-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

An Ultrasensitive Mechanism Regulates Influenza Virus-Induced Inflammation

Vaccines suffice for protecting public health against seasonal influenza viruses, but when unexpected strains appear against which the vaccine does not confer protection, alternative treatments are necessary. In this work, we used gene expression and virus growth data from influenza-infected mice to determine how moderate and deadly influenza viruses may invoke unique inflammatory responses and the role these responses play in disease pathology. We found that the relationship between virus growth and the inflammatory response for all viruses tested can be characterized by ultrasensitive response in which the inflammatory response is gated until a threshold concentration of virus is exceeded in the lung after which strong inflammatory gene expression and cytokine production occurs. This finding challenges the notion that deadly influenza viruses invoke unique cytokine and inflammatory responses and provides additional evidence that pathology is regulated by virus load, albeit in a highly nonlinear fashion. These findings suggests immunomodulatory treatments could focus on altering inflammatory response dynamics to improve disease pathology.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 11(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004856

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004856Summary

Vaccines suffice for protecting public health against seasonal influenza viruses, but when unexpected strains appear against which the vaccine does not confer protection, alternative treatments are necessary. In this work, we used gene expression and virus growth data from influenza-infected mice to determine how moderate and deadly influenza viruses may invoke unique inflammatory responses and the role these responses play in disease pathology. We found that the relationship between virus growth and the inflammatory response for all viruses tested can be characterized by ultrasensitive response in which the inflammatory response is gated until a threshold concentration of virus is exceeded in the lung after which strong inflammatory gene expression and cytokine production occurs. This finding challenges the notion that deadly influenza viruses invoke unique cytokine and inflammatory responses and provides additional evidence that pathology is regulated by virus load, albeit in a highly nonlinear fashion. These findings suggests immunomodulatory treatments could focus on altering inflammatory response dynamics to improve disease pathology.

Introduction

Invading pathogens induce acute inflammation when molecular signatures are detected by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs; e.g., RIG-I like receptors [RLRs] and Toll-like receptors [TLRs]) expressed on tissue-resident immune cells and non-immune cell types. PRR ligation triggers innate immune responses and leads to the induction of inflammatory and antiviral gene expression, which together function to limit pathogen growth, activate the adaptive immune response, and ultimately resolve the infection [1,2]. Precise regulation of PRR-mediated signaling is necessary to both avoid inadvertent tissue damage in response to non-pathogenic stimuli, and to prevent immunopathology resulting from excessive expression of inflammatory molecules. In essence, the ideal inflammatory response must exhibit a balance between appropriate activation against a genuine threat and self-limiting behavior once that threat has been controlled. Despite its importance in maintaining normal tissue homeostasis and limiting pathogen-associated diseases, the mechanisms underlying the regulation of this balance are poorly understood.

Influenza A viruses are recognized by both TLRs and RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) [3–7], and some strains are potent inducers of inflammatory and antiviral gene expression. Generally, lung tissues infected with pathogenic isolates exhibit high virus titers and robust inflammatory gene expression, as has been documented in in vivo studies with the 1918 Spanish influenza virus [8,9], highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses [10–12], and the 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza virus [13,14]. In contrast, seasonal influenza viruses typically replicate less efficiently, elicit more restrained inflammatory responses, and are usually not associated with lethal infections. Recent evidence has implicated the level of virus replication in infected lung tissues as the primary phenotypic variable driving inflammation and lethal outcomes [15,16]. Other data indicate that influenza viruses that exhibit significant differences in pathogenicity stimulate qualitatively similar host responses that differ primarily at the level of magnitude and kinetics [17]. However, these studies have not revealed the mechanisms that account for the different profile dynamics observed in infections by high and low pathogenic viruses. Such information would aid in clarifying not only how some influenza viruses induce lethal disease, but also the general mechanisms that regulate inflammatory balance.

To characterize the dynamics of influenza virus-induced inflammation, we developed a novel approach to infer gene regulatory models from dynamic gene expression data. Referred to as systems inference microarray analysis, our method builds on current approaches that use co-expression analysis to isolate modules of functional signatures in gene expression data and then extends these methods by fitting the gene expression modules to mathematical equations (models) by using segmented regression analysis. Models can be created to look for strain-dependent responses and, unlike traditional differential expression analysis, to predict gene expression under new experimental conditions. By using this method, we set out to determine how influenza viruses that exhibit variable pathogenicity profiles influence the dynamics of the inflammatory response.

Results

H1N1, pH1N1, and H5N1 have distinct virulence and growth dynamics

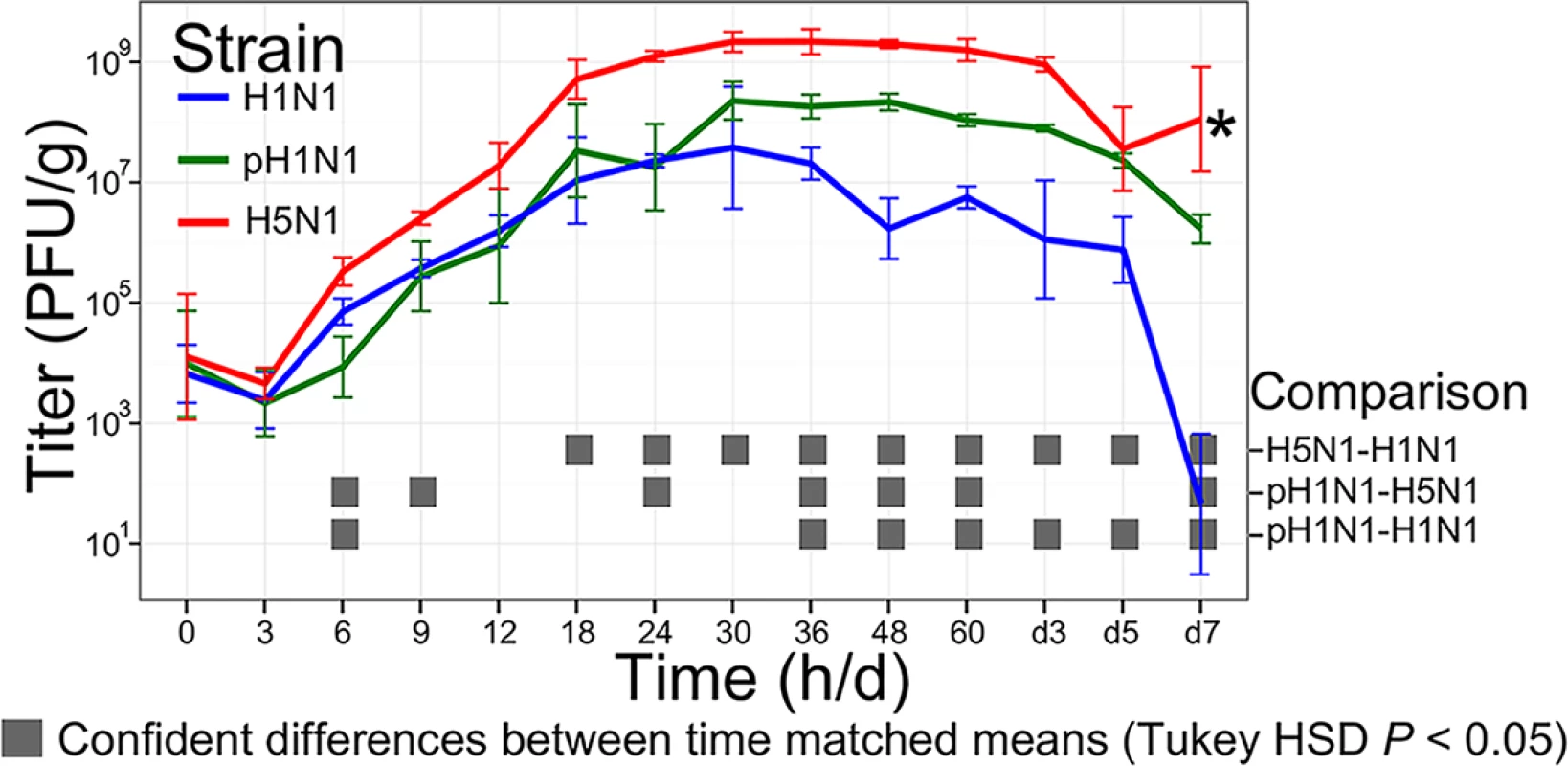

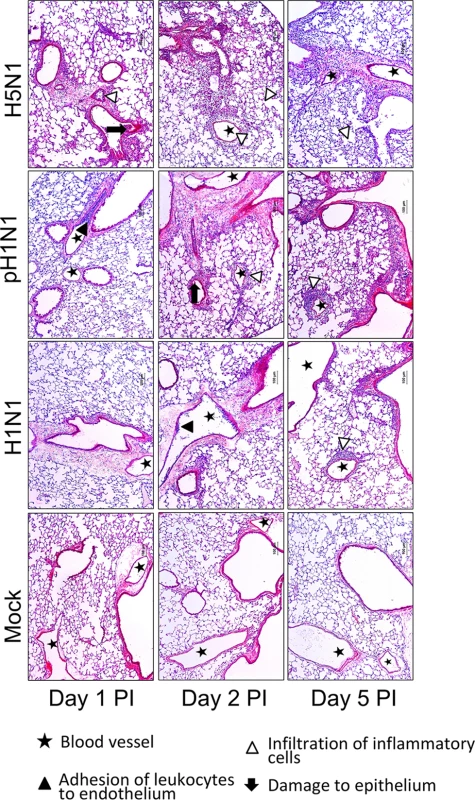

To characterize the dynamics of the host immune response to specific virus isolates, we infected mice with 105 PFU of three virus isolates with distinct pathogenicity profiles and harvested lung tissues at 14 time points after infection (from 0 to 7 days post-infection; n = 3 per virus per time point; see Fig 1) for several parallel analyses. These viruses included a low pathogenicity seasonal H1N1 influenza virus (A/Kawasaki/UTK4/2009 [H1N1]; referred to as ‘H1N1’), a mildly pathogenic virus from the 2009 pandemic season (A/California/04/2009 [H1N1]; referred to as ‘pH1N1’), and a highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus (A/Vietnam/1203/2004 [H5N1]; referred to as ‘H5N1’). An initial inoculation of 105 PFU was used as previous studies indicated that a high virus dose was needed to invoke different pathologies in H1N1 and pH1N1-infected mice [13]. As expected, lung virus titers (virus titers determined by plaque assay and reported in plaque forming units [PFU] per gram lung; Fig 1) indicated a clear hierarchy of mild, moderate, and severe virus-induced disease. Specifically, the H5N1 virus produced the highest lung titers and between days 5 and 7 post-infection, this virus also caused mortality in the animals whose lungs were to be collected on day 7 post-infection (i.e., ‘severe’ disease). In contrast, all animals infected with the H1N1 or pH1N1 viruses survived the duration of the time course study; however, pH1N1-infected animals were visibly sicker and exhibited higher lung titers relative to those infected with H1N1 at all time points observed after the first 30 h post-infection (i.e., ‘moderate’ and ‘mild’ disease, respectively). Histopathological analysis of tissue samples collected on days 1, 2, and 5 post-infection (Fig 2) also showed that H5N1-infected tissue exhibited the earliest, most severe signs of inflammation and inflammatory immune cell infiltrates followed by pH1N1-infected tissue, whereas H1N1-infected tissue showed mild evidence of inflammation and was most similar to tissue from the control mice (mock-infected mice).

Fig. 1. Virus growth dynamics.

Mice were infected with 105 PFU of H1N1, pH1N1, or H5N1 virus, three mice per infection group were euthanized at 14 time points after infection (0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 48, and 60 h and 3, 5, and 7 days), and virus titers in lung tissues were determined by plaque assays in MDCK cells. Error bars illustrate the standard deviation from the mean. The gray boxes at each time point identify significant pairwise differences between the means of the viruses indicated at the right of the figure panel (significance was determined by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Honestly Significantly Different test, P < 0.05). *, three H5N1-infected mice intended for collection on day 7 succumbed to their infections prior to sample collection. Fig. 2. Representative pathological images of influenza-infected lungs.

Symbols, as described by the key, emphasize regions of leukocyte adhesion, infiltration of inflammatory cells, and damage to the respiratory epithelium. Inflammation-associated gene co-expression is associated with inflammation pathway signaling and macrophage infiltration

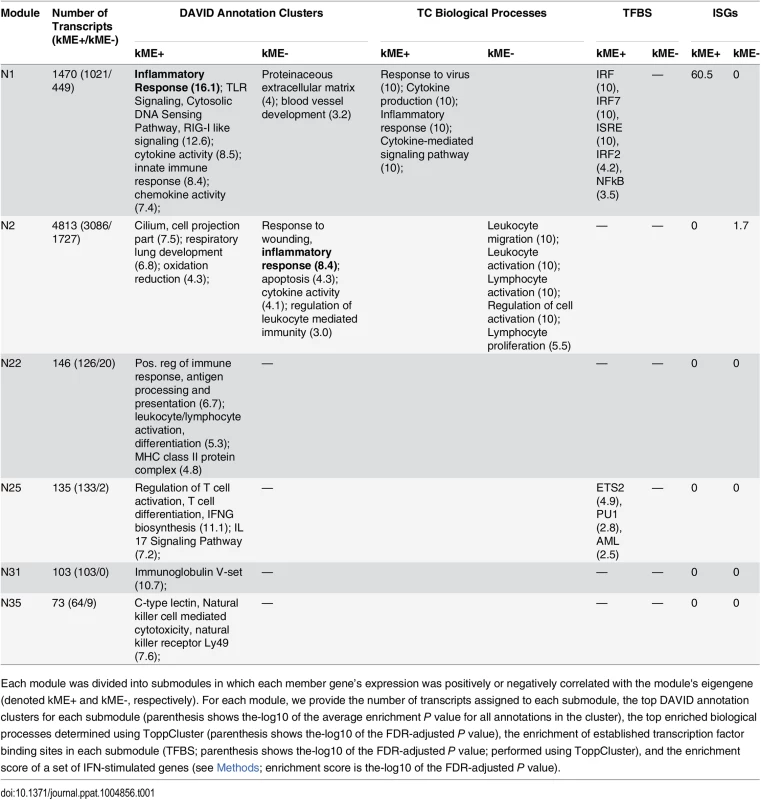

We next used co-expression analysis to integrate inflammation-associated gene expression differences between influenza-infected and control lungs into a systems level context. We first asked whether the expression of inflammation-associated genes clustered into modules of co-expressed genes. Tissues from the same animals that were used to determine virus growth were used to evaluate changes in global lung transcriptional profiles. A total of 168 microarrays were developed (three per time point for H1N1-infected, pH1N1-infected, H5N1-infected and control mice). One microarray was removed after reviewing replicate quality. After filtering transcripts for minimally confident variation (we required at least one time-matched, infected condition compared with mock-infected absolute fold change ≥ 2 and a false discovery rate [FDR]-adjusted P-value < 0.01), the log2 of the normalized intensity of the retained transcripts (16,063) for all 167 samples were then clustered by using the Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) algorithm [18]. In all, 45 distinct co-expression modules were identified (referred to as N1, N2, etc.; S1 Table provides the module assignments for all transcripts). To identify the biological role of the host response modules, we performed functional enrichment analysis on each gene module by using DAVID [19] and ToppCluster [20]. Because each module was comprised of positively and negatively correlated transcripts, we used the module eigengene (i.e., the first principle component of the gene expression matrix) to divide each module into two submodules containing transcripts that were positively or negatively correlated with the parent module’s eigengene, denoted as kME+ and kME - (referred to as module membership), respectively. This procedure allowed us to look for biological processes with similar but opposing dynamic responses to the virus infections. Functional enrichment analyses were then applied to each submodule by using two bioformatics platforms to ensure robust results.

We identified two submodules (N1 kME+ and N2 kME-, referred to as simply N1 and N2 in the remainder of the text) that were enriched for inflammatory response and inflammation-associated pathway signatures by using both bioinformatics platforms, and these two modules became the focus of our study (Table 1 summarizes the functional enrichment results for the immune and inflammatory related annotations. The complete enrichment results from ToppCluster and DAVID are available in S2 Table and S1 and S2 Files). The N1 module was uniquely enriched for cytokine activity and type I interferon (IFN) regulating TLR and RLR pathways [21], as well as transcriptional signatures associated with IFN-regulated activity (i.e., the transcription factor binding sites [TFBS] of Irf1, Irf7, Irf2, ISRE, and NF-κB). Additionally, N1 was the only module that exhibited significant enrichment with a compendium of established IFN-stimulated genes (‘ISGs’; Table 1; see Methods. The list of ISGs is available in S3 File). A more recent study identified 147 IFN stimulated genes in immortalized, human airway epithelial (Calu3) cells [22]. Of these, 90 mouse homologs were annotated on the microarrays and 70 of the homolog probes were assigned to the N1 module (Fisher’s exact test; P-value < 10–16; odds ratio = 36.4), further associating N1 interferon-stimulated gene activity.

Tab. 1. Descriptions of immune and inflammation associated gene co-expression modules.

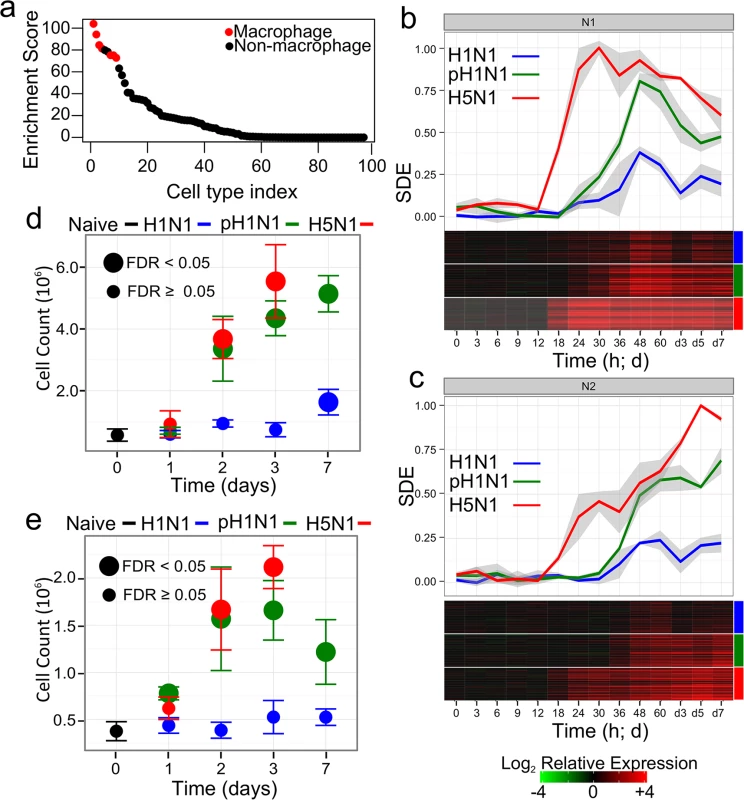

Each module was divided into submodules in which each member gene’s expression was positively or negatively correlated with the module's eigengene (denoted kME+ and kME-, respectively). For each module, we provide the number of transcripts assigned to each submodule, the top DAVID annotation clusters for each submodule (parenthesis shows the-log10 of the average enrichment P value for all annotations in the cluster), the top enriched biological processes determined using ToppCluster (parenthesis shows the-log10 of the FDR-adjusted P value), the enrichment of established transcription factor binding sites in each submodule (TFBS; parenthesis shows the-log10 of the FDR-adjusted P value; performed using ToppCluster), and the enrichment score of a set of IFN-stimulated genes (see Methods; enrichment score is the-log10 of the FDR-adjusted P value). In contrast, the N2 module was only weakly enriched for some cytokine activity related annotations and not enriched for any of the binding sequences of transcription factors that are members of canonical inflammatory pathways (such as interferons, interferon regulatory factor proteins, or NFκB). Instead, it was primarily associated with several annotations related to leukocyte and lymphocyte activity (see summary of ToppCluster enrichment results in Table 1; see S1 and S2 Files). Further analysis with CTen [23], a platform for associating clustered gene expression data with specific cell types, found N2 to be highly enriched for genes expressed in macrophages in various cellular states (e.g., bone marrow-derived macrophages exposed to lipopolysaccharide [LPS]) (Fig 3A; additional details available in S3 Table). The remaining immune-associated submodules (the kME+ N22, N25, N31, and N35 submodules; described in Table 1) were enriched for several key immune processes such as antigen presentation, and T cell and natural killer (NK) cell activity, but their further assessment would be beyond our focus and the scope of this study. Thus, bioinformatics analyses robustly associated the N1 module with inflammation, cytokine production, and type I IFN pathway activity—likely activated in resident lung cells—whereas the N2 module is associated with migration and activation of macrophages in the lung.

Fig. 3. Dynamics of inflammation-associated co-expression modules.

Panel (a) shows the enrichment scores (-log10 of the FDR-adjusted P value) of the genetic signatures of 94 cell types in the N2 module as determined using CTen[23]. Data corresponding to macrophage signatures in different cellular states are colored red (see S3 Table for the complete results). (b) and (c) The scale difference of the eigengene (SDE) for each influenza virus for the two inflammatory response-related gene co-expression modules N1 and N2, respectively. Different colors denote the specific virus with which the mice were infected, and shaded regions around the plotted data illustrate standard deviations across three biological replicates. A heatmap below each panel shows the gene expression of the top 50 genes (based on their kME) in each module. Color boxes to on the right indicate the specific virus. The fold change is relative to the mean gene expression of pooled, time-matched control samples. Panels (d) and (e) show the cell counts of macrophages and neutrophils in mouse lungs after infection with 105 PFU of influenza viruses (5 mice were used per infection condition at each time point). For each data point, colors above the panel indicate the specific strain. Large points indicate average cell counts that were significantly distinct from the average cell count observed in naïve mice (FDR < 0.05; see Methods). A closer examination of the expression dynamics of each of the inflammation response-associated modules revealed patterns of expression that were consistent with the biological roles predicted by our bioinformatics analyses. We used the scaled difference of the module eigengene to characterize the expression of all genes within each module. We subtracted the mean of the eigengene of the control samples from the eigengene of time-matched, virus-infected samples and then divided by the largest observed average difference across all conditions. The resulting scaled difference eigengene (SDE) represents the fraction of the maximum log fold change in gene expression observed across all experimental conditions (Fig 3B and 3C. S1 Fig briefly illustrates the eigengene scaling in greater detail. S4 Table provides a heatmap of the gene expression of all probes in each module).

Within the inflammation-associated modules (N1 and N2), the H5N1 virus induced the earliest gene expression changes and the highest peak expression levels, corroborating previous observations that H5N1 viruses are strong inducers of inflammatory and IFN response signaling in vivo [10,24,25]. Consistent with the prediction that N1 is involved in detecting virus in infected tissues, the N1 module eigengene was the most highly correlated with virus titer (Pearson pairwise correlation, ρ = 0.70).

Module gene expression dynamics further suggested that the N2 module gene is associated with lymphocyte infiltration. Exudate macrophages [26] and neutrophil [27] have been identified as factors of severe disease during influenza infection. To associate gene expression dynamics with changes of immune cell counts, a new population of mice were infected with the three influenza viruses, five mice per infection group were sacrificed on days 1, 2, 3 and 7 and the changes in the number of macrophages and neutrophils was assessed (see Methods). Unlike the previous study by Brandes, et al. [27], strong neutrophil infiltration was not specific to fatal infections but, instead, infiltration of both cell types had a clear hierarchical relationship with the severity of the infection (Fig 3D and 3E). The N2 module eigengene exhibited a lesser correlation to virus titer (ρ = 0.55), but was tightly correlated to macrophage influx into the lung (ρ = 0.90; P-value < 0.01 Student’s t-test). Of the 45 module identified in the studied, N2 had the highest correlation to both macrophage and neutrophil influx (the correlation of macrophage and neutrophil influx and all 45 module eigengenes are provided in S5 Table; ρ = 0.80; P-value < 0.01). The N1 module on the other hand was weakly but significantly correlated with immune cell infiltration (ρ = 0.67 [P-value = 0.03] for neutrophils; ρ = 0.60 [P-value = 0.05] for macrophages), but its eigengene was not the most highly correlated (5 other module eigengenes had a greater absolute correlation). These results further associate N2 with immune cell-specifically macrophage - infiltration, while the sum of the bioinformatics, virus titer correlations and immune cell infiltration evidences associated N1 with inflammation and type I IFN pathway activity.

Intramodular network topology suggests Irf7 as N1 module regulator

A further advantage of a network approach is that the functional relevance of genes might be inferred from their positions within the co-expression network [28]. We used the module membership (the correlation between the gene’s expression and the module eigengene, kME) to isolate potential regulators of the N1 module. Among the top intramodular hub genes (i.e., genes with the highest module memberships, see S4 Table), we found Mnda, Herc6 and Cd274 and several interferon regulated, virus replication inhibitory genes such as Oas2 and Oas3 [29]. Herc6 is involved in ubiquitination [30]. Mnda is significantly up-regulated in monocytes exposed to interferon α [31] while Cd274 is a transmembrane protein expressed on antigen presenting cells and modulates activation of T cells, B cells and myeloid cells. We also observed that interferon stimulated genes tended to have higher intramodular hub rankings, suggesting a regulatory role for interferon (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P-value < 10–12). We then considered the module membership rankings of transcription factors known to regulate interferon. Of the established interferon regulatory factors that are members of the N1 module (e.g., Irf1, Irf2, Irf7, Irf9, Stat1, and Stat2. Nfkb1 and Nfkb2 were not assigned to N1), Irf1 and Irf7 had the highest module memberships (kME = 0.94 and 0.93; ranking = 118 and 225, respectively). Irf7 expression was also several orders of magnitude greater than Irf1 (S4 Table). Together, these findings corroborate our bioinformatics analyses by suggesting that N1 is regulated by interferon, and N1 expression likely results in enhanced cytopatchic effects and regulation of the lymphocyte immune response. Network analysis further suggests that Irf7 may play a regulatory role upstream of interferon transcription.

Inflammation-associated gene expression is regulated by an ultrasensitive mechanism

Previous studies have suggested that highly pathogenic influenza virus infections induce an irregular or disproportionate inflammatory response relative to seasonal influenza viruses, and that these differences occur early in the host response [24]. For this reason, we sought to further explore the possibility of isolate-specific or isolate-independent response patterns of the cytokine-associated N1 module. We wanted to infer mathematical relationships that could describe when inflammatory-associated gene expression occurs and what magnitude of expression is expected. By using the eigengene as a representation of the scaled gene expression dynamics, we attempted to infer simple mathematical models that can be related to common signaling mechanisms.

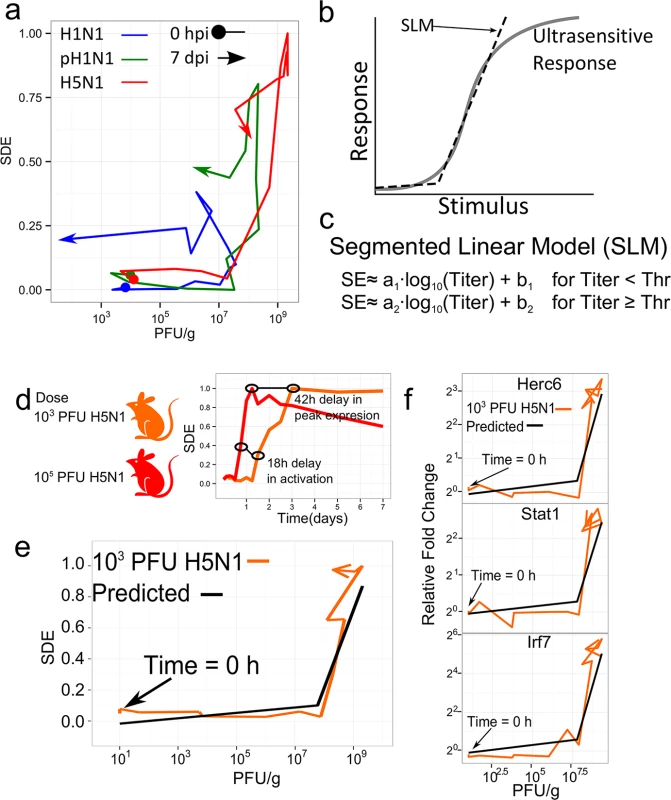

Surprisingly, when we plotted the N1 SDE for each isolate against the corresponding virus titer, we observed a consistent profile for all three viruses; regardless of intrinsic virulence, the fold change in N1 gene expression remained initially low and rapidly increased only after a virus titer of approximately ~108 PFU/g (of lung) was reached (Fig 4A). Following activation, N1 gene expression increased as a function of virus concentration at the same apparent rate for all infection conditions, and more complicated dynamics were observed only during the later phase of the infection when virus clearance was observed (i.e., when the virus titers began to decrease). These observations suggest that IFN-regulated (N1) gene expression was induced by an ultrasensitive response mechanism controlled at the level of the virus titer rather than the virus’s intrinsic virulence.

Fig. 4. N1 module gene expression is regulated by an ultrasensitive response mechanism triggered by a specific virus concentration.

Panel (a) shows a phase-plane representation of the relationship between the scaled N1 module eigengene and the virus titer for each influenza virus infection condition (different colors denote each of the three influenza viruses, which are indicated at the top of the panel. To indicate change in time, a circle indicates data at time 0 hpi and an arrow indicates data at 7 dpi). (b) An example illustration of an ultrasensitive response to increasing stimulus. In our model, the response is the change in inflammatory-associated gene expression and the stimulus is the lung virus titers. A segmented linear model (SLM) can approximate key aspects of the ultrasensitive response. In this study, the response is gene expression and the stimulus is the concentration of virus in the lung (c) The mathematical definition of an SLM. Below some threshold virus titer (Thr), the scaled eigengene (SE) is approximated by a linear model that is a function of the log of the virus titer, the slope (a1), and the intercept (b1). After the threshold virus titer is reached, the slope and intercept parameters change (a2 and b2) to describe the SE after activation. The parameters were fit to the data shown in panel (a) and used to predict the N1 SE in newly infected mice. (d) shows a comparison of the H5N1 N1 eigengene from an infection at a dose of 105 PFU (as shown in Fig 3) and an infection at a dose of 103 PFU. Panel (e) compares the predicted scaled eigengene based on the SLM versus the measured eigengene behavior in mice infected with 103 PFU of the H5N1 virus. Panel (f) shows gene expression changes for selected constituent genes of the N1 module as a function of virus titer. Ultrasensitive responses characterize the dynamics of several signaling pathways that regulate essential and often toxic biological processes such as the cell cycle [32] and apoptosis [33]. As shown in Fig 4B, ultrasensitive responses are typified by an attenuated response to low levels of stimulation but a strong response occurs once a threshold level of stimulus is reached. Cooperativity [33] and positive feedback [34] are two mechanisms that produce ultrasensitive responses. To formalize the hypothesis that the inflammatory gene response follows an ultrasensitive response profile, we selected a segmented linear model (SLM, defined in Fig 4C) to be a simplified representation of the ordinary differential equations normally used to model ultrasensitive responses, and we fit the N1 SDE to an SLM that was strictly a function of the virus titer. The optimal fit showed a threshold of 107.78±0.14 PFU/g is required for N1 module activation to occur, after which the SDE’s rate of activation (a2) was 0.5±0.07 log10(PFU/g)-1 with an intercept (b2) of -3.8 (unitless) (see the Methods and S2 Fig for additional details). Below this threshold, the model predicted minimal gene expression (a1 = 0.17; b1 = 0.03). The SLM goodness of fit on the training data was an adjusted R2 = 0.72 while an adjusted R2 = 0.41 was observed when the data was fit to a linear model. A Davie’s test confirmed that a segmented model was a significantly better fit than a linear correlation model (P-value < 2.2e-16). While the H1N1-infected lung tissue did not exceed an average peak virus titer of 107.4 PFU/g (peak titer occurs at 48 hpi in Fig 4A), we observed increased transcriptional activity in H1N1-infected mouse lung tissues after this time point, suggesting either that the actual peak virus titer occurred between 48 hpi and the subsequent time point (60 hpi), or that the model-predicted threshold was slightly over-approximated.

We next sought to validate the threshold model by attempting to predict cytokine-associated gene expression in influenza virus-infected lung when only the virus titers are known. For this, we selected the H5N1 virus, which has previously been associated with an excessive cytokine response [10]. We infected mice with 103 PFU of the H5N1 virus (a 100-fold reduced dose compared with that used in the experiments to fit the model), determined lung virus titers at the same time points used for the initial experiment (S3 Fig), and then evaluated the segmented linear model’s ability to predict cytokine-associated gene expression. First, we confirmed that the original transcripts assigned to the N1 module were again co-expressed, and thus we used the same transcripts originally assigned to the N1 module to determine the eigengene (see S4 Fig for an analysis of the conservation of the N1 module between the two experiments). In this experiment, as expected, the peak average virus titer (109.3±0.21 PFU/g) for the 103 PFU dose was delayed compared with that for the 105 PFU dose (S3 Fig, compare to Fig 1). Moreover, the SDE exhibited an 18-h delay in activation and a 42-h delay in peak expression compared with the 105 PFU N1 eigengene (Fig 4D). Importantly, based on the virus titers alone, the fitted segmented linear model accurately predicted N1-like SDE behavior (R2 = 0.71 for all time points and R2 = 0.87 for time points up to peak expression; Fig 4E and S5 Fig), and this could be further demonstrated at the individual gene level for specific N1-associated transcripts (e.g., Herc6, Stat1 and Irf7; Fig 4F). These observations provide strong evidence that activation of inflammatory-associated gene expression is dictated by a specific virus concentration in infected tissue, and further suggest the novel possibility that the pulmonary innate inflammatory response has a nonlinear, ultrasensitive-like activation profile that promotes tolerance to low concentrations of virus.

The dynamics of key inflammatory cytokines are consistent with an ultrasensitive response

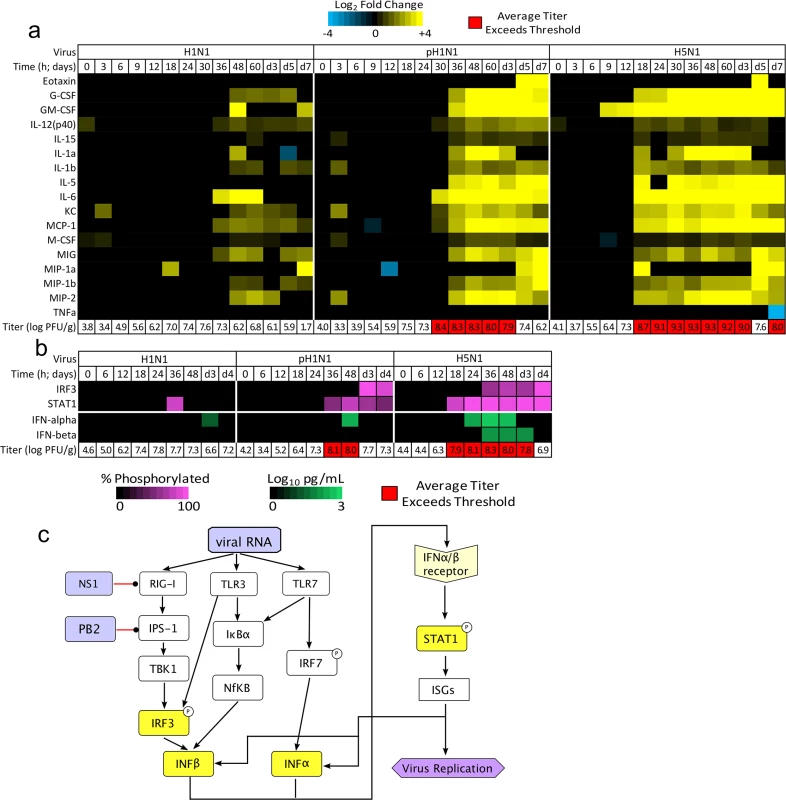

Although transcriptional activation of IFN-stimulated and inflammatory gene expression is a reasonable measure of the effects of inflammation response stimulation, we reasoned that a bona fide ultrasensitive mechanism that regulates this response should be reflected in other aspects of the associated signaling pathway(s). Indeed, of the 17 cytokines associated with the N1 module, 15—including key inflammatory proteins, such as interleukin 6 (IL-6) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)—were significantly correlated with the N1 module eigengene (Pearson’s ρ≥0.5; FDR-adjusted P-value < 0.01; see S6 Table). In addition, when the protein expression levels of these 15 cytokines were plotted against the corresponding titer data, we observed dynamics similar to that of the inflammatory-associated N1 gene module. Initially, protein expression was low but strongly increased only after the virus titers exceeded the threshold of ~108 PFU/gram determined in the gene regulation model (Fig 5A). In contrast, most of the protein levels of the other measured cytokines with transcripts that were not assigned to the N1 module did not show any obvious relationship to the proposed threshold response (S6 Fig). The only major exceptions were LIF, RANTES, and IL18 (S6 Fig). LIF’s gene transcript was not annotated on the arrays whereas IL18’s transcript was not identified as differentially expressed and therefore was not included in the clustering study. The RANTES transcript was included in the clustering study and assigned by the WGCNA algorithm to N2 although the transcript’s correlation to the N1 eigengene suggests it could also have been assigned to the N1 module (Pearson correlation = 0.84 and 0.89 to the N1 and N2 eigengene, respectively). Some proteins appeared to conform to the threshold model in pH1N1-infected, but not H1N1 - or H5N1-infected, mice. These may be cytokines that have strain-dependent responses and do not conform to the model. Overall, changes in N1-associated cytokine protein levels in influenza virus-infected mouse lungs were consistent with the proposed virus-titer regulated threshold-mechanism underlying the IFN-mediated response.

Fig. 5. Threshold-like behavior is observed on upstream and downstream components of the IFN signaling pathway.

(a) Lung tissues from the same infected mice used for the original gene expression analysis were subjected to cytokine array analysis. Thirty-two cytokine protein concentrations were measured and log scaled (data points lower than the limit of detection for each protein were set to 0.001 to allow scaling), and the average fold change relative to uninfected, time-matched lung samples was determined. The heat map illustrates protein expression values for the 17 cytokines that had transcripts assigned to the N1 module (a blue-to-yellow scale shows expression levels, as indicated by the color key at the top of the panel; time points in which the change in the cytokine levels were not significant [FDR-adjust P < 0.05] were set to zero); of these, 15 exhibited expression profiles that were highly significantly correlated with the corresponding transcript and the N1 module eigengene (Pearson’s ρ ≥ 0.4 and FDR < 0.01; eotaxin and TNF-α were the only two that did not exhibit a significant, direct correlation). Non-N1 cytokines are shown in S6 Fig. Virus titers from the same infection are shown below the heat map, with titers surpassing the threshold level identified in the SLM indicated in red. (b) Another set of mice was infected with 105 PFU of H1N1, pH1N1, or H5N1 and lung tissues were harvested (3 mice per infection per time point) for immunoblot (STAT1, phosphorylated STAT1, IRF3, and pIRF3) or ELISA (IFN-α, IFN-β) analysis; virus titers were also determined. The heat map indicates the mean percentage of phosphorylated protein (purple) or the mean interferon concentration (pg/mL; green), and virus titers for each time point are indicated below. Only significant changes are shown in the heat map (FDR-adjusted P-value < 0.05 relative to mock-infected samples). Titers highlighted in red indicate that the threshold level (as determined in the initial analysis) was exceeded. Panel (c) shows a schematic of known canonical pathways that regulate IFN production in response to virus infection. Black arrows denote induction whereas red lines denote points at which influenza virus is known to impair these pathways. IFN-α is primarily produced by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) whereas IFN-β is produced in virus-infected, non-APC cells. Both IFNs can induce STAT1 phosphorylation and expression of ISGs in responding cells. The molecular origins of the ultrasensitive behavior likely lie in pathways upstream of STAT1

We then searched for evidence of threshold-like behavior in the upstream signaling events leading to the activation of IFN-mediated, inflammation-associated gene expression: namely IFN-α/β protein expression, and IRF3 and STAT1 transcription factor phosphorylation (Figs 5B, S7 and S8. Images of representative blots are available in S9 Fig). Significant increases in the concentration of IFN-α and phosphorylated STAT1 (pSTAT1) were detectable in infections with all three virus isolates and occurred at time points after the threshold level of virus was exceeded (Fig 5B). For the H1N1 data, significant levels of pSTAT1 were observed at 36 hpi which—as noted previously—corresponds to the time immediately after the virus titers in H1N1-infected mice reached their peak (see previous discussion). On the other hand, significant increases in phosphorylated IRF3 (pIRF3) were observed only in pH1N1 and H5N1 infections, whereas significant increases in IFN-β were observed only in the H5N1 infection. Changes in the levels of IFN-β and pIRF3 occurred after significant increases in pSTAT1 and IFN-α occurred. As such, the change in the percentage of pSTAT1 was more closely correlated to the N1 eigengene than was that of pIRF3 (correlation = 0.77±0.06 and 0.67±0.09 respectively), and significant increases in pSTAT1 corresponded to time points at which the mean virus titer exceeded the threshold level identified in the gene expression analysis (~107.78 PFU/g). The greater correlation of IFNα and STAT1 activation to the inflammation-associated, N1 module’s gene expression dynamics and the enrichment of the N1 module for the IRF7 binding sequence (Table 1) suggest that the primary driver of the threshold-regulated, inflammatory gene response originates along the IRF7 → IFN-α → STAT1 axis (Fig 5C).

Discussion

Our data reveal that the activation of the IFN-associated inflammatory and antiviral response program in influenza-infected mouse lung is characterized by an ultrasensitive response driven by the virus load. The power of the threshold model is illustrated by its ability to accurately predict gene expression in infected mice, and the data further suggest that the molecular basis of threshold behavior originates upstream of IFN-α production. Threshold-like and ultrasensitive mechanisms are hypothesized to be necessary for effective management of critical cellular machinery in noisy environments, and are recognized players in the activation of the cell cycle [34], mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling [35], and apoptosis [33,36]. However, while a role for threshold behaviors have been postulated to be essential for filtering noise or errant signaling in complex biomolecular environments [35], our study is the first to directly link threshold-like behavior to the virus-induced innate immune response.

The ultrasensitive response observed in this study provides additional insight into the mechanisms that drive severe pathologies during influenza infection. Several works have suggested that viral load is a key determinant of pathology [12,15] while other works suggest that highly pathogenic influenza viruses induce early, strong inflammatory responses that are independent of the viral load [9,24,37]. Recently, it was observed that fatal influenza infections in mice coincide with a strong influx of neutrophils in what the author’s describe as a viral load-independent, “feedforward” inflammatory circuit [27]. The ultrasensitive response suggested by our study consolidates these hypotheses by suggesting that viral load drives cytokine production (and in turn immune cell infiltration) in a nonlinear manner which is capable of producing states of high and low innate immune responses. Characterization of key aspects of the inflammatory response, such as the onset and peak inflammatory gene expression, require a high temporal resolution of the virus growth and host response dynamics; an experimental design that was unique to our study. The ultrasensitive response model does not negate the significance of neutrophil infiltration [27] in determining fatal infections but suggests that viral load drives the high and low innate immune states. The observed threshold may represent the transition to immunopathology; as indicated by the histopathology results (Fig 2). Moreover, the influenza virus’ NS1 protein is crucial for inhibiting the interferon-mediated antiviral response [38]. The NS1 protein of three viruses used in this study have the SUMO1 acceptor site that indicates interferon antagonism capability [39–41]. Additional studies with NS1-mutated viruses and other pathogens may better reveal strain-dependencies for the observed thresholding behavior.

The ultrasensitive response further suggests that the innate immune response has a limited capacity to respond to influenza virus infection and supports the development of immunomodulatory therapies. Interestingly, after the threshold was exceeded, the rate of activation for inflammatory and interferon-associated gene expression (N1) was conserved for a moderately pathogenic and deadly viruses (Fig 4A). The conserved rate of activation implies that the immune response detects the virus concentration but not the virus growth rate; suggesting the innate immune response is naturally limited in its ability to respond to high growth influenza viruses. Additionally, studies in knockout mice indicate that type I IFN-associated pathways are essential for protection during primary infection [42] and that earlier initiation of these pathways coincides with increased survival in mice infected with highly pathogenic isolates [43]. In combination with these studies, the findings here suggest a novel means of protecting high risk groups by treating them with compounds that target the molecular mechanisms responsible for the threshold behavior. Lowering the threshold required to induce the cytokine response may be a means of providing protection from severe influenza infection. Since these compounds would target host proteins, such treatments would be effective against various influenza virus strains. Data from the viruses studied here suggest that post-threshold, inflammatory gene expression primarily reflects interferon-regulated tissue damage, but time-course data from additional highly pathogenic viruses are needed to assess the degree to which interferon activity is associated with virus growth suppression.

Materials and Methods

Viruses

The A/California/04/09 H1N1 virus (pH1N1) was received from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The A/Kawasaki/UTK-4/09 H1N1 virus (H1N1) served as a reference for a seasonal influenza, whereas a fatal human isolate, A/Vietnam/1203/04 H5N1 virus (H5N1), served a highly pathogenic virus.

Ethics statement

All mouse experience were performed in accordance to the University of Tokyo's Regulations for Animal Care and Use. These regulations were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of the Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo (approval number: PA10-13). The committee acknowledged and deemed acceptable the legal and ethical responsibilities for the animals, as detailed in the Fundamental Guidelines for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiment and Related Activities in Academic Research Institutions under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, 2006.

All experiments with H5N1 viruses were performed in biosafety level 3 containment laboratories at the University of Tokyo, which are approved by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, Japan.

Mouse experiments

Five-week old C57BL/6J, female mice were obtained from Japan SLC. For all experiments, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and intranasally inoculated with either 103 or 105 PFU of virus. Initially, 42 mice were inoculated with 105 PFU of the H1N1, pH1N1, or H5N1 virus or mock-infected with PBS (a total of 168 mice). At 14 time points, 3 mice per group were humanely sacrificed and their lungs harvested. The lungs were sectioned and used to assess virus titers (right-upper lobe), cytokine levels (right lower), and the initial gene expression that was used to train the segmented linear model (left-lower). Separately, 42 mice were infected with 103 PFU of the H5N1, sacrificed at the same 14 time points, and lungs sections obtained as described previously to provide the model validation data. The same inoculation method was used for all mice in this study. The numbers of mice used for flow cytometry, western blot, and interferon protein assay experiments are specific in the corresponding sections.

Cytokine protein assays

For cytokine and chemokine measurements, mouse lungs were treated with the Bio-Plex Cell Lysis Kit (Bio-Rad laboratories, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Concentrations of other cytokines were determined with the Bio-Plex Mouse Cytokine 23-Plex and 9-Plex panels (Bio-Rad laboratories) Array analysis was performed by using the Bio-Plex Protein Array system (Bio-Rad laboratories).

Virus titers

Virus titers were determined by plaque assay using MDCK cells.

RNA isolation and oligonucleotide microarray processing

Mouse lung tissues were placed in RNALater (Ambion, CA), an RNA stabilization reagent and stored at -80°C. All tissues were thawed together and homogenized for 2 minutes at 30 Hz using a TissueLyser (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. From the homogenized lung tissues, total RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Cy3-labeled cRNA preparations were hybridized onto Agilent-014868 Whole Mouse Genome 4x44K microarrays for 17 h at 65°C. Feature Extraction Software version 7 (Agilent Technologies) was used for image analysis and data extraction, and Takara Bio provided whole array quality control metrics.

Microarray normalization, replicate quality, annotation, and statistical analysis

Differential expression was assessed by using a linear regression model. By using the limma package [44] 26 version 3.14.1 from BioConductor, probe intensities were background corrected by using the “norm-exponential” method, normalized between arrays (using the quantile method), and averaged over unique probes IDs. Replicate quality was assessed using hierarchical clustering, resulting in the removal of a single array (the array corresponded to a sample collected at 3 hpi in H5N1-infected mice.) Probe intensities were fit to a linear model that compared data from infected samples to time-matched data collected from uninfected mice. Probes were annotated by matching to the probe names in the mgug4122a version 2.1 mouse annotation database available from BioConductor. All arrays in this study have been deposited on the GEO Expression Omnibus (GSE63786).

Gene co-expression analysis

Unsigned co-expression networks were constructed by using the blockwiseModules program from the WGCNA package version 1.23.1 [18] in R. The analysis was performed with several different parameterizations to ensure robust clustering. For the results reported in this text, we removed all probes that did not have a confident fold-change greater than 2 (FDR < 0.01) for at least one infected-tissue to control-tissue, time-matched comparison. We then clustered the log2 of the normalized intensities for all 167 microarrays (corresponding the three samples for each time-point for each infected or control population with the exception of data from H5N1-infected mice at 3 hpi which had two samples). Based on the scale-free topology characteristics curve, a power of n = 7 with no reassignment after clustering (reassignThreshold = 0) and a maximum cluster size of 6000 probes was used. We generally observed that allowing gene reassignment between the modules led to poorer clustering based on the distribution the gene’s module memberships (the correlation between a gene and the eigengene of the module to which it had been assigned. S10 Fig illustrates the distribution of the gene kMEs for modules N1 and N2). We then repeated the clustering using different powers (ranging from 7 to 11), allowing different cluster sizes, different subsets of the expression data (e.g., clustering data from each infection separately or together), or relaxing the differential expression condition. In all clusterings performed, the two modules discussed in the text were identifiable. Fisher exact tests between each clustering run were used to determine whether the initial modules were significantly conserved under different parameterizations.

We also considered if the N1 module would be isolated when using signed versus unsigned network construction. We constructed a signed co-expression network and found that 92% of the kME+ N1 genes are again clustered and confirmed that the gene expression dynamics were maintained (see S11 Fig).

Functional enrichment analyses

ToppCluster [20] and DAVID [19] were used for gene ontology and pathway enrichment, and ToppCluster was also used for transcription factor binding site enrichment analyses. DAVID uses clusters of related annotations constructed from several annotation databases (e.g., pathway and gene ontology annotations) to determine the function of a set of genes and scores the enrichment by averaging the unadjusted P-values (determined by Fisher’s Exact test) of the annotations within the cluster. ToppCluster uses hypergeometric tests to determine the enrichment between a set of genes and gene lists contained in 18 categories (databases) detailed in the ToppGene Suite [45]. The databases include cis-regulatory motif data [46,47], referred to as transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) in the text. Both tools were used with their default settings and the gene universe was considered to be all annotated mouse genes. For each module, we considered the enrichment of all genes assigned to the module and the kME+ and kME - subsets. Generally, the enrichment analysis of the whole module gene set reiterated the enrichment results of the kME+ and kME - subsets albeit with slightly lower but still significant enrichment. Since both tools returned similar GO and pathway enrichment results, we summarized the functional and pathway enrichment results in Table 1 using the results from DAVID.

The enrichment of interferon stimulated genes was determined by using a list of interferon stimulated genes from the Interferon Stimulated Gene Database [48] that was downloaded on May 9, 2012 (see S3 File). For each module, all module genes and the kME+ and kME - subsets were tested for enrichment using Fisher’s exact test in R. The p values were adjusted to control the false discovery rate.

CTen [23] was used to determine enriched cell signatures in select co-expression modules. The enrichment score reported is the—log10 of the false discovery rate.

Segmented model fitting and validation

Model fitting and validation was performed in R using the ‘segmented’ package [49].

Flow cytometry analysis

Five mice per time point per infection were infected with 105 PFU of the described virus. Five uninfected (naïve) mice served as negative controls. Whole lungs were collected from mice, and incubated with Collagenase D (Roche Diagnostics; final concentration: 2 μg/mL) and DNase I (Worthington; final concentration: 40 U/mL) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Single-cell suspensions were obtained from lungs by grinding tissues through a nylon filter (BD Biosciences). Red blood cells (RBCs) in a sample were lysed with RBC lysis buffer (Sigma). Samples were resuspended with PBS containing 2 mM EDTA and 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and cell number was determined by using a disposable cell counter (OneCell). To block nonspecific binding of antibodies mediated by Fc receptors, cells were incubated with purified anti-mouse CD16/32 (Fc Block, BD Biosciences). Cells were stained with appropriate combinations of fluorescent antibodies to analyze the population of each immune cell subset. The anti-F4/80 (BM8; eBioscience) antibodies were used. All samples were also incubated with 7-aminoactinomycin D (Via-Probe, BD Biosciences) for dead cell exclusion. Data from labeled cells were acquired on a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software version 9.3.1 (Tree Star).

Western blot analysis

Three mice per time point per infection group were infected with 105 PFU of the described virus. The primary antibodies of mouse anti-STAT1 (phospho Tyr701) mAb (ab29045, abcam), rabbit anti-IRF3 (phospho Ser396) mAb (4947, Cell Signaling), and mouse anti–β-actin (A2228; Sigma-Aldrich) were used; the secondary antibodies were HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (GE Healthcare) and HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (GE Healthcare). Mouse lungs were collected and homogenized with RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) containing proteinase inhibitor (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA). The lysates were then briefly sonicated and centrifuged. Each sample was electrophoresed on sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with Blocking One (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) for 30 min at room temperature, and then were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4° C, followed by the secondary antibodies. They were then washed 3 times with PBS plus Tween 20 (PBS-T) for 5 min and incubated with secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies (as described above) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by three washes with PBST. Specific proteins were detected by using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Photography and quantification of band intensity were conducted with the VersaDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The quantity of target bands from each sample was standardized by their respective β-actin.

Interferon protein assays

Three mice per time point per infection group were infected with 105 PFU of the described virus. Half the lung of each mouse was dissolved in 1 mL of RIPA buffer. We measured the Interferon-alpha and Interferon-beta by using ELISA kits (#12100, #42400, PBL Assay Science, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plates were read at an absorbance of 450 nm using a Versa Max plate reader (MolecularDevices, Menlo Park, CA).

Statistical analyses

Additional gene set overlap tests were performed in R with all of the genes annotated on the array as the reference (background) set. Statistical tests to compare means within the western blot, flow cytometry, immune cell count and protein assay data sets were performed in R using the ‘multcomp’ package [50].

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Qian C, Cao X. Regulation of Toll-like receptor signaling pathways in innate immune responses. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1283 : 67–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06786.x 23163321

2. Loo Y-M, Gale M. Immune signaling by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunity. Elsevier Inc.; 2011;34 : 680–92. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.003 21616437

3. Le Goffic R, Pothlichet J, Vitour D, Fujita T, Meurs E, Chignard M, et al. Cutting Edge: Influenza A Virus Activates TLR3-Dependent Inflammatory and RIG-I-Dependent Antiviral Responses in Human Lung Epithelial Cells. J Immunol. 2007;178 : 3368–3372. http://www.jimmunol.org/cgi/content/abstract/178/6/3368 17339430

4. Lund JM, Alexopoulou L, Sato A, Karow M, Adams NC, Gale NW, et al. Recognition of single-stranded RNA viruses by Toll-like receptor 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101 : 5598–5603. 15034168

5. Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Matsui K, et al. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006;441 : 101–105. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16625202 16625202

6. Pichlmair A, Schulz O, Tan CP, Näslund TI, Liljeström P, Weber F, et al. RIG-I-mediated antiviral responses to single-stranded RNA bearing 5’-phosphates. Science. 2006;314 : 997–1001. 17038589

7. Hornung V, Ellegast J, Kim S, Brzózka K, Jung A, Kato H, et al. 5’-Triphosphate RNA is the ligand for RIG-I. Science. 2006;314 : 994–7. 17038590

8. Kobasa D, Jones SM, Shinya K, Kash JC, Copps J, Ebihara H, et al. Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus. Nature. 2007;445 : 319–23. 17230189

9. Kash JC, Tumpey TM, Proll SC, Carter V, Perwitasari O, Thomas MJ, et al. Genomic analysis of increased host immune and cell death responses induced by 1918 influenza virus. Nature. 2006;443 : 578–81. 17006449

10. Cilloniz C, Pantin-Jackwood MJ, Ni C, Goodman AG, Peng X, Proll SC, et al. Lethal dissemination of H5N1 influenza virus is associated with dysregulation of inflammation and lipoxin signaling in a mouse model of infection. J Virol. 2010;84 : 7613–24. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00553-10 20504916

11. Neumann G, Chen H, Gao GF, Shu Y, Kawaoka Y. H5N1 influenza viruses: outbreaks and biological properties. Cell Res. Nature Publishing Group; 2010;20 : 51–61. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.124 19884910

12. De Jong MD, Simmons CP, Thanh TT, Hien VM, Smith GJD, Chau TNB, et al. Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. Nat Med. 2006;12 : 1203–7. 16964257

13. Itoh Y, Shinya K, Kiso M, Watanabe T, Sakoda Y, Hatta M, et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of new swine-origin H1N1 influenza viruses. Nature. Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved; 2009;460 : 1021–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08260 19672242

14. Shoemaker JE, Fukuyama S, Eisfeld AJ, Muramoto Y, Watanabe S, Watanabe T, et al. Integrated network analysis reveals a novel role for the cell cycle in 2009 pandemic influenza virus-induced inflammation in macaque lungs. BMC Syst Biol. BMC Systems Biology; 2012;6 : 117. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-6-117 22937776

15. Boon ACM, Finkelstein D, Zheng M, Liao G, Allard J, Klumpp K, et al. H5N1 influenza virus pathogenesis in genetically diverse mice is mediated at the level of viral load. MBio. American Society for Microbiology; 2011;2.

16. Hatta Y, Hershberger K, Shinya K, Proll SC, Dubielzig RR, Hatta M, et al. Viral replication rate regulates clinical outcome and CD8 T cell responses during highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus infection in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6: e1001139. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001139 20949022

17. Tchitchek N, Eisfeld AJ, Tisoncik-Go J, Josset L, Gralinski LE, Bécavin C, et al. Specific mutations in H5N1 mainly impact the magnitude and velocity of the host response in mice. BMC Syst Biol. 2013;7 : 69. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-7-69 23895213

18. Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9 : 559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559 19114008

19. Huang DW, Sherman BT, Tan Q, Kir J, Liu D, Bryant D, et al. DAVID Bioinformatics Resources: expanded annotation database and novel algorithms to better extract biology from large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35: W169–75. 17576678

20. Kaimal V, Bardes EE, Tabar SC, Jegga AG, Aronow BJ. ToppCluster: a multiple gene list feature analyzer for comparative enrichment clustering and network-based dissection of biological systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38: W96–102. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq418 20484371

21. Sun L, Liu S, Chen ZJ. SnapShot: pathways of antiviral innate immunity. Cell. 2010;140 : 436–436.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.041 20144765

22. Menachery VD, Eisfeld AJ, Schäfer A, Josset L, Sims AC, Proll S, et al. Pathogenic Influenza Viruses and Coronaviruses Utilize Similar and Contrasting Approaches To Control Interferon-Stimulated Gene Responses. MBio. 2014;5 : 1–11.

23. Shoemaker JE, Lopes TJS, Ghosh S, Matsuoka Y, Kawaoka Y, Kitano H. CTen: a web-based platform for identifying enriched cell types from heterogeneous microarray data. BMC Genomics. BMC Genomics; 2012;13 : 460. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-460 22953731

24. Cillóniz C, Shinya K, Peng X, Korth MJ, Proll SC, Aicher LD, et al. Lethal influenza virus infection in macaques is associated with early dysregulation of inflammatory related genes. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5: e1000604. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000604 19798428

25. Shinya K, Gao Y, Cilloniz C, Suzuki Y, Fujie M, Deng G, et al. Integrated clinical, pathologic, virologic, and transcriptomic analysis of H5N1 influenza virus-induced viral pneumonia in the rhesus macaque. J Virol. 2012;86 : 6055–66. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00365-12 22491448

26. Lin KL, Suzuki Y, Nakano H, Ramsburg E, Gunn MD. CCR2+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells and exudate macrophages produce influenza-induced pulmonary immune pathology and mortality. J Immunol. 2008;180 : 2562–72. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18250467 18250467

27. Brandes M, Klauschen F, Kuchen S, Germain RN. A systems analysis identifies a feedforward inflammatory circuit leading to lethal influenza infection. Cell. 2013;154 : 197–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.013 23827683

28. Voineagu I, Wang X, Johnston P, Lowe JK, Tian Y, Horvath S, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of autistic brain reveals convergent molecular pathology. Nature. Nature Publishing Group; 2011;474 : 380–4. doi: 10.1038/nature10110 21614001

29. Kristiansen H, Scherer C a, McVean M, Iadonato SP, Vends S, Thavachelvam K, et al. Extracellular 2’-5' oligoadenylate synthetase stimulates RNase L-independent antiviral activity: a novel mechanism of virus-induced innate immunity. J Virol. 2010;84 : 11898–904. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01003-10 20844035

30. Kim W, Bennett EJ, Huttlin EL, Guo A, Li J, Possemato A, et al. Systematic and quantitative assessment of the ubiquitin-modified proteome. Mol Cell. Elsevier Inc.; 2011;44 : 325–40. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.025 21906983

31. Carninci P, Kasukawa T, Katayama S, Gough J, Frith MC, Maeda N, et al. The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science. 2005;309 : 1559–63. 16141072

32. Trunnell NB, Poon AC, Kim SY, Ferrell JE. Ultrasensitivity in the Regulation of Cdc25C by Cdk1. Mol Cell. Elsevier Inc.; 2011;41 : 263–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.01.012 21292159

33. Bagci EZ, Vodovotz Y, Billiar TR, Ermentrout GB, Bahar I. Bistability in apoptosis: roles of bax, bcl-2, and mitochondrial permeability transition pores. Biophys J. 2006;90 : 1546–59. 16339882

34. Goulev Y, Charvin G. Ultrasensitivity and positive feedback to promote sharp mitotic entry. Mol Cell. 2011;41 : 243–4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.01.016 21292155

35. Huang CY, Ferrell JE. Ultrasensitivity in the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93 : 10078–83. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=38339&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract 8816754

36. Shoemaker JE, Doyle FJ. Identifying fragilities in biochemical networks: robust performance analysis of Fas signaling-induced apoptosis. Biophys J. Elsevier; 2008;95 : 2610–23. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.123398 18539637

37. Qi L, Kash JC, Dugan VG, Jagger BW, Lau Y, Crouch EC, et al. The Ability of Pandemic Influenza Virus Hemagglutinins to Induce Lower Respiratory Pathology is Associated with Decreased Surfactant Protein D Binding. J Virol. 2012;412 : 426–434.

38. García-Sastre a, Egorov a, Matassov D, Brandt S, Levy DE, Durbin JE, et al. Influenza A virus lacking the NS1 gene replicates in interferon-deficient systems. Virology. 1998;252 : 324–30. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9878611 9878611

39. Pal S, Rosas JM, Rosas-Acosta G. Identification of the non-structural influenza A viral protein NS1A as a bona fide target of the Small Ubiquitin-like MOdifier by the use of dicistronic expression constructs. J Virol Methods. 2010;163 : 498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.11.010 19917317

40. Xu K, Klenk C, Liu B, Keiner B, Cheng J, Zheng B-J, et al. Modification of nonstructural protein 1 of influenza A virus by SUMO1. J Virol. 2011;85 : 1086–1098. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3020006&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract doi: 10.1128/JVI.00877-10 21047957

41. Santos A, Pal S, Chacón J, Meraz K, Gonzalez J, Prieto K, et al. SUMOylation affects the interferon blocking activity of the influenza A nonstructural protein NS1 without affecting its stability or cellular localization. J Virol. 2013;87 : 5602–20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02063-12 23468495

42. Seo S-U, Kwon H-J, Song J-H, Byun Y-H, Seong BL, Kawai T, et al. MyD88 signaling is indispensable for primary influenza A virus infection but dispensable for secondary infection. J Virol. 2010;84 : 12713–22. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01675-10 20943980

43. Shinya K, Okamura T, Sueta S, Kasai N, Tanaka M, Ginting TE, et al. Toll-like receptor pre-stimulation protects mice against lethal infection with highly pathogenic influenza viruses. Virol J. BioMed Central Ltd; 2011;8 : 97. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-97 21375734

44. Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3.

45. Chen J, Bardes EE, Aronow BJ, Jegga AG. ToppGene Suite for gene list enrichment analysis and candidate gene prioritization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37: W305–11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp427 19465376

46. Xie X, Lu J, Kulbokas EJ, Golub TR, Mootha V, Lindblad-toh K, et al. Systematic discovery of regulatory motifs in human promoters and 3 UTRs by comparison of several mammals. Nature. 2005;434 : 338–345. 15735639

47. Liberzon A, Subramanian A, Pinchback R, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics. 2011;27 : 1739–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr260 21546393

48. De Veer MJ, Holko M, Frevel M, Walker E, Der S, Paranjape JM, et al. Functional classification of interferon-stimulated genes identified using microarrays. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69 : 912–920. 11404376

49. Muggeo VMR. segmented: an R package to fit regression models with broken-line relationships. 2007;2.

50. Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biometrical J. 2008;50 : 346–63. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200810425 18481363

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Clearance of Pneumococcal Colonization in Infants Is Delayed through Altered Macrophage TraffickingČlánek An Model of Latency and Reactivation of Varicella Zoster Virus in Human Stem Cell-Derived NeuronsČlánek Protective mAbs and Cross-Reactive mAbs Raised by Immunization with Engineered Marburg Virus GPsČlánek Specific Cell Targeting Therapy Bypasses Drug Resistance Mechanisms in African TrypanosomiasisČlánek Peptidoglycan Branched Stem Peptides Contribute to Virulence by Inhibiting Pneumolysin ReleaseČlánek HIV Latency Is Established Directly and Early in Both Resting and Activated Primary CD4 T CellsČlánek Sequence-Specific Fidelity Alterations Associated with West Nile Virus Attenuation in Mosquitoes

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 6- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Familiární středomořská horečka

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Introducing “Research Matters”

- Exploring Host–Pathogen Interactions through Biological Control

- Analysis of Bottlenecks in Experimental Models of Infection

- Expected and Unexpected Features of the Newly Discovered Bat Influenza A-like Viruses

- Clearance of Pneumococcal Colonization in Infants Is Delayed through Altered Macrophage Trafficking

- Recombinant Murine Gamma Herpesvirus 68 Carrying KSHV G Protein-Coupled Receptor Induces Angiogenic Lesions in Mice

- TRIM30α Is a Negative-Feedback Regulator of the Intracellular DNA and DNA Virus-Triggered Response by Targeting STING

- Targeting Human Transmission Biology for Malaria Elimination

- Two Cdc2 Kinase Genes with Distinct Functions in Vegetative and Infectious Hyphae in

- An Model of Latency and Reactivation of Varicella Zoster Virus in Human Stem Cell-Derived Neurons

- Protective mAbs and Cross-Reactive mAbs Raised by Immunization with Engineered Marburg Virus GPs

- Virulence Factors of Induce Both the Unfolded Protein and Integrated Stress Responses in Airway Epithelial Cells

- Peptide-MHC-I from Endogenous Antigen Outnumber Those from Exogenous Antigen, Irrespective of APC Phenotype or Activation

- Specific Cell Targeting Therapy Bypasses Drug Resistance Mechanisms in African Trypanosomiasis

- An Ultrasensitive Mechanism Regulates Influenza Virus-Induced Inflammation

- The Role of Human Transportation Networks in Mediating the Genetic Structure of Seasonal Influenza in the United States

- Host Delivery of Favorite Meals for Intracellular Pathogens

- Complement-Opsonized HIV-1 Overcomes Restriction in Dendritic Cells

- Inter-Seasonal Influenza is Characterized by Extended Virus Transmission and Persistence

- A Critical Role for CLSP2 in the Modulation of Antifungal Immune Response in Mosquitoes

- Twilight, a Novel Circadian-Regulated Gene, Integrates Phototropism with Nutrient and Redox Homeostasis during Fungal Development

- Surface-Associated Lipoproteins Link Virulence to Colitogenic Activity in IL-10-Deficient Mice Independent of Their Expression Levels

- Latent Membrane Protein LMP2A Impairs Recognition of EBV-Infected Cells by CD8+ T Cells

- Bank Vole Prion Protein As an Apparently Universal Substrate for RT-QuIC-Based Detection and Discrimination of Prion Strains

- Neuronal Subtype and Satellite Cell Tropism Are Determinants of Varicella-Zoster Virus Virulence in Human Dorsal Root Ganglia Xenografts

- Molecular Basis for the Selective Inhibition of Respiratory Syncytial Virus RNA Polymerase by 2'-Fluoro-4'-Chloromethyl-Cytidine Triphosphate

- Structure of the Virulence Factor, SidC Reveals a Unique PI(4)P-Specific Binding Domain Essential for Its Targeting to the Bacterial Phagosome

- Activated Brain Endothelial Cells Cross-Present Malaria Antigen

- Fungal Morphology, Iron Homeostasis, and Lipid Metabolism Regulated by a GATA Transcription Factor in

- Peptidoglycan Branched Stem Peptides Contribute to Virulence by Inhibiting Pneumolysin Release

- A Macrophage Subversion Factor Is Shared by Intracellular and Extracellular Pathogens

- A Novel AT-Rich DNA Recognition Mechanism for Bacterial Xenogeneic Silencer MvaT

- Reovirus FAST Proteins Drive Pore Formation and Syncytiogenesis Using a Novel Helix-Loop-Helix Fusion-Inducing Lipid Packing Sensor

- The Role of ExoS in Dissemination of during Pneumonia

- IRF-5-Mediated Inflammation Limits CD8 T Cell Expansion by Inducing HIF-1α and Impairing Dendritic Cell Functions during Infection

- Discordant Impact of HLA on Viral Replicative Capacity and Disease Progression in Pediatric and Adult HIV Infection

- Crystal Structure of USP7 Ubiquitin-like Domains with an ICP0 Peptide Reveals a Novel Mechanism Used by Viral and Cellular Proteins to Target USP7

- HIV Latency Is Established Directly and Early in Both Resting and Activated Primary CD4 T Cells

- HPV16 Down-Regulates the Insulin-Like Growth Factor Binding Protein 2 to Promote Epithelial Invasion in Organotypic Cultures

- The νSaα Specific Lipoprotein Like Cluster () of . USA300 Contributes to Immune Stimulation and Invasion in Human Cells

- RSV-Induced H3K4 Demethylase KDM5B Leads to Regulation of Dendritic Cell-Derived Innate Cytokines and Exacerbates Pathogenesis

- Leukocidin A/B (LukAB) Kills Human Monocytes via Host NLRP3 and ASC when Extracellular, but Not Intracellular

- Border Patrol Gone Awry: Lung NKT Cell Activation by Exacerbates Tularemia-Like Disease

- The Curious Road from Basic Pathogen Research to Clinical Translation

- From Cell and Organismal Biology to Drugs

- Adenovirus Tales: From the Cell Surface to the Nuclear Pore Complex

- A 21st Century Perspective of Poliovirus Replication

- Is Development of a Vaccine against Feasible?

- Waterborne Viruses: A Barrier to Safe Drinking Water

- Battling Phages: How Bacteria Defend against Viral Attack

- Archaea in and on the Human Body: Health Implications and Future Directions

- Degradation of Human PDZ-Proteins by Human Alphapapillomaviruses Represents an Evolutionary Adaptation to a Novel Cellular Niche

- Natural Variants of the KPC-2 Carbapenemase have Evolved Increased Catalytic Efficiency for Ceftazidime Hydrolysis at the Cost of Enzyme Stability

- Potent Cell-Intrinsic Immune Responses in Dendritic Cells Facilitate HIV-1-Specific T Cell Immunity in HIV-1 Elite Controllers

- The Mammalian Cell Cycle Regulates Parvovirus Nuclear Capsid Assembly

- Host Reticulocytes Provide Metabolic Reservoirs That Can Be Exploited by Malaria Parasites

- The Proteome of the Isolated Containing Vacuole Reveals a Complex Trafficking Platform Enriched for Retromer Components

- NK-, NKT- and CD8-Derived IFNγ Drives Myeloid Cell Activation and Erythrophagocytosis, Resulting in Trypanosomosis-Associated Acute Anemia

- Successes and Challenges on the Road to Cure Hepatitis C

- BRCA1 Regulates IFI16 Mediated Nuclear Innate Sensing of Herpes Viral DNA and Subsequent Induction of the Innate Inflammasome and Interferon-β Responses

- A Structural and Functional Comparison Between Infectious and Non-Infectious Autocatalytic Recombinant PrP Conformers

- Phosphorylation of the Peptidoglycan Synthase PonA1 Governs the Rate of Polar Elongation in Mycobacteria

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Nef Inhibits Autophagy through Transcription Factor EB Sequestration

- Sequence-Specific Fidelity Alterations Associated with West Nile Virus Attenuation in Mosquitoes

- EBV BART MicroRNAs Target Multiple Pro-apoptotic Cellular Genes to Promote Epithelial Cell Survival

- Single-Cell and Single-Cycle Analysis of HIV-1 Replication

- TRIM32 Senses and Restricts Influenza A Virus by Ubiquitination of PB1 Polymerase

- The Herpes Simplex Virus Protein pUL31 Escorts Nucleocapsids to Sites of Nuclear Egress, a Process Coordinated by Its N-Terminal Domain

- Host Transcriptional Response to Influenza and Other Acute Respiratory Viral Infections – A Prospective Cohort Study

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- HIV Latency Is Established Directly and Early in Both Resting and Activated Primary CD4 T Cells

- Battling Phages: How Bacteria Defend against Viral Attack

- A 21st Century Perspective of Poliovirus Replication

- Adenovirus Tales: From the Cell Surface to the Nuclear Pore Complex

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání