-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaDAAM Is Required for Thin Filament Formation and Sarcomerogenesis during Muscle Development in Drosophila

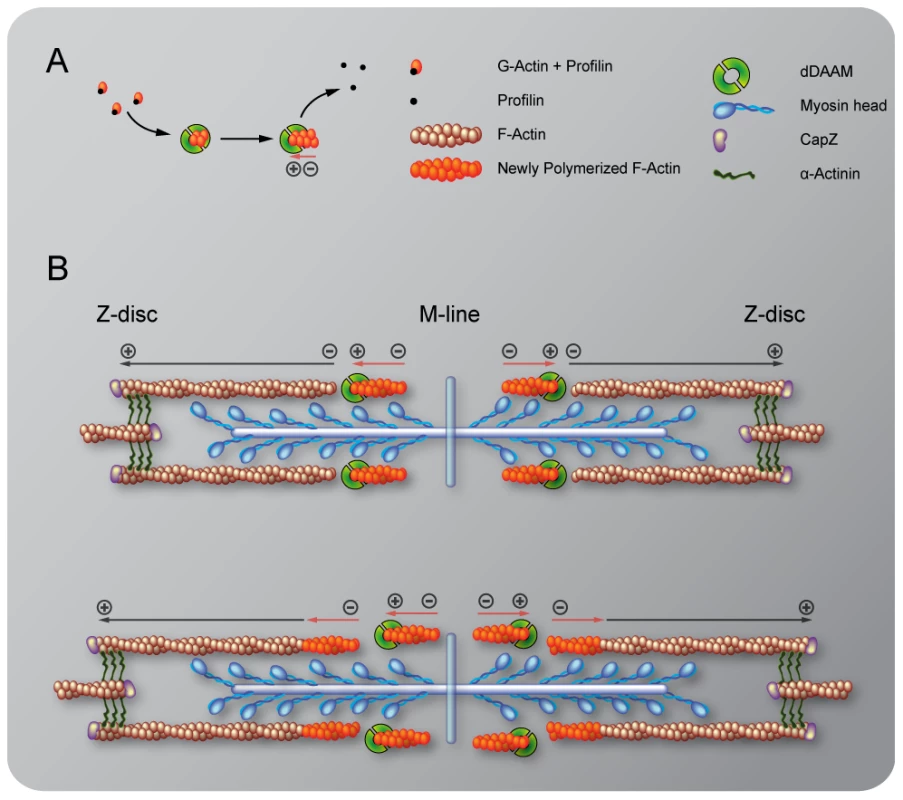

During muscle development, myosin and actin containing filaments assemble into the highly organized sarcomeric structure critical for muscle function. Although sarcomerogenesis clearly involves the de novo formation of actin filaments, this process remained poorly understood. Here we show that mouse and Drosophila members of the DAAM formin family are sarcomere-associated actin assembly factors enriched at the Z-disc and M-band. Analysis of dDAAM mutants revealed a pivotal role in myofibrillogenesis of larval somatic muscles, indirect flight muscles and the heart. We found that loss of dDAAM function results in multiple defects in sarcomere development including thin and thick filament disorganization, Z-disc and M-band formation, and a near complete absence of the myofibrillar lattice. Collectively, our data suggest that dDAAM is required for the initial assembly of thin filaments, and subsequently it promotes filament elongation by assembling short actin polymers that anneal to the pointed end of the growing filaments, and by antagonizing the capping protein Tropomodulin.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004166

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004166Summary

During muscle development, myosin and actin containing filaments assemble into the highly organized sarcomeric structure critical for muscle function. Although sarcomerogenesis clearly involves the de novo formation of actin filaments, this process remained poorly understood. Here we show that mouse and Drosophila members of the DAAM formin family are sarcomere-associated actin assembly factors enriched at the Z-disc and M-band. Analysis of dDAAM mutants revealed a pivotal role in myofibrillogenesis of larval somatic muscles, indirect flight muscles and the heart. We found that loss of dDAAM function results in multiple defects in sarcomere development including thin and thick filament disorganization, Z-disc and M-band formation, and a near complete absence of the myofibrillar lattice. Collectively, our data suggest that dDAAM is required for the initial assembly of thin filaments, and subsequently it promotes filament elongation by assembling short actin polymers that anneal to the pointed end of the growing filaments, and by antagonizing the capping protein Tropomodulin.

Introduction

Striated muscles contain cylindrical structures, myofibrils, composed of repeating elements called sarcomeres, the basic contractile units of muscle. A sarcomere, defined as the region between neighboring Z-discs, contains two filament systems, the actin-containing thin filaments and the myosin II-containing thick filaments, and their associated proteins. The thin filaments are anchored into the Z-disc where they are cross-linked by dimeric α-actinin and a number of other proteins [1]. These filaments extend in both directions from the Z-disc into neighboring sarcomeres. They consist of a filamentous actin (F-actin) core decorated with the regulatory proteins Tropomyosin (TM) and Troponin. Interdigitated with thin filaments are the bipolar thick filaments, composed largely of myosin molecules, that are at the middle of the sarcomere and crosslinked by the M-band proteins. Whereas the structural properties of these macromolecular complexes have been determined in detail in recent decades, much less is known about the in vivo assembly of the filaments and Z-discs to form the very regular sarcomeric structures [2]. In particular, the initial assembly of thin filaments and the regulation of actin dynamics during myofibril formation and maintenance remains poorly understood.

Owing to the regular assembly of actin monomers (G-actin) into F-actin, these filaments display a polarized morphology and dynamics with barbed (+) and pointed (−) ends. In vivo filament growth likely occurs only at the barbed end, whereas the pointed end is favored for depolymerization [3]. New actin filament formation critically requires a nucleation step, during which a few actin monomers combine to form a nucleation seed, prior to elongation. As nucleation is not favored kinetically, and spontaneous in vivo nucleation would lead to anarchic filament assembly, this step is promoted by nucleation factors. Nucleation factors described so far include the Arp 2/3 complex, formins, Spire, Cordon-bleu and Leimodin (Lmod) [4], [5]. Although actin nucleation factors have been extensively studied in many different model systems, the essential nucleation factors in developing muscles have not been clearly identified. Lmod and the mammalian formin Fhod3 have both been implicated in actin assembly in vertebrate striated muscles [6], [7] but subsequent work concluded that they are unlikely to contribute to actin nucleation during the initial stages of myofibril assembly [8], [9], [10], [11]. In fruit flies, the genome harbors no clear Lmod ortholog, and genetic analysis of the Drosophila Fhod ortholog, Fhos, and other members of the formin family, such as Diaphanous, Cappuccino or Form3, revealed no clear role in muscle development [12], [13], [14], [15].

Regulation of thin filament elongation and length, thought to be controlled by elongation factors and capping proteins, are also important aspects of actin dynamics in muscles. Elongation factors, such as Ena/VASP proteins or the barbed end binding formins that also function as nucleation factors, promote filament growth, whereas capping protein binding blocks polymerization. In contrast to non-muscle cells where thin filament growth is restricted to the barbed ends, sarcomeric actin filaments elongate from their pointed ends [16]. In each half sarcomere the thin filaments are aligned with the same polarity and their barbed ends are within the Z-discs, where they are capped by CapZ, whereas their pointed ends are capped by Tropomodulin (Tmod). So far Tmod, TM, Lmod and the Sarcomere Length Short (SALS) proteins have all been implicated in thin filament length regulation. Of these, Tmod binding causes thin filament shortening; conversely, loss of Tmod function causes lengthening of actin filaments [16], [17]. TM enhances Tmod binding affinity, whereas Lmod and SALS seem to antagonize the capping activity of Tmod and promote filament elongation from their pointed ends [9], [18]. Surprisingly, instead of promoting elongation, SALS appears to inhibit filament elongation in vitro. These results together with the observation that no protein was yet isolated which would catalyze F-actin assembly at the pointed end, mean that the mechanism which enables muscle thin filaments to elongate from their pointed ends remains mysterious.

Here we show that the Drosophila formin DAAM (Dishevelled associated activator of morphogenesis) plays an important role in sarcomerogenesis. The absence of dDAAM reduces larval motility, causes a flightless phenotype and complex defects in sarcomere organization. The latter include shorter and thinner sarcomeres with reduced thin filament levels and an absence of both Z-disc and M-band organization. Our protein localization studies revealed that, despite being a barbed end binding protein in non-muscle cells, dDAAM is highly enriched near the thin filament pointed ends both in Drosophila and mouse muscle cells. We propose that members of the DAAM family of formins are very good candidates for the long sought-after muscle actin/thin filament nucleators.

Results

dDAAM mutations affect flight ability and IFM development

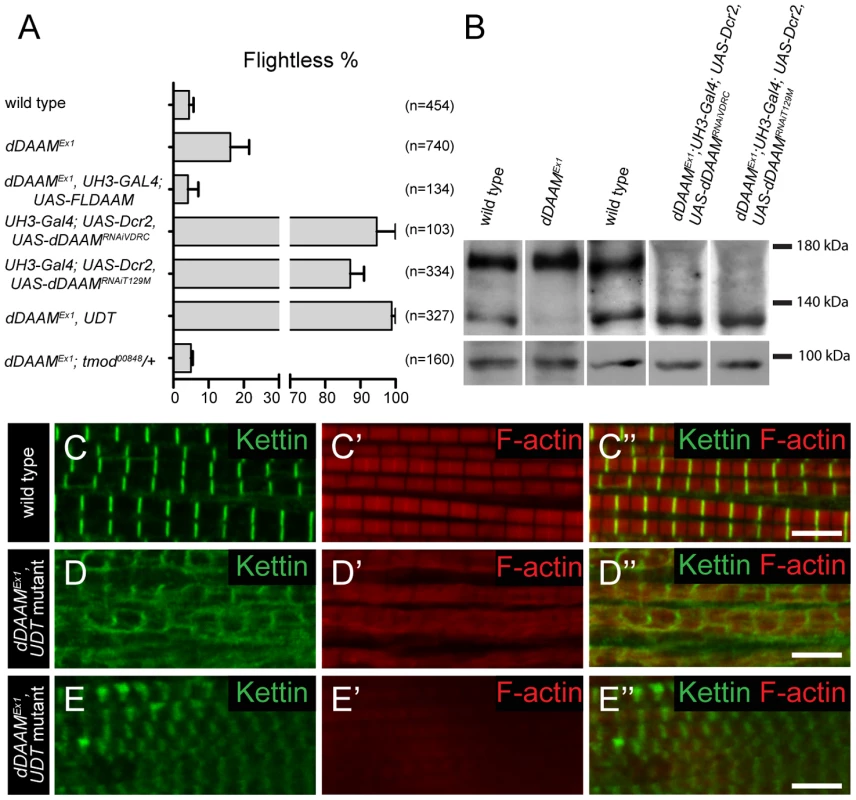

In studies of the Drosophila formin DAAM, we noticed that ∼16% of adults homozygous for the viable, hypomorphic dDAAMEx1 allele were flightless (16.2±5.3%, mean±SEM, n = 740, p = 0.02). As dDAAM null alleles are homozygous lethal, we used two dDAAM specific RNAi lines (KK102786 from VDRC and T129M constructed in our laboratory, targeting two non-overlapping parts of the mRNA) to verify the flight effect. In the presence of UAS-Dicer2 and an IFM (indirect flight muscle) specific driver (UH3-Gal4) [19], both RNAi lines produced strong flightless phenotypes (RNAiVDRC: 94.7±5.3%, mean±SEM, n = 103, p<0.001; RNAiT129M: 87.1±3.9%, mean±SEM, n = 334, p = 0.002) (Figure 1A). RNAi silencing in a dDAAM mutant background (dDAAMEx1, UH3-Gal4; UAS-Dicer2; UAS-dDAAMRNAi-T129M, subsequently referred to as dDAAMEx1, UDT) caused nearly all males to be flightless (98.9±1.1%, mean±SEM, n = 327, p<0.001) (Figure 1A). The strength of the flightless phenotypes correlates with the partial reduction of dDAAM protein levels in dDAAMEx1 IFM and its near absence in IFM from the RNAi genotypes (Figure 1B). The flightless phenotype exhibited by dDAAMEx1 mutants could be rescued by muscle-specific expression of the dDAAM protein (4.1±2.9%, mean±SEM, n = 134, p = 0.043) (Figure 1A).

Fig. 1. dDAAM impairs IFM structure.

(A) Quantification of the flight ability of wild type and dDAAM mutant flies with the genotypes indicated. Bars display mean±SEM. (B) Western blot shows that wild type IFM expresses two dDAAM protein isoforms, of 130 kD and 163 kD. The larger isoform is more highly expressed of the two. The dDAAMEx1 allele reduces the level of the 130 kD isoform, whereas RNAi silencing results in a strong reduction of the level of the 163 kD isoform. Lower panel shows the loading control (α-glycogen-phosphorylase). (C–C″) Myofibrils of a wild type IFM display a regular sarcomere organization. (D–E″) Myofibrils from two different IFMs of the dDAAMEx1, UDT mutant combination. Note the complex sarcomeric defects (D–E″) including the reduced F-actin level (in red, C′–E′), the irregularities in fiber width, the disorganized Z-discs stained with anti-Kettin (in green, C–E″) and the sarcomere length shortening in E–E″. Bars, 5 µm. In wild type or UH3-Gal4; UAS-Dicer2 flies (used as parental control), the IFM displayed, as visualized by phalloidin (labels F-actin) and anti-Kettin (a Z-disc marker) staining, its typical regular sarcomeric organization (Figure 1C–C″), with the sarcomere length of 3.19±0.04 µm (mean±SD, n = 63) found in young adults. In contrast, the IFM of dDAAM mutant flies showed significant structural alterations (Figure 1D–E″). The IFM of flightless dDAAMEx1 mutants looked largely normal, but about 25% of the myofibrils were thinner (1.42±0.32 µm, mean±SD, n = 50, p<0.001) than wild type (1.72±0.11 µm, mean±SD, n = 150) and part of the sarcomeres exhibited a reduced length (down to 2.59±0.13 µm, mean±SD, n = 73, p<0.001) (Figure S1A). In contrast, IFM from the dDAAMEx1, UDT mutant combination showed gross alterations in IFM fiber morphology (Figure S3A,B). The myofibrils were thinner than in wild type (1.18±0.3 µm, mean±SD, n = 64, p<0.001) and their organization was irregular (Figure 1D–E″). Mutant IFMs exhibited reduced F-actin staining (Figure 1D–E″) without significant alterations in the amount of G-actin (Figure S1F). Additionally, phalloidin staining suggested that many of the thin filaments were of unequal length, and similar to dDAAMEx1 mutants, shorter sarcomeres (1.97±0.28 µm, mean±SD, n = 62, p<0.001) could often be detected. M-lines could hardly be identified by Myosin immunostaining (Figure S1B–C″), while the Z-discs displayed a highly irregular and delocalized pattern compared to wild type (Figure 1D–E″). Thus, loss of dDAAM function impairs IFM structure from overall muscle shape to myofibrillar and sarcomeric organization.

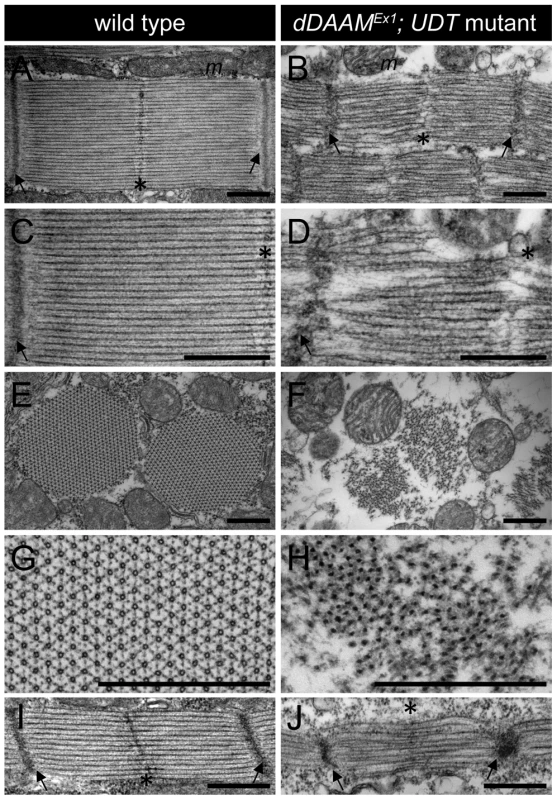

Electron microscopy (EM) of the IFM of dDAAMEx1, UDT mutants (Figure 2) confirmed and extended all the major myofibrillar defects seen in the confocal images. Notably, in longitudinal sections (Figure 2A–D) we revealed irregularly shaped, thin myofibrils with frayed edges, strong Z-disc defects, absence of M-lines and shorter sarcomeres. The thick and thin filament organization was also severely altered. Thick filaments rarely ran parallel to each other, the average thick filament number per sarcomere was strongly reduced compared to controls, and filament packing was much looser than wild type (Figure 2A–D). Most strikingly, instead of thin filaments running in parallel between the myosin filaments (Figure 2C), this space was filled with many thin filaments that formed a meshwork in some places (Figure 2D). Although the organization of these filaments was very different from wild type, their dimensions argue that they are disordered thin filaments. Possibly, but we consider it unlikely, they are connecting filaments. Such filaments containing the Sallimus/Kettin proteins link the Z-disc to the thick filaments in insect flight muscle. The transverse sections of dDAAM mutant IFMs confirmed the presence of irregularly shaped myofibrils consisting of thick filament clusters with grayish material in between of them, whereas individual thin filaments could hardly be seen (Figure 2E–H). Clearly the regular myofibrillar lattice was missing. Unlike wild type thick filaments which appear ring-shaped or hollow in transverse sections (except at the level of the M-line) (Figure 2G) [20], dDAAM mutant thick filaments were very dark, irregular in shape and almost never hollow (Figure 2H).

Fig. 2. EM analysis of IFM morphology in dDAAM mutants.

Electronmicrographs of IFM from wild type (A, C, E, G, I) and dDAAMEx1; UDT mutants (B, D, F, H, J). Longitudinal sections of adult IFM (A–D) show that, as compared to the wild type, highly ordered and tightly packed sarcomeres (A, C), the dDAAM mutant myofibrils (B, D) display Z-disc and M-band defects, and shortened sarcomeres with loosely organized thin and thick filaments. Transverse sections of wild type (E, G) muscles reveal the hexagonal lattice organization of thin and thick filaments, which is almost entirely lost in dDAAM mutant myofibrils (F, H). Instead, the mutant fibrils are irregularly shaped, consisting of clusters of thick filaments, and individual thin filaments are hardly detectable. Note: wild type thick filaments are hollow (G), while those of the dDAAM mutant are very dark, irregularly shaped and almost never hollow (H). Longitudinal sections of pupal IFM (48 hours APF) (I, J) show that, as compared to wild type (I), mutants (J) have strong Z-disc and M-line defects, shorter sarcomeres and irregular filament organisation. Arrows mark the Z-discs, asterisks mark the M-bands, m labels the mitochondria. Bars, 500 nm. At 48 hours after puparium formation (APF) (at 29°C) the pupal IFM of dDAAMEx1, UDT flies already showed all the muscle phenotypes observed in adults. These include irregular myofibrillar organization, reduced F-actin levels, lack of visible M-lines and disorganized, unequally spaced Z-discs (Figure S2A–B″). Accordingly, EM analysis revealed sarcomere shortening (2.3±0.05 µm, n = 22 in wild type; 1.53±0.08 µm, mean±SD, n = 22 in mutants, p<0.001), absence of M-lines, erratic filament packing and strong Z-disc defects (Figure 2I–J). Together, these data suggest that the IFM phenotypes observed in newly hatched dDAAM mutant adults were likely to be a consequence of loss of dDAAM function during early muscle development.

To test whether the structural alterations observed in dDAAM mutant myofibrils affect their mechanical properties an Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) was used to measure the transverse elasticity of individual myofibrils in rigor conditions (Figure S2C). The elasticity (Young's modulus) of dDAAMEx1 and dDAAMEx1, UDT mutant myofibrils was significantly lower, 6±1.63 kPa (n = 35) and 4±1.24 kPa (n = 15), than that of wild type, 22±4.91 kPa (n = 25).

In summary, the genetic impairment of dDAAM function severely affects the structural and mechanical properties of the flight muscles. These results argue that this formin is an important regulator of muscle development affecting multiple aspects of myofibril formation in flies.

dDAAM impairs somatic muscle formation and heart development

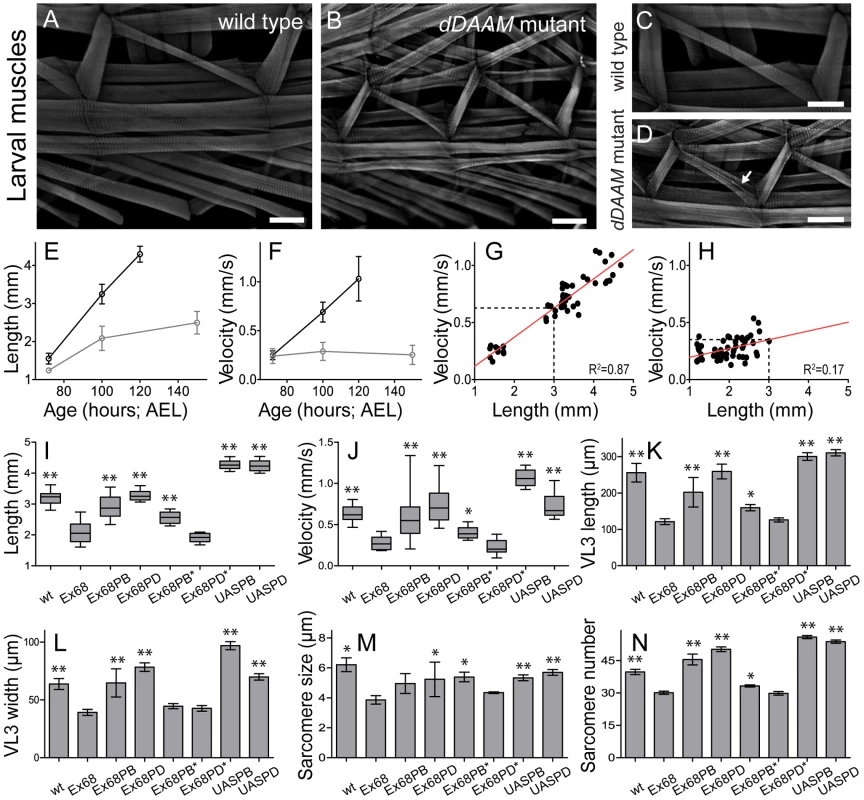

To ask whether dDAAM plays a role generally in muscle development, larval body wall muscles and the heart tube were examined. The body size and somatic musculature of dDAAMEx68 null mutant early third instar (L3) appeared normal, but late in L3, 100 hours after eggs laying (AEL), the larvae were shorter (2.08±0.31 mm; n = 30) than wild type (3.24±0.25 mm; n = 30; p<0.001; Figure 3E,I). Although gross alterations were not evident in the overall structure of the musculature, mutant muscles were also smaller, some myofibers were split and their general organization was looser than in wild type (Figure 3A–D). Measurements of the ventral longitudinal 3 (VL3) muscle showed a 53% length reduction and 38% reduction in width (Figure 3K,L) compared to wild type. Shortening of VL3 in dDAAM mutants arises both by sarcomere shortening and a reduction in sarcomere numbers (Figure 3M,N). The mean sarcomere length of wild type VL3 muscles at 100 hours AEL was 6.2±1.6 µm (n = 477 sarcomeres; 12 muscles), but was decreased in dDAAM mutants to 3.8±0.7 µm (n = 241 sarcomeres; 8 muscles; p<0.001). The serial sarcomere number of VL3 was also decreased in dDAAM mutants (30.1±2.1; n = 8) compared to wild type (39.7±4.3; n = 12; p<0.001).

Fig. 3. Structural and functional analysis of the larval body wall muscles.

Wild type (A, C) and dDAAMEx68 null mutant (B, D) larval body wall muscles stained with phalloidin. Mutant muscles are smaller, some myofibers are split (arrow on D) and the overall muscle pattern is looser than in wild type. The relationship of larval age and length (E), and of larval age and velocity (F) in wt (wild type; black line) and dDAAMEx68 (grey line) larvae. The relationship of larval length and velocity of wt (G) and dDAAMEx68 mutant (H) larvae. Quantification of larval length (I), crawling velocity (J), VL3 muscle length (K), width (L), mean sarcomere length (M) and serial sarcomere number (N) in larvae 100 hours AEL with the following genotypes: wt (wild type), Ex68 (dDAAMEx68), Ex68PB (dDAAMEx68; DMef2-Gal4; UAS-dDAAM-PB), Ex68PD (dDAAMEx68; DMef2-Gal4; UAS-dDAAM-PD), Ex68PB* (dDAAMEx68; DMef2-Gal4; UAS-dDAAM-PBI732A), Ex68PD* (dDAAMEx68; DMef2-Gal4; UAS-dDAAM-PDI732A), UASPB (DMef2-Gal4; UAS-dDAAM-PB) and UASPD (DMef2-Gal4; UAS-dDAAM-PD). Bars represent mean values with respective SDs in I–N. Statistical significance: * 0.05>p<0.001; ** p≤0.001. Wild type and rescue data were compared to dDAAMEx68 data, unless otherwise indicated in the text. Bars, 100 µm (A–D). To investigate the physiological relevance of the muscular defects observed, we examined the larval motility of dDAAM mutant larvae. Until the early L3 stages there were no differences between the wild type and the dDAAM mutant larvae, possibly due to maternally derived dDAAM (in ∼10% of dDAAMEx68 larvae the dDAAM protein could still be clearly detected at 100 hours AEL, Figure S3E,F). Consistent with the findings of the structural analysis, kinematic studies of linear larval crawling at 72 hours AEL showed that velocities of wild type and mutant larvae did not significantly differ (Figure 3F). Subsequently at 100 hours AEL their velocity was decreased by ∼60% compared to wild type (Figure 3F,J). Although, we observed a strong correlation between larval body length and crawling velocity (Figure 3G,H), the dDAAM mutant larvae are much slower than their reduced size would indicate. Rescue experiments with DMef2-Gal4 driven expression of UAS-DAAM constructs confirmed that the observed phenotypes are specific to loss of dDAAM function. Western blot analysis revealed that the IFM expresses two dDAAM protein isoforms, a short (130 kD) minor isoform and a long (163 kD) major isoform (Figure 1B). These correspond respectively to the predicted DAAM-PB and DAAM-PD proteins (Flybase annotation). The rescue experiments (above) were performed with UAS-DAAM-PB as well as with UAS-DAAM-PD. UAS-DAAM-PB expression partly rescued the velocity decrease and almost fully rescued the body and muscle size of dDAAMEx68 mutant larvae, whereas UAS-DAAM-PD expression almost completely rescued all the phenotypic traits (Figure 3I–N). Moreover, muscle-specific expression of these constructs not only rescued the larval muscle defects, but partly rescued the lethality of dDAAMEx68 to adulthood (3% for PB and 6.1% for PD). Importantly, unlike the wild type constructs, the actin polymerization incompetent mutant forms, UAS-DAAM-PBI732A and UAS-DAAM-PDI1042A mimicking the Bni1 I1431A mutation [21], failed to rescue (Figure 3I–N). These data demonstrate that the effect of dDAAM on muscle structure and larval motility is muscle autonomous, and that the actin-assembling activity of dDAAM is essential for normal muscle development. Additionally, it appears that the two muscle-specific dDAAM isoforms play largely, but not completely, redundant roles in larval muscle.

Muscle-specific expression of UAS-DAAM-PB and UAS-DAAM-PD, in a wild type background, produced significantly longer larvae (PB: 4.26±0.15 mm, n = 10, p<0.001; PD: 4.24±0.19 mm, n = 10, p<0.001) than wild type. Their VL3 muscles were longer, although in both cases sarcomere size was slightly shorter than wild type (Figure 3I,K,M). Muscle lengthening occurred by significantly increasing sarcomere number compared to wild type (PB: 56±2.8, n = 14, p<0.001; PD: 54±2.5, n = 12, p<0.001) (Figure 3N). Interestingly, the aforementioned structural aspects were almost identical in larvae overexpressing either isoform. Nevertheless, larvae expressing the PB isoform were much faster (∼55% faster, n = 10) than wild type larvae (Figure 3J), while the velocity of larvae expressing PD (∼5% faster, n = 10) and the controls (Figure 3J) were not significantly different. Lengths of PB and PD overexpressing larvae were indistinguishable but PB larvae had significantly wider VL3 muscles compared to PD larvae. Thus increasing dDAAM isoform levels is sufficient to enhance the number of sarcomeres initiated, but efficient sarcomere elongation may require cooperation of both isoforms and regulation of their ratio.

Larval heart tube size was also reduced in dDAAM mutants compared to wild type (∼40% reduction in diameter). In 100 hour old wild type larvae the maximum heart diameter was 100.33±7.39 µm; n = 9 whereas in dDAAM mutants 60.44±6.18 µm; n = 9, p<0.001 and they displayed reduced F-actin levels (Figure S3C,D). Many mutant myofibrils appeared thinner than in wild type and often deviated from the normal orientation (Figure S3D). These observations strongly suggest that the formin dDAAM may be a crucial regulator of muscle development in Drosophila with an effect in every muscle type and developmental stage examined.

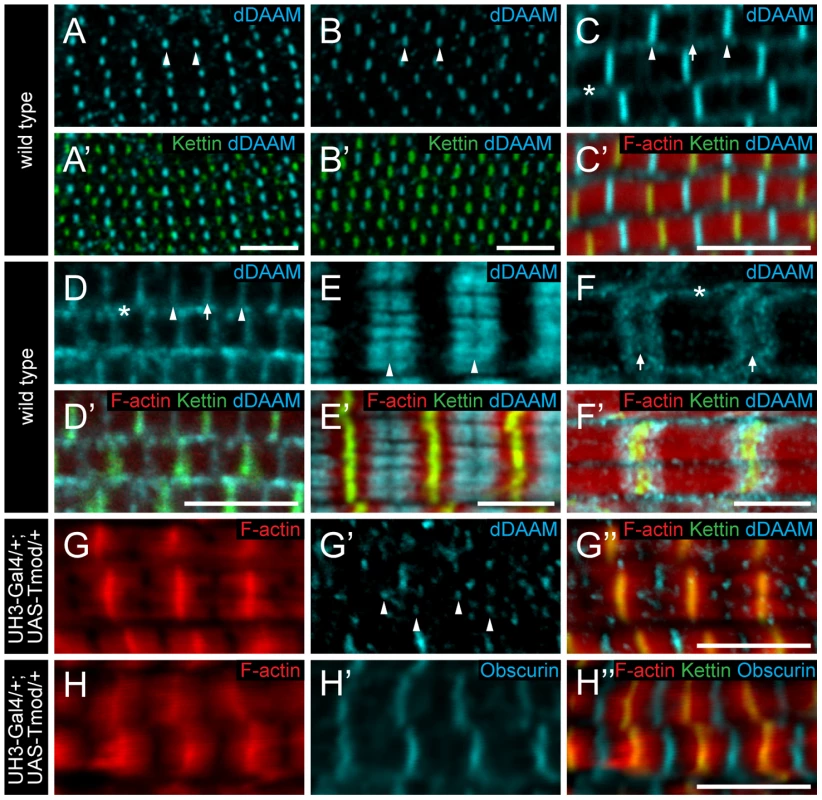

Sarcomeric localization of dDAAM

To further characterize the role of dDAAM in myofibril formation, we examined its localization pattern in the IFM. In newly eclosed adults the anti-dDAAM serum [22] produced a strong staining in the middle of IFM sarcomeres in the M-line region and a weaker staining was evident at the Z-disc and within the sarcoplasm (Figure 4C). This pattern persisted from 48 hours APF (the earliest analyzable pupal developmental timepoint) (Figure 4A–B′) until young adulthood. However, in slightly older adults the signal gradually decreased at the M-line and by 4 days after hatching, equally strong signals were detected at the M-line and Z-disc (Figure 4D). In a dDAAMEx1, UDT mutant, which is nearly protein null for dDAAM (Figure 1B), only background staining was detectable demonstrating the specificity of the antibody (Figure S4B). To complement the immunostaining we created a C-terminally GFP tagged dDAAM knock-in allele (dDAAMEGFP). The dDAAMEGFP allele is viable and fertile in either homo - or hemizygous states, and expression of this protein is entirely under the control of endogenous regulatory sequences. The dDAAM::EGFP fusion protein displayed a roughly equally strong enrichment at the M-line and Z-disc in young and 4 day-old IFMs (Figure S1D–E′). Thus, although the anti-dDAAM serum detects a partial difference between the early and late dDAAM pattern, which is not seen with dDAAMEGFP (presumably due to a difference in the accessibility of the native and the EGFP tagged C-termini), both tools confirm that sarcomeric dDAAM protein is present at both the Z-disc and the M-line.

Fig. 4. Sarcomeric localization of the dDAAM protein in the IFM and the larval body wall muscles.

dDAAM staining of the IFM myofibrils of wild type pupae 48 hours (A, A′) and 72 hours APF (B, B′), freshly eclosed adult (C, C′) and 4 day-old adult (D, D′). dDAAM accumulates at the M-line (arrowheads), at the Z-disc (arrow) and in the sarcoplasm (asterisk). Note: accumulation at Z-disc is weak in pupae and young adults (A–C), but in 4 day-old adults staining is equally strong at the M-line and the Z-disc (D). In developing larval body wall muscles (72 hours AEL) dDAAM staining resolves into two bands along the M-line (E, E′). In fully matured larval body wall muscles dDAAM staining relocates to a region flanking the Z-disc (F, F′). Arrowheads mark the M-line in E; arrows mark the Z-disc, asterisk marks the sarcoplasm in F. (G–H″) Excess Tmod in UH3-Gal4/+; UAS-Tmod/+ flies leads to shorter thin filaments that are not in perfect register and vary in length as judged by F-actin staining (G, H). In these IFMs dDAAM protein displays a punctate distribution (arrowheads in G′) most of which colocalizes with the pointed end region of the thin filaments (G″). The M-line in these mutant muscles remains nearly intact as judged by Obscurin staining (H′). Phalloidin staining is in red (C′–H″), Kettin (C′–H″) and sls-GFP (A′, B′) as Z-disc markers are in green, anti-dDAAM (A–F′, G′, G″) and anti-Obscurin (H, H′) are in cyan. Bars, 5 µm. As thin and thick filaments overlap almost entirely in Drosophila IFM, it was not possible to determine unambiguously whether dDAAM enrichment in the middle of wild type sarcomeres reflects binding to the M-line or to the thin filament ends that extend close to the M-line. In UH3-Gal4/+; UAS-Tmod/+ mutant flies excess Tmod resulted in shorter thin filaments that were not in perfect register and varied in length (Figure 4G) while M-line organization remained largely normal (Figure 4H), as judged by F-actin and Obscurin staining, respectively. In such IFMs the dDAAM protein no longer formed a distinct band at the M-line. Instead a punctate intra-sarcomeric staining occurred that mostly co-localized with the pointed end region of the actin filaments (Figure 4G–G″). This suggests that the mid-sarcomeric dDAAM enrichment, seen in wild type, is likely to be thin filament binding and not an M-line association. Consistent with this conclusion, in developing larval body wall muscles (72 hours AEL) the dDAAM staining clearly resolves into two bands along the M-line (Figure 4E). Interestingly, in full-grown larval myofibrils the dDAAM staining relocated to a region flanking the Z-disc (Figure 4F), which is similar to the pattern observed for SALS and Tmod [18]. All together these localization data indicate that dDAAM is present in the growing sarcomeres at a location consistent with a role in thin filament regulation.

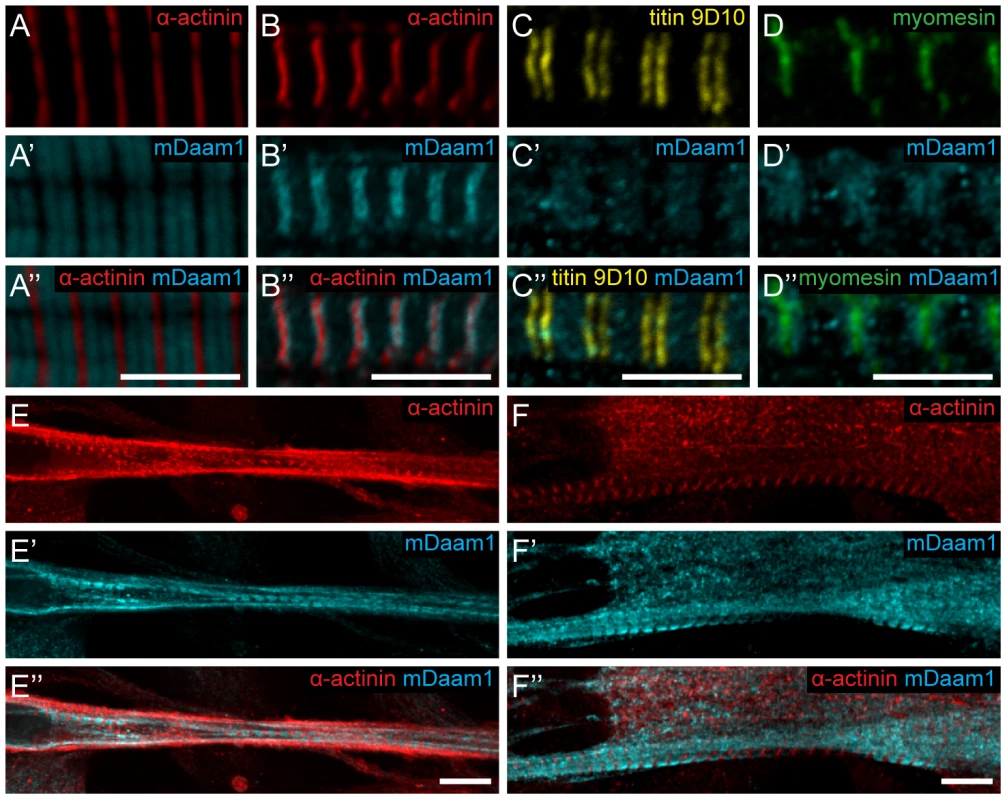

Evolutionary conservation

As many muscle proteins are evolutionary highly conserved, and the mouse Daam1 (mDaam1) gene was shown to be involved in heart development [23], we examined the localization of mDaam1 by immunostaining of skeletal muscle sections from 15 day-old animals. Interestingly, in the m. tibialis anterior two bands of sarcomeric enrichment occurred at either side of the M-line, whereas in m. vastus lateralis most protein was detected along the Z-discs (Figure 5A–B″). To verify this mDaam1 localization pattern further and its development during the early phases of myofibrillogenesis, we used the mouse myogenic cell line C2C12 [24] and α-actinin, known to be one of the earliest marker of myofibril formation [25]. In C2C12 cells that were induced to differentiate for 24 hours, mDaam1 was detected in two broad bands in the sarcomeres between the Z-bodies and the M-line (Figure 5E). In C2C12 cells differentiated for 48 or 96 hours, the same mDaam1 distribution was detected as after 24 hours of differentiation (Figure 5F). To resolve the sarcomeric position of the two bands labeled by anti-mDaam1, double staining was carried out with the anti-titin 9D10 and the anti-myomesin B4 antibodies in C2C12 cells differentiated for 96 hours. The 9D10 antibody labels the PEVK region of the giant titin protein located in the I-band close to the I-A border [26], [27], whereas B4 labels the M-line [28]. The mDaam1 staining did not significantly overlap with that of either 9D10 or B4 (Figure 5C–D″) confirming that most of the mDaam1 protein is accumulated between the M-line and the I-A border, corresponding to the thin and thick filament overlap region.

Fig. 5. Sarcomeric localization of the mDaam1 protein.

(A–B″) mDaam1 staining (in cyan) of mouse muscle sections (the Z-disc marker α-actinin is in red). In m. tibialis anterior sarcomeres mDaam1 accumulates in two bands either side of the M-line (A–A″), whereas in m. vastus lateralis it is mostly detected along the Z-discs (B–B″). In C2C12 cells differentiated for 96 hours mDaam1 (cyan) accumulates in two broad bands at the middle of the sarcomere that does not significantly overlap with titin staining (yellow; 9D10 antibody) (C–C″) or myomesin (green), an M-line marker (D–D″). (E–F″) Distribution of mDaam1 (cyan) and α-actinin (red) in C2C12 cells induced to differentiate for 24 (E–E″) or 96 hours (F–F″). Bars: 5 µm (A–D″); 15 µm (E–F″). The sarcomeric localization pattern of mDaam1 suggests two important conclusions. Firstly, despite some muscle-specific differences, the subsarcomeric localization of mDaam1 appears similar to that of Drosophila DAAM with regard to accumulation at the Z-disc and alongside the M-line. Secondly, because mDaam1 is recruited to sarcomeric complexes as early as the actin cross-linker α-actinin protein, this formin is likely to be an early determinant of myofibrillogenesis.

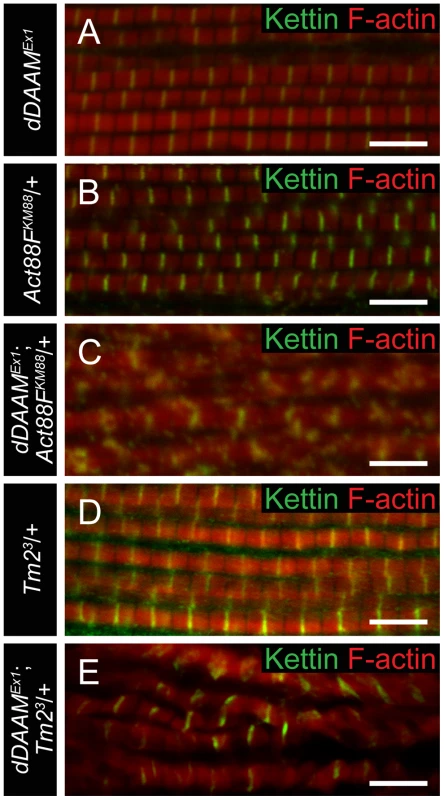

dDAAM interacts with thin filament mutants

To collect further evidence for our proposal that dDAAM has an important role in thin filament formation and regulation, genetic interactions with the IFM-specific Act88FKM88 and Tm23 mutations [29], [30] were tested. IFM structure was analyzed in heterozygous mutants in wild type and dDAAMEx1 mutant backgrounds. The results revealed that the mild dDAAMEx1 IFM phenotype (Figure 6A) is strongly enhanced by Act88FKM88 and enhanced by Tm23. Myofibrils of Act88FKM88 heterozygotes were thinner than wild type and some Z-discs were not entirely straight (Figure 6B), but the precisely repeating organization of the sarcomeres remained. In contrast, the IFM of dDAAMEx1; Act88FKM88/+ double mutants exhibited a network of very thin myofibrils often with a branched appearance, in which Z-disc and sarcomeric organization appeared to be completely abolished (Figure 6C). Similarly, in dDAAMEx1; Tm23/+ mutants the myofibrils appeared disorganized, displaying strongly varying width, unequal sarcomere and thin filament length and the frequent appearance of mini-sarcomeres (Figure 6E). As controls we examined Act5C null mutants, affecting the major non-muscle cell specific actin isoform [31] and a strong loss-of-function allele of the cytoplasmic Tm1 isoform, Tm102299 [32]. As expected, these mutations did not alter the IFM phenotype of dDAAMEx1 (Figure S5). The strong dominant genetic interaction between dDAAM and the IFM-specific Act88F and Tm2 alleles, and the complete lack of interaction with the non-muscle cell specific isoforms, suggests that the major function of dDAAM during muscle development is indeed linked to the regulation of sarcomeric actin filament formation.

Fig. 6. dDAAM interacts with thin filament mutants.

IFM myofibrils from (A) dDAAMEx1, (B) Act88FKM88/+, (C) dDAAMEx1; Act88FKM88/+, (D) Tm23/+ and (E) dDAAMEx1; Tm23/+ flies (actin in red, Kettin in green in all panels). Note: sarcomere organization in dDAAMEx1 (A) is nearly wild type; likewise Act88F (B) and Tm2 (D) heterozygotes display a largely regular myofibril and Z-disc organization. Myofibrils of the dDAAMEx1; Act88FKM88/+ (C) and dDAAMEx1; Tm23/+ (E) genotypes are extremely disorganized compared to the controls. Bars, 5 µm. dDAAM is required for thin filament elongation

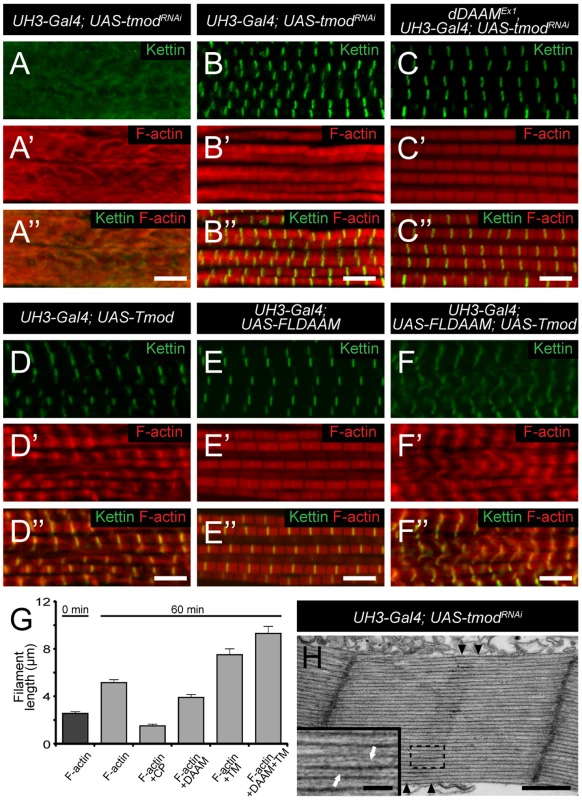

Under in vitro conditions the FH2 or FH1–FH2 domains of dDAAM behave as bona fide formins possessing both actin nucleation and elongation activities [33]. The observation that the thin filaments are shorter in dDAAM mutants than in wild type, suggested that dDAAM is a positive regulator of thin filament elongation. Consistent with the view that muscle thin filaments elongate from their pointed ends, dDAAM is present at the pointed end of actin filaments in the IFM, although, as expected for a formin, it also accumulates at barbed ends. To determine whether dDAAM is functionally important for pointed end elongation we investigated genetic interactions of dDAAM with mutations affecting the pointed end regulator proteins SALS and Tmod. SALS promotes filament elongation in vivo [18], whereas Tmod binding is thought to prevent elongation [16]. The presence of salsf07849/+ in a dDAAMEx1 mutant background had no obvious phenotypic effect. In contrast, the tmod00848 mutation entirely suppressed the weak flightless phenotype of dDAAMEx1 (4.9±0.5%, mean±SEM, n = 160, p = 0.027) (Figure 1A) suggesting that dDAAM and Tmod may act antagonistically during thin filament growth.

To investigate the dDAAM/Tmod interaction in more detail we first examined the IFM-specific RNAi silencing of tmod, and we found that in most myofibrils it severely disrupted myofibrillogenesis (Figure 7A). However, approximately 10% of the myofibrils had almost normal looking Z-discs allowing us to determine that these sarcomeres were shorter (2.62±0.11 µm; n = 26; mean±SD; p<0.001) than wild type. Phalloidin staining revealed the presence of thin filaments in the mid-sarcomeric region (Figure 7B) and impaired M-lines are evident by EM analysis (Figure 7H). The strong effect on myofibrillogenesis is in accordance with previous reports that Tmod1 in mouse and Unc-94 (tmd-1) in C. elegans are required for myofibril assembly [34], [35], [36], [37]. The decreased sarcomere length was unexpected as the inhibition of Tmod function increases sarcomere length in cultured cardiomyocytes [38] or in Drosophila primary muscles [18]. We noted however, that although sarcomere length of UH3-Gal4; UAS-tmodRNAi flight muscles was reduced, some of the thin filaments clearly failed to terminate in the H-zone of these mutant sarcomeres (Figure 7H). Therefore, individual filament length can be longer than in wild type, which would be consistent with the known function of Tmod in filament length regulation. To study whether the tmodRNAi phenotype is sensitive to dDAAM protein level, tmod silencing was carried out in a dDAAMEx1 mutant background. Most (∼80%) myofibrils displayed a striated pattern with distinct M-lines and somewhat aberrant Z-discs, and nearly normal sarcomere length (2.8±0.13 µm; n = 30; mean±SD; p<0.001) (Figure 7C). This phenotype suggests that the reduced dDAAM levels suppress the “over elongation” of the thin filaments seen in the IFM of tmodRNAi flies, and hence, these results further confirm that these two proteins have antagonistic activities in thin filament elongation.

Fig. 7. The interaction of dDAAM and tmod.

Upon silencing of tmod myofibrils get severely disrupted (A–A″), though ∼10% of them show a milder effect with regular Z-disc arrangement but missing H-zones (B–B″). In dDAAMEx1, UH3-Gal4; UAS-tmodRNAi muscles most myofibrils have a nearly wild type sarcomeric organization with regularly spaced Z-discs and M-lines, and almost normal sarcomere length (C–C″). (D–D″) In UH3-Gal4; UAS-Tmod IFMs the sarcomeric thin filaments often appear to be shorter than wild type as judged by phalloidin staining, whereas myofibrils of UH3-Gal4; UAS-FLDAAM muscle look wild type (E–E″). Simultaneous overexpression of FLDAAM and Tmod results in the same effect as the expression of Tmod alone (F–F″; compare to D–D″). Kettin in green, actin in red in A–F″. (G) An end-to-end actin annealing assay, dark grey: 0 minute control, average filament length in the presence of 1 µM F-actin (F-actin), light gray: average filament length after 60 minutes incubation, in the presence of 1 µM F-actin (F-actin), 1 µM F-actin+ 10 nM capping protein (F-actin+CP), 1 µM F-actin+100 nM DAAM-FH1-FH2 (F-actin+DAAM), 1 µM F-actin+1 µM skeletal tropomyosin (F-actin+TM), 1 µM F-actin+100 nM DAAM-FH1-FH2+1 µM skeletal tropomyosin (F-actin+DAAM+TM). Bars represent mean values with respective SEMs. (H) Electronmicrograph of a tmodRNAi IFM. Black arrowheads mark the borders of the mid-sarcomeric region where the M-line structures are not evident but thin filaments appear to cross this area. White arrows on the inset, corresponding to the dashed area, mark thin filaments that fail to terminate in the H-zone. Bars: 5 µm (A–F″); 500 nm (H) 100 nm (H, inset). Although dDAAM protein is detected in the vicinity of the pointed ends of sarcomeric thin filaments, former structural studies indicated that formins are strictly barbed end binding proteins [21], [39], [40]. This paradox would be resolved if pointed end elongation relies on the formation of short actin filaments that anneal sequentially to growing thin filaments anchored to the Z-disc. In this model, dDAAM would mediate the assembly of short actin filaments by acting as a classical barbed end binding formin, but would additionally either actively promote actin filament annealing, or at least not block it. To test this expectation, an in vitro F-actin annealing assay was carried out with the barbed end binding FH1–FH2 domains of dDAAM. We found that the presence of the FH1–FH2 fragment (100 nM) allowed the end-to-end annealing of actin filaments (Figure 7G), although in previous in vitro assays the FH1–FH2 domains of dDAAM significantly reduced barbed end assembly under similar conditions [33]. Capping protein and TM were used as controls. In accordance with former studies [41], [42], the barbed end blocking capping protein had an inhibitory effect, whereas TM enhanced the end-to-end annealing of actin filaments, and the combined effect of TM and dDAAM was even slightly higher than the one of TM alone (Figure 7G). The annealing model suggests that, even if at the pointed end sarcomeric region, dDAAM acts as a barbed end binding protein. Hence it follows that dDAAM is unlikely to directly interfere with the binding of pointed end cappers, such as Tmod. To address this issue, we investigated the effect of dDAAM and Tmod in overexpression assays. The IFM specific overexpression of Tmod resulted in thin filament shortening [43] (Figure 7D–D″), whereas the excess of dDAAM had no obvious phenotypic effect in the IFM (Figure 7E–E″). When the two proteins were expressed together, we observed the same phenotypic effect as the overexpression of Tmod alone (Figure 7F–F″). Therefore these results support the annealing model of dDAAM mediated thin filament elongation and the interaction studies are also consistent with the proposal that dDAAM affects thin filament assembly at pointed ends.

Discussion

The sarcomeric actin filaments are critical structural and functional elements of muscles, yet the mechanism of actin filament formation and its regulation during myofibrillogenesis remained unclear. The initial steps of actin filament formation require nucleation factors, of which Lmod and Fhod3 have been previously identified as muscle-specific nucleators [6], [7]. However, functional analysis led to the conclusion that Lmod and Fhod3 are crucial to myofibril maintenance but are unlikely to contribute to filament nucleation during the initial stages of myofibril assembly. Recent work in C. elegans revealed that two members of the formin family, Cyk-1 (a Diaphanous ortholog) and Fhod-1, are both enriched at the Z-disc and promote filament lattice growth and its maintenance in striated muscles [44]. Surprisingly however, the muscle phenotypes displayed by cyk-1 or fhod-1 single mutants were relatively mild and it is unresolved whether other nucleation factors are required in worm muscles. Here we provide in vivo evidence that DAAM, another formin family member, is important for sarcomeric thin filament formation. We have found that dDAAM is required for thin filament elongation and that the actin-assembling activity of dDAAM is indispensable for formation of functional muscles. In addition, we have shown that in differentiating C2C12 cells the mouse Daam1 ortholog is incorporated into sarcomeric complexes at least as early as α-actinin. Thus DAAM family formins are strong candidates for being involved in the initial assembly of myofibrillar actin filaments. Interestingly, although the F-actin content of dDAAM mutant muscles is reduced, some filaments still form. Notably however, the dDAAM mutants available for muscle studies are not protein null. This prevents us from determining whether an additional nucleation factor, such as Dia or Fhos, is involved or that residual dDAAM activity is sufficient to promote some level of F-actin formation. Nevertheless, our results demonstrate that dDAAM is a developmentally important sarcomere-associated actin assembly factor in Drosophila. Remarkably, expression of the vertebrate DAAM orthologs are known to be abundant in developing somites and heart [23], [45], and genetic analysis of mDaam1 indicated a role in sarcomere organization in cardiomyocytes [23]. Overall this suggests that the regulation of sarcomeric actin filament formation is an evolutionary conserved DAAM function.

Our studies revealed that in the IFM the dDAAM protein is mostly enriched at either end of the thin filaments, the expected positions for proteins affecting thin filament assembly. We formerly showed that in vitro dDAAM behaves as a bona fide formin, possessing all the major properties reported for other formin family members [33]. Here we propose that at Z-discs dDAAM may regulate G-actin incorporation with the well described barbed end processive capping mechanism of formins. Given that the sarcomeric dDAAM expression in the IFM, including the Z-disc accumulation, is maintained during adulthood, it appears likely that dDAAM also contributes to the maintenance of normal muscle structure and function. Besides the Z-disc enrichment, dDAAM also accumulates at the pointed end region of the thin filaments. Since dDAAM promotes thin filament formation and acts antagonistically to the F-actin pointed end capping protein, Tmod, the simplest interpretation of these data is to assume that dDAAM is involved in filament elongation from the pointed end. This is in good accordance with the evidence that in cardiac myocytes and in Drosophila primary cultures actin dynamics predominate at the pointed ends [17], [18], yet the presence at the pointed ends is unexpected for a formin, a barbed end binding protein. Because available structural studies exclude the possibility that a formin directly binds to the pointed end, dDAAM might be recruited to the pointed end by binding to a different protein than actin, or our findings indicate the presence of F-actin barbed ends in the vicinity of the pointed end of the thin filaments. Although we cannot strictly exclude the first possibility, at present the functional importance of such an association is unclear. Therefore we favor the second alternative that has interesting mechanistic implications. If barbed ends indeed exist in the region of the pointed ends, then pointed end elongation could be achieved through the end-to-end annealing of short actin filaments to the Z-disc anchored growing “mother filament” (Figure 8). Such a mechanism, demonstrated in vitro, would allow rapid filament elongation at the pointed ends. Our data are compatible with the model in which dDAAM promotes the formation of these short filaments by acting as an F-actin barbed end binding processive capper that also allows filament annealing. An important question is how long these short filaments are? In this regard, it is interesting to note that during contractile ring formation in fission yeast the formin Cdc12p was shown to nucleate short actin filaments that anneal to each other in the presence of TM [42], and consistently, TM increased the annealing process by ∼2 fold in our in vitro assay. As TM is a major myofibrillar protein, and the IFM-specific Tm2 mutation dominantly enhanced the thin filament defects of dDAAMEx1, we propose that the length of the filaments involved in the annealing process is unlikely to be shorter, but could be equal to an F-actin fragment covered by one TM dimer which is about 37–38 nm or 14 actin monomers. Whereas the ability to anneal end-to-end is an intrinsic property of actin filaments, a better understanding of this mechanism during myofibril formation awaits future studies, most importantly the visualization of the short protofilaments. Nonetheless, it is remarkable that the formin Fhod3, implicated in myofibril maintenance and maturation [10], [46], also displays an accumulation in the pointed end region [7], [47] and might regulate actin assembly with a similar mechanism as dDAAM.

Fig. 8. A model of DAAM mediated ‘pointed end elongation’.

(A) Nucleation and elongation of short actin filaments by the barbed (+) end binding formin DAAM. (B) A possible mechanism of thin filament elongation from the pointed end (−) is the end-to-end annealing of DAAM assembled short actin filaments (in orange) to the Z-disc anchored growing “mother filament” (in brown). Previously presented models of thin filament growth in Drosophila proposed a two-step mechanism [18], [43]. According to this view, during the first step short filaments are assembled, and during the second step these filaments extend to their final length. Moreover, it is presumed that, at least in larval muscles, the initial phase is SALS-independent, whereas subsequent elongation from the pointed end requires SALS activity that is thought to antagonize the effect of Tmod [18]. The shorter sarcomeres observed in dDAAM mutant muscles argue that dDAAM is required during the second step of thin filament formation. On the other hand, the severe Z-disc organization defects and the reduced sarcomere number in larval muscles, that are also typical for dDAAM mutants, indicate an earlier function that may be linked directly to the initial steps of thin filament formation. Our mDaam1 protein localization data during C2C12 cell differentiation is also consistent with an early function during sarcomerogenesis, therefore dDAAM is a good candidate for being involved already in the first steps of sarcomeric thin filament formation. Whether the annealing mechanism is at work during the first, second or both steps of actin filament formation/elongation, and whether SALS and dDAAM cooperate or act through independent mechanisms during the second step, remain open questions.

Interestingly, beyond the strong effect on thin filaments, dDAAM also affects thick filament and myofibrillar lattice organization. While these phenotypes can be the indirect consequences of the severe impairment of the sarcomeric thin filament system, another alternative could be that dDAAM plays a more complex role in sarcomerogenesis. In favor of this idea we note that the dDAAM mutants display a more poorly organized filament system than observed in Act88F null mutants which completely lack the sarcomeric thin filaments [48]. Additionally, dDAAM affects the shape of the thick filaments which is not reported for Act88F [48]. Moreover, we found that despite the lack of thin filaments, in Act88F mutants the dDAAM protein remains associated with the muscle fibers displaying a non-uniform distribution with foci that largely overlap with those of Myosin staining (Figure S4C). Taking all these observations together with the unusually strong effect on lattice organization, we speculate that, besides actin binding, dDAAM might play an important role in the integration of the thin and thick filament systems during sarcomerogenesis. Remarkably, unlike the actin isoforms [49], overexpression of the wild type dDAAM protein in larval muscles significantly increased sarcomere number and muscle size while sarcomere length remained nearly normal. Therefore dDAAM appears to play an instructive role in sarcomere formation, and to our knowledge, this is the first example reported where overexpression of a single muscle protein results in such an effect on muscle development.

Materials and Methods

Fly strains and genetics

Unless indicated otherwise, flies were raised and crossed at 25°C according to standard procedures. w1118 was used as wild-type control. In addition, the following fly stocks were used: dDAAMEx1, dDAAMEx68/FM7c, Kr-GFP and w; UAS-FLDAAM or UAS-DAAM-PB [50], y w; DMef2-Gal4 (Bloomington Stock Center), w; UH3-Gal4 [19], w; UAS-Dcr2 (Bloomington), ry506 tmod00848/TM3 (Bloomington), w; UAS Tmod (gift from J. Bai, Harvard Medical School, Boston), ry506 Act88FKM88 e [51], y w; Tm23 (Bloomington), ry506 Tm102299/TM3 (Bloomington), w; salsf07849/TM6B (Bloomington), w Act5CG0025/FM7c (Bloomington), w; sls-GFP [52], w; UAS-TmodRNAi (NIG-FLY, Kyoto) and w; UAS-dDAAMKK102786 (VDRC, Vienna).

The UAS-dDAAMRNAi-T129M dDAAM specific RNAi line, targeting nucleotides 2562–3068 of the RE67944 dDAAM cDNA clone, was created by standard cloning and transformation techniques. To create a UAS-DAAM-PD clone, the PD isoform specific region was amplified from a cDNA pool generated by reverse transcription of mRNAs isolated from the L3 stage. We first created a pENTR3C-DAAM-PD clone that subsequently was used to create pTW-DAAM-PD (UAS-DAAM-PD) destination clones suitable for transgenesis.

The UAS-DAAM-PBI732A and UAS-DAAM-PDI1042A mutants were created by standard cloning techniques using pENTR3C-DAAM-PB and pENTR3C-DAAM-PD as templates for in vitro mutagenesis.

The dDAAMEGFP knock-in mutant was created by a two-step P-element mediated gene conversion experiment. First a targeting construct was assembled in a modified pBS vector where we inserted a 1.3 kb 3′ dDAAM genomic region until the last codon, this was followed by a 2.3 kb Gal4::VP16 fragment flanked with I-SceI cut sites on both sides, next we inserted a 1150 bp fusion fragment containing the 3′ dDAAM region encoding the last 83 C-terminal aminoacids fused to an EGFP coding sequence ending with a stop codon. This was followed with the entire 3′ UTR of dDAAM and a 1.1 kb genomic region further downstream of it. This way, besides the genomic flanking sequences, the construct carries Gal4::VP16 that can be used as a marker gene which is flanked both by I-SceI sites and a ∼250 bp long genomic duplication encoding the most C-terminal dDAAM coding sequences. This targeting construct was converted into the dDAAM genomic region after remobilizing the EP(1)1542 P-element insertion located 200 bp downstream of dDAAM (see Flybase for details). To this end, EP(1)1542 virgins were crossed to ry502 Fab-71 Δ2-3 (gift from L. Sipos, BRC HAS, Szeged) males and the embryonic progeny of this cross was injected with the targeting construct. Offspring of the previous cross was crossed to w; UAS-EGFP flies en masse and put on egg laying medium. Embryos were collected on apple-juice plates, and the hatching larvae were screened for GFP fluorescence with an MZ FLIII stereo microscope (Leica, Switzerland). Larvae with GFP expression in the tracheal and nervous system were collected individually and used to set up stocks. Conversion events were confirmed by PCR and sequencing. Once the Gal4::VP16 containing construct has been successfully converted into the dDAAM gene, in a subsequent round of crosses I-SceI was used to induce DNA double strand breaks that could eventually be repaired through homologous recombination between the ∼250 bp duplicated dDAAM regions. This event, confirmed by PCR and sequencing, led to the removal of all non Drosophila sequences with the exception of EGFP, and resulted in a C-terminally GFP-tagged dDAAM allele. dDAAMEGFP is fully viable and fertile in hemi - or homozygous state indicating that the presence of EGFP does not significantly alter dDAAM function.

Immunohistochemistry

Newly eclosed adult IFMs were dissected from bisected half thoraces in 4% paraformaldehyde (PF), incubated for 15 minutes, then washed with relaxing solution (6 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM ATP, 90 mM potassium propionate, 20 mM NaPi, pH 7.0). The muscles were permeabilized overnight in Triton-X/glycerol solution (50% v/v glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100, 20 mM NaPi, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM DTT, pH 7.0) at 4°C, and washed in PBS supplemented with 0.5% Triton X-100 (PBT), then labeled with primary and secondary antibodies. For pupal IFM preparations, timed pupae were removed from their puparia and pinned by the head on dry Sylgard (Dow Corning), dorsal side down, and then submerged into 4% PF in PBS. After dissection along the ventral midline, unattached material was flushed gently away using a syringe to expose the IFMs. These were detached and incubated in fixative (4% PF in PBS) for a further 15 minutes, then transferred back to relaxing solution. For larval heart tube dissections larvae were cut along the ventral midline in relaxing solution. Then fixed with 4% PF in PBS [53]. Fat bodies and other organs were removed, then labeled with primary and secondary antibodies. For developmental staging, white pre-pupae with everted spiracles were removed into fresh vials at 25°C and harvested at required time-points. Adult flies were selected as ‘newly eclosed’ between 0 and 8 hr post-eclosion.

Primary antibodies, listed below, were applied overnight at 4°C. Muscles and heart tubes were washed three times in PBST, secondary antibodies were applied for 3 hr, then samples were rinsed three times again in PBST. The following primary antibodies were used: rat monoclonal anti-Kettin (MAC 155, 1∶200; Abcam); rat monoclonal anti-Myosin (MAC 147, 1∶200; Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP (1∶1000; Sigma) and rabbit polyclonal anti-dDAAM (1∶1000) [22]. For secondary antibodies we used the appropriate Alexa-488, Alexa-546 and Alexa-647 (1∶600), actin was stained with Rhodamine-Phalloidin (1∶100) (all from Life Technologies). Samples were mounted in PBS∶glycerol (1∶4). Confocal images were captured on an Olympus FV1000 LSM microscope, images were edited with ImageJ (NIH) and Olympus FW10-ASW (version1.7a.).

Larval length measurements and crawling assays

Aged larvae were collected and rinsed with tap water, and then gently placed onto agar plates. The plates were placed under an Olympus SZX12 dissecting microscope equipped with an Olympus C7070 digital camera. Total illumination was applied, images were acquired at 25 Hz. The recording environment (temperature, humidity, illumination) was stationary. Twenty seconds of movie was recorded with DScaler (The DScaler Project Team) for each larva. During this period of time most wild-type larvae moved out from the field of view. ImageJ (NIH) software was used to analyze the image sequences. Persistent forward movements were selected to characterize larval crawling velocity and larval length. Larval length was calculated as the average of the minimum and the maximum head to tail distance for each larva. Maximum intensity projections were used to generate larval tracks. To calculate larval crawling velocity, the lengths of these tracks were divided by the time. Tracked larvae were dissected, stained and subjected to muscle measurements made on VL3 (ventral longitudinal 3) muscles. Muscle length was measured manually as the major axis of the VL3 muscles; muscle width was measured as the minor axis of the VL3 muscles. Sarcomere number and sarcomere length were measured from gray scale intensity plots across phalloidin stained sarcomeres, sarcomere size being the distance between adjacent peaks.

Flight tests

Flight tests were carried out with three day old flies [54]. Flies were released inside a perspex box illuminated from above, and scored for the ability to fly up, horizontally or down. Flies falling into the third category (down) were counted as flightless.

Tissue culture and mouse muscles

The mouse myogenic cell line, C2C12 (ATCC), was maintained in growth medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS; GIBCO/Life Technologies). Cells were initially plated into 100-mm-diameter dishes (Greiner) at a density of 104/cm2. When cultures reached ∼80% confluence they were subcultured onto sterile glass coverslips in 35-mm-diameter dishes. Cultures were kept in growth medium until they reached 60% confluence and subsequently were switched to differentiation medium (DMEM containing 2% horse serum; GIBCO/Life Technologies). This medium was replaced every day, and samples were processed for immunostaining at selected time points. Cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes, and permeabilized in PBS+0.1% Triton-X100 for 3 minutes before staining. Primary antibodies were applied for 1 hr RT, and after 3×5 minutes washing in PBS, cells were incubated with secondary antibodies for another 1 hr. After washing three times for 5 minutes in PBS, samples were mounted in PBS∶glycerin (1∶4).

For sections of m. tibialis anterior and m. vastus lateralis, C57Bl/6 adult male mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Leg muscle was dissected, embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek) and snap-frozen in isopentane cooled by liquid nitrogen. 10 µm cryosections were fixed in prechilled acetone and kept at −80°C.

For mammalian muscle and C2C12 staining the following antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal anti-mDaam1 (1∶2000; Sigma), rabbit polyclonal anti-mDaam1 (1∶200; Abnova), mouse monoclonal anti-α-actinin (1∶80; Sigma), mouse monoclonal anti-titin 9D10 (1∶20; DSHB) and mouse monoclonal anti-myomesin (B4, 1∶1; DSHB). For secondary antibodies we used the appropriate Alexa-488, Alexa-546 and Alexa-647 (1∶600; Life Technologies). Images were taken and analyzed in a similar ways as flight muscles described above.

Electron microscopy

Muscles were dissected and fixed in 3.2% paraformaldehyde, 0.5% glutaraldehyde, 1% sucrose, 0.028% CaCl2 in 0.1 N sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4) overnight at 4°C, and washed 2× overnight in 0.1 N sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4) at 4°C. Samples were postfixed in 0.5% osmium-tetroxide for 1 hr at room temperature, and embedded into Durcupan (Fluka) by following the manufacturer's recommendations. 70–80 nm ultrathin sections were prepared from 2–3 animals per genotype, stained in Reynold's lead citrate, and evaluated using a JEM-1011 electron microscope (JEOL) equipped with Morada camera and iTEM software (Olympus).

AFM and force measurements

IFM muscle fibers, falling apart for individual myofibrils upon preparation, were mounted on a poly-L-lysine coated glass surface and measured in phosphate buffered saline. To identify the target points at which to perform individual force measurements, a rough and low resolution scan was taken (not shown). Experiments were carried out with Asylum MFP-3D head and controller (Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA). The driver program was written in IGOR Pro software (version 5.04, Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). Rectangular, gold coated, silicon nitride cantilevers were used, with a nominal spring constant of 30 pN/nm and a V shaped tip with radius of curvature of roughly 30 nm (Bio-Lever, BL-RC150 VB-C1, Olympus Optical Co. Ltd). The measurements were performed in contact mode in liquid, with the vertical piezo working in a closed loop. Constant speed of 0.6 µm/s (scan rate 0.1 Hz) and total load was kept below 1 nN during experiments.

Simple force curves were measured by lowering the probe until a desired deflection is reached and pulling it back. To calculate the sample's elasticity the contact region of the lowering part from force curves has been used. By subtracting a reference curve, recorded on a hard surface from those measured on the object of interest, the sample's force vs. indentation curve can be obtained, which provides the Young's modulus of the measured sample [55]. Several points were examined recording multiple force curves at each selected place; the average and standard deviation of which was calculated.

Protein gel electrophoresis and western blot analysis

Adult IFM samples were dissected as described above. Tissues were immediately placed in ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer and kept overnight. SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses were carried out according to standard protocols. Membranes were stained with rabbit anti-dDaam (1∶1000), and rabbit anti-glycogen phosphorylase (1∶20000) (gift from A. Udvardy, BRC HAS, Szeged) used as a loading control. Secondary antibody was α-rabbit-HRPO (1∶10000; Sigma). For chemiluminescent detection we used a Millipore Immobilon kit.

Actin filament annealing tests

To measure the annealing of actin filaments fluorescence microscopy assays were performed. Actin filaments (10 µM, F-actin) were polymerized for 2 hr at room temperature in 4 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.2 mM ATP, 0.5 mM DTT, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2 and 50 mM KCl (F-buffer). The F-actin solution was then diluted to 1 µM using F-buffer in the absence or presence of actin-binding proteins (100 nM capping protein or 100 nM dDAAM FH1-FH2 or 1 µM skeletal muscle TM or 100 nM dDAAM FH1-FH2 and 1 µM skeletal muscle TM). The samples were incubated overnight. For investigation of the annealing, Alexa-488-phalloidin labeled samples were sheared five times through a 26 gauge needle. Samples were diluted 100 fold into microscopy buffer (F-buffer supplemented with 50 mMDTT, 5 mM DABCO and 0.5% (w/v) methylcellulose) 0 and 60 minutes after shearing and processed for microscopy observations. Single actin filaments were observed with an Olympus IX81 inverted fluorescence microscope using a 100× objective (NA1.4) and a CCD camera (Orca ERG Hamamatsu). The length of the actin filaments was measured and analyzed with ImageJ. Under each condition 3–4 independent measurements were performed and 300–600 filaments were analyzed. Statistical analysis was carried out using Microsoft Excel or Microcal Origin 6.0.

Statistics

Excel (Microsoft) was used to collect and organise data. Statistical analysis was carried out using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc.) and/or SigmaPlot 12 (Systat Software Inc.). Normality of the data was verified by Shapiro-Wilk test. Pairwise comparisons were made using the Student's t test or the Mann-Whitney U test according to the normality, p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. LutherPK (2009) The vertebrate muscle Z-disc: sarcomere anchor for structure and signalling. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 30 : 171–185.

2. SparrowJC, SchockF (2009) The initial steps of myofibril assembly: integrins pave the way. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10 : 293–298.

3. PollardTD, BlanchoinL, MullinsRD (2000) Molecular mechanisms controlling actin filament dynamics in nonmuscle cells. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 29 : 545–576.

4. CampelloneKG, WelchMD (2010) A nucleator arms race: cellular control of actin assembly. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11 : 237–251.

5. ChesaroneM, GouldCJ, MoseleyJB, GoodeBL (2009) Displacement of formins from growing barbed ends by bud14 is critical for actin cable architecture and function. Dev Cell 16 : 292–302.

6. ChereauD, BoczkowskaM, Skwarek-MaruszewskaA, FujiwaraI, HayesDB, et al. (2008) Leiomodin is an actin filament nucleator in muscle cells. Science 320 : 239–243.

7. TaniguchiK, TakeyaR, SuetsuguS, KanOM, NarusawaM, et al. (2009) Mammalian formin fhod3 regulates actin assembly and sarcomere organization in striated muscles. J Biol Chem 284 : 29873–29881.

8. Skwarek-MaruszewskaA, BoczkowskaM, ZajacAL, KremnevaE, SvitkinaT, et al. (2010) Different localizations and cellular behaviors of leiomodin and tropomodulin in mature cardiomyocyte sarcomeres. Mol Biol Cell 21 : 3352–3361.

9. TsukadaT, PappasCT, MorozN, AntinPB, KostyukovaAS, et al. (2010) Leiomodin-2 is an antagonist of tropomodulin-1 at the pointed end of the thin filaments in cardiac muscle. J Cell Sci 123 : 3136–3145.

10. IskratschT, LangeS, DwyerJ, KhoAL, dos RemediosC, et al. (2010) Formin follows function: a muscle-specific isoform of FHOD3 is regulated by CK2 phosphorylation and promotes myofibril maintenance. Journal of Cell Biology 191 : 1159–1172.

11. IskratschT, ReijntjesS, DwyerJ, ToselliP, DeganoIR, et al. (2013) Two distinct phosphorylation events govern the function of muscle FHOD3. Cell Mol Life Sci 70 : 893–908.

12. AnheziniL, SaitaAP, CostaMS, RamosRG, SimonCR (2012) Fhos encodes a Drosophila Formin-like protein participating in autophagic programmed cell death. Genesis 50 : 672–684.

13. CastrillonDH, WassermanSA (1994) Diaphanous is required for cytokinesis in Drosophila and shares domains of similarity with the products of the limb deformity gene. Development 120 : 3367–3377.

14. EmmonsS, PhanH, CalleyJ, ChenW, JamesB, et al. (1995) Cappuccino, a Drosophila maternal effect gene required for polarity of the egg and embryo, is related to the vertebrate limb deformity locus. Genes Dev 9 : 2482–2494.

15. TanakaH, TakasuE, AigakiT, KatoK, HayashiS, et al. (2004) Formin3 is required for assembly of the F-actin structure that mediates tracheal fusion in Drosophila. Dev Biol 274 : 413–425.

16. LittlefieldRS, FowlerVM (2008) Thin filament length regulation in striated muscle sarcomeres: pointed-end dynamics go beyond a nebulin ruler. Semin Cell Dev Biol 19 : 511–519.

17. LittlefieldR, Almenar-QueraltA, FowlerVM (2001) Actin dynamics at pointed ends regulates thin filament length in striated muscle. Nat Cell Biol 3 : 544–551.

18. BaiJ, HartwigJH, PerrimonN (2007) SALS, a WH2-domain-containing protein, promotes sarcomeric actin filament elongation from pointed ends during Drosophila muscle growth. Dev Cell 13 : 828–842.

19. KatzemichA, KreiskotherN, AlexandrovichA, ElliottC, SchockF, et al. (2012) The function of the M-line protein obscurin in controlling the symmetry of the sarcomere in the flight muscle of Drosophila. J Cell Sci 125 : 3367–3379.

20. ReedyMC, BeallC (1993) Ultrastructure of developing flight muscle in Drosophila. I. Assembly of myofibrils. Dev Biol 160 : 443–465.

21. XuY, MoseleyJB, SagotI, PoyF, PellmanD, et al. (2004) Crystal structures of a Formin Homology-2 domain reveal a tethered dimer architecture. Cell 116 : 711–723.

22. MatusekT, DjianeA, JankovicsF, BrunnerD, MlodzikM, et al. (2006) The Drosophila formin DAAM regulates the tracheal cuticle pattern through organizing the actin cytoskeleton. Development 133 : 957–966.

23. LiDQ, HallettMA, ZhuWQ, RubartM, LiuY, et al. (2011) Dishevelled-associated activator of morphogenesis 1 (Daam1) is required for heart morphogenesis. Development 138 : 303–315.

24. YaffeD, SaxelO (1977) Serial passaging and differentiation of myogenic cells isolated from dystrophic mouse muscle. Nature 270 : 725–727.

25. Kontrogianni-KonstantopoulosA, CatinoDH, StrongJC, BlochRJ (2006) De novo myofibrillogenesis in C2C12 cells: evidence for the independent assembly of M bands and Z disks. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C626–637.

26. TrombitasK, GreaserM, FrenchG, GranzierH (1998) PEVK extension of human soleus muscle titin revealed by immunolabeling with the anti-titin antibody 9D10. J Struct Biol 122 : 188–196.

27. WangSM, GreaserML, SchultzE, BulinskiJC, LinJJ, et al. (1988) Studies on cardiac myofibrillogenesis with antibodies to titin, actin, tropomyosin, and myosin. J Cell Biol 107 : 1075–1083.

28. GroveBK, KurerV, LehnerC, DoetschmanTC, PerriardJC, et al. (1984) A new 185,000-dalton skeletal muscle protein detected by monoclonal antibodies. J Cell Biol 98 : 518–524.

29. KarlikCC, FyrbergEA (1985) An insertion within a variably spliced Drosophila tropomyosin gene blocks accumulation of only one encoded isoform. Cell 41 : 57–66.

30. OkamotoH, HiromiY, IshikawaE, YamadaT, IsodaK, et al. (1986) Molecular characterization of mutant actin genes which induce heat-shock proteins in Drosophila flight muscles. EMBO J 5 : 589–596.

31. FyrbergEA, MahaffeyJW, BondBJ, DavidsonN (1983) Transcripts of the six Drosophila actin genes accumulate in a stage - and tissue-specific manner. Cell 33 : 115–123.

32. TetzlaffMT, JackleH, PankratzMJ (1996) Lack of Drosophila cytoskeletal tropomyosin affects head morphogenesis and the accumulation of oskar mRNA required for germ cell formation. EMBO J 15 : 1247–1254.

33. BarkoS, BugyiB, CarlierMF, GombosR, MatusekT, et al. (2010) Characterization of the biochemical properties and biological function of the formin homology domains of Drosophila DAAM. J Biol Chem 285 : 13154–13169.

34. Fritz-SixKL, CoxPR, FischerRS, XuB, GregorioCC, et al. (2003) Aberrant myofibril assembly in tropomodulin1 null mice leads to aborted heart development and embryonic lethality. J Cell Biol 163 : 1033–1044.

35. McKeownCR, NowakRB, MoyerJ, SussmanMA, FowlerVM (2008) Tropomodulin1 is required in the heart but not the yolk sac for mouse embryonic development. Circ Res 103 : 1241–1248.

36. StevensonTO, MercerKB, CoxEA, SzewczykNJ, ConleyCA, et al. (2007) unc-94 encodes a tropomodulin in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Mol Biol 374 : 936–950.

37. YamashiroS, CoxEA, BaillieDL, HardinJD, OnoS (2008) Sarcomeric actin organization is synergistically promoted by tropomodulin, ADF/cofilin, AIP1 and profilin in C. elegans. J Cell Sci 121 : 3867–3877.

38. SussmanMA, BaqueS, UhmCS, DanielsMP, PriceRL, et al. (1998) Altered expression of tropomodulin in cardiomyocytes disrupts the sarcomeric structure of myofibrils. Circ Res 82 : 94–105.

39. LuJ, MengW, PoyF, MaitiS, GoodeBL, et al. (2007) Structure of the FH2 domain of Daam1: implications for formin regulation of actin assembly. J Mol Biol 369 : 1258–1269.

40. ShimadaA, NyitraiM, VetterIR, KuhlmannD, BugyiB, et al. (2004) The core FH2 domain of diaphanous-related formins is an elongated actin binding protein that inhibits polymerization. Mol Cell 13 : 511–522.

41. AndrianantoandroE, BlanchoinL, SeptD, McCammonJA, PollardTD (2001) Kinetic mechanism of end-to-end annealing of actin filaments. J Mol Biol 312 : 721–730.

42. SkauCT, NeidtEM, KovarDR (2009) Role of tropomyosin in formin-mediated contractile ring assembly in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell 20 : 2160–2173.

43. Mardahl-DumesnilM, FowlerVM (2001) Thin filaments elongate from their pointed ends during myofibril assembly in Drosophila indirect flight muscle. J Cell Biol 155 : 1043–1053.

44. Mi-MiL, VotraS, KemphuesK, BretscherA, PruyneD (2012) Z-line formins promote contractile lattice growth and maintenance in striated muscles of C. elegans. J Cell Biol 198 : 87–102.

45. NakayaMA, HabasR, BirisK, DuntyWCJr, KatoY, et al. (2004) Identification and comparative expression analyses of Daam genes in mouse and Xenopus. Gene Expr Patterns 5 : 97–105.

46. KanOM, TakeyaR, AbeT, KitajimaN, NishidaM, et al. (2012) Mammalian formin Fhod3 plays an essential role in cardiogenesis by organizing myofibrillogenesis. Biol Open 1 : 889–896.

47. Kan-oM, TakeyaR, TaniguchiK, TanoueY, TominagaR, et al. (2012) Expression and subcellular localization of mammalian formin Fhod3 in the embryonic and adult heart. PLoS One 7: e34765.

48. BeallCJ, SepanskiMA, FyrbergEA (1989) Genetic dissection of Drosophila myofibril formation: effects of actin and myosin heavy chain null alleles. Genes Dev 3 : 131–140.

49. RoperK, MaoY, BrownNH (2005) Contribution of sequence variation in Drosophila actins to their incorporation into actin-based structures in vivo. J Cell Sci 118 : 3937–3948.

50. MatusekT, GombosR, SzecsenyiA, Sanchez-SorianoN, CzibulaA, et al. (2008) Formin proteins of the DAAM subfamily play a role during axon growth. J Neurosci 28 : 13310–13319.

51. MogamiK, HottaY (1981) Isolation of Drosophila flightless mutants which affect myofibrillar proteins of indirect flight muscle. Mol Gen Genet 183 : 409–417.

52. MorinX, DanemanR, ZavortinkM, ChiaW (2001) A protein trap strategy to detect GFP-tagged proteins expressed from their endogenous loci in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 : 15050–15055.

53. AlayariNN, VoglerG, Taghli-LamallemO, OcorrK, BodmerR, et al. (2009) Fluorescent labeling of Drosophila heart structures. J Vis Exp (32) pii: 1423.

54. CrippsRM, BallE, StarkM, LawnA, SparrowJC (1994) Recovery of dominant, autosomal flightless mutants of Drosophila melanogaster and identification of a new gene required for normal muscle structure and function. Genetics 137 : 151–164.

55. VinckierA, SemenzaG (1998) Measuring elasticity of biological materials by atomic force microscopy. FEBS Lett 430 : 12–16.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Natural Polymorphisms in Influence Negative Selection and CD4∶CD8 Lineage Commitment in the RatČlánek MicroRNAs Located in the Hox Gene Clusters Are Implicated in Huntington's Disease PathogenesisČlánek Comparative RNAi Screens in and Reveal the Impact of Developmental System Drift on Gene FunctionČlánek Mutation of SLC35D3 Causes Metabolic Syndrome by Impairing Dopamine Signaling in Striatal D1 Neurons

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 2- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- IVF a rakovina prsu – zvyšují hormony riziko vzniku rakoviny?

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Fifteen Years Later: Hard and Soft Selection Sweeps Confirm a Large Population Number for HIV In Vivo

- The Same but Different: Worms Reveal the Pervasiveness of Developmental System Drift

- Serine Carboxypeptidase SCPEP1 and Cathepsin A Play Complementary Roles in Regulation of Vasoconstriction via Inactivation of Endothelin-1

- Coherent Functional Modules Improve Transcription Factor Target Identification, Cooperativity Prediction, and Disease Association

- A Long-Chain Flavodoxin Protects from Oxidative Stress and Host Bacterial Clearance

- Mammalian E-type Cyclins Control Chromosome Pairing, Telomere Stability and CDK2 Localization in Male Meiosis

- Influenza Virus Drug Resistance: A Time-Sampled Population Genetics Perspective

- Transcriptome-Wide Analyses of 5′-Ends in RNase J Mutants of a Gram-Positive Pathogen Reveal a Role in RNA Maturation, Regulation and Degradation

- Selective Disruption of Aurora C Kinase Reveals Distinct Functions from Aurora B Kinase during Meiosis in Mouse Oocytes

- X Chromosome Control of Meiotic Chromosome Synapsis in Mouse Inter-Subspecific Hybrids

- A Cohesin-Independent Role for NIPBL at Promoters Provides Insights in CdLS

- Extreme Population Differences in the Human Zinc Transporter ZIP4 (SLC39A4) Are Explained by Positive Selection in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Classic Selective Sweeps Revealed by Massive Sequencing in Cattle

- Genomic Networks of Hybrid Sterility

- Natural Polymorphisms in Influence Negative Selection and CD4∶CD8 Lineage Commitment in the Rat

- Oxidative Stress Is Not a Major Contributor to Somatic Mitochondrial DNA Mutations

- Molecular Identification of Collagen 17a1 as a Major Genetic Modifier of Laminin Gamma 2 Mutation-Induced Junctional Epidermolysis Bullosa in Mice

- Uncoupling of Molecular Maturation from Peripheral Target Innervation in Nociceptors Expressing a Chimeric TrkA/TrkC Receptor

- MicroRNAs Located in the Hox Gene Clusters Are Implicated in Huntington's Disease Pathogenesis

- Loss of Trabid, a New Negative Regulator of the Immune-Deficiency Pathway at the Level of TAK1, Reduces Life Span

- Targeted Ablation of Nesprin 1 and Nesprin 2 from Murine Myocardium Results in Cardiomyopathy, Altered Nuclear Morphology and Inhibition of the Biomechanical Gene Response

- Identification of Novel Genetic Loci Associated with Thyroid Peroxidase Antibodies and Clinical Thyroid Disease

- CEP-1, the p53 Homolog, Mediates Opposing Longevity Outcomes in Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain Mutants

- Transcriptomics and Functional Genomics of ROS-Induced Cell Death Regulation by

- Quantitative Genome-Wide Genetic Interaction Screens Reveal Global Epistatic Relationships of Protein Complexes in

- Cascades of Genetic Instability Resulting from Compromised Break-Induced Replication

- Serine- and Threonine/Valine-Dependent Activation of PDK and Tor Orthologs Converge on Sch9 to Promote Aging

- Zfp322a Regulates Mouse ES Cell Pluripotency and Enhances Reprogramming Efficiency

- Insertional Mutagenesis and Deep Profiling Reveals Gene Hierarchies and a -Dependent Bottleneck in Lymphomagenesis

- DAAM Is Required for Thin Filament Formation and Sarcomerogenesis during Muscle Development in Drosophila

- Plasma Cholesterol–Induced Lesion Networks Activated before Regression of Early, Mature, and Advanced Atherosclerosis

- High-Resolution Profiling of Stationary-Phase Survival Reveals Yeast Longevity Factors and Their Genetic Interactions

- Comparative RNAi Screens in and Reveal the Impact of Developmental System Drift on Gene Function

- Accurate and Robust Genomic Prediction of Celiac Disease Using Statistical Learning

- Sex-Specific Embryonic Gene Expression in Species with Newly Evolved Sex Chromosomes

- Chromosome X-Wide Association Study Identifies Loci for Fasting Insulin and Height and Evidence for Incomplete Dosage Compensation

- Negative Feedback and Transcriptional Overshooting in a Regulatory Network for Horizontal Gene Transfer

- DNA Sequence Explains Seemingly Disordered Methylation Levels in Partially Methylated Domains of Mammalian Genomes

- Insights into the Genomic Landscape: Comparative Genomics Reveals Variations in Ploidy and Nutrient Utilisation Potential amongst Wine Isolates

- Molecular Evidence for the Inverse Comorbidity between Central Nervous System Disorders and Cancers Detected by Transcriptomic Meta-analyses

- The Centriolar Satellite Protein AZI1 Interacts with BBS4 and Regulates Ciliary Trafficking of the BBSome

- Fine-Mapping the Region Detects Common Variants Tagging a Rare Coding Allele: Evidence for Synthetic Association in Prostate Cancer

- Transmission Distortion Affecting Human Noncrossover but Not Crossover Recombination: A Hidden Source of Meiotic Drive

- A Variant in the Neuropeptide Receptor is a Major Determinant of Growth and Physiology

- Mutation of SLC35D3 Causes Metabolic Syndrome by Impairing Dopamine Signaling in Striatal D1 Neurons