-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaReproductive Mode and the Evolution of Genome Size and Structure in Nematodes

Closely related species can vary widely in genome size, yet the genetic and evolutionary forces responsible for these differences are poorly understood. Among Caenorhabditis nematodes, self-fertilizing species have genomes 20–40% smaller than outcrossing species. Constructing a high quality de novo genome assembly in C. remanei, we find that this outcrossing species has many more protein coding genes than the self-fertilizing Caenorhabditis. Intergenic spaces are larger on the X chromosome and smaller on autosomes for both selfing and outcrossing Caenorhabditis, but protein-coding genes are larger on the X chromosome in the self-fertile C. briggsae and C. elegans and larger on autosomes in the outcrossing C. remanei. This contrasting pattern of contracting genomes and expanding genes is likely mediated by changes in the balance between genetic drift and natural selection accompanying the transition to self-fertilization.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005323

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005323Summary

Closely related species can vary widely in genome size, yet the genetic and evolutionary forces responsible for these differences are poorly understood. Among Caenorhabditis nematodes, self-fertilizing species have genomes 20–40% smaller than outcrossing species. Constructing a high quality de novo genome assembly in C. remanei, we find that this outcrossing species has many more protein coding genes than the self-fertilizing Caenorhabditis. Intergenic spaces are larger on the X chromosome and smaller on autosomes for both selfing and outcrossing Caenorhabditis, but protein-coding genes are larger on the X chromosome in the self-fertile C. briggsae and C. elegans and larger on autosomes in the outcrossing C. remanei. This contrasting pattern of contracting genomes and expanding genes is likely mediated by changes in the balance between genetic drift and natural selection accompanying the transition to self-fertilization.

Introduction

Self reproduction increases the probability of homozygosity at single loci, reducing the effective size of the population by a factor of two [1–3]. At the level of whole genomes, the reduced probability that two loci will be heterozygous within a single individual greatly decreases the efficacy of recombination, thereby increasing linkage disequilibrium within the population [4]. Increased homozygosity can expose heretofore recessive mutations to natural selection, potentially accelerating the rate of evolution at those loci, while increased linkage disequilbrium makes self-reproducing (“selfing”) species more susceptible to selective sweeps and/or background selection generated by advantageous and deleterious mutations [5]. What then should be the genomic consequences of a transition in mating system from outcrossing to selfing? The reduction in population size means that genetic drift should become more prominent, allowing for the accumulation of slightly deleterious features, such as repetitive elements, which should lead to an increase in genome size [6]. Similarly, increased linkage disequilibrium means that new advantageous mutations are more likely to bring along deleterious elements via hitchhiking as they increase in frequency [7].

Alternatively, any systematic mutational bias in the direction of DNA deletion would have a greater chance of succeeding within selfing species if such deletions are mildly deleterious [8], and even more so if the transition to selfing means that certain biological functions related to outcrossing (such as mate finding) are no longer needed. Further, increased linkage within selfing lineages increases the probability of co-inheritance of the host genome and selfish genetic elements such as transposable elements, which should lead to an increase in the efficacy of selection against the selfish elements and therefore a reduction in genome size if such elements are a significant fraction of the original ancestral genome [9]. Finally, in species with sex chromosomes, selfing has the potential to equalize the effective population size of sex chromosomes, which tend to have an Ne that is 3/4 as large as autosomes because of the reduced chromosome count in the heterogametic sex [1]. Although this is not usually an issue in plants, for which there are few species with sex chromosomes [10], in animals this change in the ratio of effective population size, as well as other sex-chromosome specific effects such as the lack of dominance in the heterogametic sex, could influence the rate of molecular evolution on sex chromosomes [11] following a transition to selfing. Thus, shifts in mating systems could potentially lead to either increases or decreases in genome size depending on the functional role and genomic context of a given segment of DNA. Determining what actually occurs in nature therefore depends both on a well-documented evolutionary transition in mating system and a set of well-annotated genomes that allow genetic function to be appropriately classified and compared.

Nematodes in the genus Caenorhabditis have made the transition from outcrossing to selfing three separate times independently [12, 13]. The well known model system C. elegans, as well as the species C. briggsae and C. tropicalis, reproduce primarily through self fertile hermaphrodites, which are essentially sperm-producing females derived from male-female (gonochoristic) ancestors. Males capable of mating with the hermaphrodites are also present at low frequencies within these species, but importantly, hermaphrodites are incapable of mating with each other. The genome sizes in Caenorhabditis nematodes are smaller by 20–40% for self-fertile hermaphrodites (C. elegans, 100.4Mb; C. briggsae, 108Mb; C. tropicalis, 79Mb) than the flow-cytometry estimated genome sizes of the larger Ne outcrossers (C. remanei, 131Mb; C. brenneri, 135Mb; C. japonica, 135Mb)[14–16]. A similar pattern of genome reduction has been observed in multiple self-reproducing plant species as well [9], which raises the possibility that genome size reduction may be a general syndrome associated with the transition to self reproduction.

Here, we combine existing genome assemblies with new functional annotation for each of these species in order to examine common features of genomic evolution that are shared across the three transitions in mating system from outcrossing to selfing within this genus. However, outcrossing nematode genome assemblies remain problematic because of remarkably high levels of DNA sequence variation in these species, including some of the most polymorphic animals currently known [17, 18]. This extreme polymorphism presents a particularly unique problem for genome assembly because the worm’s small size precludes sequencing a single animal, and so DNA must be extracted from populations that tend to remain highly polymorphic despite laboratory inbreeding [19]. Thus, in order to address questions about changes in finer-scale genomic structure under the transition to selfing, we also present a high-quality draft genome sequence for the outcrossing C. remanei and use this sequence to test theoretical predictions regarding the influence of self-fertilization on genome evolution. The combination of general comparisons across the phylogeny with specific comparisons between C. elegans, C. briggsae, and C. remanei shows that, while these nematodes share the general pattern of genome size reduction with plants, they appear to achieve it in different ways and that the particulars of the changes likely result from an interaction between genomic architecture and changes in population size and the frequency of interactions between the sexes.

Results and Discussion

Genomic comparisons

We analyzed the genome content of all Caenorhabditis members of the Elegans supergroup with genome sequences available on Wormbase [20]: the self-fertile hermaphrodites C. briggsae, C. elegans, and C. tropicalis and the outcrossing C. remanei, C. japonica, C. brenneri, and C. sinica (formerly C. sp. 5 [21]). In addition, we analyzed the outcrossing C. angaria as an outgroup [22]. We performed each analysis on both the extant C. remanei assembly and our new de novo assembly presented below. The results presented here are based on the de novo assembly, with the analysis of previously assembled (highly polymorphic) C. remanei genome sequence presented in the Supplemental Materials (S1 Table; S1 Fig). For each genome used here, we also generated a de novo functional annotation for each species using the same pipeline so as to minimize annotation bias from influencing the results (S2 Table).

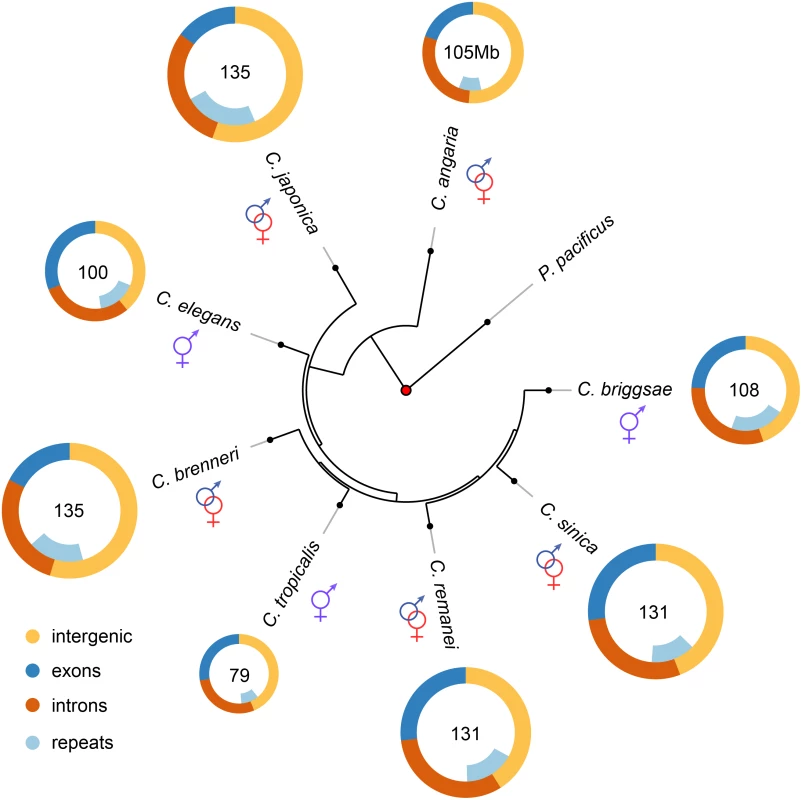

Overall, consistent with previous genome size estimates based on flow cytometry [14, 15], self-fertile species within this group have substantially smaller genomes than their most closely related outcrossing relatives (Fig 1, Table 1, S2 Table). Taking the average genome size of the outcrossing species to be 130Mb, the genomes of C. elegans, C. briggsae and C. tropicalis have been reduced by 23%, 17% and 39% respectively via the transition to selfing. These are likely to be upper bounds on the actual size reduction because of likely over-assembly of most of the outcrossing species (see below). Although the branch lengths between each is actually fairly long (on the order of tens of millions of years), the actual time of the shift to selfing within any given lineage is likely to not have been more than ~4 million years based on the rate of evolution of codon usage bias [23]. To a first order, the overall pattern of genome shrinkage is roughly proportional when summed across broad functional categories, including the total size of exons, introns, intergenic regions, and repetitive elements within each genome (Fig 1; Table 1). Importantly, it does not appear that genome shrinkage is dominated by changes within a single functional class, such as repetitive elements. Thus, this comparative analysis suggests that genomic change following the transition to selfing is generated by a general reduction in genome size across coding and non-coding regions. A more precise analysis requires a careful comparison within each functional category, which in turn requires more complete genome assemblies for outcrossing species than are currently available within this group. To this end, we generated a de novo high quality assembly of C. remanei before completing the remainder of the tests.

Fig. 1. Genome content analysis across the Caenorhabditis Elegans supergroup (with outgroup species C. angaria and the distantly related P. pacificus).

Genome content analysis does not support expansion of repeat elements in outcrossing species. The Elegans supergroup contains at least 17 species [93], but only the species whose genomes are analyzed here used are shown. The Elegans supergroup evolved from a common ancestor with a gonochoristic (e.g., male-female) mating system (identified with the red and blue symbols) and C. japonica, C. brenneri, C. remanei and C. sinica have retained the ancestral mating system. C. elegans, C. briggsae, and C. tropicalis have an androdioecious mating system with self-fertile hermaphrodites and males segregating at low levels in the populations. Tab. 1. Summary of genomic characteristics.

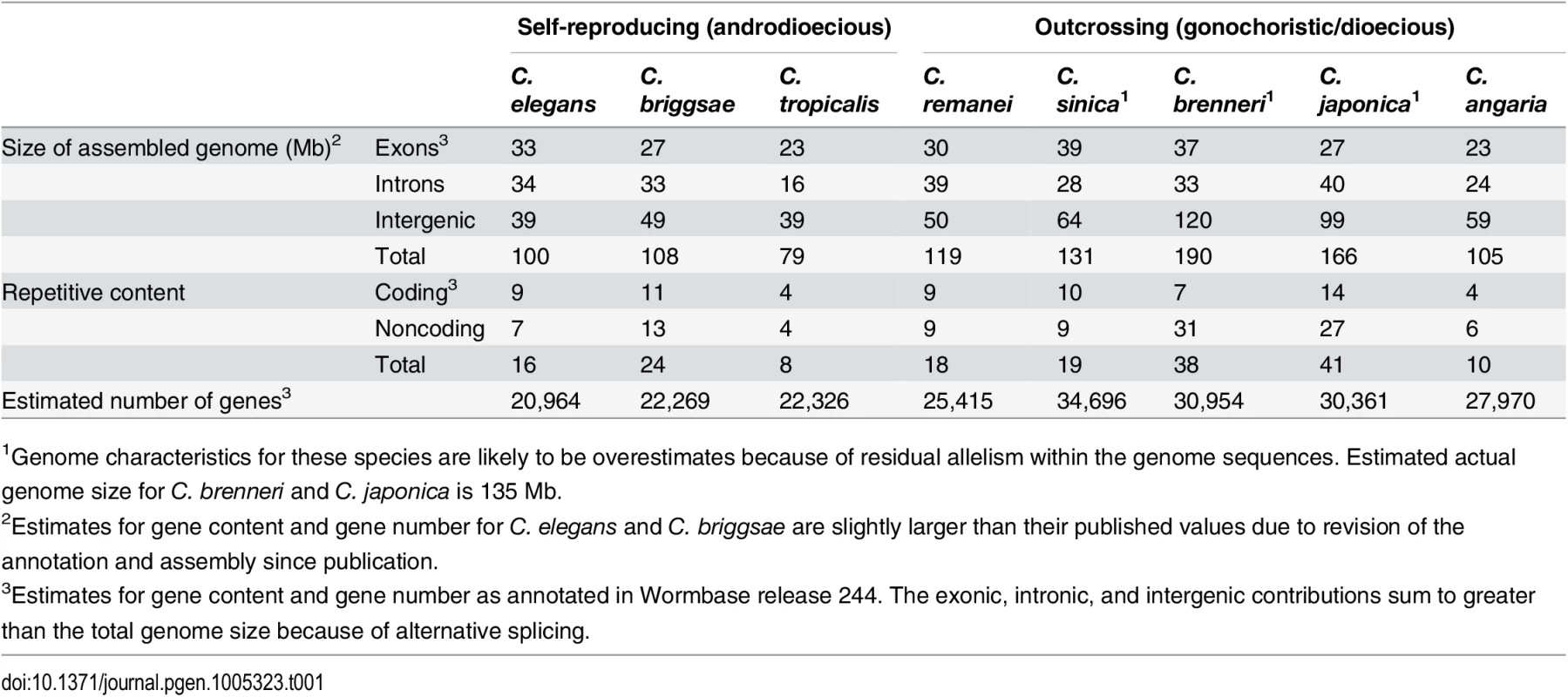

1Genome characteristics for these species are likely to be overestimates because of residual allelism within the genome sequences. Estimated actual genome size for C. brenneri and C. japonica is 135 Mb. Assembly of the C. remanei genome

To create a reliable and well-assembled genome sequence for C. remanei, we first aimed to remove residual polymorphism from extant laboratory strains. We used a novel breeding scheme to create nearly isogenic strains for deep coverage genome sequencing, genetic mapping, and high-quality genome assembly. Specifically, we performed sequential inbreeding and selection over 50 generations to purge deleterious mutations and create 2 highly inbred C. remanei lines (New York PX356 and Ohio PX439). We then assembled a de novo draft genome sequence for PX356 from ~560x coverage of paired-end shotgun sequence, and ~75x coverage of 3 sizes of mate pair libraries. We used sequenced mRNA extracts from a mixed-stage population of C. remanei to annotate protein-coding genes.

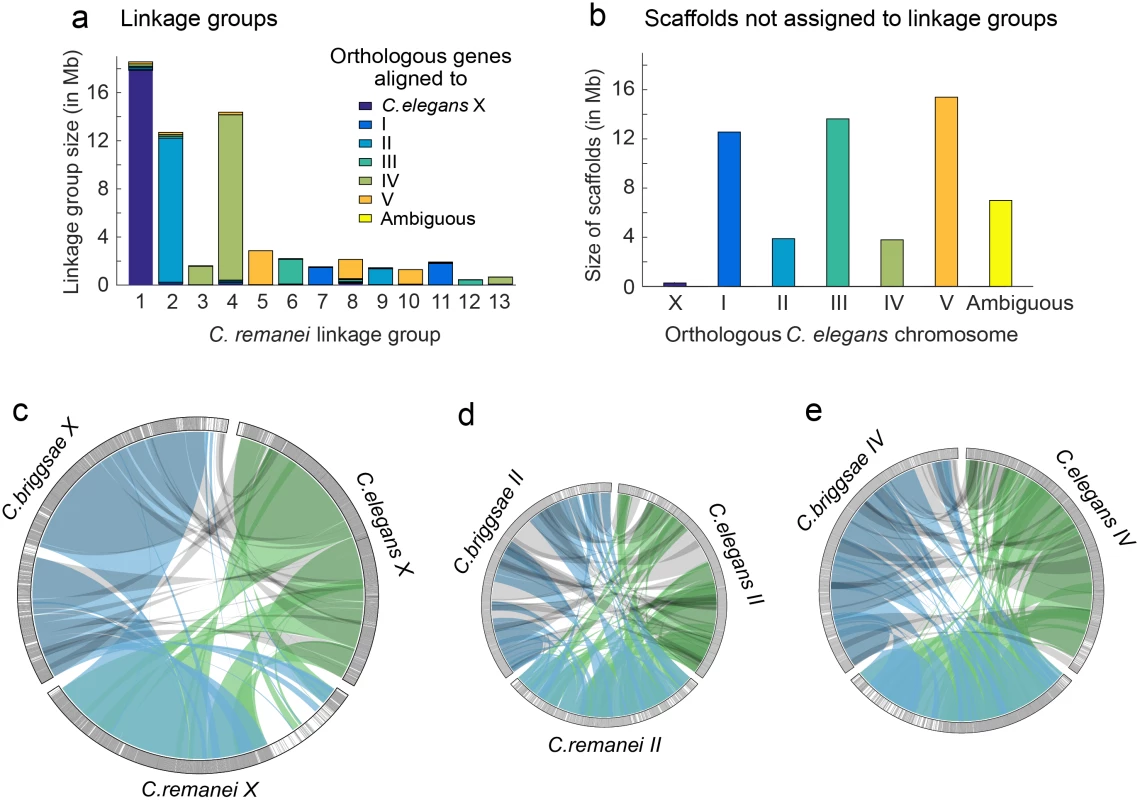

We estimated residual polymorphism in our inbred PX356 strain to occur at just ~0.01% of sites in well-assembled genic regions. In comparison, analyses of the previously assembled draft C. remanei genome [19] found allelic dimorphism for 4.7% of defined C. elegans orthologous genes and a sizable portion of DNA aligning to the C. elegans Chromosome IV (~10% of the total genome). Unfortunately, cryptic reproductive incompatibilities between PX356 and PX439 led to significant segregation distortion for several linkage groups in our genetic map. Overall, our assembly appears to provide good coverage for linkage groups orthologous to C. elegans Chromosomes II, IV, and X, with more fragmented coverage of Chromosomes I, III, and V (Fig 2). Nevertheless, gene assemblies within these large fragments are excellent. This therefore represents the first well-assembled genome from a highly polymorphic outcrossing species from this group. When looking at the evolution of genome structure we concentrate on the subset of well-assembled chromosomes, while when looking at the evolution of gene structure, we include the entire genome assembly.

Fig. 2. Whole chromosome comparisons among C. elegans, C. briggsae, and C. remanei.

The C. remanei The linkage map was sufficient to assemble and order 98.93% of the scaffolds with orthologous genes aligning to C. elegans chromosome X, 78.38% of the scaffolds with orthologous genes aligning to C. elegans chromosome II and 81.40% of the scaffolds with orthologous genes aligning to C. elegans chromosome IV. (a) C. remanei linkage groups were assigned to chromosomes based on gene orthology to C. elegans chromosomes. Reproductive incompatibility between the C. remanei strains used to construct the linkage map resulted in over-dispersion of the linkage map and 13 linkage groups instead of the 6 chromosomes expected (both C. elegans and C. briggsae have 6 chromosomes, respectively). (b) The cumulative size and orthologous gene alignments for scaffolds that were not assigned to linkage groups. c-e) Orthologous gene alignments indicated blocks of syntenic DNA between C. elegans, C. briggsae, and C. remanei. The panels c-e show orthologous genes on chromosomes X, II, and IV, with chromosome size scaled to linkage group size in C. remanei (X 18.5Mb, II 12.5Mb, IV 14.5 Mb). Orthologous genes were connected between species pairs, and grouped together if the genes were within 50,000 nucleotides of each other. Single gene translocations were excluded for clarity. Green indicates orthologs identified between C. elegans and C. remanei, blue indicates orthologs identified between C. remanei and C. briggsae, and grey indicates orthologs identified between C. briggsae and C. elegans. The outer rings are chromosomes X, II, and IV in each species. Each gray line is an orthologous gene located on the same chromosome in the other species and each black line is an orthologous gene that is located on a different chromosome in one of the other species. There are few blocks of interchromosomal translocation, and few black lines. White indicates regions of the chromosome where there were no orthologous genes identified between the species. (c) There was a large region of divergence (roughly 3.6Mb) on the C. remanei X; (d) Chromosome II is not completely assembled in C. remanei, and there were several regions of C. elegans and C. briggsae chromosome II that were not represented in C. remanei; (e) Chromosome IV. Evolution of transposable element copy number

We first tested the hypothesis that change in genome size in selfers is driven by a reduction in transposable element (TE) abundance [24]. TEs vary widely in structure, mobility, distribution, and diversity [25] and, depending on the dynamics of these factors and population size, transposons are predicted to increase genome size in selfers relative to outcrossers [26] or outcrossers relative to selfers [27].

Within this group of nematodes, the C. briggsae genome is 8Mb larger than the C. elegans genome largely owing to repeat content [28], with roughly 8% of the C. briggsae genome composed of Tc1-IS630-Pogo DNA transposons [29]. We found that the repeat content of C. remanei is intermediate between C. elegans and C. briggsae (Fig 1; Table 1; S2 Table), and therefore expansion of repetitive DNA within C. remanei can not explain genome size differences. The self-fertile C. tropicalis has the smallest genome (79Mb) of the Elegans supergroup, as well as the smallest repeat content. However, the self-fertile C. briggsae has a repeat content larger than any of the outcrossing Caenorhabditis with the exception of C. japonica. We therefore find no evidence that repeat expansion and/or shrinkage explains the majority of genome size differences between outcrossing and self-fertile Caenorhabditis, although it is a minor contributing factor for C. elegans and C. tropicalis. This is in stark contrast to plants, in which it appears that reduction in TE content is one of the major factors driving the evolution of smaller genome size within the self-compatible species [30].

Biased insertion/deletion frequencies

Accumulated biases in insertion or deletion mutations may grow or shrink genomes across different scales. For example, Hu et al.[30] examined the basis for genome size differences between the self-fertile plant Arabidopsis thaliana (with a 125Mb genome) and the outcrossing A. lyrata (with a 207Mb genome), and found hundreds of thousands of small deletions in the self-fertile A. thaliana. Alternatively, insertions and deletions could occur at the level of individual genes; A. thaliana has 17% fewer genes than A. lyrata[30]. Thomas et al.[31] found that selfing Caenorhabditis have smaller transcriptomes than related outcrossers and a specific reduction in expression of genes that show sex-biased expression in outcrossing Caenorhabditis. Large-scale rearrangements may also account for genome size differences, and comparison between the A. thaliana-A. lyrata genomes discovered 3 large deletions in the selfing species [30].

Biases in the distribution of indels can be driven by selection or via neutral processes. Rapid growth and reproduction may favor small genomes [32], and self-fertile organisms with these life cycles [33] may experience selection for DNA loss. Parasites are expected to be more frequent in outcrossing populations than selfing, and theoretical studies indicate that parasites may select against gene loss in hosts [34]. Alternatively, neutral differences in mutational processes may result in genome size differences [35, 36]. Size transmission bias, whereby the XX hermaphrodites tend to inherit chromosomes shortened by deletions and XO males tend to inherit longer chromosomes with transgenic insertions, has been reported in C. elegans[37]. Although the mechanism through which this occurs is not yet known, simulations indicate that the androdioecious mating system of self-fertilizing Caenorhabditis, with males contributing few offspring to most generations, could rapidly lead to reduced genome size via this mechanism [37].

First, we explored the role of large-scale insertions and deletions contributing to genome size differences within C. elegans, C. briggsae, and C. remanei, as this analysis requires well-assembled chromosomes. These species have diverged from a common ancestor at least 30 million years ago [38], which means that few sequences other than those within conserved coding regions can be aligned between them. In order to align large genomic regions, we identified 15,699 orthologous genes among the three species, finding that >90% of these orthologous genes are found on the same chromosome in all three (Fig 2). The X chromosome in particular retains a striking conservation of synteny, with the exception of an apparent C. remanei-specific ~3.6Mb region of divergence (Fig 2C). This latter portion of the C. remanei X chromosome contains 786 annotated genes, but only 48 of these are orthologous to genes in C. elegans (47 to genes in C. briggsae), and of these, only 17 orthologous genes are found on the C. elegans X (the same 17 genes have orthologous counterparts on the C. briggsae X). Fifty of the genes in this region are orthologous to genes in C. brenneri but in the absence of a C. brenneri genetic map we do not know if these are located on the X chromosome.

Genes within a highly divergent syntenic region may retain similar biological functions despite a lack of clear orthologous counterparts. We used Interproscan v5.3 to assign putative biological functions to protein domains for the clusters of genes with no apparent syntenic relationships across species. For example, roughly 7% of the genes in the C. elegans genome are seven transmembrane G protein-coupled serpentine receptors (7TM GPCRs)[39]. These chemosensory genes are responsible for recognition of food, environment, and other animals, and thought to be found in large numbers in Caenorhabditis because of the soil/decaying-plant-dwelling nematodes need to respond to environmental cues [39]. There are 19 families of serpentine receptors in C. elegans. The majority of members within a family occur as clusters on chromosome arms, thought to be the result of local gene duplication events [40]. The C. remanei genome contains 59 serpentine receptor class g (srg) genes. Six srg genes (10.17% of the total) are located in this region of the X chromosome (2.74% of the total genome), and the genes surrounding each of these srg genes show no functional or sequence similarity to the genes surrounding the 72 C. elegans srg genes or the 60 C. briggsae srg genes. Thus, this region of the X appears to largely hold C. remanei-specific genes and to not be translocated relative to other chromosomes in other species.

We next tested the accumulated insertion/deletion hypothesis for genome size change by focusing on indel size biases in smaller blocks of aligned sequence. Consistent with the larger-scale comparisons, we found no difference in indel size bias among species when we analyzed individual syntenic blocks of DNA between species pairs (S2 Fig). In particular, there is no evidence that these aligned regions tend to be systematically smaller in C. elegans and C. briggsae relative to C. remanei. Although there are a few specific differences among species, overall we do not find evidence that either large-scale rearrangements or small-scale indels are an important contributor to genome size differences among these species.

Protein-coding genes

Our de novo C. remanei genome assembly predicts a complement of 25,415 protein-coding genes, compared to 20,532 in C. elegans and 21,936 in C. briggsae (Table 2). The genome-wide unspliced transcript footprint in C. remanei, comprising the combination of exons, introns and untranslated regions (UTR’s), comprised ~69.33Mb (58.51% of the assembled genome; 52.92% of the estimated genome size), which is 18.83% larger than the equivalent footprint in C. briggsae (58.09Mb [28], 53.79% of the assembled genome), 18.74% larger than C. elegans (58.39Mb [20], 58.16% of the assembled genome). Consequently, the transcribed genic footprint explains the difference in assembled genome size between C. briggsae and C. remanei and ~60% of the difference in assembled genome size between C. elegans and C. remanei. Similarly, the outcrossing C. brenneri has 30,667 protein-coding genes and an unspliced transcript footprint of 70.5Mb (Fig 1), although these are likely overestimates due to allelism in the assembly [19]. Consistent with this pattern, we predict 22,326 coding genes within the self-fertile C. tropicalis (see Table 1 for all species). These results are consistent with an analysis of gene content within these species assessed by whole-genome transcriptional analysis [31]. Thus, while there is no evidence for differences in repeat content or indel biases among these species, there is strong evidence that genome size differences result from differential protein-coding gene content in self-fertile and outcrossing Caenorhabditis.

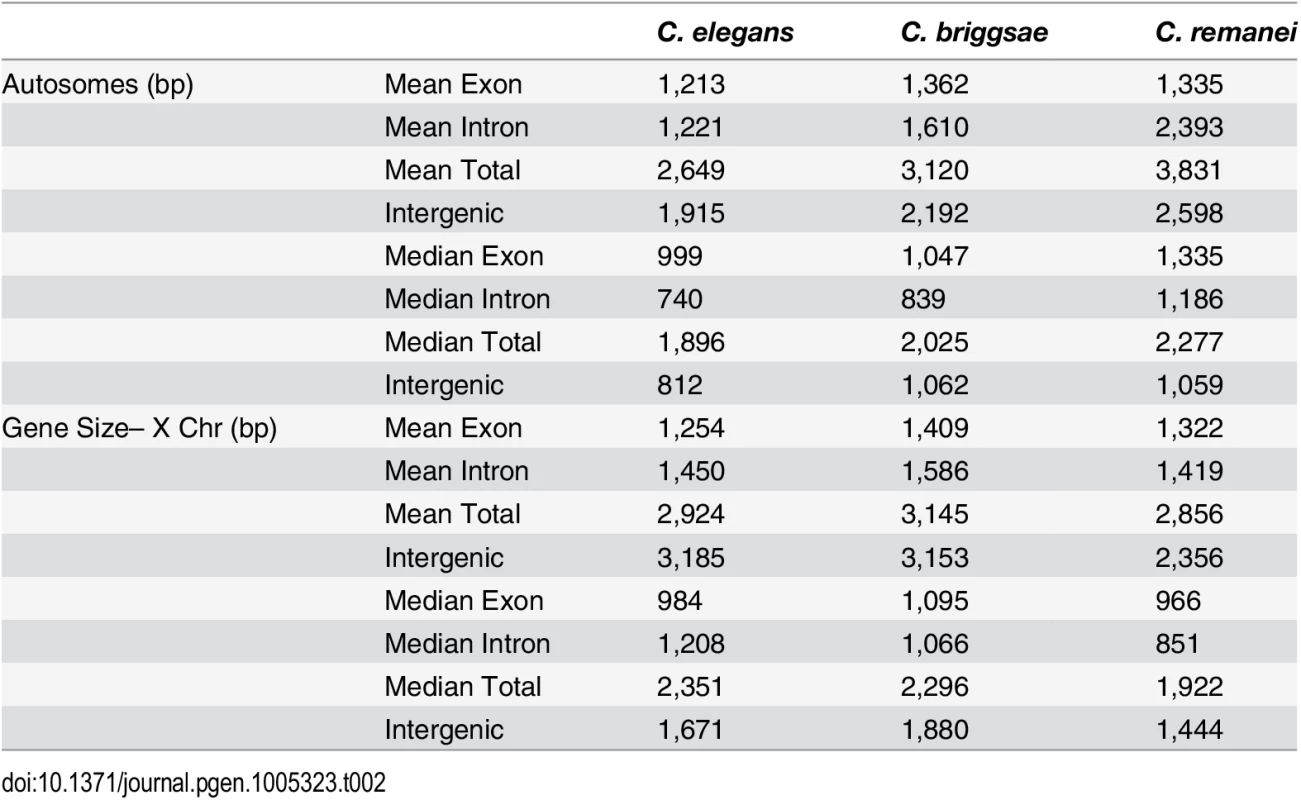

Tab. 2. Summary of gene-specific properties across species.

Intergenic distances

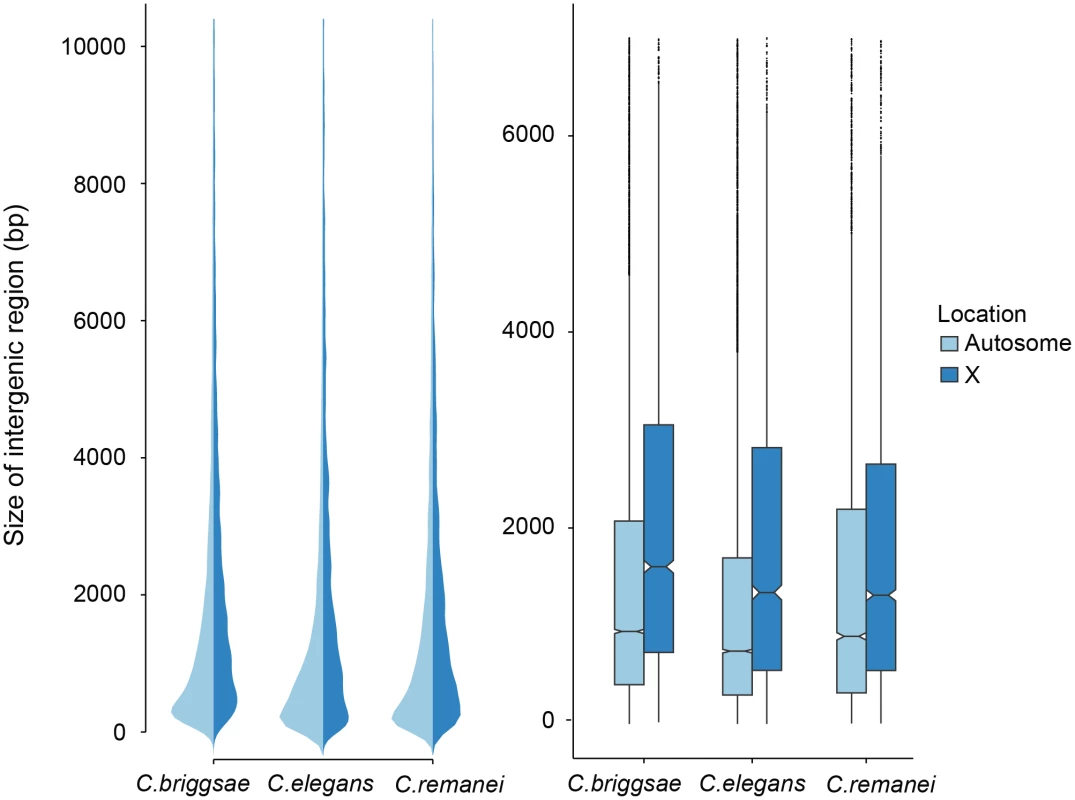

Intergenic distances vary widely within Caenorhabditis genomes, with some genes located in co-transcribed operons that are separated by a few nucleotides and other genes separated by many kilobases of sequence. Autosomal intergenic spacing for C. remanei exceeded that of both C. briggsae and C. elegans, despite these being lower bound values for C. remanei because of the potential for unincluded, unassembled regions probably underestimate C. remanei intergenic distances (Fig 3; Table 2). Across the entire genome (including scaffolds not included in linkage groups) the total intergenic content of C. remanei was 0.79Mb larger than that of C. briggsae and 10.73Mb larger than that of C. elegans.

Fig. 3. Comparison of intergenic spaces between autosomes and X chromosomes.

(a) Kernel smoothed distribution of intergenic spaces across the entire genome for C. elegans, C. briggsae and C. remanei. (b) Intergenic spaces differ between autosomes and the X chromosome in C. briggsae (Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 556.09, df = 1, p < 2x10−16), C. elegans (Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 476.32, df = 1, p < 2x10−16) and C. remanei (Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 76.76, df = 1, p < 2x10−16). The boxplot indicates the bottom and top quartiles (black lines), middle quartiles (blue boxes), and median value (central notch) with outliers are shown as black dots. Intergenic spaces differ significantly between species on autosomes (Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 328.4957; df = 2, p < 2x10−16; Bonferroni-adjusted Pairwise Wilcoxon Rank Sum C. remanei:C. elegans p < 2x10−16, C. remanei:C. briggsae p < 0.039; C. briggsae:C. elegans p < 2x10−16) and the X chromosome (Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 112.52, df = 2, p < 2x10−16; Bonferroni-adjusted Pairwise Wilcoxon Rank Sum C. remanei:C. elegans p < 1.6x10−7, C. remanei:C. briggsae p < 2x10−16; C. briggsae:C. elegans p < 0.0005). In an outcrossing population with a 50 : 50 sex ratio there are 3/4 the number of X chromosomes in a population for any given autosome. The effective population size of the X is also reduced by variance in male mating success, and under the effective population hypothesis these forces should result in increased genetic drift and the proliferation of weakly deleterious elements [6]. In contrast, the effective population size of the X chromosome should be equivalent to the autosomes in self-fertile organisms [41]. However, we found no difference in the relative ratio of intergenic regions in the selfing versus outcrossing species (Fig 3). Presumably either the evolutionary forces that are responsible for maintaining variation in the size of intergenic spaces are not sensitive to changes in effective population size, the timescale since the advent of selfing has not been long enough for the genomic features of the sex chromosome and autosomes to equilibrate in the selfers [23], or, as we discuss below, there are other genetic differences between these chromosomes that drive this pattern.

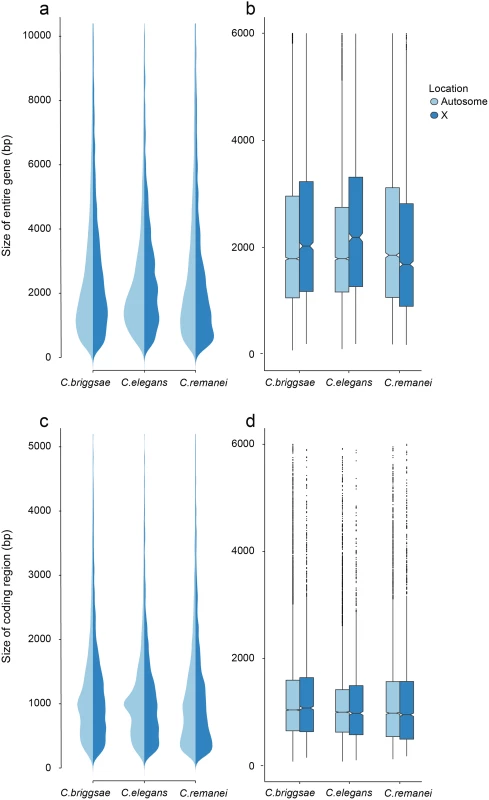

Divergence in gene structure

In order to analyze gene structure, we identified a set of co-orthologs conserved as pairs between C. remanei, C. briggsae and C. elegans (Fig 4). We found that among our co-ortholog coding sequences the average number (6) and length (~200bp) of exons per gene was similar for the three species. The total length of gene transcripts was longer on autosomes in C. remanei than in C. briggsae or C. elegans but smaller on the X chromosome in C. remanei than in C. briggsae or C. elegans (Fig 4, Table 2). The protein sequences were not significantly different between the X chromosome and autosomes in any of the three species and among the species only C. briggsae had protein sizes that differed significantly from the other species.

Fig. 4. Differences in total gene size (introns and exons) versus protein coding size (exons) in C. elegans, C. briggsae and C. remanei.

(a-b) Gene Size differs between autosomes and the X chromosome in C. briggsae (Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 24.63, df = 1, p < 6.96x10−7), C. elegans (Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 58.04, df = 1, p < 2.56x10−14) and C. remanei (Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 99.10, df = 1, p < 2x10−16) but protein size does not (C. briggsae Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 0.94, df = 1, p = 0.66; C. elegans Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 0.29, df = 1, p = 1; C. remanei Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 4.3096, df = 1, p = 0.08). Gene size differs significantly among the species on autosomes (Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 152.86; df = 2, p < 2x10−16; Bonferroni-adjusted Pairwise Wilcoxon Rank Sum C. remanei:C. elegans p < 2x10−16, C. remanei:C. briggsae p < 2x10−16; C. briggsae:C. elegans p < 6x10−5) and between C. remanei and the self-fertile hermaprodites on the X chromsome (Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 64.39; df = 2, p < 1x10−14; Bonferroni-adjusted Pairwise Wilcoxon Rank Sum C. remanei:C. elegans p < 2x10−10, C. remanei:C. briggsae p < 1.8x10−11; C. briggsae:C.elegans p = 1). (c-d) Protein size differs significantly between C. briggsae and C. elegans and C. briggsae and C. remanei on both the autosomes (Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 91.32; df = 2, p < 2x10−16; Bonferroni-adjusted Pairwise Wilcoxon Rank Sum C. remanei:C. elegans p = 1, C. remanei:C. briggsae p < 2x10−16; C. briggsae:C.elegans p < 1.5x10−11) and X chromosome (Kruskal-Wallis χ2 = 40.36; df = 2, p < 1.7x10−9; Bonferroni-adjusted Pairwise Wilcoxon Rank Sum C. remanei:C. elegans p = 0.92, C. remanei:C. briggsae p < 4x10−9; C. briggsae:C.elegans p < 2x10−5). Thus there is an interesting interaction between chromosomal gene structure and mating system, with intron size expanding on the X with the advent of selfing. Although this could reflect an accumulation of slightly deleterious DNA in the selfing species because of a decrease in effective population size [42], we would expect the same expansion to occur within autosomes. Another alternative is that increased selection on male function on males within C. remanei in turn drives stronger X-specific genomic evolution, although this seems unlikely given the fact that it appears that the X is actually enriched for genes affecting female/hermaphroditic function as opposed to male function [43].

Given that these explanations based purely on population genetics do not appear to fit the data, another explanation based on genetic differences between the chromosomes seems more likely. In C. elegans, it is known that genetic map is much more uniform on the X chromosome than on the autosomes (which tend to have very little recombination toward their centers)[44]. Indeed the molecular machinery that generates chromosome pairing and crossing over is different for the X than the autosomes [45]. Because the effective recombination rate is lower in selfers than in outcrossers, the difference in intron size between the X and autosomes within C. elegans and C. briggsae may reflect differential sensitivity to changes in effective recombination across chromosomes, coupled with the fact that the X and autosomes now experience similar effective population sizes under selfing. There may therefore be a complex interaction between recombination, drift and selection on the X that is driving this unusual pattern. Distinguishing among hypotheses will require a more careful analysis of the pattern of selection operating on the X and autosomes.

Functional divergence

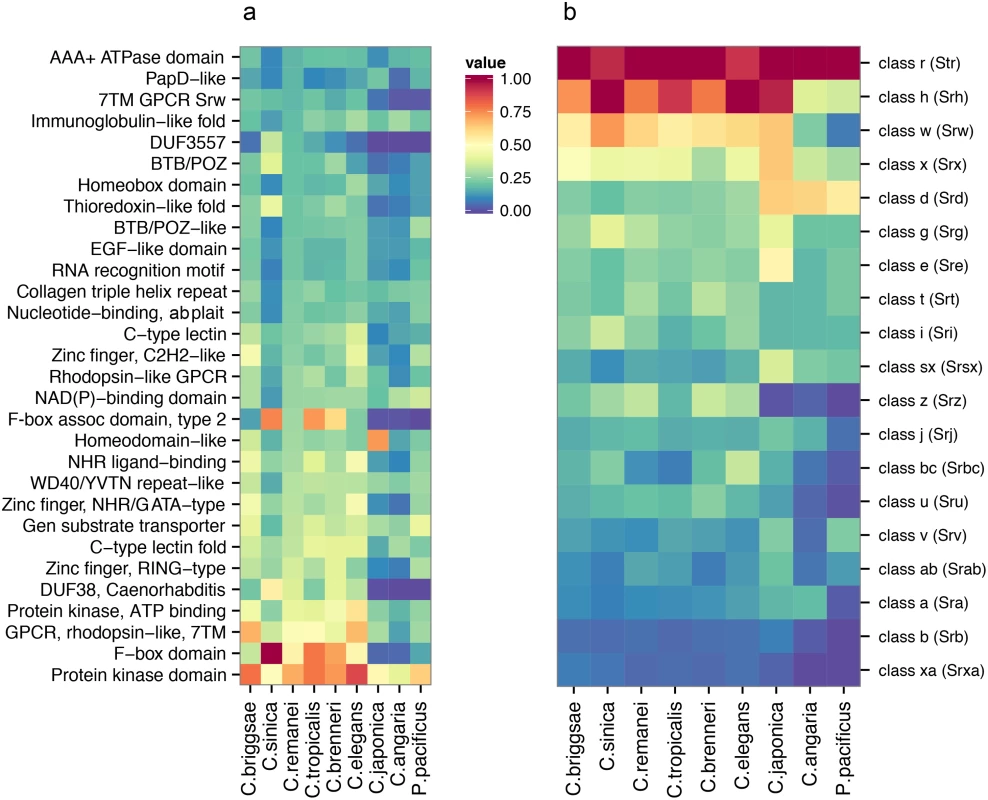

Caenorhabditis genomes have large numbers of nematode-specific and species-specific proteins [46], and high divergence makes it difficult to conclusively identify individual genes that are present in outcrossing Caenorhabditis but lost in the selfers. To accommodate this, we characterized functional divergence between self-fertile and outcrossing Caenorhabditis by analyzing putative protein domains in the genomes of Caenorhabditis and the distantly related P. pacificus (Fig 5). We found no functional groups that were significantly enriched in the outcrossing Caenorhabditis relative to the selfing Caenorhabditis. There are numerous species-specific differences, however. For example, we identified between 191 and 1,721 proteins with F-box domains (IPR001810) in C. briggsae, C. sinica, C. remanei, C. tropicalis, C. brenneri and C. elegans, 5–18 times as many as identified in C. japonica, C. angaria and P. pacificus.

Fig. 5. Comparative analysis of protein diversity.

(a) The 30 most significantly enriched protein domains (p < 0.001) in the C. remanei genome (as compared to the C. elegans genome), and the corresponding interproscan annotations across Caenorhabditis and P. pacificus. The value shown is scaled relative to the top protein domain identified in each species. The species are plotted in phylogenetic order and protein kinase domains, F-box domains, GPCRs, domain of unknown function 38, and protein of unknown function DUF3557 are found in low numbers outside the Elegans group. (b) The relative representation of each 7TM GPCR family across Caenorhabditis and P. pacificus. The species are plotted in phylogenetic order and each value is scaled relative to the top 7TM GPCR family identified in each species. Domains found in large numbers in members of the Elegans supergroup encompass functionally diverse proteins (i.e., protein kinase domains, C-type lectins, and zinc fingers), and proteins known to be important in Caenorhabditis, including the 7TM GPCRs introduced earlier, F-box domains, and the Caenorhabditis-specific Domain of Unknown Function DUF38 (Fig 5A). These proteins are clearly fundamental for Caenorhabditis biology, but for the most part there is little functional information known about these rapidly evolving protein families. To more closely examine a particularly hyper-diverse gene family, we identified 1,499 serpentine receptor genes in C. elegans, 1,125 in C. briggsae and 1,026 in C. remanei and the relative distribution among the families is similar across the Elegans supergroup (Fig 5B). Despite these large numbers there is functional evidence, direct or inferred, for only ~10 GPCRs [47]. Further analysis of similarities across whole molecular pathways are provided in the Supplementary Material (S1 Text, S3 Fig). We did find a small number of genes that are present in outcrossing species but lost in within selfing species, although no obvious classes of genes reveal themselves as being specifically lost within these groups (S1 Text). Overall, then, broad genomic comparisons do not reveal any systematic gain or loss of functional categories within and between mating system types, although each individual genome can show dramatic differences within any given gene family.

Evolution of genome size under selfing

Within-species polymorphism across Caenorhabditis varies by several orders of magnitude, with selfing species being relatively depauperate of variation [16] and outcrossing species being among the most polymorphic animals yet observed [18]. At least one likely reason for these dramatic differences in polymorphism are differences in effective population size among species, which has been estimated as <10,000 in C. elegans[48], <60,000 in C. briggsae[49] and >1,000,000 in C. remanei[17]. We would therefore expect that deleterious elements would be more likely to accumulate and expand the genomes of self-reproducing species because of their small population sizes. Instead, we find just the opposite. Genomes are smaller in selfers and intergenic spaces and protein-coding genes are larger on the X chromosome than autosomes. In the outcrossing C. remanei protein-coding genes are smaller on the X chromosome despite the reduced effective population size of the X versus the autosomes in male-female species.

The transition from outcrossing to self-fertilization is common in plants, and plant genome size is similarly positively correlated with outcrossing [9], although this relationship is weakened when corrected for phylogenetic relatedness [50]. It is possible that changes in genome size may be a consequence of ecological shifts that accompany life history differences being selfing and outcrossing species. However, the genome of the model self-fertile Arabidopsis thaliana (125Mb) is smaller than its outcrossing relative A. lyrata (207Mb) largely due to numerous small and large-scale deletions, including 17% fewer genes [30]. TEs play a major role in plant genome size evolution [24, 51, 52] and, while the genome of A. lyrata does show an increase in TE activity relative to A. thaliana, a comparison between Capsella rubella, a plant that became self-fertile less than 200,000 years ago, and the related outcrossing C. grandiflora reported few differences in TE content [53]. We find no evidence that the genome size differences between selfing and outcrossing species are mediated by TE activity and/or other forms of small indels. Instead, DNA loss in Caenorhabditis appears to have occurred specifically at the level of individual genes.

Natural selection might drive genome reduction, or genome shrinkage could accrue through deletion biases and genetic drift. DNA content is positively correlated with increased cell size and negatively correlated with cell growth and division, metabolic rate [54], and developmental rate [32], but it is unclear why self-fertility would necessarily lead to increased selection on these traits. Alternatively, selective sweeps on new beneficial mutations could lead to the fixation of weakly deleterious deletions because of increased linkage disequilibria in selfers. The fixation of such deletions would be particularly facilitated in a non-adaptive manner if deletion per se acted as a directional process. For example, deletions predominate over insertions in C. briggsae nuclear [55, 56] and mitochondrial DNA [57], however insertions predominate over deletions in C. elegans mutation accumulation lines [55, 58, 59] and under temperature stress [56]. Perhaps most interestingly, there is evidence in C. elegans that autosomal deletions are preferentially transmitted to X-bearing sperm (and thereby hermaphrodites in this XO sex determination system)[37]. This kind of bias could rapidly reduce genome size following the transition to self-fertilization. However, rather than observing systematic reduction in gene size with the selfing species, we find that both C. elegans and C. briggsae have larger introns on the X than C. remanei while maintaining similarly sized genes on the autosomes. Thus, while there are definitely deletions across the whole genome, they are at the level of whole genes instead of being randomly spread across functional elements such as introns, as would be expected if the genome size reduction were driven by a directional mutation process.

Instead, it appears that adaptation to self-fertility per se is the most likely explanation for the reduction in genome size. For instance it may be advantageous to lose/alter systems directly related to maintaining outcrossing, such as mating in the case of nematodes or floral characteristics in the case of plants [23, 60]. In keeping with this, Thomas et al.[31] found that genes with higher degrees of sex-specific expression tend to be lost more frequently than other genes within these same species. Similar loss of function changes appear to be common in other cases of adaptive phenotypic evolution [61]. Overall, then, these results suggest an evolutionary model for genome reduction following the evolution of selfing within this group of nematodes: 1) relaxed selection on specific genes, like those involved in facilitation of outcrossing [31, 53]; 2) deletion of genes and their surrounding intergenic sequences; and 3) accumulation of these deletions resulting in derived decreases in genome size. There are several other genera of nematodes within this family that also show variation in mating systems [62, 63], so it should be possible to discern if this is a general pattern of genome loss within self-fertilizing species.

Lynch [42] proposed the effective population size hypothesis as a first step in transforming “the descriptive field of comparative genomics into a more mechanistic theory of evolutionary genomics.” Our results indicate that self-fertile organisms experience loss of DNA as a general feature of the transition in mating systems but that these losses are not driven by changes in effective population size per se. The specific mechanisms by which this occurs appear to vary across groups, from plants to animals. Linking changes within specific genomic functional classes with the dynamics of natural selection and fitness differences that favor DNA loss in self-fertile organisms is the next step in understanding the influence of mating system on genome evolution.

Materials and Methods

Worm culture and strain construction

C. remanei strains were cultured using standard methods adopted from techniques developed for C. elegans[64]. The C. remanei PX356 strain was created from the canonical isofemale line EM464 originally isolated from New York (USA), which was initially named C. vulgaris but has since been synonymized with C. remanei[65]. The existing polymorphic assembly of C. remanei is based on a partially inbred line derived from this same strain (EM4641). To overcome the extreme inbreeding depression usually observed within C. remanei, we derived 200 independent lines from the original EM464 population and subjected them to brother-sister mating in order to allow the independent fixation and loss of as many recessive deleterious alleles as possible. All but two of the lines went extinct by generation 7. These two remaining lines were then crossed together and maintained as an outcrossing population for 20 generations to increase the probability that deleterious alleles alternatively fixed in the two lines could recombine. An additional 100 lines were derived from this secondary population and then subject to brother-sister mating for 23 generations. The sole surviving line from this procedure was deemed the new canonical EM464-derived line: PX356. In order to create an alternative mapping line, a similar procedure was conducted for an isofemale line (PB259) originally collected from a forest in Ohio (USA) by Scott Baird (Wright State University). This resulted in an additional, divergent inbred line: PX439.

Isolation of DNA and RNA

Genomic DNA was isolated from either starved L1 larvae following a bleach “hatch-off” or from mixed stage populations from a sucrose float using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen) with the C.elegans supplemental protocol. Total RNA was isolated from mixed stage populations using Trizol (Invitrogen). mRNA was purified using Dynabeads Oligo d(T)25 (Invitrogen) and fragmented (Ambion) before cDNA synthesis [66].

Next-generation sequencing

Paired-end genomic DNA sequencing libraries were constructed using the Nextera DNA sample preparation kit (Illumina) or the NEBNext DNA library kit for Illumina (NEB) as per the manufacturers protocols. Using the NEBNext kit, genomic DNA was fragmented with a Bioruptor sonicator (Diagenode) set on high for ten 30 second ON/OFF cycles. Final libraries were size selected on 2% agarose gels with an average genomic insert size of 180 bp as per ALLPATHS-LG recommendations. All libraries were quantified by qPCR (Life Technologies) and the proper size range was confirmed using a fragment analyzer (Advanced Analytical Technologies). Libraries were sequenced as 2 X 101nt reads using an Illumina HiSeq instrument.

The mate pair libraries were constructed using standard molecular techniques following the manufacturers recommendations. In brief, genomic DNA was sheared on the low setting for 5 seconds using a Bioruptor sonicator (Diagenode) and purified using the Desalting and Concentrating DNA section for the QIAEX-II kit (Qiagen). DNA was end-repaired using the End-it kit from epicentre. Following purification, the DNA was biotin labelled with 1mM dNTP (4% biotin), purified and run on a 0.6% agarose gel. Size ranges of 3, 5 and 7 kb were isolated and purified using the standard QIAEX II kit. Circularization was carried out overnight at 16 deg.C with ~200ng DNA using T3 ligase (Enzymatics) with T4 ligase buffer. The non-circularized DNA was digested with 3μl of DNA exonuclease (NEB) and placed at 37 deg.C for 20 min. and heat inactivated for 30 min. at 70 deg.C. The DNA was then sheared to ~400 bp using a Bioruptor for ten 30 sec. ON/OFF cycles at high and then purified. The biotin labelled DNA pieces were isolated using Dynabeads M-280 strepavidin (Invitrogen). While on the beads, the DNA fragments were end-repaired, A-tailed, and t-overhang adapters were added before PCR enrichment for 15 cycles using Phusion polymerase (NEB). Libraries were isolated from 2% agarose gels at ~ 400 bp average size range and eluted in EB buffer with 1% tween 20. Final libraries were validated for correct size and molar concentration as noted above. Mate-paired libraries were sequenced as 2 X 101nt reads using an Illumina HiSeq instrument (cDNA synthesis and RNA sequencing libraries were prepared as previously reported [66]).

Genome assembly

We constructed the C. remanei assembly from ∼ 560x coverage of 180bp paired end fragments designed to have overlapping reads on both ends. This high depth of coverage will necessarily include a large number of sequencing errors which would have complicated assembly, and a large number of repeat elements which would have increased assembly time. We pre-filtered the 180bp paired end fragments by kmer frequency spectra (here, k = 15) to address these biases. We removed reads with greater than 12 rare kmers (singletons) to eliminate possible errors and reads with greater than 51 abundant kmers (occurring more than 20,000 times in our dataset) to eliminate possible over-represented repeats (additional details are given in S1 Text). The final short-read dataset averaged 416x coverage across the estimated genome size (131Mb). We also used mate pair libraries with inserts of varying sizes: 31.5x coverage of 0.7–2kb insert paired end fragments, 29x coverage of 2–4kb insert paired end fragments, and 15x coverage of 4–7kb insert paired end fragments. We sequenced 101bp reads with 6bp inline barcodes which resulted in 95bp sequences.

We used the assembly software ALLPATHS-LG [67], which performs its own kmer spectra correction of sequencing reads (k = 25), uses a de Bruijn graph algorithm to build contiguous sequences from the 180bp reads, and constructs scaffolds with mate pair sequences. The initial heterozygosity rate was estimated as 1/176bp and we used the haploidify option to address residual heterozygosity in our inbred strain (S3 Table). We used a multi-step decision tree to identify possible contaminant sequences and removed 17Mb of contaminant scaffolds (details are given in S1 Text; S4 Fig). After assembly we aligned the paired end sequences to our final linkage groups and scaffolds with GSNAP [68] and used SAMtools [69] to summarize single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in a.vcf (variant call format) file. We analyzed this file with a custom pipeline of perl scripts that divide the annotated genomic regions into introns, exons, transposable elements, intergenic regions, transcription start sites, 5’ UTRs and 3’ UTRs and measures the number of polymorphic sites in each of these categories. Read alignments were discarded if the per-base sequencing coverage exceeded 600 (as these may be poorly assembled, collapsed repetitive regions) or if the base quality fell below 90% certainty (Q10 Phred+33). Our estimated residual polymorphism therefore applies only to the well-assembled genic regions and excludes intergenic sequences, transposable elements and other poorly assembled repeats.

Our kmer frequency spectra filtering removed over-represented sequences. In order to eliminate the possibility that this filtering may have created a bias in assembling repetitive elements we also de novo assembled the entire set of 180bp paired end fragments and mate pair libraries with ALLPATHS-LG [67]. We analyzed the repeat content of this genome sequence (methods are given below in the section Characterizing repeats) and found that the repeat content of this sequence was lower than our kmer-filtered genome sequence (13.92% vs. 15.73%). The kmer-filtered assembly was 118.5Mb with 4Mb of gapped sequence and 1,600 scaffolds (S3 Table). The unfiltered assembly was similar in size (119.1Mb) but contained 7Mb of gapped sequence and was fragmented into 3,921 scaffolds. We concluded that kmer frequency spectra did not specifically eliminate repeat elements from our genome but it did remove noise and facilitate a higher-quality, ungapped genome sequence.

Genetic map construction

We generated 64 recombinant inbred lines (RILs) from a cross between parental strains PX356 and PX439 following an advanced intercross method [70]. We then used restriction site associated DNA (RAD) markers [71], generated with EcoRI, to identify SNP markers within each of these strains, as well as in the parental lines. We used the software Stacks[72] to assign sequencing reads to genetic loci and identified 25,447 mappable (i.e., AA x BB where A is the PX356 genotype and B is the PX439 genotype) polymorphic markers. The parental strains appear to be partially reproductively isolated and so many of these SNP markers showed extensive segregation distortion (S5 Fig). We used SAMtools [69] to align the markers to our assembled scaffolds and identified scaffolds where >5 markers had parental genotype frequencies of >80% or <20% in the RILs. We eliminated all markers located on these scaffolds, markers that contained only duplicate data and those with low representation in the RILs (present in <40 lines). We constructed a genetic map in R/qtl [73] from the resulting 330 distinct SNP markers (S6–S7 Figs). We added markers with duplicate data back to the dataset and the final genetic map contains 2,688 SNP markers across 65 Mb (S8–11 Figs). The genetic map identified 4 scaffolds that were incorrectly joined in the assembly, and we broke these on the basis of parental genotype frequency in the RILs and synteny with the existing C. remanei draft assembly. We aligned the 3 large linkage groups to the C. elegans and C. briggsae chromosomes X, II, and IV but smaller linkage groups were not definitively assigned to chromosomes.

Characterizing repeats

The PX356 genome was repeat masked with RepeatMasker v4.0.5 [74] using a custom C. remanei repeat library created by RepeatModeler v1.0.8. In order to compare repeat content between nematode species we also created custom repeat libraries for C. briggsae, C. sinica, C. tropicalis, C. brenneri, C. elegans, C. japonica, C. angaria, and P. pacificus, and repeat masked each genome with the custom repeat library and RepeatMasker. We compared these custom repeat characterizations to the repeats currently annotated in each genome (Wormbase release WS244) and found that each custom characterization was within 1–2% of the currently annotated content with the exception of C. japonica for which we predicted 42% repeat content. This is consistent with previous findings that the allelism in the C. japonica assembly produced over-representation of repeat regions [19]. We present the currently annotated content in Fig 1.

Genome annotation and orthologous gene identification

We sequenced mRNA from our PX356 nematodes with a Illumina Hi-Seq machine and generated 16,250,052 paired end sequences. We assembled these data with the genome-independent Trinity RNA-seq assembly software [75] to generate a set of putative transcripts. We used the software MAKER2 [76] to annotate putative protein-coding loci, with the Trinity transcript set as EST evidence and the protein sequences from C. briggsae, C. elegans, C. brenneri, and the Uniprot/Swiss-Prot [77, 78] database (with Caenorhabditis removed) as protein homology evidence. The maximum intron size was specified as 5,000 nucleotides for evidence alignments. We used SNAP [79] and Augustus [80]ab initio gene prediction software within MAKER2 to generate a putative set of predictions, and used these initial predictions to re-train SNAP and Augustus to produce C. remanei-specific gene prediction models. We predicted 26,339 transcripts from 25,415 protein-coding genes and used a manually curated set of 169 miRNA sequences to annotate putative miRNA loci. Roughly half of the annotated genes (12,323) reside on the 13 linkage groups. Although the assembly is 9.5% shorter than the flow-cytometry estimated genome size, analysis of a core set of genes that are thought to be conserved in single copy in eukaryotes [81] indicates that 95.16% are in complete form in the assembled sequence and the remaining 4.84% are partially complete.

We used the same annotation pipeline to annotate protein-coding genes in the genomes of C. angaria, C. brenneri, C. briggsae, C. elegans, C. japonica, C. sinica and C. tropical. We found that the re-annotation estimated a similar protein-coding footprint with the exception of C. brenneri, for which we predicted >15Mb additional genic content. This is consistent with previous findings that >30% of the genes in the C. brenneri genome are found in two copies [19].

We identified protein motifs and domains with InterProScan [82] (version 5.3), which searches against public protein databases including ProDom [83], PRINTS [84, 85], Pfam [86], SMART [87], PANTHER [88] and PROSITE [89]. We used the Repbase (version 16.10) database of repetitive elements and a library of de novo repeats identified with RepeatModeler [29] to analyze transposable elements and genomic repeat content. We used OrthoMCL (version 1.4) to identify orthologous gene clusters between C. remanei, C. briggsae, C. elegans, and C. brenneri. The C. brenneri genome assembly is highly fragmented (3305 scaffolds) and conflated by ~30% allelic assembly artifacts to be 55Mb larger than the flow-cytometry estimated genome size [19], but is the only other outcrossing Caenorhabditis in the Elegans group with a genome sequence suitable for comparative analyses. Briefly, OrthoMCL [90] uses BLASTP [91] to calculate pairwise protein sequence similarities, and Markov clustering of the similarity scores to define orthologous proteins among the species and paralogous proteins within each proteome.

Characterizing genome content

In order to compare genome content between nematode species we used our MAKER2 gene annotation pipeline to identify protein-coding genes in the Wormbase release WS244 genome sequences of C. briggsae, C. sinica, C. tropicalis, C. brenneri, C. elegans, C. japonica, C. angaria, and P. pacificus (S2 Table). We found that each custom characterization was within 3–5% of the currently annotated content, with the exception of C. brannier for which we predicted a larger gene content. This is consistent with previous findings that >30% of C. elegans orthologous genes are found in two copies in the C. brenneri assembly [19]. We present the currently annotated content in Fig 1.

Measuring intergenic spaces, gene size, and protein size

We used BedTools v2.22.1 [92] to identify intergenic spaces, genic regions, and exonic regions in the genome sequences of C. elegans, C. elegans, and C. remanei. We used the statistical computing language R to calculate descriptive statistics, Kruskal-Wallis rank sum tests, and Pairwise Wilcoxon rank sum tests. We were not able to use parametric statistics because our data were nucleotide counts, each of the distributions showed severe heteroscedasticity, and the sample sizes were unbalanced. Nonparametric statistical tests can not address interaction terms or multi-factor comparisons and we performed one-way tests and Bonferroni corrected our p-values for multiple comparisons.

Accession codes

Assembly and annotation are at www.wormbase.org and are deposited in GenBank under BioProject ID PRJNA248909. De novo annotations of existing genomes are published at figshare.com at dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1399184, dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1396472, dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1396473, dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1396474, dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1396475, dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1396476, dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1396477, and dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1396478. Our analysis pipeline is available at github.com/Cutterlab/popgenome_pipeline.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Wright S (1931) Evolution in Mendelian populations. Genetics 16 : 97–159. 17246615

2. Wright S (1933) Inbreeding and homozygosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 19 : 411–420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.19.4.411 16577532

3. Wright S (1938) Size of population and breeding structure in relation to evolution. Science 87 : 430–431.

4. Charlesworth D, Wright SI (2001) Breeding systems and genome evolution. Curr Op Genet Dev 11 : 685–690. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00254-9 11682314

5. Charlesworth B (2001) The effect of life-history and mode of inheritance on neutral genetic variability. Genet Res 77 : 157–166. doi: 10.1017/S0016672301004979

6. Lynch M, Conery JS (2003) The origins of genome complexity. Science 302 : 1401–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1089370 14631042

7. Cutter AD, Payseur BA (2013) Genomics signatures of selection at linked sites: unifying the disparity among species. Nat Rev Genet 14 : 262–274. doi: 10.1038/nrg3425 23478346

8. Charlesworth D, Charlesworth B (1995) Quantitative genetics in plants: The effect of the breeding system on genetic variability. Evolution 49 : 911–920. doi: 10.2307/2410413

9. Wright SI, Ness RW, Foxe JP, Barrett SCH (2008) Genomic consequences of outcrossing and selfing in plants. Internat J Plant Sci 169 : 105–118. doi: 10.1086/523366

10. Ming R (2011) Sex chromosomes in land plants. Ann Rev Plant Biol 62 : 485–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103914

11. Mank JE, Vicoso B, Berlin S, Charlesworth B (2010) Effective population size and the faster-x effect: empirical results and their interpretation. Evolution 64 : 663–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00853.x 19796145

12. Kiontke K, Gavin NP, Raynes Y, Roehrig C, Piano F, et al. (2004) Caenorhabditis phylogeny predicts convergence of hermaphroditism and extensive intron loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101 : 9003–9008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403094101 15184656

13. Kiontke KC, Felix MA, Ailion M, Rockman MV, Braendle C, et al. (2011) A phylogeny and molecular barcodes for Caenorhabditis, with numerous new species from rotting fruits. BMC Evol Biol 11 : 339. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-339 22103856

14. Bird DM, Blaxter ML, McCarter JP, Mitreva M, Sternberg PW, et al. (2005) A white paper on nematode comparative genomics. J Nematol 37 : 408–416. 19262884

15. Haag ES, Chamberlin H, Coghlan A, Fitch DH, Peters AD, et al. (2007) Caenorhabditis evolution: if they all look alike, you aren’t looking hard enough. Trend Genet 23 : 101–104. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.01.002

16. Jovelin R, Dey A, Cutter AD (2013) Fifteen years of evolutionary genomics in Caenorhabditis. In: Encyclopedia of Life Sciences, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chicester.

17. Cutter AD, Baird SE, Charlesworth D (2006) High nucleotide polymorphism and rapid decay of linkage disequilibrium in wild populations of Caenorhabditis remanei. Genetics 174 : 901–913. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.061879 16951062

18. Dey A, Chan CKW, Thomas CG, Cutter AD (2013) Molecular hyperdiversity defines populations of the nematode Caenorhabditis brenneri. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110 : 11056–11060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303057110 23776215

19. Barriere A, Yang SP, Pekarek E, Thomas CG, Haag ES, et al. (2009) Detecting heterozygosity in shotgun genome assemblies: Lessons from obligately outcrossing nematodes. Genome Res 19 : 470–480. doi: 10.1101/gr.081851.108 19204328

20. Yook K, Harris TW, Bieri T, Cabunoc A, Chan J, et al. (2011) WormBase 2012: more genomes, more data, new website. Nuc Acid Res 40: D735–D741. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr954

21. Huang R, Ren X, Qiu Y, Zhao Z (2014) Description of Caenorhabditis sinica sp. n. (Nematoda:Rhabditidae), a nematode species used in comparative biology for C. elegans. PLoS ONE 9: e110957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110957 25375770

22. Mortazavi A, Schwarz EM, Williams B, Schaeffer L, Antoshechkin I, et al. (2010) Scaffolding a Caenorhabditis genome with RNA-seq. Genome Res 20 : 1740–7. doi: 10.1101/gr.111021.110 20980554

23. Cutter AD, Wasmuth JD, Washington NL (2008) Patterns of molecular evolution in Caenorhabditis preclude ancient origins of selfing. Genetics 178 : 2093–2104. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.085787 18430935

24. Tenaillon MI, Hufford MB, Gaut BS, Ross-Ibarra J (2011) Genome size and transposable element content as determined by high-throughput sequencing in maize and Zea luxurians. Genome Biol Evol 3 : 219–229. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr008 21296765

25. Le QH, Wright S, Yu Z, Bureau T (2000) Transposon diversity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci 97 : 7376–7381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7376 10861007

26. Wright SI, Schoen DJ (1999) Transposon dynamics and the breeding system. Genetica 107 : 139–148. doi: 10.1023/A:1003953126700 10952207

27. Bestor TH (1999) Sex brings transposons and genomes into conflict. Genetica 107 : 289–295. doi: 10.1023/A:1003990818251 10952219

28. Stein LD, Bao Z, Blasiar D, Blumenthal T, Brent MR, et al. (2003) The genome sequence of Caenorhabditis briggsae: A platform for comparative genomics. PLoS Biology 1: e5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000045

29. Price AL, Jones NC, Pevzner PA (2005) De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21: i351–i358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018 15961478

30. Hu TT, Pattyn P, Bakker EG, Cao J, Cheng JF, et al. (2011) The Arabidopsis lyrata genome sequence and the basis of rapid genome size change. Nat Genet 43 : 476–481. doi: 10.1038/ng.807 21478890

31. Thomas CG, Li R, Smith HE, Woodruff GC, Oliver B, et al. (2012) Simplification and desexualization of gene expression in self-fertile nematodes. Curr Biol 22 : 2167–2172. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.038 23103191

32. Pagel M, Johnstone RA (1992) Variation across species in the size of the nuclear genome supports the junk-DNA explanation for the C-value paradox. Proc Roy Soc B 249 : 119–124. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0093

33. Bennett MD, Leitch IJ (1997) Nuclear dna amounts in angiosperms - 583 new estimates. Annal Bot 80 : 169–196. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1997.0415

34. Salathé M, Soyer OS (2008) Parasites lead to evolution of robustness against gene loss in host signaling networks. Molecul Syst Biol 4 : 1–9.

35. Petrov DA, Sangster TA, Johnston JS, Hartl DL, Shaw KL (2000) Evidence for DNA loss as a determinant of genome size. Science 287 : 1060–1062. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1060 10669421

36. Petrov DA (2001) Evolution of genome size: new approaches to an old problem. Trend Genet 17 : 23–28. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02157-0

37. Wang J, Chen PJ, Wang GJ, Keller L (2010) Chromosome size differences may affect meiosis and genome size. Science 329 : 293. doi: 10.1126/science.1190130 20647459

38. Cutter AD (2008) Divergence times in Caenorhabditis and Drosophila inferred from direct estimates of the neutral mutation rate. Mol Biol Evol 25 : 778–786. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn024 18234705

39. Robertson HM, Thomas JS (2005) The putative chemoreceptor families of C. elegans. In: WormBook, http://www.wormbook.org: The C. elegans Research Community.

40. Thomas JH, Robertson HM (2008) The Caenorhabditis chemoreceptor gene families. BMC Biology 6 : 42. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-6-42 18837995

41. Charlesworth D (2003) Effects of inbreeding on the genetic diversity of populations. Phil Trans Royal Soc B 358 : 1051–1070. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1296

42. Lynch M (2005) The origins of eukaryotic gene structure. Mol Biol Evol 23 : 450–468. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj050 16280547

43. Albritton SE, Kranz AL, Rao P, Kramer M, Dieterich C, et al. (2014) Sex-biased gene expression and evolution of the X chromosome in nematodes. Genetics 197 : 865–83. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.163311 24793291

44. Rockman MV, Kruglyak L (2009) Recombinational landscape and population genomics of caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genetics 5: e1000419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000419 19283065

45. Phillips CM, Meng X, Zhang L, Chretien JH, Urnov FD, et al. (2009) Identification of chromosome sequence motifs that mediate meiotic pairing and synapsis in C. elegans. Nat Cell Biol 11 : 934–942. doi: 10.1038/ncb1904 19620970

46. Parkinson J, Mitreva M, Whitton C, Thomson M, Daub J, et al. (2004) A transcriptomic analysis of the phylum Nematoda. Nat Genet 36 : 1259–1267. doi: 10.1038/ng1472 15543149

47. Bargmann CI (2006) Chemosensation in C. elegans. In: WormBook, http://www.wormbook.org: The C. elegans Research Community.

48. Barriere A, Felix M (2005) High local genetic diversity and low outcrossing rate in Caenorhabditis elegans natural populations. Curr Biol 15 : 1176–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.022 16005289

49. Cutter AD, Felix M, Barriere A, Charlesworth D (2006) Patterns of nucleotide polymorphism distinguish temperate and tropical wild isolates of Caenorhabditis briggsae. Genetics 173 : 2021–2031. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.058651 16783011

50. Whitney KD, Baack EJ, Hamrick JL, Godt MJW, Barringer BC, et al. (2010) A role for nonadaptive processes in plant genome size evolution? Evolution 64 : 2097–2109. 20148953

51. Bennett MD, Leitch IJ (2005) Genome size evolution in plants. In: Gregory TR, editor, The Evolution of the Genome, Elsevier, San Diego.

52. Fedoroff NV (2012) Tranposable elements, epigenetics, and genome evolution. Science 338 : 758–767. doi: 10.1126/science.338.6108.758 23145453

53. Slotte T, Hazzouri KM, Ågren JA, Koenig D, Maumus F, et al. (2013) The Capsella rubella genome and the genomic consequences of rapid mating system evolution. Nat Genet 45 : 831–835. doi: 10.1038/ng.2669 23749190

54. Gregory TR (2005) Genome size evolution in animals. In: Gregory TR, editor, The Evolution of the Genome, Elsevier, San Diego.

55. Phillips N, Salomon M, Custer A, Ostrow D, Baer CF (2008) Spontaneous mutational and standing genetic (co)variation at dinucleotide microsatellites in Caenorhabditis briggsae and Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Evol 26 : 659–669. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn287 19109257

56. Matsuba C, Ostrow DG, Salomon MP, Tolani A, Baer CF (2012) Temperature, stress and spontaneous mutation in Caenorhabditis briggsae and Caenorhabditis elegans. Biol Let 9 : 20120334. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2012.0334

57. Howe DK, Baer CF, Denver DR (2010) High rate of large deletions in Caenorhabditis briggsae mitochondrial genome mutation processes. Genome Biol Evol 2 : 29–38. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evp055

58. Denver DR, Morris K, Lynch M, Thomas WK (2004) High mutation rate and predominance of insertions in the Caenorhabditis elegans nuclear genome. Nature 430 : 679–682. doi: 10.1038/nature02697 15295601

59. Seyfert AL, Cristescu MEA, Frisse L, Schaack S, Thomas WK, et al. (2008) The rate and spectrum of microsatellite mutation in Caenorhabditis elegans and Daphnia pulex. Genetics 178 : 2113–2121. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.081927 18430937

60. Glemin S, Galtier N (2012) Genome evolution in outcrossing versus selfing versus asexual species. Method Mol Biol 855 : 311–3335.

61. Martin A, Orgogozo V (2013) The loci of repeated evolution: A catalog of genetic hotspots of phenotypic variation. Evolution 67 : 1235–1250. 23617905

62. Felix M (2006) Oscheius tipulae. In: WormBook, http://www.wormbook.org: The C. elegans Research Community.

63. Denver DR, Clark KA, Raboin MJ (2011) Reproductive mode evolution in nematodes: Insights from molecular phylogenies and recently discovered species. Molecular Phyl Evol 61 : 584–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.07.007

64. Brenner S (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77 : 71–94. 4366476

65. Baird SE, Fitch DHA, Emmons SW (1994) Caenorhabditis vulgaris sp. n. (nematoda: Rhabditidae): A necromenic associate of pillbugs and snails. Nematologica 40 : 1–11. doi: 10.1163/003525994X00012

66. Sikkink KL, Reynolds RM, Ituarte CM, Cresko WA, Phillips PC (2014) Rapid evolution of phenotypic plasticity and shifting thresholds of genetic assimilation in the nematode Caenorhabditis remanei. G3 4 : 1103–1112. doi: 10.1534/g3.114.010553 24727288

67. Gnerre S, MacCallum I, Przybylski D, Ribeiro FJ, Burton JN, et al. (2011) High-quality draft assemblies of mammalian genomes from massively parallel sequence data. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108 : 1513–1518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017351108 21187386

68. Wu TD, Watanabe CK (2005) GMAP: a genomic mapping and alignment program for mRNA and EST sequences. Bioinformatics 21 : 1859–1875. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti310 15728110

69. Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, et al. (2009) The sequence alignment/map (SAM) format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25 : 2078–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 19505943

70. Rockman MV, Kruglyak L (2008) Breeding designs for recombinant inbred advanced intercross lines. Genetics 179 : 1069–1078. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.083873 18505881

71. Baird NA, Etter PD, Atwood TS, Currey MC, Shiver AL, et al. (2008) Rapid SNP discovery and genetic mapping using sequenced RAD markers. PLoS ONE 3: e3376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003376 18852878

72. Catchen JM, Amores A, Hohenlohe P, Cresko W, Postlethwait JH (2011) Stacks: Building and genotyping loci de novo from short-read sequences. G3 1 : 171–182. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000240 22384329

73. Broman KW, Wu H, Sen S, Churchill GA (2003) R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics 19 : 889–890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg112 12724300

74. Smit AF, Hubley R, Green P (1996–2010) Repeatmasker open-3.0.

75. Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thomspon DA, et al. (2011) Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnology 29 : 644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883 21572440

76. Holt C, Yandell M (2011) MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinformatics 12 : 491. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-491 22192575

77. Bairoch A, Apweiler R (2000) The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nuc Acid Res 28 : 45–48. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.45

78. Consortium TU (2011) Ongoing and future developments at the Universal Protein Resource. Nuc Acid Res 39: D214–D219. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1020

79. Korf I (2004) Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 5 : 59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-59 15144565

80. Stanke M, Waack S (2003) Gene prediction with a hidden markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics 19: ii215–ii225. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1080 14534192

81. Parra G, Bradnam K, Ning Z, Keane T, Korf I (2009) Assessing the gene space in draft genomes. Nuc Acid Res 37 : 289–297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn916

82. Zdobnov EM, Apweiler R (2001) InterProScan – an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics 17 : 847–848. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.847 11590104

83. Bru C, Courcelle E, Carrere S, Beausse Y, Dalmar S, et al. (2005) The ProDom database of protein domain families: more emphasis on 3D. Nuc Acid Res 33(s1).

84. Attwood TK, Beck ME (1994) PRINTS – a protein motif fingerprint database. Prot Engineer 7 : 841–848. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.7.841

85. Attwood TK, Beck ME, JBleasby A, Parry-Smith DJ (1994) PRINTS – a database of protein motif fingerprints. Nuc Acid Res 22 : 3590–3596.

86. Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, et al. (2012) The PFam protein families database. Nuc Acid Res 40(D1): D290–D301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065

87. Ponting CP, Schultz J, Milpetz F, Bork P (1999) SMART: identification and annotation of domains from signaling and extracellular protein sequences. Nuc Acid Res 27 : 229–232. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.229

88. Mi H, Lazareva-Ulitsky B, Loo R, Kejariwal A, Vandergriff J, et al. (2005) The PANTHER database of protein families, subfamilies, functions and pathways. Nuc Acid Res 33(s1): D284–D288.

89. Hulo N, Bairoch A, Bulliard V, Cerutti L, De Castro E, et al. (2005) The PROSITE database. Nuc Acid Res 34(s1): D227–D230.

90. Li L, Stoeckert CJ Jr, Roos DS (2003) Orthomcl: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res 13 : 2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503 12952885

91. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215 : 403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 2231712

92. Quinlan AR, Hall IM (2010) Bedtools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26 : 841–842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033 20110278

93. Felix MA, Braendle C, Cutter AD (2014) A Streamlined System for Species Diagnosis in Caenorhabditis (Nematoda: Rhabditidae) with Name Designations for 15 Distinct Biological Species. PLOS One 9: e94723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094723 24727800

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Germline Mutations Confer Susceptibility to Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and ThrombocytopeniaČlánek Multiple In Vivo Biological Processes Are Mediated by Functionally Redundant Activities of andČlánek Temporal Expression Profiling Identifies Pathways Mediating Effect of Causal Variant on PhenotypeČlánek Simultaneous DNA and RNA Mapping of Somatic Mitochondrial Mutations across Diverse Human CancersČlánek A Legume Genetic Framework Controls Infection of Nodules by Symbiotic and Endophytic BacteriaČlánek The Eukaryotic-Like Ser/Thr Kinase PrkC Regulates the Essential WalRK Two-Component System inČlánek The Yeast GSK-3 Homologue Mck1 Is a Key Controller of Quiescence Entry and Chronological LifespanČlánek The Role of -Mediated Epigenetic Silencing in the Population Dynamics of Transposable Elements in

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 6- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- IVF a rakovina prsu – zvyšují hormony riziko vzniku rakoviny?

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Expression of Concern: RNAi-Dependent and Independent Control of LINE1 Accumulation and Mobility in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- Orphan Genes Find a Home: Interspecific Competition and Gene Network Evolution

- Minor Cause—Major Effect: A Novel Mode of Control of Bistable Gene Expression

- Germline Mutations Confer Susceptibility to Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Thrombocytopenia

- Leveraging Identity-by-Descent for Accurate Genotype Inference in Family Sequencing Data

- Is Required for the Expression of Principal Recognition Molecules That Control Axon Targeting in the Retina

- Epigenetic Aging Signatures Are Coherently Modified in Cancer

- Silencing of DNase Colicin E8 Gene Expression by a Complex Nucleoprotein Assembly Ensures Timely Colicin Induction

- A Transposable Element within the Non-canonical Telomerase RNA of Modulates Telomerase in Response to DNA Damage

- The Orphan Gene Regulates Dauer Development and Intraspecific Competition in Nematodes by Copy Number Variation

- 9--13,14-Dihydroretinoic Acid Is an Endogenous Retinoid Acting as RXR Ligand in Mice

- The DnaA Protein Is Not the Limiting Factor for Initiation of Replication in

- FGFR3 Deficiency Causes Multiple Chondroma-like Lesions by Upregulating Hedgehog Signaling

- Multiple Changes of Gene Expression and Function Reveal Genomic and Phenotypic Complexity in SLE-like Disease

- Directed Evolution of RecA Variants with Enhanced Capacity for Conjugational Recombination

- The Regulatory T Cell Lineage Factor Foxp3 Regulates Gene Expression through Several Distinct Mechanisms Mostly Independent of Direct DNA Binding

- MreB-Dependent Inhibition of Cell Elongation during the Escape from Competence in

- DNA Damage Regulates Translation through β-TRCP Targeting of CReP

- Multiple In Vivo Biological Processes Are Mediated by Functionally Redundant Activities of and

- The Analysis of () Mutants Reveals Differences in the Fusigenic Potential among Telomeres

- The Causative Gene in Chanarian Dorfman Syndrome Regulates Lipid Droplet Homeostasis in .

- Temporal Expression Profiling Identifies Pathways Mediating Effect of Causal Variant on Phenotype

- The . Accessory Helicase PcrA Facilitates DNA Replication through Transcription Units

- AKTIP/Ft1, a New Shelterin-Interacting Factor Required for Telomere Maintenance

- Npvf: Hypothalamic Biomarker of Ambient Temperature Independent of Nutritional Status

- Transfer RNAs Mediate the Rapid Adaptation of to Oxidative Stress

- Connecting Circadian Genes to Neurodegenerative Pathways in Fruit Flies

- Response to “Ribosome Rescue and Translation Termination at Non-standard Stop Codons by ICT1 in Mammalian Mitochondria”

- Response to the Formal Letter of Z. Chrzanowska-Lightowlers and R. N. Lightowlers Regarding Our Article “Ribosome Rescue and Translation Termination at Non-Standard Stop Codons by ICT1 in Mammalian Mitochondria”

- Simultaneous DNA and RNA Mapping of Somatic Mitochondrial Mutations across Diverse Human Cancers

- Regulation of Insulin Receptor Trafficking by Bardet Biedl Syndrome Proteins

- Altered Levels of Mitochondrial DNA Are Associated with Female Age, Aneuploidy, and Provide an Independent Measure of Embryonic Implantation Potential

- Non-reciprocal Interspecies Hybridization Barriers in the Capsella Genus Are Established in the Endosperm

- Canine Spontaneous Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas Represent Their Human Counterparts at the Molecular Level

- Genetic Changes to a Transcriptional Silencer Element Confers Phenotypic Diversity within and between Species

- Functional Assessment of Disease-Associated Regulatory Variants Using a Versatile Dual Colour Transgenesis Strategy in Zebrafish

- Translational Upregulation of an Individual p21 Transcript Variant by GCN2 Regulates Cell Proliferation and Survival under Nutrient Stress