-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Cell Lineage Analysis of the Mammalian Female Germline

Fundamental aspects of embryonic and post-natal development, including maintenance of the mammalian female germline, are largely unknown. Here we employ a retrospective, phylogenetic-based method for reconstructing cell lineage trees utilizing somatic mutations accumulated in microsatellites, to study female germline dynamics in mice. Reconstructed cell lineage trees can be used to estimate lineage relationships between different cell types, as well as cell depth (number of cell divisions since the zygote). We show that, in the reconstructed mouse cell lineage trees, oocytes form clusters that are separate from hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells, both in young and old mice, indicating that these populations belong to distinct lineages. Furthermore, while cumulus cells sampled from different ovarian follicles are distinctly clustered on the reconstructed trees, oocytes from the left and right ovaries are not, suggesting a mixing of their progenitor pools. We also observed an increase in oocyte depth with mouse age, which can be explained either by depth-guided selection of oocytes for ovulation or by post-natal renewal. Overall, our study sheds light on substantial novel aspects of female germline preservation and development.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 8(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002477

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002477Summary

Fundamental aspects of embryonic and post-natal development, including maintenance of the mammalian female germline, are largely unknown. Here we employ a retrospective, phylogenetic-based method for reconstructing cell lineage trees utilizing somatic mutations accumulated in microsatellites, to study female germline dynamics in mice. Reconstructed cell lineage trees can be used to estimate lineage relationships between different cell types, as well as cell depth (number of cell divisions since the zygote). We show that, in the reconstructed mouse cell lineage trees, oocytes form clusters that are separate from hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells, both in young and old mice, indicating that these populations belong to distinct lineages. Furthermore, while cumulus cells sampled from different ovarian follicles are distinctly clustered on the reconstructed trees, oocytes from the left and right ovaries are not, suggesting a mixing of their progenitor pools. We also observed an increase in oocyte depth with mouse age, which can be explained either by depth-guided selection of oocytes for ovulation or by post-natal renewal. Overall, our study sheds light on substantial novel aspects of female germline preservation and development.

Introduction

Understanding the complex processes of embryonic development and post-natal maintenance in multi-cellular organisms requires advanced methods for cell lineage reconstruction. The mammalian female germline is a prominent example, in which fundamental aspects of these processes remain debatable. Unlike lower metazoans such as C. elegans and Drosophila, in which germ-cell progenitors are set aside during the very first embryonic divisions, in mice, primordial germ cells (PGCs) appear at a much later stage [1], [2]. The late appearance of PGCs, their long-range migration into the gonadal ridges and their co-occurrence with progenitors of hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells within the aorta-gonad-mesonephros region of the developing embryo, raised the intriguing possibility that these cell populations may be clonally related [3], [4]; however this hypothesis as well as the modes of expansion and migration of PGCs to the gonadal ridges [5] has thus far not been experimentally tested.

An additional aspect which remains poorly characterized is related to folliculogenesis, the process by which ovarian follicles mature and are selected for ovulation. Folliculogenesis begins with primordial follicles that contain a single layer of squamous pre-granulosa cells that surround an oocyte. Follicles grow through primordial, primary and secondary stages before they develop an antral cavity. The transition from pre-antral to antral follicle occurs only after puberty and is followed by cyclic recruitment of a limited, species-specific number of growing follicles, from which a subset is selected for ovulation [6]. The ‘production-line’ hypothesis suggests that the order by which follicles are selected for growth follows the order at which their oocytes embark on meiosis during embryogenesis, but evidence supporting this notion is sparse [7]–[10]. The ability to reconstruct phylogenies of individual cells and to infer the number of divisions they have undergone since the zygote can address these fundamental questions.

While the de-novo generation of oocytes has traditionally been considered to cease during fetal development in most mammals [11], several recent publications argued for continuous post-natal oocyte renewal in the mouse. These studies were based on several lines of evidence, mainly the discordant proportion between oocyte death and their depletion [12], [13], and the detection of primordial germ cell markers in conjunction with proliferative markers in different cell populations in the ovary [12], [14] and in bone marrow and peripheral blood [15]. These findings were challenged by several publications that failed to reproduce some of the reported observations [16]–[18]. Recently, putative mouse germline stem cells were successfully cultured and transplanted into ovaries of subfertile mice, giving rise to offspring of donor origin [14], suggesting that cells in the adult mouse retain the capacity for oogenesis. However the existence, source and contribution of germline stem cells during normal development remain unclear.

We have previously developed a high-throughput method that uses the information encoded in somatic mutations to reconstruct cell lineage trees [19]–[22]. This phylogenetic method, which was also applied by others [23]–[26], is based on the notion that the DNA is a molecular clock which effectively counts the number of mitotic divisions a cell has undergone since the zygote (denoted as “depth”) and that the pattern of somatic mutations in multiple loci can reveal the lineage relations among individual cells. Our analysis is based on somatic mutations accumulated in microsatellites (MS) loci that reside in intergenic regions. Since these mutations do not affect genes, they are not expected to cause phenotypic effects, and can thus serve as neutral developmental molecular clocks. Our method was validated using ex-vivo cell lineage trees [19] and applied to the lineage analysis of cells of a mouse with a tumor [20], as well as to the estimation of depth of different cell populations [22], and the study of the development of muscle stem cells. Most recently, we demonstrated the reliability of this method for the detection of stem cells and tissue dynamics in the colon [27].

Here we apply this method to address the lineage relations of oocytes and other cell types. We sampled more than 900 cells from 16 mice spanning a range of ages. Sampled cells included oocytes, bone-marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells and lymphocytes, cumulus cells (the epithelial cell surrounding the oocytes in the ovarian follicle) and pancreatic islet cells.

We found that in the reconstructed cell lineage trees of mice at all ages, oocytes form clusters that are distinct from other cell populations. Oocytes from the two ovaries, however, do not form two distinct clusters, suggesting a spatially-incoherent mode of expansion and migration of their embryonic progenitors. In the reconstructed cell lineage trees, the depth of oocytes increases with mouse age and this increase is accelerated in mice that have undergone unilateral ovariectomy. Two alternative explanations can possibly account for the age-associated depth increase, one of which is post-natal oocyte renewal from germline stem cells. The alternative interpretation of our results would go along with a depth-guided oocyte selection, posing that in a sexually mature female mouse oocytes are selected to resume meiosis according to the order in which they embarked on meiosis during embryonic life [7].

Results

Oocytes form a cluster distinct from bone marrow cells

In the current application of our method, the cellular genomic signature is derived from a set of MS loci in mismatch-repair (MMR) deficient mice (mlh1−/−). The MS mutation rate of these mice is much higher than that of wild type [28], thus increasing the precision of the cell lineage analysis. These mice are infertile and develop cancer spontaneously, however they display normal ovarian histology [29], [30] (Figure S4). Recently, it was shown that on the background of C3H, the oocytes of mlh−/ − mice complete the first meiotic division as indicated by the formation of the first polar body in a fraction which is similar to that of oocytes of a wild type mouse [31]. This is unlike a previous report demonstrating that oocytes of mlh−/ − mice on a B6 background fail to resume meiosis [28]. Similarly to mice on the C3H background, oocytes of mice used in this study, which are on a dual background of B6 and M129, complete the first meiotic division, with 100% of the ovulated oocytes extracted from the oviducts displaying a polar body (Table S3).

We sampled oocytes from 17 mice at different age groups ranging from 12 days to one year old (Table S1). These oocytes were arrested in prophase of the first meiotic division containing a nuclear structure known as germinal vesicle (GV). These oocytes were isolated from Graaffian follicles of sexually mature mice, as well as from pre-antral follicles in younger animals. Few ovulated oocytes, arrested at the second metaphase were recovered from the oviduct. In addition, we isolated other cell types, including mesenchymal stem cells, lymphocytes extracted from the spleen, thymus and lymph nodes, and cumulus cells (the inner layer of follicular epithelial cells surrounding the oocyte).

The DNA of all cells was amplified over a panel of 81 microsatellite loci (Table S2) and the size of each allele was determined, thus providing a genomic signature which is the deviation from the putative zygote in the number of microsatellite repeats at each locus. The signatures were used to reconstruct lineage trees using a maximum likelihood Neighbor Joining algorithm (Materials and Methods) and the resulting trees were used to estimate depth (the number of somatic cell divisions since the putative zygote). The genomic signature of the putative zygote was taken as the median of the signatures of all sampled cells. Relative depth was converted to absolute depth (actual number of cell divisions) by calibrating the system on an ex-vivo tree in which the number of divisions is known [22] (Text S1).

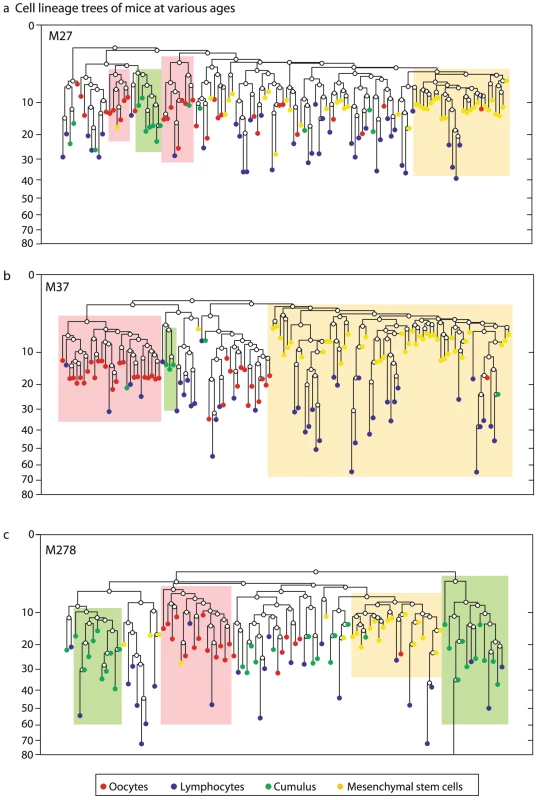

We first examined whether different cell populations form clusters on the lineage tree, by testing whether subtrees are enriched with a given cell population (Materials and Methods). Such a cluster of a cell population would suggest a small number of embryonically distinct progenitors (Text S2, Figures S2, S3). In all reconstructed cell lineage trees of all mice, young and old, oocytes from large antral follicles form a cluster that is distinct from the clusters formed by hematopoietic cells and mesenchymal stem cells (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Oocytes form a cluster distinct from bone marrow cells.

Reconstructed cell lineage tree of mice in several ages, each showing that GV oocytes from large antral follicles (red) form a cluster that is distinct from cells of bone marrow origin (mesenchymal stem cells- yellow and lymphocytes-blue). Ovarian cumulus cells are in green. Shaded boxes denote subtrees that are statistically enriched for cells of a certain cell population, using a hyper-geometric enrichment test. Mouse names represent their age in days. Y axis is depth (number of divisions since the zygote). One cell in M278 was cropped for visual clarity. We found that clustering of cell samples on the reconstructed lineage trees is indicative of the number of progenitors of the cell population studied (Text S2, Figure S1, S2 and S3). The larger the number of progenitors, the less significant clustering observed. The way that subsamples of oocytes form clusters suggests that the number of progenitors of this population is between 3 and 10 (Figure S3), in line with previous estimates based on measurements of primordial germ cells [1], [32]–[35]. Our clustering results indicate that the primordial germ cell lineage is a polyclonal population descendant from a few progenitors, which is embryonically distinct from hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells and does not significantly contribute to bone-marrow stem cell populations.

Oocytes from the two ovaries do not form two distinct clusters

We next turned to examine the clustering of oocytes sampled from different ovaries with the aim of unveiling the dynamics of primordial germ cell expansion and their migration during fetal life.

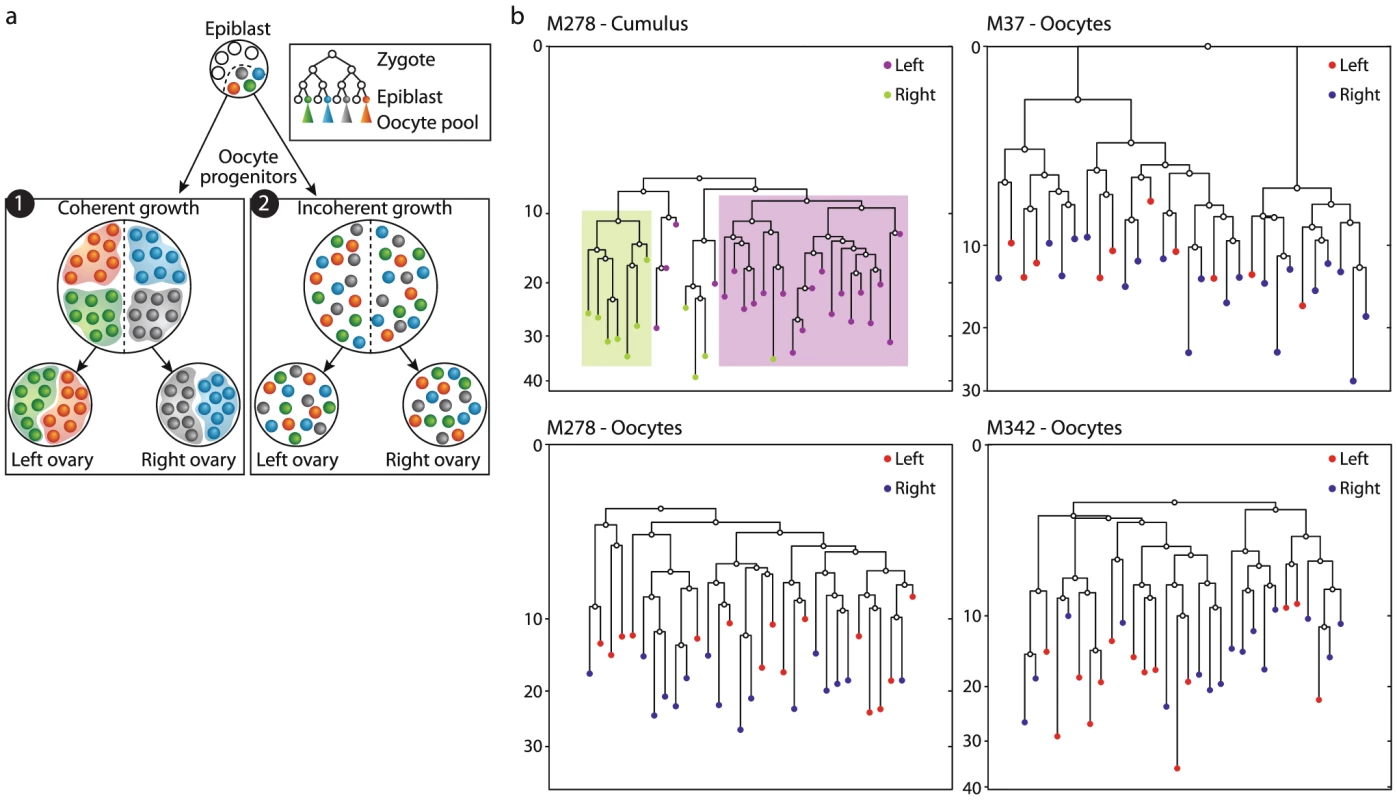

The progenitors of PGCs are set aside at the pre-gastrulation epiblast stage [1], [32] and then undergo rapid expansion while migrating to the gonadal ridges [5], where they separate to the left and right gonads. A cluster of oocytes from one ovary would be indicative of a spatially coherent migration of PGCs, with minimal physical mixing of the progenies of given clones (Figure 2a1). In contrast, if pairs of cells from the same ovary were not closer on the reconstructed lineage trees than mixed pairs, this would suggest a spatially incoherent mode of expansion-migration. Such a mode entails physical mixing of the progenies of dividing PGCs as they migrate before their allocation to different gonads. In this scenario the populations of both ovaries would form an identical sampling of the progenies of the different founder clones (Figure 2a2). As a positive control we reconstructed cell lineage trees of cumulus cells extracted from two different follicles, one from each ovary. The population of cumulus cells in a given follicle has been shown to originate from only five progenitors [36] and is thus expected to form a cluster on a reconstructed lineage tree.

Fig. 2. Lack of lineage barriers between oocytes sampled from the left and right ovary suggests a spatially incoherent mode of expansion of primordial germ cells during embryonic development.

a) Two modes of expansion-migrations of a small pool of progenitors which become lineage restricted during the epiblast stage. In a spatially coherent mode (1) progenies remain physically close together as they expand in numbers and thus separation into the two ovaries creates two distinct populations. In a spatially incoherent mode (2) progenies physically mix and thus separation into the two ovaries result in equal samples of the original progenitors. b) Reconstructed cell lineage trees show that GV oocytes from large antral follicles of the right (blue) or left (red) ovaries do not form distinct clusters. As a positive control cumulus cells sampled from two follicles – one in the right ovary (green) and one in the left (purple) do form distinct clusters, as expected given the previously estimated small number of progenitors of the epithelial population of a given follicle. Our analysis of the reconstructed cell lineage trees revealed that while cumulus cells sampled from different follicles form distinct clusters (Figure 2b), oocytes from large antral follicles from the left and right ovaries never do (Figure 2b, Figure S5). This result suggests a mode of incoherent clonal expansion during the process of primordial germ cell migration to the gonadal ridges, as depicted in Figure 2a2.

While primordial germ cells undergo several additional rounds of mitotic divisions after having settled in the gonadal ridges thus giving rise to small clones, the lack of lineage clustering between the two ovaries suggests that at this stage the number of such clones is significantly larger than the number of oocyte sampled here. Thus the probability to sample more than one oocyte from a single clone is small (Figure S2).

Oocyte depth increases with mouse age

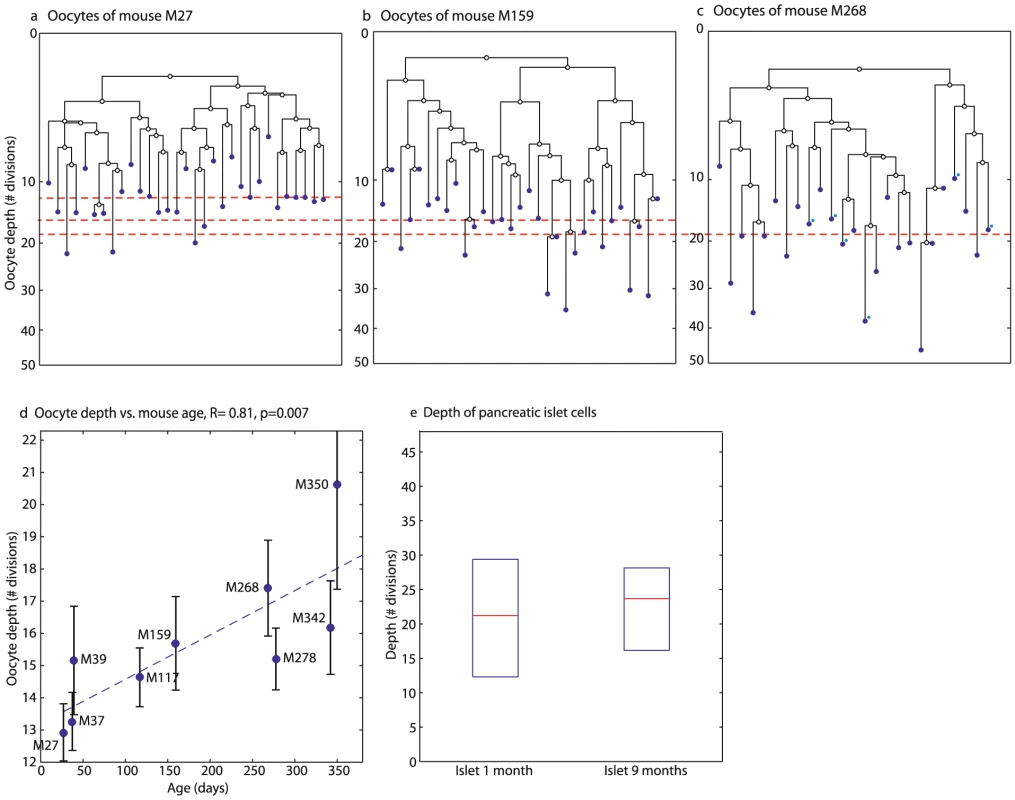

The topology of reconstructed lineage trees can shed light on the developmental processes of the oocyte lineage. To address the possibility of post-natal oocyte renewal during adulthood we next analyzed the depth of oocytes sampled from large antral follicles of mice at different ages. Analysis of the reconstructed cell lineage trees showed that oocyte depth increases significantly with mouse age (Figure 3, R = 0.81, p = 0.007, bootstrap R = 0.56).

Fig. 3. Oocyte depth increases with age.

a–c) Reconstructed lineage trees of GV oocytes from large antral follilces in three mice demonstrate an increase in oocyte depth (Y axis) with age. The putative zygote is at depth 0. Median depth of oocytes is 13 divisions in M27, a 27 day old mouse (Mouse names represent their age in days) (a), 16 divisions in mouse M159 (b) and 19 in mouse M268 which contains 6 ovulated oocytes which were marked on the tree with blue dots (c). Horizontal red lines denote the median depth. All lineage trees were reconstructed using the maximum-likelihood neighbor joining method and rooted with the median identifier of all cells. d) Median depth of GV oocytes from large antral follicels increases with age. Each blue point is the median of the depths of all oocytes sampled from a single mouse. The Pearson correlation of median depth and age is 0.81 (p = 0.007). High inter-mouse variability can be seen. Errorbars are standard errors of the means. (e) Depth of pancreatic islet cells does not increase with age. Shown are the depths of pancreatic islet cells from M36, a 1-month old mouse and from M280, a 9-month old mouse. Unlike oocytes, the depth of pancreatic islet cells, which have been shown to have a low turnover rate in adult mice [37], [38], does not increase with age (Figure 3e). On the other hand, epithelial intestinal cells display a substantial increase in depth from age 1 to 11 months [27]. The depth of other cell types sampled also increases during adulthood (Figure S6).

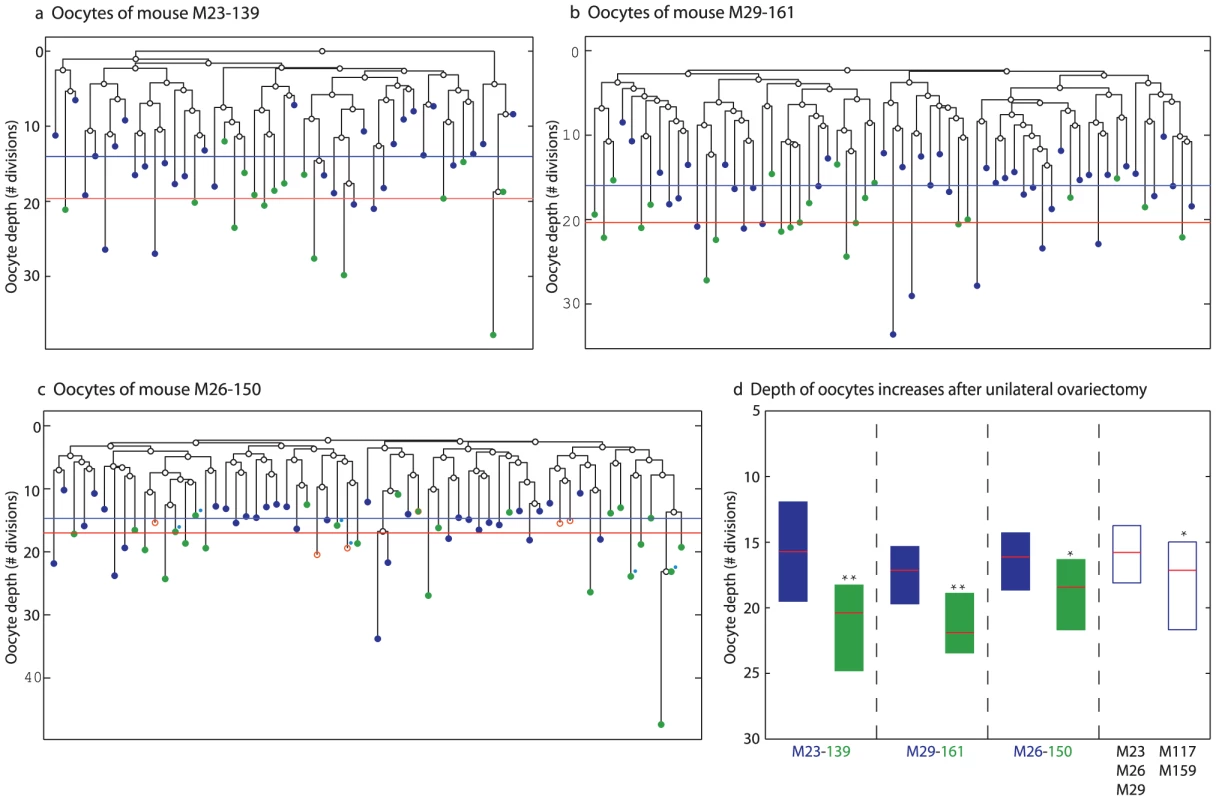

To control for the apparent inter-mouse depth variability (Figure 3d), we performed three longitudinal unilateral ovariectomy experiments in which one ovary was removed when the mouse was one month old, whereas the second ovary of this same mouse was removed at the age of four months. Analysis of the reconstructed cell lineage trees revealed that oocytes from large antral follicles harvested from the ‘old’ ovary are significantly deeper than such oocytes harvested from the ‘young’ ovary (Figure 4). Interestingly, the depth of oocytes from the ‘old’ ovary is significantly higher as compared to oocyte depth in mice at similar age that did not undergo this intervention (Figure 4d).

Fig. 4. Accelerated increase in GV oocyte from large antral follicles depth following unilateral ovariectomy.

a–c) Reconstructed lineage trees of oocytes from both ovaries of unilaterally ovariectomized mice. Blue circles are oocytes extracted from the ovary removed at a young age – 23 days (a) 29 days (b) and 26 days (c). Green circles are oocytes extracted from the contralateral ovary removed at an older age – 139 days (a) 161 days (b) and 150 days in which the ovulated oocytes were marked with blue dots (c). Horizontal lines are the average depths of young oocytes (blue) and old oocytes (green). d) Increase in depth with age following ovariectomy is accelerated relative to the increase observed for non-ovariectomized mice. Last two boxes include pooled data from the indicated mice. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01. Increase in oocyte depth is not due to spontaneous mutations

We next considered the possibility that the observed increase in microsatellite mutations in older oocytes is due to spontaneous mutations that is not dependent on cell division [39], [40]. To validate that our microsatellite loci do not accumulate mutations in cells with a low rate of replication, we analyzed pancreatic islet cells, which were previously shown to have low turnover in adult mice [37], [38]. We found that pancreatic islet cells do not accumulate microsatellite mutations with age (Figure 3e).

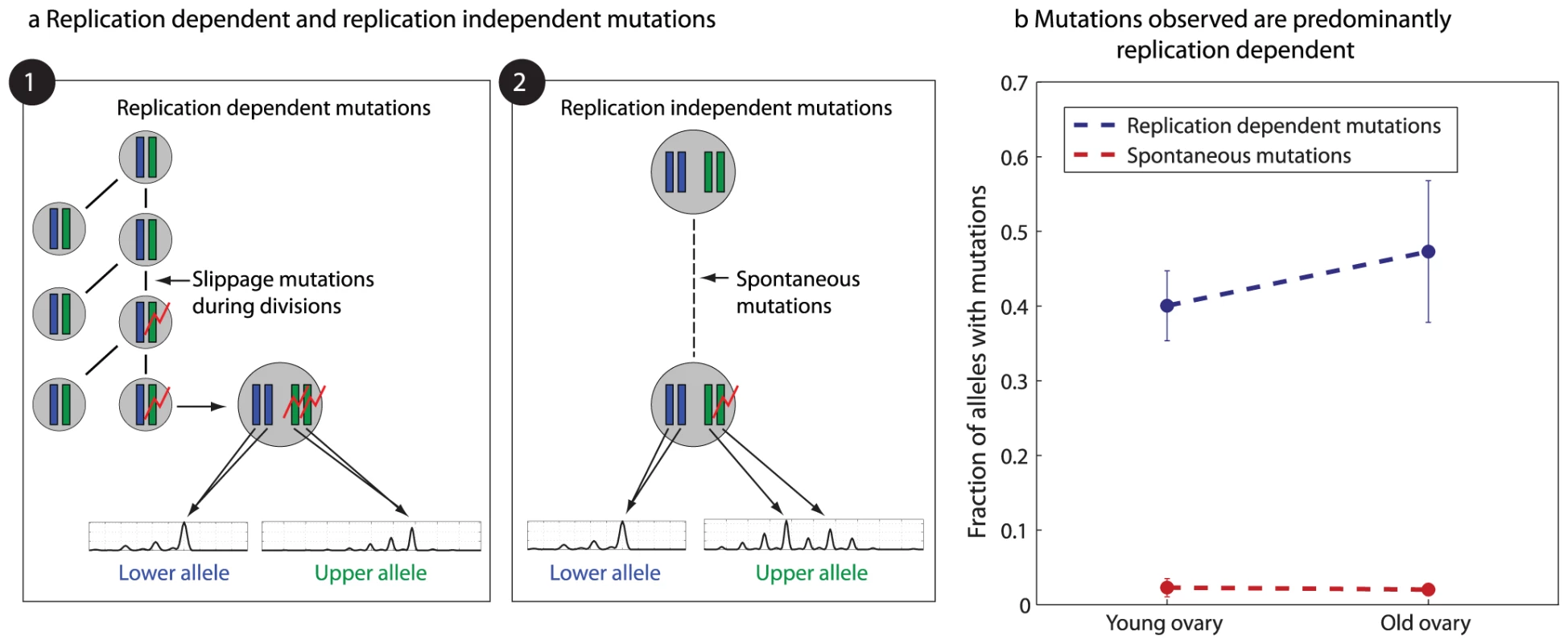

Further analysis was done to rule out the possibility that oocytes may accumulate spontaneous mutations at a higher rate than other somatic cells. The ability to detect spontaneous mutations in oocytes is facilitated by the fact that meiotically arrested, GV oocytes contain four copies of each locus rather than two (two copies for each of the two parental alleles). A spontaneous mutation that occurs during the prolonged phase of meiotic arrest would, most probably, hit only one chromosome of the four, resulting in a locus with more than two alleles. Therefore if most loci have only two alleles one can deduce that mutations have occurred in an oocyte progenitor, a stage with only two copies per locus (Figure 5a).

Fig. 5. Microsatellite mutations are replication dependent.

a) Shown are two scenarios for microsatellite mutations – replication dependent mutations that occur during mitotic divisions at a cell stage with two chromosomal copies (left), and spontaneous, replication independent mutations occurring at the quiescent oocyte stage with four chromosomal copies (right). While replication dependent mutations would result in two alleles, spontaneous mutations would mostly result in more than two alleles. The bottom plots show representative capillary signals. b) The increase with age in fraction of alleles with spontaneous mutations is significantly smaller than the increase in fraction of alleles with replication dependent mutations. Results are for the three longitudinal experiments. The analysis shows that the number of loci in which more than two alleles were observed (representing spontaneous mutations at the four allele stage) is an order of magnitude less than the total number of observed mutations (Figure 5b, Figure S7), suggesting that their role in the observed depth increase is negligible. Moreover, since all cases in which more than two alleles per locus were observed, were eliminated from our analysis, the observed increase in depth predominantly represents mutations that accumulate with cell divisions at a mitotically active progenitor, containing two alleles per locus.

The fact that oocytes in unilaterally ovariectomized mice accumulate mutations faster than in untreated mice is another indication that the mutations accumulated are not spontaneous, which would accumulate at the same rate following this treatment. In addition, we observe no increase in mutations with age in wild-type mice (Figure S8), ruling out the possibility that the mutations we observe are spontaneous and independent of the mlh1-defficiency-related mutation in our mice. Finally, the pattern of mutations observed in all experiments is consistent with a symmetric step-wise model, as expected from microsatellite mutations coupled with DNA replication [41] (Figure S9).

Depth-guided maturation versus post-natal renewal

By rejecting the explanation of spontaneous mutations for the increase with age in accumulated somatic mutations, we conclude that oocytes in older mice are deeper (undergo more mitotic divisions) than oocytes in young mice. Such divisions can occur at either embryonic development or during adult life. We next consider these two possibilities.

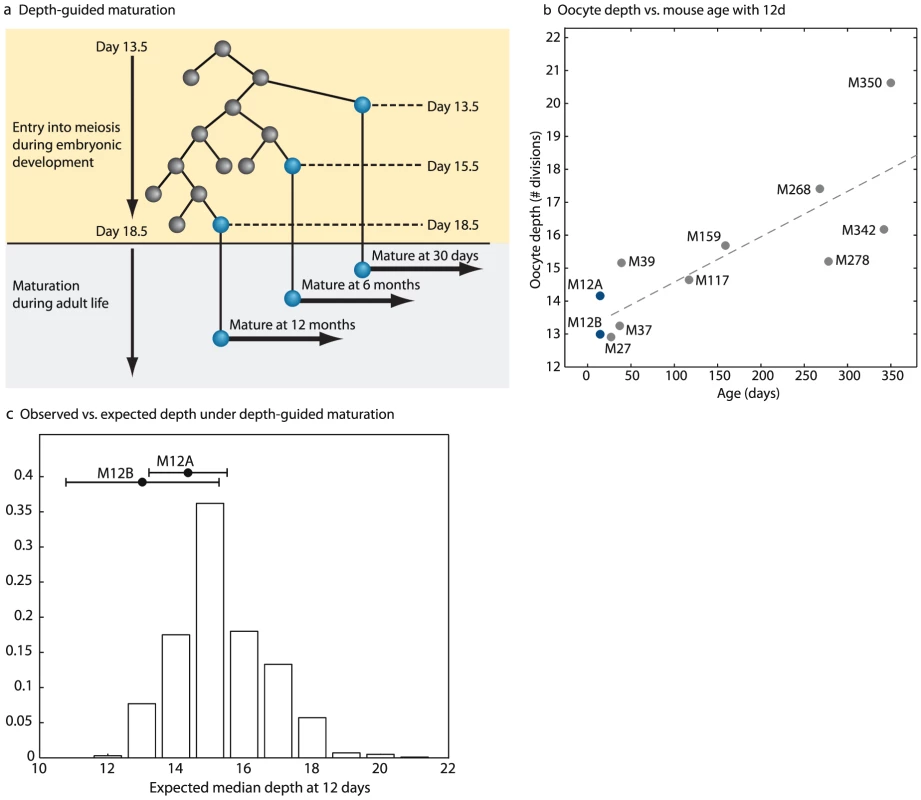

The ‘production-line’ hypothesis introduced by Henderson and Edwards [7], [10], [42], posits that the order at which oocytes are ovulated during adult life follows the order at which PGCs enter meiosis during fetal life. This would result in a lower depth of oocytes from large antral follicles in young mice as compared to oocytes recovered from such follicles of old mice (Figure 6a). Indeed, both, the order at which germ cells enter meiosis and the growth of primordial follicles have been suggested to be spatially structured [43], [44] and thus not completely arbitrary. However, the exact sequence and spatial details of these two processes have not been firmly resolved [42]. While the oocytes sampled in this study were taken from large antral follicles selected for ovulation, a wide distribution of oocyte depth extracted from pre-antral follicles at birth would be suggestive of depth-guided oocyte maturation.

Fig. 6. Depth-guided oocyte selection for ovulation accounts for the increase in oocyte depth with age.

(a) Depth-guided oocyte maturation. Shown is a hypothetical tree showing entry into meiosis during embryonic development. The hypothesis states that oocytes that enter meiosis first during embryonic life would be ovulated first during post-natal life. (b) Comparison of median depth of oocytes isolated from pre antral follicles isolated from 12 day-old mice vs. oocytes isolated pre ovulatory follicles isolated from older mice. Each point is the median of the depths of all oocytes sampled from a single mouse. (c) Depth distributions of oocytes from pre-antral follicles in 12 day-old mice are not significantly different from the expectation from the production line hypothesis. Shown is the expected distribution of median depth of oocytes assuming that the depth distribution at birth is a uniform average of all measured post-natal depth values of maturing oocytes. Filled circles denote the observed median depth in the two 12 day old mice. Error bars are standard errors of the means. To examine this possibility we sampled oocytes from 12 day-old mice, an age at which the entire population of the ovarian follicles is at the pre-antral stage. Thus, our sampling in these mice was not enriched for follicles selected for ovulation. We found that the median depth of two 12 day-old mice was similar to the median depth of young animals (Figure 6b, Figure S15). To compare the depth distributions in pre-antral follicle oocytes in 12 day old mice to that expected from the ‘production-line’ hypothesis we performed the following simulation – a putative depth distribution was create based on a uniform weighting of the depth values of oocytes measured at different ages. The depth of values sampled from this distribution was compared to that seen in the 12 day old mice, and the fraction of simulated values for which the maximal/median depth was smaller was reported as a p-value. We used Fisher's method for combining the p-values of two 12-day old mice. We found that the distribution of oocyte depths of pre-antral follicles from 12 day old mice is not statistically different from that expected from a pre-existing wide distribution that spans the entire depth range seen for all ages (Figure 6c). As such our results do not conclusively rule out the ‘production-line’ hypothesis indicating that depth-guided maturation could give rise to the observed increase in oocyte depth with age [12], [13].

Discussion

The ability of the germline to generate all somatic cell types, the analogous ability of bone-marrow derived stem cells to differentiate to a wide range of cells [45], [46], and the physical proximity of the progenitors of these populations during embryonic development, raised the intriguing possibility that these different cell populations are the progenies of a common precursor [3], [4]. Here, using cell-lineage trees reconstructed from somatic mutations, we show that the mouse female germline is embryonically distinct from cells derived from bone marrow stem cells, be they mesenchymal or hematopoietic stem cells. Thus, this study indicates that progenies of primordial germ cells do not contribute to bone-marrow stem cell populations. In addition, this study suggests that putative germline stem cells that may contribute to post-natal oocyte renewal are progenies of the primordial germline, rather than being of bone marrow origin [15]. We considered analyzing cells from the ovarian surface epithelium, which were suggested to harbor the germline stem cells. However because germline stem cells are expected to constitute a small fraction of this cell compartment [47] and thus our chances of sampling them are very low, and since we must analyze each mouse separately to obtain an informative lineage tree, we could not pursue this direction in our system. Similar cell-lineage analysis of other cell populations, such as that presented here could shed light on the embryonic development and post-natal dynamics of other tissues and cell populations, providing novel insight into the architecture of multi-cellular organisms.

The reconstructed cell lineage trees revealed that oocytes from older mice undergo more mitotic divisions since the zygote as compared to oocytes of young mice. This finding may point towards post-natal oocyte renewal. However, since sampling in our study was directed at oocytes that reside in the large antral follicles, selected for ovulation, the age-associated increase in their depth could also represent depth-guided oocyte selection [7]. The depth distribution of oocytes recovered from from pre-antral follicles of 12-day-old mice does not deny the possible depth-guided oocyte selection, thus leaving the two optional interpretations of our results open. Further cell lineage analysis studies, for example using a mouse model susceptible to post-natal induction of MMR-deficiency, are needed to decide between the two.

While previous evidence regarding the ‘production-line’ hypothesis linked the time of entry into meiosis with the time of post-natal oocyte maturation [9], [10], [42], the present study suggests that under the hypothesis of depth-guided oocyte maturation, the number of divisions rather than the embryonic day, determines the order of oocyte maturation during adult life. Similar cell-lineage analysis of other cell populations, such as that presented here, could shed light on the embryonic development and post-natal dynamics of other tissues and cell populations, providing novel insight into the architecture of multi-cellular organisms.

The accelerated increase in oocyte depth in the unilaterally ovariectomized mice may be related to the previously described phenomenon of doubling the rate of ovulation from the contralateral remaining ovary that is a subsequent to a systemic elevation of pituitary stimulating gonadotropins [48]. Our study implies that under these conditions the remaining ovary is populated by deeper oocytes. Along this line, it has been shown that hormonally-stimulated super ovulation results in oxidative damage to DNA and mitochondrial DNA mutations [49]. Thus, exposure to high doses of stimulating hormones, as is often practiced to treat infertility, may severely impair oocyte quality by introducing into the oocyte pool deeper oocytes.

In summary, we present a comprehensive analysis of the mouse oocyte lineage at the single cell level, addressing open questions regarding both the development and post-natal maintenance of female gametes. Our analysis revealed that oocytes are clustered distinctly from bone-marrow derived cells, that progenitors of oocytes from different ovaries are mixed, that oocyte depth increases significantly with mouse age, and that this increase is accelerated after ovariectomy. Our methodology can be used to infer the early developmental processes and post-natal clonal dynamics of other tissues and cell populations.

Materials and Methods

Animals and ethics

C57Bl/6 mice, Mlh1+/ − (kind donation of Prof. Michael Liskay) [50] and 129SvEv mice, Mlh1+/ − (kindly provided by Prof. Ari Elson from the Weizmann Institute, Israel) were mated to yield Mlh1−/ − progeny of the dual backgrounds, enabling us to distinguish, in all our experiments, between two alleles in the same locus. All animal husbandry and euthanasia procedures were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Weizmann Institute of Science.

Isolation and analysis of single cells

Mice were not superovulated in order to avoid any effect of external hormones on our analysis. Ovaries were removed and placed in Leibovitz's L-15 tissue culture medium (Gibco), supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Biolab, Jerusalem, Israel), penicillin (100 IU/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml, Gibco). The follicles were punctured under a stereoscopic microscope in order to release the cumulus–oocyte complexes that were then placed into acidic L-15 medium (pH 6.0) to obtain cumulus-free oocytes (Figure S14). Most of the oocytes were MI-arrested from pre-antral and from develpme, thus retaining all four meiotic products. In few cases ovulated oocytes were isolated from the oviduct and their polar body was seen and it was extracted together with the oocyte. Our oocyte samples in M268 and M26–150 included a few ovulated oocytes that have extruded their polar body (blue dots, Figure 3c and Figure 4b). Excluding them had no effect on median oocyte depths in these mice. Each oocyte was placed in a 0.2 mL tube (ABgene) in a volume of 2 µL medium. Oocytes were frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept in −80°C until DNA ampification. In the longitudinal experiment, mice were anesthetized and then underwent unilateral ovariectomy. The section was clipped and after additional 4 months the other ovary was removed when the animal was sacrificed.

Mesenchymal stem cells, B-cells, NK-cells and T-cells were isolated as described in [21]. Pancreatic islet cells where extracted from 1-month old and 9-month old male mice using single cell laser capture microdissection of Hematoxylin stained tissue, as described in [21].

DNA extracted from individual cells was amplified using whole-genome amplification (WGA) with the GenomiPhi DNA amplification kit (GE Healthcare, UK) as described in [23]. Aliquots of WGA products were used directly (without purification) as templates in subsequent PCRs. PCR repeats and negative controls (DDW) were included in every PCR plate (Figure S10 and Text S3 and Text S4). Loci that exhibited a signal in the negative control were excluded from the analysis of all samples that were run on the corresponding PCR plate. The method achieved high-throughput through the use of a liquid handling robotic system.

Tree and depth reconstruction

Microsatellite loci were chosen to have a substantial allele size difference between the two mice strains, so as not to confound allele sizing (see Figure S8 for representative capillary signals). Whole genome amplification introduced very few microsatellite mutations, but resulted in allelic drop-out of 32.5+−5%. Capillary signals that displayed more than two alleles per locus were excluded from the analysis. In addition only cells in which more than 25 alleles were amplified were included in the analysis (998 cells, Table S1). Trees were reconstructed using the distance-based neighbor joining algorithm [51], [52]. Pairs of cells were sequentially merged according to a distance matrix of lineage distances. Each entry in the distance matrix is taken as the maximum likelihood estimate of the number of divisions separating the two cells, assuming a symmetric stepwise model and an average mutation rate estimated from the ex-vivo trees, equal to 1/30 divisions (Text S1). Depth was read off the trees as the branch lengths leading from the root to each terminal leaf. Root signature was taken as the median of the allele size values of all sampled cells. This method was found to be more efficient and robust than estimating depth using a squared distance metric (Text S5).

It is important to note that we estimated the microsatellite mutation rate in this study to be one mutation per 30 cell divisions; this estimation is based on our measurements of cell divisions in ex-vivo trees (Text S1). Nevertheless, to be sure that our conclusions are not dependent on this specific mutation rate, we reconstructed trees using different mutation rates ranging from 1 mutation per 10 cell divisions to 1 mutation per 200 cell divisions. Our conclusions (i.e. the depth increase with age, the enrichment of oocytes on the lineage tree and the mixing of oocytes between left and right ovary) are robust to different mutation rates (Figure S11, S12, and S13).

While we have previously estimated a higher oocyte depth [22] our current study used a dramatically increased resolution for depth estimation, based on a larger and more informative panel of high-mutation rate microsatellite loci as well as a larger oocyte sample size.

Statistical analysis

P-value for the Pearson correlation between median depth and age was based on permutations of the median depth values. Bootstrap correlation coefficient of depth vs. age was obtained by generating 1000 median depth values extracted from sampling with replacement of the cell depths for each mouse. P-values for differences in distributions were calculated using Kolmogorov-Smirnov method. Hypergeometric tests were carried out for each internal branch to assess whether subtree leafs are enriched for a cell population. P-values declared as significant were corrected for multiple hypothesis testing using false discovery rate of 0.2. Whenever subtrees were embedded only the subtree with the most significant p-value was retained. Noteworthy, clustering of oocytes is stronger in M37 and M278 relatively to M27. We examined whether this could be attributed to allelic dropout, however we did not find any significant difference between the average amplified loci per cell in these different mice (42+−5, 51+−9 and 43+−5 in M27, M37 and M278, respectively). The variability in lineage clustering is strongly dependent on the number of cells sampled from each population and on the number of progenitors. Since oocytes are a polyclonal population, sampling in different mice could give rise to either more cells from fewer clones (leading to strong lineage clustering, Figure S2 and S3) or alternatively cells distributed equally among the progenitor clones (leading to weaker clustering). In addition, the progenitor clones themselves could be distributed differently on the progenitor lineage tree, thus affecting variability of clustering between animals. This issue is further discussed in Text S5 and Figures S2 and S3.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. McLarenA 2003 Primordial germ cells in the mouse. Dev Biol 262 1 15

2. MatovaNCooleyL 2001 Comparative aspects of animal oogenesis. Dev Biol 231 291 320

3. CowenCMeltonD 2005 “Stemness”:Definitions, Criteria, and Standards. LanzaR Essentials of stem cell biology Academic Press

4. WeissmanIL 2000 Stem cells: units of development, units of regeneration, and units in evolution. Cell 100 157 168

5. MolyneauxKWylieC 2004 Primordial germ cell migration. Int J Dev Biol 48 537 544

6. McGeeEAHsuehAJ 2000 Initial and cyclic recruitment of ovarian follicles. Endocr Rev 21 200 214

7. HendersonSAEdwardsRG 1968 Chiasma frequency and maternal age in mammals. Nature 218 22 28

8. PolaniPECrollaJA 1991 A test of the production line hypothesis of mammalian oogenesis. Hum Genet 88 64 70

9. MeredithSDoolinD 1997 Timing of activation of primordial follicles in mature rats is only slightly affected by fetal stage at meiotic arrest. Biology of Reproduction 57 63 67

10. HirshfieldAN 1992 Heterogeneity of cell populations that contribute to the formation of primordial follicles in rats. Biol Reprod 47 466 472

11. ZuckermanS 1951 The number of oocytes in the mature ovary. Rec Prog Horm Res 6 63 109

12. JohnsonJCanningJKanekoTPruJKTillyJL 2004 Germline stem cells and follicular renewal in the postnatal mammalian ovary. Nature 428 145 150

13. KerrJBDuckettRMyersMBrittKLMladenovskaT 2006 Quantification of healthy follicles in the neonatal and adult mouse ovary: evidence for maintenance of primordial follicle supply. Reproduction 132 95 109

14. ZouKYuanZYangZLuoHSunK 2009 Production of offspring from a germline stem cell line derived from neonatal ovaries. Nat Cell Biol 11 631 636

15. JohnsonJBagleyJSkaznik-WikielMLeeHJAdamsGB 2005 Oocyte generation in adult mammalian ovaries by putative germ cells in bone marrow and peripheral blood. Cell 122 303 315

16. EgganKJurgaSGosdenRMinIMWagersAJ 2006 Ovulated oocytes in adult mice derive from non-circulating germ cells. Nature 441 1109 1114

17. ByskovAGFaddyMJLemmenJGAndersenCY 2005 Eggs forever? Differentiation 73 438 446

18. Bristol-GouldSKKreegerPKSelkirkCGKilenSMMayoKE 2006 Fate of the initial follicle pool: empirical and mathematical evidence supporting its sufficiency for adult fertility. Dev Biol 298 149 154

19. FrumkinDWasserstromAKaplanSFeigeUShapiroE 2005 Genomic variability within an organism exposes its cell lineage tree. PLoS Comput Biol 1 e50 doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010050

20. FrumkinDWasserstromAItzkovitzSSternTHarmelinA 2008 Cell lineage analysis of a mouse tumor. Cancer Res 68 5924 5931

21. WasserstromAAdarRSheferGFrumkinDItzkovitzS 2008 Reconstruction of cell lineage trees in mice. PLoS ONE 3 e1939 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001939

22. WasserstromAFrumkinDAdarRItzkovitzSSternT 2008 Estimating cell depth from somatic mutations. PLoS Comput Biol 4 e1000058 doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000058

23. SalipanteSHorwitzM 2006 Phylogenetic fate mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 5448 5453

24. SalipanteSHorwitzM 2007 A phylogenetic approach to mapping cell fate. Curr Top Dev Biol 79 157 184

25. SalipanteSThompsonJHorwitzM 2008 Phylogenetic fate mapping: theoretical and experimental studies applied to the development of mouse fibroblasts. Genetics 178 967 977

26. SalipanteSKasAMcMonagleEHorwitzM 2010 Phylogenetic analysis of developmental and postnatal mouse cell lineages. Evol Dev 12 84 94

27. ReizelYCIAdarNItzkovitzRElbazSMaruvkaJ 2011 Colon stem cell and crypt dynamics exposed by cell lineage analysis. PLoS Genet 7 e1002192 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002192

28. BakerSMPlugAWProllaTABronnerCEHarrisAC 1996 Involvement of mouse Mlh1 in DNA mismatch repair and meiotic crossing over. Nat Genet 13 336 342

29. EdelmannWCohenPEKaneMLauKMorrowB 1996 Meiotic pachytene arrest in MLH1-deficient mice. Cell 85 1125 1134

30. KanRSunXKolasNKAvdievichEKneitzB 2008 Comparative analysis of meiotic progression in female mice bearing mutations in genes of the DNA mismatch repair pathway. Biol Reprod 78 462 471

31. NagaokaSIHodgesCAAlbertiniDFHuntPA 2011 Oocyte-specific differences in cell-cycle control create an innate susceptibility to meiotic errors. Curr Biol 21 651 657

32. LawsonKAHageWJ 1994 Clonal analysis of the origin of primordial germ cells in the mouse. Ciba Found Symp 182 68 84; discussion 84–91

33. HayashiKde Sousa LopesSMSuraniMA 2007 Germ cell specification in mice. Science 316 394 396

34. SaitouMPayerBO'CarrollDOhinataYSuraniMA 2005 Blimp1 and the emergence of the germ line during development in the mouse. Cell Cycle 4 1736 1740

35. UenoHTurnbullBBWeissmanIL 2009 Two-step oligoclonal development of male germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 175 180

36. TelferEAnsellJDTaylorHGosdenRG 1988 The number of clonal precursors of the follicular epithelium in the mouse ovary. J Reprod Fertil 84 105 110

37. FinegoodDTScagliaLBonner-WeirS 1995 Dynamics of beta-cell mass in the growing rat pancreas. Estimation with a simple mathematical model. Diabetes 44 249 256

38. TetaMLongSYWartschowLMRankinMMKushnerJA 2005 Very slow turnover of beta-cells in aged adult mice. Diabetes 54 2557 2567

39. PearsonCE 2003 Slipping while sleeping? Trinucleotide repeat expansions in germ cells. Trends Mol Med 9 490 495

40. BusuttilRAGarciaAMReddickRLDolleMECalderRB 2007 Intra-organ variation in age-related mutation accumulation in the mouse. PLoS ONE 2 e876 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000876

41. EllegrenH 2004 Microsatellites: simple sequences with complex evolution. Nat Rev Genet 5 435 445

42. BullejosMKoopmanP 2004 Germ cells enter meiosis in a rostro-caudal wave during development of the mouse ovary. Mol Reprod Dev 68 422 428

43. BowlesJKoopmanP 2007 Retinoic acid, meiosis and germ cell fate in mammals. Development 134 3401 3411

44. Da Silva-ButtkusPMarcelliGFranksSStarkJHardyK 2009 Inferring biological mechanisms from spatial analysis: prediction of a local inhibitor in the ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 456 461

45. JiangYJahagirdarBNReinhardtRLSchwartzREKeeneCD 2002 Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature 418 41 49

46. AlisonMRPoulsomRJefferyRDhillonAPQuagliaA 2000 Hepatocytes from non-hepatic adult stem cells. Nature 406 257

47. GopalkrishnanRKangDFisherP 2001 Molecular markers and determinants of prostate cancer metastasis. J Cell Physiol 189 245 256

48. JonesRE 1978 Control of follicular selection. JonesRE The vertebrate ovary New York Plesnum Press 763 788

49. ChaoHTLeeSYLeeHMLiaoTLWeiYH 2005 Repeated ovarian stimulations induce oxidative damage and mitochondrial DNA mutations in mouse ovaries. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1042 148 156

50. BakerSMPlugAWProllaTABronnerCEHarrisAC 1996 Involvement of mouse Mlh1 in DNA mismatch repair and meiotic crossing over. Nat Genet 13 336 342

51. SaitouNNeiM 1987 The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4 406 425

52. FelsensteinJ 2004 Inferring Phylogenies: Sinauer Associates

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2012 Číslo 2- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

- Pilotní studie: stres a úzkost v průběhu IVF cyklu

- IVF a rakovina prsu – zvyšují hormony riziko vzniku rakoviny?

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Upsetting the Dogma: Germline Selection in Human Males

- A Strong Deletion Bias in Nonallelic Gene Conversion

- Positive Selection for New Disease Mutations in the Human Germline: Evidence from the Heritable Cancer Syndrome Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2B

- Genome-Wide Association Study in East Asians Identifies Novel Susceptibility Loci for Breast Cancer

- Mixed Effects Modeling of Proliferation Rates in Cell-Based Models: Consequence for Pharmacogenomics and Cancer

- Reduction of NADPH-Oxidase Activity Ameliorates the Cardiovascular Phenotype in a Mouse Model of Williams-Beuren Syndrome

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Chromosome 10q24.32 Variants Associated with Arsenic Metabolism and Toxicity Phenotypes in Bangladesh

- Structural Basis of Transcriptional Gene Silencing Mediated by MOM1

- Genomic Restructuring in the Tasmanian Devil Facial Tumour: Chromosome Painting and Gene Mapping Provide Clues to Evolution of a Transmissible Tumour

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Novel Loci Associated with Circulating Phospho- and Sphingolipid Concentrations

- Contrasting Properties of Gene-Specific Regulatory, Coding, and Copy Number Mutations in : Frequency, Effects, and Dominance

- The Origin and Nature of Tightly Clustered Deletions in Precursor B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Support a Model of Multiclonal Evolution

- Ultrafast Evolution and Loss of CRISPRs Following a Host Shift in a Novel Wildlife Pathogen,

- Phosphorylation of Chromosome Core Components May Serve as Axis Marks for the Status of Chromosomal Events during Mammalian Meiosis

- Psoriasis Patients Are Enriched for Genetic Variants That Protect against HIV-1 Disease

- A Pathogenic Mechanism in Huntington's Disease Involves Small CAG-Repeated RNAs with Neurotoxic Activity

- The Mitochondrial Chaperone Protein TRAP1 Mitigates α-Synuclein Toxicity

- Homeobox Genes Critically Regulate Embryo Implantation by Controlling Paracrine Signaling between Uterine Stroma and Epithelium

- Developmental Transcriptional Networks Are Required to Maintain Neuronal Subtype Identity in the Mature Nervous System

- Down-Regulating Sphingolipid Synthesis Increases Yeast Lifespan

- Gene Expression and Stress Response Mediated by the Epigenetic Regulation of a Transposable Element Small RNA

- Loss of Tgif Function Causes Holoprosencephaly by Disrupting the Shh Signaling Pathway

- Sequestration of Highly Expressed mRNAs in Cytoplasmic Granules, P-Bodies, and Stress Granules Enhances Cell Viability

- Discovery of a Modified Tetrapolar Sexual Cycle in and the Evolution of in the Species Complex

- The Role of Glypicans in Wnt Inhibitory Factor-1 Activity and the Structural Basis of Wif1's Effects on Wnt and Hedgehog Signaling

- Nondisjunction of a Single Chromosome Leads to Breakage and Activation of DNA Damage Checkpoint in G2

- A Regulatory Network for Coordinated Flower Maturation

- Coexpression Network Analysis in Abdominal and Gluteal Adipose Tissue Reveals Regulatory Genetic Loci for Metabolic Syndrome and Related Phenotypes

- Diced Triplets Expose Neurons to RISC

- The Williams-Beuren Syndrome—A Window into Genetic Variants Leading to the Development of Cardiovascular Disease

- The Empirical Power of Rare Variant Association Methods: Results from Sanger Sequencing in 1,998 Individuals

- Systematic Detection of Epistatic Interactions Based on Allele Pair Frequencies

- Familial Identification: Population Structure and Relationship Distinguishability

- Raf1 Is a DCAF for the Rik1 DDB1-Like Protein and Has Separable Roles in siRNA Generation and Chromatin Modification

- Loss of Function of the Cik1/Kar3 Motor Complex Results in Chromosomes with Syntelic Attachment That Are Sensed by the Tension Checkpoint

- Computational Prediction and Molecular Characterization of an Oomycete Effector and the Cognate Resistance Gene

- The Dynamics and Prognostic Potential of DNA Methylation Changes at Stem Cell Gene Loci in Women's Cancer

- GTPase Activity and Neuronal Toxicity of Parkinson's Disease–Associated LRRK2 Is Regulated by ArfGAP1

- Evaluation of the Role of Functional Constraints on the Integrity of an Ultraconserved Region in the Genus

- Neurophysiological Defects and Neuronal Gene Deregulation in Mutants

- Genetic and Functional Analyses of Mutations Suggest a Multiple Hit Model of Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Negative Supercoiling Creates Single-Stranded Patches of DNA That Are Substrates for AID–Mediated Mutagenesis

- Rewiring of PDZ Domain-Ligand Interaction Network Contributed to Eukaryotic Evolution

- The Eph Receptor Activates NCK and N-WASP, and Inhibits Ena/VASP to Regulate Growth Cone Dynamics during Axon Guidance

- Repression of a Potassium Channel by Nuclear Hormone Receptor and TGF-β Signaling Modulates Insulin Signaling in

- The Retrohoming of Linear Group II Intron RNAs in Occurs by Both DNA Ligase 4–Dependent and –Independent Mechanisms

- Cell Lineage Analysis of the Mammalian Female Germline

- Association of a Functional Variant in the Wnt Co-Receptor with Early Onset Ileal Crohn's Disease

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Gene Expression and Stress Response Mediated by the Epigenetic Regulation of a Transposable Element Small RNA

- Contrasting Properties of Gene-Specific Regulatory, Coding, and Copy Number Mutations in : Frequency, Effects, and Dominance

- Homeobox Genes Critically Regulate Embryo Implantation by Controlling Paracrine Signaling between Uterine Stroma and Epithelium

- Nondisjunction of a Single Chromosome Leads to Breakage and Activation of DNA Damage Checkpoint in G2

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání