreatment with the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk significantly reduced the percentage of TUNEL-positive nuclei (Figure 13E, 13F). In cells treated with EHEC-Hly-free TA51 or 8033c OMVs the percentage of TUNEL-positive nuclei remained at the basal level of untreated cells during the whole experiment (Figure 13C, 13D). A detailed microscopic analysis of HBMEC and Caco-2 cells treated with TA50 or 8033 OMVs (Figure 13G, 13H) demonstrated that in addition to TUNEL-positive nuclei, the cells displayed other typical morphological signs of apoptosis including fragmented and/or condensed nuclei and cytoplasmic reduction or loss. Thus, activation of caspase-9 induced by EHEC-Hly leads to apoptotic death of HBMEC and Caco-2 cells.

Discussion

OMVs ubiquitously shed by Gram-negative bacteria are emerging as a new, highly sophisticated mechanism for secretion and a simultaneous, coordinated and direct delivery of bacterial virulence factors into host cells [19], [20], [35]–[38]. OMVs, which contain bacterial toxins, adhesins, invasins, and immunomodulatory compounds are considered as bacterial weapons that attack the host tissues and assist bacterial pathogens to establish their colonization niches, impair host cellular functions, and modulate host defense [reviewed in 39–41]. We now demonstrate that OMV-associated EHEC-Hly irreversibly injures human microvascular endothelial and intestinal epithelial cells, which are key players in the pathogenesis of EHEC-mediated diseases. Our data support the model (Figure 14) that the toxin is internalized via OMVs by dynamin-dependent endocytosis and trafficked together with its carriers to endo-lysosomal compartments (Figure 14, Step 1). During endosomal acidification EHEC-Hly is separated from OMVs (Step 2), escapes from the lysosomes, most probably via its pore-forming activity towards the lysosomal membrane (Step 3), and targets mitochondria (Step 4). The presence of EHEC-Hly in mitochondria leads to a reduction of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential and release of cytochrome c to the cytosol (Step 5). Subsequent activation of caspase-9 triggers the apoptotic cell death.

Fig. 14. Model of intracellular trafficking and action of OMV-associated EHEC-Hly.

1. After its secretion by EHEC bacteria and association with OMVs, the OMV-associated EHEC-Hly is endocytosed by dynamin-dependent endocytosis and enters the endosomal compartments of target cells. 2. During endosome acidification via the H+-ATPase the neutral pH 7.4 of endosomes drops to pH 5.0, which induces separation of EHEC-Hly from OMVs. 3. The separated toxin plausibly interacts with the endosomal/lysosomal membrane and, as a pore-forming toxin, it damages lysosomal membrane by its pore-forming activity in order to release from lysosomes. As a consequence of the membrane damage, the proton gradient of lysosomes is disrupted leading to lysosomal pH increase. 4. EHEC-Hly released from lysosomes translocates by an unknown mechanism to mitochondria. 5. This results in cytochrome c release to the cytosol, which leads to activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 and apoptotic cell death. 6. Presence of the proton ATPase inhibitor BafA1 inhibits endosomal acidification and thus prevents the toxin to be separated from OMVs. As a consequence, EHEC-Hly is trapped in endosomes/lysosomes and cannot translocate into mitochondria. The figure was produced using Servier Medical Art. Our study provides the first evidence that EHEC-Hly, when it is delivered into the host cells via OMVs, targets mitochondria and acts pro-apoptotically. To our knowledge, EHEC-Hly is the first virulence factor in general and the first RTX toxin in particular, which employs OMVs for its intracellular delivery in order to subsequently hijack mitochondria. Although several other bacterial proteins target mitochondria and cause their dysfunction [42]–[51], these molecules enter cells by other, OMV-independent mechanisms including receptor-mediated intracellular delivery or cytosolic injection via the type III secretion system [43], [49], [52]–[55]. Hence, the OMV-mediated delivery represents a novel mechanism for a bacterial toxin to enter the host cells in order to subvert mitochondrial function thereby causing cell death.

In contrast to the previously reported lytic effect of free EHEC-Hly on microvascular endothelial cells [6], the OMV-associated EHEC-Hly does not lyse either HBMEC or Caco-2 cells, even though it causes hemolysis. One reason could be the difference between the dose of free EHEC-Hly which is required for efficient endothelial cell lysis (∼40 µg/ml) [6] and the amount of EHEC-Hly associated with OMVs (∼3 µg/ml). This dose-dependent mechanism of cytotoxicity of EHEC-Hly resembles that of other RTX toxins, which in high doses lyse the target cells via their pore-forming activity, whereas in low, sublytic doses they cause a variety of other biological effects including apoptosis [45], [54], [56]–[62]. Although the mechanism underlying this phenomenon is unknown, differential extents of perturbation of mitochondrial function, which is the key factor determining the route of cell death (i.e. necrosis versus apoptosis), after exposure to the high and to the low toxin doses could play a role [54], [63]. We hypothesize that OMV-associated EHEC-Hly, rather than free EHEC-Hly, may be the pathophysiologically relevant form of the toxin because: i) free EHEC-Hly rapidly and irreversibly loses biological activity in vitro at 37°C [64] making it questionable if the toxin can reach host cells in active form in vivo during infection; ii) free EHEC-Hly has a high affinity to OMVs leading to rapid OMV association (Figure 1B–1E) [16], which increases its stability and prolongs its biological activity [16]; iii) the OMV-associated EHEC-Hly injures the cells involved in the pathogenesis of EHEC-mediated diseases.

OMV-associated EHEC-Hly is internalized via OMVs and the toxin itself is not required for OMV internalization involving dynamin-dependent and clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Figure 4A, 4B, 4D). This is similar to OMVs from Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, which also associate with target cells regardless of the presence of their cargo toxins [19], [65]. In contrast, the cell binding and internalization of OMVs containing heat labile enterotoxin (LT) of enterotoxigenic E. coli [20] or cholera toxin [37] occur via interactions of the OMV-associated toxins with their specific cell surface receptor (GM1 in both cases) and are therefore toxin-dependent [20], [37]. Interestingly, the dispensability of EHEC-Hly for adherence and internalization of EHEC-Hly-harboring OMVs by HBMEC and Caco-2 cells is in strong contrast with its mandatory requirement for interaction of EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs with erythrocytes, in which EHEC-Hly functions both as a cell-binding protein and a hemolysin [16]. This indicates that EHEC-Hly-containing OMVs use different mechanisms in their interactions with erythrocytes and nucleated cells and that other OMV components than EHEC-Hly are involved in association of such OMVs with HBMEC and Caco-2 cells. Potential candidates for such molecules are various OMV membrane proteins and/or LPS [21], [66], [67]. Mechanism(s) by which EHEC-Hly might contribute to OMV cellular binding/internalization as suggested by our flow cytometric analyses (Figure 3A, 3B) need(s) to be determined in future studies. A supportive role in uptake of OMVs from Helicobacter pylori by gastric cells has also been proposed for vacuolating toxin A (VacA) [21].

Interestingly, we observed that endosomal acidification is an essential mechanism for EHEC-Hly to separate from OMVs and escape from lysosomes, which can be blocked by BafA1 treatment (Figure 14, Step 6). As a paradox, we never observed EHEC-Hly colocalized with acidified lysosomes stained by lysotracker (Figure 10C, Figure S6B). However, we believe that EHEC-Hly as a pore-forming toxin, once separated from OMVs by a pH drop, disrupts the endo-lysosomal membrane, releasing the toxin and protons from lysosomes (Figure 14, Step 3). As a consequence of membrane damage, the proton gradient of lysosomes is disrupted, which leads to lysosomal pH increase and thus excludes detection of functional lysosomes by lysotracker. This hypothesis is supported by the fact, that after EHEC-Hly had been released from lysosomes, their function was restored (Figure 10B).

In contrast to its OMV-mediated intracellular delivery, translocation of EHEC-Hly from lysosomes to mitochondria does not require OMVs and is likely to be related to specific characteristics of the toxin itself. A putative mitochondrial targeting signal (MTS) was recently identified in the N-terminal region of EHEC-Hly sequence [50], though the ability of the toxin to target mitochondria was not investigated. MTSs are also present in N-terminal regions of secreted proteins EspF [47], [68] and Map [48], [49] of enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), leukotoxin of Mannheimia hemolytica [50], and ApxII exotoxin of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae [50] and direct these proteins to mitochondria [47], [48], [50] likely exploiting the endogenous import machinery for nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins [42], [43], [69]. The presence of MTS in the EHEC-Hly molecule thus provides a mechanistical basis for our evidence of the toxin's mitochondria-targeting activity.

The ability of EHEC-Hly to induce translocation of cytochrome c from mitochondria to the cytosol and decrease of ΔΨm suggests that the toxin permeabilizes the outer and the inner mitochondrial membranes. However, the mechanism(s) of interaction of EHEC-Hly with mitochondria is presently unknown. Two major pathways involved in mitochondrial sorting of bacterial virulence factors possessing the MTS have been identified [42], [43]. Proteins that enter the intermembrane space translocate via the translocase of the outer membrane (TOM) complex, whereas proteins that integrate into the inner mitochondrial membrane or enter the mitochondrial matrix interact with the translocase of the inner membrane (TIM) complex [42]. EspF and Map enter mitochondria via the TOM complex and are subsequently sorted to the mitochondrial matrix via the TIM complex [42], [48], [68]. Because the TOM machinery is the most common pathway for mitochondrial delivery of MTS-possessing proteins [42], [69], the presence of MTS in the EHEC-Hly molecule suggests that EHEC-Hly might be imported in mitochondria via the TOM complex. Moreover, the presence of a putative cleavage site in the EHEC-Hly MTS [50], which is also present in the EspP and Map MTSs [47]–[49] and is indicative of proteins' import across the mitochondrial membranes [69] suggests that EHEC-Hly may be transported into the mitochondrial matrix [50]. However, as for many other bacterial virulence factors that target mitochondria [42], the mitochondrial sorting route of EHEC-Hly and the mechanism of the mitochondrial injury are not yet determined.

The intracellular trafficking of OMV-delivered EHEC-Hly and the development of the EHEC-Hly-mediated apoptotic effects are delayed compared to such effects of other mitochondria-targeting virulence factors, which are delivered into the host cells as free proteins via a specific receptor or via the type III secretion system [52], [53]. Whereas EHEC-Hly was first detected in mitochondria after 16 h (Figure 5A), when also cytochrome c translocation and ΔΨm reduction were observed (Figure 11), leukotoxin of M. hemolytica colocalized with mitochondria of BL-3 cells already after 30 min of incubation [46] and cytochrome c cytosolic translocation, ΔΨm decrease and cell death occurred between 4 h and 6 h [45]. Similarly, sorting of EspF to mitochondria, loss of ΔΨm and cytosolic translocation of cytochrome c were observed after 1 h of incubation of cells with EspF-producing EPEC strains [47]. The delayed apoptotic effects of OMV-associated EHEC-Hly are in accordance with the delayed hemolysis caused by this toxin form (Figure S1E and [16]), which contrasts with the rapid hemolysis caused by free EHEC-Hly [16]. We hypothesized [16] that the delayed hemolytic effect of OMV-associated EHEC-Hly is due to structural rearrangement of the OMV-associated toxin before it can bind and lyse erythrocytes. Because OMV/EHEC-Hly complexes internalize rapidly (Figure 3A, 3B), the delay in the onset of apoptotic effects may be due to: i) the intracellular trafficking of OMV-associated EHEC-Hly to endo-lysosomes; ii) the endosomal acidification-dependent separation of EHEC-Hly from OMVs and its putative conformational change, which is plausibly required for its ability to injure the lysosomal membrane and the release from lysosomes; and iii) the translocation of the toxin to mitochondria and disruption of the mitochondrial function. The proposed conformational changes may lead to the exposure of the pore-forming region located in RTX toxins in their N-terminal region [54]. This pore-forming region is likely to be masked in OMV-associated EHEC-Hly during contact with cellular membrane resulting in the failure of this toxin form to cause cell lysis.

In conclusion, EHEC-Hly delivered into the host cells via OMVs targets mitochondria and triggers apoptosis of human microvascular endothelial and intestinal epithelial cells, representing a novel mechanism for the toxin's involvement in the EHEC pathogenesis. Mechanisms of EHEC-Hly-mediated mitochondrial injury warrant further investigations.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains

TA50 is E. coli K-12 strain MC1061 transformed with pBlueskript KS II(+) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Ca., USA) harboring the EHEC-hlyCABD operon from an HUS-associated E. coli O26:H11 [16]. TA51 (E. coli K-12 MC1061 transformed with pBlueskript KS II(+) alone) served as a vector control. Strain 8033 is an EHEC O103:H2 isolate from a patient with HUS that lost the Stx-encoding bacteriophage and Stx production [14]. The strain was selected for the study because of its strong enterohemolytic phenotype (Figure 1A) and because the absence of Stx prevents an interference of cellular effects of OMV-associated EHEC-Hly with those of Stx. Strain 8033c (cured) is a spontaneous derivative of strain 8033, which lost the EHEC-Hly-encoding gene and hereby EHEC-Hly production during in vitro passaging.

Isolation of OMVs, protein concentration and EHEC-Hly content

OMVs were isolated as described previously [16] with slight modifications. Briefly, bacterial strains were grown in 500 ml of LB broth (supplemented with 100 µg/ml of ampicillin for strains TA50 and TA51) for 15 h (37°C, 180 rpm). Bacteria were removed by centrifugation (9,800× g, 10 min, 4°C) and supernatants were filtered using Stericup filters (pore size 0.22 µm) (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). OMVs were collected from the filtered supernatants by ultracentrifugation (235,000× g, 2 h, 4°C) in a 45 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany) and the OMV pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of 20 mM TRIS-HCl (pH 8.0). Aliquots of OMV preparations were inoculated on blood agar to verify their sterility. Protein concentration in OMV preparations was determined using the Roti-Nanoquant reagent (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) and was 604±123 µg/ml, 580±161 µg/ml, 610±149 µg/ml, and 572±108 µg/ml in OMVs TA50, TA51, 8033, and 8033c, respectively (means ± standard deviations from protein determinations in 10 different OMV preparations from each strain). To quantify the amount of EHEC-Hly in OMVs, 9 µl of TA50 and 8033 OMVs and their serial dilutions (1∶10 to 1∶640), and 9 µl of the same dilutions of purified free EHEC-Hly from TA50 prepared as described previously [6] (protein concentration 30.5 µg/ml) were separated using 10% sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotted using anti-EHEC-Hly antibody [70] and alkaline-phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany). Signals were developed using a nitro blue tetrazolium chloride/5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolyl phosphate, toluidine salt (NBT/BCIP) substrate (Roche, Mannheim, Germany); signal intensities were determined using densitometry (Quantity One software, BioRad, Munich, Germany). The amounts of EHEC-Hly in TA50 and 8033 OMV preparations (µg/ml) were calculated based on a calibration curve generated from dilutions of the purified EHEC-Hly, expressed as means ± standard deviations from measurements of 10 different batches of each OMV preparation, and recalculated for 1 mg of total OMV protein. To confirm the validity of this system, in particular to determine if separation of OMV-associated EHEC-Hly in SDS-PAGE gel and its transfer to a blotting membrane are similar to those of free EHEC-Hly, we mixed EHEC-Hly-free OMVs from strains TA51 and 8033c (∼5.5 µg of OMV protein identical to the protein amounts in 9 µl of OMVs TA50 and 8033) with 3 µg/ml of free EHEC-Hly (the amount of EHEC-Hly identified in TA50 and 8033 OMVs) and incubated the mixtures for 16 h (37°C, 180 rpm) during which time a complete binding of EHEC-Hly to OMVs was expected [16]. The samples were then ultracentrifuged (235,000× g, 2 h, 4°C) and the pellets (TA51 and 8033c OMVs enriched with free EHEC-Hly) were tested for their EHEC-Hly contents in parallel with TA50 and 8033 OMVs as described above, and the EHEC-Hly amounts in the OMVs were determined based on the calibration curve of free EHEC-Hly (a representative experiment is shown in Figure S1A). The absence of any residual free EHEC-Hly in supernatants of EHEC-Hly-enriched TA51 and 8033c OMVs after ultracentrifugation was confirmed using immunoblotting with anti-EHEC-Hly antibody, demonstrating that the entire amount of free EHEC-Hly added bound to OMVs during 16 h.

Kinetics of OMV and EHEC-Hly production and EHEC-Hly-OMV association