-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Serotonergic Chemosensory Neurons Modify the Immune Response by Regulating G-Protein Signaling in Epithelial Cells

The nervous and immune systems influence each other, allowing animals to rapidly protect themselves from changes in their internal and external environment. However, the complex nature of these systems in mammals makes it difficult to determine how neuronal signaling influences the immune response. Here we show that serotonin, synthesized in Caenorhabditis elegans chemosensory neurons, modulates the immune response. Serotonin released from these cells acts, directly or indirectly, to regulate G-protein signaling in epithelial cells. Signaling in these cells is required for the immune response to infection by the natural pathogen Microbacterium nematophilum. Here we show that serotonin signaling suppresses the innate immune response and limits the rate of pathogen clearance. We show that C. elegans uses classical neurotransmitters to alter the immune response. Serotonin released from sensory neurons may function to modify the immune system in response to changes in the animal's external environment such as the availability, or quality, of food.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 9(12): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003787

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003787Summary

The nervous and immune systems influence each other, allowing animals to rapidly protect themselves from changes in their internal and external environment. However, the complex nature of these systems in mammals makes it difficult to determine how neuronal signaling influences the immune response. Here we show that serotonin, synthesized in Caenorhabditis elegans chemosensory neurons, modulates the immune response. Serotonin released from these cells acts, directly or indirectly, to regulate G-protein signaling in epithelial cells. Signaling in these cells is required for the immune response to infection by the natural pathogen Microbacterium nematophilum. Here we show that serotonin signaling suppresses the innate immune response and limits the rate of pathogen clearance. We show that C. elegans uses classical neurotransmitters to alter the immune response. Serotonin released from sensory neurons may function to modify the immune system in response to changes in the animal's external environment such as the availability, or quality, of food.

Introduction

The nervous and immune systems respond quickly and precisely to the presence of pathogenic microbes in an animal's environment. Whilst the immune system activates cellular defenses to recognize and eliminate pathogens, changes in neuronal signaling alter animal behavior to avoid these microbes. Data from mammalian models suggests that bidirectional communication between these two systems can modify responses to infection [1], and this relationship may explain why psychological stress increases susceptibility to infections [2]. Because of the complicated nature of the mammalian brain and immune system the molecular mechanisms that underlie neuronal regulation of the immune response remain unclear.

The free-living soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegans utilizes conserved signaling pathways to trigger behavioral and innate immune responses to infection by several natural and clinically-relevant pathogens provided as a food source [3]. This, together with its simple and well-described nervous system, has resulted in several studies identifying the neuronal signals that influence C. elegans behavioral and immune responses to infection [4]–[9]. In the presence of pathogens such as Serratia marcescens [8], Microbacterium nematophilum [9] and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [5], [6] C. elegans uses chemosensory neurons to recognize the pathogen triggering changes in neuronal signaling that cause it to alter its behavior and avoid these potential harmful bacteria. Interestingly, neuronal signals can also directly modify C. elegans immune responses. Release of the insulin like neuropeptide INS-7 from neuronal dense core vesicles suppresses the C. elegans intestinal immune response triggered by infection with P. aeruginosa PA14 [4] and this pathway is utilized by the pathogen to suppress host immune defenses [10]. The neuronal cytokine DBL-1(TGFβ) promotes expression of the caenacin family antimicrobial peptide cnc-2 in the epidermis during infection with the fungal pathogen Drechmeria conispora [7]. Several studies have implicated mammalian neuropeptides and peptide hormones in neuronal regulation of immunity (reviewed in [11]) suggesting that these relationships are conserved, and studies in C. elegans have identified neurons as important modifiers of the immune response. However, although an octopamine receptor has been shown to regulate the C. elegans immune response [12], the function of neurotransmitters in C. elegans immunity remains unexplored.

In mammals a number of neurotransmitters act on the immune system to modify its function [13]. One of these is the classical monoamine neurotransmitter serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) [14], [15]. Dysregulation of mammalian serotonin signaling is associated with mood disorders including depression, and depressed patients show decreased natural killer (NK) cell activity [16]. These cells are important components of the innate immune system linking serotonin signaling to immune regulation. Furthermore NK cell activity can be enhanced by treatment with anti-depressants, such as Prozac, that act as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI's) [17]. NK cells are not the only immune cells affected by serotonin. Several other cells of the immune system express serotonin receptors including dendritic cells [18], macrophages [19] and mast cells [20]. Serotonin affects both innate and adaptive immunity enhancing the proliferation of B [21] and NK cells [22], promoting stimulation of T cells by macrophages [23] and acting as a chemotactic agent for mast cells [20] and eosinophils [24]. However there is still much unknown about how serotonin functions in the immune response. Genetic approaches will be key to understanding the role of serotonin in immune function. Mice lacking the serotonin biosynthetic enzyme, tryptophan hydroxylase TPH1, have some defects in their immune function [25] however TPH1 acts redundantly with TPH2 [26] and TPH1 knockouts still retain the ability to synthesis serotonin in serotonergic regions of the brain [26]. C. elegans only has one tryptophan hydroxylase ortholog, tph-1, and animals carrying the putative null allele tph-1(mg280) are deficient for serotonin production [27] allowing the immune function of neuronal serotonin to be studied in vivo.

In C. elegans serotonin signaling allows animals to respond to changes in their environment by modulating locomotion [28], feeding [29], defecation [30] and egg laying [1], [31], [32] behaviors. Serotonin signals the presence of food causing starved animals to stop moving when they encounter a bacterial lawn. Animals lacking tph-1 behave as if they are starved, decreasing their feeding and egg laying rates [2], [27]. Interestingly serotonin signaling is also required for C. elegans to respond to infection by P. aeruginosa PA14 [3], [5], [6]. Animals that lack tph-1 are more susceptible to PA14 than wild type animals. However serotonin signaling is not required for the C. elegans immune response in this context, and changes in susceptibility of tph-1 mutant animals are due exclusively to behavioral pathogen avoidance [4]–[9]. Exposure to PA14 increases serotonin levels in chemosensory neurons and promotes aversive learning so that animals that have been previously exposed to PA14 alter their olfactory preferences to avoid these toxic bacteria [6], [8].

Using the natural C. elegans pathogen Microbacterium nematophilum we have identified a role of serotonin signaling in suppressing the immune response. Wild type C. elegans tends to avoid bacterial lawns contaminated with M. nematophilum [9] and following infection an immune response is triggered that includes swelling around the rectal opening and upregulation of host defense genes [5], [6], [33], [34]. Unlike during P. aeruginosa infection, serotonin signaling was not require for avoidance of M. nematophilum but instead suppressed the immune response by activating signaling via the G-protein GOA-1(Gαo) in rectal epithelial cells. This suppression required serotonin synthesis in the chemosensory neuron, ADF, which contacts the animal's environment via ciliated sensory endings, and the serotonin receptors SER-1 and SER-7. Our data demonstrates that C. elegans uses the classical neurotransmitter serotonin to modify its immune response. These signals may function to modify the immune system in response to changes in the animal's external environment, such as the availability of food.

Results

Exogenous serotonin inhibits the C. elegans immune response to M. nematophilum infection

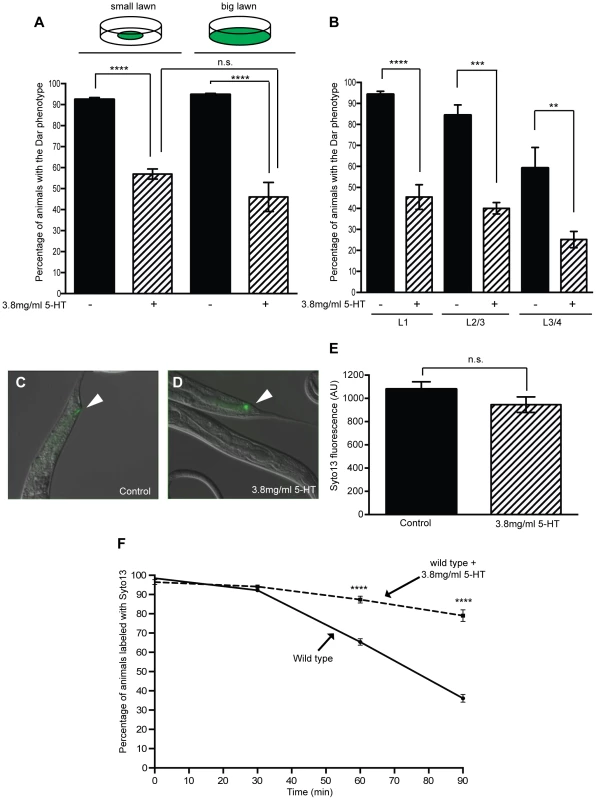

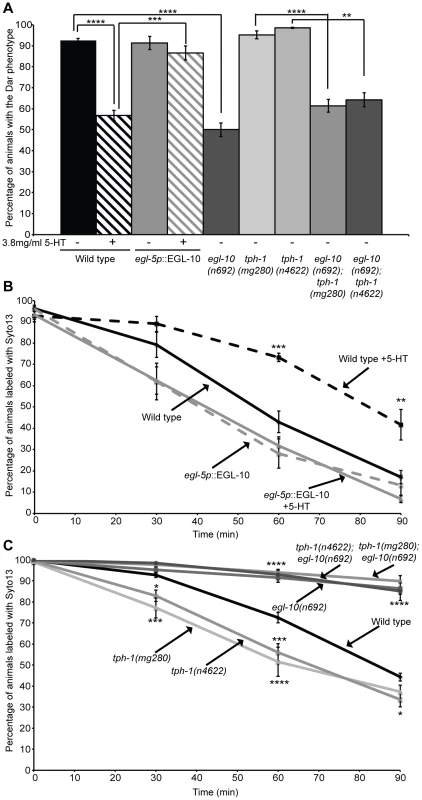

Infection of C. elegans with the naturally-occurring pathogen, Microbacterium nematophilum triggers an immune response that includes transcription of host defense genes and swelling around the rectal opening, known as the Deformed anal region (Dar) phenotype [4], [33], [34]. To determine whether serotonin was able to modulate the C. elegans immune response we exposed adult wild type animals to M. nematophilum on plates containing exogenous serotonin and scored the Dar phenotype in their progeny. Treatment with serotonin caused a decrease in the number of Dar animals when compared to untreated controls (Figure 1A and B), however serotonin treatment did not alter the ability of the pathogen to attach to the cuticle. We observed similar levels of SYTO13-labeled M. nematophilum adhering to the rectum of serotonin-treated animals that were Dar-defective and control animals (Figure 1C, D and E).

Fig. 1. Exogenous serotonin inhibits the Dar phenotype and decreases pathogen clearance rates.

Adult wild type animals were exposed to M. nematophilum on plates containing exogenous serotonin and the Dar phenotype was scored in their progeny. Treatment with 3.8 mg/ml 5-HT caused a 35% decrease in the number of Dar animals following M. nematophilum infection using standard assay conditions (small lawn) (A). A similar decrease was observed when assay conditions were modified so that animals were unable to avoid the pathogen (big lawn) (A). The Dar phenotype was still decreased when wild type animals were infected in the presence of exogenous serotonin during development, at L1 or L2/3 stage, or 10–18 hours prior to adulthood, at L3/4 stage (B). Similar amounts of M. nematophilum bacteria, labelled using the nucleic acid stain SYTO13, still attached to the anal opening following serotonin treatment (C, D and E) (the rectal opening is indicated with an arrow head in C and D). SYTO13 labeled M. nematophilum was cleared from the anal opening of wild type animals and less than 50% of animals were colonized 90 minutes after transfer to plates without food (F). Treatment of infected animals with 3.8 mg/ml 5-HT significantly decreased the clearance of labeled pathogen from the anal opening (F). In these experiments animals were exposed to exogenous serotonin throughout development raising the possibility that serotonin treatment alters development to indirectly affect the Dar phenotype. The Dar phenotype requires signaling in the rectal epithelium [35], [36], therefore we first checked that the rectal epithelial marker, LIN-48 (OVO-like transcription factor) [37], was correctly expressed following treatment with exogenous serotonin. Using transgenic animals expressing lin48p::FP we did not observe any changes in the expression of this rectal epithelial marker following treatment with exogenous serotonin (Figure S1). To confirm that post-developmental treatment with exogenous serotonin still suppressed the Dar phenotype we also infected animals on plates containing exogenous serotonin at different developmental stages and scored the Dar phenotype when they reached adulthood. Although fewer control animals became Dar when they were infected at the L3/L4 stage (as we have previously observed [10], [36]), we were still able to suppress this Dar phenotype by infecting animals in the presence of exogenous serotonin 10–18 hours prior to adulthood (L3/L4 stage), indicating that exogenous serotonin does not indirectly affect the Dar phenotype by altering development (Figure 1B).

Treatment of C. elegans with exogenous serotonin causes dramatic behavioral changes including inhibition of locomotion, stimulation of egg laying and increased pharyngeal pumping [7], [28], [29], [31], [32]. To confirm that defects in these behaviors did not alter the Dar phenotype we infected a number of mutants that phenocopy the effect of exogenous serotonin but do not act in the serotonin signaling pathway. We did not observe any significant differences in the Dar phenotype, when compared to untreated controls, (Table S1) indicating that the effects of serotonin on the immune response are specific and not a secondary consequence of these physiological changes.

Serotonin signaling modulates chemosensory avoidance responses in C. elegans [11], [38]. To ensure that the differences we observed reflected a role for serotonin in the immune response, rather than increased behavioral avoidance of the pathogen in the presence of serotonin, we modified our infection assay by spreading M. nematophilum to the edges of the plate. In this ‘big-lawn’ assay animals were unable to avoid the pathogen. Animals raised on “big lawns” still displayed a decrease in the Dar phenotype (Figure 1A), indicating that serotonin inhibits the immune response directly rather than modifying C. elegans exposure to the pathogen.

Serotonin synthesis in chemosensory neurons inhibits the Dar phenotype

Exogenous serotonin treatment inhibits the immune response, but does endogenous serotonin signaling suppress the wild type immune response? The C. elegans tryptophan hydroxlase gene tph-1 is required for endogenous serotonin biosynthesis and animals carrying the putative null allele tph-1(mg280) are deficient for serotonin production [12], [27]. Because increasing serotonin signaling suppressed the immune response we predicted that blocking serotonin signaling, using tph-1 mutants, would enhance the immune response. However, approximately 90% of wild type animals are able to mount a Dar immune response to contamination of a bacterial lawn with 10% M. nematophilum (Figure 1A and 2A), making it difficult to observe treatments that enhance this phenotype. To determine whether loss of serotonin synthesis enhanced the Dar phenotype we modified our infection assay so that bacterial lawns were contaminated with 0.05% M. nematophilum. Under these conditions 60.3% of wild type progeny became Dar (Figure 2A) although 94.65% remained infected as assessed by SYTO13 staining. These conditions allowed us to identify mutations and treatments that enhance the Dar phenotype.

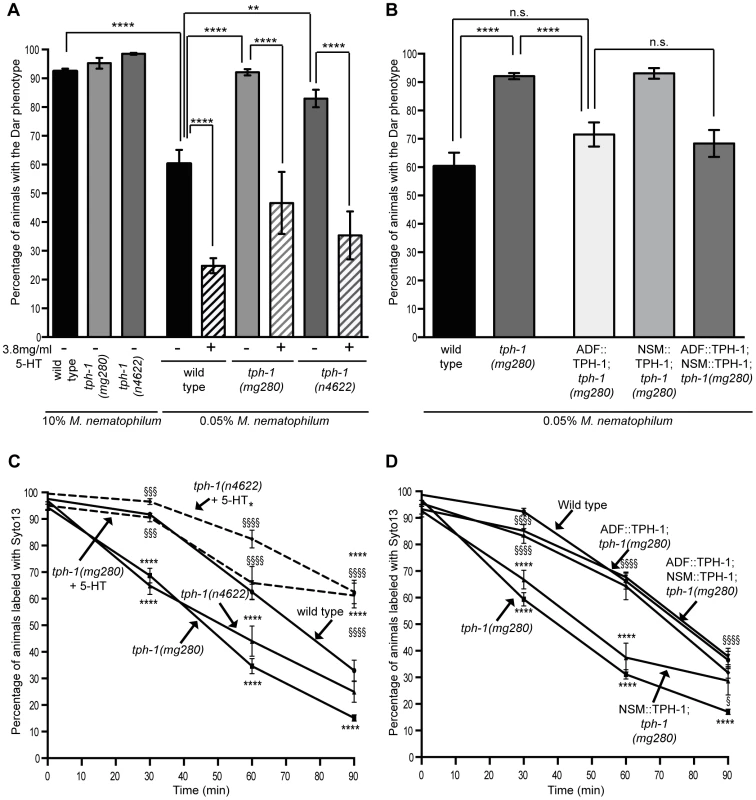

Fig. 2. The serotonin biosynthetic enzyme TPH-1 is required in chemosensory neurons to inhibit the Dar phenotype and decrease pathogen clearance rates.

Adult tph-1(mg280) or tph-1(n4622) animals lacking the serotonin biosynthetic enzyme TPH-1 were infected on lawns contaminated with 10% M. nematophilum. The percentage of tph-1(mg280) and tph-1(n4622) progeny with the Dar phenotype was indistinguishable from wild type (A). When animals were infected on lawns contaminated with 0.05% M. nematophilum the Dar phenotype was increased from 60.3% in wild type animals to 92.1% in tph-1(mg280) and 83.0% in tph-1(n4622) (A). This increase could be rescued by treatment with exogenous 5-HT (A) or expression of TPH-1 cDNA in ADF, but not NSM, neurons (B). tph-1(mg280) and tph-1(n4622) animals cleared SYTO13 labeled pathogen more quickly than wild type animals consistent with a role for TPH-1 in suppressing the immune response (C). This phenotype was rescued by 5-HT treatment (C) or expression of a TPH-1 cDNA in both ADF and NSM neurons or ADF neurons alone but not by expression in NSM alone (D). * indicates significance relative to wild type. § indicates significance relative to untreated mutant control (C) or tph-1(mg280) (D) (see materials and methods for details of statistical analysis). When tph-1(mg280), or another putative null allele tph-1(n4622), animals were grown on lawns contaminated with 0.05% M. nematophilum we observed an increase in the percentage of progeny with the Dar phenotype, when compared to wild type controls (Figure 2A). On lawns contaminated with 10% M. nematophilum wild type controls, tph-1(mg280) and tph-1(n4622) progeny were all over 90% Dar (Figure 2A).

To determine whether the enhanced Dar phenotype of tph-1(mg280) and tph-1(n4622) was due to a decrease in serotonin synthesis we grew animals lacking tph-1 on 0.05% M. nematophilum infection plates supplemented with exogenous serotonin. Treatment with exogenous serotonin was able to rescue the enhanced Dar response observed in tph-1(mg280) and tph-1(n4622) animals (Figure 2A), confirming that wild type levels of serotonin, synthesised by TPH-1, are required to suppress the wild type Dar response.

C. elegans uses behavioral avoidance strategies, as well as immune responses, to promote its survival in the presence of pathogens [6], [8], [13], [39]. tph-1(mg280) and tph-1(n4622) animals exhibit defects in avoidance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa [6], [14], [15] To analyse the role of serotonin synthesis in M. nematophilum avoidance behavior, a phenotype that is dependent on locomotion, we used the tph-1(n4622) allele, since the tph-1(mg280) allele has a background mutation that affects locomotion [40]. Over 70% of wild type animals were found outside bacterial lawns contaminated with M. nematophilum and this distribution was not altered in tph-1(n4622) animals (Figure S2A). Furthermore, both wild type and tph-1(n4622) animals showed a strong preference for E. Coli vs M. nematophilum in food choice assays (Figure S2B and C). Together our data indicates that serotonin signaling is not required for avoidance of M. nematophilum.

TPH-1 is expressed in the serotonergic neurons ADF, NSM and HSN and occasionally in AIM and RIH [16], [27]. To determine the site of action for TPH-1 in regulating the Dar phenotype we performed rescue experiments using a TPH-1 cDNA expressed from either the ADF-specific srh-142 promoter [17], [41] or the ceh-2 promoter that is expressed in NSM neurons [18], [42]. Expression of TPH-1 cDNA in ADF chemosensory neurons, but not in the neurosecretory motor neuron NSM, restored the number of Dar animals to wild type levels in tph-1(mg280) animals grown on lawns contaminated with 0.05% M. nematophilum (Figure 2B). TPH-1 cDNA expressed in both the ADF and NSM neurons of tph-1(mg280) animals did not enhance this rescue (Figure 2B). These results suggest that serotonin synthesis by TPH-1 in the ADF chemosensory neurons is able to inhibit the Dar phenotype in wild type animals.

Serotonin synthesis in chemosensory neurons prolongs M. nematophilum colonization

We next asked how the Dar response is advantageous to infected C. elegans and whether this advantage could be suppressed by serotonin's effects on the Dar phenotype. M. nematophilum is found associated with the cuticle around the C. elegans rectal opening [19], [33] and the Dar phenotype may protect animals from severe infection by distorting the animal's anal region, allowing more rapid clearance of the pathogen from the rectum. Using the vital dye Syto13 to label M. nematophilum attached to the rectal opening, we monitored clearance of the pathogen from the rectum following infection. Wild type animals were able to clear more than 50% of the Syto13 labeled M. nematophilum within 90 minutes of transfer to plates without any bacteria (Figure 1F). Animals that had cleared the SYTO13 labeled M. nematophilum after 90 minutes remained Dar (Figure S3A–C), indicating that loss of pathogen from the rectal opening is not sufficient to reverse the Dar phenotype.

Many dar-defective mutants fail to show any SYTO13 staining in the presence of M. nematophilum, indicating that these genes are required for pathogen recognition and binding [3], [20]. However, a second class of dar-defective mutants remain SYTO13 positive [3], [21], [36]. This second class of genes act downstream of pathogen binding to trigger the Dar response to infection. Using this class of Dar-defective mutants (mpk-1(ku1), unc-73(ce362) and those described in this paper) we repeated our clearance assays. When Dar and Dar-defective animals were scored indifferently for the presence of SYTO13 labeled M. nematophilum we observed a significant decrease in the ability of these mutants to clear labeled pathogen when compared to wild type controls (R. McMullan and A. Anderson, data not shown), demonstrating that the Dar phenotype protects C. elegans during infection, at least in part, by increasing the rate of pathogen clearance.

Using this clearance assay we first asked whether exogenous serotonin treatment of wild type animals; which decreases the percentage of Dar animals, was able to alter the rate of pathogen clearance. Wild type animals treated with serotonin cleared the pathogen infection significantly more slowly than control animals (Figure 1F), indicating that exogenous serotonin is able to inhibit the immune response. The Dar-defective phenotype was observed in approximately 43% of wild type progeny when animals are infected in the presence of exogenous serotonin. To confirm that this Dar-defective phenotype was associated with slower pathogen clearance rates we repeated our clearance assay separating Dar and Dar-defective animals prior to SYTO13 labeling. Almost all animals were SYTO13 positive immediately following labeling and the rate of pathogen clearance in Dar animals was similar to that observed in untreated wild type animals (Figure S3D). However pathogen clearance rates were significantly slower in Dar-defective animals (Figure S3D) confirming the ability of exogenous serotonin to decrease the Dar phenotype results in inhibition of the immune response and decreased pathogen clearance.

To determine whether endogenous serotonin was also able to alter pathogen clearance rates we performed clearance assays using tph-1(mg280) and tph-1(n4622) animals lacking endogenous serotonin synthesis. Interestingly, although these animals show a wild type Dar response when infected with 10% M. nematophilum (Figure 2A) both tph-1(mg280) and tph-1(n4622) animals cleared SYTO13 labeled M. nematophilum significantly faster than wild type animals (Figure 2C). This is consistent with our observation that tph-1(mg280) and tph-1(n4622) animals grown on lawns contaminated with 0.05% M. nematophilum have a larger percentage of Dar animals than wild type controls and suggests that TPH-1 activity in wild type animals inhibits the immune response triggered by infection by M. nematophilum.

To determine whether the enhanced immune response of tph-1(mg280) and tph-1(n4622) was due to a decrease in serotonin synthesis we grew animals lacking tph-1 on infection plates supplemented with serotonin. Treatment with exogenous serotonin was able to rescue the increased clearance rate observed in tph-1(mg280) and tph-1(n4622) animals (Figure 2C) confirming that endogenous levels of serotonin synthesis by TPH-1 are required to suppress the wild type immune response.

To determine where TPH-1 activity was required to reduce pathogen clearance rates we again expressed TPH-1 cDNA in either ADF or NSM neurons, or both. Expression of a TPH-1 cDNA in ADF chemosensory neurons, but not in the neurosecretory motor neuron NSM, was sufficient to rescue the rate of M. nematophilum clearance to wild type rates in tph-1(mg280) animals and this rescue was not enhanced when TPH-1 was expressed in both ADF and NSM (Figure 2D).

Infection with pathogenic M. nematophilum does not alter expression of the serotonin biosynthetic enzyme TPH-1

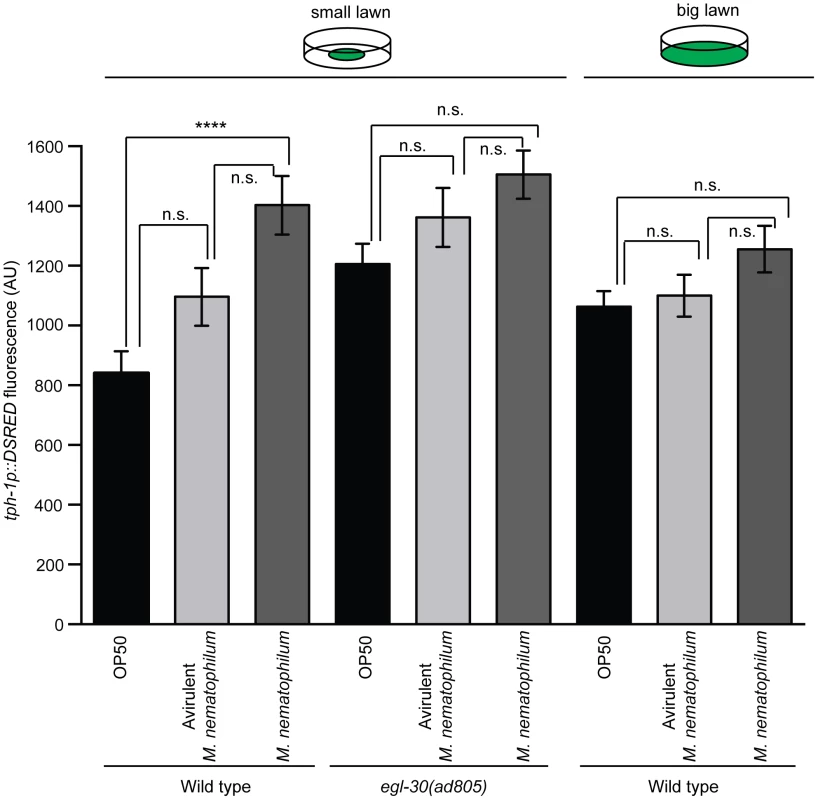

Serotonin signaling in ADF chemosensory neurons suppresses the epithelial immune response to infection with M. nematophilum, raising the possibility that these neurons are able to sense and respond to the presence of pathogen by modifying their serotonin signaling. Serotonin levels in ADF can be altered by regulating transcription of tph-1, or via post-translational mechanisms that alter TPH-1 activity. Transcription of tph-1 in ADF neurons is increased by exposure to pathogenic Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 [5], [6], [22], neuronal activity [23], [41] and heat stress [20], [43] and these changes can be monitored in vivo using strains expressing a fluorescent transgene under the control of the tph-1 promoter. To determine whether infection with M. nematophilum altered transcription of tph-1 we propagated animals stably expressing a tph-1p::DSRED transgene on small bacterial lawns contaminated with virulent, or avirulent, forms of M. nematophilum. Infection with virulent, or avirulent, forms of M. nematophilum did not alter the expression pattern of tph-1p::DSRED (data not shown) however infection increased expression levels of tph-1p::DSRED in ADF and NSM neurons relative to animals propagated on E. Coli alone (Figure 3 and Figure S4).

Fig. 3. Increased expression of TPH-1 in ADF chemosensory neurons is caused by reduced contact with contaminated bacterial lawns.

Wild type and egl-30(ad805) animals carrying an integrated tph-1p::DSRED transgene were infected with M. nematophilum or an avirulent form of M. nematophilum using standard (small lawn) or “big lawn” assay conditions. The mean tph-1p::DSRED fluorescence in ADF neurons was quantified. Expression of tph-1p::DSRED was significantly increased when wild type animals were grown on small lawns contaminated with virulent M. nematophilum. This increase in expression was not observed under conditions when animals were unable to leave the bacterial lawn; in egl-30(ad805) animals or when wild type animals were infected on “big lawns”. Wild type animals tend to avoid bacterial lawns contaminated with virulent M. nematophilum ([9], [24] and Figure S3) therefore it is possible that increased tph-1p::DSRED expression in the presence of M. nematophilum is caused by reduced contact with the bacterial lawn. To test this we first expressed the tph-1p::DSRED transgene in egl-30(ad805) animals that fail to avoid M. nematophilum contaminated lawns [36]. We did not observe any significant increases in tph-1p::DSRED expression in these egl-30(ad805) animals (Figure 3 and Figure S4). We also repeated our tph-1p::DSRED measurements using animals infected in a modified “big lawn” assay where they were unable to leave the food. Again we were unable to observed any significant increases in tph-1p::DSRED expression when animals were unable to avoid M. nematophilum contaminated lawns (Figure 3 and Figure S4). Together these results indicate that the changes in TPH-1 expression levels we observed were largely due to reduced contact with the bacterial lawn when it was contaminated with virulent M. nematophilum and not due to infection.

The Gαo RGS EGL-10 acts in the rectal epithelium to modify the immune response and affect pathogen clearance

Several receptors have been identified that bind serotonin in C. elegans, including a serotonin gated chloride channel (MOD-1) and several G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) (SER-1, SER-4 and SER-7) [25], [44]–[46]. Infection of mod-1(ok103), ser-1(ok345), ser-7(tm1325), ser-7(ok1944), ser-4(ok512) mutants and ser-1(ok345);ser-7(tm13325) double mutants indicates that at least two GPCRs (SER-1 and SER-7) are required for serotonin effects on the immune response (Figure S5).

GPCRs activate intracellular signaling via specific G-proteins. In C. elegans the effects of serotonin on neuronal activity at the neuromuscular junction are mediated by the G-protein GOA-1(Gαo) [26], [47]. Therefore we asked whether GOA-1(Gαo) signaling was also required for serotonin-mediated inhibition of the immune response. We first infected several available goa-1(Gαo) mutants (goa-1(sa734), goa-1(n1134) and goa-1(n363)) with M. nematophilum as adults or larvae to determine whether loss of GOA-1(Gαo) signaling altered the Dar phenotype. For reasons that we were unable to determine, the majority of these animals arrested at the L1/L2 larval stage and failed to reach adulthood. Therefore we were unable to score the Dar phenotype of these animals (data not shown).

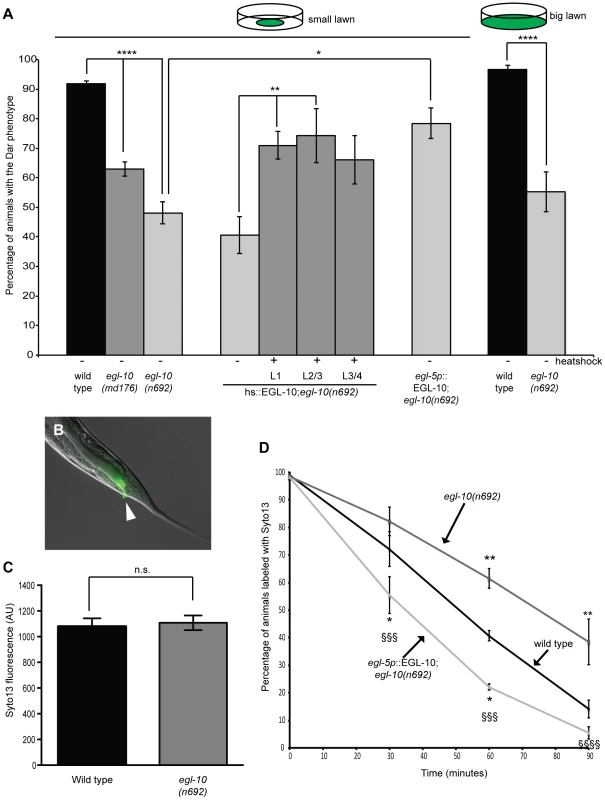

Genetic and biochemical experiments have shown that the conserved Regulator or G-protein signaling (RGS) protein, EGL-10, is a specific inhibitor of GOA-1(Gαo) activity [26], [48]. Therefore we used animals carrying null mutations in egl-10 to increase goa-1(Gαo) signaling indirectly, mimicking the effects of too much serotonin signaling. When egl-10(md176) and egl-10(n692) adults were infected with M. nematophilum we observed a significant decrease in the percentage of progeny exhibiting the Dar phenotype (Figure 4A). However similar levels of SYTO13-labeled M. nematophilum were still observed adhering to the rectum of these animals indicating that increased GOA-1(Gαo) signaling did not alter the ability of the pathogen to attach to the cuticle (Figure 4B and C). Furthermore, this decrease in the Dar phenotype was not caused by increased behavioral avoidance of the pathogen because the Dar phenotype was still decreased when egl-10(n692) were infected using a modified ‘big-lawn’ assay where they were unable to avoid the pathogen (Figure 4A). Consistent with this decrease in the Dar phenotype we observed that egl-10(n692) mutants cleared pathogen infections from their rectal opening more slowly than wild type (Figure 4D), indicating that activating GOA-1(Gαo) is able to suppress the immune response.

Fig. 4. The Gαo RGS EGL-10 is required in rectal epithelial cells to regulate the immune response and affect pathogen clearance.

egl-10 mutants were infected with M. nematophilum using either standard assay conditions (small lawn) or conditions where animals were unable to avoid the pathogen (big lawn) and the percentage of Dar progeny scored. egl-10(n692) and egl-10(md176) significantly decreased the percentage of Dar animals (A). Expression of EGL-10 cDNA, using a heatshock-inducible promoter, at L1, L2/L3 and L3/L4 stage (hs::EGL-10), or a rectal epithelial promoter (egl-5p::EGL-10), rescued the Dar phenotype in egl-10(n692) animals (A). Although egl-10(n692) animals failed to produce a wild type Dar response similar amounts of M. nematophilum, labeled using the nucleic acid stain SYTO13, still attached to the anal opening (indicated with an arrow in B) (B and C). The rate of clearance of SYTO13 labeled pathogen was significantly decreased in egl-10(n692) animals and this was rescued by expression of EGL-10 cDNA in the rectal epithelium which cleared labeled pathogen more rapidly than wild type animals (D). In D * indicates significance relative to wild type. § indicates significance relative to egl-10(n692). The Dar phenotype requires activation of multiple signaling pathways in the C. elegans rectal epithelium [27], [35], [36]. To determine the site of action for EGL-10 (and therefore GOA-1(Gαo)) in the immune response we performed rescue experiments using EGL-10 cDNA expressed in the rectal epithelial cells, using a 1.3 Kb egl-5 promoter fragment [28], [49]. Expression of EGL-10 cDNA in the rectal epithelium was sufficient to rescue the defective Dar phenotype in egl-10(n692) animals (Figure 4A). In addition rectal epithelial expression of EGL-10 rescued the slow clearance of pathogen in egl-10(n692) animals. Indeed these animals cleared labeled pathogen faster than wild type animals (Figure 4D) suggesting that overexpression of EGL-10 cDNA in these transgenic animals was able to decrease GOA-1(Gαo) activity and indicating that GOA-1(Gαo) signaling acts in the rectal epithelial cells of wild type animals to inhibit the immune response. To confirm that EGL-10 was required for the Dar response to infection rather than development of the rectal epithelium we also performed rescue experiments in egl-10(n692) mutants using a heat shock inducible EGL-10 cDNA transgene. We were able to partially rescue the Dar phenotype in egl-10(n692) mutants by expressing EGL-10 cDNA 10–18 hours prior to adulthood (L3/L4 larval stage), indicating that GOA-1(Gαo) signaling in adult animals is required for this response (Figure 4A).

Rectal epithelial EGL-10 signaling acts downstream of neuronal serotonin signaling to modify the immune response and affect pathogen clearance

Animals lacking GOA-1(Gαo) are resistant to the effects of exogenous serotonin treatment on egg laying and locomotion [29], [30], [47], [50]. To determine whether serotonin inhibits the immune response via a GOA-1(Gαo) signaling pathway we first treated adult animals with decreased rectal epithelial GOA-1(Gαo) signaling, (by overexpressing the RGS, EGL-10 in the rectal epithelial cells of wild type animals), with exogenous serotonin and scored the Dar phenotype of their progeny. Addition of exogenous serotonin during M. nematophilum infection suppressed the Dar phenotype of wild type animals but not those overexpressing EGL-10 (Figure 5A). Furthermore exogenous serotonin was no longer able to reduce the rate of pathogen clearance when EGL-10 was overexpressed in rectal epithelial cells (Figure 5B). Together these data indicate that wild type levels of GOA-1(Gαo) signaling in the rectal epithelium are required for serotonin's inhibitory effects on the immune response.

Fig. 5. Rectal epithelial EGL-10 acts downstream of serotonin to modify the immune response and affect pathogen clearance.

Treatment of wild type animals with 3.8/ml 5-HT caused a decrease in the number of Dar animals following infection with M. nematophilum (A) and decreased the clearance of SYTO13 labeled pathogen from the rectal opening (B). Serotonin was unable to decrease the percentage of Dar animals (A) or the rate of pathogen clearance (B) when EGL-10 cDNA was overexpressed in the rectal epithelium of wild type animals suggesting that GOA-1(Gáo) signaling in the rectal epithelium is required for serotonin to suppress the immune response. Animals lacking tph-1 have wild type levels of Dar response on lawns contaminated with 10% M. nematophilum (A) but are more able to clear pathogen infections than wild type (C). Conversely activation of GOA-1(Gáo) using egl-10 loss-of-function mutants results in a decrease in the percentage of Dar animals (A) and infections clear more slowly than wild type animals (C). To determine whether GOA-1(Gáo) acts downstream of serotonin we combined egl-10(n692) with tph-1(mg280) or tph-1(n4622). The percentage of Dar animals (A) and the rate of pathogen clearance was indistinguishable between egl-10(n692) and these double mutants (C). Thus GOA-1(Gáo) signaling acts downstream of serotonin synthesis to suppress the immune response to M. nematophilum infection. We also asked whether increasing GOA-1(Gαo) signaling, using egl-10(n692) mutants, was able to rescue the higher pathogen clearance rate we observed in tph-1 mutant animals unable to synthesis serotonin. Pathogen clearance rates in tph-1(mg280);egl-10(n692) and tph-1(n4622);egl-10(n692) double mutants were indistinguishable from egl-10(n692) animals (Figure 5C). We also observed a significant decrease in the Dar phenotype in these double mutants that was similar to the decrease observed in egl-10(n692) (Figure 5A) further indicating that GOA-1(Gαo) acts downstream of serotonin to inhibit the immune response.

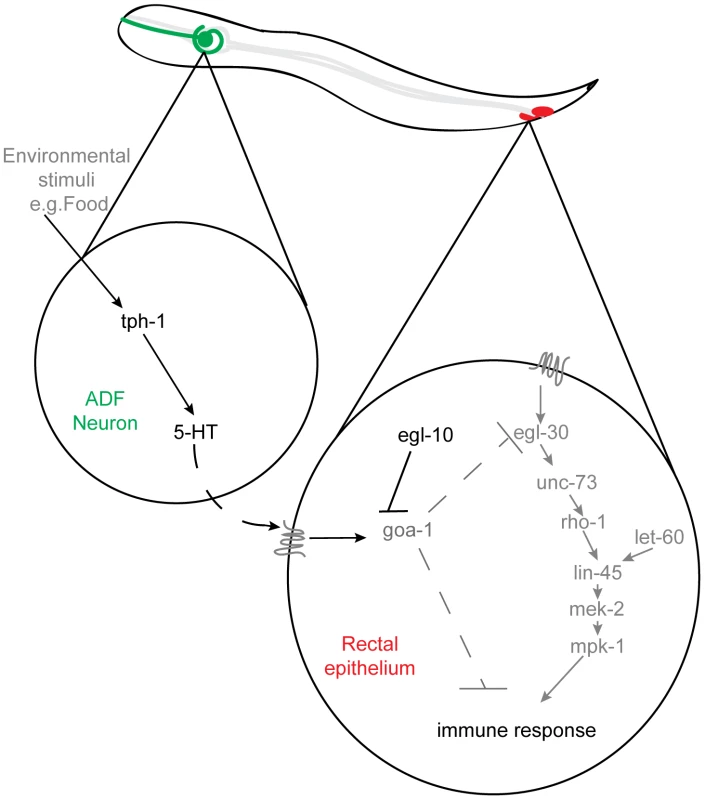

Taken together our data indicates that serotonin synthesized in ADF chemosensory neurons acts via GOA-1(Gαo) signaling in the rectal epithelium to suppress the immune response (Figure 6).

Fig. 6. Serotonin synthesis in chemosensory neurons inhibits the immune response by altering rectal epithelial G-protein signaling.

In response to environmental cues, such as the presence or absence of food, serotonin, released from ADF chemosensory neurons acts, directly or indirectly, to regulate GOA-1(Gαo) signaling in the rectal epithelium. This signaling suppresses the Dar phenotype that forms part of the innate immune response and limits the rate of pathogen clearance from the rectal opening. Serotonin signaling acts upstream of, or in parallel to, the EGL-30(Gαq) pathway to regulate the immune response

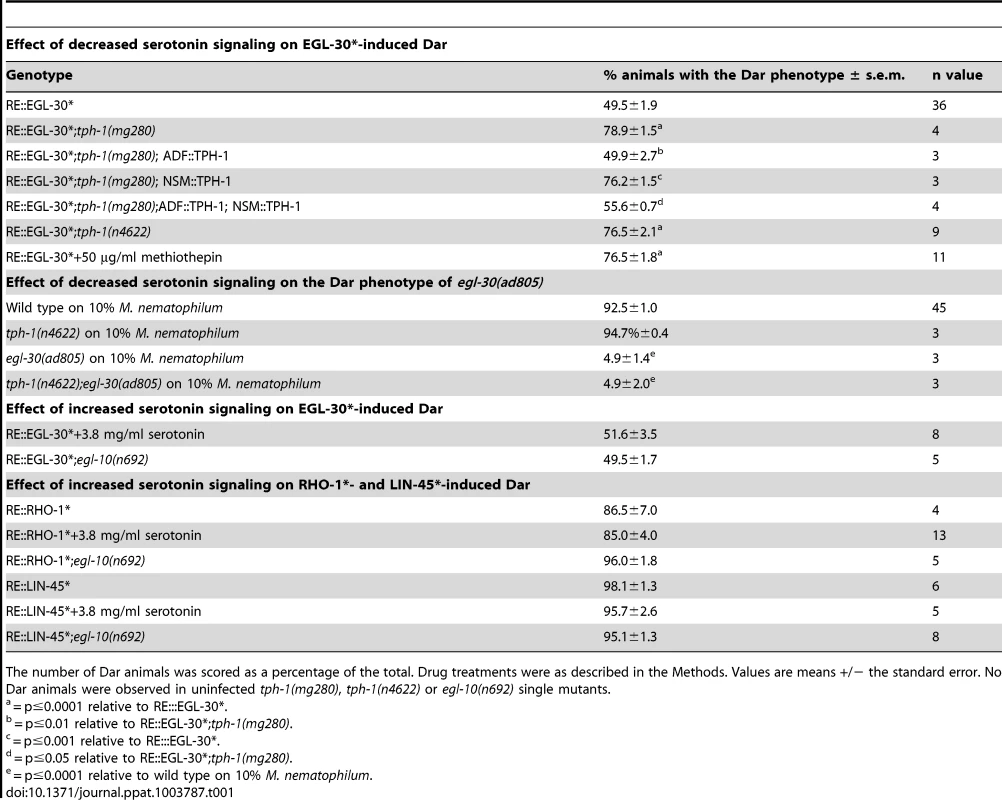

The Dar phenotype requires activation of multiple signaling pathways in the C. elegans rectal epithelium [30], [35], [36]. We have previously shown that signaling via the G-protein EGL-30(Gαq) is required for the Dar response to infection with M. nematophilum [36]. To determine whether serotonin signaling acts in this EGL-30(Gαq) pathway, or a distinct pathway, we used transgenic animals overexpressing a constitutively active form of EGL-30(Q205L) (Gαq) in the rectal epithelium (RE::EGL-30*). When this transgene is expressed in wild type animals approximately 49% of them develop the Dar phenotype in the absence of infection (Table 1 and [36]) although all animals expressing this transgene are still able to trigger the Dar phenotype when infected with M. nematophilum (data not shown).

Tab. 1. Analysis of genetic interactions between the serotonin – GOA-1(Gαo) and EGL-30(Gαq) signaling pathways.

The number of Dar animals was scored as a percentage of the total. Drug treatments were as described in the Methods. Values are means +/− the standard error. No Dar animals were observed in uninfected tph-1(mg280), tph-1(n4622) or egl-10(n692) single mutants. We asked what effect blocking serotonin signaling, in two different ways, had on the Dar phenotype caused by RE::EGL-30*. Firstly, we blocked serotonin signaling by treating uninfected RE::EGL-30* animals with the serotonin receptor antagonist methiothepin. Treatment of adult RE::EGL-30* animals with methiothepin increased the percentage of Dar progeny from 49.5% to 76.5% (Table 1). Secondly, we expressed RE::EGL-30* in tph-1(mg280), or tph-1(n4622), animals in the absence of infection. We observed an increase the percentage of Dar animals from 49.5% in wild type animals to 75.3% in tph-1(mg80) and 76.5% in tph-1(n4622) animals (Table 1). This increase could be rescued by expression of the TPH-1 cDNA in ADF, but not NSM, neurons of tph-1(mg280) (Table 1). These results support our previous observations that blocking serotonin signaling increases the Dar phenotype when animals are infected with 0.05% M. nematophilum. We also asked what effect blocking serotonin signaling had on the Dar phenotype of infected egl-30(ad805) animals. These animals are strongly Dar-defective [36] and we did not observe any significant differences in the Dar phenotype of egl-30(ad805) animals and the tph-1(n4622);egl-30(ad805) double mutant (Table 1). Taken together these results indicate that serotonin is acting either downstream of, or in parallel to, the EGL-30(Gαq) signaling pathway.

We next asked what effect activating serotonin signaling would have on the Dar phenotype triggered by RE::EGL-30*. To do this we grew uninfected RE::EGL-30* animals in the presence of exogenous serotonin for at least one generation. Serotonin treatment did not significantly alter the number of Dar animals in this transgenic strain (Table 1). EGL-30(Gαq) activates a Rho GEF TRIO – RHOA - RAF signaling pathway to trigger the Dar phenotype in response to infection and activation of downstream components of this pathway in the rectal epithelium; using cell-specific overexpression of constitutively active forms of RHO-1(G14V) (RhoA) (RE::RHO-1*) or LIN-45(S312A,S453A) (Raf) (RE::LIN-45*), also results in the Dar phenotype in the absence of infection. We observed no significant decrease in the number of Dar animals when we grew uninfected RE::RHO-1* or RE::LIN-45* animals in the presence of exogenous serotonin for at least one generation (Table 1). This data most strongly supports the hypothesis that serotonin acts upstream of the EGL-30(Gαq) signaling pathway during this response.

During neurotransmission the EGL-30(Gαq) pathway acts antagonistically to GOA-1(Gαo) [47], [51] with GOA-1(Gαo) reported to act upstream of, or in parallel to EGL-30(Gαq) [51], [52]. Our data suggests that this antagonism also exists in the C. elegans rectal epithelium where it plays an important role in modulating the immune response. Therefore we asked whether GOA-1(Gαo) and EGL-30(Gαq) act in the same, or parallel, pathways by expressing RE::EGL-30* in egl-10(n692) animals. Activation of GOA-1(Gαo) signaling in egl-10(n692) did not significantly alter the number of RE::EGL-30*-induced Dar animals relative to wild type animals (Table 1). Furthermore, when two other transgenes that cause the Dar phenotype (RE::RHO-1* and RE::LIN-45*) were expressed in uninfected egl-10(n692) animals the percentage of Dar animals was not significantly different from that observed in wild type animals expressing these transgenes (Table 1). This data supports the model that the serotonin - GOA-1(Gαo) pathway acts upstream of, or in parallel to, the EGL-30(Gαq) pathway to regulate the immune response (Figure 6).

Discussion

C. elegans uses neurotransmitters to influence the immune response

Insulin-like neuropeptides and cytokines, produced in C. elegans neurons, can influence its ability to mount an immune response to pathogen infection [4], [7]. In mammals a number of neurotransmitters can also influence the immune response [13] however the regulation of C. elegans immunity by neurotransmitters remains largely unexplored. Although Sun et. al. [12] have demonstrated that signaling downstream of the neurotransmitter octopamine suppresses the immune response to P. aeruginosa infection, the function of neurotransmitters themselves remains undetermined. Here we show that the classical neurotransmitter, serotonin, suppresses the immune response to infection with the pathogen M. nematophilum. Serotonin synthesized in chemosensory neurons acts, via at least two serotonin GPCR's, to regulate G-protein signaling in rectal epithelial cells and suppress the Dar phenotype. This leads to a reduction in the animal's ability to clear the pathogen infection.

This is the first demonstration of a role for serotonin signaling in regulation of a C. elegans immune response, however serotonin regulates both innate and adaptive mammalian immune responses [14], [15] suggesting further parallels between C. elegans and mammalian immunity.

Interestingly, although serotonin does not appear to modify immune responses triggered by infection with other pathogens, it does alter C. elegans behavioral response to these pathogens. When animals are exposed to Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 they modify their olfactory preferences so that they learn to avoid these pathogenic bacteria [6]. This learnt avoidance results in increased survival following infection [5] and requires serotonin signaling in the same chemosensory neuron required to suppress the immune response to M. nematophilum [6], Although C. elegans avoids lawns contaminated with M. nematophilum we did not observed any role for serotonin signaling in this behavioral response. Thus serotonin signaling in the same neuron can trigger distinct responses, requiring different target cells, depending on the environment C. elegans encounters. It is possible that different levels of serotonin are required to trigger these different responses. Alternatively signaling in other neurons may be regulated by infection. Changes in the activity of these neurons may modify how downstream target cells respond to the presence of serotonin.

Environmental signals alter the immune response by influencing serotonin signaling from chemosensory neurons

Although C. elegans neurons have been shown to produce insulin-like neuropeptides and cytokines that influence the immune response [4], [7] the identity of these neurons has remained largely elusive. Here we identify a single neuron that influences C. elegans immunity.

In the C. elegans adult hermaphrodite only ADF, NSM, HSN, AIM, RIH and VC4/5 neurons have been shown to contain serotonin [28], [53], [54] and the tryptophan hydroxylase TPH-1, required to synthesis serotonin, is only expressed in ADF, NSM and HSN [27], suggesting that AIM, RIH and VC4/5 take up serotonin synthesized by other neurons. Using cell specific rescue experiments we have shown that expression of TPH-1 (and therefore serotonin synthesis) in ADF is required to suppress the immune response to infection by M. nematophilum.

ADF neurons are a set of two bilaterally symmetrical chemosensory neurons that contact the external environment via sensory cilia in the amphid [55], raising the possibility that chemical cues present in the environment can alter ADF activity and influence the immune response. What are the environmental signals that trigger ADF activation leading to serotonin synthesis and suppression of the immune response following M. nematophilum infection?

One possibility is that chemical cues produced by the pathogen itself are detected by ADF. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection increases TPH-1 expression [5], [6] and stimulates ADF neuronal activity [56] to promote behavioral avoidance of the pathogen [6]. In contrast M. nematophilum does not appear to regulate serotonin synthesis in ADF, because we only observed changes in TPH-1 expression under conditions where there was decreased contact with the M. nematophilum contaminated bacterial lawn. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that other aspects of ADF activity, including regulation of TPH-1 activity or serotonin release, are regulated by the pathogen. Regardless of how infection with M. nematophilum regulates serotonin signaling, suppression of this pathway alone is not sufficient to trigger the Dar phenotype. We did not observe the Dar phenotype in uninfected tph-1 mutants or in wild type animals treated with methiothepin (R. McMullan and A. Anderson, unpublished observation) indicating that infection with M. nematophilum must regulate additional signaling pathways (including the EGL-30(Gαq) pathway) to trigger the immune response.

Another environmental cue that may alter serotonin synthesis to suppress the immune response is the presence of food. In C. elegans serotonin signals the presence of food [28], and because ADF neurons directly contact the environment it has been suggested that they may couple environmental food signals with serotonergic neurotransmission [54]. In support of this we observed that tph-1 mutant animals (that behave as if they were starved in the presence of food), were able to respond to lower levels of M. nematophilum infection than wild type animals. We have also obtained anecdotal evidence that infection causes starved animals to become Dar more easily than well-fed animals (R. McMullan and A. Anderson, unpublished observation) suggesting that the presence (or absence) of food is able to influence the immune response. Furthermore serotonin signaling is able to suppress the Dar response when it is triggered in the absence of infection (using RE::EGL-30*) because decreasing serotonin synthesis (using tph-1 mutants), or signaling (using methiothepin), both increased the percentage of Dar positive RE::EGL-30* animals. One possible explanation for these observations is that in the presence of food, wild type levels of serotonin inhibit the Dar phenotype. It is possible that the presence of food is sensed by ADF, increasing serotonin synthesis and suppressing the immune response. In this way C. elegans would be able to integrate several environmental signals including the availability of food and the presence of pathogenic microbes and respond accordingly.

Serotonin synthesized in C. elegans head neurons acts on distant target cells in the tail

We have shown that serotonin synthesized and released from the amphid chemosensory neuron ADF in the animal's head acts on rectal epithelial cells located in the animal's tail. How does serotonin released from these cells influence signaling in distant target cells in the tail?

ADF forms synapses with 17 other interneurons and sensory neurons and gap junctions with an additional two sensory neurons (www.wormweb.org). The rectal epithelial cells, where GOA-1(Gαo) signaling is required to suppress the immune response, have not been reported as postsynaptic targets of ADF suggesting that serotonin is not released directly onto these cells. In principle it is possible that infection of C. elegans with M. nematophilum alters the connectivity of ADF such that the rectal epithelium become a postsynaptic target however we did not observe any gross changes in the expression pattern of a tph-1p::DSRED reporter, that is expressed in ADF neurons, following M. nematophilum infection (data not shown) and it seems unlikely that infection would cause such dramatic reorganization of the nervous system. Alternatively, serotonin may diffuse from its release sites to act on distant cells. This is consistent with previous C. elegans work showing that serotonin released from ADF travels extrasynaptically to RIH and AIM interneurons where it accumulates using the serotonin transporter mod-5 [54]. Extrasynaptic serotonin signaling is conserved in the vertebrate brain [57] and may also contribute to serotonin regulation of the mammalian immune response as B cells take up serotonin released from the noradrenergic neurons that innervate lymphatic tissue [58].

Another possibility is that serotonin does not act directly on the rectal epithelial cells. Several studies have placed GOA-1(Gαo) signaling downstream of serotonin in the regulation of locomotion [47], [52]. These studies have defined the site of action for GOA-1(Gαo) as the cholinergic motor neurons located in the ventral nerve cord [47]. Until recently, it remained unclear whether serotonin acts directly on serotonin receptors expressed on these cells to influence GOA-1(Gαo) signaling or whether serotonin simulates interneurons to release signals that activate GOA-1(Gαo) – coupled GPCRs on these motor neurons. Work by Gürel et. al. [59] identifies the serotonin receptors required for control of locomotion as MOD-1 and SER-4. SER-4 and MOD-1 expression were detected in a non-overlapping subset of head and tail interneurons while MOD-1 expression was also found in GABAergic motor neurons located in the ventral nerve cord indicating that serotonin must act indirectly on cholinergic motor neurons to regulate GOA-1(Gαo) signaling and locomotion [59]. Could this also be the case for serotonin regulation of the immune response? At least two serotonin GPCRs; SER-1 and SER-7, mediate the effect of exogenous serotonin on the immune response however expression of these receptors has not been reported in the rectal epithelium. Perhaps M. nematophilum infection alters the expression of these receptors, and in the future determining the expression pattern of these receptors during infection will address serotonin's mechanism of action.

A conserved G-protein signaling network acts in neurons and epithelial cells to elicit different responses

In C. elegans cholinergic motor neurons a network of G-proteins regulates acetylcholine release to alter locomotion [60]. EGL-30(Gαq) and GOA-1(Gαo) act antagonistically to regulate acetylcholine release and control locomotion [51]. egl-30 mutants have decreased acetylcholine release resulting in slower locomotion rates [51] while in goa-1 mutants acetylcholine release and locomotion rates are increased [47]. Animals lacking goa-1 are resistant to the effects of serotonin on locomotion suggesting that slowing responses, triggered by serotonin in the presence of food, may be mediated by GOA-1(Gαo) signaling in cholinergic neurons [47]. We have previously shown that EGL-30(Gαq) is required in the rectal epithelium for the immune response to infection by M. nematophilum [36] and here we show that GOA-1(Gαo) acts antagonistically to EGL-30(Gαq) in these cells to suppress the immune response. Our data demonstrate that the same G-protein network is activated in different tissues (neurons and epithelial cells), to elicit different responses (locomotion and immunity).

In neurons, genetic data places GOA-1(Gαo) and EGL-30(Gαq) in parallel pathways [51] however GOA-1(Gαo) may regulate the activity of the RGS EAT-16, which inactivates EGL-30(Gαq), placing GOA-1(Gαo) signaling upstream of EGL-30(Gαq) [61]. Our genetic data suggests that GOA-1(Gαo) acts either upstream of, or in parallel to, EGL-30(Gαq) in the immune response. The Dar response provides an opportunity to study the interactions between these pathways in a new context and it will be interesting to determine whether the immune response is altered in eat-16 mutants.

Although serotonin acts upstream of G proteins in both neurons and epithelial cells, G-protein signaling activates different downstream signaling pathways in each of these cell types. In neurons EGL-30(Gαq) and GOA-1(Gαo) act antagonistically to control levels of the second messenger diacylglycerol (DAG) [47], [51] however DAG is not required to alter rectal epithelial cell shape and size and trigger the Dar phenotype (R. McMullan, unpublished observation). Conversely the ERK MAP Kinase pathway is required downstream of EGL-30(Gαq) in epithelial cells to trigger that Dar phenotype but does not appear to affect acetylcholine release [36].

C. elegans as a model to study bidirectional cross talk between neurotransmitters and the immune response

Alterations in serotonin signaling have been implicated in multiple neurological disorders including anxiety, depression, autism and Alzheimer's disease [62]–[64]. There is growing evidence of altered immune function in these disorders that may contribute to their pathology (reviewed in [15]). Indeed in 1991 Smith proposed the macrophage theory of depression suggesting that excessive secretion of cytokines caused depression by altering serotonin levels in the brain [65]. Although it is not possible to ascertain the psychological state of model organisms such as C. elegans they have proved extremely useful in investigating the conserved molecular mechanisms that underlie changes in serotonin signaling in response to the environment. We have yet to determine whether the C. elegans immune response is able to reciprocally regulate serotonin signaling however analysis of serotonin-regulated behaviors following infection should begin to address this question. Our work demonstrates that C. elegans can also be used as a model to study the reciprocal cross talk between neurotransmitters and the immune response that may be important for the pathology of disorders such as depression.

Materials and Methods

Strains

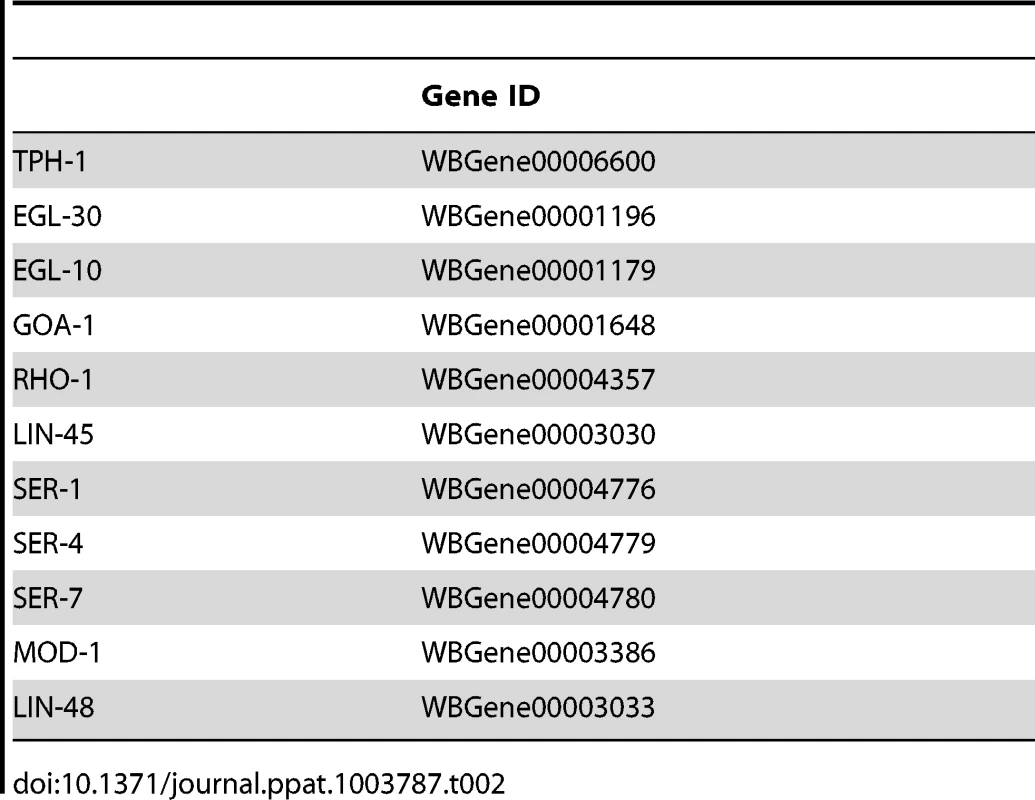

C. elegans strains used in this study are detailed in Table S1. Gene ID's for genes used are detailed in Table 2. All strains were cultivated at 20°C on nematode-growth media (NGM) plates seeded with E. Coli OP50, unless otherwise stated, and maintained as described previously [66]. Where indicated Methiothepin (50 µg/ml) or Serotonin creatine sulfate (3.8 mg/ml) was added to NGM before pouring and plates were used within 5 days. Unless indicated adult animals were transferred to drug plates and their progeny were scored.

Tab. 2. Gene ID numbers from WormBase (<a href="http://www.wormbase.org">www.wormbase.org</a>).

Transgenes and germline transformation

Plasmids (listed as pRJM) were constructed using standard techniques, and verified by sequencing. Transgenic strains (listed as impEx) were isolated by microinjection of the plasmid together with acr-2::gfp (a gift of J. Kaplan, Massachusetts General Hospital) or unc-17::gfp (a gift of S. Nurrish, University College London, UK) at 50 ng/µl as a marker. In all experiments matched animals not expressing the injection marker were assayed in parallel as a control. Data was only included if the phenotype of non-transgenic animals was comparable to that of the parental strain.

EGL-10 transgenes

The wild type EGL-10 cDNA was isolated from wild type N2 RNA using standard techniques and verified by sequencing. This cDNA was subcloned into either the pPD49_78 heat shock vector (a gift of A. Fire Stanford University CA) (pRJM174) or a vector driving expression from a 1.3 Kb egl-5 promoter fragment that drives GFP expression in B, K, F, U, P12.pa and three body wall muscles in the posterior [49] (pRJM176). These plasmids were injected at 20 ng/µl into egl-10(n692). impEx031 and impEx020 contain extrachromosomal versions of pRJM174 and pRJM176 respectively. impEx031;egl-10(n692) were backcrossed to remove the egl-10(n692) mutation in order to obtain animals overexpressing EGL-10 in the rectal epithelium.

Food choice assay

Assays were performed essentially as described in McMullan et. al. [36] with the following changes. OP50 or CBX102 bacterial cultures were grown to the same optical density in LB and 40 µl was placed on opposite sides of a 60 mm NGM plate. One-day old adult animals were transferred to NGM plates lacking food for 30 minutes and then washed in M9 and allowed to settle before aspiration. A suspension of animals in a drop of M9 was placed equidistant from each bacterial lawn, numbers of animals varied from 25 to 100. Choice index = (number of animals on lawn A - number of animals on lawn B)/number of animals on lawn A+B. In all experiments lawn A was OP50 and B was CBX102 M. nematophilum. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times.

M. nematophilum infection

Infection with M. nematophilum was performed as described previously [36]. NGM plates were seeded with either 10% or 0.05% M. nematophilum diluted in OP50 E. Coli. Unless otherwise stated adult animals were transferred from OP50 plates to infection plates and maintained at 20°C. F1 progeny were scored for the presence or absence of the Dar phenotype once they reached L4 or adult stages. In the case of hs::EGL-10;egl-10(n692) animals (Figure 4A) and wild type animals in Figure 1B synchronized populations of L1 animals were obtained by bleaching. These animals were transferred to infection plates as L1's or grown on standard E. Coli OP50 plates for 24 (L2/L3 stage), or 48 hours (L3/L4 stage), before transferring to infection plates. This generation was assayed for the presence of the Dar phenotype when animals reached L4 or adult stages. Between 30 and 50 animals were scored per plate. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times.

For experiments using exogenous serotonin plates were prepared as described above and were seeded with 10% or 0.05% M. nematophilum diluted in OP50 E. Coli. Plates were used within 5 days. Animals were not pretreated with serotonin prior to M. nematophilum infection and serotonin was present throughout infection with M. nematophilum.

For imaging experiments the avirulent M. nematophilum strain UV336 [67] was used and plates were prepared identically to plates seeded with virulent, CBX102, M. nematophilum.

SYTO13 staining was performed as described previously [35]. Following incubation with SYTO13 animals were either transferred to unseeded plates, for clearance assays as described below, or mounted for imaging.

Clearance of Syto13 labeled M. nematophilum

Animals were infected with M. nematophilum as described above and SYTO13 labeling was performed as described previously [35] except that after a 60 minute incubation with SYTO13 10–20 µl of settled, stained worms were transferred to NGM plates lacking food. After drying the number of animals colonized by SYTO13 positive M. nematophilum was scored using a Nikon SMZ1500 microscope with GFP filter. A ring of 150 mM Copper Sulphate, 2% SDS was use to prevent animals escaping from the plates. Unless indicated both Dar and Dar-defective animals were scored indifferently for the presence of SYTO13 labeling. The percentage of Dar animals was scored prior to SYTO13 labeling. To confirm that loss of SYTO13 labeling reflected a loss of M. nematophilum attachment wild type animals were washed from clearance assay plates after 90 minutes and restained with SYTO13. Approximately 10% of animals were SYTO13 positive indicating that M. nematophilum was no longer attached to the rectal opening of the majority these animals. Between 20 and 50 animals were scored per plate. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times. We observed some variability in the rate of pathogen clearance between experiments therefore assays were performed by two different people and data was only included if results were comparable. Furthermore, each graph only contains data from experiments where all genotypes presented were assayed in parallel.

Microscopy

10–20 µl of settled, SYTO13 labeled animals were added to an equal volume of 600 mg/ml 2,3-Butanedione monoxime in M9 and mounted on 2% agarose pads. Adult animals expressing tph-1p::DSRED (vsIs97) were infected with virulent or avirulent forms of M. nematophilum and the first generation progeny were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde and imaged by mounting on 2% agarose pads.

Animals were viewed on a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope using a Nikon ×40 objective (for SYTO13 labeled animals) or ×60 objective (for animals expressing tph-1p::DSRED). Images were obtained using Nikon NIS elements BR software. When tph-1p::DSRED expressing animals were used two images were acquired for each animal to allow the fluorescence intensity of ADF and NSM neuronal cell bodies to be measured.

Images were thresholded to highlight SYTO13 staining, or the ADF/NSM cell body, using Nikon NIS elements BR software and the average fluorescence intensity was the average pixel value within this thresholded area. Controls (wild type animals for SYTO13 experiments and uninfected animals for tph-1p::DSRED) were imaged in parallel and experiments were performed on at least three separate occasions. At least 30 animals were imaged per condition.

Induction of heat shock-inducible transgenes

Expression from the heat shock promoter was achieved using two rounds of heat shock for 60 min separated by 30 min at 20°C. Heat shock was performed at 0, 24 and 48 hours after transfer of L1's to M. nematophilum plates when animals were at approximately L1, L2/3 and L3/4 stage respectively. A heat shock temperature of 33°C was used. Animals were allowed to recover at 20°C before scoring for the Dar phenotype when the animals reached adulthood.

Statistical analysis

In all cases statistical analysis was performed using Prism 6 (GraphPad Software). The percentage of Dar animals was compared using an unpaired two-tailed t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSP Post hoc multiple comparison test. Food choice index data was compared using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSP Post hoc multiple comparison test. Clearance assay data was compared using a two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSP Post hoc multiple comparison test. * P≤0.05, ** P≤0.01, *** P≤0.001, **** P≤0.0001, n.s. P>0.05

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. SerafeimA, GordonJ (2001) The immune system gets nervous. Current Opinion in Pharmacology 1 : 398–403.

2. GlaserR, Kiecolt-GlaserJK (2005) Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health. Nat Rev Immunol 5 : 243–251 doi:10.1038/nri1571

3. Gravato-NobreM, HodgkinJ (2005) Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for innate immunity to pathogens. Cell Microbiol 7 : 741–792.

4. KawliT, TanM (2008) Neuroendocrine signals modulate the innate immunity of Caenorhabditis elegans through insulin signaling. Nat Immunol doi:10.1038/ni.1672

5. ShiversR, KooistraT, ChuS, PaganoD, KimD (2009) Tissue-specific activities of an immune signaling module regulate physiological responses to pathogenic and nutritional bacteria in C. elegans. Cell Host Microbe 6 : 321–351.

6. ZhangY, LuH, BargmannCI (2005) Pathogenic bacteria induce aversive olfactory learning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Cell Biol 438 : 179–184 doi:10.1038/nature04216

7. ZugastiO, EwbankJJ (2009) Neuroimmune regulation of antimicrobial peptide expression by a noncanonical TGF-β signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans epidermis. Nat Immunol 10 : 249–256 doi:10.1038/ni.1700

8. PradelE, ZhangY, PujolN, MatsuyamaT, BargmannCI, et al. (2007) Detection and avoidance of a natural product from the pathogenic bacterium Serratia marcescens by Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104 : 2295–2300 doi:10.1073/pnas.0610281104

9. YookK, HodgkinJ (2007) Mos1 mutagenesis reveals a diversity of mechanisms affecting response of Caenorhabditis elegans to the bacterial pathogen Microbacterium nematophilum. Genetics 175 : 681–697 doi:10.1534/genetics.106.060087

10. EvansEA, KawliT, TanM-W (2008) Pseudomonas aeruginosa Suppresses Host Immunity by Activating the DAF-2 Insulin-Like Signaling Pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog 4: e1000175 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000175

11. BrogdenKA, GuthmillerJM, SalzetM, ZasloffM (2005) The nervous system and innate immunity: the neuropeptide connection. Nat Immunol 6 : 558–564 doi:10.1038/ni1209

12. SunJ, SinghV, Kajino-SakamotoR, AballayA (2011) Neuronal GPCR controls innate immunity by regulating noncanonical unfolded protein response genes. Science 332 : 729–732 doi:10.1126/science.1203411

13. LeviteM (2012) The 1st International Meeting on Nerve-Driven Immunity: Neurotransmitters and Neuropeptides in the Immune System. Future Neurology 7 : 247–253.

14. AhernGP (2011) 5-HT and the immune system. Current Opinion in Pharmacology doi:10.1016/j.coph.2011.02.004

15. BaganzNL, BlakelyRD (2013) A dialogue between the immune system and brain, spoken in the language of serotonin. ACS Chem Neurosci 4 : 48–63 doi:10.1021/cn300186b

16. IrwinMM, LacherUU, CaldwellCC (1992) Depression and reduced natural killer cytotoxicity: a longitudinal study of depressed patients and control subjects. Psychol Med 22 : 1045–1050 doi:10.1017/S0033291700038617

17. FrankMG, HendricksSE, JohnsonDR, WieselerJ, BurkeWJ (1999) Antidepressants Augment Natural Killer Cell Activity: In vivo and in vitro. Neuropsychobiology 39 : 18–24 doi:10.1159/000026555

18. IdzkoM, PantherE, StratzC, MüllerT, BayerH, et al. (2004) The serotoninergic receptors of human dendritic cells: identification and coupling to cytokine release. J Immunol 172 : 6011–6019.

19. MikulskiZ, ZaslonaZ, CakarovaL, HartmannP, WilhelmJ, et al. (2010) Serotonin activates murine alveolar macrophages through 5-HT2C receptors. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 299: L272–L280 doi:10.1152/ajplung.00032.2010

20. Kushnir-SukhovNM, GilfillanAM, ColemanJW, BrownJM, BrueningS, et al. (2006) 5-hydroxytryptamine induces mast cell adhesion and migration. J Immunol 177 : 6422–6432.

21. IkenK, ChhengS, FarginA, GouletA-C, KouassiE (1995) Serotonin Upregulates Mitogen-Stimulated B Lymphocyte Proliferation through 5-HT1AReceptors. Cellular Immunology 163 : 1–9 doi:10.1006/cimm.1995.1092

22. HernandezME, Martinez-FongD, Perez-TapiaM, Estrada-GarciaI, Estrada-ParraS, et al. (2010) Evaluation of the effect of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors on lymphocyte subsets in patients with a major depressive disorder. European Neuropsychopharmacology 20 : 88–95 doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.11.005

23. M R YoungJPM (1995) Serotonin regulation of T-cell subpopulations and of macrophage accessory function. Immunology 84 : 148.

24. BoehmeSAS, LioFMF, SikoraLL, PanditTST, LavradorKK, et al. (2004) Cutting edge: serotonin is a chemotactic factor for eosinophils and functions additively with eotaxin. J Immunol 173 : 3599–3603.

25. NowakEC, de VriesVC, WasiukA, AhonenC, BennettKA, et al. (2012) Tryptophan hydroxylase-1 regulates immune tolerance and inflammation. J Exp Med 209 : 2127–2135 doi:10.1084/jem.20120408

26. WaltherDJ, PeterJ-U, BashammakhS, HörtnaglH, VoitsM, et al. (2003) Synthesis of serotonin by a second tryptophan hydroxylase isoform. Science 299 : 76–76 doi:10.1126/science.1078197

27. SzeJ, VictorM, LoerC, ShiY, RuvkunG (2000) Food and metabolic signalling defects in a Caenorhabditis elegans serotonin-synthesis mutant. Nature 403 : 560–564.

28. SawinE, RanganathanR, HorvitzH (2000) C. elegans locomotory rate is modulated by the environment through a dopaminergic pathway and by experience through a serotonergic pathway. Neuron 26 : 619–650.

29. AveryL, HorvitzHR (1990) Effects of starvation and neuroactive drugs on feeding in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Exp Zool 253 : 263–270 doi:10.1002/jez.1402530305

30. SégalatL, ElkesD, KaplanJ (1995) Modulation of serotonin-controlled behaviors by Go in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 267 : 1648–1651 doi:10.1126/science.7886454

31. WaggonerL, ZhouG, SchaferR, SchaferW (1998) Control of alternative behavioral states by serotonin in Caenorhabditis elegans. Neuron 21 : 203–217.

32. WeinshenkerD, GarrigaG, ThomasJH (1995) Genetic and pharmacological analysis of neurotransmitters controlling egg laying in C. elegans. J Neurosci 15 : 6975–6985.

33. HodgkinJ, KuwabaraPE, CorneliussenB (2000) A novel bacterial pathogen, Microbacterium nematophilum, induces morphological change in the nematode C. elegans. Curr Biol 10 : 1615–1618.

34. O'RourkeD, BabanD, DemidovaM, MottR, HodgkinJ (2006) Genomic clusters, putative pathogen recognition molecules, and antimicrobial genes are induced by infection of C. elegans with M. nematophilum. Genome Res 16 : 1005–1016 doi:10.1101/gr.50823006

35. NicholasH, HodgkinJ (2004) The ERK MAP kinase cascade mediates tail swelling and a protective response to rectal infection in C. elegans. Curr Biol 14 : 1256–1317.

36. McMullanR, AndersonA, NurrishS (2012) Behavioral and Immune Responses to Infection Require Gαq - RhoA Signaling in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002530 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002530

37. JohnsonAD, FitzsimmonsD, HagmanJ, ChamberlinHM (2001) EGL-38 Pax regulates the ovo-related gene lin-48 during Caenorhabditis elegans organ development. Development 128 : 2857–2865.

38. ChaoMY, KomatsuH, FukutoHS, DionneHM, HartAC (2004) Feeding status and serotonin rapidly and reversibly modulate a Caenorhabditis elegans chemosensory circuit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101 : 15512–15517 doi:10.1073/pnas.0403369101

39. SchulenburgH, EwbankJJ (2007) The genetics of pathogen avoidance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Microbiol 66 : 563–570 doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05946.x

40. FlavellSW, PokalaN, MacoskoEZ, AlbrechtDR, LarschJ, et al. (2013) Serotonin and the Neuropeptide PDF Initiate and Extend Opposing Behavioral States in C. elegans. Cell 154 : 1023–1035 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.001

41. ZhengX, ChungS, TanabeT, SzeJ (2005) Cell-type specific regulation of serotonergic identity by the C. elegans LIM-homeodomain factor LIM-4. Dev Biol 286 : 618–646.

42. AspöckGG, RuvkunGG, BürglinTRT (2003) The Caenorhabditis elegans ems class homeobox gene ceh-2 is required for M3 pharynx motoneuron function. Development 130 : 3369–3378 doi:10.1242/dev.00551

43. EstevezM, EstevezAO, CowieRH, GardnerKL (2003) The voltage-gated calcium channel UNC-2 is involved in stress-mediated regulation of tryptophan hydroxylase. J Neurochem 88 : 102–113 doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02140.x

44. RanganathanR, CannonSC, HorvitzHR (2000) MOD-1 is a serotonin-gated chloride channel that modulates locomotory behaviour in C. elegans. Nature 408 : 470–475 doi:10.1038/35044083

45. HobsonRJR, HapiakVMV, XiaoHH, BuehrerKLK, KomunieckiPRP, et al. (2006) SER-7, a Caenorhabditis elegans 5-HT7-like receptor, is essential for the 5-HT stimulation of pharyngeal pumping and egg laying. Genetics 172 : 159–169 doi:10.1534/genetics.105.044495

46. Carre-PierratM, BaillieD, JohnsenR, HydeR, HartA, et al. (2006) Characterization of the Caenorhabditis elegans G protein-coupled serotonin receptors. Invert Neurosci 6 : 189–205 doi:10.1007/s10158-006-0033-z

47. NurrishS, SégalatL, KaplanJM (1999) Serotonin inhibition of synaptic transmission: Galpha(0) decreases the abundance of UNC-13 at release sites. Neuron 24 : 231–242.

48. KoelleMR, HorvitzHR (1996) EGL-10 regulates G protein signaling in the C. elegans nervous system and shares a conserved domain with many mammalian proteins. Cell 84 : 115–125 doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80998-8

49. TengY, GirardL, FerreiraHB, SternbergPW, EmmonsSW (2004) Dissection of cis-regulatory elements in the C. elegans Hox gene egl-5 promoter. Dev Biol 276 : 476–492 doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.09.012

50. MendelJ, KorswagenH, LiuK, Hajdu-CroninY, SimonM, et al. (1995) Participation of the protein Go in multiple aspects of behavior in C. elegans. Science 267 : 1652–1655 doi:10.1126/science.7886455

51. LacknerM, NurrishS, KaplanJ (1999) Facilitation of synaptic transmission by EGL-30 Gqalpha and EGL-8 PLCbeta: DAG binding to UNC-13 is required to stimulate acetylcholine release. Neuron 24 : 335–381.

52. MILLERK (1999) Goα and Diacylglycerol Kinase Negatively Regulate the Gqα Pathway in C. elegans. Neuron 24 : 323–333 doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80847-8

53. HorvitzHR, ChalfieM, TrentC, SulstonJE, EvansPD (1982) Serotonin and octopamine in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 216 : 1012–1014.

54. JafariG, XieY, KullyevA, LiangB, SzeJY (2011) Regulation of Extrasynaptic 5-HT by Serotonin Reuptake Transporter Function in 5-HT-Absorbing Neurons Underscores Adaptation Behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci 31 : 8948–8957 doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1692-11.2011

55. Hall DH, Altun ZF (2008) C. elegans atlas. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 1 pp.

56. QinYY, ZhangXX, ZhangYY (2013) A neuronal signaling pathway of CaMKII and Gqα regulates experience-dependent transcription of tph-1. J Neurosci 33 : 925–935 doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2355-12.2013

57. BuninMAM, WightmanRMR (1998) Quantitative evaluation of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) neuronal release and uptake: an investigation of extrasynaptic transmission. J Neurosci 18 : 4854–4860.

58. FarajBAB, OlkowskiZLZ, JacksonRTR (1994) Expression of a high-affinity serotonin transporter in human lymphocytes. Int J Immunopharmacol 16 : 561–567 doi:10.1016/0192-0561(94)90107-4

59. GürelG, GustafsonMA, PepperJS, HorvitzHR, KoelleMR (2012) Receptors and Other Signaling Proteins Required for Serotonin Control of Locomotion in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics doi:10.1534/genetics.112.142125

60. McMullanR, NurrishS (2007) Rho deep in thought. Genes Dev 21 : 2677–2759.

61. Hajdu-CroninYMY, ChenWJW, PatikoglouGG, KoelleMRM, SternbergPWP (1999) Antagonism between G(o)alpha and G(q)alpha in Caenorhabditis elegans: the RGS protein EAT-16 is necessary for G(o)alpha signaling and regulates G(q)alpha activity. Genes Dev 13 : 1780–1793.

62. LuckiI (1998) The spectrum of behaviors influenced by serotonin. Biological psychiatry 44 : 151–162.

63. ChuganiDC (2002) Role of altered brain serotonin mechanisms in autism. Mol Psychiatry 7: S16–S17 doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001167

64. RodríguezJJ, NoristaniHN, VerkhratskyA (2012) The serotonergic system in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neurobiol 99 : 15–41 doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.06.010

65. SmithRS (1991) The macrophage theory of depression. Med Hypotheses 35 : 298–306.

66. BrennerS (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77 : 71–94.

67. AkimkinaT, YookK, CurnockS, HodgkinJ (2006) Genome characterization, analysis of virulence and transformation of Microbacterium nematophilum, a coryneform pathogen of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. FEMS Microbiol Lett 264 : 145–196.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Parental Transfer of the Antimicrobial Protein LBP/BPI Protects Eggs against Oomycete InfectionsČlánek Immune Therapeutic Strategies in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Virus or Inflammation Control?Článek Coronaviruses as DNA Wannabes: A New Model for the Regulation of RNA Virus Replication FidelityČlánek CRISPR-Cas Immunity against Phages: Its Effects on the Evolution and Survival of Bacterial PathogensČlánek The Cyst Wall Protein CST1 Is Critical for Cyst Wall Integrity and Promotes Bradyzoite PersistenceČlánek The Malarial Serine Protease SUB1 Plays an Essential Role in Parasite Liver Stage Development

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 12- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Infekční komplikace virových respiračních infekcí – sekundární bakteriální a aspergilové pneumonie

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Host Susceptibility Factors to Bacterial Infections in Type 2 Diabetes

- LysM Effectors: Secreted Proteins Supporting Fungal Life

- Influence of Mast Cells on Dengue Protective Immunity and Immune Pathology

- Innate Lymphoid Cells: New Players in IL-17-Mediated Antifungal Immunity

- Cytoplasmic Viruses: Rage against the (Cellular RNA Decay) Machine

- Balancing Stability and Flexibility within the Genome of the Pathogen

- The Evolution of Transmissible Prions: The Role of Deformed Templating

- Parental Transfer of the Antimicrobial Protein LBP/BPI Protects Eggs against Oomycete Infections

- Host Defense via Symbiosis in

- Regulatory Circuits That Enable Proliferation of the Fungus in a Mammalian Host

- Immune Therapeutic Strategies in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Virus or Inflammation Control?

- Burning Down the House: Cellular Actions during Pyroptosis

- Coronaviruses as DNA Wannabes: A New Model for the Regulation of RNA Virus Replication Fidelity

- CRISPR-Cas Immunity against Phages: Its Effects on the Evolution and Survival of Bacterial Pathogens

- Combining Regulatory T Cell Depletion and Inhibitory Receptor Blockade Improves Reactivation of Exhausted Virus-Specific CD8 T Cells and Efficiently Reduces Chronic Retroviral Loads

- Shaping Up for Battle: Morphological Control Mechanisms in Human Fungal Pathogens

- Identification of the Virulence Landscape Essential for Invasion of the Human Colon

- Nodular Inflammatory Foci Are Sites of T Cell Priming and Control of Murine Cytomegalovirus Infection in the Neonatal Lung

- Hepatitis B Virus Disrupts Mitochondrial Dynamics: Induces Fission and Mitophagy to Attenuate Apoptosis

- Mycobacterial MazG Safeguards Genetic Stability Housecleaning of 5-OH-dCTP

- Systematic MicroRNA Analysis Identifies ATP6V0C as an Essential Host Factor for Human Cytomegalovirus Replication

- Placental Syncytium Forms a Biophysical Barrier against Pathogen Invasion