-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Natural Allelic Variation Defines a Role for : Trichome Cell Fate Determination

The molecular nature of biological variation is not well understood. Indeed, many questions persist regarding the types of molecular changes and the classes of genes that underlie morphological variation within and among species. Here we have taken a candidate gene approach based on previous mapping results to identify the gene and ultimately a polymorphism that underlies a trichome density QTL in Arabidopsis thaliana. Our results show that natural allelic variation in the transcription factor ATMYC1 alters trichome density in A. thaliana; this is the first reported function for ATMYC1. Using site-directed mutagenesis and yeast two-hybrid experiments, we demonstrate that a single amino acid replacement in ATMYC1, discovered in four ecotypes, eliminates known protein–protein interactions in the trichome initiation pathway. Additionally, in a broad screen for molecular variation at ATMYC1, including 72 A. thaliana ecotypes, a high-frequency block of variation was detected that results in >10% amino acid replacement within one of the eight exons of the gene. This sequence variation harbors a strong signal of divergent selection but has no measurable effect on trichome density. Homologs of ATMYC1 are pleiotropic, however, so this block of variation may be the result of natural selection having acted on another trait, while maintaining the trichome density role of the gene. These results show that ATMYC1 is an important source of variation for epidermal traits in A. thaliana and indicate that the transcription factors that make up the TTG1 genetic pathway generally may be important sources of epidermal variation in plants.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002069

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002069Summary

The molecular nature of biological variation is not well understood. Indeed, many questions persist regarding the types of molecular changes and the classes of genes that underlie morphological variation within and among species. Here we have taken a candidate gene approach based on previous mapping results to identify the gene and ultimately a polymorphism that underlies a trichome density QTL in Arabidopsis thaliana. Our results show that natural allelic variation in the transcription factor ATMYC1 alters trichome density in A. thaliana; this is the first reported function for ATMYC1. Using site-directed mutagenesis and yeast two-hybrid experiments, we demonstrate that a single amino acid replacement in ATMYC1, discovered in four ecotypes, eliminates known protein–protein interactions in the trichome initiation pathway. Additionally, in a broad screen for molecular variation at ATMYC1, including 72 A. thaliana ecotypes, a high-frequency block of variation was detected that results in >10% amino acid replacement within one of the eight exons of the gene. This sequence variation harbors a strong signal of divergent selection but has no measurable effect on trichome density. Homologs of ATMYC1 are pleiotropic, however, so this block of variation may be the result of natural selection having acted on another trait, while maintaining the trichome density role of the gene. These results show that ATMYC1 is an important source of variation for epidermal traits in A. thaliana and indicate that the transcription factors that make up the TTG1 genetic pathway generally may be important sources of epidermal variation in plants.

Introduction

Understanding the origins, maintenance, and loss of natural variation remain important goals of evolutionary biology; ideally, we should like to know what types of molecular genetic changes generate the variation that natural selection acts on. For most traits, variation is distributed continuously in natural populations, a product of polymorphisms at many loci, environmental effects, and genotype by environment interactions [1], [2]. Common first approaches to characterizing the genetic bases of natural variation include quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping (see reviews [3]–[5]) and, more recently, genome-wide association mapping (e.g., [6]–[8]). While these methods provide many genetic insights, mapping results largely remain hypotheses regarding the molecular nature of biological diversity. To identify the genes and ultimately the polymorphisms that underlie natural variation still require detailed gene-by-gene analysis [9].

Information about the molecular changes that underlie natural variation within and among species provides important insights into the mechanisms that drive local adaptation, morphological evolution, and speciation. For example, molecular data have revealed a good deal about the evolution of flowering time in Arabidopsis thaliana [10]–[13], morphology in various groups [14]–[16], and speciation in Drosophila [17], [18]. Despite progress for specific traits, few general patterns have emerged regarding the molecular bases of natural variation. For example, King and Wilson [19] proposed the concept of “evolution at two levels” more than three decades ago, yet we still know little about the relative roles of coding versus regulatory mutations in evolution [20]. Such patterns may ultimately prove difficult to identify because they vary according to the taxonomic level of comparison, nature of the trait, or life history, but more data are required.

For plants, there are only ∼100 cases where the gene underlying natural variation has been identified and fewer than that for the causal polymorphism (reviewed in [21]). Perhaps further complicating the search for natural molecular evolutionary patterns, these data are heavily biased toward crops; however, roughly a third of the data are reported from work on the model flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Like many model species, A. thaliana has a high degree of intra-specific phenotypic variation (reviewed in [3]) and a substantial functional genetic infrastructure [22], which make it an ideal system for pursuing the genes that underlie natural variation [23]. Indeed, studying highly variable traits with well-described molecular genetic underpinnings may represent our best opportunities to identify genes of interest and ultimately elucidate broad molecular evolutionary patterns. Epidermal cell fate in Arabidopsis thaliana represents one such system.

The interaction between an organism and its environment plays a critical role in the evolution of morphology and local adaptation [24], [25]. For individual plants, which cannot migrate away from sub-optimum conditions, this interaction is all the more important and is mediated by organs such as stomata [26], [27], root hairs [28], [29], trichomes [30]–[32], anthocyanin producing cells [33], [34], and seed coats [35]. Collectively these organs make up the plant epidermis, an elaborate skin that serves as the interface between the organism and its environment. In A. thaliana, epidermal cell fate is largely regulated by the TTG1 genetic pathway [36], which is mainly comprised of many pleiotropic and epistatic transcription factors and the scaffold protein, TTG1. Among the epidermal traits regulated by this pathway, trichome density is known to play a dynamic defensive role in A. thaliana [32]; increased trichome density under herbivorous conditions results in a fitness advantage, but individuals with higher trichome density in the absence of herbivorous insects have been shown to incur a fitness cost. While this suggests that environmental heterogeneity may maintain genetic variation for trichome density (within or between populations), we know little about the molecular nature of this variation. To date, only one QTL for trichome density has been identified [37]; ETC2 encodes a single repeat MYB protein known to be a repressor of the trichome cell fate. This leaves the molecular nature of most trichome density variation within A. thaliana unexplained.

Previous QTL mapping results for trichome number [38], [39] and trichome density [40] have identified multiple QTL in A. thaliana. One QTL mapped by Symonds et al. [40], TDL5, was localized to the top of chromosome four independently in each of four Recombinant Inbred Line (RIL) populations (Figure 1). Estimates of the physical position of this QTL and the similar magnitude of effect for TDL5 across mapping populations suggested that the same locus was mapped independently in each population. In an initial screen of the region, no gene with a known trichome phenotype was discovered; however, the search did reveal a bHLH transcription factor, ATMYC1, three paralogs of which [41], [42] have reduced trichome density phenotypes when knocked out [43]–[45]. ATMYC1 is expressed in both leaves and seeds [46] but over-expression of the gene has yielded no observable phenotype [44]. More recently, Zimmerman et al. [47] demonstrated protein-protein interactions between ATMYC1 and several R2R3 MYBs with known roles in epidermal cell fate. Here, we present genetic, molecular, and protein-protein interaction data that demonstrate that ATMYC1 is involved in epidermal cell fate and is a Quantitative Trait Gene (QTG) that underlies natural variation for trichome density. The results further reveal a complex pattern of protein evolution at ATMYC1 with as yet undetermined origin and effects.

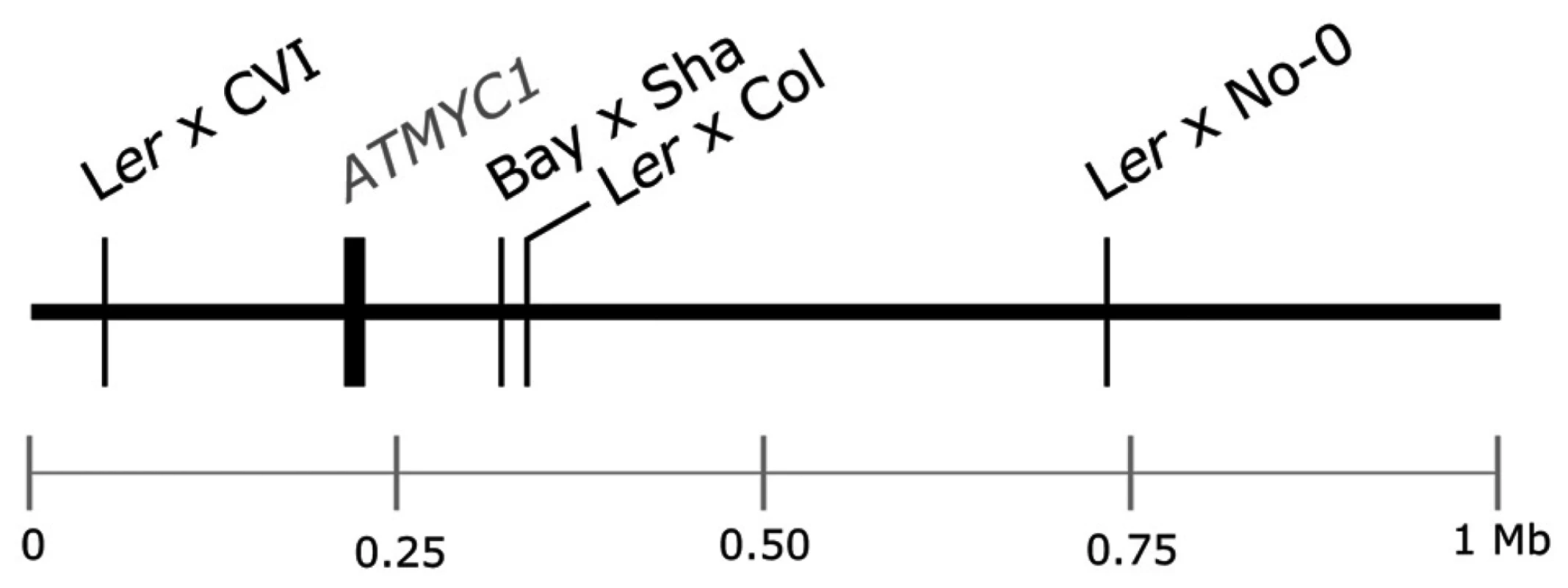

Fig. 1. Schematic of the top 1 Mb of the physical map of chromosome four of A. thaliana.

The physical position of the ATMYC1 locus and the estimated physical positions of TDL5 from four different mapping populations are indicated to scale. Confidence intervals for the QTL mapped in each population span the entire top 1 Mb of chromosome four, including the ATMYC1 locus. Results

atmyc1 trichome phenotype

Previous QTL mapping results for trichome density in A. thaliana localized a QTL to the top of chromosome four in four independent mapping populations [40]. Although no known trichome regulator was apparent in this region, ATMYC1, a paralog of three genes with known roles in trichome initiation was discovered. To determine if ATMYC1 has a role in trichome initiation, we examined TDNA insertion (knock-out) lines. A homozygous TDNA insertion line for ATMYC1 (SALK_057388) in a Col-0 background was determined to have a significantly different number of trichomes/first true leaf and trichome density phenotype on fifth true leaves relative to the wildtype Col-0 accession (Figure 2). The atmyc1 mutant produced fewer trichomes than wildtype on first true leaves and had a lower trichome density on fifth leaves. The trichome phenotype of atmyc1 has since been verified in two additional independent TDNA insertion lines of the gene (Figure S1).

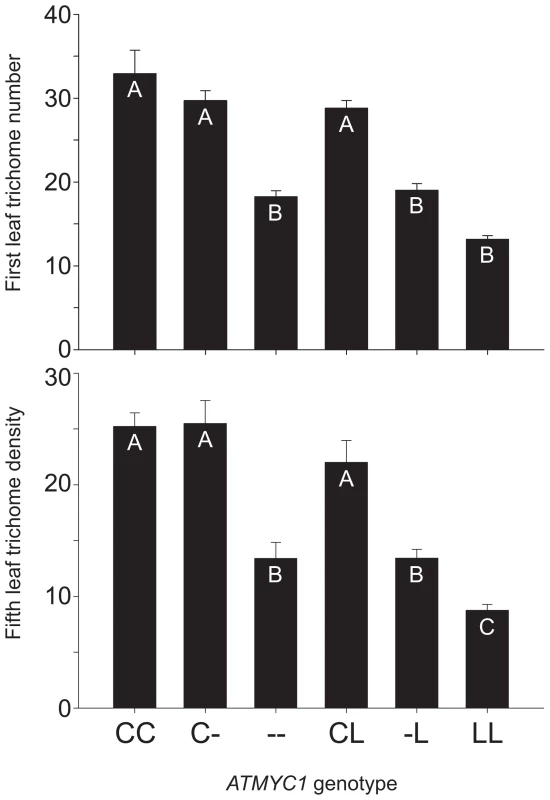

Fig. 2. Genetic complementation test results.

To test for genetic complementation of the atmyc1 mutant, a series of test-crosses were made between Col-0, Ler-0, and the atmyc1 mutant (in the Col-0 background). Two phenotypes were scored for each genotype: trichome number on first true leaves and trichome density on fifth true leaves; means (+SE) are shown for each ATMYC1 genotype and genotypes with different letters within each bar chart are significantly different from each other (p<0.01, except B vs. C (p<0.05). Both first and fifth leaf phenotypes were used in previous QTL mapping studies. Note that the trends for the two phenotypes are nearly identical, simply shifted up or down, depending on the leaf scored. By comparing the Col (CC), Col x atmyc1 (C-) and atmyc1 (--) genotypes (- denotes a nonfunctional mutant allele), all of which are in an otherwise Col-0 background, it is clear that a single copy of the Col allele of ATMYC1 recovers the mutant phenotype to near wildtype levels. In contrast, comparisons between the Col x Ler (CL) and atmyc1 x Ler (L-) genotypes, each of which is in an otherwise Col/Ler background show that the Ler allele of ATMYC1 does not recover the mutant phenotype. Quantitative complementation tests for ATMYC1

To test for a functional difference between the Col-0 and Ler-0 (hereafter, Col and Ler) alleles of ATMYC1, quantitative genetic complementation analyses were performed by comparing the trichome densities of Col, Ler, a homozygous atmyc1 mutant in a Col background, and pairwise F1s among them (Figure 2). Germination rates were variable across genotypes in each experiment, resulting in sample sizes ranging from 11–18 and 8–14 for first and fifth leaf phenotypes, respectively. A one-way ANOVA revealed that both traits were found to differ significantly across the compared groups (first leaf phenotype: F (5, 81) = 42.455, p<0.001; fifth leaf phenotype: F (5, 56) = 20.63, p<0.001) and Tukey-Kramer post-hoc tests, which account for sample size variation, were revealing in several ways. The test cross of Col x atmyc1 showed little to no evidence of a gene dose effect (Figure 2). That is, the Col x atmyc1 genotype does not differ significantly from that of the Col wildtype genotype for first and fifth leaf trichome phenotypes, showing that a single Col allele of ATMYC1 is sufficient to complement the reduced trichome phenotype of the mutant to near wildtype levels. In contrast, the Col x Ler genotype has trichome phenotypes significantly higher than the atmyc1 x Ler genotype, showing that a single copy of the Ler ATMYC1 allele does not complement the atmyc1 mutant phenotype, indicating that Ler contains a nonfunctional (with regard to trichome initiation), recessive allele of ATMYC1.

Network analysis of ATMYC1 alleles

In a screen of 72 A. thaliana accessions, considerable sequence variation was discovered among natural alleles of ATMYC1 with a total of 28 (inferred) cDNA haplotypes discovered (GenBank accession #s: JF801957-JF802028). Median-joining analyses yielded a network that is split into two diverged clusters (Figure 3); these have been labeled as Type I and Type II, with 16 and 12 haplotypes, respectively. Alleles of these two Types consistently differ by 25 substitutions, which translate to 17 amino acid replacements. Interestingly, nearly all of this variation (24 of 25 substitutions and all 17 replacements) is in exon six (Figure S2).

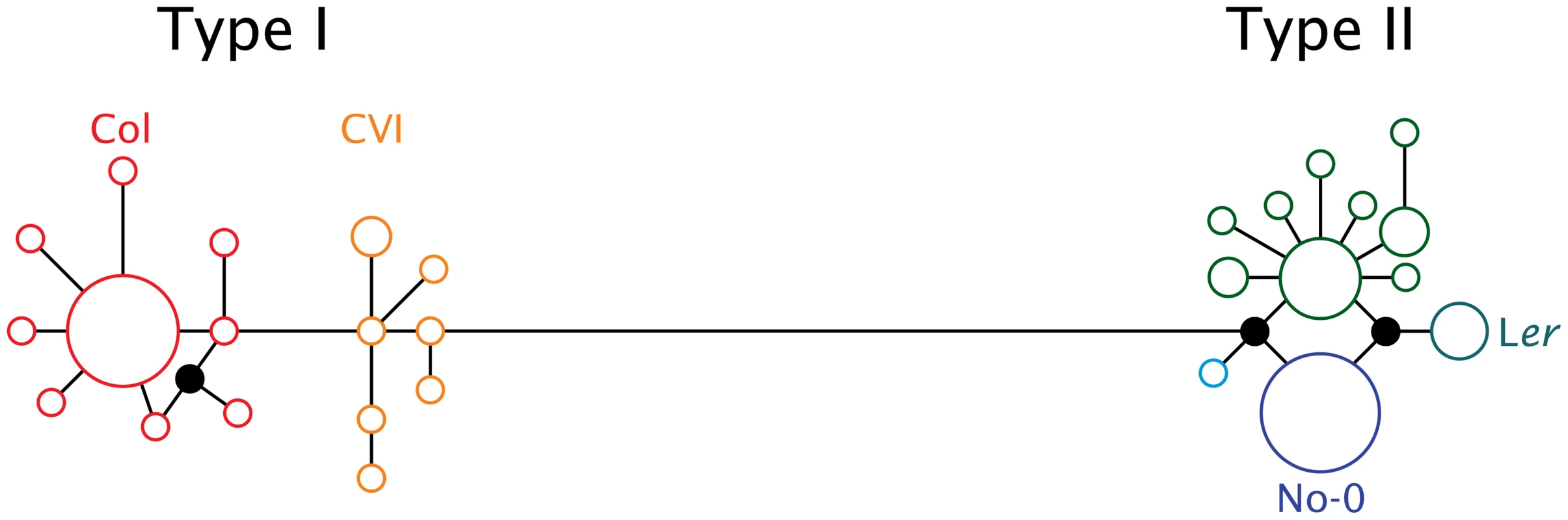

Fig. 3. Median joining network of 28 ATMYC1 inferred cDNA haplotypes representing alleles sampled from 72 A. thaliana accessions.

Each circle represents a unique coding haplotype and the area of each circle indicates the relative frequency at which each haplotype was sampled. Unsampled haplotypes required to complete the network are drawn as filled-in circles. Branch lengths reflect nucleotide change between any two haplotypes. The large block of variation within exon six falls along the long branch that connects the Type I to the Type II haplotype clusters. The accessions discussed in the text are indicated adjacent to the haplotype they possess. Both allele types are at high frequency. Of the 72 accessions for which full-length ATMYC1 sequence was obtained, 31 possess a Type I allele and 41 have a Type II allele; however, no obvious geographic pattern was evident. With regard to the four RIL mapping populations in which TDL5 was mapped previously [40], it is interesting that the six parental accessions possess five different alleles (Figure 3; only the allele carried by the four parents of the mapping populations that include Ler as a parent are labeled). Perhaps most interesting among these alleles is that which the Ler accession carries, as this allele consistently conferred lower trichome density in previous QTL mapping experiments. Three natural accessions possess this same allele, one of which is La-0 (cs6765), a wildtype accession from the same region as the progenitor of Ler; the other two are Dra-1 (cs6686) and Sg-2 (cs6859).

Molecular evolution of the ATMYC1 locus

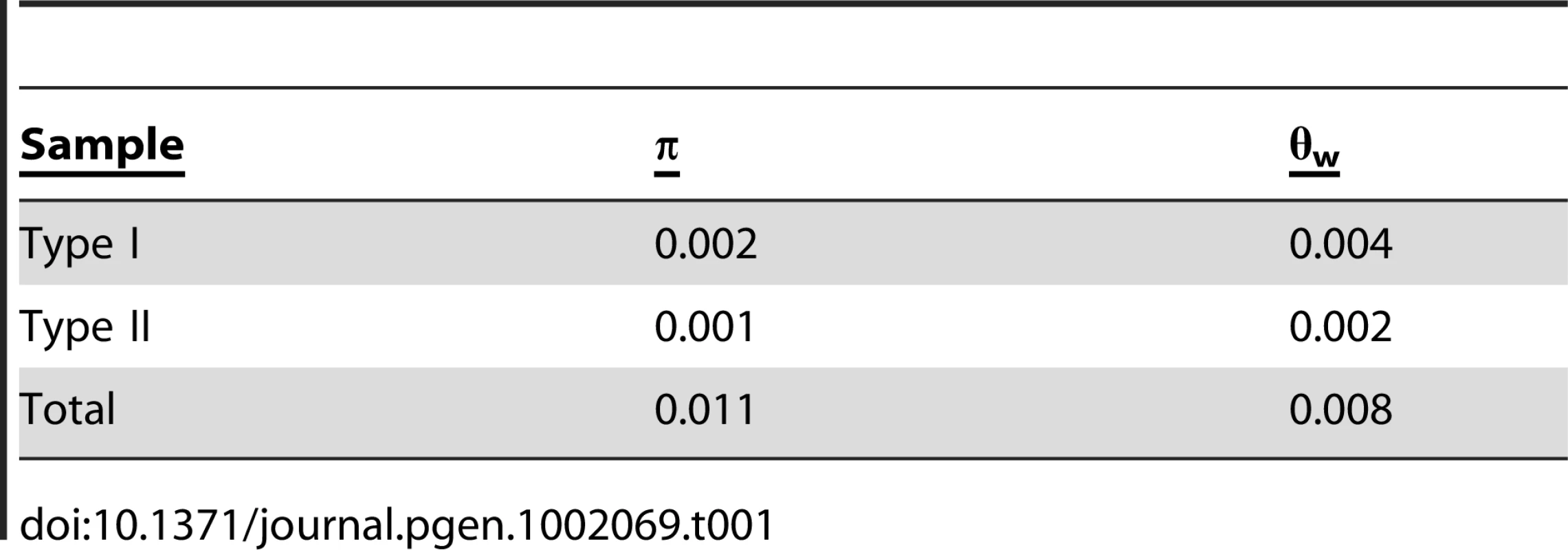

An analysis of the 72 A. thaliana alleles of ATMYC1 yielded overall levels of nucleotide diversity and polymorphism (π & θw; Table 1) that are somewhat higher than genome-wide average values reported for A. thaliana genes [48], [49]. A sliding window analysis revealed high localized levels of nucleotide diversity (Figure 4), the highest of which was detected within exon six.

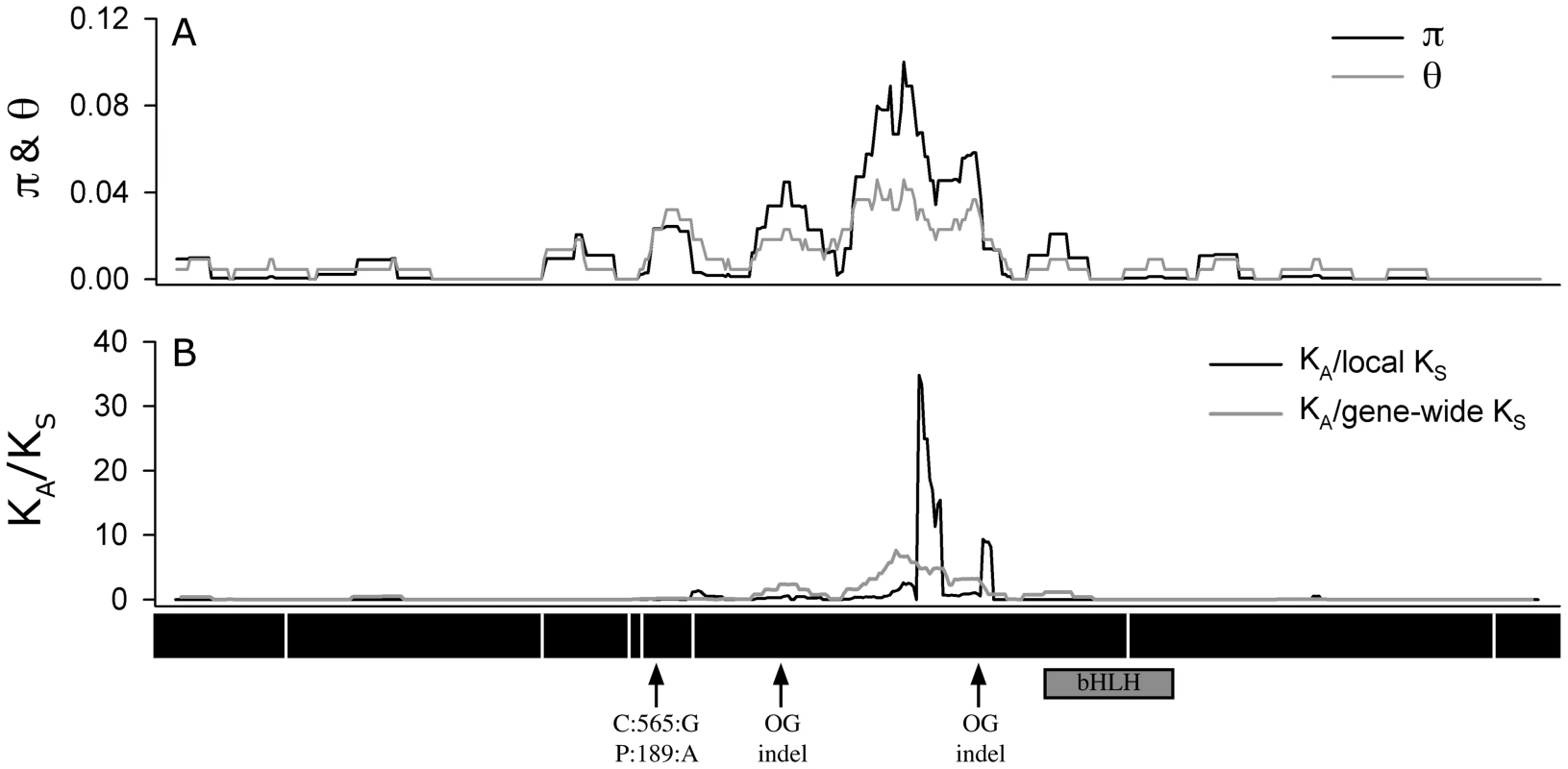

Fig. 4. Sliding window analysis.

Of (A) π and θW and (B) the ratio of nonsysnonymous substitution rate (KA) to synonymous substitution rate (KS). The diversity plots in (A) were generated with a 45 bp window moved along the length of the aligned sequences at 3 bp intervals; the black line shows π and the grey line shows θW. The plots in (B) were generated by comparing the two pools of ATMYC1 alleles (Type I and Type II) with a window size of 45 bp again slid at 3 bp intervals. The black line represents the ratio of local KA/local KS and the grey line represents the ratio of local KA/gene-wide average KS. Values near one are inferred to represent regions having undergone neutral molecular evolution, values <<1 indicate purifying selection and values >>1 indicate positive selection. The black boxes beneath the plot represent the eight exons of ATMCY1. While purifying selection is evident throughout most of the gene, strong evidence for divergent selection between Types I and II alleles is present in exon six. The positions of two indels relative to outgroup (OG) taxa are indicated with arrows. Also the position of the substitution that results in an amino acid polymorphism at position 189 between Col and Ler is indicated with an arrow. The position of the bHLH domain of ATMYC1 is represented by a grey box. Tab. 1. Summary of diversity indices for <i>ATMYC1.</i>

Because regions of high nucleotide diversity corresponded with divergence between Type I and Type II alleles, we wanted to characterize the nature of this molecular variation. To explore this, we used a sliding window method to study rates of non-synonymous (KA) and synonymous (KS) divergence between Types I and II alleles across the entire 1.58 kb coding region. These analyses revealed evidence of alternative forms of selection that are gene region-specific (Figure 4). Across most of the gene, it appears that purifying selection has acted to constrain the amino acid sequence (ratios <<1); however within exon six, extremely high rates of amino acid replacement are evident between the two Types. As a KA/KS ratio greater than one is often cited as a conservative cut-off for positive selection [50], [51], values approaching 30 are exceptional. Even the more rigorous approach using the gene-wide average KS value resulted in a KA/KS ratio greater than eight in this region. Outside of exon six, no other region of ATMYC1 showed evidence of positive selection. Interestingly, most of the divergence between the two A. thaliana ATMYC1 Types falls between two indels that differentiate all A. thaliana alleles from two distant outgroup alleles (Figure 4 and Figure S2).

Testing for an ATMYC1 Types difference for trichome density

Of the 93 ecotypes that were screened for trichome density, 50 possessed a Type I allele and 43 possessed a Type II allele. Although broad-sense heritability was relatively high for the experiment (H2 = 0.71), there was no significant difference for trichome density detected between ecotypes carrying the two alternative ATMYC1 allele Types according to a Kruskal-Wallis test (data not shown). Although variation segregating at other loci may overwhelm the effects of alternative ATMYC1 Types, it appears that the observed sequence variation in exon six has little to no effect on trichome density. Given the sample sizes and standard deviations, a power analysis indicated that a trichome density difference of at least three units should have been detectable as significant.

Conservation at Col/Ler polymorphism positions

Because a QTL was mapped for trichome density near ATMYC1 in the Col x Ler RIL population and quantitative genetic complementation tests revealed a functional difference between the Col and Ler ATMYC1 alleles, we examined polymorphisms between these two alleles. The Col and Ler accessions possess different ATMYC1 Types; however, the variation in exon six that distinguishes the two Types has no detectable effect on trichome density. Therefore, other polymorphisms between the Col and Ler alleles were investigated. The Col and Ler proteins differ at just four other positions: A13T, E83Q, P189A, and P343H (Col:aa position:Ler). Of these polymorphisms, only position 189 is highly conserved across proteins and taxa. Out of 100 homologs, representing monocots and dicots, retrieved through a protein-BLAST search of the Col ATMYC1 protein sequence, all 100 shared the Col state (proline) at ATMYC1 amino acid position 189 (data not shown). This position is also of interest as it resides within an undefined, but known MYB interaction domain in the amino end of close paralogs of ATMYC1 [44], [45]. The other three polymorphic positions were found to be far less conserved. Based on these results, yeast-2-hybrid experiments focused on the highly conserved position 189 and the non-conserved position 13 as a control.

Yeast two-hybrid results

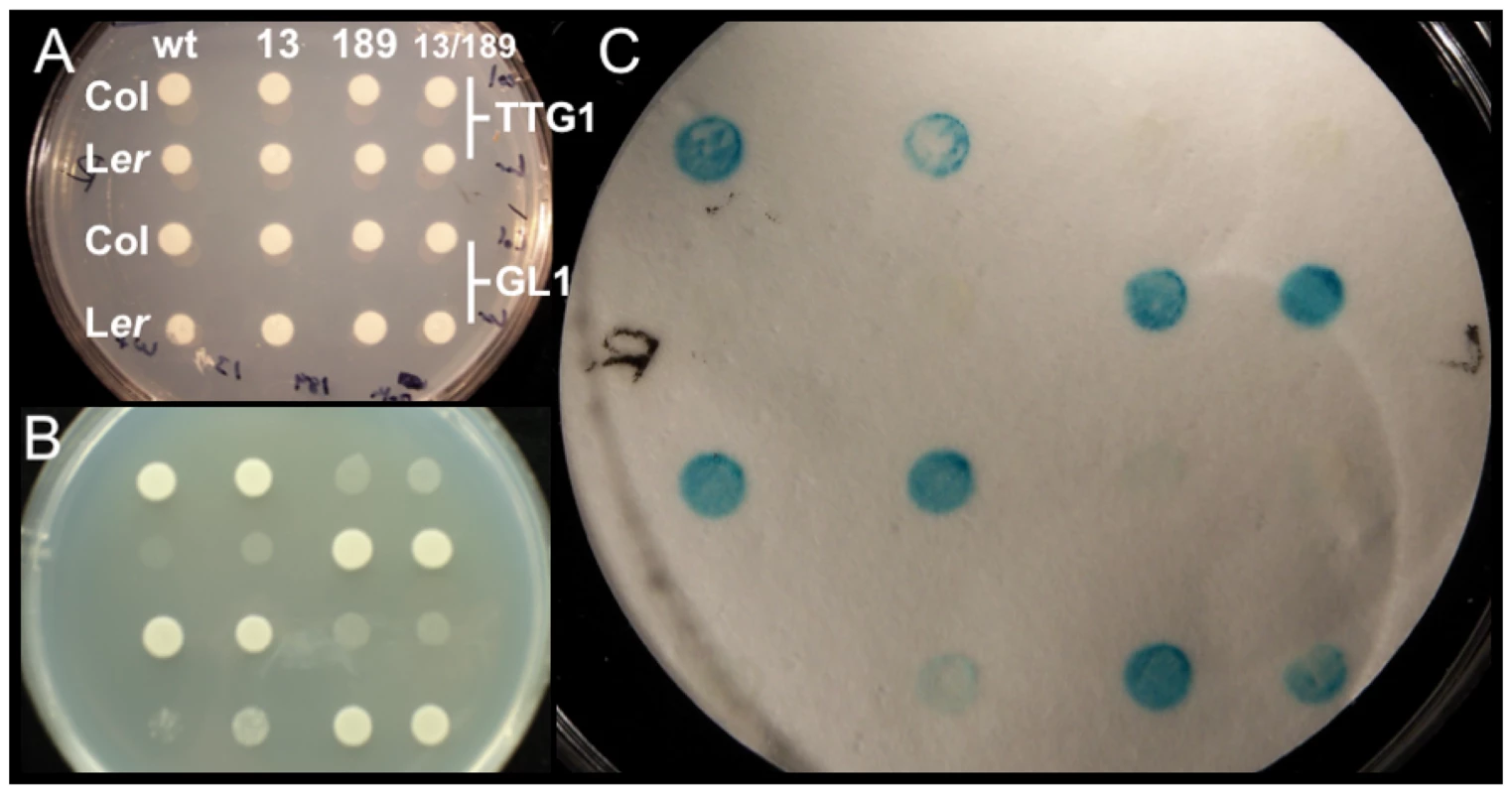

We investigated the effects of two Col/Ler ATMYC1 polymorphisms on protein-protein interactions using binding assays with known partners, TTG1 and GL1 [47], [52]. The results are clear. ATMYC1 encoded by the native Col allele interacts with TTG1 and GL1 and the ATMYC1 protein encoded by the native Ler allele does not. Reciprocal replacements at position 13 for the Col and Ler alleles had no effect on binding, while reciprocal replacements at position 189 qualitatively altered binding for both proteins. Specifically, when the Col allele was changed to match the Ler allele at position 189, the protein no longer bound to TTG1 or GL1 and when the Ler allele was changed to match the Col allele at position 189, the resulting protein then bound with TTG1 and GL1 (Figure 5).

Fig. 5. Yeast two-hybrid analysis testing Col/Ler ATMYC1 polymorphism effects on protein–protein interactions with known binding partners TTG1 and GL1.

All images show the same pattern of yeast containing ATMYC1 from Col or Ler in binding domain with either TTG1 or GL1 in the activation domain. To test whether variation at amino acid positions 13 or 189 had any effect on the function of ATMYC1, reciprocal replacements were produced between Col and Ler at these positions separately and together; wt shows interaction data for the native Col and Ler ATMYC1 proteins, 13 shows interaction data for reciprocal replacements in Col and Ler alleles at amino acid position 13, 189 shows interaction data for reciprocal replacements at position 189, and 13/189 shows interaction data for alterations at both positions. (A) Control colonies with no selection for interaction. (B) Same as A grown on Histidine dropout media. Interaction between ATMYC1 and either TTG1 or GL1 is required for growth. (C) Colonies in A were lifted on nitrocellulose, which was used in analysis of β-galactosidase activity. Blue is an indication of interaction. These results clearly show that the Col ATMYC1 allele interacts with GL1 and TTG1 while the Ler allele does not. Reciprocal replacements clearly show that the cause of the interaction difference between Col and Ler proteins is the polymorphism at amino acid position 189; the Col protein with 189A no longer interacts with TTG1 and GL1 and the Ler protein with 189P fully interacts with TTG1 and GL1. Reciprocal replacements at position 13 have no effect on binding and the combined replacements at 13/189 mirror the results of the replacement at position 189 alone. Discussion

Identifying the genes and ultimately the molecular changes that underlie natural morphological variation remain important, but largely elusive goals. Here we have taken a candidate gene approach based on QTL mapping results and have identified a function for the transcription factor, ATMYC1, in which natural molecular variation affects trichome density in A. thaliana. Furthermore, our results reveal a strong signal for directional selection restricted to one exon of ATMYC1 that has no detectable effect on trichome density but may suggest a pleiotropic role for the gene.

ATMYC1 is a Quantitative Trait Gene for trichome density

An initial TDNA insertion line of ATMYC1 in the Col background was found to have a reduced trichome density phenotype relative to wildtype Col (Figure 2); subsequent examination of additional independent insertion lines have confirmed this trichome initiation phenotype (Figure S1). The trichome phenotype is consistent with high sequence similarity between ATMYC1 and close paralogs GL3, EGL3, and TT8 [41], [42], which also have trichome phenotypes upon knock-out [43]–[45]. However, this finding is somewhat surprising, as GL3 and EGL3 have been shown to be sufficient to fulfill the bHLH role in trichome initiation; a gl3/egl3 double mutant is completely glabrous [45], suggesting that ATMYC1 may be an enhancer of GL3 and EGL3. While the precise genetic role that ATMYC1 plays in the TTG1 pathway requires more work to elucidate, the trichome cell fate function is clear. Subsequent quantitative genetic complementation tests showed that the Ler allele of ATMYC1 cannot recover the atmyc1 trichome phenotype, while the Col allele recovers it completely (Figure 2), indicating that natural molecular variation in ATMYC1 alters trichome density.

Sequence variation between Col and Ler (parents of the one of the mapping populations where TDL5 was mapped) ATMYC1 alleles prompted a broad survey of ATMYC1 from 69 ecotypes and three lab strains of A. thaliana, which revealed a striking pattern of high frequency polymorphism. The coding region of the two primary Types observed consistently differ by 25 substitutions, which translate into 17 amino acid replacements; 24 of the 25 substitutions and all 17 replacements reside within exon six. This amounts to >10% amino acid replacement within exon six; no other region of the gene has a high rate of replacement. Allelic dimorphism has been reported for some, but not all, other loci in A. thaliana (e.g., [37], [53]–[55]) and is likely the result of diverfgence between two long-isolated populations of A. thaliana with subsequent break-down of population subdivision and admixture. Regardless of the origin of the Types, the ATMYC1 results are striking due to the high frequency of amino acid replacement and because nearly all of the variation resides within one relatively small region of the gene. That the Col and Ler alleles possess different ATMYC1 Types initially suggested that the molecular variation in exon six might explain the functional difference revealed by quantitative complementation tests; however, neither association tests nor yeast 2-hybrid experiments (Figure 5) support this hypothesis.

Outside of the block of variation in exon six that differentiates the two Types, only four other changes differentiate the coding regions of the Col and Ler alleles. Yeast-2-hybrid experiments to test the known interactions between ATMYC1 and TTG1 and ATMYC1 and GL1 showed that the P189A (Col:aa position:Ler) replacement has a qualitative effect, completely eliminating these interactions for the protein encoded by the Ler allele of ATMYC1. The proline at this position is conserved, even among distant homologs of ATMYC1, and likely resides in a known, but undefined, protein-protein interaction domain identified in close paralogs of ATMYC1 [44], [45]. Indeed, simply replacing the proline for an alanine at this position in the Col allele eliminates the interaction with TTG1and GL1, while the reciprocal change, replacing the alanine for a proline in the Ler allele, restores these interactions (Figure 5). Although this may not have been the first or the only mutation in the P189A ATMYC1 allele to eliminate gene function and reduce trichome density, these data show that the P189A replacement is sufficient to explain the functional difference between the Col and Ler alleles, presumably by altering trichome initiation, thereby decreasing trichome density.

We conclude that ATMYC1 is a Quantitative Trait Gene (QTG) for trichome density in A. thaliana and that the mutation at DNA position 565 is a Quantitative Trait Nucleotide (QTN) for the trait. An interesting point to emerge here is that a single base substitution has lead to a qualitative breakdown in protein-protein interaction, which has a quantitative phenotypic effect; based on sequence similarity, this is likely due to functional redundancy between ATMYC1, GL3, EGL3, and TT8. The nature of the Ler mutation suggests that this was the same QTG mapped for trichome density by Symonds et al. [40] in two other populations that have Ler as a parent: No-0 x Ler and CVI x Ler; CVI and No-0 possess Type I and II ATMYC1 alleles, respectively, but share the proline at amino acid position 189 with Col, further supporting the conclusion that the variation differentiating the Types has little or no effect on trichome density while the replacement at position 189 underlies the mapped effect. Furthermore, QTL mapping results show that the Ler allele at TDL5 consistently confers lower trichome density than the alternative allele from Col, CVI, and No-0 and the additive effect of TDL5 was nearly identical in all three mapping populations [40].

The ATMYC1 allele carried by Ler is shared by three natural ecotypes, La-0 (Poland), Dra-1 (Czech Republic), and Sg-2 (Germany). In our sample, this allele is at a frequency of ∼5%. Because it is unknown if ATMYC1 is pleiotropic, we cannot yet address whether or not the replacement at position 189 affects other traits. However, the 189A allele shows no signs of degradation to pseudogene status in any of the three natural ecotypes. This could be due to one or both of the following: (1) the protein has other functions that are not affected by the mutation at position 189 and is maintained by purifying selection and (2) this mutation is relatively recent and there has not been sufficient time for other mutations to accumulate. With regard to the second hypothesis, the 189A allele has at least persisted long enough for migration to increase its presence to multiple populations.

Cryptic allelic variation at ATMYC1

Association tests showed no obvious trichome density difference for the two high frequency ATMYC1 Types and yeast-2-hybrid experiments suggest that the divergence between the two Types has no effect on known protein-protein interactions. If the variation in exon six has no effect on trichome density, then what explains the clear signature of divergent selection between the allele Types? There would seem to be three logical explanations. First, the association test results could reflect confounding factors, such as segregation of variation at other loci that have larger effects on trichome density and essentially swamp out a potential ATMYC1 Types effect. If this were true, the Types effect would have to be in addition to and much weaker than that found for the replacement at position 189.

Second, divergence could have been in response to selection on a trait other than trichome density; indeed, paralogs of ATMYC1 (GL3, EGL3 and TT8) are all pleiotropic for several epidermal traits [43]–[45], ATMYC1 has been shown to interact with several MYB transcription factors that coordinate other epidermal fates [47], and an ATMYC1 homolog from Vitis vinifera (Vitaceae) was recently shown to have an epidermal (anthocyanin) phenotype [56]. ATMYC1 is most highly expressed in “seeds” [46], therefore, it may be expected to be involved in testa development as well; however, we have observed no differences in comparisons between a TDNA knock-out line of ATMYC1 in the Col-0 background and Col-0 for three seed coat traits: mucilage production, condensed tannin synthesis, and seed coat cell morphology (data not shown).

Finally, the two Types may have evolved independently in response to deleterious indels. Comparisons with outgroup homologs of ATMYC1 show that the divergence between the two A. thaliana allele Types resides between or near two indels (relative to outgroup taxa) of 18 and 15 bp after coding DNA positions 705 and 927 (in Col-0 sequence), respectively (Figure 4 and Figure S2; outgroup sequence data not shown). Specifically, rather than diverging from one another, the two A. thaliana Types may have independently diverged away from a common nonfunctional ancestral copy of the gene. Although at this stage we cannot determine the origins of the indels, recombination and transposable elements seem likely candidates. Whatever the origins, in A. thaliana, isolated populations may have acquired independent compensatory mutations that became fixed in each lineage. Because trichome density is dynamic, with the fitness of a given density being relative to the environment [32], such mutations may persist for long periods, thus allowing time for compensation. All A. thaliana alleles share indel states at these two positions with A. lyrata relative to the more distant outgroups, Capsella bursa-pastoris and Crucihimalaya himalaica. Further functional and analytical tests will be required to resolve the origins and potential effects of the divergence around these indels.

Conclusions

Trichome density in A. thaliana is likely to be under alternating forms of selection, depending on the particular environment in which a plant resides. The TTG1 genetic pathway, which contains multiple and various types of transcription factors, many of which are functionally redundant, would seem a likely reservoir of genetic variation for epidermal traits and a prime pathway for “genetic tinkering” [57] with potentially a low risk of permanent unidirectional trait change. Indeed, we have shown here that a low frequency polymorphism that results in a simple amino acid replacement in ATMYC1 reduces trichome density in natural ecotypes of A. thaliana, thereby ascribing the first function to ATMYC1. Our results also revealed a high frequency block of amino acid replacements in ATMYC1 with as yet unknown effects. ATMYC1 is the second gene in the TTG1 pathway recently identified to affect natural quantitative variation for trichome density; interestingly, for the single-repeat MYB, ETC2, high frequency polymorphisms do affect trichome density [37], while a similar pattern in ATMYC1 does not seem to alter trichome density. Clearly patterns that define the types of mutations and classes of genes that underlie natural variation may be difficult to identify; however, the TTG1 pathway is quickly emerging as a good place to search.

Methods

The ATMYC1 mutant phenotype

A TDNA insertion line (SALK_057388) for the ATMYC1 locus (At4g00480) in the Col-0 background was obtained from The Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC; http://signal.salk.edu/cgi-bin/tdnaexpress). The initial batch of seed was screened using a standard PCR protocol to identify a lineage homozygous for the TDNA insertion, which resides in the first exon of the gene. Based on initial observations of a trichome density phenotype for the atmyc1 mutant, first leaf trichome number and fifth leaf trichome density phenotypes were then measured in replicates of Col-0 and atmyc1as described in the following section.

Quantitative genetic complementation tests

To test the hypothesis that variation at the ATMYC1 locus underlies trichome density variation mapped to TDL5 in previous QTL studies [40], quantitative complementation tests were performed. In the QTL mapping studies, the Ler allele at TDL5 was shown to confer lower trichome density than the alternative parents' (Col-4, CVI, and No-0) alleles in each mapping population. However, because the available atmyc1 knock-out mutation is in the Col-0 background, the most direct comparison that could be made (with regard to QTL mapping results) was between Col and Ler. Crosses were made by transferring pollen from flowers of the Ler accession onto the stigmatic surface of emasculated flowers of the atmyc1 mutant and of Col wildtype. To control for potential cytoplasmic variation among accessions, all crosses were made with Col or atmyc1 as the pollen recipient. Therefore, the resulting F1s differ only at the atmyc1 locus. This allowed for comparisons between individuals with a Col/Ler and an atmyc1/Ler genotype at ATMYC1, while holding the rest of the genome constant. That is, the only difference between the two sets of progeny is the replacement of a copy of the Col allele with a null (mutant) atmyc1 allele. To test for a dosage effect, Col was crossed to atmyc1, which yields a Col individual with a single functional ATMYC1 allele (atmyc1/Col genotype). Twenty replicates of each F1 genotype, parental accession, and the atmyc1 mutant were potted and the pots were randomized across four flats. All seed were vernalized in the dark for four days at 4°C, and subsequently moved to a fluorescently lit 20°C growth chamber. Sixteen days after emergence the number of trichomes on each of the first two true leaves of each seedling were counted under 50X magnification on a dissecting microscope; this is referred to as the “first leaf” trichome number phenotype. For the “fifth leaf' trichome density phenotype, the same experiment was set up as described above and trichome density was measured on the fifth true leaf at 21 days after emergence, as described by Symonds et al. [40]. The mean for each trait was then calculated from these data for each genotype. The genetic contribution to trichome number and trichome density variation was evaluated for first and fifth leaf phenotypes independently by ANOVA and unplanned pairwise comparisons between genotypes following the Tukey-Kramer method as described by Sokal and Rohlf [58].

Survey of natural allelic variation at ATMYC1

DNAs were isolated from 69 natural accessions and three lab strains of A. thaliana acquired from the ABRC (Table S1), following a modified CTAB method [59]. Primers were designed from the Col-0 ATMYC1 sequence (GenBank accession #NC003075) to PCR amplify the open reading frame plus ∼200 bp up - and down-stream of the start and stop codons, respectively. Primers corresponding with the first and last 21 bp of the Col-0 ATMYC1 cDNA sequence were used to amplify the ATMYC1 homolog from outgroup taxa (all Brassicaceae): Arabidopsis lyrata, Crucihimalaya himalayica, and Capsella bursa-pastoris. All primers were used with manufacturer-supplied 1X Taq buffer, 1U AccuPrime High-Fidelity Taq polymerase (Invitrogen Inc.), and ∼20 ng genomic DNA in 20 uL reactions. PCR samples were checked for amplification success on 0.7% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide, and were subsequently purified in Multiscreen PCR clean-up plates (#MANU03050, Millipore). Approximately 100 ng of each purified PCR product were then used in each of seven sequencing reactions using primers designed to anneal at staggered internal positions, providing a minimum of two overlapping sequences across the entire gene. Allelic contigs were constructed for each ecotype and sequence editing and validation were performed using sequencher v.4.2.2 (Gene Codes Corp.). Full-length genomic sequences of ATMYC1 for all accessions were aligned initially using clustalx v.1.83 [60], and subsequently corrected by hand. To generate inferred cDNA sequence alignments, introns were identified using the published Col-0 cDNA sequence as template (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative) and non-coding DNA sequence was removed from the genomic alignment in bioedit v.5.0.9 [61].

Independent cDNA haplotypes were identified using dnasp v.4.00 [62] and exported in rgl format. A haplotype network was constructed in network (Fluxus Technology, Ltd.) using the median-joining option and redrawn using indesign (Adobe, Inc.). A high level of divergence between two sets of alleles revealed by the haplotype network was the basis for identifying two Types of ATMYC1 alleles; these Types (I and II) are referenced in other sections.

Molecular evolution of the ATMYC1 locus

To examine nucleotide diversity and molecular evolution of the ATMYC1 locus, the sequence analysis software dnasp v.4.00 [62] was used. The common nucleotide diversity indices, π [63] and θw [64], were measured across the entire genomic alignment for all sequences and independently for Type I and II data sets. To assess intra-gene variation for nucleotide diversity, a sliding window analysis was run along the full-length (start to stop) cDNA sequence alignment of the 72 A. thaliana alleles; window length was set at 45 bp and moved along the alignment at 3 bp intervals.

Because of initial observations of high levels of diversity and divergence between two apparent Types of ATMYC1 alleles, we tested the null hypothesis of neutral molecular evolution at this locus by measuring the nonsynonymous substitution rate (KA) and the synonymous substitution rate (KS). By examining the ratio of KA/KS, one may identify signals indicative of positive or purifying selection [50]. KA/KS ratios near one are thought to indicate a neutrally evolving gene or region of a gene, values <<1 are expected to be under purifying selection, and values >>1 indicate positive selection. Because different regions of a gene may experience different forms of selection, a sliding window analysis was used to examine sequence divergence (KA/KS) between Types I and II ATMYC1 alleles; the window size was set at 45 bp, and was moved in 3 bp increments along the length of aligned (inferred) cDNA sequences. These ratio plots were generated in two ways: (1) using local KA over local KS measures and (2) using local KA values over the gene-wide KS value. While the former method is the convention, the latter has been suggested as an alternative to deal with false or misleading positives caused by very low local KS values [65]. For each window of sequence the KA/KS ratio was calculated using both methods and the results were plotted using sigmaplot (Systat Software, Inc.).

Testing for an ATMYC1 Types difference for trichome density

The finding of two highly diverged allele types at the ATMYC1 locus prompted an investigation of the potential effect of this sequence divergence on trichome density. To this end, trichome density was scored on fifth true leaves for a set of 96 ecotypes of A. thaliana (details on this set of ecotypes can be found in [48]) following the methods of Symonds et al. [40]. The ecotypes were screened for ATMYC1 Type using a PCR scheme with Type-specific forward and reverse primers that terminate on multiple sites that are polymorphic between the two Types; that is, only one set of primers yields a product for each ecotype, thus distinguishing the two Types. The trichome data were partitioned into the two allele classes and because the data showed a bimodal distribution, a Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test was performed using mapqtl [66] to test for a significant difference in trichome density between the two groups. Although association mapping in A. thaliana ecotype collections is potentially confounded by false positives due to population structure [67], [68], we didn't subsequently correct for population structure given our initial negative result.

Conservation and placement of Ler/Col polymorphisms

Outside of the variation that distinguishes the two ATMYC1 Types (Col and Ler possess alternative Types), four amino acid replacements differentiate the Col and Ler alleles. To assess the conservation of these four positions, the Col ATMYC1 protein sequence was submitted to a protein BLAST search and the top 100 hits were aligned and conservation at each of the four sites that differ between the Col and Ler alleles was evaluated in this alignment.

Yeast two-hybrid tests for functional differences

Based on the placement and conservation of polymorphisms between the Col and Ler alleles, two amino acid positions were selected to test for interaction effects with known partners, TTG1 and GL1: A13T and P189A (Col:aa position:Ler). ATMYC1 cDNAs were cloned by Reverse Transcription and PCR amplified using start to stop gateway primers and recombined into pDONR/Zeo (Invitrogen). These clones were then modified using Stratagene's QuikChange XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit as recommended by the manufacturer. The Col cDNA was modified to make a version with a T13A change, one with a P189A change and one with both changes. The Ler cDNA was modified to make a clone with an A13T change, one with an A189P change and one with both. Each of these clones was then recombined into the yeast two-hybrid DNA binding vector pGBT9 RFB. The WDAD (TTG1A) and SRV6 (pGL1A) activation domain vectors were described previously [44]. All clones were sequenced in their entirety. The ATMYC1 yeast vectors were transformed into the Y190 yeast strain. WDAD and SRV6 were then transformed into each of the ATMYC1 yeast lines. The yeast two-hybrid assay was performed as previously described [44] using X-gal as a substrate for β-galactosidase activity and growth on histidine dropout media as interaction markers.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. FalconerDSMackayTFC 1996 Introduction to Quantitative Genetics. Harlow, UK Addison Wesley Longman

2. LynchMWalshB 1998 Genetics and Analysis of Quantitative Traits. Sunderland, MA Sinauer Associates

3. KoornneefMAlonso-BlancoCVreugdenhilD 2004 Naturally occurring genetic variation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Annu Rev Plant Biol 55 141 172

4. MackayTF 2010 Mutations and quantitative genetic variation: lessons from Drosophila. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 365 1229 1239

5. StinchcombeJRHoekstraHE 2008 Combining population genomics and quantitative genetics: finding the genes underlying ecologically important traits. Heredity 100 158 170

6. AtwellSHuangYSVilhjalmssonBJWillemsGHortonM 2010 Genome-wide association study of 107 phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana inbred lines. Nature 627 631

7. BanghamJObbardDJKimKWHaddrillPRJigginsFM 2007 The age and evolution of an antiviral resistance mutation in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Biol Sci 274 2027 2034

8. EhrenreichIMTorabiNJiaYKentJMartisS Dissection of genetically complex traits with extremely large pools of yeast segregants. Nature 464 1039 1042

9. WeigelDNordborgM 2005 Natural variation in Arabidopsis. How do we find the causal genes? Plant Physiol 138 567 568

10. El-AssalSEDAlonso-BlancoCPeetersAJRazVKoornneefM 2001 A QTL for flowering time in Arabidopsis reveals a novel allele of CRY2. Nat Genet 29 435 440

11. FlowersJMHanzawaYHallMCMooreRCPuruggananMD 2009 Population genomics of the Arabidopsis thaliana flowering time gene network. Mol Biol Evol 26 2475 2486

12. JohansonUWestJListerCMichaelsSAmasinoR 2000 Molecular analysis of FRIGIDA, a major determinant of natural variation in Arabidopsis flowering time. Science 290 344 347

13. MichaelsSDHeYScortecciKCAmasinoRM 2003 Attenuation of FLOWERING LOCUS C activity as a mechanism for the evolution of summer-annual flowering behavior in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100 10102 10107

14. BurkeACNelsonCEMorganBATabinC 1995 Hox genes and the evolution of vertebrate axial morphology. Development 121 333 346

15. Des MaraisDLRausherMD 2010 Parallel evolution at multiple levels in the origin of hummingbird pollinated flowers in Ipomoea. Evolution 64 2044 2054

16. JeongSRebeizMAndolfattoPWernerTTrueJ 2008 The evolution of gene regulation underlies a morphological difference between two Drosophila sister species. Cell 132 783 793

17. OrrHAMaslyJPPresgravesDC 2004 Speciation genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 14 675 679

18. PhadnisNOrrHA 2009 A single gene causes both male sterility and segregation distortion in Drosophila hybrids. Science 323 376 379

19. KingMCWilsonAC 1975 Evolution at two levels in humans and chimpanzees. Science 188 107 116

20. SternDLOrgogozoV 2008 The loci of evolution: how predictable is genetic evolution? Evolution 62 2155 2177

21. Alonso-BlancoCAartsMGBentsinkLKeurentjesJJReymondM 2009 What has natural variation taught us about plant development, physiology, and adaptation? Plant Cell 21 1877 1896

22. RheeSYBeavisWBerardiniTZChenGDixonD 2003 The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): a model organism database providing a centralized, curated gateway to Arabidopsis biology, research materials and community. Nucleic Acids Res 31 224 228

23. TonsorSJAlonso-BlancoCKoornneefM 2005 Gene function beyond the single trait: natural variation, gene effects, and evolutionary ecology in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant, Cell and Environment 28 2 20

24. SinghRS 2003 Darwin to DNA, molecules to morphology: the end of classical population genetics and the road ahead. Genome 46 938 942

25. TheokritoffG 2991 Review: Biotic and abiotic factors in evolution. BioScience 42 212 213

26. BuckleyTN 2005 The control of stomata by water balance. New Phytol 168 275 292

27. TabaeizadehZ 1998 Drought-induced responses in plant cells. Int Rev Cytol 182 193 247

28. GilroySJonesDL 2000 Through form to function: root hair development and nutrient uptake. Trends Plant Sci 5 56 60

29. SchnallJAQuatranoRS 1992 Abscisic acid elicits the water-stress response in root hairs of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol 100 216 218

30. ClaussMJDietelSSchubertGMitchell-OldsT 2006 Glucosinolate and trichome defenses in a natural Arabidopsis lyrata population. J Chem Ecol 32 2351 2373

31. LopezAVVogelSMachadoIC 2002 Secretory trichomes, a substitutive floral nectar source in Lundia A. DC. (Bignoniaceae), a genus lacking a functional disc. Annals of Botany 90 169 174

32. MauricioR 1998 Costs of resistance to natural enemies in field populations of the annual plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Am Nat 151 20 28

33. MendezMJonesDGManetasY 1999 Enhanced UV-B radiation under field conditions increases anthocyanin and reduces the risk of photoinhibition but does not affect growth in the carnivorous plant Pinguicula vulgaris. New Phytologist 144 275 282

34. SaitoNHarborneJB 1992 Correlations betwen anthocyanin type, pollinator and flower color in the Labiatae. Phytochemistry 31 3009 3015

35. WesternTLSkinnerDJHaughnGW 2000 Differentiation of mucilage secretory cells of the Arabidopsis seed coat. Plant Physiol 122 345 356

36. RamsayNAGloverBJ 2005 MYB-bHLH-WD40 protein complex and the evolution of cellular diversity. Trends Plant Sci 10 63 70

37. HilscherJSchlottererCHauserMT 2009 A single amino acid replacement in ETC2 shapes trichome patterning in natural Arabidopsis populations. Curr Biol 19 1747 1751

38. LarkinJCYoungNPriggeMMarksMD 1996 The control of trichome spacing and number in Arabidopsis. Development 122 997 1005

39. MauricioR 2005 Ontogenetics of QTL: the genetic architecture of trichome density over time in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetica 123 75 85

40. SymondsVVGodoyAVAlconadaTBottoJFJuengerTE 2005 Mapping quantitative trait loci in multiple populations of Arabidopsis thaliana identifies natural allelic variation for trichome density. Genetics 169 1649 1658

41. HeimMAJakobyMWerberMMartinCWeisshaarB 2003 The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor family in plants: a genome-wide study of protein structure and functional diversity. Mol Biol Evol 20 735 747

42. Toledo-OrtizGHuqEQuailPH 2003 The Arabidopsis basic/helix-loop-helix transcription factor family. Plant Cell 15 1749 1770

43. MaesLInzeDGoossensA 2008 Functional specialization of the TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA1 network allows differential hormonal control of laminal and marginal trichome initiation in Arabidopsis rosette leaves. Plant Physiol 148 1453 1464

44. PayneCTZhangFLloydAM 2000 GL3 encodes a bHLH protein that regulates trichome development in Arabidopsis through interaction with GL1 and TTG1. Genetics 156 1349 1362

45. ZhangFGonzalezAZhaoMPayneCTLloydA 2003 A network of redundant bHLH proteins functions in all TTG1-dependent pathways of Arabidopsis. Development 130 4859 4869

46. UraoTYamaguchi-ShinozakiKMitsukawaNShibataDShinozakiK 1996 Molecular cloning and characterization of a gene that encodes a MYC-related protein in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol 32 571 576

47. ZimmermannIMHeimMAWeisshaarBUhrigJF 2004 Comprehensive identification of Arabidopsis thaliana MYB transcription factors interacting with R/B-like BHLH proteins. Plant J 40 22 34

48. NordborgMHuTTIshinoYJhaveriJToomajianC 2005 The pattern of polymorphism in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Biol 3 e196 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030196

49. SchmidKJRamos-OnsinsSRingys-BecksteinHWeisshaarBMitchell-OldsT 2005 A multilocus sequence survey in Arabidopsis thaliana reveals a genome-wide departure from a neutral model of DNA sequence polymorphism. Genetics 169 1601 1615

50. KimuraM 1977 Preponderance of synonymous changes as evidence for the neutral theory of molecular evolution. Nature 267 275 276

51. PresgravesDCBalagopalanLAbmayrSMOrrHA 2003 Adaptive evolution drives divergence of a hybrid inviability gene between two species of Drosophila. Nature 423 715 719

52. MorohashiKGrotewoldE 2009 A systems approach reveals regulatory circuitry for Arabidopsis trichome initiation by the GL3 and GL1 selectors. PLoS Genet 5 e1000396 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000396

53. InnanHTajimaFTerauchiRMiyashitaNT 1996 Intragenic recombination in the Adh locus of the wild plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 143 1761 1770

54. KawabeAInnanHTerauchiRMiyashitaNT 1997 Nucleotide polymorphism in the acidic chitinase locus (ChiA) region of the wild plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Biol Evol 14 1303 1315

55. TianDArakiHStahlEBergelsonJKreitmanM 2002 Signature of balancing selection in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 11525 11530

56. HichriIHeppelSCPilletJLeonCCzemmelS 2010 The Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Transcription Factor MYC1 Is Involved in the Regulation of the Flavonoid Biosynthesis Pathway in Grapevine. Mol Plant

57. RockmanMVSternDL 2008 Tinker where the tinkering's good. Trends Genet 24 317 319

58. SokalRRRohlfFJ 1995 Biometry. New York W. H. Freeman and Co

59. DoyleJDoyleJ 1987 A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantitites of fresh leaf material. Phytochem Bull 19 11 15

60. ThompsonJDGibsonTJPlewniakFJeanmouginFHigginsDG 1997 The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 25 4876 4882

61. HallTA 1999 BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl Acids Symp Set 41 95 98

62. RozasJSanchez-DelBarrioJCMesseguerXRozasR 2003 DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics 19 2496 2497

63. NeiM 1987 Molecular evolutionary genetics. New York, NY Columbia University Press

64. WattersonGA 1975 On the number of segregating sites in genetical models without recombination. Theor Popul Biol 7 256 276

65. ShiuSHKarlowskiWMPanRTzengYHMayerKF 2004 Comparative analysis of the receptor-like kinase family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Cell 16 1220 1234

66. Van OoijenJ 2004 MapQTL 5, Software for the mapping of quantitative trait loci in experimental populations. Wageningen, Netherlands Kyazma B. V

67. AranzanaMJKimSZhaoKBakkerEHortonM 2005 Genome-wide association mapping in Arabidopsis identifies previously known flowering time and pathogen resistance genes. PLoS Genet 1 e60 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0010060

68. LanderESSchorkNJ 1994 Genetic dissection of complex traits. Science 265 2037 2048

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Local Absence of Secondary Structure Permits Translation of mRNAs that Lack Ribosome-Binding SitesČlánek Independent Chromatin Binding of ARGONAUTE4 and SPT5L/KTF1 Mediates Transcriptional Gene SilencingČlánek Trade-Off between Bile Resistance and Nutritional Competence Drives Diversification in the Mouse GutČlánek FGF Signaling Regulates the Number of Posterior Taste Papillae by Controlling Progenitor Field SizeČlánek Mammalian BTBD12 (SLX4) Protects against Genomic Instability during Mammalian SpermatogenesisČlánek Identification of Nine Novel Loci Associated with White Blood Cell Subtypes in a Japanese PopulationČlánek Differential Effects of and Risk Variants on Association with Diabetic ESRD in African AmericansČlánek Dynamic Chromatin Localization of Sirt6 Shapes Stress- and Aging-Related Transcriptional Networks

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 6- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

- Délka menstruačního cyklu jako marker ženské plodnosti

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Local Absence of Secondary Structure Permits Translation of mRNAs that Lack Ribosome-Binding Sites

- Statistical Inference on the Mechanisms of Genome Evolution

- Revisiting Heterochromatin in Embryonic Stem Cells

- A Two-Stage Meta-Analysis Identifies Several New Loci for Parkinson's Disease

- Identification of a Sudden Cardiac Death Susceptibility Locus at 2q24.2 through Genome-Wide Association in European Ancestry Individuals

- Genomic Prevalence of Heterochromatic H3K9me2 and Transcription Do Not Discriminate Pluripotent from Terminally Differentiated Cells

- Epistasis between Beneficial Mutations and the Phenotype-to-Fitness Map for a ssDNA Virus

- Recurrent Chromosome 16p13.1 Duplications Are a Risk Factor for Aortic Dissections

- Telomere DNA Deficiency Is Associated with Development of Human Embryonic Aneuploidy

- Genome-Wide Association Study of White Blood Cell Count in 16,388 African Americans: the Continental Origins and Genetic Epidemiology Network (COGENT)

- Unexpected Role for DNA Polymerase I As a Source of Genetic Variability

- Transportin-SR Is Required for Proper Splicing of Genes and Plant Immunity

- How Chromatin Is Remodelled during DNA Repair of UV-Induced DNA Damage in

- Independent Chromatin Binding of ARGONAUTE4 and SPT5L/KTF1 Mediates Transcriptional Gene Silencing

- Two Evolutionary Histories in the Genome of Rice: the Roles of Domestication Genes

- Natural Allelic Variation Defines a Role for : Trichome Cell Fate Determination

- Multiple Common Susceptibility Variants near BMP Pathway Loci , , and Explain Part of the Missing Heritability of Colorectal Cancer

- Pathogenic Mechanism of the FIG4 Mutation Responsible for Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease CMT4J

- A Functional Variant in Promoter Modulates Its Expression and Confers Disease Risk for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Drift and Genome Complexity Revisited

- Chromosomal Macrodomains and Associated Proteins: Implications for DNA Organization and Replication in Gram Negative Bacteria

- Trade-Off between Bile Resistance and Nutritional Competence Drives Diversification in the Mouse Gut

- Pathways of Distinction Analysis: A New Technique for Multi–SNP Analysis of GWAS Data

- Web-Based Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Two Novel Loci and a Substantial Genetic Component for Parkinson's Disease

- Chk2 and p53 Are Haploinsufficient with Dependent and Independent Functions to Eliminate Cells after Telomere Loss

- Exome Sequencing Identifies Mutations in High Myopia

- Distinct Functional Constraints Partition Sequence Conservation in a -Regulatory Element

- CorE from Is a Copper-Dependent RNA Polymerase Sigma Factor

- A Single Sex Pheromone Receptor Determines Chemical Response Specificity of Sexual Behavior in the Silkmoth

- FGF Signaling Regulates the Number of Posterior Taste Papillae by Controlling Progenitor Field Size

- Maps of Open Chromatin Guide the Functional Follow-Up of Genome-Wide Association Signals: Application to Hematological Traits

- Increased Susceptibility to Cortical Spreading Depression in the Mouse Model of Familial Hemiplegic Migraine Type 2

- Differential Gene Expression and Epiregulation of Alpha Zein Gene Copies in Maize Haplotypes

- Parallel Adaptive Divergence among Geographically Diverse Human Populations

- Genetic Analysis of Genome-Scale Recombination Rate Evolution in House Mice

- Mechanisms for the Evolution of a Derived Function in the Ancestral Glucocorticoid Receptor

- Mammalian BTBD12 (SLX4) Protects against Genomic Instability during Mammalian Spermatogenesis

- Interferon Regulatory Factor 8 Regulates Pathways for Antigen Presentation in Myeloid Cells and during Tuberculosis

- High-Resolution Analysis of Parent-of-Origin Allelic Expression in the Arabidopsis Endosperm

- Specific SKN-1/Nrf Stress Responses to Perturbations in Translation Elongation and Proteasome Activity

- Graded Nodal/Activin Signaling Titrates Conversion of Quantitative Phospho-Smad2 Levels into Qualitative Embryonic Stem Cell Fate Decisions

- Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals PADI4 Cooperates with Elk-1 to Activate Expression in Breast Cancer Cells

- Trait Variation in Yeast Is Defined by Population History

- Meiosis-Specific Loading of the Centromere-Specific Histone CENH3 in

- A Genome-Wide Survey of Imprinted Genes in Rice Seeds Reveals Imprinting Primarily Occurs in the Endosperm

- Multiple Regulatory Mechanisms to Inhibit Untimely Initiation of DNA Replication Are Important for Stable Genome Maintenance

- SIRT1 Promotes N-Myc Oncogenesis through a Positive Feedback Loop Involving the Effects of MKP3 and ERK on N-Myc Protein Stability

- Bacteriophage Crosstalk: Coordination of Prophage Induction by Trans-Acting Antirepressors

- Role of the Single-Stranded DNA–Binding Protein SsbB in Pneumococcal Transformation: Maintenance of a Reservoir for Genetic Plasticity

- Genomic Convergence among ERRα, PROX1, and BMAL1 in the Control of Metabolic Clock Outputs

- Genome-Wide Association of Bipolar Disorder Suggests an Enrichment of Replicable Associations in Regions near Genes

- Identification of Nine Novel Loci Associated with White Blood Cell Subtypes in a Japanese Population

- DNA Ligase III Promotes Alternative Nonhomologous End-Joining during Chromosomal Translocation Formation

- Differential Effects of and Risk Variants on Association with Diabetic ESRD in African Americans

- Finished Genome of the Fungal Wheat Pathogen Reveals Dispensome Structure, Chromosome Plasticity, and Stealth Pathogenesis

- Dynamic Chromatin Localization of Sirt6 Shapes Stress- and Aging-Related Transcriptional Networks

- Extracellular Matrix Dynamics in Hepatocarcinogenesis: a Comparative Proteomics Study of Transgenic and Null Mouse Models

- Integrating 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine into the Epigenomic Landscape of Human Embryonic Stem Cells

- Vive La Différence: An Interview with Catherine Dulac

- Multiple Loci Are Associated with White Blood Cell Phenotypes

- Nuclear Accumulation of Stress Response mRNAs Contributes to the Neurodegeneration Caused by Fragile X Premutation rCGG Repeats

- A New Mutation Affecting FRQ-Less Rhythms in the Circadian System of

- Cryptic Transcription Mediates Repression of Subtelomeric Metal Homeostasis Genes

- A New Isoform of the Histone Demethylase JMJD2A/KDM4A Is Required for Skeletal Muscle Differentiation

- Genetic Determinants of Lipid Traits in Diverse Populations from the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Study

- A Genome-Wide RNAi Screen for Factors Involved in Neuronal Specification in

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Recurrent Chromosome 16p13.1 Duplications Are a Risk Factor for Aortic Dissections

- Statistical Inference on the Mechanisms of Genome Evolution

- Genome-Wide Association Study of White Blood Cell Count in 16,388 African Americans: the Continental Origins and Genetic Epidemiology Network (COGENT)

- Chromosomal Macrodomains and Associated Proteins: Implications for DNA Organization and Replication in Gram Negative Bacteria

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání