-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaThe Evolutionarily Conserved Mediator Subunit MDT-15/MED15 Links Protective Innate Immune Responses and Xenobiotic Detoxification

Metazoans respond to environmental threats in part through conserved pathways that coordinate protective transcriptional responses. During infection with an invasive pathogen, for example, innate immune pathways regulate the secretion of antimicrobial immune effectors. Likewise, exposure to toxic molecules leads to the induction of detoxification mechanisms that protect the host from the deleterious effects of these compounds. Here we find that a conserved transcriptional regulator MDT-15/MED15 links xenobiotic detoxification and immune responses in a manner that is important for protection during bacterial infection. We also show that MDT-15/MED15 is necessary for the host to resist the lethal effects of secreted toxins produced by pathogenic bacteria. Rapid coordination of these protective host responses through MDT-15/MED15 may therefore be part of a conserved survival strategy in the wild.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 10(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004143

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004143Summary

Metazoans respond to environmental threats in part through conserved pathways that coordinate protective transcriptional responses. During infection with an invasive pathogen, for example, innate immune pathways regulate the secretion of antimicrobial immune effectors. Likewise, exposure to toxic molecules leads to the induction of detoxification mechanisms that protect the host from the deleterious effects of these compounds. Here we find that a conserved transcriptional regulator MDT-15/MED15 links xenobiotic detoxification and immune responses in a manner that is important for protection during bacterial infection. We also show that MDT-15/MED15 is necessary for the host to resist the lethal effects of secreted toxins produced by pathogenic bacteria. Rapid coordination of these protective host responses through MDT-15/MED15 may therefore be part of a conserved survival strategy in the wild.

Introduction

In nature, organisms encounter environmental insults, such as chemical toxins, secreted microbial virulence factors and invasive pathogens, that threaten their ability to survive and reproduce. As a result, metazoans have evolved protective pathways to counter these challenges. For example, gene families such as cytochrome P450s (CYPs), glutathione-s-transferases (GSTs), and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UDPs) detoxify xenobiotic small molecule toxins and are conserved from nematodes to humans [1]. Likewise, innate immune defenses provide protection from invasive pathogens [2]. Recent publications have suggested that recognition of xenobiotic toxins is involved in the activation of immune response pathways [3], [4]. From an evolutionary perspective, it is logical that hosts respond to threats encountered in the wild at least in part through surveillance pathways that monitor the integrity of core cellular machinery, which are often the targets of xenobiotic small molecules or microbe-generated toxins. These studies predict that organisms may integrate detoxification and immune responses as a means to respond rapidly to such challenges, but the mechanisms underlying this coordinated host response have not been reported.

Our research group and others use bacterial and fungal pathogenesis assays in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans to investigate mechanisms of immune pathway activation in intestinal epithelial cells [2]. Genetic analyses of C. elegans that are hypersusceptible to bacterial infection have revealed that the nematode mounts defense responses through evolutionarily conserved innate immune pathways. For example, the C. elegans NSY-1/SEK-1/PMK-1 Mitogen Activated Protein (MAP) kinase pathway, orthologous to the ASK1 (MAP kinase kinase kinase)/MKK3/6 (MAP kinase kinase)/p38 (MAP kinase) pathway in mammals, is required for protection against pathogens [5]. C. elegans animals carrying loss-of-function mutations in this pathway have defects in the basal and pathogen-induced expression of immune effectors and are hypersusceptible to killing by bacterial and fungal pathogens [5]–[7].

We previously used a C. elegans pathogenesis assay as a means to identify small molecules that protect the host during bacterial infection [8]. One of the compounds identified in this screen, a small molecule called RPW-24, extended the survival of nematodes infected with the human bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa by stimulating the host immune response via the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 pathway [9]. A genome-wide microarray analysis of animals exposed to RPW-24 revealed that, in addition to inducing the transcription of putative immune effectors, this molecule also strongly upregulated Phase I and Phase II detoxification enzymes (CYPs, GSTs and UDPs), suggesting that RPW-24 is a xenobiotic toxin to C. elegans. Consistent with this hypothesis, RPW-24 caused a dose dependent reduction of nematode lifespan on nonpathogenic food and delayed development of animals that were exposed starting at the first larval stage.

Here we sought to use RPW-24 as a tool to characterize mechanisms of p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 pathway activation in C. elegans. We found that activation of PMK-1-regulated pathogen response genes is genetically linked to the induction of genes involved in the detoxification of small molecule toxins. We show that the evolutionarily conserved Mediator subunit MDT-15/MED15 is required for the induction of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-mediated immune effectors as well as non-PMK-1-dependent detoxification genes by RPW-24. These data demonstrate that the host response to a xenobiotic involves coordination of detoxification and innate immune responses via the Mediator subunit MDT-15. Moreover, loss of MDT-15 function has important physiological effects on the ability of an animal to mount protective immune responses, resist bacterial infection and survive challenge from lethal bacterial toxins.

Results

RNAi Screen Identifies Regulators of p38 MAP Kinase PMK-1-Dependent Genes

To investigate mechanisms of immune activation in C. elegans, we generated a GFP transcriptional reporter for the immune response gene F08G5.6. F08G5.6 is a putative immune effector that contains a CUB-like domain [6] and is transcriptionally induced by exposure of C. elegans to several bacterial pathogens, including P. aeruginosa [6], [10]. We chose F08G5.6 for these studies because it is upregulated more than 100-fold by RPW-24 in a manner that requires the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 [9].

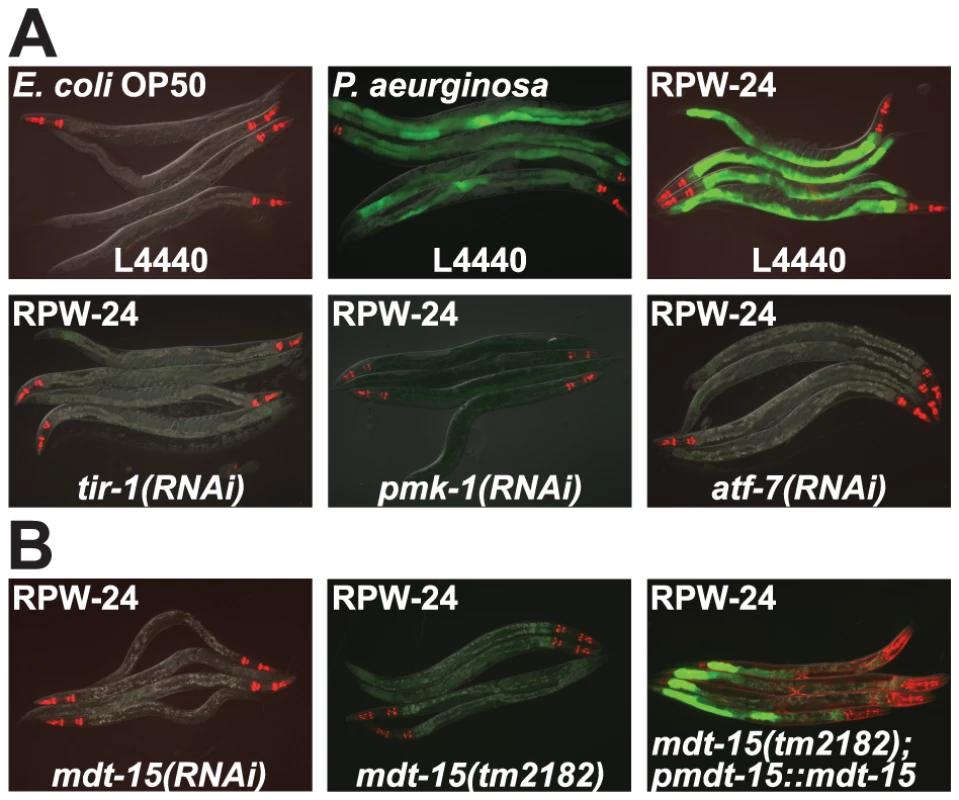

pF08G5.6::GFP was induced in the C. elegans intestine during P. aeruginosa infection and GFP expression was also robustly upregulated in pF08G5.6::GFP animals following exposure to RPW-24 when animals were feeding on nonpathogenic E. coli (Figure 1A). When three components of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 signaling cassette were individually knocked down by RNAi [tir-1 [11], pmk-1 [6] and atf-7 [12]], pF08G5.6::GFP induction by RPW-24 was entirely abrogated (Figure 1A).

Fig. 1. RNAi screen identifies a role for the C. elegans Mediator subunit MDT-15 in regulating the induction of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-dependent immune reporter pF08G5.6::GFP.

(A) C. elegans carrying the pF08G5.6::GFP immune reporter were exposed to the vector control (L4440) or the indicated RNAi strain, and then transferred at the L4 stage to either E. coli OP50 food, P. aeruginosa or E. coli OP50 supplemented with RPW-24 for 18 hours. Photographs were acquired using the same imaging conditions. (B) C. elegans mdt-15(RNAi) and mdt-15(tm2182) animals carrying the pF08G5.6::GFP immune reporter with or without agEx114 (pmdt-15::mdt-15) were exposed to RPW-24 as described above. In all animals shown in this figure, red pharyngeal expression is the pmyo-2::mCherry co-injection marker, which confirms the presence of the pF08G5.6::GFP transgene. In the mdt-15(tm2182) animals carrying the agEx114 array, the presence of the pmdt-15::mdt-15 transgene is confirmed by the pmyo-3::mCherry co-injection marker which is expressed in the body wall muscle. The level of F08G5.6 induction during bacterial infection is dependent upon the virulence of the invading pathogen (Figure S1). We exposed C. elegans to several P. aeruginosa strains, each of which was previously shown to have a different pathogenic potential toward nematodes [13] and used qRT-PCR to determine the expression levels of F08G5.6 in these animals. In general, more pathogenic P. aeruginosa strains caused significantly greater induction of F08G5.6, suggesting that some aspect of P. aeruginosa virulence, rather than a structural feature of the bacteria itself, causes the activation of F08G5.6. Consistent with these data, it was previously shown that C. elegans primarily responds to virulence-related cues to mount its innate immune defenses towards P. aeruginosa [14]–[16].

To identify genes that regulate the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 pathway in response to RPW-24, we screened a library of RNAi clones corresponding to 1,420 genes expressed in C. elegans intestinal epithelium (approximately 9% of the genome, Table S1B) for gene inactivations that abrogated the RPW-24-mediated induction of pF08G5.6::GFP. We specifically focused on intestinally expressed genes because of the recognized role for intestinal cells in coordinating the host response to ingested pathogens [2], [17], and because P. aeruginosa and RPW-24 induce F08G5.6 expression in the intestine (Figure 1A). Our initial screening effort identified 153 genes that, when inactivated by RNAi, diminished or abrogated the induction of pF08G5.6::GFP by RPW-24.

We took several steps to identify specific regulators of p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-dependent immune effectors among these 153 gene inactivations. First, we noticed that knockdown of many of these genes markedly slowed nematode growth. To eliminate genes that simply reduced GFP reporter expression as a consequence of pleiotropic effects on worm growth and development, we determined if these 153 gene inactivations also affected induction of the C. elegans immune reporter irg-1::GFP [14]. irg-1 is strongly upregulated in intestinal epithelial cells during P. aeruginosa infection or by an E. coli strain that expresses the bacterial virulence factor Exotoxin A (ToxA), but via a pathway independent of p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 signaling [14]–[16]. Moreover, RPW-24 does not cause the induction of irg-1::GFP and mutation of the zip-2 gene, which encodes the transcription factor that regulates irg-1 expression, does not affect the RPW-24-mediated induction of F08G5.6 (data not shown) or alter the ability of RPW-24 to extend the survival time of nematodes infected with P. aeruginosa [9]. We therefore discarded the genes that, when inactivated, reduced the induction of irg-1::GFP by E. coli expressing ToxA, reasoning that they were unlikely to be specific regulators of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-dependent pathogen response genes. Using this approach, we selected 56 of the 153 genes for further study.

In a tertiary screen, we determined the effects of these 56 gene inactivations on pF35E12.5::GFP, a second immune reporter that is also strongly induced in the intestine by RPW-24 in a PMK-1-dependent manner [9], [10]. 29 of the 56 RNAi clones reduced or eliminated the induction of both the pF35E12.5::GFP and pF08G5.6::GFP reporters by RPW-24 (Table S1A). Validating the screen, the 29 clones we identified as putative regulators of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-dependent genes included the three known components of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 pathway that were present in the screening library, which suggested that the screen could identify additional, unrecognized components of this signaling pathway.

To confirm further the results of the screen, we used RNAi to knockdown the expression of a representative sample of the 29 genes identified, and tested the induction levels of F08G5.6 and F35E12.5 by RPW-24 with qRT-PCR (Table S1A). For all six genes tested, we verified that inactivation of the gene by RNAi dramatically reduced the induction levels of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-regulated genes F08G5.6 and F35E12.5.

Mediator Subunit MDT-15/MED15 Regulates p38 MAP Kinase PMK-1 Pathway-Dependent Genes

One of the strongest hits from our RNAi screen was mdt-15, which encodes a subunit of the Mediator complex homologous to mammalian MED15 (78% sequence identity) [18]–[20]. Knockdown of mdt-15 eliminated all visible expression of the pF08G5.6::GFP and pF35E12.5::GFP reporters, and reduced expression of these genes by at least two orders of magnitude in response to RPW-24 (Figure 1B and Table S1). MDT-15 was previously found to regulate the transcription of detoxification genes, including cytochrome P450s, glutathione-s-transferases, and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases [19], gene classes that are strongly induced by RPW-24 [9]. To study the role of mdt-15 in the regulation of p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 gene activation, we crossed the pF08G5.6::GFP reporter into the hypomorphic mdt-15(tm2182) allele, which was previously shown to recapitulate many of the phenotypes observed in mdt-15(RNAi) animals [19], [21]. As in mdt-15(RNAi) animals, we observed no induction of GFP when mdt-15(tm2182); pF08G5.6::GFP animals were exposed to RPW-24 (Figure 1B). An extrachromosomal array containing wild-type mdt-15 under its own promoter partially restored RPW-24-induced GFP expression in mdt-15(tm2182);pF08G5.6::GFP animals (Figure 1B).

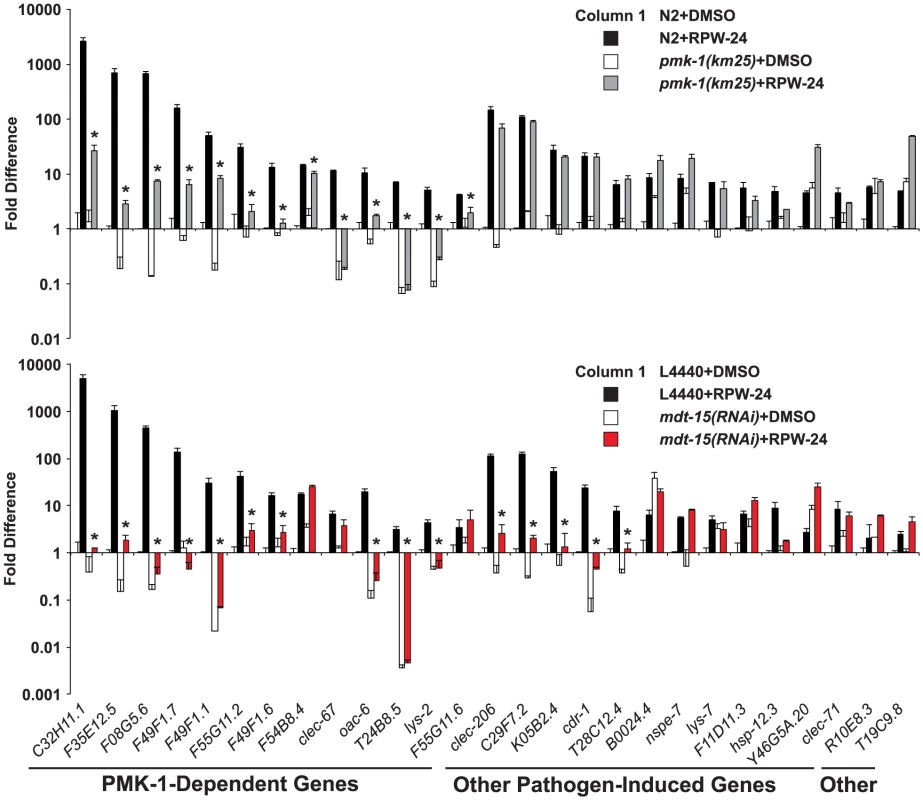

To determine if MDT-15 is required for the induction of other RPW-24-induced genes, we used NanoString nCounter gene expression analysis to generate transcription profiles of 118 C. elegans genes with known involvement in immune, stress and detoxification responses (Table S2). As in our microarray analysis [9], we found that RPW-24 caused robust transcriptional changes in wild-type nematodes. 40 of the 118 genes in the NanoString codeset were induced at least 4-fold or greater. 25 of these 40 genes are putative immune effectors upregulated during pathogen infection (shown in Figure 2) and 13 are genes putatively involved in the detoxification of small molecule toxins (discussed below). Of note, we had previously observed that 31 of these 40 genes, including 28 of the 31 most strongly induced, were also upregulated in whole genome Affymetrix GeneChip microarray analysis of wild-type animals exposed to RPW-24 versus DMSO [9]. Of the 25 pathogen-induced genes upregulated by RPW-24, 21 have been shown to be induced during P. aeruginosa infection [6], [7], [22], [23]. The RPW-24-induced expression of 13 of the 25 putative immune effectors was significantly reduced in pmk-1(km25) loss-of-function mutants compared to wild-type controls (Figure 2 top panel) in accord with the previously determined role for p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 in regulating both pathogen-induced [6] and RPW-24-induced [9] expression of putative immune effector genes.

Fig. 2. The Mediator subunit MDT-15 regulates p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-dependent and independent immune genes in response to RPW-24.

The expression of 118 C. elegans genes was analyzed using NanoString nCounter gene expression analysis in wild-type N2 and pmk-1(km25) animals (top) and in vector control (L4440) and mdt-15(RNAi) animals (bottom) exposed to either 70 µM RPW-24 or the solvent control DMSO. The 40 genes that were induced 4-fold or greater in wild-type N2 animals by RPW-24 are presented in Figures 2 and 6. The 13 genes that were dependent on the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 for their induction in the top panel are grouped and indicated in the bottom panel. Data are the average of two replicates each of which was normalized to three control genes with error bars representing standard deviation and are presented as the value relative to the average expression from the replicates of the indicated gene in the baseline condition [N2 animals (top) or vector control (L4440) animals (bottom) exposed to DMSO]. We confirmed that mdt-15 expression was significantly knocked down by mdt-15(RNAi) in each of these experiments (p<0.001)(see Figure S2A). * p<0.05 for the comparison of the RPW-24-induced conditions. Consistent with a role for MDT-15 in the expression of PMK-1 activated genes, the NanoString analysis revealed that the RPW-24-dependent induction of 10 of the 13 PMK-1-dependent genes was abrogated in mdt-15(RNAi) animals compared to controls (Figure 2 bottom panel). We used qRT-PCR to show that mdt-15 was knocked down by RNAi in this experiment and to confirm that mdt-15 depletion caused a dramatic reduction in the RPW-24-induced expression of three pmk-1-dependent immune genes (Figure S2A). Further, we found that the RPW-24-mediated induction levels of these three immune genes was reduced in the mdt-15(tm2182) mutant, which recapitulated our findings in mdt-15(RNAi) animals (Figure S2B).

Knockdown of mdt-15 reduced the expression of the top five most strongly upregulated p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-dependent immune effectors by several orders of magnitude (C32H11.1, F35E12.5, F08G5.6, F49F1.7, and F49F1.1) (Figure 2 top panel). These five genes were still induced by RPW-24 in pmk-1(km25) loss-of-function animals, albeit to levels markedly lower than in wild-type animals (Figure 2 top panel), but their induction was entirely abrogated by knockdown of mdt-15 (Figure 2 bottom panel). These data suggest that MDT-15 coordinates inputs from PMK-1 and other immune signaling pathway(s) to modulate the expression of these p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-dependent putative immune effectors. We also identified a requirement for mdt-15 in the induction of five putative immune effectors (clec-206, C29F7.2, K05B2.4, cdr-1, T28C12.4) that are not transcriptional targets of the PMK-1 pathway (Figure 2, compare top and bottom panels). Thus, MDT-15 is required for the induction of p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-dependent immune genes and a second group of defense effectors that are independent of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 signaling pathway.

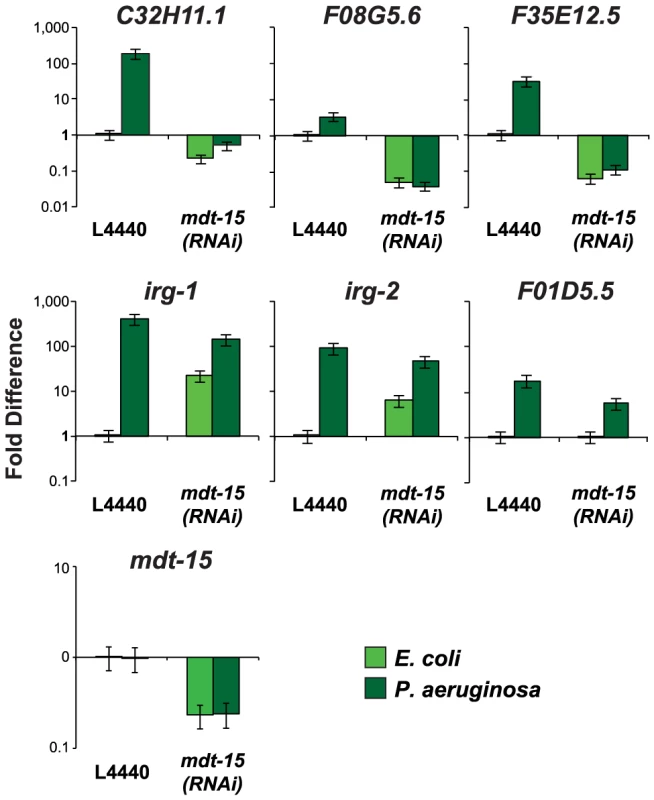

The p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 pathway plays an important role in the regulation of putative immune effectors during P. aeruginosa infection [6]. To determine whether MDT-15/MED15 is also involved in the regulation of these genes during bacterial infection, we infected C. elegans with P. aeruginosa PA14 for 8 hours and used qRT-PCR to compare the induction levels of several immune response genes in mdt-15(RNAi) and control animals. The basal and pathogen-induced expression of three p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-dependent immune effectors (C32H11.1, F08G5.6 and F35E12.5) was reduced in mdt-15(RNAi) animals by one to three orders of magnitude (Figure 3). We also tested the induction levels of three genes whose transcription is activated during P. aeruginosa infection in a manner independent of PMK-1 (irg-1, irg-2 and F01D5.5) and found that PMK-1-independent immune effectors were induced in mdt-15(RNAi) animals during P. aeruginosa infection to levels comparable to that observed in wild-type animals (Figure 3). The expression levels of irg-1 and irg-2 were higher under basal conditions in mdt-15(RNAi) animals compared to L4440 controls (Figure 3). Together, these data support the observations from our NanoString experiments that MDT-15 is required for the expression of some, but not all, immune genes that are activated in response to an environmental insult.

Fig. 3. The Mediator subunit MDT-15 regulates the induction of some, but not all, immune genes during P. aeruginosa infection.

The expression of putative C. elegans immune effectors was analyzed by qRT-PCR in vector control (L4440) and mdt-15(RNAi) animals exposed to P. aeruginosa and the negative control E. coli OP50 for 8 hours. Data are the average of three replicates each normalized to a control gene with error bars representing SEM and are presented as the value relative to the average expression from all three replicates of the indicated gene in the baseline condition (L4440 animals exposed to E. coli). mdt-15 expression was significantly knocked down by mdt-15(RNAi) in these experiments (p<0.001). One possible explanation for these observations is that the Mediator subunit MDT-15 is a general regulator of transcription that non-specifically affects the expression of a large number of genes. In the NanoString experiment, however, we identified 10 genes that were induced by RPW-24 in mdt-15(RNAi) animals to levels similar to the wild-type controls (Figure 2 bottom panel). Also of note, our secondary screen demonstrated that mdt-15(RNAi) had no effect on the induction of irg-1::GFP by ToxA. We further wondered if the defects in expression of the PMK-1 targets in mdt-15(RNAi) animals were due to direct transcriptional regulation of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 pathway components by MDT-15. However, we found that the mRNA levels of pmk-1, tir-1 and sek-1 in mdt-15(RNAi) animals were not different from the wild-type control (Figure S2C).

Taken together, the data in this section indicate that MDT-15 is required for the transcriptional activation of immune effectors controlled by the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1, and at least one other pathway. However, MDT-15 is not required for the induction of all defense-related genes.

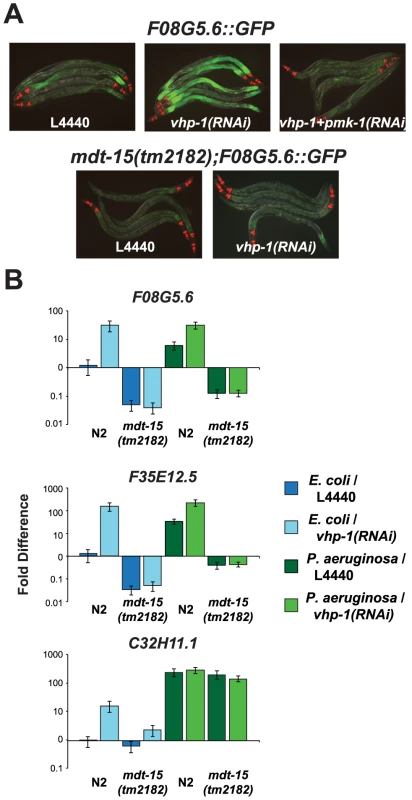

The Mediator Subunit MDT-15 Acts Downstream of the p38 MAP Kinase PMK-1 to Regulate the Induction of F08G5.6 and F35E12.5

To determine if MDT-15 acts genetically upstream or downstream of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 in coordinating the induction of immune effectors during P. aeruginosa infection, we utilized the MAP kinase phosphatase VHP-1, which is a negative regulator of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 [24]. Knockdown of vhp-1 in animals carrying the F08G5.6::GFP p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 immune reporter caused increased induction of GFP expression during P. aeruginosa infection in a manner dependent on pmk-1 expression (Figure 4A). This induction of F08G5.6::GFP by vhp-1(RNAi) was entirely suppressed in the mdt-15(tm2182) partial loss-of-function allele (Figure 4A). We used qRT-PCR to confirm this observation (Figure 4B). We found that RNAi knockdown of vhp-1 in wild-type C. elegans caused constitutive activation of F08G5.6, F35E12.5 and C32H11.1 in a manner that required mdt-15 when nematodes were growing on their normal food source, E. coli OP50 (Figure 4B). During P. aeruginosa infection, we also observed a requirement for MDT-15 in the vhp-1(RNAi)-mediated induction of F08G5.6 and F35E12.5, but not C32H11.1. The significance of this discrepancy is unclear, but may be explained by the observations of Taubert et al. who found that only 52% of mdt-15 targets were misregulated in the hypomorphic mdt-15(tm2182) allele, which encodes a truncated form of the MDT-15 protein [19], [21]. Indeed, we also observed that mdt-15(RNAi) was more effective than mdt-15(tm2182) at reducing the expression of the six mdt-15 targets we studied following exposure to RPW-24, including C32H11.1 (Figures S2A, S2B and S2D). In any case, these data suggest that MDT-15 acts downstream of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 to coordinate the induction of at least some immune effector genes.

Fig. 4. The Mediator subunit MDT-15 acts downstream of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 to regulate the induction of F08G5.6 and F35E12.5.

(A) Wild-type or mdt-15(tm2182) mutant synchronized L1 animals containing the pF08G5.6::GFP immune reporter were grown on vector control (L4440), vhp-1(RNAi) or a combination of vhp-1(RNAi) and pmk-1(RNAi) bacteria and then transferred as L4 animals to PA14 for 18 hours. Animals were photographed under the same imaging conditions. (B) qRT-PCR was used to examine the expression levels of F08G5.6, F35E12.5 and C32H11.1 in wild-type N2 and mdt-15(tm2182) mutant animals exposed to vhp-1(RNAi) or the vector control (L4440) under basal conditions (as described above) and 8 hours after exposure to P. aeruginosa. Knockdown of vhp-1 caused significant induction of F08G5.6 and F35E12.5 in wild-type N2 animals (p<0.001), but not in mdt-15(tm2182) animals (p>0.05), under baseline (E. coli) and pathogen-induced conditions. The expression of C32H11.1 was significantly induced by vhp-1(RNAi) (p<0.001) in an mdt-15-dependent manner under baseline conditions (p<0.001), but not following exposure to P. aeruginosa. Data are the average of two biological replicates each normalized to a control gene with error bars representing SEM and are presented as the value relative to the average expression of the indicated gene in the baseline condition (L4440 animals exposed to E. coli). Mediator Subunit MDT-15/MED15 Is Required for Defense against P. aeruginosa Infection

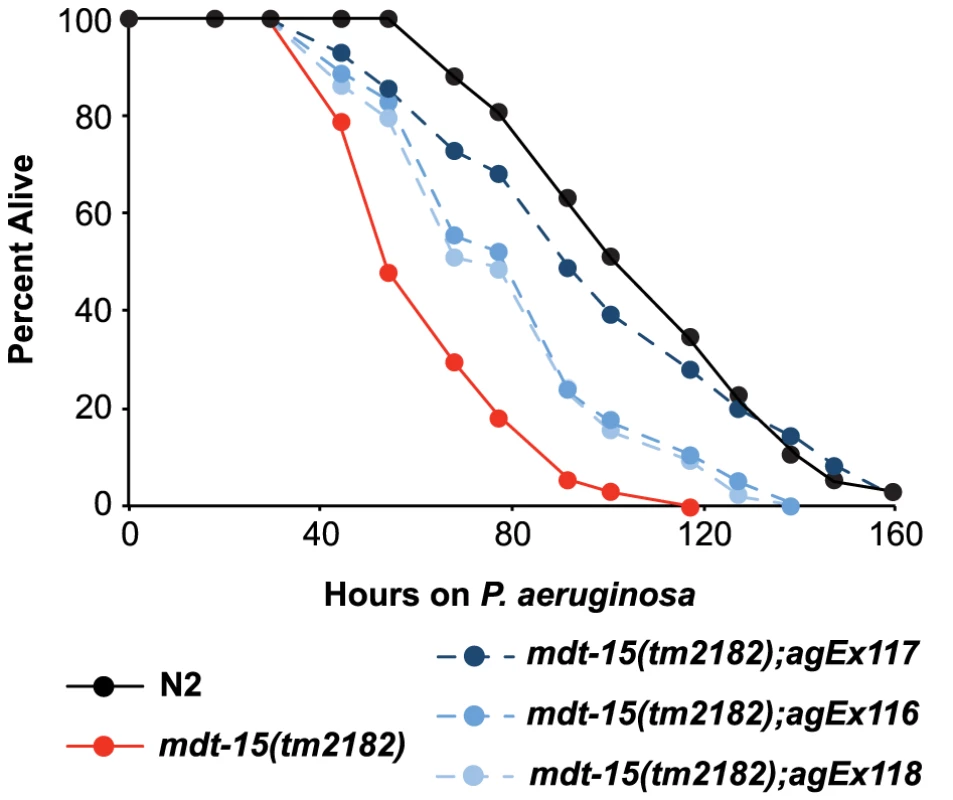

The experiments in the preceding sections show that the Mediator subunit MDT-15/MED15 is necessary for the induction of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-regulated genes, both in response to RPW-24 and during P. aeruginosa infection. We therefore reasoned that mutation or RNAi-mediated knockdown of mdt-15 would result in enhanced susceptibility to P. aeruginosa infection. Initial P. aeruginosa pathogenesis assays showed a modest, but significant and reproducible, enhanced susceptibility to infection in mdt-15(RNAi) (Figure S3A) and mdt-15(tm2182) (Figure S3B) animals compared to controls. However, both mdt-15(tm2182) and mdt-15(RNAi) animals have reduced brood sizes and varying degrees of sterility. Sterile animals are more resistant to P. aeruginosa infection than wild-type animals, due in part to daf-16-dependent induction of stress response genes [25]. To eliminate this potentially confounding effect, we made all animals in the P. aeruginosa pathogenesis assay sterile by knocking down cdc-25.1, a technique that has been used previously in C. elegans bacterial pathogenesis assays [26]. Under these conditions, we found that mdt-15(tm2182) animals were markedly hypersusceptible to P. aeruginosa infection compared to control animals (Figure 5). Moreover, injection of the mdt-15 gene under control of its own promoter partially rescued the enhanced susceptibility to P. aeruginosa phenotype of mdt-15(tm2182) animals (Figure 5). Knockdown of mdt-15 by RNAi also caused a hypersusceptibility to P. aeruginosa phenotype in C. elegans fer-15(b26);fem-1(hc17) sterile animals [6], [27], and as predicted, to a greater degree than wild-type animals that were not made sterile by cdc-25.1(RNAi) (Figure S3C).

Fig. 5. MDT-15 is required for defense against P. aeruginosa infection.

A P. aeruginosa pathogenesis assay with wild-type N2, mdt-15(tm2182) mutant worms and mdt-15(tm2182) animals carrying pmdt-15::mdt-15 (three independent lines agEx116, agEx117 and agEx118) is shown. The difference in P. aeruginosa susceptibility between mdt-15(tm2182) animals and each of the three transgenic lines carrying pmdt-15::mdt-15 is significant, as is the survival difference between N2 and mdt-15(tm2182) animals (p<0.001). For sample sizes, see Table S3. We also found that the ability of RPW-24 to extend survival of P. aeruginosa-infected wild-type and sterile nematodes was significantly attenuated in mdt-15(RNAi) animals compared to controls, suggesting that MDT-15 is required for the immunostimulatory activity of RPW-24 (Figure S3A and S3C). The degree of lifespan extension by RPW-24 during P. aeruginosa infection was reduced in mdt-15(tm2182) compared to controls, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.09)(Figure S3B). As discussed above, the gene expression defects of mdt-15 targets were more severe in mdt-15(RNAi) animals than in the hypomorphic mdt-15(tm2182) allele [19], [21], which may account for this observation.

One caveat concerning the observation that mdt-15 depleted animals are hypersusceptible to P. aeruginosa infection is that mdt-15(RNAi) and mdt-15(tm2182) animals have a reduced lifespan when grown on the normal laboratory food source E. coli OP50 compared to wild-type controls [18], [19]. Several observations indicate, however, that MDT-15 is an important modulator of nematode survival during bacterial infection. First, we have shown above that mdt-15(RNAi) animals fail to upregulate p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-dependent immune effectors both in response to a xenobiotic toxin and during P. aeruginosa infection, but retain the ability to induce other immune genes in response to pathogens and following exposure to the bacterial toxin ToxA. In addition, mdt-15(RNAi) animals do not respond to the immunostimulatory effects of RPW-24. We have shown previously that C. elegans with mutations in the ZIP-1 and FSHR-1 immune pathways, which act in parallel to the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 cassette, are hypersusceptible to P. aeruginosa infection, but retain the ability to respond to RPW-24 [9]. That mdt-15(RNAi) animals are blind to the immunostimulatory effects of RPW-24 suggests a specific role of MDT-15 in regulating p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 pathway activity. It is also important to note that despite their reduced lifespan, mdt-15(RNAi) animals are not sensitive to all environmental insults. For example, animals deficient in mdt-15 are sensitive to the toxin fluoranthene, but not β-naphthoflavone, and are not more sensitive to high temperatures than wild-type animals [19].

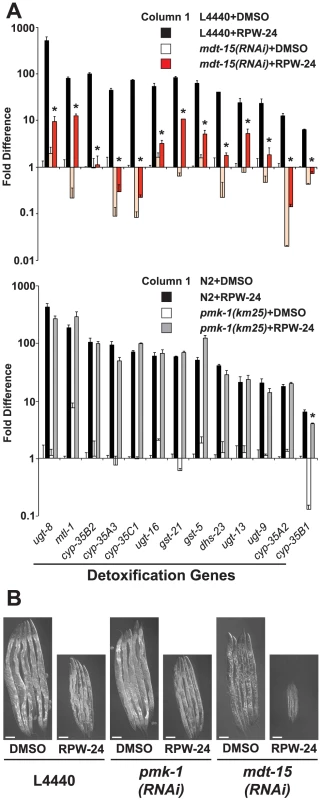

Mediator Subunit MDT-15/MED15 Regulates the Induction of p38 MAP Kinase PMK-1-Independent Detoxification Genes and Is Required to Resist the Toxic Effects of the Xenobiotic RPW-24

We previously demonstrated that RPW-24 is a xenobiotic toxin [9]. MDT-15 is known to coordinate protection from the toxin fluoranthene and regulate the transcriptional induction of CYPs [19]. We found that the RPW-24-mediated induction of the 13 detoxification genes in the NanoString codeset was nearly entirely abrogated by RNAi knockdown of mdt-15 (Figure 6A top panel and Table S2). This result was confirmed for three detoxification genes by qRT-PCR (Figures S2B and S2D). To determine if MDT-15 is required to protect C. elegans from the toxic effects of RPW-24, we studied the development of wild-type, pmk-1(RNAi) and mdt-15(RNAi) in the presence of the xenobiotic RPW-24, an assay that has been used previously to assess the toxicity of small molecules [19]. We found that RPW-24 slowed the development of control and pmk-1(RNAi) animals to similar degree, and that mdt-15(RNAi) animals were markedly delayed in the presence of RPW-24 (Figures 6B and S4). These data show that MDT-15 controls the induction of detoxification genes following exposure to RPW-24 and is required to resist the toxic effects of this xenobiotic.

Fig. 6. Protection from the toxic effects of the xenobiotic RPW-24 requires MDT-15, but not PMK-1.

(A) The thirteen xenobiotic detoxification genes that were induced 4-fold or greater by RPW-24 in the NanoString nCounter gene expression analysis are presented. The top panel compares the RPW-24-mediated induction of these genes in vector control (L4440) and mdt-15(RNAi) animals, and the bottom panel shows these data for wild-type N2 versus pmk-1(km25) animals, as described in the legend for Figure 2. * p<0.05 for the comparison of the RPW-24-induced conditions. (B) Vector control (L4440), mdt-15(RNAi) and pmk-1(RNAi) animals were exposed to 70 µM RPW-24 or the solvent control DMSO from the L1 stage and photographed after 70 hours of development at 20°C. See Figure S4 for the quantification data from this experiment. Given that MDT-15 is required for the regulation of detoxification genes and the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 pathway, we wondered if the detoxification machinery in C. elegans is regulated by the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1. We found, however, that 12 of the 13 RPW-24-induced detoxification genes were upregulated in pmk-1(km25) null mutants to levels comparable to that in wild-type animals exposed to RPW-24 (Figure 6A bottom panel). We used qRT-PCR to confirm this observation for three cytochrome P450 genes (Figure S2D). Thus, the MDT-15-dependent xenobiotic detoxification program is induced in a manner independent of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1.

MDT-15/MED15 Is Not Required for the Avoidance Behavior Induced by RPW-24

Many xenobiotic toxins, including RPW-24, induce an avoidance response wherein C. elegans leave a lawn of bacterial food, to which they are otherwise attracted, if it contains a toxic compound [3], [9]. We therefore wondered if MDT-15 is required for the avoidance behavior induced by RPW-24. However, pmk-1(km25) and mdt-15(tm2182) animals left the lawn of E. coli containing RPW-24 as readily as wild-type animals (Figure S5). We also observed a similar phenotype when we knocked down the expression of pmk-1 and mdt-15 in the neuronally-sensitive RNAi strain TU3311 (data not shown). Thus, animals lacking the function of MDT-15 and PMK-1 are still able to recognize RPW-24 as a toxin.

In summary, the data in this and the preceding section suggest that MDT-15, but not PMK-1, controls the induction of genes that are required to resist the toxic effects of RPW-24, and that neither are required for avoidance of RPW-24.

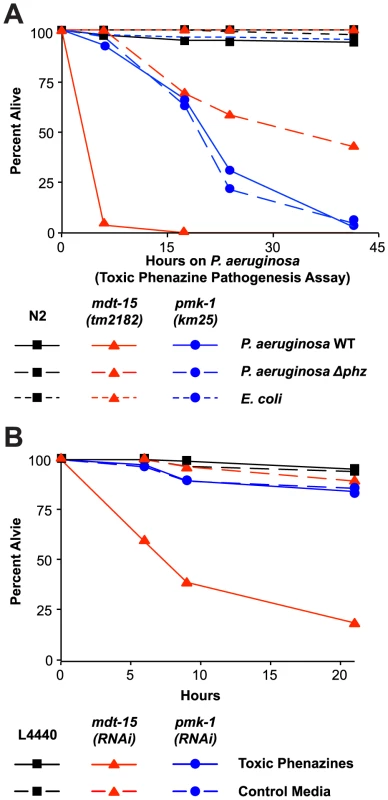

Mediator Subunit MDT-15/MED15 Promotes Resistance to Secreted P. aeruginosa Phenazine Toxins

We have shown that MDT-15 regulates the C. elegans detoxification response to the xenobiotic RPW-24. We therefore hypothesized that MDT-15 might also be required for protection from lethal secreted toxins produced by pathogenic bacteria. To address this question, we used an assay that allows the specific study of C. elegans killing by secreted low molecular weight toxins of P. aeruginosa. When P. aeruginosa is grown on high osmolarity media, phenazine toxins produced by the bacteria are lethal to nematodes [28], [29]. In contrast to the “slow killing” infection assay, which was used in the assays described above, wild-type nematodes exposed to these “fast killing” conditions die within a few hours via a process that does not require live bacteria [28], [29]. Wild-type C. elegans at the fourth larval stage of development, but not young adult animals, are exquisitely sensitive to the phenazine toxins produced by P. aeruginosa in this assay and are killed within 6 hours of exposure. We took advantage of the inherent resistance of young adult animals to test whether mdt-15(tm2182) animals are hypersusceptible to the phenazine toxins produced by P. aeruginosa. As expected, both wild-type and mdt-15(tm2182) L4 animals were rapidly killed by P. aeruginosa in the “fast kill” assay (Figure S6A). P. aeruginosa carrying deletions of both phenazine biosynthetic operons (Δphz) does not make these toxins and accordingly had reduced ability to kill both wild-type and mdt-15(tm2182) animals (Figure S6A). In contrast to L4 animals, we observed that almost no young adult, wild-type animals were killed after six hours of exposure to the phenazine toxins compared with 98% death of L4 staged animals (Figures 7A and S6A), which reproduces the findings of others [28], [29]. In contrast to wild-type animals, young adult mdt-15(tm2182) animals were dramatically susceptible to P. aeruginosa in this assay and this pathogenesis required the secretion of phenazine toxins, as P. aeruginosa Δphz was markedly less pathogenic toward mdt-15(tm2182) young adults (Figure 7A). Moreover, mdt-15(tm2182) animals were not simply hypersusceptible to the high osmolarity conditions of this assay because we observed no mortality over the course of the assay in mdt-15(tm2182) mutants exposed to “fast kill” media containing the normal nematode food source E. coli OP50 (Figure 7A).

Fig. 7. Resistance to P. aeruginosa phenazine toxins requires MDT-15.

(A) Wild-type N2, mdt-15(tm2182) and pmk-1(km25) animals were tested in the toxic phenazine P. aeruginosa pathogenesis assay (also called “fast killing” assay). C. elegans young adult animals were exposed to wild-type (WT) P. aeruginosa, P. aeruginosa carrying a deletion in both of the phenazine biosynthetic operons (Δphz) or E. coli OP50. The difference between mdt-15(tm2182) and N2 animals exposed to P. aeruginosa WT is significant (p<0.001), as is the difference in mdt-15(tm2182) animals exposed to P. aeruginosa WT and P. aeruginosa Δphz (p<0.001). There is no significant difference in pmk-1(km25) animals exposed to P. aeruginosa WT and P. aeruginosa Δphz (p>0.05). This assay is representative of two independent experiments. Figure S6A presents the control condition for this experiment showing that both C. elegans N2 and mdt-15(tm2182) at the L4 stage are sensitive to toxic phenazine-mediated killing (p<0.001). (B) Vector control (L4440), mdt-15(RNAi) and pmk-1(RNAi) animals were exposed to high osmolarity “fast kill” media (pH 5) with E. coli as the food source in the presence or absence of phenazine-1-carboxylic acid and 1-hydroxyphenazine (labeled “toxic phenazines” above) at the approximate concentrations produced by P. aeruginosa under standard assay conditions. The difference in killing between mdt-15(RNAi) animals exposed to toxic phenazines and the other conditions is significant (p<0.001). See also Figure S6. For sample sizes, see Table S3. We confirmed that phenazine toxins are lethal to mdt-15-depleted animals by supplementing “fast kill” growth media with both phenazine-1-carboxylic acid and 1-hydroxyphenazine in the absence of pathogen [28]. These two particular phenazines are toxic to wild-type nematodes [28] and, as expected, the mixture of phenazine-1-carboxylic acid and 1-hydroxyphenazine rapidly killed L4 animals (Figure S6B). Young adult wild-type animals were resistant to the lethal effects of these molecules (Figure 7B). However, mdt-15(RNAi) young adult animals were dramatically susceptible to phenazine-mediated killing (Figure 7B).

We also found that pmk-1(km25) loss-of-function mutants were more susceptible to P. aeruginosa in the “fast killing” assay than wild-type animals, although were less susceptible than mdt-15(tm2182) animals. This lethality, however, was mediated by factors other than phenazine toxins, since there was no difference in pathogenicity of the wild-type and Δphz P. aeruginosa toward pmk-1(km25) mutants (Figure 7A). Likewise, pmk-1(RNAi) animals were not more susceptible to phenazines-1-carboxylic acid and 1-hydroxyphenazine than L4440 RNAi control animals (Figure 7B).

Together, these data define a role for MDT-15, but not PMK-1, in the protection from bacterial-derived phenazine toxins.

Discussion

Detecting and countering environmental threats is central to the ability of organisms to survive and reproduce in the wild. We examined the C. elegans response to the xenobiotic RPW-24, which is able to induce a host immune response that is protective for animals infected with the lethal bacterial pathogen P. aeruginosa [9]. In an RNAi screen with RPW-24, we identified a number of genes, including mdt-15/MED15, which are required for induction of p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-dependent immune effectors. mdt-15 encodes a subunit of the highly conserved Mediator complex that controls the activation of a variety of genes involved in the response to external stress. We demonstrate that: (i) MDT-15 is required for the induction of p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-dependent immune effectors following exposure to a xenobiotic toxin, as well as during infection with P. aeruginosa, (ii) MDT-15 controls the expression of some p38 MAP kinase PMK-1-independent immune effectors, but not all defense genes, (iii), MDT-15 functions downstream of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 cascade to control the induction of at least two immune effectors, (iv) the induction of xenobiotic detoxification genes and protection from the toxic effects of RPW-24 requires MDT-15, but not the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1, and (iv) MDT-15 is necessary for protection during P. aeruginosa infection and from phenazine toxins secreted by this organism.

The Mediator complex is strongly conserved from yeasts to humans, and is required for transcription by physically interacting with and directing the activity of RNA polymerase II [30], [31]. Although initial studies from yeast described the Mediator complex as a general regulator of transcription [32], it is now becoming clear that the individual subunits of this complex, of which there are at least 26, play important roles in translating inputs from cell signaling pathways to specific outputs [30], [31], [33]. For example, the regulation of chemotherapeutic resistance in cancer cells requires MED12 [33], MED23 channels MAP kinase signaling activity to coordinate cell growth [34], and MED15 serves as a regulatory node in lipid metabolism by directing the activity of the transcriptional activator SREBP (sterol regulatory element binding protein) [20]. Interestingly, MED15's role as a lipid sensor is strongly conserved. In C. elegans, the MED15 homolog MDT-15 interacts with SBP-1, the SREBP homolog, and serves as an important regulator of lipid metabolism [18]–[20]. Likewise, the MED15 homolog in yeast (called GAL11p) serves a similar function [35].

Taubert et al. showed in a C. elegans genome-wide microarray analysis that MDT-15 coordinates the transcription of Phase I and Phase II detoxification genes, and is required to resist the lethal effects of a xenobiotic toxin [19] and agents that induce oxidative stress [21]. Consistent with these observations, we found that MDT-15 is necessary to mount a detoxification response toward and provide protection from RPW-24, a xenobiotic toxin. Our studies extend the known functions of this conserved Mediator subunit to innate immunity in demonstrating that MDT-15 plays a critical role in controlling immune and detoxification pathway activation in a manner that is important for protection from bacterial infection and from the secreted phenazine toxins of P. aeruginosa.

We propose that the Mediator subunit MDT-15 links innate immune activation to xenobiotic detoxification responses as part of a general strategy to ensure survival in harsh environments. In their natural habits, nematodes encounter numerous threats from ingested pathogens and xenobiotic toxins [1]. Thus, coupling xenobiotic detoxification to innate immune activation may have been selected for by pathogens that secrete soluble toxins during infection. Whether the protection from phenazine toxins mediated by MDT-15 requires detoxification genes or occurs via another mechanism is not known, but it is interesting to note that MDT-15's function as a regulator of host protection may be evolutionarily conserved. In yeasts, the MDT-15 homolog Gal11p coordinates a protective cellular response following xenobiotic exposure, which is manifest as the upregulation of drug efflux pumps [36].

The data presented in this study imply the existence of surveillance mechanisms that monitor for xenobiotic toxins (or their effects) and signal through MDT-15/MED15 to simultaneously activate protective detoxification and innate immune responses. Whether such activation occurs in the context of xenobiotic-induced organelle dysfunction is not known. McEwan et al. [15] and Dunbar et al. [16] found that C. elegans monitor the integrity of its translational machinery as a means to detect pathogen invasion. Inhibition of translation by the secreted bacterial toxin ToxA leads to an antibacterial response via known immune pathways involving the transcription factor ZIP-2 and the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1. Several observations suggest, however, that MDT-15-mediated regulation of immune activation and detoxification gene induction by RPW-24 does not occur via a mechanism involving translation inhibition. First, we previously found that a loss-of-function mutation in the zip-2 gene did not affect the ability of RPW-24 to extend the survival of animals infected with P. aeruginosa and genome-wide transcriptional analysis of animals exposed to RPW-24 did not suggest that this compound is an inhibitor of translation [9]. Second, the transcriptome analysis of animals exposed to ToxA did not show an abundance of Phase I and II detoxification genes [15]. Finally, we show here that the ToxA-responsive, ZIP-2-regulated genes, irg-1 and irg-2, are induced in mdt-15(RNAi) animals during P. aeruginosa infection to levels comparable to that observed in wild-type animals.

Melo et al. recently studied the behavioral response of C. elegans to xenobiotic toxins known to disrupt the function of the mitochondria, the ribosome, and the endoplasmic reticulum [3]. Inhibiting these essential processes by the action of small molecules or through targeted gene disruptions triggered an avoidance response, which required serotonergic and JNK signaling pathways. They proposed that organisms monitor disruption of core metabolic processes as a means to detect pathogen invasion and challenges from xenobiotic toxins. Based on the data reported here, however, it is not clear, whether immune signaling is an integral part of xenobiotic-elicited avoidance behavior, at least with respect to RPW-24. We found that the function of neither MDT-15 nor PMK-1 was required for the avoidance of RPW-24, indicating that the behavioral component of this protective response occurs upstream of MDT-15, or via separate mechanism altogether.

It will be interesting to determine the mechanism by which MDT-15 activates immune and detoxification responses in C. elegans. In our genetic screen for regulators of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 pathway, we identified a number of genes that are involved in fatty acid biosynthesis, including mdt-15, fat-6, fat-7, elo-5, acs-19 and C25A1.5. Indeed, MDT-15 is known to control the expression of fat-6 and fat-7 [18]–[20]. It is therefore possible that a fatty acid signaling molecule or membrane component is required for p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 activity. We found, however, in epistasis analyses with the MAP kinase phosphatase VHP-1 that MDT-15 functions downstream of PMK-1 to coordinate the expression of F08G5.6 and F35E12.5. Thus, for at least a subset of immune genes, MDT-15 likely also physically interacts with sequence-specific regulators, such as ATF-7, a transcription factor that is the downstream signaling target of the p38 MAP kinase PMK-1 pathway [12], to coordinate protective host responses mounted following exposure to xenobiotic toxins.

Materials and Methods

C. elegans and Bacterial Strains

C. elegans were grown on standard NGM plates with E. coli OP50 [37] unless otherwise noted. The previously published C. elegans strains used in this study were: N2 Bristol [37], pmk-1(km25) [5], AY101 [acIs101[pDB09.1(pF35E12.5::GFP); pRF4(rol-6(su1006))] [10], XA7702 mdt-15(tm2182) [19], [21], CF512 fer-15(b26);fem-1(hc17) [38], and AU0133 [agIs17(pirg-1::GFP; pmyo-2::mCherry)] [14]. The C. elegans strains created for this study were: AU0307 [agIs44(pF08G5.6::GFP::unc-54-3′UTR; pmyo-2::mCherry)], AU0316 [mdt-15(tm2182); agIs44], AU0325 [mdt-15(tm2182); agEx116 (mdt-15;pmyo-3::mCherry)], AU0326 [mdt-15(tm2182); agEx117 (mdt-15;pmyo-3::mCherry)], AU0327 [mdt-15(tm2182); agEx118 (mdt-15;pmyo-3::mCherry)] and AU0323 [mdt-15(tm2182); agIs44; agEx114 (mdt-15;pmyo-3::mCherry)].

The strain carrying agIs44 was constructed by PCR amplification from N2 genomic DNA of an 851 bp region upstream of the start codon of the F08G5.6 gene (primers GACTTGTCAAATGAACAATTTTATCAAATCTCA and CGCCTAGGTGTCAATTGATAATGAATA) and ligated to the GFP coding region and unc-54-3′UTR sequences amplified from pPD95.75 using published primers, and a previously described protocol [39]. The agIs44 construct was transformed into N2 animals with the co-injection marker pmyo-2::mCherry using established methods [40]. A strain carrying the pF08G5.6::GFP::unc-54-3′UTR and pmyo-2::mCherry transgenes in an extrachromosomal array was irradiated, and strains carrying the integrated array agIs44 were isolated. AU0307 was backcrossed to N2 five times.

The mdt-15 rescuing arrays agEx116, agEx117 and agEx118 contain a 4.8 kb mdt-15 genomic fragment, which includes 707 bp upstream and 1075 bp downstream of the mdt-15 coding region, amplified from N2 genomic DNA (primers GGAGTATCAGAAGCTCACGATGCTC and CCAAATAATACTAACCACCACATATCTTCCATT). This mdt-15 genomic fragment was transformed into N2 animals or AU0316 with the co-injection marker pmyo-3::mCherry using established methods.

RNAi clones presented in this study were from the Ahringer [41] or Vidal [42] RNAi libraries unless otherwise stated. The atf-7 [12] and the pmk-1 [5] RNAi clones have been previously reported. All RNAi clones presented in this study have been confirmed by sequencing. The P. aeruginosa strain PA14 were used for all studies, unless otherwise indicated. The P. aeruginosa strains used in Figure S1 have been previously described [13] and were (in order of descending virulence toward C. elegans): CF18, PA14, MSH10, S54485, PA01, PAK, 19660, and E2. The P. aeruginosa PA14 phenazine null mutant (Δphz) lacks both the phzA1-G1 and phzA2-G2 operons and has been previously described [43]. The BL21 E. coli strain that expresses the bacterial toxin Exotoxin A (ToxA) has been previously described [15].

Feeding RNAi Screen

1,420 RNAi clones that correspond to genes expressed in the C. elegans intestine based on their annotation in Wormbase (www.wormbase.org) in April, 2008 were selected from the Ahringer [41] or Vidal [42] RNAi libraries (see Table S1B). RNAi clones were pinned into 1.2 ml of LB plus 100 µg/ml carbenicillin in 96-well culture blocks (Corning Incorporated) and grown overnight at 37°C with shaking at 950 RPM in a Multitron II Shaking Incubator (Appropriate Technical Resources). 40 µL of the 10× concentrated overnight culture were added to each well of a 24-well plate containing RNAi agar medium and grown overnight at room temperature. The following day, 50–100 L1 staged AU0307 animals, which carry the agIs44 transgene, were added to each well and allowed to grow until they were at the L4 or young adult stage. Worms were then transferred to new 24-well screening plates containing 1 mL of “slow kill” media supplemented with 70 µM RPW-24 and seeded with E. coli OP50 food. Animals were dried on the screening plates for several hours at room temperature and then incubated overnight at 20C. The L4440 vector and pmk-1 RNAi clones were included on each of the screening plates as the negative and positive controls, respectively. Animals were scored for GFP expression and rated on a subjective scale from 0 (no GFP expression in response to RPW-24) to 3 (RPW-24-mediated induction of GFP expression equivalent to L4440). Exposure of the C. elegans transcriptional reporter irg-1::GFP to an E. coli strain that expresses ToxA was performed as previously described [15].

C. elegans Bacterial Infection and Other Assays

“Slow killing” P. aeruginosa infection were performed as previously described [9], [44]. In all of these assays, the final concentration of DMSO was 1% and RPW-24 was used at a concentration of 70 µM, unless otherwise indicated. The propensity of wild-type C. elegans to leave a lawn of bacteria supplemented with RPW-24 was assayed using a previously described protocol [3], [9] with minor modifications. Rather than adding the toxin on top of the small lawn of food, 20 µg of RPW-24 was mixed with E. coli OP50, which was spotted onto NGM plates. To assess the toxicity of RPW-24, we assayed the development of animals exposed to vector control (L4440), pmk-1(RNAi) and mdt-15(RNAi) in the presence of 70 µM RPW-24, as previously described [9]. P. aeruginosa “fast kill” pathogenesis assays were conducted with late L4 and early young adult animals (picked 1–3 hours after the L4 molt) obtained from timed egg lays as described [28], [29]. For the killing assay using toxic phenazines, 50 µg/ml phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (PCA) and 5 µg/ml 1-hydroxyphenazine in DMSO were added to modified “fast kill” media (1% bacto-peptone, 1% glucose, 1% NaCl, 150 mM sorbitol, 1.7% bacto agar, 5 µg/ml cholesterol and 50 mM sodium citrate, pH 5) [28]. These phenazine concentrations correspond to the amount of PCA and 1-hydroxy-phenazine that are produced under “fast kill” conditions [28]. E. coli OP50 was used as the food source. The modified “fast kill” media pH 5.0 plus 1% DMSO was used as the control condition. These assays were incubated at 21–23°C.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and NanoString nCounter Gene Expression Analyses

Synchronized L1 staged C. elegans N2 animals were grown to L4/young adult stage on the indicated RNAi strain, transferred to assay plates and incubated at 25°C for 24 hours. To prepare the assay plates, 70 µM RPW-24 or DMSO was added to 20 mL “slow killing” media [44] in 10 cm petri dishes seeded with E. coli OP50. N2 and pmk-1(km25) animals were raised on E. coli OP50 and exposed to the above conditions for 18 hours at 20°C. For qRT-PCR studies of nematodes infected with P. aeruginosa PA14 or the indicated strain of P. aeruginosa, 20 mL of “slow killing” media containing either DMSO or 70 µM RPW-24 was added to 10 cm petri dishes. Plates were seeded with either 75 µL of E. coli OP50 or P. aeruginosa, each from cultures grown for 15 hours at 37°C. The plates were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C and 24 hours at 25°C. L4/young adult animals were added to the assay plates and incubated at 25°C for eight hours. RNA was isolated using TriReagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc.) and analyzed by NanoString nCounter Gene Expression Analysis (NanoString Technologies) using a “codeset” designed by NanoString that contained probes for 118 C. elegans genes (Table S2). Probe hybridization, data acquisition and analysis were performed according to instructions from NanoString with each RNA sample normalized to the control genes snb-1, ama-1 and act-1. For the qRT-PCR studes, RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the Retroscript kit (Life Technologies) and analyzed using a CFX1000 machine (Bio-Rad) with previously published primers [6], [18]. The qRT-PCR primers for the mdt-15, pmk-1, tir-1 and sek-1 genes were designed for this study and are available upon request. All values were normalized against the control gene snb-1. Fold change was calculated using the Pfaffl method [45].

Microscopy

Nematodes were mounted onto agar pads, paralyzed with 10 mM levamisole (Sigma) and photographed using a Zeiss AXIO Imager Z1 microscope with a Zeiss AxioCam HRm camera and Axiovision 4.6 (Zeiss) software. For comparisons of GFP expression in the F08G5.6::GFP transgenic animals, photographs were acquired using the same imaging conditions.

Statistical Analyses

Differences in survival of C. elegans animals in the P. aeruginosa pathogenesis assays were determined with the log-rank test in each of two biological replicates. Differences were considered significant only if the p value was less than 0.05 for both replicates. In the manuscript, data from one experiement that is representative of both replicates is shown and the sample sizes for these experiments are given in Table S3. To determine if the increase in survival conferred by RPW-24 treatment was different in one population compared to another, we examined the difference in the effect of RPW-24 treatment on the hazard in each group using a Cox proportional hazard model (Stata13, Stata, College Station, TX) from two biological replicates, as previously described [9]. Fold changes in the qRT-PCR analyses were compared using unpaired, two-tailed student t-tests.

Accession Numbers

Accession numbers for genes and gene products are given for the publically available database Wormbase (http://www.wormbase.org). The accession numbers for the principal genes mentioned in this paper are: atf-7 (C07G2.2), C32H11.1, cyp-35A1 (C03G6.14), cyp-35B2 (K07C6.3), cyp-35C1 (C06B3.3), F35E12.5, F08G5.6, F01D5.5, fshr-1 (C50H2.1), irg-1 (C07G3.2), irg-2 (C49G7.5), mdt-15 (R12B2.5), nsy-1 (F59A6.1), pmk-1 (B0218.3), sek-1 (R03G5.2), skn-1 (T19E7.2), tir-1(F13B10.1), and zip-2 (K02F3.4). Other accession numbers are given in Figure 2, Figure 6, Table S1 and Table S2.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. LindblomTH, DoddAK (2006) Xenobiotic detoxification in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J Exp Zoolog Part A Comp Exp Biol 305 : 720–730.

2. Pukkila-WorleyR, AusubelFM (2012) Immune defense mechanisms in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestinal epithelium. Curr Opin Immunol 24 : 3–9.

3. MeloJA, RuvkunG (2012) Inactivation of conserved C. elegans genes engages pathogen - and xenobiotic-associated defenses. Cell 149 : 452–466.

4. RunkelED, LiuS, BaumeisterR, SchulzeE (2013) Surveillance-activated defenses block the ROS-induced mitochondrial unfolded protein response. PLoS Genet 9: e1003346.

5. KimDH, FeinbaumR, AlloingG, EmersonFE, GarsinDA, et al. (2002) A conserved p38 MAP kinase pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity. Science 297 : 623–626.

6. TroemelER, ChuSW, ReinkeV, LeeSS, AusubelFM, et al. (2006) p38 MAPK Regulates Expression of Immune Response Genes and Contributes to Longevity in C. elegans. PLoS Genet 2: e183.

7. Pukkila-WorleyR, AusubelFM, MylonakisE (2011) Candida albicans Infection of Caenorhabditis elegans Induces Antifungal Immune Defenses. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002074.

8. MoyTI, ConeryAL, Larkins-FordJ, WuG, MazitschekR, et al. (2009) High-throughput screen for novel antimicrobials using a whole animal infection model. ACS Chem Biol 4 : 527–533.

9. Pukkila-WorleyR, FeinbaumR, KirienkoNV, Larkins-FordJ, ConeryAL, et al. (2012) Stimulation of Host Immune Defenses by a Small Molecule Protects C. elegans from Bacterial Infection. PLoS Genet 8: e1002733.

10. BolzDD, TenorJL, AballayA (2010) A conserved PMK-1/p38 MAPK is required in Caenorhabditis elegans tissue-specific immune response to Yersinia pestis infection. J Biol Chem 285 : 10832–10840.

11. LiberatiNT, FitzgeraldKA, KimDH, FeinbaumR, GolenbockDT, et al. (2004) Requirement for a conserved Toll/interleukin-1 resistance domain protein in the Caenorhabditis elegans immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101 : 6593–6598.

12. ShiversRP, PaganoDJ, KooistraT, RichardsonCE, ReddyKC, et al. (2010) Phosphorylation of the Conserved Transcription Factor ATF-7 by PMK-1 p38 MAPK Regulates Innate Immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet 6: e1000892.

13. LeeDG, UrbachJM, WuG, LiberatiNT, FeinbaumRL, et al. (2006) Genomic analysis reveals that Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence is combinatorial. Genome Biol 7: R90.

14. EstesKA, DunbarTL, PowellJR, AusubelFM, TroemelER (2010) bZIP transcription factor zip-2 mediates an early response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107 : 2153–2158.

15. McEwanDL, KirienkoNV, AusubelFM (2012) Host Translational Inhibition by Pseudomonas aeruginosa Exotoxin A Triggers an Immune Response in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Host Microbe 11 : 364–374.

16. DunbarTL, YanZ, BallaKM, SmelkinsonMG, TroemelER (2012) C. elegans Detects Pathogen-Induced Translational Inhibition to Activate Immune Signaling. Cell Host Microbe 11 : 375–386.

17. ShiversRP, KooistraT, ChuSW, PaganoDJ, KimDH (2009) Tissue-specific activities of an immune signaling module regulate physiological responses to pathogenic and nutritional bacteria in C. elegans. Cell Host Microbe 6 : 321–330.

18. TaubertS, Van GilstMR, HansenM, YamamotoKR (2006) A Mediator subunit, MDT-15, integrates regulation of fatty acid metabolism by NHR-49-dependent and -independent pathways in C. elegans. Genes Dev 20 : 1137–1149.

19. TaubertS, HansenM, Van GilstMR, CooperSB, YamamotoKR (2008) The Mediator subunit MDT-15 confers metabolic adaptation to ingested material. PLoS Genet 4: e1000021.

20. YangF, VoughtBW, SatterleeJS, WalkerAK, Jim SunZ-Y, et al. (2006) An ARC/Mediator subunit required for SREBP control of cholesterol and lipid homeostasis. Nature 442 : 700–704.

21. GohGYS, MartelliKL, ParharKS, KwongAWL, WongMA, et al. (2013) The conserved Mediator subunit MDT-15 is required for oxidative stress responses in C. elegans. Aging Cell 13(1): 70–9.

22. WongD, BazopoulouD, PujolN, TavernarakisN, EwbankJJ (2007) Genome-wide investigation reveals pathogen-specific and shared signatures in the response of Caenorhabditis elegans to infection. Genome Biol 8: R194.

23. O'RourkeD, BabanD, DemidovaM, MottR, HodgkinJ (2006) Genomic clusters, putative pathogen recognition molecules, and antimicrobial genes are induced by infection of C. elegans with M. nematophilum. Genome Res 16 : 1005–1016.

24. KimDH, LiberatiNT, MizunoT, InoueH, HisamotoN, et al. (2004) Integration of Caenorhabditis elegans MAPK pathways mediating immunity and stress resistance by MEK-1 MAPK kinase and VHP-1 MAPK phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101 : 10990–10994.

25. MiyataS, BegunJ, TroemelER, AusubelFM (2008) DAF-16-dependent suppression of immunity during reproduction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 178 : 903–918.

26. IrazoquiJE, TroemelER, FeinbaumRL, LuhachackLG, CezairliyanBO, et al. (2010) Distinct pathogenesis and host responses during infection of C. elegans by P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000982.

27. FeinbaumRL, UrbachJM, LiberatiNT, DjonovicS, AdonizioA, et al. (2012) Genome-wide identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence-related genes using a Caenorhabditis elegans infection model. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002813.

28. CezairliyanB, VinayavekhinN, Grenfell-LeeD, YuenGJ, SaghatelianA, et al. (2013) Identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phenazines that kill Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003101.

29. Mahajan-MiklosS, TanMW, RahmeLG, AusubelFM (1999) Molecular mechanisms of bacterial virulence elucidated using a Pseudomonas aeruginosa-Caenorhabditis elegans pathogenesis model. Cell 96 : 47–56.

30. ConawayRC, ConawayJW (2011) Function and regulation of the Mediator complex. Curr Opin Genet Dev 21 : 225–230.

31. MalikS, RoederRG (2010) The metazoan Mediator co-activator complex as an integrative hub for transcriptional regulation. Nat Rev Genet 11 : 761–772.

32. HolstegeFC, JenningsEG, WyrickJJ, LeeTI, HengartnerCJ, et al. (1998) Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell 95 : 717–728.

33. HuangS, HölzelM, KnijnenburgT, SchlickerA, RoepmanP, et al. (2012) MED12 controls the response to multiple cancer drugs through regulation of TGF-β receptor signaling. Cell 151 : 937–950.

34. BoyerTG, MartinME, LeesE, RicciardiRP, BerkAJ (1999) Mammalian Srb/Mediator complex is targeted by adenovirus E1A protein. Nature 399 : 276–279.

35. ThakurJK, ArthanariH, YangF, ChauKH, WagnerG, et al. (2009) Mediator subunit Gal11p/MED15 is required for fatty acid-dependent gene activation by yeast transcription factor Oaf1p. J Biol Chem 284 : 4422–4428.

36. ThakurJK, ArthanariH, YangF, PanS-J, FanX, et al. (2008) A nuclear receptor-like pathway regulating multidrug resistance in fungi. Nature 452 : 604–609.

37. BrennerS (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77 : 71–94.

38. GariganD, HsuA-L, FraserAG, KamathRS, AhringerJ, et al. (2002) Genetic analysis of tissue aging in Caenorhabditis elegans: a role for heat-shock factor and bacterial proliferation. Genetics 161 : 1101–1112.

39. McEwanDL, WeismanAS, HunterCP (2012) Uptake of extracellular double-stranded RNA by SID-2. Mol Cell 47 : 746–754.

40. MelloCC, KramerJM, StinchcombD, AmbrosV (1991) Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J 10 : 3959–3970.

41. KamathRS, AhringerJ (2003) Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods 30 : 313–321.

42. RualJ-F, CeronJ, KorethJ, HaoT, NicotA-S, et al. (2004) Toward improving Caenorhabditis elegans phenome mapping with an ORFeome-based RNAi library. Genome Res 14 : 2162–2168.

43. DietrichLEP, Price-WhelanA, PetersenA, WhiteleyM, NewmanDK (2006) The phenazine pyocyanin is a terminal signalling factor in the quorum sensing network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 61 : 1308–1321.

44. TanMW, Mahajan-MiklosS, AusubelFM (1999) Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Pseudomonas aeruginosa used to model mammalian bacterial pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96 : 715–720.

45. PfafflMW (2001) A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29: e45.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Combined Systems Approaches Reveal Highly Plastic Responses to Antimicrobial Peptide Challenge inČlánek Two Novel Human Cytomegalovirus NK Cell Evasion Functions Target MICA for Lysosomal Degradation

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 5- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Choroby jater v ordinaci praktického lékaře – význam jaterních testů

- Diagnostický algoritmus při podezření na syndrom periodické horečky

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Surveillance for Emerging Biodiversity Diseases of Wildlife

- The Emerging Role of Urease as a General Microbial Virulence Factor

- PARV4: An Emerging Tetraparvovirus

- Epigenetic Changes Modulate Schistosome Egg Formation and Are a Novel Target for Reducing Transmission of Schistosomiasis

- The Human Adenovirus E4-ORF1 Protein Subverts Discs Large 1 to Mediate Membrane Recruitment and Dysregulation of Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase

- A Multifactorial Role for Malaria in Endemic Burkitt's Lymphoma Pathogenesis

- Structural Basis for the Ubiquitin-Linkage Specificity and deISGylating Activity of SARS-CoV Papain-Like Protease

- Cathepsin-L Can Resist Lysis by Human Serum in

- Epstein-Barr Virus Down-Regulates Tumor Suppressor Expression

- BCA2/Rabring7 Targets HIV-1 Gag for Lysosomal Degradation in a Tetherin-Independent Manner

- The Evolutionarily Conserved Mediator Subunit MDT-15/MED15 Links Protective Innate Immune Responses and Xenobiotic Detoxification

- Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 4 (SOCS4) Protects against Severe Cytokine Storm and Enhances Viral Clearance during Influenza Infection

- T Cell Inactivation by Poxviral B22 Family Proteins Increases Viral Virulence

- Dynamics of HIV Latency and Reactivation in a Primary CD4+ T Cell Model

- HIV and HCV Activate the Inflammasome in Monocytes and Macrophages via Endosomal Toll-Like Receptors without Induction of Type 1 Interferon

- Virus and Autoantigen-Specific CD4+ T Cells Are Key Effectors in a SCID Mouse Model of EBV-Associated Post-Transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorders

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Envelope Protein Ion Channel Activity Promotes Virus Fitness and Pathogenesis

- Squalene Synthase As a Target for Chagas Disease Therapeutics

- The Contribution of Viral Genotype to Plasma Viral Set-Point in HIV Infection

- Combined Systems Approaches Reveal Highly Plastic Responses to Antimicrobial Peptide Challenge in

- Anthrax Lethal Factor as an Immune Target in Humans and Transgenic Mice and the Impact of HLA Polymorphism on CD4 T Cell Immunity

- Ly49C-Dependent Control of MCMV Infection by NK Cells Is -Regulated by MHC Class I Molecules

- Two Novel Human Cytomegalovirus NK Cell Evasion Functions Target MICA for Lysosomal Degradation

- A Large Family of Antivirulence Regulators Modulates the Effects of Transcriptional Activators in Gram-negative Pathogenic Bacteria

- Broad-Spectrum Anti-biofilm Peptide That Targets a Cellular Stress Response

- Malaria Parasite Infection Compromises Control of Concurrent Systemic Non-typhoidal Infection via IL-10-Mediated Alteration of Myeloid Cell Function

- A Role for in Higher Order Structure and Complement Binding of the Capsule

- Hip1 Modulates Macrophage Responses through Proteolysis of GroEL2

- CD8 T Cells from a Novel T Cell Receptor Transgenic Mouse Induce Liver-Stage Immunity That Can Be Boosted by Blood-Stage Infection in Rodent Malaria

- Phosphorylation of KasB Regulates Virulence and Acid-Fastness in

- HIV-Infected Individuals with Low CD4/CD8 Ratio despite Effective Antiretroviral Therapy Exhibit Altered T Cell Subsets, Heightened CD8+ T Cell Activation, and Increased Risk of Non-AIDS Morbidity and Mortality

- A Novel Mechanism Inducing Genome Instability in Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Infected Cells

- Structural and Biochemical Characterization Reveals LysGH15 as an Unprecedented “EF-Hand-Like” Calcium-Binding Phage Lysin

- Hepatitis C Virus Cell-Cell Transmission and Resistance to Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents

- Different Modes of Retrovirus Restriction by Human APOBEC3A and APOBEC3G

- TNFα and IFNγ but Not Perforin Are Critical for CD8 T Cell-Mediated Protection against Pulmonary Infection

- Large Scale RNAi Reveals the Requirement of Nuclear Envelope Breakdown for Nuclear Import of Human Papillomaviruses

- The Cytoplasmic Domain of Varicella-Zoster Virus Glycoprotein H Regulates Syncytia Formation and Skin Pathogenesis

- A New Class of Multimerization Selective Inhibitors of HIV-1 Integrase

- Are We There Yet? The Smallpox Research Agenda Using Variola Virus

- High-Efficiency Targeted Editing of Large Viral Genomes by RNA-Guided Nucleases

- Dynamic Functional Modulation of CD4 T Cell Recall Responses Is Dependent on the Inflammatory Environment of the Secondary Stimulus

- Bacterial Superantigens Promote Acute Nasopharyngeal Infection by in a Human MHC Class II-Dependent Manner

- Follicular Helper T Cells Promote Liver Pathology in Mice during Infection

- A Nasal Epithelial Receptor for WTA Governs Adhesion to Epithelial Cells and Modulates Nasal Colonization

- Unexpected Role for IL-17 in Protective Immunity against Hypervirulent HN878 Infection

- Human Cytomegalovirus Fcγ Binding Proteins gp34 and gp68 Antagonize Fcγ Receptors I, II and III

- Expansion of Murine Gammaherpesvirus Latently Infected B Cells Requires T Follicular Help

- Venus Kinase Receptors Control Reproduction in the Platyhelminth Parasite

- Molecular Signatures of Hemagglutinin Stem-Directed Heterosubtypic Human Neutralizing Antibodies against Influenza A Viruses

- The Downregulation of GFI1 by the EZH2-NDY1/KDM2B-JARID2 Axis and by Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) Associated Factors Allows the Activation of the HCMV Major IE Promoter and the Transition to Productive Infection

- Inactivation of Fructose-1,6-Bisphosphate Aldolase Prevents Optimal Co-catabolism of Glycolytic and Gluconeogenic Carbon Substrates in

- New Insights into Rotavirus Entry Machinery: Stabilization of Rotavirus Spike Conformation Is Independent of Trypsin Cleavage

- Prophenoloxidase Activation Is Required for Survival to Microbial Infections in

- SslE Elicits Functional Antibodies That Impair Mucinase Activity and Colonization by Both Intestinal and Extraintestinal Strains

- Timed Action of IL-27 Protects from Immunopathology while Preserving Defense in Influenza

- HIV-1 Envelope gp41 Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies: Hurdles for Vaccine Development

- The PhoP-Dependent ncRNA Mcr7 Modulates the TAT Secretion System in

- Cellular Superspreaders: An Epidemiological Perspective on HIV Infection inside the Body

- The Inflammasome Pyrin Contributes to Pertussis Toxin-Induced IL-1β Synthesis, Neutrophil Intravascular Crawling and Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis

- Papillomavirus Genomes Associate with BRD4 to Replicate at Fragile Sites in the Host Genome

- Integrative Functional Genomics of Hepatitis C Virus Infection Identifies Host Dependencies in Complete Viral Replication Cycle

- Co-assembly of Viral Envelope Glycoproteins Regulates Their Polarized Sorting in Neurons

- Targeting Membrane-Bound Viral RNA Synthesis Reveals Potent Inhibition of Diverse Coronaviruses Including the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Virus

- Dual-Site Phosphorylation of the Control of Virulence Regulator Impacts Group A Streptococcal Global Gene Expression and Pathogenesis

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Venus Kinase Receptors Control Reproduction in the Platyhelminth Parasite

- Dual-Site Phosphorylation of the Control of Virulence Regulator Impacts Group A Streptococcal Global Gene Expression and Pathogenesis

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Envelope Protein Ion Channel Activity Promotes Virus Fitness and Pathogenesis

- High-Efficiency Targeted Editing of Large Viral Genomes by RNA-Guided Nucleases

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání