-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

SCARN a Novel Class of SCAR Protein That Is Required for Root-Hair Infection during Legume Nodulation

Characterization of Lotus japonicus mutants defective for nodule infection by rhizobia led to the identification of a gene we named SCARN. Two of the five alleles caused formation of branched root-hairs in uninoculated seedlings, suggesting SCARN plays a role in the microtubule and actin-regulated polar growth of root hairs. SCARN is one of three L. japonicus proteins containing the conserved N and C terminal domains predicted to be required for rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton. SCARN expression is induced in response to rhizobial nodulation factors by the NIN (NODULE INCEPTION) transcription factor and appears to be adapted to promoting rhizobial infection, possibly arising from a gene duplication event. SCARN binds to ARPC3, one of the predicted components in the actin-related protein complex involved in the activation of actin nucleation.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005623

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005623Summary

Characterization of Lotus japonicus mutants defective for nodule infection by rhizobia led to the identification of a gene we named SCARN. Two of the five alleles caused formation of branched root-hairs in uninoculated seedlings, suggesting SCARN plays a role in the microtubule and actin-regulated polar growth of root hairs. SCARN is one of three L. japonicus proteins containing the conserved N and C terminal domains predicted to be required for rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton. SCARN expression is induced in response to rhizobial nodulation factors by the NIN (NODULE INCEPTION) transcription factor and appears to be adapted to promoting rhizobial infection, possibly arising from a gene duplication event. SCARN binds to ARPC3, one of the predicted components in the actin-related protein complex involved in the activation of actin nucleation.

Introduction

In most eukaryotic cells, the reversible association of G-actin subunits can result in the dynamic formation of actin filaments that play essential roles in changing cell shape and controlling nuclear localization. In addition, actin filaments form a framework along which vesicles and proteins can be trafficked to localized sites on the plasma membrane. In non-plant cells, cellular protrusions of the plasma membrane are critical for cell migration and are induced by polymerization and branching of actin [1]. A complex containing actin-related proteins 2/3 (ARP2/3) induces nucleation of branched actin that can drive the cellular protrusions. In the plant kingdom, the actin nucleation activity of the ARP2/3 complex is solely regulated by the SCAR/WAVE (Suppressor of cAMP receptor defect/WASP family verprolin-homologous protein) complex [1].

Due to the presence of the cell wall, membrane protrusions do not normally occur in plant cells, but nevertheless there are highly dynamic changes to the actin filaments catalyzed by nucleation of actin branching and actin polymerization and de-polymerization [2]. However, in contrast to non-plant cells, cytoskeletal control of plant-cell shape must be indirect, primarily mediated by the delivery of cell-wall remodeling proteins to localized sites in the cell periphery [3]. The SCAR/WAVE-ARP2/3 system plays an important role in polar growth of some plant cells such as trichomes and root hairs where mutations cause developmental phenotypes.

In legumes, identification of infection-defective mutants has revealed that there is a special requirement for the SCAR/WAVE-ARP2/3 system during nodule infection. During the bacterial initiation of nitrogen-fixing nodules on the roots of legumes, the rhizobia gain entry to the root via plant-made structures called infection threads along which the bacteria grow [4]. The infection thread, which is usually initiated in a root hair, is essentially an intracellular tube formed by an invagination of the plant cell wall and membrane [4,5]. This requires a new type of inwardly-directed polar growth that appears to be controlled by the position of the root-hair nucleus [6]. Based on the patterns of induction of cell-cycle related genes and analysis of nuclear enlargement, infection thread growth appears to be associated with the activation of a partial cell cycle that involves nuclear endoreduplication but not nuclear division [7].

Establishment of infection threads in root hairs requires rhizobial production of signals called Nod factors. The first plant morphological response to Nod factors is for the root hair to deform, sometimes curling back on itself, enclosing the bacteria in an infection pocket; this involves rearrangements in the actin cytoskeleton [8–11]. A transient increase in rapidly-growing actin microfilaments is induced in root hairs 2–5 min after Nod-factor addition [12]. After rhizobial entrapment, a new phase of development in the root hair leads to the initiation of growth of the infection thread [13,14] and this involves a second phase of redistribution of actin polymerization sites, this time to the point of rhizobial entry [12]. As the infection proceeds, a second developmental program is activated in the root cortex leading to morphogenesis of the nodule structure, that will eventually be infected following the extended growth of the infection threads through the root hair cells into the root cortex [15,16].

Critical to the activation of the infection and nodule development programs is a signaling pathway activated by rhizobial Nod factors [17,18]. Following Nod-factor binding to plasma-membrane receptors, calcium oscillations are induced in and around the root-hair nuclei and these oscillations are detected by a calcium and calmodulin-dependent kinase that activates a transcription factor called CYCLOPS [19,20]. Downstream of CYCLOPS there is activation of another transcription factor NIN, which is needed for infection-pocket and infection-thread development [21]. After rhizobial entrapment, a second signaling pathway is activated; this appears to require both higher levels and higher structural specificity of Nod factors and induces a calcium influx across the plasma membrane; if the appropriate host-specific decorations are absent from the Nod factors, both the calcium influx and infection thread initiation are significantly reduced [22,23]. It has been suggested that this pathway may be activated by the ROP-GAP pathway and is also related to the production of reactive oxygen species via an NADPH oxidase on the plasma membrane [18,22]. Although there is high signaling specificity, it is evident that some endophytic rhizobia-like bacteria (lacking nod genes) can gain entry using infection threads initiated by nodulation-competent rhizobia[24].

Several nodulation-defective mutants have been identified in which infection pockets are initiated or established, but most infection thread growth is blocked; some of these mutations are in regulatory genes such as, NIN, LIN, RPG, ERN1 and NFYA1 [21,25–29]. However other mutations are in genes that appear likely to be involved with structural requirements associated with infection thread initiation. One of these is in a nodulation-specific pectate lyase gene (NPL) the product of which is thought to locally degrade plant cell walls to allow initiation of infection thread growth. The NPL gene is directly regulated by NIN in response to Nod factor signaling [30]. Three mutants with similar phenotypes to the npl mutant are in the genes NAP (for Nck-associated protein 1) [31,32], PIR (for 121F-specific p53 inducible RNA) [31] and ARPC1 (for actin related protein complex 1) [33]. These proteins participate in promoting actin nucleation via the SCAR/WAVE-ARP2/3 complex. One possibility is that the SCAR/WAVE-ARP2/3 complex directs to the sites of infection thread initiation and growth, the cell-wall degrading enzymes (such as NPL) and the cell-wall and cell-membrane synthesis enzymes that will be required to establish an infection thread. If this model is correct, analysis of genes required for infection-thread initiation may give us insights not only into how legumes accommodate infection by rhizobia, but also into aspects of how the SCAR/WAVE-ARP2/3 complex operates and can be adapted for special situations in plant development.

One of the questions with regard to the operation of the SCAR/WAVE-ARP2/3 complex in legume infection is whether it simply uses existing components or whether there is induction of components to facilitate rhizobial infection. In this work, we have identified a novel gene SCARN (SCAR-Nodulation) required for initiation of infection threads and this gene contains domains typical of SCAR proteins. However, although the gene product is conserved in legumes, it is novel because it is not closely related to any of the SCAR-family proteins identified in Arabidopsis. This gene is directly regulated by the nodulation transcription factor NIN. Intriguingly, two of the mutations in SCARN resulted in constitutive induction of root-hair branching, a phenotype normally induced by Nod-factors.

Results

Identification of four alleles of a gene required for legume infection by rhizobia

To understand the molecular mechanisms of infection thread formation during rhizobial infection of L. japonicus roots, we screened an ethyl-methane-sulfonate (EMS) mutagenized population [34–36] of L. japonicus Gifu B-129 for defects in infection by M. loti. Mutants defective for nitrogen fixation were initially identified based on nitrogen starvation (yellowing) of the leaves of plants grown under limiting nitrogen and then screening for the absence of nodules, or the presence of white nodules, indicative of an ineffective symbiosis. Candidate mutants were then inoculated with a strain of M. loti expressing a β-galactosidase (lacZ) gene and nodules formed were then stained with X-gal to determine if they were, or were not infected. The various mutants that appeared to have mostly uninfected nodules were crossed with the wild-type Miyakojima (MG20) to generate mapping populations. Rough mapping using established DNA markers http://www.kazusa.or.jp/lotus/ revealed that four of the mutations were localized on L. japonicus linkage group 3, between markers TM0111 and TM0707. These mutations were in lines SL2654-3, SL5737-2, SL6119-2 and SL1058-2 and the F2 populations generated from crosses with MG20 were scored for nodulation defects. All of the mutations segregated 3 : 1 (p < 0.05) based on the numbers (shown in parentheses) of WT and mutant plants in the F2 populations from crosses with SL2654-3 (246 Nod+/78 Nod-, x2 value = 0.0337); SL5737-2 (144 Nod+/33 Nod-, x2 value = 1.8165); SL6119-2 (236 Nod+/67 Nod-, x2 value = 0.5631) and SL1058-2 (200 Nod+/59 Nod-, x2 value = 0.244). These data suggested that we had identified four allelic monogenic recessive mutations and so allelism was tested in reciprocal crosses. When SL2654-3 was crossed with SL5737-2, SL1058-2 and SL6119-2, or SL6119-2 was crossed with SL5737-2, all the F1 plants produced no nodules or only small white bumps (S1 Table). The results of these reciprocal crosses confirmed that the four mutations are allelic, and so fine mapping for positional cloning and analyses of phenotypes were done primarily with one mutant (SL2654-3).

Identification of a mutation in a gene encoding a novel SCAR homolog

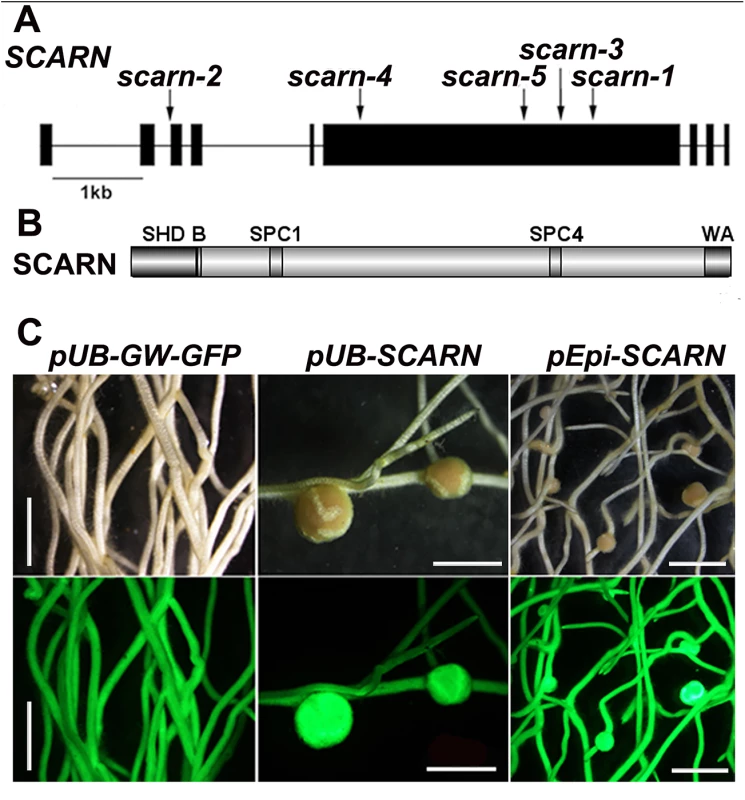

From crosses between SL2654-3 and MG20, 439 mutant progeny were identified. Genotyping of these mutants delimited the mutated locus in SL2654-3 between markers TM1465 and TM0116; there was no recombination with marker BM2233 (S1 Fig). We analyzed the predicted protein sequences of genes in this region and identified a large gene composed of nine exons (Fig 1A) encoding a predicted 1627 amino-acid protein, that has domains with similarity to domains typically found in SCAR (suppressor of cAMP receptor) proteins. SCAR proteins are components of the SCAR/WAVE complex, which is known to participate in the regulation of actin nucleation in Arabidopsis thaliana [37]. Since other components of the SCAR/WAVE complex had previously been identified as being required in legumes for root-hair infection by rhizobia, we thought the gene encoding a protein with domains showing similarity to SCAR protein was a good candidate. Amplification and sequencing of this gene from SL2654-3 revealed a C-T transition, leading to a stop codon replacing Q1199. We amplified and sequenced the gene from the other three mutants and all had mutations (Table 1 and Fig 1A): SL5737-2 has a G-A transition at the third exon splice acceptor site, SL6119-2 has a C - T transition causing a premature stop replacing at Q1100, and SL1058-2 has 1 base pair deletion in the sixth exon causing a frame shift. Some time after the detailed analyses of these mutants, we also obtained a LORE1 insertion (30053577) in this gene from the L. japonicus LORE1 retrotransposon mutagenesis pool at Aarhus University, Denmark [38,39]; this mutant was also defective for infection and nodulation.

Fig. 1. SCARN gene and protein structure and complementation of scarn-1.

(A) The SCARN gene exons are shown as black boxes. The locations of the mutations in SL2564-3 (scarn-1), SL5737-2 (scarn-2), SL6119-2 (scarn-3), SL1058-2 (scarn-4) and the LORE mutant (scarn-5) are shown. (B) The SCARN protein has an N-terminal SCAR homology domain (SHD) and C-terminal WH2 and Acidic (WA) domains. Between the SHD and WA domains there are two plant-specific conserved SCAR motifs SPC1 and SPC4. (C) Hairy roots of the scarn-1 mutant transformed by A. rhizogenes with the control plasmid (pUb-GW-GFP), and complementation of nodulation by the same plasmid containing the SCARN genomic DNA downstream of the ubiquitin (pUb:SCARN), or of the epidermal-specific promoter (pEpi:SCARN). The upper panels show bright field images and the lower panels are epifluorescence microscopy images showing GFP expression in the same transgenic roots. Scale bar 2mm. Tab. 1. <i>L</i>. <i>japonicus scarn</i> mutant alleles.

The wild-type gene was amplified from the genome of Gifu B-129 and cloned behind the ubiquitin promoter in the vector pUB-GW-GFP [40]. The construct was introduced into roots of SL2654-3 by Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated hairy root transformation. Normal nodulation was restored in the SL2654-3 mutant (Fig 1C and Table 2). Taken together, it is clear from the multiple alleles and complementation data, that mutations in the SCAR-like gene caused the defect in nodule infection. As described below, although there are conserved domains, the overall predicted protein sequence was not strongly homologous to any of the Arabidopsis SCAR proteins. Furthermore the identified gene is increased in expression during nodule infection and so we named the gene SCARN (SCAR-Nodulation). Accordingly we named the alleles in SL2654-3, SL5737-2, SL6119-2 and SL1058-2 scarn-1, scarn-2, scarn-3 and scarn-4 respectively and we named the LORE1 retrotransposon mutant allele scarn-5 (Table 1).

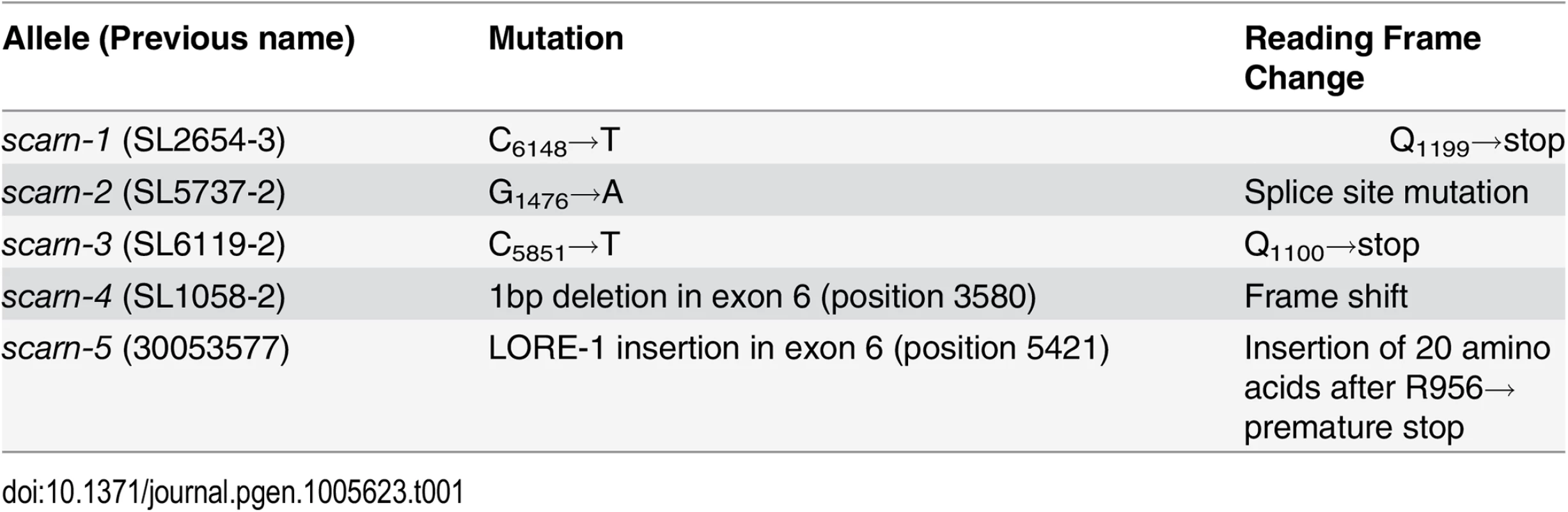

Tab. 2. Complementation of scarn-1 nodulation phenotype by hairy root transformation.

a Ratio indicates numbers of successfully transformed plants that formed nodules versus all plants of the indicated line that were successfully transformed with the indicated construct. scarn mutants produce uninfected nodules but are infected by a mycorrhizal fungus

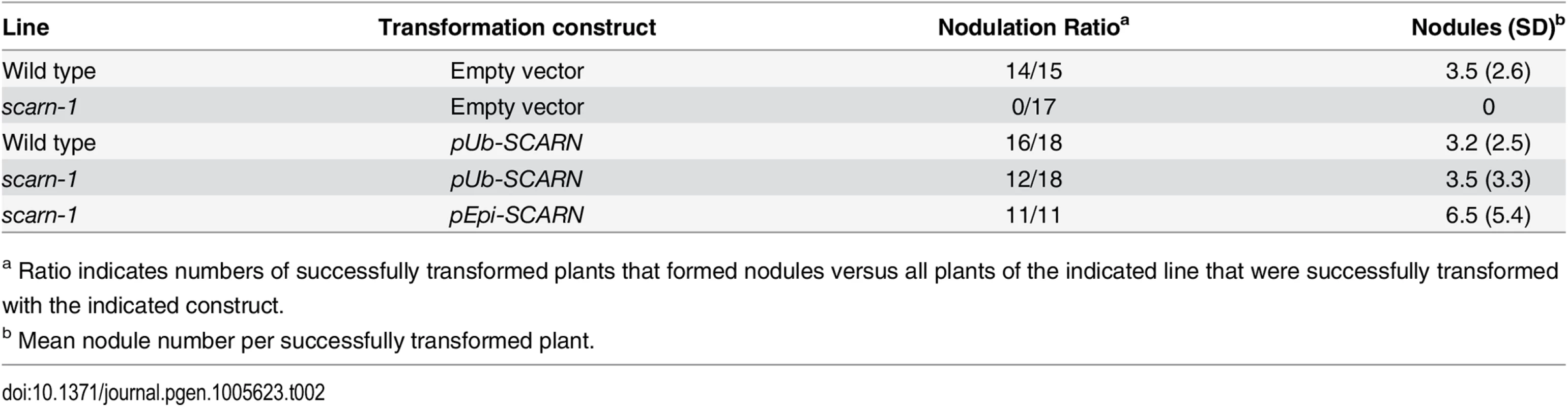

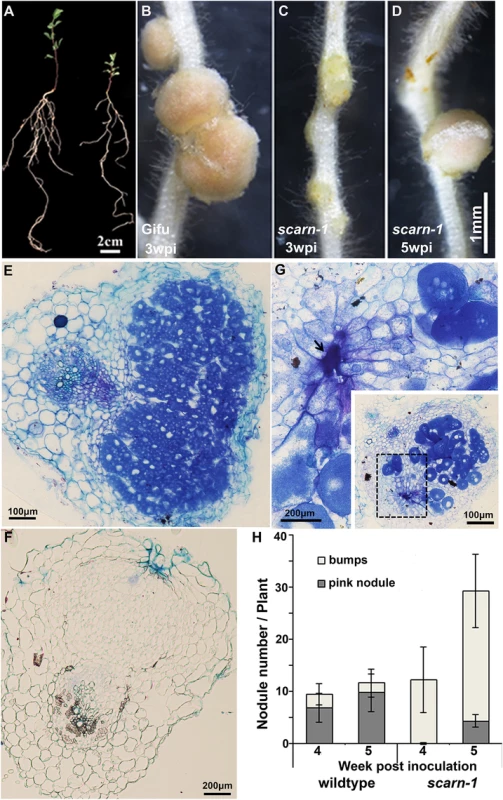

Although the scarn mutants showed symptoms of nitrogen-starvation on nitrogen-deficient nutrient medium (Fig 2A), they grew normally when supplied with nitrate (S2A Fig). All five scarn mutants produced small white nodules (hereafter called bumps) three weeks after inoculation with M. loti (Fig 2C and S2B Fig). The scarn-5 mutant had the most severe phenotype, producing only a couple of white nodule-like bumps four weeks after inoculation (S2C Fig). However, 4–5 weeks after inoculation, some scarn mutants produced a few pale-pink nodules (Fig 2D). Sections of the bumps and pale-pink nodules were examined by light microscopy showing that the bumps were uninfected nodules (Fig 2F), whereas the wild type formed fully infected nodules (Fig 2E). The occasional pale-pink nodules were partially infected and some had the characteristic ‘butterfly’ structure (Fig 2G), indicative of infections via intercellular entry [41]. The net effects of the scarn mutations on nodulation were to greatly reduce the numbers of pink nodules and to induce the formation of more white bumps compared with wild type plants (Fig 2H). Since the scarn1-4 mutants were similar, and we did not obtain the scarn-5 mutant until relatively late in the project, we used the scarn-1 mutant in all subsequent experiments except where noted.

Fig. 2. Phenotype of the L. japonicus scarn-1 mutant.

(A) Whole plants of wild-type Gifu B-129 and scarn-1 five weeks after germination and growth in a 1:1 mix of perlite and vermiculite inoculated with M. loti R7A. Left: wild-type Gifu B-129; right: SL2564-3 (scarn-1). (B-C) Nodules formed 3 weeks after M. loti inoculation of (B) wild type or (C) SL2564-3 (scarn-1). (D) A nodule formed on scarn-1 5 weeks after inoculation. Panels E, F and G show light microscopy sections of the nodules shown in B, C and D respectively. Arrow in (G) shows the pockets of intercellular bacteria. (H) Nodule numbers 4 and 5 weeks after inoculation of wildtype and SL2564-3 (scarn-1) plants inoculated with M. loti R7A (the bar indicated 95% confidence intervals): grey columns: mature, pink nodules; white columns: white immature nodule bumps. Scale bars: A, 2 cm; B-D, 1 mm; and E, 100 μm; F-G, 200μm. Some legume nodulation mutants are also defective for the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Therefore, we also scored the scarn-1 mutant for infection by the mycorrhizal fungus Glomus intraradices. Normal infection and arbuscule formation was observed (S3A–S3C Fig).

Mutation of scarn blocked infection-thread growth but not induction of early nodulation genes

The absence of bacteria in most of the nodules of the scarn mutants suggested that rhizobial infection was abnormal. Assays of infection by M. loti constitutively expressing a green fluorescent protein (GFP) or a β-galactosidase (lacZ) marker gene showed that the scarn-1 mutant was defective for infection thread formation. Unlike the wild-type, in which infection threads initiated from curled root hairs and extended through the epidermal cells (Fig 3A), most of the infections of scarn-1 were blocked at the stage of formation of infection pockets (Fig 3B) and occasionally, some infection threads grew within root hairs of the scarn-1 mutant (Fig 3C). In some of the few infections that did occur in the mutant, it appeared that the bacteria were released into the root hair cell (Fig 3D and 3E), a phenomenon that has been noted in several infection mutants [42]. After 5–7 days, infection threads in wild-type plants ramified into the cortex (Fig 3F), but in the scarn-1 mutant, although occasional infection threads extended to the base of the root hair, they did not extend deep into the cortex (Fig 3G). Analyses of infection of the scarn-1 mutant 1 and 2 weeks after inoculation (Fig 3H) revealed that the total number of initiated infections was not reduced in the scarn-1 mutant, but most of these events were arrested in the infection foci in root hairs.

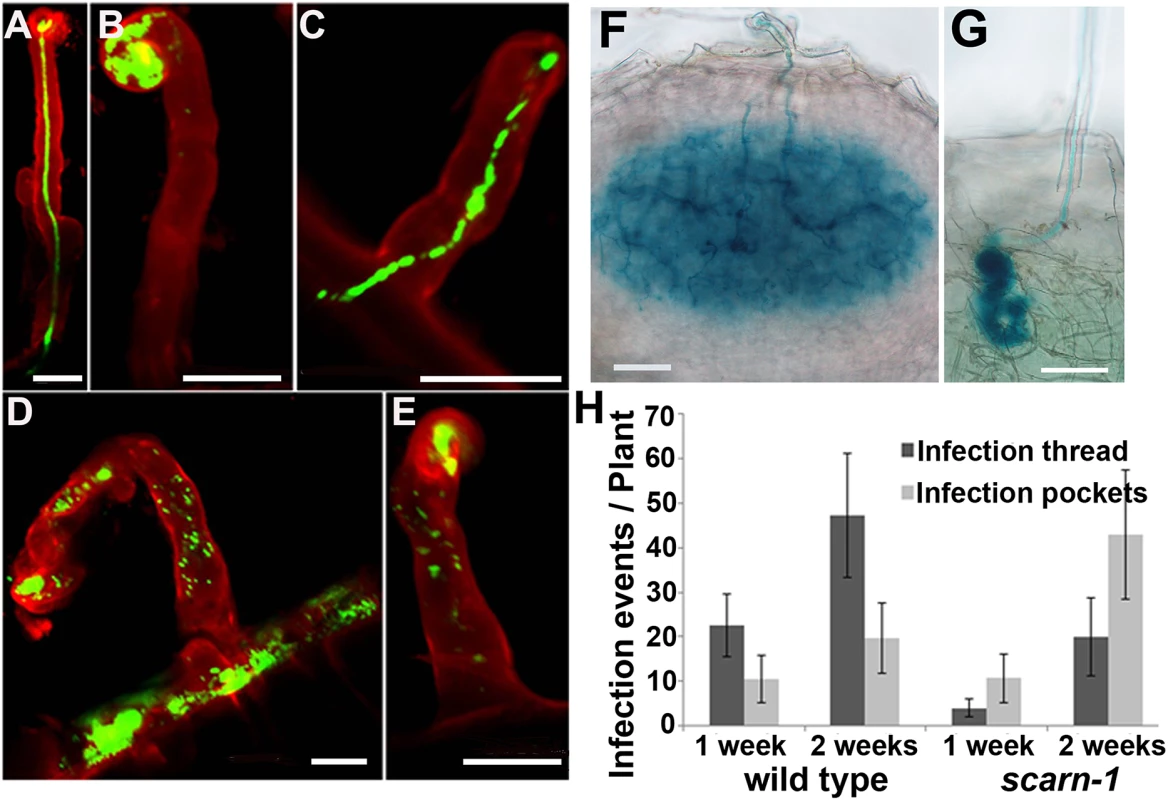

Fig. 3. Infection thread phenotype of the scarn-1 mutant (SL2564-3).

(A-E) Confocal microscopy of root hairs in wild type (A) or scarn-1 (B-E) 1 week after inoculation with M. loti R7A expressing GFP. The green fluorescence shows a normal infection thread in a curled root hair (A), whereas most of infection events were blocked in infection foci of the scarn-1 mutant (B). Sometimes, rhizobia were observed within root hairs but outside of infection threads (D, E). (F-G) Histochemical staining (X-gal) of an infection 1 week after inoculation of wild type (F) or one of the rare infection threads in SL2564-3 (scarn-1) that penetrated beyond the root-hair cell (G). Scale bars: A-E, 20 μm; F-G, 50 μm. (H) Histogram showing the average numbers (with 95% confidence levels) of infection threads plant in the wild type and the scarn-1 mutant 1 and 2 weeks after inoculation with M. loti R7A/lacZ. Infections were counted microscopically using roots stained with X-gal. During the initiation of the rhizobial-legume symbiosis, several genes including NIN, NPL and ENOD40-1, are induced in response to rhizobia or Nod factors. These genes may be involved in rhizobial infection and/or nodule organogenesis and so we used quantitative real-time PCR to assay their induction in the scarn-1 mutant by M. loti. Five days after inoculation with M. loti, the NIN, ENOD40-1 and NPL genes were strongly and similarly induced in both the scarn-1 mutant and wild-type (S4 Fig) showing that scarn is not required for their expression.

Mutations in scarn affect root-hair development and M. loti-induced root hair deformation but not trichome formation

In Arabidopsis thaliana, mutations in SCAR2 cause distorted trichomes (AtSCAR2 is also called DISTORTED3 or IRREGULAR TRICHOME BRANCH1) [43,44]. Mutations in some other components (nap, pir and arpc1) of the SCAR/WAVE-ARP2/3 complex in legumes also cause distorted trichomes, and affect root-hair growth and pod and seed development [31–33]. Visual inspection did not reveal obvious differences in trichomes in the scarn mutants (S5A Fig) and scanning electron microscopy revealed that the trichomes in wild type and scarn-1 were indistinguishable (S5B Fig). Moreover, there were no apparent defects in pod or seed development of scarn mutants compared with wild type (S5C Fig).

The scarn mutants formed slightly shorter root hairs than wild type (S5D Fig). Interestingly, the scarn-1 and scarn-3 mutants produced branched root hairs in the mature zone even in the absence of M. loti (Fig 4A).

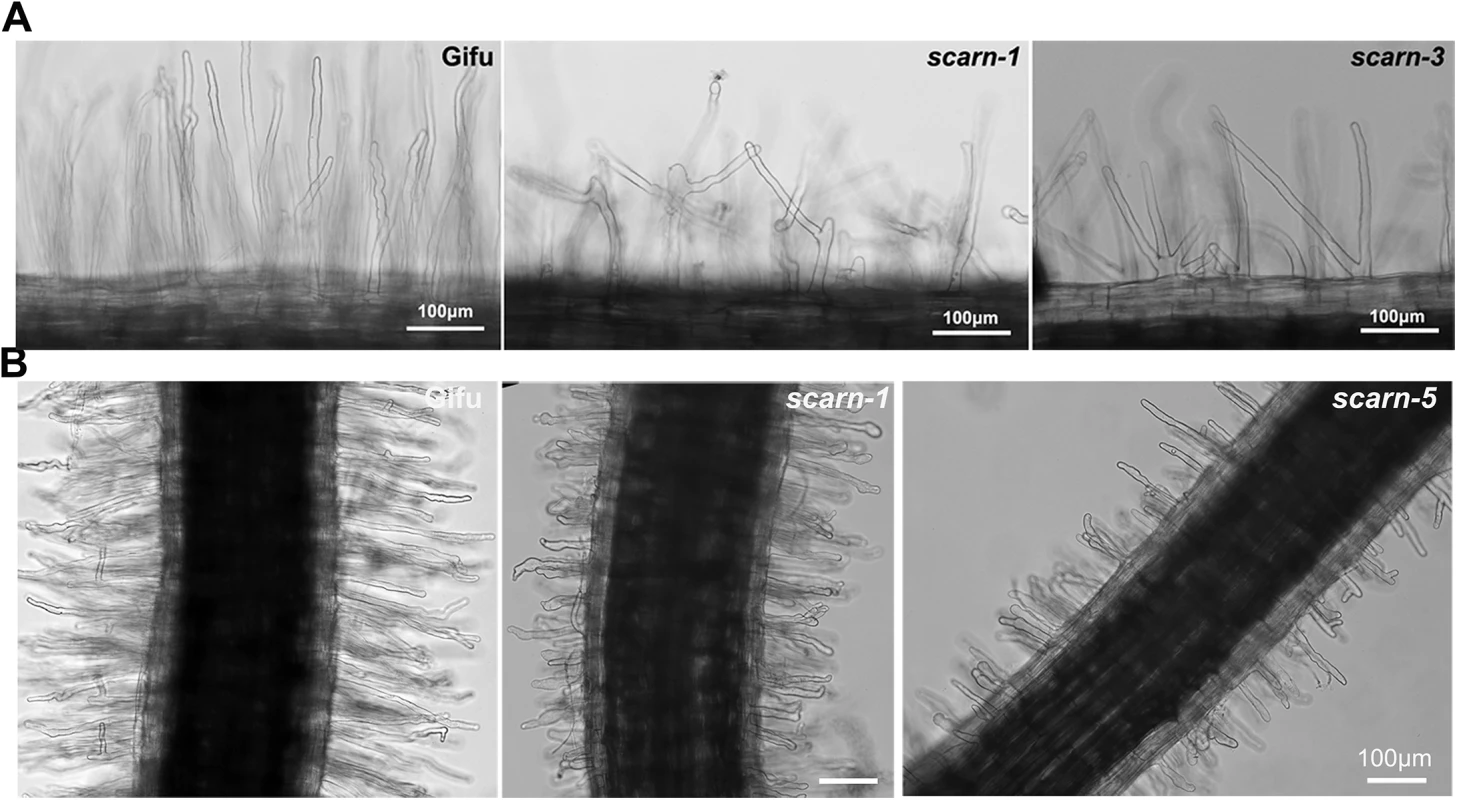

Fig. 4. Root hair and M. loti-induced root hair deformation in L. japonicus wildtype (Gifu) and scarn mutants (scarn-1 and scarn-5).

(A) Light microscopy image of the branched root hairs in the mature zone of wild type (left) and scarn-1 (middle) and scarn-3 (right) following 2 days of growth on uninoculated FP liquid medium. The root hair length of mature zone of wildtype and scarn mutants are similar, (measured about 1.0–1.5 cm to the root hair tip). Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Light microscopy images of M. loti R7A-induced root-hair deformation in the infection zone of wild type (Gifu), scarn-1 and scarn-5 mutants. Scale bar, 100 μm We assayed M. loti-induced root-hair deformation with the scarn mutants and saw that they had altered root hair deformation, with more branching and swelling of the root hairs (Fig 4B). It appeared that the root hair swelling was associated with reduced root hair growth. These observations suggest that SCARN is required for both normal tip growth following exposure to M. loti and for the establishment of polar growth of infection threads. The other subunits of the SCAR/WAVE complex, LjPIR, LjNAP, MtNAP and LjARPC1, are not only required for rhizobial infection, but are also required for normal trichome and root-hair growth, and seed development, as observed with their homologues in Arabidopsis. However, unlike the NAP, PIR and ARPC1 genes, SCARN is not required for the development of trichomes or normal pods and seeds in legumes.

Expression pattern of SCARN

We analyzed SCARN transcript levels in different organs by quantitative real-time PCR and found no significant difference in expression in shoots, leaves, flowers and roots (S6A Fig). We analyzed SCARN expression in roots at different time points after inoculation with M. loti: SCARN expression was slightly increased 1 and 7 days after inoculation, but its expression returned to basal levels 14 days after inoculation (Fig 5A). This suggested that SCARN expression is enhanced during rhizobial infection. To further investigate this we analyzed the spatial and temporal expression of SCARN by generating A. rhizogenes-induced transgenic hairy roots carrying the β-glucuronidase (GUS) gene behind the SCARN promoter (pSCARN:GUS). When inoculated with M. loti, we detected weak expression in epidermal cells under infection foci or elongated infection threads in the transformed roots (Fig 5B) confirming that SCARN is up-regulated during rhizobial infection. The strongest GUS expression was detected in young nodules (Fig 5C and S6B Fig), sections of which indicated there was GUS activity in the epidermal and outer cortical cells but not in the central tissue (Fig 5D). The observation that the scarn-1 and scarn-3 alleles caused root-hair branching (Fig 4A) implies that SCARN must be expressed in root hairs. Furthermore, the altered pattern of M. loti-induced root-hair deformation also implies that SCARN must be expressed in root hairs. However the SCARN expression must be below the level of detection by the pSCARN:GUS fusion. In mature nodules (about 2 week post inoculation), the GUS activity was primarily seen at nodule vascular bundles (Fig 5E and S6B Fig). In the absence of M. loti, pSCARN:GUS expression was detected in primary and lateral root tips, and sites of lateral root initiation, including pericycle cells and the lateral root meristem (S6C–S6F Fig).

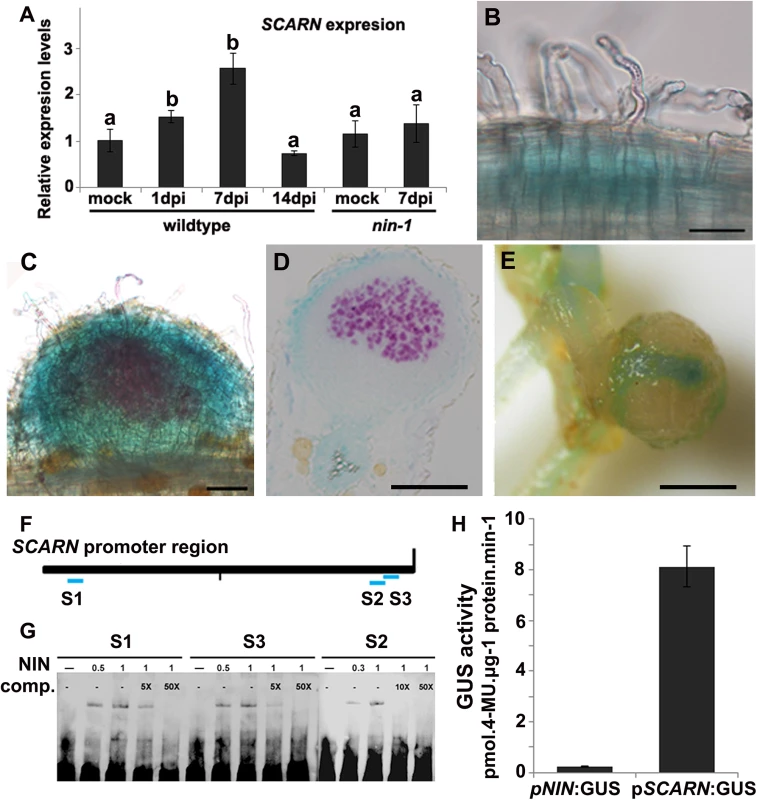

Fig. 5. SCARN expression in L. japonicus roots, and NIN directly induces SCARN expression.

(A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of SCARN expression in mock inoculated (mock) and M. loti inoculated roots of wild-type (1, 7, 14 days) and nin-1 mutant (7 days) roots of L. japonicus after inoculation of seedlings growth in perlite/vermiculite. Different letters indicate significant differences (Student-Newman-Kuels test, P < 0.05). (B-E) Histochemical localization of GUS activity in A. rhizogenes-induced hairy roots transformed with pSCARN:GUS. The hairy roots were analyzed 7 days (B-D) and 14 days (E) after inoculation with M. loti R7A/lacZ and stained with both Magenta-Gal and X-Gluc to visualize M. loti (in purple) and pSCARN:GUS expression (in blue). (B) Shows pSCARN:GUS expression in the root below M. loti-infected root hairs. (C) Shows pSCARN:GUS expression in a whole stained young nodule, and M. loti in an infection thread and young nodule (purple). (D) Shows pSCARN:GUS expression in the epidermal cells of a section of a nodule in which some the nodule cells are infected by M. loti as seen by the magenta staining. (E) Shows pSCARN:GUS expression limited mostly to the vascular bundles of a mature nodule. (B-E): Bar = 100 μm. (F) Map of the SCARN promoter region showing regions S1, S2 and S3 that show sequence homology to NIN binding sites. This entire region was used to make the pSCARN-promoter GUS fusion. (G) The S1, S2 and S3 regions marked in blue in the predicted SCARN promoter (F) were used as probes for three electrophoresis-mobility-shift assays. In each there was 0.5, 1 μg or no NIN protein added as indicated. In two lanes of each assay, a 5x, 10x or 50x excess (as indicated) of unlabeled competitor DNA fragment was added. (H) Transactivation assay in N. benthamiana leaves showing that NIN can activate pSCARN:GUS expression. The pNIN:GUS fusion was used as a negative control. GUS activity was determined histochemically and quantitatively in leaf discs. Mean values and standard deviations were determined from three biological replicates. Since (a) mutation of SCARN blocked most infections at the epidermis, and (b) SCARN was primarily expressed in epidermal cells of infected roots and in the epidermis of young nodules, we tested if epidermal-specific expression could rescue nodule infection in the scarn-1 mutant. We made a construct in which the epidermal-specific promoter pEpi [45] is upstream of the SCARN genomic DNA lacking its own promoter. We then generated A. rhizogenes-transformed hairy roots in the scarn-1 mutant using this construct (pEpi-SCARN). The observed complementation (Fig 1C and Table 2) revealed that pEpi-SCARN can rescue the infection deficiency, confirming that expression of SCARN behind an epidermal-specific promoter is sufficient to permit rhizobial infection.

SCARN expression is regulated by the NIN transcription factor

Mutation of the NODULE PECTATE LYASE (NPL) gene induced a block in nodule infection similar to that seen with the scarn mutants. The expression of NPL is regulated by the NIN-encoded transcription factor that is also required for nodulation and infection [30]. Furthermore, the pattern of NIN expression is similar to that described here for SCARN [46]. We measured (by quantitative RT-PCR) SCARN expression in the nin-1 mutant, revealing that the increased SCARN expression caused by M. loti requires NIN (Fig 5A). The NIN-binding nucleotide sequence has been identified [46,47] and analysis of the DNA sequence upstream of SCARN revealed three putative NIN-binding sites: one was 1.9 Kb upstream of the predicted translation start and two overlapping sequences of predicted NIN-binding sites are present about 50 bp upstream of the translation start (Fig 5F). We used an electrophoresis mobility shift assay to test if NIN could bind to these SCARN promoter regions. Specific retardation was observed with synthetic oligonucleotides corresponding to each of the three SCARN promoter regions when they were incubated with the carboxyl-terminal half of the NIN recombinant protein. This region of NIN contains the RWP-RK domain responsible for DNA binding [21]. Gel shift analyses and competition assays confirmed that NIN bound specifically to these promoter regions (Fig 5G).

We also co-expressed 35S:GFP-NIN with the reporter fusions pSCARN:GUS or pNIN:GUS in Nicotiana benthamiana leaf cells and GUS activity was determined histochemically and quantitatively in leaf discs. The results indicate that NIN can induce the SCARN, but not the NIN promoter (Fig 5H). Taken together, these data demonstrate that NIN directly binds to the SCARN promoter to activate its expression.

SCARN encodes an unusual protein with a SCAR homology domain and WA domain

The predicted SCARN protein (1627 amino acids) is much longer than the predicted A. thaliana SCAR1, SCAR2, SCAR3 and SCAR4 proteins (821, 1399, 1020 and 1170 amino-acids respectively) [48]. As with other plant SCAR family proteins, SCARN has an N-terminal conserved SCAR homology domain (SHD), which may mediate the assembly of the SCAR/WAVE complex. It also has a C-terminal predicted WH2 domain connected to an acidic domain (A) which has the potential to bind to G-actin and activate the Actin-Related Proteins ARP2/3 (Fig 1B and S7A Fig). The full-length SCARN protein has only 30% and 26% identity with AtSCAR2 and AtSCAR4 respectively. (For reference, the L. japonicus and Arabidopsis NAP1 proteins are 77% identical and the PIR proteins are 83% identical; [31]). The SCARN N-terminal SHD and C-terminal WA domains share 67% and 69% identity with AtSCAR2, and 91% and 86% identity respectively with its putative homologue in M. truncatula. As with the other plant SCAR proteins, SCARN lacks the poly-proline region (PPR) that promotes binding to G-actin binding protein and is normally found in non-plant WASP/SCAR/WAVE family members. Within most plant SCAR proteins there are plant-specific conserved motifs referred to as SCAR of plants central region (SPC) [3,49]. SCARN contains conserved SPC1 and SPC4 domains, but lacks the SPC2 and SPC3 conserved domains (Fig 1B and S7B Fig).

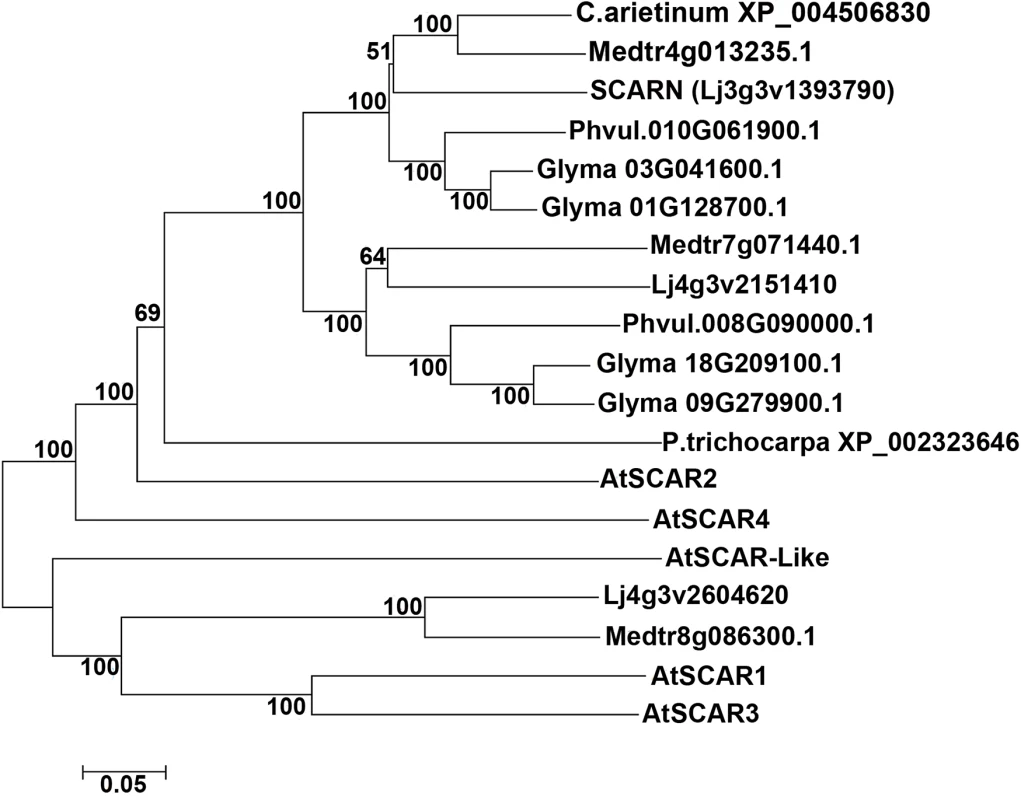

We searched for proteins containing conserved SCAR domains in L. japonicus and other legumes; this identified only three proteins, two of which fell into the same legume-specific clade of proteins. This clade could be split into two subclades, one containing SCARN and another containing a protein clearly related to SCARN. In each sub-clade there is one representative from L. japonicus, M. truncatula and Phaseolus vulgaris and (as would be expected due to its tetraploid nature) two representatives from Glycine max (Fig 6). The SCARN-like protein from L. japonicus (Lj4g3v2151410) is predicted to be 1461 amino acids long and is 48% identical with SCARN over its full length. The presence in legumes of two subclades of proteins related to SCARN fits with the suggestion [50] that ancestral polyploidy events can lead to enhanced root nodule symbiosis in the Papilionoideae. Possibly a gene duplication event may have allowed evolution of SCARN with a specialized role in legume infection.

Fig. 6. SCARN belongs to a subclade of legume WAVE/SCAR family proteins.

The tree shows a phylogenetic analysis of SCARN and other legume SCAR family proteins integrated with SCAR proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana. The protein sequence were obtained from TAIR and Phytozome 10.1, and the sequence alignment using ClustalW2, the phylogenetic tree were built using MEGA6.0, by using the neighbor-joining method with the bootstrapping value set at 1000 replications. The SCARN WA domain binds to ARPC3 in vitro

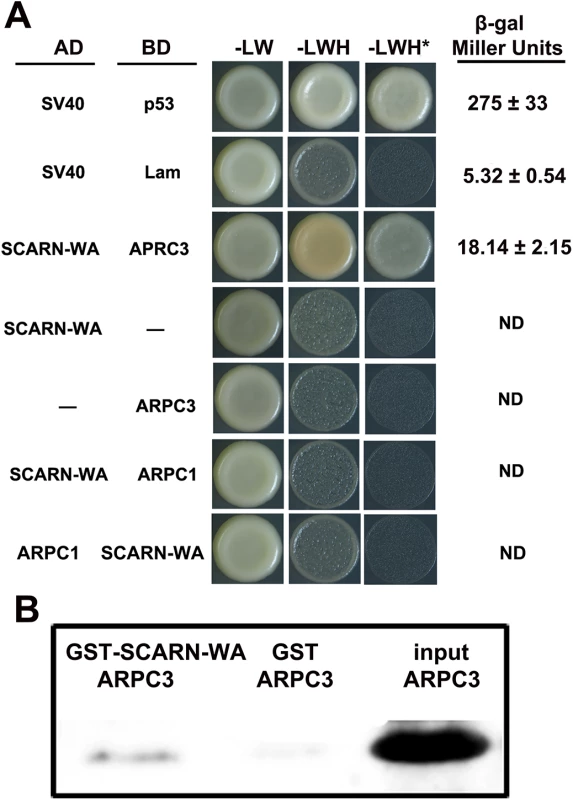

The ARP2/3 complex nucleates branched actin filament networks, but requires nucleation-promoting factors to stimulate this activity. In plants, ARP2/3 activation relies on the SCAR/WAVE family and in Arabidopsis the C-terminal WA domain of SCAR2 interacts with the ARP2/3 complex, activating actin nucleation. We tested if the WA domain of SCARN could associate with components of the ARP2/3 complex using a yeast-two-hybrid assay. Since the LjARPC1 gene is required for legume infection [33], we first tested if the WA domain of SCARN could interact with LjARPC1 in a yeast-two-hybrid assay. Co-expression of the SCARN WA domain fused to the GAL4 binding domain and LjARPC1 fused to the Gal4 activation domain did not permit growth in the absence of histidine. The reciprocal fusion constructs also did not permit growth in the absence of histidine (Fig 7A). These results indicate there is no interaction between the SCARN WA domain and LjARPC1 in the yeast-two-hybrid assay. However, when the GAL4 activation domain fused to the WA domain of SCARN was expressed together with the GAL4 binding domain fused to LjARPC3 (Lj4g3v1934510.1) the yeast strain grew well in the absence of histidine, even in the presence of 10 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole. This indicates LjARPC3 binds to the WA domain of SCARN. Quantitative analysis of the expression of the lacZ gene under the control of the GAL4 promoter confirmed that co-expression of the SCARN WA-GAL4 binding domain and LjARPC1-Gal4 activation domain increased β-galactosidase (LacZ) activity from a background of 5.3 ± 0.5 to 18.1 ± 2.1 units confirming the interaction.

Fig. 7. Assays of interaction between the WA domain of SCARN and ARPC1 and ARPC3.

(A) Yeast-two-hybrid assay of interactions. The SCARN-WA domain was cloned in frame with the yeast Gal4 activation domain (AD). ARPC1 or ARPC3 were cloned in frame with the Gal4 binding domain (BD) and S. cerevisiae AH109 was co-transformed with the AD and BD plasmids and also transformed with each construct separately. As a positive control, SV40 fused to the activation domain was co-transformed with p53 fused to the binding domain. SV40 and Lam were negative controls. Potential interactions were assayed by comparing growth in the presence (-LW) or absence of histidine (-LWH) and in the absence of histidine in medium containing 10 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (+ 10 mM 3-AT, -LHW*). Quantification of β-galactosidase assays is shown. ND, not determined. (B) Pull-down experiments to test interactions in vitro. The WA domain of SCARN fused to glutathione transferase (GST-SCARN-WA) or the glutathione transferase (GST) were purified separately from E. coli and incubated with His-tagged ARPC3 also purified from E. coli. The GST-SCARN-WA and GST proteins were adsorbed onto glutathione sepharose beads, washed extensively and eluted. The eluents along with the input His-tagged ARPC3 were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a membrane which was stained for His-tagged ARPC3 using antiserum to poly histidine. A direct interaction between the SCARN-WA domain and APRC3 was confirmed by in vitro pull-down assays. We expressed in Escherichia coli a recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST) fused to the SCARN-WA domain and purified this GST-SCARN-WA recombinant protein using Glutathione Sepharose TM 4B beads. His-tagged APRC3 was purified from E. coli, immobilized on nickel–NTA beads and then incubated with the purified GST-SCARN-WA. After washes, proteins retained on the beads were eluted and resolved by SDS-PAGE. The GST-SCARN-WA fusion protein was observed in the eluate by immunoblotting with anti-GST antibody (Fig 7B). The interaction was specific because LjAPRC3 was not pulled down by the GST protein alone (Fig 7B). These results show that the SCARN-WA can interact with ARPC3, suggesting a role for SCARN in the activation of the ARP2/3 complex.

Early actin rearrangements induced by M. loti occurs in the scarn mutant

Both rhizobial inoculation and addition of purified Nod-factors rapidly induced accumulation of fine bundles of actin filaments in the apical/subapical region of the responding root hairs [9,12,51] and mutation of L. japonicus NAP and PIR genes blocked this effect [31]. Alexa-phalloidin staining of WT and the scarn-1 root hairs showed similar long cables of actin filaments aligned longitudinally (S8A and S8B Fig), suggesting normal actin arrangements in the scarn-1 mutant. M. loti induced an accumulation of actin bundles in region II root-hair tips within 30 min of inoculation of both WT and scarn-1 mutant; we did not observe any difference in this actin rearrangement in mutant and wild type. We also checked the M. loti-induced actin rearrangement in root hairs of the scarn-4 and scarn-5 mutants using the same technique. About 55% root hairs showed normal accumulation of the actin cytoskeleton and this is consistent with wildtype and scarn-1 root-hair deformation responses (S8C and S8H Fig and S2 Table). We used the L. japonicus pir mutant as a control and observed that under the same conditions the pir mutation blocked the formation of almost all actin fine bundles in all observed root hair tips (S8D and S8I Fig). Since NIN regulates M. loti-induced SCARN expression, we also checked the M. loti-induced response in the nin-1 mutant; this revealed that 60% of the root hairs showed actin accumulation in their tips (S8E and S8J Fig and S2 Table). These results suggest that SCARN is not required for the early phase of rhizobial-induced actin cytoskeletal rearrangement in root hairs and is consistent with the observed root-hair deformation in the scarn mutants.

Overexpression of the SCARN SHD domain inhibits nodule infection

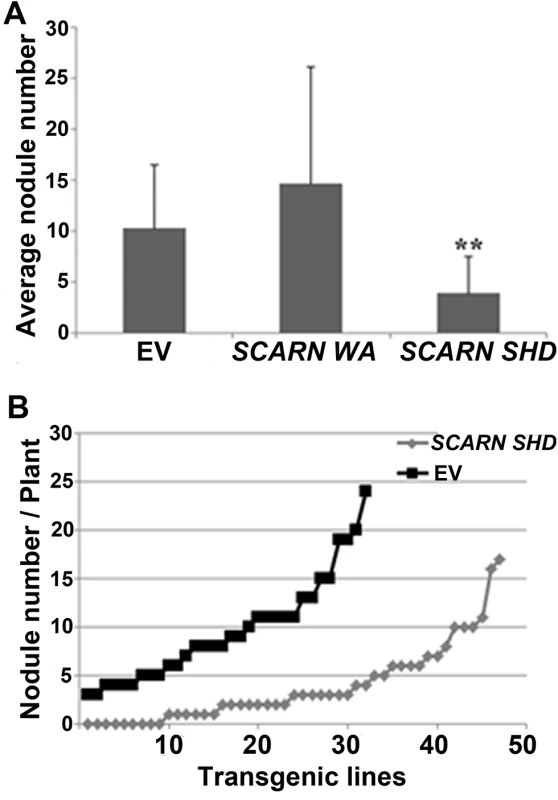

To investigate the importance of the SHD and C-terminal WA domains, we generated constructs that could express either of these SCARN domains using the ubiquitin promoter and introduced them into wild type roots by A. rhizogenes-mediated hairy root transformation. The constructs encoding the full length SCARN or the C-terminal WH2 domain had no observed effect on nodule formation compared with the empty vector control (Fig 8A). However the expression of the N-terminal SHD domain of SCARN reduced nodule formation (Fig 8A), with about one third of the transformed plants producing no nodules or inducing the formation of only one white bump (Fig 8B). Some of the plants transformed with the SHD domain produced a few pink nodules, but on average the numbers of pink nodules were consistently much lower than that seen with the control plants transformed with the vector Ubi:mCherry lacking the SCARN SHD domain (Fig 8A). These results show that strong expression of the SHD domain of SCARN can interfere with normal nodulation, although we observed no effect on root-hair growth. Similar dominant-negative effects have been seen with strong expression of the AtSCAR2 SHD domain causing abnormal trichome development [44]. The observation of a dominant negative effect of the SCARN SHD domain on nodulation (a) confirms the importance of this domain for function and (b) adds weight to the observation that SCARN plays an important role in legume nodulation.

Fig. 8. Expression of the Scar Homology Domain (SHD) of SCARN inhibits nodulation.

Transgenic hairy roots of wild-type L. japonicus were generated using A. rhizogenes carrying transformation constructs for the in planta expression of the C-terminal WA (residues 1500–1627) or N-terminal SHD (residues 1–400) of SCARN. The control was roots transformed with the empty vector (EV). Transgenic roots were identified based on the GFP marker on the vector and scored for nodulation 21 d after inoculation with M. loti. (A) Average numbers of nodules (± SD) formed per plant. ** indicates significant difference from the control (p < 0.01) n = 32 (EV), n = 10 (SCARN WA) and n = 47 (SCARN SHD). (B) The number of nodules on each of the transgenic root systems of each plant transformed plants with the empty vector (EV) or SCARN SHD domain is shown. Discussion

The actin cytoskeleton plays an important role in the polar growth of plant cells, particularly polar-growing cells such as root hairs, trichomes and pollen tubes [52]. There are dynamic interactions and cooperation between the actin cytoskeleton and microtubules [53]. Actin rearrangements are initiated via ARP2/3-mediated nucleation of new actin filaments onto the existing actin filaments; for this to occur the ARP2/3 complex must be itself be activated and this occurs by interactions between the ARP2/3 complex and the SCAR components of the SCAR/WAVE complex [54]. In plants this has been best analyzed in A. thaliana in which the C-terminal WA domain of the AtSCAR proteins bind to the ARP2/3 complex [43]. There are four SCAR components in Arabidopsis [43,48]; searches for WA domains in Arabidopsis did not identify any additional SCAR components or other potential ARP2/3 activation proteins [3]. There appears to be a degree of functional redundancy between different AtSCAR proteins because double and triple mutations increase the severity of phenotypes [48]. Mutations in AtSCAR2 have the most severe phenotype, causing mildly distorted trichomes [43,44].

The sequence of SCARN suggests it is distinct from the four Arabidopsis SCAR proteins, both in terms of its length and its overall sequence. This distinctiveness fits with the observation that one of its main roles in L. japonicus is to do with initiation and growth of infection threads during legume infection and nodulation by rhizobia. This conclusion is based on the absence of normal infections in the mutants and by the observation that overexpression of the N-terminal SHD domain of SCARN strongly inhibited nodule infection. In Arabidopsis, it is this SHD domain that enables it to interact with the BRK and ABIL1 components of the SCAR/WAVE complex [44,55]. Presumably the expression of this SHD domain in L. japonicus root-hairs can titre out the normal SCARN-binding site in the SCAR/WAVE complex, thereby reducing binding by the wild-type SCARN protein. In turn this could decrease the coupling of the SCAR/WAVE complex with the ARP2/3 complex, because we have shown that SCARN can bind to ARPC3 via the conserved C-terminal WA domain in SCARN.

There are two SCARN-like sub-clades in legumes, implying an ancient gene duplication in legumes. Ancestral polyploidization has been proposed to have enhanced development of root nodule symbioses in the papilionoideae [50]. Sequence analysis other SCAR/WAVE complex subunits revealed that orthologues of NAP, PIR or HSPC300 show very high sequence similarity [56], whereas the WASP family proteins (WASH, SCAR etc.) appear to have evolved more rapidly [49,56]. Analysis of SCARN-like proteins suggests that a species-specific gene duplication probably occurred to generate SCARN and a related protein.

In terms of the rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton, the mutations in SCARN appear not to affect the early M. loti-induced response, whereas mutations in LjNAP and LjPIR cause defects in the M. loti-induced rearrangements in the actin cytoskeleton in root hair tip [31]. This difference could be due to some genetic redundancy of SCAR proteins. In Arabidopsis there appears to be some cell-type specificity in the function of SCAR components, probably mostly related to the expression of different SCAR genes in different cell types [37]. It appears from mutant phenotypes and analysis of a reporter-GUS fusion that LjSCARN is weakly expressed in the root epidermis and in root hairs, and was more strongly expressed in the epidermis of young nodules. This nodule expression was transient such that in mature nodules expression was only observed in vascular bundles. This is rather different from NAP, PIR and ARPC1 expression which was unaffected by M. loti inoculation [31,33].

The relatively strong LjSCARN expression in developing nodules suggests that SCARN plays an important role during nodule development and this role could be related to nodule morphogenesis and/or nodule infection. Although the analyses of actin rearrangements in root hairs of the scarn mutants may imply a degree of redundancy, it is nevertheless the case that the Ljscarn mutants have a severe infection-thread deficiency. There are two phases of actin nucleation in root hairs [12], one associated with root-hair deformation (mostly changes in the fine actin filaments within 30 min of perception of Nod factors) and one associated with the development of infection threads (within 72 hours after rhizobial inoculation). The lack of infections in the scarn mutant may indicate that SCARN plays a significant role in this latter phase of actin rearrangements. It is very difficult to image actin accumulation at this stage in infection-defective mutants, because there are few sites where infections are being initiated and those abnormal infections that do form may be delayed. A few infection threads do initiate in scarn mutants, and this is also observed in nap and pir mutants that are defective for the SCAR/WAVE complex [30]. Understanding how this fits with the late phase of actin rearrangements associated with initiation of infection threads remains to be understood.

One of the unexpected phenotypes of two of the scarn mutants was that the root-hairs were branched. The scarn-1 and scarn-3 alleles causing this phenotype would both introduce missense translational stops and would be predicted to produce proteins of 1198 and 1099 residues respectively. The observation that the branching was seen in two independent mutants suggests that the phenotype is caused by these alleles. The fact that the phenotype was observed without rhizobial inoculation implies that the SCARN gene must be expressed in root hairs, but the level of expression must be low because we were unable to detect it using the pSCARN:GUS fusion. The absence of root-hair branching in the other alleles implies that the phenotype is caused by the presence of the truncated gene product. Intriguingly, branching of root hairs is induced by rhizobial Nod factors and is usually considered to be a consequence of re-initiation of root-hair growth following a pause in growth [8]. The growth of root hairs in some of the mutants appears to be somewhat slower than normal and so it is possible that scarn-1 and scarn-3 mutants can periodically show transient inhibition of root hair growth and that pauses in growth stimulate root-hair branching. Why this should be specific to these two but not the other alleles implies an unknown (and unexpected) role for the truncated gene products. Root-hair branching has been associated with action of microtubules rather than actin [57]. Interestingly, in Dictyostelium, it was found that the direction of cell migration depended on the action of a microtubule-binding protein to direct SCAR localization, revealing a role for SCAR proteins at the functional interface between actin and microtubules [58]. The root hair branching phenotype observed may therefore indicate a link between SCARN and microtubule function.

The regulation of SCARN probably occurs both during transcription and at the level of activation of the SCAR/WAVE complex. Although the SCARN gene appears to be expressed in epidermal cells prior to the symbiotic interaction, it is induced in response to M. loti. This is somewhat different from the expression pattern of the NAP, PIR or ARPC1genes which are also required for infection, but appear not to be induced during the symbiosis [31,33]. The enhanced expression of SCARN is regulated by NIN, which is required for the establishment of both nodule development and the formation of the infection foci that precede infection thread growth in root hairs. We checked if other predicted components of the SCAR/WAVE complex are induced during symbiotic interactions and noted that ABIL1 is induced by Nod factors in M. truncatula root hairs [7]. This implies that in addition to the normal expression of SCAR/WAVE and ARP2/3 complex proteins, the expression of some of the components is enhanced during early stages of the symbiotic interaction via activation of NIN. NIN is induced by CYCLOPS, which is activated by CCaMK in response to Nod-factor-induced calcium spiking [19]. This NIN-mediated regulation of SCARN is consistent with normal mycorrhization in scarn mutants, because NIN is required for rhizobial but not mycorrhizal symbioses [59].

Post-translational regulation of the ARP2/3 complex occurs in plants and animals [3,60], but in plants the regulation is thought to be less complex in this respect and appears to requires only the SCAR/WAVE nucleation promoting factors and the SCAR/WAVE regulatory complex [3]. One aspect of this regulation in Arabidopsis involves the binding of Rho-related GTP-binding protein ROP2 to PIR1 [61]. ROP-GTPases coordinate vesicular trafficking and cytoskeletal rearrangements during polar growth in Arabidopsis [62]. Nothing is known about the regulation of the ARP2/3 complex in legumes during rhizobial infection, but there is evidence for the action of ROP-GTPases in root-hair growth and rhizobial infection. In L. japonicus the Nod-factor receptor NFR5 interacts with ROP6, which is involved in infection-thread growth [63]. ROP6 also interacts with clathrin heavy chain1 which is required for normal infection and nodule development, indicating a role for endocytosis during infection and nodulation [64]. In M. truncatula the Nod-factor receptor NFP interacts with MtROP10 to regulate root hair deformation; overexpression of MtROP10, or a constitutively-active mutant form of MtROP10, leads to depolarized growth of root hairs [65]. More work will be required to establish if these or other ROPs regulate actin nucleation during rhizobial infection and if so, which actin nucleation promoting proteins they bind to.

Although the need for actin rearrangements during rhizobial infection is now well established, the physiological requirements for these are not fully known. One possibility is that the actin cytoskeleton is required for the vesicle trafficking and associated protein targeting required for initiation and maintenance of infection thread growth. If this is correct then the nodulation related pectate lysase NPL would be a likely cargo as would cell-wall and cell-membrane biosynthesis proteins. Another possibility is that actin rearrangements are required for the endocytosis that appears to be required for establishing the symbiosis [64]. Possibly the induced expression of SCARN in both the root epidermis and developing nodule cells points to multiple functions for the actin cytoskeleton during infection and nodule development. It appears likely that one of the plant SCAR proteins has been recruited to take on a specialized role in nucleating actin cytoskeletal changes that play an important role in legume infection and nodule development.

Materials and Methods

Biological materials

The L. japonicus mutants SL2654-3, SL5737-2, SL1058-2 and SL6119-2 were isolated from an EMS mutagenized population of Gifu B-129 [36]. The scarn-5 allele was obtained from a pool of L. japonicus mutants with LORE1 transposon insertions [38,39]. L. japonicus seeds were scarified with sandpaper or immersed for 5–7 min in concentrated H2SO4 then surface sterilized with 10% NaClO, washed with sterile water and then left to imbibe water. The seeds were then germinated for 4–5 days at 22°C on water agar plates. Seedlings were planted in vermiculite and perlite (1 : 1) mixed with N-free nutrient (FP) solution [66] and grown under a 16-h/8-h light/dark regime at 23°C. After 5–7 days growth, seedlings were inoculated with M. loti R7A carrying pXLGD4 (lacZ) or pMP2444 (GFP). These strains were grown for 2 days at 28°C in TY liquid containing 5μg/ml tetracycline, at OD600≈1.0, pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in water at OD600≈0.01. For hairy root transformation of L. japonicus roots, A. rhizogenes strain AR1193 was used, while for N. benthamiana transient expression, A. tumefaciens strain EHA105 was used.

Map-based cloning

Mutants were crossed with MG20, and nodulation phenotype was scored in F2 progeny from self-pollinated F1 plants. Genomic DNA was isolated and SSR markers were scanned for co-segregation with nodulation defects. Primer sequences and marker information were retrieved from the miyakogusa.jp website (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/lotus/). Rough mapping results indicated that four of the mutations fell within a similar region, so allelism was tested in the crosses described. Fine-mapping was done using SL2654-3 crossed with MG20.

Analysis of nodulation, infection threads, mycorrhizal infection and actin rearrangement

To score the time course of nodulation, seedlings were grown in N-deficient medium and the numbers of nodules were counted 4 and 5 weeks after inoculation. The number of infection events was determined by microscopy of whole root stained with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-beta-D-galacto-pyranoside (X-Gal), 7 and 14 days after inoculation with M. loti R7A carrying pXLGD4 (lacZ) using at least 15 plants at each time point. For staining, whole roots were immersed in fixative solution (0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer containing 1.25% glutaraldehyde) for 1 h, washed twice for 10 min in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer and stained for β-galactosidase activity using staining solution (200 μl 100 mM K4Fe(CN)6, 200 μl 100 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 120 μl 2% X-Gal in dimethyl formamide, 3.2 ml 0.1 M phosphate buffer). After staining in the dark overnight at room temperature, roots were rinsed 3 times with water, cleared in 1% NaClO for 1min, then washed 5 times with water. Stained roots were observed using Nikon Eclipse Ni light microscopy under bright-field illumination. Individual infection events were imaged by Nikon digital sight with lacZ-marked M. loti. GFP-marked M. loti-inoculated roots were counterstained with propidium iodide and analyzed by laser scanning confocal microscopy (Olympus FV1000). Light microscopy of nodule sections was done with nodules fixed in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde as described [67]. After fixation, tissues were embedded in Technovit 7100 (Kulzer GmbH) resin according to the manufacturer’s instructions and 10 μm transverse sections were taken. Sections were stained with 0.5% (w/v) toluidine blue O in 0.5% (w/v) sodium tetraborate buffer before taking pictures under Nikon Eclipse Ni light microscopy.

For mycorrhizal analysis, the L. japonicus seedlings were grown in pots with sand and vermiculite (1 : 1) with sterile G. intraradices spores at 22°C under a 16h-light /8h-dark cycle. Five weeks after inoculation, roots were treated with 10% KOH for 6 min at 95°C, followed by 3 min in ink at 95°C. Root length colonization was quantified using the grid line intersect method [68] using a Nikon Eclipse Ni light microscopy under bright-field illumination. 15 plants were analyzed for each treatment. Phalloidin staining and microscopy of actin rearrangements was done as described previously [31].

Root hair deformation

Seedlings prepared and grown as described previously [69] were transferred to slides containing 1ml liquid FP medium and left overnight. The seedlings were inoculated by adding fresh FP medium containing M. loti R7A (OD600 about 0.01) and then left in the dark for approximately 18 h before analysis. Images were taken using a Nikon DS-Fi2 camera mounted on a Nikon Eclipse Ni light microscope. The branched root hairs observed in the un-inoculated slides were photographed 2 days after transfer of the seedlings to the sterile FP liquid medium slides.

Complementation, analysis of promoter:GUS expression of SCARN in transformed hairy roots

SCARN genomic DNA was amplified from Gifu B-129 leaves using the primer SCARN-attFL-F and SCARN-attFL-R (S3 Table). PCR products were cloned into gateway entry vector pDONR207 and recombined into the destination vector pUB-GW-GFP [40] or pEpi-GFP [45]. A 2kb region upstream of the SCARN translation start was amplified from Gifu B-129 leaf genomic DNA using primers SCARN-Pro-F and SCARN-Pro-R. The PCR products were cloned into pDONR207 and then recombined into the destination vector pKGWFS7.0 to form pSCARN:GUS. The region of SCARN encoding the N-terminal SHD domain was amplified by primers SCARN-attFL-F and SCARN-N-R; C-terminal WA domain by primer LjSCARN C F and SCARN-attFL-R from Gifu cDNA library. The PCR products were cloned into pDONR207 and then recombined into the destination vector pUB-GW-GFP. All constructs in pDONR207 were confirmed by DNA sequencing, introduced into A. rhizogenes AR1193 by electroporation and then introduced into roots of wild type or scarn mutants by hairy root transformation on half strength B5 medium. The transformed chimeric plants were transplanted into vermiculite/perlite pot and after 5–7 days inoculated with M. loti R7A containing lacZ. The nodulation phenotypes were scored 3 weeks after inoculation after staining for β-glucuronidase or β-galactosidase activity.

Assays of protein interaction using yeast two hybrid analyses

The SCARN C-terminal WA coding domain, ARPC1 and ARPC3 were all amplified from Gifu cDNA library using the high proofreading enzyme KOD Plus (Toyobo) and the primers LjSCARN-C-F and SCARN-attFL-R, ARPC1-attB-F and ARPC1-attB-R, or ARPC3 - attB-F and ARPC3-attB-R respectively. PCR products were cloned into pDONR207, their fidelity was confirmed by DNA sequencing and were then recombined into pDEST-GBKT7 or pDEST-GADT7. The yeast strain AH109 was transformed with the constructs using lithium acetate transformation (Yeast Protocols Handbook PT3024-1, Clontech). Immunoblots were used to validate protein expression using Anti-Gal4 AD (Upstate,Cat. #06–283) and Anti-Gal4 BD (Sigma-Aldrich, 080M4814) antiserum. β-galactosidase activity was assayed following standard methods (Yeast Protocols Handbook PT3024-1, Clontech).

Pull down of glutathione-fusion proteins

The SCARN C-terminal WA coding domain was amplified from cDNA using the primers SCARN C(SalI)-F and SCARN (Not1)-R and the PCR product was inserted into SalI and NotI digested pGEX4T-1 to form SCARN-WA pGEX4T-1 for expressing a GST-SCARN-WA fusion protein. The ARPC3 full-length cDNA was amplified using primers ARPC3 (BamH1)-F and ARPC3 (BamH1)-R and the PCR product was cloned into BamHI-digested pET28b, to form ARPC3 pET28b encoding His-tagged APRC3. Plasmids expressing SCARN-WA, ARPC3 and the negative control pGEX4T-1were introduced into E.coli BL21-Codon Plus (DE3)-RIL (Stratagene). Proteins were induced during exponential growth using 0.5 mM IPTG for 4h at 28°C. The GST-tagged SCARN-WA protein was purified using Glutathione Sepharose TM 4B beads (GE Healthcare) under native conditions. The purified protein was incubated with soluble His-tagged ARPC3 in 1 mL of interaction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.2% Triton X-100, pH7.4) for 1 h on ice with gentle shaking and then the mixture was incubated with Glutathione Sepharose TM 4B beads. The beads were then washed three times with 1.0 mL of NETN100 buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl,100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.5% NP40, pH 7.4) and three times with 1.0 mL of NETN300 buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.5% NP40, pH 7.4). Retained proteins were eluted following incubation at 100°C for 5 min in 1X SDS sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 12% acrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred from the gel to a PVDF membrane for detection using anti-His antiserum (Abmart).

RNA extraction and real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIpure Isolation Reagent (Aid lab, China) according to the instruction manual and quantified using a Nano-Drop 2000 (Thermo). Reverse transcript first-strand cDNA was synthesized using TransScript one-step gDNA Removal and cDNA synthesis SuperMix (Trans Gen Biotech). Real-time RT-PCR was done with TOYOBO SYBR Green Realtime PCR Master Mix (TOYOBO) and detected using an ABI step-one Plus PCR system. Nodulation marker gene expression samples were generated from whole root of about 10 seedlings of wild type Gifu or scarn-1 that had been grown for 2 weeks on N-free nutrient solution [66] agar plates and then incubated a further 5 days after inoculation with M. loti R7A. For analysis of tissue-specific expression, plants were grown in vermiculite-perlite. All of the primers used for qRT-PCR of target transcripts are described in S3 Table quantified relative to the ubiquitin gene as internal control. Data was analyzed as described [30].

Electrophoresis mobility shift assays (EMSA)

The NIN carrying a C-terminal His tag was purified was described previously [30]. The synthetic biotin-labelled oligonucleotides used for tests of DNA binding are shown in S3 Table. After electrophoresis the gels were developed using the Light Shift chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Thermo) following the manufacturer’s instructions and the chemiluminescent images were captured using a Tanon-ttoo CCD (Tanon company,China).

Induction of pSCARN:GUS by NIN in N. benthamiana

The full-length NIN cDNA was amplified by primers LjNIN-attB-F and LjNIN-attB-R using L. japonicus cDNA library as template. PCR products were cloned into gateway entry vector pDONR207 and sequenced, then recombined into pK7WGF2 to form LjNIN pK7WGF2. LjNIN and pSCARN:GUS were introduced into A. tumefaciens strain EHA105 and infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves. Samples were harvested 2 days after agro-infiltration. The GUS activity was measured by GUS staining at least 5 leaves each pair. For fluorimetric GUS assays, about 20 mg frozen leaf tissue was ground by mortar and pestle and protein was extracted using 20 microlitres extraction buffer (50 mM K/NaPO4 buffer pH 7.0, containing 10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% sarcosyl and 0.1% Triton X-100). Extracts were centrifuged (10000 g, 15 min, 4°C) and the supernatant was used for GUS activity measurement as described with 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-D-glucuronide as substrate (Sigma-Aldrich). GUS activities were measured using DyNA Quantity200 (Hoefer, China). Mean values and standard deviations were determined from three biological replicates.

Phylogenetic analysis

The A. thaliana protein sequences were obtained from TAIR (http://www.arabidopsis.org/) and the L. japonicas protein sequence were obtained from miyakogusa.jp website (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/lotus/) Version 3.0, and other legume SCAR protein sequences were obtained from Phytozome 10.1 (http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html). All the protein sequences are imported into MEGA6.0 [70] for complete alignment using ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/). The phylogenetic tree was built using MEGA6.0 [70] and using the neighbor-joining method with the bootstrapping value set at 1000 replications.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Krause M, Gautreau A (2014) Steering cell migration: lamellipodium dynamics and the regulation of directional persistence. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15 : 577–590. doi: 10.1038/nrm3861 25145849

2. Staiger CJ, Sheahan MB, Khurana P, Wang X, McCurdy DW, et al. (2009) Actin filament dynamics are dominated by rapid growth and severing activity in the Arabidopsis cortical array. J Cell Biol 184 : 269–280. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806185 19171759

3. Yanagisawa M, Zhang C, Szymanski DB (2013) ARP2/3-dependent growth in the plant kingdom: SCARs for life. Front Plant Sci 4 : 166. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00166 23802001

4. Gage DJ (2004) Infection and invasion of roots by symbiotic, nitrogen-fixing rhizobia during nodulation of temperate legumes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 68 : 280–300. 15187185

5. Jones KM, Kobayashi H, Davies BW, Taga ME, Walker GC (2007) How rhizobial symbionts invade plants: the Sinorhizobium-Medicago model. Nat Rev Microbiol 5 : 619–633. 17632573

6. Oldroyd GE, Downie JA (2008) Coordinating nodule morphogenesis with rhizobial infection in legumes. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59 : 519–546. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092839 18444906

7. Breakspear A, Liu C, Roy S, Stacey N, Rogers C, et al. (2014) The root hair "infectome" of Medicago truncatula uncovers changes in cell cycle genes and reveals a requirement for Auxin signaling in rhizobial infection. Plant Cell 26 : 4680–4701. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.133496 25527707

8. Esseling JJ (2003) Nod Factor-induced root hair curling: continuous polar growth towards the point of Nod Factor application. Plant Physiology 132 : 1982–1988. 12913154

9. Crdenas L, Vidali L, Domnguez J, Prez H, Snchez F, et al. (1998) Rearrangement of actin microfilaments in plant root hairs responding to Rhizobium etli nodulation signals. Plant Physiol 116 : 871–877. 9501120

10. Heidstra R, Geurts R, Franssen H, Spaink HP, Van Kammen A, et al. (1994) Root hair deformation activity of nodulation factors and their fate on Vicia sativa. Plant Physiol 105 : 787–797. 12232242

11. Timmers AC, Auriac MC, Truchet G (1999) Refined analysis of early symbiotic steps of the Rhizobium-Medicago interaction in relationship with microtubular cytoskeleton rearrangements. Development 126 : 3617–3628. 10409507

12. Zepeda I, Sanchez-Lopez R, Kunkel JG, Banuelos LA, Hernandez-Barrera A, et al. (2014) Visualization of highly dynamic F-actin plus ends in growing Phaseolus vulgaris root hair cells and their responses to Rhizobium etli nod factors. Plant Cell Physiol 55 : 580–592. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct202 24399235

13. Fournier J, Timmers AC, Sieberer BJ, Jauneau A, Chabaud M, et al. (2008) Mechanism of infection thread elongation in root hairs of Medicago truncatula and dynamic interplay with associated rhizobial colonization. Plant Physiol 148 : 1985–1995. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.125674 18931145

14. Monahan-Giovanelli H, Pinedo CA, Gage DJ (2006) Architecture of infection thread networks in developing root nodules induced by the symbiotic bacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti on Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol 140 : 661–670. 16384905

15. Desbrosses GJ, Stougaard J (2011) Root nodulation: a paradigm for how plant-microbe symbiosis influences host developmental pathways. Cell Host & Microbe 10 : 348–358.

16. Foucher F, Kondorosi E (2000) Cell cycle regulation in the course of nodule organogenesis in Medicago. Plant Mol Biol 43 : 773–786. 11089876

17. Oldroyd GE, Murray JD, Poole PS, Downie JA (2011) The rules of engagement in the legume-rhizobial symbiosis. Annu Rev Genet 45 : 119–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132549 21838550

18. Downie JA (2014) Legume nodulation. Curr Biol 24: R184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.028 24602880

19. Singh S, Katzer K, Lambert J, Cerri M, Parniske M (2014) CYCLOPS, A DNA-binding transcriptional activator, orchestrates symbiotic root nodule development. Cell Host & Microbe 15 : 139–152. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.01.011 24528861

20. Mitra RM, Gleason CA, Edwards A, Hadfield J, Downie JA, et al. (2004) A Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase required for symbiotic nodule development: Gene identification by transcript-based cloning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 : 4701–4705. 15070781

21. Schauser L, Roussis A, Stiller J, Stougaard J (1999) A plant regulator controlling development of symbiotic root nodules. Nature 402 : 191–195. 10647012

22. Morieri G, Martinez EA, Jarynowski A, Driguez H, Morris R, et al. (2013) Host-specific Nod-factors associated with Medicago truncatula nodule infection differentially induce calcium influx and calcium spiking in root hairs. New Phytol 200 : 656–662. doi: 10.1111/nph.12475 24015832

23. Downie JA (2014) Calcium signals in plant immunity: a spiky issue. New Phytol 204 : 733–735. doi: 10.1111/nph.13119 25367606

24. Zgadzaj R, James EK, Kelly S, Kawaharada Y, de Jonge N, et al. (2015) A legume genetic framework controls infection of nodules by symbiotic and endophytic bacteria. PLoS Genet 11: e1005280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005280 26042417

25. Kiss E, Olah B, Kalo P, Morales M, Heckmann AB, et al. (2009) LIN, a novel type of U-box/WD40 protein, controls early infection by rhizobia in legumes. Plant Physiol 151 : 1239–1249. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.143933 19776163

26. Yano K, Shibata S, Chen WL, Sato S, Kaneko T, et al. (2009) CERBERUS, a novel U-box protein containing WD-40 repeats, is required for formation of the infection thread and nodule development in the legume-Rhizobium symbiosis. Plant J 60 : 168–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03943.x 19508425

27. Arrighi JF, Godfroy O, de Billy F, Saurat O, Jauneau A, et al. (2008) The RPG gene of Medicago truncatula controls Rhizobium-directed polar growth during infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 : 9817–9822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710273105 18621693

28. Middleton PH, Jakab J, Penmetsa RV, Starker CG, Doll J, et al. (2007) An ERF transcription factor in Medicago truncatula that is essential for Nod factor signal transduction. Plant Cell 19 : 1221–1234. 17449807

29. Laporte P, Lepage A, Fournier J, Catrice O, Moreau S, et al. (2014) The CCAAT box-binding transcription factor NF-YA1 controls rhizobial infection. J Exp Bot 65 : 481–494. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert392 24319255

30. Xie F, Murray JD, Kim J, Heckmann AB, Edwards A, et al. (2012) Legume pectate lyase required for root infection by rhizobia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 : 633–638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113992109 22203959

31. Yokota K, Fukai E, Madsen LH, Jurkiewicz A, Rueda P, et al. (2009) Rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton mediates invasion of Lotus japonicus roots by Mesorhizobium loti. Plant Cell 21 : 267–284. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.063693 19136645

32. Miyahara A, Richens J, Starker C, Morieri G, Smith L, et al. (2011) Conservation in function of a SCAR/WAVE component during infection thread and root hair growth in Medicago truncatula. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 23 : 1553–1562.

33. Hossain MS, Liao J, James EK, Sato S, Tabata S, et al. (2012) Lotus japonicus ARPC1 is required for rhizobial infection. Plant Physiol 160 : 917–928. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.202572 22864583

34. Lombardo F, Heckmann AB, Miwa H, Perry JA, Yano K, et al. (2006) Identification of symbiotically defective mutants of Lotus japonicus affected in infection thread growth. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 19 : 1444–1450. 17153928

35. Perry J, Brachmann A, Welham T, Binder A, Charpentier M, et al. (2009) TILLING in Lotus japonicus identified large allelic series for symbiosis genes and revealed a bias in functionally defective ethyl methanesulfonate alleles toward glycine replacements. Plant Physiol 151 : 1281–1291. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.142190 19641028

36. Perry JA, Wang TL, Welham TJ, Gardner S, Pike JM, et al. (2003) A TILLING reverse genetics tool and a web-accessible collection of mutants of the legume Lotus japonicus. Plant Physiol 131 : 866–871. 12644638

37. Zhang C, Mallery EL, Schlueter J, Huang S, Fan Y, et al. (2008) Arabidopsis SCARs function interchangeably to meet actin-related protein 2/3 activation thresholds during morphogenesis. Plant Cell 20 : 995–1011. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.055350 18424615

38. Urbanski DF, Malolepszy A, Stougaard J, Andersen SU (2013) High-throughput and targeted genotyping of Lotus japonicus LORE1 insertion mutants. Methods Mol Biol 1069 : 119–146. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-613-9_10 23996313

39. Fukai E, Soyano T, Umehara Y, Nakayama S, Hirakawa H, et al. (2012) Establishment of a Lotus japonicus gene tagging population using the exon-targeting endogenous retrotransposon LORE1. Plant J 69 : 720–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04826.x 22014259

40. Maekawa T, Kusakabe M, Shimoda Y, Sato S, Tabata S, et al. (2008) Polyubiquitin promoter-based binary vectors for overexpression and gene silencing in Lotus japonicus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 21 : 375–382. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-4-0375 18321183

41. Madsen LH, Tirichine L, Jurkiewicz A, Sullivan JT, Heckmann AB, et al. (2010) The molecular network governing nodule organogenesis and infection in the model legume Lotus japonicus. Nat Commun 1 : 10. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1009 20975672

42. Murray J, Karas B, Ross L, Brachmann A, Wagg C, et al. (2006) Genetic suppressors of the Lotus japonicus har1-1 hypernodulation phenotype. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 19 : 1082–1091. 17022172

43. Basu D, Le J, El-Essal Sel D, Huang S, Zhang C, et al. (2005) DISTORTED3/SCAR2 is a putative arabidopsis WAVE complex subunit that activates the Arp2/3 complex and is required for epidermal morphogenesis. Plant Cell 17 : 502–524. 15659634

44. Zhang X, Dyachok J, Krishnakumar S, Smith LG, Oppenheimer DG (2005) IRREGULAR TRICHOME BRANCH1 in Arabidopsis encodes a plant homolog of the actin-related protein2/3 complex activator Scar/WAVE that regulates actin and microtubule organization. Plant Cell 17 : 2314–2326. 16006582

45. Hayashi T, Shimoda Y, Sato S, Tabata S, Imaizumi-Anraku H, et al. (2014) Rhizobial infection does not require cortical expression of upstream common symbiosis genes responsible for the induction of Ca(2+) spiking. Plant J 77 : 146–159. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12374 24329948

46. Soyano T, Hirakawa H, Sato S, Hayashi M, Kawaguchi M (2014) Nodule Inception creates a long-distance negative feedback loop involved in homeostatic regulation of nodule organ production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111 : 14607–14612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412716111 25246578

47. Soyano T, Kouchi H, Hirota A, Hayashi M (2013) NODULE INCEPTION directly targets NF-Y subunit genes to regulate essential processes of root nodule development in Lotus japonicus. PLoS Genet 9: e1003352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003352 23555278

48. Uhrig JF, Mutondo M, Zimmermann I, Deeks MJ, Machesky LM, et al. (2007) The role of Arabidopsis SCAR genes in ARP2-ARP3-dependent cell morphogenesis. Development 134 : 967–977. 17267444

49. Kollmar M, Lbik D, Enge S (2012) Evolution of the eukaryotic ARP2/3 activators of the WASP family: WASP, WAVE, WASH, and WHAMM, and the proposed new family members WAWH and WAML. BMC Res Notes 5 : 88. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-88 22316129

50. Li QG, Zhang L, Li C, Dunwell JM, Zhang YM (2013) Comparative genomics suggests that an ancestral polyploidy event leads to enhanced root nodule symbiosis in the Papilionoideae. Mol Biol Evol 30 : 2602–2611. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst152 24008584

51. de Ruijter NCA, Bisseling T., and Emons A.M.C. (1999) Rhizobium Nod factors induce an increase in sub-apical fine bundles of actin filaments in Vicia sativa root hairs within minutes. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 12 : 829–832.

52. Rounds CM, Bezanilla M (2013) Growth mechanisms in tip-growing plant cells. Annu Rev Plant Biol 64 : 243–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120150 23451782

53. Sampathkumar A, Lindeboom JJ, Debolt S, Gutierrez R, Ehrhardt DW, et al. (2011) Live cell imaging reveals structural associations between the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23 : 2302–2313. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.087940 21693695

54. Deeks MJ, Hussey PJ (2005) Arp2/3 and SCAR: plants move to the fore. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6 : 954–964. 16341081

55. Le J, Mallery EL, Zhang C, Brankle S, Szymanski DB (2006) Arabidopsis BRICK1/HSPC300 is an essential WAVE-complex subunit that selectively stabilizes the Arp2/3 activator SCAR2. Curr Biol 16 : 895–901. 16584883

56. Veltman DM, Insall RH (2010) WASP family proteins: their evolution and its physiological implications. Mol Biol Cell 21 : 2880–2893. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-04-0372 20573979

57. Bibikova TN, Blancaflor EB, Gilroy S (1999) Microtubules regulate tip growth and orientation in root hairs of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 17 : 657–665. 10230063

58. King JS, Veltman DM, Georgiou M, Baum B, Insall RH (2010) SCAR/WAVE is activated at mitosis and drives myosin-independent cytokinesis. J Cell Sci 123 : 2246–2255. doi: 10.1242/jcs.063735 20530573

59. Marsh JF, Rakocevic A, Mitra RM, Brocard L, Sun J, et al. (2007) Medicago truncatula NIN is essential for rhizobial-independent nodule organogenesis induced by autoactive calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Plant Physiol 144 : 324–335. 17369436

60. Rotty JD, Wu C, Bear JE (2013) New insights into the regulation and cellular functions of the ARP2/3 complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 14 : 7–12. doi: 10.1038/nrm3492 23212475

61. Basu D, El-Assal Sel D, Le J, Mallery EL, Szymanski DB (2004) Interchangeable functions of Arabidopsis PIROGI and the human WAVE complex subunit SRA1 during leaf epidermal development. Development 131 : 4345–4355. 15294869

62. Yang Z (2008) Cell polarity signaling in Arabidopsis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 24 : 551–575. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123233 18837672

63. Ke D, Fang Q, Chen C, Zhu H, Chen T, et al. (2012) The small GTPase ROP6 interacts with NFR5 and is involved in nodule formation in Lotus japonicus. Plant Physiol 159 : 131–143. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.197269 22434040

64. Wang C, Zhu M, Duan L, Yu H, Chang X, et al. (2015) Lotus japonicus Clathrin Heavy Chain1 is associated with Rho-Like GTPase ROP6 and involved in nodule formation. Plant Physiol 167 : 1497–1510. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.256107 25717037

65. Lei MJ, Wang Q, Li X, Chen A, Luo L, et al. (2015) The Small GTPase ROP10 of Medicago truncatula is required for both tip growth of root hairs and Nod Factor-induced root hair deformation. Plant Cell 27 : 806–822. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.135210 25794934

66. Fahraeus G (1957) The infection of clover root hairs by nodule bacteria studied by a simple glass slide technique. J Gen Microbiol 16 : 374–381. 13416514

67. Vernie T, Moreau S, de Billy F, Plet J, Combier JP, et al. (2008) EFD is an ERF transcription factor involved in the control of nodule number and differentiation in Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell 20 : 2696–2713. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.059857 18978033

68. Giovannetti M, and Mosse B. (1980) Evaluation of techniques for measuring vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal infection in roots. New Phytol 84 : 489–500.

69. Miwa H, Sun J, Oldroyd GE, Downie JA (2006) Analysis of Nod-factor-induced calcium signaling in root hairs of symbiotically defective mutants of Lotus japonicus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 19 : 914–923. 16903357