Bacteriophage Crosstalk: Coordination of Prophage Induction by Trans-Acting Antirepressors

Many species of bacteria harbor multiple prophages in their genomes. Prophages often carry genes that confer a selective advantage to the bacterium, typically during host colonization. Prophages can convert to infectious viruses through a process known as induction, which is relevant to the spread of bacterial virulence genes. The paradigm of prophage induction, as set by the phage Lambda model, sees the process initiated by the RecA-stimulated self-proteolysis of the phage repressor. Here we show that a large family of lambdoid prophages found in Salmonella genomes employs an alternative induction strategy. The repressors of these phages are not cleaved upon induction; rather, they are inactivated by the binding of small antirepressor proteins. Formation of the complex causes the repressor to dissociate from DNA. The antirepressor genes lie outside the immunity region and are under direct control of the LexA repressor, thus plugging prophage induction directly into the SOS response. GfoA and GfhA, the antirepressors of Salmonella prophages Gifsy-1 and Gifsy-3, each target both of these phages' repressors, GfoR and GfhR, even though the latter proteins recognize different operator sites and the two phages are heteroimmune. In contrast, the Gifsy-2 phage repressor, GtgR, is insensitive to GfoA and GfhA, but is inactivated by an antirepressor from the unrelated Fels-1 prophage (FsoA). This response is all the more surprising as FsoA is under the control of the Fels-1 repressor, not LexA, and plays no apparent role in Fels-1 induction, which occurs via a Lambda CI-like repressor cleavage mechanism. The ability of antirepressors to recognize non-cognate repressors allows coordination of induction of multiple prophages in polylysogenic strains. Identification of non-cleavable gfoR/gtgR homologues in a large variety of bacterial genomes (including most Escherichia coli genomes in the DNA database) suggests that antirepression-mediated induction is far more common than previously recognized.

Published in the journal:

. PLoS Genet 7(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002149

Category:

Research Article

doi:

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002149

Summary

Many species of bacteria harbor multiple prophages in their genomes. Prophages often carry genes that confer a selective advantage to the bacterium, typically during host colonization. Prophages can convert to infectious viruses through a process known as induction, which is relevant to the spread of bacterial virulence genes. The paradigm of prophage induction, as set by the phage Lambda model, sees the process initiated by the RecA-stimulated self-proteolysis of the phage repressor. Here we show that a large family of lambdoid prophages found in Salmonella genomes employs an alternative induction strategy. The repressors of these phages are not cleaved upon induction; rather, they are inactivated by the binding of small antirepressor proteins. Formation of the complex causes the repressor to dissociate from DNA. The antirepressor genes lie outside the immunity region and are under direct control of the LexA repressor, thus plugging prophage induction directly into the SOS response. GfoA and GfhA, the antirepressors of Salmonella prophages Gifsy-1 and Gifsy-3, each target both of these phages' repressors, GfoR and GfhR, even though the latter proteins recognize different operator sites and the two phages are heteroimmune. In contrast, the Gifsy-2 phage repressor, GtgR, is insensitive to GfoA and GfhA, but is inactivated by an antirepressor from the unrelated Fels-1 prophage (FsoA). This response is all the more surprising as FsoA is under the control of the Fels-1 repressor, not LexA, and plays no apparent role in Fels-1 induction, which occurs via a Lambda CI-like repressor cleavage mechanism. The ability of antirepressors to recognize non-cognate repressors allows coordination of induction of multiple prophages in polylysogenic strains. Identification of non-cleavable gfoR/gtgR homologues in a large variety of bacterial genomes (including most Escherichia coli genomes in the DNA database) suggests that antirepression-mediated induction is far more common than previously recognized.

Introduction

Temperate bacteriophages are major players in the evolution of bacterial genomes. Phages can act as vectors for gene transfer and, by virtue of their ability to integrate in the bacterial chromosomes, they can permanently modify the properties of the host cell. Such “lysogenic conversion” is particularly prominent in enteric bacteria presumably due to their promiscuous lifestyle. Enteric species like E. coli and Salmonella typically contain multiple resident prophages whose variability in number and assortment constitutes a major source of diversity between strains [1]–[3]. Some prophages express functions that contribute to pathogenicity. Lysogenization of E. coli by bacteriophages carrying Shiga-like toxin genes converts a harmless commensal into a dreadful enteric pathogen [4]. The toxin gene stx is repressed in the lysogenic state, but is activated under conditions that elicit prophage induction [5], [6]. In Salmonella, the contribution of prophages to pathogenicity results from the synergistic action of multiple factors playing subtle and often redundant roles. The genes encoding such factors are expressed in the lysogenic state under the control of the regulatory circuitry of the host bacterium [7], [8].

Gifsy-1 and Gifsy-2 are lambdoid prophages found in most strains of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and were originally identified genetically during a study of recB suppressor mutations in strain LT2 [9]. Both phages contain recET gene orthologs that, although repressed in the lysogenic state, can be activated by mutation, resulting in the suppression of recombination defects. A third Gifsy-related prophage found in another model strain, ATCC14028, has been named Gifsy-3 [2]. All three prophages exhibit the typical modular organization of bacteriophage λ with two identifiable divergent transcription units originating from a site roughly one third away from the left end of the prophage map [8], [10]. When induced, all three prophages form virions that closely resemble λ [11]. As the genome sequences from an increasing number of serovar Typhimurium strains have become available, it has become possible to compare the sequences of their resident Gifsy prophages. This analysis revealed that Gifsy-1 displays extensive polymorphism in the region surrounding the lysogenic repressor and other regulatory elements [7], [8]. Conversely, Gifsy-2 is highly conserved throughout the serovar, while Gifsy-3 appears to be a specific acquisition of strain ATCC14028 [2], [12].

Phage circulation among strains results from conditions that relieve lysogenic repression and elicit the developmental program of the virus. The paradigm for this induction process is set by widely studied phages such as λ and P22. In both of these phages, induction results from the autocatalytic cleavage of a repressor triggered by the accumulation of RecA-DNA filaments [13], [14]. λ and P22 repressor proteins, 237 and 216 amino acids (aa), respectively, contain two domains: an N-terminal DNA-binding domain and a C-terminal oligomerization domain with the cleavage activity [15]. RecA-stimulated cleavage occurs at identical alanyl-glycil sequences near the center of both proteins [16] and is catalyzed by a highly conserved Lys/Ser dyad. Identification of the Gifsy-1/-2 phage repressor in strain LT2 revealed it to be significantly smaller (136 aa) than the λ or P22 repressors and to lack the signature motif for autocatalytic cleavage [10]. Examination of the Gifsy prophage sequences from other strains showed them to have similar small sizes, raising the question of the mechanism responsible for repressor inactivation in these prophages. The work described in this paper was aimed at answering this question. We show that the induction of Gifsy prophages does not result from repressor cleavage, but rather from repressor inactivation consequent to the binding of antirepressor proteins. The genes encoding these antirepressors are located outside the immunity region and under direct control of the LexA protein. A similar regulatory mechanism was previously described in coliphages 186 and N15 [17], [18]. Interestingly, some of the antirepressors identified here have the ability to act on non-cognate repressors, providing the basis for a molecular crosstalk that allows coordinating the induction of multiple prophages in polylysogenic bacteria.

Results

Variability of Gifsy phage repressors

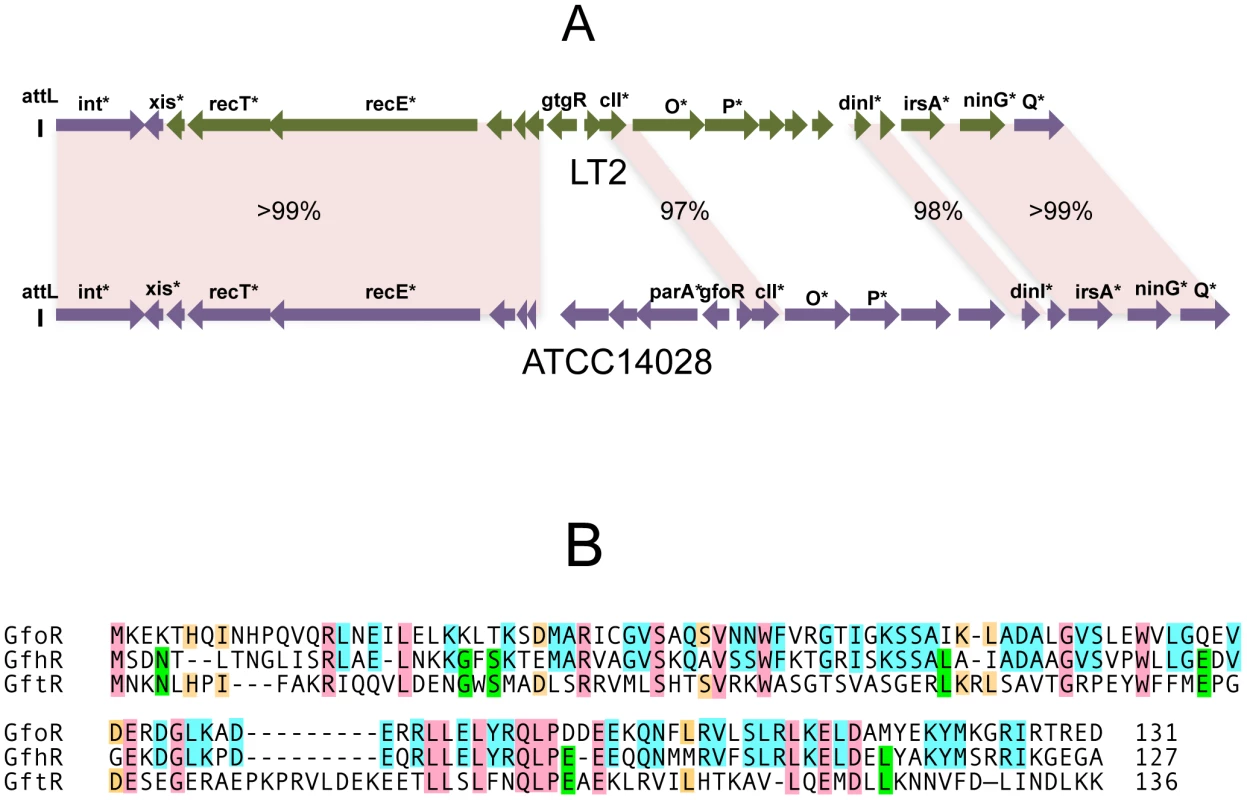

In strain LT2, an approximately 12 Kb portion of the Gifsy-2 prophage genome, including the immunity region together with replication and recombination functions, is duplicated at the corresponding position of the Gifsy-1 genome [10]. Conceivably, a recombination or conversion event homogenized the two sequences during the evolutionary history of this strain. As a result, the Gifsy-1 repressor of LT2, GogR, is a perfect copy of the Gifsy-2 repressor, GtgR, and the two phages are homoimmune [7], [10]. Sequence analysis of the Gifsy phages in strain ATCC14028 showed the immunity region of Gifsy-1 to differ extensively from that of Gifsy-1/-2 prophages of strain LT2 (Figure 1A). In contrast, Gifsy-2 sequences are nearly identical in the two strains, while Gifsy-3 carries a different immunity region. The presumptive repressor genes of the Gifsy-1, and Gifsy-3 prophages of strain ATCC14028 were named gfoR, and gfhR, respectively. GfoR (Gifsy-1) and GfhR (Gifsy-3) share 66.4% similarity in their amino acid sequences and are 32,6% and 33,8% similar to GftR (Gifsy-2), respectively (Figure 1B). The sequence of the latter is 100% identical to that of LT2's GtgR. Finally, it is worth mentioning that Gifsy-3 repressor, GfhR, is 100% identical to the repressor of a prophage found at the site of Gifsy-1 in strain SL1344, another Salmonella model strain [19](GenBank FQ312003). These findings account for the original observation that ATCC10028's Gifsy-3 and SL1344's Gifsy-1 phages are homoimmune [7] and provide further evidence for extensive module shuffling between Salmonella phages.

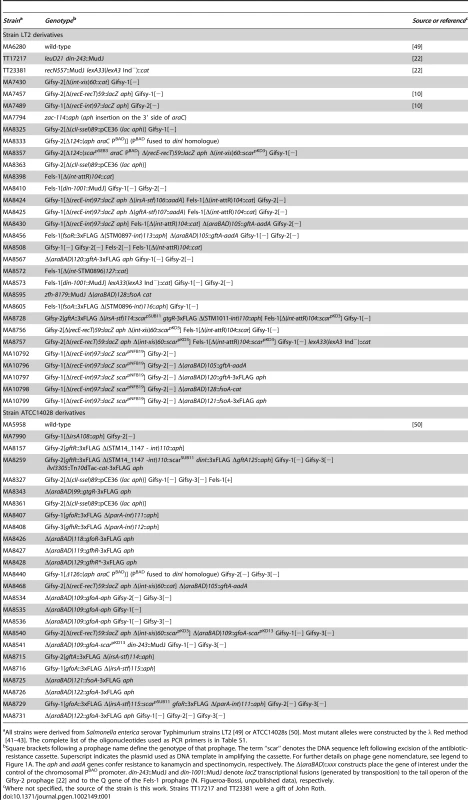

Gifsy prophage repressors are not cleaved during induction

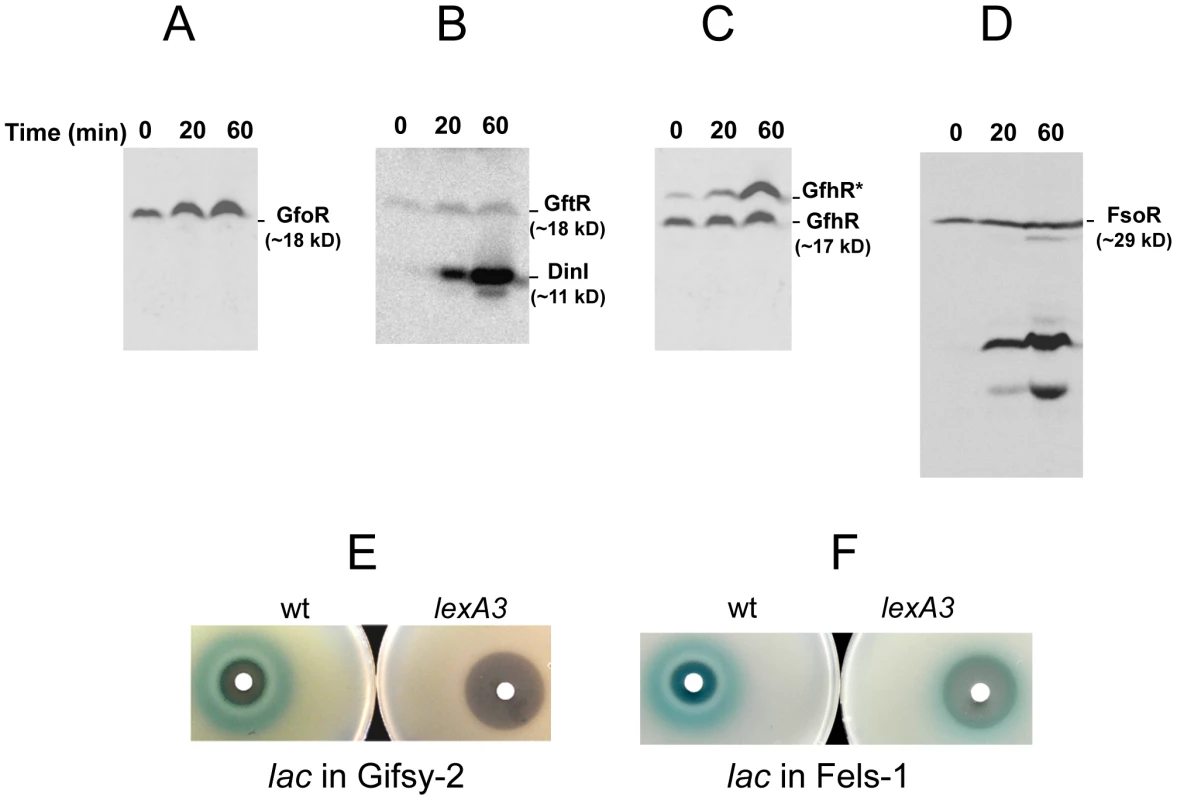

To monitor the fate of Gifsy prophage repressors under inducing conditions, variants of the gfoR, gftR and gfhR genes carrying carboxy-terminal 3xFLAG epitope tags were constructed in the ATCC14028 chromosome [20]. Tagged GfoR and GfhR remained competent to confer immunity against the corresponding phage (data not shown), suggesting that presence of the tag did not adversely affect the function of the proteins. Similar epitope tag fusions were derived from two additional genes: a dinI homologue in the Gifsy-2 left operon, to serve as a control for the transcriptional response to the inducing treatment, and a gene presumed to encode the repressor of the Fels-1 prophage of strain LT2 [21]. Fels-1 putative repressor, hereafter referred to as FsoR, is a 231 aa protein similar to λ's CI repressor and thus expected to undergo cleavage during induction. Exponentially growing cells from strains carrying the 3xFLAG-tagged genes were exposed to Mitomycin C (MitC) and processed for Western blot detection using anti-FLAG antibodies. As shown in Figure 2, none of the Gifsy repressors suffers detectable cleavage throughout the treatment, while the accumulation of the DinI protein (Figure 2B), together with the appearance of cleavage products of the FsoR repressor (Figure 2D), confirm that induction is taking place. In Gifsy-3, the MitC treatment leads to the accumulation of a GfhR variant with an N-terminal extension (marked GfhR* in Figure 2C). This protein originates from an upstream, in-frame AUG codon (Figure S1). A construct with the longer open reading frame fused to the PBAD promoter expressed the shorter version of GfhR in the absence of arabinose (Figure S1) suggesting that the gfhR promoter lies within the interval between the two AUGs. GfhR* must therefore originate from a different promoter, located upstream from the primary promoter, and apparently activated upon induction. The role of GfhR*, if any, was not further investigated here.

Gifsy prophage induction requires activation of a LexA-regulated locus outside the immunity region

The results in Figure 2 suggested that induction of the Gifsy prophages in strain ATCC14028 occurs by a mechanism not involving cleavage of repressors. Experiments with lacZ fusions supported this conclusion. Fusions of lacZ to the recE gene, or to an homologue of λ's cII gene were no longer activated by MitC when combined with deletions that remove material to the right of the DNA replication genes (see diagram in Figure S2). Thus, the induction mechanism requires one or more genes located outside of, and relatively distant from, the immunity region. A previous report identified potential LexA binding sites in Gifsy prophage genomes [22]. To assess the role of LexA in Gifsy induction, we made use of the lexA3 allele, which produces a non-cleavable form of the LexA protein [23]. The mutation was introduced into strains with recE-lacZ fusions in either Gifsy-1 or Gifsy-2 and the resulting strains were tested for their response to MitC on X-gal indicator plates. As shown for Gifsy-2 in Figure 2E, lexA3 completely abolishes MitC-dependent induction. Thus, LexA cleavage appears to be required for Gifsy prophage induction. In contrast, the lexA3 mutation does not prevent the MitC-dependent activation of a lacZ fusion in the late operon of the Fels-1 prophage (Figure 2F). The latter findings are consistent with the idea that Fels-1 induction results directly from cleavage of a CI-type repressor (Figure 2D).

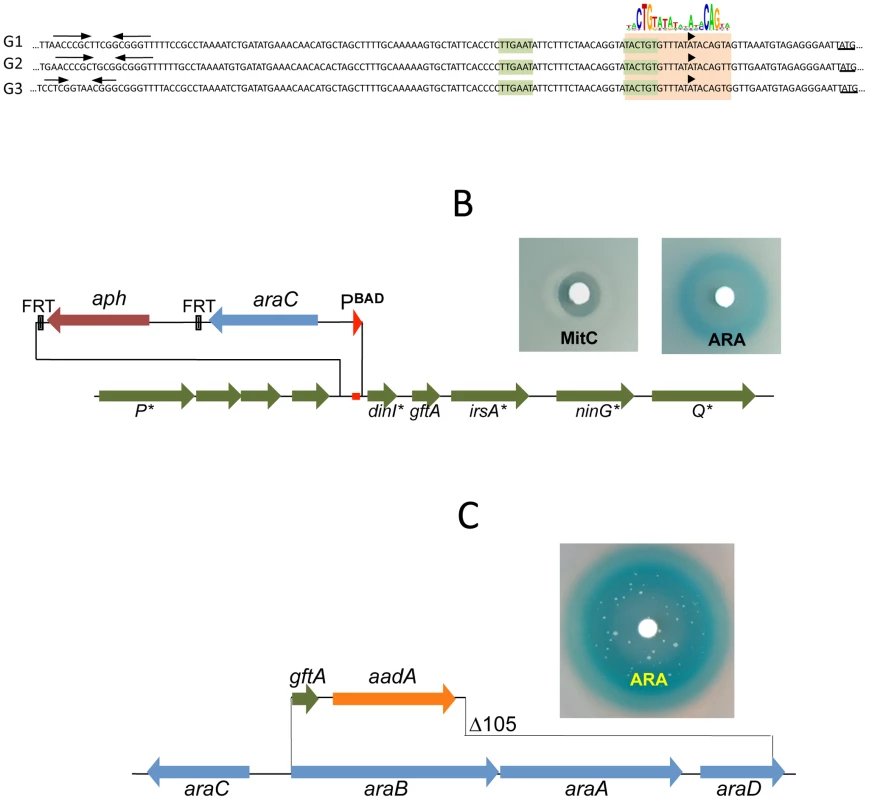

The presumptive LexA binding site lies within the region of sequence identity between Gifsy-1 and Gifsy-2 prophages of strain LT2. The site is located 1.3 Kb downstream from the replication genes and adjacent to the dinI gene homologue. The LexA box is also found at the corresponding position for all three Gifsy prophages of strain ATCC14028, in all instances preceded by palindromic sequences resembling Rho-independent transcription terminators (Figure 3A). To assess the requirement of the LexA binding motif for regulation, the segment between the putative terminator and the AUG translation initiation codon of the dinI homologue in the Gifsy-2 prophage was deleted and replaced with an araC-PBAD promoter module. The construct was combined with a recE-lacZ translational fusion in an LT2-derived strain cured for Gifsy-1. Disk tests on Lac indicator plates showed that the promoter replacement completely abolishes MitC-dependent activation and renders the recE-lacZ fusion inducible by arabinose (Figure 3B). Thus, these results confirmed the existence of an SOS locus within the Gifsy-2 genome and suggested that this locus includes one or more genes needed for induction.

Small antirepressor proteins responsible for Gifsy prophage induction

The analysis of nested deletions originating at the right end of the prophage allowed delimiting the minimal sequence required for recE-lacZ activation to the interval between the dinI and irsA homologues (Figure S2C). The region could encode a small protein starting from a non-canonical GUG codon. To assess the role of this locus in prophage induction, the ORF sequence was moved under the control of the chromosomal PBAD promoter, starting with an AUG codon corresponding to the initiation codon of the araB gene. Exposure of the resulting strain to a paper disk soaked with arabinose produced a halo of bacterial killing around the disk concomitant to the release of ß-galactosidase activity from the lysed cells (Figure 3C). Together, these effects suggested that the sequence being analyzed contained all the information needed to elicit prophage induction. Interestingly, a fortuitous single bp insertion near the 5′ end of the sequence completely abrogated arabinose-dependent killing and lac expression. Since the mutation alters the reading frame of the putative gene, these findings strongly suggested that the inducing molecule was a protein as opposed to an RNA. We postulated that this protein acts as an antirepressor and named it GftA (Gifsy-two antirepressor). As seen in Figure 3C, colonies appeared in the area of bacterial lysis upon prolonged incubation. Characterization of a number of these arabinose-resistant isolates showed some of them to result from prophage deletions while others carried mutations linked to the ara locus. One class of mutants had changes in the araC gene. Presumably these mutations affect the ability of the AraC protein to bind arabinose thus preventing PBAD promoter activation. A second class of mutation fell within the gftA coding sequence and tentatively identified residues important for antirepressor function (see below).

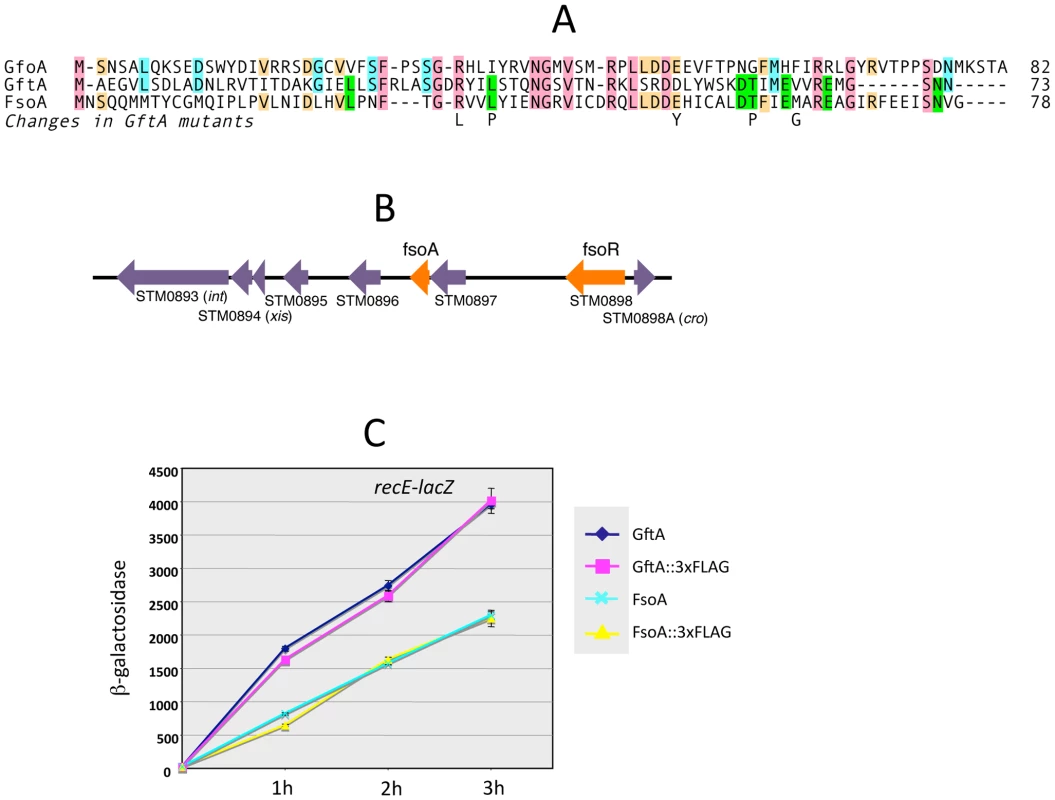

The gftA gene lies within the region of sequence identity between the Gifsy-1 and Gifsy-2 prophages of strain LT2 (see above) and is 100% identical to the corresponding gene in the Gifsy-2 genome of strain ATCC14028. Small ORFs initiating with UGG codons are found at the corresponding locations in ATCC14028's Gifsy-1 and Gifsy-3 prophages. These ORFs are 98% identical to each other but more distantly related to gftA (Figure 4A). The Gifsy-1 sequence was moved into the ara operon as done for gftA (see above). The resulting strain lysed and released high titers of phage when exposed to arabinose, consistent with the identification of this locus as an antirepressor gene. Significantly, removal of either Gifsy-1 or Gifsy-3 did not relieve the arabinose-induced lethality. Only the concomitant elimination of both prophages relieved the lethality, suggesting that the Gifsy-1 antirepressor can inactivate the Gifsy-3 repressor, GfhR, as well as GfoR. A plaque assay confirmed the presence of both phages in lysates from arabinose-treated cells (data not shown). The antirepressor genes were named GfoA (Gifsy-1) and GfhA (Gifsy-3).

A functional gftA homologue in the Fels-1 genome

Derepression of Gifsy lytic transcription can also be monitored using lacZ fusions to a cII gene ortholog in the putative early right operon [10]. These fusions can be constructed by concomitantly deleting material in the right portion of the prophage (including the antirepressor gene), making it possible to test for susceptibility to antirepressors encoded by unlinked prophages (Figure S2). Thus, a cII-lacZ fusion that removes Gifsy-2's gftA gene is still MitC-inducible in an LT2 background (strain MA8363; Table 1) but not in a strain derived from ATCC14028 (MA8361). This difference might be ascribed to the presence of a duplicate copy of the gftA gene in the Gifsy-1 genome of LT2 and its absence in ATCC14028 (see above). Surprisingly, however, the Gifsy-2-borne cII-lacZ fusion remained MitC-inducible in strain LT2 after removing Gifsy-1, suggesting that yet another prophage could complement the gftA defect. Strain LT2 carries two other prophages, Fels-1 and Fels-2. Fels-2 seemed the most likely candidate to encode such a function in light of its strong analogies with E. coli phage 186, also regulated by an antirepressor mechanism [22], [24]. Unexpectedly, however, removal of Fels-1, and not Fels-2, abolished Gifsy-2 induction. To confirm the presence of a gftA homologue in the Fels-1 genome, an ATCC14028 strain carrying the cII-lacZ ΔgftA Gifsy-2 construct was lysogenized with Fels-1 phage from strain LT2. The resulting strain proved positive for lacZ expression when challenged with MitC. Deletion analysis localized the locus responsible for lacZ activation in the interval between loci STM0896 and STM0897 in Fels-1's left operon (Figure 4B). When the presumptive antirepressor gene (named fsoA) was placed under PBAD promoter control, lacZ fusions to recE or to the cII ortholog in Gifsy-2 became derepressed in the presence of arabinose (Figure 4C and data not shown). The FsoA protein shares a number of amino acid identities or similarities with both GftA and GfoA (Figure 4A). Significantly, most of the GftA null mutations (see above) affect residues that are conserved in all three proteins. It seems conceivable that the most highly conserved residues (red boxes) fulfill general structural requirements for antirepressor function while identities restricted to GftA and FsoA (green boxes) might define residues contributing to the specificity of repressor recognition (Figure 4A). From the slope of the induction curves in Figure 4C, it is apparent that FsoA is less effective than GftA in relieving GftR-mediated repression. Addition of the 3xFLAG epitope sequence to the C-termini of the two antirepressor proteins does not appear to impair their activities to any significant extent (Figure 4C).

Phage antirepressors accumulate in response to DNA damage

Construction of epitope-tagged variants of the antirepressors allowed monitoring the regulation of these proteins by Western analysis. Figure 5 shows the results of such an experiment with cells exposed to MitC. GfoA and GftA, undetectable at the beginning of the treatment, accumulate in the presence of the drug. In contrast, as already shown in Figure 2, the levels of 3xFLAG-tagged GfoR and GftR do not change significantly throughout the treatment. Furthermore, neither the repressors nor the antirepressors were significantly affected during a one-hour chase with chloramphenicol, indicating that none of these proteins is particularly susceptible to proteolytic turnover (Figure 5). Overall, these results strongly suggest that GfoA and GftA elicit prophage induction by affecting the activity, not the concentration, of the phage repressors. Finally, the data in Figure 5 confirm that Fels-1's FsoA protein is also induced in response to DNA damage.

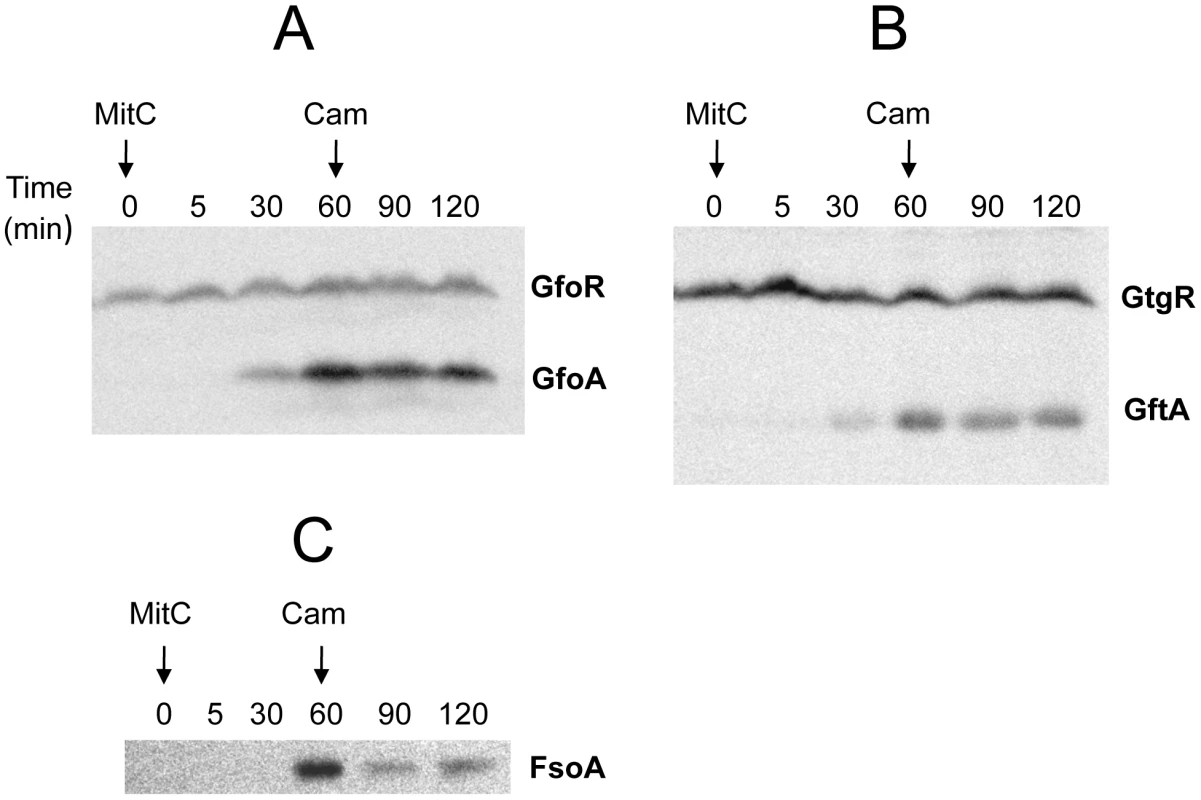

Antirepressor proteins form highly stable complexes with cognate repressors

The ability of Gifsy antirepressors to interact with their corresponding repressors was assessed by a surrogate pulldown assay. Strains harboring chromosomal 3xFLAG tagged antirepressor genes fused to the PBAD promoter and carrying or lacking 6xHis-tagged cognate repressor genes on a plasmid, were grown in the presence or absence of arabinose. Cell-free extracts were incubated with nickel nitrilotriacetic acid agarose beads. Retained material was eluted and subjected to gel electrophoresis for direct visualization of proteins and Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 6, in extracts from cells expressing the antirepressor genes, proteins with the molecular weight predicted for the 3xFLAG-tagged derivatives of GftA (panel A) or GfoA (panel B), were specifically retained along with the cognate repressors and revealed by the anti 3xFLAG monoclonal antibodies (panels C and D, respectively). Curiously, the anti 3xFLAG antibodies appear to react with the His-tagged repressors as well (Figure 6C). We considered that this reactivity might be due to the release of some antirepressor molecules from the membrane during the blotting procedure and their interaction with membrane-bound cognate repressors. To test this hypothesis, we asked whether antirepressor-repressor interactions could be detected by the “far Western” protocol [25]. Total proteins from a strain expressing GtgR were fractionated on an SDS gel, blotted on a Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The blot was split into two halves, one of which was incubated with a crude extract from a strain expressing 3xFLAG tagged GftA protein, prior to anti 3xFLAG antibody probing. The results in Figure 6E show that the GftR protein is only revealed in the membrane treated with the extract. This confirms that GftA and GtgR interact strongly with each other. Since the above analysis was carried out under denaturing conditions, the interaction must not require the proteins to be in their native conformation.

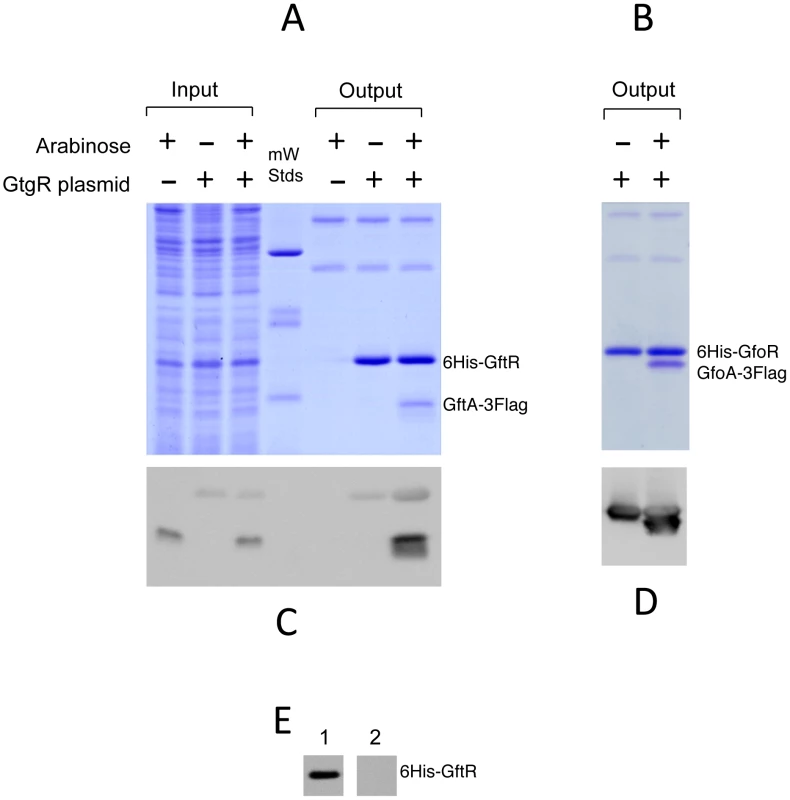

Gifsy repressors and antirepressors most likely interact as dimers

We devoted considerable effort to determining the subunit structures of Gifsy repressors, antirepressors and their complexes by gel exclusion chromatography. This work was made difficult by a marked tendency of both proteins to form non-specific aggregates and to stick to various surfaces, particularly following buffer changes. Such problems could not be solved for the antirepressors. In contrast, using N-terminally tagged versions of the repressors, satisfactory elution profiles were eventually obtained with the repressors and their complexes. Results from a representative experiment are shown in Figure 7. GfoR and the GfoR-GfoA complex elute from a G75 Sephadex column with an apparent molecular weight of about 40 kD and 60 kD, respectively. These sizes are consistent with the GfoR being a dimer and the GfoR-GfoA complex a heterotetramer (A2B2). Similar results were obtained for the GftR/GftA complex (data not shown).

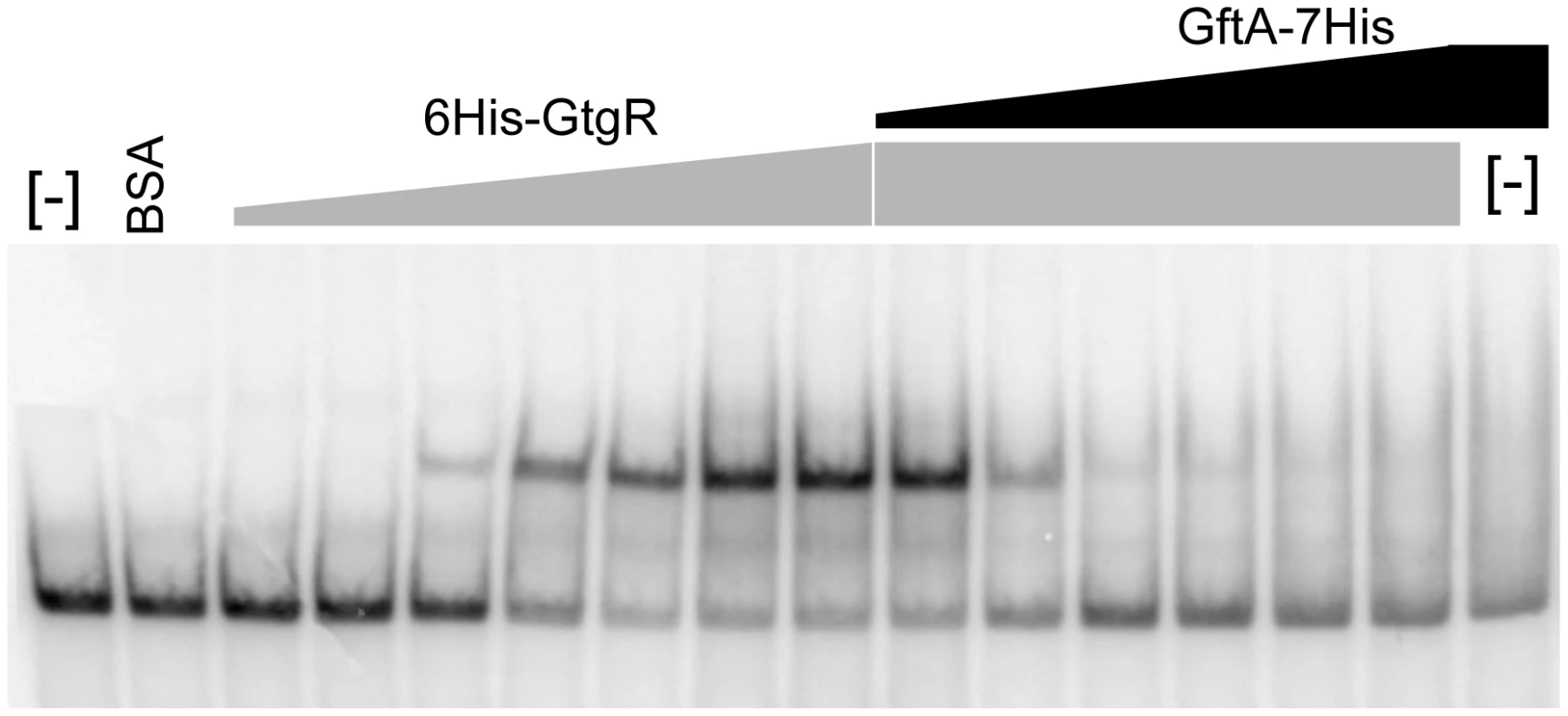

Antirepressor binding caused cognate repressor to dissociate from the DNA

Binding of repressors to the corresponding operator sites can be monitored by mobility shift assays in native gels. One such mobility shift is observed when a DNA fragment spanning the Gifsy-2 right operator is incubated with purified GtgR protein (Figure 8). Addition of increasing amounts of purified GftA protein to the preformed GtgR-DNA complex causes the operator fragment to be progressively released (Figure 8). Thus, these results suggest that GftA binding to the GtgR repressor causes the latter to lose affinity for DNA. No binding of GftA to DNA can be inferred from the data in Figure 8 or from a number of independent tests (data not shown). This leads us to conclude that the antirepressor most likely exerts its action by inducing a conformational change in cognate repressor, as opposed to competing for DNA binding.

Discussion

In the present study, we have characterized the induction mechanism of the Gifsy prophages of Salmonella. This mechanism differs from that used by model phages λ and P22. In these phages, all information needed to elicit induction is contained within the repressor sequence. Binding of the repressors to RecA-DNA filaments formed during DNA damage, stimulates the self-catalytic proteolysis of the repressor and its inactivation. Cleavage occurs within a linker region, the “connector” that separates the N-terminal DNA-binding domain from the C-terminal dimerization domain of the protein [15]. In contrast, the regulation of Gifsy prophage induction involves two spatially separated modules: one containing the repressor gene and its sites of action (the immunity region), the other carrying a transcription unit that encodes, among others, an antirepressor protein. During normal growth, this unit is repressed by LexA, the general repressor of the SOS regulon. LexA also undergoes RecA-stimulated cleavage in the presence of damaged DNA. Antirepressor is then synthesized, it binds to and inactivates the lysogenic repressor, thereby causing the induction of the lytic program. Gifsy repressor proteins GfoR and GtgR show sequence identity with the N-terminal domain of phage λ's CI repressor for nearly their entire lengths. This suggests that these proteins lack the bipartite structure of the CI repressor and are not susceptible to self-proteolysis. A survey of the bacterial genome sequence databases reveals the existence of gfoR/gtgR homologues in prophage-like elements from a large variety of bacterial species (Figure S3). Because of their relative small size (in the 150 aa range) these proteins are unlikely to undergo self-cleavage and are thus candidates for being regulated by an antirepressor. Besides being present in the Gifsy-like prophages of many Salmonella enterica serovars, gfoR/gtgR homologues are found in most Escherichia coli strains in the database (60 genes in a total of 42 strains) as well as in Citrobacter, Klebsiella, Yersinia and Enterobacter strains (Figure S3). Two relevant members of the group are the DicA and RacR repressors of the Qin and Rac prophages respectively [26].

Previous examples of LexA-controlled antirepressors include the Tum protein of phage 186 [18] and more recently the AntC protein in phage N15 [17]. Like the GfoA and GftA proteins studied here, Tum binds to its cognate repressor and prevents its binding to the operator site [18]. Tum is nearly twice the size of the GfoA and GftA proteins (146 aa) and shows significant identity to the DinI protein in the second half of its sequence. This suggests that the antirepressor and DinI sequences are fused into a single polypeptide. Consistent with this idea, the two phage 186 relatives, Salmonella Fels-2 and coliphage PSP3 have the tum coding region split into two halves by a stop codon [22]. In phage PSP3 the upstream gene encodes the antirepressor activity and the downstream gene encodes the DinI homologue (G.E. Christie, personal communication cited in [22]). This order is reversed in the Gifsy prophages where the dinI homologue is the first gene of the LexA-regulated operon, followed by the antirepressor gene and by a homologue of the irsA gene. The DinI protein is thought to modulate the SOS response through its binding to RecA-DNA filaments; however, its exact role remains elusive [27]–[29]. This is also the case for irsA, a locus originally identified as the site of Tn10 insertions impairing Salmonella growth in host cells (Chai and Heffron, unpublished). In the course of this study, non-polar deletions in the dinI or irsA homologues of Gifsy-1 and Gifsy-3 had no significant effects on the levels or on the rates of induction of recE-lacZ or cII-lacZ fusions (data not shown). Still, the conservation of the dinI-irsA region in putative prophages from Salmonella, Escherichia, Citrobacter, Klebsiella and Enterobacter species in genome sequence databases, suggests that these genes play some role in regulation. Overall, these findings strongly suggest that lysogenic regulation by repressor/antirepressor pairs is far more common than previously recognized. Consistent with this idea, several homologues of GfoA and GftA can be found in protein databases (Figure S4).

In the λ pathway of induction, proteolytic inactivation of the repressor makes the process irreversible. In contrast, the LexA/antirepressor-mediated mechanism can in principle be reversed if DNA damage is repaired. As LexA levels are replenished, the reduction in antirepressor synthesis will favor dissociation of the repressor-antirepressor complexes allowing the repressor to resume its function. This would probably limit viral replication and might promote reestablishment of lysogeny. One could envision the existence of a latency period during which the phage DNA undergoes limited replication before committing to the lytic pathway. The presence of chromosomal partitioning parA gene homologues in the left operons of the Gifsy-1 and Gifsy-3 prophages supports this idea. These properties inspire analogies with the induction pathway of Vibrio cholerae filamentous CTXφ phage. In this system, LexA directly modulates the levels of the phage repressor, RstR, by activating rstR transcription when bound to a site overlapping with the rstR promoter [30], [31]. Reconstitution of the LexA pool during recovery from DNA damage was proposed to favor the reestablishment of lysogeny [31], [32]. Interestingly, RstR is the target of an antirepressor made from CTXφ's satellite phage RS1. This protein, RstC, is not required for prophage induction; however, it is made under inducing conditions and, by inactivating RstR, is thought to prolong the RS1 and CTXφ production period [33], [34].

The latter findings highlight an interesting property of the antirepressor function, namely its potential to serve as basis for a molecular crosstalk between phages. This feature is clearly illustrated in the present study. We found that some antirepressors can inactivate repressors made by heteroimmune prophages and trigger induction of the latter. Particularly intriguing was the discovery that the FsoA protein of the Fels-1 prophage can act on the Gifsy-2 repressor GtgR. The fsoA gene lies in Fels-1 left operon and is derepressed under inducing conditions following auto-proteolysis of the FsoR repressor. By targeting GtgR, FsoA effectively uncouples Gifsy-2 induction from the SOS response and puts the Gifsy-2 regulatory circuitry under FsoR control. This regulatory hijacking is difficult to rationalize since the Fels-1 prophage is induced normally in a Gifsy-2-cured strain or when the fsoA gene is inactivated (data not shown). However, subtle differences in induction rates or thresholds might have been missed in these experiments, and the possibility that one or more function(s) expressed from the Gifsy-2 genome positively affect(s) Fels-1 development cannot be completely ruled out. Similar effects might account for the reciprocal transactivation of Gifsy-1 and Gifsy-3 gene expression demonstrated in this study. It is also worth considering that synchronization of prophage induction in polylysogenic strains might be vital to prophages with delayed induction responses (see above). “Slow-inducing” prophages are in danger of sharing the fate of host DNA and of being destroyed when present in a strain carrying prophages that are induced more rapidly. In this scenario, paradoxically, Gifsy-2 would be the one that hijacks Fels-1 functions through FsoA.

The wide specificity of antirepressor action was first recognized in Salmonella phage P22. The Ant protein of P22, besides inactivating the phage's own repressor C2, can act on the repressor of Salmonella phage L and coliphages λ and 21 [35]. The role of Ant in the P22 life cycle is not completely understood. The protein is not required for induction of the P22 prophage or for any steps of the lytic or lysogenic pathways [36]. To our knowledge, the only reported activity of Ant is its ability to transactivate early gene expression in P22 lysogens when expressed constitutively from a superinfecting P22 phage [37]. It is tempting to speculate that an important role of the Ant protein is to couple induction of P22 prophage to that of other prophages in polylysogenic strains.

Materials and Methods

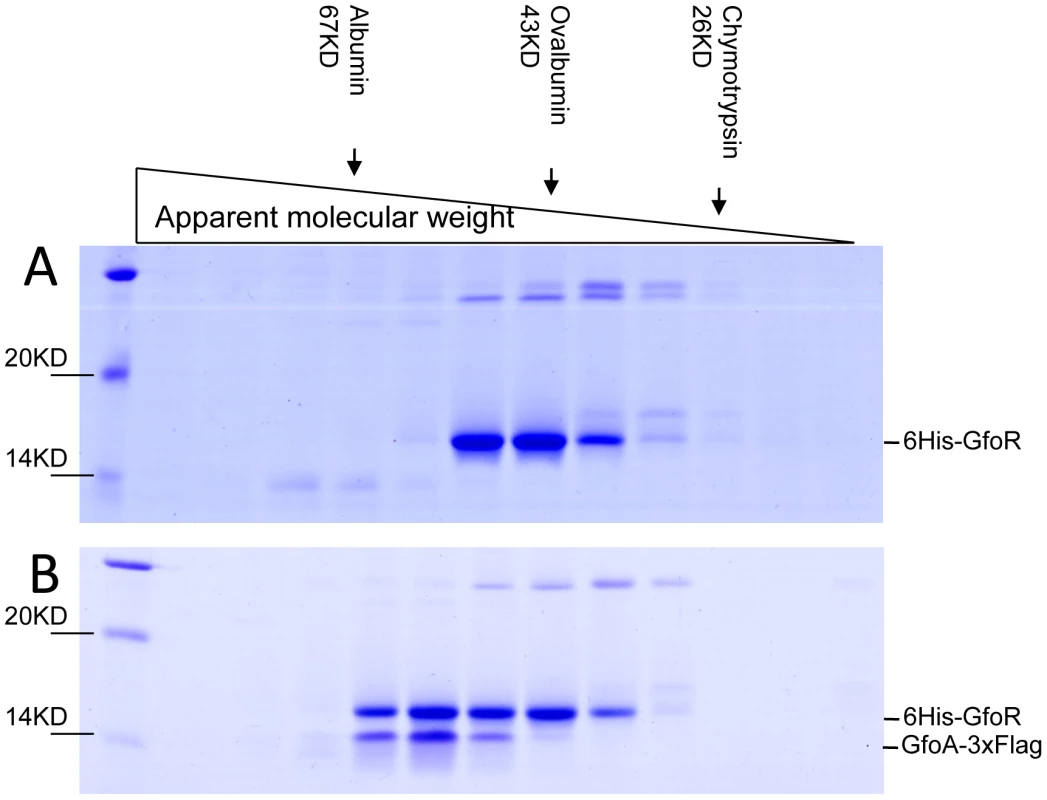

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

All strains used in this study are derivatives of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. Their genotypes are listed in Table 1. The bacteria were cultured in LB broth [38] solidified by the addition of 1.5% Difco agar when needed. When appropriate, the LB medium was supplemented with 0.2% arabinose. Antibiotics (Sigma-Aldrich) were included at the following final concentrations: chloramphenicol, 10 µg mL−1; kanamycin monosulfate, 50 µg mL−1; sodium ampicillin, 75 µg mL−1; spectinomycin dihydrochloride, 80 µg mL−1; and tetracycline hydrochloride, 25 µg mL−1. LB plates containing 40 µg mL−1 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) (Sigma-Aldrich) were used to monitor lacZ expression in bacterial colonies. Prophages were induced using Mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 1 µg mL−1 in liquid medium or by applying 5 µL from a 2 mg mL−1 stock solution on 5 mm diameter filter paper discs for plate tests. Liquid cultures were grown in New Brunswick gyratory shakers, and growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm with a Milton-Roy Spectronic 301 spectrophotometer.

Genetic techniques

Generalized transduction was carried out using the high frequency transducing mutant of phage P22, HT 105/1 int-201 [39]. Typically, P22 lysates were used at a 1∶50 dilution, mixed with aliquots from overnight cultures of recipient bacteria in a 1∶2 ratio, and incubated for 30 min at 37°C prior to being plated on selective media. Transductant colonies were purified by two sequential passages on selective plates and verified to be free of phage by streaking on Evans Blue Uranine plates [40]. Chromosomal engineering was carried out by the λ Red recombination method [41]–[43] as previously described [20]. Donor DNA fragments were generated by PCR using plasmid or chromosomal DNA templates. A complete list of the oligonucleotides used as primers in these experiments is in Table S1. Amplified fragments were electroporated into appropriate strains harboring the conditionally replicating plasmid pKD46, which carries a λ red operon under the control of the PBAD promoter [41]. Bacteria carrying pKD46 were grown at 30°C in the presence of ampicillin and exposed to arabinose (10 mM) for 3 hours prior to preparation of electrocompetent cells. Electroporation was carried out using a Bio-Rad MicroPulser under the conditions specified by the manufacturer. Recombinant colonies were selected on LB plates containing the appropriate antibiotic. Constructs were verifed by PCR and/or DNA sequencing. When needed, the antibiotic resistance cassette was excised by transforming strains with plasmid pCP20, which encodes the Flp recombinase [44].

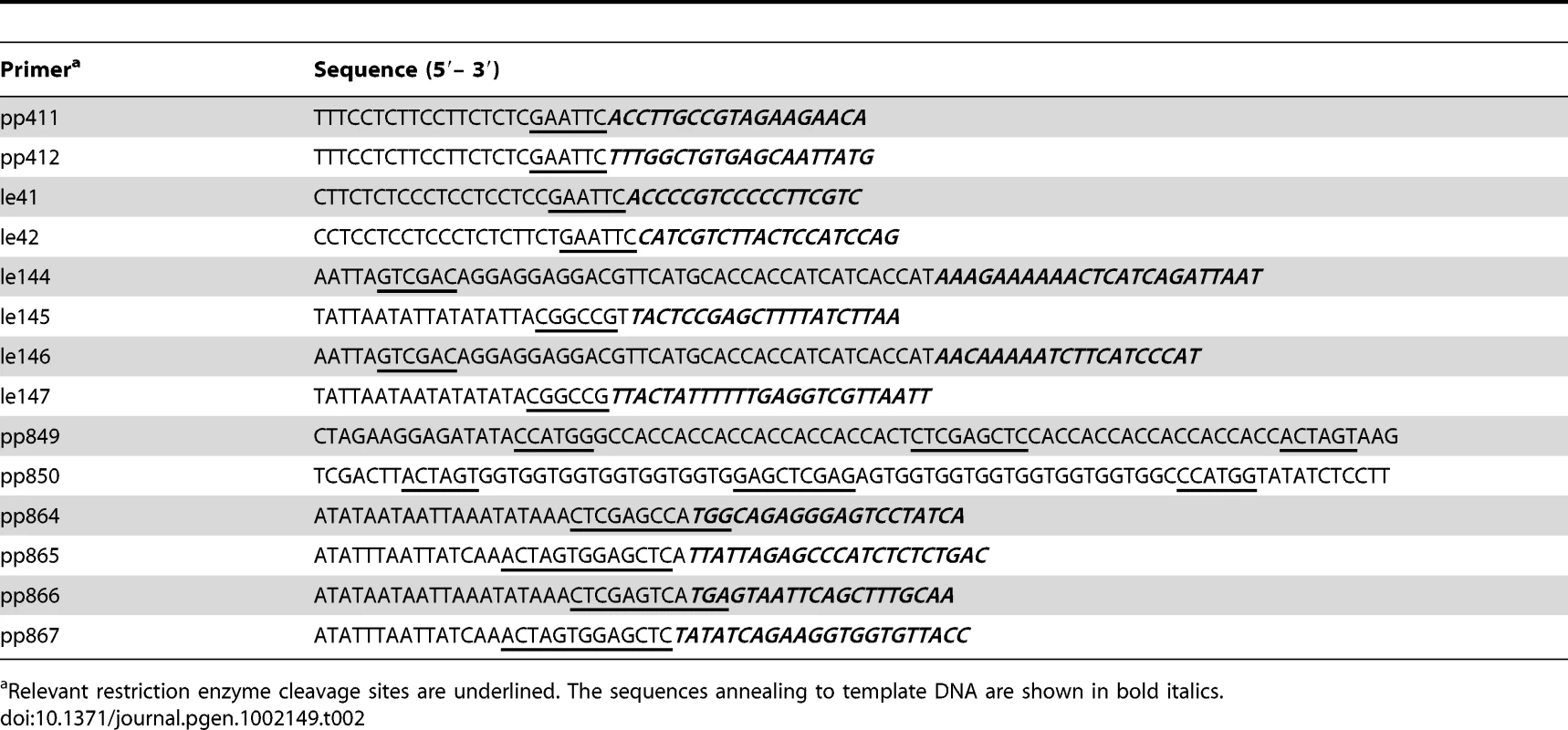

Plasmids

Plasmids used as PCR templates for λ Red-mediated gene disruptions included pKD3, pKD4 and pKD13 [41]. Plasmid pSUB11 was the template in the construction of 3x-FLAG epitope fusions [20]. Additional plasmid templates constructed in the present work were pSEB1, which carries the spectinomycin-resistance aadA cassette, and pSEB3, carrying an aph-araC-PBAD module. For the construction of pSEB1, the aadA gene of plasmid pBT22 [45] was amplified by PCR with primers pp411 and pp412 (Table 2); the resulting fragment was digested with EcoRI and ligated into EcoRI-cleaved plasmid pSUB2. The latter is a derivative of pGP704 [46] lacking the BamHI segment spanning the RP4 tra operon. Plasmid pSEB3 was derived from a chromosomal construct carrying the kanamycin-resistance aph gene immediately downstream from araC gene (strain MA7794; Table 1 and Table S1). The aph-araC-PBAD segment was amplified from MA7794 chromosomal DNA with primers le41 and le42 (Table 2), cleaved with EcoRI, and cloned into pSUB2.

A second set of recombinant plasmids was constructed to overproduce and purify phage repressor and antirepressor proteins. Repressor genes gftR and gfoR were amplified from wild-type ATCC14028 chromosomal DNA with primer pairs le146/le147 and le144/le145, respectively (Table 2). In both cases, the forward primer contained a 5′ extension designed to produce an N-terminal 6xHis tag fusion. The amplification products were doubly digested with SalI and EagI restriction endonucleases and ligated to SalI×EagI-cleaved pKTQ12 DNA [45] yielding plasmids pSEB10 (gftR) and pSEB11 (gfoR). A different vector, pNFB28, was used for cloning antirepressor genes. Plasmid pNFB28 is a derivative of Novagen's pET-16b plasmid modified so as to allow the construction of both N-terminal and C-terminal 7xHis tag fusions. The modification involved ligating a DNA fragment produced by annealing oligonucleotides pp849 and pp850 (Table 2) to pET-16b DNA doubly digested with XbaI and XhoI endonucleases. gftA and gfoA genes were amplified from wild-type ATCC14028 chromosomal DNA with primer pairs pp864/pp865 and pp866/pp867, respectively. The amplified fragments were doubly digested with NcoI and SacI (gftA), and BspHI and SacI (gfoA), and ligated to pNFB28 DNA digested with NcoI and SstI. In the resulting plasmids, pSEB12 and pSEB13, the gftA and gfoA genes carry 7xHis-encoding sequences at their 3′ ends and are under the control of the T7 promoter.

Protein purification

For the purification of repressors and repressor/antirepressor complexes, strains MA8567 (PBAD-gftA-3xFLAG) and MA8731 (PBAD-gfoA-3xFLAG), carrying or lacking plasmids pSEB10 and pSEB11, respectively, were grown to an OD600≈0.15 at 37°C and exposed to 0.1% L-arabinose (Sigma-Aldrich) or left untreated. Bacteria were cultivated at 37°C for additional 6 hours, Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10000G and rinsed once in PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 100 mM Na2HPO4 and 2 mM KH2PO4). Pellets were then submitted to several freeze-thaw cycles in a dry-ice/ethanol bath before being resuspended in IP buffer (Tris-HCl 20 mM pH 8, NaCl 500 mM, Igepal 0.1% (Sigma-Aldrich), imidazole 20 mM) and sonicated on ice until complete but gentle lysis. Cell debris was spun down and the supernatant applied to Nickel nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin (Qiagen). Incubation was continued for 2 hrs at 4°C. Liquid was removed and the resin was rinsed twice with 10 times the extract volume of buffer IP. Proteins still specifically bound to the resin were eluted in buffer IPE identical to buffer IP except for imidazole concentration (250 mM). Fractions were then adjusted to 15% glycerol and frozen at −80°C for storage. The purity as assessed from the repressor content was greater than 80% and concentration was in the range of 0.1–1 µg mL−1.

C-terminally 7xHis tagged GftA protein was purified from E. coli strain BL21 carrying plasmid pSEB12. Cells were grown essentially as described above but induction was carried out with IPTG (0.1 mM final concentration) for 3 hrs. Bacterial pellets were processed as described above, except that Igepal was omitted from IP and IPE buffers.

Size-exclusion chromatography

A Sephadex G75 column (Amersham) previously calibrated with α-chymotrypsin, ovalbumin and bovine serum albumin purchased from Sigma-Aldrich was connected to an Äkta P-9000 HPLC apparatus and a Frac-950 fraction collector. To eliminate any aggregate that might have formed during storage, protein samples were systematically centrifuged at maximum speed in a micro centrifuge for 15 min prior to loading. About 10 µg of proteins were loaded onto a column pre-equilibrated with about 2 volumes of IPE buffer. After the passage of the void volume, 0.5 mL fractions were collected and vacuum dried. Samples were resuspended in loading buffer, boiled and separated on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was conducted essentially as previously described [47]. Briefly, bacteria from 2 ml overnight cultures were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 50–80 µL of Laemmli buffer. Cells were lysed by boiling 10 min and lysates loaded onto 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Biorad's Precision Plus Kaleidoscope standards were included as migration markers. After the gel run, proteins were electro-transferred to a PVDF membrane, which was blocked with PBS containing 3% skimmed milk and 0.05% Tween 20. The blocking buffer was then replaced with a similar buffer containing the primary anti-FLAG antibody (anti-FLAG M2 from Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min. The membrane was rinsed thoroughly in PBS 0.05% Tween 20 before the secondary antibody (anti-mouse peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies from Sigma-Aldrich) was applied. Finally, results were revealed with the ECL kit from Amersham and imaged on a Fuji LAS3000 apparatus.

Gel-shift assays

A DNA fragment spanning the binding site of the GftR was amplified by PCR from strain LT2 chromosomal DNA with primers le127 (5′-GTTCGCCGATGCTCATTT-3′) and le128 (5′-CCGTGAGAGGTCAGCCATA-3′). The PCR product was then radioactively labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB) and γ-32P-ATP as recommended by the manufacturer. Labeled DNA (approximately 5 ng) was mixed with 5 µL of 5× buffer BB (Tris-HCl pH 7.5 100 mM, NaCl 250 mM, EDTA 1 mM, MgCl2 5 mM, glycerol 25%, PMSF 250 mM sonicated salmon sperm DNA 250 µg mL−1) and varying amounts of protein. The reaction volume was adjusted with water to a final reaction volume of 20 µL. When appropriate, GftA antirepressor was added to GftR∶DNA complexes formed during an initial 15 min incubation at room temperature. Incubation was continued at the same temperature for additional 30 min (for samples with or without added GftA). Samples were loaded onto a 5% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoretic separation, gels were fixed in 20% ethanol 10% acetic acid, dried, and imaged with a Storm 820 apparatus from Molecular Dynamics.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. CookeFJBrownDJFookesMPickardDIvensA 2008 Characterization of the genomes of a diverse collection of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium definitive phage type 104. J Bacteriol 190 8155 8162

2. Figueroa-BossiNUzzauSMaloriolDBossiL 2001 Variable assortment of prophages provides a transferable repertoire of pathogenic determinants in Salmonella. Mol Microbiol 39 260 271

3. ThomsonNBakerSPickardDFookesMAnjumM 2004 The role of prophage-like elements in the diversity of Salmonella enterica serovars. J Mol Biol 339 279 300

4. WaldorMKFriedmanDI 2005 Phage regulatory circuits and virulence gene expression. Curr Opin Microbiol 8 459 465

5. TylerJSMillsMJFriedmanDI 2004 The operator and early promoter region of the Shiga toxin type 2-encoding bacteriophage 933W and control of toxin expression. J Bacteriol 186 7670 7679

6. WagnerPLLivnyJNeelyMNAchesonDWFriedmanDI 2002 Bacteriophage control of Shiga toxin 1 production and release by Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 44 957 970

7. BossiLFigueroa-BossiN 2005 Prophage arsenal of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. WaldorMFriedmanDAdhyaS Phages: Their Role in Bacterial Pathogenesis and Biotechnology Washington, DC ASM Press 165 186

8. LemireSFigueroa-BossiNBossiL 2008 Prophage Contribution to Salmonella Virulence and Diversity. HenselMSchmidtH Horizontal Gene Transfer in the Evolution of Bacterial Pathogenesis Cambridge, England Cambridge University 159 191

9. Figueroa-BossiNCoissacENetterPBossiL 1997 Unsuspected prophage-like elements in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol 25 161 173

10. LemireSFigueroa-BossiNBossiL 2008 A singular case of prophage complementation in mutational activation of recET orthologs in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 190 6857 6866

11. EffantinGFigueroa-BossiNSchoehnGBossiLConwayJF 2010 The tripartite capsid gene of Salmonella phage Gifsy-2 yields a capsid assembly pathway engaging features from HK97 and λ. Virology 402 355 365

12. JarvikTSmillieCGroismanEAOchmanH 2010 Short-term signatures of evolutionary change in the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium 14028 genome. J Bacteriol 192 560 567

13. GalkinVEYuXBielnickiJNdjonkaDBellCE 2009 Cleavage of bacteriophage λ cI repressor involves the RecA C-terminal domain. J Mol Biol 385 779 787

14. NdjonkaDBellCE 2006 Structure of a hyper-cleavable monomeric fragment of phage λ repressor containing the cleavage site region. J Mol Biol 362 479 489

15. PaboCOSauerRTSturtevantJMPtashneM 1979 The λ repressor contains two domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76 1608 1612

16. SauerRTRossMJPtashneM 1982 Cleavage of the λ and P22 repressors by recA protein. J Biol Chem 257 4458 4462

17. MardanovAVRavinNV 2007 The antirepressor needed for induction of linear plasmid-prophage N15 belongs to the SOS regulon. J Bacteriol 189 6333 6338

18. ShearwinKEBrumbyAMEganJB 1998 The Tum protein of coliphage 186 is an antirepressor. J Biol Chem 273 5708 5715

19. HoisethSKStockerBA 1981 Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature 291 238 239

20. UzzauSFigueroa-BossiNRubinoSBossiL 2001 Epitope tagging of chromosomal genes in Salmonella. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 15264 15269

21. McClellandMSandersonKESpiethJCliftonSWLatreilleP 2001 Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Nature 413 852 856

22. BunnyKLiuJRothJ 2002 Phenotypes of lexA mutations in Salmonella enterica: evidence for a lethal lexA null phenotype due to the Fels-2 prophage. J Bacteriol 184 6235 6249

23. LittleJWHarperJE 1979 Identification of the lexA gene product of Escherichia coli K-12. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76 6147 6151

24. LamontIBrumbyAMEganJB 1989 UV induction of coliphage 186: prophage induction as an SOS function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86 5492 5496

25. BurgessRRArthurTMPietzBC 2000 Mapping protein-protein interaction domains using ordered fragment ladder far-western analysis of hexahistidine-tagged fusion proteins. Methods Enzymol 328 141 157

26. FaubladierMBouchéJP 1994 Division inhibition gene dicF of Escherichia coli reveals a widespread group of prophage sequences in bacterial genomes. J Bacteriol 176 1150 1156

27. LusettiSLVoloshinONInmanRBCamerini-OteroRDCoxMM 2004 The DinI protein stabilizes RecA protein filaments. J Biol Chem 279 30037 30046

28. VoloshinONRamirezBEBaxACamerini-OteroRD 2001 A model for the abrogation of the SOS response by an SOS protein: a negatively charged helix in DinI mimics DNA in its interaction with RecA. Genes Dev 15 415 427

29. YasudaTNagataTOhmoriH 1996 Multicopy suppressors of the cold-sensitive phenotype of the pcsA68 (dinD68) mutation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 178 3854 3859

30. KimseyHHWaldorMK 2009 Vibrio cholerae LexA coordinates CTX prophage gene expression. J Bacteriol 191 6788 6795

31. QuinonesMKimseyHHWaldorMK 2005 LexA cleavage is required for CTX prophage induction. Mol Cell 17 291 300

32. NickelsBE 2009 A new twist on a classic paradigm: illumination of a genetic switch in Vibrio cholerae phage CTXφ. J Bacteriol 191 6779 6781

33. DavisBMKimseyHHKaneAVWaldorMK 2002 A satellite phage-encoded antirepressor induces repressor aggregation and cholera toxin gene transfer. EMBO J 21 4240 4249

34. McLeodSMKimseyHHDavisBMWaldorMK 2005 CTXφ and Vibrio cholerae: exploring a newly recognized type of phage-host cell relationship. Mol Microbiol 57 347 356

35. SusskindMMBotsteinD 1975 Mechanism of action of Salmonella phage P22 antirepressor. J Mol Biol 98 413 424

36. SusskindMMBotsteinD 1978 Molecular genetics of bacteriophage P22. Microbiol Rev 42 385 413

37. PrellHH 1978 Ant-mediated transactivation of early genes in Salmonella prophage P22 by superinfecting virulent P22 mutants. Mol Gen Genet 164 331 334

38. BertaniG 2004 Lysogeny at mid-twentieth century: P1, P2, and other experimental systems. J Bacteriol 186 595 600

39. SchmiegerH 1972 Phage P22-mutants with increased or decreased transduction abilities. Mol Gen Genet 119 75 88

40. BochnerBR 1984 Curing bacterial cells of lysogenic viruses by using UCB indicator plates. Biotechniques 2 234 240

41. DatsenkoKAWannerBL 2000 One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 6640 6645

42. MurphyKCCampelloneKGPoteeteAR 2000 PCR-mediated gene replacement in Escherichia coli. Gene 246 321 330

43. YuDEllisHMLeeECJenkinsNACopelandNG 2000 An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 5978 5983

44. CherepanovPPWackernagelW 1995 Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158 9 14

45. SpiritoFBossiL 1996 Long-distance effect of downstream transcription on activity of the supercoiling-sensitive leu-500 promoter in a topA mutant of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol 178 7129 7137

46. MillerVLMekalanosJJ 1988 A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J Bacteriol 170 2575 2583

47. Figueroa-BossiNLemireSMaloriolDBalbontínRCasadesúsJ 2006 Loss of Hfq activates the σE-dependent envelope stress response in Salmonella enterica. Mol Microbiol 62 838 852

48. MillerJH 1992 A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics. A Laboratory Manual and Handbook for Escherichia coli and Related Bacteria Cold Spring Harbor, New York Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press

49. LilleengenK 1948 Typing of Salmonella typhimurium by means of bacteriophage. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 77 2 125

50. FieldsPISwansonRVHaidarisCGHeffronF 1986 Mutants of Salmonella typhimurium that cannot survive within the macrophage are avirulent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83 5189 5193

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicínaČlánek vyšel v časopise

PLOS Genetics

2011 Číslo 6

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Souvislost haplotypu M2 genu pro annexin A5 s opakovanými reprodukčními ztrátami

- Velké děti po kryoembryotransferu

- Intrauterinní inseminace a její úspěšnost

- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle

- Recurrent Chromosome 16p13.1 Duplications Are a Risk Factor for Aortic Dissections

- Statistical Inference on the Mechanisms of Genome Evolution

- Chromosomal Macrodomains and Associated Proteins: Implications for DNA Organization and Replication in Gram Negative Bacteria

- Maps of Open Chromatin Guide the Functional Follow-Up of Genome-Wide Association Signals: Application to Hematological Traits