-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Bmps and Id2a Act Upstream of Twist1 To Restrict Ectomesenchyme Potential of the Cranial Neural Crest

Cranial neural crest cells (CNCCs) have the remarkable capacity to generate both the non-ectomesenchyme derivatives of the peripheral nervous system and the ectomesenchyme precursors of the vertebrate head skeleton, yet how these divergent lineages are specified is not well understood. Whereas studies in mouse have indicated that the Twist1 transcription factor is important for ectomesenchyme development, its role and regulation during CNCC lineage decisions have remained unclear. Here we show that two Twist1 genes play an essential role in promoting ectomesenchyme at the expense of non-ectomesenchyme gene expression in zebrafish. Twist1 does so by promoting Fgf signaling, as well as potentially directly activating fli1a expression through a conserved ectomesenchyme-specific enhancer. We also show that Id2a restricts Twist1 activity to the ectomesenchyme lineage, with Bmp activity preferentially inducing id2a expression in non-ectomesenchyme precursors. We therefore propose that the ventral migration of CNCCs away from a source of Bmps in the dorsal ectoderm promotes ectomesenchyme development by relieving Id2a-dependent repression of Twist1 function. Together our model shows how the integration of Bmp inhibition at its origin and Fgf activation along its migratory route would confer temporal and spatial specificity to the generation of ectomesenchyme from the neural crest.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 8(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002710

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002710Summary

Cranial neural crest cells (CNCCs) have the remarkable capacity to generate both the non-ectomesenchyme derivatives of the peripheral nervous system and the ectomesenchyme precursors of the vertebrate head skeleton, yet how these divergent lineages are specified is not well understood. Whereas studies in mouse have indicated that the Twist1 transcription factor is important for ectomesenchyme development, its role and regulation during CNCC lineage decisions have remained unclear. Here we show that two Twist1 genes play an essential role in promoting ectomesenchyme at the expense of non-ectomesenchyme gene expression in zebrafish. Twist1 does so by promoting Fgf signaling, as well as potentially directly activating fli1a expression through a conserved ectomesenchyme-specific enhancer. We also show that Id2a restricts Twist1 activity to the ectomesenchyme lineage, with Bmp activity preferentially inducing id2a expression in non-ectomesenchyme precursors. We therefore propose that the ventral migration of CNCCs away from a source of Bmps in the dorsal ectoderm promotes ectomesenchyme development by relieving Id2a-dependent repression of Twist1 function. Together our model shows how the integration of Bmp inhibition at its origin and Fgf activation along its migratory route would confer temporal and spatial specificity to the generation of ectomesenchyme from the neural crest.

Introduction

The neural crest is a transient, migratory cell population that arises at the boundary between the neural and non-neural ectoderm [1]. Although both cranial and trunk neural crest cells differentiate into non-ectomesenchyme derivatives, such as neurons, glia and pigment cells, CNCCs also generate ectomesenchyme derivatives, in particular many of the cartilage-, bone-, and teeth-forming cells of the head [2]. Whereas much is known about how individual non-ectomesenchyme lineages are specified, how the ectomesenchyme lineage is specified remains actively debated [3]. When the ectomesenchyme versus non-ectomesenchyme lineage decision is made during CNCC development also remains unknown. Whereas cultured avian CNCCs can clonally generate both lineages [2], lineage tracing experiments in zebrafish embryos have failed to identify a common precursor [4], [5].

In zebrafish, CNCCs are first apparent within the anterior neural plate border at 10.5 hours-post-fertilization (hpf), when they begin to express sox10, foxd3, sox9b, and tfap2a. Within the next few hours, three streams of CNCCs can be seen migrating away from the neural tube to more ventral positions. Starting around 15.5 hpf, ectomesenchyme precursors begin to downregulate early CNCC genes such as sox10, foxd3, sox9b, and tfap2a [6], [7] and up-regulate ectomesenchyme-specific genes such as dlx2a [8] and fli1a [9]. These ectomesenchyme cells then go on to populate a series of pharyngeal arches from which develops the support skeleton of the jaw and gills in zebrafish, and the jaw, middle ear, and larynx in mammals [10]. Whereas dlx2a and fli1a are uniquely expressed in the ectomesenchyme lineage, Dlx2a appears to be dispensable for ectomesenchyme formation [8] and the function of Fli1a in ectomesenchyme development remains unknown.

One factor critical for ectomesenchyme specification in mouse is the basic-helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor Twist1. Both the conventional Twist1 knockout and a conditional Twist1 neural-crest-specific (Wnt1-CRE) knockout display defective ectomesenchyme development, including abnormal perdurance of Sox10 and loss of expression of many arch ectomesenchyme genes [11], [12]. Furthermore, the neural-crest-specific knockout showed severe reductions of the CNCC-derived craniofacial skeleton, although the lower jaw was less affected. Zebrafish have two Twist1 orthologs, with twist1b being expressed in early CNCCs and twist1a restricted to ectomesenchyme precursors from 16 hpf onwards [13]. Here, we show that these two Twist1 genes function redundantly for zebrafish ectomesenchyme development, with Twist1 depletion resulting in both perdurance of sox10 and loss of fli1a expression.

As Twist1 genes are expressed throughout the early CNCC domain, an important yet unanswered question is how Twist1 function is specifically regulated in ectomesenchyme precursors. Twist1 function can be regulated by post-translational modification (e.g. phosphorylation), as well as choice of dimerization partners. In particular, Inhibitor of differentiation (Id) proteins, which share HLH but not basic DNA-binding domains with bHLH factors, influence Twist1 homodimer versus heterodimer formation by sequestering Twist1 binding partners such as E2A [14], [15]. Id genes are widely expressed in the early neural crest, and Id2 has been shown to promote neural crest at the expense of epidermis in avians [16]. In zebrafish, Id2a has been shown to regulate neuron and glia formation in the retina, albeit non-cell-autonomously, yet its role in CNCC development has not been explored [17]. In this study we find a novel role of Id2a in CNCC lineage decisions, with down-regulation of id2a in migrating CNCCs being essential for ectomesenchyme specification.

Upstream signals that specify ectomesenchyme could originate from the ectoderm where CNCCs are born, from the mesoderm along which CNCCs migrate, or from the endoderm/ectoderm upon which CNCCs condense within the pharyngeal arches. Previous studies have suggested roles for Fgf signaling, in particular Fgf20b and Fgfr1, in ectomesenchyme specification in avians and zebrafish [18], [19]. It was further proposed that CNCCs might acquire ectomesenchyme identity upon arrival in the pharyngeal arches, potentially as a result of endoderm-secreted Fgfs [18]. In contrast, lineage-tracing experiments have revealed that CNCCs in zebrafish are largely restricted to single lineages before migration [4], [5], suggesting that ectomesenchyme fates may be specified at their birthplace within the neural plate border ectoderm.

Bmps such as bmp2b in zebrafish are prominently expressed in the non-neural ectoderm, where they influence neural crest induction, migration, survival, and differentiation [20], [21], [22]. However, a role for Bmp signaling in ectomesenchyme lineage decisions has not been previously described, likely because of the earlier essential roles of Bmps in neural crest induction [21]. By manipulating Bmp signaling specifically in migratory CNCCs, we have uncovered an additional function of Bmp signaling in restricting ectomesenchyme potential, in part by maintaining high levels of Id2a. We therefore propose a model in which the early migration of CNCCs away from an ectodermal Bmp source results in down-regulation of Bmp activity and id2a expression, which in turn promotes Twist1-dependent establishment of ectomesenchyme fates.

Results

Twist1a and Twist1b are redundantly required for ectomesenchyme specification in zebrafish

In order to test whether Twist1 genes are required for ectomesenchyme development in zebrafish, we designed translation-blocking MOs to deplete both zebrafish Twist1 orthologs -Twist1a and Twist1b. Injection of twist1a-MO or twist1b-MO alone resulted in only very subtle changes in sox10 and no changes in fli1a:GFP transgene expression (Figure S1). In contrast, embryos injected with both MOs (twist1a/1b-MO) displayed abnormal persistence of sox10 and reduced expression of fli1a in arch CNCCs at 18 and 24 hpf, respectively (Figure 1A, 1B, 1E, 1F). Analysis of doubly transgenic sox10:dsRed; fli1a:GFP embryos injected with twist1a/1b-MO confirmed that CNCCs still formed arches of largely normal size at 28 hpf in the absence of Twist1 function yet failed to initiate fli1a:GFP expression (Figure S1). Furthermore, arch expression of dlx2a was relatively unaffected in 18 hpf twist1a/1b-MO embryos (Figure 1I, 1J). Consistent with the earlier ectomesenchyme gene expression defects, we also found that depletion of both Twist1 proteins resulted in severe reductions of the ectomesenchyme-derived skeleton of the face and anterior neurocranium at 5 days-post-fertilization (dpf) (Figure 1M, 1N). Single depletion of either Twist1a or Twist1b resulted in milder craniofacial defects, particularly in the ventral mandibular and hyoid cartilages (Figure S1). Importantly, injection of a twist1b mRNA not targeted by the MOs, but not a control kikGR mRNA, partially rescued skeletal defects in twist1a/1b-MO embryos, thus showing specificity of MO-generated defects for Twist1 (Figure S1). Hence, despite differences in timing of their expression, Twist1a and Twist1b function redundantly for ectomesenchyme development.

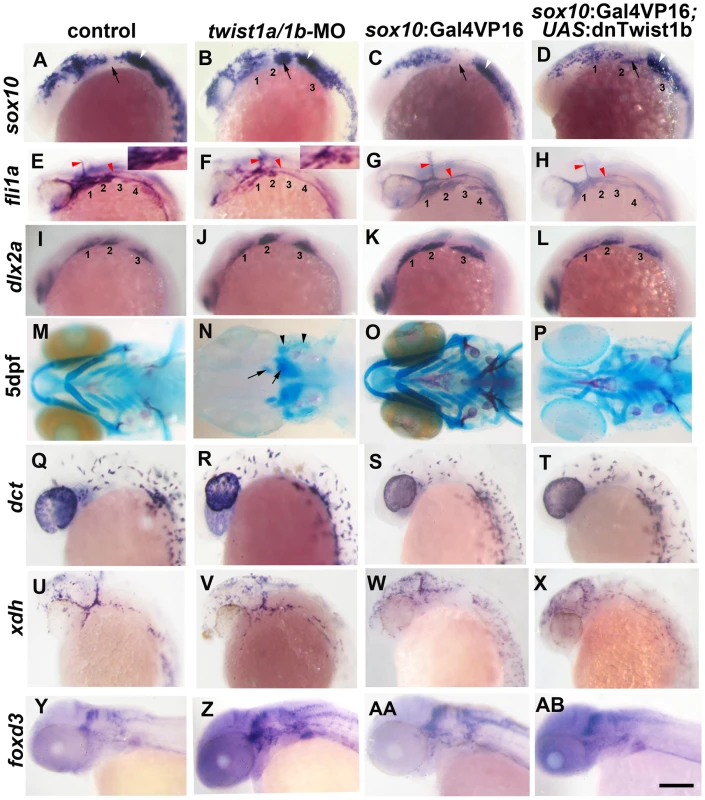

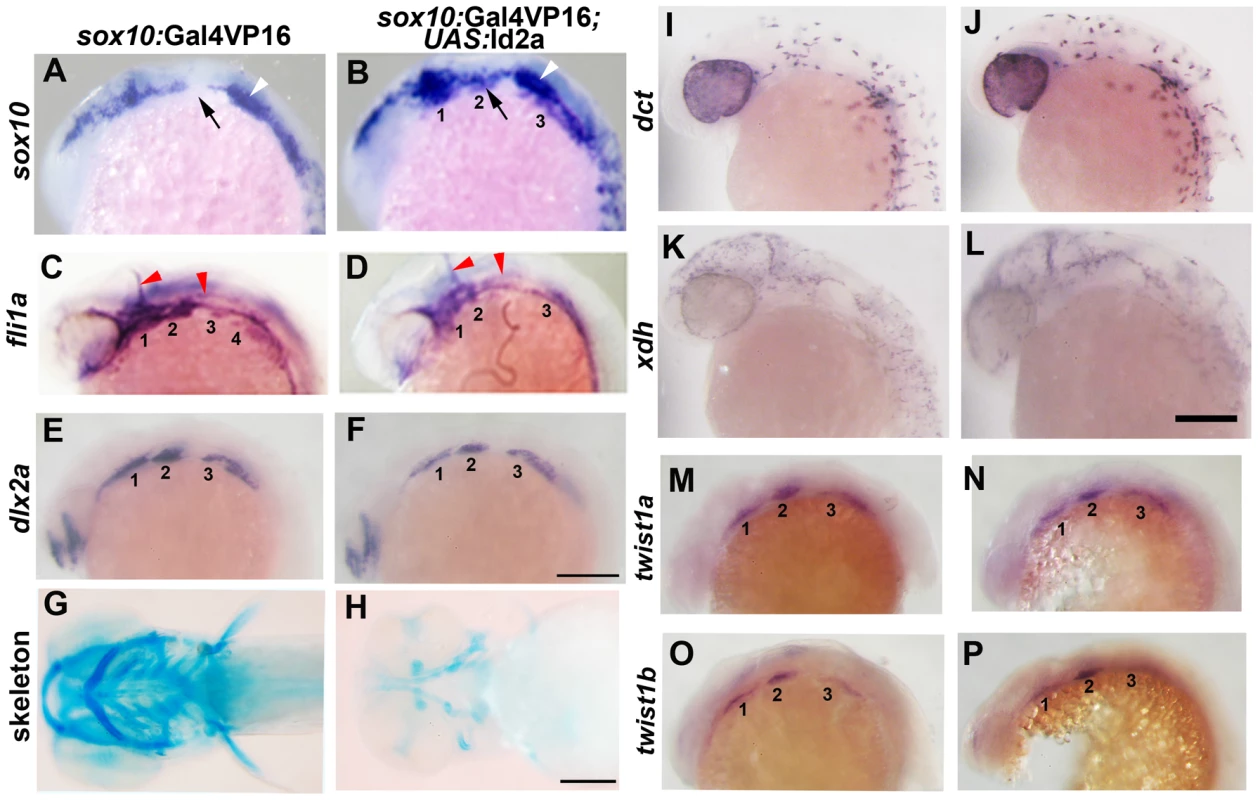

Fig. 1. Twist1 genes are required for ectomesenchyme specification in zebrafish.

(A–D) Whole mount in situ hybridizations of sox10 expression at 18 hpf show ectopic expression in the arches (numbered and second arch indicated by black arrow) of twist1a/1b-MO (n = 16/16) and sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:dnTwist1b (n = 4/4) embryos compared to un-injected (n = 0/14) and sox10:Gal4VP16 only (n = 0/9) controls. White arrowheads indicate otic expression. (E–H) Whole mount in situs at 24 hpf show reduction of fli1a expression in the arch ectomesenchyme (numbered) of twist1a/1b-MO (n = 12/12) and sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:dnTwist1b (n = 5/5) embryos compared to un-injected (n = 0/13) and sox10:Gal4VP16 only (n = 0/8) controls. Insets in E and F highlight arch ectomesenchyme which is reduced in twist1a/1b-MO embryos. Vascular expression of fli1a (red arrowheads) is unaffected. (I–L) Whole mount in situs at 18 hpf show a slight reduction of dlx2a in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:dnTwist1b embryos (n = 4/4) but not un-injected (n = 0/6), twist1a/1b-MO (n = 0/8), and sox10:Gal4VP16 only (n = 0/6) embryos. (M-P) Skeletal staining at 5 dpf shows severe loss of CNCC-derived head skeleton in twist1a/1b-MO embryos (n = 21/21) and primarily jaw reductions in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:dnTwist1b embryos (n = 9/9) compared to no defects in un-injected (n = 0/24) and sox10:Gal4VP16 only (n = 0/16) controls. Whereas only small remnants remain of the CNCC-derived skeleton (arrows), the mesoderm-derived otic capsule cartilage (arrowheads) and posterior neurocranium are less affected in twist1a/1b-MO embryos. (Q–T) In situs for dct expression at 28 hpf show normal melanophore precursors in un-injected (n = 14), twist1a/1b-MO (n = 12), sox10:Gal4VP16 only (n = 8), and sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:dnTwist1b (n = 8) embryos. (U–X) In situs for xdh expression at 28 hpf show normal xanthophore precursors in un-injected (n = 7), twist1a/1b-MO (n = 5), sox10:Gal4VP16 only (n = 9), and sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:dnTwist1b (n = 8) embryos. (Y-AB) In situs for foxd3 expression at 48 hpf reveal largely normal patterns of glia in un-injected (n = 9), twist1a/1b-MO (n = 8), sox10:Gal4VP16 only (n = 9), and sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:dnTwist1b (n = 8) embryos. Scale bar = 50 µm. Twist1 function is required in migratory CNCCs for ectomesenchyme specification

We next investigated whether Twist1 functions in CNCCs for ectomesenchyme formation. To do so, we developed a transgenic strategy to misexpress a dominant-negative Twist1b protein specifically in migratory CNCCs. Caenorhabditis elegans has a single Twist gene, hlh8, which is required for mesodermal patterning and vulval muscle development [23]. Mutation of Glutamine 29 to Lysine in the DNA-binding domain of Hlh8 has been shown to dominantly interfere with its function [24]. As this residue is conserved in zebrafish Twist1 genes (Glutamine 84 in Twist1b), we reasoned that the equivalent mutation might also result in a dominant-negative protein. We therefore constructed a transgenic line in which Twist1b-E84K (referred to as dnTwist1b) was expressed under the Gal4VP16-sensitive UAS promoter. We also constructed a second transgenic line in which the Gal4VP16 transcriptional activator was expressed under the control of a sox10 neural crest promoter [25]. Although the endogenous sox10 gene is first expressed in pre-migratory CNCCs at 10.5 hpf, in situ hybridizations for kikGR mRNA in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:kikGR embryos revealed transgene expression within migratory CNCCs at 13 hpf, but not earlier within premigratory CNCCs at 11 hpf (Figure S2). Hence, this sox10:Gal4VP16 line allows us to alter genetic pathways specifically in migratory CNCCs. Consistent with a requirement for Twist1 in migratory CNCCs, we observed persistent sox10 and reduced fli1a expression in the arches of sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:dnTwist1b embryos, similar to what we observed in twist1a/1b-MO embryos (Figure 1). We also observed a partial reduction of arch dlx2a expression upon dnTwist1b misexpression, as well as reductions of the facial skeleton, particularly in the jaw region (Figure 1K, 1L, 1O, 1P). Hence, the similar phenotypes of twist1a/1b-MO embryos and transgenic embryos with CNCC-specific disruption of Twist1 function indicate that zebrafish Twist1 genes function largely in migratory CNCCs for ectomesenchyme development.

Twist1 genes globally activate ectomesenchyme and inhibit non-ectomesenchyme gene expression

Twist1 could regulate the transition from early multipotent CNCCs to ectomesenchyme precursors, or alternatively fate choices between ectomesenchyme and non-ectomesenchyme lineages. In order to examine these possibilities without bias, we performed microarray-based gene expression profiling of purified sox10:GFP-positive CNCCs from 18 hpf un-injected or twist1a/1b-MO-injected embryos (Figure 2A, 2B). We next compared the relative enrichment of transcripts in GFP-positive versus GFP-negative CNCCs of un-injected and twist1a/1b-MO embryos to identify CNCC-specific genes up or down regulated by Twist1 depletion (Figure 2C). By comparing the GFP+/GFP − ratio between un-injected and twist1a/1b-MO embryos (as opposed to simply comparing expression levels between GFP+ fractions), we controlled for possible non-specific effects of MO toxicity on gene expression (i.e. non-specific toxicity is predicted to equally affect GFP+ and GFP − fractions and thus toxicity effects would cancel out in the ratio). By analyzing data sets with respect to published gene expression patterns (Table S1), we found that the down-regulated set included many known ectomesenchyme genes (e.g. lama4, grem2, loxl2a, pcdh18a, and fli1a) and the up-regulated set included genes expressed in non-ectomesenchyme lineages such as neurons (e.g. nr4a2b, atpa1a1, and aacs), glia (e.g. rab3ip), and pigment (e.g. gch2 and ednrb1) (Figure 2C). In order to validate several of the most differentially expressed genes, we next performed in situ hybridization. Whereas the ectomesenchyme expression of fli1a was severely reduced (Figure 1F), the non-ectomesenchyme expression domains of nr4a2b and gch2 were increased in intensity and expanded in size in twist1a/1b-MO embryos at 18 hpf (Figure 2D–2G). However, unlike sox10, nr4a2b and gch2 were not ectopically expressed in Twist1-depleted arches. As expected, sox10 was also upregulated 1.28 fold. This modest upregulation is likely due to the more widespread expression of sox10 in non-ectomesenchyme and trunk neural crest cells not affected by loss of Twist1 function, thus diluting the effect of the specific ectomesenchyme upregulation when total neural crest fractions are analyzed. This limitation indicates that other genes that behave like sox10 may have been overlooked in our analysis.

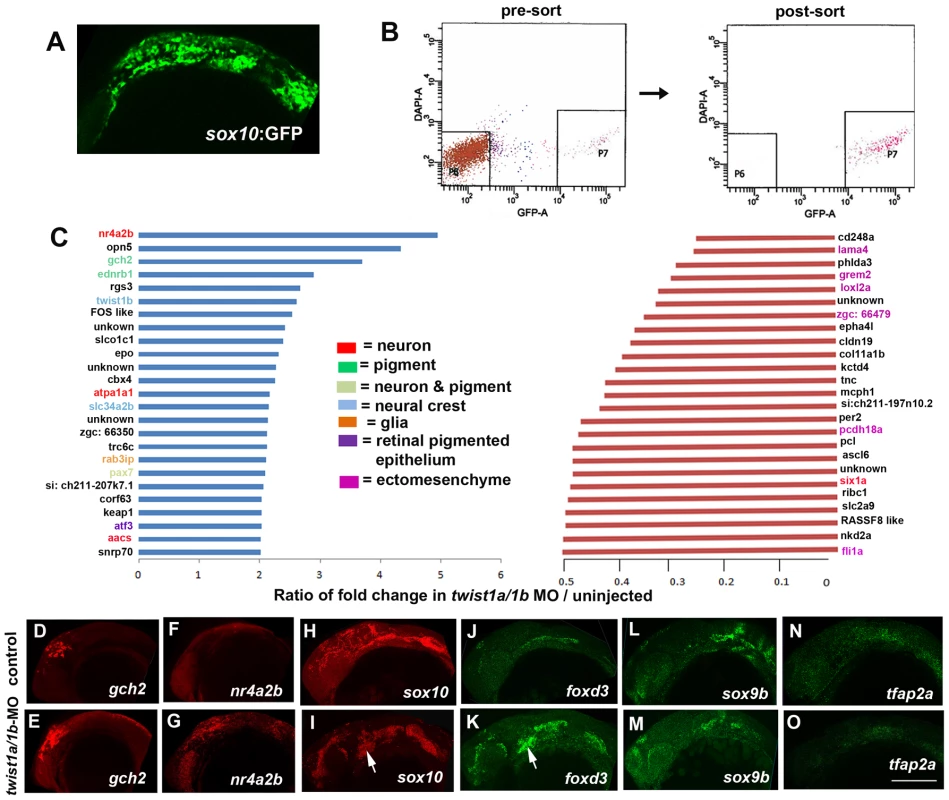

Fig. 2. Gene expression profiling in twist1a/1b-MO embryos.

(A,B) sox10:GFP-positive and -negative cells were isolated from un-injected or twist1a/1b-MO embryos at 18 hpf by FACS. (C) Fold changes of the GFP+/GFP− ratios between twist1a/1b-MO and un-injected controls show the top 25 up-regulated (blue) and down-regulated (red) genes after Twist1 depletion. Color codes indicate where genes are expressed based on the published literature (see Table S1 for references). (D–O) Confocal projections of fluorescent in situ hybridizations show expanded expression of gch2 and nr4a2b at 18 hpf, ectopic arch expression (arrows) of sox10 and foxd3 at 24 hpf, but no change in sox9b and tfap2a expression at 24 hpf in twist1a/1b-MO versus un-injected controls. Scale bar = 50 µm. Although early CNCC genes did not appear as top hits in our microarray analysis, sox10 expression did abnormally persist in twist1a/1b-MO ectomesenchyme (Figure 2I). We therefore asked whether this was a general property of genes expressed in the early CNCC domain. sox10, sox9b, tfap2a, and foxd3 are expressed in wild-type CNCCs beginning around 10.5 hpf but not in arch ectomesenchyme at 24 hpf. In Twist1-depleted embryos, we observed ectopic arch expression of foxd3 but not sox9b and tfap2a (Figure 2J–2O). Whereas several studies have established roles for Sox10 and Foxd3 in maintaining neural crest multipotency [26], these transcription factors also have later roles in promoting non-ectomesenchyme lineages such as melanocytes, neurons, and glia [27], [28]. The lack of sox9b and tfap2a upregulation in twist1a/1b-MO embryos argues against a general perdurance of early CNCC expression, with the ectopic expression of sox10 and foxd3 likely reflecting the upregulation of non-ectomesenchyme gene expression observed in our microarray analysis. However, despite the ectopic expression of sox10 and foxd3 in 24 hpf twist1a/1b-MO arches, we failed to observe ectopic foxd3-positive glia, HuC/D-positive cranial ganglionic neurons, dct-positive melanophores, or xdh-positive xanthophores in the arches of either twist1a/1b-MO or sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:dnTwist1b larvae at later stages (Figure 1Q–1AB and Figure S3). Instead, the sox10:GFP-positive arches of twist1a/1b-MO embryos were reduced at 36 hpf, and even more so at 48 hpf, with Lysotracker staining revealing increased cell death in arch CNCCs and putative CNCCs in the dorsal neural tube (Figure S4 and data not shown). In addition, expression of the early chondrocyte marker sox9a was very reduced in arch CNCCs of 48 hpf twist1a/1b-MO embryos (Figure S4G) yet was less affected in the mesoderm-derived precursors of the otic capsule cartilage which is less sensitive to loss of Twist1a/1b function (Figure 1N). Hence, arch CNCCs undergo cell death and fail to initiate skeletal gene expression in the absence of Twist1 function yet do not form ectopic non-ectomesenchyme derivatives.

Twist1 is required for Fgf signaling in ectomesenchyme precursors

As Fgf signaling has also been shown to promote ectomesenchyme fates [18], [19], we next examined whether Twist1 might be required for Fgf signaling during ectomesenchyme development. In zebrafish embryos, pea3 expression is entirely dependent on Fgf signaling [29], and we observed decreased pea3 expression in the arches of twist1a/1b-MO embryos at 18 hpf (Figure 3B), consistent with Twist1 being required for Fgf signaling in migrating CNCCs. We next investigated to what extent loss of Fgf signaling accounts for the ectomesenchyme gene expression defects seen upon Twist1 depletion. To do so, we inhibited Fgf signaling specifically in migratory CNCCs through transgenic misexpression of a dominant-negative version of Fgfr1a (dnFgfr1a). In sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:dnFgfr1a embryos, we observed persistent sox10 and reduced dlx2a expression in the arches, yet, unlike Twist1-deficient embryos, fli1a expression was largely unaffected (Figure 3C–3H). This effect of Fgf inhibition on ectomesenchyme formation was not due to transcriptional regulation of Twist1 genes as both twist1a and twist1b were expressed normally in 24 hpf sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:dnFgfr1a embryos (Figure 3I–3L). We therefore conclude that Fgf signaling likely functions downstream of Twist1 to repress sox10 and activate dlx2a expression yet plays less of a role in fli1a expression.

Fig. 3. Fgf signaling depends on Twist1 and regulates a subset of ectomesenchyme gene expression.

(A,B) In situs at 18 hpf show that expression of the Fgf target gene pea3 is reduced in the arches (numbered) of twist1a/1b-MO embryos (n = 8/8) compared to un-injected controls (n = 0/12). (C–L) sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:dnFgfr1a embryos show ectopic arch expression of sox10 at 18 hpf (n = 8/8) versus controls (n = 0/8), reduction of dlx2a at 24 hpf (n = 3/3) versus controls (n = 0/3), but no change in fli1a at 24 hpf (n = 0/7) versus controls (n = 0/5). twist1a expression was unchanged at 24 hpf in dnFgfr1a embryos (n = 10) compared to controls (n = 7), as was twist1b expression in dnFgfr1a embryos (n = 8) compared to controls (n = 8). Black arrows indicate the second arch, white arrowheads the ear, and red arrowheads the vasculature. Scale bar = 50 µm. Twist1 regulates fli1a expression through an ectomesenchyme-specific enhancer

As we determined that Fgf signaling is not required for fli1a ectomesenchyme expression, we next examined whether Twist1 might more directly activate fli1a expression. We first used a comparative genomics and transient transgenic approach to identify ectomesenchyme-specific regulatory regions of the fli1a gene. A ∼15 kb region centered around the first exon of the fli1a gene had previously been shown to drive expression in both the ectomesenchyme and vasculature [30], and we used the mVISTA program [31] to identify seven short (<500 bp) sub-regions (A–H) that were conserved between zebrafish, puffer fishes (Takifugu rubripes and Tetraodon nigroviridis), stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus), and medaka (Oryzias latipes). By testing the ability of these sub-regions to drive GFP expression in conjunction with the hsp70I core promoter, we identified two vasculature-specific enhancers (G and H) and one ectomesenchyme-specific enhancer (F) (Figure 4A). Element F, located ∼1.5 kb upstream of the fli1a promoter, was sufficient to drive GFP expression in the ectomesenchyme from 19 hpf onwards, as confirmed by co-localization with a sox10:dsRed transgene (Figure 4C). We also identified homologous sequence to enhancer F ∼1.7 kb upstream of the mouse Fli1 gene, with both the mouse and fish Fli1 genes containing a perfectly conserved element, CAGATG, that matches the bHLH binding site, CANNTG (though Twist1 most strongly prefers CATATG) [32] (Figure 4B). This putative Twist1 binding site was required for enhancer function, as mutation to GTATAC abolished the ability of the fli1a element F enhancer to direct ectomesenchyme expression in zebrafish embryos and to potentiate Twist1-dependent transgene expression in mammalian 293T cells (Figure 3D, 3G). Twist1 was also required for enhancer F activity as injection of twist1a/1b-MO prevented ectomesenchyme expression in a stable Tg(fli1a-F-hsp70I:GFP) transgenic line, though this effect could equally likely be indirect (Figure 4E, 4F). Together, our results are consistent with Twist1 activating fli1a expression through a conserved enhancer element.

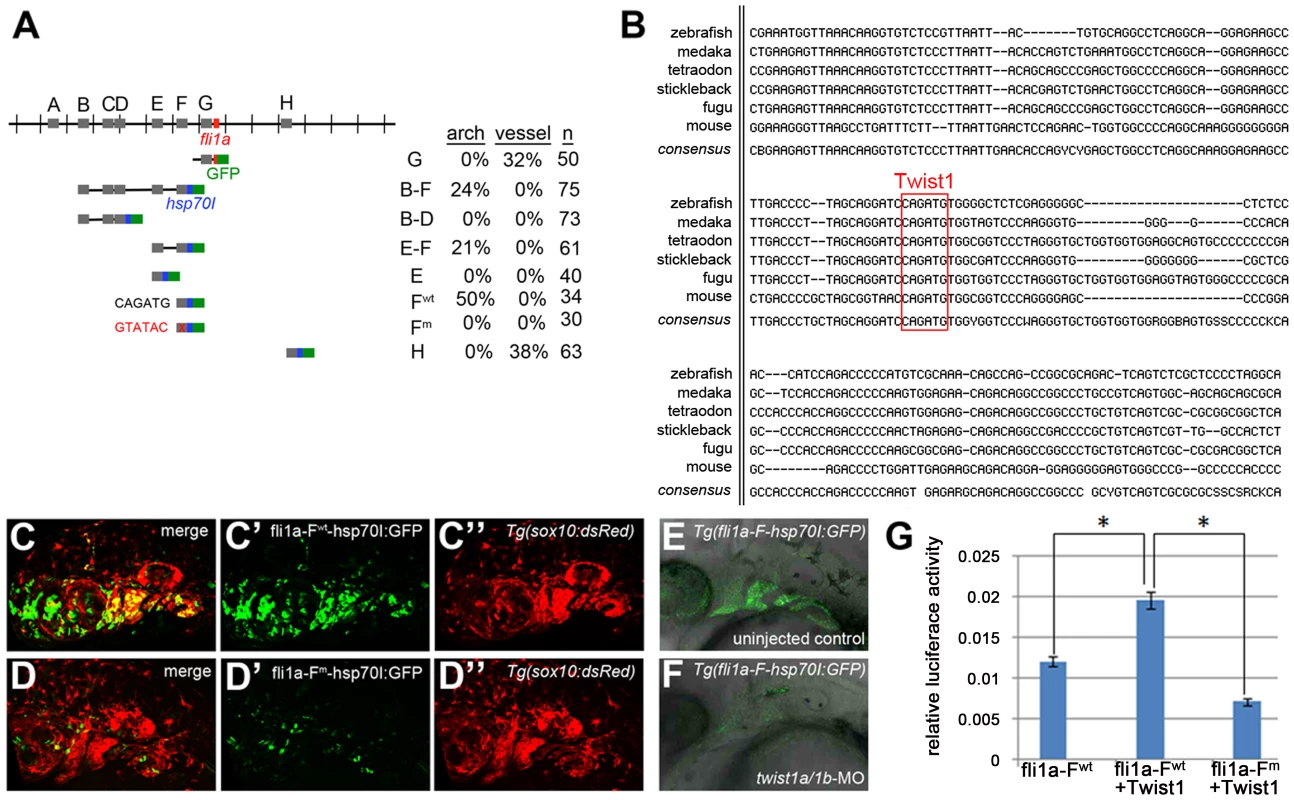

Fig. 4. Twist1 regulates fli1a expression through an ectomesenchyme-specific enhancer.

(A) Schematic shows the fli1a genomic locus with hatch marks at 1 kb intervals. Predicted enhancers (grey boxes, “A–H”) and the first exon (red box) are shown. Below are the various enhancer constructs analyzed, with the hsp70I core promoter in blue and GFP in green. Wild-type (black) and mutant (red) versions of the putative Twist1 binding site are also shown, as is the percentage of transient transgenic embryos showing GFP expression in the pharyngeal arches or vasculature. (B) Alignment of the central portion of the F enhancer between five fish species and mouse. The putative bHLH/Twist1 binding site is boxed in red. (C,D) Confocal projections of 32 hpf sox10:dsRed embryos injected at the one-cell-stage with fli1a-F enhancer constructs. The wild-type (C) but not mutant (D) enhancer drives arch expression. (E and F) Confocal sections of merged GFP and DIC channels show that a stable Tg(fli1a-F-hsp70I:GFP) line displays arch GFP expression in 32 hpf wild-type (E) but not twist1a/1b-MO (F) embryos. (G) Luciferase activity relative to renilla firefly activity in 293T cells transfected with wild-type or mutant fli1a-F enhancer reporter constructs, with or without a Twist1 expression plasmid. Asterisks indicate significant comparisons using a student's t-test (p<0.05). Arbitrary units and standard error of the mean are shown. Exclusion of id2a expression is necessary for ectomesenchyme specification

As Twist1 genes are expressed throughout the early CNCC domain (e.g. twist1b in zebrafish), we next examined whether dimerization partners might regulate the ectomesenchyme-specific function of Twist1. The Id class of proteins modulates Twist1 function by preventing the formation of Twist1-class B heterodimers [14], [15], and several Id family members are expressed in early CNCCs [33], [34], [35]. Intriguingly, we found that zebrafish id2a was broadly co-expressed with sox10 in early CNCCs (12 and 14 hpf) yet by 16.5 hpf was restricted to sox10-positive non-ectomesenchyme and excluded from ectomesenchyme expressing dlx2a and twist1a (Figure 5). As the down-regulation of id2a expression tightly correlates with ectomesenchyme specification, we next investigated whether the exclusion of Id2a from ectomesenchyme precursors was required for their differentiation. Indeed, when Id2a was misexpressed throughout migratory CNCCs in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Id2a embryos, we observed persistent expression of sox10 and reduced expression of fli1a in arch CNCCs, as well as mild reductions of dlx2a expression (Figure 6A–6F). The effect of Id2a misexpression was specific to the ectomesenchyme, as we observed severe reductions of the craniofacial skeleton but no defects in the non-ectomesenchyme-derived melanophore and xanthophore precursors (Figure 6G–6L) and HuC/D-positive cranial ganglionic neurons (Figure S3). However, we note that the sox10 promoter also drives later expression in chondrocytes [36], and thus we cannot rule out that the skeletal defects of sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Id2a animals are additionally or alternatively due to this later phase of Id2a misexpression. In any event, the ectomesenchyme specificity of gene expression and differentiation defects suggests that Id2a does not generally inhibit CNCC differentiation but instead specifically restricts ectomesenchyme fates. Furthermore, the highly similar defects seen upon Id2a misexpression and depletion of Twist1 are consistent with Id2a functioning to inhibit Twist1 in CNCCs. However, this inhibition of Twist1 function by Id2a is likely at the protein and not transcriptional level as twist1a and twist1b expression were unaffected by Id2a misexpression (Figure 6M–6P).

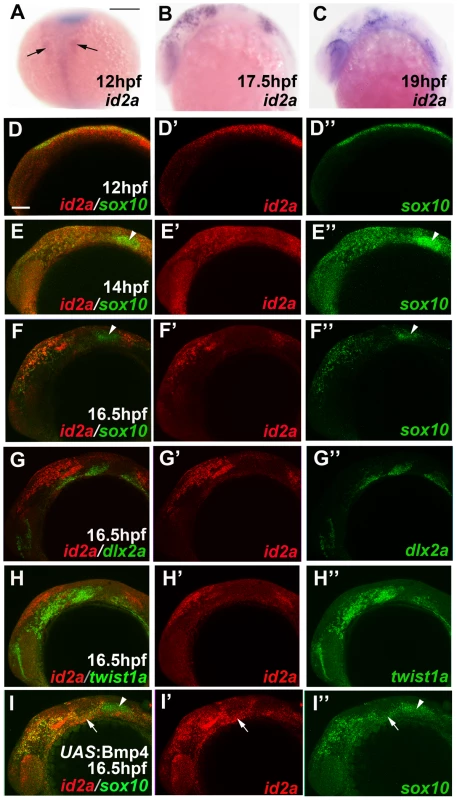

Fig. 5. id2a is regulated by Bmps and excluded from the ectomesenchyme.

(A–C) Colorimetric in situs show weak expression of id2a in pre-migratory CNCCs at 12 hpf (dorsal view with anterior up, arrows indicate bilateral CNCC fields) and increasing expression in non-ectomesenchyme precursors at 17.5 and 19 hpf (lateral views). (D–I) Confocal projections of fluorescent in situs show co-localization of id2a with sox10 in CNCCs at 12 hpf (D) and 14 hpf (E), as well as co-localization in the non-ectomesenchyme at 16.5 hpf (F). At 16.5 hpf, id2a is excluded from ectomesenchyme CNCCs marked by dlx2a (G) and twist1a (H), with twist1a also being expressed in head mesoderm. In sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4 embryos, id2a and sox10 are expressed ectopically in the ectomesenchyme (white arrows). Arrowheads indicate otic expression of sox10. Scale bars = 50 µm. Fig. 6. Forced expression of Id2a in CNCCs inhibits ectomesenchyme specification.

(A–F) Whole mount in situs show ectopic arch expression of sox10 at 18 hpf in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Id2a embryos (n = 7/7) but not sox10:Gal4VP16 only controls (n = 0/9), loss of fli1a arch expression at 24 hpf in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Id2a embryos (n = 4/4) but not sox10:Gal4VP16 only controls (n = 0/17), and mild reductions of dlx2a arch expression at 18 hpf in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Id2a embryos (n = 5/5) but not sox10:Gal4VP16 only controls (n = 0/8). Arches are numbered. Arrows denote the second arch, white arrowheads the developing ear, and red arrowheads the vasculature. (G and H) Skeletal staining at 5 dpf shows severe reduction of the craniofacial skeleton in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Id2a embryos (n = 17/17) compared to sox10:Gal4VP16 only controls (n = 0/22). (I and J) In situs for dct expression at 28 hpf show that melanophore precursors are unaffected in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Id2a embryos (n = 8) and sox10:Gal4VP16 only controls (n = 8). (K and L) In situs for xdh expression at 28 hpf show that xanthophore precursors are unaffected in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Id2a embryos (n = 4) and sox10:Gal4VP16 only controls (n = 4). (M–P) twist1a expression at 18 hpf is unaffected in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Id2a embryos (n = 12) versus sox10:Gal4VP16 only controls (n = 11). twist1b expression at 18 hpf is similarly unaffected in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Id2a embryos (n = 7) versus sox10:Gal4VP16 controls (n = 8). Id2a misexpression embryos are to the right in I–P. Scale bars = 50 µm. Bmp signaling regulates id2a expression in non-ectomesenchyme CNCCs

We next investigated the mechanism by which id2a expression becomes restricted to non-ectomesenchyme precursors. Bmps are well known regulators of Id gene expression [37], and we found that CNCC-specific misexpression of Bmp4 in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4 embryos resulted in ectopic expression of id2a in arch ectomesenchyme (Figure 5I). To analyze whether down-regulation of Bmp activity also coincides with loss of id2a expression in wild-type ectomesenchyme precursors, we performed immunostaining for the phosphorylated form of Smad1/5/8 (pSmad1/5/8), which is thought to broadly indicate canonical Bmp activity [38]. Consistent with the known role of Bmps in neural crest induction [39], all CNCCs displayed high levels of pSmad1/5/8 at pre-migratory stages (12 hpf) (Figure 7A). In contrast, ectomesenchyme precursors down-regulated pSmad1/5/8 by 16.5 hpf, while more dorsal non-ectomesenchyme precursors continued to display high pSmad1/5/8 (Figure 7B,7C). Cross-sectional views demonstrated that ventral CNCCs with low pSmad1/5/8 were located deep to the ectoderm whereas dorsal CNCCs with high pSmad1/5/8 had yet to delaminate and remained in the neural plate ectoderm (Figure 7D).

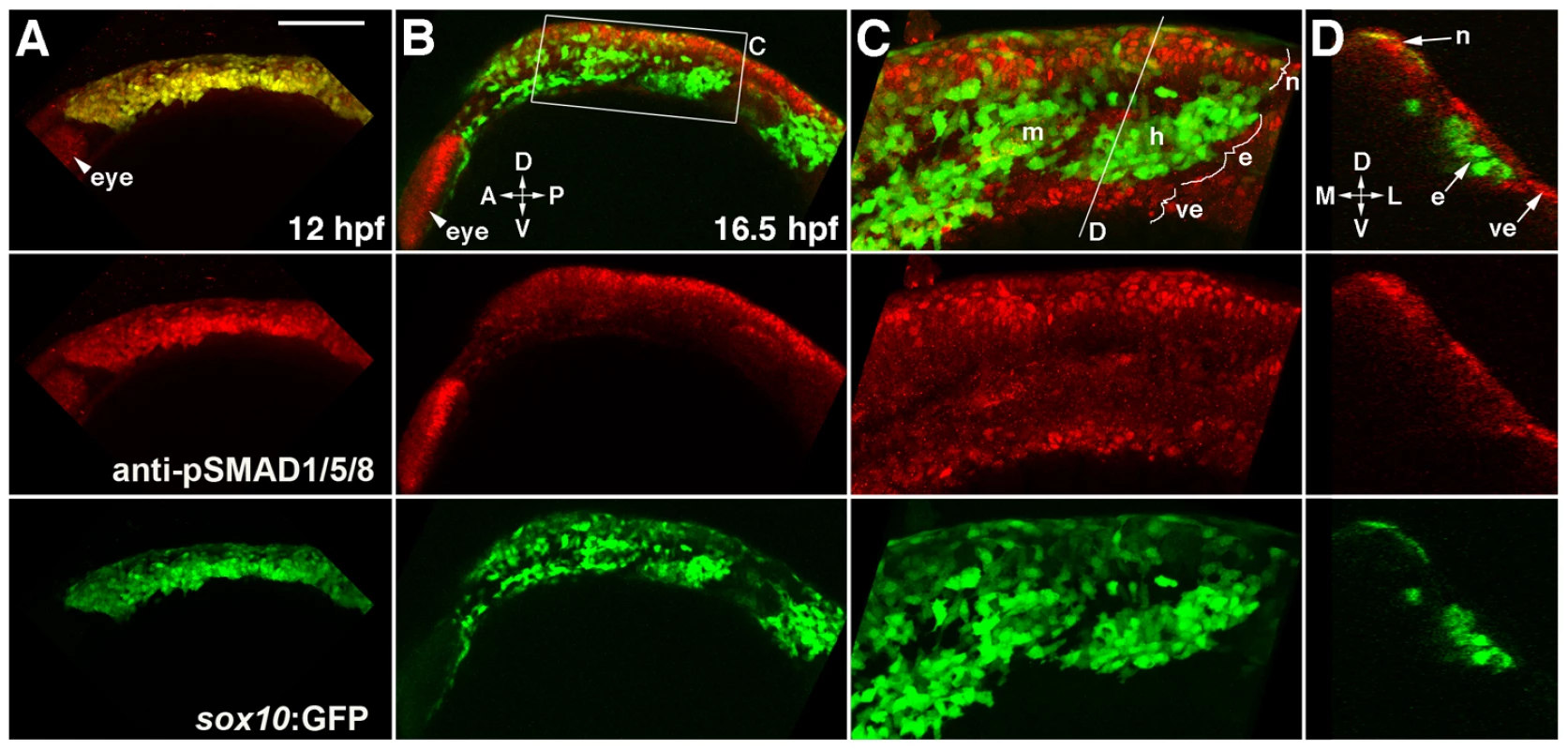

Fig. 7. Bmp activity is selectively down-regulated in ectomesenchyme precursors.

(A) Confocal projection of pSMAD1/5/8 immunostaining at 12 hpf shows that all sox10:GFP-positive CNCCs display high pSMAD1/5/8. (B–D) At 16.5 hpf, a projection (B) and a high-magnification section (C, boxed area in B) show that pSMAD1/5/8 remains high in the dorsal non-ectomesenchyme but is lower in the more ventral ectomesenchyme. An orthogonal section (D, taken at the level of the line in C) shows that high pSMAD1/5/8 CNCCs remain in the neural epithelium whereas low pSMAD1/5/8 CNCCs are positioned more medial and ventral. The eye also displays high pSMAD1/5/8. Abbreviations: D, dorsal; V, ventral; A, anterior; P, posterior; M, medial; L, lateral; m, mandibular arch ectomesenchyme; h, hyoid arch ectomesenchyme; n, non-ectomesenchyme; e, ectomesenchyme; ve, ventral epithelium. Scale bar = 50 µm. Bmp4 misexpression inhibits ectomesenchyme specification

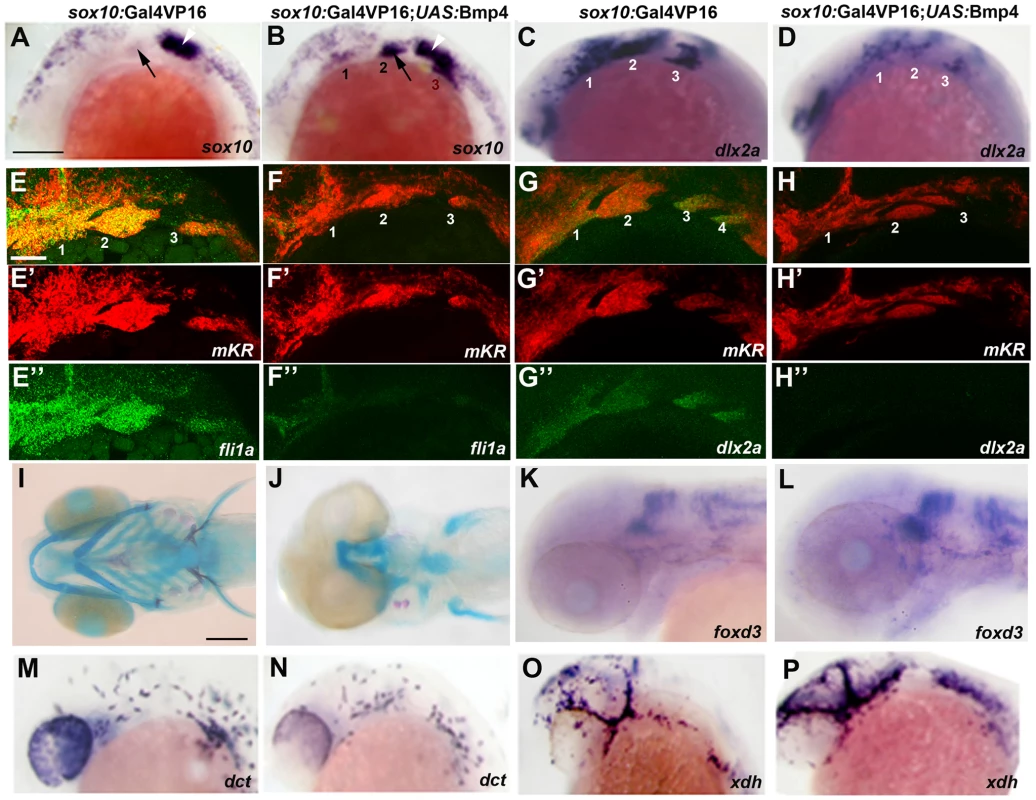

We next examined whether the observed down-regulation of Bmp activity in ectomesenchyme precursors was necessary for their formation. Strikingly, Bmp4 misexpression in migratory CNCCs of sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4 embryos resulted in profound defects in ectomesenchyme specification, including persistent sox10 expression and reduced expression of fli1a and dlx2a (Figure 8A–8H). Importantly, the reduction of fli1a and dlx2a arch expression was not simply due to a lack of CNCC formation, migration, or survival. The examination of sox10-positive CNCCs in 15 hpf Bmp4-misexpression embryos revealed no major defects in CNCC induction or migration (Figure S5), and Lysotracker staining also revealed no major increases in CNCC apoptosis (Figure S6). Moreover, although fewer CNCCs were found in the arches of Bmp4-misexpression embryos at later stages (as shown by lineage tracing using the mKR red fluorescent protein at 24 hpf), those CNCCs found in the arches also displayed reduced fli1a and dlx2a expression (Figure 8E–8H). As with Twist1 depletion or Id2a misexpression, Bmp4 misexpression also resulted in specific reductions of the ectomesenchyme-derived craniofacial skeleton without affecting the non-ectomesenchyme-derived foxd3-positive glia, dct-positive melanophores, and xdh-positive xanthophores (Figure 8I–8P).

Fig. 8. Misexpression of Bmp4 in migrating CNCCs inhibits ectomesenchyme formation.

(A–D) Whole mount in situs at 18 hpf show ectopic expression of sox10 in the arches (numbered) of sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4; UAS:mKR embryos (n = 8/8) compared to sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:mKR controls (n = 0/8) and reductions of dlx2a in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4; UAS:mKR embryos (n = 4/4) compared to sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:mKR controls (n = 0/4). Arrows indicate the second arch and white arrowheads the developing ear. (E–H) Double fluorescent in situs for mKR (red) and fli1a or dlx2a (green) at 24 hpf show reduction of fli1a arch expression in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4; UAS:mKR embryos (n = 5/5) compared to sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:mKR controls (n = 0/9) and reduction of dlx2a arch expression in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4; UAS:mKR embryos (n = 4/4) compared to sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:mKR controls (n = 0/3). The mKR transgene was included as a lineage tracer for CNCC-derived cells that migrated into the arches. (I,J) Skeletal staining at 5 dpf shows severe loss of craniofacial skeleton in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4; UAS:mKR embryos (n = 7/7) compared to sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:mKR controls (n = 0/9). (K,L) In situs for foxd3 at 48 hpf reveal largely normal patterns of glia in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4; UAS:mKR embryos (n = 8) and sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:mKR controls (n = 11). (M–P) In situs at 28 hpf show normal dct-positive melanophore precursors in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4; UAS:mKR embryos (n = 12) and sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:mKR controls (n = 15) and normal xdh-positive xanthophore precursors in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4; UAS:mKR embryos (n = 10) and sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:mKR controls (n = 10). Scale bars = 50 µm. The ectoderm is a likely source of Bmps for ectomesenchyme specification

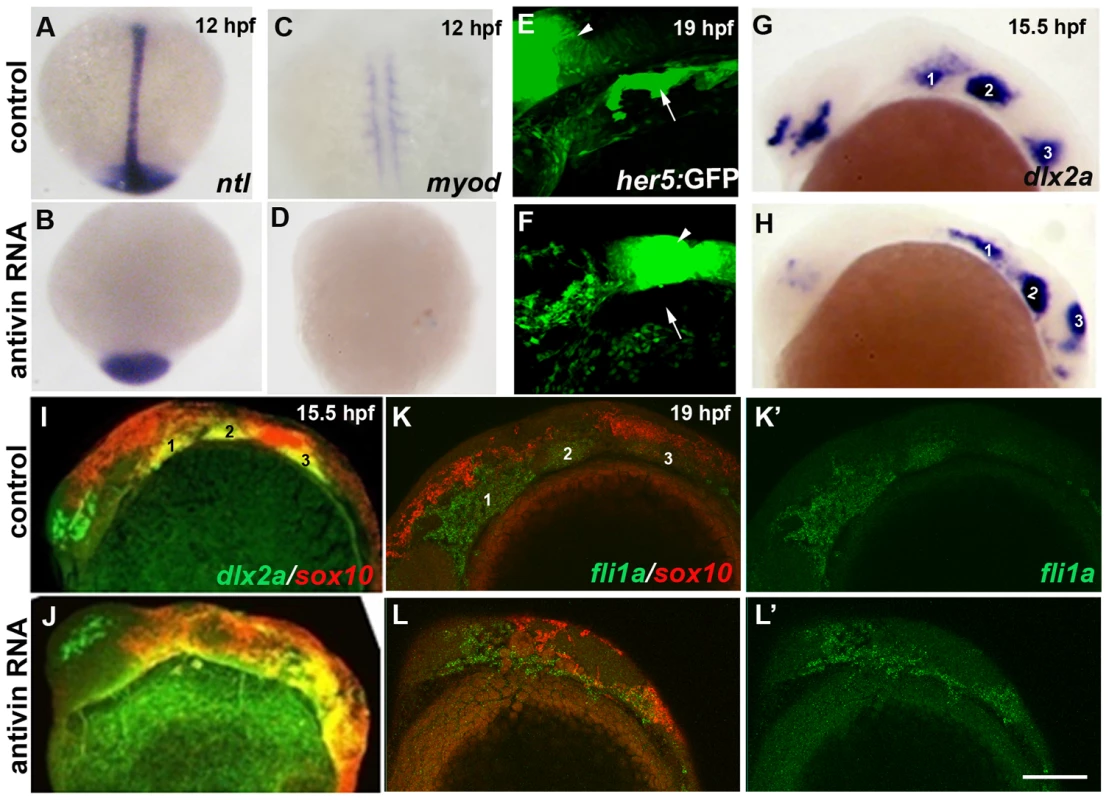

We also investigated which tissue is the likely source of Bmps for the ectomesenchyme lineage decision. A previous study had reported that ablation of mesoderm and endoderm, by injection of mRNA encoding the Nodal antagonist Antivin, resulted in severe reductions of dlx2a-positive ectomesenchyme at 24 hpf [40], yet it was unclear whether the loss of dlx2a reflected defects in the specification or later endoderm-mediated survival of ectomesenchyme precursors [41], [42], [43], [44]. By performing similar Antivin mRNA injections, we found normal dlx2a and fli1a induction at 15.5 hpf and sox10 down-regulation by 19 hpf in the presumptive ectomesenchyme of embryos lacking endoderm and mesoderm (Figure 9). Hence, rather than signals deriving from the arch endoderm and/or mesoderm [18], our data are more consistent with signals from the non-neural ectoderm, such as Bmps, influencing ectomesenchyme fates.

Fig. 9. Mesoderm and endoderm are not essential for ectomesenchyme formation.

(A–D) In situs at 12 hpf show loss of axial ntl and mesodermal myod expression in Antivin-mRNA-injected embryos compared to un-injected controls. (E,F) Confocal projections of her5:GFP expression at 19 hpf show loss of pouch endoderm (arrows) but not brain (arrowheads) in Antivin-mRNA-injected embryos compared to un-injected controls. (G,H) In situs at 15.5 hpf show normal ectomesenchyme induction of dlx2a in Antivin-mRNA-injected embryos (n = 12) and un-injected controls (n = 13). Arches are numbered. (I,J) Double fluorescent in situs at 15.5 hpf show normal induction of dlx2a (green) in sox10-positive CNCCs (red, yellow indicates co-localization) in Antivin-mRNA-injected embryos (n = 15) and un-injected controls (n = 9). (K,L) Double fluorescent in situs at 19 hpf show complementary expression of fli1a (green) in ectomesenchyme and sox10 (red) in non-ectomesenchyme in Antivin-mRNA-injected embryos (n = 5) and un-injected controls (n = 8). Scale bar = 50 µm. Id2a is required for Bmps to inhibit ectomesenchyme formation

As Id2a and Bmp4 misexpression resulted in similar ectomesenchyme defects, we next examined whether Id2a might mediate the negative effects of Bmps on ectomesenchyme development. To do so, we injected a previously validated translation-blocking id2a-MO [17] into one-cell-stage embryos to deplete Id2a protein. Whereas injection of id2a-MO caused no ectomesenchyme defects on its own, injection into sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4 embryos fully rescued persistent sox10 and reduced dlx2a arch expression, as well as partially rescuing fli1a arch expression (Figure 10). In contrast, injection of twist1b mRNA failed to rescue sox10 persistence in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4 embryos (Figure S7). Together, these results support a model in which, rather than inhibiting twist1a or twist1b at the transcriptional level, Bmps negatively regulate Twist1 ectomesenchyme function through induction of the Id2a negative regulator.

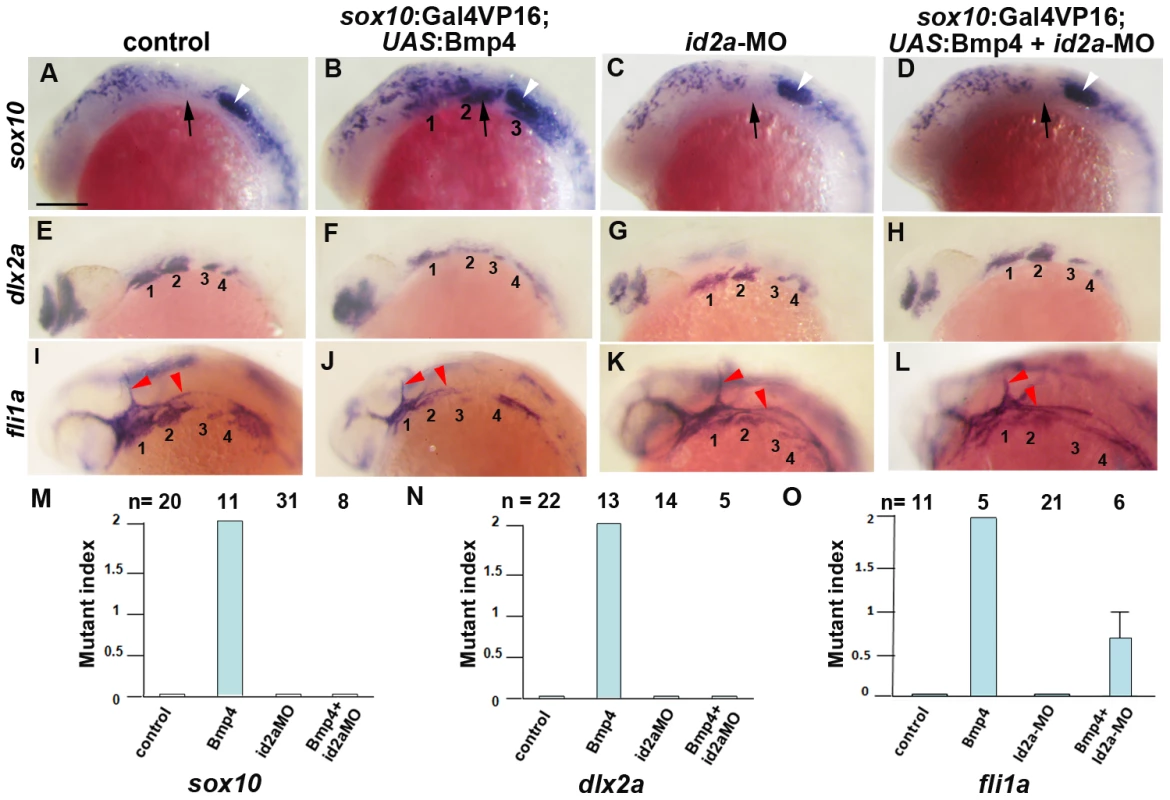

Fig. 10. Reduction of Id2a rescues the ectomesenchyme defects caused by Bmp4 misexpression.

(A–L) Colorimetric in situs show ectopic sox10 arch expression at 18 hpf and reductions of dlx2a and fli1a arch expression at 24 hpf in sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4 embryos but not sox10:Gal4VP16 control or id2a-MO-injected embryos. sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4 embryos injected with id2a-MO showed complete rescue of sox10 and dlx2a expression and partial rescue of fli1a expression. Arches are numbered and arrows denote the second arch, white arrowheads the developing ear, and red arrowheads the vasculature. Scale bar = 50 µm. (M–O) Quantification of gene expression defects. The mutant index is based on the following: 0 = normal, 1 = partially defective, 2 = fully defective. Fully defective was defined as gene expression being of equal intensity to that seen in un-injected sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4 embryos. For sox10, partially defective was defined as a reduction in the number of expressing cells and/or the intensity of arch expression compared to un-injected sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4 embryos. For fli1a and dlx2a, partially defective was defined as a level of arch expression intermediate between un-injected sox10:Gal4VP16; UAS:Bmp4 and sox10:Gal4VP16 control embryos. The rescue of Bmp4 misexpression defects with id2a-MO injection was statistically significant for all genes based on a Tukey-Kramer HSD test (α = 0.05). Standard errors of the mean are shown. Discussion

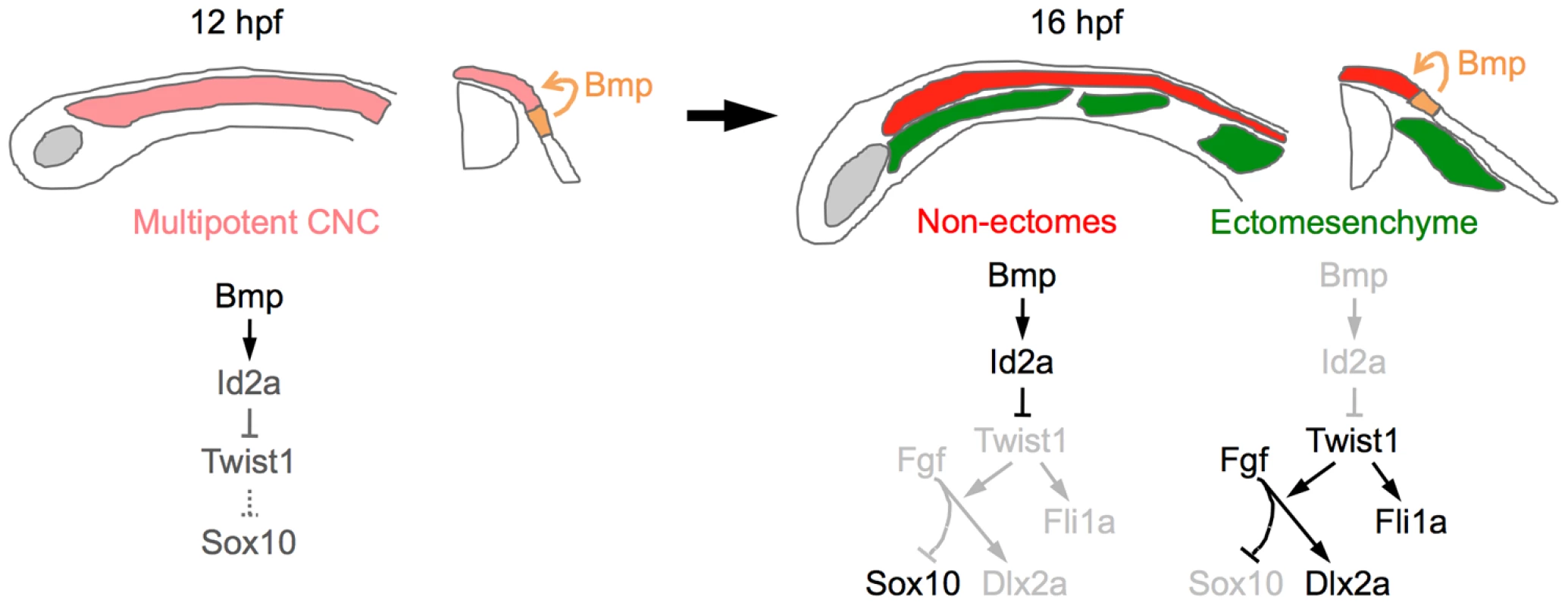

Here we present evidence for a new model of ectomesenchyme formation. Upon delamination from the neural plate border, early migrating CNCCs downregulate Bmp activity and id2a expression, thus allowing activation of Twist1. Twist1 then promotes ectomesenchyme and inhibits non-ectomesenchyme gene expression through both potentiation of Fgf signaling and activation of genes such as fli1a (Figure 11). A salient feature of our model is that the integration of Bmp inhibition at their origin and Fgf activation along their migratory route would confer temporal and spatial specificity to the generation of ectomesenchyme fates from CNCCs.

Fig. 11. Model of ectomesenchyme specification.

At 12 hpf, Bmps in the neural plate border ectoderm promote moderate expression of id2a in multipotent CNCCs. As ectomesenchyme precursors delaminate from the neuroepithelium and migrate away from the Bmp source (16 hpf), they downregulate id2a expression, which allows Twist1 to induce fli1a expression and potentiate Fgf signaling. Fgf signaling then inhibits sox10 and promotes dlx2a expression. In the non-ectomesenchyme, sustained Bmp activity and id2a expression dampens Twist1-dependent inhibition of neural, glia, and pigment gene expression programs. Lateral diagrams are shown on the left and cross-sectional diagrams on the right. Twist1 promotes ectomesenchyme at the expense of non-ectomesenchyme gene expression

The CNCC-derived craniofacial skeleton is nearly completely lost in zebrafish with reduced Twist1a and Twist1b function. This loss of skeleton does not appear to be due to defects in the generation or migration of CNCCs as shown by the presence of largely normal numbers of migrating dlx2a-positive CNCCs at 18 hpf and sox10:dsRed-positive arch CNCCs at 28 hpf in twist1a/1b-MO embryos. Instead, we found that Twist1a and Twist1b are redundantly required for a subset of ectomesenchyme gene expression, in particular the early induction of fli1a and inhibition of sox10, with the later severe loss of facial skeleton precisely correlating with a loss of pre-chondrogenic sox9a expression, as well as increased cell death in the arches. However, dlx2a expression was much less affected in twist1a/1b-MO embryos, as well as in mice with CNCC-specific deletion of Twist1, suggesting that some aspects of ectomesenchyme formation may be Twist1-independent [11]. Our data in zebrafish are generally in agreement with previous studies of Twist1 function in mouse. Conventional Twist1−/− mutant mice also displayed arch persistence of Sox10 and loss of later Sox9 expression, although Fli1 and early Dlx2 expression were not examined and lethality at E10.5–E11.5 precluded an analysis of the extent of craniofacial skeletal loss [12]. In addition, Twist1 function was required largely in CNCCs for Sox10 repression and craniofacial skeleton development in both zebrafish (this study) and mouse [11], although in both species the facial skeleton was not as affected as in twist1a/1b-MO zebrafish. These phenotypic differences might reflect incomplete efficacy of the dnTwist1b transgene at reducing endogenous Twist1 function, or alternatively additional non-autonomous roles of mesodermal Twist1 expression (which is also lost in twist1a/1b-MO larvae) in the migration, survival, and/or differentiation of arch CNCCs. Indeed, a role for mesodermal Twist1 in the migration of CNCCs has been inferred from studies in mouse, although we did not observe major defects in CNCC migration in twist1a/1b-MO zebrafish.

In theory, Twist1 could promote the transition from a multipotent CNCC precursor to a more lineage-restricted ectomesenchyme cell, or alternatively influence fate choices between ectomesenchyme and non-ectomesenchyme lineages. However, the observation that only a subset of early CNCC genes persisted in twist1a/1b-MO arches, combined with the normal development of CNCC-derived cranial pigment and glial cells, suggest that CNCCs do not remain as multipotent precursors in the absence of Twist1 function. Instead, the ectopic arch expression of sox10 and foxd3 in Twist1-depleted embryos, at a stage when these genes are normally co-expressed in the non-ectomesenchyme, suggests that presumptive ectomesenchyme precursors partially adopt a non-ectomesenchyme expression profile in the absence of Twist1. This conclusion was confirmed by our microarray analysis in which non-ectomesenchyme but not early CNCC genes were the most upregulated in Twist1-deficient embryos. Unexpectedly, some non-ectomesenchyme genes, such as nr4a2b and gch2, were upregulated in the non-ectomesenchyme domain but not ectopically expressed in Twist1-deficient arches, suggesting that Twist1 may have additional roles in restricting non-ectomesenchyme gene expression within the early non-ectomesenchyme domain. Consistent with only a subset of non-ectomesenchyme genes showing ectopic arch expression, we also found no evidence for pigment cells, functional glia, or neurons forming ectopically in Twist1-deficient arches. Hence, loss of Twist1 function is not sufficient for arch CNCCs to generate non-ectomesenchyme derivatives.

Twist1 promotes ectomesenchyme through both Fgf-dependent and -independent gene activation

Our data also indicate that Twist1 promotes ectomesenchyme fates through two largely parallel pathways. The finding that Twist1 was required for expression of the Fgf target gene pea3 in arch ectomesenchyme suggests a role for Twist1 in potentiating Fgf signaling. Twist1 might do so by regulating expression of Fgf ligands and/or receptors, as Twist1 has been shown to regulate the CNCC expression of both Fgf10 and Fgfr1 in mice [12]. Hence, Twist1 could function upstream of autocrine/paracrine Fgf signaling within CNCCs that promotes ectomesenchyme development. However, although Fgf signaling was required to repress sox10 and activate dlx2a expression, we found that fli1a ectomesenchyme expression was Fgf-independent. Instead, fli1a appears to be a potentially direct target of Twist1, and we have identified a conserved ectomesenchyme enhancer element of fli1a that is Twist1-dependent. However, chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments (currently not feasible due to the lack of a high quality Twist1 antibody) will eventually be needed to show enhancer occupancy by Twist1. Moreover, the function of Fli1a in ectomesenchyme formation also remains to be investigated. Targeted disruption of the Fli1 gene in mouse results in embryonic lethality by E12.5 due to severe hemorrhaging, thus precluding an analysis of its role in development of the ectomesenchyme-derived craniofacial skeleton [45]. In the future, the generation of zebrafish fli1a mutants and/or conditional Fli1 mouse knockouts will allow us to determine the extent to which Fli1 mediates that effects of Twist1 in craniofacial development.

Id2a restricts Twist1 activity to the ectomesenchyme

The expression of Twist1 genes throughout early CNCCs in both zebrafish [13] and mice [46], [47] suggests that Twist1 function is regulated at the post-translational level during ectomesenchyme formation, either through enzymatic modifications or changes in dimerization partners. Here we find evidence for the latter, with the Bmp target gene Id2a functioning oppositely to Twist1 for ectomesenchyme specification. Previous work suggests that Id2a does not inhibit Twist1 function per se, but instead would modulate what types of dimers Twist1 forms [14], [15]. In the future, the identification of binding partners for Twist1 in CNCCs will allow us to test what roles Twist1 heterodimers versus homodimers play in ectomesenchyme specification. Furthermore, we note that Twist1 genes continue to be expressed in arch ectomesenchyme and likely have additional roles in facial skeletal patterning, for example by interacting with other bHLH factors such as Hand2 [48]. Hence, different Twist1 heterodimers may have distinct roles during craniofacial development (i.e. ectomesenchyme formation versus arch patterning), with the later disruption of these heterodimers in Twist1-deficient and Id2a-misexpression embryos also contributing to some aspects of the observed facial skeletal defects.

A Bmp-dependent switch for ectomesenchyme formation

Previous studies have shown both temporal and spatial components to the specification of the large diversity of neural crest derivatives. In the trunk, neural crest cell fate is influenced both by migration pathways [49], [50] and signals at their destinations [51]. In contrast, CNCCs appear to be largely fate-restricted before migration in zebrafish, with Wnts from the dorsal ectoderm promoting pigment at the expense of neural and glial fates but having little effect on ectomesenchyme derivatives [4], [5]. Instead, we find that Bmps, also from the ectoderm, actively inhibit ectomesenchyme fates in more dorsal CNCCs. Furthermore, this observed role of Bmps in regulating ectomesenchyme specification is not simply an indirect effect of earlier roles of Bmps in neural crest development, as prolonging Bmp activity did not result in decreased amounts of CNCC being generated or defects in non-ectomesenchyme derivatives

The down-regulation of Bmp activity in ectomesenchyme precursors could reflect CNCCs distancing themselves from a Bmp source in the non-neural ectoderm (e.g. Bmp2b) and/or active inhibition of Bmp signaling during migration. Whereas the Bmp antagonist Noggin1 is expressed in the paraxial mesoderm surrounding migratory CNCCs in zebrafish [52], genetic ablation of endoderm and mesoderm did not disrupt ectomesenchyme gene expression, although there are likely other sources of Bmp inhibitors [53]. Alternatively, the down-regulation of Bmp activity could result from the delamination of CNCCs from the neural plate ectoderm, with the basement membrane of the ectodermal epithelium, under which CNCCs migrate, serving as a barrier to apical Bmp secretion and signaling [54].

Although we found that Bmp down-regulation was essential for ectomesenchyme formation, transgenic inhibition of Bmp (or Id2a depletion) did not result in ectopic ectomesenchyme (data not shown). Therefore, low Bmp activity is not sufficient to specify ectomesenchyme fates. Instead, Bmp down-regulation might allow CNCCs to respond to ectomesenchyme-promoting signals present only in the early CNCC milieu. In particular, our data suggest that activation of Twist1 at low Bmp levels allows migrating CNCCs to respond to Fgfs. Although the exact source of Fgfs remains to be determined, we propose that a combination of low Bmp and high Fgf signaling uniquely present in early migrating CNCCs generates ectomesenchyme fates.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animals were handled in strict accordance with good animal practice as defined by the relevant national and/or local animal welfare bodies, and all animal work was approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Zebrafish lines and transgenic constructs

Zebrafish were staged as described [55]. Previously reported lines include Tg(hsp70I:Gal4)kca4 [56], Tg(∼3.4her5:EGFP)ne1911 [57], and Tg(UAS:Bmp4; cmlc2:GFP)el49 [53]. Tg(sox10:Gal4VP16)el159, Tg(UAS:mKR; cmlc2:GFP)el15, Tg(UAS:kikGR; α-crystallin:Cerulean)el377, Tg(UAS:Id2a; α-crystallin:Cerulean)el405, Tg(UAS:dnFgfr1a; cmlc2:GFP)el28, Tg(UAS:dnTwist1b; UAS:mcherryCAAX; cmlc2:GFP)el179, Tg(sox10:dsRED)el10, Tg (sox10:LOX-GFP-LOX-hDLX3)el8, and Tg(fli1a-F-hsp70I:GFP)el411 lines were generated using Gateway cloning (Invitrogen) and the Tol2 kit as described [58]. sox10:Gal4VP16 was created by combining p5E-sox10, pME-Gal4VP16, p3E-IRES-GFP-pA, and pDestTol2pA2. The IRES-GFP was later found to be non-functional in stable transgenics. UAS:mKR, UAS:kikGR, and UAS:dnFgfr1a were generated by combining p5E-UAS; pME-mKR, pME-kikGR, or pME-dnFgfr1a; p3E-polyA; and pDestTol2CG2. UAS:dnTwist1b was made by combining p5E-UAS, pME-dnTwist1b, p3E-UAS:mCherryCAAXpA, and pDestTol2CG2. The dnTwist1b clone was made by first amplifying the full-length zebrafish twist1b cDNA with primers rTwist1bikL: 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTCGGCCACCATGCCCGAAGAGCCCGCGGAGA-3′ and Twrk: 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTACTTAGATGCAGACATGGACCAAGCGCC-3′. PCR based mutagenesis was then performed with primers twdnEK1L: 5′-GCGCTTTCGCAGAGACTTA-3′ and twdnEK1R 5′-CTGTCGCTTGCGCACGTT-3′ as described [59] to change nucleotide G250 of the twist1b cDNA to A, which results in conversion of amino acid 84E to K, with the PCR product cloned into pDONR221 to create pME-dnTwist1b. To construct pME-dnFgfr1a, we amplified a truncated form of zebrafish fgfr1a based on the previously reported dominant-negative Fgf receptor in Xenopus laevis [60] and cloned the PCR product into pDONR221; primers used were 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTCCACCATGATAATGAAGACCACGCTG-3′ and 5′GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTCTAAGAGCTGTGCATTTTGGC-3′. Full-length zebrafish id2a was amplified with primers id2a-F: 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTCGGCCACCATGAAGGCAATAAG-3′ and id2a-R: 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTGTTAACGGTAAAGTGTCCT-3′ and then cloned into pDONR221 to generate pME-Id2a. UAS:Id2a was generated by combining p5E-UAS, pME-Id2a, p3E-polyA, and pDestTol2AB2. sox10:dsRED and sox10:LOX-GFP-LOX-Dlx3 were generated by combining p5E-sox10, p3E-polyA, and pDestTol2pA2 with either pME-dsRed or pME-LOX-GFP-LOX-Dlx3, respectively. UAS:mKR was made by combining p5E-UAS, pME-mKR, p3E-polyA, and pDestTol2CG2. pME-mKR was made by PCR amplification of membraneKillerRed (mKR) with primers kilredL: 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTCGGTCGCCACCATGCTGTG-3′ and kilredR: 5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTTTAATCCTCGTCGCTACCGA-3′ and insertion into pDONR221. UAS:kikGR was made by combining p5E-UAS, pME-kikGR, p3E-polyA, and pDestTol2AB2. fli1a enhancers were amplified with the following primer sets from zebrafish genomic DNA and cloned into the pDONR-p4p1R vector: (G) Fli-2 : 5′-GGGGACAACTTTGTATAGAAAAGTTGTAGAGCGTGCTCGGTAACTG-3′ and Fli-3 : 5′-GGGGACTGCTTTTTTGTACAAACTTGGAGCCCGACAATATTCCAAA-3′, (B–F) Fli-6 : 5′-GGGGACAACTTTGTATAGAAAAGTTGTTGCACTGGGCAAACTTTAG-3′ and Fli-15 : 5′-GGGGACTGCTTTTTTGTACAAACTTGCTCTAGACGCTCAGCCAACC-3′, (B–D) Fli-6 and Fli-13 : 5′-GGGGACTGCTTTTTTGTACAAACTTGAGGCTGTCCTGACTGCTGAT-3′, (E–F) Fli-14 : 5′-GGGGACAACTTTGTATAGAAAAGTTGAGCACTTCAGGGTTTTTCCA-3′ and Fli-15, (E) Fli-14 and Fli-18 : 5′-GGGGACTGCTTTTTTGTACAAACTTGATTGCGTCCAGTTAGATCGG-3′, (F) Fli-19 : 5′-GGGGACAACTTTGTATAGAAAAGTTGATGTTGCATCACTTTTCCCC-3′ and Fli-15, and (H) Fli-16 : 5′-GGGGACAACTTTGTATAGAAAAGTTGATGGTTTGTTGCAGTCGGTT-3′ and Fli-17 : 5′-GGGGACTGCTTTTTTGTACAAACTTGCGCAGGATTACGCTGGAATA-3′. pME-hsp70I:GFP was constructed by fusion PCR of the hsp70I promoter and full-length GFP. PCR-based mutagenesis of the fli1a-F enhancer was performed using primers: 5′-GTATACTGGGGCTCTCGAGG-3′ and 5′-CTAGCAGGATCGTATACTGGG-3′. p5E enhancer vectors were then combined with pME-hsp70I:GFP, p3E-polyA, and pDestTol2pA2. To construct stable transgenics, one-cell-stage embryos were injected with vectors and transposase RNA and multiple stable lines were identified for each transgene: Tg(sox10:Gal4VP16) (1), Tg(UAS:Id2a; α-crystallin:Cerulean) (5), Tg(UAS:dnTwist1b; UAS:mcherryCAAX; cmlc2:GFP) (7), Tg(UAS:dnFgfr1a; cmlc2:GFP) (6), Tg(UAS:mKR; cmlc2:GFP) (2), Tg(UAS:kikGR; cmlc2:GFP) (3), Tg(sox10:dsRED) (1), Tg(sox10:LOX-GFP-LOX-hDLX3) (2), and Tg(fli1-F-hsp70I:GFP) (2). In the absence of CRE, Tg(sox10:LOX-GFP-LOX-hDLX3)el8 (referred to as sox10:GFP in the Results) drives similar GFP expression as the previously reported Tg(∼4725sox10:GFP)ba2 line but without neural crest cell toxicity [25]. For sox10:Gal4VP16/UAS:transgene experiments, genotyping for Gal4 and cmlc2 [61] confirmed the observed phenotypes, except for sox10:Gal4VP16/UAS:Id2a experiments where genotyping for Id2a was performed with primers id2aF: 5′-AGAACACCCCTGACAACACT-3′ and id2aR: 5′ - GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTACCGGCAGTCCAATTTC-3′.

In situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and skeletal analysis

Alcian Blue staining of cartilage and Alizarin Red staining of bone at 5 dpf, as well as in situ hybridizations, were performed as described [61]. Reported probes include sox9a and sox9b [62], tfap2a [63], and fli1a [9]. id2a, sox10, fli1a, twist1a, ntla, dct, xdh, pea3, kikGR, mKR, gch2, nr4a2b, and foxd3 probes were synthesized with T7 RNA polymerase from PCR products amplified from multistage zebrafish cDNA, with the exception of id2a which was amplified from an id2a cDNA plasmid (Zebrafish International Resource Center). We used the following primer pairs: id2a: id2aF and id2aR, twist1a: 5′-CAGAGTCTCCGGTGGACAGT-3′ and 5′-GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTCTTTTCCTGCAGCGAGTC-3′, ntla: 5′ - GACCACAAGGAAGTCCCAGA-3′ and 5′ - GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCATTGAGGAGGGAGAGGACA-3′, dct: 5′ - CGTACTGGAACTTTGCGACA-3′ and 5′-GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGACCAACACGATCAACAGCAG-3′, xdh: 5′-TGAACACTCTGACGCACCTC-3′ and 5′-GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTGTTGAAGCTCCAGCAACAC-3′, foxd3: 5′-CGGCATTGGGAATCCATA-3′ and 5′-GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCAACGAAATGAAATAGAAAGAAGGA-3′, pea3: 5′-CCCATATGATGGTCAAACAGG-3′ and 5′ - GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGATTGTCGGGAAAAGCCAAG-3′, kikGR: 5′-GAAGATCGAGCTGAGGATGG-3′ and 5′ - GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTCGTACAGCTTCACCTTGT-3′, mkr: 5′-GGGCAGAAGTTCACCATCG-3′ and 5′-GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTGGTGAAGCCGATGAAGG-3′, nr4a2b: 5′-CCAGGCTCAGTATGGGACAT-3′ and 5′-GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTATGTGACGTCGCCAGGTAG-3′, sox10: 5′-TGCATTACAAGAGCCTGCAC-3′ and 5′ - GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGAGGAGAAGGCGGAGTAGAGG-3′, and gch2: 5′ - GGAATACCAAAAGGCAGCAG-3′ and 5′-GCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCTCTCTGAACACACCCAGCA-3′. Immunostaining was performed as described [53] using the following antibodies: rabbit anti-pSMAD1/5/8 (Cell Signaling, #9511S, 1∶1000), goat anti-rabbit Alexa-568 (Molecular Probes, 1∶1000), mouse anti-HuC/D (1∶100; Molecular Probes), and goat anti-mouse Alexa-488 (Molecular Probes 1∶1000). Cell death assays with Lysotracker Red were performed as described [53].

Morpholino and mRNA injections

One-cell-stage embryos were injected with 3 nl of the following translation-blocking MOs (GeneTools, Philomath, OR, USA): twist1a-MO 5′ - ACCTCTGGAAAAGCTCAGATTGCGG-3′ (400 µM), twist1b–MO 5′-TTAAGTCTCTGCTGAAAGCGCGTG-3′ (400 µM), twist1a/1b-MO (200/200 µM), and id2a-MO 5′-GCCTTCATGTTGACAGCAGGATTTC-3′ (800 µM) [17]. For MO validation, we performed rescue experiments with in vitro transcribed mRNA generated using the Ambion Message machine kit (Applied Biosystems) from a CMV/SP6-Twist1b template generated by combining p5E-CMV/SP6, pME-Twist1b, p3E-polyA, and pDestTol2pA2. Antivin mRNA was synthesized and injected as described [40].

Imaging

Larval skeletons and colorimetric in situ hybridization embryos were imaged using a Leica MZ16F dissecting microscope using Camera Window software for a Canon60 Shot 80S digital camera. Fluorescent images were captured using a Zeiss LSM5 confocal microscope with Zen software. Identical gain settings were used to acquire fluorescent in situ images across data sets. Images were processed using Photoshop CS4 with care taken to apply identical adjustments throughout data sets.

Microarray analysis

sox10:GFP embryos were injected with twist1a/1b-MO. Control and injected embryos were sorted for GFP under a fluorescent dissecting microscope and samples were prepared for FACS using the “cell disruption for flow sorting” protocol described previously [64]. A BD Aria Sorter was used to isolate equal numbers of GFP-positive and GFP-negative cells and RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen). cDNA was then generated using the WTA2 kit (Sigma Aldrich) and hybridized to a 385K zebrafish array (Roche #05543916001). Microarray data were normalized by Nimblegen, and processed data files were analyzed using Arraystar 4.0 software (DNAstar). Three independent experiments were performed, and a cut-off value of p<0.05 was used for significance. All data was submitted to GEO (Accession #GSE32308).

Luciferase assay

The Twist1 expression vector was made by cloning the zebrafish twist1b cDNA into pCDNA3. Luciferase reporter constructs were generated by cloning wild-type and mutant versions of the fli1a-F enhancer into the Pgl3 basic vector (Progema #E1715). We then transfected 293T cells with the Twist1b expression and luciferase reporter plasmids and used the Dual Luciferase Assay kit (Promega #E1910) per manufacturer instructions to measure firefly luciferase activity relative to renilla luciferase activity 48 hours after transfection. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Statistics were performed with JMP7 software. One-way analysis of variance was calculated with a Tukey-Kramer HSD test (alpha = 0.05) and standard errors of the mean were plotted.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Le DouarinNM 1999 The neural crest Cambridge university press

2. BaroffioADupinELe DouarinNM 1991 Common precursors for neural and mesectodermal derivatives in the cephalic neural crest. Development 112 301 305

3. WestonJAYoshidaHRobinsonVNishikawaSFraserST 2004 Neural crest and the origin of ectomesenchyme: neural fold heterogeneity suggests an alternative hypothesis. Dev Dyn 229 118 130

4. DorskyRIMoonRTRaibleDW 1998 Control of neural crest cell fate by the Wnt signalling pathway. Nature 396 370 373

5. SchillingTFKimmelCB 1994 Segment and cell type lineage restrictions during pharyngeal arch development in the zebrafish embryo. Development 120 483 494

6. MeulemansDBronner-FraserM 2004 Gene-regulatory interactions in neural crest evolution and development. Dev Cell 7 291 299

7. KelshRNDuttonKMedlinJEisenJS 2000 Expression of zebrafish fkd6 in neural crest-derived glia. Mech Dev 93 161 164

8. SperberSMSaxenaVHatchGEkkerM 2008 Zebrafish dlx2a contributes to hindbrain neural crest survival, is necessary for differentiation of sensory ganglia and functions with dlx1a in maturation of the arch cartilage elements. Dev Biol 314 59 70

9. BrownLARodawayARSchillingTFJowettTInghamPW 2000 Insights into early vasculogenesis revealed by expression of the ETS-domain transcription factor Fli-1 in wild-type and mutant zebrafish embryos. Mech Dev 90 237 252

10. WadaNJavidanYNelsonSCarneyTJKelshRN 2005 Hedgehog signaling is required for cranial neural crest morphogenesis and chondrogenesis at the midline in the zebrafish skull. Development 132 3977 3988

11. BildsoeHLoebelDAJonesVJChenYTBehringerRR 2009 Requirement for Twist1 in frontonasal and skull vault development in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol 331 176 188

12. SooKO'RourkeMPKhooPLSteinerKAWongN 2002 Twist function is required for the morphogenesis of the cephalic neural tube and the differentiation of the cranial neural crest cells in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol 247 251 270

13. GermanguzILevDWaismanTKimCHGitelmanI 2007 Four twist genes in zebrafish, four expression patterns. Dev Dyn 236 2615 2626

14. ConnerneyJAndreevaVLeshemYMuentenerCMercadoMA 2006 Twist1 dimer selection regulates cranial suture patterning and fusion. Dev Dyn 235 1345 1357

15. YokotaY 2001 Id and development. Oncogene 20 8290 8298

16. MartinsenBJBronner-FraserM 1998 Neural crest specification regulated by the helix-loop-helix repressor Id2. Science 281 988 991

17. UribeRAGrossJM 2010 Id2a influences neuron and glia formation in the zebrafish retina by modulating retinoblast cell cycle kinetics. Development 137 3763 3774

18. BlenticATandonPPaytonSWalsheJCarneyT 2008 The emergence of ectomesenchyme. Dev Dyn 237 592 601

19. YamauchiHGotoMKatayamaMMiyakeAItohN 2011 Fgf20b is required for the ectomesenchymal fate establishment of cranial neural crest cells in zebrafish. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 409 705 710

20. LiemKFJrTremmlGRoelinkHJessellTM 1995 Dorsal differentiation of neural plate cells induced by BMP-mediated signals from epidermal ectoderm. Cell 82 969 979

21. NguyenVHSchmidBTroutJConnorsSAEkkerM 1998 Ventral and lateral regions of the zebrafish gastrula, including the neural crest progenitors, are established by a bmp2b/swirl pathway of genes. Dev Biol 199 93 110

22. SteventonBArayaCLinkerCKuriyamaSMayorR 2009 Differential requirements of BMP and Wnt signalling during gastrulation and neurulation define two steps in neural crest induction. Development 136 771 779

23. CorsiAKKostasSAFireAKrauseM 2000 Caenorhabditis elegans twist plays an essential role in non-striated muscle development. Development 127 2041 2051

24. CorsiAKBrodiganTMJorgensenEMKrauseM 2002 Characterization of a dominant negative C. elegans Twist mutant protein with implications for human Saethre-Chotzen syndrome. Development 129 2761 2772

25. CarneyTJDuttonKAGreenhillEDelfino-MachinMDufourcqP 2006 A direct role for Sox10 in specification of neural crest-derived sensory neurons. Development 133 4619 4630

26. StewartRAArduiniBLBerghmansSGeorgeREKankiJP 2006 Zebrafish foxd3 is selectively required for neural crest specification, migration and survival. Dev Biol 292 174 188

27. KelshRN 2006 Sorting out Sox10 functions in neural crest development. Bioessays 28 788 798

28. MundellNALaboskyPA 2011 Neural crest stem cell multipotency requires Foxd3 to maintain neural potential and repress mesenchymal fates. Development 138 641 652

29. RoehlHNusslein-VolhardC 2001 Zebrafish pea3 and erm are general targets of FGF8 signaling. Curr Biol 11 503 507

30. LawsonNDWeinsteinBM 2002 In vivo imaging of embryonic vascular development using transgenic zebrafish. Dev Biol 248 307 318

31. FrazerKAPachterLPoliakovARubinEMDubchakI 2004 VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res 32 W273 279

32. KophengnavongTMichnowiczJEBlackwellTK 2000 Establishment of distinct MyoD, E2A, and twist DNA binding specificities by different basic region-DNA conformations. Mol Cell Biol 20 261 272

33. DickmeisTRastegarSLamCSAanstadPClarkM 2002 Expression of the helix-loop-helix gene id3 in the zebrafish embryo. Mech Dev 113 99 102

34. ChongSWNguyenTTChuLTJiangYJKorzhV 2005 Zebrafish id2 developmental expression pattern contains evolutionary conserved and species-specific characteristics. Dev Dyn 234 1055 1063

35. KeeYBronner-FraserM 2005 To proliferate or to die: role of Id3 in cell cycle progression and survival of neural crest progenitors. Genes Dev 19 744 755

36. DuttonJRAntonellisACarneyTJRodriguesFSPavanWJ 2008 An evolutionarily conserved intronic region controls the spatiotemporal expression of the transcription factor Sox10. BMC Dev Biol 8 105

37. HollnagelAOehlmannVHeymerJRutherUNordheimA 1999 Id genes are direct targets of bone morphogenetic protein induction in embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem 274 19838 19845

38. WuMYHillCS 2009 Tgf-beta superfamily signaling in embryonic development and homeostasis. Dev Cell 16 329 343

39. TribuloCAybarMJNguyenVHMullinsMCMayorR 2003 Regulation of Msx genes by a Bmp gradient is essential for neural crest specification. Development 130 6441 6452

40. RaglandJWRaibleDW 2004 Signals derived from the underlying mesoderm are dispensable for zebrafish neural crest induction. Dev Biol 276 16 30

41. CrumpJGMavesLLawsonNDWeinsteinBMKimmelCB 2004 An essential role for Fgfs in endodermal pouch formation influences later craniofacial skeletal patterning. Development 131 5703 5716

42. AhlgrenSCBronner-FraserM 1999 Inhibition of sonic hedgehog signaling in vivo results in craniofacial neural crest cell death. Curr Biol 9 1304 1314

43. KikuchiYAgathonAAlexanderJThisseCWaldronS 2001 casanova encodes a novel Sox-related protein necessary and sufficient for early endoderm formation in zebrafish. Genes Dev 15 1493 1505

44. DavidNBSaint-EtienneLTsangMSchillingTFRosaFM 2002 Requirement for endoderm and FGF3 in ventral head skeleton formation. Development 129 4457 4468

45. SpyropoulosDDPharrPNLavenburgKRJackersPPapasTS 2000 Hemorrhage, impaired hematopoiesis, and lethality in mouse embryos carrying a targeted disruption of the Fli1 transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol 20 5643 5652

46. HopwoodNDPluckAGurdonJB 1989 A Xenopus mRNA related to Drosophila twist is expressed in response to induction in the mesoderm and the neural crest. Cell 59 893 903

47. GitelmanI 1997 Twist protein in mouse embryogenesis. Dev Biol 189 205 214

48. FirulliBAKrawchukDCentonzeVEVargessonNVirshupDM 2005 Altered Twist1 and Hand2 dimerization is associated with Saethre-Chotzen syndrome and limb abnormalities. Nat Genet 37 373 381

49. HenionPDWestonJA 1997 Timing and pattern of cell fate restrictions in the neural crest lineage. Development 124 4351 4359

50. EricksonCAGoinsTL 1995 Avian neural crest cells can migrate in the dorsolateral path only if they are specified as melanocytes. Development 121 915 924

51. ReissmannEErnsbergerUFrancis-WestPHRuegerDBrickellPM 1996 Involvement of bone morphogenetic protein-4 and bone morphogenetic protein-7 in the differentiation of the adrenergic phenotype in developing sympathetic neurons. Development 122 2079 2088

52. FurthauerMThisseBThisseC 1999 Three different noggin genes antagonize the activity of bone morphogenetic proteins in the zebrafish embryo. Dev Biol 214 181 196

53. ZunigaERippenMAlexanderCSchillingTFCrumpJG 2011 Gremlin 2 regulates distinct roles of BMP and Endothelin 1 signaling in dorsoventral patterning of the facial skeleton. Development 138 5147 5156

54. EomDSAmarnathSFogelJLAgarwalaS 2011 Bone morphogenetic proteins regulate neural tube closure by interacting with the apicobasal polarity pathway. Development 138 3179 3188

55. KimmelCBBallardWWKimmelSRUllmannBSchillingTF 1995 Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn 203 253 310

56. ScheerNCampos-OrtegaJA 1999 Use of the Gal4-UAS technique for targeted gene expression in the zebrafish. Mech Dev 80 153 158

57. TallafussABally-CuifL 2003 Tracing of her5 progeny in zebrafish transgenics reveals the dynamics of midbrain-hindbrain neurogenesis and maintenance. Development 130 4307 4323

58. KwanKMFujimotoEGrabherCMangumBDHardyME 2007 The Tol2kit: a multisite gateway-based construction kit for Tol2 transposon transgenesis constructs. Dev Dyn 236 3088 3099

59. HeckmanKLPeaseLR 2007 Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat Protoc 2 924 932

60. AmayaEMusciTJKirschnerMW 1991 Expression of a dominant negative mutant of the FGF receptor disrupts mesoderm formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell 66 257 270

61. ZunigaEStellabotteFCrumpJG 2010 Jagged-Notch signaling ensures dorsal skeletal identity in the vertebrate face. Development 137 1843 1852

62. YanYLWilloughbyJLiuDCrumpJGWilsonC 2005 A pair of Sox: distinct and overlapping functions of zebrafish sox9 co-orthologs in craniofacial and pectoral fin development. Development 132 1069 1083

63. FurthauerMThisseCThisseB 1997 A role for FGF-8 in the dorsoventral patterning of the zebrafish gastrula. Development 124 4253 4264

64. WesterfieldM 2000 The Zebrafish Book: A guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Danio rerio) University of Oregon Press, Eugene

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Functional Centromeres Determine the Activation Time of Pericentric Origins of DNA Replication inČlánek Dynamic Deposition of Histone Variant H3.3 Accompanies Developmental Remodeling of the TranscriptomeČlánek Integrin α PAT-2/CDC-42 Signaling Is Required for Muscle-Mediated Clearance of Apoptotic Cells inČlánek Prdm5 Regulates Collagen Gene Transcription by Association with RNA Polymerase II in Developing BoneČlánek Acquisition Order of Ras and p53 Gene Alterations Defines Distinct Adrenocortical Tumor Phenotypes

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 5- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

- Intrauterinní inseminace a její úspěšnost

- Délka menstruačního cyklu jako marker ženské plodnosti

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Slowing Replication in Preparation for Reduction

- Chromosome Pairing: A Hidden Treasure No More

- Loss of Imprinting Differentially Affects REM/NREM Sleep and Cognition in Mice

- Six Novel Susceptibility Loci for Early-Onset Androgenetic Alopecia and Their Unexpected Association with Common Diseases

- Regulation by the Noncoding RNA

- UDP-Galactose 4′-Epimerase Activities toward UDP-Gal and UDP-GalNAc Play Different Roles in the Development of

- Deletion of PTH Rescues Skeletal Abnormalities and High Osteopontin Levels in Mice

- Karyotypic Determinants of Chromosome Instability in Aneuploid Budding Yeast

- Genome-Wide Copy Number Analysis Uncovers a New HSCR Gene:

- MicroRNA-277 Modulates the Neurodegeneration Caused by Fragile X Premutation rCGG Repeats

- Functional Centromeres Determine the Activation Time of Pericentric Origins of DNA Replication in

- Dynamic Deposition of Histone Variant H3.3 Accompanies Developmental Remodeling of the Transcriptome

- Scientist Citizen: An Interview with Bruce Alberts

- YY1 Regulates Melanocyte Development and Function by Cooperating with MITF

- Congenital Heart Disease–Causing Gata4 Mutation Displays Functional Deficits

- Recombination Drives Vertebrate Genome Contraction

- KATNAL1 Regulation of Sertoli Cell Microtubule Dynamics Is Essential for Spermiogenesis and Male Fertility

- Re-Patterning Sleep Architecture in through Gustatory Perception and Nutritional Quality

- Using Whole-Genome Sequence Data to Predict Quantitative Trait Phenotypes in

- Genome-Wide Analysis of GLD-1–Mediated mRNA Regulation Suggests a Role in mRNA Storage

- Meiotic Chromosome Pairing Is Promoted by Telomere-Led Chromosome Movements Independent of Bouquet Formation

- LINT, a Novel dL(3)mbt-Containing Complex, Represses Malignant Brain Tumour Signature Genes

- The H3K27 Demethylase UTX-1 Is Essential for Normal Development, Independent of Its Enzymatic Activity

- Suppresses Senescence Programs and Thereby Accelerates and Maintains Mutant -Induced Lung Tumorigenesis

- Genome-Wide Association of Pericardial Fat Identifies a Unique Locus for Ectopic Fat

- An Essential Role for Katanin p80 and Microtubule Severing in Male Gamete Production

- Identification of Genes That Promote or Antagonize Somatic Homolog Pairing Using a High-Throughput FISH–Based Screen

- Principles of Carbon Catabolite Repression in the Rice Blast Fungus: Tps1, Nmr1-3, and a MATE–Family Pump Regulate Glucose Metabolism during Infection

- Integrin α PAT-2/CDC-42 Signaling Is Required for Muscle-Mediated Clearance of Apoptotic Cells in

- Histone H3 Localizes to the Centromeric DNA in Budding Yeast

- Collapse of Telomere Homeostasis in Hematopoietic Cells Caused by Heterozygous Mutations in Telomerase Genes

- Hypersensitive to Red and Blue 1 and Its Modification by Protein Phosphatase 7 Are Implicated in the Control of Arabidopsis Stomatal Aperture

- Extent, Causes, and Consequences of Small RNA Expression Variation in Human Adipose Tissue

- TBC-8, a Putative RAB-2 GAP, Regulates Dense Core Vesicle Maturation in

- Regulating Repression: Roles for the Sir4 N-Terminus in Linker DNA Protection and Stabilization of Epigenetic States

- Common Genetic Determinants of Intraocular Pressure and Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma

- Prdm5 Regulates Collagen Gene Transcription by Association with RNA Polymerase II in Developing Bone

- Fitness Landscape Transformation through a Single Amino Acid Change in the Rho Terminator

- Repeated, Selection-Driven Genome Reduction of Accessory Genes in Experimental Populations

- Allelic Variation and Differential Expression of the mSIN3A Histone Deacetylase Complex Gene Promote Mammary Tumor Growth and Metastasis

- DNA Demethylation and USF Regulate the Meiosis-Specific Expression of the Mouse

- Knowledge-Driven Analysis Identifies a Gene–Gene Interaction Affecting High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels in Multi-Ethnic Populations

- A Duplication CNV That Conveys Traits Reciprocal to Metabolic Syndrome and Protects against Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice and Men

- EMT Inducers Catalyze Malignant Transformation of Mammary Epithelial Cells and Drive Tumorigenesis towards Claudin-Low Tumors in Transgenic Mice

- Inactivation of a Novel FGF23 Regulator, FAM20C, Leads to Hypophosphatemic Rickets in Mice

- Genome-Wide Association for Abdominal Subcutaneous and Visceral Adipose Reveals a Novel Locus for Visceral Fat in Women

- Stratifying Type 2 Diabetes Cases by BMI Identifies Genetic Risk Variants in and Enrichment for Risk Variants in Lean Compared to Obese Cases

- New Insight into the History of Domesticated Apple: Secondary Contribution of the European Wild Apple to the Genome of Cultivated Varieties

- Activated Cdc42 Kinase Has an Anti-Apoptotic Function

- The Region Is Critical for Birth Defects and Electrocardiographic Dysfunctions Observed in a Down Syndrome Mouse Model

- COP9 Signalosome Integrity Plays Major Roles for Hyphal Growth, Conidial Development, and Circadian Function

- Bmps and Id2a Act Upstream of Twist1 To Restrict Ectomesenchyme Potential of the Cranial Neural Crest

- Psip1/Ledgf p52 Binds Methylated Histone H3K36 and Splicing Factors and Contributes to the Regulation of Alternative Splicing

- The Number of X Chromosomes Causes Sex Differences in Adiposity in Mice

- Target Gene Analysis by Microarrays and Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Identifies HEY Proteins as Highly Redundant bHLH Repressors

- Acquisition Order of Ras and p53 Gene Alterations Defines Distinct Adrenocortical Tumor Phenotypes

- ELK1 Uses Different DNA Binding Modes to Regulate Functionally Distinct Classes of Target Genes

- Histone H1 Depletion Impairs Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation

- IDN2 and Its Paralogs Form a Complex Required for RNA–Directed DNA Methylation

- Separation of DNA Replication from the Assembly of Break-Competent Meiotic Chromosomes

- Genomic Hypomethylation in the Human Germline Associates with Selective Structural Mutability in the Human Genome

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Inactivation of a Novel FGF23 Regulator, FAM20C, Leads to Hypophosphatemic Rickets in Mice

- Genome-Wide Association of Pericardial Fat Identifies a Unique Locus for Ectopic Fat

- Slowing Replication in Preparation for Reduction

- An Essential Role for Katanin p80 and Microtubule Severing in Male Gamete Production

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova