-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

BMP-FGF Signaling Axis Mediates Wnt-Induced Epidermal Stratification in Developing Mammalian Skin

Epidermis, a thin layer of stratified epithelium forming the outmost surface of the skin, provides the crucial function to protect animals from environmental insults, such as bacterial pathogens and water loss. This barrier function is established in embryogenesis, during which single layered epithelial cells differentiate into distinct layers of keratinocytes. Many human genetic diseases are featured with epidermal disruption, affecting at least one in five patients. Skin regeneration and future therapeutics require a thorough understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying epidermal stratification. Wnt ligands have been implicated in hair follicle induction during skin development and self-renewal of stem cells in the interfollicular epidermis of adult skin; however, little is known about the mechanism of how Wnt signaling controls epidermal stratification during embryogenesis. In this study, by using a genetic mouse model to disrupt Wnt production in skin development, we found that signaling of epidermal Wnt in the dermis initiate mesenchymal responses by activating a Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) and Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling cascade, and this activation is required for feedback regulations in the embryonic epidermis to control stratification. Our findings identify a genetic hierarchy of signaling essential for epidermal-mesenchymal interactions, and promote our understanding of mammalian skin development.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004687

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004687Summary

Epidermis, a thin layer of stratified epithelium forming the outmost surface of the skin, provides the crucial function to protect animals from environmental insults, such as bacterial pathogens and water loss. This barrier function is established in embryogenesis, during which single layered epithelial cells differentiate into distinct layers of keratinocytes. Many human genetic diseases are featured with epidermal disruption, affecting at least one in five patients. Skin regeneration and future therapeutics require a thorough understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying epidermal stratification. Wnt ligands have been implicated in hair follicle induction during skin development and self-renewal of stem cells in the interfollicular epidermis of adult skin; however, little is known about the mechanism of how Wnt signaling controls epidermal stratification during embryogenesis. In this study, by using a genetic mouse model to disrupt Wnt production in skin development, we found that signaling of epidermal Wnt in the dermis initiate mesenchymal responses by activating a Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) and Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling cascade, and this activation is required for feedback regulations in the embryonic epidermis to control stratification. Our findings identify a genetic hierarchy of signaling essential for epidermal-mesenchymal interactions, and promote our understanding of mammalian skin development.

Introduction

Vertebrate epidermis, the outermost layer of skin, functions as a barrier for protection against environmental insult and dehydration. At approximately embryonic day 8.5 (E8.5) during mouse embryogenesis, the single-layered surface ectoderm adopts an epidermal developmental fate by turning off the expression of keratins 8 and 18 (K8/K18) and switching on the expression of K5/K14, leading to the replacement of the unspecified ectoderm by the embryonic basal layer [1], [2]. Subsequently, the change of cell proliferation from symmetric to asymmetric division becomes evident at E12.5 to 14.5 [3]. The proliferative basal layer periodically produces intermediate suprabasal cells positive for K1/K10, programmed for terminal differentiation of keratinocytes [2]. The transient intermediate keratinocytes then exit the cell cycle, followed by detachment from the basal layer and migration outward to form the spinous layer, characterized by the expression of K1 and K10. Subsequent developmental events engage the expression of differentiation genes, including loricrin and filaggrin, as spinous keratinocytes further develop into the granular and cornified layers contributing to barrier establishment at late embryonic stages ([2].

The tumor-suppressor p53-related transcription factor, p63, encodes regulators required for initiating epithelial stratification during development and maintaining proliferative potential of the basal layer keratinocytes [4], [5], [6], [7]. Two different classes of protein are encoded by p63: the first contains the amino terminal transactivation domain (TA isoforms) and the second lacks this domain (ΔN isoforms) [8]. ΔNp63 is expressed predominantly in the basal layer keratinocytes but its expression is down-regulated in the post-mitotic suprabasal keratinocytes, suggesting that p63 plays a crucial role in proliferative capacity of the epidermal progenitors [9], [10].

Several families of secreted signaling molecules, including bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), Hedgehog (Hh), and Wnt, have been implicated in embryonic epidermal morphogenesis. Among them, Wnt appears to be the earliest signal known to promote epidermal development [11], [12], [13]. Our previous studies have demonstrated that embryonic epidermis is the source of Wnts essential for establishing and orchestrating signaling communication between the epidermis and the dermis in hair follicle initiation [14]. Overexpression of Dkk1, a Wnt antagonist, in the epidermis also results in the absence of hair follicles [11], whereas expression of a constitutively active form of β-catenin in the epithelium leads to premature development of the hair follicle placode [15]. In chicks, high levels of Wnt are able to activate BMP signaling through repression of FGF signaling, leading to a switch of neural cell fate into epidermal cell fate [16], [17]. In addition, BMP signals have also been suggested to control p63 expression during ectodermal development [18]. In an embryonic stem cell (ESC) model recapitulating the stepwise appearance of the epidermal stratification in vitro, BMP4 treatment activates the expression of ΔNp63 isoforms, promoting an induction of the proliferative basal keratinocyte makers, K5 and K14, and a progressive enhancement of the terminal differentiation markers, K1, K10, involucrin and filaggrins [19]. In addition, BMP signals have also been suggested to control p63 expression during ectodermal development. Moreover, BMP signaling is also active in the interfollicular epidermis where it may act as a morphogen by promoting epidermal development through inhibition of the hair follicle fate during skin morphogenesis [1], [11], [20], [21]. It has been suggested that FGF7 (KGF) and FGF10 function in concert via FGFR-2 (IIIb) to stimulate keratinocyte proliferation in the epidermis [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], despite the fact that targeted loss of Fgf7 has no effect on skin development in the mouse [27]. Interestingly, FGF ligands appear to be expressed in the dermis while the receptor is present in the epidermis during skin development [22], [24], [28]. However, how these developmental signals are integrated and interplayed across the epithelium and mesenchyme to control epidermal stratification remains to be elucidated.

In this study, we investigated the genetic regulation of these signaling pathways during epidermal stratification and elucidated the mechanism underlying this developmental process orchestrated by the Wnt, BMP, and FGF signaling pathways. Using a mouse model with epithelial ablation of Gpr177 (also known as Wls/Evi/Srt in Drosophila), a regulator essential for intracellular Wnt trafficking, to disrupt Wnt secretion in skin development [29], [30], [31], [32], we identified a crucial role of Wnt signaling in orchestrating epidermal stratification. We demonstrate that signaling of epidermal Wnt to the dermis initiates mesenchymal responses by activating a BMP-FGF signaling cascade. This activation is required for feedback regulations in the epidermis to control the stratification process. Our findings thus decipher a hierarchy of signaling loop essential for epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in the mammalian skin development.

Results

Epithelial Wnt secretion mediated by Gpr177 is essential for epidermal development

Gpr177 is expressed in the skin of the developing limb bud as early as E11.5 (Figure S1A, B). Similar to our previous observations in dorsal body skin [14], Gpr177 protein can be found predominantly in the epidermis and weakly in the underlying dermis (Figure 1A–C) at E11.5–13.5. To assess the requirement of epidermal Wnts in the development of skin, we generated Gpr177K14 mice in which Gpr177 is inactivated by the K14-Cre transgenic allele to disrupt the secretion of Wnt proteins [32]. Using a R26R reporter line, we examined the Cre-mediated deletion, which occurs only in the epidermis (Figure S1C, D). The loss of Gpr177 was clearly evident in the epidermis but not the dermis of Gpr177K14 (Figure 1A′–C′), indicating a targeted removal of Gpr177 in the mutants. We noted that the Cre recombination is uniformly detected in the limb skin (Figure S1C, D) but not in the dorsal body skin (Figure S1 E, F–G, F′–G′) using the K14-Cre line. Compared to the Gpr177K5 mice that exhibited a uniform expression pattern of Cre and consistent phenotypes associated the Gpr177 deletion described previously [14], the Gpr177K14 mice are not suitable for the study of the body skin due to inconsistent results on skin thickness (Figure S1 F–H, F′–H′). However, the Gpr177K14 model is ideally suited for studies on epidermal development of the limb.

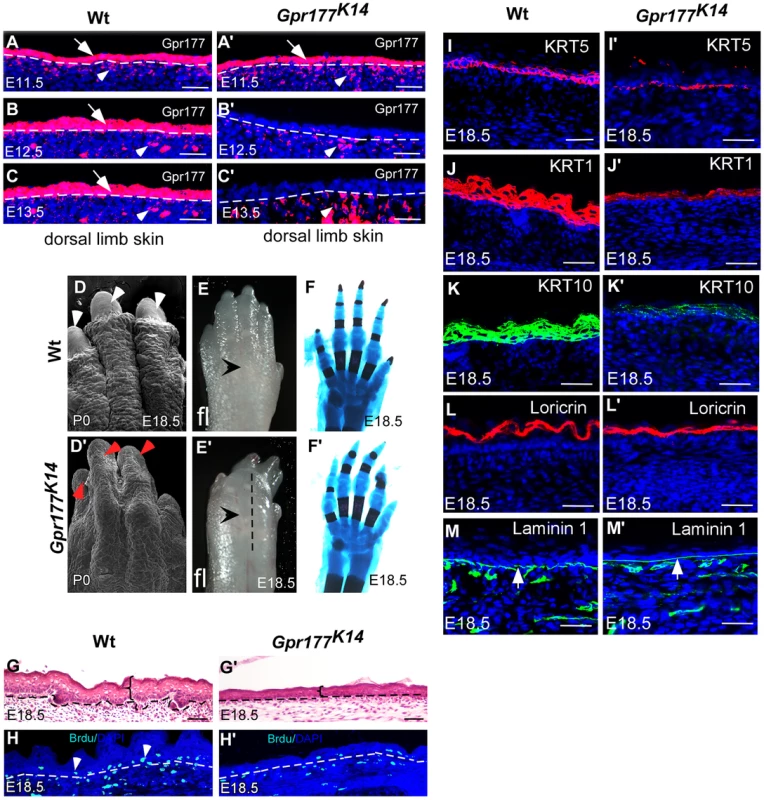

Fig. 1. Deletion of Gpr177 in embryonic epidermis results in skin defects attributing to hypoplastic spinous layer.

(A–C, A′–C′) Immunofluorscence (red) of Gpr177 expression in epidermis (arrows) and underling dermis (arrowheads) in dorsal skin of embryonic limb between E11.5 and E13.5. Note that in Gpr177K14 mutant, K14-Cre deleted Gpr177 specifically in epidermis of limb at E12.5 and E13.5 (B′ and C′). (D–E, D′–E′) Scanning electronic microscopic images show loss of nail and lack of skin wrinkles in the Gpr177K14 limb. Note obvious edematous limb surface in the mutants (E′) as compared to wild type controls (E). (F, F′) Skeletal staining by Alcian blue (blue) and Alizarian Red (red) shows comparable skeletal patterning in the Gpr177K14 and control limbs (C and F). (G, G′) H&E staining shows the hypoplastic limb skin of Gpr177K14 mice at E18.5. (H, H′) BrdU incorporation assay shows the cell proliferation in the Gpr177K14 limb skin. (I–M, I′–M′) Immunohistochemistry shows expression of KRT5 (red) for basal cells, KRT1 (red) and KRT10 (green) for spinous layer, Loricrin for granular layer (red), and laminin 1 (green) for the presence of basal membrane (green). Bars: 50 µm. The Gpr177K14 autopods displayed severe deformities including loss of nail formation (Figure 1D, D′). The interdigital and dorsal soft tissues appeared to be edematous (Figure 1E, E′), but skeletal staining revealed comparable structures between controls and mutants (Figure 1F, F′), suggesting that the dysmorphic features of the Gpr177K14 autopods is likely due to impairments in the skin tissue. Histological analysis of autopods showed a reduction in skin thickness as well as in cell proliferation rate, indicating the ablation of skin stratification in Gpr177K14 (Figure 1G–H′ and Figure S2A, B and E). To further investigate the edematous skin abnormalities, we characterized epidermal stratification of the limb skin using markers specific for basal, spinous, and granular epidermal layers. The deletion of Gpr177 diminished the number of basal cells expressing KRT5 (Figure 1I, I′). Significant reduction of the spinous layer positive for KRT1 and KRT10 was also identified in the longitudinal sections along the dorsal skin of the mutant autopods (Figure 1J–K, J′–K′). However, the granular layer positive for loricrin and the basal membrane protein, laminin 1, did not show significant alterations (Figure 1L–M, L′–M′). The results were consistent with alterations of the limb skin thickness caused by the Cre-mediated deletion of Gpr177 (Figure S2). Besides, an uneven decrease in skin thickness also occurred in the dorsal body of Gpr177K14, as shown by histology (Figure S1H, H′) and immunohistochemistry specific for the spinous and basal layers (Figure S1I–J, I′–J′). TUNEL assay did not reveal significant changes in apoptosis, indicating that defects in the spinous layer were not caused by abnormal cell death (Figure S3). Thus, the spinous hypoplasia is likely attributed to defects in the epithelial vertical expansion of Gpr177K14 mice.

Epidermal deletion of Gpr177 interferes with canonical Wnt signaling in the underlying dermis

The deletion of Gpr177 has been shown to affect Wnt signaling during the development of other organs [14], [32], [33]. This is also true during the morphogenesis of the limb skin, as the the expression of several downstream mediator critical for Wnt signal transduction including Axin2, Dkk1, Fzd1, Lef1, and TCF4 was significantly reduced in the skin of Gpr177K14 autopods (Figure 2A), and the activity of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the mesenchyme underlying the interfollicular epithelium was almost completely eliminated, evidenced by the lack of TopGal reporter activity (Figure 2B–C, B′–C′). In situ hybridization analysis further confirmed that epidermal ablation of Gpr177 affects the expression of Lef1 and Axin2 in both the epithelium and mesenchyme (Figure 2D–G, D′–G′). These observations are consistent with our observations in dorsal body skin (Figure S4A–D, E–F, E′–F′) [14], indicating a requirement of epidermal Wnt for signaling activation in both epidermal and dermal layers. Consistent with this finding, Dermo1-Cre mediated deletion of Gpr177 in the dermis did not alter the skin thickness (Figure S5), suggesting a dispensable role of dermal Wnt in epidermal stratification.

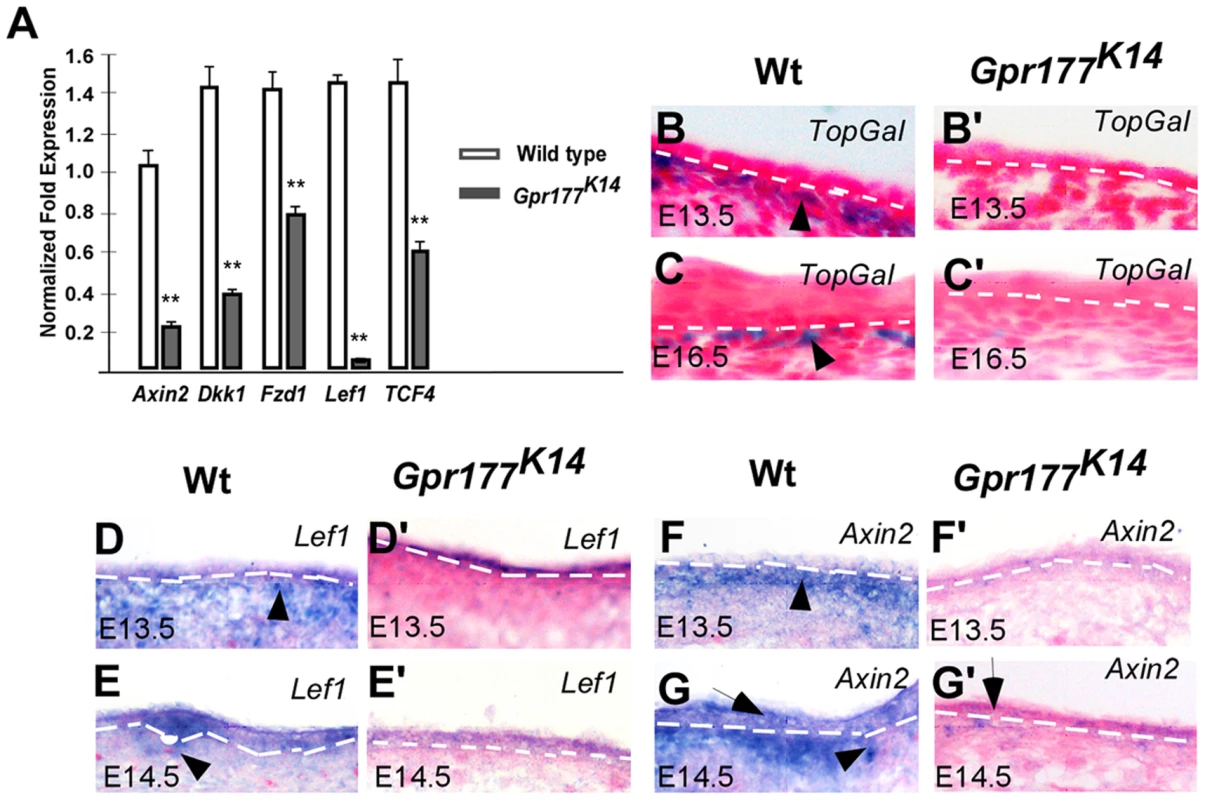

Fig. 2. Deletion of Gpr177 in embryonic epidermis leads to ablation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in dermis.

(A) Quantitative RT-PCR shows a decrease in the expression of Axin2, Dkk1, Fzd1, Lef1, TCF4 in limb skin of mutants at E16.5. **, P<0.01, compared to wild type controls. Data are represented as mean ± SD and are representatives of at least three independent experiments. (B–C, B′–C′) X-Gal staining on sections of dorsal limbs shows lack of TopGal activity in dermal mesenchyme at E13.5 and E16.5 in Gpr177K14, as compared to wild type controls (Wt). (D–G, D′–G′) In situ hybridization on the sections of embryonic limb skin shows the down-regulation of Axin2 and Lef1 in embryonic epidermal stratification of mutants at E13.5 and E14.5. Non-cell autonomous requirement of BMP signaling in Gpr177-mediated epidermal stratification

To decipher the effects of the alteration in Wnt signaling during autopod skin morphogenesis, we performed RNA expression profiling analysis using microarray to identify genes that are differentially expressed in the E15.5 distal limbs (Figure S6 and Table S1 and Table S2). Among those altered genes, members of BMP family were significantly affected in Gpr177K14. In response to β-catenin/Wnt signaling, BMP signaling in the dermal mesenchyme plays critical role in hair follicle induction [14]. Thus, we hypothesized that BMPs are downstream targets of Wnt signaling and regulate epidermal stratification. Real time RT-PCR analysis validated that Bmp2, 4, and 7 expression was decreased in the mutants (Figure 3A). During normal development of the autopod skin, Bmp2 and Bmp7 were found in both the epidermis and dermis while Bmp4 appeared to be exclusively expressed in the dermis (Figure 3B–G). However, epidermal deletion of Gpr177 caused profound reduction of Bmp2, Bmp4, and Bmp7 in the developing skin (Figure 3B′–G′ and Figure S7A–G, A′–G′), suggesting that BMP signaling, regulated by Wnt signaling, is likely to be involved in epidermal stratification.

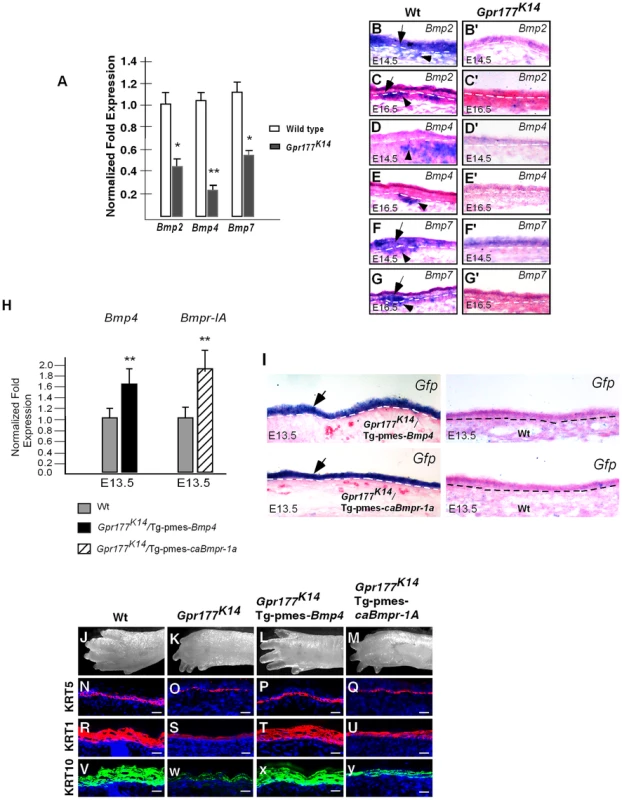

Fig. 3. Expression of Bmps requires epidermal Gpr177 and rescue of defective limbs and epidermal stratification in Gpr177K14 mutants by activation of a transgenic Bmp4 allele.

(A)Real-time PCR shows the down-regulation of Bmps in skin of Gpr177K14 mutants at E16.5. *,P<0.05; **, P<0.01, compared with Wt. Data are represented as mean ±SD and are representatives of at least three independent experiments. (B–G, B′–G′) In situ hybridization reveals the reduced transcripts of Bmp2, Bmp4, and Bmp7 in epidermis (arrows) and dermis (arrowheads) of Gpr177K14 embryonic limb skin at E14.5 and E16.5, as compared to wild type controls. (H) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR indicates that mRNA levels of Bmp4 and Bmp1a in the autopod skin are enhanced in transgenic animals, compared to wild type controls. Data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *, P<0.05, compared with wild type controls. (I) In situ hybridization on Egfp mRNA reveals epidermal-specific expression of transgenes in Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 and Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-caBmpr1a. (J-M) Morphologic defect of autopods in Gpr177K14 mice is partially rescued in Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 mice (J, K, L), but not in Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmpr1a mice (J, K, M). (N–Y) Immunohistochemistry reveals expressions of KRT5 for basal layer (N–Q), KRT1 and KRT10 for spinous keratinocytes (R–Y). Note that the rescued thickness of spinous layer in Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 (T and X) was comparable to wild type controls (R and V), but not in Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmpr-1a mice (U and V). Bars: 10 µm. To test the functional requirement of BMP signaling in the Gpr177-mediated skin morphogenesis, we used a conditional Bmp4 transgenic allele. The Tg-pmes-Bmp4 transgenic mouse was crossed onto the Gpr177K14 background to generate Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 mice. The transgenic Bmp4 expression from this transgenic allele was tightly controlled by a transcription and translation STOP cassette flanked by two loxP sites, permitting the Cre-mediated activation (Figure 3H–I) [34], [35].

The transgenic expression of Bmp4 was able to alleviate the dysmorphic phenotype caused by the deletion of Gpr177 (Figure 3J–L). The Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 autopods displayed five separated digits without skin edema (Figure 3L), suggesting that BMP4 acts downstream of Wnt signaling in skin stratification. To determine if this epidermal expression of transgenic Bmp4 could substitute for mesenchymal Bmp4 to rescue spinous layer defect, we examined the spinous layer of Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 autopods. Immunostaining of KRT5 and KRT1/10 revealed a significant enhancement in their expression (Figure 3N–P, R–T and V–X). Histological (Figure S2 C–F) and ultrastructural analyses (Figure S2 F–H) further showed that the thickness of the spinous layer was obviously increased in the E18.5 Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 epidermis, as compared to that in Gpr177K14 epidermis.

The transgenic expression of Bmp4 in the epidermis (Figure 3H–I) may exert its signaling effects in a cell autonomous or non-cell autonomous manner. For non-cell autonomous signaling, it requires the diffusion of BMP4 through an inter-tissue signal transduction mechanism. It has been shown that BMPR1A is responsible for mediating BMP signaling in epidermal development [20], [36], [37]. If the transgenic Bmp4 indeed acts in a cell autonomous manner, we assumed that activation of BMPR1A-mediated signaling in the epidermis would also alleviate the stratification defects in Gpr177K14 autopods. Accordingly, we compounded a conditional transgenic allele that expresses a constitutively active form of BMPR1A receptor (caBMPR1A) with Gpr177K14 mice (Figure 3H–I) [34]. However, ectopic activation of BMPR1A signaling neither rescued the autopod defects at the morphological (Figure 3M) and histological (Figure S2D) levels nor restored the expression of the basal and spinous layer makers, KRT5 (Figure 3Q), KRT1 (Figure 3U), and KRT10 (Figure 3V), as compared to that in Gpr177K14 mice (Figure 3O, S, W). These results thus suggest a non-cell autonomous BMP signaling across tissue layers to alleviate the epidermal defects of Gpr177K14, and the BMP4 activity in the dermal mesenchyme, but not in the epidermis, is required for proper stratification of the mammalian skin.

The role of Wnt/BMP regulatory axis in the development of suprabasal keratinocytes

Maturation of the spinous layer first requires the mitotic suprabasal intermediate cells to be replaced by the post-mitotic cells [2]. The hypoplasia developed in the Gpr177K14 spinous layer might be attributed to failure in this replacement. To test this possibility, we performed a BrdU labeling experiment to identify the KRT1 positive keratinocytes undergoing active proliferation between E13.5 and 16.5. Double labeling was able to detect cells positive for BrdU and KRT1 in the E13.5 and 14.5 wild type epidermis (Figure 4A, B). No double positive cells were found at E15.5 and 16.5 (Figure 4C, D). In addition, this replacement process did not seem to be affected by Gpr177 deletion or transgenic Bmp4 expression (Figure 4E–L and Y). Thus, the initial programming of intermediate cells to become spinous keratinocytes is independent of the Gpr177 mediated regulation and BMP signaling.

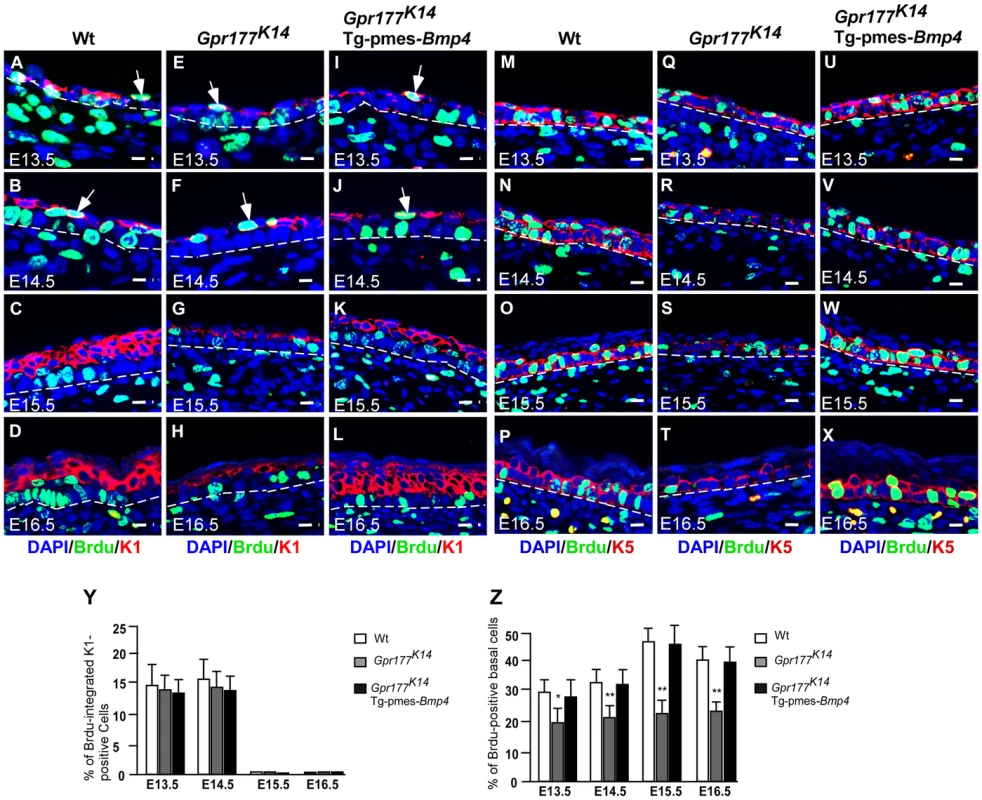

Fig. 4. The number of proliferating basal cells is affected in the Gpr177 mutant, which is rescued by transgenic Bmp4 expression.

(A–L) Immunofluorescence analysis for antibodies against KRT1 (red) and BrdU (green) on sections of dorsal skin of autopods between E13.5 and E16.5. At E13.5 and E14.5, BrdU labeled cells (green) are seen in the first transient suprabasal intermediate cells expressing KRT1 (white arrows in A,B). At E15.5 to E16.5, these cells are replaced by post-mitotic KRT1 cells when spinous layers form as multi-tier keratinocytes where KRT1 positive keratinocytes withdraw from cell cycle (C,D). These processes are comparable among three genotypes (E–H and I–L). Bars: 10 µm. (M–X) Immunofluorscence with antibodies against KRT5 (red) and BrdU (green) on sections of autopod skin. The ratio of BrdU integration in basal layer (M–P for wild type) is reduced in Gpr177K14 (Q–T) during the epidermal stratification. Overexpression of Tg-pmes-Bmp4 results in an increased ratio of BrdU incorporation in basal layer (U–X). Bars: 10 µm. Dash lines demarcate the boundary between epidermis and dermis. (Y) Statistical analysis shows similar ratios of BrdU incorporation in KRT-1 positive cells in wild type (n = 7), Gpr177K14 (n = 7), and Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 (n = 7) mice during epidermal stratification. Data are represented as mean ± SD. (Z) Percentage of BrdU incorporated KRT-5 cells in embryonic epidermis of wild type (n = 7), Gpr177K14 (n = 7), and Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 (n = 7) mice during epidermal stratification. Data are represented as means ± SD. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01, compared with wild type controls. As skin stratification requires proper proliferation of the basal cells [9], [10], we further examined if defects in basal cell division contribute to the epidermal abnormalities caused by Gpr177 deficiency. Double labeling of BrdU and KRT5 permits quantification of the ratio of basal cells proliferation. Closer examinations revealed that the number of KRT5-positive basal cells labeled with BrdU (Figure 4M–P) is significantly reduced by Gpr177 ablation (Figure 4Q–T). However, this hypoplastic feature was alleviated in the Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 mutants (Figure 4U–X), where the ratio of BrdU labelled basal cells arises between E14.5 and 16.5 to the levels close to controls (Figure 4Z). These observations suggest that the Gpr177-mediated regulation of BMP signaling maintains the high proliferative potential of the basal cells essential for epidermal stratification.

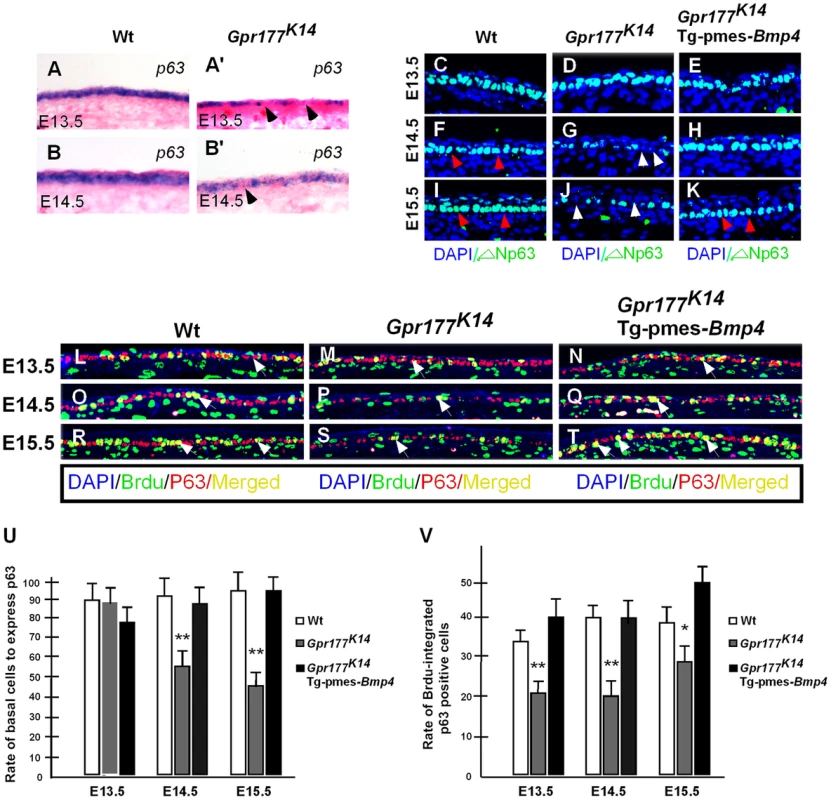

BMP4 activates basal cell proliferation through modulation of ΔNp63

It has been shown that p63 transcription factor is critical for the proliferative potential of epidermal stem cells in the stratified epithelium [9], [10], [18], [38]. We therefore tested if p63 is involved in the epidermal stratification mediated by the Wnt/BMP regulatory axis. In situ hybridization analysis showed that the expression of p63 in the epidermis was affected by Gpr177 deletion at E13.5 and 14.5 (Figure 5A–B, A′–B′). The loss of p63 transcripts in the mutants suggests a role of Wnt signaling in the maintenance of its expression in the basal cells (Figure 5A′–B′ and Figure S8A). We next examined the alteration of p63 at the protein level using antibodies against total p63 and its specific isoforms, TA-p63 and ΔNp63. The percentage of the total p63 and ΔNp63 positive basal cells was significantly decreased in Gpr177K14 mutants (Figure 5C–D, F–G, I–J and Figure S8B–J). Consistent with the previous reports [4], [5]. TA-p63 was not involved in epidermal development at these stages (Figure S8 K–P). In addition, transgenic BMP4 was able to elevate the percentage of the total p63 and ΔNp63 positive cells in the basal layer similar to that of wild type control at E13.5, 14.5 and 16.5 (Figure 5C–K and U). To further determine the role of p63 in basal cell proliferation, we performed double labeling of BrdU and p63. The number of the p63-expressing mitotic keratinocytes was reduced in the Gpr177K14 basal layer (Figure 5L–M, O–P and R–S and V), but this reduction was restored by transgenically expressed BMP4 (Figure 5N, Q, T and V), suggesting an involvement of p63 in maintaining the high proliferative potential of basal cells mediated by the Wnt/BMP regulatory axis during epidermal stratification.

Fig. 5. Transgenically expressed Bmp4 in Gpr177K14 mutants rescued the defective p63 expression.

(A–B, A′–B′) In situ hybridization shows p63 expression in the autopod skin of wild type and Gpr177K14 mice. (C–K) Immunoflurescence with antibody against ΔNp63 in epidermis between E13.5 and E15.5. Note that the reduction of ΔNp63 in Gpr177K14 mutant is restored in Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 mice (arrowheads). (L–T) Immunofluorescence with antibodies against pan-p63 (red) and BrdU (green) reveals BrdU incorporation rate in p63 expressing basal cells. Note that significantly restored merged staining in Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 mice (white arrows) at E14.5 and E15.5. (U) Statistical analysis shows the ratios of p63-positive cells in basal layer cells in wild type control (n = 6), Gpr177K14 mutant (n = 7), and Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 mice (n = 7). Data are represented as mean ± SD. **, P<0.01, compared with wild type controls. (V) Statistical analysis shows percentage of BrdU incorporation in p63 expressing cells in wild type control (n = 7), Gpr177K14 mutant (n = 6), and Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 mice (n = 6). Data are represented as mean ± SD. *P<0.05; **, P<0.01, compared with wild type controls. BMP signaling induces epidermal stratification through activation of Smad1/5/8 pathway in the dermis

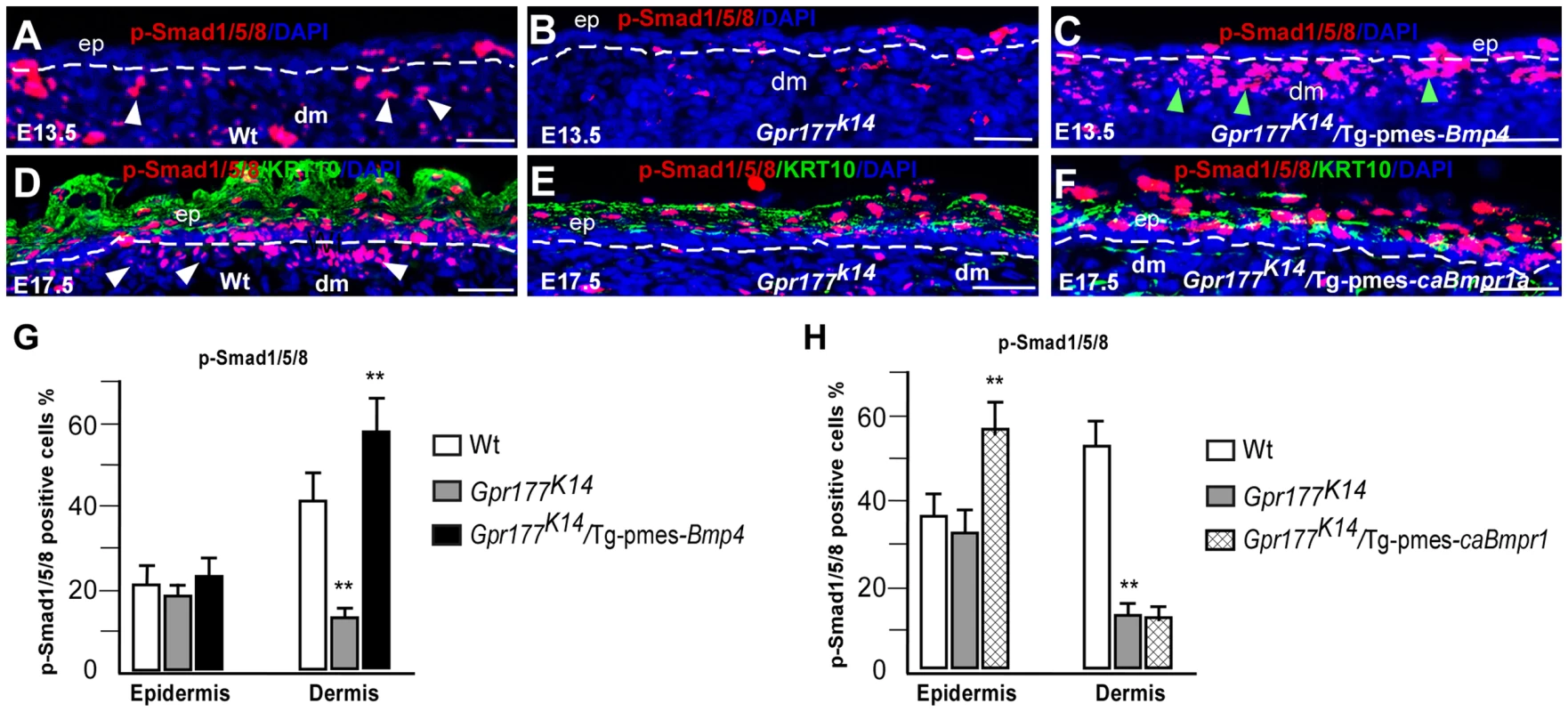

To further elucidate the mechanism underlying epidermal stratification mediated by BMP signaling, we examined the activation of Smad1/5/8 mediators that transduce the BMP canonical pathway. Immunostaining of phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 revealed that their activations were significantly affected in the dermis, but not in the epidermis of Gpr177K14 mice (Figure 6A, B, G and D, E, H). The dermal-specific effect was restored by transgenically expressed Bmp4 in Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 mutants (Figure 3H–I, Figure 6A, B, C, G and Figure S9). In contrast, activation of BMPR1A-mediated signaling failed to restore dermal activation of Smad1/5/8 in the Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-caBmpr1a mutants (Figure 6D, E, F, H and Figure S9), consistent with non-cell autonomous effects of BMP signaling on the spinous layer (Figure 3). These findings strongly suggest that BMP signaling functions primarily in the dermis, through the canonical pathway, to regulate downstream signaling molecules that act back on the epidermis to control epidermal stratification.

Fig. 6. Transgenic pmes-Bmp4 reactivates Smad1/5/8 signaling in the dermal mesenchyme in Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4.

(A–F) Immunofluorescence detections for anti-phosphorylated-Smad1/5/8 (p-Smad1/5/8, red) on sections of autopods. P-Smad1/5/8 activity (white arrowheads) is preferentially decreased in dermis of limb skin in Gpr177K14 mice and increased in dermis of Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 mice (green arrowheads) (A–C). Dash lines demarcate the border of epidermis and dermal mesenchyme. Immunofluorescence staining using antibodies against p-Smad1/5/8 (red) and KRT10 (green) on sections of dorsal autopod skin shows that p-Smad1/5/8 activity is only increased in epidermis of Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-caBmpr-1a mice (D–F). b: basal layer; ep: epidermis; dm: dermis. Bars: 50 µm. (G–H). Quantification of pSmad1/5/8 positive cells in the epidermis and dermis of Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-Bmp4 (G) and Gpr177K14/Tg-pmes-caBmpr-1a mice (H). Data are represented as mean ± SD. (**, P<0.01, n = 3–5). FGF signaling acts downstream of the BMP pathway in epidermal stratification

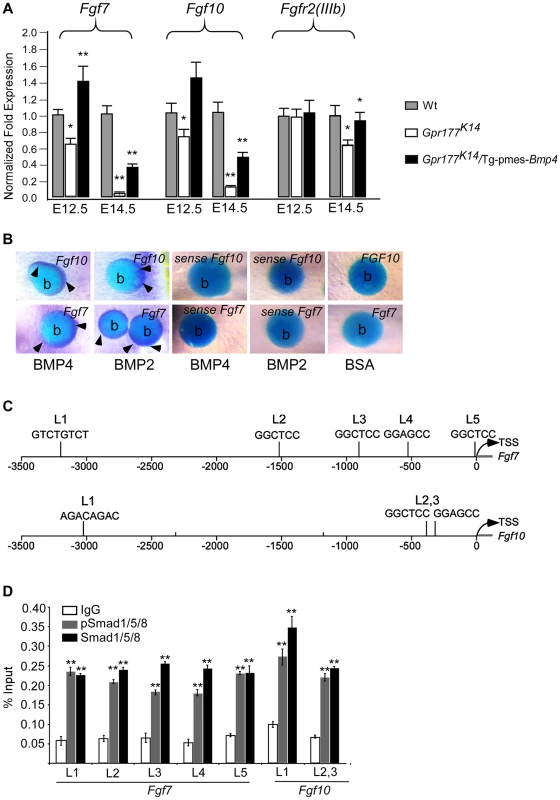

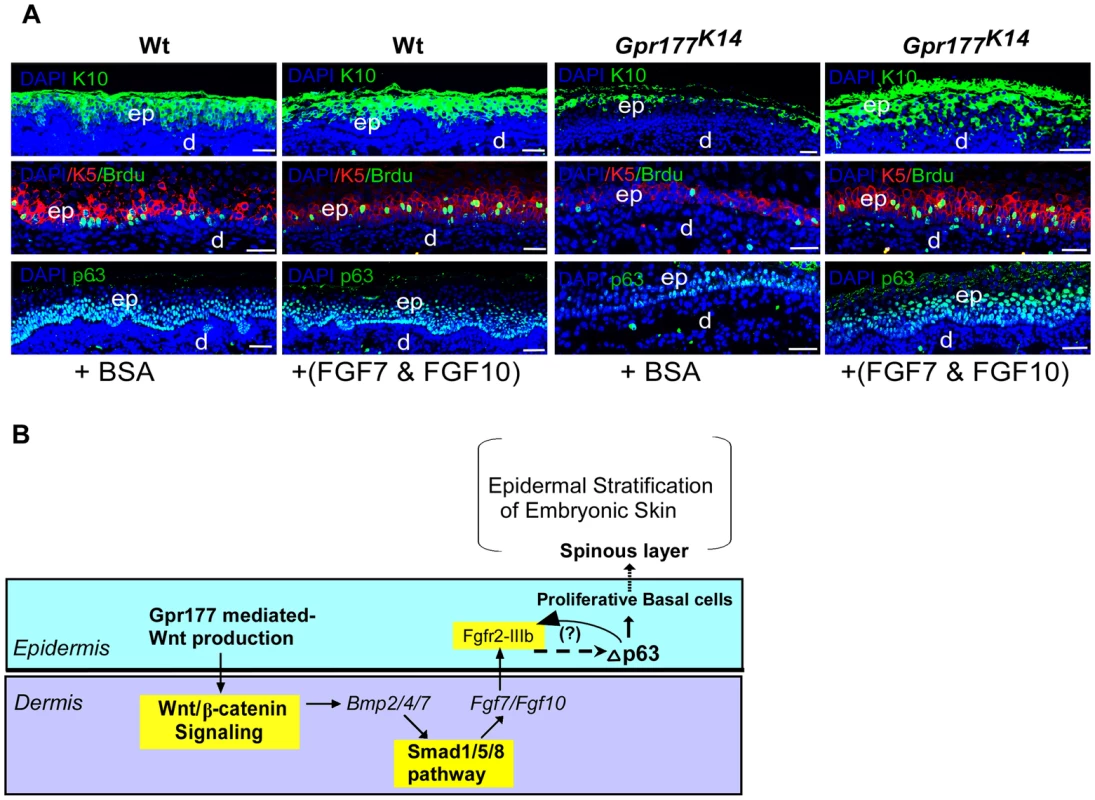

We next sought to identify the downstream mediators of BMP signaling on epidermal stratification. FGF signaling came to our attention because several FGF ligands are known to be expressed exclusively in the dermal cells [22], [39], and knockout of Fgf10 or its receptor FGFR2-IIIb leads to epidermal hypoplastic defects [23], similar to that seen in Gpr177K14 mutants (Figure 1). Using real time RT-PCR analysis, we found that Gpr177 deficiency significantly diminishes the expression of Fgf7 (KGF) and Fgf10 (Figure 7A), both working in concert to activate downstream signaling via FGFR2-IIIb [24], [26], [28], [40]. Furthermore, the reduced expression of Fgf7 and Fgf10 in Gpr177K14 mutants was restored by transgenic Bmp4 expression (Figure 7A and Figure S10A–C). Interestingly, a decrease in the expression of epidermal-specific Fgfr2IIIb was not significantly detected in the Gpr177K14 mutant at the early stage, but was observed at E14.5 (Figure 7A), suggesting an indirect consequence of activation. This reduction of Fgfr2IIIb expression was restored in Gpr177K14Tg-pmes-Bmp4 mice (Figure 7A). In vitro beads implantation assays further demonstrated that exogenously applied BMP2 or BMP4 was able to induce the expression of Fgf7 (17/20 in BMP2 implants and 15/21 in BMP4 implants) and Fgf10 (15/19 in BMP2 implants and 22/25 in BMP4 implants) in the dermal explants of Gpr177K14 mice (Figure 7B), supporting our hypothesis that FGF signaling acts downstream of the Wnt/BMP regulatory axis. To further determine if both Fgf7 and Fgf10 are transcription targets of pSmad1/5/8 signaling, we tested potential binding of pSmad1/5/8 to the regulatory region of Fgf7 and Fgf10 by in vivo chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays using embryonic limb skin samples. We utilized five sets of oligos pairs (see Methods and Materials) that amplify five potential binding sites of Smad1/5/8 [41], [42] in the regulatory regions of Fgf7 (Figure 7C) and two sets of oligo pairs for the binding sites in that of Fgf10 (Figure 7C). Quantitative PCR showed that after immunoprecipitation of linked chromatin there was specific enrichment of Smad to a DNA fragment that corresponds to one of potential sites with antibodies against either pSmad1/5/8 or Smad1/5/8 compared to IgG controls (Figure 7D). Thus, ChIP results strongly support the notion that in embryonic limb skin of mouse in vivo, activated Smad1/5/8 is present in the regulatory regions of Fgf7 and Fgf10 loci. To further demonstrate the involvement of FGF signaling in epidermal stratification, organ culture analysis was performed. The wild type and Gpr177K14 skin explants were supplemented with BSA as controls, or with exogenous FGF7 and FGF10. Immunostaining of keratinocyte markers was carried out 48 hours in organ culture. Although the wild type explants exhibited minimal response to the exogenous FGF7 and FGF10, the mutant explants exhibited increased thickness of the spinous layer, elevated number of KRT5-expressing mitotic cells, as well as enhanced expression of p63 in the presence of FGF7 and FGF10 (Figure 8A and Figure S10). Our results thus uncover a functional requirement of the Wnt/BMP/FGF signaling axis as well as their signaling interplay across the epidermis and dermis to orchestrate epidermis stratification.

Fig. 7. Genetic transduction of BMP signaling via FGF7/FGF10 in dermis to promote epidermal stratification.

(A) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR performed on mRNA isolated from dissected autopod skin at E12.5 (n = 5) and E14.5 (n = 3) reveals reduced expression of Fgf7 and Fgf10. Note that significantly reduced expression of Fgfr2-IIIb isoform is detected at E14.5. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01, compared with wild type controls. Data are represented as mean ± SD and are representatives of at least 3 independent experiments. (B) Implanted BMP2 and BMP4 protein-soaked beads in dermis explants induces the expression of Fgf7 and Fgf10 (arrowheads) around the protein beads, as shown by whole-mount in situ hybridization. Data are representatives of at least three independent experiments. b: protein beads. sense: sense riboprobes. (C) Schematic diagram shows location of Smad1/5/8-binding sites of the Fgf7 and Fgf10 regulatory region. L1-L5 represents Smad1/5/8-binding site with GGMGCC or GTCTGTCT sequence [41], [42]. (D) Quantitative levels of ChIP assays were analyzed by real-time PCR. ChIP assays were performed with Smad1/5/8 or pSmad1/5/8 antibody. Immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by real-time PCR and presented as a percentage of input. The data shown are representative of two independent experiments with similar results. Error bar represent standard deviations of the PCR reactions performed in triplicate. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. **, P<0.01. L, locus. TSS, Transcription start site. See also Figure S6. Fig. 8. FGF7/FGF10 in dermis promotes the embryonic epidermal stratification in response to Wnt signaling.

(A) Epidermal stratification was promoted in FGF7/FGF10 proteins treated and organ-cultured skin of Gpr177K14 mutant. Immunostaining using antibodies against KRT10 (green), KRT5 (red), and p63(green)shows that supplemented FGF7/FGF10 proteins in culture medium have no effect on epidermal stratification of wild type controls. Immunostaining on KRT1 and KRT10 for spinous layer, KRT5 for basal layer, and p63 shows that hypoplastic development of epidermis in the Gpr177K14 mutant skin is significantly attenuated by exogenously supplied FGF7 and FGF10 in organ culture. Note an increase in numbers of both BrdU incorporated KRT5 cells and p63 expressing cells in FGF7/FGF10 treated skin explants from Gpr177K14 mice. ep: epidermis; d: dermis. Bars: 50 µm. (B) Proposed model for a genetic hierarchy of WNT-BMP-FGF7/FGF10 signaling axis in regulating the embryonic epidermal stratification. Discussion

The Wnt, BMP, and FGF signaling pathways play critical roles in the embryonic development of the skin [11], [23], [24], [25], [43], [44]. Recent studies using mouse models with Wls/Gpr177 deletion have shown that Wnt secreted from the epidermis is essential for the dermal activation of the canonical Wnt pathway and activation of BMP signaling during hair follicle induction [14], [33]. However, how Wnt, BMP, and FGF pathways interact in the genetic networking that regulates the epidermal stratification during embryogenesis remains unclear. Here we used a transgenic Bmp4 mouse line to successfully rescue the defective epidermal stratification of Gpr177K14 mice. We dissect the sequential relationship and signaling crosstalk by which these key pathways interact and mediate epidermal stratification. Based on our results, we propose a genetic hierarchy model that integrates Wnt, BMP, and FGF signaling in the regulation of epidermal stratification (Figure 8B). In this model, a BMP/Smad1/5/8/FGF7/10 signaling cascade in the dermis is activated by epidermal Wnts and feedbacks to regulate basal cell proliferation and the subsequent epidermal stratification. Although the specificity of the Cre mouse line used in this study allows us to present this molecular circuit based on data from the limb skin, our observations from the dorsal skin suggest that the molecular responses involved in this model do not bias the body regions (Figure S1, S4, S6, S8A).

Our in vivo results showed that the proliferating basal cells expressing ΔNp63 were targets of the epidermal Wnt signal, and failed expression of ΔNp63 accounts for the hypoproliferation of these basal cells in the absence of epidermal Wnt. It is consistent with the functional importance of p63 in controlling basal cell proliferation of epidermal development and homeostasis [5], [10], [18], [45], suggesting that sustained expression of Wnt pathway regulated ΔNp63 is critical in maintaining the capability of basal keratinocytes to form the stratified epidermis in the developing mouse embryo.

ΔNp63 has been implicated in the developmental program of epidermal stratification through several mechanisms, including aymmetric division of basal cells and cell cycle exit of intermediate suprabasal cells [3], [5], [46], [47]. Although the basal layer lacking epidermal Wnt failed to maintain the proliferative capability of ΔNp63-expressing cells to form a normal spinous layer, the developmental events of epidermal stratification do take place normally, as evidenced by the occurrence of the asymmetric basal cell division to form intermediate mitotic keratinocytes and the replacement of these cells by post-mitotic keratinocytes in spite of a thinned spinous layer. Hence, our studies suggest that the mechanism by which epidermal production of Wnt affects the vertical expansion of the epidermis underlying the ΔNp63-governed basal keratinocytes is independent of both initiation of the intermediate keratinocytes and cell cycle exit for epidermal differentiation.

Notably and interestingly, unlike the effects of autocrine Wnt signaling on the interfollicular epidermal stem cells (IFESCs) of adult skin [48], loss of epidermal Wnt production in the embryonic skin in our study is not associated with premature differentiation of basal cells. Given the evidence of the embryonic epidermis as a tissue source for activation of β-catenin/Wnt signaling in the dermis of the developing skin [14], [33], there appears to exist a functional requirement for paracrine Wnt signaling in the maintenance of proliferative basal cells in epidermal stratification of embryonic skin.

Epidermal deletion of Gpr177 disrupts the canonical Wnt signaling in the dermis [14], [33] at E13.5, prior to the formation of the intermediate keratinocytic layer and maturation of the spinous layer [3], [5], [9]. Subsequently, expression of Bmp2, Bmp4, Bmp7, Fgf7, and Fgf10, critical for epidermal development [21], [22], [39], [44], [49], is specifically disrupted in the dermis [14], indicating that Wnt signaling functions upstream of these signals. BMP signaling appears to act downstream of Wnt signaling to mediate Wnt function, because activation of BMP signaling (Smad1/5/8 signaling) in the dermis of Gpr177K14 mutants successfully rescues the development of epidermal stratification and underlying molecular events. Irrespective of the contribution of BMPR1A and BMPR1B [36], [50], canonical BMP signaling is activated both in the epithelium and in the dermal mesenchyme of developing skin [51], [52], [53]. Our findings show that while the expression of transgenic Bmp4 is activated in the epidermis of Gpr177K14 mice, the activation of canonical BMP signaling in the dermis enable it to rescue epidermal stratification, suggesting that BMP/Smad1/5/8 signaling in the dermis mediates Wnt signaling to control basal cell proliferation, consistent with the recognized role of balanced BMP signaling in the maintenance of epidermal stem cells, progenitor cell differentiation, and hair follicle induction [1], [21], [36], [44], [54]. Based on the specific activation of Smad1/5/8 pathway by non-cell autonomous transgenic BMP4 seen in the dermis of Gpr177K14 mutants, we suggest that the downstream signaling feedback mechanism is required for the regulation of epidermal basal cells.

Given that loss of epidermal Wnt production at least partially phenocopies the epidermal defects in mice lacking Fgfr2-IIIb [23], the expression of Fgf7 and Fgf10 in the dermis is directly dependent on the presence of BMP/Smad1/5/8 signaling in the dermis in response to Wnt signaling. This implicates FGF7/10 as the downstream mediator for canonical BMP signaling in the dermis for the maintenance of basal cell proliferation. This hypothesis is supported by our skin organ culture experiments where exogenously applied FGF7/FGF10 are sufficient to functionally attenuate the reduction of proliferative basal cells and to rescue the hypoplastic spinous layer of the Gpr177K14 skin, consistent with the function of FGF7 and FGF10 in epidermal development [25], [28], [55]. It would be interesting to see if other keratinocyte mitogens such as EGF can exert similar rescue functions as the FGFs in future investigations. Nevertheless, we propose that in normal stratification of embryonic epidermis, FGF7 and FGF10 secreted from the dermis diffuse to the epidermis to mediate feedback regulation of Wnt and BMP/Smad1/5/8 signaling, which is required for the maintenance of proliferative keratinocytes in the basal layer through modulation of ΔNp63 [56], [57]. Consistent with previous studies that showed FGFR2 is a transcription target of p63 in the epidermis [56], [58], our quantitative RT-PCR results showing the down-regulation of Fgfr2-IIIb at the late stages of epidermal development further support a role of Fgfr2 signaling acting downstream of p63 in epidermal development. Nonetheless, our data suggest that the FGF7/FGF10 function as feedback factors to epidermis, but cannot rule out the possibility of involvement of additional feedback mechanisms [58], [59] between FGF7/10, Fgfr2, and p63 in the epidermis. However, the mechanism of how FGF7/10 signaling feedbacks to the epidermis and positively regulates ΔNp63 to maintain the proliferative basal cells remains unknown and warrants future studies.

In the adult skin, interfollicular epidermal basal cells, unlike hair follicles, proliferate throughout animal life. Recent studies on subtle genetic deletions by Millar and colleagues [60] have distinguished that Wnt/β-catenin signaling contribute to the mechanism controlling interfollicular epidermal cell (IFE) proliferation in the postnatal skin rather than the long-term maintenance of IFE stem cells. In embryonic skin development, our current study supports the notion that the epidermal Wnt initiates mesenchymal responses in the dermis by activating a BMP-FGF signaling cascade. This activation is crucial for the feedback regulations that control the stratification processes in the interfolliclular epidermis, indicating a profound effect of Wnt on signaling interplays across the epithelium and the mesenchyme in orchestrating the basal cell proliferation during epidermal stratification.

Materials and Methods

Generation and analysis of mutant mice

Mice carrying Gpr177 floxed allele [30] was crossed with K14-Cre transgenic mice [61] to generate mice with epidermal loss-of-function of Gpr177 (Gpr177K14). A Dermo1-Cre mouse was crossed to Gpr177 floxed allele to delete Gpr177 in dermal compartment of the skin [14]. TOPOGAL reporter [62], BATGAL reporter [63], R26R reporter, Dermo1-Cre mice, and transgenic K14-Cre mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, Maine. Generation of transgenic Tg-pmes-Bmp4 and Tg-pmes-caBmpr1a mice has been described previously, in which the transgenic allele expresses Bmp4 (or caBmpr1a) and Gfp (Green fluorescent protein) simultaneously via an IRES (Internal Ribosome Entry Site) [34], [35]. Animal experimental protocols were approved by The Animal Committee of Hangzhou Normal University, China.

Histology, in situ hybridization, RNA extraction, and real-time RT-PCR

Embryo collection, histology, and in situ hybridization for whole-mount and on sections were performed as previously described [32].

For real-time RT-PCR, embryonic autopods were dissected and treated with 0.1% collegenase to separate the dermal and epidermal compartments. RNA extraction using RNA isolation kit (ambion, RNAqueous-4RNA) and real-time RT-PCR analysis for RNA expression were performed as previously described [32]. The primers: QAxin2 : 5′-ACGCAC - TGACCGACGATT-3′ and 5-AAGGCAGCA - GGTTCCACA-3′; QFzd1 : 5′-GAGTTCTGGACCAGTAATCCGC-3′ and 5′ - ATGAGCCCGT - AAACCTTGGTG-3′; QLef1 : 5′ - AACGAGTCCGAAATCATCCCA-3′ and 5′ - GCCAGAGTA - ACTGGAGTAGGA-3′; QTcf4 : 5′-GATGGGACTCCCTATGACCAC-3′ and 5′ - GAAAGGGTT - CCTGGATTGCCC-3′; QBmp2 : 5′ - TCTTCCGGGAACAGATACAGG-3′ and 5′ - TGGTGTCC - AATAGTCTGGTCA-3′; QBmp4 : 5′-GACTTCGAGGCGACACTTCTA-3′ and 5′ - GAATGA - CGGCGCTCTTGCTA-3′; QBmp7 : 5′-AGGGCTTCTCCTACCCCTAC-3′ and 5′ - GGTGGTAT - CGAGGGTGGAAGA-3′; Q18S: 5′ - GAAACGGCTACCACATCC-3′ and 5′ - ACCAGAC - TTGCCCTCCA-3′; QDkk1 : 5′ - GACCTGCTACGAGACCTGGA-3′ and 5′ - CTGGAGAGGG - TATGGTTGCC-3′; QFgf7 : 5′-CAGAACAAAAGTCAAGGAGCAACCG-3′ and 5′ - GTCGCTCGGGGCTGGAACAG-3′; QFgf10 : 5′ - TCAGCGGGACCAAGAATGAAG-3′ and 5′-CGGCA - ACAACTCCGATTTCC-3′; QFgfr-IIIb: 5′ - CCTCGATGTCGTTGAACGGTC-3′ and 5′ - CAGCATCCATCTCCGTCACA-3′. QTg-Bmp4 : 5′ - GGGCTGGCCATTGAGGTGAC-3′ and 5′-ATGGCGACGGCAGTTCTTATTCTT-3′. QTg-caBmpr1a: 5′ - TAATAACACATGCATAACTAAT-3′ and 5′-GCTTTTGGTGAATCCTTGCA -3′.

BrdU labeling and apoptosis assays

Cell proliferation rate was measured by BrdU incorporation as previously described [32]. Briefly, timed pregnant mice were injected intraperitoneally with BrdU solution at a dosage of 3 mg/100 g of body weight using BrdU Labeling and Detection Kit (Roch Applied Science) 30 minutes prior to embryo collection. Cell apoptosis was detected with TUNEL assay kit (Roche Applied Science). At least 4 embryonic limbs for each genotype were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and processed for at 5–7 µm paraffin sections for immunofluorescence analysis according to manufacturer's instructions.

Immunohistochemistry

Embryonic limb were fixed in 4% PFA for 30 minutes, washed several times in PBS, and then processed for either paraffin sections or cryostat sections. For cryostat sections, samples were treated for in 5% sucrose and 15% sucrose, 2 hours each, in 30% sucrose. For 2–3 days. Samples were embedded in OCT and sectioned at 20 µm. To conduct immunohistochemical staining, sections were washed 3 times in PBST (0.1%Triton X-100/PBS), then blocked in 5% BSA for 30 minutes, and incubated with primary antibodies diluted with 5% BSA at 4°C overnight in a humid chamber. Sections were subsequently washed in PBST, 3 times for 10 minutes each. Secondary antibodies (1∶1000) and DAPI (1∶500) diluted in 5% BSA were applied for 30 minutes in the dark. Following application of secondary antibodies, the sections were washed several times with PBST, for 10 minutes for each, mounted with Mowiol (Sigma) and stored at 4°C. Primary antibodies used in this study were commercially purchased from Abcam, as detailed below: Cytokeratin 5 (ab24647), Cytokeratin 10 (ab9025), Cytokeratin 1 (ab24643), Filaggrin (ab24584), Loricrin (Ab24722), Anti-laminin (ab14055), p63 (ab53039). Antibody against ΔN-p63 was purchased from Santa Cruz (sc-8609), Antibody against BrdU was purchased from Roche (19691800) and antibody against pSmad1/5/8 purchased from Cell Signaling. Antibody against FGF10 was purchased from Santa Cruz (sc-7375).

Quantification of cell proliferation and antibody-positive cells

For quantification of proliferation, BrdU-positive cells were counted (n = 3–7 limb samples, ≥15 consecutive fields at 40× magnification) and calculated as a percentage of antibody labeled cells and total nuclear stained cells (DAPI positive) otherwise within a defined arbitrary area. For quantification of pSmd1/5/8-positive cells in either the epidermis or the underlying dermis in Figure 6G–H, the numbers of pSmad1/5/8 positive cells in every 300 DAPI positives were counted and calculated as a percentage (n = 3–5 limb samples, ≥15 fields at 40× magnification for each genotype). For quantification of epidermal p63-positive cells in Figure 5, p63-posive cells were counted and calculated in similar way as described above (n = 3 limb samples for each geneotype). Statistical significance was determined using Student's t-test.

Implantation of protein beads and culture of embryonic epidermal explants

Embryonic limbs were dissected from embryos at E13.5 and dorsal skin was separated manually using fined forceps and placed dorsal upward onto a Nucleopore membrane in a culture plate with a central well. Protein beads were soaked with BMP2 (100 ng/µl, R&D), BMP4 (100 ng/µl, R&D), BSA (l00 ng/µl). Explants were cultured at 37°C for 24 hours after implantation of beads onto explants.

Skin organ culture of the dorsal-autopod was conducted using a modification of a previously published procedure [24]. Briefly, dorsal skin portions were dissected from embryonic autopods (hands/feet) at late E13.5 with the assistance of 0.1% collagenase treatment. Skin explants were placed epidermal side up onto a Nucleopore filter (Whitman, pore-size 0.7 µm) that was coated with rat tail collagen type 1 (Sigma) in an organ culture plate with a central well, and cultured in DMEM without serum in 5% CO2 for 72 hours. Protein mixtures of recombinant FGF7 (R&D) and FGF10 (R&D) were applied onto DMEM medium at a final concentration of 250 ng/µl each, and the protein-containing media were replaced every 12 hours. In parallel experiments, BSA was applied onto DEME medium at the same concentration of proteins as control. Organ-cultured skin samples were fixed with 4% PFA and processed for paraffin sections for either immunohistochemistry or H&E staining.

Whole-mount X-gal staining and electronic microscopy

β-Gal staining for both whole-mount and cryostat sections were performed with commercial purchased Kit (Roche) according to manufacturer's instructions. For electronic microscopic analyses, embryonic limbs were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and dehydrate through graded ethanol and acetone. Samples were processed according to standard protocols

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Limb skin tissues from E13.5 mouse embryos were cut into small pieces, and then rinsed in 1% formaldehyde/PBS for 30 min on ice for cross-linking. The cross-linking reaction was stopped by adding glycine to a final concentration of 0.125 M and rotating for 5 min. The crosslinked tissues were ground by Dounce tissue grinder in tissue lysis buffer from Magna ChIP G Tissue Kit. Lysed cells were collected by spin at 10,000× g for 5 min. The pelleted cells were resuspended in 200 µl of Micrococcal nuclease buffer per 30 mg of the pelleted cells. The resuspended cells were digested with 1 µl of Micrococcal nuclease (New England Biolabs) at 37°C for 20 min. Then the reaction was stopped by adding EDTA to a final concentration of 50 mM and followed by sonication on ice at 30 W for 12 pulses of 1 second on, 3 seconds off to further disrupt and release chromatins. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed with antibody against Smad1/5/8 (Santa Cruz, sc-6031), pSmad1/5/8 (Cell signaling technology, 9511) or normal rabbit IgG (Beyotime, A7016) using Magna ChIP G Tissue Kit (Millipore) according to the user manual. For the detection of the immunoprecipitated Fgf7 and Fgf10 promoter region, eluted DNA was used as template for quantitative real time PCR analysis with primers specific for Smad-binding sites [41], [42]. Real-time PCR was performed in triplicate using SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix with CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Primers: Fgf7-L1 : 5′-CTCCATCCTGGTTTTCCTCC-3′ and 5′-GAATAGGACACAGGAAGACAG-3′; Fgf7-L2 : 5′-AACCTGCTCAGTGACATTCC-3′ and 5′-ACTACAGAATGCCCAGTCTC-3′; Fgf7-L3 : 5′-TTAGGGTGGTGATACGATGG-3′ and 5′-CTTTCCAGCCTGAGCTTGTG-3′; Fgf7-L4 : 5′-AGCTGAGCCATGGGGAAGTA-3′ and 5′-GGCTGAGAAGACCTAGTTTC-3′; Fgf7-L5 : 5′-TTGCTTCCAATGAGGTCAGC-3′ and 5′-GATTTTCTCCGTGTGTGAGC-3′; Fgf10-L1 : 5′-GGCCATAGAAACAGAGCATG-3′ and 5′-GCTTCAGATTAGAATGGTACC-3′; Fgf10-L2,3 : 5′-GCAATTAGCAGGAGCTGCAG-3′ and 5′-GATGCCTTTG - CTCTGAGCTG-3′.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. FuchsE (2007) Scratching the surface of skin development. Nature 445 : 834–842.

2. KosterMI, RoopDR (2007) Mechanisms regulating epithelial stratification. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 23 : 93–113.

3. LechlerT, FuchsE (2005) Asymmetric cell divisions promote stratification and differentiation of mammalian skin. Nature 437 : 275–280.

4. KosterMI, KimS, MillsAA, DeMayoFJ, RoopDR (2004) p63 is the molecular switch for initiation of an epithelial stratification program. Genes Dev 18 : 126–131.

5. KosterMI, DaiD, MarinariB, SanoY, CostanzoA, et al. (2007) p63 induces key target genes required for epidermal morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 3255–3260.

6. MillsAA, ZhengB, WangXJ, VogelH, RoopDR, et al. (1999) p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature 398 : 708–713.

7. YangA, SchweitzerR, SunD, KaghadM, WalkerN, et al. (1999) p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature 398 : 714–718.

8. YangA, KaghadM, WangY, GillettE, FlemingMD, et al. (1998) p63, a p53 homolog at 3q27-29, encodes multiple products with transactivating, death-inducing, and dominant-negative activities. Mol Cell 2 : 305–316.

9. LeBoeufM, TerrellA, TrivediS, SinhaS, EpsteinJA, et al. (2010) Hdac1 and Hdac2 act redundantly to control p63 and p53 functions in epidermal progenitor cells. Dev Cell 19 : 807–818.

10. SenooM, PintoF, CrumCP, McKeonF (2007) p63 Is essential for the proliferative potential of stem cells in stratified epithelia. Cell 129 : 523–536.

11. AndlT, ReddyST, GaddaparaT, MillarSE (2002) WNT signals are required for the initiation of hair follicle development. Dev Cell 2 : 643–653.

12. ReddyS, AndlT, BagasraA, LuMM, EpsteinDJ, et al. (2001) Characterization of Wnt gene expression in developing and postnatal hair follicles and identification of Wnt5a as a target of Sonic hedgehog in hair follicle morphogenesis. Mech Dev 107 : 69–82.

13. SuzukiK, YamaguchiY, VillacorteM, MiharaK, AkiyamaM, et al. (2009) Embryonic hair follicle fate change by augmented beta-catenin through Shh and Bmp signaling. Development 136 : 367–372.

14. FuJ, HsuW (2013) Epidermal Wnt controls hair follicle induction by orchestrating dynamic signaling crosstalk between the epidermis and dermis. J Invest Dermatol 133 : 890–898.

15. ZhangY, AndlT, YangSH, TetaM, LiuF, et al. (2008) Activation of beta-catenin signaling programs embryonic epidermis to hair follicle fate. Development 135 : 2161–2172.

16. SternCD (2005) Neural induction: old problem, new findings, yet more questions. Development 132 : 2007–2021.

17. WilsonSI, EdlundT (2001) Neural induction: toward a unifying mechanism. Nat Neurosci 4 Suppl: 1161–1168.

18. LaurikkalaJ, MikkolaML, JamesM, TummersM, MillsAA, et al. (2006) p63 regulates multiple signalling pathways required for ectodermal organogenesis and differentiation. Development 133 : 1553–1563.

19. MedawarA, VirolleT, RostagnoP, de la Forest-DivonneS, GambaroK, et al. (2008) DeltaNp63 is essential for epidermal commitment of embryonic stem cells. PLoS One 3: e3441.

20. KobielakK, PasolliHA, AlonsoL, PolakL, FuchsE (2003) Defining BMP functions in the hair follicle by conditional ablation of BMP receptor IA. J Cell Biol 163 : 609–623.

21. MouC, JacksonB, SchneiderP, OverbeekPA, HeadonDJ (2006) Generation of the primary hair follicle pattern. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 : 9075–9080.

22. KawanoM, Komi-KuramochiA, AsadaM, SuzukiM, OkiJ, et al. (2005) Comprehensive analysis of FGF and FGFR expression in skin: FGF18 is highly expressed in hair follicles and capable of inducing anagen from telogen stage hair follicles. J Invest Dermatol 124 : 877–885.

23. PetiotA, ContiFJ, GroseR, RevestJM, Hodivala-DilkeKM, et al. (2003) A crucial role for Fgfr2-IIIb signalling in epidermal development and hair follicle patterning. Development 130 : 5493–5501.

24. RichardsonGD, BazziH, FantauzzoKA, WatersJM, CrawfordH, et al. (2009) KGF and EGF signalling block hair follicle induction and promote interfollicular epidermal fate in developing mouse skin. Development 136 : 2153–2164.

25. TaoH, YoshimotoY, YoshiokaH, NohnoT, NojiS, et al. (2002) FGF10 is a mesenchymally derived stimulator for epidermal development in the chick embryonic skin. Mech Dev 116 : 39–49.

26. OhuchiH, HoriY, YamasakiM, HaradaH, SekineK, et al. (2000) FGF10 acts as a major ligand for FGF receptor 2 IIIb in mouse multi-organ development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 277 : 643–649.

27. GuoL, DegensteinL, FuchsE (1996) Keratinocyte growth factor is required for hair development but not for wound healing. Genes Dev 10 : 165–175.

28. GuoL, YuQC, FuchsE (1993) Targeting expression of keratinocyte growth factor to keratinocytes elicits striking changes in epithelial differentiation in transgenic mice. EMBO J 12 : 973–986.

29. BanzigerC, SoldiniD, SchuttC, ZipperlenP, HausmannG, et al. (2006) Wntless, a conserved membrane protein dedicated to the secretion of Wnt proteins from signaling cells. Cell 125 : 509–522.

30. FuJ, Ivy YuHM, MaruyamaT, MirandoAJ, HsuW (2011) Gpr177/mouse Wntless is essential for Wnt-mediated craniofacial and brain development. Dev Dyn 240 : 365–371.

31. FuJ, JiangM, MirandoAJ, YuHM, HsuW (2009) Reciprocal regulation of Wnt and Gpr177/mouse Wntless is required for embryonic axis formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 : 18598–18603.

32. ZhuX, ZhaoP, LiuY, ZhangX, FuJ, et al. (2013) Intra-epithelial requirement of canonical Wnt signaling for tooth morphogenesis. J Biol Chem 288 : 12080–12089.

33. ChenD, JarrellA, GuoC, LangR, AtitR (2012) Dermal beta-catenin activity in response to epidermal Wnt ligands is required for fibroblast proliferation and hair follicle initiation. Development 139 : 1522–1533.

34. HeF, XiongW, WangY, MatsuiM, YuX, et al. (2010) Modulation of BMP signaling by Noggin is required for the maintenance of palatal epithelial integrity during palatogenesis. Dev Biol 347 : 109–121.

35. HeF, HuX, XiongW, LiL, LinL, et al. (2014) Directed Bmp4 expression in neural crest cells generates a genetic model for the rare human bony syngnathia birth defect. Dev Biol 391 : 170–81 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.04.013

36. AndlT, AhnK, KairoA, ChuEY, Wine-LeeL, et al. (2004) Epithelial Bmpr1a regulates differentiation and proliferation in postnatal hair follicles and is essential for tooth development. Development 131 : 2257–2268.

37. SoshnikovaN, ZechnerD, HuelskenJ, MishinaY, BehringerRR, et al. (2003) Genetic interaction between Wnt/beta-catenin and BMP receptor signaling during formation of the AER and the dorsal-ventral axis in the limb. Genes Dev 17 : 1963–1968.

38. RomanoRA, SmalleyK, MagrawC, SernaVA, KuritaT, et al. (2012) DeltaNp63 knockout mice reveal its indispensable role as a master regulator of epithelial development and differentiation. Development 139 : 772–782.

39. BeerHD, GassmannMG, MunzB, SteilingH, EngelhardtF, et al. (2000) Expression and function of keratinocyte growth factor and activin in skin morphogenesis and cutaneous wound repair. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 5 : 34–39.

40. ZhangX, IbrahimiOA, OlsenSK, UmemoriH, MohammadiM, et al. (2006) Receptor specificity of the fibroblast growth factor family. The complete mammalian FGF family. J Biol Chem 281 : 15694–15700.

41. MorikawaM, KoinumaD, TsutsumiS, VasilakiE, KankiY, et al. (2011) ChIP-seq reveals cell type-specific binding patterns of BMP-specific Smads and a novel binding motif. Nucleic Acids Res 39 : 8712–8727.

42. MorikawaM, KoinumaD, MiyazonoK, HeldinCH (2013) Genome-wide mechanisms of Smad binding. Oncogene 32 : 1609–1615.

43. NguyenH, MerrillBJ, PolakL, NikolovaM, RendlM, et al. (2009) Tcf3 and Tcf4 are essential for long-term homeostasis of skin epithelia. Nat Genet 41 : 1068–1075.

44. RendlM, PolakL, FuchsE (2008) BMP signaling in dermal papilla cells is required for their hair follicle-inductive properties. Genes Dev 22 : 543–557.

45. TruongAB, KretzM, RidkyTW, KimmelR, KhavariPA (2006) p63 regulates proliferation and differentiation of developmentally mature keratinocytes. Genes Dev 20 : 3185–3197.

46. RomanoRA, OrttK, BirkayaB, SmalleyK, SinhaS (2009) An active role of the DeltaN isoform of p63 in regulating basal keratin genes K5 and K14 and directing epidermal cell fate. PLoS One 4: e5623.

47. TadeuAM, HorsleyV (2013) Notch signaling represses p63 expression in the developing surface ectoderm. Development 140 : 3777–3786.

48. LimX, TanSH, KohWL, ChauRM, YanKS, et al. (2013) Interfollicular epidermal stem cells self-renew via autocrine Wnt signaling. Science 342 : 1226–1230.

49. KandybaE, LeungY, ChenYB, WidelitzR, ChuongCM, et al. (2013) Competitive balance of intrabulge BMP/Wnt signaling reveals a robust gene network ruling stem cell homeostasis and cyclic activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 : 1351–1356.

50. PanchisionDM, PickelJM, StuderL, LeeSH, TurnerPA, et al. (2001) Sequential actions of BMP receptors control neural precursor cell production and fate. Genes Dev 15 : 2094–2110.

51. DickA, RisauW, DrexlerH (1998) Expression of Smad1 and Smad2 during embryogenesis suggests a role in organ development. Dev Dyn 211 : 293–305.

52. FessingMY, AtoyanR, ShanderB, MardaryevAN, BotchkarevVVJr, et al. (2010) BMP signaling induces cell-type-specific changes in gene expression programs of human keratinocytes and fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol 130 : 398–404.

53. FlandersKC, KimES, RobertsAB (2001) Immunohistochemical expression of Smads 1–6 in the 15-day gestation mouse embryo: signaling by BMPs and TGF-betas. Dev Dyn 220 : 141–154.

54. BlessingM, SchirmacherP, KaiserS (1996) Overexpression of bone morphogenetic protein-6 (BMP-6) in the epidermis of transgenic mice: inhibition or stimulation of proliferation depending on the pattern of transgene expression and formation of psoriatic lesions. J Cell Biol 135 : 227–239.

55. HaradaH, ToyonoT, ToyoshimaK, OhuchiH (2002) FGF10 maintains stem cell population during mouse incisor development. Connect Tissue Res 43 : 201–204.

56. CandiE, RufiniA, TerrinoniA, Giamboi-MiragliaA, LenaAM, et al. (2007) DeltaNp63 regulates thymic development through enhanced expression of FgfR2 and Jag2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 11999–12004.

57. OgawaE, OkuyamaR, EgawaT, NagoshiH, ObinataM, et al. (2008) p63/p51-induced onset of keratinocyte differentiation via the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway is counteracted by keratinocyte growth factor. J Biol Chem 283 : 34241–34249.

58. FeroneG, ThomasonHA, AntoniniD, De RosaL, HuB, et al. (2012) Mutant p63 causes defective expansion of ectodermal progenitor cells and impaired FGF signalling in AEC syndrome. EMBO Mol Med 4 : 192–205.

59. LanderAD, GokoffskiKK, WanFY, NieQ, CalofAL (2009) Cell lineages and the logic of proliferative control. PLoS Biol 7: e15.

60. ChoiYS, ZhangY, XuM, YangY, ItoM, et al. (2013) Distinct functions for Wnt/beta-catenin in hair follicle stem cell proliferation and survival and interfollicular epidermal homeostasis. Cell Stem Cell 13 : 720–733.

61. DassuleHR, LewisP, BeiM, MaasR, McMahonAP (2000) Sonic hedgehog regulates growth and morphogenesis of the tooth. Development 127 : 4775–4785.

62. DasGuptaR, FuchsE (1999) Multiple roles for activated LEF/TCF transcription complexes during hair follicle development and differentiation. Development 126 : 4557–4568.

63. MarettoS, CordenonsiM, DupontS, BraghettaP, BroccoliV, et al. (2003) Mapping Wnt/beta-catenin signaling during mouse development and in colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 : 3299–3304.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia and Infertility in Mice Deficient for miR-34b/c and miR-449 LociČlánek The Kinesin AtPSS1 Promotes Synapsis and is Required for Proper Crossover Distribution in MeiosisČlánek Payoffs, Not Tradeoffs, in the Adaptation of a Virus to Ostensibly Conflicting Selective PressuresČlánek Examination of Prokaryotic Multipartite Genome Evolution through Experimental Genome ReductionČlánek Role of STN1 and DNA Polymerase α in Telomere Stability and Genome-Wide Replication in ArabidopsisČlánek RNA-Processing Protein TDP-43 Regulates FOXO-Dependent Protein Quality Control in Stress ResponseČlánek Integrating Functional Data to Prioritize Causal Variants in Statistical Fine-Mapping StudiesČlánek Salt-Induced Stabilization of EIN3/EIL1 Confers Salinity Tolerance by Deterring ROS Accumulation inČlánek Ethylene-Induced Inhibition of Root Growth Requires Abscisic Acid Function in Rice ( L.) SeedlingsČlánek Metabolic Respiration Induces AMPK- and Ire1p-Dependent Activation of the p38-Type HOG MAPK PathwayČlánek Signature Gene Expression Reveals Novel Clues to the Molecular Mechanisms of Dimorphic Transition inČlánek A Mouse Model Uncovers LKB1 as an UVB-Induced DNA Damage Sensor Mediating CDKN1A (p21) DegradationČlánek Dominant Sequences of Human Major Histocompatibility Complex Conserved Extended Haplotypes from to

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 10- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- IVF a rakovina prsu – zvyšují hormony riziko vzniku rakoviny?

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- An Deletion Is Highly Associated with a Juvenile-Onset Inherited Polyneuropathy in Leonberger and Saint Bernard Dogs

- Licensing of Yeast Centrosome Duplication Requires Phosphoregulation of Sfi1

- Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia and Infertility in Mice Deficient for miR-34b/c and miR-449 Loci

- Basement Membrane and Cell Integrity of Self-Tissues in Maintaining Immunological Tolerance

- The Kinesin AtPSS1 Promotes Synapsis and is Required for Proper Crossover Distribution in Meiosis

- Germline Mutations in Are Associated with Familial Gastric Cancer

- POT1a and Components of CST Engage Telomerase and Regulate Its Activity in

- Controlling Meiotic Recombinational Repair – Specifying the Roles of ZMMs, Sgs1 and Mus81/Mms4 in Crossover Formation

- Payoffs, Not Tradeoffs, in the Adaptation of a Virus to Ostensibly Conflicting Selective Pressures

- FHIT Suppresses Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) and Metastasis in Lung Cancer through Modulation of MicroRNAs

- Genome-Wide Mapping of Yeast RNA Polymerase II Termination

- Examination of Prokaryotic Multipartite Genome Evolution through Experimental Genome Reduction

- White Cells Facilitate Opposite- and Same-Sex Mating of Opaque Cells in

- BMP-FGF Signaling Axis Mediates Wnt-Induced Epidermal Stratification in Developing Mammalian Skin

- Genome-Wide Association Study of CSF Levels of 59 Alzheimer's Disease Candidate Proteins: Significant Associations with Proteins Involved in Amyloid Processing and Inflammation

- COE Loss-of-Function Analysis Reveals a Genetic Program Underlying Maintenance and Regeneration of the Nervous System in Planarians

- Fat-Dachsous Signaling Coordinates Cartilage Differentiation and Polarity during Craniofacial Development

- Identification of Genes Important for Cutaneous Function Revealed by a Large Scale Reverse Genetic Screen in the Mouse

- Sensors at Centrosomes Reveal Determinants of Local Separase Activity

- Genes Integrate and Hedgehog Pathways in the Second Heart Field for Cardiac Septation

- Systematic Dissection of Coding Exons at Single Nucleotide Resolution Supports an Additional Role in Cell-Specific Transcriptional Regulation

- Recovery from an Acute Infection in Requires the GATA Transcription Factor ELT-2

- HIPPO Pathway Members Restrict SOX2 to the Inner Cell Mass Where It Promotes ICM Fates in the Mouse Blastocyst

- Role of and in Development of Abdominal Epithelia Breaks Posterior Prevalence Rule

- The Formation of Endoderm-Derived Taste Sensory Organs Requires a -Dependent Expansion of Embryonic Taste Bud Progenitor Cells

- Role of STN1 and DNA Polymerase α in Telomere Stability and Genome-Wide Replication in Arabidopsis

- Keratin 76 Is Required for Tight Junction Function and Maintenance of the Skin Barrier

- Encodes the Catalytic Subunit of N Alpha-Acetyltransferase that Regulates Development, Metabolism and Adult Lifespan

- Disruption of SUMO-Specific Protease 2 Induces Mitochondria Mediated Neurodegeneration

- Caudal Regulates the Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Pair-Rule Waves in

- It's All in Your Mind: Determining Germ Cell Fate by Neuronal IRE-1 in

- A Conserved Role for Homologs in Protecting Dopaminergic Neurons from Oxidative Stress

- The Master Activator of IncA/C Conjugative Plasmids Stimulates Genomic Islands and Multidrug Resistance Dissemination

- An AGEF-1/Arf GTPase/AP-1 Ensemble Antagonizes LET-23 EGFR Basolateral Localization and Signaling during Vulva Induction

- The Proteomic Landscape of the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus Clock Reveals Large-Scale Coordination of Key Biological Processes

- RNA-Processing Protein TDP-43 Regulates FOXO-Dependent Protein Quality Control in Stress Response

- A Complex Genetic Switch Involving Overlapping Divergent Promoters and DNA Looping Regulates Expression of Conjugation Genes of a Gram-positive Plasmid

- ZTF-8 Interacts with the 9-1-1 Complex and Is Required for DNA Damage Response and Double-Strand Break Repair in the Germline

- Integrating Functional Data to Prioritize Causal Variants in Statistical Fine-Mapping Studies

- Tpz1-Ccq1 and Tpz1-Poz1 Interactions within Fission Yeast Shelterin Modulate Ccq1 Thr93 Phosphorylation and Telomerase Recruitment

- Salt-Induced Stabilization of EIN3/EIL1 Confers Salinity Tolerance by Deterring ROS Accumulation in

- Telomeric (s) in spp. Encode Mediator Subunits That Regulate Distinct Virulence Traits

- Ethylene-Induced Inhibition of Root Growth Requires Abscisic Acid Function in Rice ( L.) Seedlings

- Ancient Expansion of the Hox Cluster in Lepidoptera Generated Four Homeobox Genes Implicated in Extra-Embryonic Tissue Formation

- Mechanism of Suppression of Chromosomal Instability by DNA Polymerase POLQ

- A Mutation in the Mouse Gene Leads to Impaired Hedgehog Signaling

- Keeping mtDNA in Shape between Generations

- Targeted Exon Capture and Sequencing in Sporadic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

- TIF-IA-Dependent Regulation of Ribosome Synthesis in Muscle Is Required to Maintain Systemic Insulin Signaling and Larval Growth

- At Short Telomeres Tel1 Directs Early Replication and Phosphorylates Rif1

- Evidence of a Bacterial Receptor for Lysozyme: Binding of Lysozyme to the Anti-σ Factor RsiV Controls Activation of the ECF σ Factor σ

- Hsp40s Specify Functions of Hsp104 and Hsp90 Protein Chaperone Machines

- Feeding State, Insulin and NPR-1 Modulate Chemoreceptor Gene Expression via Integration of Sensory and Circuit Inputs

- Functional Interaction between Ribosomal Protein L6 and RbgA during Ribosome Assembly

- Multiple Regulatory Systems Coordinate DNA Replication with Cell Growth in

- Fast Evolution from Precast Bricks: Genomics of Young Freshwater Populations of Threespine Stickleback

- Mmp1 Processing of the PDF Neuropeptide Regulates Circadian Structural Plasticity of Pacemaker Neurons

- The Nuclear Immune Receptor Is Required for -Dependent Constitutive Defense Activation in

- Genetic Modifiers of Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Associated Café-au-Lait Macule Count Identified Using Multi-platform Analysis

- Juvenile Hormone-Receptor Complex Acts on and to Promote Polyploidy and Vitellogenesis in the Migratory Locust

- Uncovering Enhancer Functions Using the α-Globin Locus

- The Analysis of Mutant Alleles of Different Strength Reveals Multiple Functions of Topoisomerase 2 in Regulation of Chromosome Structure

- Metabolic Respiration Induces AMPK- and Ire1p-Dependent Activation of the p38-Type HOG MAPK Pathway

- The Specification and Global Reprogramming of Histone Epigenetic Marks during Gamete Formation and Early Embryo Development in

- The DAF-16 FOXO Transcription Factor Regulates to Modulate Stress Resistance in , Linking Insulin/IGF-1 Signaling to Protein N-Terminal Acetylation

- Genetic Influences on Translation in Yeast

- Analysis of Mutants Defective in the Cdk8 Module of Mediator Reveal Links between Metabolism and Biofilm Formation

- Ribosomal Readthrough at a Short UGA Stop Codon Context Triggers Dual Localization of Metabolic Enzymes in Fungi and Animals

- Gene Duplication Restores the Viability of Δ and Δ Mutants

- Selection on a Variant Associated with Improved Viral Clearance Drives Local, Adaptive Pseudogenization of Interferon Lambda 4 ()

- Break-Induced Replication Requires DNA Damage-Induced Phosphorylation of Pif1 and Leads to Telomere Lengthening

- Dynamic Partnership between TFIIH, PGC-1α and SIRT1 Is Impaired in Trichothiodystrophy

- Signature Gene Expression Reveals Novel Clues to the Molecular Mechanisms of Dimorphic Transition in

- Mutations in Moderate or Severe Intellectual Disability

- Multifaceted Genome Control by Set1 Dependent and Independent of H3K4 Methylation and the Set1C/COMPASS Complex

- A Role for Taiman in Insect Metamorphosis

- The Small RNA Rli27 Regulates a Cell Wall Protein inside Eukaryotic Cells by Targeting a Long 5′-UTR Variant

- MMS Exposure Promotes Increased MtDNA Mutagenesis in the Presence of Replication-Defective Disease-Associated DNA Polymerase γ Variants

- Coexistence and Within-Host Evolution of Diversified Lineages of Hypermutable in Long-term Cystic Fibrosis Infections

- Comprehensive Mapping of the Flagellar Regulatory Network

- Topoisomerase II Is Required for the Proper Separation of Heterochromatic Regions during Female Meiosis

- A Splice Mutation in the Gene Causes High Glycogen Content and Low Meat Quality in Pig Skeletal Muscle

- KDM5 Interacts with Foxo to Modulate Cellular Levels of Oxidative Stress

- H2B Mono-ubiquitylation Facilitates Fork Stalling and Recovery during Replication Stress by Coordinating Rad53 Activation and Chromatin Assembly

- Copy Number Variation in the Horse Genome

- Unifying Genetic Canalization, Genetic Constraint, and Genotype-by-Environment Interaction: QTL by Genomic Background by Environment Interaction of Flowering Time in

- Spinster Homolog 2 () Deficiency Causes Early Onset Progressive Hearing Loss

- Genome-Wide Discovery of Drug-Dependent Human Liver Regulatory Elements

- Developmentally-Regulated Excision of the SPβ Prophage Reconstitutes a Gene Required for Spore Envelope Maturation in

- Protein Phosphatase 4 Promotes Chromosome Pairing and Synapsis, and Contributes to Maintaining Crossover Competence with Increasing Age

- The bHLH-PAS Transcription Factor Dysfusion Regulates Tarsal Joint Formation in Response to Notch Activity during Leg Development

- A Mouse Model Uncovers LKB1 as an UVB-Induced DNA Damage Sensor Mediating CDKN1A (p21) Degradation

- Notch3 Interactome Analysis Identified WWP2 as a Negative Regulator of Notch3 Signaling in Ovarian Cancer

- An Integrated Cell Purification and Genomics Strategy Reveals Multiple Regulators of Pancreas Development

- Dominant Sequences of Human Major Histocompatibility Complex Conserved Extended Haplotypes from to

- The Vesicle Protein SAM-4 Regulates the Processivity of Synaptic Vesicle Transport

- A Gain-of-Function Mutation in Impeded Bone Development through Increasing Expression in DA2B Mice

- Nephronophthisis-Associated Regulates Cell Cycle Progression, Apoptosis and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition

- Beclin 1 Is Required for Neuron Viability and Regulates Endosome Pathways via the UVRAG-VPS34 Complex

- The Not5 Subunit of the Ccr4-Not Complex Connects Transcription and Translation

- Abnormal Dosage of Ultraconserved Elements Is Highly Disfavored in Healthy Cells but Not Cancer Cells

- Genome-Wide Distribution of RNA-DNA Hybrids Identifies RNase H Targets in tRNA Genes, Retrotransposons and Mitochondria

- The Chromosomal Association of the Smc5/6 Complex Depends on Cohesion and Predicts the Level of Sister Chromatid Entanglement

- Cell-Autonomous Progeroid Changes in Conditional Mouse Models for Repair Endonuclease XPG Deficiency

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- The Master Activator of IncA/C Conjugative Plasmids Stimulates Genomic Islands and Multidrug Resistance Dissemination

- A Splice Mutation in the Gene Causes High Glycogen Content and Low Meat Quality in Pig Skeletal Muscle

- Keratin 76 Is Required for Tight Junction Function and Maintenance of the Skin Barrier

- A Role for Taiman in Insect Metamorphosis

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání