-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals Novel Genes Essential for Heme Homeostasis in

Heme is a cofactor in proteins that function in almost all sub-cellular compartments and in many diverse biological processes. Heme is produced by a conserved biosynthetic pathway that is highly regulated to prevent the accumulation of heme—a cytotoxic, hydrophobic tetrapyrrole. Caenorhabditis elegans and related parasitic nematodes do not synthesize heme, but instead require environmental heme to grow and develop. Heme homeostasis in these auxotrophs is, therefore, regulated in accordance with available dietary heme. We have capitalized on this auxotrophy in C. elegans to study gene expression changes associated with precisely controlled dietary heme concentrations. RNA was isolated from cultures containing 4, 20, or 500 µM heme; derived cDNA probes were hybridized to Affymetrix C. elegans expression arrays. We identified 288 heme-responsive genes (hrgs) that were differentially expressed under these conditions. Of these genes, 42% had putative homologs in humans, while genomes of medically relevant heme auxotrophs revealed homologs for 12% in both Trypanosoma and Leishmania and 24% in parasitic nematodes. Depletion of each of the 288 hrgs by RNA–mediated interference (RNAi) in a transgenic heme-sensor worm strain identified six genes that regulated heme homeostasis. In addition, seven membrane-spanning transporters involved in heme uptake were identified by RNAi knockdown studies using a toxic heme analog. Comparison of genes that were positive in both of the RNAi screens resulted in the identification of three genes in common that were vital for organismal heme homeostasis in C. elegans. Collectively, our results provide a catalog of genes that are essential for metazoan heme homeostasis and demonstrate the power of C. elegans as a genetic animal model to dissect the regulatory circuits which mediate heme trafficking in both vertebrate hosts and their parasites, which depend on environmental heme for survival.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(7): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001044

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001044Summary

Heme is a cofactor in proteins that function in almost all sub-cellular compartments and in many diverse biological processes. Heme is produced by a conserved biosynthetic pathway that is highly regulated to prevent the accumulation of heme—a cytotoxic, hydrophobic tetrapyrrole. Caenorhabditis elegans and related parasitic nematodes do not synthesize heme, but instead require environmental heme to grow and develop. Heme homeostasis in these auxotrophs is, therefore, regulated in accordance with available dietary heme. We have capitalized on this auxotrophy in C. elegans to study gene expression changes associated with precisely controlled dietary heme concentrations. RNA was isolated from cultures containing 4, 20, or 500 µM heme; derived cDNA probes were hybridized to Affymetrix C. elegans expression arrays. We identified 288 heme-responsive genes (hrgs) that were differentially expressed under these conditions. Of these genes, 42% had putative homologs in humans, while genomes of medically relevant heme auxotrophs revealed homologs for 12% in both Trypanosoma and Leishmania and 24% in parasitic nematodes. Depletion of each of the 288 hrgs by RNA–mediated interference (RNAi) in a transgenic heme-sensor worm strain identified six genes that regulated heme homeostasis. In addition, seven membrane-spanning transporters involved in heme uptake were identified by RNAi knockdown studies using a toxic heme analog. Comparison of genes that were positive in both of the RNAi screens resulted in the identification of three genes in common that were vital for organismal heme homeostasis in C. elegans. Collectively, our results provide a catalog of genes that are essential for metazoan heme homeostasis and demonstrate the power of C. elegans as a genetic animal model to dissect the regulatory circuits which mediate heme trafficking in both vertebrate hosts and their parasites, which depend on environmental heme for survival.

Introduction

From a nutritional perspective, heme is a readily bioavailable source of iron for human consumption [1], [2]. From a cellular perspective, heme is an iron-containing porphyrin which serves as a prosthetic group in diverse biological processes ranging from gas-sensing to microRNA processing [3]. In most eukaryotes, heme is synthesized in the mitochondrial matrix by a defined biosynthetic pathway and subsequently exported as needed for heme-containing proteins that are found in the cytoplasm and membrane-bound organelles [3]. Given the hydrophobicity and cytotoxicity associated with free heme, it is likely that specific intracellular transport pathways exist to deliver heme for assimilation into hemoproteins found in various subcellular compartments [4].

Although the pathway and intermediates for heme biosynthesis and degradation have been well defined, the intracellular networks that mediate heme homeostasis in eukaryotes remain poorly understood [4]. Heme transport molecules in animals are likely to be divergent from bacterial and yeast proteins at the genetic level; bacterial and yeast heme-binding proteins have no obvious orthologs in mammals [5]–[8]. This is demonstrated by the identification of a heme exporter, the feline leukemia virus subgroup C cellular receptor (FLVCR), which does not show any obvious similarities to known bacterial heme transport proteins [9], [10]. Genetic ablation of FLVCR in mice resulted in severe macrocytic anemia with proerythroblast maturation arrest. That a viral receptor could be a potential heme exporter in developing erythroid cells underscores the divergence among heme transport proteins and emphasizes the importance of implementing unbiased genetic approaches to elucidate the heme homeostasis pathways in tractable model systems.

Progress in understanding heme homeostasis in most eukaryotic systems is hampered by the inability to separate heme biosynthesis from downstream intracellular transport pathways. To circumvent this issue, we established the genetically tractable nematode Caenorhabditis elegans as an animal model ideally suited in which to conduct heme studies. We have previously demonstrated that this roundworm does not synthesize heme but instead relies on environmental heme for survival [11]. Moreover, analyses of available genomes from related parasitic nematodes suggest that these helminths are also heme auxotrophs [11]. The C. elegans genome encodes a repertoire of hemoproteins that have vertebrate orthologs. It is likely that the pathways for heme trafficking and incorporation are conserved in C. elegans, parasitic worms, and vertebrates [4]. The validity of the C. elegans model system was recently underscored by the discovery of HRG-1 proteins that transport heme [12]. We identified C. elegans hrg-1 and its paralog hrg-4 from microarray experiments as genes that were highly upregulated by low heme [12]. Expression of these genes and their human homolog, HRG-1, in Xenopus oocytes resulted in strong heme-induced electrophysiological currents – an indication that the corresponding proteins were heme transporters. Additionally, depletion of hrg-1 in worms led to aberrant heme homeostasis. Transient knockdown of hrg-1 in zebrafish caused severe impairment in erythropoiesis along with brain and skeletal defects; these phenotypes were fully rescued by worm hrg-1 [12]. Collectively, these studies further validated the advantage of C. elegans as a model par excellence to dissect the pathways responsible for heme transport and homeostasis in mammals. Moreover, C. elegans bridges the evolutionary divide to heme auxotrophic parasitic species and provides insight into helminthic-specific vulnerabilities in heme uptake and utilization that can be exploited for drug design [13], [14].

The current study specifically seeks to explain and draw conclusions from the genomic data that was generated from our microarray analysis. This expression array analysis using C. elegans wild-type worms grown in an axenic liquid medium at three different concentrations of heme was performed as a first step in the genome-wide identification of genes involved in heme homeostasis. Our results have identified several hundred heme-responsive genes (hrgs), some of which are evolutionarily conserved across metazoa while others are found only in nematodes. We anticipate that results from our genomic studies may be universally applicable and result in the discovery of heme homeostasis pathways in other metazoans.

Results

Strategy to profile genes that are transcriptionally regulated by heme in C. elegans

C. elegans lacks the highly conserved genes of heme biosynthesis but acquires heme from the environment for growth and development [11]. Worms cultured in axenic liquid mCeHR-2 medium in the presence of different amounts of heme revealed a characteristic growth curve [11]. The optimal concentration for worm growth and reproduction was found to be 20 µM heme, although animals grew and reproduced at concentrations ranging from ≥1.5 µM to <800 µM heme. Worms grown in the absence of exogenous heme arrested at the L4 larval stage, whereas concentrations of heme ≥800 µM caused the worms to arrest at the L2/L3 larval stages, possibly due to heme cytotoxicity. These results are consistent with metabolic labelling experiments in which the fluorescent heme analog, zinc mesoporphyrin IX (ZnMP), was used to demonstrate that the heme uptake system is regulated in C. elegans [12].

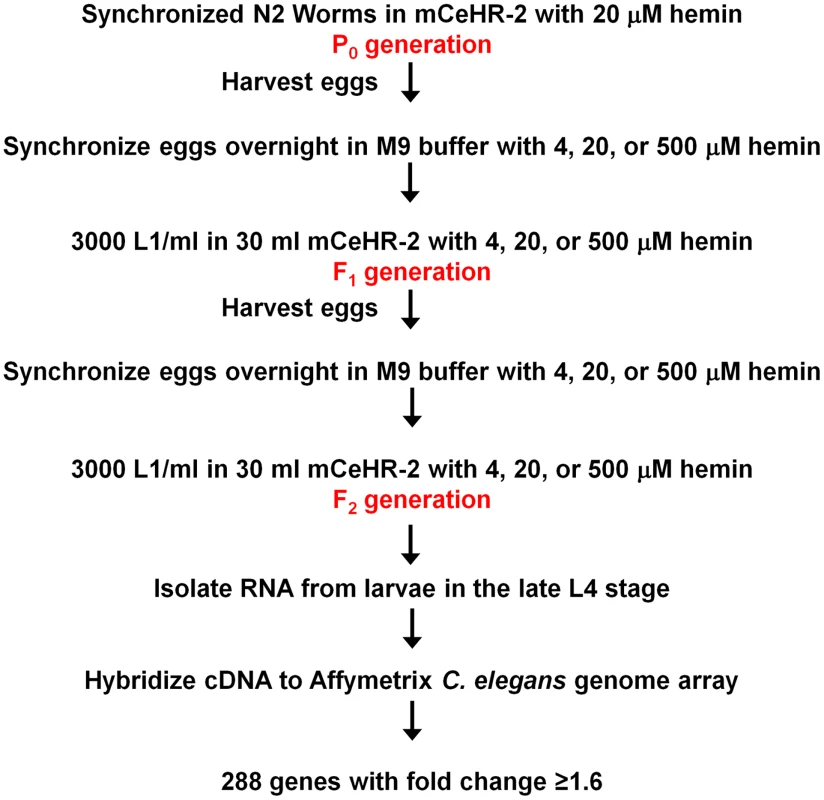

To determine if there were transcriptionally regulated components of heme uptake, wild-type N2 worms were grown at 4, 20, or 500 µM heme in axenic liquid mCeHR-2 medium; 20 µM served as the reference sample. We chose 4 and 500 µM heme because these concentrations were on either side of the biphasic growth curve. More importantly, although worms grown at these heme concentrations exhibited a 16 h growth delay, they were morphologically indistinguishable from worms grown at 20 µM heme. In order to reduce variability due to carryover of maternal heme from the P0 hermaphrodites, worms were grown in their respective heme concentrations for two successive generations (Figure 1). Synchronized, late L4 larvae from the F2 generation were harvested for RNA isolation, and corresponding cDNA probes were generated and hybridized to Affymetrix C. elegans expression microarray chips. Three biological replicates were prepared for each heme concentration.

Fig. 1. Profiling strategy for analysis of heme-responsive genes.

Worms were grown in axenic liquid mCeHR-2 medium containing 4, 20, or 500 µM hemin chloride for two synchronized generations, and late L4 larvae were harvested to extract RNA for microarray analyses. cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription and hybridized to Affymetrix C. elegans Genome Arrays containing 22,627 probe sets per chip. Affymetrix MAS 5.0 software and RMA were utilized to analyze the data. Data from worms grown at 4 and 500 µM heme were compared to control data from worms grown at 20 µM heme. The expression of 288 genes was either increased or decreased in response to heme by at least 1.6 fold. Identification of hrgs in C. elegans

Statistical analyses of the microarray data were initially performed using the Affymetrix MAS 5.0 suite software (see Materials and Methods). Of the 22,627 probe sets, 835 probe sets revealed changes at either 4 or 500 µM heme compared to the control data from 20 µM heme. We identified 288 genes with a ≥1.6-fold change in expression. To improve and augment these analyses, we also subjected the microarray results to the Robust Multichip Average method (RMA from R package) with the goal of combining the results with those obtained by MAS 5.0. The RMA analysis (minimum change in expression ≥1.2 fold) identified an additional 82 hrgs. The MAS 5.0 and RMA analyses yielded a total of 370 candidate genes. Subsequently, duplicate genes were eliminated, the minimum cut-off value for RMA analysis was increased to ≥1.6 fold, and the average of the fold-change values was calculated for the replicates. This resulted in a list of candidate genes consisting of 266 genes identified using MAS 5.0 and 22 genes selected using the RMA method. The expression of these 288 genes, eight of which were previously identified as germline genes [15], revealed a ≥1.6-fold change at either 4 or 500 µM heme compared to the 20 µM controls. Consequently, all 288 genes were classified as hrgs (Table S1).

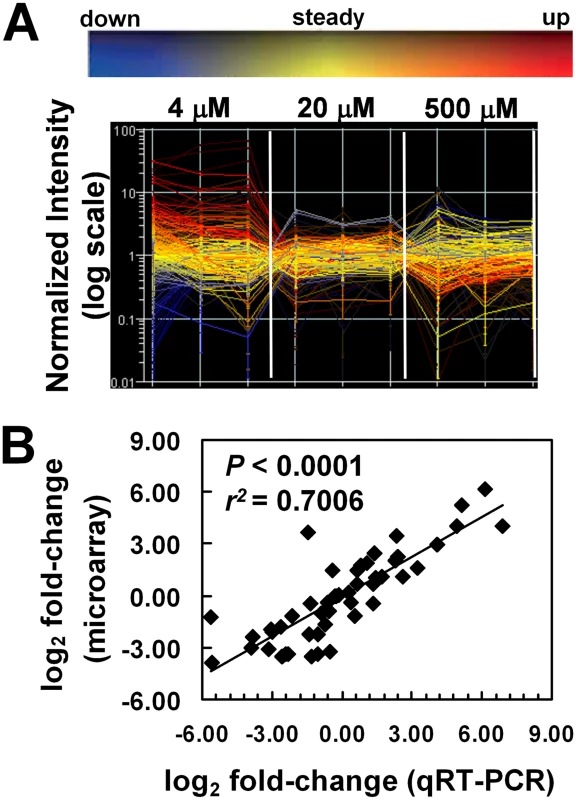

Normalized signal intensity values can be graphed to visualize the quality of microarray data generated by each replicate (Figure 2A). The value at which the colored lines cross each thin vertical line is the value of the normalized signal for that replicate. Accurate replicates should have nearly horizontal lines (all values approximately equal) within each condition that may then decrease or increase in the next condition if there is a change. In this experiment, analysis of each of the 288 hrgs revealed that individual biological replicates had nearly equal values with little variation within a particular heme concentration, indicating that changes in heme-dependent gene expression were uniform. A principal components analysis (PCA) for the hrgs showed that, with one exception, the quality of the microarray data was consistent across biological replicates for all three heme concentrations. The data obtained from one of the 4 µM heme replicates showed an inconsistent global gene expression pattern when compared to the other two replicates and was, therefore, excluded from further analysis (Figure S1).

Fig. 2. Confirmation of quality of microarray results.

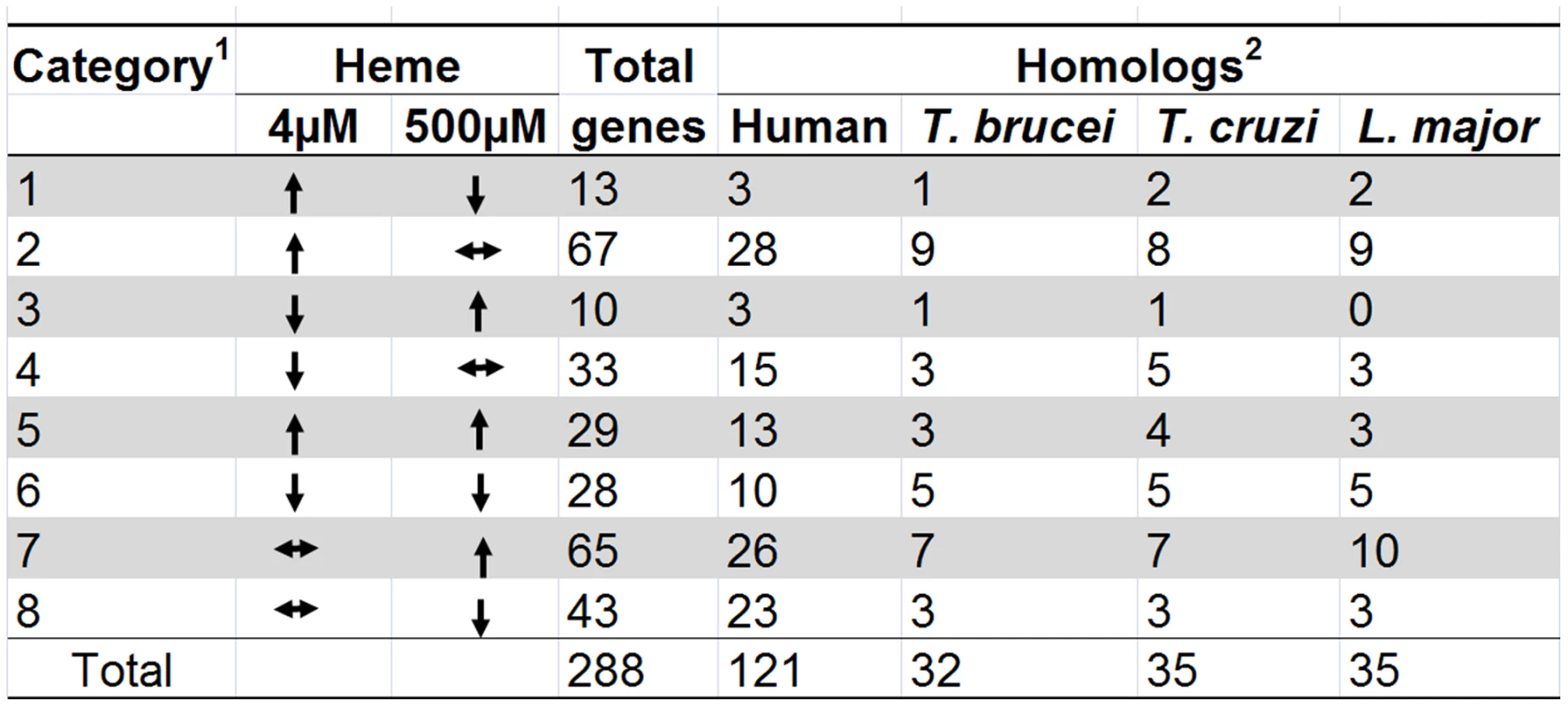

(A) Gene expression profile for the 288 hrgs identified from the microarrays. Changes in expression for the 288 hrgs are plotted for each biological replicate (thin vertical lines) of the three growth conditions with respect to heme concentration (4 µM, 20 µM, and 500 µM) as visualized with GeneSpring software (v7.2). Signal intensity values for genes in each biological replicate and each growth condition (as indicated) were normalized to the median value across the array after setting values <0.01 to 0.01 using GeneSpring software and the resulting values plotted on a log10 scale. Values for a single gene are connected by lines with the slope indicating any change in value across samples; line color coding reflects direction of change relative to the mean (as indicated by the color bar above the graph) and hue intensity reflecting statistical confidence in the value (confidence increases with increased brightness). (B) Validation of microarray results. Microarray data were verified by qRT-PCR of RNA from 24 genes of worms grown in mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with 4, 20, or 500 µM heme. RNA from 20 µM heme was used as the reference sample. Data were compared to internal GAPDH (gpd-2) control and the fold change was obtained using the 2 (-ΔΔCt) method. The significance was determined using GraphPad Instat (v. 3.06). The values for both the qRT-PCR analysis and the microarray experiment are provided in Table S4. The 288 hrgs were assigned to one of eight categories based on whether the gene expression was upregulated, downregulated, or unchanged in samples obtained from worms grown in 4 or 500 µM heme and compared to the 20 µM reference samples (Figure 3). Eighty genes were upregulated at 4 µM heme (Table S2). Seventy-five genes were upregulated at 500 µM heme (Table S3). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis (qRT-PCR) of three representative genes from each of the eight categories was performed to ensure that the changes observed in the microarray were reproducible. As determined by the significance (P<0.0001) and the Pearson's correlation coefficient, the qRT-PCR confirmed that the changes observed with the microarray results were consistent and, therefore, reliable (Figure 2B; Table S4).

Fig. 3. Heme-dependent changes in gene expression.

1The 288 hrgs were arranged into eight categories based on whether they were up-regulated, down-regulated, or unchanged at 4 µM or 500 µM heme when compared to control data from 20 µM heme. 2C. elegans protein sequences for the 288 hrgs were used to perform reciprocal BLAST searches to identify putative homologs (E-value cut-off ≥10−4) in humans and protozoans. Comparative genome analyses of hrgs in vertebrates and parasites

Since identification of the hrgs common to both C. elegans and mammals might provide unique insights into the evolutionary conservation of heme homeostasis pathways in metazoans, we performed reciprocal BLAST searches to identify putative human orthologs of each of the 288 genes (Figure 3). Searches using protein sequences revealed that there were 121 putative human orthologs (minimum E-value = 10−4) of C. elegans hrgs. The hrgs with human homologs were present among those upregulated in both extreme heme concentrations. Forty-four were upregulated at 4 µM heme and 42 were upregulated at 500 µM heme, while 28 were downregulated at 4 µM heme and 36 were downregulated at 500 µM heme (Table S1).

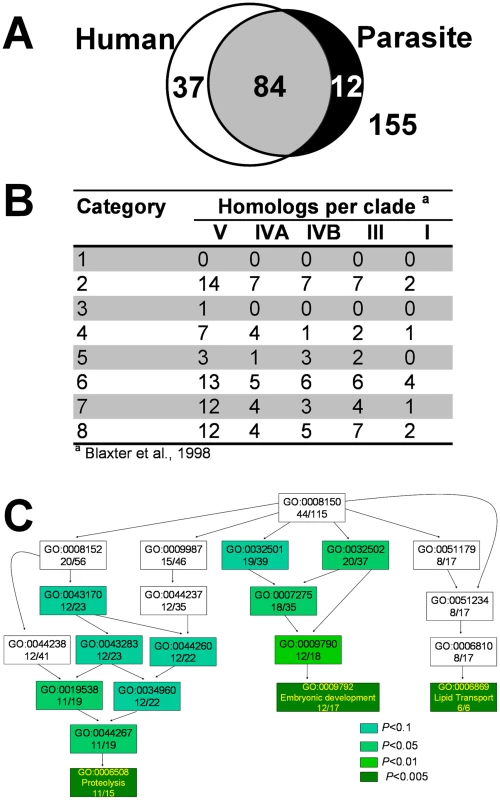

We have previously demonstrated by biochemical enzyme assays and genomic analyses that several of the parasitic nematodes with sequenced genomes lack the genes for heme synthesis enzymes and, therefore, likely rely on environmental heme to sustain growth and development [11]. Similarly, the genomes of Trypanosoma and Leishmania appear to lack most of the genes for heme synthesis [16], [17]. This suggests that these protozoa may also acquire heme from their parasitized host. Figure 3 identifies the hrg homologs in Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma cruzi, and Leishmania major. Of the 288 hrgs, only 12 genes were exclusive to these heme auxotrophs. Thirty-seven genes had homologs only in humans, and 84 genes were found in both human and parasitic genomes (Figure 4A). These results indicate that heme-regulated genes in C. elegans may have commonality with humans that are heme prototrophs and protozoan parasites which rely on environmental heme.

Fig. 4. Comparative analysis of the heme-responsive genes.

(A) Summary of overlap between hrgs across human and protozoan genomes. The sequences of proteins encoded by the 288 hrgs were obtained from Wormbase and used to search for homologs in the human genome and genomes of Trypanosoma brucei, Tryoanosoma cruzi, and Leishmania major. (B) Orthologs of hrgs in the genomes of parasitic nematodes. The 288 C. elegans hrg gene products were used to identify homologs in available parasitic nematode sequences. Based on 18S rRNA sequences, the phylum Nematoda is divided in five major clades; all five clades include parasites. Homologs were identified for 69 genes using amino acid sequences (at BLAST cut-off of 35 bits and 55% identity), and summarized on per clade level. A total of 440,012 peptides from 29 parasitic nematode species was used (clade I 29,203 peptides; clade III 145,044; clade IVA 13,636; clade IVB 92,514 and clade V 159,615 peptides). Nematode sequences used for this analysis are available on the parasitic nematodes website (http://www.nematode.net). (C) Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of hrgs upregulated at 4 µM heme. Genes upregulated at 4 µM heme were analyzed using the Fisher's exact test and the topGO package from R. The most significant GO terms and their associated parent terms were used to construct a hierarchical graph such that the specificity of the terms increased from top to bottom. The text in each rectangle provides the GO ID and the ratio of the number of genes annotated with the GO term in the tested subset to that in the total gene set. The shade of green of each rectangle corresponds to the significance of the GO result. The complete table of P-values can be found in Table S6. Full GO terms are provided solely for genes with P<0.005. A small percentage of the 288 hrgs had homologs in parasitic nematodes (Figure 4B). To date, draft genomes of several parasitic nematodes have become available [18]–[21], in addition to the partial genomes available for over 30 parasitic species. For a summary of available genomes, see [22]. Using all available sequence data divided into taxonomically distinct clades [23], we identified homologs for 62 of the 288 hrgs in the clade V nematodes (C. elegans belongs to clade V) and homologs to only 10 genes in the clade I nematodes (where the basal nematode, the zoonotic parasite Trichinella spiralis, resides). While the number of identified putative orthologs was much higher for the crown lineages than in the basal nematodes that reside at the root of the nematode evolutionary tree, two of the eight categories (categories 1 and 3) had no homologs in any of the parasitic species. Categories 1 and 3 are represented by 13 and 10 sequences in C. elegans, respectively.

hrgs are enriched in regulators for development - and transport-related processes

Gene ontology (GO) analysis [24] indicated that the hrgs identified from our microarray study were involved in processes as varied as embryonic development, electron transport, lipid metabolism, and iron-sulfur cluster assembly. Of the 288 genes in the study, 115 were annotated with a biological process (Table S5). Using the Fisher's exact test, a hierarchical graph was constructed with the most significant GO terms and their associated parent terms [25]. Highly significant GO terms (P<0.005) associated with the subset of genes that were upregulated at 4 µM heme were ‘embryonic development’, ‘lipid transport’, and ‘proteolysis’ (Figure 4C; Table S6); ‘responses to stress’ and environmental stimuli' were associated with genes that were downregulated at 4 µM heme (Figure S2 and Tables S7, S8, S9).

The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) is also frequently used to analyze complex microarray data and make functional predictions [26]. Only 10 hrgs (∼3%) have been mapped to KEGG pathways (Table S10). These hits included genes for transporters and also for metabolism of sugars, an amino acid, and fatty acids. A majority of hrgs that we identified were uncharacterized with no assigned biological pathway.

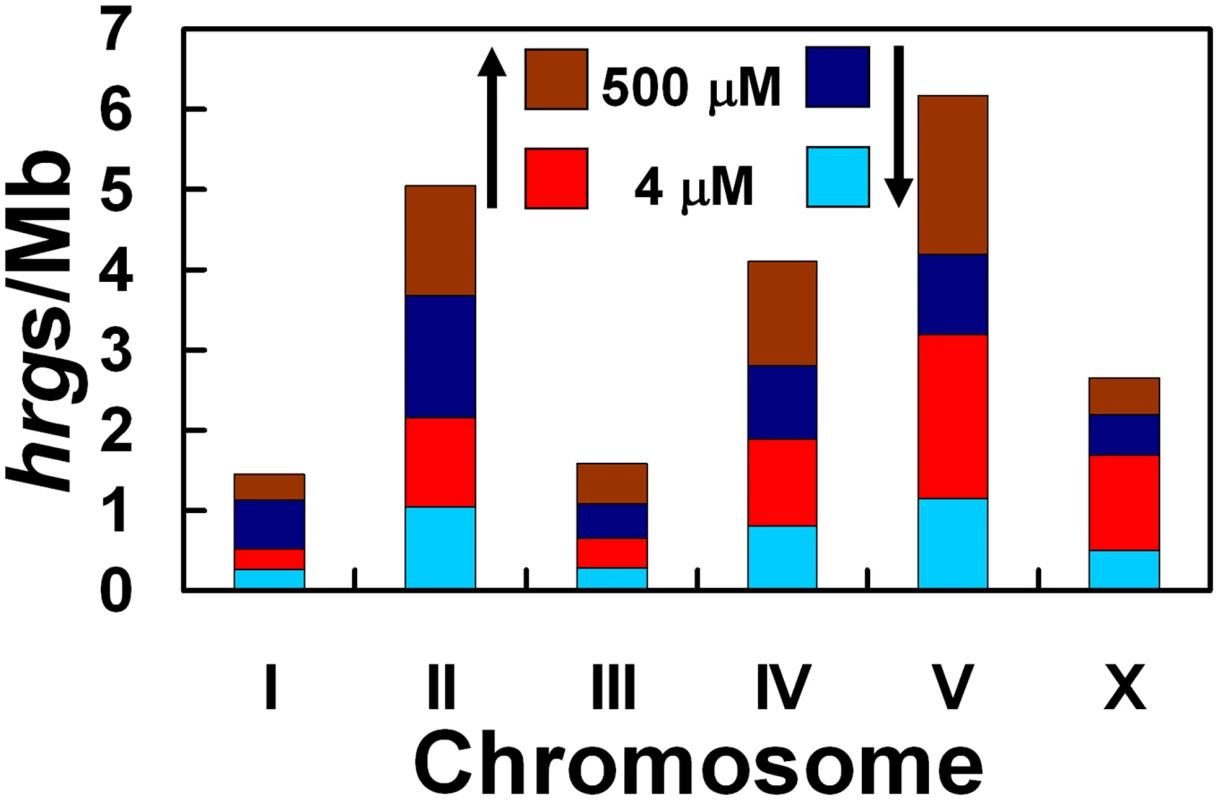

Genome sequencing has demonstrated that chromosomes I, II, III, IV, and X in C. elegans each contain roughly equivalent numbers of genes (13–17%), whereas chromosome V has the most genes (25%) [27]. Furthermore, co-regulated or functionally related genes, especially those essential for interactions with the environment, tend to reside in local clusters on the chromosome [27]. We found that Chr I and Chr III each contained just 6% of the hrgs, but 35% of all hrgs were found on Chr V (Figure 5). Additionally, of the 129 hrgs on Chr V, 43 genes were upregulated at 4 µM heme while 41 genes were upregulated at 500 µM heme (Figure 6). Our analysis suggests that the genomic distribution of hrgs was non-random, reveals gene clustering, and indicates a common biological response to an environmental stimulus such as heme.

Fig. 5. Depiction of the number of hrgs found on each chromosome relative to the number of megabases in that chromosome.

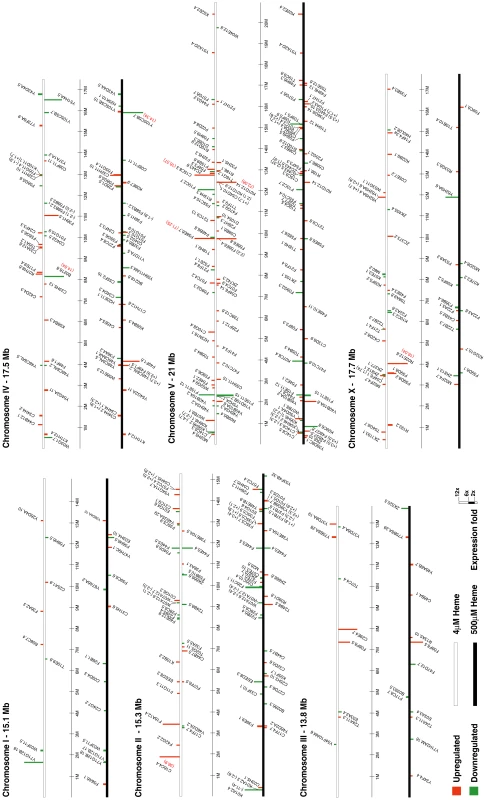

The chromosome with the highest number of hrgs is chromosome V. Red and brown regions indicate that the expression of a gene was increased at 4 and 500 µM heme, respectively. Light blue and dark blue bars represent a decrease in gene expression at 4 and 500 µM heme, respectively. Fig. 6. Chromosomal location and fold-change of each heme-responsive gene.

hrgs were arranged on each of the six chromosomes, which are depicted as white or black bars. The transcript levels of genes placed on white bars were altered at 4 µM heme, while the expression of genes on black bars was significantly altered at 500 µM heme. Vertical bars are drawn to scale and represent genes that were up-regulated (red) or down-regulated (green). If the genomic distribution of hrgs is purposeful, we reasoned that perhaps the response of the promoters of the hrgs is directed by a cis-acting element within a cluster or elements that are common to all hrgs in a specific category. First we analyzed Categories 1 and 2 for overrepresented transcription factor binding sites using all sequences against a control set of random promoter sequences but failed to identify common cis elements. We reiterated our search to encompass the presumptive promoters (≥2 kb upstream) of all 288 hrgs using TRANSFAC [28]. Once again, no common elements were identified.

Functional validation reveals novel hrgs that are essential for heme homeostasis in C. elegans

A number of genome-wide RNA-mediated interference (RNAi) experiments have been performed in C. elegans, and the data from all these experiments are available on Wormbase (http://www.wormbase.org/). Forty-six hrgs (16%) had a reported RNAi phenotype (Table S11). RNAi knockdown of these genes most often resulted in developmental defects such as sterility and embryonic lethality. These phenotypes were expected because heme is essential for growth and reproduction of C. elegans. The relatively small fraction of genes yielding a reported RNAi phenotype probably reflects redundancy of function among some of the hrgs and the limited phenotypic assays performed to date.

We have previously reported that transgenic worms expressing the hrg-1::gfp transcriptional fusion (strain IQ6011) specifically respond to heme in the growth medium. Thus, strain IQ6011 can be used as a whole animal heme sensor to interrogate changes in organismal heme homeostasis [12]. To identify the function of the hrgs in heme homeostasis, we established a functional RNAi screen using IQ6011 (see Materials and Methods for details). First, we generated a sequence-confirmed hrg mini-library in the E. coli feeding strain HT115(DE3) that expressed double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) against each of the 288 hrgs. Second, we established a sensitive GFP-based assay that conditionally screened for genetic modulators of heme homeostasis simultaneously in the presence of low (5 µM) or high (25 µM) heme. Third, we verified the positive candidate genes with a secondary screen to eliminate false positives using a vha-6::gfp transgenic worm that does not respond to heme and served as a negative control. Fourth, we confirmed the authenticity of each candidate gene by simultaneously measuring the GFP fluorescence intensity in IQ6011 and vha-6::gfp with a COPAS Biosort instrument that sorts each worm by its time of flight (axial length of object) and extinction (optical density of object).

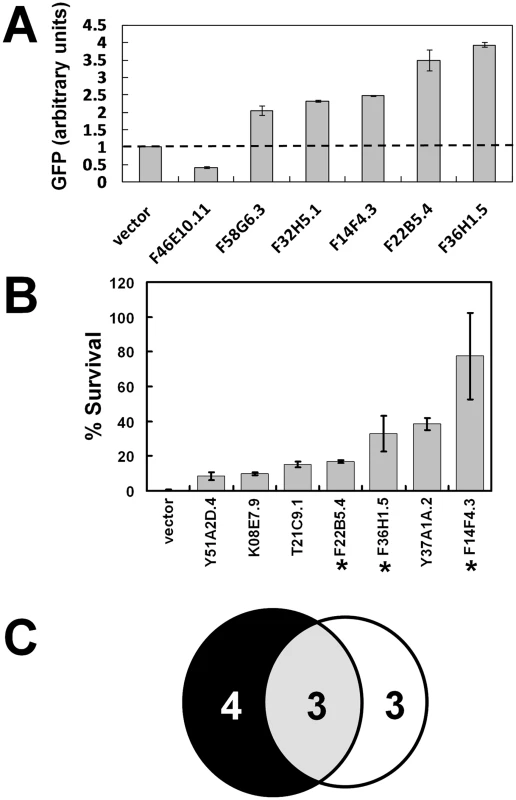

Synchronized IQ6011 worms were grown in mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with 10 µM heme to repress GFP and subsequently transferred to NGM agar plates for exposure to dsRNA produced by E. coli grown either in the presence of 5 µM or 25 µM heme on NGM agar plates. These experiments were performed in duplicate, and GFP levels and patterns in worms fed bacteria expressing each of the 288 hrgs were analyzed by eye. RNAi depletion of the 288 hrgs resulted in the identification of 32 genes that specifically upregulated or downregulated GFP expression in the IQ6011 heme-sensor strain but not in the vha-6::gfp control strain. These 32 genes were selected for further analysis by the COPAS BioSort. We identified six hrgs which caused either a two-fold increase or a two-fold decrease in GFP expression, (Figure 7A). A significant upregulation of GFP was observed at 5 µM when five hrgs that encoded either putative membrane-spanning proteins (F36H1.5/HRG-4, F14F4.3/MRP-5, F58G6.3/CTR-1, and F22B5.4/unnamed protein) or a putative lysosomal cysteine protease (F32H5.1/cathepsin-L) were depleted. In contrast, GFP was downregulated only when F46E10.11, which encodes an uncharacterized protein proposed to bind metals through cysteine residues, was depleted.

Fig. 7. Functional validation of heme-responsive genes.

(A) RNAi depletion in a transgenic heme-sensor strain. GFP quantification by COPAS BioSort in strain IQ6011 fed HT115(DE3) bacteria grown in 5 µM heme and induced to synthesize dsRNA. RNAi of 288 hrgs identified six genes which caused a 2-fold increase or 2-fold decrease in GFP levels. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM. Y-axis represents average GFP values of all the gravid worms (≥30 worms in each well) in duplicate wells normalized to the value of the GFP in worms that had fed on bacteria transformed with the empty vector. (B) RNAi depletion in the presence of a toxic heme analog. Forty-one candidate genes encoding proteins with TMD were screened by feeding RNAi to strain IQ6011 and assessing survival of progeny in the presence of the toxic heme analog GaPP. Both the total number of eggs and the number of viable larvae were counted after 5 days of exposure to 1.5 µM GaPP as described in Materials and Methods. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of two separate experiments and is depicted as percentage of survival compared to control plates with no GaPP. Knockdown of 7 genes (shown) resulted in animal survival in the presence of GaPP. Asterisk indicates genes that also altered GFP levels in strain IQ6011 worms (Figure 7A). (C) Summary of overlap between genes identified in (A,B). Six of the 288 hrgs were identified as interfering with heme homeostasis, as evidenced by their altered GFP levels at 5 µM. Seven of the 41 hrgs that encode for proteins with putative TMD protect against GaPP toxicity, as evidenced by an increase in progeny survival. When knocked down by RNAi, only three hrgs both alter the ability to sense heme and protect against GaPP toxicity. To identify potential heme transporters, we identified hrgs which encoded for proteins with transmembrane domains (TMD). TMHMM analysis predicted that 41 of the 288 hrgs encoded for proteins with at least one putative TMD (Table S12). Among these 41 genes were those encoding aquaglyceroporin-related proteins (aqp-1 and aqp-8 with six and four TMD, respectively) that transport small molecules such as glycerol, urea, and water; cyp-33C9 (one TMD) which belongs to the cytochrome P450 family of heme binding proteins; heme permeases (hrg-1 and hrg-4 with 4 TMD); and ABC transporters (mrp-5 and pgp-1 with ≥12 TMD).

To narrow the list of candidate heme transporters, we used RNAi to deplete the 41 hrgs which encoded TMD proteins and exposed the worms to gallium protoporphyrin IX (GaPP), a toxic heme analog that causes severe defects in worm growth and development [11]. We reasoned that knockdown of a putative heme transporter in the presence of GaPP would result in a concomitant increase in worm survival due to a reduced ability to transport toxic GaPP [12]. We identified seven hrgs which, when depleted by RNAi, revealed greater survival of the F1 progeny at 1.5 µM GaPP, a concentration that is lethal to wild-type worms (Figure 7B). These seven genes included F36H1.5/hrg-4, F14F4.3/mrp-5, K08E7.9/pgp-1, Y51A2D.4/hmit1.1, Y37A1A.2, T21C9.1, and F22B5.4. Three genes – hrg-4, mrp-5, and F22B5.4 – were positive in both of the RNAi screens (Figure 7C). Taken together, our genomic studies identified a small subset of genes that are not only regulated by heme at the mRNA level but are also essential for heme transport and homeostasis at the functional level.

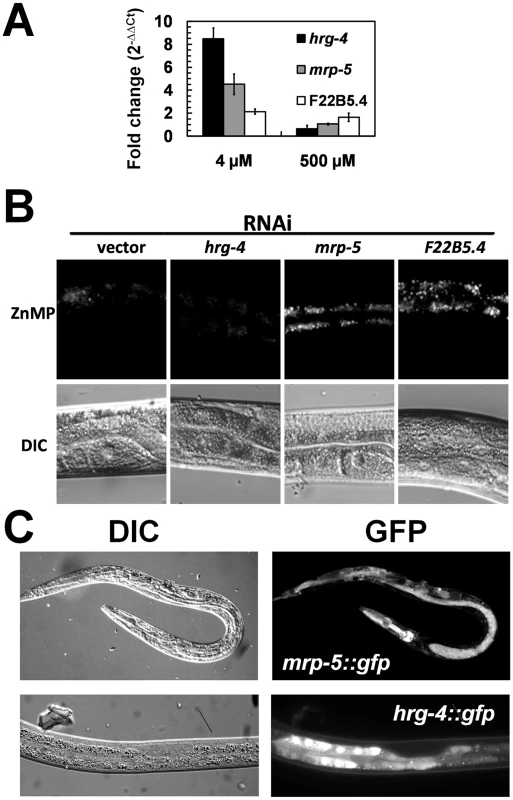

To better understand the role of hrg-4, mrp-5, and F22B5.4 in heme homeostasis, we determined their mRNA expression in response to heme and their ability to transport heme as a function of ZnMP accumulation [12]. qRT-PCR results indicated that all three genes were upregulated by heme but the magnitude of change in mRNA expression at 4 µM heme was significantly greater for hrg-4 than mrp-5 or F22B5.4 (8.5-fold versus 4.5 - and 2-fold) (Figure 8A). Heme uptake assays with ZnMP revealed that hrg-4 RNAi resulted in abrogation of ZnMP accumulation in the worm intestine compared to wild-type control worms (Figure 8B), a result consistent with our previous studies [12]. By contrast, ZnMP accumulation was dramatically increased by the knockdown of both mrp-5 and F22B5.4. Although HRG-4 has been implicated in intestinal heme transport in C. elegans, no function has been attributed to either F22B5.4 or MRP-5 in WormBase. Membrane topology algorithms predicted that, unlike F22B5.4, which is predicted to contain a single TMD, HRG-4 and MRP-5 contain four and twelve TMD respectively, a characteristic feature of membrane transporters.

Fig. 8. Characterization of the three candidate genes identified from the functional RNAi screens.

(A) Heme-dependent expression. qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate for hrg-4, mrp-5, and F22B5.4 at the indicated heme concentrations, and the fold change (mean ± SEM) is reported for each gene at each concentration of heme. (B) Accumulation of ZnMP in worms depleted of candidate genes by RNAi. Synchronized wild-type strain worms in the L1 stage were transferred from mCeHR-2 medium containing 2 µM heme to plates seeded with a lawn of bacteria producing dsRNA against vector, hrg-4, mrp-5, or F22B5.4 and allowed to develop for ≈72 h to the late L4 stage. At this point, worms were incubated in mCeHR-2 medium containing 5 µM ZnMP overnight. Images of a region of worm intestine were captured using a Leica DMIRE2 microscope equipped with a Rhodamine filter and a CCD camera. (C) Expression of hrg-4 and mrp-5 GFP transcriptional reporters. Transgenic worms expressing GFP under the control of 3 kb of the hrg-4 (bottom) or mrp-5 (top) putative promoters. Transgenic worms were grown in mCeHR-2 medium containing 4 µM heme for one generation. Representative images of worms were obtained with a Leica DMIRE2 microscope using a CCD camera. To correlate the intestinal ZnMP uptake studies with membrane transport, we examined the gene expression pattern of hrg-4 and mrp-5. We generated transgenic worms that expressed hrg-4::gfp and mrp-5::gfp transcriptional fusions. hrg-4::gfp was expressed specifically in the intestinal cells of larvae and adults (Figure 8C), and was regulated by exogenous heme (not shown). Unlike hrg-4::gfp, we found that mrp-5::gfp was expressed in almost all worm tissues examined. Altogether, these studies identify HRG-4 and MRP-5 as membrane transporters that are essential for intestinal heme homeostasis in C. elegans.

Discussion

A major impediment to the identification of heme uptake and transport pathways has been the inability to disassociate the tightly regulated process of heme synthesis from the downstream pathways for heme transport [3]. C. elegans is unique among the model organisms because it does not synthesize heme but, instead, relies solely on exogenous heme for normal growth and development [11]. Thus, worms allow the study of heme homeostatic mechanisms in response to fluctuations in environmental heme within the context of an intact, live animal.

Our study of the genome-wide transcriptional changes associated with heme availability represents, to the best of our knowledge, the first study of nutrient-gene interactions in C. elegans exploiting axenic liquid growth medium. The mCeHR-2 medium permits fine control of organismal heme levels as a function of heme in the growth medium, allowing us to identify 288 heme-responsive genes (hrgs). Some of the genes we identified were predictable, because they encode either known heme-binding proteins or permeases for transport of other small molecules. Other genes made sense in retrospect, such as glutathione transferases (GST). A recent proteomic analysis of C. elegans identified GST-19 as a highly abundant protein that was proposed to sequester heme when intracellular heme is in excess [29]. GSTs have also been shown to bind heme in helminths such as hookworms and Barber pole worms [30]–[32]. Our genomic analysis indicates that gst-22 and gst-16 were upregulated at 500 µM heme. Whether these GST proteins also bind heme remains to be determined.

GO and KEGG pathway analyses reveal that hrgs represent the full spectrum of biological processes. Interestingly, only a few hrgs are enzymes or proteins that are known to bind heme. We speculate that the transcriptional regulation by heme primarily targets the cellular pathways involved in heme homeostasis, including uptake and sequestration, rather than the genes which encode target hemoproteins. The vast majority of hrgs have no known function and, therefore, do not have any biological processes or pathways attributed to them. Furthermore, phenotypes from RNAi studies involving the 288 hrgs reported growth and developmental defects, plausibly because disruption of heme homeostasis will affect hemoprotein function in diverse biological pathways ranging from miRNA processing (DGCR8) to gas sensing (soluble guanylyl cyclases) to circadian clock control (Rev-erbα) [33]–[35].

The 288 hrgs we identified also provide the first insight into metazoan heme regulation. The fact that >40% of hrgs have human homologs suggests that our study may provide genetic insights into mammalian heme regulation. This is underscored by the presence of human homologs for genes that were positive in our functional RNAi screen. Indeed, recent studies using C. elegans as a model system have led to the identification of HRG-1 as the first bona fide metazoan heme importer that is conserved in vertebrates [12].

Analysis of the presumptive promoters of all 288 hrgs in eight categories identified no common cis elements [28]. A more detailed analysis of the 67 genes in Category 2, to which hrg-1 and hrg-4 belong, found no overrepresented transcription factor binding sites using all sequences against a control set of random promoter sequences. These in silico results corroborate our experimental studies (Chen, Sinclair, and Hamza, unpublished results) and further support the concept that regulation of organismal heme homeostasis is complex, multi-tiered, and effected by diverse cellular modulators.

Studies have demonstrated that the infectivity of hookworms, which feed on the blood of the host, is significantly lower in severely anemic hamsters fed a low-iron diet [13]. Furthermore, filarial nematodes, such as the causative agent of elephantiasis, harbor Wolbachia – an intracellular bacterial symbiont that contains the intact heme biosynthesis pathway [14], [36]. Thus, nematodes may have adapted to heme auxotrophy by evolving pathways to acquire heme either from the host (extracellular) or from the symbiotic relationship with the bacteria (intracellular). This auxotrophy can be exploited to develop drugs that block parasite-specific heme uptake or utilization. Indeed, genome database searches of heme auxotroph parasites led us to identify 12 hrg homologs in protozoans and 62 hrgs in clade V nematodes. This finding is significant because these genes may encode proteins involved in heme uptake and sequestration from the parasitized host. Further studies aimed at elucidating the role of these hrgs in heme metabolism may validate them as novel anti-parasitic drug targets.

We found that seven of the 41 hrgs that encode for proteins which contain putative TMDs showed different levels of resistance against GaPP toxicity. Among these were a heme permease (HRG-4), ABC transporters (PGP-1 and MRP-5), and Major Facilitator Superfamily transporters (HMIT-1.1 and Y37A1A.2). The remaining 247 hrgs encoded proteins without any predicted TMDs. These proteins may encode soluble effectors for heme transport such as chaperones or sequestering proteins. In support of this concept, cellular iron is stored in ferritin, a cytosolic multi-subunit protein; cytoplasmic copper is delivered to membrane bound P-type ATPases in the secretory pathway by the copper chaperone Atox1 [37], [38]. We propose that a similar network for trafficking intracellular heme and maintaining homeostasis is likely to exist in C. elegans and most metazoa [3].

Interestingly, HRG-4, MRP-5, and F22B5.4 were the only positive candidates identified in both the heme-sensor and GaPP functional RNAi screens. RNAi studies have implicated HRG-4 as a heme transporter in the C. elegans intestine [12], while the function of MRP-5 and the protein encoded by F22B5.4 are currently unknown. We speculate that MRP-5, a member of a family of membrane effluxers [39], may export heme from the intestinal cells to extra-intestinal cells. These results are consistent, in part, with the ubiquitous expression of mrp-5::gfp in worm tissues, and with the RNAi studies which show that mrp-5 depletion results in accumulation of ZnMP in the worm intestine and resistance to GaPP toxicity. Unlike HRG-4 and MRP-5 which are transporters with multiple TMD, F22B5.4 encodes a predicted Type II membrane protein with a single TMD. Although our results clearly implicate a role for F22B5.4 as an essential component of heme homeostasis in C. elegans, it is unclear how this protein may function in heme homeostasis. Excitingly, microarray and RNAi studies identified F22B5.4 as a gene that is highly upregulated by the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) transcription complex, a master regulator of hypoxia response [40]–[42]. HIF is regulated by degradation through hydroxylation of proline residues, a process which requires the presence of oxygen, 2-oxoglutarate, and iron [43]. Given the dependence of C. elegans on heme for oxygen binding and sensing [44]–[46] and as a nutritional source of iron [11], it is conceivable that F22B5.4 may play an important role in coordinating heme transport and availability with oxygen metabolism.

In the current study we have identified a novel catalog of genes that are responsive to heme in C. elegans. Although it is unclear mechanistically how worms respond to heme at the mRNA level, a thorough study to identify the cis regulatory elements and the corresponding trans acting factors will significantly accelerate our understanding of how C. elegans adapts to environmental and nutritional changes. Using the facile and genetically tractable C. elegans model system, the RNAi screen with the hrg mini-library can be easily adapted for whole genome screens to identify regulatory pathways which govern how metazoans sense and respond to heme at an organismal level.

Materials and Methods

Biological materials, strains, and worm culture

C. elegans wild-type N2 strain worms were grown either in an axenic liquid mCeHR-2 medium [47] or on NGM agar plates spotted with E. coli OP50 or HT115(DE3) strains [48]. Synchronized, L1 larvae were obtained by bleaching P0 gravid worms grown in mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with hemin chloride [11]. Hemin chloride and gallium protoporphyrin IX were purchased from Frontier Scientific, Inc (Logan, UT). Plasmids for cloning and injecting into worms were part of the Fire Vector Kit (Addgene, Cambridge, MA). Primers designed to PCR amplify worm open reading frames were based on Wormbase predictions and ordered from IDT (Coralville, IA). The PCR products were TA cloned into the L4440 plasmid.

Total RNA isolation

Equal numbers of F1 larvae in the L1 stage were inoculated in mCeHR-2 medium with 4, 20, or 500 µM hemin chloride and grown with gentle shaking at 20°C. Synchronized, F2 larvae in the L1 stage were obtained by hatching the eggs obtained from F1 gravid adults in M9 buffer containing 4, 20, or 500 µM hemin. Equal numbers of F2 larvae in the L1 stage were inoculated in mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with 4, 20, or 500 µM hemin. The F2 worms were allowed to develop to the late L4 stage, harvested, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Frozen worm pellets were ground into a fine powder, and total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA thus obtained was subjected to RNase-free DNase treatment for 1 h at 37°C and purified using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Total RNA from three biological replicates was used to make cDNA, which was then hybridized to C. elegans Whole Genome Arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA).

cDNA synthesis and quantitative real-time PCR

First strand cDNA was synthesized using 2 µg of total RNA using a Superscript II First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). For quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), primers spanning at least one intron were designed using Primer Express (Applied Biosystems) and Beacon designer 4 (Premier Biosoft) programs. PCR was performed using the iCycler iQ Real-time PCR Detection System (BioRad) with 0.12 U/µl Taq DNA polymerase, 40 nM fluorescein (Invitrogen), and SYBR Green I Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Invitrogen) diluted 1 : 10. The PCR amplification was run for 40 cycles. The PCR products were between 150 and 200 bp in length. Quality of the PCR products was determined by dissociation curve analysis and gel electrophoresis. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. Average CT values were used for 2−ΔΔCt calculations of relative fold changes in gene expression [49].

Microarray data analysis

Expression data were normalized and analyzed using MAS 5.0 suite software (Affymetrix). Data from worms grown in mCeHR-2 medium with 4 and 500 µM hemin were compared to data from worms grown in medium containing 20 µM hemin (baseline samples). Microarray data were verified with the Robust Multichip Average Method (RMA, R package). Quantile normalization and background corrections were performed using perfect match probe intensities. Using an initial cut-off of ≥1.2-fold change in mRNA expression for RMA and a ≥1.6-fold change for MAS 5.0 resulted in the identification of 370 genes. Increasing the stringency to ≥1.6-fold change for both RMA and MAS 5.0 reduced the number of genes identified as heme responsive to 288 genes. To identify putative human orthologs, worm protein sequences were used to query human genome databases at NCBI by reciprocal BLAST analysis with an E-value cut-off ≥10−4. Sequences for each of these 288 genes were obtained from WormBase and further analyzed for topology (TMHMM 2.0, SOSUI), motifs (ELM, BLOCKS, Pfam), and pathway classification (GO and KEGG).

Generation of the hrg mini-library

The Ahringer and Vidal feeding libraries were replicated to individual 96-well plates [50], [51]. Thirty-four clones in the initial list of 370 hrgs were absent from both libraries. To complete the hrg mini-library, we PCR amplified the missing genes from N2 worm genomic DNA and cloned the PCR fragments by TA cloning into the RNAi feeding vector pL4440. Only 19 of the 34 RNAi clones were in the final list of 288 hrgs. DNA for all 288 hrgs was sequenced to confirm authenticity.

Analysis of RNAi on GFP expression in the IQ6011 and vha-6::gfp strains

NGM agar plates containing IPTG, carbenicillin, and tetracycline were seeded with HT115(DE3) bacteria expressing double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) against each clone in the hrg mini-library. Duplicate bacterial cultures of each clone had been grown for 5.5 h in LB containing carbenicillin and tetracycline and 5 µM or 25 µM heme. Plates were seeded with a lawn of bacteria and dsRNA induction occurred for ≈20 h at room temperature. Subsequently, forty L1 larvae from gravid IQ6011 worms which had been grown in liquid media supplemented with 10 µM heme were added to each well of the 12-well plates. Each 12-well plate had 10 wells seeded with experimental clones and one well seeded with each of the control clones – vector and hrg-4. The plates were incubated at 15°C overnight and then incubated at 20°C for three additional days. The GFP levels in gravid adults were observed visually using a Leica Microsystems MZ16FA stereoscope. The intensity and pattern of GFP in gravid worms feeding on bacteria producing dsRNA against each hrg was compared to the intensity and pattern of GFP in same-stage worms feeding on bacteria transformed with the empty vector. Worms that displayed altered GFP in both replicates were designated as potential modulators. Potential modulators were screened in a strain that produced GFP under the control of a promoter that was not responsive to heme (vha-6::gfp). Any clone that altered GFP levels in the vha-6::gfp strain worms was removed from the list of modulators, since the change in GFP was not in response to heme.

GFP quantification in IQ6011 strain

A COPAS BioSort worm sorter (Union Biometrica, Holliston, MA) was used to measure GFP levels in live worms. Plates, bacteria, and worms were prepared and treated as described in the previous section. After 84 h on RNAi plates, P0 gravid and F1 L1-stage worms were washed from each well with 600 µL of M9 buffer containing 0.01% Tween-20, transferred to a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube, and allowed to settle for 5 min. The supernatant was removed and discarded. Each worm pellet was transferred to an individual well of a 96-well plate. Duplicate samples were transferred to successive wells in the 96-well plate and were separated from other samples by an empty well, which served to flush the flow cell where worms are analyzed and prevent contamination of subsequent samples. The contents of each well were washed, aspirated, and analyzed by a COPAS BioSort worm sorter. The GFP gain was set to 2, and the GFP PMT setting was 400. Using highly synchronized worms in the gravid stage, we had previously defined the gate settings in order to ensure that the data obtained from P0 gravid animals would be easily and quickly separated from the data obtained from worms in other developmental stages. Text file data was imported into Microsoft Excel and sorted based on the gating parameters recorded in the “Status Select” column. The worm sorter records a fluorescence profile of each worm in the form of a curve, which reflects the intensity of GFP from the mouth to the tail. The “Green” column recorded the GFP value of the area under the curve, reduced by a factor of 40,000. The background levels of GFP were subtracted from all values used to generate Figure 7A. The background level of GFP was equal to the GFP levels in IQ6011 worms feeding on HT115(DE3) bacteria transformed with the gfp RNAi vector. The COPAS BioSort detects very low levels of GFP in these worms. The mean of all values for each sample was determined, and the average of each duplicate was calculated. This mean was normalized to the average value for the GFP obtained from the vector-only sample, and reported in arbitrary units ± SEM for each clone analyzed.

GaPP toxicity assays

Synchronized, F1 wild-type worms in the L1 larval stage were obtained from P0 worms grown in mCeHR-2 containing 1.5 µM hemin. Equal numbers of these F1 worms were placed on NGM agar plates containing 2 mM IPTG, 50 µg/mL carbenicillin, 12 µg/mL IPTG and plated with a lawn of HT115(DE3) RNAi feeding bacteria harboring the respective L4440 plasmid that had been grown in LB broth with carbenicillin and tetracycline [12]. Worms were fed on the RNAi bacteria for ≈60 h and allowed to develop to the late L4 stage. At this point, worms were transferred to fresh RNAi plates containing 1.5 µM GaPP. Worms developed to the gravid stage and laid eggs. After 24 h of egg-laying, the P0 worms (all in the gravid stage) were discarded in order to prevent additional eggs from being laid. On day 5, both the total number of surviving larvae and the number of unhatched eggs were counted. P values for statistical significance were calculated by using a one-way ANOVA with Student–Newman–Keuls multiple comparisons test by using GraphPad InStat v. 3.06 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

ZnMP uptake assays

Equal numbers of synchronized N2 L1 larvae obtained from P0 worms grown in mCeHR-2 plus 2 µM hemin were exposed to the RNAi bacteria on NGM plates containing 2 mM IPTG for 72 h. This was followed by exposure to 5 µM ZnMP plus 1.5 µM hemin chloride for 16 h in mCeHR-2 medium. ZnMP fluorescence intensity was measured as described previously [12].

Generation of GFP reporter constructs

GFP reporter fusion constructs were created using the Gateway cloning system (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD). The promoter of interest, gfp gene, and the 3′ untranslated region of the unc-54 gene were cloned by recombination into the entry vectors pDONR P4-P1R, pDONR 221, and pDONR P2R-P3, respectively, using the Gateway BP Clonase kit. Sequence verified entry clones were then recombined into a destination vector pDEST R4-R3 using the Gateway LR Clonase II plus enzyme kit to produce the final recombinant plasmid.

Production of transgenic worm strains

For microparticle bombardment, ≈5×106 unc-119 (ed3) gravid worms were co-bombarded with 10 µg of Gateway reporter construct and 5 µg of unc-119 rescue plasmid (pDM016B) using the PDS-1000 particle delivery system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Worms were washed from bombardment plates and transferred to plates seeded with a lawn of E. coli strain JM109. After two-weeks at 25°C, multiple wild-type F2 worms were screened for gene integration either by PCR or transgene expression. Individual transgenic lines were isolated and transferred to axenic liquid mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with antibiotics. After two weeks of serial passages, worms were bleached and maintained as transgenic strains in axenic liquid mCeHR-2 medium.

Gene Expression Omnibus information

The microarray data was submitted to GEO on Aug 6, 2007. The GEO accession number is GSE8696 and available at

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE8696.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. UzelC

ConradME

1998 Absorption of heme iron. Semin Hematol 35 27 34

2. WestAR

OatesPS

2008 Mechanisms of heme iron absorption: Current questions and controversies. World J Gastroenterol 14 4101 4110

3. SeveranceS

HamzaI

2009 Trafficking of Heme and Porphyrins in Metazoa. Chem Rev

4. HamzaI

2006 Intracellular trafficking of porphyrins. ACS Chem Biol 1 627 629

5. StojiljkovicI

Perkins-BaldingD

2002 Processing of heme and heme-containing proteins by bacteria. DNA Cell Biol 21 281 295

6. WeissmanZ

KornitzerD

2004 A family of Candida cell surface haem-binding proteins involved in haemin and haemoglobin-iron utilization. Mol Microbiol 53 1209 1220

7. ProtchenkoO

Rodriguez-SuarezR

AndrophyR

BusseyH

PhilpottCC

2006 A screen for genes of heme uptake identifies the FLC family required for import of FAD into the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 281 21445 21457

8. ProtchenkoO

Shakoury-ElizehM

KeaneP

StoreyJ

AndrophyR

2008 Role of PUG1 in inducible porphyrin and heme transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot Cell 7 859 871

9. KeelSB

DotyRT

YangZ

QuigleyJG

ChenJ

2008 A heme export protein is required for red blood cell differentiation and iron homeostasis. Science 319 825 828

10. QuigleyJG

YangZ

WorthingtonMT

PhillipsJD

SaboKM

2004 Identification of a human heme exporter that is essential for erythropoiesis. Cell 118 757 766

11. RaoAU

CartaLK

LesuisseE

HamzaI

2005 Lack of heme synthesis in a free-living eukaryote. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 4270 4275

12. RajagopalA

RaoAU

AmigoJ

TianM

UpadhyaySK

2008 Haem homeostasis is regulated by the conserved and concerted functions of HRG-1 proteins. Nature 453 1127 1131

13. HeldMR

BungiroRD

HarrisonLM

HamzaI

CappelloM

2006 Dietary iron content mediates hookworm pathogenesis in vivo. Infect Immun 74 289 295

14. WuB

NovelliJ

FosterJ

VaisvilaR

ConwayL

2009 The Heme Biosynthetic Pathway of the Obligate Wolbachia Endosymbiont of Brugia malayi as a Potential Anti-filarial Drug Target. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3 e475 doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000475

15. ReinkeV

SmithHE

NanceJ

WangJ

Van DorenC

2000 A global profile of germline gene expression in C. elegans. Mol Cell 6 605 616

16. El-SayedNM

MylerPJ

BartholomeuDC

NilssonD

AggarwalG

2005 The genome sequence of Trypanosoma cruzi, etiologic agent of Chagas disease. Science 309 409 415

17. SahJF

ItoH

KolliBK

PetersonDA

SassaS

2002 Genetic rescue of Leishmania deficiency in porphyrin biosynthesis creates mutants suitable for analysis of cellular events in uroporphyria and for photodynamic therapy. J Biol Chem 277 14902 14909

18. AbadP

GouzyJ

AuryJM

Castagnone-SerenoP

DanchinEG

2008 Genome sequence of the metazoan plant-parasitic nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Nat Biotechnol 26 909 915

19. AbubuckerS

MartinJ

YinY

FultonL

YangSP

2008 The canine hookworm genome: analysis and classification of Ancylostoma caninum survey sequences. Mol Biochem Parasitol 157 187 192

20. GhedinE

WangS

SpiroD

CalerE

ZhaoQ

2007 Draft genome of the filarial nematode parasite Brugia malayi. Science 317 1756 1760

21. OppermanCH

BirdDM

WilliamsonVM

RokhsarDS

BurkeM

2008 Sequence and genetic map of Meloidogyne hapla: A compact nematode genome for plant parasitism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 14802 14807

22. MartinJ

AbubuckerS

WylieT

YinY

WangZ

2009 Nematode.net update 2008: improvements enabling more efficient data mining and comparative nematode genomics. Nucleic Acids Res 37 D571 578

23. BlaxterML

De LeyP

GareyJR

LiuLX

ScheldemanP

1998 A molecular evolutionary framework for the phylum Nematoda. Nature 392 71 75

24. AshburnerM

BallCA

BlakeJA

BotsteinD

ButlerH

2000 Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 25 25 29

25. AlexaA

RahnenfuhrerJ

LengauerT

2006 Improved scoring of functional groups from gene expression data by decorrelating GO graph structure. Bioinformatics 22 1600 1607

26. ArakawaK

KonoN

YamadaY

MoriH

TomitaM

2005 KEGG-based pathway visualization tool for complex omics data. In Silico Biol 5 419 423

27. ThomasJH

2006 Analysis of homologous gene clusters in Caenorhabditis elegans reveals striking regional cluster domains. Genetics 172 127 143

28. MatysV

Kel-MargoulisOV

FrickeE

LiebichI

LandS

2006 TRANSFAC and its module TRANSCompel: transcriptional gene regulation in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res 34 D108 110

29. PerallyS

LacourseEJ

CampbellAM

BrophyPM

2008 Heme Transport and Detoxification in Nematodes: Subproteomics Evidence of Differential Role of Glutathione Transferases. J Proteome Res

30. SchullerDJ

LiuQ

KriksunovIA

CampbellAM

BarrettJ

2005 Crystal structure of a new class of glutathione transferase from the model human hookworm nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus. Proteins 61 1024 1031

31. van RossumAJ

JefferiesJR

RijsewijkFA

LaCourseEJ

Teesdale-SpittleP

2004 Binding of hematin by a new class of glutathione transferase from the blood-feeding parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus. Infect Immun 72 2780 2790

32. ZhanB

LiuS

PerallyS

XueJ

FujiwaraR

2005 Biochemical characterization and vaccine potential of a heme-binding glutathione transferase from the adult hookworm Ancylostoma caninum. Infect Immun 73 6903 6911

33. FallerM

MatsunagaM

YinS

LooJA

GuoF

2007 Heme is involved in microRNA processing. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14 23 29

34. YinL

WuN

CurtinJC

QatananiM

SzwergoldNR

2007 Rev-erbα, a Heme Sensor That Coordinates Metabolic and Circadian Pathways. Science 318 1786 1789

35. SchmidtPM

RothkegelC

WunderF

SchroderH

StaschJP

2005 Residues stabilizing the heme moiety of the nitric oxide sensor soluble guanylate cyclase. Eur J Pharmacol 513 67 74

36. FosterJ

GanatraM

KamalI

WareJ

MakarovaK

2005 The Wolbachia genome of Brugia malayi: endosymbiont evolution within a human pathogenic nematode. PLoS Biol 3 e121 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030121

37. De DomenicoI

McVey WardD

KaplanJ

2008 Regulation of iron acquisition and storage: consequences for iron-linked disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9 72 81

38. KimBE

NevittT

ThieleDJ

2008 Mechanisms for copper acquisition, distribution and regulation. Nat Chem Biol 4 176 185

39. BorstP

ElferinkRO

2002 Mammalian ABC transporters in health and disease. Annu Rev Biochem 71 537 592

40. ShenC

NettletonD

JiangM

KimSK

Powell-CoffmanJA

2005 Roles of the HIF-1 hypoxia-inducible factor during hypoxia response in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem 280 20580 20588

41. ShaoZ

ZhangY

Powell-CoffmanJA

2009 Two distinct roles for EGL-9 in the regulation of HIF-1-mediated gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 183 821 829

42. GortEH

van HaaftenG

VerlaanI

GrootAJ

PlasterkRH

2008 The TWIST1 oncogene is a direct target of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha. Oncogene 27 1501 1510

43. KaelinWGJr

RatcliffePJ

2008 Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell 30 393 402

44. GrayJM

KarowDS

LuH

ChangAJ

ChangJS

2004 Oxygen sensation and social feeding mediated by a C. elegans guanylate cyclase homologue. Nature 430 317 322

45. McGrathPT

RockmanMV

ZimmerM

JangH

MacoskoEZ

2009 Quantitative mapping of a digenic behavioral trait implicates globin variation in C. elegans sensory behaviors. Neuron 61 692 699

46. PerssonA

GrossE

LaurentP

BuschKE

BretesH

2009 Natural variation in a neural globin tunes oxygen sensing in wild Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 458 1030 1033

47. NassR

HamzaI

2007 The nematode C. elegans as an animal model to explore toxicology in vivo: solid and axenic growth culture conditions and compound exposure parameters.

MainesMD

CostaLG

HodgsonE

ReedDJ

SipesIG

Current Protocols in Toxicology New York John Wiley & Sons, Inc 1.9.1 1.9.17

48. StiernagleT

2006 Maintenance of C. elegans. WormBook 1 11

49. LivakKJ

SchmittgenTD

2001 Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25 402 408

50. KamathRS

FraserAG

DongY

PoulinG

DurbinR

2003 Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421 231 237

51. ReboulJ

VaglioP

RualJF

LameschP

MartinezM

2003 C. elegans ORFeome version 1.1: experimental verification of the genome annotation and resource for proteome-scale protein expression. Nat Genet 34 35 41

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 7- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Délka menstruačního cyklu jako marker ženské plodnosti

- Vztah užívání alkoholu a mužské fertility

- Šanci na úspěšný průběh těhotenství snižují nevhodné hladiny progesteronu vznikající při umělém oplodnění

- Vliv melatoninu a cirkadiálního rytmu na ženskou reprodukci

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Question and Answer: An Anniversary Interview with Jane Gitschier

- Multi-Variant Pathway Association Analysis Reveals the Importance of Genetic Determinants of Estrogen Metabolism in Breast and Endometrial Cancer Susceptibility

- Tinkering Evolution of Post-Transcriptional RNA Regulons: Puf3p in Fungi as an Example

- The Importance of Imprinting in the Human Placenta

- Regulator of G Protein Signaling 3 Modulates Wnt5b Calcium Dynamics and Somite Patterning

- Lysosomal Dysfunction Promotes Cleavage and Neurotoxicity of Tau

- Combinatorial Binding Leads to Diverse Regulatory Responses: Lmd Is a Tissue-Specific Modulator of Mef2 Activity

- Variation, Sex, and Social Cooperation: Molecular Population Genetics of the Social Amoeba

- Comparative Analysis of DNA Replication Timing Reveals Conserved Large-Scale Chromosomal Architecture

- The Fitness Landscapes of -Acting Binding Sites in Different Promoter and Environmental Contexts

- Cohesin Is Limiting for the Suppression of DNA Damage–Induced Recombination between Homologous Chromosomes

- Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals Novel Genes Essential for Heme Homeostasis in

- Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis for Serum Calcium Identifies Significantly Associated SNPs near the Calcium-Sensing Receptor () Gene

- Rad3 Decorates Critical Chromosomal Domains with γH2A to Protect Genome Integrity during S-Phase in Fission Yeast

- Quantitative and Molecular Genetic Analyses of Mutations Increasing Life Span

- Association of Variants at with Chronic Kidney Disease and Kidney Stones—Role of Age and Comorbid Diseases

- Breast Cancer DNA Methylation Profiles Are Associated with Tumor Size and Alcohol and Folate Intake

- Calpain 8/nCL-2 and Calpain 9/nCL-4 Constitute an Active Protease Complex, G-Calpain, Involved in Gastric Mucosal Defense

- A Collection of Target Mimics for Comprehensive Analysis of MicroRNA Function in

- A Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals No Nuclear Dobzhansky-Muller Pairs of Determinants of Speciation between and , but Suggests More Complex Incompatibilities

- Microevolution of during Prolonged Infection of Single Hosts and within Families

- Id4, a New Candidate Gene for Senile Osteoporosis, Acts as a Molecular Switch Promoting Osteoblast Differentiation

- CHD7 Targets Active Gene Enhancer Elements to Modulate ES Cell-Specific Gene Expression

- Chromatin Remodeling in Development and Disease: Focus on CHD7

- Extensive DNA End Processing by Exo1 and Sgs1 Inhibits Break-Induced Replication

- Requirement of Male-Specific Dosage Compensation in Females—Implications of Early X Chromosome Gene Expression

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- CHD7 Targets Active Gene Enhancer Elements to Modulate ES Cell-Specific Gene Expression

- Extensive DNA End Processing by Exo1 and Sgs1 Inhibits Break-Induced Replication

- Question and Answer: An Anniversary Interview with Jane Gitschier

- Multi-Variant Pathway Association Analysis Reveals the Importance of Genetic Determinants of Estrogen Metabolism in Breast and Endometrial Cancer Susceptibility

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání