-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Multiple Common Susceptibility Variants near BMP Pathway Loci , , and Explain Part of the Missing Heritability of Colorectal Cancer

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified 14 tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (tagSNPs) that are associated with the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC), and several of these tagSNPs are near bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathway loci. The penalty of multiple testing implicit in GWAS increases the attraction of complementary approaches for disease gene discovery, including candidate gene - or pathway-based analyses. The strongest candidate loci for additional predisposition SNPs are arguably those already known both to have functional relevance and to be involved in disease risk. To investigate this proposition, we searched for novel CRC susceptibility variants close to the BMP pathway genes GREM1 (15q13.3), BMP4 (14q22.2), and BMP2 (20p12.3) using sample sets totalling 24,910 CRC cases and 26,275 controls. We identified new, independent CRC predisposition SNPs close to BMP4 (rs1957636, P = 3.93×10−10) and BMP2 (rs4813802, P = 4.65×10−11). Near GREM1, we found using fine-mapping that the previously-identified association between tagSNP rs4779584 and CRC actually resulted from two independent signals represented by rs16969681 (P = 5.33×10−8) and rs11632715 (P = 2.30×10−10). As low-penetrance predisposition variants become harder to identify—owing to small effect sizes and/or low risk allele frequencies—approaches based on informed candidate gene selection may become increasingly attractive. Our data emphasise that genetic fine-mapping studies can deconvolute associations that have arisen owing to independent correlation of a tagSNP with more than one functional SNP, thus explaining some of the apparently missing heritability of common diseases.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002105

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002105Summary

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified 14 tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (tagSNPs) that are associated with the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC), and several of these tagSNPs are near bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathway loci. The penalty of multiple testing implicit in GWAS increases the attraction of complementary approaches for disease gene discovery, including candidate gene - or pathway-based analyses. The strongest candidate loci for additional predisposition SNPs are arguably those already known both to have functional relevance and to be involved in disease risk. To investigate this proposition, we searched for novel CRC susceptibility variants close to the BMP pathway genes GREM1 (15q13.3), BMP4 (14q22.2), and BMP2 (20p12.3) using sample sets totalling 24,910 CRC cases and 26,275 controls. We identified new, independent CRC predisposition SNPs close to BMP4 (rs1957636, P = 3.93×10−10) and BMP2 (rs4813802, P = 4.65×10−11). Near GREM1, we found using fine-mapping that the previously-identified association between tagSNP rs4779584 and CRC actually resulted from two independent signals represented by rs16969681 (P = 5.33×10−8) and rs11632715 (P = 2.30×10−10). As low-penetrance predisposition variants become harder to identify—owing to small effect sizes and/or low risk allele frequencies—approaches based on informed candidate gene selection may become increasingly attractive. Our data emphasise that genetic fine-mapping studies can deconvolute associations that have arisen owing to independent correlation of a tagSNP with more than one functional SNP, thus explaining some of the apparently missing heritability of common diseases.

Introduction

Genome-wide association (GWA) studies of colorectal cancer (CRC) have so far identified 14 common, low-risk susceptibility variants [1]. Of these 14 variants, 3 are close to loci that are secreted members of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signalling pathway: GREM1 (rs4779584); BMP4 (rs4444235); and BMP2 (rs961253). In the colon, GREM1 is one of several BMP antagonists produced by sub-epithelial myofibroblasts (ISEMFs). GREM1 binds to and inactivates the ligands BMP2 and BMP4 that are primarily produced by inter-cryptal stromal cells.

Our GWA studies have utilised a primary phase of genome-wide typing of tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (tagSNPs), followed by larger validation phases of those SNPs with the strongest signals of association. We have previously used relatively stringent statistical thresholds to take SNPs forward into the final validation phases [1]. Whilst such a design has been cost-effective, the use of a lower threshold may have led to the discovery of more CRC SNPs, albeit at the cost of a relatively high type I error rate. One means of reducing false positives might be to select SNPs using a less stringent threshold where there is a priori evidence for candidacy. We reasoned that the best candidate loci were those already identified as harbouring CRC risk alleles. Of those 14 loci, we prioritised GREM1, BMP2 and BMP4 for further analysis owing to their strongly-related functions.

The GWA studies had identified a single tagSNP associated with CRC risk close to each of GREM1, BMP2 and BMP4 [1]. Examination of the regions around these genes in public databases such as HapMap (http://www.hapmap.org/) showed in all cases that the coding sequence and predicted surrounding regulatory regions were present within more than one linkage disequilibrium (LD) block. For each of the 3 genes, therefore, it was possible that there were additional genetic determinants of CRC risk, independent of the already-identified SNPs. We proceeded to test this hypothesis in large sets of CRC cases and controls of European origin.

Results

The rs4779584 CRC signal results from two independent SNPs close to GREM1

In order to refine the location of CRC-associated functional variation close to the GREM1, BMP4 and BMP2 loci, we genotyped 442 SNPs close to rs4779584, rs4444235 and rs961253 in 4,878 CRC cases and 4,914 controls from the UK2 and Scotland2 sample sets and imputed other SNPs within these regions. No significant localisation of a functional variant was achieved for rs4444235 or rs961253 (Figure S1), but at GREM1, rs16969681 (chr15 : 30,780,403 bases) had a notably stronger signal of association than rs4779584 (pairwise LD: r2 = 0.18, D′ = 0.70) (Figure 1 and Figure S2). We genotyped rs16969681 in additional independent CRC case-control series (UK1, UK4, VQ58, Helsinki, Cambridge and EPICOLON; see Methods). After combined analysis, a significant association between the minor allele at rs16969681 and CRC risk was seen (P = 5.33×10−8; Table 1). Unconditional logistic regression analysis, incorporating sample series as a co-variate, showed that rs16969681 was more strongly associated with CRC than rs4779584, but that the signals were non-independent (for rs16969681, OR = 1.16, 95% CI 1.07–1.25, P = 1.91×10−4; for rs4779584, OR = 1.08, 95% CI 1.02–1.14, P = 5.27×10−3). Akaike information criteria metrics for rs16969681 and rs4779584 respectively were 25608 and 25922, consistent with a superior fit of the risk model incorporating the former SNP. Intriguingly, we found that rs16969681 maps to a site of open chromatin in GREM1-expressing CRC cell lines, raising the possibility that it may be directly functional (Figure S3).

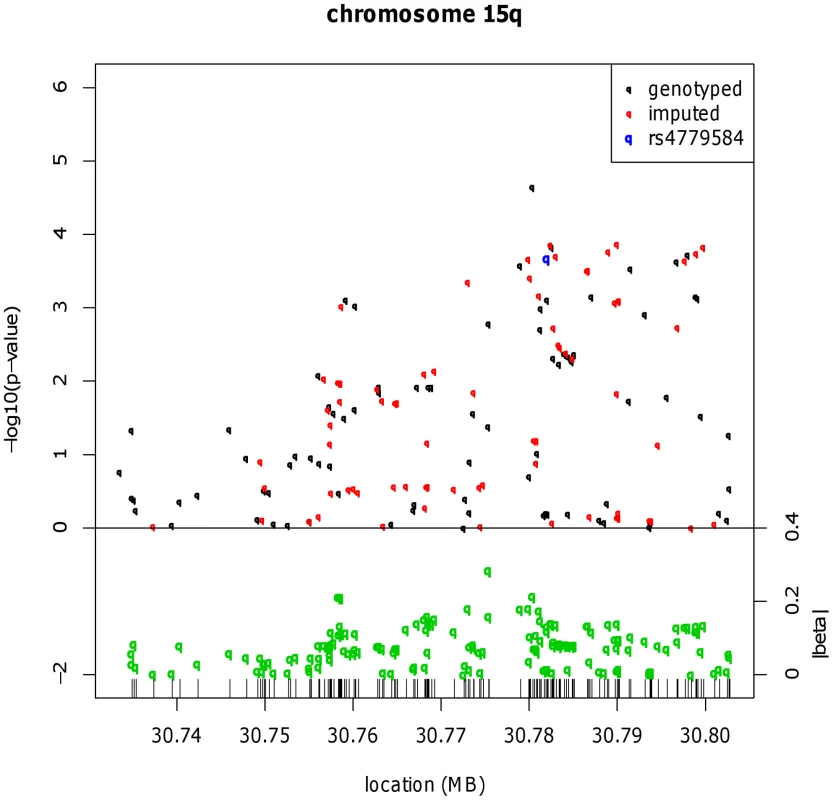

Fig. 1. Fine mapping around the known CRC risk SNP close to GREM1 (15q13.3).

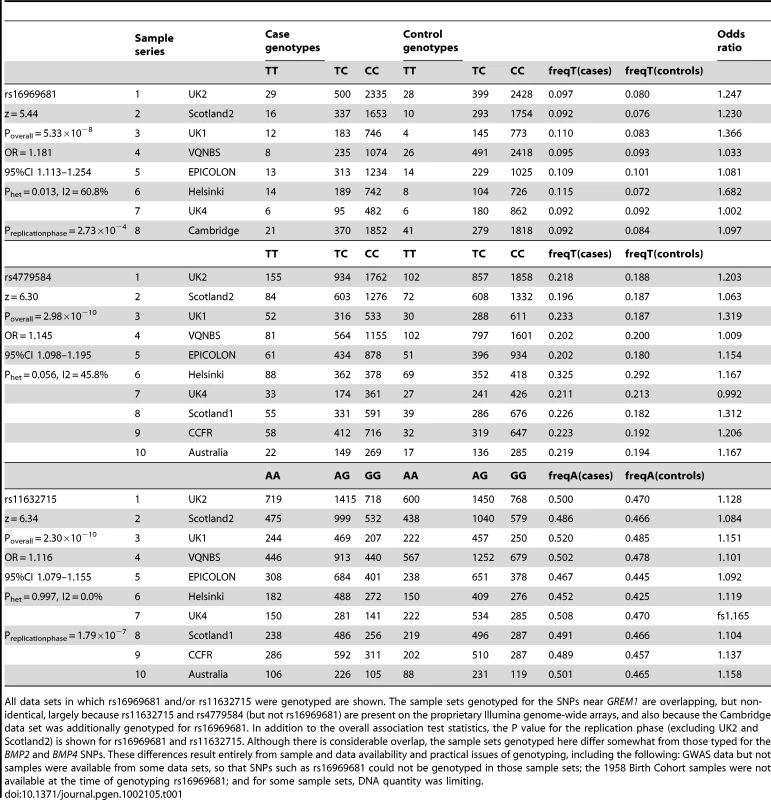

Results for meta-analysis of UK2 and Scotland2 are shown. Both significance of association (−log10(P)) and effect size (β) are presented. The original CRC-associated tagSNPs are shown in blue. The SNP with the clearly strongest association signal is the genotyped SNP rs16969681. Tab. 1. Genotype counts and statistics of association at rs16969681, rs11632715, and rs4779584.

All data sets in which rs16969681 and/or rs11632715 were genotyped are shown. The sample sets genotyped for the SNPs near GREM1 are overlapping, but non-identical, largely because rs11632715 and rs4779584 (but not rs16969681) are present on the proprietary Illumina genome-wide arrays, and also because the Cambridge data set was additionally genotyped for rs16969681. In addition to the overall association test statistics, the P value for the replication phase (excluding UK2 and Scotland2) is shown for rs16969681 and rs11632715. Although there is considerable overlap, the sample sets genotyped here differ somewhat from those typed for the BMP2 and BMP4 SNPs. These differences result entirely from sample and data availability and practical issues of genotyping, including the following: GWAS data but not samples were available from some data sets, so that SNPs such as rs16969681 could not be genotyped in those sample sets; the 1958 Birth Cohort samples were not available at the time of genotyping rs16969681; and for some sample sets, DNA quantity was limiting. Haplotype risk analysis (Table S2) provided evidence that rs16969681 alleles do not capture all the CRC risk associated with rs4779584. In brief, data from UK2 and Scotland2 showed that the risk alleles at rs16969681 and rs4779584 were defined by a TGGTC haplotype at rs16969681-rs16969862-rs12594722-rs4779584-rs9888701. The TT rs16969681-rs4779584 haplotype was at a frequency of 0.063 in cases and 0.052 in controls (P = 6.29×10−5). However, there appeared to be a residual effect of the T allele at rs4779584, since there was also an elevated risk associated with the CT rs16969681-rs4779584 haplotype (P = 0.026).

We therefore tested the hypothesis that rs4779584 tags two independent risk SNPs at GREM1. We used reverse stepwise logistic regression to search the set of GREM1 SNPs genotyped in the UK2 and Scotland2 samples (Table S1) for associations that were independent of rs16969681 genotype and that captured the residual rs4779584 signal. This analysis led to elimination of rs4779584 from the regression model and identification of a model in which only rs16969681 (P = 1.04×10−4) and another SNP, rs11632715 (P = 1.00×10−3), produced independent signals. rs11632715 (chr15 : 30,791,539) is in low LD with rs16969681 (r2 = 0.009, D′ = 0.31) and modest LD with rs4779584 (r2 = 0.18, D′ = 0.90; Figure S2). Through genotyping of additional case-control series, we showed that rs11632715 was significantly associated with CRC risk (P = 2.30×10−10; Table 1). Unconditional logistic regression in the 21,139 samples typed for both rs11632715 and rs16969681 provided confirmatory evidence of the independence of the signals (for rs16969681, P = 1.84×10−6 and for rs11632715, P = 6.36×10−7); these associations were of very similar magnitude to those obtained when each SNP was analysed individually in those sample sets (Figure S2). Incorporation of rs4779584 into the logistic regression model showed that this SNP had a weaker effect than that of either rs16969681 or rs11632715 and did not significantly improve the model fit (Table S3). Inspection of the region containing rs4779584, rs16969681 and rs11632715 (Figure S2) showed that rs4779584 lay within a recombination hotspot. This finding was consistent with our discovery that rs4779584 tags two independent functional variants that are, in turn, tagged by rs16969681 and rs11632715.

Identification of additional, independent CRC susceptibility SNPs near BMP4 and BMP2

The regions analysed for fine mapping encompassed only a minority of the transcribed and flanking regions of GREM1, BMP4 and BMP2. We therefore tested for further independent CRC-associated SNPs around these loci (Table S4) by undertaking a pooled analysis of data from 5 CRC GWA studies (UK1, Scotland1, VQ58, CCFR, Australia) and from the UK2 and Scotland2 samples that had been genotyped at 55,000 SNPs with the strongest evidence of association from meta-analysis of UK1 and Scotland1 (Figure S4) [1]. Since each of the 7 sample sets had been genotyped using different, but overlapping, SNP panels, we performed the combined analysis irrespective of the number of studies in which any SNP had been typed. Figure 2 shows the resulting signals of association from single SNP analysis in this discovery phase.

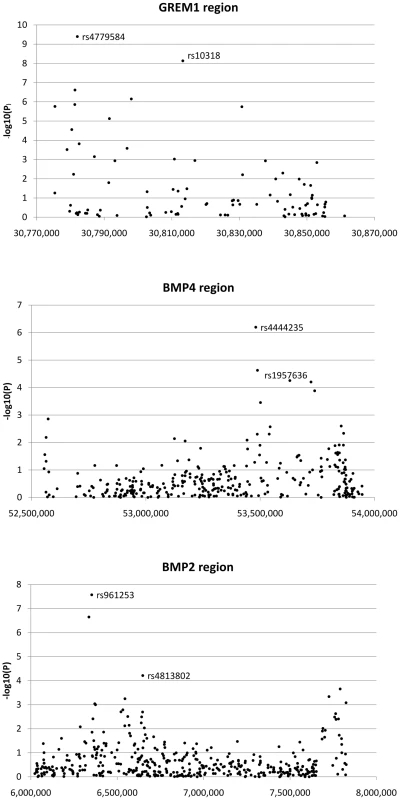

Fig. 2. Search for additional colorectal cancer susceptibility SNPs near GREM1, BMP4, and BMP2.

Association signals from discovery phase around GREM1, BMP4 and BMP2 are shown. For GREM1, the labelled SNPs are highyl correlated tagSNPs originally reported as associated with CRC; these signals are non-independent. For BMP4 and BMP2, the labelled SNPs are the original tagSNPs and the subsequently proven new signals at rs1957636 and rs4813802 respectively. We prioritised SNPs for further assessment in the replication data sets if they passed two thresholds. First, we required SNPs to show association with CRC at P<1×10−4 under the allelic or Cochran-Armitage tests; this was a less stringent threshold than that used in our previously-reported hypothesis-free GWA studies [1], [2], [3], reflecting the fact that GREM1, BMP4 and BMP2 were strong candidate susceptibility genes. Four SNPs at BMP4, 3 at BMP2 and 9 at GREM1 fulfilled this criterion (Figure 2). Second, since our aim was to test for novel, independent disease variants rather than to refine existing signals of association, we required that SNP genotypes were not correlated with each other or with previously identified risk SNPs (r2<0.05, D′<0.10). After applying these criteria, one SNP at BMP4 (rs1957636) and one at BMP2 (rs4813802) were retained for subsequent analyses.

rs1957636 and rs4813802 were then genotyped in the validation sample sets (Figure S4), comprising 15,075 CRC cases and 13,296 controls from six independent European case-control series (COIN/NBS, UK3, UK4, Scotland3, Cambridge, Helsinki). After combined analysis, significant associations (Table 2) were shown for both rs1957636, P = 1.36×10−9 (OR = 1.08, 95% CI: 1.06–1.011, Phet = 0.009, I2 = 54%) and rs4813802, P = 7.52×10−11 (OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.06–1.012, Phet = 0.42, I2 = 3%). In case-only analysis, neither SNP showed any evidence of association with age or sex (P>0.05, details not shown).

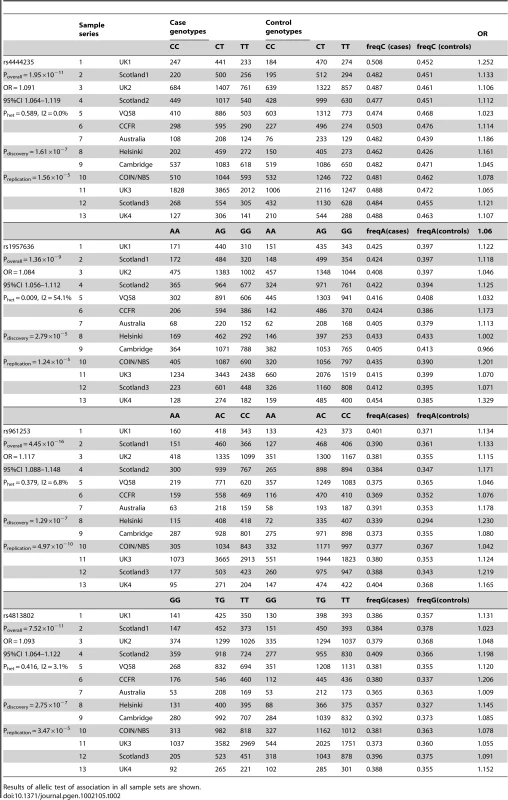

Tab. 2. Summary of individual SNP association analysis for rs4444235, rs1957636, rs961253, and rs4813802.

Results of allelic test of association in all sample sets are shown. We used unconditional logistic regression, adjusting for sample series, to test the independence of the two pairs of SNPs at BMP4 and at BMP2. In both cases, each signal remained independent, reflecting the existence of recombination hotspots between the pairs of SNPs at each locus (Figure S5 and Figure S6). For rs4444235 and rs1957636, association P-values were respectively 2.09×10−8 (I2 = 47.7%) and 3.93×10−10 (I2 = 0%)). For rs961253 and rs4813802, P-values were 1.89×10−15 (I2 = 5%) and 4.65×10−11 (I2 = 5%)). Thus, all 4 SNPs represented independent signals of association with CRC. Further imputation around BMP4 and BMP2 provided no evidence for the alternative possibility that a single variant was tagged by the two SNPs in each region (details not shown).

Annotation of the regions around rs1957636 and rs4813802

rs1957636 (chr14 : 53,629,768) is 136 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site of BMP4, 150 kb telomeric to the previously-identified CRC susceptibility SNP, rs4444235 (chr14 : 53,480,669), which is downstream of BMP4. There is a recombination hotspot at chr14 : 53,510,000 (Figure S5) and LD between rs1957636 and rs4444235 is very weak (r2 = 0.004, D′ = 0.073 from UK1). rs1957636 is within a region of LD flanked by SNPs rs431669 (chr14 : 53,512,418) and rs10150369 (chr14 : 53,873,515). This region contains no known transcripts, and the nearest gene apart from BMP4 is CDKN3 (transcriptional start site, chr14 : 53,933,476). Using SNAP (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/snap/) to search HapMap3 release 2 and 1000 Genomes Pilot 1, we identified 265 SNPs were in moderate or greater LD (r2>0.20) with rs1957636 in Europeans. Of those SNPs, several mapped to sites of potential functional importance in BMP4 transcription (H3K4Me1, H3K4Me3, DNAseI hypersensitivity, transcription factor ChIP-Seq), as evidenced by the ENCODE regulation tracks (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTrackUi?hgsid=171775907&c=chr14&g=wgEncodeReg) of the UCSC Genome Browser. For example, rs12432287 (r2 = 0.60, D′ = 1.00 with rs1957636) and rs728425 (r2 = 0.69, D′ = 1.00) lie within a region of apparently high transcriptional regulatory activity at chr14 : 53,642,340–53,652,937. Another SNP, rs8011813 (r2 = 0.822, D′ = 0.811), maps within a similar region at chr14 : 53, 728, 957–53, 731, 647. Although none of the SNPs in the region around rs1957636 is the location of a reported eQTL (http://eqtl.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/gbrowse/eqtl/), no studies relating transcription to SNP genotype have yet been undertaken in the colorectum.

rs4813802 maps to chr20 : 6,647,595, about 49 kb upstream of BMP2 and 295 kb telomeric of the previously-identified BMP2 CRC susceptibility SNP, rs961253 (chr20 : 6,352,281). There is very little LD between these two SNPs (r2 = 0.000, D′ = 0.017 from UK1) owing to a recombination hotspot at chr20 : 6,587,000 (Figure S5). rs4813802 lies within a region of LD flanked by rs727689 (chr20 : 6,636,405) and rs6117401 (chr20 : 6,664,097). This region contains 3 spliced ESTs, BX107852, BG822004 and DB094697; none of these has any known functional role or homology to other human or non-human transcripts or genes. The nearest gene to rs4813802 apart from BMP4 is FERMT1 (transcriptional start site, chr20 : 6,052,191). From HapMap3 release 2 and 1000 Genomes Pilot 1, 29 SNPs were found to be in moderate or greater LD (r2>0.20) with rs4813802 in Europeans. Of those SNPs, several in the region chr20 : 6,636,405–6,647,595 mapped to sites of potential functional importance in BMP2 transcription. None of the SNPs in the area around rs4813802 is the location of a reported eQTL.

Gene-gene interactions and other SNPs near BMP pathway loci

Using a case-control logistic regression design, we searched for pairwise gene-gene interactions between 5 SNPs associated with CRC risk (rs4444235, rs1957636, rs961253, rs4813802 and rs4779584). Risks were additive and no evidence of epistasis was detected (P>0.2 for all SNP pairs).

We also searched for evidence of CRC susceptibility alleles at tagSNPs close to other BMP pathway genes. Using the transcribed regions of flanking genes as boundaries, we identified 4,361 tagSNPs mapping to 37 BMP agonist, antagonist and receptor loci (Table S5). However, we found no statistically significant evidence of associations with disease (P>10−3 in all cases).

Discussion

We have identified two new CRC predisposition tagSNPs close to BMP4 (rs1957636) and BMP2 (rs4813802). To date, few other loci have been shown at stringent levels of significance to harbour more than one, independent cancer susceptibility variant. One notable exception is the locus proximal to MYC on chromosome 8q24.21 that contains multiple regions independently associated with the risk of prostate and other cancers [4]. Low-penetrance cancer predisposition loci are becoming increasingly hard to identify, owing to small effect sizes and/or low risk allele frequencies – and a return to candidate gene-based approaches may become increasingly attractive. It is true that in the past, candidate gene approaches have generally been unsuccessful at identifying cancer risk loci, but it is now possible to make use of information, such as expression quantitative trait locus identification, that increasingly permits a more considered approach.

We have also found good evidence that the original CRC-associated SNP near GREM1, rs4779584 [5], tags two independent functional SNPs, represented by association signals at rs16969681 and rs11632715. This finding emphasises that genetic fine-mapping studies are valuable not only for detecting stronger association signals, but also for deconvoluting tagSNP associations that have arisen owing to independent correlation of the tagSNP with more than one functional SNP. The original rs4779584 tagSNP signal could be described as an example of “synthetic association”, a term that has been used to describe a situation in which multiple, sometimes rare, variants underlie a tagSNP signal [6], [7]. Synthetic association can explain some of the apparently missing heritability of complex diseases. Here, we estimate that the 6 SNPs close to the 3 BMP pathway genes contribute approximately 2% of the heritability of CRC, about double that estimated before this study.

Finally, our data provide evidence that GREM1, BMP4 and BMP2 are the targets of the functional variation in each region. Multiple, independently-acting variants close to these loci contribute to CRC risk. Perhaps unexpectedly, there are no detectable genetic interactions among these variants. If the downstream SMAD effectors that function within both the BMP and TGF-beta pathways are included, the components of BMP signalling involved in CRC risk might comprise up to 3 high-penetrance predisposition genes (SMAD4, BMPR1A, GREM1) and 8 low-penetrance variants at GREM1, BMP4, BMP2, SMAD7 and LAMA5 (tagged respectively by rs16969681 and rs11632715, rs4444235 and rs1957636, rs961253 and rs4813802, rs4939827, and rs4925386) [1], [2], [3], [5], [8], [9], [10], [11]. Collectively these data emphasise the potential importance of genetic variants in the BMP pathway for CRC predisposition.

Methods

Ethics statement

Collection of blood samples and clinico-pathological information from patients and controls was undertaken with informed consent and ethical review board approval in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Overall strategy

The study had two main components: (i) refinement of existing GWAS signals at the GREM1, BMP4 and BMP2 loci using a dense genotyping and imputation approach in several thousand cases and controls previously used for GWAS validation; and (ii) a search for new, independent CRC tagSNPs at the same three loci using a less stringent threshold for validation than used previously, combined with multiple validation sample sets.

Discovery screen data sets

UK1 (CORGI) [1] comprised 922 cases with colorectal neoplasia (47% male) ascertained through the Colorectal Tumour Gene Identification (CoRGI) consortium. All had at least one first-degree relative affected by CRC and one or more of the following phenotypes: CRC at age 75 or less; any colorectal adenoma (CRAd) at age 45 or less; ≥3 colorectal adenomas at age 75 or less; or a large (>1 cm diameter) or aggressive (villous and/or severely dysplastic) adenoma at age 75 or less. The 929 controls (45% males) were spouses or partners unaffected by cancer and without a personal family history (to 2nd degree relative level) of colorectal neoplasia. Known dominant polyposis syndromes, HNPCC/Lynch syndrome or bi-allelic MYH mutation carriers were excluded. All cases and controls were of white UK ethnic origin.

Scotland1 (COGS) [1] included 980 CRC cases (51% male; mean age at diagnosis 49.6 years, SD±6.1) and 1,002 cancer-free population controls (51% male; mean age 51.0 years; SD±5.9). Cases were for early age at onset (age ≤55 years). Known dominant polyposis syndromes, HNPCC/Lynch syndrome or bi-allelic MYH mutation carriers were excluded. Control subjects were sampled from the Scottish population NHS registers, matched by age (±5 years), gender and area of residence within Scotland.

VQ58 comprised 1,832 CRC cases (1,099 males, mean age of diagnosis 62.5 years; SD±10.9) from the VICTOR [12] and QUASAR2 (www.octo-oxford.org.uk/alltrials/trials/q2.html) trials. There were 2,720 population control genotypes (1,391 males,) from the Wellcome Trust Case-Control Consortium 2 (WTCCC2) 1958 birth cohort (also known as the National Child Development Study), which included all births in England, Wales and Scotland during a single week in 1958 [13].

The Colon Cancer Family Registry (CCFR) data set [14] comprised 1,332 familial CRC cases and 1,084 controls Colon Cancer Family Registry (Colon-CFR) (http://epi.grants.cancer.gov/CFR/about_colon.html). The cases were recently diagnosed CRC cases reported to population complete cancer registries in the USA (Puget Sound, Washington State) who were recruited by the Seattle Familial Colorectal Cancer Registry; in Canada (Ontario) who were recruited by the Ontario Familial Cancer Registry; and in Australia (Melbourne, Victoria) who were recruited by the Australasian Colorectal Cancer Family Study. Controls were population-based and for this analysis were restricted to those without a family history of colorectal cancer.

The Australian study [15] comprised 591 patients treated for CRC at the Royal Melbourne, Western and St Francis Xavier Cabrini Hospitals in Melbourne from 1999 to 2009. The 2,353 controls were derived from Queensland or Melbourne: for the former, the controls came from the Brisbane Twin Nevus Study [16]; for the latter, individuals were participants in the Genes in Myopia study [17]. There was no overlap between the CFR and Australian data sets. Owing to potential residual ethnic heterogeneity within the Melbourne population, for the Australian cohort only we performed an additional screen to minimise heterogeneity after performing principal components analysis (PCA) to remove individuals who clustered with non-CEU individuals (see below). We achieved this by performing PCA on the Australian cases and controls without reference samples of known ancestry. We then paired each case with a control in a 1∶1 ratio based on a maximum separation of 0.050 using the first and second eigenvectors. All unpaired samples were excluded, leaving 441 cases and 441 controls in the study. The genomic inflation factor, λGC, was 1.02 after this filtering.

UK2 (NSCCG) [1] consisted of 2,854 CRC cases (58% male, mean age at diagnosis 59.3 years; SD±8.7) ascertained through two ongoing initiatives at the Institute of Cancer Research/Royal Marsden Hospital NHS Trust (RMHNHST) from 1999 onwards - The National Study of Colorectal Cancer Genetics (NSCCG) and the Royal Marsden Hospital Trust/Institute of Cancer Research Family History and DNA Registry. The 2,822 controls (41% males; mean age 59.8 years; SD±10.8) were the spouses or unrelated friends of patients with malignancies. None had a personal history of malignancy at time of ascertainment. All cases and controls had self-reported European ancestry, and there were no obvious differences in the demography of cases and controls in terms of place of residence within the UK.

Scotland2 (SOCCS) [1] comprised 2,024 CRC cases (61% male; mean age at diagnosis 65.8 years, SD±8.4) and 2,092 population controls (60% males; mean age 67.9 years, SD±9.0) ascertained in Scotland. Cases were taken from an independent, prospective, incident CRC case series and aged <80 years at diagnosis. Control subjects were population controls matched by age (±5 years), gender and area of residence within Scotland.

Replication data sets

UK3 (NSCCG) [1] comprised 7,912 CRC cases (65% male; mean age at diagnosis 59 years, SD±8.2) and 4,398 controls (40% male; mean age 62 years, SD±11.5) ascertained through NSCCG post-2005.

Scotland3 (SOCCS) [1] comprised 1,145 CRC cases (50% male; mean age at diagnosis 53.2 years, SD±15.4) and 2,203 cancer-free population controls (47% male; mean age 51.8 years, SD±11.5). Controls were recruited as part of the Generation Scotland study.

UK4 (CORGI2BCD) [1] consisted of 621 CRC cases (46% male; mean age at diagnosis 58.3 years; SD±14.1) and 1,121 cancer-free population or spouse controls (45% male; mean age 45.1 years, SD±15.9).

Cambridge/SEARCH consisted of 2,248 CRC cases (56% male; mean age at diagnosis 59.2 years, SD±8.1) and 2,209 controls (42% males; mean age 57.6 years; SD±15.1. Samples were ascertained through the SEARCH (Studies of Epidemiology and Risk Factors in Cancer Heredity, http://www.cancerhelp.org.uk/trials/a-study-looking-at-genetic-causes-of-cancer) study based in Cambridge, UK. Recruitment started in 2000; initial patient contact was though the general practitioner. Control samples were collected post-2003. Eligible individuals were sex - and frequency-matched in five-year age bands to cases.

The COIN samples [18] were 2,151 cases derived from the COIN and COIN-B clinical trials of metastatic CRC. Median age was 63 years. COIN cases were compared against genotypes from 2,501 population controls (1,237 males,) from the WTCCC2 National Blood Service (NBS) cohort (50% male; mean age at diagnosis 53.2 years, SD±15.4).

The Helsinki (FCCPS) study (http://research.med.helsinki.fi/gsb/aaltonen/) comprised 988 cases from a population-based collection centred on south-eastern Finland and 864 population controls from the same collection.

EPICOLON [19] included 1,410 cases matched with the same number of controls collected in a prospective fashion from centres in Spain. Exclusion criteria were Mendelian CRC syndromes and a personal history of inflammatory bowel disease.

In all cases CRC was defined according to the ninth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) by codes 153–154 and all cases had pathologically proven adenocarcinomas.

Sample preparation and genotyping

DNA was extracted from samples using conventional methods and quantified using PicoGreen (Invitrogen). The VQ, UK1, Scotland1 and Australia GWA cohorts were genotyped using Illumina Hap300, Hap370, or Hap550 arrays. 1958BC and NBS genotyping was performed as part of the WTCCC2 study on Hap1M arrays. The CCFR samples were genotyped using Illumina Hap1M or Hap1M-Duo arrays. In UK2 and Scotland2, genotyping was conducted using custom Illumina Infinium arrays according to the manufacturer's protocols. Some COIN SNPs were typed on custom Illumina Goldengate arrays. To ensure quality of genotyping, a series of duplicate samples was genotyped, resulting in 99.9% concordant calls in all cases.

Other genotyping was conducted using competitive allele-specific PCR KASPar chemistry (KBiosciences Ltd, Hertfordshire, UK), Taqman (Life Sciences, Carlsbad, California) or MassARRAY (Sequenom Inc., San Diego, USA). All primers, probes and conditions used are available on request. Genotyping quality control was tested using duplicate DNA samples within studies and SNP assays, together with direct sequencing of subsets of samples to confirm genotyping accuracy. For all SNPs, >99% concordant results were obtained.

Quality control and sample exclusion

We excluded SNPs from analysis if they failed one or more of the following thresholds: GenCall scores <0.25; overall call rates <95%; MAF<0.01; departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in controls at P<10−4 or in cases at P<10−6; outlying in terms of signal intensity or X∶Y ratio; discordance between duplicate samples; and, for SNPs with evidence of association, poor clustering on inspection of X∶Y plots.

We excluded individuals from analysis if they failed one or more of the following thresholds: duplication or cryptic relatedness to estimated identity by descent (IBD) >6.25%; overall successfully genotyped SNPs <95%; mismatch between predicted and reported gender; outliers in a plot of heterozygosity versus missingness; and evidence of non-white European ancestry by PCA-based analysis in comparison with HapMap samples (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). We excluded 6 duplicate samples using PCA (see below) within the UK samples that had undergone analysis of over 200 SNPs (UK1, Scotland1, UK2, Scotland2, VQ, 1958BC, NBS, COIN). We excluded duplicates from other UK cohorts on the basis of names (or initials where release of names was not possible) and dates of birth. No duplicates were found from the CCFR or Australian sample sets.

To identify individuals who might have non-northern European ancestry, we merged our case and control data from all sample sets with the 60 European (CEU), 60 Nigerian (YRI), and 90 Japanese (JPT) and 90 Han Chinese (CHB) individuals from the International HapMap Project. For each pair of individuals, we calculated genome-wide identity-by-state distances based on markers shared between HapMap2 and our SNP panel, and used these as dissimilarity measures upon which to perform principal components analysis. Principal components analysis was performed using Eigenstrat/SmartPCA using CEU, YRI and HCB HapMap samples as reference. The first two principal components for each individual were plotted and any individual not present in the main CEU cluster (that is, >5% of the PC distance from HapMap CEU cluster centroid) was excluded from subsequent analyses.

We had previously shown the adequacy of the case-control matching and possibility of differential genotyping of cases and controls using Q-Q plots of test statistics in STATA. The inflation factor λGC was calculated by dividing the mean of the lower 90% of the test statistics by the mean of the lower 90% of the expected values from a χ2 distribution with 1 d.f. Deviation of the genotype frequencies in the controls from those expected under HWE was assessed by χ2 test (1 d.f.), or Fisher's exact test where an expected cell count was <5.

SNP selection and genotyping for fine mapping

Regions selected for fine mapping were: chr15 : 30,733,560–30,802,752; chr14 : 53,430,973n 53,530,761; and chr20 : 6,292,730–6,402,661. These corresponded to the haplotype blocks and immediately flanking regions harbouring rs4779584, rs4444235, and rs961253. To define these haplotype blocks and the recombination hotspots harbouring these CRC-associated SNPs, we used Haploview and SequenceLDHot. From dbSNP (build 128), we selected all SNPs between the recombination hotspots flanking the haplotype block. All these SNPs were submitted to Illumina for assay design and those with a design score>0.3 were genotyped on custom arrays in the UK2 and Scotland2 case-control series. In total, we genotyped 81, 42 and 60 SNPs in the 15q13.3, 14q22.2 and 20p12.3 regions respectively. A list of these SNPs is shown in Table S1. Association statistics, using an additive model, were obtained with SNPTEST v2 (www.stats.ox.ac.uk/~marchini/software/gwas/snptest.html). We used genotype data from the 1000 Genomes CEPH (http://www.1000genomes.org/) and HapMap3 CEPH and TSI samples (www.hapmap.org/) and the IMPUTE v2 software (https://mathgen.stats.ox.ac.uk/impute/impute_v2.html) to generate in silico genotypes at additional SNPs in all three regions. This imputation resulted in the addition of 74, 113 and 255 markers in the chromosome 15q13.3, 14q22.2 and 20p12.3 regions respectively (for details on imputed and genotyped markers see Table S1). Association meta-analyses only included markers with proper_info scores >0.5, imputed call rates per SNP >0.9 and minor allele frequencies (MAFs) >0.01. Meta-analyses of the two sample sets were carried out with Meta (http://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/~jsliu/meta.html) using the genotype probabilities from IMPUTE v2, where a SNP was not directly typed. To test for the presence of additional independent risk alleles in each region, we carried out logistic regression analysis within each region, both pairwise with the original tagSNP and then in a backwards analysis that included all SNPs with evidence of association in the meta-analysis at P<5×10−4.

Statistical analysis

Association between SNP genotype and disease status was primarily assessed in STATA v10 (http://www.stata.com/) and PLINK v1.07 (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/) using allelic and Cochran-Armitage tests (both with 1df) respectively, or by Fisher's exact test where an expected cell count was <5. Genotypic (2df), dominant (1df) and recessive (1df) tests were also performed. The risks associated with each SNP were estimated by allelic, heterozygous and homozygous odds ratios (ORs) using unconditional logistic regression, and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

Joint analysis of data generated from multiple phases was conducted using standard methods for combining raw data based on the Mantel-Haenszel method in STATA and PLINK. The reported meta-analysis statistics were derived from analysis of allele frequencies, and joint ORs and 95% CIs were calculated assuming fixed - and random-effects models. Tests of the significance of the pooled effect sizes were calculated using a standard normal distribution. Cochran's Q statistic to test for heterogeneity [20] and the I2 statistic [21] to quantify the proportion of the total variation due to heterogeneity were calculated. Large heterogeneity is typically defined as I2≥75%. Where significant heterogeneity was identified, results from the random effects model were reported. Alongside, we also performed meta-analysis based on allele dosage (0, 1, 2) and incorporated age and sex as co-variates. Although age and sex are associated with colorectal cancer risk, they were not associated with SNP genotype and did not materially affect the significance of any of the 6 reported associations (details not shown).

We used Haploview software v4.2 (http://www.broadinstitute.org/haploview) to infer the LD structure of the genome in the regions around GREM1, BMP2 and BMP4. The combined effects of pairs of loci identified as associated with CRC risk were investigated by multiple logistic regression analysis in PLINK to test for independent effects of each SNP and stratifying by sample series. Evidence for interactive effects between SNPs (epistasis) was assessed by likelihood ratio test assuming an allelic model in PLINK.

The sibling relative risk attributable to a given SNP was calculated using the formulawhere p is the population frequency of the minor allele, q = 1−p, and r1 and r2 are the relative risks (estimated as OR) for heterozygotes and rare homozygotes, relative to common homozygotes [22]. Assuming a multiplicative interaction, the proportion of the familial risk attributable to a SNP was calculated as log(λ*)/log(λ0), where λ0 is the overall familial relative risk estimated from epidemiological studies of CRC, assumed to be 2.2 [23]. UK2/NSCCG2 samples were used for this estimation. The Akaike information criterion was calculated using the swaic command in STATA.

Genome co-ordinates were taken from the NCBI build 36/hg18 (dbSNP b126).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. HoulstonRSCheadleJDobbinsSETenesaAJonesAM 2010 Meta-analysis of three genome-wide association studies identifies susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer at 1q41, 3q26.2, 12q13.13 and 20q13.33. Nat Genet 42 973 977

2. TomlinsonIWebbECarvajal-CarmonaLBroderickPKempZ 2007 A genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility variant for colorectal cancer at 8q24.21. Nat Genet 39 984 988

3. HoulstonRSWebbEBroderickPPittmanAMDi BernardoMC 2008 Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies four new susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer. Nat Genet 40 1426 1435

4. Al OlamaAAKote-JaraiZGilesGGGuyMMorrisonJ 2009 Multiple loci on 8q24 associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet 41 1058 1060

5. JaegerEWebbEHowarthKCarvajal-CarmonaLRowanA 2008 Common genetic variants at the CRAC1 (HMPS) locus on chromosome 15q13.3 influence colorectal cancer risk. Nat Genet 40 26 28

6. DicksonSWangKKrantzIHakonarsonHGoldsteinD 2010 Rare variants create synthetic genome-wide associations. PLoS Biol 8 e1000294 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000294

7. WrayNPurcellSMVisscherPM 2011 Synthetic associations created by rare variants do not explain most GWAS results. PLoS Biol 9 e1000579 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000579

8. BroderickPCarvajal-CarmonaLPittmanAMWebbEHowarthK 2007 A genome-wide association study shows that common alleles of SMAD7 influence colorectal cancer risk. Nat Genet 39 1315 1317

9. HoweJRBairJLSayedMGAndersonMEMitrosFA 2001 Germline mutations of the gene encoding bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A in juvenile polyposis. Nat Genet 28 184 187

10. HoweJRRothSRingoldJCSummersRWJarvinenHJ 1998 Mutations in the SMAD4/DPC4 gene in juvenile polyposis. Science 280 1086 1088

11. JaegerEEWoodford-RichensKLLockettMRowanAJSawyerEJ 2003 An ancestral Ashkenazi haplotype at the HMPS/CRAC1 locus on 15q13-q14 is associated with hereditary mixed polyposis syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 72 1261 1267

12. MidgleyRSMcConkeyCCJohnstoneECDunnJASmithJL 2010 Phase III randomized trial assessing rofecoxib in the adjuvant setting of colorectal cancer: final results of the VICTOR trial. J Clin Oncol 28 4575 4580

13. PowerCJefferisBJManorOHertzmanC 2006 The influence of birth weight and socioeconomic position on cognitive development: Does the early home and learning environment modify their effects? J Pediatr 148 54 61

14. NewcombPABaronJCotterchioMGallingerSGroveJ 2007 Colon Cancer Family Registry: an international resource for studies of the genetic epidemiology of colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 16 2331 2343

15. TieJGibbsPLiptonLChristieMJorissenRN 2010 Optimizing targeted therapeutic development: Analysis of a colorectal cancer patient population with the BRAF(V600E) mutation. Int J Cancer

16. DuffyDLIlesMMGlassDZhuGBarrettJH 2010 IRF4 variants have age-specific effects on nevus count and predispose to melanoma. Am J Hum Genet 87 6 16

17. BairdPNSchacheMDiraniM 2010 The GEnes in Myopia (GEM) study in understanding the aetiology of refractive errors. Prog Retin Eye Res 29 520 542

18. AdamsRMeadeAWasanHGriffithsGMaughanT 2008 Cetuximab therapy in first-line metastatic colorectal cancer and intermittent palliative chemotherapy: review of the COIN trial. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 8 1237 1245

19. AbuliABessaXGonzalezJRRuiz-PonteCCaceresA 2010 Susceptibility genetic variants associated with colorectal cancer risk correlate with cancer phenotype. Gastroenterology 139 788 796, 796 e781–786

20. PetittiDB 1994 Coronary heart disease and estrogen replacement therapy. Can compliance bias explain the results of observational studies? Ann Epidemiol 4 115 118

21. HigginsJPThompsonSG 2002 Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 21 1539 1558

22. HoulstonRSFordD 1996 Genetics of coeliac disease. QJM 89 737 743

23. JohnsLEHoulstonRS 2001 A systematic review and meta-analysis of familial colorectal cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol 96 2992 3003

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Local Absence of Secondary Structure Permits Translation of mRNAs that Lack Ribosome-Binding SitesČlánek Independent Chromatin Binding of ARGONAUTE4 and SPT5L/KTF1 Mediates Transcriptional Gene SilencingČlánek Trade-Off between Bile Resistance and Nutritional Competence Drives Diversification in the Mouse GutČlánek FGF Signaling Regulates the Number of Posterior Taste Papillae by Controlling Progenitor Field SizeČlánek Mammalian BTBD12 (SLX4) Protects against Genomic Instability during Mammalian SpermatogenesisČlánek Identification of Nine Novel Loci Associated with White Blood Cell Subtypes in a Japanese PopulationČlánek Differential Effects of and Risk Variants on Association with Diabetic ESRD in African AmericansČlánek Dynamic Chromatin Localization of Sirt6 Shapes Stress- and Aging-Related Transcriptional Networks

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 6- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

- Intrauterinní inseminace a její úspěšnost

- Délka menstruačního cyklu jako marker ženské plodnosti

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Local Absence of Secondary Structure Permits Translation of mRNAs that Lack Ribosome-Binding Sites

- Statistical Inference on the Mechanisms of Genome Evolution

- Revisiting Heterochromatin in Embryonic Stem Cells

- A Two-Stage Meta-Analysis Identifies Several New Loci for Parkinson's Disease

- Identification of a Sudden Cardiac Death Susceptibility Locus at 2q24.2 through Genome-Wide Association in European Ancestry Individuals

- Genomic Prevalence of Heterochromatic H3K9me2 and Transcription Do Not Discriminate Pluripotent from Terminally Differentiated Cells

- Epistasis between Beneficial Mutations and the Phenotype-to-Fitness Map for a ssDNA Virus

- Recurrent Chromosome 16p13.1 Duplications Are a Risk Factor for Aortic Dissections

- Telomere DNA Deficiency Is Associated with Development of Human Embryonic Aneuploidy

- Genome-Wide Association Study of White Blood Cell Count in 16,388 African Americans: the Continental Origins and Genetic Epidemiology Network (COGENT)

- Unexpected Role for DNA Polymerase I As a Source of Genetic Variability

- Transportin-SR Is Required for Proper Splicing of Genes and Plant Immunity

- How Chromatin Is Remodelled during DNA Repair of UV-Induced DNA Damage in

- Independent Chromatin Binding of ARGONAUTE4 and SPT5L/KTF1 Mediates Transcriptional Gene Silencing

- Two Evolutionary Histories in the Genome of Rice: the Roles of Domestication Genes

- Natural Allelic Variation Defines a Role for : Trichome Cell Fate Determination

- Multiple Common Susceptibility Variants near BMP Pathway Loci , , and Explain Part of the Missing Heritability of Colorectal Cancer

- Pathogenic Mechanism of the FIG4 Mutation Responsible for Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease CMT4J

- A Functional Variant in Promoter Modulates Its Expression and Confers Disease Risk for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Drift and Genome Complexity Revisited

- Chromosomal Macrodomains and Associated Proteins: Implications for DNA Organization and Replication in Gram Negative Bacteria

- Trade-Off between Bile Resistance and Nutritional Competence Drives Diversification in the Mouse Gut

- Pathways of Distinction Analysis: A New Technique for Multi–SNP Analysis of GWAS Data

- Web-Based Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Two Novel Loci and a Substantial Genetic Component for Parkinson's Disease

- Chk2 and p53 Are Haploinsufficient with Dependent and Independent Functions to Eliminate Cells after Telomere Loss

- Exome Sequencing Identifies Mutations in High Myopia

- Distinct Functional Constraints Partition Sequence Conservation in a -Regulatory Element

- CorE from Is a Copper-Dependent RNA Polymerase Sigma Factor

- A Single Sex Pheromone Receptor Determines Chemical Response Specificity of Sexual Behavior in the Silkmoth

- FGF Signaling Regulates the Number of Posterior Taste Papillae by Controlling Progenitor Field Size

- Maps of Open Chromatin Guide the Functional Follow-Up of Genome-Wide Association Signals: Application to Hematological Traits

- Increased Susceptibility to Cortical Spreading Depression in the Mouse Model of Familial Hemiplegic Migraine Type 2

- Differential Gene Expression and Epiregulation of Alpha Zein Gene Copies in Maize Haplotypes

- Parallel Adaptive Divergence among Geographically Diverse Human Populations

- Genetic Analysis of Genome-Scale Recombination Rate Evolution in House Mice

- Mechanisms for the Evolution of a Derived Function in the Ancestral Glucocorticoid Receptor

- Mammalian BTBD12 (SLX4) Protects against Genomic Instability during Mammalian Spermatogenesis

- Interferon Regulatory Factor 8 Regulates Pathways for Antigen Presentation in Myeloid Cells and during Tuberculosis

- High-Resolution Analysis of Parent-of-Origin Allelic Expression in the Arabidopsis Endosperm

- Specific SKN-1/Nrf Stress Responses to Perturbations in Translation Elongation and Proteasome Activity

- Graded Nodal/Activin Signaling Titrates Conversion of Quantitative Phospho-Smad2 Levels into Qualitative Embryonic Stem Cell Fate Decisions

- Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals PADI4 Cooperates with Elk-1 to Activate Expression in Breast Cancer Cells

- Trait Variation in Yeast Is Defined by Population History

- Meiosis-Specific Loading of the Centromere-Specific Histone CENH3 in

- A Genome-Wide Survey of Imprinted Genes in Rice Seeds Reveals Imprinting Primarily Occurs in the Endosperm

- Multiple Regulatory Mechanisms to Inhibit Untimely Initiation of DNA Replication Are Important for Stable Genome Maintenance

- SIRT1 Promotes N-Myc Oncogenesis through a Positive Feedback Loop Involving the Effects of MKP3 and ERK on N-Myc Protein Stability

- Bacteriophage Crosstalk: Coordination of Prophage Induction by Trans-Acting Antirepressors

- Role of the Single-Stranded DNA–Binding Protein SsbB in Pneumococcal Transformation: Maintenance of a Reservoir for Genetic Plasticity

- Genomic Convergence among ERRα, PROX1, and BMAL1 in the Control of Metabolic Clock Outputs

- Genome-Wide Association of Bipolar Disorder Suggests an Enrichment of Replicable Associations in Regions near Genes

- Identification of Nine Novel Loci Associated with White Blood Cell Subtypes in a Japanese Population

- DNA Ligase III Promotes Alternative Nonhomologous End-Joining during Chromosomal Translocation Formation

- Differential Effects of and Risk Variants on Association with Diabetic ESRD in African Americans

- Finished Genome of the Fungal Wheat Pathogen Reveals Dispensome Structure, Chromosome Plasticity, and Stealth Pathogenesis

- Dynamic Chromatin Localization of Sirt6 Shapes Stress- and Aging-Related Transcriptional Networks

- Extracellular Matrix Dynamics in Hepatocarcinogenesis: a Comparative Proteomics Study of Transgenic and Null Mouse Models

- Integrating 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine into the Epigenomic Landscape of Human Embryonic Stem Cells

- Vive La Différence: An Interview with Catherine Dulac

- Multiple Loci Are Associated with White Blood Cell Phenotypes

- Nuclear Accumulation of Stress Response mRNAs Contributes to the Neurodegeneration Caused by Fragile X Premutation rCGG Repeats

- A New Mutation Affecting FRQ-Less Rhythms in the Circadian System of

- Cryptic Transcription Mediates Repression of Subtelomeric Metal Homeostasis Genes

- A New Isoform of the Histone Demethylase JMJD2A/KDM4A Is Required for Skeletal Muscle Differentiation

- Genetic Determinants of Lipid Traits in Diverse Populations from the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Study

- A Genome-Wide RNAi Screen for Factors Involved in Neuronal Specification in

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Recurrent Chromosome 16p13.1 Duplications Are a Risk Factor for Aortic Dissections

- Statistical Inference on the Mechanisms of Genome Evolution

- Genome-Wide Association Study of White Blood Cell Count in 16,388 African Americans: the Continental Origins and Genetic Epidemiology Network (COGENT)

- Chromosomal Macrodomains and Associated Proteins: Implications for DNA Organization and Replication in Gram Negative Bacteria

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání