-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

SUMO Localizes to the Central Element of Synaptonemal Complex and Is Required for the Full Synapsis of Meiotic Chromosomes in Budding Yeast

The synaptonemal complex (SC) is a widely conserved structure that mediates the intimate alignment of homologous chromosomes during meiotic prophase and is required for proper homolog segregation at meiosis I. However, fundamental details of SC architecture and assembly remain poorly understood. The coiled-coil protein, Zip1, is the only component whose arrangement within the mature SC of budding yeast has been extensively characterized. It has been proposed that the Small Ubiquitin-like MOdifier, SUMO, plays a role in SC assembly by linking chromosome axes with Zip1's C termini. The role of SUMO in SC structure has not been directly tested, however, because cells lacking SUMO are inviable. Here, we provide direct evidence for SUMO's function in SC assembly. A meiotic smt3 reduction-of-function strain displays reduced sporulation, abnormal levels of crossover recombination, and diminished SC assembly. SC structures are nearly absent when induced at later meiotic time points in the smt3 reduction-of-function background. Using Structured Illumination Microscopy we furthermore determine the position of SUMO within budding yeast SC structure. In contrast to previous models that positioned SUMO near Zip1's C termini, we demonstrate that SUMO lies at the midline of SC central region proximal to Zip1's N termini, within a subdomain called the “central element”. The recently identified SUMOylated SC component, Ecm11, also localizes to the SC central element. Finally, we show that SUMO, Ecm11, and even unSUMOylatable Ecm11 exhibit Zip1-like ongoing incorporation into previously established SCs during meiotic prophase and that the relative abundance of SUMO and Ecm11 correlates with Zip1's abundance within SCs of varying Zip1 content. We discuss a model in which central element proteins are core building blocks that stabilize the architecture of SC near Zip1's N termini, and where SUMOylation may occur subsequent to the incorporation of components like Ecm11 into an SC precursor structure.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003837

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003837Summary

The synaptonemal complex (SC) is a widely conserved structure that mediates the intimate alignment of homologous chromosomes during meiotic prophase and is required for proper homolog segregation at meiosis I. However, fundamental details of SC architecture and assembly remain poorly understood. The coiled-coil protein, Zip1, is the only component whose arrangement within the mature SC of budding yeast has been extensively characterized. It has been proposed that the Small Ubiquitin-like MOdifier, SUMO, plays a role in SC assembly by linking chromosome axes with Zip1's C termini. The role of SUMO in SC structure has not been directly tested, however, because cells lacking SUMO are inviable. Here, we provide direct evidence for SUMO's function in SC assembly. A meiotic smt3 reduction-of-function strain displays reduced sporulation, abnormal levels of crossover recombination, and diminished SC assembly. SC structures are nearly absent when induced at later meiotic time points in the smt3 reduction-of-function background. Using Structured Illumination Microscopy we furthermore determine the position of SUMO within budding yeast SC structure. In contrast to previous models that positioned SUMO near Zip1's C termini, we demonstrate that SUMO lies at the midline of SC central region proximal to Zip1's N termini, within a subdomain called the “central element”. The recently identified SUMOylated SC component, Ecm11, also localizes to the SC central element. Finally, we show that SUMO, Ecm11, and even unSUMOylatable Ecm11 exhibit Zip1-like ongoing incorporation into previously established SCs during meiotic prophase and that the relative abundance of SUMO and Ecm11 correlates with Zip1's abundance within SCs of varying Zip1 content. We discuss a model in which central element proteins are core building blocks that stabilize the architecture of SC near Zip1's N termini, and where SUMOylation may occur subsequent to the incorporation of components like Ecm11 into an SC precursor structure.

Introduction

Chromosomes must form enduring attachments with their homologous partners in order to successfully orient and segregate during the first meiotic division. Such pair-wise chromosomal attachments are ultimately generated by interhomolog crossover recombination events, which occur through the repair of programmed, double-stranded DNA breaks using the homologous partner chromosome [1], [2], [3]. The synaptonemal complex (SC), a multimeric protein structure that normally assembles downstream of initial homology recognition between partner chromosomes, mediates the close, lengthwise apposition of homologous chromosomes (synapsis) during mid-meiotic prophase and is required for a proper number and distribution of interhomolog crossover recombination events [4].

Fundamental details of SC structure and its assembly remain poorly understood. Ultrastructural studies in several different organisms led to the description of at least three substructures that define SC [5], [6]: first, a synapsed pair of chromosomes exhibit two electron dense structures, termed lateral elements, that lie in parallel to one another. Lateral elements correspond to the axial cores of each homolog which organize and maintain cohesion between sister chromatids, and which contain several meiosis-specific components, including the Red1 protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (budding yeast) [7]. A less electron-dense domain, called the central region, connects lateral elements of aligned homologs along their entire length. In many preparations, two distinct substructures within the SC central region itself are visible: transverse filaments are oriented perpendicular to lateral elements and span the central region, while a structure called the central element is oriented in parallel to lateral elements at the midline of the SC central region.

Proteins that localize to SC have been identified in several different organisms. However, despite an overall conservation of SC structure among different organisms, the lack of sequence homology between SC proteins belonging to different species means that substantial cytological and genetic characterization must be gathered for each identified SC protein, in order to determine its position within the higher order SC structure and its role in SC assembly. One conserved molecular aspect of SC among organisms is found in the secondary structure of transverse filament proteins; these components contain extensive coiled-coil motif and are predicted to form parallel homodimers [4]. Dimers of the S. cerevisiae transverse filament protein, Zip1, are predicted to generate a ∼50–80 nm rod with globular ends [8], [9]. In elegant immuno-electron microscopy experiments using Zip1 domain-specific antibodies, Dong and Roeder (2000) demonstrated that two Zip1 coiled-coil units (either dimers or tetramers) span the width of the SC, with their N termini interacting at the center of the structure and their C termini oriented toward chromosome axes [10]. Similar immuno-EM localization experiments have supported this overall structural orientation for transverse filament proteins in both Drosophila (C(3)G) and mammals (Syp1) [11], [12], [13].

Additional proteins that localize to SC but do not contain coiled-coil have been identified in yeast and other organisms [4], [11], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]. For instance, four proteins (SYCE1, SYCE2, SYCE3, TEX12) have been found to localize to the central element structure at the midline of the SC in mouse [15], [16], [18], [22], [23]. Loss-of-function of any of these proteins results in abolished or fragmented SC assembly but, in some cases, no defect in the localization of transverse filament proteins to chromosomes per se, suggesting that an interaction between central element proteins and transverse filaments is essential to drive the multimeric assembly of mature SC. Consistent with this idea, Jeffress et al. (2007) found that the N terminal region of the Drosophila transverse filament protein, C(3)G, is dispensable for the loading of C(3)G onto meiotic chromosomes but is critical for SC assembly [24]. Proteins defining the central element in budding yeast have not been identified to date.

The Small Ubiquitin-like MOdifier protein, SUMO, robustly localizes coincident with Zip1 and in a Zip1-dependent manner at the interface of length-wise aligned, synapsed chromosomes in budding yeast prophase nuclei [19] and thus may serve a structural or regulatory role in SC assembly. A role for SUMO in SC formation was suggested by the observation that a tagged version of the E2 SUMO ligase, Ubc9, results in disrupted SC assembly [19]. Moreover, several reports have suggested that SUMO or SUMO chains link Zip1's C termini to chromosome axes through an interaction between SUMOylated Red1 (a meiotic chromosomal core component) and Zip1's C terminal SUMO Interacting Motif (SIM) [25], [26], [27], [28], although one of these studies provided evidence that strains expressing an unSUMOylatable red1 allele did not have SC assembly defects [27]. A direct functional role for SUMO in SC assembly or structure has not been rigorously demonstrated.

Here we directly investigate the role of SUMO in budding yeast SC assembly. We find that SUMO and Zip1 are dependent on one another for full synapsis, while SUMO is likely dispensable for Zip1 polycomplex formation. Consistent with our SUMO loss-of-function analysis, the SUMOylated SC component Ecm11 was recently shown to be required for SC assembly [29], [30], [31]. We furthermore report that like Zip1, SUMO and Ecm11-MYC continuously incorporate into full-length SC during meiotic prophase. Finally, using superresolution microscopy we demonstrate that SUMO and the SUMOylated Ecm11 protein predominantly localize to a discrete zone corresponding to the central element of the SC. This latter observation challenges the idea that SUMO interacts with Zip1's C terminal domain within assembled SC, and adds to the accumulating evidence that central element proteins play a conserved role in facilitating the assembly and/or maintenance of the mature SC structure.

Results

SUMO-Diminished Meiotic Cells Progress to Late Prophase but Exhibit a PCH2-Dependent Decline in Sporulation Efficiency

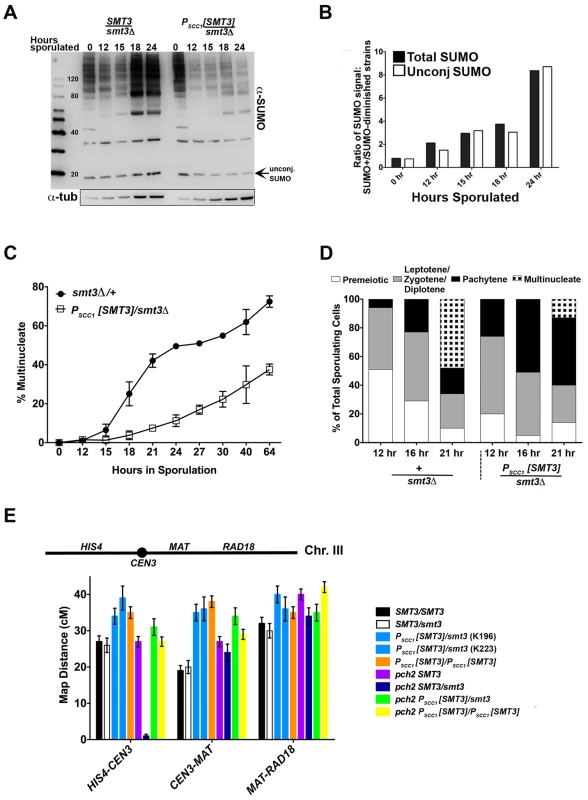

A diploid strain (LFT46) was created in which SMT3 (encoding the SUMO precursor protein) on one chromosome is under the control of the mitosis-specific MCD1/SCC1 promoter [32], [33], [34] while the other SMT3 copy is deleted. The level of SUMO signal in lysates from PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells was reduced, relative to +/smt3Δ heterozygous control (LFT36) cells, at 12, 15, 18 and 24 hours during a meiotic time course (Figure 1A, 1B). The difference in SUMO levels between control and experimental strains was progressively greater at later stages of the time course; overall levels of both SUMO-conjugated proteins and unconjugated (free) SUMO were eight fold lower in PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells relative to control cells at 24 hours of sporulation (Figure 1A, B).

Fig. 1. SUMO-diminished strains exhibit reduced sporulation and elevated crossover levels.

(A) Western blot detecting SUMO in lysates from control (smt3Δ/+, LFT36) and SUMO-diminished (PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ, LFT46) cells at 0, 12, 15 18 and 24 hours of sporulation. Bar graph in (B) gives the ratio of conjugated SUMO protein levels in LFT36 over conjugated SUMO protein levels in LFT46 (solid bars), as well as the ratio of unconjugated (free) SUMO levels in LFT36 over LFT46 (open bars) at each time point. (C) smt3Δ/+ (LFT36, closed circles) and PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ (LFT46, open squares) cells were sporulated and then assessed for the formation of multinucleate products over a time course (time points indicated on x axis). (For each strain at any given time point, the average between two independent experiments is indicated (in total, >800 nuclei were scored for each timepoint.) In (D), control and PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells were sporulated and surface spread on glass slides at the time points indicated in order to assess whether SUMO-diminished strains enter into and progress through meiotic prophase efficiently. The fraction of nuclei that had entered meiosis at each time point was recorded based on Red1 staining (not shown), while the fraction of nuclei that had reached the pachytene stage of meiotic prophase (or post-MI) were recorded based on the morphology of the DAPI-stained nucleus. Meiotic (Red1-positive) nuclei without pachytene morphology were grouped as the “Leptotene/Zygotene” (pre-pachytene) or “Diplotene” (post-pachytene) category. (E) Cartoon above graph indicates the genetic intervals used to calculate map distances on chromosome III. CEN3 is marked with an adjacent hygromycin resistance cassette and the RAD18 locus is marked with ADE2. Bar graph displays map distances (cM) for the three intervals (x axis) measured in control and SUMO-diminished strains. Error bars represent the standard error of map distance. See Table 2 for precise values and for map distances additionally calculated using tetrad analysis. Spore formation was reduced in PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ (“SUMO-diminished”) cells, as compared to control (smt3Δ/+ heterozygous) cells (13% versus 54%, Table 1). DAPI-stained whole cells that had been paraformaldehyde-fixed at various times during a sporulation time course were also assessed in order to measure the fraction of cells with multinucleate products (including encapsulated spores) at each time point (Figure 1C). Consistent with the defect in spore production, PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cultures exhibited a dramatic reduction in multinucleates at each time point, as compared to the control (SMT3/smt3Δ) strain.

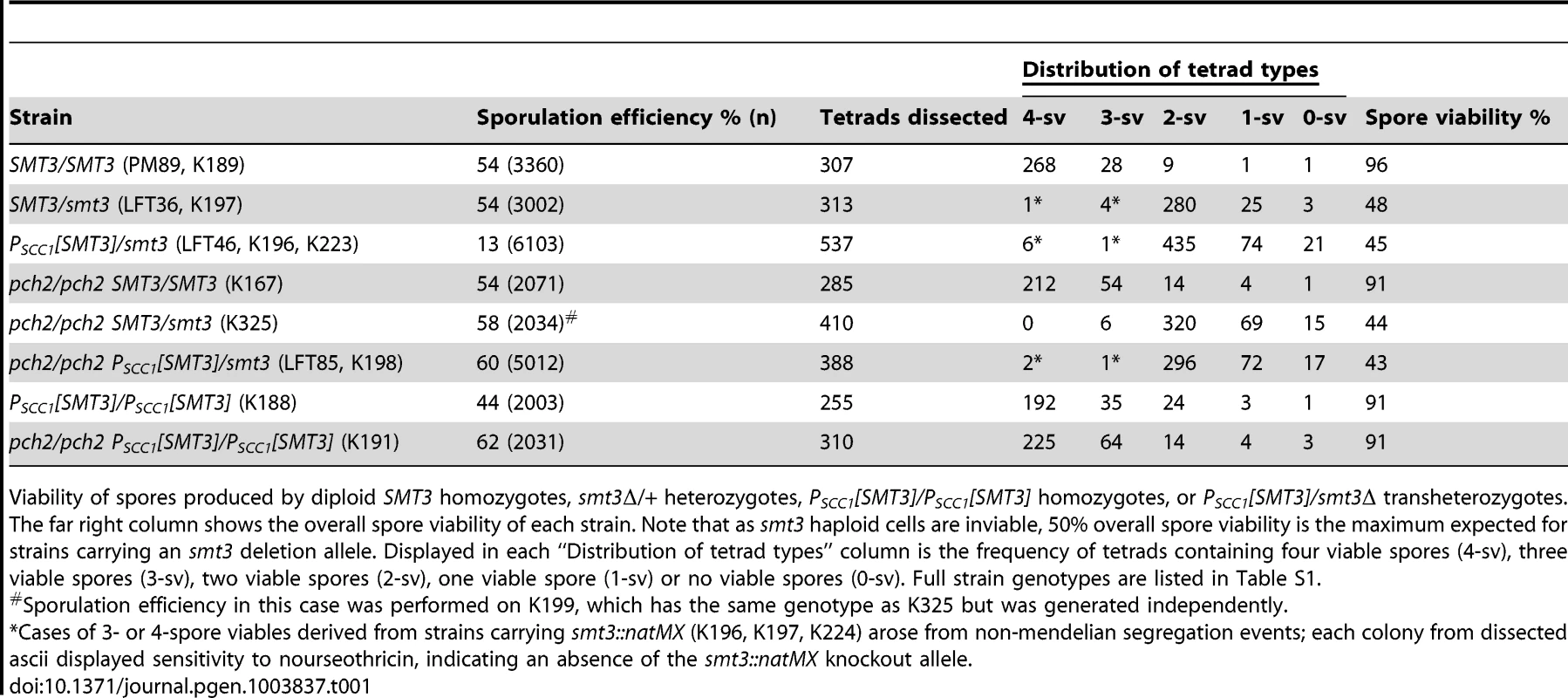

Tab. 1. Sporulation efficiency and spore viability in SUMO-diminished strains.

Viability of spores produced by diploid SMT3 homozygotes, smt3Δ/+ heterozygotes, PSCC1[SMT3]/PSCC1[SMT3] homozygotes, or PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ transheterozygotes. The far right column shows the overall spore viability of each strain. Note that as smt3 haploid cells are inviable, 50% overall spore viability is the maximum expected for strains carrying an smt3 deletion allele. Displayed in each “Distribution of tetrad types” column is the frequency of tetrads containing four viable spores (4-sv), three viable spores (3-sv), two viable spores (2-sv), one viable spore (1-sv) or no viable spores (0-sv). Full strain genotypes are listed in Table S1. The sporulation defect of SUMO-diminished meiotic cells is at least partially explained by a decreased capacity to transition from late prophase to the first meiotic division. We assessed the capacity of cells to progress into and through earlier meiotic prophase stages by assessing DNA morphology and the presence of the meiotic chromosome axis protein, Red1, on chromosome spreads of sporulating cells. We assessed the fraction of surface-spread nuclei from control (SMT3+/smt3Δ) or PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells that had progressed into meiosis (exhibited Red1 staining) at either 12, 16 or 21 hours of sporulation. Based on the morphology of the DAPI-stained nucleus, we could moreover distinguish those nuclei that had progressed to the pachytene stage of meiotic prophase (when homologous chromosomes are lengthwise-aligned and synapsed), and those that had progressed beyond the second meiotic division and had formed encapsulated haploid nuclei. At 12 and 16 hours, we observed an equal or greater fraction of Red1-positive and pachytene stage nuclei in PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ sporulating cells as compared to control cells (Figure 1D, data not shown), indicating that PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells are competent to enter the meiotic program and progress to the pachytene stage without delay. At the 21 hour time point, a deficit in the number of multinucleates was again observed for SUMO-diminished cells.

We also stained surface-spread nuclei from an independent sporulation time course with both Red1 (not shown) and alpha-tubulin antibody (Figure S1), in order to directly assess progression through the first and second meiotic divisions in control and PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells. The diplotene stage can be distinguished from leptotene/zygotene (pre-pachytene meiotic stages) based on the presence of a duplicated spindle pole body, revealed by alpha-tubulin staining [35], [36], [37]. We analyzed the fraction of Red1-positive nuclei that were either in pre-pachytene or pachytene, diplotene, MI or MII stages in wild type or PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells at 15, 20 or 24 hours of sporulation. Encapsulated spores were not included in this analysis. We found a dramatic reduction in the number of meiotic nuclei containing MI or MII spindles in PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells (Figure S1B). Instead, the vast majority of meiotic nuclei analyzed from SUMO-diminished cells appeared to be in pre-pachytene or pachytene stages.

Taken together, these analyses indicate that PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells efficiently progress to the pachytene stage of meiosis, but are delayed in progressing from the pachytene stage of meiotic prophase into meiosis I.

Pch2 enforces a late prophase meiotic checkpoint that is triggered by defects in recombination and synapsis [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]. For example, zip1 mutants fail to build SC and exhibit reduced levels of crossover recombination and are delayed in progressing from late prophase into meiosis I [8]. However, pch2 zip1 double mutants progress through the meiotic divisions and generate spores at wild-type levels [40]. In order to ask whether PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells trigger a Pch2-dependent checkpoint, we assessed sporulation efficiency of a PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3 pch2Δ/pch2Δ strain (LFT85). Indeed, deletion of PCH2 improved spore formation in PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells (60% in pch2 versus 13% in PCH2+, Table 1). This phenotype may reflect a role for SUMO in either SC assembly or in meiotic recombination.

The overall viability of spores produced by PCH2+ or pch2 Δ PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ strains was not significantly different from control cells (Table 1). However, in (PCH2+) PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ versus smt3Δ/+ strains, the fraction of 2-spore viable tetrad types was significantly reduced (two sided P value = 0.0013, Fisher's Exact test), and the fraction of 0 - and 1-spore viables among the total spores was significantly increased (two-sided P value = 0.0004 for the 0 - and 1-spore viable classes combined, Fisher's Exact test).

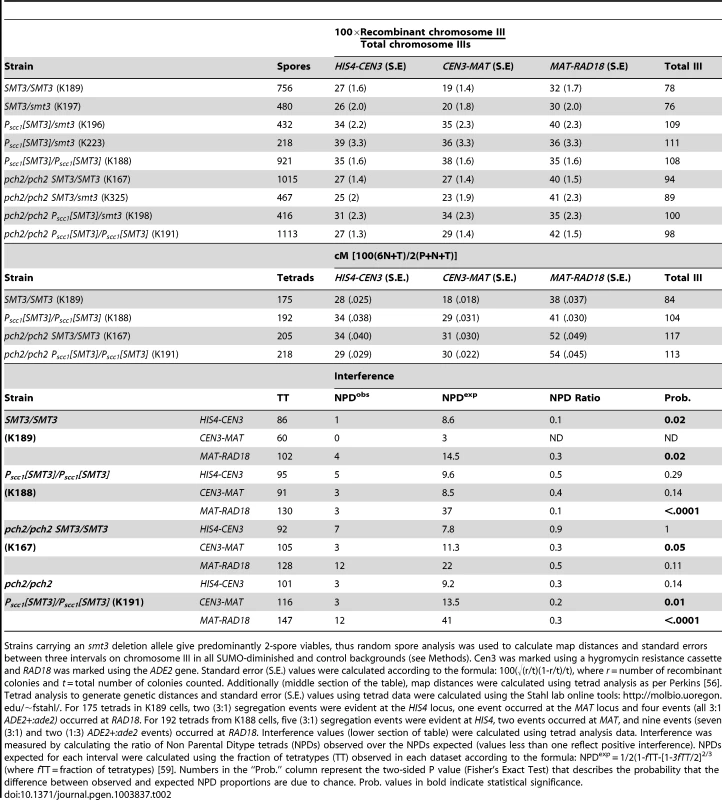

SUMO-Diminished Strains Exhibit Increased Crossover Recombination on Chromosome III

Interhomolog crossover recombination was assessed using three intervals on chromosome III in SMT3+, +/smt3Δ, and PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ strains as well as PSCC1[SMT3]/PSCC1[SMT3] homozygotes. As only 2-spore viable products result from most meioses in strains carrying an SMT3 deletion, we calculated crossover recombination frequency by measuring the fraction of colonies carrying a recombinant chromosome among the total population of viable colonies (Figure 1E, Table 2). Map distances for each interval on chromosome III were 1.2–1.5-fold increased in both PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ and PSCC1[SMT3]/PSCC1[SMT3] backgrounds relative to SMT3+ and +/smt3Δ control strains.

Tab. 2. Chromosome III map distances in SUMO-diminished strains.

Strains carrying an smt3 deletion allele give predominantly 2-spore viables, thus random spore analysis was used to calculate map distances and standard errors between three intervals on chromosome III in all SUMO-diminished and control backgrounds (see Methods). Cen3 was marked using a hygromycin resistance cassette and RAD18 was marked using the ADE2 gene. Standard error (S.E.) values were calculated according to the formula: 100(√(r/t)(1-r/t)/t), where r = number of recombinant colonies and t = total number of colonies counted. Additionally (middle section of the table), map distances were calculated using tetrad analysis as per Perkins [56]. Tetrad analysis to generate genetic distances and standard error (S.E.) values using tetrad data were calculated using the Stahl lab online tools: http://molbio.uoregon.edu/~fstahl/. For 175 tetrads in K189 cells, two (3∶1) segregation events were evident at the HIS4 locus, one event occurred at the MAT locus and four events (all 3∶1 ADE2+:ade2) occurred at RAD18. For 192 tetrads from K188 cells, five (3∶1) segregation events were evident at HIS4, two events occurred at MAT, and nine events (seven (3∶1) and two (1∶3) ADE2+:ade2 events) occurred at RAD18. Interference values (lower section of table) were calculated using tetrad analysis data. Interference was measured by calculating the ratio of Non Parental Ditype tetrads (NPDs) observed over the NPDs expected (values less than one reflect positive interference). NPDs expected for each interval were calculated using the fraction of tetratypes (TT) observed in each dataset according to the formula: NPDexp = 1/2(1-fTT-[1-3fTT/2]2/3 (where fTT = fraction of tetratypes) [59]. Numbers in the “Prob.” column represent the two-sided P value (Fisher's Exact Test) that describes the probability that the difference between observed and expected NPD proportions are due to chance. Prob. values in bold indicate statistical significance. We additionally measured map distances in SMT3+ and PSCC1[SMT3]/PSCC1[SMT3] strains using standard tetrad analysis (Table 2, middle section). This assessment also found an increase in interhomolog crossover recombination for PSCC1[SMT3]/PSCC1[SMT3] relative to SMT3+ strains.

We assessed interhomolog crossover recombination in SMT3+ and SUMO-diminished strains homozygous for a pch2 null allele, the mutation that suppresses the sporulation defect associated with SUMO-diminishment (see above). All pch2 mutant strains (controls and SUMO-diminished) exhibited elevated levels of interhomolog crossover events, relative to PCH2+ strains, in the three chromosome III intervals assessed. In the absence of Pch2, SMT3+ and SUMO-diminished strains exhibited less disparity in genetic distances on III, and in cases where a difference in map distance is observed there lacks a consistent pattern in the direction of recombination levels relative to controls.

Notably, tetrad analysis on pch2 SMT3+ versus pch2 PSCC1[SMT3]/PSCC1[SMT3] strains (Table 2, middle section) showed no significant alteration in map distances on any of the three chromosome III intervals, whereas a significant increase in map distance was found for all three intervals on III for PCH2+ PSCC1[SMT3]/PSCC1[SMT3], relative to SMT3+ strains.

Crossover recombination events during meiosis typically exhibit positive interference, meaning their distribution is such that no two crossovers occur close together. The SC is involved in achieving crossover interference, as the residual crossovers that occur in synapsis-defective mutants do not exhibit positive interference [43]. We analyzed crossover interference in control and PSCC1[SMT3] homozygotes using our tetrad analysis data (Table 2, lower section; see legend for methods). Our analysis of this dataset revealed that the interhomolog crossovers in all strains tested exhibit interference, although the statistical significance of interference values was weaker in some intervals (reflecting a higher probability that crossovers exhibit an interfering distribution due to chance) for PSCC1[SMT3] homozygotes and both pch2 strains, relative to the PCH2+ SMT3+ control.

Taken together, our recombination data indicate that SUMO-diminishment leads to an increase in interhomolog crossover recombination events, and further raise the possibility that Pch2 and SUMO may negatively regulate interhomolog crossovers in a similar pathway.

SUMO Is Required for Full SC Assembly

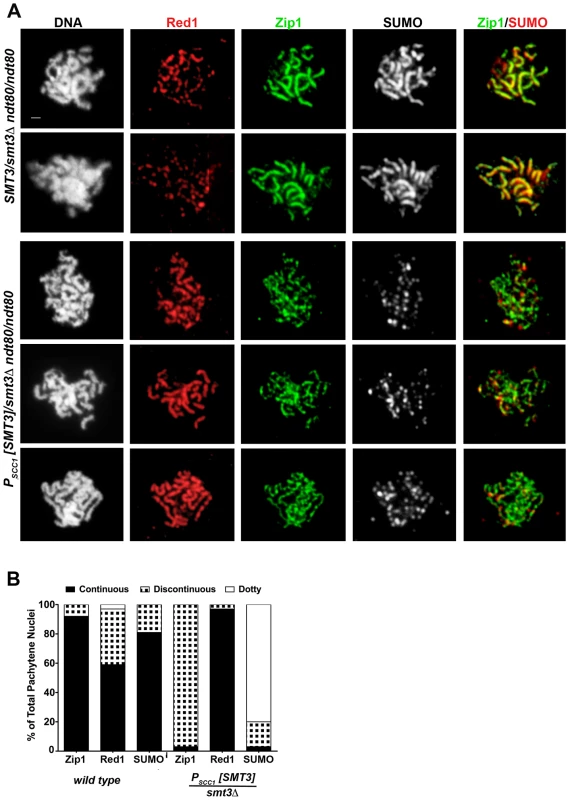

If they comprise equally fundamental structural components of SC central region, then SUMO and Zip1 may be mutually dependent on one another for their function in SC assembly. In order to directly ask whether SC assembly relies on SUMO, we analyzed Zip1 distribution on chromosomes in nuclei from PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ (LFT47) or control (smt3Δ/+, LFT37) cells after ∼24 hours of sporulation. In this analysis, both experimental and control strains were homozygous for a gene encoding the tagged version of Zip1, ZIP1-GFP [44], and for an ndt80 null allele. NDT80 activity is required for progression beyond the pachytene stage, when chromosomes exhibit full-length SC. Thus, after 24 hours of sporulation most nuclei from ndt80 homozygous strains have progressed to the pachytene stage.

As has been previously reported, surface-spread pachytene stage nuclei from control cells exhibit extensive linear stretches of Zip1-GFP coincident with SUMO at the interface of synapsed homologous chromosomes, while the meiotic chromosome axis protein, Red1, often (∼40% of the time in this analysis, n = 50) exhibits a more discontinuous staining pattern along the same interface [7], [19], [45] (Figure 2). Nuclei from PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells that had been sporulating for ∼24 hours typically exhibited foci or faint short stretches of SUMO on pachytene chromosomes (Figure 2A), indicating that SUMO is indeed diminished in these meiotic cells. Zip1 linear stretches appeared more abundantly than SUMO linear stretches on chromosome spreads from PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells, but the linear Zip1 we observed appeared abnormally discontinuous and narrow. Furthermore, Red1 appeared continuous along chromosome axes more frequently than in control nuclei (Figure 2B), reminiscent of the phenotype exhibited by the zip1 null mutant [7].

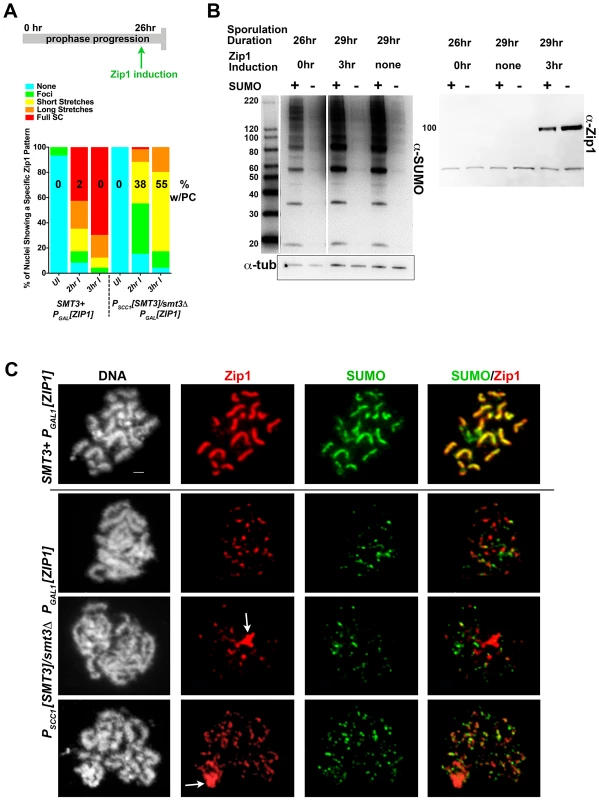

Fig. 2. SC appears discontinuous in SUMO-diminished pachytene nuclei.

(A) Shown are surface-spread meiotic nuclei from smt3Δ/+ (LFT37) and PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ (LFT47) ndt80/ndt80 strains that had been sporulated for 24 hours. DAPI (white, first column) and antibodies to Red1 (red), Zip1 (green), SUMO (white, 3rd column; red, 4th column) were used to stain nuclei and assess SC formation. Scale, 1 µm. (B) displays the percentage of nuclei (n>50 per column) from control or SUMO-diminished strains that exhibit either continuous (black), discontinuous (black/white hatched), or dotty pattern of Zip1, Red1, or SUMO staining. The abnormal Zip1 and Red1 staining patterns exhibited by PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ nuclei suggest a role for SUMO in SC assembly or maintenance. However, since the extent of SUMO-depletion in PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells depends upon the turnover of SUMO and SUMO-conjugated products formed during vegetative growth (when SMT3 is expressed in this background), the degree of SUMO-diminishment may vary depending on the timing of progression of individual cells through meiosis. Thus, the discontinuous Zip1 phenotype we observed on pachytene chromosomes in SUMO-diminished meiotic cells might reflect a mild phenotype caused by a partial reduction in SUMO during meiotic prophase.

In order to maximally diminish SUMO prior to assessing the consequences for SC assembly, we next utilized an inducible Zip1 system. As we previously reported, meiotic chromosomes that have been held at a late prophase arrest in ndt80 mutant cells are capable of de novo SC assembly after ZIP1 expression is induced, even after 26 hours of sporulation in the absence of ZIP1 [46]. We used this inducible ZIP1 system to assess whether meiotic cells, held in sporulation media for 26 hours with diminished SMT3 expression, are capable of assembling SC de novo on chromosomes. SUMO levels in SUMO-diminished (LFT65) lysates from 26 hour, sporulating cultures of our Zip1-induction strains showed up to an eight fold reduction in SUMO conjugates, as compared to the analogous SMT3+ strain (Figure 3B).

Fig. 3. Induced Zip1 assembles full SC stretches in a SUMO-dependent manner.

Cartoon in (A) depicts the Zip1 induction experiment conducted, as described ([46], this work) using LFT51 (control) and LFT65 (sumo-diminished) strains. Bar graph indicates the extent of SC assembly (Zip1 staining) on chromosomes at each time point following induction (n>50 for each time point). Number on each column indicates the percentage of each set of nuclei that exhibit a polycomplex (Zip1 aggregate) structure. Western blots in (B) show SUMO levels in cellular lysates from the sporulated cells in this experiment (left blot; SUMO signal is 2–8 fold reduced in SUMO-diminished as compared to SMT3+ cells) and Zip1 levels in uninduced and induced strains (right blot; Zip1 runs at ∼100 kD, whereas the lower band is nonspecific). (C) Examples of meiotic surface-spread chromosomes from each strain after induction of ZIP1 expression. Chromosome spreads have been labeled with DAPI (DNA, white), antibodies to Zip1 (red) and SUMO (green). Arrows indicate polycomplex structures. Scale, 1 µm. As previously observed, ndt80 homozygous cells carrying ZIP1 under the control of a ß-estradiol-inducible PGAL1 system exhibit a zip1-like meiotic chromosome phenotype at 26 hours of sporulation in the absence of ß-estradiol [46]. Little Zip1 was detected and SUMO antibodies labeled only foci on chromosome spreads from uninduced cultures of both control and SUMO-diminished genotypes (data not shown).

Control and SUMO-diminished ndt80 cells carrying inducible ZIP1 were sporulated for 26 hours and then exposed to ß-estradiol in order to induce ZIP1 expression. Two hours after induction, surface-spread chromosomes from many control cells (LFT51) exhibited extensive Zip1 with coincident SUMO linear assemblies (Figure 3A, C). In contrast, Zip1 was dramatically reduced on meiotic chromosomes from PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells carrying the ZIP1 inducible system (LFT65). Even after 3 hours of ZIP1 induction, most SUMO-diminished meiotic nuclei exhibited only Zip1 foci, or short Zip1 linear stretches that were often unassociated with a SUMO signal (Figure 3A,C). We assessed the organization of Zip1 within these short Zip1 stretches that were sometimes observed in SUMO-diminished nuclei with induced Zip1 and found that they do not reflect normal SC structure; Structured Illumination microscopy (see below, Figure S2) indicated that, unlike control cells where antibodies targeting the C termini of Zip1 often appear as parallel tracts, Zip1-C antibodies decorate chromosomes only as foci or short, single tracts on chromosomes in PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells carrying the ZIP1 inducible system (Figure S2). We conclude that Zip1 can associate with chromosomes but is not capable of forming mature SC in the vast majority of SUMO-diminished cells with induced Zip1.

Zip1 Polycomplex Forms in spo11 Mutants with Diminished SUMO

Zip1 aggregates, resembling the polycomplexes that are a hallmark of strains with a defect in synapsis, were frequently observed in PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells carrying the ZIP1 inducible system but rarely observed in control nuclei (55% versus <2%, respectively; Figure 3A, C). Interestingly, SUMO was typically undetectable in such Zip1 polycomplexes.

We additionally examined Zip1 polycomplexes in spo11 strains carrying PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ (LFT61, Figure S3). Zip1 polycomplexes were displayed by approximately half of the nuclei examined in control (SMT3+) or PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ strains (n>50). Similar to the Zip1 aggregates formed in SUMO-diminished cells with induced Zip1, Zip1 polycomplexes in nuclei from SUMO-diminished spo11 cells were typically devoid of detectable SUMO.

Taken together, our observations suggest that the elaboration of mature, stable SC structure in budding yeast relies on SUMO. However, since SUMO-free Zip1 might assemble short structures on chromatin and as polycomplex-like aggregates, SUMO may not be required for Zip1 aggregation per se. We note, however, that Zip1 structures in SUMO-diminished cells might associate with a level of SUMO that is undetectable under our immuno-staining conditions.

SUMO-Diminished Cells Exhibit Abnormal Ecm11-MYC Distribution on Meiotic Chromosomes

Ecm11-MYC was recently identified as a SUMOylated protein that both localizes to budding yeast SC in a Zip1-dependent manner and is required for full-length SC formation [29]. Thus, we assessed Ecm11-MYC distribution on meiotic chromosomes in our SUMO-diminished strain backgrounds.

Western blot analysis revealed that overall levels of SUMO-conjugated Ecm11-MYC were dramatically reduced, and overall levels of the unSUMOylated form of Ecm11-MYC were modestly reduced in PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ strains relative to SMT3+ strains (both homozygous for an ndt80 deletion) at multiple time points during a sporulation time course (Figure S4A, B).

Meiotic nuclei from SMT3+ and PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ ndt80/ndt80 cells that had been sporulating for 24 hours were surface spread and analyzed for Ecm11-MYC, Zip1 and SUMO distribution. In contrast to control cells which exhibited linear stretches of Ecm11-MYC coincident with Zip1 staining, both Zip1 and Ecm11-MYC exhibited a discontinuous, dotty distribution on pachytene stage chromosomes at 24 hours of sporulation in PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ ndt80/ndt80 homozygotes (Figure S4C, D). The Zip1 distribution on chromosomes from SUMO-diminished cells expressing ECM11-MYC appeared even more discontinuous, on average, than the Zip1 distribution on chromosomes in SUMO-diminished cells without ECM11-MYC (Figure 2), suggesting the possibility that SC assembly in the presence of Ecm11-MYC may be sensitized to SUMO-diminishment. Foci and short stretches of Zip1 and Ecm11 often localized adjacent or overlapping one another, however we often observed Ecm11 staining devoid of Zip1 and Zip1 devoid of Ecm11 in nuclei from PSCC1[SMT3]/smt3Δ cells.

Next we examined the distribution of both Ecm11-MYC and an unSUMOylatable version of Ecm11, Ecm11(K5R,K101R)-MYC [29], on meiotic chromosomes from SUMO-diminished and control strains in the context of our Zip1 induction system (Figure S5). As described above, inducible ZIP1 allows us to characterize SC assembly after maximal turnover of SUMO-conjugated proteins (when examining SUMO-diminished genotypes). In these experiments, which are analogous to the experiment shown in Figure 3, ZIP1 expression under the control of a ß-estradiol-sensitive PGAL1 system is induced after 24–25 hours of sporulation in ndt80-arrested cells homozygous for ECM11-MYC, and newly induced SCs are analyzed for Zip1 and Ecm11 distribution on chromosomes. After three hours of Zip1 induction in SMT3+ strains, many full-length SC stretches were observed on meiotic chromosomes and the distribution of Ecm11-MYC was linear and coincident with Zip1 in these SC stretches. In SUMO-diminished strains, on the other hand, both Zip1 and Ecm11-MYC formed foci and very short stretches on meiotic chromosomes. Ecm11-MYC occasionally overlapped Zip1 but often localized independent of a Zip1 entity on these meiotic chromosomes (Figure S5B).

The defects in Ecm11 distribution on meiotic chromosomes that we observe in SUMO-diminished cells, both in an otherwise normal meiosis or in the context of induced Zip1, strengthen the idea that assembly of normal budding yeast SC structure is dependent on SUMO.

Since strains homozygous for the unSUMOylatable ecm11 allele are defective in Zip1 assembly [29], we expected that Zip1 would fail to assemble SC after ZIP1 induction in cells homozygous for ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC. Indeed, after three hours of ZIP1 induction in ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC strains, the distribution of both Ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC and Zip1 was dotty on chromosomes (Figure S5A). In SUMO-diminished strains carrying inducible ZIP1 and homozygous for ecm11(K5R, K101R), Ecm11(K5R,K101R)-MYC typically formed foci and short stretches that only occasionally colocalized with the foci and short stretches of Zip1 on meiotic chromosomes (similar to the behavior of Ecm11-MYC in this genetic background).

The colocalization of Ecm11-MYC with Zip1 aggregates that form in SUMO-diminished, Zip1-inducible strains was also assessed. In SUMO-diminished strains carrying the Zip1 inducible system and homozygous for ECM11-MYC, 15/21 nuclei exhibited Zip1 aggregates at 3 hours post-induction, and Ecm11-MYC colocalized with 13/15 of the observed Zip1 aggregates (examples are shown in Figure S5B). Zip1 aggregates were reduced in frequency, on the other hand, in SUMO-diminished strains carrying inducible Zip1 and homozygous for an unSUMOylatable ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC allele (6/24 nuclei exhibited Zip1 aggregates after 3 hours of induction). Four of the six observed polycomplexes displayed no associated Ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC protein, whereas in two of the six observed polycomplexes the Ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC protein localized peripheral to the Zip1 aggregate (Figure S5B).

SUMO and Ecm11 Localize to the Central Element of the Budding Yeast SC

The localization of SUMO and Ecm11 at the interface of meiotic pachytene chromosomes depends on Zip1 [19], and loss-of-function analyses ([29], this work) suggest that these components might participate structurally in building SC central region. Immuno-electron microscopy experiments demonstrated that two Zip1 coiled coil units (dimers or tetramers, each predicted to be approximately 50–80 nm in length) span the width of the SC central region, with N termini interacting near one another and with C termini facing the lateral elements/chromosome axes of each homolog [10]. How is SUMO organized relative to Zip1 within the SC?

We used superresolution microscopy and Zip1 domain-specific antibodies to map the substructural location of SUMO and the Ecm11 protein within the budding yeast SC. Dong and Roeder [10] showed that antibodies targeting an N-terminal fragment of Zip1 label a narrow central domain at the interface of lengthwise-aligned homologs, while antibodies targeting Zip1 C termini decorate a wider domain, reflecting the proximity of Zip1-C to lateral elements. We labeled surface-spread meiotic nuclei with Zip1 domain-specific antibodies in addition to either anti-SUMO (Figure 4), or anti-MYC (on sporulated cells from strains carrying Ecm11-MYC) antibodies (Figure 5). We used Applied Precision's V4 OMX Structured Illumination microscope (access kindly provided by Stanford Neuroscience Services, Stanford University) to visualize labeled proteins on chromosome spreads.

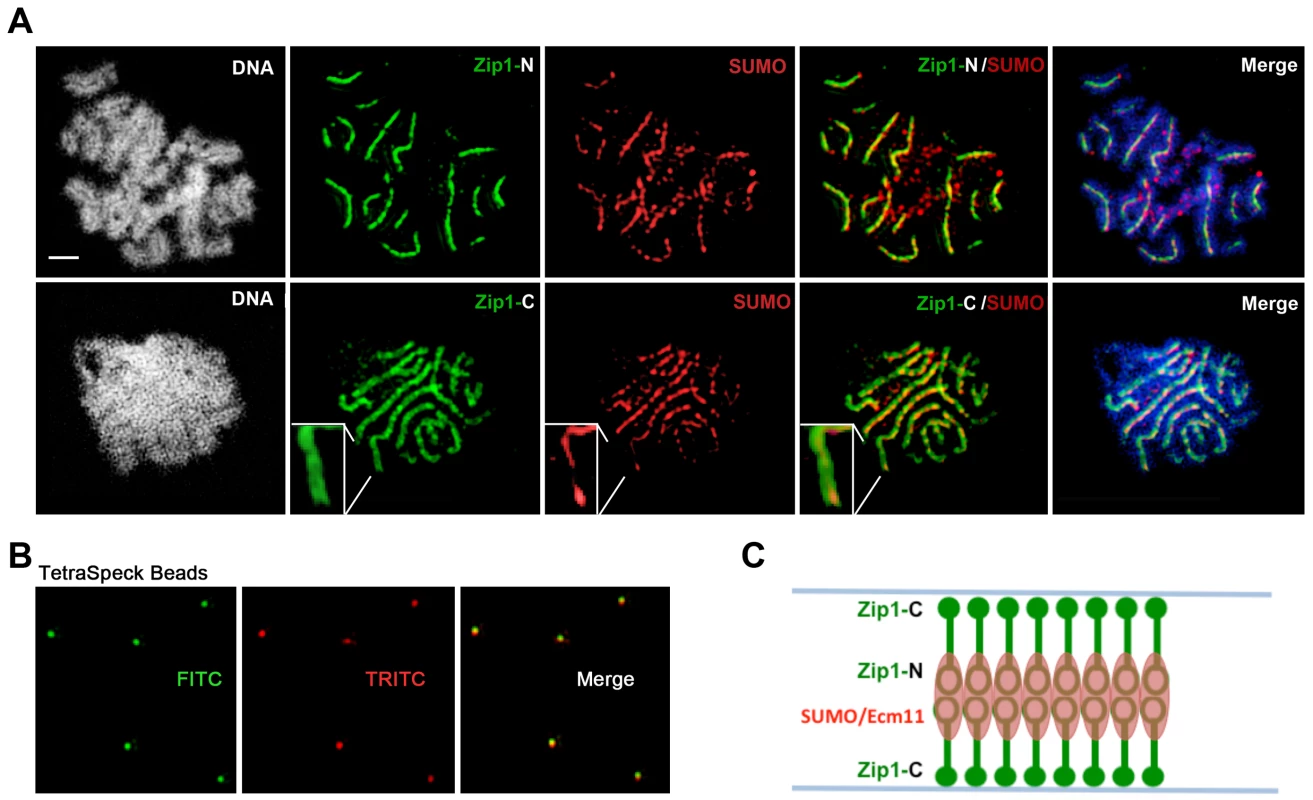

Fig. 4. SUMO is positioned at the central element of the budding yeast SC.

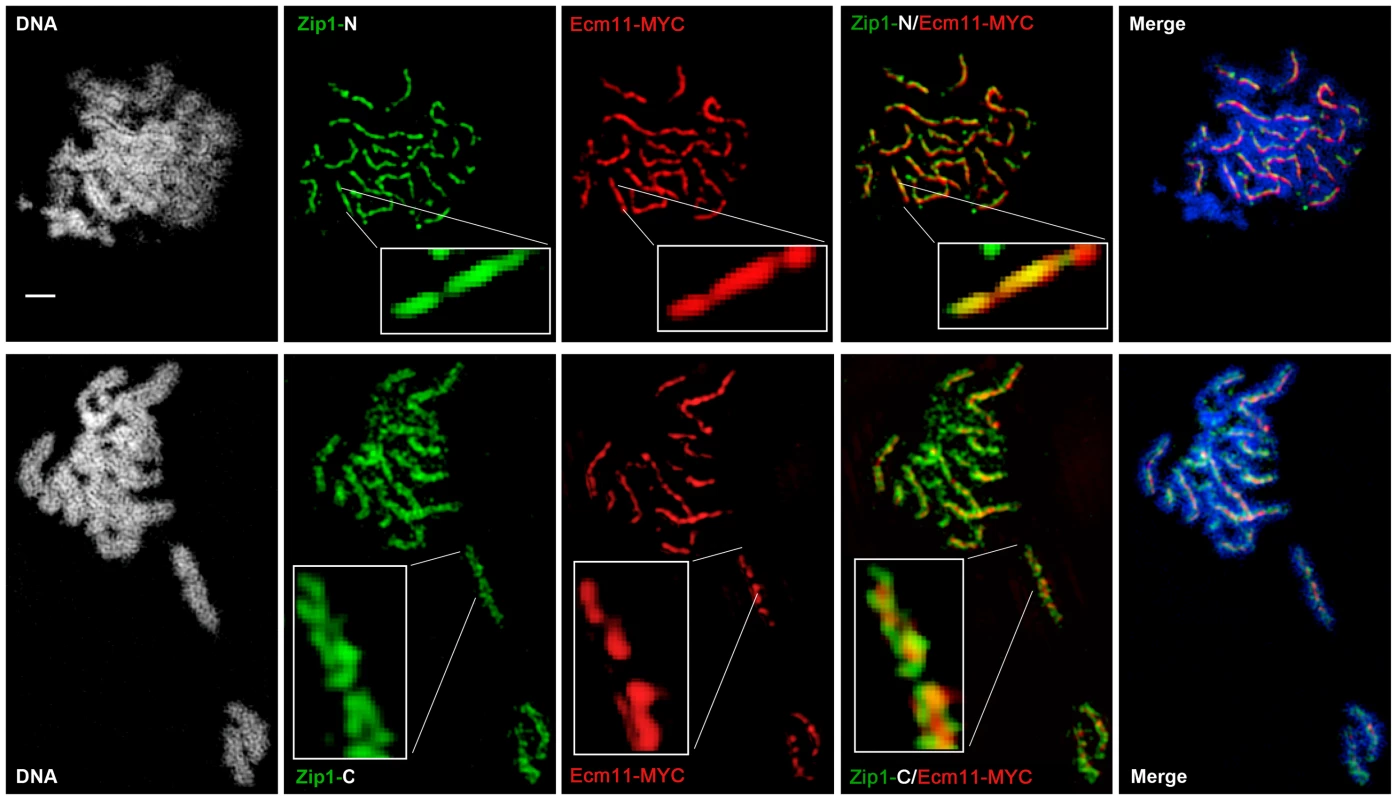

(A) Surface-spread meiotic nuclei from an ndt80 homozygous strain (AM447). Top row: nuclear spreads are stained with antibodies that target the Zip1 N terminus (green) and SUMO (red), in addition to DAPI to visualize DNA (white, blue in merged image). Bottom row: nuclei are stained with antibodies targeting a C terminal fragment of Zip1 (green) in addition to SUMO (red) and DAPI (white, blue in merged image). Inset zooms in on a portion of indicated SC. Scale, 1 µm. Images were acquired using a structured illumination microscope (Applied Precision's OMX V4, access kindly provided by Stanford Neuroscience Microscopy Service, Stanford University) that can resolve the SC central element (Zip1-N staining) from the remainder of the SC (where Zip1-C is located). The presence of a slight offset between Zip1-N and SUMO staining patterns can be attributed to a chromatic aberration during imaging, as shown in (B). (B) TetraSpeck Beads (Invitrogen), stained uniformly with both red and green fluorescent dyes, were imaged using the same mount and oil conditions as were used to image meiotic nuclei. The resultant red and green bead patterns failed to completely overlap, indicating that a slight chromatic aberration exists for the imaging conditions used. The cartoon in (C) illustrates a model for budding yeast SC structure, with SUMO and Ecm11 (see Figure 5) positioned at the N termini of Zip1 within the SC central region. Fig. 5. Ecm11-MYC is positioned at the central element of the budding yeast SC.

Surface-spread meiotic nuclei from an ECM11-MYC ndt80 homozygous strain (AM2712). Top row: nuclear spreads are stained with antibodies that target the Zip1 N terminus (green) and MYC (red), in addition to DAPI to visualize DNA (white, blue in merged image). Bottom row: nuclei are stained with antibodies targeting a C terminal fragment of Zip1 (green) in addition to MYC (red) and DAPI (white, blue in merge). Boxed insets show portions of each image with increased zoom. The images were acquired using Applied Precision's V4 OMX structured illumination microscope at Stanford Neuroscience Services (Stanford University) as described in Figure 4. Scale, 1 µm. The OMX SIM system produced images with sufficient resolution to recapitulate the results of the earlier immuno-EM study conducted by Dong and Roeder. As shown in Figures 4 and 5, antibodies targeting amino acids 20–139 at Zip1's N terminus [10] decorate a narrow, linear domain at the interface of lengthwise-aligned homologs, while antibodies raised against the 264 C-terminal amino acids of Zip1 [8], [46] exhibit a substantially wider domain of staining, wherein two parallel tracts can often be distinguished (green staining in Figures 4 and 5). Antibodies targeting the meiotic chromosomal axis component, Red1, displayed a pattern of staining that was similar to that of Zip1-C; homolog pairs often displayed parallel Red1 tracks along their lengths (Figure S6). Such positional information is completely absent from images of immuno-stained SC taken using conventional fluorescence microscopy followed by deconvolution on Applied Precision's Deltavision RT microscope system (Figure S7).

Moreover, SUMO or the SUMOylated SC component, Ecm11 [29], localize to a narrow domain that coincides with the position of Zip1's N termini, between the parallel tracks decorated by anti-Zip1-C (Figure 4 and 5). We note that a slight shift in the location of SUMO or Ecm11-MYC relative to the Zip1 N terminal domain can be accounted for by a chromatic aberration; the existence of such an aberration is demonstrated by the slight offset of red and green images produced by TetraSpeck beads, which are uniformly labeled with both green and red fluorophores (Figure 4B).

As depicted in the cartoon in Figure 4C, our structured illumination data independently confirm an organization of Zip1 within SC that was deduced using Zip1 domain-specific antibodies in conjunction with electron microscopy and furthermore demonstrate that the smaller Ecm11 and SUMO proteins assemble near Zip1's N termini. These findings thus reveal the first known components of the budding yeast SC “central element” domain.

Budding Yeast Central Element Proteins Exhibit Ongoing Incorporation into Full-Length SC

We next asked whether SUMO and Ecm11 share the dynamic behavior that Zip1 exhibits within full-length SC. Using inducible ZIP1-GFP, we have demonstrated that Zip1 continually incorporates into previously deposited, full length SC during meiotic prophase [46]. We observed that post-synapsis Zip1-GFP initially decorates full-length SC as foci and, over time, develops into a linear pattern that coincides with previously deposited SC. We used an analogous induction strategy to ask whether SUMO and Ecm11 exhibit post-synapsis incorporation into full length SC.

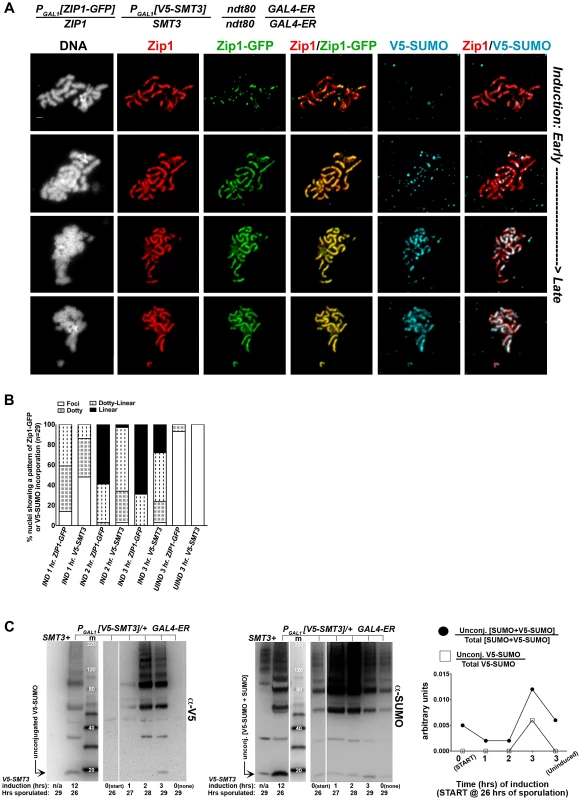

We first created an ndt80 homozygous strain carrying one copy of inducible V5-tagged SMT3, (PGAL1[V5-SMT3]), and one copy of inducible ZIP1-GFP (PGAL1[ZIP1-GFP]) in addition to one endogenous ZIP1 and SMT3 allele. This strain (AM2905) also contains the GAL4-ER gene, which induces expression from PGAL promoters upon exposure to ß-estradiol. After 26 hours in sporulation media, most AM2905 cells have deposited full-length SC, but are blocked from progressing further through meiosis due to the absence of the Ndt80 transcription factor. We induced ZIP1-GFP and V5-SMT3 expression in AM2905 cells that had been sporulated for 26 hours, and then prepared chromosome spreads from induced cultures after one, two or three hours. We also surface-spread cultures that were uninduced after three hours. We assessed the localization of Zip1, Zip1-GFP and V5-SUMO using antibodies against each protein or protein tag. As previously described [46], the majority of full-length SCs previously built with untagged Zip1 and untagged SUMO (not shown) exhibit Zip1-GFP foci and linear assemblies after one hour of induction (Figure 6A, B). After three hours of induction, most chromosome spreads exhibit linear Zip1-GFP that partially or completely coincides with the previously deposited SC. On the other hand, few nuclei exhibited robust V5-SUMO staining after one hour of induction, although approximately half of the nuclei exhibited a dotty pattern of V5-SUMO on chromosomes (Figure 6B). After two hours of induction, many chromosome spreads exhibited foci and some short linear stretches of V5-SUMO, and at three hours of induction approximately 30 percent of nuclei exhibited V5-SUMO linear stretches coincident with nearly the full length of SC. These observations demonstrate that V5-SUMO incorporates into previously deposited SC in a similar manner as Zip1-GFP, but perhaps with a different rate of incorporation.

Fig. 6. V5-SUMO continuously incorporates into previously established, full-length SC during meiotic prophase.

The strain in (A), AM2905, is homozygous for an ndt80 mutation, carries two copies of the GAL4-ER transgene, and is heterozygous for both ZIP1-GFP and V5-SMT3 under the transcriptional control of the PGAL1 promoter. Most ndt80 mutant meiotic nuclei in this strain background exhibit full-length SC by 24 hours of sporulation. Each strain was induced to express ZIP1-GFP and V5-SMT3 at 26 hours of sporulation, and then assessed at 1, 2 and 3 hours following induction. Uninduced cells were also assessed at 3 hours post-induction. Representative images of surface-spread nuclei from induced cells are shown, with top rows showing nuclei with lower levels of induced SC component incorporation and bottom rows showing SC component incorporation that is almost completely coincident with Zip1. Staining is as follows: DAPI (DNA), white; Zip1 (and/or Zip1-GFP), red; Zip1-GFP, green, V5-SUMO, blue. Scale, 1 µm. The stacked column graph in (B) indicates the fraction of nuclei with full-length Zip1 that exhibited None/Foci (open), Dotty (boxed), Dotty-linear (dotted lines), or Linear (solid) patterns of induced Zip1-GFP or V5-SUMO patterns on previously-established SC (n = 30). In (C), membranes with immobilized proteins from lysates of samples taken at the induction (START, 26 hours of sporulation), 1 hour, 2 hour and 3 hour post-induction, and a 3 hour uninduced sample were stained with anti-V5, then stripped and re-probed with anti-SUMO. Lane one contains sample from a strain containing no V5 tag, lane 2 contains AM2905 that has been induced for 12 hours, lane 3 contains MagicMarker protein standards (kDa) (Invitrogen), and lanes 4–8 contain AM2905 lysates at various time points. Unconjugated V5-SUMO and SUMO are indicated in the image. Graph at right plots the relative level of unconjugated V5-SUMO to total V5-SUMO (open boxes) and of unconjugated [V5-SUMO+SUMO] to total [V5-SUMO+SUMO] (closed circles) in each of lanes 4–8. The lag in V5-SUMO post-synapsis incorporation (relative to Zip1-GFP post-synapsis incorporation) does not appear to be due to a delay in the formation of V5-SUMO conjugates within meiotic cells per se. Induced, unconjugated (“free”) V5-SUMO comprised only a small fraction of total V5-SUMO signal in lysates from cells even at one hour post-induction; V5-SUMO remained a small fraction of total V5-SUMO at two and three hours of induction, and free untagged SUMO was detected as a similarly small fraction of total SUMO signal in the same samples (Figure 6C). We discuss potential explanations for this lag in V5-SUMO appearance on SCs in the Discussion (see below).

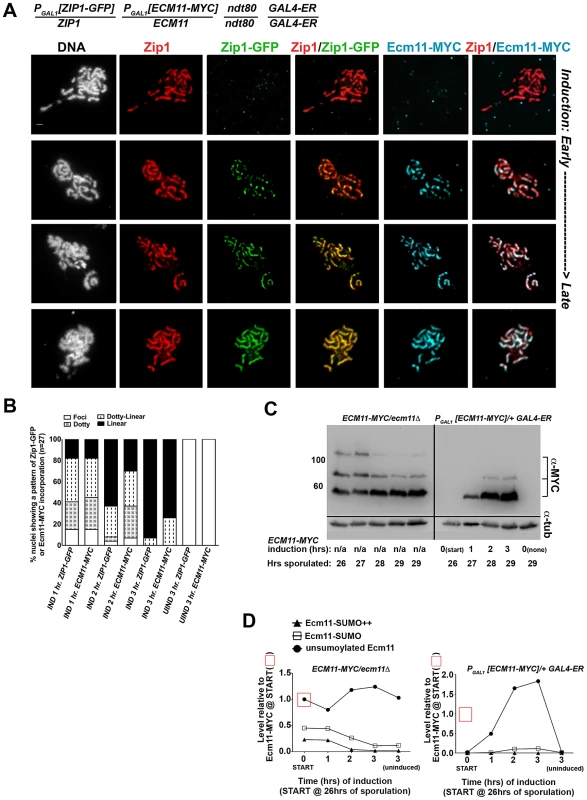

We next analyzed the post-synapsis dynamics of Ecm11-MYC using a strain (AM2865) analogous to AM2905 but carrying one copy of inducible ECM11-MYC instead of inducible V5-SMT3. We performed the induction as described above and stained for the presence of Zip1, Ecm11-MYC, or GFP using antibodies against each protein or protein tag. Analysis of induced Ecm11-MYC protein (Figure 7C, D) indicated that induced Ecm11-MYC rose to approximately 1.5 times the level of baseline Ecm11 (the level of Ecm11 present in hemizygous ECM11/ecm11Δstrains) by two hours post-induction, and reached nearly twice the level of baseline Ecm11 by three hours post-induction. Figure 7A shows examples of uninduced (top row) and induced nuclear spreads. We observed that, similar to post-synapsis Zip1-GFP and V5-SUMO, induced Ecm11-MYC incorporates into previously deposited SCs as both foci and, later, as linear assemblies that eventually coincide with the full length of the SC. Unlike V5-SUMO, initial post-synapsis incorporation of Ecm11-MYC typically appeared to the same extent as post-synapsis incorporation of Zip1-GFP in individual nuclei at each time point examined (Figure 7A, B).

Fig. 7. Ecm11-MYC continuously incorporates into previously established, full-length SC during meiotic prophase.

The strain in (A), AM2865, is homozygous for an ndt80 mutation, carries two copies of the GAL4-ER transgene, and is heterozygous for both ZIP1-GFP and ECM11-MYC under the transcriptional control of the PGAL1 promoter. Each strain was induced and assessed as described in Figure 6. Representative images of surface-spread nuclei from uninduced or induced cells are shown; staining is as follows: DAPI (DNA), white; Zip1 (and/or Zip1-GFP), red; Zip1-GFP, green, Ecm11-MYC, blue. Scale, 1 µm. The stacked column graph in (B) indicates the fraction of nuclei with full-length Zip1 that exhibited None/Foci (open), Dotty (boxed), Dotty-linear (dotted lines), or Linear (solid) patterns of induced Zip1-GFP or Ecm11-MYC patterns on previously-deposited SC (n = 30). In (C), membranes with immobilized proteins from lysates of ECM11-MYC/ecm11Δ ndt80/ndt80 (AM2892) samples (left) and AM2865 (right) taken at the induction START (26 hours of sporulation), 1 hour, 2 hour and 3 hour post-induction, and a 3 hour uninduced sample were stained with anti-MYC, stripped and re-probed with anti-α-tubulin. Hemizygous ECM11-MYC lysates were included as a reference for baseline Ecm11 levels at each timepoint. Numbers at left give molecular weight positions (kDa). Graphs in (D) at right plot the relative levels of unSUMOylated Ecm11-MYC (closed circles), SUMOylated Ecm11-MYC (open squares) and multi-SUMOylated Ecm11-MYC (closed triangles) in each lane (at each timepoint of the time course experiments); the level of unSUMOylated Ecm11-MYC at 26 hours in Ecm11-MYC/ecm11Δ is set at 1. Relative levels between lanes were normalized using the tubulin staining. These findings demonstrate that central element proteins (such as SUMO and Ecm11) and the transverse filament protein, Zip1, exhibit a similar post-synapsis dynamic of ongoing incorporation into full-length SC, consistent with a model in which Zip1, Ecm11 and SUMO (and/or SUMOylated Ecm11) represent core building blocks of the SC structure.

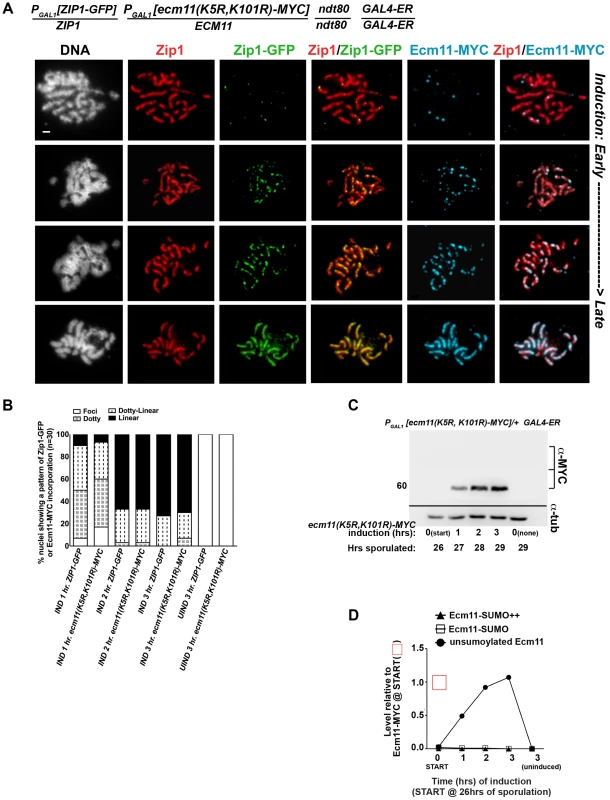

UnSUMOylatable Ecm11 Is Capable of Incorporating into SC Structure

We also assessed the post-synapsis dynamics of an unSUMOylatable version of Ecm11, Ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC. We performed the induction and staining as described above, using a strain (AM2910) carrying one copy of inducible ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC (and one copy of inducible ZIP1-GFP). Analysis of induced Ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC protein levels (Figure 7C, D and 8C, D) indicated that induced unSUMOylated Ecm11-MYC rose to approximately that of baseline Ecm11 between two and three hours post-induction.

Fig. 8. Ecm11(K5R,K101R)-MYC continuously incorporates into previously established, full-length SC during meiotic prophase.

The strain in (A), AM2910, is homozygous for an ndt80 mutation, carries two copies of the GAL4-ER transgene, and is heterozygous for both ZIP1-GFP and ECM11(K5R,K101R)-MYC under the transcriptional control of the PGAL1 promoter. Each strain was induced and assessed as described in Figure 6. Representative images of surface-spread nuclei from uninduced or induced cells are shown; staining is as follows: DAPI (DNA), white; Zip1 (and/or Zip1-GFP), red; Zip1-GFP, green, Ecm11(K5R,K101R)-MYC, blue. Scale, 1 µm. The stacked column graph in (B) indicates the fraction of nuclei with full-length Zip1 that exhibited None/Foci (open), Dotty (boxed), Dotty-linear (dotted lines), or Linear (solid) patterns of induced Zip1-GFP or Ecm11(K5R,K101R)-MYC patterns on previously-established SC (n = 30). In (C), membranes with immobilized proteins from lysates of AM2910 cells taken at the induction (START, 26 hours of sporulation), 1 hour, 2 hour and 3 hour post-induction, and a 3 hour uninduced sample were stained with anti-MYC, stripped and re-probed with anti-α-tubulin. Numbers at left give molecular weight positions. Graph in (D) plots the level of unSUMOylated Ecm11(K5R,K101R)-MYC (closed circles), SUMOylated Ecm11(K5R,K101R)-MYC (open squares) and multi-SUMOylated Ecm11(K5R,K101R)-MYC (closed triangles) at each timepoint during the induction, relative to the level of unSUMOylated Ecm11-MYC at 26 hours in Ecm11-MYC/ecm11Δ samples (from western in Figure 7D). Ecm11 levels were made comparable with blot in Figure 7C by setting the level of Ecm11(K5R,K101R) signal in lane 2 (27 hour timepoint, 1 hour of induction) to the level of Ecm11-MYC signal timepoint in lane 7 (27 hour timepoint, 1 hour of induction) of blot in Figure 7C. Relative levels between lanes were normalized using the tubulin staining. Figure 8A shows examples of uninduced (top row) and induced nuclear spreads. Somewhat surprisingly, induced Ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC incorporated into previously deposited, full length SCs as both foci and, later, as linear assemblies that eventually coincide with the full length of the SC (Figure 8A, B). The timing of incorporation of induced Ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC into previously deposited SC was not obviously different from that of induced wild-type Ecm11-MYC.

The observation that unSUMOylated Ecm11 incorporates into previously established SC was unanticipated since homozygous ecm11(K5R, K101R) mutants fail to build robust Zip1 assemblies on chromosomes [29]. Consistent with the idea that unSUMOylatable Ecm11 can incorporate into SCs built with pre-existing Ecm11, we also observed that Ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC decorates the lengths of SCs in strains heterozygous for ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC over a wild type (untagged) ECM11 allele (Figure S8). The spore viability of ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC/ECM11+ heterozygotes (92%, n = 304 spores) was indistinguishable from that of ECM11-MYC/ECM11+ heterozygotes (93%, n = 244 spores), suggesting that the incorporation of this unSUMOylatable Ecm11 protein does not have a dominant negative effect on meiotic events. It is noteworthy, in light of these findings, that the majority of Ecm11-MYC detected in otherwise wild-type meiotic cell extracts is apparently unSUMOylated (based on size).

We next investigated the pattern of incorporation of unSUMOylatable Ecm11-MYC protein within incipient SC stretches. We analyzed the localization of Ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC on the short Zip1 stretches observed after one hour of induction in Zip1-induction strains carrying one copy of ECM11(K5R, K101R)-MYC in trans with a wild-type, untagged ECM11 allele (Figure S9). The existence of subdomain(s) of Ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC within an incipient SC stretch would suggest that unSUMOylated Ecm11-MYC incorporates only after a significant stretch of SUMOylated Ecm11. However, we were unable to detect distinct subdomains of Ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC within short Zip1 stretches in these analyses. Instead, Ecm11(K5R, K101R)-MYC colocalized with induced Zip1 assemblies of all sizes with uniform staining (Figure S9).

Thus, although SUMOylatable Ecm11 is required for the formation of SC, Ecm11-MYC need not be SUMOylated for its incorporation into SC structures.

The Relative Abundance of SUMO and Ecm11-MYC Proteins Correlates with Zip1 Abundance in SC

We previously demonstrated that budding yeast SCs accumulate a progressively larger abundance of Zip1 during meiotic prophase progression, and that Zip1 abundance within SC correlates with ZIP1 copy number [46]. In order to ask whether SUMO and Ecm11-MYC proteins are also at increased levels within SCs containing a larger abundance of transverse filament protein, we measured Zip1-YFP, SUMO and Ecm11-MYC protein levels in SCs from strains with one, two, and four copies of ZIP1-YFP. We assessed the relative abundance of each protein by first defining a small domain of well-spread SC, and then determining the optimal exposure time for acquiring an image within linear range (shorter exposure times reflect a larger abundance of protein, and vice versa) (Figure S10A). When images containing small sections of SC are plotted such that their Zip1-YFP exposure time is reflected on the y axis and their SUMO exposure time is displayed on the x axis, an overall trend is observed in which relatively shorter exposure times for Zip1-YFP (i.e. SCs with a larger abundance of Zip1-YFP) correlate with relatively shorter exposure times for SUMO. (Exposure time data from individual images taken of SC from one, two and four copy ZIP1-YFP strains, plotted together on the same graph, are shown in Figure S10B.) These data indicate that SUMO abundance is larger in SCs with greater Zip1 abundance, relative to the SUMO abundance in SCs with less Zip1.

When Ecm11-MYC exposure times were plotted against Zip1-YFP exposure times (Figure S10C) a similar positive correlation was found, especially within shorter Zip1-YFP exposure times (greater Zip1-YFP abundance). The correlation coefficients for both Zip1-YFP with SUMO exposure times and Zip1-YFP with Ecm11-MYC exposure times are statistically significant (P≤0.0004, Figure S10B legend). Relative to the SUMO and Zip1-YFP correlation, however, a wider range of Ecm11-MYC exposure times (Ecm11-MYC abundance) was apparent in SC segments exhibiting Zip1-YFP exposure times above 0.5 seconds (Figure S10C). One explanation for the lower degree of correlation between Ecm11 and Zip1-YFP levels in SCs with lower Zip1-YFP abundance could be that Ecm11 both incorporates and exits from the full-length SC. Under this model the abundance of Ecm11-MYC would be expected to grow more slowly than the abundance of Zip1-YFP or SUMO within SC. An alternative explanation could be that proportionally fewer Ecm11-MYC molecules incorporate into a given unit of SC as compared to SUMO and Zip1-YFP. This latter idea is consistent with the fact that each transverse filament unit that spans the width of the SC is comprised of two (or a multiple of two) dimers of Zip1-YFP, which themselves may be linked by perhaps just one or two Ecm11 monomers. Furthermore, the Ecm11 protein has the capacity to be conjugated to more than one SUMO molecule [29]. Thus it is conceivable that proportionally fewer molecules of Ecm11 versus SUMO and Zip1 comprise a single “unit” of SC structure.

Discussion

SUMO Likely Functions as a Structural Component of the Budding Yeast SC

A role for SUMO in budding yeast SC biology has long been suspected based on the fact that SUMO exhibits Zip1-dependent localization to meiotic chromosomes and based on the SC assembly defects exhibited by mutants in which a particular SC-localized protein (such as Ubc9 or Ecm11) cannot be SUMOylated [19], [29], [47]. Here we directly reveal a role for SUMO in the assembly of mature SC in budding yeast, by analyzing meiotic mutants with reduced SUMO levels. We show that in the context of an inducible-SC system (using strains homozygous for inducible ZIP1), SUMO diminishment results in a dramatic SC assembly defect that resembles ecm11(K5R, K101R) (and other synapsis-defective) mutants [29]. This SC assembly defect, observed under the most robust SUMO-diminished conditions, leaves open the possibility that SUMO is involved exclusively in initial stages of SC elaboration. Notably, in meiotic nuclei that have normal ZIP1 regulation and overall milder SUMO reduction we also observed a discontinuous pattern of SC assembly on most pachytene stage chromosomes. This latter, highly penetrant but less dramatic SC phenotype is consistent with the idea that SC requires SUMO on an ongoing basis for its proper assembly and/or maintenance.

Furthermore, we demonstrate that SUMO and Ecm11 exhibit ongoing incorporation into previously deposited SC and that these components grow in abundance (SUMO to a greater extent than Ecm11) as SC accumulates additional Zip1 content. Together with the fact that SUMO exhibits a linear staining pattern coincident with transverse filaments along the length of SCs, these findings suggest that SUMO is a core structural component of the budding yeast SC.

If SUMO-diminishment causes aberrant SC structures, why is the spore viability of SUMO-diminished strains only slightly decreased relative to control strains? There are at least three explanations that could account for the high viability of spores produced by SUMO-diminished strains. First, it is important to note that SUMO-diminished cells do exhibit SC structures (albeit discontinuous) in cells carrying endogenous (as opposed to inducible) ZIP1; such aberrant SC structures may be capable of executing the chromosome segregation functions required for high spore viability. Second, we observed that interhomolog crossover recombination is modestly but significantly elevated in SUMO-diminished cells; it is possible that a set of “extra” crossovers protect SUMO-diminished cells from the chromosome segregation errors that might arise as a consequence of aberrant SC. Finally, it should be noted that ecm11 mutants, which show defective SC assembly, nevertheless exhibit significantly higher spore viability than other synapsis-defective mutants [29]. We wonder therefore if synapsis proteins such as Zip1, Zip2 and Zip4 function in Ecm11/SUMO-independent chromosome segregation activities outside of their role in SC structure. An obvious candidate activity with regard to this idea is the Zip1-dependent “centromere tethering” phenomenon, where centromeres associate in two-by-two pairs after SC disassembly [48], [49].

SUMO and Ecm11: The First Identified Components of the SC Central Element in Budding Yeast

While SUMO's position within the larger architecture of the SC was not known until now, based on the observations that 1) a small domain at Zip1's C-terminus has the capacity to interact with SUMO in a yeast two hybrid system [27], [50] and 2) a subset of the Red1 chromosome axis protein is SUMOylated during meiotic prophase [27], one widely-cited model proposed that SUMO associates with Zip1's C terminal domain along the length of fully assembled SC [25], [26], [28], [50].

Using superresolution microscopy in conjunction with Zip1 domain-specific antibodies, we demonstrate that instead of the scenario mentioned above, SUMO and Ecm11 lie in close proximity to Zip1-N termini within the mature SC structure. These findings make SUMO and Ecm11 the first known components of the SC central element, a subdomain at the midline of SC central region that is sometimes apparent as an electron dense entity in ultrastructural images of synapsed chromosomes.

As the defect in SC assembly exhibited by our SUMO-diminished meiotic cells closely resembles that observed for strains expressing an unSUMOylatable ecm11 allele [29], perhaps SUMOylated Ecm11 is the predominant source of SUMO within SC central element. However it remains possible that additional SC central element proteins that act in parallel or downstream of Ecm11 to promote SC assembly are also SUMOylated (e.g. see [47]).

SUMO has not yet been identified as a core component of SC structure outside of budding yeast [28], [51]. However, SUMO and Ecm11 join a growing list of central element proteins from different organisms that are critical for SC assembly. Mutants that are missing central element proteins in both Drosophila and mouse exhibit defects in establishing stable SC [15], [16], [18], [22], [23], [24]. Thus, perhaps a conserved feature of SC assembly is the role that the central element plays in properly organizing the coiled-coil proteins that form the transverse filaments.

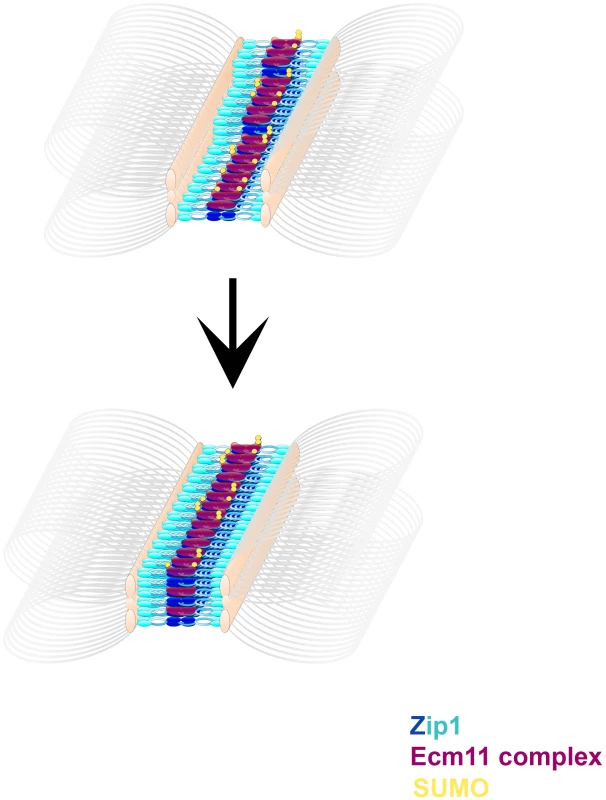

The Spatial Relationship between SUMO and Zip1 on Meiotic Chromosomes

A prior study found that an N terminal ∼160 amino acid fragment of Zip1 (representing nearly the entire N terminal globular domain) is dispensable for normal SC [52], seemingly at odds with the idea that the budding yeast SC central element plays a key role in SC assembly. However, this study also characterized three deletions within the N terminal region of Zip1's coiled-coil; strains carrying each of these zip1 deletion alleles exhibited defective SC assembly. Perhaps it is this N terminal portion of the Zip1 coiled-coil that interacts, directly or indirectly, with central element components in order to organize the mature SC structure. One way to think about such an interaction is that central element proteins, such as a complex containing SUMO and/or SUMOylated Ecm11, stabilize a self interaction between two N terminal portions of Zip1 coiled-coil units that lie head-to-head within SC central region ([52], Figure 9). Alternatively, antiparallel Zip1 units that span the SC may each independently interact with a “bridge” of central element proteins. Either model would account for the fact that deletions within Zip1's coiled-coil region narrow the SC diameter but similarly-sized deletions in Zip1's N terminal region, prior to the coiled-coil domain, assemble SC with a normal width [52].

Fig. 9. A model describing the multimeric assembly of Zip1, Ecm11 and SUMO within SC.

Cartoon images shows possible intermediate steps in a dynamic SC assembly process. Zip1 (blue, darker blue at Zip1-N termini) units are stacked with Ecm11 complex proteins (purple) arranged near Zip1 N termini. Ecm11 components are SUMOylated (yellow) to varying extents. Multiple layers of this basic arrangement of Zip1, Ecm11 and SUMO comprise more mature SC structures. Our observation that the predominant SUMO signal within budding yeast SC lies closer to Zip1 N termini does not rule out the possibility that a subset of Zip1 protein also interacts with SUMO or SUMO polymeric chains through its C terminal SUMO Interaction Motif (SIM), as has been proposed [25], [26], [27], [28]. Such an interaction might mediate a chromosomal process transiently and/or at discrete sites, such as synapsis initiation or interhomolog recombination (as has been suggested based on the phenotype of a strain carrying an unSUMOylatable red1 allele [27]), and thus escape detection in cytological preparations. Indeed, the fact that only a small fraction of total Red1 protein is SUMOylated during meiosis [27] is consistent with the idea that SUMOylated Red1 mediates functions at a limited number of discrete sites on meiotic chromosomes (instead of along the full SC length). Perhaps the elevated interhomolog crossover levels that we observed in SUMO-diminished strains are due to a reduced level of SUMOylated Red1. Alternatively the observed increase in interhomolog crossover recombination in SUMO-diminished strains might be a consequence of defective SC structures or the misregulation of a SUMOylated component of the recombination machinery.

The Stoichiometry and Timing of SC Component Assembly

Our analysis of SUMO-diminished strains is consistent with a model in which SUMO promotes and/or maintains the higher-order assembly and stability of mature SC structure. We have observed that SUMO abundance increases within SCs in proportion to Zip1 abundance. In contrast, Ecm11's abundance did not grow to the same extent as SUMO within SCs containing larger amounts of Zip1. These data raise the possibility that multiple SUMO (and multiple Zip1) proteins accompany a single Ecm11 protein in an SC unit.

Some of our observations also suggest that SUMO might not incorporate into SC structures with the same kinetics as Ecm11. First, we observed a distinct lag in the appearance of induced V5-SUMO, relative to the appearance of induced Zip1-GFP and induced Ecm11-MYC into previously established SCs. One explanation for this “lag” in post-synapsis V5-SUMO incorporation could be that induced V5-SUMO does not become efficiently conjugated to proteins, perhaps because it is competing with a larger pool of untagged SUMO. However, our analysis of free V5-SUMO versus V5-SUMO conjugates in these strains suggests that V5-SUMO molecules become conjugated to meiotic proteins efficiently after their translation (Figure 6C).

The lag in detectable post-synapsis V5-SUMO relative to Zip1-GFP and Ecm11-MYC on SCs could be the result of a technical limitation, such as a difference in the efficiency of V5-SUMO translation relative to Ecm11-MYC, or a difference in binding affinity of anti-V5 versus anti-GFP on meiotic chromosome spreads. However, if this lag truly reflects a slower incorporation rate for SUMO versus other SC components, it suggests that either 1) SUMOylation of SC components can be an event that occurs subsequent to the incorporation of the unSUMOylated versions of SUMO targets, or 2) that only a subset of Ecm11 or other SUMOylated SC proteins are SUMOylated when they incorporate into SC.

Our analysis of strains carrying a tagged ecm11(K5R, K101R) allele shows that, in fact, unSUMOylated Ecm11 readily incorporates into nascent as well as previously-deposited SC. SUMOylated Ecm11, however, is likely required for generating stable SC as strains homozygous for an ecm11(K5R, K101R) mutation fail to exhibit extensive SC [29]. These data are consistent with the idea that unSUMOylated Ecm11 may assemble into SC, but that SUMOylated Ecm11 promotes the reinforcement or stabilization of SC proteins near the N termini of Zip1.

Figure 9 displays a cartoon model for SC establishment based on the observations provided in this study. We propose that transverse filaments (Zip1 dimers) are organized near their N termini by a complex of proteins including Ecm11 and SUMOylated Ecm11, but that SUMOylated, multi-SUMOylated, and unSUMOylated versions of Ecm11 exist in the SC structure at any given time. We are intrigued with the idea that SUMOylation of Ecm11 may occur subsequent to Ecm11's positioning within an intermediate, immature SC structure, however it is also possible that Ecm11's SUMOylation status is established prior to, and cannot be modified subsequent to, its incorporation into SC. Regardless of the timing of SUMOylation, we propose that the stoichiometry of SC maturation is such that several SUMO and Zip1 proteins (eventually) accompany a smaller number of Ecm11 molecules within each SC unit. Thus as the SC builds layers, SUMO and Zip1 abundance increase to a greater extent than Ecm11 protein within the budding yeast SC.

Methods

Genetics

Strains used in this study are isogenic with BR1919-8B [53], and their genotypes are listed in Table S1. Yeast genetic manipulations were carried out via standard procedures. Two consecutive transformations on diploid cells created the SUMO-diminished strains used in this study. First, we replaced the SMT3 ORF with a dominant drug resistance cassette (hphMX4 or natMX3 [54]). Next a kanMX4-PSCC1 promoter cassette was inserted upstream of the remaining SMT3 gene. Strains were verified by assessing SUMO levels on a western blot or by immuno-staining.

Genetic map distances of three intervals on chromosome III in SUMO-diminished and control backgrounds were calculated according to the following: 100(r/t), where r = the number of colonies carrying a chromosome which is recombinant in the interval and t = the total number of colonies assessed. Only tetrads with 2 viable spores were used to determine genetic recombination data. Standard error (S.E.) values for random spore analysis were calculated according to the formula: 100(√(r/t)(1-r/t)/t) [55]. Map distances calculated using standard tetrad analysis, as per Perkins [56], were generated using the Stahl lab online tools: http://molbio.uoregon.edu/~fstahl/.

Cytological Analysis and Imaging

To determine the kinetics of multinucleate formation in Figure 1A, cells were fixed in 50% ethanol and frozen at −20°C prior to staining with DAPI [57].

Meiotic chromosome spreads, staining and imaging were carried out as previously described [46]. The following primary antibodies were used: chicken anti-GFP (1∶100) (Abcam), mouse anti c-MYC (1∶200) (9E10.3 Abcam and Invitrogen), affinity purified rabbit anti-Zip1 (1∶100) (raised at YenZym Antibodies, LLC, against a C terminal fragment of Zip1 as described in [8]), affinity purified guinea pig anti-SUMO (1∶200), rabbit anti-Red1 (1∶100) (kind gifts of G.S. Roeder, [19]), rabbit anti-V5 (1∶100) (Abcam) and rat anti-alpha tubulin (1∶200) (Santa Cruz). Secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch and used at a 1∶200 dilution. All secondary antibodies for Structured Illumination microscopy were conjugated to Alexa Fluor fluorescent dyes (Alexa Fluor 488, AlexaFluor 568, AlexaFluor 594, Molecular Probes Inc.).

Microscopy and image processing was carried out using a Deltavision RT imaging system (Applied Precision) adapted to an Olympus (IX71) microscope. The structured illumination microscopy presented in Figures 2 and 3 were carried out using Applied Precision's V4 OMX Structured Illumination Microscope system at Stanford University's Neuroscience Services facility, while the imaging done for Figure S2 was carried out on Applied Precision's OMX Blaze Structured Illumination Microscope system at The Rockefeller University's Bio-Imaging Resource Center.

Induction Experiments

The TRP1::PGAL1 promoter cassette was placed upstream of the ZIP1, V5-SUMO, or ECM11-MYC ORFs by directed transformation of a PCR product. pKB80 (GAL4.ER::URA3) was integrated at ura3 to introduce the chimeric protein that responds to β-estradiol and activates PGAL1 promoters [58]. Strains were handled and induced as described in [46].

Western Blot

Protein pellets were isolated from 5 mL of sporulating cell culture by TCA precipitation as in [19]. The final protein pellet was suspended in 2× Laemmli sample buffer supplemented with 30 mM DTT, at a concentration of ∼10 µg/µl. Protein samples were heated for 10 minutes at 65°, centrifuged at top speed and ∼150 µg was loaded onto either an 8% (for detecting Zip1or Ecm11-MYC) or a 4–20% gradient (for detecting SUMO and V5-SUMO) polyacrylamide/SDS gel. PDVF membranes were prepared according to manufacturer's (Bio-Rad) recommendation, equilibrating with Towbin buffer for 15 minutes after methanol wetting. Transfer of proteins to PDVF membranes was done following Bio-Rad Protein Blotting Guide for tank blotting using Towbin Buffer; stir bar and ice pack were used at 60 V for transfer. SUMO and V5-SUMO blots were transferred for 40 minutes whereas the Ecm11-myc and Zip1 blots were transferred for 1 hour. Ponceau S was used to detect total protein on the PVDF membrane after transfer. Guinea pig anti-SUMO (kind gift of Shirleen Roeder's lab) and rabbit anti-V5 (Abcam) were used at 1∶500 dilution. Rat anti-tubulin (Santa Cruz), mouse anti-MYC (9E10.3, Invitrogen), and rabbit anti-Zip1 were used at 1∶5000–10000, 1∶2500 and 1∶5000 dilutions respectively. Incubations in primary antibody were performed overnight at 4°C. HRP-conjugated AffiniPure Donkey anti-rabbit and anti - guinea pig, as well as goat anti-mouse (JacksonImmunoResearch) and goat anti-rat (Santa Cruz) were used at 1∶5000 in TBS-T for 1 hour at RT. Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent was used to visualize antibodies on the membranes; a Syngene G:Box was used to detect chemiluminescence and the Syngene GeneTools program was used to analyze the data. Membranes were stripped according to the ECL Prime kit protocol.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad InStat software.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. BhallaN, DernburgAF (2008) Prelude to a division. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 24 : 397–424.

2. ZicklerD, KlecknerN (1998) The leptotene-zygotene transition of meiosis. Annu Rev Genet 32 : 619–697.

3. ZicklerD, KlecknerN (1999) Meiotic chromosomes: integrating structure and function. Annu Rev Genet 33 : 603–754.

4. PageSL, HawleyRS (2004) The genetics and molecular biology of the synaptonemal complex. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 20 : 525–558.

5. MosesMJ (1968) Synaptonemal complex. Annu Rev Genet 2 : 363–412.

6. SolariAJ, MosesMJ (1973) The structure of the central region in the synaptonemal complexes of hamster and cricket spermatocytes. J Cell Biol 56 : 145–152.

7. SmithAV, RoederGS (1997) The yeast Red1 protein localizes to the cores of meiotic chromosomes. J Cell Biol 136 : 957–967.

8. SymM, EngebrechtJ, RoederGS (1993) Zip1 is a synaptonemal complex protein required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Cell 72 : 365–378.

9. SymM, RoederGS (1995) Zip1-induced changes in synaptonemal complex structure and polycomplex assembly. J Cell Biol 128 : 455–466.

10. DongH, RoederGS (2000) Organization of the yeast Zip1 protein within the central region of the synaptonemal complex. J Cell Biol 148 : 417–426.

11. AndersonLK, RoyerSM, PageSL, McKimKS, LaiA, et al. (2005) Juxtaposition of C(2)M and the transverse filament protein C(3)G within the central region of Drosophila synaptonemal complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 : 4482–4487.

12. LiuJ-G, YuanL, BrundellE, BjorkrothB, DaneholtB, et al. (1996) Localization of the N-terminus of SCP1 to the central element of the synaptonemal complex and evidence for direct interactions between the N-termini of SCP1 molecules organized head-to-head. Exp Cell Res 226 : 11–19.

13. SchmekelK, MeuwissenRLJ, DietrichAJJ, VinkACG, MarleJv, et al. (1996) Organization of SCP1 protein molecules within synaptonemal complexes of the rat. Exp Cell Res 227 : 20–30.

14. AgarwalS, RoederGS (2000) Zip3 provides a link between recombination enzymes and synaptonemal complex proteins. Cell 102 : 245–255.

15. Bolcun-FilasE, CostaY, SpeedR, TaggartM, BenaventeR, et al. (2007) SYCE2 is required for synaptonemal complex assembly, double strand break repair, and homologous recombination. J Cell Biol 176 : 741–747.

16. Bolcun-FilasE, HallE, SpeedR, TaggartM, GreyC, et al. (2009) Mutation of the mouse Syce1 gene disrupts synapsis and suggests a link between synaptonemal complex structural components and DNA repair. PLoS Genet 5: e1000393.

17. ChuaPR, RoederGS (1998) Zip2, a meiosis-specific protein required for the initiation of chromosome synapsis. Cell 93 : 349–359.

18. HamerG, GellK, KouznetsovaA, NovakI, BenaventeR, et al. (2006) Characterization of a novel meiosis-specific protein within the central element of the synaptonemal complex. J Cell Sci 119 : 4025–4032.