-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaCryo Electron Tomography of Native HIV-1 Budding Sites

The structure of immature and mature HIV-1 particles has been analyzed in detail by cryo electron microscopy, while no such studies have been reported for cellular HIV-1 budding sites. Here, we established a system for studying HIV-1 virus-like particle assembly and release by cryo electron tomography of intact human cells. The lattice of the structural Gag protein in budding sites was indistinguishable from that of the released immature virion, suggesting that its organization is determined at the assembly site without major subsequent rearrangements. Besides the immature lattice, a previously not described Gag lattice was detected in some budding sites and released particles; this lattice was found at high frequencies in a subset of infected T-cells. It displays the same hexagonal symmetry and spacing in the MA-CA layer as the immature lattice, but lacks density corresponding to NC-RNA-p6. Buds and released particles carrying this lattice consistently lacked the viral ribonucleoprotein complex, suggesting that they correspond to aberrant products due to premature proteolytic activation. We hypothesize that cellular and/or viral factors normally control the onset of proteolytic maturation during assembly and release, and that this control has been lost in a subset of infected T-cells leading to formation of aberrant particles.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 6(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001173

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1001173Summary

The structure of immature and mature HIV-1 particles has been analyzed in detail by cryo electron microscopy, while no such studies have been reported for cellular HIV-1 budding sites. Here, we established a system for studying HIV-1 virus-like particle assembly and release by cryo electron tomography of intact human cells. The lattice of the structural Gag protein in budding sites was indistinguishable from that of the released immature virion, suggesting that its organization is determined at the assembly site without major subsequent rearrangements. Besides the immature lattice, a previously not described Gag lattice was detected in some budding sites and released particles; this lattice was found at high frequencies in a subset of infected T-cells. It displays the same hexagonal symmetry and spacing in the MA-CA layer as the immature lattice, but lacks density corresponding to NC-RNA-p6. Buds and released particles carrying this lattice consistently lacked the viral ribonucleoprotein complex, suggesting that they correspond to aberrant products due to premature proteolytic activation. We hypothesize that cellular and/or viral factors normally control the onset of proteolytic maturation during assembly and release, and that this control has been lost in a subset of infected T-cells leading to formation of aberrant particles.

Introduction

HIV-1 particles are assembled at the cell membrane, as the 55 kDa viral polyprotein Gag multimerizes on its inner face [1]. Gag recruits other viral components such as the RNA genome and the surface spike proteins, as well as cellular proteins of the ESCRT machinery required for virus release [2], [3], [4]. The viral protease (PR) is essential to convert the immature form of the virion into an infectious mature particle. Both forms of the virion are pleiomorphic structures, with the repetitive structural elements of the virus arranged non-symmetrically and variably from one particle to the other.

In the immature virion, uncleaved Gag is anchored to the plasma membrane via a charged surface and a myristoyl tail in its N-terminal matrix (MA) domain [1]. As shown by cryo electron microscopy (cEM), Gag arranges in a regular manner, with its internal capsid (CA) domain forming a hexameric lattice with a spacing of 8.0 nm [5]. C-terminally of CA, the nucleocapsid (NC) domain binds the RNA genome, and the p6 domain recruits the ESCRT machinery to facilitate particle release [6], [7]. CA and NC, as well as NC and p6, are separated by short spacer peptides (SP1 and SP2, respectively) which are processed during maturation.

Proteolytic maturation of HIV-1 has been proposed to initiate at or shortly after assembly and release [8]. The active dimeric form of the viral PR cleaves Gag and GagPol at multiple sites, leading to the structural transition from the immature particle with its Gag shell forming a truncated sphere to the mature particle with its cone-shaped CA core encasing the condensed nucleoprotein complex in the interior of the virion. In an in vitro study Pettit et al. detected large differences in processing kinetics at the five cleavage sites in Gag, the cleavage at the site between SP1 and NC being an order of magnitude faster than the second fastest cleavage event [9]. These results suggested ordered processing during virion maturation, and this was supported by mutagenesis studies of individual cleavage sites [10]. Processing at all sites except NC-SP1 [11] appears to be important for infectivity and small amounts of partially processed Gag products have been shown to exhibit a strong trans-dominant negative effect on viral infectivity [12], [13], [14]. Furthermore, premature processing [15] as well as low concentrations of protease inhibitors, insufficient to significantly affect proteolytic maturation [14], [16], [17], were both shown to efficiently block viral infectivity, indicating an intricate interplay between proteolytic activation and virus formation. Morphological maturation is believed to occur rapidly following release of the immature virion as no intermediates of maturation have been observed so far and all cellular budding sites appear to carry an immature Gag shell.

The last years have seen increasingly detailed structural studies of released HIV-1 particles in their immature and mature forms [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. Analysis of immature virions by cryo electron tomography (cET) revealed that the immature lattice covers only part of the viral membrane [22], arranging as an incomplete “∼2/3” sphere [26]. These studies suggested that ESCRT involvement in HIV-1 release occurs earlier than previously thought and that so-called late budding sites carrying an almost complete Gag lattice are likely to be dead-end products rather than intermediates in the release pathway [26]. A later analysis by cET and subtomogram averaging provided a 17 Å structure of the immature Gag lattice and showed how this incomplete hexagonal lattice attains its curvature through inclusion of symmetry defects of irregular shape and size [19]. In the mature capsid, CA also forms a hexameric lattice, but with a different lattice constant and arrangement than in the immature lattice [27]. Curvature of the mature capsid is achieved by asymmetric incorporation of pentameric defects at the narrow and wide end of the cone [28]. While cET studies of released virions have significantly advanced our understanding of HIV-1 morphogenesis, we are currently lacking any three-dimensional information regarding native intracellular particle assembly and budding. These processes have hitherto been inaccessible for detailed structural studies due to the lack of an experimental system enabling their visualization by cET. Here, we present a structural study of HIV-1 assembly sites by cET of intact, plunge-frozen human cells. These snapshots allow detailed structural interpretations of the Gag lattice structure at its assembly site in situ, as well as the arrangement of the cortical actin in its immediate vicinity. We further determined the structure of a previously not reported Gag lattice type lacking the NC-RNA layer which we propose to be associated with loss of control of PR activation.

Results

Visualization of HIV-1 assembly by cryo electron tomography

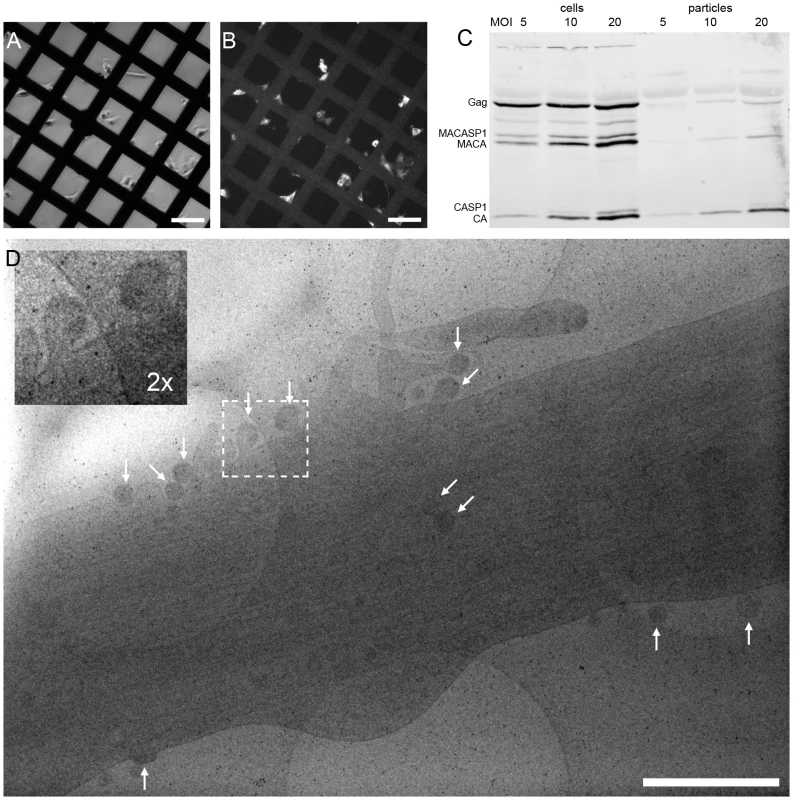

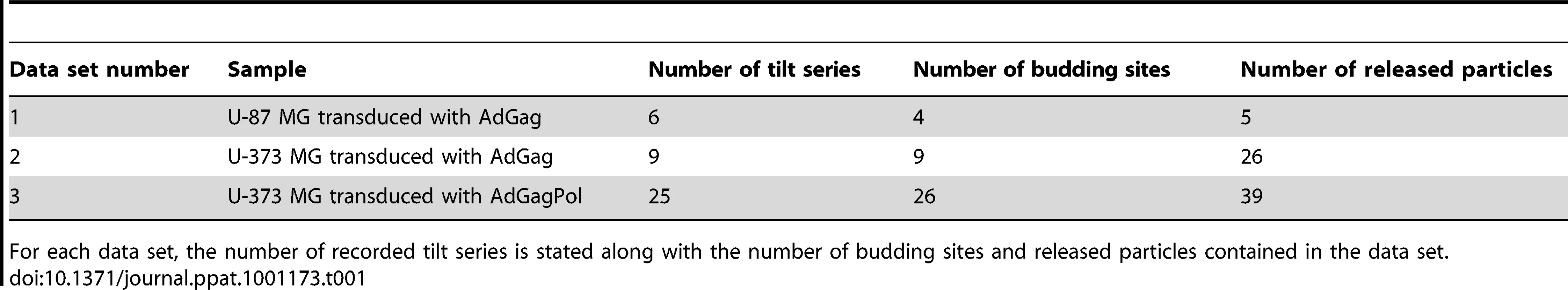

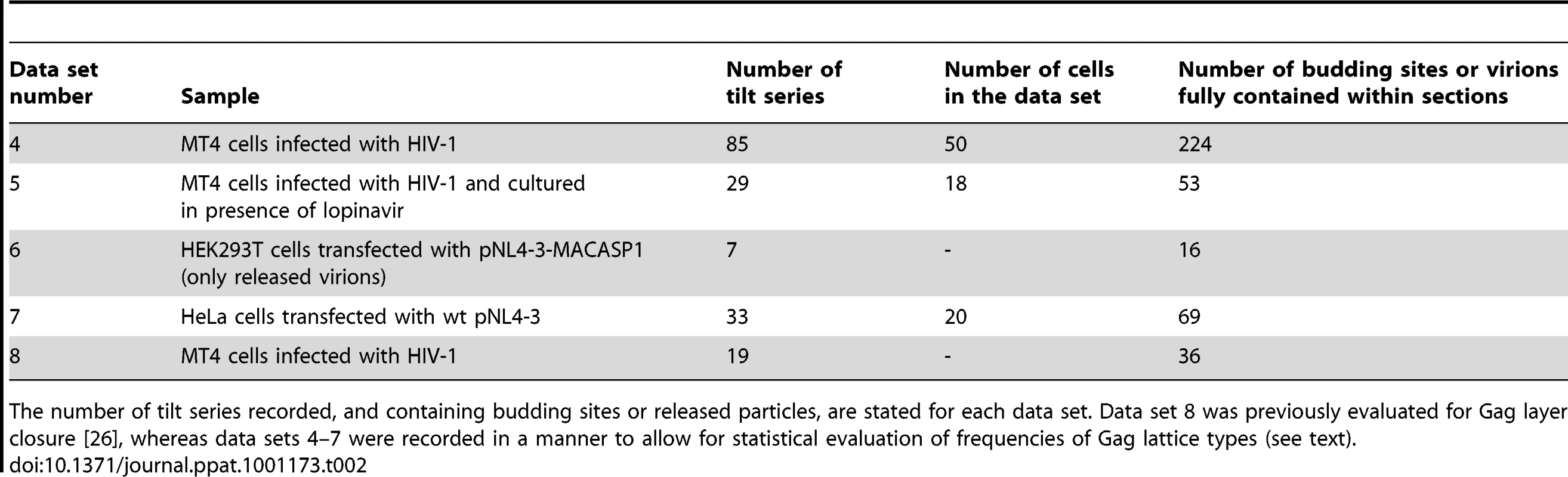

To enable structural analysis of HIV-1 assembly in its cellular context, we set out to establish a system for studying this process by cET on intact human cells. Since cET is limited to samples thinner than ∼500 nm, and thus to thin peripheral areas of adherent cells, the natural HIV-1 host cell types (T-cells and macrophages) cannot be used for cET. This led us to use two human glioblastoma cell lines, U-87 MG and U-373 MG. These cells grow adherently, have extended, thin peripheral areas, and are amenable to transfection or transduction with adenoviral vectors. Transfection efficiency proved insufficient for structural analyses, however, and we therefore constructed adenoviral vectors expressing HIV-1 Gag (AdGag) and HIV-1 Gag-Pol (AdGagPol), respectively. Both adenoviral vectors were based on Rev-independent versions of the respective genes [29], allowing expression of either Gag or Gag-Pol without co-transduction of Rev. U-87 MG or U-373 MG cells were seeded on EM sample grids concomitant with transduction using the respective adenoviral vector. Immunofluorescence staining for HIV-1 CA at 24–48 h post transduction revealed that almost 100% of the cells expressed HIV-1 Gag, while retaining normal adherent morphology (Fig. 1A–B). Furthermore, when U-373 MG cells were transduced with AdGagPol, specific cleavage products of HIV-1 Gag were found in the cell lysate and in the particle fraction purified from the culture medium (Fig. 1C), while particle release but no processing was observed for AdGag (data not shown). Cells transduced with AdGag or AdGagPol were vitrified by plunge-freezing and subjected to cEM. Upon inspection of the vitrified grids, HIV-1 assembly sites and released virions were present at low but reproducible frequencies at the periphery of the cells (Fig. 1D) in regions accessible to cET. A total of 40 tilt series were recorded on such positions of AdGag and AdGagPol infected cells, respectively (Table 1).

Fig. 1. HIV-1 assembly sites imaged by cryo electron microscopy of intact human cells.

(A) Light microscopy phase contrast and (B) immunofluorescence image of human glioblastoma cells (U-373 MG) grown adherently on carbon coated EM grids. Cells were transduced with AdGag concomitant with seeding on grids, and subjected to immunofluorescence staining for Gag two days post seeding to estimate the relative number of Gag expressing cells. (C) U373-MG cells were transduced with AdGagPol at various MOI as indicated above the panel. Cell and particle lysates were recovered 2 days after transduction and subjected to immunoblot analysis using polyclonal antiserum raised against CA. The positions of the Gag and GagPol polyproteins and of several processing products are indicated on the left. (D) Cryo electron micrograph (projection image) of a U-373 MG cell plunge-frozen two days after transduction with AdGagPol. The image shows a cell protrusion containing viral assembly sites (marked by arrows) accessible for cET (The large light circles are 2 µm diameter holes in the carbon support films that the cells grow on, the small dark spots are 10 nm colloidal gold beads). The inset in the upper left corner is a magnified view of the boxed area in the large image. Scale bars are 100 µm (A–B) and 1 µm (D). Tab. 1. Data statistics for cET of HIV-1 budding.

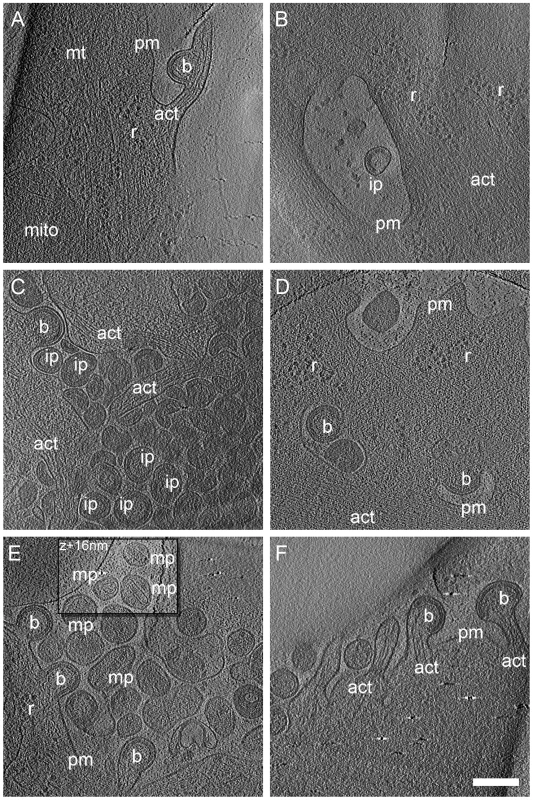

For each data set, the number of recorded tilt series is stated along with the number of budding sites and released particles contained in the data set. In cryo electron tomograms of AdGag or AdGagPol transduced cells (Fig. 2) structural features of the cytoplasm were preserved at the high level previously reported for cellular cET [30], with single ribosomes, actin filaments and microtubules being clearly resolved. Both viral budding sites (Fig. 2A, C–F) and released virions (Fig. 2B–C, E) were present in the recorded tomograms. The budding sites were found at the plasma membrane on lamellipodia–like areas (Fig. 2C, E), occasionally in membrane invaginations (Fig. 2B, D) or at the tips (Fig. 2F, 3B) or sides (Fig. 2A, 3A) of filopodial structures. In the immature Gag lattice of these budding sites and released particles, the two density layers corresponding to CA and NC-RNA could be resolved, and occasionally the hexagonal symmetry in the CA layer was apparent by eye in more tangential tomographic slices. Released immature particles (ip) were found adjacent to cells expressing Gag (Fig. 2B, D) or GagPol (Fig. 2E), whereas released particles with mature morphology (mp) were only found adjacent to cells expressing GagPol (Fig. 2E). No density attributable to components of the ESCRT complex was detected at budding sites at the current resolution.

Fig. 2. Cryo electron tomograms of HIV-1 budding sites and released particles.

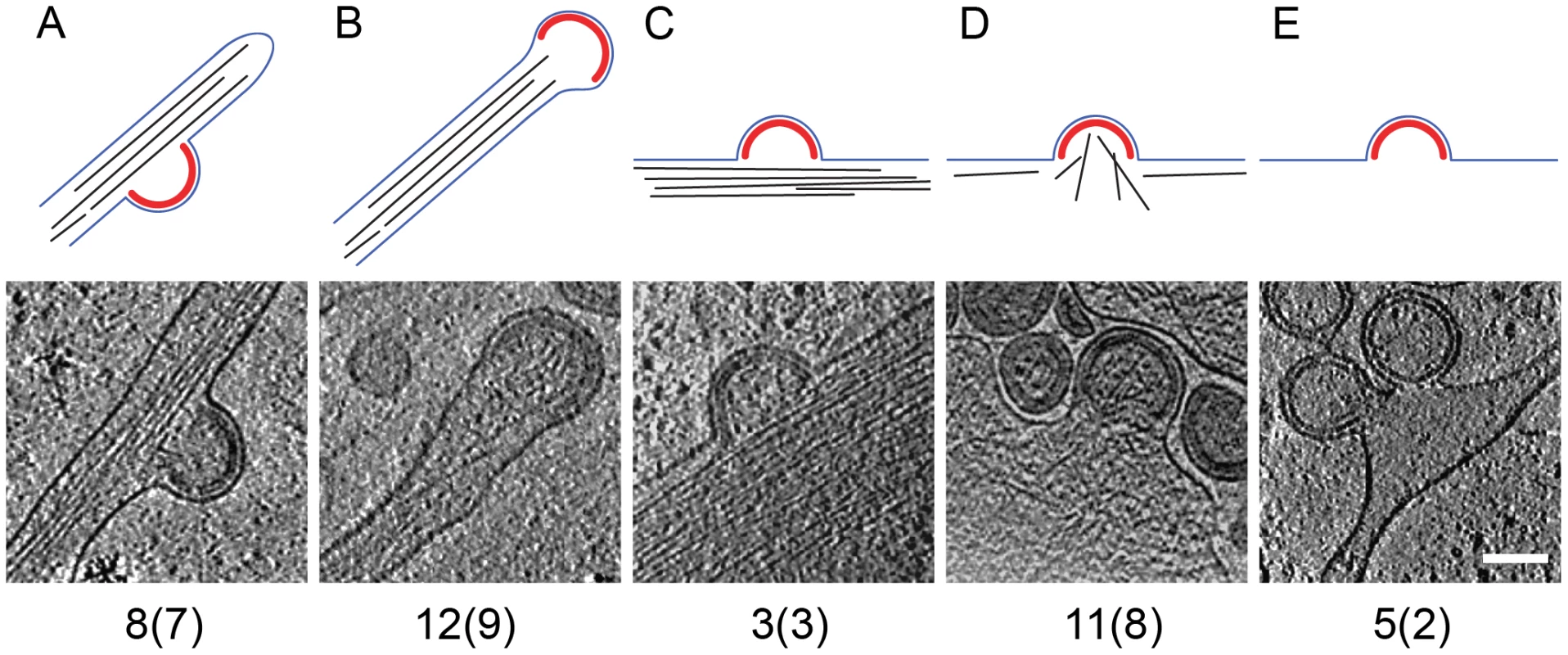

Computational slices of 1.6 nm thickness through cryo electron tomograms of U-87 MG (A–B) and U-373 MG (C–F) cells transduced with AdGag (A–C) or AdGagPol (D–F). Density is black. Bona fide designations of structures: act, actin; b, budding sites; ip, immature particles; mp, mature particles; mt, microtubule; r, ribosome; pm, plasma membrane. The inset in (E) is shifted by 16 nm perpendicular to the image plane, at which location the morphology of the mature particles appears clearer. Scale bar is 200 nm. The preservation of cytoplasmic structure in cET allowed for three-dimensional snapshots of filamentous actin associated with HIV-1 budding sites. The presence of actin filaments was generally high at budding sites (Fig. 2A, C, F and Fig.3A–D), as judged by visual inspection where F-actin is clearly resolvable from e.g. intermediate filaments. Furthermore, we often observed what appeared to be a direct interaction of actin filaments with the budding site (Fig. 2A, F; Fig. 3D). To categorize the budding sites with respect to their actin context, they were sorted into 5 classes according to the type of actin structures they were associated with (Fig.3, top panel). This classification revealed that 34 of the 39 budding sites analyzed were found adjacent to filamentous actin (Fig. 3A–D), with half of the buds (20 of 39) appearing on the sides or tips of filopodia-like structures characterized by a parallel actin organization (Fig. 3A–B).

Fig. 3. Filamentous actin at HIV-1 budding sites.

The 39 budding sites reconstructed by cryo electron tomography were sorted into five categories, based on the type of filamentous actin structures (if any) present in their vicinity. Top panels are a sketch of the category, showing the Gag lattice in red, the plasma membrane in blue and filamentous actin in black. The lower panels show a computational slice through one budding site from the category, and the numbers below state the number of budding sites (and the number of tomograms they were obtained from) in the category. (A) Budding site at the side of actin-filled filopodium; (B) budding site at the tip of actin-filled filopodium; (C) budding site with cortical actin parallel to the plasma membrane; (D) budding site with cortical actin directed towards or protruding into the budding site; (E) budding site at the plasma membrane, not adjacent to filamentous actin. Scale bar is 100 nm. In situ organization of the assembling Gag lattice

Cryo electron tomograms containing budding sites on intact cells with apparently high signal-to-noise ratio were selected for further analysis by sub-tomogram averaging as previously performed for isolated immature HIV-1 [19]. This analysis provides two kinds of information about the Gag protein lattice: the global arrangement of the repetitive elements into an ordered lattice structure (“lattice map”) and the local structure of these repetitive elements (“unit cell structure”).

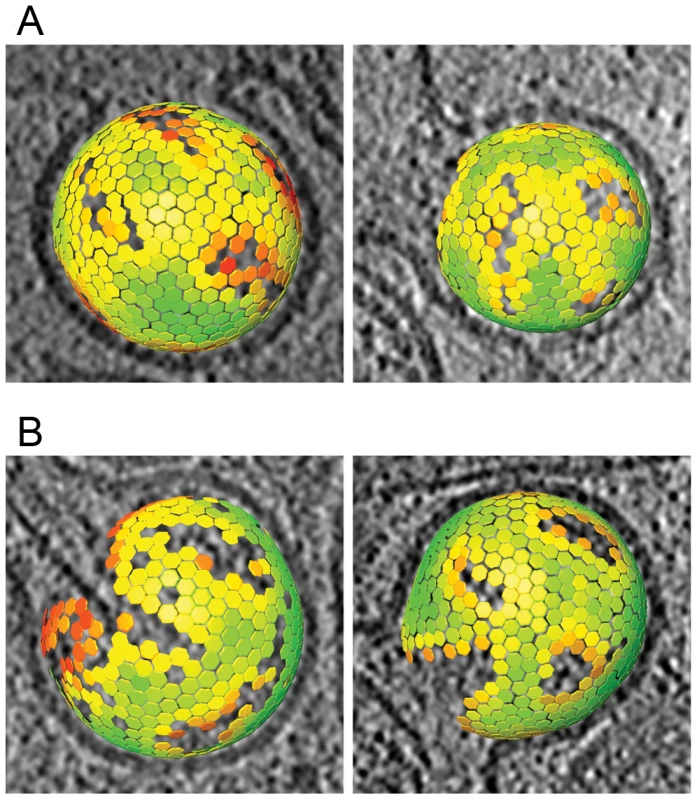

The immature Gag lattice parameters in the budding sites were the same as previously determined for released immature virions [5], [19]: a hexagonal lattice with a lattice constant of 8.0 nm. The lattice maps derived from the budding sites (Fig. 4A) revealed several sites of symmetry breakage, similarly heterogeneous in size and shape as those described for the released virions [19].

Fig. 4. Lattice maps of immature and intermediate HIV-1 budding sites.

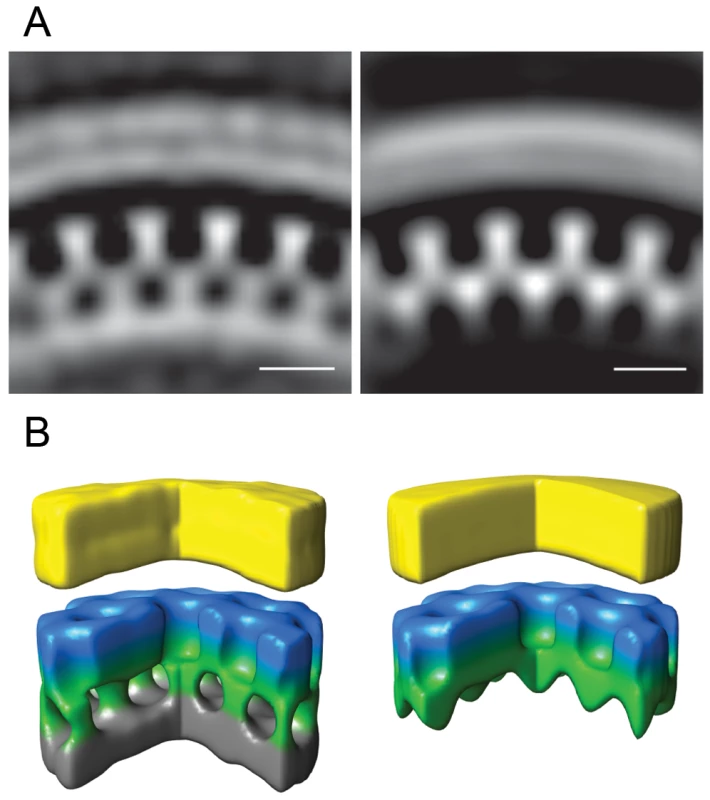

Lattice maps of budding sites. The center and orientation of each aligned subtomogram is marked with a hexagon and is colored according to the cross correlation on a scale from low (red) to high (green). The lattice maps have the threshold set to the same value used for the subtomogram averaging procedure. The lattice map has been superimposed on a slice of 8 nm thickness through the budding viruses. (A) Lattice maps showing two budding particles with the newly reported lattice. (B) Lattice maps showing two budding particles with an immature lattice. The unit cell structure derived from the cellular tomograms contained density corresponding to the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of CA, respectively, as well as density for the membrane and the NC-RNA layer (Fig. 5A). At the present resolution (roughly 40 Å by the 0.5 Fourier shell correlation criterion), this structure was indistinguishable from that previously reported for released particles [19].

Fig. 5. Gag unit cell structure in HIV-1 budding sites.

Left panels show the average of the aligned subtomograms extracted from an individual budding site with the immature lattice. The right panels show the average from an individual budding site with the newly described lattice. (A) Central radial sections from the structures. Density is white. (B) Isosurface rendering of the structures. A segment of 90° has been cut out to better reveal the internal organization of the lattice. The surfaces have been colored radially to illustrate different domains in Gag: Yellow - membrane + MA; blue/green - CA; grey - NC + RNA. Scale bars 10 nm. A previously undescribed Gag lattice form is present in tomograms of GagPol-expressing cells

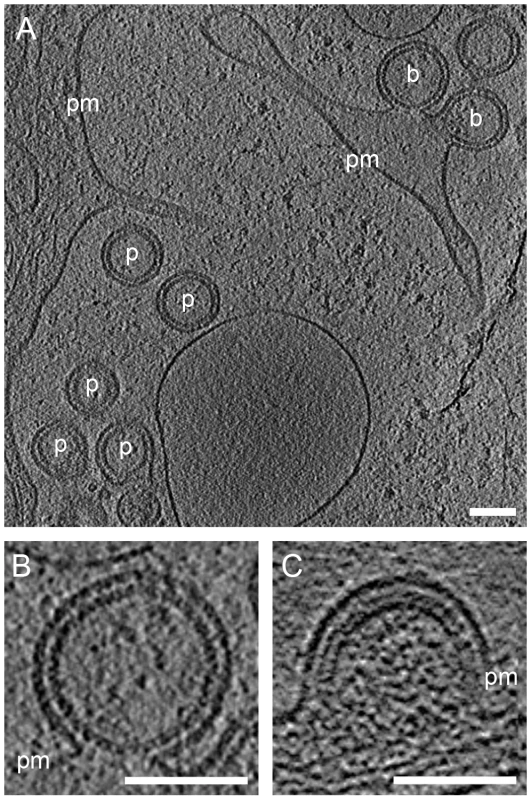

Immunoblot analysis of AdGagPol-transduced cells and the particle fraction recovered from the culture medium showed proteolytic processing of Gag (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, particles containing mature-looking cores were found in cryo electron tomograms in immediate proximity of cellular budding sites and next to immature particles (Fig. 2E). Of note, structures resembling the mature capsid were never found in budding sites still connected to the plasma membrane. Besides the well-described mature and immature particles, we observed a third, previously not described form of particles in the tomograms of AdGagPol-transduced cells (Fig. 6A). This apparently “intermediate morphology” exhibiting a thinner Gag lattice than the immature structure was observed both in extracellular particles (Fig. 6A, Fig. S2 in Supporting Information S1) and in HIV-1 budding sites connected to the cell (Fig. 6A–B). Budding sites and extracellular particles with the previously unrecognized Gag lattice were characterized by a single density layer bound to the inner face of the membrane (Figure 6B), as opposed to the two layers (CA and NC-RNA) seen in the immature lattice (Fig. 6C). Density plots orthogonal to the cell membrane confirmed that the density layer found in these novel structures was located at the same position relative to the plasma membrane (peak at −12 nm) as the CA layer of the complete immature lattice (Fig. S1 in Supporting Information S1).

Fig. 6. A previously undescribed Gag lattice in budding sites and released particles.

(A) Computational slice through cryo electron tomograms of U-373 MG cells transduced with AdGagPol. Budding sites (b) and released particles (p) exhibit a Gag lattice different from both the immature and the mature lattice. (B) Enlarged slice through the top budding site from (A). Density is observed at the expected position of the CA domain, but no prominent density corresponding to NC-RNA is detected. (C) For comparison, a slice through a budding site with the immature Gag lattice showing the characteristic two density layers underneath the plasma membrane. Thickness of computational slices through cryo electron tomograms is 1.6 nm. pm: plasma membrane. Scale bars are 100 nm. Strikingly, budding sites and released particles with this novel Gag lattice displayed the same hexagonal symmetry and lattice spacing as the immature lattice (Fig. 4B). The apparently intermediate type lattices were typically more complete with smaller lattice defects than the immature lattices, but the lattice defects were similarly heterogeneous. Furthermore, the unit cell structure of the new lattice revealed an arrangement identical to the CA region of the immature lattice, with density corresponding to the N - and C-terminal domains of CA (Fig. 5B), but lacking any density corresponding to the NC-RNA layer. The cellular budding sites and extracellular particles containing this lattice also lacked the internal density corresponding to a condensed NC-RNA complex. Such densities were readily observed within mature capsids and in virions carrying partially processed Gag proteins (de Marco et al., accompanying paper).

Budding sites with the novel Gag lattice are also observed in infected T-cell lines

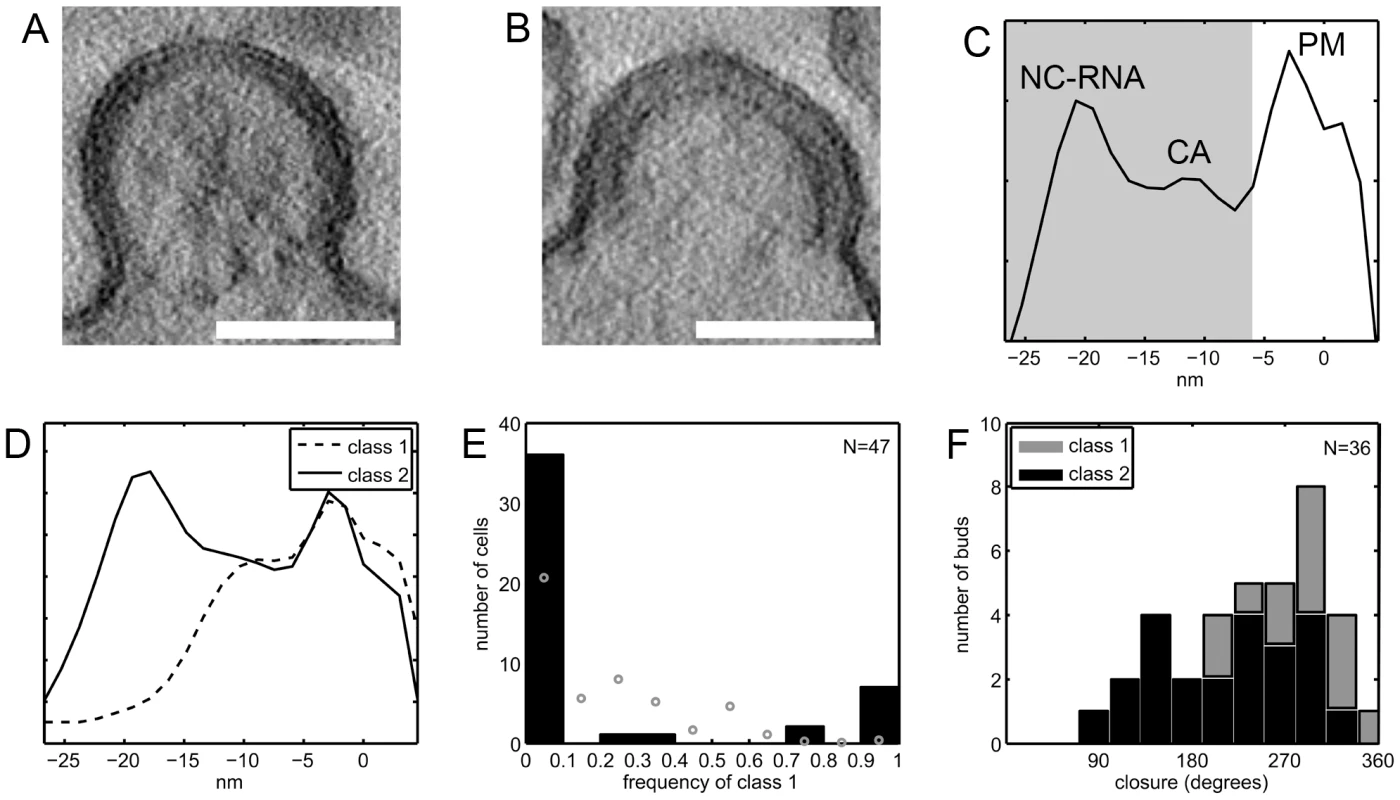

To determine whether the newly described lattice also occurs in other HIV-1 producing cells including T-cell lines, we recorded electron tomograms on sections of resin-embedded cells producing HIV-1. Although resin-embedded material is not preserved at the molecular level, it might still be possible to distinguish the two lattice types in these data, and this would allow recording sufficiently large data sets for statistical analyses. Visual inspection of resin-embedded sections from infected MT4 cells suggested the presence of a thinner density layer in some budding sites (Fig. 7A, B). This interpretation was validated based on the following criteria: (i) different types of membrane-bound densities in budding sites in resin embeddings could be classified by an unbiased scheme, and (ii) the presence of structures corresponding to the novel Gag lattice was dependent on an active viral PR.

Fig. 7. Budding sites with the novel lattice in HIV-1 infected T cells.

(A–B) Computational slices of 1.5 nm thickness through tomograms of resin-embedded HIV-1 infected MT4 cells. By eye, two types of budding sites are discernible, one type having a thinner Gag density (A) and the other (B) the typical thickness of the immature Gag lattice. (C) Linear density profile of the Gag layer in one representative resin-embedded immature budding site. The profile was calculated orthogonally to the membrane in the central part of the budding site, as described in Materials and methods. Membrane center at 0 nm, negative direction corresponds to cell interior. Peaks are discernible at the position of the membrane leaflets (PM), the NC-RNA layer, and (less strong) the CA layer of the immature lattice. The shaded area indicates the part of the plots used for classification of bud types. (D) Budding sites in resin embeddings of infected T cells were classified based on line plots like the one shown in (C). The average plots for the two major classes differ at the position of the NC/RNA layer, class 1 (dashed line) resembling the novel lattice and class 2 (solid line) resembling the immature lattice. (E) Frequency of class 1 budding sites on 47 infected MT-4 T cells. Black bars indicate the number of cells carrying either no (frequency 0) or exclusively (frequency 1) class 1 budding sites or a mixture of class 1 and class 2 budding sites. The theoretical frequency distribution which would be expected if all cells exhibited the average frequency of 18% buds in class 1 is given by grey circles. This distribution has local maxima around 25% and 50% due to the limited number of budding sites sampled per cell, as explained further in the Supplementary Information. (F) Gag layer closure in budding sites. The previously published data on the closure of the Gag layer in budding sites on MT-4 cells show a broad distribution of morphologies [26]. Separating these data into the two classes of Gag densities shows that class 2 budding sites (black bars) are more similar to released immature HIV-1 particles, whereas class 1 budding sites (grey bars) exhibit a more closed Gag layer. Scale bars are 100 nm. Classification of budding sites and particles was based on linear density plots of the membrane-bound Gag density. Fig. 7C shows a typical example, demonstrating that enough structure is retained to resolve the plasma membrane and distinct regions in the Gag layer. The classification was based on the parts of the plots containing the density bound to the inner face of the membrane (shaded area in Fig. 7C). Data were recorded on resin embeddings of HIV-1 infected MT4 cells, HeLa cells transfected with a proviral HIV-1 plasmid as well as positive and negative controls for the presence of the two lattice types (Table 2). In order to avoid overrepresentation of single cells, two tilt series were recorded per cell, and they were recorded as far apart as possible in the section plane (usually >5 µm). The same cell was never studied in consecutive sections. Our published data on infected MT4 cells [26] were also included in the analysis (Table 2, data set 8).

Tab. 2. Data sets of resin embedded samples evaluated in the classification of Gag layer types.

The number of tilt series recorded, and containing budding sites or released particles, are stated for each data set. Data set 8 was previously evaluated for Gag layer closure [26], whereas data sets 4–7 were recorded in a manner to allow for statistical evaluation of frequencies of Gag lattice types (see text). Principal component analysis of the variance in the data set revealed the presence of one major cluster with residual variance and a smaller, more homogeneous one (Fig. S3A–D in Supporting Information S1). Hierarchical clustering of the cropped line plots identified the two main classes as the two clusters observed in the PCA representation (Fig. S3E,F in Supporting Information S1). The less populated class (class 1, dashed line in Fig. 7D) lacked the innermost density peak corresponding to NC-RNA, whereas this peak was present in the more populated class (class 2, solid line in Fig. 7D). Further division of class 2 into subclasses mainly revealed a slight variation in the position and relative intensity of the NC-RNA peak (Fig. S4 in Supporting Information S1).

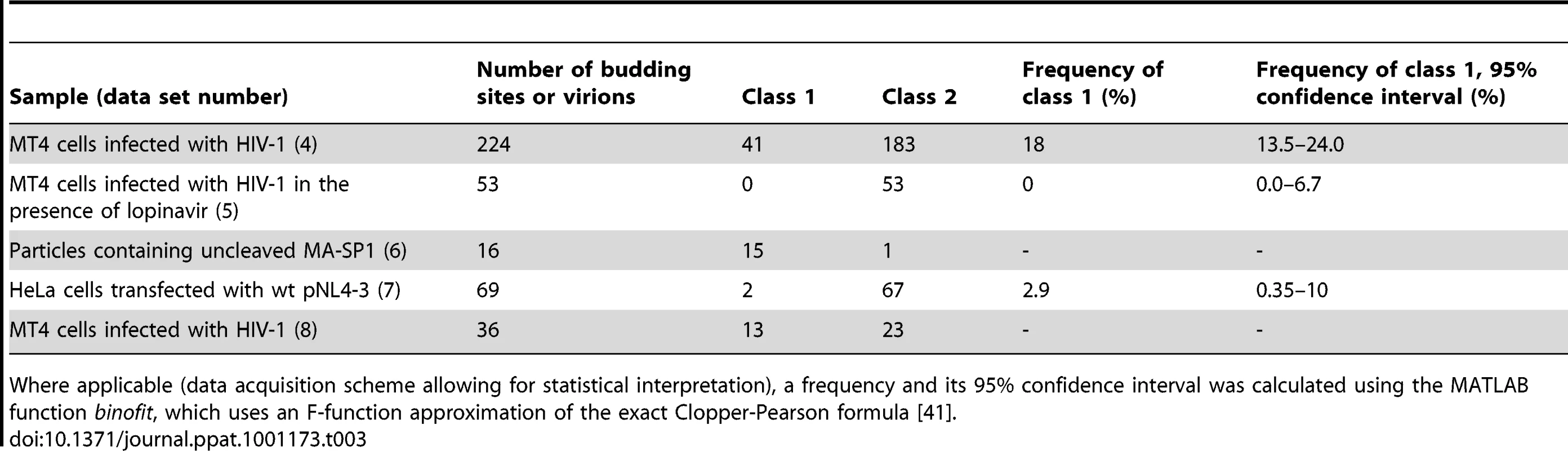

Table 3 shows the distribution of budding sites into the two classes for each sample. Class 1 contained 18% of the budding sites on HIV-1 infected MT4 cells and 2.9% of the budding sites on transfected HeLa cells. For infected MT4 cells treated with the PR inhibitor lopinavir, no class 1 budding sites were observed. As a control for the thinner Gag lattice, released virions carrying uncleaved MA-SP1 were studied. In this case, Gag processing is stalled at the MACASP1 fragment due to inactivating mutations at cleavage sites between MA and CA and CA and SP1, respectively (see [10] and accompanying paper by de Marco et al.). These particles generally fell into class 1. Taken together, these results suggest that class 1 corresponds to the newly described lattice detected by cET, while class 2 corresponds to the immature lattice.

Tab. 3. Number of budding sites or virions assigned to class 1 and class 2 Gag layer morphology, respectively, for the different sample groups.

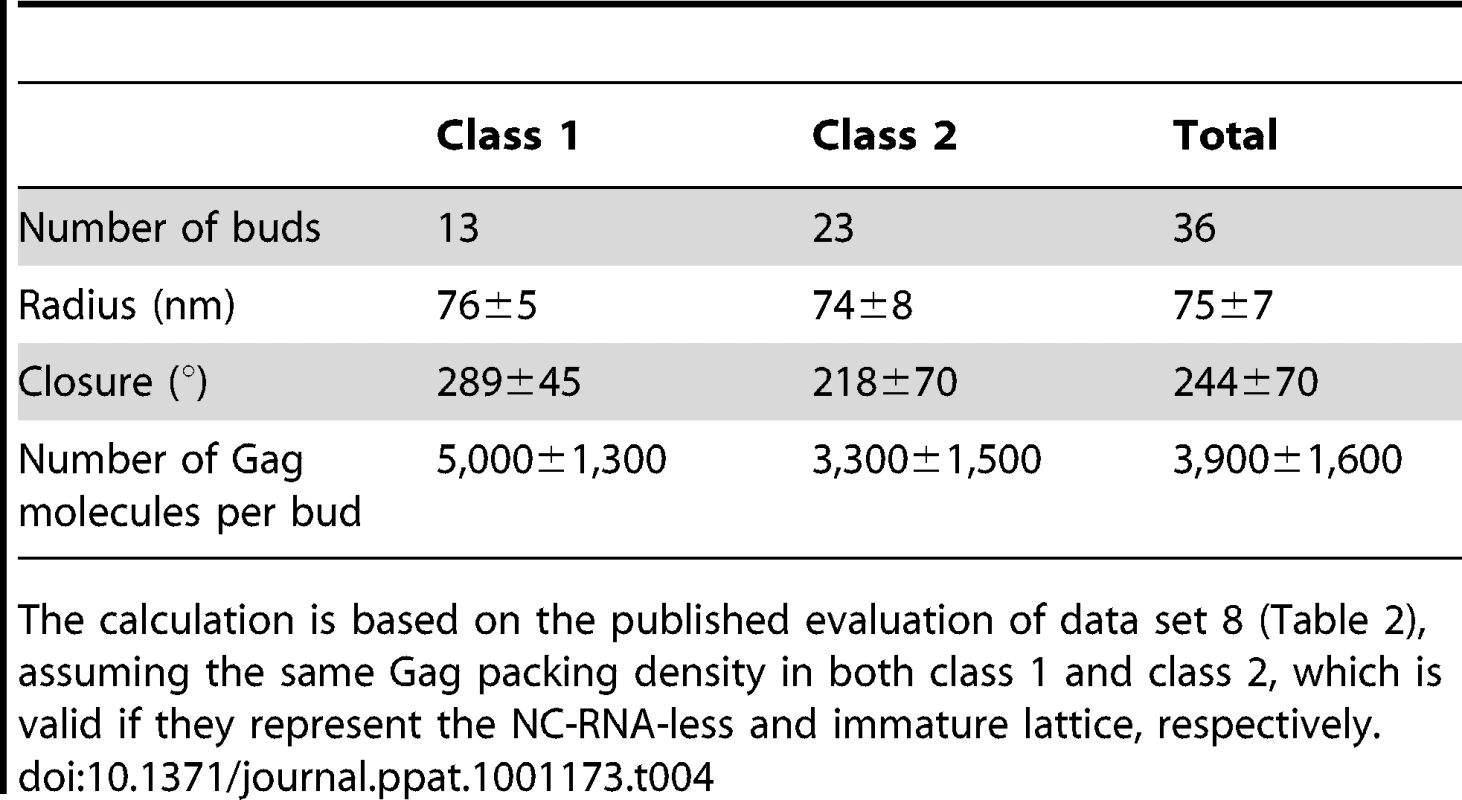

Where applicable (data acquisition scheme allowing for statistical interpretation), a frequency and its 95% confidence interval was calculated using the MATLAB function binofit, which uses an F-function approximation of the exact Clopper-Pearson formula [41]. Radius and closure of the Gag layer was calculated separately for the two classes (Table 4, Fig. 7F). Whereas the average radii of the two classes were similar, the closure of the Gag layer was significantly higher for the class 1 buds (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p = 0.0021). Assuming the same lattice packing in both classes, class 1 budding sites in this data set contain 5,000±1,300 Gag molecules while class 2 budding sites in this data set contain 3,300±1,500 Gag molecules.

Tab. 4. Properties of budding sites on MT4 cells according to Gag layer class.

The calculation is based on the published evaluation of data set 8 (Table 2), assuming the same Gag packing density in both class 1 and class 2, which is valid if they represent the NC-RNA-less and immature lattice, respectively. Finally, we asked whether individual cells carried only one class of budding sites or both. In the case of HIV-1 infected MT4 cells, 47 cells exhibited more than one budding site in the tomogram (Table 2, data set 4). Fig. 7E (black bars) shows the relative frequency of class 1 budding sites on these 47 cells, overlayed with the theoretical distribution (grey circles) that would be expected if all cells had the average of 18% class 1 budding sites. Clearly, most cells had either only class 1 or only class 2 budding sites, indicating that the budding phenotype is determined at the single cell level.

Discussion

Here, we established a system to visualize HIV-1 virus-like particle assembly and release in situ at macromolecular resolution in three dimensions using cET. This method permits structural interpretation of assembly sites and their cytoplasmic and membrane surroundings without the limitations imposed by the fixation, staining and dehydration methods commonly used in cellular electron microscopy. It allowed a detailed analysis of the Gag lattice in cellular budding sites, suggesting that the organization of the immature HIV-1 particle is already determined at the point of its intracellular assembly, and further identified a hitherto undescribed Gag lattice form. We show that this Gag lattice form is predominant in a subset of infected T-cells, and hypothesize that it is the result of premature PR activation in these cells.

The cET analysis of HIV-1 Gag and Gag-Pol expressing cells also provided unprecedented snapshots of cortical actin filaments in the vicinity of viral budding sites (Fig. 2, 3). It is well established that HIV-1 particles contain substantial amounts of actin [31], but the interplay between cortical actin and retrovirus assembly is still unknown. A recent study indicated a role for star-shaped actin filament arrangements emanating from the viral budding sites in HIV-1 assembly [32]. Our cET data provide 3D structures suggesting directed arrangement of actin filaments towards some budding sites, particularly in filopodia-associated buds. Strikingly, half of the budding sites in the current data set were present on actin-filled filopodia. To what extent this is a consequence of the particular region of the cell accessible to cET remains to be determined. Future cET studies using altered Gag constructs and selective manipulation of the actin dynamics will provide the necessary tools to untangle the molecular details of the involvement of actin at HIV-1 budding sites.

Extracellular immature HIV-1 particles are the direct products of viral budding at the plasma membrane, making it likely that their Gag protein lattice is determined during assembly. The observation that the Gag lattice is incomplete in the immature virus [22], [26] and contains defects [19], [22] raised the alternative hypothesis that Gag rearrangements occur following release. This could involve post-release association of smaller patches of Gag hexamers, or post-release symmetry breakage and dissociation of a hexagonal lattice containing evenly spaced pentameric defects [22]. Analysis of the lattice in extracellular immature virions revealed continuous hexameric symmetry over most of the lattice with curvature induced by defects of irregular size and shape [19]. These studies were performed on purified released particles, however, and the degree of order attained during assembly at the plasma membrane may have been higher (and broken after release) or lower (and subsequently assembled into a more ordered lattice). Our cET data of budding sites revealed structures of the immature Gag lattice in intact unperturbed cells prior to release, allowing us to draw conclusions on the early steps of the HIV-1 assembly process. There was no indication of separated “islands” of hexameric Gag in the in situ budding sites; upon visual inspection they consistently contained one continuous layer of Gag protein. A more detailed analysis of the lattice in the immature budding sites revealed that its unit cell structure was highly similar to that previously described for released immature virions [19], and included irregular lattice defects of similar size and distribution. This suggests that the organization of the immature HIV-1 particle is indeed determined at the point of its intracellular assembly, and not as a result of large scale post-release ordering or disordering.

Besides the described immature Gag lattice, we observed a previously undescribed lattice type in extracellular particles and in budding sites still connected to the cell. Formation of this lattice was dependent on an active HIV-1 PR. The newly discovered lattice exhibited hexagonal symmetry with a CA layer identical to the immature lattice, but lacked the second layer of density corresponding to the NC-RNA complex. The particles and budding sites also contained no visible NC-RNA condensate in the center of the particles or adjacent to the buds, suggesting that the viral genome is absent. A comparison with the analysis performed in the accompanying paper by de Marco et al. on isolated virions with specific Gag cleavage site mutations showed that the newly described lattice is most likely composed of the MA-SP1 region of HIV-1 Gag. Although the tomographic average at current resolution does not allow identification of the density corresponding to the SP1 peptide, de Marco et al. showed that this peptide is present, independent of whether the cleavage site between CA and SP1 is intact or not. Notably, the particles produced from the MA-CA and MA-SP1 cleavage site mutants which exhibit an MA-SP1 type lattice do contain a clearly distinguishable density corresponding to condensed NC-RNA (de Marco et al.), which distinguishes them from the particles with this lattice type in the current study.

As further described in the accompanying paper by de Marco et al., the MACASP1 lattice is likely to constitute a natural intermediate in the proteolytic maturation of HIV-1. Cleavage between SP1 and NC is the fastest processing step in vitro and abscission of the C-terminal NC-p6 regions from the immature lattice is required for condensation of the inner ribonucleoprotein complex of the virion prior to formation of the capsid. Thus, extracellular particles containing the MACASP1 lattice and inner density corresponding to NC-RNA are suggested to represent a “frozen” intermediate in HIV-1 maturation (de Marco et al.). Such particles were not observed for wild-type HIV-1 constructs, however, indicating that maturation intermediates are normally short-lived. An MACASP1 lattice without adjacent NC-RNA density was observed in 18% of HIV-1 budding sites on infected MT-4 cells, on the other hand, and its frequent presence suggests that it is a metastable structure with a significant lifetime in this case.

We previously reported that budding sites on infected MT4 cells have a broad distribution of Gag layer morphologies. Some resemble actual released immature virions, but some have a more complete Gag layer, containing more Gag molecules than the released virions and thus rather resemble arrested “late” budding sites not thought to be virus precursors [26]. When re-evaluating these data with respect to the type of Gag lattice, the immature lattice was predominantly found in budding sites resembling released virions, whereas the budding sites with the novel lattice had a significantly more closed Gag layer than released virions (Table 4, Fig. 7F). In the case of late-domain defective variants, formation of a closed layer is thought to be caused by a failure to recruit the ESCRT machinery and thus to drive the release process. Consequently, Gag assembly continues until reaching an equilibrium structure, but the resulting late budding sites are mostly dead-end products. It appears likely that a similar process is also relevant for the budding sites with the novel lattice. We hypothesize that premature proteolytic activation prior to confinement of virion constituents in the budding virion leads to removal of NC-p6 from Gag and of PR and downstream pol products from Gag-Pol. The cleaved C-terminal fragments are lost from the assembly site, while the MACASP1 lattice is stably retained. No ESCRT recruitment occurs since the p6 domain has been removed and no further processing occurs because PR, not being confined in a viral particle, has been lost. Accordingly, no budding structures with mature cores were observed. Further assembly of the truncated lattice may involve additional Gag molecules undergoing partial processing or addition of cytoplasmic MACASP1 molecules since a truncated MACASP1 construct has been shown to form budlike structures when overexpressed [33], [34]. The presence of extracellular particles with the MACASP1 lattice and lacking NC-RNA may indicate some ESCRT-independent release. Release of virions lacking most of the NC domain (but in this case carrying the p6 domain) has also been observed in previous studies [35], [36].

The results of the current study clearly show that morphological maturation can be initiated inside the producer cell, but indicate that it is largely non-productive if the virion constituents are not confined in a structure sequestered from the cytoplasm. Assembly, release and maturation would therefore require the sequential processes of Gag association, ESCRT recruitment (prior to closure of the Gag shell), and PR activation (after or concomitant with ESCRT-mediated sequestration of the bud). The observation of aberrant, apparently dead-end structures in a subset of cells in HIV-1 infected T-cell lines suggests that the control of these processes can be lost, however. Infected MT-4 cells generally contained only one type of budding sites indicating that this loss of control may be caused by the host cell environment. Conceivably, host cell factors may be involved in regulating the kinetics of the consecutive stages of viral assembly, budding and release, and the subset of T-cells may have lost this regulation, although a general cytopathic effect cannot be ruled out at present. Identifying viral or host factors involved in this regulation will be of great importance for our understanding of HIV-1 morphogenesis, and may also lead to new approaches to render HIV-1 infection non-productive.

Materials and Methods

Construction of adenoviral vectors for HIV-1 Gag and GagPol

Adenoviral vectors for HIV-1 Gag (AdGag) and GagPol (AdGagPol) were constructed from the Rev independent versions of these genes [29], using the BD Adeno-X Expression System 1 (BD Biosciences Clontech). Briefly, the 1539 nt gag-gene was amplified by PCR adding flanking NheI/XbaI sites and ligated into the transfer vector pShuttle2. The gag-pol gene was excised with NdeI/XbaI from pcDNA3.1syngagpol [29] and directly cloned into pShuttle2. After verification of the insert by sequence analysis, these plasmids were digested with PI-Sce/I-Ceu. The inserts were ligated into the pre-digested Adeno.X viral DNA. Resulting plasmids were verified by restriction digest and DNA sequencing. Recombinant adenoviruses were generated by transfection of the AdGag or Ad GagPol plasmids into HEK 293 cells and amplified according to the protocol supplied with the kit. Titers of adenoviral vectors were determined using the Adeno-X rapid Titer Kit (Clontech); titers of both AdGag and Ad GagPol typically reached 1–2×109/ml. Immunofluorescence staining of AdGag and AdGagPol transduced cells for HIV-1 Gag was performed using a rabbit polyclonal anti-CA antibody and a FITC-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Western blots of cell lysates and particles purified from the culture media of AdGag and AdGagPol transduced cells were performed using the same polyclonal anti-CA antibody, with an IRDye 800CW goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (LI-COR Biosciences) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Cell culture and adenoviral vector transductions for cryo electron tomography

Human glioblastoma cell lines U-87 MG and U-373 MG were maintained in DMEM and MEM, respectively, supplemented with Penicillin-Streptomycin and 10% foetal bovine serum. When grown on EM grids (CF-2/1-2AU, Protochips, inc.), cells were seeded at low density and kept in medium with 0.5% serum which increased the extent of flat areas of the cells. Transduction with AdGag or AdGagPol was performed concomitant with or one day after seeding cells on EM grids. A multiplicity of ‘infection’ (MOI) of 10 was typically used, calculated based on cell culture dish area and assuming that added vector will adhere to any substrate surface. One to three days after seeding cells on the grids, they were plunge-frozen into liquid ethane after application of 10 nm colloidal gold.

Sample preparation for electron tomography of sections of resin-embedded cells

Cell culture and preparation for sections of resin embedded cells were performed as previously described [26]. For production of immature virus, cells were grown in the presence of 1 µM lopinavir. For production of particles containing an uncleaved MA-SP1 layer, HEK293T cells were transfected with a proviral HIV-1NL4-3 plasmid carrying mutations in the cleavage sites between MA and CA and CA and SP1, respectively ([14] and accompanying paper by de Marco et al.). Cells were fixed, stained, dehydrated and EPON-embedded, and 300 nm sections of the embeddings were cut and transferred to EM grids after deposition of colloidal gold onto the EM grid support film.

Electron tomography

Cryo electron tomography was performed with a Philips CM300 or a FEI Tecnai F30 Polara transmission electron microscope (FEI; Eindhoven, The Netherlands), both equipped with 300 kV field emission guns, Gatan GIF 2002 post-column energy filters and 2048×2048 Multiscan CCD cameras (Gatan; Pleasanton, CA). All data collection was performed at 300 kV, with the energy filter operated in zero loss mode. Tilt series of cryo specimens were typically recorded from −60° to +60° with an angular increment of 1.5°, a total electron dose of 80 electrons Å−2, and a defocus of −6.0 µm to −8.0 µm. The pixel sizes at the specimen level were 8.21 Å at the CM300, and 8.05 Å or 7.13 Å at the FEI Tecnai F30 Polara, respectively. Electron tomography of resin sections was performed at an FEI Tecnai F20 transmission electron microscope (FEI; Eindhoven, The Netherlands), equipped with 200 kV field emission gun and a 4096×4096 Eagle CCD camera (FEI; Eindhoven, The Netherlands). Tilt series on resin sections were recorded at room temperature from −60° to +60° with an angular increment of 1.0°, with a one time binned pixel size of 2*3.72 Å and a defocus of -4.0 µm. For both cryo and room temperature tilt series, the applied electron dose for a given tilt angle α was proportional to 1/cos(α) to compensate for the higher effective specimen thickness at higher tilts. At the Tecnai microscopes, the SerialEM acquisition software [37] was used for tilt series acquisition. Three-dimensional reconstructions from tilt series were calculated using the weighted back-projection method [38], as implemented in the TOM toolbox [39] for MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, Massachusetts, United States) with the “exact weighting” option, or in IMOD [40].

Subtomogram averaging

Subtomogram averaging was performed using MATLAB. Sub-volumes of (38.6 nm)3 were extracted along the surface of the budding particles. The subtomograms were then iteratively aligned against the average in a reference free manner, while applying 6-fold symmetry as described in the accompanying article (de Marco et al). For individual particles, the distribution of the cross correlation values between the aligned subtomograms and the reference was bimodal. The threshold of the subtomograms that went into the reconstruction was set as minimum between the two peaks.

Classification of Gag lattice types in tomograms of resin-embedded sections

The classification of Gag densities in resin embeddings of HIV-1 budding sites was performed as described in the Supplementary Information. In brief, linear density profiles were calculated orthogonally to the plasma membrane in the budding sites. These one-dimensional density profiles were cropped to contain only the membrane-apposed density, and subjected to hierarchical clustering.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. FreedEO

1998 HIV-1 gag proteins: diverse functions in the virus life cycle. Virology 251 1 15

2. HurleyJH

2008 ESCRT complexes and the biogenesis of multivesicular bodies. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20 4 11

3. MoritaE

SundquistWI

2004 Retrovirus budding. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol 20 395 425

4. WilliamsRL

UrbeS

2007 The emerging shape of the ESCRT machinery. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8 355 368

5. BriggsJAG

SimonMN

GrossI

KräusslichHG

FullerSD

2004 The stoichiometry of Gag protein in HIV-1. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11 672 675

6. GarrusJE

von SchwedlerUK

PornillosOW

MorhamSG

ZavitzKH

2001 Tsg101 and the vacuolar protein sorting pathway are essential for HIV-1 budding. Cell 107 55 65

7. VerPlankL

BouamrF

LaGrassaTJ

AgrestaB

KikonyogoA

2001 Tsg101, a homologue of ubiquitin-conjugating (E2) enzymes, binds the L domain in HIV type 1 Pr55(Gag). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 7724 7729

8. CoffinJM

HughesSH

VarmusHE

1997 Retroviruses: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

9. PettitSC

MoodyMD

WehbieRS

KaplanAH

NantermetPV

1994 The p2 domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag regulates sequential proteolytic processing and is required to produce fully infectious virions. J Virol 68 8017 8027

10. WiegersK

RutterG

KottlerH

TessmerU

HohenbergH

1998 Sequential steps in human immunodeficiency virus particle maturation revealed by alterations of individual Gag polyprotein cleavage sites. J Virol 72 2846 2854

11. CorenLV

ThomasJA

ChertovaE

SowderRC

GagliardiTD

2007 Mutational analysis of the C-terminal Gag cleavage sites in human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 81 10047 10054

12. CheckleyMA

LuttgeBG

SoheilianF

NagashimaK

FreedEO

2010 The capsid-spacer peptide 1 Gag processing intermediate is a dominant-negative inhibitor of HIV-1 maturation. Virology 400 137 144

13. LeeSK

HarrisJ

SwanstromR

2009 A strongly transdominant mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag gene defines an Achilles heel in the virus life cycle. J Virol 83 8536 8543

14. MüllerB

AndersM

AkiyamaH

WelschS

GlassB

2009 HIV-1 Gag processing intermediates trans-dominantly interfere with HIV-1 infectivity. J Biol Chem 284 29692 29703

15. KräusslichHG

1991 Human immunodeficiency virus proteinase dimer as component of the viral polyprotein prevents particle assembly and viral infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88 3213 3217

16. KaplanAH

ZackJA

KniggeM

PaulDA

KempfDJ

1993 Partial inhibition of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease results in aberrant virus assembly and the formation of noninfectious particles. J Virol 67 4050 4055

17. MooreMD

FuW

SoheilianF

NagashimaK

PtakRG

2008 Suboptimal inhibition of protease activity in human immunodeficiency virus type 1: effects on virion morphogenesis and RNA maturation. Virology 379 152 160

18. BenjaminJ

Ganser-PornillosBK

TivolWF

SundquistWI

JensenGJ

2005 Three-dimensional structure of HIV-1 virus-like particles by electron cryotomography. J Mol Biol 346 577 588

19. BriggsJA

RichesJD

GlassB

BartonovaV

ZanettiG

2009 Structure and assembly of immature HIV. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 11090 11095

20. BriggsJAG

GrünewaldK

GlassB

FörsterF

KräusslichHG

2006 The mechanism of HIV-1 core assembly: Insights from three-dimensional reconstructions of authentic virions. Structure 14 15 20

21. LiuJ

BartesaghiA

BorgniaMJ

SapiroG

SubramaniamS

2008 Molecular architecture of native HIV-1 gp120 trimers. Nature 455 109 113

22. WrightER

SchoolerJB

DingHJ

KiefferC

FillmoreC

2007 Electron cryotomography of immature HIV-1 virions reveals the structure of the CA and SP1 Gag shells. EMBO J 26 2218 2226

23. ZhuP

LiuJ

BessJJr

ChertovaE

LifsonJD

2006 Distribution and three-dimensional structure of AIDS virus envelope spikes. Nature 441 847 852

24. ZhuP

WinklerH

ChertovaE

TaylorKA

RouxKH

2008 Cryoelectron tomography of HIV-1 envelope spikes: further evidence for tripod-like legs. PLoS Pathog 4 e1000203

25. BriggsJAG

WilkT

WelkerR

KräusslichHG

FullerSD

2003 Structural organization of authentic, mature HIV-1 virions and cores. EMBO J 22 1707 1715

26. CarlsonLA

BriggsJA

GlassB

RichesJD

SimonMN

2008 Three-dimensional analysis of budding sites and released virus suggests a revised model for HIV-1 morphogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 4 592 599

27. LiS

HillCP

SundquistWI

FinchJT

2000 Image reconstructions of helical assemblies of the HIV-1CA protein. Nature 407 409 413

28. GanserBK

LiS

KlishkoVY

FinchJT

SundquistWI

1999 Assembly and analysis of conical models for the HIV-1 core. Science 283 80 83

29. WagnerR

GrafM

BielerK

WolfH

GrunwaldT

2000 Rev-independent expression of synthetic gag-pol genes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus: implications for the safety of lentiviral vectors. Hum Gene Ther 11 2403 2413

30. MedaliaO

WeberI

FrangakisAS

NicastroD

GerischG

2002 Macromolecular architecture in eukaryotic cells visualized by cryoelectron tomography. Science 298 1209 1213

31. OttDE

CorenLV

KaneBP

BuschLK

JohnsonDG

1996 Cytoskeletal proteins inside human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions. J Virol 70 7734 7743

32. GladnikoffM

ShimoniE

GovNS

RoussoI

2009 Retroviral assembly and budding occur through an actin-driven mechanism. Biophys J 97 2419 2428

33. CristRM

DattaSA

StephenAG

SoheilianF

MirroJ

2009 Assembly properties of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag-leucine zipper chimeras: implications for retrovirus assembly. J Virol 83 2216 2225

34. HockleyDJ

NermutMV

GriefC

JowettJB

JonesIM

1994 Comparative morphology of Gag protein structures produced by mutants of the gag gene of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Gen Virol 75 Pt 11 2985 2997

35. OttDE

CorenLV

ChertovaEN

GagliardiTD

NagashimaK

2003 Elimination of protease activity restores efficient virion production to a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid deletion mutant. J Virol 77 5547 5556

36. PopovaE

PopovS

GottlingerHG

2010 Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Nucleocapsid p1 Confers ESCRT Pathway Dependence. J Virol 84 6590 6597

37. MastronardeDN

2005 Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J Struct Biol 152 36 51

38. FrankJ

2006 Electron Tomography: Methods for Three-Dimensional Visualization of Structures in the Cell Berlin: Springer

39. NickellS

FörsterF

LinaroudisA

Del NetW

BeekF

2005 TOM software toolbox: acquisition and analysis for electron tomography. Journal of Structural Biology 149 227 234

40. KremerJR

MastronardeDN

McIntoshJR

1996 Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J Struct Biol 116 71 76

41. WestfallPH

YoungSS

1993 Resampling-based multiple testing: examples and methods for P-value adjustment: Wiley-Interscience 360

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Tick Histamine Release Factor Is Critical for Engorgement and Transmission of the Lyme Disease AgentČlánek TGF-b2 Induction Regulates Invasiveness of -Transformed Leukocytes and Disease SusceptibilityČlánek The Origin of Intraspecific Variation of Virulence in an Eukaryotic Immune Suppressive ParasiteČlánek Glycosylation Focuses Sequence Variation in the Influenza A Virus H1 Hemagglutinin Globular Domain

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 11- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Familiární středomořská horečka

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Patients with Discordant Responses to Antiretroviral Therapy Have Impaired Killing of HIV-Infected T Cells

- A Molecular Mechanism for Eflornithine Resistance in African Trypanosomes

- Tyrosine Sulfation of the Amino Terminus of PSGL-1 Is Critical for Enterovirus 71 Infection

- Autoimmunity as a Predisposition for Infectious Diseases

- The Subtilisin-Like Protease AprV2 Is Required for Virulence and Uses a Novel Disulphide-Tethered Exosite to Bind Substrates

- Structural Analysis of HIV-1 Maturation Using Cryo-Electron Tomography

- Tick Histamine Release Factor Is Critical for Engorgement and Transmission of the Lyme Disease Agent

- Interferon-Inducible CXC Chemokines Directly Contribute to Host Defense against Inhalational Anthrax in a Murine Model of Infection

- TGF-b2 Induction Regulates Invasiveness of -Transformed Leukocytes and Disease Susceptibility

- The Origin of Intraspecific Variation of Virulence in an Eukaryotic Immune Suppressive Parasite

- CO Acts as a Signalling Molecule in Populations of the Fungal Pathogen

- SV2 Mediates Entry of Tetanus Neurotoxin into Central Neurons

- MAP Kinase Phosphatase-2 Plays a Critical Role in Response to Infection by

- Glycosylation Focuses Sequence Variation in the Influenza A Virus H1 Hemagglutinin Globular Domain

- Potentiation of Epithelial Innate Host Responses by Intercellular Communication

- Fcγ Receptor I Alpha Chain (CD64) Expression in Macrophages Is Critical for the Onset of Meningitis by K1

- ANK, a Host Cytoplasmic Receptor for the Cell-to-Cell Movement Protein, Facilitates Intercellular Transport through Plasmodesmata

- Analysis of the Initiating Events in HIV-1 Particle Assembly and Genome Packaging

- Evolution of Linked Avirulence Effectors in Is Affected by Genomic Environment and Exposure to Resistance Genes in Host Plants

- Structural Basis of HIV-1 Neutralization by Affinity Matured Fabs Directed against the Internal Trimeric Coiled-Coil of gp41

- Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Evades NKG2D-Dependent NK Cell Responses through NS5A-Mediated Imbalance of Inflammatory Cytokines

- Host Cell Invasion and Virulence Mediated by Ssa1

- Global Gene Expression in Urine from Women with Urinary Tract Infection

- Should the Human Microbiome Be Considered When Developing Vaccines?

- HapX Positively and Negatively Regulates the Transcriptional Response to Iron Deprivation in

- Enhancing Oral Vaccine Potency by Targeting Intestinal M Cells

- Herpes Simplex Virus Reorganizes the Cellular DNA Repair and Protein Quality Control Machinery

- The Female Lower Genital Tract Is a Privileged Compartment with IL-10 Producing Dendritic Cells and Poor Th1 Immunity following Infection

- Zn Inhibits Coronavirus and Arterivirus RNA Polymerase Activity and Zinc Ionophores Block the Replication of These Viruses in Cell Culture

- Cryo Electron Tomography of Native HIV-1 Budding Sites

- Crystal Structure and Size-Dependent Neutralization Properties of HK20, a Human Monoclonal Antibody Binding to the Highly Conserved Heptad Repeat 1 of gp41

- Modelling the Evolution and Spread of HIV Immune Escape Mutants

- The Arabidopsis Resistance-Like Gene Is Activated by Mutations in and Contributes to Resistance to the Bacterial Effector AvrRps4

- Platelet-Activating Factor Receptor Plays a Role in Lung Injury and Death Caused by Influenza A in Mice

- Genetic and Structural Basis for Selection of a Ubiquitous T Cell Receptor Deployed in Epstein-Barr Virus Infection

- Ubiquitin-Regulated Nuclear-Cytoplasmic Trafficking of the Nipah Virus Matrix Protein Is Important for Viral Budding

- Pneumolysin Activates the NLRP3 Inflammasome and Promotes Proinflammatory Cytokines Independently of TLR4

- Immune Evasion by : Differential Targeting of Dendritic Cell Subpopulations

- Survival in Selective Sand Fly Vector Requires a Specific -Encoded Lipophosphoglycan Galactosylation Pattern

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Zn Inhibits Coronavirus and Arterivirus RNA Polymerase Activity and Zinc Ionophores Block the Replication of These Viruses in Cell Culture

- The Female Lower Genital Tract Is a Privileged Compartment with IL-10 Producing Dendritic Cells and Poor Th1 Immunity following Infection

- Crystal Structure and Size-Dependent Neutralization Properties of HK20, a Human Monoclonal Antibody Binding to the Highly Conserved Heptad Repeat 1 of gp41

- The Arabidopsis Resistance-Like Gene Is Activated by Mutations in and Contributes to Resistance to the Bacterial Effector AvrRps4

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání