-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

An Essential Role of Variant Histone H3.3 for Ectomesenchyme Potential of the Cranial Neural Crest

The neural crest (NC) is a vertebrate-specific cell population that exhibits remarkable multipotency. Although derived from the neural plate border (NPB) ectoderm, cranial NC (CNC) cells contribute not only to the peripheral nervous system but also to the ectomesenchymal precursors of the head skeleton. To date, the developmental basis for such broad potential has remained elusive. Here, we show that the replacement histone H3.3 is essential during early CNC development for these cells to generate ectomesenchyme and head pigment precursors. In a forward genetic screen in zebrafish, we identified a dominant D123N mutation in h3f3a, one of five zebrafish variant histone H3.3 genes, that eliminates the CNC–derived head skeleton and a subset of pigment cells yet leaves other CNC derivatives and trunk NC intact. Analyses of nucleosome assembly indicate that mutant D123N H3.3 interferes with H3.3 nucleosomal incorporation by forming aberrant H3 homodimers. Consistent with CNC defects arising from insufficient H3.3 incorporation into chromatin, supplying exogenous wild-type H3.3 rescues head skeletal development in mutants. Surprisingly, embryo-wide expression of dominant mutant H3.3 had little effect on embryonic development outside CNC, indicating an unexpectedly specific sensitivity of CNC to defects in H3.3 incorporation. Whereas previous studies had implicated H3.3 in large-scale histone replacement events that generate totipotency during germ line development, our work has revealed an additional role of H3.3 in the broad potential of the ectoderm-derived CNC, including the ability to make the mesoderm-like ectomesenchymal precursors of the head skeleton.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 8(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002938

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002938Summary

The neural crest (NC) is a vertebrate-specific cell population that exhibits remarkable multipotency. Although derived from the neural plate border (NPB) ectoderm, cranial NC (CNC) cells contribute not only to the peripheral nervous system but also to the ectomesenchymal precursors of the head skeleton. To date, the developmental basis for such broad potential has remained elusive. Here, we show that the replacement histone H3.3 is essential during early CNC development for these cells to generate ectomesenchyme and head pigment precursors. In a forward genetic screen in zebrafish, we identified a dominant D123N mutation in h3f3a, one of five zebrafish variant histone H3.3 genes, that eliminates the CNC–derived head skeleton and a subset of pigment cells yet leaves other CNC derivatives and trunk NC intact. Analyses of nucleosome assembly indicate that mutant D123N H3.3 interferes with H3.3 nucleosomal incorporation by forming aberrant H3 homodimers. Consistent with CNC defects arising from insufficient H3.3 incorporation into chromatin, supplying exogenous wild-type H3.3 rescues head skeletal development in mutants. Surprisingly, embryo-wide expression of dominant mutant H3.3 had little effect on embryonic development outside CNC, indicating an unexpectedly specific sensitivity of CNC to defects in H3.3 incorporation. Whereas previous studies had implicated H3.3 in large-scale histone replacement events that generate totipotency during germ line development, our work has revealed an additional role of H3.3 in the broad potential of the ectoderm-derived CNC, including the ability to make the mesoderm-like ectomesenchymal precursors of the head skeleton.

Introduction

The development of multipotent, migratory NC cells was a key step in the evolution of many of the vertebrate-specific features of the head [1]. CNC cells generate the skeleton of the face and anterior skull, as well as supporting development of the brain and sense organs. NC arises from NPB ectoderm and gives rise to neurons, glia, and pigment cells along nearly the entire anterior-posterior extent of the embryo, yet CNC has a greater potential than trunk NC to generate ectomesenchymal cell types such as facial skeletal precursors [2]–[5]. Whereas we know more about how neuroglial and pigment cell types are specified, how the CNC is able to generate ectomesenchymal derivatives has remained unclear [6]. In particular, the ectomesenchyme derives from the ectoderm yet shares both gene expression signatures and skeletogenic potential with the embryonic mesoderm, suggesting that there may be a large-scale fate transition during its development.

The post-translational modification of histones is emerging as an important mechanism for regulating cell potential during development. In the embryo, early progenitors exhibit a broad potential with cis-regulatory elements for developmental genes existing in a poised state characterized by bivalent histone modifications [7]–[9] and open permissive chromatin structure [10]. A number of proteins that regulate chromatin structure are known to play essential roles in NC development, including CHD7-PBAF [11], [12] and jmjD2A [13]. The CHD7-PBAF chromatin remodeler complex has been shown to bind H3K4me1-positive enhancers of some early CNC genes, and histone demethylase jmjD2A was found to bind regulatory regions proximal to similar early NC genes and was associated with demethylation of repressive H3K9me3 marks. Disruption of CHD7-PBAF and jmjD2A function similarly resulted in reduced expression of early CNC gene expression and defects in NC derivatives, with no effect on upstream NPB/dorsal-neural-tube factors. However, these types of chromatin remodeling complexes also have more general roles in embryonic development [14]; for example CHD7 depletion also results in neural and placodal defects [11], [15]. In contrast, our genetic studies reveal a more selective role of the replacement histone H3.3 in CNC development.

Histone H3 proteins contribute to the fundamental packing unit of chromatin, the nucleosome, which consists of two molecules each of histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4, wrapped by two turns of double-stranded DNA. Whereas canonical H3 histones (H3.1 and H3.2) are incorporated into chromatin predominantly during replication, H3.3 is also incorporated outside of replication [16], which has implicated it in various histone replacement events including gene regulation. In mammals, H3.3 has been associated with large-scale histone replacement during the specification of primordial germ cells [17] and the inactivation of meiotic sex chromosomes [18]. However, a developmental requirement for H3.3 outside the germ line has yet to be described. Flies lacking both H3.3 genes are infertile yet largely adult viable with no specific developmental abnormalities [19], [20]. Similarly, mice hypomorphic for H3.3A display growth reduction and infertility but no specific developmental defects [21]. However, the presence of multiple, identical copies of histone genes, such as H3.3, has complicated loss-of-function studies, particularly in vertebrates. Through genetic studies in zebrafish, we have identified a D123N mutant form of H3.3 that allows us to dominantly interfere with H3.3 chromatin incorporation during development. In so doing, we have found that the formation of CNC cells, and their subsequent lineage potential, are particularly sensitive to defects in H3.3 incorporation.

Results

A dominant H3.3 mutation specifically disrupts CNC development

In an ethylnitrosourea mutagenesis screen, we identified a dominant zebrafish mutant, db1092, that exhibited severe reductions in fli1a:GFP-labeled ectomesenchyme [22] at 36 hours-post-fertilization (hpf) (Figure 1a, 1b). As in other vertebrates, the facial skeleton and anterior skull of the larval zebrafish derive from CNC ectomesenchyme, with the posterior skull being of mesoderm origin [23], [24]. In db1092 homozygous mutants, nearly all of the CNC-derived cartilage, bone, and teeth were lost at 5 days-post-fertilization (dpf), leaving only the mesoderm-derived skull (Figure 1c, 1d). These skeletal phenotypes were very reminiscent of those seen in foxd3; tfap2a compound mutants that completely lack CNC, again confirming the CNC specificity of the head skeletal defects in db1092 mutants [25]. db1092 homozygous larvae die by around 7 dpf, presumably due to an inability to feed. Whereas some db1092 heterozygotes survived to adulthood, others exhibited variable reductions of the jaw-support skeleton (Figure 1e, 1f). Due to the shared phenotypes of db1092 homozygous and heterozygous embryos, “db1092 mutants” will refer to both genotypes unless otherwise stated.

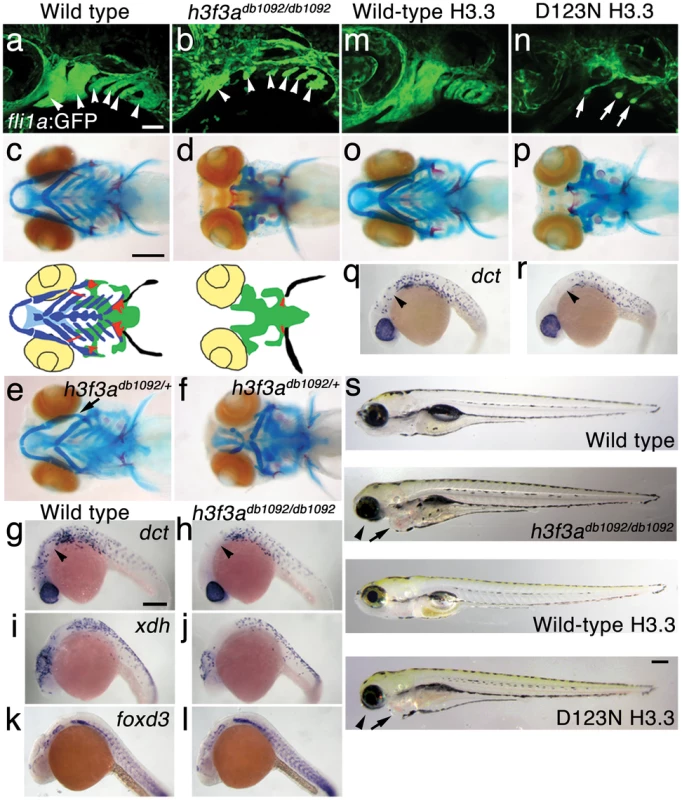

Fig. 1. A dominant H3.3 mutation results in losses of CNC–derived head skeleton and pigment cells.

a, b, fli1a:GFP-labeled arch ectomesenchyme (arrowheads) is greatly reduced, yet fli1a:GFP-positive endothelial cells (top) are unaffected, in both homozygous and heterozygous h3f3adb1092 mutants at 34 hpf (7/7 mutant; 0/10 wild-type). c, d, Homozygous h3f3adb1092/db1092 embryos specifically lack the CNC-derived head skeleton at 5 dpf (36/71 complete loss; 35/71 partial loss). Diagrams show the CNC-derived cartilage (blue) and bone and teeth (red), mesoderm-derived cartilage (green), pectoral fin cartilage (black), and eyes (yellow). e, f, h3f3adb1092/+ heterozygous larvae exhibit a wide range of craniofacial defects. In some cases, no defects are observed in the facial skeleton and heterozygotes are adult viable (not shown). In mild cases (e), dorsal cartilage and bone of the first and second arches are preferentially reduced, including the dorsal hyosymplectic cartilage and opercular bone of the second arch (arrow). In more severe cases (f), the cartilage and bone of the first arch and dorsal second arch are greatly reduced, with the anterior neurocranium and the posterior ceratobranchial cartilages being less affected. The frequency of skeletal phenotypes in h3f3adb1092/+ heterozygous larvae is highly variable between clutches. g, h, At 27 hpf, dct-positive melanophore precursors are selectively missing anterior to the ear (arrowheads) in both homozygous and heterozygous h3f3adb1092 embryos (5/5 mutant; 0/5 wild-type). i, j, At 27 hpf, cranial xdh-positive xanthophore precursors are mildly reduced in both homozygous and heterozygous h3f3adb1092 embryos (6/8 mutant; 0/4 wild-type). k, l, Wild-type and both homozygous and heterozygous h3f3adb1092 embryos have comparable numbers of foxd3-positive glial cells at 24 hpf (4 mutant; 5 wild-type). m-r, D123N h3f3a mRNA-injected but not wild-type h3f3a mRNA-injected embryos lack fli1a:GFP-positive ectomesenchyme (9/19 D123N; 0/12 wild-type), CNC-derived head skeleton (24/45 D123N; 0/21 wild-type) and cranial dct-positive melanophore precursors (anterior to the ear: arrowheads) (7/14 D123N; 0/11 wild-type). fli1a:GFP-positive blood vessels are unaffected (arrows). s, Except for the loss of the majority of the skull (no facial structures below the level of the eye: arrowheads) and mild heart edema (arrows), the overall morphologies of wild-type, homozygous and heterozygous h3f3adb1092, wild-type h3f3a-injected, and D123N h3f3a-injected larvae are indistinguishable at 5 dpf. Melanophores (black) and xanthophores (yellow) are also largely normal. Except for panels e and f, homozygous h3f3adb1092 examples are shown. Scale bars: a, b, m & n, 50 µm; c–l, o–s, 250 µm. We next examined whether other NC derivatives, such as pigment cells, glia, and neurons, were affected in db1092 mutants. Melanophore pigment cells and their dct-positive precursors were reduced in the cranial but not trunk regions of db1092 mutants, and to a lesser extent so were xanthophore pigment cells and their xdh-positive precursors (Figure 1h, 1j and Figure S1). In contrast, foxd3-positive peripheral glia (Figure 1l), neurons of the cranial ganglia (Figure S1), and the dorsal root ganglia and sympathetic neurons derived from trunk NC (data not shown) were unaffected. db1092 mutants also displayed mild heart edema, consistent with a known CNC contribution to the heart [26], but had an otherwise remarkably normal morphology at 5 dpf (Figure 1s). In summary, db1092 mutants have highly specific reductions of CNC derivatives, in particular the ectomesenchymal/skeletal components of the head.

We next used microsatellite polymorphism mapping to place db1092 within a 464 kb region on linkage group 3 which contained h3f3a, one of five genes encoding identical H3.3 proteins (Figure 2). Sequencing of h3f3a revealed a G to A transition in db1092 that converts aspartic acid 124 to asparagine (referred to as D123N due to cleavage of the amino-terminal methionine). Given the semi-dominant nature of db1092, we reasoned that the D123N mutation might result in a dominantly acting version of H3.3. To test this, we separately injected mRNAs encoding wild-type and D123N forms of H3.3 into one-cell-stage zebrafish embryos. Whereas wild-type H3.3 had no effect on CNC development, D123N H3.3 caused nearly identical losses of fli1a:GFP-positive ectomesenchyme (Figure 1n), CNC-derived head skeleton (Figure 1p), and cranial melanophore precursors (Figure 1r) as seen in the db1092 mutant, confirming D123N H3f3a as the causative mutation. As reported for other H3.3 genes in zebrafish [27], we found that h3f3a was ubiquitously expressed starting at 4 hpf and continuing through 14.5 hpf when CNC has been specified (Figure 3). At 16.5 and 27 hpf, h3f3a expression remained largely ubiquitous but was more prominent in the anterior embryo. As both the endogenous h3f3adb1092 gene product, and in particular the mRNA-injected D123N H3.3, are present uniformly throughout the embryo at CNC specification stages, the remarkable specificity of the ectomesenchyme defect is not due to a preferential expression of this particular h3f3a gene in CNC precursors. Instead, our data indicate that CNC and ectomesenchyme development are uniquely sensitive to altered H3.3 function.

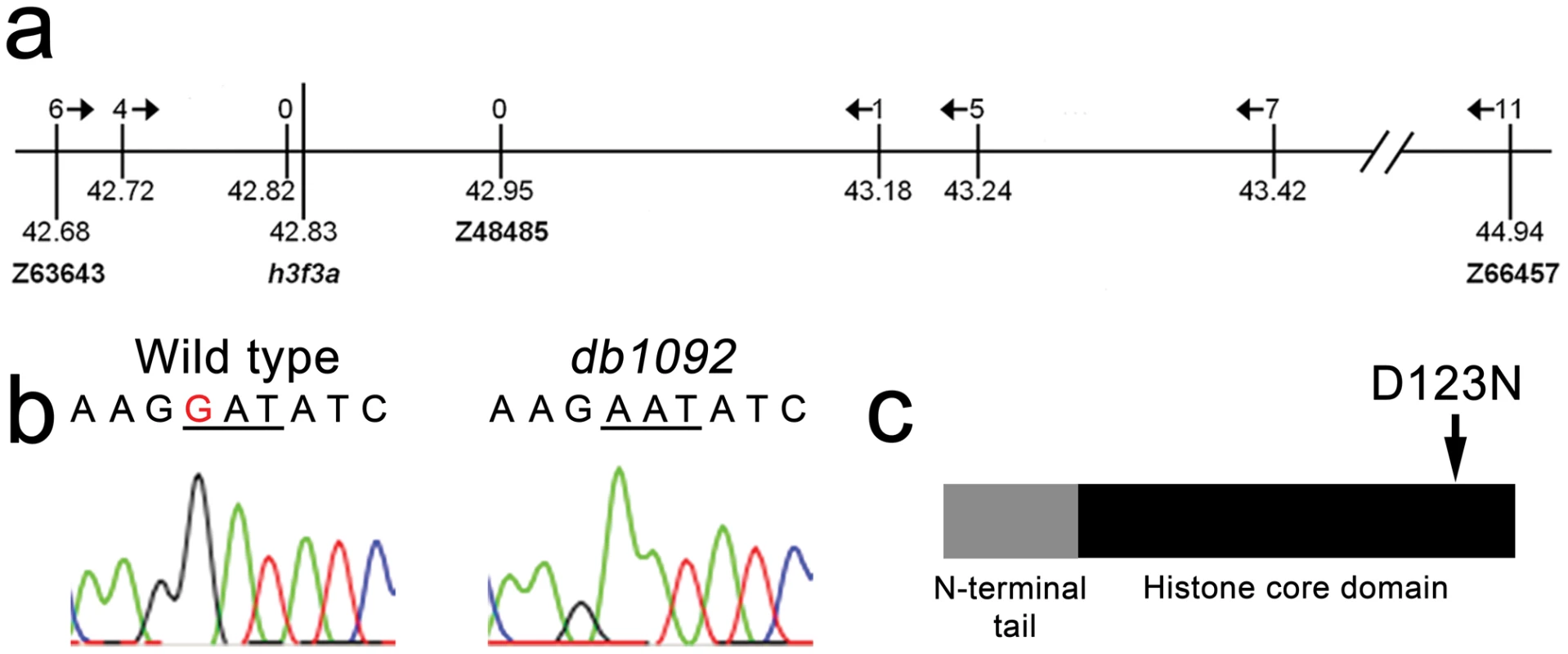

Fig. 2. Identification of the h3f3adb1092 lesion.

a, The db1092 allele was crossed to the highly polymorphic WIK strain for linkage analysis. As the db1092 mutation is semi-dominant, we enriched for putative heterozygotes by selecting for partial head skeletal loss, and events were scored as recombination only if both chromosomes displayed the wild-type WIK polymorphism. Using a set of microsatellite ‘Z’ markers spanning the zebrafish genome, we placed db1092 on linkage group 3 near Z3725 and Z20058, and subsequent linkage analysis placed it between Z63643 and Z66457. Recombinants per 1065 meioses are listed above each marker. Sequencing of 3′ UTRs identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that created or destroyed restriction sites between the mutant and WIK chromosomes. These SNPs (identified by their position in millions of base pairs) and Z48485 were then used to map db1092 to a 464 kb interval. b, Electrophoretograms show a G to A transition in the h3f3a gene of db1092 homozygotes. c, Schematic of the H3.3 variant histone protein encoded by h3f3a. The db1092 mutation results in a D123N substitution near the C-terminus of the core domain. Fig. 3. h3f3a is ubiquitously expressed throughout embryogenesis.

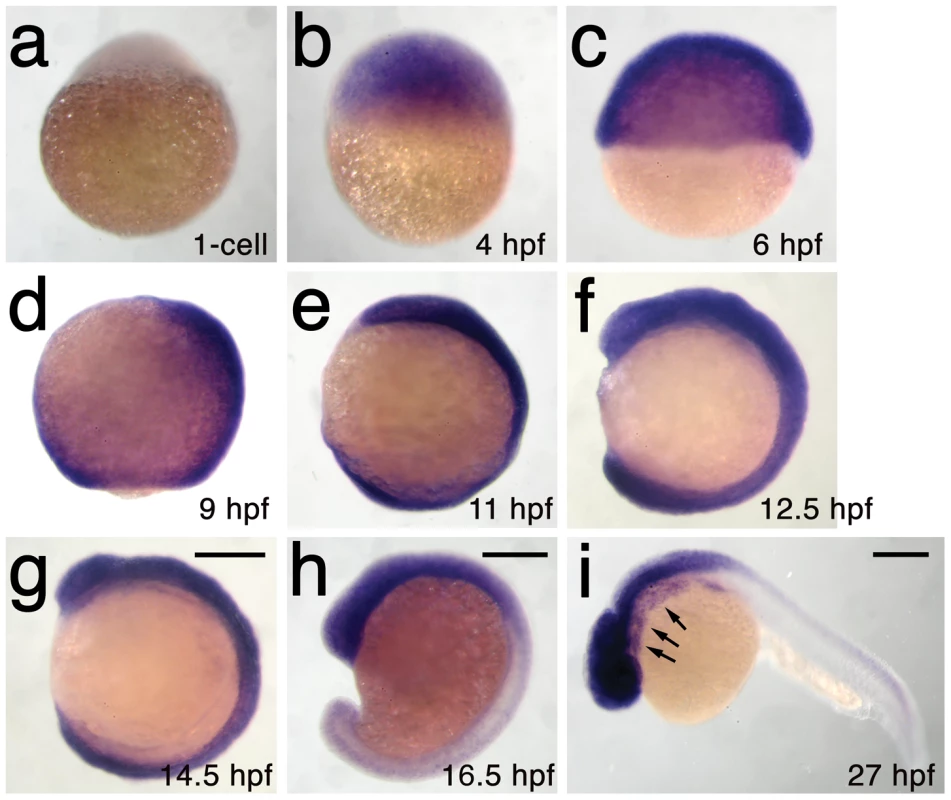

a–i, Lack of h3f3a expression at the one-cell stage shows that h3f3a mRNA is not maternally provided. From 4–14.5 hpf, h3f3a is expressed ubiquitously throughout the embryo. By 16.5 hpf and 27 hpf, h3f3a expression is still widespread, with higher levels apparent in the anterior part of the embryo, including the CNC-derived ectomesenchyme of the pharyngeal arches (arrows) at 27 hpf. Scale bars = 250 µm. Mutant D123N H3.3 dominantly interferes with H3.3 function through aberrant homodimer formation

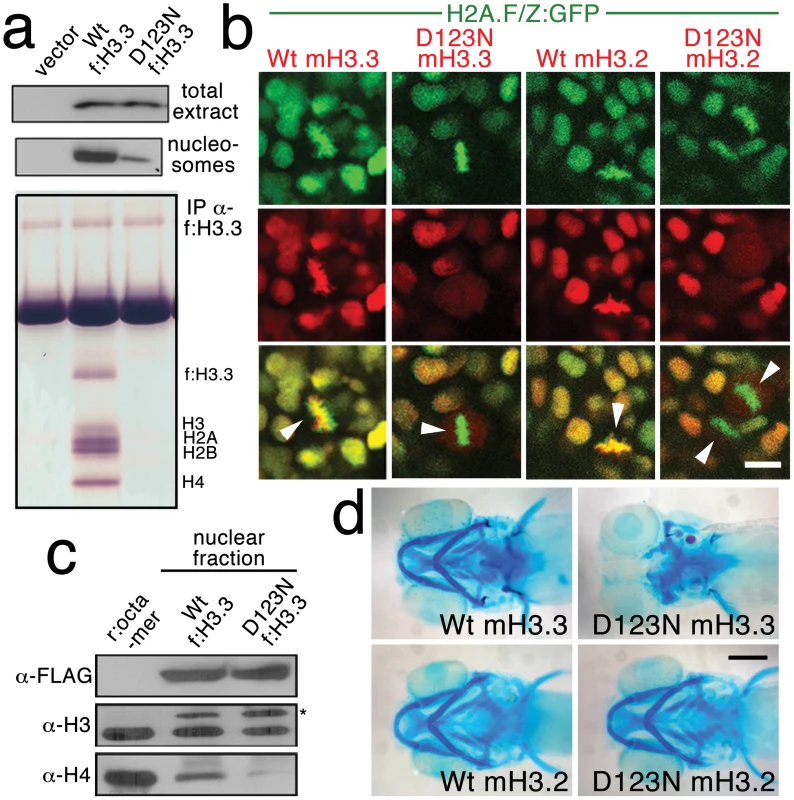

We next investigated the effect of the D123N substitution on H3.3 function. When human embryonic kidney cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged wild-type or D123N H3.3, we found D123N H3.3 to be under-enriched in purified nucleosomes compared to wild-type H3.3 (Figure 4a). The D123N mutation also prevented the incorporation of H3.3 into chromatin in zebrafish embryos. Whereas mCherry-tagged forms of both wild-type and D123N H3.3 were nuclear localized during interphase, during metaphase/anaphase, when the nuclear membrane breaks down and condensed chromosomes are easily distinguished, wild-type but not D123N H3.3 co-localized with chromatin marked by a GFP-tagged H2A.F/Z histone [28]. The failure of D123N H3.3 to associate with chromatin was observed both in the eye (Figure 4b) and in the pax3a:GFP-positive NPB precursors of CNC (Figure S2). Time-lapse recordings showed that mCherry-D123N-H3.3 nuclear fluorescence immediately returned upon resumption of interphase, indicating that the diffuse metaphase fluorescence of D123N H3.3 was due to a lack of chromatin incorporation and not degradation (Figure S3).

Fig. 4. The dominant D123N mutation prevents chromatin incorporation and promotes the formation of aberrant H3 homodimers.

a, Western blots show α-FLAG immunostaining of nuclear extracts or purified mononucleosome fractions from HEK cells transfected with vector alone or FLAG-tagged H3.3 (f:H3.3) vectors. Wild-type and D123N f:H3.3 proteins are expressed at equal levels in total extract, but wild-type f:H3.3 is present at much higher levels in the nucleosome fraction (consistent over three replicate experiments). α-FLAG immunoprecipitation from purified nucleosomes shows that wild-type but not D123N f:H3.3 is incorporated into nucleosomes containing H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 (consistent over three replicate experiments). b, Confocal images from H2A.F/Z:GFP embryos expressing wild-type and D123N versions of mCherry(m)H3.3 and mCherry(m)H3.2 fusion proteins. Merged images show that whereas all H3 proteins are nuclear localized in surrounding non-mitotic cells, wild-type mH3.3 and mH3.2, but not D123N mH3.3 and mH3.2, co-localize with H2A.F/Z:GFP in the chromosomes of metaphase/anaphase cells (arrowheads) after nuclear envelope breakdown (wild-type mH3.3, 11/11 cells in 2 embryos; D123N mH3.3, 0/25 cells in 3 embryos; wild-type mH3.2, 21/21 cells in 3 embryos; D123N mH3.2, 0/16 cells in 2 embryos). c, α-FLAG, α-H3 and α-H4 western blots for samples immunoprecipitated by α-FLAG from nuclear extracts of f:H3.3-transfected HEK cells. Recombinant octamer is used as a reference. Whereas both endogenous H3 and H4 co-immunoprecipitate with the wild-type f:H3.3 protein (*), H3 but not H4 co-immunoprecipitates with D123N f:H3.3 (asterisk marks the larger recombinant f:H3.3 protein). Results were consistent over three replicate experiments. d, mRNA injection of D123N mH3.3 (8/17), but not wild-type mH3.3 (0/26), wild-type mH3.2 (0/19), or D123N mH3.2 (0/18), results in loss of the CNC-derived head skeleton at 4 dpf. Scale bars: b, 10 µm; d, 250 µm. Nucleosome assembly normally proceeds through an H3–H4 heterodimer, an H3–H4/H3–H4 heterotetramer, and then the octamer. The C-terminal domain of H3 forms a 4-helix bundle with a second H3, thus promoting the association of the two H3–H4 pairs within the nucleosome. D123 lies within this domain and forms an intermolecular bond with histidine 113 (H113) of the alternate H3 [29]. In purified nuclear fractions from cultured cells, we found that wild-type H3.3 associated with both H3 and H4, reflecting the presence of heterotetramers and octamers. Remarkably, rather than blocking H3.3-H3 interactions, the D123N mutation resulted in H3.3 forming aberrant associations with H3 in the absence of H4 (Figure 4c). The dominant-negative function of D123N H3.3 would thus be explained by its ability to complex with wild-type H3.3 in the absence of H4, thus interfering with the ability of wild-type H3.3 to be incorporated into nucleosomes. Consistent with this, misexpression of D123A and H113A mutant versions of H3.3, which are predicted to fail to associate with H3, had no effect on CNC development (data not shown). Of note, we were unable to detect mislocalization of mCherry-tagged wild-type H3.3 within h3f3adb1092 homozygotes (Figure S4), suggesting that H3.3 is not whole-scale depleted from chromatin in mutants. Thus, the dominant effects of D123N H3.3 on CNC development could be due either to a partial depletion of wild-type H3.3 from chromatin, which falls below our level of detection, or alternatively a failure to incorporate H3.3 at a particular subset of loci, such as at poised and active enhancers. Importantly though, increasing H3.3 levels by injection of wild-type H3.3 mRNA rescued the head skeletal defects of h3f3adb1092 mutants, showing that defects are indeed due to compromised H3.3 incorporation and not neomorphic effects of mutant D123N H3.3 on unrelated pathways (Figure 5a, 5b).

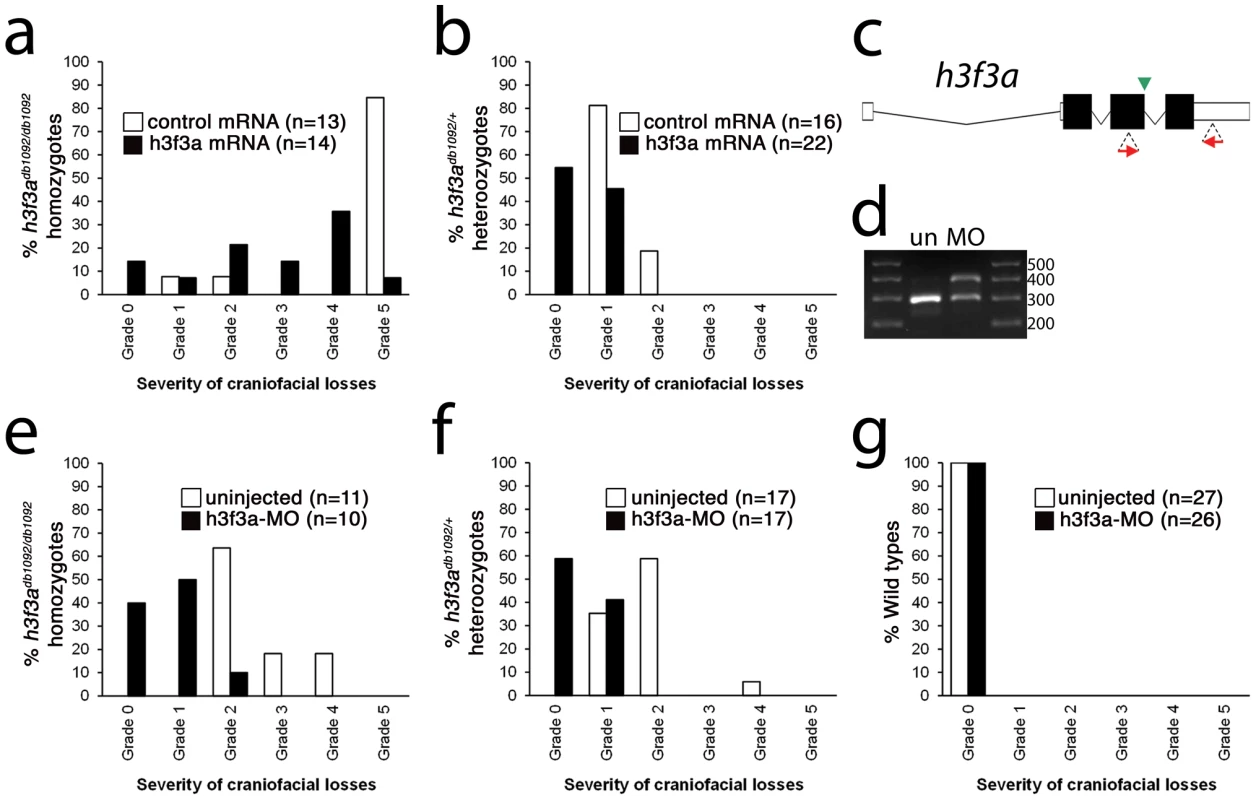

Fig. 5. Injection of wild-type H3.3 RNA and reduction of mutant H3.3 levels both rescue craniofacial skeletal development in h3f3adb1092 mutants.

a, b, Results from scoring the severity of craniofacial losses in 5 dpf larval head skeletons from h3f3adb1092 siblings injected with 450 ng/µl mRNA encoding wild-type H3.3 or a control kikGR fluorescent protein. The scoring system ranges from Grade 0 (wild-type phenotype) to Grade 5 (complete loss of CNC derivatives); see Materials and Methods for more detail. H3.3-mRNA-injected h3f3adb1092 homozygotes (a) and heterozygotes (b) exhibited a decrease in the severity of h3f3adb1092 craniofacial phenotypes over kikGR-RNA-injected controls (significant by Fisher's exact test: homozygotes, p = 7.7E-05; heterozygotes, p = 1.0E-04). c, An antisense morpholino oligonucleotide was designed to inhibit splicing at the exon 3/intron 3–4 boundary (green arrowhead) of the h3f3a transcript. Morpholinos were injected into one-cell-stage h3f3adb1092 embryos at 400 µM. d, Morpholino efficacy was demonstrated by PCR amplification between exons flanking the targeted splice junction from 10 hpf cDNA from 20 pooled embryos (position of primers shown as red arrows in c). Compared to the sample from uninjected (un) embryos, the morpholino-treated sample (MO) exhibited a partial decrease in PCR product representing spliced transcript (295 bp) and a concomitant increase in un-spliced PCR product (390 bp). e, f, Compared to uninjected siblings, both morpholino-injected h3f3adb1092 homozygotes (e) and heterozygotes (f) exhibited a decrease in the severity of h3f3adb1092 craniofacial phenotypes (significant by Fisher's exact test: homozygotes, p = 2.0E-04; heterozygotes, p = 6.3E-06). (g) Craniofacial development in wild-type embryos was unaffected by morpholino injection. Whereas misexpression of mutant D123N H3.3 results in severe CNC defects, it remains unclear whether loss of H3.3 genes can cause a similar effect. H3.3 genes are some of the most highly expressed in cells, and we were unable to generate function-blocking morpholinos that substantially reduced H3.3 levels for any of the endogenous genes (data not shown). However, injection of a morpholino that partially reduced splicing of the h3f3a gene was able to rescue h3f3adb1092 mutants by reducing D123N H3.3 levels, though it caused no CNC defects on its own (Figure 5c–5g). Mice with hypomorphic mutations in H3.3A, one of two H3.3 genes, also do not exhibit specific CNC/craniofacial defects [21]. In one model, the dominant D123N H3.3 protein is particularly effective at depleting available H3.3 levels below the threshold required for CNC development, with a general reduction in H3.3 nucleosome incorporation resulting in CNC defects. Alternatively, as discussed above, CNC defects may arise from defects in a particular subset of nucleosomal H3.3 incorporation. Indeed, recent studies suggest that distinct chaperone complexes load H3.3 at different types of genomic sites, and particular complexes could be differentially sensitive to dominant effects of mutant D123N H3.3 [30]. In the future, the generation of null mutants for some or all H3.3 genes should help address whether CNC development is particularly sensitive to reductions in general or specific modes of H3.3 nucleosomal incorporation, as well as revealing to what extent H3.3 is required in other non-CNC tissues.

CNC development depends on replication-independent H3.3 incorporation

Histone H3.3 can be incorporated into chromatin both during and outside of DNA replication. In contrast, canonical H3.2 differs from H3.3 at only four amino acids yet incorporates very poorly into chromatin outside of replication [16]. Hence, in order to test the role of replication-coupled loading of H3 histones in CNC development, we performed embryo-wide misexpression of a version of H3.2 carrying the same D123N mutation. As with H3.3, the D123N mutation blocked the incorporation of mCherry-tagged H3.2 into H2A.F/Z:GFP-labeled chromatin (Figure 4b). However, unlike D123N H3.3, D123N H3.2 had no effect on development of fli1a:GFP-positive ectomesenchyme or CNC-derived head skeleton (Figure 4d and data not shown). The inability of D123N-H3.2 to inhibit ectomesenchyme formation strongly suggests that CNC development relies on the unique replication-independent mode of H3.3 deposition.

H3.3 function is required cell-autonomously for CNC but not NPB gene expression

In order to understand at what level H3.3 functions in CNC development, we next examined gene expression in h3f3adb1092 embryos. NC arises at the juncture of neural and non-neural ectoderm by the combined action of multiple signals, including BMPs, FGFs, and WNTs [31], with these signals inducing a group of transcription factors with overlapping expression at the NPB. Subsequently, a subset of NPB cells upregulate an additional group of transcription factors in presumptive NC, with these cells delaminating and migrating away from the neural tube shortly thereafter. At 10 hpf, we found that the NPB expression of msxb, pax3a, zic2a and tfap2a was indistinguishable between wild-type and h3f3adb1092 embryos (Figure 6a–6d). Neural and otic placode patterning was also normal, as shown by forebrain (dlx2a), midbrain (pax2a), hindbrain (egr2b), and otic (sox10) gene expression (Figure 6m; Figure S5). In contrast, the expression of snai2, sox10, foxd3, and sox9b was lost or greatly reduced in the presumptive CNC domains of h3f3adb1092 embryos at 11 hpf (Figure 6g–6k), as was sox10 expression in D123N-H3.3-injected embryos (Figure 6l). However, the NPB-specific expression of msxb and pax3a remained unaffected at these stages, indicating that the loss of CNC expression was not due to cell loss (Figure 6e, 6f). In particular, the loss of tfap2a expression in the later CNC domain (Figure 6j) but not the earlier NPB domain (Figure 6d) of h3f3adb1092 mutants highlights the selective role of H3.3 in CNC gene expression. Interestingly, h3f3adb1092 embryos had no defects in trunk NC formation as assayed by crestin and sox9b expression at 11.7 hpf (Figure 7), consistent with trunk NC derivatives being unaffected. While it remains unclear why trunk NC is spared, the greater sensitivity of cranial versus trunk NC to defects in H3.3 function correlates with the greatly increased capacity of CNC to generate ectomesenchyme.

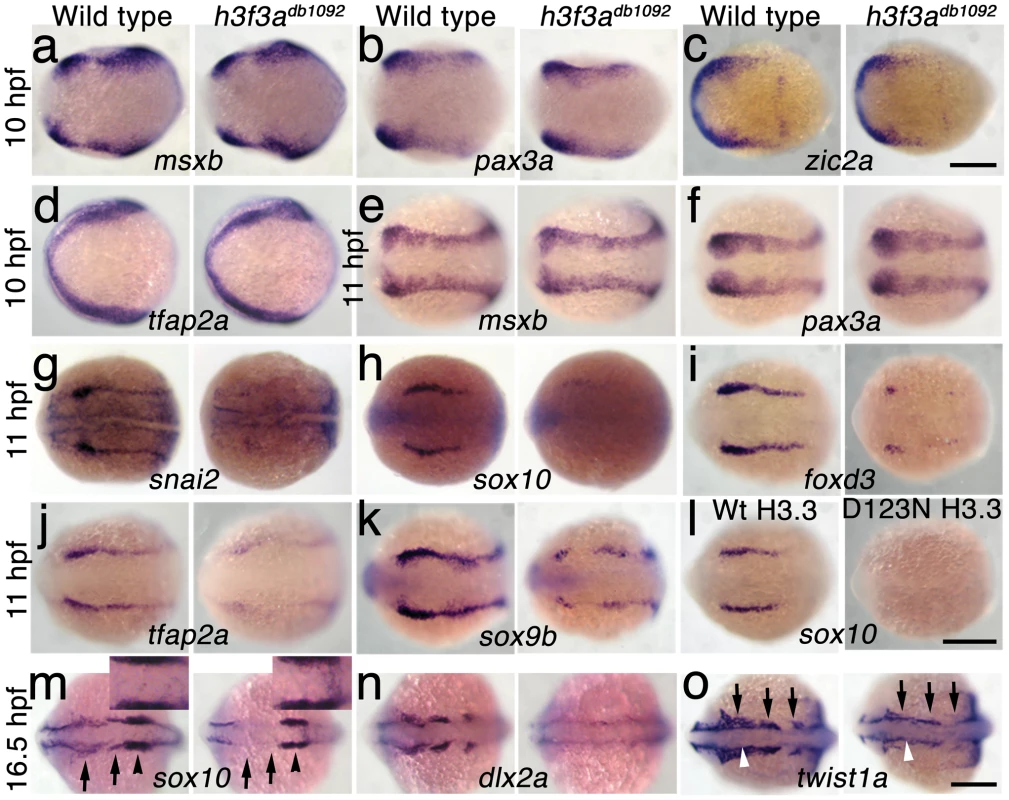

Fig. 6. H3.3 functions at the NPB–CNC transition.

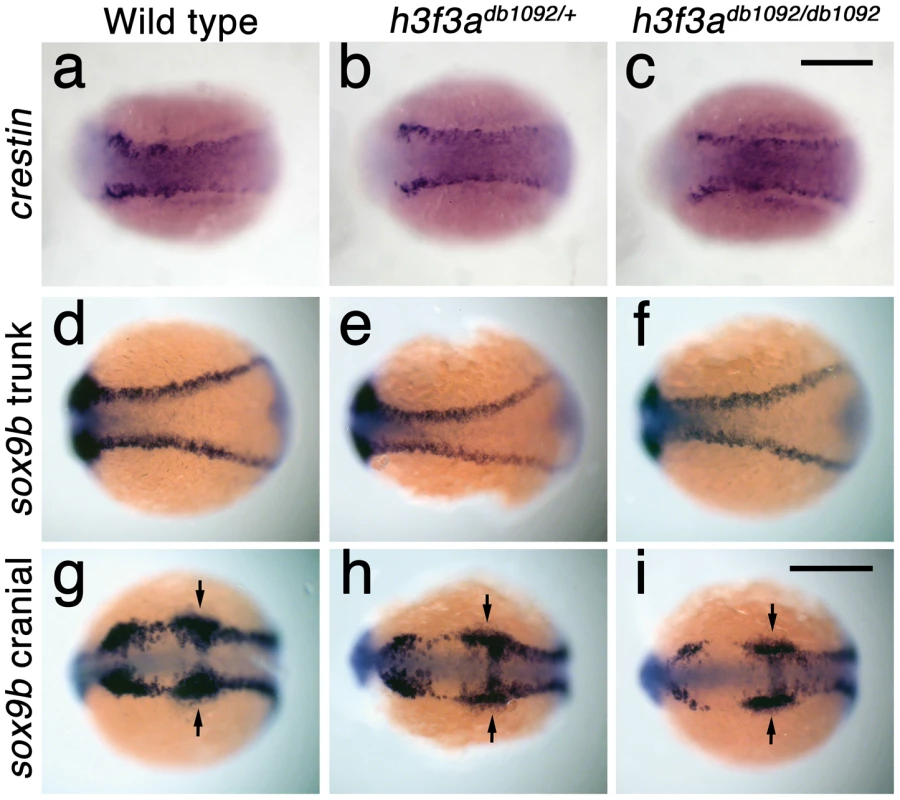

a–f, Expression of msxb, pax3a, zic2a, and tfap2a at 10 hpf and msxb and pax3a at 11 hpf is indistinguishable between wild types and both homozygous and heterozygous h3f3adb1092 mutants (mut) (n≥10 for each). g–k, At 11 hpf, both homozygous and heterozygous h3f3adb1092 mutants have severe reductions in the expression of snai2 (4/4 mut; 0/4 wt), sox10 (10/12 mut; 0/6 wild-type), foxd3 (9/9 mut; 0/5 wt), tfap2a (7/7 mut; 0/4 wt), and sox9b (8/8 mut; 0/3 wt). l, sox10 expression is also lost in embryos injected with D123N (10/12) but not wild-type (0/16) h3f3a mRNA. m, In both homozygous and heterozygous h3f3adb1092 embryos, sox10 expression partially recovers by 16.5 hpf yet is specifically reduced in presumptive CNC ectomesenchyme domains (arrows) (6/6 mut; 0/4 wt). An increase in sox10-positive cells is evident in the mutant dorsal neural tube (insert) between the sox10-positive otic placodes (arrowheads) which are unaffected in mutants. n, At 16.5 hpf, dlx2a expression in three streams of migrating ectomesenchyme is reduced in both homozygous and heterozygous h3f3adb1092 mutants (6/7 mut; 0/5 wt). o, The 16.5 hpf ectomesenchyme expression (arrows) of twist1a is reduced in both homozygous and heterozygous h3f3adb1092 mutants yet paraxial mesoderm expression is unaffected (white arrowheads) (8/8 mut; 0/5 wt). In all panels, homozygous h3f3adb1092 examples are shown. All images are dorsal views with anterior to the left. Scale bars: 250 µm. Fig. 7. Trunk NC is largely unaffected in h3f3adb1092 mutants.

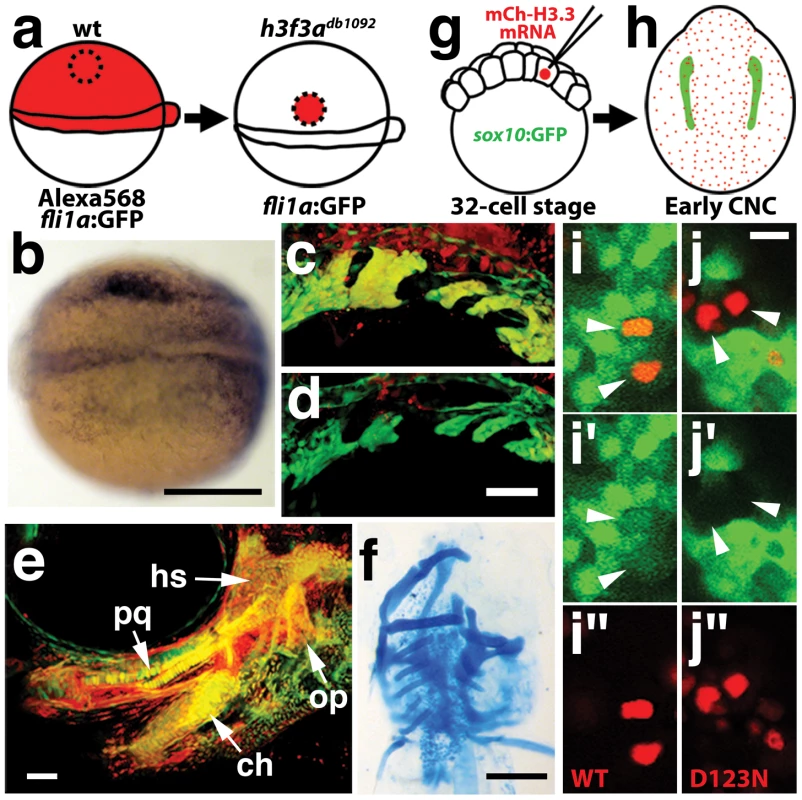

a–c, crestin expression at 11.7 hpf shows similar amounts of trunk NC in wild-type and both homozygous and heterozygous h3f3adb1092 embryos (n = 5 for each genotype). d–i, Trunk views of sox9b expression at 11.7 hpf show that trunk NC specification is largely normal in both homozygous and heterozygous h3f3adb1092 mutants (n = 10 for each genotype). Cranial views of the same embryos show reduced amounts of sox9b-expressing CNC. Arrows show the sox9b-positive otic placodes that are unaffected in mutants. Scale bars = 250 µm. Consistent with a direct role of H3.3 in CNC development, we also found H3.3 to be required both tissue - and cell-autonomously for CNC specification. Shield-stage transplantation of wild-type CNC precursors into h3f3adb1092/db1092 homozygous mutant hosts fully rescued snai2 CNC expression, fli1a:GFP-positive ectomesenchyme, and head skeleton (Figure 8a–8f). Moreover, mosaic injection of D123N-H3.3 blocked the CNC expression of a sox10:GFP transgene in a strictly cell-autonomous manner (Figure 8g–8j).

Fig. 8. H3.3 function is required tissue- and cell-autonomously for CNC development.

a, Wild-type cells were transplanted unilaterally into the CNC precursor domain of h3f3adb1092/db1092 homozygous mutants at 6 hpf. b, Compared to the non-recipient control side (bottom), expression of the early CNC marker snai2 is restored in the recipient side at 11hpf (top) (n = 17/29 with rescue). c–e, fli1a:GFP (green) marks CNC ectomesenchyme of the pharyngeal arches at 30 hpf and facial skeletal elements at 5 dpf. The red fluorescent dye, Alexa568, marks transplanted wild-type cells, whereas both donor and host cells harbor the fli1a:GFP transgene. When transplanted into an h3f3adb1092/db1092 homozygous host, wild-type Alexa568+ CNC precursors contribute to pharyngeal arch ectomesenchyme and rescue arch size (c) and form wild-type cartilage and bone (e). In contrast, the non-recipient control side (d) has reduced pharyngeal arch ectomesenchyme. Whereas wild-type donor cells appear yellow due to red Alexa568 and green fli1a:GFP, mutant host cells have only fli1a:GFP and hence appear green. Rescue of arch size was observed in 8/11 cases. f, Alcian staining at 5 dpf shows that cartilage is restored to half the face in an h3f3adb1092/db1092 larvae that received an unilateral wild-type CNC precursor transplant. Compare the recipient side (left) to the control side that forms little facial cartilage (right). Skeletal rescue was observed in 21/30 cases. g, Individual cells of 32-cell stage sox10:GFP embryos were injected with mRNA encoding mCherry-tagged versions of wild-type or D123N H3.3 to generate mosaic mCherry-H3.3 expression at later stages. h, Soon after the appearance of GFP-labeled CNC at approximately 11 hpf, mosaic embryos were assessed for incorporation of mCherry-H3.3-expressing cells (red) into the sox10:GFP-positive CNC domain (green). i/i′/i″ and j/j′/j″, Confocal images from sox10:GFP embryos with mosaic expression of wild-type (i/i′/i″) and D123N (j/j′/j″) versions of mCherry-H3.3. Cells doubly-positive for wild-type mCherry-H3.3 (red) and GFP (green) (arrowheads) were observed within the CNC domain (7/14 cells over 4 embryos), whereas mutant D123N mCherry-H3.3 cells within the CNC domain failed to up-regulate sox10:GFP (arrowheads) (0/18 cells over 4 embryos). Only cells with strong mCherry-H3.3 were used in the analysis. hs: hyosymplectic cartilage, pq: palatoquadrate cartilage, ch: ceratohyal cartilage, op: opercular bone. Scale bars: b, f, 250 µm; c–e, 50 µm; i and j,10 µm. Although defective at early stages (11 hpf), the CNC expression of sox10 partially recovered by 16.5 hpf in h3f3adb1092 mutants (Figure 6m), consistent with multiple CNC derivatives being unaffected or only mildly reduced. In contrast, the expression of the ectomesenchyme markers dlx2a and twist1a was greatly reduced in h3f3adb1092 mutants at 16.5 hpf (Figure 6n, 6o; Figure S5). The loss of ectomesenchyme expression corresponded to regions of sox10-expressing CNC that were absent in h3f3adb1092 mutants. CNC cells that normally become ectomesenchyme likely fail to migrate from the neural tube and die, as we observed an increase in sox10-positive cells in the dorsal neural tube (Figure 6m) and elevated cell death in this same domain of 16 hpf h3f3adb1092 embryos (Figure 9d–9f). Importantly, increased cell death was not observed in the h3f3adb1092 neural folds at 12.5 hpf (Figure 9a–9c), indicating that the earlier loss of CNC gene expression was not due to cell death.

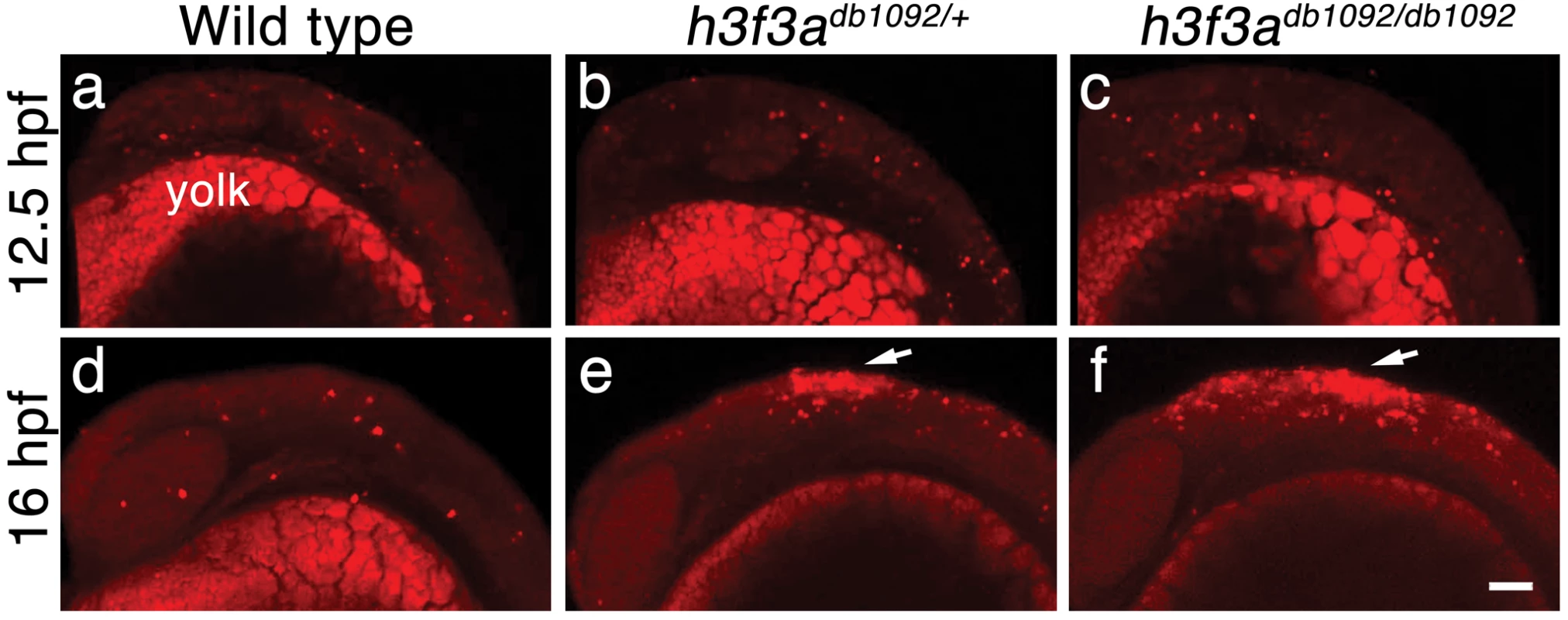

Fig. 9. Cell death in h3f3adb1092 embryos.

a–c, Lysotracker Red staining marks similar amounts of dying cells in wild-type (n = 2), h3f3adb1092/+ heterozygous (n = 5), and h3f3adb1092/db1092 homozygous (n = 3) embryos at 12.5 hpf. The bright staining in the bottom of each panel is the yolk. d–f, At 16 hpf, increased Lysotracker Red staining (arrows) was evident in the dorsal neural tube of h3f3adb1092/+ heterozygotes (2/2) and h3f3adb1092/db1092 homozygotes (3/3) but not wild types (0/4). These dying cells were located in a similar position to where CNC forms in wild-type embryos. Scale bar = 50 µm. Discussion

It is becoming increasingly appreciated that changes in chromatin states are intimately tied to changes in cellular potential. During differentiation of many stem/progenitor cells, combinatorial histone marks associated with the promoters and enhancers of poised developmental genes are progressively resolved to active or inactive states in a lineage-specific manner [7]–[10]. In the germ line, rather than progressive enzymatic modifications of histone marks, the global replacement of existing histones with H3.3 and other variant histones is thought to contribute to a dramatic alteration of lineage potential [17]. The unusual developmental history of ectomesenchyme may explain why it too is uniquely sensitive to defects in the incorporation of H3.3 replacement histones. CNC ectomesenchyme derives from the ectoderm yet expresses a gene repertoire and gives rise to derivatives (e.g. skeleton) in common with the mesoderm. One possibility then is that an H3.3-dependent histone replacement event in the NPB, which by its widespread nature is particularly sensitive to defective H3.3 incorporation, endows ectoderm-derived CNC cells with their exceptionally broad lineage potential, including the ability to generate mesoderm-like derivatives (Figure 10). The requirement for histone replacement (as opposed to enzymatic histone modifications) could reflect a need to overcome a particularly entrenched level of silencing during this fate transition, or alternatively to actively maintain mesoderm-like potential from earlier developmental stages [32]. In contrast, the progressive fate restriction of most other embryonic lineages may depend more on an incremental refinement of chromatin structure, such as the post-translational modification of histone tails and re-positioning of existing nucleosomes, and thus be less sensitive to defective H3.3 incorporation.

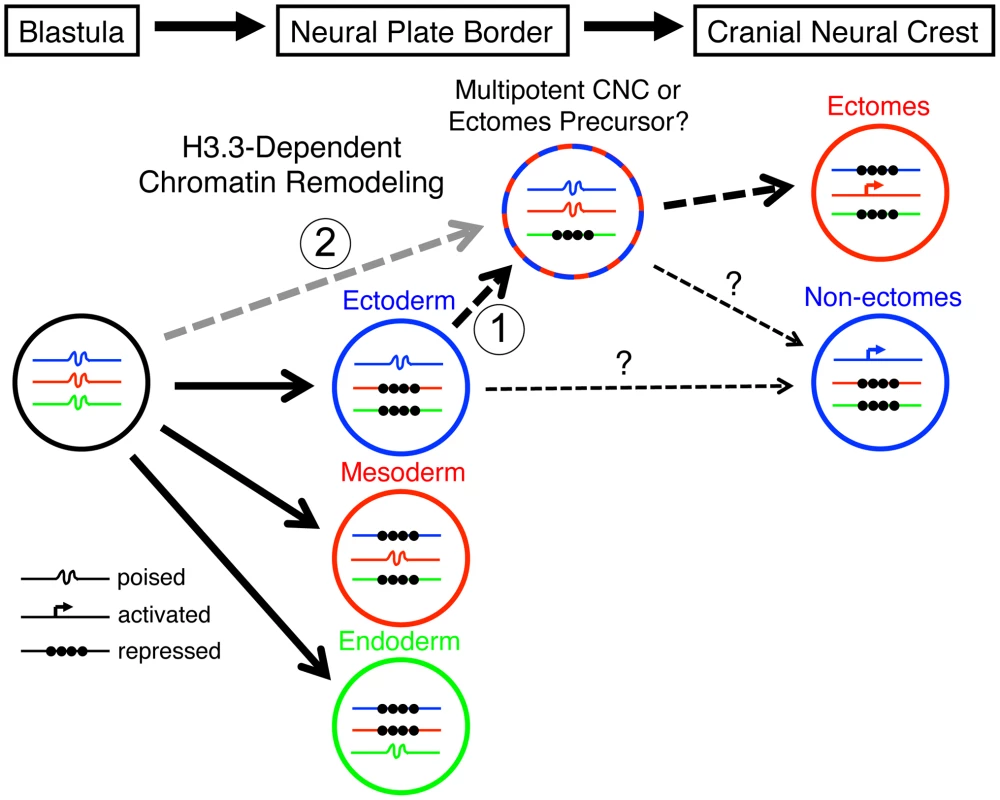

Fig. 10. Model for the role of H3.3-dependent histone replacement during CNC development.

At the early embryonic blastula stage, cells have a broad potential with cis-regulatory elements for developmental genes existing in a “poised” chromatin state. After gastrulation occurs to form the three major germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm), genes associated with a particular germ layer are activated or maintained in a poised state, whereas genes for other layers are strongly repressed at the chromatin level. The cranial neural crest (CNC) is unusual in that it is derived from ectoderm yet can give rise to mesoderm-like derivatives such as skeleton. H3.3-dependent histone replacement could thus be required to remodel the enhancers of mesodermal genes needed for ectomesenchymal fates, with the distinctive role of H3.3 in CNC correlating with the need to derepress mesodermal enhancers that have been previously silenced in the ectoderm germ layer (1). Alternatively H3.3 incorporation could act to maintain mesoderm-like potential in the CNC ectoderm from an earlier time in development (2). It also remains unresolved the extent to which ectomesenchyme derivatives (e.g. head skeleton) and non-ectomesenchyme derivatives (e.g. pigment, glia, and neurons) derive from a common multipotent precursor. Hence, the cranial pigment and ectomesenchyme defects of h3f3adb1092 mutants could arise from altered histone replacement in a common multipotent precursor, or alternatively from independent defects in different subsets of heterogeneous CNC with more limited potential. The open permissive chromatin structure at poised regulatory regions is characterized by low nucleosome occupancy and high H3.3 levels, although it remains unclear whether H3.3 simply fulfills a neutral replacement function in such areas of high turnover or has a facilitative destabilizing role [33], [34]. An important question is which genes, and in particular which regulatory regions, are targets of histone replacement in the early NPB/CNC. Early CNC genes such as sox10 and foxd3, whose expression is dramatically perturbed in the presence of mutant D123N H3.3, could be direct targets, although it is unclear why their activation would uniquely depend on H3.3. Alternatively or in parallel, the regulatory regions of a larger set of lineage-specific genes, in particular those associated with later ectomesenchyme development, could be primed by H3.3-dependent histone replacement during early CNC specification. Future chromatin immunoprecipitation studies, currently not feasible due to the rarity of CNC precursors in zebrafish embryos, will clearly be critical for determining which types of genes are direct targets of histone replacement during CNC specification.

Another unresolved question is how H3.3 incorporation is specifically targeted to CNC genes/enhancers. Several putative H3.3 chaperones have been identified, including Hira [35], [36], Daxx [37], and Dek [38]. However, effective morpholino-mediated reduction of zebrafish hira, daxx, or dek gene products, either alone or in combination, failed to cause CNC-specific defects (Figure S6). Hira−/− and Dek−/− mouse mutants also do not display CNC-specific defects [39], [40], whereas Daxx−/− embryos die around E8.5 before CNC can be extensively analyzed [41]. Whereas evidence for Hira, Daxx, or Dek mediating H3.3 incorporation in CNC is inconclusive, an intriguing alternative candidate is the chromatin remodeling complex CHD7-PBAF. Losses of CHD7-PBAF components disrupt early CNC specification in a manner similar to mutant D123N H3.3, with reduced expression of early CNC gene expression but not upstream NPB factors [11], [12], and CHD7 genomic localization coincides with H3K4me1 marks which are particularly enriched in H3.3 [34], [42]. It is less clear to what extent CHD7-PBAF, as well as the histone demethylase jmjD2A, share similar requirements with H3.3 for CNC lineage potential. As in h3f3adb1092 mutants, inhibition of CHD7 function in Xenopus laevis embryos disrupts craniofacial cartilage development, yet the effects on other NC lineages were not examined. In contrast, depletion of jmjD2A in avians affected development of the CNC-derived ganglia, a structure that is specifically spared in h3f3adb1092 mutants. Whether CHD7-PBAF and jmjD2A act together with H3.3 histone replacement at similar regulatory regions of early CNC genes, or whether these complexes have distinct roles in CNC specification and subsequent lineage diversification, will be fertile areas for future research.

h3f3adb1092 mutants display an initial delay in the expression of all CNC genes examined, which then translates into a more restricted loss of CNC-derived ectomesenchyme. How then does this specific loss of ectomesenchyme relate to the earlier delay in CNC specification? In one model, early-forming CNC cells encounter local environmental cues that promote ectomesenchymal fates [43], with a delay in CNC formation causing cells to miss such cues. Alternatively, the delay in CNC appearance, and its later inability to form the normal range of derivatives, may both result from defects in H3.3-dependent epigenetic remodeling during early CNC stages. Indeed, studies in zebrafish indicate that the future lineage potential of CNC may be determined at very early stages [25]. In addition, the cranial pigment lineage defects of h3f3adb1092 mutants indicate more general roles for H3.3 histone replacement in CNC lineage potential. In contrast to trunk NC [3], the existence of a multipotent precursor for all CNC lineages has yet to be demonstrated in vivo. Evidence in avians suggests that the ectomesenchyme arises from a temporally and spatially distinct subpopulation of CNC from precursors of other derivatives [6], [44], and lineage tracing studies in zebrafish show that CNC cells are largely unipotent at early stages of development (13 hpf) [5], [45]. Hence, despite individual cultured avian CNC cells being able to generate all derivatives [2], the embryonic CNC may be heterogeneous from initial stages. H3.3 histone replacement could therefore be selectively required for ectomesenchyme and pigment cell potential, but not neuroglial potential, within a common multipotent CNC precursor, or alternatively within distinct subpopulations of ectomesenchyme and pigment cell precursors (Figure 10). In the future, techniques to more severely perturb H3.3 histone replacement should help reveal whether the apparent lack of CNC neuroglial and trunk NC defects in h3f3adb1092 mutants reflects a fundamentally different mode of chromatin remodeling in the development of these NC populations, as well as other embryonic cell types, or merely a lower sensitivity to loss of H3.3 function.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animals were handled in strict accordance with good animal practice as defined by the relevant national and/or local animal welfare bodies, and all animal work was approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolation and genotyping of the db1092 mutation

For the genetic screen, wild-type AB adult males were mutagenized with ethylnitrosourea and crossed with fli1a:GFP females to create fli1a:GFP mutant carriers. Using early pressure to inhibit meiosis II, parthenogenic diploid F1 progeny [46] were created from these carriers and analyzed under a fluorescent dissecting microscope for fli1a:GFP defects. In order to genotype the h3f3adb1092 mutation, the following primers are used to amplify genomic DNA: 5′ - TTCAACAGGAAGCAAGTGAGG, 3′ – AACCCAATGATCGATGGAAA. As the h3f3adb1092 mutation destroys an EcoRV site, digestion with EcoRV generates a 359 bp product in mutants, and 261 bp and 98 bp fragments in wild types.

Skeletal staining, in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemistry

Zebrafish were maintained at 28.5°C and staged as described [47]. Acid-free skeletal staining was performed using Alcian Blue for cartilage and Alizarin Red for bone and teeth [48]. In situ hybridizations were performed as described [49]. For in situs, we carefully controlled for potential stage differences caused by mutants, RNA injection, and morpholinos by individually staging embryos by standardized morphological features (e.g. somite number). The following probes were the same as published: msxb [50], pax3a [51], zic2a [52], snai2 [53], sox10 [54], tfap2a [55], sox9b [56], dlx2a [57], pax2a [58], egr2b [59], and crestin [60]. dct, xdh, foxd3, twist1a, and h3f3a probes were made by cDNA amplification from mixed-stage embryos using the following primers, with a T7 RNA polymerase initiation site incorporated into the 3′ primer for probe synthesis (underlined): dct-5′ - CGTACTGGAACTTTGCGACA, dct-3′ - GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGACCAACACGATCAACAGCAG, xdh-5′ - TGAACACTCTGACGCACCTC, xdh-3′ - GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTGTTGAAGCTCCAGCAACAC, foxd3-5′ - CGGCATTGGGAATCCATA, foxd3-3′ – GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCAACGAAATGAAATAGAAAGAAGGA, twist1a-5′ - CAGAGTCTCCGGTGGACAGT, twist1a-3′ – GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTCTTTTCCTGCAGCGAGTC, and h3f3a-5′ - TTCAACTTTTAAAGAGAAACACTCAT, h3f3a-3′ - GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCCTTTATCTCTCCATTTATGGTAAAC. The h3f3a probe was made against the 3′ untranslated region, which we found to be unique among zebrafish H3.3 genes. dct, xdh, foxd3, and twist1a probes gave identical expression patterns to those previously described [61], [62]. For whole-mount immunohistochemistry, the primary antibody HuC (Molecular Probes) was used at 1∶400, a secondary goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 568 antibody (Molecular Probes) was used at 1∶200, and embryos were processed as described [63].

With the exception of the experiments in Figure S1 and Figure S5, all embryos were genotyped after image acquisition to confirm the segregation of the observed phenotypes with the h3f3adb1092 mutation. In Figure S1, reductions in the fli1a:GFP-positive ectomesenchyme (known to correlate precisely with the presence of the h3f3adb1092 mutation in our other experiments) was used to identify mutant embryos. In Figure S5, the presence of dlx2a reductions (also known to correlate with h3f3adb1092 genotype in our other experiments) was used to identify h3f3adb1092 mutants.

Construction of expression vectors and mRNA injections

Constructs used to generate mRNA were created using a Gateway cloning system (Invitrogen) that has been modified for use in zebrafish [64]. h3f3a (wild-type and db1092) and H3.2 (cDNA zgc:158629) open reading frames (ORFs) were amplified from embryonic cDNA using primers with attB1 and attB2R 5′ extensions (underlined) for cloning into the pDONR-221 middle entry vector. We also incorporated a consensus Kozak sequence immediately upstream of the start ATG in the forward primer (bold/italic). Primers used include the following: h3f3a-attB1 - GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTCCACCATGGCCCGTACTAAGCAGAC, h3f3a-attB2R – GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTTTAAGCCCTCTCTCCTCTGAT, H3.2-attB1 - GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTCCACCATGGCAAGAACCAAGCAGAC, H3.2-attB2R – GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTAGCCTTTGGGTTTAAATCAGG. PCR products were cloned into the pDONR-221 vector. Fusion PCR [65] was used to incorporate the D123N mutation into H3.2. In the first step the pDONR-221:H3.2 construct was used as template for PCR with two sets of primer pairs (A and B; C and D), with overlapping primers B and C containing the required mutation (lowercase in primer sequences): AB amplicon: Primer A (upstream of pDONR-221 integration site) - CAAATTGATGAGCAATGCTTTTT, Primer B – TGGATGTtCTTGGGCATGAT; CD amplicon: Primer C – CATGCCCAAGaACATCCAG, Primer D (downstream of pDONR-221 integration site) – GAGCTGCCAGGAAACAGCTA. In the second step these two PCR products were combined and used as template for PCR with the H3.2-attB1 and H3.2-attB2R pDONR-221 cloning primers above, followed by cloning into pDONR-221. The fusion PCR technique was also used to generate N-terminal mCherry fusions for h3f3a and H3.2 constructs. Primers were designed to amplify the mCherry ORF excluding the stop codon (primers A and B) and the h3f3a/H3.2 ORF (primers C and D), with overlapping primers B and C encoding the linker sequence GSRPVAT (used previously for YFP-H3.3 N-terminal fusions [66] ; linker sequence in lowercase below) and primers A and D having attB1 and attB2R 5′ extensions (underlined), respectively: mCherry-A - GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTCCACCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGG, mCherry-B - tgtagccacaggtctagatccCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGC, h3f3a-C - ggatctagacctgtggctacaATGGCCCGTACTAAGCAGAC, h3f3a-D - h3f3a-attB2R (above), H3.2-C - ggatctagacctgtggctacaATGGCAAGAACCAAGCAGAC, H3.2-D - H3.2-attB2R (above). PCR with AB and CD primer pairs were performed using the appropriate plasmid template (pME-mCherry, pDONR-221:h3f3a or pDONR-221:H3.2) followed by gel purification of the products. In the second step these two PCR products were combined (mCherry product AB with product CD from h3f3a or H3.2) and used as template for PCR AD with the mCherry-A and h3f3a-attB2R/H3.2-attB2R cloning primers above, followed by cloning into pDONR-221. All pDONR-221 middle entry clones were checked by sequencing, before being assembled with a 5′ entry vector (p5E-CMV/SP6 containing the Sp6 RNA polymerase promoter) and a 3′ entry vector (p3E-polyA containing the SV40 late polyA signal) within the pDestTol2pA2 destination vector using LR clonase II Plus (Invitrogen), as per manufacturer's instructions. In order to generate capped mRNA from these constructs, plasmid minipreps were first linearized using an appropriate restriction enzyme(s) (pDONR-221:h3f3a – BglII, pDONR-221:H3.2 - XbaI, pDONR-221:mCherry-h3f3a - SpeI and XhoI, pDONR-221:mCherry-H3.2 – SpeI and XhoI) and then used as template for in vitro transcription using the Sp6 Message Machine kit (Ambion). Zebrafish embryos were injected at the one-cell stage with capped mRNA at a concentration of 900 ng/µl (h3f3a, H3.2, mCherry-h3f3a and mCherry-H3.2) or 450 ng/ul (h3f3a mRNA rescue of h3f3adb1092 mutants). Alternatively individual cells of 32-cell stage embryos were injected with mRNA encoding mCherry-h3f3a (900 ng/µl) to generate mosaic expression at later stages.

For the generation of constructs expressing FLAG-HA-tagged H3.3 in HEK 293T cells, the ORF of h3f3a was first amplified from wild-type and db1092 embryonic cDNA using forward and reverse primers with 5′ extensions containing EcoR1 and BamHI sites, respectively: 5′ – GCCGACGGAATTCAGATGGCCCGTACTAAGCAGAC, 3′ - GCCTAGTGGAT CCATTAAGCCCTCTCTCCTCTGAT. Using these restriction sites the PCR products were then cloned between EcoRI and BamHI sites downstream and in-frame with a Kozak-FLAG-HA sequence within a modified pIRESneo vector (Clontech).

The pax3a:GFP line will be described in detail elsewhere. Briefly, the pax3a enhancer was identified by sequence conservation, then amplified from Fugu rubripes genomic DNA and cloned into the Tol2 transgenesis vector pGreenE (unpublished) using BP clonase (Invitrogen). Constructs were injected with transposase mRNA into one-cell-stage embryos and germline transgenic founders were identified.

Nucleosome incorporation assay

HEK 293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing FLAG-HA-tagged wild-type H3.3 (pIRES-FLAG-HA-H3.3), or mutant D123N H3.3 (pIRES-FLAG-HA-D123N-H3.3). To purify the whole cell nuclear extract, cultured cells were washed with PBS and lysed in IP lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 10% Triton X-100) followed by western blotting using FLAG antibody (Sigma). To purify mononucleosomes, cell nuclei were digested with micrococcal nuclease (0.6 U, Sigma) as previously described [67] after expression of FLAG-tagged wild-type or D123N H3.3. Purification of mononucleosomes was confirmed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. For immunoprecipitation of FLAG-H3.3-containing mononucleosomes, M2-agarose beads (Sigma) were used followed by overnight incubation. Beads were washed five times with BC300 and mononucleosomes were electrophoretically analyzed on a 15% SDS polyacrylamide gel.

Co-immunoprecipitation

HEK 293T cells were transfected with pIRES-FLAG-HA-H3.3 or pIRES-FLAG-HA-D123N-H3.3. Cells were harvested 2 days after transfection and nuclear fraction was done as previously described [68] . 1 mg of nuclear fraction was incubated with 10 µl Flag Agarose (Sigma) for 4 hr at 4°C in nuclear extraction buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 8.0), 0.6 M KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 25% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF). This was followed by three washes in IP buffer and elution with 0.2 mg/ml Flag peptide (Sigma). Eluates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis and recombinant octomer was used as a control for western blot. Antibodies used for western blots were as follows: Flag (Sigma), H3 (Abcam), and H4 (Abcam).

Antisense morpholino oligonucleotides

The following antisense morpholino oligonucleotides were designed to block splicing of exon/intron boundaries in the transcripts of target zebrafish genes (designed by and ordered from Gene Tools, LLC): h3f3a exon 3/intron 3/4 – ACAATATAATCTCACCTGAAGAGCG, hira exon 1/intron 1/2 – GTCGGTTACTGCTCTCACCATTGTG, daxx exon 3/intron 3/4 – ATTACTGTAAACAAGCATACCTCAT, dek exon 3/intron 3/4 - ATCTCAAAACAACGCCTTACAGCCC. One-cell stage embryos were injected with 3 nl of morpholino (MO) at 400 µM. RT-PCR was used to determine morpholino efficacy. Whole RNA was prepared from twenty 10 hpf embryos for each treatment (morpholino-injected and uninjected) using the RNAqeous -4PCR kit (Ambion), followed by cDNA synthesis using the RETROscript kit (Ambion). cDNA was used as template for PCR at 50 ng/µl using primers within exons flanking the targeted exon/intron boundary: h3f3a exon 3 forward - TCAGCGTCTGGTCAGAGAAA, h3f3a exon 4 reverse - TGCTTTACAAAATGACTCCAATG, hira exon 1 forward - AAGCTCTTGAAGCCGAGTTG, hira exon 2 reverse - TTGGCCACCTGTAGCAAACT, daxx exon 3 forward - CACGTGCTGAAAGTGGAGAA, daxx exon 4 reverse - TCCACAGACGTCAGAAAGGTC, dek exon 3 forward - CCGAAGATTGAGAGCAAAGG, dek exon 4 reverse - ATCCATTAAAGAGCCGCAGA.

Scoring the severity of the h3f3adb1092 phenotype

Alcian Blue-stained 4 and 5 dpf larval head skeletons were scored blind for loss of cartilage elements using the following system: Grade 0, unaffected; Grade 1, truncation of dorsal hyosymplectic and palatoquadrate cartilages; Grade 2, loss of hyosymplectic and palatoquadrate (except pterygoid process), Meckel's and ceratohyal cartilage reduced; Grade 3, loss of Meckel's, ceratohyal and pterygoid; Grade 4, ethmoid plate truncated/lost, trabeculae remain; Grade 5, all CNC-derived cartilages absent.

NC transplantation

Unilateral tissue transplants were performed as described, with the non-recipient side acting as an internal control [69]. Briefly, one-cell-stage donor fli1a:GFP embryos were injected with Alexa 568 dye (Molecular Probes) and cells were moved to the CNC precursor domain of fli1a:GFP hosts at 6 hpf.

Lysotracker staining for cell death

Live embryos were manually removed from their chorions and incubated with Lysotracker Red (Invitrogen) diluted to 5 µM in embryo medium (EM). Embryos were then incubated for 30–45 minutes in darkness. After 4–5 rinses with EM, embryos were fixed overnight with 4% PFA in PBS at 4°C. Embryos were then rinsed once with PBT before being dehydrated in a methanol/PBT series to remove background, and then stored at −20°C. Samples were subsequently rehydrated, followed by two washes in PBT, before being imaged by confocal microscopy.

Equipment and settings

Live embryos, whole-mount skeletal preparations, and in situ hybridization embryos were photographed with a Leica MZ16 stereomicroscope using a Canon PowerShotS80 digital camera and CameraWindow software. Fluorescent images were captured on a Zeiss LSM5 Pascal upright confocal microscope using excitation from Argon 488 and HeNe 543 lasers. Using Zeiss LSM software, a Z-stack of approximately 40 µM was captured for fli1a:GFP images and then digitally flattened into a single projection. For the images of fluorescently labeled histones, individual Z-sections from time-lapse movies were used. Next, all files were loaded into Adobe Photoshop CS2 and adjusted for levels and brightness and contrast. Care was taken to apply identical adjustments to images from the same set of experiments, and levels adjustments were limited to avoid removing information from the image.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. GansC, NorthcuttRG (1983) Neural Crest and the Origin of Vertebrates: A New Head. Science 220 : 268–273.

2. BaroffioA, DupinE, Le DouarinNM (1991) Common precursors for neural and mesectodermal derivatives in the cephalic neural crest. Development 112 : 301–305.

3. Bronner-FraserM, FraserSE (1988) Cell lineage analysis reveals multipotency of some avian neural crest cells. Nature 335 : 161–164.

4. PlattJB (1893) Ectodermic origin of the cartilages of the head. Anat Anz 8 : 506–509.

5. SchillingTF, KimmelCB (1994) Segment and cell type lineage restrictions during pharyngeal arch development in the zebrafish embryo. Development 120 : 483–494.

6. BreauMA, PietriT, StemmlerMP, ThieryJP, WestonJA (2008) A nonneural epithelial domain of embryonic cranial neural folds gives rise to ectomesenchyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 : 7750–7755.

7. BernsteinBE, MikkelsenTS, XieX, KamalM, HuebertDJ, et al. (2006) A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell 125 : 315–326.

8. VastenhouwNL, ZhangY, WoodsIG, ImamF, RegevA, et al. (2010) Chromatin signature of embryonic pluripotency is established during genome activation. Nature 464 : 922–926.

9. Rada-IglesiasA, BajpaiR, SwigutT, BrugmannSA, FlynnRA, et al. (2011) A unique chromatin signature uncovers early developmental enhancers in humans. Nature 470 : 279–283.

10. GargiuloG, LevyS, BucciG, RomanenghiM, FornasariL, et al. (2009) NA-Seq: a discovery tool for the analysis of chromatin structure and dynamics during differentiation. Dev Cell 16 : 466–481.

11. BajpaiR, ChenDA, Rada-IglesiasA, ZhangJ, XiongY, et al. (2010) CHD7 cooperates with PBAF to control multipotent neural crest formation. Nature 463 : 958–962.

12. ErogluB, WangG, TuN, SunX, MivechiNF (2006) Critical role of Brg1 member of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex during neurogenesis and neural crest induction in zebrafish. Dev Dyn 235 : 2722–2735.

13. Strobl-MazzullaPH, Sauka-SpenglerT, Bronner-FraserM (2010) Histone demethylase JmjD2A regulates neural crest specification. Dev Cell 19 : 460–468.

14. TakeuchiT, WatanabeY, Takano-ShimizuT, KondoS (2006) Roles of jumonji and jumonji family genes in chromatin regulation and development. Dev Dyn 235 : 2449–2459.

15. PattenSA, Jacobs-McDanielsNL, ZaouterC, DrapeauP, AlbertsonRC, et al. (2012) Role of Chd7 in zebrafish: a model for CHARGE syndrome. PLoS ONE 7: e31650 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031650.

16. AhmadK, HenikoffS (2002) The histone variant H3.3 marks active chromatin by replication-independent nucleosome assembly. Mol Cell 9 : 1191–1200.

17. HajkovaP, AncelinK, WaldmannT, LacosteN, LangeUC, et al. (2008) Chromatin dynamics during epigenetic reprogramming in the mouse germ line. Nature 452 : 877–881.

18. van der HeijdenGW, DerijckAA, PosfaiE, GieleM, PelczarP, et al. (2007) Chromosome-wide nucleosome replacement and H3.3 incorporation during mammalian meiotic sex chromosome inactivation. Nat Genet 39 : 251–258.

19. HodlM, BaslerK (2009) Transcription in the absence of histone H3.3. Curr Biol 19 : 1221–1226.

20. SakaiA, SchwartzBE, GoldsteinS, AhmadK (2009) Transcriptional and developmental functions of the H3.3 histone variant in Drosophila. Curr Biol 19 : 1816–1820.

21. CouldreyC, CarltonMB, NolanPM, ColledgeWH, EvansMJ (1999) A retroviral gene trap insertion into the histone 3.3A gene causes partial neonatal lethality, stunted growth, neuromuscular deficits and male sub-fertility in transgenic mice. Hum Mol Genet 8 : 2489–2495.

22. LawsonND, WeinsteinBM (2002) In vivo imaging of embryonic vascular development using transgenic zebrafish. Dev Biol 248 : 307–318.

23. CoulyGF, ColteyPM, Le DouarinNM (1993) The triple origin of skull in higher vertebrates: a study in quail-chick chimeras. Development 117 : 409–429.

24. KimmelCB, MillerCT, MoensCB (2001) Specification and morphogenesis of the zebrafish larval head skeleton. Dev Biol 233 : 239–257.

25. ArduiniBL, BosseKM, HenionPD (2009) Genetic ablation of neural crest cell diversification. Development 136 : 1987–1994.

26. LiYX, ZdanowiczM, YoungL, KumiskiD, LeatherburyL, et al. (2003) Cardiac neural crest in zebrafish embryos contributes to myocardial cell lineage and early heart function. Dev Dyn 226 : 540–550.

27. ThisseB, HeyerV, LuxA, AlunniV, DegraveA, et al. (2004) Spatial and temporal expression of the zebrafish genome by large-scale in situ hybridization screening. Methods Cell Biol 77 : 505–519.

28. PaulsS, Geldmacher-VossB, Campos-OrtegaJA (2001) A zebrafish histone variant H2A.F/Z and a transgenic H2A.F/Z:GFP fusion protein for in vivo studies of embryonic development. Dev Genes Evol 211 : 603–610.

29. LugerK, MaderAW, RichmondRK, SargentDF, RichmondTJ (1997) Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature 389 : 251–260.

30. GoldbergAD, BanaszynskiLA, NohKM, LewisPW, ElsaesserSJ, et al. (2010) Distinct factors control histone variant H3.3 localization at specific genomic regions. Cell 140 : 678–691.

31. MeulemansD, Bronner-FraserM (2004) Gene-regulatory interactions in neural crest evolution and development. Dev Cell 7 : 291–299.

32. NgRK, GurdonJB (2008) Epigenetic memory of an active gene state depends on histone H3.3 incorporation into chromatin in the absence of transcription. Nat Cell Biol 10 : 102–109.

33. McKittrickE, GafkenPR, AhmadK, HenikoffS (2004) Histone H3.3 is enriched in covalent modifications associated with active chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 : 1525–1530.

34. MitoY, HenikoffJG, HenikoffS (2005) Genome-scale profiling of histone H3.3 replacement patterns. Nat Genet 37 : 1090–1097.

35. Ray-GalletD, QuivyJP, ScampsC, MartiniEM, LipinskiM, et al. (2002) HIRA is critical for a nucleosome assembly pathway independent of DNA synthesis. Mol Cell 9 : 1091–1100.

36. TagamiH, Ray-GalletD, AlmouzniG, NakataniY (2004) Histone H3.1 and H3.3 complexes mediate nucleosome assembly pathways dependent or independent of DNA synthesis. Cell 116 : 51–61.

37. LewisPW, ElsaesserSJ, NohKM, StadlerSC, AllisCD (2010) Daxx is an H3.3-specific histone chaperone and cooperates with ATRX in replication-independent chromatin assembly at telomeres. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 : 14075–14080.

38. SawatsubashiS, MurataT, LimJ, FujikiR, ItoS, et al. (2010) A histone chaperone, DEK, transcriptionally coactivates a nuclear receptor. Genes Dev 24 : 159–170.

39. RobertsC, SutherlandHF, FarmerH, KimberW, HalfordS, et al. (2002) Targeted mutagenesis of the Hira gene results in gastrulation defects and patterning abnormalities of mesoendodermal derivatives prior to early embryonic lethality. Mol Cell Biol 22 : 2318–2328.

40. Wise-DraperTM, Mintz-ColeRA, MorrisTA, SimpsonDS, Wikenheiser-BrokampKA, et al. (2009) Overexpression of the cellular DEK protein promotes epithelial transformation in vitro and in vivo. Cancer research 69 : 1792–1799.

41. MichaelsonJS, BaderD, KuoF, KozakC, LederP (1999) Loss of Daxx, a promiscuously interacting protein, results in extensive apoptosis in early mouse development. Genes & development 13 : 1918–1923.

42. SchnetzMP, BartelsCF, ShastriK, BalasubramanianD, ZentnerGE, et al. (2009) Genomic distribution of CHD7 on chromatin tracks H3K4 methylation patterns. Genome Res 19 : 590–601.

43. BakerCV, Bronner-FraserM, Le DouarinNM, TeilletMA (1997) Early - and late-migrating cranial neural crest cell populations have equivalent developmental potential in vivo. Development 124 : 3077–3087.

44. WestonJA, YoshidaH, RobinsonV, NishikawaS, FraserST (2004) Neural crest and the origin of ectomesenchyme: Neural fold heterogeneity suggests an alternative hypothesis. Dev Dyn 229 : 118–130.

45. DorskyRI, MoonRT, RaibleDW (1998) Control of neural crest cell fate by the Wnt signalling pathway. Nature 396 : 370–373.

46. StreisingerG, WalkerC, DowerN, KnauberD, SingerF (1981) Production of clones of homozygous diploid zebra fish (Brachydanio rerio). Nature 291 : 293–296.

47. KimmelCB, BallardWW, KimmelSR, UllmannB, SchillingTF (1995) Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn 203 : 253–310.

48. WalkerMB, KimmelCB (2007) A two-color acid-free cartilage and bone stain for zebrafish larvae. Biotech Histochem 82 : 23–28.

49. ZunigaE, RippenM, AlexanderC, SchillingTF, CrumpJG (2011) Gremlin 2 regulates distinct roles of BMP and Endothelin 1 signaling in dorsoventral patterning of the facial skeleton. Development 138 : 5147–5156.

50. PhillipsBT, KwonHJ, MeltonC, HoughtalingP, FritzA, et al. (2006) Zebrafish msxB, msxC and msxE function together to refine the neural-nonneural border and regulate cranial placodes and neural crest development. Dev Biol 294 : 376–390.

51. SeoHC, SaetreBO, HavikB, EllingsenS, FjoseA (1998) The zebrafish Pax3 and Pax7 homologues are highly conserved, encode multiple isoforms and show dynamic segment-like expression in the developing brain. Mech Dev 70 : 49–63.

52. ToyamaR, GomezDM, ManaMD, DawidIB (2004) Sequence relationships and expression patterns of zebrafish zic2 and zic5 genes. Gene Expr Patterns 4 : 345–350.

53. ThisseC, ThisseB, SchillingTF, PostlethwaitJH (1993) Structure of the zebrafish snail1 gene and its expression in wild-type, spadetail and no tail mutant embryos. Development 119 : 1203–1215.

54. DuttonKA, PaulinyA, LopesSS, ElworthyS, CarneyTJ, et al. (2001) Zebrafish colourless encodes sox10 and specifies non-ectomesenchymal neural crest fates. Development 128 : 4113–4125.

55. FurthauerM, ThisseC, ThisseB (1997) A role for FGF-8 in the dorsoventral patterning of the zebrafish gastrula. Development 124 : 4253–4264.

56. YanYL, WilloughbyJ, LiuD, CrumpJG, WilsonC, et al. (2005) A pair of Sox: distinct and overlapping functions of zebrafish sox9 co-orthologs in craniofacial and pectoral fin development. Development 132 : 1069–1083.

57. AkimenkoMA, EkkerM, WegnerJ, LinW, WesterfieldM (1994) Combinatorial expression of three zebrafish genes related to distal-less: part of a homeobox gene code for the head. J Neurosci 14 : 3475–3486.

58. KraussS, JohansenT, KorzhV, FjoseA (1991) Expression of the zebrafish paired box gene pax[zf-b] during early neurogenesis. Development 113 : 1193–1206.

59. OxtobyE, JowettT (1993) Cloning of the zebrafish krox-20 gene (krx-20) and its expression during hindbrain development. Nucleic Acids Res 21 : 1087–1095.

60. LuoR, AnM, ArduiniBL, HenionPD (2001) Specific pan-neural crest expression of zebrafish Crestin throughout embryonic development. Dev Dyn 220 : 169–174.

61. GermanguzI, LevD, WaismanT, KimCH, GitelmanI (2007) Four twist genes in zebrafish, four expression patterns. Dev Dyn 236 : 2615–2626.

62. IgnatiusMS, MooseHE, El-HodiriHM, HenionPD (2008) colgate/hdac1 Repression of foxd3 expression is required to permit mitfa-dependent melanogenesis. Dev Biol 313 : 568–583.

63. MavesL, JackmanW, KimmelCB (2002) FGF3 and FGF8 mediate a rhombomere 4 signaling activity in the zebrafish hindbrain. Development 129 : 3825–3837.

64. KwanKM, FujimotoE, GrabherC, MangumBD, HardyME, et al. (2007) The Tol2kit: a multisite gateway-based construction kit for Tol2 transposon transgenesis constructs. Dev Dyn 236 : 3088–3099.

65. HeckmanKL, PeaseLR (2007) Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat Protoc 2 : 924–932.

66. OoiSL, PriessJR, HenikoffS (2006) Histone H3.3 variant dynamics in the germline of Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet 2: e97 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020097.

67. SarcinellaE, ZuzartePC, LauPN, DrakerR, CheungP (2007) Monoubiquitylation of H2A.Z distinguishes its association with euchromatin or facultative heterochromatin. Mol Cell Biol 27 : 6457–6468.

68. JungSY, MalovannayaA, WeiJ, O'MalleyBW, QinJ (2005) Proteomic analysis of steady-state nuclear hormone receptor coactivator complexes. Mol Endocrinol 19 : 2451–2465.

69. CrumpJG, SwartzME, KimmelCB (2004) An Integrin-Dependent Role of Pouch Endoderm in Hyoid Cartilage Development. PLoS Biol 2: e244 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020244.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Genome-Wide Association Study for Serum Complement C3 and C4 Levels in Healthy Chinese SubjectsČlánek Role of Transposon-Derived Small RNAs in the Interplay between Genomes and Parasitic DNA in RiceČlánek Tetraspanin Is Required for Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species by the Dual Oxidase System inČlánek A Mimicking-of-DNA-Methylation-Patterns Pipeline for Overcoming the Restriction Barrier of BacteriaČlánek A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Five Loci Influencing Facial Morphology in Europeans

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 9- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Heterozygous Mutations in DNA Repair Genes and Hereditary Breast Cancer: A Question of Power

- GWAS of Diabetic Nephropathy: Is the GENIE out of the Bottle?

- The Conflict within and the Escalating War between the Sex Chromosomes

- Proteome-Wide Analysis of Disease-Associated SNPs That Show Allele-Specific Transcription Factor Binding

- Exome Sequencing Identifies Rare Deleterious Mutations in DNA Repair Genes and as Potential Breast Cancer Susceptibility Alleles

- A Gene Family Derived from Transposable Elements during Early Angiosperm Evolution Has Reproductive Fitness Benefits in

- Genome-Wide Association Study for Serum Complement C3 and C4 Levels in Healthy Chinese Subjects

- Role of Transposon-Derived Small RNAs in the Interplay between Genomes and Parasitic DNA in Rice

- Co-Evolution of Mitochondrial tRNA Import and Codon Usage Determines Translational Efficiency in the Green Alga

- SIRT6/7 Homolog SIR-2.4 Promotes DAF-16 Relocalization and Function during Stress

- CNV Formation in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells Occurs in the Absence of Xrcc4-Dependent Nonhomologous End Joining

- Tetraspanin Is Required for Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species by the Dual Oxidase System in

- Citrullination of Histone H3 Interferes with HP1-Mediated Transcriptional Repression

- Variation in Genes Related to Cochlear Biology Is Strongly Associated with Adult-Onset Deafness in Border Collies

- The Long Non-Coding RNA Affects Chromatin Conformation and Expression of , but Does Not Regulate Its Imprinting in the Developing Heart

- Rif2 Promotes a Telomere Fold-Back Structure through Rpd3L Recruitment in Budding Yeast

- Is a Metastasis Susceptibility Gene That Suppresses Metastasis by Modifying Tumor Interaction with the Cell-Mediated Immunity

- The p38/MK2-Driven Exchange between Tristetraprolin and HuR Regulates AU–Rich Element–Dependent Translation

- Rare Copy Number Variants Contribute to Congenital Left-Sided Heart Disease

- A Genetic Basis for a Postmeiotic X Versus Y Chromosome Intragenomic Conflict in the Mouse

- An Essential Role of Variant Histone H3.3 for Ectomesenchyme Potential of the Cranial Neural Crest

- Characterization of Inducible Models of Tay-Sachs and Related Disease

- Hominoid-Specific Protein-Coding Genes Originating from Long Non-Coding RNAs

- Transcriptional Repression of Hox Genes by HP1/HPL and H1/HIS-24

- Integrative Genomic Analysis Identifies Isoleucine and CodY as Regulators of Virulence

- Convergence of the Transcriptional Responses to Heat Shock and Singlet Oxygen Stresses

- Genomics of Adaptation during Experimental Evolution of the Opportunistic Pathogen

- Enrichment of HP1a on Drosophila Chromosome 4 Genes Creates an Alternate Chromatin Structure Critical for Regulation in this Heterochromatic Domain

- Vsx2 Controls Eye Organogenesis and Retinal Progenitor Identity Via Homeodomain and Non-Homeodomain Residues Required for High Affinity DNA Binding

- The Long Path from QTL to Gene

- TCF7L2 Modulates Glucose Homeostasis by Regulating CREB- and FoxO1-Dependent Transcriptional Pathway in the Liver

- The Non-Flagellar Type III Secretion System Evolved from the Bacterial Flagellum and Diversified into Host-Cell Adapted Systems

- Complex Chromosomal Rearrangements Mediated by Break-Induced Replication Involve Structure-Selective Endonucleases

- Factors That Promote H3 Chromatin Integrity during Transcription Prevent Promiscuous Deposition of CENP-A in Fission Yeast

- A Mimicking-of-DNA-Methylation-Patterns Pipeline for Overcoming the Restriction Barrier of Bacteria

- Determinants of Human Adipose Tissue Gene Expression: Impact of Diet, Sex, Metabolic Status, and Genetic Regulation

- Genome-Wide Association Studies Identify Heavy Metal ATPase3 as the Primary Determinant of Natural Variation in Leaf Cadmium in

- Tethering of the Conserved piggyBac Transposase Fusion Protein CSB-PGBD3 to Chromosomal AP-1 Proteins Regulates Expression of Nearby Genes in Humans

- A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Five Loci Influencing Facial Morphology in Europeans

- Normal DNA Methylation Dynamics in DICER1-Deficient Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- H4K20me1 Contributes to Downregulation of X-Linked Genes for Dosage Compensation

- The NDR Kinase Scaffold HYM1/MO25 Is Essential for MAK2 MAP Kinase Signaling in

- Coevolution within and between Regulatory Loci Can Preserve Promoter Function Despite Evolutionary Rate Acceleration

- New Susceptibility Loci Associated with Kidney Disease in Type 1 Diabetes

- SWI/SNF-Like Chromatin Remodeling Factor Fun30 Supports Point Centromere Function in

- A Response Regulator Interfaces between the Frz Chemosensory System and the MglA/MglB GTPase/GAP Module to Regulate Polarity in

- Functional Variants in and Involved in Activation of the NF-κB Pathway Are Associated with Rheumatoid Arthritis in Japanese

- Two Distinct Repressive Mechanisms for Histone 3 Lysine 4 Methylation through Promoting 3′-End Antisense Transcription

- Genetic Modifiers of Chromatin Acetylation Antagonize the Reprogramming of Epi-Polymorphisms

- UTX and UTY Demonstrate Histone Demethylase-Independent Function in Mouse Embryonic Development

- A Comparison of Brain Gene Expression Levels in Domesticated and Wild Animals

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Enrichment of HP1a on Drosophila Chromosome 4 Genes Creates an Alternate Chromatin Structure Critical for Regulation in this Heterochromatic Domain

- Normal DNA Methylation Dynamics in DICER1-Deficient Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- The NDR Kinase Scaffold HYM1/MO25 Is Essential for MAK2 MAP Kinase Signaling in

- Functional Variants in and Involved in Activation of the NF-κB Pathway Are Associated with Rheumatoid Arthritis in Japanese

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání