-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Members of the Epistasis Group Contribute to Mitochondrial Homologous Recombination and Double-Strand Break Repair in

Mitochondria are the powerhouse of the cell, providing energy in the form of ATP. Several proteins required for the production of ATP are encoded in the mitochondrial genome, which is maintained independently from the nuclear genome. Mutations in mitochondrial DNA are responsible for several inherited diseases and are associated with certain cancers, neurological disorders, and aging. In human mtDNA, 90% of deletions, a specific type of mutation, are flanked by repetitive sequences. Deletions in this context are generally produced through homologous recombination, specifically single-strand annealing. For the first time, in this study we show that the proteins involved in nuclear homologous recombination, Rad51p, Rad52p, and Rad59p, also contribute to the formation of mitochondrial deletions. Our data also suggest a novel mitochondrial-specific role for Rad51p in the generation of this type of deletion. Further study of these repair pathways allows us to garner a better understanding of these processes that are involved in disease pathologies and aging.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005664

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005664Summary

Mitochondria are the powerhouse of the cell, providing energy in the form of ATP. Several proteins required for the production of ATP are encoded in the mitochondrial genome, which is maintained independently from the nuclear genome. Mutations in mitochondrial DNA are responsible for several inherited diseases and are associated with certain cancers, neurological disorders, and aging. In human mtDNA, 90% of deletions, a specific type of mutation, are flanked by repetitive sequences. Deletions in this context are generally produced through homologous recombination, specifically single-strand annealing. For the first time, in this study we show that the proteins involved in nuclear homologous recombination, Rad51p, Rad52p, and Rad59p, also contribute to the formation of mitochondrial deletions. Our data also suggest a novel mitochondrial-specific role for Rad51p in the generation of this type of deletion. Further study of these repair pathways allows us to garner a better understanding of these processes that are involved in disease pathologies and aging.

Introduction

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles that function as the primary source of ATP. Mitochondria contain an autonomously replicating genome that is packaged into DNA-protein structures called nucleoids. This multi-copy genome encodes subunits of electron transport chain (ETC) complexes and the rRNAs and tRNAs that are specifically required for the expression of these proteins. The number and types of proteins encoded by the mitochondrial genome are highly conserved among eukaryotes, even though the overall size and structure of the genome varies widely between species. The remaining proteins required for the ETC, as well as those required for maintenance and repair of the mitochondrial genome are encoded in the nucleus and imported into mitochondria from the cytoplasm.

Stability of the mitochondrial genome is required for the survival of most eukaryotic cells. Mutations in the mitochondrial genome cause metabolic defects that underlie multiple diseases, both inherited and spontaneous [1–6]. Accumulation of both point mutations and deletions in mtDNA are also proposed to contribute to the normal aging process [7]. Consistent with this hypothesis, transgenic mice expressing a proofreading-defective Pol γ, the replicative mitochondrial polymerase, display accelerated aging phenotypes due to the accumulation of somatic mtDNA mutations [8]. Despite its profound importance to metabolic control and cell maintenance, the mechanisms of mitochondrial mutagenesis and repair are poorly understood, particularly double-strand break repair (DSBR) [9]. Though homologous recombination (HR) in yeast, plant and mammalian mtDNA has been reported [10–15], few specific proteins involved in mitochondrial recombination have been identified [16–22]. For those proteins that have been implicated in mitochondrial HR, the inability to generate and visualize specific, controlled mitochondrial double-strand breaks has precluded a direct analysis of their role in DSBR.

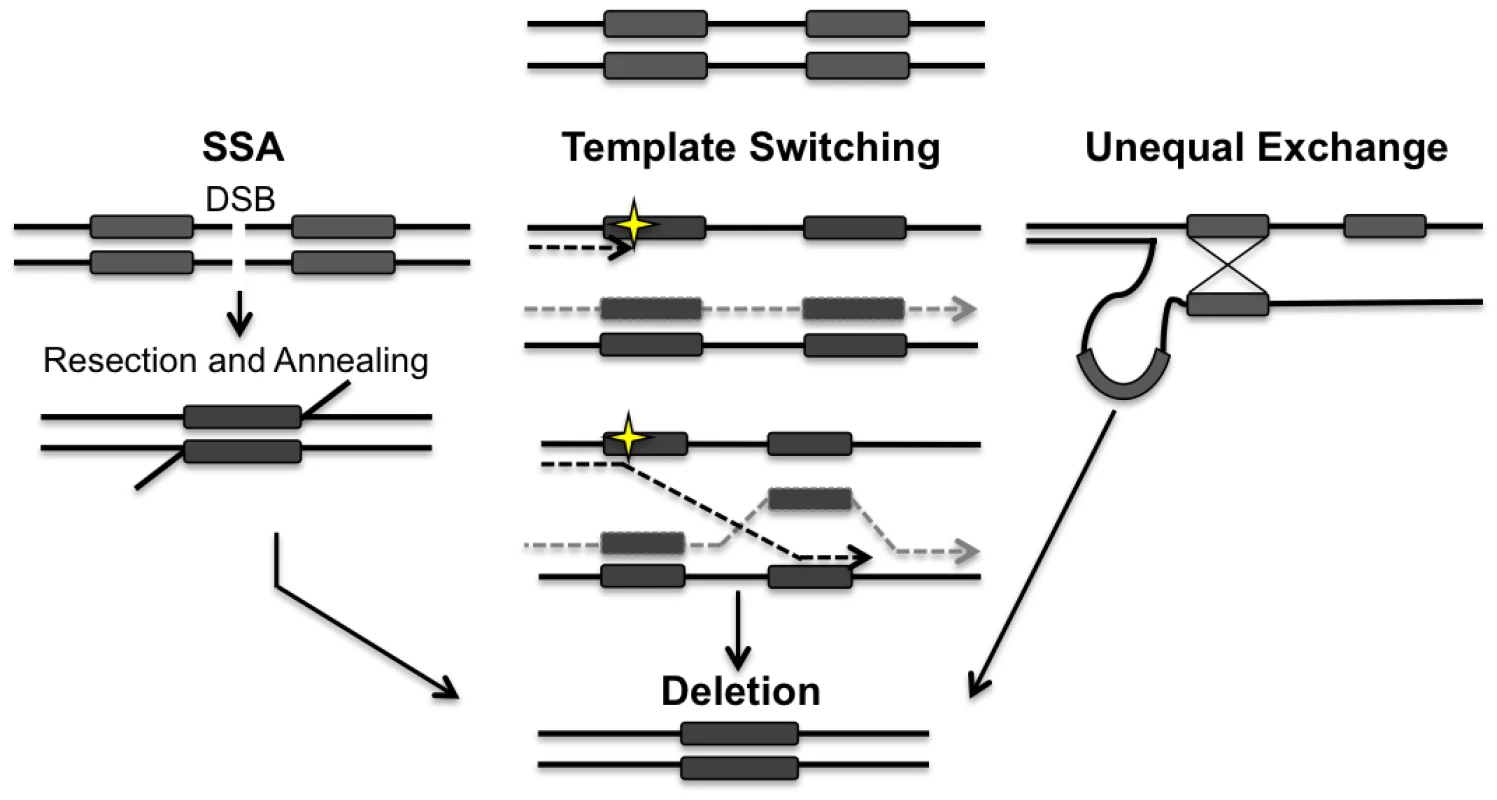

Members of the RAD52 epistasis group are essential for HR in the nucleus. Rad51p, a RecA homologue, forms a nucleoprotein filament that promotes the homologous pairing and strand exchange required for DSBR, synthesis dependent strand annealing and break induced replication [23–25]. Rad52p is required for almost all forms of HR in yeast, by promoting the exchange of RPA for Rad51p on the single-stranded ends that are generated at DSBs following resection [26]. HR is often thought of as an error-free repair pathway but there are several HR mechanisms that can lead to the generation of deletions between repetitive elements. For example single strand annealing (SSA), which is highly dependent on Rad52p and Rad59p, is an error-prone recombination pathway that occurs when a DSB or a lesion that results in a DSB arises between two repetitive sequences [27]. The annealing of these repetitive sequences after resection leads to the deletion of one repeat and the intervening sequence (Fig 1) [26,28]. A DSB that arises within a repeat can also generate a deletion if the repetitive sequences are misaligned during unequal crossing over (Fig 1) [29]. Deletions may also arise between repeated sequences due to errors in replication such as slippage or template switching (Fig 1) [30].

Fig. 1. Models for the generation of deletions between directly repeated sequences.

Repair of a double-strand break (DSB) located between directly repeated sequences (grey boxes) can result in the deletion of one of the repeats and all of the intervening sequence. 5’ to 3’ resection at the DSB reveals the direct repeats. Rad52p alone or in conjunction with Rad59p, promotes the annealing of the repeats. Template switching can occur if a lesion (yellow star) is encountered during replication. At a stalled fork, the nascent strand may invade at the incorrect repeat, leading to the generation of a deletion. Unequal exchange can occur when HR occurs between misaligned repeats leading to a deletion. Both template switching and unequal exchange can happen intramolecularly or intermolecularly. Arrowheads indicate 3’ end. Deletions have been observed in yeast, plants, flies, and mammalian mtDNA [10,11,31,32], and often these deletions involve sequences originally flanked by direct repeats. For example, in human cells nearly 90% of deletions in mtDNA are flanked by either perfect or imperfect repeats. This suggests that recombination is a possible mechanism for the generation of mtDNA deletions, but the exact mechanisms and proteins involved are currently unknown. [33,34].

Recent studies have localized members of the RAD52 epistasis group to mitochondria. In plants, a mitochondrial-specific isoform of Rad52p has been identified, and demonstrated to promote annealing of complementary DNA sequences in vitro, consistent with a role in recombination in mitochondria [35]. In human cell lines, Rad51, and two of its paralogs Rad51C and XRCC3 were found to localize to mitochondria and promote mtDNA replication upon oxidative stress [36,37]. These studies strongly suggest that at least a subset of the nuclear recombination proteins can localize to mitochondria and that once there, they may facilitate processes that require homologous sequences such as HR. Mammalian systems do not lend themselves to mechanistic studies because these organisms require intact mtDNA molecules to survive. In addition, it is not currently possible to introduce exogenous DNA reporters in vivo in these systems. Saccharomyces cerevisiae is an ideal model system for these studies due to the fact that these repair proteins are highly conserved, mtDNA is not required for cell survival, and it is possible to introduce exogenous reporter constructs directly into the mitochondrial genome.

We previously developed a reporter system for quantitatively measuring the occurrence of direct repeat mediated deletions (DRMD) in mtDNA [38–40]. This reporter introduces a unique KpnI restriction recognition site between direct repeats. By expressing mitochondrially-targeted KpnI, induction of a directed mtDNA DSB can be precisely controlled. In the work presented here, we use a modified version of this endonuclease fusion to demonstrate that loss Rad51p, Rad52p and Rad59p significantly decreases the generation of both spontaneous and DSB induced mitochondrial DRMDs. Improved control of DSB induction has also allowed us to study the kinetics of mtDNA DSBR using both genetic and molecular methods. Southern blot analysis confirms that loss of these proteins leads to delays in break processing and/or generation of deletion products. The localization of Rad51p and Rad59p to yeast mitochondria argue that these effects are direct. Analysis of double mutants indicates that the contribution of these proteins to the repair process differs between the mitochondrial and the nuclear genomes.

Results

Rad51p and Rad59p localize to the mitochondrial matrix

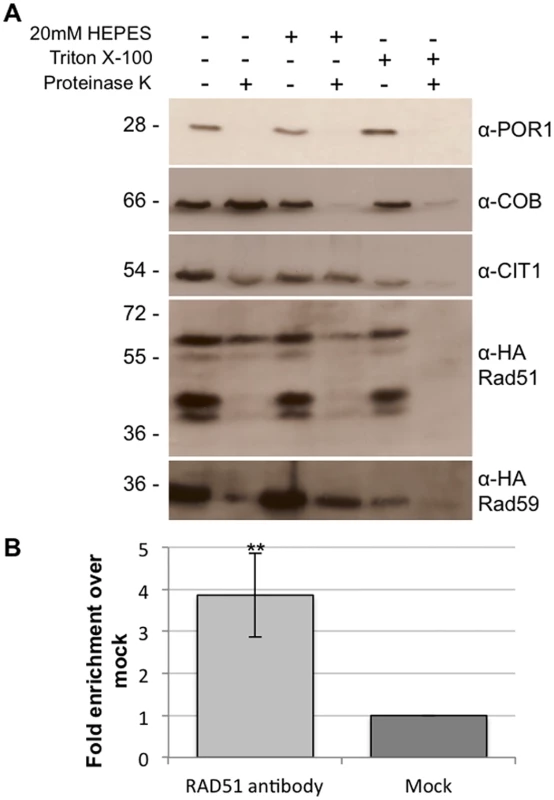

Previous studies have shown that Rad51, Rad51C and XRCC3 are found in the mitochondria of human cells [36]. In order to determine if this dual localization of Rad51 to both the nucleus and mitochondria is conserved in yeast, mitochondria were purified from cells expressing a C-terminal Rad51-HA tag expressed from the endogenous locus. We were able to detect at least four Rad51-HA specific bands in whole cell extracts and associated with the mitochondrial fraction (Fig 2A). These bands are specific to the strain expressing the Rad51-HA as they cannot be detected in whole cell extracts or mitochondrial extracts from an untagged control strain (S3 Fig). In order to determine the precise mitochondrial localization a protease protection assay was performed. Isolated mitochondria were subjected to proteinase K treatment in the presence or absence of 20mM Hepes, pH 7.4 to remove the outer mitochondrial membrane, or Triton X-100 to rupture both membranes. The inter membrane space protein, cytochrome b (Cob), is sensitive to digestion when the mitochondria are treated with 20mM Hepes (Fig 2A). The ~ 55 kDa band of Rad51p is also sensitive to digestion when the mitochondria are treated with 20mM Hepes suggesting this isoform is also found in the inter membrane space (Fig 2A, lanes 1 and 2). It is possible this isoform is also found in the matrix but is not detectable with our current system. Citrate synthase (Cit1p), a matrix protein (Fig 2A) and the ~ 60 kDa band of Rad51 remains protected from proteinase K unless treated with Triton X-100, confirming Rad51p’s localization in the matrix of the mitochondria in yeast (Fig 2A, lane 4). The specific modification(s) responsible for the larger Rad51p mitochondrial isoform(s) is currently unknown. Mitochondria were also purified in the same manner from cells expressing Rad59-HA from the endogenous locus. A protease protection assay confirmed the presence of Rad59 in the matrix of the mitochondria (Fig 2A and S3 Fig).

Fig. 2. Rad51p and Rad59p localize to the mitochondrial matrix.

(A) Intact mitochondria, mitoplasts, or Triton X-100 lysed mitochondria were treated with proteinase K and subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. Por1p, outer membrane protein; Cob, intermembrane space protein; Cit1p, matrix protein. (B) Rad51p physically interacts with mtDNA. DNA samples (3 biological replicates) were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against endogenous Rad51p or V5 epitope tag (mock). Samples were evaluated by qPCR and changes in fold enrichment were compared to the mock IP. Error bar indicates SD. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the Rad51p IP and the mock IP (** = p ≤ 0.01). In order to further confirm the mitochondrial localization of Rad51p and to determine if it binds directly to mtDNA, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed using an antibody to the native untagged Rad51 protein. Using primers that anneal to a region previously demonstrated to be near a recombination hotspot in the yeast mitochondrial genome, we were able to detect a significant 4-fold (p = 0.008) increase in mtDNA signal in the Rad51p IP compared to the mock IP (Fig 2B) [41]. The western blot and ChIP data together clearly demonstrate the Rad51p is localized to the mitochondria of S. cerevisiae.

Rad51p, Rad52p, and Rad59p promote spontaneous mitochondrial deletions

Rad51p, Rad52p, and Rad59p participate in spontaneous DRMD events and the repair of induced DSBs in the nucleus [26]. To determine whether they also contribute to spontaneous mitochondrial DRMD, we generated deletions of these genes both individually and in combination, in yeast strains containing genetic reporters for nuclear and mitochondrial DRMD events [38–40].

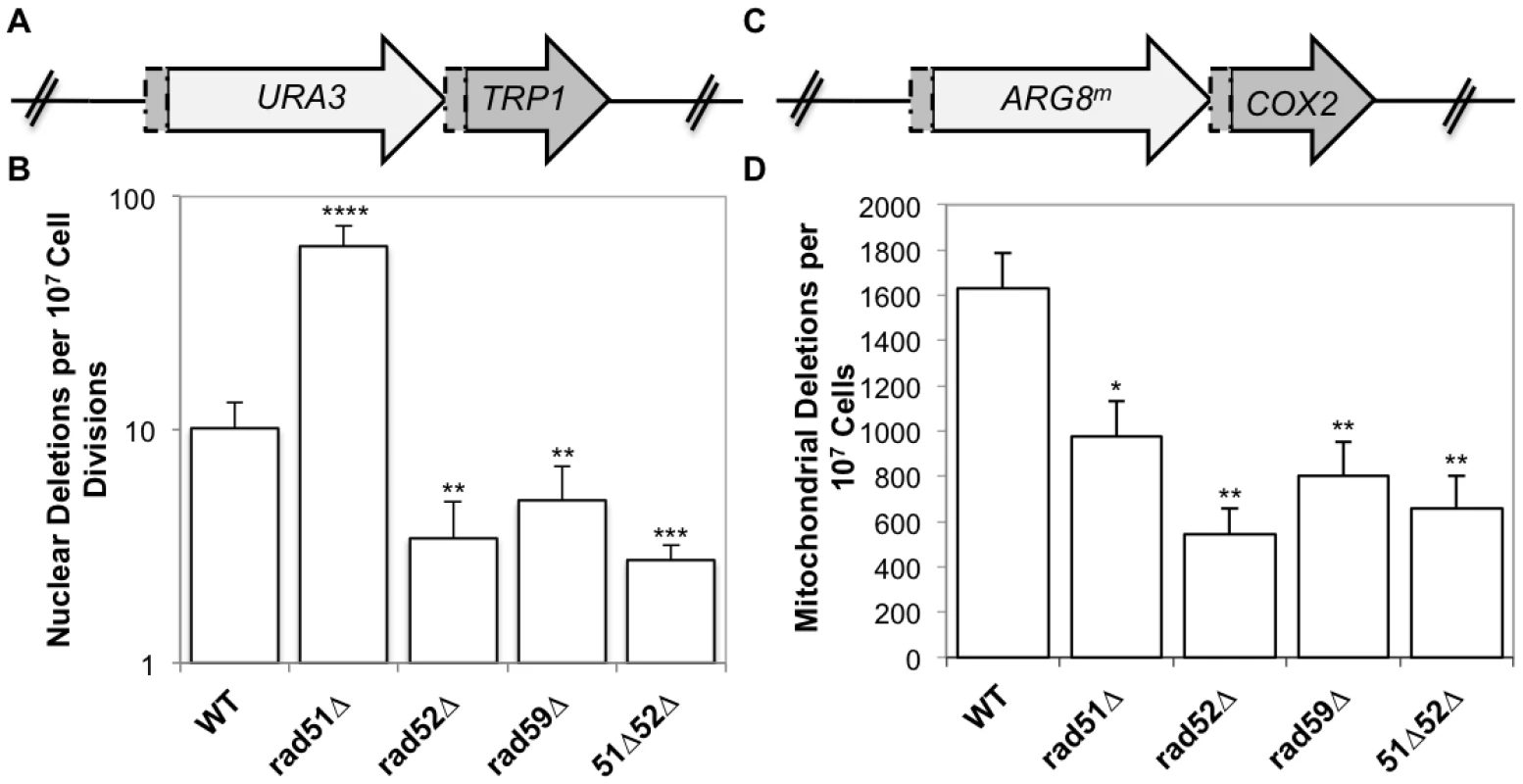

The mitochondrial reporter consists of the ARG8m gene, a mitochondrial derivative of the nuclear ARG8 gene that has been recoded to reflect the codon usage and bias of a mitochondrial gene [42]. The ARG8m gene is inserted 99 bp into the COX2 gene followed by the entire COX2 gene lacking the start codon (Fig 3B). This generates 96 bp of directly repeated sequence flanking ARG8m. Strains that contain an intact reporter are phenotypically Arg+ and respiration deficient. When a mitochondrial DRMD event occurs, the strain becomes respiration proficient and will become Arg- following sorting to homoplasmy, which occurs rapidly in yeast. The nuclear reporter is similarly constructed, with the URA3 gene inserted 99 bp into the TRP1 gene, followed by the entire TRP1 gene, generating 96bp of directly repeated sequence (Fig 3A) [39]. Strains with an intact reporter are phenotypically Ura+ and Trp-. If a nuclear DRMD event occurs, the strain becomes Ura- and Trp+. Plating of cells on the appropriate media allows selection of both mitochondrial and nuclear deletions from the same culture.

Fig. 3. Spontaneous nuclear and mitochondrial repeat mediated deletions.

(A) The nuclear DRMD reporter. The URA3 gene was inserted 99 bp into the TRP1 sequence, and is followed directly by the entire TRP1 gene lacking the start codon, resulting in a 96 bp direct repeat flanking the URA3 marker. Spontaneous deletions are selected on medium lacking tryptophan, and rates were determined using the method of the median. (B) The mitochondrial DRMD reporter. The ARG8m gene was inserted 99 bp into the COX2 sequence, and is followed directly by the entire COX2 gene lacking the start codon, resulting in a 96 bp direct repeat flanking the ARG8m marker. Spontaneous deletions are selected on medium containing glycerol as the sole carbon source, and rates were determined using the method of the median. (C) Average rates of nuclear DRMD. (D) Average rates of mitochondrial DRMD. Error bars indicate SD. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the mutant and wild-type rates (* = p ≤ 0.05, ** = p ≤ 0.01, *** = p ≤ 0.001, **** = p ≤ 0.0001). As we have previously shown, the mitochondrial deletion rate is approximately160-fold greater than the nuclear rate for similar repeats in wild-type cells. It is important to note that nuclear and mitochondrial rates should not be compared directly, since the multicopy nature of the mitochondrial genome, and its subsequent replication and segregation into daughter cells will impact the rate. Rates within each compartment are compared between wild-type and mutant strains. Deletion of RAD52 or RAD59 resulted in similar decreases of both nuclear and mitochondrial DRMDs (Fig 3C and 3D). Spontaneous nuclear and mitochondrial DRMDs decreased 3-fold in the rad52-Δ strain (p = 0.001, in each case) and 2-fold in the rad59-Δ strain (nuclear p = 0.001, mitochondrial p = 0.002) relative to wild-type. This suggests that the contribution of Rad52p and Rad59p to the generation of spontaneous deletions is equally as important in both the nucleus and mitochondria. In contrast, RAD51 deletion resulted in different nuclear and mitochondrial phenotypes, with a 6-fold increase in nuclear DRMD (p = 2 x 10-8) and an approximately 2-fold decrease in mitochondrial DRMD (p = 0.01) (Fig 3C and 3D). The nuclear spontaneous DRMD results for this strain are consistent with the current model of SSA, however, the decrease measured for mitochondrial DRMD is not. According to the current nuclear model, SSA is dependent on Rad52p and Rad59p and independent of Rad51p. Deletions generated by SSA increase in the absence of accurate repair mediated by Rad51p [28,43]. Thus, the observed decreases in nuclear DRMD events in the rad52-Δ, rad59-Δ, and rad51-Δ rad52-Δ strains, and the increase in nuclear DRMD events in rad51-Δ strains were as expected [27,28]. The decrease in mitochondrial DRMD events observed in the rad51 null mutants indicates that in contrast to the nuclear DRMD events, spontaneous mitochondrial DRMDs are at least partially dependent on Rad51p, suggesting a unique functional role for Rad51p in mitochondria.

To confirm that the decreases in mitochondrial DRMD rates in the rad mutants are due to specific deficiencies in mitochondrial pathways leading to deletions, and not due to general mitochondrial genome instability, the spontaneous frequency of petites was measured in each of the above mutants. Spontaneously arising petite colonies (ρ-) are non-respiring, usually due to large-scale deletions and rearrangements of mtDNA, and do not grow on non-fermentable carbon sources such as glycerol [10]. The mechanism by which these deletions and rearrangements occur has not been defined, although homologous recombination has been proposed [10]. None of the deletions we tested exhibited any significant change from wild-type in the frequency of respiration loss (S2 Table). This suggests that the phenotypes we observe do not result from a general increase in mtDNA instability, and these proteins are not involved in the mechanism that generates spontaneous petite colonies.

Specific mitochondrial double-strand breaks increase the frequency of mtDNA deletions

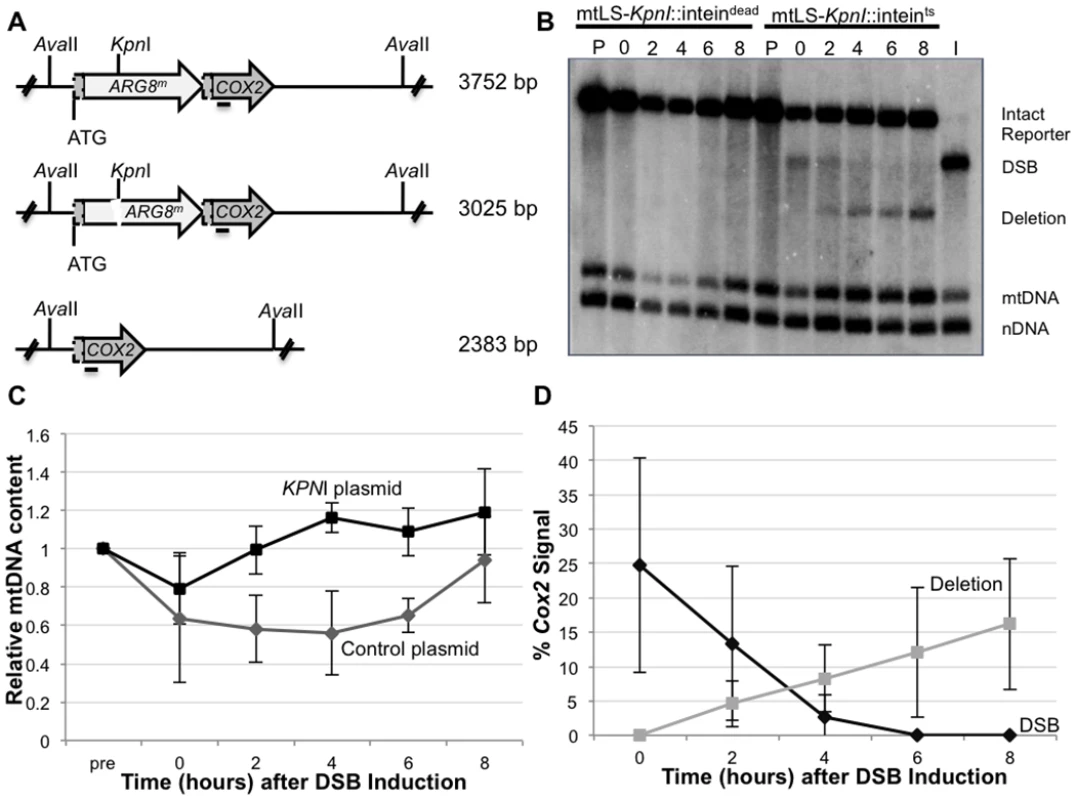

The ARG8m sequence used in our mitochondrial reporter contains a unique KpnI restriction site. Cleavage at this site generates a specific DSB 370 bp downstream of the ARG8m start codon, with 4 bp 3’ single-stranded complementary overhangs at the broken ends (Fig 4A). We previously reported that the galactose-inducible promoter regulating the expression of our mtLS-KpnI was leaky, which stimulated the generation of deletion products prior to the addition of galactose [40]. In order to ensure that we did not have premature expression of KpnI endonuclease, a temperature sensitive intein was inserted into the active site of KpnI [44]. This intein self-cleaves at 20°C generating an active KpnI enzyme. A control strain was also constructed utilizing a nonfunctional intein (intdead) that cannot self-cleave at any temperature [44].

Fig. 4. Inducing a specific mitochondrial DSB.

(A) The mitochondrial DRMD reporter, with restriction recognition sequences indicated. Horizontal line beneath COX2 indicates where the COX2 probe anneals. (B) Representative Southern blot of AvaII-digested DNA extracted from EAS748 containing pEAS115 (mtLS-KpnI-inteindead) or pEAS114 (mtLS-KpnI-inteints). Both strains were grown in SRaffinose-Arg-Ura until OD600 = 0.150. Galactose was added to a final concentration of 2%, and the strains were shifted to 20°C to induce the either mtLS-KpnI-inteints or mtLS-KpnI-inteindead. Genomic DNA in lanes labeled P are from preinduced cultures. Cultures were incubated for 16–18 hours at 20°C and samples were taken for the time 0 timepoint. The cultures then were shifted to 30°C to allow repair. Lane I contains DNA from the t = 0 timepoint of the mtLS-KpnI-inteints-containing strain digested in vitro with KpnI and AvaII to demonstrate the migration of DNA with a DSB. The 21S rRNA gene was probed to detect total mtDNA. The 25S rRNA gene was probed to detect total nuclear DNA. (C) Relative mtDNA content was determined by taking the ratio of the 21S rRNA signal and the 25S rRNA signal, then normalizing to the t = 0 sample for each strain. (D) The intensity of the COX2-hybridizing bands were measured using Image Lab software (www.biorad.com) The proportions of the total COX2 signal present in the DSB and deletion products were calculated as a percent of the total COX2 signal. This modification allows tight control of the activity of mtLS-KpnI. Southern blot analysis shows no detectible digestion at the mitochondrial KpnI recognition sequence, and no evidence of deletion product prior to induction of mtLS-KpnI-intts (Fig 4B, lane P). KpnI cleavage is achieved by inducing mtLS-KpnI-intts expression with galactose and reducing the incubation temperature to 20°C (Fig 4B, lane 0). Furthermore, the frequency of DSB-induced DRMDs increases linearly with extended incubation time at 20°C prior to assaying at 30°C, suggesting that KpnI activity is largely restricted to 20°C (S1 Fig). Longer incubations at 20°C generated a larger proportion of DSBs, but never exceeded 60% of the total COX2 signal. This result may suggest that some genomes may not be accessible to the KpnI enzyme or that alternative repair processes are rapidly repairing the break (S4 Fig). In subsequent experiments, 16–18 hours incubation at 20°C was used to ensure significant visible DSBs were generated.

Quantification of COX2-hybridizing species from independent experiments reveals that an average of 30.2 ± 16.7% of the COX2 signal appears as a specific KpnI digested fragment after 16–18 hours incubation at 20°C, and no measurable deletions are observed (Fig 4B and 4D). Two hours after cultures are returned to 30°C, deletion products can be observed, and their concentration continues to increase over the course of the experiment to represent, on average, 16.2% of the COX2 signal (Fig 4B and 4D). Thus, the percent of the COX2 signal that hybridizes to DRMD products after 8 hours at 30°C is approximately equivalent to two-thirds of the amount observed in the DSB at time 0. By 8 hours after shift to 30°C the cultures have reached saturation, and no further increase in deletion product was seen when cultures were monitored for an additional 4 hours (S4 Fig), suggesting that repair is complete by 8 hours in the wild-type strain. In addition, while breaks are stimulated at 20°C, the bulk of DRMD events occur after the cells are shifted back to 30°C, since deletions are not detected by Southern blot analysis at time of shift back to 30°C. In control cultures, expressing the mtLS-KpnI-intdead, no stimulation of DRMD was observed, indicating that no significant cleavage of the intdead occurs.

We included two additional probes in our Southern blot analysis to quantify potential changes in mtDNA content relative to nuclear DNA. The first, a mtDNA probe, hybridizes to the 21S rRNA gene approximately 10 kb from the site of the induced DSB. The second is a nuclear probe that hybridizes to the 25S rRNA gene. These probes were used to measure the ratio of mitochondrial to nuclear DNA during the course of these experiments. We find that shifting the cells to 20°C caused a slight decrease in mtDNA content relative to the nuclear control in both the mtLS-KpnI::intts strain and mtLS-KpnI::intdead strain indicating that this decrease is due to the temperature shift and not the expression of active KpnI (Fig 4C). The mtLS-KpnI::intts expressing strains recovered significantly faster than the control strain, however, both the control and mtLS-KpnI::intts strains fully recovered to pre-induction levels of mtDNA after eight hours of growth at 30°C (Fig 4C).

It has been reported that mitochondrial DNA can move to the nucleus, although this occurs rarely [45]. In order to ensure that the signal we are detecting in the Southern blots is originating from the mitochondrial genome, both pre - and post-induction wild type cultures were treated with ethidium bromide. Growth of yeast in culture medium in the presence of ethidium bromide has been demonstrated to suppress mtDNA replication [46]. Southern blot analysis confirms that greater than 98% of the signal from the COX2 and the 21S rRNA probes is lost when the cells are subjected to ethidium bromide treatment. (S2 Fig).

Eight hours after shifting to 30°C, approximately 16% of the mtDNA detected contains a deletion of the ARG8m reporter (Fig 4B and 4D). However, the distribution of the 16% of deleted genomes within the population of cells is unclear. For example, many deletions may be concentrated in a small subset of the cell population, or distributed throughout, with most cells containing one or more mitochondrial genomes with deletions. By assaying for respiring colonies, we can directly distinguish between these possibilities. Cells from time 0 in the above experiments (Fig 4B) were plated on non-selective medium, allowed to grow, and individual colonies were tested for the presence of the intact reporter (Arg+) or the deletion (respiration proficient) by replica plating. We found that 50% of the population is respiration competent, consistent with a wide distribution of mitochondrial genomes containing deletions (Fig 5). The majority of these colonies also contain Arg+ cells, indicating heteroplasmy at the time of plating. Significantly, we did not observe DSB stimulation of ρ- or ρ0 (lacking mtDNA) petites, which would be both Arg- and non-respiring. After cutting, 1.5% of the colonies from wild-type cells were both Arg- and respiration deficient. This is comparable to the percentage of spontaneous petites seen in wild-type cultures prior to KpnI-induced mtDNA DSBs, indicating the induction of the DSB does not lead to general mitochondrial genome instability (S3 Table).

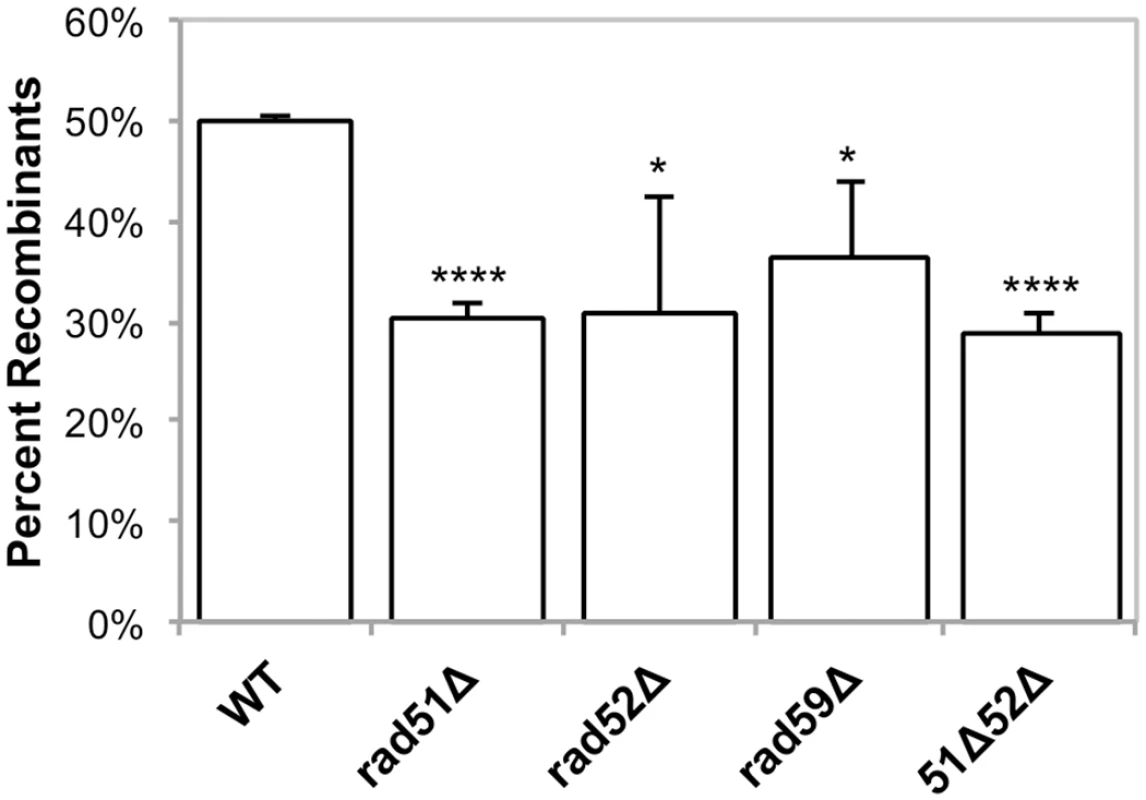

Fig. 5. Induced mitochondrial repeat mediated deletions.

Strains were grown in SRaffinose-Arg-Ura until OD600 = 0.150. Galactose was added to a final concentration of 2%, and the strains were shifted to 20°C for 16–18 hours in order to induce DSBs via mtLS-KpnI. Appropriate dilutions were plated on YPD and allowed to grow for 3 days at 30°C. The colonies were then replica plated to YPG and SD-Arg. Growth on YPG was scored in order to determine the percent of colonies that had at least some cells that had undergone a deletion after non-selective growth. Error bars indicate SD. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the mutant and wild-type rates (* = p ≤ 0.05, **** = p ≤ 0.0001). Rad51p, Rad52p, and Rad59p influence mitochondrial DSBR

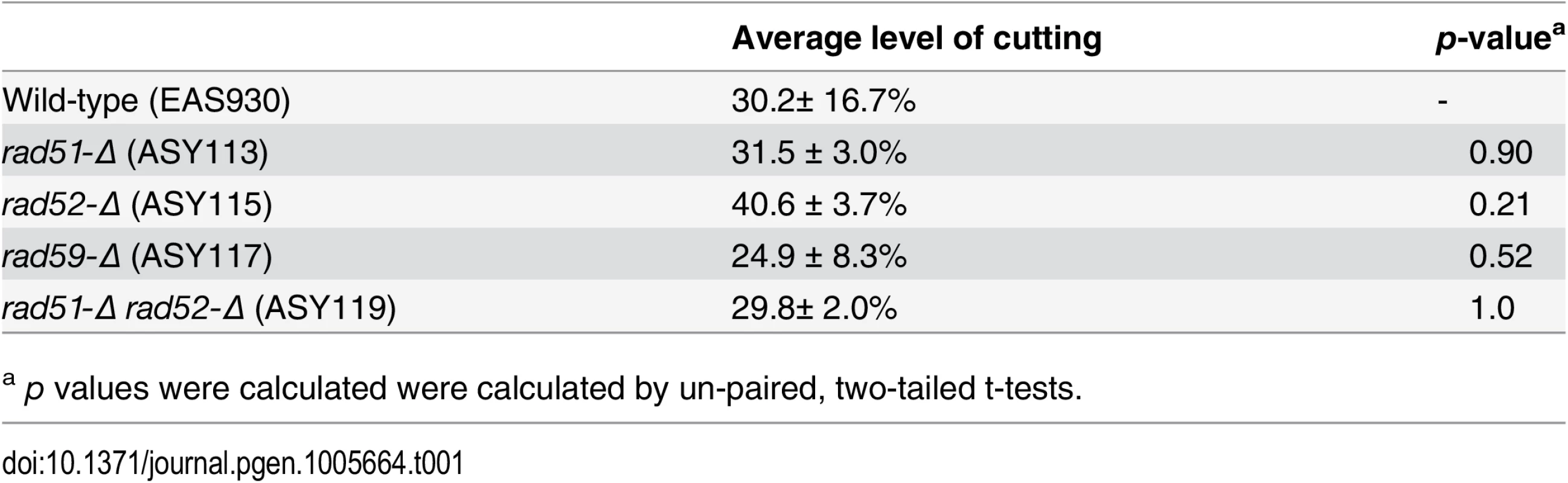

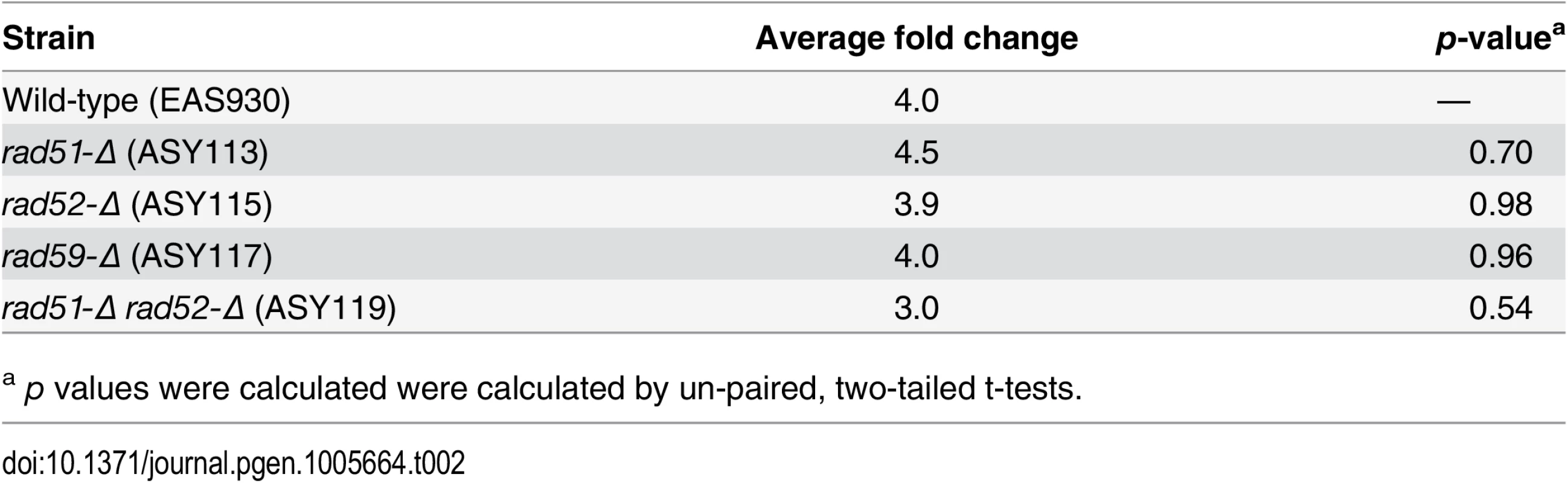

To determine the effect of Rad51p, Rad52p, and Rad59p on the repair of mitochondrial DSBs, plasmids expressing either mtLS-KpnI::intts (pEAS114) or mtLS-KpnI::intdead (pEAS115) were introduced into the mutant strains. Mitochondrial DSBs were induced as described above, and Southern blots reveal that the level of cutting by mtLSKpnI-intts at the time of shift to 30°C in all of the mutant strains is equivalent to wild-type. (Table 1).

Tab. 1. Average level of cutting after 16 hours of mtLSKpnI-intts induction.

a p values were calculated were calculated by un-paired, two-tailed t-tests. In our genetic assay for induced deletions, 50% of colonies from wild-type cells had undergone at least one selectable deletion event (Fig 5), and each of the RAD single mutants exhibited a modest, yet significant, decrease in selectable deletion events when compared to wild-type. In the rad51-Δ, rad52-Δ, rad59-Δ strains 30% (p = 4.2 x 10-5), 31% (p = 0.03), and 36% (p = 0.03) of the cells were able to give rise to respiring colonies respectively, after 16–18 hours of inducing DSBs (Fig 4). As with the wild-type strain, non-respiring and Arg- petites did not significantly increase after DSB induction in these strains (S3 Table).

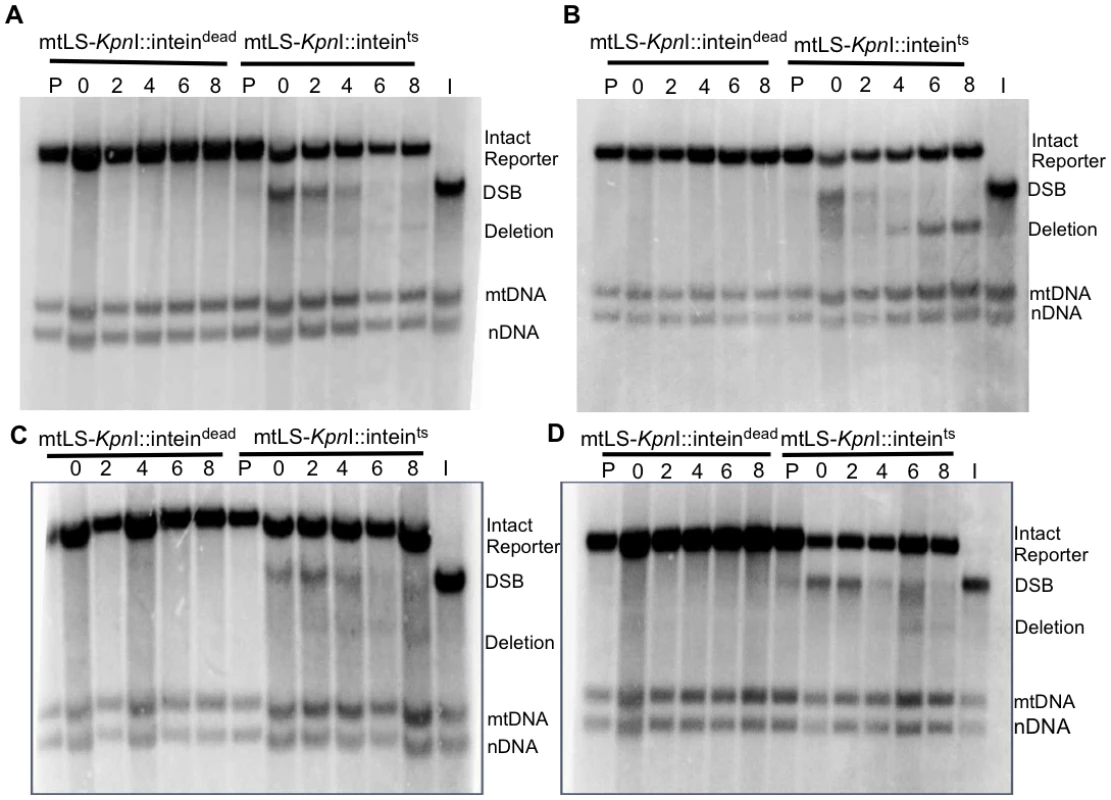

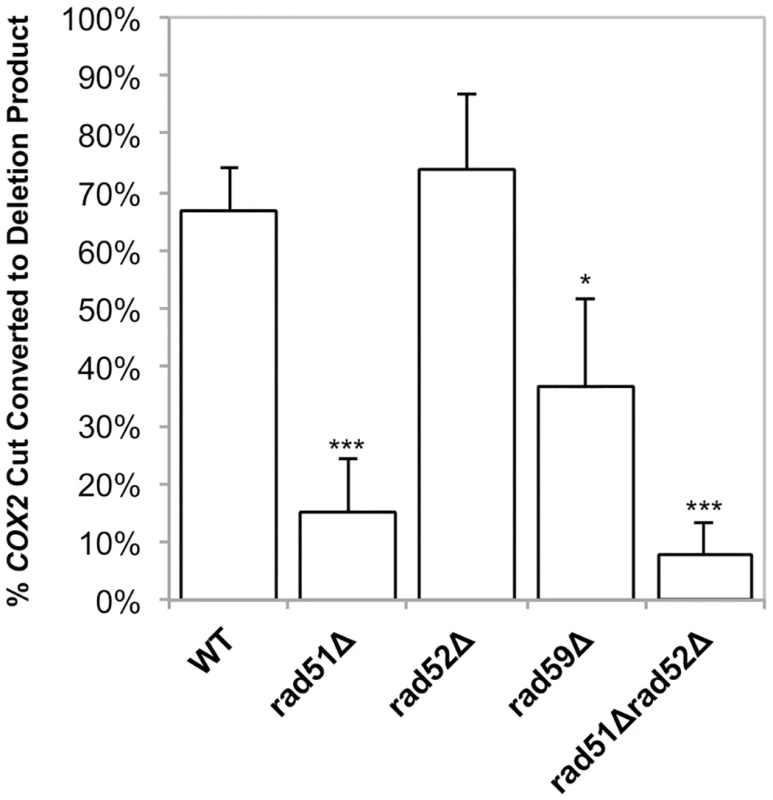

Southern blots analysis of the mtDNA in rad51-Δ and rad59-Δ strains revealed that the same proportions of the mitochondrial genomes are being cut (31% and 25%, respectively) compared to the wild-type strain (Table 1). However, consistent with the genetic data, these cut genomes are not converted to deletion products to the same extent as wild-type (Figs 6A and 6C and 7). In the rad51-Δ strain after 8 hours of recovery only 14.4% ± 7.9 (p = 0.001) of the cut COX2 signal had been converted to a deletion product compared to 66.8% ± 7.4 in the wild-type strain. In the rad59-Δ strain, 36.7% ± 14.9 (p = 0.01) of the cut COX2 signal is converted to a deletion product. The cut band is completely lost in all mutant and wild-type strains after 8 hours of recovery, suggesting that DSB processing is not being eliminated but the pathway choice is altered in the absence of Rad51p or Rad59p.

Fig. 6. Repair of induced mitochondrial DSBs in HR single mutants.

All samples were obtained after 16–18 hours of mtLS-KpnI induction. DNA was extracted from the appropriate strains and digested with AvaII. Samples in lanes labeled P are from pre-induced cultures. Lane I is the t = 0 sample from the mtLS-KpnI-inteints expressing strain digested with KpnI and AvaII to demonstrate the migration of the reporter with a DSB in relation to the other COX2 bands. (A) Representative Southern blot of rad51-Δ strains ASY114 (inteindead) and ASY113 (inteints). (B) Representative Southern blot of rad52-Δ strains ASY116 (inteindead) and ASY115 (inteints). (C) Representative Southern blot of rad59-Δ strains ASY118 (inteindead) and ASY117 (inteints). (D) A representative Southern blot of rad51-Δ rad52-Δ strains, ASY120 (inteindead) and ASY119 (inteints). Fig. 7. Conversion of DSBs to deletion product is impaired in HR mutants.

Experiments were performed as in Fig 4. The ratios of the amount of COX2 signal in the cut band at t = 0 and the amount of COX2 signal in the deletion product at t = 8 were calculated. The intensity of the COX2-hybridizing bands was measured using Image Lab software (www.biorad.com). The proportions of the total COX2 signal present in the DSB and deletion products were calculated as a percent of the total COX2 signal. Error bars indicate SD. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the mutant and wild-type rates (* = p ≤ 0.05, *** = p ≤ 0.001). Analysis of the rad52-Δ strain revealed no significant change in cut COX2 signal at time 0, 40.6% ± 2 (p = 1.0) compared to wild-type (Table 1). Surprisingly, in contrast to the genetic data, the proportion of the cut COX2 signal converted to deletion product, 55.9% ± 26.3 (p = 0.5) is equivalent to wild-type. We know that the distribution or maintenance of these genomes in the population of cells is not equivalent to wild-type because only 31% of the colonies contain respiring cells, while 50% of wild-type colonies contain respiration-competent cells after 3 days growth on solid medium.

The rad51-Δ rad52-Δ double mutant exhibited the same decrease in deletion events as the rad51-Δ and rad52-Δ single mutants, with 29% (p = 4.5 x 10-5) of colonies capable of respiration after induction of mtLS-KpnI::intts (Fig 5). Interestingly, the mtDNA in this mutant displayed a similar significant decrease in the proportion of cut COX2 signal converted to deletion product, 7.6% ± 5.7 (p = 0.0004), as the rad51-Δ strain (p = 0.3) (Figs 6D and 7). This would suggest that during the initial generation of deletion products after induction of a DSB that RAD51 is epistatic to RAD52 in the mitochondria.

We considered the possibility that the relative levels of the different COX2-hybridizing species in all cases might be affected by differences in growth rates of the mutant and wild-type strains under the conditions of the experiment. Monitoring the growth of the cultures by optical density and total cell counts throughout the protocol revealed that the rad52-Δ and rad59-Δ strains displayed a 20% increase in doubling time at 20°C, while the rad51-Δ mutant strain was comparable to the wild-type. All strains undergo one population doubling during the eight-hour recovery period. It is not likely then that the wild-type levels of deletion product generated in the rad52-Δ strain are dependent on this growth defect, considering the rad59-Δ strain also has inhibited growth at 20°C but clearly shows impaired deletion product formation. We believe there is no significant correlation of differences in growth rate with differences in DSBs or deletions (Fig 6B).

Single-stranded DNA is present at break after induction of KpnI

In the nucleus, the resection of the 5’ ends at a DSB commits the cell to repairing the lesion by HR. In order to determine if the DSBs detected by Southern blot in mitochondria are being processed, such that 3’ ssDNA is generated, the mtDNA was blotted and probed with a ssDNA probe that would anneal to 3’ single-stranded overhangs approximately 200 nucleotides from the site of the break. All of the strains exhibited a significant 3–4.5 fold increase in ssDNA after 16 hours of cleavage (Table 2). The increase in ssDNA at the site of a DSB suggests that the ends of mtDSBs are resected in a manner consistent with known nuclear HR models. The presence of similar levels of 3’ ssDNA in the wild-type, rad51-Δ, rad52-Δ, rad59-Δ, and rad51-Δ rad52-Δ strains is also consistent with HR models that show these proteins function in the repair of DSBs after resection has occurred (Table 2).

Tab. 2. Average fold change of amount of 3’ ssDNA at KpnI cleavage site after induction.

a p values were calculated were calculated by un-paired, two-tailed t-tests. Discussion

The faithful maintenance of the mitochondrial genome is required for eukaryotic cells to have a functional electron transport chain. Mutations and deletions in the mitochondrial genome can compromise energy production for the cell. However, studying mtDNA repair has been difficult, due to the necessity for intact mitochondrial genomes in most eukaryotic systems. Thus, the extent of mtDNA repair has remained unclear. For years it was believed that since there are multiple copies of the mitochondrial genome, the damaged mtDNA was simply degraded in lieu of repair [47]. While there is evidence that mitochondrial genomes are degraded under high levels of chronic damage, it is unclear if this is the response under more moderate damaging conditions [48].

Mitochondrial base excision repair has been more extensively studied [9,49,50], indicating that at least some highly conserved repair pathways exist in mitochondria. In addition, there is evidence for homologous recombination (HR) repair pathways in mitochondria of several different species including yeast, Drosophila, and mice [40,51,52]. In this study, we have shown that the HR proteins Rad51p and Rad59p localize to the matrix of the mitochondria. We have also demonstrated that Rad51p, Rad52p and Rad59p impact the rate of spontaneous mitochondrial DNA deletions and the repair of induced mitochondrial DSBs in yeast. This is the first study to demonstrate that Rad51p, Rad52p, and Rad59p impact the repair of specific mtDNA lesions.

In the present study, we have greatly improved our reporter system to introduce a maximum of a single DSB per mitochondrial genome to identify the proteins involved in the repair of these breaks. We had previously generated a plasmid expressing a galactose-inducible, mitochondrially-targeted KpnI endonuclease that showed evidence of expression under uninduced conditions [40]. To add an additional level of control over endonuclease activity, we have inserted a temperature-sensitive intein into the active site of the KpnI enzyme. This modified expression construct does not result in efficient cleavage of the mitochondrial genome, since we must incubate at the permissive temperature for 16–18 hours to observe digestion of approximately 30% of the mtDNA by Southern blot analysis (Fig 3). However, it is likely that a larger proportion of breaks are present, but these breaks are not detectible due to the end resection that occurs at the site of DSBs. We have demonstrated that 3’ single-stranded ends are present at the site of the break following cleavage. The heterogeneous nature of these intermediates would render them undetectable by our current Southern blot techniques. We would also be unable to detect any breaks that occurred and were subsequently ligated with fidelity. This system is an improvement over our previously published mtLS-KpnI construct, as there is no molecular or genetic evidence of mtDNA cleavage prior to induction, nor is there selection for cleavage-resistant genomes in our cultures. In addition, this level of digestion is sufficient to observe DNA repair over the course of 8 hours after shifting back to the non-permissive temperature for intein cleavage.

It bears noting that deletion products do not appear after extensive incubation at the permissive temperature for intein cleavage, although they are clearly visible by 2 hours after shift back to the non-permissive temperature. It is unlikely that this delay simply results from slow repair, because no deletions are visible on a Southern blot after 24 hours of incubation at the permissive temperature (S1 Fig). Rather, this observation suggests that at least one step of the deletion process is inefficient or non-functional at 20°C. Deletion formation does not appear to be the only temperature-dependent process. We observed a slight decrease in relative mtDNA copy number upon shifting the cultures to 20°C. However, a decrease was also seen in our controls expressing mtLS-KpnI-intdead, leading us to conclude that temperature shift alone is cause of this temporary decrease in mtDNA copy number (Fig 4C). Consistent with this hypothesis, both strains recover by 8 hours after shift back to 30°C. We conclude that in our system, repairable DSBs do not stimulate mtDNA loss from the population of cells. Our genetic assay supports this observation, as induction of a specific mitochondrial DSB does not stimulate an increase in the loss of functional mtDNA. Therefore, mechanisms exist in cells to maintain functional mtDNA. It is important to note that this selection cannot be applied at the level of respiratory function, or ATP production, as the genomes containing the intact DRMD reporter confer an Arg+ phenotype, and have active mitochondrial protein synthesis, but do not assemble a functional electron transport chain. In yeast, there is evidence for a mitochondrial G1-to-S phase checkpoint that is activated in response to the loss of mtDNA and not linked to respiratory capacity [53], suggesting that the cell has a mechanism for sensing mtDNA. Clearly, although mtDNA can be eliminated by treatment of cells with ethidium bromide and spontaneous petite mutants arise in yeast cultures [10] this should not be taken as evidence that mechanisms do not exist to maintain an intact genome.

Our results demonstrate that Rad51p, Rad52p, and Rad59p are involved in a portion of DSBR events. In the nucleus, SSA is the primary HR pathway that generates DSB-induced deletions between repeated sequences [26], and it seems likely to be an important pathway for spontaneous events at direct repeats as well. This mutagenic DSB repair pathway leads to the deletion of one of the repeats and any intervening sequence. In the nucleus, SSA is independent of Rad51p, but requires Rad52p and Rad59p [43]. Previous studies have shown [26,27], and this study confirms, that in the nucleus, deletion of RAD51 leads to an increase in deletions generated by a Rad52p-dependent pathway, likely SSA (Fig 3B). In contrast, in mitochondria, the deletion of RAD51 caused a significant decrease in the frequency of spontaneous deletions and those generated after inducing a DSB. Genetically, the contribution of Rad51p to the generation of DRMDs was equivalent to Rad52p and Rad59p (Figs 3D and 5). This would imply that both compartments use at least some of the same proteins to generate these deletions, but that the pathways these proteins are participating in are unique compared to the nucleus. In the absence of the full suite of nuclear HR proteins in the mitochondria we speculate that HR proteins, such as Rad51, have been co-opted to perform their HR functions in contexts that are not necessary in the nucleus.

In regard to the generation of spontaneous deletions, one possible explanation is that the initiating event that generates spontaneous mtDNA deletions is a replication error such as slippage, or a stalled fork that triggers template switching, and thus relies on a different suite of proteins, but is still dependent on the presence of homologous sequences and thus requires HR proteins, such as Rad51p. In our assay where we induced a DSB, an explanation for the increased dependence on Rad51p for deletion formation, is that the AT-rich mitochondrial genome requires further stabilization of the annealed intermediate and thus utilizes Rad51p uniquely in this manner. However, at this time, we cannot rule out the existence of a novel Rad51p dependent mechanism that generates deletions solely in the mitochondria.

The localization of Rad51p and Rad59p to mitochondria strongly suggests that the effects we observe on deletion product formation in the mutant strains are direct, for several reasons. First, we demonstrated that mitochondrial DSB repair and homology-dependent deletions were specifically affected, while mitochondrial genomes were stably maintained, as indicated by the maintenance of wild-type copy number and the lack of additional ρ- in our mutant strains. In addition, the epistatic relationships between RAD51, RAD52, RAD59 with respect to mitochondrial phenotypes were not the same as the nuclear phenotypes, most notably in the case of Rad51p, which had a similar impact on mitochondrial DRMD’s as both Rad52p and Rad59p. Finally, their action at DSBs is consistent with their known function. Identification of mitochondrial-specific factors that interact either physically or genetically with Rad51p, Rad52p, and Rad59p will help to elucidate the mitochondrial specific repair pathways or pathway components.

Materials and Methods

Media and strains

Media used in this study were previously described [39]. S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in S1 Table and are isogenic with DFS188 except NPY66, which is derived from DFS160 [38,54]. Single-deletion strains were constructed by one-step gene replacement of the wild-type gene with a kanMX marker using standard protocols [55]. Strains containing two gene replacements were constructed by mating isogenic haploid strains, dissecting diploids, and screening by PCR for the desired genotypes. The spontaneous DRMD reporter strain (LKY196) was constructed previously [39]. Gene deletions in this strain were constructed by mating and dissection. The desired genotypes were screened for by PCR. These strains were then cured of their mtDNA by treatment with ethidium bromide, and cytoduced with the mitochondrial reporter from NPY66 [56].

Mitochondrially localized, V5-tagged mtLS-KpnI was constructed by amplifying the bacterial KpnI gene from pETRK [57], using a 5’ primer containing the mitochondrial localization signal of COX4 5’-GGATCCATGCTGAGCCTGCGCCAGAGCATTCGCTTTTTTAAACCGGCGACCCGCACCCTGTGCAGCAGCCGCTATCTGGTGATGGTGATGATGGATGTCTTTGATAAAGTTTATAG-3’ and 3’ primer 5’ - TCTTTTCAATCCATAATAATTCAA-3’. The PCR product was cloned into pYES2.1 using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) then transformed into Top10F’ bacterial cells containing pACMK+, a plasmid that carries the KpnI methylase [57]. Transformants were screened by digestion with restriction endonucleases BamHI and XbaI. A positive clone was confirmed by sequencing and named pEAS101.

Mutant alleles of the VMA1 intein from yeast were obtained from C. Tan (University of Missouri) on pUGal4intdead and pS5Gal4intein TS303 [44]. Inteins were inserted into the mtLS-KpnI endonuclease gene by gap repair in pEAS101. The TS303 and intein-dead alleles were amplified from the above plasmid with 50 bp of KpnI flanking sequence using the same forward primer 5’-CAATAGATCCCGCAACTGATGTAAATGATCCTAAAATGTGGCAAGCATTGtgctttgccaagggtaccaat-3’ and reverse primers 5’-CCATTATTTGAATCCCAATAATTTTTTTTCATAACTTGATGACGTCCACAattatggacgacaacctggttggc-3’ and 5’-CCATTATTTGAATCCCAATAATTTTTTTTCATAACTTGATGACGTCCACActgatggacgacaacctgcttggc-3’, respectively. pEAS101 was digested with ZraI and contransformed into EAS748 [38] with each of the amplified intein cassettes. The primers are designed to insert the intein just before the cysteine at position 198 of KpnI. Transformants were selected on SD-Ura medium. Genomic DNA was collected from the transformants and plasmids were rescued by the transformation of E. coli Top10F’ cells and selection on LB+ampicillin. Plasmids containing the intein were screened by digestion with BamHI and BglI and confirmed by sequencing. pEAS114 contains mtLS-KpnI+inteints303. pEAS115 contained mtLS-KpnI+inteindead.

Mitochondrial isolation and protease protection assay

Mitochondria were isolated as previously described in Diekert et al., 2001 [58]. The protease protection assay was performed as previously described in Diekert et al., 2001 with the following modification. 200μg of isolated mitochondria were used in each protease protection assay for both the ASY092 (Rad51-HA) and ASY127 (Rad59-HA) strains. 100μg of isolated mitochondria were used in the protease protection assay for DFS188 (WT). Samples were subjected to western blot analysis on 10% SDS-PAGE gels. Antibodies used for detection were as follows: 1 : 2500 dilution of anti-HA-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 1 : 4000 anti-Cytb2 (generous gift from Dr. Tom Fox), 1 : 4000 anti-Cit1 (generous gift from Dr. Tom Fox), and 1 : 25,000 anti-POR1 (Invitrogen).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

A 150 ml culture (RCY248) was grown to OD600 = 0.800 in YPD and crosslinked in 1% formaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature. Cells were pelleted and washed twice in 1X TBS. Pellets were resuspended in 1ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes-KOH, pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% TritonX-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% SDS) and 0.4 g of glass beads. Cellular lysates were obtained by bead beating at 4°C for 2.5 minutes. The lysates were then sonicated to generate fragments between 400-700bp in size. Lysates were precleared by incubating with 20μl of Protein A/G magnetic beads (Thermo Scientific). One milliliter of lysate was incubated over night with either 1 μg of anti-Rad51 antibody (Abcam) or anti-V5 (mock) (Invitrogen) rocking at 4°C. Immune complexes were precipitated by incubating with 20 μl of Protein A/G magnetic beads (Thermo Scientific) for 1 hour at 4°C. Beads were washed twice with lysis buffer, once with LiCl buffer (, and twice with 1X TE. Immune complexes were eluted twice with 150μl of elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1M NaHCO3). Crosslinks were reversed by adding 0.2M NaCl and heating overnight at 65°C. DNA was purified and equal amounts of DNA were analyzed by qPCR using SYBR green mix (Biorad) with the following primer pair: 5’-GGTAAATAGCAGCCTTATTATG-3’, 5’-CGATCTATCTAATTACAGTAAAGC-3’.

Measuring nuclear and mitochondrial DRMDs and respiration loss

The rates of nuclear and mitochondrial spontaneous DRMDs and the average frequency of respiration loss were determined as previously described [39,40]. Fluctuation analyses consisted of 10–20 independent samples each. Rates were determined using the method of the median [59], and each experiment was performed a minimum of 3 times. Induced DRMDs were measured by growing strains to saturation in SRaffinose-Arg-Ura. These cultures were then diluted back to an OD600 ~ 0.08 and grown to OD600 of 0.15–0.20. A pre-induction sample was removed and an appropriate dilution was plated on YPD and incubated for 3 days at 30°C. A final concentration of 2% galactose was added to the remaining culture, which was then incubated at 20°C for 16–18 hours. A post-induction aliquot was then removed and the appropriate dilution was plated on YPD and incubated for 3 days at 30°C. All colonies were replica plated to YPG to score for deletion events, and SD-Arg to score for intact reporters. The average frequency and standard deviation of three or more independent experiments is shown. P-values were determined by un-paired, two-tailed t-tests using Microsoft Excel for Macintosh 2011.

Southern blot analysis

DNA for Southern blot analysis was prepared from cells grown as stated above. A pre-induction sample was obtained prior to induction with 2% galactose and shifting to 20°C. After 16–18 hours of cutting, the cultures were shifted back to 30°C and samples were collected after 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 hours. Total cellular DNA was extracted using standard procedures and transferred to Amersham Hybond-XL (GE Healthcare) nylon membranes following standard protocols. DNA was obtained from three independent experiments for each strain. Representative blots are shown in Figs 3, 5 and 6. The COX2, nuclear 25S rRNA, and mitochondrial 21S rRNA probes were constructed as previously described [40]. Quantification of Southern blots was performed using Image Lab software (www.biorad.com). The percentage of the COX2 signal represented by deletion product and break product was calculated by measuring the intensity of each band and dividing by the total signal for all 3 COX2-hybridizing bands.

In order to confirm that the signal from the COX2 probe was originating from the mtDNA the mitochondrial DNA from both pre-induction and time 0 cultures were diluted 1 : 1000 into minimal media containing 0.125mg of ethidium bromide and grown to saturation [46]. The saturated cultures were diluted 1 : 1000 into minimal media containing 0.125mg of ethidium bromide and grown to saturation. DNA was obtained from these cultures using standard protocol. The ethidium bromide treated cultures as well as DNA collected from these cultures prior to the ethidium bromide treatment were analyzed by Southern blot as described above.

Slot blot analysis of 3’ ssDNA

Samples collected at time 0 were also subjected to slot blot analysis in order to detect 3’-ssDNA near the KpnI cleavage site. Total cellular DNA was extracted using standard procedures. Samples were prepared as previously described [60] with the following modifications. Native genomic DNA (1μg) was prepared in 10X SSC and denatured samples (0.15μg) were prepared in 0.4N NaOH for 5 minutes. The samples were neutralized by the addition of 3M sodium acetate. Native and denatured samples were transferred to Amersham Hybond-XL (GE Healthcare) nylon membranes with a slot blot manifold following the manufacturers suggested protocol (Schleicher & Schuell). The DNA was UV cross-linked to the membrane. The membrane was prehybridized for a minimum of 1 hour in prehybridization solution (6X SSC, 5X Denhardt’s, 0.05% sodium pyrophosphate, 3 mg boiled fish sperm) at 37°C. The membrane was probed with a small synthetic end-labeled oligo (5’ CAGCAATACCAGCTGTGAAATCG 3’) overnight at 48°C. This probe anneals 213 nucleotides up stream of the KpnI cleavage site. The membrane was washed in 6X SSC, 0.05% sodium pyrophosphate at room temperature. Quantification of slot blots was performed using Image J software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). The native samples were normalized to the appropriate denatured control. p-values were determined by un-paired, two-tailed t-tests using Microsoft Excel for Macintosh 2011. Three independent experiments were performed for each strain.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Schapira AH (2012) Mitochondrial diseases. Lancet 379 : 1825–1834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61305-6 22482939

2. Ylikallio E, Suomalainen A (2012) Mechanisms of mitochondrial diseases. Ann Med 44 : 41–59. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.598547 21806499

3. Yang JL, Weissman L, Bohr VA, Mattson MP (2008) Mitochondrial DNA damage and repair in neurodegenerative disorders. DNA Repair (Amst) 7 : 1110–1120.

4. Wallace DC (2012) Mitochondria and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 12 : 685–698. doi: 10.1038/nrc3365 23001348

5. Milone M (2012) Mitochondria, diabetes, and Alzheimer's disease. Diabetes 61 : 991–992. doi: 10.2337/db12-0209 22517655

6. Federico A, Cardaioli E, Da Pozzo P, Formichi P, Gallus GN, et al. (2012) Mitochondria, oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. J Neurol Sci 322 : 254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.05.030 22669122

7. Ma YS, Wu SB, Lee WY, Cheng JS, Wei YH (2009) Response to the increase of oxidative stress and mutation of mitochondrial DNA in aging. Biochim Biophys Acta 1790 : 1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.04.012 19397952

8. Trifunovic A, Wredenberg A, Falkenberg M, Spelbrink JN, Rovio AT, et al. (2004) Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature 429 : 417–423. 15164064

9. Kazak L, Reyes A, Holt IJ (2012) Minimizing the damage: repair pathways keep mitochondrial DNA intact. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13 : 659–671. doi: 10.1038/nrm3439 22992591

10. Dujon B (1981) Mitochondrial genetics and functions. In: Jones EW, Broach JR, editors. The Molecular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces: Life Cycle and Inheritance. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. pp. 505–592.

11. Poulton J, Deadman ME, Bindoff L, Morten K, Land J, et al. (1993) Families of mtDNA re-arrangements can be detected in patients with mtDNA deletions: duplications may be a transient intermediate form. Human Molecular Genetics 2 : 23–30. 8490619

12. Thyagarajan B, Padua RA, Campbell C (1996) Mammalian mitochondria possess homologous DNA recombination activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry 271 : 27536–27543. 8910339

13. Lakshmipathy U, Campbell C (1999) Double strand break rejoining by mammalian mitochondrial extracts. Nucleic Acids Research 27 : 1198–1204. 9927756

14. Kajander OA, Karhunen PJ, Holt IJ, Jacobs HT (2001) Prominent mitochondrial DNA recombination intermediates in human heart muscle. EMBO Rep 2 : 1007–1012. 11713192

15. Kraytsberg Y, Schwartz M, Brown TA, Ebralidse K, Kunz WS, et al. (2004) Recombination of human mitochondrial DNA. Science 304 : 981. 15143273

16. Ling F, Makishima F, Morishima N, Shibata T (1995) A nuclear mutation defective in mitochondrial recombination in yeast. EMBO J 14 : 4090–4101. 7664749

17. Ling F, Morioka H, Ohtsuka E, Shibata T (2000) A role for MHR1, a gene required for mitochondrial genetic recombination, in the repair of damage spontaneously introduced in yeast mtDNA. Nucleic Acids Res 28 : 4956–4963. 11121487

18. Ling F, Shibata T (2002) Recombination-dependent mtDNA partitioning: in vivo role of Mhr1p to promote pairing of homologous DNA. EMBO J 21 : 4730–4740. 12198175

19. MacAlpine DM, Perlman PS, Butow RA (1998) The high mobility group protein Abf2p influences the level of yeast mitochondrial DNA recombination intermediates in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 : 6739–6743. 9618482

20. Sembongi H, Di Re M, Bokori-Brown M, Holt IJ (2007) The yeast Holliday junction resolvase, CCE1, can restore wild-type mitochondrial DNA to human cells carrying rearranged mitochondrial DNA. Hum Mol Genet 16 : 2306–2314. 17666405

21. Ezekiel UR, Zassenhaus HP (1993) Localization of a cruciform cutting endonuclease to yeast mitochondria. Mol Gen Genet 240 : 414–418. 8413191

22. Mookerjee SA, Sia EA (2006) Overlapping contributions of Msh1p and putative recombination proteins Cce1p, Din7p, and Mhr1p in large-scale recombination and genome sorting events in the mitochondrial genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat Res 595 : 91–106. 16337661

23. McIlwraith MJ, Van Dyck E, Masson JY, Stasiak AZ, Stasiak A, et al. (2000) Reconstitution of the strand invasion step of double-strand break repair using human Rad51 Rad52 and RPA proteins. J Mol Biol 304 : 151–164. 11080452

24. Davis AP, Symington LS (2004) RAD51-dependent break-induced replication in yeast. Mol Cell Biol 24 : 2344–2351. 14993274

25. Krogh BO, Symington LS (2004) Recombination proteins in yeast. Annu Rev Genet 38 : 233–271. 15568977

26. Symington LS (2002) Role of RAD52 epistasis group genes in homologous recombination and double-strand break repair. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 66 : 630–670, table of contents. 12456786

27. Kagawa W, Kurumizaka H, Ikawa S, Yokoyama S, Shibata T (2001) Homologous pairing promoted by the human Rad52 protein. J Biol Chem 276 : 35201–35208. 11454867

28. Sugawara N, Ira G, Haber JE (2000) DNA length dependence of the single-strand annealing pathway and the role of Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD59 in double-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol 20 : 5300–5309. 10866686

29. Prado F, Cortes-Ledesma F, Huertas P, Aguilera A (2003) Mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet 42 : 185–198. 12589470

30. Branzei D, Foiani M (2010) Maintaining genome stability at the replication fork. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11 : 208–219. doi: 10.1038/nrm2852 20177396

31. Newton KJ, Gabay-Laughan S, De Paepe R (2004) Mitochondrial mutations in plants. In: Day DA, Millar AH, Whelan J, editors. Plant Mitochondria: From Genome to Function. Great Britain: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 121–142.

32. Yui R, Ohno Y, Matsuura ET (2003) Accumulation of deleted mitochondrial DNA in aging Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Genet Syst 78 : 245–251. 12893966

33. Bianchi NO, Bianchi MS, Richard SM (2001) Mitochondrial genome instability in human cancers. Mutat Res 488 : 9–23. 11223402

34. Krishnan KJ, Reeve AK, Samuels DC, Chinnery PF, Blackwood JK, et al. (2008) What causes mitochondrial DNA deletions in human cells? Nat Genet 40 : 275–279. doi: 10.1038/ng.f.94 18305478

35. Samach A, Melamed-Bessudo C, Avivi-Ragolski N, Pietrokovski S, Levy AA (2011) Identification of plant RAD52 homologs and characterization of the Arabidopsis thaliana RAD52-like genes. Plant Cell 23 : 4266–4279. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.091744 22202891

36. Sage JM, Gildemeister OS, Knight KL (2010) Discovery of a Novel Function for Human Rad51: Maintenance of the mitochondrial genome. Journal of Biological Chemistry 285 : 18984–18990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.099846 20413593

37. Sage JM, Knight KL (2013) Human Rad51 promotes mitochondrial DNA synthesis under conditions of increased replication stress. Mitochondrion 13 : 350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2013.04.004 23591384

38. Phadnis N, Sia RA, Sia EA (2005) Analysis of repeat-mediated deletions in the mitochondrial genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 171 : 1549–1559. 16157666

39. Kalifa L, Beutner G, Phadnis N, Sheu SS, Sia EA (2009) Evidence for a role of FEN1 in maintaining mitochondrial DNA integrity. DNA Repair (Amst) 8 : 1242–1249.

40. Kalifa L, Quintana DF, Schiraldi LK, Phadnis N, Coles GL, et al. (2012) Mitochondrial genome maintenance: roles for nuclear nonhomologous end-joining proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 190 : 951–964. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.138214 22214610

41. Fritsch ES, Chabbert CD, Klaus B, Steinmetz LM (2014) A genome-wide map of mitochondrial DNA recombination in yeast. Genetics 198 : 755–771. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.166637 25081569

42. Steele DF, Butler CA, Fox TD (1996) Expression of a recoded nuclear gene inserted into yeast mitochondrial DNA is limited by mRNA-specific translational activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 93 : 5253–5257.

43. Ivanov EL, Sugawara N, Fishman-Lobell J, Haber JE (1996) Genetic requirements for the single-strand annealing pathway of double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 142 : 693–704. 8849880

44. Tan G, Chen M, Foote C, Tan C (2009) Temperature-sensitive mutations made easy: generating conditional mutations by using temperature-sensitive inteins that function within different temperature ranges. Genetics 183 : 13–22. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.104794 19596904

45. Thorsness PE, Fox TD (1990) Escape of DNA from mitochondria to the nucleus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 346 : 376–379. 2165219

46. Goldring ES, Grossman LI, Krupnick D, Cryer DR, Marmur J (1970) The petite mutation in yeast. Loss of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid during induction of petites with ethidium bromide. J Mol Biol 52 : 323–335. 5485912

47. Liu P, Demple B (2010) DNA repair in mammalian mitochondria: Much more than we thought? Environ Mol Mutagen 51 : 417–426. doi: 10.1002/em.20576 20544882

48. Shokolenko IN, Wilson GL, Alexeyev MF (2013) Persistent damage induces mitochondrial DNA degradation. DNA Repair (Amst) 12 : 488–499.

49. de Souza-Pinto NC, Eide L, Hogue BA, Thybo T, Stevnsner T, et al. (2001) Repair of 8-oxodeoxyguanosine lesions in mitochondrial dna depends on the oxoguanine dna glycosylase (OGG1) gene and 8-oxoguanine accumulates in the mitochondrial dna of OGG1-defective mice. Cancer Res 61 : 5378–5381. 11454679

50. Nishioka K, Ohtsubo T, Oda H, Fujiwara T, Kang D, et al. (1999) Expression and differential intracellular localization of two major forms of human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase encoded by alternatively spliced OGG1 mRNAs. Mol Biol Cell 10 : 1637–1652. 10233168

51. Bacman SR, Williams SL, Moraes CT (2009) Intra - and inter-molecular recombination of mitochondrial DNA after in vivo induction of multiple double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Research 37 : 4218–4226. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp348 19435881

52. Morel F, Renoux M, Lachaume P, Alziari S (2008) Bleomycin-induced double-strand breaks in mitochondrial DNA of Drosophila cells are repaired. Mutat Res 637 : 111–117. 17825327

53. Crider DG, Garcia-Rodriguez LJ, Srivastava P, Peraza-Reyes L, Upadhyaya K, et al. (2012) Rad53 is essential for a mitochondrial DNA inheritance checkpoint regulating G1 to S progression. J Cell Biol 198 : 793–798. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201205193 22927468

54. Sia EA, Butler CA, Dominska M, Greenwell P, Fox TD, et al. (2000) Analysis of microsatellite mutations in the mitochondrial DNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 : 250–255. 10618404

55. Adams A, Gottschling DE, Stearns T, Kaiser CA (1997) Methods in Yeast Genetics, 1997. A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Course Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

56. Fox TD, Folley LS, Mulero JJ, McMullin TW, Thorsness PE, et al. (1991) Analysis and manipulation of yeast mitochondrial genes. In: Guthrie C, Fink GR, editors. Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 149–165.

57. Saravanan M, Bujnicki JM, Cymerman IA, Rao DN, Nagaraja V (2004) Type II restriction endonuclease R. KpnI is a member of the HNH nuclease superfamily. Nucleic Acids Res 32 : 6129–6135. 15562004

58. Diekert KdK, A. I. P. M; Kispal G.; Lill R. (2001) Isolation and Subfractionation of Mitochondria from the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Pon LAS E. A., editor. Methods in Cell Biology. New York, NY: Academic Press. pp. 37–51. 11381604

59. Lea DE, Coulson CA (1949) The distribution of the number of mutants in bacterial populations. J Genet 49 : 264–284. 24536673

60. Sugawara N, Haber JE (1992) Characterization of double-strand break-induced recombination: homology requirements and single-stranded DNA formation. Mol Cell Biol 12 : 563–575. 1732731

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek A Hereditary Enteropathy Caused by Mutations in the Gene, Encoding a Prostaglandin TransporterČlánek Exocyst-Dependent Membrane Addition Is Required for Anaphase Cell Elongation and Cytokinesis inČlánek Spindle-F Is the Central Mediator of Ik2 Kinase-Dependent Dendrite Pruning in Sensory Neurons

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 11- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Délka menstruačního cyklu jako marker ženské plodnosti

- Vztah užívání alkoholu a mužské fertility

- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Intrauterinní inseminace a její úspěšnost

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Agricultural Genomics: Commercial Applications Bring Increased Basic Research Power

- Ernst Rüdin’s Unpublished 1922-1925 Study “Inheritance of Manic-Depressive Insanity”: Genetic Research Findings Subordinated to Eugenic Ideology

- Convergent Evolution During Local Adaptation to Patchy Landscapes

- The Locus Controls Age at Maturity in Wild and Domesticated Atlantic Salmon ( L.) Males

- A Hereditary Enteropathy Caused by Mutations in the Gene, Encoding a Prostaglandin Transporter

- Absence of Maternal Methylation in Biparental Hydatidiform Moles from Women with Maternal-Effect Mutations Reveals Widespread Placenta-Specific Imprinting

- Calibrating the Human Mutation Rate via Ancestral Recombination Density in Diploid Genomes

- Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Acts in the Mushroom Body to Negatively Regulate Sleep

- Connecting Replication and Repair: YoaA, a Helicase-Related Protein, Promotes Azidothymidine Tolerance through Association with Chi, an Accessory Clamp Loader Protein

- UFBP1, a Key Component of the Ufm1 Conjugation System, Is Essential for Ufmylation-Mediated Regulation of Erythroid Development

- Mosaic and Intronic Mutations in Explain the Majority of TSC Patients with No Mutation Identified by Conventional Testing

- Members of the Epistasis Group Contribute to Mitochondrial Homologous Recombination and Double-Strand Break Repair in

- QTL Mapping of Sex Determination Loci Supports an Ancient Pathway in Ants and Honey Bees

- Genetic Interactions Implicating Postreplicative Repair in Okazaki Fragment Processing

- Genomics of Cancer and a New Era for Cancer Prevention

- Adaptation to High Ethanol Reveals Complex Evolutionary Pathways

- Dynamics of Transcription Factor Binding Site Evolution

- Exocyst-Dependent Membrane Addition Is Required for Anaphase Cell Elongation and Cytokinesis in

- Enhancer Runaway and the Evolution of Diploid Gene Expression

- Cattle Sex-Specific Recombination and Genetic Control from a Large Pedigree Analysis

- Drosophila Mutants Model Cornelia de Lange Syndrome in Growth and Behavior

- Pleiotropic Effects of Immune Responses Explain Variation in the Prevalence of Fibroproliferative Diseases

- Leaderless Transcripts and Small Proteins Are Common Features of the Mycobacterial Translational Landscape

- Tissue-Specific Effects of Reduced β-catenin Expression on Mutation-Instigated Tumorigenesis in Mouse Colon and Ovarian Epithelium

- Genus-Wide Comparative Genomics of Delineates Its Phylogeny, Physiology, and Niche Adaptation on Human Skin

- Mapping of Craniofacial Traits in Outbred Mice Identifies Major Developmental Genes Involved in Shape Determination

- Conserved Genetic Interactions between Ciliopathy Complexes Cooperatively Support Ciliogenesis and Ciliary Signaling

- Metabolomic Quantitative Trait Loci (mQTL) Mapping Implicates the Ubiquitin Proteasome System in Cardiovascular Disease Pathogenesis

- DNA Repair Cofactors ATMIN and NBS1 Are Required to Suppress T Cell Activation

- Spindle-F Is the Central Mediator of Ik2 Kinase-Dependent Dendrite Pruning in Sensory Neurons

- Ernst Rüdin and the State of Science

- ABCs of Insect Resistance to Bt

- Epigenetic Control of O-Antigen Chain Length: A Tradeoff between Virulence and Bacteriophage Resistance

- Encodes Dual Oxidase, Which Acts with Heme Peroxidase Curly Su to Shape the Adult Wing

- The Fanconi Anemia Pathway Protects Genome Integrity from R-loops

- Controls Quantitative Variation in Maize Kernel Row Number

- Genome-Wide Association Study of Golden Retrievers Identifies Germ-Line Risk Factors Predisposing to Mast Cell Tumours

- Insect Resistance to Toxin Cry2Ab Is Conferred by Mutations in an ABC Transporter Subfamily A Protein

- A Cytosine Methytransferase Modulates the Cell Envelope Stress Response in the Cholera Pathogen

- Conserved piRNA Expression from a Distinct Set of piRNA Cluster Loci in Eutherian Mammals

- The Multi-allelic Genetic Architecture of a Variance-Heterogeneity Locus for Molybdenum Concentration in Leaves Acts as a Source of Unexplained Additive Genetic Variance

- The lncRNA Controls Cryptococcal Morphological Transition

- Sae2 Function at DNA Double-Strand Breaks Is Bypassed by Dampening Tel1 or Rad53 Activity

- A Tandem Duplicate of Anti-Müllerian Hormone with a Missense SNP on the Y Chromosome Is Essential for Male Sex Determination in Nile Tilapia,

- Ectodysplasin/NF-κB Promotes Mammary Cell Fate via Wnt/β-catenin Pathway

- The QTL within the Complex Involved in the Control of Tuberculosis Infection in Mice Is the Classical Class II Gene

- Identifying Loci Contributing to Natural Variation in Xenobiotic Resistance in

- Variation in Rural African Gut Microbiota Is Strongly Correlated with Colonization by and Subsistence

- A Flexible, Efficient Binomial Mixed Model for Identifying Differential DNA Methylation in Bisulfite Sequencing Data

- Competition between Heterochromatic Loci Allows the Abundance of the Silencing Protein, Sir4, to Regulate Assembly of Heterochromatin

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- UFBP1, a Key Component of the Ufm1 Conjugation System, Is Essential for Ufmylation-Mediated Regulation of Erythroid Development

- Metabolomic Quantitative Trait Loci (mQTL) Mapping Implicates the Ubiquitin Proteasome System in Cardiovascular Disease Pathogenesis

- Genus-Wide Comparative Genomics of Delineates Its Phylogeny, Physiology, and Niche Adaptation on Human Skin

- Encodes Dual Oxidase, Which Acts with Heme Peroxidase Curly Su to Shape the Adult Wing

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání