-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Intestinal Colonization Dynamics of

To cause the diarrheal disease cholera, Vibrio cholerae must effectively colonize the small intestine. In order to do so, the bacterium needs to successfully travel through the stomach and withstand the presence of agents such as bile and antimicrobial peptides in the intestinal lumen and mucus. The bacterial cells penetrate the viscous mucus layer covering the epithelium and attach and proliferate on its surface. In this review, we discuss recent developments and known aspects of the early stages of V. cholerae intestinal colonization and highlight areas that remain to be fully understood. We propose mechanisms and postulate a model that covers some of the steps that are required in order for the bacterium to efficiently colonize the human host. A deeper understanding of the colonization dynamics of V. cholerae and other intestinal pathogens will provide us with a variety of novel targets and strategies to avoid the diseases caused by these organisms.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 11(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004787

Category: Review

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004787Summary

To cause the diarrheal disease cholera, Vibrio cholerae must effectively colonize the small intestine. In order to do so, the bacterium needs to successfully travel through the stomach and withstand the presence of agents such as bile and antimicrobial peptides in the intestinal lumen and mucus. The bacterial cells penetrate the viscous mucus layer covering the epithelium and attach and proliferate on its surface. In this review, we discuss recent developments and known aspects of the early stages of V. cholerae intestinal colonization and highlight areas that remain to be fully understood. We propose mechanisms and postulate a model that covers some of the steps that are required in order for the bacterium to efficiently colonize the human host. A deeper understanding of the colonization dynamics of V. cholerae and other intestinal pathogens will provide us with a variety of novel targets and strategies to avoid the diseases caused by these organisms.

Introduction

The gram-negative bacterium Vibrio cholerae O1 is the etiological agent of epidemic cholera, a severe diarrheal disease. Cholera has devastated civilizations throughout history, and, to date, seven pandemics have been recorded. The most recent pandemic still affects millions of people and causes more than 100,000 deaths every year. In recent times, the bacterium has become endemic in places that had been cholera-free for centuries [1]. For instance, since the introduction of V. cholerae in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake, more than 700,000 people have contracted cholera, resulting in more than 8,500 deaths [2,3].

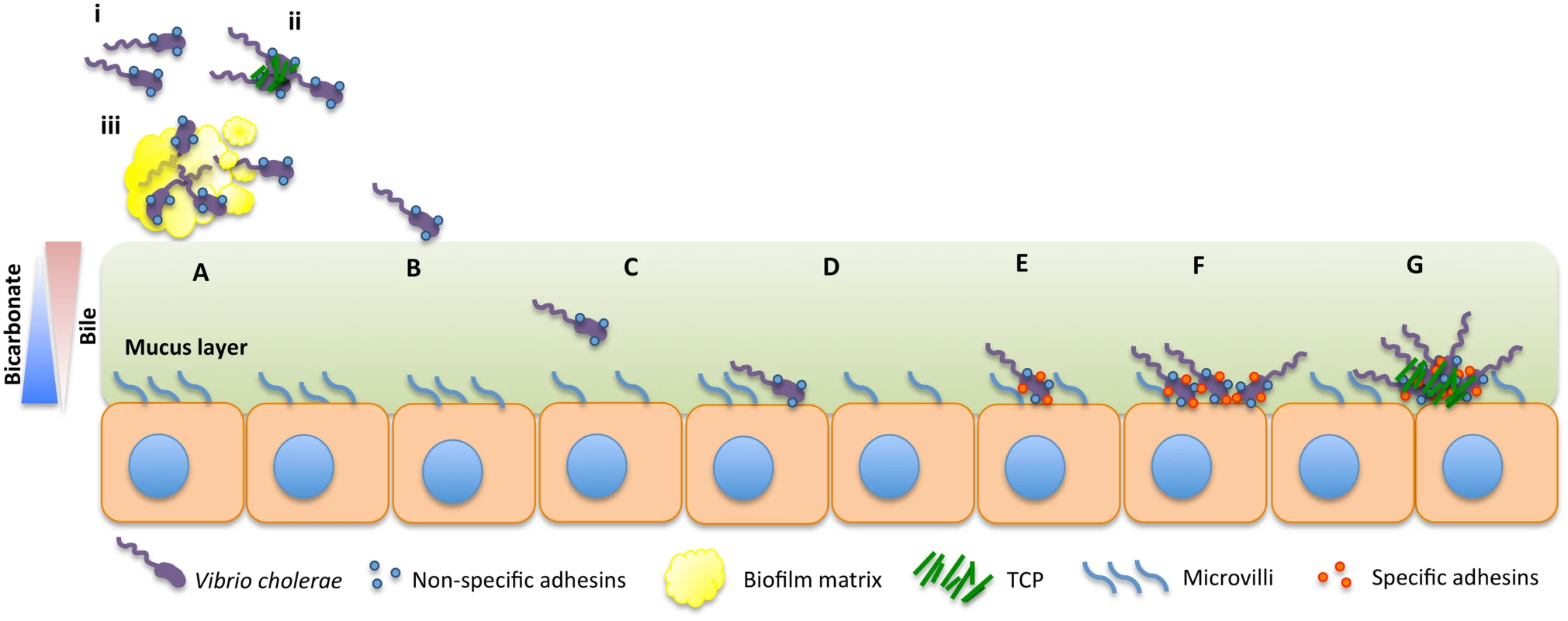

V. cholerae is a natural inhabitant of aquatic environments, such as rivers, estuaries, and oceans, where it can be found as free-living cells or attached to biotic or abiotic surfaces [4,5]. Epidemic cholera is transmitted to humans by consumption of water or food contaminated with virulent strains of V. cholerae O1 [1,6]. Recently, there have been significant advances in the understanding of some key steps in the early stages of colonization of the small intestine (SI) by V. cholerae. Here, we review these developments and propose a model for the colonization dynamics of V. cholerae (Fig 1), suggesting mechanisms to fill the gaps in our current knowledge.

Fig. 1. Model for intestinal colonization dynamics of V. cholerae.

V. cholerae may be ingested as free-living cells (i), as forming microcolonies (ii), or as part of a biofilm (iii) (A). Cells in the lumen will first come in contact with the mucus layer (B). The bacterium must reach the intestinal epithelium by penetrating through the viscous mucus layer covering it (C). Once the bacterium reaches the intestinal epithelium, we hypothesize that noncommitted (reversible) attachment occurs, mediated by adhesins such as GbpA or Mam7 (D). Subsequently, specific attachment adhesins might be produced that would allow V. cholerae to bind in a committed fashion (E), the cells multiply (F), and, once a certain concentration of cells has been reached, the toxin coregulated pilus is produced, allowing for microcolony formation and toxin production (G). Initial Stages of Colonization

Relying on and then relinquishing protection

V. cholerae has a complex acid tolerance response involving numerous factors such as the ToxR-regulated porin, OmpU, the transcriptional regulators CadC and HepA, the gluthatione synthetase GshB, and the DNA repair and recombination enzyme RecO, among others [7–9]. To date, the roles of OmpU and CadC have been corroborated by in-frame deletions [8,10]. Free-living V. cholerae cells are very sensitive to the low pH of the stomach, and the dose required to cause infection in healthy volunteers, 1011 cells, is perhaps unrealistically high [11]. However, when the pH of the stomach is buffered, the number of cells required to cause the symptoms of the disease can be reduced by several orders of magnitude, between 104–106 cells (Fig 1A) [11,12]. Furthermore, in endemic regions, some cholera patients have been found to have low gastric acid production, indicating that these individuals might be more susceptible to free-living V. cholerae than others [13–15]. With further respect to the physiological state of the bacteria, V. cholerae might also enter the human host in a dormant state called viable but nonculturable (VBNC) [16–19]. VBNC cells in other species have been shown to have increased acid tolerance [20]. V. cholerae VBNC cells were given to human volunteers, and these cells were able to effectively colonize the SI and were shed as culturable free-living cells [18].

V. cholerae might also be ingested as microcolonies or in a hyperinfectious state [21–23]. Once shed after intestinal colonization, V. cholerae cells can be found in a hyperinfectious state that is thought to lower the infectious dose required to colonize secondary individuals [21]. Furthermore, after infection, subpopulations of V. cholerae keep expressing the gene encoding TcpA, a major component of the toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP), an essential intestinal colonization factor [22,23]. Microcolonies are TCP-mediated clusters of V. cholerae cells that confer numerous properties to the bacterium (See section “Final Stages of Colonization”). It is possible that microcolonies shed from cholera patients might confer resistance to the low pH of the stomach to V. cholerae. However, to our knowledge, the role of microcolonies in low pH tolerance and how the bacterium relinquishes them upon arrival in the SI remain to be determined (Fig 1A).

Biofilms are bacterial communities that collectively produce a protective exopolysaccharide matrix, which facilitates survival during stress-inducing environmental changes such as low pH or the presence of antimicrobials [24]. V. cholerae that are ingested as part of a biofilm can successfully survive the low pH of the human stomach [25]. Cells within a biofilm may reach the stomach either attached to a substrate or as conditionally viable environmental cells (CVEC)—clumps of dormant cells embedded in a biofilm matrix that can be recovered using enriched culturing techniques (Fig 1A) [25]. Furthermore, while forming biofilm, V. cholerae can be found in a hyperinfectious physiological state [26]. The infectious dose for biofilm-derived V. cholerae is orders of magnitude lower than that of planktonic cells regardless of whether the biofilm is intact or dispersed [26]. The relationship between bile and biofilm remains contested [27,28]. Hung and Mekalanos showed that bile stimulates biofilm formation in V. cholerae as biofilms increase the resistance of the bacterium to bile acids [27]. Conversely, it was recently found that taurocholate, a component of bile, induces the degradation of V. cholerae biofilms [28]. The authors suggested that contact with bile components upon reaching the intestinal lumen might allow for the dispersal of the bacterium in the early stages of colonization (Fig 1A) [28]. Once in the lumen, the bacterium must withstand the presence of antimicrobial agents. It has been shown that OmpU protects against bile acids [29] and antimicrobial peptides [30] among others.

Overall, it is possible that in the early stages of cholera epidemics, V. cholerae might be primarily ingested attached to surfaces while forming biofilms, such as the chitinaceous shell of copepods, as CVEC or as VBNC [4,5,31–34]. However, once the cholera epidemic begins, the bacterium might be predominantly consumed as part of microcolonies shed by other cholera patients or in a hyperinfectious state [21].

Contact with and Swimming through the Mucus Layer

Directionality towards the epithelium

Motility has been shown to be a crucial element in order for V. cholerae to colonize the epithelium and cause a successful infection of the human host (Fig 1C) [35,36]. Early studies by Guentzel et al. suggested that motility could enable V. cholerae to penetrate the mucus layer covering the intestinal epithelium, as nonmotile mutants showed reduced virulence [37]. Nonetheless, it was recently shown that, even though motility is critical for colonization of the proximal SI, motility is not required for the colonization of the distal section of the SI [38]. It is possible that motility enables the dissemination of V. cholerae throughout the lumen of the SI and other nonflagellum-based processes might control its penetration into the intervillous space [38,39].

The possible role of chemotaxis in establishing a productive infection remains debated. Motile, but nonchemotactic, mutants of V. cholerae outcompete wild-type V. cholerae in the infant mouse model [36,38,40]; 10-fold fewer nonchemotactic V. cholerae are required for infection than wild type [41]. It appears that the competitive advantage of the nonchemotactic mutants is the result of an alteration in the bias of flagellar rotation from clockwise to counterclockwise [41]. Whereas wild-type V. cholerae predominantly colonizes the distal half of the SI, nonchemotactic mutants are distributed throughout the SI [36]. A recent study by Millet et al. demonstrated that the specific localization in the SI of nonchemotactic mutants does not differ from that of wild type [38]. Thus, it is possible that chemotaxis plays a more prevalent role in the overall distribution of V. cholerae across the length of the intestine than in the penetration from the lumen to the intestinal epithelium. Recent transposon-sequencing (Tn-seq) studies using the infant rabbit show contrasting results with regards to the role of chemotaxis of V. cholerae in this animal model [42,43]. Fu et al. found that mutants for genes that have chemotaxis-related functions, such as vspR, pomA, or cheA, cause hypercolonization of the infant rabbits [42]. On the other hand, Kamp et al. found that the overwhelming majority of chemotaxis genes are dispensable for infection but played a significant role in the survival of V. cholerae in pond water [43]. Further work is needed in order to determine the precise role of chemotaxis during V. cholerae infection.

Bile is a bactericide that appears to act as a chemorepellant driving V. cholerae out of the intestinal lumen and towards the mucus layer covering the epithelium (Fig 1B and 1C) [44]. V. cholerae has evolved a very strong avoidance response to bile, as bile significantly increases V. cholerae motility even at concentrations too low to cause any bactericidal effect (Fig 1B and 1C) [45]. ToxT is a master virulence regulator of V. cholerae that controls the expression of TCP and the cholera toxin (CT), the main source of the watery diarrhea that causes dehydration [46–50]. Fatty acids found in bile inhibit ToxT activity by binding to its regulatory domain, which prevents ToxT from associating with DNA [45,51–55]. ToxT inhibition by bile suggests a mechanism by which the expression of the virulence cascade would be prevented until the bacterium reaches the appropriate environment. Oppositely, bicarbonate has a positive effect on the virulence cascade of V. cholerae by increasing the affinity of ToxT for DNA [56–58]. Furthermore, the concentration of bicarbonate lumen versus mucosa is contrary to bile (Fig 1) [56,59,60]. The sum of these factors might allow the proper spatiotemporal pattern of virulence gene expression in the human host.

Movement through the mucosa

In order to reach the epithelium and deliver CT, V. cholerae must penetrate a highly viscous mucus layer approximately 150 μm thick, or roughly 50–75 times the body length of V. cholerae (Fig 1C) [61]. Recent developments support the idea that host mucins act as a physical barrier that V. cholerae needs to overcome in order to reach the intestinal epithelium [38]. N-acetyl-L-cysteine, a mucolytic agent, facilitates V. cholerae colonization in vivo [38]. In order to break down mucins, V. cholerae might rely on a mucinase complex, degrading polysaccharide and protein components of mucin in a manner analogous to known processes during V. cholerae departure from the intestine after infection [62–65]. For example, V. cholerae produces a soluble mucinase, called haemagglutinin/protease (Hap), which is encoded by hapA [62]. In a column assay, expression of hapA positively correlates with the capacity of V. cholerae to move through the mucus layer [63]. As hapA is expressed late in infection, it has been suggested that it facilitates detachment from the host epithelium and removal from the mucosa post-infection [66]. However, because mucin induces hapA promoter activity [63], it is possible that Hap also facilitates initial penetration of the mucus layer. In addition, some as-yet-undiscovered mucinases might be involved in the early stages of colonization of V. cholerae.

While a general protease seems to be involved in initial migration through the mucus, V. cholerae may express specific mucinases near the location where the bacterium preferentially colonizes the intestinal epithelium. Whereas Hap is a metalloprotease that cleaves a wide variety of substrates, TagA, another metalloprotease, may specifically modify mucin glycoproteins attached to the host cell surface [65]. TagA, which is encoded within the Vibrio pathogenicity island (VPI), is expressed and secreted by V. cholerae under virulence-inducing conditions [65]. As the protein is positively coregulated with TCP and other virulence genes, TagA may play an important role in colonization during the later stages of movement through the intestinal mucosa. Another V. cholerae virulence factor, neuraminidase (NanH) [67], is an extracellular enzyme that cleaves two sialic acid groups from the GM1 ganglioside, a sialic-acid containing oligosaccharide on the surface of epithelial cells, thereby unmasking receptors for CT [68]. As a mucinase with a specific role in infection, NanH may be important in aiding movement through the mucus to the specific site of infection.

Reversible and Irreversible Attachment

Finding the preferred site for infection

Once V. cholerae has penetrated the mucus layer and reached the epithelium, attachment to the epithelial cells likely occurs, since V. cholerae strains with deletions in genes encoding adhesins show colonization defects in the infant mouse model and in vivo studies demonstrate that V. cholerae physically interacts with the intestinal epithelium from the early stages of colonization (Fig 1D) [38,69–71]. V. cholerae produces various nonspecific adhesins that, upon initial contact with the host epithelium, seem to allow the bacterium to determine whether it has reached the appropriate niche without committing to attachment. To our knowledge, adhesins that have been identified in vivo and/or in vitro in V. cholerae include the flagellum (in addition to its function in motility) [72], Mam7 [73], GbpA [70], OmpU [74], and FrhA (Fig 1D) [71].

Outer membrane adhesion factor multivalent adhesion molecule 7 (Mam7) is one possible example of a nonspecific adhesin involved in V. cholerae colonization. Loss of Mam7 decreases attachment of V. cholerae by about 50% in cultured fibroblast cells [73]. Various results suggest the adhesin is nonspecific [73]; Mam7 does not bind to a specific receptor or molecule but instead can establish protein—protein as well as protein—lipid interactions, and Mam7 has been shown to mediate binding to diverse host cells by many gram-negative bacteria. Across pathogenic species, Mam7 is a general adhesion factor that facilitates attachment to various substrates; it is possible that each species also encodes specific adhesins that play a greater role in promoting attachment to unique host cells [73]. Overall, in V. cholerae, Mam7 likely plays a role in initial attachment to the epithelium (Fig 1D).

Another example of a nonspecific adhesin for V. cholerae is GlcNAc-binding protein (GbpA), which facilitates attachment to the intestinal epithelium and the chitinaceous surfaces of copepods [70]. GbpA binds specifically to GlcNAc molecules that are attached to glycoproteins and lipids on intestinal epithelial cells and mucus [75,76]. Furthermore, GbpA increases the production of intestinal secretory mucins (MUC2, MUC3, and MUC5AC) in HT-29 intestinal epithelial cells through up-regulation of corresponding genes [75]. However, similar to Mam7, loss of GbpA only decreases attachment in an epithelial cell assay by 50% as compared to wild type [70].

Bacterial outer membrane proteins, which are involved in a wide variety of functions, some of which include attachment, require further investigation as potential nonspecific adhesins in V. cholerae. In the genus Vibrio, outer membrane porins aid in attachment to both biotic and abiotic surfaces [74,77,78]. OmpU plays a role in the attachment of Vibrio fischeri, symbiont of the Hawaiian squid Euprymna scolopes, to the epithelium of the light organ, and plays a cell line-specific role in the attachment of V. cholerae to epithelial cells [74,78]. Nonetheless, the possibility that OmpU might play a role in the attachment of V. cholerae O1 in vivo remains to be determined.

It was recently found, through the use of atomic force microscopy, that V. cholerae O1 interacts physically with the GM1 ganglioside [79]. The cells show a 5-fold increase in attachment to lipid bilayers coated with GM1 gangliosides compared to control bilayers [79]. Thus, this raises the possibility of NanH and the GM1 ganglioside having several roles in V. cholerae O1 pathogenesis: (A) NanH releases a carbon source, N-acetylneuraminic acid, that confers a competitive advantage to the bacterium in the intestine while unmasking the GM1 ganglioside [80], and (B) the GM1 ganglioside acts as the receptor of CT [67,68] and (C) might act as receptor of a nonspecific adhesin or adhesins.

Attachment to epithelial cells appears to be required in order for V. cholerae to successfully colonize the SI [70,71,81]. Deletion strains for the adhesins gbpA and frhA have deficient intestinal colonization in the infant mouse model [70,71]. The effect on colonization of GbpA is particularly striking as, even though it shows just a 50% decrease in attachment in vitro, the mutants show 1-log decrease in colonization of the infant mouse [70]. To date, the effect of Mam-7 in the intestinal colonization of V. cholerae remains to be elucidated; nonetheless, recent Tn-seq studies did not identify it in their screenings [42,43]. It is possible that nonspecific adhesins such as Mam-7 or GbpA, given their low individual affinity, could act synergistically and that the intestinal colonization defect shown by strains with multiple deletions would be augmented.

The use of transient nonspecific adhesins as early attachment factors in colonization could confer V. cholerae the advantage of being able to detach from a substrate if it is not conducive to prolonged attachment (e.g., because of the lack of specific nutrients). It is possible that once V. cholerae attaches to a preferred substrate with nonspecific adhesins, the bacterium could subsequently produce specific adhesins that would allow for committed attachment in a manner analogous to the early stages of biofilm formation on nutrient-rich substrates in the aquatic environment (Fig 1E).

Committed attachment in chemically favorable conditions

Entering a committed attachment stage remains a possibility in the intestinal colonization of V. cholerae. Nonetheless, if the bacterium transitions from noncommitted to committed attachment, V. cholerae must be able to sense specific host signals, such as preferred carbon sources, that would indicate that V. cholerae has reached the appropriate niche. Recent studies provide evidence for preferential use of specific carbon sources by V. cholerae. For instance, the ability to utilize two amino sugars abundant in the gut, sialic acid (N-acetylneuraminic acid) and GlcNAc (N-acetylglucosamine), confers V. cholerae with a competitive advantage in the infant mouse model of infection [80,82]. Furthermore, ToxT controls the expression of a small RNA, TarA, which influences glucose uptake through its effect on the transcript encoding the glucose transporter PtsG [83]. When the virulence cascade is being expressed, TarA decreases the uptake of glucose because of its negative effect on ptsG mRNA [83]. Together, these findings suggest that V. cholerae has evolved mechanisms to utilize certain carbon sources in the gut mucosa (sialic acid and GlcNAc) in a preferential manner over others (glucose). Although evidence indicates favored use of certain carbon sources by V. cholerae and thus supports the notion that the bacterium would delay committed attachment until reaching chemically favorable conditions for virulence, no adhesins involved in committed attachment are known in V. cholerae, and the existence of this stage during intestinal colonization remains hypothetical. Once the virulence cascade is activated, the attachment of V. cholerae to intestinal epithelial cells increases [69]. A possible way to identify specific adhesins involved in committed attachment might be to ectopically express toxT in different mutant strains and identify those that attach similarly to the control strains and thus do not experience an increase in their attachment to epithelial cells.

Final Stages of Colonization

Proliferation and microcolony formation

After attachment to the intestinal epithelium, the bacterium decreases motility [84], begins to proliferate, and initiates the virulence cascade (Fig 1F). V. cholerae forms TCP-mediated clusters of bacterial cells called microcolonies (Fig 1G). It was recently shown that microcolonies originate from single cells after reaching the intestinal epithelium (Fig 1G) [38]. To date, several roles of the pilus have been determined: TCP enhances attachment to intestinal epithelial cells and facilitates bacteria—bacteria interactions, visualized in vitro as autoagglutination, by tethering the cells together; the ability to form microcolonies correlates with the ability to colonize the infant mouse and humans [23,85]. TCP acts as the receptor of the CTX phage, a filamentous bacteriophage that encodes CT [86]. Interestingly, an in-frame deletion mutant for tcpA shows highly reduced expression of the gene encoding the major subunit of CT in vivo, indicating that the presence of an intact TCP apparatus appears to be essential for effective regulation of the virulence cascade [81]. TCP is also required for the secretion of the soluble colonization factor TcpF [87]. In vivo, a tcpF mutant is severely defective for colonization, a reduction equivalent to the effect seen with a tcpA mutant, which encodes the major pilin subunit [87]. Although TcpF mutants are still able to form microcolonies, they are loosely packed and have decreased adherence around the edges; thus, it appears that TcpF functions as an enhancer of microcolony formation in vitro [69].

Forming microcolonies within the host may also be beneficial to V. cholerae for other reasons, including more efficient nutrient uptake and protection from antimicrobials like bile or bactericidal compounds produced near the intestinal epithelium [69,85]. Furthermore, it is thought that microcolonies might protect V. cholerae from being shed [38]. In strains with functional quorum-sensing systems, virulence is repressed at high cell density [66]. However, quorum sensing does not seem to play an essential role in virulence, as various toxigenic strains of V. cholerae have a naturally occurring frameshift mutation in the hapR gene, which encodes the master regulator of quorum sensing [66].

Synthesis and Next Steps

The detailed mechanisms facilitating intestinal colonization of bacterial pathogens are beginning to be understood. In this perspective, we provide a comprehensive model that draws upon recent findings in the field and proposes a series of steps that appear to be necessary for V. cholerae to effectively colonize the intestinal epithelium (Fig 1). Models such as the one described here might provide researchers with ways to generate testable hypotheses, furthering the knowledge of the field. Some areas of the intestinal colonization dynamics of V. cholerae covered in this model that need further exploration include the roles of the chemical gradients of bile and bicarbonate on V. cholerae virulence gene expression, the variable distribution of components of the mucus throughout the SI and the enzymes involved in its degradation, the specific role, if any, of chemotaxis during infection, the conditions necessary for prolonged attachment, and the confirmation and identification of specific adhesins.

Zdroje

1. Harris JB, LaRocque RC, Qadri F, Ryan ET, Calderwood SB (2012) Cholera. Lancet 379 : 2466–2476. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60436-X 22748592

2. CDC (2015) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/

3. Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Population (2015) Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Population. http://mspp.gouv.ht/newsite/

4. Lutz C, Erken M, Noorian P, Sun S, McDougald D (2013) Environmental reservoirs and mechanisms of persistence of Vibrio cholerae. Front Microbiol 4 : 375. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00375 24379807

5. Almagro-Moreno S, Taylor RK (2013) Cholera: Environmental reservoirs and impact on disease transmission. Microbiol Spectrum 1(2):OH-0003-2012.

6. Kaper JB, Morris JG, Levine MM (1995) Cholera. Clin Microbiol Rev 8 : 48–86. 7704895

7. Merrell DS, Hava DL, Camilli A (2002) Identification of novel factors involved in colonization and acid tolerance of Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol 43 : 1471–1491. 11952899

8. Merrell DS, Bailey C, Kaper JB, Camilli A (2001) The ToxR-mediated organic acid tolerance response of Vibrio cholerae requires OmpU. J Bacteriol 183 : 2746–2754. 11292792

9. Merrell DS, Camilli A (2000) Regulation of Vibrio cholerae genes required for acid tolerance by a member of the “ToxR-Like” family of transcriptional regulators. J Bacteriol 182 : 5342–5350. 10986235

10. Kovacikova G, Lin W, Skorupski K (2010) The LysR-type virulence activator AphB regulates the expression of genes in Vibrio cholerae in response to low pH and anaerobiosis. J Bacteriol 192 : 4181–4191. doi: 10.1128/JB.00193-10 20562308

11. Cash RA, Music SI, Libonati JP, Snyder MJ, Wenzel RP, et al. (1974) Response of man to infection with Vibrio cholerae. I. Clinical, serologic, and bacteriologic responses to a known inoculum. J Infect Dis 129 : 45–52. 4809112

12. Levine MM, Black RE, Clements ML, Nalin DR, Cisneros L, et al. (1981) Volunteer studies in development of vaccines against cholera and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: a review. In: Holme T, Holmgren J, Merson MH, Mollby R, editors. Acute enteric infections in children. New prospects for treatment and prevention. Amsterdam: Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Press. pp. 443–459.

13. Sack GH, Pierce NF, Hennessey KN, Mitra RC, Sack RB, et al. (1972) Gastric acidity in cholera and noncholera diarrhoea. Bull World Health Organ 47 : 31–36. 20604412

14. Nalin DR, Levine RJ, Levine MM, Hoover D, Bergquist E, et al. (1978) Cholera, non-vibrio cholera, and stomach acid. Lancet 2 : 856–859. 81410

15. Van Loon FP, Clemens JD, Shahrier M, Sack DA, Stephensen CB, et al. (1990) Low gastric acid as a risk factor for cholera transmission: application of a new non-invasive gastric acid field test. J Clin Epidemiol 43 : 1361–1367. 2254773

16. Colwell RR, Brayton PR, Grimes DJ, Roszak DB, Huq SA, et al. (1985) Viable but non-culturable Vibrio cholerae and related pathogens in the environment: Implications for release of genetically engineered microorganisms. Nat Biotechnol 3 : 817–820.

17. Alam M, Sultana M, Nair GB, Siddique AK, Hasan NA, et al. (2007) Viable but nonculturable Vibrio cholerae O1 in biofilms in the aquatic environment and their role in cholera transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104 : 17801–17806. 17968017

18. Colwell RR, Brayton P, Herrington D, Tall B, Huq A, et al. (1996) Viable but non-culturable Vibrio cholerae O1 revert to a cultivable state in the human intestine. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 12 : 28–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00327795 24415083

19. Asakura H, Ishiwa A, Arakawa E, Makino S-I, Okada Y, et al. (2007) Gene expression profile of Vibrio cholerae in the cold stress-induced viable but non-culturable state. Environ Microbiol 9 : 869–879. 17359259

20. Wong HC, Wang P (2004) Induction of viable but nonculturable state in Vibrio parahaemolyticus and its susceptibility to environmental stresses. J Appl Microbiol 96 : 359–366. 14723697

21. Merrell DS, Butler SM, Qadri F, Dolganov NA, Alam A, et al. (2002) Host-induced epidemic spread of the cholera bacterium. Nature 417 : 642–645. 12050664

22. Nielsen AT, Dolganov NA, Rasmussen T, Otto G, Miller MC, et al. (2010) A bistable switch and anatomical site control Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression in the intestine. PLoS Pathog 6: e1001102. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001102 20862321

23. Taylor RK, Miller VL, Furlong DB, Mekalanos JJ (1987) Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84 : 2833–2837. 2883655

24. O'Toole G, Kaplan HB, Kolter R (2000) Biofilm formation as microbial development. Annu Rev Microbiol 54 : 49–79. 11018124

25. Faruque SM, Biswas K, Udden SMN, Ahmad QS, Sack DA, et al. (2006) Transmissibility of cholera: in vivo-formed biofilms and their relationship to infectivity and persistence in the environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103 : 6350–6355. 16601099

26. Tamayo R, Patimalla B, Camilli A (2010) Growth in a Biofilm Induces a Hyperinfectious Phenotype in Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun 78 : 3560–3569. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00048-10 20515927

27. Hung DT, Zhu J, Sturtevant D, Mekalanos JJ (2006) Bile acids stimulate biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol 59 : 193–201. 16359328

28. Hay AJ, Zhu J (2015) Host intestinal signal-promoted biofilm dispersal induces Vibrio cholerae colonization. Infect Immun 83 : 317–323. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02617-14 25368110

29. Provenzano D, Schuhmacher DA, Barker JL, Klose KE (2000) The virulence regulatory protein ToxR mediates enhanced bile resistance in Vibrio cholerae and other pathogenic Vibrio species. Infect Immun 68 : 1491–1497. 10678965

30. Mathur J, Waldor MK (2004) The Vibrio cholerae ToxR-regulated porin OmpU confers resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Infect Immun 72 : 3577–3583. 15155667

31. Colwell RR, Huq A, Islam MS, Aziz KMA, Yunus M, et al. (2003) Reduction of cholera in Bangladeshi villages by simple filtration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100 : 1051–1055. 12529505

32. Huq A, Yunus M, Sohel SS, Bhuiya A, Emch M, et al. (2010) Simple sari cloth filtration of water is sustainable and continues to protect villagers from cholera in Matlab, Bangladesh. mBio 1 : 1e00034–10

33. Colwell RR, Huq A (1994) Environmental reservoir of Vibrio cholerae. The causative agent of cholera. Ann N Y Acad Sci 740 : 44–54. 7840478

34. Faruque SM (2006) Transmissibility of cholera: In vivo-formed biofilms and their relationship to infectivity and persistence in the environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103 : 6350–6355. 16601099

35. Liu Z, Miyashiro T, Tsou A, Hsiao A, Goulian M, et al. (2008) Mucosal penetration primes Vibrio cholerae for host colonization by repressing quorum sensing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105 : 9769–9774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802241105 18606988

36. Lee SH, Butler SM, Camilli A (2001) Selection for in vivo regulators of bacterial virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98 : 6889–6894. 11391007

37. Guentzel MN, Berry LJ (1975) Motility as a virulence factor for Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun 11 : 890–897. 1091563

38. Millet YA, Alvarez D, Ringgaard S, Andrian von UH, Davis BM, et al. (2014) Insights into Vibrio cholerae intestinal colonization from monitoring fluorescently labeled bacteria. PLoS Pathog 10: e1004405. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004405 25275396

39. Brown II, Häse CC (2001) Flagellum-independent surface migration of Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 183 : 3784–3790. 11371543

40. Freter R, O'Brien PC (1981) Role of chemotaxis in the association of motile bacteria with intestinal mucosa: fitness and virulence of nonchemotactic Vibrio cholerae mutants in infant mice. Infect Immun 34 : 222–233. 7298184

41. Butler SM, Camilli A (2004) Both chemotaxis and net motility greatly influence the infectivity of Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101 : 5018–5023. 15037750

42. Fu Y, Waldor MK, Mekalanos JJ (2013) Tn-Seq analysis of Vibrio cholerae intestinal colonization reveals a role for T6SS-mediated antibacterial activity in the host. Cell Host Microbe 14 : 652–663. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.001 24331463

43. Kamp HD, Patimalla-Dipali B, Lazinski DW, Wallace-Gadsden F, Camilli A (2013) Gene fitness landscapes of Vibrio cholerae at important stages of its life cycle. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003800. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003800 24385900

44. Gunn JS (2000) Mechanisms of bacterial resistance and response to bile. Microbe Infect 2 : 907–913. 10962274

45. Gupta S, Chowdhury R (1997) Bile affects production of virulence factors and motility of Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun 65 : 1131–1134. 9038330

46. Matson JS, Withey JH, DiRita VJ (2007) Regulatory networks controlling Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression. Infect Immun 75 : 5542–5549. 17875629

47. DiRita VJ, Parsot C, Jander G, Mekalanos JJ (1991) Regulatory cascade controls virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88 : 5403–5407. 2052618

48. Higgins DE, Nazareno E, DiRita VJ (1992) The virulence gene activator ToxT from Vibrio cholerae is a member of the AraC family of transcriptional activators. J Bacteriol 174 : 6974–6980. 1400247

49. Champion GA, Neely MN, Brennan MA, DiRita VJ (1997) A branch in the ToxR regulatory cascade of Vibrio cholerae revealed by characterization of toxT mutant strains. Mol Microbiol 23 : 323–331. 9044266

50. Sanchez J, Holmgren J (2008) Cholera toxin structure, gene regulation and pathophysiological and immunological aspects. Cell Mol Life Sci 65 : 1347–1360. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7496-5 18278577

51. Chatterjee A, Dutta PK, Chowdhury R (2007) Effect of fatty acids and cholesterol present in bile on expression of virulence factors and motility of Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun 75 : 1946–1953. 17261615

52. Schuhmacher DA, Klose KE (1999) Environmental signals modulate ToxT-dependent virulence factor expression in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 181 : 1508–1514. 10049382

53. Prouty MG, Osorio CR, Klose KE (2005) Characterization of functional domains of the Vibrio cholerae virulence regulator ToxT. Mol Microbiol 58 : 1143–1156. 16262796

54. Childers BM, Cao X, Weber GG, Demeler B, Hart PJ, et al. (2011) N-terminal residues of the Vibrio cholerae virulence regulatory protein ToxT involved in dimerization and modulation by fatty acids. J Biol Chem 286 : 28644–28655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.258780 21673111

55. Lowden MJ, Skorupski K, Pellegrini M, Chiorazzo MG, Taylor RK, et al. (2010) Structure of Vibrio cholerae ToxT reveals a mechanism for fatty acid regulation of virulence genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107 : 2860–2865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915021107 20133655

56. Abuaita BH, Withey JH (2009) Bicarbonate induces Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression by enhancing ToxT activity. Infect Immun 77 : 4111–4120. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00409-09 19564378

57. Thomson JJ, Withey JH (2014) Bicarbonate increases binding affinity of Vibrio cholerae ToxT to virulence gene promoters. J Bacteriol 196 : 3872–3880. doi: 10.1128/JB.01824-14 25182489

58. Thomson JJ, Plecha SC, Withey JH (2015) A small unstructured region in Vibrio cholerae ToxT mediates the response to positive and negative effectors and ToxT proteolysis. J Bacteriol 197 : 654–668. doi: 10.1128/JB.02068-14 25422303

59. Hogan DL, Ainsworth MA, Isenberg JI (1994) Gastroduodenal bicarbonate secretion. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 8 : 475–488. 7865639

60. Flemström G, Isenberg JI (2001) Gastroduodenal mucosal alkaline secretion and mucosal protection. News Physiol Sci 16 : 23–28. 11390942

61. McGuckin MA, Lindén SK, Sutton P, Florin TH (2011) Mucin dynamics and enteric pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol 9 : 265–278. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2538 21407243

62. Booth BA, Boesman-Finkelstein M, Finkelstein RA (1983) Vibrio cholerae soluble hemagglutinin/protease is a metalloenzyme. Infect Immun 42 : 639–644. 6417020

63. Silva AJ, Pham K, Benitez JA (2003) Haemagglutinin/protease expression and mucin gel penetration in El Tor biotype Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology 149 : 1883–1891. 12855739

64. Zhu J, Mekalanos JJ (2003) Quorum sensing-dependent biofilms enhance colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Dev Cell 5 : 647–656. 14536065

65. Szabady RL, Yanta JH, Halladin DK, Schofield MJ, Welch RA (2011) TagA is a secreted protease of Vibrio cholerae that specifically cleaves mucin glycoproteins. Microbiology 157 : 516–525. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.044529-0 20966091

66. Zhu J, Miller MB, Vance RE, Dziejman M, Bassler BL, et al. (2002) Quorum-sensing regulators control virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99 : 3129–3134. 11854465

67. Galen JE, Ketley JM, Fasano A, Richardson SH, Wasserman SS, et al. (1992) Role of Vibrio cholerae neuraminidase in the function of cholera toxin. Infect Immun 60 : 406–415. 1730470

68. Holmgren J, Lönnroth I, Månsson J, Svennerholm L (1975) Interaction of cholera toxin and membrane GM1 ganglioside of small intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 72 : 2520–2524. 1058471

69. Krebs SJ, Taylor RK (2011) Protection and attachment of Vibrio cholerae mediated by the toxin-coregulated pilus in the infant mouse model. J Bacteriol 193 : 5260–5270. doi: 10.1128/JB.00378-11 21804008

70. Kirn TJ, Jude BA, Taylor RK (2005) A colonization factor links Vibrio cholerae environmental survival and human infection. Nature 438 : 863–866. 16341015

71. Syed KA, Beyhan S, Correa N, Queen J, Liu J, et al. (2009) The Vibrio cholerae flagellar regulatory hierarchy controls expression of virulence factors. J Bacteriol 191 : 6555–6570. doi: 10.1128/JB.00949-09 19717600

72. Attridge SR, Rowley D (1983) The role of the flagellum in the adherence of Vibrio cholerae. J Infect Dis 147 : 864–872. 6842021

73. Krachler AM, Ham H, Orth K (2011) Outer membrane adhesion factor multivalent adhesion molecule 7 initiates host cell binding during infection by gram-negative pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108 : 11614–11619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102360108 21709226

74. Sperandio V, Girón JA, Silveira WD, Kaper JB (1995) The OmpU outer membrane protein, a potential adherence factor of Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun 63 : 4433–4438. 7591082

75. Bhowmick R, Ghosal A, Das B, Koley H, Saha DR, et al. (2008) Intestinal adherence of Vibrio cholerae involves a coordinated interaction between colonization factor GbpA and mucin. Infect Immun 76 : 4968–4977. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01615-07 18765724

76. Wong E, Vaaje-Kolstad G, Ghosh A, Hurtado-Guerrero R, Konarev PV, et al. (2012) The Vibrio cholerae colonization factor GbpA possesses a modular structure that governs binding to different host surfaces. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002373. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002373 22253590

77. Tarsi R, Pruzzo C (1999) Role of surface proteins in Vibrio cholerae attachment to chitin. Appl Environ Microbiol 65 : 1348–1351. 10049907

78. Aeckersberg F, Lupp C, Feliciano B, Ruby EG (2001) Vibrio fischeri outer membrane protein OmpU plays a role in normal symbiotic colonization. J Bacteriol 183 : 6590–6597. 11673429

79. Adams EL, Almagro-Moreno S, Boyd EF (2011) An atomic force microscopy method for the detection of binding forces between bacteria and a lipid bilayer containing higher order gangliosides. J Microbiol Methods 84 : 352–354. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.12.014 21192989

80. Almagro-Moreno S, Boyd EF (2009) Sialic acid catabolism confers a competitive advantage to pathogenic Vibrio cholerae in the mouse intestine. Infect Immun 77 : 3807–3816. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00279-09 19564383

81. Lee SH, Hava DL, Waldor MK, Camilli A (1999) Regulation and temporal expression patterns of Vibrio cholerae virulence genes during infection. Cell 99 : 625–634. 10612398

82. Ghosh S, Rao KH, Sengupta M, Bhattacharya SK, Datta A (2011) Two gene clusters co-ordinate for a functional N-acetylglucosamine catabolic pathway in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol 80 : 1549–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07664.x 21488982

83. Richard AL, Withey JH, Beyhan S, Yildiz F, DiRita VJ (2010) The Vibrio cholerae virulence regulatory cascade controls glucose uptake through activation of TarA, a small regulatory RNA. Mol Microbiol 78 : 1171–1181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07397.x 21091503

84. Watnick PI, Fullner KJ, Kolter R (1999) A role for the mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin in biofilm formation by Vibrio cholerae El Tor. J Bacteriol 181 : 3606–3609. 10348878

85. Kirn TJ, Lafferty MJ, Sandoe CM, Taylor RK (2000) Delineation of pilin domains required for bacterial association into microcolonies and intestinal colonization by Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol 35 : 896–910. 10692166

86. Waldor MK, Mekalanos JJ (1996) Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science 272 : 1910–1914. 8658163

87. Kirn TJ, Bose N, Taylor RK (2003) Secretion of a soluble colonization factor by the TCP type 4 pilus biogenesis pathway in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol 49 : 81–92. 12823812

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Neutrophil-Derived MMP-8 Drives AMPK-Dependent Matrix Destruction in Human Pulmonary TuberculosisČlánek Circumventing . Virulence by Early Recruitment of Neutrophils to the Lungs during Pneumonic PlagueČlánek Admixture in Humans of Two Divergent Populations Associated with Different Macaque Host SpeciesČlánek Human and Murine Clonal CD8+ T Cell Expansions Arise during Tuberculosis Because of TCR SelectionČlánek Selective Recruitment of Nuclear Factors to Productively Replicating Herpes Simplex Virus GenomesČlánek Fob1 and Fob2 Proteins Are Virulence Determinants of via Facilitating Iron Uptake from FerrioxamineČlánek Remembering MumpsČlánek Human Cytomegalovirus miR-UL112-3p Targets TLR2 and Modulates the TLR2/IRAK1/NFκB Signaling PathwayČlánek Induces the Premature Death of Human Neutrophils through the Action of Its Lipopolysaccharide

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 5- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Choroby jater v ordinaci praktického lékaře – význam jaterních testů

- Diagnostický algoritmus při podezření na syndrom periodické horečky

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Parasites and Their Heterophagic Appetite for Disease

- The Elusive Role of the Prion Protein and the Mechanism of Toxicity in Prion Disease

- Intestinal Colonization Dynamics of

- Activation of Typhi-Specific Regulatory T Cells in Typhoid Disease in a Wild-Type . Typhi Challenge Model

- The Engineering of a Novel Ligand in gH Confers to HSV an Expanded Tropism Independent of gD Activation by Its Receptors

- Neutrophil-Derived MMP-8 Drives AMPK-Dependent Matrix Destruction in Human Pulmonary Tuberculosis

- Group Selection and Contribution of Minority Variants during Virus Adaptation Determines Virus Fitness and Phenotype

- Phosphatidic Acid Produced by Phospholipase D Promotes RNA Replication of a Plant RNA Virus

- A Ribonucleoprotein Complex Protects the Interleukin-6 mRNA from Degradation by Distinct Herpesviral Endonucleases

- Characterization of Transcriptional Responses to Different Aphid Species Reveals Genes that Contribute to Host Susceptibility and Non-host Resistance

- Circumventing . Virulence by Early Recruitment of Neutrophils to the Lungs during Pneumonic Plague

- Natural Killer Cell Sensing of Infected Cells Compensates for MyD88 Deficiency but Not IFN-I Activity in Resistance to Mouse Cytomegalovirus

- Manipulation of the Xanthophyll Cycle Increases Plant Susceptibility to

- Ly6C Monocytes Regulate Parasite-Induced Liver Inflammation by Inducing the Differentiation of Pathogenic Ly6C Monocytes into Macrophages

- Admixture in Humans of Two Divergent Populations Associated with Different Macaque Host Species

- Expression in the Fat Body Is Required in the Defense Against Parasitic Wasps in

- Experimental Evolution of an RNA Virus in Wild Birds: Evidence for Host-Dependent Impacts on Population Structure and Competitive Fitness

- Inhibition and Reversal of Microbial Attachment by an Antibody with Parasteric Activity against the FimH Adhesin of Uropathogenic .

- The EBNA-2 N-Terminal Transactivation Domain Folds into a Dimeric Structure Required for Target Gene Activation

- Human and Murine Clonal CD8+ T Cell Expansions Arise during Tuberculosis Because of TCR Selection

- The NLRP3 Inflammasome Is a Pathogen Sensor for Invasive via Activation of α5β1 Integrin at the Macrophage-Amebae Intercellular Junction

- Sequential Conformational Changes in the Morbillivirus Attachment Protein Initiate the Membrane Fusion Process

- A Two-Component DNA-Prime/Protein-Boost Vaccination Strategy for Eliciting Long-Term, Protective T Cell Immunity against

- cAMP-Signalling Regulates Gametocyte-Infected Erythrocyte Deformability Required for Malaria Parasite Transmission

- Response Regulator VxrB Controls Colonization and Regulates the Type VI Secretion System

- Evidence for a Novel Mechanism of Influenza Virus-Induced Type I Interferon Expression by a Defective RNA-Encoded Protein

- Dust Devil: The Life and Times of the Fungus That Causes Valley Fever

- TNF-α Induced by Hepatitis C Virus via TLR7 and TLR8 in Hepatocytes Supports Interferon Signaling via an Autocrine Mechanism

- The Recent Evolution of a Maternally-Inherited Endosymbiont of Ticks Led to the Emergence of the Q Fever Pathogen,

- L-Rhamnosylation of Wall Teichoic Acids Promotes Resistance to Antimicrobial Peptides by Delaying Interaction with the Membrane

- Rapid Sequestration of by Neutrophils Contributes to the Development of Chronic Lesion

- Selective Recruitment of Nuclear Factors to Productively Replicating Herpes Simplex Virus Genomes

- The Expression of Functional Vpx during Pathogenic SIVmac Infections of Rhesus Macaques Suppresses SAMHD1 in CD4 Memory T Cells

- Fob1 and Fob2 Proteins Are Virulence Determinants of via Facilitating Iron Uptake from Ferrioxamine

- TRAF1 Coordinates Polyubiquitin Signaling to Enhance Epstein-Barr Virus LMP1-Mediated Growth and Survival Pathway Activation

- Vaccine-Elicited Tier 2 HIV-1 Neutralizing Antibodies Bind to Quaternary Epitopes Involving Glycan-Deficient Patches Proximal to the CD4 Binding Site

- Remembering Mumps

- The Role of Horizontal Gene Transfer in the Evolution of the Oomycetes

- Advances and Challenges in Computational Prediction of Effectors from Plant Pathogenic Fungi

- Investigating Fungal Outbreaks in the 21st Century

- Systems Biology for Biologists

- How Does the Dinoflagellate Parasite Outsmart the Immune System of Its Crustacean Hosts?

- FCRL5 Delineates Functionally Impaired Memory B Cells Associated with Exposure

- Phospholipase D1 Couples CD4 T Cell Activation to c-Myc-Dependent Deoxyribonucleotide Pool Expansion and HIV-1 Replication

- Influenza A Virus on Oceanic Islands: Host and Viral Diversity in Seabirds in the Western Indian Ocean

- Geometric Constraints Dominate the Antigenic Evolution of Influenza H3N2 Hemagglutinin

- Widespread Recombination, Reassortment, and Transmission of Unbalanced Compound Viral Genotypes in Natural Arenavirus Infections

- Gammaherpesvirus Co-infection with Malaria Suppresses Anti-parasitic Humoral Immunity

- A Single Protein S-acyl Transferase Acts through Diverse Substrates to Determine Cryptococcal Morphology, Stress Tolerance, and Pathogenic Outcome

- Survives with a Minimal Peptidoglycan Synthesis Machine but Sacrifices Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance

- Mechanisms of Stage-Transcending Protection Following Immunization of Mice with Late Liver Stage-Arresting Genetically Attenuated Malaria Parasites

- The Myelin and Lymphocyte Protein MAL Is Required for Binding and Activity of ε-Toxin

- Genome-Wide Identification of the Target Genes of AP2-O, a AP2-Family Transcription Factor

- An Atypical Mitochondrial Carrier That Mediates Drug Action in

- Human Cytomegalovirus miR-UL112-3p Targets TLR2 and Modulates the TLR2/IRAK1/NFκB Signaling Pathway

- Helminth Infection and Commensal Microbiota Drive Early IL-10 Production in the Skin by CD4 T Cells That Are Functionally Suppressive

- Circulating Pneumolysin Is a Potent Inducer of Cardiac Injury during Pneumococcal Infection

- ExoT Induces Atypical Anoikis Apoptosis in Target Host Cells by Transforming Crk Adaptor Protein into a Cytotoxin

- Discovery of a Small Non-AUG-Initiated ORF in Poleroviruses and Luteoviruses That Is Required for Long-Distance Movement

- Induces the Premature Death of Human Neutrophils through the Action of Its Lipopolysaccharide

- Varicella Viruses Inhibit Interferon-Stimulated JAK-STAT Signaling through Multiple Mechanisms

- Paradoxical Immune Responses in Non-HIV Cryptococcal Meningitis

- Recovery of Recombinant Crimean Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus Reveals a Function for Non-structural Glycoproteins Cleavage by Furin

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Human Cytomegalovirus miR-UL112-3p Targets TLR2 and Modulates the TLR2/IRAK1/NFκB Signaling Pathway

- Paradoxical Immune Responses in Non-HIV Cryptococcal Meningitis

- Expression in the Fat Body Is Required in the Defense Against Parasitic Wasps in

- Survives with a Minimal Peptidoglycan Synthesis Machine but Sacrifices Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání