-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Distinct Functional Constraints Partition Sequence Conservation in a -Regulatory Element

Different functional constraints contribute to different evolutionary rates across genomes. To understand why some sequences evolve faster than others in a single cis-regulatory locus, we investigated function and evolutionary dynamics of the promoter of the Caenorhabditis elegans unc-47 gene. We found that this promoter consists of two distinct domains. The proximal promoter is conserved and is largely sufficient to direct appropriate spatial expression. The distal promoter displays little if any conservation between several closely related nematodes. Despite this divergence, sequences from all species confer robustness of expression, arguing that this function does not require substantial sequence conservation. We showed that even unrelated sequences have the ability to promote robust expression. A prominent feature shared by all of these robustness-promoting sequences is an AT-enriched nucleotide composition consistent with nucleosome depletion. Because general sequence composition can be maintained despite sequence turnover, our results explain how different functional constraints can lead to vastly disparate rates of sequence divergence within a promoter.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002095

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002095Summary

Different functional constraints contribute to different evolutionary rates across genomes. To understand why some sequences evolve faster than others in a single cis-regulatory locus, we investigated function and evolutionary dynamics of the promoter of the Caenorhabditis elegans unc-47 gene. We found that this promoter consists of two distinct domains. The proximal promoter is conserved and is largely sufficient to direct appropriate spatial expression. The distal promoter displays little if any conservation between several closely related nematodes. Despite this divergence, sequences from all species confer robustness of expression, arguing that this function does not require substantial sequence conservation. We showed that even unrelated sequences have the ability to promote robust expression. A prominent feature shared by all of these robustness-promoting sequences is an AT-enriched nucleotide composition consistent with nucleosome depletion. Because general sequence composition can be maintained despite sequence turnover, our results explain how different functional constraints can lead to vastly disparate rates of sequence divergence within a promoter.

Introduction

The advent of genome sequencing introduced the practice of searching for regulatory elements in evolutionarily conserved regions [1]–[5]. However, functional elements are by no means strictly confined to regions of high primary sequence conservation [6]–[9]. In fact, cis-regulatory elements can retain functionality over great evolutionary distances despite sharing little or no identifiable sequence similarity, and can correctly drive reporter gene expression when placed in a distantly related species [10]–[12].

Two questions arise from these observations. First, how do different functional constraints account for different degrees of sequence conservation? Whereas the relationship between function and sequence conservation in not well understood in general, this problem is particularly acute for cis-elements [13]. A major obstacle is that we do not have a cis-regulatory code akin to that for protein-coding sequences. For example, even within conserved cis-regulatory elements there are interspersed nonconserved sequences that seem to be important for their function [12], [14]–[18]. In other cases, cis-regulatory architecture can be cryptically conserved despite sequence divergence [19]–[21]. In yet other promoters, not even the architecture appears to be conserved [22], [23].

Second, since gene expression is increasingly considered to be a quantitative trait for which populations vary [24], [25], functional comparisons of regulatory elements ought to be made with quantitative measurements across populations of individuals [26] or cells [27]. Only then can expression patterns be compared in terms of how much they differ, and how intrinsically variable they are.

Variation of gene expression can take many forms, for instance the number of cells expressing a gene or the amount of transcript made in individual cells. Despite variation, gene expression, like many other biological processes, exhibits substantial robustness, that is, resilience to perturbations by genetic and environmental challenges [28]–[31]. Robustness of expression, much like pattern of expression, is encoded in regulatory elements [32], [33]. One way of encoding robustness in cis is with redundant or “shadow” enhancers [34]. The loss of one “shadow” enhancer does not substantially perturb gene expression, unless the organism is challenged by genetic or environmental stresses [35], [36]. Another documented mechanism that confers robustness in cis is the presence of miRNA target sites in 3′ UTR [37], [38].

Our goal is to understand the relationship between function and sequence evolution in a single cis-element. We studied a promoter of the Caenorhabditis elegans unc-47 gene, which drives a simple, easily quantifiable expression pattern. This promoter contains regions of high and low sequence conservation when compared to orthologs from four closely related [39] Caenorhabditis nematodes. We quantified functional similarities and differences of these promoters to infer the constraints that gave rise to the observed patterns of sequence evolution.

Results

Conserved cis-elements recapitulate qualitative aspects of the expression pattern

We first tested the hypothesis that an evolutionarily conserved expression pattern results from evolutionarily conserved regulatory sequences alone. In C. elegans, the unc-47 gene is expressed in all 26 GABAergic neurons, including 19 D-type neurons of the ventral nerve cord and the postanal cell DVB (Figure 1A) [40]. We selected these cells because they are easy to recognize due to a characteristic morphology, and they reside close to the body surface, thus easing the quantification of expression. The endogenous pattern of unc-47 is recapitulated when a reporter construct containing a 1.2 kb sequence immediately 5′ of the gene (we refer to it as a full-length promoter as it extends to the locus of the upstream gene) is used to drive green fluorescent protein (GFP) in C. elegans (Figure 1B). A construct containing a promoter of the same length of the C. briggsae unc-47 ortholog is expressed in a qualitatively indistinguishable pattern in C. briggsae (Figure 1C). Indeed the C. briggsae promoter drives expression in the same neurons even in C. elegans (see below). These results suggest that expression patterns of unc-47 orthologs have been conserved since their common ancestor and that the information required for driving proper expression is contained within ∼1.2 kb promoters upstream of the genes.

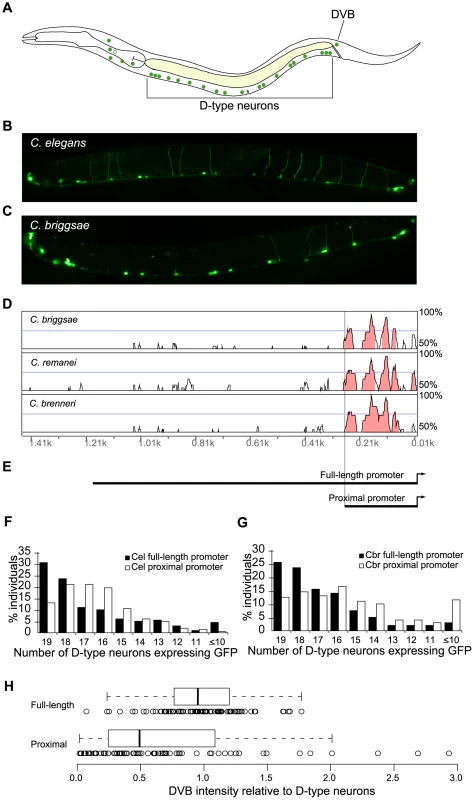

Fig. 1. Conserved portions of unc-47 promoters direct spatially correct, but not robust, expression.

(A) A schematic depiction of GABAergic neurons in C. elegans. (B) Expression pattern of C. elegans promoter unc-47::GFP in C. elegans. (C) Expression pattern of C. briggsae promoter unc-47::GFP in C. briggsae. Photographs of worms are composites of multiple exposures of the same individual that capture the full complement of D-type neurons, in all focal planes, expressing GFP. (D) Vista plot of primary sequence conservation in the promoter region of unc-47 from C. briggsae, C. remanei and C. brenneri aligned to C. elegans. Window size = 20 bp, threshold = 70%. (E) Schematic depiction of full-length and proximal promoters. Consistency of GFP expression in D-type neurons for full-length and proximal promoters from C. elegans (F) and C. briggsae (G). For both C. elegans and C. briggsae, the average number of cells expressing GFP is lower for the proximal promoter compared to full-length (Wilcoxon test, p = 3.2×10−3 and p = 3.4×10−8, respectively). (H) Distribution of ratios of GFP expression intensity in DVB relative to D-type neurons for the full-length and proximal promoters at 20°C. Each strain is represented by 100 animals. The two distributions are significantly different (Wilcoxon test, p = 1.8×10−5; Kolmogorov-Smironov test, p = 1.1×10−8). Because expression patterns of nematode unc-47 orthologs are conserved, we investigated whether expression is mediated solely by conserved cis-regulatory elements. We aligned the C. briggsae sequence along with those of two other close relatives C. brenneri and C. remanei, to the C. elegans unc-47 promoter. As reported previously [41], sequence conservation in this promoter is heavily biased to the most proximal ∼250 bp (Figure 1D, Figure S1, Table S1). We carried out extensive analyses which showed that little sequence conservation can be found distal to the ∼250 bp boundary (Figure S2, Table S1). This does not exclude the possibility that there exist short and conserved motifs in the distal promoter; they are simply below our level of detection. Some may exist and even be functional; nonetheless, the rates of sequence divergence are profoundly different between the proximal and the distal portions of this promoter.

If the conserved expression patterns result from solely the conserved portions of the cis-regulatory elements, then the proximal promoters of both C. elegans and C. briggsae should be sufficient to recapitulate the entire pattern. We therefore compared functions, in C. elegans, of both full-length and proximal promoters (Figure 1E) derived from C. elegans and C. briggsae. Strains bearing each of these four constructs exhibited qualitatively similar patterns of expression. However, we noticed that the proximal C. briggsae promoter was not robust – it drove both weak and inconsistent expression. In contrast, a robust promoter would express strongly and consistently, as do the full-length promoters. We next quantified and compared expression patterns driven by these promoters.

Regulatory elements lacking sequence conservation are required for robust gene expression

The expression patterns driven by the proximal and full-length promoters from both species were qualitatively correct, that is, all cells that were expected to show reporter gene expression were GFP-positive in at least some of the examined animals. To obtain a precise measure of variability, we counted the number of D-type neurons that were expressing GFP in 200 individuals bearing each construct. We examined animals from multiple independent strains for each construct and found that overall inter-strain variance was modest for all constructs (data not shown). We conducted the counts in a blinded fashion to exclude the possibility of unconscious experimenter bias (see Methods). The results of these counts address the first aspect of robustness – consistency of expression pattern. We found that the full-length C. elegans promoter drove somewhat more consistent pattern than the proximal promoter (Figure 1F; Wilcoxon test, p = 3.2×10−3), and that the full-length promoters of C. elegans and C. briggsae were indistinguishable (p = 0.7). The C. briggsae proximal promoter was not expressed as consistently in D-type neurons as the full-length promoter (Figure 1G; Wilcoxon test, p = 3.4×10−8).

In a parallel approach we quantified the intensity of GFP fluorescence in DVB and D-type neurons. This allowed us to assess the second aspect of robust expression – consistency of relative expression levels from one cell type to another within an individual. Expression levels in D-type neurons and DVB were relatively similar in animals carrying the full-length promoter (note the mean ratio of one and a tight, normal scatter, Figure 1H). In contrast, individuals with the proximal promoter exhibited a significant increase in variance (Ansari-Bradley test, p = 1.6×10−3), despite a lower relative expression in DVB (Wilcoxon test, p = 1.8×10−5). We thus concluded that the C. briggsae proximal promoter directs less robust expression than the full-length promoter.

To ensure that the apparent decrease in robustness of the proximal promoter was not an artifact of using extrachromosomal arrays, we generated transgenic strains in which single-copy full-length or proximal promoters were integrated into the same genomic location. Whereas the absolute levels of expression were considerably lower for all integrated strains (20–400 fold), the shorter promoter was weaker than the full-length (4–6 fold) and significantly less consistent in its expression (Figure S3; Wilcoxon test, p = 1.9×10−10). Thus the shorter promoter was weaker and less consistently expressed regardless of whether it was tested as an integrated or extrachromosomal transgene. This concordance allowed us to utilize extrachromosomal transgenes for the remainder of this study, because integrated strains showed weak expression that was at the limit of detection.

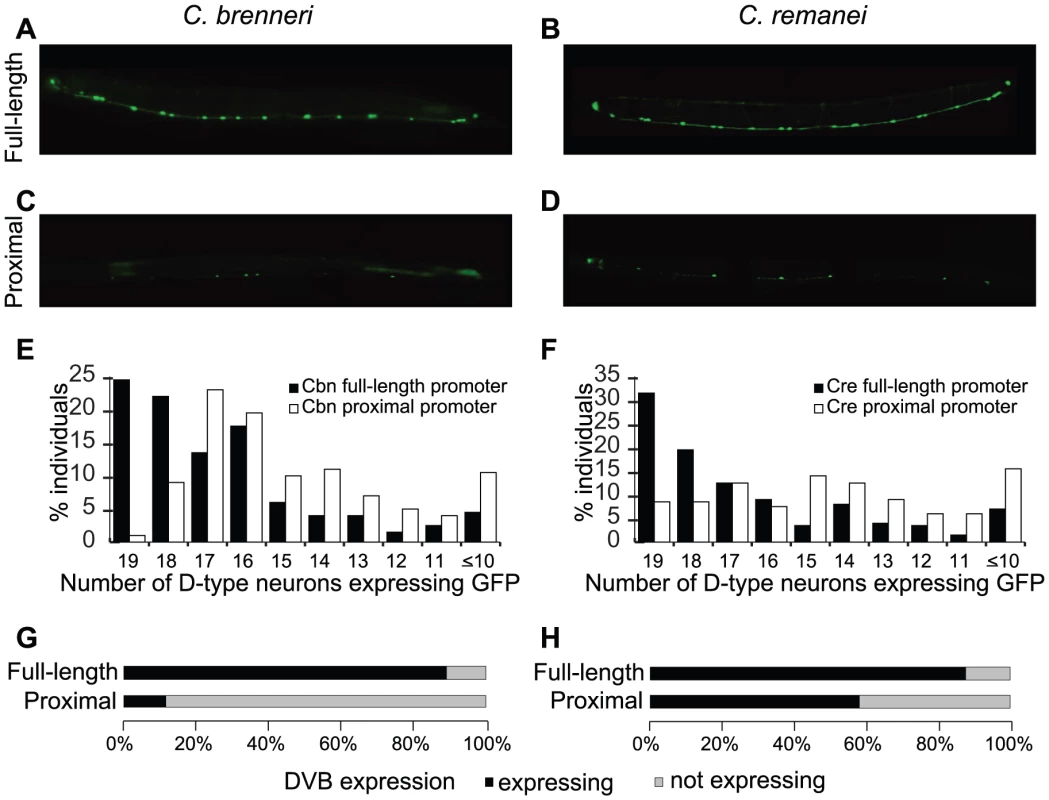

It is formally possible that our observation of the decreased robustness of the proximal promoter compared to the full-length version was due to a peculiar nature of the C. briggsae regulatory sequence. We therefore tested orthologous cis-regulatory sequences of two additional species, C. brenneri and C. remanei, in C. elegans. Their full-length promoters drove GFP in a strong and consistent pattern, statistically indistinguishable from those of C. elegans and C. briggsae orthologs (Figure 2A, 2B). Both proximal promoters, truncated at the orthologous position at the boundary of conserved sequences around 250 bp, directed weaker (Figure 2C, 2D) and less robust (Figure 2E, 2F; Wilcoxon test, C. brenneri p = 1.2×10−13 and C. remanei p = 1.3×10−13) expression in D-type neurons. Expression of the proximal promoters was also less consistent in the tail neuron DVB (Figure 2G, 2H).

Fig. 2. Promoters of C. brenneri and C. remanei unc-47 require the distal sequences for consistent expression.

GFP expression driven by full-length C. brenneri (A) and C. remanei (B) and proximal C. brenneri (C) and C. remanei (D) unc-47 promoters in a C. elegans host. As in Figure 1F, 1G, 200 individuals bearing each transgene were counted, and the percentages of those individuals with the indicated number of D-type neurons expressing GFP is shown (E–F). (G–H) Presence/absence of GFP expression in the cell DVB in the same 200 individuals for each of the four promoters. Photographs of worms are composites of multiple exposures of the same individual that capture the full complement of D-type neurons, in all focal planes, expressing GFP. Our results suggest that the cis-regulatory elements of unc-47 from the four examined nematodes have similar architectural properties – the proximal, highly conserved promoter is sufficient to deliver the qualitatively correct expression pattern, whereas the distal, nonconserved portion is required for consistent expression. It is important to note that this distal sequence is not alone sufficient to direct any expression in D-type neurons or DVB [41]. It therefore contributes to robustness via a mechanism different from that of recently described “shadow” enhancers [35], [36], each of which is sufficient to drive expression independently. Furthermore “shadow” enhancers are conserved, whereas the distal promoter of unc-47 is not.

Distal nonconserved promoter sequences are required to confer environmental robustness

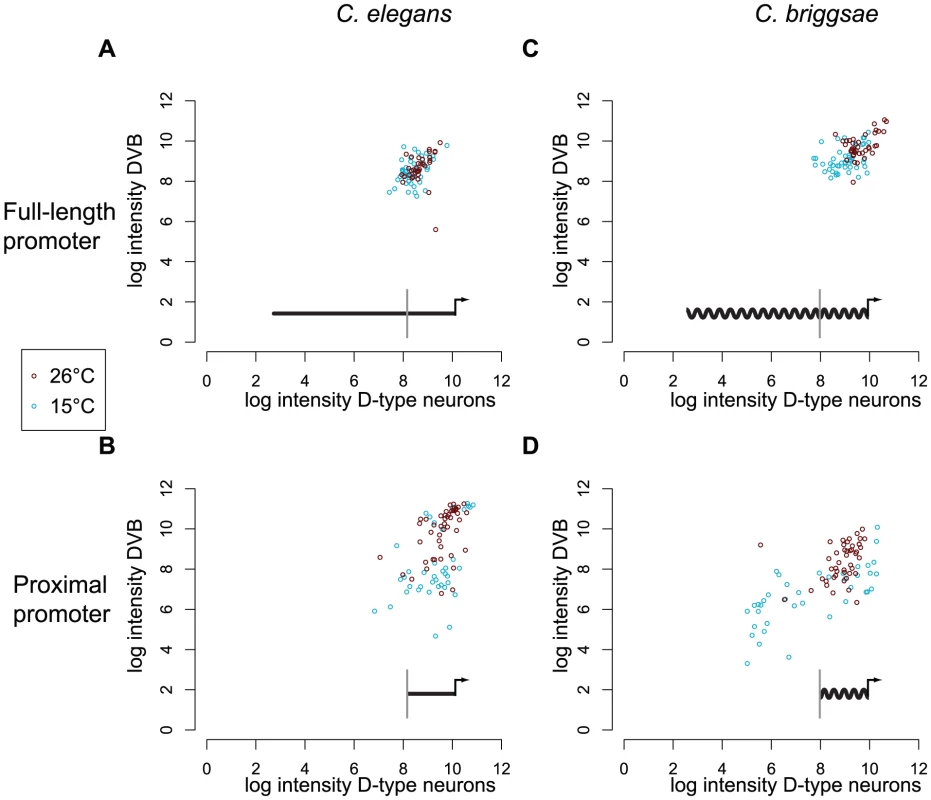

Distal promoters were required for stronger and more consistent expression, even when worms were reared under constant and nearly optimal growth conditions (20°C). We tested whether these sequences could also buffer against environmental challenges. We compared GFP expression levels directed by the full-length and proximal promoters in worms reared at a high temperature of 26°C and a low of 15°C. We measured the intensity of GFP-fluorescence in D-type neurons and DVB and observed several trends. First, expression levels driven by the full-length C. elegans promoter (Figure 3A) were more consistent than those driven by the proximal promoter (Figure 3B) at both the 26°C (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p = 2.9×10−5) and 15°C (p = 1.2×10−6). Second, the full-length promoter was comparably consistent in its expression at 26°C and 15°C (Figure 3A, Table S2). In contrast, consistency of expression of the proximal promoter differed dramatically between the two temperatures (Figure 3B, Table S2).

Fig. 3. Only full-length promoters of C. elegans and C. briggsae unc-47 can direct robust expression.

Distribution of fluorescence intensity driven by C. elegans full-length (A) and proximal (B), and C. briggsae full-length (C) and proximal (D) promoters in C. elegans at two temperatures (red for 26°C and blue for 15°C). For each individual, the log intensity in D-type neurons is plotted against the log intensity in DVB. Individuals that did not show any fluorescence in DVB were excluded from analysis. Data for additional strains are given in Figure S4. Superimposed on each graph is a schematic of the construct used: a straight line represents C. elegans promoter of unc-47, a wavy line represents C. briggsae promoter of unc-47. The gray vertical bar indicates the 5′ boundary of the proximal promoter. Similar results were observed for the C. briggsae promoters. The full-length promoter (Figure 3C) directed more consistent expression than the proximal promoter (Figure 3D) at both temperatures (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, at 26°C p = 1.2×10−2, at 15°C p = 2.2×10−14). Temperature had a minor effect on the consistency of expression of the full-length promoter, but a more substantial effect on the proximal promoter (Table S2). We repeated measurements for multiple independent strains carrying full-length and proximal promoters from C. elegans and C. briggsae and observed concordant results (Figure S4, Table S2).

We concluded that full-length promoters are more robust to temperature stress, regardless of their species of origin (compare Figure 3A and 3C). Proximal promoters, primarily composed of conserved sequences, were significantly less robust, particularly after the cold treatment (Figure 3B and 3D). These results indicate that a robustness-conferring function is encoded in distal promoters in both species, and is thus conserved despite the lack of detectable sequence conservation.

Distinct sequences in distal promoters can contribute to robust expression

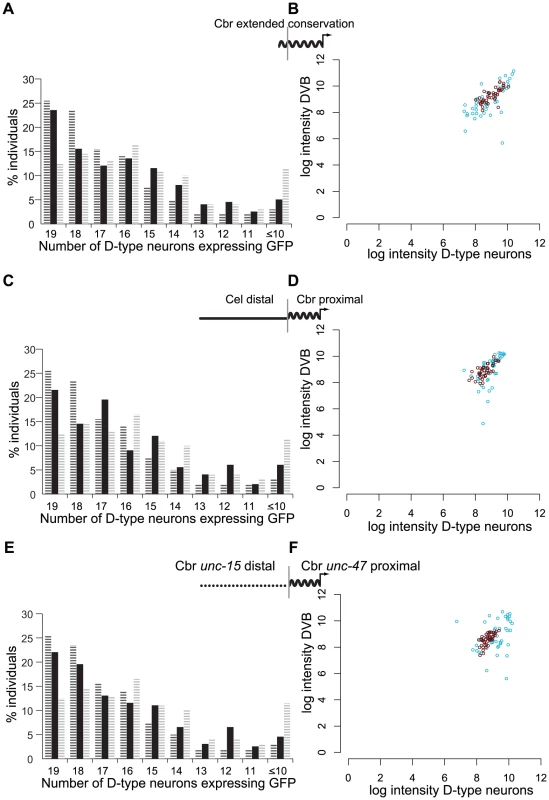

We dissected the distal promoters to determine which of their components were necessary for robust expression. The proximal promoters contain all of the densely arranged blocks of sequence conservation. Additionally, a pair of short motifs (8 and 6 bp) that is shared by all four examined nematodes is located approximately 50 bp distal to the boundary of greatest conservation (1). We considered the distal extent of these motifs to be the absolute boundary of the evolutionarily conserved promoter sequence, because in the remaining distal promoter there were no sequences longer than 10 bp that were shared by all four species. We tested a promoter encompassing all of this “extended conservation” for the ability to drive robust expression. It performed intermediately in terms of consistency of expression between the full-length C. briggsae promoter (Figure 4A; Wilcoxon test, p = 1.4×10−2) and the proximal promoter alone (p = 4.0×10−3). We next examined intensity of GFP expression in the D-type neurons and DVB in animals reared under temperature stress. At 15°C, although not at 26°C, this promoter produced more variable expression than the full-length C. briggsae promoter (compare Figure 4B and Figure 3C; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p = 5.2×10−4), but significantly less variable expression than the proximal promoter (compare Figure 4B and Figure 3D; p = 7.7×10−5). Therefore the two conserved motifs and the sequences that surround them contribute to, but do not entirely account for the robustness of the longer promoter.

Fig. 4. Different components of the distal promoter sequences regulate consistent expression and expression levels under temperature stress.

(A) Percentage of 200 individuals expressing GFP in the indicated number of D-type neurons under control of C. briggsae promoter with extended conservation, shown in solid black bars compared to C. briggsae full-length (black hashed bars) and proximal (gray hashed bars) promoters. (B) Intensity of GFP expression in D-type neurons and the cell DVB for animals bearing the extended conservation promoter reared at 26°C (red) or 15°C (blue). (C) Percentage of 200 individuals expressing GFP in the indicated number of D-type neurons under control of chimeric promoter fusion of C. elegans distal unc-47 promoter sequence and C. briggsae proximal promoter. For comparison, distributions for C. briggsae full-length and proximal promoters are shown in black and gray hashes, respectively. (D) Intensity of GFP in D-type neurons and the cell DVB for animals bearing the chimeric promoter reared at 26°C (red) or 15°C (blue). The chimeric promoter drives robust expression under temperature stress. (E) Percentage of 200 individuals expressing GFP in indicated number of D-type neurons from a chimeric promoter composed of distal C. briggsae unc-15 sequence and the C. briggsae unc-47 proximal promoter (black bars). For comparison, C. briggsae unc-47 full-length and proximal promoters are shown in black and gray hashed bars, respectively. The unc-15/unc-47 chimera is indistinguishable from the C. briggsae full-length promoter (Wilcoxon test p = 0.37), and it is significantly more consistent than the proximal promoter (Wilcoxon test p = 1.3×10−5). (F) Robustness of unc-15/unc-47 chimeric promoter under temperature stress. Our results suggest that, despite substantial sequence divergence, distal promoters of C. elegans and C. briggsae unc-47 confer robust expression to their respective proximal promoters (Figure 1F, 1G, Figure 3). To test whether distal promoters confer robustness in a species-specific manner, we asked whether the distal promoter of C. elegans could restore robust expression when fused to the proximal promoter of C. briggsae. We reasoned that if the distal and proximal sequence function as a unit and make up a single cis-regulatory element, the distal part of which has diverged considerably in its sequence, we should expect a chimeric construct not to rescue robustness. If, on the other hand, the proximal, highly conserved promoter and the distal promoter are two distinct functional units, they should be modular.

The C. elegans-distal-C. briggsae-proximal chimeric unc-47 promoter drove expression with a consistency intermediate between the full-length and proximal promoters in terms of cell number (Figure 4C; Wilcoxon test, different from C. briggsae full-length p = 8.0×10−3; different from C. briggsae proximal p = 5.6×10−3). However, at both 15°C and 26°C this promoter was no more variable than the full-length C. briggsae construct (Figure 4D; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, at 26°C p = 0.6, at 15°C p = 0.1), constituting a significant rescue of robustness relative to the proximal promoter alone (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, at 26°C p = 4.6×10−4, at 15°C p = 1.2×10−10). Because much, although perhaps not all, of the robustness of expression can be rescued by this chimeric construct, we conclude that the proximal and distal sequences encode distinct and separable regulatory functions. Multiple chimeric and “extended conservation” constructs were consistent with these results (Figure S5, Table S2).

The robustness function of the distal element must have much less stringent sequence requirements than the proximal promoter, because distal sequences have diverged considerably but maintain this function. We next tested whether another genomic fragment lacking detectable sequence similarity to the distal unc-47 sequences could confer robustness of expression. We selected an approximately 1.3 kb fragment upstream of unc-15 because it does not share significant similarity with the C. briggsae unc-47 distal promoter (Figure S2). Furthermore, unc-15 encodes a paramyosin ortholog that is expressed in muscles [42], and thus is not expressed in any of the same cells as unc-47. The overall length of this sequence is comparable, however, and it is also an intergenic sequence as poorly conserved between C. elegans and C. briggsae as is the distal portion of the unc-47 promoter (data not shown).

We were surprised to find that the chimeric promoter containing this distal C. briggsae unc-15 sequence fused to the proximal C. briggsae unc-47 promoter displayed robust expression as consistent as the full-length C. briggsae unc-47 promoter in terms of cell number (Figure 4E; Wilcoxon test, p = 0.37). We observed markedly improved consistency of the expression pattern over the C. briggsae proximal promoter alone (Figure 4F; difference from proximal promoter, Wilcoxon test, p = 1.3×10−5). At 26°C this promoter drove as consistent expression as the full-length C. briggsae promoter (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, at 26°C p = 0.1; compare Figure 4F, Figure S5 and Figure 3C). Whereas at 15°C, it was less consistent than the full-length C. briggsae promoter (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, at 15°C p = 2.4×10−4), it was significantly more consistent than the proximal promoter at both temperatures (compare Figure 4F, Figure S5 and Figure 3D; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, at 15°C p = 4.1×10−7, at 26°C p = 1.4×10−5).

Next, we tested whether another non-conserved intergenic sequence, from upstream of the C. briggsae promoter of gene unc-25 could rescue robustness of the proximal C. briggsae promoter of unc-47. Unlike unc-15, unc-25 is co-expressed with unc-47 [43], yet it shares no detectable sequence similarity within promoter elements (data not shown). It did indeed show substantially increased robustness of expression, comparable to the full-length promoter (Figure S6; indistinguishable from C. briggsae full-length Wilcoxon test, p = 0.4; different from C. briggsae proximal Wilcoxon test, p = 1.3×10−5). These results show that unrelated intergenic sequences are capable of conferring robust expression on a proximal promoter that directs the pattern.

Sequences that confer robust expression are AT-enriched

To understand why such different sequences were able to restore robustness of expression of the proximal C. briggsae unc-47 promoter, we examined them for general features they might have in common. Specifically, we calculated nucleotide frequencies in the distal unc-47, unc-15 and unc-25 promoters, and compared them to those of the 1.1 kb of vector DNA sequence that lies distal to all of the inserted promoters. Since this vector sequence, when it lies directly upstream of the proximal promoter, is not able to confer robustness, we sought out features that are shared by distal promoters but not the vector sequence.

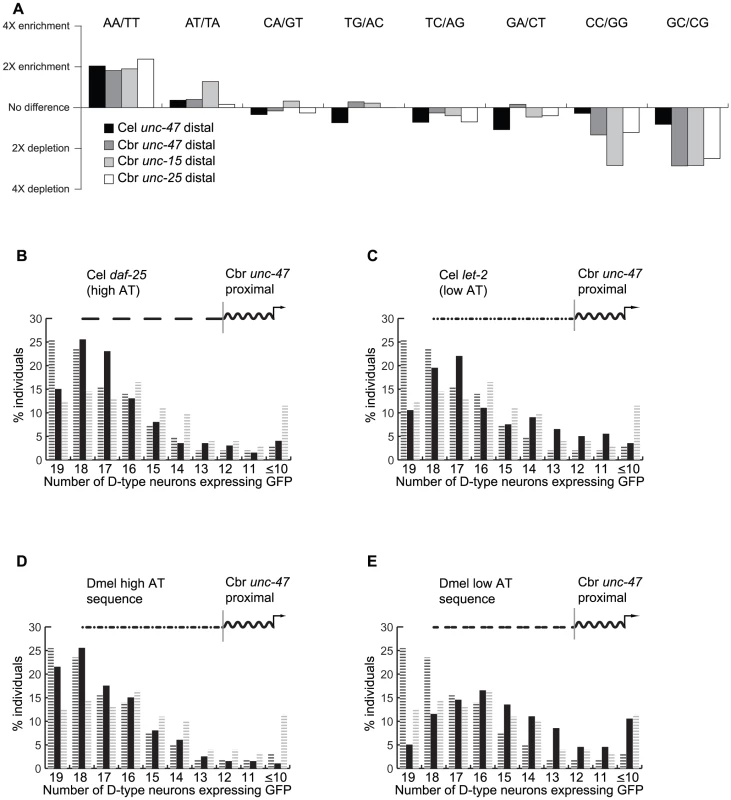

Dinucleotide frequencies differ dramatically between distal unc-47, unc-15 and unc-25 promoter sequences and the upstream vector sequence. There is systematic enrichment for two dinucleotide classes, relative to the vector sequence, and a depletion of two other dinucleotide classes (Figure 5A). While there are between-sequence enrichment differences, the overall biases towards the AA/TT dinucleotides and away from the GC/CG dinucleotides is consistent among all sequences that confer robustness.

Fig. 5. Promoter regions that confer robustness are enriched for nucleosome-depleted sequences.

(A) Enrichment/depletion of dinucleotides in the distal promoters of unc-15, unc-25 and unc-47 genes relative to the sequence of the pPD95.75 vector (log scale). Percentage of 200 individuals expressing GFP in indicated number of D-type neurons from a chimeric promoter composed of AT-rich sequence from the C. elegans daf-25 locus (B), AT-poor sequence from the C. elegans let-2 locus (C), AT-rich sequence from the D. melanogaster ChAT locus (D), and AT-poor sequence from the D. melanogaster CG8394.2 locus (E), fused upstream of the C. briggsae unc-47 proximal promoter. For comparison, C. briggsae unc-47 full-length and proximal promoters are shown in black and gray hashed bars, respectively. This analysis suggests a simple hypothesis, namely that AT-enriched sequences (more specifically those enriched for AA/TT dinucleotides) should promote robust expression, whereas sequences depleted for these dinucleotides and enriched for GC/CG pairs (and to some extent CC/GG pairs) should not. To test this prediction, we subdivided the genome of C. elegans into 1 kb fragments, matching in size the previously tested distal sequences, and computed the extent of their AT-enrichment. A sequence located downstream of the daf-25 locus is enriched for AA/TT dinucleotides to an extent similar to distal promoters of unc-47, unc-15 and unc-25. This 1 kb fragment, when placed upstream of the proximal promoter of C. briggsae unc-47, was able to confer robustness similarly to the distal unc-47 promoter (Figure 5B; indistinguishable from C. briggsae full-length Wilcoxon test, p = 0.09; different from C. briggsae proximal Wilcoxon test, p = 1.9×10−5). In contrast, a 1 kb AT-depleted sequence from the let-2 locus was unable to rescue robustness (Figure 5C; different from C. briggsae full-length Wilcoxon test, p = 1.1×10−5; indistinguishable from C. briggsae proximal Wilcoxon test, p = 0.14). Furthermore, the construct containing the daf-25 sequence drove a more consistent expression than the one containing the let-2 sequence (Wilcoxon test, p = 4×10−3).

To ensure that the ability to rescue expression robustness is not restricted to AT-enriched sequences from nematode genomes, we tested whether sequences from distantly related species can perform this function. We segmented the genome of D. melanogaster into 1 kb fragments and selected one AT-enriched and one AT-depleted sequence using the same criteria as were applied to the fragments from the C. elegans genome. As predicted, a construct carrying the AT-enriched sequence drove substantially more robust expression than the proximal promoter alone (Figure 5D; indistinguishable from C. briggsae full-length Wilcoxon test, p = 0.2; different from C. briggsae proximal Wilcoxon test, p = 1.5×10−5). A construct carrying the AT-depleted sequence was no more robust than the proximal promoter alone (Figure 5E; different from C. briggsae full-length Wilcoxon test, p = 3.7×10−15; indistinguishable from C. briggsae proximal Wilcoxon test, p = 0.04).

Together these results suggest three important conclusions. First, AT-enrichment of a sequence can predict its ability to confer robustness of expression. Second, because two different AT-depleted sequences were not able to improve consistency of transgene expression, it is unlikely that robustness results from simply separating the proximal promoter from unknown repressive effects of the vector sequence. Sequence composition must play a critical role. Third, because multiple unrelated nematode sequences and an AT-enriched Drosophila sequence conferred robust expression, it is unlikely that short, gene - or species-specific motifs play a major role in improving consistency of expression. Our data imply that the mechanism responsible for conferring expression robustness relies on the overall nucleotide composition of promoters rather then on specific sequence motifs.

Discussion

Our results suggest that promoters of Caenorhabditis unc-47 orthologs are organized into two domains that are markedly distinct in functions and evolutionary dynamics. Whereas proximal promoters are highly conserved and are sufficient to direct the appropriate spatial expression pattern, the distal sequences diverge rapidly and their primary function is to confer robustness of expression. The distal sequences within promoters of unc-47 are not capable of directing expression patterns on their own [41] and must therefore confer robustness via a mechanism distinct from redundant and evolutionarily conserved “shadow” enhancers [35], [36].

The shared nucleotide composition (Figure 5A) of the four sequences that promote robust expression – distal promoters of C. elegans and C. briggsae unc-47 as well as upstream regions of two unrelated genes, unc-15 and unc-25 – hints at a potential mechanism of action. Overall sequence composition plays a large role in establishing chromatin states throughout the genome [44]. In particular, AT-rich sequences tend to be associated with nucleosome-poor regions, although multiple factors determine whether DNA is bound to nucleosomes. Recent studies suggest that sequence-composition codes that displace nucleosomes may be common in active metazoan promoters [45], [46]. Intriguingly, the genomic sequence precisely corresponding to the distal, nonconserved portion of the C. elegans unc-47 promoter is depleted of nucleosomes [47] (Figure S7).

Trinucleotide frequencies are a better predictor of nucleosome positioning than dinucleotides [47]. The robustness-conferring sequences are two-fold enriched for trinucleotides that are preferentially found in nucleosome-depleted regions of the C. elegans genome, far more so than the conserved proximal promoters (Figure S7). Nucleosome occupancy can differ even in evolutionarily conserved promoters [46], [48], [49], still similar levels of enrichment for nucleosome-depleted trinucleotides were seen in the distal unc-47 promoters of C. brenneri and C. remanei (Figure S7). All sequences that confer robustness bear a signature consistent with nucleosome depletion, and the C. elegans sequences were shown to be depleted of nucleosomes (Figure S7). The AT-poor let-2 locus, on the other hand, is enriched for nucleosomes, and other sequences which are unable to improve consistency of expression, show a trinucleotide signature of nucleosome enrichment (Figure S7). We therefore hypothesize that open chromatin may promote robust expression.

We favor the hypothesis that the robustness function is executed by configuring chromatin in an accessible state for other factors to bind the promoter sequence. This hypothesis is consistent with the finding that variability of gene expression may be encoded in nucleosome-positioning sequences [50], and that chromatin regulators may contribute to environmental canalization [51]. Whether this mechanism of robustness arises as a byproduct of other forces that shape nucleotide composition of intergenic sequences, or whether it is directly selected upon, it has been conserved at the unc-47 locus.

We propose a simple scenario to account for the different evolutionary rates between the distal and proximal portions of the unc-47 promoter. The proximal promoter is responsible for directing the expression pattern because it contains numerous transcription factor binding sites. It appears that in the context of the proximal promoter most substitutions are deleterious and thus it evolves relatively slowly. The distal promoter, on the other hand, evolves at a considerably faster rate. Noting that the ability to confer robustness is conserved between distal promoters of unc-47 orthologs, we infer that it is maintained by selection that does not require maintenance of specific sequence identity. Indeed, unrelated sequences from the C. elegans unc-15, unc-25, and daf-25 loci and even an AT-rich sequence from D. melanogaster can rescue robustness of expression. Thus the distal promoters appear to be under a simpler constraint – they are only required to maintain a certain nucleotide composition, for instance that which is consistent with nucleosome depletion, to confer robustness of gene expression. Sequences that satisfy this requirement are quite degenerate, so the element tolerates a relatively high rate of sequence turnover, while retaining functional conservation. This hypothesis is consistent with a report of selection on sequence composition that encodes nucleosome organization in yeast [52]. We consider the distal promoter of the unc-47 gene to be an example of a weakly constrained functional sequence [53]. Such low constraint allows developmental systems drift [54], in which conserved molecular functions are mediated by divergent genetic systems.

Methods

Constructs and strains

To generate reporter constructs, promoter sequences were PCR amplified from genomic DNA and cloned upstream of GFP into pPD95.75. In all cases, reverse primers overlapped the start codon of the unc-47 ortholog. Prior to injections, constructs were sequenced to ensure accuracy. Precise boundaries of full-length, extended conservation and proximal constructs are given in Figure S1. To generate strains carrying extrachromosomal arrays, we injected a mixture (5 ng/µL promoter::GFP plasmid, 5 ng/µL pha-1 rescue construct, 100 ng/µL salmon sperm DNA) into C. elegans pha-1 (e2123) strain [55]. Transformants were selected at 25°C. The C. briggsae strains carrying Cbr promoter unc-47::GFP were produced by injecting a mixture (5 ng/µL promoter::GFP plasmid and 100 ng/µL salmon sperm DNA) into AF16 strain. Single copy integrated strains were generated following an established protocol [56]. Copy number of inserts was verified through quantitative PCR of GFP (normalized to genomic unc-47).

Counting the number of expressing cells

Mixed-stage populations of C. elegans carrying transgenes were grown at 20°C with abundant food and young adult - or L4-stage worms were selected. These were immobilized on agar slides with 100 mM NaN3 in M9 buffer. The slides were examined on a Leica DM5000B compound microscope under 400× magnification. Each worm was positioned such that the ventral nerve cord with its D-type neurons could be seen clearly, and the number of cell bodies expressing GFP were counted manually. Worms without any visible GFP expression were assumed to have lost the transgene. For each construct studied, multiple independent transgenic lines were generated, and final counts of 100–200 individuals (see figure legends/text for details) were derived from a mixture of these lines (inter-line variance is generally low). To mitigate against experimenter bias census counts were taken in a blinded fashion. Individual strains were coded by one investigator to obscure their identity. Another investigator then examined 100 individuals of each of these strains. Once all counting was finished, strain identities were revealed and data were analyzed.

Fluorescence measurements and temperature stress experiments

Intensity of GFP expression in individual cells was measured on a Leica DM5000B compound scope fitted with a Qimaging Retiga2000 camera. Images of cells were outlined in imageJ, average intensity was measured and the background subtracted. Multiple strains carrying the same transgene were examined throughout and tested for concordance.

For integrated strains we used 125 ms exposure, 100% excitation. Pictures of 7 cells (DD1, VD1, VD2, DD3, VD6, VD13, DVB) were taken. For each strain and treatment (15°C, 20°C, 26°C) 25 L4-staged worms were measured. For temperature stress experiments (these were conducted on strains carrying extrachromosomal arrays) worms were reared at 15°C or 26°C for at least two generations. Then 50 L4 individuals were mounted for each treatment and strain and intensity of GFP was measured (125 ms exposure, variable excitation) for D-type neurons (average values recorded) and DVB.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R. In all cases, the logarithm of measured GFP intensity was used. Wilcoxon test was used to assess consistency of the number of cells expressing different constructs. To assess the amount of scatter in fluorescence measurements (data reported in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figures S4 and S5, and in Table S2), we computed geometric distances between all data points for a particular strain/treatment and the mean of that strain/treatment. To test whether distributions of distances derived in such a way were significantly different for different strains/treatments, we conducted Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. We used Ansari-Bradley test to determine whether the relative DVB fluorescence was more variable for proximal compared to full-length promoters.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. XieXMikkelsenTSGnirkeALindblad-TohKKellisM 2007 Systematic discovery of regulatory motifs in conserved regions of the human genome, including thousands of CTCF insulator sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 17 7145 7150

2. BejeranoGPheasantMMakuninIStephenSKentWJ 2004 Ultraconserved elements in the human genome. Science 304 5675 1321 1325

3. BoffelliDNobregaMARubinEM 2004 Comparative genomics at the vertebrate extremes. Nature Reviews Genetics 5 6 456 465

4. PennacchioLARubinEM 2001 Genomic strategies to identify mammalian regulatory sequences. Nature Reviews Genetics 2 2 100 109

5. AparicioSMorrisonAGouldAGilthorpeJChaudhuriC 1995 Detecting conserved regulatory elements with the model genome of the japanese puffer fish, fugu rubripes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92 5 1684 1688

6. BlowMJMcCulleyDJLiZZhangTAkiyamaJA 2010 ChIP-seq identification of weakly conserved heart enhancers. Nat Genet 42 9 806-U107

7. RitterDILiQKostkaDPollardKSGuoS 2010 The importance of being cis: Evolution of orthologous fish and mammalian enhancer activity. Mol Biol Evol 27 10 2322 2332

8. McGaugheyDMVintonRMHuynhJAl-SaifABeerMA 2008 Metrics of sequence constraint overlook regulatory sequences in an exhaustive analysis at phox2b. Genome Res 18 2 252 260

9. MarguliesEHCooperGMAsimenosGThomasDJDeweyCN 2007 Analyses of deep mammalian sequence alignments and constraint predictions for 1% of the human genome. Genome Res 17 6 760 774

10. HareEEPetersonBKIyerVNMeierREisenMB 2008 Sepsid even-skipped enhancers are functionally conserved in drosophila despite lack of sequence conservation. PLoS Genet 4 e1000106 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000106

11. FisherSGriceEAVintonRMBesslingSLMcCallionAS 2006 Conservation of RET regulatory function from human to zebrafish without sequence similarity. Science 312 5771 276 279

12. RomanoLAWrayGA 2003 Conservation of Endo16 expression in sea urchins despite evolutionary divergence in both cis and trans-acting components of transcriptional regulation. Development 130 17 4187 4199

13. WrayGAHahnMWAbouheifEBalhoffJPPizerM 2003 The evolution of transcriptional regulation in eukaryotes. Mol Biol Evol 20 9 1377 1419

14. SwansonCIEvansNCBaroloS 2010 Structural rules and complex regulatory circuitry constrain expression of a notch - and EGFR-regulated eye enhancer. Developmental Cell 18 3 359 370

15. NokesEBVan Der LindenAMWinslowCMukhopadhyaySMaK 2009 Cis-regulatory mechanisms of gene expression in an olfactory neuron type in caenorhabditis elegans. Developmental Dynamics 238 12 3080 3092

16. CrockerJTamoriYErivesA 2008 Evolution acts on enhancer organization to fine-tune gradient threshold readouts. PLoS Biol 6 e263 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060263

17. JohnsonDSDavidsonBBrownCDSmithWCSidowA 2004 Noncoding regulatory sequences of gona exhibit strong correspondence between evolutionary constraint and functional importance. Genome Res 14 12 2448 2456

18. SmallSArnostiDNLevineM 1993 Spacing ensures autonomous expression of different stripe enhancers in the even-skipped promoter. Development 119 3 767 772

19. BrownCDJohnsonDSSidowA 2007 Functional architecture and evolution of transcriptional elements that drive gene coexpression. Science 317 5844 1557 1560

20. PapatsenkoDLevineM 2007 A rationale for the enhanceosome and other evolutionarily constrained enhancers. Current Biology 17 22 R955 R957

21. ErivesALevineM 2004 Coordinate enhancers share common organizational features in the drosophila genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 11 3851 3856

22. WeirauchMTHughesTR 2010 Conserved expression without conserved regulatory sequence: The more things change, the more they stay the same. Trends in Genetics 26 2 66 74

23. ArnostiDNKulkarniMM 2005 Transcriptional enhancers: Intelligent enhanceosomes or flexible billboards? J Cell Biochem 94 5 890 898

24. BradleyRKLiXTrapnellCDavidsonSPachterL 2010 Binding site turnover produces pervasive quantitative changes in transcription factor binding between closely related drosophila species. PLoS Biol 8 e1000343 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000343

25. GiladYRifkinSAPritchardJK 2008 Revealing the architecture of gene regulation: The promise of eQTL studies. Trends in Genetics 24 8 408 415

26. PriceALPattersonNHancksDCMyersSReichD 2008 Effects of cis and trans genetic ancestry on gene expression in african americans. PLoS Genet 4 e1000294 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000294

27. RajARifkinSAAndersenEvan OudenaardenA 2010 Variability in gene expression underlies incomplete penetrance. Nature 463 7283 913-U84

28. MaselJSiegalML 2009 Robustness: Mechanisms and consequences. Trends in Genetics 25 9 395 403

29. BraendleCFelixM 2008 Plasticity and errors of a robust developmental system in different environments. Developmental Cell 15 5 714 724

30. FelixMWagnerA 2008 Robustness and evolution: Concepts, insights and challenges from a developmental model system. Heredity 100 2 132 140

31. SiegalMLBergmanA 2002 Waddington's canalization revisited: Developmental stability and evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 16 10528 10532

32. ManuSurkovaSSpirovAVGurskyVVJanssensH 2009 Canalization of gene expression in the drosophila blastoderm by gap gene cross regulation. PLoS Biol 7 e1000049 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000049

33. SzoellosiGJDerenyiI 2009 Congruent evolution of genetic and environmental robustness in micro-RNA. Mol Biol Evol 26 4 867 874

34. HongJHendrixDALevineMS 2008 Shadow enhancers as a source of evolutionary novelty. Science 321 5894 1314 1314

35. FrankelNDavisGKVargasDWangSPayreF 2010 Phenotypic robustness conferred by apparently redundant transcriptional enhancers. Nature 466 7305 490-U8

36. PerryMWBoettigerANBothmaJPLevineM 2010 Shadow enhancers foster robustness of drosophila gastrulation. Current Biology 20 17 1562 1567

37. LiXCassidyJJReinkeCAFischboeckSCarthewRW 2009 A MicroRNA imparts robustness against environmental fluctuation during development. Cell 137 2 273 282

38. HerranzHCohenSM 2010 MicroRNAs and gene regulatory networks: Managing the impact of noise in biological systems. Genes Dev 24 13 1339 1344

39. KiontkeKGavinNPRaynesYRoehrigCPianoF 2004 Caenorhabditis phylogeny predicts convergence of hermaphroditism and extensive intron loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 24 9003 9008

40. McIntireSLReimerRJSchuskeKEdwardsRHJorgensenEM 1997 Identification and characterization of the vesicular GABA transporter. Nature 389 6653 870 876

41. RuvinskyIRuvkunG 2003 Functional tests of enhancer conservation between distantly related species. Development 130 21 5133 5142

42. KagawaHGengyoKMclachlanADBrennerSKarnJ 1989 Paramyosin gene (unc-15) of caenorhabditis-elegans - molecular-cloning, nucleotide-sequence and models for thick filament structure. J Mol Biol 207 2 311 333

43. EastmanCHorvitzHRJinYS 1999 Coordinated transcriptional regulation of the unc-25 glutamic acid decarboxylase and the unc-47 GABA vesicular transporter by the caenorhabditis elegans UNC-30 homeodomain protein. Journal of Neuroscience 19 15 6225 6234

44. SegalEWidomJ 2009 What controls nucleosome positions? Trends in Genetics 25 8 335 343

45. GuertinMJLisJT 2010 Chromatin landscape dictates HSF binding to target DNA elements. PLoS Genet 6 e1001114 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001114

46. KhoueiryPRothbacherUOhtsukaYDaianFFrangulianE 2010 A cis-regulatory signature in ascidians and flies, independent of transcription factor binding sites. Current Biology 20 9 792 802

47. ValouevAIchikawaJTonthatTStuartJRanadeS 2008 A high-resolution, nucleosome position map of C. elegans reveals a lack of universal sequence-dictated positioning. Genome Res 18 7 1051 1063

48. TiroshISigalNBarkaiN 2010 Divergence of nucleosome positioning between two closely related yeast species: Genetic basis and functional consequences. Molecular Systems Biology 6 365

49. TsankovAMThompsonDASochaARegevARandoOJ 2010 The role of nucleosome positioning in the evolution of gene regulation. PLoS Biol 8 e1000414 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000414

50. ChoiJKKimY 2009 Intrinsic variability of gene expression encoded in nucleosome positioning sequences. Nat Genet 41 4 498 503

51. GibertJKarchFSchloettererC 2011 Segregating variation in the polycomb group gene cramped alters the effect of temperature on multiple traits. PLoS Genet 7 e1001280 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001280

52. KenigsbergEBarASegalETanayA 2010 Widespread compensatory evolution conserves DNA-encoded nucleosome organization in yeast. PLoS Comput Biol 6 e1001039 doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001039

53. CooperGMBrownCD 2008 Qualifying the relationship between sequence conservation and molecular function. Genome Res 18 2 201 205

54. TrueJRHaagES 2001 Developmental system drift and flexibility in evolutionary trajectories. Evol Dev 3 2 109 119

55. GranatoMSchnabelHSchnabelR 1994 Pha-1, a selectable marker for gene-transfer in C-elegans. Nucleic Acids Res 22 9 1762 1763

56. Frokjaer-JensenCDavisMWHopkinsCENewmanBJThummelJM 2008 Single-copy insertion of transgenes in caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Genet 40 11 1375 1383

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Local Absence of Secondary Structure Permits Translation of mRNAs that Lack Ribosome-Binding SitesČlánek Independent Chromatin Binding of ARGONAUTE4 and SPT5L/KTF1 Mediates Transcriptional Gene SilencingČlánek Trade-Off between Bile Resistance and Nutritional Competence Drives Diversification in the Mouse GutČlánek FGF Signaling Regulates the Number of Posterior Taste Papillae by Controlling Progenitor Field SizeČlánek Mammalian BTBD12 (SLX4) Protects against Genomic Instability during Mammalian SpermatogenesisČlánek Identification of Nine Novel Loci Associated with White Blood Cell Subtypes in a Japanese PopulationČlánek Differential Effects of and Risk Variants on Association with Diabetic ESRD in African AmericansČlánek Dynamic Chromatin Localization of Sirt6 Shapes Stress- and Aging-Related Transcriptional Networks

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 6- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Hypogonadotropní hypogonadismus u žen a vliv na výsledky reprodukce po IVF

- Molekulární vyšetření pro stanovení prognózy pacientů s chronickou lymfocytární leukémií

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Local Absence of Secondary Structure Permits Translation of mRNAs that Lack Ribosome-Binding Sites

- Statistical Inference on the Mechanisms of Genome Evolution

- Revisiting Heterochromatin in Embryonic Stem Cells

- A Two-Stage Meta-Analysis Identifies Several New Loci for Parkinson's Disease

- Identification of a Sudden Cardiac Death Susceptibility Locus at 2q24.2 through Genome-Wide Association in European Ancestry Individuals

- Genomic Prevalence of Heterochromatic H3K9me2 and Transcription Do Not Discriminate Pluripotent from Terminally Differentiated Cells

- Epistasis between Beneficial Mutations and the Phenotype-to-Fitness Map for a ssDNA Virus

- Recurrent Chromosome 16p13.1 Duplications Are a Risk Factor for Aortic Dissections

- Telomere DNA Deficiency Is Associated with Development of Human Embryonic Aneuploidy

- Genome-Wide Association Study of White Blood Cell Count in 16,388 African Americans: the Continental Origins and Genetic Epidemiology Network (COGENT)

- Unexpected Role for DNA Polymerase I As a Source of Genetic Variability

- Transportin-SR Is Required for Proper Splicing of Genes and Plant Immunity

- How Chromatin Is Remodelled during DNA Repair of UV-Induced DNA Damage in

- Independent Chromatin Binding of ARGONAUTE4 and SPT5L/KTF1 Mediates Transcriptional Gene Silencing

- Two Evolutionary Histories in the Genome of Rice: the Roles of Domestication Genes

- Natural Allelic Variation Defines a Role for : Trichome Cell Fate Determination

- Multiple Common Susceptibility Variants near BMP Pathway Loci , , and Explain Part of the Missing Heritability of Colorectal Cancer

- Pathogenic Mechanism of the FIG4 Mutation Responsible for Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease CMT4J

- A Functional Variant in Promoter Modulates Its Expression and Confers Disease Risk for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Drift and Genome Complexity Revisited

- Chromosomal Macrodomains and Associated Proteins: Implications for DNA Organization and Replication in Gram Negative Bacteria

- Trade-Off between Bile Resistance and Nutritional Competence Drives Diversification in the Mouse Gut

- Pathways of Distinction Analysis: A New Technique for Multi–SNP Analysis of GWAS Data

- Web-Based Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Two Novel Loci and a Substantial Genetic Component for Parkinson's Disease

- Chk2 and p53 Are Haploinsufficient with Dependent and Independent Functions to Eliminate Cells after Telomere Loss

- Exome Sequencing Identifies Mutations in High Myopia

- Distinct Functional Constraints Partition Sequence Conservation in a -Regulatory Element

- CorE from Is a Copper-Dependent RNA Polymerase Sigma Factor

- A Single Sex Pheromone Receptor Determines Chemical Response Specificity of Sexual Behavior in the Silkmoth

- FGF Signaling Regulates the Number of Posterior Taste Papillae by Controlling Progenitor Field Size

- Maps of Open Chromatin Guide the Functional Follow-Up of Genome-Wide Association Signals: Application to Hematological Traits

- Increased Susceptibility to Cortical Spreading Depression in the Mouse Model of Familial Hemiplegic Migraine Type 2

- Differential Gene Expression and Epiregulation of Alpha Zein Gene Copies in Maize Haplotypes

- Parallel Adaptive Divergence among Geographically Diverse Human Populations

- Genetic Analysis of Genome-Scale Recombination Rate Evolution in House Mice

- Mechanisms for the Evolution of a Derived Function in the Ancestral Glucocorticoid Receptor

- Mammalian BTBD12 (SLX4) Protects against Genomic Instability during Mammalian Spermatogenesis

- Interferon Regulatory Factor 8 Regulates Pathways for Antigen Presentation in Myeloid Cells and during Tuberculosis

- High-Resolution Analysis of Parent-of-Origin Allelic Expression in the Arabidopsis Endosperm

- Specific SKN-1/Nrf Stress Responses to Perturbations in Translation Elongation and Proteasome Activity

- Graded Nodal/Activin Signaling Titrates Conversion of Quantitative Phospho-Smad2 Levels into Qualitative Embryonic Stem Cell Fate Decisions

- Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals PADI4 Cooperates with Elk-1 to Activate Expression in Breast Cancer Cells

- Trait Variation in Yeast Is Defined by Population History

- Meiosis-Specific Loading of the Centromere-Specific Histone CENH3 in

- A Genome-Wide Survey of Imprinted Genes in Rice Seeds Reveals Imprinting Primarily Occurs in the Endosperm

- Multiple Regulatory Mechanisms to Inhibit Untimely Initiation of DNA Replication Are Important for Stable Genome Maintenance

- SIRT1 Promotes N-Myc Oncogenesis through a Positive Feedback Loop Involving the Effects of MKP3 and ERK on N-Myc Protein Stability

- Bacteriophage Crosstalk: Coordination of Prophage Induction by Trans-Acting Antirepressors

- Role of the Single-Stranded DNA–Binding Protein SsbB in Pneumococcal Transformation: Maintenance of a Reservoir for Genetic Plasticity

- Genomic Convergence among ERRα, PROX1, and BMAL1 in the Control of Metabolic Clock Outputs

- Genome-Wide Association of Bipolar Disorder Suggests an Enrichment of Replicable Associations in Regions near Genes

- Identification of Nine Novel Loci Associated with White Blood Cell Subtypes in a Japanese Population

- DNA Ligase III Promotes Alternative Nonhomologous End-Joining during Chromosomal Translocation Formation

- Differential Effects of and Risk Variants on Association with Diabetic ESRD in African Americans

- Finished Genome of the Fungal Wheat Pathogen Reveals Dispensome Structure, Chromosome Plasticity, and Stealth Pathogenesis

- Dynamic Chromatin Localization of Sirt6 Shapes Stress- and Aging-Related Transcriptional Networks

- Extracellular Matrix Dynamics in Hepatocarcinogenesis: a Comparative Proteomics Study of Transgenic and Null Mouse Models

- Integrating 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine into the Epigenomic Landscape of Human Embryonic Stem Cells

- Vive La Différence: An Interview with Catherine Dulac

- Multiple Loci Are Associated with White Blood Cell Phenotypes

- Nuclear Accumulation of Stress Response mRNAs Contributes to the Neurodegeneration Caused by Fragile X Premutation rCGG Repeats

- A New Mutation Affecting FRQ-Less Rhythms in the Circadian System of

- Cryptic Transcription Mediates Repression of Subtelomeric Metal Homeostasis Genes

- A New Isoform of the Histone Demethylase JMJD2A/KDM4A Is Required for Skeletal Muscle Differentiation

- Genetic Determinants of Lipid Traits in Diverse Populations from the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Study

- A Genome-Wide RNAi Screen for Factors Involved in Neuronal Specification in

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Recurrent Chromosome 16p13.1 Duplications Are a Risk Factor for Aortic Dissections

- Statistical Inference on the Mechanisms of Genome Evolution

- Genome-Wide Association Study of White Blood Cell Count in 16,388 African Americans: the Continental Origins and Genetic Epidemiology Network (COGENT)

- Chromosomal Macrodomains and Associated Proteins: Implications for DNA Organization and Replication in Gram Negative Bacteria

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání