-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Advancing Cervical Cancer Prevention Initiatives in

Resource-Constrained Settings: Insights from the Cervical Cancer Prevention

Program in Zambia

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 8(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001032

Category: Health in Action

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001032Summary

article has not abstract

Summary Points

-

Invasive cervical cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related death and morbidity among women in the developing world.

-

Screening coverage rates are very low in developing countries despite there being proven, simple, “screen and treat” approaches for cervical cancer prevention.

-

In 2006 we initiated a partnership with the public health system in Zambia and created the Cervical Cancer Prevention Program in Zambia (CCPPZ), targeting the highest risk HIV-infected women, and have provided services to over 58,000 women (regardless of HIV status) over the past 5 years.

-

We have demonstrated a strategy for using the availability, momentum, and capacity-building efforts of vertical HIV/AIDS care and treatment programs to implement a setting-appropriate protocol for cervical cancer prevention within public health infrastructures.

-

We report our lessons learned to help other cervical cancer prevention initiatives succeed in the developing world and to avoid additional burdens on health systems.

The Challenge of Implementing Cervical Cancer Prevention in the Developing World

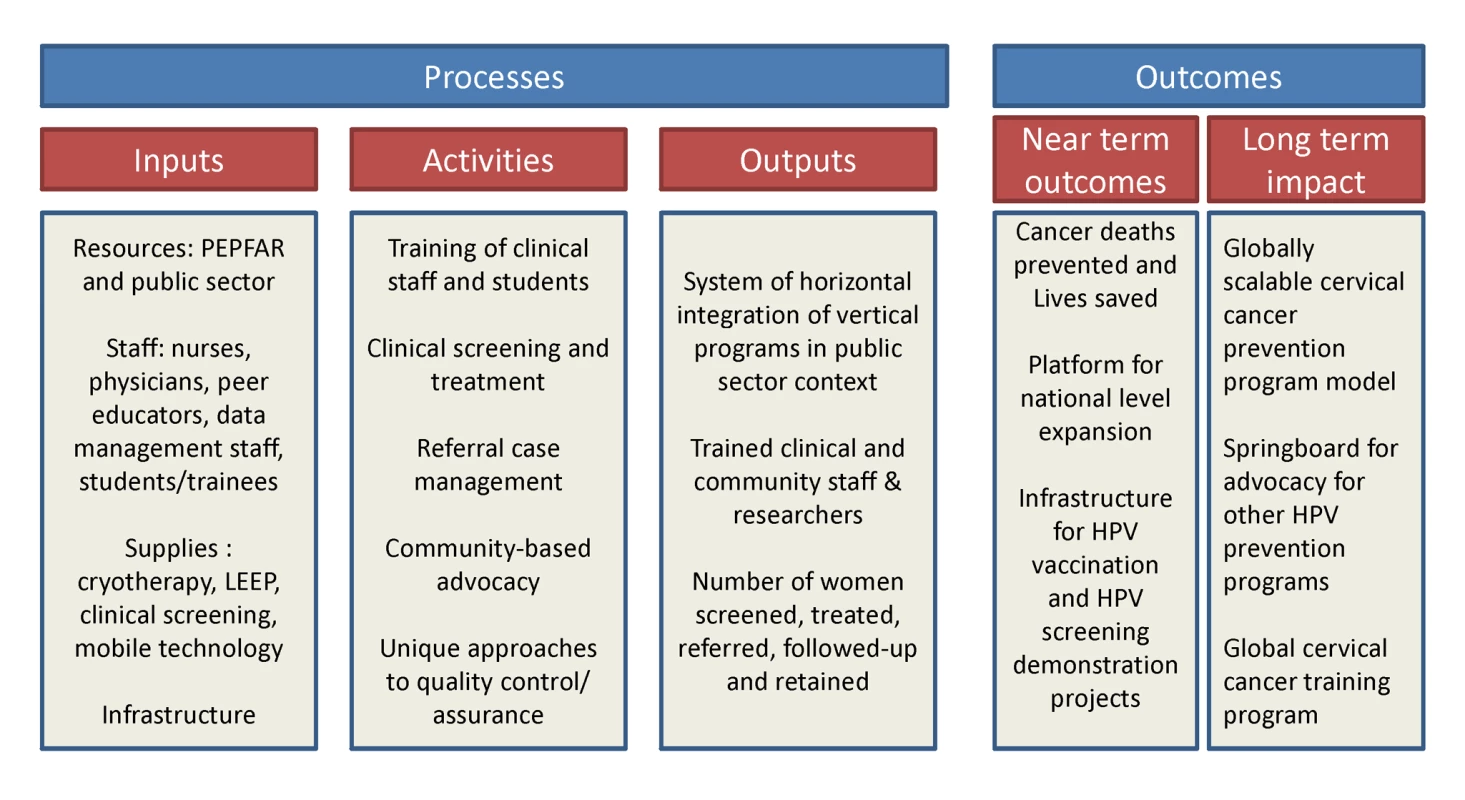

Invasive cervical cancer (ICC) is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality and morbidity among women in the developing world [1]. Numerous demonstration projects have proven the efficacy of simplified “screen and treat” approaches (such as visual inspection with acetic acid [VIA] and immediate cryotherapy) for cervical cancer prevention in low income countries [2]–[5]. Yet, rarely have they been adopted and scaled up by governments in such settings, and as a result rates of screening coverage in the developing world remain low [6]. In Zambia, which has the world's second highest annual cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates [1], we initiated a unique partnership for providing cervical cancer prevention services within the public sector health care system. The Cervical Cancer Prevention Program in Zambia (CCPPZ), launched in 2006 and initially targeting the highest risk HIV-infected women, has cumulatively provided services to over 58,000 women (regardless of HIV status) over the past 5 years [7],[8] (Figure 1). Our previous reports have described the disease burden [9],[10],[11], program implementation experience [7], telecommunications matrix utilized for distance consultation and quality assurance [8], outcomes of a referral system for women ineligible for treatment with cryotherapy [12], common myths and misconceptions surrounding cervical cancer [13], and an analysis of outcomes and effectiveness of screening among women with HIV [11]. In this article, we discuss the unique attributes of the program's successful implementation, including its adoptability to the conditions of a resource-constrained environment, integration with infrastructure of an HIV/AIDS program, use of innovative quality assurance measures, and the potential for sustainability and collateral impact (Figure 2). The global “call to action” for cancer control in low income countries is emerging [14], yet funding for stand-alone cancer prevention initiatives is virtually non-existent. Our experience may provide insights and guidance for advancing cancer prevention initiatives in resource-constrained settings.

The Cervical Cancer Prevention Program in Zambia (CCPPZ)

CCPPZ is a unique partnership between Zambian and United States partner institutions from the academic (University Teaching Hospital [UTH] in Lusaka and University of Alabama at Birmingham [UAB]), research (Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia [CIDRZ]), and governmental (Zambian Ministry of Health) sectors. Prevention efforts have been rapidly scaled up, taking advantage of a historical circumstance of increased attention and funding in the HIV/AIDS sector through the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) program [15]. Trained nurses form the backbone of the program, providing free personalized clinical screening examinations for all eligible women who attend the clinic [7],[11]. VIA aided by a low-cost digital camera adaptation (“digital cervicography”) is used to provide results immediately [11]. Decisions about offering immediate cryotherapy (“screen-and-treat”) or referral are made independently by nurses in most cases, or aided by telemedicine consultations with local doctors [11]. VIA-negative women are advised to follow-up after 1 year, VIA-positive and cryotherapy-eligible women are treated by the nurses, and those needing referral are advised to attend the Gynecologic Cancer Prevention Unit in the UTH [12]. Administrative support is provided by CIDRZ, while program operations are integrated with the Zambian Ministry of Health's public sector health care infrastructure [7]. From 2006 to March 2011, over 58,000 women, regardless of HIV status, have been screened in this program. Of the initial 21,010 women who were provided services in the program (31% of whom had HIV), 38% were VIA positive, of whom 62% were eligible for cryotherapy and 38% were referred for histologic evaluation. Forty-nine percent of patients referred for histologic evaluation complied, and pathology results revealed benign abnormalities in 8%, CIN1 in 28%, CIN2/3 in 26%, and ICC in 19% (of which 55% were early stage).

Low-Tech Yet Scalable Prevention Intervention Modality

The dearth of adequately trained cytotechnologists and pathologists, and the requirement for multiple patient visits, preclude successful utilization of cervical cytology (“Pap smears”) in most of the developing world [5]. Testing for cervical human papillomavirus (HPV) is a highly accurate screening approach, [16],[17] but the high cost of current commercially available HPV testing technology makes routine implementation in low income countries impractical, if not impossible [18]. VIA linked to cryotherapy has unique strengths (it can be done by mid-level health care providers, and has immediate results that allow linking screening and treatment in the same visit), but also antecedent weaknesses (higher potential for false-positive results, and limitations in ensuring quality assurance [5]). Nonetheless, VIA remains the only available option for a setting like Zambia. We enhanced its application through the use of digital photography (cervicography) as a routine adjunct to ensure quality as well as help with patient education and electronic record keeping, and rapid distance consultation with the limited number of available physician experts, when necessary [8]. Our model facilitated program scale-up, despite limited resources. In fact, our experience suggests that while the accuracy of a screening test is an important attribute, it is only a small part of the equation for mitigating cervical cancer. Ultimately, the success of cervical cancer prevention interventions is largely determined by how screening and treatment activities are integrated within the routine health care system to ensure maximal impact, an enduring goal of our program.

Horizontal Integration with Donor-Funded HIV/AIDS Care and Treatment Programs

The increasing expansion, over the past decade, of bilateral (e.g., PEPFAR) and multilateral (e.g., Global Fund) donor funding for HIV/AIDS programs has transformed health care delivery in resource limited settings, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa [19]. With support from PEPFAR and private donations, CCPPZ's cervical cancer prevention clinics are co-located within public health clinics offering HIV/AIDS care and treatment. Manifold advantages of this strategy include resource and infrastructure sharing, availability of a wider range of women's health services for HIV-infected/at-risk women, and opportunities for referral between the clinic systems and maximization of participation in both programs. Yet, the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS continues to be a challenge in Zambia, which drove our decision to keep service provisions and the identities of the cervical cancer and HIV/AIDS care programs distinct, albeit in the same premises. Women attending cervical cancer screening clinics with unknown HIV status are offered HIV testing within the confidential environment of the screening rooms. Indeed, cervical cancer itself is stigmatized, and anxiety and fear often keep women from getting screened [13]. In response, the program is branded as a “Cervical Health” program, which deemphasizes cancer while denoting a positive (“health”) connotation to the effort.

Innovations Using Information Technology

One of the most enabling and transforming aspects of the program involves utilizing information technology tools for enhancing the program's operations and enabling quality assurance. Telemedicine consultation through the “electronic cervical cancer control” model [8] is a mobile health application that has enhanced clinical care services and improved quality assurance of nurse-led VIA. The use of community volunteers as patient-tracking officers, taking advantage of the wide usage of cell phone–based communication among the patient population, is now promoting adherence to the already minimized follow-up visit requirements. The use of point-of-care online data entry (undertaken by nurses and their community volunteer assistants), and a centralized Web-based patient clinical and laboratory records management system are enhancing program monitoring and outcomes evaluation.

Collateral Impact and the Promise of Sustainability

The program is, by design, integrated with the operations of the public health system run and operated by the Zambian Ministry of Health, a model that has helped its transition from being a foreign-funded/led project to a locally/nationally “owned” program. Program nurses are recruited from the public sector health care system, with add-on financial incentives to facilitate retention. The program also employs community-based volunteers to serve as “peer educators” to facilitate community awareness, counteract misconceptions and myths, and serve patient support functions [13]. All referral services are located within UTH, the only state-run tertiary hospital in Zambia, which permits medical and surgical services (including loop electrosurgical excision procedures [LEEP], hysterectomy, radiation, and chemotherapy) at low-to-no cost to patients. The need for coordination of various administrative, clinical, and laboratory (referral-level) services are achieved through locally employed Zambian nationals, with technical assistance from expatriate American clinicians and administrators living within the country, in a “shared leadership” model (Figure 3). The motto of the program (“Every woman has the right to live a life free from cervical cancer”) encapsulates the rights-based approach to women's health, designed to promote community-based acceptance of this program. The program's infrastructure has facilitated the development of a linked clinical, epidemiological, and translational research platform supported by numerous extramural research and training grants and contracts. Opportunities abound for engaging Zambian and foreign clinical and research trainees. The program's successful expansion in the Lusaka area has leveraged political will for nationwide expansion, as well as eventual roll out of HPV vaccination and HPV-based screening [20] as the logical next steps in its evolution (Figure 2). As with any expanding program, unique challenges may arise with future geographic expansion, yet we believe that the lessons learnt during our initial years as well as the improved awareness that the program has engendered, will likely generate unique solutions.

Conclusion

For cancer prevention initiatives to succeed in the developing world, programs must avoid placing additional burdens on health systems already stretched thin due to competing priorities. We have demonstrated a strategy for using the availability, momentum, and capacity-building efforts of vertical HIV/AIDS care and treatment programs to implement other disease-specific initiatives such as cervical cancer prevention [19]. By integrating a setting-appropriate protocol for cervical cancer prevention into public health infrastructures, and promoting shared leadership with government ownership, our program has not just saved lives [11], but has also established a new solution for routine prevention intervention in resource-constrained environments.

Zdroje

1. FerlayJShinHRBrayFFormanDMathersC

2010

Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN

2008.

Int J Cancer

127

2893

2917

2. SankaranarayananREsmyPORajkumarRMuwongeRSwaminathanR

2007

Effect of visual screening on cervical cancer incidence and

mortality in Tamil Nadu, India: a cluster-randomised trial.

Lancet

370

398

406

3. BlumenthalPDGaffikinLDeganusSLewisREmersonM

2007

Cervical cancer prevention: safety, acceptability, and

feasibility of a single-visit approach in Accra, Ghana.

Am J Obstet Gynecol

196

407

e401–408; discussion 407 e408–409

4. GaffikinLBlumenthalPDEmersonMLimpaphayomK

2003

Safety, acceptability, and feasibility of a single-visit approach

to cervical-cancer prevention in rural Thailand: a demonstration

project.

Lancet

361

814

820

5. SankaranarayananRBoffettaP

2010

Research on cancer prevention, detection and management in low-

and medium-income countries.

Ann Oncol

21

1935

1943

6. GakidouENordhagenSObermeyerZ

2008

Coverage of cervical cancer screening in 57 countries: low

average levels and large inequalities.

PLoS Med

5

e132

doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050132

7. MwanahamuntuMHSahasrabuddheVVPfaendlerKSMudendaVHicksML

2009

Implementation of ‘see-and-treat’ cervical cancer

prevention services linked to HIV care in Zambia.

AIDS

23

N1

N5

8. ParhamGPMwanahamuntuMHPfaendlerKSSahasrabuddheVVMyungD

2010

eC3–a modern telecommunications matrix for cervical cancer

prevention in Zambia.

J Low Genit Tract Dis

14

167

173

9. ParhamGPSahasrabuddheVVMwanahamuntuMHShepherdBEHicksML

2006

Prevalence and predictors of squamous intraepithelial lesions of

the cervix in HIV-infected women in Lusaka, Zambia.

Gynecol Oncol

103

1017

1022

10. SahasrabuddheVVMwanahamuntuMHVermundSHHuhWKLyonMD

2007

Prevalence and distribution of HPV genotypes among HIV-infected

women in Zambia.

Br J Cancer

96

1480

1483

11. ParhamGPMwanahamuntuMHSahasrabuddheVVWestfallAOKingKE

2010

Implementation of cervical cancer prevention services for

HIV-infected women in Zambia: measuring program

effectiveness.

HIV Therapy

4

713

722

12. PfaendlerKSMwanahamuntuMHSahasrabuddheVVMudendaVStringerJS

2008

Management of cryotherapy-ineligible women in a

“screen-and-treat” cervical cancer prevention program targeting

HIV-infected women in Zambia: lessons from the field.

Gynecol Oncol

110

402

407

13. ChirwaSMwanahamuntuMKapambweSMkumbaGStringerJ

2010

Myths and misconceptions about cervical cancer among Zambian

women: rapid assessment by peer educators.

Glob Health Promot

17

47

50

14. FarmerPFrenkJKnaulFMShulmanLNAlleyneG

2010

Expansion of cancer care and control in countries of low and

middle income: a call to action.

Lancet

376

1186

1193

15. StringerJSZuluILevyJStringerEMMwangoA

2006

Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in

Zambia: feasibility and early outcomes.

JAMA

296

782

793

16. SankaranarayananRNeneBMShastriSSJayantKMuwongeR

2009

HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India.

N Engl J Med

360

1385

1394

17. DennyLKuhnLHuCCTsaiWYWrightTCJr

2010

Human papillomavirus-based cervical cancer prevention: long-term

results of a randomized screening trial.

J Natl Cancer Inst

102

1557

1567

18. TropeLAChumworathayiBBlumenthalPD

2009

Preventing cervical cancer: stakeholder attitudes toward

CareHPV-focused screening programs in Roi-et Province,

Thailand.

Int J Gynecol Cancer

19

1432

1438

19. DennyCCEmanuelEJ

2008

US health aid beyond PEPFAR: the Mother & Child

Campaign.

JAMA

300

2048

2051

20. QiaoYLSellorsJWEderPSBaoYPLimJM

2008

A new HPV-DNA test for cervical-cancer screening in developing

regions: a cross-sectional study of clinical accuracy in rural

China.

Lancet Oncol

9

929

936

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek The Transit Phase of Migration: Circulation of Malaria and Its Multidrug-Resistant Forms in AfricaČlánek If You Could Only Choose Five Psychotropic Medicines: Updating the Interagency Emergency Health Kit

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 5- Není statin jako statin aneb praktický přehled rozdílů jednotlivých molekul

- Magnosolv a jeho využití v neurologii

- Moje zkušenosti s Magnosolvem podávaným pacientům jako profylaxe migrény a u pacientů s diagnostikovanou spazmofilní tetanií i při normomagnezémii - MUDr. Dana Pecharová, neurolog

- Biomarker NT-proBNP má v praxi široké využití. Usnadněte si jeho vyšetření POCT analyzátorem Afias 1

- Antikoagulační léčba u pacientů před operačními výkony

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Primary Prevention of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Large-for-Gestational-Age Newborns by Lifestyle Counseling: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial

- Meta-analyses of Adverse Effects Data Derived from Randomised Controlled Trials as Compared to Observational Studies: Methodological Overview

- Effectiveness of Early Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation to Improve Survival among HIV-Infected Adults with Tuberculosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study

- Characterizing the Epidemiology of the 2009 Influenza A/H1N1 Pandemic in Mexico

- The Joint Action and Learning Initiative: Towards a Global Agreement on National and Global Responsibilities for Health

- Let's Be Straight Up about the Alcohol Industry

- Advancing Cervical Cancer Prevention Initiatives in Resource-Constrained Settings: Insights from the Cervical Cancer Prevention Program in Zambia

- The Transit Phase of Migration: Circulation of Malaria and Its Multidrug-Resistant Forms in Africa

- Health Aspects of the Pre-Departure Phase of Migration

- Aripiprazole in the Maintenance Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: A Critical Review of the Evidence and Its Dissemination into the Scientific Literature

- Threshold Haemoglobin Levels and the Prognosis of Stable Coronary Disease: Two New Cohorts and a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- If You Could Only Choose Five Psychotropic Medicines: Updating the Interagency Emergency Health Kit

- Migration and Health: A Framework for 21st Century Policy-Making

- Maternal Influenza Immunization and Reduced Likelihood of Prematurity and Small for Gestational Age Births: A Retrospective Cohort Study

- The Impact of Retail-Sector Delivery of Artemether–Lumefantrine on Malaria Treatment of Children under Five in Kenya: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial

- Medical Students' Exposure to and Attitudes about the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Systematic Review

- Estimates of Outcomes Up to Ten Years after Stroke: Analysis from the Prospective South London Stroke Register

- Low-Dose Adrenaline, Promethazine, and Hydrocortisone in the Prevention of Acute Adverse Reactions to Antivenom following Snakebite: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Low-Dose Adrenaline, Promethazine, and Hydrocortisone in the Prevention of Acute Adverse Reactions to Antivenom following Snakebite: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

- Effectiveness of Early Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation to Improve Survival among HIV-Infected Adults with Tuberculosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study

- Medical Students' Exposure to and Attitudes about the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Systematic Review

- Estimates of Outcomes Up to Ten Years after Stroke: Analysis from the Prospective South London Stroke Register

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání