-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

CDP-Diacylglycerol Synthetase Coordinates Cell Growth and Fat Storage through Phosphatidylinositol Metabolism and the Insulin Pathway

During development, animals undergo a rapid increase in cell size and number, which requires large amounts of lipids, in the form of phospholipids, for the expansion of cell membranes. Once the growth phase ends, excess lipids are usually stored as body fat, in the form of triacylglycerol (TAG), for use when nutrients are limited. How cells coordinate growth and fat storage is not fully understood. By screening for genes that affect lipid storage in the fruitfly Drosophila we discovered that the enzyme CDP-diacylglycerol synthetase (CdsA) coordinates cell growth and fat storage. Phospholipids and TAG have a common precursor, phosphatidic acid, which is diverted by CdsA from TAG synthesis to synthesis of the phospholipid phosphatidylinositol (PI). We also uncovered a link between CdsA and the insulin signaling pathway, which plays a major role in regulating cell and tissue growth. CdsA regulates the level of PI, which modulates insulin pathway activity; insulin pathway activity, in turn, influences the level of CdsA. The lipid metabolism pathways and the insulin signaling pathway are conserved in other animals including humans. Our findings may therefore provide further insights into clinically important imbalances in fat storage such as obesity.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004172

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004172Summary

During development, animals undergo a rapid increase in cell size and number, which requires large amounts of lipids, in the form of phospholipids, for the expansion of cell membranes. Once the growth phase ends, excess lipids are usually stored as body fat, in the form of triacylglycerol (TAG), for use when nutrients are limited. How cells coordinate growth and fat storage is not fully understood. By screening for genes that affect lipid storage in the fruitfly Drosophila we discovered that the enzyme CDP-diacylglycerol synthetase (CdsA) coordinates cell growth and fat storage. Phospholipids and TAG have a common precursor, phosphatidic acid, which is diverted by CdsA from TAG synthesis to synthesis of the phospholipid phosphatidylinositol (PI). We also uncovered a link between CdsA and the insulin signaling pathway, which plays a major role in regulating cell and tissue growth. CdsA regulates the level of PI, which modulates insulin pathway activity; insulin pathway activity, in turn, influences the level of CdsA. The lipid metabolism pathways and the insulin signaling pathway are conserved in other animals including humans. Our findings may therefore provide further insights into clinically important imbalances in fat storage such as obesity.

Introduction

During development, animals grow rapidly by both cell proliferation and cell growth. Cell growth is a heavily energy-dependent process and requires large amounts of phospholipids for expansion of cellular membranes and other cellular needs. Fat storage on the other hand is an energy-saving process which stores neutral lipids in the form of triacylglycerol (TAG) for utilization under nutrient-limited conditions such as starvation. In the de novo biosynthetic pathway, fatty acyl-CoA is utilized either for TAG synthesis or for phospholipid production (Figure 1A), so it is reasonable to propose that growth and fat storage might be balanced during normal development [1]. Indeed, numerous observations support such a balance. For example, Caenorhabditis elegans Tor mutants grow slowly and exhibit excess fat storage [2]. Drosophila melanogaster insulin pathway chico mutants are less than half the size of wild type, but show an almost 2-fold increase in lipid levels [3].

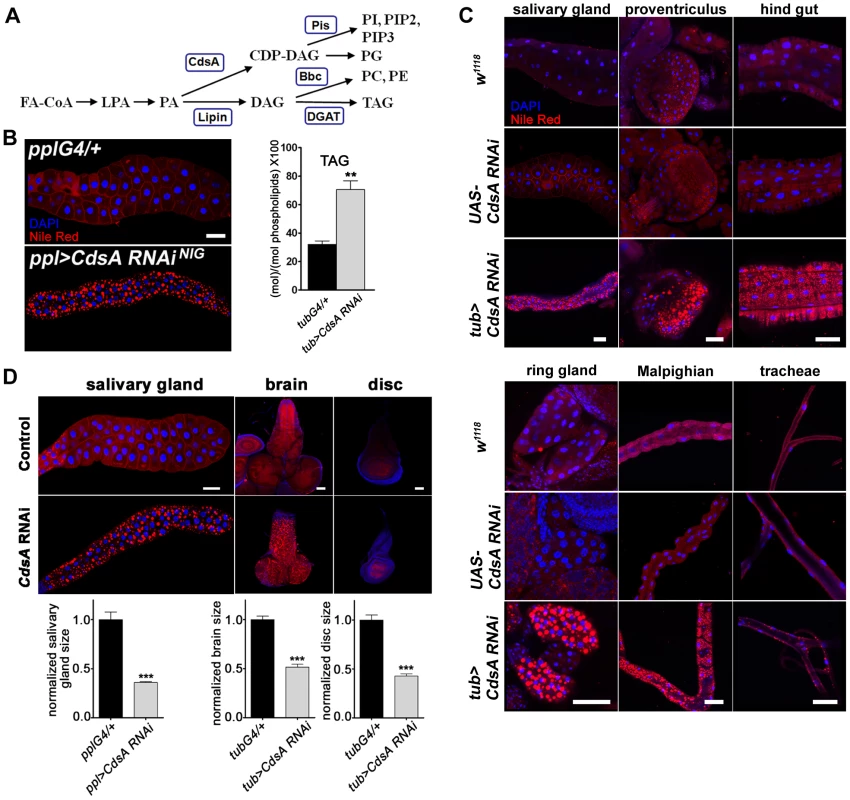

Fig. 1. CdsA broadly affects fat storage.

(A) Simplified schematic of phospholipid and glycerolipid synthesis. FA-CoA: Fatty acyl CoA; LPA: lysophosphatidic acid; PA: phosphatidic acid; DAG: diacylglycerol; TAG: triacylglycerol; CDP-DAG: cytidine diphosphate diacylglycerol; PC: phosphatidylcholine; PE: phosphatidylethanolamine; PI: phosphatidylinositol; PG: phosphatidylglycerol. CdsA adds CTP to PA and generates CDP-DAG; Pis catalyzes the donation of the phosphatidyl group from CDP-DAG to inositol and produces PI, which is the precursor of all PI derivatives, such as PIP2 and PIP3; Bbc synthesizes PC and PE from DAG, which can also be converted to TAG by DGAT. (B) (left) RNAi knockdown of CdsA in salivary gland causes massive lipid accumulation. pplG4/+: the ppl-Gal4 driver only; ppl>CdsA RNAi: UAS-CdsA RNAi driven by ppl-Gal4. Blue: DAPI staining for nuclei; red: Nile red staining for neutral lipids. (right) TAG levels of fat body-removed whole larval samples measured by mass spectrometry. The level of TAG is normalized to total phospholipids. (C) CdsA affects fat storage in many tissues. In wandering 3rd instar tub>CdsA RNAi larvae, massive fat storage in many non-adipose tissues is detected by Nile red staining. Blue: DAPI staining for nuclei; red: Nile red staining for neutral lipids. (D) CdsA RNAi reduces salivary gland, brain, and wing disc tissue size. CdsA was knocked down with ppl-Gal4 in salivary gland and tub-Gal4 in brain and wing disc. Different tissues dissected from wandering 3rd instar larvae of Gal4 controls and CdsA RNAi were stained by Nile red (red) or DAPI (blue). Relative tissue sizes were quantified in multiple samples (salivary gland: n = 8; brain and wing disc: n = 10) based on the area occupied. Scale bar (B, C, D): 50 µm. The mechanisms that coordinate cell growth and neutral lipid storage are largely unknown and many intriguing questions remain to be addressed. During development, animals usually have an initial phase of rapid growth, which involves expansion of cell number and size, followed by a homeostatic state, when growth ceases and excess fat is stored in adipose tissue. How is the balance between cell growth and neutral lipid storage regulated in these two different developmental stages? How is the balance regulated in different tissues or cells? For example, how is the balance regulated in the adipocyte, since it both grows large and stores fat? In some disease states, ectopic lipid accumulation in non-adipose tissues such as muscle, pancreas, and liver is often observed [4]. How is the balance regulated in non-adipose tissues? Answering these questions would definitely lead to a significant advance of our knowledge in the fields of both fat storage and cell growth.

The insulin pathway is a conserved signaling pathway that is essential for cell growth in response to nutrient conditions [5]–[9]. The core components of the insulin pathway include the insulin receptor (InR), insulin receptor substrates (IRS), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), the protein kinase Akt, and the transcription factor FOXO. PI3K, which generates phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) from phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), and PTEN, the phosphoprotein phosphatase that converts PIP3 to PIP2, are positive and negative regulators of the insulin pathway, respectively [10], [11]. PIP4K, which generates PIP2 from phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate (PIP) also positively regulates insulin pathway activity [12]. Therefore, various enzymes that affect the level of PIP3 provide an important layer of regulation of insulin pathway activity. Recently, several novel components of the insulin pathway were identified, including miRNAs (miR-8 and miR-14) and secreted proteins (Upd and SDR) [13]–[16].

It is well known that the insulin pathway regulates lipid homeostasis and couples nutritional conditions with systemic growth and metabolism. Besides inhibiting lipolysis, it also promotes fatty acid synthesis through activating the expression of different target genes, including acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), fatty acid synthase (FAS), and sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP) [17]–[19]. Recently acyl-CoA synthetase (ACS)/Pudgy has been identified as a direct target of FOXO [20]. Since many of these regulators have been studied during the homeostatic stage, it is not known whether they contribute to the balance of cell growth and neutral lipid storage during the developmental stage. Furthermore, additional regulators or targets of the insulin pathway in balancing cell growth and fat storage remain to be identified.

With its exquisite genetic tools and evolutionarily conserved metabolic pathways, Drosophila melanogaster has been accepted as a model for studying lipid metabolism [21]–[24]. Through continuous feeding, Drosophila larvae grow rapidly with a nearly 200-fold increase in body mass during the 4-day larval stage. During this time most tissues, such as brain, salivary gland, and imaginal discs, store very little neutral lipid, while the fat body accumulates large amounts of fat [23]. The fat body is a specialized energy storage organ, equivalent to the vertebrate adipose tissue, and most of the dietary fats and de novo-synthesized fats from the intestine are transported to the fat body via lipoproteins in the hemolymph [25]. As in mammals, many questions remain to be answered in Drosophila. How do Drosophila larvae coordinate cell growth and neutral lipid storage in non-adipose tissues? What mechanisms are used in the fat body to balance the storage of fat along with cell growth?

In this study, we identified that Drosophila CDP-diacylglycerol synthetase, CdsA, coordinates cell growth and neutral lipid storage through phosphatidylinositol (PI) metabolism and the insulin pathway. We also found that when CdsA is defective, a DAG-to-PE route mediated by the choline/ethanolamine phosphotransferase Bbc may contribute to the growth of fat cells.

Results

CdsA broadly affects fat storage

We previously reported that mutants of dSeipin, the Drosophila homolog of human lipodystrophy gene Seipin which is important for fat storage and lipid droplet size [26], [27], exhibit ectopic lipid droplets in salivary glands, which can be stained by the neutral lipid dyes Nile red or Bodipy [28]. The Drosophila salivary gland is large and easy to manipulate and has been previously used as an in vivo system to study cell death and autophagy, cell growth and proliferation, and signal transduction, for example in Hedgehog signaling [29]. Hence, we investigated neutral lipid storage regulation in salivary glands by screening for genes which, when knocked down or overexpressed, caused an ectopic lipid droplet phenotype in salivary gland. We used ppl-Gal4, which drives strong gene expression in both larval salivary gland and fat body. The strongest ectopic lipid storage phenotype was caused by CdsA RNAi (Figure 1B). The phenotype was also verified with an independent CdsA RNAi line (Figure S1A). In addition, CdsA1, a weak allele of CdsA, was previously found to have a dSeipin-like ectopic lipid storage phenotype in the salivary gland [28], demonstrating that CdsA affects fat storage. CdsA is the sole Drosophila CDP diglyceride synthetase (Cds), and diverts phosphatidic acid (PA) from TAG synthesis to the synthesis of cytidine diphosphate diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG), the precursor of two phospholipids, PI and phosphatidylglycerol (PG) (Figure 1A).

According to results from the Drosophila gene expression database FlyAtlas (http://www.flyatlas.org), CdsA is widely expressed in different larval tissues. In adults, CdsA is highly enriched in the eye and is important for the phototransduction pathway [30]. We confirmed the larval expression profile with Q-RT-PCR (Figure S1B) and a Lac-Z enhancer trap line. The Lac-Z signal was detected in many places, including salivary gland, fat body, proventriculus, hind gut, brain, muscle, Malpighian tubules, and tracheal tubes (Figure S1C). The broad expression of CdsA and the strong salivary gland fat storage phenotype of CdsA RNAi provide a unique opportunity to address whether other non-adipose tissues have the same capacity as salivary glands to store excess fat.

When we drove UAS-CdsA RNAi transgene expression using the ubiquitous tub-Gal4 driver, a strong, fully penetrant phenotype was observed. The level of CdsA transcripts was reduced to about 40% with RNAi. The tub>CdsA RNAi larvae accumulated excess fat in many non-adipose tissues, including salivary gland, proventriculus, hind gut, Malpighian tubules, and trachea (Figure 1C). Among the tissues examined, the most prominent lipid storage phenotype was found in salivary gland and prothoracic gland, both of which have polyploid cells. The excess lipid accumulation phenotype of tub>CdsA RNAi was reproduced using various tissue-specific Gal4 lines, suggesting that CdsA acts tissue-autonomously (data not shown). To direct measure the accumulation of TAG in non-adipose tissues, we measured the level of TAG from the fat body-removed whole larval samples. Compared to control, tub>CdsA RNAi animals have much higher level of TAG, consistent with the Nile red staining results (Figure 1B). Together, these results indicate that although the fat body is the main energy reservoir for larvae, neutral lipids can still be stored in significant amounts in many non-adipose tissues when CdsA function is lost. However, it remains to be determined whether excess lipid accumulation in these non-adipose tissues can fulfill the energy reservoir function of the fat body, or causes deterioration of these tissues.

CdsA regulates salivary gland fat storage and cell size

Beside the fat storage phenotype, we noticed a significantly reduced organ size phenotype in tub>CdsA RNAi larvae. The imaginal discs, salivary gland, and brain are all smaller in tub>CdsA RNAi larvae than controls (Figure 1D). This phenotype could be due to a decrease in cell size, or cell number, or both. We quantified the cell size and cell number in the salivary gland and found that while the cell number is not changed, the cell size is greatly reduced in tub>CdsA RNAi larvae (data not shown). Therefore, reduced cell size is the likely cause of the small organ size in CdsA RNAi larvae.

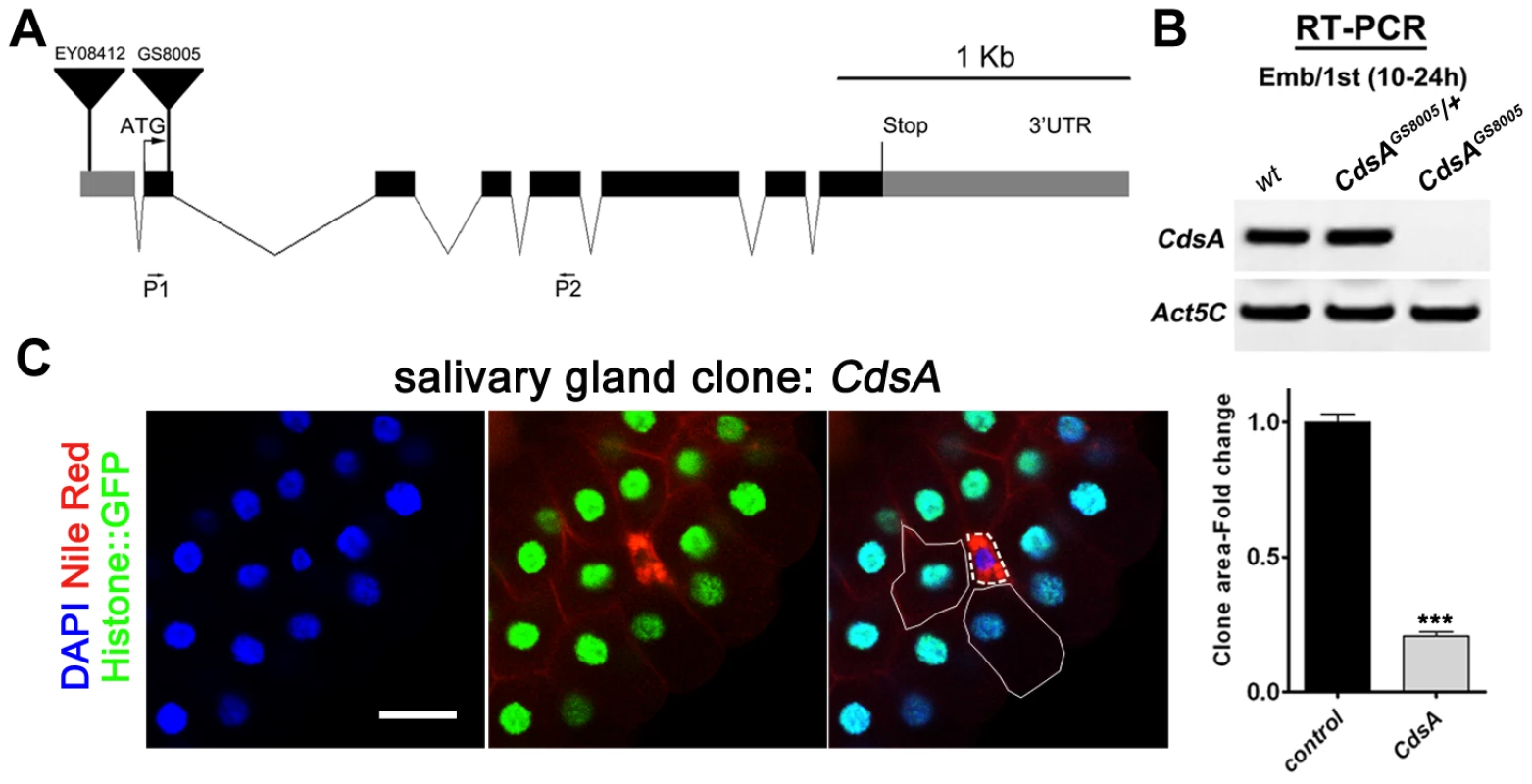

To rule out a possible off-target effect of RNAi, we turned to CdsA mutants. CdsA1 is a weak and viable allele of CdsA and does not cause an obvious small cell size phenotype (data not shown). In the CdsAGS8005 allele, a transposon element inserted into the second exon of CdsA disrupts transcription (Figure 2A). CdsAGS8005 animals died at late embryonic to early larval stages. By RT-PCR, CdsAGS8005 is likely a strong loss-of-function or null allele (Figure 2B). We generated CdsAGS8005 mutant clones in the salivary gland. Consistent with the RNAi result, CdsAGS8005 mutant salivary gland cells are smaller in size and accumulate large amounts of fat compared to neighboring control cells (Figure 2C), further demonstrating that CdsA functions cell-autonomously. On average, the size of CdsAGS8005 mutant salivary gland cells is only about 20% of wild-type cells. Together, these results suggest that CdsA plays a key role in balancing fat storage and cell growth.

Fig. 2. CdsA mutations affect salivary gland fat storage and cell size.

(A) Schematic representation of the CdsA (CG7962) genomic locus. The location within CdsA of two P element insertions, EY08412 (for overexpression studies) and GS8005 (for mutant clonal analysis) are shown. P1 and P2: primers for RT-PCR in (B). (B) The CdsAGS8005 allele is likely a null. Embryo/1st instar larval (10–24 hr) RNA of wt, trans-heterozygous or homozygous CdsAGS8005 was analyzed by RT-PCR. Note that there is no detectable CdsA transcript in CdsAGS8005 mutants. Act5C is a control for RT-PCR. (C) A CdsA mutant cell (non-GFP, dashed white circle) is small and contains more neutral lipids compared with neighboring control cells (solid white circle). CdsA mutant salivary gland clones were induced by flp/FRT-mediated recombination during embryogenesis and visualized in wandering 3rd instar larvae. Blue: DAPI staining for nuclei; red: Nile red staining for neutral lipids; green: Histone::GFP. Histogram: n = 8. Scale bar (C): 50 µm. Error bars (C) represent SEM. (*) P<0.05; (**) P<0.01; (***) P<0.001 (Student's t-test). CdsA regulates salivary gland cell growth by affecting PI metabolism and insulin pathway activity

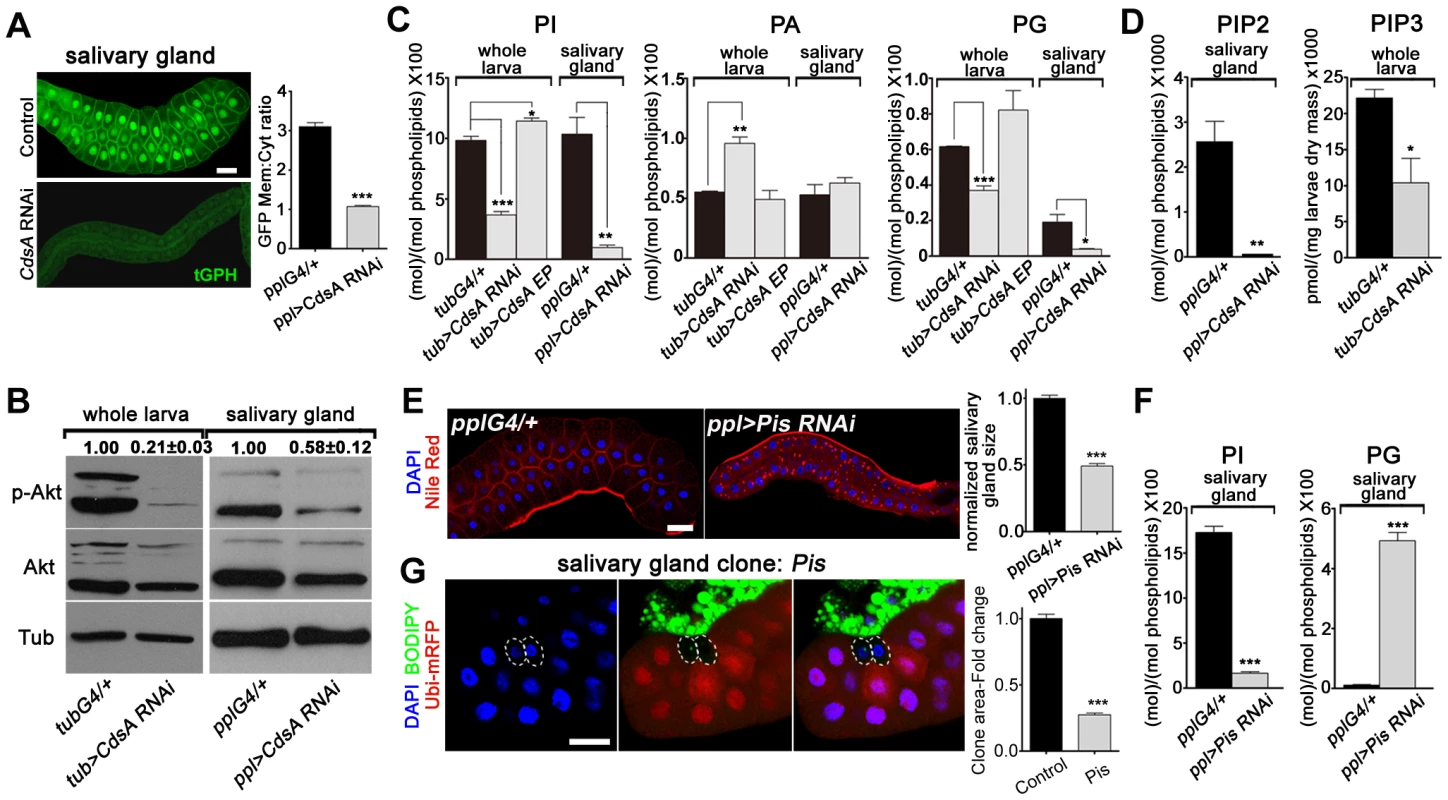

Cell growth depends on nutrient conditions and is well-known to be regulated by the insulin signaling pathway. The activity of the insulin pathway is regulated by the PI-derived lipid PIP3. Since CdsA is a key enzyme involved in the production of PI from PA through CDP-DAG (Figure 1A), and PI is the precursor of PIP, PIP2, and PIP3, we speculated that in CdsA RNAi or mutant animals, the total level of PI is reduced, resulting in a reduction in PIP3, which would lead to low insulin pathway activity and defective cell growth. To test this hypothesis, we first examined the level of PIP3 with a PIP3-specific GFP reporter, tGPH (tubulin-GFP-Pleckstrin homology), in the salivary gland [10]. GFP is recruited to the plasma membrane by binding to PIP3; therefore, the ratio of plasma membrane to cytosol GFP intensity reflects the relative level of PIP3. In controls, the GFP signal is strong in both plasma membranes and nuclei. In CdsA RNAi larvae, the overall GFP intensity is much lower due to unknown reasons and the plasma membrane to cytosol GFP intensity ratio is only 30% of wild type, indicating reduced levels of PIP3 (Figure 3A). To further probe the activity of the insulin pathway in CdsA RNAi, we also determined the level of phosphorylation of residue S505 of the protein kinase Akt (P-AktS505, equivalent to S473 in mammalian Akt), which has often been used as an indicator of insulin pathway activity. The P-AktS505 level is significantly decreased in CdsA RNAi whole larvae and salivary glands (Figure 3B).

Fig. 3. CdsA RNAi affects PI metabolism and insulin pathway activity.

(A) tGPH reporter assay in salivary gland cells. The cell membrane fluorescence signal is significantly weaker and more diffuse in CdsA RNAi than in the ppl-Gal4 control. Images were taken with the same exposure time. Membrane-to-cytoplasmic GFP intensity ratios were calculated from measurements of mean pixel intensities within equal areas of membrane versus cytoplasm. Histogram: n = 21. (B) Total Akt and phosphorylated Akt (Ser505) levels were detected by western blotting. α-tubulin (Tub) was used as a loading control. Average and standard deviation of relative band intensity ratio of p-Akt versus total Akt from three replicates is indicated at the top after normalization. The Western blot result from one experiment is shown here. In whole larva and salivary gland, RNAi of CdsA diminished Akt phosphorylation at serine505. (C) Phospholipid levels obtained by lipid profiling of whole larva or salivary gland samples from wandering 3rd instar larvae with the following genotypes: Gal4 control (G4/+), CdsA RNAi, and CdsA overexpression (CdsA EP). CdsA was knocked down with ppl-Gal4 in salivary gland and tub-Gal4 in whole larvae. Assays were done in triplicate. Note that the PI level in the CdsA RNAi salivary gland sample is less than 10% of that in the Gal4 control. The levels of PI, PA, and PG are normalized to total phospholipids. (D) PIP2 and PIP3 levels measured by mass spectrometry and ELISA kit, respectively. Assays were done at least in triplicate. The level of PIP2 is normalized to total phospholipids. The level of PIP3 is normalized to dry weigh. (E) Silencing Pis reduces salivary gland size and causes accumulation of lipid droplets. Blue: DAPI staining for nuclei; red: Nile red staining for neutral lipids. Histogram: n = 9. (F) Phospholipid levels obtained by profiling of salivary gland samples from control and Pis RNAi wandering 3rd instar larvae. Assays were done in triplicate. The levels of PI and PG are normalized to total phospholipids. (G) Pis mutant salivary gland cells (marked by the absence of RFP, dashed white circles) are significantly smaller than neighboring wild-type cells. Pis mutant salivary gland clones were induced during embryogenesis and visualized in wandering 3rd instar larvae. Blue: DAPI staining for nuclei; green: BODIPY staining for neutral lipids; red: Ubi-mRFP, which marks cytosol. Histogram: n = 11. Scale bar (A, E, G): 50 µm. Error bars (A, C, D, E, F, G) represent SEM. (*) P<0.05; (**) P<0.01; (***) P<0.001 (Student's t-test). To obtain direct evidence of reduced PI levels, we quantified PI lipids in whole larval and salivary gland samples using mass spectrometry. We found that in both whole larvae and salivary glands, the total level of PI is greatly reduced in CdsA RNAi samples compared to controls and the level of PI in salivary glands is reduced more than ten-fold (Figure 3C). CdsA RNAi also causes a reduction in the total level of PG, accompanied by an increase in PA (Figure 3C). In addition, ubiquitous overexpression of CdsA slightly increases the levels of PI and PG in whole larval samples (Figure 3C). These data are consistent with the role of CdsA in catalyzing the conversion of PA to CDP-DAG, the precursor of PI and PG. Besides, compared to measurable amount of PIP2 in control, the level of PIP2 in CdsA RNAi salivary gland samples is below the threshold level detected by mass spectrometry (Figure 3D). Moreover, likely due to the small size of the salivary glands, we were unable to measure the abundance of PIP3 in both control and CdsA RNAi samples with mass spectrometry. Instead, we measured the level of PIP3 in whole larval samples using an ELISA method. In CdsA knockdown larvae, the PIP3 level is reduced to less than half of the control (Figure 3D). Taken together, our results indicate that CdsA influences insulin pathway activity and PI metabolism in the salivary gland.

These results predict that blocking de novo PI synthesis in the salivary gland should mimic the CdsA mutant clone phenotype in affecting salivary gland cell growth. Phosphatidylinositol synthase (Pis) is the only enzyme which synthesizes PI from CDP-DAG and inositol (Figure 1C). Similar to CdsA RNAi salivary glands, Pis RNAi salivary glands are small and accumulate lipid droplets (Figure 3E). Similar to CdsA RNAi, the level of PI in salivary glands is greatly reduced in Pis RNAi samples compared to controls (Figure 3F). On the other hand, the level of PG is significantly increased in Pis RNAi (Figure 3F). We further examined Pis1, a likely null mutant of Pis [31]. The Pis1 mutation is lethal, like CdsAGS8005, so we generated Pis1 mutant clones. Interestingly, Pis1 mutant salivary gland cells do not accumulate large numbers of lipid droplets (Figure 3G), suggesting that Pis mutations likely increase the level of CDP-DAG, which is converted to PG, without significantly elevating the level of PA. Similar to CdsAGS8005 mutant salivary gland cells, Pis1 mutant salivary gland cells are significantly smaller than wild-type cells (Figure 3G). On average, the size of Pis1 mutant salivary gland cells is only about 25% of wild-type cells. The reduction of cell size in CdsA and Pis mutants is not as strong as in insulin pathway mutants, where salivary gland cell size can be reduced by over 90% [10], [32], suggesting that PI from other resources, such as uptaken externally or inherited from mother cells, may partly contribute to salivary gland cell growth. Taking these results together, we conclude that CdsA regulates salivary gland cell growth by affecting PI metabolism and insulin pathway activity.

The insulin pathway genetically interacts with CdsA and affects CdsA transcription levels

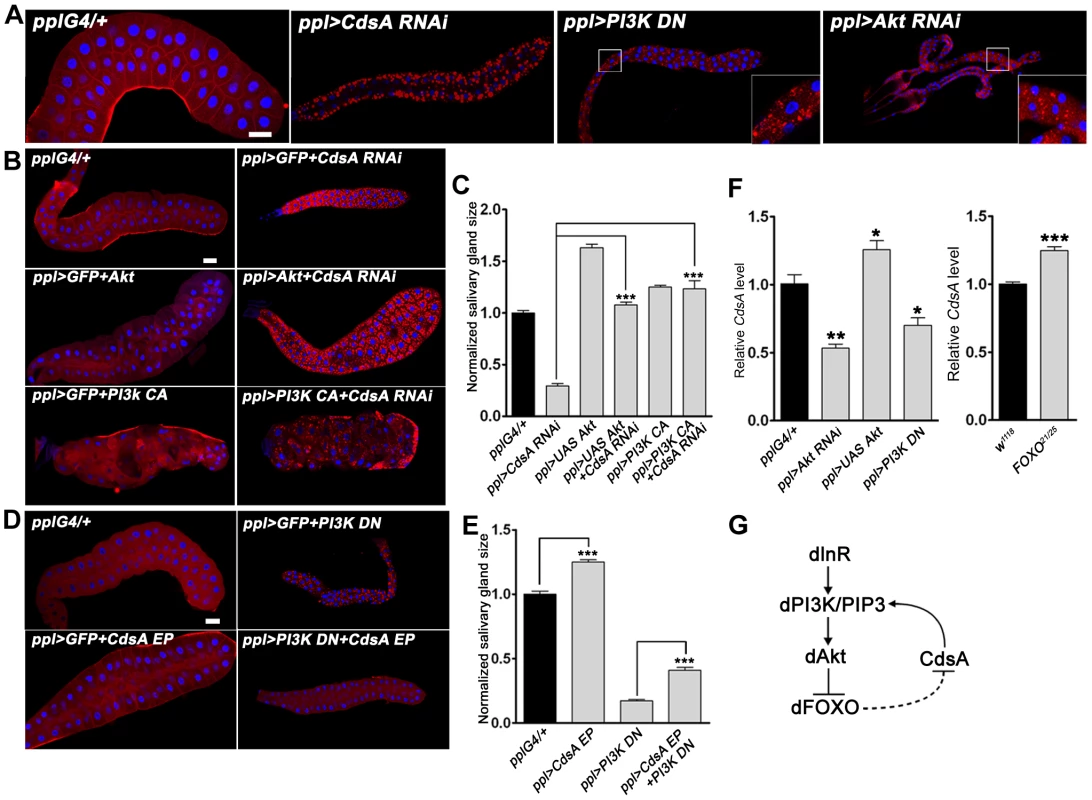

To further reveal the connections between CdsA, PI metabolism, and the insulin pathway, we turned to genetic interaction assays. In the salivary gland genetic screen, we identified two insulin pathway components, PI3K and Akt, in addition to CdsA. Knockdown of PI3K by dominant-negative PI3K (PI3K DN) or of Akt by RNAi leads to small cell size and ectopic lipid storage phenotypes in the salivary gland, although the lipid storage phenotype is weaker than that of CdsA RNAi (Figure 4A and S2A). Since both CdsA RNAi and reduced insulin pathway activity have the same phenotypes in the salivary gland, we examined their genetic interaction by gain of insulin pathway activity in CdsA RNAi larvae and vice versa. We found that overexpressing wild-type Akt or constitutively active PI3K (PI3K CA) fully suppressed the small cell size phenotype of CdsA RNAi (Figure 4B and 4C). Although we can't rule out the possibility that CdsA and insulin pathway act redundantly in a common pathway, these results are consistent with the notion that CdsA acts upstream of PI3K in positively regulating insulin pathway activity. Interestingly, the ectopic lipid accumulation phenotype of CdsA RNAi is partially rescued by overexpression of PI3K CA, but not Akt (Figure 4B and S2B).

Fig. 4. The insulin pathway genetically interacts with CdsA and affects the transcription level of CdsA.

(A) Perturbation of insulin pathway activity affects salivary gland size and fat storage. Expression of dominant-negative PI3K (PI3K DN) or knockdown of Akt by RNAi leads to lipid accumulation in salivary glands of dramatically reduced size, reminiscent of CdsA RNAi. Blue: DAPI staining for nuclei; red: Nile red staining for neutral lipids. (B, C) Elevation of insulin pathway activity by overexpressing Akt or by expressing constitutively active PI3K (PI3K CA) fully rescues the small salivary gland size phenotype of CdsA RNAi. Note that the massive fat accumulation in CdsA RNAi salivary gland is also partially rescued by PI3K CA expression. Blue: DAPI staining for nuclei; red: Nile red staining for neutral lipids. (D, E) Overexpressing CdsA partially but significantly rescues the small salivary gland phenotype of PI3K DN. Note that the lipid accumulation in PI3K DN can be fully suppressed by CdsA overexpression. Blue: DAPI staining for nuclei; red: Nile red staining for neutral lipids. (F) The insulin pathway positively regulates CdsA expression. Relative CdsA mRNA levels were quantified by qRT-PCR on dissected salivary glands from wandering 3rd instar larvae of each genotype. Measurements were made in triplicate. (G) The positive feedback loop between the insulin pathway and CdsA. CdsA affects insulin pathway activity by regulating PI/PIP3 levels, while the insulin pathway regulates the CdsA transcription level. Histogram (C, E): n≥8 for each genotype. Scale bar (A, B, D): 50 µm. Error bars (C, E, F) represent SEM. (*) P<0.05; (**) P<0.01; (***) P<0.001 (Student's t-test). We then tested whether overexpression of CdsA can rescue the cell size and ectopic lipid storage phenotypes caused by impaired insulin pathway activity. On its own, CdsA overexpression slightly increases the size of the salivary gland (Figure 4D and 4E). Interestingly, CdsA overexpression partially, but significantly, rescued the small cell size phenotype of PI3K DN (Figure 4D and 4E). Moreover, the salivary gland ectopic lipid storage phenotype of PI3K DN can be fully suppressed by CdsA overexpression (Figure 4D and S2B). These results raise the possibility that insulin pathway activity may influence the CdsA level.

Since insulin signaling regulates lipid homeostasis mainly at the level of gene transcription and the forkhead box protein dFOXO can transcriptionally activate the upstream target InR via a feedback regulatory loop [33], we asked whether the transcription of CdsA is affected by the insulin pathway. We examined the level of CdsA under conditions which perturb insulin pathway activity. Compared to controls, CdsA transcription levels in PI3K DN or Akt RNAi salivary glands were reduced significantly to 40–50% as assayed by quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 4F). Conversely, CdsA transcription levels slightly increased when Akt was overexpressed (Figure 4F). Likewise, loss of FOXO slightly increased the level of CdsA (Figure 4F). Taken together, these results pinpoint a positive feedback loop between insulin signaling and CdsA in modulating the balance of cell growth and lipid storage. In this positive feedback loop (Figure 4G), CdsA positively regulates the activity of the insulin pathway through PI, and the insulin pathway affects the transcription of CdsA.

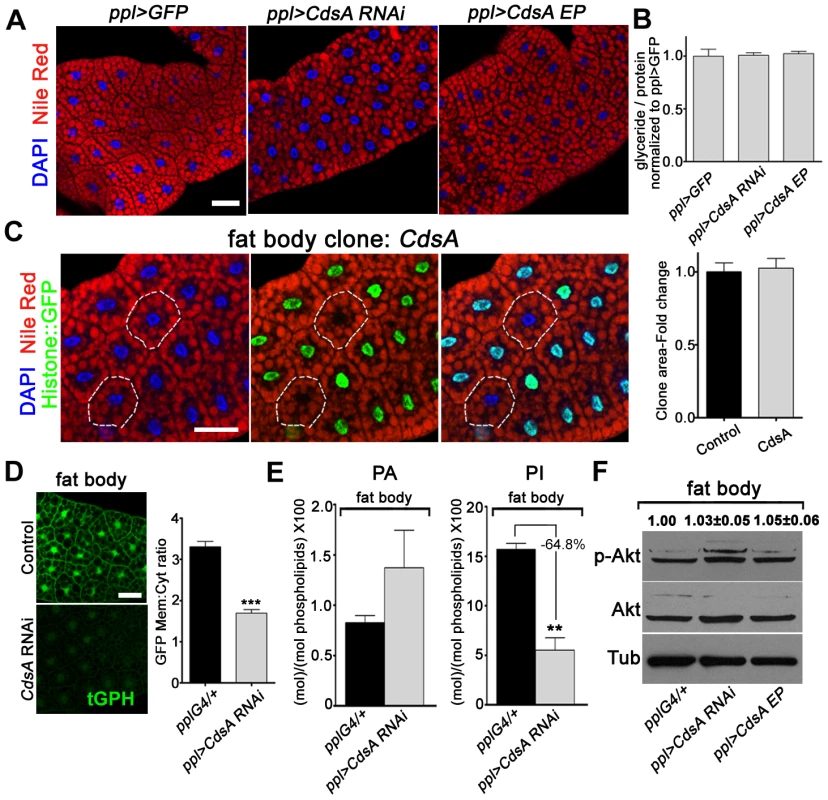

Fat body cell growth and neutral lipid storage are not affected by CdsA

Besides salivary gland, we also examined the role of CdsA in fat body by both loss-of-function and gain-of-function analyses. To our surprise, fat body-specific CdsA RNAi or CdsA overexpression using ppl-Gal4 or cg-Gal4 did not result in a significant lipid storage phenotype in the fat body (Figure 5A and data not shown). Consistent with this, the total levels of glycerides are not significantly different in control, CdsA RNAi, and CdsA-overexpressing animals (Figure 5B). The fat cell size is also unchanged in CdsA RNAi and CdsA-overexpressing animals (Figure 5A). Although the RNAi efficiency was verified by Q-RT-PCR (data not shown), it is still possible that knockdown by CdsA RNAi is not efficient enough to cause a cell growth or fat storage phenotype in the fat body. To rule out this possibility and to obtain more definitive answers, we analyzed CdsA mutants. In contrast to the small size and massive neutral lipid storage of CdsAGS8005 mutant salivary gland cells (Figure 2C), CdsAGS8005 mutant fat body cells are normal in size and fat storage (Figure 5C), which is consistent with the RNAi result. Therefore, we concluded that fat body cell growth and neutral lipid storage are not affected by CdsA under normal conditions.

Fig. 5. Loss of function of CdsA does not affect fat cell lipid storage and growth.

(A) Nile red staining of wandering 3rd instar larval fat body of ppl>GFP control, CdsA RNAi, and CdsA overexpression. Neither silencing nor overexpressing CdsA affects fat body lipid storage. Blue: DAPI staining for nuclei; red: Nile red staining for neutral lipids. (B) Total body fat (normalized to total protein) of wandering 3rd instar male larvae of ppl>GFP control, CdsA RNAi, and CdsA overexpression. Glyceride assays shown here are representative experiments based on triplicate measurements with a total of ≥15 male larvae per genotype. The level of glyceride is normalized to total proteins. (C) Fat body CdsA mutant cells (non-GFP, dashed white circles) are normal in size and lipid content. Fat body CdsA mutant clones were induced by mitotic recombination 8 hr after egg laying and visualized in wandering 3rd instar larvae. Blue: DAPI staining for nuclei; red: Nile red staining for neutral lipids; green, Histone::GFP. Histogram: n = 7. (D) tGPH reporter assay in fat body cells. CdsA RNAi leads to reduced membrane-to-cytoplasm ratio of the tGPH GFP fluorescence. Images were all taken with the same exposure time. Note that the total GFP fluorescence is also diminished. Histogram: n = 18. (E) Phospholipid levels of ppl-Gal4 control and ppl>CdsA RNAi fat body from wandering 3rd instar larvae. Note that the PI level in the CdsA RNAi fat body sample is reduced to approximately one third of that in the Gal4 control. Assays were done in triplicate. The levels of PA and PI are normalized to total phospholipids. (F) Neither silencing nor overexpressing CdsA affects larval fat body Akt phosphorylation at Ser505. Total Akt and phosphorylated Akt (Ser505) levels were detected by western blotting. α-tubulin (Tub) was used as a loading control. Average and standard deviation of relative band intensity ratio of p-Akt versus total Akt from three replicates is indicated at the top after normalization. Western blot result for one experiment is shown here. Scale bar (A, C, D): 50 µm. Error bars (B, C, D, E) represent SEM. (*) P<0.05; (**) P<0.01; (***) P<0.001 (Student's t-test). The lack of a neutral lipid storage phenotype in CdsA RNAi fat bodies suggests that PA and probably de novo lipogenesis from fatty acyl-CoA contribute little to final TAG content in the fat body under normal conditions. Indeed, it was reported that DAG is the major form in which lipids are transferred, via lipoproteins, from the intestine to the fat body for storage [25]. Our results are also consistent with a previous finding that unknown mechanism(s) maintain the level of fat body lipid storage within a narrow range [25].

Next, we asked why CdsA does not affect fat body cell growth. As we showed before, CdsA affects PI levels in the salivary gland and subsequently the activity of the insulin pathway (Figure 3). Is it possible that PI or insulin signaling is not important for fat body cell growth? Several previous reports involving manipulations of insulin pathway activity in fat cells clearly rule out this possibility [10], [16], [34]. Alternatively, it is possible that the PI level is not reduced in CdsA RNAi or mutant fat cells compared to salivary gland. We therefore examined the levels of PI and PIP3 in CdsA RNAi fat body cells. Similar to salivary gland, the overall tGPH reporter intensity is much lower in CdsA RNAi fat cell compare to control. The ratio of plasma membrane to cytosol GFP signal intensity from the tGPH reporter is reduced to around 50% of wild type in CdsA RNAi fat body cells (Figure 5D). By lipid content analysis, the level of PA is slightly increased in CdsA RNAi fat bodies (Figure 5E). However, compared to the >10-fold reduction of PI levels in the CdsA RNAi salivary gland, the level of PI is only reduced to 35% of wild type in the CdsA RNAi fat body (Figure 5E). Interestingly, the P-AktS505 level is not changed in the CdsA RNAi fat body (Figure 5F), consistent with the cell size phenotype. These results raise the possibility that although the level of PI, and probably PIP3, is reduced by CdsA RNAi, the reduction is not sufficient to affect Akt phosphorylation or other compensatory mechanism(s) that exist to support fat cell growth.

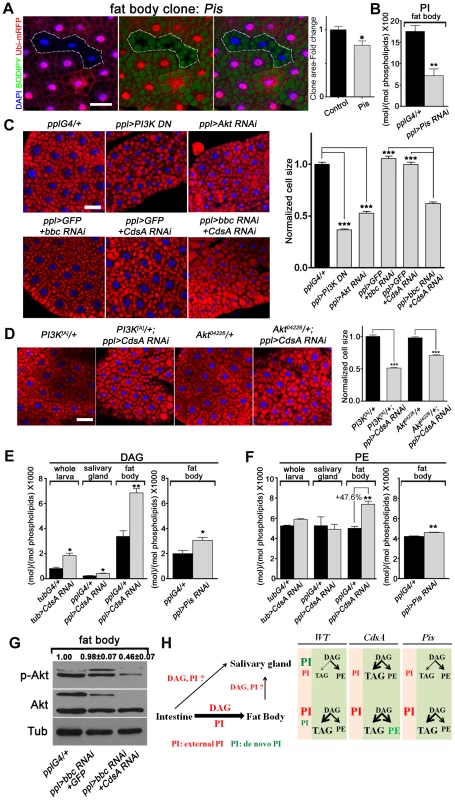

A DAG-to-PE route mediated by the choline/ethanolamine phosphotransferase Bbc may contribute to fat cell growth in CdsA RNAi larvae

To further explore why the fat cell growth is not affected in CdsA mutant, we turned to Pis null mutant and Pis RNAi again. Pis1 mutant fat body cells are about 30% smaller on average than control cells (Figure 6A) and in Pis RNAi fat body, the PI level reduced to less than half of the control (Figure 6B). Expression of dominant negative PI3K or Akt RNAi reduces the size of fat body cells by over 50% (Figure 6C). Together, these results suggest that de novo-synthesized PI contributes partly to fat cell growth and PI from other origins (i.e. transported from other cells/tissues or inherited from mother cells) may contribute significantly to the growth of fat cells. If so, why is a cell growth phenotype not exhibited by CdsA mutant clones? To examine the CdsA mutant phenotype in a sensitive genetic background, we crossed CdsA RNAi to PI3K or Akt mutants. We found that reducing PI3K or Akt to one copy in the CdsA RNAi background results in a reduction in fat cell size of around 50% (Figure 6D). These dosage-sensitive interactions suggest that CdsA RNAi mildly impairs fat cell growth.

Fig. 6. A DAG-to-PE route mediated by Bbc may support cell growth in CdsA RNAi fat body.

(A) Fat body Pis mutant cells (marked by absence of RFP, dashed white area) are slightly smaller than neighboring twin-spot wild-type cells. Fat body Pis mutant clones were induced 8 hr after egg laying and visualized in wandering 3rd instar larvae. Blue: DAPI staining; green: BODIPY staining for neutral lipids; red: Ubi-mRFP, which marks cytosol. Histogram: n = 7. (B) Total PI levels in control and Pis RNAi fat body. The level of PI is normalized to total phospholipids. (C) Nile red staining of fat bodies in larvae with loss of function of insulin pathway components or silencing of CdsA and bbc. Silencing CdsA or bbc alone does not affect fat body cell size, whereas reduced insulin pathway activity dramatically decreases the cell size. Double silencing of CdsA and bbc also significantly reduces fat body cell size. Histogram: n≥94 for each genotype. Blue: DAPI staining for nuclei; red: Nile red staining for neutral lipids. (D) Removing one copy of PI3K or Akt in a ppl>CdsA RNAi background is sufficient to reduce fat body cell size. Histogram: n≥80 for each genotype. Blue: DAPI staining for nuclei; red: Nile red staining for neutral lipids. (E, F) DAG and PE levels obtained by lipid measurements of whole larva, salivary gland or fat body of wandering 3rd instar larvae of Gal4 control, CdsA RNAi, CdsA overexpression and Pis RNAi. CdsA or Pis was knocked down with ppl-Gal4 in salivary gland and fat body and tub-Gal4 in whole larva. Assays were done in triplicate. Note that the PE level in the CdsA RNAi fat body sample was 47.6% higher than the Gal4 control. The levels of DAG and PE are normalized to total phospholipids. (G) Double silencing of CdsA and bbc decreases larval fat body Akt phosphorylation at Ser505. Total Akt and phosphorylated Akt (Ser505) levels were detected by western blotting. α-tubulin (Tub) was used as a loading control. Average and standard deviation of relative band intensity ratio of p-Akt versus total Akt from three replicates is indicated at the top after normalization. The Western blot result from one experiment is shown here. (H) Schematic model depicting the underlying mechanisms of different phenotypes observed in CdsA and Pis mutants. In wild type, de novo-synthesized PI contributes most to the growth of salivary gland cells, while PI from an external source along with DAG, probably from the intestine, contributes most to the growth and fat storage of fat body cells. Both CdsA and Pis mutations lead to ∼80% growth reduction in salivary gland due to the loss of de novo-synthesized PI. In fat body, the loss of de novo-synthesized PI in Pis mutants results in ∼30% reduction of cell growth, while the increase in PE (marked in green) in CdsA mutants compensates for the loss of de novo-synthesized PI. Fat storage in the salivary gland of CdsA mutants increases dramatically. Scale bar (A, C, D): 50 µm. Error bars (A, B, C, D, E, F) represent SEM. (*) P<0.05; (**) P<0.01; (***) P<0.001 (Student's t-test). In addition, because CdsA acts one step earlier than Pis in PI biosynthesis (Figure 1A), it is possible that accumulation of or lack of certain metabolites compensates for the mild growth defect in CdsA mutants. Through lipid measurements, we found that the levels of DAG and PE are significantly increased in CdsA RNAi fat body samples. In fat body, the DAG level is doubled and the PE level is increased by about 50%, while in salivary gland, the PE level is unchanged (Figure 6E and 6F). In contrast, the levels of DAG and PE are only slightly increased in Pis RNAi fat body (Figure 6E and 6F). PEBP, a PE binding protein, has been reported to affect Akt phosphorylation, suggesting that PE may be linked to insulin signaling [35]. If the growth compensation is through the DAG-to-PE route, blocking the synthesis of PE from DAG in CdsA RNAi animals might lead to a more obvious fat cell growth phenotype. Choline/ethanolamine phosphotransferase (Cept) Bbc is a key enzyme in Drosophila that converts DAG to PE (Figure 1A) [36]. While bbc RNAi did not affect the P-AktS505 level (Figure 6G) and did not obviously affect the fat cell size (Figure 6C), CdsA and bbc double RNAi exhibits a synergistic effect: the fat cell size is drastically decreased to a level comparable to Akt or PI3K RNAi (Figure 6C). Moreover, the fat body P-AktS505 level is greatly reduced by CdsA and bbc double RNAi (Figure 6G). In contrast, the salivary gland cell size of CdsA and bbc double RNAi is comparable to CdsA single RNAi (Figure S3). Together, these results suggest that the elevated conversion of DAG to PE mediated by the choline/ethanolamine phosphotransferase Bbc may contribute to fat cell growth in CdsA RNAi larvae.

Discussion

The regulation of cell growth in terms of both cell size and cell number has been studied intensively, and is known to involve many key core signaling pathways such as the insulin pathway, the Hippo pathway, and the mTOR pathway, as well as cross-talk between these pathways [5], [7], [37]. The downstream targets that execute and coordinate various specific aspects of cell growth are just starting to be elucidated. In this study we have revealed the intrinsic connections between CDP-diacylglycerol synthetase, PI metabolism, and insulin pathway activity in coordinating cell growth and neutral lipid storage.

Lipid storage is a basic function of a cell. Within an organ, glycerol and fatty acyl-CoA is the precursor of all phospholipids, which are mainly utilized within the cell, and glycerolipids, which are largely destined for neutral lipid storage. Therefore, under normal developmental conditions when resources are not unlimited, a balance must be achieved between cell growth and storage (fast growth and less storage, or slow growth and increased storage). Moreover, at the systematic level, the tissue specificity of insulin action and the lipid flow between different tissues make this balance more complicated [38]. For non-adipose tissues, fast cell growth and low levels of storage are beneficial for maximizing growth potential. However, the balance encounters a problem in adipose tissue because both growth and storage are required. Several predictions can be made here. First, the key enzymes that act at the branch points of phospholipid and TAG synthesis are good candidates for controlling the balance between growth and storage. Second, the factors that control the difference in balance regulation between adipose tissue and non-adipose tissue likely sit after the regulatory points. Alternatively, adipose tissue may have two developmental phases, a growing phase and a fat storage phase. The timing of the switch between these two phases would determine the final size and storage capacity of adipose tissue. Third, excess nutrients may saturate the balance mechanism, leading to overload in both directions. Indeed, our results depict a scenario in which CDP-diacylglycerol synthetase coordinates cell growth and fat storage by partitioning the flow of fatty acyl-CoA between PI synthesis and TAG synthesis. Moreover, our results reveal different contributions of de novo-synthesized PI and PI derived from external sources to the growth of fat cells and salivary gland cells. De novo-synthesized PI contributes most to the growth of salivary gland cells, while fat body cell growth is mainly stimulated by externally-derived PI (Figure 6H). Therefore, the role of CdsA in fat cell growth is only revealed under conditions in which growth is mildly compromised. Besides that, an external supply of DAG, most likely from the intestine, may bypass the CdsA-gated coordination, allowing adipose tissue (fat body) cells to both grow large and store fat (Figure 6H). Consistent with this, it was previously reported that intestine-derived lipids, including DAG, are mainly transported to the fat body via lipoproteins, while relatively low levels of lipids are transported to non-adipose tissues either directly from the intestine or indirectly via the fat body [25], [39].

By responding to environmental and nutritional cues, the insulin pathway regulates cell growth [5], [9]. Through genetic analyses, GFP reporter assays, and lipidomics, we have presented evidence for a positive feedback loop between the insulin pathway and CdsA levels (Figure 4G). In this loop, lowering insulin pathway activity reduces CdsA transcription, leading to less PI production, which further decreases insulin pathway activity. There are numerous previous findings of FOXO as a transcriptional activator [20], [33], [40], but dFOXO appears to be a repressor of CdsA transcription. Microarray and ChIP studies have identified many other targets of FOXO repression [41]. At this point, we do not know whether dFOXO represses CdsA directly or indirectly. The widespread cell growth and fat storage phenotype caused by CdsA RNAi suggests that the insulin pathway-CdsA feedback loop operates widely in various tissues. In addition, it shows that the fat storage capacity of most non-adipose tissues is enormous.

The insulin pathway-CdsA feedback regulation allows cells to take full advantage of the environmental conditions to grow fast and stop growth quickly when necessary. For example, in a nutrient-rich environment, animals that can grow quickly have a tremendous competitive advantage over slow-growing ones. In nutrient-poor conditions, the ability to quickly convert growth to fat storage is beneficial for animals to survive through harsh times. This is not the first time that feedback regulation of the insulin pathway has been reported [33], suggesting that it might be a common mechanism to augment pathway sensitivity and ensure a rapid response to changes in nutrient conditions. Regulation of the insulin pathway by lipids is already known to occur at the points of PIP to PIP2 and PIP2 to PIP3 conversion. Compared to regulation by PI3K and PTEN, CdsA provides a new layer of control at the level of available lipids. Together with other pathways regulated by available nutrients/small molecules, such as the mTOR pathway, which responds to amino acid levels, and the AMPK pathway, which responds to ATP levels [42], [43], this new regulatory mechanism helps cells to cope with diverse environmental changes.

The insulin-CdsA feedback loop is important during cell development. When cells reach the homeostasis phase, the growth-favored loop must be switched towards fat storage. In the future, it will be interesting to determine what triggers the switch. In addition, the existence of the positive feedback loop suggests that excess nutrients will overload the fatty acyl-CoA partitioning mechanism and disrupt the balance. Therefore, impairing the insulin-CdsA feedback loop by genetic mutations or environmental conditions may cause an imbalance in fat storage, resulting in metabolic diseases such as obesity and related disorders. Re-establishing the feedback loop could be a way of treating these disorders.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila stocks and husbandry

Drosophila stocks were maintained in standard cornmeal food. w1118 was used as wild type. All RNAi stocks were obtained from the VDRC or NIG RNAi stock centers. ppl-Gal4 was generously provided by Dr. Pierre Leopold. The expression pattern of ppl-Gal4 was confirmed with UAS-GFP. Other stocks used were: tub-Gal4, y1 w67c23; P{EPgy2}CdsAEY08412, y1 w67c23; P{GSV3}GS8005/TM3 Sb1 Ser1, y1 w*; P{w[+mC] = Dp110[D954A]}2, y1 w1118; P{w[+mC] = UAS-Akt1.Exel}2, P{w[+mC] = Dp110-CAAX}1, dFOXO21, dFOXO25, w1118; P{w[+mC] = tGPH}2; Sb1/TM3 Ser1, Pis1/FM7a; P{w[+mC] = hs-Pis.MYC}3/TM2, w*; Df(3R)Pi3K92E[A] H[A] Pi3K92E[A], P{ry[+7.2] = HBS}3/TM6B Tb1, ry506 P{ry[+t7.2] = PZ}Akt1[04226]/TM3 ryRK Sb1 Ser1, P{w[+mC] = Ubi-mRFP.nls}1, w* P{ry[+t7.2] = hsFLP}122 P{ry[+t7.2] = neoFRT}19A, hsflp122;sp/Cyo;FRT2A histone:GFP/TM6B, ry506 P{HZ}CdsA1.

RNAi screen and genetic analysis

ppl-Gal4 virgin females were crossed to males harboring UAS-RNAi inserts to knock down target gene expression in the larval salivary gland. Wandering 3rd instar larvae harboring both the Gal4 and the UAS-RNAi transgene were dissected and mounted on glass slides with PBS. For visualization, specimens were examined with a Zeiss DIC microscope. For GAL4/UAS experiments, flies were grown at 29°C to allow for maximal GAL4 activity. For tissue or clonal analysis, unless stated otherwise, all larvae were dissected at the wandering 3rd instar stage. Salivary gland clones were generated by heat shock at 37°C for 1 hr immediately after collection of eggs for 4 hr. Fat body clones were induced 8 hr after egg laying for 1 hr at 37°C.

Staining and microscopy

After crossing ppl-Gal4 with RNAi lines, wandering 3rd instar larval progeny were dissected and stained with Nile red or Bodipy, which are fluorescent dyes that specifically mark neutral lipids. For lipid droplet staining, larvae were dissected in PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. Tissues were then rinsed twice with PBS, incubated for 30 min in a 1∶2500 dilution with PBS of 0.5 mg/ml Nile red (Sigma), and then rinsed twice with distilled water. Stained samples were mounted in 80% glycerol for photo-taking. For β-galactosidase staining, dissected tissues were fixed for 2 min in 0.5% glutaraldehyde on ice. The tissues were washed three times for 10 min each in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBT) and then placed in X-gal staining solution (0.2% X-gal, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM K4[Fe(CN)6], 5 mM K3[Fe(CN)6]) overnight at 37°C. All images were taken using a Nikon confocal scope or Zeiss fluorescent scope. Quantification of mutant clone areas was performed by calculating the size of the area occupied by mutant clones versus wild-type cells. Quantification of the size of whole salivary gland, brain, and wing disc or the size of fat body cells was performed by measuring the area occupied by these organs/cells. To quantify lipid storage in salivary glands, the Nile red positive areas of salivary glands per genotype were measured and normalized to the whole cell area as previously described [25]. The average lipid storage in salivary glands of CdsA RNAi was set as 1. For tGPH signal quantification, membrane-to-cytoplasmic GFP ratios were calculated from measurements of mean pixel intensities within equal areas of membrane versus cytoplasm. All measurements were done using Nikon Br analysis software.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. To quantify CdsA transcript levels in tub>CdsA RNAi and tub/+ controls, three groups of 5 larvae per genotype were collected at the wandering 3rd instar larval stage. To quantify CdsA transcript levels in different tissues such as salivary gland, fat body, brain, and gut, three groups of 30 tissues per genotype were dissected and collected from wandering 3rd instar larvae. To quantify CdsA transcript levels in larval salivary gland with loss of function or overexpression of insulin pathway components, salivary glands were dissected and collected in three groups of 50 pairs per genotype from wandering 3rd instar larvae. For each sample, 3 µg total RNA was used to synthesize single-stranded cDNA using a SuperScript II reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) experiments (Agilent Stratagene Mx3000P system, SYBR Green PCR mix) were performed using specific primer pairs (5′ GCAATGATGTCATGGCGTAC 3′ and 5′ AAATCCAGAGGCAAAGAAGC 3′). The level of each transcript was normalized to rp49 in the same sample. All qRT-PCR experiments were repeated at least three times.

Western blot and quantification

Whole larva, salivary gland, and fat body extracts were prepared by dissecting wandering 3rd instar larvae in groups of 6, 120, and 30 larvae/tissues respectively. Extracts were lysed by homogenizing equal masses of control or RNAi larval tissues on ice in 200 µl of ice-cold 1% SDS lysis buffer (1% SDS, 40 mM Tris-Cl PH7.45, 1 mM PMSF, 1 tablet Protease inhibitor, PH7-8). For western blotting, 30 µg of protein sample were loaded, blotted, and detected with the following antibodies: rabbit anti-Akt (Cell Signaling, diluted at 1∶1000), rabbit anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) (Cell Signaling, diluted at 1∶1000), and rabbit anti-α-tubulin (Abcam, diluted at 1∶4000). Quantification of band intensities was done using Image J (National Institutes of Health) software.

PIP3 ELISA assay

The extraction and measurement of PIP3 were performed using the PIP3 Mass ELISA Kit (Echelon), according to the manufacturer's instructions. For extraction of PIP3, four groups of 20 larvae per genotype were collected at the wandering 3rd instar larval stage. The level of PIP3 was normalized to larval dry mass in each group. The PIP3 ELISA assay was repeated four times.

Lipid analysis and quantification of total glycerides

Lipids were extracted from salivary glands of 50 larvae, fat bodies of 50 larvae, 12 whole larvae or 6 fat body-removed larvae carcass (three sets of samples per genotype). An Agilent high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) 1260 system coupled with an Applied Biosystem Triple Quadrupole/Ion Trap mass spectrometer (4500Qtrap) was used to quantify individual lipids. Polar lipids were analyzed using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) scans [44]. Separation of individual polar lipids was carried out using a Phenomenex Luna 3u silica column (i.d. 150×2.0 mm). Individual lipid species were quantified by referencing to spiked internal standards. PC-14 : 0/14 : 0, PE-14 : 0/14 : 0, PS-34 : 1/d31, PA-17 : 0/17 : 0, PG-14 : 0/14 : 0 and PI-34 : 1/d31 were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids. Neutral lipids were analyzed using a sensitive HPLC/ESI/MS method modified from a previous method [45]. DAGs were quantified using 4ME 16∶0 Diether DG (Avanti) as an internal standard. Quantitative analysis of PIP2 was carried out as described [46] using a Dionex Ion Chromatography 5000 system. Lipid extracts were deacylated by incubation with 0.5 ml of methylamine reagent [MeOH/40% methylamine in water/1-butanol/water (47∶36∶9∶8)] at 50°C for 45 min. The aqueous phase was dried, resuspended in 0.5 ml of 1-butanol/petroleum ether/ethyl formate (20∶40∶1), and extracted twice with an equal volume of water. Aqueous extracts were dried, resuspended in water, and subjected to anion-exchange HPLC on an Ionpac AS11-HC column. Lipid levels were calculated using deacylated anionic phospholipids as standards.

Total body glycerides were measured by homogenizing six groups of 5 male larvae per genotype in 100 µl PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST). The homogenate was immediately heat-treated at 70°C for 10 min. Then, 20 µl samples were incubated with 200 µl Triglyceride Reagent (Triglycerides Kit, ZhongShengBeiKong) for 10 min at 37°C and the absorbance at 540 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer. The total protein content of the same samples was measured by Bradford assay (Sigma). Glyceride levels were normalized to total protein amounts in each sample.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. ColemanRA, LewinTM, MuoioDM (2000) Physiological and nutritional regulation of enzymes of triacylglycerol synthesis. Annu Rev Nutr 20 : 77–103.

2. JiaK, ChenD, RiddleDL (2004) The TOR pathway interacts with the insulin signaling pathway to regulate C. elegans larval development, metabolism and life span. Development 131 : 3897–3906.

3. BohniR, Riesgo-EscovarJ, OldhamS, BrogioloW, StockerH, et al. (1999) Autonomous control of cell and organ size by CHICO, a Drosophila homolog of vertebrate IRS1-4. Cell 97 : 865–875.

4. SamuelVT, ShulmanGI (2012) Mechanisms for insulin resistance: common threads and missing links. Cell 148 : 852–871.

5. HietakangasV, CohenSM (2009) Regulation of tissue growth through nutrient sensing. Annu Rev Genet 43 : 389–410.

6. GeminardC, RulifsonEJ, LeopoldP (2009) Remote control of insulin secretion by fat cells in Drosophila. Cell Metab 10 : 199–207.

7. EdgarBA (2006) How flies get their size: genetics meets physiology. Nat Rev Genet 7 : 907–916.

8. Sousa-NunesR, YeeLL, GouldAP (2011) Fat cells reactivate quiescent neuroblasts via TOR and glial insulin relays in Drosophila. Nature 471 : 508–512.

9. TelemanAA (2010) Molecular mechanisms of metabolic regulation by insulin in Drosophila. Biochem J 425 : 13–26.

10. BrittonJS, LockwoodWK, LiL, CohenSM, EdgarBA (2002) Drosophila's insulin/PI3-kinase pathway coordinates cellular metabolism with nutritional conditions. Dev Cell 2 : 239–249.

11. GoberdhanDC, ParicioN, GoodmanEC, MlodzikM, WilsonC (1999) Drosophila tumor suppressor PTEN controls cell size and number by antagonizing the Chico/PI3-kinase signaling pathway. Genes Dev 13 : 3244–3258.

12. GuptaA, ToscanoS, TrivediD, JonesDR, MathreS, et al. (2013) Phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase (PIP4K) regulates TOR signaling and cell growth during Drosophila development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 : 5963–5968.

13. VargheseJ, LimSF, CohenSM (2010) Drosophila miR-14 regulates insulin production and metabolism through its target, sugarbabe. Genes Dev 24 : 2748–2753.

14. RajanA, PerrimonN (2012) Drosophila cytokine unpaired 2 regulates physiological homeostasis by remotely controlling insulin secretion. Cell 151 : 123–137.

15. OkamotoN, NakamoriR, MuraiT, YamauchiY, MasudaA, et al. (2013) A secreted decoy of InR antagonizes insulin/IGF signaling to restrict body growth in Drosophila. Genes Dev 27 : 87–97.

16. HyunS, LeeJH, JinH, NamJ, NamkoongB, et al. (2009) Conserved MicroRNA miR-8/miR-200 and its target USH/FOG2 control growth by regulating PI3K. Cell 139 : 1096–1108.

17. SaltielAR, KahnCR (2001) Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature 414 : 799–806.

18. WongRH, SulHS (2010) Insulin signaling in fatty acid and fat synthesis: a transcriptional perspective. Curr Opin Pharmacol 10 : 684–691.

19. LaplanteM, SabatiniDM (2009) An emerging role of mTOR in lipid biosynthesis. Curr Biol 19: R1046–1052.

20. XuX, GopalacharyuluP, Seppanen-LaaksoT, RuskeepaaAL, AyeCC, et al. (2012) Insulin signaling regulates fatty acid catabolism at the level of CoA activation. PLoS Genet 8: e1002478.

21. BakerKD, ThummelCS (2007) Diabetic larvae and obese flies-emerging studies of metabolism in Drosophila. Cell Metab 6 : 257–266.

22. LeopoldP, PerrimonN (2007) Drosophila and the genetics of the internal milieu. Nature 450 : 186–188.

23. KuhnleinRP (2011) The contribution of the Drosophila model to lipid droplet research. Prog Lipid Res 50(4): 348–56.

24. BiJ, XiangY, ChenH, LiuZ, GronkeS, et al. (2012) Opposite and redundant roles of the two Drosophila perilipins in lipid mobilization. J Cell Sci 125 : 3568–3577.

25. PalmW, SampaioJL, BrankatschkM, CarvalhoM, MahmoudA, et al. (2012) Lipoproteins in Drosophila melanogaster–assembly, function, and influence on tissue lipid composition. PLoS Genet 8: e1002828.

26. FeiW, ShuiG, GaetaB, DuX, KuerschnerL, et al. (2008) Fld1p, a functional homologue of human seipin, regulates the size of lipid droplets in yeast. J Cell Biol 180 : 473–482.

27. FeiW, ShuiG, ZhangY, KrahmerN, FergusonC, et al. (2011) A role for phosphatidic acid in the formation of “supersized” lipid droplets. PLoS Genet 7: e1002201.

28. TianY, BiJ, ShuiG, LiuZ, XiangY, et al. (2011) Tissue-autonomous function of Drosophila seipin in preventing ectopic lipid droplet formation. PLoS Genet 7: e1001364.

29. ZhuAJ, ZhengL, SuyamaK, ScottMP (2003) Altered localization of Drosophila Smoothened protein activates Hedgehog signal transduction. Genes Dev 17 : 1240–1252.

30. WuL, NiemeyerB, ColleyN, SocolichM, ZukerCS (1995) Regulation of PLC-mediated signalling in vivo by CDP-diacylglycerol synthase. Nature 373 : 216–222.

31. WangT, MontellC (2006) A phosphoinositide synthase required for a sustained light response. Journal of Neuroscience 26 : 12816–12825.

32. ChengLY, BaileyAP, LeeversSJ, RaganTJ, DriscollPC, et al. (2011) Anaplastic lymphoma kinase spares organ growth during nutrient restriction in Drosophila. Cell 146 : 435–447.

33. PuigO, MarrMT, RuhfML, TjianR (2003) Control of cell number by Drosophila FOXO: downstream and feedback regulation of the insulin receptor pathway. Genes Dev 17 : 2006–2020.

34. WerzC, KohlerK, HafenE, StockerH (2009) The Drosophila SH2B family adaptor Lnk acts in parallel to chico in the insulin signaling pathway. PLoS Genet 5: e1000596.

35. LiH, WangX, LiN, QiuJ, ZhangY, et al. (2007) hPEBP4 resists TRAIL-induced apoptosis of human prostate cancer cells by activating Akt and deactivating ERK1/2 pathways. J Biol Chem 282 : 4943–4950.

36. LimHY, WangW, WessellsRJ, OcorrK, BodmerR (2011) Phospholipid homeostasis regulates lipid metabolism and cardiac function through SREBP signaling in Drosophila. Genes Dev 25 : 189–200.

37. CsibiA, BlenisJ (2012) Hippo-YAP and mTOR pathways collaborate to regulate organ size. Nat Cell Biol 14 : 1244–1245.

38. ChoH, MuJ, KimJK, ThorvaldsenJL, ChuQ, et al. (2001) Insulin resistance and a diabetes mellitus-like syndrome in mice lacking the protein kinase Akt2 (PKB beta). Science 292 : 1728–1731.

39. CarvalhoM, SampaioJL, PalmW, BrankatschkM, EatonS, et al. (2012) Effects of diet and development on the Drosophila lipidome. Mol Syst Biol 8 : 600.

40. TelemanAA, ChenYW, CohenSM (2005) 4E-BP functions as a metabolic brake used under stress conditions but not during normal growth. Genes Dev 19 : 1844–1848.

41. TelemanAA, HietakangasV, SayadianAC, CohenSM (2008) Nutritional control of protein biosynthetic capacity by insulin via Myc in Drosophila. Cell Metab 7 : 21–32.

42. HardieDG, RossFA, HawleySA (2012) AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13 : 251–262.

43. LaplanteM, SabatiniDM (2012) mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149 : 274–293.

44. ShuiG, StebbinsJW, LamBD, CheongWF, LamSM, et al. (2011) Comparative plasma lipidome between human and cynomolgus monkey: are plasma polar lipids good biomarkers for diabetic monkeys? PLoS One 6: e19731.

45. ShuiG, GuanXL, LowCP, ChuaGH, GohJS, et al. (2010) Toward one step analysis of cellular lipidomes using liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry: application to Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe lipidomics. Mol Biosyst 6 : 1008–1017.

46. NasuhogluC, FengS, MaoJ, YamamotoM, YinHL, et al. (2002) Nonradioactive analysis of phosphatidylinositides and other anionic phospholipids by anion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography with suppressed conductivity detection. Anal Biochem 301 : 243–254.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Sex Chromosome Turnover Contributes to Genomic Divergence between Incipient Stickleback SpeciesČlánek Final Pre-40S Maturation Depends on the Functional Integrity of the 60S Subunit Ribosomal Protein L3

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 3- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

- Délka menstruačního cyklu jako marker ženské plodnosti

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- , a Gene That Influences the Anterior Chamber Depth, Is Associated with Primary Angle Closure Glaucoma

- Genomic View of Bipolar Disorder Revealed by Whole Genome Sequencing in a Genetic Isolate

- The Rate of Nonallelic Homologous Recombination in Males Is Highly Variable, Correlated between Monozygotic Twins and Independent of Age

- Genetic Determinants Influencing Human Serum Metabolome among African Americans

- Heterozygous and Inherited Mutations in the Smooth Muscle Actin () Gene Underlie Megacystis-Microcolon-Intestinal Hypoperistalsis Syndrome

- Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis of Homocysteine and Methionine Metabolism Identifies Five One Carbon Metabolism Loci and a Novel Association of with Ischemic Stroke

- Cancer Evolution Is Associated with Pervasive Positive Selection on Globally Expressed Genes

- Genetic Diversity in the Interference Selection Limit

- Integrating Multiple Genomic Data to Predict Disease-Causing Nonsynonymous Single Nucleotide Variants in Exome Sequencing Studies

- An Evolutionary Analysis of Antigen Processing and Presentation across Different Timescales Reveals Pervasive Selection

- Cleavage Factor I Links Transcription Termination to DNA Damage Response and Genome Integrity Maintenance in

- DNA Dynamics during Early Double-Strand Break Processing Revealed by Non-Intrusive Imaging of Living Cells

- Genetic Basis of Metabolome Variation in Yeast

- Modeling 3D Facial Shape from DNA

- Dysregulated Estrogen Receptor Signaling in the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian Axis Leads to Ovarian Epithelial Tumorigenesis in Mice

- Photoactivated UVR8-COP1 Module Determines Photomorphogenic UV-B Signaling Output in

- Local Evolution of Seed Flotation in Arabidopsis

- Chromatin Targeting Signals, Nucleosome Positioning Mechanism and Non-Coding RNA-Mediated Regulation of the Chromatin Remodeling Complex NoRC

- Nucleosome Acidic Patch Promotes RNF168- and RING1B/BMI1-Dependent H2AX and H2A Ubiquitination and DNA Damage Signaling

- The -Induced Arabidopsis Transcription Factor Attenuates ABA Signaling and Renders Seedlings Sugar Insensitive when Present in the Nucleus

- Changes in Colorectal Carcinoma Genomes under Anti-EGFR Therapy Identified by Whole-Genome Plasma DNA Sequencing

- Selection of Orphan Rhs Toxin Expression in Evolved Serovar Typhimurium

- FAK Acts as a Suppressor of RTK-MAP Kinase Signalling in Epithelia and Human Cancer Cells

- Asymmetry in Family History Implicates Nonstandard Genetic Mechanisms: Application to the Genetics of Breast Cancer

- Co-translational Localization of an LTR-Retrotransposon RNA to the Endoplasmic Reticulum Nucleates Virus-Like Particle Assembly Sites

- Sex Chromosome Turnover Contributes to Genomic Divergence between Incipient Stickleback Species

- DWARF TILLER1, a WUSCHEL-Related Homeobox Transcription Factor, Is Required for Tiller Growth in Rice

- Functional Organization of a Multimodular Bacterial Chemosensory Apparatus

- Genome-Wide Analysis of SREBP1 Activity around the Clock Reveals Its Combined Dependency on Nutrient and Circadian Signals

- The Yeast Sks1p Kinase Signaling Network Regulates Pseudohyphal Growth and Glucose Response

- An Interspecific Fungal Hybrid Reveals Cross-Kingdom Rules for Allopolyploid Gene Expression Patterns

- Temperate Phages Acquire DNA from Defective Prophages by Relaxed Homologous Recombination: The Role of Rad52-Like Recombinases

- Dying Cells Protect Survivors from Radiation-Induced Cell Death in

- Determinants beyond Both Complementarity and Cleavage Govern MicroR159 Efficacy in

- The bHLH Factors Extramacrochaetae and Daughterless Control Cell Cycle in Imaginal Discs through the Transcriptional Regulation of the Phosphatase

- The First Steps of Adaptation of to the Gut Are Dominated by Soft Sweeps

- Bacterial Regulon Evolution: Distinct Responses and Roles for the Identical OmpR Proteins of Typhimurium and in the Acid Stress Response

- Final Pre-40S Maturation Depends on the Functional Integrity of the 60S Subunit Ribosomal Protein L3

- Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Pathway Regulates Branching by Remodeling Epithelial Cell Adhesion

- CDP-Diacylglycerol Synthetase Coordinates Cell Growth and Fat Storage through Phosphatidylinositol Metabolism and the Insulin Pathway

- Coronary Heart Disease-Associated Variation in Disrupts a miR-224 Binding Site and miRNA-Mediated Regulation

- TBX3 Regulates Splicing : A Novel Molecular Mechanism for Ulnar-Mammary Syndrome

- Identification of Interphase Functions for the NIMA Kinase Involving Microtubules and the ESCRT Pathway

- Is a Cancer-Specific Fusion Gene Recurrent in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma

- LILRB2 Interaction with HLA Class I Correlates with Control of HIV-1 Infection

- Worldwide Patterns of Ancestry, Divergence, and Admixture in Domesticated Cattle

- Parent-of-Origin Effects Implicate Epigenetic Regulation of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis and Identify Imprinted as a Novel Risk Gene

- The Phospholipid Flippase dATP8B Is Required for Odorant Receptor Function

- Noise Genetics: Inferring Protein Function by Correlating Phenotype with Protein Levels and Localization in Individual Human Cells

- DUF1220 Dosage Is Linearly Associated with Increasing Severity of the Three Primary Symptoms of Autism

- Sugar and Chromosome Stability: Clastogenic Effects of Sugars in Vitamin B6-Deficient Cells

- Pheromone-Sensing Neurons Expressing the Ion Channel Subunit Stimulate Male Courtship and Female Receptivity

- Gene-Based Sequencing Identifies Lipid-Influencing Variants with Ethnicity-Specific Effects in African Americans

- Telomere Shortening Unrelated to Smoking, Body Weight, Physical Activity, and Alcohol Intake: 4,576 General Population Individuals with Repeat Measurements 10 Years Apart

- A Combination of Activation and Repression by a Colinear Hox Code Controls Forelimb-Restricted Expression of and Reveals Hox Protein Specificity

- An ER Complex of ODR-4 and ODR-8/Ufm1 Specific Protease 2 Promotes GPCR Maturation by a Ufm1-Independent Mechanism

- Epigenetic Control of Effector Gene Expression in the Plant Pathogenic Fungus

- Genetic Dissection of Photoreceptor Subtype Specification by the Zinc Finger Proteins Elbow and No ocelli

- Validation and Genotyping of Multiple Human Polymorphic Inversions Mediated by Inverted Repeats Reveals a High Degree of Recurrence

- CYP6 P450 Enzymes and Duplication Produce Extreme and Multiple Insecticide Resistance in the Malaria Mosquito

- GC-Rich DNA Elements Enable Replication Origin Activity in the Methylotrophic Yeast

- An Epigenetic Signature in Peripheral Blood Associated with the Haplotype on 17q21.31, a Risk Factor for Neurodegenerative Tauopathy

- Lsd1 Restricts the Number of Germline Stem Cells by Regulating Multiple Targets in Escort Cells

- RBPJ, the Major Transcriptional Effector of Notch Signaling, Remains Associated with Chromatin throughout Mitosis, Suggesting a Role in Mitotic Bookmarking

- The Membrane-Associated Transcription Factor NAC089 Controls ER-Stress-Induced Programmed Cell Death in Plants

- The Functional Consequences of Variation in Transcription Factor Binding

- Comparative Genomic Analysis of N-Fixing and Non-N-Fixing spp.: Organization, Evolution and Expression of the Nitrogen Fixation Genes

- An Insulin-to-Insulin Regulatory Network Orchestrates Phenotypic Specificity in Development and Physiology

- Suicidal Autointegration of and Transposons in Eukaryotic Cells

- A Multi-Trait, Meta-analysis for Detecting Pleiotropic Polymorphisms for Stature, Fatness and Reproduction in Beef Cattle

- Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis Predicts an Epigenetic Switch for GATA Factor Expression in Endometriosis

- Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis of Human Pancreatic Islets from Type 2 Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Donors Identifies Candidate Genes That Influence Insulin Secretion

- The and Hybrid Incompatibility Genes Suppress a Broad Range of Heterochromatic Repeats

- The Kil Peptide of Bacteriophage λ Blocks Cytokinesis via ZipA-Dependent Inhibition of FtsZ Assembly

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Worldwide Patterns of Ancestry, Divergence, and Admixture in Domesticated Cattle

- Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis of Human Pancreatic Islets from Type 2 Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Donors Identifies Candidate Genes That Influence Insulin Secretion

- Genetic Dissection of Photoreceptor Subtype Specification by the Zinc Finger Proteins Elbow and No ocelli

- GC-Rich DNA Elements Enable Replication Origin Activity in the Methylotrophic Yeast

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání