-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaGlobal Functional Analyses of Cellular Responses to Pore-Forming Toxins

Here we present the first global functional analysis of cellular responses to pore-forming toxins (PFTs). PFTs are uniquely important bacterial virulence factors, comprising the single largest class of bacterial protein toxins and being important for the pathogenesis in humans of many Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria. Their mode of action is deceptively simple, poking holes in the plasma membrane of cells. The scattered studies to date of PFT-host cell interactions indicate a handful of genes are involved in cellular defenses to PFTs. How many genes are involved in cellular defenses against PFTs and how cellular defenses are coordinated are unknown. To address these questions, we performed the first genome-wide RNA interference (RNAi) screen for genes that, when knocked down, result in hypersensitivity to a PFT. This screen identifies 106 genes (∼0.5% of genome) in seven functional groups that protect Caenorhabditis elegans from PFT attack. Interactome analyses of these 106 genes suggest that two previously identified mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, one (p38) studied in detail and the other (JNK) not, form a core PFT defense network. Additional microarray, real-time PCR, and functional studies reveal that the JNK MAPK pathway, but not the p38 MAPK pathway, is a key central regulator of PFT-induced transcriptional and functional responses. We find C. elegans activator protein 1 (AP-1; c-jun, c-fos) is a downstream target of the JNK-mediated PFT protection pathway, protects C. elegans against both small-pore and large-pore PFTs and protects human cells against a large-pore PFT. This in vivo RNAi genomic study of PFT responses proves that cellular commitment to PFT defenses is enormous, demonstrates the JNK MAPK pathway as a key regulator of transcriptionally-induced PFT defenses, and identifies AP-1 as the first cellular component broadly important for defense against large - and small-pore PFTs.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 7(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001314

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1001314Summary

Here we present the first global functional analysis of cellular responses to pore-forming toxins (PFTs). PFTs are uniquely important bacterial virulence factors, comprising the single largest class of bacterial protein toxins and being important for the pathogenesis in humans of many Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria. Their mode of action is deceptively simple, poking holes in the plasma membrane of cells. The scattered studies to date of PFT-host cell interactions indicate a handful of genes are involved in cellular defenses to PFTs. How many genes are involved in cellular defenses against PFTs and how cellular defenses are coordinated are unknown. To address these questions, we performed the first genome-wide RNA interference (RNAi) screen for genes that, when knocked down, result in hypersensitivity to a PFT. This screen identifies 106 genes (∼0.5% of genome) in seven functional groups that protect Caenorhabditis elegans from PFT attack. Interactome analyses of these 106 genes suggest that two previously identified mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, one (p38) studied in detail and the other (JNK) not, form a core PFT defense network. Additional microarray, real-time PCR, and functional studies reveal that the JNK MAPK pathway, but not the p38 MAPK pathway, is a key central regulator of PFT-induced transcriptional and functional responses. We find C. elegans activator protein 1 (AP-1; c-jun, c-fos) is a downstream target of the JNK-mediated PFT protection pathway, protects C. elegans against both small-pore and large-pore PFTs and protects human cells against a large-pore PFT. This in vivo RNAi genomic study of PFT responses proves that cellular commitment to PFT defenses is enormous, demonstrates the JNK MAPK pathway as a key regulator of transcriptionally-induced PFT defenses, and identifies AP-1 as the first cellular component broadly important for defense against large - and small-pore PFTs.

Introduction

Pore-forming toxins (PFTs) are proteinaceous virulence factors that play a major role in bacterial pathogenesis [1], [2], [3]. PFTs constitute the single largest class of bacterial virulence factors, comprising ∼25–30% of all bacterial protein toxins [3], [4]. PFTs have been demonstrated to be important in vivo virulence factors for Staphylococcus aureus, Group A and B streptococci, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis, uropathogenic Escherichia coli, Clostridium septicum, and Vibrio cholerae [2], [5], [6], [7], [8]. There are various ways of grouping PFTs, based on the structure of the pore, based on their pore size as determined by structural or functional data, or even based on the organisms that produce them [9], [10]. With regards to pore size, they generally can be grouped into two categories, those that form small (1–2 nm) diameter pores and those that form large (≥30 nm) diameter pores [9], [10]. Regardless of these groupings, PFTs as a class play a singularly important role in bacterial pathogenesis in mammals.

The mode of PFT action is simple yet elegant—they poke holes in the plasma membrane, breaching cellular integrity and disrupting ion balances and membrane potential [10]. As a consequence, cells die or malfunction, which significantly aids bacterial pathogenesis. Although unregulated pores at the cell surface might be expected to be catastrophic, cells have apparently evolved some mechanisms to protect against low-moderate doses of PFTs. First shown in Caenorhabditis elegans and then demonstrated in mammalian cells, the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway was the first intracellular pathway demonstrated to protect cells against PFTs [11], [12], [13], [14]. C. elegans animals or mammalian cells lacking p38 MAPK are more susceptible to killing by PFTs. Three different downstream targets of the p38 PFT defense pathway were identified in C. elegans—two toxin-regulated targets of MAPK called ttm-1 and ttm-2, and the IRE-1 – XBP-1 unfolded protein response (UPR) pathway [11], [14]. The ttm genes and the UPR are all required for PFT defenses, are all induced by crystal toxin PFT in C. elegans, and all require the p38 pathway for their induction. Conserved induction of the UPR in mammalian cells by a PFT that makes similar in size to crystal toxin was demonstrated [14]. A few other scattered studies have identified hypoxia inducible factor (hif-1), wwp-1 (part of the insulin pathway), and sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP) as involved in cellular defenses against PFTs [15], [16], [17].

These studies raise the question as to how extensive cellular defenses to PFT attack are. In a broader sense, since PFTs likely act similar to membrane damage that occurs in daily the life of cell [3], [10], these studies raise the question as to how cells deal with unregulated holes at their membranes. How many genes are involved? Are PFT defenses relatively limited or are they extensive? Is there a coordinated pathway for defensive responses or are multiple parallel pathways involved? Little work has been done in this area since it was assumed that unregulated pores at the membrane are catastrophic, likely leading to osmotic lysis. In essence, PFT attack was assumed to be too simple for detailed scientific research.

To address the extent to which cells respond to PFT attack, we report here on the first high-level systematic study of PFT responses in cells. Namely, we perform a C. elegans RNAi screen to characterize on a genome-wide scale the genes involved in PFT defenses. Follow up of this data led us to investigate the relative importance of two MAPK pathways in regulating PFT defenses. The combination of these data with other functional and molecular data using both small - and large-pore PFTs in C. elegans and mammalian cells reveal important insights into the extent of their genome that cells employ to neutralize proteinaceous membrane pores and how cellular responses to PFTs are regulated.

Results

Genome-Wide RNAi Screen for Genes That Protect Against a Small-Pore PFT

C. elegans is susceptible to crystal (Cry) protein PFTs, such as Cry5B, made by the soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) [18], [19]. Based on homology modeling using several available Cry toxin structures as templates [20], Cry5B is a member of the three-domain Bt Cry PFTs that generally form small 1–2 nm diameter pores similar in size to those of α-toxin from S. aureus and cytolysin from V. cholerae [1], [3], [21]. To directly demonstrate that Cry5B is a PFT, we examined the ability of purified, activated Cry5B to permeabilize artificial phospholipid membranes. Current transitions between open and closed states demonstrate clearly that Cry5B forms ion channels in planar lipid bilayers (Figure 1A), and is therefore a functional PFT. Furthermore, the conductance of the pores is 125pS or less, consistent with that of other Cry toxins tested under identical experimental conditions [22], and whose pore size has been determined to be in the 1–1.3 nm radius [23]. Thus, Cry5B intoxication of C. elegans is a valid model of a small-pore PFT attack upon eukaryotic cells in vivo.

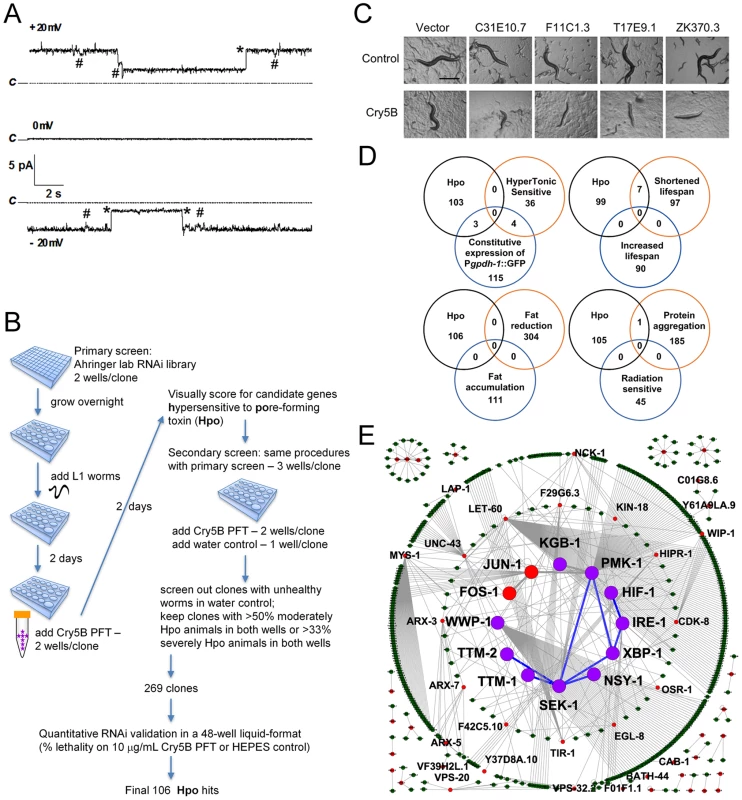

Fig. 1. Genome-wide identification of hpo genes involved in PFT defenses.

(A) Cry5B is a PFT. Representative channel current traces recorded at various holding voltages across a planar lipid bilayer into which activated Cry5B (5–10 µg/mL) was inserted under symmetrical 150 mM KCl conditions. Upwards jumps at +20mV and downwards jumps at −20mV correspond to the current flowing in channels in the open state. Dotted lines (marked “C”) indicate the zero current, corresponding to all channels being in their closed state. Records show large jumps (marked with *), corresponding to a channel conductance of 125 pS, and smaller transitions (marked with #) of about 21 pS that may represent subconductance states of the channel. (B) Flow chart for genome-wide RNAi screening and validation of genes affecting defense to Cry5B. (C) Photographs of typical Hpo hits in the primary screen. Scale bar: 0.5 mm. (D) Venn diagrams illustrating the distribution of common genes between the genome-wide Hpo screen and eight other genome-wide RNAi screens in C. elegans. (E) Putative PFT defense networks assembled from C. elegans interactome databases. Purple circles: previously published hpo genes. Red circles: hpo genes from our RNAi screen. Green circles: other genes connected to hpo genes within the network. Blue lines: known interactions for hpo genes. Grey lines: interactions based on interactome. To ascertain globally how extensive cellular commitment to protection against PFTs is, we performed a genome-wide RNAi screen using the Ahringer bacterial RNAi feeding library, which targets 16000+ C. elegans genes or about 85% of the C. elegans genome [24] (Figure 1B). Each of the 16000+ individual gene knock-downs were fed Cry5B PFT and assayed in duplicate wells for the Hpo (hypersensitive to pore-forming toxin) phenotype (Figure 1C). Hpo animals display a significantly higher level of intoxication compared to wild-type animals when exposed to a sublethal PFT dose. Intoxicated animals are dead or pale, shrunken, and less motile. Several hundred initial hits were retested for the Hpo phenotype in a second round of semi-quantitative knock-down assays (see Materials and Methods). At this round, each gene knock-down was also counter assayed for health in the absence of PFT attack; RNAi clones that caused obvious ill health in the absence of PFT were eliminated from future consideration. RNAi treatments that replicated the Hpo phenotype in the second round were then subjected to a third round of testing, namely quantitative mortality assays in the presence or absence of a fixed dose of Cry5B PFT (10 µg/mL, triplicate wells). We kept genes for which knock down resulted in ≤60% viability on 10 µg/mL PFT relative to empty vector controls and ≥83% viability in the absence of PFT relative to empty vector controls. These criteria were selected to maintain a balance between gene knock-downs with solid Hpo phenotypes and relatively good health in the absence of toxin.

One hundred and six gene knock-downs passed the three rounds of testing (Table 1). Relative to no knock-down controls, 1) for 92/106 genes, there is ≤10% lethality in the absence of toxin, 2) for 91/106 genes there is ≥50% lethality in the presence of toxin, and 3) there is ≥4X more lethality in the presence of toxin than in the absence of toxin for all but two genes. To demonstrate the robustness of the list, we selected 12 of these hpo genes that span the range of PFT hypersusceptibility and, in a fourth round of testing, repeated PFT lethality assays with knock-downs in four independent trials. All twelve knock-downs were statistically confirmed to be Hpo relative to no knock-down controls and healthy in the absence of PFT (Table S1).

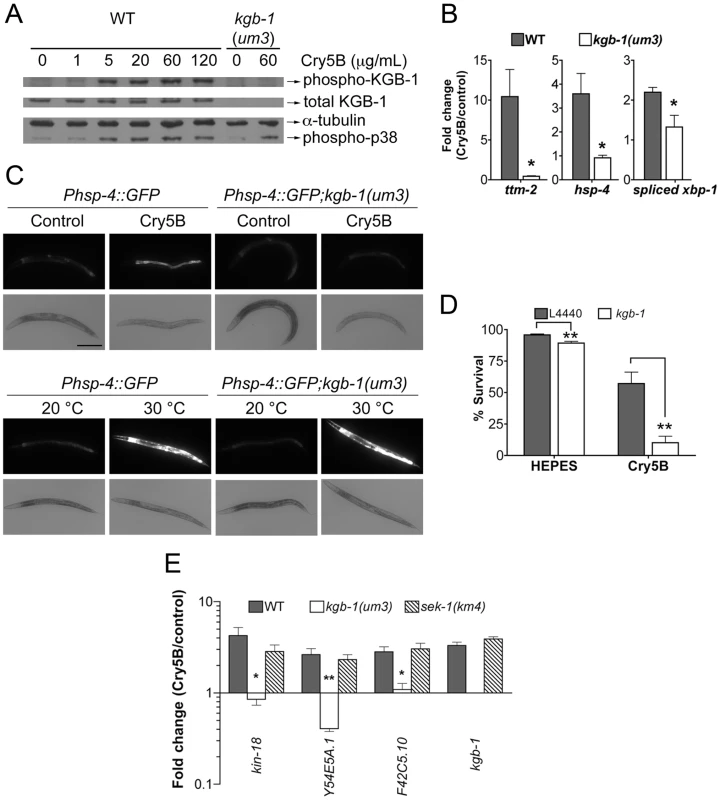

Tab. 1. RNAi clones that render the animals hypersensitive to Cry5B PFT.

The gene names were annotated based on WormBase release WS221. All the previously unnamed genes were named either ttm or hpo based on their phenotypes. Interestingly, of the eight known hpo genes identified in previous screens and present in the RNAi library, we found all three of the genes that mutate to a strong Hpo phenotype and none of the four genes that mutate to a weak to moderate Hpo phenotype (see Table 1 legend; knock down of the eighth gene is sickly in the absence of toxin and would have been screened out). Thus, we have likely identified many of the genes that mutate to a strong Hpo phenotype and likely missed an equally large number of genes that mutate to a weak-moderate Hpo phenotype.

The 106 strong hpo genes constitute >0.5% of the C. elegans genome (∼20,000 genes). Based on the Wormbase annotation, we manually classified them into the following nine categories: G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), ligand and cell surface related, signal transduction, transcription factor and gene expression, transporter, vesicular trafficking, metabolism, miscellaneous, and uncharacterized (Figure S1). Thirteen of these genes have been previously implicated in, or are homologues of genes involved in innate immunity, indicating that much of the defense against PFTs is uncharacterized relative to established immune pathways. The most highly represented group is that containing genes associated with metabolic activities, suggesting cells may alter metabolism to mount an appropriate defense and repair in response to PFTs. Among the 106 hpo genes, we also identified many genes associated with vesicle trafficking and membrane transporters, both of which have been previously implicated, but not demonstrated to be involved, in PFT defenses [25], [26]. Other significant groupings include GPCR, signal transduction, and transcription factor and gene expression. Such genes might include key components for the sensing of upstream signals, and downstream effector genes for PFT defenses [11], [13]. We found that the majority of these 106 genes have orthologs or homologs in fly (71%), mouse (71%), and humans (75%) (Table 1). Taken together, these findings support the idea that metazoans employ an extensive and conserved response to counteract PFTs and breaches of the plasma membrane.

To understand how functional responses against PFTs compare to responses to other stressors and conditions, we compared our list of 106 hpo genes with published genome-wide RNAi screens in C. elegans for hypertonic stress sensitivity [27], osmo-regulation [28], life-span regulation [29], [30], fat content regulation [31], protein aggregation regulation [32] and irradiation sensitivity [33] (no other screens involving a challenge related to bacterial pathogenesis have been published to our knowledge) (Figure 1D). The comparison revealed a statistically significant (P = 0.000051) overlap of the hpo genes with only one set of genes, those that upon inactivation lead to reduced life-span [30]. The lack of overlap with most other biological processes suggests that protection against small pores involves a specialized protective response and/or integrates many different responses, none of which are singularly dominant.

c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase (JNK)-like MAPK but not p38 MAPK is a Master Regulator of Cry5B PFT-Induced Transcriptional Responses

To make sense of these 106 genes, we mapped potential interactions among them (along with a few others from our previous publications) using the C. elegans interactome database that contains protein-protein interactions and genetic interactions based on yeast-2-hybrid data and literature [34]. Using this unbiased approach, a major interconnected network containing one-third (38) of all the hpo genes emerges. This network contains at its center two MAPK pathways, the p38 MAPK pathway and the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) MAPK pathway (Figure 1E). Thus, based on interactions from our genome-wide RNAi screen, we hypothesized that MAPK pathways play a central role in cellular PFT responses.

The identification of p38 MAPK as important in PFT defenses in C. elegans, insect, and mammalian cells has been noted above and characterized in detail [11], [12], [13], [14]. The conservation of the p38 pathway in PFT defenses suggested it might be the central regulator of these defenses. On the other hand, the JNK-like MAPK pathway, in C. elegans represented by the JNK-like MAPK KGB-1, was briefly noted as playing a role in Cry5B defenses [11] but not functionally studied in detail in any system. Whether it might be central to PFT defenses or a peripheral player was unknown. The quantitative data from our genome-wide RNAi screen suggested kgb-1 might be important since knock-down results in a quantitatively strong hypersensitivity to PFT phenotype (Table 1, Table S1). Knock-down in the MAPKK gene, mek-1, known to function upstream of KGB-1 JNK-like MAPK [35], also results in hypersensitivity to PFT (Figure S2).

To determine the relative importance of the JNK and p38 pathways in PFT defenses, we turned to microarray analyses. Since inductive transcriptional responses are an important part of MAPK-mediated responses, we hypothesized that, if important for PFT defenses, KGB-1 might play an important role in PFT-induced gene transcription.

We previously used microarray analyses to determine to what extent the p38 MAPK pathway controlled Cry5B PFT-induced transcriptional responses and to identify two downstream targets of the p38 pathway, ttm-1 and ttm-2, both of which phenotypically play a minor role in Cry5B PFT defenses [11]. Here, we carried out a similar microarray study with the JNK MAPK pathway in order to determine how many gene transcripts that are normally induced by Cry5B PFT are dependent upon the JNK pathway for their induction. We exposed wild-type and kgb-1(um3) JNK-like MAPK mutant animals either to Cry5B PFT-expressing bacteria or to bacteria carrying the empty vector (no-toxin control), each for three hours. The kgb-1(um3) loss-of-function mutant lacks 1.2 kb of genomic DNA and deletes most of the kinase domain [36], [37]. That kgb-1(um3) represents a null mutant is supported by our Western blotting experiments (see below). RNA was isolated from these animals in three independent repeats and hybridized to Affymetrix-based C. elegans whole genome microarrays. We then compared these data with those found in the p38 MAPK microarray experiment [11].

From the total of six wild-type expression profiling microarrays (three repeats for the sek-1 set and three for the kgb-1 set, both with and without toxin), we found that at a 2-fold cut-off, 572 transcripts were induced in wild-type C. elegans upon exposure to Cry5B PFT; that number increases to 1117 transcripts if the cut-off is set to 1.5-fold (P<0.01 for both). Of repressed transcripts, we found that 707 transcripts repressed at the 2-fold cut-off and 1428 repressed at the 1.5-fold cut-off (P<0.01 for both) (Figure 2A; see Supporting Information S1 for a complete list of differentially expressed transcripts). We cross-checked these transcripts with the 106 hpo genes identified above, and found that 15 hpo genes were induced ≥1.5 fold and 8 were induced ≥2 fold. Statistically, there is a significant enrichment of induced genes on the hpo list (P = 0.00041 and P = 0.0148 respectively). In contrast, the overlap between repressed genes and hpo genes is not significant (P = 0.345 with 1.5 fold cutoff, seven gene overlap, and P = 0.652 with 2 fold cut-off, four gene overlap), indicating that the appearance of repressed genes on the list of hpo genes is likely from random chance.

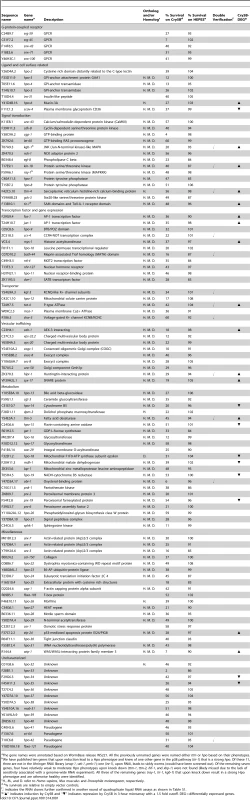

Fig. 2. MAPK pathway-dependent transcriptional responses to PFT attack.

(A) Heat-map of PFT-responsive genes in microarray experiments. Cry5B responsive genes with ≥2-fold induction (yellow) or repression (blue) relative to non-treated animals are shown. Brighter shades of color correspond to greater fold changes in expression. Different comparisons of treatments are presented at the top of each column. Wt Cry5B: Fold change in Cry5B-treated/non Cry5B-treated glp-4(bn2) animals. sek-1 Cry5B: Fold change in Cry5B-treated/non Cry5B-treated glp-4(bn2);sek-1(km4) animals. kgb-1 Cry5B: Fold change in Cry5B-treated/non Cry5B-treated glp-4(bn2);kgb-1(um3) animals. sek-1 basal: Fold change in glp-4(bn2);sek-1(km4)/glp-4(bn2) animals (both non Cry5B-treated). kgb-1 basal: Fold change in glp-4(bn2);kgb-1(um3)/glp-4(bn2) animals (both non Cry5B-treated). glp-4(bn2) animals lack a functional germline and have otherwise normal response to Cry5B (see Materials and Methods). Use of these animals removes a major tissue from the animals, allowing for intestinal mRNAs to represent a larger portion of the total RNA population. The values in the parenthesis after the slash indicating the number of the genes in each cluster (I and IV strongly up- or down-regulated; II and III moderately up- or down-regulated), with the values before slash denoting the genes with known PANTHER ontologies. The corresponding enriched PANTHER biological processes and molecular functions are shown in each cluster indicated with Roman numerals. For genes involved in immunity/defense processes, we found 14 in cluster II and 22 in cluster III. (B) Summary of number of genes up- and down-regulated by Cry5B, and their dependence upon KGB-1 and SEK-1. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of selected genes from microarray analysis. Results are the average of three experiments and error bars are standard error of the mean. Each gene behaved in the qRT-PCR experiment as was found in the microarray experiment. In this and other figures, * for P≤0.05, ** for P≤0.01 and *** for P≤0.001. We then classified the dependence of all the transcripts (≥2-fold cut-off) into one of four categories: 1) transcripts dependent upon only the p38 MAPK pathway for their induction or repression by Cry5B PFT, 2) transcripts dependent upon only the JNK MAPK pathway for their induction or repression by Cry5B PFT, 3) transcripts dependent upon both p38 and JNK MAPK pathways for their induction or repression, and 4) transcripts whose induction or repression by Cry5B PFT are independent of either MAPK pathway (Figure 2B). The results of these analyses were stunning: whereas the p38 MAPK pathway was responsible for regulating 8% (48/572) and 2% (14/707) of the PFT-induced and -repressed transcripts respectively, the JNK MAPK pathway controlled 51% (290/572) and 24% (172/707) of the PFT-induced and -repressed transcripts respectively. Thus, the JNK pathway controls more than half of the induced transcripts and more than six times the total number of transcripts controlled by the p38 pathway. Furthermore, the JNK pathway controls 85% (41/48) of the p38 MAPK-dependent induced transcripts and 43% (6/14) of these p38-dependent repressed transcripts. To validate the microarray data, we chose one up - and one down-regulated gene from each of the four categories, isolated RNA from three independent experiments (minus or plus Cry5B PFT), and performed quantitative real-time (qRT) PCR analyses (Figure 2C). The qRT-PCR results validate the microarray results. Since the JNK MAPK pathway is important for the PFT-induced transcripts, we predicted the pathway itself would be activated upon exposure to PFT. We first showed that there is no detectable KGB-1 protein in kgb-1(um3) mutant animals and further confirmed that the JNK-like MAPK pathway is activated in C. elegans treated with Cry5B PFT (Figure 3A), as has been seen with the mammalian cell responses to PFTs [38], [39]. Interestingly, in kgb-1(um3) mutant animals, we detected the phosphorylated form of p38 MAPK (Figure 3A) induced by Cry5B PFT indicating that the p38 MAPK activation is not directly regulated by KGB-1.

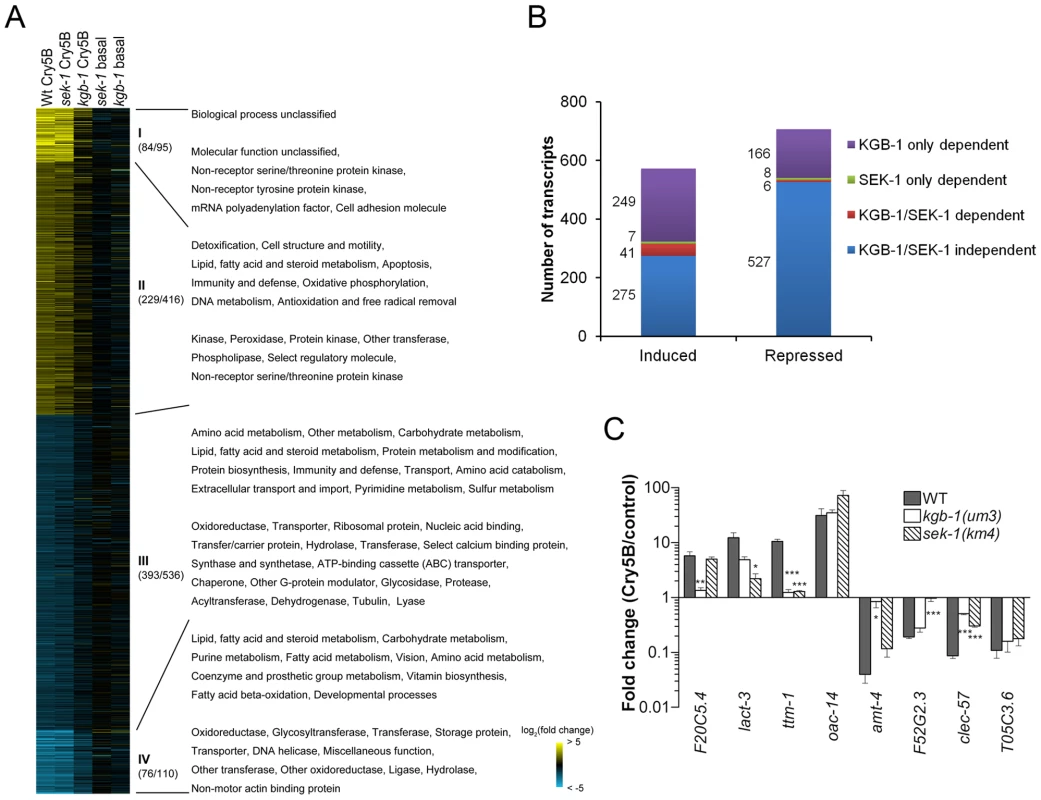

Fig. 3. KGB-1 JNK-like MAPK regulates p38-dependent and -independent pathways involved in PFT defenses.

(A) Activation of KGB-1 by Cry5B PFT. Activation was assessed by Western blotting using antibodies specific for phosphorylated and total KGB-1. α-tubulin served as an equal-loading control and phosphorylated p38 MAPK was also tested. Specificity of the antibody was verified by probing kgb-1(um3) mutant animals. The experiment shown is representative of three experiments with similar results. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of known p38 MAPK downstream target genes in response to PFT. All three target genes are regulated by KGB-1. Average of three experiments, error bars are standard error of the mean. (C) In vivo induction of Phsp-4::GFP in the intestine by Cry5B requires KGB-1. The strains Phsp-4::GFP and Phsp-4::GFP;kgb-1(um3) were fed either control E. coli or E. coli expressing Cry5B for 8 hours or shifted to 30°C for 5 hours in the heat shock treatment. Cry5B induces GFP within the intestinal cells of the strain Phsp-4::GFP but not in the strain containing the kgb-1(um3) mutant. General stress induction of Phsp-4::GFP via heat shock is independent of KGB-1. The experiment was performed three times and representative worms are shown. Scale bar is 0.2 mm. (D) Intestinal kgb-1 is required for protection against Cry5B PFT. Intestine-specific knockdown of kgb-1 in VP303 animals are quantitatively hypersensitive to purified Cry5B, compared to empty vector control (L4440). Results are the average of three different experiments; error bars indicate standard error of the mean. (E) qRT-PCR analysis of four KGB-1-dependent hpo genes in response to PFT. All these genes show a KGB-1 dependent/SEK-1 independent induction by Cry5B PFT. Average of three experiments, error bars are standard error of the mean. In addition to the fact that JNK MAPK is important for induction of most of the PFT-induced transcripts, including those regulated by p38, we wanted to know if JNK MAPK is also important for induction of PFT-induced transcripts that are functionally important (e.g., knock-down to Hpo phenotype). We therefore tested whether or not KGB-1 regulates p38-controlled transcripts/pathway that play a role in PFT defenses, namely ttm-1 and ttm-2 and the UPR [11], [14]. We find that the induction of both ttm-1 (Figure 2C) and ttm-2 (Figure 3B) in response to PFT is dependent upon the JNK MAPK pathway. Cry5B PFT-induced activation of the UPR PFT defense pathway is also dependent upon JNK MAPK, as ascertained by induction of the downstream transcriptional target hsp-4 transcript levels and by induction of xbp-1 splicing (Figure 3B). As with p38 MAPK-dependent activation of the UPR by PFT [14], JNK-dependent UPR activation occurs in the intestine in response to Cry5B PFT (the tissue directly targeted by the PFT; Figure 3C, upper panels) but not in response to an unrelated stressor like heat (Figure 3C, lower panels). The UPR-activation data suggest that the JNK pathway functions cell autonomously in the intestine for PFT defenses. To confirm this, we performed intestine-specific RNAi of kgb-1, and found that animals lacking KGB-1 in the intestine are hypersensitive to Cry5B PFT (Figure 3D). Thus, the JNK MAPK pathway regulates all currently known p38-dependent PFT protection genes in the target tissue of the PFT.

We next set out to determine, apart from known p38-dependent PFT defense genes, what other defense genes JNK MAPK might regulate. For this information, we turned back to our genome-wide RNAi list of hpo genes, examined all eight of the genes that are induced by PFT (2X cut-off), and asked, based on our microarray data, if their induction is dependent upon either the p38 or JNK MAPK pathways. We found four of eight (50%) induced hpo genes (namely kin-18, Y54E5A.1, F42C5.10 and kgb-1 itself) require JNK MAPK for their induction whereas none of the eight genes require the p38 MAPK pathway for their induction. The dependence of these four genes upon the KGB-1 and not the p38 MAPK pathway for their induction was confirmed via qRT-PCR (Figure 3E). The same conclusion is reached if one examines genes required for PFT defenses induced at the 1.5-fold cutoff: 7/15 or ∼50% of these genes are dependent upon JNK; none are dependent upon SEK-1. Although the p38 MAPK pathway has been studied in more detail, these data taken together indicate that the JNK MAPK pathway plays a more central role in coordinating induced PFT defenses.

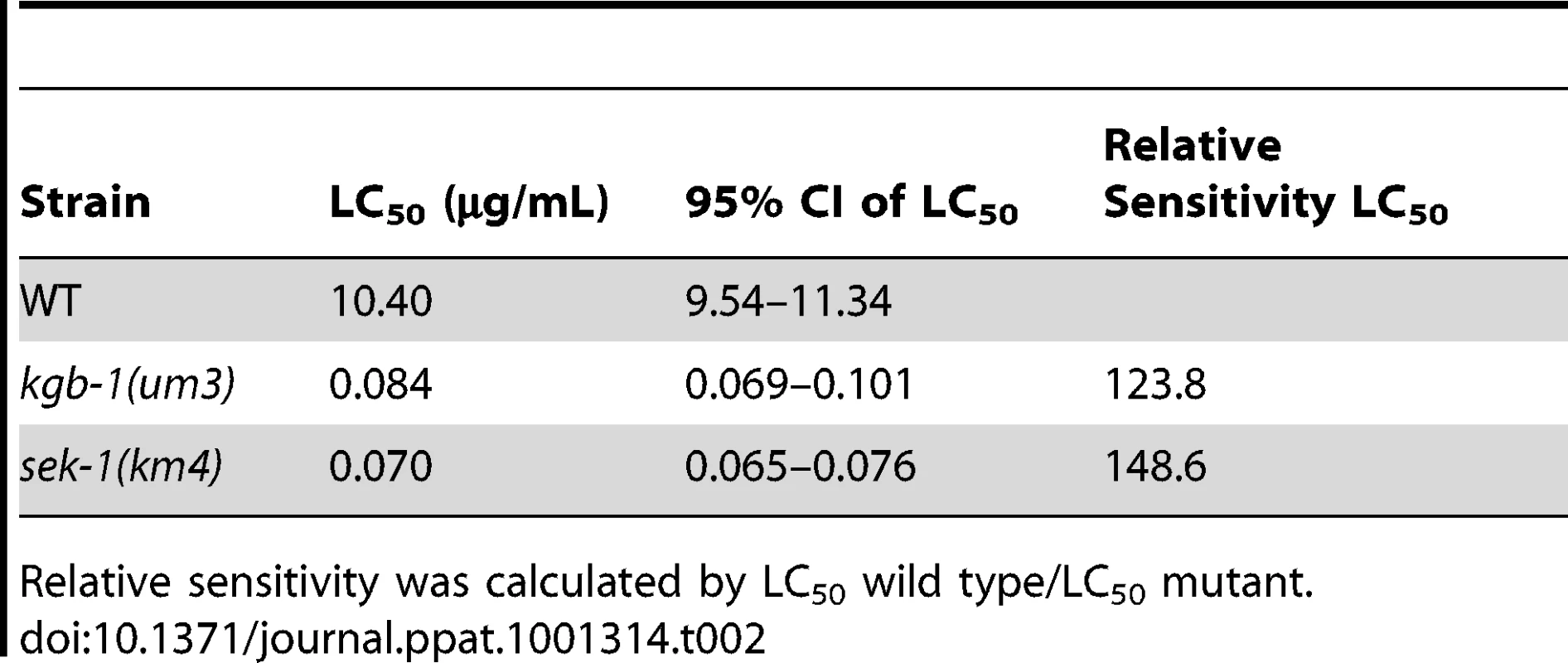

Since KGB-1 is a master regulator of ∼50% of Cry5B PFT-responsive genes, including those that are functionally relevant, we were interested to see how susceptible kgb-1 mutant animals are to Cry5B PFT attack. Using a dose-dependent lethality assay, we determined the LC50 (lethal concentrations at which 50% of the animals die) of the wild-type, sek-1(km4) p38 MAPKK-minus, and kgb-1(um3) JNK-like MAPK-minus animals treated with Cry5B PFT for 8 days. We find that both kgb-1(um3) and sek-1(km4) mutant animals have similar LC50 values and are both significantly hypersensitive to PFT relative to wild type animals (Table 2). These results were unexpected since, based on the fact that KGB-1 regulates more PFT-induced genes functionally required for PFT protection than the p38 pathway, we predicted that kgb-1 mutant animals would be more hypersensitive to PFT than sek-1 mutant animals. There are several explanations for this finding. First, it might suggest that KGB-1, but not SEK-1, transcriptionally regulates many genes required for induced PFT defenses and also some genes that inhibit PFT defenses. Such genes could be temporally segregated—e.g., KGB-1 JNK-like MAPK could initially up-regulate transcriptional responses that are protective (our microarray data is taken at 3 hr post-PFT treatment) and later down-regulate responses that inhibit protection (our LC50 data is taken at 8 days). Eventual down-regulation of protection is an important part of induced immune responses and serves to protect cells from the adverse effects of a prolonged or overwhelming immune response. Such positive and negative regulation of a cellular response by the JNK pathway is with precedent [40], [41]. Second, it might also suggest that whereas KGB-1 JNK-like MAPK is a master regulator of transcriptionally-induced PFT defenses, the p38 pathway may play an important role in other (e.g., constitutive) PFT defenses, hence resulting in a more severe sek-1 phenotype than predicted.

Tab. 2. LC50 values along with 95% confidence intervals.

Relative sensitivity was calculated by LC50 wild type/LC50 mutant. JNK MAPK Protects Against Large-Pore PFTs

Given its importance in the hierarchy of coordinating transcriptionally-induced defenses against a small-pore PFT and its activation in both C. elegans treated with small-pore PFT (our data; see above) and mammalian cells treated with large-pore PFT (referenced above), we hypothesized that JNK MAPK might broadly coordinate defenses against PFTs—i.e., it might be required for defense against both small - and large-pore PFTs. To date, no gene has been shown to play a protective role against both large - and small-pore PFTs.

We therefore tested whether a large-pore PFT could intoxicate C. elegans using streptolysin O (SLO). SLO binds to cholesterol in cell membranes, forms large 30 nm diameter pores (versus 1–2 nm pores for Cry PFTs), and is an important virulence factor of human-pathogenic streptococci [42]. The repair of the pores formed by SLO in mammalian cells membranes is calcium dependent [25], and a lytic-mutant N402 SLO has been shown to be defective in generating pores in membranes [43]. Whether SLO or any other cholesterol-dependent cytolysin affects C. elegans has not been previously reported.

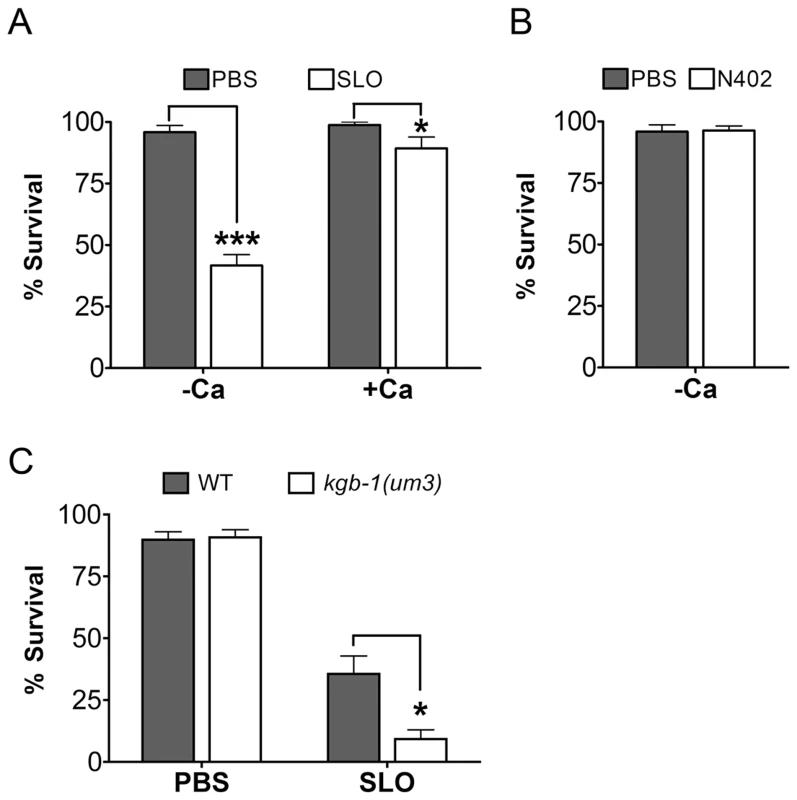

We find that wild-type C. elegans are intoxicated by wild-type SLO at 50 µg/mL with 58% of animals killed in calcium-free medium and 11% killed in calcium-containing medium in 6 days (Figure 4A). The inhibitory effect of calcium in SLO-mediated killing of C. elegans is consistent with known effects of SLO on mammalian cells [25]. Furthermore, the killing of C. elegans by SLO is completely dependent upon pore formation since wild-type worms are not killed by the non-lytic SLO mutant N402 (Figure 4B). Thus, the interaction of SLO with C. elegans parallels that of the toxin with mammalian cells and the intoxication of C. elegans by SLO is a valid model of large-pore PFT intoxication.

Fig. 4. Intoxication of C. elegans by SLO and the requirement of kgb-1 in protecting C. elegans against SLO.

(A) Viability of wild-type animals is significantly lower than wild-type animals on the mammalian PFT SLO in calcium-free S-medium. In calcium-complete medium, SLO shows a dampened toxicity to wild-type animals. (B) The mammalian PFT SLO mutant, N402, does not intoxicate wile-type C. elegans in calcium-free S-medium. (C) JNK-like MAPK protects against mammalian PFTs. Viability of kgb-1 (um3) loss-of-function animals is significantly lower than wild-type animals on the mammalian PFT SLO in calcium-free S-medium. Results are the average of three different experiments; error bars indicate standard error of the mean. We then tested whether or not JNK is required for defense against SLO in C. elegans. Wild-type animals and kgb-1(um3) mutant animals were exposed to SLO at a dose of 50 µg/mL. Significantly more kgb-1(um3) mutant animals are killed by SLO than wild-type animals (Figure 4C), demonstrating that the JNK MAPK pathway is also required for defense against a large-pore PFT.

AP-1 is a Key Downstream Target of the JNK MAPK PFT Protection Pathway Against Both Small - and Large-Pore PFTs and in Mammalian Cells

C. elegans fos-1 and jun-1 were found in our genome-wide RNAi screen as genes important for defense against Cry5B PFT (Table 1). Together, these proteins make up the heterodimeric transcription factor known as activating protein 1 (AP-1). AP-1 is a well-defined regulator of innate immunity and stress responses in mammalian cells and a known downstream target of JNK MAKP pathway in these responses [44]. To date, neither jun-1 nor fos-1 has been demonstrated to be involved in protective responses in C. elegans nor in PFT protection in any system.

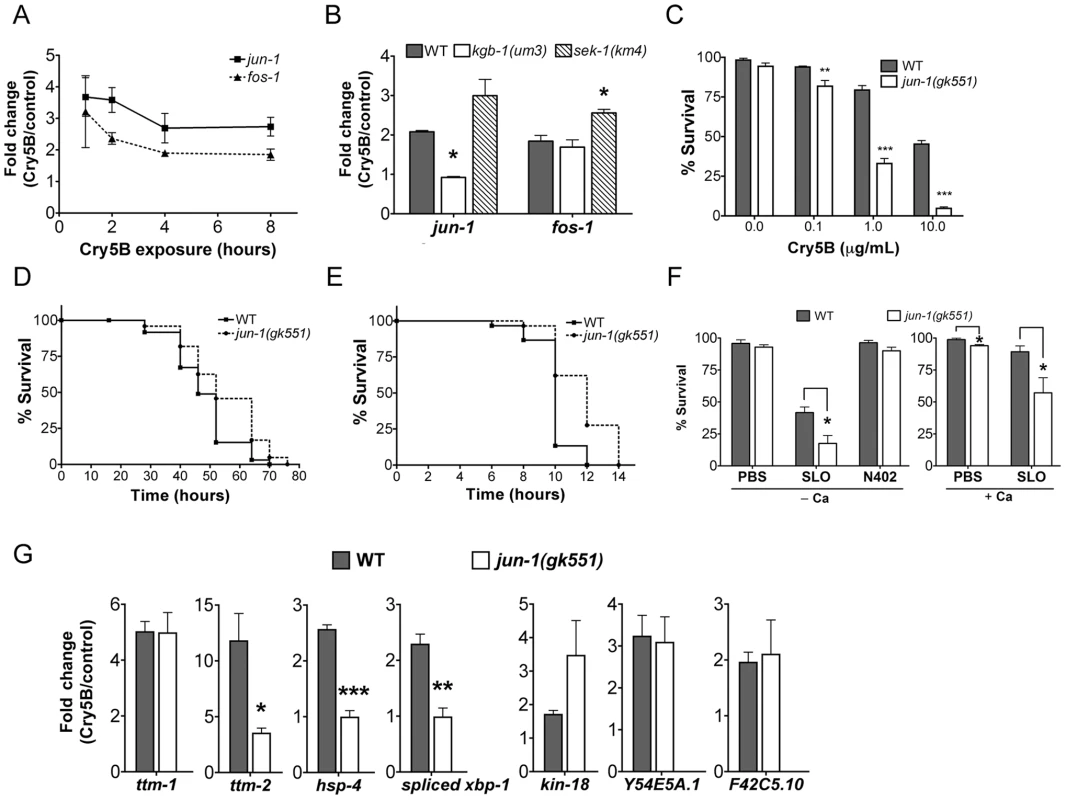

Both C. elegans AP-1 homologs, fos-1 and jun-1 were found to be up-regulated by Cry5B PFT in our microarray study (P<0.001). To confirm their induction, we performed qRT-PCR analysis of C. elegans jun-1 and fos-1 expression upon treatment with PFT at 1, 2, 4, and 8 hr. Both are robustly induced by Cry5B, with maximum induction at the earliest time point tested (Figure 5A). jun-1 induction by Cry5B PFT is KGB-1-dependent and SEK-1 independent whereas fos-1 induction is independent of both (Figure 5B). These inductions are consistent with our microarray data (1.5-fold cut-off) and demonstrate that jun-1 is a downstream target of KGB-1 during PFT protective responses.

Fig. 5. Induction of jun and fos transcripts by Cry5B PFT and specificity of jun-1 in protecting C. elegans against PFTs.

(A) qRT-PCR results showing time-course of induction of jun-1 and fos-1 by Cry5B PFT. (B) Cry5B-induced jun-1 expression is KGB-1 dependent and SEK-1 independent. Data shown were based on 3 hours of PFT treatment. For A and B, three RNA samples independent from each other and from the microarray experiments. (C) Viability of wild-type and jun-1(gk551) animals on three different doses of Cry5B PFT. (D, E) Viability of wild-type and jun-1(gk551) animals on (D) heat stress and (E) P. aeruginosa PA14. For A, B, and C results are the average of at least three different experiments; error bars indicate standard error of the mean. For D and E, the data presented are a single representative from three independent assays. (F) Viability of wild-type and jun-1(gk551) loss-of-function animals on the mammalian PFT SLO and N402 SLO in calcium-free S-medium and calcium-containing S-medium. Results are the average of at least three different experiments; error bars indicate standard error of the mean. (G) Three known p38 MAPK downstream target genes in response to Cry5B-PFT are regulated via JUN-1. Cry5B-induced ttm-2, hsp-4 and spliced xbp-1 expression is JUN-1 dependent. Cry5B-induced ttm-1, kin-18, Y54E5A.1 and F42C5.10 was not attenuated in jun-1 mutant animals. Results are the average of three experiments, and error bars are standard error of the mean. To quantitate the protective function of AP-1 during small-pore PFT attack, we performed Cry5B PFT mortality assays using the available jun-1 mutant, jun-1(gk551) (as opposed to jun-1 RNAi; the jun-1(gk551) allele is likely a null as it deletes 1.4 kb of DNA from the jun-1 locus, including the DNA binding domain). We found that jun-1(gk551) animals are significantly more sensitive than wild-type animals at all doses of Cry5B tested and overall are ∼10 fold more sensitive to PFT (Figure 5C). This level of jun-1(gk551) hypersusceptibility to PFTs is greater than that of mutants in other non-MAPK hpo genes quantitated to date (namely, xbp-1, hif-1, ttm-1, ttm-2, wwp-1). We also exposed jun-1(gk551) mutant animals to heat stress, and find that, compared to wild-type animals, they are actually slightly resistant to heat stress (Figure 5D; Table S2; Figure S3). When tested against a second form of pathogenic attack, namely Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14, we find that jun-1(gk551) mutant animals are resistant relative to wild-type animals (Figure 5E, Table S2, Figure S4). Thus, the sensitivity of jun-1 mutant animals to PFT is not due to generally compromised health and there is specificity in its role as protecting against PFTs.

To determine whether C. elegans jun, like JNK MAPK, is protective against large-pore PFTs, we treated jun-1(gk551) animals with 50 µg/mL SLO and compared the percentage killed to wild-type animals exposed to the same dose. Animals lacking jun-1 are hypersensitive to SLO PFT in the absence or presence of calcium, with 82% and 43% killed respectively (Figure 5F; for wild-type the numbers killed are 58% and 11%). jun-1(gk551) animals are not killed by SLO N402, indicating that killing by SLO in jun-1 mutant animals is dependent upon pore formation (Figure 5F). Thus, jun-1 is required for C. elegans protection against both large - and small-pore PFTs. Since KGB-1, as the master regulator of PFT defenses, controls the induction of p38-dependent sub-pathways (ttm-1, ttm-2, hsp-4, and xbp-1) and p38-independent sub-pathways (kin-18, Y54E5A.1, and F42C5.10), we further examined whether JUN-1 being the downstream of KGB-1 contributes to these gene regulation. The qRT-PCR analysis in wild-type versus jun-1(gk551) mutant animals indicated that jun-1 is required for the Cry5B-triggered ttm-2 and hsp-4 but not ttm-1, kin-18, Y54E5A.1, and F42C5.10 induction (Figure 5G). Consistently, we found that increased splicing (activation) of xbp-1 in response to Cry5B does not occur in jun-1(gk551) mutant animals (Figure 5G). These results indicate that KGB-1-regulated genes could be further parsed to be either JUN-1 dependent or independent.

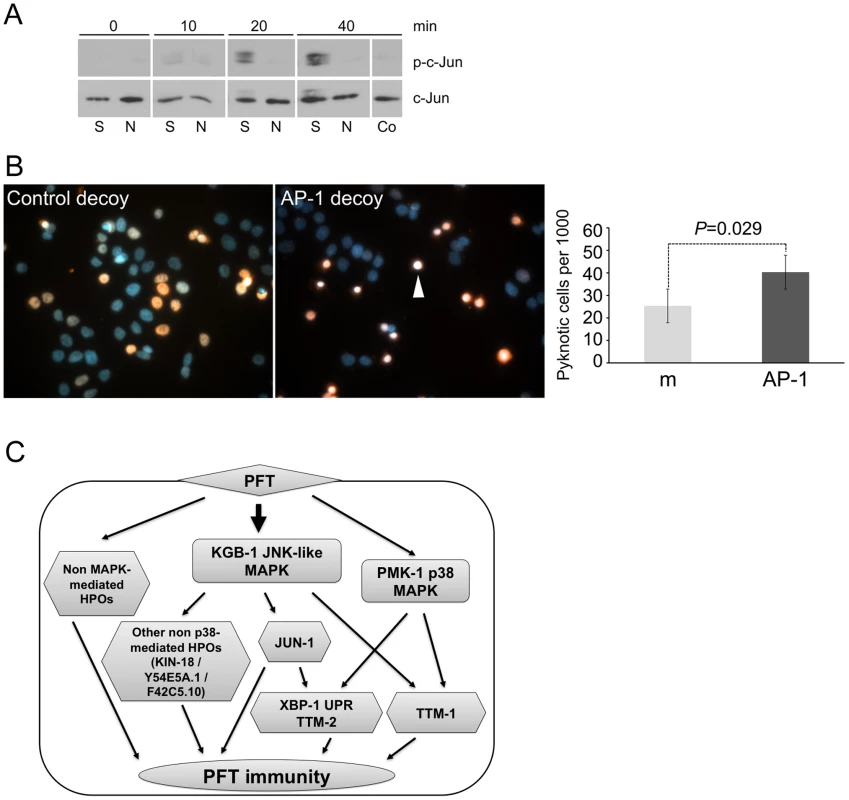

We then considered whether our finding that AP-1 is important for PFT responses in C. elegans extends to mammalian cells. Using commercially available antibodies, we found that 125 ng/mL of lytic, wild-type SLO induces activation (phosphorylation) of c-JUN in HaCaT cells and that the non-lytic SLO mutant does not (Figure 6A). To test whether AP-1 is functionally important for survival of SLO-treated mammalian cells, we employed a transcription factor decoy approach [45]. HaCaT cells were simultaneously exposed to SLO and biotinylated double-stranded deoxyoligonucleotides comprising a consensus AP-1 binding site (decoy oligonucleotide), which competes with AP-1 sites of genomic promoters for binding of the transcription factor. A mismatched oligonucleotide, which does not bind AP-1, served as a control. The AP-1 decoy oligonucleotide specifically increased the proportion of pyknotic nuclei (Figure 6B). The combination of activation and decoy oligonucleotide data supports the notion that AP-1 is protective against PFT attack in mammalian cells, as it is in C. elegans.

Fig. 6. AP-1 protects against mammalian PFTs.

(A) Western blot of mammalian c-JUN in HaCaT cells treated with 125 ng/mL SLO for time indicated. Abbreviations: S: constitutively active version of SLO, N: non-lytic mutant N402 SLO; Co: no-SLO control. (B) HaCaT cells were treated with SLO and biotinylated AP-1 decoy-oligonucleotide (right panel) or biotinylated control oligonucleotide (left panel). Oligonucleotide is stained red (SA-Alexa594), and DNA is stained blue (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole/DAPI). The images presented are a single representative from three independent assays. Cells treated with AP-1 decoy show a greater proportion of intoxicated cells with condensed chromosomes, characteristic of becoming pyknotic (e.g., white arrowhead). The proportion of pyknotic cells was quantified as described in the Materials and Methods section; the bar graph shows mean values from three independent experiments (m = mismatched oligonucleotide; AP-1 = AP-1 decoy; error bars: standard error of the mean, P value was determined with paired, one-tailed student's t-test). (C) A model for interconnected regulation of defense to PFT. The KGB-1 JNK-like MAPK regulates both p38 MAPK–dependent (e.g., ttm-1, ttm-2, UPR) and p38 MAPK-independent (e.g., jun-1, kin-18) PFT-induced protection genes. There are also PFT protection genes that, to date, have not been linked to either MAPK pathway. Discussion

We present the first genome-wide study of functional cellular responses to a PFT. We identify 106 hpo genes important for cellular protection against an attack by a small-pore PFT, Cry5B. Interactome network analysis of these genes emphasizes the importance of two MAPK pathways, p38 and JNK, in coordinating this protection. The stringency of our experimental design led us to all previously known genes that mutate to a strong Hpo phenotype and none that mutate to a weak to moderate Hpo phenotype. All of the genes on this list except two are previously uncharacterized with regards to PFT defenses. A comparison of the genes induced by PFT with these 106 important for protection against PFT revealed a statistically significant enrichment of transcriptionally-induced, but not transcriptionally-repressed, genes on the list of PFT-protective genes. These data indicate that transcriptional induction is important for PFT protection.

Our findings demonstrate that >0.5% of genes in the C. elegans genome play a major role in protection against pore-forming toxins. This number is large by any standard for a single cellular process. Given the likely parallels between cellular responses to pore-forming toxins and membrane ruptures that occur to cells during their normal existence, these data suggest that cells devote such a large portion of their genome to protecting against membrane holes and that this list of genes represents a rich starting point for understanding how cells cope with PFT attack and membrane damage. It is interesting to note that plasma membrane pore-formation has been suggested to play a significant role in neurological diseases of ageing, such as Alzheimer's or Parkinson's disease [10]. The significant overlap of the 106 hpo PFT protection genes with genes involved in promoting long life-span, suggest indeed that small ruptures of the plasma membrane play a significant role in the aging process. The fact that JNK and AP-1 are important for protection against both large-pore and small-pore PFTs indicates that at least some of the pathways cells use to deal with pores of various sizes are conserved, in contrast to previous suggestions [10], [13].

Based on interactome analyses from our genome-wide RNAi screen, we examined the requirement of the JNK MAPK pathway for PFT defenses. JNK MAPK has not been studied in any detail for its role in PFT defenses. Indeed, to date the only signal transduction pathway studied in detail has been the p38 MAPK pathway. Our study of the JNK MAPK pathway identifies it, and not p38, as the first master regulator of PFT transcriptionally-induced cellular protection. This conclusion is based on the following observations and results: 1) the JNK MAPK pathway is induced in mammalian and C. elegans cells by small-pore and large-pore PFTs (this study and others [38], [39]; 2) more than 50% of all genes transcriptionally induced by PFT depend upon the JNK pathway for their induction (this study); 3) 85% of the p38-dependent PFT-induced transcriptional response is controlled by JNK MAPK (this study); 4) all three of the known p38-dependent PFT-induced functional responses are dependent upon JNK (this study); 5) 50% of the hpo genes that mutate to a strong Hpo phenotype and that are induced by PFT are dependent upon JNK; and 6) JNK protects against both large and small-pore PFTs in C. elegans, the first such gene so identified. Our analyses also identify the first known downstream targets of the JNK MAPK-regulated PFT protection pathway, namely, kin-18, jun-1, Y54E5A.1, and F42C5.10. While JNK MAPK is the master regulator of induced responses, our Western blotting data suggest that JNK is not hierarchically upstream of p38 MAPK activation in response to PFT. Based on our findings we propose a model whereby the JNK pathway converges in parallel on p38-regulated PFT responsive genes to regulate the transcriptionally-induced defense response to Cry5B (Figure 6C).

Our genome-wide analyses also led to the discovery of AP-1, a key regulator of mammalian innate immunity downstream of JNK and the toll-like receptor (TLR) pathway, as important for defense against small - and large-pore PFTs in C. elegans and against a large-pore PFT in mammalian cells. This study is the first to identify AP-1 as involved in immunity in C. elegans. We also demonstrated that the UPR and ttm-2 Cry5B-induced defense sub-pathways, but not the ttm-1, kin-18, Y54E5A.1, and F42C5.10 Cry5B-induced defense sub-pathway, are transcriptionally regulated via JUN-1. Thus, AP-1 mediates some, but not all, of JNK-regulated PFT defenses (Figure 6C). As indicated by our data and reflected in our model, regulation of transcriptionally-induced cellular defenses against PFTs involves an intricately connected network of sub-pathways, with the JNK pathway hierarchically at the top of known regulators.

AP-1 is the first transcription factor to be shown to be broadly required for metazoan cells to defend against PFTs. Since the TLR does not appear to be important for C. elegans immunity [46], our data suggest that the role of the JNK-AP-1 pathway in protection against PFTs is one of its most ancestral functions, predating that of its role in TLR-mediated immunity.

In summary, we report the first large-scale functional study of genes involved in protecting against a small-pore PFTs, place JNK as the master regulator of known cellular defenses against small - and large-pore PFTs, and identify AP-1 as an ancient factor conserved from worms to humans involved in PFT defenses. This study demonstrates the power of integrated genome-scale approaches in vivo to provide vital insights and significant breakthroughs into what has been to date a daunting scientific challenge, namely understanding defenses against breaches of plasma membrane integrity.

Materials and Methods

C. elegans Strains and Microscopy

Strains were maintained at 20°C as described [47], except strains containing glp-4(bn2), which were maintained at 15°C. Images for the genome-wide RNAi screen were acquired using an Olympus SZ60 dissecting microscope. Strain VP303 rde-1(ne219); kbEx200 [rol-6(su1006);pnhx-2::RDE-1] was provided by Kevin Strange (Vanderbilt University) [48]. Phsp-4::GFP and Phsp-4::GFP;kgb-1(um3)) animals were placed on 2% agarose pads containing 0.1% sodium azide and were imaged on an Olympus BX60 microscope with a 10x objective.

Toxin Preparation

Purified Cry5B was prepared as described [49] and suspended either in water for the genome-wide RNAi screen, or dissolved in 20 mM HEPES (pH 8.0) for liquid mortality assays. E. coli-expressed Cry5B was prepared as described previously [50], except the overnight culture was 5 times diluted before IPTG induction in OP50 expression system. For the microarray experiment, conditions were carried out as described [11].

Cry5B Activation and Ion Channel Currents Recording in Planar Lipid Bilayers

Solubilized Cry5B protoxin was incubated at 30°C for two weeks, allowing co-purifying native Bt protease(s) to activate it into a 59 kDa fragment. The 59 kDa Cry5B was purified by gel filtration (Superdex 75 16/60). Ionic currents passing through activated Cry5B proteins (5-10 µg/mL) reconstituted into planar lipid bilayers were recorded at various holding voltages applied to phospholipid membranes (phosphatidylethanolamine∶phosphatidylcholine∶cholesterol (7∶2∶1 w/w)) painted across a 250-µm hole drilled in a Teflon wall separating two 600-µl chambers filled with 150 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 9.0. Data were recorded with an Axopatch-1D amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA), filtered at 600Hz, digitized and analyzed using pClamp6 software (Axon Instruments) [51].

Genome-Wide RNAi Screen and Liquid RNAi Assays

RNAi feeding for the genome-wide screen was performed in a 24-well format modified from a published protocol [52]. Bacteria containing each RNAi clone were cultured in 100 µL Luria Broth media containing 50 µg/mL carbenicillin in a 96-well format for 16–18 hrs. 30 µl of each culture was seeded in one well of a 24-well plate containing NGM agar, 1 mM IPTG and 50 µg/ml carbenicillin (each plate was set up in duplicate). For each batch of RNAi clones tested, empty vector (L4440) and tir-1 RNAi clones were included as negative (no knock-down) and positive (Hpo) controls respectively. After overnight incubation, ∼20 synchronized RNAi-sensitive rrf-3(pk1426) L1 worms were placed in each well and allowed to develop to L4 stage at 20°C. 30 µL of total 1 µg purified Cry5B resuspended in water was added to RNAi-fed worms in each well (rrf-3 mutants have a normal response to Cry5B [11]). The plates were covered with porous Rayon films (VWR, West Chester, PA) to allow air exchange. Hypersensitivity to PFT relative to no knock-down (empty vector) controls was assessed after 48 hours by light phase microscopy. The initial Hpo hits were individually retested in duplicate under the same conditions (second round). In addition, for each RNAi clone, a single well was set up and treated with water alone (no toxin) to assay for ill health in the absence of toxin. To be considered a hpo gene, we looked for lack of ill health and developmental problems in the no-toxin well and either >50% moderately Hpo animals in both wells or >33% severely Hpo animals in both wells. Two hundred and sixty nine such genes were found in total. For the quantitative validation test (third round), bacteria from these RNAi hits were cultured overnight, induced with 1mM IPTG for 1 hour at 37°C, and resuspended in S-media. We then added ∼20 glp-4(bn2);rrf-3(pk1426) L1 animals to each well of a 48-well plate with RNAi bacteria (triplicate wells for each clone). The plates were gently rocked at 25°C for ∼30 hours until the animals had developed to the L4 stage. Then we added 10 µg/mL Cry5B or 20 mM HEPES pH 8.0 control into each well and quantitated the percentage of worms that were killed after six days at 25°C. The worm viability was determined based on movement and worms failed to respond to several gentle touches with a platinum pick were scored as dead. The survival on each RNAi treatment was normalized to L4440 treatment in the same batch, to help account for differences in toxicity from batch to batch of the experiment. We sequenced the 106 hpo gene clones to confirm their identities. The quadruplicate repeat triple-well verification was performed with the similar procedures except that no plate rocking was performed and data were analyzed via analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett's post-test. Statistical data analyses here and elsewhere were performed using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

For intestinal-specific liquid RNAi, bacteria for kgb-1 RNAi or L4440 empty vector were first cultured overnight, induced with 1mM IPTG for 1 hour at 37°C, and resuspended in S-media. Approximately 20 synchronized L1 stage VP303 worms were fed with kgb-1 or L4440 RNAi in 48 wells plates, grown to the L4 stage in ∼40 hours at 25°C and FUdR was then added to a final concentration of 200 µM. Then Cry5B to a final concentration of 10 µg/mL or 20 mM HEPES pH 8.0 control were added into each well and the percentage of worms that were killed after six days at 25°C was scored. The comparison of survivals between kgb-1 RNAi and empty control was done with one-tailed Student's t-test.

Microarrays and Bioinformatics

The RNA samples were collected from three independent experiments as described [11]. glp-4(bn2) animals lack a functional germline and have otherwise normal response to Cry5B [11]. Use of these animals removes a major tissue from the animals, allowing for intestinal mRNAs to represent a larger portion of the total RNA population. Raw microarray datasets were normalized using Bioconductor's [53] Robust Multi-array Analysis (RMA) [54], [55] in R language. Linear Models for Microarray Data (LIMMA) [56] was used to determine a set differentially expressed genes. The cutoff p-value used was 0.01 with minimum 1.5 or 2 fold change. The data were clustered to reveal prominent groups of transcripts with similar changes in expression pattern using a κ-means (κ = 4) algorithm.

The gene enrichment analysis for microarray was done with DAVID PANTHER annotation tool [57]. Only enriched categories with three or more counts and P<0.05 were kept. The statistical significance of the observed overlap between different gene lists (e.g., genome-wide RNAi screens, hpo vs. induced genes) was calculated by a modified Fisher's exact test [58]. The PFT immunity interaction network was generated by combining data from our genome-wide RNAi screen and a modified C. elegans integrated functional network (WI8∪Literature∪Interolog∪Genetic) database with several manually curated interactions [34]. Interactions were only maintained if at least one of the nodes was hpo. The resulting networks were visualized using Cytoscape 2.6.3 [59].

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from approximately 5,000 L4 worms and cDNA was made from 2 µg of total RNA with MoMLV-reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI) and oligo-dT primers for 90 minutes at 42°C in 20 µl reaction mixtures. qRT-PCR (triplicate independent experiments, normalization to eft-2) was then carried out as described [14]. Primers for qRT-PCR are listed in Table S3 except for eft-2, ttm-2, hsp-4, and xbp-1 spliced form, which have been described before [14], [15]. Transcript levels among mutants and wild-type animals for a given gene were compared using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD post hoc test or one-tailed Student's t-test (Figure 3A and 5G only).

KGB-1 Immunoblotting

Approximately 750 L1 stage worms were grown in a single well of a 48 well plate, treated with indicated concentrations of Cry5B and prepared as described before for phospho p38 MAPK and α-tubulin [14]. The same PVDF membranes were stripped with Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) and reprobed as needed. The probing order is phospho-KGB-1 (1∶1000) first, phospho-p38 MAPK and α-tubulin second, and total KGB-1 antiserum (1∶5000) third.

C. elegans Mortality Assays with Mutants

Cry5B mortality assays with wild-type animals and kgb-1 and sek-1 mutants were carried out for 8 days at 20°C in three independent experiments as per standard protocol[50]. LC50 values and confidence intervals were calculated as described [60]. For SLO and N402 assays, synchronized L4 worms were prepared in complete or calcium-free S-medium with 50 µg/mL of toxin dissolved in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; PBS alone was used in negative controls). The survival of animals was scored after six days at 25°C and differences analyzed by analyzed with one-tailed Student's t-test. The P. aeruginosa PA14 survival assay was performed on slow-killing plates as described [14]. For the heat stress analysis, synchronized N2 and jun-1(gk551) animals were shifted to 35°C as two-day-old adults and survival was scored every two hours after the treatment as described [61]. Three lifespan assays per worm strain were done, and all show the same trends. The data presented in the paper are from a representative experiment. Data are plotted as a Kaplan–Meier survival plot and analyzed for significance using the Log Rank test.

Preparation of SLO and Mammalian Cell Experiments

Recombinant streptolysin O and non-lytic mutant N402 were prepared as described previously [43], [62]. Growth of the human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT has been previously described [63]. Cells were seeded at a density of 0.5x106 cells in 12-well plates, cultured overnight and treated with 125 ng/ml SLO or non-lytic mutant N402 for indicated times. After washing with PBS, cells were lysed by addition of 50 µl 2xSDS-loading buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membrane, incubated with rabbit anti-phospho Ser63-c-jun (1∶1000; Cell Signaling Technology) over night at 4°C, washed, and incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP-conjugate (1∶2000; New England Biolabs). After three washes, bound antibody was detected by ECL. The same membrane was stripped with TBS containing 2% SDS and 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol for 50 min at 50°C and reprobed with rabbit anti-c-jun (1∶1000; Cell Signaling Technology).

For the AP-1 decoy experiment, HaCaT cells were treated in Ca2+-free medium with 500 ng/mL SLO and 3 µM biotinylated AP-1 decoy oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN), or mismatched AP-1 decoy ODN for 30 min, (Genedetect, Auckland, New Zealand). Subsequently, cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated in full culture medium. After incubation for 4 hours, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% triton-X100. Biotinylated ODN were stained with AlexaFluor594-conjugated streptavidin; nuclei were visualized with DAPI stain (10 µg/mL). After washing, cells were examined by fluorescence microscopy using an Axiovert 200M microscope (Zeiss, Germany). The relative intensity of DAPI staining was quantified for ca. 800 cells per treatment and experiment, applying the analysis tool of Photoshop to digital images in RGB-mode. Nuclei were considered pyknotic if they were condensed to a diameter<50% of average and showed more intense DAPI uptake (>2-fold of average intensity)[64].

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. HuffmanDL

BischofLJ

GriffittsJS

AroianRV

2004 Pore worms: using Caenorhabditis elegans to study how bacterial toxins interact with their target host. Int J Med Microbiol 293 599 607

2. AroianR

van der GootFG

2007 Pore-forming toxins and cellular non-immune defenses (CNIDs). Curr Opin Microbiol 10 57 61

3. GonzalezMR

BischofbergerM

PernotL

van der GootFG

FrecheB

2008 Bacterial pore-forming toxins: the (w)hole story? Cell Mol Life Sci 65 493 507

4. AloufJE

2003 Molecular features of the cytolytic pore-forming bacterial protein toxins. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 48 5 16

5. WellmerA

ZyskG

GerberJ

KunstT

Von MeringM

2002 Decreased virulence of a pneumolysin-deficient strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae in murine meningitis. Infect Immun 70 6504 6508

6. KayaogluG

OrstavikD

2004 Virulence factors of Enterococcus faecalis: relationship to endodontic disease. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 15 308 320

7. O'HanleyP

LalondeG

JiG

1991 Alpha-hemolysin contributes to the pathogenicity of piliated digalactoside-binding Escherichia coli in the kidney: efficacy of an alpha-hemolysin vaccine in preventing renal injury in the BALB/c mouse model of pyelonephritis. Infect Immun 59 1153 1161

8. OlivierV

Haines GK3rd

TanY

SatchellKJ

2007 Hemolysin and the multifunctional autoprocessing RTX toxin are virulence factors during intestinal infection of mice with Vibrio cholerae El Tor O1 strains. Infect Immun 75 5035 5042

9. ParkerMW

FeilSC

2005 Pore-forming protein toxins: from structure to function. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 88 91 142

10. BischofbergerM

GonzalezMR

van der GootFG

2009 Membrane injury by pore-forming proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol 21 589 595

11. HuffmanDL

AbramiL

SasikR

CorbeilJ

van der GootFG

2004 Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways defend against bacterial pore-forming toxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 10995 11000

12. Cancino-RodeznoA

AlexanderC

VillasenorR

PachecoS

PortaH

2010 The mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 is involved in insect defense against Cry toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 40 58 63

13. HusmannM

DerschK

BobkiewiczW

BeckmannE

VeerachatoG

2006 Differential role of p38 mitogen activated protein kinase for cellular recovery from attack by pore-forming S. aureus alpha-toxin or streptolysin O. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 344 1128 1134

14. BischofLJ

KaoCY

LosFC

GonzalezMR

ShenZ

2008 Activation of the unfolded protein response is required for defenses against bacterial pore-forming toxin in vivo. PLoS Pathog 4 e1000176

15. BellierA

ChenCS

KaoCY

CinarHN

AroianRV

2009 Hypoxia and the hypoxic response pathway protect against pore-forming toxins in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog 5 e1000689

16. ChenCS

BellierA

KaoCY

YangYL

ChenHD

2010 WWP-1 is a novel modulator of the DAF-2 insulin-like signaling network involved in pore-forming toxin cellular defenses in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS ONE 5 e9494

17. GurcelL

AbramiL

GirardinS

TschoppJ

van der GootFG

2006 Caspase-1 activation of lipid metabolic pathways in response to bacterial pore-forming toxins promotes cell survival. Cell 126 1135 1145

18. MarroquinLD

ElyassniaD

GriffittsJS

FeitelsonJS

AroianRV

2000 Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) toxin susceptibility and isolation of resistance mutants in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 155 1693 1699

19. WeiJZ

HaleK

CartaL

PlatzerE

WongC

2003 Bacillus thuringiensis crystal proteins that target nematodes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 2760 2765

20. XiaLQ

ZhaoXM

DingXZ

WangFX

SunYJ

2008 The theoretical 3D structure of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry5Ba. J Mol Model 14 843 848

21. IacovacheI

van der GootFG

PernotL

2008 Pore formation: an ancient yet complex form of attack. Biochim Biophys Acta 1778 1611 1623

22. SchwartzJL

GarneauL

SavariaD

MassonL

BrousseauR

1993 Lepidopteran-specific crystal toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis form cation - and anion-selective channels in planar lipid bilayers. J Membr Biol 132 53 62

23. PeyronnetO

NiemanB

GenereuxF

VachonV

LapradeR

2002 Estimation of the radius of the pores formed by the Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1C delta-endotoxin in planar lipid bilayers. Biochim Biophys Acta 1567 113 122

24. KamathRS

AhringerJ

2003 Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods 30 313 321

25. IdoneV

TamC

GossJW

ToomreD

PypaertM

2008 Repair of injured plasma membrane by rapid Ca2+-dependent endocytosis. J Cell Biol 180 905 914

26. HusmannM

BeckmannE

BollerK

KloftN

TenzerS

2009 Elimination of a bacterial pore-forming toxin by sequential endocytosis and exocytosis. FEBS Lett 583 337 344

27. ChoeKP

StrangeK

2008 Genome-wide RNAi screen and in vivo protein aggregation reporters identify degradation of damaged proteins as an essential hypertonic stress response. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295 C1488 1498

28. LamitinaT

HuangCG

StrangeK

2006 Genome-wide RNAi screening identifies protein damage as a regulator of osmoprotective gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 12173 12178

29. HamiltonB

DongY

ShindoM

LiuW

OdellI

2005 A systematic RNAi screen for longevity genes in C. elegans. Genes Dev 19 1544 1555

30. SamuelsonAV

CarrCE

RuvkunG

2007 Gene activities that mediate increased life span of C. elegans insulin-like signaling mutants. Genes Dev 21 2976 2994

31. AshrafiK

ChangFY

WattsJL

FraserAG

KamathRS

2003 Genome-wide RNAi analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans fat regulatory genes. Nature 421 268 272

32. NollenEA

GarciaSM

van HaaftenG

KimS

ChavezA

2004 Genome-wide RNA interference screen identifies previously undescribed regulators of polyglutamine aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 6403 6408

33. van HaaftenG

RomeijnR

PothofJ

KooleW

MullendersLH

2006 Identification of conserved pathways of DNA-damage response and radiation protection by genome-wide RNAi. Curr Biol 16 1344 1350

34. SimonisN

RualJF

CarvunisAR

TasanM

LemmensI

2009 Empirically controlled mapping of the Caenorhabditis elegans protein-protein interactome network. Nat Methods 6 47 54

35. MizunoT

HisamotoN

TeradaT

KondoT

AdachiM

2004 The Caenorhabditis elegans MAPK phosphatase VHP-1 mediates a novel JNK-like signaling pathway in stress response. Embo J 23 2226 2234

36. SmithP

Leung-ChiuWM

MontgomeryR

OrsbornA

KuznickiK

2002 The GLH proteins, Caenorhabditis elegans P granule components, associate with CSN-5 and KGB-1, proteins necessary for fertility, and with ZYX-1, a predicted cytoskeletal protein. Dev Biol 251 333 347

37. OrsbornAM

LiW

McEwenTJ

MizunoT

KuzminE

2007 GLH-1, the C. elegans P granule protein, is controlled by the JNK KGB-1 and by the COP9 subunit CSN-5. Development 134 3383 3392

38. AguilarJL

KulkarniR

RandisTM

SomanS

KikuchiA

2009 Phosphatase-dependent regulation of epithelial mitogen-activated protein kinase responses to toxin-induced membrane pores. PLoS ONE 4 e8076

39. StassenM

MullerC

RichterC

NeudorflC

HultnerL

2003 The streptococcal exotoxin streptolysin O activates mast cells to produce tumor necrosis factor alpha by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase - and protein kinase C-dependent pathways. Infect Immun 71 6171 6177

40. KimT

YoonJ

ChoH

LeeWB

KimJ

2005 Downregulation of lipopolysaccharide response in Drosophila by negative crosstalk between the AP1 and NF-kappaB signaling modules. Nat Immunol 6 211 218

41. KimLK

ChoiUY

ChoHS

LeeJS

LeeWB

2007 Down-regulation of NF-kappaB target genes by the AP-1 and STAT complex during the innate immune response in Drosophila. PLoS Biol 5 e238

42. TwetenRK

2005 Cholesterol-dependent cytolysins, a family of versatile pore-forming toxins. Infect Immun 73 6199 6209

43. Abdel GhaniEM

WeisS

WalevI

KehoeM

BhakdiS

1999 Streptolysin O: inhibition of the conformational change during membrane binding of the monomer prevents oligomerization and pore formation. Biochemistry 38 15204 15211

44. KawaiT

AkiraS

2006 TLR signaling. Cell Death Differ 13 816 825

45. TomitaN

OgiharaT

MorishitaR

2003 Transcription factors as molecular targets: molecular mechanisms of decoy ODN and their design. Curr Drug Targets 4 603 608

46. IrazoquiJE

UrbachJM

AusubelFM

2010 Evolution of host innate defence: insights from Caenorhabditis elegans and primitive invertebrates. Nat Rev Immunol 10 47 58

47. BrennerS

1974 The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77 71 94

48. EspeltMV

EstevezAY

YinX

StrangeK

2005 Oscillatory Ca2+ signaling in the isolated Caenorhabditis elegans intestine: role of the inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and phospholipases C beta and gamma. J Gen Physiol 126 379 392

49. GriffittsJS

WhitacreJL

StevensDE

AroianRV

2001 Bt toxin resistance from loss of a putative carbohydrate-modifying enzyme. Science 293 860 864

50. BischofLJ

HuffmanDL

AroianRV

2006 Assays for Toxicity Studies in C. elegans With Bt Crystal Proteins. Methods Mol Biol 351 139 154

51. PuntheeranurakT

UawithyaP

PotvinL

AngsuthanasombatC

SchwartzJL

2004 Ion channels formed in planar lipid bilayers by the dipteran-specific Cry4B Bacillus thuringiensis toxin and its alpha1-alpha5 fragment. Mol Membr Biol 21 67 74

52. KamathRS

Martinez-CamposM

ZipperlenP

FraserAG

AhringerJ

2001 Effectiveness of specific RNA-mediated interference through ingested double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Biol 2 RESEARCH0002

53. ScholtensD

VidalM

GentlemanR

2005 Local modeling of global interactome networks. Bioinformatics 21 3548 3557

54. IrizarryRA

HobbsB

CollinF

Beazer-BarclayYD

AntonellisKJ

2003 Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4 249 264

55. BolstadBM

IrizarryRA

AstrandM

SpeedTP

2003 A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19 185 193

56. SmythGK

2004 Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol 3 Article3

57. HuangDW

ShermanBT

LempickiRA

2009 Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 4 44 57

58. HosackDA

Dennis GJr

ShermanBT

LaneHC

LempickiRA

2003 Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with EASE. Genome Biol 4 R70

59. KillcoyneS

CarterGW

SmithJ

BoyleJ

2009 Cytoscape: a community-based framework for network modeling. Methods Mol Biol 563 219 239

60. HuY

PlatzerEG

BellierA

AroianRV

2010 Discovery of a highly synergistic anthelmintic combination that shows mutual hypersusceptibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 5955 5960

61. HsuAL

MurphyCT

KenyonC

2003 Regulation of aging and age-related disease by DAF-16 and heat-shock factor. Science 300 1142 1145

62. WellerU

MullerL

MessnerM

PalmerM

ValevaA

1996 Expression of active streptolysin O in Escherichia coli as a maltose-binding-protein—streptolysin-O fusion protein. The N-terminal 70 amino acids are not required for hemolytic activity. Eur J Biochem 236 34 39

63. HaugwitzU

BobkiewiczW

HanSR

BeckmannE

VeerachatoG

2006 Pore-forming Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin triggers epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent proliferation. Cell Microbiol 8 1591 1600

64. WyttenbachA

SauvageotO

CarmichaelJ

Diaz-LatoudC

ArrigoAP

2002 Heat shock protein 27 prevents cellular polyglutamine toxicity and suppresses the increase of reactive oxygen species caused by huntingtin. Hum Mol Genet 11 1137 1151

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Spatial Distribution and Risk Factors of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) H5N1 in ChinaČlánek HIV Integration Targeting: A Pathway Involving Transportin-3 and the Nuclear Pore Protein RanBP2Článek The Stealth Episome: Suppression of Gene Expression on the Excised Genomic Island PPHGI-1 from pv.Článek Sex and Death: The Effects of Innate Immune Factors on the Sexual Reproduction of Malaria ParasitesČlánek KIR Polymorphisms Modulate Peptide-Dependent Binding to an MHC Class I Ligand with a Bw6 MotifČlánek Viral EncephalomyelitisČlánek Longistatin, a Plasminogen Activator, Is Key to the Availability of Blood-Meals for Ixodid Ticks

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 3- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Choroby jater v ordinaci praktického lékaře – význam jaterních testů

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- The Strain-Encoded Relationship between PrP Replication, Stability and Processing in Neurons is Predictive of the Incubation Period of Disease

- Blood Meal-Derived Heme Decreases ROS Levels in the Midgut of and Allows Proliferation of Intestinal Microbiota

- Human Macrophage Responses to Clinical Isolates from the Complex Discriminate between Ancient and Modern Lineages

- Dendritic Cells and Hepatocytes Use Distinct Pathways to Process Protective Antigen from

- Spatial Distribution and Risk Factors of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) H5N1 in China

- Rhesus TRIM5α Disrupts the HIV-1 Capsid at the InterHexamer Interfaces

- HIV Integration Targeting: A Pathway Involving Transportin-3 and the Nuclear Pore Protein RanBP2

- Antigenic Variation in Malaria Involves a Highly Structured Switching Pattern

- The Stealth Episome: Suppression of Gene Expression on the Excised Genomic Island PPHGI-1 from pv.

- Invasive Extravillous Trophoblasts Restrict Intracellular Growth and Spread of

- Novel Escape Mutants Suggest an Extensive TRIM5α Binding Site Spanning the Entire Outer Surface of the Murine Leukemia Virus Capsid Protein

- Global Functional Analyses of Cellular Responses to Pore-Forming Toxins

- Sex and Death: The Effects of Innate Immune Factors on the Sexual Reproduction of Malaria Parasites

- Lung Adenocarcinoma Originates from Retrovirus Infection of Proliferating Type 2 Pneumocytes during Pulmonary Post-Natal Development or Tissue Repair

- Botulinum Neurotoxin D Uses Synaptic Vesicle Protein SV2 and Gangliosides as Receptors

- The Moving Junction Protein RON8 Facilitates Firm Attachment and Host Cell Invasion in

- KIR Polymorphisms Modulate Peptide-Dependent Binding to an MHC Class I Ligand with a Bw6 Motif

- The Coxsackievirus B 3C Protease Cleaves MAVS and TRIF to Attenuate Host Type I Interferon and Apoptotic Signaling

- Dissection of the Influenza A Virus Endocytic Routes Reveals Macropinocytosis as an Alternative Entry Pathway

- Viral Encephalomyelitis

- Sheep and Goat BSE Propagate More Efficiently than Cattle BSE in Human PrP Transgenic Mice

- Longistatin, a Plasminogen Activator, Is Key to the Availability of Blood-Meals for Ixodid Ticks

- Metabolite Cross-Feeding Enhances Virulence in a Model Polymicrobial Infection

- A Toxin that Hijacks the Host Ubiquitin Proteolytic System

- Dynamic Imaging of the Effector Immune Response to Infection

- The Lectin Receptor Kinase LecRK-I.9 Is a Novel Resistance Component and a Potential Host Target for a RXLR Effector

- Host Iron Withholding Demands Siderophore Utilization for to Survive Macrophage Killing

- The Danger Signal S100B Integrates Pathogen– and Danger–Sensing Pathways to Restrain Inflammation

- The RNome and Its Commitment to Virulence

- A Novel Nuclear Factor TgNF3 Is a Dynamic Chromatin-Associated Component, Modulator of Nucleolar Architecture and Parasite Virulence

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- A Toxin that Hijacks the Host Ubiquitin Proteolytic System

- Invasive Extravillous Trophoblasts Restrict Intracellular Growth and Spread of

- Blood Meal-Derived Heme Decreases ROS Levels in the Midgut of and Allows Proliferation of Intestinal Microbiota

- Metabolite Cross-Feeding Enhances Virulence in a Model Polymicrobial Infection

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání