-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Identification of a Tissue-Selective Heat Shock Response Regulatory Network

The heat shock response (HSR) is essential to survive acute proteotoxic stress and has been studied extensively in unicellular organisms and tissue culture cells, but to a lesser extent in intact metazoan animals. To identify the regulatory pathways that control the HSR in Caenorhabditis elegans, we performed a genome-wide RNAi screen and identified 59 genes corresponding to 7 positive activators required for the HSR and 52 negative regulators whose knockdown leads to constitutive activation of the HSR. These modifiers function in specific steps of gene expression, protein synthesis, protein folding, trafficking, and protein clearance, and comprise the metazoan heat shock regulatory network (HSN). Whereas the positive regulators function in all tissues of C. elegans, nearly all of the negative regulators exhibited tissue-selective effects. Knockdown of the subunits of the proteasome strongly induces HS reporter expression only in the intestine and spermatheca but not in muscle cells, while knockdown of subunits of the TRiC/CCT chaperonin induces HS reporter expression only in muscle cells. Yet, both the proteasome and TRiC/CCT chaperonin are ubiquitously expressed and are required for clearance and folding in all tissues. We propose that the HSN identifies a key subset of the proteostasis machinery that regulates the HSR according to the unique functional requirements of each tissue.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003466

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003466Summary

The heat shock response (HSR) is essential to survive acute proteotoxic stress and has been studied extensively in unicellular organisms and tissue culture cells, but to a lesser extent in intact metazoan animals. To identify the regulatory pathways that control the HSR in Caenorhabditis elegans, we performed a genome-wide RNAi screen and identified 59 genes corresponding to 7 positive activators required for the HSR and 52 negative regulators whose knockdown leads to constitutive activation of the HSR. These modifiers function in specific steps of gene expression, protein synthesis, protein folding, trafficking, and protein clearance, and comprise the metazoan heat shock regulatory network (HSN). Whereas the positive regulators function in all tissues of C. elegans, nearly all of the negative regulators exhibited tissue-selective effects. Knockdown of the subunits of the proteasome strongly induces HS reporter expression only in the intestine and spermatheca but not in muscle cells, while knockdown of subunits of the TRiC/CCT chaperonin induces HS reporter expression only in muscle cells. Yet, both the proteasome and TRiC/CCT chaperonin are ubiquitously expressed and are required for clearance and folding in all tissues. We propose that the HSN identifies a key subset of the proteostasis machinery that regulates the HSR according to the unique functional requirements of each tissue.

Introduction

The heat shock response (HSR) has been studied extensively as a cellular response to acute stress such as elevated temperature [1]. The master regulator of the HSR is Heat Shock Factor 1 (HSF1), a stress responsive transcription factor that regulates the inducible transcription of a family of genes encoding heat shock proteins (HSPs), many of which are molecular chaperones. In the absence of a stress signal, HSF1 is inhibited by a negative feedback loop mediated by the molecular chaperones HSP70 and HSP90 [2]–[7]. Upon heat shock, HSF1 is activated as the equilibrium of chaperones shifts toward association with metastable polypeptides.

Many key aspects of the HSR have been well established at a cellular level in cultured cells and unicellular organisms, yet the HSR has additional features that are only apparent in multicellular organisms. Heat shock inducible promoters contain multiple cis elements and can be differentially expressed across tissues [8]–[18]. The HSR is intimately associated with numerous tissue-specific and age-dependent human diseases and regulated cell non-autonomously by neuronal control [19], [20]. Finally, HSF1 has important roles during development and longevity, and activation of the HSR is attenuated during aging [13], [21]–[24]. However, despite the importance of the HSR in organismal physiology, relatively little is known about its regulation in multicellular organisms and the extent of differential regulation across distinct tissues is unexplored.

A comprehensive genetic analysis of the HSR regulatory pathways has not previously been possible in any system, in part because traditional forward genetic screens are inadequately suited to the identification of genes that regulate the HSR. These approaches depend on the introduction of mutations, which can destabilize the folding of the corresponding proteins, resulting in indirect induction of the HSR due to the expression of misfolded species. Indeed, a forward genetic screen in Drosophila described such mutations in a muscle-specific actin [25], [26]. RNAi based genetic screening resolves the limitations associated with traditional genetic screens associated with the HSR and has been used to gain important insights into many regulatory networks including those associated with models of aggregation-prone proteins, longevity, and stress responses [27]–[34].

In this study, we have used genome-wide RNAi screening to identify factors important for the positive and negative regulation of the HSR in the metazoan Caenorhabditis elegans in order to establish a comprehensive understanding of its regulation on an organismal level. Further, we used a fluorescent reporter to allow for the analysis of regulation in different tissues. This approach reveals a complex network of positive and negative HSR regulators with critical roles in maintenance of proteostasis that confer differential tissue-selective patterns of heat shock gene expression.

Results

Genome-Wide Screens for HSR Regulators

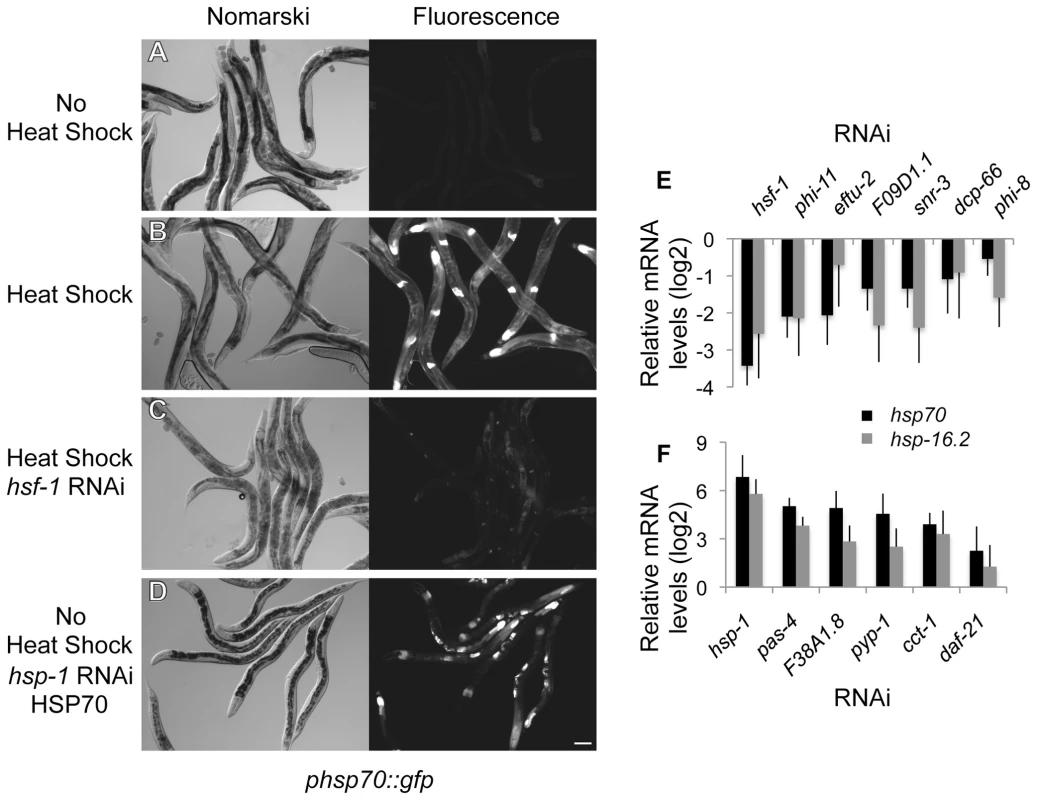

The genetic network upstream of HSF1 and the HSR was identified using a genome-wide RNAi screen in transgenic C. elegans expressing the heat shock (HS)-inducible fluorescent reporter phsp70::gfp constructed from the promoter of the C12C8.1 gene [13]. Expression of this reporter is not detected under ambient growth conditions of development and adulthood (Figure 1A) and is induced strongly by HS (Figure 1B). The threshold sensitivity of the screen was established using RNAi knockdown of hsf-1 to suppress HS-induction of the reporter as a reference control for positive regulators (Figure 1C), and RNAi knockdown of hsp-1, a member of the HSP70 family that negatively regulates the HSR, resulting in constitutive expression of the reporter as a reference control for negative regulators (Figure 1D).

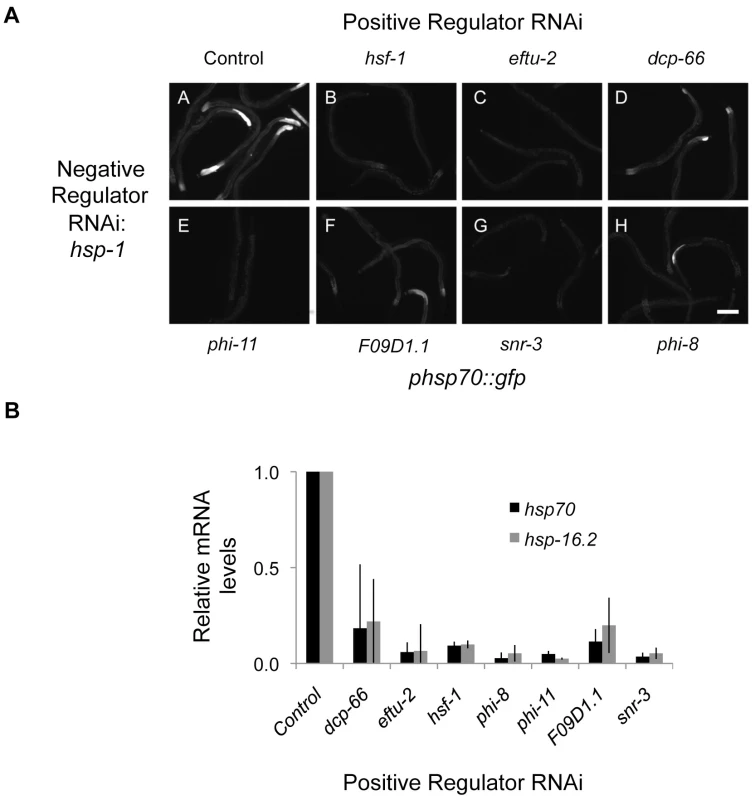

Fig. 1. Genome-wide RNAi screen for HSR regulators.

(A–D) Nomarski and fluorescent images corresponding to the phsp70::gfp reporter strain. (A) Control animals show little reporter expression and only faint autofluorescence of the intestine. (B) Reporter induction in animals exposed to heat shock at 33°C for 1 hour. (C) RNAi knockdown of hsf-1 decreases induction of the reporter by heat shock. (D) RNAi knockdown of hsp-1 causes constitutive induction of the reporter in the absence of heat shock. The scale bar corresponds to 100 µm. (E–F) Quantitation of the effects on endogenous hsp70 and hsp-16.2 genes using qRT-PCR. (E) HSR positive regulators normalized to the heat shocked empty vector control. (F) HSR negative regulators normalized to empty vector control. Averages are from at least three biological replicates and error bars represent SEM. Genetic modifiers of the HSR were identified by visual scoring of the phsp70::gfp reporter upon RNAi-mediated knockdown. A representative subset from each functional class was validated by analysis of endogenous hsp70 gene expression using qRT-PCR (Figure 1E and 1F). We also extended our analysis to another heat shock gene, hsp-16.2, a member of the small HSP family. Consistent with the HSR reporter results, HS-dependent induction of hsp70 and hsp-16.2 were reduced upon hsf-1 knockdown. Likewise, the basal expression of hsp70 and hsp-16.2 were increased upon hsp-1 knockdown. These experiments established the utility of the phsp70::gfp reporter and RNAi as a methodology for the identification of both positive and negative regulators of the HSR in C. elegans.

Having established the criteria for two classes of HSR genetic modifiers, we performed a genome-wide RNAi screen for genes whose knockdown blocked HS-dependent reporter induction, and for genes whose knockdown resulted in constitutive expression of the reporter. These screens were performed by RNAi feeding using a library containing RNAi constructs targeted against approximately 86% of genes in C. elegans [35].

Identification of HSR Positive Regulators

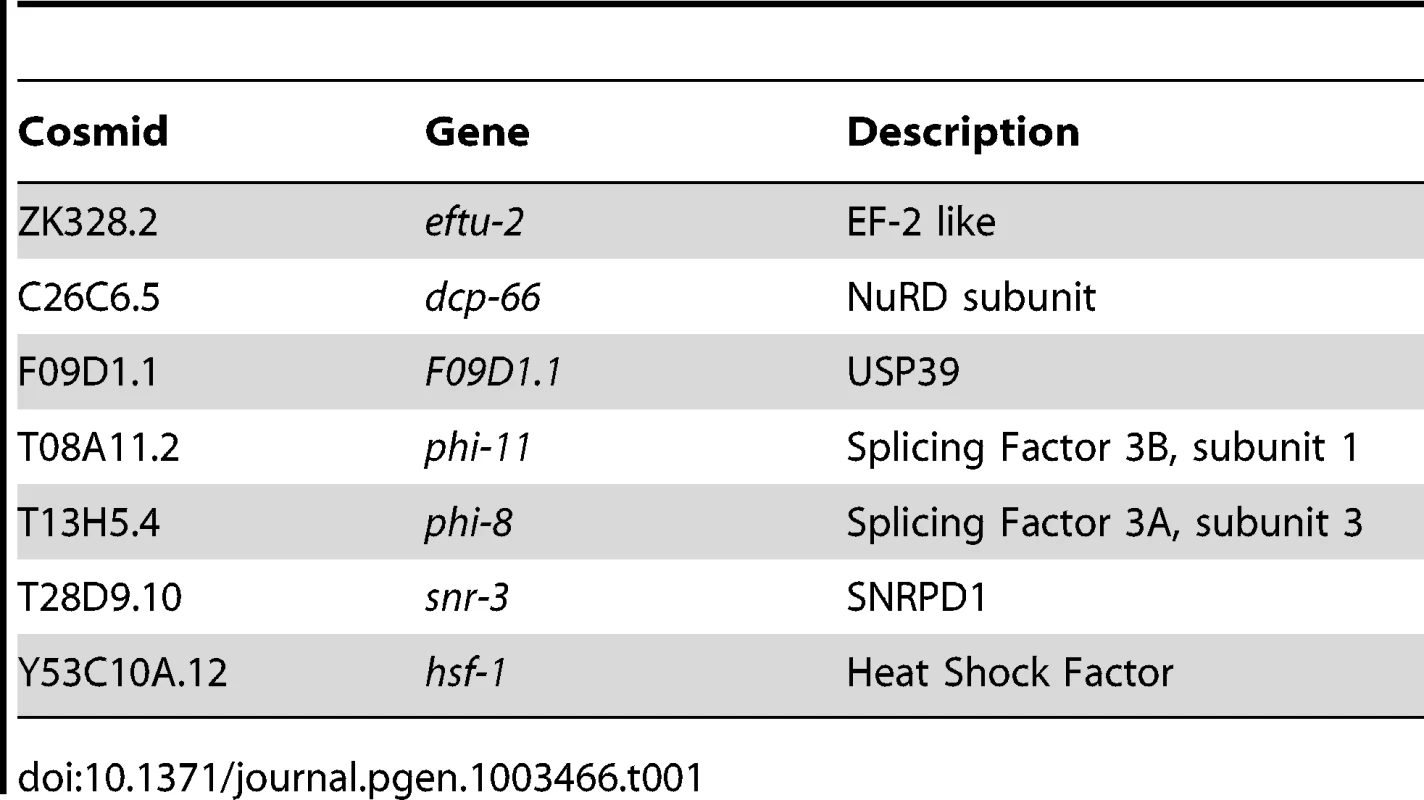

The screen for positive regulators of the HSR identified genes with properties similar to hsf-1, whose knockdown suppressed induction of the HSR reporter. To ensure that decreased fluorescence of the reporter did not arise from indirect effects, such as transgene silencing, we performed a counter-screen against suppression of a phsp-4::gfp reporter, an ER stress-inducible gene that is not dependent on HSF1 [36], [37]. This led to the identification of seven positive regulators that are conserved to humans and function in chromatin remodeling, RNA processing, and protein synthesis (Figure 1E, Table 1, Table S1). None of these genes has been previously linked to HSR regulation, however each has been either associated with HS or implicated in the HSR. For example, dcp-66 is a subunit of the NuRD complex, of which other subunits in this complex have been shown to interact with human HSF1 [38]. Our data provide evidence that the HSF1-NuRD interaction has functional consequences on the regulation of the HSR. Likewise, Mi-2, a subunit of several complexes including NuRD, has been shown to affect the levels of HS genes in Drosophila [39]. Among the other positive regulators are genes associated with mRNA splicing and translation, biosynthetic processes that are highly sensitive to HS stress. F09D1.1 is a homologue of USP39, which has been implicated in recycling of the triple-snRNP complex, a step of splicing that is particularly sensitive to temperature. phi-8 and phi-11 are subunits of Splicing Factor 3, which has been shown to regulate alternative splicing, snr-3 is an sm protein which is expected to have a general role in mRNA splicing, and eftu-2 is an elongation factor 2-like protein predicted to have a general role in translational elongation. Finally, as expected, hsf-1 was identified in the screen as predicted for its central role in the HSR.

Tab. 1. Positive Regulators of the HSR.

Identification of HSR Negative Regulators

The screen for negative regulators of the HSR identified genes whose reduced expression resulted in the constitutive expression of the phsp70::gfp reporter. To ensure that these regulators activated the HSR in an HSF1-dependent manner, we employed a subsequent counter-screen using a hypomorphic hsf-1 mutant [40]. Candidate negative regulators were also tested for their ability to constitutively activate endogenous heat shock genes by qRT-PCR (Figure 1F). This strategy led to the identification of fifty-two genes that have the functional properties of negative regulators of the HSR (Table 2, Table S1).

Tab. 2. Negative regulators of the HSR and hsp70::gfp reporter induction.

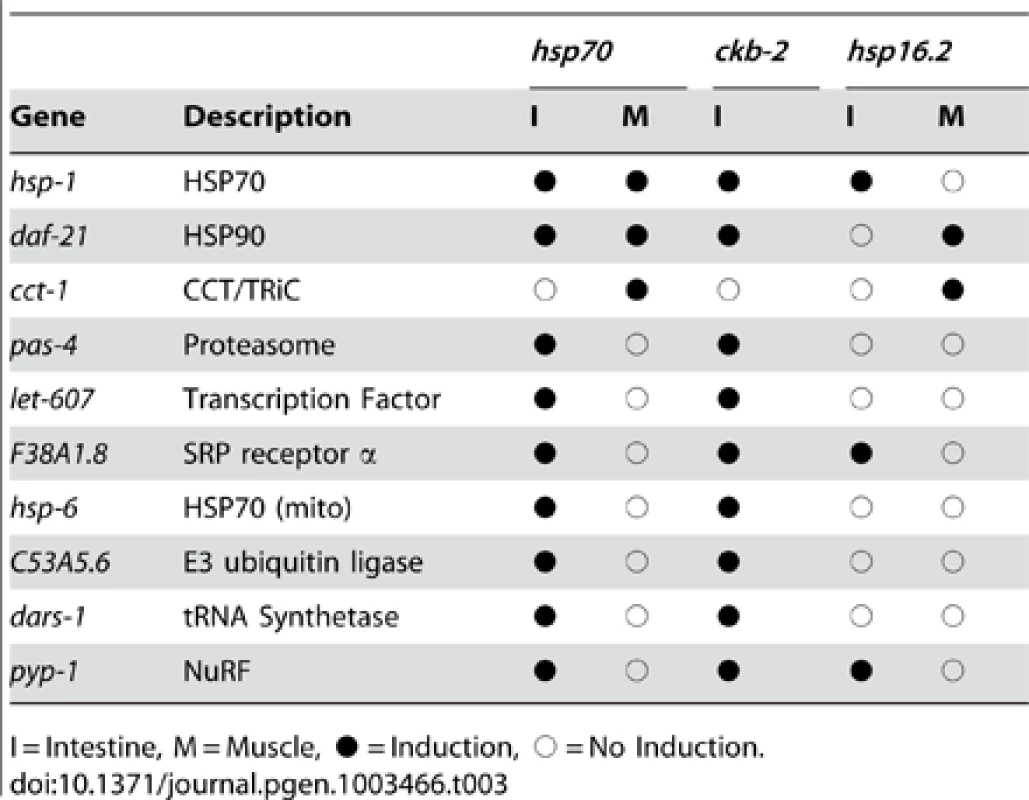

S = Spermatheca, I = Intestine, M = Muscle, • = Induction, ○ = No Induction. Each of these negative regulators of the HSR function in specific steps of proteostasis and affect either gene expression, protein folding, trafficking, and clearance, and are conserved to humans. Among the regulators that affect protein folding are three prominent molecular chaperone machines corresponding to HSP70 (hsp-1), HSP90 (daf-21) and TRiC/CCT (cct-1, cct-2, cct-3, cct-4, cct-5, cct-6, cct-7, and cct-8) and three cochaperones (sgt-1, unc-45, and cyn-11). HSP70 and HSP90 are predicted from previous studies that identified them as negative regulators of HSF1 and the HSR. Likewise, a role for the TRiC/CCT chaperonin in the regulation of the HSR has been suggested from studies on a small molecule that interacts with TRiC/CCT and induces human HSF1 [41]. Regulation of the HSR by chaperonins is functionally conserved in bacteria, as downregulation of the prokaryotic chaperonin GroEL induces the HSR in E. coli [41], [42]. The selectivity of these genes representing three chaperone machines and three cochaperones as regulators of the HSN is unexpected given that C. elegans expresses nearly 200 chaperone genes, which suggests a high degree of selectivity for chaperone regulation of the HSR.

Other negative regulators of the HSR correspond to components of trafficking including subunits of the signal recognition particle (SRP) and other secretory pathway genes (F55C5.8, F08D12.1, F25G6.8, F38A1.8, R186.3, F38E11.5 and T14G10.5, hsp-3, T24H7.2, let-607) and mitochondrial import (hsp-6, T09B4.9). Consistent with this, knockdown of SRP subunits in yeast and E. coli has been shown to induce the HSR [43], [44] and our study now extends these observations to metazoans. Clearance components include ubiquitin associated (phi-32, uba-1, C53A5.6) and proteasomal subunits (pas-4, pas-5, pas-6, pbs-2, pbs-3, pbs-4, pbs-5, pbs-6, pbs-7, rpt-1, rpt-3, rpt-4, rpt-5, rpt-6, rpn-1, rpn-2, rpn-6, rpn-7, rpn-8, and rpn-11). Inhibition of the proteasome by small molecules has previously been shown to induce the HSR [45], [46]. It is intriguing that only the proteasome, and not autophagy or other proteases, functions as a regulator of the HSR, given the large number of components involved in protein clearance. The final class of regulators are involved in protein synthesis (dars-1) and gene expression (W04A4.5, pyp-1, and mdt-15). Microarray results confirm the induction of HSR genes upon mdt-15 knockdown [47]. While the pyp-1 subunit of the NuRF chromatin remodeler has not been previously linked to the HSR, other subunits of NuRF have been suggested to positively affect HSR gene expression [48]. Because we identified only one of 171 predicted E3-ligases (C53A5.6) and only one of 33 predicted tRNA synthetases (dars-1) in the C. elegans genome, we rescreened all members of these gene families and found no additional HSR regulators [49], [50].

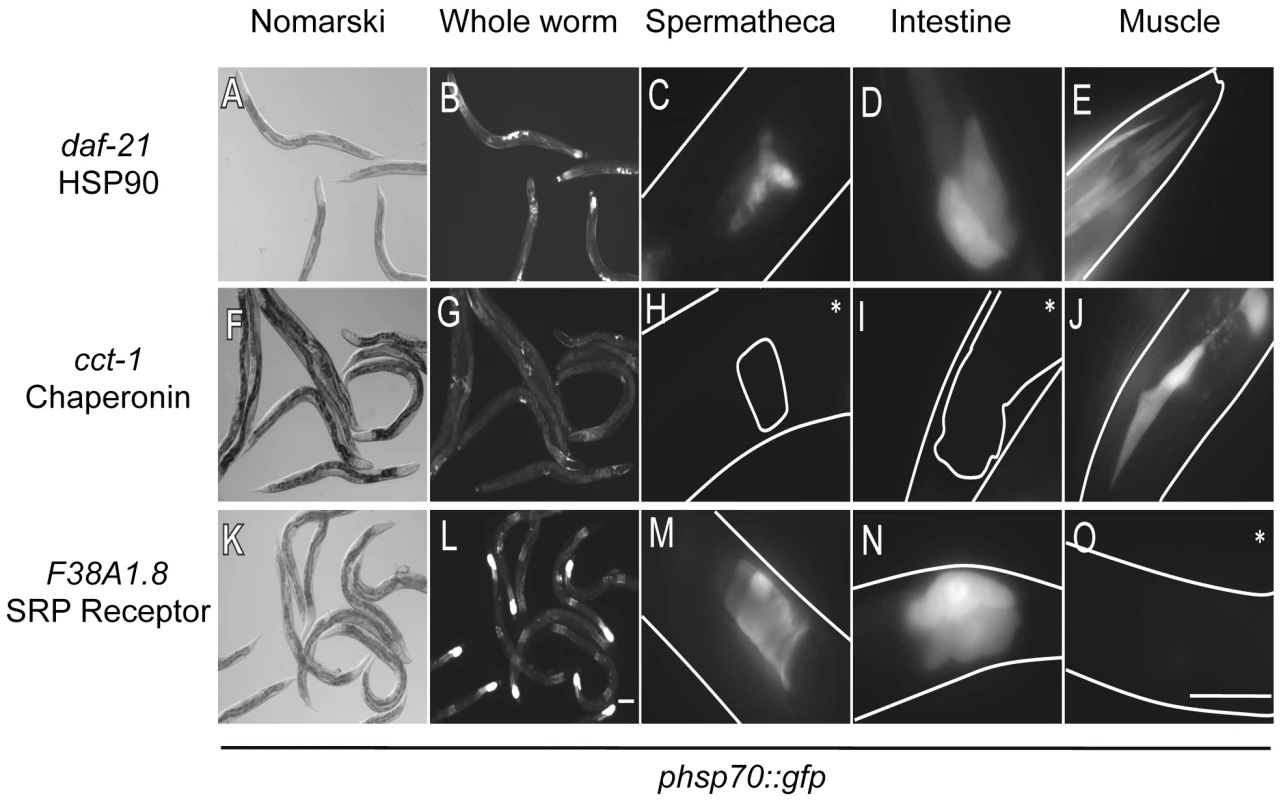

HSR Negative Regulators Exhibit Distinct Tissue-Selective Patterns

A striking feature of the negative regulators of the HSR is that the HSR reporter in not uniformly induced across all tissues, but rather displays tissue-selective expression patterns in the intestine, muscle, and spermatheca (Figure 2, Table 2). Of the negative regulators, only knockdown of HSP70 and HSP90 induced expression of the reporter in all three tissues. By comparison, knockdown of the three cochaperones and all eight subunits of the TRiC/CCT chaperone machine induced the reporter only in the muscle. In contrast, downregulation of subunits of the proteasome and many secretory pathway genes induced the reporter only in the intestine and spermatheca, but not in the muscle. Knockdown of the remaining genes induced the reporter only in the intestine. These patterns are unlikely to be due to RNAi artifacts because the tissue-selective patterns of reporter induction were similar for all subunits within specific complexes, yet non-overlapping between different complexes (i.e., all proteasomal subunits induced in intestine and spermatheca, and all TRiC/CCT subunits induced in the muscle).

Fig. 2. Tissue-selective induction of the phsp70::gfp reporter by knockdown of negative regulators.

Nomarski and fluorescent images corresponding to whole animals and fluorescent images of the spermatheca, intestine, and muscle tissue are shown. The boundary of the animals, intestine and spermatheca taken from Nomarski images are added as a visual aide to some images. (A–E) RNAi knockdown of daf-21 leads to induction of the reporter in all three tissues. (F–J) RNAi knockdown of cct-1 causes induction only in muscle. (K–O) knockdown of F38A1.8 causes induction in the intestine and spermatheca. Images are taken at different exposures to maximize fluorescence of each image. Scale bars of whole animal images correspond to 100 µm, while scale bars of the images depicting specific tissues correspond to 50 µm. Asterisks denote only autofluorescence. Tissue-selective expression of the HSR reporter was unexpected as nearly all of the negative regulators are ubiquitously expressed components of essential cellular machines. For example, even though proteasomal subunits do not induce the HSR in muscle, it has been shown in C. elegans that most, if not all, proteasomal subunits are expressed in muscle and that RNAi knockdown of proteasomal subunits yields muscle specific phenotypes such as stabilization of a ubiquitin-GFP reporter in the muscle and early onset aggregation of a polyQ disease model expressed only in the muscle [28], [51]. These results also suggest that depletion of subunits from complexes such as the proteasome does not induce the HSR simply by misfolding other subunits in that complex since these effects would not be expected to have tissue selectivity.

To further investigate the tissue-selective patterns of HSR regulation, we examined the expression of two additional reporters that are inducible by heat shock and dependent on HSF1. The phsp-16.2::gfp reporter is inducible in the intestine, muscle and excretory system, and is dependent on HSF1 and DAF-16 (Figure S1) [52], [53]. The pckb-2::gfp reporter is inducible only in the intestine and is also activated by the unfolded protein response, an ER stress response [54]. Knockdown of HSR negative regulators revealed highly overlapping patterns of tissue-specific induction with all three reporters (Table 3). In the muscle, there was a highly consistent pattern of induction between the C12C8.1 and hsp16.2 reporters, with two genes inducing both, seven inducing neither, and only a single gene showing differential induction. In the intestine, HSR negative regulators gave identical patterns of induction for the C12C8.1 and the ckb-2 reporters, with nine out of ten causing induction, yet only a smaller subset, three out of ten, also induced the hsp16.2 reporter. Given the differences in the regulation and function of the three genes, the three reporters demonstrate remarkably consistent patterns of tissue-selective HSR induction.

Tab. 3. Tissue-selective patterns for multiple HSR reporters.

I = Intestine, M = Muscle, • = Induction, ○ = No Induction. We next validated the tissue-selective effects using pharmacological inhibitors and mutants. We found that incubation of L4-staged worms with MG132, a pharmacological inhibitor of the proteasome, caused induction of the phsp70::gfp reporter in the intestine and the spermatheca, but not in the muscle tissue (Figure 3A). This pattern matches that seen with RNAi knockdown of proteasomal subunits, providing further support that the tissue-selective effects are unlikely to be an RNAi artifact. Most of the negative regulators are essential, however we were able to test the effects of mutations in T24H7.2, an ER localized HSP70, and the cochaperones unc-45, sgt-1, and cyn-11, and found using qRT-PCR that the expression of endogenous HSR genes was induced (Figure 3B). We further demonstrated that this induction was tissue-selective using qRT-PCR analysis on dissected intestinal cells. We found that T24H7.2 mutant animals, but not unc-45 mutant animals, induced endogenous hsp70 in the intestine (Figure 3C). The tissue-selective induction of endogenous genes in the intestine by these mutations matched the induction of the phsp70::gfp reporter by RNAi knockdown, thus providing a validation of both the use of RNAi and the fluorescent reporter.

Fig. 3. Validation of tissue-selective effects using small molecules and mutants.

A) Incubation with 100 µM MG132, a small molecule inhibitor of the proteasome, but not DMSO alone, causes tissue-selective induction of the phsp70::gfp reporter in the intestine and spermatheca (arrows), similar to RNAi knockdown of proteasomal subunits. The scale bar corresponds to 200 µm. Asterisks denote only autofluorescence. B) Mutations in T24H7.2, sgt-1, cyn-11, and unc-45 cause induction of the HSR in whole worms measured using qRT-PCR. C) Mutation of T24H7.2, but not unc-45, causes induction in the intestine relative to N2 control animals, measured by qRT-PCR analysis of hsp70 in dissected intestinal tissue. Averages shown are from at least two biological replicates. Analysis of the HSR Regulatory Network

The genes that we identified form a genetic regulatory network of the HSR in C. elegans. To characterize the relationship between these regulators, we utilized an interaction network from previous physical, genetic, and predicted interaction data [55]. A network representation of the interaction data, in which HSR regulators are nodes and interactions between them are edges, reveals that HSR negative regulators are enriched in interactions with other HSR negative regulators: 39 of 52 negative regulator genes are connected in a single interaction network (Figure 4). We next applied a community detection algorithm to determine the structure of this interaction network [56], [57]. This analysis shows that the network is composed of three distinct modules, indicated by the shapes of the nodes. The modular structure of this network is unlikely to have arisen by chance since it does not appear in randomized networks containing the same number of nodes and connections (p<10−4). The three modules are primarily composed of clearance, cytoplasmic protein folding, and gene expression and protein synthesis components, respectively. While it is unsurprising that proteasome or protein folding subunits cluster together into distinct modules, the existence of the third module is entirely unexpected. The modules identified using the interaction data (node shapes) correspond closely with the observed tissue patterns of reporter induction (node colors) thus providing additional validation of both the specificity of tissue expression and network structure. These results further suggest that the underlying functional modules give rise to the tissue-specific patterns of HSR induction.

Fig. 4. Network analysis of HSR regulators.

Shown is a network with HSR negative regulator genes depicted as nodes and interactions as edges. Node shape denotes grouping corresponding to a community detection algorithm based on the structure of the interaction network. Node color corresponds to the tissue-specific phsp70::gfp reporter induction. Cartoons of worms depicting the tissue specificity appear next to nodes containing those colors. To further probe the genetic properties of the HSN, we investigated the relationships between the positive and negative regulators to provide a systems-level pathway analysis. We tested whether depletion of positive regulators (that decrease reporter induction by heat shock) would suppress reporter induction mediated by depletion of negative regulators. We found that knockdown of each positive regulator prior to knockdown of the negative regulator hsp-1 (HSP70) decreased induction of the reporter (Figure 5A). This indicates that the positive HSR regulators are epistatic to HSP70. These data are consistent with a model in which the positive regulators of the HSR act at or downstream of chaperone-mediated regulation of the HSR. Similar results were obtained for other negative regulators including daf-21 (HSP90), pas-4 (proteasome), C53A5.6 (E3 ubiquitin ligase), let-607 (ER transcription factor), F38A1.8 (SRP), hsp-6 (mitochondrial HSP70), and dars-1 (Asp tRNA synthetases).

Fig. 5. Epistasis analysis of HSR regulators.

The effects of HSR positive regulator knockdown on induction of the reporter by negative HSR regulator knockdown were measured using the phsp70::gfp reporter. (A) Images showing the results from double RNAi with each positive regulator and the negative regulator hsp-1. In each case, knockdown of the positive regulator decreased reporter fluorescence compared to knockdown of hsp-1 alone. (B) Quantitation of the effects of HSR positive regulator knockdown using RNAi on induction of endogenous HSR genes by the HSR negative regulator T24H7.2 mutant reveals that the positive regulators are epistatic to T24H7.2. These results, in addition to the tissue-independent nature of the positive regulators and their association with biosynthetic processes, further distinguish the roles of the positive regulators from the negative regulators. RNAi knockdown is not equivalent to genetic ablation, so these relationships correspond to sensitivities rather than absolute dependencies. Therefore, we tested the effects of depletion of the positive regulators in a strain containing a deletion in the negative regulator T24H7.2, an ER localized HSP70. Each of the positive regulators decreased induction of the HSR upon mutation of T24H7.2, thereby confirming the results with double RNAi (Figure 5B). Together, our data indicate that the positive regulators are epistatic to the negative regulators and either function downstream or at the same step in the pathway. We favor the latter model and propose that the positive and negative regulators function together in an integrated HSR regulatory network (Figure 6).

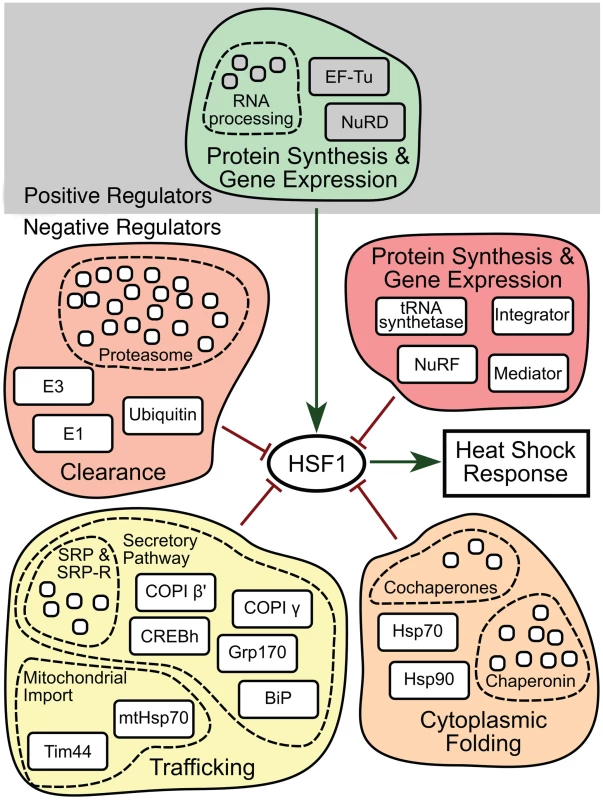

Fig. 6. HSR regulatory network model.

Each HSR regulator, denoted by common terminology, is indicated as a box and is grouped according to its presence in a multi-subunit complex or functional pathway (i.e., the proteasome or secretory pathway). Positive or negative effects on HSR regulation are indicated by either a green arrow or red line respectively. Positive regulators are further separated from negative regulators by grey shading in the background. At the center of the network, HSF1 integrates signals from the various regulators and establishes a coordinated HSR. Discussion

Our findings indicate that the heat shock regulatory network (HSN) enables the HSR to sense and respond to a wide range of disruptions in proteostasis, thus providing a direct link between the function of the HSR and its regulation. The four functional clusters of the HSN each identify a small subset of the entire proteostasis machinery that functions in gene expression and protein synthesis, folding, trafficking, and clearance. The negative regulators fall within each of these functional categories, whereas the positive HSR regulators are more restrictive and cluster only to gene regulation and protein synthesis. Previous studies on the mitochondrial stress response have revealed that depletion of specific subunits of electron transport chain complexes leads to induction of the mitochondrial stress response; however in our screen we did not identify subunits of macromolecular complexes as regulators of the HSR, thus revealing differences in how these two compartments detect and respond to a proteostatic imbalance [58].

The negative regulators of the HSN displayed a surprising extent of tissue-selective effects on HS gene expression, which may arise from differences in the expression levels or activity of the regulators between tissues. One clear example of differential tissue specific expression of HSR regulators occurs in activated B cells, that rely heavily rely upon the secretory pathway and exhibit high expression levels of secretory pathway components (for a review, see [59], [60]). But as described in the results section, nearly all components of the HSN are broadly expressed. For example, TRiC/CCT is required for the folding of actin and tubulin, which are expressed in every cell [61]. However, the specialized function of muscle tissue could necessitate a stronger dependency for actin and myosin, which in turn explains the functional requirement for TRiC/CCT and account for the enhanced sensitivity of muscle to TRiC/CCT depletion. In addition to differential sensitivity to the regulators, our results indicate that each tissue exhibits distinct profiles of HS-inducible genes, which likely arises from tissue-specific factors that influence HS gene inducibility. Together, these data indicate that in addition to its unique proteome and specialized function, each tissue may contain a distinct complement of the proteostasis machinery, a differential sensitivity to disruption of proteostasis networks, and a distinct response to proteostasis disruption.

Induction of the HSR has been shown to be protective in multiple models for diseases of protein conformation; therefore, knockdown of the negative regulators and induction of the HSR would be predicted to suppress protein aggregation. Instead, there is substantial overlap (twenty out of fifty-two genes) between the negative regulators of the HSR and a separate genome-wide screen for enhancement (early onset) of polyQ aggregation in muscle (Table S1). The common gene set includes the TRiC/CCT chaperonin (6), HSP70, mitochondrial HSP70, the proteasome (10), ubiquitin, and the E1 ubiquitin ligase. Therefore, it is likely that knockdown of these genes leads to both a disruption of proteostasis and activation of the HSR. Consistent with this model, there is almost no overlap with another genome-wide screen for suppression of polyQ aggregation in muscle. In contrast, knockdown of positive regulators, which suppresses the HSR, would be predicted to cause early-onset polyQ aggregation, and indeed, five of the seven positive HSR regulators have this phenotype and none suppress polyQ aggregation.

The paradigm for HSR regulation has previously focused on HSF1 and the negative feedback loops consisting of the HSP70 and HSP90 chaperones. Our results reveal that the network that regulates the HSR is much larger and corresponds to at least fifty-nine genes of this newly defined HSN. Many of these genes have been previously linked to HSR regulation in other systems, including prokaryotes, suggesting that this regulatory network is likely conserved through evolution. The precise mechanistic links between many of these genes and the HSR and other components of the HSN remains to be defined, and it will be important to investigate whether the tissue-selective regulation of the HSR is also conserved. Nevertheless, the identification of these genes in a comprehensive genetic screen for HSR regulators not only validates their functional properties but also reinforces the evolutionary conservation of the HSR. In summary, the systems-level identification and characterization of the HSR regulatory network described in this paper provides several important insights into regulation of the HSR during stress and provides a basis for future analysis of HSR regulation during development, ageing, and human disease.

Materials and Methods

Nematode Strains and Cultures

Nematodes were handled and analyzed using standard laboratory techniques and cultured at 20°C [62]. Worms were synchronized by bleaching with hypochlorite (NaOCl) and hatching overnight in M9. Where indicated, intestines were dissected from living animals in M9 media. All nematode strains were derived from the N2 Bristol wild-type strain. The following strains were used: 1) AM446 rmIs223[phsp70::gfp; pRF4(rol-6(su1006))]; 2) SJ4005 zcIs[phsp-4::gfp]V; 3) CL2070 dvIs70 [phsp-16.2::gfp; rol-6(su1006)]; 4) BC14636 dpy-5(e907) I; sIs13872[rCesB0285.9::gfp+pCeh361]; 5) PS3551 hsf-1(sy441)I; 6) AM658 hsf-1(sy441)I; rmIs223[phsp70::gfp; rol-6 (su1006)]; 7) RB1694 T24H7.2(ok2107) II; 8) RB703 unc-45(ok468) III; 9) RB1053 R05F9.10(ok1000) II; and 10) VC1372, rab-21&cyn-11(ok1879) II [13], [37], [40], [52], [63].

RNAi

Genome-wide RNAi screening was performed using a bacterial feeding approach with a library targeting approximately 86% of the C. elegans genome (MRC Geneservice, Cambridge, U.K.). Bacterial cultures were grown overnight in LB with 5 µg/ml tetracycline and 50 µg/ml ampicillin and induced with 1 mM IPTG for four hours. To avoid L1-stage developmental arrest associated with essential genes, L1 larvae were allowed to develop for 19 hours on plates containing OP50 bacteria prior to exposure to RNAi.

The genome-wide screen was performed in 96-well liquid cultures containing approximately 10 animals, 50 µl M9, 5 µg/ml cholesterol, 5 µg/ml tetracycline, 50 µg/ml ampicillin, 0.4 mM IPTG, 0.1 µg/ml fungizone, and 75 µl of RNAi bacterial suspension and grown at 20°C for 60 hours in a temperature-controlled shaker. For the heat shock screens, the animals were sensitized by exposure for two hours at 24°C, 24 hours before screening for reporter induction. The heat shock conditions are at 31.5°C for two hours followed by 24 hours of recovery at 20°C prior to screening for stress-induced fluorescence. Screening was performed using Leica MZ16-FA fluorescence microscope equipped with a GFP2 filter.

Validation and analysis of the regulators from the primary screen were done using solid RNAi plates containing nematode growth medium (NGM) agar with 5 µg/ml tetracycline, 50 µg/ml ampicillin and 1 mM IPTG and seeded with RNAi bacteria. Synchronized worms grown on OP50 bacteria for 19 hours were incubated on RNAi plates for 48 hours before analysis of induction (negative regulators) or wrapped in parafilm and heat shocked in a water bath at 33°C for 1 hour and then recovered for 24 hours prior to analysis (positive regulators). Worms were immobilized in levamisole and imaged using either a BD Pathway 435 High-content Bioimager (BD Biosciences) or a Zeiss Axiovert 200 fluorescent microscope. A gene was scored as positive only if >20% of animals demonstrated induction. Epistasis analysis was performed by knockdown of each positive regulator as before followed by double RNAi of the positive and negative regulators together.

Each RNAi construct was validated by sequencing. Functional information on the identified genes was collected using WormBase [64].

Drug Assay

Pharmacological inhibition of the proteasome was conducted using transgenic animals carrying the phsp70::gfp reporter grown on standard NGM plates seeded with OP50 bacteria. L4 larval stage animals were incubated with 100 µM MG132 (AG Scientific) in 0.5% DMSO or 0.5% DMSO alone for 2–3 hours and returned to plates. Fluorescence was scored the next day in young adult animals.

Fluorescence Imaging and Tissue Identification

Transgenic animals carrying the fluorescent reporter were mounted on 3% agarose pads, immobilized with 2 mM levamisole and viewed using the Zeiss Axiovert 200. Animals were imaged using 10X/0.25 A-Plan and 100X/1.4 oil DIC Plan-APOCHROMAT objectives. Images were captured using a Hamamatsu digital camera (C4742-98) with Axiovision Release 4.7 software. Tissue-identification was based on nematode anatomy and tissue morphology using images from the C. elegans atlas [65]. A tissue was scored as positive only if >20% of animals demonstrated induction.

qRT–PCR

RNA was isolated from whole animals lysed by vortexing for twenty minutes after addition of TRIzol (Invitrogen) and DNA was removed using a DNA-free Kit (Ambion) according to standard protocols. cDNA synthesis was performed using an iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad) and qRT-PCR was performed using an iQ SYBR Green Supermix Kit (BioRad) using provided protocols and run on a BioRad iCycler. 18S RNA was used as a normalization control.

Network Analysis

We utilized a graph partitioning scheme that separates the network into groups of nodes, which collectively maximizes the density of within-partition edges in the network [56], [57]. The significance of the number of interactions between the negative regulators was tested by comparing their density to the density of interactions predicted genome-wide in C. elegans. The significance of the modularity of the HSR negative regulator network was tested by sampling Monte Carlo realizations in which we exchanged pairs of edges, maintaining the degree distribution of the network.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. AkerfeltM, MorimotoRI, SistonenL (2010) Heat shock factors: integrators of cell stress, development and lifespan. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8 : 545–555.

2. CraigEA, GrossCA (1991) Is hsp70 the cellular thermometer? Trends Biochem Sci 16 : 135–140.

3. AbravayaK, MyersMP, MurphySP, MorimotoRI (1992) The human heat shock protein hsp70 interacts with HSF, the transcription factor that regulates heat shock gene expression. Genes Dev 6 : 1153–1164.

4. BalerR, WelchWJ, VoellmyR (1992) Heat shock gene regulation by nascent polypeptides and denatured proteins: hsp70 as a potential autoregulatory factor. J Cell Biol 117 : 1151–1159.

5. MosserDD, DuchaineJ, MassieB (1993) The DNA-binding activity of the human heat shock transcription factor is regulated in vivo by hsp70. Mol Cell Biol 13 : 5427–5438.

6. ShiY, MosserDD, MorimotoRI (1998) Molecular chaperones as HSF1-specific transcriptional repressors. Genes Dev 12 : 654–666.

7. ZouJ, GuoY, GuettoucheT, SmithDF, VoellmyR (1998) Repression of heat shock transcription factor HSF1 activation by HSP90 (HSP90 complex) that forms a stress-sensitive complex with HSF1. Cell 94 : 471–480.

8. ElefantF, PalterKB (1999) Tissue-specific expression of dominant negative mutant Drosophila HSC70 causes developmental defects and lethality. Mol Biol Cell 10 : 2101–2117.

9. MathurSK, SistonenL, BrownIR, MurphySP, SargeKD, et al. (1994) Deficient induction of human hsp70 heat shock gene transcription in Y79 retinoblastoma cells despite activation of heat shock factor 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91 : 8695–8699.

10. MarcuccilliCJ, MathurSK, MorimotoRI, MillerRJ (1996) Regulatory differences in the stress response of hippocampal neurons and glial cells after heat shock. J Neurosci 16 : 478–485.

11. BatulanZ, ShinderGA, MinottiS, HeBP, DoroudchiMM, et al. (2003) High threshold for induction of the stress response in motor neurons is associated with failure to activate HSF1. J Neurosci 23 : 5789–5798.

12. BlakeMJ, GershonD, FargnoliJ, HolbrookNJ (1990) Discordant expression of heat shock protein mRNAs in tissues of heat-stressed rats. J Biol Chem 265 : 15275–15279.

13. MorleyJF, MorimotoRI (2004) Regulation of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans by heat shock factor and molecular chaperones. Mol Biol Cell 15 : 657–664.

14. WuBJ, WilliamsGT, MorimotoRI (1987) Detection of three protein binding sites in the serum-regulated promoter of the human gene encoding the 70-kDa heat shock protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84 : 2203–2207.

15. WilliamsGT, McClanahanTK, MorimotoRI (1989) E1a transactivation of the human HSP70 promoter is mediated through the basal transcriptional complex. Mol Cell Biol 9 : 2574–2587.

16. MorganWD, WilliamsGT, MorimotoRI, GreeneJ, KingstonRE, et al. (1987) Two transcriptional activators, CCAAT-box-binding transcription factor and heat shock transcription factor, interact with a human hsp70 gene promoter. Mol Cell Biol 7 : 1129–1138.

17. GreeneJM, LarinZ, TaylorIC, PrenticeH, GwinnKA, et al. (1987) Multiple basal elements of a human hsp70 promoter function differently in human and rodent cell lines. Mol Cell Biol 7 : 3646–3655.

18. AbravayaK, PhillipsB, MorimotoRI (1991) Heat shock-induced interactions of heat shock transcription factor and the human hsp70 promoter examined by in vivo footprinting. Mol Cell Biol 11 : 586–592.

19. MorimotoRI (2008) Proteotoxic stress and inducible chaperone networks in neurodegenerative disease and aging. Genes Dev 22 : 1427–1438.

20. PrahladV, CorneliusT, MorimotoRI (2008) Regulation of the cellular heat shock response in Caenorhabditis elegans by thermosensory neurons. Science 320 : 811–814.

21. Ben-ZviA, MillerEA, MorimotoRI (2009) Collapse of proteostasis represents an early molecular event in Caenorhabditis elegans aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 : 14914–14919.

22. HsuAL, MurphyCT, KenyonC (2003) Regulation of aging and age-related disease by DAF-16 and heat-shock factor. Science 300 : 1142–1145.

23. XiaoX, ZuoX, DavisAA, McMillanDR, CurryBB, et al. (1999) HSF1 is required for extra-embryonic development, postnatal growth and protection during inflammatory responses in mice. EMBO J 18 : 5943–5952.

24. JedlickaP, MortinMA, WuC (1997) Multiple functions of Drosophila heat shock transcription factor in vivo. EMBO J 16 : 2452–2462.

25. Parker-ThornburgJ, BonnerJJ (1987) Mutations that induce the heat shock response of Drosophila. Cell 51 : 763–772.

26. BonnerJJ, ParksC, Parker-ThornburgJ, MortinMA, PelhamHR (1984) The use of promoter fusions in Drosophila genetics: isolation of mutations affecting the heat shock response. Cell 37 : 979–991.

27. SilvaMC, FoxS, BeamM, ThakkarH, AmaralMD, et al. (2011) A genetic screening strategy identifies novel regulators of the proteostasis network. PLoS Genet 7: e1002438 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002438.

28. NollenEA, GarciaSM, van HaaftenG, KimS, ChavezA, et al. (2004) Genome-wide RNA interference screen identifies previously undescribed regulators of polyglutamine aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 : 6403–6408.

29. ShoreDE, CarrCE, RuvkunG (2012) Induction of cytoprotective pathways is central to the extension of lifespan conferred by multiple longevity pathways. PLoS Genet 8: e1002792 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002792.

30. MeloJA, RuvkunG (2012) Inactivation of conserved C. elegans genes engages pathogen - and xenobiotic-associated defenses. Cell 149 : 452–466.

31. WangMC, MinW, FreudigerCW, RuvkunG, XieXS (2011) RNAi screening for fat regulatory genes with SRS microscopy. Nat Methods 8 : 135–138.

32. CurranSP, RuvkunG (2007) Lifespan regulation by evolutionarily conserved genes essential for viability. PLoS Genet 3: e56 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030056.

33. HansenM, HsuAL, DillinA, KenyonC (2005) New genes tied to endocrine, metabolic, and dietary regulation of lifespan from a Caenorhabditis elegans genomic RNAi screen. PLoS Genet 1: e17 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0010017.

34. WangJ, Robida-StubbsS, TulletJM, RualJF, VidalM, et al. (2010) RNAi screening implicates a SKN-1-dependent transcriptional response in stress resistance and longevity deriving from translation inhibition. PLoS Genet 6: e1001048 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001048.

35. KamathRS, FraserAG, DongY, PoulinG, DurbinR, et al. (2003) Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421 : 231–237.

36. KapulkinWJ, HiesterBG, LinkCD (2005) Compensatory regulation among ER chaperones in C. elegans. FEBS Lett 579 : 3063–3068.

37. CalfonM, ZengH, UranoF, TillJH, HubbardSR, et al. (2002) IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature 415 : 92–96.

38. KhalequeMA, BhartiA, GongJ, GrayPJ, SachdevV, et al. (2008) Heat shock factor 1 represses estrogen-dependent transcription through association with MTA1. Oncogene 27 : 1886–1893.

39. MurawskaM, HasslerM, Renkawitz-PohlR, LadurnerA, BrehmA (2011) Stress-induced PARP activation mediates recruitment of Drosophila Mi-2 to promote heat shock gene expression. PLoS Genet 7: e1002206 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002206.

40. Hajdu-CroninYM, ChenWJ, SternbergPW (2004) The L-type cyclin CYL-1 and the heat-shock-factor HSF-1 are required for heat-shock-induced protein expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 168 : 1937–1949.

41. NeefDW, TurskiML, ThieleDJ Modulation of heat shock transcription factor 1 as a therapeutic target for small molecule intervention in neurodegenerative disease. PLoS Biol 8: e1000291 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000291.

42. GuisbertE, HermanC, LuCZ, GrossCA (2004) A chaperone network controls the heat shock response in E. coli. Genes Dev 18 : 2812–2821.

43. PoritzMA, BernsteinHD, StrubK, ZopfD, WilhelmH, et al. (1990) An E. coli ribonucleoprotein containing 4.5S RNA resembles mammalian signal recognition particle. Science 250 : 1111–1117.

44. ArnoldCE, WittrupKD (1994) The stress response to loss of signal recognition particle function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 269 : 30412–30418.

45. ZhouM, WuX, GinsbergHN (1996) Evidence that a rapidly turning over protein, normally degraded by proteasomes, regulates hsp72 gene transcription in HepG2 cells. J Biol Chem 271 : 24769–24775.

46. MathewA, MathurSK, MorimotoRI (1998) Heat shock response and protein degradation: regulation of HSF2 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Mol Cell Biol 18 : 5091–5098.

47. TaubertS, HansenM, Van GilstMR, CooperSB, YamamotoKR (2008) The Mediator subunit MDT-15 confers metabolic adaptation to ingested material. PLoS Genet 4: e1000021 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000021.

48. BadenhorstP, VoasM, RebayI, WuC (2002) Biological functions of the ISWI chromatin remodeling complex NURF. Genes Dev 16 : 3186–3198.

49. KipreosET (2005) Ubiquitin-mediated pathways in C. elegans. WormBook 1–24.

50. AndersonLL, MaoX, ScottBA, CrowderCM (2009) Survival from hypoxia in C. elegans by inactivation of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Science 323 : 630–633.

51. SegrefA, TorresS, HoppeT (2011) A screenable in vivo assay to study proteostasis networks in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 187 : 1235–1240.

52. LinkCD, CypserJR, JohnsonCJ, JohnsonTE (1999) Direct observation of stress response in Caenorhabditis elegans using a reporter transgene. Cell Stress Chaperones 4 : 235–242.

53. MurphyCT, McCarrollSA, BargmannCI, FraserA, KamathRS, et al. (2003) Genes that act downstream of DAF-16 to influence the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 424 : 277–283.

54. CarusoME, JennaS, BouchecareilhM, BaillieDL, BoismenuD, et al. (2008) GTPase-mediated regulation of the unfolded protein response in Caenorhabditis elegans is dependent on the AAA+ ATPase CDC-48. Mol Cell Biol 28 : 4261–4274.

55. ZhongW, SternbergPW (2006) Genome-wide prediction of C. elegans genetic interactions. Science 311 : 1481–1484.

56. NewmanME, GirvanM (2004) Finding and evaluating community structure in networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys 69 : 026113.

57. GuimeraR, AmaralLA (2005) Cartography of complex networks: modules and universal roles. J Stat Mech 2005: nihpa35573.

58. YonedaT, BenedettiC, UranoF, ClarkSG, HardingHP, et al. (2004) Compartment-specific perturbation of protein handling activates genes encoding mitochondrial chaperones. J Cell Sci 117 : 4055–4066.

59. RonD, WalterP (2007) Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8 : 519–529.

60. ReddyPS, CorleyRB (1999) The contribution of ER quality control to the biologic functions of secretory IgM. Immunol Today 20 : 582–588.

61. DunnAY, MelvilleMW, FrydmanJ (2001) Review: cellular substrates of the eukaryotic chaperonin TRiC/CCT. J Struct Biol 135 : 176–184.

62. BrennerS (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77 : 71–94.

63. McKaySJ, JohnsenR, KhattraJ, AsanoJ, BaillieDL, et al. (2003) Gene expression profiling of cells, tissues, and developmental stages of the nematode C. elegans. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 68 : 159–169.

64. HarrisTW, AntoshechkinI, BieriT, BlasiarD, ChanJ, et al. WormBase: a comprehensive resource for nematode research. Nucleic Acids Res 38: D463–467.

65. Hall DH, Altun ZF (2008) C. elegans atlas. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. x, 348 p. p.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek The G4 GenomeČlánek Mondo/ChREBP-Mlx-Regulated Transcriptional Network Is Essential for Dietary Sugar Tolerance inČlánek RpoS Plays a Central Role in the SOS Induction by Sub-Lethal Aminoglycoside Concentrations inČlánek Tissue Homeostasis in the Wing Disc of : Immediate Response to Massive Damage during DevelopmentČlánek Disruption of TTDA Results in Complete Nucleotide Excision Repair Deficiency and Embryonic LethalityČlánek DJ-1 Decreases Neural Sensitivity to Stress by Negatively Regulating Daxx-Like Protein through dFOXO

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 4- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- IVF a rakovina prsu – zvyšují hormony riziko vzniku rakoviny?

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Epigenetic Upregulation of lncRNAs at 13q14.3 in Leukemia Is Linked to the Downregulation of a Gene Cluster That Targets NF-kB

- A Big Catch for Germ Cell Tumour Research

- The Quest for the Identification of Genetic Variants in Unexplained Cardiac Arrest and Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation

- A Nonsynonymous Polymorphism in as a Risk Factor for Human Unexplained Cardiac Arrest with Documented Ventricular Fibrillation

- The Hourglass and the Early Conservation Models—Co-Existing Patterns of Developmental Constraints in Vertebrates

- Smaug/SAMD4A Restores Translational Activity of CUGBP1 and Suppresses CUG-Induced Myopathy

- Balancing Selection on a Regulatory Region Exhibiting Ancient Variation That Predates Human–Neandertal Divergence

- The G4 Genome

- Extensive Natural Epigenetic Variation at a Originated Gene

- Mouse Oocyte Methylomes at Base Resolution Reveal Genome-Wide Accumulation of Non-CpG Methylation and Role of DNA Methyltransferases

- The Environment Affects Epistatic Interactions to Alter the Topology of an Empirical Fitness Landscape

- TIP48/Reptin and H2A.Z Requirement for Initiating Chromatin Remodeling in Estrogen-Activated Transcription

- Aconitase Causes Iron Toxicity in Mutants

- Tbx2 Terminates Shh/Fgf Signaling in the Developing Mouse Limb Bud by Direct Repression of

- Mondo/ChREBP-Mlx-Regulated Transcriptional Network Is Essential for Dietary Sugar Tolerance in

- Sex-Differential Selection and the Evolution of X Inactivation Strategies

- Identification of a Tissue-Selective Heat Shock Response Regulatory Network

- Phosphorylation-Coupled Proteolysis of the Transcription Factor MYC2 Is Important for Jasmonate-Signaled Plant Immunity

- RpoS Plays a Central Role in the SOS Induction by Sub-Lethal Aminoglycoside Concentrations in

- Six Homeoproteins Directly Activate Expression in the Gene Regulatory Networks That Control Early Myogenesis

- Rtt109 Prevents Hyper-Amplification of Ribosomal RNA Genes through Histone Modification in Budding Yeast

- ATP-Dependent Chromatin Remodeling by Cockayne Syndrome Protein B and NAP1-Like Histone Chaperones Is Required for Efficient Transcription-Coupled DNA Repair

- Iron-Responsive miR-485-3p Regulates Cellular Iron Homeostasis by Targeting Ferroportin

- Mutations in Predispose Zebrafish and Humans to Seminomas

- Cytotoxic Chromosomal Targeting by CRISPR/Cas Systems Can Reshape Bacterial Genomes and Expel or Remodel Pathogenicity Islands

- Tissue Homeostasis in the Wing Disc of : Immediate Response to Massive Damage during Development

- All SNPs Are Not Created Equal: Genome-Wide Association Studies Reveal a Consistent Pattern of Enrichment among Functionally Annotated SNPs

- Functional 358Ala Allele Impairs Classical IL-6 Receptor Signaling and Influences Risk of Diverse Inflammatory Diseases

- The Tissue-Specific RNA Binding Protein T-STAR Controls Regional Splicing Patterns of Pre-mRNAs in the Brain

- Neutral Genomic Microevolution of a Recently Emerged Pathogen, Serovar Agona

- Genetic Requirements for Signaling from an Autoactive Plant NB-LRR Intracellular Innate Immune Receptor

- SNF5 Is an Essential Executor of Epigenetic Regulation during Differentiation

- Dialects of the DNA Uptake Sequence in

- Reference-Free Population Genomics from Next-Generation Transcriptome Data and the Vertebrate–Invertebrate Gap

- Senataxin Plays an Essential Role with DNA Damage Response Proteins in Meiotic Recombination and Gene Silencing

- High-Resolution Mapping of Spontaneous Mitotic Recombination Hotspots on the 1.1 Mb Arm of Yeast Chromosome IV

- Rod Monochromacy and the Coevolution of Cetacean Retinal Opsins

- Evolution after Introduction of a Novel Metabolic Pathway Consistently Leads to Restoration of Wild-Type Physiology

- Disruption of TTDA Results in Complete Nucleotide Excision Repair Deficiency and Embryonic Lethality

- Insulators Target Active Genes to Transcription Factories and Polycomb-Repressed Genes to Polycomb Bodies

- Signatures of Diversifying Selection in European Pig Breeds

- The Chromosomal Passenger Protein Birc5b Organizes Microfilaments and Germ Plasm in the Zebrafish Embryo

- The Histone Demethylase Jarid1b Ensures Faithful Mouse Development by Protecting Developmental Genes from Aberrant H3K4me3

- Regulates Synaptic Development and Endocytosis by Suppressing Filamentous Actin Assembly

- Sensory Neuron-Derived Eph Regulates Glomerular Arbors and Modulatory Function of a Central Serotonergic Neuron

- Analysis of Rare, Exonic Variation amongst Subjects with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Population Controls

- Scavenger Receptors Mediate the Role of SUMO and Ftz-f1 in Steroidogenesis

- DNA Double-Strand Breaks Coupled with PARP1 and HNRNPA2B1 Binding Sites Flank Coordinately Expressed Domains in Human Chromosomes

- High-Resolution Mapping of H1 Linker Histone Variants in Embryonic Stem Cells

- Comparative Genomics of and the Bacterial Species Concept

- Genetic and Biochemical Assays Reveal a Key Role for Replication Restart Proteins in Group II Intron Retrohoming

- Genome-Wide Association Studies Identify Two Novel Mutations Responsible for an Atypical Hyperprolificacy Phenotype in Sheep

- The Genetic Correlation between Height and IQ: Shared Genes or Assortative Mating?

- Comprehensive Assignment of Roles for Typhimurium Genes in Intestinal Colonization of Food-Producing Animals

- An Essential Role for Zygotic Expression in the Pre-Cellular Drosophila Embryo

- The Genome Organization of Reflects Its Lifestyle

- Coordinated Cell Type–Specific Epigenetic Remodeling in Prefrontal Cortex Begins before Birth and Continues into Early Adulthood

- Improved Detection of Common Variants Associated with Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder Using Pleiotropy-Informed Conditional False Discovery Rate

- Site-Specific Phosphorylation of the DNA Damage Response Mediator Rad9 by Cyclin-Dependent Kinases Regulates Activation of Checkpoint Kinase 1

- Npc1 Acting in Neurons and Glia Is Essential for the Formation and Maintenance of CNS Myelin

- Identification of , a Retrotransposon-Derived Imprinted Gene, as a Novel Driver of Hepatocarcinogenesis

- Aag DNA Glycosylase Promotes Alkylation-Induced Tissue Damage Mediated by Parp1

- DJ-1 Decreases Neural Sensitivity to Stress by Negatively Regulating Daxx-Like Protein through dFOXO

- Asynchronous Replication, Mono-Allelic Expression, and Long Range -Effects of

- Differential Association of the Conserved SUMO Ligase Zip3 with Meiotic Double-Strand Break Sites Reveals Regional Variations in the Outcome of Meiotic Recombination

- Focusing In on the Complex Genetics of Myopia

- Continent-Wide Decoupling of Y-Chromosomal Genetic Variation from Language and Geography in Native South Americans

- Breakpoint Analysis of Transcriptional and Genomic Profiles Uncovers Novel Gene Fusions Spanning Multiple Human Cancer Types

- Intrinsic Epigenetic Regulation of the D4Z4 Macrosatellite Repeat in a Transgenic Mouse Model for FSHD

- Bisphenol A Exposure Disrupts Genomic Imprinting in the Mouse

- Genetic and Genomic Architecture of the Evolution of Resistance to Antifungal Drug Combinations

- Transposable Elements Are Major Contributors to the Origin, Diversification, and Regulation of Vertebrate Long Noncoding RNAs

- Functional Dissection of the Condensin Subunit Cap-G Reveals Its Exclusive Association with Condensin I

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- The G4 Genome

- Neutral Genomic Microevolution of a Recently Emerged Pathogen, Serovar Agona

- The Histone Demethylase Jarid1b Ensures Faithful Mouse Development by Protecting Developmental Genes from Aberrant H3K4me3

- The Tissue-Specific RNA Binding Protein T-STAR Controls Regional Splicing Patterns of Pre-mRNAs in the Brain

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání