-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Fungal Chitin Dampens Inflammation through IL-10 Induction Mediated by NOD2 and TLR9 Activation

Chitin is an essential structural polysaccharide of fungal pathogens and parasites, but its role in human immune responses remains largely unknown. It is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature after cellulose and its derivatives today are widely used for medical and industrial purposes. We analysed the immunological properties of purified chitin particles derived from the opportunistic human fungal pathogen Candida albicans, which led to the selective secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. We identified NOD2, TLR9 and the mannose receptor as essential fungal chitin-recognition receptors for the induction of this response. Chitin reduced LPS-induced inflammation in vivo and may therefore contribute to the resolution of the immune response once the pathogen has been defeated. Fungal chitin also induced eosinophilia in vivo, underpinning its ability to induce asthma. Polymorphisms in the identified chitin receptors, NOD2 and TLR9, predispose individuals to inflammatory conditions and dysregulated expression of chitinases and chitinase-like binding proteins, whose activity is essential to generate IL-10-inducing fungal chitin particles in vitro, have also been linked to inflammatory conditions and asthma. Chitin recognition is therefore critical for immune homeostasis and is likely to have a significant role in infectious and allergic disease.

Authors Summary:

Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature after cellulose and an essential component of the cell wall of all fungal pathogens. The discovery of human chitinases and chitinase-like binding proteins indicates that fungal chitin is recognised by cells of the human immune system, shaping the immune response towards the invading pathogen. We show that three immune cell receptors – the mannose receptor, NOD2 and TLR9 recognise chitin and act together to mediate an anti-inflammatory response via secretion of the cytokine IL-10. This mechanism may prevent inflammation-based damage during fungal infection and restore immune balance after an infection has been cleared. By increasing the chitin content in the cell wall pathogenic fungi may influence the immune system in their favour, by down-regulating protective inflammatory immune responses. Furthermore, gene mutations and dysregulated enzyme activity in the described chitin recognition pathway are implicated in inflammatory conditions such as Crohn's Disease and asthma, highlighting the importance of the discovered mechanism in human health.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 10(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004050

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004050Summary

Chitin is an essential structural polysaccharide of fungal pathogens and parasites, but its role in human immune responses remains largely unknown. It is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature after cellulose and its derivatives today are widely used for medical and industrial purposes. We analysed the immunological properties of purified chitin particles derived from the opportunistic human fungal pathogen Candida albicans, which led to the selective secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. We identified NOD2, TLR9 and the mannose receptor as essential fungal chitin-recognition receptors for the induction of this response. Chitin reduced LPS-induced inflammation in vivo and may therefore contribute to the resolution of the immune response once the pathogen has been defeated. Fungal chitin also induced eosinophilia in vivo, underpinning its ability to induce asthma. Polymorphisms in the identified chitin receptors, NOD2 and TLR9, predispose individuals to inflammatory conditions and dysregulated expression of chitinases and chitinase-like binding proteins, whose activity is essential to generate IL-10-inducing fungal chitin particles in vitro, have also been linked to inflammatory conditions and asthma. Chitin recognition is therefore critical for immune homeostasis and is likely to have a significant role in infectious and allergic disease.

Authors Summary:

Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature after cellulose and an essential component of the cell wall of all fungal pathogens. The discovery of human chitinases and chitinase-like binding proteins indicates that fungal chitin is recognised by cells of the human immune system, shaping the immune response towards the invading pathogen. We show that three immune cell receptors – the mannose receptor, NOD2 and TLR9 recognise chitin and act together to mediate an anti-inflammatory response via secretion of the cytokine IL-10. This mechanism may prevent inflammation-based damage during fungal infection and restore immune balance after an infection has been cleared. By increasing the chitin content in the cell wall pathogenic fungi may influence the immune system in their favour, by down-regulating protective inflammatory immune responses. Furthermore, gene mutations and dysregulated enzyme activity in the described chitin recognition pathway are implicated in inflammatory conditions such as Crohn's Disease and asthma, highlighting the importance of the discovered mechanism in human health.Introduction

Chitin is a robust β-1,4-linked homopolymer of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and is an essential polysaccharide of the cell wall of all fungal pathogens. It is absent in humans but is also found in the skeletal elements in oomycetes, insects, crustaceans and parasitic nematodes [1], [2], [3], [4]. In terms of global biomass, chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature after cellulose.

Candida albicans is a common mucosal pathogen in humans that can cause life-threatening infections in patients suffering trauma or immune dysfunction [5]. Under normal growth conditions, chitin is a minor component of the C. albicans cell wall, comprising only 2 to 3% of its dry weight [6]. However, the chitin content of the fungal cell wall increases in response to β-1,3 glucan damage, for example as inflicted by echinocandin antifungal drug treatment [7]. This leads to chitin exposure at the cell surface as well as reduced efficacy of caspofungin in vitro and in vivo [8]. The discovery of human chitinases and chitinase-like proteins (CLPs), including some that are constitutively expressed by macrophages and epithelial cells of the lung and digestive tract, suggests the presence of a first line of defence against chitin-containing pathogens, as well as mechanisms for chitin recognition, breakdown and immune-modulation in the human host [9], [10]. Dysregulated chitinase - and CLP-expression has been linked to inflammatory and allergic conditions such as asthma and inflammatory bowel disease [11]. Furthermore, recent work has identified additional chitin binding proteins, such as RegIIIg (HIP/PAP), a C-type lectin secreted by Paneth cells in the small intestine that also binds peptidoglycan from Gram-positive bacteria [12], and FIBCD1, a high affinity receptor for chitin and chitin fragments that is highly expressed in the gastrointestinal tract [9].

Studies performed using commercially available sources of chitin from crab/shrimp shell, suggest that the ability of chitin to modulate immune responses depends on the size of the chitin particle. Medium-sized chitin particles (40–70 µm) have been shown to activate TNF and IL-17 production in a TLR2 - and dectin-1-dependent fashion, whereas small-size chitin particles (<40 µm) are strong stimulators of TNF and IL-10 in a manner that involves TLR2, dectin-1 and the mannose receptor (MR) [13]. TLR2, dectin-1 and NOD2 have also been implicated in the induction of chitotriosidase expression if stimulated by their specific ligands [14]. However, these studies were performed using commercially available sources of chitin from crab/shrimp shell - a source that is likely to be found in marine and shell fish processing environments and is often relatively impure. In terrestrial environments, arthropods and fungi represent the major source of chitin. Such organisms are also common indoor environments, resulting in chronic exposure due to the inhalation of chitin-containing particles.

We set out to identify chitin pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in myeloid cells and to investigate the relationship between chitin particle size and chitin recognition. We report here that ultra-pure fungal chitin dominantly induces the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 through uptake mediated by the mannose receptor and signalling that involves NOD2 and TLR9 activation. Polymorphisms in these receptors predispose individuals to inflammatory conditions such as asthma or Crohn's disease (CD), conditions that have been shown to be significantly influenced by exposure to chitin. These findings therefore open new avenues for the understanding and treatment of these diseases.

Results

Concentration - dependent immune response to chitin

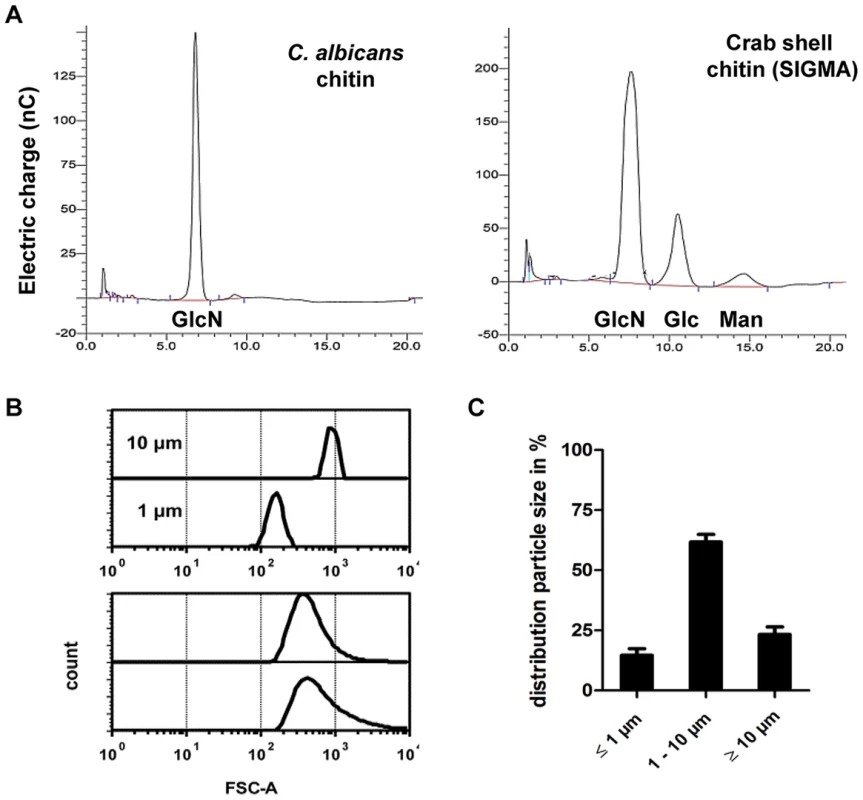

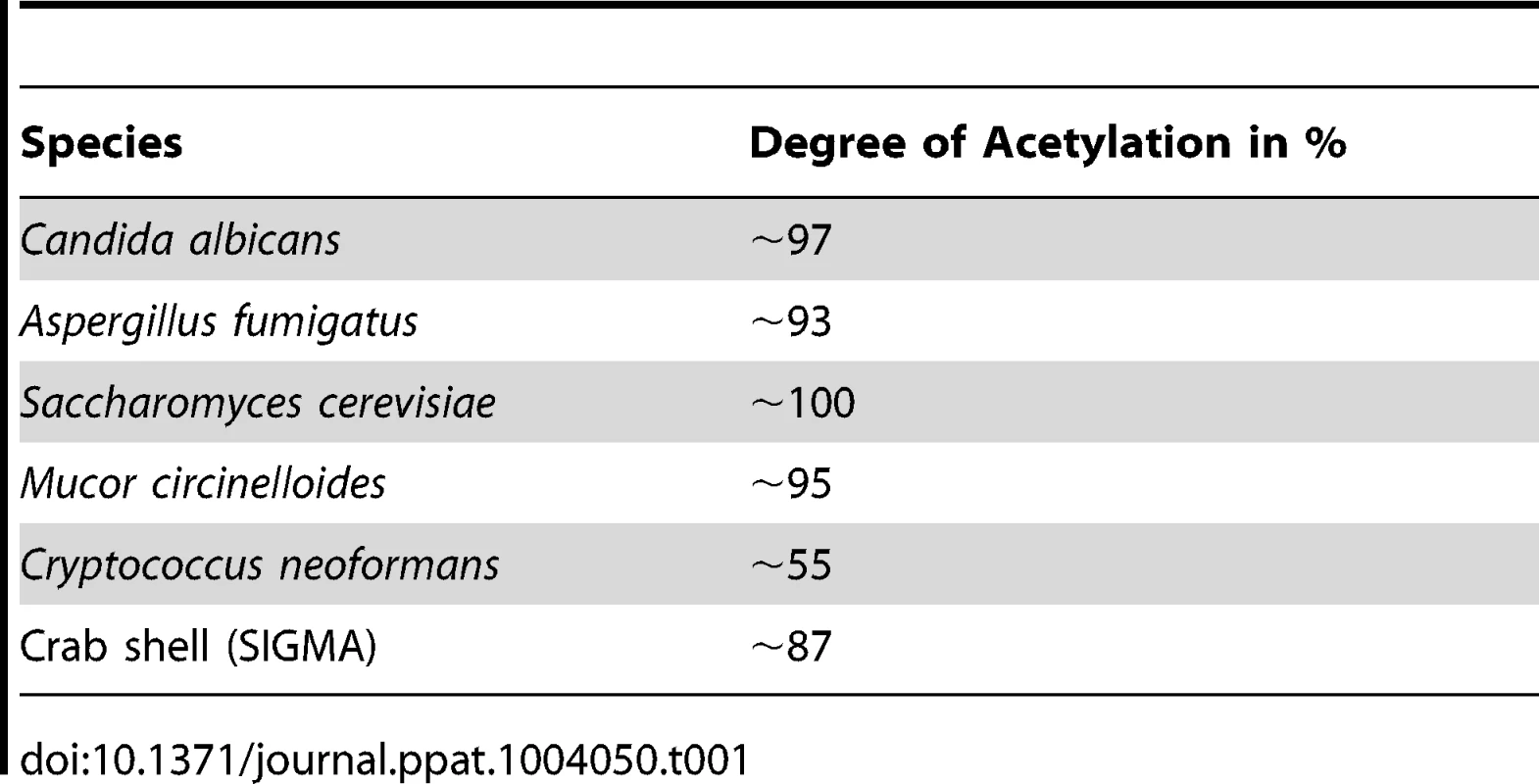

Most immunological studies of chitin have focussed on semi-purified crustacean sources of chitin of relatively large particle size [13]. Here we established the role of ultra-pure fungal cell wall chitin of a determined size in immune regulation. All fungal chitin preparations used for experiments were pyrogen-free, microbiologically sterile and had a purity of over 98% as analysed by HPLC (Fig. 1A). In contrast, commercial crab shell chitin contained only 60% glucosamine (Fig. 1A). All chitin preparations used were between 55% and 100% acetylated, depending on the source of chitin as listed in Table 1. If not stated otherwise, work was performed with chitin extracted from yeast cells of the human pathogen C. albicans, which was >97% acetylated. To investigate the size of fungal chitin particles used for experiments, we performed flow cytometry with 1 and 10 µm beads as size standards (Fig. 1B). The majority of fungal derived chitin particles were found to be between 1 to 10 µm in size (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. Chitin purity and size.

(A) HPLC analysis of TFAA hydrolysed C. albicans-chitin (left) compared to commercial crab shell chitin (right). GlcN Glucosamine, Glc Glucose, Man Mannan. (B) Chitin particle size determined by flow cytometry. (C) Chitin size distribution in percentage of analysed chitin extractions, presented as mean ± SEM, n = 6. Tab. 1. Acetylation degree of purified chitin.

To characterise the immunological properties of chitin we first analysed a series of cytokines and chemokines in the supernatants of chitin (10 µg/ml) stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (hPBMCs, 5×105 cells) and mouse bone-marrow derived macrophages (mBMMφs, 1×105 cells). Chitin stimulation significantly increased the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 along with the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF in hPBMCs (Fig. 2A), whereas in mouse macrophages only IL-10 secretion was significantly increased (Fig. 2B). INFγ and IL-17, known to be involved in establishing a protective T-helper (Th) 1/Th17 response to C. albicans infections, were not induced in hPBMCs by chitin exposure (Fig. 2A) and chitin did not induce Th1, Th2 or Th17 cytokines in mouse macrophages or any of the pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines tested (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Chitin induced cytokines and synergistic effect on IL-10 secretion.

(A) Cytokine induction in hPBMCs incubated with chitin for 24 h, n = 6, ***p<0.001. (B) Cytokine induction in mBMMφ's incubated with chitin for 24 h, n = 4, *p<0.05. (C) IL-10 and TNF induction after 24 h in mBMMφs incubated with increasing chitin concentrations, n = 4, ***p<0.001 for IL-10, °°°p<0.001 for TNF compared to untreated control. (D) IL-10 and TNF induction in hPBMCs incubated with chitin isolated from different species, n = 3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. (E) Co-incubation of hPBMCs with either LPS, zymosan, curdlan, Pam3CSK4, flagellin, CpG ODN or C. albicans cell wall proteins (CWPs) and chitin, n = 6, *p<0.05. All data are presented as mean values ± SEM. We tested whether the observed IL-10 induction by fungal chitin was concentration-dependent. Low chitin concentrations (1–10 µg/ml) induced high IL-10 secretion; high chitin concentrations (250–1000 µg/ml) instead strongly induced TNF secretion (Fig. 2C) and intermediate concentrations of chitin (50–100 µg/ml) induced equal amounts of both cytokines (Fig. 2C).

Next we investigated the immunostimulatory effects of chitin particles (10 µg/ml) derived from different fungal species in comparison to purified commercial crab shell chitin. Nearly all tested chitin preparations significantly induced IL-10 secretion in hPBMCs (Fig. 2D) and no obvious differences were observed between different sources of chitin. We also investigated the ability of chitin to block or increase cytokine secretion induced by specific PRR ligands. Co-incubation of hPBMCs (5×105 cells) with lipopolysaccharide (LPS;10 µg/ml), zymosan (10 µg/ml), curdlan (100 µg/ml), Pam3CSK4 (1 µg/ml), flagellin (100 ng/ml), CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (CpG ODN; 1 µM) or C. albicans-derived cell wall mannoproteins (CWP; 100 µg/ml) together with chitin (10 µg/ml) for 24 h resulted in increased IL-10 secretion (Fig. 2E). This increase in IL-10 was significant for all pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) tested except for CpG ODN (Fig. 2E), indicating a competitive effect of chitin on CpG-TLR9 interactions. All other cytokines analysed (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF, IFN-γ and TGF-β) showed no significant differences in cytokine induction, although a trend for INF-γ, TGF-β and IL-1β secretion was observed that was ameliorated when hPBMCs were co-stimulated with chitin (Supplementary Fig. S1).

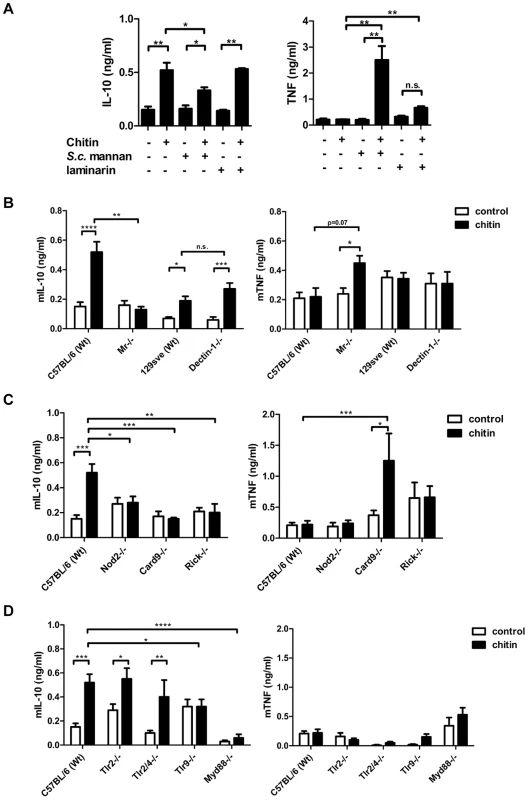

Mannose receptor-dependent IL-10 secretion

We next aimed to identify the receptors whose interaction with fungal chitin mediated the observed IL-10 induction. As mentioned above, intermediate-sized chitin particles (40–70 µm) have been reported to induce a pro-inflammatory immune response (TNF secretion) through dectin-1/TLR2 signalling, whilst small-sized particles (<40 µm) have been reported to induce an anti-inflammatory response (IL-10 secretion) through dectin-1/TLR2 and the mannose receptor [13]. To examine possible chitin-MR/dectin-1 interactions further, we used soluble mannans purified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. c. mannan) and laminarin (β-1,3 glucan from an alga) to block potential receptor interactions. S. c. mannan and laminarin (100 µg/ml) alone were immunological inert and no cytokine response was observed (Fig. 3A). Pre-incubation with S. c. mannan reduced chitin-triggered mBMMφ IL-10 secretion by 40%, whilst laminarin treatment did not affect IL-10 secretion (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, blocking MR with S. c. mannan significantly increased TNF secretion (Fig. 3A). To confirm these blocking experiments, we exposed mBMMφs from MR - and dectin-1-deficient mice to fungal chitin. Cytokine analysis reinforced the results of the blocking experiments, with increased TNF induction and reduced IL-10 secretion occurring in chitin-stimulated MR-deficient macrophages (Fig. 3B). Dectin-1 deficiency did not influence chitin-triggered IL-10 secretion (Fig. 3B). Blocking dectin-1 in MR-deficient macrophages with laminarin instead confirmed that the observed chitin triggered TNF secretion in S. c. mannan pre-treated wild type macrophages (Fig. 3A) and MR-deficient macrophages (Fig. 3B) were Dectin-1 dependent (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Fig. 3. Chitin induced IL-10 secretion depends on mannose receptor, TLR9- and NOD2-signalling.

(A) mBMMφs were incubated with S. c. mannan or laminarin 1 h prior stimulation with chitin, n = 4. (B) mBMMφs from wild type mice (C57BL/6 and 129Sve), dectin-1- and MR –deficient mice were stimulated with chitin, n = 4. (C) mBMMφs from wild type mice (C57BL/6), NOD2-, RICK- and CARD9-deficient mice stimulated with chitin for 24 h, n = 4. (D) mBMMφs from wild type mice (C57BL/6), TLR2-, TLR2/4-, TLR9- and MyD88-deficient mice stimulated with chitin for 24 h, n = 4. All data are presented as mean values ± SEM, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. NOD2 and TLR9 mediate IL-10 induction

Chitin is a homopolymer of N-acetyl-glucosamine. Together with N-acetyl-muramic acid, N-acetyl-glucosamine also forms the backbone of bacterial peptidoglycan. Peptidoglycan is known to be recognised by TLR2 and muramyl dipeptide (MDP) by NOD2. Therefore we tested whether chitin is recognised by TLR2 or NOD2 using mBMMφs from TLR2 - and NOD2-deficient mice along with mBMMφs from other PRR - and signalling-deficient mutant mice, including TLR2/4-, TLR9-, MyD88-, RICK - and CARD9-knock-outs (Fig. 3C and D). IL-10 secretion was reduced in Tlr2/4−/− -macrophages, but still significantly increased compared to untreated control cells (Fig. 3D). Similar IL-10 levels were secreted by Tlr2−/− -macrophages and wild type macrophages. Chitin failed to induce IL-10 secretion in Nod2−/−-, Myd88−/−-, Card9−/−-, Rick−/− - and Tlr9−/− - macrophages over background levels measured in untreated control cells (Fig. 3C and D). Because the IL-10 induction was TLR9-dependent, we also treated the chitin preparations with DNase I prior to stimulation to exclude contaminating DNA as a trigger for IL-10 secretion. DNase I-treated chitin induced similar amounts of IL-10 secretion in wild type macrophages as untreated chitin (Supplementary Fig. S3), indicating a direct role for TLR9 in chitin recognition and induction of IL-10 secretion. This finding is supported by the observed competitive effect of CpG ODN and chitin in hPBMCs (Fig. 2E). Therefore, the intracellular receptors NOD2 and TLR9 together with their downstream signalling adapter proteins are necessary for chitin-induced IL-10 secretion.

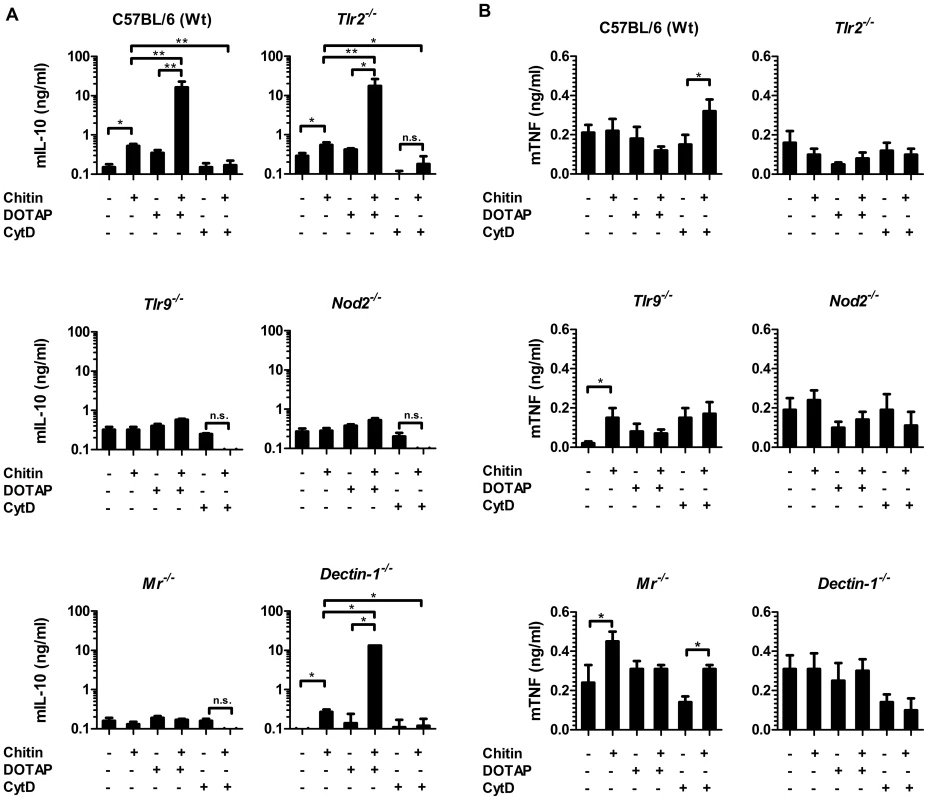

Uptake via MR directs chitin recognition

To further investigate the role of the MR and dectin-1 in chitin recognition, intracellular delivery and induction of IL-10 secretion, we forced chitin uptake into the cytoplasm of wild type, Tlr2−/−-, Tlr9−/−-, Nod2−/−-, Mr−/− - and dectin-1−/−-macrophages by liposomal transfection using DOTAP (10 µg/ml), or blocked chitin uptake with the endocytosis inhibitor cytochalasin D (CytD; 5 µM) (Fig. 4). Chitin transfection into wild type, Tlr2−/− - and dectin-1−/− - macrophages significantly increased IL-10 secretion, whereas no IL-10 induction occurred in chitin-transfected Nod2−/−-, Mr−/− - or Tlr9−/− - macrophages (Fig. 4A). Moreover, the inhibition of endocytosis with CytD abrogated the IL-10 secretion in all macrophages (Fig. 4A), whereas TNF secretion was significantly increased in wild type and Mr−/− - macrophages (Fig. 4B). Increased TNF levels were absent in Tlr2−/− - and dectin-1−/− - macrophages (Fig. 4B), therefore the observed TNF secretion after inhibition of endocytosis was mediated by TLR2 and dectin-1 signalling.

Fig. 4. Chitin induced IL-10 secretion requires mannose receptor interaction but not uptake.

(A) Chitin was incubated with liposomal transfection reagent DOTAP for 15 min at room-temperature before used to stimulate mBMMφs from wild type, TLR2, TLR9, NOD2, MR and dectin-1-deficient mice for 24 h or (A and B) mBMMφs were treated with CytD for 1 h prior chitin stimulation. Values represent mean ± SEM, n = 4, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Microscopy was performed to visualise MR, NOD2 and TLR9 localisation in chitin stimulated macrophages (Fig. 5). Co-localisation of chitin with MR (Fig. 5B) as well as co-localisation of TLR9 (Fig. 5A and B) and NOD2 (Fig. 5A and C) with chitin could be observed after 20 min of incubation. F-actin staining with phalloidin showed phagocytic uptake of chitin (Fig. 5).Fluorescence profiles confirmed overlay of fluorescence signals for MR and chitin (Fig. 5B and C), TLR9 and chitin (Fig. 5A and B) and NOD2 and chitin (Fig. 5A and C). In wild type, Tlr2−/− - and dectin-1−/− - macrophages, chitin (green) co-localised with NOD2 (Fig. 6A) and TLR9 (Fig. 6B) as indicated by fluorescence overlay (yellow). Chitin still co-localised with TLR9 in the absence of NOD2 (Fig. 6B). In MR-deficient macrophages, intracellular chitin was detected but no co-localisation with NOD2 and/or TLR9 was observed (Fig. 6A and B). Chitin did not co-localise with TLR2 in wild type macrophages or tested mutants (Fig. 6C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that chitin uptake via MR is required for NOD2 - and TLR9-dependent chitin recognition and for the induction of an anti-inflammatory immune response through IL-10 secretion. Blocking chitin uptake mediated by the MR or MR-deficiency shifted the anti-inflammatory response to a pro-inflammatory response through TNF secretion that is Dectin-1 and TLR2-dependent and phagocytosis independent.

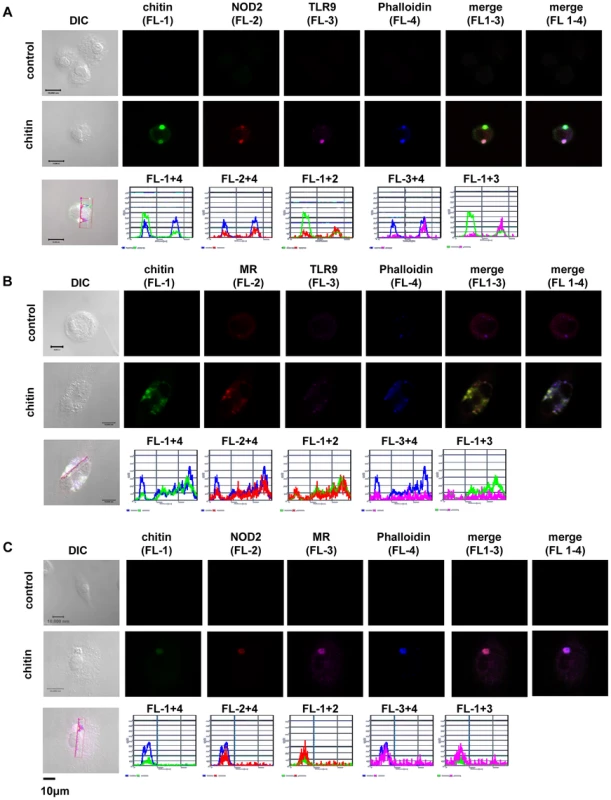

Fig. 5. Chitin co-localisation with NOD2, TLR9 and MR.

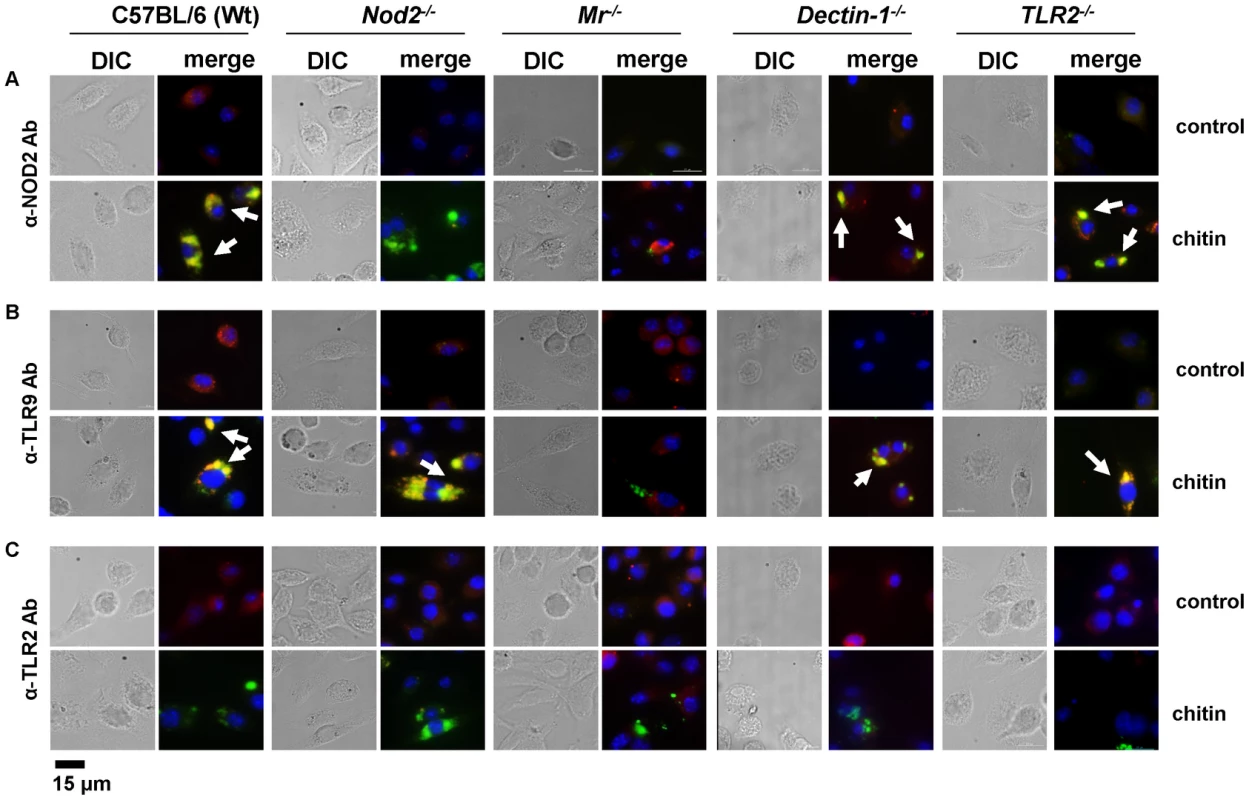

Confocal fluorescence microscopy of mBMMφs from wild type mice stimulated with chitin for 20 min. NOD2 protein was detected with anti-mouse NOD2 antibody, TLR9 with anti-mouse TLR9 antibody, MR with anti-mouse CD206-antibody and chitin was detected using a chitin-binding reporter construct (ChBD-HuCκ). Images show chitin co-localisation with NOD2 (A and C), TLR9 (A and B) and MR (B and C). Images are representative of two independent experiments, scale bars = 10 µm. Fig. 6. Chitin co-localisation with NOD2 and TLR9 depends on MR.

Fluorescence microscopy of mBMMφs from wild type, TLR2-, NOD2-, MR- and dectin-1-deficient mice stimulated with chitin for 1 h. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue) and chitin was detected using a chitin-binding reporter construct (ChBD-HuCκ, green). (A) NOD2 protein was detected with anti-mouse NOD2 antibody (red) (B) TLR9 protein was detected with anti-mouse TLR9 antibody (red) and (C) TLR2 protein was detected with anti-mouse TLR2 antibody (red). White arrows indicate co-localisation of chitin with NOD2 and/or TLR9 (yellow). Chitin did not co-localise with TLR2 in all tested cells (C) and no chitin co-localisation with NOD2 or TLR9 was detectable in MR-deficient macrophages (A and B). Images (A to C) are representative of two independent experiments, scale bars = 15 µm. Chitin dampens LPS-induced inflammation in vivo

We showed that fungal chitin particles co-stimulated IL-10 and reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines in vitro. Next we investigated the ability of chitin to reduce inflammation in vivo. Wild type mice were injected intraperitoneally with saline, chitin (100 µg), LPS (10 µg) or chitin and LPS in combination and infiltrating immune cells and cytokines analysed after 4 h, 24 h and 4 days (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. S4). Injection of chitin, LPS and chitin/LPS significantly increased the number of total infiltrating immune cells in the peritoneal cavity after 4 h compared to saline (Supplementary Fig. S4A). After 24 h, chitin - and LPS-injected mice had increased immune cell infiltrates, whereas chitin/LPS-injected mice had significantly less (Supplementary Fig. S4B). By day 4 no significant differences could be observed between the different groups (Supplementary Fig. S4C).

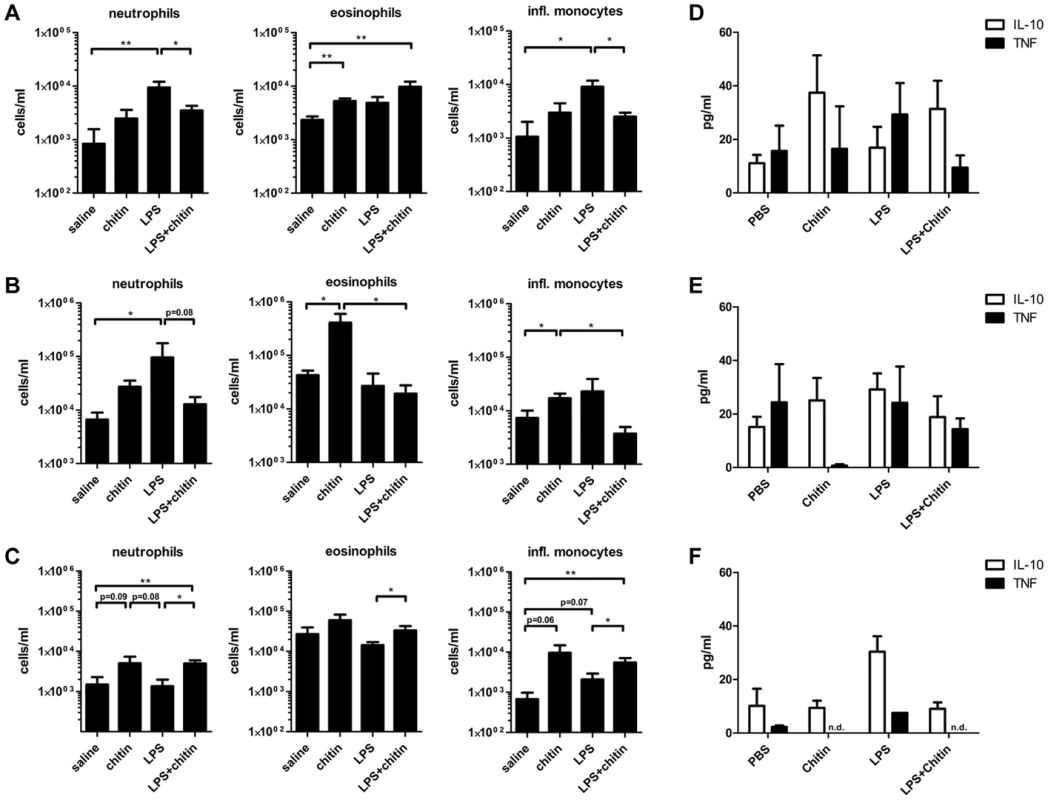

Fig. 7. Chitin dampens LPS induced inflammation in vivo.

C57BL/6 mice were injected intraperitoneal with saline, chitin, LPS or chitin and LPS in combination. Infiltrating immune cells and cytokine production were analysed after 4 h (A and D), 24 h (B and E) and 4 days (C and F). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM, n = 5 mice per group, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Inflammatory immune cells, e.g. neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes, were significantly increased in the LPS-injected group after 4 h (Fig. 7A). Chitin injection alone induced only a slight increase of neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes after 4 h, but significantly increased the number of eosinophils after 4 h and 24 h (Fig. 7A and B). After 4 h a combination of chitin and LPS significantly reduced the number of neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes compared to injection of LPS alone (Fig. 7A). Co-injection of chitin with LPS also reduced the number of neutrophils after 24 h (Fig. 7B). Four days after injection, the chitin and LPS/chitin-injected group still had increased numbers of neutrophils, eosinophils and inflammatory monocytes in the peritoneal cavity, whilst the LPS-injected group showed no evidence of inflammation (Fig. 7C).

Cytokine analysis revealed that chitin increased IL-10 levels in the peritoneal cavity after 4 h and 24 h (Fig. 7D and E). LPS-injection increased TNF levels after 4 h (Fig. 7D) and induced equal amounts of IL-10 and TNF secretion after 24 h (Fig. 7E). The combination of chitin together with LPS shifted the cytokine response towards a more pronounced IL-10 response similar to that induced by chitin alone (Fig. 7D and E). In summary, these results show that chitin dampened the inflammatory response to LPS in vivo.

Reduced cell wall chitin in C. albicans and inhibition of chitinase activity influences cytokine secretion

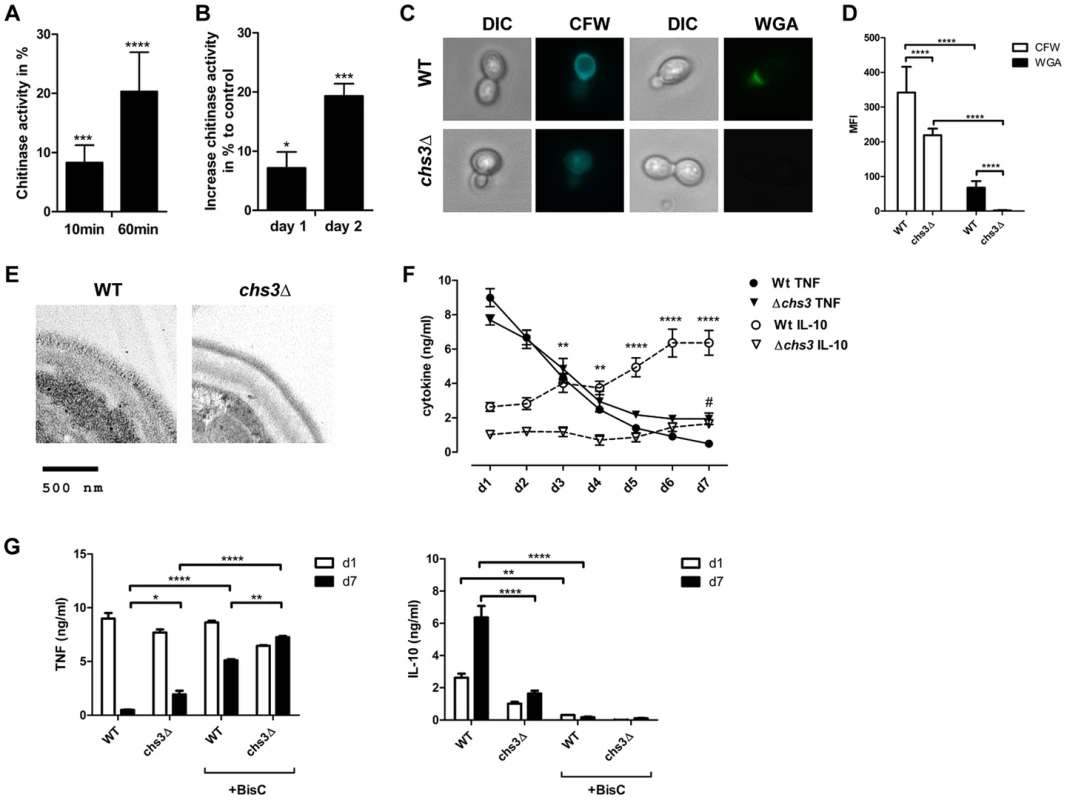

We also examined whether IL-10-inducing chitin particles were released from fungal cells during infections. Human chitotriosidase (CHIT-1) is expressed constitutively in phagocytic cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages and expression levels increase during monocyte to macrophage differentiation [15]. Stimulation of PRRs (e.g. TLR2, Dectin-1 and NOD2) with their specific ligands has been shown to influence CHIT-1 expression [14], [16] and recombinant human chitotriosidase exhibits antifungal activity against several different fungal species [17]. Nonetheless, it has not been determined whether CHIT-1 secretion increases during fungal infections. We therefore co-incubated human neutrophils (Fig. 8A) and macrophages (Fig. 8B) with C. albicans and analysed CHIT-1 activity in the cell supernatants and lysates. The total CHIT-1 activity increased significantly over time for neutrophils (Fig. 8A) and macrophages (Fig. 8B) when stimulated with live C. albicans yeast cells in comparison to uninfected cells. These results suggest that IL-10-inducing particles are generated during infection due to the digestion of fungal cell wall chitin by CHIT-1. Next we incubated hPBMCs with heat-treated C. albicans yeast cells over a period of 7 days and measured cytokine levels daily. We included heat-treated yeast cells from the C. albicans chitin synthase 3 mutant strain (chs3Δ) which has a greater than 80% reduction in the total amount of chitin in the cell wall (Fig. 8C and D) [18]. Heat-treatment did not differentially alter the cell wall structure of wild type and chs3Δ-mutant as evidenced by transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 8E). Wild type and chs3Δ mutant cells induced equal amounts of TNF from day 1 to 4, but as the response to the wild type yeast cells decreased to control levels from day 5 to 7, the amount of TNF in the chs3Δ mutant samples remained significantly higher (Fig. 8F). In contrast, in the wild type samples IL-10 levels significantly increased over time, but this did not occur in the chitin-deficient chs3Δ mutant samples (Fig. 8F). Finally we investigated the importance of human chitinases in generating IL-10 inducing particles from C. albicans. We repeated the experiment described above in the absence or presence of the chitinase inhibitor Bisdionin C (50 µM) (Fig. 8G). The presence of Bisdionin C did not affect the pro-inflammatory TNF response on day 1, but interestingly lead to significantly higher TNF levels on day 7 compared to the samples without Bisdionin C (Fig. 8G). On the other side, inhibition of the chitinase-activity completely abolished the induction of IL-10 in wild type and chs3Δ mutant treated samples (Fig. 8G).

Fig. 8. Reduced cell wall chitin effects late phase cytokine response to C. albicans.

CHIT-1-activity of (A) hPMNs and (B) hMφ's incubated with live C. albicans yeast cells, MOI = 0.4. Values represent means ± SEM, n = 4, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. (C) Heat-treated yeast cells from C. albicans wild type and chs3Δ mutant were stained for total chitin content with Calcofluor White (CFW) and surface presented chitin with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) and (D) mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was analysed. Values are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 30, ****p<0.0001. (E) TEM analysis of heat-treated yeast cells from C. albicans wild type and chs3Δ mutant. Images shown are representative for all analysed yeast cells. (F and G) hPBMCs were incubated with heat-treated C. albicans wild type yeast cells or C. albicans chs3Δ, MOI = 0.4 in the presence or absence of the chitinase inhibitor Bisdionin C. TNF and IL-10 secretion was monitored for a period of 7 days. Values represent means ± SEM, n = 4, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001. These observations indicate that the release of cell wall chitin during the end/late-phase of infection when the pathogen has been defeated by the immune system contribute to the resolution of the immune response by the induction of IL-10 thereby preventing collateral inflammatory-mediated damage (Fig. 9).

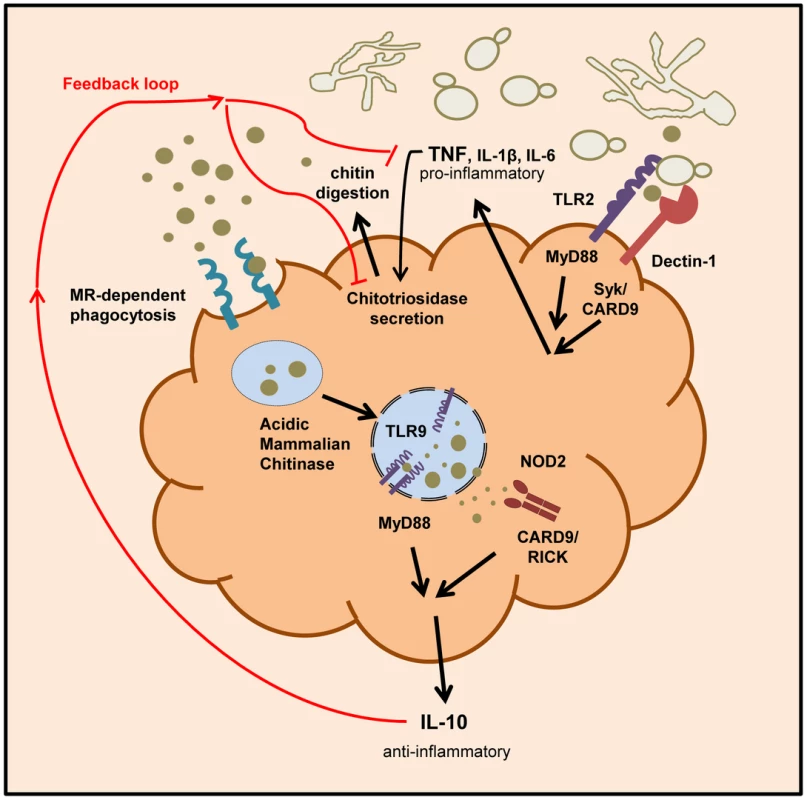

Fig. 9. Schematic overview of chitin recognition and involved pathways in negative regulation of inflammation.

Innate recognition of fungal cells by PRRs like Dectin-1 and TLR2 leads to the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF. The pathogen recognition together with the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines induces the secretion of chitinases (e.g. chitotriosidase) from neutrophils and macrophages. Chitin digestion leads to the generation of small sized chitin particles that are taken up by the mannose receptor and induce IL-10 secretion via the TLR9 and NOD2 pathway. The anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 dampens the inflammatory response by down-regulating pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion. Discussion

Chitin is an abundant molecule in nature and is a component of pathogens, parasites and food products of humans [1], [2], [3], [4]. Chitin exposure and degradation has been linked to a variety of human diseases, such as allergic asthma and Crohn's disease [19]. Therefore, chitin recognition and chitin-triggered immune responses are of broad interest to studies of immunity and inflammation. To date, most immunological studies have mostly used semi-purified commercial sources of chitin derived from shrimp or crab shells [10], making interpretations of the immunological effects of chitin difficult. Here we investigated the immune regulatory ability of ultrapure fungal chitin as a PAMP and describe several classes of immune receptors that are involved in chitin recognition (Fig. 9). We show that fungal chitin acts as a concentration - dependent stimulus of pro - and anti-inflammatory cytokine secretion in vitro and in vivo. Chitin particles (1–10 µm), resembling a size that is most likely to be found in the natural environment of the host, stimulated mainly IL-10 secretion at lower concentrations. Higher chitin concentrations induced TNF secretion. Lower chitin concentrations were only able to induce TNF secretion when intracellular uptake of chitin was inhibited. In this case, chitin-induced TNF secretion was dependent on TLR2 and dectin-1 recognition as blocking chitin uptake abolished TNF induction in TLR2 - and dectin-1-deficient macrophages. Our findings support and explain recent observations reporting that chitin acts as a size-dependent stimulus of IL-10 and TNF, mediated through MR, TLR2 and dectin-1 signalling pathways [13], but also help explain observed variations in chitin-induced immune responses related to chitin particle size and chitin concentration [20].

Whilst the inhibition of chitin uptake led to an increase chitin-induced TNF secretion, IL-10 induction was markedly increased by liposomal transfection, indicating that intracellular recognition was responsible for the anti-inflammatory properties of chitin. By screening mice that were deficient for various PRRs, we showed that NOD2 and TLR9 were required for chitin recognition, IL-10 induction and TNF suppression. Interaction with these two intracellular receptors required chitin to be first recognised by the MR before delivered to the inside of the cell since Mr−/− macrophages failed to induce IL-10, even when chitin was delivered using DOTAP as a liposomal transfecting agent. TLR9 recognises unmethylated CpG motifs in bacterial DNA, and has also been shown to recognise fungal DNA [21]. However, recent studies implicate TLR9 in fungal recognition independent of fungal viability or DNA availability, and TLR9 recruitment to fungus-loaded phagosomes has been shown to depend on the inner fungal cell wall layer rather than the outer wall mannoproteins [22]. In addition, siRNA knock-down of TLR9 expression in hPBMCs demonstrated that TLR9 signalling suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion (e.g. TNF and IL-6) and antimicrobial activity [23]. Interestingly, a protective role for TLR9 in acute allergic airway diseases driven by Aspergillus spp or house mite containing dust has been implied, since CpG administration inhibits allergic Th2 cytokine production [24], [25]. This effect might be mediated though competitive binding of CpG and chitin to TLR9, as CpG was the only PAMP used in our experiments, which did not show a synergistic effect on IL-10 secretion together with chitin. TLR2, dectin-1 and TLR9 have also been shown to be required for Aspergillus fumigatus strains to exhibit paradoxical growth upon exposure to caspofungin inside the host [26]. Paradoxical growth during echinocandin treatment has been linked to the ability of the fungi to upregulate chitin synthesis to restore the cell wall integrity after echinocandin-mediated cell wall damage [7], [27]. We showed previously that C. albicans cells with high chitin levels in their cell wall survive exposure to caspofungin in a mouse infection model [8], and that mice inoculated with high-chitin cells do not exhibit the inflammation-based pathology of the kidney that is characteristic of infection with C. albicans cells with normal chitin levels. Subsequently, mice with high kidney burdens of chitin-rich yeast cells survived infection [8]. Therefore, the immunopathology of fungal infections and the immune response of patients treated with echinocandins may be influenced by the recognition of cell wall chitin and the consequential dampening or exacerbation of the antifungal inflammatory response.

TLR9 SNPs have been linked with a higher susceptibility to CD [28] - a disease which is also associated with mutations in the NOD2 gene. Moreover, recent studies suggest that the normal immune interactions between TLR9 and NOD2 are lost in CD patients [28], [29]. NOD2 is a cytosolic innate immune receptor that mediates pro-inflammatory and antibacterial responses through recognition of bacterial cell wall components. The underlying mechanism governing how NOD2 variants lead to CD development is unknown, but current hypotheses suggest that the impaired function of NOD2 leads to deficiencies in the epithelial-barrier function, leading to increased bacterial invasion and inflammation of the intestine [30]. C. albicans colonises all segments of the digestive tract without any known benefit for the host, but commensal colonisers are also the source of fungal cells that invade the mucosa, leading to life-threatening systemic infections in immunocompromised individuals [31]. Recent investigations described high serum levels of antibodies in 50–60% of CD patients, that recognise major epitopes of the fungal cell wall, including mannan, β-glucan and chitin [32]. These antibodies are produced during C. albicans infection and normally subside after antifungal therapy; however serum levels remain high in CD patients [32]. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that healthy relatives of CD patients are more frequently colonised by C. albicans in the gut compared to healthy control families [33]. Moreover, analysis of the gut fungal microbiota in healthy and CD patients revealed that the fungal diversity is significantly elevated in inflamed mucosa compared to healthy controls, thereby showing an expansion of pathogenic species like Candida spp [34]. Therefore the fungal gut microflora may be an important immunomodulator of CD.

The Th1/Th17 response is known to be protective against mucosal Candida infections [35], however Th17 responses have also been implicated in the pathology of CD, allergy and asthma [36]. Elevated IL-17 levels and Th17 cells are found in the intestinal mucosa of CD patients [37] and IL-10-treatment of mice with established colitis suppressed Th17 and Th17/Th1 cell development [38]. IL-10 has an important role in regulating gut immunity and intestinal homeostasis, and CD-associated NOD2 mutations have been shown to inhibit IL-10 expression [39]. Two recent studies investigated the modulation of intestinal inflammation by yeast cell wall extracts (C. albicans and S. cerevisiae) and chitin micro particles (1–10 µm), both demonstrated increased IL-10 levels and stimulation of IL-10 producing cells in the colon with consequent improvement of inflammation [40], [41].

Low concentrations of small chitin particles are likely to be released by commensal fungi in the gut and on other mucosal surfaces, as well as from the cell walls of fungi that have been killed by the action of the immune system. The release of such chitin particles and chitin oligosaccharides has the potential to induce IL-10 secretion, via NOD2 and TLR9 signalling, promoting the attenuation of inflammatory-mediated diseases and consequent immune homeostasis [42]. High concentrations of chitin particles generated during pathogen invasion and infection may promote inflammation through dectin-1 and TLR2 signalling. However, chitin is also able to promote Th2-associated inflammation which is central to the pathogenesis of allergy and asthma [43], [44]. Our data therefore suggest that the two signature polysaccharides in the fungal cell wall, β-1,3 glucan and chitin, induce markedly different responses in the sentinel cells of the innate immune system and explain why chitin and chitin recognition pathways are implicated in the immunology of asthma, CD and allergies.

Materials and Methods

Chitin purification and analysis

C. albicans strain NGY152 [45] was used in this study as a main source of chitin. All other strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Chitin was isolated and purified as described previously [46] with minor adaptations. Briefly, cells were grown in YPD broth (1% (w/v) yeast extract, 2% (w/v) mycological peptone, 2% (w/v) glucose) at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm overnight. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed three times with deionised water, resuspended in 5% (w/v) KOH and boiled at 100°C for 30 min. This procedure was repeated twice before cells were resuspended in 40% H2O2/glacial acetic acid solution (1∶1) and boiled at 100°C for 45 min. Chitin was collected by low speed centrifugation and washed several times with deionised water before being resuspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and stored at 4°C.

To analyse the quantity and purity of the chitin preparations, samples were hydrolysed with 13 M (99% (w/v)) trifluoroacetic acid (TFAA) at 100°C for 4 h for purity analysis or 6 M HCl at 100°C overnight for chitin yield measurements. Acid was evaporated at 65°C–70°C, the debris washed twice with deionised water by evaporation and finally resuspended in deionised water. Samples were analysed together with carbohydrate standards by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) in a carbohydrate analyzer system from Dionex (Surrey, UK) as described previously [47]. Prior to experiments, chitin samples were tested for endotoxin contamination using the limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) assay (QCL-1000; Lonza) and the amount detected was less than 0.3 EU/ml (<30 pg/ml). The degree of chitin acetylation/deacetylation was determined by Cibacon Brilliant Red 3B-A dye binding [48]. Possible bacterial and fungal contamination were excluded by incubating 20 µl of each chitin sample in YPD broth (fungi) or LB broth (1% (w/v) tryptone, 0.5% (w/v) yeast extract, 0.5% (w/v) NaCl) (bacteria) for 24 h to 4 h at 37°C. Chitin particle size was determined by flow cytometry using 1 and 10 µm latex beads as size standards (Sigma-Aldrich) as described elsewhere [49].

Microbial ligands and chemicals

All chemicals used in the study were of cell culture grade and endotoxin-free. Pattern recognition receptor ligands used in this study were purchased from InvivoGen (LPS, Pam3CSK4, CpG ODN 2395, zymosan, MDP and flagellin) and curdlan, laminarin and S.c. mannan from Sigma-Aldrich. All samples were prepared in endotoxin-free water. The endocytosis inhibitor Cyt D was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, the transfection reagent DOTAP from Roche and DNase I from Invitrogen. The chitinase inhibitor Bisdionin C was a kind gift from I. Eggleston (Bath).

Ethics statement, animals and receptor-deficient mice

All animal experiments were approved by ethical committees of respective institutes, and conducted according to local guidelines and regulations. For all experiments age - and sex-matched KO mice and co-housed wild type animals between 6–12 weeks of age were used.

C57BL/6 (wild type), Tlr2−/−, Nod2−/−, Myd88−/−, Card9−/− and Rick−/− mice were housed in the SJCRH animal resource center, which is a specific pathogen free (SPF) and AAALAC accredited facility. Experiments were conducted under protocols approved by the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Committee on Use and Care of Animals (Protocol #482) and were performed in accordance with institutional policies, AAALAC guidelines, the AVMA Guidelines on Euthanasia NIH regulations (Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals), and the United States Animal Welfare Act (1966).

C57BL/6, Tlr2−/−, Tlr4−/−, Tlr2/4−/−, Nod2−/− and Tlr9−/− mice were bred under specific pathogen-free conditions in the animal facility of the University of Tübingen according to European guidelines (FELASA) and to the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals of the German Animal Protection Law. Protocols were approved by the board institution animal facility of the University of Tübingen and the local authorities Regierungspräsidium Tübingen with the permit numbers §4 Abs. 3 Az v. 01.07.09 according to German Animal Protection Law. Tlr2−/− mice were a kind gift from C. Kirschning (Technical University Munich), Tlr4−/− mice were kindly provided by Dr. S. Akira (Osaka University). Tlr2/4−/− mice were generated by mating TLR2-deficient mice with TLR4-deficient mice.

C57BL/6 (wild type), Mr−/−, 129/Sve (wild type) and Clec7a−/− (dectin-1−/−) mice were bred and housed under pathogen-free conditions in the animal facility at the University of Aberdeen. Experimentation involving animals was carried out under a UK Home Office Project Licence granted to Dr Donna MacCallum (PPL 60/4135) and Prof Gordon Brown (PPL60/4007), and all work was approved by the UK Home Office and the University of Aberdeen Ethical Review Committee, and conforms to European Union directive 2010/63/EU. Mr−/− mice were a kind gift from S. Gordon (Oxford).

In vivo stimulation and analysis

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with indicated concentrations of chitin and LPS in 200 µl sterile saline. Mice were sacrificed at the indicated time points and peritoneal inflammatory cells were harvested in PBS containing 5 mM EDTA. Cells were stained with CD11b-PECy7, CD11c-PerCPCy5.5, 7/4-FITC, SiglecF-PE, Ly6G-APC and F4/80-AF700 (BD Biosciences) to distinguish neutrophils (F4/80neg, 7/4pos, Ly6Ghigh), eosinophils (F4/80neg, 7/4neg, Ly6Gpos, SiglecFpos), inflammatory monocytes (F4/80pos, 7/4pos, Ly6Gneg) and macrophages (F4/80pos, 7/4neg, Ly6Gneg). Data was acquired on FACS LSRII and analysed using FlowJo.

Isolation, differentiation and cytokine production by mouse bone-marrow derived macrophages

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (mBMMφs) were prepared as described previously [50]. Briefly, bone marrow was isolated from femurs of 6–12 week-old mice and cultured in IMDM (Gibco) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 20% L929 cell-conditioned medium, 1% MEM non-essential amino acids (NEAA (100×), Gibco), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After 5–7 days cells were collected and plated in 96-well plates at a density of 1×105 cells/well in IMDM containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 1% NEAA and antibiotics. Macrophages were cultured overnight and primed with 1 µg/ml LPS for 4 h prior to main experiments. Supernatants and cells were then separated and stored at −20°C until cytokine assays were performed. Cyt D treated cells were lysed with 0.1% Triton-X 100 in media at room temperature for 60 min. Cell lysates were stored at −20°C until cytokine measurements were performed.

Isolation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, neutrophils and monocyte to macrophage differentiation

Human polymorphonuclear (hPMNs) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (hPBMCs) were isolated from EDTA-blood samples, freshly taken from healthy donors according to the local guidelines and regulations, approved by the College Ethics Review Board of the University of Aberdeen (CERB/2012/11/676). Polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cell fractions were obtained by density centrifugation using Histopaque-1119 and -1077 (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufactures instructions. hPBMCs were washed twice with PBS and suspended in RPMI 1640 (Dutch modification) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 100 µg/ml gentamicin for stimulation experiments and transferred into a 96-well suspension culture plate at a density of 5×105 cells/well. After experiments supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C until cytokine assays were performed.

To obtain human macrophages (hMφs), mononuclear cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 (Dutch modification) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1% MEM non-essential amino acids (NEAA (100×), Gibco), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin and 50 ng/ml recombinant hGM-CSF (Gibco), seeded into cell culture flasks and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After 5–7 days cells were collected and seeded into 12-well plates at a density of 5×105 cells/well and cultured overnight before stimulation. Supernatants and cells were separated after experiments and stored at −20°C until further assays were performed.

hPMNs were washed twice with PBS after isolation step and remaining red blood cells were lysed using hypotonic salt solutions. hPMNs were suspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 0.5% heat-inactivated FBS. hPMNs (2×106 cells) were stimulated with live C. albicans yeast cells (2×106 cells, MOI = 1) for 10 and 60 min. hPMNs were separated from the supernatant by centrifugation and cells were lysed in 0.1% (v/v) TritonX-100 in PBS. Cell lysates and supernatants were stored at −20°C until further analysis.

Stimulation with heat-treated yeast cells and chitin determination

C. albicans wild type and chs3Δ-null mutant strains were grown overnight in YPD broth at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Cells were diluted to an OD600 of 0.2 in fresh YPD broth and cultured at 30°C until cells reached mid-exponential growth phase (OD600 0.6–0.8). Yeast cells were harvested and washed twice with PBS before they were heat killed by incubation at 65°C for 2 h. hPBMCs (5×105 cells/well) were incubated for 7 days with 2×105 yeast cells (MOI = 0.4). Aliquots of supernatant were collected each day and stored at −20°C until cytokine assays were performed.

Surface presentation of chitin was analysed by staining of heat-treated yeast cells with FITC conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA-FITC, 100 µg/ml) in the dark for 30 min and total cell wall chitin was stained with Calcofluor White (CFW, 10 µg/ml).

Chitotriosidase-activity assay

Chitotriosidase-activity in the supernatants and lysates of stimulated cells was analysed as described elsewhere [51]. Briefly, chitinase-activity was analysed by mixing 10 µl sample with 100 µl substrate (20 µM 4-methylumbelliferyl β-d-N,N′-diacetylchitotrioside hydrate (4-[MU]-(GlcNAc)3, Sigma-Aldrich) in McIlvain buffer (0.1 M citric acid, 0.2 M sodium phosphate, pH 5.2) and incubated for 20 min at 37°C in the dark. The reaction was stopped by adding 200 µl 0.3 M glycine-NaOH buffer, pH 10.5 and converted substrate was measured fluorometrically (Ex.360/Em.450 nm). A serial dilution of 4-[MU] was used as standard.

Immunofluorescence and high-pressure, freeze-substitution transmission electron microscopy

Bone marrow-derived macrophages were plated into chamber-slides (BD Falcon) at a density of 1×105 cells/chamber and grown overnight prior to stimulation. After stimulation, cells were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature or at 4°C overnight and permeabilised with 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 5–10 min. Non-specific binding was blocked with 5% goat serum in PBS for 30 min, before samples were stained using anti-NOD2 (clone H-300), anti-TLR9 (clone H-100), anti-TLR2 (clone H-175) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-TLR9 (clone1E8) (Sigma-Aldrich) or anti-CD206 (cloneMR5D3) (AbD Serotec) together with the chitin-binding reporter construct (ChBD-HuCκ) that contained the chitin binding domain (ChBD) from Bacillus circulans chitinase A1 fused to the human kappa light chain (HuCκ) and a 6×His tag for purification (Lenardon M.D., unpublished), followed by detection with the fluorochrome-coupled goat anti-mouse-TRITC (Sigma-Aldrich), goat anti-mouse-AF647 (Molecular Probes), goat anti-rabbit-TRITC (Sigma-Aldrich), goat anti-rat-TRITC (AbD Serotec), goat anti-rat-AF647 (Molecular Probes) or goat anti-human-κ light chain-FITC secondary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). Slides were mounted with mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories).

For structural cell wall analysis C. albicans wild type and chs3Δ-mutant were grown in YPD at 30°C overnight, diluted into fresh media and harvested in mid-exponential growth phase. Cells were heat-killed at 65°C for 2 h before processed for transmission electron microscopy as described elsewhere [52].

Statistical analyses

All experiments were performed at least 3 times and revealed comparable results. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using One-way ANOVA or Two-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc analysis including Tukey method. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. AraujoAC, Souto-PadronT, de SouzaW (1993) Cytochemical localization of carbohydrate residues in microfilariae of Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi. J Histochem Cytochem 41 : 571–578.

2. FuhrmanJA, PiessensWF (1985) Chitin synthesis and sheath morphogenesis in Brugia malayi microfilariae. Mol Biochem Parasitol 17 : 93–104.

3. NevilleAC, ParryDA, Woodhead-GallowayJ (1976) The chitin crystallite in arthropod cuticle. J Cell Sci 21 : 73–82.

4. ShahabuddinM, KaslowDC (1994) Plasmodium: parasite chitinase and its role in malaria transmission. Exp Parasitol 79 : 85–88.

5. BrownGD, DenningDW, GowNA, LevitzSM, NeteaMG, et al. (2012) Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med 4 : 165rv113.

6. KlisFM, de GrootP, HellingwerfK (2001) Molecular organization of the cell wall of Candida albicans. Med Mycol 39 Suppl 1 : 1–8.

7. WalkerLA, MunroCA, de BruijnI, LenardonMD, McKinnonA, et al. (2008) Stimulation of chitin synthesis rescues Candida albicans from echinocandins. PLoS Pathog 4: e1000040.

8. LeeKK, MaccallumDM, JacobsenMD, WalkerLA, OddsFC, et al. (2011) Elevated cell wall chitin in Candida albicans confers echinocandin resistance in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56 : 208–217.

9. SchlosserA, ThomsenT, MoellerJB, NielsenO, TornoeI, et al. (2009) Characterization of FIBCD1 as an acetyl group-binding receptor that binds chitin. J Immunol 183 : 3800–3809.

10. VegaK, KalkumM (2012) Chitin, chitinase responses, and invasive fungal infections. Int J Microbiol 2012 : 920459.

11. LeeCG, Da SilvaCA, Dela CruzCS, AhangariF, MaB, et al. (2010) Role of chitin and chitinase/chitinase-like proteins in inflammation, tissue remodeling, and injury. Annu Rev Physiol 73 : 479–501.

12. CashHL, WhithamCV, BehrendtCL, HooperLV (2006) Symbiotic bacteria direct expression of an intestinal bactericidal lectin. Science 313 : 1126–1130.

13. Da SilvaCA, ChalouniC, WilliamsA, HartlD, LeeCG, et al. (2009) Chitin is a size-dependent regulator of macrophage TNF and IL-10 production. J Immunol 182 : 3573–3582.

14. van EijkM, ScheijSS, van RoomenCP, SpeijerD, BootRG, et al. (2007) TLR - and NOD2-dependent regulation of human phagocyte-specific chitotriosidase. FEBS Lett 581 : 5389–5395.

15. Di RosaM, De GregorioC, MalaguarneraG, TuttobeneM, BiazzoF, et al. (2013) Evaluation of AMCase and CHIT-1 expression in monocyte macrophages lineage. Mol Cell Biochem 374 : 73–80.

16. van EijkM, Voorn-BrouwerT, ScheijSS, VerhoevenAJ, BootRG, et al. (2010) Curdlan-mediated regulation of human phagocyte-specific chitotriosidase. FEBS Lett 584 : 3165–3169.

17. van EijkM, van RoomenCP, RenkemaGH, BussinkAP, AndrewsL, et al. (2005) Characterization of human phagocyte-derived chitotriosidase, a component of innate immunity. Int Immunol 17 : 1505–1512.

18. MunroCA, SchofieldDA, GoodayGW, GowNA (1998) Regulation of chitin synthesis during dimorphic growth of Candida albicans. Microbiology 144(Pt 2): 391–401.

19. GoldmanDL, VicencioAG (2012) The chitin connection. MBio 3.

20. MuzzarelliRA (2010) Chitins and chitosans as immunoadjuvants and non-allergenic drug carriers. Mar Drugs 8 : 292–312.

21. MiyazatoA, NakamuraK, YamamotoN, Mora-MontesHM, TanakaM, et al. (2009) Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation of myeloid dendritic cells by Deoxynucleic acids from Candida albicans. Infect Immun 77 : 3056–3064.

22. KasperkovitzPV, KhanNS, TamJM, MansourMK, DavidsPJ, et al. (2011) Toll-like receptor 9 modulates macrophage antifungal effector function during innate recognition of Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Infect Immun 79 : 4858–4867.

23. van de VeerdonkFL, NeteaMG, JansenTJ, JacobsL, VerschuerenI, et al. (2008) Redundant role of TLR9 for anti-Candida host defense. Immunobiology 213 : 613–620.

24. RamaprakashH, HogaboamCM (2009) Intranasal CpG therapy attenuated experimental fungal asthma in a TLR9-dependent and -independent manner. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 152 : 98–112.

25. VissersJL, van EschBC, JeurinkPV, HofmanGA, van OosterhoutAJ (2004) Stimulation of allergen-loaded macrophages by TLR9-ligand potentiates IL-10-mediated suppression of allergic airway inflammation in mice. Respir Res 5 : 21.

26. MorettiS, BozzaS, D'AngeloC, CasagrandeA, Della FaziaMA, et al. (2012) Role of innate immune receptors in paradoxical caspofungin activity in vivo in preclinical aspergillosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56 : 4268–4276.

27. LenardonMD, MunroCA, GowNA (2010) Chitin synthesis and fungal pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol 13 : 416–423.

28. TorokHP, GlasJ, EndresI, TonenchiL, TeshomeMY, et al. (2009) Epistasis between Toll-like receptor-9 polymorphisms and variants in NOD2 and IL23R modulates susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol 104 : 1723–1733.

29. HotteNS, SalimSY, TsoRH, AlbertEJ, BachP, et al. (2012) Patients with inflammatory bowel disease exhibit dysregulated responses to microbial DNA. PLoS One 7: e37932.

30. LecatA, PietteJ, Legrand-PoelsS (2010) The protein Nod2: an innate receptor more complex than previously assumed. Biochem Pharmacol 80 : 2021–2031.

31. MirandaLN, van der HeijdenIM, CostaSF, SousaAP, SienraRA, et al. (2009) Candida colonisation as a source for candidaemia. J Hosp Infect 72 : 9–16.

32. PoulainD, SendidB, Standaert-VitseA, FradinC, JouaultT, et al. (2009) Yeasts: neglected pathogens. Dig Dis 27 Suppl 1 : 104–110.

33. Standaert-VitseA, SendidB, JoossensM, FrancoisN, Vandewalle-El KhouryP, et al. (2009) Candida albicans colonization and ASCA in familial Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol 104 : 1745–1753.

34. LiQ, WangC, TangC, HeQ, LiN, et al. (2013) Dysbiosis of Gut Fungal Microbiota is Associated With Mucosal Inflammation in Crohn's Disease. J Clin Gastroenterol [Epub ahead of print].

35. McDonaldDR (2012) TH17 deficiency in human disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 129 : 1429–1435 quiz 1436–1427.

36. MaddurMS, MiossecP, KaveriSV, BayryJ (2012) Th17 cells: biology, pathogenesis of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, and therapeutic strategies. Am J Pathol 181 : 8–18.

37. WilkeCM, WangL, WeiS, KryczekI, HuangE, et al. (2011) Endogenous interleukin-10 constrains Th17 cells in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Transl Med 9 : 217.

38. HuberS, GaglianiN, EspluguesE, O'ConnorWJr, HuberFJ, et al. (2011) Th17 cells express interleukin-10 receptor and are controlled by Foxp3(-) and Foxp3+ regulatory CD4+ T cells in an interleukin-10-dependent manner. Immunity 34 : 554–565.

39. NoguchiE, HommaY, KangX, NeteaMG, MaX (2009) A Crohn's disease-associated NOD2 mutation suppresses transcription of human IL10 by inhibiting activity of the nuclear ribonucleoprotein hnRNP-A1. Nat Immunol 10 : 471–479.

40. JawharaS, HabibK, MaggiottoF, PignedeG, VandekerckoveP, et al. (2012) Modulation of intestinal inflammation by yeasts and cell wall extracts: strain dependence and unexpected anti-inflammatory role of glucan fractions. PLoS One 7: e40648.

41. NagataniK, WangS, LladoV, LauCW, LiZ, et al. (2012) Chitin microparticles for the control of intestinal inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis 18 : 1698–1710.

42. RomaniL, PuccettiP (2006) Protective tolerance to fungi: the role of IL-10 and tryptophan catabolism. Trends Microbiol 14 : 183–189.

43. ReeseTA, LiangHE, TagerAM, LusterAD, Van RooijenN, et al. (2007) Chitin induces accumulation in tissue of innate immune cells associated with allergy. Nature 447 : 92–96.

44. Van DykenSJ, GarciaD, PorterP, HuangX, QuinlanPJ, et al. (2011) Fungal chitin from asthma-associated home environments induces eosinophilic lung infiltration. J Immunol 187 : 2261–2267.

45. BrandA, MacCallumDM, BrownAJ, GowNA, OddsFC (2004) Ectopic expression of URA3 can influence the virulence phenotypes and proteome of Candida albicans but can be overcome by targeted reintegration of URA3 at the RPS10 locus. Eukaryot Cell 3 : 900–909.

46. Mora-MontesHM, NeteaMG, FerwerdaG, LenardonMD, BrownGD, et al. (2011) Recognition and blocking of innate immunity cells by Candida albicans chitin. Infect Immun 79 : 1961–1970.

47. PlaineA, WalkerL, Da CostaG, Mora-MontesHM, McKinnonA, et al. (2008) Functional analysis of Candida albicans GPI-anchored proteins: roles in cell wall integrity and caspofungin sensitivity. Fungal Genet Biol 45 : 1404–1414.

48. MuzzarelliRA (1998) Colorimetric determination of chitosan. Anal Biochem 260 : 255–257.

49. KogisoM, NishiyamaA, ShinoharaT, NakamuraM, MizoguchiE, et al. (2011) Chitin particles induce size-dependent but carbohydrate-independent innate eosinophilia. J Leukoc Biol 90 : 167–176.

50. KannegantiTD, LamkanfiM, KimYG, ChenG, ParkJH, et al. (2007) Pannexin-1-mediated recognition of bacterial molecules activates the cryopyrin inflammasome independent of Toll-like receptor signaling. Immunity 26 : 433–443.

51. GorzelannyC, PoppelmannB, PappelbaumK, MoerschbacherBM, SchneiderSW (2010) Human macrophage activation triggered by chitotriosidase-mediated chitin and chitosan degradation. Biomaterials 31 : 8556–8563.

52. HallRA, BatesS, LenardonMD, MaccallumDM, WagenerJ, et al. (2013) The Mnn2 mannosyltransferase family modulates mannoprotein fibril length, immune recognition and virulence of Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003276.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Affinity Proteomics Reveals Elevated Muscle Proteins in Plasma of Children with Cerebral MalariaČlánek The Transcriptional Activator LdtR from ‘ Liberibacter asiaticus’ Mediates Osmotic Stress ToleranceČlánek Complement-Related Proteins Control the Flavivirus Infection of by Inducing Antimicrobial PeptidesČlánek Parasite Fate and Involvement of Infected Cells in the Induction of CD4 and CD8 T Cell Responses to

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 4- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Familiární středomořská horečka

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- , , , Genetic Variability: Cryptic Biological Species or Clonal Near-Clades?

- Early Mortality Syndrome Outbreaks: A Microbial Management Issue in Shrimp Farming?

- Wormholes in Host Defense: How Helminths Manipulate Host Tissues to Survive and Reproduce

- Plastic Proteins and Monkey Blocks: How Lentiviruses Evolved to Replicate in the Presence of Primate Restriction Factors

- The 2010 Cholera Outbreak in Haiti: How Science Solved a Controversy

- Affinity Proteomics Reveals Elevated Muscle Proteins in Plasma of Children with Cerebral Malaria

- Noncanonical Role for the Host Vps4 AAA+ ATPase ESCRT Protein in the Formation of Replicase

- Efficient Parvovirus Replication Requires CRL4-Targeted Depletion of p21 to Prevent Its Inhibitory Interaction with PCNA

- Host-to-Pathogen Gene Transfer Facilitated Infection of Insects by a Pathogenic Fungus

- The Transcriptional Activator LdtR from ‘ Liberibacter asiaticus’ Mediates Osmotic Stress Tolerance

- Coxsackievirus B Exits the Host Cell in Shed Microvesicles Displaying Autophagosomal Markers

- TCR Affinity Associated with Functional Differences between Dominant and Subdominant SIV Epitope-Specific CD8 T Cells in Rhesus Monkeys

- Coxsackievirus-Induced miR-21 Disrupts Cardiomyocyte Interactions via the Downregulation of Intercalated Disk Components

- Ligands of MDA5 and RIG-I in Measles Virus-Infected Cells

- Kind Discrimination and Competitive Exclusion Mediated by Contact-Dependent Growth Inhibition Systems Shape Biofilm Community Structure

- Structural Differences Explain Diverse Functions of Actins

- HSCARG Negatively Regulates the Cellular Antiviral RIG-I Like Receptor Signaling Pathway by Inhibiting TRAF3 Ubiquitination Recruiting OTUB1

- Vaginitis: When Opportunism Knocks, the Host Responds

- Complement-Related Proteins Control the Flavivirus Infection of by Inducing Antimicrobial Peptides

- Fungal Chitin Dampens Inflammation through IL-10 Induction Mediated by NOD2 and TLR9 Activation

- Microbial Pathogens Trigger Host DNA Double-Strand Breaks Whose Abundance Is Reduced by Plant Defense Responses

- Alveolar Macrophages Are Essential for Protection from Respiratory Failure and Associated Morbidity following Influenza Virus Infection

- An Interaction between Glutathione and the Capsid Is Required for the Morphogenesis of C-Cluster Enteroviruses

- Concerted Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Imported DNA and ComE DNA Uptake Protein during Gonococcal Transformation

- Potent Dengue Virus Neutralization by a Therapeutic Antibody with Low Monovalent Affinity Requires Bivalent Engagement

- Regulation of Human T-Lymphotropic Virus Type I Latency and Reactivation by HBZ and Rex

- Functionally Redundant RXLR Effectors from Act at Different Steps to Suppress Early flg22-Triggered Immunity

- The Pathogenic Mechanism of the Virulence Factor, Mycolactone, Depends on Blockade of Protein Translocation into the ER

- Role of Calmodulin-Calmodulin Kinase II, cAMP/Protein Kinase A and ERK 1/2 on -Induced Apoptosis of Head Kidney Macrophages

- An Overview of Respiratory Syncytial Virus

- First Experimental Model of Enhanced Dengue Disease Severity through Maternally Acquired Heterotypic Dengue Antibodies

- Binding of Glutathione to Enterovirus Capsids Is Essential for Virion Morphogenesis

- IFITM3 Restricts Influenza A Virus Entry by Blocking the Formation of Fusion Pores following Virus-Endosome Hemifusion

- Parasite Fate and Involvement of Infected Cells in the Induction of CD4 and CD8 T Cell Responses to

- Deficient IFN Signaling by Myeloid Cells Leads to MAVS-Dependent Virus-Induced Sepsis

- Pernicious Pathogens or Expedient Elements of Inheritance: The Significance of Yeast Prions

- The HMW1C-Like Glycosyltransferases—An Enzyme Family with a Sweet Tooth for Simple Sugars

- The Expanding Functions of Cellular Helicases: The Tombusvirus RNA Replication Enhancer Co-opts the Plant eIF4AIII-Like AtRH2 and the DDX5-Like AtRH5 DEAD-Box RNA Helicases to Promote Viral Asymmetric RNA Replication

- Mining Herbaria for Plant Pathogen Genomes: Back to the Future

- Inferring Influenza Infection Attack Rate from Seroprevalence Data

- A Human Lung Xenograft Mouse Model of Nipah Virus Infection

- Mast Cells Expedite Control of Pulmonary Murine Cytomegalovirus Infection by Enhancing the Recruitment of Protective CD8 T Cells to the Lungs

- Cytosolic Peroxidases Protect the Lysosome of Bloodstream African Trypanosomes from Iron-Mediated Membrane Damage

- Abortive T Follicular Helper Development Is Associated with a Defective Humoral Response in -Infected Macaques

- JC Polyomavirus Infection Is Strongly Controlled by Human Leucocyte Antigen Class II Variants

- Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides Promote Microbial Mutagenesis and Pathoadaptation in Chronic Infections

- Estimating the Fitness Advantage Conferred by Permissive Neuraminidase Mutations in Recent Oseltamivir-Resistant A(H1N1)pdm09 Influenza Viruses

- Progressive Accumulation of Activated ERK2 within Highly Stable ORF45-Containing Nuclear Complexes Promotes Lytic Gammaherpesvirus Infection

- Caspase-1-Like Regulation of the proPO-System and Role of ppA and Caspase-1-Like Cleaved Peptides from proPO in Innate Immunity

- Is Required for High Efficiency Viral Replication

- Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Triggers Type I IFN Production in Murine Conventional Dendritic Cells via a cGAS/STING-Mediated Cytosolic DNA-Sensing Pathway

- Evidence That Bank Vole PrP Is a Universal Acceptor for Prions

- Rapid Response to Selection, Competitive Release and Increased Transmission Potential of Artesunate-Selected Malaria Parasites

- Inactivation of Genes for Antigenic Variation in the Relapsing Fever Spirochete Reduces Infectivity in Mice and Transmission by Ticks

- Exposure-Dependent Control of Malaria-Induced Inflammation in Children

- A Neutralizing Anti-gH/gL Monoclonal Antibody Is Protective in the Guinea Pig Model of Congenital CMV Infection

- The Apical Complex Provides a Regulated Gateway for Secretion of Invasion Factors in

- A Highly Conserved Haplotype Directs Resistance to Toxoplasmosis and Its Associated Caspase-1 Dependent Killing of Parasite and Host Macrophage

- A Quantitative High-Resolution Genetic Profile Rapidly Identifies Sequence Determinants of Hepatitis C Viral Fitness and Drug Sensitivity

- Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Romidepsin Induces HIV Expression in CD4 T Cells from Patients on Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy at Concentrations Achieved by Clinical Dosing

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- The 2010 Cholera Outbreak in Haiti: How Science Solved a Controversy

- , , , Genetic Variability: Cryptic Biological Species or Clonal Near-Clades?

- Efficient Parvovirus Replication Requires CRL4-Targeted Depletion of p21 to Prevent Its Inhibitory Interaction with PCNA

- An Overview of Respiratory Syncytial Virus

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání