-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Stage-Dependent and Locus-Specific Role of Histone Demethylase Jumonji D3 (JMJD3) in the Embryonic Stages of Lung Development

A chromosome in the eukaryotic nucleus is an organized package of DNA coiled around histone proteins. DNA contains genes and other nucleotide sequences as well as histone proteins including H1, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Gene expression is dynamically regulated by DNA and histone modifications, such as methylation and demethylation. The protein Jumonji domain containing-3 (Jmjd3) is a critical demethylase that regulates gene expression. Here, we found that Jmjd3 plays an important role in the regulation of mouse lung development. Global Jmjd3 deletion results in perinatal lethality that is associated with respiratory failure caused by defective lung development. Tissue and stage-specific deletion show that Jmjd3 is dispensable for mouse lung development in the later stages (after E9.5). Jmjd3 deficiency downregulates the expression of genes critical for lung development through interactions with specific transcription factors and epigenetic protein complexes. Our findings provide new insights into the role and molecular mechanism of action of Jmjd3 in embryonic lung development.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(7): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004524

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004524Summary

A chromosome in the eukaryotic nucleus is an organized package of DNA coiled around histone proteins. DNA contains genes and other nucleotide sequences as well as histone proteins including H1, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Gene expression is dynamically regulated by DNA and histone modifications, such as methylation and demethylation. The protein Jumonji domain containing-3 (Jmjd3) is a critical demethylase that regulates gene expression. Here, we found that Jmjd3 plays an important role in the regulation of mouse lung development. Global Jmjd3 deletion results in perinatal lethality that is associated with respiratory failure caused by defective lung development. Tissue and stage-specific deletion show that Jmjd3 is dispensable for mouse lung development in the later stages (after E9.5). Jmjd3 deficiency downregulates the expression of genes critical for lung development through interactions with specific transcription factors and epigenetic protein complexes. Our findings provide new insights into the role and molecular mechanism of action of Jmjd3 in embryonic lung development.

Introduction

Gene expression is epigenetically regulated through DNA methylation as well as covalent chromatin modifications such as acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, and methylation of histones. Histone methylation state is dynamically regulated by histone methyltransferases and demethylases [1]–[5]. The trimethylation of histone 3 (H3K4) at lysine 4 is usually associated with the activation of gene expression, whereas trimethylation of histone 3 at lysine 27 (H3K27) is associated with the repression of gene expression [1]–[5]. The polycomb repressive complex, which contains the H3K27 methyltransferase Ezh2 [5], [6], dimethylates and trimethylates H3K27 (H3K27me2/3). Recently, the H3K27 demethylase Jumonji domain containing-3 (Jmjd3; KDM6B) was found to catalyze the demethylation of H3K27me2/3 in vitro [7]–[11].

Despite the identification of Jmjd3 as a key H3K27 demethylase, little is known regarding its in vivo function. Jmjd3 expression is induced by vitamin D and proinflammatory stimuli in macrophages and is required for the expression of INK4A-ARF, Nodal, and Irf4 in fibroblasts, mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs), and macrophages, respectively [12]–[16]. Recently, we showed that Jmjd3 plays a vital role in induced pluripotent stem cell reprogramming by regulating INK4a/Arf expression and PHF20 degradation [17]. Several studies using Jmjd3 knockout (KO) mice have demonstrated the importance of Jmjd3 in differentiation and development in vivo. Jmjd3 has been shown to play a crucial role in the regulation of macrophage development and differentiation [15] and mesoderm differentiation and cardiovascular lineage commitment in mouse ESCs [18]. Furthermore, the embryonic and postnatal lethality of Jmjd3 deletion in mice indicate the critical requirement for Jmjd3 during development [15], [18], [19]. However, the role and mechanism of action of Jmjd3 in differentiation and developmental processes remain largely unknown.

Lung development is a complex process that requires the participation of many transcription factors and developmentally regulated genes at several different stages. This complex process begins with the formation of airways from embryonic lung buds that originate from the foregut endoderm and branch into the millions of alveoli required for the first breath after birth [20]–[22]. Lung alveoli are lined by type I and II pneumocytes that are required for gas exchange and surfactant production to reduce surface tension, respectively. Failure of the lung to expand after the first breath is one of the most common causes of neonatal morbidity and mortality from diseases such as infant respiratory distress syndrome [22], [23]. Among the surfactant proteins expressed in type II cells, including surfactant protein A (SP-A), SP-B, SP-C, and SP-D [24], [25], SP-B is required for postnatal lung function and survival [26]–[28]. Complete deficiency of SP-B in mice and humans results in lethal neonatal RDS, which is characterized by a virtual absence of lung compliance and increased amounts of incompletely processed proprotein SP-C [26], [27], [29]–[31]. Loss or partial reduction of SP-B expression has been observed in patients without SP-B gene mutation [27], but whether such losses or reductions in SP-B expression are associated with epigenetic alterations remains largely unknown.

To investigate the function and mechanisms of Jmjd3 in vivo, we generated Jmjd3 global and tissue-specific knockout mice. We found that Jmjd3 ablation induces perinatal lethality associated with respiratory failure caused by defective lung development. Tissue-specific deletion of Jmjd3 and tamoxifen (TM)-induced temporal deletion revealed Jmjd3 is dispensable in the later embryonic development (after E9.5) stages. Gene expression profiling, tissue staining, and chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-Seq) analyses showed that Jmjd3 deficiency markedly reduces a set of genes critical for lung development, in particular SP-B. Jmjd3-mediated changes in target gene expression are associated with alterations in H3K27 and H3K4 methylation levels in the proximal promoter region. Jmjd3 regulates SP-B expression in a locus-specific manner through interactions with the transcription factor Nkx2.1 and the epigenetic protein Brg1. Together, our findings show that Jmjd3 plays a stage-dependent and locus-specific role during embryonic lung development. This function of Jmjd3 is associated with the epigenetic regulation of lung surfactant protein gene expression.

Results

Jmjd3 deletion causes multiple embryonic defects

To study the in vivo functions of Jmjd3 during development, Jmjd3 KO mice were generated by homologous recombination technique [17]. Heterozygous Jmjd3+/− mice were fertile and viable. However, homozygous Jmjd3-deficient mice were not recovered at weaning time (P21) from the heterozygous Jmjd3+/− mating pairs (Table S1), suggesting that Jmjd3 deficiency induces postnatal lethality. To confirm this, the embryos were genotyped and found to be consistent with a Mendelian ratio distribution at the late gestation stages (E11.5, E14.5, E17.5, E19.5) up to postnatal day 0 (P0). However, homozygous Jmjd3-deficient mice died shortly after birth (P0) with kyphosis and severe lordosis (Figure 1A). Jmjd3-deficient newborns and their wild-type (WT) littermates had pink skin color at birth; however, Jmjd3-deficient newborns became cyanotic within minutes due to respiratory failure (Figure 1A). Consistent with this observation, we found that the lungs of Jmjd3-deficient mice were not inflated with air and much smaller in size compared with the lungs of WT mice (Figure 1B). Hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining revealed that Jmjd3-deficient lungs were arrested in the late canalicular stage with limited sac spaces, undilated acinar bibules, and buds apparent in the peripheral regions. In contrast, WT lungs contained well-developed pre-alveoli and thinned out mesenchyme (Figures 1C and S1A). The alveolar sacs and associated capillary beds were less developed in Jmjd3-deficient lungs compared with WT lungs. At E17.5, Jmjd3-deficienct lungs were smaller with less developed lobes compared with WT lungs (Figure S1B). H&E staining revealed the severe development defects (Figure S1C). Together, these observations indicate that Jmjd3 is essential for lung development.

Fig. 1. Postnatal lethality and multiple organ defects of Jmjd3−/− embryos.

(A) Postnatal lethality of Jmjd3−/− mice. The skin color of Jmjd3−/− mice became cyanotic minutes after birth. Arrowhead indicates defective lordosis in Jmjd3−/− newborns. (B) The lungs of Jmjd3−/− mice were smaller and not expanded at P0 compared with Jmjd+/+ mice. (C) H&E staining of P0 lung sections from Jmjd3−/− mice indicates arrested tissue maturation. (D) Less developed yolk sac vascular plexus of Jmjd3−/− embryos at E14.5. (E) Subcutaneous edema on the dorsal region of Jmjd3−/− embryos at E14.5. (F) H&E staining of sagittal sections of Jmjd3−/− embryos at E11.5 indicating defective spinal cord and somite development. S, spinal cord; So, somite; Drg, dorsal root ganglion; H, heart; Lu, lung; Li, liver; C3, centrum of C3; TV, third ventricle; FV, fourth ventricle; MV, mesencephalic vesicle. (G) Failure of umbilical cord resorption (arrowhead) in E18.5 Jmjd3−/− embryos. (H) The spleens of Jmjd3-deficient embryos at E17.5 were smaller than those of WT embryos. (I) H&E staining showing multiple hyperemic areas in the spleen of Jmjd3−/− embryos. (J) Body weight of Jmjd3−/− embryos was significantly lower than that of WT and Jmjd3+/− controls. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Differences in body weight were analyzed using the Student's t-test. In addition to the lung, Jmjd3 deficiency caused other embryonic defects. The yolk sac vascular plexus was less developed in Jmjd3-deficient embryos than in WT embryos at E14.5 (Figure 1D). Jmjd3−/− embryos developed subcutaneous edema in the upper back at E14.5, reflecting defective muscle and skeletal development (Figure 1E). Consistent with these observations, H&E staining of sagittal sections of Jmjd3-deficient E11.5 embryos revealed multiple developmental defects, including delayed ganglia, somite, and spinal cord development (Figure 1F). We also observed that the umbilical hernia at E18.5 was not absorbed in Jmjd3-deficient mice, which is hazardous for newborn mice survival (Figure 1G). Because Jmjd3 has been associated with immune cell-mediated inflammation [32], we examined the spleens of Jmjd3-deficient and WT embryos. The spleens of Jmjd3-deficient embryos were smaller and had multiple hyperemic areas compared with WT embryos (Figure 1H). H&E staining also revealed the accumulation of blood cells in Jmjd3-deficient spleens (Figure 1I). Jmjd3-deficient mice were also markedly smaller than their WT littermates at birth (Figure 1A, 1J). These results indicate that Jmjd3 plays an important role in embryonic development.

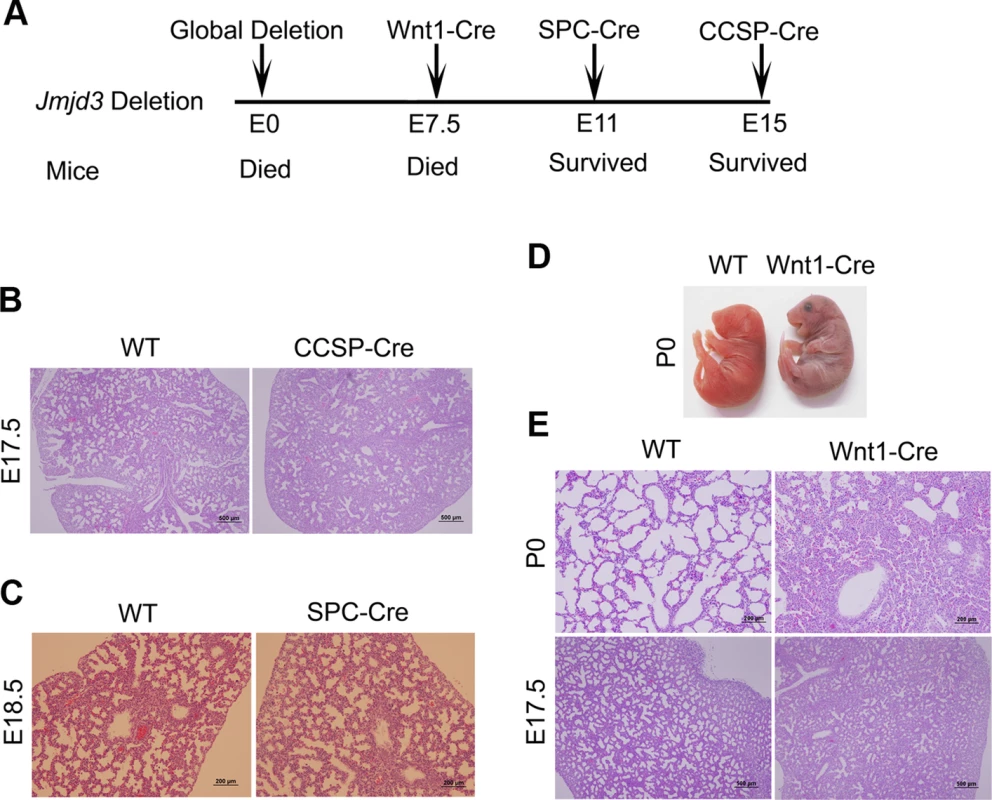

Tissue-specific deletion of Jmjd3 in lung development

Because Jmjd3-deficient newborn mice died shortly after birth of respiratory failure, we sought to determine whether tissue-specific ablation of Jmjd3 recapitulates the global deletion phenotype. To do this, we first crossed Jmjd3f/f mice with CCSP-Cre mice in which Cre is expressed under the control of the CCSP promoter in Clara cells at early E15 [33]. Lung structure was similar between Jmjd3f/f:CCSP-Cre and WT mice (Figure 2A, 2B), suggesting that Jmjd3 may not be important in Clara cells during lung development after E15. Next, we crossed Jmjd3f/f mice with SPC-Cre mice in which the SPC promoter drives the expression of Cre recombinase gene in distal progenitor cells at E11.5 [34]. We found that Jmjd3f/f:SPC-Cre mice were viable from birth to adulthood without any dramatic defects in the lung architecture (Figure 2A, 2C). To rule out the possibility that the H3K27me2/3 demethylase UTX compensates for the loss of Jmjd3 function in Jmjd3 deficient mice, we generated both Jmjd3 and UTX specific deletion mice by crossing Jmjd3floxed and Utxfloxed with SPC-Cre mice. Jmjd3f/f:Utxf/f:SPC-Cre mice exhibit a similar phenotype to that of Jmjd3f/f:SPC-Cre pups, indicating that UTX does not compensate for the loss of Jmjd3 (Figure S2).

Fig. 2. Effect of tissue-specific Jmjd3 deletion on mouse survival and lung development.

(A) Schematic drawing showing the effects of tissue-specific Cre expression on mouse survival. (B) H&E staining of lung tissues from Jmjd3f/f:CCSP-Cre and WT embryos at E17.5. (C) H&E staining of lung tissues from Jmjd3f/f:SPC-Cre and WT embryos at E18.5. (D) Postnatal lethality (within 8 h) was observed in Jmjd3f/f:Wnt1-Cre embryos. (E) H&E staining of lung tissues from Jmjd3f/f:Wnt1-Cre and WT embryos at P0 and E17.5. Because SPC and CCSP-driven expression of Cre are detectable after lung development initiation [35], [36], we reasoned that Jmjd3 is not critical in epithelial cells once lung development is initiated. To test this possibility, Jmjd3f/f mice were crossed with Wnt1-Cre mice in which Cre expression is driven by the Wnt1 gene promoter [37], [38]. The Wnt1 protein is predominantly expressed in the inner cell mass of the blastocyst during the early stages of embryonic development (E7.5) [39]. Wnt1-driven Cre is mainly expressed in neural crest cells [38] and intrinsic innervation of the lung [37]. Intrinsic nerve ganglia, which are derived from neural crest cells, are required for normal lung development and function [36]. Although the Wnt1-Cre model is often used to study neural crest formation, it is also used to study gene function during organogenesis in mice [39]. We found that all Jmjd3f/f:Wnt1-Cre newborn pups died within 8 h of respiratory failure (Figure 2D). H&E staining showed that lung structure was severely affected with fewer sac spaces and undilated acinar bibules at different embryonic stages (Figure 2E), suggests the potential involvement of Jmjd3 in the early embryonic stage of lung development.

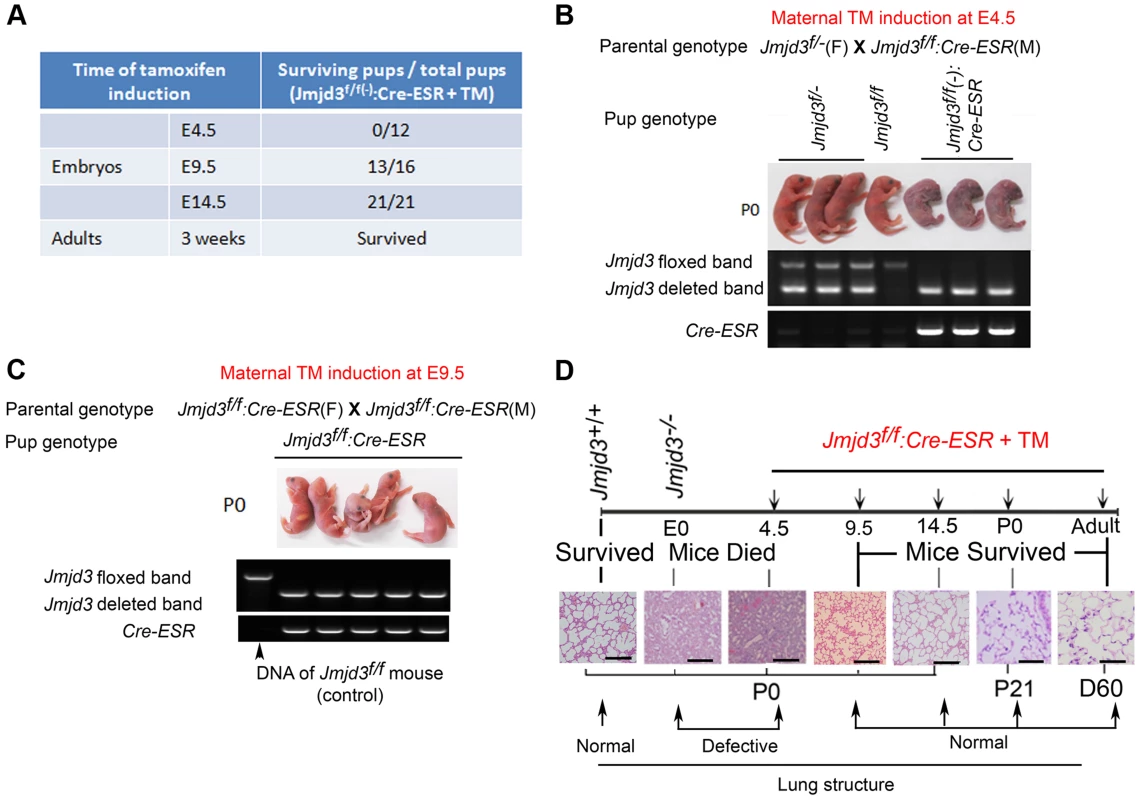

Jmjd3 is dispensable for lung development at E9.5 or later embryonic stages

Because Jmjd3 is required for the early embryonic lung development, we further studied the importance of Jmjd3 at different embryonic stages. To do this, we crossed Jmjd3f/f mice with CAG-Cre/ESR mice in which Cre expression is globally induced with TM. Jmjd3f/f:CAG-Cre/ESR offspring from TM-treated maternal mice at E4.5 stage died shortly after birth and exhibited a phenotype similar to that of Jmjd3-deficienct embryos, whereas Jmjd3f/f and WT offspring of the same litter survived (Figure 3A, 3B). In contrast, the survival rate was increased in Jmjd3f/f:CAG-Cre/ESR offspring from TM-treated maternal mice at E9.5 or later stages (Figure 3A, 3C). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis showed Jmjd3 deletion in the lethal and surviving Jmjd3f/f:CAG-Cre/ESR pups (Figure 3B, 3C). H&E staining showed that the lung structure of Jmjd3f/f;CAG-Cre/ESR offspring from TM-treated maternal mice at E4.5 was comparable to that of Jmjd3−/− newborns, whereas lung structure was similar between Jmjd3f/f:CAG-Cre/ESR surviving offspring from TM-treated maternal mice at E9.5 or later and WT mice (Figure 3D). The lungs of Jmjd3f/f:CAG-Cre/ESR adult mice treated with TM did not show any structural abnormalities (Figure 3D). Taken together, these findings indicate that Jmjd3 is dispensable in the later E9.5 embryonic stage of lung development.

Fig. 3. Stage-specific deletion reveals that Jmjd3 is dispensable for lung development in later E9.5 embryonic stage.

(A) Jmjd3f/f mice were crossed with CAG-Cre/ESR mice in which Cre expression is globally induced with TM. The survival of Jmjd3f/f:Cre/ESR pups from maternal mice treated with TM at E4.5, E9.5, and E14.5 was determined. (B) PCR analysis of Jmjd3 deletion efficiency in Jmjd3f/f:Cre/ESR pups from maternal mice treated with TM at E4.5. (C) PCR analysis of Jmjd3 deletion efficiency in Jmjd3f/f:Cre/ESR pups from maternal mice treated with TM at E9.5. (D) H&E staining showing the stage-dependent effects of Jmjd3 deletion on lung architecture and its correlation with embryo viability. Bar = 500 µm. Identification of the surfactant protein family as Jmjd3 targets in lung tissue

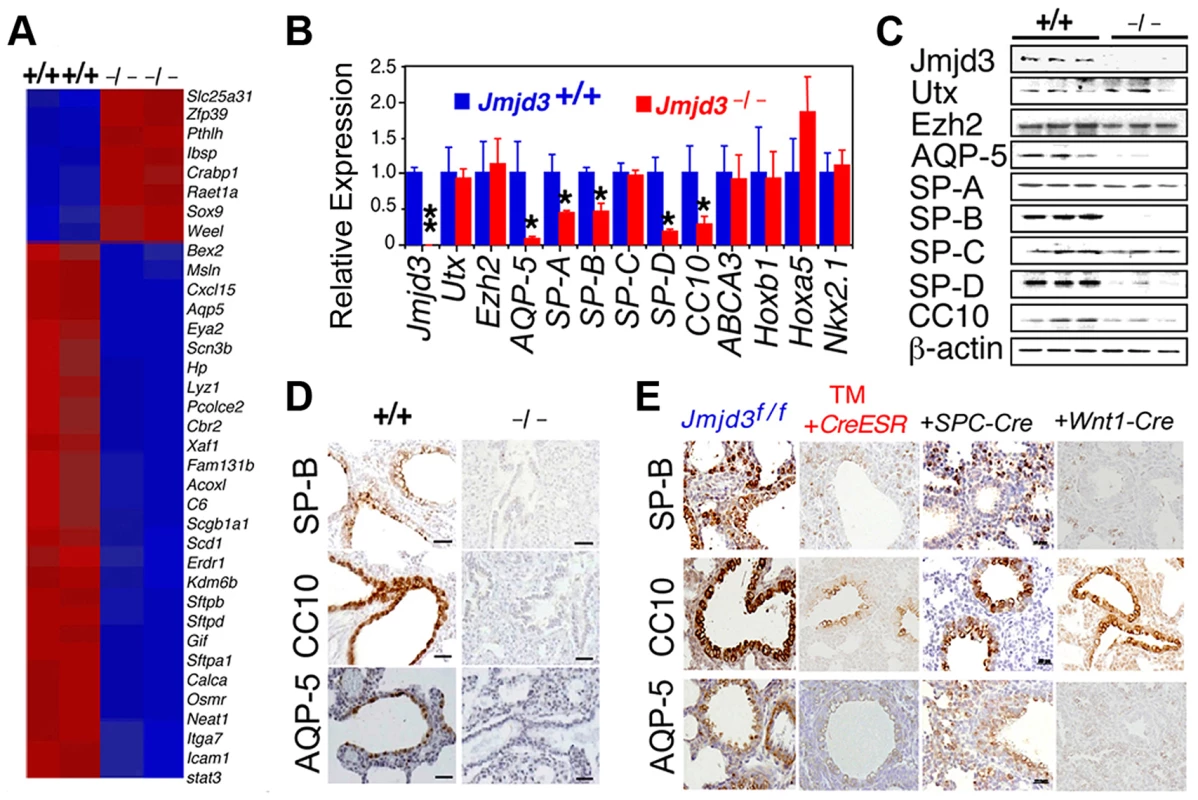

Having established a role for Jmjd3 in lung development, we next investigated the underlying molecular mechanisms by identifying the target genes of Jmjd3 in lung tissue. Affymetrix microarray analysis was performed on RNA samples isolated from WT and Jmjd3−/− E17.5 lungs. Of the 45,000 probes analyzed, 244 genes were downregulated and 190 genes were upregulated in Jmjd3-deficient lung tissues compared with WT lung tissues (Table S2). Representative genes with altered expression (>2 fold) are shown in Figure 4A. Importantly, Jmjd3 deficiency downregulated the expression of genes known to play important roles in lung development and function, including aquaporin-5 (AQP-5), SP-A, SP-B, SP-D, and Clara cell 10 kDa secretory protein (CC10). Consistent with this observation, qPCR and immunoblot analyses showed that AQP-5, SP-B, SP-D, and CC10 mRNA and protein expression were markedly reduced in Jmjd3-deficient lung tissues compared with WT lung tissues (Figure 4B, 4C). These results were further supported by histological analysis of AQP-5, SP-B, and CC10 protein expression in Jmjd3-deficient lung tissues (Figure 4D). SP-A RNA, but not protein, expression was significantly reduced in Jmjd3-deficient lung tissues compared with WT controls, whereas SP-C expression was not appreciably different (Figure 4B, 4C). Although UTX and Ezh2 are involved in the control of H3K27 methylation, their expression levels were not affected by Jmjd3 deficiency in lung tissues (Figure 4B, 4C). As a recent report implicated respiratory rhythm generator (RRG) and pre-Bötzinger complex dysfunction in the impaired respiratory function of Jmjd3 deficient mice [19], we analyzed the expression of RRG-related and pre-Bötzinger complex genes in Jmjd3-deficient brainstem and lung tissues. qPCR analysis showed that the expression of several pre-Bötzinger complex-specific genes including Esrrg, Kirrel3, and March4 was unchanged at E17.5, but increased rather than decreased at P0 in the Jmjd3 deficient brainstem compared with the WT brainstem (Figure S3A). Furthermore, the expression of these pre-Bötzinger complex-specific genes was not different between Jmjd3-deficient and WT E17.5 lung tissues (Figure S3B). Respiratory muscles, including diaphragm and intercostal muscles, play an important role in breathing-like movement. Expression analysis of genes in diaphragm development including Fog2, COUP-TFII and Wt1 by qPCR did not reveal a significant difference between WT and Jmjd3-deficient mice (Figure S3C).

Fig. 4. Jmjd3 regulates the expression of genetic markers of lung development.

(A) Microarray analysis showing representative genes that were differentially expressed between WT and Jmjd3−/− lung tissues at E17.5. Red, upregulated genes; blue, downregulated genes. (B) qPCR was done to validate the expression of selected genes in WT and Jmjd3−/− lung tissues. Gene expression levels were normalized to β-actin. Gene expression levels in WT lung tissue were defined as 1. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 and **P<0.001 (Student's t test). (C) Immunoblot analysis of the protein expression of selected genes in the lung tissues of Jmjd3+/+ and Jmjd3−/− embryos at E19.5. (D) Immunohistocytochemical staining of SP-B, CC10, and AQP-5 protein expression in the lung tissues of Jmjd3+/+ and Jmjd3−/− embryos at E19.5. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Bar = 50 µm. (E) Immunohistocytochemical staining of SP-B, CC10, and AQP-5 expression in the lungs of Jmjd3f/f, Jmjd3f/f:CreESR/TM, Jmjd3f/f:SPC-Cre, and Jmjd3f/f:Wnt1-Cre mice. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Bar = 50 µm. To determine the stage-specific requirement of Jmjd3 in the regulation of lung development genes, we used the TM inducible and Wnt1-Cre deletion models. SP-B, CC10, and AQP-5 immunostaining were negative in the lung tissues of Jmjd3f/f:CAG-Cre/ESR offspring from TM-treated maternal mice at E4.5 but were readily detectable in the lung tissues of Jmjd3f/f offspring from similarly treated maternal mice (Figure 4E). This finding indicates that Jmjd3 deletion at E4.5 effectively reduces SP-B, CC10, and AQP-5 expression in lung tissues, leading to defects in lung development and function. SP-B and AQP-5 immunostaining were also dramatically decreased in lung tissues of Jmjd3f/f:Wnt1-Cre mice at P0 (Figure 4E). Together, these results suggest that Jmjd3 ablation specifically reduces the expression of AQP-5, SP-B, SP-D, and CC10 genes in lung tissues and underscores the importance of Jmjd3 in the temporal and spatial regulation of genes that are critically required for lung development during embryonic development.

Regulation of target gene expression by Jmjd3 through locus-specific histone demethylation

Jmjd3 functions as a H3K27 demethylase in vitro [7]–[11]; therefore, we determined whether Jmjd3 ablation affects H3K27 methylation in vivo in the lung. Global H3K27 di - and trimethylation (H3K27me2 and H3K27me3, respectively) were markedly increased in Jmjd3-deficient lungs compared with WT lungs (Figure S4A). H3K4me3 was also slightly higher in Jmjd3-deficient lungs than in WT lungs, whereas H3K9 methylation was similar between Jmjd3-deficient and WT lungs (Figure S4A). We also examined the methylation status in Jmjd3-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) by immunofluorescence staining and found increased H3K27me2 and H3K27me3 in Jmjd3−/− MEFs (Figure S4B). Furthermore, immunoblot analysis also revealed that both H3K27me2 and H3K27me3 were markedly increased in Jmjd3−/− MEFs compared with WT MEFs, whereas appreciable differences in the methylation of H3K4 and H3K9 were not observed (Figure S4C). To address whether the increase in H3K27 di - and trimethylation was directly related to Jmjd3 deletion, we examined the methylation status of Jmjd3-deficient MEFs transiently transfected with a FLAG-tagged Jmjd3-expressing retrovirus. H3K27 dimethylation and trimethylation were decreased in FLAG-tagged Jmjd3-overexpressing Jmjd3−/− MEFs (Figure S4D), suggesting that Jmjd3 deletion alters global H3K27 methylation levels in MEFs and lung tissues.

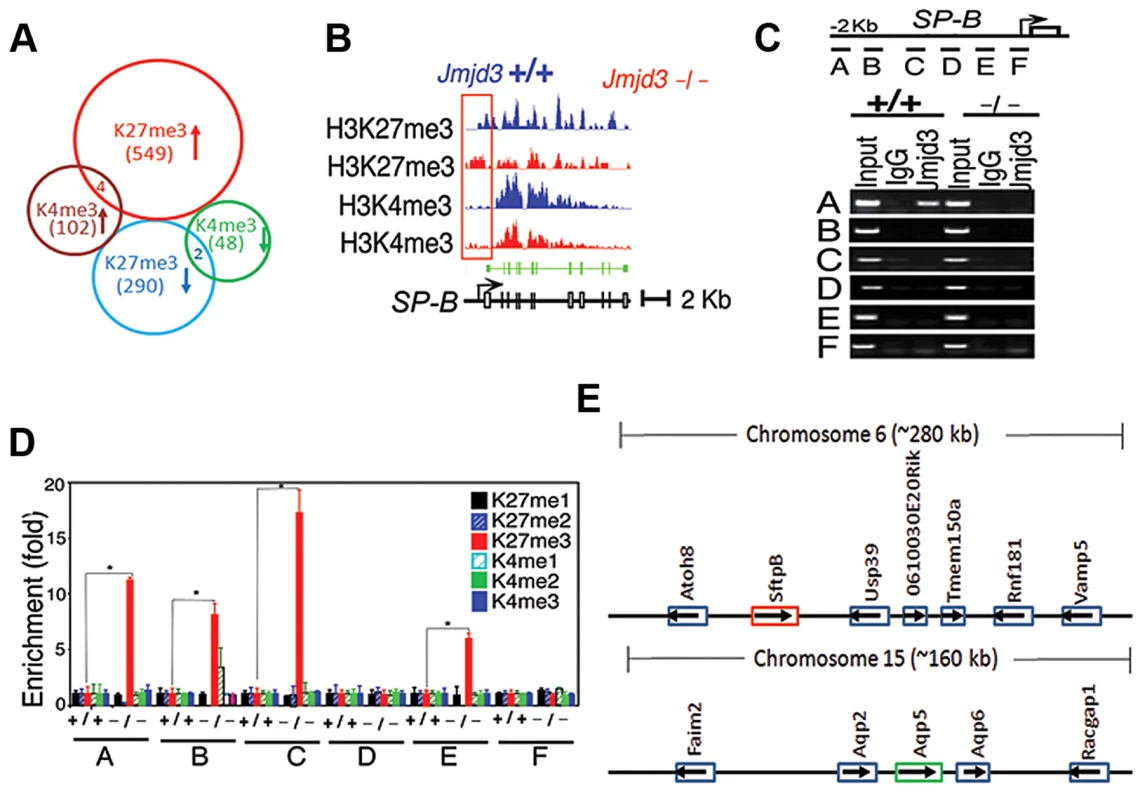

To further define changes in the H3K4 and H3K27 methylation status of Jmjd3 target genes in lung tissue, we performed ChIP-Seq analysis on WT and Jmjd3-deficienct lung tissues. Among the 35,000 RefSeq genes, 553 genes had increased H3K27me3 around 5 kb of the transcription start site (TSS) and 292 genes had decreased H3K27me3 in Jmjd3-deficient lungs compared with WT controls (Figure 5A; Table S3). The number of genes with increased H3K4me3 was greater than the number of genes with decreased H3K4me3 in Jmjd3-deficient lungs (106 vs. 50; Tables S3, S4), which was consistent with the immunoblot analysis of H3K4 methylation (Figure 5A).

Fig. 5. Jmjd3 ablation affects global histone methylation in lung tissues and methylation status of the promoter regions of target genes.

(A) Global gene methylation analysis of Jmjd3+/+ and Jmjd3−/− lung tissues at E17.5 by ChIP-Seq. ↑, methylation increased; ↓, methylation decreased. (B) ChIP-Seq analysis of H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 levels in the promoter and gene body regions of the SP-B gene in Jmjd3+/+ and Jmjd3−/− lung tissues at E17.5. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Jmjd3 binding to the SP-B promoter in lung tissues was determined by ChIP-PCR. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated from the lung tissues of E17.5 Jmjd3+/+ and Jmjd3−/− embryos. Primer design for the ChIP-PCR assay of mouse SP-B promoter regions (top panel). The primers sets cover the following regions: A, −2347–−2142; B, −2065–−1835; C, −1451–−1334; D, −1001–−878; E, −516–−383; F, −218–+14. ChIP-PCR assay showing Jmjd3 binding around 2 kb upstream of the TSS of the SP-B promoter region (bottom panel). (D) ChIP-qPCR analysis of histone methylation levels in the SP-B promoter region in the lung tissues of E17.5 Jmjd3+/+ and Jmjd3−/− embryos. (E) Locus-specific demethylation analysis of Jmjd3 by ChIP-Seq. ChIP-Seq was done to determine the H3K27 and H3K4 methylation level of genes located in the region (∼280 kb) containing SP-B on chromosome 6 and the region (∼160 kb) containing AQP-5 on chromosome 15. Arrows indicate the gene expression direction. ChIP-Seq analysis of individual genes revealed that H3K27me3 amounts in the upstream promoter regions of the TSS of SP-B were markedly increased in Jmjd3-deficient lung tissues compared with WT controls, whereas H3K4me3 in the gene body regions of SP-B was slightly reduced in Jmjd3-deficient lung tissues (Figure 5B). The amounts of H3K4me3 around the TSS and gene body regions of AQP-5, SP-D, and CC10 were also markedly decreased in Jmjd3-deficient lung tissues compared with WT controls (Figure S5A). In contrast, we did not observe any appreciable differences in H3K4 and H3K27 methylation in the promoter and body regions of SP-C, ABCA3, Nkx2.1, Hoxb1, Hoxa5, Ezh2, and UTX, whereas H3K4me3, but not H3K27me3, was slightly decreased in the SP-A gene (Figure S5A). ChIP-Seq analysis also revealed that H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 methylation levels in the promoter regions or gene bodies of the RRG-related genes Phox2b, Tshz3, Task2, Maoa, Phox2a, Reln, and March4 were not different between Jmjd3-deficient and WT E17.5 lung tissues (Figure S5B). To further validate the ChIP-Seq results, we performed ChIP-PCR analysis on WT and Jmjd3-deficient lung tissues at E17.5. A strong band was detected around 2 kb upstream of the TSS of SP-B (Figure 5C), indicating that Jmjd3 is recruited to the regulatory region of the SP-B gene. In addition, Jmjd3 was also bound to the upstream regions of the TSS of AQP-5, SP-A, SP-D, and CC10, but not to those of SP-C (Figure S5C).

Next, we assessed the effect of Jmjd3 on the histone methylation status of the SP-B promoter region using ChIP-qPCR. H3K27me3 was markedly increased in the A, B, C, and E regions of the SP-B gene promoter in Jmjd3-deficient lungs compared with WT controls (Figure 5D). Increased levels of H3K27me3 were also observed in the promoter regions of CC10 and SP-D, but not in those of AQP-5, in Jmjd3-deficient lungs (Figure S5D). In contrast, the methylation levels of H3K4me3 in the promoter regions (i.e., B and C regions near the TSS) of AQP-5, CC10, and SP-D were markedly lower in Jmjd3-deficient lungs than in WT controls (Figure S5D). These results indicate that Jmjd3 ablation in lung tissues affects H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 levels in the promoter and gene body regions of target genes.

To determine whether Jmjd3-mediated changes in histone methylation status were chromosome or locus-specific, we randomly analyzed the H3K27 and H3K4 methylation level of genes located in the region (∼280 kb) containing SP-B on chromosome 6 and the region (∼160 kb) containing AQP-5 on chromosome 15. Our ChIP-Seq data showed that H3K27 and H3K4 methylation of both SP-B and AQP-5 were altered, whereas H3K27 and H3K4 methylation in neighbouring loci were not significantly changed. This data suggests that Jmjd3 targets specific loci for histone demethylation and does not affect histone methylation in adjacent chromosome regions (Figure 5E).

Jmjd3 regulates target gene expression by interacting with transcription and epigenetic factors

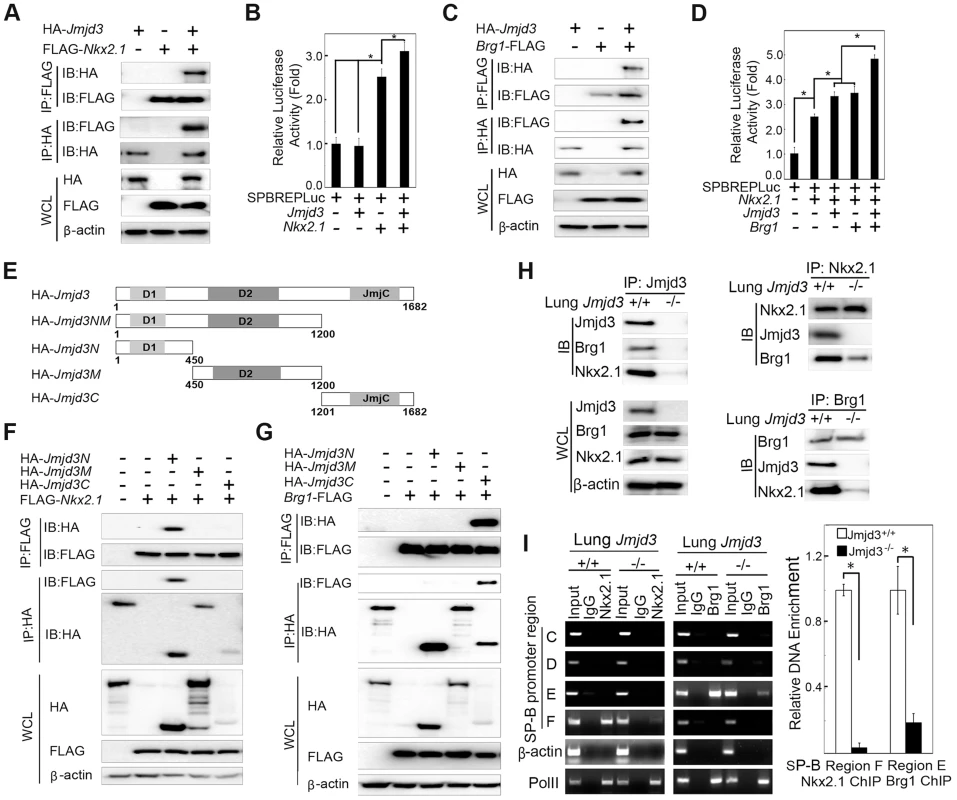

Jmjd3 is a general H3K27 demethylase without specific DNA binding properties and the mechanisms by which it regulates specific gene expression remain unknown. Therefore, we reasoned that Jmjd3 might be recruited to specific gene promoters through interactions with key transcription factors and/or epigenetic proteins. To test this possibility, we first determined whether Jmjd3 regulates target gene expression by interacting with Nkx2.1. Nkx2.1 (also known as thyroid transcription factor 1) is a key transcriptional activator of SP-B gene expression [40]. Coimmunoprecipitation and immunoblot analyses revealed that Jmjd3 interacted with Nkx2.1 in 293T cells expressing HA-tagged Jmjd3 and FLAG-tagged Nkx2.1 (Figure 6A). To determine whether Jmjd3 affects the transcriptional activity of Nkx2.1, we performed a luciferase assay on 293T cells cotransfected with Nkx2.1, Jmjd3, and mouse SP-B promoter-linked episomal luciferase vector (containing Nkx2.1 binding sites) [40], [41]. Jmjd3 alone did not affect luciferase activity; however, it significantly increased the ability of Nkx2.1 to enhance SP-B-mediated luciferase activity (Figure 6B). In contrast, an interaction between exogenous UTX and Nkx2.1 was not observed in 293T cells (Figure S6). Thus, the Nkx2.1 interaction appears to be specific to histone demethylase Jmjd3. These findings suggest that Jmjd3 regulates SP-B expression by interacting with Nkx2.1 in the SP-B promoter region.

Fig. 6. Jmjd3 coregulates SP-B expression with Nkx2.1 and Brg1.

(A) The interaction between Jmjd3 and Nkx2.1 was evaluated by coimmunoprecipitation (CoIP) analysis of 293T cells expressing HA-tagged Jmjd3 and FLAG-tagged Nkx2.1. (B) A cell-based luciferase assay was used to evaluate SP-B promoter activity in 293T cells cotransfected with Nkx2.1, Jmjd3, and mouse SP-B promoter-linked episomal luciferase vector (containing Nkx2.1 binding sites). (C) The interaction between Jmjd3 and Brg1 was determined by CoIP analysis of 293T cells expressing HA-tagged Jmjd3 and FLAG-tagged Brg1. (D) Cell-based luciferase assay was used to evaluate SP-B promoter activity in 293T cells cotransfected with Nkx2.1, Jmjd3, Brg1, and mouse SP-B promoter-linked episomal luciferase vector. *P<0.05 (Student's t test). (E) Generation of Jmjd3 deletion constructs. Numbers represent the corresponding amino acid residue position in the Jmjd3 coding region. (F) CoIP analysis of the interaction between Nkx2.1 and HA-tagged truncated Jmjd3 proteins. (G) CoIP analysis of the interaction between Brg1 and truncated Jmjd3 proteins. (H) CoIP analysis of the interaction among endogenous Nkx2.1, Brg1, and Jmjd3 in WT and Jmjd3-deficient lung tissues. (I) ChIP-PCR and ChIP-qPCR analysis of Nkx2.1 and Brg1 binding to SP-B promoter regions in WT and Jmjd3-deficient lung tissues. *P<0.05 (Student's t test). Brg1, an ATPase subunit of the Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complex, has been shown to cooperate with Nkx2-1 to regulate SP-B expression [40]. Jmjd3 interacted with Brg1 in 293T cells expressing HA-tagged Jmjd3 and FLAG-tagged Brg1 (Figure 6C), consistent with the results of a previous study [42]. Furthermore, Jmjd3 significantly enhanced Nkx2.1 and Brg1-mediated SP-B promoter activity (Figure 6D). To determine the region of Jmjd3 that interacts with Nkx2.1 and Brg1, we generated four HA-tagged Jmjd3 truncated constructs: Jmjd3N (1–450 aa), Jmjd3M (450–1200 aa), Jmjd3C (1201–1682 aa), and Jmjd3NM (1–1200 aa) (Figure 6E). The N-terminus of Jmjd3 (Jmjd3N) strongly interacted with Nkx2.1, whereas the C-terminus of Jmjd3 (Jmjd3C) specifically interacted with Brg1 (Figure 6F, 6G). Importantly, the endogenous interaction of Jmjd3 with Nkx2.1 and Brg1 was readily detected in WT, but not in Jmjd3-deficient, lung tissues at E17.5 (Figure 6H), suggesting that Jmjd3 may be required for Nkx2.1/Brg1 complex formation on the SP-B promoter region. However, the interaction between Nkx2.1 and Brg1 was still detected in Jmjd3-deficient lung tissues, although to a lesser extent compared with WT tissues (Figure 6H). Therefore, Jmjd3 may also influence the interaction between Nkx2.1 and Brg1. The role of Jmjd3 in the Nkx2.1/Brg1 interaction was confirmed by ChIP-qPCR, which showed a marked reduction in Nkx2.1 and Brg1 binding to SP-B promoter regions in Jmjd3-deficient lung tissues (Figure 6I). Taken together, our results suggest that Jmjd3 activates SP-B expression by specifically interacting with Nkx2.1 and Brg1 to form Nkx2.1-Brg1-Jmjd3 complexes.

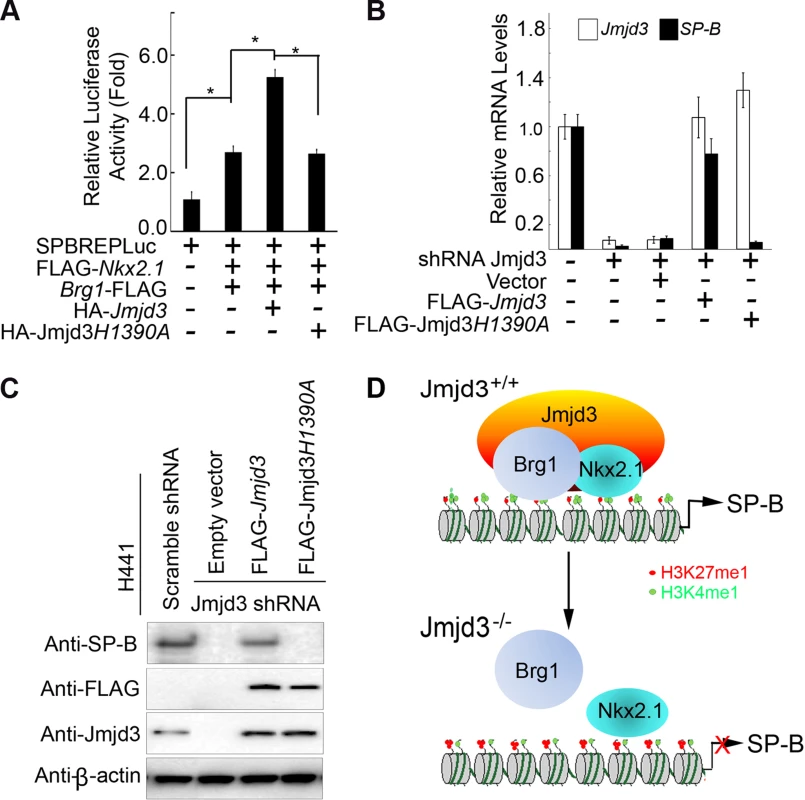

Regulation of SP-B expression by Jmjd3 is dependent on its H3K27 demethylase activity

We next asked whether the demethylase activity of Jmjd3 is required for regulating SP-B expression. To address this, a luciferase assay was performed on 293T cells cotransfected with SP-B promoter-linked episomal luciferase vector, Nkx2.1, and Brg1 in the presence of WT or mutant Jmjd3 (a loss of function mutation in H1390A in the catalytic domain of the demethylase). WT Jmjd3 significantly enhanced Nkx2.1 and Brg1-mediated SP-B promoter activity, whereas mutant Jmjd3 failed to do so (Figure 7A). To further test the ability of mutant Jmjd3 to rescue SP-B expression, WT and mutant Jmjd3 constructs were ectopically expressed in human H441 cells stably transfected with Jmjd3-specific shRNA. WT, but not mutant, Jmjd3 rescued endogenous SP-B mRNA and protein expression (Figure 7B, 7C). We next determined whether the catalytic domain (located at the C-terminus) of Jmjd3 was sufficient to regulate SP-B expression. Full-length Jmjd3 markedly enhanced the luciferase activity of the SP-B promoter compared with truncated Jmjd3 containing only the catalytic domain (Figure S7). Taken together, these results suggest that full-length Jmjd3 is required for regulating SP-B expression in a demethylase activity-dependent manner.

Fig. 7. The demethylase activity of Jmjd3 is required for the regulation of SP-B expression.

(A) WT, but not mutant, Jmjd3 enhanced NKx2.1 and Brg1-mediated SP-B promoter activity. Data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *P<0.05 (Student's t test). (B) qPCR analysis of SP-B expression in Jmjd3-specific shRNA-expressing H441 cells transfected with WT or mutant Jmjd3. Data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. (C) Immunoblot analysis of SP-B protein in Jmjd3-specific shRNA-expressing H441 cells transfected with WT or mutant Jmjd3. (D) A proposed model explaining how Jmjd3 specifically upregulates SP-B expression by interacting with Nkx2.1 and Brg1 in the SP-B promoter. Discussion

In this study, we show that Jmjd3 is important for organogenesis during embryonic development, as evidenced by the multiple organs defects induced by global Jmjd3 deficiency. The importance of Jmjd3 in embryonic lung development appears to be associated with its epigenetic regulation of target genes required for lung development and function. However, our results obtained from lung epithelial cell-specific deletion of Jmjd3 crossed with SPC-Cre and CCSP-Cre mice suggest Jmjd3 is dispensable for lung development at E9.5 or later embryonic stages. This notion is further supported by results obtained with Jmjd3 deletion in TM-inducible Cre mouse models. To investigate whether Jmjd3 plays a role in the lung mesenchyme or the communication between the mesenchyme and epithelium cells, further experiments using other Cre mice such as Dermo-Cre for Jmjd3 deletion are needed and currently under way. Our study identifies key target genes including SP-B, CC10 and AQP-5, involved in lung development and function. Changes in jmjd3 target gene expression are associated with locus-specific methylation alterations of H3K27 and H3K4, providing new insights into the role and molecular mechanism of action of Jmjd3 in embryonic lung development.

Our results show that the global deletion of Jmjd3 results in perinatal lethality in mice shortly after birth. Similarly, several studies have also shown that Jmjd3 deficiency is associated with a lethal phenotype in mice; however, the severity of the lethal phenotype varies according to the deletion strategy used to generate Jmjd3 KO mice [15], [18], [19]. In the present study, deletion of the demethylase catalytic domain of Jmjd3 induces perinatal lethality 30 min after birth. Satoh et al. [15] reported similar findings with conventional deletion of the same Jmjd3 catalytic domain. In both our own and the Satoh et al. [15] studies, the perinatal lethality of the Jmjd3 global deletion phenotype is associated with respiratory failure caused by defects in lung development. By contrast, Jmjd3 deletion mice generated using a gene trap strategy to insert a neo-cassette between exons 1 and 2 exhibit postnatal lethality, some pups survive up to one day [19]. The surviving pups may be attributed to the leaky expression of Jmjd3 associated with the gene-trap strategy. Despite similar postnatal lethality caused by respiratory failure, lung development and structure are normal in the Jmjd3 TRAP insertion mice [19], suggesting that two inactivation strategies (targeted deletion of functional domain and gene-trap) show different phenotypes in lung development and function. Furthermore, Ohtani et al. [18] showed that mice with complete abrogation of Jmjd3 expression through a deletion (exons 4 to 5)-induced frameshift exhibit a more severe phenotype characterized by embryonic lethality before E6.5. Taken together, these studies show that mice generated by different Jmjd3 deletion strategies develop different phenotypes.

It is likely that Jmjd3 deletion causes multiple defects in different organs or tissues by affecting different Jmjd3 target genes through different mechanisms. In our study, Jmjd3-deficient mice die shortly after birth of respiratory failure associated with defective lung development. Consistent with our findings, Satoh et al. [15] showed that conventional deletion of the Jmjd3 catalytic domain results in premature lung development in mice; however, target genes and mechanistic study of Jmjd3 in lung development was not provided in their study. In a recent study, Burgold et al. [19] also found that the perinatal lethality of Jmjd3 deficiency is caused by respiratory failure. However, lung development was normal in Jmjd3-deficient mice, and postnatal lethality was associated with Jmjd3-mediated disruption of the embryonic respiratory neuronal network and RRG. To determine whether Jmjd3 deficiency affects RRG-related or pre-Bötzinger complex gene expression in lung tissues at E17.5, we fail to provide evidence that RRG-related or pre-Bötzinger complex gene expression is altered in our Jmjd3-deficient mice. Consistent with these findings, Jmjd3 deficiency does not affect H3K27me3 or H3K4me3 methylation levels in either the promoter regions or gene bodies of RRG-related genes. Furthermore, we show no appreciable difference in the expression of Fog2, COUP-TFII and Wt1 genes in respiratory muscles at P0 between WT and Jmjd3-deficient mice. Different phenotypes observed in different Jmjd3 inaction mice might be due to differences in leaky expression, targeted deletion of catalytic domain or whole coding region. It has been demonstrated that Jmjd3 affects different target gene expression or proteins through demethylase activity-dependent and independent mechanisms [15], [17], [43]. Taken together, these studies suggest that more than one mechanism is responsible for the observed different phenotypes.

Our findings presented here indicate that Jmjd3 deficiency downregulates a set of genes including SP-B critical to lung maturation and function at E17.5. SP-B, a surfactant expressed in type II cells, is required for postnatal lung function and survival [26]–[28]. Complete SP-B deficiency in mice and humans results in lethal, neonatal RDS [23], which is characterized by a virtual absence of lung compliance and increased amounts of incompletely processed proprotein SP-C [26], [27], [29]–[31]. Similar to the Jmjd3 deletion phenotype, SP-B-deficient mice die of respiratory failure immediately after birth [30]. Together, these findings indicate that the impaired respiratory function in the Jmjd3 deletion phenotype is associated with Jmjd3-mediated regulation of lung-specific gene expression. To provide definitive evidence that the phenotype of Jmjd3-deficient mice is caused by downregulation of SP-B gene, experiments using Jmjd3-deficient mice crossed with SP-B-inducible mice in a SP-B deficient background are under way to determine whether inducible SP-B expression could rescue the phenotype of Jmjd3-deficient mice.

Since Jmjd3 has been shown to regulate gene expression in a demethylase activity-independent [43] and -dependent manner [15], we determine whether the demethylase activity of Jmjd3 is required for the regulation of target gene expression. Jmjd3 deletion alters the H3K27 and H3K4 methylation levels in the promoter and gene body regions of a select set of target genes associated with lung function and development. A strong correlation between H3K4 and H3K27 methylation level and AQP-5, SP-B, SP-D, and CC10 expression is also observed, whereas a weak correlation is observed in many other genes. Our findings are consistent with a previous study showing that changes in H3K27me3 level and gene expression are associated in a limited number of genes in Jmjd3-deficient macrophages [15]. SP-B deficiency caused by genetic mutations has been implicated as the principal cause of infant RDS; however, loss or partial reduction of SP-B expression has also been observed in patients without SP-B gene mutations [27]. These observations suggest the potential involvement of epigenetic mechanisms in surfactant expression. Using ChIP-qPCR, we found that Jmjd3 deficiency markedly increases H3K27me3 at the SP-B promoter in lung tissues. Thus, Jmjd3 deletion may lead to the loss of SP-B epigenetic regulation. The chromatin modifier Brg1 has been shown to cooperate with Nkx2-1 to regulate SP-B and SP-A expression [40]. Consistent with these reports, we found that Jmjd3 specifically upregulates SP-B expression by interacting with Nkx2-1 and Brg1.

Our ChIP-Seq analysis also indicates that Jmjd3 demethylation is locus-dependent. There are several possible reasons for this. First, the H3K27 demethylase UTX may functionally overlap with Jmjd3 and control methylation in the same or different set of genes. A recent study showed that UTX deletion results in embryonic lethality associated with cardiac defects [44]. In our study, we found that UTX does not compensate for the loss of Jmjd3 as evidenced by the similar phenotype between Jmjd3f/f:Utxf/f:SPC-Cre and Jmjd3f/f:SPC-Cre mice. Furthermore, Jmjd3, but not UTX, specifically interacts with Nkx2.1 to regulate SP-B expression, indicating that these two demethylases regulate distinct subsets of genes. Second, recent studies have indicated that the methylation status of enhancer regions is critically important in the control of gene expression [45], [46]. Thus, Jmjd3 may also control gene expression by affecting H3K27me3 level in gene enhancer regions rather than promoter regions. Third, similar to UTX, Jmjd3 may also form a complex with other histone modification proteins, such as H3K4 methyltransferases [32], [47]. Thus, Jmjd3 deletion may potentially affect both H3K27 and H3K4 methylation in the promoter and gene-body regions of target genes, which is supported by our results. Finally, Jmjd3 is recruited to the SP-B promoter through N-terminal and C-terminal interactions with Nkx2.1 and Brg1, respectively. Therefore, Jmjd3 activates SP-B expression by acting as a bridge to promote the formation of Nkx2.1-Brg1 stable complexes.

In summary, through the generation of conventional and conditional Jmjd3 KO mice, our study provides in vivo evidence that Jmjd3 is required for the early lung development, but dispensable for lung development at E9.5 or later embryonic stages. Furthermore, we have identified important Jmjd3 target genes that are critical for lung development and potential mechanisms by which Jmjd3 interacts with Brg1 and NKx2.1 to regulate histone methylation status in the promoter regions of these lung development genes.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Jmjd3 floxed mice (Jmjd3f/f) and Jmjd3−/− mice were generated by homologous recombination technique [17]. Mice were bred and maintained at the pathogen-free animal facilities of Baylor Medical School and the Houston Methodist Research Institute. Animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Baylor College of Medicine and Houston Methodist Research Institute. To generate inducible Jmjd3 deletion in mice, TM (Sigma T5648) was dissolved in corn oil (Sigma) at a concentration of 10 mg/ml and intraperitoneally (IP) injected into 8-week-old mice at 9 mg TM/40 g of body weight [48], [49]. Pregnant mice received 3–4 mg TM/40 g of body weight by IP injection for 2 consecutive days. Pregnant mice were injected with TM at different time points to recover E4.5, E9.5, and E14.5 embryos. The newborn pups were genotyped with tail and lung tissue, and lung structure and development were assessed. The Wnt1-Cre strain was obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (022137). SPC-Cre, and CCSP-Cre and Utxfloxed mice were kindly provided by Dr. Brigid Hogan (Duke University Medical Center), Dr. Frank DeMayo (Baylor College of Medicine) and Dr. Kai Ge (National Institutes of Health), respectively.

RNA preparation, reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, and qPCR

Total RNAs were isolated from E17.5 lung tissues and primary MEFs using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). A total of 1 µg of RNA was converted to cDNA using Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Qiagen) with random hexamer primers. qPCR was carried out using SYBR Green mix on the ABI 7000 PCR machine. Jmjd3 expression in heterozygous and homozygous WT MEFs and WT and Jmjd3−/− E17.5 lung tissues was determined using the following Jmjd3 primer set: (forward) 5′-AAGTGGGGACAAGGAGACCT and (reverse) 5′-AAGTGGGGACAAGGAGACCT. WT and Jmjd3−/− E17.5 lung tissues were also evaluated for the expression of SP-A (5′-CTCCAGACCTGTGCCCATATG and 5′-ACCTCCAGTCATGGCACAGTAA), SP-B (5′-ACGTCCTCTGGAAGCCTTCA and 5′-TGTCTTCTTGGAGCCACAACAG), SP-C (5′-ACCCTGTGTGGAGAGCTACCA and 5′-TTTGCGGAGGGTCTTTCCT), SP-D (5′-CTCTGAGGCAGCAGATGGA and 5′-ATCAGGGAACAATGCAGCTT), CC10 (5′-TCCTAACAAGTCCTCTGTGTAAGA and 5′-AGGAGACACAGGGCAGTGACA), AQP-5 (5′-ATGAACCCAGCCCGATCTTT and 5′-ACGATCGGTCCTACCCAGAAG), ABCA3 (5′-TTGCCCTCATTGGAGAGCCTG and 5′-TCCGGCCATCCTCAGTGGTGGG), Nkx2.1 (5′-TCCAGCCTATCCCATCTGAACT and 5′-CAAGCGCATCTCACGTCTCA), UTX (5′-ATCCCAGCTCAGCAGAAGTT and 5′-GGAGGAAAGAAAGCATCACG), Ezh2 (5′-GCCAGACTGGGAAGAAATCTG and 5′-TGTGCTGGAAAATCCAAGTCA), Hoxa5 (5′-TCTCGTTGCCCTAATTCATCTTT and 5′-CATTCAGGACAAAGAGATGAACAGAA), Hoxb1 (5′-TTGCCCTGGAAACTGTAAAG and 5′-AATTTGCCAACAACCCATC), Esrrg (5′ - TGCACCGGGCTCTGTCAAGGAA and 5′-AATCCATGTGCGCCCGACAACC), Reln (5′-TCCAGGCTCAGCACCAAGCCAA and 5′ - TGGATCTTGCCTTCTGACGCCCTT), Kirrel3 (5′-AGAAAGTCACAGCTCCGCTCGGT and 5′-ACGGGAGGGTTGCAGAAAGGCT), March4 (5′-GCCCCTCCCCTTGGTTCCATCAAA and 5′-CGAGGAGGAGAAAGCGAAGCCACT), Fog2 (5′-CGCCTTTGTGGTGGACTTTGACT and 5′-GCTTCTCGTTGCCTCCCACTACA), COUP-TFII (5′-AGTACTGCCGCCTCAAAAAG and 5′-CGTTGGTCAGGGCAAACT), Wt1 (5′-AATGCGCCCTACCTGCCCA and 5′ - CCGTCGAAAGTGACCGTGCTGTAT) and β-Actin (5′-GTGGGCCGCTCTAGGCACCA and 5′-TGGCCTTAGGGTTCAGGG).

Microarray

Microarray analysis was performed on RNA samples prepared from E17.5 Jmjd3+/+ and Jmjd3−/− lungs using the Affymetrix Genechip microarray system. RNA quality assessment and microarray analysis were performed by the Microarray Core Facility of Baylor College of Medicine. RNA quality was checked using the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Total RNA samples of 250 ng were labeled using the 3′ IVT Express Kit with the new standard Affymetrix linear amplification protocol and then reverse transcribed to produce double-stranded cDNA. The cDNA product was used as a template for the in vitro transcription of biotin-labeled cRNA. The labeled cRNA was quantified using the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. A total of 15.0 µg of the labeled cRNA was fragmented and the concentration rechecked. A hybridization cocktail containing Affymetrix spike-in controls and fragmented labeled cRNA was loaded onto a GeneChip array. The array was hybridized for 16 h at 45°C with rotation at 60 rpm and then washed and stained with a strepavidin, R-phycoerythrin conjugate stain. Signal amplification was done using biotinylated anti-streptavidin. The stained array was scanned on the Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000. The images were then analyzed and quality control metrics were recorded using Affymetrix GCOS software version 1.1.2. Pairwise comparisons were made between WT and Jmjd3-deficient lungs. Raw P values were adjusted by the Benjamini-Hochberg method for 5% false discovery rate to yield adjusted p values. The criteria for significance of differentially regulated genes were established as ≥1.3-fold change with an adjusted P value<0.05. Pathways were analyzed (Ingenuity Systems) to determine the ratios of known genes within each pathway that were significantly changed between WT and KO lungs.

Immunoblotting analysis

Lung tissues were collected, ground into fine powders in liquid nitrogen, and transferred to lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 0.1% SDS) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete Mini Protease Inhibitor, 14132300) and 2 µM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF). Cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), harvested, and lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail and 2 µM PMSF. After sonication and centrifugation, protein supernatants were collected, and protein concentrations were determined using a Bradford Protein Assay Kit (Sigma). Protein extracts were boiled in SDS sample buffer for 5 min, loaded directly onto a 4–12% SDS gel, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad), blocked with 5% milk, and incubated with primary and corresponding secondary antibodies. The following antibodies were used: anti-H3K4me1 (07-436), anti-H3K4me2 (07-030), anti-H3K4me3 (07-473), anti-H3K9me1 (07-450), anti-H3K9me2 (07-441), anti-H3K9me3 (07-442), anti-H3K27me1 (07-448), anti-H3K27me2 (07-452), and anti-H3K27me3 (07-449) from Millipore; anti-SP-A (sc-7700), anti-AQP-5 (sc-9891); anti-SP-B (sc-13978), anti-SP-C (sc-13979), anti-SP-D (sc-13980), and anti-CC10 (sc-25555) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; anti-H3(9715) and Ezh2 (4905) from Cell Signaling; anti-CD11b (17-0113-81), anti-F4/80 (15-4801-82), and anti-Gr1 (17-5931-81) from eBioscience; mouse anti-Flag, anti-HRP-flag, and anti-β-actin from Sigma; rabbit anti-UTX (ab36938) from (Abcam); and anti-Jmjd3 (ab1022a) from Abgent.

Immunohistochemistry and tissue staining

Tissues and embryos were fixed in 10% neutral formalin. The fixation time was dependent on embryonic stage: E<12.5 were fixed for 2 h, E12.5-E17 for 4 h, and E>17.5 for 24–48 h as previously described [50]. After fixation, tissues and embryos were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-µm thick sections. H&E staining and immunostaining were performed according to standard protocols [51]. MEFs were isolated from WT and Jmjd3 KO embryos at E11.5 [51]. Immunocytofluorescence was performed according to a standard protocol using primary antibodies as mentioned above and corresponding goat anti-FITC-conjugated rabbit secondary antibodies (115-096-003; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) or goat anti-Texas Red-conjugated mouse secondary antibodies (81–6114; ZyMax Grade).

ChIP-PCR and ChIP-qPCR analyses

Chromatin was prepared from lung tissues of E17.5 embryos. ChIP-PCR and ChIP-qPCR were performed using Jmjd3 antibody (Abgent) and selected histone marks, respectively. Immunoprecipitated chromatin DNA and input were used for ChIP-PCR and ChIP-qPCR with specific primers. Briefly, whole lungs of E17.5 embryos were quickly chopped into tiny pieces with a scalpel and fixed in 1% formaldehyde in 1X PBS at room temperature for 15 min. Glycine was added to a final concentration of 0.125 M. Samples were rotated at room temperature for another 5 min, centrifuged at low speed for 5 min, and the supernatants decanted. The pellets were washed once with ice-cold 1X PBS and disaggregated mechanically through a 0.5-µm cell strainer in 1 ml of ice-cold 1X PBS. Immunoprecipitation was performed on single cell suspensions using the ChIP Assay Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore, 17–295). Antibodies used included anti-Jmjd3; anti-mono-, di-, and trimethylated H3K4 antibodies; anti-mono-, di-, and trimethylated H3K9 antibodies; and anti-mono-, di-, and trimethylated H3K27 antibodies. DNA binding of Jmjd3 and methylation of lung marker genes including AQP-5, SP-A, SP-B, SP-C, SP-D, and CC10 were evaluated by ChIP-PCR and ChIP-qPCR using the following specific primers: AQP-5-AF, 5′-AACCTGCGGAGGGGGAAGGT; AQP-5-AR, 5′-CGTCCCCACCCCCACTCCAT; AQP-5-BF, 5′-CACCACCCCAGGGTCCCCAA; AQP-5-BR, 5′-CCTGCTCTGCGCTCGGCAAT; AQP-5-CF, 5′-CAGGAGAGCCCAGCACGCAC; AQP-5-CR, 5′-CAGTGTAGACTGGCCCGGCG, SP-A-AF, 5′-GCACACGTACGGAAGCCGGA; SP-A-AR, 5′-CCTGCGGTGCTCAGTGGCAA; SP-A-BF, 5′-CCTTTCTGCTTCTTTCCTATGGCCG; SP-A-BR, 5′-AGCAAAACATCAGAACAACCAAAACTA; SP-A-CF, 5′-ATGGCTGCTTCCTGTCCGGC; SP-A-CR, 5′-CCCGCACACAGAGCCTGCAA, SP-B-AF, 5′-AGGGCCCGGACACATAGAGG; SP-B-AR, 5′-CTGAGGCCCAGGGCAGAGGT; SP-B-BF, 5′-GGGTGTGAGGTGACACGCCG; SP-B-BR, 5′-CTGTGGTGGGGGTGACCACG; SP-B-CF, 5′-TGTCACCAGTGGCACAGTGGAA; SP-B-CR, 5′-AGGTGAGCACTGCCATACCAGG; SP-B-DF: 5′-GTAGAGGATTGAGAAGCCT; SP-B-DR, 5′-CAGCCTGACTTTGTTCAC; SP-B-EF, 5′-CGTGACTCTCTGAAGAAGGC; SP-B-ER: 5′-AAACGACACCCTGGAAGTG; SP-B-FF, 5′-CCCTTGTTTGACGGTGAA; SP-B-FR: 5′-TGGCTGCCTACTGCTTAGT; SP-C-AF, 5′-ACAGGCAATCCCAGATCGCTGA; SP-C-AR: 5′-GTCCCAGCCATCTCTGCCCCT; SP-C-BF, 5′-AGAGGGGCAGAGATGGCTGGG; SP-C-BR, 5′-GCTTGGGACAGCACCTGGGG; SP-C-CF, 5′-AGGCCCAGTCCTTCACCCCTG; SP-C-CR, 5′-GCCTACTGGAGGATGGACAGTCA; SP-D-AF, 5′-TCAGAGGACTAATGACAGCCTT; SP-D-AR, 5′-CAGCAGGGACAGACATACCA; SP-D-BF, 5′-GGAAGATGGAAGAACAAGGG; SP-D-BR, 5′-CTACAAAGGCAGCAACCTG; SP-D-CF, 5′-TGTGTGTGTGTGTGTGTGTGA; SP-D-CR, 5′-CACCTCTGTTTGTCAGGCTC; CC10-AF, 5′-TCCCACCAGCACCATAGTA; CC10-AR, 5′-CACCTTCTCCATTTCCACA; CC10-BF, 5′-CTAACAATGCCCAAGAATCG ; CC10-BR, 5′-GGAGACCCTTCAGGAATCA; CC10-CF, 5′-CTCCACTGCCTGAATACTCC; CC10-CR, 5′-ACTTGGTCATCTTCTCCGTG.

ChIP-Seq analysis

Lungs of E17.5 Jmjd3+/+ and Jmjd3−/− embryos were collected and prepared for ChIP-PCR as previously described [17]. A total of 200 ng of DNA was used for the ChIP-Seq library construction. Illumina sequencing was performed as previously described [52]–[54]. Sequencing reads from H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 ChIP-Seq libraries were aligned to the mouse mm8 genome using ELAND software. To reduce PCR amplification bias, only one uniquely mapped read per genomic position was retained. The histone modification changes upon Jmjd3 knockout were assessed using the fold changes of background-subtracted read densities around 5 kb and 2 kb of the TSSs. The statistical significance of the fold change was assessed using the MA-plot-based method. The fold change and the false discovery rate cutoffs were set to 1.5 and 10%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) where indicated. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t test with GraphPad Prism 4.0 software. A P value<0.05 was considered significant.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. KloseRJ, ZhangY (2007) Regulation of histone methylation by demethylimination and demethylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8 : 307–318.

2. CloosPA, ChristensenJ, AggerK, HelinK (2008) Erasing the methyl mark: histone demethylases at the center of cellular differentiation and disease. Genes Dev 22 : 1115–1140.

3. MosammaparastN, ShiY (2010) Reversal of histone methylation: biochemical and molecular mechanisms of histone demethylases. Annu Rev Biochem 79 : 155–179.

4. ChiP, AllisCD, WangGG (2010) Covalent histone modifications–miswritten, misinterpreted and mis-erased in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer 10 : 457–469.

5. MargueronR, ReinbergD (2011) The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature 469 : 343–349.

6. CaoR, WangL, WangH, XiaL, Erdjument-BromageH, et al. (2002) Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science 298 : 1039–1043.

7. AggerK, CloosPA, ChristensenJ, PasiniD, RoseS, et al. (2007) UTX and JMJD3 are histone H3K27 demethylases involved in HOX gene regulation and development. Nature 449 : 731–734.

8. HongS, ChoYW, YuLR, YuH, VeenstraTD, et al. (2007) Identification of JmjC domain-containing UTX and JMJD3 as histone H3 lysine 27 demethylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 18439–18444.

9. JepsenK, SolumD, ZhouT, McEvillyRJ, KimHJ, et al. (2007) SMRT-mediated repression of an H3K27 demethylase in progression from neural stem cell to neuron. Nature 450 : 415–419.

10. LanF, BaylissPE, RinnJL, WhetstineJR, WangJK, et al. (2007) A histone H3 lysine 27 demethylase regulates animal posterior development. Nature 449 : 689–694.

11. KouzaridesT (2007) Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128 : 693–705.

12. BarradasM, AndertonE, AcostaJC, LiS, BanitoA, et al. (2009) Histone demethylase JMJD3 contributes to epigenetic control of INK4a/ARF by oncogenic RAS. Genes Dev 23 : 1177–1182.

13. AggerK, CloosPA, RudkjaerL, WilliamsK, AndersenG, et al. (2009) The H3K27me3 demethylase JMJD3 contributes to the activation of the INK4A-ARF locus in response to oncogene - and stress-induced senescence. Genes Dev 23 : 1171–1176.

14. DahleO, KumarA, KuehnMR (2010) Nodal signaling recruits the histone demethylase Jmjd3 to counteract polycomb-mediated repression at target genes. Sci Signal 3: ra48.

15. SatohT, TakeuchiO, VandenbonA, YasudaK, TanakaY, et al. (2010) The Jmjd3-Irf4 axis regulates M2 macrophage polarization and host responses against helminth infection. Nat Immunol 11 : 936–944.

16. PereiraF, BarbachanoA, SilvaJ, BonillaF, CampbellMJ, et al. (2011) KDM6B/JMJD3 histone demethylase is induced by vitamin D and modulates its effects in colon cancer cells. Hum Mol Genet 20 : 4655–4665.

17. ZhaoW, LiQ, AyersS, GuY, ShiZ, et al. (2013) Jmjd3 inhibits reprogramming by upregulating expression of INK4a/Arf and targeting PHF20 for ubiquitination. Cell 152 : 1037–1050.

18. OhtaniK, ZhaoC, DobrevaG, ManavskiY, KlugeB, et al. (2013) Jmjd3 Controls Mesodermal and Cardiovascular Differentiation of Embryonic Stem Cells. Circ Res 113 : 856–862.

19. BurgoldT, VoituronN, CaganovaM, TripathiPP, MenuetC, et al. (2012) The H3K27 Demethylase JMJD3 Is Required for Maintenance of the Embryonic Respiratory Neuronal Network, Neonatal Breathing, and Survival. Cell Rep 2 : 1244–1258.

20. MaedaY, DaveV, WhitsettJA (2007) Transcriptional control of lung morphogenesis. Physiol Rev 87 : 219–244.

21. MendelsonCR (2000) Role of transcription factors in fetal lung development and surfactant protein gene expression. Annu Rev Physiol 62 : 875–915.

22. TurgeonB, MelocheS (2009) Interpreting neonatal lethal phenotypes in mouse mutants: insights into gene function and human diseases. Physiol Rev 89 : 1–26.

23. EneCI, EdwardsL, RiddickG, BaysanM, WoolardK, et al. (2012) Histone Demethylase Jumonji D3 (JMJD3) as a Tumor Suppressor by Regulating p53 Protein Nuclear Stabilization. PLoS One 7: e51407.

24. CrouchE, WrightJR (2001) Surfactant proteins a and d and pulmonary host defense. Annu Rev Physiol 63 : 521–554.

25. HawgoodS, PoulainFR (2001) The pulmonary collectins and surfactant metabolism. Annu Rev Physiol 63 : 495–519.

26. HamvasA, ColeFS, NogeeLM (2007) Genetic disorders of surfactant proteins. Neonatology 91 : 311–317.

27. NogeeLM (2004) Alterations in SP-B and SP-C expression in neonatal lung disease. Annu Rev Physiol 66 : 601–623.

28. WeaverTE, ConkrightJJ (2001) Function of surfactant proteins B and C. Annu Rev Physiol. 63 : 555–578.

29. BeersMF, MulugetaS (2005) Surfactant protein C biosynthesis and its emerging role in conformational lung disease. Annu Rev Physiol 67 : 663–696.

30. ClarkJC, WertSE, BachurskiCJ, StahlmanMT, StrippBR, et al. (1995) Targeted disruption of the surfactant protein B gene disrupts surfactant homeostasis, causing respiratory failure in newborn mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92 : 7794–7798.

31. MeltonKR, NessleinLL, IkegamiM, TichelaarJW, ClarkJC, et al. (2003) SP-B deficiency causes respiratory failure in adult mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 285: L543–549.

32. De SantaF, TotaroMG, ProsperiniE, NotarbartoloS, TestaG, et al. (2007) The histone H3 lysine-27 demethylase Jmjd3 links inflammation to inhibition of polycomb-mediated gene silencing. Cell 130 : 1083–1094.

33. RawlinsEL, PerlAK The a“MAZE”ing world of lung-specific transgenic mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 46 : 269–282.

34. OkuboT, HoganBL (2004) Hyperactive Wnt signaling changes the developmental potential of embryonic lung endoderm. J Biol 3 : 11.

35. YangL, NaltnerA, KreinerA, YanD, CowenA, et al. (2003) An enhancer region determines hSP-B gene expression in bronchiolar and ATII epithelial cells in transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 284: L481–488.

36. WertSE, GlasserSW, KorfhagenTR, WhitsettJA (1993) Transcriptional elements from the human SP-C gene direct expression in the primordial respiratory epithelium of transgenic mice. Dev Biol 156 : 426–443.

37. FreemLJ, EscotS, TannahillD, DruckenbrodNR, ThaparN, et al. (2010) The intrinsic innervation of the lung is derived from neural crest cells as shown by optical projection tomography in Wnt1-Cre;YFP reporter mice. J Anat 217 : 651–664.

38. CassimanD, BarlowA, Vander BorghtS, LibbrechtL, PachnisV (2006) Hepatic stellate cells do not derive from the neural crest. J Hepatol 44 : 1098–1104.

39. KempC, WillemsE, AbdoS, LambivL, LeynsL (2005) Expression of all Wnt genes and their secreted antagonists during mouse blastocyst and postimplantation development. Dev Dyn 233 : 1064–1075.

40. CaoY, VoT, MillienG, TagneJB, KottonD, et al. (2010) Epigenetic mechanisms modulate thyroid transcription factor 1-mediated transcription of the surfactant protein B gene. J Biol Chem 285 : 2152–2164.

41. LiuR, LiuH, ChenX, KirbyM, BrownPO, et al. (2001) Regulation of CSF1 promoter by the SWI/SNF-like BAF complex. Cell 106 : 309–318.

42. MillerSA, MohnSE, WeinmannAS (2010) Jmjd3 and UTX play a demethylase-independent role in chromatin remodeling to regulate T-box family member-dependent gene expression. Mol Cell 40 : 594–605.

43. ChenS, MaJ, WuF, XiongLJ, MaH, et al. (2012) The histone H3 Lys 27 demethylase JMJD3 regulates gene expression by impacting transcriptional elongation. Genes Dev 26 : 1364–1375.

44. LeeS, LeeJW, LeeSK (2012) UTX, a histone H3-lysine 27 demethylase, acts as a critical switch to activate the cardiac developmental program. Dev Cell 22 : 25–37.

45. OngCT, CorcesVG (2011) Enhancer function: new insights into the regulation of tissue-specific gene expression. Nat Rev Genet 12 : 283–293.

46. Rada-IglesiasA, BajpaiR, SwigutT, BrugmannSA, FlynnRA, et al. (2011) A unique chromatin signature uncovers early developmental enhancers in humans. Nature 470 : 279–283.

47. ChoYW, HongT, HongS, GuoH, YuH, et al. (2007) PTIP associates with MLL3 - and MLL4-containing histone H3 lysine 4 methyltransferase complex. J Biol Chem 282 : 20395–20406.

48. ParrBA, McMahonAP (1995) Dorsalizing signal Wnt-7a required for normal polarity of D-V and A-P axes of mouse limb. Nature 374 : 350–353.

49. HayashiS, McMahonAP (2002) Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: a tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev Biol 244 : 305–318.

50. CrawfordLW, FoleyJF, ElmoreSA (2010) Histology atlas of the developing mouse hepatobiliary system with emphasis on embryonic days 9.5–18.5. Toxicol Pathol 38 : 872–906.

51. LiQ, ChuMJ, XuJ (2007) Tissue - and nuclear receptor-specific function of the C-terminal LXXLL motif of coactivator NCoA6/AIB3 in mice. Mol Cell Biol 27 : 8073–8086.

52. BarskiA, CuddapahS, CuiK, RohTY, SchonesDE, et al. (2007) High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129 : 823–837.

53. QiHH, SarkissianM, HuGQ, WangZ, BhattacharjeeA, et al. (2010) Histone H4K20/H3K9 demethylase PHF8 regulates zebrafish brain and craniofacial development. Nature 466 : 503–507.

54. WangL, FengZ, WangX, ZhangX (2010) DEGseq: an R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics 26 : 136–138.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Comparative Phylogenomics Uncovers the Impact of Symbiotic Associations on Host Genome EvolutionČlánek Distribution and Medical Impact of Loss-of-Function Variants in the Finnish Founder PopulationČlánek Common Transcriptional Mechanisms for Visual Photoreceptor Cell Differentiation among PancrustaceansČlánek Integrative Genomics Reveals Novel Molecular Pathways and Gene Networks for Coronary Artery DiseaseČlánek An ARID Domain-Containing Protein within Nuclear Bodies Is Required for Sperm Cell Formation inČlánek Knock-In Reporter Mice Demonstrate that DNA Repair by Non-homologous End Joining Declines with Age

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 7- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Délka menstruačního cyklu jako marker ženské plodnosti

- Vztah užívání alkoholu a mužské fertility

- Šanci na úspěšný průběh těhotenství snižují nevhodné hladiny progesteronu vznikající při umělém oplodnění

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Cuba: Exploring the History of Admixture and the Genetic Basis of Pigmentation Using Autosomal and Uniparental Markers

- Clonal Architecture of Secondary Acute Myeloid Leukemia Defined by Single-Cell Sequencing

- Mechanisms of Functional Variants That Impair Regulated Bicarbonate Permeation and Increase Risk for Pancreatitis but Not for Cystic Fibrosis

- Nucleosomes Shape DNA Polymorphism and Divergence

- Functional Diversification of Hsp40: Distinct J-Protein Functional Requirements for Two Prions Allow for Chaperone-Dependent Prion Selection

- Comparative Phylogenomics Uncovers the Impact of Symbiotic Associations on Host Genome Evolution

- Activation of the Immune System by Combinations of Common Alleles

- Age-Associated Sperm DNA Methylation Alterations: Possible Implications in Offspring Disease Susceptibility

- Muscle-Specific SIRT1 Gain-of-Function Increases Slow-Twitch Fibers and Ameliorates Pathophysiology in a Mouse Model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

- MDRL lncRNA Regulates the Processing of miR-484 Primary Transcript by Targeting miR-361

- Hypersensitivity of Primordial Germ Cells to Compromised Replication-Associated DNA Repair Involves ATM-p53-p21 Signaling

- Intrapopulation Genome Size Variation in Reflects Life History Variation and Plasticity

- SlmA Antagonism of FtsZ Assembly Employs a Two-pronged Mechanism like MinCD

- Distribution and Medical Impact of Loss-of-Function Variants in the Finnish Founder Population

- Determinative Developmental Cell Lineages Are Robust to Cell Deaths

- DELLA Protein Degradation Is Controlled by a Type-One Protein Phosphatase, TOPP4

- Wnt Signaling Interacts with Bmp and Edn1 to Regulate Dorsal-Ventral Patterning and Growth of the Craniofacial Skeleton

- Common Transcriptional Mechanisms for Visual Photoreceptor Cell Differentiation among Pancrustaceans

- UVB Induces a Genome-Wide Acting Negative Regulatory Mechanism That Operates at the Level of Transcription Initiation in Human Cells

- The Nesprin Family Member ANC-1 Regulates Synapse Formation and Axon Termination by Functioning in a Pathway with RPM-1 and β-Catenin

- Combinatorial Interactions Are Required for the Efficient Recruitment of Pho Repressive Complex (PhoRC) to Polycomb Response Elements

- Recombination in the Human Pseudoautosomal Region PAR1

- Microsatellite Interruptions Stabilize Primate Genomes and Exist as Population-Specific Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms within Individual Human Genomes

- An Intronic microRNA Links Rb/E2F and EGFR Signaling

- An Essential Nonredundant Role for Mycobacterial DnaK in Native Protein Folding

- Integrative Genomics Reveals Novel Molecular Pathways and Gene Networks for Coronary Artery Disease

- The Genomic Landscape of the Ewing Sarcoma Family of Tumors Reveals Recurrent Mutation

- Evolution and Genetic Architecture of Chromatin Accessibility and Function in Yeast

- An ARID Domain-Containing Protein within Nuclear Bodies Is Required for Sperm Cell Formation in

- Stage-Dependent and Locus-Specific Role of Histone Demethylase Jumonji D3 (JMJD3) in the Embryonic Stages of Lung Development

- Genome Wide Association Identifies Common Variants at the Locus Influencing Plasma Cortisol and Corticosteroid Binding Globulin

- Regulation of Feto-Maternal Barrier by Matriptase- and PAR-2-Mediated Signaling Is Required for Placental Morphogenesis and Mouse Embryonic Survival

- Apomictic and Sexual Germline Development Differ with Respect to Cell Cycle, Transcriptional, Hormonal and Epigenetic Regulation

- Functional EF-Hands in Neuronal Calcium Sensor GCAP2 Determine Its Phosphorylation State and Subcellular Distribution , and Are Essential for Photoreceptor Cell Integrity

- Comparison of Methods to Account for Relatedness in Genome-Wide Association Studies with Family-Based Data

- Knock-In Reporter Mice Demonstrate that DNA Repair by Non-homologous End Joining Declines with Age

- Cis and Trans Effects of Human Genomic Variants on Gene Expression

- 8.2% of the Human Genome Is Constrained: Variation in Rates of Turnover across Functional Element Classes in the Human Lineage

- Novel Approach Identifies SNPs in and with Evidence for Parent-of-Origin Effect on Body Mass Index

- Hypoxia Adaptations in the Grey Wolf () from Qinghai-Tibet Plateau

- A Loss of Function Screen of Identified Genome-Wide Association Study Loci Reveals New Genes Controlling Hematopoiesis

- Unraveling Genetic Modifiers in the Mouse Model of Absence Epilepsy

- DNA Topoisomerase 1α Promotes Transcriptional Silencing of Transposable Elements through DNA Methylation and Histone Lysine 9 Dimethylation in

- The Coding and Noncoding Architecture of the Genome

- A Novel Locus Is Associated with Large Artery Atherosclerotic Stroke Using a Genome-Wide Age-at-Onset Informed Approach

- Brg1 Loss Attenuates Aberrant Wnt-Signalling and Prevents Wnt-Dependent Tumourigenesis in the Murine Small Intestine

- The PTK7-Related Transmembrane Proteins Off-track and Off-track 2 Are Co-receptors for Wnt2 Required for Male Fertility

- The Co-factor of LIM Domains (CLIM/LDB/NLI) Maintains Basal Mammary Epithelial Stem Cells and Promotes Breast Tumorigenesis

- Essential Genetic Interactors of Required for Spatial Sequestration and Asymmetrical Inheritance of Protein Aggregates

- Meiosis-Specific Cohesin Component, Is Essential for Maintaining Centromere Chromatid Cohesion, and Required for DNA Repair and Synapsis between Homologous Chromosomes

- Silencing Is Noisy: Population and Cell Level Noise in Telomere-Adjacent Genes Is Dependent on Telomere Position and Sir2

- The Two Cis-Acting Sites, and , Contribute to the Longitudinal Organisation of Chromosome I

- A Broadly Conserved G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Kinase Phosphorylation Mechanism Controls Smoothened Activity

- Requirements for Acute Burn and Chronic Surgical Wound Infection

- LIN-42, the PERIOD homolog, Negatively Regulates MicroRNA Transcription

- WAPL Is Essential for the Prophase Removal of Cohesin during Meiosis

- Expression in Planarian Neoblasts after Injury Controls Anterior Pole Regeneration

- Sox11 Is Required to Maintain Proper Levels of Hedgehog Signaling during Vertebrate Ocular Morphogenesis

- Accumulation of a Threonine Biosynthetic Intermediate Attenuates General Amino Acid Control by Accelerating Degradation of Gcn4 via Pho85 and Cdk8

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Wnt Signaling Interacts with Bmp and Edn1 to Regulate Dorsal-Ventral Patterning and Growth of the Craniofacial Skeleton

- Novel Approach Identifies SNPs in and with Evidence for Parent-of-Origin Effect on Body Mass Index

- Hypoxia Adaptations in the Grey Wolf () from Qinghai-Tibet Plateau

- DNA Topoisomerase 1α Promotes Transcriptional Silencing of Transposable Elements through DNA Methylation and Histone Lysine 9 Dimethylation in

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání