-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Pathogenic VCP/TER94 Alleles Are Dominant Actives and Contribute to Neurodegeneration by Altering Cellular ATP Level in a IBMPFD Model

Inclusion body myopathy with Paget's disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia (IBMPFD) is caused by mutations in Valosin-containing protein (VCP), a hexameric AAA ATPase that participates in a variety of cellular processes such as protein degradation, organelle biogenesis, and cell-cycle regulation. To understand how VCP mutations cause IBMPFD, we have established a Drosophila model by overexpressing TER94 (the sole Drosophila VCP ortholog) carrying mutations analogous to those implicated in IBMPFD. Expression of these TER94 mutants in muscle and nervous systems causes tissue degeneration, recapitulating the pathogenic phenotypes in IBMPFD patients. TER94-induced neurodegenerative defects are enhanced by elevated expression of wild-type TER94, suggesting that the pathogenic alleles are dominant active mutations. This conclusion is further supported by the observation that TER94-induced neurodegenerative defects require the formation of hexamer complex, a prerequisite for a functional AAA ATPase. Surprisingly, while disruptions of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and the ER–associated degradation (ERAD) have been implicated as causes for VCP–induced tissue degeneration, these processes are not significantly affected in our fly model. Instead, the neurodegenerative defect of TER94 mutants seems sensitive to the level of cellular ATP. We show that increasing cellular ATP by independent mechanisms could suppress the phenotypes of TER94 mutants. Conversely, decreasing cellular ATP would enhance the TER94 mutant phenotypes. Taken together, our analyses have defined the nature of IBMPFD–causing VCP mutations and made an unexpected link between cellular ATP level and IBMPFD pathogenesis.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001288

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001288Summary

Inclusion body myopathy with Paget's disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia (IBMPFD) is caused by mutations in Valosin-containing protein (VCP), a hexameric AAA ATPase that participates in a variety of cellular processes such as protein degradation, organelle biogenesis, and cell-cycle regulation. To understand how VCP mutations cause IBMPFD, we have established a Drosophila model by overexpressing TER94 (the sole Drosophila VCP ortholog) carrying mutations analogous to those implicated in IBMPFD. Expression of these TER94 mutants in muscle and nervous systems causes tissue degeneration, recapitulating the pathogenic phenotypes in IBMPFD patients. TER94-induced neurodegenerative defects are enhanced by elevated expression of wild-type TER94, suggesting that the pathogenic alleles are dominant active mutations. This conclusion is further supported by the observation that TER94-induced neurodegenerative defects require the formation of hexamer complex, a prerequisite for a functional AAA ATPase. Surprisingly, while disruptions of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and the ER–associated degradation (ERAD) have been implicated as causes for VCP–induced tissue degeneration, these processes are not significantly affected in our fly model. Instead, the neurodegenerative defect of TER94 mutants seems sensitive to the level of cellular ATP. We show that increasing cellular ATP by independent mechanisms could suppress the phenotypes of TER94 mutants. Conversely, decreasing cellular ATP would enhance the TER94 mutant phenotypes. Taken together, our analyses have defined the nature of IBMPFD–causing VCP mutations and made an unexpected link between cellular ATP level and IBMPFD pathogenesis.

Introduction

IBMPFD is a progressive autosomal dominant disorder, characterized by the adult onset of muscle degeneration, abnormal bone metabolism, and drastic behavior changes. This disease has been linked to mutations in VCP (known as p97 in mouse or CDC48 in yeast), a hexameric AAA (ATPase associated with various cellular activities) ATPase known to participate in numerous cellular events [1], including ubiquitinated protein processing [2], [3], homotypic membrane fusion [4]–[6], nuclear envelope reconstruction [7], and cell cycle regulation [8]. Despite these advances in understanding VCP functions, it is unclear which of the aforementioned VCP roles are critical for causing IBMPFD.

VCP protein contains an N-terminal CDC48 domain and two ATPase domains (D1 and D2). In VCP hexamers, the D1 and D2 domains of each monomer align in a head-to-tail manner [9], [10]. It is thought that ATP hydrolysis causes major conformational changes to the hexamer [11], [12], thus generating the mechanical force required for VCP function. The ATPase activity of VCP appears to be mediated mainly by D2, whereas D1 contributes to heat-induced activity [13]. In support of this, mutations disrupting the residues required for the ATP-binding and ATP-hydrolysis in D2 have been used to dominantly interfere with endogenous VCP function [14]–[16]. The N-terminal CDC48 domain has been shown to bind cofactors and ubiquitin. As VCP is implicated in numerous processes, the cooperation with different cofactors may account for its functional diversity. For instance, VCP associates with p47 in mediating homotypic Golgi membrane fusion [6], [17], with p37 in ER and Golgi biogenesis [18], and with Ufd1/Npl4 in ERAD [19] and nuclear envelope reassembly [7].

Nearly all of the VCP mutations implicated in IBMPFD are located in the N-terminal CDC48 domain, the N-D1 linker, and the D1 ATPase domain. The R155 residue in the CDC48 domain has been mutated into different amino acids (C, H, and P) in 14 familial IBMPFD cases [20]. Mutations disrupting R191 (in N-D1 linker) and A232 (linker-D1 junction) are also implicated in familial IBMPFD cases, and it has been shown that individuals carrying the VCPA232E mutation exhibited more severe symptoms [20]. It is peculiar that the D2 domain, while essential for VCP function in vitro, has not been disrupted by any of the currently known IBMPFD-causing mutations (Figure S1). It is possible that, as VCP functions as hexamers, mutations in the D2 domain will dominantly deplete the pool of functional VCP hexamers, resulting in early demises of heterozygous individuals. Alternatively, the integrity of the D2 domain may be required for VCP mutants to cause IBMPFD.

To decipher the mechanistic link between IBMPFD and VCP mutations, efforts have been made to establish animal models expressing VCP mutants. Overexpression of VCPR155H in mice caused accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins, implying that UPS is an underlying cause for IBMPFD [21]. However, recent reports showed that cells expressing VCPR155H also exhibited impaired ERAD [22] and autophagy [23], [24], indicating that the expression of IBMPFD-causing VCP mutants could hamper multiple cellular pathways. Redistribution of TAR DNA-binding protein-43 has also been implicated as a cause for VCP-induced toxicity [25]. Biochemical analysis showed that IBMPFD-causing VCP mutants have elevated ATPase activity [15], although the significance of this finding is unclear.

Drosophila contains a single VCP homolog TER94 [26], which shares ∼83% protein sequence identity with human VCP. Of the twelve known VCP amino acid substitutions in IBMPFD, nine residues are conserved in TER94 (Figure S1), suggesting that Drosophila is a suitable model for IBMPFD. Here we show that expression of TER94 carrying mutations analogous to those implicated in IBMPFD mutants could disrupt muscle integrity and cause progressive neurodegenerative defects. Genetic evidence suggests that IBMPFD-causing VCP mutations are dominant active alleles. Mutational analysis shows that the ability of TER94 to form hexamers is essential for the mutant proteins to induce neurodegenerative defects, further suggesting that the IBMPFD-causing VCP mutations are not simple loss-of-function mutations. Using reporters specific for ERAD and UPS, we found the disruptions of these pathways are unlikely to be the underlying cause for the neurodegenerative defects in our model. Instead, the TER94-dependent neurodegenerative defects correlate with cellular ATP reduction, and could be suppressed by increasing cellular ATP level and enhanced by decreasing cellular ATP level. These observations, along with earlier report that IBMPFD-linked VCP mutants have elevated ATPase activity, suggest that depleting cellular ATP is a contributing factor for VCP mutant–induced tissue degeneration.

Results

Establishing a Drosophila IBMPFD model

To establish a Drosophila model for IBMPFD, we introduced amino acid substitutions at three residues in TER94: R152H, R188Q and A229E, to simulate the human VCP mutations R155H, R191Q and A232E respectively (Figure 1A). The R152H mutation is expected to affect the N-terminal CDC48 domain, whereas R188Q and A229E are located in the linker 1 (L1) region and L1-D1 junction respectively. As human versions of these Drosophila alleles have been linked to IBMPFD, they will be referred as “IBMPFD mutants” hereafter. To investigate the importance of ATPase activity in VCP function, we also generated flies expressing mutant TER94 defective in ATP-binding (K248A & K521A; K2A for short) or ATP-hydrolysis (E302Q & E575Q; E2Q for short) (Figure 1A). As disruption of the nucleotide hydrolysis cycle of protomer can affect the configuration and function of VCP hexamer [14], expression of these ATPase mutants is expected to dominantly impair the activity of endogenous TER94.

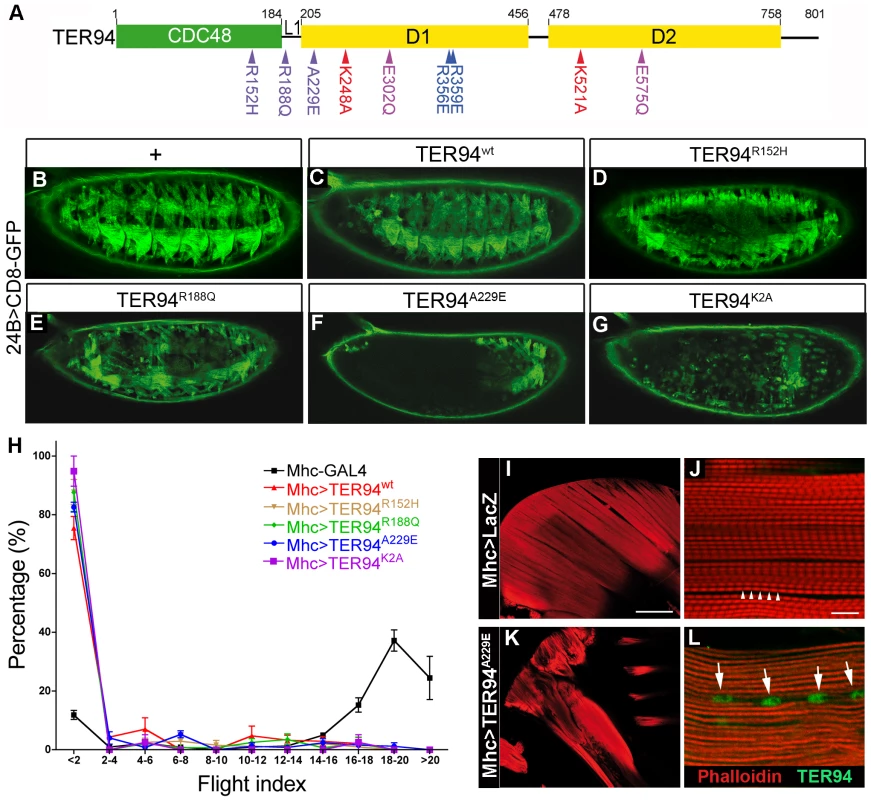

Fig. 1. Tissue-specific expression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants disrupts muscle integrity.

(A) A schematic drawing of TER94 functional domains and the alleles used in this study. Green and yellow boxes represent the N-terminal CDC48 domain and the two ATPase domains, respectively. The IBMPFD, ATP-binding defective, ATP-hydrolysis defective, and monomeric mutations are indicated in purple, red, lilac, and blue, respectively. (B–G) Fluorescent micrographs of lateral views of stage 16 embryos expressing indicated transgenes and mCD8-GFP under the control of 24B-GAL4. In all panels, anterior is to the left and dorsal is up. (H) Flight behavioral tests of Mhc>TER94 flies. Flies of indicated genotypes were used for flight behavioral tests, and results from four independent experiments were plotted. Higher percentage in smaller flight index numbers denotes flightless phenotype, whereas higher percentage in larger flight index numbers denotes normal flight behavior. Values shown represent mean ± SE (standard error of the mean). (I and K) Phalloidin-stained sections show normal dorsal longitudinal muscles (DLM) within IFM in control Mhc>LacZ (I) and irregular DLM in Mhc>TER94A229E (K). (J and L) Confocal images of Mhc>LacZ (J) and Mhc>TER94A229E (L) DLM sarcomeres stained with phalloidin and anti-VCP antibody (green). Scale bars: 100 µm (I and K), 10 µm (J and L). Genotypes: (B) 24B-GAL4,UAS-CD8-GFP/+, (C) 24B-GAL4,UAS-CD8-GFP/UAS-TER94wt, (D) 24B-GAL4,UAS-CD8-GFP/UAS-TER94R152H, (E) 24B-GAL4,UAS-CD8-GFP/UAS-TER94R188Q, (F) UAS-TER94A229E/+; 24B-GAL4,UAS-CD8-GFP/+, (G) UAS-TER94K2A/+; 24B-GAL4,UAS-CD8-GFP/+, (I and J) Mhc-GAL4/w;UAS-LacZ/+, (K and L) Mhc-GAL4/w;UAS-TER94A229E/+. Expression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants disrupts muscle integrity

While IBMPFD affects multiple tissues, the most prevalent pathology is myopathy. To ask if our model could recapitulate this defect, we utilized 24B-GAL4 [27] (an early driver active in myoblasts) and Mhc-GAL4 (a muscle-specific driver active from larval stage onward) to examine the effect of mutant TER94 expression on muscle development and maintenance respectively. The muscle fibers, visualized using mCD8-GFP (a membrane-bound GFP), were organized in segmental fashion in wild type at late embryonic stage (Figure 1B). In 24B>TER94wt embryos, mCD8-GFP localization appeared comparable to wild type, indicating that muscle fibers developed normally up to this stage (Figure 1C). In contrast, muscle fibers in embryos expressing TER94 IBMPFD mutants appeared disorganized and loss of GFP signals was seen in some segments (Figure 1D–1F). Among the three IBMPFD mutants, there appeared to be a difference in phenotypic severity, as the disruption of muscle fiber development seemed strongest in 24B>TER94A229E, coinciding with the observation that patients bearing VCPA232E allele had more severe symptoms [20]. This difference in phenotypic severity was not caused by differences in TER94 transgene expression, as quantitative Western blots showed comparable levels of TER94 proteins in lines used in our analysis (Figure S2). Furthermore, TER94 expression from transgenes inserted at identical genomic location (generated by integrase-mediated transformation [28] to eliminate positional effect) showed that TER94A229E caused the strongest photoreceptor degeneration among the three IBMPFD mutants (Figure S3; see below). Compared to IBMPFD mutants, the phenotype in 24B>TER94K2A was even more severe, as developing muscle fibers were completely absent (Figure 1G). This strong phenotype in 24B>TER94K2A is consistent with the hypothesis that mutations disrupting the ATPase activity are more debilitating than the disease alleles.

To determine the effect of TER94 alleles on mature muscles, adult flies expressing TER94 mutants under the control of Mhc-GAL4 [29] were subjected to flight tests. Those lacking functional muscles, as caused by mutant TER94 expression, were expected to perform poorly in this simple behavior assay. Indeed, flies expressing all TER94 mutants tested showed disrupted flight behavior (Figure 1H). Interestingly, Mhc>TER94wt also exhibited impaired flight (Figure 1H), suggesting that excessive TER94 activity could disrupt muscle function. To ensure that the flightless phenotype was caused by muscle defect, phalloidin staining was performed to determine the integrity of indirect flight muscles (IFMs, Figure 1I–1L). In Mhc>lacZ control, typical pattern of myofibril with clear A-bands was seen (arrowheads in Figure 1J), indicating that IFMs were normal. In contrast, myofibril from Mhc>TER94A229E showed disrupted sarcomeres without repetitive A-bands (compare Figure 1J to Figure 1L), suggesting that the flightless phenotype was caused by structural defects in IFMs. To monitor TER94 localization in IFMs, we stained Mhc>lacZ and Mhc>TER94A229E tissues with an αVCP antibody (Cell Signaling) that could recognize Drosophila TER94 (Figure S2). Interestingly, while endogenous TER94 was localized diffusely in Mhc>lacZ, Mhc>TER94A229E myofibrils contained TER94-positive inclusion-like structures (arrows in Figure 1L), reminiscent of the rimmed vacuoles found in IBMPFD patient's muscles [1], [30].

To ensure that this flight impairment was caused by muscle degeneration, temperature-sensitive GAL80 (GAL80ts) was used to prevent GAL4 from activating TER94 expression until adulthood. Mhc>tub-GAL80ts >TER94A229E flies raised at 25°C exhibited normal flight, demonstrating that muscles had formed normally at permissive temperature. However, the same flies lost their ability to fly after being shifted to 29°C for 10 days. In comparison, such temperature shift did not affect the flight ability of Mhc>tub-GAL80ts >LacZ flies (data not shown). Together, our results suggest that expression of the TER94 IBMPFD mutants can affect both the development and maintenance of muscles.

Expression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants in brain causes learning deficit

In addition to myopathy, mutations in VCP have been implicated in frontotemporal lobar degeneration [31]. To examine the effect of VCP mutations in brain, we used elav-GAL4, a driver active in all neuronal cells, to express TER94 IBMPFD mutants. In addition, UAS-mCD8-GFP was included to label the plasma membrane of Elav-positive neurons. While mCD8-GFP localization remained normal in elav>LacZ and elav>TER94wt brains (Figure 2A and 2B), elav>TER94 IBMPFD mutant brains had a midline-crossing phenotype in the β/γ lobes of the mushroom body (arrows in Figure 2C–2E). The penetrance of this defect was lowest for elav>TER94R152H (22%, n = 18), but higher for elav>TER94R188Q (80%, n = 15) and elav>TER94A229E (62%, n = 21). The midline-crossing phenotype was seen in newly eclosed elav>TER94 IBMPFD mutant adults (data not shown), indicating that expression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants in neuronal cells may disrupt axonal guidance during brain development.

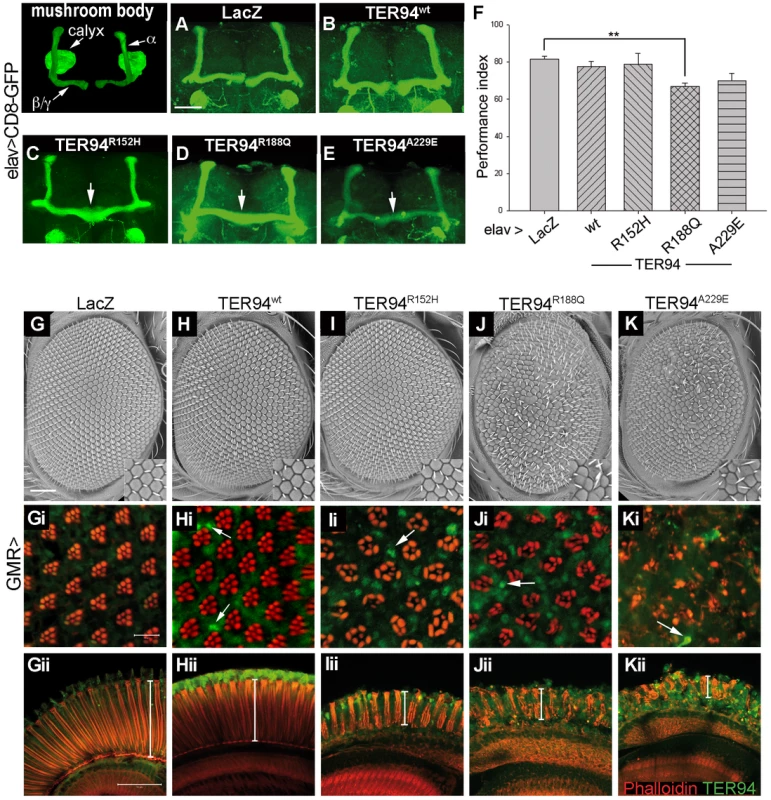

Fig. 2. Tissue-specific expression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants impairs neuronal structure and function.

(A–E) Confocal images of mushroom bodies (labeled by mCD8-GFP) from adult brains expressing indicated transgenes under the control of elav-GAL4. A segmented adult brain illustrates the major structures of mushroom body, and arrows indicate the midline crossing of mushroom bodies in IBMPFD mutants. (F) The Pavlovian learning test of flies expressing TER94 transgenes or LacZ control. Values shown represent mean ± SE from four independent tests. **p<0.01 relative to LacZ control (Student's t test). (G–K) Scanning electron micrographs (SEM) of the 2-day old adult eyes expressing indicated transgenes under the control of GMR-GAL4. Insets show enlarged views of the bristles on the eye surface. In all SEM panels, anterior is to the left and dorsal is up. (Gi–Kii) Confocal images of tangential (Gi–Ki) and longitudinal sections (Gii–Kii) of retinas from flies of corresponding genotypes at the same age stained with phalloidin (red) and anti-VCP (green). TER94-positive structures in eyes expressing TER94 transgenes are indicated with white arrows. White lines indicate the thicknesses of the retina in the longitudinal views. Scale bars: 50 µm (A–E), 100 µm (G–K), 10 µm (Gi–Ki), 50 µm, (Gii–Kii). Genotypes: (A) UAS-GAL4,elav-GAL4C155/w; UAS-LacZ/+; UAS-mCD8-GFP/+, (B) UAS-GAL4,elav-GAL4C155/w; UAS-mCD8-GFP/UAS-TER94 wt, (C) UAS-GAL4,elav-GAL4C155/w; UAS-mCD8-GFP/UAS-TER94R152H, (D) UAS-GAL4,elav-GAL4C155/w; UAS-mCD8-GFP/UAS-TER94R188Q, (E) UAS-GAL4,elav-GAL4C155/w; UAS-TER94A229E/+; UAS-mCD8-GFP/+, (G) GMR-GAL4/UAS-LacZ, (H) UAS-TER94wt/w; GMR-GAL4/+, (I) GMR-GAL4/+; UAS-TER94R152H/+, (J) GMR-GAL4/+; UAS-TER94R188Q/+, (K) GMR-GAL4/UAS-TER94A229E. The midline-crossing phenotype observed in elav>TER94 IBMPFD mutants is reminiscent of those described for linotte, a Drosophila memory mutant [32]. We thus performed olfactory learning tests to see if elav>TER94 IBMPFD mutants had learning deficit. elav>TER94R152H, which had the lowest penetrance of midline-crossing defects, did not exhibit detectable deficit in olfactory learning. On the other hand, elav>TER94R188Q, the mutant that exhibited the highest penetrance of midline-crossing defects, had the most severe learning deficit (Figure 2F). elav>TER94A229E flies showed intermediate decline in both the midline-crossing assay and the learning tests (Figure 2F).

Overexpressing TER94 IBMPFD mutants causes photoreceptor degeneration

To further understand the effect of TER94 IBMPFD mutants on neuronal cells, we used GMR-GAL4 driver, which is active in photoreceptor cells (R cells) in the developing eye. The development and maintenance of R cells in fly eye has been a powerful model for analyzing genes contributing to human neurodegenerative diseases [33]. As shown in Figure 2G and 2H, external morphologies of GMR>lacZ (a negative control) and GMR>TER94wt eyes were normal. Phalloidin staining showed that GMR>lacZ and GMR>TER94wt retina both had normal arrangement of rhabdomeres (the light-sensing organelles in R cells) (Figure 2Gi and 2Hi), indicating the presence of normal complement of R cells. In contrast, the rhabdomere arrangement was disorganized in animals expressing TER94 IBMPFD mutants under the control of GMR-GAL4. Similar to muscle formation, expression of TER94R152H had the weakest effect on eye formation, as GMR>TER94R152H eyes actually appeared normal externally (Figure 2I). However, the rhabdomeres in GMR>TER94R152H retina were noticeably disorganized (Figure 2Ii), and many clusters contained fewer rhabdomeres, indicative of loss of R cells. On the other hand, GMR>TER94R188Q and GMR>TER94A229E both exhibited noticeable eye roughness (Figure 2J and 2K). Furthermore, the severe defect in their rhabdomere organization suggested that both GMR>TER94R188Q and GMR>TER94A229E retina also lost significant numbers of R cells (Figure 2Ji and 2Ki). In addition to disruption in rhabdomere organization in tangential sections, GMR>TER94R152H, GMR>TER94R188Q, and GMR>TER94A229E retinas all showed reduced thicknesses and disorganizations in the longitudinal sections (Figure 2Iii–2Kii). This defect further strengthens the notion that expression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants could interfere with R cell development.

To understand the effect of VCP mutations on R cell maintenance, we used Rh1-GAL4 to express TER94 IBMPFD mutants. Rh1-GAL4 becomes active in the outer R cells (those with large rhabdomeres; R1-6 in Figure 3A), but not in the inner R cells (those with small rhabdomeres; R7 in Figure 3A), at late pupal stage. Thus, this driver will allow us to circumvent the potentially detrimental effect of TER94 on development and focus on its effect on mature neurons, and ask if the neurodegenerative defect is cell autonomous. Retina from young Rh1>TER94 (in all tested transgenic alleles) adults all showed normal rhabdomere organization (Figure 3B–3E). However, in the retina of 28 day-old TER94 IBMPFD mutants, rhabdomere staining was disorganized and significant loss of R cells was evident (Figure 3H–3J). It should be noted that only the outer R cells suffered degeneration, indicating that the effect of TER94 on neurodegeneration is cell autonomous. Furthermore, the fact that older flies, but not the young ones, displayed loss of photoreceptors demonstrates that expression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants could cause progressive degeneration of R cells.

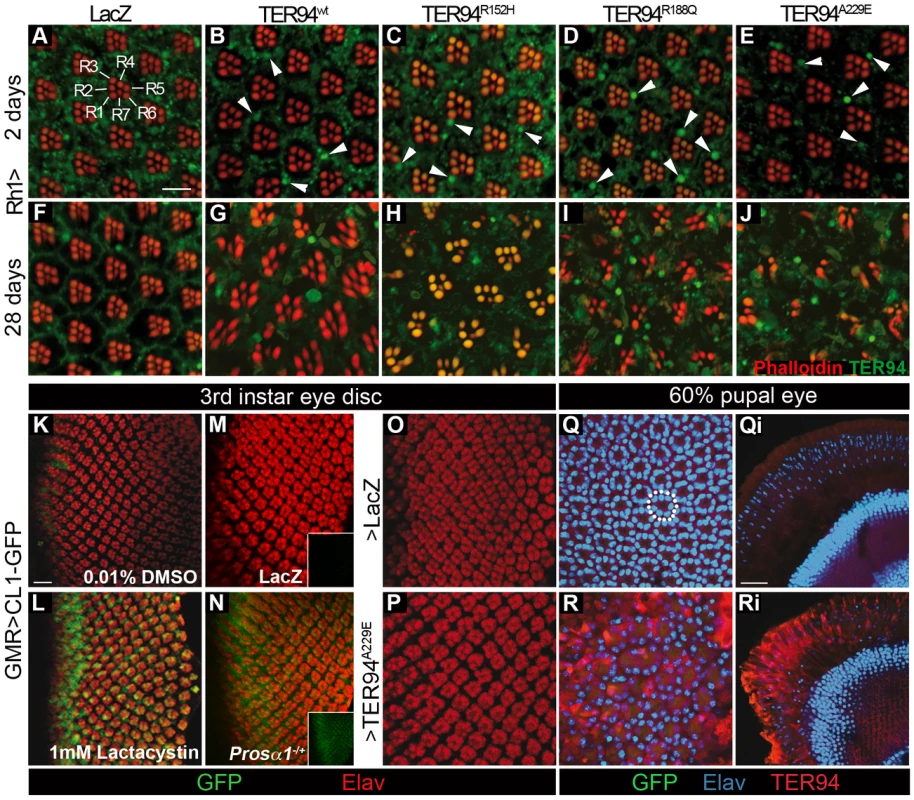

Fig. 3. Formation of TER94-containing structures and UPS impairment can be dissociated from IBMPFD mutant-induced toxicity.

(A–J) Confocal images of 2 day- (A–E) or 28 day-old (F–J) adult retinas expressing indicated transgenes under the control of Rh1-GAL4 stained with phalloidin (red) and anti-VCP (green). TER94-containing structures in eyes expressing TER94 transgenes are indicated with white arrowheads. The green autofluorescence in rhabdomeres is caused by eye pigment. (K–P) Larval eye discs expressing CL1-GFP and indicated transgenes (M, O, and P) or in heterozygous Prosα1 background (N) under the control of GMR-GAL4 stained with anti-Elav (red). (K and L) The GMR>CL1-GFP eye discs are treated with either 0.01% DMSO (K) or 1 mM lactacystin (L). Insets show green channel of the corresponded images (M and N). (Q-Ri) Tangential (Q and R) and longitudinal (Qi and Ri) sections of 60% pupal eyes stained for Elav (blue) and TER94 (red). A normal cluster of photoreceptors nuclei is indicated with a white dashed circle. Please note that while nuclear clusters are drastically disrupted in TER94A229E pupal eye, the CL1-GFP signal remains undetectable (R). Scale bars: 10 µm (A-J), 5 µm (K–P), 20 µm (Oi–Pi). Genotypes: (A and F) UAS-LacZ/+;Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+, (B and G) UAS-TER94 wt/w;Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+, (C and H) Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/UAS-TER94R152H, (D and I) Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/UAS-TER94R188Q, (E and J) UAS-TER94A229E/+;Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+, (K and L) GMR-GAL4/+;UAS-CL1-GFP/+, (M, O, Q and Oi) GMR-GAL4/UAS-LacZ; UAS-CL1-GFP/+, (N) GMR-GAL4/Prosα1l(2)SH2342;UAS-CL1-GFP/+, (P, R and Ri) GMR-GAL4/UAS-TER94A229E; UAS-CL1-GFP/+. Formation of large TER94-positive structures and TER94-induced photoreceptor degeneration can be uncoupled

The presence of ubiquitinated inclusions, which also contain VCP mutant proteins, has been suggested as the underlying mechanism of IBMPFD pathogenesis [21], [34]. To test whether TER94 associates with aggregates in our model, retina of various genotypes were stained with αVCP antibody to monitor its localization. We reasoned that, if the formation of VCP-containing aggregates causes IBMPFD, a strong correlation between the extent of aggregate formation and the severity of neurodegenerative defects should be observed.

While rhabdomere organization was normal in young Rh1>TER94 (both wild type and IBMPFD mutants; Figure 3B–3E), scattered large structures with intense TER94 staining could be seen (arrowheads in Figure 3B–3E). Immunostaining with FK2 antibody (specific for polyubiquitin) suggests that most of these structures did not contain polyubiquitinated proteins (data not shown). In 28 day-old flies, progressive degeneration of R cells was observed, along with these TER94-containing structures (Figure 3G–3J). However, while the TER94-induced degeneration could be suppressed by increasing cellular ATP level (see below), the level of large TER94-positive structures was unaffected (compare Figure 9E to Figure 9Ei, and Figure 10D to Figure 10Di). Similarly, while R cell formation was unaffected in GMR>TER94wt retina, large TER94-positive structures were detected (arrows in Figure 2Hi). Thus, in this fly IBMPFD model, it appears that the phenotypes of large TER94-positive structures and TER94-induced neurodegeneration could be uncoupled.

TER94 IBMPFD mutant-induced neurodegeneration is not associated with UPS impairment

It has been suggested that impaired UPS, caused by VCP mutations, results in the deposition of proteinaceous aggregates and IBMPFD [21]. To test whether the expression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants disrupts UPS, UAS-CL1-GFP (kindly provided by Dr. Paul Taylor) [35] was co-expressed with UAS-TER94A229E (the IBMPFD mutant that exhibited strongest muscle and R cell defects) in the eye discs. To demonstrate that CL1-GFP could monitor proteasome function, GMR>CL1-GFP eye discs were treated with lactacystin, a proteasome inhibitor. As shown in Figure 3K and 3L, 1 mM of lactacystin could elicit robust GFP signal, whereas DMSO alone had no effect, indicating that this reporter responded to disruption of proteasome function. Furthermore, GFP intensity increased in GMR>CL1-GFP when one copy of the 20S proteasome α1 subunit gene (Prosα1l(2)SH2342) was mutated (Figure 3N). However, although this reporter appeared to be sensitive, no GFP signal was detected in GMR>TER94A229E larval eye discs (Figure 3P). In pupal GMR>TER94A229E eye where large TER94-containing structures and R cell disruption were evident, CL1-GFP signal remained undetectable (compare Figure 3Q to Figure 3R, and Figure 3Qi to Figure 3Ri). Thus, expression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants does not appear to cause UPS impairment in our model.

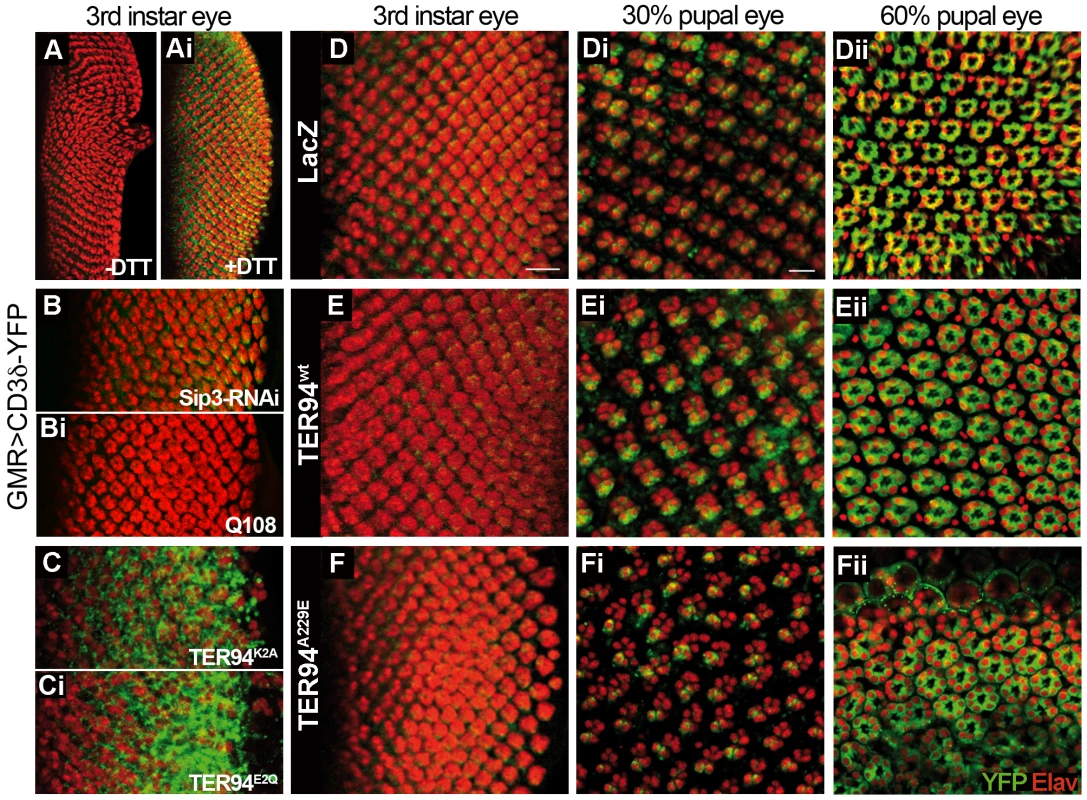

TER94 IBMPFD mutant-induced neurodegeneration is not associated with ERAD impairment

Impairment of ERAD, caused by VCP mutants, has also been suggested as a mechanism for IBMPFD pathogenesis [22]. To test whether expression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants disrupts ERAD, we generated transgenic flies carrying UAS-CD3δ-YFP, a well-established ERAD reporter in cell culture and mouse [36], [37]. To test if CD3δ-YFP could be a potent ERAD reporter in fly, GMR>CD3δ-YFP eye discs were treated with 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), a reducing agent capable of eliciting ER stress. While no YFP signal was seen in untreated tissues, intense YFP signal was observed in DTT-treated GMR>CD3δ-YFP eye discs (Figure 4A and 4Ai). Moreover, GFP intensity increased in GMR>CD3δ-YFP when Sip3, the Drosophila homolog of a key ERAD component Hrd1, was knockdown by dsRNA-mediated RNA interference (RNAi) (Figure 4B). It is worth noting that expression of toxic polyglutamine (Q108), which does not have apparent role in ERAD, did not elicit CD3δ-YFP signals (Figure 4Bi). These data demonstrated that CD3δ-YFP, a mammalian T-cell receptor subunit, is specific and capable of detecting ERAD in Drosophila.

Fig. 4. Expressing TER94 IBMPFD mutant in neurons does not impair ERAD.

(A and Ai) Fluorescent images of GMR>CD3δ-YFP larval eye discs without (A) or with 5 mM DTT treatment (Ai). (B–Ci) Fluorescent images of GMR>CD3δ-YFP larval eye discs co-expressing indicated transgenes. (D–Fii) Fluorescent images of GMR>CD3δ-YFP larval (D-F) and pupal (30%, Di–Fi; 60% Dii–Fii) eye discs co-expressing LacZ (D–Dii), TER94 wt (E–Eii), and TER94A229E (F–Fii). In all panels, anti-Elav antibody (red) labels the nuclei of retinal neurons. Scale bars, 10 µm (D–F), 5 µm (Di–Fii). Genotypes: (A and Ai) UAS-CD3δ-YFP/w; GMR-GAL4/+, (B) UAS-CD3δ-YFP/w; GMR-GAL4/+; UAS-Sip3-RNAiv6870/+, (Bi) UAS-CD3δ-YFP/w; GMR-GAL4/UAS-Q108, (C)UAS-CD3δ-YFP/w; GMR-GAL4/UAS-TER94K2A, (Ci) w,UAS-CD3δ-YFP/w; GMR-GAL4/UAS-TER94E2Q, (D-Dii) UAS-CD3δ-YFP/w; GMR-GAL4/UAS-LacZ, (E-Eii) UAS-CD3δ-YFP/w; GMR-GAL4/+;UAS-TER94wt/+, (F-Fii) UAS-CD3δ-YFP/w;GMR-GAL4/UAS-TER94A229E. Consistent with the notion that TER94 has a role in ERAD, robust YFP signals were detected in GMR>TER94K2A and GMR>TER94E2Q larval eye discs (Figure 4C and 4Ci). However, in larval eye discs expressing TER94 IBMPFD mutants, the CD3δ-YFP signal was nearly undetectable (Figure 4D–4F and data not shown). Subsequent examinations of two pupal stages revealed that GMR>TER94A229E retina exhibited aberrant arrangement of R cells, whereas GMR>TER94wt had normal complement of R cells. Yet the CD3δ-YFP signals in both GMR>TER94A229E and GMR>TER94wt were comparable (compare Figure 4Fi to Figure 4Di and 4Ei, and Figure 4Fii to Figure 4Dii and 4Eii). This lack of correlation between the CD3δ-YFP signal and the photoreceptor defects suggests that impaired ERAD is not a major factor for the R cell loss.

To independently confirm this finding, we used xbp1-EGFP (kindly provided by Dr. Hermann Steller) to detect the unfolded protein response (UPR) in TER94-expressing eye discs [38]. Similar to CD3δ-YFP, robust xbp1-EGFP signal was detected when eye discs were treated with DTT (Figure S4B) or expressing TER94K2A (Figure S4G and S4Gi). In contrast, no detectable xbp1-EGFP signal was seen in GMR>TER94 IBMPFD mutants (Figure S4D, S4E, S4F). These observations suggest that overexpressing TER94 IBMPFD mutants does not trigger ERAD impairment or UPR in our fly model.

IBMPFD pathogenesis depends on hexameric configuration

VCP is known to act as hexamer, and a recent report showed that p97R155P and p97A232E are capable of forming hexamer in vitro [15]. To ask if the ability of these IBMPFD mutants to disrupt R cells requires hexameric formation, we made monomeric forms of TER94 (mTER94) by mutating R356 and R359, two positively charged arginine residues in D1 domain, to negatively charged glutamic acids (Figure 1A). Although these mutations were chosen based on literature [39], blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) was performed to ensure that these mTER94 mutants were indeed monomers. In GMR-GAL4 extract under native conditions, αVCP antibody detected a band migrating at ∼676 kDa, corresponding to the hexameric TER94 (Figure 5A). In extracts from GMR>TER94wt, GMR>TER94A229E, and GMR>TER94R188Q, the intensity of this ∼676 kDa band became elevated, indicating that TER94 proteins made from the transgenes were capable of forming hexamers (Figure 5A). In contrast, in extracts from GMR>mTER94wt, GMR>mTER94A229E, and GMR>mTER94R188Q, the intensity of ∼676 kDa band was reduced to the GMR-GAL4 level (Figure 5A). Immunoblots of the same extracts in SDS-PAGE detected ∼95 kDa monomer in mTER94 lines with intensity that was significantly higher than endogenous protein in GMR-GAL4 control (Figure 5B), demonstrating that these mTER94 proteins were expressed, but incapable of forming hexamers. Although overexpressed mTER94 proteins were seen in SDS-PAGE, we did not detect mTER94 in the native PAGE in several attempts (Figure 5A and data not shown). It is possible that the epitope is masked in native mTER94 proteins.

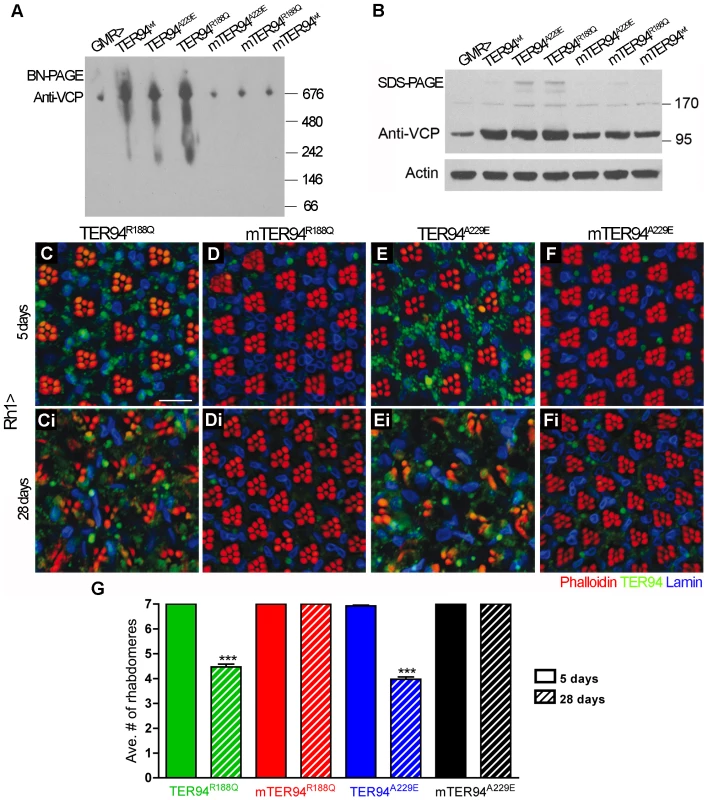

Fig. 5. Formation of hexamers is crucial for the cytotoxicity of disease proteins.

BN-PAGE (A) and SDS-PAGE (B) of lysates from GMR-GAL4-driven TER94 IBMPFD mutants (genotypes are indicated above the blots). The blots are probed with anti-VCP antibody, and anti-Actin antibody blot serves as a loading control. (C–Fi) Confocal images of 5 day- (C–F) and 28 day-old (Ci–Fi) adult retinas expressing indicated transgenes under the control of Rh1-GAL4 stained with phalloidin (red), anti-VCP (green), and anti-Lamin (blue). Scale bar: 10 µm. (G) Quantification of rhabdomere numbers per unit eye from 5 days and 28 days flies of indicated genotypes. 91 to 174 unit eyes from ≥ six eyes are scored in each group. Values shown represent mean ± SE. ***p<0.001 compares 5 days to 28 days conditions in each genotype (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test). Genotypes: (GMR> in A and B) GMR-GAL4/+, (TER94wt in A and B) UAS-TER94wt/w; GMR-GAL4/+, (mTER94wt in A and B) GMR-GAL4/+; UAS-mTER94wt/+, (TER94R188Q in A, B and C-Ci) GMR-GAL4/+; UAS-TER94R188Q/+, (mTER94R188Q in A, B and D-Di) GMR-GAL4/+; UAS-mTER94R188Q/+, (TER94A229E in A, B and E-Ei) GMR-GAL4/UAS-TER94A229E, (mTER94A229E in A, B and F-Fi) GMR-GAL4/+; UAS-mTER94A229E/+. To ask whether the monomeric TER94 IBMPFD mutants could still elicit neurodegenerative defects, we expressed these transgenes with Rh1-GAL4 and examined R cell organization. In young (5-day old) Rh1>mTER94A229E or Rh1>mTER94R188Q, the number and arrangement of R cells was completely normal (Figure 5C–5F). In 28 day-old flies, the R cells remained normal in Rh1>mTER94A229E or Rh1>mTER94R188Q eyes; however, the R cells were severely degenerated in eyes expressing TER94R188Q or TER94A229E (compare Figure 5Ci to Figure 5Di, Figure 5Ei to Figure 5Fi, and Figure 5G). These observations suggest the ability to form hexamers is essential for TER94-dependent R cell degeneration.

IBMPFD mutations are dominant active alleles

While the inheritance of IBMPFD is dominant, the nature of these VCP mutations remains unclear. To distinguish whether these mutations were dominant-active or dominant-negative, we examined the effect of altering TER94 gene dose on the eye phenotypes of TER94 IBMPFD mutants. We reasoned that if TER94 IBMPFD mutations are dominant-active, the rough eye phenotypes of GMR>TER94 IBMPFD mutants should be suppressed by inactivating one copy of the endogenous TER94 and enhanced by overexpressing wild type TER94. Conversely, if TER94 IBMPFD mutations act as dominant negatives, the rough eye phenotypes of GMR>TER94 IBMPFD mutants should be enhanced further by inactivating one copy of the endogenous TER94 and suppressed by overexpressing wild type TER94. As shown in Figure 6, the rough eye and R cell defects of GMR>TER94R152H, GMR>TER94R188Q, and GMR>TER94A229E were suppressed by inactivating one copy of TER94 and noticeably enhanced by overexpressing TER94wt transgene. To demonstrate the specificity of these genetic interactions, we tested the effect of TER94wt overexpression on GMR>TER94K2A, a known dominant negative. GMR>TER94K2A animals died at larval or early pupal stage (possibly due to GMR-GAL4 leaky expression elsewhere); however, this lethality could be rescued by overexpressing TER94wt (Figure 6J and 6Ji). Together, these results strongly suggest that IBMPFD mutations are dominant actives, and TER94 IBMPFD mutants and TER94K2A confer cytotoxicity through distinct mechanisms.

Fig. 6. TER94 IBMPFD mutants are dominant actives.

SEM (A-K) and confocal (Ai-Ki) images of 2 day-old adult eyes expressing indicated transgenes under the control of GMR-GAL4. (Ai–Ki) The adult retinas are stained with phalloidin (red), anti-VCP (green) and anti-Lamin (blue) antibodies. Scale bar: 10 µm (Ai–Ki). Genotypes: (A and Ai) GMR-GAL4/UAS-LacZ; UAS-TER94R152H/+, (B and Bi) GMR-GAL4/TER94l(2)k15502; UAS-TER94R152H/+, (C and Ci) UAS-TER94wt/w; GMR-GAL4/+; UAS-TER94R155H/+, (D and Di) GMR-GAL4/UAS-LacZ; UAS-TER94R188Q/+, (E and Ei) GMR-GAL4/TER94l(2)k15502; UAS-TER94R188Q/+, (F and Fi) UAS-TER94wt/w; GMR-GAL4/+; UAS-TER94R188Q/+, (G and Gi) GMR-GAL4,UAS-TER94A229E/UAS-LacZ, (H and Hi) GMR-GAL4,UAS-TER94A229E/TER94l(2)k15502, (I and Ii) UAS-TER94wt/w; GMR-GAL4,UAS-TER94A229E/+, (J and Ji) UAS-TER94wt/w; GMR-GAL4/UAS-TER94K2A, (K and Ki) UAS-TER94wt/w; GMR-GAL4/+. Energy expenditure associates with IBMPFD pathogenesis in fly model

Hexamers consisted of VCP disease proteins have recently been shown to possess increased ATPase activity in vitro [15] and in vivo [40]. As IBMPFD seems to preferentially affect tissues with high energy-demand, we speculated that this elevated ATPase activity of VCP mutants might contribute to IBMPFD pathogenesis by depleting cellular ATP. To test whether TER94 IBMPFD mutants could deplete ATP, cellular ATP levels from thorax (eyes were not used because eye pigment would interfere with the ATP assay) of flies expressing TER94 IBMPFD mutants driven by hs-GAL4 driver were measured. After three cycles of induction by heat shocks, hs>TER94wt and hs>TER94R152H did not show significant reduction in ATP level when compared to hs>LacZ control (Figure 7). However, significant reduction in ATP level was seen in hs>TER94A229E and hs>TER94R188Q, the alleles associated with strong defects in muscles and photoreceptors. While this reduction in ATP level appears modest, it is worth mentioning that mouse kidney cells undergo apoptosis when cellular ATP is depleted to ∼70% of normal level [41]. Thus it is entirely possible that similar level of ATP reduction could cause muscle and R cell degeneration in flies. In any case, our results are consistent with the notion that TER94 IBMPFD mutants could alter cellular ATP level.

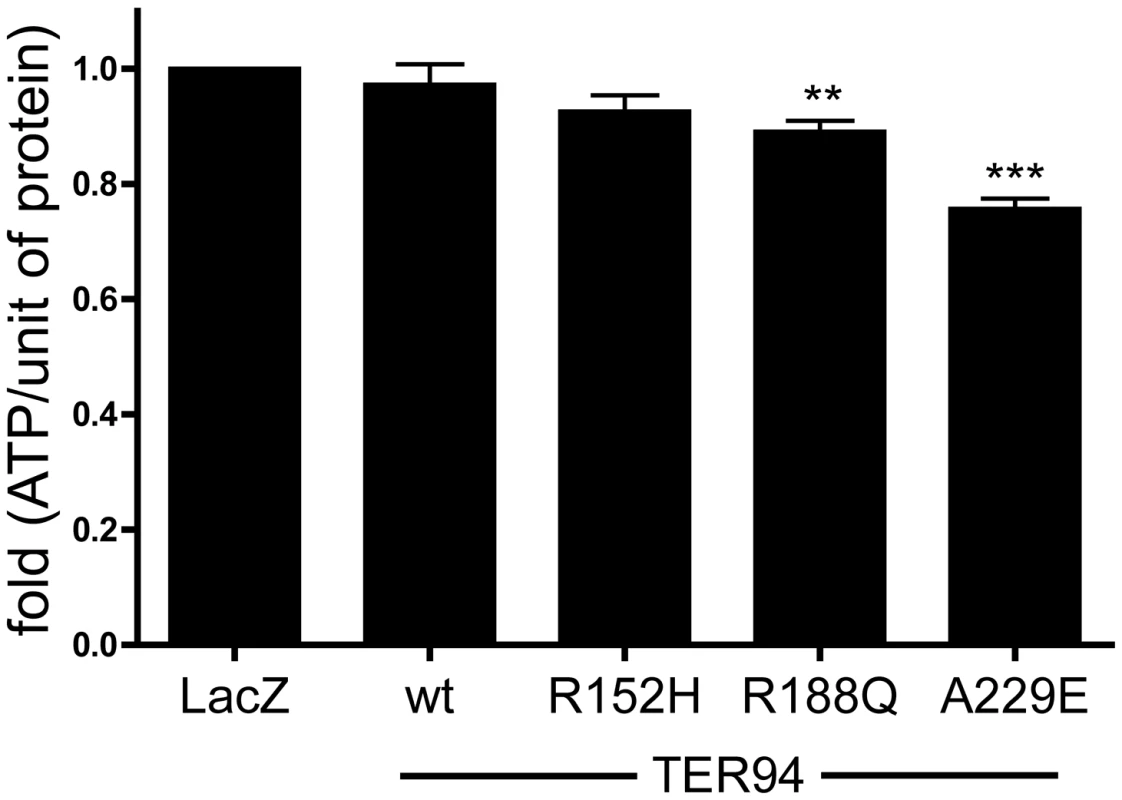

Fig. 7. Expression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants reduces cellular ATP level.

ATP measurement of flies expressing TER94 transgenes driven by hs-GAL4. hs>LacZ serves as control. Values are obtained from 6 independent experiments. Fold changes of the normalized ATP content are compared. Values shown represent mean ± SE. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 (repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test). If this ATP depletion contributes to the neurodegenerative defects of TER94 IBMPFD mutants, it should be possible to suppress the phenotypes by boosting cellular ATP production or reducing energy consumption. To test this, we subjected TER94 flies to dietary restriction (DR), a regimen known to boost energy production by either increasing the number of electron transport chains during mitochondrial biogenesis [42], or enhancing the metabolic adaptation to reduce overall energy expenditure [43]. Freshly eclosed Rh1>TER94 flies were raised on either normal food or DR food (reduction of two-third of sucrose and yeast). In support of the notion that energy expenditure plays a role in IBMPFD pathogenesis, the progressive degeneration of R cells was markedly mitigated for all tested TER94 IBMPFD mutants raised under DR condition for 10 days (data not shown). This diet-dependent suppression of R cell degeneration was still seen in most of the TER94 IBMPFD mutants raised under DR condition for 20 days (Figure 8). The only exception was Rh1>TER94A229E, which had the most severe R cell degeneration and showed only mild response to DR condition at this age (Figure 8). This suppression appears specific to IBMPFD, as DR had no evident effect on expanded polyglutamine-induced neurodegeneration (Figure 8E–8F).

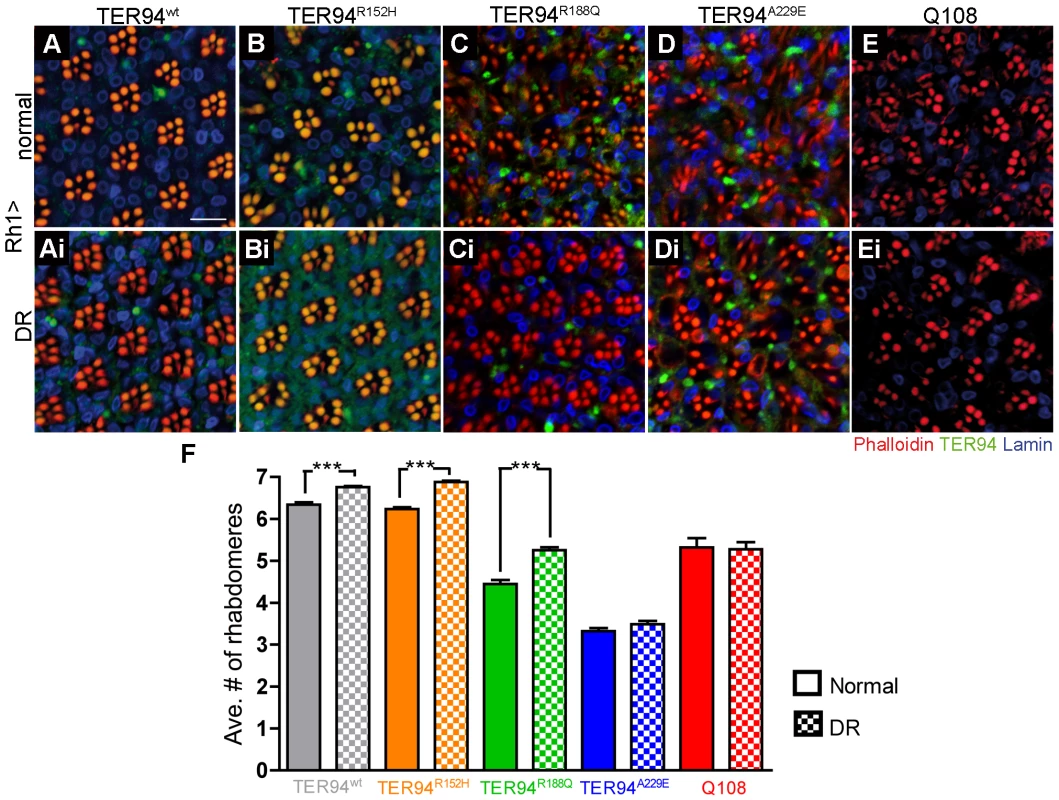

Fig. 8. Dietary restriction (DR) alleviates neurodegeneration induced by pathogenic TER94 mutants.

(A–Ei) Confocal images of adult retinas expressing indicated transgenes under the control of Rh1-GAL4 stained with phalloidin (red), anti-VCP (green), and anti-Lamin (blue) antibodies. After eclosion, these flies were raised on normal (A–E) or DR food (Ai–Ei) for 20 days (A–Di) or 35 days (E–Ei). Scale bar: 10 µm. (F) Quantification of rhabdomere numbers per unit eye from normal and DR treated flies of indicated genotypes. 155 to 360 unit eyes from ≥ six eyes are scored in each group. Values shown represent mean ± SE. ***p<0.001 compares normal to DR conditions in each genotypes (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test). Genotypes: (A and Ai) UAS-TER94wt/w; Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+, (B and Bi) Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/UAS-TER94R152H, (C and Ci) Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/UAS-TER94R188Q, (D and Di) UAS-TER94A229E/+; Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+, (E and Ei) UAS-Q108/+; Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+. To independently verify this energy expenditure idea, we took advantage of R cell physiology to assess the role of ATP in IBMPFD. It is known that fly R cells consume at least 5-fold more ATP under illuminated condition than in the dark [44]. Freshly eclosed (<12 h) Rh1>TER94 and controls flies were raised under a normal 12 hours light/12 hours dark cycles (L/D, light intensity ∼520 lux), constant light (L/L), or completely dark (D/D) conditions, and the presence of the R cells in these flies were compared. The progressive neurodegeneration of R cells was easily seen in TER94 IBMPFD mutant-expressing flies raised under the L/D condition (Figure 9). This loss of R cells was rescued when these flies were raised under the D/D condition (compare Figure 9C to Figure 9Ci, Figure 9D to Figure 9Di, Figure 9E to Figure 9Ei, and Figure 9I). Although this darkness treatment rescued the R cell defect in all TER94 IBMPFD mutants, it failed to restore the degeneration caused by overexpressing TER94K2A (compare Figure 9F to Figure 9Fi, and Figure 9I) or two expanded polyglutamine disease models (compare Figure 9G to Figure 9Gi, Figure 9H to Figure 9Hi, and Figure 9I) [45]–[47]. This suggests that the reduction of ATP expenditure is not a universal antidote for neurodegeneration, but specific to these TER94 IBMPFD mutants. The R cell degeneration was strongly enhanced under L/L condition for all TER94 IBMPFD mutants (data not shown). However, L/L condition also caused mild R cell degeneration in control and flies expressing TER94wt, likely due to retinopathy induced by continuous light exposure [48]. In any case, data from both DR and light conditioning experiments support energy expenditure as a pathophysiological mechanism in this Drosophila IBMPFD model.

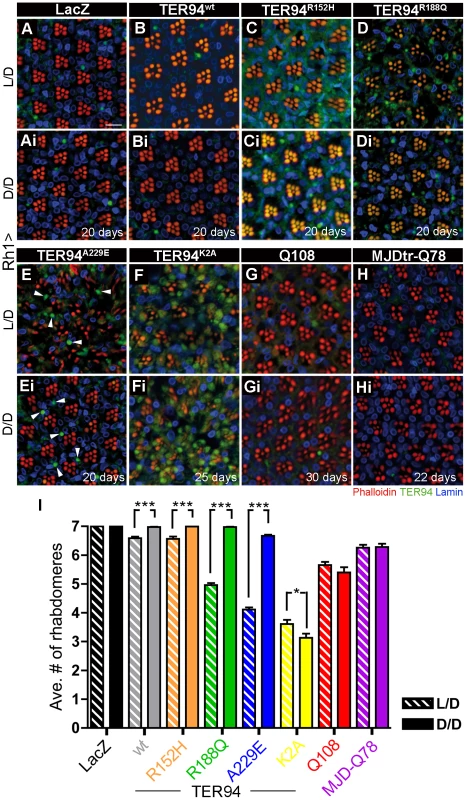

Fig. 9. Neurodegeneration induced by pathogenic TER94 mutants can be suppressed under dark conditions.

(A–Hi) Confocal images of adult retinas expressing indicated transgenes under the control of Rh1-GAL4 stained with phalloidin (red), anti-VCP (green), and anti-Lamin (blue) antibodies. Freshly eclosed flies were raised under L/D (A–H), or D/D condition (Ai–Hi). Arrowheads in E and Ei indicate large TER94-containing structures in degenerated (E) and recovered (Ei) retinas. Scale bar: 10 µm. (I) Quantification of rhabdomere numbers per unit eye under L/D and D/D conditions. 210 to 388 unit eyes from ≥ six eyes are scored in each group. Values shown represent mean ± SE. * p<0.05; ***p<0.001 compares L/D to D/D conditions in each genotypes (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test). Genotypes: (A and Ai) UAS-LacZ/+; Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+, (B and Bi) UAS-TER94wt/w; Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+, (C and Ci) Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/UAS-TER94R152H, (D and Di) Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/UAS-TER94R188Q, (E and Ei) UAS-TER94A229E/+; Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+, (F and Fi) UAS-TER94K2A/+; Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+, (G and Gi) UAS-Q108/+; Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+, (H and Hi) UAS-MJDtr-Q78/+; Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+. Knockdown of Drosophila plip suppresses pathogenic mutants-induced neurodegeneration

To further strengthen our energy expenditure hypothesis, we used genetic approaches to modulate ATP levels in fly IBMPFD model. As the electron transport chain of mitochondria generates the majority of ATP in animal cells, we found that RNAi knockdown of components in the catalytic core of F1 ATP synthase of complex V could significantly enhance R cells degeneration in Rh1>TER94A229E flies (Figure S5). Conversely, reducing ATP consumption through RNAi knockdown of two ATPases, ATP-citrate lyase [49] or a putative human copper transporter DmATP7 [50], could suppress Rh1>TER94A229E-induced R cell degeneration (Figure S5), further supporting the notion that ATP level is a key to the disease.

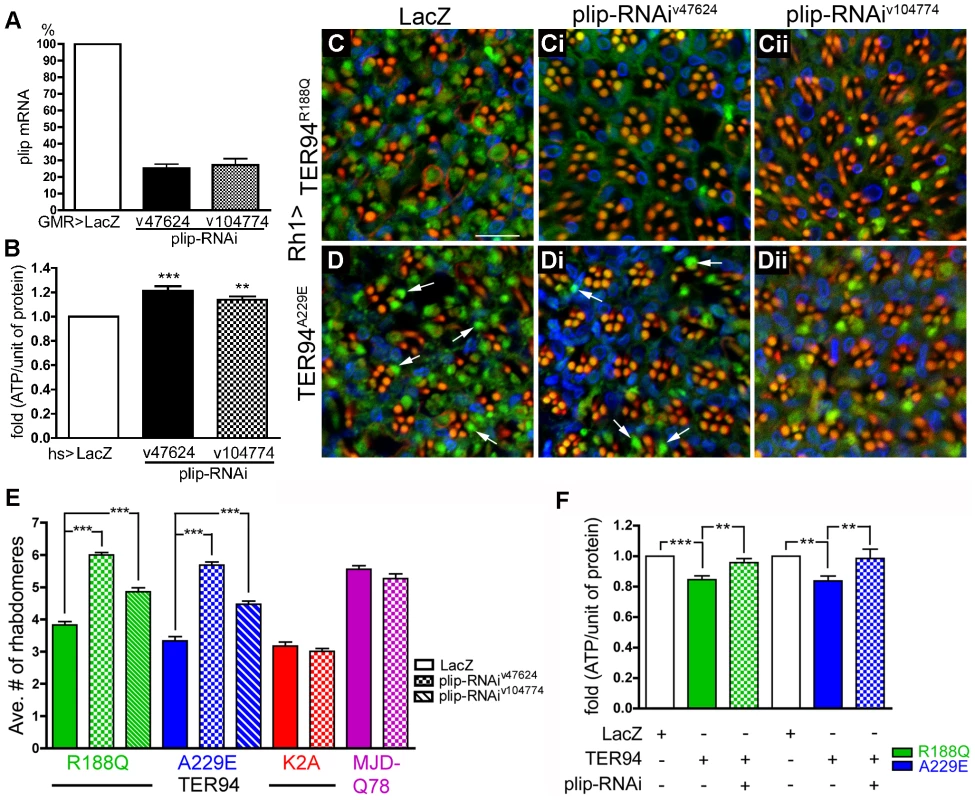

To genetically boost cellular ATP production, we took advantage of an observation that RNAi knockdown of mitochondrial phosphatase PTPMT1 (a protein tyrosine phosphatase localized to the mitochondrion) could markedly increase ATP production in mouse cells [51]. We thus expressed RNAi transgenes that target plip, the Drosophila homolog of PTPMT1, to analyze its effect on our disease model (Figure 10A). To avoid off-target effect, two independent plip-RNAi constructs v104774 and v47624, which target partially overlapped plip mRNA sequence, were used [52]. Knockdown with v104774 and v47624 both decreased the level of plip mRNA (Figure 10A) and elevated cellular ATP level (Figure 10B), although the increase in ATP level was higher with v47624. Expression of either v104774 or v47624 in outer R cells using Rh1-GAL4 had no effect on R cells (data not shown). However, expression of these plip-RNAi lines could significantly suppress the R cell degeneration in RH1>TER94R188Q and RH1>TER94A229E (compare Figure 10C to Figure 10Ci and Figure 10Cii, Figure 10D to Figure 10Di and Figure 10Dii, and Figure 10E). This suppression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants by plip-RNAi is specific, as knockdown of plip had no significant effect on the R cell degeneration in Rh1>TER94K2A or mutant MJDtr-Q78 (Figure 10E). To determine whether the suppression of TER94-dependent R cell degeneration correlates with ATP level, we measured ATP content in flies that co-express plip-RNAiv47624 with TER94R188Q or TER94A229E. Compared to TER94R188Q and TER94A229E alone, co-expressing plip-RNAiv47624 showed elevated ATP content (Figure 10F), further supporting a role of cellular ATP level in IBMPFD mutant-induced neurodegeneration.

Fig. 10. Neurodegeneration induced by pathogenic TER94 mutants can be suppressed by the knockdown of plip.

(A) The knockdown of endogenous plip mRNA by plip-RNAi lines v47624 (plip-RNAiv47624) and v104774 (plip-RNAiv104774). Data from three independent RT-PCR experiments are averaged and present in respect to control. (B) Measurement of ATP content from hs>plip-RNAiv47624 or hs>plip-RNAiv104774 flies after three cycles of heat shocks at 37°C. (C–Dii) Confocal images of 20 day-old adult retinas expressing indicated transgenes under the control of Rh1-GAL4 stained with phalloidin (red), anti-VCP (green), and anti-Lamin (blue) antibodies. Scale bar: 10 µm. (E) Quantification of the effect of plip knockdown on rhabdomere numbers in TER94 IBMPFD mutants, TER94K2A, and MJD-trQ78. 121 to 358 unit eyes from more than nine eyes are scored in each group. (F) Measurement of ATP content from flies expressing TER94A229E and TER94R188Q alone, or with plip-RNAiv47624 under the control of hs-GAL4 driver. hs>LacZ serves as control. Values in A are normalized to the internal control and obtained from three independent experiments. Values in B and F are fold changes of the normalized ATP content from ≥ three independent experiments. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 (repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test). Values shown in E represent mean ± SE. ***p<0.001 compares LacZ to plip-RNAi lines for each genotype (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test). Genotypes: (C) UAS-TER94R188Q/UAS-LacZ; Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+, (Ci) UAS-TER94R188Q/+; Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/UAS-plip-RNAiv47624, (Cii) UAS-TER94R188Q/UAS-plip-RNAiv104774; Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+, (D) UAS-TER94A229E/UAS-LacZ; Rh1-GAL4/+, (Di) UAS-TER94A229E/+; Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/UAS-plip-RNAiv47624, (Dii) UAS-TER94A229E/UAS-plip-RNAiv104774; Rh1-GAL4,UAS-LacZ/+. Discussion

In this study, we introduced IBMPFD-causing mutations in Drosophila TER94 to elucidate the pathogenesis of VCP mutants. Expression of these TER94 IBMPFD mutants in mature muscle cells causes loss of muscle tissues. Similarly, expression of these TER94 mutants in mature photoreceptor cells causes progressive neurodegeneration. Moreover, the observation that TER94A229E consistently had the strongest phenotypes correlates well with the allelic strength of its counterpart in human. Thus, although the fly model differs from human IBMPFD in the sense that TER94 mutant proteins are overexpressed, the fact that the expression of these TER94 mutants could recapitulate phenotypic and genetic features of IBMPFD suggests that our fly model is an appropriate system to analyze VCP mutations.

Using early muscle - and R cell-specific drivers, we show that overexpression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants during development can interfere with the formation of muscle and neuronal cells. Thus, although IBMPFD is an adult onset disease, the cytotoxic effect of IBMPFD-causing VCP mutant proteins may not be restricted to mature muscle and neuronal cells. It is likely that if expressed at high level, these VCP mutant proteins can cause deterioration of other cell types and manifest their cytotoxicity at earlier stages. Given the onset age of IBMPFD varies broadly (range 20 to >60 yrs) [20], [53], it seems plausible that subtle defects may have occurred in the development of muscle and neuronal tissues in IBMPFD individuals.

What is the nature of these IBMPFD-causing VCP mutations? The autosomal dominant inheritance of IBMPFD suggests that these mutations are not simple loss-of-function mutations. One possible scenario is that TER94 IBMPFD mutants interfere with wild type TER94 by forming non-functional hexamers. We showed that expression of TER94K2A, a known dominant negative, could disrupt muscles and R cells. However, while TER94K2A expression readily elicits ERAD and UPR responses, expression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants has little effect on these processes, suggesting that TER94K2A and TER94 IBMPFD mutants cause cytotoxicity through distinct mechanisms. Indeed, several results argue that TER94 IBMPFD alleles are dominant actives. First, disruptions of flight and R cell organization, phenotypes associated with TER94 IBMPFD mutants, could be mimicked by elevated expression of TER94wt. Moreover, IBMPFD-causing VCP mutants are known to possess elevated ATPase activity [15], [40] and we demonstrated that hexameric formation is critical for the IBMPFD mutants to disrupt photoreceptors. Most importantly, we showed that the eye defects of GMR>TER94 IBMPFD mutants could be enhanced by additional wild type TER94 expression. Taken together, these data argue strongly that IBMPFD-causing VCP alleles are gain-of-function mutations.

It is well documented that VCP participates in UPS and ERAD [19], [54]. The phenotypes of TER94 mutants defective in ATP-binding or ATP-hydrolysis also demonstrated that this AAA ATPase is indispensible for ERAD in Drosophila. The key question, however, is whether the disruption of UPS or ERAD is the cause that VCP mutations induce IBMPFD. Using reporters capable of monitoring UPS and ERAD, we showed that expression of TER94 IBMPFD mutants had little, if any, effect on both processes. The disconnect between the ability of TER94 IBMPFD mutants to induce neurodegeneration and their ability to impact UPS and ERAD is surprising because expression of pathogenic VCP mutants has been shown to disrupt ERAD and caused the accumulation of ubiquitinated aggregates in mice [21], [22], [34]. It is not clear why this difference exists between the two model systems. One possible explanation is that the reporters we used were not sensitive enough. Although we cannot formally exclude this possibility, CL1-GFP was capable of detecting a 50% reduction of gene dose in the 20S proteasome α1 subunit gene, suggesting that the UPS reporter is sensitive.

It should also be mentioned that in mammals, expression of VCP mutant does not always result in disruption of UPS and ERAD. Analysis of primary IBMPFD myoblasts (VCPH155C) and cells transfected with IBMPFD mutants did not reveal obvious increase of polyubiquitinated aggregates [55]. In cells expressing VCP mutant R155H or A232E, UbG76V-YFP and CD3δ-YFP reporters did not detect impairment to UPS and ERAD respectively [56]. Moreover, biochemical analysis showed that wild type and three disease proteins had identical binding affinity to cofactors Ufd1, Npl4, and Ataxin-3 [55]. In support of this, we have been unable to detect any genetic interaction between TER94 IBMPFD mutants and the VCP cofactors Ufd1, Npl4, and Eyc (Chang and Sang, unpublished data). It is possible that VCP mutant proteins can cause IBMPFD through multiple mechanisms, and in the Drosophila model, impairment of UPS and ERAD is not the main cause for TER94-induced R cell degeneration.

All VCP mutants implicated in IBMPFD hold increased ATPase activity [15], [40]. In addition, the symptoms of IBMPFD appear to manifest in tissues with high energy-demands. These observations prompt us to examine whether there is a mechanistic link between the TER94 mutant-induced neurodegenerative defects and the cellular ATP level. We show that expression of TER94A229E and TER94R188Q could reduce cellular ATP level. More strikingly, the neurodegenerative defects in TER94 IBMPFD mutant expressing eyes could be modified by perturbations in ATP level. Increasing ATP level by dietary restriction, dark conditions, or plip knockdown could all suppress the TER94 IBMPFD mutant-induced R cell degeneration. We further demonstrated that plip-dependent suppression of TER94A229E-induced neurodegeneration coincides with increase in cellular ATP level. Conversely, decreasing ATP level could enhance these degenerative defects. This phenotypic modulation by ATP level is specific, as these treatments had no impact on the degeneration caused by ATP-binding defective TER94 and polyglutamine expansion-containing proteins.

Several other observations lend support to this energy expenditure hypothesis. We showed that TER94 IBMPFD mutant-induced neurodegeneration requires hexameric formation, which is necessary for a functional ATPase. As the model stipulates that the ATPase activity would be essential for the pathogenesis, it makes sense that no IBMPFD-causing mutation resides in D2. Taken together, these results suggest that elevated ATPase activities may have a prominent role in IBMPFD pathology. It is imaginable that pathogenic VCP mutants may spend excessive amount of energy in performing their functions, thereby gradually deteriorating other energy-dependent pathways and causing progressive tissue degenerations.

In addition to improve our understanding of how VCP mutations cause IBMFPFD, another major goal of establishing a Drosophila IBMPFD model is to facilitate the identification of targets for designing therapeutic agents. Our demonstration that RNAi-mediated knockdown of plip could suppress TER94-induced neurodegeneration clearly suggests that this is a viable strategy. Furthermore, our demonstration that dietary restrictions and illumination conditions could modify TER94 phenotypes suggests a potential avenue of treating IBMPFD using environmental approach.

Materials and Methods

Molecular biology and transgenic flies

The Drosophila TER94 cDNA clone (GM02885), obtained from the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center (Indiana, USA), was subcloned into the transformation vectors pUAST and pattB-UAST as an EcoRI-XhoI fragment. Mutations in the TER94 cDNA were introduced using QuikChange (Stratagene), according to instructions from the manufacturer, and primers used for the site-directed mutagenesis of TER94 are listed in Table S1. CD3δ-YFP cDNA was purchased from Addgene [37], and subcloned into pUAST as an EcoRI-NotI fragment. All constructs were verified by sequencing prior to transgenic fly production. Flies carrying pUAST-based transgenes were generated by P element-mediated transformation, and flies carrying pattB-UAST-based constructs were generated by phiC31-mediated integration (Bestgene, California, USA).

Drosophila genetics

Flies were raised in standard cornmeal food at 25°C in 12 hours light/12 hours dark cycles unless otherwise noted. 24B-GAL4 and elav-GAL4c155 were obtained from the Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, Indiana, USA). GMR-GAL4 has been described previously [46]. Rh1-GAL4 and UAS-mCD8-GFP stocks were originally obtained from Dr. Larry Zipursky. An enhancer trap line l(2)SH2342 that allelic to CG18495 in which encodes Proteasome α1 subunit was acquired from Szeged Drosophila Stock Center (Hungary). All transgenic RNAi lines were provided by the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center. The UAS-CL1-GFP was a generous gift from Dr. Paul Taylor. Dr. Hermann Steller kindly provided the UAS-xbp1-EGFP stocks. Standard genetic markers and balancer chromosomes were used to generate specific genotypes.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Analyses of eye morphology using scanning electron microscopy and whole-mount preparation of fly eyes were performed as described previously [46]. Primary antibodies used were the following: anti-VCP (1∶100, Cell Signaling), anti-Elav (1∶20, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, DSHB), anti-LaminDm (1∶20, DSHB). FITC, Cy3, and Cy5 conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used at 1∶100 dilutions. F-Actin enriched rhabdomere was labeled by Rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (Sigma). Whole-mount brain preparation was performed as described previously [57]. The mushroom body was examined as a projected image that covered the whole structure. Zeiss LSM-510 or 710 confocal microscopes were used for collecting all fluorescent images. Photoshop CS was used for image processing. For experiments that comparing fluorescent-labeled probes among different genotypes, the sample preparation and image processing was performed in the same procedure and setting.

Behavior assays

For the learning test, the classical T-maze paradigm (Pavlovian) conditioning procedure was followed [58]. Briefly, flies were trained by exposure to electroshock paired with one odor of either 3-octanol (OCT) or 4-methycyclohexanol (MCH) for 1 minute, and subsequent exposure to the second odor (either OCT or MCH) without electroshock. Immediately after training, learning was measured by allowing flies to choose between the two odors used during training. Avoidance of the odor previously paired with electroshock produced a performance index. For each test, more than a hundred flies from each genotype were analyzed.

For measuring flight ability, a classical flightless assay was adopted [59]. 30–40 flies aged to 3 to 5 days were gently empted into a 2-liter graduated cylinder that coated with vacuum pump oil through a funnel at the top. Flies with normal flight ability were trapped in oil on the wall at higher cylinder marks, whereas flightless flies landed on the lower level or fell to the bottom. The numbers of flies stuck on the cylinder wall was counted into 10 divisions with higher index that indicates normal flight behavior and vise versa.

Immunoblotting

Protein preparation for SDS-PAGE from Drosophila heads followed the procedures described previously [46]. For the BN-PAGE experiment, the proteins extraction and separation followed manufacture's direction (Invitrogen). Primary antibodies were used as the following dilutions: anti-VCP (1∶3000, Cell Signaling) and anti-β-Actin (1∶5000, Abcam). Secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used in 1∶5000 dilutions. All loading controls were prepared by stripping off the reagents from the original membrane and then re-immunoblotting with anti-β-Actin following the standard procedures. ImageJ was used to quantify bands intensity.

Quantification of rhabdomeres in adult retina

A naïve examiner who was blinded to the genotype counted the number of rhabdomeres in each unit eye. At least six individual eyes were scored in each experimental group. Data plotting and statistics were processed using Prism (GraphPad software) or SigmaPlot 10 (Systat software).

RT-PCR

Adult eyes from GMR>LacZ, GMR>plip-RNAiv47624 and GMR>plip-RNAiv104774 were dissected for RNA isolation using TRI Reagent (Sigma). 2 µg RNA was used for reverse transcription (SuperScript First Strand, Invitrogen) following the manufacture's direction. Subsequent PCR amplification was performed with about 1.5 µg cDNA and specific primer pairs for plip (forward: 5′-CATGTTCGCACGCGTTTC-3′, reverse: 5′-GGTCATGATTTCGTCTCCAC-3′) and internal control G3PDH (forward: 5′-CCACTGCCGAGGAGGTCAACTA-3′, reverse: 5′-GCTCAGGGTGATTGCGTATGCA-3′). The amplification was done for 24 cycles (95°C 30 sec, 52°C 45 sec, 72°C 1 min).

ATP assay

Drosophila ATP assay was performed as following a previous report [60]. Briefly, the fly thoraces were dissected and homogenized in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride in extraction buffer (100 mM Tris and 4 mM EDTA, pH7.8) to denature endogenous ATPases. The supernatant fraction of the homogenate was collected after centrifugation at 16,100 g and then diluted in 1/750 with extraction buffer. The protein concentration was determined using the Bradford protein assay system (Bio-Rad). The ATP level was determined by ATP determination kit (Invitrogen) and measured by Victor 3 plate reader (PerkinElmer). The relative ATP level was then calculated by dividing the luminescence readout with the protein concentration and then normalized to control.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. WattsGD

WymerJ

KovachMJ

MehtaSG

MummS

2004

Inclusion body myopathy associated with Paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia is caused by mutant valosin-containing protein.

Nat Genet

36

377

381

2. DaiRM

LiCC

2001

Valosin-containing protein is a multi-ubiquitin chain-targeting factor required in ubiquitin-proteasome degradation.

Nat Cell Biol

3

740

744

3. JaroschE

TaxisC

VolkweinC

BordalloJ

FinleyD

2002

Protein dislocation from the ER requires polyubiquitination and the AAA-ATPase Cdc48.

Nat Cell Biol

4

134

139

4. LatterichM

FröhlichKU

SchekmanR

1995

Membrane fusion and the cell cycle: Cdc48p participates in the fusion of ER membranes.

Cell

82

885

893

5. RabouilleC

LevineTP

PetersJM

WarrenG

1995

An NSF-like ATPase, p97, and NSF mediate cisternal regrowth from mitotic Golgi fragments.

Cell

82

905

914

6. KondoH

RabouilleC

NewmanR

LevineTP

PappinD

1997

p47 is a cofactor for p97-mediated membrane fusion.

Nature

388

75

78

7. HetzerM

MeyerHH

WaltherTC

Bilbao-CortesD

WarrenG

2001

Distinct AAA-ATPase p97 complexes function in discrete steps of nuclear assembly.

Nat Cell Biol

3

1086

1091

8. CaoK

NakajimaR

MeyerHH

ZhengY

2003

The AAA-ATPase Cdc48/p97 regulates spindle disassembly at the end of mitosis.

Cell

115

355

367

9. ZhangX

ShawA

BatesPA

NewmanRH

GowenB

2000

Structure of the AAA ATPase p97.

Mol Cell

6

1473

1484

10. DeLaBarreB

BrungerAT

2003

Complete structure of p97/valosin-containing protein reveals communication between nucleotide domains.

Nat Struct Biol

10

856

863

11. RouillerI

ButelVM

LatterichM

MilliganRA

Wilson-KubalekEM

2000

A major conformational change in p97 AAA ATPase upon ATP binding.

Mol Cell

6

1485

1490

12. DaviesJM

BrungerAT

WeisWI

2008

Improved structures of full-length p97, an AAA ATPase: implications for mechanisms of nucleotide-dependent conformational change.

Structure

16

715

726

13. SongC

WangQ

LiCC

2003

ATPase activity of p97-valosin-containing protein (VCP). D2 mediates the major enzyme activity, and D1 contributes to the heat-induced activity.

J Biol Chem

278

3648

3655

14. OguraT

WilkinsonAJ

2001

AAA+ superfamily ATPases: common structure–diverse function.

Genes Cells

6

575

597

15. HalawaniD

LeBlancAC

RouillerI

MichnickSW

ServantMJ

2009

Hereditary inclusion body myopathy-linked p97/VCP mutations in the NH2 domain and the D1 ring modulate p97/VCP ATPase activity and D2 ring conformation.

Mol Cell Biol

29

4484

4494

16. KobayashiT

TanakaK

InoueK

KakizukaA

2002

Functional ATPase activity of p97/valosin-containing protein (VCP) is required for the quality control of endoplasmic reticulum in neuronally differentiated mammalian PC12 cells.

J Biol Chem

277

47358

47365

17. MeyerHH

KondoH

WarrenG

1998

The p47 co-factor regulates the ATPase activity of the membrane fusion protein, p97.

FEBS Lett

437

255

257

18. UchiyamaK

TotsukawaG

PuhkaM

KanekoY

JokitaloE

2006

p37 is a p97 adaptor required for Golgi and ER biogenesis in interphase and at the end of mitosis.

Dev Cell

11

803

816

19. YeY

MeyerHH

RapoportTA

2001

The AAA ATPase Cdc48/p97 and its partners transport proteins from the ER into the cytosol.

Nature

414

652

656

20. KimonisVE

FulchieroE

VesaJ

WattsG

2008

VCP disease associated with myopathy, Paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia: review of a unique disorder.

Biochim Biophys Acta

1782

744

748

21. WeihlCC

MillerSE

HansonPI

PestronkA

2007

Transgenic expression of inclusion body myopathy associated mutant p97/VCP causes weakness and ubiquitinated protein inclusions in mice.

Hum Mol Genet

16

919

928

22. WeihlCC

DalalS

PestronkA

HansonPI

2006

Inclusion body myopathy-associated mutations in p97/VCP impair endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation.

Hum Mol Genet

15

189

199

23. JuJS

FuentealbaRA

MillerSE

JacksonE

Piwnica-WormsD

2009

Valosin-containing protein (VCP) is required for autophagy and is disrupted in VCP disease.

J Cell Biol

187

875

888

24. VesaJ

SuH

WattsGD

KrauseS

WalterMC

2009

Valosin containing protein associated inclusion body myopathy: abnormal vacuolization, autophagy and cell fusion in myoblasts.

Neuromuscul Disord

19

766

772

25. RitsonGP

CusterSK

FreibaumBD

GuintoJB

GeffelD

2010

TDP-43 mediates degeneration in a novel Drosophila model of disease caused by mutations in VCP/p97.

J Neurosci

30

7729

7739

26. PintérM

JékelyG

SzepesiRJ

FarkasA

TheopoldU

1998

TER94, a Drosophila homolog of the membrane fusion protein CDC48/p97, is accumulated in nonproliferating cells: in the reproductive organs and in the brain of the imago.

Insect Biochem Mol Biol

28

91

98

27. BrandAH

PerrimonN

1993

Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes.

Development

118

401

415

28. GrothAC

FishM

NusseR

CalosMP

2004

Construction of transgenic Drosophila by using the site-specific integrase from phage phiC31.

Genetics

166

1775

1782

29. DiAntonioA

PetersenSA

HeckmannM

GoodmanCS

1999

Glutamate receptor expression regulates quantal size and quantal content at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction.

J Neurosci

19

3023

3032

30. WeihlCC

PestronkA

KimonisVE

2009

Valosin-containing protein disease: inclusion body myopathy with Paget's disease of the bone and fronto-temporal dementia.

Neuromuscul Disord

19

308

315

31. van der ZeeJ

GijselinckI

PiriciD

Kumar-SinghS

CrutsM

2007

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions: a molecular genetic update.

Neurodegener Dis

4

227

235

32. Moreau-FauvarqueC

TaillebourgE

BoissoneauE

MesnardJ

DuraJM

1998

The receptor tyrosine kinase gene linotte is required for neuronal pathway selection in the Drosophila mushroom bodies.

Mech Dev

78

47

61

33. BilenJ

BoniniNM

2005

Drosophila as a model for human neurodegenerative disease.

Annu Rev Genet

39

153

171

34. JuJS

MillerSE

HansonPI

WeihlCC

2008

Impaired protein aggregate handling and clearance underlie the pathogenesis of p97/VCP-associated disease.

J Biol Chem

283

30289

30299

35. PandeyUB

NieZ

BatleviY

McCrayBA

RitsonGP

2007

HDAC6 rescues neurodegeneration and provides an essential link between autophagy and the UPS.

Nature

447

859

863

36. YangH

ParkhouseRM

1998

Differential activation requirements associated with stimulation of T cells via different epitopes of CD3.

Immunology

93

26

32

37. Menéndez-BenitoV

VerhoefLG

MasucciMG

DantumaNP

2005

Endoplasmic reticulum stress compromises the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

Hum Mol Genet

14

2787

2799

38. RyooHD

DomingosPM

KangMJ

StellerH

2007

Unfolded protein response in a Drosophila model for retinal degeneration.

Embo J

26

242

252

39. WangQ

SongC

IrizarryL

DaiR

ZhangX

2005

Multifunctional roles of the conserved Arg residues in the second region of homology of p97/valosin-containing protein.

J Biol Chem

280

40515

40523

40. MannoA

NoguchiM

FukushiJ

MotohashiY

KakizukaA

2010

Enhanced ATPase activities as a primary defect of mutant valosin-containing proteins that cause inclusion body myopathy associated with Paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia.

Genes Cells

15

911

922

41. LieberthalW

MenzaSA

LevineJS

1998

Graded ATP depletion can cause necrosis or apoptosis of cultured mouse proximal tubular cells.

Am J Physiol

274

F315

327

42. GuarenteL

2008

Mitochondria–a nexus for aging, calorie restriction, and sirtuins?

Cell

132

171

176

43. RedmanLM

HeilbronnLK

MartinCK

de JongeL

WilliamsonDA

2009

Metabolic and behavioral compensations in response to caloric restriction: implications for the maintenance of weight loss.

PLoS ONE

4

e4377

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004377

44. NivenJE

VähäsöyrinkiM

KauranenM

HardieRC

JuusolaM

2003

The contribution of Shaker K+ channels to the information capacity of Drosophila photoreceptors.

Nature

421

630

634

45. MarshJL

WalkerH

TheisenH

ZhuYZ

FielderT

2000

Expanded polyglutamine peptides alone are intrinsically cytotoxic and cause neurodegeneration in Drosophila.

Hum Mol Genet

9

13

25

46. SangTK

LiC

LiuW

RodriguezA

AbramsJM

2005

Inactivation of Drosophila Apaf-1 related killer suppresses formation of polyglutamine aggregates and blocks polyglutamine pathogenesis.

Hum Mol Genet

14

357

372

47. WarrickJM

PaulsonHL

Gray-BoardGL

BuiQT

FischbeckKH

1998

Expanded polyglutamine protein forms nuclear inclusions and causes neural degeneration in Drosophila.

Cell

93

939

949

48. JacobsonSG

McInnesRR

2002

Blinded by the light.

Nat Genet

32

215

216

49. KnowlesSE

JarrettIG

FilsellOH

BallardFJ

1974

Production and utilization of acetate in mammals.

Biochem J

142

401

411

50. SouthonA

BurkeR

NorgateM

BatterhamP

CamakarisJ

2004

Copper homoeostasis in Drosophila melanogaster S2 cells.

Biochem J

383

303

309

51. PagliariniDJ

WileySE

KimpleME

DixonJR

KellyP

2005

Involvement of a mitochondrial phosphatase in the regulation of ATP production and insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells.

Mol Cell

19

197

207

52. DietzlG

ChenD

SchnorrerF

SuKC

BarinovaY

2007

A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila.

Nature

448

151

156

53. StojkovicT

Hammouda elH

RichardP

López de MunainA

Ruiz-MartinezJ

2009

Clinical outcome in 19 French and Spanish patients with valosin-containing protein myopathy associated with Paget's disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia.

Neuromuscul Disord

19

316

323

54. HalawaniD

LatterichM

2006

p97: The cell's molecular purgatory?

Mol Cell

22

713

717

55. HübbersCU

ClemenCS

KesperK

BöddrichA

HofmannA

2007

Pathological consequences of VCP mutations on human striated muscle.

Brain

130

381

393

56. TresseE

SalomonsFA

VesaJ

BottLC

KimonisV

2010

VCP/p97 is essential for maturation of ubiquitin-containing autophagosomes and this function is impaired by mutations that cause IBMPFD.

Autophagy

6

217

227

57. SangTK

ChangHY

LawlessGM

RatnaparkhiA

MeeL

2007

A Drosophila model of mutant human parkin-induced toxicity demonstrates selective loss of dopaminergic neurons and dependence on cellular dopamine.

J Neurosci

27

981

992

58. WuCL

XiaS

FuTF

WangH

ChenYH

2007

Specific requirement of NMDA receptors for long-term memory consolidation in Drosophila ellipsoid body.

Nat Neurosci

10

1578

1586

59. KoanaT

HottaY

1978

Isolation and characterization of flightless mutants in Drosophila melanogaster.

J Embryol Exp Morphol

45

123

143

60. SchwarzeSR

WeindruchR

AikenJM

1998

Oxidative stress and aging reduce COX I RNA and cytochrome oxidase activity in Drosophila.

Free Radic Biol Med

25

740

747

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Break to Make a ConnectionČlánek A New Testing Strategy to Identify Rare Variants with Either Risk or Protective Effect on DiseaseČlánek The Architecture of Gene Regulatory Variation across Multiple Human Tissues: The MuTHER Study

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 2- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

- Délka menstruačního cyklu jako marker ženské plodnosti

- Intrauterinní inseminace a její úspěšnost

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Break to Make a Connection

- A New Testing Strategy to Identify Rare Variants with Either Risk or Protective Effect on Disease

- Single-Tissue and Cross-Tissue Heritability of Gene Expression Via Identity-by-Descent in Related or Unrelated Individuals

- Pervasive Adaptive Protein Evolution Apparent in Diversity Patterns around Amino Acid Substitutions in

- The Architecture of Gene Regulatory Variation across Multiple Human Tissues: The MuTHER Study

- MiRNA Control of Vegetative Phase Change in Trees

- New Functions of Ctf18-RFC in Preserving Genome Stability outside Its Role in Sister Chromatid Cohesion

- Genome-Wide Association Studies of the PR Interval in African Americans

- Mapping of the Disease Locus and Identification of As a Candidate Gene in a Canine Model of Primary Open Angle Glaucoma

- Mapping a New Spontaneous Preterm Birth Susceptibility Gene, , Using Linkage, Haplotype Sharing, and Association Analysis

- A Population Genetic Approach to Mapping Neurological Disorder Genes Using Deep Resequencing

- and Genes Modulate the Switch between Attraction and Repulsion during Behavioral Phase Change in the Migratory Locust

- Targeted Sister Chromatid Cohesion by Sir2

- Correlated Evolution of Nearby Residues in Drosophilid Proteins

- Parallel Evolution of a Type IV Secretion System in Radiating Lineages of the Host-Restricted Bacterial Pathogen

- Lipophorin Receptors Mediate the Uptake of Neutral Lipids in Oocytes and Imaginal Disc Cells by an Endocytosis-Independent Mechanism

- Genome-Wide Association Study of Coronary Heart Disease and Its Risk Factors in 8,090 African Americans: The NHLBI CARe Project

- The Evolution of Host Specialization in the Vertebrate Gut Symbiont

- Genome-Wide Association of Familial Late-Onset Alzheimer's Disease Replicates and and Nominates in Interaction with

- Risk Alleles for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in a Large Case-Control Collection and Associations with Clinical Subphenotypes

- Association between Common Variation at the Locus and Changes in Body Mass Index from Infancy to Late Childhood: The Complex Nature of Genetic Association through Growth and Development

- AID Induces Double-Strand Breaks at Immunoglobulin Switch Regions and Causing Chromosomal Translocations in Yeast THO Mutants

- A Study of CNVs As Trait-Associated Polymorphisms and As Expression Quantitative Trait Loci

- Whole-Genome Comparison Reveals Novel Genetic Elements That Characterize the Genome of Industrial Strains of

- Prevalence of Epistasis in the Evolution of Influenza A Surface Proteins

- Srf1 Is a Novel Regulator of Phospholipase D Activity and Is Essential to Buffer the Toxic Effects of C16:0 Platelet Activating Factor

- Two Frizzled Planar Cell Polarity Signals in the Wing Are Differentially Organized by the Fat/Dachsous Pathway

- Phosphoinositide Regulation of Integrin Trafficking Required for Muscle Attachment and Maintenance

- Pathogenic VCP/TER94 Alleles Are Dominant Actives and Contribute to Neurodegeneration by Altering Cellular ATP Level in a IBMPFD Model

- Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies in Celiac Disease and Rheumatoid Arthritis Identifies Fourteen Non-HLA Shared Loci

- A Genome-Wide Study of DNA Methylation Patterns and Gene Expression Levels in Multiple Human and Chimpanzee Tissues

- Nucleosomes Containing Methylated DNA Stabilize DNA Methyltransferases 3A/3B and Ensure Faithful Epigenetic Inheritance