-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Exploits Asparagine to Assimilate Nitrogen and Resist Acid Stress during Infection

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is an intracellular pathogen. Within macrophages, M. tuberculosis thrives in a specialized membrane-bound vacuole, the phagosome, whose pH is slightly acidic, and where access to nutrients is limited. Understanding how the bacillus extracts and incorporates nutrients from its host may help develop novel strategies to combat tuberculosis. Here we show that M. tuberculosis employs the asparagine transporter AnsP2 and the secreted asparaginase AnsA to assimilate nitrogen and resist acid stress through asparagine hydrolysis and ammonia release. While the role of AnsP2 is partially spared by yet to be identified transporter(s), that of AnsA is crucial in both phagosome acidification arrest and intracellular replication, as an M. tuberculosis mutant lacking this asparaginase is ultimately attenuated in macrophages and in mice. Our study provides yet another example of the intimate link between physiology and virulence in the tubercle bacillus, and identifies a novel pathway to be targeted for therapeutic purposes.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 10(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003928

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003928Summary

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is an intracellular pathogen. Within macrophages, M. tuberculosis thrives in a specialized membrane-bound vacuole, the phagosome, whose pH is slightly acidic, and where access to nutrients is limited. Understanding how the bacillus extracts and incorporates nutrients from its host may help develop novel strategies to combat tuberculosis. Here we show that M. tuberculosis employs the asparagine transporter AnsP2 and the secreted asparaginase AnsA to assimilate nitrogen and resist acid stress through asparagine hydrolysis and ammonia release. While the role of AnsP2 is partially spared by yet to be identified transporter(s), that of AnsA is crucial in both phagosome acidification arrest and intracellular replication, as an M. tuberculosis mutant lacking this asparaginase is ultimately attenuated in macrophages and in mice. Our study provides yet another example of the intimate link between physiology and virulence in the tubercle bacillus, and identifies a novel pathway to be targeted for therapeutic purposes.

Introduction

With nearly 1.3 million lives claimed in 2012, as reported by the World Health Organization, tuberculosis (TB) remains the major cause of death due to a single bacterial pathogen. A better understanding of the interactions between Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the etiologic agent of TB, and its human host may help improve current therapies. In particular, unraveling the microbial mechanisms involved in uptake and catabolism of host-derived nutrients required by the pathogen during its life cycle may identify targets for novel antimicrobials [1]–[3].

The TB bacillus is an intracellular microorganism that thrives inside host macrophages. Although M. tuberculosis can be found in the host cell cytosol at later stages of infection [4]–[6], the prevailing consensus is that the pathogen resides and multiplies mostly within phagosomes, which fuse poorly with host cell lysosomes and barely acidify (pH∼6.5) [7]–[10]. In macrophages activated by immune cell-derived cytokines, such as interferon (IFN) - γ, and microbial ligands, such as Escherichia coli-derived lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the pH of the mycobacterial phagosome drops below 5.5, and mycobacterial growth is constrained to some extent [8], [11], [12]. The ability to block phagosome maturation and avoid lysosomal degradation is considered chief among M. tuberculosis virulence strategies, although the molecular mechanisms involved in this process are likely to be multiple and remain yet to be fully elucidated [10]. In addition to being slightly acidic, the mycobacterial phagosome is considered an environment in which nutrient availability is limited [1], [3], [13]. Such multiple stresses typically translate into a marked remodeling of the mycobacterial transcriptional landscape soon after phagocytosis, as supported, for example, by the induction of acid-responsive genes and those involved in utilization of alternative carbon sources, such as host-derived fatty acids and cholesterol [14]–[18]. Carbon metabolism reprogramming, in particular, appears instrumental in mycobacteria adaptation to their host, and a number of studies identified major pathways used by M. tuberculosis to gather carbon during infection [19]–[24].

In addition to carbon, nitrogen is an essential component of biomolecules, such as amino acids, nucleotides and organic co-factors. Although several studies provided insight into the regulation mechanisms of the central nitrogen metabolism in M. tuberculosis, showing in particular the key role of the glutamine synthetase GlnA1 and its regulator GlnE in this process [25]–[29], the mechanisms by which nitrogen is acquired by the bacillus, and the main nitrogen sources used during infection remain poorly characterized. In this context, we recently reported that M. tuberculosis employs the membrane transporter AnsP1/Rv2127 to capture aspartate and exploit this amino acid species as a nitrogen source during infection [30], [31]. Here we further report that the AnsP1 homologue AnsP2 (AroP2/Rv0346c), a predicted asparagine transporter, and that AnsA (Rv1538c), a predicted asparaginase [32], allow asparagine uptake and deamination, respectively. The hydrolysis of asparagine in turn allows M. tuberculosis to assimilate nitrogen into downstream metabolites such as glutamate and glutamine. In parallel, this system of asparagine acquisition supports the in vitro mycobacterial growth in acidic conditions through ammonia release and pH buffering. Finally, we provide evidence that AnsA is released into the M. tuberculosis culture filtrate in vitro and within the mycobacterial phagosome. Thus AnsA is important for phagosome acidification arrest and intracellular survival of the pathogen inside macrophages, ultimately serving as a virulence factor. Collectively, these results provide compelling evidence that asparagine is an important additional source of nitrogen for M. tuberculosis during host colonization, and identify AnsA and the asparagine transport system as potential novel targets to be considered for therapeutic purposes.

Results

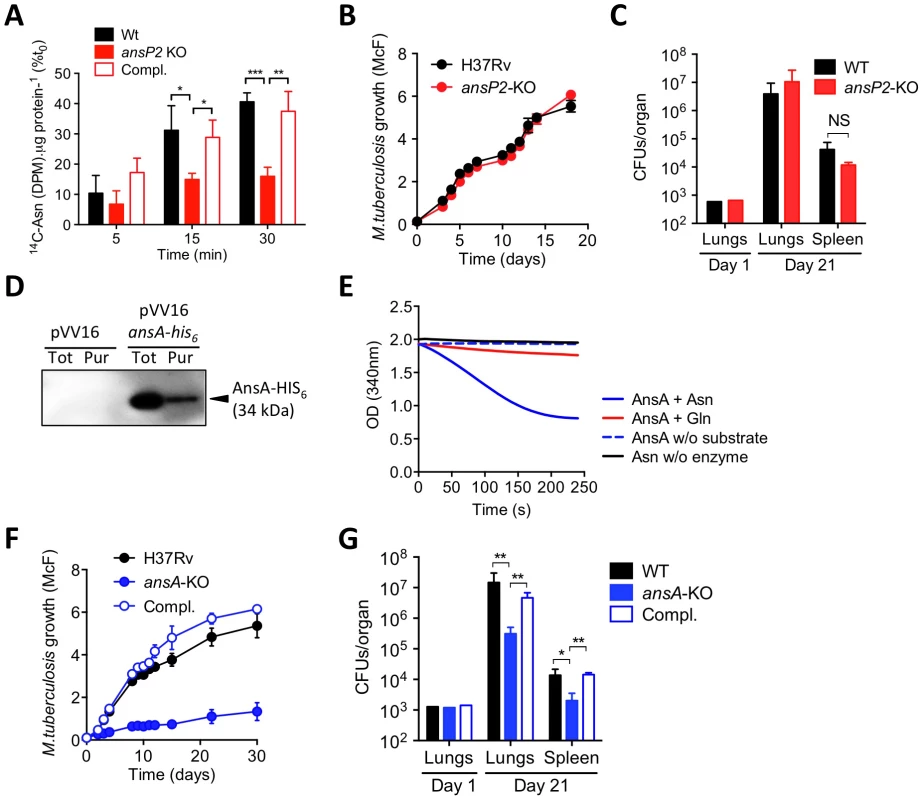

Asparagine catabolism plays a role in M. tuberculosis virulence

Because asparagine is known to be one of the best nitrogen sources used by M. tuberculosis in vitro [33], [34], we reasoned that the pathogen may have a transport system in place to scavenge this amino acid from its host. Among putative transporters, AnsP2/Rv0346c became an obvious candidate based on its high primary sequence identity (58%) with the Salmonella enterica asparagine transporter AnsP [35]. Moreover, ansP2 expression is markedly induced in M. tuberculosis in the lungs of patients with TB, which may reflect an important role for this putative transporter in a natural setting [36]. In order to evaluate whether AnsP2 transports asparagine, we first performed a 14C-asparagine uptake experiment with wild-type M. tuberculosis H37Rv and an ansP2-deficient mutant strain that we generated by recombineering [30], [37]. In agreement with the functional annotation of AnsP2, we found asparagine transport was partially impaired in the mutant as compared to its wild-type counterpart (Fig. 1A). This phenotype was reversed upon genetic complementation of the mutant strain with an integrative cosmid harboring the ansP2 gene region (Fig. 1A), thus demonstrating the implication of AnsP2 in asparagine uptake. Based on these results, we hypothesized the ansP2-KO mutant should be affected in its ability to grow in the presence of asparagine as sole nitrogen source. Surprisingly, we found the mutant multiplied equally to the wild-type strain under this condition (Fig. 1B), indicating the reduced amount of asparagine imported by the mutant strain (Fig. 1A) was nevertheless sufficient to promote bacterial growth. Moreover, the ansP2-KO mutant was not attenuated in immune-competent mice (Fig. 1C). Altogether, while these results identify AnsP2 as an asparagine transporter in M. tuberculosis, they also allude to the presence of one or more additional yet to be identified transporter(s) responsible for the uptake of this amino acid species.

Fig. 1. The function and in vivo relevance of AnsP2 and AnsA in asparagine utilization in M. tuberculosis.

(A) U-14C-Asn uptake assay with M. tuberculosis H37Rv, the ansP2-KO mutant and its complemented strains (Compl.). Bacteria previously grown in 7H9 with 5 mM Asn, were harvested and resuspended in an uptake buffer containing a mix of 14C-labeled and non-labeled asparagine to obtain a final concentration of 20 µM asparagine. Bacteria were incubated at 37°C and samples were removed and bacteria-associated 14C radioactivity was quantified at the indicated time points. Data are expressed as the percentage of the number of disintegrations per minute (DPM) per total protein concentration (14C-Asn (DPM). µg protein−1), as compared to the values obtained at t0. (B) Growth of M. tuberculosis H37Rv and the ansP2-KO mutant strain in the presence of asparagine as sole nitrogen source. (C) C57BL/6 mice were infected intranasally with 1,000 CFUs M. tuberculosis wild type (H37Rv) or the ansP2-KO mutant. Three weeks later, lungs and spleen were recovered, homogenized and plated onto agar for CFU scoring. (D) Western blotting analysis of total protein extracts (Tot) or a Ni-NTA purified fraction (Pur) from M. smegmatis containing a pVV16 control plasmid (pVV16) or an ansA-his6 cassette cloned into pVV16 (pVV16 ansA-his6), using an anti-HIS6 monoclonal antibody. 1 µg of proteins were loaded in the “Tot” lanes, 0.5 µg of proteins were loaded in the “Pur” lanes. The expected molecular weight of recombinant AnsA-HIS6 fusion protein is of 34 kDa. (E) Asparaginase activity, as monitored by NADPH disappearance at OD340 (see Materials & Methods), of recombinant AnsA in the presence of asparagine (Asn) or glutamine (Gln). Control reactions lack (w/o) substrate or enzyme. (F) Growth of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, the ansA-KO mutant strain, and the ansA-KO complemented strain (Compl.) in minimal medium containing 5 mM asparagine as sole nitrogen source. (G) C57BL/6 mice were infected intranasally with 1,000 CFUs M. tuberculosis wild type (H37Rv), the ansA-KO mutant or its complemented strain (Compl.). Three weeks later, lungs and spleen were recovered, homogenized and plated onto agar for CFU scoring. All data are representative of at least two independent experiments. In (A), (C), (F) and (G), data represent mean±s.d. of triplicate samples and were analyzed using the Student's t test; *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. NS, not significant. Once asparagine is scavenged by the bacillus, we inferred it must undergo an assimilation process carried out by asparaginases, which hydrolyze this amino acid into aspartate and ammonia. Indeed, asparaginase activity was described several decades ago in lysates of various mycobacteria species, including M. tuberculosis [38], [39]. In the M. tuberculosis genome, a unique gene by the name of ansA is predicted to encode an asparaginase [32], and whose homologue was recently proven to hydrolyze asparagine in vitro in the closely related attenuated vaccine strain Mycobacterium bovis BCG [40]. Building upon these observations, we decided to produce and purify a recombinant HIS6-tagged version of AnsA in the M. tuberculosis-related fast grower Mycobacterium smegmatis in order to evaluate its asparaginase activity. The recombinant enzyme, with a predicted molecular weight of 34 kDa, was immuno-detected both in total bacterial lysate and after purification on a nickel column using an appropriate anti-HIS6 antibody (Fig. 1D). The ability of recombinant AnsA to hydrolyze asparagine was then assessed in a coupled enzymatic reaction in which the ammonia generated after asparagine deamination is used in a secondary reaction to form glutamate via a NADPH-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase. Disappearance of NADPH was followed as a marker of asparagine consumption in the reaction mixture, and revealed that AnsA mediates asparagine hydrolysis (Fig. 1E). By contrast, we found AnsA could not hydrolyze glutamine (Fig. 1E), indicating the enzyme is void of any significant glutaminase activity frequently associated to asparaginases [30], [41].

Since AnsA is the only predicted asparaginase in M. tuberculosis [32], as opposed to in other bacteria such as E. coli [42], we deduced that the genetic inactivation of AnsA should have a significant impact on asparagine metabolism in this species. Given that ansA might be essential in M. tuberculosis [24], we designed a conditional inactivation strategy to knock this gene out [43] (Figure S1). Unexpectedly, we could readily generate a viable ansA-KO mutant strain, revealing ansA is not essential in M. tuberculosis, as suggested by other studies [44], [45]. The apparent contradiction between the observed viability of the mutant and the essentiality predicted by Griffin et al. [24] can be reconciled when considering that for the high density transposon insertion screen asparagine was used as the main nitrogen source in the culture medium; it is most likely that under these conditions an ansA-KO mutant is impaired in growth. Consistent with this assumption, and with the observed enzymatic activity of AnsA in vitro, we found the growth of the ansA-KO mutant was impaired, although not fully abolished, when asparagine was provided as sole nitrogen donor (Fig. 1F). It is likely that the remaining minimal growth of the mutant observed under this condition is due to residual asparagine deamination mediated by other yet to be identified amidases present in M. tuberculosis. As a control, the ansA-KO mutant replicated equally to the wild-type strain in the presence of another nitrogen source, such as glutamate (Figure S2), suggesting that ansA inactivation does not lead to general growth defects. Equally important, we found the ansA-KO mutant was impaired in host tissue colonization (Fig. 1G), thus suggesting a role for asparagine catabolism in M. tuberculosis virulence.

AnsP2 and AnsA are involved in nitrogen incorporation from asparagine in M. tuberculosis

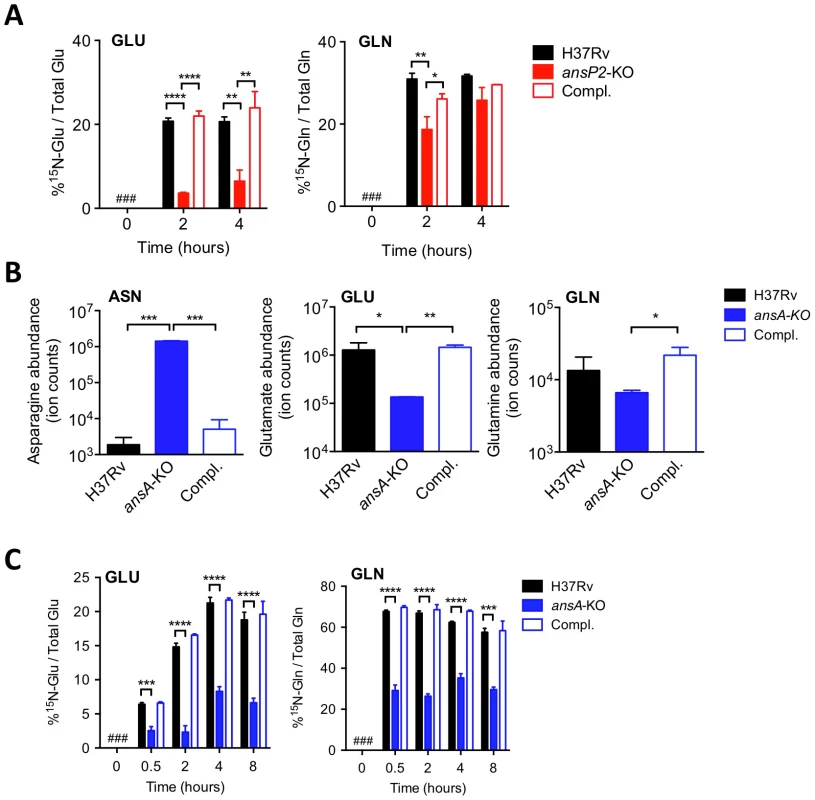

The results above suggested M. tuberculosis exploits asparagine from host tissues during infection to support growth. In agreement with previous studies reporting asparagine is a preferred source of nitrogen in M. tuberculosis [33], [34], we found this amino acid does not support mycobacterial growth when provided as sole carbon and energy source (Figure S3). To further understand the role of asparagine assimilation in M. tuberculosis, we used targeted metabolomics to follow nitrogen incorporation in the ansP2 - and ansA-KO mutants during growth on 15N2-labeled asparagine. As compared to wild-type M. tuberculosis, we found the ansP2-KO mutant was impaired in nitrogen incorporation from asparagine into other amino acids, such as glutamate and glutamine, which serve as initial nitrogen providers in the central nitrogen metabolism; this phenotype was reversed upon genetic complementation with a functional ansP2 allele (Fig. 2A). Strikingly, total asparagine content of the ansA-KO strain at the steady state in a medium containing asparagine as sole nitrogen provider was found ∼1,000-fold higher than in its wild-type and complemented counterparts (Fig. 2B), a likely consequence arising from the impaired asparagine catabolism in the mutant. In line with this hypothesis, the amounts of total (Fig. 2B), as well as newly synthetized (Fig. 2C), glutamate and glutamine were reduced in the mutant strain, further indicating a clear impairment of nitrogen incorporation from asparagine into downstream metabolites in the absence of AnsA. Of notice, nitrogen assimilation from asparagine was not completely abolished in the ansA-KO mutant, and this phenotype paralleled the residual growth of the mutant in the presence of asparagine reported above (Fig. 1F). Altogether, these results reveal that asparagine-derived nitrogen is fully assimilated in M. tuberculosis, and that AnsP2 and AnsA are involved in this process.

Fig. 2. AnsP2 and AnsA are involved in nitrogen incorporation from asparagine in M. tuberculosis.

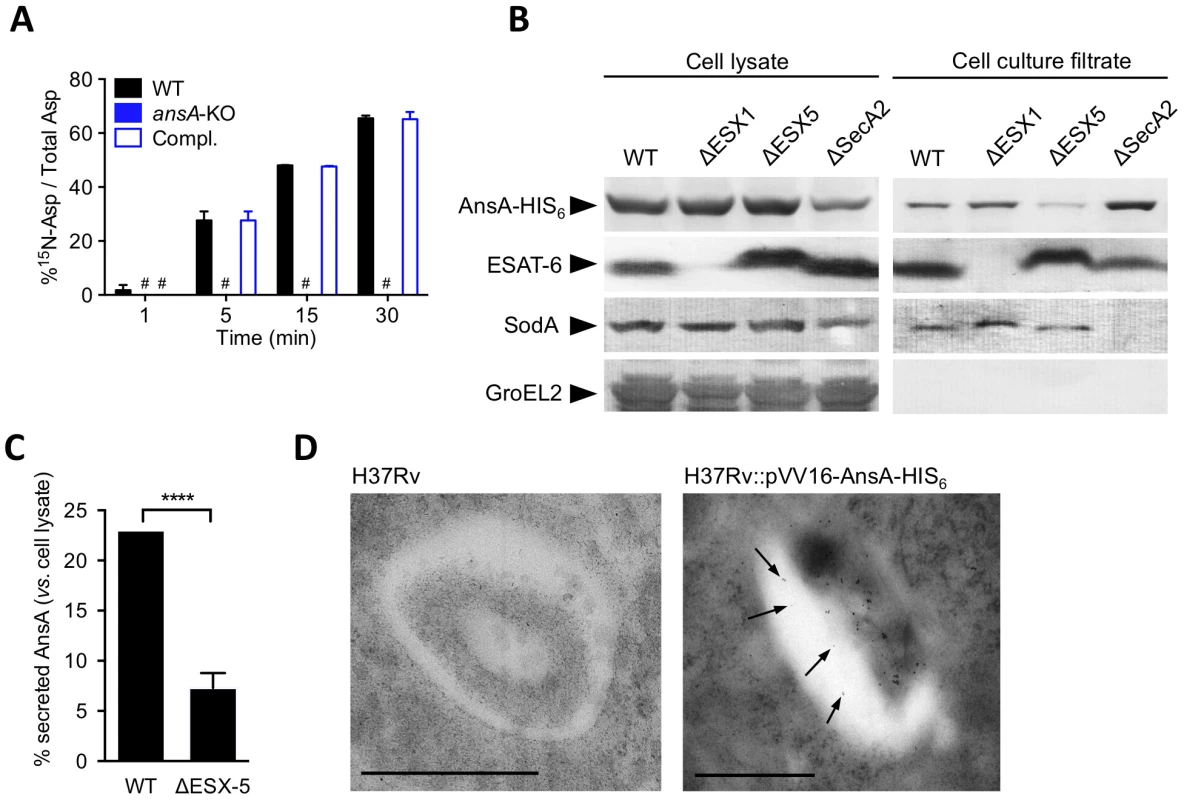

(A) Frequency of 15N-glutamate (GLU) and 15N-glutamine (GLN) detected in the presence of U-15N-Asn (2 mM) in M. tuberculosis wild type (H37Rv), the ansP2-KO mutant and its complemented strain (Compl.). (B) Total asparagine (ASN), glutamate (GLU) and glutamine (GLN) ion counts in M. tuberculosis wild type (H37Rv), the ansA-KO mutant and its complemented strain (Compl.). (C) Frequency of 15N-glutamate (GLU) and 15N-glutamine (GLN) detected in M. tuberculosis wild type (H37Rv), the ansA-KO mutant and its complemented strain (Compl.) cultivated in minimal medium in the presence of 2 mM 15N-asparagine as sole nitrogen source. #, not detected. Data represent mean±s.d. of triplicate samples, are representative of two independent experiments, and were analyzed using the Student's t test; *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001. Asparagine catabolism in M. tuberculosis mediates resistance to acid stress and intracellular survival

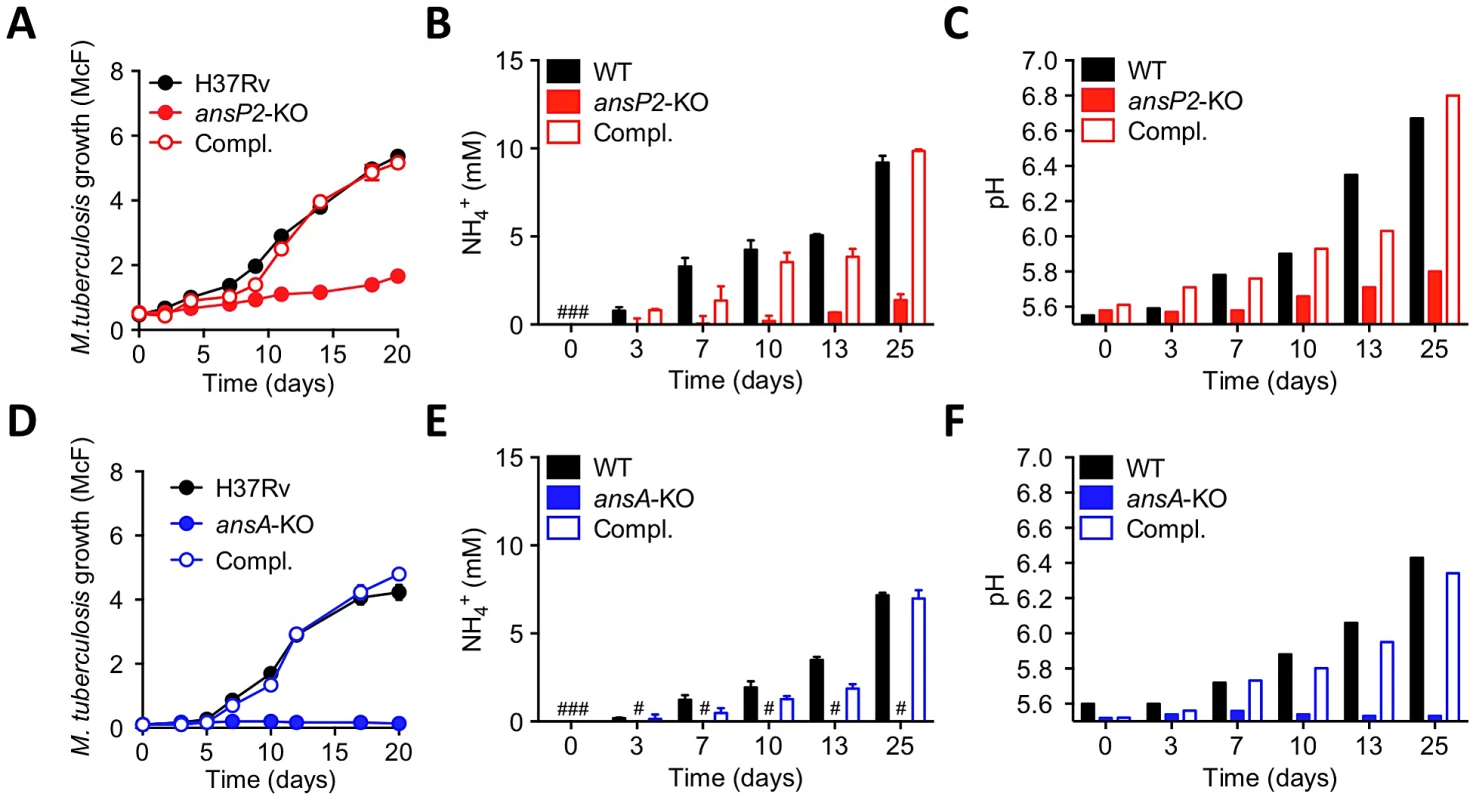

A recent study reported asparagine is the best among the few amino acids that can support M. tuberculosis resistance to acid stress [46]. This feature most likely relies on the specific release of the weak base ammonia and subsequent pH buffering that accompany asparagine consumption [46]. Building upon this observation, we found the growth of the ansP2-KO strain, in the presence of asparagine as sole nitrogen provider, was greatly reduced at pH 5.5 as compared to the wild-type and complemented strains (Fig. 3A). This phenotype correlated with a markedly diminished capacity of the mutant to secrete ammonia and neutralize pH of the culture medium (Fig. 3B,C). In the same conditions, the phenotypes of the ansA-KO mutant were even more pronounced. Indeed, mycobacterial growth, asparagine-mediated ammonia secretion and pH buffering were totally abolished in the absence of AnsA (Fig. 3D–F). In line with these results, nitrogen assimilation from asparagine into glutamate and glutamine was fully abrogated in the ansA-KO mutant at acidic pH (Figure S4A). In order to rule out the possibility that the observed defect in ammonia secretion and pH buffering in the ansA-KO mutant was due to the growth defect of the mutant at acidic pH, we repeated the experiment reported in Fig. 3D–F using a more dense bacterial suspension and a shorter time course, with and without asparagine as sole nitrogen source. We resuspended bacteria at an OD600 of 1.5 in acidic culture medium and measured ammonia secretion and pH at 0, 2, 4, 18 and 24 hours after inoculation. In these conditions, the ansA-KO mutant was still completely impaired in ammonia secretion and pH buffering, as compared to its wild-type and complemented counterparts (Figure S4B–D). Collectively, these results unequivocally demonstrate that, in particular in an acidic environment, asparagine catabolism partially requires AnsP2 and is strictly dependent on AnsA to sustain M. tuberculosis growth in the presence of asparagine. These results also underline that asparagine hydrolysis, ammonia release, pH buffering and growth in acidic conditions are intrinsically linked molecular events in M. tuberculosis.

Fig. 3. Varied requirement of AnsP2 and AnsA for M. tuberculosis resistance to acid stress in vitro.

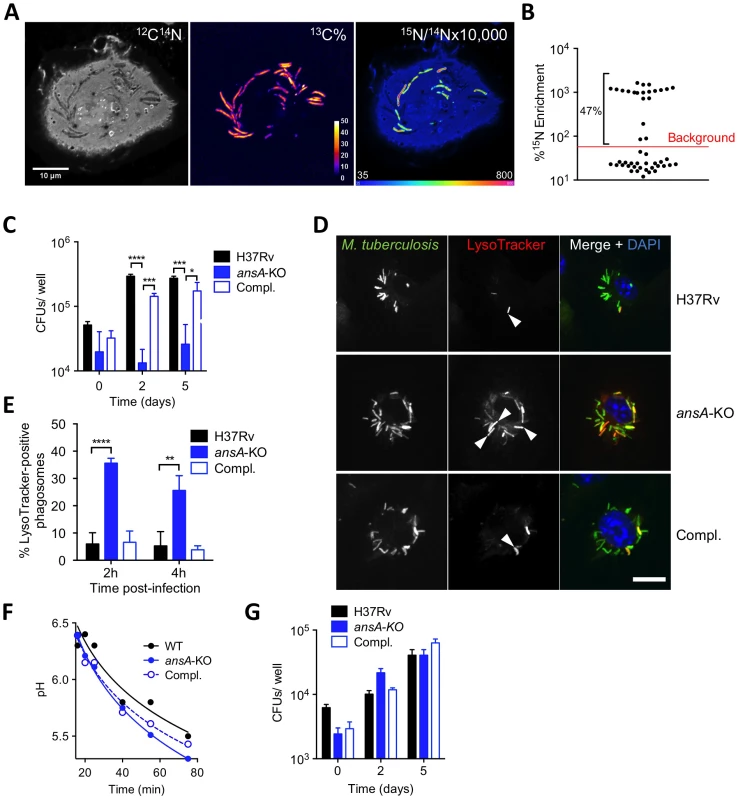

(A–C) Growth (A), culture supernatant NH4+ concentration (B) and pH (C) of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, the ansP2-KO mutant strain, or the ansP2-KO complemented strain (Compl.) at acidic pH (5.5) in the presence of asparagine as sole nitrogen source. (D–F) Growth (D), culture supernatant NH4+ concentration (E) and pH (F) of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, the ansA-KO mutant strain, or the ansA-KO complemented strain (Compl.) at acidic pH (5.5) in the presence of asparagine as sole nitrogen source. Data represent mean±s.d. of triplicate samples and are representative of at least three independent experiments. #, not detected. We next evaluated to what extent the sensitivity of our mutants to acid stress may impact their ability to survive in an acidic phagosome and to parasitize host macrophages. We first assessed whether asparagine can access the mycobacterial phagosome inside infected cells. To this aim, we employed secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS), a method that allows the visualization of isotopic labeling and metabolites in biological samples with sub-micrometer resolution. We infected mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) with 13C-labelled M. tuberculosis H37Rv for 20 hours, and pulsed the infected cells with 15N-asparagine for 4 h before SIMS analysis. Our data clearly indicate that exogenously provided asparagine accumulates in the mycobacterial phagosome (in ≈50% of them in Fig. 4A), as compared to the host cell cytosol (Fig. 4A,B). Regarding mycobacterial growth, the ansP2-KO mutant was found not affected in its ability to survive in IFNγ - and LPS-activated BMMs, in which the pH of the mycobacterial phagosome readily drops below 5.5 ([8]; Figure S5). This result correlates with the remaining amount of ammonia secretion observed in this mutant (Fig. 3B). On the other hand, the intracellular survival of the ansA-KO strain was strongly impaired in activated BMMs (Fig. 4C). Strikingly, labeling of infected cells with the acidotropic dye LysoTracker and phagosomal pH measurement at early time-points after infection revealed that the phagosomes harboring the ansA-KO mutant acidified more readily compared to those containing the wild type or complemented strains (Fig. 4D–F). In line with this finding, we also found that V-ATPase, the proton pump responsible for phagosomal acidification, accumulated in larger amounts in phagosomes containing the ansA-KO mutant than in vacuoles containing its wild-type or complemented counterparts (Figure S6A,B). Consistent with these observations, treatment of BMMs with bafilomycin A1, a specific V-ATPase inhibitor preventing phagosome acidification [47], restored the ability of the ansA-KO mutant to multiply intracellularly (Fig. 4G). Whether the attenuation phenotype of the ansA-KO mutant inside macrophages is a cause or a consequence of impaired asparagine hydrolysis and subsequent reduced ammonia production and pH buffering capacity is difficult to delineate, as these molecular events are intrinsically linked one to each other; nevertheless, our results clearly establish AnsA is required for intracellular survival of M. tuberculosis.

Fig. 4. Requirement of AnsP2 and AnsA for M. tuberculosis resistance to acid in host macrophages.

(A,B) Exogenous asparagine accumulates in the mycobacterial phagosome. (A) Images from a representative infected cell showing the locations of M. tuberculosis (13C% map, middle) and 15N-asparagine uptake (15N/14N ratio map, right), as derived from secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) analysis of M. tuberculosis H37Rv-infected mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs). 13C-labeled bacteria were used to infect BMMs at a multiplicity of infection of 10 bacteria per cell. At 20 h post-infection, infected cells were pulsed for 4 h with 5 mM 15N1 (amine)-asparagine, and 13C and 15N isotope proportions were analyzed. (B) Quantification of 15N isotope enrichment in surface areas chosen in the intracellular 13C-labeled bacteria; “background” indicates the level of enrichment measured in the host cell cytoplasm. For more details about the technique, see [30]. (C) IFNγ- and LPS-activated BMMs were infected with M. tuberculosis wild type (H37Rv), the ansA-KO mutant or its complemented strain (Compl.) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 bacterium/cell for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were washed and further incubated with fresh medium for 0, 2 or 5 days. At the indicated time-points, cells lysates were plated for CFU scoring. (D) Confocal microscopy analysis of activated BMMs infected for 1 h with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled M. tuberculosis wild type (H37Rv), the ansA-KO mutant or its complemented strain (Compl.) (green), and stained with LysoTracker Red DND-99 (red) and DAPI (blue) to visualize nuclei. Bar represents 10 µm. Arrowheads point to example phagosomes considered positive for LysoTracker staining. (E) Quantification of LysoTracker-positive phagosomes in samples prepared as in (h) 2 or 4 h after infection. Colocalisation events were recorded in ≈300 phagosomes observed in ≈10 different fields. (F) Phagosomal pH measured by flow cytometry in activated BMMs infected with M. tuberculosis wild type (H37Rv), the ansA-KO mutant or its complemented counterpart (Compl.). (G) Cells were pre-incubated with 100 nM bafilomycin A1 for 1 h, infected as in (C) and bafilomycin A1 was removed after 24 h. All data are representative of at least three independent experiments. In (C), (E) and (G), data represent mean±s.d. of triplicate samples, and were analyzed using the Student's t test. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001. AnsA is a secreted asparaginase in M. tuberculosis

Strikingly, M. tuberculosis AnsA is more similar to the periplasmic (type II) asparaginase AnsB than to the cytosolic (type I) enzyme AnsA from E. coli (35% vs. 28% identity, respectively) [42], suggesting AnsA might be a secreted asparaginase in M. tuberculosis. We addressed this important issue using different and complementary approaches: i) quantification of asparaginase activity in cell-free culture supernatants by mass spectrometry (MS); ii) immune-detection of AnsA-HIS6 fusion protein in culture filtrates from recombinant M. tuberculosis strains; iii) analysis of AnsA secretion in phagosomes of M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages by electron microscopy (EM). We incubated bacterial culture supernatants from the wild type, ansA-KO and complemented strains with 15N-asparagine and monitored 15N-aspartate production by MS. Our data revealed that an asparaginase activity could be detected in the M. tuberculosis culture supernatant, unless ansA was genetically inactivated (Fig. 5A). Consistently, we immuno-detected the AnsA-HIS6 fusion protein in culture filtrate, as well as in the cell pellet, of recombinant M. tuberculosis by Western blotting (Fig. 5B). As expected, the strictly cytosolic protein GroEL2 was detected in the cell pellet only, indicating the absence of bacterial lysis. Because AnsA does not contain a classical signal peptidase I cleavage site in its N-terminal end, we investigated whether alternative secretion systems, such as the SecA2 secretion system [48], [49] or the ESX-1 and ESX-5 type VII secretion systems [50] might be involved in AnsA secretion. To this aim, we transformed ESX-1, ESX-5 and SecA2-KO mutants with the AnsA-HIS6 fusion-encoding plasmid, purified the culture filtrate from exponentially growing cultures, and immuno-detected the fusion protein using the anti-HIS6 antibody. Our data indicate that AnsA secretion is independent of SecA2 and ESX-1 (Fig. 5B). As a control, the SecA2-dependent protein SodA was not detected in the supernatant of the SecA2-KO strain. Surprisingly, secretion of AnsA was impaired in the ESX-5 mutant (Fig. 5B,C), indicating the involvement of this type VII secretion system in the secretion of the enzyme. In order to evaluate whether AnsA is also secreted in the phagosomal lumen inside macrophages, we used EM and Ni-NTA-Nanogold to detect AnsA-HIS6 in ultrathin sections of cells infected with M. tuberculosis carrying or not the AnsA-HIS6 fusion-encoding genetic construct. Gold particles were detected in the phagosomal lumen, strongly suggesting AnsA is also secreted in host cells during infection (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5. In vitro expression and localization of recombinant AnsA-His6 in M. tuberculosis wild-type and ESX-1, ESX-5 or SecA2 mutant strains.

(A) Asparaginase activity in the supernatant of M. tuberculosis ansA-KO mutant and its wild-type and complemented counterparts. Fifty mL of cultures (OD600≈0.5) were concentrated 50 times. The concentrates were incubated with 15N1 (amine)-asparagine at 37°C; at the indicated time points, the reaction mixtures were mixed with an equal volume of acetonitrile:methanol:water (2∶2∶1) and analyzed by MS for the presence of 15N-aspartate. (B) Expression and secretion of AnsA-His6 in M. tuberculosis wild-type and ΔESX-1 [63], ΔESX-5 [62], ΔSecA2 (Bottai et al. unpublished data) mutants. Fifteen µg of total cell lysates or culture filtrate proteins from the different mycobacterial strains were subjected to SDS-PAGE and tested in Western blotting by using a mouse anti-His6 monoclonal antibody. As control, samples were tested with the anti-ESAT-6 and anti-SodA monoclonal antibodies. Preparations were also tested with the anti-GroEL2 antibody, which was used for lysis control. As expected, cell lysates and cell culture filtrates from all M. tuberculosis strains transformed with the empty vector p-VV16 were negative when tested with the anti-His6 monoclonal antibody (data not shown). (C) Quantification of the relative expression of AnsA-HIS6 in the culture filtrate, as compared to in the cell pellet, in the WT and ESX-5-KO strains. Data represent mean±s.d. of triplicate samples, and were analyzed using the Student's t test. ****, P<0.0001. (D) Ni-NTA-Nanogold detection of AnsA-HIS6 by electron microscopy in ultrathin sections of M. tuberculosis-infected BMMs. Bar indicates 0.5 µm; arrowheads indicate gold particles in the phagosomal lumen. Collectively, this study puts forward an acquisition system for asparagine that not only protects against phagosomal acidification, but also serves to assimilate nitrogen from this amino acid species, with a central role for the asparaginase AnsA in enhancing the fitness of M. tuberculosis during host colonization.

Discussion

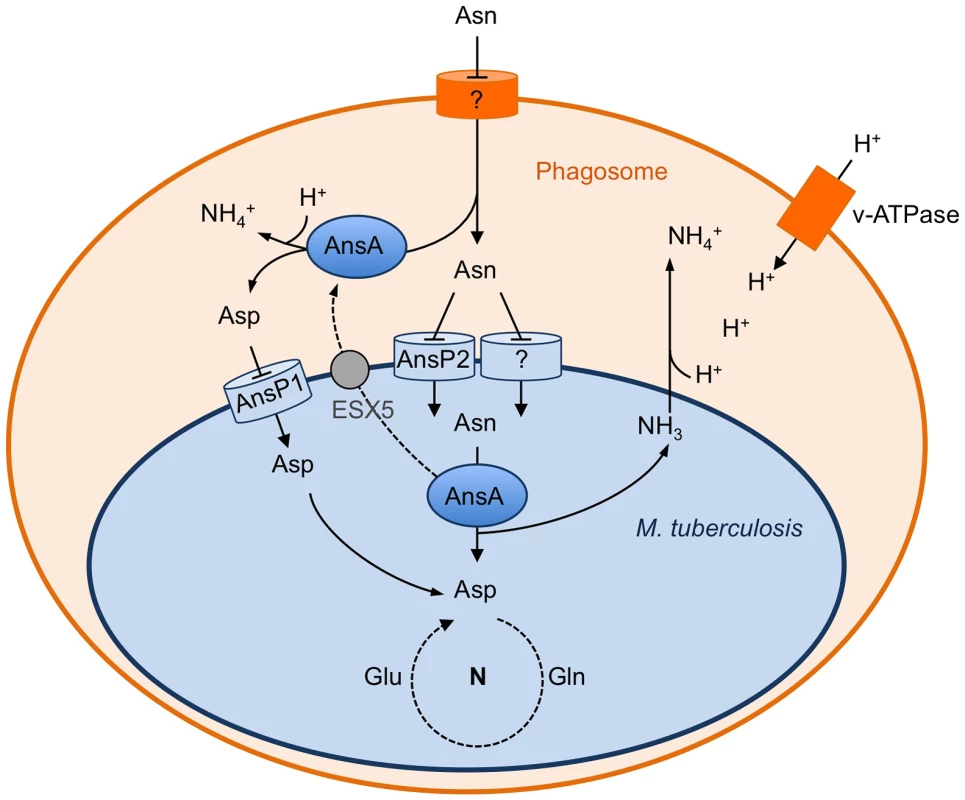

Identifying the nutrients used by M. tuberculosis to assimilate essential elements, such as carbon and nitrogen, is key to understanding host-pathogen interactions in TB. In this context, we recently reported that aspartate is a key nitrogen source used by M. tuberculosis during infection [30], [31]. Here we further show that asparagine can serve as an additional source of nitrogen for the pathogen through transport by the amino acid permease AnsP2, and subsequent hydrolysis by the asparaginase AnsA (Fig. 6). Furthermore, our results establish a unique link between mycobacterial physiology and virulence since we show AnsA has a dual function in both nitrogen assimilation and in protection against acid stress in vitro and inside host cells (Fig. 4). Our results are most likely relevant from a physiological viewpoint since asparagine is present at 50–60 µM in the human plasma [51], and is 2 - to 4-fold more concentrated in white blood cells [29], [51], [52]. In addition, we further show here that asparagine accumulates in the mycobacterial vacuole inside infected macrophages. Altogether, these observations indicate that asparagine is most likely readily accessible to M. tuberculosis during infection in vivo.

Fig. 6. Schematic representation of the role of asparagine catabolism in nitrogen incorporation, resistance to acid and intracellular survival.

Within macrophages, asparagine enters the M. tuberculosis phagosome through an unknown mechanism. Asparagine is captured by M. tuberculosis through AnsP2 and one or more other yet to be identified transporter(s), and hydrolyzed by cytosolic AnsA resulting in nitrogen assimilation into glutamine and glutamate, and release of ammonia. AnsA is secreted in the lumen of the phagosome through, at least in part, an ESX-5-dependent mechanism. AnsA can also hydrolyze asparagine in the lumen of the phagosome, resulting in the production of aspartate and ammonia. Aspartate is imported by AnsP1 [30] for nitrogen assimilation. In the phagosomal lumen, ammonia reacts with protons transported by the V-ATPase to form ammonium ions allowing phagosomal pH buffering. Regarding asparagine uptake in M. tuberculosis, it is clear from the present study that one or more transporter(s) complement the function of AnsP2, since the ansP2-KO mutant was only partially impaired in nitrogen incorporation from asparagine in vitro, and it was not attenuated inside host cells and in vivo. The AnsP2 paralogue AnsP1 (72% identity) is an obvious candidate to fulfill this function [32]. However, we previously reported that the M. tuberculosis ansP1-KO mutant grows and incorporates asparagine equally well, compared to the wild-type strain, when grown on asparagine as sole nitrogen source [30]. Furthermore, we found the ansP1-KO mutant transports asparagine to the same extent as the wild-type strain in vitro (data not shown). In addition to AnsP1, two other putative amino acid transporters, namely CycA/Rv1704c and GabP/Rv0522 [32], show some similarity with AnsP2 (38% and 34% identity, respectively) and may contribute to asparagine transport. The construction of multiple mutants inactivated in two or more of these candidates will be required in order to uncover the complete asparagine transport machinery in M. tuberculosis, which will be the purpose of future study. Nevertheless, our results identify AnsP2 as an important asparagine transporter in M. tuberculosis, in particular at acidic pH.

Beyond the complexity of asparagine uptake, further efforts should be allocated to deciphering the exact contribution of AnsA to mycobacterial virulence. Whether attenuation of the ansA-KO mutant in vivo is due to its inability to counteract phagosome acidification and/or to incorporate nitrogen from asparagine resulting in an impaired fitness will require careful investigation; however such an investigation will be made difficult by the intrinsically linked nature of the asparagine hydrolysis, ammonia release and pH buffering phenomenons in M. tuberculosis, as revealed by our study and in a previous report [46]. In this context, it is worth noticing that, like AnsA, another mycobacterial hydrolase, namely the urease, was proposed to play a part both in nitrogen acquisition and in counteracting phagosome acidification through hydrolysis of urea and subsequent release of ammonia [53]–[55]. However, unlike for AnsA, mycobacterial mutants deficient in urease production are barely impaired in intracellular survival and their capacity to persist or multiply in vivo is not affected [53]–[55].

Finally, a role for asparaginase in virulence of other bacterial pathogens, including Helicobacter pylori, Campylobacter jejuni and Salmonella typhimurium, has been reported [56]–[60]. In these species, asparaginase is secreted into the periplasm and is thought to contribute to host colonization either through direct microbial asparagine utilization in vivo [56], or through indirect starvation-mediated exhaustion of immune cells following asparagine depletion in infected tissues [57]–[60]. The M. tuberculosis asparaginase AnsA does not contain any detectable signal sequence in its N-terminal end. Yet, we show that this enzyme is secreted in vitro and inside infected macrophages through an alternative SecA2 - and ESX-1-independent pathway that relies, at least partially, on the ESX-5 type VII secretion system [50]. The exact mechanism of AnsA secretion, and the extent to which ESX-5 is involved in this process, remain to be further delineated; however it is worth noticing that AnsA contains two sequences resembling the ESX secretion signal consensus YXXXD/E: Y207PGSD211 and Y282GPGHD287 [61]. Whether these motifs play a part in AnsA secretion will need to be understood; equally important will be to understand the role of AnsA beyond nitrogen supply to the pathogen, possibly in asparagine depletion and immune cell exhaustion, as reported for other pathogens [57].

In conclusion, our study provides yet another example of the tight connections forged throughout evolution between physiology and virulence in microbial pathogens. It also highlights the need to further explore the expanding field of metabolism and infection in order to accelerate the identification and validation of novel strategies to combat infections and disease.

Materials & Methods

Mycobacteria and culture conditions

Mycobacteria were grown at 37°C in Middlebrook 7H9 medium (Difco) supplemented with 10% albumin-dextrose-catalase (ADC, Difco) and 0.05% Tween-80 (Sigma), or on Middlebrook 7H11 agar medium (Difco) supplemented with 10% oleic acid-albumindextrose - catalase supplement (OADC, Difco). When required, kanamycin, hygromycin, streptomycin (50 µg/mL) or zeocin (25 µg/mL) were added to the culture media. The ESX-1 and ESX-5 mutants have been described previously [62], [63]. A SecA2 mutant carrying a kanamycin-inactivated copy of the secA2/rv1821 gene was constructed using a similar strategy based on the ts-SacB technology (Bottai et al. Unpublished data). For growth tests with asparagine as a carbon source, bacteria were grown in Sauton's modified medium (pH 6.5–7.0) containing, 0.5 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L MgSO4, 50 mM asparagine, 0.05% tyloxapol (Sigma) and supplemented with or without 10 g/L glycerol and 15 mM (NH4)2SO4. For growth tests with asparagine as sole nitrogen source, bacteria were grown in Sauton's modified medium containing 0.05% Tween-80, 0.5 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L MgSO4, 2 g/L citric acid, 10 g/L glycerol and 5 mM asparagine prepared in tap water and neutralized to pH 7.0 or pH 5.5 with NaOH before autoclaving. Cultures were performed in triplicate in glass tubes and bacterial growth was monitored measuring turbidity (in McFarland units) over time using a Densimat apparatus (BioMerieux).

Construction of ansP2-KO and ansA-KO mutants and complemented strains

The ansP2-KO mutant strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv containing a disrupted ansP2 (Rv0346c)::KanR allele was constructed by allelic exchange using recombineering [30], [37]. H37Rv:pJV53 was grown in 7H9-ADC-Tween 80 in the presence of hygromycin until mid-log phase and expression of the recombineering enzyme was induced by 0.2% acetamide (Sigma) overnight at 37°C. After induction, electrocompetent bacteria were prepared. Electroporation was performed with a linearized fragment of a kanamycin resistance cassette-interrupted ansP2 gene flanked with homologous regions (400–500 bp length). After 72 h incubation at 37°C, bacteria were plated onto 7H11-OADC agar medium in the presence of kanamycin. For the complementation of the ansP2-KO strain, we used the pYUB412-derived integrative cosmid I541, which contains a hygromycin resistance cassette and harbors a fragment encompassing the region 398 to 432 kbp in the genome of M. tuberculosis H37Rv. For the ansA-KO strain construction, a second copy of the ansA gene was first integrated in the chromosome of wild type H37Rv at the bacteriophage insertion site attL5. For this, we used the plasmid pGMCS-Puv15-ansA which contains the ansA gene under the control of the Psmyc promoter and a streptomycin resistance cassette[64]. After selection of streptomycin resistant clones, the original ansA gene was disrupted using a linearized digestion fragment of kanamycin resistance cassette-interrupted ansA gene flanked with homologous regions (450–600 bp length). The additional copy of ansA was then deleted by replacing pGMCS-Puv15-ansA with the plasmid pGMCZq17, which contains a zeocine resistance cassette. Selection of a zeocin resistant clone resulted in an ansA-KO strain and proved that ansA is not essential. For complementation of the ansA-KO strain, the pYUB412-derived integrative cosmid I16 encompassing the region 1,719 to 1,756 kbp in the genome of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, and containing a hygromycin resistance cassette was used.

14C-Asparagine uptake experiment

Asparagine uptake experiments were carried out as described elsewhere with minor modifications [46]. Briefly, bacteria were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 containing 0.05% Tween 80 and asparagine (5 mM) at 37°C. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation when an OD600∼0.5 was reached. Bacterial pellets were washed twice in uptake buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.9, 15 mM KCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.05% Tween 80] and resuspended in the same buffer. Radiolabeled 14C-asparagine (PerkinElmer) and non-labeled asparagine (Sigma) were mixed (3∶1) and added to 5 mL of cell suspensions to obtain a final concentration of 20 µM asparagine. The mixtures were incubated at 37°C and 250 µL of samples were removed at the indicated time points. Bacteria were collected on a 0.45 µm Spin-X centrifuge tube filter (Costar) by mixing with an equal volume of 10% paraformaldehyde (Polyscience, Inc) containing 0.1 M LiCl (Sigma). Filters radioactivity was determined in a liquid scintillation counter (Packard). The uptake rate was expressed in desintegration per minute (DPM) per total protein concentration (14C-Asn (DPM). µg protein-1).

Ammonium and pH measurement

Bacteria were grown in supplemented 7H9 with 0.05% Tween-80 until OD600∼1. 10 mL of cultures were removed and washed twice with DPBS and used for inoculation of 200 mL Sauton's modified medium containing 0.05% Tween-80, 0.5 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L MgSO4, 2 g/L citric acid, 10 g/L glycerol and 5 mM asparagine prepared in tap water and buffered to pH 5.5 with NaOH before autoclaving. Bacteria were incubated at 37°C and, at indicated time points, 1 mL of culture was removed and centrifuged at 1,300 rpm for 2 min to collect supernatants. To determine ammonium concentration, supernatants were diluted 4-fold in DPBS and 50 µL of diluted samples were mixed in a 96 plate with 50 µL of Nessler's reagent (Fluka) and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. 100 µL of NaOH were then added to stop the reaction prior to measurement of OD520 using a µQuant apparatus (BIO-TEK instruments, Inc). pH was measured directly in 1 mL of culture supernatant using a pH-meter.

Expression, purification and measure of enzymatic activity of recombinant HIS6-tagged AnsA

The ansA gene was cloned into a pVV16 vector allowing the constitutive expression of C-terminus HIS6-tagged fusion proteins under the control of a GroEL2 promoter and carrying kanamycin and hygromycin resistance cassettes. The pVV16 ansA-his6 vector was electroporated into the non-pathogenic fast-grower Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155 strain and clones containing pVV16 ansA-his6 were selected on solid medium containing kanamycin and hygromycin.

At OD600∼1,5, 15 mL of cultures were centrifuged and washed with DPBS and bacteria were resuspended in 1 mL of lysis buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4 pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazole and broken with glass beads (0.1–0.25 mm) for 10 min at 30 m/s using a Bead Beater apparatus (Retscher, BioBrock scientific). AnsA-HIS6 protein was purified from 600 µL of lysates using the Ni-NTA Spin kit (QIAGEN) and eluted in an elution buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl and 400 mM imidazole at pH 8. AnsA-HIS6 purified fraction was quantified using the Bradford method.

For enzymatic tests, we used the L-Asparagine/L-Glutamine/Ammonia Assay Kit (Megazyme) following manufacturer's recommendations and using asparagine or glutamine (final concentration 0.6 mM) as substrates. The buffer used in this assay contains glutamate dehydrogenase, NADPH and 2-oxoglutarate, so that enzymatic activities were measured by following the disappearance of NADPH along time as an indirect indication of asparagine deamination at 340 nm using a SAFAS Monaco mc2 spectrophotometer and the SAFAS SP 2000 software.

Preparation of culture filtrates and total lysates from M. tuberculosis strains and immunoblotting

The procedures were as previously described [62]. Immunoblot analyses were carried out with mouse monoclonal antibodies raised against EsxA (Hyb76-08, Antibodyshop, BioPorto Diagnostics) or SodA (NR-13810, clone CS-18, produced in vitro, received from BEI resources N°SOE76725), or with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the HIS6 tag (eBioscience). As control, culture supernatants were also analyzed by Western blot for the presence of GroEL2 (anti-GroEL2 monoclonal antibody, Colorado State University, NIH, NIAID contract N°AI75320).

Metabolite extraction experiments

Bacteria were cultivated to an OD600 of 1 in 7H9-0.05% Tween-80. Bacteria were centrifuged and resuspended in DPBS (3-fold concentration). 1 mL was transferred to a filter (Fisher) mounted on a filtration device (Fisher) and connected to a trap and vacuum line. Filters were transferred to a 7H10 based agar medium (Sigma) supplemented with asparagine (2 mM) or to solid media containing 0.5 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L MgSO4, 2 g/L citric acid, 10 g/L glycerol, aspartate (2 mM) and 1.5% agar (Invitrogen) prepared in tap water and neutralized to pH 6.5–7.0 with NaOH before autoclaving. Plates were incubated for 5 days at 37°C. Three filters were used per strain and time point. For labeling experiments, filters were transferred on equivalent plates where aspartate was replaced by 15N2-asparagine (2 mM, Sigma, Purity 98 atom % 15N) and incubated for 0.5, 2, 4 or 8 h at 37°C. At each time point, filters were plunged into 1 mL acetonitrile/methanol/water (2∶2∶1, v/v/v) mixture at −40°C. Bacteria were then broken by glass beads using a bead-beater (5 min at 30 m/s). After centrifugation, supernatants were collected and filtered through a Spin-X column 0.2 µm at 14,000 rpm for 15 min. Extracts were stored at −80°C before analysis.

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

Aqueous normal phase liquid chromatography was performed using an Agilent 1200 LC system equipped with a solvent degasser, binary pump, temperature-controlled auto-sampler (set at 4°C) and temperature-controlled column compartment (set at 20°C), containing a Cogent Diamond Hydride Type C silica column (150 mm×2.1 mm; dead volume 315 µl), from Microsolv Technology Corporation. Flow-rate of 0.4 ml/min was used. Elution of polar metabolites was carried out using gradient 3[65]. Briefly, solvent A consists in deionized water (Resistivity ∼ 18 MΩ cm), 0.2% acetic acid and solvent B consists in acetonitrile and 0.2% acetic acid, and the gradient as follows: 0 min 85% B; 0–2 min 85% B; 2–3 min to 80% B; 3–5 min 80% B; 5–6 min to 75% B; 6–7 min 75% B; 7–8 min to 70% B; 8–9 min 70% B; 9–10 min to 50% B; 10–11 min 50% B; 11–11.1 min to 20% B; 11.1–14 min hold 20% B. Accurate mass spectrometry was carried out using an Agilent Accurate Mass 6230 TOF apparatus. Dynamic mass axis calibration was achieved by continuous infusion, post-chromatography, of a reference mass solution using an isocratic pump connected to a multimode ionization source, operated in the positive-ion mode. ESI capillary and fragmentor voltages were set at 3,500 V and 100 V, respectively. The nebulizer pressure was set at 40 psi and the nitrogen drying gas flow rate was set at 10 L/min. The drying gas temperature was maintained at 250°C. The MS acquisition rate was 1.5 spectra/sec and m/z data ranging from 80-1,200 were stored. This instrument routinely enabled accurate mass spectral measurements with an error of less than 5 parts-per-million (ppm), mass resolution ranging from 10,000–25,000 over the m/z range of 121–955 atomic mass units, and a 100,000-fold dynamic range with picomolar sensitivity. Data were collected in the centroid mode in the 4 GHz (extended dynamic range) mode. Detected m/z were deemed to be identified metabolites on the basis of unique accurate mass-retention time identifiers for masses exhibiting the expected distribution of accompanying isotopomers (21035735). Typical variation in abundance for most of the metabolites stayed between 5 and 10% under these experimental conditions.

15N-labeling analysis

Under the experimental conditions described above, M+1 arising from 15N incorporation can be readily distinguished from M+1 arising from natural abundance 13C, therefore allowing direct monitoring of 15N labeling. The extent of 15N labeling for each metabolite was determined by dividing the summed peak height ion intensities of all 15N labeled species by the ion intensity of both labeled and unlabeled species, expressed in percent.

Macrophages & infection procedure

Bone marrow cells were flushed from the femurs and tibias of 6–8 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice, and cultured in Petri dishes (2.106 cells/dish) in RPMI 1640 GlutaMax (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Pan-Biotech) and 20 ng/mL macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF, Peprotech) at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. At day 6, cells were transferred to 24-well plastic plates (2.105 cells/well). For macrophage activation, cells were incubated with 10 ng/mL interferon gamma (IFNγ, Peprotech) and 5 ng/mL LPS (Invivogen) overnight prior to infection. Infection was performed in triplicate at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 bacterium per cell for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were then washed 2 times with DPBS before addition of fresh medium. At day 0, 2 and 5, cells were lysed in 0.01% Triton X-100 (Sigma), and serial dilutions of the lysates were plated onto 7H11-OADC agar medium for CFU scoring. For infection experiments using Bafilomycin A1 (Sigma), cells were pre-incubated 1 h with 100 nM bafilomycin A1 prior to infection and removed at 24 h post-infection.

Secondary ion mass spectrometry

SIMS analysis was carried out using a modified version of a previously described protocol [30]. Briefly, for 13C labeling, bacteria were grown in minimal medium containing 0.5 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L MgSO4, 15 mM NH4SO4, 10 g/L 13C glycerol supplemented with 0.05% tyloxapol (Sigma) and neutralized to pH 6.5–7.0 with NaOH before filtration. In order to overcome the difficulties encountered during the sample preparation stage in our previous experiments due to incomplete resin infiltration [30], in the present study cells were deposited directly on clean Silicon chips, and were infected and labeled. Macrophages were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 10 bacteria per cell with 13C labeled-bacteria for 4 hours. At 20 h post-infection, the culture medium was replaced by fresh RPMI containing 10% FCS and 5 mM 15N1 (amine)-asparagine. After 4 h at 37°C, cells were fixed with 4% PFA, 2.5% glutaraldehyde in a 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). The detailed analytical conditions for SIMS imaging were described previously [30]. Briefly, a NanoSIMS-50 Ion microprobe (CAMECA, Gennevilliers, France) operating in scanning mode was used [66]. A Cs+ primary ion beam steps over the surface of the sample and four secondary ion species (12C−, 13C−, 12C14N−, 12C15N−) were monitored simultaneously to create images of these selected ion species. The identification of bacteria location was highlighted by high 13C content while the asparagine uptake was revealed by 15N enrichment. Prior to image acquisition, the upper layer of the cells was eroded away using high density primary Cs+ ion bombardment until the underlying structures with 13C-labeled bacteria could be observed. Consequently, analysis of 15N enrichment could be performed. The image acquisition was then carried out using multiframe mode. The primary beam intensity was 1 pA with a typical probe size of 100 nm (distance between 16%–84% of peak intensity from a line scan) and the raster size ranges from 40 to 50 µm in order to image a whole cell with an image definition of 512×512 pixels. With a dwell time of 2 ms per pixel, up to 25 frames were acquired and the total analysis time was 3 hours. Image treatment was performed using ImageJ software [67]. First, multiframe images were properly aligned using CN− images as reference before a summed image was obtained for each ion species. A map of 13C atomic fraction was deduced from 12C− and 13C− images. In parallel, regions of interest were manually defined based on the 13C− map so as to outline individual bacterium for data extraction. For 15N/14N ratio quantification, a sample containing no labeled cells was used as working reference for adjusting the detectors. Finally, the 13C map, as well as the one for 15N/14N ratio, are displayed in Hue-Saturation-Intensity (HSI) mode. These HSI color images were generated using OpenMIMS, an ImageJ plugin developed by Claude Lechene's Laboratory (http://nrims.harvard.edu/software) [68]. Although the cellular structures were less visible using this method compared to the ones obtained with thin sections of resin-embedded cells, we have shown in the previous study [30] that the results were similar, either for 13C labeling, or for 15N enrichment.

Immuno-electron microscopy

Mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages infected with either the wild type strain of M. tuberculosis H37Rv or the recombinant strain over-expressing His-tagged AnsA were first fixed for 1 h at room temperature with a mixture of EM grade 2.5% paraformaldehyde (Euromedex) and 0.1% glutaraldehyde (Sigma) prepared in 0.1 M Na-cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2, containing 5 mM CaCl2, 5 mM MgCl2 and 0.1 M sucrose. Cells were then washed twice with the same buffer for 15 min each, once with the same buffer containing 50 mM NH4Cl for 15 min and once with the same buffer devoid of sucrose for 5 min. Cells were scraped off the culture dishes with a rubber policeman and concentrated in 1% agar prepared in the same buffer devoid of sucrose. Cells were then processed for embedding in Lowicryl HM20 using the PLT (progressive lowering of temperature) procedure [69]. High-resolution labeling of His-tagged AnsA was performed on thin sections (90 nm-thick) deposited onto carboned-coat nickel EM grids as previously described [70], [71]. Briefly, grids were sequentially floated on i) water for 5–10 min, ii) PBS-1% BSA for 5 min to block unspecific sites, iii) 5 nm Ni-NTA-Nanogold diluted 5-fold in PBS containing 0.5% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20 for 30 min, iv) 5 mM imidazole for 1 min, v) PBS for 3×1 min, and vi) distilled H2O for 2×5 min. All incubations were carried out at room temperature. Sections were either not stained or slightly stained for 30 sec with 1% uranyl acetate in distilled water, and observed under the electron microscope (Zeiss 912).

Confocal microscopy & flow cytometry

Murine macrophages were prepared as described above, plated after 6 days of differentiation on cover glasses at 2.105 cells/well in a 24-well plates, and activated with IFNγ (10 ng/mL) and LPS (5 ng/mL) overnight prior to infection. 10 mL of bacteria grown until OD600 of 1 in complete 7H9 were centrifuged for 7 min at 4,000 rpm, and washed two times with 20 mL DPBS. For bacteria labeling, pellets were suspended in 250 µL of Alexa Fluor 488 succinimidyl ester (Fisher) (1.5 µL Alexa Fluor 488 in 248.5 µL DPBS) or, for intra-phagosomal pH measurement, in 250 µL Alexa Fluor 647-NHS ester and 5-carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (Fisher) (1.5 µL each in 247 µL DPBS), and incubated at room temperature for 45 min. Bacteria were then washed two times with 20 mL DPBS and disaggregated manually for 30 sec with sterile glass beads. Bacteria were then resuspended in 7 mL of complete RPMI and centrifuged for 5 min at 1,200 rpm to remove aggregates. The OD600 of bacterial suspensions was then measured to determine the number of bacteria. Cells were infected at an MOI of 10 bacteria/cell for 1 h at 37°C and washed two times with DPBS before addition of fresh medium. After 1 and 3 h infection, cells were stained with 1 µM LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Molecular Probes) in complete RPMI for 1 h, washed with DPBS and fixed for 2 h with PFA 4% at room temperature. For immuno-detection of the V-ATPase, a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Synaptic Systems) was used at 1/100 dilution. Cover glasses were then mounted on glass slides using a VECTASHIELD Hardset Mounting Medium with DAPI (Cliniscience) and stored overnight at 4°C. Images were acquired with an LSM710 microscope equipped with a 40× 1.30 NA objective (Carl Zeiss, Inc.), recorded with Zen software (Carl Zeiss, Inc.), and analyzed with ImageJ software. All images were acquired with the same confocal microscope settings. The LysoTracker or V-ATPase signal intensity of every phagosome was measured with ImageJ software and the same threshold was applied for each condition to count the proportions of LysoTracker - or V-ATPase-positive phagosomes. See Figure 3 and S6 for examples of phagosomes that were considered positive for LysoTracker and V-ATPase, respectively. Quantification of LysoTracker - and V-ATPase-positive phagosomes was realized for ≈300 phagosomes per condition. For phagosomal pH measurement, we used a modified version of a protocol we previously described [72]. Briefly, macrophages were pulsed with the dual dye-coupled (Alexa Fluor 647, 5-Carboxyfluorescein) mycobacteria (MOI 50) for 15 min and washed 3 times with PBS. The cells were then incubated at 37°C for the indicated times and immediately analyzed by FACS, using a gating FSC/SSC selective for macrophages. The ratio of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) emission between the two dyes was determined. Values were compared with a standard curve obtained by resuspending the cells that had phagocytosed labeled bacteria for 1 h at a fixed pH (ranging from pH 5.7 to 7.3) and containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Cells were immediately analyzed by FACS to determine the emission ratio of the two fluorescent probes at each pH value.

Mouse infection

All animal experiments were performed in animal facilities that meet all legal requirements in France and by qualified personnel in such a way to minimize discomfort for the animals. All procedures including animal studies were conducted in strict accordance with French laws and regulations in compliance with the European community council directive 68/609/EEC guidelines and its implementation in France. All protocols were reviewed and approved by the Comité d'Ethique Midi-Pyrénées (reference MP/04/26/07/03). Six - to eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized with a cocktail of ketamine (60 mg/kg; Merial) and xylasine (10 mg/kg; Bayer) and infected intranasally with 1,000 CFUs of the various mycobacterial strains in 25 µL of PBS-0.01% Tween 80. At 21 days post-infection, five mice per strain tested were sacrificed and lung and spleen homogenates were plated onto 7H11 agar plates for CFU scoring.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Cook GM, Berney M, Gebhard S, Heinemann M, Cox RA, et al.. (2009) Physiology of mycobacteria. Adv Microb Physiol 55: : 81–182, 318–189.

2. SchnappingerD (2006) Schoolnik GK, Ehrt S (2006) Expression profiling of host pathogen interactions: how Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the macrophage adapt to one another. Microbes Infect 8 : 1132–1140.

3. ZhangYJ, RubinEJ (2013) Feast or famine: the host-pathogen battle over amino acids. Cell Microbiol 15 : 1079–1087.

4. LeeBY, ClemensDL, HorwitzMA (2008) The metabolic activity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, assessed by use of a novel inducible GFP expression system, correlates with its capacity to inhibit phagosomal maturation and acidification in human macrophages. Mol Microbiol 68 : 1047–1060.

5. SimeoneR, BobardA, LippmannJ, BitterW, MajlessiL, et al. (2012) Phagosomal rupture by Mycobacterium tuberculosis results in toxicity and host cell death. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002507.

6. van der WelN, HavaD, HoubenD, FluitsmaD, van ZonM, et al. (2007) M. tuberculosis and M. leprae translocate from the phagolysosome to the cytosol in myeloid cells. Cell 129 : 1287–1298.

7. de ChastellierC (2009) The many niches and strategies used by pathogenic mycobacteria for survival within host macrophages. Immunobiology 214 : 526–542.

8. EhrtS, SchnappingerD (2009) Mycobacterial survival strategies in the phagosome: defence against host stresses. Cell Microbiol 11 : 1170–1178.

9. RussellDG (2001) Mycobacterium tuberculosis: here today, and here tomorrow. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2 : 569–577.

10. RussellDG (2011) Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the intimate discourse of a chronic infection. Immunol Rev 240 : 252–268.

11. SchaibleUE, Sturgill-KoszyckiS, SchlesingerPH, RussellDG (1998) Cytokine activation leads to acidification and increases maturation of Mycobacterium avium-containing phagosomes in murine macrophages. J Immunol 160 : 1290–1296.

12. ViaLE, FrattiRA, McFaloneM, Pagan-RamosE, DereticD, et al. (1998) Effects of cytokines on mycobacterial phagosome maturation. J Cell Sci 111 (Pt 7): 897–905.

13. AppelbergR (2006) Macrophage nutriprive antimicrobial mechanisms. J Leukoc Biol 79 : 1117–1128.

14. HomolkaS, NiemannS, RussellDG, RohdeKH (2010) Functional genetic diversity among Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex clinical isolates: delineation of conserved core and lineage-specific transcriptomes during intracellular survival. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000988.

15. RohdeKH, AbramovitchRB, RussellDG (2007) Mycobacterium tuberculosis invasion of macrophages: linking bacterial gene expression to environmental cues. Cell Host Microbe 2 : 352–364.

16. RohdeKH, VeigaDF, CaldwellS, BalazsiG, RussellDG (2012) Linking the transcriptional profiles and the physiological states of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during an extended intracellular infection. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002769.

17. SchnappingerD, EhrtS, VoskuilMI, LiuY, ManganJA, et al. (2003) Transcriptional Adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within Macrophages: Insights into the Phagosomal Environment. J Exp Med 198 : 693–704.

18. TailleuxL, WaddellSJ, PelizzolaM, MortellaroA, WithersM, et al. (2008) Probing host pathogen cross-talk by transcriptional profiling of both Mycobacterium tuberculosis and infected human dendritic cells and macrophages. PLoS One 3: e1403.

19. de CarvalhoLP, FischerSM, MarreroJ, NathanC, EhrtS, et al. (2010) Metabolomics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals compartmentalized co-catabolism of carbon substrates. Chem Biol 17 : 1122–1131.

20. MarreroJ, TrujilloC, RheeKY, EhrtS (2013) Glucose phosphorylation is required for Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence in mice. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003116.

21. McKinneyJD, Honer zu BentrupK, Munoz-EliasEJ, MiczakA, ChenB, et al. (2000) Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature 406 : 735–738.

22. PandeyAK, SassettiCM (2008) Mycobacterial persistence requires the utilization of host cholesterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 : 4376–4380.

23. RheeKY, de CarvalhoLP, BrykR, EhrtS, MarreroJ, et al. (2011) Central carbon metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: an unexpected frontier. Trends Microbiol 19 : 307–314.

24. GriffinJE, PandeyAK, GilmoreSA, MizrahiV, McKinneyJD, et al. (2012) Cholesterol catabolism by Mycobacterium tuberculosis requires transcriptional and metabolic adaptations. Chem Biol 19 : 218–227.

25. AmonJ, TitgemeyerF, BurkovskiA (2009) A genomic view on nitrogen metabolism and nitrogen control in mycobacteria. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 17 : 20–29.

26. CarrollP, PashleyCA, ParishT (2008) Functional analysis of GlnE, an essential adenylyl transferase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol 190 : 4894–4902.

27. HarperC, HaywardD, WiidI, van HeldenP (2008) Regulation of nitrogen metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a comparison with mechanisms in Corynebacterium glutamicum and Streptomyces coelicolor. IUBMB Life 60 : 643–650.

28. HarthG, Maslesa-GalicS, TulliusMV, HorwitzMA (2005) All four Mycobacterium tuberculosis glnA genes encode glutamine synthetase activities but only GlnA1 is abundantly expressed and essential for bacterial homeostasis. Mol Microbiol 58 : 1157–1172.

29. TulliusMV, HarthG, HorwitzMA (2003) Glutamine synthetase GlnA1 is essential for growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human THP-1 macrophages and guinea pigs. Infect Immun 71 : 3927–3936.

30. GouzyA, Larrouy-MaumusG, WuT-D, PeixotoA, LevillainF, et al. (2013) Mycobacterium tuberculosis nitrogen assimilation and host colonization require aspartate. Nat Chem Biol 9 : 674–676.

31. GouzyA, PoquetY, NeyrollesO (2013) A central role for aspartate in Mycobacterium tuberculosis physiology and virulence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3 : 68.

32. ColeST, BroschR, ParkhillJ, GarnierT, ChurcherC, et al. (1998) Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393 : 537–544.

33. LyonRH, HallWH, Costas-MartinezC (1970) Utilization of Amino Acids During Growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Rotary Cultures. Infect Immun 1 : 513–520.

34. LyonRH, HallWH, Costas-MartinezC (1974) Effect of L-asparagine on growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and on utilization of other amino acids. J Bacteriol 117 : 151–156.

35. JenningsMP, AndersonJK, BeachamIR (1995) Cloning and molecular analysis of the Salmonella enterica ansP gene, encoding an L-asparagine permease. Microbiology 141 (Pt 1): 141–146.

36. RachmanH, StrongM, UlrichsT, GrodeL, SchuchhardtJ, et al. (2006) Unique transcriptome signature of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in pulmonary tuberculosis. Infect Immun 74 : 1233–1242.

37. van KesselJC, HatfullGF (2007) Recombineering in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Methods 4 : 147–152.

38. Katayama T, Tanaka S, Aoki K (1954) [Aminoacids metabolism of tubercle bacillus. II. Studies on the asparaginase].Kekkaku 29: : 472–476; English summary, 510–471 .

39. KirchheimerF, WhittakerCK (1954) Asparaginase of Mycobacteria. Am Rev Tuberc 70 : 920–921.

40. CaiX, WuB, FangY, SongH (2012) [Asparaginase mediated acid adaptation of mycobacteria]. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao 52 : 1467–1476.

41. JackDL, PaulsenIT, SaierMH (2000) The amino acid/polyamine/organocation (APC) superfamily of transporters specific for amino acids, polyamines and organocations. Microbiology 146 (Pt 8): 1797–1814.

42. SrikhantaYN, AtackJM, BeachamIR, JenningsMP (2013) Distinct physiological roles for the two L-asparaginase isozymes of Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 436(3): 362–5.

43. EhrtS, GuoXV, HickeyCM, RyouM, MonteleoneM, et al. (2005) Controlling gene expression in mycobacteria with anhydrotetracycline and Tet repressor. Nucleic Acids Res 33: e21.

44. SassettiCM, BoydDH, RubinEJ (2003) Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol 48 : 77–84.

45. ZhangYJ, IoergerTR, HuttenhowerC, LongJE, SassettiCM, et al. (2012) Global assessment of genomic regions required for growth in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002946.

46. SongH, HuffJ, JanikK, WalterK, KellerC, et al. (2011) Expression of the ompATb operon accelerates ammonia secretion and adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to acidic environments. Mol Microbiol 80 : 900–918.

47. RecchiC, ChavrierP (2006) V-ATPase: a potential pH sensor. Nat Cell Biol 8 : 107–109.

48. BraunsteinM, BrownAM, KurtzS, JacobsWRJr (2001) Two nonredundant SecA homologues function in mycobacteria. J Bacteriol 183 : 6979–6990.

49. BraunsteinM, EspinosaBJ, ChanJ, BelisleJT, JacobsWRJr (2003) SecA2 functions in the secretion of superoxide dismutase A and in the virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 48 : 453–464.

50. AbdallahAM, Gey van PittiusNC, ChampionPA, CoxJ, LuirinkJ, et al. (2007) Type VII secretion—mycobacteria show the way. Nat Rev Microbiol 5 : 883–891.

51. CooneyDA, CapizziRL, HandschumacherRE (1970) Evaluation of L-asparagine metabolism in animals and man. Cancer Res 30 : 929–935.

52. CanepaA, FilhoJC, GutierrezA, CarreaA, ForsbergAM, et al. (2002) Free amino acids in plasma, red blood cells, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and muscle in normal and uraemic children. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17 : 413–421.

53. LinW, MathysV, AngEL, KohVH, Martinez GomezJM, et al. (2012) Urease activity represents an alternative pathway for Mycobacterium tuberculosis nitrogen metabolism. Infect Immun 80 : 2771–2779.

54. ReyratJM, Lopez-RamirezG, OfredoC, GicquelB, WinterN (1996) Urease activity does not contribute dramatically to persistence of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin. Infect Immun 64 : 3934–3936.

55. SendideK, DeghmaneAE, ReyratJM, TalalA, HmamaZ (2004) Mycobacterium bovis BCG urease attenuates major histocompatibility complex class II trafficking to the macrophage cell surface. Infect Immun 72 : 4200–4209.

56. HofreuterD, NovikV, GalanJE (2008) Metabolic diversity in Campylobacter jejuni enhances specific tissue colonization. Cell Host Microbe 4 : 425–433.

57. KullasAL, McClellandM, YangHJ, TamJW, TorresA, et al. (2012) L-asparaginase II produced by Salmonella typhimurium inhibits T cell responses and mediates virulence. Cell Host Microbe 12 : 791–798.

58. LeducD, GallaudJ, StinglK, de ReuseH (2010) Coupled amino acid deamidase-transport systems essential for Helicobacter pylori colonization. Infect Immun 78 : 2782–2792.

59. ScottiC, SommiP, PasquettoMV, CappellettiD, StivalaS, et al. (2010) Cell-cycle inhibition by Helicobacter pylori L-asparaginase. PLoS One 5: e13892.

60. ShibayamaK, TakeuchiH, WachinoJ, MoriS, ArakawaY (2011) Biochemical and pathophysiological characterization of Helicobacter pylori asparaginase. Microbiol Immunol 55 : 408–417.

61. DalekeMH, UmmelsR, BawonoP, HeringaJ, Vandenbroucke-GraulsCM, et al. (2012) General secretion signal for the mycobacterial type VII secretion pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 : 11342–11347.

62. BottaiD, Di LucaM, MajlessiL, FriguiW, SimeoneR, et al. (2012) Disruption of the ESX-5 system of Mycobacterium tuberculosis causes loss of PPE protein secretion, reduction of cell wall integrity and strong attenuation. Mol Microbiol 83 : 1195–1209.

63. BottaiD, MajlessiL, SimeoneR, FriguiW, LaurentC, et al. (2011) ESAT-6 secretion-independent impact of ESX-1 genes espF and espG1 on virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 203 : 1155–1164.

64. Woong ParkS, KlotzscheM, WilsonDJ, BoshoffHI, EohH, et al. (2011) Evaluating the sensitivity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to biotin deprivation using regulated gene expression. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002264.

65. PesekJJ, MatyskaMT, FischerSM, SanaTR (2008) Analysis of hydrophilic metabolites by high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry using a silica hydride-based stationary phase. J Chromatogr A 1204 : 48–55.

66. Guerquin-KernJL, WuTD, QuintanaC, CroisyA (2005) Progress in analytical imaging of the cell by dynamic secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS microscopy). Biochim Biophys Acta 1724 : 228–238.

67. SchneiderCA, RasbandWS, EliceiriKW (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9 : 671–675.

68. LecheneC, HillionF, McMahonG, BensonD, KleinfeldAM, et al. (2006) High-resolution quantitative imaging of mammalian and bacterial cells using stable isotope mass spectrometry. J Biol 5 : 20.

69. CarlemalmE, VilligerW, HobotJA, AcetarinJD, KellenbergerE (1985) Low temperature embedding with Lowicryl resins: two new formulations and some applications. J Microsc 140 : 55–63.

70. HainfeldJF, LiuW, HalseyCM, FreimuthP, PowellRD (1999) Ni-NTA-gold clusters target His-tagged proteins. J Struct Biol 127 : 185–198.

71. ReddyV, LymarE, HuM, HainfeldJF (2005) 5 nm Gold-Ni-NTA Binds His Tags. Microsc Microanal 11 Suppl 21118–1119.

72. BrodinP, PoquetY, LevillainF, PeguilletI, Larrouy-MaumusG, et al. (2010) High content phenotypic cell-based visual screen identifies Mycobacterium tuberculosis acyltrehalose-containing glycolipids involved in phagosome remodeling. PLoS Pathog 6: e1001100.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Structure of the Membrane Anchor of Pestivirus Glycoprotein E, a Long Tilted Amphipathic HelixČlánek Iron Acquisition in : The Roles of IlsA and Bacillibactin in Exogenous Ferritin Iron MobilizationČlánek AvrBsT Acetylates ACIP1, a Protein that Associates with Microtubules and Is Required for ImmunityČlánek Viral MicroRNA Effects on Pathogenesis of Polyomavirus SV40 Infections in Syrian Golden HamstersČlánek Genome-Wide RNAi Screen Identifies Broadly-Acting Host Factors That Inhibit Arbovirus Infection

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 2- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Jak souvisí postcovidový syndrom s poškozením mozku?

- Familiární středomořská horečka

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Viral Enhancer Mimicry of Host Innate-Immune Promoters

- The Epstein-Barr Virus-Encoded MicroRNA MiR-BART9 Promotes Tumor Metastasis by Targeting E-Cadherin in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

- Implication of PMLIV in Both Intrinsic and Innate Immunity

- The Consequences of Reconfiguring the Ambisense S Genome Segment of Rift Valley Fever Virus on Viral Replication in Mammalian and Mosquito Cells and for Genome Packaging

- Substrate-Induced Unfolding of Protein Disulfide Isomerase Displaces the Cholera Toxin A1 Subunit from Its Holotoxin

- Male-Killing Induces Sex-Specific Cell Death via Host Apoptotic Pathway

- Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapies Are Effective against HIV-1 Cell-to-Cell Transmission

- The microRNAs in an Ancient Protist Repress the Variant-Specific Surface Protein Expression by Targeting the Entire Coding Sequence

- Transmission-Blocking Antibodies against Mosquito C-Type Lectins for Dengue Prevention

- Type III Secretion Protein MxiI Is Recognized by Naip2 to Induce Nlrc4 Inflammasome Activation Independently of Pkcδ

- Lundep, a Sand Fly Salivary Endonuclease Increases Parasite Survival in Neutrophils and Inhibits XIIa Contact Activation in Human Plasma

- Induction of Type I Interferon Signaling Determines the Relative Pathogenicity of Strains

- Structure of the Membrane Anchor of Pestivirus Glycoprotein E, a Long Tilted Amphipathic Helix

- Foxp3 Regulatory T Cells Delay Expulsion of Intestinal Nematodes by Suppression of IL-9-Driven Mast Cell Activation in BALB/c but Not in C57BL/6 Mice

- Iron Acquisition in : The Roles of IlsA and Bacillibactin in Exogenous Ferritin Iron Mobilization

- MicroRNA Editing Facilitates Immune Elimination of HCMV Infected Cells

- Reversible Silencing of Cytomegalovirus Genomes by Type I Interferon Governs Virus Latency

- Identification of Host-Targeted Small Molecules That Restrict Intracellular Growth

- A Cyclophilin Homology Domain-Independent Role for Nup358 in HIV-1 Infection

- Engagement of NKG2D on Bystander Memory CD8 T Cells Promotes Increased Immunopathology following Infection

- Suppression of RNA Silencing by a Plant DNA Virus Satellite Requires a Host Calmodulin-Like Protein to Repress Expression

- CIB1 Synergizes with EphrinA2 to Regulate Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Macropinocytic Entry in Human Microvascular Dermal Endothelial Cells

- A Gammaherpesvirus Bcl-2 Ortholog Blocks B Cell Receptor-Mediated Apoptosis and Promotes the Survival of Developing B Cells

- Metabolic Reprogramming during Purine Stress in the Protozoan Pathogen

- The Post-transcriptional Regulator / Activates T3SS by Stabilizing the 5′ UTR of , the Master Regulator of Genes, in

- Tailored Immune Responses: Novel Effector Helper T Cell Subsets in Protective Immunity

- AvrBsT Acetylates ACIP1, a Protein that Associates with Microtubules and Is Required for Immunity

- Epstein-Barr Virus Large Tegument Protein BPLF1 Contributes to Innate Immune Evasion through Interference with Toll-Like Receptor Signaling

- The Major Cellular Sterol Regulatory Pathway Is Required for Andes Virus Infection

- Insights into the Initiation of JC Virus DNA Replication Derived from the Crystal Structure of the T-Antigen Origin Binding Domain

- Domain Shuffling in a Sensor Protein Contributed to the Evolution of Insect Pathogenicity in Plant-Beneficial

- Lectin-Like Bacteriocins from spp. Utilise D-Rhamnose Containing Lipopolysaccharide as a Cellular Receptor

- A Compositional Look at the Human Gastrointestinal Microbiome and Immune Activation Parameters in HIV Infected Subjects

- Exploits Asparagine to Assimilate Nitrogen and Resist Acid Stress during Infection

- Interleukin-33 Increases Antibacterial Defense by Activation of Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase in Skin

- Protective Vaccination against Papillomavirus-Induced Skin Tumors under Immunocompetent and Immunosuppressive Conditions: A Preclinical Study Using a Natural Outbred Animal Model

- Gem-Induced Cytoskeleton Remodeling Increases Cellular Migration of HTLV-1-Infected Cells, Formation of Infected-to-Target T-Cell Conjugates and Viral Transmission

- Viral MicroRNA Effects on Pathogenesis of Polyomavirus SV40 Infections in Syrian Golden Hamsters

- Genome-Wide RNAi Screen Identifies Broadly-Acting Host Factors That Inhibit Arbovirus Infection

- Inflammatory Monocytes Orchestrate Innate Antifungal Immunity in the Lung

- Quantitative and Qualitative Deficits in Neonatal Lung-Migratory Dendritic Cells Impact the Generation of the CD8+ T Cell Response

- Human Genome-Wide RNAi Screen Identifies an Essential Role for Inositol Pyrophosphates in Type-I Interferon Response

- The Master Regulator of the Cellular Stress Response (HSF1) Is Critical for Orthopoxvirus Infection

- Code-Assisted Discovery of TAL Effector Targets in Bacterial Leaf Streak of Rice Reveals Contrast with Bacterial Blight and a Novel Susceptibility Gene

- Competitive and Cooperative Interactions Mediate RNA Transfer from Herpesvirus Saimiri ORF57 to the Mammalian Export Adaptor ALYREF

- The Type III Secretion Chaperone Slc1 Engages Multiple Early Effectors, Including TepP, a Tyrosine-phosphorylated Protein Required for the Recruitment of CrkI-II to Nascent Inclusions and Innate Immune Signaling

- Yeasts: How Many Species Infect Humans and Animals?

- Clustering of Pattern Recognition Receptors for Fungal Detection

- Distinct Antiviral Responses in Pluripotent versus Differentiated Cells

- Igniting the Fire: Virulence Factors in the Pathogenesis of Sepsis

- Inactivation of the Host Lipin Gene Accelerates RNA Virus Replication through Viral Exploitation of the Expanded Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane

- Inducible Deletion of CD28 Prior to Secondary Infection Impairs Worm Expulsion and Recall of Protective Memory CD4 T Cell Responses

- Clonal Expansion during Infection Dynamics Reveals the Effect of Antibiotic Intervention

- The Secreted Triose Phosphate Isomerase of Is Required to Sustain Microfilaria Production

- Unifying Viral Genetics and Human Transportation Data to Predict the Global Transmission Dynamics of Human Influenza H3N2

- ‘Death and Axes’: Unexpected Ca Entry Phenologs Predict New Anti-schistosomal Agents

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo