-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Proteasome Nuclear Activity Affects Chromosome Stability by Controlling the Turnover of Mms22, a Protein Important for DNA Repair

To expand the known spectrum of genes that maintain genome stability, we screened a recently released collection of temperature sensitive (Ts) yeast mutants for a chromosome instability (CIN) phenotype. Proteasome subunit genes represented a major functional group, and subsequent analysis demonstrated an evolutionarily conserved role in CIN. Analysis of individual proteasome core and lid subunit mutations showed that the CIN phenotype at semi-permissive temperature is associated with failure of subunit localization to the nucleus. The resultant proteasome dysfunction affects chromosome stability by impairing the kinetics of double strand break (DSB) repair. We show that the DNA repair protein Mms22 is required for DSB repair, and recruited to chromatin in a ubiquitin-dependent manner as a result of DNA damage. Moreover, subsequent proteasome-mediated degradation of Mms22 is necessary and sufficient for cell cycle progression through the G2/M arrest induced by DNA damage. Our results demonstrate for the first time that a double strand break repair protein is a proteasome target, and thus link nuclear proteasomal activity and DSB repair.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000852

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000852Summary

To expand the known spectrum of genes that maintain genome stability, we screened a recently released collection of temperature sensitive (Ts) yeast mutants for a chromosome instability (CIN) phenotype. Proteasome subunit genes represented a major functional group, and subsequent analysis demonstrated an evolutionarily conserved role in CIN. Analysis of individual proteasome core and lid subunit mutations showed that the CIN phenotype at semi-permissive temperature is associated with failure of subunit localization to the nucleus. The resultant proteasome dysfunction affects chromosome stability by impairing the kinetics of double strand break (DSB) repair. We show that the DNA repair protein Mms22 is required for DSB repair, and recruited to chromatin in a ubiquitin-dependent manner as a result of DNA damage. Moreover, subsequent proteasome-mediated degradation of Mms22 is necessary and sufficient for cell cycle progression through the G2/M arrest induced by DNA damage. Our results demonstrate for the first time that a double strand break repair protein is a proteasome target, and thus link nuclear proteasomal activity and DSB repair.

Introduction

Genomic instability is recognized as being an important predisposing condition that contributes to the development of cancer [1]. A major class of genome instability is Chromosome Instability (CIN), a phenotype that involves changes in chromosome number and structure. Studies in yeast have shown that multiple overlapping pathways contribute to genomic stability [2]. The current view is that most spontaneous chromosomal rearrangements result from DSBs created mainly during DNA replication as a result of broken, stalled or collapsed replication forks [3]. In eukaryotes, DSBs are repaired either by Homologous Recombination (HR) or by Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) mechanisms. Defects in either repair pathway result in high frequencies of genomic instability [4]. The HR pathway utilizes a homologous sequence to faithfully restore the DNA continuity at the DSB [5]. In contrast, NHEJ is a mechanism able to join DNA ends with no or minimal homology [6]. Recent studies suggest a role for the proteasome in DSB repair pathways: The Sem1/DSS1 protein is a newly identified subunit of the 19S proteasome in both yeast and human cells. In yeast, Sem1 is recruited to DSB sites with the 19S and 20S proteasome particles, and is required for efficient repair of DSBs by HR and NHEJ [7]. Human DSS1 physically binds to the breast cancer susceptibility protein BRCA2, that plays an integral role in the repair of DSBs, and is required for its stability and function and consequently for efficient formation of RAD51 nucleofilaments [8],[9].

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is the supramolecular machinery that mediates the ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of damaged or misfolded proteins, or of short-lived regulatory proteins. The 26S proteasome comprises the 20S core particle (CP) and the 19S regulatory particle (RP), which represent the base and lid substructures, respectively [10]. Nuclear targets that are degraded by the proteasome include proteins involved in pathways critical for chromosome integrity. For example, degradation of polyubiquitinated mitotic cyclin and of the anaphase inhibitor Pds1/securin allow sister chromatids to dissociate at the onset of anaphase [for a review see [11]]. The protein levels of the tumor suppressor protein p53 are also subtly controlled by ubiquitin-mediated degradation [12].

Previous studies suggest that the amino-terminal ubiquitin-like (Ubl) domain of Rad23 protein can recruit the proteasome for a stimulatory role during nucleotide excision repair (NER) in S. cerevisiae. It has also been shown that the 19S regulatory complex of the yeast proteasome can affect nucleotide excision repair independently of Rad23 protein [13]. Other studies suggested a model for the regulation of Xeroderma Pigmentosum protein C (XPC), which plays a role in the primary DNA damage sensing in mammalian global genome NER. According to this model the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway has a positive regulatory role for optimal NER in mammalian cells, and appears to act by facilitating the recruitment of XPC to DNA damage sites [13]–[18].

A putative role for the proteasome at DSB sites could be to degrade components of the DNA damage response after their function is completed. However, so far no protein involved in DSB repair has been described as a direct target of the proteasome.

In this paper, we describe a systematic screen of a recently released collection of temperature - sensitive (Ts) yeast alleles [19], to find a set of novel CIN genes. The screen and subsequent analysis of individual mutants revealed that proteasomal subunits represent a major functional group, with an evolutionarily conserved role in CIN. We found that the CIN phenotype is associated with a failure of proteasomes to localize to the nucleus in viable cells, and show that proteasome dysfunction affects chromosome stability by impairing the kinetics of DSB repair. We also identify the DNA repair protein Mms22 as a proteasome target, and demonstrate that the impaired DNA repair phenotype can be attributed to a failure in the recruitment and subsequent degradation of ubiquitinated chromatin-bound Mms22.

Results

CIN mutants from a new collection of Temperature sensitive (Ts) alleles in essential genes

In this study we expanded a recent screen for mutants affecting chromosome stability [19], by assessing the chromosome transmission fidelity (Ctf) phenotype (for details see Materials and Methods) in an additional 208 Ts strains. The functional distribution of the identified genes reveals that proteasome subunits are highly represented (Figure 1A and Table S1), we therefore decided to examine the mechanisms by which mutations in proteasome subunits cause CIN.

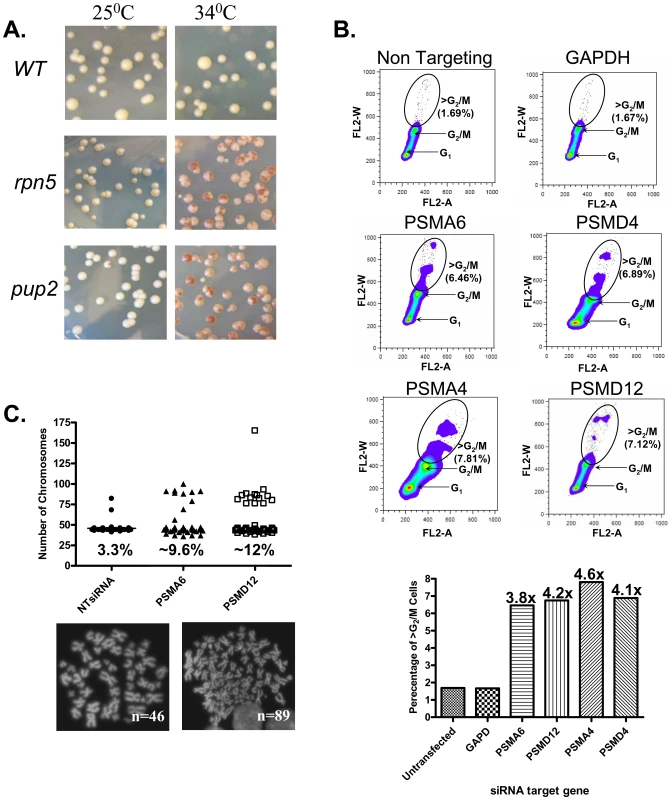

Fig. 1. The CIN Phenotype of proteasome subunits is conserved from yeast to human cells.

(A) Chromosome transmission fidelity (ctf) phenotype of yeast mutants defective for the proteasome subunits pup2 and rpn5ΔC at a semi-permissive temperature (34°C) is scored by the appearance of sectored colonies, and compared to the isogenic wt strain. (B) DNA content dot plots of asynchronous HCT116 cells following siRNA knockdown in control, and test cases generated from cell populations harvested 5-days after transfection. HCT116 cell line, a mismatch repair-deficient cell line, was used, as it is a chromosomally stable, near diploid colorectal cell line that does not inherently exhibit CIN. Cells were labeled with propidium iodide and subjected to flow cytometry. Circles delineate the population of cells having >G2/M DNA contents. The graph summarizes the relative increase in this cell population as compared to the non-targeting and GAPDH controls. (C) Scatter plot depicting the total chromosome number distribution after targeted knockdown of PSMA6, PSMD12, or a non targeting (NT) RNAi control. Percentage of mitotic spreads with greater than 46 chromosomes is indicated at the base of each column; (below) Representative images of DAPI-stained mitotic spreads from untransfected cells (N = 46 chromosomes) and aneuploid cells after treatment with PSMA6 siRNA (N = 89 chromosomes). Diminished levels of proteasome subunits in mammalin cells causes CIN

To test whether the CIN phenotype associated with proteasome dysfunction is evolutionarily conserved, we examined whether diminished proteasome subunit levels would cause a CIN phenotype in human cell lines. Small interfering RNAs (siRNAi) were used to target two human proteasome core (PSMA6 and PSMA4) and two lid subunits (PSMD4 and PSMD12) in the HCT116 cell line. To reduce the off-target effect, each experiment was performed with the two most effective siRNA duplexes (pointed by black arrows in Figure S1A). As shown in Figure 1B, relative to the controls, knockdown of Psma6, Psma4, Psmd4 and Psmd12 resulted in an increase in the frequency of cells with DNA contents greater than that of G2/M cells. Chromosome spreads after targeted knockdown of PSMA6 and PSMD12 established that the increase in DNA content is due to a dramatic increase in the number of cells with a total chromosome number above 46 (Figure 1C). Taken together, these results suggest that the proteasome lid and core components have a role in chromosome stability maintenance.

Proteasome CIN mutations cause nuclear mislocalization

Previously it was established that the 26S proteasome localizes to the nucleus [20]. Here we confirmed the nuclear localization of the proteasomal lid and core subunits both in yeast and human cells (Figure 2A and 2B). The CIN phenotype caused by Ts alleles of proteasome subunits suggests that a nuclear function of the proteasome is impaired in the mutants. Sequence analysis of the rpn5 Ts allele reveals a single base pair insertion that introduces a premature stop codon, resulting in truncation of 39 amino acids at the C-terminus (Figure 2C). To analyze the localization of this truncated form, termed rpn5ΔC, GFP was fused in frame at its N-terminus. As a control, an identical N-terminal GFP fusion was constructed for the wt RPN5 gene (both expressed from a galactose-inducible promoter). The results show that whereas the control GFP-Rpn5 protein localizes predominantly to the nucleus, GFP-Rpn5ΔC localizes predominantly to the cytoplasm (Figure 2D). Similar nuclear mislocalization results were obtained for the mutated core subunit, Pup2Ts-GFP (Figure 2D). The mislocalization of the rpn5ΔC mutant protein indicates that the C-terminal domain (CTD) is important for Rpn5 nuclear localization in yeast.

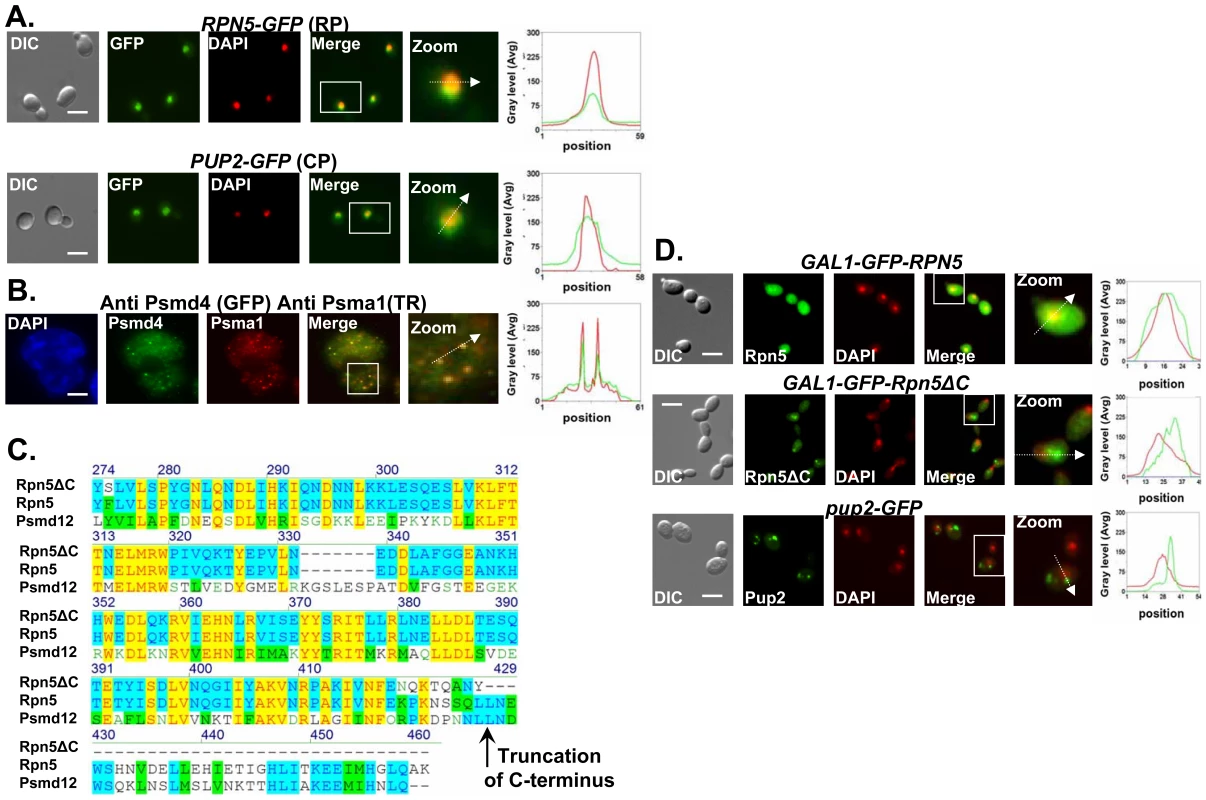

Fig. 2. Proteasome subunits in yeast and mammalian cells localize to the nucleus; the Ts allele of rpn5 is truncated at the C-terminus; proteasome CIN mutants show nucleus mislocalization of proteasome subunits.

(A,B) Proteasome subunits in yeast and mammalian cells localize to the nucleus. (C) The Ts allele of rpn5 is truncated at the C-terminus. (D) Proteasome CIN mutants show nucleus mislocalization of proteasome subunits. The panels represent high resolution (x100) representative images of yeast or mammalian cells. A region identified by the white box is further magnified (zoom panel). The position of the white arrow within the zoom panel delineates the line scan that was used to quantitate the fluorescent signal intensities per pixel in the line scan graphs (right panel). Unless otherwise stated, all the images represent a 3-D projection of x100 Z-series images extending above and below the entire nucleus. Scale bars, 3 µm. (A) Logarithmic yeast cultures were permeabilized and DNA was DAPI stained to mark the nucleus. The panels depict the nuclear localization of the yeast Regulatory Particle (RP) Rpn5-GFP, and Core Particle (CP) Pup2-GFP. GFP and DAPI are represented by green and red curves in the line scan graphs, respectively. (B) Nuclear enrichment and foci colocalization of immunofluorescently labeled mammalian proteasomal subunits Psma1 (CP) and Psmd4 (RP). Cells were DAPI stained and visualized by GFP, Texas Red (TR) and DAPI. Red and green lines represent TR and GFP, respectively. Panels represent a 3-D projection of x100 Z-series images extending above and below the entire nucleus. (C) The rpn5-Ts allele was sequenced and its predicted translation product aligned to the wt yeast protein Rpn5, and its human homolog, Psmd12. The truncation point of Rpn5ΔC is indicated by a black arrow. (D) Localization analysis of N-terminal GFP fusion of Rpn5ΔC, and Rpn5 control (both expressed from a galactose-inducible promoter). The images depict the localization of GAL1-GFP-Rpn5 vs. GAL1-GFP-Rpn5ΔC. GFP-Rpn5 localizes to the nucleus (overlap between the DAPI and GFP channels). Lack of overlap in GFP-Rpn5ΔC indicates nuclear mislocalization. Similar results were obtained for pup2-Ts (Pup2-GFP) (compare to Figure 2A). Mutated proteasome subunits affect DNA DSBs repair kinetics

Next we wanted to address the underlying defect in proteasome function that results in CIN. First we examined the proteasomal CIN mutants for sensitivity to Bleomycin (bleo) [21], and to hydroxyurea (HU)[22]. Mutants involved in DSB repair are usually sensitive to both drugs [23],[24]. We show that at semi-restrictive temperatures all proteasome mutants display varying degrees of sensitivity to these drugs (Figure 3A and Figure S1B). These results support a previous study showing that other proteasome mutants show sensitivity to DNA damaging agents [7]. Moreover, Ts alleles of rpn5ΔC and pup2, display a synthetic growth defect when either one is combined with rad52, a key factor in the DSB repair pathway [25] (for details see Figure 3B).

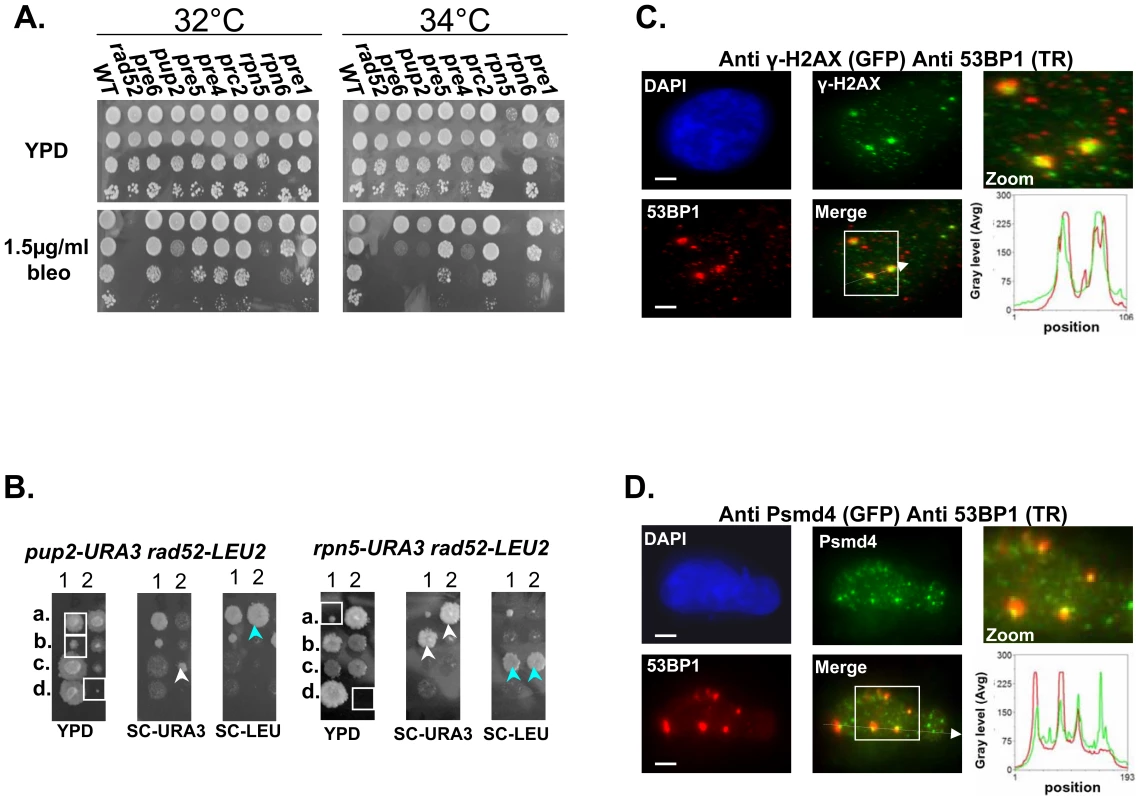

Fig. 3. Mutated proteasome subunits affect the repair of DNA DSBs.

(A) Most of proteasomal Ts mutants are sensitive to bleomycin (bleo). Five-fold serial dilutions of the indicated proteasomal subunits mutants were spotted on YPD medium lacking or supplemented with 1.5 µ/ml of bleo. Cells were incubated at 32°C and 34°C to find the semi-permissive temperature of each Ts mutant. (B) rpn5ΔC and pup2 show synthetic growth defect with rad52. To examine whether there could be a link between the proteasome and the repair of DSBs, we created and sporulated heterozygous diploid strains containing Ts alleles of either rpn5ΔC and pup2 combined with rad52. Tetrad dissection showed that Ts alleles of rpn5ΔC and pup2 cause a synthetic growth defect when either one is combined with rad52. The synthetic growth defect of the double mutant spores (encircled by white squares on the YPD plate) is evident when compared to the single haploid mutants (pointed out by white or light blue arrows). (C,D) Protesomal subunits associate with DSB markers in mammalian cells. HeLa cells were treated for 2 hrs with 5 µ/ml of bleo prior to subjection to IIF microscopy. Primary antibodies were recognized with appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with either Alexa-fluor 488 (GFP filter), or Cy-3 (TR filter). Scale bars, 3 µm. (C) IIF to demonstrate the colocalization pattern of 53BP1 and γ-H2AX in bleo-treated cells. The DSB markers 53BP1 and γ-H2AX show clear co-localization at large foci, likely to represent DSB sites. Red and green curves on the line scan graph represent 53BP1, and γ-H2AX respectively. (D) Representative images demonstrating an association of the RP subunit Psmd4 with DSB sites, represented by the large 53BP1 foci. Red and green curves on the line scan graph represent 53BP1 and Psmd4 respectively. In support of a role for the yeast proteasome in DSB repair, previous ChIP experiments have provided evidence for the recruitment of the proteasome to DSB sites [7]. To test whether this phenomenon is conserved in mammalian cells, we performed Indirect ImmunoFluorescent (IIF) on Hela cells treated with Bleo, to look at the association of the RP subunit Psmd4 with DSB sites, represented by 53BP1 large foci (Figure 3D). In 183/200 53BP1 large foci counted, the Psmd4 focus was peripherally associated with the DSB site (Figure 3D). As a control we analyzed a similar number of unchallenged cells; in this case a significantly lower number of 53BP1 foci (44) could be detected, 21 of which were associated with a Psmd4 focus. As was previously shown [26],[27], these foci likely represent spontaneous DNA DSBs generated during DNA replication. In addition, we quantitated the signals of 50 Psmd4 foci that were associated with 53BP1 as a result of Bleo treatment; in 95% of the cases this signal was 5–10 times more intense than the average signal representing the Psmd4 foci not associated with 53BP1. These results provide evidence for an association of the proteasome with DSBs sites in human cells.

In order to examine the nature of the observed difference in DSB repair under proteasome dysfunction we studied the effect of the well-characterized proteasome inhibitor, MG132 [28] on the repair kinetics of a single defined chromosomal break in the yeast genome using the strain MK203 [29] (for more details see Figure 4A, and Materials and Methods). The strain used carried a mutation in the PDR5 gene, to prevent the cells from pumping the drug out of the cell [30].

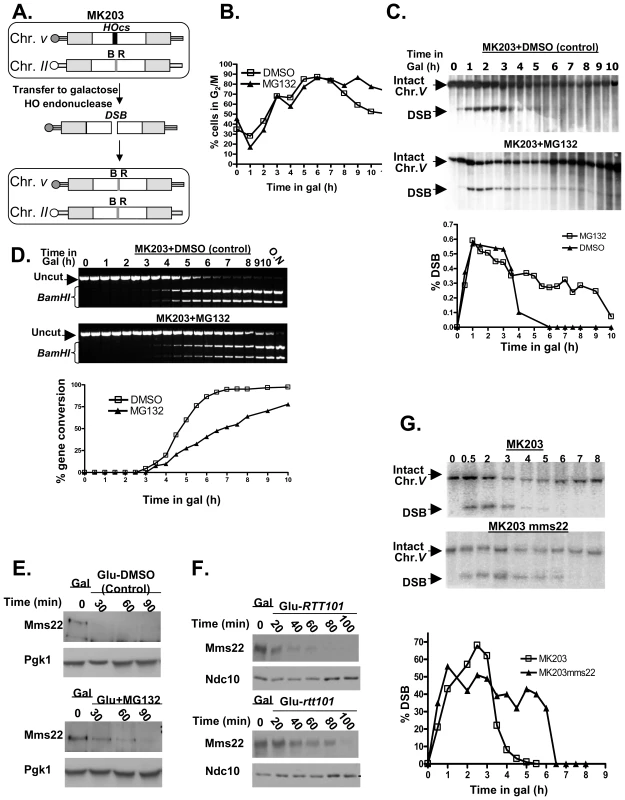

Fig. 4. Proteasome mutants exhibit defective DSB repair kinetics; the turn over of Mms22 is regulated by the proteasome; Mms22 plays a role in DSB repair.

(A–D) Proteasome mutants exhibit defective DSB repair kinetics. (E,F) The turn over of Mms22 is regulated by the proteasome. (G) Mms22 plays a role in DSB repair. (A) Schematic representation of MK203 (for more details see Materials and Methods, DSB repair kinetic experiments). White rectangles represent the ura3 alleles on chromosomes II and V. A black bar within the ura3 alleles represents the HO cut site (HOcs); a grey bar depicts the inactive HOcs-inc flanked by the BamHI (B) and EcoRI (R) restriction sites. Transfer of the cells to galactose-containing medium results in a DSB that is repaired by homologous recombination. (B–D) DSB repair kinetics of MK203 cells in the presence of proteasome inhibitor. MK203 pdr5 cells were grown to mid-logarithmic phase in glycerol-containing medium (gly) (no HO-induction) containing 20 mM MG132, or DMSO control. Cells were then transferred to galactose-containing medium (gal; constitutive HO-induction and DSB formation at the URA3 locus) containing the same concentration of the drug. Samples were collected for analysis at timely intervals, and subjected to microscopic examination and Southern blot analysis. (B) Microscopic examination of dumbbell shaped cells indicates the percentage of G2/M in the control, or cells subjected to MG132, at each of the indicated time points. (C) Southern blot analysis and quantification graph (bottom) of the DSB repair kinetics in MK203 cells treated with MG132. (D) PCR analysis of the kinetics of the gene conversion product formation. PCR reaction followed by BamHI restriction digest detect the final step of the repair, which is the re-ligation of the broken ends and transfer of the two polymorphic restriction sites on either side of the HOcs from chromosome II to chromosome V [29]. MG132 treated cells show a delay in gene conversion product formation, as apparent from the quantification graph (bottom). (E) Western Blot detects the levels of Mms22 following a GAL1 promoter shut-off chase experiment. The expression of GAL1-HA-Mms22 was induced by growing the cells in 2% galactose (Gal) for 3 hours (t-0). Cells were released into 2% glucose to shut-off the expression of Mms22. Glucose was supplemented with 20 mM MG132, or with DMSO (control), Pgk1 was used as a loading control. (F) RTT101 regulates the levels of Mms22. GAL1 shut-off chase experiment was performed as in (E), this time wt cells vs. rtt101 strains were released into 2% glucose. Ndc10 was used as a loading control. (G) Southern blot analysis and quantification graph (bottom) of the DSB repair kinetics in wt MK203 cells versus mms22. As previously described [29], the control and MG132-treated cells arrest at G2/M three hrs after DSB induction. However, while the control cells exited from the arrest after 8 hrs, MG132-treated cells remained arrested even 10 hrs after DSB induction (Figure 4B). Southern blot analysis detected complete repair of the broken chromosome by 5 hrs following induction in control cells. In contrast, MG132-treated cells exhibited only partial repair of the DSB. Nine hours after transfer to galactose (which induces DSB repair), more than 30% of the cells still carry a broken chromosome (Figure 4C). At later times this proportion is reduced, probably due to outgrowth of cells with a repaired chromosome V.

We next examined the kinetics of formation of the gene conversion (GC) repair product (Figure 4D). In the control cells, GC can be detected 3.5 hrs after DSB induction, and the whole cell population was completely repaired by 6.5 hrs. In contrast, in MG132-treated cells only 70% of the cells exhibited repair 10 hrs after DSB induction (Figure 4D). Taken together, these results demonstrate that inhibition of proteasome activity affects the ability of yeast cells to carry out repair of a DSB, resulting in a prolonged cell cycle arrest. Moreover, MG132-treated cells also exhibit a higher level of CIN, measured using the a-faker-like (ALF) genome instability test [31] (Figure 2SA).

The expression of Mms22 is regulated by the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS)

One possible explanation for the requirement of an active proteasome to complete the DSB repair is that the proteasome could be required to degrade one or more components of the DSB repair machinery. We looked for potential proteasome targets with a role in DSB repair. Such a target is expected to exhibit phenotypes that include both CIN (similar to that of proteasomal mutants), and sensitivity to DNA damaging agents, such as ionizing radiation or radiomimetic drugs such as methyl methanesulfonate (MMS). We recently used the Sacharomyces cerevisiae deletion collection to systematically screen for mutants exhibiting a CIN phenotype [31]. The mms22 mutant, which shows sensitivity to several DNA damaging agents that cause DSBs [32],[33] was among the mutants exhibiting the strongest CIN phenotype. To test whether Mms22 is a substrate of the proteasome, a strain carrying an inducible tagged protein (GAL1-HA-Mms22) was subjected to a promoter shutoff experiment. Figure 4E shows that under these conditions in wt cells Mms22p is degraded; in contrast, in the presence of MG132, the level of Mms22 protein stays high, and appears to be degraded to a lesser degree.

To further assess MMS22 function, we conducted a two-hybrid screen using Mms22 as the bait. This approach identified Rtt101/Cul8 as a protein that interacts with Mms22. We confirmed this interaction by IP. Consistent with a recent study [34], we concluded that Mms22 and Rtt101 proteins interact in vivo (Figure S2B and S2C). Rtt101 is one of four cullins in S. cerevisiae, with demonstrable ubiquitin ligase activity in vitro, but as yet no known substrate in vivo [35]. Based on the physical interactions seen between Mms22p and Rtt101, it has been suggested that Mms22 is a functional subunit of the Rtt101-based ubiquitin ligase [34]. Our results show that Mms22 is targeted by the proteasome; we therefore hypothesized that the turnover of Mms22 could be mediated by the Rtt101 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. A promoter shut-off chase was used again to analyze the stability of the Mms22 protein in the presence or absence of the Rtt101 cullin. Figure 4F shows that Mms22p accumulated to a higher level during the induction period in rtt101 mutants in comparison to wt cells. To rule out the possibility that only the overexpressed proteins were being degraded by the proteasome, and to show that similar results can be observed in the context of endogenous levels of Mms22, we have performed cyclohexamide chase experiments in cells expressing Mms22-HA (Figure S2D). Western blot analysis revealed that, as observed in the GAL-driven overexpression experiments, Mms22 is also degraded in wt cells. Notably, Mms22 accumulated to higher levels in the presence of MG132, or in a Δrtt101 background. These results clearly demonstrate that the turnover of Mms22 is regulated by the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS), and mediated by the Rtt101 cullin.

Mms22 plays a role in DSB repair

mms22 cells show sensitivity to several DNA damaging agents that cause DSBs [32],[33]. To directly examine the kinetics of DSB repair in mms22 mutants, we used the MK203 system again, to compare repair kinetics of wt vs. mms22 cells following induction of a DSB. As seen in cells under proteasome inhibition, mms22 mutants show a delay in the disappearance of the broken chromosome compared to wt cells (Figure 4G). Additionally, and also similarly to MG132-treated cells, mms22 cells show a difference in gene conversion kinetics compared to wt cells (Figure S2E).

Ubiquitination of Mms22 is induced by DNA damage in a RTT101 dependent manner

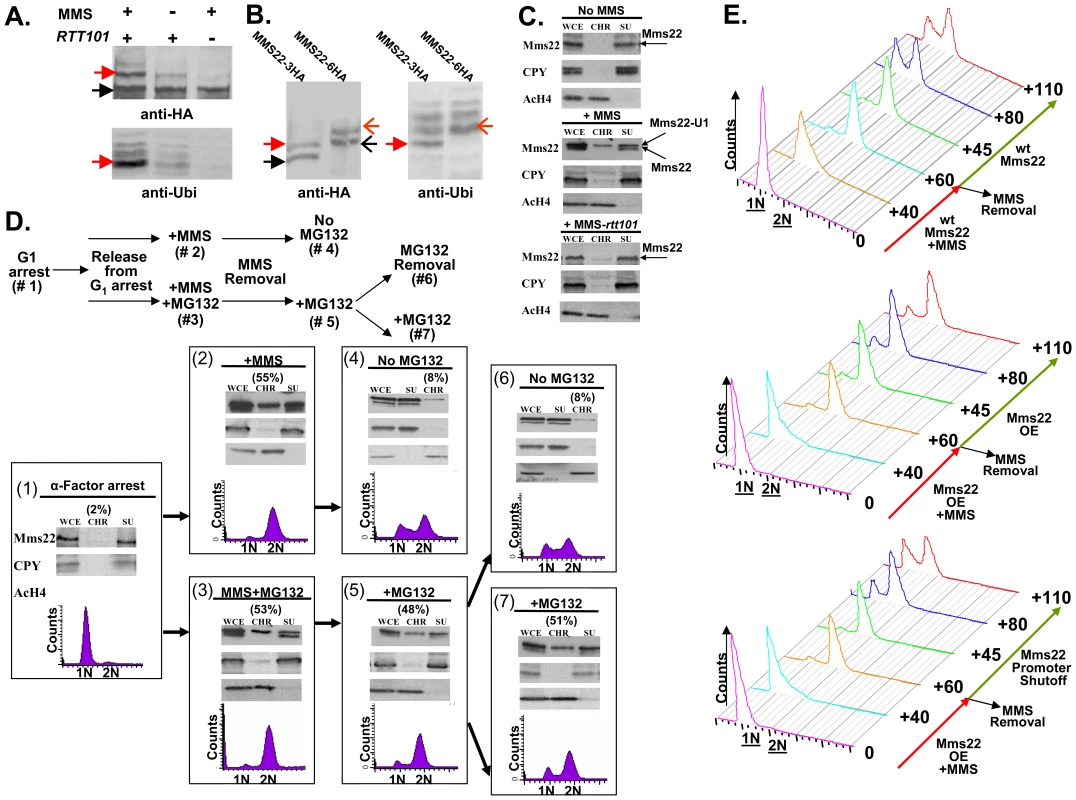

Substrates are usually targeted for degradation by the proteasome by polyubiquitination [10]. To test the ubiquitination levels of Mms22, we performed the experiments described in Figure 5A and Figure S2F. IP of Mms22-HA followed by immunoblotting reveals an additional band which migrates slower than Mms22-HA. This band most probably represents the ubiquitinated form of Mms22, as revealed by successive immunoblotting with an anti-Ubi antibody (Figure 5A). Additional proof that this band represents ubiquitinated Mms22 was obtained by successive immunoblotting with an anti-Myc antibody in a strain carrying a myc-tagged version of the ubiquitin protein (Figure 2SF). The results also show that Mms22 ubiquitination is RTT101 dependent. Finally, a 4 -fold increase in Mms22 ubiquitination was observed when cells were exposed to DNA damage, suggesting that the ubiquitination of Mms22 plays a functional role in DNA repair (Figure 5A).

Fig. 5. Ubiquitination of Mms22 is induced by DNA damage in a RTT101 dependent manner; Mms22 is recruited to chromatin upon DNA damage in a RTT101 dependent manner; degradation of Mms22 from chromatin is associated with exit from the DNA damage induced G2/M arrest.

(A, B) Ubiquitination of Mms22 is induced by DNA damage in a RTT101 dependent manner. (C) Mms22 is recruited to chromatin upon DNA damage in a RTT101 dependent manner. (D,E) Degradation of Mms22 from chromatin is associated with exit from the DNA damage induced G2/M arrest. (A) 3HA-tagged Mms22 cells were grown in the presence of 20mM MG132, with or without 0.025% MMS, and subjected to IP. After electrophoresis on a low percentage gel (6%), the precipitated protein was blotted to a membrane which was successively immunobloted with an anti-HA, and an anti-Ubi antibody. Black arrow labels Mms22-3HA, red arrow labels the modified form of Mms22-3HA. (B) In vivo demonstration that the ubiquitinated proteins observed in (A). are a series of polyubiquitinated forms of Mms22. Cells carrying Mms22 tagged with either 3HA, or 6HA were grown in the presence of 20 mM MG132, and 0.025% MMS, and subjected to IP. After electrophoresis the precipitated proteins were blotted to membranes which were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-HA, and anti-Ubi antibodies. Black and open black arrows label Mms22-3HA and Mms22-6HA respectively. Red and open red arrows label the mono-ubiquitinated form of Mms22-3HA and Mms22-6HA respectively. (C) Cell extracts (WCE) were separated into supernatant (SU) and chromatin (CH) fractions. HA-tagged Mms22 was detected by immunoblotting in wt (middle), or rtt101 deleted cells (right), treated with 0.025% MMS, and compared to the untreated wt control (left). Anti Carboxy peptidase-Y (CPY), and Anti Acetylated Histon H4 (AcH4) served as a SU and CH fractions controls respectively. (D) (Top)-Experimental design. Chromatin fractionation assay was performed as in (B). The quantity of Mms22 on the chromatin bound fraction is represented as percentage of the WCE. Cells were synchronized to G1 (#1), and released from the arrest in the presence of 0.025% MMS (#2), or MMS+MG132 (#3). Next, MMS was removed, and samples were allowed to recover in the presence (#5), or absence (#6) of MG132. Sample #6 and #7 represent a division of sample #6 to a sample without, or with MG132 respectively. (E) Failure to degrade Mms22 impairs progression of repair, leading to prolonged cell cycle arrest. G1 arrested cells were released into YEP-Gal medium (inducing overexpression of GAL1-MMS22 cells) containing 0.025% MMS. MMS was washed from the G2/M arrested cells, and cells were allowed to recover in YEP-Gal or YEP-Glu (thus keeping either high or low expression levels of Mms22 in GAL1-MMS22 cells respectively). Top panel: wt expression levels of Mms22. Middle panel: Mms22 was over-expressed (OE) before, and after the removal of MMS. Bottom panel: Mms22 was OE before the removal of MMS, while its GAL1 promoter was shut off following MMS removal. Samples were collected at timely intervals and subjected to FACs analysis; numbers along the red and green arrows represent the time (minutes) since the release from the G1 arrest, or following MMS removal respectively. To provide a rigorous in vivo demonstration that the ubiquitinated proteins observed by Western blotting were indeed a series of polyubiquitinated forms of Mms22, we performed the following experiment in which the 3HA and 6HA tagged versions of Mms22 were used in parallel. Cells were grown in the presence of MMS, and subjected to IP followed by immunoblotting with anti-HA. As expected from the results shown in Figure 5A, treatment with MMS led to an additional band which migrated more slowly than the band representing Mms22. Importantly, this band changed its electrophoretic mobility upon switching the tag on Mms22 from 3HA to 6HA, demonstrating unequivocally that it represents a specific in vivo modification of Mms22 (Figure 5B, left). This modification is indeed the specific ubiquitination of Mms22 as revealed by a similar electrophoretic shift of the bands that appeared following a successive immunoblotting with an anti-Ubiquitin antibody (Figure 5B, right). Alignment of the anti-HA and anti-Ubi antibody membranes, and the observed co-alignment of the electrophoretic shifts characteristic of the differentially tagged Mms22 protein species, indicates that the additional band that migrates slower than Mms22-HA is the mono-ubiquitinated form of Mms22.

Upon exposure to DNA damage Mms22 is associated with chromatin in a RTT101- dependent manner

Genome-wide genetic interaction results have shown that MMS22 clusters with RTT109, and ASF1 [36], two proteins required for histone H3 modification [37]. We therefore hypothesized that the ubiquitinatation of Mms22 may facilitate its recruitment to chromatin upon DNA damage. To test this idea we separated whole cell extracts (WCE) into soluble (SU) and chromatin-bound (CHR) fractions. Fractions were then subjected to immunoblotting using anti HA (Mms22-HA). The results clearly show that in unchallenged cells Mms22 is mainly present at the SU fraction (Figure 5C top). Treatment with MMS, however, leads to an enrichment of ubiquitinated Mms22 on the chromatin-bound fraction (Figure 5C middle). This enrichment was significantly reduced in the absence of RTT101 or RTT109 (Figure 5C bottom and Figure S3A).

Taken together, our results suggest that the ubiquitinated form of Mms22 on chromatin plays a functional role in dealing with DNA damage. A similar experimental approach was used to show chromatin enrichment of the proteasomal lid subunit Rpn5 upon exposure to MMS (Figure 3SB), which is consistent with ChIP analysis of proteasomal subunits at induced DSBs sites [7].

Mms22 degradation by the proteasome is important for its function in DNA repair

DNA damage induces the recruitment of both Mms22 and the Proteasome to chromatin, predicting that Mms22 degradation by the proteasome plays an important role in performing DNA repair. To test this idea we performed the experiment described in Figure 5D. MMS treatment resulted in G2/M arrest, and a chromatin fractionation assay revealed that Mms22 was recruited to chromatin in the presence, or in the absence, of MG132 (Figure 5D-2 and 5D-3). These results indicate that the recruitment of Mms22 to chromatin is proteasome-independent. The recruitment to chromatin is not cell cycle dependent, since a similar recruitment of Mms22 to chromatin was detected even when cells were kept in G1 during MMS treatment (data not shown). In contrast, the exit from the G2/M arrest following the removal of MMS was proteasome dependent, since only removal of MG132 from the medium led to the degradation of Mms22 from chromatin, which was associated with the exit from the G2/M arrest (compare 6D-5 vs. 6D-6 and 6D-7). To rule out the possibility that the prolonged exposure to MG132 and not MMS treatment led to the G2/M accumulation, we performed the control experiment described in Figure S3C. We show that samples released from the G1 arrest and constantly exposed to MG132 continued cycling normally in contrast to samples from a similar time point exposed to MMS+MG132 (compare Figure 5D-5 to Figure S3C).

Next we wanted to test whether the correlation between the accumulation of Mms22 on chromatin, and the failure to recover from cell cycle arrest upon DNA damage can be attributed (among other factors) to the specific accumulation of Mms22 in cells with defective proteasome activity. We therefore tested whether overexpression (OE) of Mms22 (which simulates the accumulation of Mms22 in proteasome mutants) also results in impaired recovery from DNA damage induced by MMS. While wt cells start to recover from the G2/M arrest 80 min after the removal of MMS from the medium (Figure 5E top), cells that overexpress Mms22 were still arrested even after 110 min (Figure 5E middle). Importantly, the removal of MMS together with Mms22 promoter shutoff (leading to the degradation of Mms22, data not shown), led to enhanced recovery from the G2/M arrest, when compared to cells still overexpressing Mms22 (Figure 5E middle versus bottom).

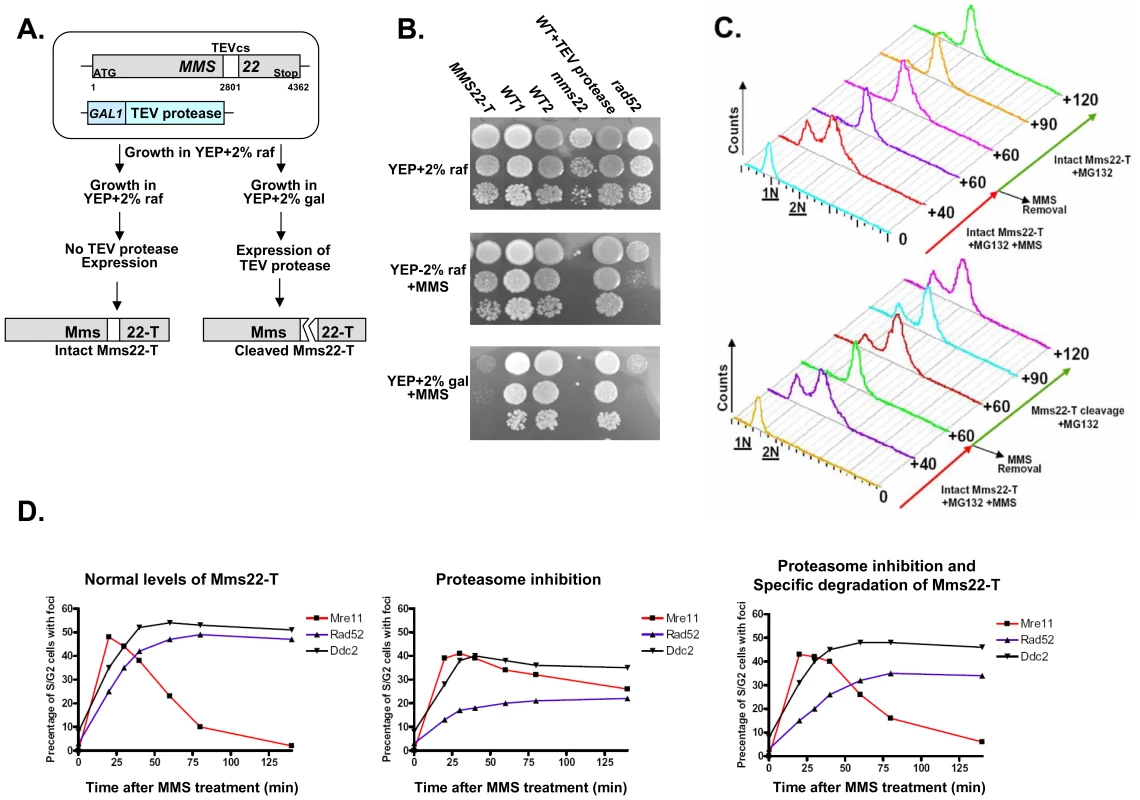

Having shown that degradation of Mms22 can promote exit from the G2/M arrest, we tested whether the specific degradation of Mms22 is sufficient for the exit. We created yeast strains carrying an allele of Mms22 (Mms22-T) that is expressed from its endogenous promoter and can be cleaved by the tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease [38],[39]. This protease can be conditionally expressed (for details see Figure 6A). Induction of the TEV protease leads to cleavage and inactivation of the Mms22-T protein (Figure 6A and 6B). When we conditionally expressed the protease in the presence of MG132 in cells arrested in G2/M as a result of MMS treatment, the cleavage of Mms22-T resulted in a clear release from the DNA damage-induced G2/M arrest (Figure 6C, compare top and bottom panels). Thus, degradation of Mms22 is essential for release from the cell cycle arrest induced by DNA damage.

Fig. 6. Degradation of Mms22 is sufficient to allow exit from the DNA damage induced G2/M arrest.

(A,B) Schematic representation of the experimental design, and growth phenotypes. The TEV protease consensus cleavage site (cs) was introduced at position 2801 of Mms22 which is expressed from its endogenous promoter (MMS22-T). The cells also contain the TEV protease under the control of the inducible GAL promoter [39]. YEP medium supplemented with 2% raffinose (raf) suppresses the expression of the TEV protease, and keeps Mms22-T functional, as indicated by its normal growth on YEP+raf+MMS media (compare to mms22 strain). Transfer of the cells to medium containing 2% galactose (gal) results in TEV protease induction, and the specific cleavage of Mms22-T. The inactivation of Mms22-T is indicated by its impaired growth on YEP+gal+MMS medium. (C) G1 arrested cells were released into YEP-raf medium (which blocks the expression of the TEV-protease), containing 0.025% MMS and 20 mM MG132. MMS was then washed from the G2/M arrested cells, and cells were allowed to recover in YEP-raf (top), or YEP-gal (bottom) (intact, or specific cleavage of Mms22-T respectively), both supplemented with MG132. Samples were collected at timely intervals and subjected to FACS analysis. Numbers along the red and green arrows represent the time (minuets) since the release from the G1 arrest, or following the removal of MMS respectively. (D) Temporal analysis of Mre11, Ddc2, and Rad52 focus formation following DNA damage and proteasome inhibition. Yeast strains containing Mms22-T, GAL inducible TEV-protease, and a YFP tagged version of either Mre11, Ddc2, or Rad52 were released into non-inducing YEP-raf medium containing 0.025% MMS and 20 mM MG132 (intact Mms22-T). Following the induction of DNA damage MMS was washed from the media, and cells were allowed to recover in YEP-raf (left: wt levels of Mms22), YEP-raf+MG132 (middle: accumulation of intact Mms22-T), or YEP-gal+MG132 (right: inducing the specific cleavage of Mms22-T by the TEV protease). Following the removal of MMS, samples were collected at timely intervals, fixed, and subjected to fluorescent microscopy. At each of the indicated time points at least 150 S/G2 cells (budded) were analyzed for the presence/absence of Mre11, Ddc2, or Rad52 foci. Mms22 degradation by the proteasome is essential for the progression of DNA repair

We have shown that the degradation of Mms22 is essential for release from damage-induced cell cycle arrest. Next, we tested whether the prolonged G2/M arrest is also associated with impaired response to DNA damage. Using yeast strains tagged with fluorescent versions of three major components of the DNA DSB repair machinery: Mre11, Ddc2, Rad52, we conducted temporal analysis of focus formation following DNA damage (Figure 6D). Consistent with previous data [40] we show that Mre11 (a member of the MRX complex) is the earliest protein to form foci. Mre11 foci formation is followed by later recruitment of Ddc2 (the yeast orthologue of human ATR-interacting protein ATRIP) and the repair protein Rad52. We show (Figure 6D, left) that in wt cells, as Rad52 and Ddc2 were recruited, Mre11 foci disassembled. This disassembly was circumvented when cells were exposed to a proteasome inhibitor, and led to delayed and reduced focus formation of Rad52 (Figure 6D, middle). Remarkably, the specific degradation of Mms22 resulted in a clear disassembly of Mre11 foci and recovery of Rad52 foci (Figure 6D, right). Our results demonstrate that degradation of Mms22 is essential for the normal course of DNA DSB repair, and for the release from the cell cycle arrest induced by DNA damage.

Discussion

We describe the first systematic screen of a recently released resource (still under development) consisting of Ts mutants of all essential yeast genes for which no Ts-allele had previously been isolated [19]. Among the 40 genes identified, 8 encoded proteasomal subunits. Genetic and biochemical analysis showed that CIN was associated with the failure of proteosomal subunits to localize to the nucleus, impaired kinetics of DSB repair, and failure to turnover the DNA repair protein Mms22 targeted for degradation by the proteasome.

Recent studies have suggested a role for the proteasome in the repair of DSB in yeast [7], and mammalian cells [41],[42]. In our current work, we show that mutations in the proteasome subunits rpn5ΔC and pup2, which cause nuclear mislocalization, are associated with impaired DSB repair. All other proteasomal Ts mutants tested were sensitive to drugs inducing DSBs, implying that the proteolytic activity of the proteasome is required for DNA repair. By examining the kinetics of DSB repair in cells treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132, we obtained evidence for delayed kinetics of repair (Figure 4C). We showed that both the disappearance of the break as well as the kinetics of formation of the gene conversion product were delayed in treated cells compared to untreated cells (Figure 4D). As MG132-treated cells arrest in G2/M similarly to untreated cells, it is evident that checkpoint regulation due to DSB is not impaired in the treated cells. The delay in DSB repair suggests that proteasome activity might be required for the regulation of the DNA repair machinery.

A potential role for regulation of DSB repair by the proteasome in mammalian cells is supported by a recent study showing that proteasome inhibition affected the choice of HR repair pathways [41]. A different study showed that proteasome-dependent protein degradation substantially contributes to HR but not NHEJ [42]. It is tempting to speculate that the proteasome accumulates at sites of DSB, and that its proteolytic activity is required to degrade one or more components of the DSB repair machinery, or DNA damage response/repair proteins.

To date no protein involved in DSB repair has previously been described as a direct target of the proteasome. In this study, we identify Mms22, a protein required for efficient repair of DSBs (Figure 4G and Figure S2E), as a direct target of the proteasome degradation pathway (Figure 4E and 4F and Figure 2SD). Recently, Zaidi and colleagues [34] showed that Mms22 physically interacts with Rtt101, and suggested that Mms22 is a functional component of the SCFrtt101 ligase, perhaps as a substrate specificity factor. Although our studies do not address whether Mms22 is a subunit of SCFrtt101, we show clear evidence that Mms22 is a substrate of the SCFrtt101 and that proteasome-mediated turnover of Mms22 is important for the process of DNA repair.

The effect of MMS22 accumulation on the course of DSB repair (Figure 6D) suggests that Mms22 activity facilitates the recruitment of the HR machinery to DSBs. Histone modification occurs readily at sites of DSB or UV damage [43],[44] and it is becoming increasingly clear that proper chromatin handling is essential for successful repair. Indeed, we show that DNA damage results in Mms22 recruitment to the chromatin bound fraction (Figure 5C). Importantly, our results also show that recruitment of Mms22 to chromatin is not sufficient for the normal course of DNA repair, and that an essential step is a proteasome-mediated degradation of Mms22. These results thus identify for the first time a proteasome target that links proteasomal nuclear activity and DNA double strand break repair.

We propose the following model for the mechanism by which nuclear activity of the proteasome contributes to repair of DSBs. DNA damage results in a SCFrtt101 E3 ubiquitin ligase-dependent accumulation of the ubiquitinated form of Mms22 on chromatin that, as suggested above, plays a role in dealing with DNA damage. Subsequent degradation of ubiquitinated Mms22 by the proteasome is an important step in completion of the DNA repair process. Once Mms22 executes its function in DNA repair it becomes a target for degradation by the UPS, and is removed from chromatin. Failure to degrade Mms22 results in impaired DNA repair and prolonged cell cycle arrest. In support of our model, we show that reactivation of an inhibited proteasome results in degradation of the accumulated chromatin-bound Mms22, and in recovery from the G2 arrest induced by DNA damage (Figure 5D).

The synthetic genetic interaction that we describe for the proteasome and the rad52 mutant points to additional roles of the proteasome in DNA repair. Given its central role in protein degradation, it is indeed very likely that, in addition to Mms22, the proteasome regulates additional proteins involved in DNA repair. In this regard, proteasome inhibition in combination with DNA damage probably results in the accumulation of many proteins besides Mms22, which altogether may lead to the impaired recovery from the cell cycle arrest. We show, however, that specific accumulation of Mms22 by overexpression causes defects in recovery from DNA damage-induced G2/M arrest, whereas turnover of Mms22 after promoter shutoff allows recovery to occur (Figure 5E). Moreover, we also show that the specific degradation of Mms22 in the presence of proteasome inhibitor is sufficient for the exit from the DNA damage-induced G2/M arrest (Figure 6C). The arrest by itself was not affected by proteasome inhibition, which is consistent with the normal kinetics of foci formation of the checkpoint protein Ddc2. In contrast, proteasome inhibition affected the disassembly of Mre11, which in turn impaired the recruitment of the repair machinery, as demonstrated by the kinetics of Rad52 foci formation (Figure 6D). A similar phenotype was previously reported for Δsae2 mutants, supporting the notion that Sae2 is required for the transition from Mre11 binding to the recombinational repair function carried out by Rad52 [40],[45]. Our results suggest that degradation of Mms22 occurs at the same transition stage and that when this transition is impaired, cells can no longer proceed with the normal course of DNA repair. Suggestions about the possible activity of Mms22 at this transition stage comes from genetic interaction data [36]. In these studies, MMS22 clusters with RTT109, and ASF1, which are required for histone H3 acetylation [37]. These results suggest that Mms22, in association with Rtt109, and Asf1 are recruited to the sites of DNA lesions to modify their chromatin structure, perhaps facilitating DNA resection and recruitment of downstream-acting repair proteins such as Rad52. Recruitment of Rad52 in the form of foci depends on the removal Mms22 from DNA by the proteasome.

Taken together, we show that Mms22 is a proteasome target that links nuclear proteasomal activity and DSB repair. We believe that the CIN phenotype and impaired DNA repair caused by proteasome dysfunction can, in part, be attributed to the specific accumulation of Mms22. This idea is further supported by the observation that accumulation of Mms22 sensitizes the cells to DNA damaging agents, and results in CIN (Figure 2SA and Figure 3SD–3SF), and by previous studies showing that mutants in genes that play roles in DSB repair cause CIN phenotype in yeast and mammalian cells [31],[46]. It is likely that additional proteasomal targets important for genome stability await discovery. The mechanism of regulation of Mms22 may serve as a paradigm to understand how these additional proteins are regulated by the proteasome.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains

Yeast strains that were used for the CTF screen are the result of backcrossing the haploid Ts strain (MATa ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 his3Δ1 lys2Δ0 (or LYS2) met15Δ0 (or MET15) can1Δ::LEU2-MFA1pr::His3 yfeg-ts::URA3), to the Donor strain SB1 (MATα ade2-101::NAT his3 ura3 lys2 can1Δ mfa1Δ::MFA1pr-HIS3 CFVII(RAD2.d)::LYS2), and selecting for a Lys+ spore clone (indicating the presence of CFVII(RAD2.d)::LYS2) resistant to ClonNAT (thus carrying the ade2-101 ochre mutation) and Ura+ (yfeg-ts::URA3) [for more details see [19]]. Other strains that were used in this study are listed in Table S2. The following strains were generated by crossing the indicated strains (in brackets), and selecting for the appropriate spores: SB162-(SB158xTs944), SB163-(SB160xTs944), SB220-(SB158xTs670), SB223-(SB160xTs670), SB258-(SB256xSB148), SB259-(SB256xSB147), SB175-(Ts602Xsb132). Yeast strains used for DSB repair assay are isogenic derivatives of strain MK203 (MATa-inc ura3::HOcs lys2::ura3::HOcs-inc ade3::GALHO ade2-1 leu2-3,112 his3-11,15 trp1-1 can1-100) [29],[47], a derivative of W303. In SB276, a TEV protease consensus cleavage site was introduced at position 2801 of Mms22 in the strain K9127 [39] by a two-step gene replacement.

Co-immunoprecipitations

Were preformed as previously described [48].

Chromatin fractionation assay

Was performed as previously described [49]. Cells were grown to O.D600-0.5 in 50 ml culture. Samples were spun down in 50 ml conical tubes for 5 min, resuspended in 3 ml of 100 mM PIPES/KOH pH 9.4, 10 mM DTT, 0.1% Na-Azide, and incubated for 10 min at RT. Samples were then spun for 2 min. Supernatant was aspirated off, and samples were resuspended in 2 ml of 50 mM KPi, pH 7.4, 0.6M Sorbitol, 10 mM DTT, and transferred to 2 ml microfuge tubes. 10 ul aliquot was then diluted in 990 ul H2O in a cuvette. 4 ul of 20 mg/ml Zymolase T-100 was added for 10 min, in 37°C water bath (tubes were gently inverted every 2–3 minutes). After about 1 min, 10 ul aliquot was used to measure the O.D600 (for hypotonic lysis). The O.D of the 1∶100 dilutions after spheroplasting was less the 10% of the value before. From this point on everything was done in a cold room. Tubes were spun for 1 min, cells were then washed with 1 ml of 50 mM HEPES/KOH pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.4M sorbitol. Tubes were spun for 1 min, and resuspended in equal pellet volume EB (around 80 ul). 1/40 volume 10% Triton X-100 (0.25% final, e.g. 4 ul for 160 ul suspension), was added and cells were incubated for 3 min for lysis on ice, (vortexed occasionally). This sample represents the whole cell extract (WCE). 20 ul sample was removed and 20 ul of SDS loading buffer was added (WCE). 100 ul EBX-S was prepared in separate microfuge tubes. 100 ul of whole cell extracts were laid onto the EBX-S, and microfuge tubes were spun for 10 min. The resulted fractions represent a white chromatin pellet (CHR), the clear sucrose layer, and above a yellow supernatant fraction (SUP). 20 ul of SDS loading buffer was added to 20 ul of the SUP fraction (SUP). The rest of supernatant and sucrose buffer were then aspirated. The chromatin pellet was resuspended in 100 ul EBX, and spun for 5 min. Supernatant was aspirated off, and chromatin pellet was resuspended again in 100 ul EBX. 20 ul sample was then removed and added to 20 ul of SDS loading buffer (CHR). EB: 50 mM HEPES/KOH pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 20 ug/ml leupeptin, 2 mM benzamidine, 2 ug/ml aprotinin, 0.2 mg/ml bacitracin, 2 ug/ml pepstatin A, 1 mM PMSF (add it just before use). EBX: EB +0.25% Triton X-100. EBX-S: EBX +30% Sucrose.

Immunofluorescent labeling

Cells were plated onto sterilized glass coverslips so that they were 50% to 80% confluent on the following day. Subsequent to fixation for 5 min at 25°C with fresh 4.0% paraformaldehyde, cells were permeabilized with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.5) containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Cells were washed twice with PBS and subjected to sequential series of 30-min incubations with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies. Wash steps consisted of a single wash with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and two washes with PBS. The following primary antibodies were used: anti Psmd4 (Abcam ab20239), Psma1 (Abcam ab3325), anti 53BP1 (Abcam ab21083) and anti γH2AX (Abcam ab18311). Primary antibodies were recognized with appropriate mouse or rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated with either Alexa-fluor 488 or Cyanin-3 (Cy-3) (MolecularProbes, and the Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories respectively). Coverslips were mounted onto slides containing approximately 10 µl of a 90% glycerol-PBS–based medium containing 1 mg/mL parapheylenediamine and 0.5 µg/ml DAPI. Image acquisition and processing was preformed as detailed previously [50] using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 digital imaging microscope equipped with a ×63 (1.3 numerical aperture) and a x100 (1.4 numerical aperture) plan-apochromat oil-immersion lens, a Coolsnap HQ cooled charge-coupled device camera (Roper Scientific), and Metamorph imaging software (Universal Imaging Corp).

The following procedures were performed as previously described [51], in brief:

Cell culture and siRNA transfection

HCT116 and Hela cells were cultured in McCoy's 5A and DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS in a 37°C humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. siRNA duplexes targeting PSMA6, PSMD12, PSMD4 and PSMA4 were purchased from Dharmacon. Transient transfection of HCT116 or Hela cells was performed using DharmaFECT 1 reagent as described by the manufacturer (Dharmacon).

Western blot analysis

To confirm protein knockdown and identify the most effective siRNA duplexes for each target, Western blots were conducted on proteins extracted from asynchronous and subconfluent cells 4 days post-transfection. Following protein transfer nitrocellulose membranes were blotted using the following Antibodies: anti PSMD4 (Abcam ab20239), anti PSMA4 (Abcam ab55625) and anti PSMA6 (Abcam ab2265). Alpha-tubulin mouse monoclonal antibody (Abcam ab7291) and GAPDH (Abcam ab9485) were used as a loading control.

Flow cytometry

Duplicate populations of asynchronous and subconfluent cells were harvested five days post-transfection, washed with PBS and permeablized with 70% Ethanol before PI-labeling. Cells were briefly sonicated to render a single cell suspension immediately before DNA content analysis.

Chromosome spreads and painting

To enrich for mitotic chromosomes, subconfluent cells were treated with KaryoMAX colcemid (0.1 µg/ml; Gibco) for 2 h before harvesting. Cells were trypsinized, pelleted (800 rpm, 5 min) and resuspended in hypotonic solution (75 mM KCl) for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were pelleted (5 min) and resuspended in freshly made methanol∶glacial acetic acid (3∶1), added drop-wise. Cells were repelleted (5 min), and resuspended in methanol∶glacial acetic acid as above. Two or three drops of suspended cells were applied to pre-cleaned blood smear glass slides.

CTF assay

CTF assay was performed as detailed previously [19],[31]. Each Ts allele was tested in a wide range of semi-and non-permissive temperatures (25°C, 30°C, 32°C, 34°C, and 37°C). Colony sectoring phenotypes were scored qualitatively as mild, intermediate and severe (indicated as 1, 2, and 3, respectively in Table S1).

cDNA isolation and RNA analysis

Was performed to verify the knock down of PSMD12 as a result of siRNAi treatment. RNAs were extracted with a RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). 350 ng of RNA were use for a first strand DNA synthesis (Invitrogen). cDNA was used as a template to detect the RNA levels of PSMD12 (Forward primer: TTTGTCTATTTGTAAGCACT/Reverse Primer: TTAAAAGATCCTTGTATTTG) and, GAPDH (Forward primer: TGACAACAGCCTCAAGATCA; Reverse Primer: CATCCACAGTCTTCTGGGTG).

DSB repair kinetic experiments

Were performed as previously described [29],[47]. In brief, the S. cerevisiae haploid test strain contains two copies of the URA3 gene. One copy, located on chromosome V, carries the recognition site for the yeast HO site specific endonuclease (ura3-HOcs). The second copy, located on chromosome II, carries a similar site containing a single-base-pair mutation that prevents recognition by the HO endonuclease (ura3-HOcs-inc). In addition, the ura3 alleles differ at two restriction sites, located to the left (BamHI) and to the right (EcoRI) of the HOcs-inc insertion. These polymorphisms are used to follow the transfer of information between the chromosomes. In these strains, the HO-endonuclease gene is under the transcriptional control of the GAL1 promoter. When cells are transferred to a galactose containing medium, the HO-endonuclease creates a single DSB. The broken chromosome is then repaired by a mechanism that copies the HOcs-inc information together with the flanking markers, resulting in a gene conversion event.

Media and growth conditions

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains were grown at 30°C, unless specified otherwise. Standard YEP medium (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone) supplemented with 3% glycerol (YEPGly), 2% galactose (YEPGal), or 2% dextrose (YEPD) was used for nonselective growth. 1.8% Bacto Agar was added for solid media.

DSB induction experiments

Single colonies were resuspended in rich YEPGly medium, grown to logarithmic phase, centrifuged and resuspended in YEPGly with and without 20 µM MG132 (CALBIOCHEM) for 2 hrs, followed by centrifugation and resuspension in YEPGal with and without 20 µM MG132. At timely intervals, samples were collected for FACS analysis, cells were inspected for cell cycle stage, and DNA was extracted and subjected to the different assays.

Southern blot analysis for DSB repair kinetics experiments

Was carried out as described previously [47]. The experiments shown in Figure 4 are reproducible, with a SD of about 10%. Rather than adding error bars to each of the data points presented, we show a representative example.

PCR assays

Portions (5 ng) of genomic DNA were amplified in each sample. Reactions were allowed to proceed to cycle 35. Taq polymerase was used in standard reaction conditions. The sequence of individual primers are available upon request.

Quantitation of results

Southern blot images were acquired by exposing the hybridized membrane to a standard X-ray film (FUJI) followed by scanning of the film to the computer.

Gel images were acquired by filming the EtBr stained gel under UV light.

Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels and Southern blots were quantified using the GelQuant computer program (DNR Bio-imaging systems).

Genome-wide yeast-two-hybrid screens

MMS22, was cloned into pOBD2 as described in [52]. The Gal4p-Mms22p-DNA binding domain fusion protein was functional as determined by rescuing sensitivity of mms22Δ to 0.2M HU, 10 µg/ml camptothecin and 0.01% MMS (data not shown). Genome-wide two-hybrid screens were performed as described in [53]. Briefly, each screen was performed in duplicate, and positives that were identified twice were put into a mini-array for retest. Some reproducible positives were observed in many different screens with baits of unrelated function. These were considered as common false positives and were excluded from further analyses.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. LengauerC

KinzlerKW

VogelsteinB

1998 Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature 396 643 649

2. MyungK

KolodnerRD

2002 Suppression of genome instability by redundant S-phase checkpoint pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 4500 4507

3. BranzeiD

FoianiM

2007 Interplay of replication checkpoints and repair proteins at stalled replication forks. DNA Repair (Amst) 6 994 1003

4. KolodnerRD

PutnamCD

MyungK

2002 Maintenance of genome stability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 297 552 557

5. SymingtonLS

2002 Role of RAD52 epistasis group genes in homologous recombination and double-strand break repair. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 66 630 670, table of contents

6. AylonY

KupiecM

2004 DSB repair: the yeast paradigm. DNA Repair (Amst) 3 797 815

7. KroganNJ

LamMH

FillinghamJ

KeoghMC

GebbiaM

2004 Proteasome involvement in the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell 16 1027 1034

8. LiJ

ZouC

BaiY

WazerDE

BandV

2006 DSS1 is required for the stability of BRCA2. Oncogene 25 1186 1194

9. GudmundsdottirK

LordCJ

WittE

TuttAN

AshworthA

2004 DSS1 is required for RAD51 focus formation and genomic stability in mammalian cells. EMBO Rep 5 989 993

10. HershkoA

CiechanoverA

1998 The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem 67 425 479

11. NasmythK

2002 Segregating sister genomes: the molecular biology of chromosome separation. Science 297 559 565

12. BrooksCL

GuW

2003 Ubiquitination, phosphorylation and acetylation: the molecular basis for p53 regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 15 164 171

13. GilletteTG

HuangW

RussellSJ

ReedSH

JohnstonSA

2001 The 19S complex of the proteasome regulates nucleotide excision repair in yeast. Genes Dev 15 1528 1539

14. JelinskySA

EstepP

ChurchGM

SamsonLD

2000 Regulatory networks revealed by transcriptional profiling of damaged Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells: Rpn4 links base excision repair with proteasomes. Mol Cell Biol 20 8157 8167

15. WangQE

WaniMA

ChenJ

ZhuQ

WaniG

2005 Cellular ubiquitination and proteasomal functions positively modulate mammalian nucleotide excision repair. Mol Carcinog 42 53 64

16. NgJM

VermeulenW

van der HorstGT

BerginkS

SugasawaK

2003 A novel regulation mechanism of DNA repair by damage-induced and RAD23-dependent stabilization of xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein. Genes Dev 17 1630 1645

17. HiyamaH

YokoiM

MasutaniC

SugasawaK

MaekawaT

1999 Interaction of hHR23 with S5a. The ubiquitin-like domain of hHR23 mediates interaction with S5a subunit of 26 S proteasome. J Biol Chem 274 28019 28025

18. SugasawaK

OkudaY

SaijoM

NishiR

MatsudaN

2005 UV-induced ubiquitylation of XPC protein mediated by UV-DDB-ubiquitin ligase complex. Cell 121 387 400

19. Ben-AroyaS

CoombesC

KwokT

O'DonnellKA

BoekeJD

2008 Toward a Comprehensive Temperature-Sensitive Mutant Repository of the Essential Genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell 30 248 258

20. EnenkelC

LehmannA

KloetzelPM

1999 GFP-labelling of 26S proteasomes in living yeast: insight into proteasomal functions at the nuclear envelope/rough ER. Mol Biol Rep 26 131 135

21. WorthLJr

FrankBL

ChristnerDF

AbsalonMJ

StubbeJ

1993 Isotope effects on the cleavage of DNA by bleomycin: mechanism and modulation. Biochemistry 32 2601 2609

22. RittbergDA

WrightJA

1989 Relationships between sensitivity to hydroxyurea and 4-methyl-5-amino-1-formylisoquinoline thiosemicarbazone (MAIO) and ribonucleotide reductase RNR2 mRNA levels in strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Cell Biol 67 352 357

23. AouidaM

PageN

LeducA

PeterM

RamotarD

2004 A genome-wide screen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals altered transport as a mechanism of resistance to the anticancer drug bleomycin. Cancer Res 64 1102 1109

24. ParsonsAB

BrostRL

DingH

LiZ

ZhangC

2004 Integration of chemical-genetic and genetic interaction data links bioactive compounds to cellular target pathways. Nat Biotechnol 22 62 69

25. KroghBO

SymingtonLS

2004 Recombination proteins in yeast. Annu Rev Genet 38 233 271

26. McManusKJ

HendzelMJ

2005 ATM-dependent DNA damage-independent mitotic phosphorylation of H2AX in normally growing mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell 16 5013 5025

27. LisbyM

MortensenUH

RothsteinR

2003 Colocalization of multiple DNA double-strand breaks at a single Rad52 repair centre. Nat Cell Biol 5 572 577

28. GaczynskaM

OsmulskiPA

2005 Small-molecule inhibitors of proteasome activity. Methods Mol Biol 301 3 22

29. AylonY

LiefshitzB

Bitan-BaninG

KupiecM

2003 Molecular dissection of mitotic recombination in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 23 1403 1417

30. LeeDH

GoldbergAL

1996 Selective inhibitors of the proteasome-dependent and vacuolar pathways of protein degradation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 271 27280 27284

31. YuenKW

WarrenCD

ChenO

KwokT

HieterP

2007 Systematic genome instability screens in yeast and their potential relevance to cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 3925 3930

32. HanwayD

ChinJK

XiaG

OshiroG

WinzelerEA

2002 Previously uncharacterized genes in the UV - and MMS-induced DNA damage response in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 10605 10610

33. ChangM

BellaouiM

BooneC

BrownGW

2002 A genome-wide screen for methyl methanesulfonate-sensitive mutants reveals genes required for S phase progression in the presence of DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 16934 16939

34. ZaidiIW

RabutG

PovedaA

ScheelH

MalmstromJ

2008 Rtt101 and Mms1 in budding yeast form a CUL4(DDB1)-like ubiquitin ligase that promotes replication through damaged DNA. EMBO Rep 9 1034 1040

35. MichelJJ

McCarvilleJF

XiongY

2003 A role for Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cul8 ubiquitin ligase in proper anaphase progression. J Biol Chem 278 22828 22837

36. CollinsSR

MillerKM

MaasNL

RoguevA

FillinghamJ

2007 Functional dissection of protein complexes involved in yeast chromosome biology using a genetic interaction map. Nature 446 806 810

37. HanJ

ZhouH

HorazdovskyB

ZhangK

XuRM

2007 Rtt109 acetylates histone H3 lysine 56 and functions in DNA replication. Science 315 653 655

38. ParksTD

HowardED

WolpertTJ

ArpDJ

DoughertyWG

1995 Expression and purification of a recombinant tobacco etch virus NIa proteinase: biochemical analyses of the full-length and a naturally occurring truncated proteinase form. Virology 210 194 201

39. UhlmannF

WernicD

PoupartMA

KooninEV

NasmythK

2000 Cleavage of cohesin by the CD clan protease separin triggers anaphase in yeast. Cell 103 375 386

40. LisbyM

BarlowJH

BurgessRC

RothsteinR

2004 Choreography of the DNA damage response: spatiotemporal relationships among checkpoint and repair proteins. Cell 118 699 713

41. GudmundsdottirK

LordCJ

AshworthA

2007 The proteasome is involved in determining differential utilization of double-strand break repair pathways. Oncogene 26 7601 7606

42. MurakawaY

SonodaE

BarberLJ

ZengW

YokomoriK

2007 Inhibitors of the proteasome suppress homologous DNA recombination in mammalian cells. Cancer Res 67 8536 8543

43. van AttikumH

FritschO

HohnB

GasserSM

2004 Recruitment of the INO80 complex by H2A phosphorylation links ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling with DNA double-strand break repair. Cell 119 777 788

44. BerginkS

SalomonsFA

HoogstratenD

GroothuisTA

de WaardH

2006 DNA damage triggers nucleotide excision repair-dependent monoubiquitylation of histone H2A. Genes Dev 20 1343 1352

45. MimitouEP

SymingtonLS

2008 Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature 455 770 774

46. McManusKJ

BarrettIJ

NouhiY

HieterP

2009 Specific synthetic lethal killing of RAD54B-deficient human colorectal cancer cells by FEN1 silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 3276 3281

47. InbarO

KupiecM

1999 Homology search and choice of homologous partner during mitotic recombination. Mol Cell Biol 19 4134 4142

48. KoborMS

VenkatasubrahmanyamS

MeneghiniMD

GinJW

JenningsJL

2004 A protein complex containing the conserved Swi2/Snf2-related ATPase Swr1p deposits histone variant H2A.Z into euchromatin. PLoS Biol 2 e131 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020131

49. LiangC

StillmanB

1997 Persistent initiation of DNA replication and chromatin-bound MCM proteins during the cell cycle in cdc6 mutants. Genes Dev 11 3375 3386

50. McManusKJ

StephensDA

AdamsNM

IslamSA

FreemontPS

2006 The transcriptional regulator CBP has defined spatial associations within interphase nuclei. PLoS Comput Biol 2 e139 doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020139

51. BarberTD

McManusK

YuenKW

ReisM

ParmigianiG

2008 Chromatid cohesion defects may underlie chromosome instability in human colorectal cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 3443 3448

52. CagneyG

UetzP

FieldsS

2000 High-throughput screening for protein-protein interactions using two-hybrid assay. Methods Enzymol 328 3 14

53. UetzP

GiotL

CagneyG

MansfieldTA

JudsonRS

2000 A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 403 623 627

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Nuclear Pore Proteins Nup153 and Megator Define Transcriptionally Active Regions in the GenomeČlánek Deletion of the Huntingtin Polyglutamine Stretch Enhances Neuronal Autophagy and Longevity in MiceČlánek Analysis of the Genome and Transcriptome Uncovers Unique Strategies to Cause Legionnaires' DiseaseČlánek Population Genomics of Parallel Adaptation in Threespine Stickleback using Sequenced RAD TagsČlánek Wing Patterns in the Mist

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 2- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Nuclear Pore Proteins Nup153 and Megator Define Transcriptionally Active Regions in the Genome

- The Scale of Population Structure in

- Allelic Exchange of Pheromones and Their Receptors Reprograms Sexual Identity in

- Genetic and Functional Dissection of and in Age-Related Macular Degeneration

- A Single Nucleotide Polymorphism within the Acetyl-Coenzyme A Carboxylase Beta Gene Is Associated with Proteinuria in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes

- The Genetic Interpretation of Area under the ROC Curve in Genomic Profiling

- Genome-Wide Association Study in Asian Populations Identifies Variants in and Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Cdk2 Is Required for p53-Independent G/M Checkpoint Control

- Uncoupling of Satellite DNA and Centromeric Function in the Genus

- Genomic Hotspots for Adaptation: The Population Genetics of Müllerian Mimicry in the Clade

- Use of DNA–Damaging Agents and RNA Pooling to Assess Expression Profiles Associated with and Mutation Status in Familial Breast Cancer Patients

- Cheating by Exploitation of Developmental Prestalk Patterning in

- Replication and Active Demethylation Represent Partially Overlapping Mechanisms for Erasure of H3K4me3 in Budding Yeast

- Cdk1 Targets Srs2 to Complete Synthesis-Dependent Strand Annealing and to Promote Recombinational Repair

- A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Susceptibility Variants for Type 2 Diabetes in Han Chinese

- Genome-Wide Identification of Susceptibility Alleles for Viral Infections through a Population Genetics Approach

- Transcriptional Rewiring of the Sex Determining Gene Duplicate by Transposable Elements

- Genomic Hotspots for Adaptation: The Population Genetics of Müllerian Mimicry in

- Proteasome Nuclear Activity Affects Chromosome Stability by Controlling the Turnover of Mms22, a Protein Important for DNA Repair

- Deletion of the Huntingtin Polyglutamine Stretch Enhances Neuronal Autophagy and Longevity in Mice

- Structure, Function, and Evolution of the spp. Genome

- Human and Non-Human Primate Genomes Share Hotspots of Positive Selection

- A Kinase-Independent Role for the Rad3-Rad26 Complex in Recruitment of Tel1 to Telomeres in Fission Yeast

- Analysis of the Genome and Transcriptome Uncovers Unique Strategies to Cause Legionnaires' Disease

- Molecular Evolution and Functional Characterization of Insulin-Like Peptides

- Molecular Poltergeists: Mitochondrial DNA Copies () in Sequenced Nuclear Genomes

- Population Genomics of Parallel Adaptation in Threespine Stickleback using Sequenced RAD Tags

- Wing Patterns in the Mist

- DNA Binding of Centromere Protein C (CENPC) Is Stabilized by Single-Stranded RNA

- Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals Multiple Loci Associated with Primary Tooth Development during Infancy

- Mutations in , Encoding an Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporter ENT3, Cause a Familial Histiocytosis Syndrome (Faisalabad Histiocytosis) and Familial Rosai-Dorfman Disease

- Genome-Wide Identification of Binding Sites Defines Distinct Functions for PHA-4/FOXA in Development and Environmental Response

- Ku Regulates the Non-Homologous End Joining Pathway Choice of DNA Double-Strand Break Repair in Human Somatic Cells

- Nucleoporins and Transcription: New Connections, New Questions

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Genome-Wide Association Study in Asian Populations Identifies Variants in and Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Nucleoporins and Transcription: New Connections, New Questions

- Nuclear Pore Proteins Nup153 and Megator Define Transcriptionally Active Regions in the Genome

- The Genetic Interpretation of Area under the ROC Curve in Genomic Profiling

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání