-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Adenylate Cyclase Toxin Mobilizes Its β Integrin Receptor into Lipid Rafts to Accomplish Translocation across Target Cell Membrane in Two Steps

Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin (CyaA) binds the αMβ2 integrin (CD11b/CD18, Mac-1, or CR3) of myeloid phagocytes and delivers into their cytosol an adenylate cyclase (AC) enzyme that converts ATP into the key signaling molecule cAMP. We show that penetration of the AC domain across cell membrane proceeds in two steps. It starts by membrane insertion of a toxin ‘translocation intermediate’, which can be ‘locked’ in the membrane by the 3D1 antibody blocking AC domain translocation. Insertion of the ‘intermediate’ permeabilizes cells for influx of extracellular calcium ions and thus activates calpain-mediated cleavage of the talin tether. Recruitment of the integrin-CyaA complex into lipid rafts follows and the cholesterol-rich lipid environment promotes translocation of the AC domain across cell membrane. AC translocation into cells was inhibited upon raft disruption by cholesterol depletion, or when CyaA mobilization into rafts was blocked by inhibition of talin processing. Furthermore, CyaA mutants unable to mobilize calcium into cells failed to relocate into lipid rafts, and failed to translocate the AC domain across cell membrane, unless rescued by Ca2+ influx promoted in trans by ionomycin or another CyaA protein. Hence, by mobilizing calcium ions into phagocytes, the ‘translocation intermediate’ promotes toxin piggybacking on integrin into lipid rafts and enables AC enzyme delivery into host cytosol.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 6(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000901

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000901Summary

Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin (CyaA) binds the αMβ2 integrin (CD11b/CD18, Mac-1, or CR3) of myeloid phagocytes and delivers into their cytosol an adenylate cyclase (AC) enzyme that converts ATP into the key signaling molecule cAMP. We show that penetration of the AC domain across cell membrane proceeds in two steps. It starts by membrane insertion of a toxin ‘translocation intermediate’, which can be ‘locked’ in the membrane by the 3D1 antibody blocking AC domain translocation. Insertion of the ‘intermediate’ permeabilizes cells for influx of extracellular calcium ions and thus activates calpain-mediated cleavage of the talin tether. Recruitment of the integrin-CyaA complex into lipid rafts follows and the cholesterol-rich lipid environment promotes translocation of the AC domain across cell membrane. AC translocation into cells was inhibited upon raft disruption by cholesterol depletion, or when CyaA mobilization into rafts was blocked by inhibition of talin processing. Furthermore, CyaA mutants unable to mobilize calcium into cells failed to relocate into lipid rafts, and failed to translocate the AC domain across cell membrane, unless rescued by Ca2+ influx promoted in trans by ionomycin or another CyaA protein. Hence, by mobilizing calcium ions into phagocytes, the ‘translocation intermediate’ promotes toxin piggybacking on integrin into lipid rafts and enables AC enzyme delivery into host cytosol.

Introduction

The secreted adenylate cyclase toxin-hemolysin (CyaA, ACT, or AC-Hly) plays a key role in virulence of Bordetellae. This multifuctional protein binds the αMβ2 integrin (CD11b/CD18, CR3 or Mac-1) of myeloid phagocytic cells and delivers into their cytosol a calmodulin-activated adenylate cyclase enzyme that ablates bactericidal capacities of phagocytes by uncontrolled conversion of cytosolic ATP to the key signaling molecule cAMP [1]–[5]. In parallel, the hemolysin moiety of CyaA forms oligomeric pores that permeabilize cell membrane for monovalent cations and contribute to overall cytoxicity of CyaA towards phagocytes [6]–[10].

The toxin is a 1706 residues-long protein, in which a calmodulin-activated adenylate cyclase (AC) enzyme domain of ∼400 N-terminal residues is fused to a ∼1300 residue-long RTX (Repeats in ToXin) cytolysin moiety [11]. The latter consists itself of three functional domains typical for RTX hemolysins. It harbors, respectively, (i) a hydrophobic pore-forming domain, (ii) a segment recognized by the protein acyltransferase CyaC, activating proCyaA by covalent post-translational palmitoylation at ε-amino groups of Lys860 and Lys983 [12], [13], and (iii) an assembly of five blocks of the characteristic glycine and aspartate-rich nonapeptide RTX repeats that form numerous (∼40) calcium-binding sites [14].

Since no structural information on the RTX cytolysin moiety is available, the mechanistic details of toxin translocation across the lipid bilayer of cell membrane remain poorly understood. Delivery of the AC domain into cells occurs directly across the cytoplasmic membrane, without the need for toxin endocytosis [15] and requires structural integrity of the CyaA molecule [6], unfolding of the AC domain [16] and a negative membrane potential [17]. Recently, we described that CyaA forms a calcium-conductive path in cell membrane and mediates influx of extracellular Ca2+ ions into cell cytosol concomitantly with translocation of the AC domain polypeptide into cells [18].

The current working model predicts that both Ca2+ influx and AC translocation depend on a different membrane-inserted CyaA conformer than the pore-forming activity [19], [20]. The two membrane activities of CyaA, however, appear to use the same essential amphipatic transmembrane segments within the pore-forming domain (α-helix502–522 and α-helix565–591), employing them in an alternative and mutually exclusive way. These segments harbor two pairs of negatively charged glutamate residues (Glu509/Glu516 and Glu570/Glu581) that were found to play a central role in toxin action on cell membrane. These control, respectively, the translocation of the positively charged AC domain, the formation of oligomeric CyaA pores and the cation-selectivity of the CyaA pore. Charge-reversing, neutral or helix-breaking substitutions of these glutamates were found to shift the balance between AC translocating and pore-forming activities of CyaA on cell membrane [8], [10], [19], [20].

The very high specific AC enzyme activity of CyaA allowed previously to detect its capacity to promiscuously bind and penetrate at reduced levels also numerous cell types lacking the CD11b/CD18 receptor [21], [22]. This is likely due to a weak lectin activity of CyaA, which would enable interaction of the toxin with cell surface gangliosides [23] and glycoproteins [24]. Indeed, binding of CyaA to CD11b/CD18 was recently found to depend on initial interaction with the N-linked glycan antenna of the receptor [24], where the specificity of CyaA for CD11b/CD18 appears to be determined by a segment of the stalk domain of the CD11b subunit (Osicka et al., manuscript in preparation).

CD11b/CD18 belongs to the β2 subfamily of polyfunctional integrins playing a major role in leukocyte function. The same β2 subunit (CD18) can, indeed, pair with four distinct α subunits to yield the αLβ2 (CD11a/CD18, LFA-1), αMβ2 (CD11b/CD18, CR3, Mac1), αXβ2 (CD11c/CD18, p150/195) and αDβ2 (CD11d/CD18) receptors, respectively [25]. Among key features of these integrins is their capacity of bi-directional signaling, where the avidity and conformation of the integrins is regulated by intracellular signals in the ‘inside-out’ signaling mode. In turn, binding of ligands or counter-receptors results in ‘outside-in’ signaling [26]. Among other effects, the latter yields actin cytoskeletal rearrangements and can result in lateral segregation of the β2 integrins from the bulk phase of the plasma membrane into distinct lipid assemblies known as lipid rafts [27], [28]. These were first detected as detergent-resistant membrane (DRM), characterized by insolubility in some detergents under certain conditions and enriched in cholesterol, sphingolipids, and glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins [29]–[32]. Besides playing an important role in signal transduction, receptor internalization, vesicular sorting or cholesterol transport [33], the components of lipid rafts are often exploited as specific receptors mediating cell entry of toxins, pathogenic bacteria, or viruses [34]–[36].

Here, we show that CyaA-mediated influx of Ca2+ ions into cells induces mobilization of the toxin-receptor complex into lipid rafts, where translocation of the AC domain across cytoplasmic membrane is accomplished.

Results

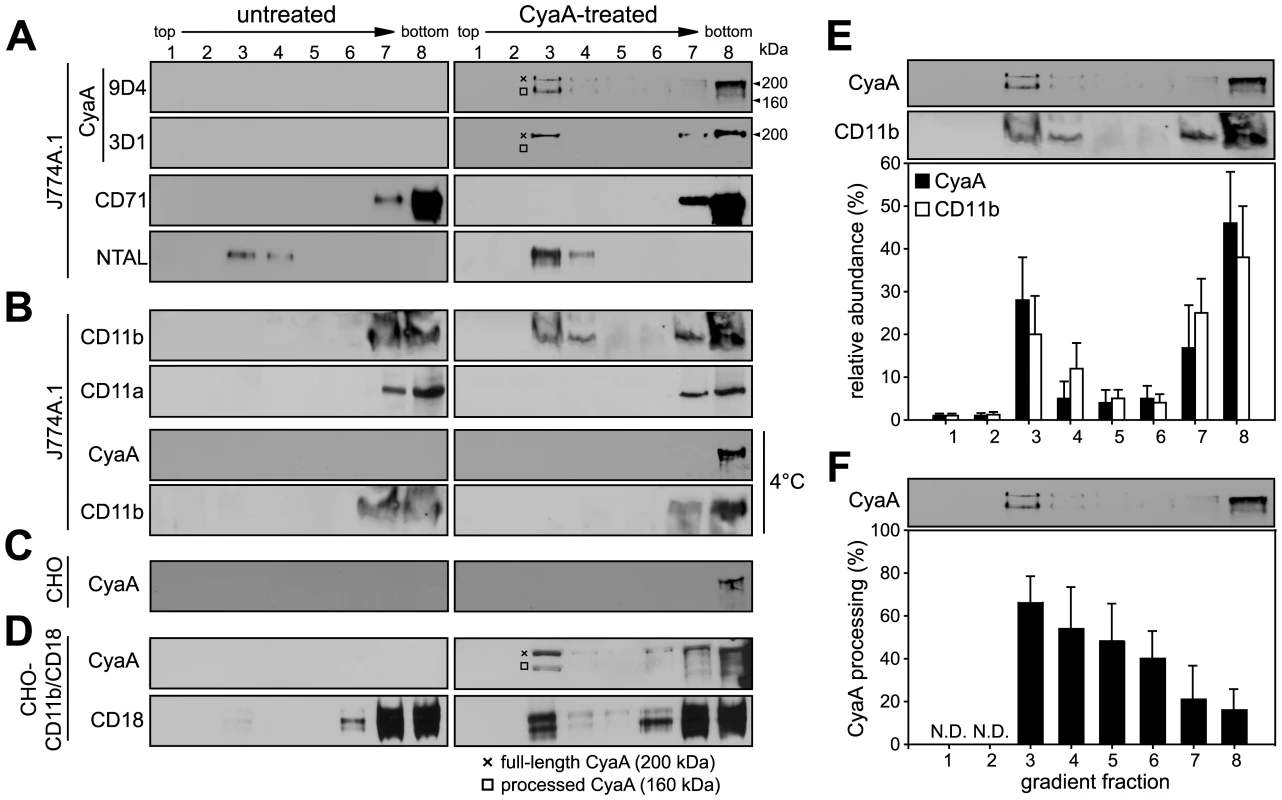

CyaA entrains its CD11b/CD18 receptor into lipid rafts

To examine whether CyaA localizes to lipid rafts, murine J774A.1 monocytes exposed to 1 nM CyaA (176 ng/ml, 37°C, 10 min) were lyzed with ice-cold Triton X-100 and detergent-resistant membrane (DRM) was separated from soluble cell extracts by flotation through sucrose density gradients. As shown in Fig. 1A, while the CD71 marker of bulk membrane phase was exclusively detected in the soluble extract at the bottom of the gradient, up to 30% of total loaded CyaA was found to float in fraction 3 at a lower buoyant density towards the top of the gradient, together with the DRM marker protein NTAL (see Fig. 1E for quantification).

Fig. 1. CyaA entrains CD11b/CD18 into lipid rafts.

J774A.1 cells were mock-treated with buffer, or incubated with 1 nM CyaA at 37°C for 10 min (CyaA-treated). Cells were placed on ice and extracted at 4°C for 60 minutes in buffer containing 1% Triton X-100. Cell lyzates were fractionated by flotation in buoyant sucrose density gradients at 150,000×g in a Beckman SW60Ti rotor at 4°C for 16 h. Gradient fractions were analyzed by Western blotting. (A) Unless otherwise stated, CyaA was detected using the 9D4 monoclonal antibody (MAb) recognizing the C-terminal RTX repeats. The 3D1 MAb was used to specifically detect the distal part (aa 373–400) of the AC domain of CyaA [37]. The full-length CyaA (∼200 kDa) and the processed form of CyaA (∼160 kDa) are indicated by a crossline (×) and a square symbol (□), respectively. (B) CD11b was detected with the OKM-1 antibody on native immunoblots of Blue-native PAGE gels, while conventional Western blots were used for detection of CyaA and CD11a by 9D4 and MEM-25 antibodies, respectively. (C) Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were mock-treated or incubated with 113 nM CyaA at 37°C for 10 min. (D) CHO cells stably transfected with genes encoding the human CD11b/CD18 integrin subunits (CHO-CD11b/CD18) were incubated with 1 nM CyaA at 37°C for 10 min. CyaA and CD18 were detected with 9D4 and MEM-48, respectively. Lanes 1–8 correspond to gradient fractions. Representative immunoblots from at least 3 independent experiments are shown. (E) Distribution of CyaA (filled bars) and CD11b (open bars) across sucrose density gradient. The values for relative amounts of CyaA and CD11b, detected in a given fraction of the gradient and expressed as % of total detected protein, were derived from densitometric analysis of immunoblots. (F) Relative abundance of the processed form of CyaA (160 kDa) was expressed as % of total CyaA detected within a given fraction of the gradient. Values represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. N.D., not determined. Notably, while over 50% of the full-length CyaA molecules (∼200 kDa) remained in the soluble phase at the bottom of the gradient, the floating DRM fractions were selectively enriched in a processed CyaA form of ∼160 kDa, representing up to 60% of total CyaA in the fraction 3 of the gradient (see Fig. 1F for quantification). This appeared to have the entire AC domain-cleaved off, as it could only be detected by the 9D4 antibody recognizing the C-terminal RTX repeats and not by the 3D1 antibody binding between residues 373 and 399 of the C-terminal end of the AC domain of CyaA [37]. Most CyaA molecules accumulating in DRM appeared, hence, to have the AC domain translocated across cellular membrane and accessible to processing by intracellular proteases [10], [38].

As further documented in Fig. 1B, no CD11b was floating with DRM from mock-treated J774A.1 cells, or when toxin binding occurred at 4°C. In turn, exposure of monocytes to 1 nM CyaA at 37°C, resulted in mobilization of over 30% of total cellular CD11b into the floating DRM, showing that CyaA relocated from the bulk of the membrane to DRM together with its αMβ2 integrin receptor. This was, however, not due to any generalized clustering and mobilization of β2 integrins into rafts resulting from toxin action, as the highly homologous CD11a subunit of the other β2 integrin expressed by J774A.1 cells (LFA-1), was not mobilized into DRM (Fig. 1B). Hence, the relocation of CD11b/CD18 into rafts was specifically due to interaction with CyaA.

To assess whether CyaA association with DRM depended on toxin interaction with CD11b/CD18, we used Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells that do not express any β2 integrins unless transfected by genes encoding CD11b and CD18 subunits (CHO-CD11b/CD18). As shown in Fig. 1C, even when the CyaA concentration was raised to 113 nM, to obtain detectable amounts of the toxin associated with mock-transfected CHO cells, CyaA was detected exclusively in the soluble extract at the bottom of the gradient. In contrast, association of CyaA and CD11b/CD18 with DRM was detected already upon treatment of CHO-CD11b/CD18 transfectants with 1 nM CyaA (Fig. 1D). This showed that CyaA depended on binding to CD11b/CD18 for association with DRM and it was able to mobilize CD11b/CD18 into DRM independently of the myeloid cell background.

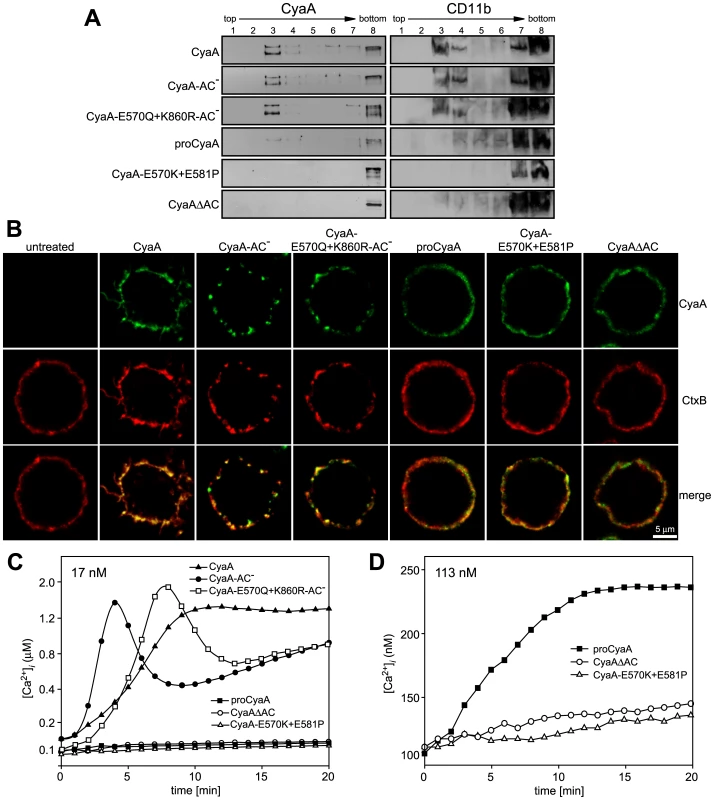

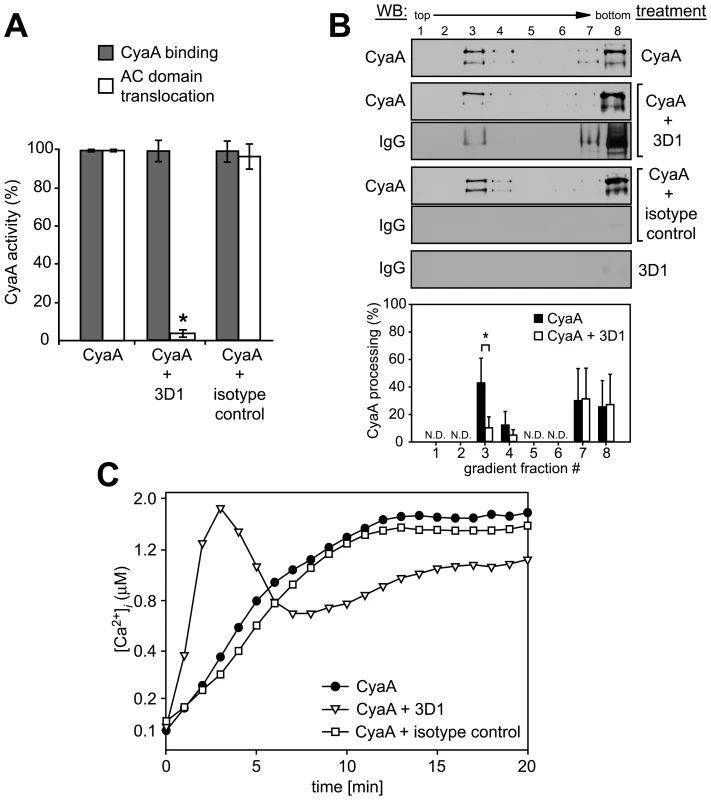

Mobilization of the CyaA-CD11b/CD18 complex into lipid rafts depends on AC domain translocation and influx of extracellular calcium ions

Since CyaA exerts several activities on cells in parallel, we analyzed which of them enabled mobilization of the CyaA-CD11b/CD18 complex into DRM. Towards this aim, we used a specific set of CyaA variants that retain the capacity to bind CD11b/CD18, while lacking one or more of the other CyaA activities (Table 1). As documented in Fig. 2A, the capacity of CyaA to elevate cellular cAMP concentrations was not required for mobilization of CyaA into DRM. The enzymatically-inactive CyaA-AC− construct, unable to catalyze conversion of ATP into cAMP, was indeed accumulating in DRM with the same efficacy as the intact CyaA (fractions 3–4). Fatty-acylation of CyaA as such was also not essential for association of CyaA with DRM. As further shown in Fig. 2A, the non-acylated proCyaA was detected in DRM despite an importantly reduced capacity to associate with cells. Moreover, the pore-forming activity of CyaA was both insufficient and dispensable for mobilization of CyaA into DRM. The acylated CyaAΔAC construct, lacking the entire AC domain but retaining an intact pore-forming (hemolytic) capacity, was unable to mobilize into DRM (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the CyaA-E570Q+K860R-AC− construct unable to permeabilize cells to any significant extent, but exhibiting an intact capacity to translocate the AC domain across cell membrane was, indeed, recruited into DRM together with CD11b/CD18 as efficiently as intact CyaA. In turn, the CyaA-E570K+E581P double mutant that was unable to form CyaA pores, or to translocate the AC domain across membrane, and retained only the CD11b-binding capacity (Table 1), was also unable to associate with DRM.

Fig. 2. Mobilization of CyaA into lipid rafts depends on CyaA-mediated Ca2+ influx.

(A) J774A.1 cells were incubated with 1 nM CyaA-derived proteins at 37°C for 10 min, cell lyzates were fractionated on sucrose gradients and proteins were detected by immunoblots as described for Fig. 1. (B) J774A.1 cells were incubated at 37°C for 10 min with 6 nM CyaA proteins labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 before 5 µg/ml of Alexa Fluor 594-labeled recombinant cholera toxin subunit B (CtxB) was added for additional 5 min. The cell-bound proteins were visualized by fluorescence microscopy and co-localization of CyaA (green) with CtxB (red) was assessed in the merged images (yellow). Representative images from two independent experiments are shown. Note that intact CyaA induced the reported cAMP-dependent ruffling of J774A.1 cells [2]. (C and D) CyaA induces increase of cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i). J774A.1 cells were loaded with the Ca2+ probe Fura-2/AM (3 µM) at 25°C for 30 min and exposed to 17 nM (C) or 113 nM (D) CyaA proteins. Time course of Ca2+ entry was recorded as the ratio of fluorescence intensities (excitation at 340/380 nm, emmision 505 nm), as previously described [18]. The shown curves are representative of at least three independent experiments. Tab. 1. Relative toxin activities of CyaA-derived constructs.

Capacity to catalyze conversion of ATP to cAMP. To corroborate these observations, we used fluorescence microscopy to examine the distribution of individual CyaA proteins in cell membrane. As documented in Fig. 2B, the intact CyaA, CyaA-AC− and CyaA-E570Q+K860R-AC− proteins were found to induce formation of, and to localize within, patches on cell membrane. Moreover, the same patches were labeled to high extent also with B subunit of cholera toxin (CtxB), which specifically binds the GM1 ganglioside accumulating in lipid rafts. Hence, the three CyaA variants capable of associating with DRM (cf. Fig. 2A) were also found to co-localize with CtxB within membrane patches. In turn, no formation of membrane patches, a diffuse distribution on cell surface, and low if any co-localization with CtxB, were observed for the CyaAΔAC and CyaA-E570K+E581P constructs that were unable to associate with DRM, too.

The pattern of DRM association, processing to the 160 kDa form and co-localization of the different CyaA variants with CtxB, respectively, resembled strongly the pattern of structure-function relationships observed recently for the capacity of CyaA to promote influx of extracellular calcium ions into J774A.1 cells [18]. Indeed, as documented in Fig. 2C by measurements of intracellular calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]i), the CyaA, CyaA-AC− and CyaA-E570Q+K860R-AC−proteins (17 nM) exhibited an expected capacity to promote Ca2+ influx into J774A.1 cells (see [18] for details on different kinetics of Ca2+ entry for AC− and AC+ constructs). In contrast, the CyaA-E570K+E581P and CyaAΔAC constructs, failed to mediate any increase of [Ca2+]i even when used at a 113 nM concentration (Fig. 2D). Collectively, hence, these results show that the capacity of different CyaA variants to associate with DRM and co-localize with CtxB within coalesced lipid rafts was mirrored by the capacity to promote Ca2+ influx into cells.

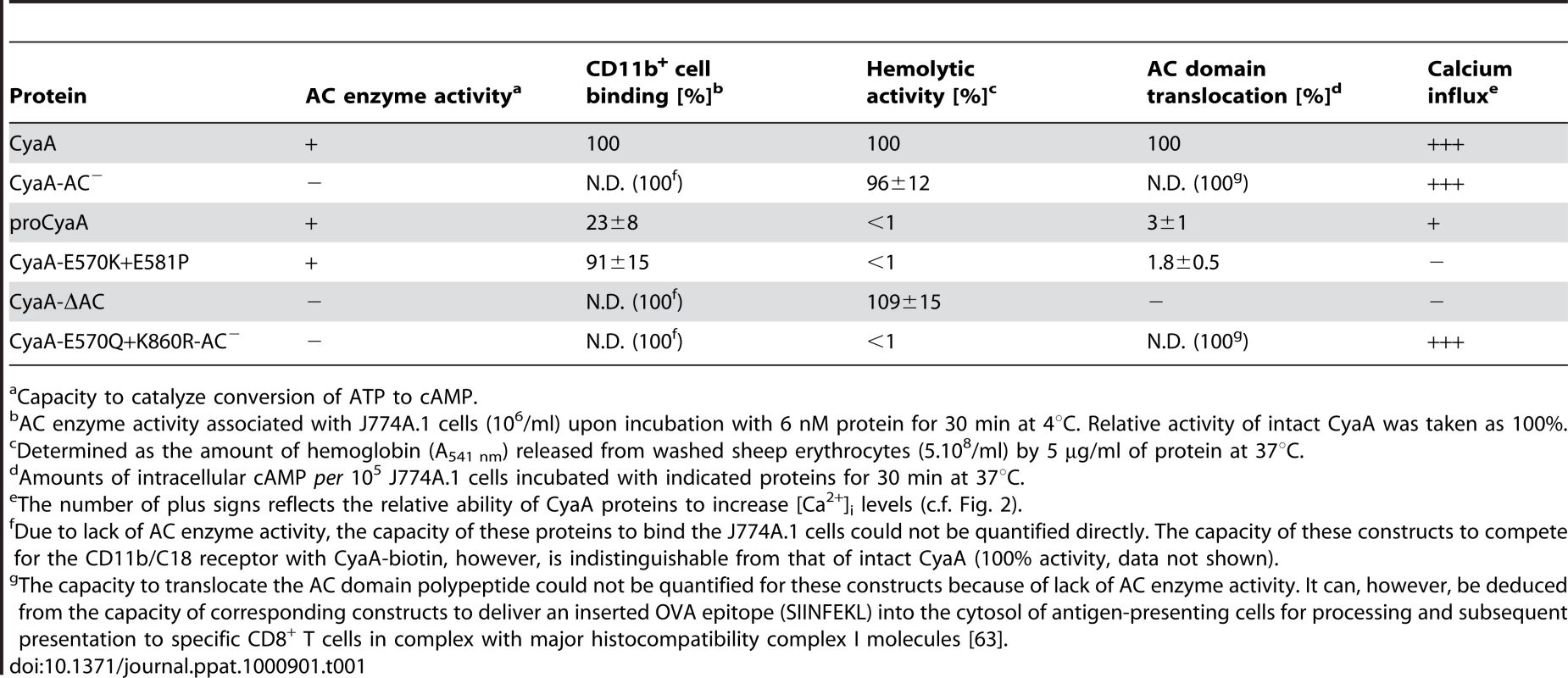

Membrane insertion of a ‘translocation intermediate’ allows calcium influx and CyaA association with DRM

We showed recently that CyaA-mediated influx of Ca2+ into cells is independent of the AC enzyme or pore-forming (hemolytic) activities of CyaA and occurs concomitantly to translocation of the AC domain across target cell membrane [18]. It remained, however, to assess whether it was the mere insertion of a CyaA translocation precursor into cell membrane, or whether the accomplishment of translocation of the AC domain across cell membrane was required for formation of a calcium conductive path in cell membrane. Towards this aim, we used the 3D1 monoclonal antibody (MAb) that binds to the distal end of the AC domain (residues 373 to 400) and was previously shown to block membrane translocation of the AC domain of cell-associated CyaA [39]. As expected and documented in Fig. 3A, preincubation of CyaA with the 3D1 MAb did not affect the capacity of CyaA to bind J774A.1 cells, while strongly inhibiting AC domain delivery and cAMP concentration elevation in cells. However, as revealed by detection of both CyaA and 3D1 in the fraction 3 of the sucrose gradient shown in Fig. 3B, the membrane-inserted CyaA with bound 3D1 MAb still associated with DRM at the same levels as CyaA alone. Moreover, as also shown in Fig. 3B, due to 3D1-mediated inhibition of AC domain translocation, the relative amount of processed CyaA (∼160 kDa) in the DRM fractions decreased to 10 to 15% of total present CyaA, while over 50% of CyaA in DRM was processed in the presence of isotype control.

Fig. 3. Binding of 3D1 antibody uncouples AC translocation from membrane insertion and CyaA-mediated Ca2+ influx.

(A) 17 nM CyaA was preincubated for 20 min at 37°C with 20 µg/ml of 3D1 MAb (CyaA+3D1) or the Tu-01 IgG1 isotype control MAb (CyaA+isotype control), before 6 nM toxin was added to J774A.1 cells. CyaA binding was determined as the amount of total cell-associated AC enzyme activity upon cells incubation with 6 nM CyaA for 10 min at 37°C in the presence or absence of the indicated antibody. AC domain translocation was assessed by determining the intracellular concentration of cAMP generated in cells in the presence or absence of the indicated antibodies, following incubation of cells with four different toxin concentrations from within the linear range of the dose-response curve (0.05, 0.1, 0.25, and 0.5 nM). The % of cAMP accumulation in cells at each toxin concentration was calculated, taking cAMP values for CyaA preincubated in buffer alone as 100%. The average of such determined % activity values is given. An asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (*, p<0.01; Student's t test). (B) J774A.1 cells were exposed to 1 nM CyaA alone, or to 1 nM CyaA preincubated with 3D1 or IgG1 isotype MAb as above. Cell lyzates were separated on sucrose density gradients and analyzed as in Fig. 1. The 3D1 and isotype IgG1 MAbs were detected with anti-mouse IgG antibody. The relative amounts of processed CyaA (∼160 kDa) within individual gradient fractions were determined as in Fig. 1F. Values represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. An asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (*, p<0.05; Student's t test). N.D., not determined. (C) J774A.1 cells were loaded with Fura-2/AM as above and exposed to 17 nM CyaA alone, or to CyaA preincubated with 3D1 or an IgG1 isotype control MAb. Ca2+ influx was recorded as above and the shown curves are representative of three independent experiments. As shown in Fig. 3C, however, despite arrested AC domain translocation, the CyaA-3D1 complex promoted elevation of [Ca2+]i in cells with kinetics resembling the Ca2+ influx produced by CyaA-AC− (cf. Fig. 2C). Hence, 3D1 binding uncoupled translocation of the AC domain from membrane insertion of CyaA and ‘locked’ the toxin in the conformation of a ‘translocation intermediate’ that permeabilized cells for Ca2+ ions and associated with DRM.

Influx of Ca2+ induces association of CyaA with DRM

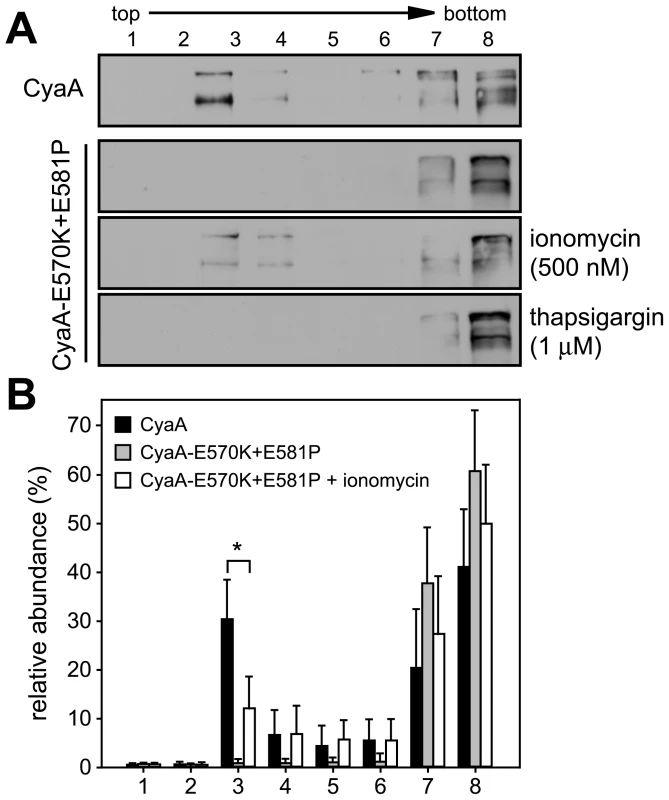

Next, we aimed to determine whether elevation of [Ca2+]i as such would mobilize into DRM also the CyaA-E570K+E581P protein unable to associate with DRM on its own (cf. Fig. 2). As demonstrated in Fig. 4, upon permeabilization of cells for extracellular Ca2+ ions with the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (500 nM), up to 15% of the added CyaA-E570K+E581P was found associated with DRM. In contrast, no association of CyaA-E570K+E581P with DRM was observed upon treatment of cells with 1 µM thapsigargin that increases [Ca2+]i by triggering Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. This showed that entry of extracellular Ca2+ across the cytoplasmic membrane was required for mobilization of CyaA into DRM.

Fig. 4. Mobilization of CyaA into lipid rafts depends on influx of extracellular Ca2+ ions into cells.

(A) J774A.1 cells were incubated at 37°C for 10 min with 1 nM CyaA and CyaA-E570K+E581P, in the presence or absence of 500 nM ionomycin , or of 1 µM thapsigargin, respectively. Cell lyzates were analyzed on sucrose density gradients as above. The blots are representative of four independent experiments. (B) Distribution of CyaA proteins in gradient fractions was quantified as in Fig. 1 and the values represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. An asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (*, p<0.05; Student's t test). Recruitment of CyaA-CD11b/CD18 complexes into rafts depends on cleavage of cytosolic talin by the Ca2+-activated protease calpain

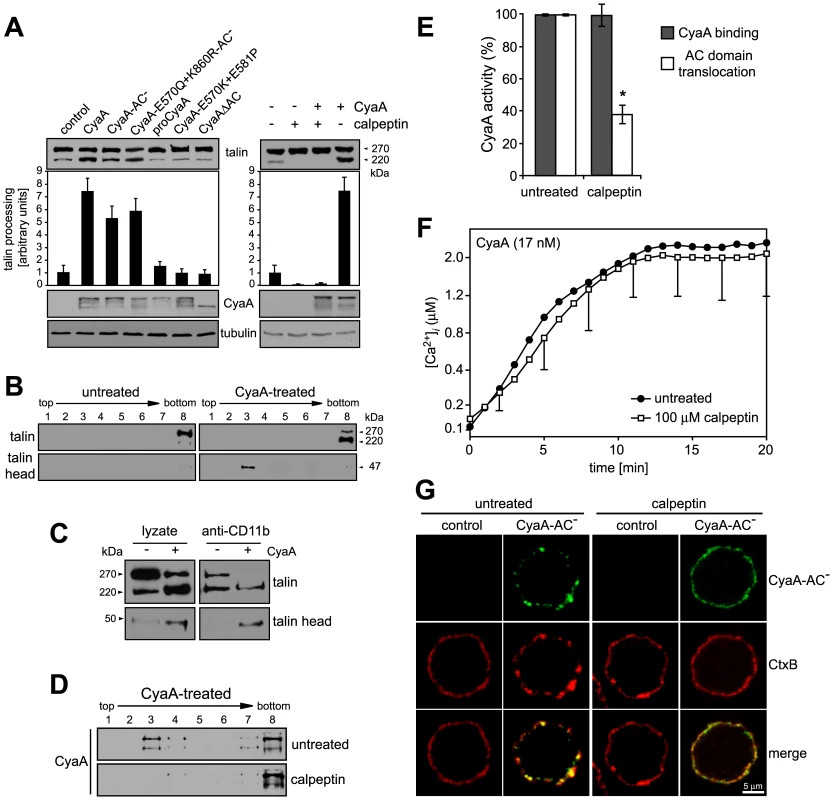

Influx of extracellular Ca2+ during leukocyte activation was reported to induce mobilization of integrins in cell membrane by calpain-mediated cleavage of talin that tethers β2 integrins to actin cytoskeleton [40], [41]. Therefore, we examined whether CyaA-promoted recruitment of the toxin receptor into rafts depended on talin processing. As shown in Fig. 5A, intact talin (∼270 kDa) was largely predominating in lyzates of cells treated with the CyaA-ΔAC or CyaA-E570K-E581P proteins that are unable to promote Ca2+ entry into cells. In contrast exposure of cells to the CyaA, CyaA-AC−, or CyaA-E570Q+K860R-AC− proteins, promoting influx of Ca2+ into cells, increased about seven-fold the detected amounts of the ∼220 kDa C-terminal fragment of processed talin (Fig. 5A, left panel). Concomitantly, increased amounts of the 47-kDa N-terminal fragment of talin (talin head) were detected in cell lyzates. Moreover, tightly associated talin head was found to float together with the CD11b/CD18 heterodimer in DRM (Fig. 5B) and could be co-immunoprecipitated with the integrin on beads coated with anti-CD11b antibody (Fig. 5C). This CyaA-induced processing of talin was clearly due to activation of calpain, as preincubation of cells with 100 µM calpain inhibitor, calpeptin, blocked talin cleavage in CyaA-treated cells (Fig. 5A, right panel). Remarkably, pretreatment of cells with calpeptin strongly inhibited also the association of CyaA with DRM (Fig. 5D) and decreased by at least a factor of two the capacity of cell-associated CyaA to translocate the AC enzyme into target cells (Fig. 5E). In turn, no effect of calpain inhibition was observed for CyaA-mediated Ca2+ influx (Fig. 5F). In line with these results, pretreatment of cells with 100 µM calpeptin blocked effectively also the formation of CyaA-AC− patches in cell membrane and ablated co-localization of CyaA-AC− with CtxB, as documented in Fig. 5G. It can, hence, be concluded that CyaA-mediated influx of Ca2+ into cells activated cleavage of talin by calpain and this was required for mobilization of CyaA-CD11b/CD18 complexes into lipid rafts.

Fig. 5. Mobilization of CyaA into lipid rafts depends on talin cleavage by calpain.

(A) J774A.1 cells were incubated with 30 nM CyaA proteins at 37°C for 10 min (left panel). Talin, CyaA and α-tubulin were detected in cell lyzates by Western blotting using 8d4, 9D4 and Tu-01 MAbs, respectively. Calpain activation was inhibited by preincubation of cells with 100 µM calpeptin at 37°C for 30 min (right panel). Talin processing was determined from Western blots as relative increase of the amount of the 220-kDa talin fragment, taking the value for untreated cells as 1. Data represent the mean ± S.D. from three experiments. (B) Cells were kept in buffer or pretreated with 100 µM calpeptin at 37°C for 30 min before incubation with 1 nM CyaA at 37°C for 10 min. Talin, talin head and CyaA were detected in cell lyzates separated on sucrose density gradients using 8d4, TA-205 and 9D4 MAbs, respectively. The shown blots are representative of four independent experiments. (C) CyaA-mediated talin cleavage promotes CD11b/CD18 release from cytoskeletal constraints. J774A.1 cells were incubated with 30 nM CyaA for 30 min at 37°C. Cell lyzates were prepared and incubated with anti-CD11b monoclonal antibody (MEM-174) covalently coupled to CNBr-activated Sepharose beads. The beads were washed, bound proteins were eluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer, and talin and talin head were detected by Western blotting with 8d4 and TA-205 antibody, respectively. (D) DRM association of CyaA in J774A.1 cells kept in buffer or preincubated with 100 µM calpeptin was analyzed as above. (E) AC translocation into control and calpeptin-pretreated J774A.1 cells were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 3. (F) CyaA-mediated influx of Ca2+ into untreated and calpeptin-pretreated J774A.1 cells was measured as in Fig. 2. Values represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. An asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (*, p<0.05; Student's t test). (G) J774A.1 cells grown on coverslips were kept in buffer or pretreated with 100 µM calpeptin at 37°C for 30 min before membrane distribution of fluorescently labeled CyaA-AC− (6 nM, green) and CtxB (5 µg/ml, red) was visualized as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Ca2+ influx, lipid raft association and AC translocating activity of CyaA depend on cholesterol content of target cell membrane

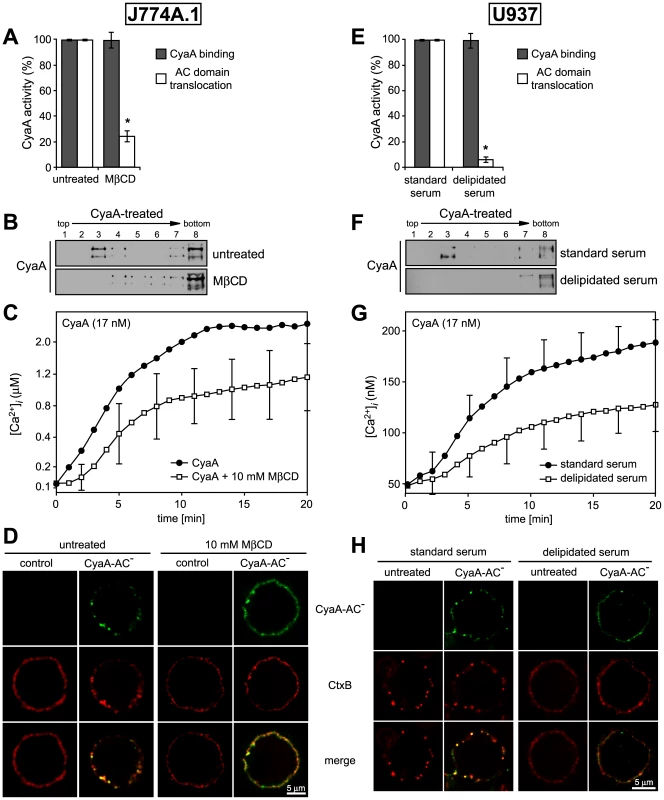

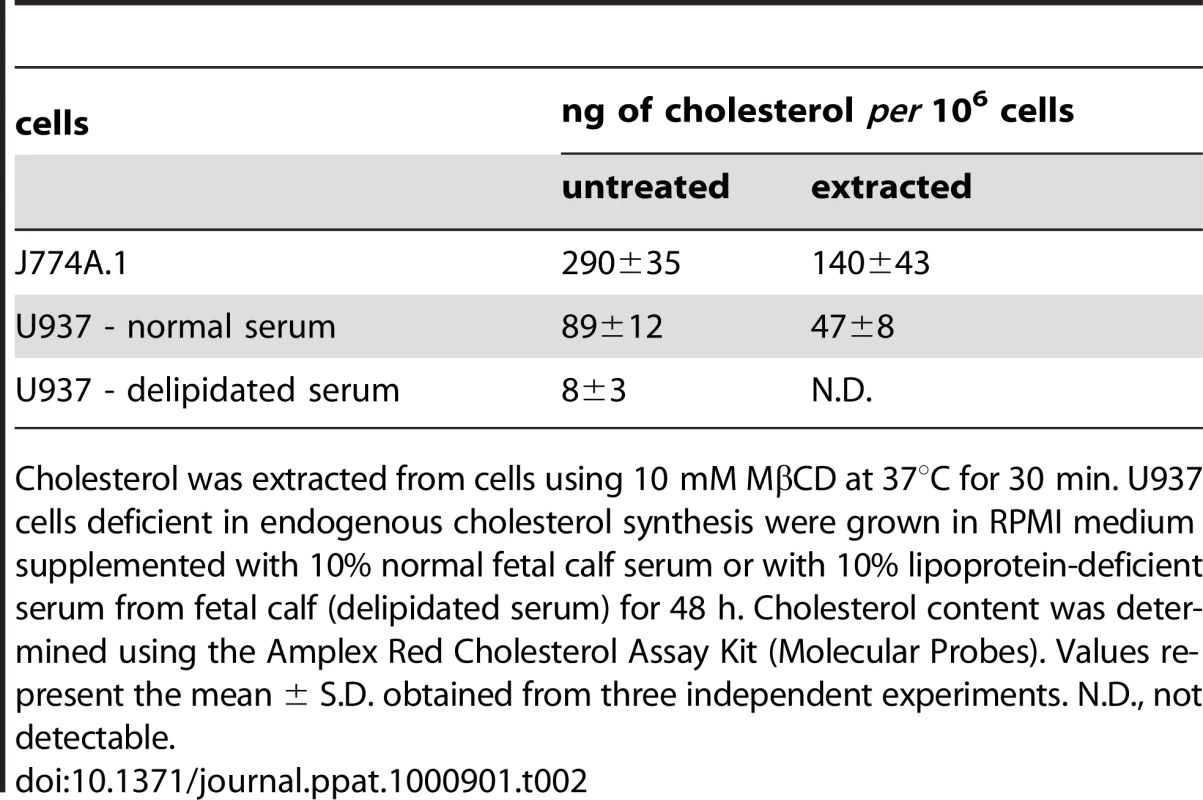

To determine what role does association of CyaA with lipid rafts play in the mechanism of toxin action on cellular membrane, we analyzed the activities of CyaA on cells having the rafts disrupted by depletion of cholesterol. As shown in Table 2, the total cholesterol content of J774A.1 cells could be decreased about two-fold by cholesterol extraction with 10 mM MβCD for 30 min. While the disruption of raft structures did not impact on association of CyaA with cells (Fig. 6A and Fig. S1), the modest decrease of cellular cholesterol content yielded an about five-fold decrease of the capacity of CyaA to translocate the AC domain across cell membrane. This defect was further mirrored by decreased DRM association of CyaA in MβCD-extracted cells, as shown in Fig. 6B. In parallel, the specific capacity of CyaA to promote Ca2+ influx into cholesterol-depleted cells was reduced and the [Ca2+]i increase ensuing toxin addition was delayed by several minutes, reaching a plateau at about a half-maximal [Ca2+]i concentration, as compared to non-depleted cells (Fig. 6C). In line with this, the two-fold decrease of cellular cholesterol level moderately decreased also the co-localization of CyaA with CtxB in lipid rafts (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6. Cholesterol depletion inhibits translocation of AC domain across target cytoplasmic membrane.

(A) J774A.1 cells were kept in buffer or treated with 10 mM MβCD at 37°C for 30 min, before CyaA was added for additional 10 min. CyaA binding and AC domain translocation were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Values represent the mean ± S.D. from four independent experiments performed in triplicates. An asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (*, p<0.01; Student's t test). (B) J774A.1 cells were kept in buffer or pretreated with 10 mM MβCD at 37°C for 30 min and incubated with 1 nM CyaA for 10 min. Cell lyzates were analyzed as in Fig. 1A. (C) J774A.1 cells were loaded with the Ca2+ probe Fura-2/AM prior to cholesterol extraction with 10 mM MβCD at 30°C for 30 min. CyaA-mediated Ca2+ influx was recorded as above. Standard deviations were calculated for mean values at indicated time points and the shown curves are representative of at least three independent experiments. (D) J774A.1 cells grown on coverslips were kept in buffer or pretreated with 10 mM MβCD at 37°C for 30 min. Membrane distribution of fluorescently labeled CyaA-AC− (6 nM, green) and CtxB (5 µg/ml, red) was visualized as described in the legend to Fig. 2. (E) U937 cells were grown for 48 hours in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (standard serum) or with 10% lipoprotein-deficient serum from fetal calf (delipidated serum). CyaA binding and AC domain translocation were determined as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Values represent the mean ± S.D. from four independent experiments performed in triplicates. An asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (*, p<0.01; Student's t test). (F) U937 cells grown in standard or delipidated serum were incubated with 1 nM CyaA at 37°C for 10 min, cell lyzates were separated on sucrose density gradients and analyzed as in Fig. 1. (G) U937 cells grown in standard or delipidated serum were loaded with the Ca2+ probe Fura-2/AM (3 µM) at 25°C for 30 min, exposed to CyaA (17 nM) and the time course of Ca2+ entry was recorded as above. Standard deviations were calculated for mean values at indicated time points and the shown curves are representative of at least three independent experiments. (H) U937 cells cultured with standard or delipidated serum were mounted on polylysin-coated coverslips and membrane distribution of fluorescently labeled CyaA-AC− (6 nM, green) and CtxB (5 µg/ml, red) was visualized as described above. Tab. 2. Cholesterol content in J774 and U937 cells.

Cholesterol was extracted from cells using 10 mM MβCD at 37°C for 30 min. U937 cells deficient in endogenous cholesterol synthesis were grown in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% normal fetal calf serum or with 10% lipoprotein-deficient serum from fetal calf (delipidated serum) for 48 h. Cholesterol content was determined using the Amplex Red Cholesterol Assay Kit (Molecular Probes). Values represent the mean ± S.D. obtained from three independent experiments. N.D., not detectable. Therefore, the above described experiments were replicated on monocytic U937 histiocytic lymphoma cells (CD11b+) that are defective in endogenous cholesterol synthesis. These cells can be efficiently depleted of cholesterol without losing viability, by them growing for 48 hours in media containing cholesterol-free (delipidated) serum. As shown in Table 2, such treatment reduced the cholesterol content of U937 cells almost 10-times.

As shown in Fig. 6E, a pronounced, over ten-fold decrease of specific AC translocation capacity of CyaA was observed on U937 cells grown in media with delipidated serum, as compared to CyaA activity on cells grown with standard serum. At the same time, however, the total amounts of cell-associated CyaA remained equal, irrespective of cell treatment. However, by difference to well-detectable DRM association of CyaA on cholesterol-replete U937 cells, grown with standard serum, no association of CyaA with DRM was observed in lyzates of cholesterol-depleted U937 cells grown in delipidated serum, respectively (Fig. 6F).

Intriguingly, compared to the Ca2+ influx elicited by equal concentrations of CyaA in J774A.1 cells, about an order of magnitude lower amplitude and delayed kinetics of CyaA-mediated Ca2+ influx was observed for U937 cells grown in media with standard serum (cf. Fig. 6C and Fig. 6G). These cells exhibited a 3-fold lower cholesterol content than the J774A.1 cells (see Table 2), suggesting that the low cholesterol content of U937 cells might have accounted for the poor capacity of CyaA to elicit Ca2+ influx in these cells. Indeed, when cholesterol content of J774A.1 cells was reduced about two-fold by cholesterol extraction with 10 mM MβCD, a delayed kinetics of CyaA-induced influx of Ca2+ into J774A.1 cells and a two-fold lower final [Ca2+]i reached in 20 minutes, were also observed (cf. Fig. 6C). Similarly, a delayed influx of Ca2+ and a lower final level of [Ca2+]i was observed also upon addition of equal CyaA concentrations to U937 cells depleted of cholesterol by growth in delipidated media, as compared to U937 cells grown in standard media, as shown in Fig. 6G. At the same time, however, the respective amounts of CyaA associated per 106 J774A.1 or U937 cells remained the same (∼5 ng of CyaA bound per 106 cells), irrespective of whether the cholesterol content of cells was decreased by the treatments (cf. Fig. 6A and 6E). These results, hence, strongly point towards a close relation between the overall content of cholesterol in cellular membrane and the propensity of the membrane-inserted CyaA to adopt the ‘translocation intermediate’ conformation, which would account for the Ca2+ conducting path across cell membrane (cf. Fig. 3 and [18]).

Finally, a correspondingly reduced CtxB binding and little if any co-localization of CtxB with CyaA were observed on cholesterol-depleted U937 cells, grown in delipidated serum, as compared to binding and some observable co-localization of CyaA with CtxB on cholesterol-replete U937 cells (Fig. 6).

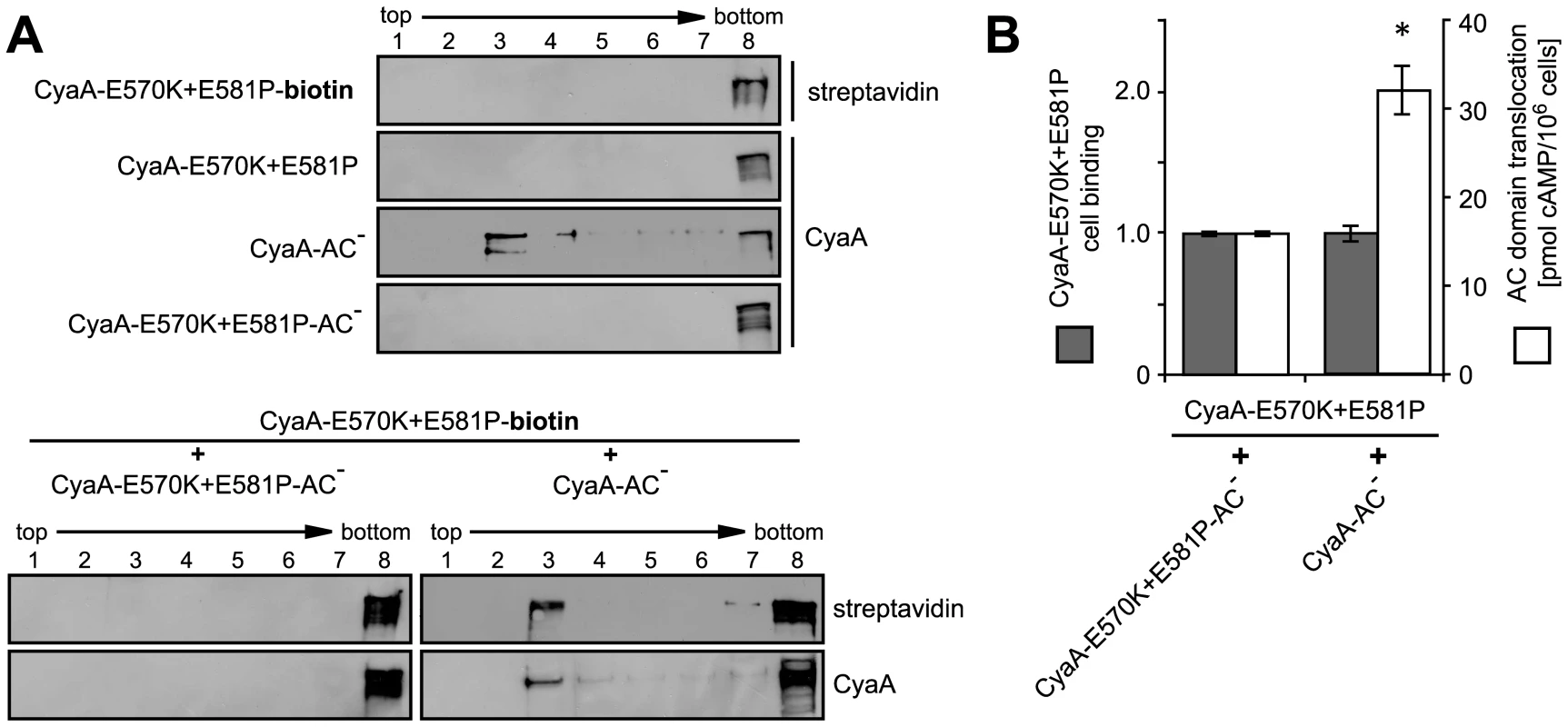

Mobilization of CyaA into lipid rafts enables translocation of AC domain across membrane

In the light of the above results, we aimed to test the hypothesis that AC translocation across membrane was supported and accomplished upon recruitment of the membrane-associated toxin into the cholesterol-rich environment of lipid rafts. Therefore, we examined whether the inactive CyaA-E570K+E581P construct would gain any capacity to translocate its enzymatically active AC domain across cellular membrane upon mobilization into lipid rafts. Since this mutant is intact for receptor binding but fails to promote Ca2+ influx into cells, we reasoned that mobilizing Ca2+ ions into cells in trans, by co-incubation with a translocating CyaA-AC− toxoid, might promote recruitment of CyaA-E570K+E581P mutant into rafts to some extent.

As shown in Fig. 7A, when biotinylated CyaA-E570K+E581P was added to cells alone, or when it was co-incubated with equal amounts of the enzymatically inactive CyaA-E570K+E581P-AC− toxoid, unable to cause calcium influx, the CyaA-E570K+E581P-biotin failed to associate with DRM. In contrast, upon co-incubation with equal amounts of the translocating CyaA-AC− toxoid (1∶1), a significant fraction of CyaA-E570K+E581P-biotin associated with DRM. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 7B, this mobilization into DRM was paralleled by a doubling of the residual capacity of the CyaA-E570K+E581P variant to deliver the AC domain across cell membrane and elevate cytosolic cAMP concentrations (Fig. 7B). Thus, recruitment into cholesterol-rich lipid rafts enhanced the residual AC translocating activity of this defective CyaA variant.

Fig. 7. AC domain of CyaA translocates across cellular membrane from lipid rafts.

(A) J774A.1 cells were incubated at 37°C for 10 min with 1 nM individual CyaA proteins (upper panel) or with their 1∶1 mixtures (lower panel). CyaA and biotinylated CyaA-E570K+E581P (CyaA-E570K+E581P-biotin) were detected in gradient fractions using 9D4 and streptavidine, respectively. (B) J774A.1 cells were incubated at 37°C for 10 min with the indicated pairs of proteins (12 nM) mixed in a 1∶1 molar ratio. Binding of CyaA-E570K+E581P-biotin was determined as the amount of total cell-associated AC enzyme activity upon exposure of cells to the protein mixtures and expressed as relative value. Enhancement of the residual capacity of CyaA-E570K+E581P to translocate AC domain into J774A.1 cell cytosol (1.8±0.5% of intact CyaA activity) was measured by determination of intracellular cAMP amounts accumulated in 106 cells upon exposure for 10 min at 37°C to the indicated 1∶1 protein mixtures (12 nM). The values represent the mean ± S.D. from four independent experiments performed in duplicate. An asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (*, p<0.01; Student's t test). Discussion

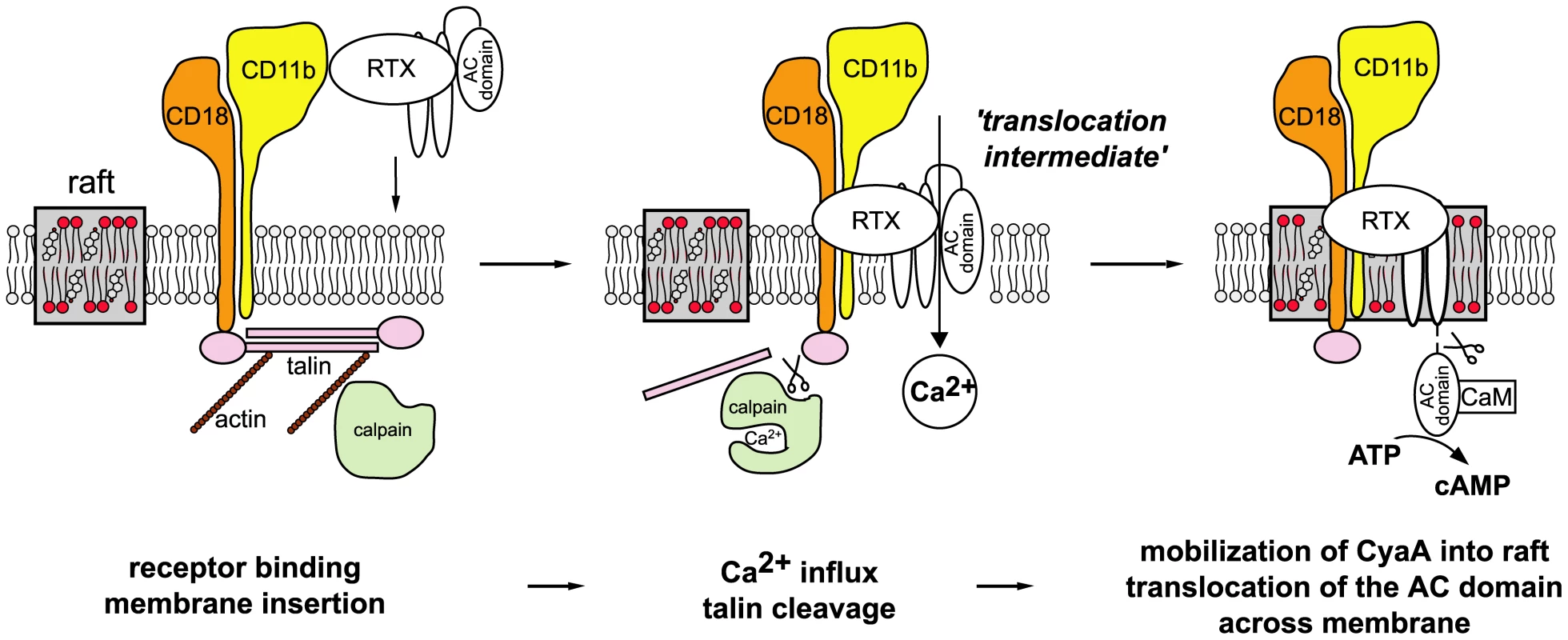

We show here that membrane translocation of the adenylate cyclase domain of CyaA occurs by a two step mechanism and involves toxin piggybacking on the αMβ2 integrin for relocation into lipid rafts. The present results allow us to propose a new model of CyaA mechanism of action, as summarized in Fig. 8. Upon initial binding of CyaA to the CD11b/CD18 receptor distributed in the bulk phase of cell membrane, a ‘translocation intermediate’ of CyaA would insert into the cytoplasmic membrane. It is assumed that in this ‘translocation intermediate’ a part of the AC domain is already inserted within the membrane and is shielded form the lipids by association with the amphipathic α-helical transmembrane segments of the hydrophobic domain of CyaA (residues 502–522, 529–549, 571–591, 607–627 and 678–698 [19], [20]). This ‘translocation intermediate’ then forms a path conducting external Ca2+ ions across cellular membrane into the submembrane compartment of cells. Incoming calcium ions activate the Ca2+-dependent protease calpain, located in the submembrane compartment, which produces cleavage of the talin tether. This liberates the toxin-receptor complex from association with actin cytoskeleton and mobilizes it for recruitment into lipid rafts. Within the specific liquid-ordered environment of cholesterol-rich lipid rafts, translocation of the positively charged AC domain across the cellular membrane is completed, driven by the negative gradient of membrane potential.

Fig. 8. Model of CyaA translocation across target cell membrane.

In the first step, CyaA binds the CD11b/CD18 integrin receptor dispersed in the bulk of the membrane phase outside of lipid rafts, having the cytoplasmic tail of the CD18 subunit tethered to actin cytoskeleton via the linker protein talin. Upon receptor engagement, a ‘translocation intermediate’ of CyaA inserts into the lipid bilayer of cell membrane with the AC domain partially penetrating into cell membrane together with the pore-forming segments of the toxin and participating in formation of a transiently opened Ca2+-conducting path across cell membrane. Influx of external calcium ions into cells induces activation of the Ca2+-dependent protease calpain, yielding talin cleavage and liberation of the CyaA-CD11b/CD18 complex from binding to actin cytoskeleton. Consequently, CyaA is recruited with CD11b/CD18 into cholesterol-enriched lipid rafts, where the liquid-ordered packing of lipids and the specific presence of cholesterol enable completion of AC domain translocation across cytoplasmic membrane. Upon exposure at the cytosolic side of cell membrane, the AC domain is cleaved-off from the RTX cytolysin moiety of CyaA by a protease residing inside the cell. Binding of cytosolic calmodulin (CaM) then activates the AC enzyme and unregulated conversion of ATP to cAMP is catalyzed. Deciphering this fine-tuned mechanism of toxin action on cell membrane fosters our understanding of the key role played by CyaA in virulence of Bordetellae during the early phases of bacterial colonization of host respiratory mucosa. It allows to propose the following scenario. The produced CyaA targets the CD11b/CD18 receptor of incoming myeloid phagocytic cells, such as neutrophils, macrophages and dendritic cells [42]. As CyaA action does not depend on receptor-mediated endocytosis, the toxin recruited into lipid rafts can rapidly translocate its highly active AC enzyme domain across the cytoplasmic membrane of cells, in a process exhibiting a half-time of only about ∼30 seconds [38]. Mobilization of toxin-receptor complexes into lipid rafts than promotes their clustering and potentially induces recruitment of cellular cAMP-responding elements, such as the protein kinase A anchored to AKAPs, the specific A-kinase anchoring scaffolds [43]–[45]. This would allow maximization of toxin action through subversive cAMP production in close vicinity of components of the cAMP-regulated PKA signaling pathway. This capacity to hijack the spatio-temporal regulation of cellular cAMP/PKA signaling would then endow CyaA with the high potency in paralyzing the central bactericidal mechanisms employed by myeloid phagocytic cells. Indeed, few picomoles of CyaA (1 ng/ml or less) were previously reported to instantaneously suppress the oxidative burst capacity of neutrophils [46], or the phagocytosis of complement-opsonized particles by macrophages [2].

Several other bacterial protein toxins appear, indeed, to utilize lipid rafts as a portal of cell entry, exploiting as specific receptors directly certain raft components, such as cholesterol, sphingolipids or GPI-anchored proteins [47]–[50]. In contrast, we found here that CyaA associates with rafts only upon binding and mobilization (hijacking) of its receptor CD11b/CD18. Unless activated in the process of leukocyte activation, this β2 integrin is distributed diffusely over the entire cellular membrane. As outlined above, we show here that upon binding of CyaA the integrin relocates into lipid rafts, due to toxin-induced and calcium-activated cleavage of talin by calpain. Moreover, the recently discovered capacity of CyaA to bind N-linked oligosaccharides of CD11b/CD18 [24] might also play a role in this process. It is, indeed, plausible to propose that CyaA interaction with terminal sialic acid residues of glycan chains of raft sphingolipids might also be contributing to accumulation of the CyaA-CD11b/CD18 complex in lipid rafts, as well as it may contribute to clustering of lipid rafts containing CyaA later-on. An evidence for CyaA interactions with gangliosides can, indeed, be deduced from the previously observed inhibition of CyaA activity on macrophages by the presence of micromolar concentrations of free gangliosides, such as GT1b [23].

It remains to be addressed in future studies if CyaA can form oligomeric pores also once engaged in interaction with the target cell membrane through binding of the CD11b/CD18 receptor and whether CyaA can form pore-forming oligomers also in phagocyte membrane. We have recently succeeded in demonstrating the presence of the long-predicted CyaA oligomers within the membrane of cells lacking the receptor CD11b/CD18, such as erythrocytes [10]. Vojtova-Vodolanova with co-authors (2009), indeed, showed that formation of CyaA oligomers underlies the pore-forming activity of CyaA towards erythrocytes. However, despite significantly higher amounts of CyaA binding per single phagocyte cell through the CD11b/CD18 receptor, fairly high concentrations (>1 µg/ml) of the recombinant enzymatically inactive but fully pore-forming CyaA-AC− variants are needed to provoke lysis of cells like J774A.1 monocytes in several hours [8]. While this resistance to colloid-osmotic lysis is likely to be to large extent due to membrane recycling mechanisms and pore removal form phagocyte cytoplasmic membrane, it remains to be shown that CyaA can form oligomeric pores in leukocyte membrane as well.

The results presented here do not indicate any role of CyaA oligomers in promoting calcium influx, toxin mobilization into rafts, or AC enzyme translocation into CD11b+ phagocytes. Early dose-dependence studies indicated that the AC domain was delivered across target cell membrane by CyaA monomers. Indeed, toxin molecules with the AC domain cleaved-off by cytosolic proteases, upon AC translocation into cells, were detected exclusively in form of CyaA monomers within erythrocyte membranes and were excluded from the detected CyaA oligomers [10]. Moreover, we used here the CyaA-E570Q+K860R-AC− protein, which essentially lacks any pore-forming activity and fails to permeabilize the membrane of J774A.1 cells, thus being unlikely to form any CyaA oligomers (Table 1 and [51]). On the other hand, this construct is fully capable to translocate the AC domain into cytosol of CD11b-expressing J774A.1 cells, to promote calcium influx and to associate with DRM, or to co-localize with CtxB in coalesced rafts, respectively (cf. Fig. 2). It appears, therefore, unlikely that oligomerization plays a role in DRM association of CyaA.

We also observed here that the levels of binding of CyaA to CD11b-expressing cells were not affected upon cholesterol depletion of cell membrane, while the translocation of the AC domain across the membrane depended strongly on the cholesterol content. This suggests that by modulating the physical properties lipid bilayers, cholesterol was specifically supporting the translocation of the AC domain across cell membrane. Indeed, cholesterol removal was previously found to impair the residual penetration capacity of CyaA on artificial membranes and erythrocytes [52], [53]. This goes well with the impact of cholesterol concentration on membrane fluidity, lateral phase separation, formation of liquid-ordered structures and the propensity of lipids to adopt the inverted hexagonal phase [54], [55]. The same membrane properties would also be expected to support AC domain translocation into cells by lowering the energy barrier for polypeptide penetration into and across the lipid bilayer [56]. It is plausible to speculate that membrane translocation of the AC domain requires the presence of cholesterol-dependent liquid-ordered (lo) phase, in which the acyl chains of lipids are tightly packed, while the individual lipid molecules have a high degree of lateral mobility. The relative mobility of lipids in lo domains represents, indeed, a likely prerequisite for passage of the AC domain across lipid bilayer. A high condensation and immobility of lipids in liquid-disordered (ld)-phase domains would, in turn, be expected to interfere with AC polypeptide translocation. The requirement for sufficient membrane fluidity for AC translocation to occur is also indicated by the block of AC translocation at 4°C [38].

Recently, we demonstrated that AC domain translocation across target cell membrane is accompanied by entry of Ca2+ ions into cells. Moreover, the AC domain polypeptide as such was found to participate in formation of the transiently opened calcium influx path in cell membrane [18]. Here, we used the 3D1 MAb recognizing a distal segment of the AC domain and show that blocking of AC domain translocation across cell membrane can lock CyaA in a ‘translocation intermediate’ conformation that forms a path for Ca2+ influx across cell membrane (cf. Fig. 3). Moreover, this ‘translocation intermediate’ was found to be recruited into lipid rafts (Fig. 3). The sum of the data hence allows us to answer the question what happens first, whether calcium influx precedes toxin mobilization into rafts, or whether recruitment of CyaA into rafts precedes calcium influx and AC translocation.

We showed here that calpeptin-mediated inhibition of calcium-activated processing of talin by calpain yields (i) inhibition of CyaA recruitment into rafts and (ii) it inhibits AC translocation across membrane. Collectively, hence, these results strongly suggest that the transient influx of Ca2+ into cells accompanies the earliest step of membrane insertion of the toxin ‘translocation intermediate’. This would precede and be essential for subsequent recruitment of CyaA into lipid rafts, whereupon AC translocation is accomplished.

It remains, however, to be determined what is the threshold of the calcium signal required for initiation of talin cleavage and mobilization of CyaA into lipid rafts. Two major isoforms of calpain have, indeed, been so far identified in eukaryotic cells. The calpain I (μ-calpain) is activated at µM Ca2+ concentrations, while calpain II (m-calpain) only responds to mM concentrations of Ca2+ [57]. Here we observed that CyaA relocalization into DRM occurred at 1 nM toxin concentration, which is about two-times less than the lowest CyaA concentrations still allowing to elicit a [Ca2+]i increase detectable in cells by the Fura-2/AM probe [18]. Moreover, only influx of extracellular Ca2+ ions into cells, and not the elevation of cytosolic [Ca2+]i due to Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, enabled the accumulation of CyaA in DRM (cf. Fig. 4). This differs importantly from the mechanism reported for localization of the leukotoxin (LtxA) of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans into rafts. LtxA binds yet another β2 integrin of human leukocytes, the LFA-1 or CD11a/CD18 heterodimer. Horeover, LtxA appears to first adsorb on cell membrane of T lymphocytes in a receptor-independent manner, to trigger, somehow the store-operated elevation of cytosolic [Ca2+]i, to induce talin cleavage, and upon relocation into rafts, the Ltx clusters with LFA-1 within rafts to promote cell lysis [58].

With CyaA, all the Ca2+ ions entering macrophage cytoplasm due to toxin action appear to come from extracellular medium [18]. It is generally accepted that there exists a gradient of about four orders of magnitude in Ca2+ concentrations between the external medium (∼2 mM) and cell cytosol (∼100 nM). Therefore, numerous Ca2+-buffering proteins accumulate beneath the inner face of cell membrane, accounting for formation of local Ca2+ gradients and controlling signaling induced by alterations of Ca2+ concentrations in the submembrane compartment. These concentrations can, indeed, be still much higher, and rise more rapidly, than the bulk Ca2+ levels in cell cytosol [59]. Therefore, it is likely that even an importantly lower CyaA concentration than used here (1 nM = 176 ng/ml), may still be generating sufficiently high local Ca2+ signal beneath cell membrane in order to promote activation of μ-calpain at the inner face of cell membrane. It appears, thus, plausible to assume that mobilization of CyaA into rafts in phagocyte membrane, and translocation of the AC domain from rafts directly into the cytosolic compartment of phagocytes, are indeed taking place also during natural Bordetella infections in vivo. This would account for the remarkable efficacy of CyaA in disarming the sentinel cells of the host innate defense.

Materials and Methods

Expression and purification of CyaA-derived proteins

Intact recombinant CyaA and its mutant variants were expressed and purified as previously described [19]. Except of pro-CyaA, the CyaA proteins were produced in E. coli XL1-Blue in the presence of the co-expressed toxin-activating acyltransferase CyaC, as previously described [20]. Lipopolysaccharide was eliminated by repeated 60% isoporopanol washes of CyaA bound to the Phenyl Sepharose resin [60]. This reduced the final endotoxin content below 50 EU/mg of purified protein, as determined by the Limulus amebocyte lyzate assay (QCL-1000, Cambrex, NJ, USA). For fluorescence microscopy, the CyaA proteins were labeled while bound to Phenyl-Sepharose resin during the final purification step. Briefly, the CyaA eluates from a DEAE-Sepharose columns (GE Healthcare) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 8 M urea, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 200 mM NaCl, were diluted 1∶4 with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1 M NaCl and 1 mg of CyaA was loaded on an 0.5 ml Phenyl-Sepharose column. The columns were extensively washed with 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate (pH 9), 1 M NaCl. Next 10 µg/ml Alexa Fluor 488 succinimidylester solution (Molecular Probes) was loaded and labeling proceeded at 25°C for 1 hour. The columns were washed with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1 M NaCl, and the CyaA-Alexa Fluor 488 conjugates were eluted in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 8 M urea and 2 mM EDTA. Unreacted dye was separated from labeled CyaA on Sephadex G-25 columns (GE Healthcare). Efficiency of protein labeling was assessed spectrophotometrically and a molar ratio of about 1∶4 (protein∶dye) was found for all CyaA preparations. It was verified that this extent of labeling did not affect the biological activities of CyaA.

Antibodies, reagents, cell lines, SDS-PAGE, BN-PAGE and Western blotting

See Protocol S1 for full description.

Isolation of detergent-resistant membranes

Detergent-resistant membranes (DRM) were separated by flotation in discontinuous sucrose density gradients. Briefly, J774A.1 cells (2.107) were washed with prewarmed DMEM and incubated with 1 nM CyaA proteins at 37°C for 10 min. Cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), scraped from the Petri dish and extracted at 4°C for 60 min using 200 µl of TBS buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) containing 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF and a Complete Mini proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The lyzates were clarified by centrifugation at 250×g for 5 min and the post-nuclear supernatants were mixed with equal volumes of 90% sucrose in TBS. The suspensions were placed at the bottom of centrifuge tubes and overlaid with 2.5 ml of 30% sucrose and 1.5 ml of 5% sucrose in TBS. Membrane flotation according buoyant density was achieved by centrifugation at 150,000×g in a Beckman SW60Ti rotor for 16 h at 4°C. Fractions of 0.5 ml were removed from the top of the gradient.

Ca2+ influx into cells

Calcium influx into J774A.1 and U937 cells was measured as previously described [18]. Briefly, cells were loaded with 3 µM Fura-2/AM (Molecular Probes) at 25°C for 30 min and the time course of calcium entry into cells induced by addition 3 µg/ml of CyaA proteins was determined as ratio of fluorescence intensities (excitation at 340/380 nm, emmision 505 nm), using a FluoroMax-3 spectrofluorometer equipped with DataMax software (Jobin Yvon Horriba, France).

Depletion of cholesterol

J774A.1 cells were incubated in DMEM supplemented with 10 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) at 37°C for 30 min. Cholesterol-depleted U937 cells were obtained upon growth in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% of delipidated serum (lipoprotein-deficient serum from fetal calf, Sigma) for 48 h. Cholesterol content was determined using an Amplex Red Cholesterol Assay Kit (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions. Viability of cells was tested by trypan blue staining and no significant cell death occurred upon cholesterol extraction.

Fluorescence microscopy

U937 cells were grown in media with 10% standard, or delipidated serum, and were mounted on polylysin-coated coverslips prior to incubation with labeled proteins. J774.A1 cells (5.104) were grown directly on coverslips (∅ φ12 mm) and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled CyaA proteins (6 nM) at 37°C for 10 min, before cells were washed and 5 µg/ml of Alexa Fluor 594-labeled cholera toxin subunit B (CtxB) was added for additional 5 min. The unbound proteins were washed-off with ice-cold PBS, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 25°C for 20 min, and mounted in Mowiol solution (Sigma). Fluorescence images were taken using a CellR Imaging Station (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) based on Olympus IX 81 fluorescence microscope, using a 100× oil immersion objective (N.A. 1.3). Digital images were processed using ImageJ software.

Immunoprecipitation

J774.A1 cells (106) were incubated with 17 nM CyaA in DMEM for 30 min at 37°C, washed with Hank's Buffered Salt Solution buffer (HBSS), and lyzed at 4°C during 30 min in 500 µl of Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.4) supplemented with 1% Triton X-100 and EDTA-free Complete Mini proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The lyzate was centrifuged for 15 min at 10,000×g at 4°C, and the supernatant was incubated with MEM-174 MAb covalently linked to CNBr-activated Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) at 4°C for 1 h. The beads were washed five times with 1 ml of the lysis buffer and the bound proteins were eluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting.

CyaA binding to cells

J774A.1 or U937 cells (106) were incubated with 6 nM CyaA proteins at 37°C for 10 min, washed repeatedly in buffer, and the amount of cell-associated adenylate cyclase (AC) activity was determined in cell lyzates as previously described by [61].

cAMP assay

J774A.1 or U937 cells (106) were incubated with CyaA proteins at indicated concentrations for 10 min at 37°C and intracelular cAMP concentrations were determined in cell lyzates using a competitive ELISA as previously described [62].

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. FriedmanRL

FiederleinRL

GlasserL

GalgianiJN

1987 Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase: effects of affinity-purified adenylate cyclase on human polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions. Infect Immun 55 135 140

2. KamanovaJ

KofronovaO

MasinJ

GenthH

VojtovaJ

2008 Adenylate cyclase toxin subverts phagocyte function by RhoA inhibition and unproductive ruffling. J Immunol 181 5587 5597

3. ConferDL

EatonJW

1982 Phagocyte impotence caused by an invasive bacterial adenylate cyclase. Science 217 948 950

4. WeingartCL

WeissAA

2000 Bordetella pertussis virulence factors affect phagocytosis by human neutrophils. Infect Immun 68 1735 1739

5. GoodwinMS

WeissAA

1990 Adenylate cyclase toxin is critical for colonization and pertussis toxin is critical for lethal infection by Bordetella pertussis in infant mice. Infect Immun 58 3445 3447

6. BellalouJ

SakamotoH

LadantD

GeoffroyC

UllmannA

1990 Deletions affecting hemolytic and toxin activities of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase. Infect Immun 58 3242 3247

7. BenzR

MaierE

LadantD

UllmannA

SeboP

1994 Adenylate cyclase toxin (CyaA) of Bordetella pertussis. Evidence for the formation of small ion-permeable channels and comparison with HlyA of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 269 27231 27239

8. BaslerM

MasinJ

OsickaR

SeboP

2006 Pore-forming and enzymatic activities of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin synergize in promoting lysis of monocytes. Infect Immun 74 2207 2214

9. HewlettEL

DonatoGM

GrayMC

2006 Macrophage cytotoxicity produced by adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis: more than just making cyclic AMP! Mol Microbiol 59 447 459

10. Vojtova-VodolanovaJ

BaslerM

OsickaR

KnappO

MaierE

2009 Oligomerization is involved in pore formation by Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin. Faseb J 23 2831 2843

11. VojtovaJ

KamanovaJ

SeboP

2006 Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin: a swift saboteur of host defense. Curr Opin Microbiol 9 69 75

12. HackettM

GuoL

ShabanowitzJ

HuntDF

HewlettEL

1994 Internal lysine palmitoylation in adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis. Science 266 433 435

13. HackettM

WalkerCB

GuoL

GrayMC

Van CuykS

1995 Hemolytic, but not cell-invasive activity, of adenylate cyclase toxin is selectively affected by differential fatty-acylation in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 270 20250 20253

14. RoseT

SeboP

BellalouJ

LadantD

1995 Interaction of calcium with Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Characterization of multiple calcium-binding sites and calcium-induced conformational changes. J Biol Chem 270 26370 26376

15. GordonVM

LepplaSH

HewlettEL

1988 Inhibitors of receptor-mediated endocytosis block the entry of Bacillus anthracis adenylate cyclase toxin but not that of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Infect Immun 56 1066 1069

16. GmiraS

KarimovaG

LadantD

2001 Characterization of recombinant Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxins carrying passenger proteins. Res Microbiol 152 889 900

17. OteroAS

YiXB

GrayMC

SzaboG

HewlettEL

1995 Membrane depolarization prevents cell invasion by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. J Biol Chem 270 9695 9697

18. FiserR

MasinJ

BaslerM

KrusekJ

SpulakovaV

2007 Third activity of Bordetella adenylate cyclase (AC) toxin-hemolysin. Membrane translocation of AC domain polypeptide promotes calcium influx into CD11b+ monocytes independently of the catalytic and hemolytic activities. J Biol Chem 282 2808 2820

19. BaslerM

KnappO

MasinJ

FiserR

MaierE

2007 Segments crucial for membrane translocation and pore-forming activity of Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin. J Biol Chem 282 12419 12429

20. OsickovaA

OsickaR

MaierE

BenzR

SeboP

1999 An amphipathic alpha-helix including glutamates 509 and 516 is crucial for membrane translocation of adenylate cyclase toxin and modulates formation and cation selectivity of its membrane channels. J Biol Chem 274 37644 37650

21. LadantD

UllmannA

1999 Bordatella pertussis adenylate cyclase: a toxin with multiple talents. Trends Microbiol 7 172 176

22. PaccaniSR

Dal MolinF

BenagianoM

LadantD

D'EliosMM

2008 Suppression of T-lymphocyte activation and chemotaxis by the adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun 76 2822 2832

23. GordonVM

YoungWWJr

LechlerSM

GrayMC

LepplaSH

1989 Adenylate cyclase toxins from Bacillus anthracis and Bordetella pertussis. Different processes for interaction with and entry into target cells. J Biol Chem 264 14792 14796

24. MorovaJ

OsickaR

MasinJ

SeboP

2008 RTX cytotoxins recognize beta2 integrin receptors through N-linked oligosaccharides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 5355 5360

25. HarrisES

McIntyreTM

PrescottSM

ZimmermanGA

2000 The leukocyte integrins. J Biol Chem 275 23409 23412

26. HynesRO

2002 Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110 673 687

27. LeitingerB

HoggN

2002 The involvement of lipid rafts in the regulation of integrin function. J Cell Sci 115 963 972

28. KraussK

AltevogtP

1999 Integrin leukocyte function-associated antigen-1-mediated cell binding can be activated by clustering of membrane rafts. J Biol Chem 274 36921 36927

29. StefanovaI

HorejsiV

AnsoteguiIJ

KnappW

StockingerH

1991 GPI-anchored cell-surface molecules complexed to protein tyrosine kinases. Science 254 1016 1019

30. SimonsK

IkonenE

1997 Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature 387 569 572

31. BrownDA

2006 Lipid rafts, detergent-resistant membranes, and raft targeting signals. Physiology (Bethesda) 21 430 439

32. JacobsonK

MouritsenOG

AndersonRG

2007 Lipid rafts: at a crossroad between cell biology and physics. Nat Cell Biol 9 7 14

33. HelmsJB

ZurzoloC

2004 Lipids as targeting signals: lipid rafts and intracellular trafficking. Traffic 5 247 254

34. LafontF

van der GootFG

2005 Bacterial invasion via lipid rafts. Cell Microbiol 7 613 620

35. ManesS

del RealG

MartinezAC

2003 Pathogens: raft hijackers. Nat Rev Immunol 3 557 568

36. FivazM

AbramiL

van der GootFG

1999 Landing on lipid rafts. Trends Cell Biol 9 212 213

37. LeeSJ

GrayMC

GuoL

SeboP

HewlettEL

1999 Epitope mapping of monoclonal antibodies against Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Infect Immun 67 2090 2095

38. RogelA

HanskiE

1992 Distinct steps in the penetration of adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis into sheep erythrocytes. Translocation of the toxin across the membrane. J Biol Chem 267 22599 22605

39. GrayMC

LeeSJ

GrayLS

ZaretzkyFR

OteroAS

2001 Translocation-specific conformation of adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis inhibits toxin-mediated hemolysis. J Bacteriol 183 5904 5910

40. SampathR

GallagherPJ

PavalkoFM

1998 Cytoskeletal interactions with the leukocyte integrin beta2 cytoplasmic tail. Activation-dependent regulation of associations with talin and alpha-actinin. J Biol Chem 273 33588 33594

41. StewartMP

McDowallA

HoggN

1998 LFA-1-mediated adhesion is regulated by cytoskeletal restraint and by a Ca2+-dependent protease, calpain. J Cell Biol 140 699 707

42. GuermonprezP

KhelefN

BlouinE

RieuP

Ricciardi-CastagnoliP

2001 The adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis binds to target cells via the alpha(M)beta(2) integrin (CD11b/CD18). J Exp Med 193 1035 1044

43. VangT

TorgersenKM

SundvoldV

SaxenaM

LevyFO

2001 Activation of the COOH-terminal Src kinase (Csk) by cAMP-dependent protein kinase inhibits signaling through the T cell receptor. J Exp Med 193 497 507

44. WilloughbyD

WongW

SchaackJ

ScottJD

CooperDM

2006 An anchored PKA and PDE4 complex regulates subplasmalemmal cAMP dynamics. Embo J 25 2051 2061

45. TaskenK

StokkaAJ

2006 The molecular machinery for cAMP-dependent immunomodulation in T-cells. Biochem Soc Trans 34 476 479

46. SteedLL

AkporiayeET

FriedmanRL

1992 Bordetella pertussis induces respiratory burst activity in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect Immun 60 2101 2105

47. LafontF

AbramiL

van der GootFG

2004 Bacterial subversion of lipid rafts. Curr Opin Microbiol 7 4 10

48. PartonRG

1994 Ultrastructural localization of gangliosides; GM1 is concentrated in caveolae. J Histochem Cytochem 42 155 166

49. FivazM

VilboisF

ThurnheerS

PasqualiC

AbramiL

2002 Differential sorting and fate of endocytosed GPI-anchored proteins. Embo J 21 3989 4000

50. WaheedAA

ShimadaY

HeijnenHF

NakamuraM

InomataM

2001 Selective binding of perfringolysin O derivative to cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains (rafts). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 4926 4931

51. OsickovaA

MasinJ

FayolleC

KrusekJ

BaslerM

2010 Adenylate cyclase toxin translocates across target cell membrane without forming a pore. Mol Microbiol 75 1550 1562

52. VojtovaJ

KofronovaO

SeboP

BenadaO

2006 Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin induces a cascade of morphological changes of sheep erythrocytes and localizes into clusters in erythrocyte membranes. Microsc Res Tech 69 119 129

53. MartinC

RequeroMA

MasinJ

KonopasekI

GoniFM

2004 Membrane restructuring by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin, a member of the RTX toxin family. J Bacteriol 186 3760 3765

54. AhmedSN

BrownDA

LondonE

1997 On the origin of sphingolipid/cholesterol-rich detergent-insoluble cell membranes: physiological concentrations of cholesterol and sphingolipid induce formation of a detergent-insoluble, liquid-ordered lipid phase in model membranes. Biochemistry 36 10944 10953

55. SilviusJR

del GiudiceD

LafleurM

1996 Cholesterol at different bilayer concentrations can promote or antagonize lateral segregation of phospholipids of differing acyl chain length. Biochemistry 35 15198 15208

56. ScottoAW

ZakimD

1986 Reconstitution of membrane proteins: catalysis by cholesterol of insertion of integral membrane proteins into preformed lipid bilayers. Biochemistry 25 1555 1561

57. GollDE

ThompsonVF

LiH

WeiW

CongJ

2003 The calpain system. Physiol Rev 83 731 801

58. FongKP

PachecoCM

OtisLL

BaranwalS

KiebaIR

2006 Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin requires lipid microdomains for target cell cytotoxicity. Cell Microbiol 8 1753 1767

59. DaviesEV

HallettMB

1998 High micromolar Ca2+ beneath the plasma membrane in stimulated neutrophils. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 248 679 683

60. FrankenKL

HiemstraHS

van MeijgaardenKE

SubrontoY

den HartighJ

2000 Purification of his-tagged proteins by immobilized chelate affinity chromatography: the benefits from the use of organic solvent. Protein Expr Purif 18 95 99

61. LadantD

1988 Interaction of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase with calmodulin. Identification of two separated calmodulin-binding domains. J Biol Chem 263 2612 2618

62. KarimovaG

FayolleC

GmiraS

UllmannA

LeclercC

1998 Charge-dependent translocation of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin into eukaryotic cells: implication for the in vivo delivery of CD8(+) T cell epitopes into antigen-presenting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 12532 12537

63. OsickaR

OsickovaA

BasarT

GuermonprezP

RojasM

2000 Delivery of CD8(+) T-cell epitopes into major histocompatibility complex class I antigen presentation pathway by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase: delineation of cell invasive structures and permissive insertion sites. Infect Immun 68 247 256

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Mouse Senile Amyloid Fibrils Deposited in Skeletal Muscle Exhibit Amyloidosis-Enhancing ActivityČlánek The Role of Intestinal Microbiota in the Development and Severity of Chemotherapy-Induced MucositisČlánek Crystal Structure of HIV-1 gp41 Including Both Fusion Peptide and Membrane Proximal External RegionsČlánek Demonstration of Cross-Protective Vaccine Immunity against an Emerging Pathogenic Ebolavirus Species

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 5- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Infekční komplikace virových respiračních infekcí – sekundární bakteriální a aspergilové pneumonie

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Quorum Sensing Inhibition Selects for Virulence and Cooperation in

- The HMW1C Protein Is a Glycosyltransferase That Transfers Hexose Residues to Asparagine Sites in the HMW1 Adhesin

- Analysis of Virion Structural Components Reveals Vestiges of the Ancestral Ichnovirus Genome

- Mouse Senile Amyloid Fibrils Deposited in Skeletal Muscle Exhibit Amyloidosis-Enhancing Activity

- Global Migration Dynamics Underlie Evolution and Persistence of Human Influenza A (H3N2)

- The Type III Effectors NleE and NleB from Enteropathogenic and OspZ from Block Nuclear Translocation of NF-κB p65

- VEGF Promotes Malaria-Associated Acute Lung Injury in Mice

- Identification of a Mutant PfCRT-Mediated Chloroquine Tolerance Phenotype in

- The Early Stage of Bacterial Genome-Reductive Evolution in the Host

- Host-Detrimental Role of Esx-1-Mediated Inflammasome Activation in Mycobacterial Infection

- Elevation of Intact and Proteolytic Fragments of Acute Phase Proteins Constitutes the Earliest Systemic Antiviral Response in HIV-1 Infection

- The Pleiotropic CymR Regulator of Plays an Important Role in Virulence and Stress Response

- Alternative Sigma Factor σ Modulates Prophage Integration and Excision in

- Effect of Neuraminidase Inhibitor–Resistant Mutations on Pathogenicity of Clade 2.2 A/Turkey/15/06 (H5N1) Influenza Virus in Ferrets

- Massive APOBEC3 Editing of Hepatitis B Viral DNA in Cirrhosis

- NK Cells and γδ T Cells Mediate Resistance to Polyomavirus–Induced Tumors

- Is Genetically Diverse in Animals and Appears to Have Crossed the Host Barrier to Humans on (At Least) Two Occasions

- Adenylate Cyclase Toxin Mobilizes Its β Integrin Receptor into Lipid Rafts to Accomplish Translocation across Target Cell Membrane in Two Steps

- The Role of Intestinal Microbiota in the Development and Severity of Chemotherapy-Induced Mucositis

- HIV-1 Transmitting Couples Have Similar Viral Load Set-Points in Rakai, Uganda

- Few and Far Between: How HIV May Be Evading Antibody Avidity

- Galectin-9/TIM-3 Interaction Regulates Virus-Specific Primary and Memory CD8 T Cell Response

- Perforin Expression Directly by HIV-Specific CD8 T-Cells Is a Correlate of HIV Elite Control

- The Set3/Hos2 Histone Deacetylase Complex Attenuates cAMP/PKA Signaling to Regulate Morphogenesis and Virulence of

- Infidelity of SARS-CoV Nsp14-Exonuclease Mutant Virus Replication Is Revealed by Complete Genome Sequencing

- Combining ChIP-chip and Expression Profiling to Model the MoCRZ1 Mediated Circuit for Ca/Calcineurin Signaling in the Rice Blast Fungus

- Internalin B Activates Junctional Endocytosis to Accelerate Intestinal Invasion

- A Complex Small RNA Repertoire Is Generated by a Plant/Fungal-Like Machinery and Effected by a Metazoan-Like Argonaute in the Single-Cell Human Parasite

- Opc Invasin Binds to the Sulphated Tyrosines of Activated Vitronectin to Attach to and Invade Human Brain Endothelial Cells

- Muc2 Protects against Lethal Infectious Colitis by Disassociating Pathogenic and Commensal Bacteria from the Colonic Mucosa

- PdeH, a High-Affinity cAMP Phosphodiesterase, Is a Key Regulator of Asexual and Pathogenic Differentiation in

- Isolates with Antimony-Resistant but Not -Sensitive Phenotype Inhibit Sodium Antimony Gluconate-Induced Dendritic Cell Activation

- The Microbiota and Allergies/Asthma

- Environmental Factors Determining the Epidemiology and Population Genetic Structure of the Group in the Field

- Prolonged Antigen Presentation Is Required for Optimal CD8+ T Cell Responses against Malaria Liver Stage Parasites

- Crystal Structure of HIV-1 gp41 Including Both Fusion Peptide and Membrane Proximal External Regions

- Susceptibility to Anthrax Lethal Toxin-Induced Rat Death Is Controlled by a Single Chromosome 10 Locus That Includes

- Demonstration of Cross-Protective Vaccine Immunity against an Emerging Pathogenic Ebolavirus Species

- Effective, Broad Spectrum Control of Virulent Bacterial Infections Using Cationic DNA Liposome Complexes Combined with Bacterial Antigens

- High Multiplicity Infection by HIV-1 in Men Who Have Sex with Men

- The -Specific Human Memory B Cell Compartment Expands Gradually with Repeated Malaria Infections

- EBV Promotes Human CD8 NKT Cell Development

- Persistent Growth of a Human Plasma-Derived Hepatitis C Virus Genotype 1b Isolate in Cell Culture

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Quorum Sensing Inhibition Selects for Virulence and Cooperation in

- The Role of Intestinal Microbiota in the Development and Severity of Chemotherapy-Induced Mucositis

- Crystal Structure of HIV-1 gp41 Including Both Fusion Peptide and Membrane Proximal External Regions

- Susceptibility to Anthrax Lethal Toxin-Induced Rat Death Is Controlled by a Single Chromosome 10 Locus That Includes

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání