-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Protein Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation Regulates Immune Gene Expression and Defense Responses

Fine-tuning of gene expression is a key feature of successful immune responses. However, the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. Through a genetic screen in model plant Arabidopsis, we reveal that protein poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation) post-translational modification plays a pivotal role in controlling plant immune gene expression and defense to pathogen attacks. PARylation is primarily mediated by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), which transfers ADP-ribose moieties from NAD+ to acceptor proteins. The covalently attached poly(ADP-ribose) polymers on the accept proteins could be hydrolyzed by poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG). We further show that members of Arabidopsis PARPs and PARGs possess differential in vivo and in vitro enzymatic activities. Importantly, the Arabidopsis parp mutant displayed reduced, whereas parg mutant displayed enhanced, immune gene activation and immunity to pathogen infection. Moreover, Arabidopsis PARP2 activity is elevated upon pathogen signal perception. Compared to the lethality of their mammalian counterparts, the viability and normal growth of Arabidopsis parp and parg null mutants provide a unique genetic system to understand protein PARylation in diverse biological processes at the whole organism level.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004936

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004936Summary

Fine-tuning of gene expression is a key feature of successful immune responses. However, the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. Through a genetic screen in model plant Arabidopsis, we reveal that protein poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation) post-translational modification plays a pivotal role in controlling plant immune gene expression and defense to pathogen attacks. PARylation is primarily mediated by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), which transfers ADP-ribose moieties from NAD+ to acceptor proteins. The covalently attached poly(ADP-ribose) polymers on the accept proteins could be hydrolyzed by poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG). We further show that members of Arabidopsis PARPs and PARGs possess differential in vivo and in vitro enzymatic activities. Importantly, the Arabidopsis parp mutant displayed reduced, whereas parg mutant displayed enhanced, immune gene activation and immunity to pathogen infection. Moreover, Arabidopsis PARP2 activity is elevated upon pathogen signal perception. Compared to the lethality of their mammalian counterparts, the viability and normal growth of Arabidopsis parp and parg null mutants provide a unique genetic system to understand protein PARylation in diverse biological processes at the whole organism level.

Introduction

Plants sense the presence of pathogens by the cell surface-localized pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which perceive evolutionarily conserved pathogen - or microbe-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs or MAMPs), including bacterial flagellin, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), peptidoglycan (PGN), elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu), and fungal chitin [1]–[3]. A 22-amino-acid peptide corresponding to a region near the amino-terminus of flagellin (flg22) is recognized by the Arabidopsis PRR Flagellin-Sensing 2 (FLS2), a leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase (LRR-RLK) [4], [5]. Perception of flg22 by FLS2 induces instantaneous association with another LRR-RLK, Brassinosteroid Insensitive 1 (BRI1)-Associated Kinase 1 (BAK1), mainly through ectodomain heterodimerization of flg22-activated FLS2/BAK1 complex [6]–[9]. The receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases (RLCKs), BIK1 and its homolog PBL1, constitutively associate with FLS2 and BAK1, and are released from the receptor complex upon flg22 perception [10]–[12]. BAK1 directly interacts and phosphorylates BIK1 at both serine, threonine and tyrosine residues, thereby activating downstream signaling [12], [13]. In addition, both BAK1 and BIK1 complex with PRR EFR (receptor for EF-Tu) [11], [14], AtPEPR1 (receptor for endogenous danger signal Pep1) [12], [15], [16], and plant brassinosteroid hormone receptor BRI1 [17]–[19]. Activation of PRR complex by the corresponding MAMP triggers a series of defense responses, including rapid activation of MAP kinases (MAPKs) and calcium-dependent protein kinases, transient reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and calcium influx, stomatal closure, callose deposition and massive transcriptional reprogramming [1]–[3]. It has been shown recently that BIK1 is able to phosphorylate plasma membrane-resident NADPH oxidase family member respiratory burst oxidase homolog D (RBOHD), thereby contributing to ROS production [20], [21]. However, it remains largely unknown how PRR complex activation leads to profound immune gene transcriptional reprograming.

Protein poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation), an important post-translational modification process, plays a crucial role in a broad array of cellular responses including DNA damage detection and repair, cell division and death, chromatin modification and gene transcriptional regulation [22]–[24] (S1 Fig.). PARylation is primarily mediated by members of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), which transfer ADP-ribose moieties from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to different acceptor proteins at glutamate (Glu), aspartate (Asp) or lysine (Lys) residues resulting in the formation of linear or branched poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) polymers on acceptor proteins (S1 Fig.). PAR activities and PARPs have been found in a wide variety of organisms from archaebacteria to mammals and plants, but they are apparently absent in yeast [25]. Human PARP-1 (HsPARP-1) is the most abundant and ubiquitous PARP among a family of 17 members, and it catalyzes the covalent attachment of PAR polymers on itself (auto-PARylation) and other target proteins, including histones, DNA repair proteins, transcription factors, and chromatin modulators [22]. HsPARP-1 possesses three functional domains with a DNA binding domain at N-terminus, auto-modification domain in the middle and a catalytic domain at C-terminus (S2A Fig.). PARylation is a reversible reaction and the covalently attached PAR on the target proteins can be hydrolyzed to free PAR or mono-(ADP-ribose) by poly (ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG) [22], [23] (S1 Fig.). PARG contains both endo - and exo-glycohydrolase activities that promote rapid catabolic destruction of PAR of target proteins [26]. There is only one PARG gene in humans with three different isoforms: PARG99 and PARG102 in the cytoplasm and PARG110 in the nucleus [26]. Mammalian PARG possesses a regulatory and targeting domain (A-domain) at the N-terminus, a mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS) in the middle and a conserved catalytic domain at the C-terminus [27] (S2B Fig.). The catalytic core containing “GGG-X6-8-QEE” PARG signature motif interacts with PAR and executes hydrolysis activity [28]. Despite of their apparently opposing activities, members of PARPs and PARGs coordinately regulate protein PARylation and play essential roles in a wide range of cellular processes and contribute to the pathogenicity of various diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular diseases, stroke, metabolic disorders, diabetes and autoimmunity [25].

The Arabidopsis genome encodes three members of PARPs, AtPARP1 (At2g31320), AtPARP2 (At4g02390) and AtPARP3 (At5g22470) and two members of PARGs, AtPARG1 (At2g31870) and AtPARG2 (At2g31865) [23], [29] (S2 Fig.). AtPARP1 (it was originally named as AtPARP2) shares the conserved domain structure with HsPARP-1, whereas AtPARP2 (it was originally named as AtPARP1) and AtPARP3 more closely resemble HsPARP-2 and HsPARP-3 [29] (S2A Fig.). As their mammalian counterparts, plant PARPs are implicated in DNA repair, cell cycle and genotoxic stress [29]-[32]. Importantly, plant PARPs play an essential role in response to abiotic stresses. Transgenic Arabidopsis or oilseed rape (Brassica napus) plants with reduced PARP gene expression were more resistant to various abiotic stresses, including drought, high light and heat, partially attributed to a maintained energy homeostasis of reduced NAD+ and ATP consumption and alternation in plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA) levels in the transgenic plants [33], [34]. The two Arabidopsis PARG genes, AtPARG1 and AtPARG2, which were likely derived from a tandem duplication event, locates next to each other on the same chromosome [23]. AtPARG1 (TEJ) was originally identified as a regulator of circadian rhythm and flowering in Arabidopsis [35]. Interestingly, the AtPARG2 gene was robustly induced by the treatments of MAMPs and various pathogens [36]. The plants carrying mutation in AtPARG1, but not AtPARG2, showed the elevated elf18 (a 18-amino-acid peptide of EF-Tu)-mediated seedling growth inhibition and phenylpropanoid pigment accumulation, suggesting a negative role of Arabidopsis PARG in certain plant immune responses [37]. Similar to AtPARP1, AtPARG1 also plays a role in plant drought, osmotic and oxidative stress tolerance [38]. In contrast to the extensive research efforts on PARPs/PARGs in animal systems, the biochemical activities and molecular actions of plant PARPs/PARGs remain poorly characterized.

To elucidate the signaling networks regulating immune gene activation, we developed a sensitive genetic screen with an ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS)-mutagenized population of Arabidopsis transgenic plants carrying a luciferase reporter gene under the control of the FRK1 promoter (pFRK1::LUC). The FRK1 (flg22-induced receptor-like kinase 1) gene is a specific and early immune responsive gene activated by multiple MAMPs [39], [40]. A series of mutants with altered pFRK1::LUC activity upon flg22 treatment were identified and named as Arabidopsis genes governing immune gene expression (aggie). In this study, we isolated and characterized the aggie2 mutant, which exhibited elevated immune gene expression upon multiple MAMP treatments. Map-based cloning coupled with next generation sequencing revealed that Aggie2 encodes AtPARG1. Extensive biochemical analysis demonstrates that both AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 carry poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity, whereas AtPARG1, but not AtPARG2, possesses poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase activity in vivo and in vitro. Significantly, the enzymatic activity of AtPARP2 is enhanced upon flg22 perception, suggesting the potential involvement of protein PARylation in MAMP-triggered immunity. The aggie2 mutation (G450R) occurs at a highly conserved PARG residue which is essential for both Arabidopsis AtPARG1 and human HsPARG enzymatic activity. Consistent with the negative role of AtPARG1 in plant innate immunity, AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 positively regulate immune gene activation and plant resistance to virulent bacterial pathogen infection. Our results indicate that the reversible posttranslational PARylation process mediated by AtPARPs and AtPARGs plays a crucial role in mounting successful innate immune responses upon MAMP perception in Arabidopsis.

Results

The aggie2 mutant displays enhanced immune gene expression

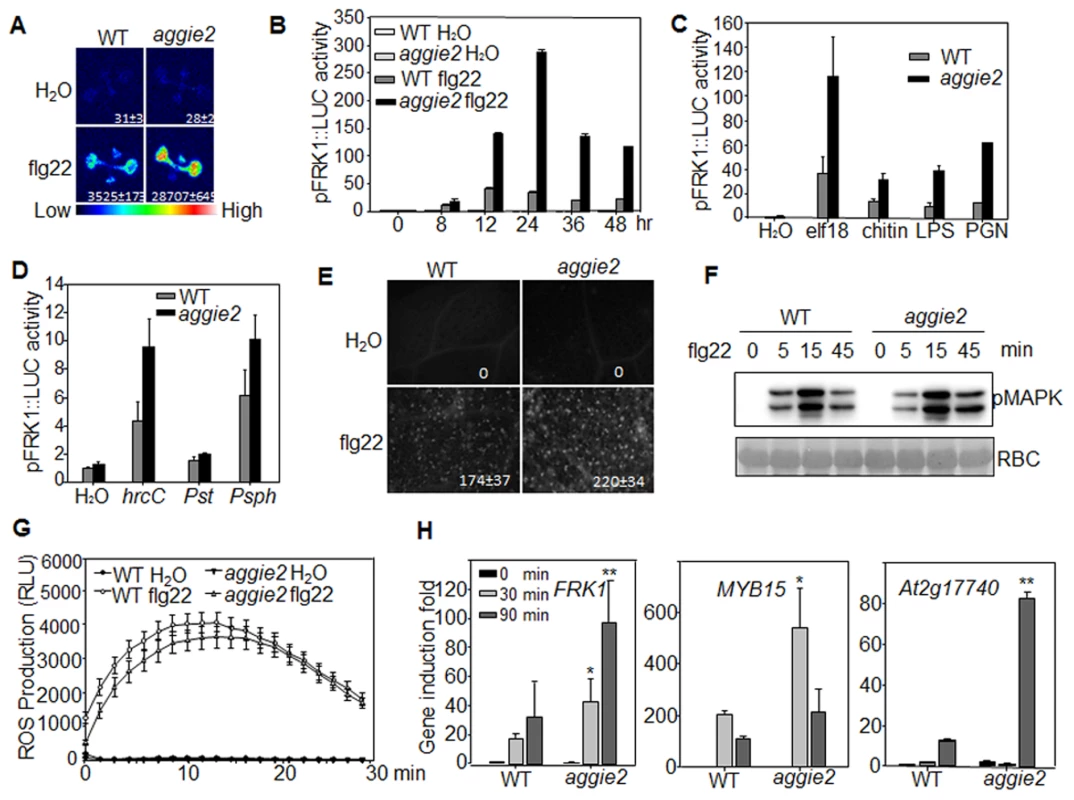

The aggie2 mutant isolated from a genetic screen of the EMS-mutagenized pFRK1::LUC transgenic plants exhibits elevated FRK1 promoter activity upon flg22 treatment compared to its parental line, pFRK1::LUC (WT) (Fig. 1A). The elevated luciferase activity in the aggie2 mutant was observed over a 48-hr time course period upon flg22 treatment (Fig. 1B). Notably, the aggie2 mutant did not display detectable enhanced FRK1 promoter activity in the absence of flg22 treatment, suggesting its specific regulation in plant defense. In addition to flg22, other MAMPs, including elf18, LPS, PGN and fungal chitin, also elicited the enhanced FRK1 promoter activity in the aggie2 mutant (Fig. 1C), indicating that Aggie2 functions as a convergent component downstream of multiple MAMP receptors. Consistently, the aggie2 mutant displayed the enhanced FRK1 promoter activity in response to the non-pathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst) DC3000 hrcC defective in type III secretion of effectors, and a non-adaptive bacterium P. syringae pv. phaseolicola NPS3121 (Fig. 1D). The pathogenic bacterium Pst DC3000 failed to activate pFRK1::LUC, likely due to the suppression function of multiple effectors secreted from virulent bacterium [40]. Pathogen infection or purified MAMPs could induce callose deposits in leaves or cotyledons of Arabidopsis, which has emerged as an indicator of plant immune responses [41]. We compared callose deposits by aniline blue staining in WT and aggie2 mutant plants upon flg22 treatment. The aggie2 mutant deposited more callose than WT plants 12 hr after flg22 treatment, and the size of each callose deposit appeared bigger in the aggie2 mutant than that in WT plants (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1. Elevated pFRK1::LUC expression and MAMP-triggered immune response in aggie2 mutant.

(A) Luciferase activity from 10-day-old pFRK1::LUC (WT) and aggie2 seedlings treated with or without 10 nM flg22 for 12 hr. The photograph was taken with an EMCCD camera. The number below indicates quantified signal intensity shown as means ± se from 12 seedlings. (B) Time-course of pFRK1::LUC activity in response to 100 nM flg22 treatment. The data are shown as means ± se from at least 20 seedlings for each time point. (C) The pFRK1::LUC activity in response to different MAMPs. Ten-day-old seedlings were treated with 100 nM elf18, 50 µg/ml chitin, 1 µM LPS, or 500 ng/ml PGN for 12 hr. The data are shown as means ± se from at least 12 seedlings for each treatment. (D) The pFRK1::LUC activity triggered by different bacteria. Four-week-old soil-grown plants were hand-inoculated with different bacteria at the concentration of OD600 = 0.5. The data are shown as means ± se from at least 12 leaves for each treatment at 24 hr post-inoculation (hpi). (E) flg22-induced callose deposition in aggie2 mutant. Leaves of 6-week-old plants were infiltrated with 0.5 µM flg22 for 12 hr and callose deposits were detected by aniline blue staining and quantified by ImageJ software. (F) flg22-induced MAPK activation in aggie2 mutant. Seedlings were treated with 100 nM flg22 and collected at the indicated time points. The MAPK activation was detected with an α-pErk antibody (top panel) and the protein loading was indicated by Ponceau S staining for RuBisCo (RBC) (bottom panel). (G) flg22-triggered ROS burst in aggie2 mutant. Leave discs from 4-week-old plants were treated with H2O or 100 nM flg22 over 30 min. The data are shown as means ± se from 20 leaf discs. (H) Endogenous MAMP-induced marker gene expression. Ten-day-old seedlings were treated with 100 nM flg22 for 30 and 90 min for qRT-PCR analysis. The data are shown as means ± se from three biological repeats with Student's t-test. * indicates p<0.05 and ** indicates p<0.01 when compared to WT. The above experiments were repeated 3 times with similar results. We also detected MAPK activation and ROS production, two early events triggered by multiple MAMPs, in WT and aggie2 mutant. The flg22-induced MAPK activation detected by an α-pERK antibody did not show significant and reproducible difference in WT and aggie2 seedlings (Fig. 1F), suggesting that Aggie2 acts either independently or downstream of MAPK cascade. The flg22-induced ROS burst appeared to be similar in the aggie2 mutant compared to that in WT plants (Fig. 1G). We did not observe reproducible disease alternation in the aggie2 mutant compared to WT plants in response to Pst DC3000 infection either by hand-infiltration or spray-inoculation with various inoculums and conditions (S3A Fig.). Among 7 times of disease assays with Pst DC3000 hand-infiltration, we observed that aggie2 was slightly more resistant than WT plants for 4 times, whereas we did not see the significant difference between aggie2 and WT for other 3 times (S3A Fig). By contrast, the aggie2 mutant showed enhanced susceptibility to a necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea compared to WT plants as evidenced by symptom development and lesion progression after infection (S3B Fig).

We further detected endogenous FRK1 expression in flg22-treated seedlings of WT and aggie2 mutant with quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis. The FRK1 expression was significantly elevated in the aggie2 mutant compared to that of WT pFRK1::LUC transgenic plants at both 30 min and 90 min after flg22 treatment (Fig. 1H). Similarly, the expression of several other early MAMP marker genes, including MYB15 and At2g17740 was also enhanced in the aggie2 mutant (Fig. 1H). Taken together, the results indicate that Aggie2 negatively regulates the expression of certain flg22-induced genes.

Aggie2 encodes a putative poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase

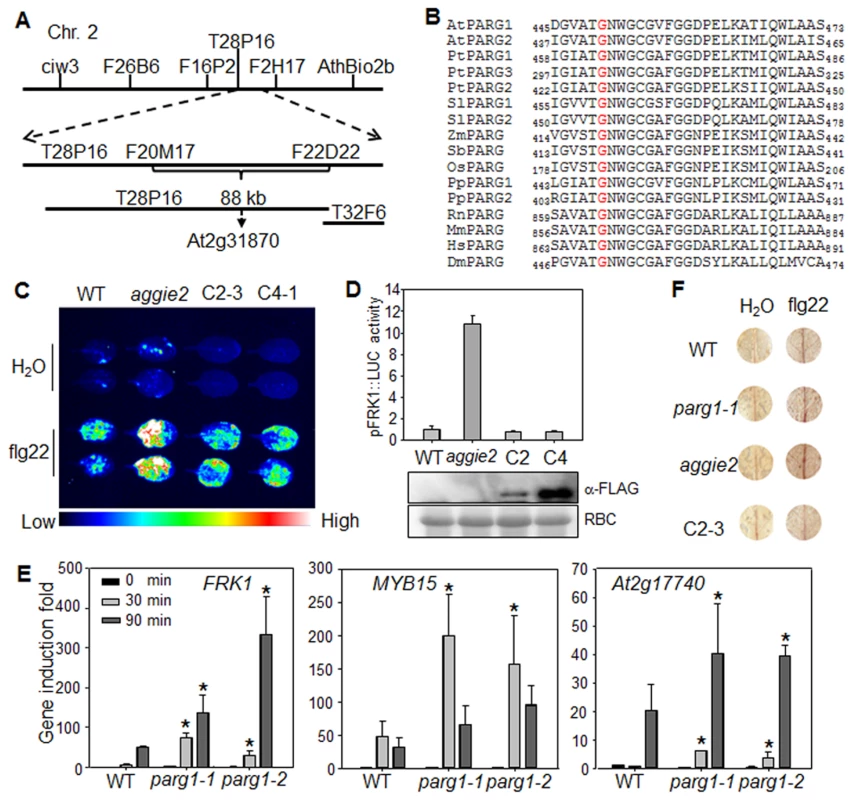

To isolate the causative mutation in aggie2, we crossed aggie2 (in the Col-0 accession background) with the Ler accession and mapped aggie2 to an 88 kilobase pair (kb) region between markers F20M17 and F22D22 on Chromosome 2 (Fig. 2A). We then performed Illumina whole genome sequencing of aggie2 and WT pFRK1::LUC transgenic plants. The comparative sequence analysis identified a G to A mutation at the position 1348 bp of At2g31870 within this 88 kb region. The mutation was further confirmed by Sanger sequencing of the genomic DNA of At2g31870. At2g31870 encodes AtPARG1 and the mutation in the aggie2 mutant causes an amino acid change of Glycine (G) at 450 to Arginine (R) (G450R) (Fig. 2B). The G450 in AtPARG1 resides in a highly conserved region at the C-terminus with unknown function. Notably, this residue is invariable in different species of plants and animals, including Arabidopsis, poplar, tomato, maize, sorghum, rice, moss, rat, mouse, human and fruit fly, suggesting the essential role of this residue in PARG functions (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Aggie2 encodes AtPARG1.

(A) Mapping of aggie2 on chromosome 2 and NGS identified a G to A mutation in At2g31870, which encodes AtPARG1. (B) G450 (red) in AtPARG1, which was mutated to Arginine (R) in aggie2, is highly conserved among different PARGs from plants to animals, thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana, At), poplar (Populus trichocarpa, Pt), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum, Sl), maize (Zea mays, Zm), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor, Sb), rice (Oryza sativa, Os), moss (Physcomitrella patens, Pp), rat (Rattus norvegicus, Rn), mouse (Mus musculus, Mm), human (Homo sapiens, Hs), fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster, Dm). (C) and (D) AtPARG1 complements aggie2 mutant phenotype. Leaves of 4-week-old soil-grown plants were treated with or without 100 nM flg22 for 12 hr and photographed with an EMCCD camera (C) and quantification data are shown in (D). The pFRK1::LUC transgenic plants (WT), aggie2 mutant and two independent homozygous lines, 2-3 and 4-1, of pAtPARG1::AtPARG1-FLAG transgenic plants in aggie2 mutant background were included in the assay. The data are shown as means ± se from at least 10 seedlings. The protein expression of the transgene was detected with an α-FLAG Western blot. (E) Enhanced immune gene expression in atparg1 mutant. Ten-day-old seedlings were treated with 100 nM flg22 for 30 and 90 min for qRT-PCR analysis. The data are shown as means ± se from three biological repeats with Student's t-test. * indicates p<0.05 when compared to WT. (F) flg22-induced lignin biosynthesis precursors in aggie2 mutant. Leaves of 6-week-old plants were incubated with 100 nM flg22 for 12 hr and lignin precursors, O-4-linked-coniferyl and sinapyl aldehydes, were detected by Wiesner staining. The images were scanned by HP officejet Pro 8600 Premium. The above experiments were repeated 3 times with similar results. To confirm that the G450R lesion in AtPARG1 is the causative mutation in aggie2, we complemented the aggie2 mutant with a construct carrying AtPARG1 cDNA fused with a FLAG epitope tag under the control of its native promoter (pAtPARG1::AtPARG1-FLAG). Two homozygous T3 transgenic lines, one line with relatively low (C2-3) and another line with moderate (C4-1) expression of AtPARG1-FLAG, were chosen for complementation assays. Both lines restored WT level of pFRK1::LUC activity upon flg22 treatment either imaged with an EMCCD camera (Fig. 2C) or quantified by a luminometer (Fig. 2D), confirming that the enhanced FRK1 promoter activity in aggie2 is caused by the mutation in AtPARG1. We also isolated T-DNA insertion line of AtPARG1, parg1-1 (SALK_147805) and parg1-2 (SALK_116088), and examined flg22-induced immune gene activation. Similar to the aggie2 mutant, parg1-1 and parg1-2 displayed the elevated activation of FRK1, MYB15 and At2g17740 after flg22 treatment compared to WT Col-0 plants (Fig. 2E). PARP inhibitor disrupted MAMP-induced cell wall lignification [37]. We found that both parg1-1 and aggie2 mutants showed the enhanced accumulation of lignin biosynthesis precursors, O-4-linked-coniferyl and sinapyl aldehydes, upon flg22 treatment by Wiesner staining (Fig. 2F). The complementation line C2-3 restored accumulation of these lignin biosynthesis precursors to the WT level (Fig. 2F). Consistent with a previous report [36], the transcript of AtPARG2, but not AtPARG1, was induced by flg22 treatment (S4A Fig.).

AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 carry poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity in vitro

AtPARG1 encodes a putative poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase with a predicated activity to remove poly(ADP-ribose) polymers on the acceptor proteins catalyzed by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs). To elucidate the biochemical activity and function of AtPARGs, we first characterized the function of AtPARPs and established in vivo and in vitro protein PARylation assays. The Arabidopsis genome encodes three PARPs, AtPARP1, AtPARP2 and AtPARP3, with each consisting of a conserved PARP catalytic domain and a variable DNA binding domain (S2 Fig.). AtPARP1 and AtPARP3 carry zinc-finger domains for DNA binding, which is similar with human HsPARP-1, whereas AtPARP2 contains two SAP domains with putative DNA binding activity. The SAP domain was named after scaffold attachment factor A/B (SAF-A/B), apoptotic chromatin condensation inducer in the nucleus (Acinus) and protein inhibitors of activated STAT (PIAS), which all have DNA and chromatin binding ability and regulate chromatin structure and/or transcription [42]. Analysis of their tissue expression pattern suggests that AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 are expressed in leaves, whereas AtPARP3 is primarily expressed in developing seeds (S4B-S4C Fig.). Thus, we focused on AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 for the functional studies.

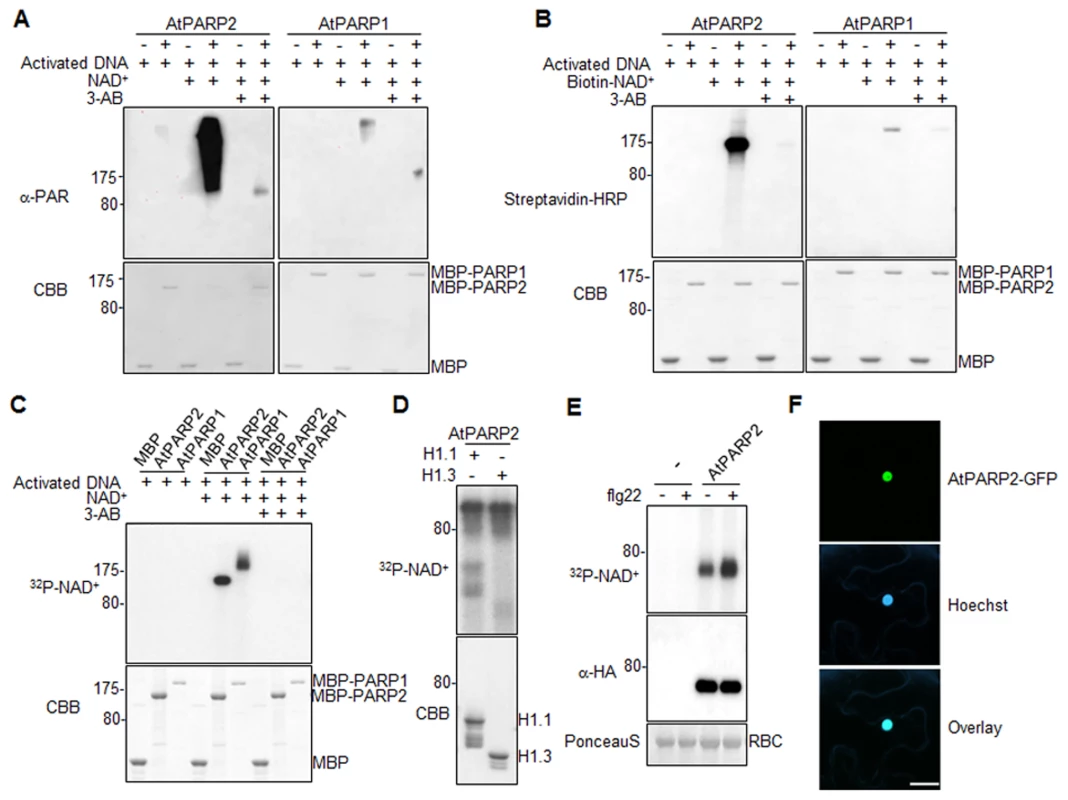

We first tested whether AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 carry poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity with recombinant proteins of AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 fused with Maltose Binding Protein (MBP). In the presence of activated DNA, both AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 could catalyze PARylation reaction by repeatedly transferring ADP-ribose groups from NAD+ to itself (auto-PARylation) as appeared a ladder-like smear with high-molecular-weight proteins in a Western blot using an α-PAR antibody which detects the PAR polymers of PARylated proteins (Fig. 3A). Apparently, AtPARP2 exhibited stronger in vitro enzymatic activity than AtPARP1 when detected by α-PAR antibody. The enzymatic activity of AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 was blocked by 3-AB, a competitive inhibitor of PARP (Fig. 3A). The activity of AtPARP2 is comparable with that of human HsPARP-1 (S5A Fig.). In addition, both AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 were able to transfer ADP-ribose from Biotin-NAD+ to itself and a relatively discrete band could be detected by horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated streptavidin (Fig. 3B). The specificity of PARP activity was confirmed with 3-AB treatment, which dramatically reduced auto-PARylation. Similar with the observation using α-PAR antibody, AtPARP2 exhibited stronger in vitro enzymatic activity than AtPARP1 when detected by streptavidin-HRP for biotinylated NAD+. We further developed a PARylation assay with radiolabeled 32P-NAD+ as the ADP-ribose donor (Fig. 3C). Clearly, both AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 were able to transfer ADP-ribose from 32P-NAD+ to itself as shown with SDS-PAGE autoradiograph (Fig. 3C). The formation of relatively discrete band was likely caused by these assay conditions, which favor synthesis of short polymers due to limited amount of NAD+ [43]. Together, the data support that both AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 are active poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases in vitro. It has been shown that human HsPARP-1 could modify linker histone H1 proteins and thereby create a chromatin structure more accessible to RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) to regulate transcription [44]. We further examined whether AtPARP2 was also able to PARylate Arabidopsis histone proteins. As detected with radiolabeled 32P-NAD+, AtPARP2 could PARylate two Arabidopsis histone proteins H1.1 and H1.3 (Fig. 3D). It is possible that Arabidopsis PARPs may use a similar mechanism for transcriptional regulation.

Fig. 3. Arabidopsis AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 are functional poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases.

(A) AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 in vitro activity detected by α-PAR antibody. MBP, MBP-AtPARP1 or MBP-AtPARP2 proteins were incubated with activated DNA with or without NAD+. 3-AB is a competitive inhibitor of PARP and could block PAR reactions. The PARylated proteins were detected in a Western blot using α-PAR antibody (top Panel) and the protein inputs were indicated by Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining (bottom panel). The blot exposure time for AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 was same. (B) AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 in vitro activity detected by Biotin-labelled NAD+. (C) AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 in vitro activity detected by autoradiograph with 32P-NAD+. (D) AtPARP2 PARylates Arabidopsis Histone H1.1 and H1.3 in vitro. The PARylated proteins were detected by autoradiography with 32P-NAD+. (E) flg22 treatment enhances AtPARP2 activity in vivo. Protoplasts were transfected with AtPARP2-HA, treated with 100 nM flg22 for 30 min and fed with 32P-NAD+. The AtPARP2-HA proteins were immunoprecipitated with an α-HA antibody and detected by autoradiography (Top panel). The input of AtPARP2 proteins is shown with an α-HA Western blot (middle panel), and the protein loading control is shown by Ponceau S staining for RBC (bottom panel). (F) AtPARP2 localizes in nucleus. AtPARP2-GFP was transiently expressed in N. benthamiana and the images were taken with a confocal microscope 2 days after inoculation. For nuclear staining, Hoechst 33342 (1 µg/ml) was infiltrated into the N. benthamiana leaf one hour before imaging. Scale bar is 20 µm. The above experiments were repeated at least 3 times with similar results. Flg22 induces AtPARP2 activity in vivo

We further developed an in vivo PARylation assay with transiently expressed AtPARP2 tagged with an HA epitope at the C-terminus in Arabidopsis protoplasts. After feeding the cells with 32P-NAD+, the AtPARP2 proteins were immunoprecipitated with an α-HA antibody and separated in SDS-PAGE. A band corresponding to the predicated molecular weight of AtPARP2 was observed with autoradiograph, indicating in vivo AtPARP2 activity (Fig. 3E). This band is specific to AtPARP2 since it was absent in the vector control transfected cells. Strikingly, the flg22 treatment enhanced AtPARP2 in vivo PARylation activity as detected by increased band intensity with autoradiograph. Apparently, the flg22-mediated enhancement of AtPARP2 activity was not due to the increase of protein expression after treatment (Fig. 3E). The data demonstrate that AtPARP2 possesses poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity in vivo and AtPARP2-mediated protein PARylation is regulated by flg22 signaling. We further examined AtPARP2-GFP localization with Agrobacterium-mediated Nicotiana benthamiana transient assay. A strong fluorescence signal from AtPARP2-GFP was exclusively detected in the nucleus (Fig. 3F), which is consistent with its potential role in DNA repair, chromatin modulation and transcriptional regulation.

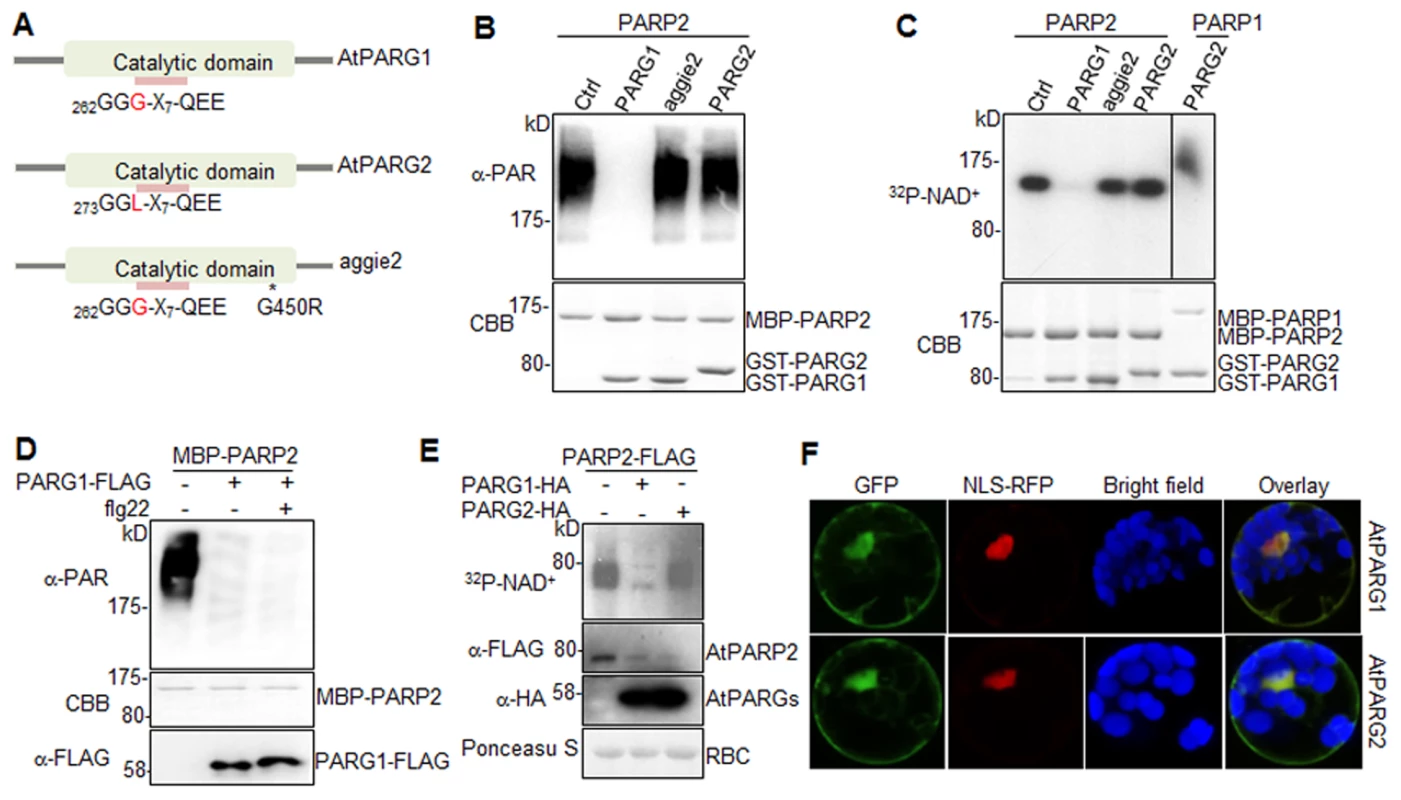

AtPARG1, but not AtPARG2, is a functional PARG enzyme

We next tested whether AtPARG1 and AtPARG2 possess poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase activity (Fig. 4A). We isolated and purified AtPARG1 and AtPARG2 proteins fused with glutathione S-transferase (GST) expressed from E. coli, and established an in vitro PARG assays to examine whether AtPARGs could remove PAR from auto-PARylated AtPARP2 in vitro. As shown in Fig. 4B, AtPARG1 diminished the formation of the ladder-like smear of auto-PARylated AtPARP2 detected in a Western blot with an α-PAR antibody, suggesting the PARG activity of AtPARG1 towards AtPARP2. However, AtPARG2 appeared to be inactive towards auto-PARylated AtPARP2 in this assay (Fig. 4B). Similarly, AtPARG1, but not AtPARG2, could remove PAR polymers from auto-ADP-ribosylated AtPARP2 as detected with 32P-NAD+ autoradiograph (Fig. 4C). We further examined whether AtPARG2 may possess PARG activity specifically towards AtPARP1 but not AtPARP2. As shown in Fig. 4C, AtPARG2 did not remove PAR polymers from auto-ADP-ribosylated AtPARP1. The 6xHistidine (His6)-tagged AtPARG2 also did not display in vitro enzymatic activity (S5B Fig.). Similar to the above assays using in vitro expressed AtPARG1 proteins (Fig. 4B & 4C), the immunoprecipitated AtPARG1 expressed in Arabidopsis protoplasts almost completely removed PAR polymers from in vitro PARylated AtPARP2 (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, AtPARG1 was able to remove PAR polymers from auto-PARylated human HsPARP-1 (S5C Fig.). Similarly, human HsPARG was also able to remove PAR polymers from AtPARP2 (S5D Fig.), suggesting the functional conservation of human and Arabidopsis PARPs/PARGs.

Fig. 4. AtPARG1, but not aggie2 or AtPARG2, has poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase activity.

(A) Schematic catalytic domain of AtPARG1, AtPARG2 and aggie2. The sequence of the PARG signature motif is shown and the number indicates the position of the first glycine (G) residue with a polymorphic residue G and L (leucine) between AtPARG1 and AtPARG2 highlighted in red. * denotes the point mutation in aggie2. (B) AtPARG1, but not AtPARG2 nor aggie2, possesses in vitro PAR glycohydrolase activity towards auto-PARylated AtPARP2 proteins detected by α-PAR antibody. MBP-AtPARP2 proteins were auto-PARylated and further subjected for in vitro PARG assay using GST-tagged AtPARG1, aggie2 or AtPARG2 proteins. The PARylated proteins were detected with an α-PAR Western blot (top panel) and the protein inputs are shown with CBB staining (bottom panel). (C) The AtPARG in vitro activity detected with 32P-NAD+. AtPARG1, but not AtPARG2 or aggie2, possesses in vitro PARG activity towards auto-PARylated AtPARP2 proteins (left part of top panel) and AtPARG2 does not have PARG activity towards auto-PARylated AtPARP1 proteins (right part of top panel). MBP-AtPARP1 or AtPARP2 proteins were auto-PARylated and further subjected for in vitro PARG assays using GST-tagged PARG1, aggie2 or PARG2 proteins in the presence of 32P-NAD+. The PARylated proteins were detected with autoradiograph (top panel) and the protein inputs are shown with CBB staining (bottom panel). (D) Protoplast-expressed AtPARG1 possesses PARG activity towards in vitro auto-PARylated AtPARP2 proteins. Arabidopsis protoplasts were transfected with AtPARG1-FLAG or vector control and treated with or without 100 nM flg22 for 15 min. PARG1 proteins were immunoprecipitated with α-FLAG antibody and subjected for in vitro PARG assay with in vitro auto-PARylated MBP-AtPARP2 proteins. The PARylated proteins were detected in an α-PAR Western blot (top panel), MBP-AtPARP2 protein input is shown with CBB staining (middle panel) and AtPARG1-FLAG protein expression in protoplasts is shown with an α-FLAG Western blot (bottom panel). (E) AtPARG1, but not AtPARG2, has in vivo PAR glycohydrolase activity. AtPARP2-FLAG was co-expressed with vector control, AtPARG1-HA or AtPARG2-HA in protoplasts and, the protoplasts were fed with 32P-NAD+. The PARylated proteins were detected with autoradiograph after immunoprecipitation with α-FLAG antibody (top panel). The PARP and PARG protein expression was detected with Western blot (middle panels) and the protein loading is shown with Ponceau S staining (bottom panel). (F) Subcellular localization of AtPARG1 and AtPARG2 in protoplasts. AtPARG1-GFP or AtPARG2-GFP was transiently expressed in protoplasts and the images were taken 12 hr after transfection using a confocal microscope. NLS-RFP was co-transfected for nuclear localization control. The above experiments were repeated 3 times with similar results. To test whether AtPARGs carry enzymatic activity in vivo, HA-tagged AtPARG1 or AtPARG2 was co-expressed with FLAG-tagged AtPARP2 transiently expressed in Arabidopsis protoplasts. After feeding the protoplasts with 32P-NAD+, AtPARP2 activity was detected with autoradiograph after immunoprecipitation with an α-FLAG antibody. Significantly, co-expression of AtPARG1, but not AtPARG2, substantially removed PAR polymers from in vivo PARylated AtPARP2 (Fig. 4E). The expression level of AtPARG1 and AtPARG2 was similar in protoplasts as detected by an α-HA Western blot (Fig. 4E). Taken together, our data indicate that AtPARG1 has in vivo and in vitro poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase activity and AtPARG2 activity was not detected. Consistently, the parg1 mutant, but not parg2 mutant, accumulated higher PAR polymers than Col-0 with dot blotting of nuclear proteins by α-PAR antibody (S5E Fig.). Subcellular localization study indicates that AtPARG1-GFP and AtPARG2-GFP reside mainly in nucleus, but also in plasma membrane and cytoplasm when transiently expressed in Arabidopsis protoplasts (Fig. 4F).

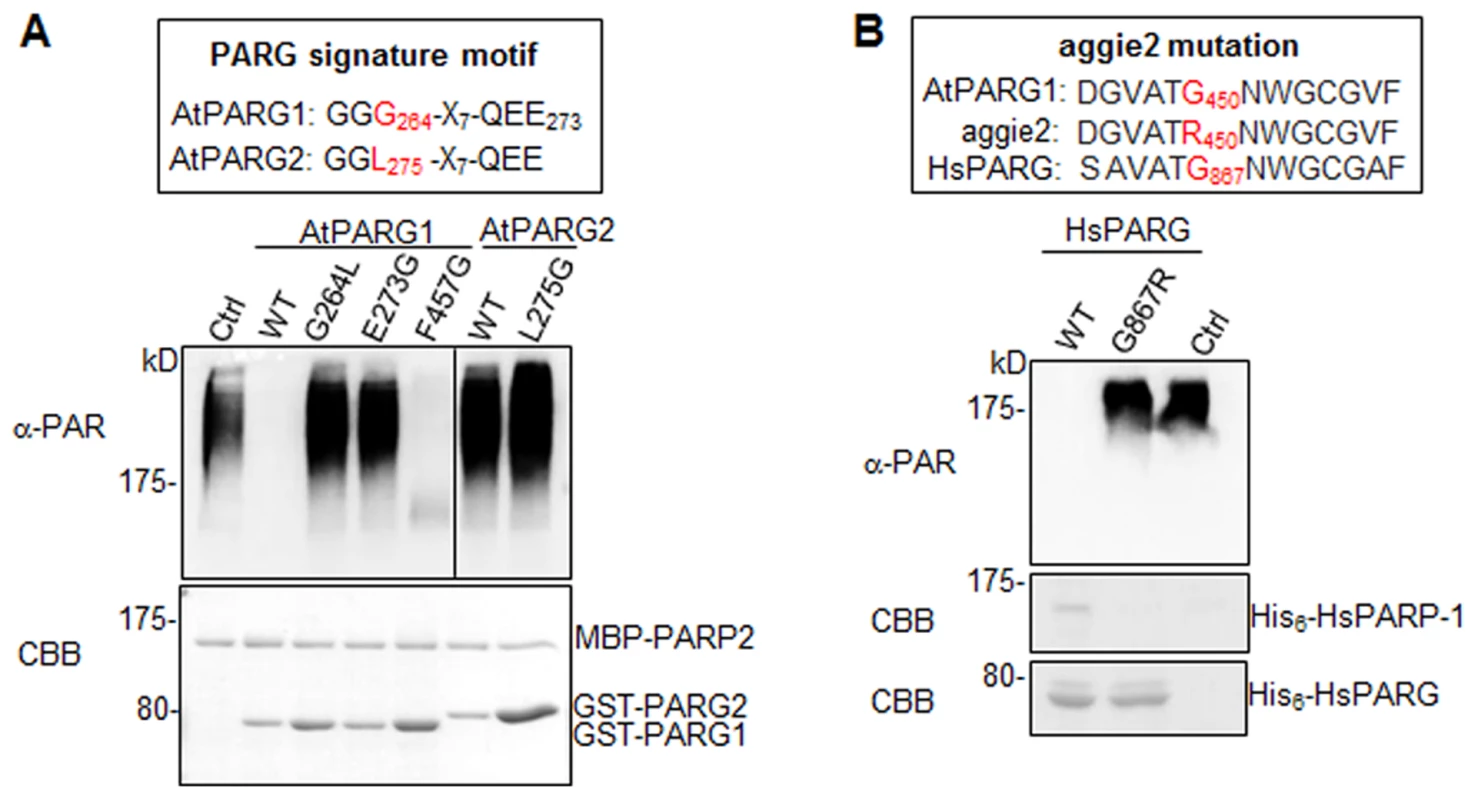

Notably, AtPARG1 protein possesses a PARG signature motif with the conserved sequence of “GGG-X7-QEE”. Mutation of E273 (the last E in the signature motif) in AtPARG1 to glycine (E273G) blocked its enzymatic activity, implicating the importance of this signature motif in PARG enzymatic activity (Fig. 5A). Examination of AtPARG2 sequence revealed that AtPARG2 has a polymorphism in the PARG signature motif. Instead of the conserved sequence “GGG-X7-QEE”, AtPARG2 possesses “GGL-X7-QEE” (Fig. 4A and 5A). The importance of this residue was shown by that the mutation of G264 (third G in the signature motif) in AtPARG1 to leucine (G264L) blocked its PARG enzymatic activity (Fig. 5A). We further determined whether lack of enzymatic activity of AtPARG2 (Fig. 4B, 4C & 4E) is due to this polymorphism in the PARG signature motif. We mutated leucine (L275) in AtPARG2 to glycine and generated the conserved “GGG-X7-QEE” motif. However, AtPARG2L275G mutant with a perfectly conserved PARG signature motif still did not show any detectable poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase activity (Fig. 5A). The data suggest that the polymorphism of the PARG signature motif in AtPARG2 is not the sole determinant of its lack of detectable enzymatic activity and additional polymorphisms/deletions also account for its loss of PARG functions. There are only about 52% amino acid identity and 66% similarity between AtPARG1 and AtPARG2 (S6 Fig.).

Fig. 5. The signature motif and residue G450 are essential for PARG enzymatic activity.

(A) The conserved residues G264 and E273 in the PARG signature motif of AtPARG1 are required for its enzymatic activity (left part of top panel) and creating a conserved PARG signature motif in AtPARG2 did not make it enzymatically active (right part of top panel). The sequences of PARG signature motif in AtPARG1 and AtPARG2 are shown on the top with the polymorphic residue labeled in red. F457 locates outside of the PARG signature motif in AtPARG1 and is not required for its enzymatic activity. AtPARP2 proteins were auto-PARylated and further subjected for PARG assay with WT AtPARG1, AtPARG2 or different mutated variants of AtPARGs. The PARylated proteins were detected with an α-PAR Western blot (top panel) and protein inputs are shown with CBB staining (bottom panel). (B) G450 in AtPARG1 is an essential residue in human HsPARG. Alignment of sequences of AtPARG1, aggie2 and HsPARG around AtPARG1G450 (red) residue is shown on the top. The corresponding G867R mutation in HsPARG blocked its activity to hydrolyze auto-PARylated human HsPARP-1. The auto-PARylated human HsPARP-1 proteins were incubated with WT or mutant form of HsPARG for PARG assay. The PARylated proteins were detected with an α-PAR Western blot (top panel) and protein inputs are shown with CBB staining (middle & bottom panels). The above experiments were repeated 3 times with similar results. The aggie2 mutation occurs at a conserved and essential PARG residue

We further addressed whether the aggie2 (G450R) mutation affected its PARG activity. Significantly, the aggie2 (G450R) mutant of AtPARG1 completely abolished its enzymatic activity detected by either α-PAR antibody (Fig. 4B) or 32P-NAD+ autoradiograph-based assay (Fig. 4C). Notably, the G450 in AtPARG1 is highly conserved among PARGs of different species (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the corresponding mutation in human HsPARG (G867R) also abolished its activity towards HsPARP-1 and AtPARP2, suggesting the essential role of this highly conserved residue in different PARGs (Fig. 5B and S5D Fig.). The phenylalanine (F) at position 227 in bacterium Thermomonospora curvata PARG is implicated in positioning the terminal ribose and the mutation of which rendered the enzyme inactive [28]. Surprisingly, mutation of the corresponding residue F457 to glycine (F457G) in AtPARG1 did not affect its enzymatic activity (Fig. 5A), suggesting a possible distinct function mediated by this residue in different PARGs and potentially divergent evolution.

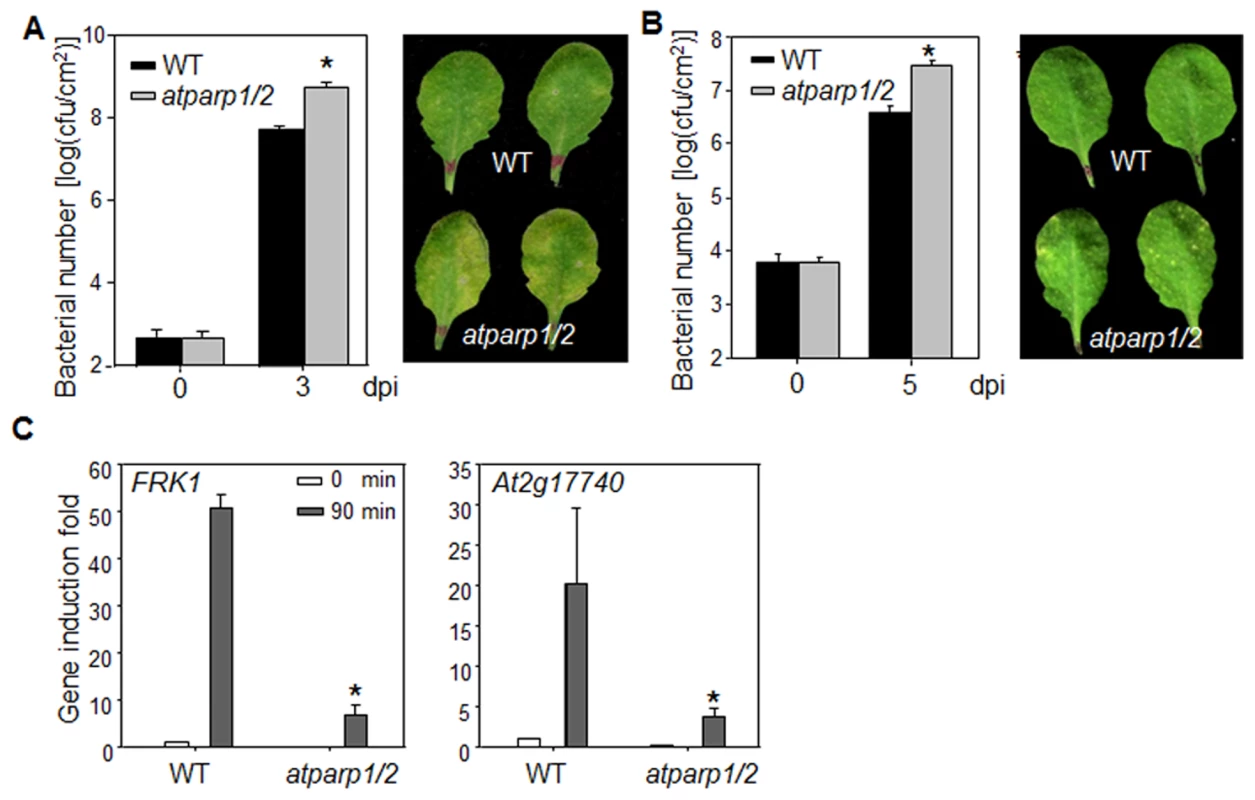

AtPARPs positively regulate plant immunity

We tested the involvement of AtPARPs in plant innate immunity and immune gene activation. Because of the potential functional redundancy of AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 [30], [31], we performed disease assay and analyzed defense gene expression in atparp1atparp2 (atparp1/2) double mutant. The atparp1/2 mutant plants were more susceptible to virulent P. syringae pv. maculicola ES4326 (Psm) infection compared to WT plants as indicated by more than 10 fold increase of bacterial growth in the atparp1/2 mutant (Fig. 6A). The disease symptom development was more pronounced in the atparp1/2 mutant than WT plants (Fig. 6A). Similarly, the atparp1/2 mutant plants showed the enhanced susceptibility with bacterial growth and symptom development to the infections by Pst DC3000 and a less virulent bacterium Pst DC3000ΔavrPtoavrPtoB (Fig. 6B & S7 Fig.). In addition, the atparp1/2 mutant plants showed the reduced induction of MAMP marker genes, including FRK1 and At2g17740, compared to WT plants at 90 min after flg22 treatment (Fig. 6C). Together, these data indicate that AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 are positive regulators in plant immunity and defense gene activation to bacterial infections.

Fig. 6. AtPARPs positively regulate Arabidopsis immunity.

(A) The atparp1/2 double mutant is more susceptible to Psm infection. WT (Col-0) and atparp1/2 double mutant plants were hand-inoculated with Psm at OD600 = 5 × 10−4, and the bacterial counting was performed 0 and 3 days post-inoculation (dpi). The data are shown as mean ± se from three independent repeats with Student's t-test. * indicates p<0.05 when compared to WT (Left panel). The disease symptom is shown at 3 dpi (right panel). (B) The atparp1/2 double mutant is more susceptible to Pst DC3000ΔavrPtoavrPtoB infection. WT and atparp1/2 double mutant plants were hand-inoculated with Pst DC3000ΔavrPtoavrPtoB at OD600 = 5 × 10-4, and the bacterial counting was performed 0 and 5 dpi (left panel) and the disease symptom is shown at 5 dpi (right panel). (C) Reduced immune gene expression in atparp1/2 mutant. Ten-day-old seedlings were treated with 100 nM flg22 for 90 min for qRT-PCR analysis. The data are shown as means ± se from three biological repeats. * indicates p<0.05 when compared to WT. The above experiments were repeated 4 times with similar results. Discussion

Protein PARylation mediated by PARPs and PARGs is an important, but less understood posttranslational modification process implicated in the regulation of diverse cellular processes and physiological responses [26]. In this study, an unbiased genetic screen revealed that Arabidopsis AtPARG1 plays an important role in regulating immune gene expression upon pathogen infection. We established and performed extensive in vitro and in vivo biochemical assays of PARP and PARG enzymatic activities. We have shown for the first time that Arabidopsis AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 are able to transfer ADP-ribose moieties from NAD+ to itself and acceptor proteins in vitro and in vivo. Thus, they are bona fide poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases. Interestingly, in contrast to their mammalian counterparts, AtPARP2 is more enzymatically active than AtPARP1. Significantly, MAMP perception promotes substantial enhancement of AtPARP2 enzymatic activity in vivo, reconciling the biological importance of PARPs/PARGs in regulating immune gene expression. AtPARG1, but not AtPARG2, is able to remove PAR polymers from PARylated proteins in vivo and in vitro and it is a bona fide poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase. The Arabidopsis parg1 (aggie2) mutant plants exhibited elevated expression of several MAMP-induced genes and callose deposition. Conversely, the Arabidopsis atparp1/2 mutant showed reduced expression of MAMP-induced genes and enhanced susceptibility to virulent Pseudomonas infections. Thus, the data suggest that protein PARylation positively regulates certain aspects of plant immune responses. Notably, the viability and normal growth of Arabidopsis parp and parg null mutants represent a unique opportunity to study protein PARylation regulatory mechanisms in diverse biological processes at the whole organismal level.

Our results lend support to a previous study that treatment of pharmacological inhibitor of PARPs, 3-AB, disrupted elf18 - and/or flg22-induced callose and lignin deposition, pigment accumulation and phenylalanine ammonia lyase activity [37]. However, the flg22-induced defense genes (FRK1 and WRKY29) were not affected by 3-AB treatment [37]. Our study with Arabidopsis parg and parp genetic mutants revealed a previously unrecognized function of protein PARylation in regulating immune gene expression upon pathogen infection. This is consistent with the general role of human PARPs and PARG in transcriptional regulation and chromatin modification [43], [45] and further substantiates the hypothesis that plant PARPs could ameliorate the cellular stresses caused by antimicrobial defenses (e.g. the effects of elevated ROS levels) [23]. Interestingly, ADP-ribosylation has also been exploited by pathogens as a means to quell plant immunity. Two Pseudomonas syringae effectors, HopU1 and HopF2, mono-ADP-ribosylate RNA-binding protein GRP7 and MAPK kinase MKK5 respectively, and interfere with their activities in plant defense transcription regulation and signaling [46], [47].

Unlike mammals and most other animals that encode a single PARG gene, the Arabidopsis genome encodes two adjacent PARG genes, AtPARG1 and AtPARG2, as well as a pseudogene At2g31860. Surprisingly, only AtPARG1, but not AtPARG2, possesses detectable poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase activity in vitro and in vivo with our extensive biochemical assays. Sequence analysis identified a polymorphism in the conserved PARG signature motif “GGG-X7-QEE”, where the third G is replaced with an L in AtPARG2. The PARG signature motif is absolutely required for its enzymatic activity as mutations at this motif in AtPARG1 completely abolished its activity. However, creation of the conserved signature motif in AtPARG2 was unable to gain its PARG activity suggesting that other polymorphisms in AtPARG2 are also responsible for its lack of enzymatic activity. Consistent with our biochemical assays, the PAR polymer concentration was much higher in atparg1 mutant than that in WT plants. A similar conclusion was reached on tej mutant, which carries a G262E mutation in the invariable signature motif of AtPARG1 [35]. The atparg1, but not atparg2 mutant, affected elf18-induced seedling growth inhibition and pigment formation, and sensitivity to DNA-damaging agent [37]. Interestingly, AtPARG2 is substantially induced in multiple plant-pathogen interactions [36] and it is required for plant resistance to B. cinerea infections [37]. Thus, despite of lacking detectable enzymatic activity, AtPARG2 may still play certain role in plant immunity. It is possible that AtPARG2 may regulate AtPARG1 activity. It is also possible that AtPARG2 has evolved novel functions in plant immune responses. Several other plant species, including rice, poplar, tomato and maize, are also predicted to encode multiple PARGs [23] (S8 Fig.). Unlike Arabidopsis PARGs, different PARG members in other species have invariant signature motif. For example, all three PARGs in poplar contain GGG-X7-QEE signature motif (S8 Fig.). However, a few other species such as Eutrema salsugineum, Capsella rubella, Phaseolus vulgaris, Oikopleura dioica, and Xenopus laevis, contain PARGs with an AtPARG2-like signature GGL-X7-QEE. It remains unknown how many PARGs are enzymatic active in the species with multiple PARGs.

Although there are 17 PARPs in mammals, the parp-1parp-2 double mutant mice are not viable and die at the onset of gastrulation, suggesting the essential role of protein PARylation during early embryogenesis [48]. The lethality of parp-1parp-2 double mutant mice might be due to genomic instability. However, Arabidopsis atparp1/2 double mutant is largely morphologically similar with WT plants and does not display any obvious growth defects. Although Arabidopsis atparp1/2 double mutant was hypersensitive to genotoxic stress, they did not have significant changes in telomere length nor end-to-end chromosome fusions [30]. Albeit mainly expressed in developing seeds, AtPARP3 may have redundant functions with AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 in maintaining genome stability. It remains interesting whether atparp1/2/3 triple mutant will exert abnormal plant growth and development. Consistent with the essential function of PARylation during embryogenesis, PARG-deficient mice and Drosophila are embryonic lethal which is probably due to the accumulation of PAR polymers and uncontrolled PAR-dependent signaling [49], [50]. The normal plant growth phenotype of atparg1 mutant might be due to the redundant function of AtPARG2. However, our extensive biochemical analysis indicates that AtPARG1, but not AtPARG2, accounts for most of PARG enzymatic activity. As AtPARG1 and AtPARG2 reside next to each other on the same chromosome, it is challenging to generate the double mutant. It remains possible that other PAR-degrading enzymes with distinct sequences exist in Arabidopsis. In vertebrate, ADP-ribosyl hydrolase 3 (ARH3), a structurally distinct enzyme from PARG, could also degrade PAR polymers associated with the mitochondrial matrix [26].

We observed that AtPARP2 activity was rapidly and substantially stimulated by flg22 treatment. In line with this observation, it has been shown that bacterial infections induced the increase of PAR polymers in Arabidopsis [37]. It is well established that damaged DNA stimulates PARP activity. Recent studies have shown that pathogen treatments induce DNA damage [51], [52], which could potentially serve as a trigger to activate PARP. Treatments with virulent or avirulent Pst strains for hours could induce DNA damage in Arabidopsis as detected by abundance of histone γ-H2AX, a sensitive indicator of DNA double-strand breaks or by DNA comet assays [51]. Prolonged pathogen treatment is often accompanied with the elevated accumulation of plant defense hormone salicylic acid (SA). It has also been shown that SA can also trigger DNA damage in the absence of a genotoxic agent [53]. However, treatments of flg22 or elf18 did not induce detectable DNA damage [51]. In addition, flg22-mediated stimulation of AtPARP2 activity occurs rather rapidly and within 30 min after treatment. Apparently, flg22 signaling could directly activate AtPARP2. It is well known that human HsPARP-1 is regulated by different posttranslational modification processes, such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation and cleavage [22]. HsPARP-1 could be activated by phosphorylated MAPK ERK2 in a broken DNA-independent manner, thereby enhancing ERK-induced Elk1 phosphorylation, core histone acetylation, and transcription of the Elk1-target genes [54]. MAPK cascade plays a central role functioning downstream of multiple MAMP receptors. It will be interesting to test whether flg22-activated MAPKs directly modulate PARP and/or PARG activities.

Our genetic and biochemical analyses revealed that PARP/PARG-mediated PAR dynamics regulates immune gene expression in Arabidopsis. Mammalian PARPs/PARG regulate gene expression through a variety of mechanisms including modulating chromatin, functioning as transcriptional co-regulators and mediating DNA methylation [55]. PARylation of histone lysine demethylase KDM5B maintains histone H3 lysine 4 trimethyl (H3K4me3), a histone mark associated with active promoters, by inhibiting KDM5B demethylase activity and interactions with chromatin. In addition, HsPARP-1 is able to promote exclusion of H1 and opening of promoter chromatin, which collectively lead to a permissive chromatin environment that allows loading of the RNAPII machinery [45]. HsPARG is also able to promote the formation of a chromatin environment suitable for retinoic acid receptor (RAR)-mediated transcription by removing PAR polymer from PARylated H3K9 demethylase KDM4D/JMJD2D thereby activating KDM4D/JMJD2D to inhibit H3K9me2, a histone mark associated with transcriptional repression [43]. Arabidopsis PARPs and PARGs are localized in the nucleus, and AtPARP2 could PARylate Histone H1. It is plausible to speculate that similar modes of action of protein PARylation-mediated transcriptional regulation exist in plants. Future identification of PARP/PARG targets (promoters and proteins) and PAR-associated proteins, especially during plant immune responses, will elucidate how protein PARylation modulates plant immune gene expression.

Materials and Methods

Plant and pathogen materials and growth conditions

Arabidopsis accession Col-0, pFRK1::LUC transgenic plants, aggie2 mutant, atparg1-1 (SALK_147805), atparg1-2 (SALK_16088), atparg2 (GABI-Kat 072B04), atparp1/atparp2 (GABI-Kat 692A05/SALK_640400), pPARG1::PARG1-FLAG transgenic plants were grown in soil (Metro Mix 366) at 23°C, 60% humidity and 75 µE m−2s−1 light with a 12-hr light/12-hr dark photoperiod. Four-week-old plants were used for protoplast isolation and transient expression assays according to the standard procedure [56]. Seedlings were germinated on ½ Murashige and Skoog (MS) plate containing 1% sucrose, 0.8% Agar and grown at 23°C and 75 µE m-2s−1 light with a 12-hr light/12-hr dark photoperiod for 12 days, transferred to a 6-well tissue culture plate with 2 ml H2O for overnight, and then treated with 100 nM flg22 or H2O for indicated time.

Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst) DC3000, hrcC, ΔavrPtoavrPtoB, P. syringae pv. maculicola ES4326 (Psm), or P. syringae pv. phaseolicola NPS3121 strains were cultured overnight at 28°C in the KB medium with 50 µg/ml rifampicin or streptomycin. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation, washed, and adjusted to the desired density with 10 mM MgCl2. Leaves of 4-week-old plants were hand-infiltrated with bacterial suspension using a 1-ml needleless syringe and collected at the indicated time for luciferase activity or bacterial growth assays. To measure bacterial growth, two leaf discs were ground in 100 µl H2O and serial dilutions were plated on TSA medium (1% Bacto tryptone, 1% sucrose, 0.1% glutamic acid, 1.5% agar) with appropriate antibiotics. Bacterial colony forming units (cfu) were counted 2 days after incubation at 28°C. Each data point is shown as triplicates. Botrytis cinerea strain BO5 was cultured on Potato Dextrose Agar (Difco) and incubated at room temperature. Conidia were re-suspended in distilled water and spore concentration was adjusted to 2.5 × 105 spores/ml. Gelatin (0.5%) was added to conidial suspension before inoculation. Leaves of six-week-old plants were drop-inoculated with B. cinerea at the concentration of 2.5 × 105 spores/ml. Lesion size was measured 2 days post-inoculation.

Mutant screening, map-based cloning and next generation sequencing

The pFRK1::LUC construct in a binary vector was transformed into Arabidopsis Col-0 plants. The homozygous transgenic plants with flg22-inducible pFRK1::LUC were selected for mutagenesis. The seeds were mutagenized with 0.4% ethane methyl sulfonate (EMS). Approximately 6,000 M2 seedlings were screened for their responsiveness to flg22 treatment. The seedlings were germinated in liquid ½ MS medium for 14 days, and then transferred to water for overnight and treated with 10 nM flg22. After 12 hr flg22 treatment, the individual seedlings were transferred to a 96-well plate, sprayed with 0.2 mM luciferin and kept in dark for 20 min. The bioluminescence from induced pFRK1::LUC expression was recorded by a luminometer (Perkin Elmer, 2030 Multilabel Reader, Victor X3). The candidate mutants with altered flg22 responsiveness were recovered on ½ MS plate for 10 days, and then transferred to soil for seeds.

The aggie2 mutant was crossed with Arabidopsis Ler accession, and an F2 population was used for map-based cloning. Mapping with 270 F2 plants with aggie2 mutant phenotype placed the causal mutation in an 88 kb region between marker F20F17 and F22D22 on chromosome 2. The aggie2 genomic DNA was sequenced with the 100 nt paired-end sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform at Texas AgriLife Genomics and Bioinformatics Service (TAGS) (College Station, TX, USA). Ten-fold genome coverage was obtained with 11M reads. The Illumina reads were analyzed using CLC Genomics Workbench 6.0.1 software. By mapping to Col-0 genomic sequence (TAIR10 release), SNPs were identified as candidates of aggie2 mutation. In the aforementioned 88 kb region, a G to A mutation at the position of 1348 nt of At2g31870 was identified with 100% frequency. The mutation was confirmed by Sanger sequencing of aggie2 genomic DNA.

Plasmid constructs for protoplasts and transgenic plants

The AtPARP1, AtPARP2, AtPARG1, AtPARG2 and Histone H1.1 (At1g06760) genes were amplified from Arabidopsis Col-0 cDNA and cloned into a plant transient expression vector (pHBT vector) with an HA, FLAG or GFP epitope tag at the C-terminus via restriction sites NcoI or BamHI and StuI respectively. The oligos used to amplify aforementioned cDNAs are listed in S1 Table. The target genes were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The cloned genes in plant expression vector were then sub-cloned into protein fusion vectors, pGEX-4T (Pharmacia, USA), pMAL-c (NEB, USA) or pET28a (EMD Millipore, USA), for protein expression in bacteria. For Histone H1.3 (At2g18050), we ordered cDNA from ABRC (G13366) and cloned it into a modified pMAL-c via SfiI site. Point mutations were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis PCR. The AtPARG1 promoter (1163 bp upstream of start codon ATG) was amplified from the genomic DNA of Col-0 and digested with KpnI and NcoI. The AtPARG1-FLAG-NOS terminator fragment was released from pHBT-AtPARG1-FLAG via NcoI and EcoRI digestion. The two fragments were ligated and sub-cloned into a binary vector, pCAMBIA2300 via KpnI and EcoRI sites to yield expression construct (pAtPARG1::AtPARG1-FLAG). The resulting binary vector was transformed into aggie2 via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation.

The primers for cloning and point mutations were listed in the S1 Table.

In vitro and in vivo PARP and PARG assays

Expression and purification of GST, His6 and MBP fusion proteins were performed according to the manufacturer's manuals. For in vitro auto-PARylation reaction, 1.2 µg of MBP-AtPARP2 or MBP-AtPARP1 proteins were incubated in a 20 µl reaction with 1 × PAR reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH8.0, 50 mM NaCl) with 0.2 mM NAD+, and 1 × activated DNA (Trevigen, USA). To inhibit PAR reaction, 2.5 mM PARP inhibitor, 3-Aminobenzamide (3-AB, Sigma, USA), was added to the reaction. The reactions were kept at room temperature for 30 min and stopped by adding SDS loading buffer. To detect PARG activity, about 1.0 µg of purified GST, GST-AtPARG1 or GST-AtPARG2 proteins together with 2.5 mM 3-AB were added to auto-PARylated AtPARP2 proteins derived from the above PAR reactions and incubated at room temperature for another 30 min. PARylated proteins were separated in 7.5% SDS-PAGE and detected with an α-PAR polyclonal antibody (Trevigen, USA). For Biotin NAD+ PAR assay, 25 µM Biotin-NAD+ (Trevigen, USA) was added to replace NAD+ in the reaction described above. The PAR polymer formation was detected by Streptavidin-HRP (Pierce, USA). For in vitro 32P-NAD+-mediated PAR assays, 1.0 µg of MBP-AtPARP2 or MBP-AtPARP1 proteins were incubated in a 20 µl reaction in the buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH8.0, 4 mM MgCl2, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 µg/ml BSA, 1 × activated DNA, 1 µCi 32P-NAD+ (Perkin Elmer, USA) and 100 nM cold NAD+ for 30 min at room temperature. For Histone PARylation assays, 2.0 µg of MBP-H1.1 or MBP-H1.3 proteins were added in the above reactions. The radiolabeled proteins were separated in SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography.

For in vivo PAR assays, 500 µl Arabidopsis protoplasts at the concentration of 2 × 105/ml were transfected with 100 µg of plasmid DNA of pHBT-AtPARP2-HA. After 12 hr incubation, the protoplasts were treated with 100 nM flg22 for 30 min and fed with 1 µCi 32P-NAD+ for 1 hr. The protoplasts were then lysed in IP buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton, 1 × protease inhibitor, 1 mM DTT, 2 mM NaF and 2 mM Na3VO4) and the AtPARP2-HA proteins were immunoprecipitated with α-HA antibody (Roche, USA) and protein-G-agarose (Roche, USA) in a shaker for 3 hr at 4°C. In vivo PARylated proteins enriched on the beads were then separated in 10% SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. For in vivo PARG assay, AtPARG1-HA or AtPARG2-HA plasmid DNA was co-transfected with AtPARP2-FLAG plasmid DNA into protoplasts, and expressed for 12 hr. The protoplasts were fed with 32P-NAD+ and subjected to immunoprecipitation as described above. The AtPARP2-FLAG proteins were immunoprecipitated with α-FLAG agarose gel (Sigma, USA), separated in 10% SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. The expression of AtPARPs and AtPARGs was detected with Western blot (WB) using the corresponding antibodies.

Detection of PAR polymers from protein extract of nuclei

The 12-day old seedlings grown on ½ MS plates were harvested and ground into fine powder in liquid nitrogen. Isolation of nuclei with Honda buffer was performed according to published procedure [57]. Nuclear proteins were released in 1xPBS buffer with 1% SDS and spotted on nitrocellulose membrane. The protein loaded on the membrane was normalized by using α-Histone H3 antibody (Abcam, USA), and the PAR polymers were detected by α-PAR antibody. The relative PAR level was determined by calculating the ratio of PAR signal to Histone H3 signal after quantification of hybridization intensity with ImageJ software.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

For RNA isolation, 12-day-old seedlings grown on ½ MS plate were transferred to 2 ml H2O in a 6-well plate to recover for 1 day, and then treated with 100 nm flg22 for 30 or 90 min. RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, USA) and quantified with NanoDrop. The RNA was treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase I (Promega, USA) for 30 min at 37°C, and then reverse transcribed with M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (NEB, USA). Real-time RT-PCR was carried out using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, USA) on 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). The primers used to detect specific transcript by real-time RT-PCR are listed in S2 Table.

Callose deposition

Leaves of six-week-old plants grown in soil were hand-inoculated with 0.5 µM flg22 or H2O for 12 hr. The leaves were then transferred into FAA solution (10% formaldehyde, 5% acetic acid and 50% ethanol) for 12 hr, de-stained in 95% ethanol for 6 hr, washed twice with ddH2O, and incubated in 0.01% aniline blue solution (150 mM KH2PO4, pH 9.5) for 1 hr. The callose deposits were visualized with a fluorescence microscope. Callose deposits were counted using ImageJ 1.43U software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Lignin deposition

Leaves of six-week-old plants grown in soil were surface-sterilized by 70% ethanol, rinsed with H2O and incubated with 100 nM flg22 or H2O for 12 hr. The leaves were then de-stained in 95% ethanol with 2% chloroform for 12 hr and 95% ethanol for 6 hr, washed twice with 95% ethanol, and incubated in 2% phloroglucinol solution (20% ethanol, 20% HCl) for 5 min. The images were scanned by HP officejet Pro 8600 Premium.

MAPK assay

Ten-day-old seedlings germinated on ½MS plate were transferred to 2ml H2O in a 6-well plate to recover for 1 day, and then treated with 100 nM flg22 for 5, 15 or 45 min. The seedlings were grinded in IP buffer. The cleared lysate was mixed with SDS sample buffer and loaded onto 12.5% SDS-PAGE. Activated MAPKs were detected with α-pErk1/2 antibody (Cell Signaling, USA).

ROS analyses

ROS burst was determined by a luminol-based assay. At least 10 leaves of four-week-old Arabidopsis plants for each genotype were excised into leaf discs of 0.25 cm2, followed by an overnight incubation in 96-well plate with 100 µl of H2O to eliminate the wounding effect. H2O was replaced by 100 µl of reaction solution containing 50 µM luminol and 10 µg/ml horseradish peroxidase (Sigma, USA) supplemented with or without 100 nM flg22. The measurement was conducted immediately after adding the solution with a luminometer (Perkin Elmer, 2030 Multilabel Reader, Victor X3), with a 1.5 min interval reading time for a period of 30 min. The measurement values for ROS production from 20 leaf discs per treatment were indicated as means of RLU (Relative Light Units).

GFP localization assay

Arabidopsis protoplasts were transfected with various GFP-tagged pHBT constructs as indicated in the figures. Fluorescence signals in the protoplasts were visualized under a confocal microscope 12 hr after transfection. To construct 35S::AtPARP2-GFP binary plasmid for Agrobacterium-mediated transient assay, the NcoI-PstI fragment containing AtPARP2-GFP was released from pHBT-35S::AtPARP2-GFP and ligated into pCB302 binary vector. For tobacco transient expression, Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 containing pCB302-35S::AtPARP2-GFP was cultured at 28°C for 18 hr. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at a speed of 3500 rpm and re-suspended with infiltration buffer (10 mM MES pH = 5.7, 10 mM MgCl2, 200 µM acetosyringone). Cell solution at OD600 = 0.75 was used to infiltrate 3-week-old Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Fluorescence signals were detected 2 days post-infiltration. Fluorescence images were taken with Nikon-A1 confocal laser microscope systems and images were processed using NIS-Elements Microscope Imaging Software. The excitation lines for imaging GFP, RFP and chloroplast were 488, 561 and 640 nm, respectively.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. BollerT, FelixG (2009) A renaissance of elicitors: perception of microbe-associated molecular patterns and danger signals by pattern-recognition receptors. Annu Rev Plant Biol 60 : 379–406.

2. DoddsPN, RathjenJP (2010) Plant immunity: towards an integrated view of plant-pathogen interactions. Nat Rev Genet 11 : 539–548.

3. MachoAP, ZipfelC (2014) Plant PRRs and the activation of innate immune signaling. Mol Cell 54 : 263–272.

4. ChinchillaD, BauerZ, RegenassM, BollerT, FelixG (2006) The Arabidopsis receptor kinase FLS2 binds flg22 and determines the specificity of flagellin perception. Plant Cell 18 : 465–476.

5. Gomez-GomezL, BollerT (2000) FLS2: an LRR receptor-like kinase involved in the perception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin in Arabidopsis. Mol Cell 5 : 1003–1011.

6. HeeseA, HannDR, Gimenez-IbanezS, JonesAM, HeK, et al. (2007) The receptor-like kinase SERK3/BAK1 is a central regulator of innate immunity in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 12217–12222.

7. ChinchillaD, ZipfelC, RobatzekS, KemmerlingB, NurnbergerT, et al. (2007) A flagellin-induced complex of the receptor FLS2 and BAK1 initiates plant defence. Nature 448 : 497–500.

8. SchulzeB, MentzelT, JehleAK, MuellerK, BeelerS, et al. (2010) Rapid heteromerization and phosphorylation of ligand-activated plant transmembrane receptors and their associated kinase BAK1. J Biol Chem 285 : 9444–9451.

9. SunY, LiL, MachoAP, HanZ, HuZ, et al. (2013) Structural basis for flg22-induced activation of the Arabidopsis FLS2-BAK1 immune complex. Science 342 : 624–628.

10. LuD, WuS, GaoX, ZhangY, ShanL, et al. (2010) A receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase, BIK1, associates with a flagellin receptor complex to initiate plant innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 : 496–501.

11. ZhangJ, LiW, XiangT, LiuZ, LalukK, et al. (2010) Receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases integrate signaling from multiple plant immune receptors and are targeted by a Pseudomonas syringae effector. Cell Host Microbe 7 : 290–301.

12. LinW, LiB, LuD, ChenS, ZhuN, et al. (2014) Tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase complex BAK1/BIK1 mediates Arabidopsis innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111 : 3632–3637.

13. XuJH, WeiXC, YanLM, LiuD, MaYY, et al. (2013) Identification and functional analysis of phosphorylation residues of the Arabidopsis BOTRYTIS-INDUCED KINASE1. Protein & Cell 4 : 771–781.

14. RouxM, SchwessingerB, AlbrechtC, ChinchillaD, JonesA, et al. (2011) The Arabidopsis leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinases BAK1/SERK3 and BKK1/SERK4 are required for innate immunity to hemibiotrophic and biotrophic pathogens. Plant Cell 23 : 2440–2455.

15. PostelS, KufnerI, BeuterC, MazzottaS, SchwedtA, et al. (2010) The multifunctional leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase BAK1 is implicated in Arabidopsis development and immunity. Eur J Cell Biol 89 : 169–174.

16. LiuZ, WuY, YangF, ZhangY, ChenS, et al. (2013) BIK1 interacts with PEPRs to mediate ethylene-induced immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 : 6205–6210.

17. LiJ, WenJ, LeaseKA, DokeJT, TaxFE, et al. (2002) BAK1, an Arabidopsis LRR receptor-like protein kinase, interacts with BRI1 and modulates brassinosteroid signaling. Cell 110 : 213–222.

18. NamKH, LiJ (2002) BRI1/BAK1, a receptor kinase pair mediating brassinosteroid signaling. Cell 110 : 203–212.

19. LinW, LuD, GaoX, JiangS, MaX, et al. (2013) Inverse modulation of plant immune and brassinosteroid signaling pathways by the receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase BIK1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 : 12114–12119.

20. Kadota Y, Sklenar J, Derbyshire P, Stransfeld L, Asai S, et al.. (2014) Direct Regulation of the NADPH Oxidase RBOHD by the PRR-Associated Kinase BIK1 during Plant Immunity. Mol Cell.

21. LiL, LiM, YuL, ZhouZ, LiangX, et al. (2014) The FLS2-Associated Kinase BIK1 Directly Phosphorylates the NADPH Oxidase RbohD to Control Plant Immunity. Cell Host Microbe 15 : 329–338.

22. LuoX, KrausWL (2012) On PAR with PARP: cellular stress signaling through poly(ADP-ribose) and PARP-1. Genes Dev 26 : 417–432.

23. BriggsAG, BentAF (2011) Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in plants. Trends Plant Sci 16 : 372–380.

24. KalischT, AmeJC, DantzerF, SchreiberV (2012) New readers and interpretations of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation. Trends Biochem Sci 37 : 381–390.

25. KrausWL, LisJT (2003) PARP goes transcription. Cell 113 : 677–683.

26. GibsonBA, KrausWL (2012) New insights into the molecular and cellular functions of poly(ADP-ribose) and PARPs. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 13 : 411–424.

27. KimIK, KieferJR, HoCM, StegemanRA, ClassenS, et al. (2012) Structure of mammalian poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase reveals a flexible tyrosine clasp as a substrate-binding element. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19 : 653–656.

28. SladeD, DunstanMS, BarkauskaiteE, WestonR, LafiteP, et al. (2011) The structure and catalytic mechanism of a poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase. Nature 477 : 616–620.

29. LambRS, CitarelliM, TeotiaS (2012) Functions of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase superfamily in plants. Cell Mol Life Sci 69 : 175–189.

30. BoltzKA, JastiM, TownleyJM, ShippenDE (2014) Analysis of poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerases in Arabidopsis telomere biology. PLoS One 9: e88872.

31. JiaQ, den Dulk-RasA, ShenH, HooykaasPJ, de PaterS (2013) Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerases are involved in microhomology mediated back-up non-homologous end joining in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 82 : 339–351.

32. SchulzP, JansseuneK, DegenkolbeT, MeretM, ClaeysH, et al. (2014) Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase activity controls plant growth by promoting leaf cell number. PLoS One 9: e90322.

33. De BlockM, VerduynC, De BrouwerD, CornelissenM (2005) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in plants affects energy homeostasis, cell death and stress tolerance. Plant J 41 : 95–106.

34. VanderauweraS, De BlockM, Van de SteeneN, van de CotteB, MetzlaffM, et al. (2007) Silencing of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in plants alters abiotic stress signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 15150–15155.

35. PandaS, PoirierGG, KaySA (2002) tej defines a role for poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in establishing period length of the arabidopsis circadian oscillator. Dev Cell 3 : 51–61.

36. Adams-PhillipsL, WanJ, TanX, DunningFM, MeyersBC, et al. (2008) Discovery of ADP-ribosylation and other plant defense pathway elements through expression profiling of four different Arabidopsis-Pseudomonas R-avr interactions. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 21 : 646–657.

37. Adams-PhillipsL, BriggsAG, BentAF (2010) Disruption of Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation Mechanisms Alters Responses of Arabidopsis to Biotic Stress. Plant Physiology 152 : 267–280.

38. LiGJ, NasarV, YangYX, LiW, LiuB, et al. (2011) Arabidopsis poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase 1 is required for drought, osmotic and oxidative stress responses. Plant Science 180 : 283–291.

39. AsaiT, TenaG, PlotnikovaJ, WillmannMR, ChiuWL, et al. (2002) MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature 415 : 977–983.

40. HeP, ShanL, LinNC, MartinGB, KemmerlingB, et al. (2006) Specific bacterial suppressors of MAMP signaling upstream of MAPKKK in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Cell 125 : 563–575.

41. LunaE, PastorV, RobertJ, FlorsV, Mauch-ManiB, et al. (2011) Callose deposition: a multifaceted plant defense response. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 24 : 183–193.

42. AravindL, KooninEV (2000) SAP - a putative DNA-binding motif involved in chromosomal organization. Trends Biochem Sci 25 : 112–114.

43. Le MayN, IltisI, AmeJC, ZhovmerA, BiardD, et al. (2012) Poly (ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase regulates retinoic acid receptor-mediated gene expression. Mol Cell 48 : 785–798.

44. KrishnakumarR, GambleMJ, FrizzellKM, BerrocalJG, KininisM, et al. (2008) Reciprocal binding of PARP-1 and histone H1 at promoters specifies transcriptional outcomes. Science 319 : 819–821.

45. KrishnakumarR, KrausWL (2010) PARP-1 regulates chromatin structure and transcription through a KDM5B-dependent pathway. Mol Cell 39 : 736–749.

46. WangY, LiJ, HouS, WangX, LiY, et al. (2010) A Pseudomonas syringae ADP-ribosyltransferase inhibits Arabidopsis mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases. Plant Cell 22 : 2033–2044.

47. FuZQ, GuoM, JeongBR, TianF, ElthonTE, et al. (2007) A type III effector ADP-ribosylates RNA-binding proteins and quells plant immunity. Nature 447 : 284–288.

48. de MurciaJMN, RicoulM, TartierL, NiedergangC, HuberA, et al. (2003) Functional interaction between PARP-1 and PARP-2 in chromosome stability and embryonic development in mouse. Embo Journal 22 : 2255–2263.

49. KohDW, LawlerAM, PoitrasMF, SasakiM, WattlerS, et al. (2004) Failure to degrade poly(ADP-ribose) causes increased sensitivity to cytotoxicity and early embryonic lethality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 : 17699–17704.

50. HanaiS, KanaiM, OhashiS, OkamotoK, YamadaM, et al. (2004) Loss of poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase causes progressive neurodegeneration in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 : 82–86.

51. SongJ, BentAF (2014) Microbial pathogens trigger host DNA double-strand breaks whose abundance is reduced by plant defense responses. PLoS Pathog 10: e1004030.

52. TollerIM, NeelsenKJ, StegerM, HartungML, HottigerMO, et al. (2011) Carcinogenic bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori triggers DNA double-strand breaks and a DNA damage response in its host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 : 14944–14949.

53. YanS, WangW, MarquesJ, MohanR, SalehA, et al. (2013) Salicylic acid activates DNA damage responses to potentiate plant immunity. Mol Cell 52 : 602–610.

54. Cohen-ArmonM, VisochekL, RozensalD, KalalA, GeistrikhI, et al. (2007) DNA-independent PARP-1 activation by phosphorylated ERK2 increases Elk1 activity: a link to histone acetylation. Mol Cell 25 : 297–308.

55. KrausWL, HottigerMO (2013) PARP-1 and gene regulation: progress and puzzles. Mol Aspects Med 34 : 1109–1123.

56. HeP, ShanL, SheenJ (2007) The use of protoplasts to study innate immune responses. Methods Mol Biol 354 : 1–9.

57. KinkemaM, FanW, DongX (2000) Nuclear localization of NPR1 is required for activation of PR gene expression. Plant Cell 12 : 2339–2350.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Phosphorylation of Elp1 by Hrr25 Is Required for Elongator-Dependent tRNA Modification in YeastČlánek Naturally Occurring Differences in CENH3 Affect Chromosome Segregation in Zygotic Mitosis of HybridsČlánek Insight in Genome-Wide Association of Metabolite Quantitative Traits by Exome Sequence AnalysesČlánek ALIX and ESCRT-III Coordinately Control Cytokinetic Abscission during Germline Stem Cell DivisionČlánek Deciphering the Genetic Programme Triggering Timely and Spatially-Regulated Chitin Deposition

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 1- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- The Combination of Random Mutagenesis and Sequencing Highlight the Role of Unexpected Genes in an Intractable Organism

- Ataxin-3, DNA Damage Repair, and SCA3 Cerebellar Degeneration: On the Path to Parsimony?

- α-Actinin-3: Why Gene Loss Is an Evolutionary Gain

- Origins of Context-Dependent Gene Repression by Capicua

- Transposable Elements Contribute to Activation of Maize Genes in Response to Abiotic Stress

- No Evidence for Association of Autism with Rare Heterozygous Point Mutations in Contactin-Associated Protein-Like 2 (), or in Other Contactin-Associated Proteins or Contactins

- Nur1 Dephosphorylation Confers Positive Feedback to Mitotic Exit Phosphatase Activation in Budding Yeast

- A Regulatory Hierarchy Controls the Dynamic Transcriptional Response to Extreme Oxidative Stress in Archaea

- Genetic Variants Modulating CRIPTO Serum Levels Identified by Genome-Wide Association Study in Cilento Isolates

- Small RNA Sequences Support a Host Genome Origin of Satellite RNA

- Phosphorylation of Elp1 by Hrr25 Is Required for Elongator-Dependent tRNA Modification in Yeast

- Genetic Mapping of MAPK-Mediated Complex Traits Across

- An AP Endonuclease Functions in Active DNA Demethylation and Gene Imprinting in

- Developmental Regulation of the Origin Recognition Complex

- End of the Beginning: Elongation and Termination Features of Alternative Modes of Chromosomal Replication Initiation in Bacteria

- Naturally Occurring Differences in CENH3 Affect Chromosome Segregation in Zygotic Mitosis of Hybrids

- Imputation of the Rare G84E Mutation and Cancer Risk in a Large Population-Based Cohort

- Polycomb Protein SCML2 Associates with USP7 and Counteracts Histone H2A Ubiquitination in the XY Chromatin during Male Meiosis

- A Genetic Strategy for Probing the Functional Diversity of Magnetosome Formation

- Interactions of Chromatin Context, Binding Site Sequence Content, and Sequence Evolution in Stress-Induced p53 Occupancy and Transactivation

- The Yeast La Related Protein Slf1p Is a Key Activator of Translation during the Oxidative Stress Response

- Integrative Analysis of DNA Methylation and Gene Expression Data Identifies as a Key Regulator of COPD

- Proteasomes, Sir2, and Hxk2 Form an Interconnected Aging Network That Impinges on the AMPK/Snf1-Regulated Transcriptional Repressor Mig1

- Functional Interplay between the 53BP1-Ortholog Rad9 and the Mre11 Complex Regulates Resection, End-Tethering and Repair of a Double-Strand Break

- Estrogenic Exposure Alters the Spermatogonial Stem Cells in the Developing Testis, Permanently Reducing Crossover Levels in the Adult

- Protein Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation Regulates Immune Gene Expression and Defense Responses

- Sumoylation Influences DNA Break Repair Partly by Increasing the Solubility of a Conserved End Resection Protein

- A Discrete Transition Zone Organizes the Topological and Regulatory Autonomy of the Adjacent and Genes

- Elevated Mutation Rate during Meiosis in

- The Intersection of the Extrinsic Hedgehog and WNT/Wingless Signals with the Intrinsic Hox Code Underpins Branching Pattern and Tube Shape Diversity in the Airways

- MiR-24 Is Required for Hematopoietic Differentiation of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- Tissue-Specific Effects of Genetic and Epigenetic Variation on Gene Regulation and Splicing

- Heterologous Aggregates Promote Prion Appearance via More than One Mechanism

- The Tumor Suppressor BCL7B Functions in the Wnt Signaling Pathway

- , A -Acting Locus that Controls Chromosome-Wide Replication Timing and Stability of Human Chromosome 15

- Regulating Maf1 Expression and Its Expanding Biological Functions

- A Polyubiquitin Chain Reaction: Parkin Recruitment to Damaged Mitochondria

- RecFOR Is Not Required for Pneumococcal Transformation but Together with XerS for Resolution of Chromosome Dimers Frequently Formed in the Process

- An Intracellular Transcriptomic Atlas of the Giant Coenocyte

- Insight in Genome-Wide Association of Metabolite Quantitative Traits by Exome Sequence Analyses

- The Role of the Mammalian DNA End-processing Enzyme Polynucleotide Kinase 3’-Phosphatase in Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3 Pathogenesis

- The Global Regulatory Architecture of Transcription during the Cell Cycle