-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Balancing Stability and Flexibility within the Genome of the Pathogen

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 9(12): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003764

Category: Pearls

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003764Summary

article has not abstract

Over the last 30 years, the growing immunocompromised population has created fertile ground for opportunistic pathogens, particularly those from the Kingdom Fungi. While the range of fungal species causing infections is increasing, there remain three key culprits [1]. Firstly, the ascomycete yeast Candida albicans is responsible for the greatest number of fungal infections, particularly those acquired in a hospital setting. Secondly, the mould Aspergillus fumigatus, also an ascomycete, has become a cause of high mortality, particularly in transplant patients and those with hematological diseases. Finally, the basidiomycete yeast Cryptococcus neoformans has become a scourge of AIDS patients, accounting for an estimated 624,000 deaths per annum [2]. The genomes of C. albicans and A. fumigatus were published in 2004 [3] and 2005 [4] respectively, and the C. neoformans var. neoformans genome was published in 2005 [5]. Excitingly, the var. grubii genome, the variety responsible for the majority of infections [6], is nearing publication [G. Janbon, personal communication]. The analysis of these C. neoformans sequences, coupled with earlier karyotypic analyses, has uncovered a paradox: a pathogen with a highly stable genome that appears to have the capacity to undergo gross chromosomal rearrangement when required. This “flexible stability” could potentially represent an adaptive strategy supporting the opportunistic nature of this important pathogen.

Early Insights into the Cryptococcus Genome

The earliest genomic studies in C. neoformans came from analysis of electrophoretic karyotype [7]. Surveys of the pathogen by John Perfect's group described variation in chromosome size and number between isolates, suggesting the genome was highly flexible and tolerant of rearrangement [8]. Extensive karyotyping by Teun Boekhout's laboratory followed, confirming the extent of the variability within the population and demonstrating a role for the sexual cycle in generating karyotypic diversity within the species [9], [10]. Excitingly, this early work suggested a link between genomic change and infection; in some instances, serial clinical isolates exhibited changes in chromosome sizes between infections, as did half of strains passaged through a mouse model of infection [11]. Such high frequency of variability strongly suggested these changes contribute to adaptability under selective pressure encountered in the host, consistent with the observation that these strains often exhibit changes in virulence-associated phenotypes [12], [13].

The nature of the gross chromosomal changes leading to such karyotypic diversity was extremely difficult to elucidate in the pregenomics era. Our first insights into C. neoformans chromosomal rearrangement came from study of the evolution of the mating-type (MAT) locus. C. neoformans has a bipolar mating-type system consisting of MATα and MATa alleles that encode sex-determining homeodomain transcription factors, pheromones, and pheromone receptors. Over a decades' work performed by several laboratories gradually revealed that in this pathogen the MAT locus is large. In comparison to the ∼2.5 kb of S. cerevisiae [14], early estimates of MAT size were between 35 and 75 kb [15], [16], and finally yielded sizes of 105 and 117 kb for var. neoformans α and a respectively, and 103 and 127 kb for var. grubii [17]. Phylogenetic and synteny analyses support the locus having evolved through a translocation bringing ancient homeodomain and pheromone/pheromone receptor loci together. Subsequent inversions, gene conversions and transposon accumulation resulted in a highly divergent gene order within the locus, in contrast with the synteny of the flanking regions [17], [18].

Cryptococcus Enters the Genomic Era

The study of MAT provided the groundwork for understanding the C. neoformans genome and how it is evolving, the next stage of which began with the generation of linkage maps outlining the genomic architecture of the species [19], [20] and supporting the subsequent publication of the full genome sequence of C. neoformans var. neoformans in 2005 [5]. Sequencing of two related strains, JEC21 and B-3501A, revealed a 20 Mb haploid genome consisting of 14 chromosomes ranging in size from 762 kb to 2.3 Mb and each containing a regional centromere in the form of a transposon cluster. Over 6,500 genes were identified with an average size of 1.9 kb distributed over an average of 6.3 exons. Transposons represented ∼5% of the genome and clustered not only at regional centromeres but also adjacent to the rDNA repeats and within MAT.

During assembly, an anomaly was observed: only 13 chromosomes were evident for JEC21, one of which contained two transposon clusters rather than the single predicted centromeric clusters on the other 12. Interrogation of this unusual assembly by Joe Heitman's group revealed a unique genomic event [21]. It became apparent that during construction of the JEC20/JEC21 congenic laboratory pair, a telomere-telomere fusion had occurred followed by breakage of the dicentric intermediate and duplication of a 62 kb fragment containing 22 genes. While it is unknown whether this event was a result of a recombination between subtelomeric transposable elements or of nonhomologous end joining, it did further indicate a propensity for large-scale genomic events in C. neoformans.

The release of the genome for C. neoformans var. neoformans, as with all important species, heralded a proliferation of comparative genomic analyses. The initial comparison was with the var. grubii type strain H99, the genome of which had been available in draft format since 2001 as a collaboration between Duke University and the Broad Institute. The genomes of these closely related varieties share 85–90% sequence identity and are largely colinear [22], although this colinearity breaks down in the subtelomeric regions [23], centromeres, and MAT. In contrast to the early karyotypic analyses, such similarity supports a model of high genome stability since divergence of the varieties an estimated 18.5 million years ago [24].

During comparisons of var. neoformans and var. grubii, Fred Dietrich and colleagues discovered a 40 kb region containing 14 genes where the two varieties were almost identical (98.5% similar), which was dubbed the Identity Island [22]. Significantly this region was located on nonhomologous chromosomes: chromosome 6 in var. neoformans and 5 in var. grubii. Through comparison with C. gattii, it was determined that the Island had introgressed into var. neoformans from var. grubii, explaining the high nucleotide identity. Such an event could occur during formation of hybrid diploids [25]. Since the acquisition of the Identity Island the native copy of the region has been mostly eradicated in var. neoformans. Interestingly, JEC21 also contains a duplication of a 14 kb segment of the Identity Island.

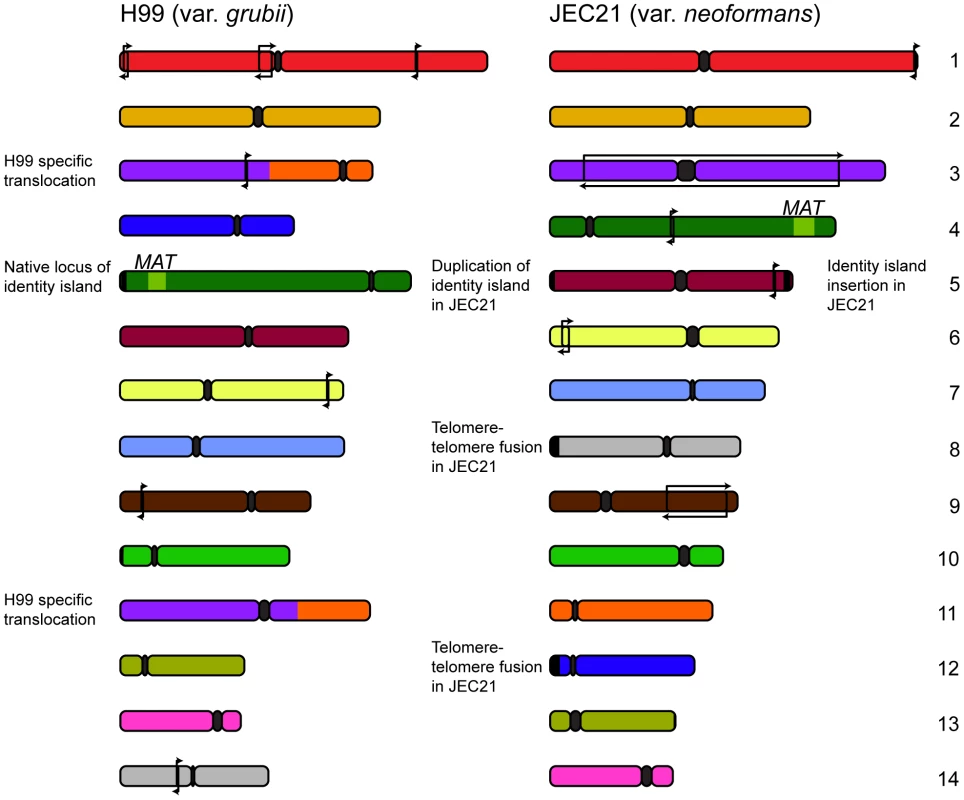

Further comparative studies by Sun and Xu revealed more insights into the evolutionary changes in these varieties' genomes, describing a number of small rearrangements [26]. The source of these changes was implied by the presence of transposable elements in association with around half of the events. Transposons are a principal source of genomic rearrangement in S. cerevisiae [27], a trend that appears to also hold true in C. neoformans. Further analysis conducted by our own group permitted the designation of each of the rearrangements occurring outside MAT or the centromeres as either var. grubii or var. neoformans specific [28] (Figure 1). Given the previously observed karyotypic variability, the relatively small number of changes fixed within the two varieties over millions of years is somewhat astonishing.

Fig. 1. Genomic comparisons between var. grubii and var. neoformans reveal relatively few rearrangements.

Since divergence 18.5 million years ago, the two varieties of C. neoformans have maintained a largely syntenic genome structure with only a few inversions specific to each variety (marked with arrows). Comparisons also uncovered several strain-specific events: a translocation in the case of the var. grubii type strain H99 and telomere-telomere fusion and introgression in the case of var. neoformans JEC21. In addition to these small events, a translocation involving chromosomes 3 and 11 was found to be unique to the var. grubii type strain H99 [26]. Sequencing across the translocation breakpoint on chromosomes 3 and 11 identified a 3 bp microhomology consistent with the event arising via nonhomologous end joining [28]. Significantly, this sole karyotypically observable event was found within a clinically derived lineage, suggesting this type of selective pressure as a necessary precursor.

Microevolution and Beyond

While these sequence-based studies relied on data from just a few strains, the advent of more high-throughput genomic technologies made larger-scale studies possible. Initially, comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) by Jim Kronstad and colleagues uncovered a significant number of previously unobserved amplifications and deletions in comparisons within both var. neoformans and var. grubii [29]. Most importantly, CGH uncovered a propensity for aneuploidy within C. neoformans, and this characteristic was found to be responsible for the intrinsic heteroresistance to the widely used antifungal fluconazole characterised by June Kwon-Chung's group [30], [31]. Resistant strains were found to have duplications of chromosome 1 (all strains) in addition to chromosomes 4, 10, and 14 in some strains [30]. Aneuploid strains were also found in freshly obtained clinical isolates and could be generated via passage through mice [32].

Key to the observations of karyotypic variability of clinical isolates, aneuploidy in association with heteroresistance and infection, and translocations specific to clinical lineages, is the application of selective pressure encountered in the host. This situation is similar to that seen in C. albicans, where genomic reorganization has been proposed as a mechanism of coping with selective pressure [33]. However, selective pressure is not only encountered in the host. What then is behind the overall stability of the genome? One possibility is a requirement for retention of a sexual cycle by the species. Spores produced as a result of matings enable dispersal in times of stress and are also infectious [34], [35]. Strains with genomes too far from the norm could be filtered out by this process either through sexual isolation, as seen in the separation of C. gattii [36], or through disruption of key genes required for mating. Increased genomic reorganization in asexual species such as C. glabrata, including the generation of novel chromosomes, supports this idea [37].

Sex in nature between opposite mating types of C. neoformans is known to occur in some populations [6]. However, the overwhelming global predominance of the α mating type of var. grubii means it is a parasexual cycle between isolates of the same mating type that is most relevant, and evidence of recombination within single-sex subpopulations supports its occurrence in the environment [38], [39]. Laboratory-passaged isolates often lose their ability to mate, indicating the requirement for selective pressure to maintain the process and therefore some associated advantage [40]. One advantage to a predominantly single-sex population could be the generation of novel diversity, as opposed to the mixing of existing diversity, recently demonstrated by Joe Heitman and colleagues to be a result of homothallic mating [41]. Thus sex not only permits dispersal but is a source of genome flexibility in closely related strains.

Genome resequencing projects are the next step toward fully understanding the balance between stability and flexibility within the genome of C. neoformans. This approach enables the detailed comparison of multiple isolates from a single patient and thus has the potential to fully assess the impact of long-term culture of C. neoformans in the human body on genomic variability. The first analysis of this type carried out by our laboratory compared two strains obtained from a female AIDS patient 77 days apart and uncovered aneuploidy of chromosome 12: two copies of the entire chromosome in the first isolate and one complete copy plus two additional copies of the left arm in the later isolate, observable as a mini-chromosome during pulsed-field gel electrophoresis [42]. The first isolate also contained a large inversion. Analysis at the nucleotide level revealed the isolates were separated by three SNPs and two indels, one of which leads to loss of a predicted transcriptional regulator causing changes in carbon source utilization and virulence. For the first time, this study provided evidence of large-scale plasticity between very closely related isolates. Now what is required is the confirmation of to what extent this flexibility is induced by the host environment.

The power of genome resequencing projects lies in their ability to be performed on an increasingly large scale. Bulk analysis of sequential clinical isolates will overcome the inevitable difficulties associated with dealing with the uncontrolled experimental environment of the human host and permit the designation of a typical level of genome flexibility that can be incorporated into the definition of mixed infection [43]. In addition, controlled mouse experiments coupled with sequencing will provide the required temporal data to associate genome changes with infection. The extensively curated annotations of var. grubii, now available to the community via the Broad Institute as a prelude to the highly anticipated genome paper, complete the foundation on which this future work will build.

Zdroje

1. PfallerMA, PappasPG, WingardJR (2006) Invasive fungal pathogens: current epidemiological trends. Clin Infect Dis 43: S3–S14.

2. ParkBJ, WannemuehlerKA, MarstonBJ, GovenderN, PappasPG, et al. (2009) Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS 23 : 525–530.

3. JonesT, FederspielNA, ChibanaH, DunganJ, KalmanS, et al. (2004) The diploid genome sequence of Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 : 7329–7334.

4. NiermanWC, PainA, AndersonMJ, WortmanJR, KimHS, et al. (2005) Genomic sequence of the pathogenic and allergenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Nature 438 : 1151–1156.

5. LoftusBJ, FungE, RoncagliaP, RowleyD, AmedeoP, et al. (2005) The genome of the basidiomycetous yeast and human pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Science 307 : 1321–1324.

6. LitvintsevaAP, ThakurR, VilgalysR, MitchellTG (2006) Multilocus sequence typing reveals three genetic subpopulations of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii (Serotype A), including a unique population in Botswana. Genetics 172 : 2223–2238.

7. PolacheckI, LebensGA (1989) Electrophoretic karyotype of the pathogenic yeast Cryptococcus neoformans. J Gen Microbiol 135 : 65–71.

8. PerfectJR, KetabchiN, CoxGM, IngramCW, BeiserCL (1993) Karyotyping of Cryptococcus neoformans as an epidemiologic tool. J Clin Microbiol 31 : 3305–3309.

9. BoekhoutT, van BelkumA, LeendersACAP, VerbrughHA, MukamurangwaP, et al. (1997) Molecular typing of Cryptococcus neoformans: taxonomic and epidemiological aspects. Int J Syst Bacteriol 47 : 432–442.

10. BoekhoutT, van BelkumA (1997) Variability of karyotypes and RAPD types in genetically related strains of Cryptococcus neoformans. Curr Genet 32 : 203–208.

11. FriesBC, ChenFY, CurrieBP, CasadevallA (1996) Karyotype instability in Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J Clin Microbiol 34 : 1531–1534.

12. CherniakR, MorrisLC, BelayT, SpitzerED, CasadevallA (1995) Variation in the structure of the glucuronoxylomannan in isolates from patients with recurrent cryptococcal meningitis. Infect Immun 63 : 1899–1905.

13. CurrieB, SanatiH, IbrahimAS, EdwardsJE, CasadevallA, et al. (1995) Sterol compositions and susceptibilities to amphotericin B of environmental Cryptococcus neoformans isolates are changed by murine passage. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39 : 1934–1937.

14. AstellCR, Ahlstrom-JonassonL, SmithM, TatchellK, NasmythKA, et al. (1981) The sequence of the DNAs coding for the mating-type loci of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 27 : 15–23.

15. MooreTDE, EdmanJC (1993) The α-mating type locus of Cryptococcus neoformans contains a peptide pheromone gene. Mol Cell Biol 13 : 1962–1970.

16. WickesBL, EdmanU, EdmanJC (1997) The Cryptococcus neoformans STE12α gene: a putative Saccharomyces cerevisiae STE12 homologue that is mating type specific. Mol Microbiol 26 : 951–960.

17. LengelerKB, FoxDS, FraserJA, AllenA, ForresterK, et al. (2002) Mating-type locus of Cryptococcus neoformans: a step in the evolution of sex chromosomes. Eukaryot Cell 1 : 704–718.

18. FraserJA, DiezmannS, SubaranRL, AllenA, LengelerKB, et al. (2004) Convergent evolution of chromosomal sex-determining regions in the animal and fungal kingdoms. PLoS Biol 2: e384 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020384

19. ScheinJE, TangenKL, ChiuR, ShinH, LengelerKB, et al. (2002) Physical maps for genome analysis of serotype A and D strains of the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Genome Res 12 : 1445–1453.

20. MarraRE, HuangJC, FungE, NielsenK, HeitmanJ, et al. (2004) A genetic linkage map of Cryptococcus neoformans variety neoformans serotype D (Filobasidiella neoformans). Genetics 167 : 619–631.

21. FraserJA, HuangJC, Pukkila-WorleyR, AlspaughJA, MitchellTG, et al. (2005) Chromosomal translocation and segmental duplication in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell 4 : 401–406.

22. KavanaughLA, FraserJA, DietrichFS (2006) Recent evolution of the human pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans by intervarietal transfer of a 14-gene fragment. Mol Biol Evol 23 : 1879–1890.

23. ChowEWL, MorrowCA, DjordjevicJT, WoodIA, FraserJA (2012) Microevolution of Cryptococcus neoformans driven by massive tandem gene amplification. Mol Biol Evol 29 : 1987–2000.

24. XuJP, VilgalysR, MitchellTG (2000) Multiple gene genealogies reveal recent dispersion and hybridization in the human pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Ecol 9 : 1471–1481.

25. LengelerKB, CoxGM, HeitmanJ (2001) Serotype AD strains of Cryptococcus neoformans are diploid or aneuploid and are heterozygous at the mating-type locus. Infect Immun 69 : 115–122.

26. SunS, XuJ (2009) Chromosomal rearrangements between serotype A and D strains in Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS ONE 4: e5524 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005524

27. DunhamMJ, BadraneH, FereaT, AdamsJ, BrownPO, et al. (2002) Characteristic genome rearrangements in experimental evolution of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 : 16144–16149.

28. MorrowCA, LeeIR, ChowEWL, OrmerodKL, GoldingerA, et al. (2012) A unique chromosomal rearrangement in the Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii type strain enhances key phenotypes associated with virulence. mBio 3: e00310–00311.

29. HuG, LiuI, ShamA, StajichJE, DietrichFS, et al. (2008) Comparative hybridization reveals extensive genome variation in the AIDS-associated pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Genome Biol 9: R41.

30. SionovE, LeeH, ChangYC, Kwon-ChungKJ (2010) Cryptococcus neoformans overcomes stress of azole drugs by formation of disomy in specific multiple chromosomes. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000848 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000848

31. SionovE, ChangYC, GarraffoHM, Kwon-ChungKJ (2009) Heteroresistance to fluconazole in Cryptococcus neoformans is intrinsic and associated with virulence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53 : 2804–2815.

32. HuG, WangJ, ChoiJ, JungWH, LiuI, et al. (2011) Variation in chromosome copy number influences the virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans and occurs in isolates from AIDS patients. BMC Genomics 12 : 526.

33. SelmeckiA, ForcheA, BermanJ (2010) Genomic plasticity of the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell 9 : 991–1008.

34. VelagapudiR, HsuehYP, Geunes-BoyerS, WrightJR, HeitmanJ (2009) Spores as infectious propagules of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun 77 : 4345–4355.

35. GilesSS, DagenaisTRT, BottsMR, KellerNP, HullCM (2009) Elucidating the pathogenesis of spores from the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun 77 : 3491–3500.

36. D'SouzaCA, KronstadJW, TaylorG, WarrenR, YuenM, et al. (2011) Genome variation in Cryptococcus gattii, an emerging pathogen of immunocompetent hosts. mBio 2: e00342–00310.

37. PolakovaS, BlumeC, ZarateJA, MentelM, Jorck-RambergD, et al. (2009) Formation of new chromosomes as a virulence mechanism in yeast Candida glabrata. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 : 2688–2693.

38. BuiT, LinX, MalikR, HeitmanJ, CarterD (2008) Isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans from infected animals reveal genetic exchange in unisexual, α mating type populations. Eukaryot Cell 7 : 1771–1780.

39. LinXR, HullCM, HeitmanJ (2005) Sexual reproduction between partners of the same mating type in Cryptococcus neoformans. Nature 434 : 1017–1021.

40. XuJP (2002) Estimating the spontaneous mutation rate of loss of sex in the human pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Genetics 162 : 1157–1167.

41. NiM, FeretzakiM, LiW, Floyd-AveretteA, MieczkowskiP, et al. (2013) Unisexual and heterosexual meiotic reproduction generate aneuploidy and phenotypic diversity de novo in the yeast Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Biol 11: e1001653 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001653

42. OrmerodKL, MorrowCA, ChowEWL, LeeIR, ArrasSDM, et al. (2013) Comparative genomics of serial isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans reveals gene associated with carbon utilization and virulence. G3 (Bethesda) 3 : 675–686.

43. Desnos-OllivierM, PatelS, SpauldingAR, CharlierC, Garcia-HermosoD, et al. (2010) Mixed infections and in vivo evolution in the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. mBio 1: e00091–00010.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Parental Transfer of the Antimicrobial Protein LBP/BPI Protects Eggs against Oomycete InfectionsČlánek Immune Therapeutic Strategies in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Virus or Inflammation Control?Článek Coronaviruses as DNA Wannabes: A New Model for the Regulation of RNA Virus Replication FidelityČlánek CRISPR-Cas Immunity against Phages: Its Effects on the Evolution and Survival of Bacterial PathogensČlánek The Cyst Wall Protein CST1 Is Critical for Cyst Wall Integrity and Promotes Bradyzoite PersistenceČlánek The Malarial Serine Protease SUB1 Plays an Essential Role in Parasite Liver Stage Development

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 12- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Choroby jater v ordinaci praktického lékaře – význam jaterních testů

- Diagnostický algoritmus při podezření na syndrom periodické horečky

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Host Susceptibility Factors to Bacterial Infections in Type 2 Diabetes

- LysM Effectors: Secreted Proteins Supporting Fungal Life

- Influence of Mast Cells on Dengue Protective Immunity and Immune Pathology

- Innate Lymphoid Cells: New Players in IL-17-Mediated Antifungal Immunity

- Cytoplasmic Viruses: Rage against the (Cellular RNA Decay) Machine

- Balancing Stability and Flexibility within the Genome of the Pathogen

- The Evolution of Transmissible Prions: The Role of Deformed Templating

- Parental Transfer of the Antimicrobial Protein LBP/BPI Protects Eggs against Oomycete Infections

- Host Defense via Symbiosis in

- Regulatory Circuits That Enable Proliferation of the Fungus in a Mammalian Host

- Immune Therapeutic Strategies in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Virus or Inflammation Control?

- Burning Down the House: Cellular Actions during Pyroptosis

- Coronaviruses as DNA Wannabes: A New Model for the Regulation of RNA Virus Replication Fidelity

- CRISPR-Cas Immunity against Phages: Its Effects on the Evolution and Survival of Bacterial Pathogens

- Combining Regulatory T Cell Depletion and Inhibitory Receptor Blockade Improves Reactivation of Exhausted Virus-Specific CD8 T Cells and Efficiently Reduces Chronic Retroviral Loads

- Shaping Up for Battle: Morphological Control Mechanisms in Human Fungal Pathogens

- Identification of the Virulence Landscape Essential for Invasion of the Human Colon

- Nodular Inflammatory Foci Are Sites of T Cell Priming and Control of Murine Cytomegalovirus Infection in the Neonatal Lung

- Hepatitis B Virus Disrupts Mitochondrial Dynamics: Induces Fission and Mitophagy to Attenuate Apoptosis

- Mycobacterial MazG Safeguards Genetic Stability Housecleaning of 5-OH-dCTP

- Systematic MicroRNA Analysis Identifies ATP6V0C as an Essential Host Factor for Human Cytomegalovirus Replication

- Placental Syncytium Forms a Biophysical Barrier against Pathogen Invasion

- The CD8-Derived Chemokine XCL1/Lymphotactin Is a Conformation-Dependent, Broad-Spectrum Inhibitor of HIV-1

- Cyclin A Degradation by Primate Cytomegalovirus Protein pUL21a Counters Its Innate Restriction of Virus Replication

- Genome-Wide RNAi Screen Identifies Novel Host Proteins Required for Alphavirus Entry

- Zinc Sequestration: Arming Phagocyte Defense against Fungal Attack

- The Cyst Wall Protein CST1 Is Critical for Cyst Wall Integrity and Promotes Bradyzoite Persistence

- Biphasic Euchromatin-to-Heterochromatin Transition on the KSHV Genome Following Infection

- The Malarial Serine Protease SUB1 Plays an Essential Role in Parasite Liver Stage Development

- HIV-1 Vpr Accelerates Viral Replication during Acute Infection by Exploitation of Proliferating CD4 T Cells

- A Human Torque Teno Virus Encodes a MicroRNA That Inhibits Interferon Signaling

- The ArlRS Two-Component System Is a Novel Regulator of Agglutination and Pathogenesis

- An In-Depth Comparison of Latent HIV-1 Reactivation in Multiple Cell Model Systems and Resting CD4+ T Cells from Aviremic Patients

- Enterohemorrhagic Hemolysin Employs Outer Membrane Vesicles to Target Mitochondria and Cause Endothelial and Epithelial Apoptosis

- Overcoming Antigenic Diversity by Enhancing the Immunogenicity of Conserved Epitopes on the Malaria Vaccine Candidate Apical Membrane Antigen-1

- The Type-Specific Neutralizing Antibody Response Elicited by a Dengue Vaccine Candidate Is Focused on Two Amino Acids of the Envelope Protein

- Tmprss2 Is Essential for Influenza H1N1 Virus Pathogenesis in Mice

- Signatures of Pleiotropy, Economy and Convergent Evolution in a Domain-Resolved Map of Human–Virus Protein–Protein Interaction Networks

- Interference with the Host Haemostatic System by Schistosomes

- RocA Truncation Underpins Hyper-Encapsulation, Carriage Longevity and Transmissibility of Serotype M18 Group A Streptococci

- Gene Fitness Landscapes of at Important Stages of Its Life Cycle

- Phagocytosis Escape by a Protein That Connects Complement and Coagulation Proteins at the Bacterial Surface

- t Is a Structurally Novel Crohn's Disease-Associated Superantigen

- An Increasing Danger of Zoonotic Orthopoxvirus Infections

- Myeloid Dendritic Cells Induce HIV-1 Latency in Non-proliferating CD4 T Cells

- Transcriptional Analysis of Murine Macrophages Infected with Different Strains Identifies Novel Regulation of Host Signaling Pathways

- Serotonergic Chemosensory Neurons Modify the Immune Response by Regulating G-Protein Signaling in Epithelial Cells

- Genome-Wide Detection of Fitness Genes in Uropathogenic during Systemic Infection

- Induces an Unfolded Protein Response via TcpB That Supports Intracellular Replication in Macrophages

- Intestinal CD103+ Dendritic Cells Are Key Players in the Innate Immune Control of Infection in Neonatal Mice

- Emerging Functions for the RNome

- KSHV MicroRNAs Mediate Cellular Transformation and Tumorigenesis by Redundantly Targeting Cell Growth and Survival Pathways

- HrpA, an RNA Helicase Involved in RNA Processing, Is Required for Mouse Infectivity and Tick Transmission of the Lyme Disease Spirochete

- A Toxin-Antitoxin Module of Promotes Virulence in Mice

- Real-Time Imaging of the Intracellular Glutathione Redox Potential in the Malaria Parasite

- Hypoxia Inducible Factor Signaling Modulates Susceptibility to Mycobacterial Infection via a Nitric Oxide Dependent Mechanism

- Novel Strategies to Enhance Vaccine Immunity against Coccidioidomycosis

- Dual Expression Profile of Type VI Secretion System Immunity Genes Protects Pandemic

- —What Makes the Species a Ubiquitous Human Fungal Pathogen?

- αvβ6- and αvβ8-Integrins Serve As Interchangeable Receptors for HSV gH/gL to Promote Endocytosis and Activation of Membrane Fusion

- -Induced Activation of EGFR Prevents Autophagy Protein-Mediated Killing of the Parasite

- Semen CD4 T Cells and Macrophages Are Productively Infected at All Stages of SIV infection in Macaques

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Influence of Mast Cells on Dengue Protective Immunity and Immune Pathology

- Host Defense via Symbiosis in

- Coronaviruses as DNA Wannabes: A New Model for the Regulation of RNA Virus Replication Fidelity

- Myeloid Dendritic Cells Induce HIV-1 Latency in Non-proliferating CD4 T Cells

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání