-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

DWARF TILLER1, a WUSCHEL-Related Homeobox Transcription Factor, Is Required for Tiller Growth in Rice

Plant architecture is important for crop yield. In most plants, branches grow smaller than the main shoot, largely due to the ‘apical dominance’. However, in several cereal crops, including rice, wheat, and barley, the branches (tillers) have a height and size indistinguishable from the main shoot. The genetic basis of uniform tiller growth has remained elusive. We identified DWARF TILLER1, a WUSCHEL-related homeobox (WOX) transcription factor, as a positive regulator of tiller growth. Most dwt1 mutant plants show normal main shoot but dwarf tillers and reduced panicle size. Tiller growth in dwt1 appears to be inhibited by the main shoot, as removal of the main shoot releases the first tiller. The non-elongating internodes in dwt1 show reduced cell number and cell size, while DWT1 was mainly expressed in the panicles but not internodes, suggesting that DWT1 plays a long distance regulatory role in promoting internode elongation. Genome-wide expression analysis revealed that the expression of genes related to cell division and elongation, as well as to homeostasis and signaling of cytokinin and gibberellin were affected in dwt1 un-elongated internodes. This study reveals that a WOX transcription factor controls the growth uniformity of tillers and the main shoot in rice.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004154

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004154Summary

Plant architecture is important for crop yield. In most plants, branches grow smaller than the main shoot, largely due to the ‘apical dominance’. However, in several cereal crops, including rice, wheat, and barley, the branches (tillers) have a height and size indistinguishable from the main shoot. The genetic basis of uniform tiller growth has remained elusive. We identified DWARF TILLER1, a WUSCHEL-related homeobox (WOX) transcription factor, as a positive regulator of tiller growth. Most dwt1 mutant plants show normal main shoot but dwarf tillers and reduced panicle size. Tiller growth in dwt1 appears to be inhibited by the main shoot, as removal of the main shoot releases the first tiller. The non-elongating internodes in dwt1 show reduced cell number and cell size, while DWT1 was mainly expressed in the panicles but not internodes, suggesting that DWT1 plays a long distance regulatory role in promoting internode elongation. Genome-wide expression analysis revealed that the expression of genes related to cell division and elongation, as well as to homeostasis and signaling of cytokinin and gibberellin were affected in dwt1 un-elongated internodes. This study reveals that a WOX transcription factor controls the growth uniformity of tillers and the main shoot in rice.

Introduction

Rice is one of the most important crops in the world and feeds more than half of the world population. Thousands of years of domestication and breeding have selected many desirable traits in rice, including a plant architecture optimized for grain yield and quality. A mature rice plant has a main shoot and several lateral branches (tillers), with each bearing an inflorescence (panicle) at the apex. Despite their differences in bud initiation time, the main shoot and all tillers grow to a uniform height and flower at the same time [1]. This is in contrast to its wild progenitor (Oryza rufipogon) and most wild grasses, which have dominant main shoot growth. The uniform growth of tillers and the main shoot in many cultivated cereal crops, such as rice, wheat, barley, is an important agricultural trait because it ensures not only uniform grain size, but also synchronized maturation time and a uniform panicle layer which facilitates harvesting [2]. However, the genetic basis underlying the uniform development of tillers and the main shoot in these crops remains unknown.

The height of the rice culm is mainly determined by the length of the uppermost four or five internodes, which elongate rapidly after the initiation of reproductive growth. Internode elongation involves cell division in the intercalary meristem and subsequent cell elongation in the upper elongation zone [3]. Dwarf and semi-dwarf traits have increased rice yield by improving the harvest index and reducing lodging. Previous studies have demonstrated that gibberellin (GA) and brassinosteroid (BR) are two major hormones that promote internode elongation [4], [5]. However, none of the previously isolated rice mutants disrupt the uniform growth of the main shoot and tillers.

Members of the WOX8/9 subclade of homeobox (WOX) gene family have been shown to play important roles in region-specific transcription programs during many developmental processes. STIMPY/WOX9 and STIP-LIKE (STPL, WOX8) are indispensable for embryonic patterning, shoot apical meristem maintenance, and cell proliferation during embryonic and post-embryonic development, mutants of WOX8/9 display reduced cell division and lethality during embryo and seedling developmental stages in Arabidopsis [6]–[8]. Homologs of WOX8/9 in petunia and tomato plants were reported to play important roles in shaping inflorescence architecture by promoting the separation of lateral inflorescence meristems from the apical floral meristem [9],[10]. Here, we show that DWT1, a homolog of Arabidopsis WOX8/9, is required for the balanced growth of tillers and the main shoot in rice. The dwt1 mutant exhibits an altered architecture with reduced height of tillers and over-growth of the main shoot panicle. Functional analysis revealed that DWT1 acts through a non-cell-autonomous mechanism to promote tiller growth downstream of SLR1. This finding reveals a DWT1-mediated genetic pathway synchronizing the development of tillers and the main shoot in rice.

Results

The dwt1 mutant displays a dominant main shoot

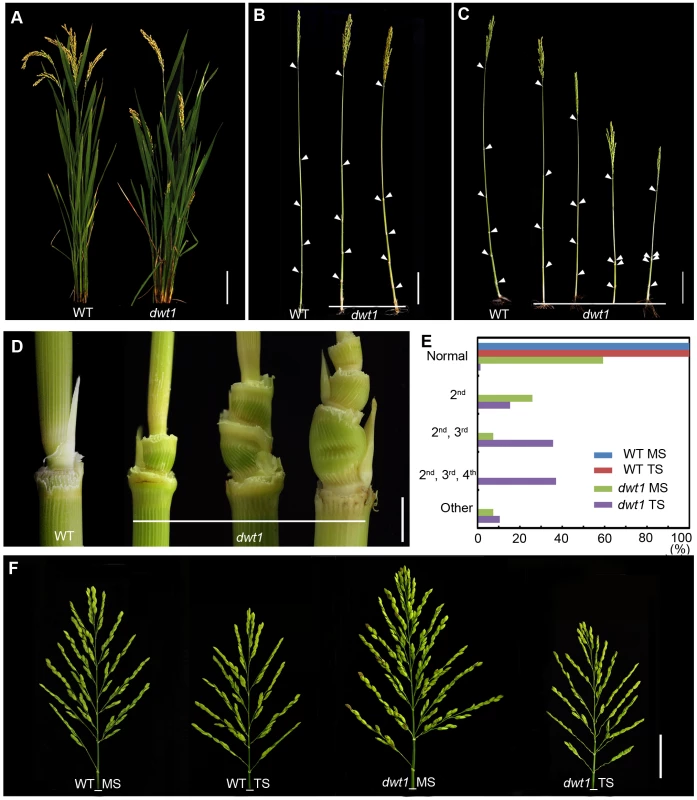

We recently identified a mutant, dwarf tiller1 (dwt1), which exhibits disruption of the synchronized growth of tillers and the main shoot at maturity [11]. Genetic analysis showed that the dwt1 mutant is a recessive allele based on the observations that the F1 progeny of backcross displays the wild-type phenotype and F2 plants segregate about 3∶1 for normal and mutant plants [11]. Unlike wild-type plants, all dwt1 tillers form shorter culm and smaller panicles (Fig. 1A), but most dwt1 main shoots exhibit similar height at maturity as the wild type (Fig. 1B, E). Although all the dwt1 main shoots exhibited a normal height at maturity, 26% of the main shoots had defects in the second internode elongation and about 7% of the main shoots had shorter length of both the second and third internodes compared with the wild type (Fig. 1B, E). However a compensatory elongation of the other internodes, especially the first internode retained the same height of the dwt1 main stem as wild-type plants (Fig. 1B, right 1).

Fig. 1. The dwt1 mutant plants display morphological defects.

A. Morphology of the wild type and dwt1 plants after heading. Bar = 10 cm. B. Mature main shoots with leaves removed from the culm. Arrowheads point to the nodes. Bar = 10 cm. C. Mature tillers with leaves removed from the culm. Arrowheads point to the nodes. Bar = 10 cm. D. Close-up view of the internodes after heading stage. From left to right: the 2nd node of the wild type, the 2nd internode, the 2nd and 3rd internodes, the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th internodes of dwt1 mutant. Bar = 0.5 cm. E. Frequency of normal and short internodes in wild-type and dwt1 main shoot (MS) and tiller shoot (TS). 2nd: only 2nd internode short; 2nd, 3rd: both 2nd and 3rd internodes short; 2nd, 3rd, 4th: all 2nd, 3rd, 4th internodes short. Elongation pattern of main shoots and tillers of both wild type and dwt1 mutants were evaluated at mature stage, and 25 main shoots and 100 tillers of wild type and 25 main shoots and 143 tillers of mutant plants were observed. F. Morphology of panicles from the main shoot (MS) and tillers (TS) of wild type (WT) and dwt1 after heading. Bar = 2 cm. The degree of dwarfism varied among the tillers of the same dwt1 plant (Fig. 1 C). About 15% of dwt1 tillers displayed a shorter length for only the second internode (22/143) (dm-type, Fig. 1C, D and E). About 36% of the tillers (51/143) had a shorter length for both the second and third internodes (Fig. 1C, D, and E), and 37% of the tillers (53/143) had a shorter length for the second, third and fourth internodes (d6-type, Fig. 1C, D and E) [12]. Even though the tiller height is dramatically reduced, the tiller number is not obviously affected in the dwt1 mutant, and both the wild type and dwt1 plants have about eight tillers. In addition, the short internodes appear twisted and distorted in the dwt1 mutant at the mature developmental stage (Fig. 1D).

In contrast to the defective internode development, the dwt1 main shoot develops a larger and denser panicle compared with that of the wild type (Fig. 1F). The average number of primary branches and secondary branches on dwt1 main shoot panicles increases by 119% and 193%, respectively, compared to the wild-type main shoot (Table S1). Consequently, the average number of spikelets in dwt1 main shoots increases by about 162% compared to the wild type, and the weight of 1000 grains from the dwt1 main shoot increases by approximately 107% compared to that of the wild-type main shoot (Table S1). On the other hand, the seed weight of 1000 grains from the dwt1 tillers decreases compared with that of wild-type tillers (Table S1). These observations suggest that dwt1 has defects in growth uniformity between the main shoot and tillers, and its main shoot appears to be dominant compared to tillers.

Suppression of lateral branches by the apex of the main shoot is a common phenomenon in plants, known as apical dominance. Elimination of apical dominance by decapitation usually promotes axillary bud outgrowth [13]. To determine whether the dwt1 phenotype is related to apical dominance, the main shoot and each tiller of dwt1 at the vegetative stage were separated and replanted individually in the paddy field. Each of the regenerated plants from the main shoot or tillers of dwt1 plants developed an architecture similar to dwt1 exhibiting dwarf tillers but a normal main shoot (Fig. 2A and B). In addition, when the main shoot of the dwt1 plant was removed before flowering transition, the first formed tiller became a dominant shoot while subsequent tillers still remained dwarf. However, decapitation after the initiation of reproductive stage did not reestablish the main shoot dominance. Therefore we conclude that dwt1 mutant plants have a characteristic main shoot dominance, which can be partially released by removing the developed main shoot during vegetative growth.

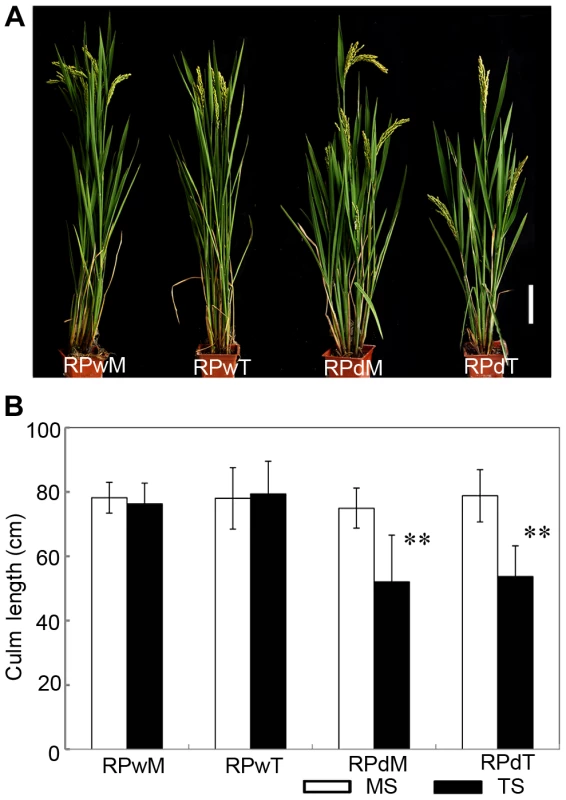

Fig. 2. The replanted main shoot and tiller of dwt1 reproduce the main-shoot-dominance phenotype.

A. Morphology of mature plants developed from replanted main shoot of the wild type (RPwM), replanted tillers of the wild type (RPwT), replanted main shoot of dwt1 (RPdM) and replanted tillers of dwt1 (RPdT). Bar = 5 cm. B. The culm length of both main shoots (MS) and tillers (TS) of replanted plants. Culm length of 15 main shoots and 60 tillers of wild-type plants, 15 main shoots and 55 tillers of mutant plants were measured at mature stage. Error bars indicate SD, and the very significant differences from the wild type are marked (**p<0.01, Student's t test). dwt1 has defects in cell proliferation and cell elongation in tiller internodes

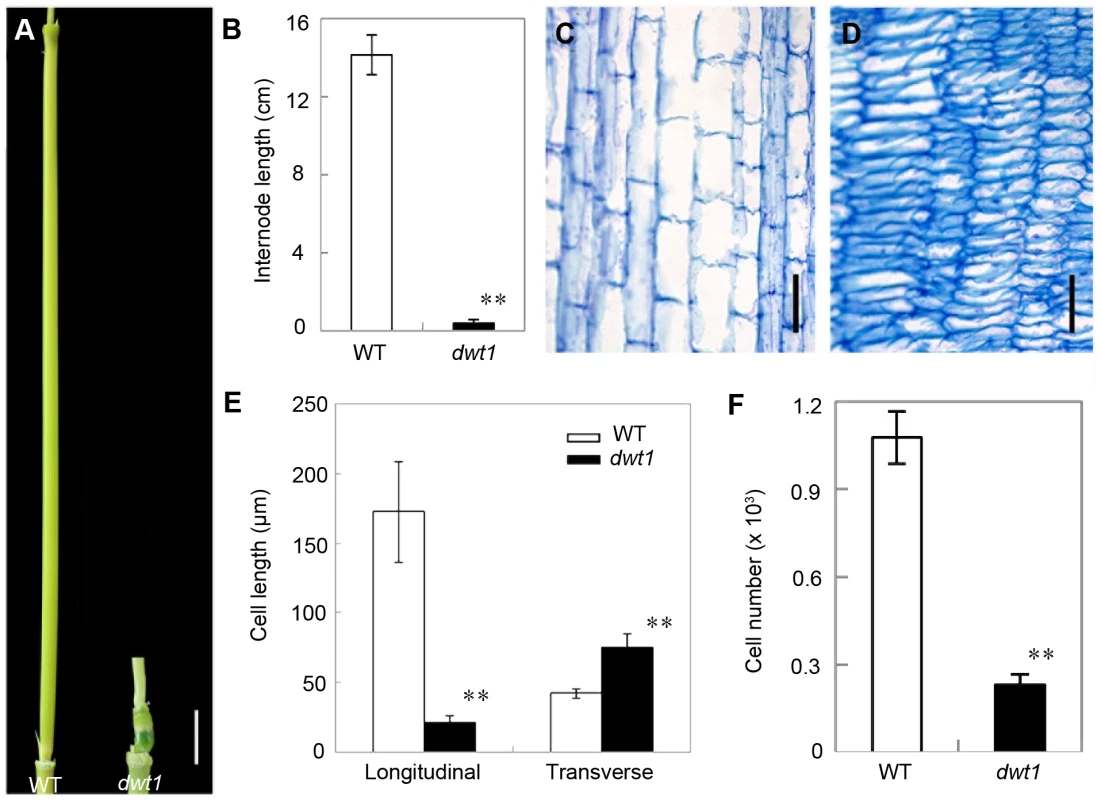

Rice internode elongation involves cell division followed by cell elongation [3]. Because the un-elongated internodes in dwt1 mutants are dramatically shorter (0.4±0.2 cm, n = 30) compared with wild-type plants (14.1±1.0 cm, n = 30) (Fig. 3A and B), we performed longitudinal sections of the second internodes which display obvious defective elongation in the mutant. The results show that the cells in the wild type are slender and elongated, with a cell length of about 172.6±36.2 µm (n = 30) (Fig. 3C and E). However, dwt1 cells in the shorter internodes appear flat with a longitudinal length of about 20.9±3.7 µm (n = 30) (Fig. 3D and E). Furthermore, the dwt1 second un-elongated internode had a dramatic reduction in cell number per internode (247±35, n = 5) in the longitudinal direction compared with the wild type (1077±90, n = 5) (Fig. 3F), suggesting that dwt1 has defects in both cell proliferation and cell elongation along the longitudinal direction in the tiller internodes.

Fig. 3. dwt1 has defects in cell elongation and cell proliferation.

A. The second internode of mature wild-type (left) and dwt1 (right) plants. Bar = 1 cm. B. The length of second internode at mature stage. n = 30. Error bars indicate SD, and the very significant differences from wild type are marked (**p<0.01, Student's t test). C and D. Longitudinal sections through the middle of the second internode of the wild type (C) and dwt1 (D) after the heading stage. Bar = 100 µm. E. Longitudinal and transverse length of the cells in the second internode. 12 second internodes from 3 individual mature plants were used, and 10 cells of each internode were measured. Error bars indicate SD, and the very significant differences from wild type are marked (**p<0.01, Student's t test). F. Cell number of the whole second internodes in mature plants. n = 5. Internode sample harvested from 5 individual plants were used for section. Error bars indicate SD, and the very significant differences from wild type are marked (**p<0.01, Student's t test). On the other hand, the transverse size of the un-elongated internodes in dwt1 is abnormally larger than that of the wild type (Fig. S1). The transverse section of wild-type internodes appeared a round shape with a perimeter of about 9.8±0.2 mm (n = 10); however, the dwt1 un-elongated internodes exhibited an elliptic shape with a perimeter of about 11.2±0.3 mm (n = 10). The increase of the width in dwt1 results from the increase of both the cell number and cell size in radial direction. The radial cell number in un-elongated internodes of dwt1 was about 62 cells along the major axis and 45 cells along minor axis, which is more than that in the wild type (40 cells, n = 10).

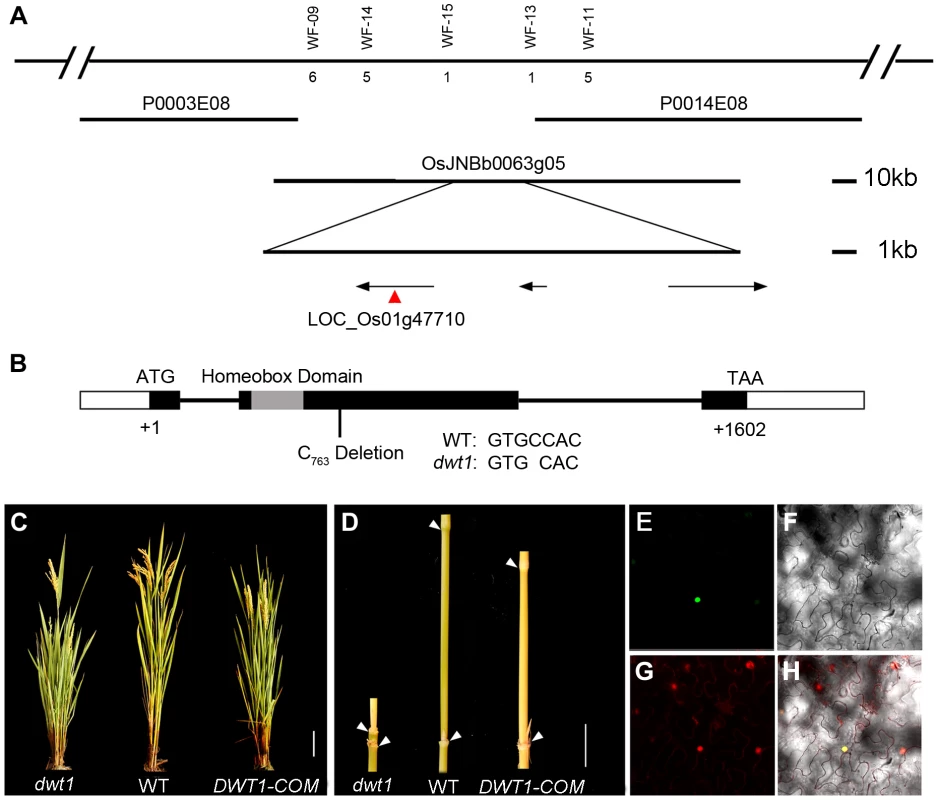

DWT1 encodes a WOX transcription factor

To identify the DWT1 gene, we mapped the dwt1 locus to a 22 kilo-base (kb) region on the BAC clone OSJNBb0063G05 (Fig. 4A) [11]. Three annotated open reading frames in this region were sequenced, and a single base pair deletion was observed in one of the genes, LOC_Os01g47710 (Fig. 4B), which was predicted to encode a putative WUSCHEL-like homeobox (WOX) protein [14]. This deletion results in a frame shift that replaces the C-terminal 279 residues with 162 new amino acids, downstream of the homeobox domain (Fig. 4B). We transformed dwt1 plants with a 6.7-kb genomic sequence of LOC_Os01g47710. All nine transformed plants exhibited a wild-type appearance with normally elongated internodes and uniform panicle size (Fig. 4C, D), confirming that the loss-of-function mutation of this gene is responsible for the dwt1 phenotype. Furthermore, the DWT1 protein fused with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) is localized in the nucleus when transformed into tobacco leaves (Fig. 4E–H), consistent with the prediction of a transcription factor of WOX protein [15].

Fig. 4. Molecular characterization of DWT1.

A. Map-based cloning of the DWT1 gene. The chromosomal region containing DWT1 is diagrammed as the top line with molecular markers shown above the line. The number below the corresponding markers indicates the numbers of recombinants between the markers and DWT1. The BAC clones are shown as overlapping lines. B. Structure of the DWT1 gene. The mutant sequence has one nucleotide C763 deletion in the second exon. Black boxes indicate exons, white boxes indicate UTRs and lines indicate introns. The grey box shows the homeobox domain. C. The plant stature of dwt1, the wild type, and complemented transgenic plants (DWT1-COM). Bar = 10 cm. D. The morphology of the second internodes of dwt1, wild type, and complemented transgenic plants (DWT1-COM). Bar = 2 cm. E–H. Nuclear localization of DWT1 protein. YFP fluorescence image (E), light view (F), PI stained image (G) and overlay of the three images (H) of Nicotiana benthamiana leaf epidermal cell transformed with the 35S:DWT1-YFP construct. The transcribed region of the DWT1 gene was revealed by comparing the genomic sequence with the released EST clone (OSIGCFA219G01) from the Rice Indica cDNA Database (RICD, http://www.ncgr.ac.cn/ricd/), and with sequences of our reverse transcription (RT)-PCR products. The predicted wild-type DWT1 protein is 533 amino acids in length and contains a conserved WUSCHEL (WUS)-like homeobox domain (amino acids 65 to 132 Fig. S2), which shares the highest sequence similarity with WOX8 and WOX9 proteins in Arabidopsis [14]. In addition to the homeobox domain, DWT1 also shares conserved N-terminal and C-terminal domains with WOX8/9-related proteins, but not with WUS (Fig. S2). Previous studies showed that the C-terminal domain might contribute to the dimerization of WUS proteins in Arabidopsis and snapdragon [16], [17]. The C-terminal deletion of DWT1 protein might disturb the dimerization of the DWT1 protein.

Phylogenetic analysis showed that the WOX8/9 subfamily of dicots and monocots are divided into two clades, and this subfamily is believed to be generated by gene duplication after the evolutionary separation of dicots and monocots (Fig. S3) [18]. In dicot plants, WOX8 and WOX9 proteins apparently arose by gene duplication from an ancestral gene. The EVERGREEN (EVG) and SISTER OF EVERGREEN (SOE) from petunia [9], and COMPOUND INFLORESCENCE in tomato [10] are more similar to STIP than STPL of Arabidopsis. In rice, there are three predicted WOX9 homologs, DWT1, DWT-LIKE 1 (DWL1, LOC_Os07g34880) and DWT-LIKE 2 (DWL2, LOC_Os05g48990). DWT1 and DWL1 are separated from DWL2 in two subclades with homologs of maize. These gene duplications suggest that after the divergence of monocots and eudicots, these subgroups in the WOX8/9 clade have been expanded, possibly with functional diversification (Fig. S3).

To understand the evolutionary role of DWT1, we did sequence analysis of DWT1 in cultivated rice and wild rice strains. Investigation of the SNP dataset of 508 indica and 341 temperate japonica rice cultivars [19] revealed 14 SNPs in the non-coding sequence and no SNP in the coding sequence of a 4.3-Kb DWT1genomic region. By contrast, we observed 4 nucleotide variations between these cultivated rice and 11 wild rice strains in the coding region. A 2-bp nucleotide change in exon 2, CA (1284–1285) in cultivated rice changed to GC in 11 wild rice strains (6 Oryza. rufipogon and 5 Oryza. nivara strains), causing the amino acid change from glutamine to alanine (Fig. S4). Whether this sequence variation causes rice morphological difference between cultivated rice and wild rice remains to be elucidated.

DWT1 functions in a non-cell autonomous manner

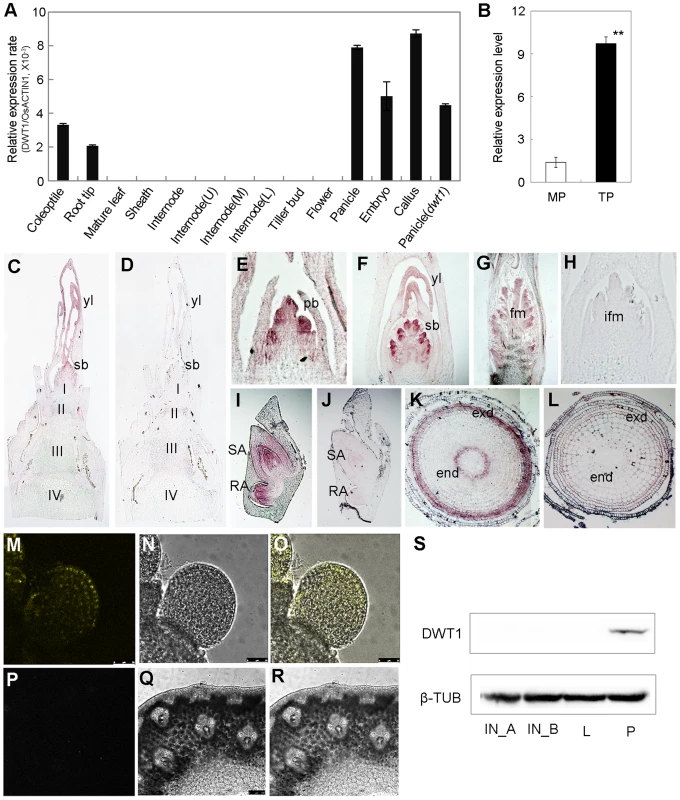

Quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR analysis revealed the expression of DWT1 mRNA in the callus, young panicle, young embryo, root tip and coleoptile, but not in the mature leaves, and mature spikelets (Fig. 5A). A higher expression level of DWT1 was observed in panicles of tillers than that of the main shoot (Fig. 5B). Notably, no obvious expression signal of DWT1 was detectable in the wild-type internodes where the dwt1 mutation causes the most severe phenotype (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, in situ hybridization confirmed no detectable expression of DWT1 in the elongating internode (Fig. 5C), but high DWT1 expression in the panicle meristem including the primordia of primary and secondary branches, floral meristem, and leaf primordia surrounding these meristems (Fig. 5E–G). Consistent with qRT-PCR results, DWT1 transcripts were observed in the young embryo 10 days after fertilization (Fig. 5I), and in the endodermis and exodermis layers of the elongation zone in root tip (Fig. 5K).

Fig. 5. Expression pattern of DWT1 transcripts and proteins.

A. qRT-PCR analysis of DWT1 gene expression levels in the wild-type tissues including coleoptiles (36 h after seed germination), root tips, mature leaf and sheath, the second internode during elongating (1 cm in length), segments of the upper (U), middle (M), and lower (L) parts of the second internode with 3 cm in length, dormant tiller bud, panicle (less than 1 cm in length), spikelet at stage Sp8 during development of pistil [63], young embryo (10 days after fertilization), and callus with 20–days regeneration. Rice ACTIN1 (OsACTIN1) was used as a control. Error bars indicate SD. n = 3. B. qRT-PCR analysis of DWT1 gene expression levels in young panicle of wild type. This experiment was biologically repeated three times, and 30 young panicles of the main shoot (MP, Length = 5 mm), and the tiller (TP, Length = 5 mm) respectively were used in each test. Error bars indicate SD, and the significant differences from panicle of main shoot are marked (**p<0.01, Student's t test). C–L. In situ hybridization of DWT1. Signals were detected in the primary branch meristem (E), secondary branch meristem (C, F), top portion of the panicle (G), shoot apical and radical apical of young embryo (I), and endodermis and exodermis of root tip (K). D, H, J and L were corresponding sections hybridized with the sense probe.I,II,III,IV, the first, second, third and the forth internode, respectively; pb, primary branch meristem; sb, secondary branch meristem; yl, young leave; fm, floral meristem; ifm, inflorescence meristem; exd, exodermis layer; end, endodermis layer. M–R. YFP fluorescence image of the branch meristem (M–O) and the internode (P–R) in transgenic plants expressing pDWT1:DWT1-YFP. M and P are fluorescence image, N and Q are light view, O and R are overlapping of fluorescence image and light view. S. Western-blot analysis of DWT1 protein levels. DWT1 protein was analyzed by immunoblotting using an anti-DWT1 antibody using mature flag leaf (L, 3 leaves from 3 different plants), elongating internodes (IN_A, length = 0.5 cm; IN_B, length = 3 cm, 10 internodes from different plants) and young panicle (P, length less than 2 mm, 50 panicles from different plants). β-tubulin was used as a control. These experiments were biologically repeated three times. To further understand the function of the rice WOX8/9 clade, we analyzed the tissue-specific expression pattern of two DWT1 homologs. According to rice microarray data (http://bar.utoronto.ca/efprice/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi), DWL2 has high expression level in the inflorescence meristem and embryo, but not in the internode. qRT-PCR analysis confirmed the expression of DWL1 and DWL2 in the panicle meristem but not in the internode, and no significant expression change in the dwt1 mutant (Fig. S5). The overlapping expression pattern of DWT1 and its two homologs suggest that the three rice WOX8/9 homologs may have similar function as DWT1.

Both qRT-PCR and in situ hybridization did not detect the transcripts of DWT1 in the internode, strongly suggesting a non-cell-autonomous manner of DWT1 function. One possibility is that DWT1 acts as a mobile protein signal, moving from the panicle meristem to the underneath internode. Alternatively, DWT1 may promote the production of a mobile signal in the panicle meristem. To test these possibilities, we detected the DWT1 protein localization in the transgenic plants harboring DWT1 protein fused with YFP (yellow fluorescence protein), driven by the native DWT1 promoter. We could only observe the DWT1 protein in the young panicle but not in elongating internodes (Fig. 5M–R). Consistently, western-blot only detected DWT1 proteins in panicle meristem tissues (Fig. 5S), suggesting that DWT1 may regulate the internode elongation by producing a mobile signal in the panicle.

Un-elongated internodes in dwt1 have changed expression of genes involved in cell division and cell elongation

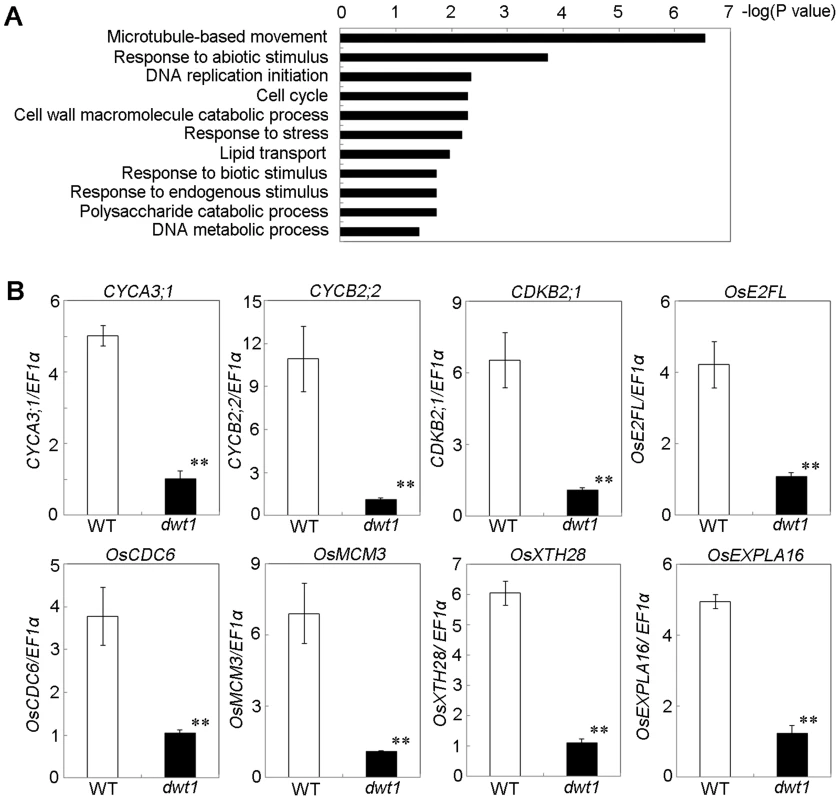

To understand the molecular mechanism of DWT1 in regulating rice internode development, we analyzed gene expression changes of the un-elongated second internode of dwt1 tillers during the elongation stage using the Affymetrix rice genomic arrays. Compared with the wild type, a total of 476 genes were up-regulated and 499 genes down-regulated in dwt1 after statistical analysis (>threefold change; P<0.001; Table S2). Functional analysis by gene ontology (GO) enrichment showed that eleven GO categories were enriched from the differential expressed genes (Fig. 6A, Table S3). The most enriched one was “microtubule-based movement”, which contains genes encoding kinesins, tubulins and other cytoskeleton related proteins. Kinesins belong to a class of microtubule-associated proteins with a motor domain for binding and moving along the microtubules. Some of these kinesin members, including AtKINESIN5 (ATK5), PHRAGMOPLAST ORIENTING KINESIN 1 and 2 (POK1, POK2), KCA1 and KCA2 are implicated in multiple mitosis-related processes, such as spindle formation, phragmoplast formation and cell plate formation [20]–[22]. Moreover, most of tubulin proteins differentially expressed are beta-tubulins, among which OsTUB6 was previously reported as a component of the spindle skeleton in mitosis [23].

Fig. 6. DWT1 affects the expression of genes related to cell division and cell elongation.

A. Identification of GO biological process categories for the genes differentially expressed in dwt1 shorter internodes. The negative logarithm (base 10) of the adjusted P value was used as the bar length. B. qRT-PCR confirmed the differential expression of genes involved in cell division and cell elongation in the elongating second internode of the wild type and dwt1. . Rice ELONGATION FACTOR 1 ALPHA (EF1α) gene was used as a control. This experiment was biologically repeated three times, and 10 elongating second internodes of tillers (Length = 0.5 cm) were used for each biological repeat. Error bars indicate SD, and the significant differences from the wild type are marked (**p<0.01, Student's t test). In addition, the enriched GO categories “DNA replication initiation”, “DNA metabolic process” and “cell cycle” from dwt1 microarray data are directly related to cell division (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, reduced expression of OsCYCA3;1, CYCLINB2;2 (CYCB2;Os2), CYCLIN-DEPENDENT KINASE B2;1 (CDKB2;1/CDC2OS3), homologs of CELL DIVISION CONTROL 6 (CDC6), MINI CHROMOSOME MAINTENANCE (MCM3) and E2 PROMOTER-BINDING FACTOR (E2F), OsEXPA16 and OsXTH28 were confirmed by qRT-PCR in dwt1 (Fig. 6 B), which closely correlates with the microarray data (Pearson correlation = 0.96) (Table S2, S4). CDC6 and MCM3 are involved in the DNA replication under the control of the E2F transcription factor in Arabidopsis [24], [25]. OsCYCA3;1 encodes a type-A cyclin, a homolog of tobacco Nicta;CYCA3;2, CYCB2;Os2 encodes a type-B cyclin, and CDKB2;1/CDC2OS3 encodes a cyclin-dependent kinase, which are implicated in cell cycle control [26], [27]. OsEXPA16 encodes a α-expansin protein known to increase cell wall extensibility [28], and OsXTH28 encodes a homolog of XTH28, a xyloglucan endotransglycosylase involved in cell growth in stamen filament development in Arabidopsis [29].

In plants, cytokinin plays a central role in promoting cell division. Cytokinin response is positively regulated by the cytokinin-inducible type-B Response Regulators (RRs) but negatively regulated by the type-A RRs [30]. Three type-A RRs: OsRR6, OsRR9, OsRR10, were upregulated in the shortened internode of dwt1 (Table S5, Fig. S6). In addition, the expression of OsCYTOKININ OXIDASE 4 (OsCKX4) and OsCKX9 encoding cytokinin-inactivating enzymes was elevated in dwt1 (Fig. S6). These results suggest that altered cytokinin signaling and reduced amount of active cytokinin may contribute to the reduced activity of cell division in dwt1.

DWT1 provides an activity required for GA promotion of cell elongation

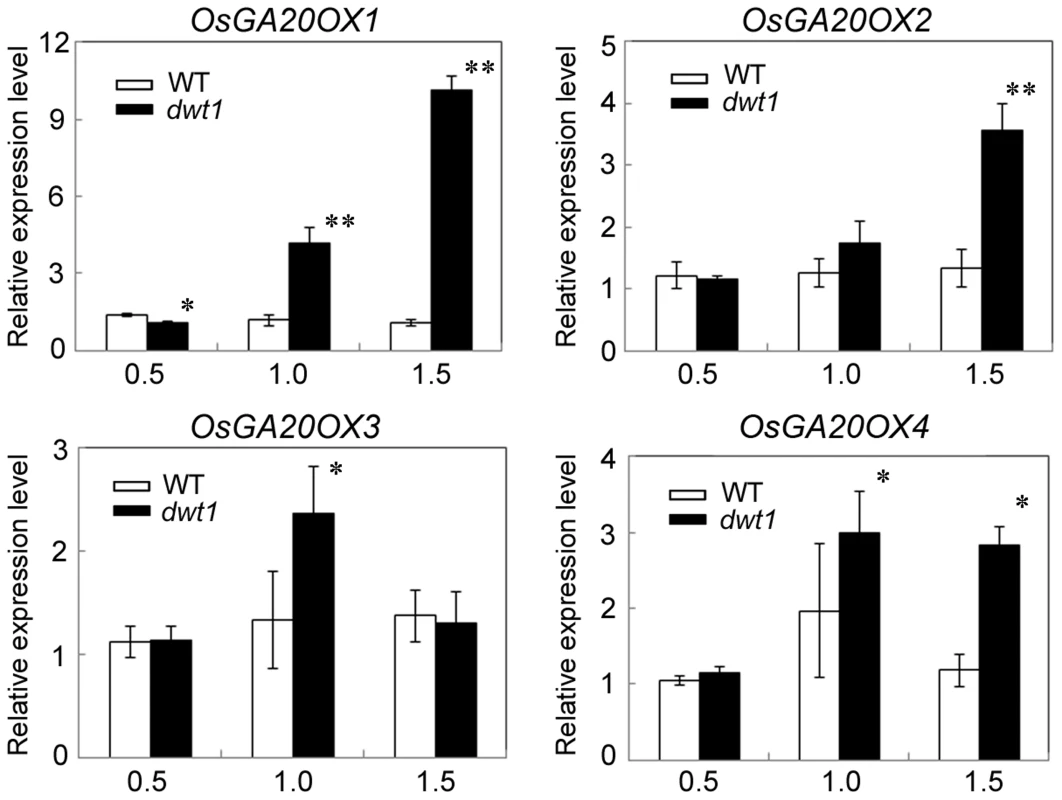

Gibberellin (GA) is a crucial phytohormone in promoting the stem elongation in rice [31], [32]. We observed that the expression level of OsENT-COPALYL DIPHOSPHATE SYNTHETASE 1 (OsCPS1) encoding a GA biosynthetic enzyme was reduced, and that of OsGIBBERELLIN 2-OXIDASE 1(OsGA2OX1) encoding a GA-deactivating enzyme was upregulated in the un-elongated internode of dwt1 (Table S5). In addition, four genes encoding GA20-oxidases (OsGA20OX1, OsGA20OX2, OsGA20OX3, and OsGA20OX4), which are feedback inhibited by GA signaling, displayed increased expression in dwt1 (Fig. 7). Therefore the developmental defects of dwt1 internodes may be associated with altered GA homeostasis or signaling

Fig. 7. OsGA20OX genes have increased expression in dwt1.

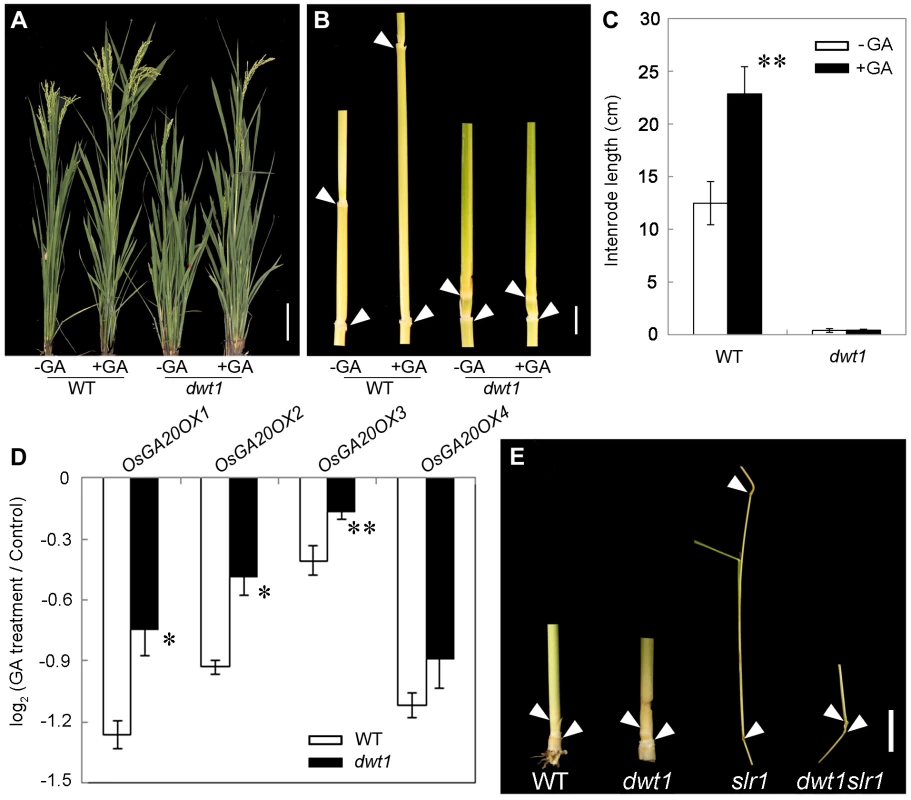

Transcript levels of OsGA20OX1, OsGA20OX2, OsGA20OX3 and OsGA20OX4 in the second internodes of the wild type and dwt1. The EF1α gene was used as a control. Three sequential developmental stages of elongating internode of wild type (Length = 0.5 cm, 1 cm and 3 cm) and dwt1 at the corresponding developmental stage of wild type were analyzed. This experiment was biologically repeated three times, and 10 internodes were used for each biological repeat. Error bars indicate SD. Significant differences from the wild type are marked (*P<0.05, ** P<0.01, Student's t test). To further test whether dwt1 has a defect in GA synthesis or signaling, we treated the wild-type and dwt1 mutant plants with active GA3 after the transition to the reproductive stage. Unlike the normal response to GA of the wild-type internodes and the normal internodes in dwt1, the defective internodes of dwt1 showed little response to GA (Fig. 8A, B and C, Fig. S7). Consistent with the reduced morphological response, the expression levels of OsGA20OX1, OsGA20OX2, OsGA20OX3, and OsGA20OX4 were less responsive to GA treatment in dwt1 un-elongated internodes than normal ones of the wild type (Fig. 8D), suggesting a defect in GA signaling in these internodes.

Fig. 8. The dwt1 tiller internodes are insensitive to GA treatment, and DWT1 may act downstream of SLR1 in the tiller internode elongation.

A. Morphological comparison of the wild type and dwt1 treated with mock solution or 100 µM GA3. 20 plants were uses for each treatment and representative images are shown. Bar = 10 cm. B. The second internodes of the wild type and dwt1 treated with mock solution or 100 µM GA3. Representative images of tiller internodes are shown. Bar = 1 cm. C. The internode length of the wild type and dwt1 treated with mock solution or 100 µM GA3. Length of 20 tiller internodes were measured 20 days after treatment. Error bars indicate SD, and the significant differences from no GA treated control are marked (** P<0.01, Student's t test). D. qRT–PCR analysis of OsGA20OX genes in the elongating internode of the wild type and dwt1 treated with mock solution or 100 µM GA3. EF1α gene was used as a control. This experiment was biologically repeated three times, and 5 internodes (Length = 5 mm) were used for each biological repeat. Error bars indicate SD. Significant differences from the wild type are marked (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01, Student's t test). E. Phenotype of basal internodes in the wild type, dwt1, slr1 and dwt1 slr1double mutant. Arrows point to the nodes on the culm. Bar = 1 cm. SLENDER RICE1 (SLR1) is a nuclear-localized DELLA-domain protein that functions as a central suppressor of GA signaling in rice [33], [34]. Compared with the wild type, slr1 mutants display a quick elongation of the basal internode at the seedling stage because of the constitutively activated GA response. To determine the genetic relationship between SLR1 and DWT1, we crossed dwt1 with slr1, and identified the double mutant by genotyping (see methods). The slr1 dwt1 double mutant showed a subset of twisted and shorter internodes similar to dwt1 plants (Fig. 8E, Fig. S8 C, F), while other internodes elongated as those of slr1 mutant (Fig. S8 A, B, D, E), suggesting that the DWT1-dependent activity is required for the internode elongation in the absence of SLR1.

Discussion

Shoot branching is one of the most important developmental processes that determine crop yields. While most wild plants have dominant main shoot and weaker branches, two extreme branching traits have been selected during the domestication of cereal crops. Some crops, such as maize and sorghum, exhibit enhanced apical dominance and suppression of branches compared to their highly branched ancestors [35]. Suppression of branch development reduces the competition for resources and thus enhances the productivity of the main shoot. In contrast, other cultivated species, including rice, wheat and barley, have been selected for multiple tillers that develop from buds at the basal un-elongated nodes of the main shoot but bearing panicles that reach similar size as the main shoot [35]. The intra-plant panicle uniformity is essential for the high yield in these species, but the underlying mechanism has remained elusive. Our study identified DWT1, a WOX member, as an essential genetic component specifying this trait in rice.

DWT1 represents a key switch determining rice architecture

The WOX genes form a plant specific clade of the homeobox transcription factor superfamily. Studies in dicot plants indicate that the WOX8/9 subclade genes play important roles in a wide range of developmental processes, such as embryonic patterning, stem-cell maintenance, inflorescence architecture development and organ formation [8], [9], [10], [15], [36]. Rice has three WOX members within the WOX8/9 subclade, and these members were assumed to be generated by duplication after the divergence of monocots from dicots [14]. Based on the functional analysis of DWT1 in this study, we hypothesize that DWT1 plays a key role in controlling the developmental uniformity of main shoot and tillers and may have been selected during rice domestication.

The activated tiller buds develop their own adventitious roots, and thus gain a certain degree of independence from the main shoot. It is not clear whether the tiller development is also under the control of the main shoot after this transition. The dwt1 mutant shows not only dwarfed tillers bearing smaller panicles, but also an enhanced growth of the panicle on the main shoot, suggesting an enhanced apical dominance. It is also possible that a defect in tiller growth reduces the competition against the main shoot, resulting in quicker main shoot growth compared to wild type. The individual dwt1 tiller separated from the main shoot is able to grow into a whole rice plant with a near normal main shoot and dwarf tillers, suggesting that DWT1 suppresses the apical dominance in rice. Alternatively, the higher expression level of DWT1 in tiller panicles than the main shoot panicle may provide an enhanced growth vigor to the tillers, or a higher level of growth-promoting signal to the tiller internodes, which is essential for successful competition against the main shoot.

It has been demonstrated that TEOSINTE BRANCHED 1 (TB1) is the major contributor to the enhanced apical dominance during the domestication of maize. One tb1 allele with a transposon inserted in the regulatory region was selected from the maize wild ancestor teosinte. The inserted retro-element causes a two-fold increase in TB1 expression, which is strong enough for the transformation of a highly branched architecture of teosinte to the modern maize architecture [37]. It is not clear whether DWT1 is a key target being selected during the domestication of rice. Sequence analysis revealed an amino acid variation in the C-terminus of DWT1 coding region between cultivated rice and wild rice strains (Fig. S4). The C-terminal domain may be required for the homo - or heterodimerization of the DWT1 protein. The effect of this sequence variation on DWT1 function remains to be elucidated.

DWT1 enhances tiller growth vigor but does not affect tiller bud initiation

Lateral branch development involves bud formation, bud outgrowth and branch growth. In most plants, the early events of lateral bud formation and outgrowth are inhibited by the apex of the main shoot, due to the apical dominance. How growth vigor of the branch is influenced by the main shoot is less understood. Apical dominance is mediated by the biosynthesis and transport of the phytohormone auxin [38]. Auxin is transported basipetally from the apical bud and inhibits the outgrowth of lateral buds. It is proposed that the repressive effect of auxin is mediated by secondary messengers. Strigolactone is synthesized in both the roots and the shoots and transported acropetally, and it plays an important role in repressing bud growth in several species, such as pea, petunia, Arabidopsis and rice, possibly by reducing auxin transport in the main shoot [39]. Cytokinin, mostly synthesized in the root and transported acropetally, is able to initiate the outgrowth of lateral buds [40]–[43]. Several WOX genes, including the DWT1 homologs in Arabidopsis, have been shown to be able to directly regulate genes involved in auxin and cytokinin biosynthesis, homeostasis, transportation and signaling. But none of them have been reported to be required for the main shoot dominance.

The dwt1 mutant does not show an obvious difference in tiller number compared with the wild type, indicating that the initiation and outgrowth of tiller buds are not affected. Accordingly, no significant expression change of genes related to strigolactone biosynthesis and signaling pathway was observed in the leaf, root and basal shoot of dwt1 (Fig. S9). In addition, the expression levels of cytokinin-related genes, OsRR6, OsRR9, OsRR10, OsCKX4 and OsCKX9, are altered in the internodes, but not in the root or basal shoot of dwt1 (Fig. S10), suggesting that dwt1 does not have a defect in cytokinin signaling during lateral branch initiation and outgrowth. Thus, we propose that DWT1 enhances tiller growth vigor at late stages after the outgrowth of tiller buds.

The higher expression level of DWT1 and more severe phenotypes in tillers than in main stem suggest that the differential DWT1 activity counter balance the weaker growth vigor of the tillers. The main shoot enters reproductive growth a bit earlier than tillers, thus may gain growth priority over tillers. The observation that removal of main shoot releases suppression of the next tiller in dwt1 suggests that DWT1 provides a competitive advantage to the younger tillers. The low percentage of un-elongated internodes observed in dwt1 main shoot suggests a minor but also positive function of DWT1 in promoting internode elongation in the main shoot, consistent with the lower level of DWT1 expression in main shoot panicles compared to tillers. It is likely that DWT1 is required for promoting internode growth and the higher level of DWT1 expression in tillers enhances the growth vigor to overcome the main shoot dominance. In addition, there may be an as yet unknown main shoot factor specifically responsible for establishing the main shoot dominance independent of DWT1 function, as a compensatory elongation of other internodes was observed in main shoots with an un-elongated internode.

DWT1 may regulate internode growth through a mobile signal

The phenotype of reduced internodes of dwt1 tillers seems similar to the dwarfism of mutants with defective synthesis or signaling of GA or brassinosteroids (BRs) [44]–[48]. However, no obvious expression change of genes relative to BR biosynthesis, metabolism and signaling pathways was seen in dwt1 (Table. S4). In addition, BR related mutants display dark green, rugose, and erect leaves [45]–[47], which are not observed in dwt1. In addition, none of the previously reported BR-related mutants have distorted internodes or a distinction between main shoot and tillers, suggesting that the elongation defect of dwt1 internodes is unlikely due to BR deficiency. On the other hand, the un-elongated internodes and expression of GA20OX genes showed insensitivity to GA treatment in dwt1, suggesting a defect in GA response. The slr1 mutation was unable to suppress the dwarf-tiller phenotype of dwt1, indicating that the action of DWT1 on internode elongation, possibly mediated by a mobile signal, is downstream, or independent of SLR1.

The dwarfed tillers of dwt1 show reduced cell division and cell elongation. In the shorter internode of dwt1 mutant, not surprisingly, a set of cell cycle related genes were observed to have decreased expression, while the expression of the negative regulators of cytokinin signaling and some cytokinin-inactivating enzymes were increased. Both type-A RR genes and CKX genes have been shown to function as negative regulators in cytokinin signaling and cell division [49]. OsWOX11 directly represses one of the type-A RR genes, RR2, leading to enhanced cytokinin signaling and crown root development in rice [50]. WUS directly represses the transcription of several ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR (ARR) genes to positively regulate stem cells in Arabidopsis [51]. As no DWT1 expression was detectable in the elongating internode, it is quite possible that the DWT1 may indirectly repress the expression of type-A RRs by promoting a mobile signal from the apical region where DWT1 is expressed. Alternatively, given the repressing effect of GA on the expression of type-A ARR genes and activation of type-A gene ARR5 by GA response inhibitor SPINDLY (SPY) in Arabidopsis [52], the change of cytokinin pathway in dwt1 mutant may result from the secondary effect of abnormal GA signaling.

DWT1 is expressed in the panicle meristem at stages when the 2nd, 3rd and 4th internodes start to elongate [53]. Consistently, only the elongation of internodes at these positions is affected in the dwt1 mutant, suggesting that DWT1 has a spatiotemporal specific function. The frequency of un-elongated internodes inversely correlated with the distance from the apical meristem. The loss of the function of the apically expressed DWT1 leads to elongation defects in 92% of the second internodes, 75% of the third internodes and only 39% of the fourth internodes. It is clear that internodes closest to the apical meristem were most affected, while internodes far away were less affected, implicating a signal gradient emanating from the apical meristem which determines the cell division and elongation potential of internodes underneath. The activation of DWT1 at early reproductive stage may be required for preventing the production of a mobile growth inhibitor, which prevents the premature elongation of the internodes, or may promote the production of a growth promotion signal. Such alteration may enhance the responsiveness of cells in the upper internodes to GA or cytokinin.

A function in inter-organ coordination has recently been shown for a receptor-like kinase homologous to Arabidopsis CLAVATA1, named HYPERNODULATION ABERRANT ROOT FORMATION1 (HAR1). HAR1 is an important regulator of shoot-to-root communication during root nodulation in Lotus japonicas. It was proposed that HAR1 negatively regulates nodulation by promoting the production and transportation of a putative shoot-derived inhibitor [54], [55]. As a homolog of the CLAVATA1 downstream component WUS, DWT1 may regulate intra-panicle uniformity also by controlling long-distance coordination between the panicle and internodes or between main shoot and tillers. The nature of the mobile signal, if involved, and the molecular mechanism by which DWT1 ensures uniform tiller growth in rice require further study. Nevertheless, our study establishes DWT1 as a key genetic component responsible for uniform tiller growth in domesticated rice. Whether DWT1 is responsible for this trait during rice domestication and whether it can provide or improve tiller uniformity in other crops are also outstanding questions for future study.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

All plants (Oryza sativa) were grown in the paddy field of Shanghai Jiao Tong University. The 11 wild rice strains (Table S6) were ordered from International Rice Research Institute. For GA treatment, wild type and dwt1 mutants were grown in the paddy field, and at internodes elongation stage, GA3 (100 µM) was sprayed to the plant for 3 times at a 2-day interval within 6 days. For the control, 1 mL of 95% alcohol was added to 1L sterilized water. The length of culm and the internode was measured 6 days after treatment, and the final elongation pattern were counted after heading (20 days after treatment). The Nicotiana benthamiana (tobacco) plants were grown in the green house under 16 hours light-long day conditions.

Cell number calculation in the internodes and statistical analysis

Five normal wild-type elongated second internodes and five un-elongated second internodes in the mutant were harvested from different individual plants to count the total longitudinal cell number. The wild type internodes which were separated into 10–15 pieces and the un-elongated dwt1 internodes at the corresponding stages based on the size of wild-type internodes were embedded into the paraffin and sectioned longitudinally. The cell number of each piece in the longitudinal direction between two vascular bundles were counted under microscope (Motic B3) and calculated. The statistical tests were performed by Student's t-test, and the variation is expressed as standard deviation (SD).

Genotyping of double mutants

The dwt1 mutant was crossed with the slr1 mutant. dwt1-like and slr1-like mutants in F2 generation were genotyped by sequencing. The genotyping fragments for SLR (nucleotides 569–1325 of the coding sequence) and DWT1 (nucleotides 508–1662 of the coding sequence) were amplified by PCR, and sequenced. Three dwt1slr1 double mutants were identified from 17 slr1-like plants in 100 F2 plants. The genotyping primers are listed in Table S7.

Cloning of DWT1 and complementation

The F2 mapping population was generated from a cross between dwt1 mutant (Oryza sativa ssp. japonica) and Longtepu B (Oryza sativa ssp. indica). A 6.7-kb genomic fragment containing the open reading frame, 2.5-kb upstream and 0.6-kb downstream sequences of the DWT1, was obtained by PCR from BAC clone OSJNBb0063G05. The genomic fragment was inserted into a binary vector pCAMBIA1301, then was introduced into the dwt1 mutant by the Agrobacterium-mediated transformation method [56]. The pDWT1: DWT-YFP was constructed by fusing an YFP to the C-terminal of DWT1 cDNA, which was driven by the native DWT1 promoter. This fragment was then inserted to the binary vector pCAMBIA1301 and transformed into the wild type. The SNP dataset was obtained from Rice Genome Knowledgebase (RGKbase, http://rgkbase.big.ac.cn/RGKbase/index.php) [57]. SNP sites within a specific region in the genome were extracted using customary Perl script according to gene feature file (GFF) of MSU 6.1 annotation. (ftp://ftp.plantbiology.msu.edu/pub/data/Eukaryotic_Projects/o_sativa/annotation_dbs/pseudomolecules/version_6.1/).

Phylogenetic analysis

The amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE 3.6 with the default settings [58], and then adjusted manually using GeneDoc (version 2.6.002) software (Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center; http://www.psc.edu/biomed/genedoc/). Using the MEGAsoftware (version 3.1; http://www.megasoftware.net/index.html) and based on full-length protein sequences, midpoint-rooted neighbor-joining trees were constructed with the following parameters: Poisson correction, pairwise deletion, and bootstrap (1000 replicates; random seed) [59]. The accession numbers are list in Table S8.

Transient transformation

The 35S::DWT1-YFP vector was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101, and the cultured bacteria were infiltrated into young leaves of 4-week-old tobacco plants. YFP fluorescence was visualized with a confocal scanning microscope (Leica TCS SP5 II) 40–48 hours after infiltration [60].

Total RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from different tissues of wide type and dwt1 mutant. The first-strand cDNAs were synthesized using MLV reverse transcriptase (Ferments). Quantitative real-time PCR analyses were performed on a CFX96 (Biorad, US) using a SYBR green detection protocol according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RT-PCR was repeated at least three times for separately harvested samples. The primers used in this article are listed in Table S7.

Western blot

Total proteins were extracted from internodes, leaves and panicles of wild type with 2× SDS loading buffer, separated on SDS/PAGE gels, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and hybridized with anti-DWT1 antibody. The DWT1 antibody was prepared by Shanghai ImmunoGen Biological Technology and used at 1∶1000 dilution in the immunoblot analysis. Anti-β-tubulin was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and was used at 1∶1,000 dilution in the experiment.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA were isolated from elongating internodes (Length = 1.0 cm) of dwt1 mutant and wild-type plants using TRIzol (Invitrogen). Using the standard Affymetrix protocol, three biological repeats of the microarray experiment were performed with Affymetrix rice genome array by Gene Tech Biotechnology Company, which contains probe sets to detect transcripts from all of the high-quality expressed sequence from the entire rice genome. Significance analysis of microarray was used to identify differentially expressed genes. Genes with at least a threefold change in expression (P values<0.001) were chosen for additional analysis.

GO enrichment analysis

GO annotations of Microarray genes were downloaded from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), UniProt (http://www.uniprot.org/), TIGR (rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/) and the Gene Ontology (http://www.geneontology.org/). The “elim Fisher” algorithm was used to do GO enrichment test [61]. Gene ontology categories with an adjust p-value<0.05 were reported.

In situ hybridization

DWT1-specific fragment (nucleotides 1458–1701 of the coding sequence) was amplified by PCR from the cDNA clone and then inserted into pBluescript SK(+) (Stratagene). Preparation of probes and the in situ hybridization were performed according to the previous description [62].

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. GrilloMA, LiCB, FowlkesAM, BriggemanTM, ZhouAL, et al. (2009) Genetic Architecture for the Adaptive Origin of Annual Wild Rice, Oryza Nivara. Evolution 63 : 870–883.

2. MaLY, BaoJ, GuoLB, ZengDL, LiXM, et al. (2009) Quantitative Trait Loci for Panicle Layer Uniformity Identified in Doubled Haploid Lines of Rice in Two Environments. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 51 : 818–824.

3. UozuS, Tanaka-UeguchiM, KitanoH, HattoriK, MatsuokaM (2000) Characterization of XET-related genes of rice. Plant Physiology 122 : 853–859.

4. WangYH, LiJY (2008) Molecular basis of plant architecture. Annual Review of Plant Biology 59 : 253–279.

5. HongZ, Tanaka-UeguchiM, MATSUOKAM (2004) Brassinosteroids and Rice Architecture. J Pestic Sci 29 : 184–188.

6. BreuningerH, RikirschE, HermannM, UedaM, LauxT (2008) Differential expression of WOX genes mediates apical-basal axis formation in the Arabidopsis embryo. Developmental Cell 14 : 867–876.

7. WuX, ChoryJ, WeigelD (2007) Combinations of WOX activities regulate tissue proliferation during Arabidopsis embryonic development. Developmental Biology 309 : 306–316.

8. WuXL, DabiT, WeigelD (2005) Requirement of homeobox gene STIMPY/WOX9 for Arabidopsis meristem growth and maintenance. Current Biology 15 : 436–440.

9. RebochoAB, BliekM, KustersE, CastelR, ProcissiA, et al. (2008) Role of EVERGREEN in the development of the cymose petunia inflorescence. Developmental Cell 15 : 437–447.

10. LippmanZB, CohenO, AlvarezJP, Abu-AbiedM, PekkerI, et al. (2008) The Making of a Compound Inflorescence in Tomato and Related Nightshades. Plos Biology 6 : 2424–2435.

11. WangW, ChuH, ZhangD, LiangW (2013) Fine mapping and analysis of Dwarf Tiller 1 in controlling rice architecture. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 40 : 493–495.

12. TAKEDAK (1977) Gamma Field Symposia. Internode elongation and dwarfism in some gramineous plants 1–18.

13. ThimannKV, SkoogF (1933) Studies on the growth hormone of plants III. The inhibitory action of the growth substance on bud development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 19 : 714–716.

14. ZhangX, ZongJ, LiuJ, YinJ, ZhangD (2010) Genome-wide analysis of WOX gene family in rice, sorghum, maize, Arabidopsis and poplar. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 52 : 1016–1026.

15. van der GraaffE, LauxT, RensingSA (2009) The WUS homeobox-containing (WOX) protein family. Genome Biology 10 : 248.

16. BuschW, MiotkA, ArielFD, ZhaoZ, FornerJ, et al. (2010) Transcriptional control of a plant stem cell niche. Developmental Cell 18 : 849–861.

17. NagasakiH, MatsuokaM, SatoY (2005) Members of TALE and WUS subfamilies of homeodomain proteins with potentially important functions in development form dimers within each subfamily in rice. Genes Genet Syst 80 : 261–267.

18. NardmannJ, ReisewitzP, WerrW (2009) Discrete Shoot and Root Stem Cell-Promoting WUS/WOX5 Functions Are an Evolutionary Innovation of Angiosperms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 26 : 1745–1755.

19. HuangX, ZhaoY, WeiX, LiC, WangA, et al. (2012) Genome-wide association study of flowering time and grain yield traits in a worldwide collection of rice germplasm. Nat Genet 44 : 32–39.

20. VanstraelenM, InzeD, GeelenD (2006) Mitosis-specific kinesins in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci 11 : 167–175.

21. MullerS, HanS, SmithLG (2006) Two kinesins are involved in the spatial control of cytokinesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Current Biology 16 : 888–894.

22. VanstraelenM, Torres AcostaJA, De VeylderL, InzeD, GeelenD (2004) A plant-specific subclass of C-terminal kinesins contains a conserved a-type cyclin-dependent kinase site implicated in folding and dimerization. Plant Physiology 135 : 1417–1429.

23. AmbroseJC, CyrR (2007) The kinesin ATK5 functions in early spindle assembly in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19 : 226–236.

24. de JagerSM, MengesM, BauerUM, MurrayJAH (2001) Arabidopsis E2F1 binds a sequence present in the promoter of S-phase-regulated gene AtCDC6 and is a member of a multigene family with differential activities. Plant Molecular Biology 47 : 555–568.

25. StevensR, MaricontiL, RossignolP, PerennesC, CellaR, et al. (2002) Two E2F sites in the Arabidopsis MCM3 promoter have different roles in cell cycle activation and meristematic expression. Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 : 32978–32984.

26. LeeJ, DasA, YamaguchiM, HashimotoJ, TsutsumiN, et al. (2003) Cell cycle function of a rice B2-type cyclin interacting with a B-type cyclin-dependent kinase. Plant Journal 34 : 417–425.

27. YuY, SteinmetzA, MeyerD, BrownS, ShenWH (2003) The tobacco A-type cyclin, Nicta;CYCA3;2, at the nexus of cell division and differentiation. Plant Cell 15 : 2763–2777.

28. LeeY, KendeH (2002) Expression of alpha-expansin and expansin-like genes in deepwater rice. Plant Physiology 130 : 1396–1405.

29. KurasawaK, MatsuiA, YokoyamaR, KuriyamaT, YoshizumiT, et al. (2009) The AtXTH28 gene, a xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase, is involved in automatic self-pollination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 50 : 413–422.

30. HiroseN, MakitaN, KojimaM, Kamada-NobusadaT, SakakibaraH (2007) Overexpression of a type-A response regulator alters rice morphology and cytokinin metabolism. Plant Cell Physiol 48 : 523–539.

31. RaskinI, KendeH (1984) Role of Gibberellin in the Growth-Response of Submerged Deep-Water Rice. Plant Physiology 76 : 947–950.

32. HoffmannbenningS, KendeH (1992) On the Role of Abscisic-Acid and Gibberellin in the Regulation of Growth in Rice. Plant Physiology 99 : 1156–1161.

33. ItohH, Ueguchi-TanakaM, SatoY, AshikariM, MatsuokaM (2002) The gibberellin signaling pathway is regulated by the appearance and disappearance of SLENDER RICE1 in nuclei. Plant Cell 14 : 57–70.

34. IkedaA, Ueguchi-TanakaM, SonodaY, KitanoH, KoshiokaM, et al. (2001) slender rice, a constitutive gibberellin response mutant, is caused by a null mutation of the SLR1 gene, an ortholog of the height-regulating gene GAI/RGA/RHT/D8. Plant Cell 13 : 999–1010.

35. Harlan JR (1992) Crops and Man (2nd edition), Jack R. Harlan. Madison, Wisconsin: American Society of Agronomy. 295 pp.

36. HaeckerA, Gross-HardtR, GeigesB, SarkarA, BreuningerH, et al. (2004) Expression dynamics of WOX genes mark cell fate decisions during early embryonic patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 131 : 657–668.

37. StuderA, ZhaoQ, Ross-IbarraJ, DoebleyJ (2011) Identification of a functional transposon insertion in the maize domestication gene tb1. Nat Genet 43 : 1160–1163.

38. DomagalskaMA, LeyserO (2011) Signal integration in the control of shoot branching. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12 : 211–221.

39. BrewerPB, KoltaiH, BeveridgeCA (2013) Diverse roles of strigolactones in plant development. Mol Plant 6 : 18–28.

40. VadasseryJ, RitterC, VenusY, CamehlI, VarmaA, et al. (2008) The role of auxins and cytokinins in the mutualistic interaction between Arabidopsis and Piriformospora indica. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 21 : 1371–1383.

41. ChenCM, ErtlJR, LeisnerSM, ChangCC (1985) Localization of cytokinin biosynthetic sites in pea plants and carrot roots. Plant Physiology 78 : 510–513.

42. NordstromA, TarkowskiP, TarkowskaD, NorbaekR, AstotC, et al. (2004) Auxin regulation of cytokinin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana: a factor of potential importance for auxin-cytokinin-regulated development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 : 8039–8044.

43. TanakaM, TakeiK, KojimaM, SakakibaraH, MoriH (2006) Auxin controls local cytokinin biosynthesis in the nodal stem in apical dominance. Plant Journal 45 : 1028–1036.

44. SakamotoT, MiuraK, ItohH, TatsumiT, Ueguchi-TanakaM, et al. (2004) An overview of gibberellin metabolism enzyme genes and their related mutants in rice. Plant Physiology 134 : 1642–1653.

45. YamamuroC, IharaY, WuX, NoguchiT, FujiokaS, et al. (2000) Loss of function of a rice brassinosteroid insensitive1 homolog prevents internode elongation and bending of the lamina joint. Plant Cell 12 : 1591–1605.

46. HongZ, Ueguchi-TanakaM, UmemuraK, UozuS, FujiokaS, et al. (2003) A rice brassinosteroid-deficient mutant, ebisu dwarf (d2), is caused by a loss of function of a new member of cytochrome P450. Plant Cell 15 : 2900–2910.

47. TanabeS, AshikariM, FujiokaS, TakatsutoS, YoshidaS, et al. (2005) A novel cytochrome P450 is implicated in brassinosteroid biosynthesis via the characterization of a rice dwarf mutant, dwarf11, with reduced seed length. Plant Cell 17 : 776–790.

48. Ueguchi-TanakaM, AshikariM, NakajimaM, ItohH, KatohE, et al. (2005) GIBBERELLIN INSENSITIVE DWARF1 encodes a soluble receptor for gibberellin. Nature 437 : 693–698.

49. HwangI, SheenJ, MullerB (2012) Cytokinin signaling networks. Annual Review of Plant Biology 63 : 353–380.

50. ZhaoY, HuYF, DaiMQ, HuangLM, ZhouDX (2009) The WUSCHEL-Related Homeobox Gene WOX11 Is Required to Activate Shoot-Borne Crown Root Development in Rice. Plant Cell 21 : 736–748.

51. LeibfriedA, ToJP, BuschW, StehlingS, KehleA, et al. (2005) WUSCHEL controls meristem function by direct regulation of cytokinin-inducible response regulators. Nature 438 : 1172–1175.

52. Greenboim-WainbergY, MaymonI, BorochovR, AlvarezJ, OlszewskiN, et al. (2005) Cross talk between gibberellin and cytokinin: the Arabidopsis GA response inhibitor SPINDLY plays a positive role in cytokinin signaling. Plant Cell 17 : 92–102.

53. ItohJ, NonomuraK, IkedaK, YamakiS, InukaiY, et al. (2005) Rice plant development: from zygote to spikelet. Plant Cell Physiol 46 : 23–47.

54. SuzakiT, ItoM, KawaguchiM (2013) Genetic basis of cytokinin and auxin functions during root nodule development. Front Plant Sci 4 : 42.

55. SuzakiT, YanoK, ItoM, UmeharaY, SuganumaN, et al. (2012) Positive and negative regulation of cortical cell division during root nodule development in Lotus japonicus is accompanied by auxin response. Development 139 : 3997–4006.

56. HieiY, KomariT, KuboT (1997) Transformation of rice mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Plant Molecular Biology 35 : 205–218.

57. WangD, XiaY, LiX, HouL, YuJ (2013) The Rice Genome Knowledgebase (RGKbase): an annotation database for rice comparative genomics and evolutionary biology. Nucleic Acids Res 41: D1199–1205.

58. EdgarRC (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32 : 1792–1797.

59. KumarS, TamuraK, NeiM (2004) MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform 5 : 150–163.

60. GampalaSS, KimTW, HeJX, TangW, DengZ, et al. (2007) An essential role for 14-3-3 proteins in brassinosteroid signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Developmental Cell 13 : 177–189.

61. AlexaA, RahnenfuhrerJ, LengauerT (2006) Improved scoring of functional groups from gene expression data by decorrelating GO graph structure. Bioinformatics 22 : 1600–1607.

62. ChuHW, QianQ, LiangWQ, YinCS, TanHX, et al. (2006) The floral organ number4 gene encoding a putative ortholog of Arabidopsis CLAVATA3 regulates apical meristem size in rice. Plant Physiology 142 : 1039–1052.

63. IkedaK, SunoharaH, NagatoY (2004) Developmental course of inflorescence and spikelet in rice. Breeding Science 54 : 147–156.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Sex Chromosome Turnover Contributes to Genomic Divergence between Incipient Stickleback SpeciesČlánek Final Pre-40S Maturation Depends on the Functional Integrity of the 60S Subunit Ribosomal Protein L3

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 3- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

- Délka menstruačního cyklu jako marker ženské plodnosti

- Intrauterinní inseminace a její úspěšnost

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- , a Gene That Influences the Anterior Chamber Depth, Is Associated with Primary Angle Closure Glaucoma

- Genomic View of Bipolar Disorder Revealed by Whole Genome Sequencing in a Genetic Isolate

- The Rate of Nonallelic Homologous Recombination in Males Is Highly Variable, Correlated between Monozygotic Twins and Independent of Age

- Genetic Determinants Influencing Human Serum Metabolome among African Americans

- Heterozygous and Inherited Mutations in the Smooth Muscle Actin () Gene Underlie Megacystis-Microcolon-Intestinal Hypoperistalsis Syndrome

- Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis of Homocysteine and Methionine Metabolism Identifies Five One Carbon Metabolism Loci and a Novel Association of with Ischemic Stroke

- Cancer Evolution Is Associated with Pervasive Positive Selection on Globally Expressed Genes

- Genetic Diversity in the Interference Selection Limit

- Integrating Multiple Genomic Data to Predict Disease-Causing Nonsynonymous Single Nucleotide Variants in Exome Sequencing Studies

- An Evolutionary Analysis of Antigen Processing and Presentation across Different Timescales Reveals Pervasive Selection

- Cleavage Factor I Links Transcription Termination to DNA Damage Response and Genome Integrity Maintenance in

- DNA Dynamics during Early Double-Strand Break Processing Revealed by Non-Intrusive Imaging of Living Cells

- Genetic Basis of Metabolome Variation in Yeast

- Modeling 3D Facial Shape from DNA

- Dysregulated Estrogen Receptor Signaling in the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian Axis Leads to Ovarian Epithelial Tumorigenesis in Mice

- Photoactivated UVR8-COP1 Module Determines Photomorphogenic UV-B Signaling Output in

- Local Evolution of Seed Flotation in Arabidopsis

- Chromatin Targeting Signals, Nucleosome Positioning Mechanism and Non-Coding RNA-Mediated Regulation of the Chromatin Remodeling Complex NoRC

- Nucleosome Acidic Patch Promotes RNF168- and RING1B/BMI1-Dependent H2AX and H2A Ubiquitination and DNA Damage Signaling

- The -Induced Arabidopsis Transcription Factor Attenuates ABA Signaling and Renders Seedlings Sugar Insensitive when Present in the Nucleus

- Changes in Colorectal Carcinoma Genomes under Anti-EGFR Therapy Identified by Whole-Genome Plasma DNA Sequencing

- Selection of Orphan Rhs Toxin Expression in Evolved Serovar Typhimurium

- FAK Acts as a Suppressor of RTK-MAP Kinase Signalling in Epithelia and Human Cancer Cells

- Asymmetry in Family History Implicates Nonstandard Genetic Mechanisms: Application to the Genetics of Breast Cancer

- Co-translational Localization of an LTR-Retrotransposon RNA to the Endoplasmic Reticulum Nucleates Virus-Like Particle Assembly Sites

- Sex Chromosome Turnover Contributes to Genomic Divergence between Incipient Stickleback Species

- DWARF TILLER1, a WUSCHEL-Related Homeobox Transcription Factor, Is Required for Tiller Growth in Rice

- Functional Organization of a Multimodular Bacterial Chemosensory Apparatus

- Genome-Wide Analysis of SREBP1 Activity around the Clock Reveals Its Combined Dependency on Nutrient and Circadian Signals

- The Yeast Sks1p Kinase Signaling Network Regulates Pseudohyphal Growth and Glucose Response

- An Interspecific Fungal Hybrid Reveals Cross-Kingdom Rules for Allopolyploid Gene Expression Patterns

- Temperate Phages Acquire DNA from Defective Prophages by Relaxed Homologous Recombination: The Role of Rad52-Like Recombinases

- Dying Cells Protect Survivors from Radiation-Induced Cell Death in

- Determinants beyond Both Complementarity and Cleavage Govern MicroR159 Efficacy in

- The bHLH Factors Extramacrochaetae and Daughterless Control Cell Cycle in Imaginal Discs through the Transcriptional Regulation of the Phosphatase

- The First Steps of Adaptation of to the Gut Are Dominated by Soft Sweeps

- Bacterial Regulon Evolution: Distinct Responses and Roles for the Identical OmpR Proteins of Typhimurium and in the Acid Stress Response

- Final Pre-40S Maturation Depends on the Functional Integrity of the 60S Subunit Ribosomal Protein L3

- Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Pathway Regulates Branching by Remodeling Epithelial Cell Adhesion

- CDP-Diacylglycerol Synthetase Coordinates Cell Growth and Fat Storage through Phosphatidylinositol Metabolism and the Insulin Pathway

- Coronary Heart Disease-Associated Variation in Disrupts a miR-224 Binding Site and miRNA-Mediated Regulation

- TBX3 Regulates Splicing : A Novel Molecular Mechanism for Ulnar-Mammary Syndrome

- Identification of Interphase Functions for the NIMA Kinase Involving Microtubules and the ESCRT Pathway

- Is a Cancer-Specific Fusion Gene Recurrent in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma

- LILRB2 Interaction with HLA Class I Correlates with Control of HIV-1 Infection

- Worldwide Patterns of Ancestry, Divergence, and Admixture in Domesticated Cattle

- Parent-of-Origin Effects Implicate Epigenetic Regulation of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis and Identify Imprinted as a Novel Risk Gene

- The Phospholipid Flippase dATP8B Is Required for Odorant Receptor Function

- Noise Genetics: Inferring Protein Function by Correlating Phenotype with Protein Levels and Localization in Individual Human Cells

- DUF1220 Dosage Is Linearly Associated with Increasing Severity of the Three Primary Symptoms of Autism

- Sugar and Chromosome Stability: Clastogenic Effects of Sugars in Vitamin B6-Deficient Cells

- Pheromone-Sensing Neurons Expressing the Ion Channel Subunit Stimulate Male Courtship and Female Receptivity

- Gene-Based Sequencing Identifies Lipid-Influencing Variants with Ethnicity-Specific Effects in African Americans

- Telomere Shortening Unrelated to Smoking, Body Weight, Physical Activity, and Alcohol Intake: 4,576 General Population Individuals with Repeat Measurements 10 Years Apart

- A Combination of Activation and Repression by a Colinear Hox Code Controls Forelimb-Restricted Expression of and Reveals Hox Protein Specificity

- An ER Complex of ODR-4 and ODR-8/Ufm1 Specific Protease 2 Promotes GPCR Maturation by a Ufm1-Independent Mechanism

- Epigenetic Control of Effector Gene Expression in the Plant Pathogenic Fungus

- Genetic Dissection of Photoreceptor Subtype Specification by the Zinc Finger Proteins Elbow and No ocelli

- Validation and Genotyping of Multiple Human Polymorphic Inversions Mediated by Inverted Repeats Reveals a High Degree of Recurrence

- CYP6 P450 Enzymes and Duplication Produce Extreme and Multiple Insecticide Resistance in the Malaria Mosquito

- GC-Rich DNA Elements Enable Replication Origin Activity in the Methylotrophic Yeast

- An Epigenetic Signature in Peripheral Blood Associated with the Haplotype on 17q21.31, a Risk Factor for Neurodegenerative Tauopathy

- Lsd1 Restricts the Number of Germline Stem Cells by Regulating Multiple Targets in Escort Cells

- RBPJ, the Major Transcriptional Effector of Notch Signaling, Remains Associated with Chromatin throughout Mitosis, Suggesting a Role in Mitotic Bookmarking

- The Membrane-Associated Transcription Factor NAC089 Controls ER-Stress-Induced Programmed Cell Death in Plants

- The Functional Consequences of Variation in Transcription Factor Binding

- Comparative Genomic Analysis of N-Fixing and Non-N-Fixing spp.: Organization, Evolution and Expression of the Nitrogen Fixation Genes

- An Insulin-to-Insulin Regulatory Network Orchestrates Phenotypic Specificity in Development and Physiology

- Suicidal Autointegration of and Transposons in Eukaryotic Cells

- A Multi-Trait, Meta-analysis for Detecting Pleiotropic Polymorphisms for Stature, Fatness and Reproduction in Beef Cattle

- Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis Predicts an Epigenetic Switch for GATA Factor Expression in Endometriosis

- Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis of Human Pancreatic Islets from Type 2 Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Donors Identifies Candidate Genes That Influence Insulin Secretion

- The and Hybrid Incompatibility Genes Suppress a Broad Range of Heterochromatic Repeats

- The Kil Peptide of Bacteriophage λ Blocks Cytokinesis via ZipA-Dependent Inhibition of FtsZ Assembly

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Worldwide Patterns of Ancestry, Divergence, and Admixture in Domesticated Cattle

- Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis of Human Pancreatic Islets from Type 2 Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Donors Identifies Candidate Genes That Influence Insulin Secretion

- Genetic Dissection of Photoreceptor Subtype Specification by the Zinc Finger Proteins Elbow and No ocelli

- GC-Rich DNA Elements Enable Replication Origin Activity in the Methylotrophic Yeast

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání