-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Requirement of Male-Specific Dosage Compensation in Females—Implications of Early X Chromosome Gene Expression

Dosage compensation equates between the sexes the gene dose of sex chromosomes that carry substantially different gene content. In Drosophila, the single male X chromosome is hypertranscribed by approximately two-fold to effect this correction. The key genes are male lethal and appear not to be required in females, or affect their viability. Here, we show these male lethals do in fact have a role in females, and they participate in the very process which will eventually shut down their function—female determination. We find the male dosage compensation complex is required for upregulating transcription of the sex determination master switch, Sex-lethal, an X-linked gene which is specifically activated in females in response to their two X chromosomes. The levels of some X-linked genes are also affected, and some of these genes are used in the process of counting the number of X chromosomes early in development. Our data suggest that before the female state is set, the ground state is male and female X chromosome expression is elevated. Females thus utilize the male dosage compensation process to amplify the signal which determines their fate.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(7): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001041

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001041Summary

Dosage compensation equates between the sexes the gene dose of sex chromosomes that carry substantially different gene content. In Drosophila, the single male X chromosome is hypertranscribed by approximately two-fold to effect this correction. The key genes are male lethal and appear not to be required in females, or affect their viability. Here, we show these male lethals do in fact have a role in females, and they participate in the very process which will eventually shut down their function—female determination. We find the male dosage compensation complex is required for upregulating transcription of the sex determination master switch, Sex-lethal, an X-linked gene which is specifically activated in females in response to their two X chromosomes. The levels of some X-linked genes are also affected, and some of these genes are used in the process of counting the number of X chromosomes early in development. Our data suggest that before the female state is set, the ground state is male and female X chromosome expression is elevated. Females thus utilize the male dosage compensation process to amplify the signal which determines their fate.

Introduction

When the sex chromosomes carry substantially different gene numbers, dosage compensation is necessary to equalize gene expression between the two sexes. In the three best studied model systems Drosophila, C. elegans and mammals where males are XY and females XX, this involves targeting X-specific components which modify the chromatin and transcription of X-linked genes. In each of these cases the end result is different; Drosophila upregulates transcription of the male X by about two-fold, C. elegans downregulates transcription of both X chromosomes in the hermaphrodite by approximately half, and mammals generally shut down transcription of one of the two female X chromosomes (reviewed in [1]).

As it is the Drosophila male which requires dosage compensation, mutation of genes strictly dedicated to this process results in male lethality. The first male specific lethal identified, maleless (mle; [2]), is indeed involved in dosage compensation as are the next identified male lethals, msl-1 and msl-2 [3]. msl-3 identified by Uchida et al. [4] and males absent on the first (mof; [5]) complete the proteins collectively known as the male specific lethals (msls; reviewed in [1], [6], [7]). In addition to these proteins, two RNAs on the X chromosome (the roX RNAs), which are not present in females, are also essential for dosage compensation [8]. Although roX1 and roX2 show no sequence similarity and do not have an open reading frame that could encode a significantly sized protein, they function redundantly; either roX is adequate for function, while loss of both RNAs is required for a failure in dosage compensation and male lethality [9]. The MSL proteins and roX RNAs function as a complex, coating the male X chromosome; the X chromosome is hypertranscribed and MOF acetylates histone H4 on lysine 16. Finally, a protein that appears to be part of the dosage compensation complex (DCC) but is required by both sexes is the JIL histone H3 kinase. JIL is also enriched on the male X chromosome but its loss leads to lethality in both sexes [10].

In 1980, Skripsky and Lucchessi [11] reported that females heterozygous for a Sex-lethal (Sxl) null allele, Sxlf1, and homozygous for mle showed morphological characteristics indicative of sex transformations. Sxl is the Drosophila sex determination master switch, which is on in females but off in males. The Sxlf1/+; mle/mle sex transformation result was confirmed and extended by Uenoyama et al. [12] who observed similar effects with two different mle alleles as well as msl-2 and msl-3. This argued that this phenomenon was not unique to mle, but likely a general property of the msls.

These results, a requirement of male specific genes in females, present a paradox. First, homozygous msl− females show no sex transformations and are fully viable [3]. Second, besides controlling differentiation, a key function of Sxl is to turn off the male dosage compensation system to prevent hypertranscription of the two female X chromosomes, which would otherwise lead to female lethality. As a splicing and translation regulator, Sxl alters the splicing and inhibits translation of msl-2 mRNA so preventing assembly of the DCC [13]–[17]. The absence of MSL-2 also destabilizes MSL-1 and MSL-3 assuring inactivation of the dosage compensation machinery.

The initial activation of Sxl is transcriptional, at the Sxl ‘establishment’ promoter, SxlPe [18]. In cycle 12 of embryogenesis, SxlPe responds to activating X linked genes (known members: sisterless-a (sis-a), sisterless-b (sis-b), runt (run) and unpaired (upd)), in conjunction with positive maternal factors such as Daughterless, balancing their dose against the negative effect of genes on the autosomes (deadpan (dpn), the only identified member) and maternal factors such as Groucho (Gro) and Extramacrochetae (hereafter collectively referred to as the X∶A ratio; reviewed in [19]). Protein from SxlPe transcripts alters the splicing of transcripts from the ‘maintenance’ promoter, SxlPm, first transcribed in cycle 14 in both sexes. In the absence of Sxl protein, default splicing includes a translation terminating exon into the transcripts from SxlPm. As male embryos do not activate SxlPe, Sxl protein is absent and a splicing change on SxlPm transcripts is only effected in females. Females thus set in motion a splicing autoregulatory feedback loop which serves to maintain Sxl expression, and sexual identity, through the rest of the life cycle [20].

Returning to the paradox of a female requirement of male specific genes, one explanation is that XX embryos with only one copy of Sxl fail to reliably activate the gene. These XX cells would be male and are presumably eliminated, due to the gene imbalance from inappropriate dosage compensation. However, when one or more of the msls is mutant, these masculinized XX cells might survive since assembly of the male DCC is prevented. The resulting clones grow but are sexually transformed, so accounting for the observed sex transformations.

Results

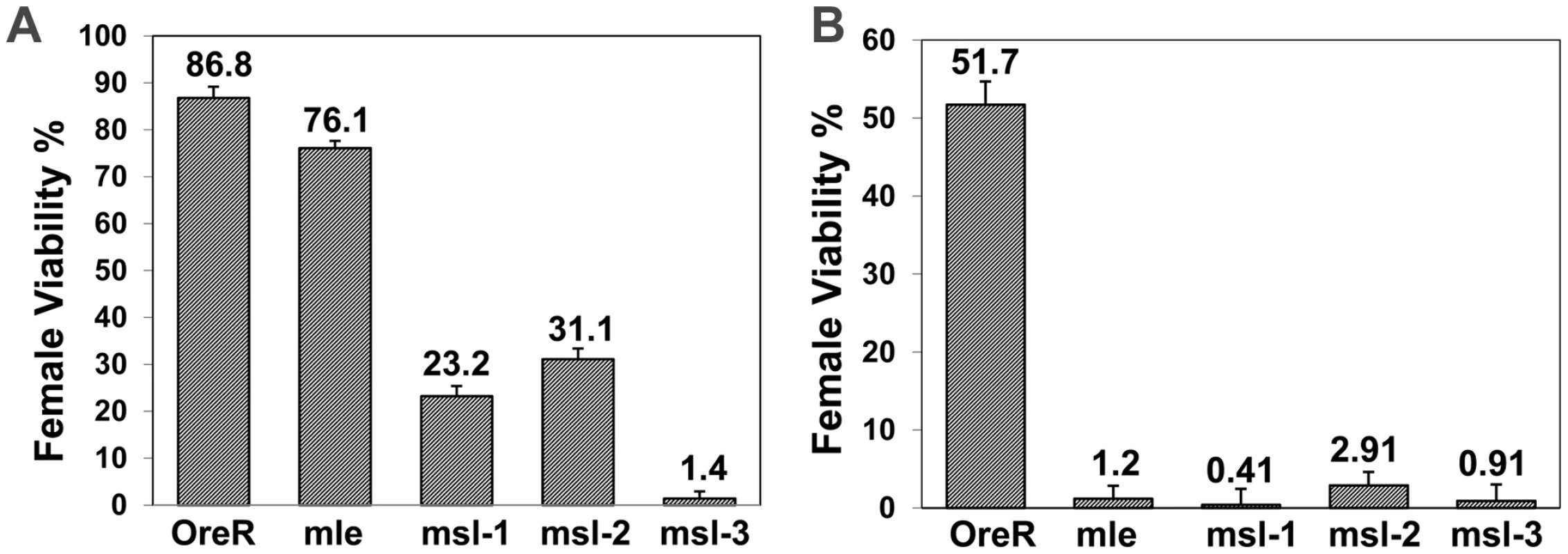

While plausible, the above explanation does not account for the recessive nature of Sxl null alleles, which have very high viability (Figure 1A). This high viability requires these females survive the removal of those pockets of male tissue with inappropriate dosage compensation, as Sxl hemizygous females show no male differentiation. Figure 1A also shows that the viability of females with only one Sxl+ allele is badly compromised if maternal MSL-3 is removed. Maternal MSL-1 was next most effective followed by MSL-2, while the effect of MLE was negligible relative to wild type. These data demonstrate a synergism of these msls with Sxl for female viability, as one wild type copy of both Sxl and the msl, is present in these animals. Contrary to the expectation that female survival might be improved if partially masculinized tissue did not perform male dosage compensation effectively, it would appear that females have a need for the msls, when the dose of Sxl is halved. Consistent with our findings, some of the Sxlf1/+; msl/msl combinations in Uenoyama et al. [12] also showed reduced female viability.

Fig. 1. Removal of maternal msls reduces female viability when female determining gene dose is compromised.

Genotype of mothers shown on x-axis; percent female viability relative to their brothers is shown with percentage standard error. (A) Ore R or homozygous mle1, msl-1L60, msl-21 or msl-31 females mated to y, w, cm, SxlfP7B0/Y (test classes total n = 439, 1088, 522, 489, 1065, respectively). Females homozygous for the SxlfP7B0 deficiency are lethal but males with the deficiency are viable. (B) Ore R or homozygous mle1, msl-1L60, msl-21 or msl-31 females mated to w, sis-bsc3-1, sis-a1, m/Y (test classes total n = 270, 934, 593, 849, 555, respectively). msls interact with numerator genes for female viability

The above viability results prompted us to analyze whether key activators of Sxl - the numerator genes sis-a and sis-b, would show a similar interaction with the msls. Figure 1B shows that the effect of a sis-a, sis-b double mutant chromosome is more extreme than a Sxl null, when crossed to mothers mutant for each of the msls. The greater effect of the sis genes is not surprising, given they function in a dose sensitive process to activate Sxl and so determine female sex. What is surprising is that the msls interact with the numerators to promote female viability.

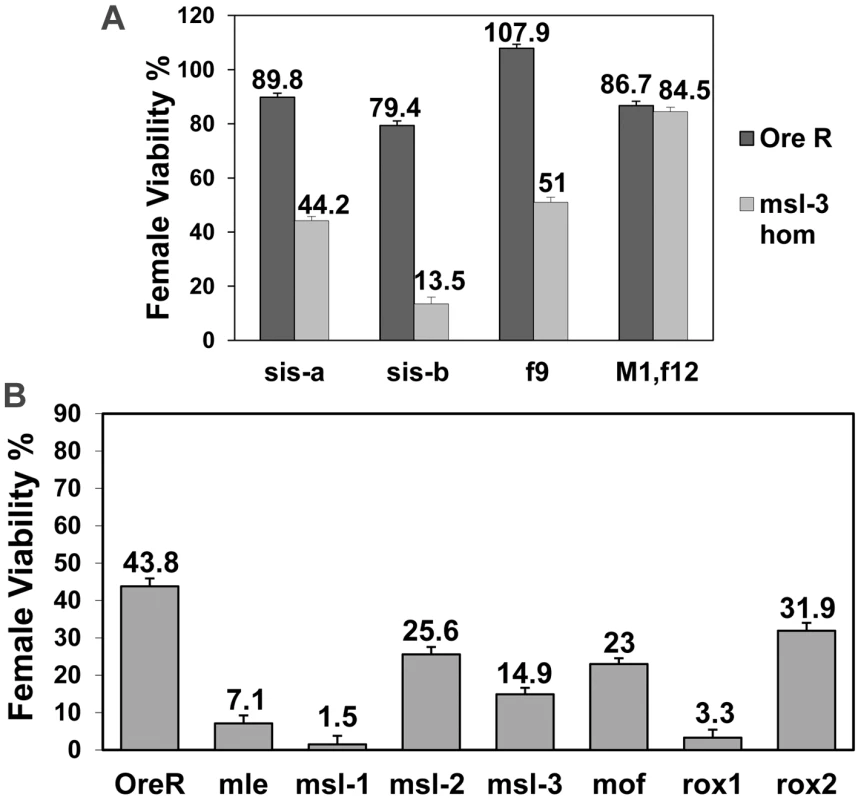

To test whether the loss of a single numerator gene could also affect females, we performed crosses with reduced dose of either sis-a or sis-b. Since msl-3 showed the strongest overall interaction, this msl was examined. Figure 2A shows that sis-a as well as sis-b alone affected females, with sis-b having the stronger effect. The sis gene interactions suggest that very early steps in the female sex determination process are compromised. Testing two Sxl alleles, an early (Sxlf9) versus a late (SxlM1,f12) defective allele, indicated that the early defective allele had an effect, almost as strong as sis-a alone, while the late defective allele did not. These data are consistent with the view that early, dose sensitive events in female sex determination are influenced by the msls. The late Sxl transcripts may not turnover or be as dose sensitive as the early transcripts, so a 50% reduction may not be sufficient to sensitize the females.

Fig. 2. msls act early in the female sex determination process, and all key components of the dosage compensation complex, affect female viability.

(A) msl-31 homozygous mothers mated to males mutant for single numerator gene (sis-a1 or sis-bsc3-1) or Sxl early phase (f9) or late phase defective (M1, f12) allele (test class total n = 1135, 1047, 879, 404, 1129, 696, 915, 924, respectively). sis-bsc3-1 cross was done at 29°C, the non-permissive temperature for this temperature-sensitive allele. Percent viability of females relative to their brothers is shown with percentage standard error. Relevant genotype of fathers shown on x-axis. (B) w, sis-bsc3-1, sis-a1, m/FM7 females were mated to either Ore R, mle1/CyO, msl-1L60/CyO, msl-21/CyO, msl-31/TM3, mof2/Y; 18H1[mof+]/+, roX1ex6/Y or roX2−/Y males (test class total n = 420, 241, 208, 285, 363, 447, 408, 418, respectively). Percent viability of sis-a, b/+ females with the msl mutation relative to their FM7/+ sisters also carrying the msl mutation is shown, with percentage standard error. For mof it is for females that did not receive the 18H1[mof+] transgene. Relevant msl genotype of fathers shown on x axis. sis-a and sis-b are zygotic in their role in female sex determination. To determine whether the effect observed with the msls was maternal or zygotic, reciprocal crosses to Figure 1B were performed. Under these conditions, halving the dose of each of the four msls, including msl-2, reduced female viability (Figure 2B). The zygotic effect was generally weaker than the maternal.

A maternal effect of msl-2 is surprising given that the protein is not detected in females [13], [15], [17]. We note that a maternal effect of msl-2 was also described by Uenoyama et al. [12]. msl-2 RNA is deposited into the egg (Flybase microarray data; http://www.flybase.org/), so the strength of the zygotic effect is presumably influenced by the amount of maternal protein/RNA of each of the msls.

As the msls, particularly MSL-3 and MOF, have been shown to bind to both autosomal and X-linked genes where they might perform an unknown role, we wondered whether the entire male DCC, including MOF and the roX RNAs, influenced female viability. With the numerator gene dose compromised, halving mof dose had an effect, as did roX1 which was much stronger in effect than roX2 (Figure 2B). Since the roX RNAs function redundantly, the impact of roX1 and the weaker interaction of roX2 can be explained by the fact that first expression during embryogenesis is later for roX2than for roX1 [9]. Combined, these results indicate that the msls affect an early event and that the entire male DCC is required for promoting female viability.

Transcription of Sxl is affected by the msls

The foregoing suggests an event early in Sxl expression is altered by the DCC. To directly assess the effect of the DCC on Sxl transcription, in situs were performed with Sxl probes specific for either the early or late transcripts. Embryos from homozygous mutant mle1, msl-1L-60, msl-21, msl-31 or roX1ex6, roX2− double mutant mothers, mated to heterozygous msl males were analyzed. For the roX1, roX2 double mutant embryos, the roX1−, roX2− males have a duplication of roX2+ on their Y chromosome so only the females are roX1−, roX2−.

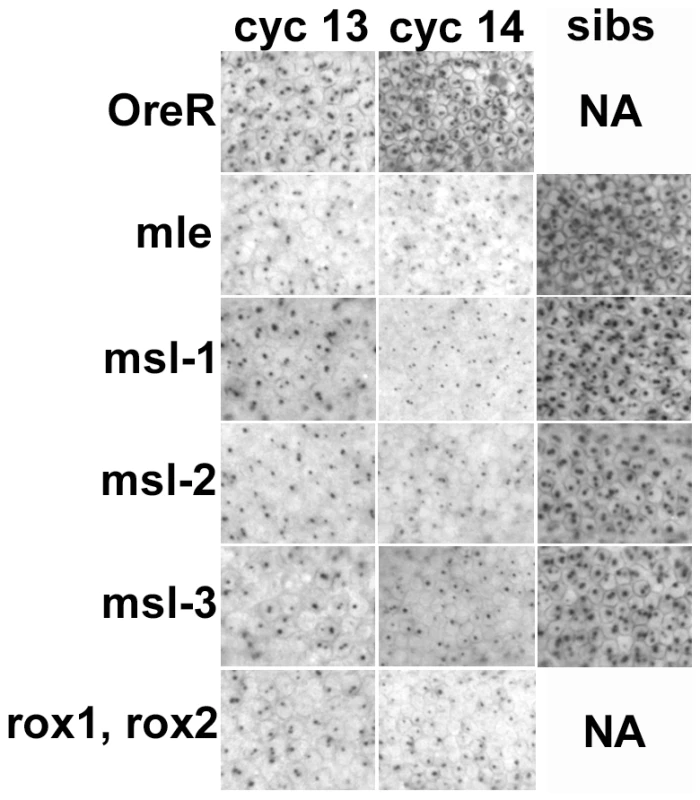

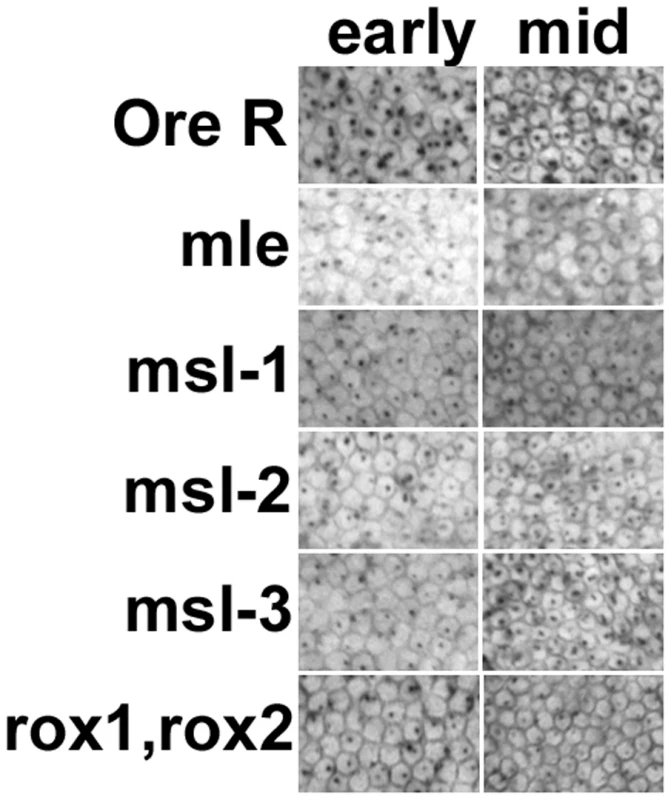

In wild type embryos, SxlPe is not activated until cycle 12, its expression becomes stronger in cycles 13 and 14 before it rapidly ceases expression early in cycle 14. For all the msls about half the embryos showed weaker than normal expression of SxlPe, as judged by the size and intensity of the in situ dots on their X chromosomes (Figure 3). The fraction was higher in the roX1−, roX2− cross where all the females are expected to be mutant. These data indicate that the entire DCC complex is used to upregulate transcription from SxlPe.

Fig. 3. Transcription from the X chromosome dose sensitive promoter of Sxl, SxlPe, is reduced in embryos homozygous for the msls.

In situs on embryos with an early transcript specific probe reveals two dots/nucleus at the sites of transcription on the X chromosomes during cycles 13 and 14 in development. The roX double mutants had a reduction in expression in most embryos as all the females are mutant, the msls showed reduced expression in about 50% of the embryos (crosses described in text). The ‘sibs’ panels show the signal from normal looking cycle 14 embryos in the same collection, presumably the heterozygous siblings. NA – not applicable. All embryos photographed at 40× mag. A constitutive Sxl allele rescues females from msl-promoted lethality

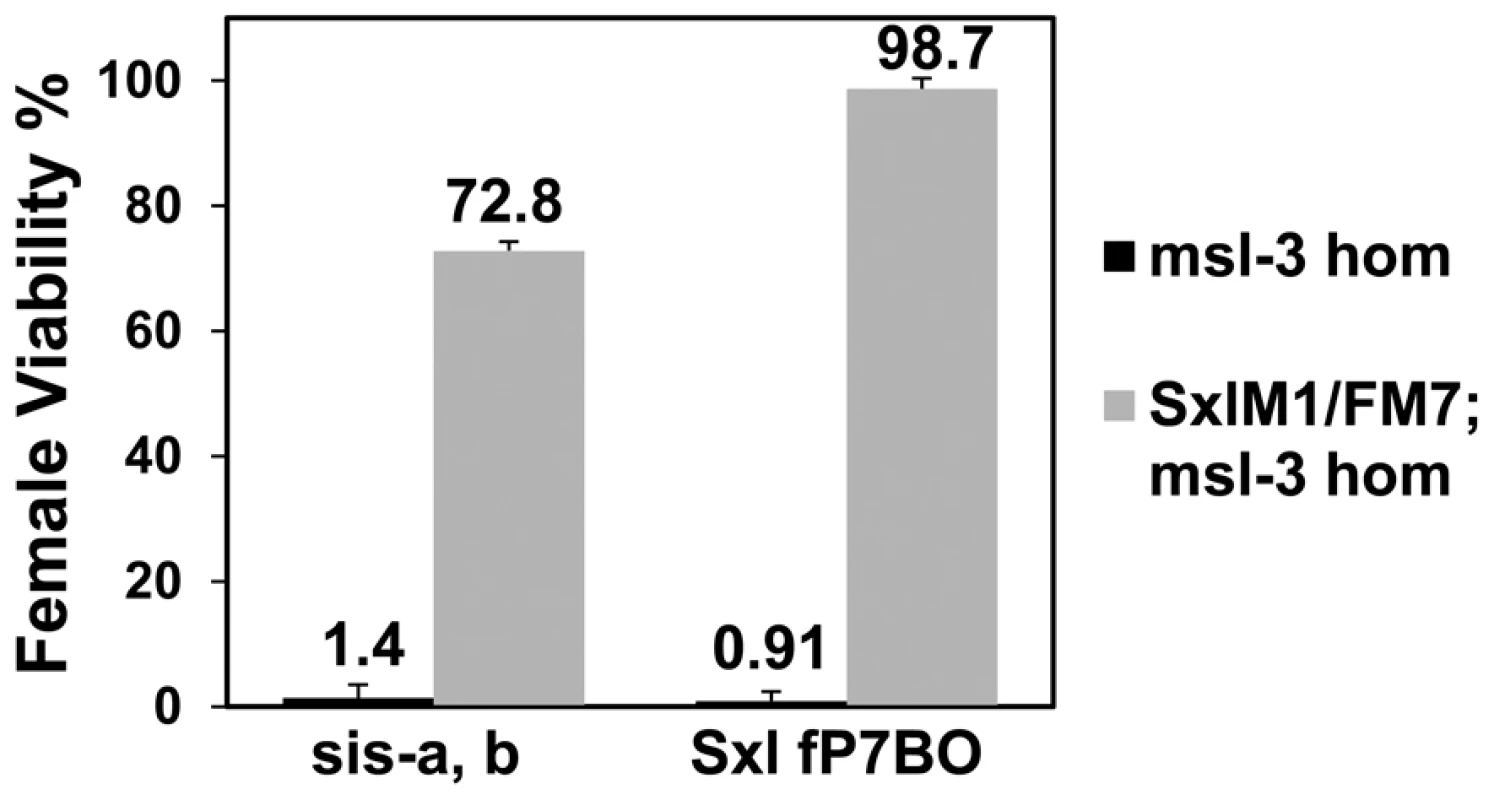

If, as the data suggest, the primary reason for female lethality is the failure to activate Sxl, a constitutive allele (such as SxlM1) which bypasses the X∶A ratio should rescue them. Since msl-3 showed the strongest interaction in the genetic tests, we determined whether the presence of SxlM1 could rescue the lethality of sis-a, b or Sxl dose reduction in embryos from mothers homozygous for msl-31. The rescue (Figure 4) of 72.8% and 98.7% of the females by SxlM1 for sis-a, b or Sxl dose reduction, respectively, demonstrates that female lethality is primarily caused by the inadequate expression of Sxl.

Fig. 4. A constitutive Sxl allele rescues the female lethality from loss of msl-3. y, cm, SxlM1/FM7; msl-31 females mated to w, sis-bsc3-1, sis-a1, m/Y or y, w, cm, SxlfP7B0/Y males (test class total n = 555, 851, 1065, 681 respectively).

Percent viability of females relative to their brothers is shown with percentage standard error. Genotype of fathers shown on x-axis. As the reference males were the balancer FM7/Y, correction for their reduced viability (48.7%) was determined relative to SxlM1/+ females from a mating of y, cm, SxlM1/FM7; msl-31 to Ore R males. Both Sxl promoters are affected by the DCC

We next examined whether transcripts from the maintenance promoter, SxlPm, were affected. As shown in Figure 5, this promoter was also affected by loss of DCC components. For msl-1, msl-2 and msl-3 about 50% of the embryos, presumably the homozygotes, showed weaker expression. For mle and the roX1−, roX2− double mutants almost all the females (2-dots/cell embryos) showed weaker than normal expression. As noted for SxlPe, most of the females are mutant for roX1−, roX2− (excepting the few non-disjunction embryos that also receive the Y with a duplicated roX2+ gene), however, only 50% of the embryos are homozygous for mle1. The mle1 data suggest the maternal contribution of MLE is important for SxlPm expression, an effect that appears distinct from the loss of the DCC since for SxlPe only half the embryos were affected. This may be an outcome of SxlPm relying more heavily on maternal MLE compared to the other msls. Alternatively, because MLE also affects the stability of roX1 RNA, which has a larger role in sex determination than roX2 (Figure 2B), the effect of mutating MLE may be amplified as it not only eliminates the maternal MLE but also reduces the levels of roX1 RNA, acting as a double mutation. Despite this unexplained effect on SxlPm by maternal MLE, the data together indicate that both Sxl promoters are susceptible to the DCC and suggest that Sxl, which resides on the X, is a dosage compensated gene. Consistent with the idea that transcription elongation and not initiation is altered by the DCC [21], transcription from both Sxl promoters, which are regulated by different factors, is affected.

Fig. 5. Transcription from the Sxl maintenance promoter, SxlPm, is also reduced in embryos homozygous for the msls.

In situs of embryos using a Sxl late transcript specific probe during early and mid cycle 14. As cellularization proceeds during cycle 14, the membranes between the nuclei drop into the embryo, the cell volume changes allowing embryo staging. Only females are shown. Male embryos also transcribe SxlPm – single X chromosome dots – not shown. All embryos photographed at 40× mag. Although the in situs of Ore R embryos did not show the distinctly different classes we observed with the msl embryos, to control for the possibility that the quality of the in situs was responsible for generating a poor signal in half the embryos from msl mutant mothers, in situs for SxlPm transcripts were simultaneously performed with a distinguishable second probe - the segmentation gene hairy which has a striped pattern of expression. As seen in Figure 6, embryos from msl mutant mothers that are at the same developmental stage as Ore R embryos have comparable hairy stripes but poor SxlPm signal, indicating that the poor signal is not an artifact of the in situs but an effect of the msls on Sxl transcription.

Fig. 6. Reduced in situ signal in Sxl is not accompanied by reduced signal in another unrelated gene.

In situs for SxlPm transcripts performed simultaneously with the segmentation gene hairy. Embryos from msl mothers show the normal hairy striping pattern of expression for the same developmental stage as Ore R embryos (left set of panels), but poor SxlPm signal (right set of panels—enlarged view to show cells). All embryos photographed at 40× mag. Quantitation of Sxl expression in embryos from msl mothers

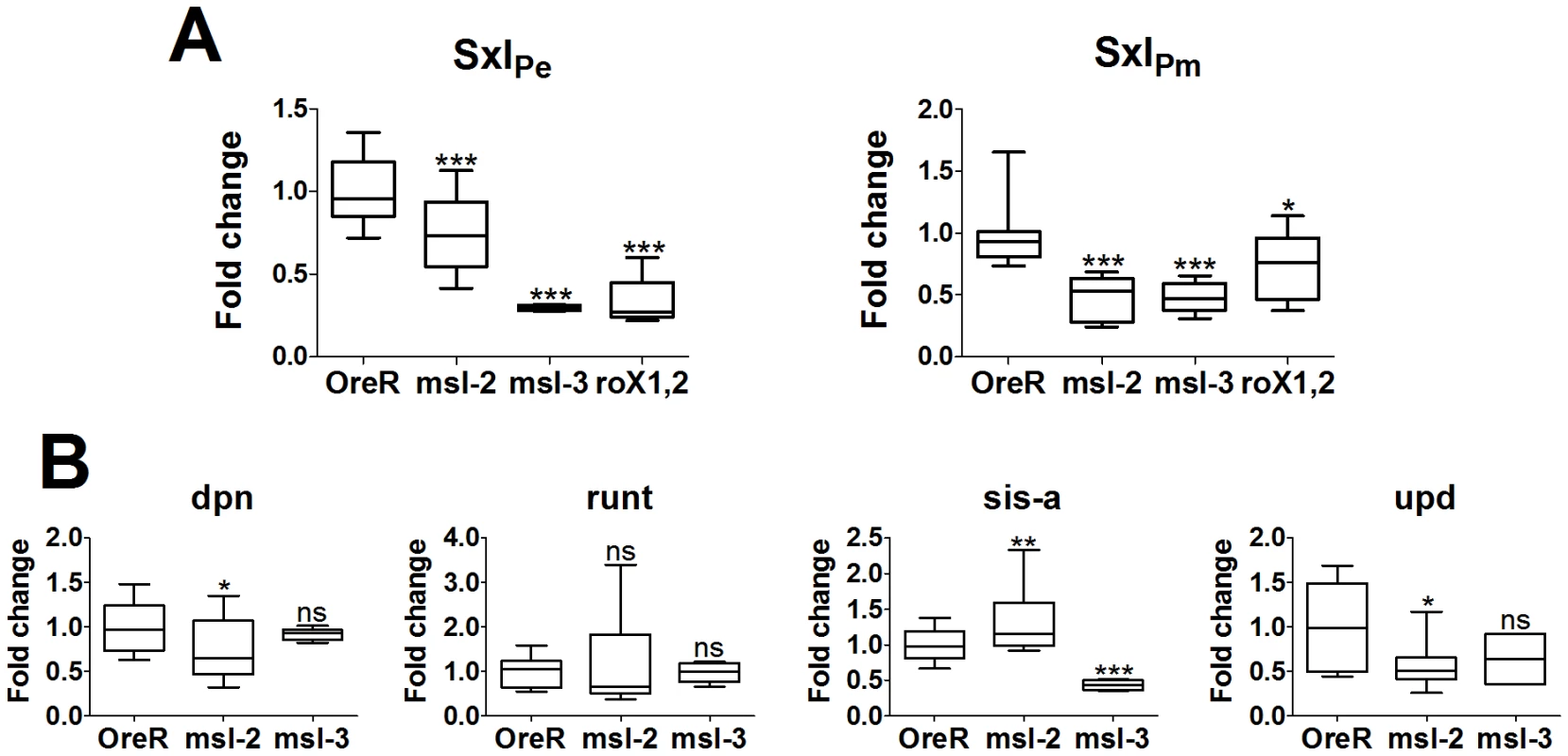

The in situs are qualitative and the nuclear dots detect transcription directly off the chromosomes, indicating only high levels of transcription. For a better measure, we performed quantitative RT-PCR analysis on 2–3 h and 2.5–3.5 h embryos for SxlPe and SxlPm expression, respectively. Embryos were from homozygous mutant mothers for msl-21, msl-31 or roX1ex6, roX2− double mutants, mated to heterozygous msl males. As for the in situs, in the roX1−, roX2− embryos only the females are doubly mutant as males have a duplication of roX2+ on their Y. RNA levels were normalized to tubulin levels and compared to Ore R embryos which were set to 1.

Figure 7 shows that SxlPe is expressed at lower levels than Ore R embryos in all three msl genotypes. The median for msl-21 embryos was slightly above, for msl-31 and roX1−, roX2− embryos the median slightly below half of Ore R. The medians for SxlPm were also close to half, except for the roX1−, roX2− genotype which was closer to 0.7. SxlPm is transcribed in both sexes and all the males have a functional roX2 gene in the roX1−, roX2− embryos. In these embryos, SxlPm gave a value of 0.7, suggesting males are transcribing SxlPm at close to normal levels while the females express SxlPm at close to half. This would suggest that functional roX2 RNA is present mid-way through cycle 14, a little earlier than in situs can detect [9].

Fig. 7. Change in mRNA expression for dosage compensated and control genes compared to Ore R.

All replicates are plotted and display the 25 and 75 percentiles (boxed), median (line in boxes), max and min (whiskers) of the data set. Significance is measured using an unpaired t-test with a Welch's variance correction, levels indicated above whiskers as *** for p<.001, ** for .001<p<.01, * for .01<p<.05, and ‘ns’ for p>.05. (A) SxlPe and SxlPm transcripts show a highly significant drop in expression when DCC function is compromised by mutation in msl-2, msl-3 or the roX genes. Embryo genotype on the x-axis. As noted in the text, the lower significance in the change in SxlPm levels for the roX- genotype is most likely the influence of males which have a wild type roX2 gene. (B) dpn and run, show almost no significant change in expression, with the slight exception of dpn in the msl-21 mutants. sis-a and upd show significant change in a DCC-compromised backgrounds, with specific differences between mutant genotypes. sis-a shows the expected drop in expression for msl-31embryos but shows a slight increase in expression for msl-21embryos. This appears to arise from an additional role of MSL-2, affecting mRNA levels (see Figure S1). upd is affected by the loss of MSL-2 but is essentially unaffected by the loss of MSL-3, as would be expected for a gene with close DCC entry sites. A value close to 0.5 for both promoters (excepting SxlPm for roX1−, roX2−) was a little surprising given the in situ results which show about half the embryos have close to normal levels of transcription. It suggests that the DCC may be upregulating the expression of Sxl by a little more than two-fold, not unlike the roX genes [22]. Alternatively, and not mutually exclusive, it may also indicate that at 2–3 h of development most of the DCC is assembled primarily from maternal reserves and the presence of one wild type chromosome in half the embryos (from the heterozygous fathers) makes a small contribution. With respect to SxlPe, the qRT-PCRs score embryos whose average age is slightly younger than the in situs, at cycles 13 and 14 (2.75–3.25 h). Close examination of those in situs shows few embryos in early cycle 13 with uniform, wild type levels of SxlPe expression. However, when the membranes begin to drop between the nuclei later in cycle 13, the class with more uniform expression resembling wild type, is more readily observed (data not shown). By late cycle 13 and cycle 14, the zygotic contribution of the wild type chromosome from the heterozygous fathers must begin, and the two different classes are more readily apparent in cycle 14 embryos (Figure 3). For SxlPm, the data are more consistent with the DCC having slightly greater than a two-fold effect.

Effects of the DCC were also scored for some of the sex determination genes in the 2–3 h collections from homozygous msl-21 or msl-31 mothers. msl-31 embryos show sis-a, like Sxl, with a median expression close to 0.5, while run and dpn gave medians close to 1 as expected for non-dosage compensated genes (sis-b could not be reliably scored as it has an anti-sense transcript, CG32816). upd appeared reduced to ∼0.7 but this was not statistically significant and the data showed greater variability than for the other genes. This may be because upd begins expression later (cyc 13; [23]), and half the embryos are beginning to perform normal dosage compensation. Also, there are 2 DCC high-affinity sites (see Discussion below) relatively close to upd. These are predicted to make upd less sensitive to the loss of MSL-3, since MSL-3 is required for spreading of the DCC from its initial entry sites.

For msl-21 embryos, the upd median did drop to ∼0.5, consistent with the loss of MSL-2 having a greater effect than MSL-3 for genes with close DCC entry sites. run did not show a significant change from wild type. However, unlike for the msl-31 embryos, sis-a was slightly elevated relative to wild type, while dpn mRNA, at a low level of significance, showed a small decrease. As the msl-31 embryos show that sis-a is dependent on the DCC, these latter data suggest that besides dosage compensation, MSL-2 may have an additional role, one that perhaps affects mRNA stability. MSL-2 affects the steady state levels of the roX RNAs [24]; such an activity could explain the greater variability in the values we measured for msl-21 embryos. To test this, in situs of sis-a mRNA were performed to determine if over time, the mRNA levels would show a change consistent with accumulation. Indeed, we found this to be the case (Figure S1), suggesting that in the case of sis-a MSL-2 may serve to destabilize its RNA. During the early cycles, embryos from msl-21 mothers had signal which was generally weaker than wild type, but by cycle 12 when the message has its highest accumulation in wild type [25], the accumulated levels in the msl-21 embryos were even higher. While alternative explanations, e.g. repression of the sis-a promoter by MSL-2 are also plausible, this effect would have to occur at some but not all stages of sis-a transcription and be independent of the DCC, as loss of MSL-3 shows the predicted 2-fold drop in sis-a mRNA levels.

Despite the suggestion of an additional role beyond dosage compensation for MSL-2, the qRT-PCR data show that the 2 Sxl promoters are expressed at approximately half their normal levels by the loss of the DCC. Expression of other X-linked genes also appears to be similarly affected, very clearly evident in the msl-31 embryos. This indicates the DCC functions relatively early, and may also affect the handful of genes known to be expressed during these early stages of embryonic development [26], [27].

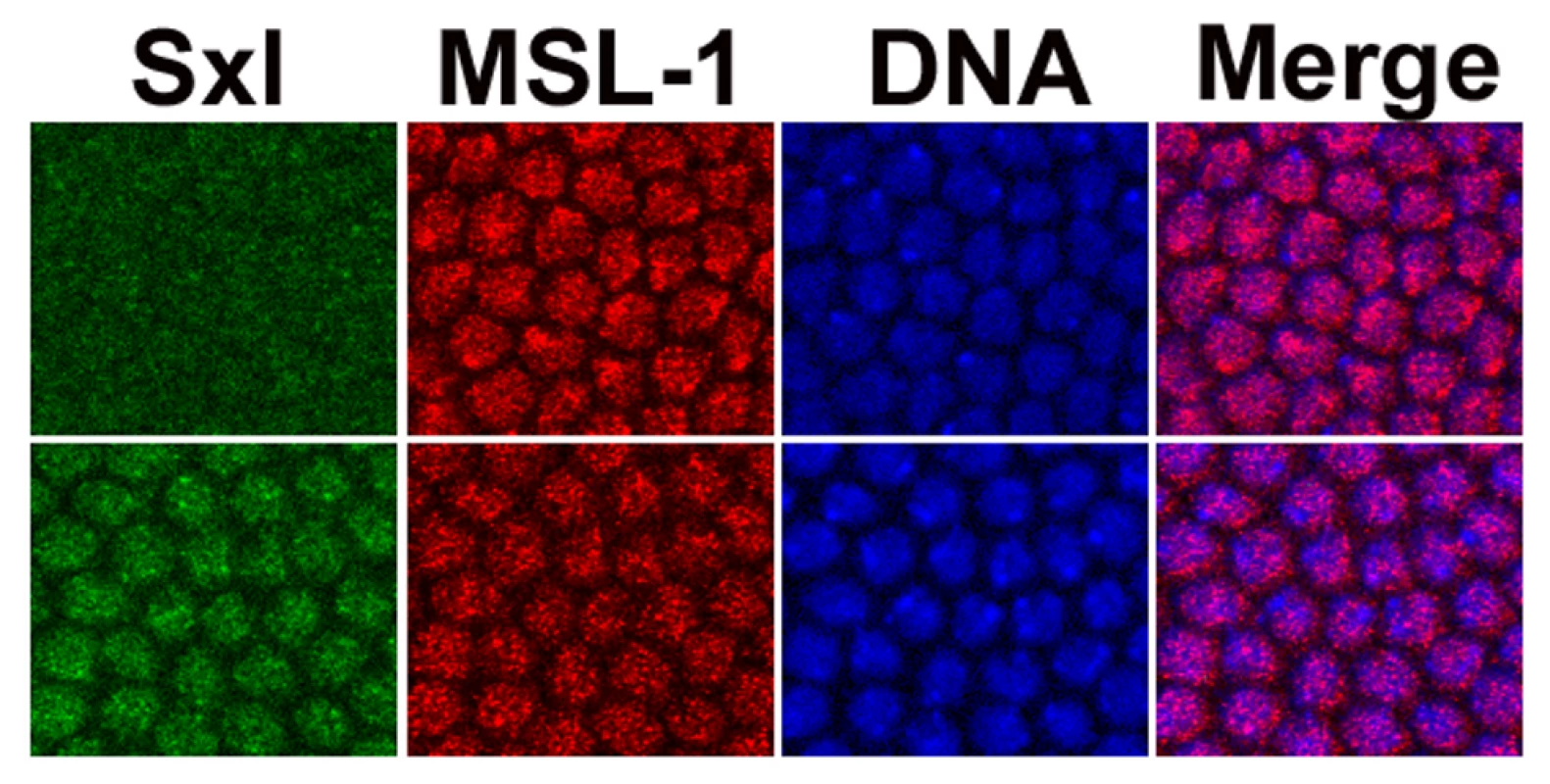

Transient expression of the DCC in females

The data argue for a role of the male DCC in females, a function not ascribed to it, and the complex has not been detected in female embryos [28]–[30]. Our data suggest that prior to the full activation of Sxl there is a brief window of male dosage compensation in females, after which Sxl protein is predicted to shut down MSL-2 expression, and destabilize the entire DCC. Not all anti-MSL antibodies have been reported to detect the complex at this early stage, even in males (see [30]). Given this limitation, we used an anti-MSL-1 antibody from the Lucchesi lab which has high sensitivity and enhanced the signal with an M3TAP construct [31]. These embryos were co-stained with anti-Sxl antibodies and closely examined around the cellular blastoderm stage. Figure 8 shows that there is indeed a very brief stage, in mid cycle 14, when it is possible to simultaneously detect both Sxl and the DCC in females. The ant-MSL-1 signal in the female nuclei is not as bright and generally covers an area of DNA larger than in males, presumably the two X chromosomes.

Fig. 8. Sxl and the DCC are transiently co-expressed in female embryos.

During mid cycle 14, Sxl (green) and the DCC (red - mostly from anti-MSL-1 antibody) can be simultaneously detected in females. MSL-1 overlaid on DNA (blue) signal (Merge). Top set of images from males, as determined by the lack of specific Sxl signal, lower set is of females. The ant-MSL-1 signal in the female nuclei is less intense and generally covers a larger area than in males, as might be expected for their double dose of X chromosomes. As previously noted [46], the signal in males is more frequently at the nuclear periphery. Discussion

The effect of the DCC on Sxl transcription early in embryogenesis explains the contradiction of why genes that are normally off in females are required to promote their viability. In the absence of the msls and a functional male DCC, transcription of some of the genes on the X chromosome as well as Sxl is not elevated by two-fold. This effectively weakens the X∶A ratio and lowers the levels of the Sxl early as well as late transcripts, which when low enough leads to female lethality. With respect to SxlPe, insufficient levels of early protein are produced and splicing of SxlPm transcripts into the female mode is compromised. With respect to SxlPm, a reduction may compromise establishment of the female state as the autoregulatory splicing feedback loop would have to rely on reduced mRNA and protein levels.

In the absence of mutations in feminizing genes, lowering of Sxl expression by the msls is not detrimental, presumably as the very process which would lead to female lethality - male dosage compensation - is no longer functional, while the Sxl positive autoregulatory feedback loop slowly establishes itself into the female state. Without the DCC, however, reduced dose of feminizing genes, particularly the dose sensing X-linked genes or numerators, lowers SxlPe transcript levels further, and has deleterious consequences for females. Sxl dose also has an effect, but unlike the numerators Sxl is not strictly dose sensitive, and not unexpectedly, when its copy number is halved, has a less profound effect on female viability. It should be noted that extremely low levels of Sxl in females, even in the absence of the male DCC is lethal [32]. Sxl protein directly performs a female dosage compensation role, reducing the levels of X-linked genes such as run [33]; the latter is not upregulated by the male DCC [[34]; Figure 7].

Early X chromosome expression is elevated in females

Our data indicate that some of the earliest expressed genes on the X, the numerators as well as Sxl, are dosage compensated. Dosage compensation is a chromosome wide phenomenon, and, at the least, the effect of the msls can be detected as early as cycle 13. Previous work timed the DCC in males at cellular blastoderm (Stage 5, [30]) and early gastrulation (Stage 6, [29]). Our data (qRT-PCRs and in situs) suggest dosage compensation sets in earlier, by 2–3 h in development and appears to initially rely on maternal stores and the zygotic expression of the roX RNAs (roX1 primarily). As discussed by McDowell et al. [30] antibody sensitivity sets the limit for the prior studies. The present studies relied on different assays, which may account for the difference. Indeed, we were also unable to detect convincing signal in males, which is normally stronger, much before blastoderm by antibody staining (Figure 8). It is also possible that early in development the DCC is harder to detect directly as there are fewer genes being transcribed, so less of the complex may have assembled onto the X chromosome before cycle 14, when the mid-blastula transition occurs and there is a large transcriptional burst. The zygotic expression of roX1 RNA has been placed at around 2 h of embryogenesis [9], consistent with the effects we observe.

Targeting of the DCC to the X chromosome, rather than the autosomes, is thought to rely on transcription marks, sequence elements (∼150 MREs – MSL recognition elements and ∼130 HAS – high affinity sites), and other unknown elements [35], [36]. The identified sequence element set is still incomplete since the two data sets show an overlap of 69%; it is predicted that the X chromosome may have as many as 240–300 elements (reviewed in [7]). Examination of the published MRE and HAS shows the closest element to Sxl ∼139 Kbp 5′ of the gene. This distance is on the large side, although it should be noted that all elements which target the DCC to genes on the X remain to be identified; as an example, the white gene has its closest known MRE/HAS 93 Kbp away but its mini form in transgenes, which does not include this site, is clearly dosage compensated. Finally, ChIP data (modENCODE, Flybase) show Sxl with strong H4K16 acetylation marks, a modification dependent on the DCC. ChIP data for JIL-1 kinase also suggest the DCC is at Sxl.

None of the other sex determination genes, other than upd (two 3′ elements at ∼5.6 and 6.8 Kbp away) had an element within 10 Kbp (sis-a ∼26 Kbp, sis-b ∼38 Kbp), consistent with the observation that the msls involved in spreading the DCC from its entry sites on the X (MSL-3, MOF and the roX RNAs), are required for their elevated expression. upd, the exception, showed greater sensitivity to the loss of MSL-2 than MSL-3, as might be expected for dosage compensation which is less dependent on spreading. An interesting correlation is that run which is not compensated, had its closest elements ∼343 (5′) and ∼273 Kbp (3′) away, further than the rest of the other known key sex determination genes.

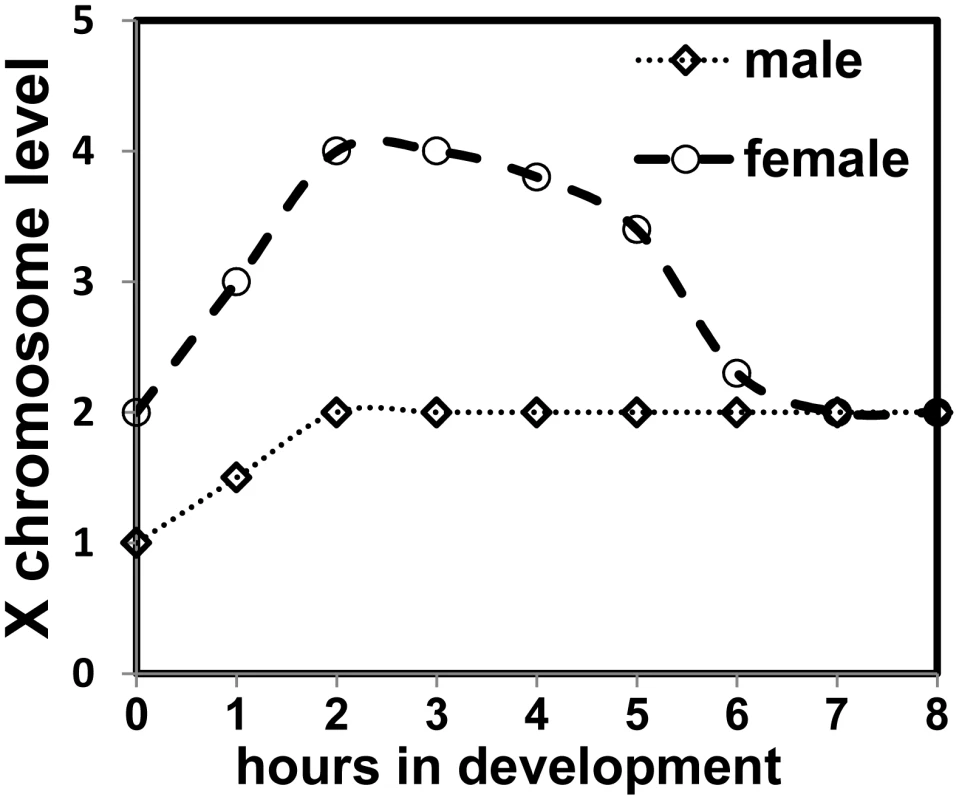

Default mode is male

By using the DCC before the female state is established, Sxl capitalizes on the default male state. Transcription from SxlPe is amplified, an effect unique to females as males do not transcribe from SxlPe. Determination of female identity is thus consolidated. As expression of Sxl protein levels is established, Sxl protein subsequently shuts down the DCC and eliminates the very difference in gene dose between the sexes which set in motion, as well as augmented, its own activation. Implicit, is that before the establishment of Sxl expression, each X-chromosome in females is transcribed at 2X levels, as in males, and our qRT-PCR data of some of the key sex determination genes would support this view. The conventional X∶ A ratio would then be 4∶2 rather than 2∶2, and in males 2∶2 rather than 1∶2 (Figure 9).

Fig. 9. Model depicting X chromosome expression levels in the two sexes.

At 25°C cycle 13 is around 2 h 15 min and cycle 14 concludes around 3 h 15 min. Reduction of the DCC effect is shown as being gradual as the female mode of Sxl splicing is established, and repression of MSL-2 expression is more complete. In that there is a 2-fold difference between the sexes, this scenario is mathematically the same. However, there are practical and functional implications. An X∶ A ratio that is transiently 4∶2 rather than 2∶2 in females, would have some of the X-linked genes which activate SxlPe at twice the level of their putative counteracting autosomal or denominator genes. In a screen which seeks suppression of a female-specific lethal condition due to a decrease in numerator elements, it would require the equivalent of two autosomal genes to be mutated to reestablish an X∶ A ratio favorable for female survival. Obtaining two mutations in genes functioning in the same process at once is unlikely, which may have skewed the outcome of screens which sought to identify zygotic autosomal genes. It may not be a coincidence that the only autosomal acting component identified is dpn [37], [38]. As both Dpn and Run bind the co-repressor Gro [39], [40] but have opposing effects on SxlPe, it has been speculated they may antagonize each other [39], [41]. Screens may have repeatedly identified dpn as it would be counteracting a gene expressed at its chromosomal equivalent, since run is not upregulated by the male DCC.

Elevated X chromosome transcription

On a more general level, our data suggest an upregulation of transcription of the Drosophila X, and may reflect a universal requirement of elevated X chromosome expression to avoid monosomy. Recent microarray analysis of mouse ES cells indicates that mammalian dosage compensation is more complex than previously thought: there is higher expression of the X chromosome relative to the autosomes giving them equivalence, i.e. chromosome per chromosome the X is overexpressed by about two-fold relative to each autosome [42]–[44]. As differentiation proceeds, females lose expression of one of their X chromosomes, silencing it through inactivation. Put in other words, the mammalian X chromosome is not monosomic in expression but rather is hyperactive, and the process of dosage compensation appears to shut down elevated X chromosome transcription in females. (Hyperactive X chromosome expression in C. elegans has also been suggested [42], so dosage compensation in the hermaphrodite would then serve to lower the X chromosomes to match autosome levels).

In this regard, Drosophila would not be very different from mammals except that rather than inactivating one of the female X's, Sxl inactivates the mechanism which upregulates X chromosome specific expression. In all cases, dosage compensation avoids tetrasomy of the X. What the components are which specifically upregulate the mammalian or C. elegans X chromosome—the Drosophila male DCC counterpart—remain to be determined.

Materials and Methods

Fly crosses

Flies were reared under uncrowded conditions on standard cornmeal medium. All crosses were done at 25°C; Ore R was the wild type control. Progeny were counted out to 8 days from the first day of eclosion. Description of genes can be found in Flybase (http://www.flybase.org/).

In situs and immunofluorescence

These were done as in Erickson and Cline [25]. The Sxl early (407 nt) and late (1039 nt) transcript specific probes were generated by the primers, respectively: 5′ GTTCCACTCGTGACAAGTCC 3′and 5′ GTTTCTAAGCAGATCCCG 3′; 5′ GCGAAACGTGCACACTGC 3′ and 5′ GGGCGATGCTTGCATGTTGC 3′ (T7 promoter sequence removed). For hairy, the primers 5′ CCAGAACCTGCTGCTCAT TCG 3′ and 5′ GGGAAAGCGGCTA ACCTCGTTC 3′; for sis-a the primers 5′ CAAAATGCACTACGCCGACG 3′ and 5′ GCATCGTGTCCAACATGACG 3′ were used. All in situs were repeated at least once. Each batch was done simultaneously with an Ore R control, and had sufficient embryos so that several representatives of each cycle could be examined. M3TAP embryos [31] were stained for Sxl (mouse) and MSL-1 (rabbit) as previously described [45]. To enhance the MSL signal, the M3TAP was first bound (blocked) by the same anti-rabbit fluorescent secondary used for the anti-MSL-1 primary before addition of the primary antibody.

qRT–PCRs

Embryos were collected on apple juice agar plates for one hour and aged for the appropriate time. They were washed off the plate, dechorionated with 50% chlorox, washed extensively with 1x PBST and frozen at −80°C. RNA was extracted from the frozen embryos using tri-reagent as per manufacturer's protocol. An additional phenol extraction was performed on the purified RNA, followed by DNAse treatment. A PCR test was performed on the RNA to confirm the lack of DNA, after which 4 ug of the RNA was reverse transcribed (RT) with AMV RT at 50°C for 15 min followed by 1.5 h at 42°C. A small amount (2 ng) of Sxl primer (5′ CGT GTC CAG CTG ATC GTC GG 3′) was added to the oligo-dT mix (100 ng) per RT, as the stage specific 5′ exons of Sxl are distant from the polyA tail. The quantitative PCRs were performed in triplicate on a Bio-Rad iQ5 thermocycler; Ct values that showed a difference of greater than 0.5 from the other two replicates were discarded. For each genotype a minimum of 3 separate RNA samples was analyzed. PCR products were between 200 and 300 bp; primers for SxlPe 5′ CTGTTCGACCATGTCGTCCTA C and CTA CCACCGCTGCCCAGCGAC, SxlPm 5′ GTGGTTATCCCCCATATGGC 3′ and 5′ CTA CCACCGCTGCCCAGCGAC 3′, sis-a 5′ CGTATACGCACCGTATCGCGG 3′ and 5′ GCATCGTGTCCAACATGACG, runt 5′ CGACGAAAACTACTGCGGCG 3′ and CCAGCCAAGCGGGATTCAGC, upd 5′ GAAAGCGGAACAGCAACTGG 3′ and 5′CAGGAACTTGTAGTTGTGCG 3′, dpn 5′ CCGATTATGGAGAAACGTCGC 3′ and 5′ CTGAGCCGCTGACGAACACC. Statistical data analysis was completed using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. LucchesiJC

KellyWG

PanningB

2005 Chromatin remodeling in dosage compensation. Annual Review of Genetics 39 615 51

2. FukunagaA

TanakaA

OishiK

1975 Maleless, a recessive autosomal mutant of Drosophila melanogaster that specifically kills male zygotes. Genetics 81 135 141

3. BeloteJ

LucchesiJC

1980 Male-specific lethal mutations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 96 165 186

4. UchidaS

UenoyamaT

OishiK

1981 Studies on the sex-specific lethal of Drosophila melanogaster III. A third chromosome male-specific lethal mutant. Jpn J Genet 56 523 527

5. HilfickerA

Hilfiker-KleinerD

PannutiA

LucchesiJC

1997 mof, a putative acetyl transferase gene related to the Tip60 and MOZ human genes and to the SAS genes of yeast, is required for dosage compensation in Drosophila. EMBO J 16 2054 2060

6. KelleyRL

2004 Path to equality strewn with roX. Dev Biol 269 18 25

7. GelbartME

KurodaMI

2009 Drosophila dosage compensation: a complex voyage to the X chromosome. Development 136 1399 1410

8. FrankeA

BakerBS

1999 The roX1 and roX2 RNAs Are Essential Components of the Compensasome, which Mediates Dosage Compensation in Drosophila. Mol Cell 4 117 122

9. MellerVH

2003 Initiation of dosage compensation in Drosophila embryos depends on expression of the roX RNAs. Mech Dev 120 759 67

10. JinY

WangY

WalkerDL

DongH

ConleyC

1999 JIL-1: A Novel Chromosomal Tandem Kinase Implicated in Transcriptional Regulation in Drosophila. Mol Cell 4 129 135

11. SkripskyT

LucchesiJC

1980 Females with sex-combs. Genetics 94 s98 s99

12. UenoyamaT

FukunagaA

OishiK

1982 Studies on the sex-specific lethals of Drosophila melanogaster V. sex transformation caused by interactions between a female-specific lethal, Sxlf#1, and the male-specific lethals mle(3)132, ms1-227, and mle. Genetics 102 233 243

13. BashawGJ

BakerBS

1995 The msl-2 dosage compensation gene of Drosophila encodes a putative DNA-binding protein whose expression is sex specifically regulated by Sex-lethal. Development 121 3245 58

14. BashawGJ

BakerBS

1997 The regulation of the Drosophila msl-2 gene reveals a function for Sex-lethal in translational control. Cell 89 789 798

15. KelleyRL

SolovyevaI

LymanLM

RichmanR

SolovyevV

1995 Expression of msl-2 causes assembly of dosage compensation regulators on the X chromosomes and female lethality in Drosophila. Cell 81 867 877

16. KelleyRL

WangJ

BellL

KurodaMI

1997 Sex lethal controls dosage compensation in Drosophila by a non-splicing mechanism. Nature 387 195 199

17. ZhouS

YangY

ScottMJ

PannutiA

FehrKC

1999 Male-specific lethal 2, a dosage compensation gene of Drosophila, undergoes sex-specific regulation and encodes a protein with a RING finger and a metallothionein-like cysteine cluster. EMBO J 14 2884 2895

18. KeyesLN

ClineTW

SchedlP

1992 The Primary Sex Determination Signal of Drosophila Acts at the Level of Transcription. Cell 68 933 943

19. SchuttC

NothigerR

2000 Structure, function and evolution of sex-determining systems in Dipteran insects. Development 127 667 677

20. BellL

HorabinJ

SchedlP

ClineT

1991 Positive autoregulation of Sex-lethal by alternative splicing maintains the female determined state in Drosophila. Cell 65 229 239

21. KindJ

AkhtarA

2007 Cotranscriptional recruitment of the dosage compensation complex to X-linked target genes. Genes Dev 21 2030 2040

22. BaiX

AlekseyenkoAA

KurodaMI

2004 Sequence-specific targeting of MSL complex regulates transcription of the roX RNA genes. EMBO J 23 2853 61

23. AvilaFW

EricksonJW

2007 Drosophila JAK/STAT pathway reveals distinct initiation and reinforcement steps in early transcription of Sxl. Curr Biol 17 643 648

24. LiF

SchiemannAH

ScottMJ

2008 Incorporation of the noncoding roX RNAs alters the chromatin-binding specificity of the Drosophila MSL1/MSL2 complex. Mol Cell Biol 28 1252 64

25. EricksonJW

ClineTW

1993 A bZIP protein, sisterless-a, collaborates with bHLH transcription factors early in Drosophila development to determine sex. Genes Dev 7 1688 1702

26. ten BoschJR

BenavidesJA

ClineTW

2006 The TAGteam DNA motif controls the timing of Drosophila pre-blastoderm transcription. Development 133 1967 1977

27. De RenzisS

ElementoO

TavazoieS

WieschausEF

2007 Unmasking activation of the zygotic genome using chromosomal deletions in the Drosophila embryo. PLoS Biol 5 e117 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050117. Erratum in: PLoS Biol 8:e213.doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050213

28. RastelliL

RichmanR

KurodaMI

1995 The dosage compensation regulators MLE, MSL-1 and MSL-2 are interdependent since early embryogenesis in Drosophila. Mech Dev 53 223 33

29. FrankeA

DernburgA

BashawGJ

BakerBS

1996 Evidence that MSL-mediated dosage compensation in Drosophila begins at blastoderm. Development 122 2751 60

30. McDowellKA

HilfikerA

LucchesiJC

1996 Dosage compensation in Drosophila: the X chromosome binding of MSL-1 and MSL-2 in female embryos is prevented by the early expression of the Sxl gene. Mech Dev 57 113 9

31. AlekseyenkoAA

LarschanE

LaiWR

ParkPJ

KurodaMI

2006 High-resolution ChIP–chip analysis reveals that the Drosophila MSL complex selectively identifies active genes on the male X chromosome. Genes Dev 20 848 857

32. ClineT

1984 Autoregulatory functioning of a Drosophila gene product that establishes and maintains the sexually determined state. Genetics 107 231 277

33. GergenJP

1987 Dosage Compensation in Drosophila: Evidence That daughterless and Sex-lethal Control X Chromosome Activity at the Blastoderm Stage of Embryogenesis. Genetics 117 477 485

34. SmithER

AllisCD

LucchesiJC

2001 Linking global histone acetylation to the transcription enhancement of X-chromosomal genes in Drosophila males. J Biol Chem 276 31483 31486

35. AlekseyenkoAA

PengS

LarschanE

GorchakovAA

LeeO

2008 A Sequence Motif within Chromatin Entry Sites Directs MSL Establishment on the Drosophila X Chromosome. Cell 134 599 609

36. StraubT

GrimaudC

GilfillanGD

MitterwegerA

BeckerPB

2008 The Chromosomal High-Affinity Binding Sites for the Drosophila Dosage Compensation Complex. PLoS Genetics 4 e1000302 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000302

37. Younger-ShepherdS

VaessinH

BierE

JanLY

JanYN

1992 deadpan, an essential pan-neural gene encoding an HLH protein, acts as a denominator in Drosophila sex determination. Cell 70 911 922

38. BarbashDA

ClineTW

1995 Genetic and molecular analysis of the autosomal component of the primary sex determination signal of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 141 1451 71

39. AronsonBD

FisherAL

BlechmanK

CaudyM

GergenJP

1997 Groucho-dependent and -independent repression activities of Runt domain proteins. Mol Cell Biol 17 5581 7

40. GiotL

BaderJS

BrouwerC

ChaudhuriA

KuangB

2003 A protein interaction map of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 302 1727 36

41. KramerSG

JinksTM

SchedlP

GergenJP

1999 Direct activation of Sex-lethal transcription by the Drosophila runt protein. Development 126 191 200

42. GuptaV

ParisiM

SturgillD

NuttallR

DoctoleroM

2006 Global analysis of X-chromosome dosage compensation. J Biol 5 3

43. NguyenDK

DistecheCM

2006 Dosage compensation of the active X chromosome in mammals. Nat.Genet 38 47 53

44. LinH

GuptaV

VermilyeaMD

FalcianiF

LeeJT

2007 Dosage compensation in the mouse balances up-regulation and silencing of X-linked genes. PLoS Biol 5 e326 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050326

45. WalthallSL

MosesM

HorabinJI

2007 A large complex containing both Patched and Smoothened initiates Hedgehog signaling in Drosophila. J Cell Science 120 826 837

46. MendjanS

TaipaleM

KindJ

HolzH

GebhardtP

2006 Nuclear pore components are involved in the transcriptional regulation of dosage compensation in Drosophila. Mol Cell 21 811 23

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 7- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Délka menstruačního cyklu jako marker ženské plodnosti

- Vztah užívání alkoholu a mužské fertility

- Šanci na úspěšný průběh těhotenství snižují nevhodné hladiny progesteronu vznikající při umělém oplodnění

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Question and Answer: An Anniversary Interview with Jane Gitschier

- Multi-Variant Pathway Association Analysis Reveals the Importance of Genetic Determinants of Estrogen Metabolism in Breast and Endometrial Cancer Susceptibility

- Tinkering Evolution of Post-Transcriptional RNA Regulons: Puf3p in Fungi as an Example

- The Importance of Imprinting in the Human Placenta

- Regulator of G Protein Signaling 3 Modulates Wnt5b Calcium Dynamics and Somite Patterning

- Lysosomal Dysfunction Promotes Cleavage and Neurotoxicity of Tau

- Combinatorial Binding Leads to Diverse Regulatory Responses: Lmd Is a Tissue-Specific Modulator of Mef2 Activity

- Variation, Sex, and Social Cooperation: Molecular Population Genetics of the Social Amoeba

- Comparative Analysis of DNA Replication Timing Reveals Conserved Large-Scale Chromosomal Architecture

- The Fitness Landscapes of -Acting Binding Sites in Different Promoter and Environmental Contexts

- Cohesin Is Limiting for the Suppression of DNA Damage–Induced Recombination between Homologous Chromosomes

- Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals Novel Genes Essential for Heme Homeostasis in

- Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis for Serum Calcium Identifies Significantly Associated SNPs near the Calcium-Sensing Receptor () Gene

- Rad3 Decorates Critical Chromosomal Domains with γH2A to Protect Genome Integrity during S-Phase in Fission Yeast

- Quantitative and Molecular Genetic Analyses of Mutations Increasing Life Span

- Association of Variants at with Chronic Kidney Disease and Kidney Stones—Role of Age and Comorbid Diseases

- Breast Cancer DNA Methylation Profiles Are Associated with Tumor Size and Alcohol and Folate Intake

- Calpain 8/nCL-2 and Calpain 9/nCL-4 Constitute an Active Protease Complex, G-Calpain, Involved in Gastric Mucosal Defense

- A Collection of Target Mimics for Comprehensive Analysis of MicroRNA Function in

- A Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals No Nuclear Dobzhansky-Muller Pairs of Determinants of Speciation between and , but Suggests More Complex Incompatibilities

- Microevolution of during Prolonged Infection of Single Hosts and within Families

- Id4, a New Candidate Gene for Senile Osteoporosis, Acts as a Molecular Switch Promoting Osteoblast Differentiation

- CHD7 Targets Active Gene Enhancer Elements to Modulate ES Cell-Specific Gene Expression

- Chromatin Remodeling in Development and Disease: Focus on CHD7

- Extensive DNA End Processing by Exo1 and Sgs1 Inhibits Break-Induced Replication

- Requirement of Male-Specific Dosage Compensation in Females—Implications of Early X Chromosome Gene Expression

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- CHD7 Targets Active Gene Enhancer Elements to Modulate ES Cell-Specific Gene Expression

- Extensive DNA End Processing by Exo1 and Sgs1 Inhibits Break-Induced Replication

- Question and Answer: An Anniversary Interview with Jane Gitschier

- Multi-Variant Pathway Association Analysis Reveals the Importance of Genetic Determinants of Estrogen Metabolism in Breast and Endometrial Cancer Susceptibility

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání