-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Mutation in the Gene Encoding Ubiquitin Ligase LRSAM1 in Patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) represents a family of related sensorimotor neuropathies. We studied a large family from a rural eastern Canadian community, with multiple individuals suffering from a condition clinically most similar to autosomal recessive axonal CMT, or AR-CMT2. Homozygosity mapping with high-density SNP genotyping of six affected individuals from the family excluded 23 known genes for various subtypes of CMT and instead identified a single homozygous region on chromosome 9, at 122,423,730–129,841,977 Mbp, shared identical by state in all six affected individuals. A homozygous pathogenic variant was identified in the gene encoding leucine rich repeat and sterile alpha motif 1 (LRSAM1) by direct DNA sequencing of genes within the region in affected DNA samples. The single nucleotide change mutates an intronic consensus acceptor splicing site from AG to AA. Direct analysis of RNA from patient blood demonstrated aberrant splicing of the affected exon, causing an obligatory frameshift and premature truncation of the protein. Western blotting of immortalized cells from a homozygous patient showed complete absence of detectable protein, consistent with the splice site defect. LRSAM1 plays a role in membrane vesicle fusion during viral maturation and for proper adhesion of neuronal cells in culture. Other ubiquitin ligases play documented roles in neurodegenerative diseases. LRSAM1 is a strong candidate for the causal gene for the genetic disorder in our kindred.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(8): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001081

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001081Summary

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) represents a family of related sensorimotor neuropathies. We studied a large family from a rural eastern Canadian community, with multiple individuals suffering from a condition clinically most similar to autosomal recessive axonal CMT, or AR-CMT2. Homozygosity mapping with high-density SNP genotyping of six affected individuals from the family excluded 23 known genes for various subtypes of CMT and instead identified a single homozygous region on chromosome 9, at 122,423,730–129,841,977 Mbp, shared identical by state in all six affected individuals. A homozygous pathogenic variant was identified in the gene encoding leucine rich repeat and sterile alpha motif 1 (LRSAM1) by direct DNA sequencing of genes within the region in affected DNA samples. The single nucleotide change mutates an intronic consensus acceptor splicing site from AG to AA. Direct analysis of RNA from patient blood demonstrated aberrant splicing of the affected exon, causing an obligatory frameshift and premature truncation of the protein. Western blotting of immortalized cells from a homozygous patient showed complete absence of detectable protein, consistent with the splice site defect. LRSAM1 plays a role in membrane vesicle fusion during viral maturation and for proper adhesion of neuronal cells in culture. Other ubiquitin ligases play documented roles in neurodegenerative diseases. LRSAM1 is a strong candidate for the causal gene for the genetic disorder in our kindred.

Introduction

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) comprises a set of genetically heterogeneous disorders of the peripheral nervous system, affecting motor and sensory function. CMT is the most common inherited neuromuscular disorder, with a wide range of clinical presentations, but as described by OMIM (118200), the salient features of CMT include a slowly progressive weakness and atrophy of the musculature, predominantly of the distal lower limb. This weakness often affects the patients ability to walk or run, and eventually can progress to reach the upper extremity. Within the broad group of patients defined clinically, there are various categories of CMT defined by neurophysiological subphenotypes, pathological findings on biopsy, modes of familial transmission, and specific mutated genes identified in individual patients. These criteria have been extensively reviewed in recent literature [1]–[17]. A query of OMIM for genes causing Charcot-Marie-Tooth yields 26 separate entries with allelic variants; the database of inherited peripheral neuropathies notes 31 gene entries for CMT plus an additional 7 described as causing distal hereditary motor neuropathy. Nonetheless, mutations in new genes associated with CMT continue to be reported[18].

The functions of genes whose mutation yields a CMT or closely related motor neuropathy phenotype span a wide range of disparate biochemical activities including structural components of myelin (PMP22, P0), a mitochondrial transport and fusion protein (MFN2), transcription factors (SOX, EGR2), components of protein degradation pathways (DNM2, RAB7, LITAF), tRNA synthetases (GARS, YARS), a nuclear structural component (LMNA) and others [19]. Thus, novel CMT genes are difficult to predict through selection of biological candidates for sequencing in unexplained patients. The best approach for identifying the genetic cause of unexplained CMT remains linkage mapping in multiplex families, with adequate statistical power dependent on the mode of transmission, the specifics of pedigree and local population structure.

We report the mapping of a novel form of autosomal recessive axonal CMT through homozygosity mapping in an extended consanguineous pedigree of a local founder population. The identified gene appears to play a role in vesicle metabolism, consistent with some other CMT genes.

Results/Discussion

In the course of clinical work, we ascertained a patient with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, most closely similar to subtype AR-CMT2 (recessive, axonal), although this clinical presentation has sometimes been included as a type of CMT4[16]. The index patient noted the gradual onset of weakness around age 20, particularly affecting his distal lower extremities, but also present in the hands. He noted episodic muscle cramping of extremity and trunk muscles. He lost the ability to run in his early 20s. He denied sensory symptoms. He had erectile dysfunction and urgency of urination, but no other autonomic symptoms or evidence of spasticity. At the time of examination he demonstrated bilateral pes cavus, with marked wasting of distal lower extremity muscles and mild wasting of hand intrinsic muscles. Fasciculations were present in upper and lower extremity muscles. In the lower extremities he had grade 4 out of 5 ankle dorsiflexion strength (MRC scale), grade 4 hand intrinsic muscle strength and other muscles were grade 5. He could not walk on either the toes or heels. There was no gait ataxia. Upper and lower extremity tendon reflexes were absent. He had mild loss of sensation on the fingertips and severe loss of sensation in the feet and legs, most markedly to vibration, but also involving proprioception and pain perception. Laboratory investigation demonstrated an elevated serum creatine kinase (CK) from 1082 to 1921 U/L (18-199 U/L). Nerve conduction studies and needle electromyography demonstrated a diffuse sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy. There was no evidence of a primary muscle disorder. The predominant electrophysiological pattern was consistent with axonal degeneration (see Table S1). Sensory nerve action potentials were small or absent. All of the upper extremity motor nerve conduction velocities were faster than 38 m/s. The ulnar compound muscle action potential amplitude was small and a repeat study 2 years later demonstrated both median and ulnar compound muscle action potential amplitudes were small with normal motor conduction velocities. These are accepted criteria for an axonal CMT [1]. Upper and lower extremity muscles demonstrated ample denervation and partial reinnervation, with fibrillation and reduced recruitment of large motor unit potentials. Denervation of paraspinal muscles indicated axonal degeneration was present at very proximal nerve levels. Temporal dispersion was seen in some motor nerve conductions, but no conduction block, which may be an indication of an element of secondary demyelination, but the predominant electrophysiologic pattern was axonal.

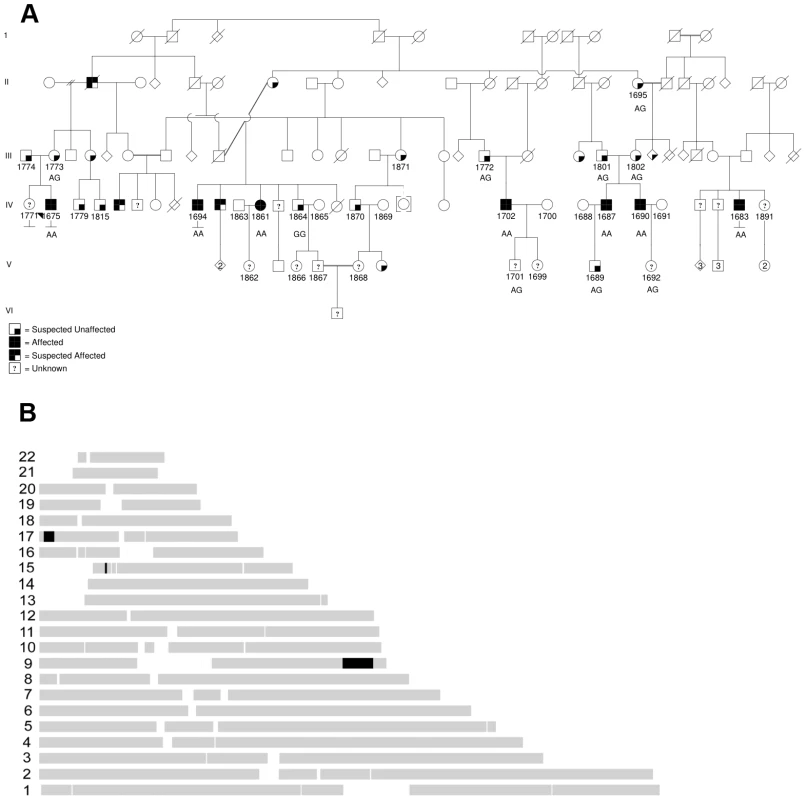

The proband is a member of an extended multiply consanguineous family derived from a rural eastern Canadian population isolate; the extended pedigree includes five additional affected individuals with similar suites of symptoms (Figure 1A). Other affected family members exhibited sensory and motor dysfunction with pes cavus. Autonomic symptoms have not been consistently reported. Weakness and wasting has usually been moderate and predominantly in distal lower extremity muscles. The onset of symptoms has usually been in early adult years. One patient was not aware of any difficulties, but had examination abnormalities in his 40's. Some of the affected individuals are able to ambulate into later years, though others have become wheelchair dependent. Sensory symptoms are sometimes not reported, but sensory examination is consistently markedly abnormal, with loss of vibration sense often up to proximal legs and hips. Proprioception loss has been severe in some affecteds with accompanying sensory ataxia. Laboratory abnormalities that are available in only a few patients include mild increased CSF protein and increased serum CK. One patient had significant essential tremor, but that has not usually been reported. When EMG data is available, the pattern is typically predominantly axonal degeneration with only mildly slowed or normal motor nerve conduction velocities and no upper extremity motor nerve conduction velocities slower than 38 m/s. One other patient had evidence of paraspinal muscle denervation, with a normal MRI of the spine, suggesting axonal degeneration at very proximal nerve levels from the neuropathy.

Fig. 1. Maritime family with Charcot-Marie-Tooth and genetic mapping.

(A) Pedigree, with affected patients shaded in black, sampled individuals have four digit id numbers directly below symbols, proband 1675 is indicated with black arrowhead. Sequenced individuals have mutation status indicated (wild type is GG, homozygous mutant is AA, heterozygous mutant is AG). (B) Homozygous haplotype (HH) analysis. Map of the RCHH intervals shared by 5 patients identified by Homozygosity Haplotype algorithm with a cutoff of 3.0 cM. Based on transmission of the trait in the pedigree, the genetics are consistent with an autosomal recessive disorder. Given the isolation of the regional population, it seemed likely that all affected individuals in our cohort might be homozygous for the same causal mutation, sharing a chromosomal haplotype around the causal gene. We sampled DNA from six affected patients and related family members. We performed high density genome-wide SNP genotyping of five affected individuals. Formal linkage analysis using a recessive model was not deemed useful, given the highly consanguineous pedigree structure and also the impossibility of obtaining reliable marker allele frequencies for this small subpopulation. Instead, we used the homozygous haplotype (HH) method to test for linkage to any of 23 known relevant CMT loci. The HH method is a rapid non-parametric algorithm that utilizes the subset of completely homozygous markers in samples from affected individuals, and looks for consistent loci by excluding regions where affected individuals are homozygous for different alleles of a given SNP [20], [21]. The method is robust due to the high density of commercial genotyping panels. In this case, HH confidently excluded all of the known relevant CMT loci, under the assumption that all five affected individuals in our pedigree are homozygous for the same causal allele. HH flagged three chromosomal regions as potentially linked, on chromosomes 9, 15 and 17 (Figure 1B).

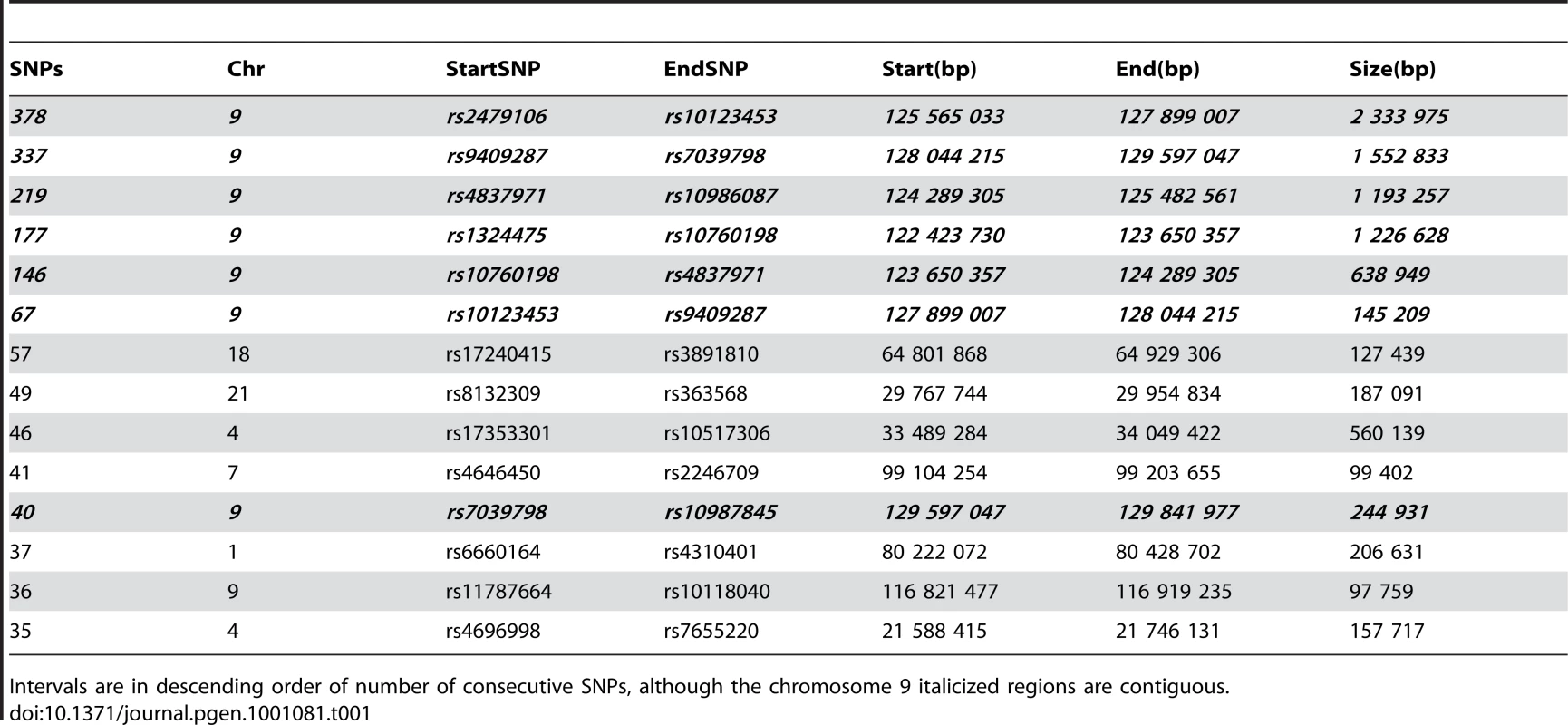

Subsequently we genotyped additional pedigree members including one more affected, and looked for regions of extended homozygosity shared identical-by-state (IBS) in the six affected individuals but not in unaffecteds. As shown in Table 1, among the longest series of consecutive homozygous SNPs, a region on chromosome 9 appeared as a clear outlier. This region corresponds to that predicted from HH analysis, and extends from rs1324475 at 122,423,730 Mbp to rs10987845 at 129,841,977 Mbp. It is interrupted by several single heterozygous SNPs, mostly in one particular sample; these presumably represent false heterozygote genotype calls. In contrast, the potential regions found by HH on chromosomes 15 and 17 were not homozygous in all six affected individuals when all marker data was considered. The likely linked interval is 7.42 Mbp in size on chromosome 9, and includes 84 RefSeq annotated genes, including a cluster of 14 olfactory receptor genes which were not considered likely candidates.

Tab. 1. All intervals of 35 or more consecutive SNPs homozygous and identical by state among the six affected CMT samples.

Intervals are in descending order of number of consecutive SNPs, although the chromosome 9 italicized regions are contiguous. We prioritized genes likely to have neuronal or neuromuscular function based on manual review. In all we sequenced 314 coding exons of 18 genes (HSPA5, DENND1A, RABGAP1, RAB14, STXBP1, DNM1, SPTAN1, DAB2IP, LHX2, TOR1A, GSN, LHX6, LMX1B, CDK9, CDK5RAP2, FPGS, SH2D3C, LRSAM1), until we observed a particular homozygous variant in the gene LRSAM1 (Figure 2A). This variant changes a coding exon consensus splice acceptor AG dinucleotide to an AA. There are three RefSeq annotated isoforms of LRSAM1, differing in the 5′ noncoding region, generating transcripts of either 25 or 26 exons. All three splice forms predict the same open reading frame; the variant identified in our patients lies in the penultimate coding exon, either 24 (isoforms 1, 2) or 25 (isoform 3). The variant was found homozygous in all six affected individuals, and either wild type or heterozygous as expected among sequenced parents and siblings (Figure 1A). This variant is not present in dbSNP build 130 which includes 2 million novel SNPS recently submitted by the 1000 Genomes project, nor was it detected in any of 150 local control (a mix of anglo - and franco-phonic individuals) or 96 CEPH Caucasian control samples, totalling almost 500 control chromosomes. No other homozygous coding variants were detected by sequencing this set of candidate genes.

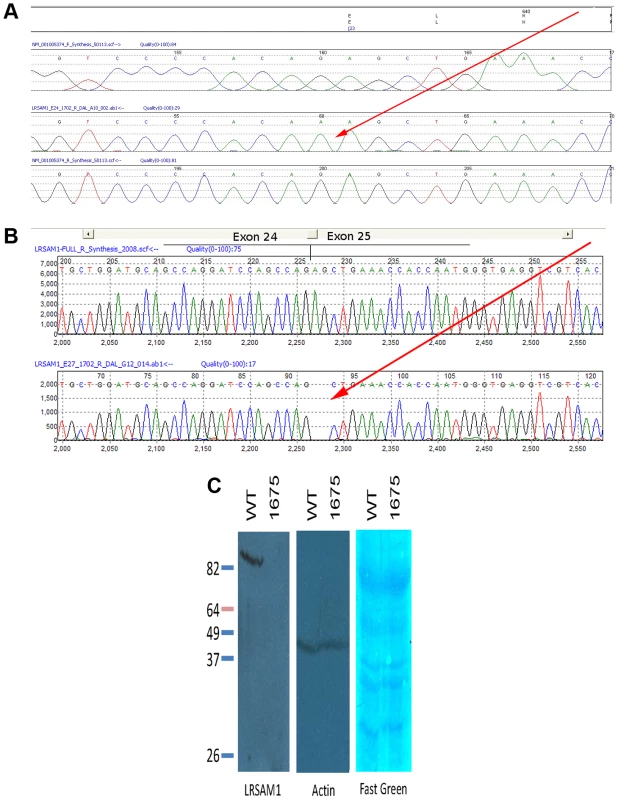

Fig. 2. Sequence showing mutation in genomic and cDNA of affected patient.

(A) Mutation of splice acceptor site AG of LRSAM1 exon 24 (25 in alternative isoform 3) to dinucleotide AA in genomic DNA of patient 1702. Upper to lower panels: translation of coding exon; virtual chromatogram of consensus genomic sequence forward direction; sequence chromatogram of affected patient reverse direction; virtual chromatogram of consensus genomic sequence reverse direction. Red arrow points to homozygous mutation. (B) Sequence of cDNA from RNA of patient 1702 showing aberrant splice site utilization and frameshift of encoded protein. Upper panel, sequence chromatogram of correctly spliced cDNA from exon 24 to 25 (per isoform 3); lower panel, sequence chromatogram of incorrectly spliced cDNA from affected patient. Two base deletion caused by splicing interior to exon 25 (red arrow). (C) Western blot of LRSAM1 protein in cells cultured from patient homozygous for LRSAM1 mutation. EBV-transformed B- lymphocytes from control or patient 1675 were extracted and Western blotted with anti-LRSAM1 antibody. Left, anti-LRSAM1; center, anti-actin; right, Fast green total protein stain. The variant in question changes the consensus splice acceptor site. We tested three splice site prediction programs (Berkeley Drosophila Project, NetGene2 and SplicePort) to see whether they were sensitive to the alternative site used in the homozygous patients. All three programs correctly predicted the bona fide splice acceptor site in the wild type sequence. The Berkeley tool failed to predict the alternative AG two nucleotides internally in the mutant sequence, while NetGene2 and SplicePort predicted this acceptor site though with low confidence. We were able to test directly whether splicing of the exon was altered, using total RNA extracted from a fresh blood sample from one affected patient (1702). By qualitative RT-PCR, we saw a product of the appropriate size in both a control sample and the affected patient sample, at roughly equivalent intensities (d.n.s.) Although the resolution of the electrophoresis was much less than single nucleotide, sequencing of the sample product from the affected patient showed that splicing was to the next AG directly following the true acceptor site, two bases into penultimate exon 24 (or 25 as per isoform 3) (Figure 2B). This causes an obligatory frameshift, leading to an altered open reading frame and premature truncation of the protein after 643 (out of 723) residues in all three spliced isoforms. The effect of this change on protein expression was tested directly by Western blot using EBV-transformed B-lymphocyte cell lines (B-LCL) derived from a healthy control and from one of the affected CMT patients. While a single strong band was detected by the anti-LRSAM1 antibody in the control B-LCL (molecular weight approximately 78 kDa), no protein was detected in the B-LCL derived from the CMT patient (Figure 2C). Either the truncated protein is rapidly degraded, or else is rendered non-reactive with our antibody. In either case, the result is most likely to be a significant loss-of-function of the gene product, although unusual gain-of-function effects of a truncated protein can be imagined (though these might be expected to behave in a dominant not recessive fashion).

LRSAM1, leucine rich repeat and sterile alpha motif containing 1, is predicted to be an E3 type ubiquitin ligase [22]. It is also known as TAL (TSG101-associated ligase) and RIFLE. TSG101 itself is a tumor suppressor gene, with a reported role in maturation of human immunodeficiency virus, and LRSAM1 is implicated in its metabolism directly by polyubiquitination. TSG101 is involved in retroviral vacuolar budding. Interestingly, another TSG101-ubiquitinating ligase is known, (Mahogunin, or MGRN1), for which knockout mice exist and exhibit a neurodegenerative phenotype. Moreover, the known CMT gene LITAF, also called SIMPLE, interacts with mouse ubiquitin ligase gene product NEDD4 [23], also potentially with TSG101 [24], and may itself be an E3 ubiquitin ligase [25], These related findings support the interpretation that mutation of LRSAM1 is probably causal in our patients. It remains to be determined whether the pathogenic effects of mutations in these protein degradation pathway genes act directly via specific neuron-specific proteins (such as PMP22) or more generally through decreasing cell viability.

The currently recommended diagnostic paradigm for Charcot-Marie-Tooth entails a complex flow chart combining clinical, familial and molecular genetic analyses [3]. While this approach makes sense when DNA sequencing technologies are cost-limiting, this mixed paradigm could soon be replaced by a more comprehensive and pre-emptive molecular analysis. With the advent of whole genome reagents such as all-exon hybridization capture oligonucleotide libraries, together with the tremendous cost-reductions in DNA sequencing using next-generation nanotechnologies, it should soon be feasible to sequence either entire patient genomes, or entire exomes, for less than the cost of traditional Sanger-based fluorescent capillary sequencing of sets of candidate genes [26]–[28]. We envisage an analysis paradigm whereby all patients with a potential genetic diagnosis, across any medical subdiscipline, may first be sequenced to identify likely pathogenic variants, which can then be cross-indexed with clinical parameters to flag likely causal genes. This approach has recently been shown to be feasible in a research context, including detection of a pathogenic variant in a family segregating a known form of CMT [29]–[32].

Materials and Methods

Clinical ascertainment and consent

Approval for the research study was obtained from the Capital Health research ethics board. Patients were identified in the course of routine clinical ascertainment and treatment of movement disorders in the neurology clinic at the Halifax Infirmary. All sampled family members provided informed consent to participate in the study. DNA was obtained from blood samples using routine extraction methods.

Genotyping and analysis

Whole-genome SNP scanning was performed at the McGill University and Genome Quebec Centre for Innovation, using the Illumina Human610-Quadv1_B panel. Data were scanned using the Bead Array Reader, plate Crane Ex, and Illumina BeadLab software, on Infinium II fast scan setting. Allele calls were generated using Beadstudio version 3.1 with genotyping module. Data are generated in three different output formats, AB, Forward strand, and Top strand (as defined by Illumina). We used AB format for all linkage analyses.

Homozygosity haplotype (HH) analysis was performed according to the method of Miyazawa [21]. The source code of HH program was modified to customize the format of output. The parameter LARGEGAP defined in the header file, which is used to define large gap of two consecutive SNPs like centromere, was changed from the default value 300,000 bp to 400,000 bp to accommodate some non-centromere spaces for HumanHap610 genotypes. The revised C source code of HH program was compiled with GNU compiler on a Linux-based operating system Fedora. HH analysis requires a SNP annotation file, which includes SNP name, physical coordinates, genetic distances, and minor allele frequencies. The SNP annotation file provided by HH software is for the Affymetrix 500K GeneChips Human Mapping Array Set. The HH format annotation of Illumina HumanHap610 for CEPH population was created from the SNP annotations downloaded from Illumina website. The genetic distances of SNPs with empty value, inconsistent value, or zero were interpolated according to the physical coordinates of their flanking SNPs. HH analysis was performed with a cutoff value 3.0 cM. Homozygosity analysis was performed using customized scripts and manual inspection comparing samples from affected and unaffected pedigree members.

Mutation detection and analysis

Annotated coding exons were amplified by PCR using standard methods, and sequenced at Dalhousie University, using Sanger fluorescent sequencing and capillary electrophoresis. Sequence traces were analyzed using MutationSurveyor (Soft Genetics, Inc.) Specific primers for amplification of LRSAM1 exons and PCR conditions are provided in Table S2.

Western blot

EBV-transformed B-LCL cells derived from a healthy subject or CMT patient 1675 were cultured in RPMI with 10% FBS and 1% pen/strep in 5% CO2. Cells were pelleted and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100 with 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitor tablet (Sigma) added to ice cold buffer immediately prior to use). Cells were broken by vortexing for 1 minute. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 16000×g for 10 minutes. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Sigma). Samples were diluted to 6 microg/microL in lysis buffer, then to 2 microg/microL in sample dye (125 mM Tris-HCL ph 6.8 with 20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 0.04% bromophenol blue, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol). Samples were heated to 95°C for 5 minutes prior to separation of 50 ug sample on a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel. Benchmark pre-stained protein ladder (Invitrogen) was included on the gel. Protein was transferred by wet transfer to methanol-wetted PVDF membrane in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris-base, 192 mM glycine). Membranes were blocked overnight in blocking buffer (5% skim milk powder, 0.05% Tween 20, in PBS pH 7.4). Anti-LRSAM1 antibody (abcam) diluted 1∶500 in blocking buffer was incubated overnight at 4 degrees. Blots were washed in PBS - (0.05% Tween 20 in PBS pH 7.4) 15 minutes plus 3×5 minutes. HRP labelled secondary anti-mouse antibody, diluted 1∶2500 in blocking buffer, was incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were washed as above. HRP was visualized using SuperSignal West Pico Substrate (Fisher Scientific) and exposing to X-ray film for 3-5 minutes. Protein transfer to the gel was confirmed by staining the PVDF membrane with Fast Green.

The URLs for the data and analytic approaches presented herein are as follows:

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/

UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/

NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

Database of inherited peripheral neuropathies, http://www.molgen.ua.ac.be/CMTMutations/Home/Default.cfm

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. ReillyMM

ShyME

2009 Diagnosis and new treatments in genetic neuropathies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 80 1304 1314

2. PareysonD

MarchesiC

SalsanoE

2009 Hereditary predominantly motor neuropathies. Curr Opin Neurol 22 451 459

3. BanchsI

CasasnovasC

AlbertiA

De JorgeL

PovedanoM

2009 Diagnosis of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Biomed Biotechnol 2009 985415

4. KabzinskaD

Hausmanowa-PetrusewiczI

KochanskiA

2008 Charcot-Marie-Tooth disorders with an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance. Clin Neuropathol 27 1 12

5. Jani-AcsadiA

KrajewskiK

ShyME

2008 Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathies: diagnosis and management. Semin Neurol 28 185 194

6. CasasnovasC

CanoLM

AlbertiA

CespedesM

RigoG

2008 Charcot-Marie-tooth disease. Foot Ankle Spec 1 350 354

7. BarisicN

ClaeysKG

Sirotkovic-SkerlevM

LofgrenA

NelisE

2008 Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: a clinico-genetic confrontation. Ann Hum Genet 72 416 441

8. ReillyMM

2007 Sorting out the inherited neuropathies. Pract Neurol 7 93 105

9. ParmanY

2007 Hereditary neuropathies. Curr Opin Neurol 20 542 547

10. OuvrierR

GeevasinghaN

RyanMM

2007 Autosomal-recessive and X-linked forms of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy in childhood. Muscle Nerve 36 131 143

11. ZuchnerS

VanceJM

2006 Molecular genetics of autosomal-dominant axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuromolecular Med 8 63 74

12. SzigetiK

NelisE

LupskiJR

2006 Molecular diagnostics of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and related peripheral neuropathies. Neuromolecular Med 8 243 254

13. SchroderJM

2006 Neuropathology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth and related disorders. Neuromolecular Med 8 23 42

14. PareysonD

ScaioliV

LauraM

2006 Clinical and electrophysiological aspects of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuromolecular Med 8 3 22

15. DubourgO

AzzedineH

VernyC

DurosierG

BiroukN

2006 Autosomal-recessive forms of demyelinating Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuromolecular Med 8 75 86

16. BernardR

De Sandre-GiovannoliA

DelagueV

LevyN

2006 Molecular genetics of autosomal-recessive axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathies. Neuromolecular Med 8 87 106

17. Auer-GrumbachM

MaukoB

Auer-GrumbachP

PieberTR

2006 Molecular genetics of hereditary sensory neuropathies. Neuromolecular Med 8 147 158

18. LandoureG

ZdebikAA

MartinezTL

BurnettBG

StanescuHC

2010 Mutations in TRPV4 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2C. Nat Genet 42 170 174

19. NiemannA

BergerP

SuterU

2006 Pathomechanisms of mutant proteins in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuromolecular Med 8 217 242

20. JiangH

OrrA

GuernseyDL

RobitailleJ

AsselinG

2009 Application of homozygosity haplotype analysis to genetic mapping with high-density SNP genotype data. PLoS ONE 4 e5280 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005280

21. MiyazawaH

KatoM

AwataT

KohdaM

IwasaH

2007 Homozygosity haplotype allows a genomewide search for the autosomal segments shared among patients. Am J Hum Genet 80 1090 1102

22. AmitI

YakirL

KatzM

ZwangY

MarmorMD

2004 Tal, a Tsg101-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase, regulates receptor endocytosis and retrovirus budding. Genes Dev 18 1737 1752

23. StreetVA

BennettCL

GoldyJD

ShirkAJ

KleopaKA

2003 Mutation of a putative protein degradation gene LITAF/SIMPLE in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease 1C. Neurology 60 22 26

24. ShirkAJ

AndersonSK

HashemiSH

ChancePF

BennettCL

2005 SIMPLE interacts with NEDD4 and TSG101: evidence for a role in lysosomal sorting and implications for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Neurosci Res 82 43 50

25. SaifiGM

SzigetiK

WiszniewskiW

ShyME

KrajewskiK

2005 SIMPLE mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and the potential role of its protein product in protein degradation. Hum Mutat 25 372 383

26. HodgesE

XuanZ

BalijaV

KramerM

MollaMN

2007 Genome-wide in situ exon capture for selective resequencing. Nat Genet 39 1522 1527

27. NgPC

LevyS

HuangJ

StockwellTB

WalenzBP

2008 Genetic variation in an individual human exome. PLoS Genet 4 e1000160 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000160

28. WheelerDA

SrinivasanM

EgholmM

ShenY

ChenL

2008 The complete genome of an individual by massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nature 452 872 876

29. NgSB

BuckinghamKJ

LeeC

BighamAW

TaborHK

2009 Exome sequencing identifies the cause of a mendelian disorder. Nat Genet 42 30 35

30. NgSB

TurnerEH

RobertsonPD

FlygareSD

BighamAW

2009 Targeted capture and massively parallel sequencing of 12 human exomes. Nature 461 272 276

31. ChoiM

SchollUI

JiW

LiuT

TikhonovaIR

2009 Genetic diagnosis by whole exome capture and massively parallel DNA sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 19096 19101

32. LupskiJR

ReidJG

Gonzaga-JaureguiC

Rio DeirosD

ChenDC

2010 Whole-Genome Sequencing in a Patient with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Neuropathy. N Engl J Med

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 8- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- A Model for Damage Load and Its Implications for the Evolution of Bacterial Aging

- Mutation in the Gene Encoding Ubiquitin Ligase LRSAM1 in Patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease

- Identification of the Bovine Arachnomelia Mutation by Massively Parallel Sequencing Implicates Sulfite Oxidase (SUOX) in Bone Development

- Did Genetic Drift Drive Increases in Genome Complexity?

- The 5p15.33 Locus Is Associated with Risk of Lung Adenocarcinoma in Never-Smoking Females in Asia

- An Alpha-Catulin Homologue Controls Neuromuscular Function through Localization of the Dystrophin Complex and BK Channels in

- Epigenetically-Inherited Centromere and Neocentromere DNA Replicates Earliest in S-Phase

- Survival and Growth of Yeast without Telomere Capping by Cdc13 in the Absence of Sgs1, Exo1, and Rad9

- Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 1 Regulates dE2F1 Expression during Development and Cooperates with RBF1 to Control Proliferation and Survival

- Disease-Associated Mutations That Alter the RNA Structural Ensemble

- The Transcriptomes of Two Heritable Cell Types Illuminate the Circuit Governing Their Differentiation

- Inactivation of VCP/ter94 Suppresses Retinal Pathology Caused by Misfolded Rhodopsin in

- Multiple Independent Loci at Chromosome 15q25.1 Affect Smoking Quantity: a Meta-Analysis and Comparison with Lung Cancer and COPD

- Transcriptional Regulation by CHIP/LDB Complexes

- Conserved Role of in Ethanol Responses in Mutant Mice

- A Global Overview of the Genetic and Functional Diversity in the Pathogenicity Island

- Common Inherited Variation in Mitochondrial Genes Is Not Enriched for Associations with Type 2 Diabetes or Related Glycemic Traits

- Extracellular Dopamine Potentiates Mn-Induced Oxidative Stress, Lifespan Reduction, and Dopaminergic Neurodegeneration in a BLI-3–Dependent Manner in

- Genetic Analysis of Baker's Yeast Msh4-Msh5 Reveals a Threshold Crossover Level for Meiotic Viability

- Genome-Wide Association Studies of Serum Magnesium, Potassium, and Sodium Concentrations Identify Six Loci Influencing Serum Magnesium Levels

- Something New: An Interview with Radoje Drmanac

- The Extinction Dynamics of Bacterial Pseudogenes

- Microtubule Actin Crosslinking Factor 1 Regulates the Balbiani Body and Animal-Vegetal Polarity of the Zebrafish Oocyte

- Consistent Association of Type 2 Diabetes Risk Variants Found in Europeans in Diverse Racial and Ethnic Groups

- Transmission of Mitochondrial DNA Diseases and Ways to Prevent Them

- Telomere Disruption Results in Non-Random Formation of Dicentric Chromosomes Involving Acrocentric Human Chromosomes

- Chromosome Axis Defects Induce a Checkpoint-Mediated Delay and Interchromosomal Effect on Crossing Over during Drosophila Meiosis

- Dynamic Chromatin Organization during Foregut Development Mediated by the Organ Selector Gene PHA-4/FoxA

- Ancient Protostome Origin of Chemosensory Ionotropic Glutamate Receptors and the Evolution of Insect Taste and Olfaction

- A Wnt-Frz/Ror-Dsh Pathway Regulates Neurite Outgrowth in

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Identification of the Bovine Arachnomelia Mutation by Massively Parallel Sequencing Implicates Sulfite Oxidase (SUOX) in Bone Development

- Common Inherited Variation in Mitochondrial Genes Is Not Enriched for Associations with Type 2 Diabetes or Related Glycemic Traits

- A Model for Damage Load and Its Implications for the Evolution of Bacterial Aging

- Did Genetic Drift Drive Increases in Genome Complexity?

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání