-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

An Alpha-Catulin Homologue Controls Neuromuscular Function through Localization of the Dystrophin Complex and BK Channels in

The large conductance, voltage - and calcium-dependent potassium (BK) channel serves as a major negative feedback regulator of calcium-mediated physiological processes and has been implicated in muscle dysfunction and neurological disorders. In addition to membrane depolarization, activation of the BK channel requires a rise in cytosolic calcium. Localization of the BK channel near calcium channels is therefore critical for its function. In a genetic screen designed to isolate novel regulators of the Caenorhabditis elegans BK channel, SLO-1, we identified ctn-1, which encodes an α-catulin homologue with homology to the cytoskeletal proteins α-catenin and vinculin. ctn-1 mutants resemble slo-1 loss-of-function mutants, as well as mutants with a compromised dystrophin complex. We determined that CTN-1 uses two distinct mechanisms to localize SLO-1 in muscles and neurons. In muscles, CTN-1 utilizes the dystrophin complex to localize SLO-1 channels near L-type calcium channels. In neurons, CTN-1 is involved in localizing SLO-1 to a specific domain independent of the dystrophin complex. Our results demonstrate that CTN-1 ensures the localization of SLO-1 within calcium nanodomains, thereby playing a crucial role in muscles and neurons.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(8): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001077

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001077Summary

The large conductance, voltage - and calcium-dependent potassium (BK) channel serves as a major negative feedback regulator of calcium-mediated physiological processes and has been implicated in muscle dysfunction and neurological disorders. In addition to membrane depolarization, activation of the BK channel requires a rise in cytosolic calcium. Localization of the BK channel near calcium channels is therefore critical for its function. In a genetic screen designed to isolate novel regulators of the Caenorhabditis elegans BK channel, SLO-1, we identified ctn-1, which encodes an α-catulin homologue with homology to the cytoskeletal proteins α-catenin and vinculin. ctn-1 mutants resemble slo-1 loss-of-function mutants, as well as mutants with a compromised dystrophin complex. We determined that CTN-1 uses two distinct mechanisms to localize SLO-1 in muscles and neurons. In muscles, CTN-1 utilizes the dystrophin complex to localize SLO-1 channels near L-type calcium channels. In neurons, CTN-1 is involved in localizing SLO-1 to a specific domain independent of the dystrophin complex. Our results demonstrate that CTN-1 ensures the localization of SLO-1 within calcium nanodomains, thereby playing a crucial role in muscles and neurons.

Introduction

Precise control of membrane excitability, largely determined by ion channels, is of utmost importance for neuronal and muscle function. The regulation of ion channel localization, density and gating properties thus provides an effective way to control the excitability within these cells [1]. Indeed, the localization and gating properties of ion channels are often regulated or modified by cytoskeletal and signaling proteins, or auxiliary ion channel subunits expressed in a cell-type specific manner [2]. Potassium channels are critical in determining the excitability of cells, because potassium ions are dominant charge carriers at the cell resting potential. Among potassium channels, the large conductance, voltage - and calcium-dependent potassium BK channels (also called SLO-1 or Maxi-K) are uniquely gated by coincident calcium signaling and membrane depolarization [3], [4]. This feature of BK channels provides a crucial negative feedback mechanism for calcium-induced functions, and plays an important role in determining the duration of action potentials [3]. BK channels are widely expressed in a variety of cell types and are implicated in many physiological processes, including the regulation of blood pressure [5], neuroendocrine signaling [6], smooth muscle tone [7], and neural network excitability [8], [9].

Mounting evidence indicates that BK channels can interact with a variety of proteins that modulate channel function, or control membrane trafficking. For example, the Drosophila BK channel, dSLO, interacts with SLO binding protein (slob), which in turn modulates the channel gating properties [10]. Similarly, mammalian BK channels associate with auxiliary beta subunits that influence channel activation time course and voltage-dependence [11]. In yeast two hybrid screens, the cytoplasmic C-terminal tail of mammalian BK channels has been shown to interact with several proteins, including cytoskeletal elements, such as actin-binding proteins [12], [13] and a microtubule-associated protein [14]. These cytoskeletal proteins are partially co-localized with BK channels, and appear to increase cell surface expression of BK channels in cultured cells [12], [13]. However, it remains to be determined whether these proteins have any role in controlling the localization of BK channels to specific areas of the plasma membrane in vivo. Robust activation of BK channels requires higher intracellular calcium concentrations (>10 µM), which only occur in the immediate vicinity of calcium-permeable channels [4]. Hence, the localization of BK channels to specific areas (i.e. calcium nanodomains) where calcium-permeable ion channels are located is physiologically important for BK channel activation.

In C. elegans, loss-of-function mutations in slo-1 partially compensate for the synaptic release defects of C. elegans syntaxin (unc-64) mutants [15] and lead to altered alcohol sensitivity [16]. Recent studies in C. elegans have also implicated SLO-1 in muscle function [17]. slo-1 mutants display an exaggerated anterior body angle, referred to as the head-bending phenotype that is shared by mutants that are defective in the C. elegans dystrophin complex [18]–[20]. Recent evidence that the C. elegans dystrophin complex interacts with SLO-1 channels via SLO-1 interacting protein, ISLO-1, explains this phenotypic overlap [21]. However, C. elegans dystrophin complex mutants do not appear to alter the biophysical properties of BK channels per se [17]. Similarly, ISLO-1 does not modify SLO-1 channel properties [21]. Rather, ISLO-1 tethers SLO-1 near the dense bodies of muscle membranes, where L-type calcium channels (EGL-19) are localized [21]. Consequently, defects in the dystrophin complex or ISLO-1 cause a large reduction in SLO-1 protein levels in muscle membrane, which in turn causes muscle hyper-excitability leading to enhanced intracellular calcium levels. This perturbation of calcium homeostasis has been postulated to be one of the first steps in the degenerative muscle pathogenesis associated with disruption of the dystrophin complex [22].

In this study, we performed a forward genetic screen to identify additional genes responsible for SLO-1 localization and function in C. elegans. We identified ctn-1, an orthologue of α-catulin, as a novel gene that controls SLO-1 localization and function in muscles and neurons. Our analysis showed that ctn-1 uses different strategies to localize SLO-1 in these two cell types. In muscles, CTN-1 utilizes the dystrophin complex to localize SLO-1 near L-type calcium channels via ISLO-1. In neurons, CTN-1 localizes SLO-1 independent of the dystrophin complex.

Results

A genetic screen for suppressor mutants of gain-of-function slo-1 identifies genes that interact with the dystrophin gene

Loss-of-function slo-1 mutants exhibit a jerky locomotion and head bending phenotype [15]. By contrast, gain-of-function slo-1 mutants exhibit sluggish movement combined with low muscle tone [16]. When slo-1(gf) mutant animals are mechanically stimulated, they fail to make a normal forward movement, and tend to curl ventrally (Video S1). To identify genes that regulate slo-1 function, we performed a forward genetic screen to isolate mutants that suppress the phenotypes of the slo-1(ky399) gain-of-function mutant. Based on a previous genetic study [21], suppressor genes were expected to encode slo-1, components of the dystrophin complex, as well as novel proteins that control neuronal or muscular function of SLO-1. As expected, several loss-of-function alleles of slo-1 were isolated. In addition to these intragenic suppressors, several mutants could be segregated away from slo-1(gf) (Figure 1A and Video S1) and exhibited the head bending phenotype. Genetic mapping and complementation testing determined that these extragenic suppressors include dyb-1 and stn-1 which encode two homologous components of the dystrophin complex, dystrobrevin and syntrophin respectively. Additionally we isolated cim6 and eg1167 suppressors that represent novel genes. Compared to slo-1(ky399) and cim6;slo-1(ky399) mutants, eg1167;slo-1(ky399) mutants exhibited a profound improvement in the locomotion speed (Figure 1A).

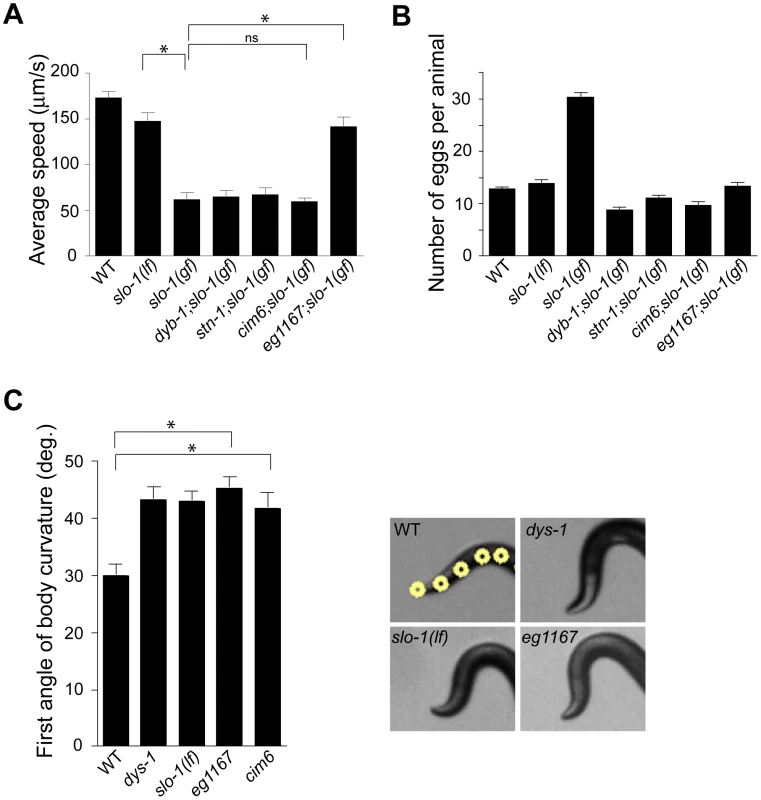

Fig. 1. A genetic screen for slo-1(gf) suppressor mutants yields genes encoding components of the dystrophin complex and a novel gene.

(A) The average speed of mutants identified in a genetic screen for suppressors of slo-1(gf). dyb-1, a dystrobrevin homolog; dys-1, a dystrophin homolog; stn-1, a syntrophin homolog. Error bars represent s. e. m. (n>10). Asterisks represent significant difference (P<0.05). (B) The number of eggs retained in uteri of slo-1(gf) suppressor mutants. Error bars represent s. e. m. Data points between slo-1(gf) and all of other strains are significantly different (P<0.001). (C) Quantitative analysis for the first angle of head bending. Each data set for the first angle is significantly different from that of wild-type animals (P<0.01). Yellow dots indicate the five most anterior of the 13 midline points for a wild-type animal (See also Materials and Methods). Error bars represent s. e. m. (n = 10). It was previously observed that slo-1(gf) mutants retain significantly more eggs than wild-type animals due to low activity of the egg-laying muscles [16]. We found that suppressor mutants abolish an egg laying defect of slo-1(gf) mutants and retain eggs in uteri at levels similar to wild-type animals (Figure 1B).

ctn-1 encodes an α-catulin orthologue that has homology to α-catenin and vinculin

To understand the role of novel genes in slo-1 function, we pursued the identification of genes that mapped to chromosomal locations neither previously implicated in BK channel function, nor encoding known components of the dystrophin complex. Two mutations, cim6 and eg1167, both mapped to the left side of chromosome I and failed to complement each other for head bending, suggesting that these two mutations represent alleles of the same gene. Our quantitative analysis for locomotion and egg laying phenotypes showed that the locomotion speed of eg1167;slo-1(gf) was higher than that of cim6;slo-1(gf) whereas egg laying was comparable in both strains (Figure 1A and 1B). We further mapped eg1167 to a 250 kb interval and rescued the phenotype of eg1167 by generating transgenic animals with the fosmid WRM0621cC01 (Figure S1). Next, we rescued the head bending phenotype of eg1167 with a transgene consisting of the ctn-1 gene (Y23H5A.5) and approximately 4 kb upstream of the translation initiation codon (Figure 2A and 2B). The same transgene caused eg1167;slo-1(gf) double mutants to revert to the slo-1(gf) phenotype, displaying sluggish movement and retention of late-staged eggs in uteri (Figure 2C and 2D). These results indicate that a genetic defect in ctn-1 is responsible for suppression of the slo-1(gf) phenotypes.

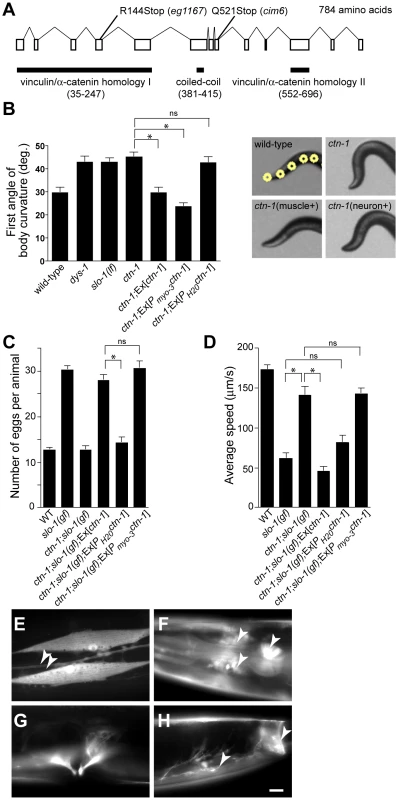

Fig. 2. ctn-1, an α-catulin homologue, has two distinct roles in mediating SLO-1 function.

(A) The gene structure of ctn-1. Our genome analysis indicates that unlike WormBase annotation (WS210) ctn-1 consists of 13 exons and is predicted to encode a 784 amino-acid protein (Figure S1). The homology regions with α-catenin/vinculin I (homologous to the N-terminal talin/α-actinin-binding region of vinculin, 213 amino acids), α-catenin/vinculin II (homologous to the C-terminal F-actin/inositol phospholipids-binding region of vinculin, 145 amino acids) and the coiled-coil domain (35 amino acids) are depicted at the bottom of the gene structure. The mutation sites for two different alleles (eg1167 and cim6) are shown on the top of the gene structure. The predicted amino acid sequence is available in Figure S1. (B) Rescue of the head bending phenotype with a variety of ctn-1 constructs. Ex[ctn-1] represents the transgene carrying the genomic ctn-1 DNA extrachromosomal array. Ex[Pmyo-3ctn-1] represents the muscle-specific myo-3 promoter-driven ctn-1 transgene, whereas Ex[PH20ctn-1] represents the neuron-specific H20 promoter-driven ctn-1 transgene. Error bars represent s. e. m. (n = 10). Single asterisks indicate significant difference between two groups (P<0.001, unpaired two-tailed t-test) whereas ns indicates no significant difference. (C) Rescue of the defect in egg-laying muscle with a variety of ctn-1 constructs. Error bars represent s. e. m. (n = 15). Single asterisks indicate significant difference between two groups (P<0.001, unpaired two-tailed t-test) whereas ns indicates no significant difference. (D) Rescue of the average locomotory speed with a variety of ctn-1 constructs. Error bars represent s. e. m. (n>10). Single asterisks indicate significant difference between two groups (P<0.001, unpaired two-tailed t-test) whereas ns indicates no significant difference. (E–H) The expression pattern of a ctn-1 promoter-tagged GFP reporter. Expression in (E) body wall muscles and the ventral cord neurons (arrowheads), (F) nerve ring (arrowheads) and pharyngeal muscle (arrow), (G) egg-laying muscle, and (H) enteric (arrow) and sphincter (arrowhead) muscle. Scale bar, 10 µm. The ctn-1 gene is orthologous to mammalian α-catulin (39.4% identity to human α-catulin), and is named on the basis of sequence similarity to both α-catenin and vinculin (Figure 2A) [23]. Vinculin and α-catenin are membrane-associated cytoskeletal proteins found in focal adhesion plaques and cadherens junctions. In C. elegans, vinculin (DEB-1) is localized to the dense bodies of body wall muscle and is essential for attachment of actin thin filaments to the sarcolemma [24], whereas α-catenin (HMP-1) is localized to hypodermal adherens junctions and is essential for proper enclosure and elongation of the embryo [25]. Based on its homology to vinculin/α-catenin and the localization of mammalian α-catulin [26], CTN-1 is likely to interact with other cytoskeletal proteins, which may in turn affect SLO-1 function. Additionally, the ctn-1 gene encodes a predicted coiled-coil domain. Such a coiled-coil domain mediates the interaction between dystrophin and dystrobrevin [27], two components of the dystrophin complex, although we do not know if the coiled-coil domain of CTN-1 is important for the interaction with these proteins (Figure 2A).

We determined nucleotide sequence of the predicted exons and exon-intron boundaries of the ctn-1 gene in eg1167 and cim6. The mutation sites found in both alleles create translation-termination codons (R144>STOP in eg1167, Q521>STOP in cim6) (Figure 2A). eg1167 exhibits complete suppression of slo-1(gf) phenotypes (see below) and is hence considered as a severe loss-of-function or null allele. All subsequent experiments were carried out with eg1167, unless mentioned otherwise. Although both eg1167 and cim6 mutants alone exhibit the head-bending phenotype, they differ with respect to suppression of slo-1(gf) phenotypes. Whereas ctn-1(eg1167) suppresses all aspects of the slo-1(gf) phenotype, ctn-1(cim6) completely suppresses the egg-laying defect of slo-1(gf) (Figure 1B), but not the locomotory defect (Figure 1A). These results suggest that the C-terminal third of CTN-1 is required for normal egg laying and head bending, but is not necessary to mediate the locomotion speed defect of slo-1(gf) mutants.

To elucidate the function of CTN-1, we examined the expression pattern of the ctn-1 gene using a ctn-1 promoter-tagged GFP reporter (Figure 2E–2H). We observed GFP fluorescence in body wall muscles, pharyngeal muscle, egg-laying muscle and enteric muscle of transgenic animals as well as in most, if not all, neurons of the nerve ring and ventral nerve cord.

CTN-1 has two distinct functions in neurons and muscles

Based on the ctn-1 expression pattern and the phenotypic differences between eg1167 and cim6, we investigated whether the head-bending phenotype and the suppression of sluggish movement of slo-1(gf) mutants are separable by expressing ctn-1 minigenes under the control of either muscle - or neuron-specific promoters in ctn-1 and ctn-1;slo-1(gf) mutant animals. Muscle, but not neuronal, expression of ctn-1 rescued the head-bending phenotype of the ctn-1 mutant (Figure 2B and Figure S1C). These results are consistent with previous reports that the head-bending phenotype is due to perturbations in muscle function [17]–[19]. Furthermore, muscle expression of ctn-1 in ctn-1;slo-1(gf) mutants resulted in egg retention to the level observed in slo-1(gf) mutants, whereas neuronal expression of ctn-1 did not alter the number of eggs retained in the uteri of ctn-1;slo-(gf) mutants (Figure 2C). Conversely, neuronal expression of ctn-1 in ctn-1;slo-1(gf) mutants reverted the seemingly normal locomotion of ctn-1;slo-1(gf) to the sluggish, uncoordinated locomotion of the slo-1(gf) mutant, whereas muscle expression of ctn-1 did not (Figure 2D). These results indicate that the sluggish, uncoordinated locomotory phenotype of slo-1(gf) mutants comes from presynaptic depression, but not from direct suppression of muscle excitability. Together with the allele specific phenotypic differences indicating different regions of CTN-1 are required for normal locomotory speed and head bending, these results suggest that CTN-1 uses two distinct mechanisms for mediating SLO-1 function in muscle and neurons by interacting with different sets of genes.

CTN-1 controls the integrity of the dystrophin complex and the localization of SLO-1 in muscle

Most, if not all, of the mutants that exhibit the head bending phenotype have a defect in either a component of the dystrophin complex or proteins that interact with the dystrophin complex [17]–[19]. The dystrophin complex is localized near muscle dense bodies [21]. Because ctn-1 mutants exhibit the head bending phenotype, we determined the subcellular localization of CTN-1 using a GFP-tagged CTN-1 transgene, which rescues the head bending phenotype (data not shown). GFP::CTN-1 exhibited a punctate expression pattern that resembled that of the dense bodies (Figure 3A). To further define the localization of CTN-1, we stained GFP-tagged CTN-1 transgenic animals with GFP antibodies and vinculin/DEB-1 antibodies that recognize the attachment plaque and dense bodies. CTN-1::GFP is localized in close proximity to, or partially colocalized with, vinculin/DEB-1 in dense bodies, but not in the attachment plaques, indicating that CTN-1 is localized near dense bodies (Figure 3A). This expression pattern of CTN-1, along with the head bending phenotype of ctn-1 mutants, prompted us to examine whether the ctn-1 mutation disrupts the integrity of the dystrophin complex. We compared the expression pattern of a component of the dystrophin complex, SGCA-1 (an α-sarcoglycan homolog) in wild-type, dys-1, slo-1 and ctn-1 animals using a GFP-tagged SGCA-1 that rescues the head bending phenotype of sgca-1 mutants [21] (Figure 3B). GFP::SGCA-1 exhibited a punctate expression pattern in the muscle membrane of wild-type and slo-1 mutant animals. By contrast, GFP puncta were greatly diminished in dys-1 and ctn-1 mutants. These results indicate that ctn-1 is critical for maintaining the dystrophin complex near the dense bodies.

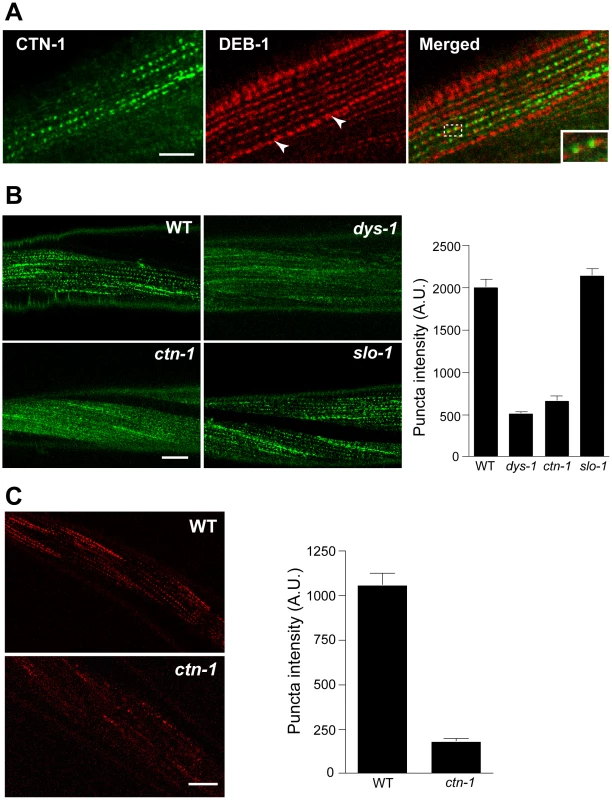

Fig. 3. ctn-1 mutation disrupts normal localization of the dystrophin complex and ISLO-1.

(A) An integrated transgenic line expressing the lowest level of GFP-tagged CTN-1 was used for staining with anti-GFP (CTN-1, green) and anti-vinculin/DEB-1 (DEB-1, red) antibodies. Dashed box area is enlarged in the bottom left of the panel (Merged) to show detail. Arrowheads indicate the attachment plaques that adhere tightly adjacent muscle cells. Scale bar, 10 µm. (B) Transgenic animals expressing integrated GFP-tagged SGCA-1 were used to analyze the localization of SGCA-1 in wild-type (WT), dys-1 ctn-1 and slo-1 animals. Scale bar, 10 µm. The graph shows quantified puncta intensities. Error bars, s.e.m. Wild-type vs. dys-1 (P<0.01), Wild-type vs. ctn-1 (P<0.01), Wild-type vs. slo-1 (P>0.05). (C) Transgenic animals expressing integrated mCherry-tagged ISLO-1 were used for analyzing the localization of ISLO-1 in wild-type (WT) and ctn-1 animals. Scale bar, 10 µm. The graph shows quantified puncta intensities. Error bars, s.e.m. Wild-type vs. ctn-1 (P<0.0001). We previously demonstrated that ISLO-1 interacts with STN-1 through a PDZ domain-mediated interaction, thereby linking SLO-1 to the dystrophin complex [21]. Because we failed to observe a component of the dystrophin complex in the muscle membrane of ctn-1 mutants, we examined mCherry-tagged ISLO-1 in the muscle membrane of wild-type and ctn-1 mutant animals. The punctate mCherry::ISLO-1 fluorescence was observed in wild-type muscle membranes, but was greatly reduced in ctn-1 mutant (Figure 3C). These results further strengthen the notion that CTN-1 is required for maintaining the integrity of the dystrophin complex.

Based on the genetic interaction between ctn-1 and slo-1, and the observation that the integrity of the dystrophin complex and ISLO-1 localization are disrupted in ctn-1 mutants, we hypothesized that CTN-1 regulates the localization of SLO-1 in muscle. To test this hypothesis, we examined the localization of GFP-tagged SLO-1 in muscles of wild-type, dys-1, and ctn-1 animals (Figure 4A and 4B). The punctate SLO-1::GFP expression pattern in the muscle membrane of wild-type animals was greatly diminished in the muscles of either dys-1 or ctn-1 mutant. Interestingly, the protein levels of SLO-1::GFP were not significantly different in wild-type, dys-1 and ctn-1 animals (Figure S2B), indicating that mislocalized SLO-1 does not necessarily undergo degradation. The mislocalization of SLO-1 in dys-1 mutants is consistent with the requirement of the dystrophin complex for ISLO-1 localization [21]. These results further indicate that CTN-1 stabilizes or maintains the punctate muscle expression of SLO-1::GFP in a dystrophin complex-dependent manner.

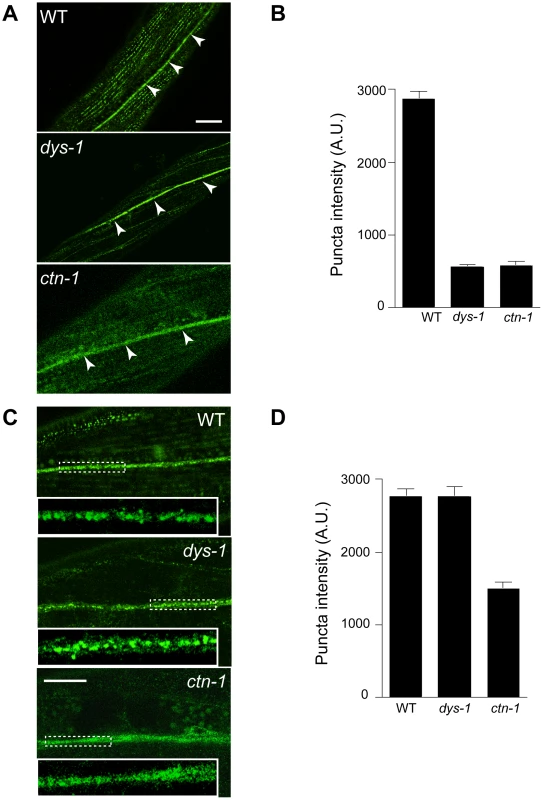

Fig. 4. ctn-1 mutation impairs normal localization of SLO-1 in muscles and neurons.

The same integrated array, SLO-1::GFP, was used for this analysis in different genetic backgrounds. (A–B) Muscular localization of SLO-1::GFP in wild-type, dys-1 and ctn-1 animals. Arrowheads represent the ventral (or dorsal) nerve cords. (B) The graph showing quantification of puncta intensities. Error bars, s.e.m. Wild-type vs. dys-1 or ctn-1 (P<0.0001). Scale bar, 10 µm. (C–D) Neuronal localization of SLO-1::GFP in wild-type, dys-1 and ctn-1 animals (See also Figure S2). Regions of the ventral nerve cord (dashed boxes) are enlarged in the bottom left of each panel to show detail. (D) The graph showing quantification of puncta intensities. Error bars, s.e.m. Wild-type vs. dys-1 (P>0.05), Wild-type vs. ctn-1 (P<0.0001). Scale bar, 10 µm. CTN-1 regulates presynaptic release by controlling the localization of SLO-1

In mammals, BK channels are found in neuronal somata, dendrites and presynaptic terminals [28], [29]. An immunoelectron microscopy study indicates that BK channels are not homogeneously distributed in neurons, but are clustered, presumably near calcium channels [30]. We addressed whether SLO-1 is evenly distributed or clustered in C. elegans neurons by examining SLO-1::GFP. Wild-type animals displayed patches of fluorescence along the ventral nerve cord or near cell bodies under high magnification (Figure 4C and 4D, Figure S2). Tissue-specific rescue experiments demonstrated that ctn-1 mediates SLO-1 function in neurons independent of the dystrophin complex (Figure 2D). Therefore, we compared neuronal SLO-1::GFP expression in dys-1 and ctn-1 mutant animals. The clustered GFP expression observed along the ventral cord of both wild-type and dys-1 mutant animals contrasted with the uniform GFP localization in ctn-1 mutants (Figure 4C and 4D). These results indicate that ctn-1 mutation disrupts the neuron-specific clustering of SLO-1::GFP independent of the dystrophin complex.

SLO-1 contributes to the repolarization of the synaptic terminal following neuronal stimulation, thereby terminating neurotransmitter release. Consequently loss-of-function slo-1 mutants are hypersensitive to the paralyzing effects of aldicarb, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, a phenotype indicative of enhanced acetylcholine release. Consistent with this interpretation, electrophysiological recordings from neuromuscular junctions of slo-1 loss-of-function mutants exhibit prolonged evoked synaptic responses [15], [16]. If CTN-1 regulates SLO-1 localization in motor neurons and thus slo-1 function, we would expect ctn-1 mutants to exhibit similar pharmacological and synaptic changes. Indeed, we found that ctn-1 mutants were hypersensitive to aldicarb compared to wild-type animals (Figure S3). To confirm this observation directly, we measured synaptic responses from the neuromuscular junctions of dissected wild-type and ctn-1 mutant animals engineered to express channelrhodopsin-2 in motor neurons [31] (Figure 5). Evoked synaptic responses were elicited by blue light activation of channelrhodopsin-2 and recorded from voltage-clamped post-synaptic body wall muscle cells. Consistent with our pharmacological data and localization results, recordings from ctn-1 showed prolonged evoked synaptic responses similar to those of slo-1(lf) mutants (Figure 5B and 5C). Furthermore, muscular expression of ctn-1 in ctn-1 mutant animals rescued the head-bending phenotype (Figure 2B), but did not rescue prolonged evoked synaptic responses (Figure S3B). These data strongly suggest that altered synaptic responses of ctn-1 mutants result from a neuronal defect.

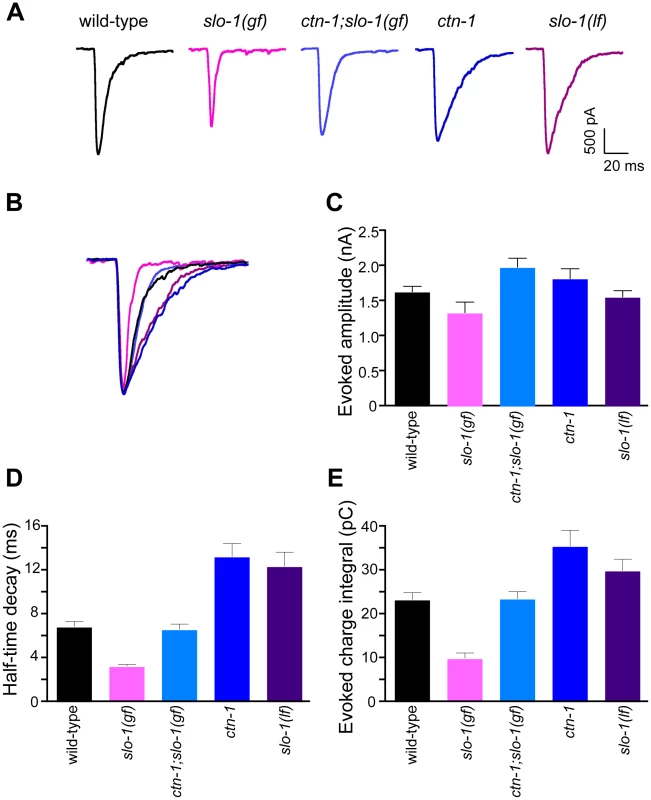

Fig. 5. ctn-1 mutation suppresses defects of slo-1(gf) evoked synaptic responses at the neuromuscular junctions.

(A) Representative evoked current responses from wild-type, slo-1(gf), ctn-1;slo-1(gf), ctn-1 and slo-1(lf) animals. (B) Normalized evoked current responses from (A). (C) Evoked amplitude response. Wild-type (n = 31), slo-1(gf) (n = 15), ctn-1;slo-1(gf) (n = 12), ctn-1 (n = 16), slo-1(lf) (n = 21). There is no significant difference between wild-type and each genotype used (P>0.05). (D) Half-time decay. Wild-type vs. slo-1(gf), P<0.05; wild-type vs. ctn-1;slo-1(gf), P>0.05; wild-type vs. ctn-1, P<0.05; wild-type vs. slo-1, P<0.01. (E) Evoked charge integral. Wild-type vs. slo-1(gf), P<0.01. In contrast to the slo-1(lf) mutants, evoked responses of slo-1(gf) mutants were short-lived (Figure 5C), and the charge integral, a measure of total ion flux during the evoked response, was significantly reduced (Figure 5E). Our genetic analyses demonstrated that the ctn-1 mutation suppresses the sluggish locomotory phenotype of slo-1(gf) mutants and disrupts SLO-1 localization (Figure 1A, Figure 4C and 4D). If this is due to loss of neuronal SLO-1(gf) channels, the ctn-1 mutation should suppress the evoked response defects of slo-1(gf). Consistent with this prediction, the decay time of the ctn-1;slo-1(gf) double mutants (t1/2 = 6.61±0.53 ms) was significantly longer than slo-1(gf) (t1/2 = 3.23±0.21 ms) (Figure 5D), and the charge integral was restored to wild-type levels (Figure 5E). Interestingly, ctn-1 mutants did not convert the decay time of slo-1(gf) evoke responses to that of slo-1(lf), indicating that residual SLO-1 function may be mediated by dispersed SLO-1 channels.

Discussion

In a genetic screen to identify novel regulators of SLO-1, we found two alleles of ctn-1, a gene which encodes an α-catulin orthologue. CTN-1 mediates normal bending of the anterior body through SLO-1 localization near the dense bodies of body wall muscles. CTN-1 also maintains normal locomotory speed through SLO-1 localization within neurons. Based on our data, we propose a model for ctn-1 function in localizing SLO-1 (Figure 6). In muscles, CTN-1 interacts with the dystrophin complex. It is also possible that CTN-1 may influence the stability of another protein that directly interacts with the dystrophin complex. Loss of CTN-1 function disrupts the integrity of the dystrophin complex, thus compromising ISLO-1 and SLO-1 localization near muscle dense bodies, where L-type calcium channels are present. Disruption of SLO-1 localization is expected to uncouple local calcium increases from SLO-1-dependent outward-rectifying currents, resulting in muscle hyper-excitation. Previous studies have shown that the head bending phenotype, shared among mutants that have a defect in the dystrophin complex or its associated proteins, results from muscle hyperexcitability [17]–[19], [32]. Our data further show that this head-bending phenotype does not result from a synaptic transmission defect, but from a muscle excitation and contraction defect. In neurons, SLO-1 localization is not mediated through the dystrophin complex, suggesting that CTN-1 interacts with other proteins to localize SLO-1 to specific neuronal domains.

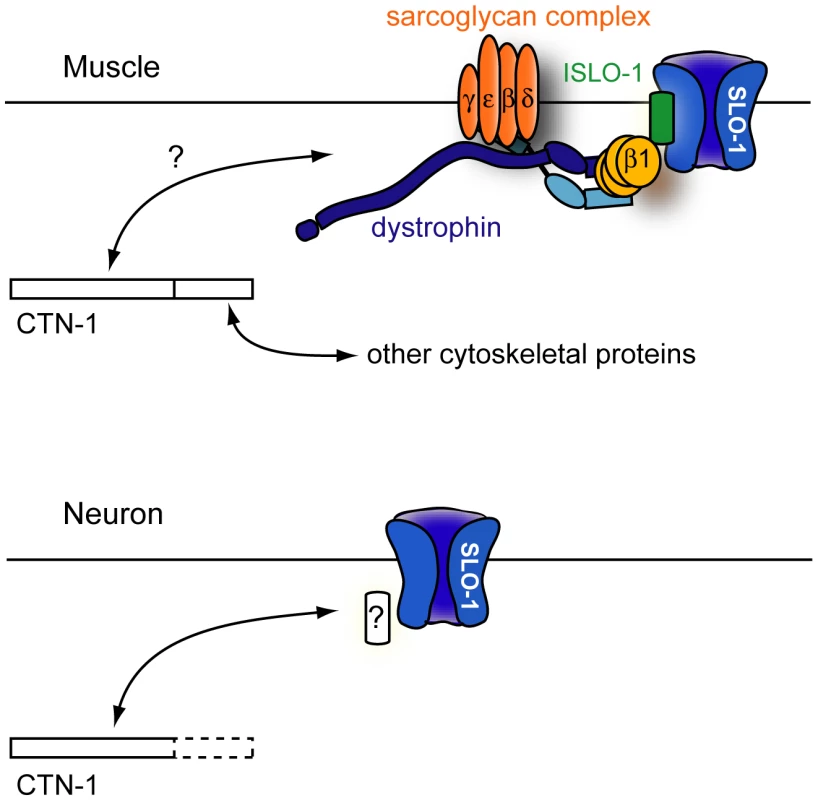

Fig. 6. A model for CTN-1 function.

In muscles, CTN-1 interacts with the dystrophin complex. ISLO-1 links the dystrophin complex to SLO-1. The N-terminal region or the coiled-coiled domain of CTN-1 is likely to interact with the dystrophin complex. The C-terminal region may interact with other cytoskeletal proteins. In neurons, CTN-1 interacts with SLO-1 through possible unknown intermediates other than the dystrophin complex. Why does CTN-1 use two distinct mechanisms to localize SLO-1 to subcellular regions of muscles and neurons? BK channels are functionally coupled with several different calcium channels (including voltage-gated L-type and P/Q-type calcium channels and IP3 receptors) that are localized in different subcellular regions [30], [33], [34]. Although it has not been determined whether all of these calcium channels are functionally coupled with SLO-1 in C. elegans, these calcium channels are distributed in different regions of neurons. For example, the L-type calcium channel (EGL-19) is mainly expressed in the cell body and the P/Q type calcium channel (UNC-2) is concentrated at the presynaptic terminals [35], [36]. A distinct set of proteins is perhaps required for SLO-1 channel localization near different calcium channels.

How CTN-1 interacts with the dystrophin complex in muscle remains to be determined. It has been suggested that mammalian α-catulin interacts with the hydrophobic C-terminus of dystrophin resulting from alternative splicing [37]. However, the C. elegans dys-1 gene does not encode a hydrophobic C-terminus. Thus, CTN-1 may interact with a different domain of dystrophin, or with another component of the dystrophin complex. In this regard, it is noteworthy that both mammalian dystrophin and C. elegans DYS-1 have multiple spectrin repeat domains, and that the N-terminal region of vinculin which exhibits homology to that of α-catulin (Figure S1) is known to bind the spectrin repeat domain of α-actinin [38]. By extension, we speculate that the N-terminal region of CTN-1 may bind the spectrin repeat domain of DYS-1 directly. Alternatively, the coiled-coil domain of dystrophin, which is known to interact with the coiled-coil domain of dystrobrevin [27], may potentially bind the coiled-coil domain of CTN-1. Interestingly, CTN-1 exhibits high homology to vinculin in both the N-terminal and C-terminal regions (Figure S1B). The C-terminal region of vinculin interacts with cytoskeletal molecules or regulators (F-actin, inositol phospholipids and paxillin) in focal adhesion and adherens junctions [39]. Because the C-terminal region of CTN-1 is also necessary for normal head bending, we speculate that this C-terminal region may be important for tethering the dystrophin complex to other cytoskeletal proteins.

In mammalian striated muscle, dystrophin is enriched in costameres [40] which are analogous to C. elegans dense bodies. A costamere is a subsarcolemmal protein assembly that connects Z-disks to the sarcolemma, and is considered to be a muscle-specific elaboration of the focal adhesion in which integrin and vinculin are abundant. Compromised costameres have been postulated to be an underlying cause of several different myopathies [40]. It was recently shown that ankyrin-B and -G recruit the dystrophin complex to costameres [41]. Based on overall high homology of ctn-1 to vinculin and α-catenin, we speculate that CTN-1 similarly interacts with cytoskeletal proteins in the dense bodies, and links the dystrophin complex to the dense bodies.

Another intriguing conclusion from our data is that loss of CTN-1 does not completely abolish SLO-1 function. Complete abolishment of SLO-1 function in ctn-1 mutant should alter the decay time for evoked synaptic responses of ctn-1;slo-1(gf) to the same degree as slo-1(lf) mutants, rather than to that of wild-type animals (Figure 5D). Mutants including slo-1(gf), that have defects in neural activation or membrane depolarization, are reported to cause str-2, a candidate odorant receptor gene, to be expressed in both AWC olfactory neurons whereas wild-type animals express str-2 in only one of the AWC pair [42]. We find that ctn-1 mutation does not suppress the misexpression of str-2 in both AWC neurons in slo-1(gf) mutants, suggesting that ctn-1 mutations do not completely abolish SLO-1 function (unpublished observations, HK). It is thus likely that the defect in SLO-1 localization in ctn-1 mutants makes it less responsive to local calcium nanodomains found at presynaptic terminals and dense bodies, but still able to respond to depolarization-induced global calcium increases, albeit at a lower level.

In conclusion, we have identified ctn-1, a gene encoding the C. elegans homolog of α-catulin, and demonstrated that CTN-1 mediates SLO-1 localization in muscles and neurons by dystrophin complex-dependent and -independent mechanisms, respectively. How SLO-1 is localized to certain neuronal domains will require further screening of slo-1(gf) suppressor mutants. Given that proteins affecting components of the dystrophin complex are likely to contribute to the pathogenesis of muscular dystrophy, α-catulin is a candidate causal gene for a form of muscular dystrophy in humans.

Materials and Methods

Strains and genetics

The genotypes of animals used in this study are: N2 (wild-type), CB4856, dys-1(eg33) I, stn-1(tm795) I, ctn-1(eg1167) I, ctn-1(cim6) I, slo-1(eg142) V, slo-1(ky399gf) V and sgca-1(tm1232) X. The following transgenes were used in this study: cimIs1[slo-1a::GFP, rol-6(d)] [21], cimIs5[mCherry::islo-1, ofm-1::GFP] [21], zxIs6[unc-17::chop-2(H134R)-yfp; lin-15(+)] [31], cimIs6[GFP::sgca-1, rol-6(d)], cimEx5[ctn-1, ofm-1::GFP], cimIs7[GFP::ctn-1, rol-6(d)], cimEx6[Pmyo-3ctn-1, Pmyo-3GFP, ofm-1::GFP] and cimEx7[PH20ctn-1, PH20GFP,ofm-1::GFP].

Genetic screen for suppressor mutants of slo-1(ky399)

Gain-of-function slo-1(ky399) mutants were mutagenized by exposure to 50 mM EMS (ethane methyl sulfonate) for 4 h [43]. Suppressors that suppress or ameliorate the sluggish locomotory phenotype of slo-1(ky399gf) mutants were selected from F2 progeny of the mutagenized animals. We screened approximately 5,000 haploid genome size for suppressor mutants and identified a total of 17 suppressor mutants. Genetic analysis of these suppressor mutants indicates that three of these have a second mutation in the slo-1 gene. In addition, we found that eight have mutations in genes causing head-bending phenotype (2 alleles of dyb-1, 3 alleles of stn-1 and 2 alleles of ctn-1). The remaining six mutants do not exhibit distinct locomotory phenotypes when segregated from slo-1(gf).

Genetic mapping and cloning

For genetic mapping, slo-1(ky399) mutants were outcrossed 12 times to the CB4856 strain. The resulting strain was used for SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) mapping [44]. Alternatively, we used CB4856 as a mapping strain when mapping is based on the head-bending phenotype. For transgenic rescue, fosmid clones purchased from Gene services Inc. (Cambridge, UK) were injected into the gonad of ctn-1 mutant at 2 ng/µl along with ofm-1::GFP marker (30 ng/µl). Once we rescued the head bending phenotype of ctn-1 with a single fosmid, we rescued ctn-1 mutant with a genomic DNA fragment encompassing the entire coding sequence of ctn-1 and approximately 4 kb upstream of the putative translation site.

To verify the predicted coding sequence of ctn-1, we first performed BLAST search analysis using the genomic sequences of C. briggsae and C. remanei. This analysis suggested that the first and 12th exons are longer than predicted in WormBase (WS208), and that an additional exon (10th exon) is present. Second, we sequenced C. elegans ORF ctn-1 clone (9349620) and confirmed the 10th and the 12th exon sequences. Third, we performed sequence analysis of the DNA fragment obtained from RT-PCR with a primer set (SL1 and an internal primer) and identified the trans-splicing site which is 29 bp upstream of the newly-defined translation initiation site. Our analysis indicates that ctn-1 encodes a predicted protein with 784 amino acids (Figure S1B).

Constructs and transformation

The ctn-1 genomic DNA (approximately 4 kb upstream of the promoter and the entire coding sequence) was amplified by the expand long template PCR system (Roche Applied Science) and used directly for rescue. For PH20ctn-1 and Pmyo-3ctn-1 constructs, the neuron-specific H20 [45] or muscle-specific myo-3 promoter sequences were fused to the translation initiation site of the ctn-1 genomic DNA in frame by the overlapping extension PCR (Roche). For localization of CTN-1, we inserted the GFP sequence to the translation initiation site of ctn-1 cDNA, and then the ctn-1 promoter sequence was inserted before the GFP sequence. The resulting construct rescued the head-bending phenotype of ctn-1 mutants and was used for generating integrated transgenic animals. For GFP::sgca-1 construct, the GFP sequence was inserted in-frame right after the signal sequence of sgca-1 open-reading frame as described previously [21]. Transgenic strains were made as described [46] by injecting DNA constructs (2–10 ng/µl) along with a co-injection marker DNA (pRF4(rol-6(d)) or ofm-1::GFP) into the gonad of hermaphrodite animals at 100 ng/µl. We obtained at least 3 independent transgenic lines for rescue, and found that all lines show similar results.

Measurement of locomotory speed

To remove bacteria attached to animals, approximately fifteen age-matched (30 hr after L4 stage) hermaphrodite animals for each genotype were placed on a NGM (nematode growth medium) agar plate without bacteria for 15 min. The animals were then placed inside one of two copper rings embedded in a NGM plate. We found that age of agar plate influences the speed of animals, probably because the surface tension resulting from the liquid surrounding animals slows down movement. We used approximately one week-old plates for our assay, and compared with the speed of wild-type control animals. Video frames from two different genotypes were simultaneously acquired with a dissecting microscope equipped with Go-3 digital camera (QImaging) for 2 min with a 500 ms interval and 20 ms exposure. We measured the average speed of animals by using Track Objects from ImagePro Plus (Media Cybernetics).

Measurement of the number of eggs

The activity of egg laying muscle was measured indirectly by counting eggs retained in uteri. Single age-matched (30 hrs post-L4) animals (total 15 for each genotype) were placed in each well of a 96 well plate that contains 1% alkaline hypochlorite solution. The eggshells protect embryos from dissolution by alkaline hypochlorite. After 15 min incubation, the remaining eggs were counted in each well.

Body curvature analysis

Body curvature analysis was previously described [47]. A single animal was transferred to an agar plate and its movement was recorded at 20 frames per second. We limited image acquisition within 15 to 60 seconds after transfer, because the head bending phenotype is prominent when animals are stimulated to move forward rapidly. A custom-written software automatically recognizes the animal and assigns thirteen points spaced equally from the tip of nose to the tail along the midline of the body, and produces the pixel coordinates of thirteen points. First supplementary angles were calculated from the coordinates of the first three points with MATLAB software. First angle data were obtained when the head swing of an animal reached the maximal extension to the dorsoventral side.

Western blot analysis

Mixed stage worms were washed and collected in M9 buffer. Equal volume of 2× Laemmli sample buffer was added to the worm pellets. The resulting worm suspension was heated at 90 °C for 10 min, centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 min, and then immediately loaded on 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel. The Western blot analysis was performed using anti-GFP antibody (Clontech, JL-8) and anti-α-tubulin antibody (Developmental hybridoma bank, AA4.3).

Microscopy imaging

Fixation and immunostaining procedures are previously described [21]. Fluorescence images were observed under a Zeiss Axio Observer microscope with 40× objective (water-immersion, NA: 1.2) or an Olympus Fluoview 300 confocal microscope with a 60× objective (oil-immersion, NA: 1.4) or 100× objective (oil-immersion, NA: 1.4). We typically observed more than 50 animals for each genotype. Images for quantification were acquired under an identical exposure time, gains and pinhole diameter. The intensity of puncta from acquired images was analyzed using linescan (Metamorph, Molecular Devices) and presented as values obtained by subtracting background levels from the peak grey levels of puncta.

Electrophysiological recordings

Electrophysiological methods were as previously described [48]. Briefly, animals raised on 80 µM retinal plates, were immobilized with cyanoacrylic glue and a lateral cuticle incision was made to expose the ventral medial body wall muscles. Muscle recordings were made in the whole-cell voltage-clamp configuration (holding potential −60 mV) using an EPC-10 patch-clamp amplifier and digitized at 2.9 kHz. The extracellular solution consisted of (in mM): NaCl 150; KCl 5; CaCl2 5; MgCl2 4, glucose 10; sucrose 5; HEPES 15 (pH 7.3, ∼340mOsm). The patch pipette was filled with (in mM): KCl 120; KOH 20; MgCl2 4; (N-tris[Hydroxymethyl] methyl-2-aminoethane-sulfonic acid) 5; CaCl2 0.25; Na2ATP 4; sucrose 36; EGTA 5 (pH 7.2, ∼315mOsm). All of the animals carry a transgene (zxIs6) that expresses channelrhodopsin-2 under the control of the cholinergic motor neuron (unc-17)-specific promoter. Evoked currents were recorded in a body-wall muscle after eliciting neurotransmitter release by a 10 ms illumination using a 470 nm LED (Thor labs) triggered with a TTL pulse from the EPC10 pulse generator [31]. Evoked post-synaptic responses were acquired using Pulse software (HEKA) run on a Dell computer. Subsequent analysis and graphing was performed using Pulsefit (HEKA), Mini analysis (Synaptosoft Inc) and Igor Pro (Wavemetrics). The data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. LaiHC

JanLY

2006 The distribution and targeting of neuronal voltage-gated ion channels. Nat Rev Neurosci 7 548 562

2. LevitanIB

2006 Signaling protein complexes associated with neuronal ion channels. Nat Neurosci 9 305 310

3. SalkoffL

ButlerA

FerreiraG

SantiC

WeiA

2006 High-conductance potassium channels of the SLO family. Nat Rev Neurosci 7 921 931

4. FaklerB

AdelmanJP

2008 Control of K(Ca) channels by calcium nano/microdomains. Neuron 59 873 881

5. BrennerR

PerezGJ

BonevAD

EckmanDM

KosekJC

2000 Vasoregulation by the beta1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature 407 870 876

6. LovellPV

McCobbDP

2001 Pituitary control of BK potassium channel function and intrinsic firing properties of adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurosci 21 3429 3442

7. WernerME

ZvaraP

MeredithAL

AldrichRW

NelsonMT

2005 Erectile dysfunction in mice lacking the large-conductance calcium-activated potassium (BK) channel. J Physiol 567 545 556

8. DuW

BautistaJF

YangH

Diez-SampedroA

YouSA

2005 Calcium-sensitive potassium channelopathy in human epilepsy and paroxysmal movement disorder. Nat Genet 37 733 738

9. ShrutiS

ClemRL

BarthAL

2008 A seizure-induced gain-of-function in BK channels is associated with elevated firing activity in neocortical pyramidal neurons. Neurobiol Dis 30 323 330

10. SchopperleWM

HolmqvistMH

ZhouY

WangJ

WangZ

1998 Slob, a novel protein that interacts with the Slowpoke calcium-dependent potassium channel. Neuron 20 565 573

11. LuR

AliouaA

KumarY

EghbaliM

StefaniE

2006 MaxiK channel partners: physiological impact. J Physiol 570 65 72

12. TianL

ChenL

McClaffertyH

SailerCA

RuthP

2006 A noncanonical SH3 domain binding motif links BK channels to the actin cytoskeleton via the SH3 adapter cortactin. FASEB J 20 2588 2590

13. KimEY

RidgwayLD

DryerSE

2007 Interactions with filamin A stimulate surface expression of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in the absence of direct actin binding. Mol Pharmacol 72 622 630

14. ParkSM

LiuG

KubalA

FuryM

CaoL

2004 Direct interaction between BKCa potassium channel and microtubule-associated protein 1A. FEBS Lett 570 143 148

15. WangZW

SaifeeO

NonetML

SalkoffL

2001 SLO-1 potassium channels control quantal content of neurotransmitter release at the C. elegans neuromuscular junction. Neuron 32 867 881

16. DaviesAG

Pierce-ShimomuraJT

KimH

VanHovenMK

ThieleTR

2003 A central role of the BK potassium channel in behavioral responses to ethanol in C. elegans. Cell 115 655 666

17. Carre-PierratM

GrisoniK

GieselerK

MariolMC

MartinE

2006 The SLO-1 BK channel of Caenorhabditis elegans is critical for muscle function and is involved in dystrophin-dependent muscle dystrophy. J Mol Biol 358 387 395

18. KimH

RogersMJ

RichmondJE

McIntireSL

2004 SNF-6 is an acetylcholine transporter interacting with the dystrophin complex in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 430 891 896

19. BessouC

GiugiaJB

FranksCJ

Holden-DyeL

SegalatL

1998 Mutations in the Caenorhabditis elegans dystrophin-like gene dys-1 lead to hyperactivity and suggest a link with cholinergic transmission. Neurogenetics 2 61 72

20. GieselerK

BessouC

SegalatL

1999 Dystrobrevin - and dystrophin-like mutants display similar phenotypes in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Neurogenetics 2 87 90

21. KimH

Pierce-ShimomuraJT

OhHJ

JohnsonBE

GoodmanMB

2009 The dystrophin complex controls bk channel localization and muscle activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet 5 e1000780 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000780

22. AldertonJM

SteinhardtRA

2000 Calcium influx through calcium leak channels is responsible for the elevated levels of calcium-dependent proteolysis in dystrophic myotubes. J Biol Chem 275 9452 9460

23. JanssensB

StaesK

van RoyF

1999 Human alpha-catulin, a novel alpha-catenin-like molecule with conserved genomic structure, but deviating alternative splicing. Biochim Biophys Acta 1447 341 347

24. BarsteadRJ

WaterstonRH

1989 The basal component of the nematode dense-body is vinculin. J Biol Chem 264 10177 10185

25. CostaM

RaichW

AgbunagC

LeungB

HardinJ

1998 A putative catenin-cadherin system mediates morphogenesis of the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. J Cell Biol 141 297 308

26. WiesnerC

WinsauerG

ReschU

HoethM

SchmidJA

2008 Alpha-catulin, a Rho signalling component, can regulate NF-kappaB through binding to IKK-beta, and confers resistance to apoptosis. Oncogene 27 2159 2169

27. Sadoulet-PuccioHM

RajalaM

KunkelLM

1997 Dystrobrevin and dystrophin: an interaction through coiled-coil motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94 12413 12418

28. HuH

ShaoLR

ChavoshyS

GuN

TriebM

2001 Presynaptic Ca2+-activated K+ channels in glutamatergic hippocampal terminals and their role in spike repolarization and regulation of transmitter release. J Neurosci 21 9585 9597

29. SailerCA

KaufmannWA

KoglerM

ChenL

SausbierU

2006 Immunolocalization of BK channels in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Eur J Neurosci 24 442 454

30. KaufmannWA

FerragutiF

FukazawaY

KasugaiY

ShigemotoR

2009 Large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in purkinje cell plasma membranes are clustered at sites of hypolemmal microdomains. J Comp Neurol 515 215 230

31. LiewaldJF

BraunerM

StephensGJ

BouhoursM

SchultheisC

2008 Optogenetic analysis of synaptic function. Nat Methods 5 895 902

32. GieselerK

MariolMC

BessouC

MigaudM

FranksCJ

2001 Molecular, genetic and physiological characterisation of dystrobrevin-like (dyb-1) mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Mol Biol 307 107 117

33. EdgertonJR

ReinhartPH

2003 Distinct contributions of small and large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels to rat Purkinje neuron function. J Physiol 548 53 69

34. PrakriyaM

LingleCJ

1999 BK channel activation by brief depolarizations requires Ca2+ influx through L - and Q-type Ca2+ channels in rat chromaffin cells. J Neurophysiol 81 2267 2278

35. GrachevaEO

HadwigerG

NonetML

RichmondJE

2008 Direct interactions between C. elegans RAB-3 and Rim provide a mechanism to target vesicles to the presynaptic density. Neurosci Lett 444 137 142

36. SahekiY

BargmannCI

2009 Presynaptic CaV2 calcium channel traffic requires CALF-1 and the alpha(2)delta subunit UNC-36. Nat Neurosci 12 1257 1265

37. BiggarWD

KlamutHJ

DemacioPC

StevensDJ

RayPN

2002 Duchenne muscular dystrophy: current knowledge, treatment, and future prospects. Clin Orthop Relat Res 88 106

38. BoisPR

BorgonRA

VonrheinC

IzardT

2005 Structural dynamics of alpha-actinin-vinculin interactions. Mol Cell Biol 25 6112 6122

39. ZieglerWH

LiddingtonRC

CritchleyDR

2006 The structure and regulation of vinculin. Trends Cell Biol 16 453 460

40. ErvastiJM

2003 Costameres: the Achilles' heel of Herculean muscle. J Biol Chem 278 13591 13594

41. AyalonG

DavisJQ

ScotlandPB

BennettV

2008 An ankyrin-based mechanism for functional organization of dystrophin and dystroglycan. Cell 135 1189 1200

42. TroemelER

SagastiA

BargmannCI

1999 Lateral signaling mediated by axon contact and calcium entry regulates asymmetric odorant receptor expression in C. elegans. Cell 99 387 398

43. BrennerS

1974 The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77 71 94

44. WicksSR

YehRT

GishWR

WaterstonRH

PlasterkRH

2001 Rapid gene mapping in Caenorhabditis elegans using a high density polymorphism map. Nat Genet 28 160 164

45. ShioiG

ShojiM

NakamuraM

IshiharaT

KatsuraI

2001 Mutations affecting nerve attachment of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 157 1611 1622

46. MelloCC

KramerJM

StinchcombD

AmbrosV

1991 Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. Embo J 10 3959 3970

47. Pierce-ShimomuraJT

ChenBL

MunJJ

HoR

SarkisR

2008 Genetic analysis of crawling and swimming locomotory patterns in C. elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 20982 20987

48. RichmondJE

2006 Electrophysiological recordings from the neuromuscular junction of C. elegans. WormBook 1 8

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 8- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- A Model for Damage Load and Its Implications for the Evolution of Bacterial Aging

- Mutation in the Gene Encoding Ubiquitin Ligase LRSAM1 in Patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease

- Identification of the Bovine Arachnomelia Mutation by Massively Parallel Sequencing Implicates Sulfite Oxidase (SUOX) in Bone Development

- Did Genetic Drift Drive Increases in Genome Complexity?

- The 5p15.33 Locus Is Associated with Risk of Lung Adenocarcinoma in Never-Smoking Females in Asia

- An Alpha-Catulin Homologue Controls Neuromuscular Function through Localization of the Dystrophin Complex and BK Channels in

- Epigenetically-Inherited Centromere and Neocentromere DNA Replicates Earliest in S-Phase

- Survival and Growth of Yeast without Telomere Capping by Cdc13 in the Absence of Sgs1, Exo1, and Rad9

- Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 1 Regulates dE2F1 Expression during Development and Cooperates with RBF1 to Control Proliferation and Survival

- Disease-Associated Mutations That Alter the RNA Structural Ensemble

- The Transcriptomes of Two Heritable Cell Types Illuminate the Circuit Governing Their Differentiation

- Inactivation of VCP/ter94 Suppresses Retinal Pathology Caused by Misfolded Rhodopsin in

- Multiple Independent Loci at Chromosome 15q25.1 Affect Smoking Quantity: a Meta-Analysis and Comparison with Lung Cancer and COPD

- Transcriptional Regulation by CHIP/LDB Complexes

- Conserved Role of in Ethanol Responses in Mutant Mice

- A Global Overview of the Genetic and Functional Diversity in the Pathogenicity Island

- Common Inherited Variation in Mitochondrial Genes Is Not Enriched for Associations with Type 2 Diabetes or Related Glycemic Traits

- Extracellular Dopamine Potentiates Mn-Induced Oxidative Stress, Lifespan Reduction, and Dopaminergic Neurodegeneration in a BLI-3–Dependent Manner in

- Genetic Analysis of Baker's Yeast Msh4-Msh5 Reveals a Threshold Crossover Level for Meiotic Viability

- Genome-Wide Association Studies of Serum Magnesium, Potassium, and Sodium Concentrations Identify Six Loci Influencing Serum Magnesium Levels

- Something New: An Interview with Radoje Drmanac

- The Extinction Dynamics of Bacterial Pseudogenes

- Microtubule Actin Crosslinking Factor 1 Regulates the Balbiani Body and Animal-Vegetal Polarity of the Zebrafish Oocyte

- Consistent Association of Type 2 Diabetes Risk Variants Found in Europeans in Diverse Racial and Ethnic Groups

- Transmission of Mitochondrial DNA Diseases and Ways to Prevent Them

- Telomere Disruption Results in Non-Random Formation of Dicentric Chromosomes Involving Acrocentric Human Chromosomes

- Chromosome Axis Defects Induce a Checkpoint-Mediated Delay and Interchromosomal Effect on Crossing Over during Drosophila Meiosis

- Dynamic Chromatin Organization during Foregut Development Mediated by the Organ Selector Gene PHA-4/FoxA

- Ancient Protostome Origin of Chemosensory Ionotropic Glutamate Receptors and the Evolution of Insect Taste and Olfaction

- A Wnt-Frz/Ror-Dsh Pathway Regulates Neurite Outgrowth in

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Identification of the Bovine Arachnomelia Mutation by Massively Parallel Sequencing Implicates Sulfite Oxidase (SUOX) in Bone Development

- Common Inherited Variation in Mitochondrial Genes Is Not Enriched for Associations with Type 2 Diabetes or Related Glycemic Traits

- A Model for Damage Load and Its Implications for the Evolution of Bacterial Aging

- Did Genetic Drift Drive Increases in Genome Complexity?

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání