-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Axon Regeneration Is Regulated by Ets–C/EBP Transcription Complexes Generated by Activation of the cAMP/Ca Signaling Pathways

An axon’s ability to regenerate after injury is governed by cell-intrinsic regeneration pathways. In C. elegans, the JNK and p38 MAPK pathways play an important role in axon regeneration. The JNK pathway is activated by growth factor SVH-1, which signals through its receptor SVH-2. It is known that expression of the svh-2 gene is induced in response to axonal injury, however the molecular mechanisms underlying this induction have been unknown. Here, we demonstrate that induction of svh-2 expression in response to axon injury involves the transcription factors ETS-4 and CEBP-1, which function downstream of the cAMP and Ca2+–p38 MAPK pathways, respectively. Our results suggest that these two injury-signaling pathways converge to regulate expression of the svh-2 gene and thereby promote axon regeneration.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005603

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005603Summary

An axon’s ability to regenerate after injury is governed by cell-intrinsic regeneration pathways. In C. elegans, the JNK and p38 MAPK pathways play an important role in axon regeneration. The JNK pathway is activated by growth factor SVH-1, which signals through its receptor SVH-2. It is known that expression of the svh-2 gene is induced in response to axonal injury, however the molecular mechanisms underlying this induction have been unknown. Here, we demonstrate that induction of svh-2 expression in response to axon injury involves the transcription factors ETS-4 and CEBP-1, which function downstream of the cAMP and Ca2+–p38 MAPK pathways, respectively. Our results suggest that these two injury-signaling pathways converge to regulate expression of the svh-2 gene and thereby promote axon regeneration.

Introduction

The ability of a neuron to regenerate following injury is dependent on both its intrinsic growth capacity and the extracellular environment. When an axon is injured, intracellular levels of calcium (Ca2+) and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) increase [1]. The increase in cAMP levels activates protein kinase A (PKA), which in turn activates the axon regeneration-promoting transcription factor CREB. PKA also promotes remodeling of the cytoskeleton, which is necessary for the formation and maintenance of the growth cone, a specialized structure necessary to initiate regeneration. Upon axon severance, regeneration signals are retrogradely transported from sites of damage and imported into the nucleus, where they induce the up-regulation of several transcription factors and drive the increased synthesis of proteins involved in neurite outgrowth [2,3]. Manipulation of these processes can improve the chances for successful axon regeneration. Nonetheless, our understanding of the intrinsic signaling pathways that promote this regenerative ability remains limited.

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has recently emerged as a genetic model for studying the molecular control of axon regeneration [4,5]. Recent genetic studies have demonstrated that C. elegans axon regeneration is regulated by the p38 and JNK MAP kinase (MAPK) pathways, which consist of DLK-1 (MAPKKK)–MKK-4 (MAPKK)–PMK-3 (MAPK) and MLK-1(MAPKKK)–MEK-1(MAPKK)–KGB-1 (MAPK), respectively [6–8]. The p38 MAPK signaling pathway promotes axon regeneration by activating the MAP kinase-activated protein kinase MAK-2, which functions to stabilize the mRNA encoding the C/EBP family transcription factor CEBP-1 [7]. CEBP-1 in turn promotes axon regeneration, although the specific targets that mediate this response remain unknown. MAPK cascades can be inactivated by members of the MAPK phosphatase (MKP) family [9]. In C. elegans, the vhp-1 gene encodes a MKP that negatively regulates both the DLK-1–MKK-4–PMK-3 and MLK-1–MEK-1–KGB-1 MAPK pathways [8,10]. vhp-1 mutant animals are arrested during larval development, due to hyperactivation of the MAPK pathways. Furthermore, axon regeneration is enhanced in vhp-1 mutants [8]. In a previous effort to identify additional components involved in MAPK-mediated signaling, we isolated a number of svh (suppressor of vhp-1) genes, which function as suppressors of vhp-1 larval lethality [11]. Two of these, svh-1 and svh-2, encode a growth factor and its cognate receptor tyrosine kinase, respectively. SVH-1–SVH-2 signaling mediates the activation of the JNK cascade following axonal injury, a molecular event essential for neuronal regeneration but not for neuronal development. This specific effect on axon regeneration is determined by svh-2 gene expression, which is induced following axon injury in severed neurons (Fig 1A) [11].

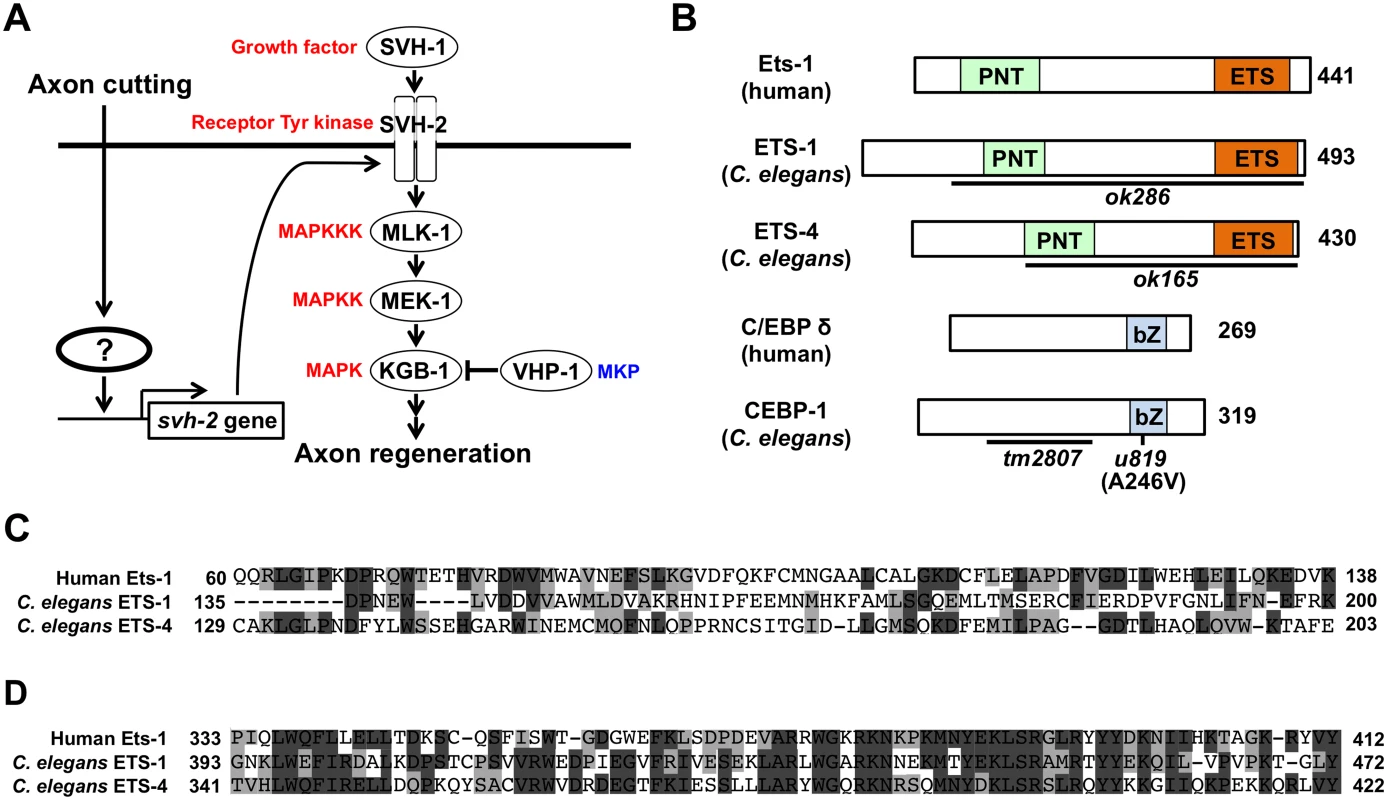

Fig. 1. Identification of transcription factors acting in JNK cascade in C. elegans.

(A) The JNK MAPK pathway is required for axon regeneration in C. elegans. Activation of SVH-2 receptor tyrosine kinase by SVH-1 growth factor activates the JNK pathway [11]. Axon cutting by laser microsurgery induces the transcription of the svh-2 gene in severed neurons. However, the mechanism by which the svh-2 gene is induced in response to axon cutting has been unknown. (B) Structures of ETS-1, ETS-4 and CEBP-1. Schematic diagrams of ETS-1, ETS-4, CEBP-1 and their human counterparts are shown. Domains are shown as follows: a pointed domain (PNT), an Ets DNA-binding domain (ETS), and a basic leucine-zipper domain (bZ). The bold lines underneath indicate the extent of the deleted region in each deletion mutant. The u819 point mutation site is indicated. (C) Comparisons of PNT domains among human Ets-1, C. elegans ETS-1 and ETS-4. Identical and similar residues are highlighted with black and gray shading, respectively. (D) Comparisons of Ets domains among human Ets-1, C. elegans ETS-1 and ETS-4. Identical and similar residues are highlighted with black and gray shading, respectively. In the present study, we investigated ets-4 and cebp-1, two genes that emerged from our previous screen, and examined their potential roles in the regulation of axon regeneration. We demonstrate that ETS-4 and CEBP-1 act as transcriptional activators of svh-2 expression in response to axon injury. ETS-4 and CEBP-1 function as downstream effectors of the cAMP and Ca2+–p38 MAPK pathways, respectively. Our results indicate that the cAMP and Ca2+–p38 MAPK pathways, induced in response to axon injury, converge through the formation of an ETS-4–CEBP-1 transcription factor complex to transactivate svh-2 gene expression and SVH-2 receptor expression, which in turn activates the JNK pathway. Thus, the cAMP and Ca2+–p38 MAPK signaling pathways induce a transcription factor complex that ultimately up-regulates the JNK pathway and promotes axon regeneration.

Results

ETS-4 is required for efficient axon regeneration

To identify the transcription factors involved in axon injury-induced activation of svh-2 expression, we asked if any of the svh genes encode transcription factors. Among our svh genes we identified svh-5, which encodes a member of the Ets transcription factor family and contains an Ets DNA binding domain and a PNT domain, a protein-protein interaction domain conserved in a subset of Ets proteins (Fig 1B, 1C and 1D) [12]. We therefore renamed svh-5 as ets-1. To examine the effect of ets-1 on axon regeneration, we assayed regrowth after laser axotomy in γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-releasing D-type motor neurons, which extend their axons from the ventral to the dorsal nerve cord (Fig 2A) [4,6]. In young adult wild-type animals, laser-severed axons were able to initiate regeneration within 24 hr (Fig 2A and 2B and S1 Table). Although the ets-1(ok286) deletion mutation (Fig 1B) slightly inhibited axon regeneration, this effect was not statistically significant (Fig 2B and S1 Table). The C. elegans genome contains ten ets genes, among which PNT domains are found in only ETS-1 and ETS-4 (Fig 1B and 1C) [13,14]. We found that in contrast to ets-1, the frequency of axon regeneration in ets-4(ok165) deletion mutants (Fig 1B) was reduced significantly (Fig 2A and 2B and S1 Table). The morphology of D-type motor neurons was normal in ets-4 mutants. These results suggest that ets-1 and ets-4 are involved in vhp-1-mediated larval development and axon regeneration, respectively. To test whether ETS-4 can act in a cell-autonomous manner, we expressed the ets-4 cDNA from the unc-25 or mec-7 promoters in ets-4 mutants. The ets-4 defect was rescued by expression of ets-4 in D-type motor neurons by the unc-25 promoter but not by expression in sensory neurons by the mec-7 promoter (Fig 2C and S1 Table). These results demonstrate that ETS-4 functions cell autonomously in D-type motor neurons.

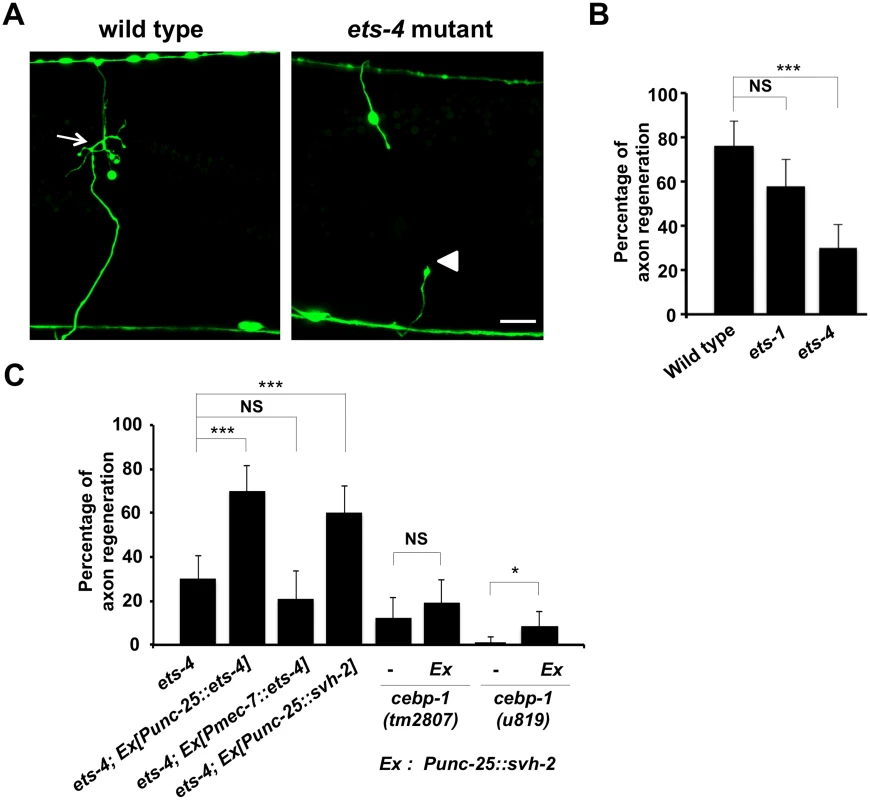

Fig. 2. ETS-4 is required for efficient axon regeneration in C. elegans.

(A) Representative D-type motor neurons in wild-type and ets-4 mutant animals 24 hr after laser surgery. In wild-type animals, severed axons have regenerated growth cones (arrows). In ets-4 mutants, the proximal end of axon failed to regenerate (arrowhead). Scale bar = 10 μm. (B, C) Percentages of axons that initiated regeneration 24 hr after laser surgery. Error bars indicate 95% SI. ***P<0.001; *P<0.05; NS, not significant. ETS-4 and CEBP-1 are required for the transcriptional induction of the svh-2 gene in response to axon injury

Since expression of svh-2 is induced by axon injury [11], we next examined whether ETS-4 is involved in svh-2 expression in response to axon injury. For this purpose we used the transgene Psvh-2::nls::venus, which consists of the svh-2 promoter driving the fluorescent protein VENUS fused to a nuclear localization signal (NLS) [11]. In wild-type animals, Psvh-2::nls::venus expression was induced in D-type neurons in 52% of the animals following laser surgery (Fig 3A and 3B and S1 Fig). In contrast, we found that the ets-4(ok165) mutation abolished Psvh-2::nls::venus induction in response to laser surgery in D-type neurons (Fig 3A and 3B). These results suggest that ETS-4 is a transcription factor required for axon injury-induced up-regulation of svh-2 expression. If ETS-4 is required for axon regeneration through activation of svh-2 gene expression, the ets-4 defect should be suppressed by constitutive expression of svh-2. We replaced the svh-2 promoter with the unc-25 promoter to generate the Punc-25::svh-2 transgene and introduced this as an extrachromosomal array into an ets-4(ok165) mutant. As expected, this construct was able to rescue the ets-4(ok165) animals (Fig 2C and S1 Table). These results support the idea that ETS-4 acts as a transcription factor regulating svh-2 expression in response to axon injury.

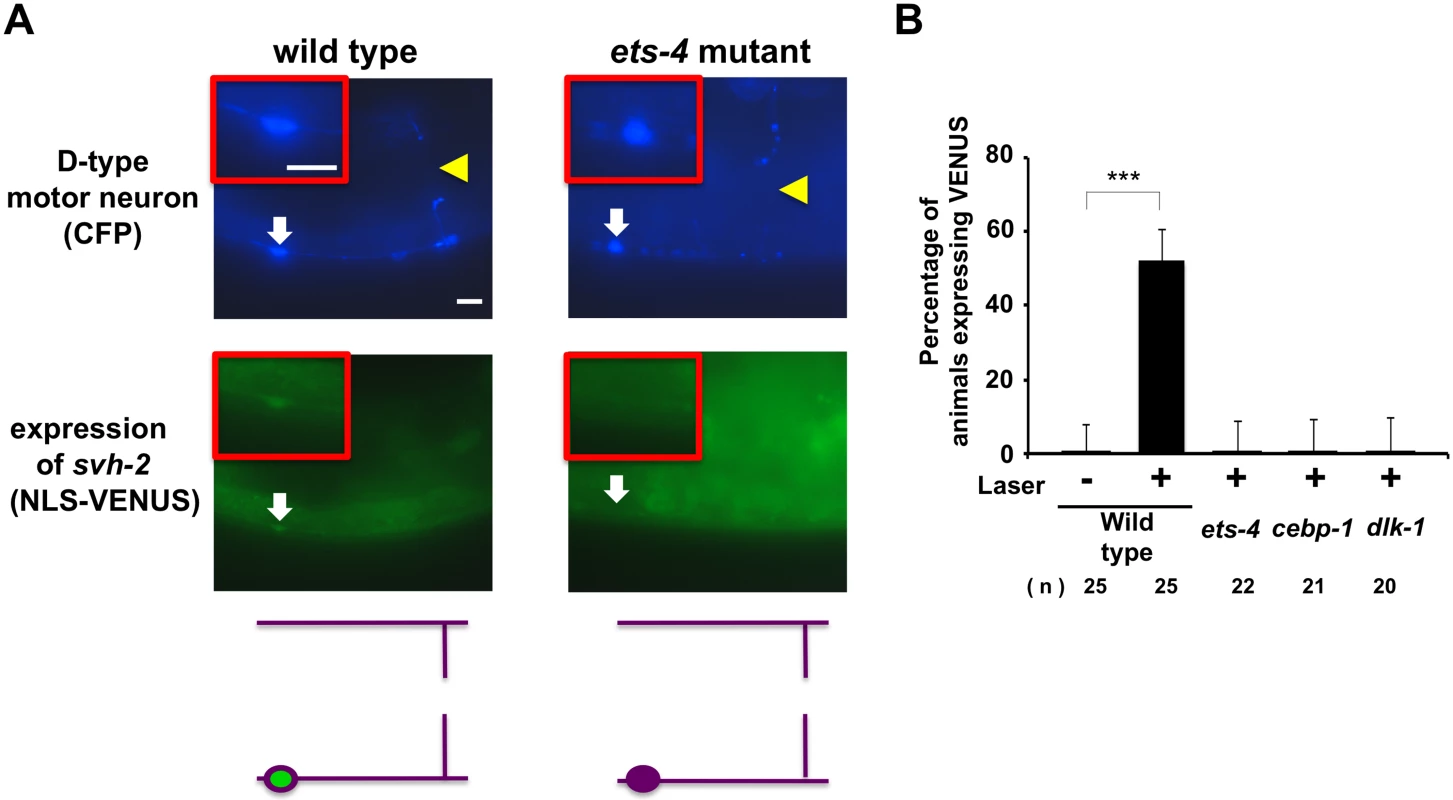

Fig. 3. ETS-4 and CEBP-1 are required for the transcriptional induction of the svh-2 gene in response to axon injury.

(A) Induction of Psvh-2::nls::venus expression in D-type motor neurons by laser surgery. Expression of fluorescent proteins in D-type motor neurons of wild-type and ets-4 mutants 3 hr after laser surgery are shown. Yellow arrowheads and white arrows indicate axon and cell bodies, respectively, of D-type neurons after laser surgery. D neurons are visualized by CFP under control of the unc-25 promoter. Cell bodies of D-type neurons are magnified and shown within the upper boxes. A schematic representation of D-type motor neurons is shown below. Scale bars = 10 μm. (B) Percentages of animals expressing svh-2. Induction of Psvh-2::nls::venus expression in D-type motor neurons with (+) or without (-) laser surgery was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. The numbers (n) of animals examined are shown. Error bars indicate 95% SI. ***P<0.001. Another gene obtained in our svh screen [11] was the svh-8/cebp-1 gene, which encodes a homolog of mammalian C/EBP (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein) (Fig 1B), and which indeed is known to be involved in axon regeneration [7]. We confirmed that animals having the cebp-1(tm2807) mutation (Fig 1B) are defective in axon regeneration in D-type motor neurons (Fig 2C and S1 Table). Therefore, we examined whether CEBP-1 is required for expression of the svh-2 gene in response to axon injury. We found that in cebp-1(tm2807) mutants, laser surgery was unable to induce the expression of Psvh-2::nls::venus in D-type neurons (Fig 3B). Yan et al. showed that axotomy-induced signaling via the DLK-1–p38 MAPK pathway promoted the local translation and stabilization of cebp-1 transcripts, accumulation of which is required for axon regeneration [7]. Since CEBP-1 functions downstream of the DLK-1–p38 MAPK pathway in axon regeneration, we investigated whether the DLK-1 pathway is involved in axon injury-induced expression of svh-2. We found that expression of the svh-2 reporter in D-type neurons was not induced by axon injury in dlk-1(km12) null mutants (Fig 3B). These results support the possibility that the DLK-1–p38 MAPK pathway is involved in axon injury-induced expression of the svh-2 gene. If the svh-2 gene is the only transcriptional target of CEBP-1, the cebp-1 defect should be suppressed by constitutive expression of svh-2. However, in contrast to ets-4, the Punc-25::svh-2 transgene was unable to rescue the defect associated with the cebp-1(tm2807) mutation (Fig 2C and S1 Table). Partial rescue of the phenotype may be expected if CEBP-1 has additional transcriptional targets that act in parallel to promote regeneration. Consistent with this, the Punc-25::svh-2 transgene weakly suppressed the regeneration defect caused by a different, stronger allele of cebp-1(u819) (Fig 2C and S1 Table). These results suggest that CEBP-1 has other target(s) in addition to svh-2 that function in regeneration after axon injury.

The svh-2 promoter region is required for regeneration and gene expression in response to axon injury

To determine the region in the svh-2 promoter important for axon regeneration and gene induction following axon injury, we generated a series of svh-2 promoter deletions (Fig 4A). We have previously demonstrated that a 6.2 kb region of the svh-2 promoter, driving the svh-2 gene, is sufficient to rescue defective axon regeneration in svh-2 mutants (Fig 4B and S1 Table). We observed here that a 2.6 kb region of the promoter upstream of the translational start site is also sufficient to rescue this defect, but a 0.5 kb promoter region is not (Fig 4B and S1 Table). Consistent with this, we confirmed that expression of a Psvh-2::nls::venus construct in D-type neurons after exposure to axon injury could be induced by the 2.6 kb promoter region, but not by the 0.5 kb region (Fig 4C). These results indicate that the promoter region of the svh-2 gene between 0.5 kb and 2.6 kb upstream of the translational start site is important for the transcriptional induction of the svh-2 gene and for axon regeneration.

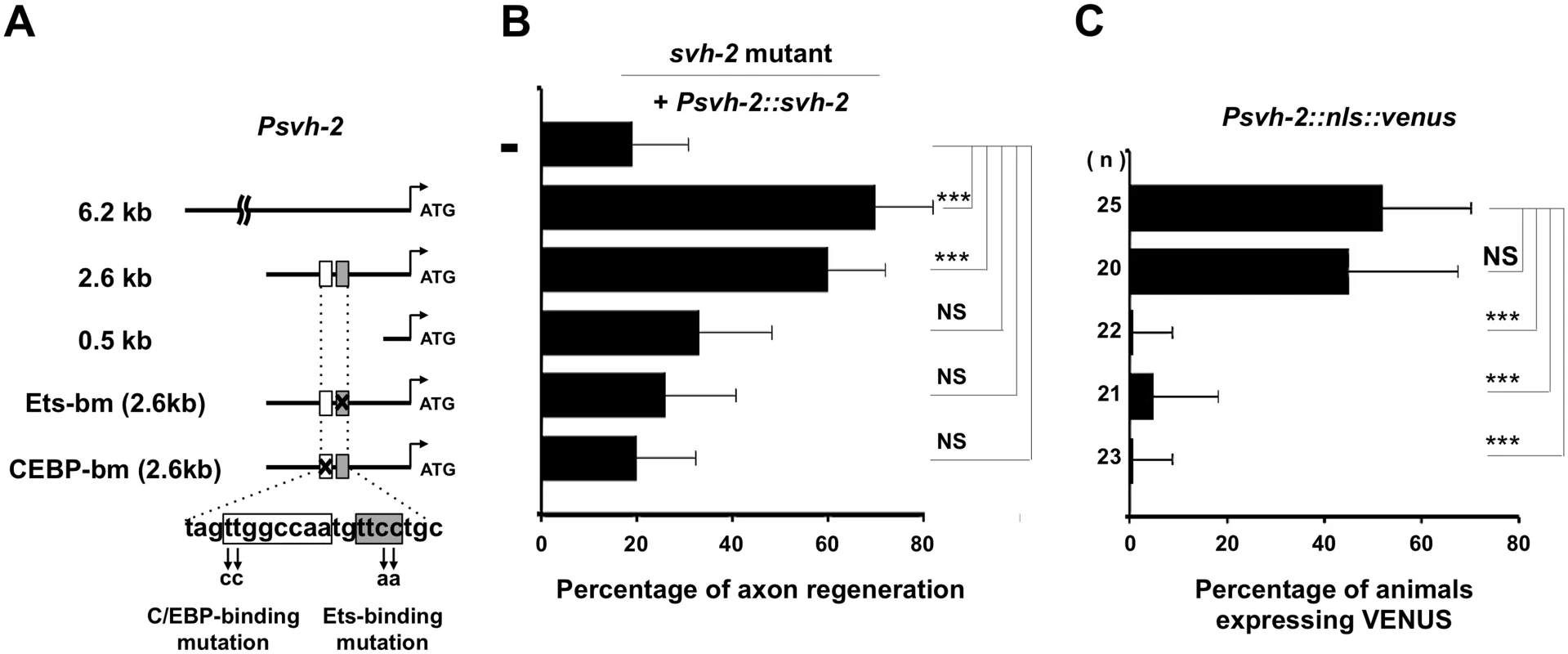

Fig. 4. Promoter analysis of the svh-2 gene.

(A) The svh-2 promoter region. Schematic diagram of the svh-2 transgenes used in rescue experiments are shown. The positions of binding sites for Ets and C/EBP in the svh-2 promoter are indicated by shaded and white boxes, respectively. (B) Identification of the svh-2 promoter region required for axon regeneration. Each construct was transfected into svh-2 mutants and analysed for axon regeneration. The percentages of axons that initiated regeneration 24 hr after laser surgery are shown. Error bars indicate 95% SI. ***P<0.001; NS, not significant. (C) Identification of the svh-2 promoter region required for induction of Psvh-2::nls::venus expression in D-type motor neurons by laser surgery. Each construct was transfected into animals and analysed for svh-2 gene induction in response to laser surgery. The percentages of animals expressing Psvh-2::nls::venus in D-type motor neurons following laser surgery are shown. The numbers (n) of animals examined are shown. Error bars indicate 95% SI. ***P<0.001; NS, not significant. To assess whether ETS-4 and CEBP-1 directly regulate svh-2 expression, we searched the svh-2 promoter region for Ets - and C/EBP-binding sites. Mammalian Ets binds the consensus sequence, 5’-GGAA/T-3’ [15], and the promoter region of the svh-2 gene between 0.5 kb and 2.6 kb contains several possible Ets-binding motifs. This promoter region also has two C/EBP-binding motifs (5’-TTGNNCAA-3’) [16]. Of particular note, there is an Ets - and a C/EBP-binding site located in close proximity to one another at 1370 and 1378 base pairs upstream of the translational start site, respectively (Fig 4A). To determine whether these binding sites are required for axon regeneration and axon injury-induced expression of the svh-2 gene, we converted the Ets consensus GGAA sequence to TTAA and the C/EBP consensus TTGGCCAA to CCGGCCAA (Fig 4A). We found that svh-2 gene constructs carrying either of these point mutations in their promoter failed to rescue the svh-2 defect in axon regeneration (Fig 4B and S1 Table). Furthermore, we found that axon injury-induced Psvh-2::nls::venus expression in D-type neurons was abolished by alteration of either of the Ets or C/EBP binding motif (Fig 4C). These results suggest that ETS-4 and CEBP-1 bind to the svh-2 promoter via their respective binding site, and therein drive svh-2 expression in response to axon injury. Thus, svh-2 promoter activity appears to depend primarily on this combined Ets–C/EBP motif, raising the possibility that ETS-4 and CEBP-1 may physically interact at this site to drive svh-2 gene expression. In a yeast two-hybrid assay we found that ETS-4 and CEBP-1 could indeed interact (Fig 5A and 5B), suggesting that ETS-4 may cooperate with CEBP-1 on the svh-2 promoter to activate transcription.

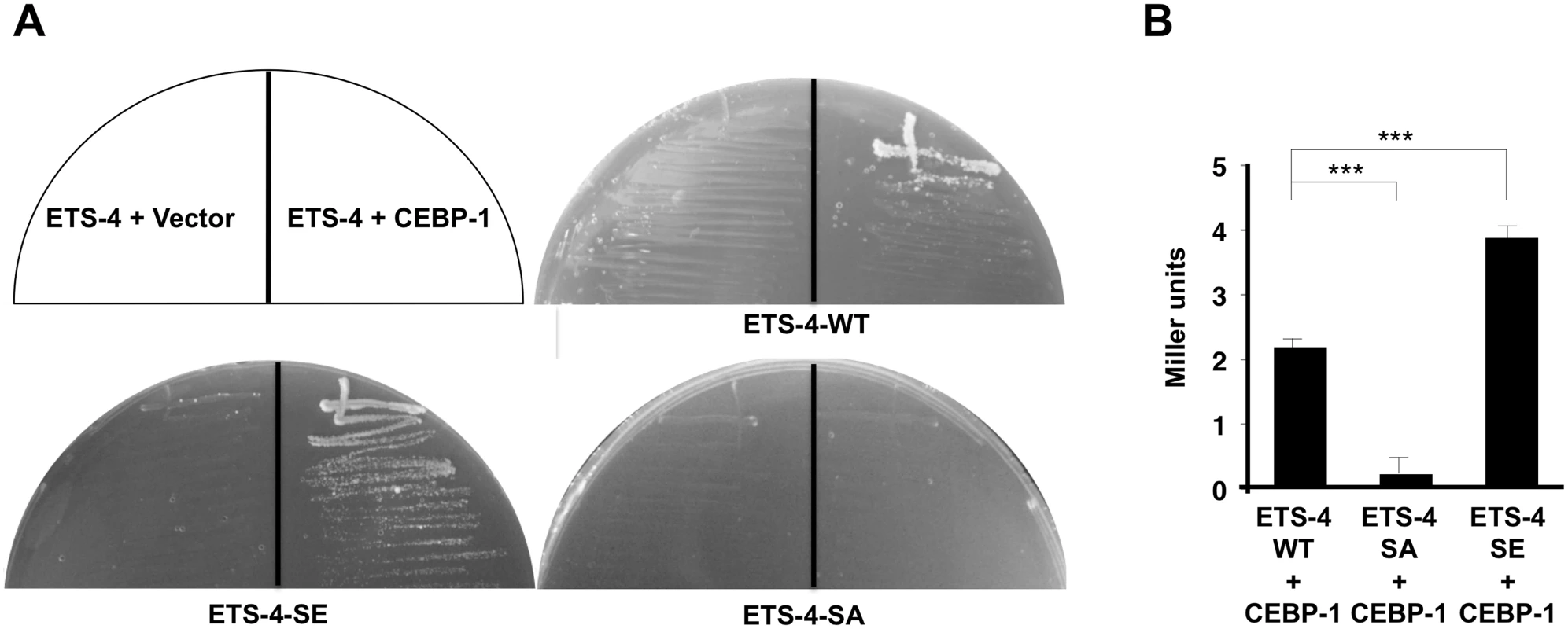

Fig. 5. Interaction of ETS-4 with CEBP-1 by yeast two-hybrid assays.

(A) The reporter yeast strain L40u was cotransformed with expression vectors encoding LexA DBD-ETS-4, LexA DBD-ETS-4(S73E), LexA DBD-ETS-4(S73A) and GAL4 AD-CEBP-1 as indicated. Yeasts carrying the indicated plasmids were grown on a selective plate lacking histidine and containing 80 mM 5-aminotriazole for 4 days. (B) The reporter yeast strain NMY51 was cotransformed with expression vectors as indicated. Yeasts carrying the indicated plasmids were grown and β-galactosidase activity was determined in cellular extracts as described in Materials and Methods. Backgrounds were determined by cotransforming cells with the control vector pACTII along with the corresponding pBTM116-ETS-4(WT, S73A or S73E,) and the β-galactosidase activities obtained were subtracted from each set of data. Values are given in Miller units. The data are combined from ten independent experiments and quantified by the Welch’s t test. ***P < 0.001. Error bars represent SEM. ETS-4 functions downstream of the cAMP pathway

How is ETS-4 regulated in axon regeneration? The functions of mammalian Ets transcription factors are regulated by phosphorylation [12,17]. As ETS-4 contains a protein kinase A (PKA) phosphorylation consensus sequence (Arg-Arg-Xxx-Ser) at Ser-73 near its PNT domain (Fig 6A), we asked whether PKA phosphorylates ETS-4 at this residue. We performed in vitro kinase assays with active PKA and immuno-purified HA-tagged ETS-4 and confirmed that PKA phosphorylated HA-ETS-4 (Fig 6B). To determine if PKA can phosphorylate ETS-4 on Ser-73, we generated a mutant form of ETS-4 [ETS-4(S73A)], in which Ser-73 is mutated to alanine. In vitro kinase assays showed that the S73A mutation abolished phosphorylation of ETS-4 by PKA (Fig 6B). These results demonstrate that PKA phosphorylates Ser-73 of ETS-4 in vitro.

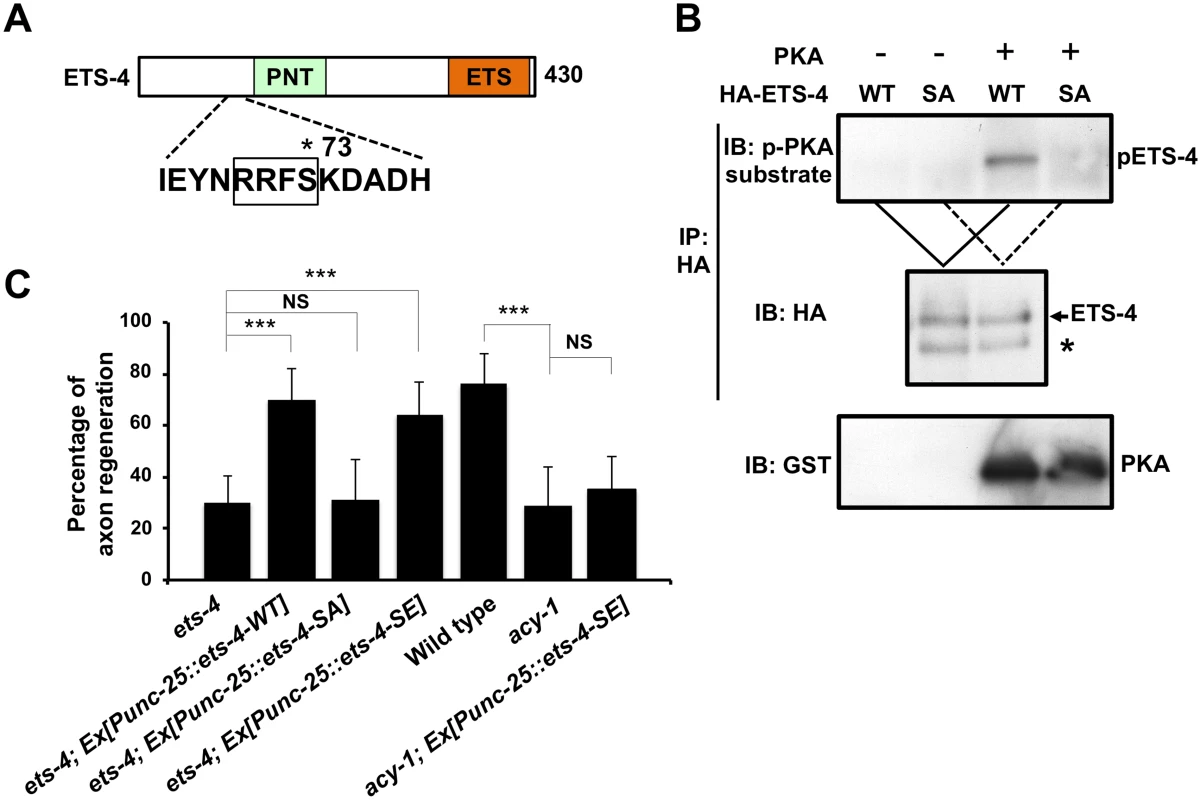

Fig. 6. ETS-4 functions downstream of the cAMP pathway.

(A) A schematic diagram of ETS-4. The amino acid sequence around a PKA phosphorylation consensus site is shown below. The consensus site for PKA phosphorylation is boxed. The Ser-73 residue is indicated by an asterisk. (B) PKA phosphorylates ETS-4 at Ser-73 in vitro. In vitro phosphorylation of ETS-4 protein by PKA is shown in the lower panels. COS-7 cells were transfected with HA-ETS-4 (WT) or HA-ETS-4(S73A) (SA), and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody. The immunoprecipitates were divided and then subjected to in vitro kinase assays using recombinant GST-fused active PKA. Phosphorylated ETS-4 was detected by immunoblotting with anti-phospho-PKA substrate rabbit monoclonal antibody. Asterisk indicates a heavy chain of IgG. (C) Percentages of axons that initiated regeneration 24 hr after laser surgery. Error bars indicate 95% SI. ***P<0.001; NS, not significant. We next addressed the biological importance of ETS-4 Ser-73 phosphorylation. When the phosphorylation-defective mutant ETS-4(S73A) was expressed under the control of the unc-25 promoter in ets-4(ok165) null mutants, the defect in axon regeneration was not rescued (Fig 6C and S1 Table). In contrast, expression of a phospho-mimetic form of ETS-4, ETS-4(S73E), in ets-4(ok165) mutants by the unc-25 promoter was able to rescue the regeneration defect (Fig 6C and S1 Table). Thus, phosphorylation of Ser-73 is important for the function of ETS-4 in the activation of the regeneration pathway.

We next asked how PKA-mediated phosphorylation might regulate ETS-4 in this regeneration pathway. Since Ser-73 is located near the PNT domain, which is a protein-protein interaction domain, we examined the effect of ETS-4 Ser-73 phosphorylation on its interaction with CEBP-1. We found that a non-phosphorylatable ETS-4(S73A) mutant form lost the ability to associate with CEBP-1, whereas a phosphorylation mimicking mutant ETS-4(S73E) was able to interact with CEBP-1 (Fig 5A and 5B). Furthermore, the interaction of ETS-4(S73E) with CEBP-1 was stronger than that of wild-type ETS-4 (Fig 5B). These results suggest that PKA-mediated phosphorylation of ETS-4 Ser-73 promotes the formation of an ETS-4–CEBP-1 complex.

PKA is activated by cAMP, and cAMP signals have been implicated in axonal regeneration in many systems [18–21]. The C. elegans acy-1 gene encodes the neuronal adenylyl cyclase, and we observed that animals expressing a loss-of-function mutant, acy-1(nu329), were defective in axon regeneration (Fig 6C and S1 Table) [18]. We also found that in animals carrying acy-1(nu329), Psvh-2::nls::venus was not induced in D-type neurons in response to axon injury (Fig 7A). To examine whether ETS-4 functions downstream of cAMP in axon regeneration, we tested the effects of the phosphor-mimetic ets-4 mutation on acy-1 phenotypes. Expression of ETS-4(S73E) by the unc-25 promoter failed to suppress the regeneration defect observed in acy-1(nu329) mutants (Fig 6C and S1 Table). This result is consistent with the fact that cAMP is known to be important for regeneration and regulates many pathways. Thus, ETS-4 is not the only target of cAMP signaling that functions in axon regeneration. In contrast to axon regeneration, we found that expression of ETS-4(S73E), but not wild-type ETS-4, was able to induce svh-2 expression in acy-1(nu329) mutants (Fig 7A). However, this induction by ETS-4(S73E) was not constitutive and was not observed in the absence of axon injury. This result suggests that induction of svh-2 expression requires the injury-dependent activation of both ETS-4 and CEBP-1 and that activation of ETS-4 alone is not sufficient to induce svh-2 expression. Thus, ETS-4 is required for the induction of svh-2 transcription in response to axonal injury, and this occurs downstream of cAMP signaling through PKA-mediated phosphorylation.

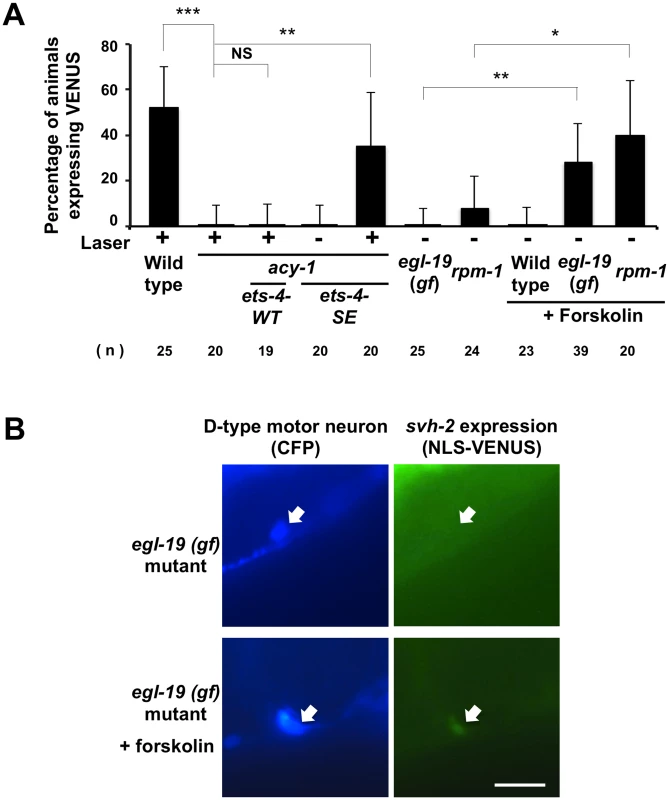

Fig. 7. Activation of both cAMP and Ca2+–p38 MAPK signaling pathways is required for the induction of svh-2 transcription.

(A) Percentages of animals expressing svh-2. Induction of Psvh-2::nls::venus expression in D-type motor neurons with (+) or without (-) laser surgery was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. The numbers (n) of animals examined are shown. Error bars indicate 95% SI. ***P<0.001; **P<0.01; *P<0.05; NS, not significant. (B) Psvh-2::nls::venus expression in D-type motor neurons. Expression of fluorescent proteins in D-type motor neurons of egl-19(gf) mutants with or without forskolin treatment are shown. Arrows indicate cell bodies of D-type neurons. D neurons are visualized by CFP under control of the unc-25 promoter. Scale bar = 10 μm. Activation of both cAMP and Ca2+–p38 MAPK signaling pathways is required for the induction of svh-2 transcription

Axotomy induces an intracellular increase in Ca2+ via the action of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, and this can promote axon regeneration in a manner dependent on the DLK-1-p38 MAPK pathway [18,22]. Previous studies have shown that a gain-of-function (gf) mutation in a subunit of one voltage-gated Ca2+ channel, egl-19(ad695gf), enhances Ca2+ influx in PLM neurons after axotomy and, subsequently, drives the formation of an active DLK-1 homomeric protein complex [22]. We therefore investigated whether activation of the p38-CEBP-1 pathway by the egl-19(ad695gf) mutation affects expression of the svh-2 gene. We found that the egl-19(ad695gf) mutation did not cause constitutive expression of the Psvh-2::nls::venus reporter in D-type neurons (Fig 7A and 7B and S2 Fig). Since the ETS-4 transcription factor is regulated by the cAMP-PKA pathway, we examined the effect of activation of the cAMP pathway on the transcriptional induction of the svh-2 gene. Treatment of animals with forskolin is expected to cause an increase in cAMP levels by activating adenylyl cyclase [18]. Forskolin treatment of wild-type animals not subjected to axon injury failed to induce Psvh-2::nls::venus expression in D-type neurons (Fig 7A). Thus, activation of either the p38-CEBP-1 or cAMP-ETS-4 pathway is not sufficient to induce transcription of the svh-2 gene. We therefore speculated that simultaneous activation of both pathways might be required. Consistent with this, we found that when egl-19(ad695gf) mutants were treated with forskolin, 28% of the animals expressed the Psvh-2::nls::venus reporter in D-type neurons, even in the absence of axon injury (Figs 7A and 7B and S2).

We next examined whether the effect of the egl-19 gf mutation on svh-2 expression is mediated by the DLK-1 pathway. Activated DLK-1 kinase is targeted for degradation by the E3 ubiquitin ligase RPM-1, thereby modulating the duration of signaling [7]. Constitutive activation of the DLK-1 pathway induces developmental defects that mimic rpm-1mutants. Moreover, rpm-1 mutants display a MAPK-dependent improvement in axon regeneration [8]. We found that the rpm-1 mutation caused constitutive expression of the svh-2 gene in D-type neurons when cultured in the presence of forskolin (Fig 7A). Taken together, these results suggest that induction of the svh-2 gene is dependent on activation of both cAMP and Ca2+-DLK-1 signaling through an Ets-C/EBP transcription factor complex.

Discussion

MAPK signaling cascades are evolutionally conserved in eukaryotes from yeast to mammals and play key roles in many aspects of neuronal development and function [23]. Recent genetic studies have shown that the DLK-1–MKK-4–PMK-3 p38 MAPK and the MLK-1–MEK-1–KGB-1 JNK pathways regulate axon regeneration in C. elegans [6–8]. The DLK MAPKKKs are required for axon regeneration in both Drosophila melanogaster and mice [24–26]. Similarly, JNK-mediated activation of c-Jun is important for axonal outgrowth of neurons in axotomized rat nodose and dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and mouse DRG [27,28]. These discoveries suggest that the core machinery that regulates axon regeneration is conserved from worms to mammals.

In C. elegans, the DLK-1 p38 MAPK pathway promotes mRNA stability and local axonal translation of the bZip transcription factor CEBP-1 through the MAPKAP kinase MAK-2 [7]. Although the precise steps by which DLK-1 is activated in axon regeneration remain unknown, a Ca2+-dependent mechanism of activation has been recently described [22]. The JNK MAPK pathway is activated following axonal injury by growth factor-like SVH-1 engagement of its cognate receptor tyrosine kinase SVH-2 (Fig 8) [11]. SVH-1 belongs to the HGF/plasminogen family and SVH-2 is homologous to the HGF receptor Met, suggesting that SVH-1–SVH-2 functions as a ligand–receptor pair in axon regeneration. The svh-1 gene is constitutively expressed in ADL sensory neurons in the head and SVH-1 acts on injured neurons. In contrast, expression of svh-2 is induced by axonal injury [11]. SVH-1-SVH-2 signaling does not affect axon development per se, but rather is specific to axon regeneration. This specificity is determined by the injury-induced expression of the svh-2 gene.

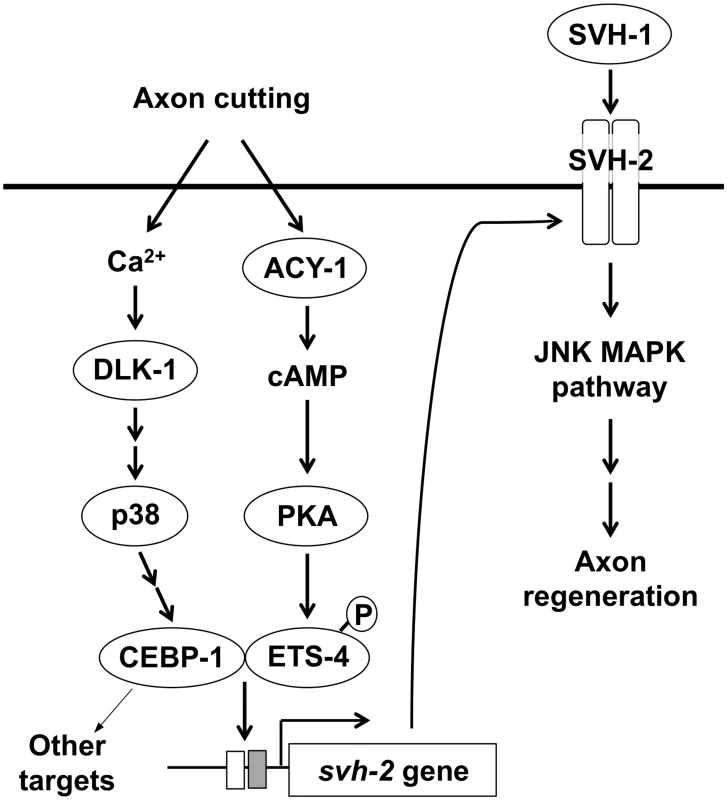

Fig. 8. Schematic model for the regulation of JNK MAPK pathway by Ca<sup>2+</sup>–p38 MAPK and cAMP signaling pathways in axon regeneration.

In this study, we found that the transcription factor CEBP-1 is required for the injury-induced transcriptional activation of svh-2 expression. Although there remains the possibility that EGL-19–DLK-1 – CEBP-1 pathway may activate svh-2 expression through another MAPK, it is known that CEBP-1 acts in the p38 MAPK pathway [7]. Since SVH-2 functions in the JNK MAPK pathway [11], these results suggest the p38 MAPK pathway functions upstream of JNK MAPK activation in the response to axon injury (Fig 8). Enforced expression of svh-2 in cebp-1 mutants failed to efficiently suppress the defect in axon regeneration seen in these mutants, indicating that CEBP-1 transcriptionally regulates other targets in addition to the svh-2 gene in response to p38 MAPK activation.

ETS-4 was also identified as another transcription factor involved in the activation of svh-2 expression in response to axon injury. A previous study demonstrated that ETS-4 functions in lipid transport, lipid metabolism and innate immunity [14]. ETS-4 is a transcriptional regulator of aging, and shares transcriptional targets with the GATA and FOXO transcriptional regulators. An expression profiling study identified seventy ETS-4-target genes, 54 of which have identifiable Ets-binding consensus motifs in their promoter regions [14]. However, this analysis did not identify the svh-2 gene as an ETS-4 target, presumably because ETS-4-dependent svh-2 expression occurs only in severed neurons and not under normal conditions. We show that ETS-4 acts downstream of cAMP signaling, and that transcriptional up-regulation of svh-2 by ETS-4 requires PKA-dependent phosphorylation at Ser-73. However, a mutant of ETS-4 that mimics constitutive phosphorylation of the Ser-73 residue failed to rescue the defect in axon regeneration in acy-1 mutants defective in cAMP production. These results suggest that cAMP activates other pathways, in addition to the SVH-2–JNK MAPK pathway, that are required for axon regeneration.

We demonstrate that phosphorylation of ETS-4 by PKA leads to the formation of a complex containing ETS-4 and CEBP-1, and that this protein-protein interaction is necessary for activation of svh-2 expression in response to axon injury. It has been shown for mammals that direct interactions between C/EBPs and specific Ets family members are important for eosinophil lineage determination [29]. In this case, the physical interaction between Ets-1 and C/EBPα proteins is mediated by their DNA-binding domains, and these complexes transactivate their target genes by high-affinity binding to combined motifs in the target promoters. Similarly, the svh-2 promoter region has an Ets - and a C/EBP-binding site located in close proximity to one another and these binding sites are required for axon injury-induced expression of the svh-2 gene. It is tempting to speculate that the high affinity of the CEBP-1–ETS-4 interaction is important for synergy between the two factors. We conclude that CEBP-1 is a biologically important and relevant interacting partner of ETS-4 that is involved in the transcriptional activation of svh-2 gene expression.

Similar to vertebrate neurons, increased Ca2+ and cAMP facilitate axon regeneration in severed C. elegans neurons [18]. It is likely that some effects of elevated Ca2+ or cAMP on axon regeneration are mediated at the transcriptional level [30]. Interestingly, CEBP-1 acts downstream of the Ca2+–p38 MAPK pathway and ETS-4 functions downstream of the cAMP signaling pathway. Based on our findings, we propose a model wherein axon injury initiates cAMP signaling and the Ca2+–p38 MAPK pathway, which together function to induce the formation of an ETS-4–CEBP-1 transcription factor complex. This complex binds to the svh-2 promoter to induce svh-2 expression, and SVH-1 signaling via SVH-2 then activates the JNK pathway (Fig 8). Thus, two injury-signaling pathways (p38 MAPK and cAMP/PKA) converge to regulate expression of the svh-2 gene after injury, which ultimately promotes axon regeneration. The identification and characterization of the signaling pathways that regulate axon regeneration in C. elegans should yield numerous insights into the mechanisms used by nervous systems to regulate similar processes across metazoans.

Materials and Methods

C. elegans strains

C. elegans strains used in this study are listed in S2 Table. All strains were maintained on nematode growth medium (NGM) plates and fed with bacteria of the OP50 strain, as described previously [31].

Axotomy

Axotomy and microscopy were performed as described previously [11]. All animals were subjected to axotomy at the young adult stage. The imaged commissures that had growth cones or small branches present on the proximal fragment were counted as “regenerated”. The proximal fragments that showed no change after 24 hr were counted as “no regeneration”. A minimum of 20 individuals with 1–3 axotomized commissures were observed for most experiments.

Microscopy

Standard fluorescent images of transgenic worms were observed under a Zeiss Plan-APOCHROMAT 63 X objective of a Zeiss Axioplan II fluorescent microscope and photographed with a Hamamatsu 3CCD camera. Confocal fluorescent images were taken on an Olympus FV500 confocal laser scanning microscope with a 40 X objective.

Plasmids

Punc-25::ets-4 and Pmec-7::ets-4 were generated by inserting the ets-4 cDNA isolated from a cDNA library into the pCZ325 vector and pPD52.102 vectors, respectively. Punc-25::ets-4(S73A) and Punc-25::ets-4(S73E) were made by oligonucleotide-directed PCR using Punc-25::ets-4 as a template and the mutations were verified by DNA sequencing. pLexA-ETS-4, pLexA-ETS-4(S73A) and pLexA-ETS-4(S73E) plasmids were constructed by inserting the wild-type and mutagenized ets-4 cDNAs into the pBTM116 vector. The Psvh-2(6.2 kb)::nls::venus plasmid has been described previously [11]. For the construction of Psvh-2(2.6 kb)::nls::venus and Psvh-2(0.5 kb)::nls::venus plasmids, Psvh-2(6.2 kb)::nls::venus was digested with either HindIII or PsiI, respectively, and then self-ligated. Psvh-2(Ets-bm)::nls::venus and Psvh-2(C/EBP-bm)::nls::venus plasmids were made by oligonucleotide-directed PCR using Psvh-2(2.6 kb)::nls::venus as a template and the mutations were verified by DNA sequencing. These mutated promoters were then used to make Psvh-2(6.2 kb)::svh-2, Psvh-2(2.6 kb)::svh-2, Psvh-2(0.5 kb)::svh-2, Psvh-2(Ets-bm)::svh-2 and Psvh-2(C/EBP-bm)::svh-2, respectively. The pCMV-HA-ETS-4 plasmid was made by inserting the ets-4 cDNA into the pCMV-HA vector. The pACTII-CEBP-1 plasmid was made by inserting the cebp-1 cDNA, isolated from a C. elegans cDNA library by PCR, into the pACTII vector. The lin-15 plasmid is a gift from Dr. S. Takagi (Nagoya University). Other plasmids, including Pttx-3::gfp, Pmyo-2::dsredm, Punc-25::cfp and Punc-25::svh-2 have been described previously [11, 32].

Transgenic animals

Transgenic animals were obtained as described [33]. Psvh-2(6.2 kb)::svh-2 (25 ng/μl), Psvh-2(2.6 kb)::svh-2 (25 ng/μl), Psvh-2(0.5 kb)::svh-2 (25 ng/μl), Psvh-2(Ets-bm)::svh-2 (25 ng/μl) and Psvh-2(C/EBP-bm)::svh-2 (25 ng/μl) plasmids were used in kmEx529 [Psvh-2(6.2 kb)::svh-2 + Pmyo-2::dsredm], kmEx530 [Psvh-2(2.6 kb)::svh-2 + Pmyo-2::dsredm], kmEx531 [Psvh-2(0.5 kb)::svh-2 + Pmyo-2::dsredm], kmEx532 [Psvh-2(Ets-bm)::svh-2 + Pmyo-2::dsredm], kmEx533 [Psvh-2(C/EBP-bm)::svh-2 + Pmyo-2::dsredm], respectively. Punc-25::ets-4 (25 ng/μl), Pmec-7::ets-4 (25 ng/μl), Punc-25::ets-4(S73A) (25 ng/μl) and Punc-25::ets-4(S73E) (25 ng/μl) plasmids were used in kmEx534 [Punc-25::ets-4 + Pmyo-2::dsredm], kmEx535 [Pmec-7::ets-4 + Pmyo-2::dsredm], kmEx536 [Punc-25::ets-4(S73A) + Pmyo-2::dsredm], kmEx537 [Punc-25::ets-4(S73E) + Pmyo-2::dsredm], kmEx544 [Punc-25::ets-4 + Pttx-3::gfp] and kmEx545 [Punc-25::ets-4(S73E) + Pttx-3::gfp], respectively. Punc-25::cfp (50 ng/μl), Psvh-2(6.2 kb)::nls::venus (75 ng/μl), Psvh-2(2.6 kb)::nls::venus (75 ng/μl), Psvh-2(Ets-bm)::nls::venus (75 ng/μl) and Psvh-2(C/EBP-bm)::nls::venus (75 ng/μl) plasmids were used in kmEx538 (Punc-25::cfp + lin-15), kmEx539 [Psvh-2(6.2 kb)::nls::venus + Pmyo-2::dsredm], kmEx540 [Psvh-2(2.6 kb)::nls::venus + Pmyo-2::dsredm], kmEx541 [Psvh-2(0.5 kb)::nls::venus + Pmyo-2::dsredm], kmEx542 [Psvh-2(Ets-bm)::nls::venus + Pmyo-2::dsredm] and kmEx543 [Psvh-2(C/EBP-bm)::nls::venus + Pmyo-2::dsredm], respectively.

Yeast two-hybrid assays

pBTM116-ETS-4(WT, S73E, S73A) and pACTII-CEBP-1 plasmids were cotransformed into the Saccharomyces cerevisiae reporter strain L40u [MATa trp1 ura3 leu2 his3 LYS2::(lexAop)4-HIS3] and allowed to grow on SC-Leu-Trp plates. Transformants grown on these plates were streaked out onto SC-Leu-Trp-His plates containing 80 mM 5-aminotriazole and incubated at 30℃ for 4 days. For β-galactosidase assays, the NMY51 [MATa trp1 ura3::(lexAop)8-lacZ leu2 his3 LYS2::(lexAop)4-HIS3 ade2::(lexAop)8-ADE2 GAL4] strain (Dualsystems Biotech) was used as the host strain. The β-galactosidase assay was performed as described previously [34].

DAPI staining

To examine nuclei of D neuron cells, we fixed worms in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hr and permeabilized with methanol for 5 min. Next, the worms were stained with 0.1 μg/ml of the DNA-binding dye 4,6-diamidino-2-phenyl-indole and mounted on 2% agarose slides for viewing using fluorescence imaging.

Quantification of VENUS expression

Expression of VENUS fluorescence was quantified using the ImageJ program (NIH). The cell bodies of severed D neurons were outlined with closed polygons and the fluorescent intensities within these areas were determined (Is). The cell bodies of unsevered D neurons in the same animal were analyzed similarly as controls (Iu). To determine the background intensity of each cell, the same polygon was placed in the area neighboring the cell body and fluorescence measured (Ibs and Ibu, respectively). The relative signal intensity (Ir) was calculated as (Is-Ibs)/(Iu-Ibu). Cells having an Ir>5 were categorized as “expressed”.

Biochemical analyses

Transfection of transgenes into COS-7 cells, preparation of the cell lysates and immunoblotting procedures have been described previously [10]. Anti-phospho-PKA substrate (RRX(p)S/(p)T) [(p), phosphorylated] rabbit monoclonal antibody (100G7E), was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out as described previously [11]. Briefly, confidence intervals (95%) were calculated by the modified Wald method and two-tailed P values were calculated using Fisher’s exact test (http://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/contingency1/). The Welch’s t -test was performed by using t-test calculator (http://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/ttest1/).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Mar FM, Bonni A, Sousa MM (2014) Cell intrinsic control of axon regeneration. EMBO Rep 15 : 254–263. doi: 10.1002/embr.201337723 24531721

2. Abe N, Cavalli V (2008) Nerve injury signaling. Curr Opin Neurobiol 18 : 276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.06.005 18655834

3. Bradke F, Fawcett JW, Spira ME (2012) Assembly of a new growth cone after axotomy: the precursor to axon regeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci 13 : 183–193. doi: 10.1038/nrn3176 22334213

4. Yanik MF, Cinar H, Cinar HN, Chisholm AD, Jin Y, Ben-Yakar A (2004) Neurosurgery: functional regeneration after laser axotomy. Nature 432 : 822. 15602545

5. O’Brien GS, Sagasti A (2009) Fragile axons forge the path to gene discovery: a MAP kinase pathway regulates axon regeneration. Sci Signal 2: e30.

6. Hammarlund M, Nix P, Hauth L, Jorgensen EM, Bastiani M (2009) Axon regeneration requires a conserved MAP kinase pathway. Science 323 : 802–806. doi: 10.1126/science.1165527 19164707

7. Yan D, Wu Z, Chisholm AD, Jin Y (2009) The DLK-1 kinase promotes mRNA stability and local translation in C. elegans synapses and axon regeneration. Cell 138 : 1005–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.023 19737525

8. Nix P, Hisamoto N, Matsumoto K, Bastiani M (2011) Axon regeneration requires coordinate activation of p38 and JNK MAPK pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108 : 10738–10743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104830108 21670305

9. Camps M, Nichols A, Arkinstall S (2000) Dual specificity phosphatases: a gene family for control of MAP kinase function. FASEB J 14 : 6–16. 10627275

10. Mizuno T, Hisamoto N, Terada T, Kondo T, Adachi M, Nishida E, et al. (2004) The Caenorhabditis elegans MAPK phosphatase VHP-1 mediates a novel JNK-like signaling pathway in stress response. EMBO J 23 : 2226–2234. 15116070

11. Li C, Hisamoto N, Nix P, Kanao S, Mizuno T, Bastiani M, et al. (2012) The growth factor SVH-1 regulates axon regeneration in C. elegans via the JNK MAPK cascade. Nat Neurosci 15 : 551–557. doi: 10.1038/nn.3052 22388962

12. Sharrocks AD (2001) The ETS-domain transcription factor family. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2 : 827–837. 11715049

13. Hart AH, Reventar R, Bernstein A (2000) Genetic analysis of ETS genes in C. elegans. Oncogene 19 : 6400–6408. 11175356

14. Thyagarajan B, Blaszczak AG, Chandler KJ, Watts JL, Johnson WE, Graves BJ (2010) ETS-4 is a transcriptional regulator of life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet 6: e1001125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001125 20862312

15. Sharrocks AD, Brown AL, Ling Y, Yates PR (1997) The ETS-domain transcription factor family. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 29 : 1371–1387. 9570133

16. Kfouty N, Kapatos G (2009) Identification of neuronal target genes for CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins. Mol Cell Neurosci 40 : 313–327. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.11.004 19103292

17. Tootle TL, Rebay I (2005) Post-translational modifications influence transcription factor activity: a view from the ETS superfamily. BioEssays 27 : 285–298. 15714552

18. Ghosh-Roy A, Wu Z, Goncharov A, Jin Y, Chisholm AD (2010) Calcium and cyclic AMP promote axonal regeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans and require DLK-1 kinase. J Neurosci 30 : 3175–3183. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5464-09.2010 20203177

19. Bhatt DH, Otto SJ, Depoister B, Fetcho JR (2004) Cyclic AMP-induced repair of zebrafish spinal circuits. Science 305 : 254–258. 15247482

20. Spencer T, Filbin MT (2004) A role for cAMP in regeneration of the adult mammalian CNS. J Anat 204 : 49–55. 14690477

21. Neumann SF, Tessier-Lavigne M, Basbaum AI (2002) Regeneration of sensory axons within the injured spinal cord induced by intraganglionic cAMP elevation. Neuron 34 : 885–893. 12086637

22. Yan D, Jin Y (2012) Regulation of DLK-1 kinase activity by calcium-mediated dissociation from an inhibitory isoform. Neuron 76 : 534–548. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.043 23141066

23. Thomas GM, Huganir RL (2004). MAPK cascade signalling and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci 5 : 173–183. 14976517

24. Valakh V, Walker LJ, Skeath JB, DiAntonio A (2013) Loss of the spectraplakin short stop activates the DLK injury response pathway in Drosophila. J Neurosci 33 : 17863–17873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2196-13.2013 24198375

25. Shin JE, Cho Y, Beirowski B, Milbrandt J, Cavalli V, DiAntonio A (2012) Dual leucine zipper kinase is required for retrograde injury signaling and axonal regeneration. Neuron 74 : 1015–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.028 22726832

26. Itoh A, Horiuchi M, Bannerman P, Pleasure D, Itoh T (2009) Impaired regenerative response of primary sensory neurons in ZPK/DLK gene-trap mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 383 : 258–262. Epub 2009 Apr 7 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.009 19358824

27. Lindwall C, Dahlin L, Lundborg G, Kanje M (2004) Inhibition of c-Jun phosphorylation reduces axonal outgrowth of adult rat nodose ganglia and dorsal root ganglia sensory neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci 27 : 267–279. 15519242

28. Barnat M, Enslen H, Propst F, Davis RJ, Soares S, Nothias F (2010) Distinct roles of c-Jun N-terminal kinase isoforms in neurite initiation and elongation during axonal regeneration. J Neurosci 30 : 7804–7816. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0372-10.2010 20534829

29. McNagny KM, Sieweke MH, Döderlein G, Graf T, Nerlov C (1998) Regulation of eosinophil-specific gene expression by a C/EBP–Ets complex and GATA-1. EMBO J 17 : 3669–3880. 9649437

30. Cai D, Deng K, Mellado W, Lee J, Ratan RR, Filbin MT (2002) Arginase I and polyamines act downstream from cyclic AMP in overcoming inhibition of axonal growth MAG and myelin in vitro. Neuron 35 : 711–719. 12194870

31. Brenner S (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77 : 71–94. 4366476

32. Byrd DT, Kawasaki M, Walcoff M, Hisamoto N, Matsumoto K, Jin Y (2001) UNC-16, a JNK-signaling scaffold protein, regulates vesicle transport in C. elegans. Neuron 32 : 787–800. 11738026

33. Mello CC, Kramer JM, Stinchcomb D, Ambros V (1991) Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J 10 : 3959–3970. 1935914

34. Miller JH (1972) Assay of β-galactosidase. In: Miller JH, editor. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, New York; 352–355.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Evidence of Selection against Complex Mitotic-Origin Aneuploidy during Preimplantation DevelopmentČlánek A Novel Route Controlling Begomovirus Resistance by the Messenger RNA Surveillance Factor PelotaČlánek A Follicle Rupture Assay Reveals an Essential Role for Follicular Adrenergic Signaling in OvulationČlánek Canonical Poly(A) Polymerase Activity Promotes the Decay of a Wide Variety of Mammalian Nuclear RNAsČlánek FANCI Regulates Recruitment of the FA Core Complex at Sites of DNA Damage Independently of FANCD2Článek Hsp90-Associated Immunophilin Homolog Cpr7 Is Required for the Mitotic Stability of [URE3] Prion inČlánek The Dedicated Chaperone Acl4 Escorts Ribosomal Protein Rpl4 to Its Nuclear Pre-60S Assembly SiteČlánek Chromatin-Remodelling Complex NURF Is Essential for Differentiation of Adult Melanocyte Stem CellsČlánek A Systems Approach Identifies Essential FOXO3 Functions at Key Steps of Terminal ErythropoiesisČlánek Integration of Posttranscriptional Gene Networks into Metabolic Adaptation and Biofilm Maturation inČlánek Lateral and End-On Kinetochore Attachments Are Coordinated to Achieve Bi-orientation in OocytesČlánek MET18 Connects the Cytosolic Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Pathway to Active DNA Demethylation in

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 10- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Gene-Regulatory Logic to Induce and Maintain a Developmental Compartment

- A Decad(e) of Reasons to Contribute to a PLOS Community-Run Journal

- DNA Methylation Landscapes of Human Fetal Development

- Single Strand Annealing Plays a Major Role in RecA-Independent Recombination between Repeated Sequences in the Radioresistant Bacterium

- Evidence of Selection against Complex Mitotic-Origin Aneuploidy during Preimplantation Development

- Transcriptional Derepression Uncovers Cryptic Higher-Order Genetic Interactions

- Silencing of X-Linked MicroRNAs by Meiotic Sex Chromosome Inactivation

- Virus Satellites Drive Viral Evolution and Ecology

- A Novel Route Controlling Begomovirus Resistance by the Messenger RNA Surveillance Factor Pelota

- Sequence to Medical Phenotypes: A Framework for Interpretation of Human Whole Genome DNA Sequence Data

- Your Data to Explore: An Interview with Anne Wojcicki

- Modulation of Ambient Temperature-Dependent Flowering in by Natural Variation of

- The Ciliopathy Protein CC2D2A Associates with NINL and Functions in RAB8-MICAL3-Regulated Vesicle Trafficking

- PPP2R5C Couples Hepatic Glucose and Lipid Homeostasis

- DCA1 Acts as a Transcriptional Co-activator of DST and Contributes to Drought and Salt Tolerance in Rice

- Intermediate Levels of CodY Activity Are Required for Derepression of the Branched-Chain Amino Acid Permease, BraB

- "Missing" G x E Variation Controls Flowering Time in

- The Rise and Fall of an Evolutionary Innovation: Contrasting Strategies of Venom Evolution in Ancient and Young Animals

- Type IV Collagen Controls the Axogenesis of Cerebellar Granule Cells by Regulating Basement Membrane Integrity in Zebrafish

- Loss of a Conserved tRNA Anticodon Modification Perturbs Plant Immunity

- Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Adaptation Using Environmentally Predicted Traits

- Oriented Cell Division in the . Embryo Is Coordinated by G-Protein Signaling Dependent on the Adhesion GPCR LAT-1

- Disproportionate Contributions of Select Genomic Compartments and Cell Types to Genetic Risk for Coronary Artery Disease

- A Follicle Rupture Assay Reveals an Essential Role for Follicular Adrenergic Signaling in Ovulation

- The RNAPII-CTD Maintains Genome Integrity through Inhibition of Retrotransposon Gene Expression and Transposition

- Canonical Poly(A) Polymerase Activity Promotes the Decay of a Wide Variety of Mammalian Nuclear RNAs

- Allelic Variation of Cytochrome P450s Drives Resistance to Bednet Insecticides in a Major Malaria Vector

- SCARN a Novel Class of SCAR Protein That Is Required for Root-Hair Infection during Legume Nodulation

- IBR5 Modulates Temperature-Dependent, R Protein CHS3-Mediated Defense Responses in

- NINL and DZANK1 Co-function in Vesicle Transport and Are Essential for Photoreceptor Development in Zebrafish

- Decay-Initiating Endoribonucleolytic Cleavage by RNase Y Is Kept under Tight Control via Sequence Preference and Sub-cellular Localisation

- Large-Scale Analysis of Kinase Signaling in Yeast Pseudohyphal Development Identifies Regulation of Ribonucleoprotein Granules

- FANCI Regulates Recruitment of the FA Core Complex at Sites of DNA Damage Independently of FANCD2

- LINE-1 Mediated Insertion into (Protein of Centriole 1 A) Causes Growth Insufficiency and Male Infertility in Mice

- Hsp90-Associated Immunophilin Homolog Cpr7 Is Required for the Mitotic Stability of [URE3] Prion in

- Genome-Scale Mapping of σ Reveals Widespread, Conserved Intragenic Binding

- Uncovering Hidden Layers of Cell Cycle Regulation through Integrative Multi-omic Analysis

- Functional Diversification of Motor Neuron-specific Enhancers during Evolution

- The GTP- and Phospholipid-Binding Protein TTD14 Regulates Trafficking of the TRPL Ion Channel in Photoreceptor Cells

- The Gyc76C Receptor Guanylyl Cyclase and the Foraging cGMP-Dependent Kinase Regulate Extracellular Matrix Organization and BMP Signaling in the Developing Wing of

- The Ty1 Retrotransposon Restriction Factor p22 Targets Gag

- Functional Impact and Evolution of a Novel Human Polymorphic Inversion That Disrupts a Gene and Creates a Fusion Transcript

- The Dedicated Chaperone Acl4 Escorts Ribosomal Protein Rpl4 to Its Nuclear Pre-60S Assembly Site

- The Influence of Age and Sex on Genetic Associations with Adult Body Size and Shape: A Large-Scale Genome-Wide Interaction Study

- Parent-of-Origin Effects of the Gene on Adiposity in Young Adults

- Chromatin-Remodelling Complex NURF Is Essential for Differentiation of Adult Melanocyte Stem Cells

- Retinoic Acid Receptors Control Spermatogonia Cell-Fate and Induce Expression of the SALL4A Transcription Factor

- A Systems Approach Identifies Essential FOXO3 Functions at Key Steps of Terminal Erythropoiesis

- Protein O-Glucosyltransferase 1 (POGLUT1) Promotes Mouse Gastrulation through Modification of the Apical Polarity Protein CRUMBS2

- KIF7 Controls the Proliferation of Cells of the Respiratory Airway through Distinct Microtubule Dependent Mechanisms

- Integration of Posttranscriptional Gene Networks into Metabolic Adaptation and Biofilm Maturation in

- Lateral and End-On Kinetochore Attachments Are Coordinated to Achieve Bi-orientation in Oocytes

- Protein Homeostasis Imposes a Barrier on Functional Integration of Horizontally Transferred Genes in Bacteria

- A New Method for Detecting Associations with Rare Copy-Number Variants

- Histone H2AFX Links Meiotic Chromosome Asynapsis to Prophase I Oocyte Loss in Mammals

- The Genomic Aftermath of Hybridization in the Opportunistic Pathogen

- A Role for the Chaperone Complex BAG3-HSPB8 in Actin Dynamics, Spindle Orientation and Proper Chromosome Segregation during Mitosis

- Establishment of a Developmental Compartment Requires Interactions between Three Synergistic -regulatory Modules

- Regulation of Spore Formation by the SpoIIQ and SpoIIIA Proteins

- Association of the Long Non-coding RNA Steroid Receptor RNA Activator (SRA) with TrxG and PRC2 Complexes

- Alkaline Ceramidase 3 Deficiency Results in Purkinje Cell Degeneration and Cerebellar Ataxia Due to Dyshomeostasis of Sphingolipids in the Brain

- ACLY and ACC1 Regulate Hypoxia-Induced Apoptosis by Modulating ETV4 via α-ketoglutarate

- Quantitative Differences in Nuclear β-catenin and TCF Pattern Embryonic Cells in .

- HENMT1 and piRNA Stability Are Required for Adult Male Germ Cell Transposon Repression and to Define the Spermatogenic Program in the Mouse

- Axon Regeneration Is Regulated by Ets–C/EBP Transcription Complexes Generated by Activation of the cAMP/Ca Signaling Pathways

- A Phenomic Scan of the Norfolk Island Genetic Isolate Identifies a Major Pleiotropic Effect Locus Associated with Metabolic and Renal Disorder Markers

- The Roles of CDF2 in Transcriptional and Posttranscriptional Regulation of Primary MicroRNAs

- A Genetic Cascade of Modulates Nucleolar Size and rRNA Pool in

- Inter-population Differences in Retrogene Loss and Expression in Humans

- Cationic Peptides Facilitate Iron-induced Mutagenesis in Bacteria

- EP4 Receptor–Associated Protein in Macrophages Ameliorates Colitis and Colitis-Associated Tumorigenesis

- Fungal Infection Induces Sex-Specific Transcriptional Changes and Alters Sexual Dimorphism in the Dioecious Plant

- FLCN and AMPK Confer Resistance to Hyperosmotic Stress via Remodeling of Glycogen Stores

- MET18 Connects the Cytosolic Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Pathway to Active DNA Demethylation in

- Sex Bias and Maternal Contribution to Gene Expression Divergence in Blastoderm Embryos

- Transcriptional and Linkage Analyses Identify Loci that Mediate the Differential Macrophage Response to Inflammatory Stimuli and Infection

- Mre11 and Blm-Dependent Formation of ALT-Like Telomeres in Ku-Deficient

- Genome Wide Identification of SARS-CoV Susceptibility Loci Using the Collaborative Cross

- Identification of a Single Strand Origin of Replication in the Integrative and Conjugative Element ICE of

- The Type VI Secretion TssEFGK-VgrG Phage-Like Baseplate Is Recruited to the TssJLM Membrane Complex via Multiple Contacts and Serves As Assembly Platform for Tail Tube/Sheath Polymerization

- The Dynamic Genome and Transcriptome of the Human Fungal Pathogen and Close Relative

- Secondary Structure across the Bacterial Transcriptome Reveals Versatile Roles in mRNA Regulation and Function

- ROS-Induced JNK and p38 Signaling Is Required for Unpaired Cytokine Activation during Regeneration

- Pelle Modulates dFoxO-Mediated Cell Death in

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Single Strand Annealing Plays a Major Role in RecA-Independent Recombination between Repeated Sequences in the Radioresistant Bacterium

- The Rise and Fall of an Evolutionary Innovation: Contrasting Strategies of Venom Evolution in Ancient and Young Animals

- Genome Wide Identification of SARS-CoV Susceptibility Loci Using the Collaborative Cross

- DCA1 Acts as a Transcriptional Co-activator of DST and Contributes to Drought and Salt Tolerance in Rice

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání