-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

HacA-Independent Functions of the ER Stress Sensor IreA Synergize with the Canonical UPR to Influence Virulence Traits in

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is a condition in which the protein folding capacity of the ER becomes overwhelmed by an increased demand for secretion or by exposure to compounds that disrupt ER homeostasis. In yeast and other fungi, the accumulation of unfolded proteins is detected by the ER-transmembrane sensor IreA/Ire1, which responds by cleaving an intron from the downstream cytoplasmic mRNA HacA/Hac1, allowing for the translation of a transcription factor that coordinates a series of adaptive responses that are collectively known as the unfolded protein response (UPR). Here, we examined the contribution of IreA to growth and virulence in the human fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Gene expression profiling revealed that A. fumigatus IreA signals predominantly through the canonical IreA-HacA pathway under conditions of severe ER stress. However, in the absence of ER stress IreA controls dual signaling circuits that are both HacA-dependent and HacA-independent. We found that a ΔireA mutant was avirulent in a mouse model of invasive aspergillosis, which contrasts the partial virulence of a ΔhacA mutant, suggesting that IreA contributes to pathogenesis independently of HacA. In support of this conclusion, we found that the ΔireA mutant had more severe defects in the expression of multiple virulence-related traits relative to ΔhacA, including reduced thermotolerance, decreased nutritional versatility, impaired growth under hypoxia, altered cell wall and membrane composition, and increased susceptibility to azole antifungals. In addition, full or partial virulence could be restored to the ΔireA mutant by complementation with either the induced form of the hacA mRNA, hacAi, or an ireA deletion mutant that was incapable of processing the hacA mRNA, ireAΔ10. Together, these findings demonstrate that IreA has both HacA-dependent and HacA-independent functions that contribute to the expression of traits that are essential for virulence in A. fumigatus.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 7(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002330

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002330Summary

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is a condition in which the protein folding capacity of the ER becomes overwhelmed by an increased demand for secretion or by exposure to compounds that disrupt ER homeostasis. In yeast and other fungi, the accumulation of unfolded proteins is detected by the ER-transmembrane sensor IreA/Ire1, which responds by cleaving an intron from the downstream cytoplasmic mRNA HacA/Hac1, allowing for the translation of a transcription factor that coordinates a series of adaptive responses that are collectively known as the unfolded protein response (UPR). Here, we examined the contribution of IreA to growth and virulence in the human fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Gene expression profiling revealed that A. fumigatus IreA signals predominantly through the canonical IreA-HacA pathway under conditions of severe ER stress. However, in the absence of ER stress IreA controls dual signaling circuits that are both HacA-dependent and HacA-independent. We found that a ΔireA mutant was avirulent in a mouse model of invasive aspergillosis, which contrasts the partial virulence of a ΔhacA mutant, suggesting that IreA contributes to pathogenesis independently of HacA. In support of this conclusion, we found that the ΔireA mutant had more severe defects in the expression of multiple virulence-related traits relative to ΔhacA, including reduced thermotolerance, decreased nutritional versatility, impaired growth under hypoxia, altered cell wall and membrane composition, and increased susceptibility to azole antifungals. In addition, full or partial virulence could be restored to the ΔireA mutant by complementation with either the induced form of the hacA mRNA, hacAi, or an ireA deletion mutant that was incapable of processing the hacA mRNA, ireAΔ10. Together, these findings demonstrate that IreA has both HacA-dependent and HacA-independent functions that contribute to the expression of traits that are essential for virulence in A. fumigatus.

Introduction

Approximately one third of the eukaryotic proteome is dedicated to secreted and membrane proteins, making the secretory pathway one of the most active biosynthetic processes in the cell. Many intracellular eukaryotic pathogens use the secretory system for the expression of virulence factors that are crucial for pathogenesis, including adhesion, motility, host cell invasion or the co-opting of host cellular processes [1], [2]. By contrast, the filamentous fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus is predominantly extracellular, with no known virulence factors that are specialized derivatives of the secretory pathway. Nevertheless, a highly developed secretory system is an important virulence attribute of this organism because it provides a mechanism for the delivery of hydrolytic enzymes and membrane transporters into, and across, the membrane, which is essential for nutrient acquisition from the host [3]. Many of these enzymes are responsible for damaging host tissues, which contributes to the high mortality rates associated with A. fumigatus infections [4].

Protein secretion begins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), an extensive membrane network that provides a segregated compartment for the precise folding, modification and export of extracellular and membrane proteins. The ability of this organelle to meet the demand for secretion is limited by the level of ER-resident chaperones, foldases and other modifying enzymes that assist in protein folding [5]. Thus, misfolded proteins can accumulate when the demand for secretion exceeds the protein folding capacity of the ER. Misfolded proteins are prone to non-specific interactions with other molecules in the crowded intracellular environment, resulting in nonfunctional protein aggregates that disrupt ER homeostasis [6].

The unfolded protein response (UPR) is an intracellular signaling pathway that buffers fluctuations in ER homeostasis by increasing ER folding capacity whenever abnormal proteins accumulate in the ER [7]. In fungi, most of what is known about UPR signaling comes from studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [8]. Upstream control of the yeast UPR is mediated by Ire1p, a type I membrane protein that has an ER lumenal sensing domain and a bifunctional cytosolic tail comprised of a protein kinase domain linked to an endoribonuclease domain [9]. In the absence of ER stress, the lumenal domain is complexed with the ER-resident chaperone BiP, which helps to maintain Ire1 in an inactive state [10]. As unfolded proteins accumulate, due to either adverse environmental conditions or periods of intense protein secretion, BiP dissociates from Ire1 to assist with protein folding. This is followed by high-order oligomerization of Ire1 in the ER membrane, which allows for trans-autophosphorylation and activation of the C-terminal endoribonuclease domain [11], [12], [13]. The only known target of Ire1 endoribonuclease activity is a cytoplasmic mRNA known as HAC1 in S. cerevisiae, hacA in filamentous fungi and XBP1 in humans [14], [15]. Once activated, the endoribonuclease domain of Ire1 cleaves an unconventional intron from the HAC1 mRNA, producing a frame-shift that directs the translation of the bZIP transcription factor Hac1p that serves as the master transcriptional regulator of the UPR. After translocating to the nucleus, Hac1p restores the biosynthetic capability of the secretory pathway by upregulating the expression of ER chaperones and foldases and enhancing the degradation of proteins that ultimately fail to fold accurately [14].

In contrast to higher eukaryotes, which possess at least three proximal ER stress sensors, the only known sensor in fungi is Ire1/IreA [8]. The current paradigm of UPR signaling in A. fumigatus follows the single linear model established in yeast, in which IreA coordinates the splicing of the uninduced hacAu mRNA into its induced form, hacAi. Here, we demonstrate an expanded functional scope for IreA in A. fumigatus, involving both HacA-dependent and HacA-independent pathways. In addition, we establish a novel role for IreA as a central regulator of virulence, coordinating the expression of multiple virulence-related attributes that collectively support the fitness of A. fumigatus in the host environment.

Results

Deletion of A. fumigatus ireA

The ireA cDNA was cloned in two overlapping fragments from reverse-transcribed RNA. A comparison of the genomic and cDNA sequences revealed a 3.4 kb gene with a single intron that would encode a protein of 1,144 amino acids. Structural predictions for the IreA protein revealed a similar domain organization to that of S. cerevisiae, Ire1p, including a signal sequence of 27 amino acids, a 477 amino acid ER lumenal domain, a 19 amino acid transmembrane domain and a 621 amino acid cytoplasmic C-terminal region (Figure S1). The cytoplasmic region, which is the most conserved segment of the protein between genera, contains a predicted serine-threonine protein kinase linked to a kinase extension nuclease (KEN) domain [16], the latter of which provides the endoribonuclease activity that is required for regulated splicing of the HAC1 mRNA in S. cerevisiae [17].

In contrast to Aspergillus niger, in which the ireA gene appears to be essential [18], we found that a ΔireA mutant of A. fumigatus is viable. The ireA gene was deleted from A. fumigatus by replacing the entire coding region with a phleomycin resistance cassette and homologous integrants were identified by genomic Southern blot analysis (Figure S2). Loss of the ireA gene had the expected effect of increasing sensitivity to agents that cause acute ER stress by disrupting protein folding, such as tunicamycin (Figure S3).

Identification of a Core Inducible UPR That Depends on the Canonical IreA-HacA Pathway

Studies of differentially expressed genes during secretion stress have been previously performed in a number of filamentous fungal species [19], [20], [21]. However, these studies were performed on the wild type (wt) organism, so the specific contributions of IreA or HacA could not be evaluated. To address this, a genome-wide expression profile was generated for wt A. fumigatus in the presence of acute ER stress and compared to that of the two mutant strains that are deficient in UPR signaling, ΔhacA [15] and ΔireA. Acute ER stress was accomplished by treating the fungus with dithiothreitol (DTT) or tunicamycin (Tm), each of which induces the UPR but through different mechanisms; DTT unfolds proteins by interfering with disulfide bond formation and tunicamycin inhibits the N-linked glycosylation that is necessary for proper protein folding [14]. Because high concentrations of DTT (20 mM for 2 h) have been shown to induce changes in gene expression that are unrelated to the UPR [20], we used a mild DTT treatment (1 mM DTT for 1 h) to minimize these non-UPR effects. Nevertheless, DTT treatment of wt A. fumigatus induced changes in mRNA abundance that were higher in both magnitude and scope than treatment with Tm, similar to what has been reported elsewhere (Figure 1) [19], [20].

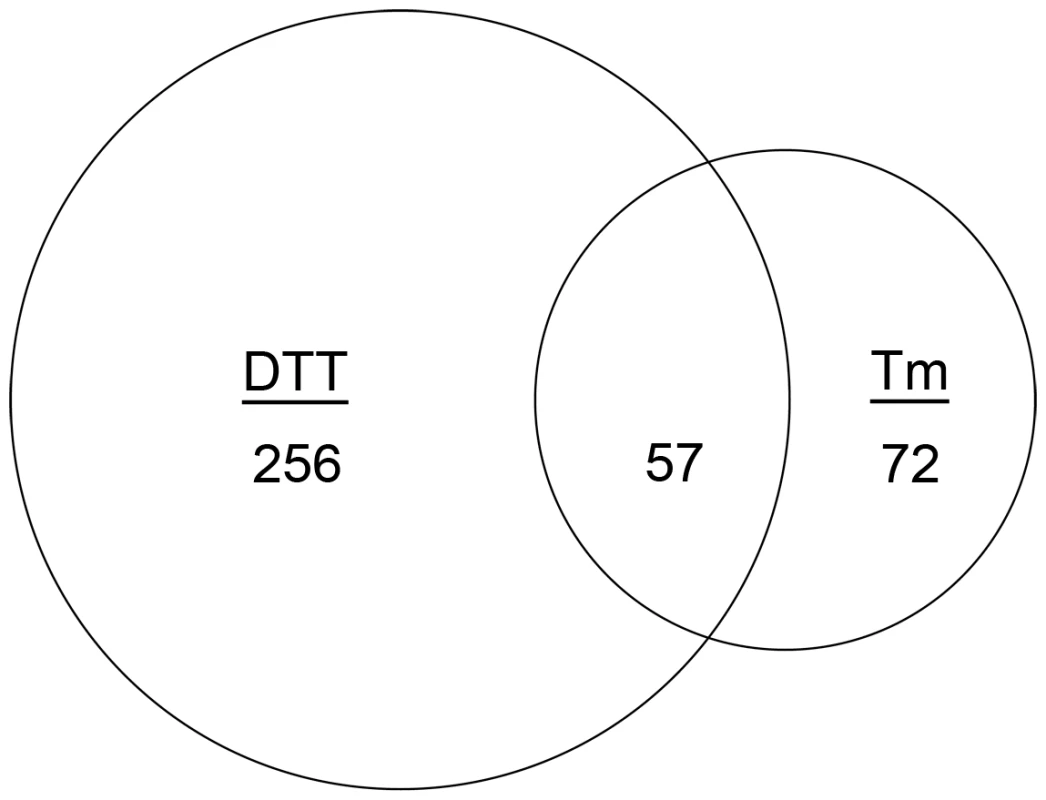

Fig. 1. Identification of the core inducible UPR of A. fumigatus.

Venn diagram demonstrating the overlap between the number of transcripts with increased abundance in the presence of DTT and those that show increased abundance in the presence of Tm. The area of the circles is scaled to the number of transcripts and the values represent distinct counts in each category. We employed three criteria to define UPR-regulated genes under conditions of acute ER stress. First, since hacA is a known target of the UPR [22], and its mRNA increased in abundance at least 1.5-fold when treated with either DTT or Tm in this study, we set 1.5-fold as the threshold for differential expression (up or down). The resulting data revealed that 256 mRNAs were differentially expressed following treatment with DTT (but not Tm), while 72 mRNAs showed altered abundance following Tm treatment (but not by DTT) (Figure 1). Second, to maximize the detection of UPR-regulated genes, and avoid the identification of genes that are influenced by chemical-specific off-target effects, the dataset was restricted to the 57 mRNAs with altered abundance following both DTT and Tm treatment (Figure 1). Third, mRNAs that failed to change in both the ΔhacA and ΔireA mutants in response to DTT and Tm treatment, but did change in the wt strain under these conditions, were considered dependent on both IreA and HacA for differential expression, thus defining them as components of the canonical IreA-HacAi UPR pathway. The data revealed that the vast majority (95%) of the 57 DTT/Tm-responsive mRNAs identified above were unaffected by DTT/Tm treatment in the ΔhacA and ΔireA mutants, demonstrating that A. fumigatus responds to extreme conditions of ER stress predominantly through the IreA-HacAi pathway. Of these 57 mRNAs, 45 increased in abundance under acute ER stress (Table 1), suggesting that they represent the core components of an inducible UPR (i-UPR) in A. fumigatus.

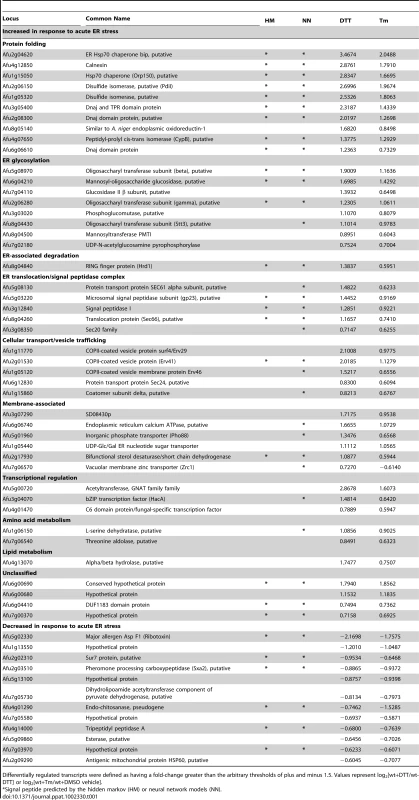

Tab. 1. Functional classification of genes with altered mRNA abundance under conditions of acute ER stress (treatment with DTT or Tm).

Differentially regulated transcripts were defined as having a fold-change greater than the arbitrary thresholds of plus and minus 1.5. Values represent log2[wt+DTT/wt-DTT] or log2[wt+Tm/wt+DMSO vehicle]. Most of the i-UPR proteins contain predicted signal peptide sequences, consistent with membrane association or secretion functions (Table 1). The largest group contains proteins with functions that are known to facilitate protein folding in the ER, such as chaperones, isomerases and carbohydrate modifying enzymes. As expected from previous studies in other species, most of the genes in the i-UPR dataset affect the secretory pathway at multiple levels and are already known to be downstream of the UPR, such as BiP, Hsp70, protein disulfide isomerase, calnexin and mannosyl-oligosaccharide glucosidase [20], [22], [23]. The presence of these established UPR genes in the i-UPR dataset provides confidence that the microarray hybridization conditions and analysis criteria were appropriate for the identification of UPR genes in A. fumigatus.

A small subset of mRNAs decreased in abundance during acute ER stress (Table 1). One of these genes encodes Sur7, a multifunctional transmembrane protein implicated in plasma membrane organization, endocytosis and cell wall biogenesis [24], [25]. A reduction in mRNA encoding Sur7 has also been reported to occur during ER stress in A. niger [20]. ER stress in fungi has also been associated with reduced levels of a number of mRNAs encoding secreted proteins, mediated by a pathway known as repression under ER stress (RESS) [26]. The observed decrease in mRNAs encoding tripeptidyl peptidase A, carboxypeptidase and the secreted ribotoxin AspF1 in this study is consistent with the existence of such a mechanism in A. fumigatus.

Identification of a HacAi-Independent Gene Regulatory Network Mediated by IreA in the Absence of Acute ER Stress

We found that a substantial amount of hacAu mRNA processing into hacAi could always be detected in wt A. fumigatus grown under standard laboratory conditions, suggesting that the IreA-HacAi UPR is active during filamentous growth. To test this, we compared patterns of gene expression under normal growth conditions in the absence of any ER stress-inducing agent. Using a 1.5-fold change in expression level as the cut-off, a total of 1305 mRNAs showed altered abundance in the two mutants, demonstrating a much larger contribution of IreA and HacA to the gene expression signature associated with normal growth than to that associated with acute ER stress (Figure 2). Among these differentially expressed mRNAs, 243 were shared between the ΔhacA and ΔireA mutants, suggesting that they are under the control of the canonical IreA-HacAi pathway. Interestingly, only 9 of these mRNAs overlapped with the i-UPR dataset. This suggests that the canonical Ire-HacAi UPR directs a pattern of gene expression that can be broadly divided into a ‘basal’ response and an inducible response, with the basal UPR constituting 80% of the 291 genes in the total IreA-HacAi dataset and the i-UPR representing the remaining 20%. These are likely to represent opposite ends of a spectrum of gene expression that varies in proportion to the level of ER stress, with the basal UPR predominating in the absence of ER stress and the i-UPR dominating under acute ER stress. Gene Ontology (GO) mapping of the basal UPR category revealed enrichment of genes related to mitochondrial function, suggesting that the canonical IreA-HacAi UPR is linked to the regulation of metabolic adaptation during normal filamentous growth (Figure S4).

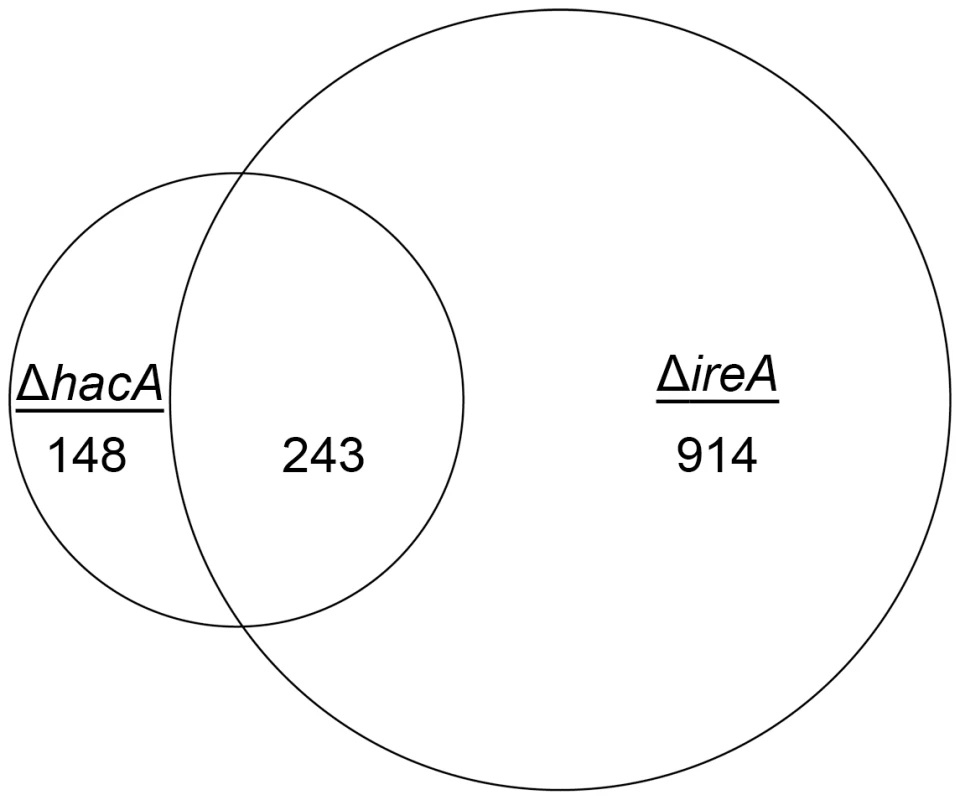

Fig. 2. Identification of a HacA-independent gene regulatory network mediated by IreA.

Venn diagram demonstrating the overlap between the number of transcripts with decreased abundance in the ΔhacA mutant and those that show decreased abundance in the ΔireA mutant relative to wt. The area of the circles is scaled to the number of transcripts and the values represent distinct counts for each category. The list of genes corresponding to each pathway is included in Figure S11. Since the only known function of Ire1 signaling in yeast is HAC1 mRNA splicing, a surprising finding from this analysis was that 914 genes had decreased abundance uniquely in the ΔireA mutant, supporting the idea that IreA has functions in filamentous growth that are both broader in scope and independent of HacA. In addition, a small subset of mRNAs (148) were reduced in the ΔhacA mutant, but not in the ΔireA mutant, raising the possibility that the predicted protein encoded by the uninduced form of the hacA mRNA, HacAu, also influences gene expression independently of both HacAi and IreA.

GO mapping was performed on the list of genes that showed dependence on HacA and/or IreA for expression (Figure 3). The results demonstrated that the two pathways control a similar proportion of genes in the oxidoreductase category, which is attributed mainly to genes involved in the mitochondrial respiratory chain (Figure S4). Genes with functions in transcriptional regulation and kinase activity were also abundant in the IreA dataset but were conspicuously absent from the HacAi dataset, consistent with the notion that IreA has HacAi-independent functions that may connect with other intracellular pathways. Although hydrolases, transferases and transporters were enriched in both groups, their inferred functions were much broader in scope in the IreA group. For example, peptidases, representing a sub-group of all hydrolases, were limited to the IreA subset, further supporting the existence of IreA functions that do not entirely overlap with those of HacAi.

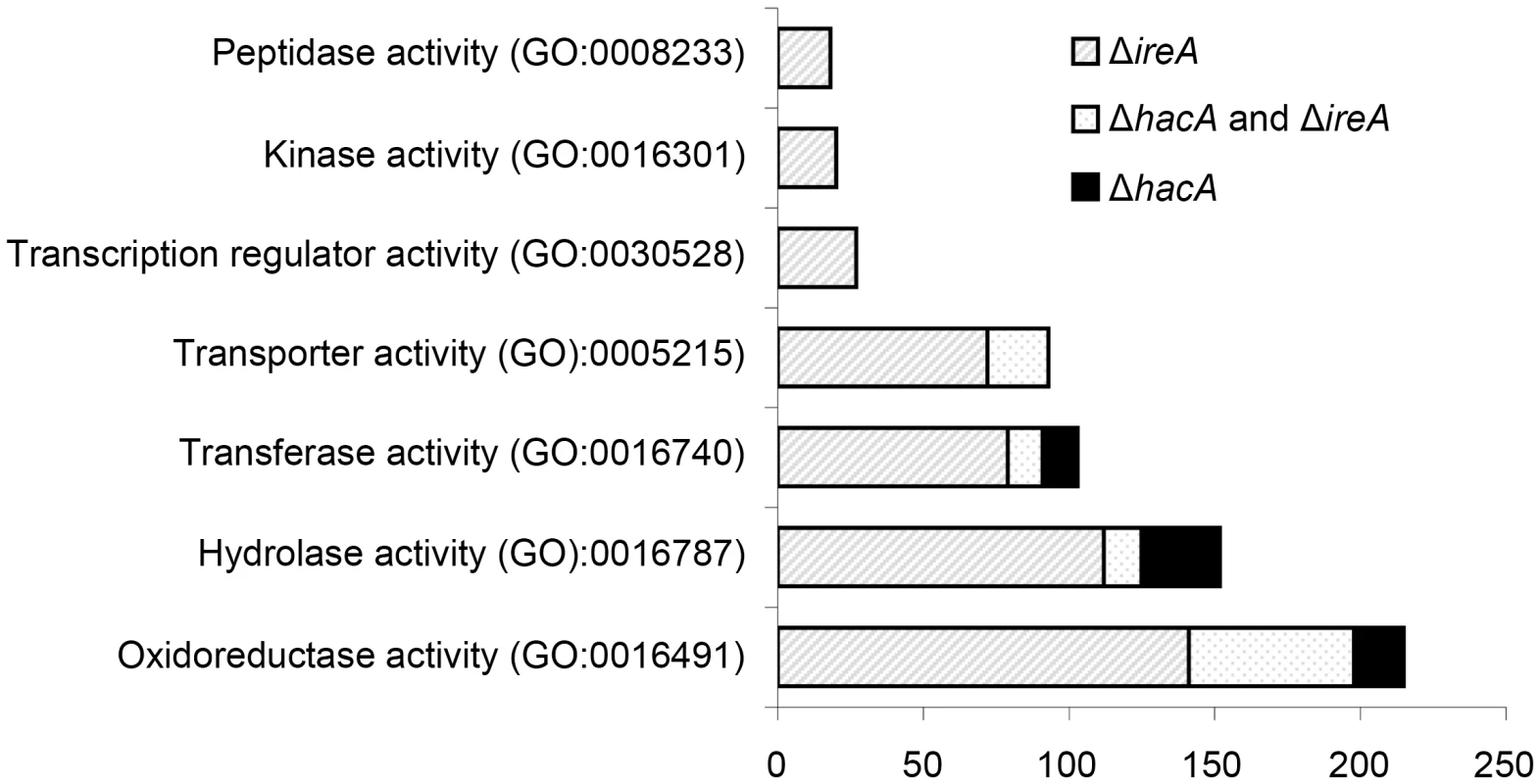

Fig. 3. Gene Ontology mapping of differentially expressed genes in ΔhacA and ΔireA mutants.

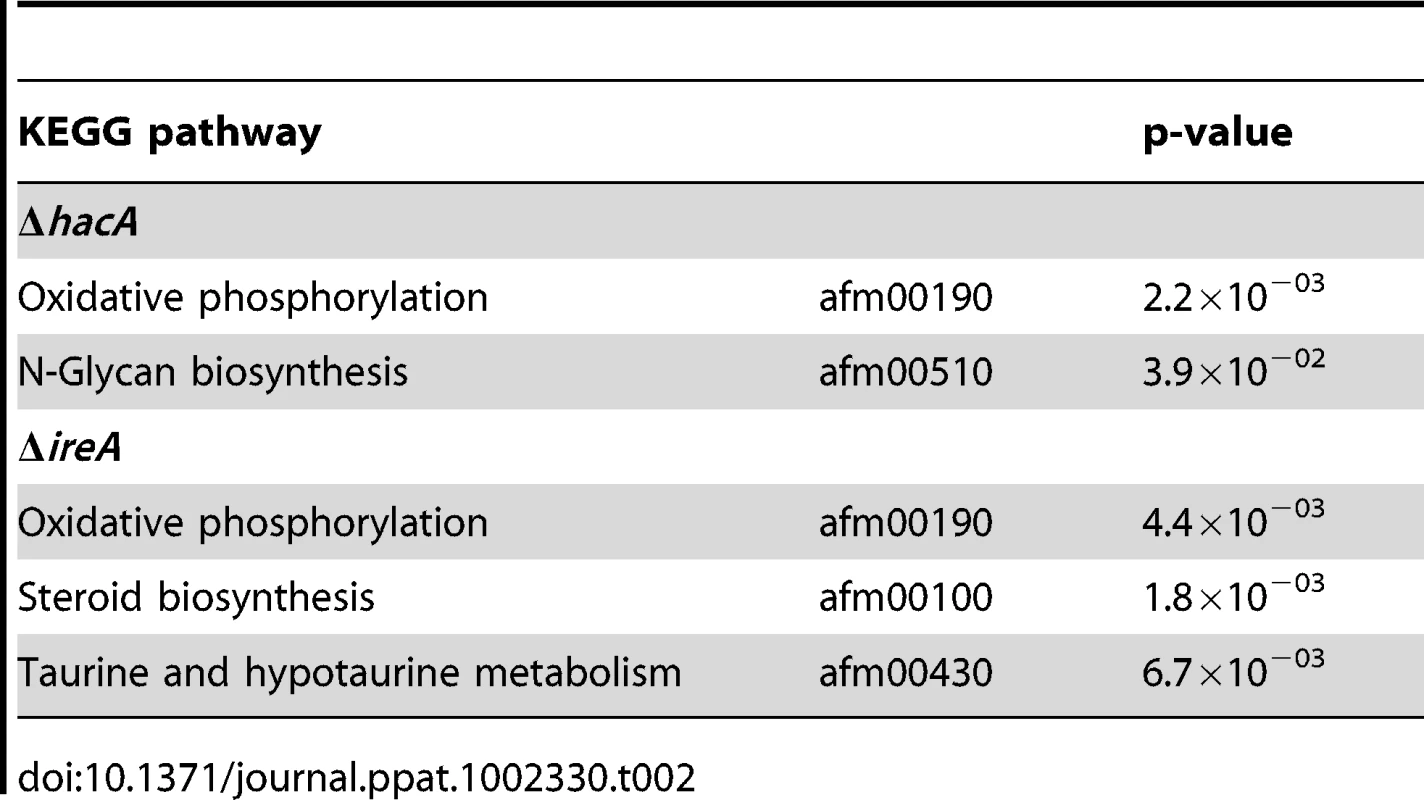

Graphical representation of selected multi-level GO categories (from the parent group of Molecular Function) among genes that showed decreased abundance in the ΔireA and ΔhacA mutants. The genes were functionally categorized using A. fumigatus annotations obtained from BLAST2GO functional annotation repository (taxa ID: 330979). The dataset is limited to genes that were assigned to a GO category at the time of writing and contains 258 genes in the ΔhacA dataset and 779 genes belonging to the ΔireA dataset. A pathway-based enrichment analysis using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database revealed that oxidative phosphorylation was over-represented among mRNAs with decreased abundance in both ΔhacA and ΔireA (Table 2). This supports a link between UPR signaling and mitochondrial function in A. fumigatus, similar to the recently reported cross-talk between the ER and mitochondrial compartments during ER stress in mammalian cells [27]. N-linked glycosylation showed the greatest enrichment among mRNAs with decreased abundance in ΔhacA, consistent with the prominent role of N-linked glycosylation in the maturation of secretory proteins [28]. Steroid biosynthesis and taurine metabolism were also enriched in the dataset of reduced mRNAs in ΔireA, suggesting potential defects in membrane homeostasis and nutritional versatility.

Tab. 2. Over-represented KEGG pathways among genes that show decreased abundance in Δ<i>hacA</i> or Δ<i>ireA</i> under standard growth conditions.

HacAi-Independent Functions of IreA Synergize with the Canonical UPR to Support Virulence

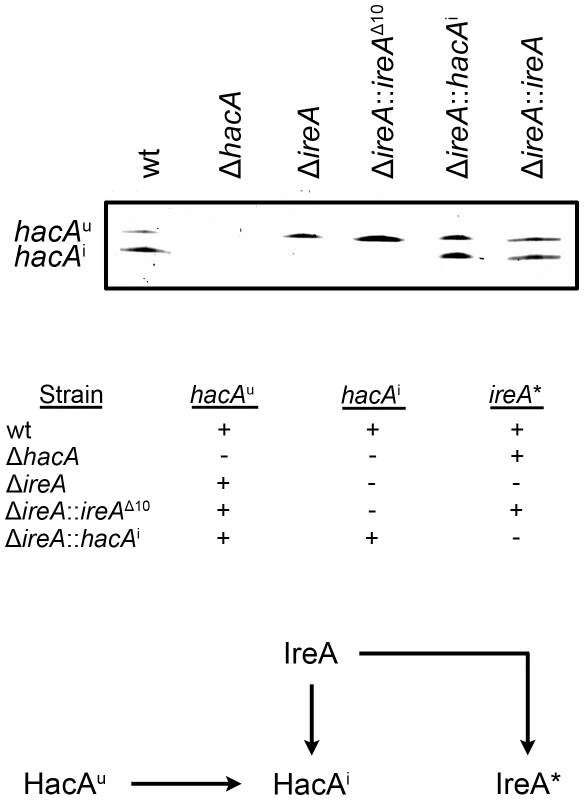

To determine how changes in IreA - and HacA-dependent gene expression influence virulence, the mutants were compared in a mouse model of invasive aspergillosis. Since the ΔireA mutant is deficient in both HacAi-dependent and HacAi-independent functions of IreA, two additional ireA mutant strains were constructed to separate the two functions (Figure 4). First, an endoribonuclease-deficient IreA strain, ΔireA::ireAΔ10, was generated by replacing the ireA gene with a deletion mutant that is missing 10 conserved amino acids (1076–1085) from the endoribonuclease domain (Figure S1). This domain contains three amino acids that form the essential catalytic center of the endoribonuclease domain of S. cerevisiae Ire1p [16]. The ΔireA::ireAΔ10 mutant would be expected to lack hacAu mRNA processing capacity, but retain any HacAi-independent functions that are not dependent on endoribonuclease activity (Figure 4). Secondly, a spliced hacAi expression cassette was introduced into the ΔireA mutant to generate a strain that would possess constitutive HacAi signaling but be deficient in HacAi-independent functions of IreA. A summary of these strains is shown in Figure 4. As expected, neither the ΔireA nor ΔireA::ireAΔ10 mutants were able to process hacAu mRNA into hacAi, thereby establishing the dependence of hacAu mRNA processing on the endoribonuclease activity of IreA in A. fumigatus. Reconstitution of the ΔireA mutant with either hacAi or ireA restored hacAi expression (Figure 4, top panel).

Fig. 4. Analysis of hacA mRNA splicing in hacA and ireA-deficient mutants.

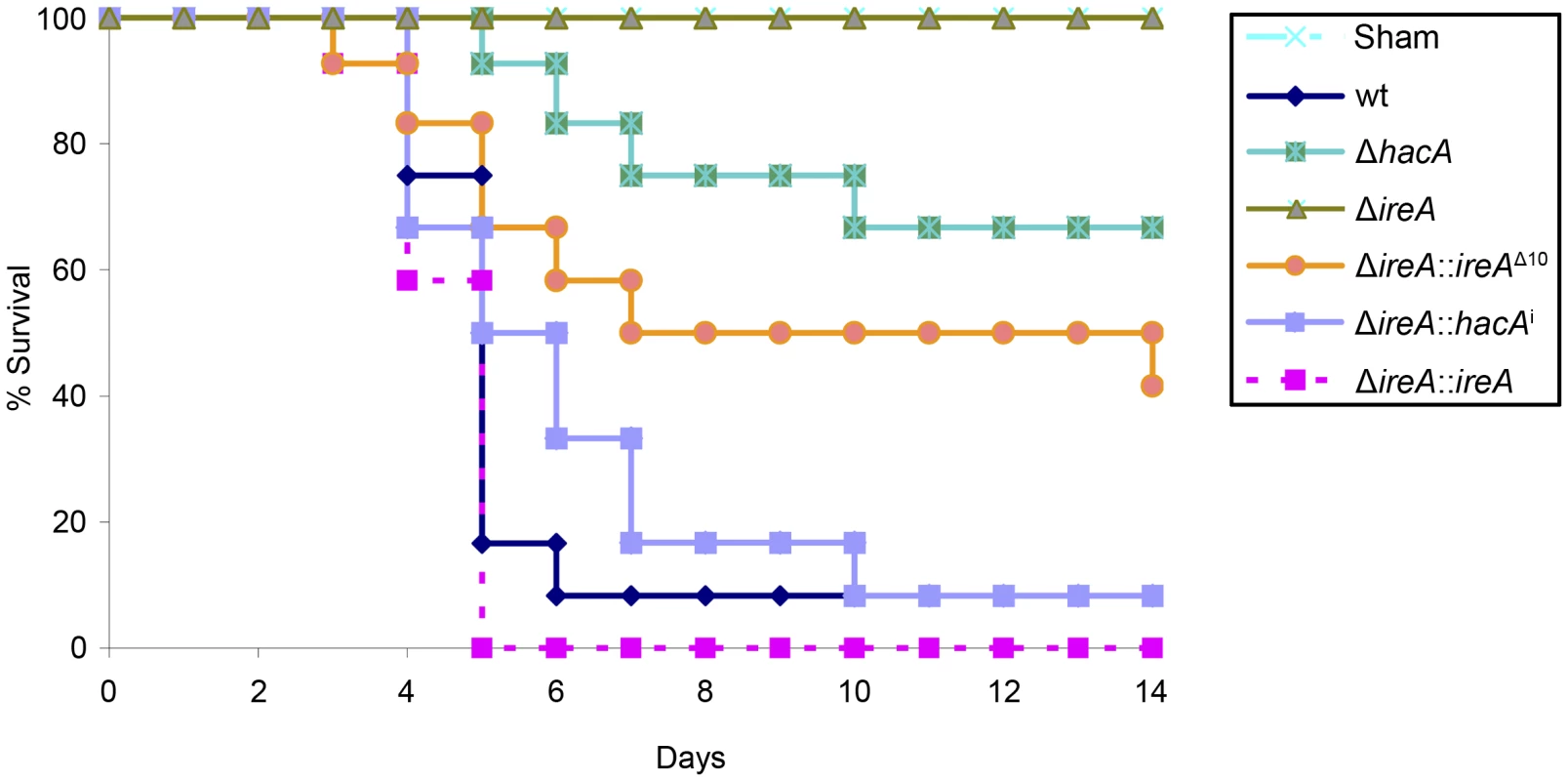

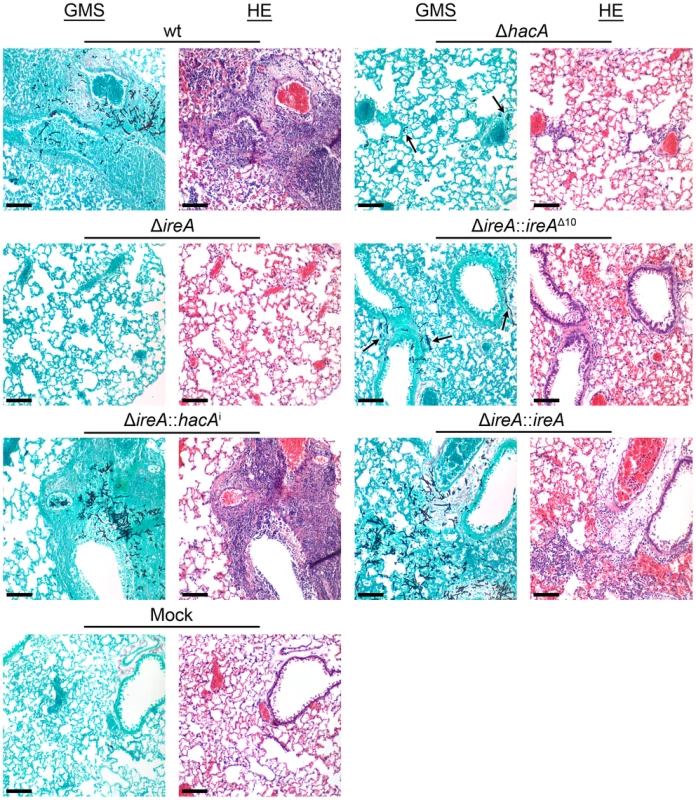

The hacA mRNA was amplified by RT-PCR using primers that span the 20 nucleotide unconventional intron and PCR products were separated on a denaturing acrylamide gel (top figure). The ΔireA and the endoribonuclease-deficient ΔireA::ireAΔ10 mutants lack the ability to process the hacAu mRNA into hacAi. The inability of ΔireA to process hacAu was rescued by transforming ΔireA with the constitutively spliced hacAi cDNA (ΔireA::hacAi) or the wt ireA gene (ΔireA::ireA). The presence (+) or absence (−) of hacA/ireA-dependent functions in these strains is summarized in the table: hacAu: IreA-independent functions mediated by the unspliced form of the hacA mRNA, hacAi: canonical UPR functions mediated by the induced form of the hacA mRNA, ireA*: HacAi-independent functions of IreA revealed by the microarray RNA analysis in this study. A schematic illustration of the relationship between the pathways described in this study is shown below. The ΔireA mutant was avirulent, which contrasted the partial virulence of ΔhacA (Figure 5), suggesting that IreA contributes to pathogenicity independently of HacA. In support of this conclusion, we found that reconstitution of ΔireA with the ireAΔ10 mutant partially restored virulence and reconstitution with a constitutively spliced hacAi gene fully restored virulence. Histopathologic analysis of infected lungs on day 3 post-infection was consistent with these mortality data (Figure 6). Mice infected with the wt, ΔireA::ireA and ΔireA::hacAi strains revealed extensive fungal growth surrounded by inflammation and tissue necrosis. However, very little fungal growth or inflammation was observed in the ΔireA-infected mice at the same time point. Although a few swollen conidia could be identified in ΔireA-infected lungs on the day following infection (Figure S6), no viable fungus could be recovered from surviving mice at the end of the experiment (data not shown), indicating that the mice were able to clear the infection. Mice infected with the ΔireA::ireAΔ10 and ΔhacA strains revealed an intermediate amount of fungal growth (Figure 6, arrows) that was associated with a small amount of inflammation. These data suggest that the canonical IreA-HacAi UPR works together with the HacAi-independent functions of IreA to support the virulence of A. fumigatus.

Fig. 5. IreA is essential for virulence.

Groups of 12 CF-1 outbred mice were immunosuppressed with triamcinolone acetonide and infected intranasally with 2×106 conidia from the indicated strains and mortality was monitored for 14 days. The ΔireA strain was avirulent in this model (p<0.001), which contrasts the partially attenuated virulence of ΔhacA (p<0.05) and ΔireA::ireAΔ10 (p<0.05). The virulence of the ΔireA::hacAi and ΔireA::ireA strains was statistically indistinguishable from wt. The avirulence of ΔireA was confirmed in a separate experiment (Figures S5 and S6). Fig. 6. Histopathology of infected lung tissue.

Mice were infected as described in Figure 5 and sacrificed on day 3 post-infection. The lungs were sectioned at 5 µm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Grocott methenamine silver (GMS). Microscopic examinations were performed on an Olympus BH-2 microscope and imaging system using Spot software version 4.6. Scale bar represents 100 µm. IreA Supports Growth at 37°C

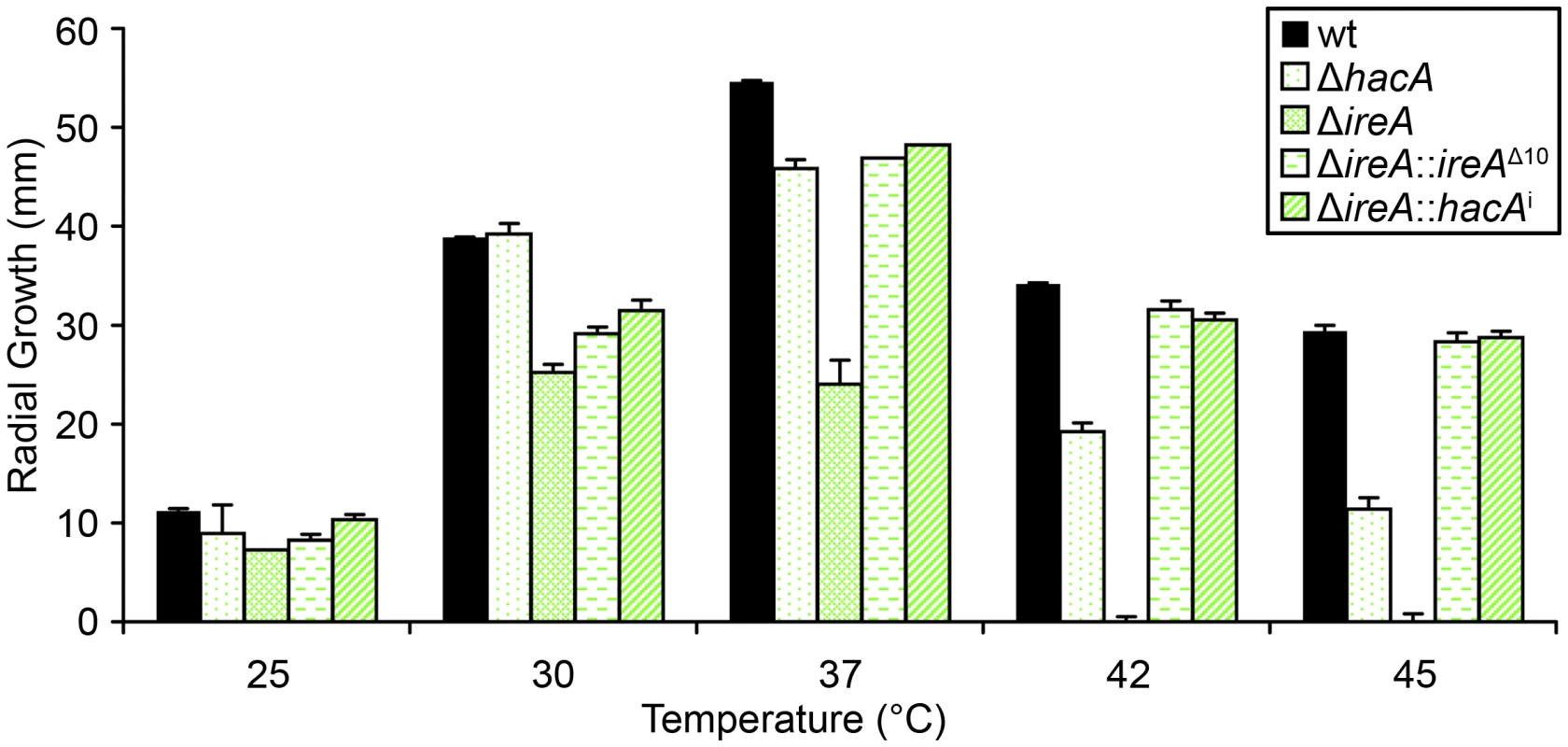

The avirulence of the ΔireA mutant suggests that IreA contributes to the expression of adaptive traits that the fungus requires for optimal fitness in the host. We therefore examined the ΔireA mutant for its ability to withstand different types of stress that may be encountered in the host during infection [29]. The ability to grow rapidly at mammalian body temperature is one of the major virulence determinants of A. fumigatus [30], [31], [32]. Since higher temperatures induce conformational changes in proteins, and IreA is the major sensor of misfolded proteins in the ER, IreA is uniquely positioned to coordinate adaptive responses to thermal stress. Analysis of growth rates at different temperatures confirmed that IreA promotes growth at 37°C and was essential for growth at 42°C (Figure 7). The ΔhacA mutant was also thermosensitive, but to a lesser extent. Interestingly, the expression of ireAΔ10 or hacAi in the ΔireA background corrected most, though not all, of the thermosensitivity of ΔireA (Figure 7), indicating that both IreA and HacA contribute to functions that are needed for optimal growth at mammalian body temperature.

Fig. 7. IreA contributes to thermotolerant growth.

Equal numbers of conidia from the indicated strains were spotted onto the center of a plate of rich medium (YPD) and radial growth (colony diameter) was measured after 4 days at the indicated temperatures. IreA Supports Growth in Hypoxia

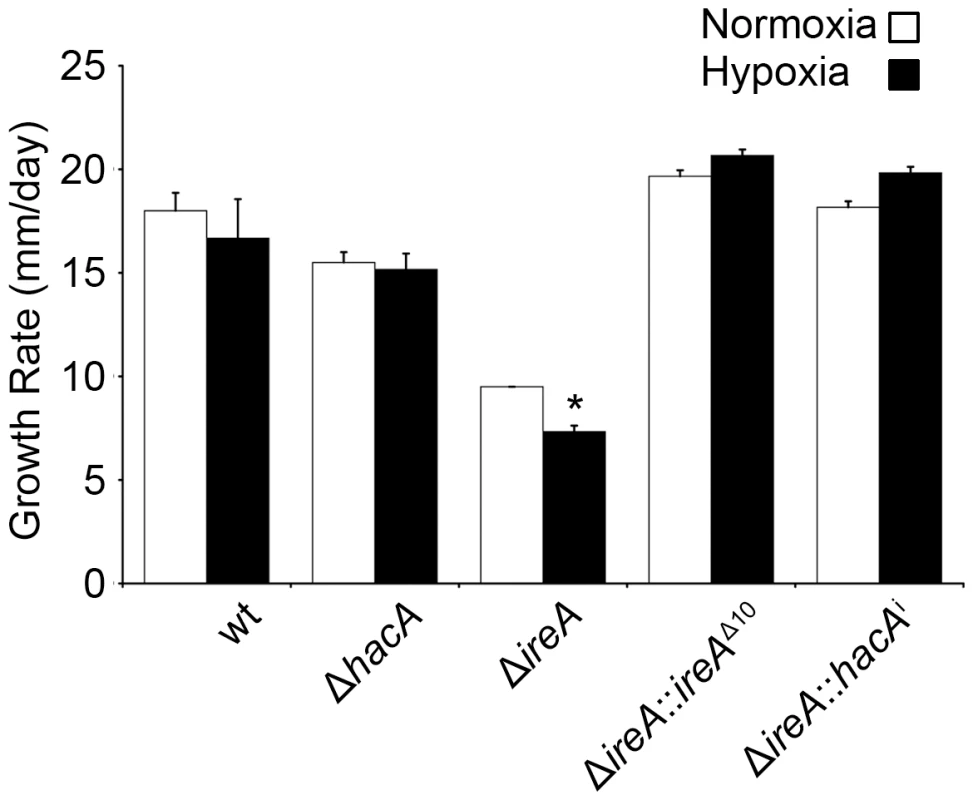

A. fumigatus encounters areas of limited oxygen availability in the host, and the ability of the fungus to adapt to these hypoxic zones is an established virulence determinant for this organism [33]. Because the UPR has been implicated in hypoxia adaptation in mammalian cells [34], we compared the growth of ΔhacA and ΔireA at levels of oxygen that are similar to those encountered in host tissues [33]. As shown in Figure 8, the ΔireA mutant was the only strain that was adversely affected by hypoxia, displaying a 23% reduction in growth rate relative to growth under normoxic conditions. This indicates that IreA supports the fitness of A. fumigatus when oxygen tension is low, which may contribute to the observed lack of virulence of ΔireA.

Fig. 8. IreA contributes to growth in hypoxia.

Equal numbers of conidia were placed in the center of YPD plates and cultured under normoxic (21%) or hypoxic (1% 02) conditions for 4 days at 37°C. The growth rates from triplicate plates were calculated in 24 hour intervals between 48 and 96 hours of incubation and the average growth rate was plotted. The ΔireA mutant was the only strain that showed reduced growth under hypoxia relative to normoxia. *Statistically significant (p<0.001). IreA Supports Cell Wall and Membrane Homeostasis

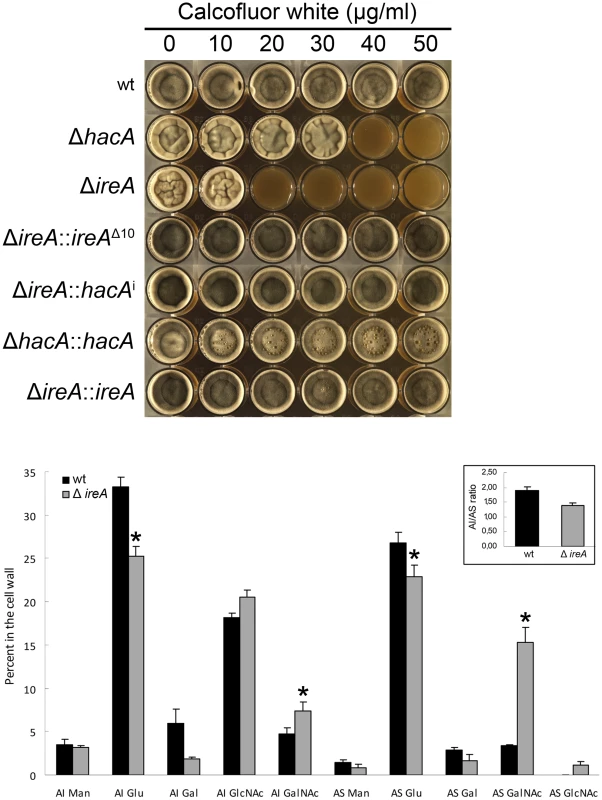

The cell wall of A. fumigatus provides a rigid, yet permeable, barrier that represents the major interface between the fungus and the host environment [35]. We have previously demonstrated that the ΔhacA mutant is hypersensitive to cell wall stress, suggesting that the support provided by HacA to the secretory system is important for cell wall homeostasis. Here, we demonstrate that the ΔireA mutant is even more profoundly affected by cell wall stress, showing reduced growth at concentrations of the cell wall damaging agent calcofluor white (CFW) that had minimal effect on the ΔhacA mutant (Figure 9, top panel). The expression of ireAΔ10 or hacAi in the ΔireA background restored CFW resistance to wt levels.

Fig. 9. IreA contributes to cell wall homeostasis.

Top: Equal numbers of conidia were inoculated into the center of each well of a multi-well plate containing YPD agar supplemented with the indicated concentrations of calcofluor white and incubated for 96 h at 30°C. Below: monosaccharide composition of the alkali-insoluble and alkali-soluble fractions of wt and ΔireA mycelial walls. Results are expressed as the percent of individual monosaccharides in the cell wall. Values represent the average of four replicates ± standard deviation. *Statistically significant (p<0.01). The AI/AS ratio was 1.90±0.1 for wt and 1.39±0.1 for ΔireA (inset). The A. fumigatus cell wall can be divided biochemically into an alkali insoluble fraction comprised of β(1–3)-glucan, chitin and galactomannan, and an alkali soluble fraction containing predominantly α(1–3)-glucan and galactomannan [36]. Analysis of the cell wall monosaccharide composition confirmed that the ΔireA cell wall was abnormal. Decreased glucose was found in the two major cell wall fractions, as well as increased galactose in the alkali insoluble fraction and increased N-acetylgalactosamine in the alkali soluble fraction (Figure 9, bottom panel).

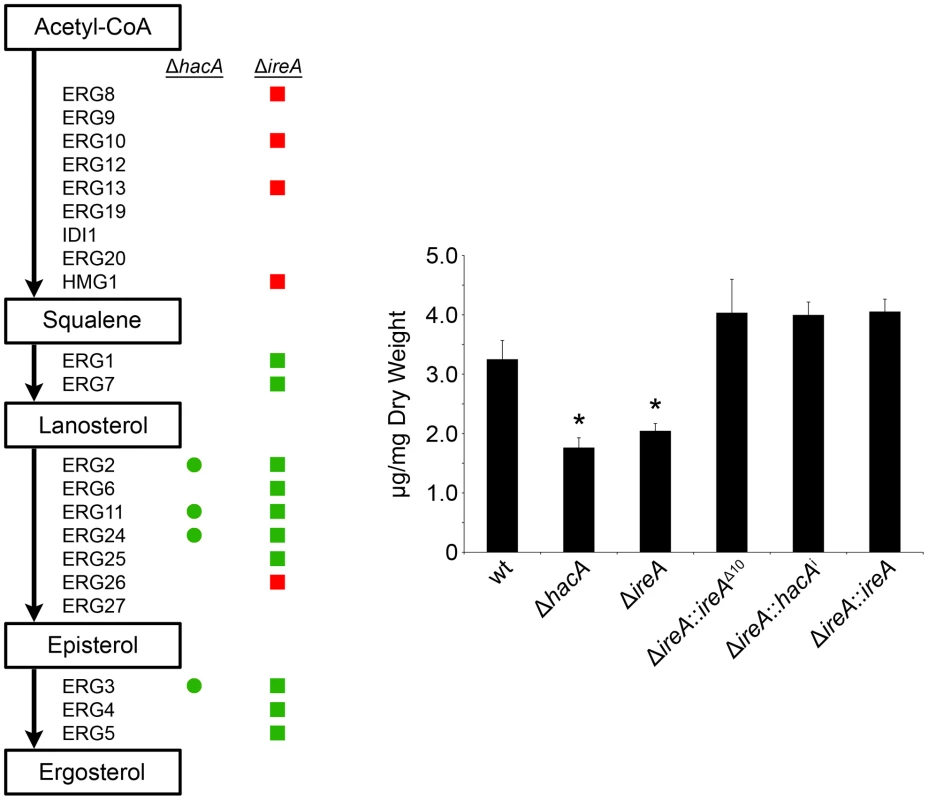

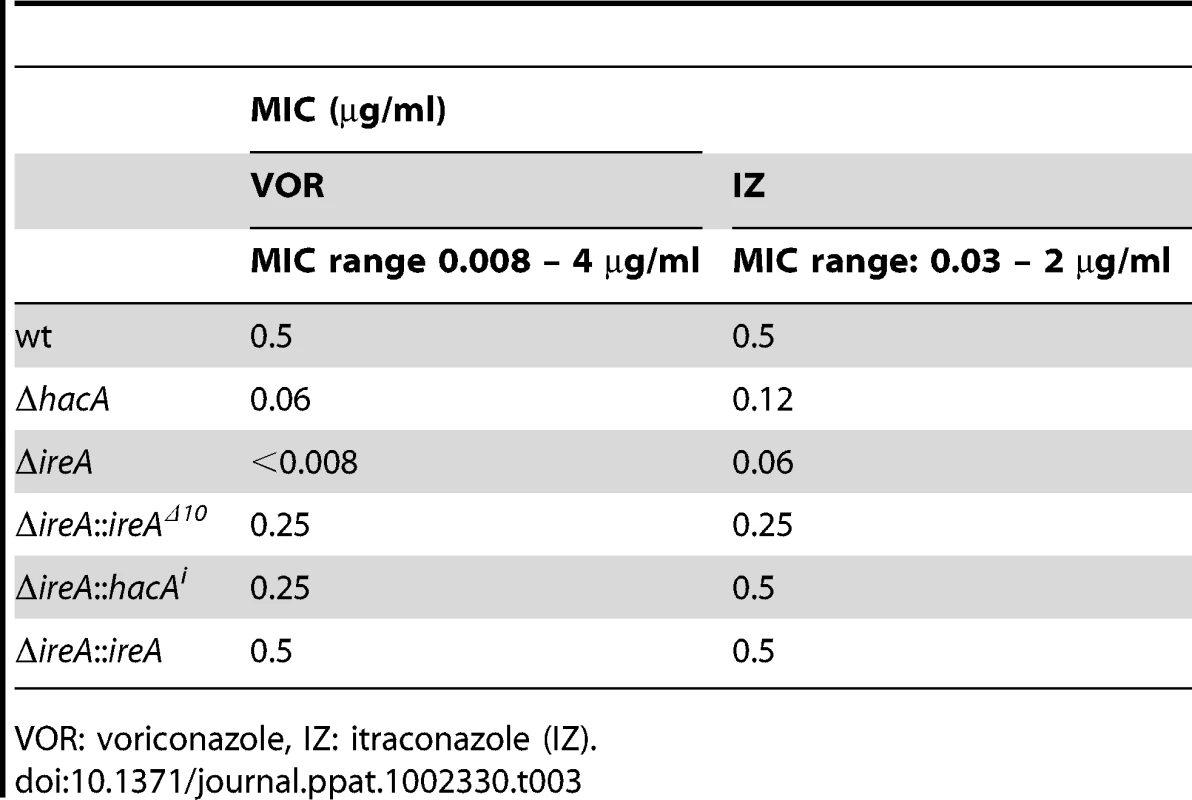

Ergosterol is the major sterol in fungal membranes, responsible for controlling membrane fluidity and regulating the distribution of membrane proteins [37]. Our microarray analysis revealed that a number of mRNAs involved in ergosterol biosynthesis [38] had decreased abundance in both ΔhacA and ΔireA relative to wt (summarized in Figure 10, full dataset is shown in Figure S11). Analysis of mycelial sterols by gas chromatography revealed decreased ergosterol levels in both strains (Figure 10, right panel), suggesting that the UPR integrates with the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway in A. fumigatus. Both strains also had increased sensitivity to azole antifungal drugs, presumably due to further inhibition of ergosterol biosynthesis caused by the inhibitory action of azoles against the ERG11 enzyme (Table 3). A hierarchical clustering of genes in the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway that show differential expression in ΔhacA or ΔireA is shown in Figure S7. Interestingly, the ΔireA mutant revealed increased expression of 4 mRNAs that are upstream of squalene in the ergosterol pathway (Figure 10). Although this could be due to compensatory upregulation, the fact that it was not seen in the ΔhacA mutant suggests that the loss of IreA has effects on this pathway that are HacA-independent.

Fig. 10. IreA contributes to ergosterol biosynthesis.

Left: Schematic representation of genes in the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway that show a ≥1.5-fold decrease (green) or increase (red) in ΔhacA (circles) or ΔireA (squares) relative to wt. The ergosterol pathway is derived from S. cerevisiae. Right: comparison of ergosterol content. Values represent the average of three replicates, expressed as µg ergosterol per mg dry fungal biomass. *Statistically significant (p<0.05). Tab. 3. Azole antifungal susceptibility using the Sensititre YeastOne© method.

VOR: voriconazole, IZ: itraconazole (IZ). IreA Supports Nutritional Versatility

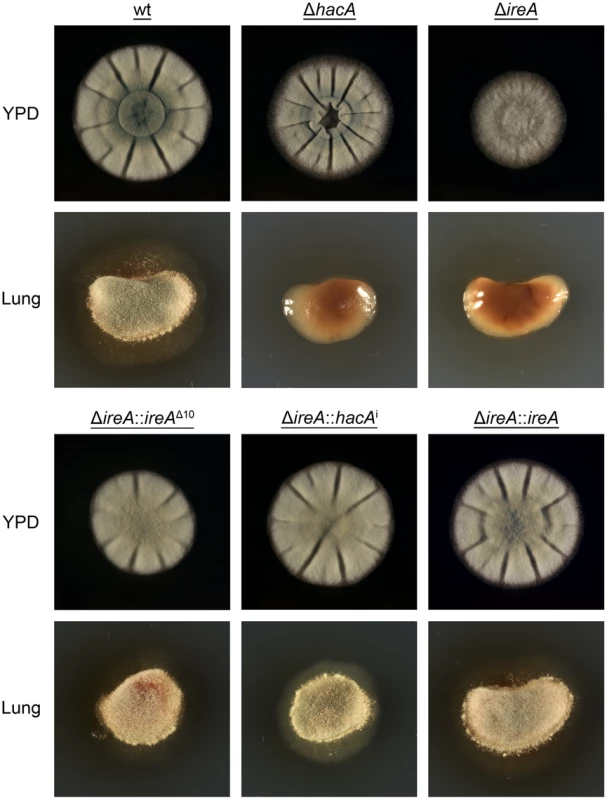

A. fumigatus encounters nutritional stress in the host environment, which requires metabolic reprogramming by the fungus to effectively use the host as a nutrient source [3], [29]. To determine the importance of IreA to nutritional versatility, growth was compared on plates of YPD medium (representing a rich substrate of pre-digested proteins) or on explants of mouse lung tissue (representing an undigested substrate of complex biological material that the fungus encounters during infection). Although the ΔireA mutant was able to grow on YPD medium, it was unable to do so when inoculated onto a lung explant, even after 7 days of incubation (Figure 11). The ΔhacA strain was also impaired on lung tissue, as previously reported [15], although some growth could be detected on the surface of the explant when examined microscopically (data not shown).

Fig. 11. IreA promotes growth on lung tissue.

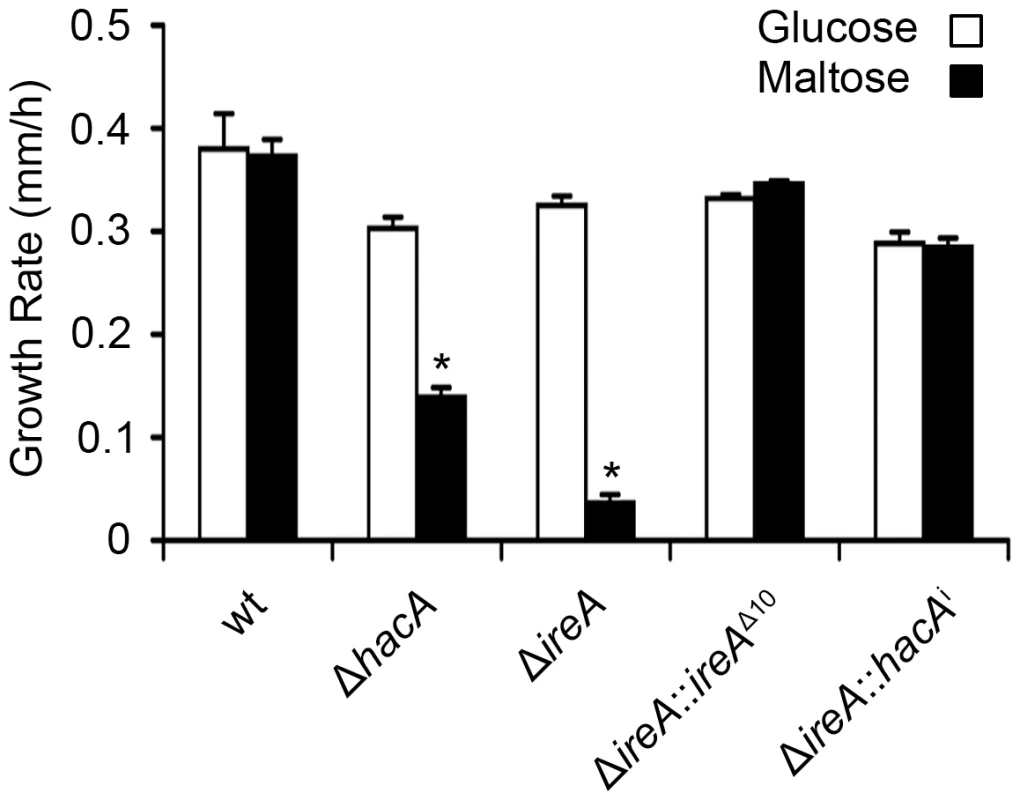

Equal numbers of conidia from the indicated strains were inoculated into the center of a plate of YPD or onto an explant of mouse lung tissue that was placed onto the surface of a plate of 1% agarose in sterile distilled water. The plates were photographed after 2 days of incubation at 37°C. All filamentous fungi modulate the activity of the secretory pathway in response to the conditional need for extracellular enzymes. Previous studies have shown that the growth of A. niger on the disaccharide maltose elicits a high rate of protein secretion that is accompanied by a transcriptional response resembling the UPR [39]. The ΔireA mutant showed a striking growth defect on maltose relative to growth on a monosaccharide (glucose). This could be rescued by reconstitution with ireAΔ10 or hacAi, consistent with a role for IreA in the adaptation to maltose-induced secretion stress (Figure 12). The ΔhacA mutant was also impaired on maltose, but to a lesser extent than ΔireA.

Fig. 12. HacA and IreA promote growth on maltose medium.

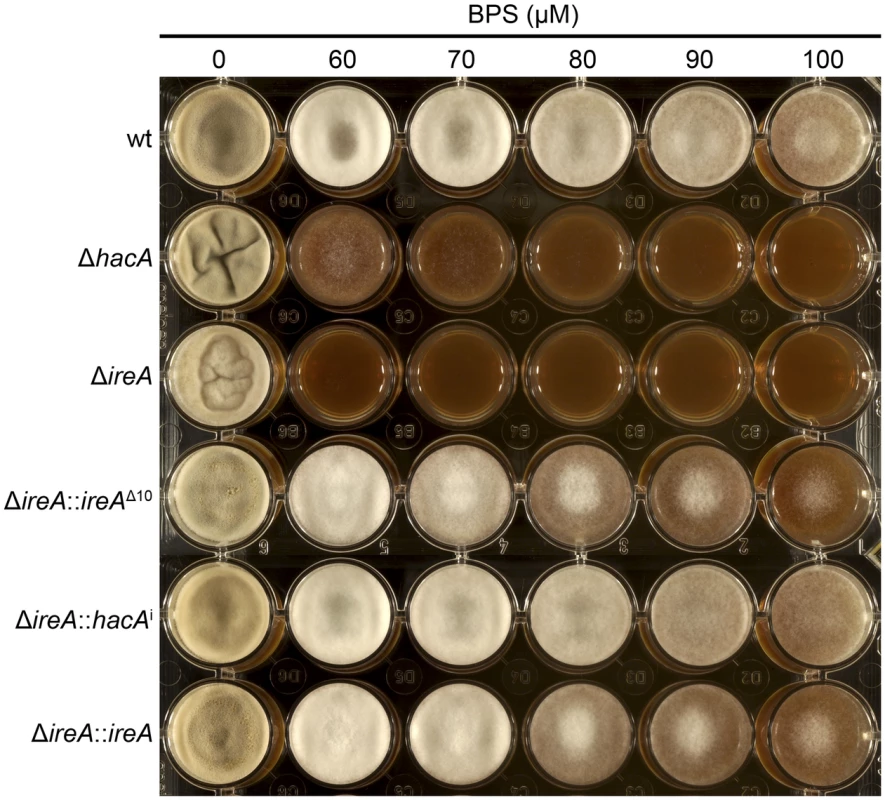

Equal numbers of conidia from the indicated strains were spotted onto plates of Aspergillus minimal medium containing either 1% maltose or glucose as the carbon source and growth rate (mm/h) was calculated after 3 days of incubation at 30°C. A. fumigatus faces iron starvation during infection because the host immune system uses iron-sequestration mechanisms to withhold this essential nutrient from invading microbes [40]. A. fumigatus adapts to these conditions by upregulating iron acquisition pathways, which have been shown to be necessary for virulence [41], [42]. Our microarray data showed that at least three mRNAs encoding proteins involved in siderophore-mediated iron acquisition had decreased abundance in ΔireA, as well as components of reductive iron assimilation in both ΔhacA and ΔireA. (Figure S11). To determine whether these changes influence iron homeostasis, growth was compared in medium that was rendered iron-deficient by the addition of the iron chelator bathophenanthroline disulfonate (BPS). As shown in Figure 13, the ΔireA mutant was unable to grow in the presence of concentrations of BPS that only partially inhibited ΔhacA and had little-to-no effect on wt. The ability to grow in BPS could be rescued by complementation of ΔireA with ireAΔ10 or hacAi, confirming that IreA has both HacAi-dependent and HacAi-independent functions that facilitate adaption to iron starvation conditions.

Fig. 13. IreA facilitates adaptation to iron starvation.

Equal numbers of conidia from the indicated strains were spotted onto YPD medium containing the indicated concentrations of the iron chelator BPS and incubated for 72 h at 30°C. The ΔhacA and ΔireA mutants showed increased sensitivity to BPS. Discussion

To gain insight into the scope of the UPR in A. fumigatus we have compared the genome-wide expression profiles of ΔhacA and ΔireA mutants in the presence or absence of ER stress. The data revealed that HacA and IreA collectively influence the expression of over 1300 genes, constituting over 13% of all defined open reading frames in this organism. We found that A. fumigatus responds to extreme conditions of ER stress by signaling through the canonical IreA-HacAi pathway, resulting in the activation of a program of gene expression (the i-UPR) that is qualitatively similar to what has been described in yeast [23]. However, we also discovered that the IreA-HacAi UPR was active in the absence of exogenous ER stress, signifying a requirement for basal UPR activity during normal filamentous growth. Since the UPR has been shown to facilitate budding yeast cytokinesis [43], we speculate that A. fumigatus requires subtle changes in UPR signaling to buffer dynamic fluctuations in ER stress caused by the constant cell wall remodeling that occurs during hyphal growth [44]. Interestingly, the gene expression profile of the i-UPR during acute ER stress was strikingly different from that of the basal UPR in the absence of ER stress. This suggests that A. fumigatus can qualitatively modify the output of the response in proportion to the level of stress, possibly by integrating with other pathways that influence ER homeostasis.

Surprisingly, we found that 70% of the differentially expressed genes in the absence of ER stress were HacAi-independent, providing evidence for novel IreA functions during normal filamentous growth. These expanded functions for IreA differ from what has been described in yeast, where the only known function of Ire1 is the activation of the downstream UPR. A possible explanation for this difference is the spatial segregation of function in the interconnected hyphal compartments of a filamentous fungus [45]. This represents an increased level of complexity relative to yeast that may have driven the need for greater flexibility in IreA function. Unique functions for Ire1 have been previously suggested in higher eukaryotes [46], [47]. However, to our knowledge, this is the first report in fungi to demonstrate major regulatory functions for the IreA sensor that go beyond the canonical IreA-HacAi UPR. Interestingly, a small subset of mRNAs showed decreased abundance in the ΔhacA mutant, but not in ΔireA, suggesting that the uninduced form of the hacA mRNA, hacAu, can influence gene expression independently of both HacAi and IreA. It is not yet clear whether this is due to the hacAu mRNA or its encoded product. However, the association of hacAu mRNA with polysomes, together with the high degree of conservation of the predicted HacAu protein among filamentous fungi (data not shown), argues in favor of the translation of hacAu mRNA in A. fumigatus.

The changes in gene expression caused by loss of UPR function correlated with a reduction in virulence for the ΔhacA strain and a complete loss of virulence for the ΔireA mutant, suggesting that the HacAi-independent gene regulatory networks controlled by IreA are functionally entwined with the canonical IreA-HacAi pathway to influence the expression of key virulence attributes. One of these traits is likely to involve thermotolerance. The ΔireA mutant was much more growth impaired than the ΔhacA mutant at 37°C, revealing a key function of IreA in the regulation of growth at mammalian body temperature. The reduced ergosterol content of both of these strains may contribute to their inability to tolerate high temperatures. Ergosterol is the major sterol in fungal membranes and, like its mammalian counterpart cholesterol, is responsible for decreasing membrane fluidity by restricting the flexibility of phospholipid acyl chains and limiting permeability to small molecules [37], [48]. Since high temperatures also increase membrane fluidity and permeability [49], the combined effects of reduced ergosterol and thermal stress is likely to disrupt membrane stability and interfere with rapid growth.

Gene expression profiling of A. fumigatus during the early stages of infection has suggested that A. fumigatus is under nutrient stress in the host environment, requiring upregulation of pathways involved in iron transport and hydrolase secretion to maximize nutrient acquisition from the host [50]. The ΔireA and ΔhacA mutants had reduced expression of a number of iron acquisition genes (summarized in the full dataset, Figure S11), which correlated with the reduced growth of both strains under iron limited conditions (Figure 11). Since the ability of A. fumigatus to adapt to iron starvation is crucial for pathogenicity [41], the more severe iron starvation defect of ΔireA relative to ΔhacA correlates well with the avirulence of ΔireA and the partial virulence of ΔhacA. We also found that the ΔireA mutant was more growth impaired than ΔhacA when challenged to grow on complex nutrient sources that require secreted hydrolases for nutrient acquisition, providing further support for a role for IreA in the nutritional versatility of this fungus.

A reduction in glucose content was observed in both fractions of the ΔireA mutant cell wall, indicating decreased levels of β(1–3)-glucan and α(1–3)-glucan. This is similar to what was reported in the ΔhacA mutant [15], suggesting that it is caused by the loss of IreA-HacAi signaling. A substantial increase in the proportion of N-acetylgalactosamine was found in the ΔireA cell wall, which was not previously seen in the ΔhacA mutant [15]. However, the significance of this change is not yet known due the limited understanding of the role of galactose polymers in cell wall homeostasis. It is conceivable that some of these cell wall changes could influence virulence by unmasking carbohydrate epitopes that promote phagocytic clearance by the immune system. However, we found only a slight increase (10–15%) in neutrophil-mediated killing of the gΔireA mutant relative to wt (data not shown), suggesting that the major virulence defect in this mutant is more likely to be a consequence of poor fitness in the host environment than altered susceptibility to phagocytic killing, particularly in the context of an immunocompromised host.

The UPR has been implicated in hypoxia adaptation in mammalian cells, a function that is attributed to XBP1 [34]. This contrasts our findings in A. fumigatus, where IreA, but not HacA, was required for optimal growth in hypoxia. The growth of ΔireA in limited oxygen was 23% lower than what was observed under normoxic conditions. Although this is a relatively modest reduction when compared to the effects of deleting SrbA, the major regulator of hypoxia adaptation in A. fumigatus [33], it is one of multiple defects in the ΔireA mutant that are likely to act synergistically to impair the pathogenic potential of the fungus in the host environment. Since optimum growth under hypoxia requires the mitochondrial respiratory chain [51], the decreased abundance of oxidative phosphorylation mRNAs in the ΔireA mutant may contribute, at least in part, to the observed hypoxia growth defect. SrbA is the ortholog of fission yeast Sre1, an ER membrane-bound protein that monitors sterol synthesis as an indirect measure of oxygen supply [52]. Since IreA and SreA are both ER-membrane proteins that are linked to both ergosterol synthesis and hypoxia adaptation, it is intriguing to speculate that there is cross-talk between the two pathways and experiments to test this possibility are underway.

The findings from this study demonstrate that HacAu, HacAi and IreA have independent functions that influence the biology of A. fumigatus. The ΔireA mutant lacks two of these functions, mediated by HacAi or the HacAi-independent activities of IreA. Reconstitution of ΔireA with either hacAi or ireAΔ10 genes restored one of the two pathways, which largely rescued the in vitro phenotypes, suggesting that A. fumigatus requires at least two of these three functions to support optimal growth under stress conditions. In addition, we found that partial or full virulence could be restored to the ΔireA mutant by complementation with either hacAi or ireAΔ10 genes, demonstrating that virulence is regulated by the HacAi-dependent and HacAi-independent functions of IreA. Although the ability of the hacAi gene to fully restore virulence suggests that HacAi signaling was sufficient to restore pathogenicity to ΔireA, an important caveat to this interpretation is that the reconstituted hacAi gene is not under the control of regulated hacA mRNA processing, which could increase protein expression and influence virulence. Nevertheless, the fact that reconstitution with hacAi or ireAΔ10 was able to restore some virulence potential to the avirulent ΔireA mutant provides strong support for overlapping functions of IreA and HacA in the pathogenicity of A. fumigatus.

Overall, the data in this study are consistent with the following model for IreA function in A. fumigatus. In the absence of ER stress, IreA coordinates basal HacAi activity to buffer dynamic fluctuations in ER stress that are likely to occur in response to the normal demands of filamentous fungal physiology. Under conditions of severe ER stress, such as a sudden increase in the demand for secretion or exposure to adverse environmental conditions that cause widespread protein folding, IreA increases hacAu mRNA splicing, resulting in the activation of the i-UPR. The pattern of gene expression that characterizes the i-UPR benefits the fungus under extreme conditions because it is more narrowly focused on the secretory pathway than is the basal UPR, allowing for a speedy recovery of ER homeostasis. Although the canonical IreA-HacAi pathway controls both the basal UPR and the i-UPR, it is assisted by complementary signaling networks driven by the HacAi-independent functions of IreA, most notably for the expression of traits that are essential for virulence. The precise mechanism by which IreA controls gene expression independently of HacA is not yet known, but an intriguing possibility is that the kinase domain, and/or putative ligand-binding pockets recently identified at the dimer interface of the KEN domain [53], can functionally integrate IreA with other signaling pathways. Regardless of how this is accomplished, the reliance of A. fumigatus on IreA for virulence underscores the future potential for targeting the functions of this protein with novel antifungal therapy. Moreover, the recent discovery that HacA is required for virulence of the plant fungal pathogen Alternaria brassicicola [54] suggests that targeting the UPR could have broad implications for the control of both human and plant fungal pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Culture Conditions

The A. fumigatus strains used in the study are listed in Figure S8. Conidia were harvested from colonies grown on OSM plates (Aspergillus minimal medium [55] containing 10 mM ammonium tartrate and osmotically stabilized with 1.2 M sorbitol). Radial growth rates were measured by spotting 5,000 conidia onto the center of a 100 mm plate containing 40 mL of YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) and monitoring colony diameter daily. YPD was selected because it best supports the growth of the ΔireA mutant. For analysis of cell wall stress response, 2,000 conidia were spotted in a 5 µl volume in each well of a 24-well plate containing YPD supplemented with various concentrations CFW. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 6 days before being photographed. An incubation temperature of 30°C was used wherever possible because it minimized the difference in growth rate between wt and the ΔireA mutant. For analysis of growth in iron-depleted medium, 2,000 conidia were inoculated into YPD medium containing the iron chelator BPS (Sigma #11890) and incubated for 72 h at 30°C. For analysis of growth on lung tissue, explants of mouse lung were placed onto the surface of a plate of 1% agarose in sterile distilled water. The lung tissue was inoculated with 2,000 conidia in a 5 µl volume of sterile water and fungal growth was monitored daily for 7 days at 37°C.

Hypoxic Cultivation

Normoxic conditions were considered general atmospheric levels within the lab (∼21%). For hypoxia conditions, an INVIVO2 400 Hypoxia Workstation (Ruskinn Technology Limited, Bridgend, UK) was used to maintain an atmosphere of 1% O2, 5% CO2 and 94% N2. Colony growth was quantified as described [33]. Briefly, 5 µl aliquots containing 1×106 conidia from freshly harvested OSM plates were placed onto the center of a plate of YPD and incubated for 4 days under normoxic or hypoxic conditions at 37°C. The experiment was performed in three biological replicates.

Disruption and Reconstitution of the A. fumigatus ireA Gene

All PCR primers used in this study are shown in Figure S9. A complete deletion of the A. fumigatus ireA gene (Genbank accession XP_749922) was accomplished using the split-marker approach. The 5′ flank of the ireA gene was PCR-amplified from genomic DNA (primers 529 and 530) to create PCR product #1, and the 3′ flank was PCR-amplified with primers 531 and 532 to generate PCR product #2. The phleomycin resistance cassette was PCR amplified into two partially overlapping fragments using primers 398 and 399 to generate PCR product #3 and primers 409 and 410 to generate product #4. Overlap PCR was then used to combine PCR products #1 and #3 into PCR product #5 (primers 529 and 408), and PCR products #2 and #4 into PCR product #6 (primers 410 and 532). PCR products #5 and #6 were then cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Invitrogen) to create p558 and p559, respectively. The inserts from p558 and p559 were excised by digestion with XhoI and HindIII and gel purified, and 10 µg of each was used to transform wt-ΔakuA protoplasts as previously described [15]. Loss of the ireA gene in phleomycin-resistant monoconidial transformants was confirmed by genomic Southern blot analysis, as described in the Results section.

The ΔireA mutant was complemented by introducing the ireA gene into the ΔireA mutant as an ectopic transgene. The ireA gene, including 550 bp upstream of the ATG start site was PCR-amplified from wt genomic DNA using primers 647 and 650 and cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Invitrogen) to generate plasmid 564. Ten micrograms of p564 was then linearized with NotI and cotransformed into ΔireA protoplasts with 1 µg of a plasmid containing the hygromycin resistance cassette (p373). Successful reconstitution of the ireA gene was confirmed in hygromycin-resistant monoconidial transformants by genomic Southern blot analysis (data not shown).

Disruption of the endoribonuclease domain of ireA was accomplished by deleting the nucleotide sequences encoding amino acids 1076–1085 using the Quickchange site-directed mutagenesis system (Stratagene). The complete ireA gene, together with 550 bp of promoter sequence, was PCR-amplified from wt genomic DNA and cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Invitrogen) to generate plasmid 564. Next, p564 was used as a template for site-directed mutagenesis using the mutagenic oligonucleotides 701 and 702, according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Sequence analysis of the resulting plasmid (p596) confirmed the accuracy of the deletion. The ireAΔ10 strain was constructed by linearizing 10 µg of p596 with NotI and co-transforming the plasmid into ΔireA protoplasts together with 1 µg of p373, containing the hygromycin resistance cassette. Successful re-integration of the ireAΔ10 allele into the ireA locus was confirmed by genomic Southern blot analysis and PCR sequencing on hygromycin-resistant monoconidial isolates.

The ΔireA::hacAi strain was constructed by introducing the induced form of the hacA cDNA, hacAi, into the background of the ΔireA mutant. The hacAi cDNA was PCR amplified from reverse-transcribed cDNA using primer 493 (located 15 bp upstream of the ATG) and primer 572 (located 145 bp downstream of the hacAi stop codon). The PCR product was then cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Invitrogen) to generate p576. The hacAi insert was excised from p576 by XbaI-SacI digestion and inserted downstream of the constitutive gpdA promoter (PgpdA) using the same restriction sites to create p614. The PgpdA-hacAi cassette was excised from p614 with HindIII and SacI and 10 µg was transformed into ΔireA protoplasts and incubated at 37°C. Since the ΔireA mutant is growth impaired at this temperature, colonies that appeared on the transformed plates before they started to appear on the untransformed ΔireA control plates were transferred to fresh medium and ectopic integration of the hacAi expression cassette was confirmed by genomic Southern blot analysis and PCR.

Analysis of hacA Splicing by RT-PCR

Overnight cultures of A. fumigatus were treated with 1 mM DTT for 1 h prior to extraction of total RNA. The RNA was prepared by crushing the mycelium in liquid nitrogen and resuspending in TRI reagent LS (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH). One microgram of the total RNA was reverse-transcribed with AMV reverse transcriptase using oligonucleotide 718 as the primer. The first-strand cDNA was then used as a template for PCR using primers 717 and 718, which flank the unconventional intron in the hacAu sequence. The PCR products were fractionated under denaturing conditions to remove hybrids between spliced and unspliced single-stranded DNA that can arise during PCR amplification (12% acrylamide/7M urea gel in 1X TBE) [56]. The samples were heated to 95°C for 5 min in RNA loading buffer (formamide-EDTA) prior to loading. The PCR products were stained with SYBR green II and fluorescence was quantified on a Personal Molecular Imager (PMI, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules CA) using Quantity One and Image Lab software.

For validation of differentially expressed genes by qPCR, reverse transcription was performed using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (cat. no. 11904-018, Invitrogen) using an oligo-(dT)18 primer or an 18S rRNA-specific primer (primer #713) together with 1 µg of total RNA as template. The qPCR reaction was performed using the SYBR GreenER qPCR Super Mix (cat. no. 11762-100, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol, using primer sets for the relevant target gene (Figure S9). The reactions were analyzed using a Smart Cycler II (Cepheid) with a standard two-step cycling program of 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min; specificity and primer dimer formations were monitored using a melting curve. The Ct values were obtained using smart cycler software (v 2.0) and the relative changes in gene expression were calculated using the comparative Ct method, using 18S rRNA as the endogenous control and wt as the reference sample.

Microarray Analysis

Cultures were inoculated with 5×106 conidia in 5 ml of YG medium (0.5% yeast extract, 2% glucose) and incubated for 16 h with shaking at 37°C. Where indicated, the UPR was induced by treating 16 h-cultures with 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) or 10 µg/ml tunicamycin for 1 h. Total RNA was extracted by crushing the mycelium in liquid nitrogen and resuspending in TRI reagent LS (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH). The RNA labeling reactions and hybridizations were performed as described in the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) standard operating procedure (http://pfgrc.jcvi.org/index.php/microarray/protocols.html) and transcriptional profiles were generated by interrogating the Af293 DNA amplicon microarray containing 9,516 genes [57]. Each gene was present in triplicate on the array, and all hybridizations were repeated in dye swap experiments. The data for each gene were averaged from the triplicate genes on each array and the duplicate dye swap experiment (a total of six readings for each gene) and the gene expression ratios were log2-transformed. Datasets were limited to genes that showed ≥1.5-fold change (log2-value of ±0.585). Functional annotation of genes present within the dataset was analyzed using BLAST2GO suite (PMID: 18445632) with standard settings (score alpha value set at 0.6). Gene Ontology Term Enrichment was performed using AmiGO Term Enrichment [58]. KEGG pathways associated with Aspergillus fumigatus were downloaded from the KEGG database [59]. Statistical significance of over-represented KEGG pathways was assessed using Fisher's exact test followed by correction using the Bonferroni method; a cutoff value of P<0.05 was assigned for statistical significance. Hierarchical clustering was performed using Cluster 3.0 [60] and the cluster tree was visualized using JAVA Treeview [61]. Microarray data was validated by demonstrating increased expression of known UPR target genes following DTT and Tm treatment (Table 1), by confirming expected phenotypic changes that correspond to specific changes in gene expression (Figure 10 and Figure 13) and by qPCR analysis of a subset of genes (Figure S10).

Antifungal Susceptibility

Susceptibility to azole drugs was determined in broth culture using the Sensititre YeastOne kit (TREK Diagnostic Systems). The assay was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations, with the exception of using Aspergillus minimal medium and an incubation temperature of 30°C to minimize the difference in growth rate between the wt and mutant strains. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) is the lowest antifungal concentration showing inhibition of growth as indicated by the absence of a color change.

Cell Wall Analysis

Mycelial cell wall fractionation was performed according to the method of Fontaine et al. [62], with slight modification. Briefly, the strains were grown in liquid YPD medium at 30°C with gentle shaking (150 rpm). After 24 h of growth, the mycelia were collected by filtration, washed extensively with water and disrupted in 50 mL Falcon tubes using the FastPrep-24 instrument (MP Biomedicals, Solon, United States). Disruptions were performed using 1 mm glass beads at 4°C, 6 m/s for one minute each, twice. The disrupted mycelial suspensions were centrifuged (3,000 g, 10 min) and the cell wall fractions (pellet) obtained was washed three times with water. Subsequent removal of proteins using SDS and β-mercaptoethanol, alkali-fractionation and estimation of the hexose composition by gas-liquid chromatography was performed as reported previously [15].

Analysis of Ergosterol Content

A total of 1×107 conidia were inoculated into 5 mL of YPD medium in a 50 mL conical tube and incubated at 30°C for 24 h, with gentle shaking (200 rpm). The biomass was washed with sterile distilled water and dried under vacuum. The dried mycelium was weighed prior to crushing under liquid nitrogen and then saponified in 1 mL of alcoholic KOH (3% KOH in ethanol). Stigmastanol was added as an internal standard and sterols were extracted into petroleum ether (hexane). The sterol concentrations were analyzed by gas chromatography using a known ratio of ergosterol and stigmastanol as the external standard. Values are presented as µg ergosterol per mg dry weight.

Mouse Model of Invasive Aspergillosis

Conidia were harvested from OSM plates and resuspended in sterile saline. Groups of 12 CF-1 out-bred female mice (22 – 32 g, 6–8 weeks of age) were immunosuppressed with a single dose of triamcinolone acetonide (40 mg kg-1 of body weight) injected subcutaneously on day -1. The mice were anesthetized with 3.5% isofluorane and inoculated intranasally with 2×106 conidia in a 20 µl suspension of saline. Survival was monitored for 2 weeks and persistence of the infection was assessed by plating the lungs of surviving mice onto inhibitory mold agar (IMA). Statistical significance of the mortality curve was assessed by Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA using Sigma Stat 3.5. A p-value of <0.001 was considered statistically significant.

For histopathological analysis of lung tissue, mice were infected as described above and sacrificed on days 1 and 3 post-infection. The lungs were fixed by inflation with 4% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde, dehydrated and embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 µm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Grocott methenamine silver (GMS). Microscopic examinations were performed on an Olympus BH-2 microscope and imaging system using Spot software version 4.6.

Ethics Statement

Animal experiments were carried out in strict accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the Public Health Service Policy on the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and all U.S. Animal Welfare Act Regulations. The experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Cincinnati (protocol # 06-01-03-02). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering.

Genbank Accession Numbers for Genes in This Study

A. fumigatus IreA annotated in Genbank (XP_749922), A. fumigatus IreA cDNA sequenced in this study (JN653078), A. fumigatus hacAi (EU877964), A. fumigatus hacA (XM_743634).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. RavindranSBoothroydJC 2008 Secretion of proteins into host cells by Apicomplexan parasites. Traffic 9 647 656

2. Sam-YelloweTY 2009 The role of the Maurer's clefts in protein transport in Plasmodium falciparum. Trends Parasitol 25 277 284

3. FleckCBSchobelFBrockM 2011 Nutrient acquisition by pathogenic fungi: Nutrient availability, pathway regulation, and differences in substrate utilization. Int J Med Microbiol 301 400 407

4. NeofytosDFishmanJAHornDAnaissieEChangCH 2010 Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis 12 220 229

5. RomischK 2004 A cure for traffic jams: small molecule chaperones in the endoplasmic reticulum. Traffic 5 815 820

6. DobsonCM 2003 Protein folding and misfolding. Nature 426 884 890

7. MalhotraJDKaufmanRJ 2007 The endoplasmic reticulum and the unfolded protein response. Semin Cell Dev Biol 18 716 731

8. MoriK 2009 Signalling pathways in the unfolded protein response: development from yeast to mammals. J Biochem 146 743 750

9. SidrauskiCWalterP 1997 The transmembrane kinase Ire1p is a site-specific endonuclease that initiates mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response. Cell 90 1031 1039

10. PincusDChevalierMWAragonTvan AnkenEVidalSE 2010 BiP binding to the ER-stress sensor Ire1 tunes the homeostatic behavior of the unfolded protein response. PLoS Biol 8 e1000415

11. CoxJSShamuCEWalterP 1993 Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell 73 1197 1206

12. MoriKMaWGethingMJSambrookJ 1993 A transmembrane protein with a cdc2+/CDC28-related kinase activity is required for signaling from the ER to the nucleus. Cell 74 743 756

13. LiHKorennykhAVBehrmanSLWalterP 2010 Mammalian endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor IRE1 signals by dynamic clustering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 16113 16118

14. BackSHSchroderMLeeKZhangKKaufmanRJ 2005 ER stress signaling by regulated splicing: IRE1/HAC1/XBP1. Methods 35 395 416

15. RichieDLHartlLAimaniandaVWintersMSFullerKK 2009 A role for the unfolded protein response (UPR) in virulence and antifungal susceptibility in Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathog 5 e1000258

16. LeeKPDeyMNeculaiDCaoCDeverTE 2008 Structure of the dual enzyme Ire1 reveals the basis for catalysis and regulation in nonconventional RNA splicing. Cell 132 89 100

17. LeeKTirasophonWShenXMichalakMPrywesR 2002 IRE1-mediated unconventional mRNA splicing and S2P-mediated ATF6 cleavage merge to regulate XBP1 in signaling the unfolded protein response. Genes Dev 16 452 466

18. MulderHJNikolaevI 2009 HacA-dependent transcriptional switch releases hacA mRNA from a translational block upon endoplasmic reticulum stress. Eukaryot Cell 8 665 675

19. SimsAHGentMELanthalerKDunn-ColemanNSOliverSG 2005 Transcriptome analysis of recombinant protein secretion by Aspergillus nidulans and the unfolded-protein response in vivo. Appl Environ Microbiol 71 2737 2747

20. GuillemetteTvan PeijNNGoosenTLanthalerKRobsonGD 2007 Genomic analysis of the secretion stress response in the enzyme-producing cell factory Aspergillus niger. BMC Genomics 8 158

21. ArvasMPakulaTLanthalerKSaloheimoMValkonenM 2006 Common features and interesting differences in transcriptional responses to secretion stress in the fungi Trichoderma reesei and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Genomics 7 32

22. MulderHJSaloheimoMPenttilaMMadridSM 2004 The transcription factor HACA mediates the unfolded protein response in Aspergillus niger, and up-regulates its own transcription. Mol Genet Genomics 271 130 140

23. TraversKJPatilCKWodickaLLockhartDJWeissmanJS 2000 Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell 101 249 258

24. WaltherTCBricknerJHAguilarPSBernalesSPantojaC 2006 Eisosomes mark static sites of endocytosis. Nature 439 998 1003

25. WangHXDouglasLMAimaniandaVLatgeJPKonopkaJB 2011 The Candida albicans Sur7 protein is needed for proper synthesis of the fibrillar component of the cell wall that confers strength. Eukaryot Cell 10 72 80

26. PakulaTMLaxellMHuuskonenAUusitaloJSaloheimoM 2003 The effects of drugs inhibiting protein secretion in the filamentous fungus Trichoderma reesei. Evidence for down-regulation of genes that encode secreted proteins in the stressed cells. J Biol Chem 278 45011 45020

27. BravoRVicencioJMParraVTroncosoRMunozJP 2011 Increased ER-mitochondrial coupling promotes mitochondrial respiration and bioenergetics during early phases of ER stress. J Cell Sci 124 2143 2152

28. HeleniusAAebiM 2004 Roles of N-linked glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu Rev Biochem 73 1019 1049

29. HartmannTSasseCSchedlerAHasenbergMGunzerM 2011 Shaping the fungal adaptome - Stress responses of Aspergillus fumigatus. Int J Med Microbiol 301 408 416

30. AraujoRRodriguesAG 2004 Variability of germinative potential among pathogenic species of Aspergillus. J Clin Microbiol 42 4335 4337

31. PaisleyDRobsonGDDenningDW 2005 Correlation between in vitro growth rate and in vivo virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. Med Mycol 43 397 401

32. BhabhraRMileyMDMylonakisEBoettnerDFortwendelJ 2004 Disruption of the Aspergillus fumigatus gene encoding nucleolar protein CgrA impairs thermotolerant growth and reduces virulence. Infect Immun 72 4731 4740

33. WillgerSDPuttikamonkulSKimKHBurrittJBGrahlN 2008 A sterol-regulatory element binding protein is required for cell polarity, hypoxia adaptation, azole drug resistance, and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathog 4 e1000200

34. Romero-RamirezLCaoHNelsonDHammondELeeAH 2004 XBP1 is essential for survival under hypoxic conditions and is required for tumor growth. Cancer Res 64 5943 5947

35. LatgeJP 2007 The cell wall: a carbohydrate armour for the fungal cell. Mol Microbiol 66 279 290

36. GasteboisAClavaudCAimaniandaVLatgeJP 2009 Aspergillus fumigatus: cell wall polysaccharides, their biosynthesis and organization. Future Microbiol 4 583 595

37. SturleySL 2000 Conservation of eukaryotic sterol homeostasis: new insights from studies in budding yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta 1529 155 163

38. Alcazar-FuoliLMelladoEGarcia-EffronGLopezJFGrimaltJO 2008 Ergosterol biosynthesis pathway in Aspergillus fumigatus. Steroids 73 339 347

39. JorgensenTRGoosenTHondelCARamAFIversenJJ 2009 Transcriptomic comparison of Aspergillus niger growing on two different sugars reveals coordinated regulation of the secretory pathway. BMC Genomics 10 44

40. WeinbergED 1999 The role of iron in protozoan and fungal infectious diseases. J Eukaryot Microbiol 46 231 238

41. SchrettlMBignellEKraglCJoechlCRogersT 2004 Siderophore biosynthesis but not reductive iron assimilation is essential for Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. J Exp Med 200 1213 1219

42. SchrettlMBeckmannNVargaJHeinekampTJacobsenID 2010 HapX-mediated adaption to iron starvation is crucial for virulence of Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathog 6 e1001124

43. BicknellAABabourAFederovitchCMNiwaM 2007 A novel role in cytokinesis reveals a housekeeping function for the unfolded protein response. J Cell Biol 177 1017 1027

44. ReadND 2011 Exocytosis and growth do not occur only at hyphal tips. Mol Microbiol 81 4 7

45. VinckATerlouMPestmanWRMartensEPRamAF 2005 Hyphal differentiation in the exploring mycelium of Aspergillus niger. Mol Microbiol 58 693 699

46. ShenXEllisRESakakiKKaufmanRJ 2005 Genetic interactions due to constitutive and inducible gene regulation mediated by the unfolded protein response in C. elegans. PLoS Genet 1 e37

47. HollienJLinJHLiHStevensNWalterP 2009 Regulated Ire1-dependent decay of messenger RNAs in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol 186 323 331

48. SprongHvan der SluijsPvan MeerG 2001 How proteins move lipids and lipids move proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2 504 513

49. SimoninHBeneyLGervaisP 2007 Cell death induced by mild physical perturbations could be related to transient plasma membrane modifications. J Membr Biol 216 37 47

50. McDonaghAFedorovaNDCrabtreeJYuYKimS 2008 Sub-telomere directed gene expression during initiation of invasive aspergillosis. PLoS Pathog 4 e1000154

51. PoytonROCastelloPRBallKAWooDKPanN 2009 Mitochondria and hypoxic signaling: a new view. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1177 48 56

52. PorterJRBurgJSEspenshadePJIglesiasPA 2010 Ergosterol regulates SREBP cleavage in fission yeast. J Biol Chem 285 41051 41061

53. WisemanRLZhangYLeeKPHardingHPHaynesCM 2010 Flavonol activation defines an unanticipated ligand-binding site in the kinase-RNase domain of IRE1. Mol Cell 38 291 304

54. JoubertASimoneauPCampionCBataille-SimoneauNIacomi-VasilescuB 2011 Impact of the unfolded protein response on the pathogenicity of the necrotrophic fungus Alternaria brassicicola. Mol Microbiol 79 1305 1324

55. CoveDJ 1966 The induction and repression of nitrate reductase in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Biochim Biophys Acta 113 51 56

56. ShangJLehrmanMA 2004 Discordance of UPR signaling by ATF6 and Ire1p-XBP1 with levels of target transcripts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 317 390 396

57. NiermanWCPainAAndersonMJWortmanJRKimHS 2005 Genomic sequence of the pathogenic and allergenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Nature 438 1151 1156

58. BoyleEIWengSGollubJJinHBotsteinD 2004 GO::TermFinder–open source software for accessing Gene Ontology information and finding significantly enriched Gene Ontology terms associated with a list of genes. Bioinformatics 20 3710 3715

59. KanehisaMGotoSKawashimaSOkunoYHattoriM 2004 The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res 32 D277 280

60. EisenMBSpellmanPTBrownPOBotsteinD 1998 Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 14863 14868

61. SaldanhaAJ 2004 Java Treeview–extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics 20 3246 3248

62. FontaineTSimenelCDubreucqGAdamODelepierreM 2000 Molecular organization of the alkali-insoluble fraction of Aspergillus fumigatus cell wall. J Biol Chem 275 41528

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Quorum Sensing in Fungi: Q&AČlánek Blood Feeding and Insulin-like Peptide 3 Stimulate Proliferation of Hemocytes in the MosquitoČlánek The DEAD-box RNA Helicase DDX6 is Required for Efficient Encapsidation of a Retroviral GenomeČlánek A Phenome-Based Functional Analysis of Transcription Factors in the Cereal Head Blight Fungus,Článek A Wide Extent of Inter-Strain Diversity in Virulent and Vaccine Strains of AlphaherpesvirusesČlánek The Anti-Sigma Factor TcdC Modulates Hypervirulence in an Epidemic BI/NAP1/027 Clinical Isolate ofČlánek Critical Roles for LIGHT and Its Receptors in Generating T Cell-Mediated Immunity during InfectionČlánek Frequent and Recent Human Acquisition of Simian Foamy Viruses Through Apes' Bites in Central Africa

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 10- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Infekční komplikace virových respiračních infekcí – sekundární bakteriální a aspergilové pneumonie

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Quorum Sensing in Fungi: Q&A

- Discovery of an Ebolavirus-Like Filovirus in Europe

- Toll-like Receptor 7 Controls the Anti-Retroviral Germinal Center Response

- Tubule-Guided Cell-to-Cell Movement of a Plant Virus Requires Class XI Myosin Motors

- Herpesvirus Telomerase RNA (vTR) with a Mutated Template Sequence Abrogates Herpesvirus-Induced Lymphomagenesis

- Mitochondrial Peroxiredoxin Plays a Crucial Peroxidase-Unrelated Role during Infection: Insight into Its Novel Chaperone Activity

- Sustained CD8+ T Cell Memory Inflation after Infection with a Single-Cycle Cytomegalovirus

- Novel Mouse Xenograft Models Reveal a Critical Role of CD4 T Cells in the Proliferation of EBV-Infected T and NK Cells

- Toll-8/Tollo Negatively Regulates Antimicrobial Response in the Respiratory Epithelium

- Exhausted Cytotoxic Control of Epstein-Barr Virus in Human Lupus

- Structural and Functional Analysis of Laninamivir and its Octanoate Prodrug Reveals Group Specific Mechanisms for Influenza NA Inhibition

- Infection Drives IL-17-Mediated Neutrophilic Allergic Airways Disease

- Blood Feeding and Insulin-like Peptide 3 Stimulate Proliferation of Hemocytes in the Mosquito

- HIV-1 Replication in the Central Nervous System Occurs in Two Distinct Cell Types

- Deep Molecular Characterization of HIV-1 Dynamics under Suppressive HAART

- Fitness Landscape of Antibiotic Tolerance in Biofilms

- The DEAD-box RNA Helicase DDX6 is Required for Efficient Encapsidation of a Retroviral Genome

- Preventing Sepsis through the Inhibition of Its Agglutination in Blood

- A Phenome-Based Functional Analysis of Transcription Factors in the Cereal Head Blight Fungus,

- IFITM3 Inhibits Influenza A Virus Infection by Preventing Cytosolic Entry

- Targeting Cattle-Borne Zoonoses and Cattle Pathogens Using a Novel Trypanosomatid-Based Delivery System

- A Wide Extent of Inter-Strain Diversity in Virulent and Vaccine Strains of Alphaherpesviruses

- Coordinated Destruction of Cellular Messages in Translation Complexes by the Gammaherpesvirus Host Shutoff Factor and the Mammalian Exonuclease Xrn1

- Signal Transduction through CsrRS Confers an Invasive Phenotype in Group A

- Biochemical and Structural Insights into the Mechanisms of SARS Coronavirus RNA Ribose 2′-O-Methylation by nsp16/nsp10 Protein Complex

- Histone Deacetylase 8 Is Required for Centrosome Cohesion and Influenza A Virus Entry

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Envelope Protein Regulates Cell Stress Response and Apoptosis

- Co-opts the FGF2 Signaling Pathway to Enhance Infection

- IRAK-2 Regulates IL-1-Mediated Pathogenic Th17 Cell Development in Helminthic Infection

- Trafficking of Hepatitis C Virus Core Protein during Virus Particle Assembly

- The Anti-interferon Activity of Conserved Viral dUTPase ORF54 is Essential for an Effective MHV-68 Infection

- A Viral Nuclear Noncoding RNA Binds Re-localized Poly(A) Binding Protein and Is Required for Late KSHV Gene Expression

- Suppression of Methylation-Mediated Transcriptional Gene Silencing by βC1-SAHH Protein Interaction during Geminivirus-Betasatellite Infection

- ISG15 Is Critical in the Control of Chikungunya Virus Infection Independent of UbE1L Mediated Conjugation

- Non-Hematopoietic Cells in Lymph Nodes Drive Memory CD8 T Cell Inflation during Murine Cytomegalovirus Infection

- RNA Polymerase II Stalling Promotes Nucleosome Occlusion and pTEFb Recruitment to Drive Immortalization by Epstein-Barr Virus

- Noninfectious Retrovirus Particles Drive the / Dependent Neutralizing Antibody Response

- Endophytic Life Strategies Decoded by Genome and Transcriptome Analyses of the Mutualistic Root Symbiont

- An Integrated Approach to Elucidate the Intra-Viral and Viral-Cellular Protein Interaction Networks of a Gamma-Herpesvirus

- as an Animal Model for the Study of Biofilm Infections

- Homeostatic Proliferation Fails to Efficiently Reactivate HIV-1 Latently Infected Central Memory CD4+ T Cells

- The Anti-Sigma Factor TcdC Modulates Hypervirulence in an Epidemic BI/NAP1/027 Clinical Isolate of

- Enhances Protective and Detrimental HLA Class I-Mediated Immunity in Chronic Viral Infection

- The Mouse IAPE Endogenous Retrovirus Can Infect Cells through Any of the Five GPI-Anchored EphrinA Proteins

- The Urgent Need for Robust Coral Disease Diagnostics

- HacA-Independent Functions of the ER Stress Sensor IreA Synergize with the Canonical UPR to Influence Virulence Traits in

- A Novel Core Genome-Encoded Superantigen Contributes to Lethality of Community-Associated MRSA Necrotizing Pneumonia

- Critical Roles for LIGHT and Its Receptors in Generating T Cell-Mediated Immunity during Infection

- The SARS-Coronavirus-Host Interactome: Identification of Cyclophilins as Target for Pan-Coronavirus Inhibitors

- Frequent and Recent Human Acquisition of Simian Foamy Viruses Through Apes' Bites in Central Africa

- Mechanisms of Trafficking to the Brain

- Defining Emerging Roles for NF-κB in Antivirus Responses: Revisiting the Enhanceosome Paradigm

- The Role of Sialyl Glycan Recognition in Host Tissue Tropism of the Avian Parasite

- Evolutionarily Divergent, Unstable Filamentous Actin Is Essential for Gliding Motility in Apicomplexan Parasites

- The Herpes Simplex Virus-1 Transactivator Infected Cell Protein-4 Drives VEGF-A Dependent Neovascularization

- Distinct Single Amino Acid Replacements in the Control of Virulence Regulator Protein Differentially Impact Streptococcal Pathogenesis

- Soluble Rhesus Lymphocryptovirus gp350 Protects against Infection and Reduces Viral Loads in Animals that Become Infected with Virus after Challenge

- A Genetic Screen Reveals Arabidopsis Stomatal and/or Apoplastic Defenses against pv. DC3000

- Hepatitis C Virus Reveals a Novel Early Control in Acute Immune Response

- Fumarate Reductase Activity Maintains an Energized Membrane in Anaerobic

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Envelope Protein Regulates Cell Stress Response and Apoptosis

- The SARS-Coronavirus-Host Interactome: Identification of Cyclophilins as Target for Pan-Coronavirus Inhibitors