-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaChondrocytes Transdifferentiate into Osteoblasts in Endochondral Bone during Development, Postnatal Growth and Fracture Healing in Mice

During endochondral bone formation, which is responsible for the generation of most bones in mammals and many other species, osteoblasts deposit a bone-specific matrix on the surface of cartilage scaffolds made by chondrocytes and hypertrophic chondrocytes. It has long been thought that the terminally differentiated chondrocytes in this cartilage scaffold undergo cell death. Here we demonstrate that chondrocytes can transdifferentiate into osteoblasts and that these transdifferentiated osteoblasts represent a substantial fraction of the bone forming cells in mice, We also provide evidence that chondrocytes can transdifferentiate into osteoblasts during bone fracture repair, a process similar to endochondral bone formation.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(12): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004820

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004820Summary

During endochondral bone formation, which is responsible for the generation of most bones in mammals and many other species, osteoblasts deposit a bone-specific matrix on the surface of cartilage scaffolds made by chondrocytes and hypertrophic chondrocytes. It has long been thought that the terminally differentiated chondrocytes in this cartilage scaffold undergo cell death. Here we demonstrate that chondrocytes can transdifferentiate into osteoblasts and that these transdifferentiated osteoblasts represent a substantial fraction of the bone forming cells in mice, We also provide evidence that chondrocytes can transdifferentiate into osteoblasts during bone fracture repair, a process similar to endochondral bone formation.

Introduction

Long bones, ribs, vertebrae, and other parts of the vertebrate skeleton are formed through a precisely synchronized process known as endochondral ossification. The highly complex endochondral bone tissue, which is generated through a cartilage intermediate, consists of multiple types of cells, including mesenchymal-derived chondrocytes, osteoblasts and osteocytes, as well as osteoclasts and bone marrow cells, which have a hematopoietic origin [1].

Endochondral bone is made of an outer compact bone (cortex) and an inner spongy bone tissue within the bone marrow cavity. The conversion from the nonvascular cartilage template to fully mineralized endochondral bones proceeds in distinct and closely coupled steps [2]. The first step is initiated when chondrocytes in the center of the cartilage models undergo hypertrophic differentiation and cells in the perichondrium surrounding the hypertrophic zone differentiate into osteoblasts to form the interim bone cortex (bone collar). Concurrently, the initial vascular invasion occurs in the same region importing blood vessel-associated pericytes, osteoclasts and progenitor cells in the circulating blood. Immediately following the onset of bone collar formation, hypertrophic chondrocytes and the mineralized cartilage matrix in the center of the cartilage template are replaced by a highly vascularized trabecular bone tissue as well as bone marrow. Bone trabeculae in the primary spongiosa are formed by deposition of osteoid by osteoblasts on the surface of calcified cartilage spicules.

Until recently, the precise origins of the trabeculae-producing osteoblasts had remained largely undefined. A lineage tracing study using tamoxifen-inducible CreER transgenic mice harboring a ROSA26R conditional allele showed that Osx-expressing immature osteoblast precursors, labeled in the perichondrium before the development of the primary ossification center, were able to migrate into the cartilage along with blood vessels and were responsible, at least in part, for trabeculae formation [3], [4].

Besides perichondrium cells, several other cellular sources have also been examined as potential candidates to account for the formation of the primary spongiosa, including pericytes associated with the invading blood vessels, bone marrow progenitor cells and hypertrophic chondrocytes [4].

During endochondral ossification, terminally differentiated hypertrophic chondrocytes are eventually completely removed from the initial cartilage template or growth plates. Some of these chondrocytes have been shown to be eliminated through either apoptosis or autophagy (type II programmed cell death) [5], [6], [7], [8]. However, the fate of the hypertrophic chondrocytes not accounted for by either of these processes of cell death continues to be debated. It has been shown that hypertrophic chondrocytes also express osteoblast markers, such as Alkaline Phosphatase (ALPL), Osteonectin (SPARC), Osteocalcin (BGLAP), Osteopontin (SPP1) and Bone sialoprotein (IBSP), implicating potential complex functions of these cells [5], [6]. Indeed, a number of studies have reported that in cell cultures containing ascorbic acid or in organ cultures, hypertrophic chondrocytes, instead of becoming extinct, resume cell proliferation and undergo asymmetric cell division, giving rise to cells with morphological and phenotypic characteristics of osteoblasts capable of producing a mineralized bone matrix in vitro [6], [7], [8], [9]. In addition, histological experiments suggested that in embryonic chicks, long bone chondrocytes differentiated to bone-forming cells and deposited bone matrix inside their lacunae [10], further promoting the notion of a direct role of hypertrophic chondrocytes in trabecular bone formation. However, most of the evidence supporting transdifferentiation was based on either histological observations during skeletal development or on in vitro studies [11]. Overall, it was suggested that these studies were not fully conclusive (3). The result of an earlier ex vivo experiment that modified mouse embryonic limb tissue was consistent with a hypothetical transdifferentiation of chondrocytes into osteoblasts but the cells were not further characterized [12]. However, the conclusions of two more recent lineage tracing studies did not support a contribution of mature chondrocytes to the osteoblast/osteocyte pool in the central metaphyseal regions below the growth cartilage [3], [13].

Mature osteoblasts develop from Runx2-expressing osteoblast precursors that are derived from mesenchymal progenitors [14], [15]. Osterix (Osx, Sp7) is a key transcription factor required for the full differentiation of Runx2-expressing osteoblast precursors into mature osteoblasts and osteocytes [16]. Osx is expressed in osteoblasts and osteocytes but also, at a lower level, in prehypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocytes and in bone marrow mesenchymal progenitor cells during and after embryonic development [17]. Inactivation of Osx during and after embryonic development completely arrested osteoblast differentiation and bone formation [16], [17].

The purpose of this study was to examine whether hypertrophic chondrocytes may acquire an osteogenic fate in vivo. We specifically labeled either hypertrophic chondrocytes with a Cre recombinase driven by a Collagen 10 BAC transgene (Col10a1-Cre) [18] or chondrocytes with an inducible Cre recombinase, the DNA of which was inserted by knock-in in the 3′ UTR of the Aggrecan gene (Agc1-CreERT2) [19]. Labeling occurred with either EGFP [20], LacZ [21] or Tomato expression [22]. LacZ and Tomato expression were from conditional alleles in the ROSA locus. The EGFP DNA preceded by a LoxP site was inserted 3′ to the poly-A site of Osx whereas in this allele the other LoxP site was placed in the first intron of the Osx gene [23]. In mice harboring this allele, high expression of EGFP occurs only in Osx-expressing cells after the LoxP sites recombine (S1A Figure) [23]. Neither of the two Cres was expressed in the perichondrium or the periosteum of endochondral bones [18], [19]. Upon recombination, ROSA26R reporter mouse expresses secreted β-galactosidase (LacZ), ROSA-Tomato reporter mouse expresses cytoplasmic tandem dimer Tomato, and Osx floxed mouse expresses cytoplasmic EGFP. Whereas labeling of mature chondrocytes in mice harboring Col10a1-Cre occurred constitutively once its expression begun and persisted as long as the Col10a1 promoter remained active, the timing of labeling of chondrocytes by Agc1-CreERT2 was controlled by the administration of tamoxifen and this labeling period persisted for a short period. One advantage of the Osx/EGFP allele in cell fate experiments was that if one would detect non-chondrocytic cells expressing EGFP, these cells would likely be osteoblast lineage cells [16], [23].

Our data show that labeled non-chondrocytic cells appeared in the primary spongiosa of Col10a1-Cre or of tamoxifen activated Agc1-CreERT2 embryos and mice. In the case of Col10a1-Cre embryos and in Agc1-CreERT2 embryos treated with tamoxifen earlier than E14.5, these non-chondrocytic reporter+ cells started to appear at the onset of primary ossification. Later they were found throughout the primary ossification centers and subsequently in the endosteum and within the bone matrix. Their appearance could also be induced in the primary spongiosa postnatally. Many of these cells expressed the mature osteoblast marker Osteocalcin and exhibited osteoblast-specific Col1a1-promoter activity. Likewise, in tamoxifen treated Agc1-CreERT2 mice chondrocyte-derived reporter+ non-chondrocytic cells were present in the repair callus of fractured tibiae. Later these reporter+ cells, which were associated with the ossified bone matrix in the calluses, also displayed Col1a1-promoter activity. Our results provide in vivo evidence that chondrocytes, both in cartilage primordium and in established growth plates, as well as chondrocytes in bone repair calluses, have the capacity to transdifferentiate into osteoblasts and represent a major source of osteoblasts in endochondral bones.

Results

Abundance of Col10a1-Cre induced reporter+ cells throughout the primary spongiosa of Col10a1-Cre reporter-containing embryos and mice

In Col10a1-Cre transgenic mice, Cre recombinase activity was previously detected specifically in all hypertrophic chondrocytes starting from E13.5 throughout endochondral skeletal development and into the postnatal stage [18]. Here we further confirmed that in the femurs and tibias of E15.5 Col10a1-Cre; ROSA26R mice, only hypertrophic chondrocytes, not cells in the perichondrium and periosteum, were positive for LacZ (S1B-a, b Figure.), indicating that Cre activity driven by the Col10a1 regulatory elements occurred specifically in hypertrophic chondrocytes in these Col10a1-Cre transgenic mice. This was also confirmed by in situ hybridization of Col10a1 and Cre mRNA which was only observed in the hypertrophic zone (S1C Figure). To test the hypothesis that some of the Col10a1-expressing hypertrophic chondrocytes might transdifferentiate into osteoblasts, we crossed Col10a1-Cre with Osx flox/flox mice to generate Col10a1-Cre; Osx flox/+ embryos. In these embryos EGFP expression labels Osx-expressing cells, which either expressed Col10a1 or were derived from Col10a1-expressing cells (Figure S1A).

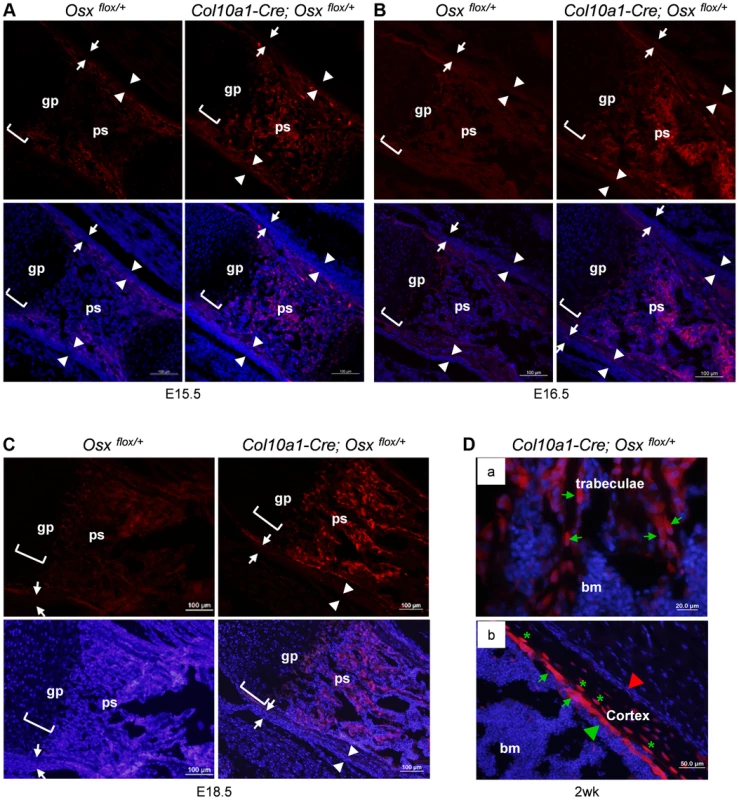

Immunofluorescence (IF) with anti-EGFP showed that in the femurs of Col10a1-Cre; Osx flox/+ embryos, abundant EGFP-positive (EGFP+) cells were present throughout the primary ossification centers (Fig. 1), where only very few, if any, Col10a1 - or Cre-expressing cells were detected (S1C Figure). The appearance of these EGFP+ cells was concurrent with the onset of primary ossification at E15.5 (Fig. 1A). These EGFP+ cells continued to be present in the primary spongiosa at E16.5 (Fig. 1B), E18.5 (Fig. 1C) to after birth (Fig. 1D). The EGFP expression levels of these cells increased from E15.5 to E18.5 in parallel to the increasing levels of Osx expression in the same regions. In the 2-week-old Col10a1-Cre; Osx flox/+ mice, EGFP+ cells were found throughout the trabecular surfaces, also lining the endosteum of the distal half of the femur, and even embedded within the bone matrix of the cortical bone and trabeculae (Figure S1D, Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1. Presence of abundant EGFP+ (Osx−/+) cells throughout the primary spongiosa of Col10a1-Cre; Osxflox/+ embryos and mice.

Anti-EGFP immunofluorescence (IF) showed that EGFP+ (Osx−/+) cells (red) were found in the primary spongiosa of E15.5 (A), E16.5 (B) and E18.5 (C) Col10a1-Cre; Osx flox/+ femurs (right panels), but not in the Osx flox/+ control embryos (left panels). The controls showed auto-fluorescence produced by mineralized tissue and bone marrow cells, but no EGFP+ cells. Upper panels: anti-EGFP (red); Lower panels: anti-EGFP and DAPI (blue). There were virtually no EGFP+ cells in the perichondrium (between white arrows) or periosteum (between white arrowheads) of the Col10a1-Cre; Osx flox/+ embryos. D: In the femurs of 2-week-old Col10a1-Cre; Osxflox/+ mice, EGFP+ (Osx−/+) cells (green arrows) were found throughout the trabeculae (panel a), on the endosteum surface (panel b), and embedded within the cortex (green asterisks). Red arrowhead: periosteum; Green arrowhead: endosteum; gp: growth plate (white brackets); ps: primary spongiosa; bm: bone marrow. In the Osx flox/+ control embryos, weak EGFP+ cells were present in the perichondrium and periosteum area (also in Fig. 3C), indicating that there was a low level read through of EGFP independent of Cre-mediated excision of floxed Osx allele. Such EGFP+ non-chondrocytic cells were completely absent in intramembranous skeletal elements such as the calvariae of E18.5 Col10a1-Cre; Osx flox/+ embryos (Figure S1E). In addition to its expression in hypertrophic chondrocytes and osteoblasts in the primary spongiosa, Osx was also highly expressed in periosteum and perichondrium [16]. However, EGFP+ cells were only detected in primary ossification centers and, as to be expected at lower levels in the hypertrophic zone, not in periosteum and perichondrium. This indicated that these EGFP+ non-chondrocytic cells were cells in which the Osx floxed allele was recombined by Col10a1-Cre and that these cells were unlikely to be derived from periosteum or perichondrium cells (Fig. 1). Staining of EGFP+ hypertrophic chondrocytes was not strong enough to be clearly shown due to strong autofluorescence from mineralized cartilage and bone matrix and from blood cells in the bone marrow.

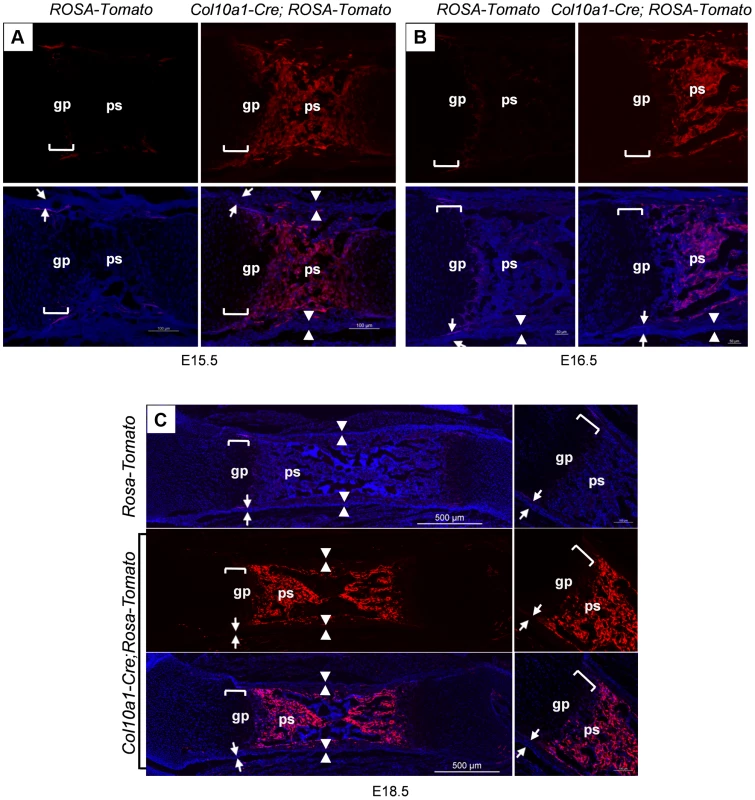

Similarly, Col10a1-Cre induced Tomato+ cells were found throughout the primary spongiosa of Col10a1-Cre; ROSA-tdTomato embryos (Fig. 2A, B and C) in the same pattern as in the Col10a1-Cre; Osx flox/+ embryos. This result confirmed our observation that cells derived from Col10a1-Cre expressing hypertrophic chondrocytes were indeed present in the primary spongiosa. In the femurs of 6-month-old Col10a1-Cre; ROSA-tdTomato;Osx flox/+ mice, Tomato+ cells continued to be present, however, the number of these cells on the endosteum surface was reduced and these cells were distributed more evenly from endosteum to periosteum within the cortex (S1F Figure). By 8 months, there were almost no Tomato+ cells present in the primary spongiosa. The Tomato+ cells were distributed mostly within the bone matrix or in the growth plate. Besides a few strong Tomato+ chondrocytes in the growth plate, the fluorescence intensity of a majority of Tomato+ cells were much weaker than in the younger mice (Figure S1G).

Fig. 2. Presence of abundant Tomato+ cells throughout the primary spongiosa of Col10a1-Cre; ROSA-tdTomato embryos.

Col10a1-Cre;ROSA-tdTomato embryos were generated to verify the observations made in the Col10a1-Cre;Osx flox/+ embryos. Abundant Tomato+ non-chondrocytic cells (red) were present throughout the primary spongiosa in femurs of E15.5 (A), E16.5 (B) and E18.5 (C) Col10a1-Cre;ROSA-tdTomato embryos (right panels). Tomato+ non-chondrocytic cells were completely absent from the ROSA-tdTomato control embryos in all stages evaluated (left panels in A and B, upper panel in C). Upper panels in A and B and middle panel in C: red channel; Lower panels: red and blue channels. Right panels in C: magnified images. There were virtually no Tomato+ cells within the perichondrium (between white arrows) or periosteum (between white arrowheads) of the Col10a1-Cre; ROSA-tdTomato embryos. gp: growth plate (white brackets); ps: primary spongiosa; bm: bone marrow. The non-chondrocytic reporter+ cells in the primary spongiosa of Col10a1-Cre or tamoxifen-treated Agc1-CreERT2 embryos and mice are derived from mature chondrocytes

To verify the presence in the primary spongiosa of reporter+ cells that were labeled by Col10a1-Cre, and to further delineate the origin of these cells we generated inducible Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R mouse models. In Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R mice, tamoxifen-induced Cre recombinase activity occurred efficiently in all chondrocytes including hypertrophic chondrocytes during and after development [19]. In the limbs of E14.5 Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R embryos retrieved from a female treated with tamoxifen at E13.5, the majority of chondrocytes, including pre - and hypertrophic chondrocytes, were positive for LacZ, while essentially no LacZ+ cells were found in the perichondrium, indicating that the Agc1-CreERT2-mediated recombination took place specifically in chondrocytes, not in perichondrium cells (Figure S2A-a, a′, b, b′).

As described in our previous report [19], E12.5 Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R embryos were negative for LacZ when treated with tamoxifen at E11.5 (Table S1), while E13.5 Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R embryos were positive for LacZ when treated with tamoxifen at E12.5. Experiments detailed in the next paragraph imply that it took between 9 and 18 hours after tamoxifen administration to accumulate enough β–galactosidase in order to obtain a clear readout in Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R embryos. Hence it is likely that E12.5 was the earliest embryonic stage for Agc1-CreERT2 activity in the femur of these embryos. To determine the length of time that tamoxifen remains capable of activating Agc1-CreERT2 after intraperitoneal injection, E13.5 Agc1-CreERT2;ROSA26R embryos were retrieved from pregnant females treated with tamoxifen at either E8.5, E9.5 or E11. E13.5 Agc1-CreERT2;ROSA26R embryos treated with tamoxifen at E11 were positive for LacZ staining, while E13.5 Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R embryos treated with tamoxifen at E8.5 or E9.5 were negative for LacZ, indicating that tamoxifen has a Cre activation window of three days or less after injection (Figure S2B and Table S1).

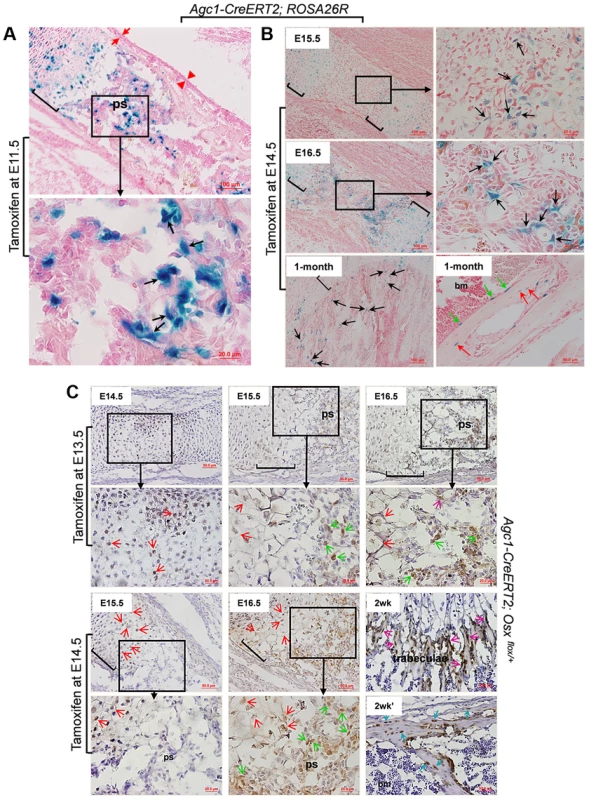

To further assess the dynamics of the LacZ labeling after tamoxifen injection, we administered tamoxifen to pregnant females of E15.5 Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R embryos and followed the appearance of LacZ+ cells in the femur of these embryos at successive times post-injection. At 9 hours post-injection weak LacZ+ chondrocytes including hypertrophic chondrocytes started to appear, at 18 hours many chondrocytes and hypertrophic chondrocytes were strongly positive for LacZ and very few LacZ+ cells were detected in the primary spongiosa. At 24 hours post injection significantly more cells in the primary spongiosa were positive for LacZ (Figure S2C). This suggested that there was a sequential appearance of LacZ staining first in chondrocytes between 9 and 18 hours and then in cells of the primary spongiosa after tamoxifen injection at E15.5 the time when ossification is initiated in femurs. We then injected tamoxifen in pregnant females of E11.5 Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R embryos four days earlier than the onset of primary ossification at E15.5 in the femur, a time when the Cre-inducing activity of tamoxifen was no longer retained in this tissue. These embryos were then sacrificed at E16.5. LacZ staining was observed not only in chondrocytes but also in non-chondrocytic cells in the primary spongiosa (Fig. 3A). This experiment largely ruled out that the presence of LacZ+ cells in the primary spongiosa might be due to transient ectopic expression of Agc1-CreERT2 in nascent osteoblasts at E15.5 coupled with the tamoxifen induction of Cre recombinase in these cells. This experiment suggested that the labeled cells in the primary spongiosa were derived from chondrocytes, in which the ROSA locus was recombined by tamoxifen induction of Cre recombinase.

Fig. 3. The non-chondrocytic reporter+ cells in the primary spongiosa of tamoxifen-treated Agc1-CreERT2 embryos and mice are derived from mature chondrocytes.

A: The LacZ stained femur section of E16.5 Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R embryo treated with tamoxifen at E11.5. The black arrows indicate the non-chondrocytic LacZ+ cells in the primary spongiosa. Black brackets: hypertrophic zone. No LacZ+ cells were detected within the perichondrium (red arrows) and periosteum (red arrowheads). B: LacZ staining of Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R femurs treated with tamoxifen at E14.5 and euthanized 1 and 2 days after injections or at 1 month postnatally. At E15.5, LacZ+ non-chondrocytic cells (black arrows) were only present right beneath the growth plates, while at E16.5, the number of LacZ+ non-chondrocytic cells was increased. At 1 month, LacZ+ cells were still present on the trabecular surfaces (black arrows), endosteum (green arrows) and within bone matrix (red arrows). Black brackets: hypertrophic zone. C: Anti-EGFP Immunohistochemical analysis (IHC) of Agc1-CreERT2; Osx flox/+ mice treated with tamoxifen at E13.5 or E14.5 and euthanized 1, 2 and 3 days after injections or 2 weeks postnatally. The data show that there were abundant non-chondrocyte EGFP+ (Osx−/+) cells in the primary spongiosa of the femur of E15.5 Agc1-CreERT2; Osx flox/+ embryos treated with tamoxifen at E13.5. However, there were almost no non-chondrocyte EGFP+ cells in the primary spongiosa of E15.5 Agc1-CreERT2; Osx flox/+ embryos treated with tamoxifen at E14.5. Red arrows: EGFP+ (Osx−/+) hypertrophic chondrocytes. Green arrows: preosteoblast-like EGFP+ (Osx−/+) cells. Purple arrows: mature osteoblast-like EGFP+ (Osx−/+) cells. Blue arrows: EGFP+ (Osx−/+) osteocytes. Black brackets: hypertrophic zone; ps: primary spongiosa. Also,in the limbs of E15.5 Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R embryos collected 1 day after tamoxifen injection at E14.5, only chondrocytes (including hypertrophic chondrocytes), and a few non-chondrocytic cells residing immediately below the proximal growth plate, were positive for LacZ, but no LacZ+ cells were present in the center of the marrow cavity in these embryos (Fig. 3B). By comparison, E15.5 Col10a1-Cre;Osx flox/+ and E15.5 Col10a1-Cre; ROSA-tdTomato embryos (Figs. 1A and 2A) showed more abundant labeled cells in the primary spongiosa because recombination and labeling of the hypertrophic chondrocytes occurred earlier. However, when embryos were retrieved at E16.5, 2 days after tamoxifen injection, non-chondrocytic LacZ+ cells were found from right under the growth plates gradually extending to the center of the marrow cavity (Fig. 3B). In the 1-month-old Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R mice, born to a female treated with tamoxifen at E14.5, LacZ+ cells were localized on the surfaces of trabeculae and the endosteum and embedded within the bone matrix (Fig. 3B). Together these results substantiated the notion that the tamoxifen-mediated appearance of non-chondrocytic LacZ+ cells in the primary spongiosa was specifically linked to the CreERT2 activity in chondrocytes and could be dissociated from the onset of primary ossification at E15,5.

To further validate our observations in Agc1-CreERT2;ROSA26R embryos and mice, we generated Agc1-CreERT2; Osx flox/+ embryos and mice, which were retrieved from tamoxifen-treated pregnant females or were the offspring of these female mice. In the femurs of E14.5 Agc1-CreERT2; Osx flox/+ embryos collected 1 day after tamoxifen treatment at E13.5 pre - and hypertrophic chondrocytes were positive for EGFP, consistent with the notion that the Osx floxed allele was recombined only in chondrocytes (Fig. 3C). In the femurs of E15.5 and E16.5 Agc1-CreERT2; Osx flox/+ embryos collected 2 and 3 days after tamoxifen treatment, not only were hypertrophic chondrocytes positive for EGFP but so were non-chondrocytic cells in priFmary ossification centers, similar to the findings in the Col10a1-Cre; Osx flox/+ embryos (Fig. 1). However when we pulsed tamoxifen in E14.5 pregnant mice to tag the EGFP+ (Osx−/+) cells 1 day prior to the onset of primary ossification, almost no non-chondrocytic EGFP+ (Osx−/+) cells were detected in the primary ossification centers at E15.5, except a few at the proximal chondro-osseous interface (Fig. 3C). Whereas at E16.5, in addition to hypertrophic chondrocytes, abundant numbers of non-chondrocytic cells in the primary ossification centers were also positive for EGFP (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, in a 2-week-old Agc1-CreERT2; Osx flox/+ mice, an offspring of a female treated with tamoxifen at E14.5, the EGFP+ (Osx−/+) cells were lining the surfaces of trabeculae and endosteum. They were also found within the bone matrix (Fig. 3C), but were totally absent in calvariae (S2E Figure), similar to what was seen in the 2-week-old Col10a1-Cre; Osx flox/+ mice (Fig. 1D). Nevertheless, unlike the findings in the 2-week-old Col10a1-Cre; Osx flox/+ mice, in which Cre activity persisted in Col10a1-expressing cells, the hypertrophic chondrocytes were no longer positive for EGFP in the Agc1-CreERT2; Osx flox/+ mice. Together these experiments in Agc1-CreERT2; Osx flox/+ embryos indicated that the labeling of chondrocytes preceded the time of appearance of labeled non-chondrocytic cells in the primary spongiosa. The timing of these distinct processes was controlled by the time of tamoxifen injection in the pregnant females.

In a separate experiment a pregnant Agc1-CreERT2;ROSA26R female was treated with tamoxifen at E17.5 when growth plates in the femurs were fully established (Figure S2D) and her offspring was sacrificed two days after birth. In these pups LacZ+ non-chondrocytic cells were present in the primary spongiosa and were distributed in an dome-shaped area under the growth plate, suggesting that mature chondrocytes in the established growth plate continued to be an important source of these LacZ+ cells.

Collectively, the distinct temporal and spatial presence of reporter+ non-chondrocytic cells observed after recombination by either Col10a1-Cre or Agc1-CreERT2 strongly suggested that these reporter+ non-chondrocytic cells were derived from mature chondrocytes.

Chondrocytes have the ability to become bone-forming osteoblasts

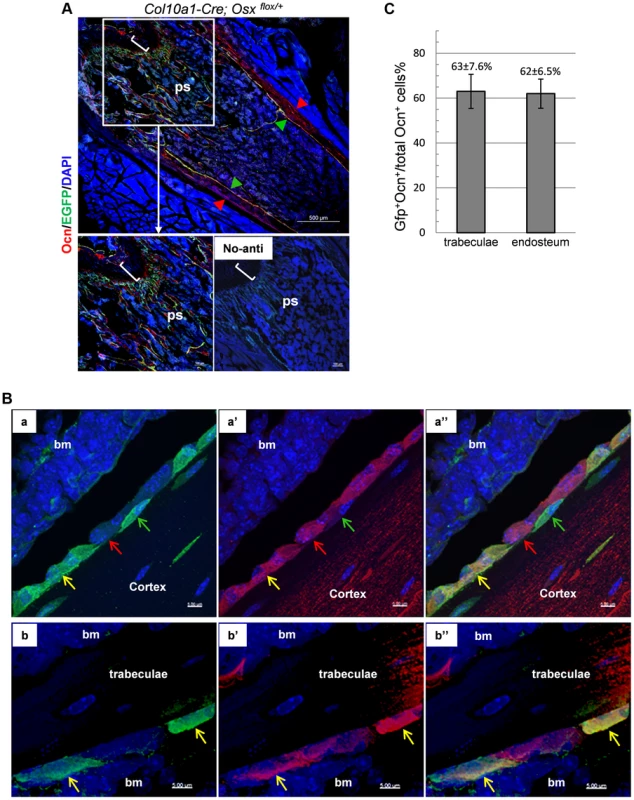

If the reporter+ cells, labeled at the time they existed as chondrocytes but later found in the trabecular region and in the endosteum, were functional osteoblasts, these cells should express typical osteoblast markers. To test this hypothesis we first performed double immunofluorescence (DIF) experiments with anti-EGFP and anti-Osteocalcin (Ocn) on the femur of 1-month-old Col10a1-Cre;Osx flox/+ mice. Non-chondrocytic EGFP+ cells represented cells derived from hypertrophic chondrocytes whereas cells positive for intracellular Osteocalcin (Ocn+) corresponded to mature osteoblasts. Hence cells that are positive for both markers (EGFP+Ocn+) are cells derived from chondrocytes that are functional osteoblasts. Shown in Fig. 4A, the EGFP+Ocn+ cells were indeed present in the femur of 1-month-old Col10a1-Cre;Osx flox/+ mice. High resolution confocal microscopy revealed that these Ocn+EGFP+ cells exhibited a characteristic mature osteoblast morphology (Fig. 4B). It was evident that not all Ocn+ cells on the bone surfaces were positive for EGFP, implying that there were other sources of osteoblasts besides hypertrophic chondrocytes. In addition, not all EGFP+ cells were positive for Ocn, since EGFP+ cells represented cells derived from mature chondrocytes at different stages of osteoblast differentiation. In the trabecular region, approximate 63% of Ocn+ cells were Ocn+EGFP+ cells, and about 62% Ocn+ endosteal cells were Ocn+EGFP+ cells (Fig. 4C and Table S2).

Fig. 4. A double Immunofluorescence experiment revealed that the EGFP+ (Osx−/+) cells in the primary spongiosa and endosteum of Col10a1-Cre; Osxflox/+ mice are mature osteoblasts.

A, B and C: DIF experiment with anti-Ocn and anti-GFP using femur frozen sections of 1-month-old Col10a1-Cre; Osxflox/+ mice. A: Lower right panel: no primary antibodies control. Upper and lower left panels: DIF experiment with anti-Ocn and anti-GFP. Anti-Ocn (red), anti-GFP (green) and DAPI (blue). White brackets indicate growth plate. ps: primary spongiosa. Red arrowhead: periosteum; Green arrowhead: endosteum. B: Magnified cell images of part of the upper panel in A. Panels a, a′ and a″: magnified cortical region. a: blue and green channels; a′: blue and red channels; a″: blue, green and red channels. Panels b, b′ and b″: magnified trabecular region. b: blue and green channels; b′: blue and red channels; b″: blue, green and red channels. Red arrows indicate Ocn+EGFP− cells. Green arrows indicate EGFP+Ocn− cells. Yellow arrows indicate Ocn+EGFP+ cells. Bm: bone marrow. Blue channel: 405 nm; Green channel: 488 nm; Red channel: 555 nm. C: Percent of Ocn+ mature osteoblasts which were derived from Col10a1-expressing mature chondrocytes in trabeculae and endosteum regions. Consistent with this result, DIF with anti-EGFP and anti-Col1a1 antibodies revealed that the EGFP+ (Osx−/+) cells in the primary spongiosa were tightly associated with type I collagen in the femurs of E18.5 Col10a1-Cre; Osx flox/+ embryos (S3A Figure). Likewise, IHC with anti - BSP showed that many of the LacZ+ cells in the primary spongiosa were closely associated with BSP in the femur of E16.5 Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R treated with tamoxifen at E14.5 (Figure S3B).

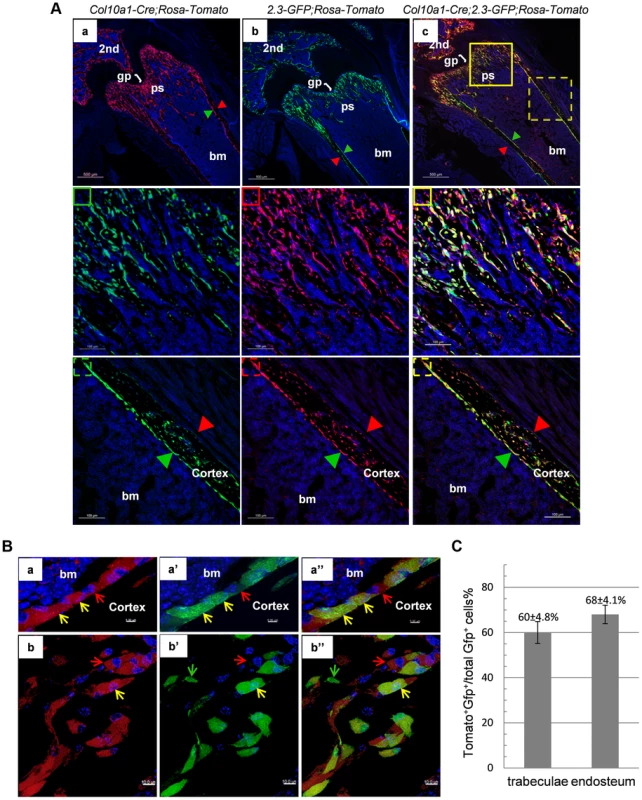

We further generated Col10a1-Cre; 2.3Col1-GFP; ROSA-tdTomato triple transgenic mice to assess co-localization of Col10a1-Cre induced reporter+ cells and an osteoblast-specific marker in vivo. In these mice, a Tomato+ non-chondrocytic cell represented a Col10a1-Cre marked cell whereas a EGFP+ cell corresponded to a functional osteoblast [24]. Thus a Tomato and GFP double positive (Tomato+EGFP+) cell represented an osteoblast derived from Col10a1 - expressing chondrocytes. In the femur of 3-week-old Col10a1-Cre;2.3Col1-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato mice there was an abundance of Tomato+EGFP+ cells throughout the trabecular and endosteal surfaces (Fig. 5A). These Tomato+EGFP+ cells in both trabeculae and cortical region were further examined by high resolution microscopy (Fig. 5B). As the Ocn+EGFP+ cells shown in Fig. 4B, the Tomato+EGFP+ cells in the femur of 3-week-old Col10a1-Cre;2.3col1-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato mice had a typical osteoblast morphology. In the trabecular area, approximately 60% of total EGFP+ cells were also Tomato+, and around 68% of EGFP+ cells on the endosteum surface were positive for Tomato (Fig. 5C and Table S3). This result indicated that the hypertrophic chondrocyte-derived osteoblasts contributed to more than half of the osteoblast population in the 3-week-old mice in vivo.

Fig. 5. Cellular colocalization of the chondrocyte-derived tomato marker and a 2.3Col1-GFP osteoblast specific marker in femur sections of Col10a1-Cre;2.3Col1-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato triple transgenic mice.

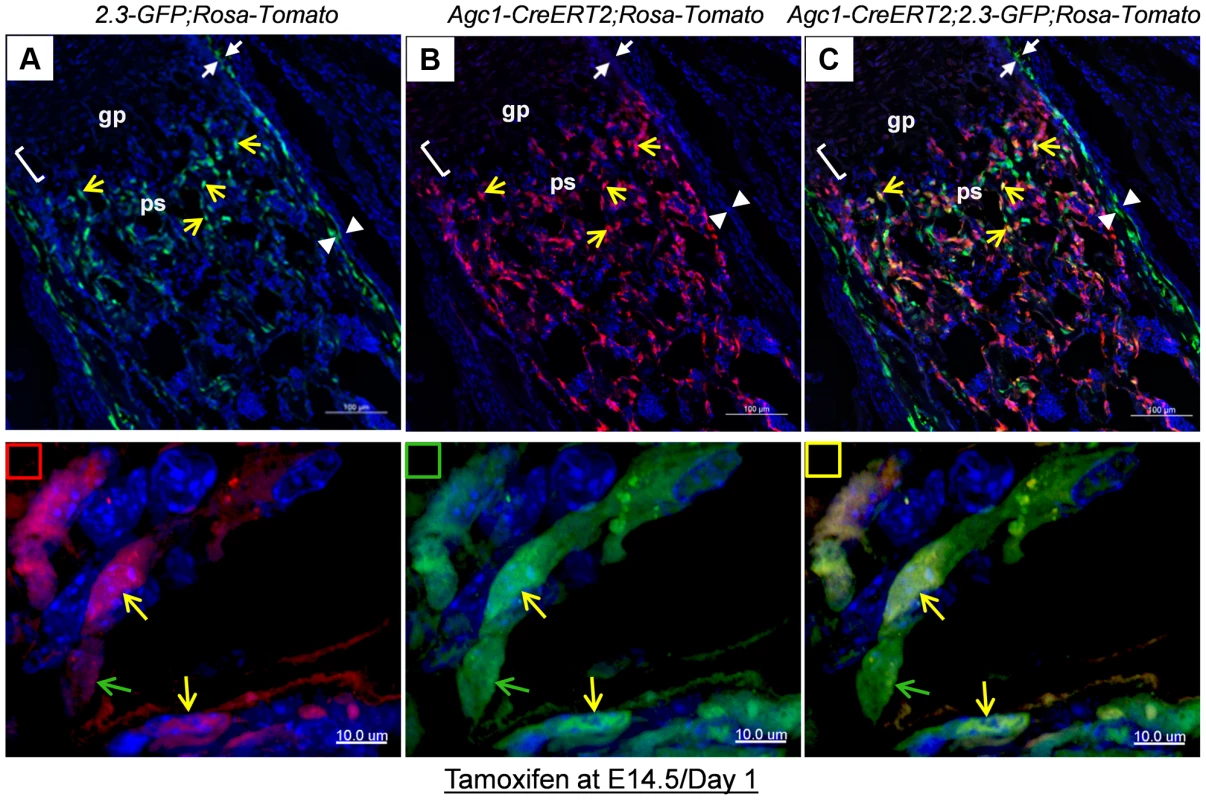

A: The femur fluorescence images of 3-week-old Col10a1-Cre;2.3Col1-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato mouse and Col10a1-Cre; ROSA-tdTomato and 2.3Col1-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato control mice. Panel a: only Tomato+ cells (red) no EGFP+ (green) cells were present in Col10a1-Cre; ROSA-tdTomato control mice. Panel b: only EGFP+ cells no Tomato+ cells were present in 2.3Col1-GFP; ROSA-tdTomato control mice. Panel c: Tomato+, EGFP+ and Tomato+EGFP+ cells were distributed in the trabecular region, on the endosteum and in the secondary ossification center. The solid square in panel c indicates the enlarged trabeculae region; The dashed square in panel c indicates the enlarged cortical region; The green squares: blue and green channels; The red squares: blue and red channels; The yellow squares: blue, green and red channels; Red arrowhead: periosteum; Green arrowhead: endosteum. 2nd: secondary ossification center. B: Magnified images of cells in A-c. Panels a, a′ and a″: magnified cortical region. a: blue and red channels; a′: blue and green channels; a″: blue, red and green channels. Panels b, b′ and b″: magnified trabecular region. b: blue and red channels; b′: blue and green channels; b″: blue, red and green channels. Red arrows indicate Tomato+EGFP− cells. Green arrows indicate Tomato−GFP+ cells. Yellow arrows indicate Tomato+EGFP+ cells. Bm: bone marrow. C: The percent quantitation of EGFP+ cells which were derived from Col10a1-expressing mature chondrocytes in trabecular and cortical regions respectively. As in the case of Col10a1-Cre;2.3Col1-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato mice, Tomato+EGFP+ cells were also present in the femur of newborn Agc1-CreERT2;2.3Col1-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato mice treated with tamoxifen at E14.5 (Fig. 6). The Tomato+ and Tomato+EGFP+ cells were specifically located in the primary spongiosa, but not in perichondrium and periosteum, tissues that were also marked by EGFP expression. This result further substantiated our hypothesis that hypertrophic chondrocytes were capable of differentiating into bone–forming osteoblasts in vivo.

Fig. 6. Cellular colocalization of the chondrocyte-derived tomato marker and the osteoblast-specific 2.3Col1-GFP marker in femurs of tamoxifen treated Agc1-CreERT2;2.3Col1-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato triple transgenic mice.

The femur fluorescence images of postnatal day 1 Agc1-CreERT2;2.3Col1-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato mouse treated with tamoxifen at E14.5. Panel a: blue and green channels; Panel b: blue and red channels; Panel c: blue, red and green channels; The lower panels indicated by small squares represent magnified images of cells from top panels. Red square: red and blue channels; Green square: green and blue channels; Yellow square: red, green and blue channels; The green arrows indicate the Tomato−EGFP+ cells. The yellow arrows indicate the Tomato+EGFP+ cells. Only EGFP+ cells no Tomato+ cells were present in the perichondrium (between white arrows) and periosteum (between white arrow heads). Together, these results suggested that osteoblasts, which were derived from chondrocytes in cartilage anlagen constitute a major source of osteoblasts responsible for trabecular and endosteal bone formation in the growing endochondral skeleton.

Growth plate mature chondrocytes continue to contribute to the osteoblast pool during early postnatal growth

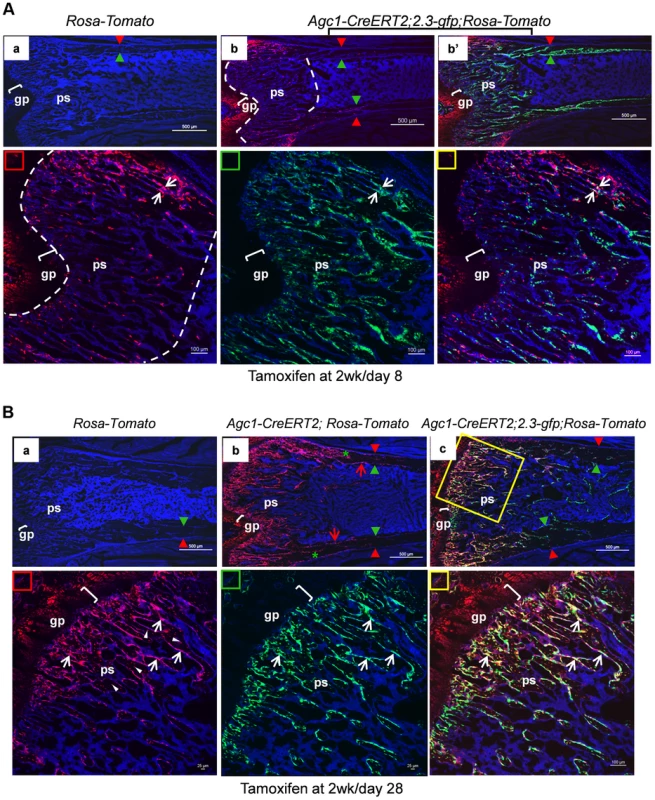

To evaluate whether the growth plate chondrocytes during postnatal growth also contribute to the osteoblast pool in the primary spongiosa as is the case during embryonic development, we generated inducible Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato and Agc1-CreERT2; 2.3Col1-GFP; ROSA-tdTomato mice to specifically tag and trace the growth plate chondrocytes after birth. At 2 weeks, the Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato or Agc1-CreERT2; 2.3Col1-GFP; ROSA-tdTomato and control mice were treated with tamoxifen and subsequently sacrificed at different time points after tamoxifen injections. ISH showed that Agc1 was specifically expressed in growth plate chondrocytes, not in cells in primary spongiosa of 2 and 3-week-old Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato and Agc1-CreERT2; 2.3Col1-GFP; ROSA-tdTomato mice (Figure S4A). At post tamoxifen day 1, a majority of growth plate chondrocytes were weakly positive for Tomato and very few Tomato+ cells were present at the chondro-osseous junction in the primary spongiosa of a Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato mouse, while no Tomato+ cells were detected in the ROSA-tdTomato control (Fig. 7A). At post tamoxifen day 2 in Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato mouse, more non-chondrocytic Tomato+ cells appeared below the growth plates in the primary spongiosa in addition to the Tomato+ chondrocytes. The fluorescence signal of day 2 Tomato+ chondrocytes was more intense than the day 1 Tomato+ chondrocytes (Fig. 7B). Unlike in the 2-week-old Col10a1-Cre; Osx flox/+ mice (Fig. 1D), there were no Tomato+ cells on the endosteum or embedded within the cortex in 2-week-old Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato mice both 1 and 2 days post tamoxifen injection.

Fig. 7. Presence in the primary spongiosa of non-chondrocytic cells derived from postnatal growth plate mature chondrocytes.

Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato and control mice were treated with tamoxifen at 2 weeks postnatally and were sacrificed at day 1 (A) and day 2 (B) post injection. All images in this figure are images of femur sections. Left panels (A and B): Tomato+ cells were completely absent in ROSA-Tomato control mice. Right panels (A and B): Tomato+ non-chondrocytic cells (red arrows) were present in the primary spongiosa under the growth plate. More Tomato+ non-chondrocytic cells were seen in the primary spongiosa in the post injection day 2 mouse, and these Tomato+ non-chondrocytic cells of the post injection day 2 mouse were distributed in a wider area than in the day 1 mouse. The white dotted lines outlines the area within which non-chondrocytic Tomato+ cells were present. Red arrowhead: periosteum; Green arrowhead: endosteum; gp: growth plate (white brackets); ps: primary spongiosa. At 8 days post tamoxifen treatment, the number of non-chondrocytic Tomato+ cells in the primary spongiosa was substantially increased and these cells were distributed in a broader area under the growth plates than in the post tamoxifen day 1 and day 2 mice (Fig. 8Ab). A majority of the non-chondrocytic Tomato+ cells in the day 8 primary spongiosa were small in size and as those in day 1 and day 2 mice were not found within the trabeculae or cortex. Only some of the Tomato+ cells in the vicinity of periostea displayed a larger and elongated morphology and some of them were also positive for EGFP, suggesting the presence of chondrocyte derived osteoblasts in the primary spongiosa of these mice (Fig. 8Ab′). In the 6-week-old Agc1-CreERT2; 2.3Col1-GFP; ROSA-tdTomato mice, which were treated with tamoxifen at 2weeks, the number of non-chondrocytic Tomato+ cells was substantially increased and the cells were distributed throughout the breadth of the primary spongiosa. These cells were morphologically similar to those in the vicinity of periostea in the post tamoxifen day 8 mice. A considerable number of Tomato+ cells were also embedded within trabeculae and a few were found on the endosteum and within the cortex (Fig. 8B). Moreover, the number of Tomato+EGFP+ cells were very substantially increased compared to the post tamoxifen day 8 mice. Thus there was a considerable time lag between the initial labeling of growth plate chondrocytes, the presence of abundant chondrocyte-derived non-chondrocytic cells in primary spongiosa and particularly the formation of large numbers of chondrocyte-derived functional osteoblasts. Note that the number of Tomato+ cells on the endosteum and within the cortex in these mice was much less than in the 3-week-old Col10a1-Cre; 2.3Col1-GFP; ROSA-tdTomato mice (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 8. Growth plate mature chondrocytes contribute to the osteoblast pool during postnatal growth.

Two-week-old Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato, Agc1-CreERT2; 2.3-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato and control mice were treated with tamoxifen and sacrificed 8 days (A) and 28 days post injection (B). All images in this figure are images of femur sections. A: Panel a: neither Tomato nor EGFP signals were detected in the ROSA-tdTomato control. Panel b (blue and red channels): the fluorescence image revealed that there were more Tomato+ cells in the primary spongiosa in the post injection day 8 Agc1-CreERT2; 2.3-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato mouse compared to the post injection day 2 mouse (Fig. 7B right panels), and the Tomato+ cells in the day 8 mouse were distributed in an even broader area than in the day 2 mouse. Very few Tomato+ cells were found on the endosteum and within the cortex. Panel b′: blue, red and green channels. Lower panels: magnified images of primary spongiosa in b′. Lower left (red rectangle): red and blue channels; Lower middle (green rectangle): green and blue channels; Lower right (yellow rectangle): red, green and blue channels: a few Tomato+EGFP+ cells (white arrows) were present in the primary spongiosa especially in proximity of the periosteum. B: Panel a: no Tomato or GFP signals were detected in the post tamoxifen day 28 ROSA-tdTomato control. Panel b: in the post tamoxifen day 28 Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato mouse, not only was the number of Tomato+ cells in the primary spongiosa increased compared to the post injection day 8 mouse, but some of these Tomato+ cells were on the endosteum (red arrows) and embedded within the cortex (green asterisk). Panel c: there were many more Tomato+EGFP+ cells (white arrows in magnified lower right panel) in the day 28 Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato mouse than in the day 8 mouse (Fig. 8A). Lower left panel: magnified trabecular area of panel c (red and blue channels) showed that there were many Tomato+ cells on the trabecular surfaces (white arrows) and embedded within the trabeculae (white arrowheads). Red arrowhead: periosteum; Green arrowhead: endosteum; gp: growth plate (white brackets); ps: primary spongiosa. When 11-week-old Agc1-CreERT2; 2.3Col1-GFP; ROSA-tdTomato mice were treated with tamoxifen and were sacrificed two weeks later, the Tomato+ cells were present in a narrower area under the growth plate (Figure S4B) than in the mice sacrificed 8 days after tamoxifen injection at 2 weeks (Fig. 8A); in these 13-week-old mice there were also very few Tomato+EGFP+ cells.

Overall, these results indicate that postnatal growth plate chondrocytes continued to contribute to the osteoblasts pool during the period of rapid postnatal growth in juvenile mice.

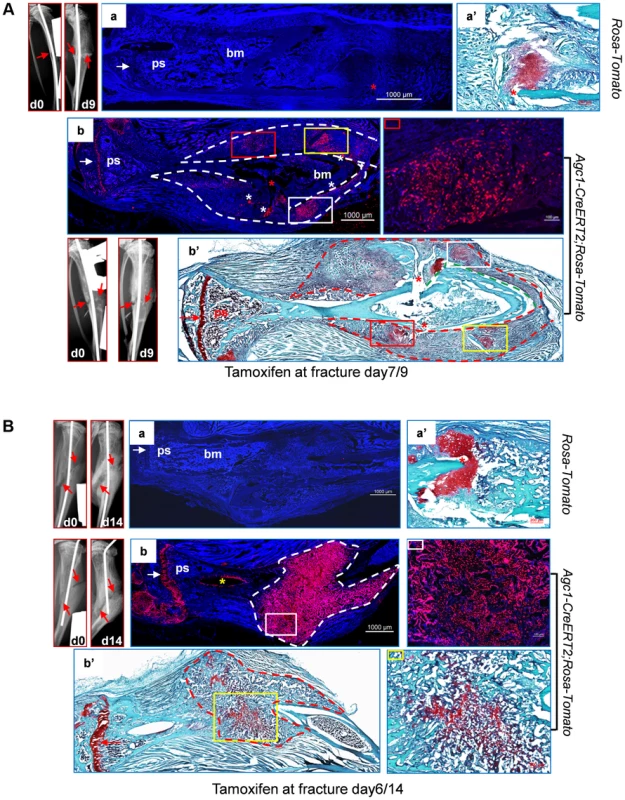

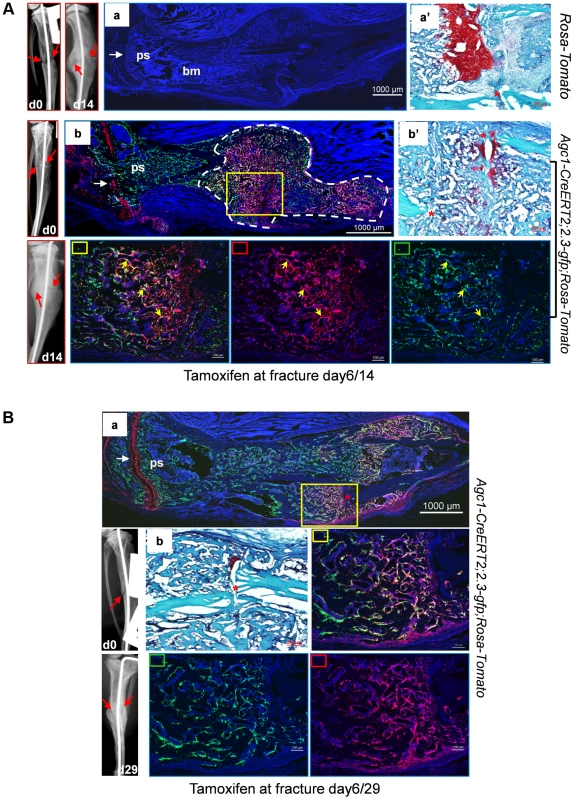

Osteoblasts derived from mature chondrocytes in the repair callus are involved in bone fracture healing

Bone fracture healing occurs mostly through processes similar to developmental endochondral ossification, which involves a cartilage intermediate [25], [26]. To test the hypothesis that mature chondrocytes present in the repair callus may be a source of osteoblasts contributing to bone formation during fracture healing, we generated semi-stabilized fractures of the tibia in 2 to 3-month-old Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato or Agc1-CreERT2;2.3Col1-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato and control mice and subsequently injected tamoxifen into these mice at 6 to 7 days post-surgery, a time which is prior to or around the time of chondrocyte differentiation [25], [26].

In the tibia of a post-surgery day 9 Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato mouse treated with tamoxifen 7 days after surgery, the Tomato+ cells were found in the growth plate and in the repair callus but not in the region between these two areas (Fig. 9Ab). No Tomato+ chondrocytes were detected in the ROSA-tdTomato control (Fig. 9Aa). In these mice 9 days after surgery, chondrocyte differentiation occurred in some but not all of the callus cells. Interestingly, the areas of Tomato+ cells in the repair callus were completely matching the chondrocyte areas stained maroon red by Saf-O (Fig. 9Ab′), suggesting that these Tomato+ callus cells were in fact chondrocytes in the cartilage callus.

Fig. 9. Abundant Agc1-CreERT2 labeled Tomato+ cells were present in the repair callus during fracture healing.

A: The left tibia of 2.5-month-old Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato mouse and ROSA-tdTomato control mouse were subjected to semi-stabilized fracture surgery. At 7 days after surgery, these mice were treated with tamoxifen and were sacrificed 2 days post tamoxifen. The panels left to panel a: X-ray images of fractured tibiae of ROSA-tdTomato control mouse. day0: right after surgery; day9: 9 days after surgery. Red arrows indicate the fractures. Panel a: the fluorescence image of fractured tibiae of ROSA-tdTomato mouse. Panel a′: Saf-O staining indicates the presence of chondrocytes (red staining) in the repair callus of ROSA-tdTomato fractured tibiae. Panel b: fluorescence image of the fractured tibiae of Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato mouse, Tomato+ cells were present specifically in the growth plate (white arrow) and in the repair callus outlined by the dotted lines. The colored rectangles indicate the locations of Tomato+ cells in the callus. The panel right to panel b: magnified fluorescence image of the area marked by a red rectangle in b. White asterisks indicate non-specific fluorescence signals. The white arrow indicates the growth plates. Panel b′: Saf-O staining of the fractured tibiae. The red dotted lines outline the repair callus. The colored rectangles mark the areas of red staining. The matching areas in b and b′ are marked by the same colored rectangles. Red asterisks: fracture sites. The red arrow indicates the growth plate. B: The left tibia of 2-month-old Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato mouse and ROSA-tdTomato control mouse were subjected to semi-stabilized fracture surgery. At 6 days after surgery, these mice were treated with tamoxifen and were sacrificed 8 days post tamoxifen. Panel a: fluorescence image of fractured tibiae of ROSA-tdTomato mouse. Panel a′: Saf-O staining of repair callus in fractured tibiae in panel a. The panels left to panel a: X-ray images of fractured tibiae of ROSA-tdTomato. Panel b: fluorescence image of fractured tibiae of Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato mouse. Almost all cells in the callus outlined by the white dotted lines were Tomato+ cells. The panel right to panel b: magnified fluorescence image of the area marked by the white rectangle. The white arrow indicates the growth plates. Panel b′: Saf-O staining of the fractured tibiae. The red stippled line outlines the repair callus. The image right to b′: the Saf-O staining of area marked by a yellow rectangle in b′. The red arrow indicates the growth plate. In the tibia of a post-surgery day 14 Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato mouse treated with tamoxifen 6 days after surgery, Saf-O staining indicated that the repair callus was partially ossified, showing a mixture of both bone (green) and cartilage (red) tissues (Fig. 9Bb′). However, almost all cells in the repair callus, both in the cartilage and in the bone regions were positive for Tomato (Fig. 9Bb), suggesting the presence of non-chondrocytic Tomato+ cells in the repair callus. As in the case of the post-surgery day 9 fractured tibia (Fig. 9Ab), the Tomato+ cells were not found in the region between the growth plate and the repair calluses, implying that the Tomato+ cells in the repair callus were in fact either callus chondrocytes or cells derived from callus chondrocytes, and hence that these Tomato+ cells were not derived from growth plate chondrocytes.

In the repair callus of a post-surgery day 14 Agc1-CreERT2; 2.3Col1-GFP; ROSA-tdTomato mouse treated with tamoxifen at 6 days after surgery, many of the Tomato+ cells were also positive for GFP (Tomato+EGFP+), implying that the mature chondrocytes present in the repair callus have the ability to become Col1a1-expressing bone forming osteoblasts (Fig. 10Ab, Figure S5a).

Fig. 10. Osteoblasts derived from mature chondrocytes in the repair callus are involved in bone fracture healing.

A: Left tibia of a 2.5-month-old Agc1-CreERT2; 2.3-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato mouse and a ROSA-tdTomato control mouse were subjected to semi-stabilized fracture surgery. At 6 days after surgery, these mice were treated with tamoxifen and were scarified 8 days post tamoxifen. Panel a: fluorescence image shows no Tomato and GFP signals in the fractured tibiae of ROSA-tdTomato control. Panel a′: Saf-O staining of the repair callus in a. Images left to a: X-ray images of fractured tibia of control mouse. Panel b: in the fractured tibiae of Agc1-CreERT2; 2.3-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato mouse, Tomato+ cells are present specifically in growth plate (white arrow) and in the repair callus outlined by dotted white lines. Some of the Tomato+ cells were also positive for GFP (Tomato+EGFP+ indicated by yellow arrows). The white arrow indicates the growth plate, which was partly broken by the pin inserted into the fractured tibia. Panel b′: Saf-O staining of the callus in b. B: The left tibia of 2.5-month-old Agc1-CreERT2; 2.3-GFP;ROSA-tdTomato mouse was subjected to semi-stabilized fracture surgeries. At 6 days after surgery, the mouse was treated with tamoxifen and scarified 23 days post tamoxifen. Panel a: the fluorescence image revealed that there were more Tomato+EGFP+ cells in the callus compared to the callus collected 14 days after surgery (Fig. 10A). Rectangle marked panels: magnified images corresponding to the yellow rectangle in panel a. Middle right panel: blue, red and green channels; Bottom middle panel: blue and green channels; Bottom right panel: blue and red channels. Panel b: Saf-O staining shows very little red tissue, suggesting that the callus was almost all ossified. At day 29 post-surgery, ossification was almost complete in the repair callus of an Agc1-CreERT2; 2.3Col1-GFP; ROSA-tdTomato mouse treated with Tamoxifen 6 days post-surgery (Figure S5b). The number of Tomato+EGFP+ cells was very substantially increased compared to the day 14 callus (Fig. 10Ba).

Thus the appearance of Tomato+ cells in the early callus, their localization corresponding to the cartilage callus, the absence of Tomato+ cells between the growth plate and the callus, and the presence of abundant Tomato+EGFP+ cells in the ossifying callus strongly suggested that chondrocytes in the repair callus were a source of osteoblasts involved in bone fracture healing.

Discussion

Our objective was to follow the fate of chondrocytes in endochondral ossification and to test the hypothesis whether chondrocytes may undergo transdifferentiation into functional osteoblasts in vivo.

In studying the fate of labeled chondrocytes in both Col10a1-Cre-containing embryos and tamoxifen treated Agc1-CreERT2–containing embryos, we observed that, in addition to labeled chondrocytes and hypertrophic chondrocytes, from E15.5 on numerous labeled cells with a different morphology than that of hypertrophic chondrocytes were present in the primary ossification center, where neither Col10a1-Cre nor Agc1-CreERT2 were expressed. Later labeled cells were found within the matrix of bone trabeculae and postnatally in the endosteum and within the cortical bone. The reporter+ cells were lining the endosteum continuously from the distal growth plate down to the femur shaft. The area of the endosteum covered by reporter+ cells was gradually increasing with time, from up to mid-shaft at 2weeks to about three quarts of the length at 1 month after birth. Although we occasionally observed very rare reporter+ cells in the perichondrium or periosteum area, the number of these reporter+ cells were too low to account for the abundant reporter+ cells in the primary spongiosa.

In Col10a1-Cre;reporter embryos the appearance of the non-chondrocytic labeled cells in the primary spongiosa occurred synchronously with the onset of primary ossification. However, the use of Agc1-CreERT2;reporter embryos allowed us to control the timing of Cre recombination in chondrocytes and the subsequent appearance of labeled cells in the primary ossification centers by varying the timing of tamoxifen administration.

The tamoxifen pulse experiments with Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA26R embryos (Fig. 3, Figure S2B, Figure S2C and Table S1) clearly established that the labeling of chondrocytes and the appearance of non-chondrocytic cells in the primary spongiosa were two sequential events and that the latter could be dissociated from the start of osteogenesis. These experiments provided compelling evidence that the labeled cells in the primary ossification centers were derived from chondrocytes, and that their presence was not due to a hypothetical Cre activity in emerging osteoblasts.

The finding that the labeled cells present in the trabecular and endosteal regions of Col10a1-Cre-containing mice expressed two osteoblast markers namely Osteocalcin and a osteoblast-specific Col1a1 promoter-driven EGFP strongly suggested that these cells were functional osteoblasts. In the femur trabeculae of tamoxifen-treated Agc1-CreERT2-containing mice the presence of chondrocyte-derived osteoblasts was also confirmed by co-expression of the tomato reporter and EGFP driven by the osteoblast-specific Col1a1 promoter. Our results further revealed that about 60 percent of osteoblasts in the femurs of 3 - and 4-week-old mice were derived from chondrocytes. These numbers were computed in Col10a1-Cre;reporter mice, although one cannot completely exclude that the 60 percent figure maybe an overestimate, if for the instance there was the unlikely possibility of an ectopic Col10a1-Cre promoter activity. The labeling of chondrocytes after a single tamoxifen injection in pregnant females of AgcCreERT2 embryos was unlikely to be complete. In the newborn Agc1-CreERT2; 2.3Col1-GFP; ROSA-tdTomato mice treated with tamoxifen at E14.5 (Fig. 6), and in the 3-week and 6-week-old mice treated with tamoxifen at 2-week (Fig. 8), some of the osteoblasts (EGFP+ cells) in the primary spongiosa were derived from mature chondrocytes prior to tamoxifen injections. This population of EGFP+ cells would therefore not be labeled by Agc1-CreERT2 and these cells would thus be negative for Tomato. Hence, the number of Tomato+ EGFP+ cells would not reflect the actual number of chondrocyte-derived osteoblasts present in these mice.

Our data revealed that both mature chondrocytes in cartilage primordia prior to the establishment of growth plates, and mature chondrocytes in established growth plates, transdifferentiated and contributed to the osteoblast pools. The reporter+ cells labeled by Agc-CreERT2 around E14.5, before the establishment of the growth plate persisted into the growth period after birth, since they were still found on the surfaces of trabeculae and endosteum, and embedded within the bone matrix at 2 weeks and 1 month (Figs. 3B and 3C). After the establishment of growth plates, mature chondrocytes in growth plates maintained their ability to become osteoblasts both during late embryonic development and postnatal growth (Figure S2D, Figs. 7 and 8). During the rapid growth period at 2 weeks, the Agc1-CreERT2 induced more non-chondrocytic reporter+ cells in the primary spongiosa in less time (Figs. 7 and 8) than during the late growth period at 11 weeks (Figure S4B). These results suggested the hypothesis that the contribution of growth plate chondrocytes to the osteoblast pool could possibly be associated with growth plate activity and that this contribution might even eventually stop sometime after the growth period.

After the growth period the Col10a1-Cre induced reporter+ cells were still present in the metaphyseal and cortical regions in 6-month-old mice (Figure S1F). However, more of these cells were embedded within the bone matrix, and less of them were found on the bone surfaces, compared to the 2 - and 3-week-old mice (Fig. 1D and Fig. 5A), implying that the number of active osteoblasts derived from chondrocytes was likely reduced after the growth period. At 8-month, there were almost no Col10a1-Cre induced reporter+ cells in the primary spongiosa and very few were on the bone surfaces. In addition, the fluorescence intensities of Tomato+ cells were much weaker than that in the younger mice (Figure S1G). These results implied that the Col10a1-Cre induced cells in the 8-month-old mice were probably derived from the growth plate chondrocytes during the growing period, further suggesting an association between the appearance of chondrocyte-derived osteoblasts and the growth plate activities.

In the fractured tibiae, Agc1-CreERT2 induced Tomato+ cells were present specifically in the articular cartilage, growth plate and repair calluses when tamoxifen was injected at post surgery day 6 or day 7 around the time of chondrocyte differentiation in the callus [25], [26]. The Agc1-CreERT2 induced Tomato+ cells continued to be present in calluses after 14 and 29 days post-surgery, when Agc1-CreERT2 was no longer active, suggesting that these Tomato+ cells were either callus chondrocytes labeled at the time of tamoxifen injection around post fracture day 7 or cells derived from these labeled chondrocytes. Importantly there were no significant numbers of Tomato+ cells observed in the region between growth plates and calluses during the repair process, indicating that the Tomato+ cells present in calluses were unlikely derived from growth plate chondrocytes (Figs. 9 and 10). The Tomato+EGFP+ cells were found in the partially ossified callus at post surgery day 14, and the appearance of these Tomato+EGFP+ cells was temporally and spatially associated with callus ossification. These data substantiated that chondrocytes in the repair callus were a clear source of osteoblasts responsible for bone formation during fracture healing.

Several laboratories have attempted to address the question whether chondrocytes had the ability to transdifferentiate into osteoblasts. In an earlier ex vivo experiment, in which vascular invasion and endochondral ossification were inhibited by removal of the perichondrium, Col1a1 expressing cells were observed in an area between the cartilage anlagens [12]. Although these cells were not further characterized, they were hypothesized to be either hypertrophic chondrocytes arrested at a terminal stage of differentiation or having undergone transdifferentiation. The drawback of this ex vivo experiment was the absence of perichondrium, which may be essential for complete chondrocytes transdifferentiation. We consider the present study as an extension of this previous experiment.

In an in vivo study in Col2a1-CreER; ROSA26R embryos specific cells at the cartilage/perichondrium interface, which expressed the Col2a1-CreER transgene, were shown to give rise to some likely osteoblasts mainly in the endosteal region [3]. While this study concluded that hypertrophic chondrocytes did not make a detectable contribution to the osteoblast/osteocyte pool in the central metaphyseal regions under the growth plate within a 3-day time frame, this may be explained by the short time span after tamoxifen administration. In another in vivo study transgenic mice were used harboring both a Col10a1-mCherry and either a 2.3kbCol1a1-Emerald transgene or a 3.6kbCol1a1-Topaz osteoblast-specific transgene. MCherry fluorescence was detected in the primary spongiosa but not mCherry mRNA. Although much of the mCherry fluorescence was attributed to decaying hypertrophic chondrocytes some of it was present in live cells which did not express the emerald or topaze transgenes. It was speculated that these cells might be a rare population of hypertrophic chondrocytes showing a phenotype different from or preceding that of differentiated osteoblasts. However, the study concluded that transdifferentiation was unlikely to be involved in this phenotype. [13]. Also here, the time lag between labeling of chondrocytes and their appearance as osteoblast marker-expressing cells, as observed in our work, may explain the seeming discrepancy between the studies.

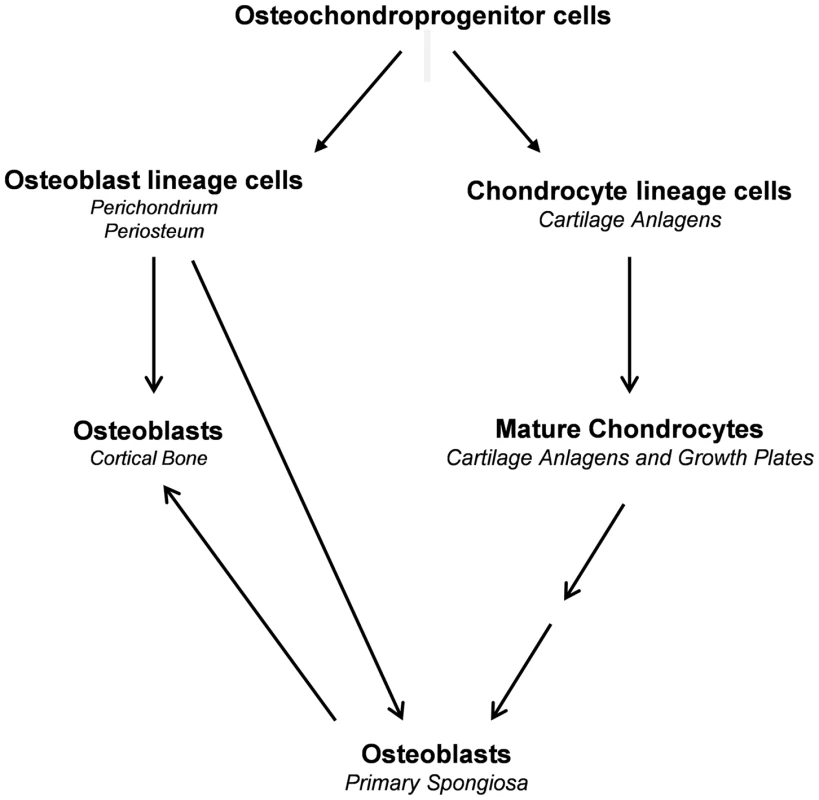

During endochondral bone formation, osteoblast lineage cells first segregate from Sox9-expressing mesenchymal progenitor cells in a process that involves canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling as well as Runx2 and Osx expression and silencing of Sox9 expression and Sox9 activity to form the perichondrium and periosteum [16], [27], [28], [29], [30]. These osteoblast precursors differentiate further into osteoblasts to form the initial cortical bone. They also invade the cartilage anlagen together with osteoclasts and blood vessels to differentiate into mature osteoblasts that generate bone trabeculae [3]. In parallel to the segregation of osteoblast lineage cells, chondrogenic cells segregate from the same progenitors and in a stepwise fashion differentiate into chondrocytes, which express high levels of Sox9 to form the initial cartilage anlagen [31]. The last step in this chondrogenic pathway is the formation of hypertrophic chondrocytes, in which Sox9 is no longer expressed. Our current results provide evidence that hypertrophic chondrocytes both before and after the establishment of the growth plate constitute a second major source of osteoblasts that participate in the formation of trabecular and cortical bones (Fig. 11). This property of these chondrocytes to be a direct source of osteoblasts persists until at least three months of age. The same property of chondrocytes to give rise to osteoblasts is also very active in the bone fracture repair process.

Fig. 11. Proposed model illustrating the sources of osteoblasts in endochondral bone.

Recent advances have reshaped the conventional view of differentiated mammalian cells in terms of their plasticity [32]. As is the case in other instances of transdifferentiation [33] it is possible that hypertrophic chondrocytes might first dedifferentiate, then proliferate before these cells redifferentiate into osteoblasts. Our preliminary unpublished experiments revealed the existence of cells in the bone marrow that were derived from Col10a1-expressing chondrocytes. These cells displayed properties of mesenchymal progenitor cells and were able to differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes and adipocytes in vitro, although we do not know whether these cells had the ability to become osteoblast cells in vivo. This preliminary result suggests the possibility that “hypertrophic chondrocytes to osteoblasts” transdifferentiation may indeed involve a dedifferentiation and then a redifferentiation process. We noted that in juvenile mice the chondrocyte-derived reporter+ cells, which were negative for osteoblast markers, persisted in the primary spongiosa for a considerable amount of time before becoming functional osteoblasts (Figs. 8A and 8B). We further speculate that these two hypothetical steps may be independently regulated by different signaling pathways.

Collectively, our mouse models provide evidences that chondrocytes, both in cartilage anlagen and in growth plate, are a direct source of osteoblasts responsible for endochondral bone formation during development and postnatal growth. Likewise, chondrocytes in repair calluses undergo transdifferentiation to become osteoblasts contributing to callus ossification in fracture repair. We speculate that chondrocyte-derived osteoblasts may also be involved in other endochondral ossification processes, such as osteophyte formation in osteoarthritis [34] and heterotopic ossification in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva disorder [35], [36].

While this manuscript was in the final stage of revision, a study [37] was published which reached similar conclusions as those in the present paper.

Methods

Ethics statement

All mice work were conducted strictly according to the NIH guidelines.

Generation of embryos and mice for analysis

The Col10a1-Cre mice were generated by Dr. Klaus von der Mark [18]. The Agc1-CreERT2 and Osx flox/flox mice were previously generated in Dr. de Crombrugghe's laboratory [19], [23]. The 2.3Col1a1-GFP mice were generously provided by Dr. David Rowe [24]. The ROSA26R (B6.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1Sor/J, stock number: 003474) and ROSA-tdTomato (B6;129S6-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J, stock number:009705) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. The mice were injected intraperitoneally with1.5 mg/10 g body weight of tamoxifen solution on the desired embryonic days. Tamoxifen was dissolved in 10% ethanol and 90% corn oil. Tamoxifen (Sigma, T5648) was first mixed with 1/10th volume of ethanol and then emulsified in corn oil (Sigma,C8267).

X-Gal staining of β-galactosidase activity

The embryos or mice were fixed in 0.2% glutaraldehyde and 0.8% formaldehyde (pH 7.5 for embryos, pH 7.8 for mice) at room temperature for 1 hour and stained in 1 mg/ml X-gal overnight at room temperature. After staining, the samples were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) at 4°C overnight and dehydrated for paraffin embedding. The post-fixed bones were decalcified prior to embedding.

In situ hybridization

ISH with digoxin (DIG)-labeled riboprobes was carried out on 10-µM frozen sections as previously described [38]. Instead of dehydration for paraffin sections, the frozen sections were washed twice in PBS (pH 7.4) for 5 minutes.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Bones fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) overnight were decalcified and embedded for CryoJane frozen sections as previously described [39]. Sections were treated with hyaluronidase (Sigma, H4272, 2 mg/ml in PBS [pH 5.0]) at 37°C for 20 minutes for embryonic samples or 30 minutes for postnatal samples and incubated with anti-EGFP (Invitrogen A11122) at room temperature for 1 hour or with anti-mouse collagen type I (Millipore AB765P) at 4°C overnight. For IHC, the sections were then incubated with HRP polymer conjugates (Invitrogen 87-9263) and developed with a Vectastain ABC kit (Vector PK-4000). For IF, the sections were then incubated with anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen A21428). For anti-EGFP and anti-col1a1 double IF, after incubation with anti-EGFP and anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555, the sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled (Invitrogen A10468) anti-mouse collagen type I at 4°C overnight. For anti-EGFP and anti-Ocn double IF, after incubation with anti-EGFP (abcam ab13970) and anti-Ocn (A93876), the sections were incubated with anti-chicken Alexa 488 (abcam) and anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen A21428). All IF sections were mounted with Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen P36931).

Semi-stabilized tibia fracture healing models

The 2 to 3-month-old Agc1-CreERT2; ROSA-tdTomato or Agc1-CreERT2; 2.3Col1-GFP; ROSA-tdTomato and control mice were used in the fracture surgery. The procedure was described in [3].

Confocal microscope and analysis

Fluorescence cell images were captured using a A1 Laser scanning confocal microscope made by Nikon Instruments.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Akiyama H, de Crombrugghe B (2009) Transcription control of chondrocyte differentiation. The skeletal system: Cold spring harbor laboratory press. pp. 147–170.

2. MackieEJ, AhmedYA, TatarczuchL, ChenKS, MiramsM (2008) Endochondral ossification: how cartilage is converted into bone in the developing skeleton. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40 : 46–62.

3. MaesC, KobayashiT, SeligMK, TorrekensS, RothSI, et al. Osteoblast precursors, but not mature osteoblasts, move into developing and fractured bones along with invading blood vessels. Dev Cell 19 : 329–344.

4. ClarkinC, OlsenBR On bone-forming cells and blood vessels in bone development. Cell Metab 12 : 314–316.

5. GerstenfeldLC, ShapiroFD (1996) Expression of bone-specific genes by hypertrophic chondrocytes: implication of the complex functions of the hypertrophic chondrocyte during endochondral bone development. J Cell Biochem 62 : 1–9.

6. BiancoP, CanceddaFD, RiminucciM, CanceddaR (1998) Bone formation via cartilage models: the “borderline” chondrocyte. Matrix Biol 17 : 185–192.

7. KirschT, SwobodaB, von der MarkK (1992) Ascorbate independent differentiation of human chondrocytes in vitro: simultaneous expression of types I and X collagen and matrix mineralization. Differentiation 52 : 89–100.

8. RoachHI, ErenpreisaJ, AignerT (1995) Osteogenic differentiation of hypertrophic chondrocytes involves asymmetric cell divisions and apoptosis. J Cell Biol 131 : 483–494.

9. ErenpreisaJ, RoachHI (1996) Epigenetic selection as a possible component of transdifferentiation. Further study of the commitment of hypertrophic chondrocytes to become osteocytes. Mech Ageing Dev 87 : 165–182.

10. RoachHI (1997) New aspects of endochondral ossification in the chick: chondrocyte apoptosis, bone formation by former chondrocytes, and acid phosphatase activity in the endochondral bone matrix. J Bone Miner Res 12 : 795–805.

11. ShapiroIM, AdamsCS, FreemanT, SrinivasV (2005) Fate of the hypertrophic chondrocyte: microenvironmental perspectives on apoptosis and survival in the epiphyseal growth plate. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 75 : 330–339.

12. ColnotC, LuC, HuD, HelmsJA (2004) Distinguishing the contributions of the perichondrium, cartilage, and vascular endothelium to skeletal development. Dev Biol 269 : 55–69.

13. MayeP, FuY, ButlerDL, ChokalingamK, LiuY, et al. Generation and characterization of Col10a1-mcherry reporter mice. Genesis 49 : 410–418.

14. KomoriT, YagiH, NomuraS, YamaguchiA, SasakiK, et al. (1997) Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell 89 : 755–764.

15. OttoF, ThornellAP, CromptonT, DenzelA, GilmourKC, et al. (1997) Cbfa1, a candidate gene for cleidocranial dysplasia syndrome, is essential for osteoblast differentiation and bone development. Cell 89 : 765–771.

16. NakashimaK, ZhouX, KunkelG, ZhangZ, DengJM, et al. (2002) The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell 108 : 17–29.

17. ZhouX, ZhangZ, FengJQ, DusevichVM, SinhaK, et al. Multiple functions of Osterix are required for bone growth and homeostasis in postnatal mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 : 12919–12924.

18. GebhardS, HattoriT, BauerE, SchlundB, BoslMR, et al. (2008) Specific expression of Cre recombinase in hypertrophic cartilage under the control of a BAC-Col10a1 promoter. Matrix Biol 27 : 693–699.

19. HenrySP, JangCW, DengJM, ZhangZ, BehringerRR, et al. (2009) Generation of aggrecan-CreERT2 knockin mice for inducible Cre activity in adult cartilage. Genesis 47 : 805–814.

20. MaoX, FujiwaraY, ChapdelaineA, YangH, OrkinSH (2001) Activation of EGFP expression by Cre-mediated excision in a new ROSA26 reporter mouse strain. Blood 97 : 324–326.

21. SorianoP (1999) Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet 21 : 70–71.

22. ShanerNC, CampbellRE, SteinbachPA, GiepmansBN, PalmerAE, et al. (2004) Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol 22 : 1567–1572.

23. AkiyamaH, KimJE, NakashimaK, BalmesG, IwaiN, et al. (2005) Osteo-chondroprogenitor cells are derived from Sox9 expressing precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 : 14665–14670.

24. KalajzicZ, LiuP, KalajzicI, DuZ, BrautA, et al. (2002) Directing the expression of a green fluorescent protein transgene in differentiated osteoblasts: comparison between rat type I collagen and rat osteocalcin promoters. Bone 31 : 654–660.

25. SchindelerA, McDonaldMM, BokkoP, LittleDG (2008) Bone remodeling during fracture repair: The cellular picture. Semin Cell Dev Biol 19 : 459–466.

26. GerstenfeldLC, CullinaneDM, BarnesGL, GravesDT, EinhornTA (2003) Fracture healing as a post-natal developmental process: molecular, spatial, and temporal aspects of its regulation. J Cell Biochem 88 : 873–884.

27. DayTF, GuoX, Garrett-BealL, YangY (2005) Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Dev Cell 8 : 739–750.

28. HillTP, SpaterD, TaketoMM, BirchmeierW, HartmannC (2005) Canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling prevents osteoblasts from differentiating into chondrocytes. Dev Cell 8 : 727–738.

29. RoddaSJ, McMahonAP (2006) Distinct roles for Hedgehog and canonical Wnt signaling in specification, differentiation and maintenance of osteoblast progenitors. Development 133 : 3231–3244.

30. HuH, HiltonMJ, TuX, YuK, OrnitzDM, et al. (2005) Sequential roles of Hedgehog and Wnt signaling in osteoblast development. Development 132 : 49–60.

31. Akiyama H, de Crombrugghe B (2009) Transcription control of chondrocyte differentiation. The skeletal system: Cold spring harbor laboratory press. pp. 147–170.

32. JoplingC, BoueS, Izpisua BelmonteJC Dedifferentiation, transdifferentiation and reprogramming: three routes to regeneration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12 : 79–89.

33. TsonisPA, MadhavanM, TancousEE, Del Rio-TsonisK (2004) A newt's eye view of lens regeneration. Int J Dev Biol 48 : 975–980.

34. van der KraanPM, van den BergWB (2007) Osteophytes: relevance and biology. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 15 : 237–244.

35. RamirezDM, RamirezMR, ReginatoAM, MediciD (2014) Molecular and cellular mechanisms of heterotopic ossification. Histol Histopathol

36. ShoreEM, KaplanFS (2010) Inherited human diseases of heterotopic bone formation. Nat Rev Rheumatol 6 : 518–527.

37. YangL, TsangKY, TangHC, ChanD, CheahKS (2014) Hypertrophic chondrocytes can become osteoblasts and osteocytes in endochondral bone formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111 : 12097–12102.

38. FuX, SunH, KleinWH, MuX (2006) Beta-catenin is essential for lamination but not neurogenesis in mouse retinal development. Dev Biol 299 : 424–437.

39. JiangX, KalajzicZ, MayeP, BrautA, BellizziJ, et al. (2005) Histological analysis of GFP expression in murine bone. J Histochem Cytochem 53 : 593–602.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Large-scale Metabolomic Profiling Identifies Novel Biomarkers for Incident Coronary Heart DiseaseČlánek Notch Signaling Mediates the Age-Associated Decrease in Adhesion of Germline Stem Cells to the NicheČlánek Phosphorylation of Mitochondrial Polyubiquitin by PINK1 Promotes Parkin Mitochondrial TetheringČlánek Natural Variation Is Associated With Genome-Wide Methylation Changes and Temperature SeasonalityČlánek Overlapping and Non-overlapping Functions of Condensins I and II in Neural Stem Cell DivisionsČlánek Unisexual Reproduction Drives Meiotic Recombination and Phenotypic and Karyotypic Plasticity inČlánek Tetraspanin (TSP-17) Protects Dopaminergic Neurons against 6-OHDA-Induced Neurodegeneration inČlánek ABA-Mediated ROS in Mitochondria Regulate Root Meristem Activity by Controlling Expression inČlánek Mutations in Global Regulators Lead to Metabolic Selection during Adaptation to Complex EnvironmentsČlánek The Evolution of Sex Ratio Distorter Suppression Affects a 25 cM Genomic Region in the Butterfly

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 12- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- IVF a rakovina prsu – zvyšují hormony riziko vzniku rakoviny?

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Stratification by Smoking Status Reveals an Association of Genotype with Body Mass Index in Never Smokers

- Genome Wide Meta-analysis Highlights the Role of Genetic Variation in in the Regulation of Circulating Serum Chemerin

- Occupancy of Mitochondrial Single-Stranded DNA Binding Protein Supports the Strand Displacement Mode of DNA Replication

- Distinct Genealogies for Plasmids and Chromosome

- Large-scale Metabolomic Profiling Identifies Novel Biomarkers for Incident Coronary Heart Disease

- Non-coding RNAs Prevent the Binding of the MSL-complex to Heterochromatic Regions

- Plasmid Flux in ST131 Sublineages, Analyzed by Plasmid Constellation Network (PLACNET), a New Method for Plasmid Reconstruction from Whole Genome Sequences

- Epigenome-Guided Analysis of the Transcriptome of Plaque Macrophages during Atherosclerosis Regression Reveals Activation of the Wnt Signaling Pathway

- The Inventiveness of Nature: An Interview with Werner Arber

- Mediation Analysis Demonstrates That -eQTLs Are Often Explained by -Mediation: A Genome-Wide Analysis among 1,800 South Asians

- Generation of Antigenic Diversity in by Structured Rearrangement of Genes During Mitosis

- A Massively Parallel Pipeline to Clone DNA Variants and Examine Molecular Phenotypes of Human Disease Mutations

- Genetic Analysis of the Cardiac Methylome at Single Nucleotide Resolution in a Model of Human Cardiovascular Disease

- Genetic Analysis of Circadian Responses to Low Frequency Electromagnetic Fields in

- The Dissection of Meiotic Chromosome Movement in Mice Using an Electroporation Technique

- Altered Chromatin Occupancy of Master Regulators Underlies Evolutionary Divergence in the Transcriptional Landscape of Erythroid Differentiation

- Syd/JIP3 and JNK Signaling Are Required for Myonuclear Positioning and Muscle Function

- Notch Signaling Mediates the Age-Associated Decrease in Adhesion of Germline Stem Cells to the Niche

- Mutation of Leads to Blurred Tonotopic Organization of Central Auditory Circuits in Mice

- The IKAROS Interaction with a Complex Including Chromatin Remodeling and Transcription Elongation Activities Is Required for Hematopoiesis

- RAN-Binding Protein 9 is Involved in Alternative Splicing and is Critical for Male Germ Cell Development and Male Fertility

- Enhanced Longevity by Ibuprofen, Conserved in Multiple Species, Occurs in Yeast through Inhibition of Tryptophan Import

- Phosphorylation of Mitochondrial Polyubiquitin by PINK1 Promotes Parkin Mitochondrial Tethering

- Recurrent Loss of Specific Introns during Angiosperm Evolution

- Natural Variation Is Associated With Genome-Wide Methylation Changes and Temperature Seasonality

- SEEDSTICK is a Master Regulator of Development and Metabolism in the Arabidopsis Seed Coat

- Overlapping and Non-overlapping Functions of Condensins I and II in Neural Stem Cell Divisions

- Unisexual Reproduction Drives Meiotic Recombination and Phenotypic and Karyotypic Plasticity in

- Tetraspanin (TSP-17) Protects Dopaminergic Neurons against 6-OHDA-Induced Neurodegeneration in

- ABA-Mediated ROS in Mitochondria Regulate Root Meristem Activity by Controlling Expression in

- Mutations in Global Regulators Lead to Metabolic Selection during Adaptation to Complex Environments

- Global Analysis of Photosynthesis Transcriptional Regulatory Networks

- Mucolipin Co-deficiency Causes Accelerated Endolysosomal Vacuolation of Enterocytes and Failure-to-Thrive from Birth to Weaning

- Controlling Pre-leukemic Thymocyte Self-Renewal

- How Malaria Parasites Avoid Running Out of Ammo

- Echoes of the Past: Hereditarianism and

- Deep Reads: Strands in the History of Molecular Genetics

- Keep on Laying Eggs Mama, RNAi My Reproductive Aging Blues Away

- Analysis of a Plant Complex Resistance Gene Locus Underlying Immune-Related Hybrid Incompatibility and Its Occurrence in Nature

- Epistatic Adaptive Evolution of Human Color Vision

- Increased and Imbalanced dNTP Pools Symmetrically Promote Both Leading and Lagging Strand Replication Infidelity

- Genetic Basis of Haloperidol Resistance in Is Complex and Dose Dependent

- Genome-Wide Analysis of DNA Methylation Dynamics during Early Human Development