-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Medical Students' Exposure to and Attitudes about the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Systematic Review

Background:

The relationship between health professionals and the pharmaceutical industry

has become a source of controversy. Physicians' attitudes towards the

industry can form early in their careers, but little is known about this keystage of development.

Methods and Findings:

We performed a systematic review reported according to PRISMA guidelines to

determine the frequency and nature of medical students' exposure to the

drug industry, as well as students' attitudes concerning pharmaceutical

policy issues. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, and ERIC from

the earliest available dates through May 2010, as well as bibliographies of

selected studies. We sought original studies that reported quantitative or

qualitative data about medical students' exposure to pharmaceutical

marketing, their attitudes about marketing practices, relationships with

industry, and related pharmaceutical policy issues. Studies were separated,

where possible, into those that addressed preclinical versus clinical

training, and were quality rated using a standard methodology. Thirty-two

studies met inclusion criteria. We found that 40%–100%

of medical students reported interacting with the pharmaceutical industry. A

substantial proportion of students (13%–69%) were

reported as believing that gifts from industry influence prescribing. Eight

studies reported a correlation between frequency of contact and favorable

attitudes toward industry interactions. Students were more approving of

gifts to physicians or medical students than to government officials.

Certain attitudes appeared to change during medical school, though a time

trend was not performed; for example, clinical students

(53%–71%) were more likely than preclinical students

(29%–62%) to report that promotional information helpseducate about new drugs.

Conclusions:

Undergraduate medical education provides substantial contact with

pharmaceutical marketing, and the extent of such contact is associated with

positive attitudes about marketing and skepticism about negative

implications of these interactions. These results support future research

into the association between exposure and attitudes, as well as any

modifiable factors that contribute to attitudinal changes during medicaleducation.

:

Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 8(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001037

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001037Summary

Background:

The relationship between health professionals and the pharmaceutical industry

has become a source of controversy. Physicians' attitudes towards the

industry can form early in their careers, but little is known about this keystage of development.

Methods and Findings:

We performed a systematic review reported according to PRISMA guidelines to

determine the frequency and nature of medical students' exposure to the

drug industry, as well as students' attitudes concerning pharmaceutical

policy issues. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, and ERIC from

the earliest available dates through May 2010, as well as bibliographies of

selected studies. We sought original studies that reported quantitative or

qualitative data about medical students' exposure to pharmaceutical

marketing, their attitudes about marketing practices, relationships with

industry, and related pharmaceutical policy issues. Studies were separated,

where possible, into those that addressed preclinical versus clinical

training, and were quality rated using a standard methodology. Thirty-two

studies met inclusion criteria. We found that 40%–100%

of medical students reported interacting with the pharmaceutical industry. A

substantial proportion of students (13%–69%) were

reported as believing that gifts from industry influence prescribing. Eight

studies reported a correlation between frequency of contact and favorable

attitudes toward industry interactions. Students were more approving of

gifts to physicians or medical students than to government officials.

Certain attitudes appeared to change during medical school, though a time

trend was not performed; for example, clinical students

(53%–71%) were more likely than preclinical students

(29%–62%) to report that promotional information helpseducate about new drugs.

Conclusions:

Undergraduate medical education provides substantial contact with

pharmaceutical marketing, and the extent of such contact is associated with

positive attitudes about marketing and skepticism about negative

implications of these interactions. These results support future research

into the association between exposure and attitudes, as well as any

modifiable factors that contribute to attitudinal changes during medicaleducation.

:

Please see later in the article for the Editors' SummaryIntroduction

The relationship between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry has become a major topic of concern for health services researchers [1] and policymakers [2], as well as in the lay media. While opinions about such relationships vary [3]–[6], it is clear that physicians have a high level of exposure to industry marketing in a variety of forms, which impacts clinical decision making [4].

Industry involvement in medical education occurs on multiple levels, including one-on-one meetings between trainees and pharmaceutical sales representatives (PSRs) and sponsored publications and educational events (such as Continuing Medical Education courses). Because pharmaceutical companies recognize the potential for education to be used as a marketing tool [7],[8], there is concern that such exposure may communicate a biased message encouraging overuse of particular products [9],[10]. Interactions with PSRs can increase prescriptions of the drug being promoted and shift prescribing in ways that may not be consistent with evidence-based guidelines [11]–[13]. One common outcome is the use of expensive treatments without therapeutic advantage over less costly alternatives [4],[14],[15]. Industry-sponsored education may also influence physicians' ability to weigh the risk-benefit profiles of new, heavily promoted drugs. For example, in the case of rofecoxib (Vioxx), pharmaceutical manufacturer–sponsored educational materials downplayed the drug's cardiac risks (a nearly 2-fold increased risk of heart attack and stroke) [16].

Why does pharmaceutical industry marketing have such a substantial effect on physician behavior [17]? One explanation may be that physicians' attitudes towards the industry and their propensity to be influenced by its marketing form very early in their careers. The socialization effect of professional schooling is strong [18]–[20], and plays a lasting role in shaping students' views and behaviors [21]. For example, a study examining the behavior of physicians trained in residency programs that limit contact with PSRs found that such policies shape subsequent decision making [22]. Therefore, encouraging more rational prescribing among practicing physicians may require a better understanding of how medical students interact with the pharmaceutical industry.

Moves to limit industry influence on undergraduate medical education have been contentious. In recent years, medical schools have taken proactive steps to limit students' and faculties' contact with industry [23]. These steps have included instituting guidelines for speaking and consulting relationships and mandating faculty disclosure of potential conflicts of interest on a public website [24],[25]. However, some have argued that these restrictions are detrimental to students' education and the future of biomedical research [26],[27].

Given the controversy over the pharmaceutical industry's role in undergraduate medical training, synthesizing the current state of knowledge is useful for setting priorities for changes to educational practices and the establishment of a research agenda. We systematically examined the peer-reviewed literature through May 2010 to collect empirical data quantifying medical students' exposure to and perspectives on pharmaceutical marketing practices, including their behaviors related to prescribing and attitudes about important drug policy topics. Specifically, we examined the extent of pharmaceutical industry interactions with medical students, whether such interactions influenced students' views on related topics, and whether any differences exist between students in their preclinical versus clinical years or in different learning environments in relation to these issues.

Methods

Data Sources and Searches

We searched MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE, Web of Science, and ERIC (EBSCOHost) for peer-reviewed articles from the earliest available dates through May 2010 with the help of a medical librarian. For search terms, two main subject heading domains were combined with the AND operator: one to designate the population (e.g., “medical students”) and the other to designate the topics relevant to the research question (e.g., “pharmaceutical industry” and “conflict of interest”). A full list of search terms is available in Table S1. Both Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms (or equivalent) and free text were utilized. No language requirement was placed on the search. Nine additional abstracts not captured by the search strategy were identified through review of the bibliographies of included articles.

Study Selection

We developed a screening strategy using three criteria. First, studies were required to present data specific to medical students. If a study did not indicate whether the year of the students reflected clinical or preclinical training, this information was obtained from descriptions of the medical curricula on the institutional website(s) where the survey was conducted.

Second, studies had to include an observational or experimental design and employ quantitative or qualitative methods. We excluded editorials and other nonempirical opinion pieces. If the study reported pretests and post-tests related to an educational intervention, only preintervention data were analyzed (this occurred in six studies).

Finally, studies were required to report data on either (a) students' exposures to pharmaceutical industry marketing (e.g., counts of meetings with PSRs, gifts, and attendance at industry-sponsored educational events), or (b) students' knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors relating to industry, prescribing practices, or pharmaceutical policy issues, including the educational value of marketing materials, the costs of drug development or treatment regimens, and generic drug use. We excluded studies reporting students' perspectives on complementary and alternative medicines, use of specific therapeutic classes (such as antipsychotics), and medical errors and safety as long as those studies did not also examine industry marketing practices in relation to those topics.

Our screening criteria were applied separately in a pilot phase by two authors (KEA and ASK) on a selection of 10% of the pulled abstracts to ensure clarity of the criteria and reproducibility of the results. Then, one of us (KEA) reviewed the entire list of abstracts and identified articles for full review.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

We noted the study type and characteristics of the populations studied, including year in medical school (preclinical versus clinical), country, sample size, and response rate. Next, we extracted primary data using a piloted extraction tool, including: exposure to industry (type of interaction and frequency); student attitudes about pharmaceutical marketing practices; views and practices related to evidence-based prescribing; and perspectives on use of generic drugs, drug development, and cost of treatment. We identified any correlations between measures (such as exposure and attitudes) and the methodology used to test the correlation. Non-English language articles were translated by a native speaker.

We assessed quality of survey studies using the Glaser and Bero protocol [28], a five-point scale for rating surveys based on study population, generalizability, survey content and construction, and data analysis. Other investigators have also used this strategy in systematic reviews of articles presenting survey data [29]. Two authors (KEA and ASK) independently rated each study and disagreements (which occurred in seven out of the 29 rated) were resolved by consensus.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Given the heterogeneity of studies, qualitative rather than quantitative synthesis of data was performed. We sorted studies on the basis of population training level: “preclinical” (defined as predominantly classroom education), “clinical” (defined as primarily clinical education, including clerkship), or “both.” Data regarding student attitudes were grouped according to type of marketing practice or industry relationship queried. We also performed a sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of excluding older studies (those performed before 2000) and those of lower methodological strength (score 0–2) from our results. The funders of the study played no role in the design of the study, data interpretation, or manuscript preparation. The PRISMA flowchart is available in Text S1.

Results

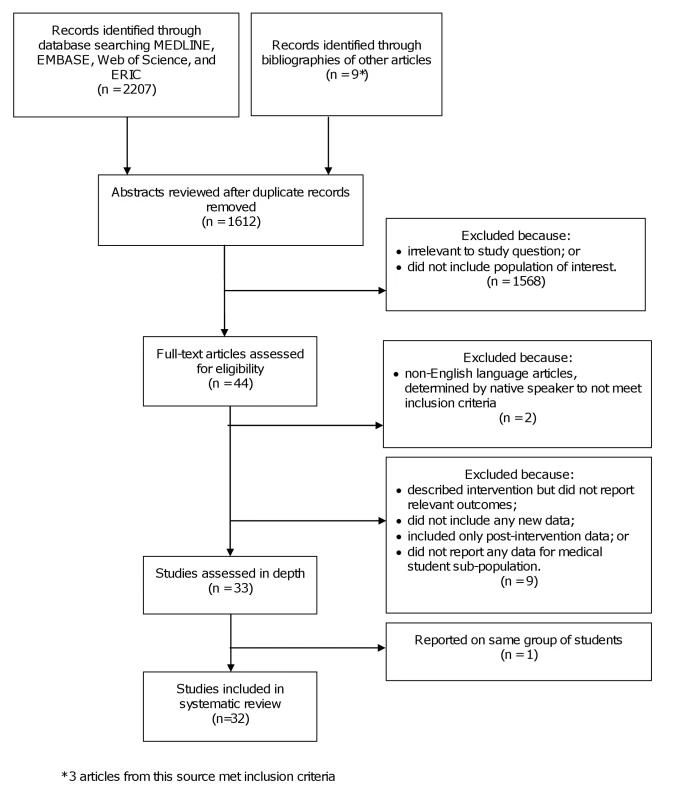

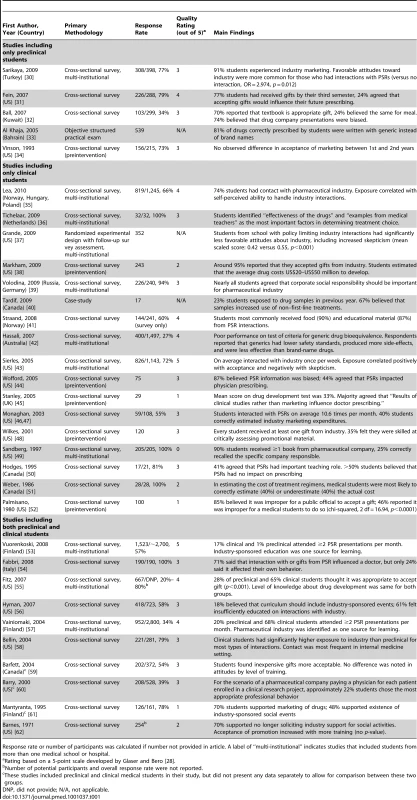

Our search strategy produced 1,603 abstracts. We identified 48 articles for full review and confirmed 33 [30]–[62] as eligible for analysis (Figure 1) [63]. Two papers [46],[47] reported overlapping data from the same sample of students, so we combined them for an effective total of 32 studies. The vast majority of studies (29/32, 91%) [30]–[32],[34]–[36],[38]–[39],[41]–[62] used a cross-sectional survey as the primary methodology, occasionally supplemented with other techniques, such as informant interviews [54] and analyses of student journals [30]. The remaining study designs included a practical exam [33], a case study [40], and a randomized experiment [37]. In total, studies assessed approximately 9,850 medical students at 76 medical schools or hospitals (one study [49] did not specify participants' school affiliation). All studies reviewed are listed in Table 1.

Fig. 1. PRISMA schematic of systematic review search process.

Tab. 1.

Rating based on a 5-point scale developed by Glaser and Bero <em class="ref">[28]</em>. The studies included in this review were published between 1971 and 2010; however, only seven (7/32, 22%) were published before 2000, and the majority of these (5/7, 71%) received a score of 0, 1, or 2 for methodological quality. Over half assessed medical students from the US (15/32, 47%) or Canada (4/32, 13%), but Australia, Russia, and countries in Europe and the Middle East were also represented. Nearly all employed a self-report cross-sectional survey design; many employed additional qualitative methodologies including free-text response, focus groups, and analysis of student journal entries. Seventeen (53%) evaluated only clinical students, five (16%) preclinical students, and ten (31%) compared clinical and preclinical students. Sample sizes ranged from 17 to 1,523. The median methodological quality score was 3 out of 5 (interquartile range = 2–4).

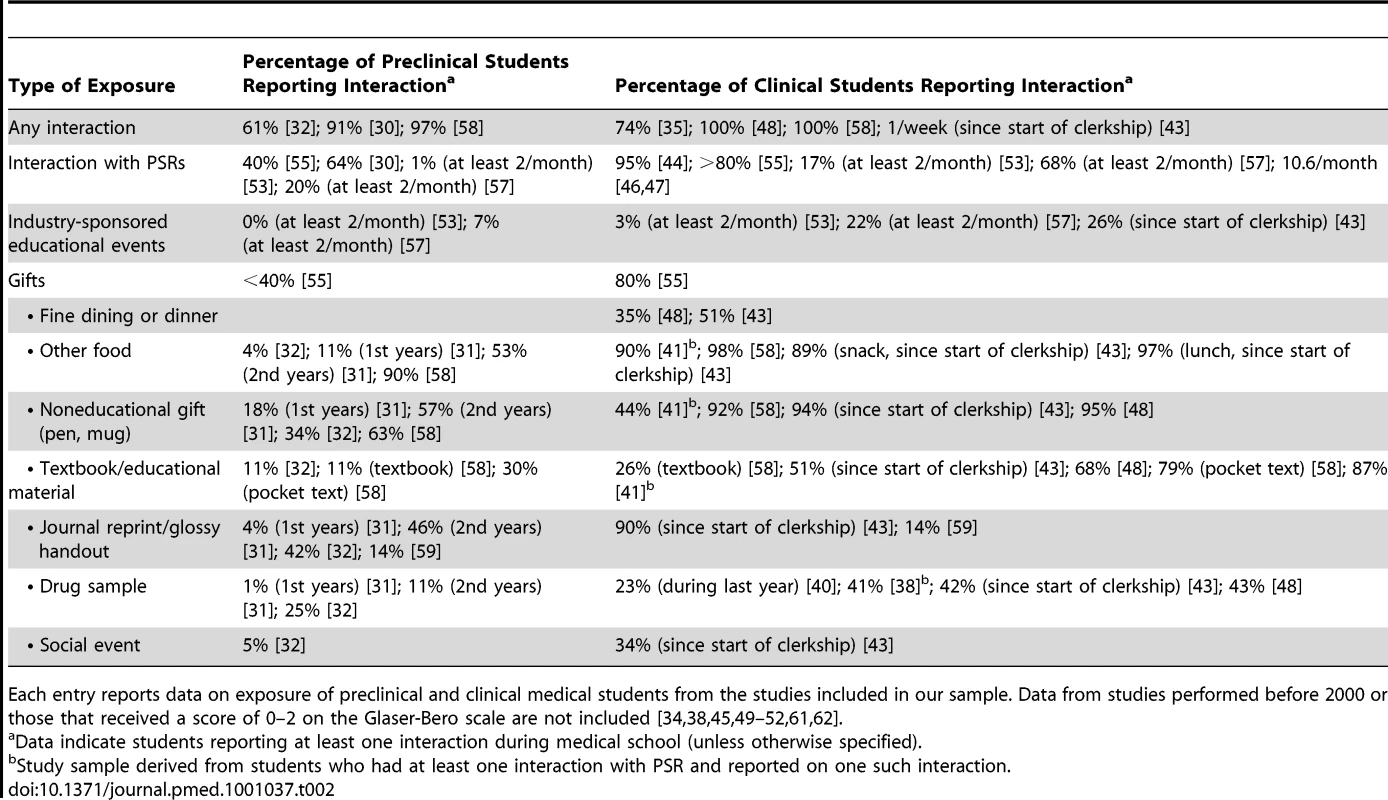

Exposure to Pharmaceutical Marketing

Medical students reported frequently interacting with the pharmaceutical industry (Table 2). Common types of interactions include involved gifts [31],[32],[40],[43],[48]–[50],[55],[58], industry-sponsored educational sessions [43],[53],[57], and direct communications with sales representatives [30],[41],[44],[46],[47],[50],[53],[55],[57]. We found that 89%–98% of students in the clinical years reported having accepted a lunch or snack provided by the pharmaceutical industry [43],[58]; one study of clinical students reporting on interactions with PSRs reported that 90% of exchanges involved food [41]. One multi-institution study from 2005 calculated that third-year American medical students interacted with industry on average once per week [43]. Up to 90% [41],[43],[49] of surveyed students in their clinical years had received educational materials such as textbooks or journal reprints from industry. Substantial variability was noted between studies performed in different countries, with the highest level of exposure occurring in the US, including two studies [48],[58] that found 100% of students had at least one interaction.

Tab. 2. Exposures of medical students to the pharmaceutical industry.

Overall, contact with the pharmaceutical industry increased over the course of medical school. This trend was observed both in studies reporting cumulative incidence (total number of exposures since starting medical school) in preclinical and clinical populations [30]–[32],[35],[38],[44],[48],[49],[55],[58], as well as studies considering exposure during a single academic year or per month [40],[43],[46],[47],[50],[53],[57]. This increase was consistent across most of the types of interactions listed in Table 2.

Attitudes about Marketing Practices

Students' attitudes about pharmaceutical marketing practices were variable and occasionally contradictory (Table 3). Many students approved of meals [31],[32],[35],[43],[46],[47],[59], small promotional items [32],[43],[46],[48],[59],[62], and gifts with an educational purpose [31],[32],[35],[43],[46]–[48],[59], but were less accepting of social events [31],[32],[43],[61],[62] and travel [31],[32],[35],[43],[46]–[48]. However, 75% of students in an Italian study said they would renounce gifts from industry [54]. Students justified their entitlement to gifts by citing financial hardship (48%–80%) [31],[37],[43] or by asserting that most others accepted gifts [54].

When asked about the appropriateness of accepting gifts from industry overall, students at different levels of training expressed divergent opinions. In most studies, the majority of students in their clinical training years found it ethically permissible for medical students to accept gifts from drug manufacturers [37],[43],[52],[55],[56], while a smaller percentage (28%–48%) of preclinical students reported such attitudes [31],[32],[55],[56]. This same trend was seen in student opinion regarding whether physicians should accept gifts [48],[55]. Many students displayed exceptionalism with regard to the medical profession, as approximately 85% reported that it would be inappropriate for a government official to accept similar gifts [52],[55]. Two surveys found no change in perceived appropriateness of gifts from industry as students progressed in their training [32],[34].

One of the most consistently held student attitudes was the belief that education from industry sources is biased [32],[37],[43],[44], especially among clinical students (67%–92%) [37],[43],[44]. Despite this, students variably reported (22%–89%) that information obtained from industry sources was useful and a valuable part of their education [30]–[32],[35],[37],[43],[44],[46]–[48],[50], with clinical students more frequently endorsing the utility.

In most studies, almost two-thirds of students reported that they were immune to bias induced by promotion [53],[57], gifts [31],[32],[37],[43],[46],[47], or interactions with sales representatives in general [46],[47],[54]. This perception of immunity to bias was prevalent in both the preclinical and clinical years. It appeared that students were more likely to report that fellow medical students (38%–69%) or doctors (13%–71%) are influenced by such encounters than they were personally (24%–63%) [31],[37],[43],[46],[47],[54].

Effect of Marketing Practices on Attitudes

Eight studies reported a relationship between exposure to the pharmaceutical industry and positive attitudes about industry interactions and marketing strategies (though not all included supportive statistical data) [30],[32],[35],[43],[49],[50],[53],[57]. In a national survey, students' overall level of exposure to pharmaceutical marketing was inversely correlated with the attitude that these interactions were inappropriate (r = −0.155; p<0.001) and with the belief that these educational sources were biased and influenced prescribing (r = −0.171; p<0.001) [43]. Students who interacted with PSRs were more likely than those who did not meet with PSRs to report positive perceptions of industry marketing (odds ratio [OR] = 2.974, p = 0.012) and were less likely to perceive this marketing as negative (OR = 0.408, p = 0.004) [30]. Lea et al. found that degree of industry exposure was associated with students' attitudes that they had the ability to self-regulate interactions with industry (31% versus 41% versus 50% versus 60%, p<0.001) and with the belief that accepting meals from industry was appropriate (82% versus 67%, p<0.001) [35]. As with all correlational studies, these data cannot demonstrate causation. A study of medical students, physicians, and other health professionals found a relationship between the number of gifts received and the belief that sales representatives do not influence prescribing (rs = 0.24; p<0.04) [50], although this comes from one of the older studies in our sample and data specific to the medical student subgroup were not provided. Only one study found no relationship between students' total number of previous contacts with PSRs and perception of the educational value of PSR interactions (ANOVA p = 0.08) [44].

Students in different learning environments had significant differences in their reported attitudes [35],[37],[43],[53] with perspectives generally consistent with the policies of their schools. One randomized controlled trial exposed students to small promotional items and found differences in implicit attitudes between fourth-year students at two different schools that differed in the strength of their institutional policies regarding industry access [37]. In one national sample, the subset of students participating in clinical clerkships at hospitals that restricted direct industry marketing had less exposure to industry, according to mean exposure index (a measure of number of interactions experienced during a month of clerkship; 2.5 versus 4.6; p<0.001). On a skepticism scale derived from six of the survey questions (range, 0–1; mean skepticism score = 0.43), these students also displayed a significantly higher level of skepticism about marketing messages (mean skepticism score 0.45 versus 0.43; p = 0.03) [43]. A separate study found significant differences in attitudes regarding pharmaceutical marketing between students at two medical schools (mean skepticism score 0.55 versus 0.42; p<0.001) and attributed this divergence to the presence of restrictive policies present at one of the schools (with more skeptical attitudes expressed by these students) [37]. After a national reform limiting pharmaceutical marketing in clinical settings, the percentage of Finnish medical students who believed that marketing would influence their future clinical decisions decreased significantly [53].

Attitudes on Reform

In the studies we identified, students generally did not support excluding sales representatives [31],[32],[37],[43],[46],[47] or industry presentations [35] from the learning environment. Student opinions were split on whether physician–industry interactions should be regulated by medical schools or the government; surveys from Italy and Kuwait reported more support for rule-setting than a US study [32],[54],[56]. Eighty-six percent of American medical students reported that during their residencies they would like to interact with PSRs (86%) [48], and two Finnish surveys [53],[57] found that 24%–57% of students wanted more industry-sponsored education. Faculty disclosure of conflicts of interest before lecturing was endorsed by 69%–77% of students across all studies [31],[35].

Most medical students reported not feeling adequately educated on physician–industry interactions [43],[46],[47],[53],[54],[56] with 62%–86% requesting more instruction in this area [31],[35],[43],[53],[54]. While 39% of clinical students reported being adequately educated on the topic, only 11% of preclinical students reported that the amount of instruction they received was sufficient [53].

Other Pharmaceutical Policy Issues

The pharmaceutical industry was identified as one source of information used by students to learn about therapeutics (16%–49%) [46],[47],[53],[57]. But in one study, students who had interacted with a PSR reported that side effects, interactions, and contraindications of the promoted therapy were either not discussed or inadequately covered in these encounters [41].

Medical students reported little knowledge of drug costs or spending on pharmaceutical marketing [38],[45],[46],[47],[55], except in one survey of Italian medical students, in which 62% were knowledgeable [54]. Two surveys found no change in knowledge about these areas over the course of undergraduate medical training [54],[55]. When asked to estimate the actual cost of treatment described in six clinical scenarios, students underestimated the actual cost in 40% cases, which was similar to the responses of residents or attending physicians [51]. However, this study had methodological flaws and was conducted in 1986; we did not locate more recent studies to confirm this observation.

One study found that knowledge regarding generic medications was poor overall [42]. Students reported negative attitudes about generic drugs, with nearly all agreeing that they were less effective (95%) and of inferior quality (94%), and caused more side effects (93%) than branded drugs. However, in another study evaluating behavior, students from Bahrain tended to prescribe drugs more frequently using their generic name [33].

Sensitivity Analysis

The oldest [34],[49]–[52],[61],[62] and lowest-quality studies [38],[45],[49],[51],[52],[61],[62]—a total of 9 studies—amounted to a total of 8 data points in our analysis (4.2% of the total number of data points). These data were used for supportive purposes only and the results of these studies are not included in Tables 2 and 3.

Discussion

This comprehensive systematic review of medical students' interactions with the pharmaceutical industry found that students are frequently exposed to pharmaceutical marketing, even in the preclinical years when learning is mostly done in the classroom setting. However, we also found that the extent of students' contact with industry is associated with positive attitudes about marketing and skepticism about any negative implications of these interactions. These findings are compatible with the results of a more limited review [64] that examined PubMed-listed English language studies of medical student surveys related to pharmaceutical industry marketing. The year of training and the presence of policies restricting drug industry interactions with trainees appear to influence students' attitudes about the role of marketing and other important pharmaceutical policy issues.

Students' opinions about the pharmaceutical industry differed between the preclinical and clinical years. Compared with preclinical students, those in their clinical years reported more educational value in industry-provided material [31],[32],[35],[41],[44],[46]–[48],[50] and were more accepting of gifts from industry [37],[43],[48],[52],[54],[55],[56]—both to themselves and to professional physicians [31],[32],[55],[56]. Long hours spent working and studying and increasing financial hardship [65] may have contributed to these feelings of entitlement. Preclinical students were less likely to feel sufficiently educated on the topic of physician–industry interactions with the pharmaceutical industry [53],[56], though confidence on this topic was also uncommon among clinical students [43],[46],[47],[53],[54],[56].

Some evidence showed that student opinions varied by medical school and the extent of industry interactions in those communities. Sierles et al. observed that students placed at hospitals with policies limiting interactions with PSRs expressed significantly more critical views of industry than the other students surveyed, though it is not clear whether self-selection played a role [43]. Similar differences were found by Grande et al., with clinical students at the school with a strong policy regarding student-industry interactions differing in their attitudes with students at a school without a strong policy and as compared to the findings of Sierles et al. [37]. Few studies rigorously evaluate whether observed changes in attitude over the course of medical or among different learning environments are causal or simply correlational; this represents a significant limitation of the current literature.

Why would attitudes change over the course of medical education, or why do they differ between two groups of clinical students at different schools? One possible explanation is that industry representatives are effective in directly molding medical students' attitudes about these issues. Another possibility is that the characteristics of medical students' learning environments shape attitudes about the pharmaceutical industry. The implicit lessons communicated through institutional policies and role models have been described as the “hidden curriculum” by scholars of learning theory [66],[67]. The importance of role modeling is explicitly recognized, as students reported “examples from medical teachers” as one important influence on their prescribing decisions [36]. This socialization process has been implicated in other attitudinal changes seen over the course of medical training, such as cynicism [68], burnout [69], and lack of interest in primary care [70].

A number of features of medical education may potentiate these educational cues. First, students are rapidly developing a professional identity and forming a foundation of professional values, making it likely that they will absorb the norms of their surroundings in creating these attitudes. Second, their behavior is constrained by their position at the bottom of the social hierarchy. For example, one study found that 93% of third-year students had been asked or required to attend an industry-sponsored lunch by a superior [43]. This dynamic may help explain why students are likely to accept gifts from pharmaceutical industry representatives even if they believe it is inappropriate. Passive adoption of the norms displayed by role models and actions in contrast to personal values contribute to the socialization of medical students and may in turn impact their professional practice.

Medical students' attitudes in some domains were similar to those reported by residents and practicing physicians. We found that students were more approving of small gifts from industry and those said to have an educational purpose, as compared to large gifts [30]–[32],[34],[35],[46],[47],[54],[59],[62]. In a prior review, Wazana observed a similar pattern in residents and physicians [4]. However, other attitudes appeared to evolve over the course of medical education and practice. For example, more medical students in our analysis reported believing that gifts influence prescribing (24%–63%) [31],[32],[37],[43],[46]–[48],[54] than did practicing physicians in the Wazana review (8%–13%, Likert scale [LS] 1.6–1.8) [4]. Shifts in attitude that occur during the course of training may be attributable to clinicians' greater confidence in their ability to objectively evaluate scientific evidence and distinguish credible information from overstatements in marketing messages. Practicing physicians, however, have been found to be far less adept at this skill than they report [4],[12]. Thus, medical school may be an optimal time to educate about problematic issues associated with learning about drugs through pharmaceutical marketing channels.

Our study has several limitations. Most of the included studies were cross-sectional surveys, which have typical limitations of sampling response rate (representativeness and size), and the difficulty of imputing longitudinal change from cross-sectional data. The heterogeneity of survey questions made it impossible to combine results into a formal meta-analysis because of the risk of false-positive conclusions [71]. Nonetheless, we took steps to address the limitations of a narrative synthesis, such as introduction a formal grading system of each study's methodological strength. Our sensitivity analysis confirmed that the results reported are driven by the newest and highest quality studies identified. Since variability in phrasing of survey questions was common, we took a conservative approach to categorizing responses and reporting response ranges. Publication bias could have also impacted our conclusions.

Since relationships between the pharmaceutical industry and organized medicine are context dependent, some variability could be an effect of country or year of study that was not captured by analysis of the learning environment. We noted some cross-cultural similarities and differences in exposures and attitudes, but none of the included studies were designed specifically to address this issue and more robust data are needed. Likewise, some surveys did not account for confounders within the learning environment that could be important in shaping students' exposures and attitudes or secular trends. For instance, while most studies did not consider gender differences, one found that women were less willing to accept gifts from industry [54]. Future longitudinal surveys following individual trainees could more clearly map the trajectory of beliefs toward the pharmaceutical industry and related issues over the course of professional development and determine which characteristics (institutional, environmental, and personal) most strongly impact this process.

Despite these limitations, this review of the literature provides important insights into the nexus between the pharmaceutical industry and undergraduate medical education and in our view helps elucidate an agenda for moving forward. Our findings demonstrate a significant hole in the existing research, most notably the need for studies that can determine whether changes in student attitudes toward the pharmaceutical industry are caused by contact with industry sources, the influence of role models, institutional policies, or other factors.

Our review also is relevant to those who teach medical students, including those outside of the US (given the diversity of settings of the studies analyzed). Strategies to educate students on physician–industry interactions should directly address misconceptions about the effects of marketing and other biases that can emerge from industry interactions. Support for reforms such as prelecture disclosure of relevant faculty relationships with industry are likely to be well received by students. However, education alone may be insufficient if policymakers are not also engaged. Modifiable institutional characteristics, including rules regulating industry interactions, can play an important role in shaping students' attitudes. Interventions that decrease students' contact with industry and eliminate gifts may have a positive effect on building the “healthy skepticism” that evidence-based medical practice requires. Given the potential for educational and institutional messages to be counteracted by the hidden curriculum, changes should be directed at faculty and residents who serve as role models for medical students. These changes can help move medical education a step closer to two important goals: the cultivation of strong professional values, as well as the promotion of a respect for scientific principles and critical review of evidence that will later inform clinical decision-making and prescribing practices.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. BrennanTRothmanDBlankLBlumenthalDChimonasSC

2006

Health industry practices that create conflicts of interest: a

policy proposal for academic medical centers.

JAMA

295

429

433

2. WilsonD

18 Nov 2009

Medical schools quizzed on ghostwriting.

New York Times. Available: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/08/health/policy/08grassley.html?scp=11&sq=&st=nyt.

Accessed 1 November 2010

3. Institute of Medicine

2009

Conflict of interest in medical research, education, and

practice

Washington (D.C.)

The National Academies Press

4. WazanaA

2000

Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: is a gift ever just a

gift?

JAMA

283

373

380

5. LexchinJBeroLDjulbegovicBClarkO

2003

Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and

quality: a systematic review.

BMJ

326

1167

1177

6. AvornJ

2004

Powerful medicines: the benefits, risks, and costs of prescription

drugs

New York

Knopf

7. AvornJChoudhryN

2010

Funding for medical education: maintaining a healthy separation

from industry.

Circulation

121

2228

2234

8. KesselheimASMelloMMStuddertDM

2011

Strategies and practices in off-label marketing of

pharmaceuticals: a retrospective analysis of whistleblower

complaints.

PLoS Med

8

e1000431

doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000431

9. LandefeldCSSteinmanMA

2009

The Neurontin legacy–marketing through misinformation and

manipulation.

N Engl J Med

360

103

106

10. ZieglerMGLewPSingerBC

1995

The accuracy of drug information from pharmaceutical sales

representatives.

JAMA

273

1296

1298

11. HaayerF

1982

Rational prescribing and sources of information.

Social Sci Med

16

2017

2023

12. ChrenM-MLandefeldCS

1994

Physicians' behavior and their interactions with drug

companies: a controlled study of physicians who requested additions to a

hospital drug formulary.

JAMA

271

684

689

13. ManchandaPHonkaE

2005

The effects and role of direct-to-physician marketing in the

pharmaceutical industry: an integrative review.

Yale J Health Policy Law & Ethics

5

785

812

14. AvornJChenMHartleyR

1982

Scientific versus commercial sources of influence on the

prescribing behavior of physicians.

Amer J Med

73

4

8

15. CaudillTSJohnsonMSRichECMcKinneyWP

1996

Physicians, pharmaceutical sales representatives, and the cost of

prescribing.

Arch Fam Med

5

201

206

16. BerensonA

21 Aug 2005

For Merck, Vioxx paper trail won't go away.

New York Times. Available: http://www.nytimes.com/2005/08/21/business/21vioxx.html.

Accessed 1 November 2010

17. KornDEhringhausS

2007

The scientific basis of influence and reciprocity: a symposium

Washington (D.C.)

Association of American Medical Colleges

18. ErlangerHSKlegonDA

1978

Socialization effects of professional school.

Law & Soc Rev

13

11

35

19. MaheuxBBelandF

1987

Changes in students' sociopolitical attitudes during medical

school: socialization or maturation effect?

Social Sci Med

24

619

624

20. CrandallSDavidSBroesekerAHildebrandtC

2008

A longitudinal comparison of pharmacy and medical students'

attitudes toward the medically underserved.

Am J Pharm Educ

72

article 148

21. PapadakisMATeheraniABanachMAKnettlerTRRathnerSL

2005

Disciplinary action by medical boards and prior behavior in

medical school.

N Engl J Med

353

2673

2682

22. McCormickBTomlinsonGBrill-EdwardsPDetskyA

2001

Effect of restricting contact between pharmaceutical company

representatives and internal medicine residents on post-training attitudes

and behavior.

JAMA

286

1994

1999

23. AMSA PharmFree Scorecard

2008–2009

(updated 24 August 2010)

Reston (Virginia)

American Medical Student Association

Available: http://www.amsascorecard.org/. Accessed 1 November

2010

24. University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

12 November 2007

Policy on conflicts of interest and interactions between representatives

of certain industries and faculty, staff, and students of the Schools of

Health Sciences and personnel employed by UPMC at all domestic

locations

Pittsburg (Pennsylvania)

University of Pittsburgh

Available: http://www.coi.pitt.edu/industryrelationships/Policies/IndustryRelationshipsPolicy.pdf.

Accessed 1 November 2010

25. Stanford University School of Medicine

October 2006

(updated 22 July 2010) Policy and guidelines for interactions between

the Stanford University School of Medicine, the Stanford Hospital and

Clinics, and Lucile Packard Children's Hospital with the

pharmaceutical, biotech, medical device, and hospital and research equipment

and supplies industries

Stanford (California)

Stanford University School of Medicine

Available: http://med.stanford.edu/coi/siip/policy.html#iv. Accessed 1

November 2010

26. StosselT

2008

Has the hunt for conflicts of interest gone too far?

Yes.

BMJ

336

476

27. WilsonD

2 March 2009

Harvard Medical School in ethics quandary.

New York Times. Available: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/03/business/03medschool.html.

Accessed 1 November 2010

28. GlaserBBeroL

2005

Attitudes of academic and clinical researchers towards financial

ties in research: a systematic review.

Science and Engineering Ethics

11

553

573

29. LicurseABarberEJoffeSGrossC

2010

The impact of disclosing financial ties in research and clinical

care: a systematic review.

Arch Intern Med

170

675

682

30. SarikayaOCivanerMVatanseverK

2009

Exposure of medical students to pharmaceutical marketing in

primary care settings: frequent and influential.

Adv in Health Sci Educ

14

713

724

31. FeinEVermillionMUijtdehaagS

2007

Pre-clinical medical students' exposure to and attitudes

toward pharmaceutical industry marketing.

Med Educ Online

12

Available: http://www.med-ed-online.net/index.php/meo/article/viewArticle/4465.

Accessed 1 November 2010

32. BallDAl-ManeaS

2007

Exposure and attitudes to pharmaceutical promotion among pharmacy

and medical students in Kuwait.

Pharmacy Education

7

303

313

33. Al KhajaKHanduSMathurJSequeiraR

2005

Assessing prescription writing skills of pre-clerkship medical

students in a problem-based learning curriculum.

Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther

43

429

435

34. VinsonDMcCandlessBHosokawaM

1993

Medical students' attitudes toward pharmaceutical marketing:

possibilities for change.

Fam Med

25

31

33

35. LeaDSpigsetOSlordalL

2010

Norwegian medical students' attitudes towards the

pharmaceutical industry.

Eur J Clin Pharmacol

66

727

733

36. TichelaarJRichirMAvisHScholtenHAntoniniN

2010

Do medical students copy the drug treatment choices of their

teachers or do they think for themselves?

Eur J Clin Pharmacol

66

407

412

37. GrandeDFroschDPerkinsAKahnB

2009

Effect of exposure to small pharmaceutical promotional items on

treatment preferences.

Arch Intern Med

169

887

893

38. MarkhamFDiamondJFayockK

2009

The effect of a seminar series on third year students'

attitudes toward the interactions of drug companies and

physicians.

The Internet Journal of Family Practice

7

Available: http://www.ispub.com/ostia/index.php?xmlFilePath=journals/ijfp/vol7n1/series.xml.

Accessed 1 November 2010

39. VolodinaASaxSAndersonS

2009

Corporate social responsibility in countries with mature and

emerging pharmaceutical sectors.

Pharmacy Practice

7

Available: http://www.pharmacypractice.org. Accessed 1 November

2010

40. TardifLBaileyBBussieresJLebelDSoucyG

2009

Perceived advantages and disadvantages of using drug samples in a

university hospital center: a case study.

Ann Pharmacother

43

57

63

41. StraandJChristensenJ

2008

The quality of pharmaceutical consultant visits in general

practice.

Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen

128

555

557

42. HassaliMKongDStewartK

2007

A comparison between senior medical students' and pharmacy

pre-registrants' knowledge and perceptions of generic

medicines.

Med Educ

41

703

710

43. SierlesFBrodkeyAClearlyLMcCurdyFAMintzM

2005

Medical students' exposure to and attitudes about drug

company interactions.

JAMA

294

1034

1042

44. WoffordJOhlC

2005

Teaching appropriate interactions with pharmaceutical company

representatives: the impact of an innovative workshop on student

attitudes.

BMC Med Educ

8

5

12

45. StanleyAJacksonDBarnettD

2005

The teaching of drug development to medical students:

collaboration between the pharmaceutical industry and medical

school.

Br J Clin Pharmacol

69

464

474

46. MonaghanMTurnerPHoughtonBMarkertRJGaltKA

2003

Pharmacotherapy cost comparison among health professional

students.

Am J Pharm Educ

67

article 81

47. MonaghanMGaltKTurnerPHoughtonBLRichEC

2003

Student understanding of the relationship between the health

professions and the pharmaceutical industry.

Teach Learn Med

15

14

20

48. WilkesMHoffmanJR

2001

An innovative approach to educating medical students about

pharmaceutical promotion.

Acad Med

75

1271

1277

49. SandbergWCarlosRSandbergERoizenM

1997

The effect of educational gifts from pharmaceutical firms on

medical students' recall of company names or products.

Acad Med

72

916

918

50. HodgesB

1995

Interactions with the pharmaceutical industry: experiences and

attitudes of psychiatry residents, interns and clerks.

Can Med Assoc J

153

553

559

51. WeberMAugerCClerouxR

1986

Knowledge of medical students, pediatric residents, and

pediatricians about the cost of some medications.

Pediatr Pharmacol (New York)

5

281

285

52. PalmisanoPEdelsteinJ

1980

Teaching drug promotion abuses to health professional

students.

J Med Educ

55

453

454

53. VuorenkoskiLValtaMHelveO

2008

Effect of legislative changes in drug promotion on medical

students: questionnaire survey.

Med Educ

42

1172

1177

54. FabbriAArdigoMGrandoriLRealiCBodiniC

2008

Conflicts of interest between physicians and the pharmaceutical

industry. A quali-quantitative study to assess medical students'

attitudes at the University of Bologna.

Ricerca Sul Campo

24

242

254

55. FitzMHomnaDReddySGriffithCBakerE

2007

The hidden curriculum: medical students' changing opinions

toward the pharmaceutical industry.

Acad Med

82

S1

S3

56. HymanPHochmanMShawJSteinmanM

2007

Attitudes of preclinical and clinical medical students toward

interactions with the pharmaceutical industry.

Acad Med

82

94

99

57. VainiomakiMHelveOVuorenkoskiL

2004

A national survey on the effect of pharmaceutical promotion on

medical students.

Med Teach

26

630

634

58. BellinMMcCarthySDrevlowLPierachC

2004

Medical students' exposure to pharmaceutical industry

marketing: a survey at one U.S. medical school.

Acad Med

79

1041

1045

59. BarfettJLantingBLeeJLeeMNgV

2004

Pharmaceutical marketing to medical students: the student

perspective.

McGill J Med

8

21

27

60. BarryDCyranEAndersonR

2000

Common issues in medical professionalism: room to

grow.

Amer J Med

108

136

142

61. MantyrantaTHemminkiE

1994

Medical students and drug promotion.

Acad Med

69

736

62. BarnesCHolcenbergJ

1971

Student reactions to pharmaceutical promotion

practices.

Northwest Med

70

262

266

63. LiberatiAAltmanDGTetzlaffJMulrowCGøtzschePC

2009

The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and

meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions:

explanation and elaboration.

Ann Intern Med

151

W65

W94

64. CarmodyDMansfieldP

2010

What do medical students think about pharmaceutical

promotion?

Australian Med Student J

1

56

59

65. American Association of Medical Colleges

26 Oct 2009

2009 medical school graduation questionnaire: all schools summary

report.

Available: http://www.aamc.org/data/gq/allschoolsreports/gqfinalreport_2009.pdf.

Accessed 1 November 2010

66. HaffertyFFranksR

1994

The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of

medical education.

Acad Med

69

861

871

67. HaffertyF

1998

Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine's hidden

curriculum.

Acad Med

73

403

407

68. HojatMVergareMMaxwellKBrainardGHerrineSK

2009

The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion

of empathy in medical school.

Acad Med

84

1182

1191

69. WoloschukWHarasymPTempleW

2004

Attitude change during medical school: a cohort

study.

Medical Education

38

522

534

70. RabinowitzH

1990

The change in specialty preference by medical students over time:

an analysis of students who prefer family medicine.

Fam Med

22

62

63

71. HigginsJThompsonS

2004

Controlling the risk of spurious findings from

meta-regression.

Stat Med

23

1663

1682

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 5- Není statin jako statin aneb praktický přehled rozdílů jednotlivých molekul

- Magnosolv a jeho využití v neurologii

- Moje zkušenosti s Magnosolvem podávaným pacientům jako profylaxe migrény a u pacientů s diagnostikovanou spazmofilní tetanií i při normomagnezémii - MUDr. Dana Pecharová, neurolog

- Biomarker NT-proBNP má v praxi široké využití. Usnadněte si jeho vyšetření POCT analyzátorem Afias 1

- S prof. Vladimírem Paličkou o racionální suplementaci kalcia a vitaminu D v každodenní praxi

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Primary Prevention of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Large-for-Gestational-Age Newborns by Lifestyle Counseling: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial

- Meta-analyses of Adverse Effects Data Derived from Randomised Controlled Trials as Compared to Observational Studies: Methodological Overview

- Effectiveness of Early Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation to Improve Survival among HIV-Infected Adults with Tuberculosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study

- Characterizing the Epidemiology of the 2009 Influenza A/H1N1 Pandemic in Mexico

- The Joint Action and Learning Initiative: Towards a Global Agreement on National and Global Responsibilities for Health

- Let's Be Straight Up about the Alcohol Industry

- Advancing Cervical Cancer Prevention Initiatives in Resource-Constrained Settings: Insights from the Cervical Cancer Prevention Program in Zambia

- The Transit Phase of Migration: Circulation of Malaria and Its Multidrug-Resistant Forms in Africa

- Health Aspects of the Pre-Departure Phase of Migration

- Aripiprazole in the Maintenance Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: A Critical Review of the Evidence and Its Dissemination into the Scientific Literature

- Threshold Haemoglobin Levels and the Prognosis of Stable Coronary Disease: Two New Cohorts and a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- If You Could Only Choose Five Psychotropic Medicines: Updating the Interagency Emergency Health Kit

- Migration and Health: A Framework for 21st Century Policy-Making

- Maternal Influenza Immunization and Reduced Likelihood of Prematurity and Small for Gestational Age Births: A Retrospective Cohort Study

- The Impact of Retail-Sector Delivery of Artemether–Lumefantrine on Malaria Treatment of Children under Five in Kenya: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial

- Medical Students' Exposure to and Attitudes about the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Systematic Review

- Estimates of Outcomes Up to Ten Years after Stroke: Analysis from the Prospective South London Stroke Register

- Low-Dose Adrenaline, Promethazine, and Hydrocortisone in the Prevention of Acute Adverse Reactions to Antivenom following Snakebite: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Low-Dose Adrenaline, Promethazine, and Hydrocortisone in the Prevention of Acute Adverse Reactions to Antivenom following Snakebite: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

- Effectiveness of Early Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation to Improve Survival among HIV-Infected Adults with Tuberculosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study

- Medical Students' Exposure to and Attitudes about the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Systematic Review

- Estimates of Outcomes Up to Ten Years after Stroke: Analysis from the Prospective South London Stroke Register

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání