-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Genetic Architecture of Aluminum Tolerance in Rice () Determined through Genome-Wide Association Analysis and QTL Mapping

Aluminum (Al) toxicity is a primary limitation to crop productivity on acid soils, and rice has been demonstrated to be significantly more Al tolerant than other cereal crops. However, the mechanisms of rice Al tolerance are largely unknown, and no genes underlying natural variation have been reported. We screened 383 diverse rice accessions, conducted a genome-wide association (GWA) study, and conducted QTL mapping in two bi-parental populations using three estimates of Al tolerance based on root growth. Subpopulation structure explained 57% of the phenotypic variation, and the mean Al tolerance in Japonica was twice that of Indica. Forty-eight regions associated with Al tolerance were identified by GWA analysis, most of which were subpopulation-specific. Four of these regions co-localized with a priori candidate genes, and two highly significant regions co-localized with previously identified QTLs. Three regions corresponding to induced Al-sensitive rice mutants (ART1, STAR2, Nrat1) were identified through bi-parental QTL mapping or GWA to be involved in natural variation for Al tolerance. Haplotype analysis around the Nrat1 gene identified susceptible and tolerant haplotypes explaining 40% of the Al tolerance variation within the aus subpopulation, and sequence analysis of Nrat1 identified a trio of non-synonymous mutations predictive of Al sensitivity in our diversity panel. GWA analysis discovered more phenotype–genotype associations and provided higher resolution, but QTL mapping identified critical rare and/or subpopulation-specific alleles not detected by GWA analysis. Mapping using Indica/Japonica populations identified QTLs associated with transgressive variation where alleles from a susceptible aus or indica parent enhanced Al tolerance in a tolerant Japonica background. This work supports the hypothesis that selectively introgressing alleles across subpopulations is an efficient approach for trait enhancement in plant breeding programs and demonstrates the fundamental importance of subpopulation in interpreting and manipulating the genetics of complex traits in rice.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 7(8): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002221

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002221Summary

Aluminum (Al) toxicity is a primary limitation to crop productivity on acid soils, and rice has been demonstrated to be significantly more Al tolerant than other cereal crops. However, the mechanisms of rice Al tolerance are largely unknown, and no genes underlying natural variation have been reported. We screened 383 diverse rice accessions, conducted a genome-wide association (GWA) study, and conducted QTL mapping in two bi-parental populations using three estimates of Al tolerance based on root growth. Subpopulation structure explained 57% of the phenotypic variation, and the mean Al tolerance in Japonica was twice that of Indica. Forty-eight regions associated with Al tolerance were identified by GWA analysis, most of which were subpopulation-specific. Four of these regions co-localized with a priori candidate genes, and two highly significant regions co-localized with previously identified QTLs. Three regions corresponding to induced Al-sensitive rice mutants (ART1, STAR2, Nrat1) were identified through bi-parental QTL mapping or GWA to be involved in natural variation for Al tolerance. Haplotype analysis around the Nrat1 gene identified susceptible and tolerant haplotypes explaining 40% of the Al tolerance variation within the aus subpopulation, and sequence analysis of Nrat1 identified a trio of non-synonymous mutations predictive of Al sensitivity in our diversity panel. GWA analysis discovered more phenotype–genotype associations and provided higher resolution, but QTL mapping identified critical rare and/or subpopulation-specific alleles not detected by GWA analysis. Mapping using Indica/Japonica populations identified QTLs associated with transgressive variation where alleles from a susceptible aus or indica parent enhanced Al tolerance in a tolerant Japonica background. This work supports the hypothesis that selectively introgressing alleles across subpopulations is an efficient approach for trait enhancement in plant breeding programs and demonstrates the fundamental importance of subpopulation in interpreting and manipulating the genetics of complex traits in rice.

Introduction

Aluminum (Al) toxicity is the major constraint to crop productivity on acid soils, which comprise over 50% of the world's arable land [1]. Under highly acidic soil conditions (pH<5.0), Al is solubilized into the soil solution as Al3+, which is highly phytotoxic, causing a rapid inhibition of root growth that leads to a reduced and stunted root system, thus having a direct effect on the ability of a plant to acquire both water and nutrients.

Cereal crops (Poaceae) have been a primary focus of Al tolerance research [2]. This research has demonstrated that levels of Al tolerance vary widely both within and between species [3]–[8]. Of the major cereal species that have been extensively studied (rice, maize, wheat, barley and sorghum), rice demonstrates superior Al tolerance under both field and hydroponic conditions [3], [8]. Although rice is 6–10 times more Al tolerant than other cereals, very little is known about the genes underlying this tolerance. Based on its high level of Al tolerance and numerous genetic and genomic resources, rice provides a good model for studying the genetics and physiology of Al tolerance.

In wheat, sorghum, and barley, Al tolerance is inherited as a simple trait, controlled by one or a few genes [9]–[11]. However, in maize, rice, and Arabidopsis, tolerance is quantitatively inherited [12], [13]. Al tolerance genes have been cloned in wheat and sorghum. The wheat resistance gene, ALMT1, encodes an Al-activated malate transporter [14]. The sorghum resistance gene, SbMATE, encodes a member of the multidrug and toxic compound - extrusion (MATE) family and is an Al-activated, root citrate efflux transporter [15]–[17].

Four mutant genes that lead to Al sensitivity in rice have recently been cloned, STAR1 (Sensitive to Al rhizotoxicity1), STAR2 (Sensitive to Al rhizotoxicity2), ART1 (Aluminum rhizotoxicity 1), and Nrat1 (Nramp aluminum transporter 1) [18]–[20]. The products of STAR1 and STAR2 are expressed mainly in the roots and are components of a bacterial-type ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter. Both are transcriptionally activated by exposure to Al and loss of function of either gene results in hypersensitivity to Al. STAR1 and STAR2 are similar to two Al sensitive mutants in Arabidopsis, als1 and als3, also encoding ABC transporters [21], [22]. ART1 is a novel C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factor that interacts with the promoter region of STAR1. ART1 is reported to regulate at least 30 down-stream genes, some of which are involved in Al detoxification and serve as strong candidate genes controlling rice Al tolerance [19]. Nrat1 is one of the genes that is regulated by ART1 and was recently demonstrated to be an Al transporter that is localized to the root cell plasma membrane [18], [20]. It is hypothesized that Nrat1 confers Al tolerance by transporting Al into the cell and reducing the concentration of Al in the cell wall [20]. None of the four cloned rice genes described above have been demonstrated to be involved in natural genetic variation of Al tolerance in rice and only one (Nrat1) maps to a previously reported Al tolerance QTL [23], suggesting that these genes may be involved in basal Al tolerance [19], [20], [24]. A more thorough analysis is necessary to determine whether there might be natural variation associated with these loci that would help trace their evolutionary origins and clarify their contribution to the high levels of Al tolerance observed in rice.

Seven QTL studies on Al tolerance have been reported in rice using 6 different inter - and intra-specific mapping populations [13], [25]–[29]. Together, these studies report a total of 33 QTLs, located on all 12 chromosomes, with three intervals (on chromosomes 1, 3, and 9) being detected in multiple studies. In all of the QTL studies, Al tolerance was estimated based on relative root growth (RRG), and specifically on inhibition of the growth (elongation) of the longest root (elongation of the longest root in Al treatment/root growth of controls). Rice has a very fine and fibrous root system without dominant seminal roots. We recently showed that there is a weak correlation between rice Al tolerance based on RRG of the longest root and RRG of the total root system (R2 = 0.17) [8]. This raises the question whether mapping Al tolerance QTL using total root and longest root RRG indices independently might identify novel loci, helping to integrate QTL studies with studies based on induced mutations.

Historically, O. sativa has been classified into two varietal groups, Indica and Japonica, based on morphological characteristics, ecological adaptation, crossing ability and geographic origin [30]. These two varietal groups are believed to represent independent domestications from a pre-differentiated ancestral gene pool (O. rufipogon), followed by significant gene flow among and between subpopulations [17], [31]–[39]. These two varietal groups (names are italicized with an upper case first letter, i.e., Indica and Japonica) have been further divided into five major subpopulations (subpopulation names are italicized using all lower-case letters) (indica, aus, tropical japonica, temperate japonica, and aromatic [group V]) based on DNA markers (SSR, SNPs, indels) [40]–[42]. Genotypes that share <80% ancestry across subpopulations or varietal groups are classified as admixed varieties [42], while smaller groups adapted to specific ecosystems may be recognized as upland, deep water, or floating varieties [43], [44]. Upland varieties, which are generally grown at high altitudes on dry (non-irrigated) soils, are those most commonly exposed to acidic, Al-toxic soil conditions. These varieties are almost invariably of tropical japonica origin, suggesting a priori that the tropical japonica subpopulation would be a likely source of superior alleles for Al tolerance in rice.

Diverse panels of O. sativa are reported to have similar, or slightly elevated levels of linkage disequilibrium (LD) compared to species such as Arabidopsis, maize and human. The average extent of LD in rice has been estimated at between 50–500 kb [45]–[49], depending on the germplasm evaluated, compared to 10–250 kb in Arabidopsis and human [50]–[57], 100–500 kb in commercial elite maize inbreds and 1–2 kb in diverse maize landraces [58], [59]. The inbreeding nature of O. sativa, coupled with its demographic history, are major determinants of genome-wide patterns of LD. Strong selective pressure over the course of rice domestication has also lead to deep population substructure (Fst = 0.23 to 0.57) [40], [42], which sets it apart from Arabidopsis, in which population structure is gradual across geographic distances [60], [61]. Population substructure can lead to false-positives in association mapping studies, and must be taken into account [61]–[63]. The mixed-model has been demonstrated to work well in both maize and Arabidopsis [61], [63], and it has also shown its ability to greatly reduce the false positive rates in rice when used within a single subpopulation [64], though it may introduce false negatives when used on a diversity panel representing all domesticated subpopulations [65].

A diversity panel consisting of 413 O. sativa accessions, representing the genetic diversity of the primary gene pool of domesticated rice [66], was recently genotyped with 44,000 SNPs (∼10 SNPs/kb) [65], [67], [68] as the basis for GWA studies. The slow decay of LD, while facilitating GWA analysis, limits the resolution of association mapping in rice. The first targeted association mapping study in rice [45] demonstrated that LD decay in the aus subpopulation was approximately 90 kb (∼5 genes) in a region on chromosome 5 containing the xa5 resistance gene. LD is expected to decay more quickly in O. rufipogon (<50 kb, or 1–3 genes) [48], providing higher resolution for LD mapping, and more slowly in the japonica subpopulations [47]–[49]. Nonetheless, when compared to the resolution of a typical QTL study (250 lines) (∼10–20 cM resolution, where 1 cM = ∼250 kb), association mapping is expected to provide between 10–200 times higher resolution for a population of similar size as long as sufficient marker density is obtained to exploit the historical recombination. Thus, an association mapping study that uses markers densities similar to a QTL study will not have the increased resolution and will increase the risk of type-2 error. For both GWA and QTL analysis in rice, fine-mapping and/or mutant analysis is generally required to identify the gene(s) underlying a QTL of interest. However, the fine-mapping phase can generally be focused on a smaller target region following GWA analysis.

In this study, the genetic architecture of rice Al tolerance was investigated via bi-parental QTL analysis in two mapping populations using relative root growth of the longest root, the primary root system, and the total root system quantified with the digital root phenotyping methods described previously for rice Al tolerance [8]. Subsequently, genome wide association (GWA) analysis was undertaken using 36,901 high quality SNPs that had been genotyped on the rice diversity panel [65]. Regions identified by GWA were compared with regions identified as QTLs in bi-parental mapping populations for both this and previous studies, as well as with Al sensitive mutants and/or candidate genes. Phenotypic outliers identified in the diversity panel were further investigated to identify regions of subpopulation-admixture that accounted for extreme Al tolerance phenotypes.

Results

Al Tolerance in Rice

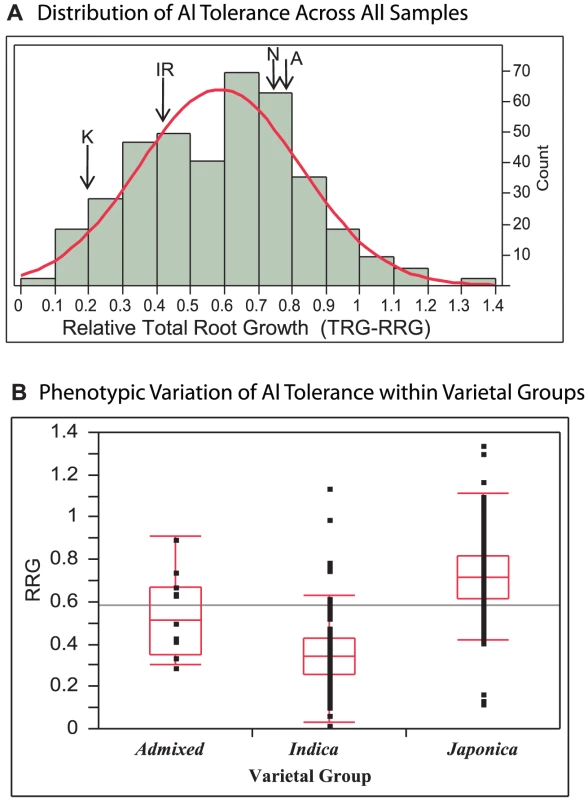

Three hundred eighty three diverse O. sativa accessions from the rice diversity panel [42], [67](Table S1) were evaluated for Al tolerance using an Al3+ activity of 160 µM in a hydroponic nutrient solution. This Al3+ activity had been previously determined to be optimal for evaluating a wide range of Al tolerance in diverse rice germplasm [8]. In the diversity panel, Al tolerance, measured as the relative root growth of the total root system (TRG-RRG), was normally distributed around a mean of 0.59 +/−0.24(SD) and ranged from 0.03–1.35 (Figure 1A). Some varieties were inhibited by as much as 97%, while 16 varieties (representing three subpopulations) showed enhanced root growth in the presence of 160 µM Al3+ (Table S1).

Fig. 1. Distribution of Al Tolerance in Rice Diversity Panel.

A) Distribution of Al tolerance across 383 diverse accessions of O. sativa at 160 µM Al3+. Aluminum tolerance (TRG-RRG) was normally distributed around a mean of 0.59 +/−0.24(SD) and ranged from 0.03–1.35. The Al tolerance of the QTL mapping parents are indicated: K = Kasalath, IR = IR64, N = Nipponbare, A = Azucena. B) Variation of Al tolerance (RRG) within genetic varietal groups (>80% ancestry). Admixed accessions share <80% ancestry with either group. The Japonica varietal group (temperate and tropical japonica and aromatic subpopulations) is significantly more tolerant than the Indica varietal group (indica and aus subpopulations) (p<0.0001). Five Indica accessions were identified to be highly Al tolerant outliers and six Japonica outlier accessions were identified, three as highly Al susceptible and three as highly tolerant. When accessions were grouped based on varietal group (>80% ancestry) the Japonica varietal group (consisting of the temperate japonica, tropical japonica and aromatic subpopulations) was significantly more Al tolerant than the Indica varietal group (indica and aus subpopulations) (p<0.0001) (Figure 1B). The Japonica varieties had a mean Al tolerance value of RRG = 0.72, an interquartile range of 0.61–0.82, and ranged from 0.13–1.35. The Indica varieties had a mean Al tolerance value of RRG = 0.36, an interquartile range of 0.27–0.43, and ranged from 0.03–1.15 (Figure 1B). Eleven accessions were classified as “admixed” between varietal groups, and these had a mean Al tolerance equal to the mean of all 372 accessions (TRG-RRG = 0.59) with >80% ancestry to either varietal group. A one-way ANOVA demonstrated that subpopulation explained 57% of the phenotypic variation observed for Al tolerance (TRG-RRG) among the 274 accessions that carried a subpopulation classification. Despite the differences in mean TRG-RRG between subpopulations, considerable variation was also detected within each subpopulation (Figure S1).

QTL Analysis

Two immortalized QTL mapping populations were analyzed for Al tolerance. One consisted of 134 recombinant inbred lines (RIL) derived from the cross IR64/Azucena [69], and the other was comprised of 78 backcross inbred lines (BIL) derived from the cross Nipponbare/Kasalath//Nipponbare [70]. These populations were used to evaluate Al tolerance using three different indices of relative root growth (RRG), (1) longest root growth (LRG-RRG), (2) primary root growth (PGR-RRG) and (3) total root growth (TRG-RRG) (see Materials and Methods for details). The phenotypic distribution was approximately normal for each population, no matter which root screening index was used (illustrated for TRG-RRG in Figure S2A and S2B). The QTL mapping populations allowed us to determine which of the three root evaluation methods would be most useful for evaluating the diversity panel as a whole.

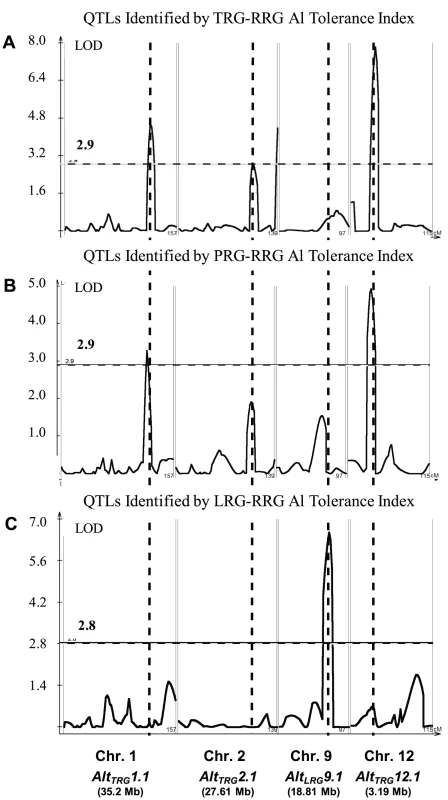

The method of phenotyping, specifically, the RRG index used to estimate Al tolerance, directly impacted the significance of QTLs detected by composite interval mapping (Figure 2A–2C and Figure S3A–S3C). In the RIL population, three Al tolerance (Alt) QTL were detected using total root growth (the TRG-RRG index), AltTRG1.1 on chromosome 1, AltTRG2.1 on chromosome 2, and AltTRG12.1 on chromosome 12 (Figure 2A–2C Table 1). The Azucena allele conferred increased tolerance at the loci on chromosomes 1 and 12 and reduced tolerance at the locus on chromosome 2. QTLs were detected in the same positions on chromosomes 1 and 12 using RRG based on primary root growth (the PRG-RRG index), although with lower LOD scores (Figure 2A–2C; Table 1). Using longest root growth (the LRG-RRG index), a single QTL was detected on chromosome 9, AltLRG9.1, and this QTL was not detected when the other root indices were used. The major QTL on chromosome 12 (AltTRG12.1), which explained >19% of the variation in Al tolerance based on TRG-RRG, is located between 2.69–5.10 Mb and encompasses the Al sensitive rice mutant art1, which is located at 3.59 Mb [19].

Fig. 2. QTLs Identified in IR64 × Azucena RIL Mapping Population.

A–C) Composite interval mapping output for QTL detected in the RIL mapping population using three Al tolerance RRG indices. The Y-axis is the LOD score and the horizontal line is the significant LOD threshold based on 1000 permutations. QTL name and approximate physical position are along bottom of figure and co-localization of QTLs identified with different Al tolerance indices are indicated with dashed vertical lines. A) Total root growth (TRG-RRG); B) Primary root growth (PRG-RRG); C) Longest root growth (LRG-RRG). Tab. 1. Summary of significant QTLs (1000 permutations) identified by composite interval mapping in the RIL and BIL populations.

Al tolerance (RRG) QTLs were identified using three root growth parameters, total root growth (TRG), primary root growth (PRG), and longest root growth (LRG). The parent contributing the tolerance allele is indicated in parentheses under additive effect. In the BIL population, two QTL were detected using the TRG index, AltTRG1.2 on chromosome 1, which co-localized with the AltTRG1.1 QTL identified in the RIL population, and AltTRG12.2 on chromosome 12, which did not overlap with the AltTRG12.1 identified in the RIL population (Figure 2A–2C, Figure S3A–S3C, Table 1). The Nipponbare allele conferred tolerance at the chromosome 1 locus and the Kasalath allele conferred tolerance at the AltTRG12.2 locus. No QTLs were detected on chromosome 2 in the BIL population. Using the PRG-RRG index, one QTL was detected on chromosome 6, where the Kasalath allele conferred resistance. No QTLs were detected using the LRG-RRG index in the BIL population.

The Al tolerance index used for evaluating the phenotype directly affected both the identity and the significance of the QTLs detected. Al tolerance index-specific QTLs were detected in both populations and no QTL locus was detected across all three indices. Based on number of QTL detected, significance of QTL, and variance explained by the QTL, total root growth (TRG) proved to be the single most powerful Al tolerance index. However, rice QTLs detected using different evaluation methods are likely to confer Al tolerance by different mechanisms, such as tolerance of primary, secondary, lateral, or all roots, and thus they are complementary and together provide a robust evaluation of the genetic architecture of Al tolerance than any single index alone.

Identification of Al Tolerance Loci through GWA Mapping

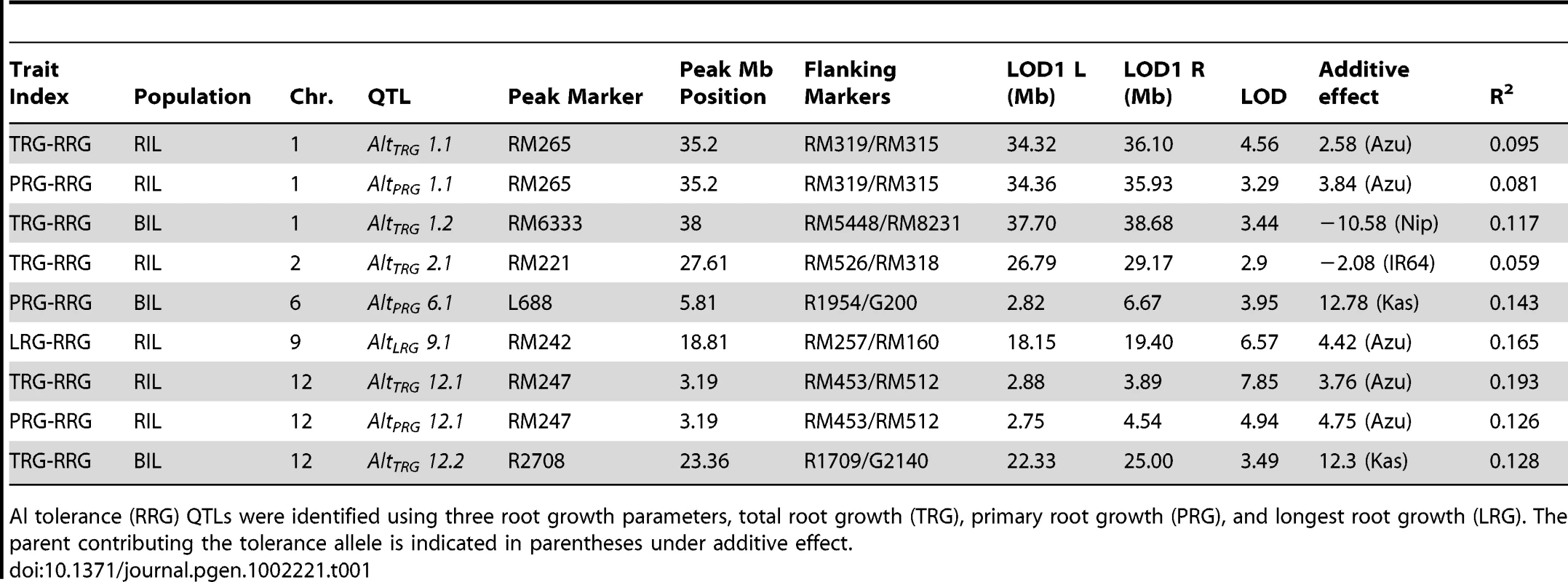

To identify Al tolerance loci based on genome-wide association (GWA) mapping, we used an existing genotypic dataset consisting of 36,901 SNPs [65], and the total root growth (TRG-RRG) Al tolerance phenotype generated on 373 O. sativa accessions over the course of this study. GWA mapping was conducted, using SNPs with a MAF>0.05, across all 373 genotypes as well as independently within the indica, aus, temperate japonica, and tropical japonica subpopulations (Figure 3). The Efficient Mixed-Model Association (EMMA) [71] model was used in each analysis (both within and across subpopulations) to correct for confounding effects due to subpopulation structure and relatedness between individuals. As the subpopulation structure was highly correlated with Al tolerance, it was observed that analyzing all samples (373) together with the EMMA model resulted in an overcorrection (causing type 2 error) and a corresponding reduction in SNP significance (Figure S4). To address this problem, a PCA approach was also employed when analyzing all (373) samples together. However, the PCA approach resulted in a slight under-correction for population structure (Figure S4), demonstrating that results from each GWA method has limitations when used across all germplasm in this highly structured diversity panel.

Fig. 3. GWA Analysis of Al Tolerance within and across Rice Subpopulations.

GWA analysis across and within subpopulations (IND = indica; AUS = aus; TRJ = tropical japonica; TEJ = temperate japonica). A priori candidate genes are listed across the top, with those identified within 200 kb of significant SNPs colored red. Color bands indicate the 23 bi-parental QTL positions from previous reports (grey) or from this study (yellow). SNP color indicates co-localization with QTLs (blue) or candidate genes (red). A total of ∼48 distinct Al tolerance genomic regions were identified by GWA mapping (Figure 3). Twenty-one regions were detected (p<0.0001) across all (373) accessions using the PCA model (Figure 3), while only two SNPs were above the significance threshold when all (373) accessions were analyzed together using the EMMA model (Figure 3), both of which were also detected by PCA. The threshold of p<1.0E-04 was determined based on the upper-limit false discovery rate (FDR), determined from the candidate genes in the same approach as in Li et al. [72] (Table S2). Thirty-two regions were significantly associated with Al tolerance in the indica subpopulation (Figure 3), including five regions that were also detected across all (373) samples using the PCA model. In the aus subpopulation, a single, highly significant, region was detected on chromosome 2 that was unique to this subpopulation and contained the Nrat1 candidate gene LOC_Os02g03900 (Figure 3). No significant SNPs (MAF>0.05) were detected in the temperate japonica or tropical japonica subpopulations. The GWA mapping results indicate that the majority of significant loci are subpopulation-specific and that phenotypic variation for Al tolerance within given subpopulations is largely controlled by alleles that are unique to that subpopulation.

SNPs identified by GWA were also compared to a set of 46 a priori candidate genes as well as to positions of QTL regions identified through bi-parental mapping (this study and previous reports) (Table 1 and Figure 3). Two regions of highly significant SNP clusters, one within the aus (8 SNPs; p = 2.8E-07) subpopulation on chr. 2 and one within the indica (32 SNPs; p = 2.9E-07) subpopulation on chr. 3, co-localized to previously reported QTLs in populations in which an aus and indica parent served as the susceptible parents, respectively [17], [23]. The list of 46 a-priori Al tolerance candidate genes (Table 2) was compiled based on published information on Al sensitive mutants from rice and Arabidopsis [20]–[22], [24], cloned Al tolerance genes from wheat and sorghum [14], [15], expression profiles from Al treated maize and rice roots [19], [73], and an association study on specific candidate Al tolerance genes of maize [74]. Significant SNPs (p<1.0E-04) within a 200 kb window of the a priori candidate genes were enriched 2.4 times compared to other SNPs (p>0.0001) outside of the a priori and QTL regions. The 200 kb window was selected to fall within the estimated window of LD decay in rice (∼50–500 kb [45]–[49] and the upper-limit false discovery rate for the a priori genes was 42%. In addition, four of the 46 gene candidates (∼9%) were located within a 200 kb window enriched for GWA SNPs in this study (Figure 3 and Table 2). One of the candidate genes (Nrat1) on chr. 2, co-localized with both GWA SNPs and a previously reported QTL (Figure 3). The relationship between the four candidates that co-localized with GWA SNPs are discussed in order of their positions on the rice genome below.

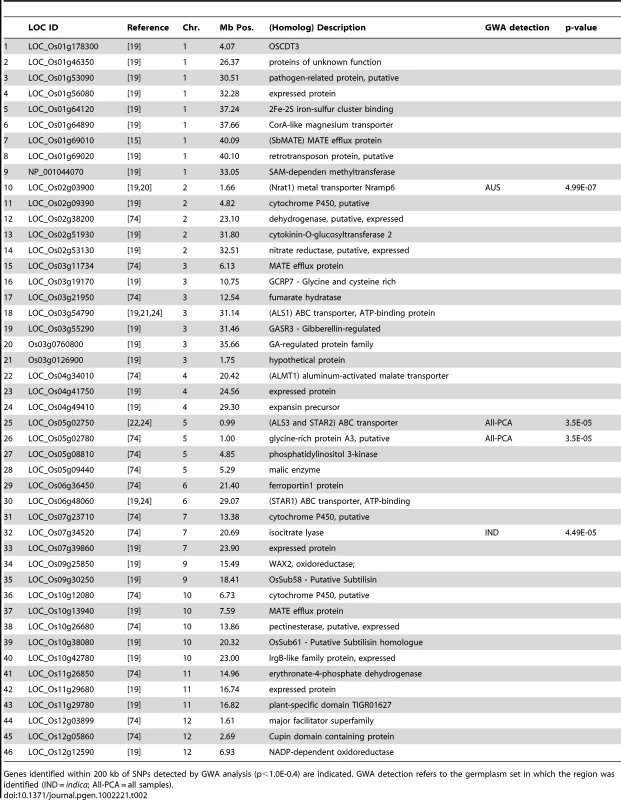

Tab. 2. List of 46 a priori Al tolerance candidate genes.

Genes identified within 200 kb of SNPs detected by GWA analysis (p<1.0E-0.4) are indicated. GWA detection refers to the germplasm set in which the region was identified (IND = indica; All-PCA = all samples). A cluster of eight highly significant SNPs (p-values = 2.3×10−5–2.8×10−7) on chromosome 2 between 1.536 Mb–1.675 Mb was associated with Al tolerance within the aus subpopulation (Figure 3 and Table 2). Previously, a QTL had been reported in the same location (0.536–1.9 Mb) where the susceptible parent was of aus origin [26]. The LD decay in the aus subpopulation at this region was calculated to be 150 kb and a strong candidate gene was identified within the target region. The gene (LOC_Os02g03900 located at 1.66 Mb) encodes a Nramp6 metal transporter and was demonstrated to have altered expression patterns in Al-treated roots of the Al sensitive art1 rice mutant [19]. This Nramp6 metal transporter was recently reported as Nrat1, a plasma membrane-located transporter for Al with enhanced sensitivity to Al in the knockout mutant [20]. As was the case with the ART1 gene itself, the Nrat1 metal transporter has not been associated with natural variation for Al tolerance prior to this study.

On chromosome 5, a significant region was detected across all samples (373 genotypes) by PCA, co-localizing with the STAR2 gene (LOC_Os05g02750) (Figure 3 and Table 2). The LD decay across this region was estimated at >500 kb, and encompassed two significant regions detected across all samples (PCA), one of which was also detected within the indica subpopulation. STAR2 is the rice ortholog of the Arabidopsis Al sensitive mutant als3 [21]. It encodes the transmembrane domain of a bacterial-type ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter and the star2 mutant is Al sensitive [24]. STAR2 was also found to be part of a gene network showing altered expression in response to Al in the art1 mutant compared to the ART1 wild type [19]. This study provides the first evidence that there may be natural variation for Al tolerance in rice at the STAR2 locus; however it is important to recognize that the PCA approach may under-correct for the effect of subpopulation in this study, thus it will be necessary to confirm the effect of the STAR2 alleles identified in this diversity panel.

A significant GWAS region identified in the indica subpopulation on chromosome 7 co-localized with LOC_Os07g34520, a rice ortholog of a maize isocitrate lyase a priori candidate gene associated with Al tolerance in maize [73], [74]. The LD decay across this region within the indica subpopulation was 250 kb.

Three highly significant regions detected within indica were further investigated to identify whether any clear Al tolerance candidate genes were located within these SNP clusters. The first region was a cluster of 32 significant SNPs (p = 3.0E-7) between 28.782–27.863 Mb on chr. 3 that co-localized with a previously reported QTL (Nguyen et al., 2002). Two clear candidates were identified among the 13 genes in this cluster; a nucleobase-ascorbate transporter (LOC_Os03g48810) and a chloride channel protein (LOC_Os03g48940). The second region was a 10 SNP cluster (p = 9.3E-12) between 26.986–27.479 Mb on chr. 7. Of the 80 genes in this region, 34 of which were retrotransposons, there were three strong candidate genes; a glycosyl transferase protein (LOC_Os07g45260), a cytochrome P450 protein (LOC_Os07g45290) and a zing finger RING type protein (LOC_Os07g45350). This region on chr. 7 was also identified in the introgression analysis as a localized introgressed region from Japonica into the highly tolerant Indica outliers (discussed below). The third region was an 8 SNP cluster between 4.892–5.164 Mb on chr. 11. Among the 48 genes in this region, there were two major classes of candidate genes observed, including 12 F-box proteins and a zinc finger CCHC protein.

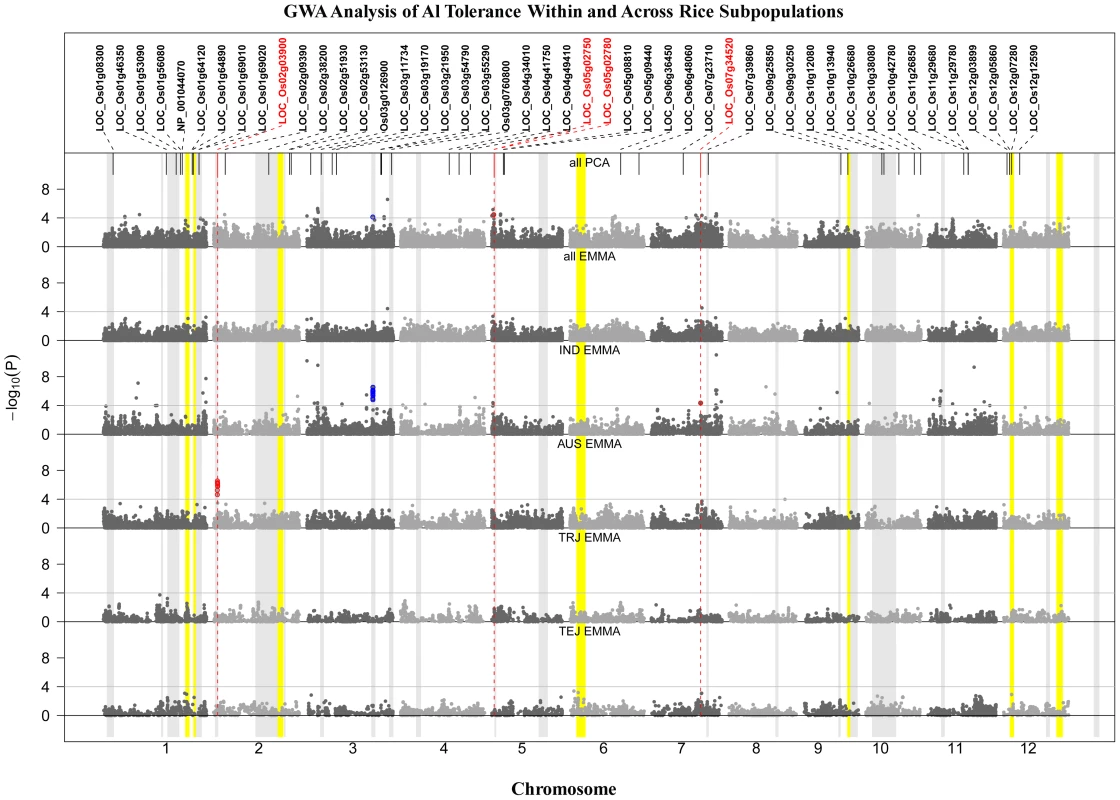

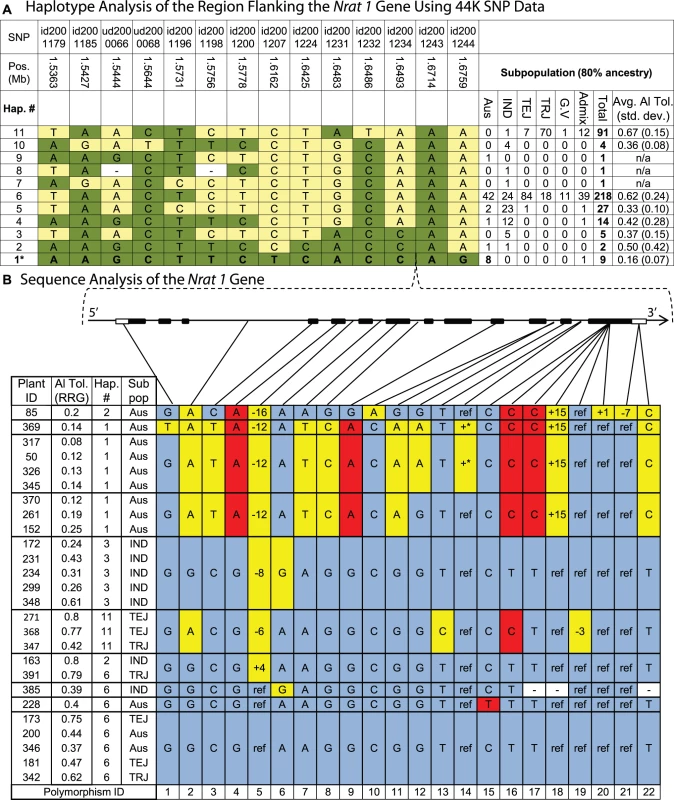

Haplotype Analysis of Nrat1 Gene Region on Chromosome 2

We chose to further investigate the variation in and around the Nrat1 gene on chromosome 2 because multiple independent lines of evidence supported the existence of a gene(s) in this region responsible for a significant portion of the variation for Al tolerance in rice. Evidence included a strong GWA peak in the aus subpopulation, a previously reported QTL [26], and the localization of the Nrat1 Al transporter gene. Using the 44 K SNP data, LD in this region was calculated to be ∼150 kb in the aus subpopulation and 11 distinct haplotypes were observed in the entire diversity panel across a 139 kb region around the Nrat1 gene (1.536 Mb–1.675 Mb on chr. 2) (Figure 4A). Haplotype 1 (Hap. 1), which was unique to the aus subpopulation, was found in 8 Al sensitive aus accessions and one Al sensitive aus/indica admixed line. These 9 genotypes were among the least Al tolerant (7th percentile, mean RRG = 0.16) of the 373 accessions screened (Table S1). Haplotype 1 explained 40% of the phenotypic variation for Al tolerance within the aus subpopulation (Figure S5). In addition, four aus accessions that were highly or moderately Al tolerant were found to contain a tropical japonica introgression across this region (described in the section on Introgression analysis below).

Fig. 4. Haplotype analysis of the Nrat1 gene region.

A) Haplotypes observed in 373 accessions using the 44,000 SNP data. Haplotype 1 was unique to aus ancestry and associated with Al susceptibility within the aus subpopulation, explaining 40% of the Al tolerance variation within aus. Haplotypes 1, 2, and 3 share the same 4-SNP haplotype (id2001231-id2001243) flanking the Nrat1 gene (1.66 Mb). SNP positions are based on MSU6 annotation and subpopulations are abbreviated as follows: IND = indica, TEJ = temperate japonica, TRJ = tropical japonica, G.V. = groupV/aromatic, Admix = admixed lines without 80% ancestry to any one subpopulation. B) Haplotypes at the Nrat1 gene (1.66 Mb) in the (9) aus and (6) indica accessions sharing the 4-SNP haplotype flanking the Nrat1 gene. Polymorphisms are identified with numbers along bottom of figure. A STOP codon occurs in exon 13 between polymorphism 17 and 18. Gray shaded cells represent the reference allele and plant ID# 173 is the reference genotype ‘Nipponbare’. Yellow shaded cells represent polymorphisms in introns or synonymous polymorphisms in exons. Red shaded cells represent polymorphisms that result in amino acid substitutions (Indel or non-synonymous), unshaded cells marked with “−” indicate missing data, and +* indicates an intron insertion >500 bp. Haplotype 2 (Hap. 2) was found in one aus and one indica accession, and was most similar to Hap. 1, differing at only 2/14 SNPs (Figure 4A). The two lines containing haplotype 2 had very different levels of Al tolerance; the aus variety, Kasalath (ID 85), was highly susceptible, with a RRG = 0.2, while the indica variety, Taducan (ID 163), was tolerant, with a RRG = 0.8, suggesting that this extensive 14-SNP haplotype across the 139 kb region was not predictive of Al tolerance. However, when the haplotype was built using only the four SNPs immediately flanking the Nrat1 gene, a group of 16 accessions sharing the same haplotype at these four SNPs was clearly identified. These 16 accessions, included the 10 susceptible aus accessions (including one aus/indica admixed line) carrying haplotype 1 and haplotype 2 and six indica accessions (of varying Al tolerance) carrying haplotype 2 and haplotype 3 (Figure 4A).

To determine if the four-SNP haplotype flanking the Nrat1 gene could be further resolved, we focused more deeply on the Nrat1 gene itself. We sequenced all 13 exons (including introns) of Nrat1 (1874 bp) in 26 susceptible and tolerant varieties representing the aus, indica, tropical japonica and temperate japonica subpopulations (Figure 4B). The accessions carried haplotypes 1, 2, 3, 6 and 11, as described in Figure 4A; where haplotype 1 was aus-specific and corresponded to the most sensitive group of accessions in the diversity panel; haplotype 2 was found in phenotypically divergent aus and indica accessions as described above; haplotype 3 was found in moderately tolerant indica varieties; haplotype 6, which appeared to be the ancestral haplotype, was the most common haplotype in all subpopulations and was associated with moderately high levels of tolerance; and haplotype 11, which was found in a majority of tropical japonica varieties, all of which were Al tolerant. Based on the 22 SNPs and/or indels identified across the 1,874 bp of Nrat1 sequence, highly resolved, gene haplotypes were constructed (Figure 4B). The gene haplotypes corresponded fairly well to the extended haplotype groups that had been constructed using the data from the 44 K SNP chip, except in the case of haplotype 2, where varieties differed at 10/22 (45%) of the SNPs across the Nrat1 gene. This fully resolved haplotype at the Nrat1 gene resulted in the susceptible Kasalath clustering with the other highly susceptible aus varieties and the tolerant Taducan clustering with other highly tolerant varieties (Figure 4).

Three non-synonymous SNPs (polymorphisms 4, 16, 17) were shared among the 9 highly susceptible aus accessions. When the Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource (http://elm.eu.org) was used to identify functional sites in the Nrat1 gene, polymorphism 16 was identified as a functional site where a C→T SNP caused an amino acid change from valine→alanine (amino acid 500). This protein site was predicted to be involved in PKA-type AGC kinase phosphorylation, with the functional site spanning amino acids 497–503. Thus, polymorphism 16 was identified as a strong functional polymorphism candidate underlying natural variation in Nrat1. The fact that polymorphism 16 was also observed in two Al tolerant temperate japonica and one moderately tolerant tropical japonica accession (haplotype 11) suggested that SNP 16 alone was not predictive of Al tolerance. However, a combination of polymorphisms 4, 16, and 17 was entirely predictive of Al susceptibility.

This study demonstrates the power of whole genome association analysis to integrate divergent pieces of evidence from independent bi-parental and mutant studies, enabling us to associate gene-based diversity with germplasm resources and natural variation that is of immediate use to plant breeders.

Introgression Analysis

There is a clear difference in the degree of Al tolerance found in the Japonica varietal group and the Indica varietal group, with the 10th percentile of Al tolerance of Japonica (0.53) being nearly equal to the 90th percentile of Indica (0.55) (Figure 1B). However, there are clear outliers within each varietal group. Five Indica accessions are highly Al tolerant (ID 30, 66, 142, 163, 337), ranging from 2.1–3.2 times the mean Indica Al tolerance, and three Japonica accessions (ID 12, 52, 112) are highly susceptible, each approximately 0.19 of the mean Japonica Al tolerance (Figure 1B and Table S1).

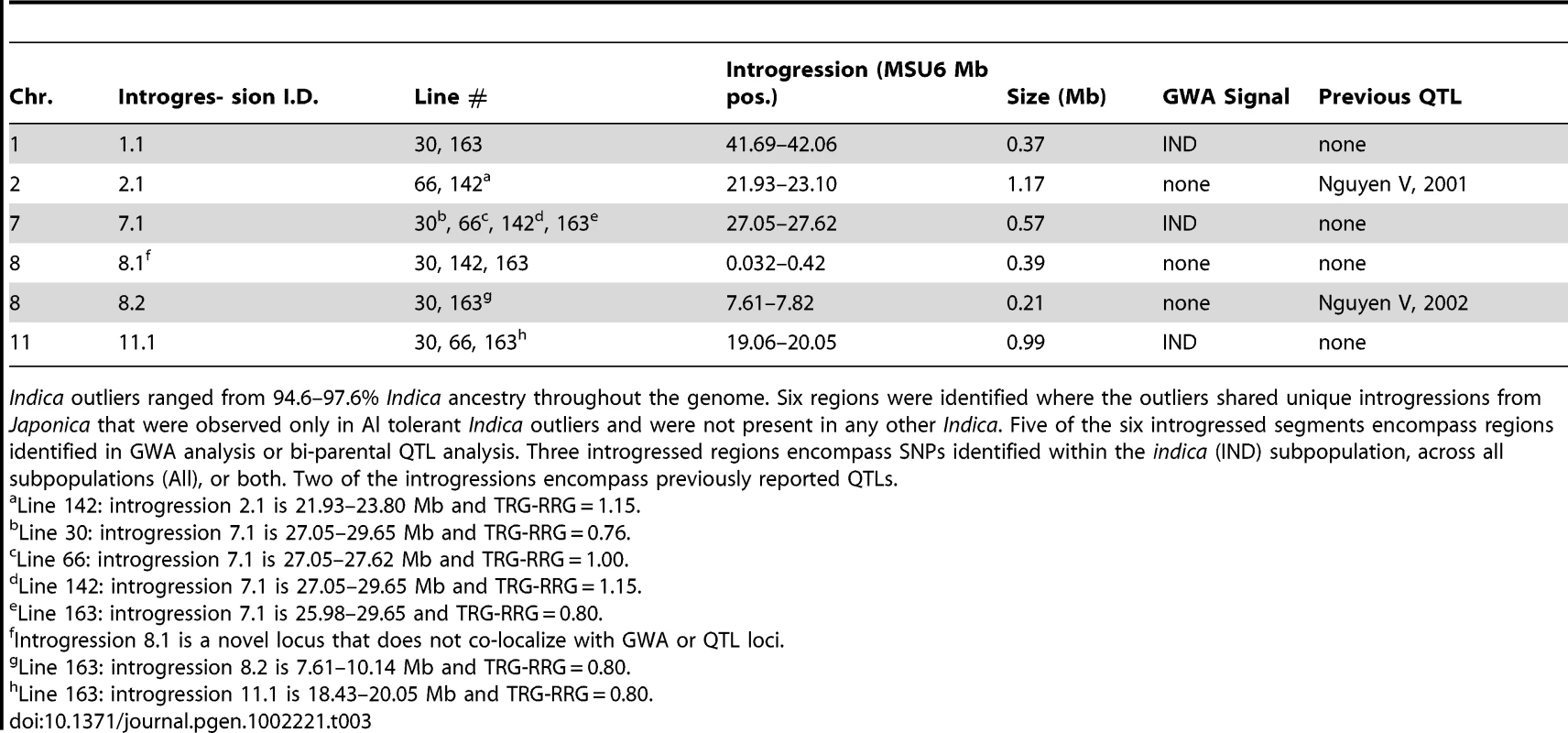

To determine if these outliers were the result of introgressions across varietal groups, we calculated the allele ancestry of 5,467 SNPs distributed throughout the genome and identified specific genomic regions where historical Indica×Japonica admixture was detected only in the respective Indica or Japonica outlier lines. To do this, Japonica introgressions identified in highly Al tolerant Indica lines were used to query all other Indica accessions and only those Japonica introgressions that were uniquely present in the highly Al tolerant outlier Indica lines were considered as candidate regions underlying the outlier phenotype. When the five Indica outliers were used for this analysis, a few, well-defined regions comprising 2.4–4.9% of the genome corresponded to regions of Japonica introgression (Table 3). In the case of the three highly Al susceptible Japonica varieties, the genetic background was highly heterogeneous and the small number of lines precluded doing any admixture analysis. Therefore, the admixture analysis was conducted only on the five highly tolerant Indica outliers.

Tab. 3. Summary of Japonica introgressions in the Indica outliers.

Indica outliers ranged from 94.6–97.6% Indica ancestry throughout the genome. Six regions were identified where the outliers shared unique introgressions from Japonica that were observed only in Al tolerant Indica outliers and were not present in any other Indica. Five of the six introgressed segments encompass regions identified in GWA analysis or bi-parental QTL analysis. Three introgressed regions encompass SNPs identified within the indica (IND) subpopulation, across all subpopulations (All), or both. Two of the introgressions encompass previously reported QTLs. In the five outlier Indica accessions, 6 Japonica introgressions (median size = 780 kb) were identified that were specific only to these 5 lines. Three of these introgressions were present in two genotypes, two of the introgressions were present in three genotypes, and one introgression was present in four of the outliers (Table 3). Three introgressions encompass SNPs identified by GWA analysis and two co-localized with bi-parental QTL. The introgression that was present in four of the indica outlier genotypes was located on chromosome 7 between 27.05–28.62 Mb and contained 94 annotated genes. This introgression included a cluster of GWA SNPs that were highly significant within the indica subpopulation (p = 2.6×10−5, MAF = 0.10) and was one of the top 100 most significant SNPs identified when the diversity panel as a whole was analyzed.

Discussion

Utilization of GWA and Bi-Parental QTL Mapping

In this study, we utilized bi-parental QTL mapping and GWA analysis to examine the genetic architecture of Al tolerance in rice and to identify Al tolerance loci. Phenotyping of the diversity panel provided valuable information about the range and distribution of Al tolerance in O. sativa and offered new insights into the evolution of the trait. The mean Al tolerance in Japonica was twice that of Indica (p<0.0001), and 57% of the phenotypic variation was explained by subpopulation. The relative degree of Al tolerance in the five subpopulations (temperate japonica>tropical japonica>aromatic>indica = aus) was consistent with the level of genetic relatedness among them [42], [44] and suggests that temperate and tropical japonica germplasm contain alleles that would be useful sources of genetic variation for enhancing levels of Al tolerance within indica and aus. This is supported by the identification of highly tolerant indica varieties from the rice diversity panel that contain introgressions from Japonica in regions characterized by GWA peaks. The highly tolerant Indica outliers demonstrate the feasibility of using a targeted approach to increase Al tolerance in Indica varieties by introgressing genes from Japonica.

While less obvious, our QTL analysis demonstrated the ability to increase Al tolerance in Japonica using targeted introgressions from Indica. This was demonstrated within both QTL populations by the identification of two loci in which alleles from the highly susceptible Kasalath parent conferred enhanced levels of Al tolerance in the Nipponbare genome (temperate japonica) and one locus where the moderately susceptible IR64 parent conferred enhanced tolerance in crosses with Azucena (tropical japonica) (Table 1). To date, only a few indica and aus accessions have been used in QTL mapping populations and the identification of a large number of GWA loci in indica, coupled with the fact that indica is significantly more diverse than all other O. sativa subpopulations [40], [42] suggests that there are likely to be many novel alleles that could be mined from the indica subpopulation. Further evidence of the value of this approach in the context of plant breeding comes from the transgressive variation observed in both QTL populations, where some RILs and BILs exceeded the Al tolerance observed in the tolerant tropical and temperate japonica parents, Azucena and Nipponbare, respectively, due to alleles derived from the susceptible indica (IR64) or aus (Kasalath) parents, respectively.

The significant differences in Al tolerance among varietal groups and subpopulations, and evidence that different genes and/or alleles contribute to Al tolerance within the major varietal groups, is consistent with Indica and Japonica domestication from pre-differentiated, wild O. rufipogon gene pools that differed in Al tolerance. Future experiments will test this hypothesis by comparing levels of Al tolerance found in wild populations of O. rufipogon. The inherently higher levels of Al tolerance found in the Japonica varietal group may help explain why tropical japonica varieties are so often found in the acid soils of upland environments.

Compared to QTL mapping, GWA significantly increases the range of natural variation that can be surveyed in a single experiment and the number of significant regions that are likely to be identified. Furthermore, GWA provides higher resolution than QTL mapping, facilitating fine-mapping and gene discovery. This was illustrated by the two highly significant regions detected by GWA that overlapped with previously reported QTLs. GWA detected a highly significant cluster of 32 SNPs (p = 2.9E-07) on chr. 3 within the indica subpopulation, defining the candidate region to 81 kb window containing 13 genes, while the previously reported QTL interval was 1,720 kb [17], containing 260 genes. Similarly, the Nrat1 locus identified within the aus subpopulation on chromosome 2 initially narrowed the target region to 139 kb containing 27 genes by GWA, while the previously reported [26] QTL interval was 1,360 kb and contained 234 genes.

Surprising, the Nrat1 region was not significant in the BIL population, in which the resistant parent (Nipponbare) contained a resistant haplotype at Nrat1 and the susceptible parent (Kasalath) contained the susceptible haplotype at Nrat1. The fact that a significant signal was not detected in the BIL population can likely be explained by one or more of the following: 1) the bias inherent in the small population size (78 BILs), 2) the backcross population structure in which only 11 individuals (14% of BILs) contained the Kasalath allele at the Nrat1 locus and/or 3) the effects of genetic background on the Nrat1 QTL region. The Nrat1 QTL region was detected in one previous QTL study by Ma et al. [23] where a BIL population consisting of 183 lines was used, with Kasalath as the susceptible aus parent and Koshihikari as the tolerant temperate japonica parent [23]. In that study, the Nrat1 QTL region was of minor significance (LOD = 2.81; R2 = 7%), and it is noteworthy that the two other (more significant) QTLs detected in that study were the two QTLs detected in our BIL population using only 78 lines. The fact that the Nrat1 QTL region was not detected in our BIL mapping population and was of low significance in the Ma et al. QTL study suggests that the effect of the Kasalath allele is likely to be influenced by genetic background effects (GXG). In an aus genetic background, the Nrat1 susceptible haplotype explains 40% of the phenotypic variation, and the diversity panel contains enough aus varieties for this to be statistically significant using GWA; however, in the BIL population where Nipponbare served as the recurrent parent, the aus alleles exist in a largely temperate japonica background. Given the extent of GXG observed in inter-sub-population crosses, and the small size of our BIL population, this appears to be the most likely explanation as to why the Nrat locus was not detected in our QTL experiment.

Although GWA significantly increased the power and resolution of QTL detection, nearly all the significant loci detected were subpopulation-specific. This is entirely consistent with the strong subpopulation structure in rice and the high correlation of Al tolerance with subpopulation, justifying our GWA analysis on each subpopulation independently. So the question might be asked as to why it is also necessary to conduct GWA in the diversity panel as a whole? The answer to this question lies in the complex biology and demographic or breeding history of O. sativa. In this study GWA was conducted both within and across subpopulations, and it demonstrated that GWA on the diversity panel as a whole leveraged power to detect alleles that were segregating across multiple subpopulations, even if they were rare within any one subpopulation group, while when used on independent subpopulations, it was useful in detecting alleles that segregated only within one or two subpopulations but tended to be fixed in others. This is what would be expected from what we know about the evolutionary history of rice with its examples of shared domestication alleles [35], [75] coupled with myriad subpopulation-specific alleles [41], [48], [76]–[78] that provide each subpopulation with its specific identity and spectrum of ecological adaptations.

There are cases in which QTLs discovered by bi-parental mapping are not detected by GWA analysis. One reason for this is that QTL mapping can readily detect alleles that are rare in a diversity panel, are subpopulation-specific, or where the phase of the allelic association differs across subpopulations, while GWA analysis has limited power to do so. This is important in the case of rice, because of the degree of differentiation between the subpopulations and the significant evolutionary differences between the Indica and Japonica varietal groups, as discussed above. Thus, while variation that is strongly correlated with subpopulation structure is undetectable by GWA analysis, these loci can be easily detected by QTL analysis if crosses between sub-populations are used. This is illustrated by the identification of the Al tolerance QTL, (AltTRG12.1) encompassing the ART1 locus on chromosome 12. This large-effect QTL (LOD = 7.85, R2 = 0.193) was clearly detected in the RIL population but was not detected by GWA analysis. The QTL mapping populations utilized in this study were of limited population size and thus largely underpowered [79]. As a result it is likely that some QTL effects were overestimated and that other small effect QTL were not detected. Although we cannot be certain of the exact amount of variance explained by a particular QTL, it is reasonable to conclude that the major QTL detected (AltTRG12.1) is, in fact, the most significant QTL in the population.

GWA mapping also provides a valuable link between functional genomics and natural variation, and in the case of rice, highlights the subpopulation-specific distribution of specific alleles and phenotypes. We implicate the involvement of the STAR2 (chr. 6)/ALS3 (Arabidopsis Al sensitive mutant) gene, previously identified as induced mutations in rice and Arabidopsis, respectively [22], [23], and document the detection of highly resolved, novel Al tolerance loci in the indica and aus subpopulations. This is a critical bridge for germplasm managers and plant breeders who look for alleles of interest in germplasm collections rather than as sequences in GenBank.

Analysis of Nrat1 Gene

Our strongest example of the value of linking functional genomics and natural variation is illustrated by the GWA region on chromosome 2, where we demonstrate that the aus-specific susceptible haplotype in this region is functionally related to an Nramp gene. This gene was previously identified to have altered expression in the art1 (transcription factor) Al sensitive mutant [19] and was recently reported as Nrat1 (for Nramp aluminum transporter), an Al transporter localized to the plasma membrane of root cells, which when knocked out, enhances Al susceptibility. This is consistent with this transporter serving to mediate Al uptake by moving it directly into root cells, presumably into the vacuole, and away from the root cell wall [20]. Our haplotype analysis of the GWA region on chromosome 2 and sequence analysis of the Nrat1 gene identified putative sensitive and tolerant haplotypes that implicate the Nrat1 gene, and further identified two putative functional polymorphisms specific to the Al sensitive aus accessions. These data provides valuable information for identifying Nrat1 alleles that can be used to test the hypothesis put forth by Xia et al. [20], namely that Al tolerance is conferred by reducing Al concentrations in the cell wall. It will be interesting to see if the sensitive alleles of this gene encode an Nramp transporter that is less effective at mediating Al uptake. Furthermore, the observation that three of the four most Al tolerant aus accessions contain tropical japonica introgressions across this gene region strongly suggests that Al tolerance of aus genotypes can be increased by the targeted introgression of tropical japonica DNA at the Nrat 1 region.

Phenotyping Methods Affect QTL Detection

One of the objectives of this study was to determine if the Al tolerance index employed (longest root growth [LRG], primary root growth [PRG], or total root growth [TRG]) affected the detection and/or significance of Al tolerance QTL. In a recent publication from our research team, it was demonstrated that significantly different Al tolerance scores were obtained with the different indices [8]. In all previous QTL studies, Al tolerance was determined based on relative root growth (RRG) of the longest root. This study demonstrated that the Al tolerance index has a direct effect on the detection and significance of QTLs. Total root growth (TRG) was the single most powerful Al tolerance index, based on number of QTL detected, significance of QTL and variance explained by the QTL. However, it is relevant to point out that LRG-RRG identified a large-effect QTL (AltLRG9.1) in the RIL population that was not detected using any other index, and PRG-RRG identified a unique QTL on chromosome 6 where the susceptible Kasalath variety carried the resistance allele. These observations suggest that different root evaluation methods are likely to identify Al tolerance QTLs that confer tolerance mediated by different types of roots, or possibly by different patterns of gene expression detectable only when specific phenotypic evaluation protocols are used.

The strongest example of the importance of utilizing the TRG-RRG index is demonstrated by the identification of the AltTRG12.1 QTL in the RIL mapping population. The ART1 gene, a C2H2-type zinc finger-type transcription factor that causes Al hypersensitivity when mutated, is located close to the center of the Alt12.1 QTL peak. When this gene was first identified, it was suggested that it was not involved in natural variation of Al tolerance in rice, as no QTL had ever been identified in the region [19]. Based on our results, it is likely that this QTL was not previously identified because relative root growth was measured only based on LRG, rather than on TRG-RRG. Further fine-mapping of this locus, along with sequence and expression analysis, is underway to determine whether the ART1 locus underlies this QTL and to understand the mechanism by which it contributes to natural variation for Al tolerance.

Previous studies in other cereals have reported that the correlation of Al tolerance between hydroponics and field conditions is >70% [80] and studies on rice Al tolerance mutants have demonstrated that tolerance/susceptibility observed in hydroponics screens is also observed under soil conditions [24]. To accurately assess the value of the loci detected in this study as targets of selection in rice breeding programs, we are currently developing experiments to determine the effect of the key loci detected in this work under Al-toxic field conditions. Furthermore, four sets of reciprocal NILs (8 NILs total) for the four QTLs detected in the RIL population are being developed to determine the effect of each QTL under both hydroponic and field conditions. Finally, field experiments will be conducted to determine which hydroponic root measurement phenotype (TRG, PRG, or LRG) is the best for predicting a genotypes Al tolerance under field conditions.

Implications for Rice Breeding

This study provides the most comprehensive analysis of the genetic architecture of Al tolerance in rice to date. It demonstrates the power of whole genome association analysis to identify phenotype-genotype relationships and to integrate disparate pieces of evidence from QTL studies, mutant analysis, and candidate gene evaluation into a coherent set of hypotheses about the genes and genomic regions underlying quantitative variation. By tracing the origin of Al tolerance alleles within and between rice subpopulations, we provide new insights into the evolution and combinatorial potential of different alleles that will be invaluable in breeding new varieties for acid soil environments. This work demonstrates how genetic and phenotypic diversity is partitioned by subpopulation in O. sativa and provides support for the hypothesis that the most efficient approach to enhancing many quantitative traits in rice is to selectively introgress genes/alleles from one subpopulation into another. Our study also lays the foundation for understanding the genetic basis of Al tolerance mechanisms that enable rice to withstand significantly higher levels of Al than do other cereals. It not only facilitates more efficient selection of tolerant genotypes of rice, but it points the way toward using this knowledge to enhance levels of Al tolerance in other plant species.

Materials and Methods

Plant Growth Conditions and Germplasm

Plants were grown hydroponically in a growth chamber as described by Famoso et al. [8]. Al tolerance was determined based on relative root growth (RRG) after three days in Al (160 µM Al3+) or control solution. The hydroponic solution used in this study was chemically designed and optimized for rice Al tolerance screening; for a detailed comparison of the phenotypic procedures employed in this work compared to previously published rice Al tolerance work see Famoso et al. (2010). To obtain uniform seedlings, 80 seeds were germinated and the 30 most uniform seedlings were visually selected and transferred to a control hydroponic solution for a 24 hour adjustment period. After the 24 hour adjustment period, root length was measured with a ruler and the 20 most uniform seedlings were selected and distributed to fresh control solution (0 uM Al3+) or Al treatment solution (160 uM Al3+). Plants were grown in their respective treatments for ∼72 hours and the total root system growth was quantified using an imaging and root quantification system as described by Famoso et al. (2010). The mean total root growth was calculated for Al treated and control plants and RRG was calculated as mean growth (Al)/mean growth (control). The 373 genotypes screened for Al tolerance and used in the association analysis are part of a set of 400 O. sativa genotypes that have been genotyped with 44,000 SNPs as described by Zhao et al. [65].

QTL Analysis and Heritability

The QTL populations consisted of a population of 134 recombinant inbred lines (RILs) derived from a cross between Azucena (tolerant tropical japonica) and IR64 (susceptible indica) [67], [70] and a population of 78 backcross introgression lines (BILs) derived from a cross between Nipponbare (tolerant temperate japonica) and Kasalath (susceptible aus) and backcrossed to Nipponbare. The Al3+ activity at which Al tolerance was screened was determined by identifying the Al3+ activity that provided the greatest difference in tolerance between the parents. The tolerant parent of the RIL population, Azucena, and the tolerant parent of the BIL population, Nipponbare, are similar in Al tolerance, whereas the susceptible parent of the RIL population, IR64, is significantly more tolerant than the susceptible parent of the BIL population, Kasalath (Figure 1A). To ensure that a normal distribution was obtained in each population, a different Al3+ concentration was used for each mapping population. The RIL population was screened at 250 µM Al3+ because the Azucena parent is very Al tolerant and the IR64 parent is only moderately susceptible. The BIL population was screened at 120 µM Al3+ because the Kasalath parent is extremely Al sensitive, though the Nipponbare parent is very Al tolerant. Figure 1 displays the Al tolerance of each mapping parent in reference to the 373 genetically diverse rice accessions screened at 160 µM Al3+. The genetic component of the phenotypic variance was calculated as VarG = VarG+Var(GxE)+error. QTL analysis was conducted using composite interval mapping (CIM) function in QTL Cartographer [81]. The significance threshold was determined by 1000 permutations.

Genome-Wide Association Analysis

Genome-Wide Association Analysis was performed using three approaches in all samples (373) with phenotypes. The first approach was the naïve approach, which is simply the linear regression of phenotype on the genotype for each SNP marker. The second approach was principle component analysis (PCA), where we obtained the four main PCs (principle components) that reflect the global main subpopulations in the sample to correct population structure estimated from software EIGENSOFT. [82]. The first four PCs are included as cofactors in the regression model to correct population structure: .

Here β and γ are coefficient vectors for SNP effects and subpopulation PCs respectively. and are the corresponding SNP vector and first 4 PC vectors, and is the random error term. The third approach was the linear mixed model proposed by [62], [63], implemented in the R package EMMA [71], which models the different levels of population structure and relatedness. The model can be written in a matrix form as: y = Xβ+Cγ+Zμ+e where β and γ are the same as above, both of which are fixed effects, and is the random effect accounting for structures and relatedness, is corresponding design matrices, and is the random error term. Assume μ∼N(0,σ2gK) and e∼N(0,σ2eI), and K is the IBS matrix, as in [62]. We also conducted GWA using both the naïve approach and the mixed model approach in each of the four main subpopulations (IND, AUS, TEJ, TRJ). For the mixed model, the model was changed to y = Xβ+Zu+e, since there was no main subpopulation division within each subpopulation sample. Linkage disequilibrium decay and haploblocks were calculated at specific chromosome/gene regions using Haploview software [83].

Admixture Analysis

Population structure was analyzed employing Expectation-Maximization techniques on an HMM model of per-marker ancestry along a chromosome with a weak linkage model between adjacent markers on the same chromosome induced by the HMM's state dependence on the previous marker's subpopulation assignment (M. Wright, Cornell University, personal communication). The 5,467 SNPs used for admixture analysis were a subset of the 36,901 high quality SNPs on the 44 K chip, and were selected based on their information content and ability to distinguish genetic groups, rather than individuals. The two main criteria used to select the subset of SNPs were a) good genomic distribution and minimal LD among those used in the analysis, and b) MAF>0.05 in at least one subpopulation. The state of the HMM at each marker corresponds to the subpopulation of origin for the marker (and by extension, the region containing the marker and its adjacent markers). The number of a priori distinct subpopulations was K = 5, consistent with that reported previously by Garris et al. 2005 and Ali et al., 2011 [40], [66]. A set of 50 standard non-admixed “control” lines, 10 representing each of the Garris et al. subpopulations, that were genotyped on the 44 K rice SNP array were used to develop and evaluate the method. All 50 lines were correctly assigned to each of the subpopulations and concordant with previous results using STRUCTURE [84], with little or no admixture or introgressions detected. The EM/HMM method was favored over the corresponding “linkage model” of recent versions of STRUCTURE because the EM/HMM model explicitly modeled inbreeding and estimated the inbreeding coefficient for each line independently, permitting lines in various stages of purification or inbreeding to homozygosity to be analyzed. The lines phenotyped in this study that were also genotyped on the 44 K SNP array were then analyzed, combined with these 50 control lines and the local ancestry along chromosomes were assigned by maximizing the state path of the HMM while simultaneously estimating subpopulation specific allele frequencies using the forward-backward algorithm. Using this method, introgressions from a foreign subpopulation into a line with a vast majority of the genetic background originating from a single subpopulation were detected.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. von UexküllHRMutertE 1995 Global extent, development and economic impact of acid soils. DateRAGrundonNJRaymetGEProbertME Plant-Soil Interactions at Low pH: Principles and Management Dordrecht, Netherlands Kluwer Academic Publishers 5 19

2. KochianLVPinerosMAHoekengaOA 2005 The physiology, genetics and molecular biology of plant aluminum tolerance and toxicity. Plant and Soil 274 175 195

3. FoyC 1988 Plant adaptation to acid, aluminum-toxic soils. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 19 959 987

4. SasakiTRyanPDelhaizeEHebbDOgiharaY 2006 Sequence upstream of the wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) ALMT1 gene and its relationship to aluminum resistance. Plant and Cell Physiology 47 1343

5. PinerosMShaffJManslankHCarvalho AlvesVKochianL 2005 Aluminum resistance in maize cannot be solely explained by root organic acid exudation. A comparative physiological study. Plant Physiology 137 231

6. FurukawaJYamajiNWangHMitaniNMurataY 2007 An aluminum-activated citrate transporter in barley. Plant and Cell Physiology 48 1081

7. CaniatoFGuimaraesCSchaffertRAlvesVKochianL 2007 Genetic diversity for aluminum tolerance in sorghum. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 114 863 876

8. FamosoAClarkRShaffJCraftEMcCouchS 2010 Development of a novel Aluminum tolerance phenotyping platform used for comparisons of cereal Aluminum tolerance and investigations into rice Aluminum tolerance mechanisms. Plant Physiology 153 1678

9. SasakiTYamamotoYEzakiBKatsuharaMAhnS 2004 A wheat gene encoding an aluminum-activated malate transporter. The Plant Journal 37 645 653

10. MagalhaesJGarvinDWangYSorrellsMKleinP 2004 Comparative mapping of a major aluminum tolerance gene in sorghum and other species in the Poaceae. Genetics 167 1905 1914

11. MinellaESorrellsM 1992 Aluminum tolerance in barley: genetic relationships among genotypes of diverse origin. Crop Science 32 593 598

12. Ninamango-CardenasFTeixeira GuimarãesCMartinsPNetto ParentoniSPortilho CarneiroN 2003 Mapping QTLs for aluminum tolerance in maize. Euphytica 130 223 232

13. NguyenVTBurowMDNguyenHTLeBTLeTD 2001 Molecular mapping of genes conferring aluminum tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Theoretical and Applied Genetics 102 1002 1010

14. SasakiTYamamotoYEzakiEKatsuharaMRyanPR 2004 A gene encoding an aluminum-activated malate transporter segregates with aluminum tolerance in wheat. Plant Journal 37 645 653

15. MagalhaesJLiuJGuimarãesCLanaUAlvesV 2007 A gene in the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family confers aluminum tolerance in sorghum. Nature Genetics 39 1156 1161

16. HoekengaOVisionTShaffJMonforteALeeG 2003 Identification and characterization of aluminum tolerance loci in Arabidopsis (Landsberg erecta x Columbia) by quantitative trait locus mapping. A physiologically simple but genetically complex trait. Plant Physiology 132 936

17. NguyenVNguyenBSarkarungSMartinezCPatersonA 2002 Mapping of genes controlling aluminum tolerance in rice: comparison of different genetic backgrounds. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 267 772 780

18. HuangXFengQQianQZhaoQWangL 2009 High-throughput genotyping by whole-genome resequencing. Genome Research 19 1068

19. YamajiNHuangCNagaoSYanoMSatoY 2009 A zinc finger transcription factor ART1 regulates multiple genes implicated in aluminum tolerance in rice. The Plant Cell 21 3339 3349

20. XiaJYamajiNKasaiTMaJ 2010 Plasma membrane-localized transporter for aluminum in rice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 18381

21. LarsenPCancelJRoundsMOchoaV 2007 Arabidopsis ALS1 encodes a root tip and stele localized half type ABC transporter required for root growth in an aluminum toxic environment. Planta 225 1447 1458

22. LarsenPGeislerMJonesCWilliamsKCancelJ 2005 ALS3 encodes a phloem localized ABC transporter like protein that is required for aluminum tolerance in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 41 353 363

23. MaJFShenRZhaoZWissuwaMTakeuchiY 2002 Response of rice to Al stress and identification of quantitative trait Loci for Al tolerance. Plant Cell Physiology 43 652 659

24. HuangCYamajiNMitaniNYanoMNagamuraY 2009 A bacterial-type ABC transporter is involved in aluminum tolerance in rice. The Plant Cell 21 655 667

25. NguyenBDBrarDSBuiBCNguyenTBPhamLN 2003 Identification and mapping of the QTL for aluminum tolerance introgressed from the new source, Oryza rufipogon Griff., into indica rice (Oryza sativa L.). Theoretical and Applied Genetics 106 583 593

26. MaJShenRZhaoZWissuwaMTakeuchiY 2002 Response of rice to Al stress and identification of quantitative trait loci for Al tolerance. Plant and Cell Physiology 43 652

27. XueYJiangLSuNWangJDengP 2007 The genetic basic and fine-mapping of a stable quantitative-trait loci for aluminium tolerance in rice. Planta 227 255 262

28. XueYWanJJiangLWangCLiuL 2006 Identification of quantitative trait loci associated with aluminum tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Euphytica 150 37 45

29. WuPLiaoCDHuBYiKKJinWZ 2000 QTLs and epistasis for aluminum tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) at different seedling stages. Theoretical Applied Genetics 100 1295 1303

30. OkaHI 1988 Indica-Japonica differentiation of rice cultivars. OkaHI Origin of Cultivated Rice Tokyo Elsevier Science/Japan Scientific Societies Press 141 179

31. BarbierP 1989 Genetic variation and ecotypic differentiation in the wild rice species O. rufipogon II. Influence of the mating system and life history traits on the genetic structure of populations. Japanese Journal of Genetics 63 273 285

32. MaJBennetzenJL 2004 Rapid recent growth and divergence of rice nuclear genomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101 12404 12410

33. VitteCIshiiTLamyFBrarDPanaudO 2004 Genomic paleontology provides evidence for two distinct origins of Asian rice (Oryza sativa L.). Molecular Genetics and Genomics 272 504 511

34. LondoJChiangYHungKChiangTSchaalB 2006 Phylogeography of Asian wild rice, Oryza rufipogon, reveals multiple independent domestications of cultivated rice, Oryza sativa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103 9578

35. KovachMJSweeneyMTMcCouchSR 2007 New insights into the history of rice domestication. Trends in Genetics 23 578 587

36. KovachMMcCouchS 2008 Leveraging natural diversity: back through the bottleneck. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 11 193 200

37. ZhuQGeS 2005 Phylogenetic relationships among A-genome species of the genus Oryza revealed by intron sequences of four nuclear genes. New Phytologist 167 249 265

38. ZhouHXieZGeS 2003 Microsatellite analysis of genetic diversity and population genetic structure of a wild rice (Oryza rufipogon Griff.) in China. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 107 332 339

39. SweeneyMThomsonMChoY-GParkY-JWilliamsonS 2007 Global dissemination of a single mutation conferring white pericarp in rice. PLoS Genet 3 e133 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030133

40. GarrisAJTaiTHCoburnJRKresovichSMcCouchS 2005 Genetic structure and diversity in Oryza sativa L. Genetics 169 1631 1638

41. CaicedoALWilliamsonSHHernandezRDBoykoAFledel-AlonA 2007 Genome-wide patterns of nucleotide polymorphism in domesticated rice. PLoS Genet 3 e163 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030163

42. ZhaoKWrightMKimballJEizengaGMcClungA 2010 Genomic diversity and introgression in O. sativa reveal the impact of domestication and breeding on the rice genome. PLoS ONE 5 e10780 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010780

43. KhushG 1997 Origin, dispersal, cultivation and variation of rice. Plant Molecular Biology 35 25 34

44. GlaszmannJC 1987 Isozymes and classification of Asian rice varieties. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 74 21 30

45. GarrisAJMcCouchSRKresovichS 2003 Population structure and its effect on haplotype diversity and linkage disequilibrium surrounding the xa5 locus of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Genetics 165 759 769

46. OlsenKCaicedoAPolatoNMcClungAMcCouchS 2006 Selection under domestication: evidence for a sweep in the rice Waxy genomic region. Genetics 173 975

47. MatherKCaicedoAPolatoNOlsenKMcCouchS 2007 The extent of linkage disequilibrium in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Genetics 177 2223

48. RakshitSRakshitAMatsumuraHTakahashiYHasegawaY 2007 Large-scale DNA polymorphism study of Oryza sativa and O. rufipogon reveals the origin and divergence of Asian rice. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 114 731 743

49. McNallyKLChildsKLBohnertRDavidsonRMZhaoK 2009 Genomewide SNP variation reveals relationships among landraces and modern varieties of rice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 12273 12278

50. ReichDCargillMBolkSIrelandJSabetiP 2001 Linkage disequilibrium in the human genome. Nature 411 199 204

51. DalyMRiouxJSchaffnerSHudsonTLanderE 2001 High-resolution haplotype structure in the human genome. Nature Genetics 29 229 232

52. JeffreysAKauppiLNeumannR 2001 Intensely punctate meiotic recombination in the class II region of the major histocompatibility complex. Nature Genetics 29 217 222

53. KimSPlagnolVHuTTToomajianCClarkRM 2007 Recombination and linkage disequilibrium in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature Genetics 39 1151 1155

54. NordborgMBorevitzJOBergelsonJBerryCCChoryJ 2002 The extent of linkage disequilibrium in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature Genetics 30 190 193

55. JungMChingABhattramakkiDDolanMTingeyS 2004 Linkage disequilibrium and sequence diversity in a 500-kbp region around the adh1 locus in elite maize germplasm. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 109 681 689

56. YuJBucklerES 2006 Genetic association mapping and genome organization of maize. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 17 155 160

57. ChingACaldwellKJungMDolanMSmithO 2002 SNP frequency, haplotype structure and linkage disequilibrium in elite maize inbred lines. BMC Genetics 3 19

58. TenaillonMSawkinsMLongAGautRDoebleyJ 2001 Patterns of DNA sequence polymorphism along chromosome 1 of maize (Zea mays ssp. mays L.). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98 9161

59. RemingtonDThornsberryJMatsuokaYWilsonLWhittS 2001 Structure of linkage disequilibrium and phenotypic associations in the maize genome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98 11479

60. PlattAHortonMHuangYLiYAnastasioA 2010 The scale of population structure in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet 6 e1000843 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000843

61. AtwellSHuangYSVilhjalmssonBJWillemsGHortonM 2010 Genome-wide association study of 107 phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana inbred lines. Nature 465 627 631

62. ZhaoKAranzanaMKimSListerCShindoC 2007 An Arabidopsis example of association mapping in structured samples. PLoS Genet 3 e4 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030004

63. YuJPressoirGBriggsWBiIYamasakiM 2005 A unified mixed-model method for association mapping that accounts for multiple levels of relatedness. Nature Genetics 38 203 208

64. HuangXWeiXSangTZhaoQFengQ 2010 Genome-wide association studies of 14 agronomic traits in rice landraces. Nature Genetics 42 926 927

65. ZhaoKTCWEizengaGCWrightMHAliMLPriceAHNortonGJIslamMRReynoldsAMezeyJMcClungAMBustamanteCDMcCouchSR 2011 Genome-wide association mapping reveals rich genetic architecture of complex traits in Oryza sativa. Nature Communications (Accepted)

66. AliMMcClungAMJiaMHKimballJAMcCouchSREizengaGC 2011 Rice Diversity Panel “evaluated for genetic and agro-morphological diversity between subpopulations and its geographic distribution”. Crop Science (Accepted March 18, 2011)

67. TungC-WZhaoKWrightMAliMJungJ 2010 Development of a research platform for dissecting phenotype–genotype associations in rice (Oryza spp.). Rice 1 13

68. McCouchSRZhaoKWrightMTungC-WEbanaK 2010 Development of genome-wide SNP assays for rice. Breeding Science 60 524 535

69. AhmadiNDubreuil-TranchantCCourtoisBFoncekaDThisD IRRI, editor New resources and integrated maps for IR64 × Azucena: a reference population in rice. 2005 19–23 November 2005 Manila, Philippines International Rice Research Institute

70. LinSYSasakiTYanoM 1998 Mapping quantitative trait loci controlling seed dormancy and heading date in rice, Oryza sativa L., using backcross inbred lines. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 96 997 1003

71. KangHZaitlenNWadeCKirbyAHeckermanD 2008 Efficient control of population structure in model organism association mapping. Genetics 178 1709

72. LiYHuangYBergelsonJNordborgMBorevitzJO 2010 Association mapping of local climate-sensitive quantitative trait loci in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 21199 21204

73. MaronLGKirstMMaoCMilnerMJMenossiM 2008 Transcriptional profiling of aluminum toxicity and tolerance responses in maize roots. New Phytologist 179 116 128

74. KrillAKirstMKochianLBucklerEHoekengaO 2010 Association and linkage analysis of Aluminum tolerance genes in maize. PLoS ONE 5 e9958 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009958

75. SangTGeS 2007 The puzzle of rice domestication. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 49 760 768

76. HanBXueY 2003 Genome-wide intraspecific DNA-sequence variations in rice. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 6 134 138

77. LiuXLinFWangLPanQ 2007 The in silico map-based cloning of Pi36, a rice coiled-coil–nucleotide-binding site–leucine-rich repeat gene that confers race-specific resistance to the blast fungus. Genetics 176 2541 2549

78. KumagaiMWangLUedaS 2010 Genetic diversity and evolutionary relationships in genus Oryza revealed by using highly variable regions of chloroplast DNA. Gene 462 44 51

79. BeavisWD 1994 The power and deceit of QTL experiments: lessons from comparative QTL studies. 250 265 Proceedings of the 49th Annual Corn and Sorghum Research Conference, American Seed Trade Association, Washington, DC

80. BaierACSomersDJGusiafsonJP 1995 Aluminium tolerance in wheat: correlating hydroponic evaluations with field and soil performances. Plant Breeding 114 291 296

81. BastenCWeirBZengZ 2002 QTL Cartographer, version 1.16. Department of Statistics, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC

82. PriceAPattersonNPlengeRWeinblattMShadickN 2006 Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nature Genetics 38 904 909

83. BarrettJCFryBMallerJDalyMJ 2005 Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 21 263 265

84. PritchardJStephensMDonnellyP 2000 Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155 945

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek The T-Box Factor MLS-1 Requires Groucho Co-Repressor Interaction for Uterine Muscle SpecificationČlánek B Chromosomes Have a Functional Effect on Female Sex Determination in Lake Victoria Cichlid FishesČlánek Distinct Cdk1 Requirements during Single-Strand Annealing, Noncrossover, and Crossover RecombinationČlánek Specification of Corpora Cardiaca Neuroendocrine Cells from Mesoderm Is Regulated by Notch SignalingČlánek Ongoing Phenotypic and Genomic Changes in Experimental Coevolution of RNA Bacteriophage Qβ and

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 8- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

- Délka menstruačního cyklu jako marker ženské plodnosti

- Farmakogenetické testování pomáhá předcházet nežádoucím efektům léčiv

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Polo, Greatwall, and Protein Phosphatase PP2A Jostle for Pole Position

- Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Incident Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) in African Americans: A Short Report

- The T-Box Factor MLS-1 Requires Groucho Co-Repressor Interaction for Uterine Muscle Specification

- B Chromosomes Have a Functional Effect on Female Sex Determination in Lake Victoria Cichlid Fishes