-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Genome-Wide Analysis of GLD-1–Mediated mRNA Regulation Suggests a Role in mRNA Storage

Translational repression is often accompanied by mRNA degradation. In contrast, many mRNAs in germ cells and neurons are “stored" in the cytoplasm in a repressed but stable form. Unlike repression, the stabilization of these mRNAs is surprisingly little understood. A key player in Caenorhabditis elegans germ cell development is the STAR domain protein GLD-1. By genome-wide analysis of mRNA regulation in the germ line, we observed that GLD-1 has a widespread role in repressing translation but, importantly, also in stabilizing a sub-population of its mRNA targets. Additionally, these mRNAs appear to be stabilized by the DDX6-like RNA helicase CGH-1, which is a conserved component of germ granules and processing bodies. Because many GLD-1 and CGH-1 stabilized mRNAs encode factors important for the oocyte-to-embryo transition (OET), our findings suggest that the regulation by GLD-1 and CGH-1 serves two purposes. Firstly, GLD-1–dependent repression prevents precocious translation of OET–promoting mRNAs. Secondly, GLD-1 – and CGH-1–dependent stabilization ensures that these mRNAs are sufficiently abundant for robust translation when activated during OET. In the absence of this protective mechanism, the accumulation of OET–promoting mRNAs, and consequently the oocyte-to-embryo transition, might be compromised.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 8(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002742

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002742Summary

Translational repression is often accompanied by mRNA degradation. In contrast, many mRNAs in germ cells and neurons are “stored" in the cytoplasm in a repressed but stable form. Unlike repression, the stabilization of these mRNAs is surprisingly little understood. A key player in Caenorhabditis elegans germ cell development is the STAR domain protein GLD-1. By genome-wide analysis of mRNA regulation in the germ line, we observed that GLD-1 has a widespread role in repressing translation but, importantly, also in stabilizing a sub-population of its mRNA targets. Additionally, these mRNAs appear to be stabilized by the DDX6-like RNA helicase CGH-1, which is a conserved component of germ granules and processing bodies. Because many GLD-1 and CGH-1 stabilized mRNAs encode factors important for the oocyte-to-embryo transition (OET), our findings suggest that the regulation by GLD-1 and CGH-1 serves two purposes. Firstly, GLD-1–dependent repression prevents precocious translation of OET–promoting mRNAs. Secondly, GLD-1 – and CGH-1–dependent stabilization ensures that these mRNAs are sufficiently abundant for robust translation when activated during OET. In the absence of this protective mechanism, the accumulation of OET–promoting mRNAs, and consequently the oocyte-to-embryo transition, might be compromised.

Introduction

The oocyte-to-embryo transition (OET), which encompasses oocyte maturation, ovulation, fertilization, and early embryogenesis, occurs while Pol II dependent transcription is globally repressed. This is why OET is largely driven by maternal mRNAs that are stored in the egg cytoplasm in a repressed but, importantly, also stable form [1]. In contrast to translational repression, stabilization of repressed mRNAs remains little understood. In Xenopus oocytes, mRNA stability is attributed to a global inhibition of decapping activity [2], [3]. On the other hand, in developing Drosophila oocytes, stabilization of the bicoid mRNA depends on the binding of a specific protein, BSF [4]. This suggests that, at least in some species, global inhibition of mRNA decay is not a general feature of oogenesis and thus mechanisms stabilizing specific germline messages might exist.

In C. elegans, the DDX6-like RNA helicase, CGH-1, associates with a large number of germline mRNAs [5]. Some of these mRNAs are less abundant in CGH-1 (-) germ cells, suggesting that this helicase plays a role in mRNA stabilization [5]. The DDX6-like helicases are present in various cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein (RNP) particles such as processing (P) bodies [5]–[14]. In the C. elegans germ line, CGH-1 localizes to P granules, which are associated with the nuclear envelope, and to P body-like cytoplasmic granules [15]. In contrast to P bodies, the latter granules seem to be largely devoid of RNA decay enzymes and have thus been proposed to serve as vehicles of mRNA storage, which is consistent with a role of CGH-1 in mRNA stabilization, [5], [16]–[22]. However, because somatic P body formation is thought to be the consequence, not the cause, of mRNA repression [23], [24], the functional significance of these RNA granules for mRNA stabilization remains to be demonstrated.

Here, we report the C. elegans STAR-protein GLD-1 as a potential player in maternal mRNA storage. GLD-1 is expressed in the medial gonad (Figure 1A), where it promotes meiosis, oogenesis, and maintenance of germ cell identity by repressing the translation of diverse mRNAs [25]–[30]. Recently, we have shown that GLD-1 associates with hundreds of germline transcripts, and that this association is determined by the number and strength of 7-mer GLD-1 binding motifs (GBMs) within untranslated regions (UTRs) [31]. To understand how GLD-1 regulates its mRNA targets, we undertook a functional genomics approach. By transcriptome-wide polysome profiling, we found that GLD-1 has a widespread role in repressing translation. Our results also suggest that GLD-1 stabilizes many targets, which additionally involves the DDX6-like RNA helicase CGH-1. Because the stabilized mRNAs encode proteins critical for OET, and their stability appears to be important for efficient accumulation in oocytes, GLD-1 dependent mRNA storage might be important for a successful oocyte-to-embryo transition.

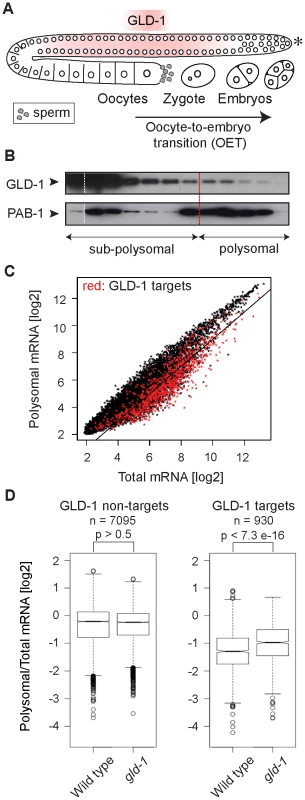

Fig. 1. GLD-1 has a widespread role in repressing translation.

(A) Schematic of a C. elegans gonad and the oocyte-to-embryo transition (OET). The distal-most gonad contains stem cells and is marked here and in subsequent figures by an asterisk. The medial gonad contains germ cells undergoing meiosis that are expressing GLD-1. Growing oocytes are present in the proximal gonad. OET, including ovulation, fertilization, and early stages of embryonic development, occurs while Pol II transcription is globally repressed. (B) GLD-1 mostly co-fractionates with non-translated mRNAs. Distribution of GLD-1 and PAB-1 proteins, detected with specific antibodies by western blotting, between fractions from a polysome profiling experiment. (C) Identification of non-translated mRNAs, including many GLD-1 targets, by a transcriptome-wide survey of translational repression. Polysomal and total mRNAs from wild-type animals were analyzed by polysome profiling followed by microarray-based detection. Polysomal mRNA levels were plotted against total mRNA levels. Each dot in this and subsequent scatter plots represents a single mRNA. Transcripts that are more than two-fold depleted from polysomal fractions are below the black line. GLD-1 targets are colored in red (see Figure S1D). (D) GLD-1 represses translation initiation. Box plots represent the distribution of polysomal/total mRNA ratios for GLD-1 targets and non-targets in wild type and gld-1(q485) mutants (called simply gld-1). The polysomal/total mRNA ratio of non-targets is similar in wild-type and gld-1 animals (left panel). In contrast, GLD-1 targets shift to polysomes in gld-1 mutants (right panel). Sample sizes (n) and p values are indicated. The p values were calculated with a t test. Results

GLD-1 has a widespread role in repressing translation

It is currently unknown how GLD-1 represses translation. By ‘polysome profiling’, in which poly-ribosomes (polysomes) are separated from single ribosomes and ribosomal subunits by sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation, two of the GLD-1 targets, tra-2 and pal-1, have been suggested to be repressed at the initiation or elongation stage of translation, respectively [30], [32]. To globally examine the effect of GLD-1 on the translation of its targets, we performed polysome profiling on a transcriptome-wide scale. In general, while polysomal fractions contain translated mRNAs (as well as mRNAs repressed at the elongation or termination stage of translation), sub-polysomal fractions contain poorly translated mRNAs and transcripts repressed at the initiation stage of translation (Figure S1A–S1C). To determine the distribution of GLD-1 between fractions, we used monoclonal antibodies raised against GLD-1, and, as a control, against the translational activator polyA-binding protein, PAB-1. As expected, PAB-1 was enriched in polysomal fractions (Figure 1B). In contrast, the majority of GLD-1 was present in the sub-polysomal fractions (Figure 1B). By comparing polysomal and total mRNA levels by microarray analysis, we found that also most GLD-1 targets (Table S1 and Figure 1C and Figure S1D; mRNAs more than 3-fold enriched in GLD-1 IPs; also [31]) were enriched in sub-polysomal fractions (Figure 1C; GLD-1 targets are in red; transcripts more than 2-fold depleted from polysomes, including 64% of GLD-1 targets, are below the black line). To examine GLD-1 dependent repression, we tested whether GLD-1 targets shift to polysomal fractions in gld-1(q485) null mutant worms (hereafter called gld-1 mutants). Because gld-1 mutants develop germline tumors, we only examined young adults, in which the gonads contained large numbers of pachytene cells and only few ectopically proliferating cells [26], [33]. To collect sufficient quantities of mutant animals, gld-1 homozygous mutants were separated from heterozygous animals, carrying a GFP-tagged balancer, by fluorescence-activated sorting. Expectedly, we found that the loss of GLD-1 had little effect on the polysomal/total mRNA ratio of non-GLD-1 targets and of targets of an unrelated RBP, FBF [34] (Figure 1D and Figure S1E). In contrast, the loss of GLD-1 caused GLD-1 targets to shift to polysomes (Figure 1D; p<7.3e−16; p values were calculated with a t test). While the polysomal/total mRNA ratio of GLD-1 targets remained relatively low in gld-1 mutants compared to non-targets (possibly due to residual repression by other RBPs as has been observed for several GLD-1 targets [30], [35], [36]), these results collectively suggest that, although additional mechanisms may exist and contribute to repression, GLD-1 binding inhibits translational initiation.

GLD-1 is required for the accumulation of many mRNA targets

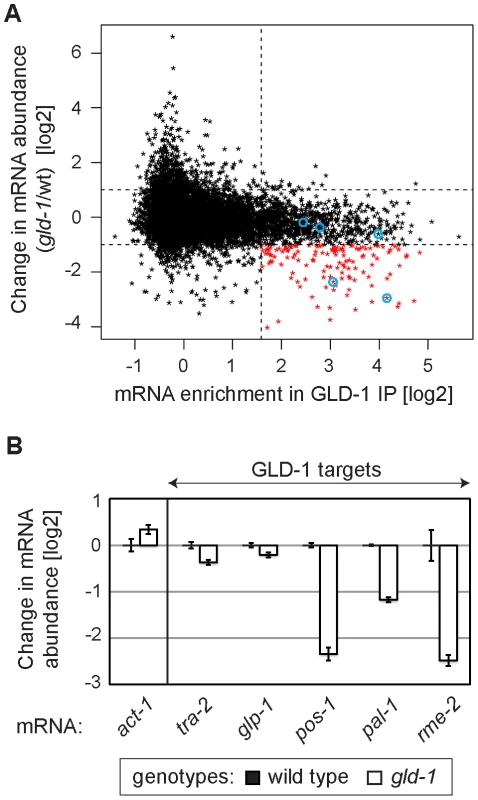

Several GLD-1 targets have been observed by others to be less abundant in gld-1 mutants [26]–[29], [37], [38]. To globally determine a potential function of GLD-1 in mRNA stabilization, we analyzed the abundance of mRNAs in wild-type and gld-1 mutant gonads by microarray analysis. We then compared changes in the mRNA abundance in gld-1 mutants to GLD-1 binding (Table S1 and Figure 2A; the vertical dotted line separates non-targets on the left from presumed GLD-1 targets on the right and the horizontal lines demarcate a 2-fold change of mRNA abundance). We observed that a subset of GLD-1 targets (14%) were less abundant in gld-1 mutants (Figure 2A, transcripts marked in red, those encircled in blue were confirmed by RT-qPCR in 2B). Because these mRNAs also tend to shift to polysomes in gld-1 mutants (Figure S2), our results suggest that GLD-1 may control both their repression and stability.

Fig. 2. GLD-1 is required for the accumulation of many mRNA targets.

(A) Many GLD-1 targets are less abundant in gld-1 mutants. Abundance of mRNAs in dissected wild-type and gld-1 gonads was measured by microarrays. The change in mRNA abundance in gld-1 mutants was plotted against GLD-1 IP enrichment. The vertical line separates non-targets on the left from GLD-1 targets on the right. Horizontal lines demarcate a 2-fold change of mRNA abundance in gld-1 gonads. mRNAs verified in Figure 2B are encircled in blue. (B) A decrease in the levels of several GLD-1 targets was independently confirmed by RT-qPCR. Transcripts are arranged according to their GLD-1 IP enrichment in Figure 2A (the blue circles begin on the left with tra-2 and end with rme-2 on the right). The levels of indicated mRNAs were normalized to tbb-2 mRNA. Shown are changes in mRNA levels in gld-1 mutants relative to wild-type animals. Error bars here, and in subsequent figures, represent SEM of at least three biological replicates. GLD-1 interacts with conserved components of germline granules and P bodies

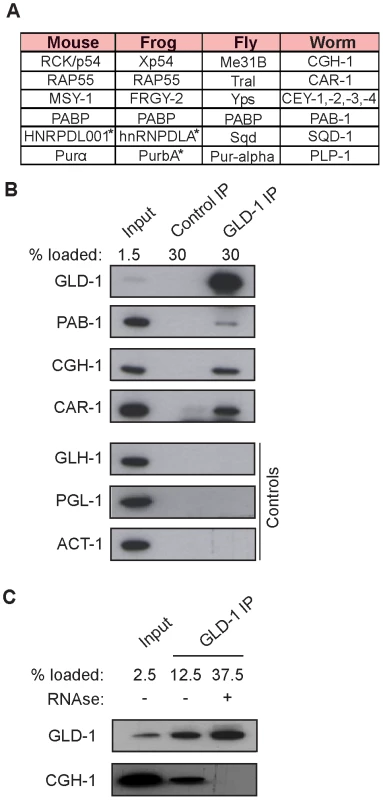

To investigate potential partners of GLD-1 in mRNA stabilization, we immunopurified GLD-1 and analyzed co-purifed proteins by mass spectrometry. Top proteins most enriched in GLD-1 immunoprecipitates (IPs), together with their counterparts in other animals, are listed in Figure 3A (also see Figure S3A). These include the DDX6-like RNA helicase CGH-1, the Y-box proteins CEY-1-4, the Sm-like domain protein CAR-1, and the cytoplasmic polyA binding protein PAB-1, all of which are conserved components of repressive RNPs in germ cells and somatic cells, and which have been previously shown to interact with each other [5], [8]–[14], [22]. Using available antibodies, we confirmed by western blot analysis that the interactions between GLD-1 and CGH-1, CAR-1, and PAB-1, were specific (Figure 3B). CGH-1 has previously been implicated in the stabilization of at least some maternal mRNA [5], which is why we pursued its interaction with GLD-1 further. We observed that the GLD-1/CGH-1 interaction was dependent on RNA (Figure 3C) and confocal microscopy revealed that only a minor fraction of GLD-1 co-localized with CGH-1 in the germline cytoplasm (Figure S3B).

Fig. 3. GLD-1 interacts with conserved components of RNA granules.

(A) A table summarizing top GLD-1 interacting proteins and their counterparts in other species. Shown are GLD-1 co-precipitated proteins (identified by mass spectrometry) and their homologs. Proteins marked with asterisks are predicted based on available transcripts. (B) Confirmation of some interactions by western blot analysis of GLD-1 IPs. GLH-1/Vasa, PGL-1, and ACT-1/actin are negative controls. (C) The interaction between GLD-1 and CGH-1 depends on RNA. RNAse treatment of GLD-1 IPs prevents CGH-1 from co-immunoprecipitating with GLD-1. GLD-1 and CGH-1 are required for the accumulation of common mRNAs

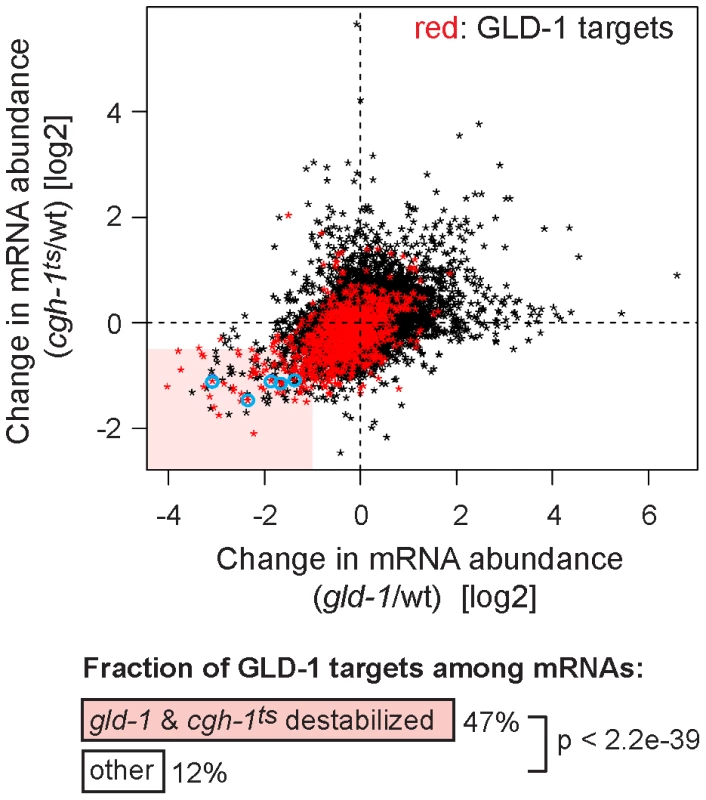

Despite the indirect (RNA-mediated) interaction between GLD-1 and CGH-1, we tested if the two proteins may be functionally related. Because we were unable to create a strain containing both gld-1(q485) and cgh-1(ok492) null mutations, the temperature-sensitive cgh-1(tn691) allele, hereafter called cgh-1ts, was used in many experiments. This is an antimorphic allele (Ikuko Yamamoto and David Greenstein, personal communication; Figure S3E), which nevertheless induces oocyte defects and sheet-like CAR-1 containing structures also observed in cgh-1 null or cgh-1(RNAi) gonads (data not shown; [5], [39]). We initially confirmed that the loss of CGH-1 activity had no obvious effect on the levels and distribution of GLD-1 ([39] and Figures S3C and S4B), nor did the loss of GLD-1 affect CGH-1 ([15] and Figure S3D). By microarrays, we examined the abundance of mRNAs in gonads dissected from cgh-1ts mutants grown at the restrictive temperature, and compared the changes in mRNA levels between gld-1 and cgh-1ts gonads (Table S1 and Figure 4; encircled transcripts were confirmed by RT-qPCR in subsequent figures). Importantly, we observed that similar transcripts were reduced in each mutant (Figure 4; Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.426) and that 47% of the transcripts reduced in both gld-1 and cgh-1ts mutants were also GLD-1 targets (Figure 4, GLD-1 targets are in red); about four-fold more than expected by chance (p<2.2e-39, t test; only 12% of all germline mRNAs are bound by GLD-1). To make sure that the observed changes in mRNA levels were not unique to the cgh-1ts allele, we additionally analyzed mRNA changes in animals subjected to cgh-1 RNAi and in cgh-1 null mutants, and obtained similar results (Table S1 and Figure S4A–S4D). Combined, these results suggest that the mRNAs stabilized by GLD-1 are also stabilized by CGH-1. For the purpose of this study, we refer to those transcripts simply as ‘co-regulated mRNAs’ (Table S2; mRNAs that are GLD-1 targets, and which are less abundant in both gld-1 and cgh-1ts mutants).

Fig. 4. GLD-1 and CGH-1 are both required for the accumulation of a subset of GLD-1 targets.

mRNA levels in dissected wild-type, gld-1, and cgh-1ts gonads were measured by microarrays. The change in mRNA abundance in cgh-1ts mutants was plotted against the change in mRNA abundance in gld-1 mutants. GLD-1 targets are marked in red. mRNAs verified in Figure 6A and Figure S4A and S4C are encircled in blue. The light red rectangle contains mRNAs whose abundance drops the most in both mutants. These mRNAs are 4-fold enriched for GLD-1 targets compared to all germline mRNAs (p<2.2e−39, t test). GLD-1 binding directly elicits translational repression and mRNA stabilization

GLD-1 binds its mRNA targets via specific GLD-1 binding motifs (GBMs), which are mostly present in 3′ UTRs [31]. This enabled us to test a direct versus indirect role of GLD-1 in both mRNA repression and stabilization in wild-type animals, by creating a series of reporters containing either wild-type or mutated GBMs. Specifically, a constitutive germline promoter (mex-5) was used to drive transcription of GFP fused to histone H2B (which concentrates GFP in the nucleus to facilitate detection) [40]. The GFP reporter was fused to various 3′ UTRs of co-regulated mRNAs that either contained wild-type GBMs (GBMwt), allowing GLD-1 binding and regulation, or mutated GBMs (GBMmut), preventing GLD-1 binding and regulation (Figure 5A). We examined the effect of GLD-1 binding on mRNA stability by analyzing the levels of GBMwt/mut reporter pairs by RT-qPCR and found that, in each case, the GBMmut mRNA was less abundant than the corresponding GBMwt mRNA (Figure 5B and Figure S5A). Because these reporters were expressed and analyzed in wild-type animals, and mutated GBMs do not cause destabilization when introduced into the 3′ UTR of a non-target mRNA [31], these results suggest that GLD-1 stabilizes at least some of the co-regulated mRNAs by directly associating with their 3′ UTRs.

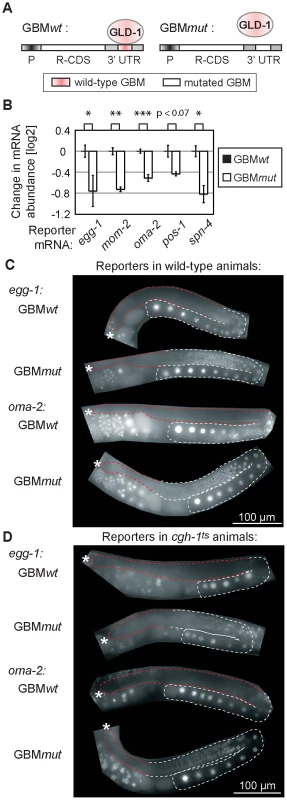

Fig. 5. GLD-1 binding elicits mRNA stabilization and translational repression.

(A) Schematic of reporters that were used to test the effect of GLD-1 binding motifs (GBMs) on mRNA stability and translation. P: a germ line-specific promoter (mex-5); R-CDS: reporter's coding sequence consisting of GFP fused to histone H2B; 3′UTR: GLD-1 target 3′ UTR containing either wild-type GBMs (GBMwt), or mutated GBMs (GBMmut) that no longer recruit GLD-1. (B) Mutating GBMs reduced mRNA levels of several reporters (shown is one reporter line per construct, for additional lines see S5A). Reporter mRNA levels were analyzed by RT-qPCR and normalized to tbb-2 mRNA. Shown are mRNA level changes of GBMmut reporters relative to GBMwt reporters. One asterisk indicates p<0.05, two asterisks p<0.01, and three asterisks p<0.001 (p values were calculated with a t test). (C) Mutating GBMs caused egg-1 and oma-2 reporter de-repression in the medial gonad. Shown are photomicrographs of gonads (outlined; red highlighting repressed regions) from live, transgenic, and otherwise wild-type animals. (D) The same reporters were not (or additionally) de-repressed when crossed into cgh-1ts mutants. See also Figure S5B–S5C. Expectedly, we observed that the GBMmut reporters were de-repressed in the medial germ line (Figure 5C and Figure S5B). To test the effect of CGH-1 on translational repression, we crossed the GBMwt and mut reporters into the cgh-1ts mutant, and additionally subjected reporter strains to cgh-1 RNAi. Consistently with the observation that endogenous glp-1 and rme-2 mRNAs are not de-repressed in the medial gonad of cgh-1(RNAi) animals [39], we found that the GBMwt reporters were de-repressed in neither cgh-1ts nor cgh-1(RNAi) animals, nor were the GBMmut variants additionally de-repressed (Figure 5D and Figure S5C). These results suggest that, while CGH-1 contributes to the stabilization of GLD-1 targets, it does not appear to have a general role in their repression.

GLD-1 and CGH-1 stabilize mRNAs independently of each other

GLD-1 and CGH-1 may depend on each other for mRNA stabilization or function independently. To test whether GLD-1 and CGH-1 affect mRNA stability in an additive fashion, we determined the levels of endogenous co-regulated mRNAs in gld-1 and cgh-1ts single, and gld-1; cgh-1ts double mutants. We found that mRNA levels, which were reduced in both single mutants, were even further reduced in the gld-1; cgh-1ts double mutant (Figure 6A), suggesting that GLD-1 and CGH-1 may stabilize mRNAs by acting in parallel pathways. Furthermore, to investigate if GLD-1 and CGH-1 depend on each other for mRNA binding, endogenous co-regulated mRNAs were co-precipitated with GLD-1 and CGH-1, from extracts of wild-type and mutant animals. One caveat of this analysis is that the RNA levels in mutant animals are reduced and obtained values need to be normalized to the corresponding input levels. By this approach, we observed that GLD-1 could still bind mRNAs in cgh-1ts and cgh-1(RNAi) animals, and likewise CGH-1 could bind mRNAs in the absence of GLD-1 (Figure 6B–6C and Figure S6). To test this further, we IP-ed GBMwt and GBMmut variants of the co-regulated oma-2 reporter with GLD-1 and CGH-1 from worm lysates. As expected, we found that mutating GBMs in the oma-2 3′UTR dramatically decreased GLD-1 binding (Figure 6D). In contrast, we observed no reduction in CGH-1 binding (Figure 6D). Together, these results suggest that GLD-1 and CGH-1 are recruited to an mRNA independently of each other and that, although GLD-1 and CGH-1 stabilize largely the same mRNAs, their contributions appear to be distinct.

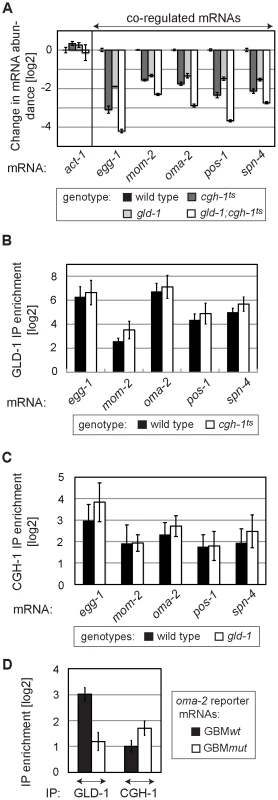

Fig. 6. GLD-1 and CGH-1 stabilize mRNAs independently of each other.

(A) GLD-1 and CGH-1 affect mRNA stability in an additive fashion. The levels of indicated mRNAs in wild-type, gld-1, cgh-1ts, and gld-1;cgh-1ts animals were measured by RT-qPCR and normalized to tbb-2. Shown are changes in mRNA abundance relative to the wild type. (B) GLD-1 binds co-regulated mRNAs in cgh-1ts animals. GLD-1 IPs were performed on lysates from wild-type and cgh-1ts animals and normalized to control (FLAG) IPs, to input mRNA levels, and finally to tbb-2 mRNA. For similar IPs on cgh-1 RNAi animals see Figure S6. (C) CGH-1 binds co-regulated mRNAs in the absence of GLD-1. CGH-1 IPs were performed on lysates from wild-type and gld-1 animals and normalized to control (IgG) IPs, to input mRNA levels, and finally to tbb-2 mRNA. (D) GLD-1 and CGH-1 are recruited to an mRNA independently of each other. GLD-1 and CGH-1 IPs were performed on lysates from oma-2 GBMwt and GBMmut reporter-expressing animals and normalized to control IPs (FLAG and IgG respectively), to input mRNA levels and to tbb-2 mRNA. GLD-1 and CGH-1 co-regulated mRNAs encode OET regulators and accumulate in oocytes

Many of the co-regulated mRNAs encode proteins that have been studied in at least some detail. Remarkably, most of them (34/38) are important during the oocyte-to-embryo transition (Table S2). Some of these proteins function specifically during oogenesis (for example PUF-5; [35]), fertilization (EGG-1; [41]), or early embryogenesis (POS-1; [42]). Others, such as OMA-2, function at multiple times during OET [43]–[45]. Thus, GLD-1 and CGH-1 appear to stabilize messages related by their function in promoting OET. This was unexpected, because GLD-1 is expressed in the medial germ line but is absent from oocytes. To examine this seeming discrepancy, we tested by in situ hybridization whether the reporters of co-regulated mRNAs accumulate in oocytes in a GBM-dependent manner. Indeed, we found that the GBMmut reporters were less abundant not only in the medial, GLD-1 expressing part of the gonad, but also in the proximal gonad, suggesting that GLD-1 mediated stabilization is important for OET mRNA accumulation in oocytes (Figure 7A; position of oocytes is indicated by red brackets; see discussion).

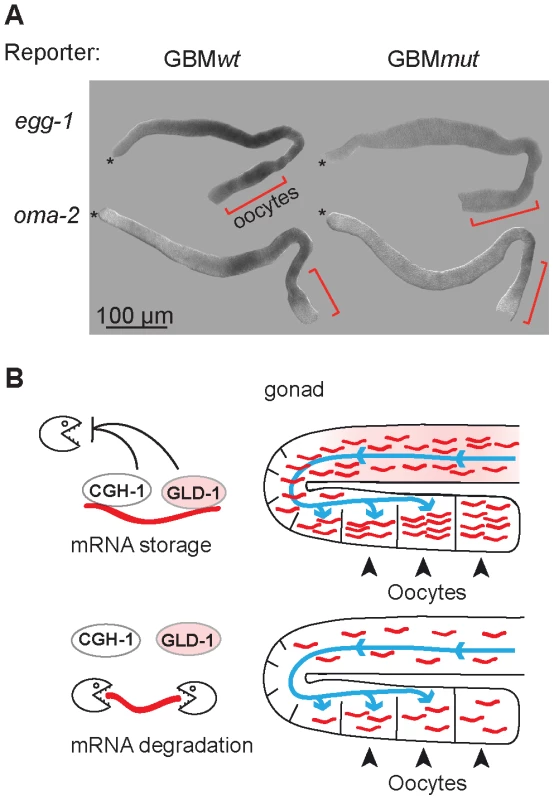

Fig. 7. GLD-1 and CGH-1 co-regulated mRNAs accumulate in oocytes.

(A) The expression patterns of GBMwt and GBMmut reporters as determined by in situ hybridization against gfp RNA. Wild-type gonads, not expressing a GFP reporter, were negative. Oocytes are indicated with brackets. (B) Model of how GLD-1 and CGH-1 mediated mRNA stabilization may lead to mRNA accumulation in oocytes. The blue lines indicate a general influx of the cytoplasm from undifferentiated germ cells to oocytes as reported by Wolke et al, 2007. GLD-1 and CGH-1 mediated protection in the medial part ensures that mRNAs are transported into oocytes (top). In the absence of this protection, mRNAs are degraded by an unknown mechanism(s) and thus fail to accumulate in oocytes. Discussion

GLD-1 mediated translational repression

Previously, we identified hundreds of germline transcripts associated with GLD-1 [31]. Although the precise mechanism(s) remain unknown, here we present evidence that in general these messages are repressed by GLD-1, consistently with a recent report describing global protein changes in GLD-1 depleted animals [46]. We found that GLD-1 interacts with components of repressive germline mRNA complexes, including the DDX6 helicase CGH-1. In Xenopus and Drosophila, similar complexes also contain eIF4E-binding proteins (4E-BPs), suggesting that they repress translation by interfering with the assembly of the basic translation initiation factor eIF4F [12], [14], [47]–[50]. Interestingly, in Drosophila, the same proteins have also been implicated in oskar mRNA repression by a cap-independent mechanism, presumably by sequestering mRNAs away from the translation machinery [51]. Because we found neither basic initiation factors nor 4E-BPs among GLD-1 interacting proteins, one possibility is that GLD-1 represses its targets via a similar ‘sequestering’ mechanism, which might also protect them from the decay machinery. However, since GLD-1 appears to stabilize only a subset of its targets, and CGH-1 seems to protect but not repress them, translational repression and mRNA stabilization of co-regulated mRNAs are not necessarily coupled.

GLD-1 and CGH-1 mediated mRNA stabilization

Our findings suggest that, in addition to repressing translation, GLD-1 stabilizes a subpopulation of its targets. The most compelling evidence comes from the GBM+/ − reporter studies, which directly demonstrate that GLD-1 binding can stabilize a target mRNA. However, we noticed that the changes in mRNA levels induced by GBM mutations were smaller than the changes in the endogenous mRNAs observed between wild type and gld-1 mutants. This could be due to a number of differences between the synthetic and endogenous mRNAs (such as expression from different promoters, splicing, potential additional regulatory motifs, etc.) or reflect a stronger decrease in mRNA levels in the mutant due to indirect effects. Thus, the precise magnitude of GLD-1 mediated stabilization remains to be determined. Besides GLD-1, our findings additionally implicate CGH-1 in the stabilization of some GLD-1 targets, but suggest that the two proteins regulate mRNA stability independently of each other. Possible interpretations of this data are that these proteins largely associate with separate cytoplasmic pools of mRNAs and/or protect mRNAs in different parts of the gonad. Yet, inconsistently with the later scenario, we noticed that the levels of several mRNAs tested by in situ hybridization were reduced also in the medial, GLD-1 expressing parts of cgh-1ts gonads (our unpublished observation). Interestingly, while CGH-1 appears to affect the stability of specific GLD-1 targets, it may be dispensable for their repression. This contrasts with the function of DDX6 helicases in translational repression in some models [12], [48], [49] but agrees with the role of the protist DDX6-like helicase, DOZI, which stabilizes repressed transcripts in female gametocytes [52]. Thus, either DDX6 helicases have distinct roles in different organisms, or their function in mRNA stabilization and/or mRNA repression depends on a specific mRNA.

The flip side of OET mRNA stabilization—degradation of unprotected transcripts

Our finding, that GLD-1 and CGH-1-dependent stabilization may be important for efficient accumulation of OET transcripts, implies that the decay machinery responsible for the degradation of unprotected mRNAs is active in the germ line. Two GLD-1 targets containing upstream open reading frames are thought to be protected by GLD-1 from nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) [37]. However, we found no evidence that the degradation of unprotected GLD-1 targets described here depends on NMD (Figure S7). Interestingly, many OET mRNAs protected by GLD-1 and CGH-1 are degraded in early embryos (our unpublished observation). Thus, one possibility is that the machinery degrading maternal transcripts in the embryo degrades also unprotected OET mRNAs in the germ line. In D. melanogaster, the embryonic degradation of maternal mRNAs requires the protein Smaug and miRNAs [53]–[55]. Whether related factors degrade maternal mRNAs in the C. elegans embryo and/or unprotected OET mRNAs in the gonad remains to be tested.

GLD-1 – and CGH-1–dependent accumulation of OET mRNAs in oocytes

Intriguingly, our findings suggest that GLD-1 dependent stabilization of mRNAs is important for their accumulation in oocytes, i.e. in cells in which GLD-1 is no longer present. In C. elegans, oocyte growth depends on an influx of cytoplasmic material originating in undifferentiated, GLD-1 expressing cells, which may be analogous to the cytoplasmic transport from nurse cells into oocytes in the Drosophila ovary [56]. Thus, one explanation for GLD-1 dependent accumulation of mRNAs in oocytes is that GLD-1 binding protects mRNAs before and/or during their transport into growing oocytes (Figure 7B). Once in oocytes, these mRNAs might be stable due to a general suppression of mRNA decay, as described in Xenopus oocytes [2], [3]. Alternatively, GLD-1 might only be required for the initiation but not the maintenance of mRNA protection, which in oocytes may depend on CGH-1 and/or other RBPs.

Materials and Methods

Nematode culture, RNAi, mutants, transgenic strains, and worm sorting

Animals were typically maintained at 25°C using standard procedures, unless indicated otherwise. The temperature sensitive strain cgh-1(tn691) was maintained at 15°C and shifted to 25°C as L4 larvae for subsequent analysis of adult animals. Synchronous cultures were obtained by collecting eggs from bleached adults and synchronizing larvae by starvation before feeding. In all experiments young adults that produced oocytes but not yet embryos were analyzed. For RNAi experiments, we used the Open Biosystems cgh-1 and smg-2 bacterial strains and, as a control, bacteria harboring an ‘empty’ vector. Larvae were transferred to RNAi feeding plates directly after synchronization and animals were cultured at 25°C.

The following mutant and transgenic strains have been described previously: cgh-1(ok492)/hT2[qIs48]; gld-1(q485)/hT2[qIs48]; rrrSi 38/39/40 [mex-5 pro::PEST:GFP-H2B::oma-2 3′UTR; unc-119(+)]II; and rrrSi 53/54/56[mex-5 pro::PEST:GFP-H2B::oma-2 GBMmut 3′UTR; unc-119(+)]II [11], [31], [57]. The cgh-1(tn691) strain was obtained from CGC (DG1701); the cgh-1(tn691) mutation induces 100% sterility at the restrictive temperature (25°C).

To minimize variation between ‘GBMwt’ and ‘GBMmut’ pairs of reporters, transgenic strains were created by Mos1 transposase mediated Single Copy gene Insertion (MosSCI) into a single genomic locus as previously described [31], [58]. GBM mutations introduced are shown in Table S3. Oligos used to amplify 3′ UTR sequences (from the STOP codon to 50 bp downstream of the polyA site) are described in Table S4. All strains were outcrossed at least twice against wild-type animals before being analyzed. Table S5 shows all reporter strains utilized in this study. The 7 nt substitution that was used to mutate GBMs (in GBMmut reporters) does not by itself destabilize mRNA [31].

We used the COPAS Biosort from Union Biometrica to separate homozygous GFP (−) gld-1 mutants from heterozygous GFP (+) gld-1(q485)/hT2[qIs48] animals.

Polysome profile analysis and isolation of RNA and proteins

The assay was performed as previously described [59], with the following changes. Synchronized worms were harvested as young adults, frozen in 100 µl ‘worm pellet’ aliquots. Subsequently, each aliquot was re-suspended in 500 µl lysis buffer. An initial centrifugation step was included (5 min at 5000 g, 4°C) and worm lysates were layered on 5% (w/v) to 45% (w/v) sucrose gradients. To correct for variations in RNA isolation and reverse transcription efficiency between sucrose fractions, we added 2 µg of total RNA from mouse brain (Stratagene) to each fraction. RNA from fractions was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. RNA integrity was confirmed on ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels before proceeding to RT. Proteins from fractions were isolated by chloroform/methanol precipitation and investigated by western blotting. To analyze mRNAs by tiling arrays, we extracted RNA from pooled fractions 8 to 12 (polysomal) and fractions 1–12 (total), in four biological replicates.

RNA isolation from dissected gonads, whole animals, or RNAi–treated animals

50 gonads from wild-type, gld-1(q485), and cgh-1(tn691) worms were dissected in triplicates in M9 buffer for tiling array analysis. The PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit was used according to the manufacturer's recommendations to extract RNA from gonads (Figure 2A and Figure 4). To analyze the mRNA abundance of various strains, RNA from 30 animals was extracted with the PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit (Figure 2B, Figure 5B, Figure 6A; Figures S4A, S5A, S7). To determine mRNA levels in mock and cgh-1 RNAi treated animals, RNA was Trizol extracted from Input IP samples according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Antibodies

Peptides (Bachem) were used to generate mouse monoclonal antibodies according to standard procedures (PAB-1 = aa 542–560; GLD-1 = aa 65–79). PAB-1 antibody was diluted 1∶50 for western blot analysis. The mouse monoclonal GLD-1 antibody was used for immunoprecipitation (100 µl per reaction). Rabbit polyclonal GLD-1 antibody was used for western blot analysis (1∶50 dilution) and immunostaining (1∶500 dilution) [38]. Additional antibodies used: ACT-1 (MAB1501, Chemicon), CAR-1, CGH-1 [11], FLAG M2 (Sigma), GLH-1 [60], Myc (9E10), PGL-1 [61], GLH-1 [62].

Immunoprecipitation and analysis of co-precipitated RNA

GLD-1 and CGH-1 immunoprecipitations were performed as previously described [5], [26], [31]. To globally identify GLD-1 targets by tiling arrays we compared anti-GLD-1 IPs with anti-Myc IPs. To determine GLD-1 mRNA binding in cgh-1ts and cgh-1(RNAi) animals, and CGH-1 mRNA binding in gld-1 animals we compared anti-GLD-1 IPs with anti-FLAG IPs, and anti-CGH-1 IPs with anti-IgG IPs. RNA was eluted from beads with TRIzol. Precipitation efficiency was enhanced by adding 5 µg total RNA from mouse brain (Stratagene) to each IP sample.

GLD-1 immunoprecipitation and analysis of co-precipitated proteins

GLD-1-associated proteins were identified by comparing anti-GLD-1 IPs with anti-FLAG IPs. RNase treated IP samples were incubated with 0.1 mg/ml RNase A (Qiagen) for 15 minutes at 37°C. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie stained. Bands were cut, washed and in-gel digested with trypsin overnight at 37°C. Tryptic peptides were separated on an Agilent 1100 nanoLC system (Agilent Technologies) coupled to an LTQ Orbitrap Velos hybrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). The LC system was equipped with a Peptide CapTrap column (Michrom BioResources, Inc.) and a capillary column with integrated nanospray tip (75 mm i.d.×100 mm, Swiss BioAnalytics AG) filled with MagicC18 (Michrom Bioresources, Inc.). Elution was performed with a gradient of 0–45% solvent B in 30 min at a flow rate of 400 nl/min. Solvent A consisted of 0.1% formic acid/2% acetonitrile, solvent B was composed of 0.1% formic acid/80% acetonitrile. The mass spectrometer operated in positive mode using the top 20 DDA method. Peptides were identified searching UniProt 15.14 using Mascot Distiller 2.3 and Mascot 2.2 (Matrix Science). Results were compiled in Scaffold 2.06. (Proteome Software).

RT–qPCR

Reverse transcription reactions were performed using the ImProm-II Reverse Transcription System (Promega). To ensure that we are detecting full-length, polyadenylated transcripts we used oligo dT(15) primers for RT reactions on RNA from polysome profile fractions. Identical results were obtained using random hexamer oligonucleotides. To compare total mRNA levels and analyze co-immunoprecipitated RNA, cDNA was generated using random hexamer primers. qPCR reactions were performed as described previously [26]. At least one primer in each pair is specific for an exon-exon junction (Table S4). Mouse RNA (Cyt-c) was added to polysomal fractions before RNA isolation and RT, allowing us to normalize all obtained qPCR results to Cyt-c, thereby correcting for variations in RNA isolation and RT. To compare mRNA levels between different mutants and analyze co-immunoprecipitated RNA, qPCR results were normalized as indicated.

RNA hybridization to tiling arrays

300 ng of RNA (pooled gradient fractions, IP, RNAi treated animal extracts) or 5 µl of RNA (corresponding to 25 dissected gonads and isolated with the PicoPure Kit) were amplified once into dsDNA. 7.5 µg of cDNA was subsequently fragmented and labeled according to the “GeneChip Expression Analysis Technical Manual" (Affymetrix). 6 µg of fragmented and labeled DNA were hybridized to the Affymetrix C. elegans tiling array chip according to the Affymetrix Expression Analysis Technical Manual. Microarray sample preparation, hybridization and scanning were performed in the FMI genomics facility.

Analysis of tiling array data

Tiling arrays were processed in R (www.r-project.org; [63]) using bioconductor [64], and the packages tilingArray [65] and preprocessCore. The arrays were RMA background corrected and log2 transformed on the oligo level using the command:We mapped the oligos from the tiling array (bpmap file from www.affymetrix.com) to the C. elegans genome assembly ce6 (www.genome.ucsc.edu) using bowtie [66] allowing no error and unique mapping position. Expression of individual transcripts was calculated by intersecting the genomic positions of oligos with transcript annotation (WormBase WS190) and averaging the intensity of the respective oligos. Quantile normalization: each of the datasets was processed with an individual quantile normalization scheme. For IP experiments, no quantile normalization was performed as the distribution between GLD-1 IPs and control IPs differs substantially. In the case of the polysome dataset (containing polysome and total RNA samples) quantile normalization was performed twice. Once containing all the polysome samples and once for all the total RNA samples. The dataset containing either total RNA from purified gonads or total RNA from mock and cgh-1(RNAi) treated animals were each quantile normalized in one single step.

Averages, fold changes (including polysomal shifts) and standard deviations of all analyses are shown in Table S6. The p values in Figure 1D, Figure 4, Figure 5B; Figures S1E, S2 and S5A were calculated with a t test. To further investigate co-regulated mRNAs, we used the following cut-offs: gld-1/wild-type [log2]<−1; cgh-1ts/wild-type [log2]<−0.5. Data discussed in this publication has been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus and is accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE33084 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE33084).

RNA in situ hybridization, immunolocalization, and microscopy

RNA in situ hybridization was performed and analyzed as previously described [26]. The probes generated from cDNA correspond to 1–714 (gfp) (Table S4). gfp antisense control on wild-type animals was included and negative. More than 60 gonads were scored and we obtained the following numbers (n = number of scored gonads):

oma-2 GBMwt (n = 85; 27% strong; 65% medium; 6% weak); shown is a medium stained gonad

oma-2 GBMmut (n = 65; 12% medium; 88% weak); shown is a weakly stained gonad

egg-1 GBMwt (n = 70; 16% strong; 81% medium; 3% weak); shown is a medium stained gonad

egg-1 GBMmut (n = 68; 35% medium; 65% weak); shown is a weakly stained gonad

Unless indicated otherwise, images were captured with a Zeiss AxioImager Z1 microscope, equipped with an Axiocam MRm REV2 CCD camera. Images were acquired in the linear mode of the Axiovision software (Zeiss) and processed with Adobe Photoshop CS4 in an identical manner.

Confocal microscopy and deconvolution

An LSM700 confocal microscope equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.40 Oil DIC M27 objective was used to capture images with a voxel size of 0.052 µm×0.052 µm×0.2 µm (x, y, z). Used lasers: track 1 : 405 nm (2%) and 555 nm (10%); track 2 : 488 nm (4%). Beam splitters: MBS 405/488/555/639; DBS1 : 531 nm (track1) and 578 nm (track 2). Filters: SP490 (Track 1,Channel 1); LP 560 (Track 1, Channel 2); 0–587 (Track 2, Channel 1). Pinhole: 40 µm (Track 1); 41 µm (Track 2). Pictures were deconvolved with the Huygens software, using Remote Manager v1.2.3, a SNR of 8, 8, 8, 100 iterations, and the cmle deconvolution algorithm (quality change stopping criterion: 0.1). Deconvolved images were processed in Imaris XP 7.1.1 using the coloc function. In Figure S3C, only 5.41% of the total data set voxels co-localize.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. SpirinAS 1966 “Masked" forms of mRNA. Curr Top Dev Biol 1 1 38

2. ZhangSWilliamsCJWormingtonMStevensAPeltzSW 1999 Monitoring mRNA decapping activity. Methods 17 46 51

3. VoeltzGKSteitzJA 1998 AUUUA sequences direct mRNA deadenylation uncoupled from decay during Xenopus early development. Mol Cell Biol 18 7537 7545

4. ManceboRZhouXShillinglawWHenzelWMacdonaldPM 2001 BSF binds specifically to the bicoid mRNA 3′ untranslated region and contributes to stabilization of bicoid mRNA. Mol Cell Biol 21 3462 3471

5. BoagPRAtalayARobidaSReinkeVBlackwellTK 2008 Protection of specific maternal messenger RNAs by the P body protein CGH-1 (Dhh1/RCK) during Caenorhabditis elegans oogenesis. J Cell Biol 182 543 557

6. CougotNBabajkoSSeraphinB 2004 Cytoplasmic foci are sites of mRNA decay in human cells. J Cell Biol 165 31 40

7. ShethUParkerR 2003 Decapping and decay of messenger RNA occur in cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science 300 805 808

8. PeplingMEWilhelmJEO'HaraALGephardtGWSpradlingAC 2007 Mouse oocytes within germ cell cysts and primordial follicles contain a Balbiani body. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 187 192

9. WilhelmJEBuszczakMSaylesS 2005 Efficient protein trafficking requires trailer hitch, a component of a ribonucleoprotein complex localized to the ER in Drosophila. Dev Cell 9 675 685

10. PayntonBV 1998 RNA-binding proteins in mouse oocytes and embryos: expression of genes encoding Y box, DEAD box RNA helicase, and polyA binding proteins. Dev Genet 23 285 298

11. BoagPRNakamuraABlackwellTK 2005 A conserved RNA-protein complex component involved in physiological germline apoptosis regulation in C. elegans. Development 132 4975 4986

12. NakamuraAAmikuraRHanyuKKobayashiS 2001 Me31B silences translation of oocyte-localizing RNAs through the formation of cytoplasmic RNP complex during Drosophila oogenesis. Development 128 3233 3242

13. MinshallNReiterMHWeilDStandartN 2007 CPEB interacts with an ovary-specific eIF4E and 4E-T in early Xenopus oocytes. J Biol Chem 282 37389 37401

14. LadomeryMWadeESommervilleJ 1997 Xp54, the Xenopus homologue of human RNA helicase p54, is an integral component of stored mRNP particles in oocytes. Nucleic Acids Res 25 965 973

15. NavarroREBlackwellTK 2005 Requirement for P granules and meiosis for accumulation of the germline RNA helicase CGH-1. Genesis 42 172 180

16. LinMDJiaoXGrimaDNewburySFKiledjianM 2008 Drosophila processing bodies in oogenesis. Dev Biol 322 276 288

17. NobleSLAllenBLGohLKNordickKEvansTC 2008 Maternal mRNAs are regulated by diverse P body-related mRNP granules during early Caenorhabditis elegans development. J Cell Biol 182 559 572

18. SwetloffAConneBHuarteJPitettiJLNefS 2009 Dcp1-bodies in mouse oocytes. Mol Biol Cell 20 4951 4961

19. FlemrMMaJSchultzRMSvobodaP 2010 P-body loss is concomitant with formation of a messenger RNA storage domain in mouse oocytes. Biol Reprod 82 1008 1017

20. AndersonPKedershaN 2009 RNA granules: post-transcriptional and epigenetic modulators of gene expression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10 430 436

21. GalloCMMunroERasolosonDMerrittCSeydouxG 2008 Processing bodies and germ granules are distinct RNA granules that interact in C. elegans embryos. Dev Biol 323 76 87

22. LallSPianoFDavisRE 2005 Caenorhabditis elegans decapping proteins: localization and functional analysis of Dcp1, Dcp2, and DcpS during embryogenesis. Mol Biol Cell 16 5880 5890

23. EulalioABehm-AnsmantISchweizerDIzaurraldeE 2007 P-body formation is a consequence, not the cause, of RNA-mediated gene silencing. Mol Cell Biol 27 3970 3981

24. DeckerCJTeixeiraDParkerR 2007 Edc3p and a glutamine/asparagine-rich domain of Lsm4p function in processing body assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 179 437 449

25. MarinVAEvansTC 2003 Translational repression of a C. elegans Notch mRNA by the STAR/KH domain protein GLD-1. Development 130 2623 2632

26. BiedermannBWrightJSenftenMKalchhauserISarathyG 2009 Translational repression of cyclin E prevents precocious mitosis and embryonic gene activation during C. elegans meiosis. Dev Cell 17 355 364

27. LeeMHSchedlT 2001 Identification of in vivo mRNA targets of GLD-1, a maxi-KH motif containing protein required for C. elegans germ cell development. Genes Dev 15 2408 2420

28. JanEMotznyCKGravesLEGoodwinEB 1999 The STAR protein, GLD-1, is a translational regulator of sexual identity in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J 18 258 269

29. SchumacherBHanazawaMLeeMHNayakSVolkmannK 2005 Translational repression of C. elegans p53 by GLD-1 regulates DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Cell 120 357 368

30. MootzDHoDMHunterCP 2004 The STAR/Maxi-KH domain protein GLD-1 mediates a developmental switch in the translational control of C. elegans PAL-1. Development 131 3263 3272

31. WrightJEGaidatzisDSenftenMFarleyBMWesthofE 2011 A quantitative RNA code for mRNA target selection by the germline fate determinant GLD-1. EMBO J 30 533 545

32. GoodwinEBOkkemaPGEvansTCKimbleJ 1993 Translational regulation of tra-2 by its 3′ untranslated region controls sexual identity in C. elegans. Cell 75 329 339

33. FrancisRBartonMKKimbleJSchedlT 1995 gld-1, a tumor suppressor gene required for oocyte development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 139 579 606

34. KershnerAMKimbleJ 2010 Genome-wide analysis of mRNA targets for Caenorhabditis elegans FBF, a conserved stem cell regulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 3936 3941

35. LublinALEvansTC 2007 The RNA-binding proteins PUF-5, PUF-6, and PUF-7 reveal multiple systems for maternal mRNA regulation during C. elegans oogenesis. Dev Biol 303 635 649

36. CioskRDePalmaMPriessJR 2004 ATX-2, the C. elegans ortholog of ataxin 2, functions in translational regulation in the germline. Development 131 4831 4841

37. LeeMHSchedlT 2004 Translation repression by GLD-1 protects its mRNA targets from nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in C. elegans. Genes Dev 18 1047 1059

38. JonesARFrancisRSchedlT 1996 GLD-1, a cytoplasmic protein essential for oocyte differentiation, shows stage - and sex-specific expression during Caenorhabditis elegans germline development. Dev Biol 180 165 183

39. NavarroREShimEYKoharaYSingsonABlackwellTK 2001 cgh-1, a conserved predicted RNA helicase required for gametogenesis and protection from physiological germline apoptosis in C. elegans. Development 128 3221 3232

40. MerrittCRasolosonDKoDSeydouxG 2008 3′ UTRs are the primary regulators of gene expression in the C. elegans germline. Curr Biol 18 1476 1482

41. KadandalePStewart-MichaelisAGordonSRubinJKlancerR 2005 The egg surface LDL receptor repeat-containing proteins EGG-1 and EGG-2 are required for fertilization in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol 15 2222 2229

42. TabaraHHillRJMelloCCPriessJRKoharaY 1999 pos-1 encodes a cytoplasmic zinc-finger protein essential for germline specification in C. elegans. Development 126 1 11

43. Guven-OzkanTNishiYRobertsonSMLinR 2008 Global transcriptional repression in C. elegans germline precursors by regulated sequestration of TAF-4. Cell 135 149 160

44. DetwilerMRReubenMLiXRogersELinR 2001 Two zinc finger proteins, OMA-1 and OMA-2, are redundantly required for oocyte maturation in C. elegans. Dev Cell 1 187 199

45. ShimadaMYokosawaHKawaharaH 2006 OMA-1 is a P granules-associated protein that is required for germline specification in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Genes Cells 11 383 396

46. JungkampACStoeckiusMMecenasDGrunDMastrobuoniG In vivo and transcriptome-wide identification of RNA binding protein target sites. Mol Cell 44 828 840

47. Stebbins-BoazBCaoQde MoorCHMendezRRichterJD 1999 Maskin is a CPEB-associated factor that transiently interacts with elF-4E. Mol Cell 4 1017 1027

48. MinshallNStandartN 2004 The active form of Xp54 RNA helicase in translational repression is an RNA-mediated oligomer. Nucleic Acids Res 32 1325 1334

49. NakamuraASatoKHanyu-NakamuraK 2004 Drosophila cup is an eIF4E binding protein that associates with Bruno and regulates oskar mRNA translation in oogenesis. Dev Cell 6 69 78

50. Kim-HaJKerrKMacdonaldPM 1995 Translational regulation of oskar mRNA by bruno, an ovarian RNA-binding protein, is essential. Cell 81 403 412

51. ChekulaevaMHentzeMWEphrussiA 2006 Bruno acts as a dual repressor of oskar translation, promoting mRNA oligomerization and formation of silencing particles. Cell 124 521 533

52. MairGRBraksJAGarverLSWiegantJCHallN 2006 Regulation of sexual development of Plasmodium by translational repression. Science 313 667 669

53. TadrosWGoldmanALBabakTMenziesFVardyL 2007 SMAUG is a major regulator of maternal mRNA destabilization in Drosophila and its translation is activated by the PAN GU kinase. Dev Cell 12 143 155

54. De RenzisSElementoOTavazoieSWieschausEF 2007 Unmasking activation of the zygotic genome using chromosomal deletions in the Drosophila embryo. PLoS Biol 5 e117 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050117

55. BushatiNStarkABrenneckeJCohenSM 2008 Temporal reciprocity of miRNAs and their targets during the maternal-to-zygotic transition in Drosophila. Curr Biol 18 501 506

56. WolkeUJezuitEAPriessJR 2007 Actin-dependent cytoplasmic streaming in C. elegans oogenesis. Development 134 2227 2236

57. CioskRDePalmaMPriessJR 2006 Translational regulators maintain totipotency in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Science 311 851 853

58. Frokjaer-JensenCDavisMWHopkinsCENewmanBJThummelJM 2008 Single-copy insertion of transgenes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Genet 40 1375 1383

59. DingXCGrosshansH 2009 Repression of C. elegans microRNA targets at the initiation level of translation requires GW182 proteins. EMBO J 28 213 222

60. OrsbornAMLiWMcEwenTJMizunoTKuzminE 2007 GLH-1, the C. elegans P granule protein, is controlled by the JNK KGB-1 and by the COP9 subunit CSN-5. Development 134 3383 3392

61. KawasakiIShimYHKirchnerJKaminkerJWoodWB 1998 PGL-1, a predicted RNA-binding component of germ granules, is essential for fertility in C. elegans. Cell 94 635 645

62. GruidlMESmithPAKuznickiKAMcCroneJSKirchnerJ 1996 Multiple potential germ-line helicases are components of the germ-line-specific P granules of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93 13837 13842

63. IhakaRGentlemanR 1996 A language for Data Analysis and Graphics. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics 5 299 314

64. GentlemanRCCareyVJBatesDMBolstadBDettlingM 2004 Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol 5 R80

65. HuberWToedlingJSteinmetzLM 2006 Transcript mapping with high-density oligonucleotide tiling arrays. Bioinformatics 22 1963 1970

66. LangmeadBTrapnellCPopMSalzbergSL 2009 Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10 R25

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Functional Centromeres Determine the Activation Time of Pericentric Origins of DNA Replication inČlánek Dynamic Deposition of Histone Variant H3.3 Accompanies Developmental Remodeling of the TranscriptomeČlánek Integrin α PAT-2/CDC-42 Signaling Is Required for Muscle-Mediated Clearance of Apoptotic Cells inČlánek Prdm5 Regulates Collagen Gene Transcription by Association with RNA Polymerase II in Developing BoneČlánek Acquisition Order of Ras and p53 Gene Alterations Defines Distinct Adrenocortical Tumor Phenotypes

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 5- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Slowing Replication in Preparation for Reduction

- Chromosome Pairing: A Hidden Treasure No More

- Loss of Imprinting Differentially Affects REM/NREM Sleep and Cognition in Mice

- Six Novel Susceptibility Loci for Early-Onset Androgenetic Alopecia and Their Unexpected Association with Common Diseases

- Regulation by the Noncoding RNA

- UDP-Galactose 4′-Epimerase Activities toward UDP-Gal and UDP-GalNAc Play Different Roles in the Development of

- Deletion of PTH Rescues Skeletal Abnormalities and High Osteopontin Levels in Mice

- Karyotypic Determinants of Chromosome Instability in Aneuploid Budding Yeast

- Genome-Wide Copy Number Analysis Uncovers a New HSCR Gene:

- MicroRNA-277 Modulates the Neurodegeneration Caused by Fragile X Premutation rCGG Repeats

- Functional Centromeres Determine the Activation Time of Pericentric Origins of DNA Replication in

- Dynamic Deposition of Histone Variant H3.3 Accompanies Developmental Remodeling of the Transcriptome

- Scientist Citizen: An Interview with Bruce Alberts

- YY1 Regulates Melanocyte Development and Function by Cooperating with MITF

- Congenital Heart Disease–Causing Gata4 Mutation Displays Functional Deficits

- Recombination Drives Vertebrate Genome Contraction

- KATNAL1 Regulation of Sertoli Cell Microtubule Dynamics Is Essential for Spermiogenesis and Male Fertility

- Re-Patterning Sleep Architecture in through Gustatory Perception and Nutritional Quality

- Using Whole-Genome Sequence Data to Predict Quantitative Trait Phenotypes in

- Genome-Wide Analysis of GLD-1–Mediated mRNA Regulation Suggests a Role in mRNA Storage

- Meiotic Chromosome Pairing Is Promoted by Telomere-Led Chromosome Movements Independent of Bouquet Formation

- LINT, a Novel dL(3)mbt-Containing Complex, Represses Malignant Brain Tumour Signature Genes

- The H3K27 Demethylase UTX-1 Is Essential for Normal Development, Independent of Its Enzymatic Activity

- Suppresses Senescence Programs and Thereby Accelerates and Maintains Mutant -Induced Lung Tumorigenesis

- Genome-Wide Association of Pericardial Fat Identifies a Unique Locus for Ectopic Fat

- An Essential Role for Katanin p80 and Microtubule Severing in Male Gamete Production

- Identification of Genes That Promote or Antagonize Somatic Homolog Pairing Using a High-Throughput FISH–Based Screen

- Principles of Carbon Catabolite Repression in the Rice Blast Fungus: Tps1, Nmr1-3, and a MATE–Family Pump Regulate Glucose Metabolism during Infection

- Integrin α PAT-2/CDC-42 Signaling Is Required for Muscle-Mediated Clearance of Apoptotic Cells in

- Histone H3 Localizes to the Centromeric DNA in Budding Yeast

- Collapse of Telomere Homeostasis in Hematopoietic Cells Caused by Heterozygous Mutations in Telomerase Genes

- Hypersensitive to Red and Blue 1 and Its Modification by Protein Phosphatase 7 Are Implicated in the Control of Arabidopsis Stomatal Aperture

- Extent, Causes, and Consequences of Small RNA Expression Variation in Human Adipose Tissue

- TBC-8, a Putative RAB-2 GAP, Regulates Dense Core Vesicle Maturation in

- Regulating Repression: Roles for the Sir4 N-Terminus in Linker DNA Protection and Stabilization of Epigenetic States

- Common Genetic Determinants of Intraocular Pressure and Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma

- Prdm5 Regulates Collagen Gene Transcription by Association with RNA Polymerase II in Developing Bone

- Fitness Landscape Transformation through a Single Amino Acid Change in the Rho Terminator

- Repeated, Selection-Driven Genome Reduction of Accessory Genes in Experimental Populations

- Allelic Variation and Differential Expression of the mSIN3A Histone Deacetylase Complex Gene Promote Mammary Tumor Growth and Metastasis

- DNA Demethylation and USF Regulate the Meiosis-Specific Expression of the Mouse

- Knowledge-Driven Analysis Identifies a Gene–Gene Interaction Affecting High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels in Multi-Ethnic Populations

- A Duplication CNV That Conveys Traits Reciprocal to Metabolic Syndrome and Protects against Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice and Men

- EMT Inducers Catalyze Malignant Transformation of Mammary Epithelial Cells and Drive Tumorigenesis towards Claudin-Low Tumors in Transgenic Mice

- Inactivation of a Novel FGF23 Regulator, FAM20C, Leads to Hypophosphatemic Rickets in Mice

- Genome-Wide Association for Abdominal Subcutaneous and Visceral Adipose Reveals a Novel Locus for Visceral Fat in Women

- Stratifying Type 2 Diabetes Cases by BMI Identifies Genetic Risk Variants in and Enrichment for Risk Variants in Lean Compared to Obese Cases

- New Insight into the History of Domesticated Apple: Secondary Contribution of the European Wild Apple to the Genome of Cultivated Varieties

- Activated Cdc42 Kinase Has an Anti-Apoptotic Function

- The Region Is Critical for Birth Defects and Electrocardiographic Dysfunctions Observed in a Down Syndrome Mouse Model

- COP9 Signalosome Integrity Plays Major Roles for Hyphal Growth, Conidial Development, and Circadian Function

- Bmps and Id2a Act Upstream of Twist1 To Restrict Ectomesenchyme Potential of the Cranial Neural Crest

- Psip1/Ledgf p52 Binds Methylated Histone H3K36 and Splicing Factors and Contributes to the Regulation of Alternative Splicing

- The Number of X Chromosomes Causes Sex Differences in Adiposity in Mice

- Target Gene Analysis by Microarrays and Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Identifies HEY Proteins as Highly Redundant bHLH Repressors

- Acquisition Order of Ras and p53 Gene Alterations Defines Distinct Adrenocortical Tumor Phenotypes

- ELK1 Uses Different DNA Binding Modes to Regulate Functionally Distinct Classes of Target Genes

- Histone H1 Depletion Impairs Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation

- IDN2 and Its Paralogs Form a Complex Required for RNA–Directed DNA Methylation

- Separation of DNA Replication from the Assembly of Break-Competent Meiotic Chromosomes

- Genomic Hypomethylation in the Human Germline Associates with Selective Structural Mutability in the Human Genome

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Inactivation of a Novel FGF23 Regulator, FAM20C, Leads to Hypophosphatemic Rickets in Mice

- Genome-Wide Association of Pericardial Fat Identifies a Unique Locus for Ectopic Fat

- Slowing Replication in Preparation for Reduction

- An Essential Role for Katanin p80 and Microtubule Severing in Male Gamete Production

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání