-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Complex Chromosomal Rearrangements Mediated by Break-Induced Replication Involve Structure-Selective Endonucleases

DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair occurring in repeated DNA sequences often leads to the generation of chromosomal rearrangements. Homologous recombination normally ensures a faithful repair of DSBs through a mechanism that transfers the genetic information of an intact donor template to the broken molecule. When only one DSB end shares homology to the donor template, conventional gene conversion fails to occur and repair can be channeled to a recombination-dependent replication pathway termed break-induced replication (BIR), which is prone to produce chromosome non-reciprocal translocations (NRTs), a classical feature of numerous human cancers. Using a newly designed substrate for the analysis of DSB–induced chromosomal translocations, we show that Mus81 and Yen1 structure-selective endonucleases (SSEs) promote BIR, thus causing NRTs. We propose that Mus81 and Yen1 are recruited at the strand invasion intermediate to allow the establishment of a replication fork, which is required to complete BIR. Replication template switching during BIR, a feature of this pathway, engenders complex chromosomal rearrangements when using repeated DNA sequences dispersed over the genome. We demonstrate here that Mus81 and Yen1, together with Slx4, also promote template switching during BIR. Altogether, our study provides evidence for a role of SSEs at multiple steps during BIR, thus participating in the destabilization of the genome by generating complex chromosomal rearrangements.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 8(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002979

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002979Summary

DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair occurring in repeated DNA sequences often leads to the generation of chromosomal rearrangements. Homologous recombination normally ensures a faithful repair of DSBs through a mechanism that transfers the genetic information of an intact donor template to the broken molecule. When only one DSB end shares homology to the donor template, conventional gene conversion fails to occur and repair can be channeled to a recombination-dependent replication pathway termed break-induced replication (BIR), which is prone to produce chromosome non-reciprocal translocations (NRTs), a classical feature of numerous human cancers. Using a newly designed substrate for the analysis of DSB–induced chromosomal translocations, we show that Mus81 and Yen1 structure-selective endonucleases (SSEs) promote BIR, thus causing NRTs. We propose that Mus81 and Yen1 are recruited at the strand invasion intermediate to allow the establishment of a replication fork, which is required to complete BIR. Replication template switching during BIR, a feature of this pathway, engenders complex chromosomal rearrangements when using repeated DNA sequences dispersed over the genome. We demonstrate here that Mus81 and Yen1, together with Slx4, also promote template switching during BIR. Altogether, our study provides evidence for a role of SSEs at multiple steps during BIR, thus participating in the destabilization of the genome by generating complex chromosomal rearrangements.

Introduction

The maintenance of genome integrity is crucial to prevent cell death in all organisms. Chromosomal rearrangements such as reciprocal translocations, deletions, inversions and duplications threaten genomic stability and must be avoided to prevent cancer development and genomic disorders [1]. The occurrence of unfaithful repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) is widely admitted to be the main source of chromosomal rearrangements [2]–[5]. Nonhomologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homologous recombination (HR) constitute the main pathways of DSB repair. While NHEJ seal the broken DNA ends by simple religation, HR uses sequence homology between the DSB ends and an intact template for repair and is typically considered as error free. Nevertheless, in a number of cases, such as when HR occurs between non-allelic DNA sequences or DNA repeated sequences or HR is used for the repair of DSB ends containing different levels of similarity, irreversible genomic changes can take place. Thus, when only one end of a DSB shares homology with other sequences in the genome, repair by HR can occur through a replication mechanism termed break-induced replication (BIR) that often gives rise to non-reciprocal translocations (NRTs) [6]–[9].

BIR requires HR canonical factors such as Rad52 and Rad51 to allow efficient strand invasion of the repair template and to form a Displacement-loop (D-loop) that can be extended by DNA synthesis from the invading 3′ DSB end [10], [11]. In the absence of another DSB end to capture the newly synthesized strand or to independently invade the homologous template, the strand invasion intermediate is thought to be converted into a DNA replication fork capable of replicating an entire chromosome arm until encountering a telomere, a centromere, or a converging replication fork [12]–[15]. A key factor in this process is Pol32, the non-essential subunit of DNA polymerase δ, which is dispensable for normal replication but essential for BIR [13]. Another feature of BIR is the unstable nature of its replication intermediates. It has been shown that DSB repair by BIR can occur through several rounds of strand invasion, synthesis, and dissociation from the invaded template [16]. Within dispersed repeated sequences, template switching during BIR can generate complex chromosomal rearrangements [16]–[21]. BIR reactions can also be aborted to end in half-crossovers [22], [23]. Half-crossovers cause NRTs, leaving the template that has been used for repair broken. They are similar to the NRTs observed in humans, which are involved in the cascade of genomic instability characteristic of human cancer cells [24].

Little is known about how BIR intermediates are processed to allow the establishment of a replication fork after strand invasion, and to cause template switching and half-crossovers. Eukaryotic cells have evolved a set of DNA structure-selective endonucleases (SSEs) that possess different substrate specificity for various DNA branched molecules during HR, such as D-loops, replication forks, flaps and Holliday junctions (HJs). Conversion of a D-loop into a replication fork during BIR may require the endonucleolytic resolution of a single Holliday junction [16], [25]. In budding yeast, Mus81-Mms4 and Yen1 are the only nuclear enzymes capable of cleaving intact HJs with high efficiency in vitro [26], [27]. In vivo, their functions seem to overlap during DSB repair [28]–[31]. Notably, Mus81-Mms4 is required for recombination-mediated DNA repair at replication forks [32]–[34] and has been shown to play a role in BIR intermediate processing [23]. Additionally, the Slx1–Slx4 nuclease complex may cleave perturbed replications forks [35]–[37]. Loss of Slx1–Slx4, as loss of Mus81-Mms4, increases the number of gross chromosomal rearrangements in yeast [38]. Slx4 also acts independently of the Slx1 catalytic subunit to interact with several other factors. For instance, Slx4 binds to the 3′ flap endonuclease complex Rad1–Rad10 to facilitate the removal of non-homologous tails during HR [39], [40]. Rad1–Rad10 complex, which functions in nucleotide excision repair (NER) as well as in DSB repair, has also been involved in the formation of translocations in yeast through a single-strand annealing (SSA) mechanism [41], [42]. Together, these SSEs form a complex network to ensure genome stability but their specific roles and their interactions at recombination structures remain unclear.

In this study, we used a new assay that generates chromosomal rearrangements after DSB repair using dispersed repeated sequences. Chromosomal rearrangements involved multiple rounds of template switching and some events ended in half-crossovers, generating NRTs. We investigated the role of SSEs in the processing of BIR intermediates combining mutations of Mus81, Rad1, Yen1, Slx1 and Slx4. Our results show that these SSEs act at multiple steps during BIR. First, we uncovered that Mus81 and Yen1 function to allow efficient BIR, thus causing translocations. In the absence of Mus81, Yen1 and Slx4, we observed that template switching during BIR decreased significantly. Altogether, our results led to new insights into the BIR mechanism and the functional role of SSEs in chromosomal rearrangements.

Results

A new assay for DSB–induced chromosomal rearrangements

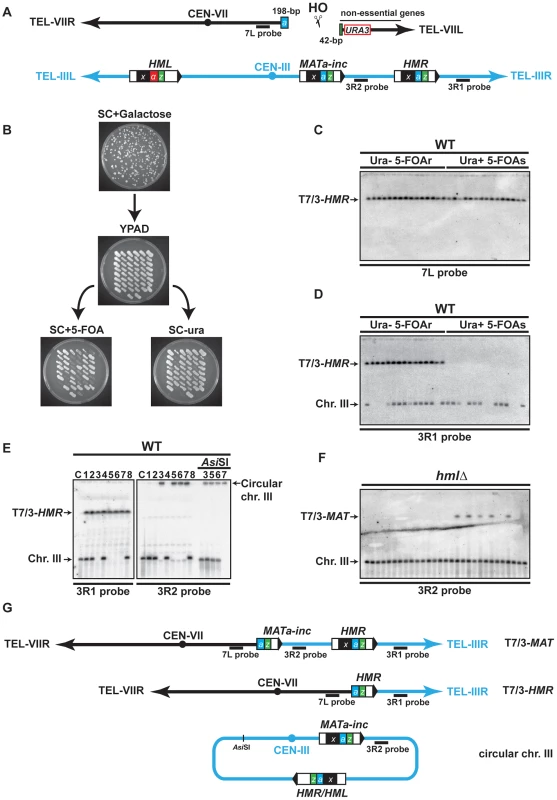

We designed an experimental system using DNA repeated sequences dispersed over two yeast chromosomes for the analysis of chromosomal rearrangements induced by a single DSB. We took advantage of the presence of the MAT, HMR and HML loci on chromosome III, involved in mating-type switching. The MAT locus is composed of five regions called W, X, Y, Z1 and Z2 [43]. MATa differs from MATα by the Ya and the Yα sequences, respectively. MATa shares Ya with HMR and MATα shares Yα with HML. Together, MAT, HMR and HML share two homologous regions flanking the Y sequences, termed X and Z1 (see Figure 1A). All three loci contain a cleavage site for the HO endonuclease at the junction between the Y and Z1 regions, but only the MAT locus is susceptible to being cleaved upon HO expression because of the active repression of HMR and HML loci [44]. The strains used in this study harbor a MATa-inc mutation, a G to A substitution at position Z1–2, which impedes HO cleavage at MAT [45], [46]. The HO endonuclease gene under control of the GAL1 inducible promoter was integrated at the ADE3 locus and a 240-bp Ya-Z1 fragment containing a HO-cleavable site, along with the URA3 marker, was inserted in the chromosome VII left arm at the ADH4 locus (Figure 1A). Upon galactose addition to the culture medium, HO would cleave this Ya-Z1 fragment asymmetrically into a centromeric 198-bp fragment and a telomeric 42-bp fragment (Figure 1A).

Fig. 1. Description of the assay used in this study.

(A) Schematic representation of chromosomes VII (black) and III (blue) in the haploid strain; X region (x, black box), Yα region (α, red box), Ya region (a, blue box) and Z1 region (z, green box) are indicated on chromosome III, as well as the Ya-Z1 fragment on chromosome VII. See text for more details. (B) Determination of translocation events. Cells were plated on solid synthetic medium containing galactose and survivor colonies were restreaked on rich YPAD medium containing glucose and subsequently replica-plated on SC+5-FOA and SC-ura. (C) (D) Translocations between chromosomes VII and III were detected by PFGE followed by Southern analysis using the 7L and the 3R1 probe (see panel A). Chromosomal DNA samples were extracted from previously selected Ura− 5-FOAr survivor colonies. (E) Detection of circular chromosome III after PFGE and Southern analysis. Chromosomes III that were not hybridized with the 3R1 probe were detected in the gel wells using 3R2 probe (see panel A). The DNA samples corresponding to circular chromosome III were digested with AsiSI to linearize chromosome III. C, control strain without translocation. (F) PFGE followed by Southern analysis using the 3R2 probe of Ura− 5-FOAr survivors in hmlΔ strain. Black arrows indicate the positions of the T7/3-MAT and the T7/3-HMR translocations and the circular and linear chromosomes III (Chr. III). PFGE, pulse-field gel electrophoresis. 5-FOAr and 5-FOAs refers to colonies either resistant or sensitive to 5-FOA. (G) Schematic representation of the predominant chromosomal rearrangements observed in this study. To assay DSB repair in this system, we plated cells on a synthetic medium (SC) with either 2% glucose or 2% galactose to assay survival after HO expression and successive breakage of chromosome VII. The WT strain exhibited a survival frequency of 82% (Figure S1), demonstrating efficient DSB repair. We restreaked survivor colonies from galactose-containing plates on glucose medium to repress HO expression. Then, survivors were concomitantly replica-plated on media lacking uracil and on media containing 5-FOA, a drug that generates a toxic metabolite in Ura+ cells, to distinguish between the colonies that maintained or lost the URA3 marker of chromosome VII (Figure 1B). We recollected Ura− 5-FOA-resistant (20%), Ura+ 5-FOA-sensitive (12%), and Ura+ 5-FOA-resistant colonies (68%). The latter contained both Ura+ and Ura− cells and may result from differential repair of two DSBs generated on sister chromatids during the S or G2 phase of the cell cycle. To analyze mixed Ura+ 5-FOA-resistant colonies, we first separated Ura+ cells from 5-FOA-resistant cells by restreaking colonies on media lacking uracil or containing 5-FOA. Further analyses of 5-FOA-resistant and Ura+ cells were performed by pulse-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) to look for chromosomal translocations. Southern analysis using a probe specific to chromosome VII, proximal to the DSB site, and a probe specific to the region between HMR locus and chromosome III telomere (7L probe and 3R1 probe, respectively, Figure 1A) revealed the presence of non-reciprocal translocations (NRTs) between chromosome VII and chromosome III in all 5-FOA-resistant cells (Figure 1C, 1D, and Figure S2A, S2B). NRTs were rarely observed in Ura+ cells (Figure S2B). Given a survival rate of 82%, the frequency of translocants (frequency of 5-FOA-resistant survivors among the whole population that did not undergo DSB induction) was 44% in the WT strain. We mainly observed two types of NRTs, which contained chromosome III sequences starting from the MAT or HMR loci to the telomere fused to chromosome VII at the break site (termed T7/3-MAT and T7/3-HMR translocations for more clarity, Figure 1G).

Interestingly, some survivors lacked linear chromosome III at its expected size in the PFGE analysis (Figure 1D, 1E). When we used a probe specific to the region between MAT and HMR loci (3R2 probe, Figure 1A), chromosome III was detected in the well, consistent with a particular structure that did not allow it to enter the gel (Figure 1E). One possibility was that chromosome III became circular, as had been observed more than three decades ago [47], [48]. To test this, we digested chromosomal DNA with AsiSI, which cuts chromosome III at a unique inner location. Indeed, AsiSI digestion released chromosome III into the gel (Figure 1E). Circular chromosomes III have been shown to be the product of recombination between unrepressed HMR and HML loci, which share extensive homology in the X and Z1 regions (Figure 1A) [47]. We observed that the size of the AsiSI linearized chromosome was concordant with a chromosome III that would have lost all subtelomeric sequences located beyond the HM loci. To further demonstrate that circular chromosomes III occurred by recombination between HMR and HML, we assayed whether chromosome III circularization would be seen in hmlΔ cells. We observed that, in the absence of HML locus, all survivors contained a linear chromosome III at its expected size (Figure 1F).

Chromosome III circularization pushed us to investigate the occurrence of a DSB at HMR. HMR is naturally packed into heterochromatin to repress its expression and also to impede cleavage by HO [44]. We asked if HMR invasion would release its repression and cause HO cleavage. We first assayed HMR cleavage by Southern at several times after induction of chromosome VII cleavage by HO and did not observe any cuts in the WT (Figure S3C). We only detected HMR cleavage in a hmlΔ matΔ strain, in which HMR cleavage represented about a third of chromosome VII cleavage by HO (17% versus 46% after 3 h of induction; Figure S3B, S3C). Indeed HMR cleavage was dependent on cleavage at chromosome VII since no cuts were observed in the hmlΔ matΔ strain without HO cut site on chromosome VII (Figure S3D). We concluded that the induction of a single DSB by HO in chromosome VII permitted another less efficient DSB in chromosome III at the HMR locus as a secondary event. The efficiency of HMR cleavage is expected to be even less than 17% in the WT strain since the MATa-inc locus is also available as a template for strand invasion in this strain. HMR cleavage likely induced chromosome III circularization, which we observed in 50% of translocants in the WT strain. Apart from T7/3-MAT, T7/3-HMR translocations and chromosome III circularization, we also observed rare types of rearrangements of chromosome VII and III whose nature has not been addressed in this study.

Together, these results demonstrate that complex chromosomal rearrangements are occurring at a high frequency in our experimental system, allowing us to investigate the molecular and genetic bases of these events.

DSB repair involves template switching between MATa-inc, HMR, and HML

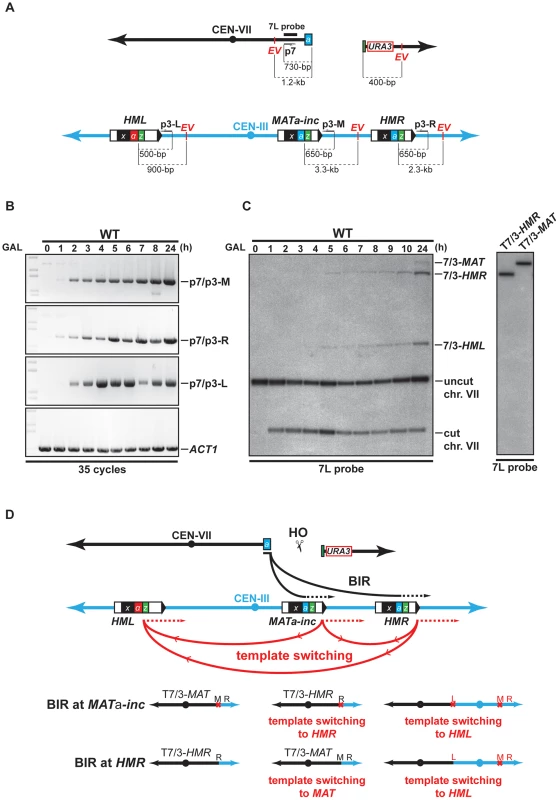

We performed kinetic experiments to follow the recombination intermediates that gave rise to chromosomal rearrangements using our system. First, a PCR-based assay was used to monitor new DNA synthesis primed from the 3′ end of the invading strand of chromosome VII. Genomic DNA was extracted at different times after HO induction and PCR was made with one primer specific to chromosome VII (p7, Figure 2A), proximal to the DSB, and primers specific to each potential template used for recombination, MATa-inc and HMR (p3-M and p3-R, Figure 2A). In WT cells, 35 cycles of PCR amplification permitted to detect products that most likely correspond to newly synthesized DNA fragments at both MAT and HMR loci 1 h after DSB induction (Figure 2B). Using more quantitative conditions, we detected the same products after 25 cycles of PCR amplification at 2 h of DSB induction (Figure S4). The amount of products increased over time. We then monitored the appearance of repair intermediates directly by Southern analysis of genomic DNA digested by EcoRV, using a probe specific to chromosome VII, proximal to the DSB site (7L probe). We detected recombination intermediates between chromosome VII and chromosome III at HMR (7/3-HMR, Figure 2C, left), which most likely correspond to newly synthesized DNA fragments 5 h after DSB induction. At MAT, we observed recombination intermediates 24 h after DSB induction (7/3-MAT, Figure 2C, left).

Fig. 2. Template switching occurs between MATa-inc, HMR, and HML loci.

(A) Schematic representation of chromosomes VII and III showing the positions of the PCR primers, EcoRV sites (EV) and the 7L probe used for the analysis. Distances between the primers and EcoRV sites and the HO cut sites are indicated. (B) Appearance of BIR repair product, as monitored by PCR, in the WT strain. DNA samples used for PCR were extracted at intervals after HO induction with galactose. PCR reactions were performed with the p7 primer and either the p3-M, p3-R or p3-L primer (see panel A). A primer pair corresponding to ACT1 locus on chromosome VI was used to control the amount of genomic DNA used for PCR at each time point. 35 cycles of PCR amplifications were performed. (C) Appearance of BIR repair products, as monitored by Southern analysis with the 7L probe, in the WT strain. DNA samples were extracted as for the PCR assay. Positions of the bands corresponding to 7/3-MAT, 7/3-HMR and 7/3-HML intermediates, and to the uncut and cut chromosome VII (chr. VII) are indicated. Two genomic DNA samples coming from survivor colonies containing T7/3-MAT and T7/3-HMR translocations were included in the experiment. GAL, galactose; h, hours. (D) Schematic representation of BIR events involving template switching likely occurring in our assay. Black arrows indicate the first invasion events while red arrows indicate the secondary template switching events. The different possible final outcomes are depicted. The red cross indicates the presence of inc non-cleavable sequences. M; MAT; R, HMR; L, HML. See text for more details. Southern analysis also detected an unexpected band that corresponded in size to chromosome VII fused to chromosome III sequences at the HML locus (7/3-HML, Figure 2C, left). We confirmed this assumption by re-probing the Southern membrane with a probe specific to HML (data not shown). The 7/3-HML band most likely corresponds to newly synthesized DNA fragments primed from chromosome VII DSB end at HML and appeared concomitantly with 7/3-HMR intermediates 5 h after DSB induction (Figure 2C). We monitored what was most likely new DNA synthesis primed from the 3′ DSB end of chromosome VII invading HML by PCR. We detected intermediates 2 h after DSB induction (p7/p3-L, Figure 2B, Figure S4). The DSB end of chromosome VII assayed by PCR and Southern only shares sequence homology with MATa-inc and HMR. Hence, the signals detected at HML would be the consequence of a template switching from MATa-inc or HMR to HML after duplication of the Z1 region that is common to the three loci. In a similar way, template switching could occur between MATa-inc and HMR. 7/3-HMR and 7/3-HML intermediates detected by Southern appeared about 3–4 h after detection of priming of the 3′ invading DSB end by PCR (Figure 2B, 2C). This difference could be due to the difference of sensitivity between the two techniques. Alternatively, this could reflect a transition between the elongation of the 3′ invading DSB end, a step that is common to GC and BIR, and the establishment of an active replication fork required for BIR [11], [14]. Using translocants containing T7/3-MAT and T7/3-HMR translocations, we confirmed the size of the repair intermediates detected by Southern (Figure 2C, right). We did not recover any translocant containing translocations corresponding to repair intermediates detected at HML.

Together, these data show that one unique feature of our experimental system is that it allows the detection of events of template switching between MATa-inc and HML and possibly between MATa-inc and HMR during chromosomal rearrangement. These events of template switching likely participated to give rise to the formation of T7/3-MAT and T7/3-HMR translocations and dicentric chromosomes resulting from BIR completed from HML (Figure 2D). Because dicentric chromosomes are known to be unstable [49], this may be why we could not detect such type of chromosomal rearrangement. We noted that BIR initiation at HMR by the broken chromosome VII would restore an HO cleavable site that might not be properly silenced in the resulting translocations. In the latter case, HO cleavage would destabilize these translocations and their stabilization would require repair by gene conversion (GC) using the non-cleavable sequences at MATa-inc.

Mus81 and Yen1 promote chromosomal rearrangements

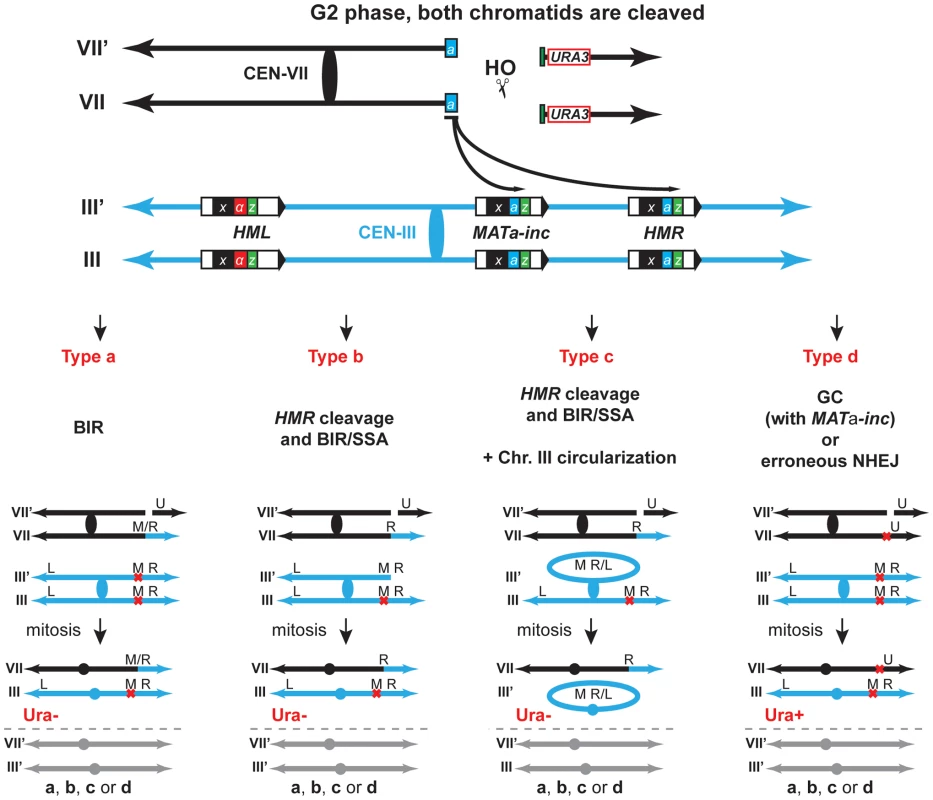

Observed chromosomal rearrangements likely occurred by BIR through the invasion of the MATa-inc and HMR loci. Homology of the centromeric 198-bp Ya-Z1 fragment present at one DSB end would be used to invade MATa-inc or HMR loci at the Ya region and to duplicate chromosome III sequences until reaching its right telomere, generating T7/3-MAT and T7/3-HMR NRTs (type a, Figure 3). Alternatively, since we observed the cleavage of chromosome III as a consequence of HMR invasion, it is also possible that T7/3-HMR translocations occurred by BIR followed by single-strand annealing (SSA), co-segregating with an intact chromosome III (type b, Figure 3). Finally, cleaved chromosome III could circularize and co-segregate with the translocation (type c, Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Various pathways give rise to chromosomal rearrangements.

Schematic representation of the different types of repair giving rise to the chromosomal rearrangements scored in this study. Repair of DSBs in G2 can occur either by BIR, BIR/SSA following HMR cleavage with/without circularization of chromosome III, gene conversion (GC) or erroneous NHEJ. The repair types of only one DSB are depicted for simplification. The other DSBs are repaired via either one of the different types. VII, VII′ and III, III′ indicate chromosome VII and chromosome III sister-chromatids, respectively. U, URA3; M; MAT; R, HMR; L, HML; M/R, MAT or HMR. See text for more details. To confirm genetically the involvement of BIR in the generation of translocations using our experimental system, we assayed mutants of Rad52, Rad51 and Pol32 as representative key functions in BIR. Next, we asked whether DNA nucleases acting on branched structures such as D-loops, replication forks or HJs would have a role in the cascade of recombination events that led to translocations. We chose to study the genetic role of Mus81, Rad1, Yen1, Slx1 and Slx4 because of their known functions in recombination processes [25]. Because none of the genes coding for these SSEs are essential for viability, we assayed deletion mutants and combined mutants between them to assay redundancy of functions. Although Slx1 and Slx4 form a heterodimer complex, such as Mus81-Mms4 and Rad1–Rad10, we decided to study slx1Δ and slx4Δ mutations separately because Slx4 seems to have additional roles in DSB repair apart from regulating the Slx1 nuclease activity [50], [51]. We also included the DNA helicase Sgs1 because of its known role in HJ dissolution (Figure 4A).

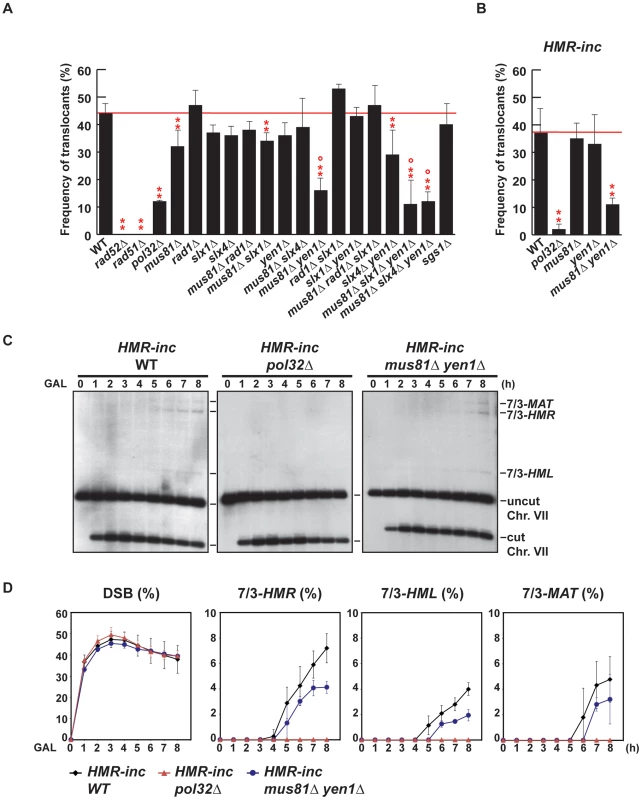

Fig. 4. Genetic analysis of BIR intermediates processing in SSE mutants.

(A) (B) Frequency of translocants of the different strains tested. See Material and Methods for details. ** and *, differences with the WT statistically significant (p<0.01 and p<0.05, respectively, χ2 with Yates' correction) °, statistically different from mus81Δ (p<0.01, χ2 with Yates' correction). Error bars represent standard deviations. (C) Appearance of BIR products as monitored by Southern analysis in HMR-inc WT, HMR-inc pol32Δ and HMR-inc mus81Δ yen1Δ strains. Experiments were performed as described in Figure 2C. A representative Southern analysis is shown for each genotype analyzed. Positions of the bands corresponding to 7/3-MAT, 7/3-HMR and 7/3-HML intermediates, and to the uncut and cut chromosome VII (Chr. VII) are indicated. GAL, galactose; h, hours. (D) Quantification of BIR product accumulation. Quantification results of chromosome VII cleavage (DSB), 7/3-HMR, 7/3-HML and 7/3-MAT BIR intermediates are shown as percentage. Mean values and standard deviations for 2–3 independent experiments are shown. For each mutant assayed, we recovered survivors after HO endonuclease induction and selected colonies that contained translocations between chromosome VII and chromosome III, as described above (5-FOA-resistant colonies). We did not recover any translocants in rad52Δ and rad51Δ mutants, in which strand invasion fails to occur (Figure 4A). POL32 deletion reduced 4-fold the frequency of translocations in comparison with the WT (χ2, p<0.01), arguing in favor of the involvement of the Pol32-dependent BIR pathway in the generation of the translocations analyzed in this study. We did not observe any increase of translocations in sgs1Δ cells, even though SGS1 gene had been identified as a suppressor of translocations involving template switching events [19]. Among the nuclease single mutants, only mus81Δ showed a slight but significant decrease in the frequency of translocants (χ2, p<0.01) when compared to the WT. In contrast, we observed significant decreases in the frequency of translocants between the WT, mus81Δ rad1Δ and mus81Δ rad1Δ slx1Δ mutants, but these effects were found to be epistatic with mus81Δ (Figure 4A; χ2, p<0.01). On the contrary, we observed further significant decreases (χ2, p<0.01) in mus81Δ yen1Δ mutants, of about 3.5-fold and 2.5-fold compared to the WT and mus81Δ, respectively (Figure 4A). We conclude that Mus81 and Yen1 are both required for translocations in our assay.

Since it existed the possibility that the translocations were also produced by BIR/SSA, we assayed translocation formation in an HMR-inc strain, in which HMR locus would not be susceptible to HO cleavage and translocations would only be produced by BIR. We observed that survival dropped from 82% in the original HMR WT strain to 52% in the HMR-inc WT strain, although the frequency of translocants remained around 40% (Figure 4B and Figure S1). In the control HMR-inc background, POL32 deletion reduced 18.5-fold the frequency of translocations in comparison with the WT (Figure 4B; χ2, p<0.01). This result demonstrates a clear dependency of translocations on the Pol32-dependent BIR pathway in this background. We observed a significant decrease of 3.4-fold in HMR-inc mus81Δ yen1Δ mutants compared to the HMR-inc WT but no decrease in the HMR-inc mus81Δ and HMR-inc yen1Δ single mutants (Figure 3B; χ2, p<0.01). These results indicate that Mus81 and Yen1 have overlapping functions in BIR. To confirm this, we performed time-course experiments to monitor the kinetics of appearance of BIR intermediates in these mutants (Figure 4C). Kinetics of DSB formation in the mutants was similar to the WT, allowing us to directly compare the accumulation of BIR intermediates at each time point (Figure 4D). In HMR-inc WT cells, 7/3-HMR and 7/3-HML intermediates appeared 4 h and 5 h after DSB induction, respectively (Figure 4C, 4D). 7/3-MAT intermediates were detected 6 h after DSB induction (Figure 4C, 4D), showing that their delayed appearance in the original HMR WT strain was partly due to HMR cleavage. No BIR intermediate could be detected in HMR-inc pol32Δ cells (Figure 4C, 4D). In HMR-inc mus81Δ yen1Δ cells, a decrease of BIR intermediates was reproducibly observed at all time points (Figure 4C, 4D). We concluded that Mus81 and Yen1 are both required for promoting efficient Pol32-dependent BIR.

Template switching is affected in structure-selective endonuclease mutants

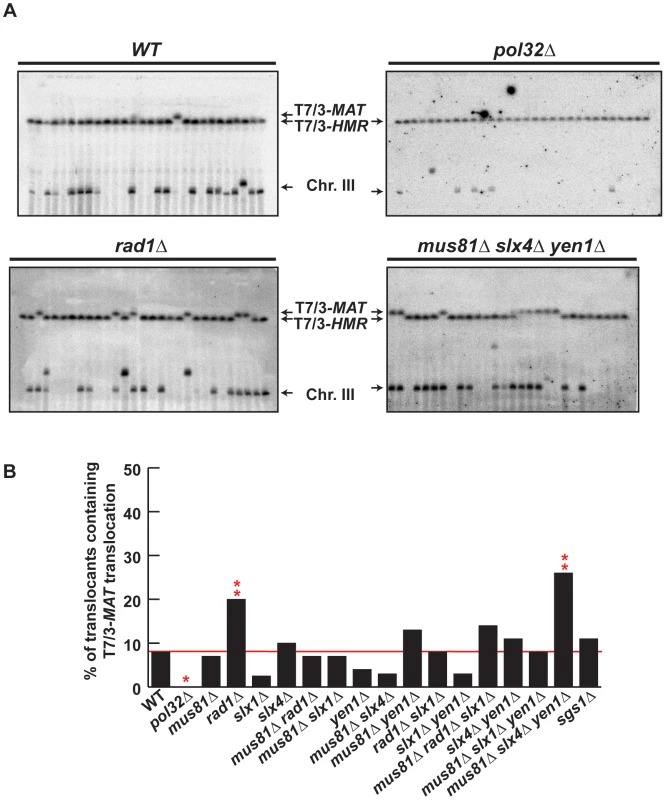

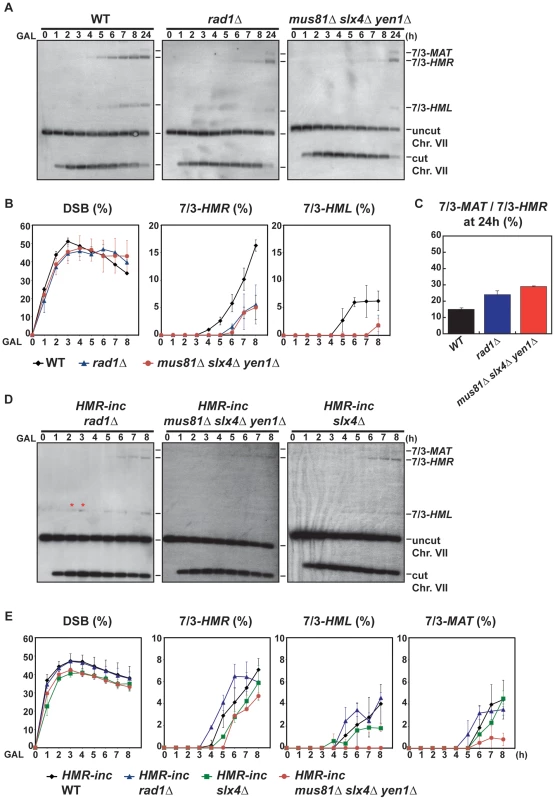

We confirmed by PFGE that all 5-FOA-resistant survivors analyzed in mutant backgrounds contained chromosome translocations between chromosome VII and chromosome III (Figure 5A and Figures S5, S6). Notably, a very low amount of T7/3-MAT translocations (8%) were recovered in WT cells (Figure 5B). In pol32Δ cells, no T7/3-MAT translocation was recovered (n = 59, χ2, p<0.05), showing that this type of translocation has a complete dependency on Pol32 (Figure 5A, 5B). Among the nuclease mutants, rad1Δ showed a significant increase of T7/3-MAT translocations, up to 20% of total translocations (2.5-fold, n = 59, χ2, p<0.01), which was not observed in double mutants with mus81Δ and slx1Δ (Figure 5A, 5B). The concomitant absence of Mus81, Slx4 and Yen1 engendered an even higher increase (3.1-fold) of T7/3-MAT translocations that reached up to 25% of total translocations (n = 58, χ2, p<0.01) (Figure 5A, 5B). In kinetic experiments, both 7/3-HMR and 7/3-HML intermediates accumulated in the rad1Δ and mus81Δ slx4Δ yen1Δ mutants with kinetics clearly delayed (2–3 h) respect to the WT, demonstrating a defect of repair in these mutants (Figure 6A, 6B). At 24 h, signals for 7/3-HMR, 7/3-HML and 7/3-MAT that likely correspond to final repair products were detected in all strains. Notably, we observed a clear increase in the 7/3-MAT/7/3-MAT ratio, up to 24% and 29% in rad1Δ and mus81Δ slx4Δ yen1Δ, respectively, compared to the 15% seen in the WT (Figure 6C). This observation correlated with the increase of T7/3-MAT translocations previously observed in these mutants (Figure 5B).

Fig. 5. PFGE analysis of T7/3 translocations in SSE mutants.

(A) PFGE followed by Southern analysis using the 3R1 probe (See Figure 1G) of Ura− 5-FOAr survivors in WT, pol32Δ, rad1Δ and mus81Δ slx4Δ yen1Δ strains. Black arrows indicate the positions of the T7/3-MAT and T7/3-HMR translocations and of the linear chromosome III (Chr. III). PFGE, pulse-field gel electrophoresis. (B) Graphical plotting of percent of translocants containing T7/3-MAT translocations of each strain tested. ** and *, differences with the WT statistically significant (p<0.01 and p<0.05, respectively, χ2 with Yates' correction). See Table S1 for complete statistical analysis. Fig. 6. Template switching is affected in mus81Δ slx4Δ yen1Δ but not in rad1Δ mutants.

(A) Appearance of BIR repair products, as monitored by Southern analysis, in WT, rad1Δ and mus81Δ slx4Δ yen1Δ strains. Experiments were performed as described in Figure 2C. (B) Quantification of BIR product accumulation. Quantification results for chromosome VII cleavage (DSB), 7/3-HMR and 7/3-HML BIR intermediate accumulation are shown in percent. (C) Quantification of 7/3-MAT/7/3-HMR BIR intermediate ratios 24 h after HO induction. Mean values and standard deviations for 2–3 independent experiments are shown. (D) Appearance of BIR repair products, as monitored by Southern analysis, in HMR-inc rad1Δ, HMR-inc mus81Δ slx4Δ yen1Δ and HMR-inc slx4Δ strains. (E) Quantification of BIR product accumulation. Quantification results for chromosome VII cleavage (DSB), 7/3-HMR, 7/3-HML and 7/3-MAT BIR intermediate accumulation are shown in percent. Mean values and standard deviations for 2–3 independent experiments are shown. A representative Southern analysis is shown for each genotype analyzed. Positions of the bands corresponding to 7/3-MAT, 7/3-HMR and 7/3-HML intermediates, and to the uncut and cut chromosome VII (Chr. VII) are indicated. Bands marked with a red asterisk likely result from partial digestion. GAL, galactose; h, hours. The defects observed in rad1Δ and mus81Δ slx4Δ yen1Δ mutants could be explained by the known functions of Rad1 and Slx4 in SSA [50], which would be required for T7/3-HMR translocation formation by BIR/SSA. Indeed, in the control HMR-inc WT strain, the T7/3-MAT translocations represented about 55% of the translocations observed in 5-FOA-resistant survivors (Figure S7B). These results confirmed that the cleavage of the HMR locus upon its invasion in the HMR WT strain facilitated the formation of T7/3-HMR translocations as opposed to T7/3-MAT translocations. Additionally, possible cleavage of HMR upon the passage of the BIR fork initiated at MATa-inc impaired the formation of T7/3-MAT translocations. Nevertheless, slx4Δ single mutants did not show any increase of T7/3-MAT translocations and mus81Δ slx4Δ yen1Δ mutants showed a higher increase of T7/3-MAT translocations than rad1Δ mutants (Figure 5B). We hypothesized that this was due to a processing defect of BIR intermediates formed at MATa-inc that impeded subsequent template switching to HMR and HML. To explore this possibility, we analyzed the kinetics of appearance of BIR intermediates in mus81Δ slx4Δ yen1Δ mutants, as well as in the rad1Δ and slx4Δ single mutants, in the HMR-inc background (Figure 6D, 6E). In HMR-inc strains, BIR/SSA does not occur and the accumulation of 7/3-HML intermediates serves as an indicator of the efficiency of template switching during BIR. In contrast to the HMR-inc rad1Δ and HMR-inc slx4Δ mutants, which did not show any significant difference compared to the HMR-inc WT strain, 7/3-HML intermediates were reproducibly not detected at all time points in HMR-inc mus81Δ slx4Δ yen1Δ mutants. Accumulation of 7/3-HMR and 7/3-MAT intermediates was also significantly lower in the latter strain, probably reflecting the BIR defect previously observed in HMR-inc mus81Δ yen1Δ cells.

Altogether, these data indicate that DSB repair was altered in cells lacking Rad1, defective in BIR/SSA, and in cells lacking all three SSE factors Mus81, Slx4 and Yen1 that show a defect of template switching during BIR.

Chromosome III circularization and crossover activity

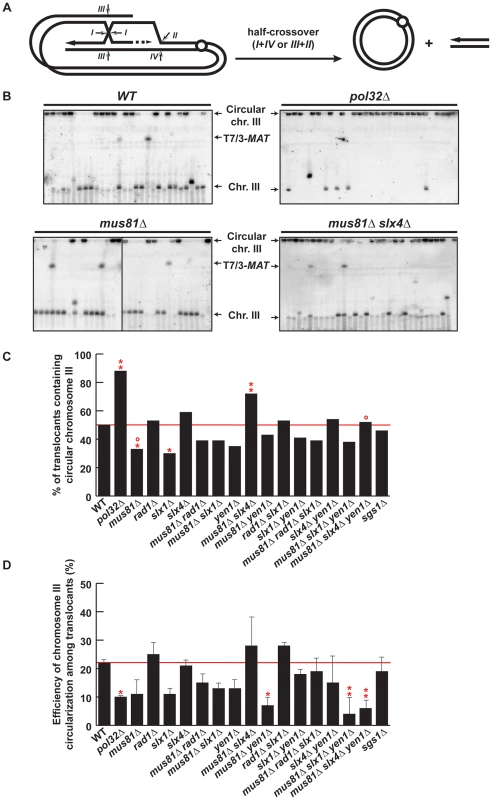

Among the chromosomal rearrangements generated in our strains, circularization of chromosome III occurred at a high frequency. No chromosome III circularization was observed in the control HMR-inc WT strain (Figure S7B), demonstrating that HMR cleavage induced this secondary recombination event (type c, Figure 3). HMR cleavage and translocations via BIR/SSA would leave chromosome III with a one-ended DSB. Thus, circularization of chromosome III is thought to occur by a recombination event that ended in a half-crossover, characterized by a reciprocal exchange between HMR and HML that caused the loss of the chromosome III left telomere and the formation of a chromosome circle (Figure 7A). Circularization of chromosome III is not mandatory for survival of BIR/SSA-mediated translocants since the translocation can co-segregate with the uninvolved chromatid of chromosome III (type b, Figure 3). Therefore, we took advantage of chromosome III circularization events to investigate the ability of SSE mutant cells to produce half-crossovers.

Fig. 7. PFGE analysis of chromosome III circularization in SSE mutants.

(A) Schematic representation of circularization of chromosome III by BIR plus half-crossover. Arrows indicate different ways of intermediate cleavage. (B) PFGE followed by Southern analysis using the 3R2 probe (See Figure 1G) of Ura− 5-FOAr survivors in WT, pol32Δ, mus81Δ, slx4Δ, mus81Δ slx4Δ and mus81Δ slx4Δ yen1Δ strains. Black arrows indicate the positions of T7/3-MAT translocations, and the circular and linear chromosomes III (Chr. III). PFGE, pulse-field gel electrophoresis. (C) Graphical plotting of percent of translocants containing circular chromosome III for each strain tested. (D) Frequency of chromosome III circularization among translocants. ** and *, differences with the WT statistically significant (p<0.01 and p<0.05, respectively, χ2 with Yates' correction) °, differences with mus81Δ slx4Δ statistically significant (p<0.01, χ2 with Yates' correction). Error bars represent standard deviations. See Table S1 for complete statistical analysis. PFGE analyses allowed us to detect circular chromosome III in all strains as signals appearing in the wells (Figure 7B and Figures S8, S9). In addition to the well signal, we also detected in some strains a faint signal for the truncated linear chromosome III. This faint signal corresponds in size to the circular chromosome III cleaved by AsiSI (Figure 1E). Since we did not find any linkage between the presence of this signal and a particular genetic background, we conclude that this is likely due to breakage occurring during DNA extraction or PFGE. To get further insight into the mechanism that gave rise to circular chromosomes, we have evaluated the percent of translocants that contained circular versus linear chromosomes III for each genotype (Figure 7C). Whereas about 50% of WT translocants contained a circular chromosome III, this percent increased significantly to 88% (n = 59, χ2, p<0.01) in pol32Δ mutants (Figure 7B, 7C). This result is concordant with previous observations showing that pol32Δ defects led to D-loop processing during BIR that generated half-crossovers [22], [23]. Among the SSE mutants tested, the proportion of translocants containing circular chromosomes III decreased significantly to 33% and 30% in mus81Δ and slx1Δ mutants, respectively (χ2, p<0.05) (Figure 7B, 7C). In contrast to this observation, the percentage of translocants containing circular chromosomes III increased significantly up to 72% in mus81Δ slx4Δ double mutants (χ2, p<0.01) (Figure 7B, 7C). These results suggest that Mus81 and Slx4 have different roles regarding crossover formation. Additionally, we observed that yen1Δ mutation suppressed the increase detected in mus81 slx4Δ mutants, suggesting that Yen1 action may be possible only in the absence of Slx4. We conclude that Slx4, which has been described as acting as a platform with different nuclease complexes [52], might regulate Mus81 and Yen1 accessibility to recombination intermediates or their nuclease activity to generate crossovers.

We also analyzed chromosome III circularization in Ura+ survivors, which did not contain translocations and likely performed DSB repair by GC or NHEJ (Figure S10). Analogously to what we observed in the Ura− translocants, 36% of WT Ura+ survivors contained a circular chromosome III and this percentage increased significantly to 90% in pol32Δ mutants (Figure S10E). This suggests that chromosome III circularization does not depend on the translocation event and happens similarly in all survivors whether Ura+ or Ura−. Finally, we calculated the efficiency of chromosome III circularization for each genotype (Figure 7D). Pol32 appears to be required for efficient chromosome III circularization since the calculated efficiency went down significantly from 22% in WT to 10% in pol32Δ translocants (χ2, p<0.05) (Figure 7D). This probably explains the low survival of pol32Δ mutants to the DSB induction (Figure S1). Similarly, we observed a significant decrease in the efficiency of chromosome III circularization in mus81Δ yen1Δ mutants (Figure 7D). This is consistent with the conclusion that Mus81 and Yen1 play an important role in the formation of the majority of circular chromosomes III.

Discussion

We developed an assay to study the molecular mechanisms that lead to complex chromosomal rearrangements upon induction of a DSB. DSB repair occurred by recombination between repeated DNA sequences dispersed over two different chromosomes and generated translocations and circularization of chromosomes at a high frequency. Our data indicate that chromosomal rearrangements occurred primarily by BIR, a HR sub-pathway that involves the invasion of an intact homologous DNA duplex by only one end of the DSB and subsequent replication primed from the invading strand. We have shown with this assay that the structure-selective endonuclease (SSE) factors Mus81, Yen1, and Slx4 may process recombination intermediates at different steps during BIR and cause template switching and half-crossovers.

In our assay, induction of the HO endonuclease produced a DSB on chromosome VII. Translocants can only be detected if both chromatids were broken in G2 phase (Figure 3), otherwise the DSB would be preferentially repaired by sister-chromatid recombination [53], [54], restoring the HO cut site. DSB ends on chromosome VII display homology to MAT and HMR loci that is mainly restricted to one end (198-bp out of 240-bp). As previously described, this feature favors DSB repair by BIR against a conventional gene conversion mechanism [11]. The centromeric 198-bp DSB end would invade MAT or HMR at the Ya region and prime BIR synthesis to produce the observed translocations, which contained chromosome III sequences from MAT or HMR to the telomere fused to chromosome VII at the break site, termed T7/3-MAT and T7/3-HMR translocations. Consequently, the loss of the chromosome VII arm, distal to the DSB and containing the URA3 marker and non-essential genes, would lead to the 5-FOA-resistant (Ura−) phenotype of the translocants (type a, Figure 3). Eventually, the URA3 marker could be used to convert the endogenous ura3-1 allele on chromosome V and lead to the rarely observed Ura+ cells containing translocations (Figure S2B). Alternatively, secondary cleavage of HMR upon its invasion would promote repair by BIR/SSA and the production of the same types of translocations (type b, Figure 3). HMR cleavage would stimulate the circularization of chromosome III, which could co-segregate with the translocation (type c, Figure 3). Repair by BIR/SSA and chromosome III circularization do not happen in the HMR-inc background. The latter observation discards the possibility that the T7/3 translocations were the products of half-crossovers, with the translocation co-segregating with the uninvolved chromatid of chromosome III (analogous to type b, Figure 3), since breakage of chromosome III would stimulate its circularization. Lastly, DSB repair by GC with inc non-cleavable sequences or by erroneous NHEJ could seal the break leading to a mutated and non-cleavable form of HO site without chromosomal rearrangement and would maintain the URA3 marker on chromosome VII. This would lead to the formation of Ura+ survivors. (type d, Figure 3). Altogether, the differential repair of both DSBs on chromosome VII chromatids gave rise to the observed Ura+/Ura− phenotypes of survivor colonies.

Absence of Pol32 impedes template switching and forces crossover formation

An important aspect that remains unclear is the apparent instability of the BIR fork, which may be cleaved during its advance, promoting template switching or producing half-crossovers. All essential DNA replication factors except those for pre-replication complex assembly are required for BIR [14], playing in favor of fork stability. However, the DNA damage checkpoint is activated during BIR and dNTP levels are elevated to facilitate repair, which is thought to happen in the G2 phase of the cell cycle [11], [13], [55]. Consequently, DNA synthesis during BIR has been found to be highly inaccurate [56] and replication fork progression may be perturbed by the absence of S phase-specific factors. Interestingly, the nonessential DNA polymerase δ subunit Pol32 seems to represent a key factor for BIR completion but performs a function that is still unknown. In our assay, we observed that pol32Δ mutants had a clear defect in producing translocations, but not as strong as the one observed in rad52Δ and rad51Δ mutants (Figure 4A), confirming that some translocations were produced via BIR/SSA, in which extensive DNA synthesis would not be required. However, Pol32 became essential for translocations in the absence of HMR cleavage in the control HMR-inc strains (Figure 4B). In these strains, we could not detect any BIR intermediate (Figure 4C), meaning that Pol32 is required for DNA synthesis of few kilobases and that the latter was necessary for template switching. Surprisingly, we observed in pol32Δ survivors an extremely high level of chromosome III circularization, even in Ura+ survivors that likely repaired the DSB on chromosome VII by GC or NHEJ (Figure 7 and Figure S10). This would mean that DSBs induced at HMR could not be repaired by HR with MATa-inc sequences in pol32Δ cells. Indeed, preferential formation of crossovers between MAT and HMR would lead to the extrusion of genes essential for viability, whereas crossovers between HMR and HML would lead to the formation of stable circular chromosomes. Preferential processing of recombination intermediates into crossovers in pol32Δ mutants have been reported in other studies, in which BIR events were aborted and resulted in half-crossovers [22], [23].

Mus81 and Yen1 redundantly promote BIR

We determined the role of SSEs in the generation of chromosomal rearrangements using our assay as the goal to identify the nucleases that are required during BIR. Overall, we observed a significant decrease of chromosomal rearrangements in mus81Δ single mutants that was aggravated in mus81Δ yen1Δ mutants (Figure 4A). We have confirmed that the frequency of translocants only decreased in the mus81Δ yen1Δ mutants in the HMR-inc background (Figure 4B), in which BIR, and not BIR/SSA, is expected to occur. This indicates that Mus81 may play a role in BIR/SSA and that Mus81 functions can be fully taken over by other proteins during BIR. However, our data show that both Mus81 and Yen1 carry out redundant or equivalent activities, which are needed for BIR completion. Mus81 and Yen1 have already been implicated in DSB repair by recombination but not directly in BIR. Mus81 has been shown to act at replication forks. It has been proposed that Mus81 could cleave stalled forks but also to participate in recombination-mediated repair of cleaved or collapsed forks to allow their restart in yeast and humans [32]–[34], [57]. Mus81 is also required in humans for telomere recombination to allow proliferation of telomerase-negative cancer cells [58]. Formally, both mechanisms of replication fork restart and telomere recombination are equivalent to BIR. Yen1 roles in recombination have been revealed in the absence of Mus81. While yen1Δ mutants are repair proficient, mus81Δ yen1Δ double mutants exhibit a higher sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents that disturb replication fork progression than mus81Δ mutants [28], [30], [31]. Together, these data point out that Mus81 and Yen1 may promote a replication fork restart mechanism. In vitro, Yen1 is a specialized Holliday junction resolvase [26] whereas the Mus81-Mms4 complex prefers branched DNA substrates that contain a discontinuity or a nick adjacent to the branch point, but also cleaves normal HJs [27], [59]–[61]. Here, we have demonstrated genetically that both Mus81 and Yen1 were required for efficient BIR. According to previously published data, we propose that Mus81 and Yen1 would act to establish the replication fork required for BIR by processing recombination intermediates such as D-loops or HJs. Nevertheless, BIR still occurred at a low frequency in mus81Δ yen1Δ mutants, suggesting that other factors could promote this critical step of BIR in the absence of Mus81 and Yen1.

Interplay between Slx4, Mus81, and Yen1 causes template switching and half-crossovers

Our results are consistent with additional roles of Mus81 and Yen1 in later steps of BIR. We have demonstrated that Mus81, Slx4 and Yen1 were required together for efficient template switching during BIR. The mus81Δ slx4Δ yen1Δ mutants showed an increased occurrence of T7/3-MAT translocations (Figure 5B), which we infer as being partly due to a defect in template switching from MAT to the HM loci (Figure 6). However, we did not observe any increase of T7/3-MAT in mus81Δ slx1Δ yen1Δ mutants, even though Slx1 is the catalytic subunit of Slx1-Slx4 nuclease heterodimer. On the contrary, we observed a WT or decreased level of T7/3-MAT translocations in all slx1Δ mutants. We concluded that Slx4 and Slx1 act independently in BIR, presumably because of Slx4 additional functions apart from Slx1 at the replication fork [51], [62], [63]. Regarding the involvement of SSEs in half-crossover production, the absence of Mus81 or Slx1 significantly decreased the amount of circular chromosomes III among translocants (Figure 7C). Notably, no further decrease was observed when removing Mus81, Slx1/Slx4 or Yen1, all of which have been involved in crossover formation during meiosis in yeast [64], [65]. This could be due to the involvement of other nucleases such as Mlh3 and Exo1, as recently reported during the revision of this manuscript [65].

Our assay does not permit a direct analysis of the role of SSEs in half-crossover since the formation of circular chromosomes III is limited by the frequencies of translocations, template switching and HMR cleavage. In principle, HML could also be cleaved upon invasion so that an HMR/HML double cleavage could lead to a circular chromosome III by an SSA-like mechanism. However, this hypothesis is not supported by our results as we observed a similar frequency of circular chromosomes III in rad1Δ mutants and WT. Instead, circularization of chromosome III via SSA would generate a heterologous single-stranded DNA overhang that would require Rad1 for its removal [66] and, indeed, we have observed a requirement of Rad1 in the formation of T7/3-HMR translocations via BIR/SSA in our assay (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Despite the limitations of our assay, our genetic data suggest an interesting interaction between Mus81, Yen1 and Slx4 SSEs. Whereas mus81Δ translocants showed a decrease in the frequency of circular chromosomes III, mus81Δ slx4Δ translocants showed a significant increase, which was suppressed in the additional absence of Yen1 (Figure 7C). These results suggest that Slx4 may have a specific role in regulating the ability of Mus81 and Yen1 to catalyze half-crossovers. It has been previously shown that Mus81 is involved in half-crossovers following BIR [23] and that Mus81 and Yen1 independently promote crossovers during gene conversion, Yen1 serving as a backup function in mus81Δ cells [30]. However, here we uncover two parallel pathways, one using Mus81 and Slx4 and the other Yen1. This is in agreement with a similar involvement recently described for these nucleases in two pathways of crossover formation during sister-chromatid recombination [67]. It remains unclear how Slx4 may regulate Mus81 and Yen1. A recent cell-cycle analysis of Mus81-Mms4 and Yen1 revealed that their catalytic activities are regulated by phosphorylation events. In mitotic cells, Mus81-Mms4 is hyperactivated by Cdc5-mediated phosphorylation at G2/M while Yen1 is activated later by dephosphorylation in M phase [27]. Nevertheless, it remains unknown if Yen1 can be activated earlier in the absence of Mus81 or upon DSB induction. Mec1/Tel1 kinases phosphorylate Slx4 in response to DNA damage [50], [51] and may participate in modulating context-specific protein interactions between Slx4, Mus81 and Yen1 and allow substrate accessibility to activated Mus81 and Yen1. Altogether, our results suggest that Slx4 plays a central role during BIR. Slx4 may regulate Mus81 and Yen1, whose cleavage activities are required for replication fork establishment and could either cause template switching or half-crossovers.

In the case of one-ended DSBs, it has been proposed that dynamic displacement of the invading strand out of the D-loop would contribute to template switching [16]. This implies that the invading strand would be displaced early during BIR, after a short tract of DNA synthesis. Nevertheless, events of template switching have been observed in later steps of BIR, as far as 10-kb downstream of the site of invasion [16], [23]. Such a synthesis would expose long tracts of single-stranded DNA if it were the result of the sole extension of the invading strand. Despite the fact that such long single-stranded DNA tails have been involved in gene conversion events monitored in mitotic gap repair assays, we propose that, at some point, priming of lagging strand synthesis would ensure a better protection of the recombination intermediates, safeguarding genome stability. Thus, we propose that template switching events would happen after the establishment of the BIR fork and priming of lagging strand synthesis. In vitro data showed that canonical replication forks are among the preferred substrates of Mus81-Mms4 and Yen1 [25], [68], therefore we propose that Mus81, Slx4 and Yen1 would act on the replication fork during BIR to cause template switching and half-crossovers.

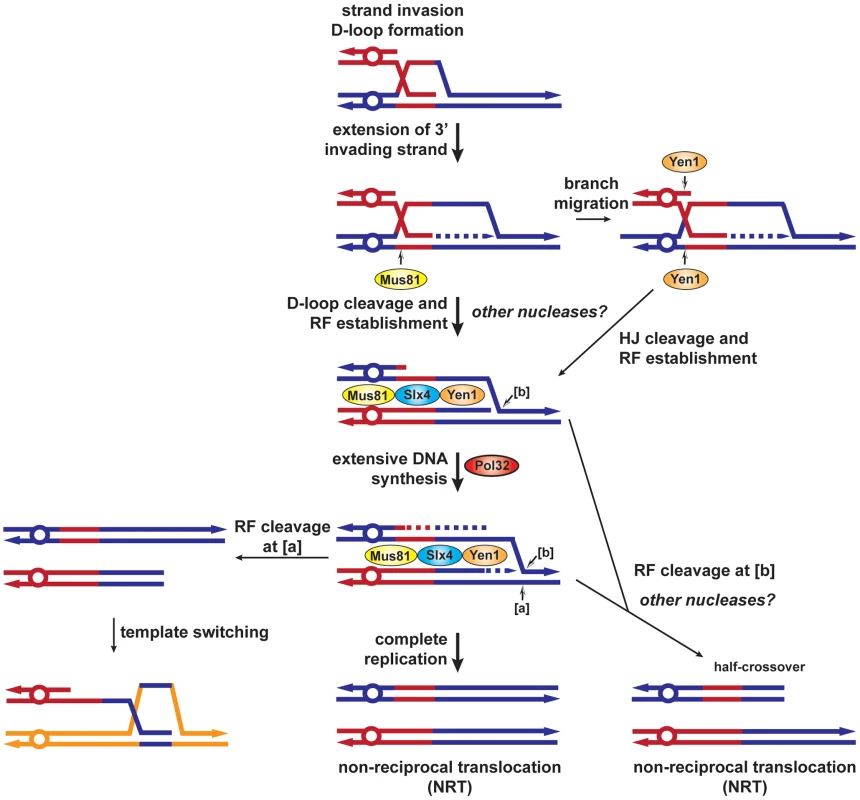

An integrated model to explain BIR–mediated chromosomal rearrangements and the role of structure-selective endonucleases

Our results together with previous data permit us to propose a new model for BIR and the role of the different SSEs used in this study (Figure 8). During HR, priming of synthesis from the 3′ invading end extends the initial D-loop and failure to capture the other DSB end would promote BIR. We propose that Mus81 would cleave the extended D-loop structure to allow the establishment of a replication fork. In the absence of Mus81, branch migration of the D-loop would create an intact Holliday junction, which could be processed by Yen1 with the same outcome. Pol32 would promote extensive DNA synthesis and complete replication would generate a non-reciprocal translocation (NRT). We propose that the BIR fork could stall and be processed by Mus81-Slx4-Yen1 to cause template switching ([a], Figure 8). Differential cleavage of the BIR fork by Mus81-Slx4-Yen1 would terminate BIR at the expense of a half-crossover ([b], Figure 8).

Fig. 8. BIR model showing SSEs involvement in template switching and half-crossovers.

After invasion of the homologous template by one end of the DSB, a D-loop is formed and extended by the priming of DNA synthesis from the invading strand 3′ end. The D-loop can be specifically cleaved by Mus81 or branch migrated to create a HJ cleavable by Yen1, to establish a replication fork. Extensive replication, which requires Pol32, would complete BIR and generate a non-reciprocal translocation (NRT). Alternatively, [a] cleavage of the replication fork by Mus81-Slx4-Yen1 would allow re-invasion of the same template or template switching. [b] cleavage of the replication fork by Mus81-Slx4-Yen1 would terminate the BIR event, causing a half-crossover (NRT). RF, replication fork, HJ, Holliday junction. Altogether, this work brings a clearer view about the involvement of SSEs in the BIR mechanism of DSB repair. Importantly, we show that SSEs are involved in replication template switching and half-crossovers, which generate complex chromosomal rearrangements and prolonged cycles of genomic instability. Such events are thought to be at the origin of various genomic disorders and cancer development [24], [69].

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains and plasmids

All Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast strains used in this study are in W303-1a background (his3-11, 15 leu2-3, 112, trp1-1 ura3-1 ade2-1 can1-100 rad5-535) [70] and harbor MATa-inc, ade3Δ::gal-HO and leu2Δ::SFA1 alleles [53]. The MATa-inc HMR-inc strain was obtained by mating-type switching inducing HO expression in a MATα HMR-inc strain. Independent survivors to HO expression were selected and the MAT and HMR loci were sequenced to verify the MATa-inc HMR-inc genotype. Deletion mutants were either obtained by the PCR-based gene replacement method (verified by PCR and Southern) or by genetic crosses (verified by tetrad analysis). Deletion of MAT is only partial (matΔYZ) because of the presence of other genes overlapping with MAT. Only the Y and Z sequences, containing the HO cut site, have been removed. Insertion of a HO-cleavable 240-bp HMR fragment at the ADH4 locus has been conducted as follows. Two 5′ and 3′ADH4 fragments were amplified by PCR with the following primer pairs ADH4-5′#1 GCGCGCGGTACCGAATTCAAACCGCTGATTACATCAAA and ADH4-5′#2 GCGCGCAGATCTATCGATCTCGAGTCTAGACTAGACCAGTAGCAGCAGTC, and ADH4-3′#1 GCGCGCAGATCTGCTAGCACTAGTGGATCCCTTAGTCGCTGCATACAAAG and ADH4-3′#2 GCGCGCGAGCTCGAATTCGCACACGCATAATTGACGTT. These two fragments were cloned by the gap repair method in pBluescript II(SK+) previously digested by KpnI and SacI to create pBP99 plasmid. A BglII-BamHI URA3 containing fragment from sp392 plasmid [71] was then cloned in pBP99 digested with BglII to create pBP102. Finally, the HMR fragment was amplified from genomic DNA with the primer pair HO-HMR-Hind3 GCGCGCAAGCTTCAACCACTCTACAAAACCAAAACCA and HO-HMR-Nhe1 GCGCGCGCTAGCAGAAGAAGTTGCAAAGAAATGTGGC and cloned into pBP102 after digestion with HindIII and NheI, to create pBP102-HO. pBP102-HO was linearized with PvuII and transformed into yeast. Integration was selected by uracile prototrophy and verified by PCR and Southern analysis.

Determination of survival and translocation frequencies

Yeast cells were grown in yeast extract-peptone-adenine-dextrose (YPAD) until reaching the exponential phase of growth, appropriately diluted with H2O and plated on synthetic complete (SC) medium containing either 2% glucose or 2% galactose as a carbon source. Survivor colonies on galactose-containing plates were then restreaked on YPAD plates and replica-plated on SC plates containing 5-FOA (USBiological), a drug that generates a toxic metabolite in Ura+ cells, or on SC plates lacking uracil. Frequencies were calculated as follows: survival frequency = cfu galactose/cfu glucose; translocants frequency = (cfu galactose Ura−5-FOAr+(cfu galactose Ura+5-FOAr)/2)/cfu glucose. 96 to 288 survivor colonies, recovered from 2 to 3 independent induction experiments, were analyzed for each strain tested. Statistical analysis was performed using the χ2 test with Yates' correction.

Kinetic analysis of BIR intermediates by PCR and Southern analysis

Yeast cells were grown at 30°C in liquid YPAD until reaching the exponential phase of growth, washed twice with synthetic complete medium SGL (3% glycerol, 2% lactate) and cultured overnight in SGL until reaching an OD600 nm≈0.5 when galactose was added at a final concentration of 2%. Cells were taken at different times after galactose induction and genomic DNA was extracted in agarose plugs according to standard procedures. Agarose plugs were incubated twice in 200 µl 1× β-Agarase I reaction buffer for 30 min, melted at 65°C for 10 min, equilibrated at 42°C for 15 min and treated with β-Agarase I (New England BioLabs) at 42°C for 1 h before PCR amplification. These were performed with 250 ng of genomic DNA (estimated with NanoDrop, Thermo Scientific) in a total volume of 30 µl in the following conditions: 1× Phusion HF buffer, 200 µM each dNTP, 0.6 U Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes), 0.5 µM each primer. Samples were denatured for 45 s at 98°C, then cycled 25–35 times with 20 s denaturation (98°C), 30 s annealing (57°C) and 45 s extension (72°C) followed by a final extension step of 5 min at 72°C. PCR was performed with primer p7 GCACACGCATAATTGACGTT and primers p3-M GAAGACTTGTGGCGAAGA, p3-R CCAACATTTAGGAAAAAACG or p3-L CGGATGGCACAAGGAACACGCATTT. Control PCR was performed with primers corresponding to ACT1 locus, ACT1up TTCACGCTTACTGCTTTTTTC and ACT1low CAAGGCGACGTAACATAGTTT. PCR products were subjected to gel electrophoresis in 0.8% agarose and stained with ethidium bromide. Instead of β-Agarase I treatment, plugs were digested with 30 U of EcoRV restriction enzyme for 5 h at 37°C and loaded in a 1% agarose gel for Southern analysis. Electrophoresis was run at 80 V for 16 h30 and DNA was transferred into Hybond-XL membranes (GE Healthcare) in alkaline conditions. Membranes were probed with dCT32P-labelled PCR fragments obtained with ADH4-3′#1 and ADH4-3′#1 primers (7L probe). Quantification of DNA signals was made relative to the total DNA of each lane and was performed using ImageGauge 4.2 (Fujifilm) program.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis

For each strain, 28 to 84 independent Ura - 5-FOAr survivor colonies were grown in 2,5 ml of YPAD medium overnight at 30°C. Agarose plugs containing chromosomal DNA were made according to the manufacturer's instructions (Bio-Rad). AsiSI digestion was performed incubating agarose plugs twice in 1 ml 1× NEBuffer 4 for 30 min and digested in 200 µl 1× NEBuffer 4 with 30 U of AsiSI restriction enzyme for 5 h (New England Biolabs). Agarose gels (0.9%) were run in a Bio-Rad CHEF MapperXA apparatus for 16 h at 6 V/cm with a switch time of 70 s and for an additional 12 h at 6 V/cm with a switch time of 120 s. Then, gels were stained with ethidium bromide and DNA was transferred into Hybond-XL membranes (GE Healthcare) in alkaline conditions. Membranes were probed with dCT32P-labelled PCR fragments obtained with primers ADH7#1 TGTTGGCTAAAGCTATGG and ADH7#2 TTCTTCGCTGATCGG (3R1 probe), ARS315#1 AAACCAGTCTTTAACCGCCATAATG and ARS315#2 CAGAGCCCAAGAGATAGCCGAACTT (3R2 probe), and with primers HML+HMR-F CAAACATCTTAGTAGTGTCTGAGGA and HML+HMR-R CTGTAATTTACCTAAGTTACCAGAG (X probe). Chromosomal rearrangements different from T7/3-MAT or T7/3-HMR translocations or circular chromosomes III and revealed by the PFGE analysis were not included in the statistical analyses.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. ChenJM, CooperDN, FerecC, Kehrer-SawatzkiH, PatrinosGP (2010) Genomic rearrangements in inherited disease and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 20 : 222–233.

2. AgarwalS, TafelAA, KanaarR (2006) DNA double-strand break repair and chromosome translocations. DNA Repair (Amst) 5 : 1075–1081.

3. RichardsonC, JasinM (2000) Frequent chromosomal translocations induced by DNA double-strand breaks. Nature 405 : 697–700.

4. KhannaKK, JacksonSP (2001) DNA double-strand breaks: signaling, repair and the cancer connection. Nat Genet 27 : 247–254.

5. RothkammK, LobrichM (2002) Misrepair of radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks and its relevance for tumorigenesis and cancer treatment (review). Int J Oncol 21 : 433–440.

6. BoscoG, HaberJE (1998) Chromosome break-induced DNA replication leads to nonreciprocal translocations and telomere capture. Genetics 150 : 1037–1047.

7. KangLE, SymingtonLS (2000) Aberrant double-strand break repair in rad51 mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 20 : 9162–9172.

8. AguileraA (2001) Double-strand break repair: are Rad51/RecA–DNA joints barriers to DNA replication? Trends Genet 17 : 318–321.

9. McEachernMJ, HaberJE (2006) Break-induced replication and recombinational telomere elongation in yeast. Annu Rev Biochem 75 : 111–135.

10. DavisAP, SymingtonLS (2004) RAD51-dependent break-induced replication in yeast. Mol Cell Biol 24 : 2344–2351.

11. MalkovaA, NaylorML, YamaguchiM, IraG, HaberJE (2005) RAD51-dependent break-induced replication differs in kinetics and checkpoint responses from RAD51-mediated gene conversion. Mol Cell Biol 25 : 933–944.

12. MorrowDM, ConnellyC, HieterP (1997) “Break copy” duplication: a model for chromosome fragment formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 147 : 371–382.

13. LydeardJR, JainS, YamaguchiM, HaberJE (2007) Break-induced replication and telomerase-independent telomere maintenance require Pol32. Nature 448 : 820–823.

14. LydeardJR, Lipkin-MooreZ, SheuYJ, StillmanB, BurgersPM, et al. (2010) Break-induced replication requires all essential DNA replication factors except those specific for pre-RC assembly. Genes Dev 24 : 1133–1144.

15. HashimotoY, PudduF, CostanzoV (2012) RAD51 - and MRE11-dependent reassembly of uncoupled CMG helicase complex at collapsed replication forks. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19 : 17–24.

16. SmithCE, LlorenteB, SymingtonLS (2007) Template switching during break-induced replication. Nature 447 : 102–105.

17. LeeJA, CarvalhoCM, LupskiJR (2007) A DNA replication mechanism for generating nonrecurrent rearrangements associated with genomic disorders. Cell 131 : 1235–1247.

18. RuizJF, Gomez-GonzalezB, AguileraA (2009) Chromosomal translocations caused by either Pol32-dependent or Pol32-independent triparental break-induced replication. Mol Cell Biol 29 : 5441–5454.

19. SchmidtKH, ViebranzE, DoerflerL, LesterC, RubensteinA (2010) Formation of complex and unstable chromosomal translocations in yeast. PLoS ONE 5: e12007 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012007.

20. LiuP, ErezA, NagamaniSC, DharSU, KolodziejskaKE, et al. (2011) Chromosome catastrophes involve replication mechanisms generating complex genomic rearrangements. Cell 146 : 889–903.

21. ZhangF, KhajaviM, ConnollyAM, TowneCF, BatishSD, et al. (2009) The DNA replication FoSTeS/MMBIR mechanism can generate genomic, genic and exonic complex rearrangements in humans. Nat Genet 41 : 849–853.

22. DeemA, BarkerK, VanhulleK, DowningB, VaylA, et al. (2008) Defective break-induced replication leads to half-crossovers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 179 : 1845–1860.

23. SmithCE, LamAF, SymingtonLS (2009) Aberrant double-strand break repair resulting in half crossovers in mutants defective for Rad51 or the DNA polymerase delta complex. Mol Cell Biol 29 : 1432–1441.

24. SabatierL, RicoulM, PottierG, MurnaneJP (2005) The loss of a single telomere can result in instability of multiple chromosomes in a human tumor cell line. Mol Cancer Res 3 : 139–150.

25. SchwartzEK, HeyerWD (2011) Processing of joint molecule intermediates by structure-selective endonucleases during homologous recombination in eukaryotes. Chromosoma 120 : 109–127.

26. IpSC, RassU, BlancoMG, FlynnHR, SkehelJM, et al. (2008) Identification of Holliday junction resolvases from humans and yeast. Nature 456 : 357–361.

27. MatosJ, BlancoMG, MaslenS, SkehelJM, WestSC (2011) Regulatory Control of the Resolution of DNA Recombination Intermediates during Meiosis and Mitosis. Cell 147 : 158–172.

28. BlancoMG, MatosJ, RassU, IpSC, WestSC (2010) Functional overlap between the structure-specific nucleases Yen1 and Mus81-Mms4 for DNA-damage repair in S. cerevisiae. DNA Repair (Amst) 9 : 394–402.

29. TayYD, WuL (2010) Overlapping roles for Yen1 and Mus81 in cellular Holliday junction processing. J Biol Chem 285 : 11427–11432.

30. HoCK, MazonG, LamAF, SymingtonLS (2010) Mus81 and Yen1 promote reciprocal exchange during mitotic recombination to maintain genome integrity in budding yeast. Mol Cell 40 : 988–1000.

31. AgmonN, YovelM, HarariY, LiefshitzB, KupiecM (2011) The role of Holliday junction resolvases in the repair of spontaneous and induced DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res 39 : 7009–7019.

32. FrogetB, BlaisonneauJ, LambertS, BaldacciG (2008) Cleavage of stalled forks by fission yeast Mus81/Eme1 in absence of DNA replication checkpoint. Mol Biol Cell 19 : 445–456.

33. RoseaulinL, YamadaY, TsutsuiY, RussellP, IwasakiH, et al. (2008) Mus81 is essential for sister chromatid recombination at broken replication forks. Embo J 27 : 1378–1387.

34. DoeCL, AhnJS, DixonJ, WhitbyMC (2002) Mus81-Eme1 and Rqh1 involvement in processing stalled and collapsed replication forks. J Biol Chem 277 : 32753–32759.

35. KaliramanV, BrillSJ (2002) Role of SGS1 and SLX4 in maintaining rDNA structure in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet 41 : 389–400.

36. CoulonS, NoguchiE, NoguchiC, DuLL, NakamuraTM, et al. (2006) Rad22Rad52-dependent repair of ribosomal DNA repeats cleaved by Slx1-Slx4 endonuclease. Mol Biol Cell 17 : 2081–2090.

37. CoulonS, GaillardPH, ChahwanC, McDonaldWH, YatesJR3rd, et al. (2004) Slx1-Slx4 are subunits of a structure-specific endonuclease that maintains ribosomal DNA in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell 15 : 71–80.

38. ZhangC, RobertsTM, YangJ, DesaiR, BrownGW (2006) Suppression of genomic instability by SLX5 and SLX8 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair (Amst) 5 : 336–346.

39. TohGW, SugawaraN, DongJ, TothR, LeeSE, et al. (2010) Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation of Slx4 stimulates Rad1-Rad10-dependent cleavage of non-homologous DNA tails. DNA Repair (Amst) 9 : 718–726.

40. LyndakerAM, GoldfarbT, AlaniE (2008) Mutants defective in Rad1-Rad10-Slx4 exhibit a unique pattern of viability during mating-type switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 179 : 1807–1821.

41. HwangJY, SmithS, MyungK (2005) The Rad1-Rad10 complex promotes the production of gross chromosomal rearrangements from spontaneous DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 169 : 1927–1937.

42. PannunzioNR, MantheyGM, BailisAM (2010) RAD59 and RAD1 cooperate in translocation formation by single-strand annealing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet 56 : 87–100.

43. HaberJE (1998) Mating-type gene switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Genet 32 : 561–599.

44. LustigAJ (1998) Mechanisms of silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Opin Genet Dev 8 : 233–239.

45. NickoloffJA, SingerJD, HeffronF (1990) In vivo analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae HO nuclease recognition site by site-directed mutagenesis. Mol Cell Biol 10 : 1174–1179.

46. WeiffenbachB, RogersDT, HaberJE, ZollerM, RussellDW, et al. (1983) Deletions and single base pair changes in the yeast mating type locus that prevent homothallic mating type conversions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 80 : 3401–3405.

47. KlarAJ, StrathernJN, HicksJB, PrudenteD (1983) Efficient production of a ring derivative of chromosome III by the mating-type switching mechanism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 3 : 803–810.

48. StrathernJN, NewlonCS, HerskowitzI, HicksJB (1979) Isolation of a circular derivative of yeast chromosome III: implications for the mechanism of mating type interconversion. Cell 18 : 309–319.

49. ThrowerDA, BloomK (2001) Dicentric chromosome stretching during anaphase reveals roles of Sir2/Ku in chromatin compaction in budding yeast. Mol Biol Cell 12 : 2800–2812.

50. FlottS, AlabertC, TohGW, TothR, SugawaraN, et al. (2007) Phosphorylation of Slx4 by Mec1 and Tel1 regulates the single-strand annealing mode of DNA repair in budding yeast. Mol Cell Biol 27 : 6433–6445.

51. FlottS, RouseJ (2005) Slx4 becomes phosphorylated after DNA damage in a Mec1/Tel1-dependent manner and is required for repair of DNA alkylation damage. Biochem J 391 : 325–333.

52. FekairiS, ScaglioneS, ChahwanC, TaylorER, TissierA, et al. (2009) Human SLX4 is a Holliday junction resolvase subunit that binds multiple DNA repair/recombination endonucleases. Cell 138 : 78–89.

53. Gonzalez-BarreraS, Cortes-LedesmaF, WellingerRE, AguileraA (2003) Equal sister chromatid exchange is a major mechanism of double-strand break repair in yeast. Mol Cell 11 : 1661–1671.

54. KadykLC, HartwellLH (1992) Sister chromatids are preferred over homologs as substrates for recombinational repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 132 : 387–402.

55. ChabesA, GeorgievaB, DomkinV, ZhaoX, RothsteinR, et al. (2003) Survival of DNA damage in yeast directly depends on increased dNTP levels allowed by relaxed feedback inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase. Cell 112 : 391–401.

56. DeemA, KeszthelyiA, BlackgroveT, VaylA, CoffeyB, et al. (2011) Break-induced replication is highly inaccurate. PLoS Biol 9: e1000594 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000594.

57. HanadaK, BudzowskaM, DaviesSL, van DrunenE, OnizawaH, et al. (2007) The structure-specific endonuclease Mus81 contributes to replication restart by generating double-strand DNA breaks. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14 : 1096–1104.

58. ZengS, XiangT, PanditaTK, Gonzalez-SuarezI, GonzaloS, et al. (2009) Telomere recombination requires the MUS81 endonuclease. Nat Cell Biol 11 : 616–623.

59. EhmsenKT, HeyerWD (2008) Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mus81-Mms4 is a catalytic, DNA structure-selective endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res 36 : 2182–2195.

60. EhmsenKT, HeyerWD (2009) A junction branch point adjacent to a DNA backbone nick directs substrate cleavage by Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mus81-Mms4. Nucleic Acids Res 37 : 2026–2036.

61. FrickeWM, Bastin-ShanowerSA, BrillSJ (2005) Substrate specificity of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mus81-Mms4 endonuclease. DNA Repair (Amst) 4 : 243–251.

62. OhouoPY, Bastos de OliveiraFM, AlmeidaBS, SmolkaMB (2010) DNA damage signaling recruits the Rtt107-Slx4 scaffolds via Dpb11 to mediate replication stress response. Mol Cell 39 : 300–306.

63. RobertsTM, KoborMS, Bastin-ShanowerSA, IiM, HorteSA, et al. (2006) Slx4 regulates DNA damage checkpoint-dependent phosphorylation of the BRCT domain protein Rtt107/Esc4. Mol Biol Cell 17 : 539–548.

64. De MuytA, JessopL, KolarE, SourirajanA, ChenJ, et al. (2012) BLM helicase ortholog Sgs1 is a central regulator of meiotic recombination intermediate metabolism. Mol Cell 46 : 43–53.

65. ZakharyevichK, TangS, MaY, HunterN (2012) Delineation of joint molecule resolution pathways in meiosis identifies a crossover-specific resolvase. Cell 149 : 334–347.

66. IvanovEL, HaberJE (1995) RAD1 and RAD10, but not other excision repair genes, are required for double-strand break-induced recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 15 : 2245–2251.

67. Munoz-GalvanS, TousC, BlancoMG, SchwartzEK, EhmsenKT, et al. (2012) Distinct roles of mus81, yen1, slx1-slx4, and rad1 nucleases in the repair of replication-born double-strand breaks by sister chromatid exchange. Mol Cell Biol 32 : 1592–1603.

68. RouseJ (2009) Control of genome stability by SLX protein complexes. Biochem Soc Trans 37 : 495–510.

69. ZhangF, CarvalhoCM, LupskiJR (2009) Complex human chromosomal and genomic rearrangements. Trends Genet 25 : 298–307.

70. ZouH, RothsteinR (1997) Holliday junctions accumulate in replication mutants via a RecA homolog-independent mechanism. Cell 90 : 87–96.

71. Frank-VaillantM, MarcandS (2001) NHEJ regulation by mating type is exercised through a novel protein, Lif2p, essential to the ligase IV pathway. Genes Dev 15 : 3005–3012.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Genome-Wide Association Study for Serum Complement C3 and C4 Levels in Healthy Chinese SubjectsČlánek Role of Transposon-Derived Small RNAs in the Interplay between Genomes and Parasitic DNA in RiceČlánek Tetraspanin Is Required for Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species by the Dual Oxidase System inČlánek An Essential Role of Variant Histone H3.3 for Ectomesenchyme Potential of the Cranial Neural CrestČlánek A Mimicking-of-DNA-Methylation-Patterns Pipeline for Overcoming the Restriction Barrier of BacteriaČlánek A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Five Loci Influencing Facial Morphology in Europeans

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 9- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Hypogonadotropní hypogonadismus u žen a vliv na výsledky reprodukce po IVF

- Molekulární vyšetření pro stanovení prognózy pacientů s chronickou lymfocytární leukémií

- Prof. Petr Urbánek: Potřebujeme najít pacienty s nediagnostikovanou akutní intermitentní porfyrií

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Heterozygous Mutations in DNA Repair Genes and Hereditary Breast Cancer: A Question of Power

- GWAS of Diabetic Nephropathy: Is the GENIE out of the Bottle?

- The Conflict within and the Escalating War between the Sex Chromosomes

- Proteome-Wide Analysis of Disease-Associated SNPs That Show Allele-Specific Transcription Factor Binding

- Exome Sequencing Identifies Rare Deleterious Mutations in DNA Repair Genes and as Potential Breast Cancer Susceptibility Alleles

- A Gene Family Derived from Transposable Elements during Early Angiosperm Evolution Has Reproductive Fitness Benefits in

- Genome-Wide Association Study for Serum Complement C3 and C4 Levels in Healthy Chinese Subjects

- Role of Transposon-Derived Small RNAs in the Interplay between Genomes and Parasitic DNA in Rice

- Co-Evolution of Mitochondrial tRNA Import and Codon Usage Determines Translational Efficiency in the Green Alga

- SIRT6/7 Homolog SIR-2.4 Promotes DAF-16 Relocalization and Function during Stress

- CNV Formation in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells Occurs in the Absence of Xrcc4-Dependent Nonhomologous End Joining

- Tetraspanin Is Required for Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species by the Dual Oxidase System in

- Citrullination of Histone H3 Interferes with HP1-Mediated Transcriptional Repression

- Variation in Genes Related to Cochlear Biology Is Strongly Associated with Adult-Onset Deafness in Border Collies

- The Long Non-Coding RNA Affects Chromatin Conformation and Expression of , but Does Not Regulate Its Imprinting in the Developing Heart

- Rif2 Promotes a Telomere Fold-Back Structure through Rpd3L Recruitment in Budding Yeast

- Is a Metastasis Susceptibility Gene That Suppresses Metastasis by Modifying Tumor Interaction with the Cell-Mediated Immunity

- The p38/MK2-Driven Exchange between Tristetraprolin and HuR Regulates AU–Rich Element–Dependent Translation

- Rare Copy Number Variants Contribute to Congenital Left-Sided Heart Disease

- A Genetic Basis for a Postmeiotic X Versus Y Chromosome Intragenomic Conflict in the Mouse

- An Essential Role of Variant Histone H3.3 for Ectomesenchyme Potential of the Cranial Neural Crest

- Characterization of Inducible Models of Tay-Sachs and Related Disease

- Hominoid-Specific Protein-Coding Genes Originating from Long Non-Coding RNAs

- Transcriptional Repression of Hox Genes by HP1/HPL and H1/HIS-24

- Integrative Genomic Analysis Identifies Isoleucine and CodY as Regulators of Virulence

- Convergence of the Transcriptional Responses to Heat Shock and Singlet Oxygen Stresses